Title: The History of Silk, Cotton, Linen, Wool, and Other Fibrous Substances;

Author: Clinton G. Gilroy

Release date: July 31, 2021 [eBook #65967]

Language: English

Credits: Turgut Dincer, SF2001, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

[Frontis]

[Pg i]

INCLUDING OBSERVATIONS ON

SPINNING, DYEING AND WEAVING.

ALSO AN ACCOUNT OF THE

PASTORAL LIFE OF THE ANCIENTS, THEIR SOCIAL STATE

AND ATTAINMENTS IN THE DOMESTIC ARTS.

WITH APPENDICES

ON PLINY’S NATURAL HISTORY; ON THE ORIGIN AND MANUFACTURE

OF LINEN AND COTTON PAPER; ON FELTING, NETTING, &C.

DEDUCED FROM

COPIOUS AND AUTHENTIC SOURCES.

ILLUSTRATED BY STEEL ENGRAVINGS.

NEW YORK:

HARPER & BROTHERS, 82 CLIFF STREET.

1845.

[Pg ii]

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1845,

BY HARPER & BROTHERS,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the United States,

for the Southern District of New York.

[Pg iii]

TO THE

PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES,

THIS VOLUME

IS RESPECTFULLY

INSCRIBED.

[Pg v]

History, until a recent period, was mainly a record of gigantic crimes and their consequent miseries. The dazzling glow of its narrations lighted never the path of the peaceful Husbandman, as his noiseless, incessant exertions transformed the howling wilderness into a blooming and fruitful garden, but gleamed and danced on the armor of the Warrior as he rode forth to devastate and destroy. One year of his labors sufficed to undo what the former had patiently achieved through centuries; and the campaign was duly chronicled while the labors it blighted were left to oblivion. The written annals of a nation trace vividly the course of its corruption and downfall, but are silent or meagre with regard to the ultimate causes of its growth and eminence. The long periods of peace and prosperity in which the Useful Arts were elaborated or perfected are passed over with the bare remark that they afford little of interest to the reader, when in fact their true history, could it now be written, would prove of the deepest and most substantial value. The world might well afford to lose all record of a hundred ancient battles or sieges if it could thereby regain the knowledge of one lost art, and even the Pyramids bequeathed to us by Egypt in her glory would be well exchanged for a few of her humble workshops and manufactories, as they stood in the days of the Pharaohs. Of the true history of mankind only a few chapters have yet been written, and now, when the deficiencies of that we have are beginning to be realized, we find that the materials for supplying them have in good part perished in the lapse of time, or been trampled recklessly beneath the hoof of the war-horse.

In the following pages, an effort has been made to restore a portion of this history, so far as the meagre and careless traces [Pg vi] scattered through the Literature of Antiquity will allow.—Of the many beneficent achievements of inventive genius, those which more immediately minister to the personal convenience and comfort of mankind seem to assert a natural pre-eminence. Among the first under this head may be classed the invention of Weaving, with its collateral branches of Spinning, Netting, Sewing, Felting, and Dyeing. An account of the origin and progress of this family of domestic arts can hardly fail to interest the intelligent reader, while it would seem to have a special claim on the attention of those engaged in the prosecution or improvement of these arts. This work is intended to subserve the ends here indicated. In the present age, when the resources of Science and of Intellect have so largely pressed into the service of Mechanical Invention, especially with reference to the production of fabrics from fibrous substances, it is somewhat remarkable that no methodical treatise on this topic has been offered to the public, and that the topic itself seems to have almost eluded the investigations of the learned. With the exception of Mr. Yates’s erudite production, “Textrinum Antiquorum,” we possess no competent work on the subject; and valuable as is this production for its authority and profound research, it is yet, for various reasons, of comparative inutility to the general reader.

That a topic of such interest deserved elucidation will not be denied when it is remembered that, apart from the question of the direct influence these important arts have ever exerted upon the civilization and social condition of communities, in various ages of the world, there are other and scarcely inferior considerations to the student, involved in their bearing upon the true understanding of history, sacred and profane. To supply, therefore, an important desideratum in classical archæology, by thus seeking the better to illustrate the true social state of the ancients, thereby affording a commentary on their commerce and progress in domestic arts, is one of the leading objects contemplated by the present work. In addition to this, our better acquaintance with the actual condition of these arts in early times will tend, in many instances, to confirm the historic accuracy and elucidate the idiom of many portions of Holy Writ.

[Pg vii]

How many of the grandest discoveries in the scientific world owe their existence to accident! and how many more of the boasted creations of human skill have proved to be but restorations of lost or forgotten arts! How much also is still being revealed to us by the monumental records of the old world, whose occult glyphs, till recently, defied the most persevering efforts of the learned for their solution!

To be told that the Egyptians, four thousand years ago, were cunning artificers in many of the pursuits which constitute lucrative branches of our modern industry, might surprise some readers: yet we learn from undoubted authorities that such they were. They also were acquainted with the fabrication of crapes, transparent tissues, cotton, silk, and paper, as well as the art of preparing colors which still continue to defy the corrosions of defacing time.

If the spider may be regarded as the earliest practical weaver upon record—the generic name Textoriæ, supplying the root from which is clearly derived the English terms, texture and textile, as applied to woven fabrics, of whatever materials they may be composed—the wasp may claim the honor of having been the first paper-manufacturer, for he presents us with a most undoubted specimen of clear white pasteboard, of so smooth a surface as to admit of being written upon with ease and legibility. Would the superlative wisdom of man but deign, with microscopic gaze, to study the ingenious movements of the insect tribe more minutely, it would not be easy to estimate how much might thereby be achieved for human science, philosophy, and even morals!

For those who love to add to their fund of general knowledge, especially in the department of natural history, the author trusts that much valuable and interesting information will be found comprised in those pages of this work which delineate the habits of the Silk-Worm, the Sheep, the Goat, the Camel, the Beaver, &c.; while another department, being devoted to the history of the Pastoral Life of the Ancients, will naturally enlist the sympathies of such as take a deeper interest in the records of ages and nations long since passed away. From a mass of heterogeneous, though highly valuable materials, it has [Pg viii] been the design of the author to select, arrange, and conserve all that was apposite to his subject and of intrinsic value. Thus has he endeavored to render the piles of antiquity, to adopt the words of a recent writer, well compacted—a process which has been begun in our times, and with such eminent success that even the men of the present age may live to see many of the thousand and one folios of the ancients handed over without a sigh to the trunk-maker.

The ample domains of Learning are fast being submitted to fresh irrigation and renewed culture,—the exclusiveness of the cloister has given place to an unrestricted distribution of the intellectual wealth of all times. What civilization has accomplished in the physical is also being achieved in the mental world. The sterile and inaccessible wilderness is transformed into the well-tilled garden, abounding in luxurious fruits and fragrant flowers. It is the golden age of knowledge—its Paradise Regained. The ponderous works of the olden time have been displaced by the condensing process of modern literature; yielding us their spirit and essence, without the heavy, obscuring folds of their former verbal drapery. We want real and substantial knowledge; but we are a labor-saving and a time-economizing people,—it must therefore be obtained by the most compendious processes. Except those with whom learning is the business of life, we are too generally ignorant of the mighty mysteries which Nature has heaped around our path; ignorant, too, of many of the discoveries of science and philosophy, in ancient as well as modern times. To meet the exigencies of our day, a judgment in the selection and condensation of works designed for popular use is demanded—a facility like that of the alchymist, extracting from the crude ores of antiquity the fine gold of true knowledge.

The plan of this work naturally divides itself into four departments. The first division is devoted to the consideration of Silk, its early history and cultivation in China and various other parts of the world; illustrated by copious citations from ancient writers: From among whom to instance Homer, we learn that embroidery and tapestry were prominent arts with the Thebans, that poet deriving many of his pictures of domestic [Pg ix] life from the paintings which have been found to ornament their palaces. Thus it is evident that some of the proudest attainments of art in our own day date their origin from a period coeval at least with the Iliad. Again we find that the use of the distaff and spindle, referred to in the Sacred Scriptures, was almost as well understood in Egypt as it now is in India; while the factory system, so far from being a modern invention, was in full operation, and conducted under patrician influence, some three thousand years ago. The Arabians also, even so far back as five centuries subsequent to the deluge, were, it is stated on credible authority, skilled in fabricating silken textures; while, at a period scarcely less remote, we possess irrefragable testimony in favor of their knowledge of paper made from cotton rags. The inhabitants of Phœnicia and Tyre were, it appears, the first acquainted with the process of dyeing: the Tyrian purple, so often noticed by writers, being of so gorgeous a hue as to baffle description. The Persians were also prodigal in their indulgence in vestments of gold, embroidery and silk: the memorable army of Darius affording an instance of sumptuous magnificence in this respect. An example might also be given of the extravagance of the Romans in the third century, in the fact of a pound of silk being estimated literally by its weight in gold. The nuptial robes of Maria, wife of Honorius, which were discovered in her coffin at Rome in 1544, on being burnt, yielded 36 pounds of pure gold! In the work here presented, much interesting as well as valuable information is given under this section, respecting the cultivation and manufacture of Silk in China, Greece and other countries.

The second division of the work, comprising the history of the Sheep, Goat, Camel, and Beaver, it is hoped will also be found curious and valuable. The ancient history of the Cotton manufacture follows—a topic that has enlisted the pens of many writers, though their essays, with two or three exceptions, merit little notice. The subsequent pages embody many new and important facts, connected with its early history and progress, derived from sources inaccessible to the general reader. The fourth and last division, embracing the history of the Linen manufacture, includes notices of Hemp, Flax, Asbestos, &c. [Pg x] This department again affords a fruitful theme for the curious, and one that will be deemed, perhaps, not the least attractive of the volume. Completing the design of the work, will be found the Appendices, comprising rare and valuable extracts, derived from unquestionable authorities.

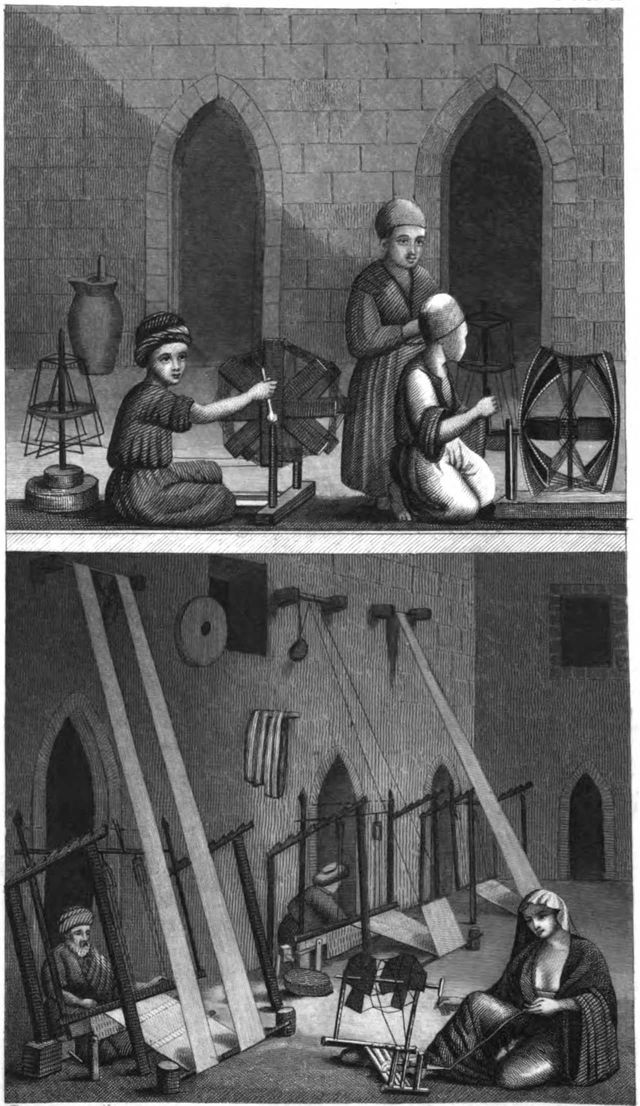

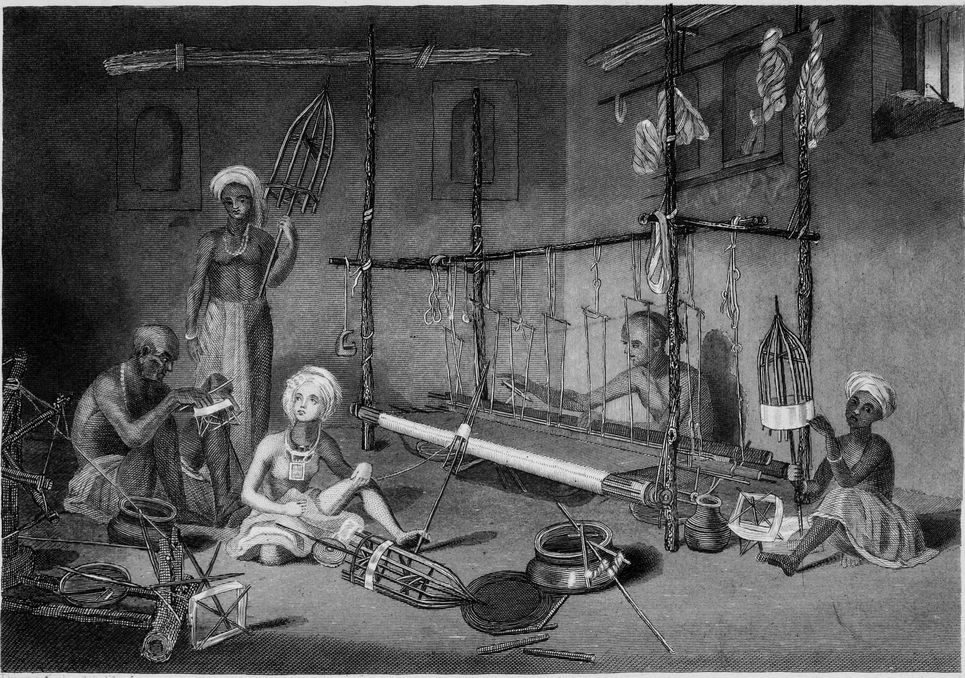

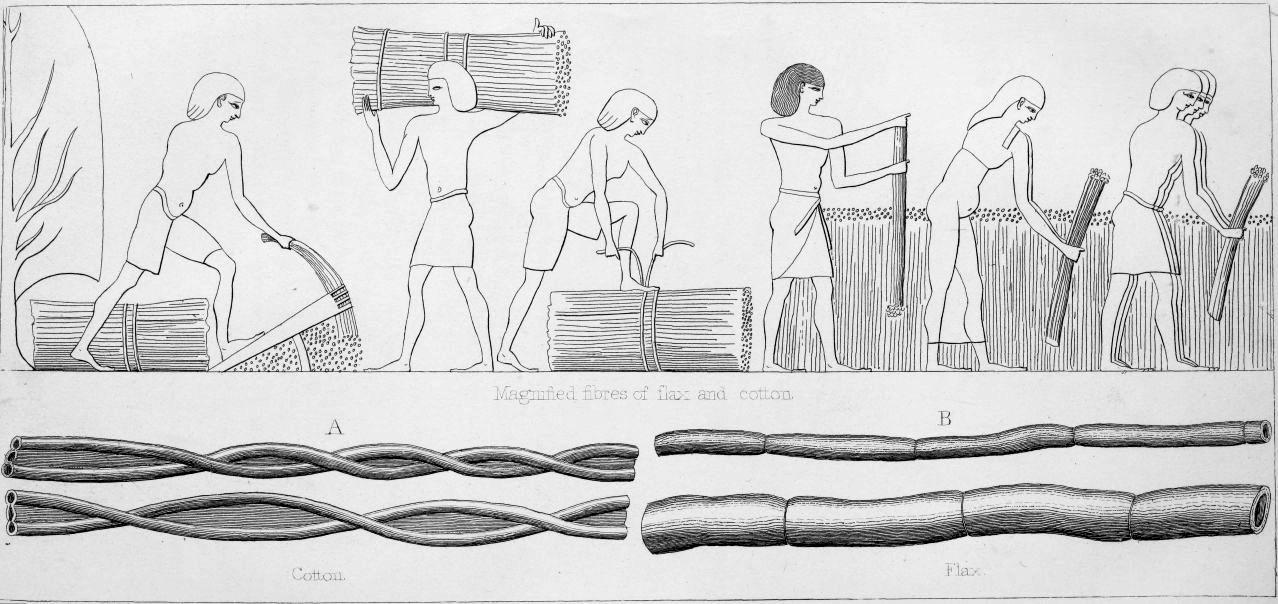

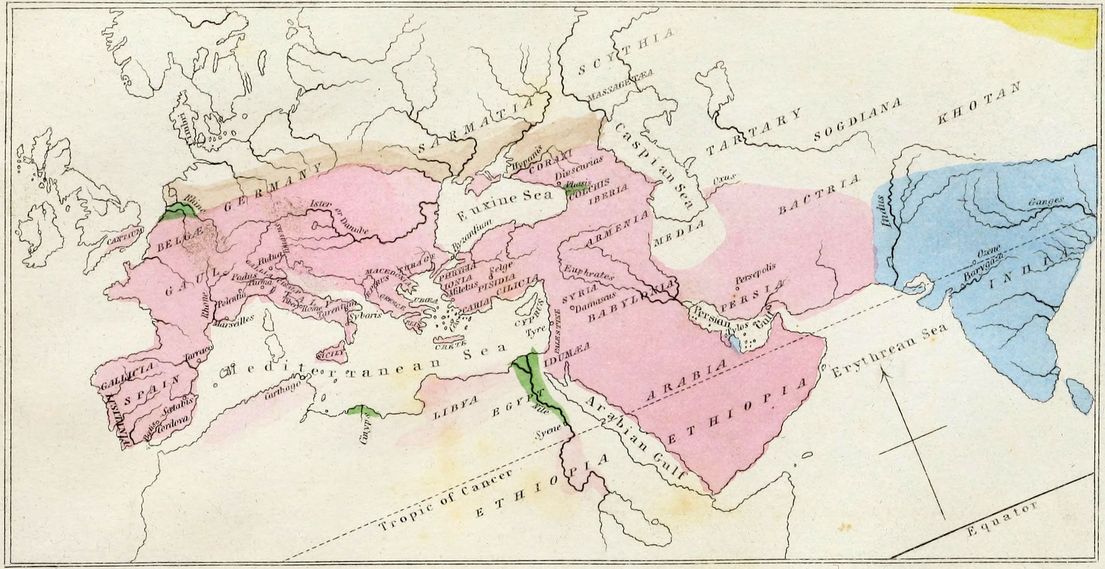

Of the Ten Illustrations herewith presented, five are entirely original. It is hoped that these, at least, will be deemed worthy the attention of the scholar as well as of the general reader, and that their value will not be limited by their utility as elucidations of the text. Among these, especial notice is requested to the engraving of the Chinese Loom, a reduced fac-simile, copied by permission from a magnificent Chinese production, recently obtained from the Celestial Empire, and now in the possession of the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions in this city. Another, equally worthy of notice, represents an Egyptian weaving factory, with the processes of Spinning and Winding; also a reduced fac-simile, copied from Champollion’s great work on Egypt. The Spider, magnified with his web, and the Indian Loom, it is presumed, will not fail to attract attention.

Throughout the entire work, the most diligent care has been used in the collation of the numerous authorities cited, as well as a rigid regard paid to their veracity. As a work so elaborate in its character would necessarily have to depend, to a considerable extent, for its facts and illustrations, upon the labors of previous writers, the author deems no apology necessary in thus publicly and gratefully avowing his indebtedness to the several authors cited in order at the foot of his pages; but he would especially mention the eminent name of Mr. Yates, to the fruits of whose labors the present production owes much of its novelty, attractiveness, and intrinsic value.

New York, Oct. 1st, 1845.

[Pg xi]

| CHAPTER I. | |

| SPINNING, DYEING, AND WEAVING. | |

| Whether Silk is mentioned in the Old Testament—Earliest Clothing—Coats of Skin, Tunic, Simla—Progress of Invention—Chinese chronology relative to the Culture of Silk—Exaggerated statements—Opinions of Mailla, Le Sage, M. Lavoisnè, Rev. J. Robinson, Dr. A. Clarke, Rev. W. Hales, D.D., Mairan, Bailly, Guignes, and Sir William Jones—Noah supposed to be the first emperor of China—Extracts from Chinese publications—Silk Manufactures of the Island of Cos—Described by Aristotle—Testimony of Varro—Spinning and Weaving in Egypt—Great ingenuity of Bezaleel and Aholiab in the production of Figured Textures for the Jewish Tabernacle—Skill of the Sidonian women in the Manufacture of Ornamental Textures—Testimony of Homer—Great antiquity of the Distaff and Spindle—The prophet Ezekiel’s account of the Broidered Stuffs, etc. of the Egyptians—Beautiful eulogy on an industrious woman—Helen the Spartan, her superior skill in the art of Embroidery—Golden Distaff presented her by the Egyptian queen Alcandra—Spinning a domestic occupation in Miletus—Theocritus’s complimentary verses to Theuginis on her industry and virtue—Taste of the Roman and Grecian ladies in the decoration of their Spinning Implements—Ovid’s testimony to the skill of Arachne in Spinning and Weaving—Method of Spinning with the Distaff—Described by Homer and Catullus—Use of Silk in Arabia 500 years after the flood—Forster’s testimony | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| HISTORY OF THE SILK MANUFACTURE CONTINUED TO THE 4TH CENTURY. | |

| SPINNING, DYEING, AND WEAVING.—HIGH DEGREE OF EXCELLENCE ATTAINED IN THESE ARTS. | |

| Testimony of the Latin poets of the Augustan age—Tibullus—Propertius—Virgil—Horace—Ovid—Dyonisius Perigetes—Strabo. Mention of silk by authors in[Pg xii] the first century—Seneca the Philosopher—Seneca the Tragedian—Lucan—Pliny—Josephus—Saint John—Silius Italicus—Statius—Plutarch—Juvenal—Martial—Pausanias—Galen—Clemens Alexandrinus—Caution to Christian converts against the use of silk in dress. Mention of silk by authors in the second century—Tertullian—Apuleius—Ulpian—Julius Pollux—Justin. Mention of silk by authors in the third century—Ælius Lampidius—Vopiscus—Trebellius Pollio—Cyprian—Solinus—Ammianus—Marcellinus—Use of silk by the Roman emperors—Extraordinary beauty of the textures—Use of water to detach silk from the trees—Invectives of these authors against extravagance in dress—The Seres described as a happy people—Their mode of traffic, etc.—(Macpherson’s opinion of the Chinese.)—City of Dioscurias, its vast commerce in former times.—(Colonel Syke’s account of the Kolissura silk-worm—Dr. Roxburgh’s description of the Tusseh silk-worm.) | 22 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| HISTORY OF THE SILK MANUFACTURE FROM THE THIRD TO THE SIXTH CENTURY. | |

| SPINNING, DYEING, AND WEAVING.—HIGH DEGREE OF EXCELLENCE ATTAINED IN THESE ARTS. | |

| Fourth Century—Curious account of silk found in the Edict of Diocletian—Extravagance of the Consul Furius Placidus—Transparent silk shifts—Ausonius describes silk as the produce of trees—Quintus Aur Symmachus, and Claudian’s testimony of silk and golden textures—Their extraordinary beauty—Pisander’s description—Periplus Maris Erythræi—Dido of Sidon. Mention of silk in the laws of Manu—Rufus Festus Avinus—Silk shawls—Marciannus Capella—Inscription by M. N. Proculus, silk manufacturer—Extraordinary spiders’ webs—Bombyces compared to spiders—Wild silk-worms of Tsouen-Kien and Tiao-Kien—M. Bertin’s account—Further remarks on wild silk-worms. Christian authors of the fourth century—Arnobius—Gregorius Nazienzenus—Basil—Illustration of the doctrine of the resurrection—Ambrose—Georgius Pisida—Macarius—Jerome—Chrysostom—Heliodorus—Salmasius—Extraordinary beauty of the silk and golden textures described by these authors—Their invectives against Christians wearing silk. Mention of silk by Christian authors in the fifth century—Prudentius—Palladius—Theodosian Code—Appollinaris Sidonius—Alcimus Avitus. Sixth century—Boethius. (Manufactures of Tyre and Sidon—Purple—Its great durability—Incredible value of purple stuffs found in the treasury of the King of Persia.) | 41 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| HISTORY OF THE SILK MANUFACTURE CONTINUED FROM THE INTRODUCTION OF SILK-WORMS INTO EUROPE, A. D. 530, TO THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY. | |

| A. D. 530.—Introduction of silk-worms into Europe—Mode by which it was effected—The Serinda of Procopius the same with the modern Khotan—The[Pg xiii] silk-worm never bred in Sir-hind—Silk shawls of Tyre and Berytus—Tyrannical conduct of Justinian—Ruin of the silk manufactures—Oppressive conduct of Peter Barsames—Menander Protector—Surprise of Maniak the Sogdian ambassador—Conduct of Chosroes, king of Persia—Union of the Chinese and Persians against the Turks—The Turks in self-defence seek an alliance with the Romans—Mortification of the Turkish ambassador—Reception of the Byzantine ambassador by Disabul, king of the Sogdiani—Display of silk textures—Paul the Silentiary’s account of silk—Isidorus Hispalensis. Mention of silk by authors in the seventh century—Dorotheus, Archimandrite of Palestine—Introduction of silk-worms into Chubdan, or Khotan—Theophylactus Simocatta—Silk manufactures of Turfan—Silk known in England in this century—First worn by Ethelbert, king of Kent—Use of by the French kings—Aldhelmus’s beautiful description of the silk-worm—Simile between weaving and virtue. Silk in the eighth century—Bede. In the tenth century—Use of silk by the English, Welsh, and Scotch kings. Twelfth century—Theodoras Prodromus—Figured shawls of the Seres—Ingulphus describes vestments of silk interwoven with eagles and flowers of gold—Great value of silk about this time—Silk manufactures of Sicily—Its introduction into Spain. Fourteenth century—Nicholas Tegrini—Extension of the Silk manufacture through Europe, illustrated by etymology—Extraordinary beauty of silk and golden textures used in the decoration of churches in the middle ages—Silk rarely mentioned in the ninth, eleventh, or thirteenth centuries | 66 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| SILK AND GOLDEN TEXTURES OF THE ANCIENTS. | |

| HIGH DEGREE OF EXCELLENCE ATTAINED IN THIS MANUFACTURE. | |

| Manufacture of golden textures in the time of Moses—Homer—Golden tunics of the Lydians—Their use by the Indians and Arabians—Extraordinary display of scarlet robes, purple, striped with silver, golden textures, &c., by Darius, king of Persia—Purple and scarlet cloths interwoven with gold—Tunics and shawls variegated with gold—Purple garments with borders of gold—Golden chlamys—Attalus, king of Pergamus, not the inventor of gold thread—Bostick—Golden robe worn by Agrippina—Caligula and Heliogabalus—Sheets interwoven with gold used at the obsequies of Nero—Babylonian shawls intermixed with gold—Silk shawls interwoven with gold—Figured cloths of gold and Tyrean purple—Use of gold in the manufacture of shawls by the Greeks—4,000,000 sesterces (about $150,000) paid by the Emperor Nero for a Babylonish coverlet—Portrait of Constantius II.—Magnificence of Babylonian carpets, mantles, &c.—Median sindones | 84 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| SILVER TEXTURES, ETC., OF THE ANCIENTS. | |

| EXTREME BEAUTY OF THESE MANUFACTURES. | |

| Magnificent dress worn by Herod Agrippa, mentioned in Acts xii. 21—Josephus’s account of this dress, and dreadful death of Herod—Discovery of ancient Piece-[Pg xiv]goods—Beautiful manuscript of Theodolphus, Bishop of Orleans, who lived in the ninth century—Extraordinary beauty of Indian, Chinese, Egyptian, and other manufactured goods preserved in this manuscript—Egyptian arts—Wise regulations of the Egyptians in relation to the arts—Late discoveries in Egypt by the Prussian hierologist, Dr. Lepsius—Cloth of glass | 93 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

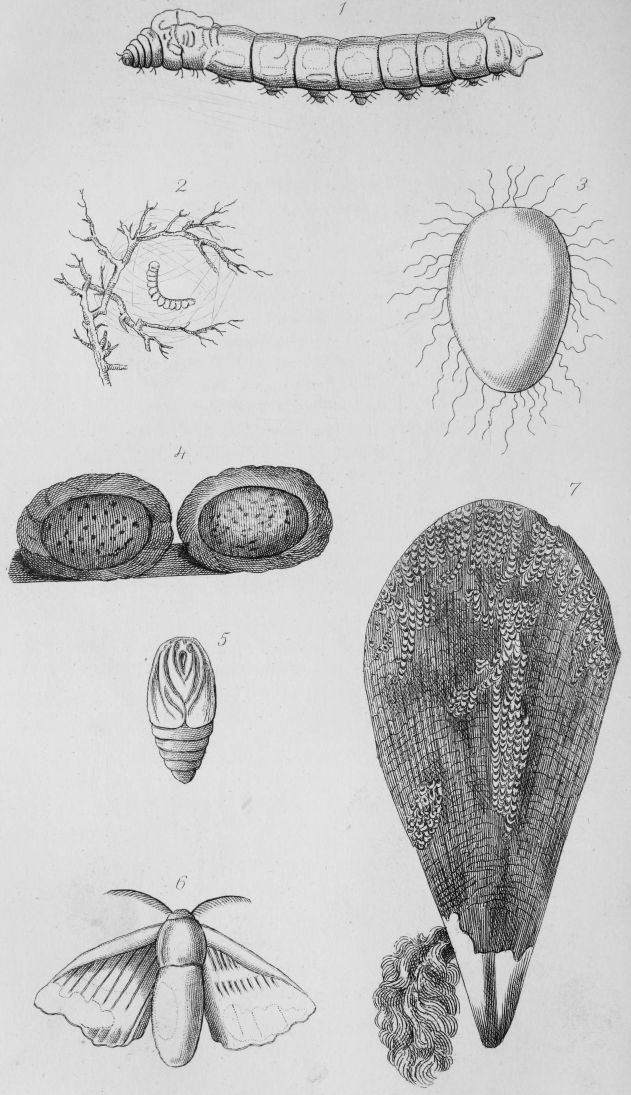

| DESCRIPTION OF THE SILK-WORM, ETC. | |

| Preliminary observations—The silk-worm—Various changes of the silk-worm—Its superiority above other worms—Beautiful verses on the May-fly, illustrative of the shortness of human life—Transformations of the silk-worm—Its small desire of locomotion—First sickness of the worm—Manner of casting its Exuviæ—Sometimes cannot be fully accomplished—Consequent death of the insect—Second, third, and fourth sickness of the worm—Its disgust for food—Material of which silk is formed—Mode of its secretion—Manner of unwinding the filaments—Floss-silk—Cocoon—Its imperviousness to moisture—Effect of the filaments breaking during the formation of the cocoon—Mr. Robinet’s curious calculation on the movements made by a silk-worm in the formation of a cocoon—Cowper’s beautiful lines on the silk-worm—Periods in which its various progressions are effected in different climates—Effects of sudden transitions from heat to cold—The worm’s appetite sharpened by increased temperature—Shortens its existence—Various experiments in artificial heating—Modes of artificial heating—Singular estimate of Count Dandolo—Astonishing increase of the worm—Its brief existence in the moth state—Formation of silk—The silken filament formed in the worm before its expulsion—Erroneous opinions entertained by writers on this subject—The silk-worm’s Will | 98 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| GENERAL OBSERVATIONS ON THE CHINESE MODE OF REARING SILK-WORMS, ETC. | |

| Great antiquity of the silk-manufacture in China—Time and mode of pruning the Mulberry-tree—Not allowed to exceed a certain height—Mode of planting—Situation of rearing-rooms, and their construction—Effect of noise on the silk-worm—Precautions observed in preserving cleanliness—Isan-mon, mother of the worms—Manner of feeding—Space allotted to the worms—Destruction of the Chrysalides—Great skill of the Chinese in weaving—American writers on the Mulberry-tree—Silk-worms sometimes reared on trees—(M. Marteloy’s experiments in 1764, in rearing silk-worms on trees in France)—Produce inferior to that of worms reared in houses—Mode of delaying the hatching of the eggs—Method of hatching—Necessity for preventing damp—Number of meals—Mode of stimulating the appetite of the worms—Effect of this upon the quantity of silk produced—Darkness injurious to the silk-worm—Its effect on the Mulberry-leaves—Mode of preparing the cocoons for the reeling process—Wild[Pg xv] silk-worms of India—Mode of hatching, &c.—(Observations on the cultivation of silk by Dr. Stebbins—Dr. Bowring’s admirable illustration of the mutual dependence of the arts upon each other.) | 119 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| THE SPIDER. | |

| ATTEMPTS TO PROCURE SILKEN FILAMENTS FROM SPIDERS. | |

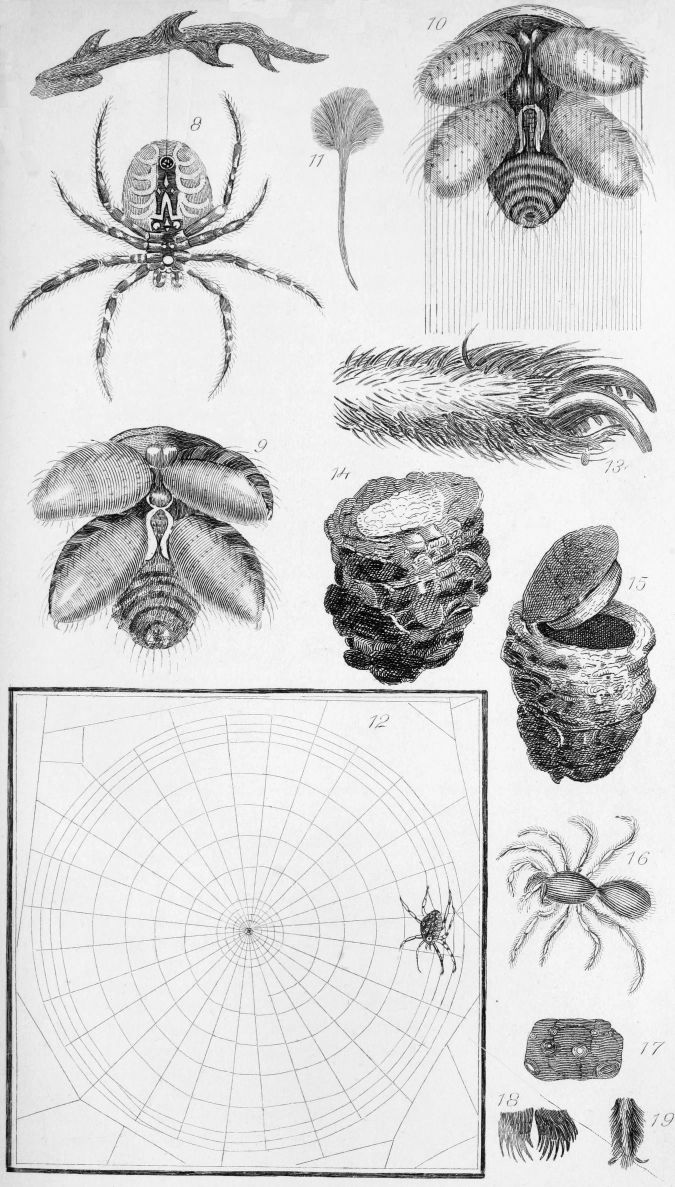

| Structures of spiders—Spiders not properly insects, and why—Apparatus for spinning—Extraordinary number of spinnerules—Great number of filaments composing one thread—Réaumur and Leeuwenhoeck’s laughable estimates—Attachment of the thread against a wall or stick—Shooting of the lines of spiders—1. Opinions of Redi, Swammerdam, and Kirby—2. Lister, Kirby, and White—3. La Pluche and Bingley—4. D’Isjonval, Murray, and Bowman—5.—Experiments of Mr. Blackwall—His account of the ascent of gossamer—6. Experiments by Rennie—Thread supposed to go off double—Subsequent experiments—Nests, Webs, and Nets of Spiders—Elastic satin nest of a spider—Evelyn’s account of hunting spiders—Labyrinthic spider’s nest—Erroneous account of the House Spider—Geometric Spiders—Attempts to procure silken filaments from Spiders’ bags—Experiments of M. Bon—Silken material—Manner of its preparations—M. Bon’s enthusiasm—His spider establishment—Spider-silk not poisonous—Its usefulness in healing wounds—Investigation of M. Bon’s establishment by M. Réaumur—His objections—Swift’s satire against speculators and projectors—Ewbank’s interesting observations on the ingenuity of spiders—Mason-spiders—Ingenious door with a hinge—Nest from the West Indies with spring hinge—Raft-building Spider—Diving Water-Spider—Rev. Mr. Kirby’s beautiful description of it—Observations of M. Clerck—Cleanliness of Spiders—Structure of their claws—Fanciful account of them patting their webs—Proceedings of a spider in a steamboat—Addison—His suggestions on the compilation of a “History of Insects” | 138 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| FIBRES OR SILKEN MATERIAL OF THE PINNA. | |

| The Pinna—Description of—Delicacy of its threads—Réaumur’s observations—Mode of forming the filament or thread—Power of continually producing new threads—Experiments to ascertain this fact—The Pinna and its Cancer Friend—Nature of their alliance—Beautiful phenomenon—Aristotle and Pliny’s account—The Greek poet Oppianus’s lines on the Pinna, and its Cancer friend—Manner of procuring the Pinna—Poli’s description—Specimens of the Pinna in the British Museum—Pearls found in the Pinna—Pliny and Athenæus’s account—Manner of preparing the fibres of the Pinna for weaving—Scarceness of this material—No proof that the ancients were acquainted with the art of knitting—Tertullian the first ancient writer who makes mention of the manufacture of cloth from the fibres of the Pinna—Procopius mentions a[Pg xvi] chlamys made of the fibres of the Pinna, and a silken tunic adorned with sprigs or feathers of gold—Boots of red leather worn only by Emperors—Golden fleece of the Pinna—St. Basil’s account—Fibres of the Pinna not manufactured into cloth at Tarentum in ancient times, but in India—Diving for the Pinna at Colchi—Arrian’s account | 174 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| FIBRES, OR SILKEN MATERIAL OF THE PINE-APPLE. | |

| Fibres of the Pine-Apple—Facility of dyeing—Manner of preparing the fibres for weaving—Easy cultivation of the plant—Thrives where no other plant will live—Mr. Frederick Burt Zincke’s patent process of manufacturing cloth from the fibres of this plant—Its comparative want of strength—Silken material procured from the Papyfera—Spun and woven into cloth—Cloth of this description manufactured generally by the Otaheiteans, and other inhabitants of the South Sea Islands—Great strength (supposed) of ropes made from the fibres of the aloe—Exaggerated statements | 185 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| MALLOWS. | |

| CULTIVATION AND USE OF THE MALLOW AMONG THE ANCIENTS.—TESTIMONY OF LATIN, GREEK, AND ATTIC WRITERS. | |

| The earliest mention of Mallows is to be found in Job xxx. 4.—Varieties of the Mallow—Cultivation and use of the Mallow—Testimony of ancient authors—Papias and Isidore’s mention of Mallow cloth—Mallow cloth common in the days of Charlemagne—Mallow shawls—Mallow cloths mentioned in the Periplus as exported from India to Barygaza (Baroch)—Calidāsa the Indian dramatist, who lived in the first century B. C.—His testimony—Wallich’s (the Indian botanist) account—Mantles of woven bark, mentioned in the Sacontăla of Calidāsa—Valcălas, or Mantles of woven bark, mentioned in the Ramayana, a noted poem of ancient India—Sheets made from trees—Ctesias’ testimony—Strabo’s account—Testimony of Statius Cæcilius and Plautus, who lived 169 B. C. and 184 B. C.—Plautus’s laughable enumeration of the analogy of trades—Beauty of garments of Amorgos mentioned by Eupolis—Clearchus’s testimony—Plato mentions linen shifts—Amorgine garments first manufactured at Athens in the time of Aristophanes | 191 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| SPARTUM OR SPANISH BROOM. | |

| CLOTH MANUFACTURED FROM BROOM BARK, NETTLE, AND BULBOUS PLANT.—TESTIMONY OF GREEK AND LATIN AUTHORS. | |

| Authority for Spanish Broom—Stipa Tenacissima—Cloth made from Broom-bark—Albania—Italy—France—Mode of preparing the fibre for weaving—[Pg xvii]Pliny’s account of Spartum—Bulbous plant—Its fibrous coats—Pliny’s translation of Theophrastus—Socks and garments—Size of the bulb—Its genus or species not sufficiently defined—Remarks of various modern writers on this plant—Interesting communications of Dr. Daniel Stebbins, of Northampton, Mass. to Hon. H. L. Ellsworth | 202 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| SHEEP’S WOOL. | |

| SHEEP-BREEDING AND PASTORAL LIFE OF THE ANCIENTS—ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE SCRIPTURES, ETC. | |

| The Shepherd Boy—Sheep-breeding in Scythia and Persia—Mesopotamia and Syria—In Idumæa and Northern Arabia—In Palestine and Egypt—In Ethiopia and Libya—In Caucasus and Coraxi—The Coraxi identified with the modern Caratshai—In Asia Minor, Pisidia, Pamphylia, Samos, &c.—In Caria and Ionia—Milesian wool—Sheep-breeding in Thrace, Magnesia, Thessaly, Eubœa, and Bœotia—In Phocis, Attica, and Megaris—In Arcadia—Worship of Pan—Pan the god of the Arcadian Shepherds—Introduction of his worship into Attica—Extension of the worship of Pan—His dances with the nymphs—Pan not the Egyptian Mendes, but identical with Faunus—The philosophical explanation of Pan rejected—Moral, social, and political state of the Arcadians—Polybius on the cultivation of music by the Arcadians—Worship of Mercury in connection with sheep-breeding and the wool trade—Present state of Arcadia—Sheep-breeding in Macedonia and Epirus—Shepherds’ dogs—Annual migration of Albanian shepherds | 217 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| SHEEP-BREEDING AND PASTORAL LIFE OF THE ANCIENTS—ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE SCRIPTURES, ETC. | |

| Sheep-breeding in Sicily—Bucolic poetry—Sheep-breeding in South Italy—Annual migration of the flocks—The ram employed to aid the shepherd in conducting his flock—The ram an emblem of authority—Bells—Ancient inscription at Sepino—Use of music by ancient shepherds—Superior quality of Tarentine sheep—Testimony of Columella—Distinction of the coarse and soft kinds—Names given to sheep—Supposed effect of the water of rivers on wool—Sheep-breeding in South Italy, Tarentum, and Apulia—Brown and red wool—Sheep-breeding in North Italy—Wool of Parma, Modena, Mantua, and Padua—Ori[Pg xviii]gin of sheep-breeding in Italy—Faunus the same with Pan—Ancient sculptures exhibiting Faunus—Bales of wool and the shepherd’s dress—Costume, appearance, and manner of life of the ancient Italian shepherds | 256 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| SHEEP-BREEDING AND PASTORAL LIFE OF THE ANCIENTS—ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE SCRIPTURES, ETC. | |

| Sheep-breeding in Germany and Gaul—In Britain—Improved by the Belgians and Saxons—Sheep-breeding in Spain—Natural dyes of Spanish wool—Golden hue and other natural dyes of the wool of Bætica—Native colors of Bætic wool—Saga and chequered plaids—Sheep always bred principally for the weaver, not for the butcher—Sheep supplied milk for food, wool for clothing—The moth | 282 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| GOATS-HAIR. | |

| ANCIENT HISTORY OF THE GOAT—ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE SCRIPTURES, ETC. | |

| Sheep-breeding and goats in China—Probable origin of sheep and goats—Sheep and goats coeval with man, and always propagated together—Habits of Grecian goat-herds—He-goat employed to lead the flock—Cameo representing a goat-herd—Goats chiefly valued for their milk—Use of goats’-hair for coarse clothing—Shearing of goats in Phrygia, Cilicia, &c.—Vestes caprina, cloth of goats’-hair—Use of goats’-hair for military and naval purposes—Curtains to cover tents—Etymology of Sack and Shag—Symbolical uses of sack-cloth—The Arabs weave goats’-hair—Modern uses of goats’-hair and goats’-wool—Introduction of the Angora or Cashmere goat into France—Success of the Project | 293 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| BEAVERS-WOOL. | |

| Isidorus Hispalensis—Claudian—Beckmann—Beavers’-wool—Dispersion of Beavers through Europe—Fossil bones of Beavers | 309 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| CAMELS-WOOL AND CAMELS-HAIR. | |

| Camels’-wool and Camels’-hair—Ctesias’s account—Testimony of modern travellers—Arab tent of Camels’-hair—Fine cloths still made of Camels’-wool—The use of hair of various animals in the manufacture of beautiful stuffs by the ancient Mexicans—Hair used by the Candian women in the manufacture of broidered stuffs—Broidered stuffs of the negresses of Senegal—Their great beauty | 312 |

[Pg xix]

| CHAPTER I. | |

| GREAT ANTIQUITY OF THE COTTON MANUFACTURE IN INDIA—UNRIVALLED SKILL OF THE INDIAN WEAVER. | |

| Superiority of Cotton for clothing, compared with linen, both in hot and cold climates—Cotton characteristic of India—Account of Cotton by Herodotus, Ctesias, Theophrastus, Aristobulus, Nearchus, Pomponius Mela—Use of Cotton in India—Cotton known before silk and called Carpasus, Carpasum, Carbasum, &c.—Cotton awnings used by the Romans—Carbasus applied to linen—Last request of Tibullus—Muslin fillet of the vestal virgin—Linen sails, &c., called Carbasa—Valerius Flaccus introduces muslin among the elegancies in the dress of a Phrygian from the river Rhyndacus—Prudentius’s satire on pride—Apuleius’s testimony—Testimony of Sidonius Apollinaris, and Avienus—Pliny and Julius Pollux—Their testimony considered—Testimony of Tertullian and Philostratus—Of Martianus Capella—Cotton paper mentioned by Theophylus Presbyter—Use of Cotton by the Arabians—Cotton not common anciently in Europe—Marco Polo and Sir John Mandeville’s testimony of the Cotton of India—Forbes’s description of the herbaceous Cotton of Guzerat—Testimony of Malte Brun—Beautiful Cotton textures of the ancient Mexicans—Testimony of the Abbé Clavigero—Fishing nets made from Cotton by the inhabitants of the West India Islands, and on the Continent of South America—Columbus’s testimony—Cotton used for bedding by the Brazilians | 315 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| SPINNING AND WEAVING—MARVELLOUS SKILL DISPLAYED IN THESE ARTS. | |

| Unrivalled excellence of India muslins—Testimony of the two Arabian travellers—Marco Polo, and Odoardo Barbosa’s accounts of the beautiful Cotton textures of Bengal—Cæsar Frederick, Tavernier, and Forbes’s testimony—Extraordinary fineness and transparency of Decca muslins—Specimen brought by Sir Charles Wilkins; compared with English muslins—Sir Joseph Banks’s experiments—Extraordinary fineness of Cotton yarn spun by machinery in England—Fineness of India Cotton yarn—Cotton textures of Soonergong—Testimony of R. Fitch—Hamilton’s account—Decline of the manufactures of Dacca accounted for—Orme’s testimony of the universal diffusion of the Cotton manufacture in India—Processes of the manufacture—Rude implements—Roller gin—Bowing. (Eli Whitney inventor of the cotton gin—Tribute of respect paid to his memory—Immense value of Mr. Whitney’s invention to growers and manufacturers of Cotton throughout the world.) Spinning wheel—Spinning without[Pg xx] a wheel—Loom—Mode of weaving—Forbes’s description—Habits and remuneration of Spinners, Weavers, &c.—Factories of the East India Company—Marvellous skill of the Indian workman accounted for—Mills’s testimony—Principal Cotton fabrics of India, and where made—Indian commerce in Cotton goods—Alarm created in the woollen and silk manufacturing districts of Great Britain—Extracts from publications of the day—Testimony of Daniel De Foe (Author of Robinson Crusoe.)—Indian fabrics prohibited in England, and most other countries of Europe—Petition from Calcutta merchants—Present condition of the City of Dacca—Mode of spinning fine yarns—Tables showing the comparative prices of Dacca and British manufactured goods of the same quality | 333 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| FLAX. | |

| CULTIVATION AND MANUFACTURE OF FLAX BY THE ANCIENTS—ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE SCRIPTURES, ETC. | |

| Earliest mention of Flax—Linen manufactures of the Egyptians—Linen worn by the priests of Isis—Flax grown extensively in Egypt—Flax gathering—Envelopes of Linen found on Egyptian mummies—Examination of mummy-cloth—Proved to be Linen—Flax still grown in Egypt—Explanation of terms—Byssus—Reply to J. R. Forster—Hebrew and Egyptian terms—Flax in North Africa, Colchis, Babylonia—Flax cultivated in Palestine—Terms for flax and tow—Cultivation of Flax in Palestine and Asia Minor—In Elis, Etruria, Cisalpine Gaul, Campania, Spain—Flax of Germany, of the Atrebates, and of the Franks—Progressive use of linen among the Greeks and Romans | 358 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| HEMP. | |

| Cultivation and Uses of Hemp by the Ancients—Its use limited—Thrace Colchis—Caria—Etymology of Hemp | 387 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| ASBESTOS. | |

| Uses of Asbestos—Carpasian flax—Still found in Cyprus—Used in funerals—Asbestine-cloth—How manufactured—Asbestos used for fraud and superstition by the Romish monks—Relic at Monte Casino | 390 |

[Pg xxi]

| APPENDIX A. | |

| ON PLINY’S NATURAL HISTORY. | |

| Sheep and wool Price of wool in Pliny’s time—Varieties of wool and where produced—Coarse wool used for the manufacture of carpets—Woollen cloth of Egypt—Embroidery—Felting—Manner of cleansing—Distaff of Tanaquil—Varro—Tunic—Toga—Undulate or waved cloth—Nature of this fabric—Figured cloths in use in the days of Homer (900 B. C.)—Cloth of gold—Figured cloths of Babylon—Damask first woven at Alexandria—Plaided textures first woven in Gaul—$150,000 paid for a Babylonish coverlet—Dyeing of wool in the fleece—Observations on sheep and goats—Dioscurias a city of the Colchians—Manner of transacting business | 401 |

| APPENDIX B. | |

| ON THE ORIGIN AND MANUFACTURE OF LINEN AND COTTON PAPER. | |

| THE INVENTION OF LINEN PAPER PROVEN TO BE OF EGYPTIAN ORIGIN—COTTON PAPER MANUFACTURED BY THE BUCHARIANS AND ARABIANS, A. D. 704. | |

| Wehrs gives the invention of Linen paper to Germany—Schönemann to Italy—Opinion of various writers, ancient and modern—Linen paper produced in Egypt from mummy-cloth, A. D. 1200—Testimony of Abdollatiph—Europe indebted to Egypt for linen paper until the eleventh century—Cotton paper—The knowledge of manufacturing, how procured, and by whom—Advantages of Egyptian paper manufacturer’s—Clugny’s testimony—Egyptian manuscript of linen paper bearing date A. D. 1100—Ancient water-marks on linen paper—Linen paper first introduced into Europe by the Saracens of Spain. (The Wasp a paper-maker—Manufacture of paper from shavings of wood, and from the stalks or leaves of Indian-corn.) | 404 |

| APPENDIX C. | |

| ON FELT. | |

| MANUFACTURE AND USE OF FELTING BY THE ANCIENTS. | |

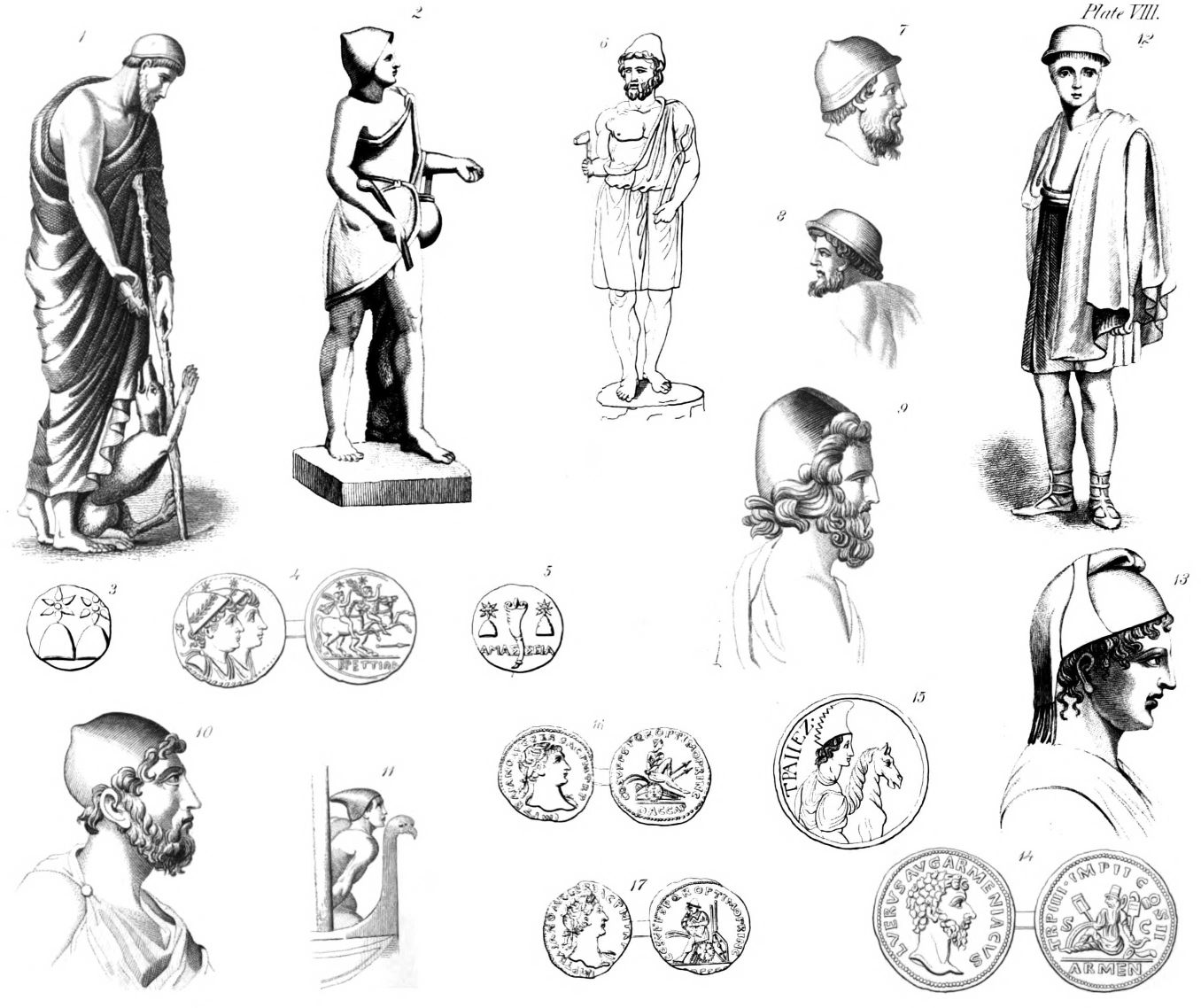

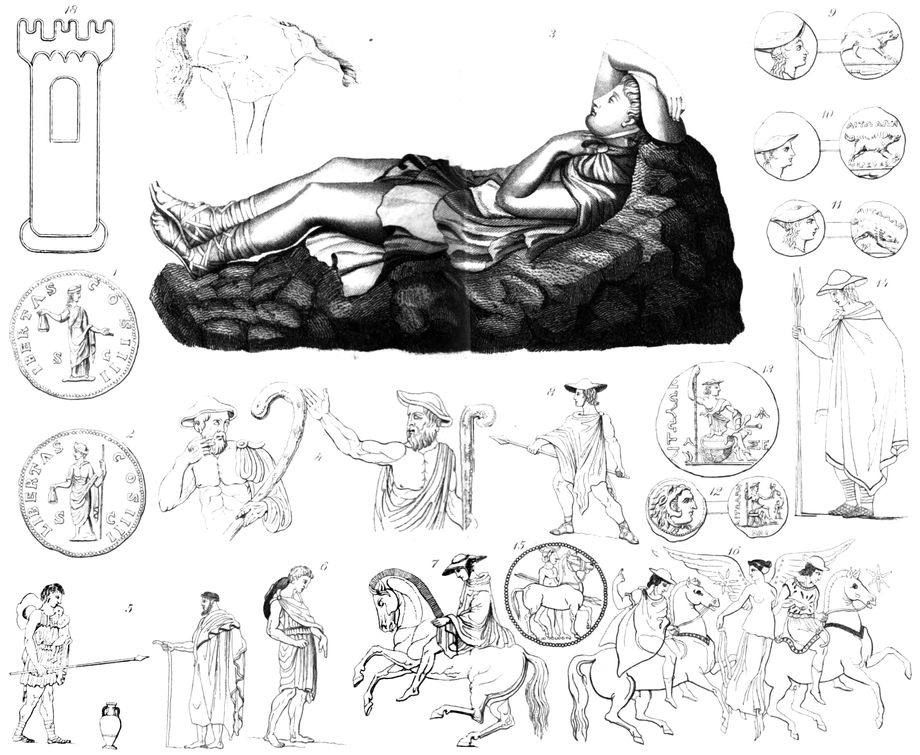

| Felting more ancient than weaving—Felt used in the East—Use of it by the Tartars—Felt made of goats’-hair by the Circassians—Use of felt in Italy and Greece—Cap worn by the Cynics, Fishermen, Mariners, Artificers, &c.—Cleanthes compares the moon to a skull-cap—Desultores—Vulcan—Ulysses—Phrygian bonnet—Cap worn by the Asiatics—Phrygian felt of Camels’-hair—Its great stiffness—Scarlet and purple felt used by Babylonish decorators—Mode of manufacturing—Felt Northern nations of Europe—Cap of liberty—[Pg xxii]Petasus—Statue of Endymion—Petasus in works of ancient art—Hats of Thessaly and Macedonia—Laconian or Arcadian hats—The Greeks manufacture Felt 900 B. C.—Mercury with the pileus and petasus—Miscellaneous uses of Felt | 414 |

| APPENDIX D. | |

| ON NETTING. | |

| MANUFACTURE AND USE OF NETS BY THE ANCIENTS—ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE SCRIPTURES, ETC. | |

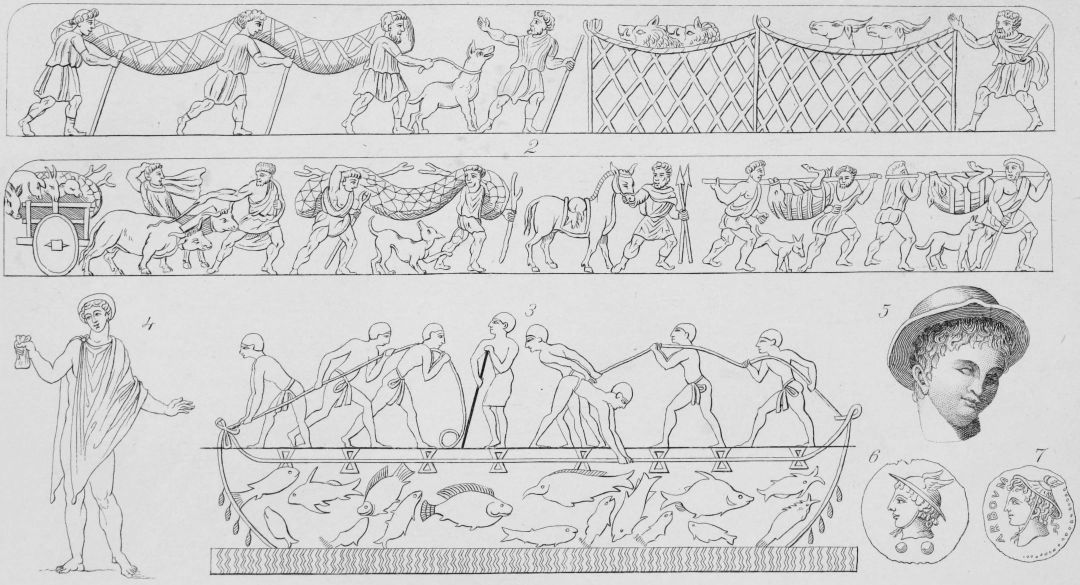

| Nets were made of Flax, Hemp, and Broom—General terms for nets—Nets used for catching birds—Mode of snaring—Hunting-nets—Method of hunting—Hunting-nets supported by forked stakes—Manner of fixing them—Purse-net or tunnel-net—Homer’s testimony—Nets used by the Persians in lion-hunting—Hunting with nets practised by the ancient Egyptians—Method of hunting—Depth of nets for this purpose—Description of the purse-net—Road-net—Hallier—Dyed feathers used to scare the prey—Casting-net—Manner of throwing by the Arabs—Cyrus king of Persia—His fable of the piper and the fishes—Fishing-nets—Casting-net used by the Apostles—Landing-net (Scap-net)—The Sean—Its length and depth—Modern use of the Sean—Method of fishing with the Sean practised by the Arabians and ancient Egyptians—Corks and leads—Figurative application of the Sean—Curious method of capturing an enemy practised by the Persians—Nets used in India to catch tortoises—Bag-nets and small purse-nets—Novel scent-bag of Verres the Sicilian prætor | 436 |

[Pg xxiii]

[Pg 1]

Whether Silk is mentioned in the Old Testament—Earliest Clothing—Coats of Skin, Tunic, Simla—Progress of Invention Chinese chronology relative to the Culture of Silk—Exaggerated statements—Opinions of Mailla, Le Sage, M. Lavoisnè, Rev. J. Robinson, Dr. A. Clarke, Rev. W. Hales, D.D., Mairan, Bailly, Guignes, and Sir William Jones—Noah supposed to be the first emperor of China—Extracts from Chinese publications—Silk Manufactures of the island of Cos—Described by Aristotle—Testimony of Varro—Spinning and Weaving in Egypt—Great ingenuity of Bezaleel and Aholiab in the production of Figured Textures for the Jewish Tabernacle—Skill of the Sidonian women in the Manufacture of Ornamental Textures—Testimony of Homer—Great antiquity of the Distaff and Spindle—The prophet Ezekiel’s account of the Broidered Stuffs, etc. of the Egyptians—Beautiful eulogy on an industrious woman—Helen the Spartan, her superior skill in the art of Embroidery—Golden Distaff presented her by the Egyptian queen Alcandra—Spinning a domestic occupation in Miletus—Theocritus’s complimentary verses to Theuginis on her industry and virtue—Taste of the Roman and Grecian ladies in the decoration of their Spinning Implements—Ovid’s testimony to the skill of Arachne in Spinning and Weaving—Method of Spinning with the Distaff—Described by Homer and Catullus—Use of Silk in Arabia 500 years after the flood—Forster’s testimony.

Whether silk is ever mentioned in the Old Testament cannot perhaps be determined.

In Ezek. xvi. 10 and 13, “silk” is used in the common English bible for משי, which occurs no where except here, but which, as appears from the context, certainly meant some [Pg 2] valuable article of female dress. Le Clerc and Rosenmüller translate it “serico;” Cocceius, Schindler, Buxtorf, in their Lexicons, and Dr. John Taylor in his Concordance, give the same interpretation. Augusti and De Wette in their German translation make it signify “a silken veil.” Others give different interpretations. The only ground, on which silk of any kind is supposed to be meant, is that in the Alexandrine or Septuagint version משי is translated τρίχαπτον, and τρίχαπτον is explained by Hesychius to mean “the silken web fitted to be placed over the hair of the head” (τὸ βομβύκινον ὕφασμα ὑπὲρ τῶν τριχῶν τῆς κεφαλῆς ἁπτόμενον), and that other ancient Greek lexicographers also suppose a silken garment to be meant.[1] But the meaning of τρίχαπτον is in reality as obscure as that of משי. Jerome could not discover it, and concluded that the word was invented by the Greek translator. It is now extant no where else except in a passage of the comic Pherecrates preserved in Athenæus. Schneider, followed by Passow, supposes it to mean some garment made of hair, and quotes to this effect the explanation of Pollux (2. 24.), πλέγμα ἐκ τριχῶν. Although, therefore, the term in question may possibly have denoted some elegant and costly ornament for the head, made at least partly of silk, yet this opinion appears to rest altogether upon the assumption, first, that the ancient lexicographers are accurate in their use of the epithet βομβύκινον, and secondly, that the Alexandrine version is accurate in adopting the word τρίχαπτον.

[1] See Schleusner, Lexicon in LXX., v. Τρίχαπτον.

In Isaiah xix. 9, according to King James’s Translators and Bishop Lowth, mention is made of those “that work in fine flax,” in the original עבדי פשתים שריקות. Rosenmüller adopts nearly the same interpretation, which is founded upon the use of the verb שרק or סרק in the Chaldee and Syriac dialects to denote the operation of combing flax, wool, hair, and other substances. In this sense the word has been taken by the author of the Alexandrine Version, τοὺς ἐργαζομένους τὸ λίνον τὸ σχιστὸν; by Symmachus, who instead of σχιστὸν uses κτενιστὸν; and by Jerome, “qui operabantur linum pectentes.”

[Pg 3]

In the Targum of Jonathan and in the Syriac Version the same root is taken to denote silk; רסריקין פלחי כתנא Targ. ܥܒܕܝ ܟܬܢܐ ܕܣܪܩܝܢ Syr. Both of these seem to admit of the following literal translation, “those who make silken tunics,” or in Latin, “Factores tunicarum e sericis.”

Kimchi supposes שריקות to mean silk webs, observing that silk is called אל שרק by the Arabs. The same opinion has been adopted by Nicholas Fuller[2], Buxtorf, and other modern critics. Kennicott, however, arranges the words in two lines as follows,

According to this arrangement, which seems most suitable to the rules of grammatical construction, we have three co-ordinate phrases in the plural number, denoting three different classes of artificers. The second, שריקות, would by its termination denote female artificers, viz. women employed in combing wool, flax, or other substances. On the whole we are inclined to adopt this explanation of the word, as it appears to be attended with the least difficulty, either grammatical or etymological.

[2] Miscellanea Sacra, l. ii. c. 11.

Silk is mentioned Prov. xxxi. 22. in King James’s Translation, i. e. the common English version, and in the margin of Gen. xli. 42. But the use of the word is quite unauthorized.

After a full examination of the whole question Braunius[3] decides that there is no mention of silk in the whole of the Old Testament, and that it was unknown to the Hebrews in ancient times.

“There can be no doubt,” says Professor Hurwitz, “that manufactures and the arts must have attained a high degree of perfection at the time when Moses wrote; and that many of them were known long before that period, we have the evidence of Scripture. It is true that inventions were at first [Pg 4] few, and their progress very slow, but they were suited to the then condition and circumstances of man, as is evident even in the art of clothing. Placed in the salubrious and mild air of paradise, our first parents could hardly want any other covering than what decency required. Accordingly we find that the first and only article of dress was the חגורה chagora, the belt, (not aprons, as in the established version). The materials of which it was made were fig leaves; (Gen. iii. 7.) the same tree that afforded them food and shelter, furnished them likewise with materials for covering their bodies. But when in consequence of their transgressions they were to be ejected from their blissful abode, and forced to dwell in less favourable regions, a more substantial covering became necessary, their merciful Creator made them (i. e. inspired them with the thoughts of making for themselves) כתנות עור coats of skins. (Gen. iii. 21.) The original word is כתנת c’thoneth, whence the Greek χιτὼν the tunic, a close garment that was usually worn next the skin, it reached to the knees, and had sleeves (in after times it was made either of wool or linen.) After man had subdued the sheep (Hebrew כבשׂ caves from כגש to subdue[4]) and learned how to make use of its wool, we find a new article of dress, namely the שמלה simla, an upper garment: it consisted of a piece of cloth about six yards long and two or three wide, in shape not unlike our blankets. This will explain Gen. ix. 23, ‘And Shem and Japheth took a garment, and laid it upon both their shoulders, and went backward and covered the nakedness of their father.’ It served as a dress by day, as a bed by night, (Exod. xxii. 26,) [Pg 5] ‘If thou at all take thy neighbour’s raiment to pledge, thou shalt deliver it unto him by that the sun goeth down; for that is his covering only; it is his raiment for his skin: wherein shall he sleep?’ And sometimes burdens were carried in it, (Exod. xii. 34,) ‘And the people took their dough before it was leavened, their kneading-troughs being bound up in their clothes upon their shoulders.’

“In the course of time various other garments came into use, as mentioned in several other parts of Scripture. The materials of which these garments were usually made are specified in Leviticus xiii. 47-59, ‘The garment also that the plague of the leprosy is in, whether it be a woollen garment or a linen garment, whether it be in the warp or woof, of linen or of woollen; whether in a skin, or in anything made of skin, &c.’”

[3] De vestitu Heb. Sacerdotum, l. 1. cap. viii. § 8.

[4] There is not the least shadow of truth in support of such a deduction; and particularly so since the general tenor of the Scriptures leads to a very different conclusion. We are, therefore, not authorized to give our support to any such hypothesis. The history of the Sheep and Goat is so interwoven with the history of man, that those naturalists have not reasoned correctly, who have thought it necessary to refer the first origin of either of them to any wild stock at all. Such view is, we imagine, more in keeping with the inferences to be drawn from Scripture History with regard to the early domestication of the sheep. Abel, we are told, was a keeper of sheep, and it was one of the firstlings of his flock that he offered to the Lord, and which, proving a more acceptable sacrifice, excited the implacable and fatal jealousy of his brother Cain. (See Part ii. pp. 217 and 293.)

In our search for the distant origin of any art or science, or in looking through the long vista of ages remote even to nations extinct before our own, we are favored with satisfactory evidence so long as we are accompanied with authentic records: beyond, all is dark, obscure, tradition, fable. On such ground it would be credulous or rash in the extreme to repeat as our own, an affirmation, when that rests on the single testimony of one party or interest, especially when that is of a very questionable character. It is even safer, when history or well authenticated records fail us, to appeal to philosophy, or to the well known laws of mind, from which all arts and science spring. The former favors us with the commanding evidence of certainty and decision; and though the latter may only afford the testimony of analogy, yet, is its probability more safe, at least, than what rests on misguided calculations or on the legendary tales of artifice and fiction.

We have, however, authentic testimony that the inventive faculty existed at a very early period. The peculiar condition of man at that time must have afforded many imperative occasions for its exertion. Hence we read that “Jabal was the father of such as dwell in tents” (i. e. inventor of tent-making); that “Jubal, his brother, was the father” (inventor) of musical instruments: such as the kinnor, harp, or stringed instruments, [Pg 6] and the ugab, organ, or wind instruments; that “Tubal-cain was the instructor of every artificer in brass and iron, the first smith on record, or one to teach how to make instruments and utensils out of brass and iron; and that the sister of Tubal-cain was Naamah, whom the Targum of Jonathan ben Uzziel affirms to have been the inventrix of plaintive or elegiac poetry[5]. Here is then an account of the inventive faculty being in exercise 3504 years before the Christian era; or 1156 years prior to the deluge; or 804 years before the earliest period assigned to the Chinese for the discovery of silk. And of whatever arts or sciences existing amongst men prior to the deluge, there is no difficulty in conceiving the possibility of the transmission of the leading and most essential parts, at least, to the post-diluvians, by the family of Noah.

[5] As a proof that the inventive faculty, as to every thing truly useful to man, originally proceeded from the only “Giver of every good and perfect gift,” consult Isa. xxviii. 24-29: and also a beautiful comment by Dr. A. Clarke on, “And thou shalt speak unto all that are wise hearted, whom I have filled with the spirit of wisdom.” Exod. xxviii. 3: and also on, “I have filled him with the spirit of God in wisdom, and in understanding, and in knowledge, and in all manner of workmanship; to devise cunning works, to work in gold, and in silver, and in brass; and in cutting of stones, to set them, and in carving of timber, to work in all manner of curious workmanship.” Exod. xxxi. 3, 4, and 5.

But instead of giving our unqualified assent to what has been servilely copied from book to book from the most accessible account, we shall advert to the great discrepancy relative to Chinese chronology, amongst those who have had equal access to their records. Thus the time of Fohi, the first emperor, has been said to be 2951 B. C., by some 2198 B. C., and by others 2057, or about 300 years after the deluge: of Hoang-ti, 2700 B. C., by Mailla it is quoted at 2602 B. C., by Le Sage at 2597 B. C., and by Robinson and others at 1703 B. C. Similar disagreements might, would our limits allow, be observed concerning the rest, and particularly of the emperors, Hiao-wenti, Chim-ti, Ming-ti, Youen-ti, Wenti, Wou-ti, and Hiao-wou-ti. Even in more modern times, and relative to a character so notorious as Confucius, no less than three dates are [Pg 7] equally affirmed to be true. As to Hoang-ti, who is said to have begun the culture of silk, we are inclined to prefer the latter account, 1703 B. C., which makes him contemporary with Joseph, when prime minister over the land of Egypt.

As a confirmation of this, it may be stated, that by referring to the account given of nine[6] of the patriarchs at this period, we shall find that the average age of human life, before much greater, soon after rapidly declined. Now the average duration of the reigns of the first three[7] Chinese emperors, including Hoang-ti, was 118 years; of the five that immediately succeeded, only 68 years. After this, until the Christian era, the average duration of a single reign did not exceed 23 years, and thence until the present time not 13 years. Since, therefore, the average duration of the reign of the first three emperors bears an evident and fit proportion to that of the age of man at the period specified, though not at any other before or after, being in the former case as much too small as it would in the latter be too great, the opinion now offered is the only one that can be consistent with these striking facts; and, if duly considered, presents an argument strongly corroborating this view of the subject.

[6] Peleg, Reu, Serug, Nahor, Terah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Joseph: Gen. xi. 16-26; xlvii. 28; and l. 26.

[7] Fohi, Eohi Chinun, and Hoang-ti.

To attempt to establish any greater certainty, in a case of this nature, the Chinese during the dynasty of Tschin, having, to conceal the truth, destroyed everything authentic, would be in vain. It would be even more rational to have recourse to the Vedas, or sacred books of the Brahmins, or to records in the Sanscrit, were it not a well known fact, that nearly all ancient nations, except the Jews, actuated by the same ambition, have betrayed a wish to have their origin traced as far back as the creation. And in the gratification of this passion none are so notoriously pre-eminent as the Egyptians, Hindoos, and Chinese.[8] For them the limits of the creation itself have been too narrow, and days, weeks, and even months too short, unless multiplied into years.[9]

[Pg 8] The chronology relative to the early culture of silk, as found in Chinese documents, for several irrefragable objections already assigned, is exceedingly questionable, and therefore we are by no means pledged to affirm that either in the authenticity of the books, or in the correctness of the dates have we any faith. M. Lavoisnè dates the commencement of the Chinese dynasties at A. M.[10] 1816, or 159 years after the deluge. The Rev. J. Robinson of Christ Col., Cam., at A. M. 1947. We have already given as strong reasons, as under the extreme incertitude of the case, can, perhaps, be offered, for preferring the latter; the important points may be briefly stated, thus:

| End of the deluge | [11]1657 A. M. |

| Fohi, first emperor, began to reign | 1947 A. M. |

| Noah died | 2007 A. M. |

| Eohi Chinun, second emperor, began to reign | 2061 A. M. |

| Hoang-ti, the third emperor, began to reign | 2201 A. M. |

| Hoang-ti after establishing the silk culture, died | 2301 A. M. |

Hoang-ti was therefore contemporary with Joseph when administering the affairs of Egypt.[12] But would we know what account the Chinese themselves give relative to the earliest introduction of the silk culture, we shall find it in the French version of the Chinese Treatises, by M. Stanislas Julien, or in the following words of pages 77 and 78, as translated and published in 1838, at Washington, under the title of “Summary of the principal Chinese Treatises upon the Culture of the Mulberry, and the rearing of Silk-worms.”

[10] A. M. signifies Anno Mundi, that is in the year of the World. The Year of Our Lord always commences on the first day of January, the day on which Christ was circumcised, being eight days old. From the Creation until the birth of Christ, was 4004 years.

Tirin places the birth of Christ in the 36th year of Herod, the 40th of Augustus, the 28th from the battle of Actium, the 749th of Rome, and the 4th of the 193d Olympiad.

[11] It will here not be improper to observe that the Samaritan text and Septuagint version of the Hebrew, carry the deluge as far back as to the year 3716 before Christ; or 1000 years before the Chinese account of Hoang-ti. On this subject see the New Analysis of Chronology, by the Rev. W. Hales, D.D. 4to., 3 vol.

[12] Joseph died in the 2369th year from the Creation.

[Pg 9] In the book on silk-worms, we read: “The lawful wife of the emperor Hoang-ti, named Si-ling-chi, began the culture of silk. It was at that time that the emperor Hoang-ti invented the art of making garments(!).” The same fact is mentioned more in detail in the general history of China, by P. Maillà, in the year 2602, before our era (4447 years ago).

“This great prince (Hoang-ti) was desirous that Si-ling-chi, his legitimate wife, should contribute to the happiness of his people. He charged her to examine the silk-worms, and to test the practicability of using the thread. Si-ling-chi had a large quantity of these insects collected, which she fed herself, in a place prepared for that purpose, and discovered not only the means of raising them, but also the manner of reeling the silk, and of employing it to make garments.”

“It is through gratitude for so great a benefit,” says the history, entitled Wai-ki, “that posterity has deified Si-ling-chi, and rendered her particular honors under the name of the goddess of silk-worms.” (Memoirs on the Chinese, vol. 13, p. 240.)

We have seen that the most probable account relative to the time of Fohi, said to have been the first Chinese emperor, is that he reigned 2057 years before the Christian era, or in the year of the world 1947. “According to the most current opinion,” says M. Lavoisnè, “China was founded by one of the colonies formed at the dispersion of Noah’s posterity under the conduct of Yao, who took for his colleague Chun, afterwards his successor. But most writers consider Fohi to have been Noah himself(!).”

Now the deluge terminated A. M. 1657, and Noah lived after the deluge 350 years[13], and therefore died A. M. 2007; and as Fohi is said to have reigned 114 years, before Eohi Chun or Chinun succeeded him, he was contemporary, at least, with Noah. The ark rested on Mount Ararat, which is generally allowed to be one of the mountains of Armenia, to the east of the head of the Tigris. And here the same author remarks, that “in rather less than a century and a half, after [Pg 10] the birth of Peleg, it is supposed that Noah, being then about his 840th year, wearied with the growing depravity of his descendants, retired with a select company to a remote corner of Asia, and there began what in after ages has been termed the Chinese monarchy.”[14] This view of the subject, we believe, coincides perfectly with the reputable testimonies presented by Mairan, Bailly, Guignes, and Sir William Jones, and demonstrates that the transit of more central aborigines, since the deluge, to the extremes of China, was perfectly feasible,[15] and a matter of even high probability.

[13] Gen. ix. 28.

[14] Clarke’s “Treatise on the Mulberry-tree, and Silk-worm,” pp. 14, 18, 20, 21, 27, and 34.

[15] See chap. iv. p. 67. Also Plate VII. (Map.)

The first ancient author, who affords any evidence respecting the use of silk, is Aristotle. He does not, however, appear to have been accurately acquainted with the changes of the silk-worm; nor does he say, that the animal was bred or the raw material produced in Cos. He only says, “Pamphile, daughter of Plates, is reported to have first woven it in Cos.” (See Chapters ii. iii. and iv. of this Part.)

Long before the time of Aristotle a regular trade had been established in the interior of Asia, which brought its most valuable productions, and especially those which were most easily transported, to the shores opposite this flourishing island. Nothing therefore is more likely than that the raw silk from the interior of Asia was brought to Cos and there manufactured. We shall see hereafter from the testimony of Procopius, that it was in like manner brought some centuries later to be woven in the Phœnician cities, Tyre and Berytus.

The arts of spinning and weaving, which rank next in importance to agriculture, having been found among almost all the nations of the old and new continents, even among those little removed from barbarism, are reasonably supposed to[Pg 11] have been invented at a very remote period of the world’s history[16]. They evidently existed in Egypt in the time of Joseph (1700 years before the Christian era), as it is recorded that Pharaoh “arrayed him in vestures of fine linen.” (Genesis xli. 42.) Two centuries later, the Hebrews carried with them on their departure from that ancient seat of civilization, the arts of spinning, dyeing, weaving, and embroidery; for when Moses constructed the tabernacle in the wilderness, “the women that were wise-hearted did spin with their hands, and brought that which they had spun, both of blue, and of purple, and of scarlet, and of fine linen.” (Exod. xxxv. 25.) They also “spun goats’ hair;” and Bezaleel and Aholiab “worked all manner of work, of the engraver, and of the cunning workman, and of the embroiderer, in blue, and of purple, and in scarlet, and in fine linen, and of the weaver.” These passages contain the earliest mention of woven clothing, which was linen, the national manufacture of Egypt. The prolific borders of the Nile furnished from the remotest periods, as at the present time, abundance of the finest flax[17]; and it appears, from the testimony both of sacred and profane history, that linen continued to be almost the only kind of clothing used in Egypt till after the Christian era[18]. The Egyptians exported their “linen yarn,” and “fine linen,” to the kingdom of Israel, in the days of Solomon, (2 Chron. i. 16; Prov. vii. 16;) their “fine linen with broidered work,” to Tyre, (Ezek. xxvii. 7.)

[16] According to Pliny, Semiramis, the Assyrian queen, was believed to have been the inventress of the art of weaving. Minerva is in some of the ancient statutes represented with a distaff, to intimate that she taught men the art of spinning; and this honor is given by the Egyptians to Isis, by the Mohammedans to a son of Japhet, by the Chinese to the consort of their emperor Yao, and by the Peruvians to Mamaoella, wife to Manco-Capac, their first sovereign. These traditions serve only to carry the invaluable arts of spinning and weaving up to an extremely remote period, long prior to that of authentic history.

[17] Paintings representing the gathering and preparation of flax have been found on the walls of the ancient sepulchres at Eleithias and Beni Hassan, in Upper Egypt, and are described and copied by Hamilton.—“Remarks on several parts of Turkey, and on ancient and modern Egypt,” pp. 97 and 287, plate 23.

The women of Sidon before the Trojan war, were especially celebrated for the skill in embroidery: and Homer, who lived 900 years B. C., mentions Helen as being engaged in embroidering the combats of the Greeks and Trojans.

[Pg 12] The transition from vegetable fibre to the use of animal staples, such as wool and hair, could not have been very difficult; indeed, as already stated, it took place at a period of which we possess no very authentic written record.

The instrument used for spinning in all countries, from the earliest times, was the distaff and spindle. This simple apparatus was put by the Greek mythologists into the hands of Minerva and the Parcæ; Solomon employs upon it the industry of the virtuous woman; to the present day the distaff is used in India, Egypt, and other eastern countries.

The ancient spindle or distaff was a very simple instrument. The late Lady Calcott informs us, that it continued even to our own days to be used by the Hindoos in all its primitive simplicity. “I have seen,” she says, “the rock or distaff formed simply of the leading shoot of some young tree, carefully peeled, it might be birch or elder, and, further north, of fir or pine; and the spindle formed of the beautiful shrub Euonymus, or spindle-tree.”[19]

[19] The superior fineness of some Indian muslins, and their quality of retaining, longer than European fabrics, an appearance of excellence, has occasioned a belief that the cotton wool of which they are woven is superior to any known elsewhere; this, however, is so far from being the fact, that no cotton is to be found in India which at all equals in quality the better kinds produced in the United States of America. The excellence of India muslins must be wholly ascribed to the skilfulness and patience of the workmen, as shown in the different processes of spinning and weaving. (See Plate v.) Their yarn is spun upon the distaff, and it is owing to the dexterous use of the finger and thumb in forming the thread, and to the moisture which it thus imbibes, that its fibres are more perfectly incorporated than they can be through the employment of any mechanical substitutes.

Spinning among the Egyptians, as among our ancestors of no very distant age, was a domestic occupation in which ladies of rank did not hesitate to engage. The term “spinster” is yet applied to unmarried ladies of every rank, and there are persons yet alive who remember to have seen the spinning wheel an ordinary piece of furniture in domestic economy.

[Pg 13]

We are told that “Solomon had horses brought out of Egypt and linen yarn; the king’s merchants received the linen yarn at a price.” (1 Kings, x. 28.) And the linen of Egypt was highly valued in Palestine, for the seducer, in Proverbs, says, “I have decked my bed with coverings of tapestry, with carved works, with fine linen of Egypt.” (Prov. vii. 16.) The prophet Ezekiel also declares that the export of the textile fabrics was an important branch of Phœnician commerce; for in his enumeration of the articles of traffic in Tyre, he says: “Fine linen with broidered work from Egypt was that which thou spreadest forth to be thy sail; blue and purple from the isles of Elisha was that which covered thee.” (Ezek. xxvii. 7.)

It deserves to be remarked that the prophet here joins Egypt with the isles of Elisha or Elis, that is, the districts of western Greece, and thus confirms the ancient tradition recorded by Herodotus of some Egyptian colonists having settled in that country, which the sceptics of the German school of history have thought proper to deny.[20] Spinning was wholly a female employment; it is rather singular that we find this work frequently performed by a large number collected together, as if the factory system had been established 3000 years ago.

[20] The sceptical school of history, founded by Niebuhr, in Germany, and extended by his disciples to a sweeping incredulity, far beyond what was contemplated by the founder, has labored hard to prove, that the Greek system of civilization was indigenous, and that the candid confession of Herodotus, attributing to Egyptian colonies the first introduction of the arts of life into Hellas, was an idle tale, or a groundless tradition. But the examination of the monuments has proved that Greek art originated in Egypt; and that the elements of the architectural, sculptural, and pictorial wonders which have rendered Greece and Italy illustrious, were derived from the valley of the Nile.

We have, however, many specimens of spinning as a domestic employment. Indeed, attention to the spindle and distaff forms a leading feature in king Lemuel’s description of a virtuous woman. “Who can find a virtuous woman? for her price is far above rubies. The heart of her husband[Pg 14] doth safely trust in her, so that he shall have no need of spoil. She will do him good and not evil all the days of her life. She seeketh wool and flax, and worketh willingly with her hands. She is like the merchant’s ships; she bringeth her food from afar. She riseth also while it is yet night, and giveth meat to her household, and a portion to her maidens. She considereth a field, and buyeth it; with the fruit of her hands she planteth a vineyard. She girdeth her loins with strength, and strengtheneth her arms. She perceiveth that her merchandise is good: her candle goeth not out by night. She layeth her hands to the spindle, and her hands hold the distaff. She stretcheth out her hand to the poor; yea, she reacheth forth her hands to the needy. She is not afraid of the snow for her household: for all her household are clothed with scarlet. She maketh herself coverings of tapestry; her clothing is silk and purple. Her husband is known in the gates, when he sitteth among the elders of the land. She maketh fine linen, and selleth it; and delivereth girdles unto the merchant.” (Prov. xxxi. 10-24.)

Hamilton and Wilkinson have already shown that many of the descriptions of combats we meet in the Iliad appear to have been derived from the battle pieces on the walls of the Theban palaces, which the poet himself pretty plainly intimates that he had visited. The same observation may be applied to most of Homer’s pictures of domestic life. We find the lady of the mansion superintending the labors of her servants, and using the distaff herself. Her spindle made of some precious material, richly ornamented, her beautiful work-basket, or rather vase, and the wool dyed of some bright hue to render it worthy of being touched by aristocratic fingers, remind us of the appropriate present which the Egyptian queen, Alcandra, made to the Spartan Helen; for the beauty of that frail fair one scarcely is less celebrated than her skill in embroidery and every species of ornamental work. After Polybus had given his presents to Menelaus, who stopped at Egypt on his return from Troy,

In the hieroglyphics over persons employed with the spindle on the Egyptian monuments, it is remarkable that the word saht, which in Coptic signifies to twist, constantly occurs. The spindles were generally of wood, and in order to increase their impetus in turning, the circular head was occasionally of gypsum, or composition: some, however, were of a light plaited work, made of rushes, or palm leaves, stained of various colors, and furnished with a loop of the same materials, for securing the twine after it was wound[21]. Sir Gardner Wilkinson found one of these spindles at Thebes, with some of the linen thread upon it, and is now in the Berlin Museum.

[21] The ordinary distaff does not occur in these subjects, but we may conclude they had it. Homer mentions one of gold, given to Helen by “Alcandra the wife of Polybus,” who lived in Egyptian Thebes.—Od. iv. 131.

Theocritus has given us a very striking proof of the pleasure which the women of Miletus took in these employments; for, when he went to visit his friend Nicias, the Milesian physician, to whom he had previously addressed his eleventh and thirteenth Idylls, he carried with him an ivory distaff as a present for Theugenis, his friend’s wife. He accompanied his gift with the following verses, which modestly commend the matron’s industry and virtue, and, at the same time, throw an interesting light on the domestic economy of the ladies of Miletus:

[22] Miletus was called “the towers of Nileus,” from its having been founded by Nileus, the son of the celebrated king Codrus, who devoted himself for the safety of Athens. Nileus was so indignant at the abolition of royalty on his father’s death, that he migrated to Ionia.

[Pg 16] The Roman and Grecian ladies displayed not less taste in the decoration of their various spinning implements, than those of modern times in the ornaments of their work-table. The calathus or qualus was the basket in which the wool was kept for the fair spinsters. It was usually made of wicker-work. Thus Catullus in his description of the nuptials of Peleus and Thetis, says:

[Pg 17] Homer asserts that the Egyptian queen Alcandra presented Helen with a silver work-basket as well as a golden distaff (Odyss. iv.); and from the paintings on ancient vases, we see that the calathi of ladies of rank were tastefully wrought and richly ornamented. From the term qualus or quasillus, equivalent to calathus, the Romans called the female slaves employed in spinning quasillariæ.

The material prepared for spinning was wrapped loosely round the distaff, the wool being previously combed, or the flax hackled by processes not very dissimilar to those used at the present day amongst the peasantry in the west of Ireland. The ball thus formed on the distaff required to be arranged with some neatness and skill, in order that the fibres should be sufficiently loose to be drawn out by the hand of the spinner. Ovid declares, that Arachne’s skill in this simple process excited the wonder of the nymphs who came to see her triumphs in the textile art, not less than the finished labors of the loom.

The distaff was generally about three feet in length, commonly a stick or reed, with an expansion near the top for holding the ball. It was sometimes, as we have shown, composed of richer materials. The distaff was usually held under the left arm, and the fibres were drawn out from the projecting ball, being, at the same time, spirally twisted by the forefinger and thumb of the right hand. The thread so produced was wound upon the spindle until the quantity was as great as it would carry.

The spindle was made of some light wood, or reed, and was [Pg 18] generally from eight to twelve inches in length. At the top of it was a slit, or catch, to which the thread was fixed, so that the weight of the spindle might carry the thread down to the ground as fast as it was finished. Its lower extremity was inserted into a whorl, or wheel, made of stone, metal, or some heavy material which both served to keep it steady and to promote its rotation. The spinner, who, as we have said before, was usually a female, every now and then gave the spindle a fresh gyration by a gentle touch so as to increase the twist of the thread. Whenever the spindle reached the ground a length was spun; the thread was then taken out of the slit, or clasp, and wound upon the spindle; the clasp was then closed again, and the spinning of a new thread commenced. All these circumstances are briefly mentioned by Catullus, in a poem from which we have already quoted:—

In order to understand this description of Catullus, it is necessary to bear in mind, that as the bobbin of each spindle was loaded with thread, it was taken off from the whorl and placed in a basket until there was a sufficient quantity for the weavers to commence their operations.

Homer incidentally mentions the spool or spindle on which the weft-yarn was wound, in his description of the race at the funeral-games in honor of Patroclus:

[Pg 19]

In India women of all castes prepare the cotton thread for the weaver, spinning it on a piece of wire, or a very thin rod of polished iron with a ball of clay at one end; this they turn round with the left hand, and supply the cotton with the right; the thread is then wound upon a stick or pole, and sold to the merchants or weavers; for the coarser thread the women make use of a wheel very similar to that of the Irish spinster, though upon a smaller construction. (For further information on the manufactures of India, their present state, &c., see Part III.)

The Reverend Mr. C. Forster of Great Britain, has lately published a very curious work on Arabia, being the result of many years’ untiring research in that part of the world; from which we learn the very interesting fact, that the ancient Arabians were skilled in the manufacture of silken textures, at as remote a period as within 500 years of the flood!

Mr. Forster has, it appears, succeeded in deciphering many very remarkable inscriptions found on some ancient monuments near Adon on the coast of Hadramant. These records, it is said, restore to the world its earliest written language, and carry us back to the time of Jacob, and within 500 years of the flood.