Title: The Lords of High Decision

Author: Meredith Nicholson

Illustrator: Arthur Ignatius Keller

Release date: October 3, 2021 [eBook #66455]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Doubleday, Page & Company

Credits: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

OTHER BOOKS BY

MEREDITH NICHOLSON

The Main Chance

Zelda Dameron

The House of a Thousand Candles

Poems

The Port of Missing Men

Rosalind at Red Gate

The Little Brown Jug at Kildare

The Hoosiers

(Historical. In National Studies in

American Letters)

JEAN MORLEY

The

Lords of High Decision

By

MEREDITH NICHOLSON

Illustrated by

ARTHUR I. KELLER

New York

Doubleday, Page & Company

1909

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, INCLUDING THAT OF TRANSLATION

INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES, INCLUDING THE SCANDINAVIAN

COPYRIGHT, 1909, BY DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

PUBLISHED, OCTOBER, 1909

TO BOWMAN ELDER AND EDWARD ROBINETTE

IN REMEMBRANCE OF OUR CANOE FLIGHT THROUGH THE

MAINE WOODS, WITH A BACKWARD GLANCE

AT INDIAN JOE

WHO FAILED TO FIND THE MOOSE

Mackinac Island,

September 20, 1909.

And the Fourth Kingdom shall be strong as iron: forasmuch as iron breaketh in pieces and subdueth all things: and as iron that breaketh all these, shall it break in pieces and bruise.

And whereas thou sawest the feet and toes, part of potters’ clay, and part of iron, the kingdom shall be divided; but there shall be in it of the strength of the iron, forasmuch as thou sawest the iron mixed with miry clay.

And as the toes of the feet were part of iron, and part of clay, so the kingdom shall be partly strong and partly broken.

The Book of Daniel.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Face in the Locket | 3 |

| II. | The Lady of Difficult Occasions | 21 |

| III. | A Letter, a Bottle and an Old Friend | 28 |

| IV. | The Ways of Wayne Craighill | 42 |

| V. | A Child of the Iron City | 59 |

| VI. | Before a Portrait by Sargent | 73 |

| VII. | Wayne Counsels his Sister | 86 |

| VIII. | The Coming of Mrs. Craighill | 101 |

| IX. | “Help Me to be a Good Woman” | 114 |

| X. | Mr. Walsh Meets Mrs. Craighill | 126 |

| XI. | Paddock Delivers an Invitation | 144 |

| XII. | The Shadows Against the Flame | 155 |

| XIII. | Jean Morley | 160 |

| XIV. | A Light Supper for Two | 175 |

| XV. | Mrs. Blair is Displeased | 190 |

| XVI. | The Trip to Boston | 206 |

| XVII. | Mrs. Craighill Bides at Home | 224 |

| XVIII. | The Snow-storm at Rosedale | 240 |

| XIX. | Mr. Wingfield Calls on Mr. Walsh | 262 |

| XX. | Evening at the Craighills’ | 274 |

| XXI. | Soundings in Deep Waters | 292 |

| XXII. | A Conference at the Allequippa | 299 |

| XXIII. | The End of a Sleigh-ride | 307 |

| XXIV. | Jean Answers a Question | 317[viii] |

| XXV. | Colonel Craighill is Annoyed | 327 |

| XXVI. | Colonel Craighill Scores a Point | 335 |

| XXVII. | “I’m Going Back to Joe” | 344 |

| XXVIII. | Closed Doors | 355 |

| XXIX. | “You Love Another Man, Jean” | 368 |

| XXX. | The House of Peace | 378 |

| XXXI. | Wayne Sees Jean Again | 397 |

| XXXII. | An Angry Encounter | 408 |

| XXXIII. | The High Moment of Their Lives | 416 |

| XXXIV. | The Heart of the Bugle | 428 |

| XXXV. | Golden Bridge | 446 |

| XXXVI. | Two Old Friends Seek Wayne | 460 |

| XXXVII. | Wayne Visits His Father’s House | 467 |

| XXXVIII. | “They’re Callin’ Strikes on Me” | 475 |

| XXXIX. | We See Walsh Again | 487 |

| XL. | The Belated Appearance of John McCandless Blair | 493 |

| XLI. | “My City—Our City” | 498 |

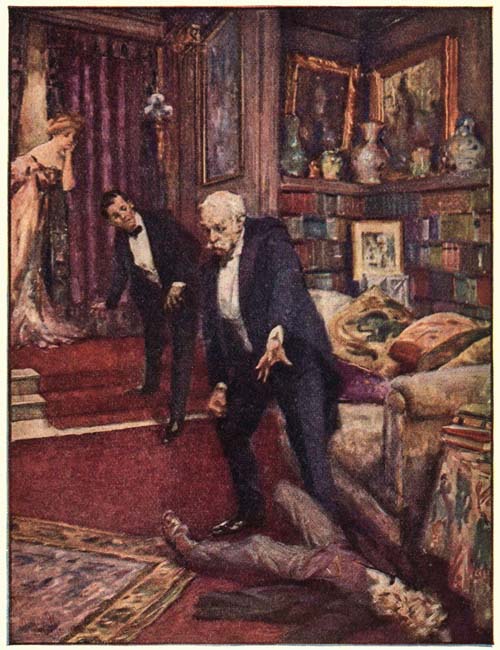

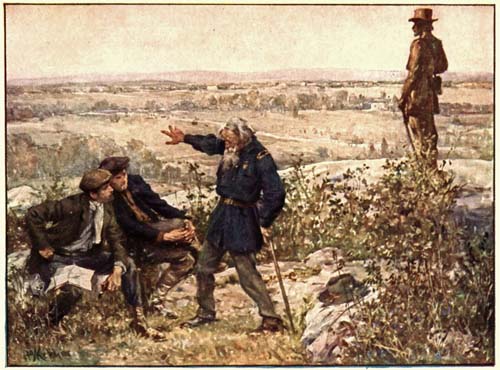

| Jean Morley | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| “Men who work with their hands—these things!” | 322 |

| “There was a dull sound as of a blow struck” | 422 |

| “Ghosts, the ghosts of dead soldiers” | 442 |

THE LORDS OF HIGH DECISION

The Lords of High Decision

AS Mrs. John McCandless Blair entered the house her brother, Wayne Craighill, met her in the hall. The clock on the stair landing was striking seven.

“On time, Fanny? How did it ever happen?” he demanded as she caught his hands and peered into his face. He blinked under her scrutiny; she always gave him this sharp glance when they met,—and its significance was not wasted on him; but she was satisfied and kissed him, and then, as he took her wrap:

“For heaven’s sake what’s up, Wayne? Father was ominously solemn in telephoning me to come over. John’s dining at the Club—I think father wants to see us alone.”

“It rather looks that way, Fanny,” replied Wayne, laughing at his sister’s earnestness.

“Well, is he going to do it at last?”

“There’s no use kicking if he is, so be prepared for the worst.”

“Well, if it’s that Baltimore woman——”

“Or that Philadelphia woman, or the person he met in Berlin—the one from nowhere——”

[4]Their voices had reached Colonel Craighill and he came into the hall and greeted his daughter affectionately.

“Give me credit, papa! I was on time to-night!”

“We will give John credit for sending you. How’s the new car working?”

“Oh, more or less the usual way!”

Dinner was announced and they went out at once, Mrs. Blair taking a place opposite her father at the round table, with Wayne between them.

Roger Craighill was an old citizen; it may be questioned whether he was not, by severe standards, the first citizen of Pittsburg. There were, to be sure, richer men, but his identification with the soberer past of the City of the Iron Heart—before the Greater City had planted its guidons as far as now along the rivers and over the hills—gave indubitable value and dignity to his name. He was interested in many philanthropies and reforms, and he had just returned from Washington where he had attended a conference of the American Reform Federation, of which he was a prominent and influential member. Colonel Craighill, like his son, dressed with care and followed the fashion, and to-night in his evening clothes his daughter thought him unusually handsome and distinguished. He had kept his figure, and his fine colouring had prompted Mr. Richard Wingfield, the cynic of the Allequippa Club, to bestow upon him the soubriquet of Rosy Roger, a pleasantry for which Wingfield had been censured by the[5] governors. But Colonel Craighill’s fine height and his noble head with its crown of white hair, set him apart for admiration in any gathering. He walked a mile a day and otherwise safeguarded his health, which an eminent New York physician assured him once a year was perfect.

Roger Craighill was by all tests the most eligible widower in western Pennsylvania, and gossip had striven for years to marry him to any one of a dozen women imaginably his equals. When the local possibilities were exhausted attention shifted to women of becoming age and social standing in other cities—New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore—Colonel Craighill’s frequent absences from home lending faint colour of truth to these speculations. His daughter, Mrs. John McCandless Blair, had often discussed the matter with her brother, but without resentment, save occasionally when some woman known to them and distasteful or particularly unsuitable from their standpoint was suggested. It was indicative of the difference in character and temperament between brother and sister that Wayne was more captious in his criticisms of the presumptive candidates for their mother’s place in the old home than his sister. When, shortly after Mrs. Craighill’s death, Wayne’s dissolute habits became a town scandal there were many who said that things would have gone differently if his mother had lived; that Mrs. Craighill had understood Wayne, but that his father was wholly out of sympathy with him.

[6]Mrs. John McCandless Blair was immensely aroused now by the suspicion that her father was about to bring home a second wife, and she steeled her heart against the unknown woman. She was not in the least abashed by her father, who never took her seriously. He began describing his visit to Washington, to cover the four courses of the family dinner that must be eaten before—with proper deliberation and the room freed of the waitress—he apprised his children of the particular purpose of this family gathering.

Colonel Craighill was a capital talker and he gave an intimate turn to his account of the Washington meeting, uttering the names of his distinguished associates in the Federation with frank pride in their acquaintance. A Southern bishop, far-famed as a story-teller, was a member and Colonel Craighill repeated several anecdotes with which the clergyman had enlivened the conferences. He quoted one or two periods from his own speech at the dinner, and paused for Mrs. Blair and Wayne to admire their aptness. With a nice sense of climax he mentioned last his invitation to luncheon at the White House, where there was only one other guest—a famous English statesman and man of letters.

“It was really quite en famille. My impression of the President was delightful; I confess that I had wholly misjudged him. He addressed many questions to me directly—asking about political conditions here at home in such a way that I had[7] to do a good deal of talking. As I was leaving he detained me a moment and asked my opinion of the business outlook. I was amazed to see how familiar he appeared to be with the range of my own interests. He told me that if I had suggestions at any time as to financial policies he wished I would come down and talk to him personally. But the published reports of my visit to the White House annoyed me greatly. I thought it only just to myself to write him a line to repudiate the interview attributed to me. There have, of course, been rumours of cabinet changes, but I don’t want office—all I ask is to be of some service to my fellow-men in the rôle of a private citizen.”

Mrs. Blair murmured sympathetic responses through this recital. Wayne ate his salad in silence. He knew that his father enjoyed nothing so much as these conferences in behalf of good causes; they required a great deal of time, but Colonel Craighill had reached an age at which he could afford to indulge himself. If he enjoyed delivering addresses and making after-dinner speeches it was none of Wayne’s affair. Their natures were antipodal. Wayne cared little what his father did, one way or another.

Mrs. Blair fell to chaffing her father about the work of the Federation. Her curiosity as to the nature of the announcement he had said he wished to make grew more acute as the minutes passed, and she talked with rather more than her usual nervous volubility.

[8]“Just think,” she exclaimed, “of drinking champagne over the building of schools for poor negroes! If you would send them the champagne how much more sensible it would be! There’s a beautiful idea. Why not found a society for providing free champagne for the poor and needy!”

“It’s not for you to deride, Fanny. Only a little while ago you were raising a fund for the restoration of a Buddhist temple somewhere in darkest Japan—the merest fad. I remember that Doctor McAllister wrote me a letter expressing surprise that a daughter of mine should be aiding a heathen enterprise.”

“It was too bad, papa! But the temple is all restored now, and we had a little fund left over after the work was done—I was treasurer and didn’t know what else to do with it—so I gave it to help build an Episcopal parish house at Ironstead. And to-day I was out there in the machine and behold! Jimmy Paddock is running that parish house and a mission and is no end of a power in the place.”

“Paddock? What Paddock?” asked Wayne.

“Why, Jimmy Paddock. Don’t you remember him? You knew him in your prep. school, and he was on the eleven at Harvard while you were at the ‘Tech.’”

“Not the same man,” declared Wayne. “I knew my Jimmy like a top; he was no monk—not by a long shot. Besides, his family had money to burn. No parish house larks for Jim. He knew how to order a dinner!”

[9]“It just happens,” replied Mrs. Blair, “that I knew Jimmy, too, back in your college days and I declare that I saw him this afternoon at Ironstead. I was out there looking for a maid who used to work for us and I met Jimmy Paddock in the street—a very disagreeable street it was, too. You know he was always shy and he seemed terribly embarrassed. It was hard work getting anything out of him; but he’s our old Jimmy and he’s a regular minister—went off and did it all by himself and has been out there at Ironstead for six months—all through the hot weather.”

“Does he wear a becoming habit and hold quiet days for women?” asked Wayne. “I remember that you affected the Episcopalians for a while—for about half of one Lent! That was just before those table-tippers buncoed you into introducing them to our first families.”

“That is unworthy of you, Wayne!” and Mrs. Blair frowned at her brother with mock indignation. “Nobody ever really explained some of the things those mediums did. They certainly told me things——!”

“I’ll wager they did,” laughed Wayne. “But go on about Jimmy.”

“He’s just a plain little minister—no habit or anything like that. He’s wonderful with men and boys. He thanked me for helping with the parish house, and when candour compelled me to tell him that I didn’t know it was his enterprise and that he had got what was left after restoring a Buddhist[10] temple, he smiled in just his old boyish way, and I made him get in the machine and take me to see the place, which is the simplest. There was a sign on the door of the parish house that said, ‘Boxing Lessons Tuesday Night, by a Competent Instructor. All Welcome.’ And it was signed ‘J. Paddock, Rector.’”

“If this minister is the boy we knew when Wayne was at St. John’s I should think he would have come to see us,” remarked Colonel Craighill. “We used to meet his family now and then.”

“I scolded him for not telling us he’s here; and he said he had been too busy. He asked all about you, Wayne—said he was going to look you up; but when I asked him to come and dine with us he was so unhappy in trying to get out of it that I told him not to bother. He’s perfectly devoted to his work, and they say the people out there are crazy about him.”

“Dear old Jimmy!” mused Wayne. “I wonder how he’s kept it so dark. You never can tell! Jimmy used to exhaust his chapel cuts the first week every term. If he’s taken to saving souls, though, he’ll do it; he hangs on like a bull pup. I can see him now at that last Thanksgiving game going down the field with the ball under his arm—he was as fast as lightning. I’d like to take a few boxing lessons from Jimmy myself, if he’s in the business.”

Coffee was served; Mrs. Blair dropped the Reverend James Paddock and watched her father choose his single lump of sugar. He refused a cigar but[11] waited until Wayne had lighted a cigarette before he dismissed the waitress and began.

“It must have occurred to you both that I might at some time marry again.”

“Yes, father; I suppose that possibility has occurred to many people,” replied his daughter, feeling that something was required at once. Wayne said nothing, but drew his chair back from the table and crossed his legs.

“I want you to understand that your dead mother’s life is a precious—a very precious memory. My determination to marry means no disloyalty to her.”

He bowed his head and drew one hand lightly across the table.

“I have been lonely at times; the management of the house in itself has been a burden, but I have not liked to give it up. I might have gone to live with you, Fanny,—you and John have been kind in urging me—but you have your own family; and as long as Wayne is unmarried the old place must be his home. The change I propose making will have no effect on your status in my house, Wayne—none whatever!”

“Thank you; I appreciate that, sir.”

“In fact,” continued Colonel Craighill, addressing his son, “you both understand that the house is really yours—I have only a life tenancy here—that was your mother’s wish and she so made her will. Maybe you don’t remember that this property was never mine. Your mother inherited a large[12] tract of land up here from her father, and after I built the house the title remained in her name—the homestead will be yours, Wayne; your mother made it up to Fanny in other ways.”

“I understand—but wouldn’t it be better for me to leave—for a time at least—after your marriage?”

“No; I couldn’t think of that, and I’m sure Adelaide would be very uncomfortable if she felt you were being driven from home. And, moreover, you know how prone people are to gossip. It must not be said that my son left his father’s house through any act of mine.”

“The old story of the cruel stepmother!” smiled Wayne; but his father went on gravely, as though to rebuke this levity.

“There are ways in which you have been a great grief to me; I had not meant to speak of that, but Fanny has been a good sister to you and she knows the whole story. I should like you to remember—to remember that you are my son!”

Wayne nodded, but did not speak. After a moment his father resumed, addressing them both.

“I have known the lady I am to marry a comparatively short time, but I have become deeply attached to her. She is young, but that is not her fault”—and Colonel Craighill smiled—“or mine! Her father died when she was still a child, and she has lived abroad with her mother much of the time. She is of an old Vermont family. The marriage is to take place in a fortnight and by our own wish[13] will be altogether simple and quiet. Please do not mention this; I have to go to Cleveland to-morrow for a day or two and I shall make the announcement when I return. I have thought to save your feelings and to prevent embarrassment all round by not asking either of you to the ceremony. We shall meet in New York and go quietly to Doctor McAllister’s residence—he is an old friend whom I have known long in church affairs—and we shall come home immediately. The name of the lady is Allen—Miss Adelaide Allen. I am sure you will learn to like her—that you and Fanny will see and appreciate the fine qualities in Miss Allen that have won my admiration and affection.”

There was a moment’s silence when he concluded. The candle nearest him sputtered and he adjusted it carefully. Then Mrs. Blair rose and kissed him.

“You sly old daddy!” she broke out; “and you never told a soul! Well”—and she seated herself again at the table and nibbled a bonbon—“tell us what she’s like, and her ways and her manners. I suppose, of course, she’s a teacher in one of your negro schools, or a foreign missionary or something noble like that! Tell us everything—everything——” and Mrs. Blair, elbows on table, denoted the breadth of her demand by an outward sweep of her hands from the wrists.

Colonel Craighill smiled indulgently in the enjoyment of his daughter’s eagerness.

“Tell us everything—her just being from Vermont doesn’t mean much. Is she a blonde?”

[14]“Well,” replied Colonel Craighill, colouring slightly, “Now that I think of it, I believe she is!”

“I knew it!” exclaimed Mrs. Blair; “they’re always blondes! What are her eyes?”

“Blue.”

“Stout or thin?”

“I think her proportions are about right for her age.”

“Which is——?”

“Twenty-nine.”

“Are you sure about that, papa? You know they sometimes forget to count their birthdays.”

“Whom do you mean by they?” asked Colonel Craighill guardedly.

“I mean the members of my delightful sex. Let me see, you are sixty-five, if I remember right. Twice twenty-nine is”—she made the computation on her slim, supple fingers—“fifty-eight: you’re rather more than twice her age.”

“It would be more polite, to say that she’s rather less than half mine.”

“Oh, it all gets to the same place! It will have the advantage of making me appear young to have a stepmother a few years my junior. But what a blow to these old dowagers who have been suspected of having designs on you! They little knew that all the time they were pursuing you to consult about their investments or church or charity schemes, you were casting about for some lovely young thing still in the lawful possession of her own hair and teeth. Why, if I’d known that was your idea there[15] are lots of nice girls here in town that I should love to have in the family. Wayne, you will be careful not to flirt with her!”

“Fanny!”

Colonel Craighill struck the table so sharply that the candlesticks jumped. He was angry, and the colour deepened in his face.

“Please, papa,—I didn’t mean to be rude!”

Mrs. Blair touched her father’s coat-sleeve lightly with her hand. She loved her brother very dearly, and the effect upon him of this marriage was already, in her vivid imagination, the chief thing in it. She had long felt that her father had given Wayne up; that he believed the passion for drink that took hold of his son at times was in the nature of a disease, to be suffered patiently and borne with Christian fortitude.

Wayne was vexed at his sister’s manner; he disliked contention and there was nothing to be gained by being disagreeable over their father’s marriage. He left the room to find fresh cigarettes and when he came back the air had cleared. Colonel Craighill, anxious on his part to be conciliatory, was laughing at a renewal of Fanny’s cross-questioning.

“Where did Miss Allen attend school?” she was asking.

“I believe she had private teachers,” replied Colonel Craighill, though not positively.

“And she isn’t a teacher herself or a philanthropist? Has she money?”

“She and her mother are, I believe, in comfortable[16] circumstances. I hope that you and Wayne will appreciate the difficulties before this lady in becoming my wife—that she is stepping into a place where she will be criticized unkindly from the very fact of my position here and the disparity in our years and fortunes. I appeal to you, Fanny, as to one woman on behalf of another. You can make her way easy if you will.”

He had, with the best intentions in the world, struck the wrong note. In so many words, he was asking mercy where there had been no accusation. Mrs. Blair had not the slightest intention of committing herself to any policy toward her father’s new wife. So far as the public was concerned she would carry off the situation with outward acceptance and approval; but just now she declined to consider the question in the key her father had sounded. To him she was a frivolous person with unaccountably erratic ways, and with nothing of his own measure or sobriety. She made no reply whatever to his appeal, but chose another bonbon and ate it with exasperating slowness. Wayne saw—as her father did not—that she was angry; but Mrs. Blair fell back upon the half-mocking mood with which she had begun, demanding:

“Is she modish? Does she wear her clothes with an air?”

“I hope,” said Colonel Craighill, betrayed into the least show of resentment by her refusal to meet his question—“I hope, Fanny, that she dresses like a lady.”

[17]“So do I, papa, if it comes to that! You haven’t told us yet how you came to meet Miss Allen.”

“It was last spring when I went to Bermuda. She and her mother were on the steamer. I saw a good deal of them then; and I have since seen them in New York, which is now really their home.”

“Have they ever been here?—I have known Allens.”

“I’m quite sure you have never met them, Fanny. Since Adelaide’s father died they have travelled much of the time.”

“So your frequent trips to New York haven’t been wholly philanthropy and business! You speak her name as though you had got well used to it. It’s funny, but I’ve never known Adelaides. Have you ever known an Adelaide, Wayne?”

“A lot of them; so have you if you will think of it,” answered her brother. He saw that his father was growing restive and he knew that Fanny was going too far. There was a point at which she could vex those who loved her most, but being wiser than she seemed she usually knew it herself. She pushed away the bonbon dish and slapped her hands together lightly.

“Wayne,” she cried, “what are we thinking of? We must see her picture! Now, papa! you know you have it in your pocket!”

“Certainly, we must see Miss Allen’s picture,” echoed Wayne, relieved at his sister’s change of tone.

[18]“Later—later!” but Colonel Craighill’s annoyance passed and he smiled again.

“It isn’t dignified in you to invite teasing, papa. You know you have her photograph. Out with it, please!”

She bent toward him as though threatening his pockets. He laughed, but coloured deeply; then he drew from his waistcoat a thin silver case a trifle larger than a silver dollar, and suffered Fanny to take it.

“Now,” said Colonel Craighill, settling himself in his chair, “you see I am not afraid, Fanny, of even your severe judgment.”

She weighed the unopened trinket in her palm as though taunting her curiosity. Wayne lighted a fresh cigarette and turned toward his sister. He was surprised at his own indifference; but he feigned curiosity to please his father, who naturally wished his children to be interested and pleased. Fanny opened the locket and studied it carefully for an instant.

“Charming! Perfectly charming!” she exclaimed; and then, holding it close and turning her head and pursing her lips as she studied the face, “but I thought you didn’t like such fussy hair dressing—you always told me so. I don’t like the ultra-marcelling; but it’s well done—and if it’s all hers and she can manage it without a rat she’s a wonder. You’ve always decried the artificial, but I see you’re finding that Nature has her weak points. Those eyes are just a trifle inscrutable, a little heavy-lidded[19] and dreamy—but we’ll have to see the original. Her nose seems regular enough, and her mouth—well, I wouldn’t trust any photograph to tell the truth about a mouth. She’s young—my own lost youth smites me! Here, Wayne, behold her counterfeit presentment!”

Wayne inhaled a last deep draught of his cigarette and dropped it into the ash tray. He took the case into his fingers and bent over it, a slight smile on his lips.

“Be careful! Be careful!” ejaculated his sister. “This is a crucial moment.”

Wayne’s empty hand that lay on the table slowly opened and shut; the smile left his lips, but he continued to study the picture.

“Well, Wayne! Are you having so much trouble to make up your mind?” demanded Mrs. Blair, her keen sensibilities aroused by the fixedness of Wayne’s stare at the likeness before him and the resulting interval of suspense. There was something here that she did not grasp, and she was a woman who resented being left in the dark. This interview with her father had been trying enough, but her brother’s manner struck her ominously. Colonel Craighill smiled urbanely, undisturbed by his son’s prolonged scrutiny of the face in the locket; he attached no great importance to Wayne’s opinions on any subject. To Mrs. Blair, however, the silence became intolerable and she demanded:

“Are you hypnotized—or what has struck you, Wayne?”

[20]“Nothing at all!” he laughed, closing the locket and handing it back. “I have no criticism—most certainly none. Father, I offer my congratulations.”

And this happened midway of September, in the year of our Lord nineteen hundred and seven.

THE Lady of Difficult Occasions—such was the title conferred upon Mrs. John McCandless Blair by Dick Wingfield—looked less than her thirty-two years. A slender, nervous woman, Mrs. Blair had contributed from early girlhood to the picturesqueness of life in her city. Her interests were many and varied; she did what she liked and was supremely indifferent to criticism. She wore colours that no other woman would have dared; for colour, she maintained, possesses the strongest psychical significance, and to keep in tune with things infinite one’s wardrobe must reflect the rainbow. She had tried all extant religions and had revived a number long considered obsolete; her garret was a valhalla of discarded gods. One day the scent of joss-sticks clung to the draperies of her library, the next she dipped her finger boldly in the holy water font at the door of the Catholic cathedral and sent a subscription to the Little Sisters of the Poor.

She appeared fitfully in the Blair pew at Memorial Presbyterian Church, where her father was ruling elder and her husband passed the plate; and Memorial, we may say, was the most fashionable[22] house of prayer and worship in town, frowning down severely upon the Allequippa Club over the way. “Fanny Blair is sure of heaven,” Dick Wingfield said, “for she has tickets to all the gates.” Mrs. Blair was generous in her quixotic fashion; her husband had inherited wealth, and he was, moreover, a successful lawyer, who admired her immensely and encouraged her foibles. She dressed her twin boys after portraits of the Stuart princes, and their velvet and long curls caused many riots at the public school they attended—sent there, she said, that they might grow up strong in the democratic spirit.

When they had adjourned to the library Mrs. Blair spoke in practical ways of the new wife’s home-coming. She tendered her own services in any changes her father wished in the house. Some of her mother’s personal belongings she frankly stated her purpose to remove. They were things that did not, to Colonel Craighill’s masculine mind, seem particularly interesting or valuable. Wayne grew restless as his father and sister considered these matters. He moved about idly, throwing in a word now and then when Mrs. Blair appealed to him directly. Evenings at home had become unusual events, and domestic affairs bored him. Mrs. Blair was, however, sensitive to his moods and she continued her efforts to hold him within the circle of their talk.

“Don’t you think a reception—something large and general—would be a good thing at the start, Wayne?”

[23]“Yes; oh, yes, by all means,” he replied, looking up from a publisher’s advertisement that he had been reading.

He left the room unnoticed a few minutes later and wandered into the wide hall, feeling the atmosphere of the house flow around him. It was the local custom, in our ready American fashion of conferring antiquity, to speak of the mansion as the old Craighill place. The house, built originally in the early seventies, had recently been remodelled and enlarged. It occupied half a block, and the grounds were beautifully kept, faithful to traditions of Mrs. Craighill’s taste. The full force of the impending change in his father’s life now struck Wayne for the first time. There is no eloquence like that of absence. He stood by the open drawing room door with his childhood and youth calling to all his senses. The thought of his mother stole across his memory—a gentle, bright, smiling spirit. The pictures on the walls; the familiar furniture; the broad fireplace; the tall bronze vases that guarded the glass doors of the conservatory, whose greenery showed at the end of the long room—those things cried to him now with a new appeal. A great bowl of yellow chrysanthemums, glowing in a far corner, struck upon his sight like flame. He walked the length of the room and gazed up at a portrait of his mother, painted in Paris by a famous artist. Its vitality had in some way vanished; the figure no longer seemed poised, ready to step down into the room. The luminous quality of the[24] face was gone; the eyes were not so brightly responsive as of old—he was so sure of these differences that he flashed off the frame lights with a half-conscious feeling that a shadow had fallen upon the spirit represented there, and that it was kinder to leave it in darkness.

His sister called him on some pretext—he was very dear to her and the fact that he and his father were so utterly unsympathetic increased her tenderness—and repeated the programme of entertainments which she had proposed.

“It’s quite ample. There’s never any question about your doing enough, Fanny,” he remarked indifferently.

Colonel Craighill announced that he must go down to the Club to a meeting of the Executive Committee of the Greater City Improvement League, in which his son-in-law was interested.

“Wayne, you will take Fanny home in your own car, won’t you? Or maybe you’ll wait for John to stop?”

“I must go soon; Wayne will look after me,” she said, and they both went to the door to see their father off.

“It’s like old times,” she sighed, as the motor moved away; “but those times won’t come any more.”

Then with a change of manner she turned upon Wayne and seized his hands.

“Wayne, have you ever seen that woman before?”

He shook himself free with a roughness that was unlike him.

[25]“Don’t be silly: of course not. I never heard of her. How did you get that idea?”

“You looked as though you were seeing a ghost when you looked at her picture.”

“I was thinking of ghosts, Fanny, but I wasn’t seeing one.” He lighted a cigar. “I must say that your tact sometimes leaves you at fatal moments. The Colonel was almost at the point of getting mad. He wanted to be jollied—and you did all you could to irritate him.”

“I had a perfect right to say what I pleased to him. How do you suppose he came to walk into this adventuress’s trap? A girl of twenty-nine! The hunt will be up as soon as he makes the announcement and the whole town will join the pack.”

“The town will have to stand it if we can.”

“It’s the loss of his own dignity, it’s the affront to mother’s memory—this young thing with her pretty marcelled head! There are some things that ought to be sacred in this world, and father ought to remember what our mother was—how noble and beautiful!”

“Well, we know it, Fanny; she’s our memory now—not his,” said Wayne gently; and upon this they were silent for a time, and Fanny wept softly. When Wayne spoke again it was in a different key.

“Well, father has his nerve to be getting married right on the verge of a panic. Perhaps he is doing it merely to reassure the public, to steady the market, so to speak.”

[26]“But papa says there will be no panic. The Star printed a long interview with him only yesterday. He says there must be a readjustment of values, that’s all; he must be right about it.”

“Bless you, yes, Fanny. If father says there won’t be any panic, why, there won’t! What does John say?”

“Well, John is always cautioning me about our expenses,” she admitted ruefully, so that he laughed at her. “But great heavens, Wayne!” she exclaimed.

“Well, what’s the matter now?”

“Why, he never told us a thing about her. Who do you suppose introduced him to her?”

“My dear Fanny,” began Wayne, thrusting his long legs out at comfortable ease, “can you imagine our father dear being worked? He backed off and sparred for time when you wanted to marry John, though John belongs to our old Scotch-Irish Brahmin caste, because a Blair once owned a distillery back in the dark ages, and there was no telling but the sins of the rye juice might be visited on your children to the third and fourth generation if you married John. And if I had craved the Colonel’s permission to marry some girl in another town—some girl, let us say, that I had met on a steamer going to Bermuda—you may be dead sure he would have put detectives on her family and had a careful assay made of her moral character. Trust the Colonel, Fanny, for caution in such matters! Don’t you think for a minute that he[27] hasn’t investigated Miss Adelaide Allen’s family into its most obscure and inaccessible recesses! Our father was not born yesterday; our father is the great Colonel Roger Craighill, a prophet honoured even on his own Monongahela. Father never makes mistakes, Fanny. I’m his only mistake. I’m a great grief to father. He has frequently admitted it. He begs me please not to forget that I am his son. I am beyond any question a bad lot; I have raised no end of hell; I have frequently been drunk—beastly, fighting drunk. And father will go to his dear pastor and ask him to pray for me, and he will admit to old sympathizing friends that I’m an awful disappointment to him. That’s the reason he stopped lecturing me long ago; he doesn’t want me to keep sober; when I get drunk and smash bread wagons in the dewy dawn with my machine after a night among the ungodly he puts on his martyr’s halo and asks his pastor to plead with God for me!”

“Wayne! Wayne! What’s the matter with you?”

He had spoken rapidly and with a bitterness that utterly confounded her; and he laughed now mirthlessly.

“It’s all right, Fanny. I’m a rotten bad lot. No wonder the Colonel has given me up; but I have the advantage of him there: I’ve given myself up! Yes, I’ve given myself up,” he repeated, and nodded his head several times as though he found pleasure in the thought.

WHEN Wayne had taken Mrs. Blair to her own home and had promised on her doorstep to be “good” and to come to her house soon for a further discussion of family affairs, he told Joe, the chauffeur, that he wished to drive the machine, and was soon running toward town at maximum speed.

Joe, huddled in an old ulster, watched the car’s flight with misgivings, for this mad race preluded one of Wayne’s outbreaks; and Joe was no mere hireling, but a devoted slave who grieved when Wayne, as Joe put it, “scorched the toboggan.”

Joe Denny’s status at the Craighill house was not clearly defined. He lodged in the garage and appeared irregularly in the servants’ dining room with the recognized chauffeur who drove the senior Craighill in his big car. It had been suggested in some quarters that Colonel Craighill employed Joe Denny to keep track of Wayne and to take care of him when he was tearing things loose; but this was not only untrue but unjust to Joe. Joe had been a coal miner before he became the “star” player of the Pennsylvania State League, and Wayne had marked his pitching one day while[29] killing time between trains at Altoona. His sang froid—an essential of the successful pitcher, and the ease with which he baffled the batters of the opposing nine, aroused Wayne’s interest. Joe Denny enjoyed at this time a considerable reputation, his fame penetrating even to the discriminating circles of the National League, with the result that “scouts” had been sent to study his performances. When a fall from an omnibus interrupted Joe’s professional career, Wayne, who had kept track of him, paid his hospital charges, and Joe thereupon moved his “glass” arm to Pittsburg. By shrewd observation he learned the management of a motor car, and attached himself without formality to the person of Wayne Craighill. For more than a year he had thus been half guardian, half protégé. Wayne’s friends had learned to know him; they even sent for him on occasions to take Wayne home when he was getting beyond control; and Wayne himself had grown to depend upon the young fellow. It was something to have a follower whom one could abuse at will without having to apologize afterward. Besides, Joe was wise and keen. He knew all the inner workings of the Craighill household; he advised the Scotch gardener in matters pertaining to horticulture, to the infinite disgust of that person; he adorned the barn with portraits of leading ball players, cut from sporting supplements, and this gallery of famous men was a source of great irritation to Colonel Craighill’s solemn German chauffeur, who had not[30] the slightest interest in, or acquaintance with, the American national game. Joe’s fidelity to Wayne’s interests was so unobtrusive and intelligent that Wayne himself was hardly conscious of it. Such items of news as the prospective arrival or departure of Colonel Craighill; the fact that he was trading his old machine for a new one; or that Walsh, Colonel Craighill’s trusted lieutenant, had bought a new team of Kentucky roadsters for his daily drive in the park—or that John McCandless Blair, Wayne’s brother-in-law, was threatened with a nomination for mayor on a Reform ticket—such items as these Joe collected through agencies of his own and imparted to Wayne for his better instruction.

To-night the lust for drink had laid hold upon Wayne and his rapid flight through the cool air sharpened the edge of his craving in every tingling, excited nerve. His body swayed over the wheel; he passed other vehicles by narrow margins that caused Joe to shudder; and policemen, looking after him, swore quietly and telephoned to headquarters that young Craighill was running wild again. He had started for the Allequippa Club, but, remembering that his father was there, changed his mind. The governors of the Penn, the most sedate and exclusive of the Greater City’s clubs, had lately sent a polite threat of expulsion for an abuse of its privileges during a spree, and that door was shut in his face. The thought of this enraged him now as he spun through the narrow streets[31] in the business district. Very likely all the clubs in town would be closed against him before long. Then with increased speed he drove the car to the Craighill building, told Joe to wait, passed the watchman on duty at the door and ascended to the Craighill offices.

A lone book-keeper was at work, and Wayne spoke to him and passed on to his own room.

He turned on the lights and began pulling out the drawers of his desk, turning over their contents with a feverish haste that increased their disorder. Presently he found what he sought: a large envelope marked “Private, W. C.” in his own hand. He slapped it on the desk to free it of dust, then tore it open and drew out a number of letters, addressed in a woman’s hand to himself, and a photograph, which he held up and scrutinized with eyes that were disagreeably hard and bright. It was not the same photograph that his father had shown at the dinner table, but it represented another view of the same head—there was no doubt of that. He studied it carefully; it seemed, indeed, to exercise a spell upon him. He recalled what Mrs. Blair had said about the eyes; but in this picture they seemed to conspire with a smile on the girl’s lips to tease and tantalize.

A number of letters that had been placed on his desk after he left the office caught his eye. One or two invitations to large social affairs he tossed into the waste-paper basket; he was only bidden now to the most general functions. He caught up an[32] envelope bearing the legend of a New York hotel and a typewritten superscription. He tore this open, still muttering his wrath at the discarded invitations, and then sat down and read eagerly a letter in a woman’s irregular hand dated two days earlier:

“My dear Wayne:

“You wouldn’t believe I could do it, and I am not sure of it yet myself; but I wanted to prepare you before he breaks the news. There’s a whole lot to tell that I won’t bore you with—for you do hate to be bored, you crazy boy. Wayne, I’m going to marry your father! Don’t be angry—please! I know everything that you will think when you read this—but mama has driven me to it. She never forgave me for letting you go, and life with her has become intolerable. And please believe this, Wayne. I really respect and admire your father more than any man I have met, and can’t you see what it will mean to me to get away from this hideous life I have been leading? Why, Wayne, I’d rather die than go on as we have lived all these years, knocking around the world and mama raising money to keep us going in ways I can’t speak of. You know the whole story of that. I let mama think I am doing this to please her, but I am not. I am doing it to get away from her. I have made her promise to let me alone, and I will do all I can for her. She’s going abroad right after my marriage and I hate to say it of my own mother, but I hope never to see her again.

“Of course you could probably stop the marriage by telling your father how near we came to hitting it off. I have always felt that you were unjust to[33] me in that—I really cared more for you than I knew—but that’s all over now. That was another of mama’s mistakes. She let her greed get the better of her and I suffered. But let us be good friends—shan’t we? You know more about me than anybody, Wayne—how ignorant I am, and all that. Why, I had to study hard—mama suggested it, that’s the kind of thing she can do—to learn to talk to your father about politics and philanthropy and those things. If anything should happen—if you should spoil it all, I don’t know what mama would do; but it would be something unpleasant, be sure of that. She sold everything we had to follow your father about to those small, select places he loves so well.

“I am going to try to live up to your father’s good name. I don’t believe I’m bad. I’m just a kind of featherweight; and you will be nice to me, won’t you, when I come? Your father has told me everything—about the old house and how it belongs to you. Of course you won’t run away and leave me and you will help me to hit it off with your sister, too. He says she’s a little difficult, but I know she must be interesting. As you see, I’ve taken mama’s name by her second marriage since our little affair. Explanations had grown tiresome and mama enjoys playing to the refined sensibilities of those nice people who think three marriages are not quite respectable for one woman....”

He read on to the end, through more in the same strain. He flinched at the reference to the home and to his sister, but at the close he lighted a cigarette and re-read the whole calmly.

[34]“It was your dear mother that caught the Colonel, Addie; you are pretty and you like clothes and you know how to wear them, but you haven’t your dear mother’s strategic mind. Oh, you were a sucker, Colonel, and they took you in! You are so satisfied with your own virtue, and you are so pained by my degradation! Let’s see where you come out.”

He continued to mutter to himself as he re-folded the letter. He grinned his appreciation of the care which had caused its author to avoid the placing of any tell-tale handwriting on the envelope. “I’m a bad, bad lot, Colonel, but there are traps my poor wandering feet have not stumbled into.”

He glanced hurriedly at the packet of letters that he had found with the photograph and then thrust this latest letter in with the others and locked them all in a tin box he found in one of the drawers. When this had been disposed of he pulled the desk out from the wall and drew from a hidden cupboard in the back of it a quart bottle of whiskey and a glass. The sight of the liquor caused the craving of an hour before to seize upon him with renewed fury. He felt himself suddenly detached, alone, with nothing else in the world but himself and this bright fluid. It flashed and sparkled alluringly, causing all his senses to leap. At a gulp his blood would run with fire, and the little devils would begin to dance in his brain, and he could plan a thousand evil deeds that he was resolved to do. He was the Blotter, and a blotter was a worthless[35] thing to be used and tossed aside by everyone as worthless. He would accept the world’s low appraisement without question, but he would take vengeance in his own fashion. He grasped the bottle, filled the glass to the brim and was about to carry it to his lips when the clerk whom he had passed in the outer office knocked sharply, and, without waiting, flung open the door.

“Beg pardon, but here’s a gentleman to see you, Mr. Craighill.”

With the glass half raised, Wayne turned impatiently to greet a short man who stood smiling at the door.

“Hello, Craighill!”

“Jimmy Paddock!” blurted Wayne.

The odour of whiskey was keen on the air and Wayne’s hand shook with the eagerness of his appetite; but the fool of a clerk had surprised him at a singularly inopportune moment. He slowly lowered the glass to the desk, his eyes upon his caller, who paused on the threshold for an instant, then strode in with outstretched hand.

“That delightful chauffeur of yours told me you were here and I thought I wouldn’t wait for a better chance to look you up. Had to come into town on an errand—was waiting for the trolley—recognized your man and here I am! Well!”

The glass was at last safe on the desk and Wayne, still dazed by the suddenness with which his thirst had been defrauded, turned his back upon it and greeted Paddock coldly. The Reverend James[36] Paddock had already taken a chair, with his face turned away from the bottle, and he plunged into lively talk to cover Craighill’s embarrassment. They had not met for five years, and then it had been by mere chance in Boston, when they were both running for trains that carried one to the mountains and the other to the sea. Their ways had parted definitely when they left their preparatory school, Wayne to enter the “Tech,” Paddock to go to Harvard. Wayne was not in the least pleased to see this old comrade of his youth: there was a wide gulf of time to bridge and Wayne shrank from the effort of flinging his memory across it. As Paddock unbuttoned his topcoat, Wayne noted the clerical collar—noted it, it must be confessed, with contempt. He remembered Paddock as a rather silent boy, but the young minister talked eagerly with infinite good spirits, chuckling now and then in a way that Wayne remembered. As his resentment of the intrusion passed, some reference to their old days at St. John’s awakened his curiosity as to one or two of their classmates and certain of the masters, and Wayne began to take part in the talk.

Jimmy Paddock had been a homely boy, and the years had not improved his looks. His skin was very dark, and his hair black, but his eyes were a deep, unusual blue. A sad smile somehow emphasized the plainness of his clean-shaven face. He spoke with a curious rapidity, the words jumbling at times, and after trying vaguely to recall some[37] idiosyncrasy that had set the boy apart, Wayne remembered that Paddock had stammered, and this swift utterance with its occasional abrupt pauses was due to his method of conquering the difficulty. Behind the short, well-knit figure Wayne saw outlined the youngster who had been the wonder of the preparatory school football team for two years, and later at Harvard the hero of the ’Varsity eleven. There was no question of identification as to the physical man; but the boy he had known had led in the wildest mischief of the school. He distinctly recollected occasions on which Jimmy Paddock had been caned, in spite of the fact that he belonged to a New England family of wealth and social distinction. Paddock, with his chair tipped back and his hands thrust into his pockets, volunteered answers to some of the questions that were in Wayne’s mind.

“You see, Craighill, when I got out of college my father wanted me to go into the law, but I tried the law school for about a month and it was no good, so I chucked it. The fact is, I didn’t want to do anything, and I used to hit it up occasionally and paint things to assert my independence of public opinion. It was no use; couldn’t get famous that way; only invited the parental wrath. Then a yellow newspaper printed a whole page of pictures of American degenerates, sons of rich families, and would you believe it, there I was, like Abou Ben Adhem, leading all the rest! It almost broke my mother’s heart, and my father stopped speaking[38] to me. It struck in on me, too, to find myself heralded as a common blackguard, so I went into exile—way up in the Maine woods and lived with the lumber-jacks. Up there I met Paul Stoddard. He’s the head of the Brothers of Bethlehem who have a house over here in Virginia. The brothers work principally among men—miners, sailors, lumbermen. It’s a great work and Stoddard’s a big chap, as strong as a bull, who knows how to get close to all kinds of people. I learned all I know from Stoddard. One night as I lay there in my shanty it occurred to me that never in my whole stupid life had I done anything for anybody. Do you see? I wasn’t converted, in the usual sense”—his manner was wholly serious now, and he bent toward Wayne with the sad little smile about his lips—“I didn’t feel that God was calling me or anything of that kind; I felt that Man was calling me: I used to go to bed and lie awake up there in the woods and hear the wind howling and the snow sifting in through the logs, and that idea kept worrying me. A lot of the jacks got typhoid fever, and there wasn’t a doctor within reach anywhere, so I did the best I could for them. For the first time in my life I really felt that here was something worth doing, and it was fun, too. Stoddard went from there down to New York to spend a month in the East Side and I hung on to him—I was afraid to let go of him. He gave me things to do, and he suggested that I go into the ministry—said my work would be more effective with an[39] organization behind me—but I ducked and ducked hard. I told him the truth, about what I didn’t believe, this and that and so on; but he put the thing to me in a new way. He said nobody could believe in man who didn’t believe in God, too! Do you get the idea? Well, I was a long time coming to see it that way.

“It was no good going home to knock around and no use discussing such a thing with my family, and I knew people would think me crazy. Stoddard was going West, to do missionary stunts in Michigan, where there were more lumber camps, so I went along. I used to help him with the lumber-jacks, and try to keep the booze out of them; and first thing I knew he had me reading and getting ready for orders; he said I’d better keep clear of divinity schools; and I guess he had figured it out that if I got too much divinity I would get scared and back water. Then I went home and broke the news to the family. They didn’t take much stock in it; they thought I would take a tumble and be a worse disgrace than ever. But there was plenty of money and I had no head for business, anyhow, and there was a chance that I might become respectable, so I got ordained very quietly three years ago at a mission away up on Lake Superior where a bishop had taken an interest in me—and here I am.”

The minister drew a pipe from his pocket, filled and lighted it, shaking his head at Craighill’s offer of a cigar.

“Thanks; I prefer this. Hope the smoke won’t[40] be painful to you; it’s a brand they affect out in my suburb, but it’s better than what we used to have up in the lumber camps. I still take the comfort of a pipe, but the drink I cut out and the swearing. As I remember, it was you who taught me to cuss in school because my stammering made it sound so funny.”

Wayne had recalled a good many things about Paddock but the mood he had brought from his father’s house did not yield readily to the confessions of this boyhood friend who had reappeared in the livery of the Christian ministry. The new status was difficult for Craighill to accept and, conscious of the antagonism his recital had awakened, Paddock regretted that he had volunteered his story. The Craighill whom he had known was a big, generous, outspoken fellow whom everybody liked; the man before him was morose and obstinately resentful: and the fact that he had caught him in his own office at an unusual hour, about to indulge his notorious appetite for drink, was in itself an unhappy circumstance. The bottle and the glass were, to say the least, an unfortunate background for reunion. Paddock touched Wayne’s knee lightly; he wished to regain the ground he had lost by his frankness, which had so signally failed of response.

“You have certainly deviated considerably,” remarked Wayne without humour. “I believe they call your kind of thing Christian sociology, and it’s all right. I congratulate you on having struck something interesting in this life. It’s more than[41] I’ve been able to do. Your story is romantic and beautiful; mine had better not be told, Jimmy. I’m as bad as they’re made; I’ve hit the bottom hard. When you came in I had just reached an important conclusion, and was going to empty a quart to celebrate the event.”

“Well?” inquired the minister, studying anew the fine head; the eyes with their hard glitter; the lips that twitched slightly; the fingers whose trembling he had noted in the lighting of repeated cigarettes. “Be sure I shall value your confidence, old man,” said the minister encouragingly, smiling his sad little smile.

“I’m glad you’re interested, Jimmy, but we’ve chosen different routes. Mine, I guess, has scenic advantages over yours and the pace is faster. You’re headed for the heavenly kingdom. I’m going to hell.”

FOUR days passed. Wayne Craighill ceased twirling and knotting the curtain cord and held his right hand against the strong light of the office window to test his nerves. The fingers twitched and trembled, and he turned away impatiently and flung himself into a chair by his desk, hiding his hands and their tell-tale testimony deep in his pockets. Half a dozen times he shook himself petulantly and attacked his work with frenzied eagerness, as though to be rid of it in a single spurt; but after an hour thus futilely spent he threw himself back and glared at a large etching, depicting a storm-driven galleon riding wildly under a frightened moon, that hung against the dark-olive cartridge paper on the wall above his desk. Shadows appeared now and then on the ground-glass outer door, and lingered several times, testifying to their physical embodiment by violently seizing and rattling the knob. Craighill scowled at every assault, and presently when some importunate visitor had both shaken and kicked the door, he yawned and sought the window again, looking moodily down, as from a hill-top, upon the city of his birth, where practically all his life had been[43] spent, the City of the Iron Heart, lying like a wedge at the confluence of the two broad rivers.

Wayne had used himself hard, as the lines in his smooth-shaven face testified; but the vigour of the Scotch-Irish stock survived in him, and even to-day he carried his tall frame erectly. His head covered with brown hair in which there was a reddish glint, was really fine and his blue eyes, not just now at their clearest, had in them the least hint of the dreamer. His suit of brown—a solid colour—became him: he was dressed with an added scrupulousness as though in conformity to an inner contrition and rehabilitation. He was in his thirtieth year but appeared older to-day as his gaze lay upon the drifting, shifting smoke-cloud that hung above the Greater City.

The son of Colonel Roger Craighill was inevitably a conspicuous person in his native city and his dissipated habits had long been the subject of despairing comment by his fellow-citizens, and the text of occasional lightly veiled sermons in press and pulpit. Dick Wingfield had once remarked that is was too bad that there were only ten commandments, as this small number painfully limited Wayne Craighill’s possible infractions. It was Wingfield who named Wayne Craighill the Blotter, in appreciation of Wayne’s amazing capacity for drink; and it was he who said that Wayne’s sins were merely an expression of the law of compensation and were thrown into the scale to offset[44] Colonel Craighill’s nobility and virtue. Whatever truth may lie in this, it is indisputable that the elder Craighill’s rectitude tended to heighten the colour of his son’s iniquities.

The Blotter had been drunk again. This is what would be said all over the Greater City. At the clubs it would be remarked that he had also had a fight with two policemen, and that he had been put in pickle at the Country Club and then smuggled to his office to await the arrival of Colonel Craighill, who had been to Cleveland to address something or other. The nobler his father’s errands abroad, the wickeder were the Blotter’s diversions in his absences. The last time that Roger Craighill had attended the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church Wayne had amused himself by violating all the city ordinances that interposed the slightest barriers to the enjoyment of life as he understood it. But the Blotter, it is only just to say, was still capable of shame. His physical and moral reaction to-day were acute; and he shrank from facing the world again. More than all, the thought of meeting his father face to face sent the hot blood surging to his head, intensifying its dull ache. His sister Fanny would be likely to show her sympathy and confidence by promptly giving a tea or a dinner to which he would be specially bidden, to demonstrate to the world that in spite of his derelictions his family still stood by him. The remembrance of past offenses, and of the definite routine that his restorations followed,[45] only increased his misery. The usual interview with his father, with whose mild, martyr-like forbearance he had long been familiar, rose before him intolerably.

A light tap at the inner door of Wayne’s room caused him to leap to his feet and stand staring for a moment at a shadow on the ground glass. The door led into Roger Craighill’s room, and as he had been thinking of his father, the knock struck upon his senses ominously. He hesitated an instant, curbing an impulse to fly; then the door opened cautiously, and Joe Denny slipped in, seated himself carelessly on a table in the centre of the room, and nursed his knee.

Consider Joe a moment; he is not the humblest figure in this chronicle: a tall, lithe young fellow, unmistakably Irish-American, with a bang of black hair across his forehead, and a humorous light in his dark eyes. His grin is captivating but we are conscious also of shrewdness in his face. (It took sharp sprinting to steal second when Joe had the ball in his hand!) He is trimly dressed in ready-made exaggeration of last year’s style. His red cravat is fastened with a gold pin in the similitude of crossed bats supporting a tiny ball, symbol of our later Olympian nine. You may, if you like, look up Joe Denny’s batting record for the time he pitched in the Pennsylvania State League, and you will thereby gauge the extent of New York’s loss in having bought his “release” only a week before he broke his wizard’s arm.

[46]Joe, at ease on the table, viewed Mr. Wayne Craighill critically, but with respect. In his more tranquil moments Joe spoke a fairly reputable English derived from the public schools of his native hills, but his narrative style frequently took colour of the idiom of the diamond, and under stress of emotion he departed widely from the instruction imparted by the State of Pennsylvania on the upper waters of the Susquehanna.

“Say, the Colonel’s due on the 4:30.”

Wayne straightened himself unconsciously and his glance fell upon the desk on which lay an accumulation of papers awaiting his inspection and signature.

“Who said so? I thought he wasn’t due till to-morrow.”

“I was up at the house when Walsh telephoned for the machine to go to the station. I guess the Colonel wired Walsh.”

“I’d like to know why Walsh couldn’t have done me the honour to tell me,” said Wayne sourly.

“I guess Walsh don’t know you’re back. They asked me in the front office a while ago and I told ’em I guessed you were up at the Club; and then I came in here through the Colonel’s room to see if you had stayed put.”

Craighill was silent for a moment, then he asked:

“How long was I gone this time, Joe?”

He addressed young Denny without condescension, in a tone of kindness that minimized the obvious differences between them.

[47]“It was Wednesday night you broke loose, and this is Saturday all right.”

“I must have bumped some of the high places—my head feels like it. How about the newspapers?”

“Nothing doing! Walsh fixed that up all right. You see it was like this: you made a row on the steps of the Allequippa Club when I was trying to steer you home. I’d been waiting on the curb with a machine till about 1 A. M., and some of the gents followed you out of the Club and wanted you to come back and go to bed; and when a couple of cops came along, properly not seeing anything, and not letting on, you must up and jump on one of ’em and pound his head. Then the other cop broke into the fuss, and there was a good deal doing and I got you into the machine and slid for the Country Club and got a chauffeur’s bed in the garage and sat on you till you went to sleep.”

Wayne shrugged his shoulders.

“Was that all I did? It sounds pretty tame; I must be getting better—or worse.”

He drew a cigarette from his case and struck a match before he remembered a rule that forbade smoking in office hours; then he found a cigar and chewed it unlighted. Joe eyed the littered desk reflectively.

“Say, you’d better brush that off before the Colonel comes.”

“Put that stuff out of sight,” commanded Wayne and tossed him his keys. “See here, Joe, I started Wednesday night and Thursday night I made a[48] row on the Club steps, and you took me out to Rosedale in the machine and kept me there till you smuggled me in here this afternoon. That’s all right enough, but there was another chap in the row at the Club—I thought I was fighting the whole force, and you say there were two policemen there. There was another fellow besides the policemen.”

“Forget it! Forget it!” grinned Denny, waving his hand airily. “The bases were full for a few minutes and a young gent came along and took our side against the cops, see? The two cops had us going some and this little chap blowing in out of a minor league rapped a two-bagger on the biggest cop’s chin. ‘You Mr. Craighill’s chauffeur?’ he says to me, sweet and gentle-like; and between us we picked you up and threw you into the machine and I cut for the tall, green hills. As the coal-oil lit up and she got in motion, I looked back, and our little friend that hit the cop was a handin’ the cop his card.”

Craighill frowned fiercely with the effort of memory.

“Who was this man that took my part? He must have followed me out of the Club.”

“Nit; he was new talent; and listen—he was a Bible-barker.”

“A minister?”

“Sure. He wore his collar buttoned behind and a three-story vest. He wasn’t as tall as you or me but he was good and husky and he lined out[49] three on the cop’s mug, snappy and zippy, like a triple-play in a tied game.”

“A priest? It wasn’t Father Ryan?”

“It wasn’t the father; it was new talent, I tell you. The gent who came up here to see you the night you broke loose. He was out looking for you Thursday night; guess he heard you were going some. And after he spiked the cop and we got off in the machine there he stood bowing and tipping his dice to the cops and handing ’em his card.”

Light suddenly dawned upon Wayne.

“Paddock; O Lord!” he ejaculated.

A clock tinkled five on the mantel and Wayne’s manner changed. He pointed to the outer door.

“You’d better clear out. Stop in the front office and tell Mr. Walsh I’m here, do you understand?”

“Say, Mrs. Blair’s been lookin’ for you; she’s had the ’phone goin’ for two days. She flew in her machine to Rosedale to look for you but they were on and didn’t give it away. You better call her up.”

“Yes, I’ll attend to it; clear out.”

Already Colonel Craighill had quietly entered the adjoining room followed by an office boy bearing a travelling bag. On his desk lay a dozen sheets of paper, hardly larger than a playing card, and these he examined with the swift ease of habit. They were reports, condensed to the smallest compass, and expressed in bald dollars and tons all the Craighill enterprises. It was thus that[50] Roger Craighill, like a great commander, viewed the broad field of his operations through the eyes of others. Bank balances; totals of bills payable and receivable; so much coal mined at one point; so many tons of coke ready for shipment at another; the visible tonnage in the general market; the day’s prices—these bare data were communicated to the chief daily at the close of business, and in his frequent absences were sent to him by wire. He summoned a boy.

“Please say to Mr. Walsh that I’m ready to see him.”

Walsh appeared instantly: he had, indeed, been awaiting the summons, and was prepared for it. A definite routine attended every return of the chief to his headquarters. He invariably called Walsh, his chief of staff; and thereafter was ready to see his son. In every business office the high powers are merely tolerated by the subordinates, to whom the senior partner or the president is usually “the boss” or “the old man.” Roger Craighill was not to be so apostrophized even behind his back: he was “the Colonel” to everyone. To a few contemporaries only was Craighill “Roger” and these were citizens bound together by memories of the old city, who as young men had cheered Kossuth through the streets in 1851, and who a decade later had met in the Committee of Safety or marched South with musket or sword in hand.

“Ah, Walsh, how is everything going? I see that the pumps at No. 18 are out of order again. I[51] think I’d better go after the Watkins people personally about that; we’ve been patient enough with them.”

Walsh nodded. He was short and thick and quite bald. He had formerly been the “credit man” of one of the Craighill enterprises, which, it happened, was a wholesale grocery; but he had grown into the confidence of Roger Craighill and when Craighill organized the grocery business into a corporation and began directing it from the fourteenth story of the Craighill building, Walsh became Craighill’s confidential man of affairs, with broad administrative powers.

Walsh thrust his hands into the pockets of his office coat and began talking at once of several matters of importance connected with the Craighill interests. Craighill nodded oftener than he spoke as Walsh made his succinct statements. There was no sentiment in Walsh; his voice was as dry and hard as his facts. He had studied credits so long that his life’s chief concern was solvency. He could tell you any day in the week the amount of bituminous coal in the bins at Cincinnati or Louisville; or whether the corner grocers of Johnstown or Youngstown had paid for their last purchases from the Wayne-Craighill Company. Craighill’s inquiries were largely perfunctory, a fact not lost upon Walsh, who fidgeted in his chair.

“Everything seems all right,” said Craighill, turning round and facing Walsh. “By the way, did the home papers report my address before the[52] Western Reserve Society? Here’s a very fair account of it from the Cleveland papers. I’d be glad if you’d look it over. I’m often troubled, Walsh, by the amount of time these public and semi-public matters take, but in one way and another I am well repaid. They inject a certain variety into my life, and the acquaintances and friendships I have made among statesmen, educators, financiers and men of affairs are really of great value to me.”

“Um.”

Walsh twirled the clipping in his fingers. The discussion of anything outside the range of business embarrassed him. It was perfectly proper for Roger Craighill to spend his time with other gentlemen of wealth and influence in making after-dinner speeches and in seeking ways and means of ameliorating the condition of the poor whites or the poor blacks of the South, or in stimulating interest in the merit system, or in reforming the currency. Walsh thought favourably of these things, though he did not think of them deeply or often.

“Ah, Wayne!”

The moment had arrived for the son to show himself and Wayne Craighill entered from his own room and walked quickly to his father’s desk. Walsh rose and examined the young man critically with his small, shrewd eyes, then left with an abrupt good night. Father and son greeted each other cordially; the father held the young man’s hand a moment as they stood by the desk.

“Wayne, my boy!” said the elder warmly, “sit[53] down. How’s Fanny? She came home from York Harbour rather early this year.”

“Oh, she’s all right,” replied Wayne, though he had not seen his sister during his father’s absence. He assumed that the fact of his latest escapade was known to his father. Everyone always seemed to know, though for several years Roger Craighill had suspended the rebukes, threats and expostulations with which he had met Wayne’s earlier lapses. His father’s cordiality put Wayne on guard at once: he suspected that he was to be taken to task for his sins with a severity that had drawn interest during his immunity.

“I am sorry to see that you have overdrawn your account somewhat,” remarked Colonel Craighill, holding up one of the papers and examining it through his eye-glasses. His manner was now that of a teacher who has summoned an erring student for reproof. The mildness of his manner irritated Wayne, who was, moreover, honestly surprised by his father’s statement.

“I didn’t know that; in fact I don’t believe that can be right, sir. What’s the amount?”

“Four thousand dollars.”

Wayne’s surprise increased.

“It’s an error. I have overdrawn no such amount; I’m sure of that.” But his head still ached and he sought vainly for an explanation of the item on the sheet his father passed over to him.

“Wayne,” began Colonel Craighill, “I simply cannot have you do this sort of thing. It’s bad[54] for you, for you can have no need of any such sum of money in addition to your regular income and your salary; and it’s bad for the office discipline. I have prided myself that some of the foremost men of the country have placed their sons in my care. Think of the effect on these young men out there,”—he waved his hand toward the outer offices—“of your extravagant, wasteful ways.”

Wayne was familiar enough with the black depths of his infamy and he knew his value as an example; but he groped blindly for an explanation of the overdraft. Suddenly the knowledge flashed upon him that it represented the price of some shares in a coal-mining company in which his father was interested. They had been offered for sale in the settlement of an estate and as he supposed that the Craighill interests already controlled the property he had purchased them on his own account a few days before, with a view to turning them over to his father on his return if he wished them. The amount was small as such transactions go, and as he had not the required sum in bank he overdrew his account in the office. His own income from various sources—real estate, bonds and shares representing his half of the considerable fortune left by Mrs. Craighill—was collected through the office, where he kept an open account. His father’s readiness to pillory him increased the irritability left by his latest dissipation. A four-year-old child will not brook injustice; there is nothing a man resents more. He could very quickly[55] turn his father’s criticism by an explanation; but just now in his bitterness he shrank from commendation. The gravamen of his offense was trifling; he had been misjudged; his pride had been touched; he refused to justify himself.

He returned to his own room where a little later Walsh found him. Walsh, having tapped on the outer door, was admitted in sulky silence and squeezed his fat bulk into a chair by Wayne’s desk. He gazed at the son of his chief with what, for Walsh, approximated benevolence.

“I’ve been drunk,” remarked Wayne, with an air of suggesting an inevitable topic of conversation.

“Um,” growled Walsh. “I had heard something of it.”

“I suppose everybody has heard it. My sprees seem to lack a decent cloistral quiet some way. Joe told me you had shut up the newspapers. When my head stops aching I’ll try to thank you in proper language.”

“I’ll tell you how you can avoid getting drunk in the future if you are interested,” remarked Walsh.

“If you mean burning down the distilleries I’d like you to know that I’m not in a mood for joking.”

“Um. I was not going to advise you to commit arson. I have never offered you any advice before; I’m going to give you some now. You’ve got about all there is out of drink and you’d better get interested in something else. The only way to stop is to quit, and you can do it. I’ve a notion[56] that you and I are going to be better acquainted in the future. Such being the idea I’d like to be sure that you are going to keep straight. You make me tired.”

Wayne was not sure that he understood. No one, least of all his father’s grim, silent lieutenant, had ever spoken to him in just this tone, and he was surprised to find that Walsh’s method of attack interested him. He was humble before the old fellow in the linen coat.

“What’s the use, Tom? I’m well headed for the bottom; better let me go on down.”

“The top is less crowded and more comfortable than the bottom. Just as a matter of my own dignity I’d stay up as high as I could if I were you. I had a good chance to go down myself once, but I took a dip or two and it didn’t look good down below—too many bones. Um. That’s all of that.”

He chewed an unlighted cigar ruminantly until Wayne spoke.

“The Colonel’s going to get married.”

“Um,” Walsh nodded. His emotions were always under control and Wayne did not know whether he had imparted fresh information or not. He imagined he had, for it was not likely that his father would make a confidant of Walsh in any social matter.

“The Colonel knows his own business.”

“As a matter of fact, does he?”

“Um.”

[57]Walsh’s cigar pointed to a remote corner of the ceiling, but his eyes were fixed on Wayne. He had apparently no intention of discussing Colonel Craighill’s marriage and he abruptly changed the subject.

“You bought fifty shares of Sand Creek stock the other day from the Moore estate.”

Wayne scowled; these were the shares he had overdrawn his office account to buy, with the intention of turning them over to his father, and his father’s criticism of the overdraft rankled afresh.

“Yes; I bought fifty shares. How did you find it out?”

“Tried to buy ’em myself and found you had beat me to ’em.”

“I overdrew my office account to buy them. I thought father would want them; but now he can’t have them.”

“Why?”

“Because in a fit of righteousness he jumped me for my overdraft. It was the first time I was ever over; you know that, and it would have squared itself in a few days anyhow. But if you want those shares——”