Title: Turkey, the Great Powers, and the Bagdad Railway: A study in imperialism

Author: Edward Mead Earle

Release date: September 5, 2021 [eBook #66221]

Language: English

Credits: Turgut Dincer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TURKEY, THE GREAT POWERS,

AND THE BAGDAD RAILWAY

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO · DALLAS ·

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA ·

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

A Study in Imperialism

BY

EDWARD MEAD EARLE, Ph.D.

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORY IN

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1924

All rights reserved

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Copyright, 1923,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and electrotyped. Published July, 1923.

ReprintedJuly, 1924

Press of

J. J. Little & Ives Company

New York, U. S. A.

“When the history of the latter part of the nineteenth century will come to be written, one event will be singled out above all others for its intrinsic importance and for its far-reaching results; namely, the conventions of 1899 and of 1902 between His Imperial Majesty the Sultan of Turkey and the German Company of the Anatolian Railways.”—Charles Sarolea, The Bagdad Railway and German Expansion as a Factor in European Politics (Edinburgh, 1907), p. 3.

“The Turkish Government, I know, have been accused of being corrupt. I venture to submit that it has not been for want of encouragement from Europeans that the Turks have been corrupt. The sinister—I think it is not going too far to use that word—effect of European financiers on Turkey has had more to do with the misgovernment than any Turk, young or old.”—Sir Mark Sykes, in the House of Commons, March 18, 1914.

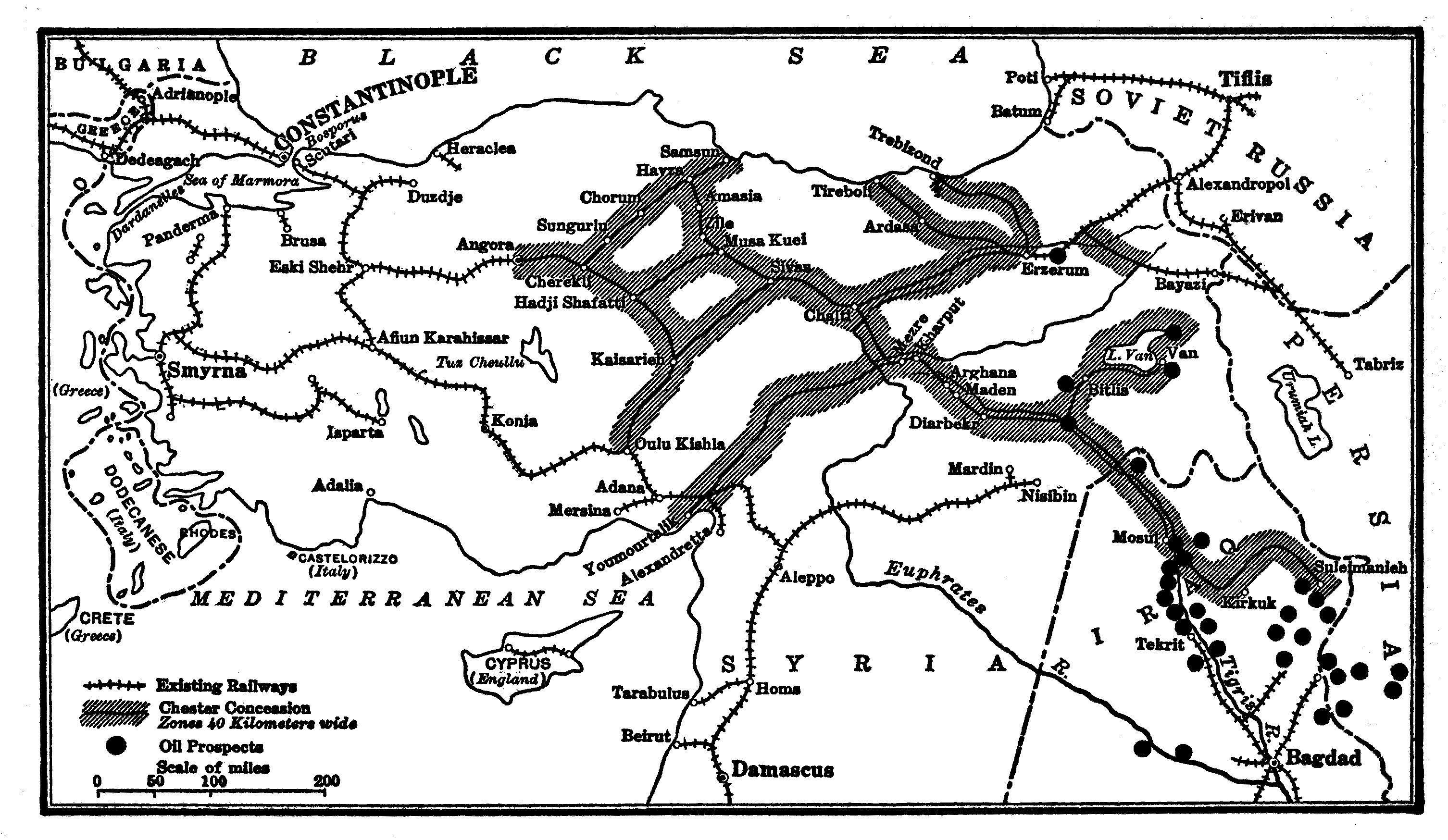

The Chester concessions and the Anglo-American controversy regarding the Mesopotamian oilfields are but two conspicuous instances of the rapid development of American activity in the Near East. Turkey, already an important market for American goods, gives promise of becoming a valuable source of raw materials for American factories and a fertile field for the investment of American capital. Thus American religious interests in the Holy Land, American educational interests in Anatolia and Syria, and American humanitarian interests in Armenia, are now supplemented by substantial American economic interests in the natural resources of Asia Minor. Political stability and economic progress in Turkey no longer are matters of indifference to business men and politicians in the United States; therefore the Eastern Question—so often a cause of war—assumes a new importance to Americans. This book will have served a useful purpose if—in discussing the conflicting political, cultural, and economic policies of the Great Powers in the Near East during the past three decades—it contributes to a sympathetic understanding of a very complicated problem and suggests to the reader some dangers which American statesmanship would do well to avoid. Students of history and international relations will find in the story of the Bagdad Railway a laboratory full of rich materials for an analysis of modern economic imperialism and its far-reaching consequences.

The assistance of many persons who have been iviiintimately associated with the Bagdad Railway has enabled the author to examine records and documents not heretofore available to the historian. To these persons the author is glad to assign a large measure of any credit which may accrue to this book as an authoritative and definitive account of German railway enterprises in the Near East. He wishes especially to mention: Dr. Arthur von Gwinner, of the Deutsche Bank, president of the Anatolian and Bagdad Railway Companies; Dr. Karl Helfferich, formerly Imperial German Minister of Finance, erstwhile managing director of the Deutsche Bank, and at present a member of the Reichstag; Sir Henry Babington Smith, an associate of the late Sir Ernest Cassel, a director of the Bank of England, president of the National Bank of Turkey, and at one time representative of the British bondholders on the Ottoman Public Debt Administration; Djavid Bey, Ottoman Minister of Finance during the régime of the Young Turks, an economic expert at the first Lausanne Conference, and at present Turkish representative on the Ottoman Public Debt Administration; Mr. Ernest Rechnitzer, a banker of Paris and London, a competitor for the Bagdad Railway concession in 1898–1899; Rear Admiral Colby M. Chester, of the United States Navy (retired), beneficiary of the “Chester concessions.”

Valuable assistance in the collection and preparation of material has been rendered, also, by the following persons, to whom the author expresses his grateful appreciation: Sir Charles P. Lucas, director, and Mr. Evans Lewin, librarian, of the Royal Colonial Institute; Sir John Cadman, director of His Majesty’s Petroleum Department; Professor George Young, of the University of London, formerly attaché of the British embassy at Constantinople; Mr. Charles V. Sheehan, sub-manager in London of the National City Bank of New York; Mr. M. Zekeria,ix chief of the Turkish Information Service in the United States; Mr. René A. Wormser, an American attorney who assisted the author in research work in Germany during the summer of 1922. Dr. Gottlieb Betz, of Columbia University, and Dr. John Mez, American correspondent of the Frankfurter Zeitung, have aided in the translation of important documents.

Professors Carlton J. H. Hayes and William R. Shepherd, of Columbia University, have been patient advisers and judicious critics of the author during the preparation of his manuscript. To them he owes much, as teachers who stimulated his interest in international relations, and as colleagues who cheerfully coöperate in any useful enterprise. Professor Parker Thomas Moon, of Columbia University, also has read the manuscript and offered many valuable suggestions.

EDWARD MEAD EARLE

Columbia University

June, 1923

| CHAPTER | PAGE |

| I | An Ancient Trade Route is Revived | 1 |

| II | Backward Turkey Invites Economic Exploitation | 9 |

| Turkish Sovereignty is a Polite Formality | 9 | |

| The Natural Wealth of Asiatic Turkey Offers Alluring Opportunities | 13 | |

| Forces Are at Work for Regeneration | 17 | |

| III | Germans Become Interested in the Near East | 29 |

| The First Rails Are Laid | 29 | |

| The Traders Follow the Investors | 35 | |

| The German Government Becomes Interested | 38 | |

German Economic Interests Make for Near Eastern Imperialism | 45 | |

| IV | The Sultan Mortgages His Empire | 58 |

| The Germans Overcome Competition | 58 | |

| The Bagdad Railway Concession is Granted | 67 | |

| The Locomotive is to Supplant the Camel | 71 | |

| The Sultan Loosens the Purse-Strings | 75 | |

| Some Turkish Rights Are Safeguarded | 81 | |

| V | Peaceful Penetration Progresses | 92 |

| The Financiers Get Their First Profits | 92 | |

| The Bankers’ Interests Become More Extensive | 97 | |

| Broader Business Interests Develop | 101 | |

| Sea Communications Are Established | 107 | |

| VI | The Bagdad Railway Becomes an Imperial Enterprise | 120 |

| Political Interests Come to the Fore | 120 | |

| Religious and Cultural Interests Reënforce Political and Economic Motives | 131 | |

| xii | Some Few Voices Are Raised in Protest | 137 |

| VII | Russia Resists and France is Uncertain | 147 |

| Russia Voices Her Displeasure | 147 | |

| The French Government Hesitates | 153 | |

| French Interests Are Believed to be Menaced | 157 | |

| The Bagdad Railway Claims French Supporters | 165 | |

| VIII | Great Britain Blocks the Way | 176 |

| Early British Opinions Are Favorable | 176 | |

| The British Government Yields to Pressure | 180 | |

| Vested Interests Come to the Fore | 189 | |

| Imperial Defence Becomes the Primary Concern | 195 | |

| British Resistance is Stiffened by the Entente | 202 | |

| IX | The Young Turks Are Won Over | 217 |

| A Golden Opportunity Presents Itself to the Entente Powers | 217 | |

| The Germans Achieve a Diplomatic Triumph | 222 | |

| The German Railways Justify Their Existence | 229 | |

| The Young Turks Have Some Mental Reservations | 235 | |

| X | Bargains Are Struck | 239 |

| The Kaiser and the Tsar Agree at Potsdam | 239 | |

| French Capitalists Share in the Spoils | 244 | |

| The Young Turks Conciliate Great Britain | 252 | |

| British Imperial Interests Are Further Safeguarded | 258 | |

| Diplomatic Bargaining Fails to Preserve Peace | 266 | |

| XI | Turkey, Crushed to Earth, Rises Again | 275 |

| Nationalism and Militarism Triumph at Constantinople | 275 | |

| Asiatic Turkey Becomes One of the Stakes of the War | 279 | |

| Germany Wins Temporary Domination of the Near East | 287 | |

| “Berlin to Bagdad” Becomes but a Memory | 292 | |

| To the Victors Belong the Spoils | 300 | |

| “The Ottoman Empire is Dead. Long Live Turkey!” | 303 | |

| XII | The Struggle for the Bagdad Railway is Resumed | 314 |

| Germany is Eliminated and Russia Withdraws | 314 | |

| France Steals a March and is Accompanied by xiiiItaly | 318 | |

| British Interests Acquire a Claim to the Bagdad Railway | 327 | |

| America Embarks on an Uncharted Sea | 336 | |

| Index | 355 | |

| The Railways of Asiatic Turkey | Frontispiece |

| The Chester Concessions | 340 |

TURKEY, THE GREAT POWERS,

AND THE BAGDAD RAILWAY

TURKEY, THE GREAT POWERS

AND THE BAGDAD RAILWAY

A Study in Imperialism

Many a glowing tale has been told of the great Commercial Revolution of the sixteenth century and of the consequent partial abandonment of the trans-Asiatic trade routes to India in favor of the newer routes by water around the Cape of Good Hope. It is sometimes overlooked, however, that a commercial revolution of the nineteenth century, occasioned by the adaptation of the steam engine to land and marine transportation, was of perhaps equal significance. Cheap carriage by the ocean greyhound instead of the stately clipper, by locomotive-drawn trains instead of stage-coach and caravan, made possible the extension of trade to the innermost and outermost parts of the earth and increased the volume of the world’s commerce to undreamed of proportions. This latter commercial revolution led not only to the opening of new avenues of communication, but also to the regeneration of trade-routes which had been dormant or decayed for centuries. During the nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth, the medieval trans-Asiatic highways to the East were rediscovered.

The first of these medieval trade-routes to be revived by modern commerce was the so-called southern route. In the fifteenth century curious Oriental craft had brought their wares from eastern Asia across the Indian Ocean and up the Red Sea to some convenient port on the Egyptian shore; here their cargoes were trans-shipped via caravan to Alexandria and Cairo, marts of trade with the European cities of the Mediterranean. The completion of the Suez Canal, in 1869, transformed this route of medieval merchants into an avenue of modern transportation, incidentally realizing the dream of Portuguese and Spanish explorers of centuries before—a short, all-water route to the Indies. Less than forty years later the northern route of medieval commerce—from the “back doors” of China and India to the plains of European Russia—was opened to the twentieth-century locomotive. With the completion of the Trans-Siberian Railway in 1905 the old caravan trails were paralleled with steel rails. The Trans-Siberian system linked Moscow and Petrograd with Vladivostok and Pekin; the Trans-Caspian and Trans-Persian railways stretched almost to the mountain barrier of northern India; the Trans-Caucasian lines provided the link between the Caspian and Black Seas.

The heart of the central route of Eastern trade in the fifteenth century was the Mesopotamian Valley. Oriental sailing vessels brought commodities up the Persian Gulf to Basra and thence up the Shatt-el-Arab and the Tigris to Bagdad. At this point the route divided, one branch following the valley of the Tigris to a point north of Mosul and thence across the desert to Aleppo; another utilizing the valley of the Euphrates for a distance before striking across the desert to the ports of Syria; another crossing the mountains into Persia. From northern Mesopotamia and northern Syria caravans crossed Armenia and Anatolia to Constantinople. This historic highway—the last of3 the three great medieval trade-routes to be opened to modern transportation—was traversed by the Bagdad Railway. The locomotive provided a new short cut to the East.

That a commercial revolution of the nineteenth century should revive the old avenues of trade with the East was a matter of the utmost importance to all mankind. To the Western World the expansion of European commerce and the extension of Occidental civilization were incalculable, but certain, benefits. Statesmen and soldiers, merchants and missionaries alike might hail the new railways and steamship lines as entitled to a place among the foremost achievements of the age of steel and steam. To the East, also, closer contacts with the West held out high hopes for an economic and cultural renaissance of the former great civilizations of the Orient. Alas, however, the reopening of the medieval trade-routes served to create new arenas of imperial friction, to heighten existing international rivalries, and to widen the gulf of suspicion and hate already hindering cordial relationships between the peoples of Europe and the peoples of Asia. Economic rivalries, military alliances, national pride, strategic maneuvers, religious fanaticism, racial prejudices, secret diplomacy, predatory imperialism—these and other formidable obstacles blocked the road to peaceful progress and promoted wars and rumors of wars. The purchase of the Suez Canal by Disraeli was but the first step in the acquisition of Egypt, an imperial experiment which cost Great Britain thousands of lives, which more than once brought the empire to the verge of war with France, and which colored the whole character of British diplomacy in the Middle East for forty years. No sooner was the Trans-Siberian Railway completed than it involved Russia in a war with Japan. So it was destined to be with the Bagdad Railway. Itself a project of great promise for4 the economic and political regeneration of the Near East, it became the source of bitter international rivalries which contributed to the outbreak of the Great War. It is one of the tragedies of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that the Trans-Siberian Railway, the Suez Canal, and the Bagdad Railway—potent instruments of civilization for the promotion of peaceful progress and material prosperity—could not have been constructed without occasioning imperial friction, political intrigues, military alliances, and armed conflict.

The geographical position of the Ottoman Empire, the enormous potential wealth of its dominions, and the political instability of the Sultan’s Government contributed to make the Bagdad Railway one of the foremost imperial problems of the twentieth century. At the time of the Bagdad Railway concession of 1903 Turkey held dominion over the Asiatic threshold of Europe, Anatolia, and the European threshold of Asia, the Balkan Peninsula. Constantinople, the capital of the empire, was the economic and strategic center of gravity for the Black Sea and eastern Mediterranean basins. By possession of northern Syria and Mesopotamia, the Sultan controlled the “central route” of Eastern trade throughout its entire length from the borders of Austria-Hungary to the shores of the Persian Gulf. The contiguity of Ottoman territory to the Sinai Peninsula and to Persia held out the possibility of a Turkish attack on the Suez and trans-Persian routes to India and the Far East. In fact, the Sultan’s dominions from Macedonia to southern Mesopotamia constituted a broad avenue of communication, an historic world highway, between the Occident and the Orient. To a strong nation, this position would have been a source of strength. To a weak nation it was a source of weakness. As Gibraltar and Suez and Panama were staked out by the empire-builders, so were Constantinople and5 Smyrna and Koweit. Strategically, the region traversed by the Bagdad Railway is one of the most important in the world.

Turkey-in-Asia, furthermore, was wealthy. It possessed vast resources of some of the most essential materials of modern industry: minerals, fuel, lubricants, abrasives. Its deposits of oil alone were enough to arouse the cupidity of the Great Powers. Irrigation, it was believed, would accomplish wonders in the revival of the ancient fertility of Mesopotamia. By the development of the country’s latent agricultural wealth and the utilization of its industrial potentialities, it was anticipated that the Ottoman Empire would prove a valuable source of essential raw materials, a satisfactory market for finished products, and a rich field for the investment of capital. Economically, the territory served by the Bagdad Railway was one of the most important undeveloped regions of the world.

Neither the geographical position nor the economic wealth of the Ottoman Empire, however, need have been a cause for its exploitation by foreigners. Had the Sultan’s Government been strong—powerful enough to present determined resistance to domestic rebellion and foreign intrigue—Turkey would not have been an imperial problem. But Abdul Hamid and his successors, the Young Turks, showed themselves incapable of governing a vast empire and a heterogeneous population. They were unable to resist the encroachments of foreigners on the administrative independence of their country or to defend its borders against foreign invasion. That the Ottoman Empire, under these circumstances, should fall a prey to the imperialism of the Western nations was to be expected. Its strategic importance was a “problem” of military and naval experts. Its wealth was an irresistible lure to investors. Its political instability was the excuse offered by European nations for intervening in the affair6s of the empire on behalf of the financial interests of the business men or the strategic interests of the empire-builders. Diplomatically, then, the region traversed by the Bagdad Railway was an international “danger zone.”

The problem of maintaining stable government in Turkey was complicated by the religious heritage of the Ottoman Empire. It was the homeland of the Jews, the birthplace of Christianity, the cradle of Mohammedanism. European crusaders had waged war to free the Holy Land from Moslem desecrators; the followers of the Prophet had shed their blood in defence of this sacred soil against infidel invaders; the sons of Israel looked forward to a revival of Jewish national life in this, their Zion. It is small wonder that Turkey-in-Asia was a great field for missions—Protestant missions to convert the Mohammedan to the teachings of Christ; Catholic missions to win over, as well, the schismatics; Orthodox missions to retain the loyalty of adherents to the Greek Church. Despite their cultural importance in the development of modern Turkey, the missions presented serious political problems to the Sultan. They hindered the development of Turkish nationalism by teaching foreign languages, by strengthening the separatist spirit of the religious minorities, and by introducing Occidental ideas and customs. They weakened the autocracy by idealizing the democratic institutions of the Western nations. They occasioned international complications, arising out of diplomatic protection of the missionaries themselves and the racial and religious minorities in whose interest the missions were maintained. In no country more than in Turkey have the emissaries of religion proved to be so valuable—however unwittingly—as advance pickets of imperialism.

Complicating and bewildering as the Near Eastern question always has been, the construction of the Anatolian and Bagdad Railways made it the more complicating7 and bewildering. The development of rail transportation in the Ottoman Empire was certain to raise a new crop of problems: the strategic problem of adjusting military preparations to meet new conditions; the economic problem of exploiting the great natural wealth of Turkey-in-Asia; the political problem of prescribing for a “Sick Man” who was determined to take iron as a tonic. These problems, of course, were international as well as Ottoman in their aspects. The economic and diplomatic advance of Germany in the Near East, the resurgent power of Turkey, the military coöperation between the Governments of the Kaiser and the Sultan were not matters which the other European powers were disposed to overlook. Russia, pursuing her time-honored policy, objected to any bolstering up of the Ottoman Empire. France looked with alarm upon the advent of another power in Turkish financial affairs and, in addition, was desirous of promoting the political ambitions of her ally, Russia. Great Britain became fearful of the safety of her communications with India and Egypt. Thus the Bagdad Railway overstepped the bounds of Turco-German relationships and became an international diplomatic problem. It was a concern of foreign offices as well as counting houses, of statesmen and soldiers as well as engineers and bankers.

The year 1888 ushered in an epoch of three decades during which two cross-currents were at work in Turkey. On the one hand, earnest efforts were made by Turks, old and young, to bring about the political and economic regeneration of their country. On the other, the steady growth of Balkan nationalism, the relentless pressure of European imperialism, and the devastation of the Great War gradually reduced to ruins the once great empire of Suleiman the Magnificent. The history of those three decades is concerned largely with the struggles of European capitalists to acquire profitable concessions in A8siatic Turkey and of European diplomatists to control the finances, the vital routes of communication, and even the administrative powers of the Ottoman Government. The coincidence between the economic motives of the investors and the political and strategical motives of the statesmen, made Turkey one of the world’s foremost areas of imperial friction. Its territories and its natural wealth were “stakes of diplomacy” for which cabinets maneuvered on the diplomatic checkerboard and for which the flower of the world’s manhood fought on the sands of Mesopotamia, the cliffs of Gallipoli, and the plains of Flanders. To tell the story of the Bagdad Railway is to emphasize perhaps the most important single factor in the history of Turkey during the last thirty eventful years.

The reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (1876–1909) began with a disastrous foreign war; it terminated in the turmoil of revolution. And during the intervening three decades of his régime the Ottoman Empire was forced to wage a fight for its very existence—a fight against disintegration from within and against dismemberment from without.

One of the principal problems of Abdul Hamid was the government of his vast empire in spite of domestic dissension and foreign interference. His subjects were a polyglot collection of peoples, bound together by few, if any, common ties, obedient to the Sultan’s will only when overawed by military force. In Turkey-in-Asia alone, Turks, Arabs, Armenians, Kurds, Jews, Greeks combined to form a conglomerate population, professing a variety of religious faiths, speaking a diversity of languages and dialects, and adhering to their own peculiar social customs. Of these, the Armenians were receiving the sympathy, support, and encouragement of Russia; the Kurds were living by banditry, terrorizing peasants and traders alike; the Arabs were in open revolt.1

Nature seemed to make more difficult the task of bringing these dissentient peoples under subjection. The mountainous relief of the Anatolian plateau lent itself to the success of guerrilla bands against the gendarmerie; a high mountain barrier separated Anatolia, the homeland of the Turks, from the hills and deserts of Syria and Mesopotamia, the strongholds of the Arabs. The vast extent of the empire—it is as far from Constantinople to Mocha as it is from New York to San Francisco—still further complicated an already tangled problem, for there were not even the poorest means of communication. Under these circumstances the authority of the Sultan was as often disregarded as obeyed. To police the country from the Adriatic to the Indian Ocean, from the borders of Persia to the eastern coast of the Mediterranean, was a physical impossibility. Universal military service was enforced only in the less rebellious provinces. It was almost out of the question to mobilize the military strength of the empire for defence against foreign invasion or for the suppression of domestic insurrection. Efforts to build up effective administration from Constantinople were paralyzed by incompetent, insubordinate, and corrupt officials.2

To these problems of maintaining peace and order at home there was added the equally difficult problem of preventing the extension of foreign interference and control in Ottoman affairs. The integrity of Turkey already was seriously compromised by the hold which the Great Powers possessed on Turkish governmental functions. Under the Capitulations foreigners occupied a special and privileged position within the Ottoman Empire. Nationals of the European nations and the United States were practically exempt from taxation; they could be tried for civil and criminal offences only un11der the laws of their own country and in courts under the jurisdiction of their own diplomatic and consular officials; in fact, they enjoyed favors comparable to diplomatic immunity. By virtue of treaties with the Sultan the Powers exercised numerous extra-territorial rights in Turkey, such, for example, as the maintenance of their own postal systems.3

The finances of Turkey, furthermore, were under the control of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration, composed almost entirely of representatives of foreign bondholders and responsible only to them. The Council of Administration of the Public Debt—composed of one representative each from the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and Turkey—had complete control of assessment, collection, and expenditure of certain designated revenues. In fact, it controlled Ottoman financial policy and exercised its control in the interest of European bankers and investors. Customs duties of the Sultan’s dominions might be increased only with the consent of the Great Powers. Almost all administrative and financial questions in Turkey were directly or indirectly subject to the sanction of foreigners.4

European governments were not content to interfere in the affairs of the Ottoman Empire. They sought to destroy it. Their zeal in this latter respect was limited only by their jealousies as to who should become the heir of the Sick Man. Russia encouraged the Balkan and Transcaucasian peoples to resist Turkish domination; France acquired control of Tunis and built up a sphere of interest in Syria; Great Britain occupied Egypt; Italy cast longing glances at Tripoli and finally seized it; Greece fomented insurrection in Crete. Germany and Austria-Hungary sought to bring all of Turkey into the economic and political orbit of Central12 Europe. The Powers rendered lip-service to the sovereignty and the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire, but they never allowed their solemn professions to interfere with their imperial practices. At best Turkish sovereignty was a polite fiction—it was always a fiction, if not always polite.

The economic backwardness of Turkey emphasized the existing political confusion and instability. From one end of the empire to the other, it seemed, obstacle was piled on obstacle to prevent the modernizing of the nation. Brigandage made trade hazardous; there were almost no roads; the rivers of Anatolia and Cilicia were not navigable; the mineral resources of the country had been neglected; internal and foreign customs duties were the last straws to break the camel’s back—business was taxed to death. Agriculture, the occupation of the great majority of the people, was in a state of stagnation. The absence of systems of drainage and irrigation made the countryside the victim of alternate floods and droughts. Methods of cultivation were archaic: the wooden plow, used by the Hittites centuries before, was among the most advanced types of agricultural implements in use in Anatolia and Syria; harvesting and threshing were performed in the most antiquated manner; fertilization and cultivation were practically unknown. Markets were inaccessible; the peasant could not dispose of a surplus if he had it; therefore, production was limited to the needs of the family, and the Turkish peasant acquired a widespread reputation for inherent laziness.

Industrially, the Ottoman Empire had back of it a great past. The fine and dainty fabrics of Mosul; the famous mosque lamps, wonder-art of the glass-workers of Mesopotamia; the master workmanship of the coppersmiths of Diarbekr; the tiles of Erzerum; the steel work and the enamels of Damascus—all of these had been f13ar-famed articles of world commerce for centuries. But Turkey in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was, industrially as well as politically, a “backward nation.” Her manufactures were conducted under the time-honored handicraft system, which long since had been discarded by her European neighbors. In other words, Turkey had not experienced the Industrial Revolution which was the modern foundation of Western society and civilization. But Turkey was victimized by the Industrial Revolution. Her manufactures—with the exception of some luxuries of incomparable craftsmanship—produced by outworn methods, found it increasingly difficult to compete even in the markets of the Ottoman Empire with the cheaper machine-made goods of Europe. The pitiless competition of the industrialized West eliminated the cottage spinner and weaver, the town tailor and cobbler. And yet for Turkey to adopt European methods—to introduce the machine, the factory, and the factory town—was for a time impracticable. There was no mobile fund of capital for the purpose, and even Young Turks were not in a position to furnish the necessary technical skill. As for foreign capital and foreign directing genius, they could be obtained only under promises and guarantees which might still further jeopardize the independence of the Ottoman Empire.5

It was not because of a lack of natural resources that Turkey was a “backward nation.” The Sultan’s Asiatic dominions were rich in raw materials, in fuel, and in agricultural possibilities. Anatolia, for example, is a great storehouse of important metals. A fine quality of chrome ore is to be found in the region directly south of th14e Sea of Marmora and in Cilicia, constituting sources of supply which were sufficient to assure Turkey first position among the chrome-producing nations until 1900, when exports from Russia and Rhodesia offered serious competition. There are valuable deposits of antimony in the vilayets of Brusa and Smyrna, as well as commercially profitable lead and zinc mines near Brusa, Ismid, and Konia. These metals, particularly chrome and antimony, are not only valuable for peace-time industry, but are almost indispensable in the manufacture of armor-plate, shells and shrapnel, guns, and armor-piercing projectiles.6

In the vicinity of Diarbekr there are mines, which, although not entirely surveyed, promise to yield large supplies of copper. Southern Anatolia is the world’s greatest source of emery and other similar abrasives. The famous meerschaum mines near Eski Shehr enjoy practically a universal monopoly. Boracite, mercury, nickel, iron, manganese, sulphur, and other minerals are to be found in Anatolia, although there is some question of the commercial possibilities of the deposits.7

Although Anatolia is not ranked among the principal fuel-producing countries of the world, its coal deposits are not inconsiderable. Operation of the chief of the coalfields, in the vicinity of Heraclea, was begun in 1896 by a French corporation, La Société française d’Héraclée, which invested in the enterprise during the succeeding seven years more than a million francs. The venture proved to be profitable, for by 1910 the mines were producing in excess of half a million tons of coal annually. In addition to coal, Anatolia possesses large deposits of lignite which, mixed with coal, is suitable fuel for ships, locomotives, gasworks, and factories.8

Oil exists in large quantities in Mesopotamia and in smaller quantities in Syria. The deposits are said to be part of a vast petroliferous area stretching from the shores15 of the Caspian Sea to the coast of Burma. As early as 1871 a commission of experts visited the valleys of the Tigris and the Euphrates for the purpose of studying the possibility of immediate exploitation of the petroleum wells in that region. They reported that although there was a plentiful supply of petroleum of good quality, difficulties of transportation made it extremely doubtful if the Mesopotamian fields could compete with the Russian and American at that time. The oil supply was then being exploited on a small scale by the Arabs and proved to be of sufficient local importance, as well as of sufficient profit, to warrant its being taken over by the Ottoman Civil List, in 1888, as a government monopoly.9

In 1901 a favorable report by a German technical commission on Mesopotamian petroleum resources stated that the region was a veritable “lake of petroleum” of almost inexhaustible supply. It would be advisable, it was pointed out, to develop these oilfields if for no other purpose than to break the grip of the “omnipotent Standard,” which, in combination with Russian interests, might speedily monopolize the world’s supply.10 Shortly afterward, Dr. Paul Rohrbach, a celebrated German publicist, visited the Mesopotamian valley and wrote that the district seemed to be “virtually soaked with bitumen, naphtha, and gaseous hydrocarbons.” He was of the opinion that the oil resources of the region offered far greater opportunity for profitable development than had the Russian Transcaucasian fields.11 In 1904 the Deutsche Bank, of Berlin, promoters of the Bagdad Railway, obtained the privilege of making a thorough survey of the oilfields of the Tigris and Euphrates valleys, with the option within one year of entering into a contract with the Ottoman Government for their exploitation.12 Shortly thereafter Rear Admiral Colby M. Chester, of the United States Navy, became interested in the development of the oil industry in Asiatic Turkey.13

The Near East possesses not only mineral wealth but potential agricultural wealth as well. Mesopotamia, for example, gives promise of becoming one of the world’s chief cotton-growing regions. In antiquity the Land of the Two Rivers was an important center of cotton production, and recent experiments have held out great inducements for a revival of cotton culture there. The climate of Mesopotamia is ideal for such a purpose. The length of the summer season is from six to seven months, with a constantly rising temperature, as contrasted with a shorter season and variable temperatures in America and Egypt. Frost is almost unknown. Rainfall is plentiful during the early part of the year and scarce, as it should be, during the growing period. The soil contains a good percentage of the essential phosphorus, potash, and nitrogen. It is believed that Mesopotamia can grow cotton as good as the best Egyptian and better than the best American product and at a considerably higher yield per acre.14

Extravagant prophecies have been made regarding the rôle of irrigation in bringing about an agricultural renaissance in Turkey-in-Asia. A writer in the Vienna Zeit of August 31, 1901, predicted that as soon as the economic effects of irrigation and of the Bagdad Railway should be fully realized, “Anatolia, northern Syria, Mesopotamia, and Irak together will export at least as much grain as all of Russia exports to-day.” Dr. Rohrbach claimed that this probably would prove to be an exaggeration, but that certainly Mesopotamia would become one of the great granaries of the world.15 Sir William Willcocks, the distinguished English engineer who had planned and supervised the construction of the famous irrigation works of the Nile, was no less enthusiastic about the prospects of Mesopotamia. “With the Euphrates and Tigris floods really controlled,” he wrote, “the delta of the two17 rivers would attain a fertility of which history has no record; and we should see men coming from the West, as well as from the East, making the Plain of Shinar a rival of the land of Egypt. The flaming swords of inundation and drought would have been taken out of the hands of the offended Seraphim, and the Garden of Eden would have again been planted.... Speaking in less poetical language we might say that the value of every acre in the joint delta of the two rivers would be immediately trebled before the irrigation works were carried out, and again increased many fold more the day the works were completed. Every town and hamlet in the valley from Bagdad to Basra would find itself freed from the danger, expense, and intolerable nuisance of flooding, and the resurrection of this ancient land would have been an accomplished fact.”16

Here in the Near East, then, was a great empire awaiting exploitation by Western capital and Western technical skill. No man could adequately predict its ultimate contributions in raw materials to Western industry, or accurately foretell its ultimate capacity in consumption of the products of Western factories, or confidently prophesy its final rôle in the promotion of Western commerce. But a trained and intelligent observer, surveying the situation at the opening of the twentieth century, could have said with a certain amount of assurance that there were two essential conditions to even a partial realization of the economic possibilities of the Ottoman Empire: the provision of adequate railway communications and the establishment of political security. The former of these conditions was met, in part, during the régime of Abdul Hamid and his successors, the Young Turks. The second, in spite of earnest efforts by loyal Ottomans, has not yet been satisfied.

Probably there was no group of men more fully aware of the needs of Turkey than the members of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration. They were concerned, it is true, solely with obtaining prompt payment of interest and principal of Ottoman bonds and with improving Ottoman credit in European financial markets. But the accomplishment of this purpose, they realized, was altogether out of the question in the continued presence of political instability and economic stagnation. One must feed the goose which lays the golden eggs. They sought some means, therefore, of establishing domestic order in the Ottoman Empire, of lessening the constant danger of foreign invasion, and of providing a tonic for the economic life of the nation. All of these purposes, it was believed, would be served by the encouragement of railway construction in Turkey.

The interest and imagination of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration were stimulated by the plans of the eminent German railway engineer Wilhelm von Pressel, one of the Sultan’s technical advisers. Von Pressel had established an international reputation because of his services in the construction of important railways in Switzerland and the Tyrol. In 1872 he was retained by the Ottoman Government to develop plans for railways in Turkey, and a few years later he assumed a prominent part in the construction of the trans-Balkan lines of the Oriental Railways Company. No one knew more than von Pressel of the railway problems of Turkey; few were more enthusiastic about the rôle which rail communications might play in a renaissance of the Near East.

Von Pressel foresaw the possibility of establishing a great system of Ottoman railways extending from the borders of Austria-Hungary to the shores of the Persian Gulf. In this manner the far-flung territories of the19 empire would be brought into communication with one another and with the capital, and an era would be begun of unprecedented development in agriculture, mining, and commerce. A market would be provided for the crops of the peasantry; the hinterland of the ports of Constantinople, Smyrna, Mersina, Alexandretta, and Basra would be opened up; heretofore inaccessible mineral resources would be exploited. Foreign commerce might be restored to the prosperity it had once enjoyed before the Commercial Revolution of the sixteenth century replaced the caravan routes of the Near East by the new sea routes to the Indies. Mesopotamia might be transformed into a veritable economic paradise. The railways also would insure political stability, for rapid mobilization and transportation of the gendarmerie to danger points would enable the Sultan’s Government to suppress rebellions of the turbulent tribesmen of Kurdistan, Mesopotamia, and Arabia. Peace and prosperity were goals within easy reach, thought von Pressel, if Turkey could be provided with a comprehensive system of railways.17

To the Ottoman Public Debt Administration peace and prosperity were means to reaching another goal—a full treasury. Greater income for the Turkish farmer, miner, artisan, and trader would mean greater opportunities for the extension of tax levies. And the greater the tax receipts the greater would be the payments to the European bondholders and the greater the value of the bonds themselves. Obviously, railway construction would improve Turkish credit in the financial centers of the world. But, for the time, the Ottoman Government had at its disposal neither the capital nor the technical skill to carry into execution the plans for an ambitious program of railway building, and private enterprise showed no disposition to interest itself without substantial guarantees. It was under these circumstances, therefore, that the Ottoman Public Debt Administration recommended to the Sultan that c20ertain revenues of his empire should be set aside for the payment of subsidies to railway companies.18

The Public Debt Administration were not unaware that the payment of railway subsidies would materially increase the amount of the imperial debt and mortgage certain of the imperial revenues. But they were confident that railways would be a powerful stimulant to economic prosperity in Turkey and would ultimately increase the revenues of the Government by an amount in excess of the amount of the subsidies. They believed that generous initial expenditures in a worth-while enterprise might yield generous final returns. As an instance of this they could point to the development of sericulture in Turkey. Under the auspices of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration tens of thousands of dollars were expended in the reclamation of more than 130,000 acres of land and the planting thereon of over sixty million mulberry trees. As a result, the silk crop increased more than tenfold during the years 1890–1910, with a result that there was a corresponding increase in the 10% levy (or tithe) on agricultural products in the regions affected. If the Public Debt Administration were actuated by self-interest, at least it was intelligent and far-sighted self-interest.19

But Sultan Abdul Hamid was no less interested than foreign bondholders in the extension of railway construction in his empire. Railways could be utilized, he believed, to serve his dynastic and imperial ambitions. Effective transportation was essential to the solution of at least three vexatious political problems: first, the problem of exercising real, as well as nominal, authority over rebellious and indifferent subjects in Syria, Mesopotamia, Kurdistan, Arabia, and other outlying provinces; second, the problem of compelling these provinces, by military force if necessary, to contribute their share of blood 21and treasure to the defence of the empire;20 third, the problem of perfecting a plan of mobilization for war, on whatever front it might be necessary to conduct hostilities. The maintenance of order, the enforcement of universal military service, the collection of taxes in all provinces of the empire, and defence against foreign invasion—all of these policies would be seriously handicapped, if not paralyzed, by the absence of adequate railway communications.

For strategic reasons, if for no other, Abdul Hamid would have especially favored the Bagdad Railway. For strategic reasons, also, he supplemented the Bagdad system with the famous Hedjaz Railway—from Damascus to the holy cities of Medina and Mecca—one of the achievements of which the wily old Sultan was most proud.21 The completion of these two railways would have extended Turkish military power from the Black Sea to the Persian Gulf, from the Bosporus to the Persian Gulf. General von der Goltz epitomized their military importance in the following terms: “The great distance dividing the southern provinces from the rest of the empire was not the only difficulty in holding them in control; it made Turkey unable to concentrate her strength in case of great danger in the north. It must not be forgotten that the Osmanlie Empire in all former wars on the Danube and in the Balkans has only been able to utilize half her forces. Not only did the far-off provinces not contribute men, but, on the contrary, they necessitated strong reënforcements to prevent the danger of their being tempted into rebellion. This will be quite changed when the railroads to the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea are completed. The empire will then be rejuvenated and have renewed strength.”22 The General might have added that the new railways might conceivably be utilized for the transportation to the Sinai Peninsula of an army intended to threaten the Suez Canal and Egypt.23

The Ottoman Government made it plain from the very start that the Bagdad Railway, in particular, was intended to serve military, as well as purely economic, purposes. The concession of 1903 contained a number of explicit provisions regarding official commandeering of the lines for the objects of suppressing rebellion, conducting military maneuvers, or mobilizing in the event of war. Furthermore, the Ottoman military authorities insisted that strategic considerations be taken into account when the railway was constructed. For example, the sections of the Bagdad line from Adana to Aleppo were carried through the Amanus Mountains, in spite of formidable engineering difficulties and enormous expense, although the railway could have been carried along the Mediterranean coast with greater ease and economy. The latter course, however, would have exposed to the guns of a hostile fleet the jugular vein of Turkish rail communications. From an economic point of view the Amanus tunnels were the most expensive and most unremunerative part of the Bagdad Railway; strategically, they were indispensable. This point was emphasized in 1908, when the Ottoman General Staff refused to consider a proposal to divert the line from the mountain passes to the shore.24

One of the most frequent criticisms of Turkish railway enterprises in general, and of the Bagdad Railway in particular, is that they were military as well as economic in character. Such criticisms, however, must be discounted, for potentially every railway is of military value. And in the European countries few railways were constructed without frank consideration of their adaptability to military purposes in time of war. Railways, in fact, were one of the most important branches of Europe’s “preparedness” for war. Which European nation, therefore, was in a position to cast a stone at Turkey for adopting this lesson from the civilized Occident? If the Ottoman Empi23re had a right to prepare for defence against invasion, it had the right to make that defence effective—at least until such time as its neighbors, Russia and Austria, should abandon military measures of potential menace to Turkey.

Germans and Turkish Nationalists contended that there was a certain amount of cant in the righteous indignation of the Powers that Turkey should become militaristic. Was Russia, they said, as much interested in the welfare of Turkey as she was angered at the active measures of the Sultan to prevent a Russian drive at Constantinople via the southern shore of the Black Sea? Was France as much concerned with the safety of Turkey as she was solicitous of the imperial interests of her ally? Was Great Britain engaged in preserving the peace of the Near East, or was she fearful of a stiffened Turkish defence of Mesopotamia or of a Turkish thrust at Egypt?25 For the Sultan to have admitted that foreign powers had the right to dictate what measures he might or might not take for the defence of his territories would have been equivalent to a surrender of the last vestige of his sovereignty. Obviously this was an admission he could not afford to make.

Whatever else Abdul Hamid may have been, he was no fool. To assume that this shrewd and unscrupulous autocrat walked into a German trap when he granted the Bagdad Railway concession is naïve and absurd. Abdul Hamid was not in the habit of giving things away, if he could avoid it, without adequate compensation for himself and his empire. As Lord Curzon said, there was no axiom dearer to the Sultan’s heart than that charity not only begins, but stays, at home.26 Abdul Hamid knew that the granting of railway subsidies would mortgage his empire. He knew that mortgages have their disadvantages, not the least of which is foreclosure. But mortgages also have their advantages. Abdul Hamid24 granted extensive railway concessions, carrying with them heavy subsidies, because he hoped the new railways would strengthen his authority within the Ottoman Empire and improve the political position of Turkey in the Near East.

1 Count L. Ostrorog, The Turkish Problem (Paris, 1915, English translation, London, 1919), Chapter II; Leon Dominian, The Frontiers of Language and Nationality in Europe (London, 1917); V. Bérard, Le Sultan, l’Islam, et les puissances (Paris, 1907), pp. 15 et seq.; E. Fazy, Les Turcs d’aujourd’hui (Paris, 1898); A. Vamberry, Das Türkenvolk (Leipzig, 1885); A. Geiger, Judaism and Islam (London, 1899). Regarding Arab nationalism, in particular, cf. N. Azoury, Le réveil de la nation arabe (Paris, 1905); E. Jung, Les puissances devant la révolte arabe (Paris, 1906). A fascinating tale of the Arab separatist movement during the Great War is that of L. Thomas, “Lawrence: the Soul of the Arabian Revolution,” in Asia (New York), April, May, June, 1920. Cf., also, H. S. Philby, The Heart of Arabia (2 volumes, New York, 1923).

2 There is a wealth of material upon the problems of the Ottoman Empire during the reign of Abdul Hamid. In particular, consult the following: A. Vamberry, La Turquie d’aujourd’hui et d’avant quarante ans (Paris, 1898); C. Hecquard, La Turquie sous Abdul Hamid (Paris, 1901); G. Dory, Abdul Hamid Intime (Paris, 1901); Sir Edwin Pears, The Life of Abdul Hamid (London, 1917); W. Miller, The Ottoman Empire, 1801–1913 (Cambridge, 1913), Chapters XVI-XVIII; N. Verney and G. Dambmann, Les puissances étrangères dans le Levant, en Syrie, et en Palestine (Paris, 1900); Baron von Oppenheim, Von Mittelmeer zum persischen Golfe (2 volumes, Berlin, 1899–1900); Lavisse and Rambaud, Histoire Générale (12 volumes, 1894–1901), Volume XI, Chapter XV; Volume XII, Chapter XIV; R. Davey, The Sultan and His Subjects (London, 1897); V. Cardashian, The Ottoman Empire of the Twentieth Century (Albany, N. Y., 1908).

3 The texts of the various treaties of capitulation may be found in G. E. Noradounghian (ed.), Recueil d’actes internationaux de l’Empire ottoman, 1300–1902 (4 volumes, Paris, 1897–1903), Volume I, documents numbers 153, 170, 196, 201, etc., ad lib., Volume II, numbers 499, 593, etc., ad lib.; also Recueil des traités de la Porte ottomane avec les puissances étrangères, 1536–1901 (10 volumes, Paris, 1864–1901), passim; E. A. Van Dyck, Report on the Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire, Forty-seventh Congress, Special Session, Senate Executive Document No. 3, First25 Session, Senate Executive Document No. 87 (Washington, 1881–1882); G. Pelissie du Rausas, Le régime des capitulations dans l’Empire ottoman (2 volumes, Paris, 1902–1905); A. R. von Overbeck, Die Kapitulationen des osmanischen Reiches (Breslau, 1917); W. Lehman, Die Kapitulationen (Weimar, 1917); P. M. Brown, Foreigners in Turkey, Their Juridical Status (Princeton, 1914).

4 For an account of the establishment, functions, and operation of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration, cf. George Young (ed.), Corps de droit ottoman—Recueil des codes, lois, réglements, ordonnances, et actes les plus importants du droit intérieur, et d’études sur le droit coutumier de l’Empire ottoman (7 volumes, Oxford, 1905–1906), Volume V, Chapter LXXXV; A. Heidborn, Manuel de droit public et administratif de l’Empire ottoman (2 volumes, Vienna, 1912), Volume II; C. Morawitz, Les finances de Turquie (Paris, 1902); A. du Velay, Essai sur l’histoire financière de la Turquie (Paris, 1903), Parts V and VI; L. Delaygue, Essai sur les finances ottomanes (Paris, 1911).

5 There were a few factories erected in Turkey by foreign capitalists, notably those of the Oriental Carpet Manufacturers, Ltd., the American Tobacco Company, and the Deutsche-Levantischen Baumwollgesellschaft. In general, however, the factory and the factory town were not common phenomena in Asiatic Turkey. An interesting account of the effects of the Industrial Revolution upon economic conditions in Turkey is that of Talcott Williams, Turkey a World Problem of Today (Garden City, 1921), pp. 268 et seq.; W. S. Monroe, Turkey and the Turks: an Account of the Lands, Peoples and Institutions of the Ottoman Empire (London, 1909), Chapter X; M. J. Garnett, Turkish Life in Town and Country (London, 1904).

6 J. E. Spurr (ed.), Political and Commercial Geology (New York, 1921), pp. 109, 115–116, 172–173, 184–185; Anatolia, No. 17 in a series of handbooks published by the Historical Section of the Foreign Office (London, 1920), pp. 88–90.

7 Spurr, op. cit., pp. 358–359; Armenia and Kurdistan, No. 62 of the Foreign Office Handbooks, p. 60; L. Dominian, “The Mineral Wealth of Asia Minor,” in The Near East, May 26, 1916, p. 91; E. Banse, Auf den Spuren der Bagdadbahn (Weimar, 1913), pp. 140–145; L. de Launay, La Géologie et les richesses minerales de l’Asie (Paris, 1911); R. Fitzner, Anatolien, Wirtschaftsgeographie (Berlin, 1902); P. Rohrbach, Die wirtschaftliche Bedeutung Westasiens (Halle, 1902); G. Carles, La Turquie économique (Paris, 1906); E. Mygind, “Anatolien und seine wirtschaftliche Bedeutung,” in Die Balkan Revue, Volume 4 (1917), pp. 1–6.

8 L. Dominian, “Fuel in Turkey: an Analysis of Coal Deposits,” in The Near East, June 23, 1916, pp. 186–187; J. Kirsopp, “The26 Coal Resources of the Near East,” ibid., October 10, 1919, pp. 393–394.

9 F. Maunsell, “The Mesopotamian Petroleum Field,” in the Geographical Journal, Volume IX (1897), pp. 523–532; L. Dominian, “Fuel in Turkey: Petroleum,” in The Near East, July 14, 1917; Mesopotamia, No. 63 of the Foreign Office Handbooks, pp. 34, 85–86; Syria and Palestine, No. 60 of the Foreign Office Handbooks, p. 111.

10 Parliamentary Papers, 1921, Cmd. 675; The Near East, October 26, 1917, p. 516.

11 Die Bagdadbahn (1903), pp. 26–28.

12 Parliamentary Papers, 1921, Cmd. 675. For some reason or other this option was allowed to lapse.

13 H. Woodhouse, “American Oil Claims in Turkey,” in Current History (New York), Volume XV (1922), pp. 953–959.

14 Report of the Department of Agriculture in Mesopotamia, 1920 (Bagdad, 1921); The Cultivation of Cotton in Mesopotamia (Bagdad, 1922); “Cotton Growing in Mesopotamia,” in the Bulletin of the Imperial Institute, Volume 18 (1920), pp. 73–82.

15 Rohrbach, op. cit., pp. 30–46.

16 Quoted in The Near East, October 6, 1916, pp. 545–546. For an elaboration of the views of Sir William Willcocks see the following of his books and articles: The Recreation of Chaldea (Cairo, 1903); The Irrigation of Mesopotamia (London, 1905, and Constantinople, 1911); “Mesopotamia, Past, Present and Future,” in the Geographical Journal, January, 1910, pp. 1–18. For further works on the economic resources of Turkey-in-Asia consult, also, the following: K. H. Müller, Die wirtschaftliche Bedeutung der Bagdadbahn (Hamburg, 1917); L. Blanckenhorn, Syrien und die deutsche Arbeit (Weimar, 1916); L. Schulmann, Zur türkischen Agrarfrage (Weimar, 1916); A. Ruppin, Syrien als Wirtschaftsgebiet (Berlin, 1917).

17 W. von Pressel, Les chemins de fer en Turquie d’Asie (Zurich, 1902), pp. 4–5, 52–59, etc. ad lib. For statements of the importance of von Pressel in the development of railways in Turkey cf. André Chéradame, La question d’Orient: la Macédoine, le chemin de fer de Bagdad (Paris, 1903), pp. 25 et seq.; C. A. Schaefer, Die Entwicklung der Bagdadbahnpolitik (Weimar, 1916), p. 13.

18 Corps de droit ottoman, Volume IV, pp. 62–64.

19 Sir H. P. Caillard, Article “Turkey” in the Encyclopedia Britannica, eleventh edition, Volume 27, p. 439; Reports of the Ottoman Public Debt (London, 1884 et seq.), passim.

20 In Turkey all Mussulmans over 20 years of age were liable to military service for a period of 20 years, 4 of which were with the colors in the regular army. Residents in the outlyin27g territories, notably the Arabs and the Kurds, constantly avoided military service and went unpunished because of the inability of the Government to send punitive expeditions into these regions. Railways would have produced satisfactory bases of operations for such expeditions and would have shortened their lines of communication. The Statesman’s Year Book, 1903, pp. 1168–1170.

21 The Hedjaz Railway was a great national enterprise which indicated the strength of Moslem feeling in Turkey and which proved the desire of the Ottoman Government to construct national railways as far as capital and technical skill could be obtained. So far as Abdul Hamid was concerned, the railway was an attempt to gain prestige for his claim to the Caliphate, as well as a move to strengthen his political position in Syria and the Hedjaz. In April, 1900, the Sultan announced to the Faithful his determination to construct a railway from Damascus to the holy cities of Medina and Mecca. An appeal was issued to Mohammedans the world over for funds to carry out the work. The Sultan headed the list with a subscription of about a quarter of a million dollars, and by 1904 over three and a half million dollars had been collected. The only compulsory contributions were the levies of 10% on the salary of every official in the civil and military service of the empire. It is estimated that the contributions eventually amounted to almost fifteen million dollars. The engineers in charge of the construction were Italians, although the great bulk of the work was done by the army and the peasantry. Nearly seven hundred thousand persons were employed on the construction work at one time or another, the non-Moslems being replaced as quickly as Mussulmans could be trained to take their places. On August 31, 1908, the thirty-second anniversary of the accession of Abdul Hamid, the railway was completed to Medina, where construction was halted temporarily because of the Young Turk Revolution and the international complications which followed it. Corps de droit ottoman, Volume IV, pp. 242–244; A. Hamilton, Problems of the Middle East (London, 1909), pp. 273–292; Annual Register, 1908, pp. 328–329.

22 Quoted by Hamilton, op. cit., pp. 274–275.

23 Via the Bagdad Railway and the Syrian system Turkish troops could have been transported to a point less than 200 miles from Suez. A successful attack on the Canal, of course, would have severed British communications with the East. In addition, it would have given the Sultan an opportunity to attack, and assert his suzerainty over, Egypt. Dr. Rohrbach made a great point of this alleged menace to the British position in Egypt. Cf. Die Bagdadbahn, pp. 18–19; German World Policies, pp. 165–167. This program, however, would have been an altogeth28er too ambitious one for the military strength of the Ottoman Empire, which had such far-flung frontiers to defend. In any event, British statesmen seemed to realize that the Sinai Peninsula was a formidable natural defence against an attack on the Suez Canal and that such an expedition would be merely a pin-prick in the imperial flesh. Parliamentary Debates, House of Lords, fifth series, Volume 7 (1911), pp. 601 et seq. The termination in a fiasco of the Turkish drive of 1914–1915 against the Canal confirmed this prophecy.

24 Infra, p. 83; Kurt Wiedenfeld, Die deutsch-türkische Wirtschaftsbeziehungen (Leipzig, 1915), p. 23; Report of the Bagdad Railway Company, 1908, pp. 4–5.

26 Persia and the Persian Question, Volume I, p. 634.

During the summer of 1888 the Oriental Railways—from the Austrian frontier, across the Balkan Peninsula via Belgrade, Nish, Sofia, and Adrianople, to Constantinople—were opened to traffic. Connections with the railways of Austria-Hungary and other European countries placed the Ottoman capital in direct communication with Vienna, Paris, Berlin, and London (via Calais). The arrival at the Golden Horn, August 12, 1888, of the first through express from Paris and Vienna was made the occasion of great rejoicing in Constantinople and was generally hailed by the European press as marking the beginning of a new era in the history of the Ottoman Empire. To thoughtful Turks, however, it was apparent that the opening of satisfactory rail communications in European Turkey but emphasized the inadequacy of such communications in the Asiatic provinces. Anatolia, the homeland of the Turks, possessed only a few hundred kilometres of railways; the vast areas of Syria, Mesopotamia, and the Hedjaz possessed none at all. Almost immediately after the completion of the Oriental Railways, therefore, the Sultan, with the advice and assista30nce of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration, launched a program for the construction of an elaborate system of railway lines in Asiatic Turkey.1

The existing railways in Asia Minor were owned, in 1888, entirely by French and British financiers, with British capital decidedly in the predominance. The oldest and most important railway in Anatolia, the Smyrna-Aidin line—authorized in 1856, opened to traffic in 1866, and extended at various times until in 1888 it was 270 kilometres in length—was owned by an English company. British capitalists also owned the short, but valuable, Mersina-Adana Railway, in Cilicia, and held the lease of the Haidar Pasha-Ismid Railway. French interests were in control of the Smyrna-Cassaba Railway, which operated 168 kilometres of rails extending north and east from the port of Smyrna. It was not until the autumn of 1888 that Germans had any interest whatever in the railways of Asiatic Turkey.2

The first move of the Sultan in his plan to develop railway communication in his Asiatic provinces was to authorize important extensions to the existing railways of Anatolia. The French owners of the Smyrna-Cassaba line were granted a concession for a branch from Manissa to Soma, a distance of almost 100 kilometres, under substantial subsidies from the Ottoman Treasury. The British-controlled Smyrna-Aidin Railway was authorized to build extensions and branches totalling 240 kilometres, almost doubling the length of its line. A Franco-Belgian syndicate in October, 1888, received permission to construct a steam tramway from Jaffa, a port on the Mediterranean, to Jerusalem—an unpretentious line which proved to be the first of an important group of Syrian railways constructed by French and Belgian promoters. Shortly afterward the concession for a railway from Beirut to Damascus was awarded to French interests31.3

But the great dream of Abdul Hamid was the great dream of Wilhelm von Pressel: the vision of a trunk line from the Bosporus to the Persian Gulf, which, in connection with the existing railways of Anatolia and the new railways of Syria, would link Constantinople with Smyrna, Aleppo, Damascus, Beirut, Mosul, and Bagdad. As early as 1886 the Ottoman Ministry of Public Works had suggested to the lessees of the Haidar Pasha-Ismid Railway that they undertake the extension of that line to Angora, with a view to an eventual extension to Bagdad. The proposal was renewed in 1888, with the understanding that the Sultan was prepared to pay a substantial subsidy to assure adequate returns on the capital to be invested. The lessees of the Haidar Pasha-Ismid line, however, were unable to interest investors in the enterprise and were compelled to withdraw altogether from railway projects in Turkey-in-Asia. Thereupon Sir Vincent Caillard, Chairman of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration, endeavored to form an Anglo-American syndicate to undertake the construction of a Constantinople-Bagdad railway, but he met with no success.4

The opportunity which British capitalists neglected German financiers seized. Dr. Alfred von Kaulla, of the Württembergische Vereinsbank of Stuttgart, who was in Constantinople selling Mauser rifles to the Ottoman Minister of War, became interested in the possibilities of railway development in Turkey. With the coöperation of Dr. George von Siemens, Managing Director of the Deutsche Bank, a German syndicate was formed to take over the existing railway from Haidar Pasha to Ismid and to construct an extension thereof to Angora. On October 6, 1888, this syndicate was awarded a concession for the railway to Angora and was given to understand that it was the intention of the Ottoman Government to32 extend that railway to Bagdad via Samsun, Sivas, and Diarbekr. The Sultan guaranteed the Angora line a minimum annual revenue of 15,000 francs per kilometre, for the payment of which he assigned to the Ottoman Public Debt Administration the taxes of certain districts through which the railway was to pass. Thus came into existence the Anatolian Railway Company (La Société du Chemin de Fer Ottomane d’Anatolie), the first of the German railway enterprises in Turkey.5

The German concessionaires were not slow to realize the possibilities of their concession. They elected Sir Vincent Caillard to the board of directors of their Company, in order that they might receive the enthusiastic coöperation of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration and in order that they might interest British capitalists in their project. With the assistance of Swiss bankers they incorporated at Zurich the Bank für orientalischen Eisenbahnen, which floated in the European securities markets the first Anatolian Railways loan of eighty million francs—more than one fourth of the loan being underwritten in England. Shortly thereafter this same financial group, under the leadership of the Deutsche Bank, acquired a controlling interest in more than 1500 kilometres of railways in the Balkan Peninsula, by purchasing the holdings of Baron Hirsch in the Oriental Railways Company. The Bank für orientalischen Eisenbahnen became a holding company for all of the Deutsche Bank’s railway enterprises in the Near East.6

Under the direction of German engineers, in the meantime, construction of the Anatolian Railway proceeded at so rapid a rate that the 485 kilometres of rails were laid and trains were in operation to Angora by January, 1893. About the same time a German engineering commission, assisted by two technical experts representing the Ottoman Ministry of Public W33orks and by two Turkish army officers, submitted a report on their preliminary survey of the proposed railway to Bagdad. This was enthusiastically received by the Sultan, who reiterated his intention of constructing a line into Mesopotamia at the earliest practicable date.7

In 1887 there was no German capital represented in the railways of Asiatic Turkey. Five years later the Deutsche Bank and its collaborators controlled the railways of Turkey from the Austro-Hungarian border to Constantinople; they had constructed a line from the Asiatic shore of the Straits to Angora; they were projecting a railway from Angora across the hills of Anatolia into the Mesopotamian valley. In coöperation with the Austrian and German state railways they could establish through service from the Baltic to the Bosporus and, by ferry and railway, into hitherto inaccessible parts of Asia Minor. Almost overnight, as history goes, Turkey had become an important sphere of German economic interest. Thus was born the idea of a series of German-controlled railways from Berlin to Bagdad, from Hamburg to the Persian Gulf!

The Ottoman Government apparently was well pleased with the energetic action of the German concessionaires in the promotion of their railway enterprises in Turkey. In any event, a tangible evidence of appreciation was extended the Anatolian Railway Company by an imperial iradé of February 15, 1893, which authorized the construction of a branch line of 444 kilometres from Eski Shehr (a town about midway between Ismid and Angora) to Konia. The new line, like its predecessor, was guaranteed a minimum annual return of 15,000 francs per kilometre, payments to be made under the supervision of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration. The obvious advantages of developing the potentially rich regions of southern Anatolia, and of providing improved communication between Constantinople and the interior of Asia34 Minor, led the Anatolian Company to hasten construction, with the result that service to Konia was inaugurated in 1896.8

Simultaneously with the granting of the second Anatolian concession the Sultan authorized an important extension to the French-owned Smyrna-Cassaba Railway. The existing line was to be prolonged a distance of 252 kilometres from Alashehr to Afiun Karahissar, at which latter town a junction was to be effected with the Anatolian Railway. Another French company was awarded a concession for the construction of the Damascus-Homs-Aleppo railway, in Syria, under substantial financial guarantees from the Ottoman Treasury. It was said that these concessions to French financiers were “compensatory” in character and were granted upon the urgent representations of the French ambassador in Constantinople.9

Between 1896 and 1899 no further definite steps were taken to extend the Anatolian Railway beyond Angora, as had been provided by the original concession. In the latter year, however, largely because of Russian objections to the further development of railways in northern Asia Minor, the Sultan took under consideration the advisability of projecting and building, instead, a line from Konia to Bagdad via Aleppo and Mosul. Early in 1899 a German commission left Constantinople to make a thorough survey of the economic and strategic possibilities of such a line. Included in the commission were Dr. Mackensen, Director of the Prussian State Railways; Dr. von Kapp, Surveyor for the State Railways of Württemberg; Herr Stemrich, the German Consul-General at Constantinople; Major Morgen, German military attaché; representatives of the Ottoman Ministry of Public Works. It was this commission that finally decided upon the route of the Bagdad Railway.10

At the close of the nineteenth century, therefore, the sceptre of railway power in the Near East was passing from the hands of Frenchmen and Englishmen into the hands of Germans. In a period of about ten years the German-owned Anatolian Railway Company had constructed almost one thousand kilometres of railway lines in Asia Minor. A German mission was blazing a trail through Syria and Mesopotamia for the extension of the Anatolian Railway to the valley of the Tigris River and the head of the Persian Gulf. German prestige seemed to be in the ascendancy: the Directors of the Anatolian Company reported to the stockholders in 1897 that, “as in former years, our Company has concerned itself continuously with the development of trade, industry, and agriculture in the region served by the Railway. As a result our enterprise has enjoyed in every sense the whole-hearted support and the powerful protection of His Majesty the Sultan. Our relationships with the Imperial Ottoman Government, the local authorities, and all classes of the people themselves are more cordial than ever.”11

The system of railways thus founded had been conceived by a German railway genius; it had been constructed by German engineers with materials made by German workers in German factories; it had been financed by German bankers; it was being operated under the supervision of German directors. In the minds of nineteenth-century neo-mercantilists this was a matter for national pride. A Pan-German organ hailed the Anatolian Railways and the proposed Bagdad enterprise in glowing terms: “The idea of this railway was conceived by German intelligence; Germans made the preliminary studies; Germans overcame all the serious obstacles which stood in the way of its execution. We should be all the more pleased with this success because the Russians and the English busied themselves at the Golden Horn endeavoring to block the German project.”12

The construction of the Anatolian Railways by German capitalists was accompanied by a considerable expansion of German economic interests in the Near East. In 1889, for example, a group of Hamburg entrepreneurs established the Deutsche Levante Linie, which inaugurated a direct steamship service between Hamburg, Bremen, Antwerp, and Constantinople. It was the expectation of the owners of this line that the construction of the Anatolian railways would materially increase the volume of German trade with Turkey—an expectation which was justified by subsequent developments. In 1888, the year of the original railway concession to the Deutsche Bank, exports from Germany to Turkey were valued at 11,700,000 marks; by 1893, when the line was completed to Angora, they mounted to a valuation of 40,900,000 marks, an increase of about 350%. Imports into Germany from Turkey during the same period rose from 2,300,000 marks to 16,500,000 marks, showing an increase of over 700%. No small proportion of the phenomenal increase in the volume of German exports to Turkey can be attributed to the use of German materials on the Ismid-Angora railway. In any event, there was no further substantial development of this export trade between 1895 and 1900, although imports into Germany from Turkey reached the high figure of 28,900,000 marks at the close of the century.13

That German traders should follow German financiers into the Ottoman Empire was to be expected. The Deutsche Bank—sponsor of the Anatolian Railways—had been notably active in the promotion of German foreign commerce. From its very inception it had devoted itself energetically to the promotion of industrial and commer37cial activity abroad, thus carrying out the object announced in its charter “of fostering and facilitating commercial relations between Germany, other European countries, and oversea markets.” By the establishment of foreign branches, by the liberal financing of import and export shipments, by the introduction of German bills of exchange in the four corners of the earth, and by other similar methods, this great bank was largely responsible for the emancipation of German traders from their former dependence upon British banking facilities. The Anatolian Railways concessions marked the initial efforts of the Deutsche Bank at Constantinople. What it had done elsewhere it could be expected to do in the interests of German business men operating in Turkey.14

The London Times of October 28, 1898, contained a significant review of the status of German enterprise in the Ottoman Empire during the decade immediately preceding. Whereas ten years before, the finance and trade of Turkey were practically monopolized by France and Great Britain, the Germans were now by far the most active group in Constantinople and in Asia Minor. Hundreds of German salesmen were traveling in Turkey, vigorously pushing their wares and studiously canvassing the markets to learn the wants of the people. The Krupp-owned Germania Shipbuilding Company was furnishing torpedoes to the Turkish navy; Ludwig Loewe and Company, of Berlin, was equipping the Sultan’s military machine with small arms; Krupp, of Essen, was sharing with Armstrong the orders for artillery. German bicycles were replacing American-made machines. There was a noticeable increase of German trade with Palestine and Syria. In 1899 a group of German financiers founded the Deutsche Palästina Bank, which proceeded to establish branches at Beirut, Damascus, Gaza, Haifa, Jaffa, Jerusalem, Nablus, Nazareth, and Tripoli-in-Syria.

Promoters, bankers, traders, engineers, munitions manufacturers, ship-owners, and railway builders all were playing their parts in laying a substantial foundation for a further expansion of German economic interests in the Ottoman Empire.15

In a sense, German diplomacy had paved the way for the Anatolian Railway concessions. For numerous reasons, which need not be discussed here, French and British influence at the Sublime Porte gradually declined during the decades of 1870–1890. British prestige, in particular, waned after the occupation of Egypt in 1882. The German ambassador at Constantinople during most of this period was Count Hatzfeld, an unusually shrewd diplomatist, who perceived the extraordinary opportunity which then existed to increase German prestige in the Near East. His place in the counsels of the Sultan became increasingly important, as he missed no chance to seize privileges surrendered by France or Great Britain.16