Title: Life and Remarkable Adventures of Israel R. Potter

Author: Israel Potter

Author of introduction, etc.: Leonard Kriegel

Contributor: Herman Melville

Release date: November 7, 2021 [eBook #66684]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Corinth Books

Credits: Steve Mattern and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

The Life and Remarkable Adventures of

ISRAEL R. POTTER

The autobiography of America’s first tragic

hero—

the basis of Herman Melville’s famous novel

Introduction by Leonard Kriegel

CORINTH AE 16 $1.25

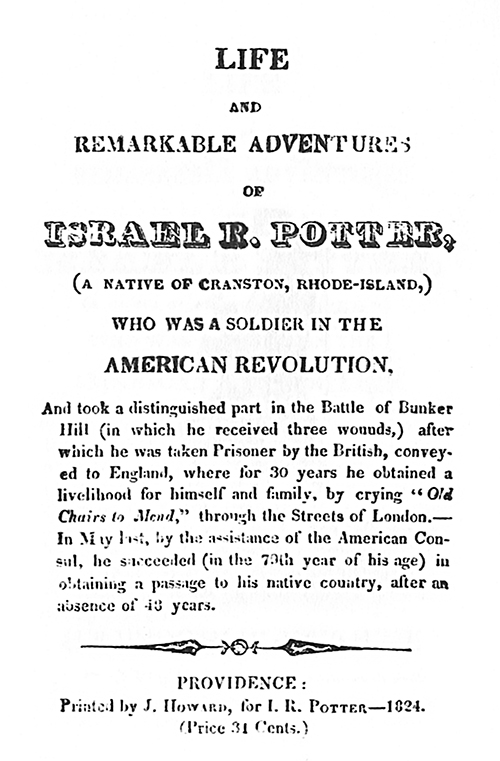

LIFE AND REMARKABLE

ADVENTURES OF ISRAEL R. POTTER

“Shortly after his return in infirm old age to his native land, a little narrative of his adventures, forlornly published on sleazy gray paper, appeared among the peddlers, written, probably not by himself, but taken down from his lips by another. But like the crutch-marks of the cripple by the Beautiful Gate, this blurred record is now out of print.”

So Herman Melville, on June 17th, 1854, described this original volume in the Dedication (To His Highness, The Bunker Hill Monument) of his fictionalized version of Potter’s autobiography.

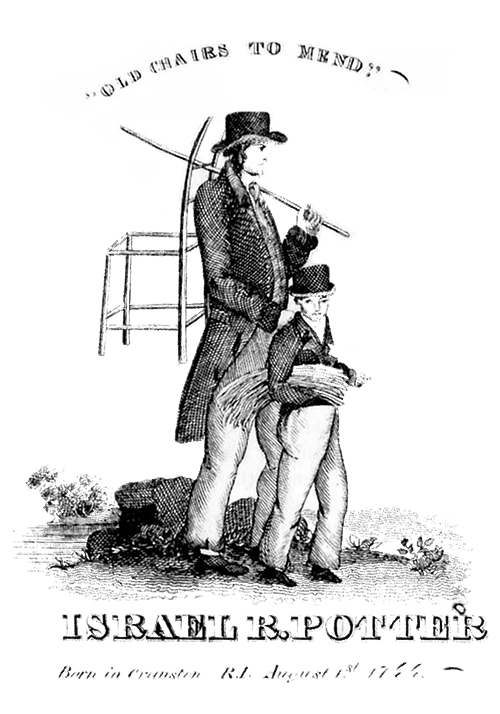

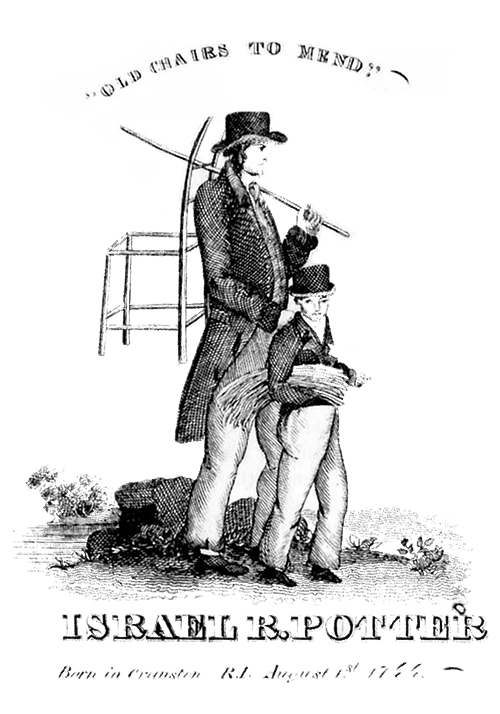

The present edition is a faithful republication of Potter’s own story, reset from the Henry Trumbull printing in 1824. The reproduction of the original title page and frontispiece illustration are from a copy in the New York Public Library and used with their kind permission. Also reproduced is the title page and frontispiece illustration of the J. Howard printing in the same year.

In an Appendix, the final chapters of Herman Melville’s Israel Potter have been reproduced from the 1855 first edition printing.

LIFE

and

REMARKABLE ADVENTURES

of

ISRAEL R. POTTER

Introduction by Leonard Kriegel

CONSULTING EDITOR: HENRY BAMFORD PARKES

CORINTH BOOKS

NEW YORK

LEONARD KRIEGEL is an Instructor of English at The City College of New York. He has edited a book on the political philosophy of the Founding Fathers which is soon to be published and has written a number of stories and articles.

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 62-10046

Copyright © 1962 Corinth Books, Inc.

THE AMERICAN EXPERIENCE SERIES

Published by Corinth Books Inc.

32 West Eighth Street, New York 11, N. Y.

Distributed by The Citadel Press

222 Park Avenue South, New York 3, N. Y.

Printed in the U.S.A.

Noble Offset Printers, Inc.

New York 3, N. Y.

The Life and Remarkable Adventures of Israel Potter has been read, when it has been read at all, in the same way as college sophomores studying Shakespeare read Plutarch’s Lives, not for the moral homilies of a great biographer but rather as notes for the study of Julius Caesar or Antony and Cleopatra. In the case of Israel Potter’s Life, however, such an approach can at least be partially justified, since its primary significance remains as a source for Herman Melville’s “Revolutionary narrative of a beggar.” That Melville was unable to mold the source to fit his artistic conception becomes readily apparent when we read these memoirs for ourselves and then turn to his novel. Only after making such a comparison does one realize the truth of F. O. Matthiessen’s assertion that for Melville, by the time he wrote Israel Potter, tragedy “had become so real that it could not be written.” But despite his artistic failure, Melville’s choice of subject remains interesting, both for what it tells us about Melville’s deepening sense of despair and for what it tells us about individualism and democracy. For in these ghostwritten memoirs, a pensioner’s plea to the government by “one of the few survivors who fought and bled for American Independence,” Melville caught a striking reflection of his own state of mind. The real Israel Potter, like Melville’s “Revolutionary beggar,” was another name added to the long list of the world’s victims. And it is as a victim that this “plebian Lear” speaks to us, too.

vi Not only is Israel a victim, he is—and for Melville’s purposes this was most significant—an American victim. It is this quality, this peculiarly “frontier” attempt to reconcile the promise of life with the actualities of existence, that stamps the real Israel Potter. Somehow, for the American, life is never as good, as ennobling, or as fulfilling as he feels it was meant to be. For against his dream of selfhood the American is forced to measure the accidental evil of existence itself. It was as such a gauge that Melville attempted to make use of this short Life of an insignificant “native of Cranston, Rhode Island.” Despite his artistic failure, his instinct was undoubtedly sound. For Israel Potter is not merely another good man adrift in a world devoid of goodness: he is, above all, an American, whose ideals and aims are derived from that same self-reliant democratic ethos which Whitman and Emerson were later to celebrate. Hired laborer, farmer, chain bearer, hunter, trapper, Indian trader, merchant sailor, whaler, soldier, courier, spy, carpenter, and beggar, through it all, Israel remains the American, the man who, even in the hardships of exile, insists that all will be well once he can again walk “on American ground.”

As it proved to be with so many of his countrymen, success was Israel’s failure. He returned, in May, 1823, after an absence of 48 years, to an America that was already far different from the country he remembered leaving at the age of 31. He had grown older and now he looked back; America, too, had grown older, but now it looked forward. Israel had come home to die; America was far too busy in the conquest of itself to give death anything more than the platitudinous comfort of words. Israel petitioned the government for a pension; but the government was now stable, a government of laws and not ofvii men, and so his petition was rejected. After his long exile Israel had come to understand that there were boundaries to any existence; American optimism made even the recognition of such boundaries an impossibility.

Melville, to his credit, saw all of this. That he was not able to integrate such insights into the novel that evolved from these memoirs is not overly important; one year after the publication of Israel Potter, he quit work on his uncompleted philosophical novel, The Confidence Man, which, despite its manifold faults, must be read as a savage indictment of the shallow humanitarianism against which the real Israel Potter proved to be so helpless. It was in this novel that Melville provided his nihilistic answer to the fragile, confused optimism with which Israel attempted to confront living.

The differences between what Melville saw in Israel’s life and what Israel himself saw are interesting enough: for Melville, who saw the truth so intensely that he found himself unable to commit his perceptions to paper, Israel’s life was further proof of man’s insignificance in a universe whose order remains completely beyond his comprehension; but Israel, who is neither what Madison Avenue or Socrates calls a “thinking man,” constantly confuses the what is of life with the what ought to be. One sees the limitations of Israel’s perception in his attitude towards Benjamin Franklin; Israel praises Franklin as “that great and good man,” the living embodiment of all that the American dream promises. For Melville, on the other hand, Franklin is not the embodiment but the decay of that dream, the sophisticated but soulless statesman who is damned as “everything but a poet.” The real Israel dismisses Franklin in two pages, but Melville cannot dismiss him for six chapters. “It’s wisdom that’s cheap, and it’sviii fortune that’s dear,” Melville has his Israel say as he disgustedly slams down a copy of Poor Richard. But the real Israel was a believer in wisdom; wisdom, along with goodness and self-reliance and Christianity, was the way to fortune. And it is because of this lack of perception that his own story is a far truer portrayal of the mystique of victimization than is Melville’s novel. Israel consistently does the admirable thing at the right time, only to see himself mocked by circumstance or fate or whatever label we choose to give to the quiet terror that life so frequently breeds.

Perhaps it was also his limited perception that enabled Israel to devote almost half these memoirs to his years of exile; he records his sufferings in detail, a record that was so painful to Melville that he could do no more than hurriedly outline it in a few short, concluding chapters. One can scarcely see what other choice Melville could have made—such intense and unalleviated suffering can easily make of its victim a mock-epic buffoon. In his own story, Israel manages to avoid this fate, but only because he does not fully understand what is happening to him. Melville saw the truth; because it was so painful, however, he found himself unable to write it.

The Life and Remarkable Adventures of Israel Potter was published in Providence in 1824, one year after Israel “succeeded in the (79th year of his age) in obtaining a passage to his native country after an absence of 48 years.” This small book, written and published by Henry Trumbull, a Providence, Rhode Island printer, did not help him achieve his objective: his quest for a pension proved unsuccessful, and he died soon after, on “the same day,” Melville tells us, “that the oldest oak in his native hills was blown down.” He took with him whatever was leftix of his dream and his pride, an end which, to some extent, all victims share. “Kings as clowns,” Melville wrote bitterly, “are codgers—who ain’t a nobody?” It is a fitting epitaph for all the Israel Potters.

Leonard Kriegel

The City College of New York

LIFE

AND

REMARKABLE ADVENTURES

OF

ISRAEL R. POTTER,

(A NATIVE OF CRANSTON, RHODE-ISLAND,)

WHO WAS A SOLDIER IN THE

AMERICAN REVOLUTION,

And took a distinguished part in the Battle of Bunker Hill (in which he received three wounds,) after which he was taken Prisoner by the British, conveyed to England, where for 30 years he obtained a livelihood for himself and family, by crying “Old Chairs to Mend,” through the Streets of London.—In May last, by the assistance of the American Consul, he succeeded (in the 79th year of his age) in obtaining a passage to his native country, after an absence of 48 years.

PROVIDENCE:

Printed by J. Howard, for I. R. Potter—1824.

(Price 31 Cents.)

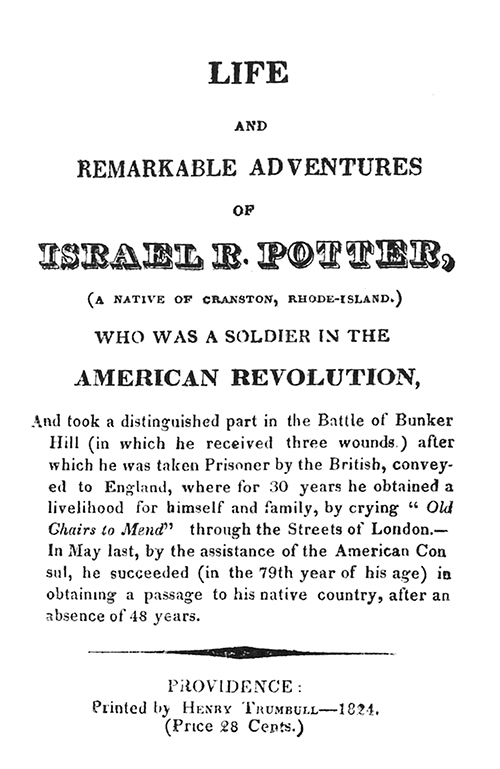

LIFE

AND

REMARKABLE ADVENTURES

OF

ISRAEL R. POTTER,

(A NATIVE OF CRANSTON, RHODE-ISLAND.)

WHO WAS A SOLDIER IN THE

AMERICAN REVOLUTION,

And took a distinguished part in the Battle of Bunker Hill (in which he received three wounds,) after which he was taken Prisoner by the British, conveyed to England, where for 30 years he obtained a livelihood for himself and family, by crying “Old Chairs to Mend” through the Streets of London.—In May last, by the assistance of the American Consul, he succeeded (in the 79th year of his age) in obtaining a passage to his native country, after an absence of 48 years.

PROVIDENCE:

Printed by Henry Trumbull—1824.

(Price 28 Cents.)

IN the foregoing pages we have attempted a simple narrative of the life and extraordinary adventures of one of the few survivors who fought and bled for American Independence. There is not probably another now living who took an equally active part in the Revolutionary war, whose life has been marked with more extraordinary events, and who has drank deeper of the cup of adversity, than the aged veteran with whose History we now beg liberty to present the American public. Doomed by the fate of War to be early separated from kindred and friends, and to be conveyed by a foreign foe a prisoner of war from his native land, to a far distant country, where after having for 48 years experienced almost every hardship and deprivation of which adverse fortune is productive, providence appears at length to have so far interfered in his behalf, as to provide means whereby he has been enabled at an advanced age once more to visit and inhale the pure air of his native land. At the age of Seventy-Nine, an age in which it cannot be expected that the lamp of human life can long remain unextinguished, he has arrived among us, in a state of penury and want, to seek in common with his countrymen the enjoyment of a few of the blessings produced by American valour, in her memorable conflict with the mother country and in which he took a distinguished part.

As it yet remains doubtful whether (in consequence of his long absence) he will be so fortunate as to be included in that number to whom Government has granted pensions for their Revolutionary services, it is to obtain if possible a humble pittance as a remuneration, in part, for the unprecedented privations and sufferings of which he has been the unfortunate subject, that he is now induced to present the public with the following concise and simple narration of the most extraordinary incidents of his life.

I WAS born of reputable parents in the town of Cranston, State of Rhode Island, August 1st, 1744.—I continued with my parents there in the full enjoyment of parental affection and indulgence, until I arrived at the age of 18, when, having formed an acquaintance with the daughter of a Mr. Richard Gardner, a near neighbour, for whom (in the opinion of my friends) entertaining too great a degree of partiality, I was reprimanded and threatened by them with more severe punishment, if my visits were not discontinued. Disappointed in my intentions of forming an union (when of suitable age) with one whom I really loved, I deemed the conduct of my parents in this respect unreasonable and6 oppressive, and formed the determination to leave them, for the purpose of seeking another home and other friends.

It was on Sunday, while the family were at meeting, that I packed up as many articles of my cloathing as could be contained in a pocket handkerchief, which, with a small quantity of provision, I conveyed to and secreted in a piece of woods in the rear of my father’s house; I then returned and continued in the house until about 9 in the evening, when with the pretence of retiring to bed, I passed into a back room and from thence out of a back door and hastened to the spot where I had deposited my cloathes, &c.—it was a warm summer’s night, and that I might be enabled to travel with the more facility the succeeding day, I lay down at the foot of a tree and reposed myself until about 4 in the morning when I arose and commenced my journey, travelling westward, with an intention of reaching if possible the new countries, which I had heard highly spoken of as affording excellent prospects for industrious and enterprising young men—to evade the pursuit of my friends, by whom I knew I should be early missed and diligently sought for, I confined my travel to the woods and shunned the public roads, until I had reached the distance of about 12 miles from my father’s house.

At noon the succeeding day I reached Hartford, in Connecticut, and applied to a farmer in that town for work, and for whom I agreed to labour for one7 month for the sum of six dollars. Having completed my month’s work to the satisfaction of my employer, I received my money and started from Hartford for Otter Creek; but, when I reached Springfield, I met with a man bound to the Cahos country, and who offered me four dollars to accompany him, of which offer I accepted, and the next morning we left Springfield and in a canoe ascended Connecticut river, and in about two weeks after much hard labour in paddling and poling the boat against the current, we reached Lebanon (N. H.), the place of our destination. It was with some difficulty and not until I had procured a writ, by the assistance of a respectable innkeeper in Lebanon, by the name of Hill, that I obtained from my last employer the four dollars which he had agreed to pay me for my services.

From Lebanon I crossed the river to New-Hartford (then N. Y.) where I bargained with a Mr. Brink of that town for 200 acres of new land, lying in New Hampshire, and for which I was to labour for him four months. As this may appear to some a small consideration for so great a number of acres of land, it may be well here to acquaint the reader with the situation of the country in that quarter, at that early period of its settlement—which was an almost impenetrable wilderness, containing but few civilized inhabitants, far distantly situated from each other and from any considerable settlement; and whose temporary habitations with a few exceptions were constructed of logs in their natural state—the8 woods abounded with wild beasts of almost every description peculiar to this country, nor were the few inhabitants at that time free from serious apprehension of being at some unguarded moment suddenly attacked and destroyed, or conveyed into captivity by the savages, who from the commencement of the French war, had improved every favourable opportunity to cut off the defenceless inhabitants of the frontier towns.

After the expiration of my four months labour the person who had promised me a deed of 200 acres of land therefor, having refused to fulfill his engagements, I was obliged to engage with a party of his Majesty’s Surveyors at fifteen shillings per month, as an assistant chain bearer, to survey the wild unsettled lands bordering on the Connecticut river, to its source. It was in the winter season, and the snow so deep that it was impossible to travel without snow shoes—at the close of each day we enkindled a fire, cooked our victuals and erected with the branches of hemlock a temporary hut, which served us for a shelter for the night. The Surveyors having completed their business returned to Lebanon, after an absence of about two months. Receiving my wages I purchased a fowling-piece and ammunition therewith, and for the four succeeding months devoted my time in hunting Deer, Beavers, &c. in which I was very successful, as in the four months I obtained as many skins of these animals as produced me forty dollars—with my money I9 purchased of a Mr. John Marsh, 100 acres of new land, lying on Water Quechy River (so called) about five miles from Hartford (N. Y.). On this land I went immediately to work, erected a small log hut thereon, and in two summers without any assistance, cleared up thirty acres fit for sowing—in the winter seasons I employed my time in hunting and entraping such animals whose hides and furs were esteemed of the most value. I remained in possession of my land two years, and then disposed of it to the same person of whom I purchased it, at the advanced price of 200 dollars, and then conveyed my skins and furs which I had collected the two preceding winters, to NO. 4 (now Charlestown), where I exchanged them for Indian blankets, wampeag and such other articles as I could conveniently convey on a hand sled, and with which I started for Canada, to barter with the Indians for furs.—This proved a very profitable trip, as I very soon disposed of every article at an advance of more than two hundred per cent, and received payment in furs at a reduced price, and for which I received in NO. 4, 200 dollars, cash. With this money, together with what I was before in possession of, I now set out for home, once more to visit my parents after an absence of two years and nine months, in which time my friends had not been enabled to receive any correct information of me. On my arrival, so greatly effected were my parents at the presence of a son whom they had considered dead, that10 it was sometime before either could become sufficiently composed to listen to or to request me to furnish them with an account of my travels.

Soon after my return, as some atonement for the anxiety which I had caused my parents, I presented them with most of the money that I had earned in my absence, and formed the determination that I would remain with them contented at home, in consequence of a conclusion from the welcome reception that I met with, that they had repented of their opposition, and had become reconciled to my intended union—but, in this, I soon found that I was mistaken; for, although overjoyed to see me alive, whom they had supposed really dead, no sooner did they find that my long absence had rather increased than diminished my attachment for their neighbor’s daughter, than their resentment and opposition appeared to increase in proportion—in consequence of which I formed the determination again to quit them, and try my fortune at sea, as I had now arrived at an age in which I had an unquestionable right to think and act for myself.

After remaining at home one month, I applied for and procured a birth at Providence, on board the Sloop ——, Capt. Fuller, bound to Grenada—having completed her loading (which consisted of stone lime, hoops, staves, &c.) we set sail with a favourable wind, and nothing worthy of note occurred until the 15th day from that on which we left Providence, when the sloop was discovered to be on fire, by a11 smoke issuing from her hold—the hatches were immediately raised, but as it was discovered that the fire was caused by water communicating with the lime, it was deemed useless to make any attempts to extinguish it—orders were immediately thereupon given by the captain to hoist out the long boat, which was found in such a leaky condition as to require constant bailing to keep her afloat; we had only time to put on board a small quantity of bread, a firkin of butter and a ten gallon keg of water, when we embarked, eight in number, to trust ourselves to the mercy of the waves, in a leaky boat and many leagues from land. As our provision was but small in quantity, and it being uncertain how long we might remain in our perilous situation, it was proposed by the captain soon after leaving the sloop, that we should put ourselves on an allowance of one biscuit and half a pint of water per day, for each man, which was readily agreed to by all on board—in ten minutes after leaving the sloop she was in a complete blaze, and presented an awful spectacle. With a piece of the flying-jib, which had been fortunately thrown into the boat, we made shift to erect a sail, and proceeded in a south-west direction in hopes to reach the spanish maine, if not so fortunate as to fall in with some vessel in our course—which, by the interposition of kind providence in our favour, actually took place the second day after leaving the sloop—we were discovered and picked up by a Dutch ship bound from Eustatia12 to Holland, and from the captain and crew met with a humane reception, and were supplied with every necessary that the ship afforded—we continued on board one week when we fell in with an American sloop bound from Piscataqua to Antigua, which received us all on board and conveyed us in safety to the port of her destination. At Antigua I got a birth on board an American brig bound to Porto Rico, and from thence to Eustatia. At Eustatia I received my discharge and entered on board a Ship belonging to Nantucket, and bound on a whaling voyage, which proved an uncommonly short and successful one—we returned to Nantucket full of oil after an absence of the ship from that port of only 16 months. After my discharge I continued about one month on the island, and then took passage for Providence, and from thence went to Cranston, once more to visit my friends, with whom I continued three weeks, and then returned to Nantucket. From Nantucket I made another whaling voyage to the South Seas and after an absence of three years, (in which time I experienced almost all the hardships and deprivations peculiar to Whalemen in long voyages) I succeeded by the blessings of providence in reaching once more my native home, perfectly sick of the sea, and willing to return to the bush and exchange a mariner’s life for one less hazardous and fatiguing.

I remained with my friends at Cranston a few weeks, and then hired myself to a Mr. James Waterman,13 of Coventry, for 12 months, to work at farming. This was in the year 1774, and I continued with him about six months, when the difficulties which had for some time prevailed between the Americans and Britons, had now arrived at that crisis, as to render it certain that hostilities would soon commence in good earnest between the two nations; in consequence of which, the Americans at this period began to prepare themselves for the event—companies were formed in several of the towns in New England, who received the appellation of “minute men,” and who were to hold themselves in readiness to obey the first summons of their officers, to march at a moment’s notice;—a company of this kind was formed in Coventry, into which I enlisted, and to the command of which Edmund Johnson, of said Coventry, was appointed.

It was on a Sabbath morning that news was received of the destruction of the provincial stores at Concord, and of the massacre of our countrymen at Lexington, by a detached party of the British troops from Boston: and I immediately thereupon received a summons from the captain, to be prepared to march with the company early the morning ensuing—and, although I felt not less willing to obey the call of my country at a minute’s notice, and to face her foes, than did the gallant Putnam, yet, the nature of the summons did not render it necessary for me, like him, to quit my plough in the field; as14 having the day previous commenced the ploughing of a field of ten or twelve acres, that I might not leave my work half done, I improved the sabbath to complete it.

By the break of day Monday morning I swung my knapsack, shouldered my musket, and with the company commenced my march with a quick step for Charlestown, where we arrived about sunset and remained encamped in the vicinity until about noon of the 16th June; when, having been previously joined by the remainder of the regiment from Rhode Island, to which our company was attached, we received orders to proceed and join a detachment of about 1000 American troops, which had that morning taken possession of Bunker Hill, and which we had orders immediately to fortify, in the best manner that circumstances would admit of. We laboured all night without cessation and with very little refreshment, and by the dawn of day succeeded in throwing up a redoubt of eight or nine rods square. As soon as our works were discovered by the British in the morning, they commenced a heavy fire upon us, which was supported by a fort on Copp’s hill; we however (under the command of the intrepid Putnam) continued to labour like beavers until our breast-work was completed.

About noon, a number of the enemy’s boats and barges, filled with troops, landed at Charlestown, and commenced a deliberate march to attack us—we were now harangued by Gen. Putnam, who reminded15 us, that exhausted as we were, by our incessant labour through the preceding night, the most important part of our duty was yet to be performed, and that much would be expected from so great a number of excellent marksmen—he charged us to be cool, and to reserve our fire until the enemy approached so near as to enable us to see the white of their eyes—when within about ten rods of our works we gave them the contents of our muskets, and which were aimed with so good effect, as soon to cause them to turn their backs and to retreat with a much quicker step than with what they approached us. We were now again harangued by “old General Put,” as he was termed, and requested by him to aim at the officers, should the enemy renew the attack—which they did in a few moments, with a reinforcement—their approach was with a slow step, which gave us an excellent opportunity to obey the commands of our General in bringing down their officers. I feel but little disposed to boast of my own performances on this occasion, and will only say, that after devoting so many months in hunting the wild animals of the wilderness, while an inhabitant of New Hampshire, the reader will not suppose me a bad or unexperienced marksman, and that such were the fare shots which the epauletted red coats presented in the two attacks, that every shot which they received from me, I am confident on another occasion would have produced me a deer skin.

16 So warm was the reception that the enemy met with in their second attack, that they again found it necessary to retreat, but soon after receiving a fresh reinforcement, a third assault was made, in which, in consequence of our ammunition failing, they too well succeeded—a close and bloody engagement now ensued—to fight our way through a very considerable body of the enemy, with clubbed muskets (for there were not one in twenty of us provided with bayonets) were now the only means left us to escape;—the conflict, which was a sharp and severe one, is still fresh in my memory, and cannot be forgotten by me while the scars of the wounds which I then received, remain to remind me of it!—fortunately for me, at this critical moment, I was armed with a cutlass, which although without an edge, and much rust-eaten, I found of infinite more service to me than my musket—in one instance I am certain it was the means of saving my life—a blow with a cutlass was aimed at my head by a British officer, which I parried and received only a slight cut with the point on my right arm near the elbow, which I was then unconscious of, but this slight wound cost my antagonist at the moment a much more serious one, which effectually dis-armed him, for with one well directed stroke I deprived him of the power of very soon again measuring swords with a “yankee rebel!” We finally however should have been mostly cut off, and compelled to yield to a superiour and better equipped force, had not a body of three or four hundred17 Connecticut men formed a temporary breast work, with rails &c. and by which means held the enemy at bay until our main body had time to ascend the heights, and retreat across the neck;—in this retreat I was less fortunate than many of my comrades—I received two musket ball wounds, one in my hip and the other near the ankle of my left leg—I succeeded however without any assistance in reaching Prospect Hill, where the main body of the Americans had made a stand and commenced fortifying—from thence I was soon after conveyed to the Hospital in Cambridge, where my wounds were dressed and the bullet extracted from my hip by one of the Surgeons; the house was nearly filled with the poor fellows who like myself had received wounds in the late engagement, and presented a melancholly spectacle.

Bunker Hill fight proved a sore thing for the British, and will I doubt not be long remembered by them; while in London I heard it frequently spoken of by many who had taken an active part therein, some of whom were pensioners, and bore indelible proofs of American bravery—by them the Yankees, by whom they were opposed, were not unfrequently represented as a set of infuriated beings, whom nothing could daunt or intimidate: and who, after their ammunition failed, disputed the ground, inch by inch, for a full hour with clubbed muskets, rusty swords, pitchforks and billets of wood, against the British bayonets.

18 I suffered much pain from the wound which I received in my ankle, the bone was badly fractured and several pieces were extracted by the surgeon, and it was six weeks before I was sufficiently recovered to be able to join my Regiment quartered on Prospect Hill, where they had thrown up entrenchments within the distance of little more than a mile of the enemy’s camp, which was full in view, they having entrenched themselves on Bunker Hill after the engagement.

On the 3d July, to the great satisfaction of the Americans, General Washington arrived from the south to take command—I was then confined in the Hospital, but as far as my observations could extend, he met with a joyful reception, and his arrival was welcomed by every one throughout the camp—the troops had been long waiting with impatience for his arrival as being nearly destitute of ammunition and the British receiving reinforcements daily, their prospects began to wear a gloomy aspect.

The British quartered in Boston began soon to suffer much from the scarcity of provisions, and General Washington took every precaution to prevent their gaining a supply—from the country all supplies could be easily cut off, and to prevent their receiving any from Tories, and other disaffected persons by water, the General found it necessary to equip two or three armed vessels to intercept them—among these was the brigantine Washington of 10 guns, commanded by Capt. Martindale,—as seamen at this19 time could not easily be obtained, as most of them had enlisted in the land service, permission was given to any of the soldiers who should be pleased to accept of the offer, to man these vessels—consequently myself with several others of the same regiment went on board of the Washington, then lying at Plymouth, and in complete order for a cruise.

We set sail about the 8th December, but had been out but three days when we were captured by the enemy’s ship Foy, of 20 guns, who took us all out and put a prize crew on board the Washington—the Foy proceeded with us immediately to Boston bay where we were put on board the British frigate Tartar and orders given to convey us to England.—When two or three days out I projected a scheme (with the assistance of my fellow prisoners, 72 in number) to take the ship, in which we should undoubtedly have succeeded, as we had a number of resolute fellows on board, had it not been for the treachery of a renegade Englishman, who betrayed us—as I was pointed out by this fellow as the principal in the plot, I was ordered in irons by the Officers of the Tartar, and in which situation I remained until the arrival of the ship at Portsmouth (Eng.) when I was brought on deck and closely examined, but protesting my innocence, and what was very fortunate for me in the course of the examination, the person by whom I had been betrayed, having been proved a British deserter, his story was discredited and I was relieved of my irons.

20 The prisoners were now all thoroughly cleansed and conveyed to the marine hospital on shore, where many of us took the small-pox the natural way, by some whom we found in the hospital effected with that disease, and which proved fatal to nearly one half our number. From the hospital those of us who survived were conveyed to Spithead, and put on board a Guard Ship, and where I had been confined with my fellow prisoners about one month, when I was ordered into the boat, to assist the bargemen (in consequence of the absence of one of their gang) in rowing the lieutenant on shore. As soon as we reached the shore and the officer landed, it was proposed by some of the boat’s crew to resort for a few moments to an ale-house, in the vicinity, to treat themselves to a few pots of beer; which being agreed to by all, I thought this a favourable opportunity and the only one that might present to escape from my Floating Prison, and felt determined not to let it pass unimproved; accordingly, as the boat’s crew were about to enter the house, I expressed a necessity of my separating from them a few moments, to which they (not suspecting any design), readily assented. As soon as I saw them all snugly in and the door closed, I gave speed to my legs, and ran, as I then concluded, about four miles without once halting—I steered my course toward London as when there by mingling with the crowd, I thought it probable that I should be least suspected.

When I had reached the distance of about ten21 miles from where I quit the bargemen and beginning to think myself in little danger of apprehension, should any of them be sent by the lieutenant in pursuit of me, as I was leisurely passing a public house, I was noticed and hailed by a naval officer at the door with “ahoi, what ship?”—“no ship,” was my reply, on which he ordered me to stop, but of which I took no other notice than to observe to him that if he would attend to his own business I would proceed quietly about mine—this rather increasing than diminishing his suspicions that I was a deserter, garbed as I was, he gave chase—finding myself closely pursued and unwilling again to be made a prisoner of, if it was possible to escape, I had once more to trust to my legs, and should have again succeeded had not the officer, on finding himself likely to be distanced, set up a cry of “stop thief!” this brought numbers out of their houses and work shops, who, joining in the pursuit, succeeded after a chase of nearly a mile in overhauling me.

Finding myself once more in their power and a perfect stranger to the country, I deemed it vain to attempt to deceive them with a lie, and therefore made a voluntary confession to the officer that I was a prisoner of war, and related to him in what manner I had that morning made my escape. By the officer I was conveyed back to the Inn, and left in custody of two soldiers—the former (previous to retiring) observing to the landlord that believing me22 to be a true blooded yankee, requested him to supply me at his expense with as much liquor as I should call for.

The house was thronged early in the evening by many of the “good and faithful subjects of King George,” who had assembled to take a peep at the “yankee rebel,” (as they termed me) who had so recently taken an active part in the rebellious war, then raging in his Majesty’s American provinces—while others came apparently to gratify a curiosity in viewing, for the first time, an “American Yankee!” whom they had been taught to believe a kind of non descripts—beings of much less refinement than the ancient Britains, and possessing little more humanity than the Buccaneers.

As for myself I thought it best not to be reserved, but to reply readily to all their inquiries; for while my mind was wholly employed in devising a plan to escape from the custody of my keepers, so far from manifesting a disposition to resent any of the insults offered me, or my country, to prevent any suspicions of my designs, I feigned myself not a little pleased with their observations, and in no way dissatisfied with my situation. As the officer had left orders with the landlord to supply me with as much liquor as I should be pleased to call for, I felt determined to make my keepers merry at his expense, if possible, as the best means that I could adopt to effect my escape.

The loyal group having attempted in vain to irritate23 me, by their mean and ungenerous reflections, by one (who observed that he had frequently heard it mentioned that the yankees were extraordinary dancers), it was proposed that I should entertain the company with a jig! to which I expressed a willingness to assent with much feigned satisfaction, if a fiddler could be procured—fortunately for them, there was one residing in the neighbourhood, who was soon introduced, when I was obliged (although much against my own inclination) to take the floor—with the full determination, however that if John Bull was to be thus diverted at the expense of an unfortunate prisoner of war, uncle Jonathan should come in for his part of the sport before morning, by showing them a few Yankee steps which they then little dreamed of.

By my performances they were soon satisfied that in this kind of exercise, I should suffer but little in competition with the most nimble footed Britain among them nor would they release me until I had danced myself into a state of perfect perspiration; which, however, so far from being any disadvantage to me, I considered all in favour of my projected plan to escape—for while I was pleased to see the flowing bowl passing merrily about, and not unfrequently brought in contact with the lips of my two keepers, the state of perspiration that I was in, prevented its producing on me any intoxicating effects.

The evening having become now far spent and24 the company mostly retiring, my keepers (who, to use a sailor’s phrase I was happy to discover “half seas over”) having much to my dissatisfaction furnished me with a pair of handcuffs spread a blanket by the side of their bed on which I was to repose for the night. I feigned myself very grateful to them for having humanely furnished me with so comfortable a bed, and on which I stretched myself with much apparent unconcern, and remained quiet about one hour, when I was sure that the family had all retired to bed. The important moment had now arrived in which I was resolved to carry my premeditated plan into execution, or die in the attempt—for certain I was that if I let this opportunity pass unimproved, I might have cause to regret it when it was too late—that I should most assuredly be conveyed early in the morning back to the floating prison from which I had so recently escaped, and where I might possibly remain confined until America should obtain her independence, or the differences between Great-Britain and her American provinces were adjusted. Yet should I in my attempt to escape meet with more opposition from my keepers, than what I had calculated from their apparent state of inebriety, the contest I well knew would be very unequal—they were two full grown stout men, with whom (if they were assisted by no others) I should have to contend, handcuffed! but, after mature deliberation, I resolved that however hazardous the attempt, it should be made, and that immediately.

25 After remaining quiet, as I before observed, until I thought it probable that all had retired to bed in the house, I intimated to my keepers that I was under the necessity of requesting permission to retire for a few moments to the back yard; when both instantly arose and reeling toward me seized each an arm, and proceeded to conduct me through a long and narrow entry to the back door, which was no sooner unbolted and opened by one of them, than I tripped up the heels of both and laid them sprawling, and in a moment was at the garden wall seeking a passage whereby I might gain the public road—a new and unexpected obstacle now presented, for I found the whole garden enclosed with a smooth bricken wall, of the heighth of twelve feet at least, and was prevented by the darkness of the night from discovering an avenue leading therefrom—in this predicament, my only alternative was either to scale this wall handcuffed as I was, and without a moment’s hesitation, or to suffer myself to be made a captive of again by my keepers, who had already recovered their feet and were bellowing like bullocks for assistance—had it not been a very dark night, I must certainly have been discovered and re-taken by them;—fortunately before they had succeeded in rallying the family, in groping about I met with a fruit tree situated within ten or twelve feet of the wall, which I ascended as expeditiously as possible, and by an extraordinary leap from the branches reached the top of the wall, and was in an instant on26 the opposite side. The coast being now clear, I ran to the distance of two or three miles, with as much speed as my situation would admit of;—my next object now was to rid myself of my handcuffs, which fortunately proving none of the stoutest, I succeeded in doing after much painful labour.

It was now as I judged about 12 o’clock, and I had succeeded in reaching a considerable distance from the Inn from which I had made my escape, without hearing or seeing any thing of my keepers, whom I had left staggering about in the garden in search of their “Yankee captive!”—it was indeed to their intoxicated state, and the extreme darkness of the night, that I imputed my success in evading their pursuit.—I saw no one until about the break of day, when I met an old man, tottering beneath the weight of his pick-ax, hoe and shovel, clad in tattered garments, and otherwise the picture of poverty and distress; he had just left his humble dwelling, and was proceeding thus early to his daily labour;—and as I was now satisfied that it would be very difficult for me to travel in the day time garbed as I was, in a sailor’s habit, without exciting the suspicions of his Royal Majesty’s pimps, who (I had been informed) were constantly on the look-out for deserters, I applied to the old man, miserable as he appeared, for a change of cloathing, offering those which I then wore for a suit of inferior quality and less value—this I was induced to do at that moment, as I thought that the proposal could be made with perfect safety, for whatever27 might have been his suspicions as to my motives in wishing to exchange my dress, I doubted not, that with an object of so much apparent distress, self-interest would prevent his communicating them.—The old man however appeared a little surprised at my offer, and after a short examination of my pea-jacket, trousers, &c. expressed a doubt whether I would be willing to exchange them for his “Church suit,” which he represented as something worse for wear, and not worth half so much as those I then wore—taking courage however from my assurances that a change of dress was my only object, he deposited his tools by the side of a hedge, and invited me to accompany him to his house, which we soon reached and entered, when a scene of poverty and wretchedness presented, which exceeded every thing of the kind that I had ever before witnessed—the internal appearance of the miserable hovel, I am confident would suffer in a comparison with any of the meanest stables of our American farmers—there was but one room, in one corner of which was a bed of straw covered with a coarse sheet, and on which reposed his wife and five small children. I had heard much of the impoverished and distressed situation of the poor in England, but the present presented an instance of which I had formed no conception—little indeed did I then think that it would be my lot, before I should meet with an opportunity to return to my native country, to be placed in an infinitely worse situation! but, alas, such was my hard fortune!

28 The first garment presented by the poor old man, of his best, or “church suit,” as he termed it, was a coat of very coarse cloth, and containing a number of patches of almost every colour but that of the cloth of which it was originally made—the next was a waistcoat and a pair of small cloathes, which appeared each to have received a bountiful supply of patches to correspond with the coat—the coat I put on without much difficulty, but the two other garments proved much too small for me, and when I had succeeded with considerable difficulty in putting them on, they set so taut as to cause me some apprehension that they might even stop the circulation of blood!—my next exchange was my buff cap for an old rusty large brimmed hat.

The old man appeared very much pleased with his bargain, and represented to his wife that he could now accompany her to church much more decently clad—he immediately tried on the pea-jacket and trousers, and seemed to give himself very little concern about their size, although I am confident that one leg of the trousers was sufficiently large to admit his whole body—but, however ludicrous his appearance, in his new suit, I am confident that it could not have been more so than mine, garbed as I was, like an old man of seventy!—From my old friend I learned the course that I must steer to reach London, the towns and villages that I should have to pass through, and the distance thereto, which was between 70 and 80 miles. He likewise represented to me that the29 country was filled with soldiers, who were on the constant look-out for deserters from the navy and army, for the apprehension of which they received a stipulated reward.

After enjoining it on the old man not to give any information of me, should he meet on the road anyone who should enquire for such a person, I took my leave of him, and again set out with a determination to reach London, thus disguised, if possible;—I travelled about 30 miles that day, and at night entered a barn in hopes to find some straw or hay on which to repose for the night, for I had not money sufficient to pay for a night’s lodging at a public house, had I thought it prudent to apply for one—in my expectation to find either hay or straw in the barn I was sadly disappointed, for I soon found that it contained not a lock of either, and after groping about in the dark in search of something that might serve for a substitute, I found nothing better than an undressed sheep-skin—with no other bed on which to repose my wearied limbs I spent a sleepless night; cold, hungry and weary, and impatient for the arrival of the morning’s dawn, that I might be enabled to pursue my journey.

By break of day I again set out and soon found myself within the suburbs of a considerable village, in passing which I was fearful there would be some risk of detection, but to guard myself as much as possible against suspicion, I furnished myself with a crutch, and feigning myself a cripple, hobbled through the town without meeting with any interruption. In two30 hours after, I arrived in the vicinity of another still more considerable village, but fortunately for me, at the moment, I was overtaken by an empty baggage waggon, bound to London—again feigning myself very lame, I begged of the driver to grant a poor cripple the indulgence to ride a few miles, to which he assenting, I concealed myself by lying prostrate on the bottom of the waggon, until we had passed quite through the village; when, finding the waggoner disposed to drive much slower than what I wished to travel, after thanking him for the kind disposition which he had manifested to oblige me, I quit the waggon, threw away my crutch and travelled with a speed, calculated to surprise the driver with so suddenly a recovery of the use of my legs—the reader will perceive that I had now become almost an adept at deception, which I would not however have so frequently practiced, had not self-preservation demanded it.

As I thought there would be in my journey to London, infinitely more danger of detection in passing through large towns or villages, than in confining myself to the country, I avoided them as much as possible; and as I found myself once more on the borders of one, apparently of much larger size than any that I had yet passed, I thought it most expedient to take a circuitous route to avoid it; in attempting which, I met with an almost insurmountable obstacle, that I little dreamed of—when nearly abreast of the town, I found my route31 obstructed by a ditch, of upwards of 19 feet in breadth, and of what depth I could not determine; as there was now no other alternative left me, but to leap this ditch, or to retrace my steps and pass through the town, after a moment’s reflection I determined to attempt the former, although it would be attempting a fete of activity, that I supposed myself incapable of performing; yet, however incredible it may appear, I assure my readers that I did effect it, and reached the opposite side with dry feet!

I had now arrived within about 16 miles of London, when night approaching, I again sought lodgings in a barn; which containing a small quantity of hay, I succeeded in obtaining a tolerable comfortable night’s rest. By the dawn of day I arose somewhat refreshed, and resumed my journey with the pleasing prospect of reaching London before night—but, while encouraged and cheered by these pleasing anticipations, an unexpected occurrence blasted my fair prospects—I had succeeded in reaching in safety a distance so great from the place where I had been last held a prisoner, and within so short a distance of London, the place of my destination, that I began to think myself so far out of danger, as to cause me to relax in a measure, in the precautionary means which I had made use of to avoid detection;—as I was passing through the town of Staines, (within a few miles of London) about 11 o’clock in the forenoon, I was met by32 three or four British soldiers, whose notice I attracted, and who unfortunately for me, discovered by the collar (which I had not taken the precaution to conceal) that I wore a shirt which exactly corresponded with those uniformly worn by his Majesty’s seamen—not being able to give a satisfactory account of myself, I was made a prisoner of, on suspicion of being a deserter from his Majesty’s service, and was immediately committed to the Round House; a prison so called, appropriated to the confinement of runaways, and those convicted of small offenses—I was committed in the evening, and to secure me the more effectually, I was handcuffed, and left supperless by my unfeeling jailor, to pass the night in wretchedness.

I had now been three days without food (with the exception of a single two-penny loaf) and felt myself unable much longer to resist the cravings of nature—my spirits, which until now had armed me with fortitude began to forsake me—indeed I was at this moment on the eve of despair! when, calling to mind that grief would only aggravate my calamity, I endeavoured to arm my soul with patience; and habituate myself as well as I could, to woe.—Accordingly I roused my spirits; and banishing for a few moments, these gloomy ideas, I began to reflect seriously, on the methods how to extricate myself from this labyrinth of horror.

My first object was to rid myself of my handcuffs, which I succeeded in doing after two hours33 hard labour, by sawing them across the grating of the window; having my hands now at liberty, the next thing to be done was to force the door of my apartment, which was secured on the outside by a hasp and padlock; I devised many schemes but for the want of tools to work with, was unable to carry them into execution—I however at length succeeded, with the assistance of no other instrument than the bolt of my handcuffs; with which, thrusting my arm through a small window or aperture in the door, I forced the padlock, and as there was now no other barrier to prevent my escape, after an imprisonment of about five hours, I was once more at large.

It was now as I judged about midnight, and although enfeebled and tormented with excessive hunger and fatigue, I set out with the determination of reaching London, if possible, early the ensuing morning. By break of day I reached and passed through Brintford, a town of considerable note and within six miles of the Capital—but so great was my hunger at this moment, that I was under serious apprehension of falling a victim to absolute starvation, if not so fortunate soon to obtain something to appease it. I recollected of having read in my youth, accounts of the dreadful effects of hunger, which had led men to the commission of the most horrible excesses, but did not then think that fate would ever thereafter doom me to an almost similar situation.

34 When I made my escape from the Prison ship, six English pennies was all the money that I possessed—with two I had purchased a two penny loaf the day after I had escaped from my keepers at the Inn, and the other four still remained in my possession, not having met with a favourable opportunity since the purchase of the first loaf to purchase food of any kind. When I had arrived at the distance of one and an half miles from Brintford, I met with a labourer employed in building a pale fence, to whom my deplorable situation induced me to apply for work; or for information of any one in the neighbourhood, that might be in want of a hand to work at farming or gardening. He informed me that he did not wish himself to hire, but that Sir John Miller, whose seat he represented but a short distance, was in the habit of employing many hands at that season of the year (which was in the spring of 1776) and he doubted not but that I might there meet with employment.

With my spirits a little revived, at even a distant prospect of obtaining something to alleviate my sufferings, I started in quest of the seat of Sir John, agreeable to the directions which I had received; in attempting to reach which, I mistook my way, and proceeded up a gravelled and beautifully ornamented walk, which unconsciously led me directly to the garden of the Princess Amelia—I had approached within view of the Royal Mansion when a glimpse of a number of “red coats” who thronged the yard, satisfied me of my mistake, and caused me35 to make an instantaneous and precipitate retreat, being determined not to afford any more of their mess an opportunity of boasting of the capture of a “Yankee Rebel,”—indeed, a wolf or a bear, of the American wilderness, could not be more terrified or panic-struck at the sight of a firebrand, than I then was at that of a British red coat!

Having succeeded in making good my retreat from the garden of her highness, without being discovered, I took another path which led me to where a number of labourers were employed in shovelling gravel, and to whom I repeated my enquiry if they could inform me of any in want of help, &c.—“why in troth friend (answered one in a dialect peculiar to the labouring class of people of that part of the country) me master, Sir John, hires a goodly many, and as we’ve a deal of work now, may-be he’ll hire you; ’spose he stop a little with us until work is done, he may then gang along, and we’ll question Sir John, whither him be wanting another like us or no!”

Although I was sensible that an application of this kind, might lead to a discovery of my situation, whereby I might be again deprived of my liberty, and immured in a loathsome prison; yet, as there was now no other alternative left me but to seek in this way, something to satisfy the cravings of hunger, or to yield a victim to starvation, with all its attending horrors: of the two evils I preferred the least, and concluded as the honest labourer had36 proposed, to await until they had completed their work, and then to accompany them home to ascertain the will of Sir John.

As I had heard much of the tyrannical and domineering disposition of the rich and purse-proud of England, and who were generally the lords of the manor, and the particular favourites of the crown; it was not without feeling a very considerable degree of diffidence, that I introduced myself into the presence of one whom I strongly suspected to be of that class—but, what was peculiarly fortunate for me, a short acquaintance was sufficient to satisfy me that as regarded this gentleman, my apprehensions were without cause. I found him walking in his front yard in company with several gentlemen, and on being made acquainted with my business, his first enquiry was whether I had a hoe, or money to purchase one, and on being answered in the negative, he requested me to call early the ensuing morning, and he would endeavour to furnish me with one.

It is impossible for me to express the satisfaction that I felt at this prospect of a deliverance from my wretched situation. I was now by so long fasting reduced to such a state of weakness, that my legs were hardly able to support me, and it was with extreme difficulty that I succeeded in reaching a baker’s shop in the neighbourhood, where with my four remaining pennies, which I had reserved for a last resource, I purchased two two-penny loaves.

37 After four days of intolerable hunger, the reader may judge how great must have been my joy, to find myself in possession of even a morsel to appease it—well might I have exclaimed at this moment with the unfortunate Trenck—“O nature! what delight hast thou combined with the gratification of thy wants! remember this ye who rack invention to excite appetite, and which yet you cannot procure; remember how simple are the means that will give a crust of mouldy bread a flavour more exquisite than all the spices of the east, or all the profusion of land or sea; remember this, grow hungry, and indulge your sensuality.”

Although five times the quantity of the “staff of life” would have been insufficient to have satisfied my appetite, yet, as I thought it improbable that I should be indulged with a mouthful of any thing to eat in the morning, I concluded to eat then but one loaf, and to reserve the other for another meal; but having eaten one, so far from satisfying, it seemed rather to increase my appetite for the other—the temptation was irresistable—the cravings of hunger predominated, and would not be satisfied until I had devoured the remaining one.

The day was now far spent and I was compelled to resort with reluctance to a carriage house, to spend another night in misery; I found nothing therein on which to repose my wearied limbs but the bare floor, which was sufficient to deprive me of sleep, however much exhausted nature required38 it; my spirits were however buoyed up by the pleasing consolation that the succeeding day would bring relief;—as soon as day light appeared, I hastened to await the commands of one, whom, since my first introduction, I could not but flatter myself would prove my benefactor, and afford me that relief which my pitiful situation so much required—it was an hour much earlier than that at which even the domestics were in the habit of arising, and I had been a considerable time walking back and forth in the barn yard, before any made their appearance. It was now about 4 o’clock, and by the person of whom I made the enquiry, I was informed that 8 o’clock was the usual hour in which the labourers commenced their day’s work—permission was granted me by this person (who had the care of the stable) to repose myself on some straw beneath the manger, until they should be in readiness to depart to commence their day’s work—in the four hours I had a more comfortable nap than any that I had enjoyed the four preceding nights. At 8 o’clock precisely all hands were called, and preparations made for a commencement of the labours of the day—I was furnished with a large iron fork and a hoe, and ordered by my employer to accompany them, and although my strength at this moment was hardly sufficient to enable me to bear even so light a burden, yet was unwilling to expose my weakness, so long as it could be avoided—but, the time had now arrived in which it was impossible for me any longer39 to conceal it, and had to confess the cause to my fellow labourers, so far as to declare to them, that such had been my state of poverty, that (with the exception of the four small loaves of bread) I had not tasted food for four days! I was not I must confess displeased nor a little disappointed to witness the evident emotions of pity and commiseration, which this woeful declaration appeared to excite in their minds: as I had supposed them too much accustomed to witness scenes of misery and distress, to have their feelings much effected by a brief recital of my sufferings and deprivations—but in justice to them I must say, that although a very illiterate, I found them (with a few exceptions) a humane and benevolent people.

About 11 o’clock we were visited by our employer, Sir John: who, noticing me particularly, and perceiving the little progress I made in my labour, observed, that although I had the appearance of being a stout hearty man, yet I either feigned myself or really was a very weak one! on which it was immediately observed by one of my friendly fellow labourers, that it was not surprising that I lacked strength, as I had eaten nothing of consequence for four days! Mr. Millet, who appeared at first little disposed to credit the fact, on being assured by me that it was really so, put a shilling into my hand, and bid me go immediately and purchase to that amount in bread and meat—a request which the reader may suppose I did not hesitate to comply with.

40 Having made a tolerable meal, and feeling somewhat refreshed thereby, I was on my return when I was met by my fellow labourers on their return home, four o’clock being the hour in which they usually quit work. As soon as we arrived, some victuals was ordered for me by Sir John, when the maid presenting a much smaller quantity, than what her benevolent master supposed sufficient to satisfy the appetite of one who had been four days fasting, she was ordered to return and bring out the platter and the whole of its contents, and of which I was requested to eat my fill, but of which I ate sparingly to prevent the dangerous consequences which might have resulted from my voracity in the debilitated state to which my stomach was reduced.

My light repast being over, one of the men were ordered by my hospitable friend to provide for me a comfortable bed in the barn, where I spent the night on a couch of clean straw, more sweetly than ever I had done in the days of my better fortune. I arose early much refreshed, and was preparing after breakfast to accompany the labourers to their work, which was no sooner discovered by Sir John, than smiling, he bid me return to my couch and there remain until I was in a better state to resume my labours; indeed the generous compassion and benevolence of this gentleman was unbounded. After having on that day partook of an excellent dinner, which had been provided expressly for me, and the domestics having been ordered to retire, I was not a little surprised41 to hear myself thus addressed by him—“my honest friend, I perceive that you are a sea-faring man, and your history probably is a secret which you may not wish to divulge; but, whatever circumstances may have attended you, you may make them known to me with the greatest safety, for I pledge my honour I will never betray you.”

Having experienced so many proofs of the friendly disposition of Mr. Millet, I could not hesitate a moment to comply with his request, and without attempting to conceal a single fact, made him acquainted with every circumstance that had attended me since my first enlistment as a soldier—after expressing his regret that there should be any of his countrymen found so void of the principles of humanity, as to treat thus an unfortunate prisoner of war, he assured me that so long as I remained in his employ he would guarantee my safety—adding, that notwithstanding (in consequence of the unhappy differences which then prevailed between Great Britain and her American colonies) the inhabitants of the latter were denominated Rebels, yet they were not without their friends in England, who wished well to their cause, and would cheerfully aid them whenever an opportunity should present—he represented the soldiers (whom it had been reported to me, were constantly on the look out for deserters) as a set of mean and contemptible wretches, little better than a lawless banditti, who, to obtain the fee awarded by government, for the apprehension of a deserter, would betray their best friends.

42 Having been generously supplied with a new suit of cloathes and other necessaries by Mr. M. I contracted with him for six months, to superintend his strawberry garden, in the course of which so far from being molested, I was not suspected by even his own domestics of being an American—at the expiration of the six months, by the recommendation of my hospitable friend, I got a berth in the garden of the Princess Amelia, where although among my fellow labourers the American Rebellion was not unfrequently the topic of their conversation, and the “d—d Yankee Rebels” (as they termed them) frequently the subjects of their vilest abuse, I was little suspected of being one of that class whom they were pleased thus to denominate—I must confess that it was not without some difficulty, that I was enabled to surpress the indignant feelings occasioned by hearing my countrymen spoken so disrespectfully of, but as a single word in their favour might have betrayed me, I could obtain no other satisfaction than by secretly indulging the hope that I might before the conclusion of the war, have an opportunity to repay them, in their own coin, with interest.

I remained in the employ of the Princess about three months, and then in consequence of a misunderstanding with the overseer, I hired myself to a farmer in a small village adjoining Brintford, where I had not been three weeks employed before rumour was afloat that I was a Yankee Prisoner of war! from whence the report arose, or by what occasioned, I43 never could learn—it no sooner reached the ears of the soldiers, than they were on the alert, seeking an opportunity to seize my person—fortunately I was appraised of their intentions before they had time to carry them into effect; I was however hard pushed, and sought for by them with that diligence and perseverance that certainly deserved a better cause—I had many hair breadth escapes, and most assuredly should have been taken, had it not been for the friendship of those whom I suspect felt not less friendly to the cause of my country, but dare not publicly avow it—I was at one time traced by the soldiers in pursuit of me to the house of one of this description, in whose garret I was concealed, and was at that moment in bed; they entered and enquired for me, and on being told that I was not in the house, they insisted on searching, and were in the act of ascending the chamber stairs for that purpose, when seizing my cloathes, I passed up through the scuttle, and reached the roof of the house, and from thence half naked passed to those of the adjoining ones to the number of ten or twelve, and succeeded in making my escape without being discovered.

Being continually harassed by night and day by the soldiers, and driven from place to place, without an opportunity to perform a day’s work, I was advised by one whose sincerity I could not doubt, to apply for a berth as a labourer in a garden of his Royal Majesty, situated in the village of Quew, a few miles from Brintford; where, under the protection44 of his Majesty, it was represented to me that I should be perfectly safe, as the soldiers dare not approach the royal premises, to molest any one therein employed—he was indeed so friendly as to introduce me personally to the overseer, as an acquaintance who possessed a perfect knowledge of gardening, but from whom he carefully concealed the fact of my being an American born, and of the suspicion entertained by some of my being a prisoner of war, who had escaped the vigilance of my keepers.

The overseer concluded to receive me on trial;—it was here that I had not only frequent opportunities to see his Royal Majesty in person, in his frequent resorts to this, one of his country retreats, but once had the honour of being addressed by him. The fact was, that I had not been one week employed in the garden, before the suspicion of my being either a prisoner of war, or a Spy, in the employ of the American Rebels, was communicated, not only to the overseer and other persons employed in the garden, but even to the King himself! As I was one day busily engaged with three others in gravelling a walk, I was unexpectedly accosted by his Majesty: who, with much apparent good nature, enquired of me of what country I was—“an American born, may it please your Majesty,” was my reply (taking off my hat, which he requested me instantly to replace on my head),—“ah! (continued he with a smile) an American, a45 stubborn, a very stubborn people indeed!—and what brought you to this country, and how long have you been here?” “the fate of war, your Majesty—I was brought to this country a prisoner about eleven months since,”—and thinking this a favourable opportunity to acquaint him with a few of my grievances, I briefly stated to him how much I had been harassed by the soldiers—“while here employed they will not trouble you,” was the only reply he made, and passed on. The familiar manner in which I had been interrogated by his Majesty, had I must confess a tendency in some degree to prepossess me in his favour—I at least suspected him to possess a disposition less tyrannical, and capable of better view than what had been imputed to him; and as I had frequently heard it represented in America, that uninfluenced by such of his ministers, as unwisely disregarded the reiterated complaints of the American people, he would have been foremost to have redressed their grievances, of which they so justly complained.

I continued in the service of his Majesty’s gardner at Quew, about four months, when the season having arrived in which the work of the garden required less labourers I with three others was discharged; and the day after engaged myself for a few months, to a farmer in the town and neighbourhood where I had been last employed—but, not one week had expired before the old story of my being an American prisoner of war &c. was revived and industriously circulated,46 and the soldiers (eager to obtain the proffered bounty) like a pack of blood-hounds were again on the track seeking an opportunity to surprise me—the house wherein I had taken up my abode, was several times thoroughly searched by them, but I was always so fortunate as to discover their approach in season to make good my escape by the assistance of a friend—to so much inconvenience however did this continual apprehension and fear subject me, that I was finally half resolved to surrender myself a prisoner to some of his Majesty’s officers, and submit to my fate, whatever it might be, when by an unexpected occurrence, and the seasonable interposition of providence in my favour, I was induced to change my resolution.

I had been strongly of the opinion by what I had myself experienced, that America was not without her friends in England, and those who were her well wishers in the important cause in which she was at that moment engaged; an opinion which I think no one will disagree with me in saying, was somewhat confirmed, by a circumstance of that importance, as entitles it to a conspicuous place in my narrative. At a moment when driven almost to a state of despondency by continual alarms and fears of falling into the hands of a set of desperadoes, who for a very small reward would willingly have undertaken the commission of almost any crime; I received a message from a gentleman of respectability of Brintford (J. Woodcock Esq.) requesting me to repair immediately47 to his house—the invitation I was disposed to pay but little attention to, as I viewed it nothing more than a plan of my pursuers to decoy and entrap me—but, on learning from my confidential friend that the gentleman by whom the message had been sent, was one whose loyalty had been doubted, I was induced to comply with the request.

I reached the house of ’Squire Woodcock about 8 o’clock in the evening, and after receiving from him at the door assurances that I might enter without fear or apprehension of any design on his part against me, I suffered myself to be introduced into a private chamber, where were seated two other gentlemen, who appeared to be persons of no mean rank, and proved to be no other than Horne Tooke and James Bridges Esquires—as all three of these gentlemen have long since paid the debt of nature, and are placed beyond the reach of such as might be disposed to persecute or reproach them for their disloyalty, I can now with perfect safety disclose their names—names which ought to be dear to every true American.

After having (by their particular request) furnished these gentlemen with a brief account of the most important incidents of my life, I underwent a very strict examination, as they seemed determined to satisfy themselves, before they made any important advances or disclosures, that I was a person in whom they could repose implicit confidence. Finding me firmly attached to the interests of my country, so48 much so as to be willing to sacrifice even my life if necessary in her behalf, they began to address me with less reserve; and after bestowing the highest encomiums on my countrymen, for the bravery which they had displayed in their recent engagements with the British troops, as well as for their patriotism in publicly manifesting their abhorrence and detestation of the ministerial party in England, who to alienate their affections and to enslave them, had endeavoured to subvert the British constitution; they enquired of me if (to promote the interests of my country) I should have any objection to take a trip to Paris, on an important mission, if my passage and other expences were paid, and a generous compensation allowed me for my trouble; and which in all probability would lead to the means whereby I might be enabled to return to my country—to which I replied that I should have none. After having enjoined upon me to keep every thing which they had communicated, a profound secret, they presented me with a guinea, and a letter for a gentleman in White Waltam (a country town about 30 miles from Brintford) which they requested me to reach as soon as possible, and there remain until they should send for me, and by no means to fail to arrive at the precise hour that they should appoint.

After partaking of a little refreshment I set out at 12 o’clock at night, and reached White Waltam at half past 11 the succeeding day, and immediately49 waited on and presented the letter to the gentleman to whom it was directed, and who gave me a very cordial reception, and whom I soon found was as real a friend to America’s cause as the three gentlemen in whose company I had last been. It was from him that I received the first information of the evacuation of Boston by the British troops, and of the declaration of Independence, by the American Congress—he indeed appeared to possess a knowledge of almost every important transaction in America, since the memorable battle of Bunker-Hill, and it was to him that I was indebted for many particulars, not a little interesting to myself, and which I might otherwise have remained ignorant of, as I have always found it a principle of the Britains, to conceal every thing calculated to diminish or tarnish their fame, as a “great and powerful nation!”

I remained in the family of this gentleman about a fortnight, when I received a letter from ’Squire Woodcock, requesting me to be at his house without fail precisely at 2 o’clock the morning ensuing—in compliance of which I packed up and started immediately for Brintford, and reached the house of ’Squire Woodcock at the appointed hour—I found there in company with the latter, the two gentlemen whose names I have before mentioned, and by whom the object of my mission to Paris was now made known to me—which was to convey in the most secret manner possible a letter to Dr. Franklin; every thing was in readiness, and a chaise ready harnessed50 which was to convey me to Charing Cross, waiting at the door—I was presented with a pair of boots, made expressly for me, and for the safe conveyance of the letter of which I was to be the bearer, one of them contained a false heel, in which the letter was deposited, and was to be thus conveyed to the Doctor. After again repeating my former declarations, that whatever might be my fate, they should never be exposed, I departed, and was conveyed in quick time to Charing Cross, where I took the post coach for Dover, and from thence was immediately conveyed in a packet to Calais, and in fifteen minutes after landing, started for Paris; which I reached in safety, and delivered to Dr. Franklin the letter of which I was the bearer.