Title: The City of the Saints, and Across the Rocky Mountains to California

Author: Sir Richard Francis Burton

Release date: November 22, 2021 [eBook #66791]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Tim Lindell, Harry Lamé and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

The cover image has been created for this text, and is in the public domain.

The illustrations as displayed in this text may be enlarged by opening them in a new window or tab (not available in all formats).

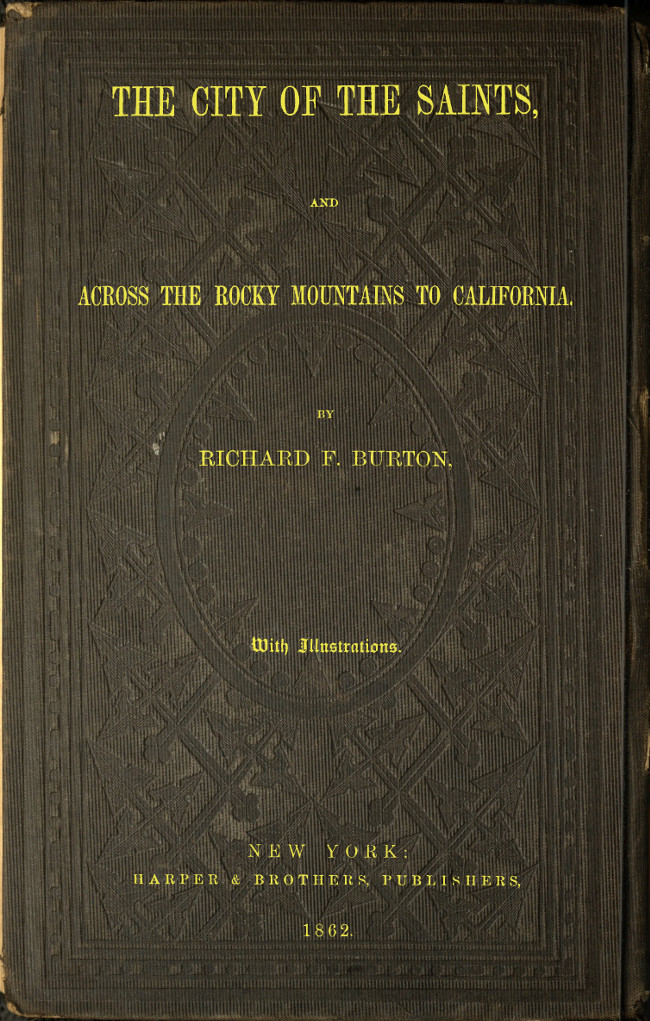

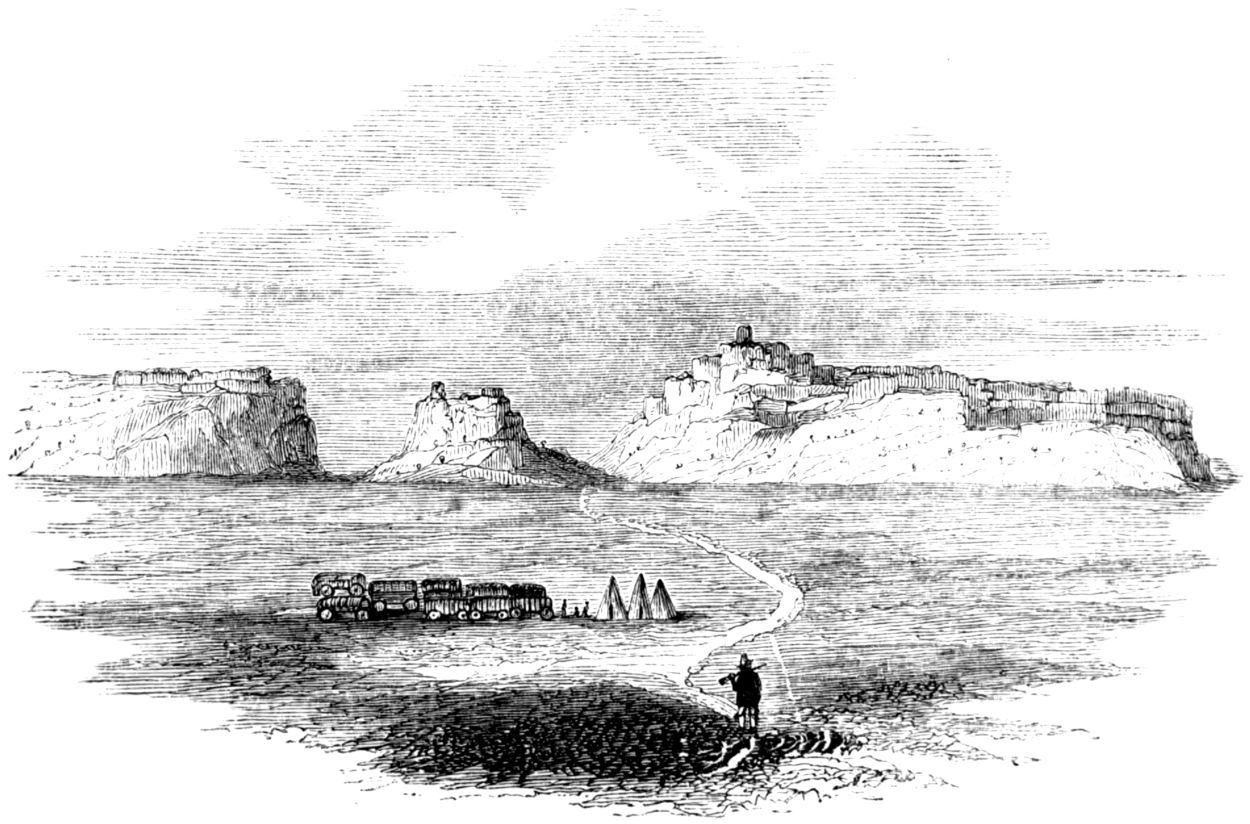

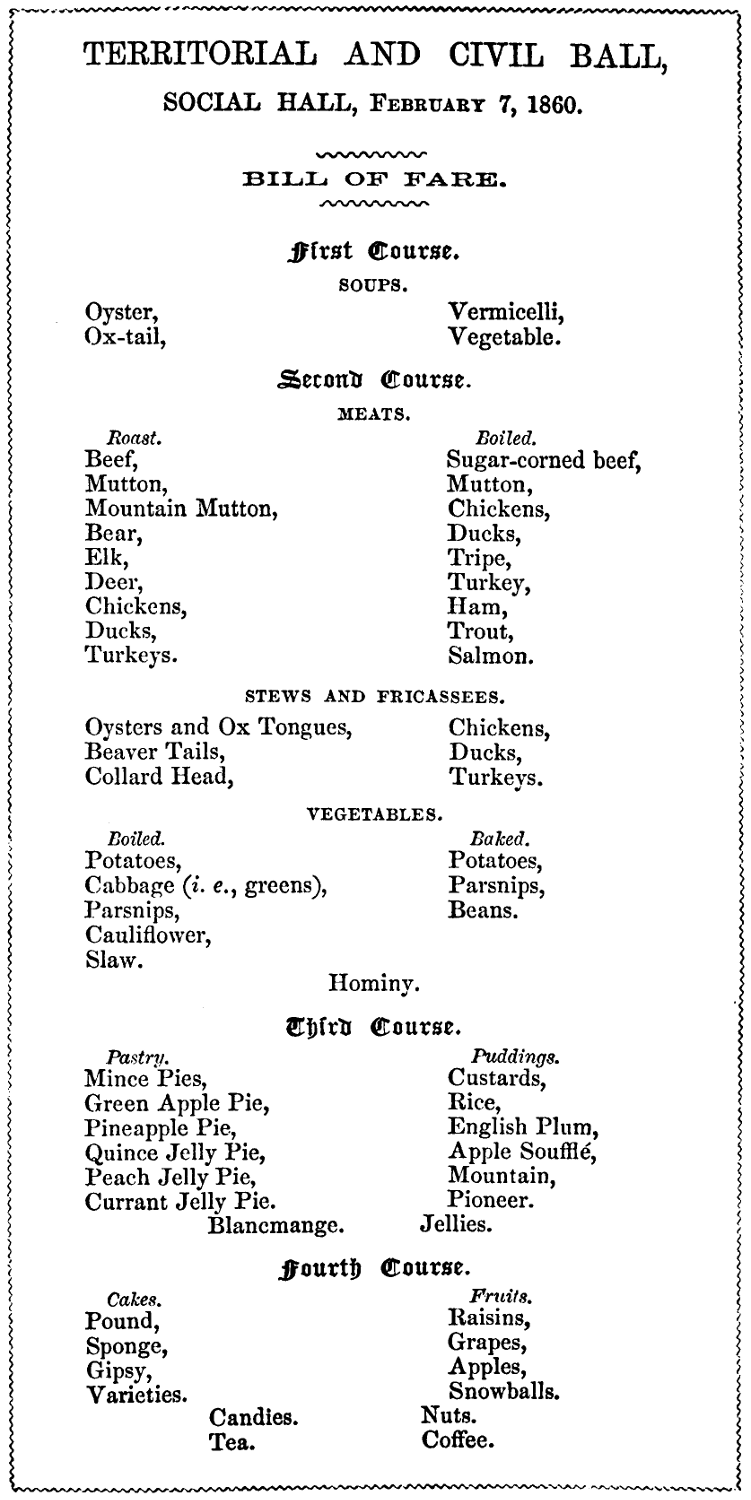

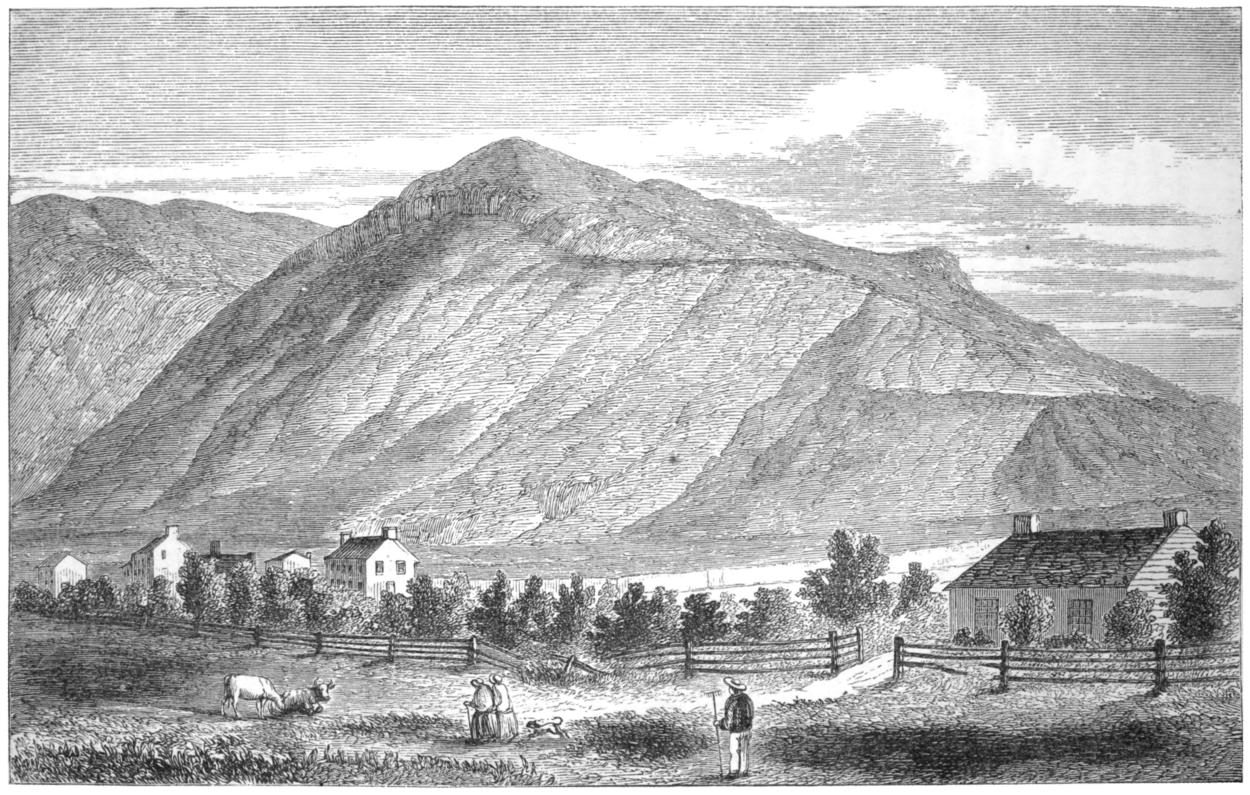

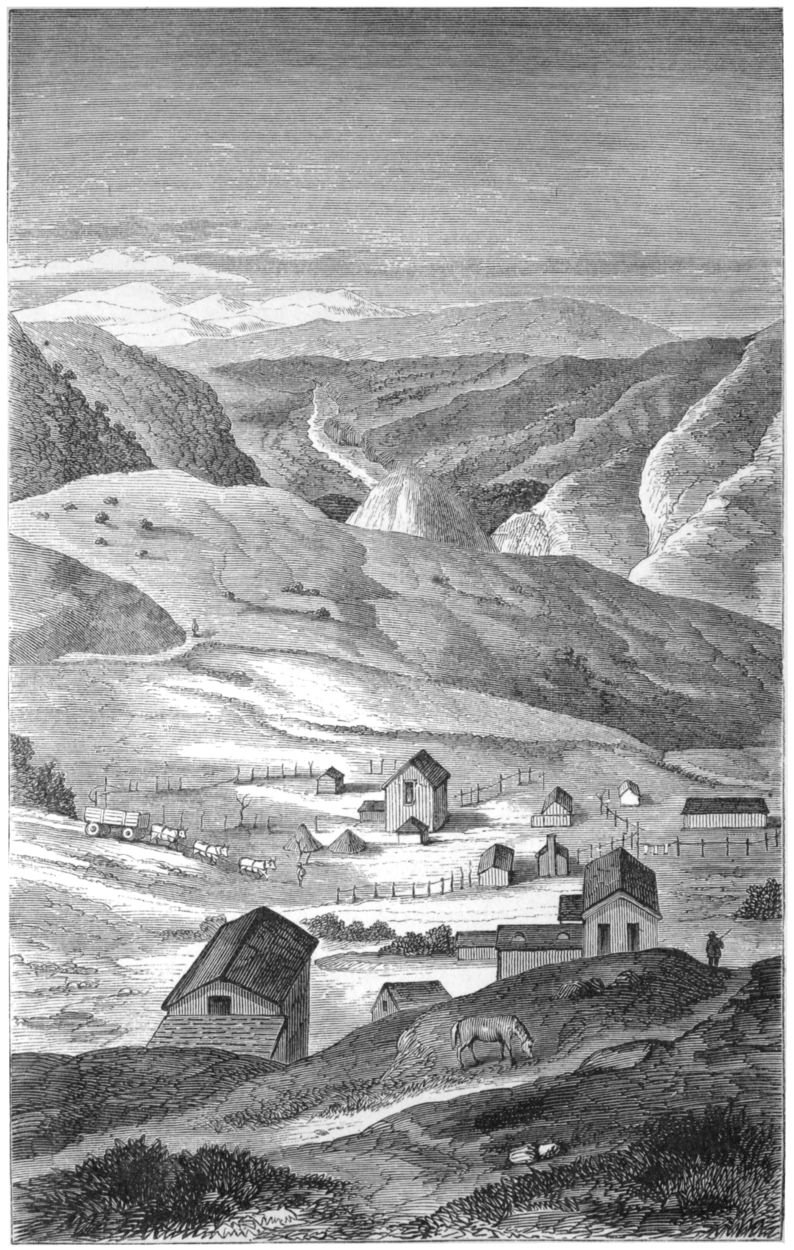

GREAT SALT LAKE CITY. (From the North.)

BY

RICHARD F. BURTON,

AUTHOR OF

“THE LAKE REGIONS OF CENTRAL AFRICA,” ETC.

With Illustrations.

NEW YORK:

HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS,

FRANKLIN SQUARE.

1862.

“Clear your mind of cant.”—Johnson.

“Montesinos.—America is in more danger from religious fanaticism. The government there not thinking it necessary to provide religious instruction for the people in any of the new states, the prevalence of superstition, and that, perhaps, in some wild and terrible shape, may be looked for as one likely consequence of this great and portentous omission. An Old Man of the Mountain might find dupes and followers as readily as the All-friend Jemima; and the next Aaron Burr who seeks to carve a kingdom for himself out of the overgrown territories of the Union, may discern that fanaticism is the most effective weapon with which ambition can arm itself; that the way for both is prepared by that immorality which the want of religion naturally and necessarily induces, and that camp-meetings may be very well directed to forward the designs of military prophets. Were there another Mohammed to arise, there is no part of the world where he would find more scope or fairer opportunity than in that part of the Anglo-American Union into which the older states continually discharge the restless part of their population, leaving laws and Gospel to overtake it if they can, for in the march of modern colonization both are left behind.”

This remarkable prophecy appeared from the pen of Robert Southey, the Poet-Laureate, in March, 1829 (“Sir Thomas More; or, Colloquies on the Progress and Prospects of Society,” vol. i., Part II., “The Reformation—Dissenters—Methodists.”)

Dedication.

TO

RICHARD MONCKTON MILNES.

I HAVE PREFIXED YOUR NAME, DEAR MILNES, TO “THE CITY OF THE SAINTS:”

THE NAME OF A LINGUIST, TRAVELER, POET, AND, ABOVE ALL, A MAN

OF INTELLIGENT INSIGHT INTO THE THOUGHTS AND

FEELINGS OF HIS BROTHER MEN.

[ix]

Unaccustomed, of late years at least, to deal with tales of twice-told travel, I can not but feel, especially when, as in the present case, so much detail has been expended upon the trivialities of a Diary, the want of that freshness and originality which would have helped the reader over a little lengthiness. My best excuse is the following extract from the lexicographer’s “Journey to the Western Islands,” made in company with Mr. Boswell during the year of grace 1773, and upheld even at that late hour as somewhat a feat in the locomotive line.

“These diminutive observations seem to take away something from the dignity of writing, and therefore are never communicated but with hesitation, and a little fear of abasement and contempt. But it must be remembered that life consists not of a series of illustrious actions or elegant enjoyments; the greater part of our time passes in compliance with necessities, in the performance of daily duties, in the removal of small inconveniences, in the procurement of petty pleasures, and we are well or ill at ease as the main stream of life glides on smoothly, or is ruffled by small obstacles and frequent interruptions.”

True! and as the novelist claims his right to elaborate, in the “domestic epic,” the most trivial scenes of household routine, so the traveler may be allowed to enlarge, when copying nature in his humbler way, upon the subject of his little drama, and, not confining himself to the great, the good, and the beautiful, nor suffering himself to be wholly engrossed by the claims of cotton, civilization, and Christianity, useful knowledge and missionary enterprise, to desipere in loco by expatiating upon his bed, his meat, and his drink.

The notes forming the ground-work of this volume were written on patent improved metallic pocket-books in sight of the objects which attracted my attention. The old traveler is again right when he remarks: “There is yet another cause of error not[x] always easily surmounted, though more dangerous to the veracity of itinerary narratives than imperfect mensuration. An observer deeply impressed by any remarkable spectacle does not suppose that the traces will soon vanish from his mind, and, having commonly no great convenience for writing”—Penny and Letts are of a later date—“defers the description to a time of more leisure and better accommodation. He who has not made the experiment, or is not accustomed to require rigorous accuracy from himself, will scarcely believe how much a few hours take from certainty of knowledge and distinctness of imagery; how the succession of objects will be broken, how separate parts will be confused, and how many particular features and discriminations will be found compressed and conglobated with one gross and general idea.” Brave words, somewhat pompous and diffused, yet worthy to be written in letters of gold. But, though of the same opinion with M. Charles Didier, the Miso-Albion (Séjour chez le Grand-Chérif de la Mekkeh, Preface, p. vi.), when he characterizes “un voyage de fantaisie” as “le pire de tous les romans,” and with Admiral Fitzroy (Hints to Travelers, p. 3), that the descriptions should be written with the objects in view, I would avoid the other extreme, viz., that of publishing, as our realistic age is apt to do, mere photographic representations. Byron could not write verse when on Lake Leman, and the traveler who puts forth his narrative without after-study and thought will produce a kind of Persian picture, pre-Raphaelitic enough, no doubt, but lacking distance and perspective—in artists’ phrase, depth and breadth—in fact, a narrative about as pleasing to the reader’s mind as the sage and saleratus prairies of the Far West would be to his ken.

In working up this book I have freely used authorities well known across the water, but more or less rare in England. The books principally borrowed from are “The Prairie Traveler,” by Captain Marcy; “Explorations of Nebraska,” by Lieutenant G. A. Warren; and Mr. Bartlett’s “Dictionary of Americanisms.” To describe these regions without the aid of their first explorers, Messrs. Frémont and Stansbury, would of course have been impossible. If I have not always specified the authority for a statement, it has been rather for the purpose of not wearying the reader by repetitions than with the view of enriching my pages at the expense of others.

In commenting upon what was seen and heard, I have endeavored[xi] to assume—whether successfully or not the public will decide—the cosmopolitan character, and to avoid the capital error, especially in treating of things American, of looking at them from the fancied vantage-ground of an English point of view. I hold the Anglo-Scandinavian[1] of the New World to be in most things equal, in many inferior, and in many superior, to his cousin in the Old; and that a gentleman, that is to say, a man of education, probity, and honor—not, as I was once told, one who must get on onner and onnest—is every where the same, though living in separate hemispheres. If, in the present transition state of the Far West, the broad lands lying between the Missouri River and the Sierra Nevada have occasionally been handled somewhat roughly, I have done no more than I should have permitted myself to do while treating of rambles beyond railways through the semi-civilized parts of Great Britain, with their “pleasant primitive populations”—Wales, for instance, or Cornwall.

[1] The word is proposed by Dr. Norton Shaw, Secretary to the Royal Geographical Society, and should be generally adopted. Anglo-Saxon is to Anglo-Scandinavian what Indo-Germanic is to Indo-European; both serve to humor the absurd pretensions of claimants whose principal claim to distinction is pretentiousness. The coupling England with Saxony suggests to my memory a toast once proposed after a patriotic and fusional political feed in the Isle of the Knights—“Malta and England united can conquer the world.”

I need hardly say that this elaborate account of the Holy City of the West and its denizens would not have seen the light so soon after the appearance of a “Journey to Great Salt Lake City,” by M. Jules Remy, had there not been much left to say. The French naturalist passed through the Mormon Settlements in 1855, and five years in the Far West are equal to fifty in less conservative lands; the results of which are, that the relation of my experiences will in no way clash with his, or prove a tiresome repetition to the reader of both.

If in parts of this volume there appear a tendency to look upon things generally in their ludicrous or absurd aspects—from which nothing sublunary is wholly exempt—my excuse must be sic me natura fecit. Democritus was not, I believe, a whit the worse philosopher than Heraclitus. The Procreation of Mirth should be a theme far more sympathetic than the Anatomy of Melancholy, and the old Roman gentleman had a perfect right to challenge all objectors with

[xii]

Finally, I would again solicit forbearance touching certain errors of omission and commission which are to be found in these pages. Her most gracious majesty has been pleased to honor me with an appointment as Consul at Fernando Po, in the Bight of Biafra, and the necessity of an early departure has limited me to a single revise.

14 St. James’ Square, 1st July, 1861.

[xiii]

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | WHY I WENT TO GREAT SALT LAKE CITY. — THE VARIOUS ROUTES. — THE LINE OF COUNTRY TRAVERSED. — DIARIES AND DISQUISITIONS. | 1 |

| II. | THE SIOUX OR DAKOTAHS. | 93 |

| III. | CONCLUDING THE ROUTE TO THE GREAT SALT LAKE CITY. | 131 |

| IV. | FIRST WEEK AT GREAT SALT LAKE CITY. — PRELIMINARIES. | 203 |

| V. | SECOND WEEK AT GREAT SALT LAKE CITY. — VISIT TO THE PROPHET. | 237 |

| VI. | DESCRIPTIVE GEOGRAPHY, ETHNOLOGY, AND STATISTICS OF UTAH TERRITORY. | 272 |

| VII. | THIRD WEEK AT GREAT SALT LAKE CITY. — EXCURSIONS. | 322 |

| VIII. | EXCURSIONS CONTINUED. | 343 |

| IX. | LATTER-DAY SAINTS. — OF THE MORMON RELIGION. | 361 |

| X. | FARTHER OBSERVATIONS AT GREAT SALT LAKE CITY. | 417 |

| XI. | LAST DAYS AT GREAT SALT LAKE CITY. | 441 |

| XII. | TO RUBY VALLEY. | 443 |

| XIII. | TO CARSON VALLEY. | 473 |

| CONCLUSION. | 499 | |

| APPENDICES. | 503 |

[xiv]

[xv]

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

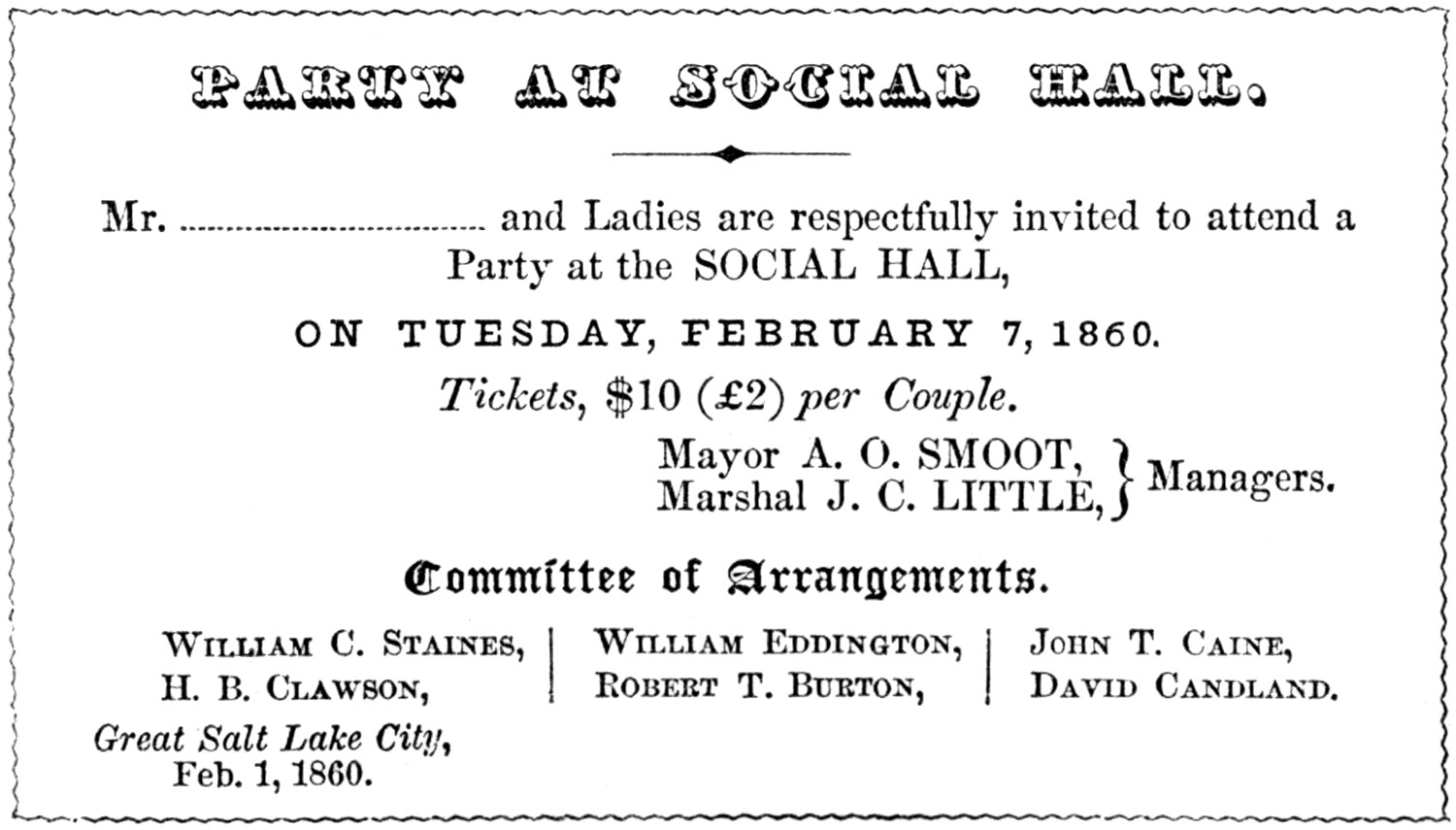

| 1. | GREAT SALT LAKE CITY FROM THE NORTH | Frontispiece. |

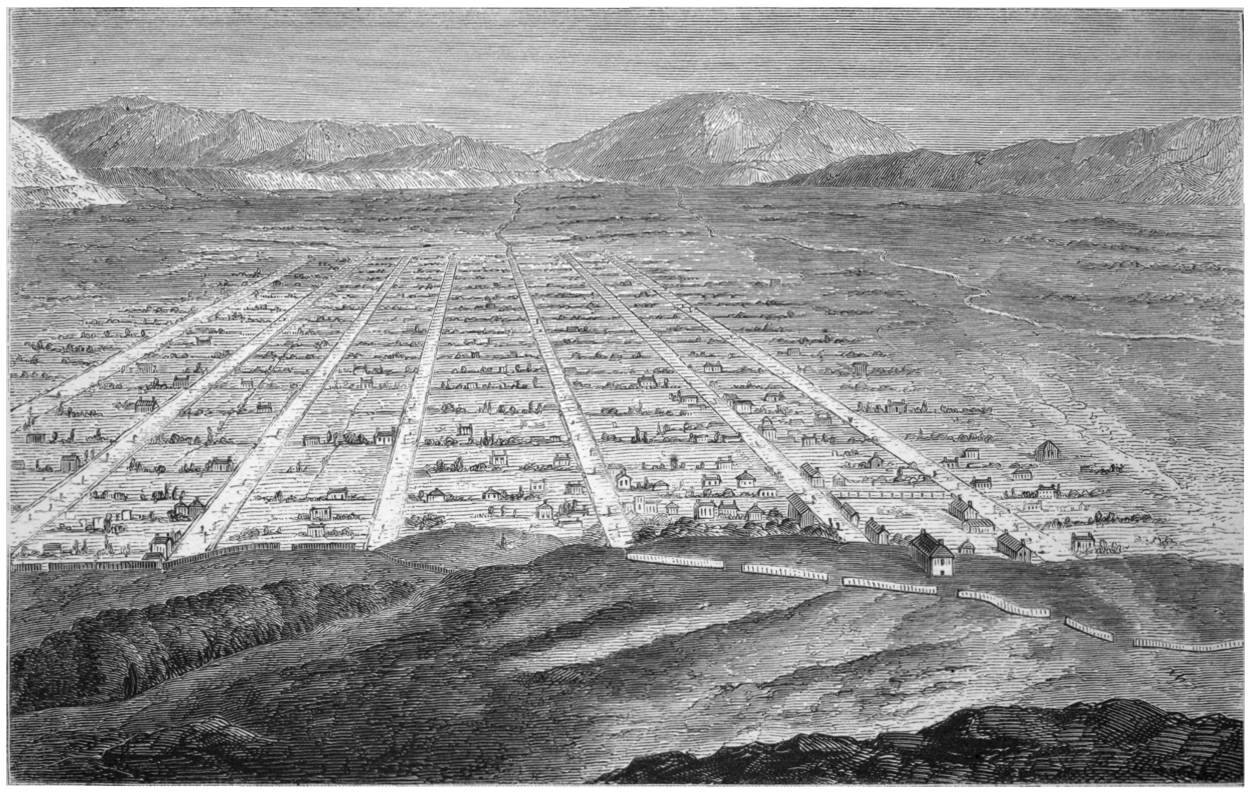

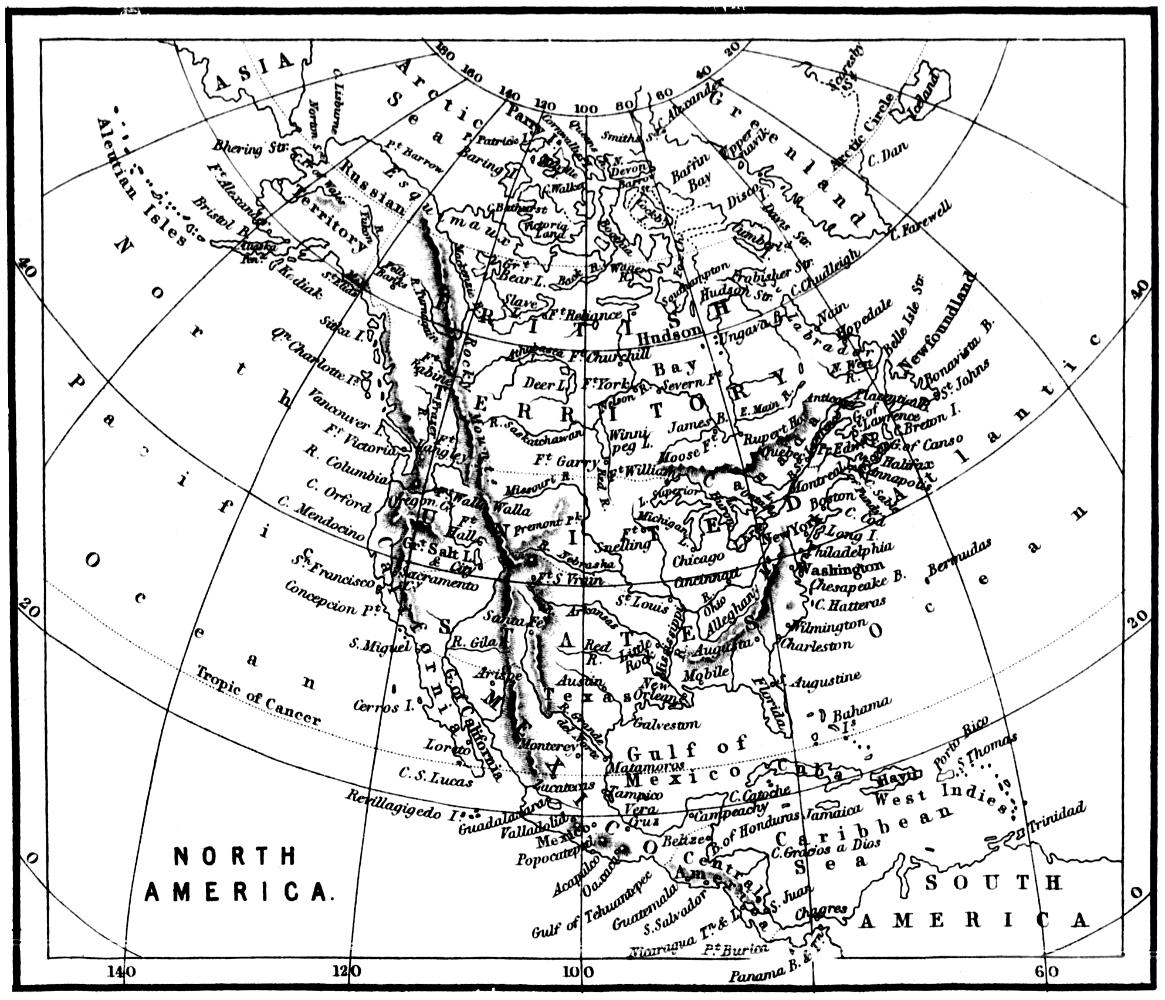

| 2. | ROUTE FROM THE MISSOURI RIVER TO THE PACIFIC | to face 1 |

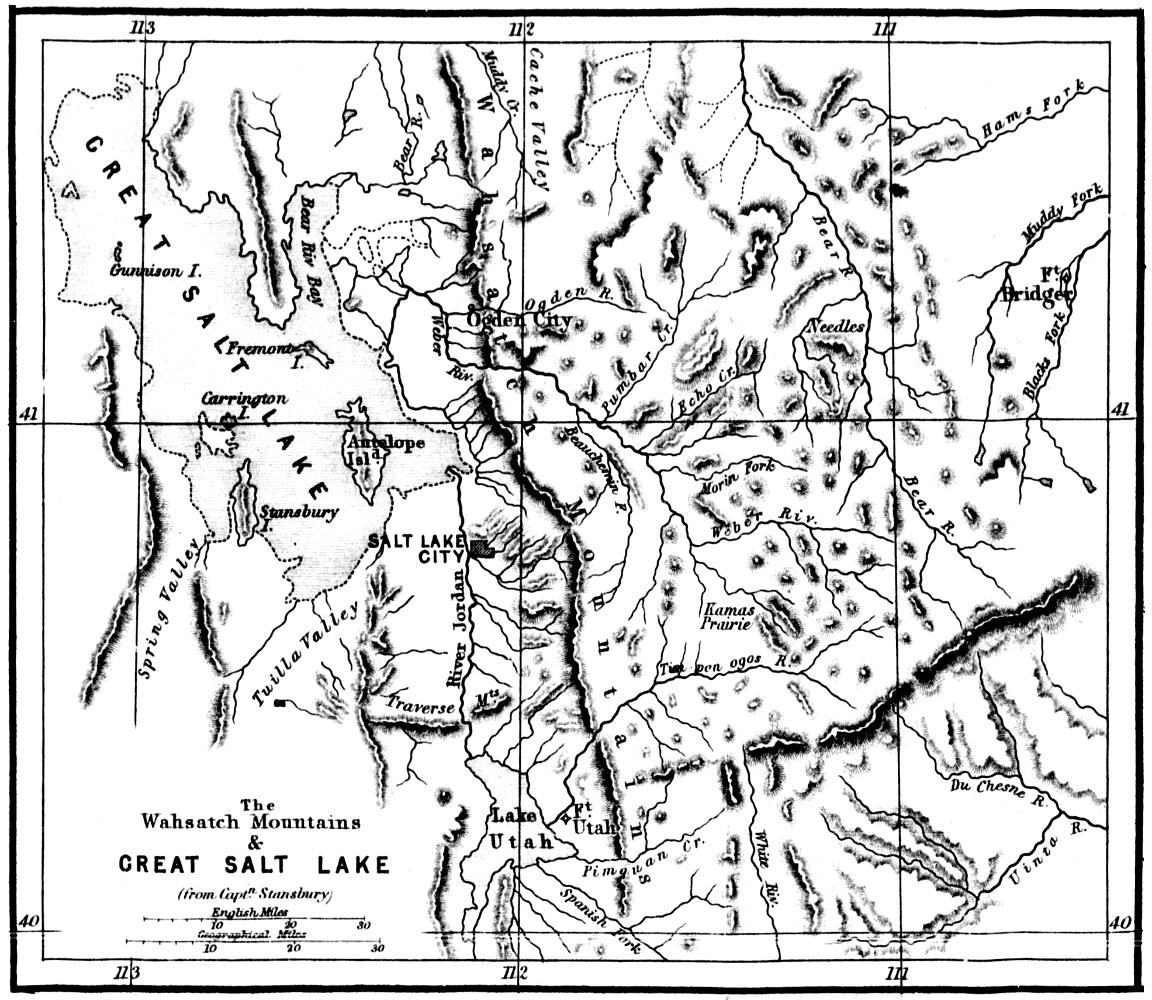

| 3. | MAP OF THE WASACH MOUNTAINS AND GREAT SALT LAKE | „ 1 |

| 4. | GENERAL MAP OF NORTH AMERICA | „ 1 |

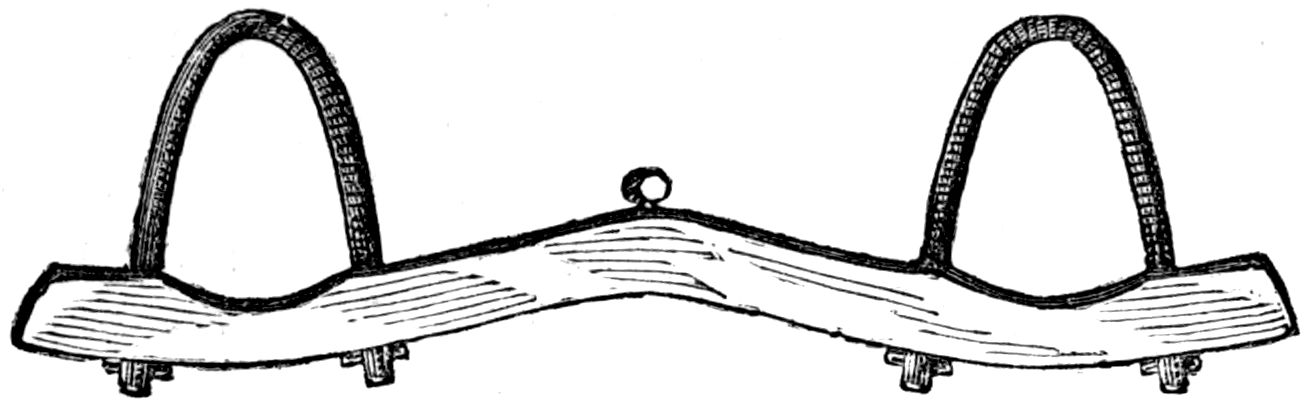

| 5. | THE WESTERN YOKE | 23 |

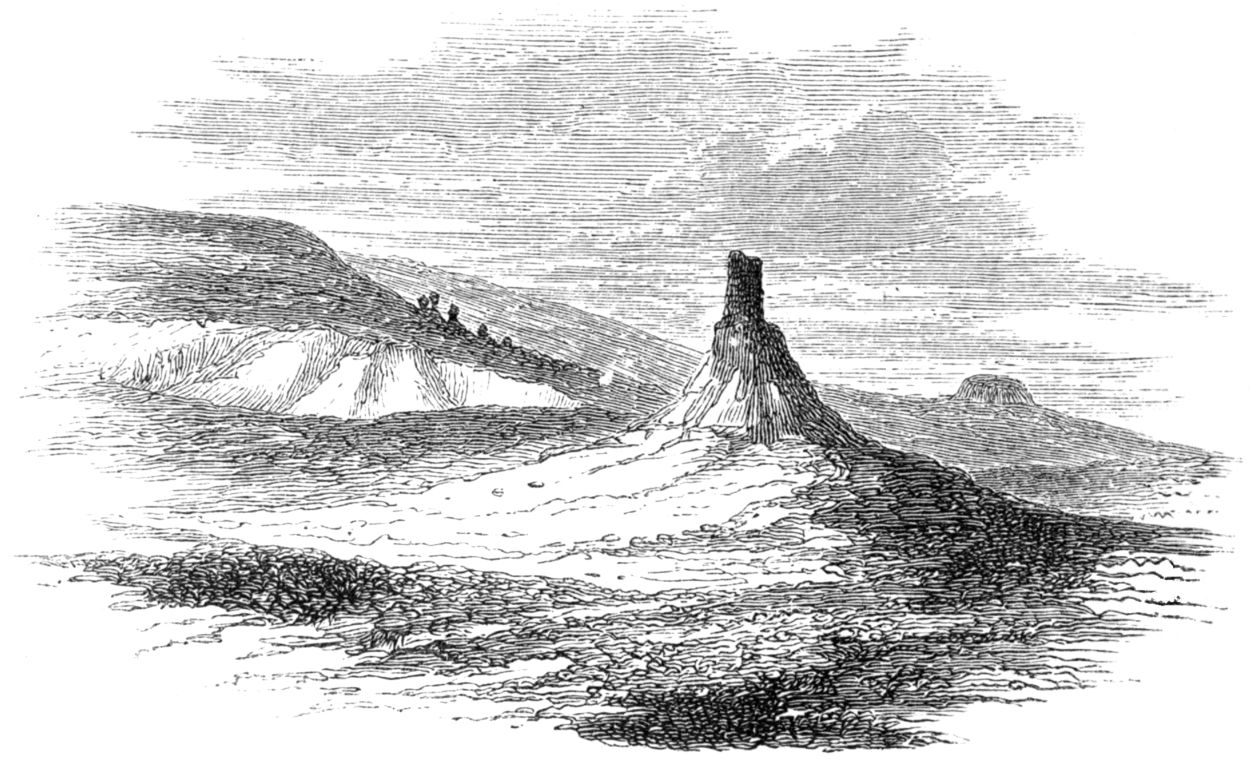

| 6. | CHIMNEY ROCK | 74 |

| 7. | SCOTT’S BLUFFS | 77 |

| 8. | INDIANS | 94 |

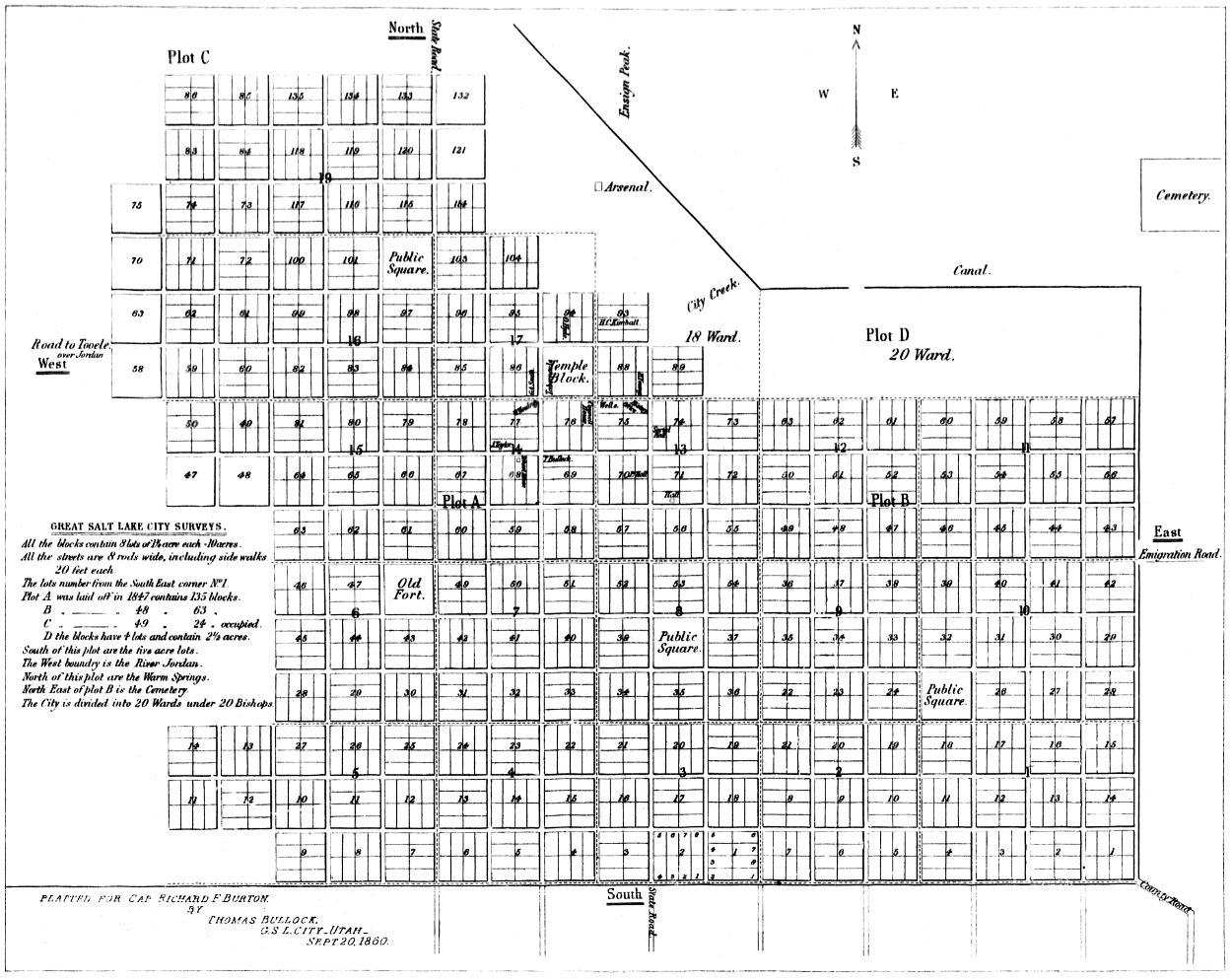

| 9. | PLAN OF GREAT SALT LAKE CITY | to face 193 |

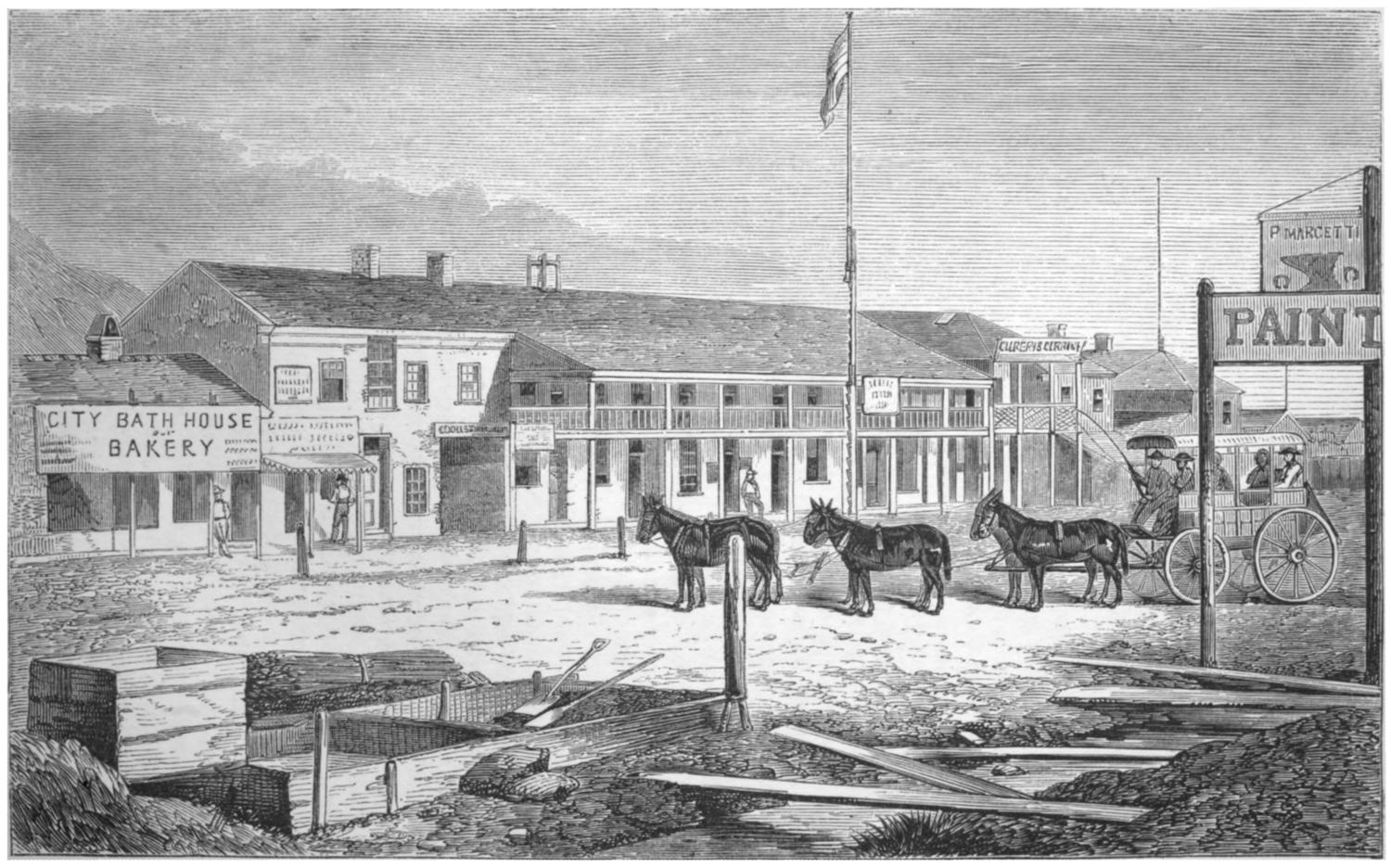

| 10. | STORES IN MAIN STREET | 199 |

| 11. | ENDOWMENT HOUSE AND TABERNACLE | 221 |

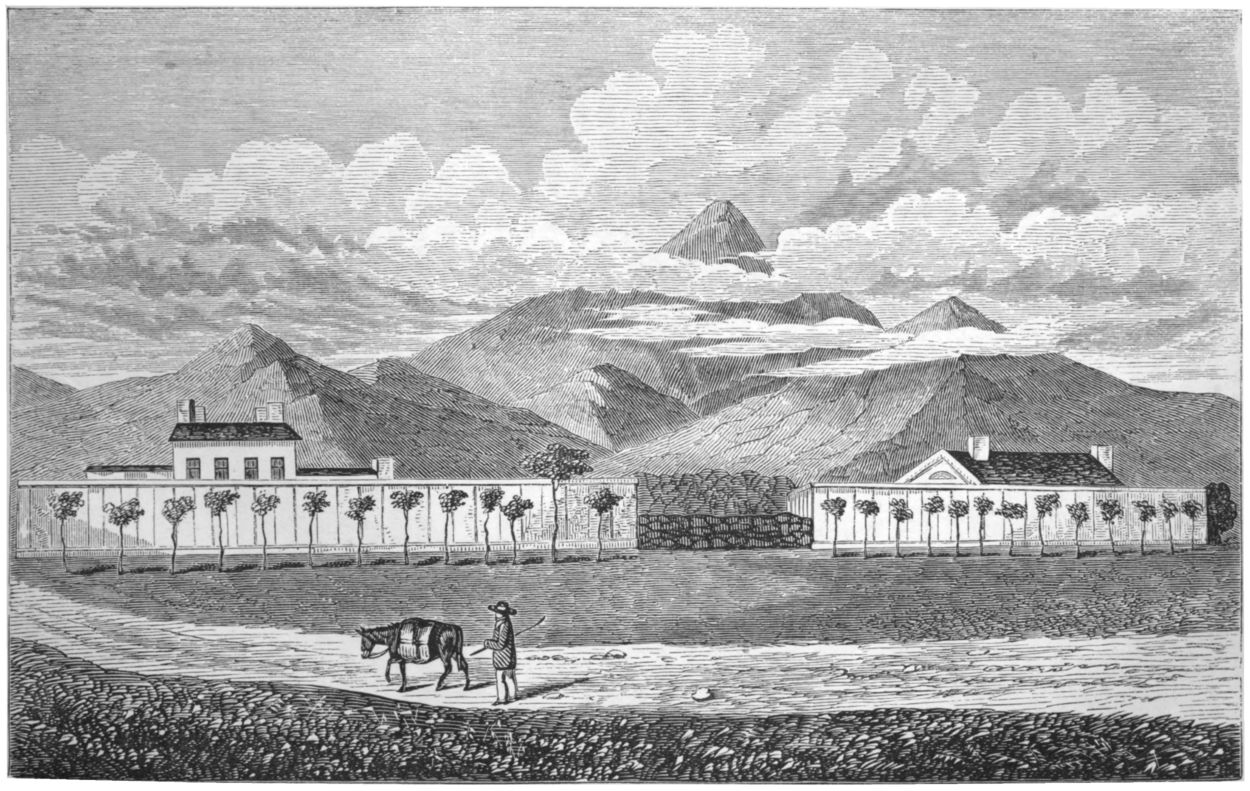

| 12. | THE PROPHET’S BLOCK | 247 |

| 13. | THE TABERNACLE | 259 |

| 14. | ANCIENT LAKE BENCH-LAND | 272 |

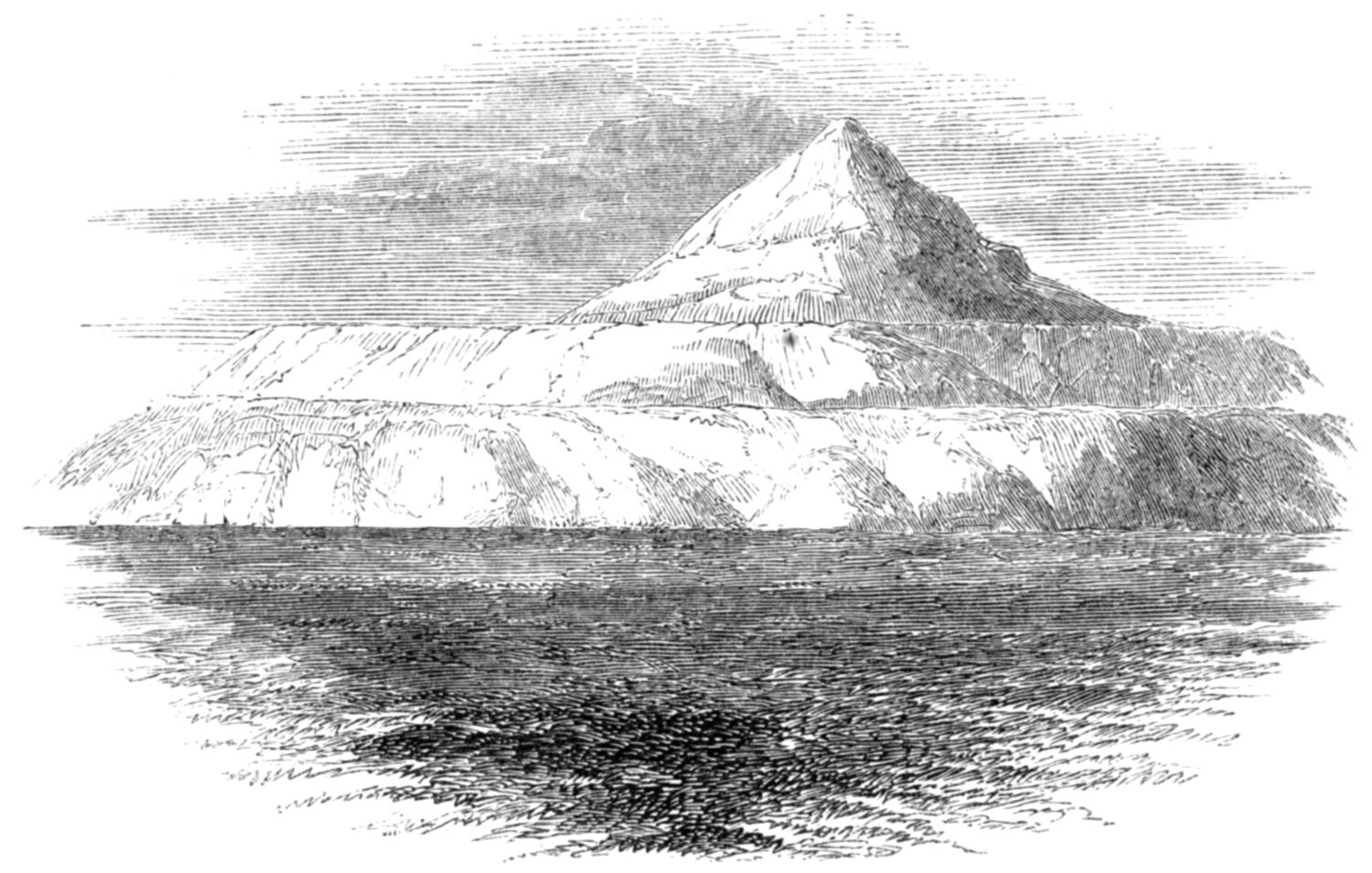

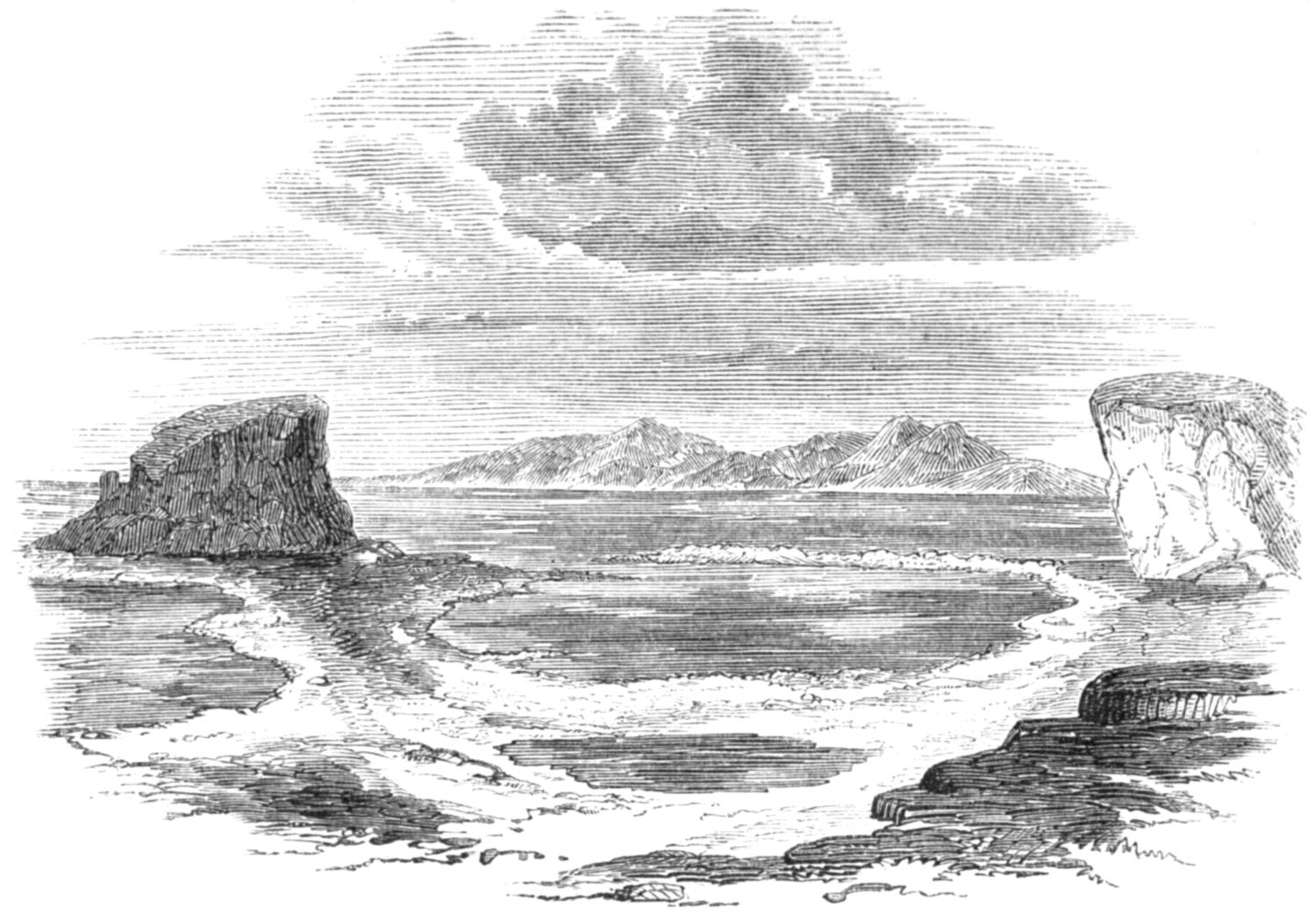

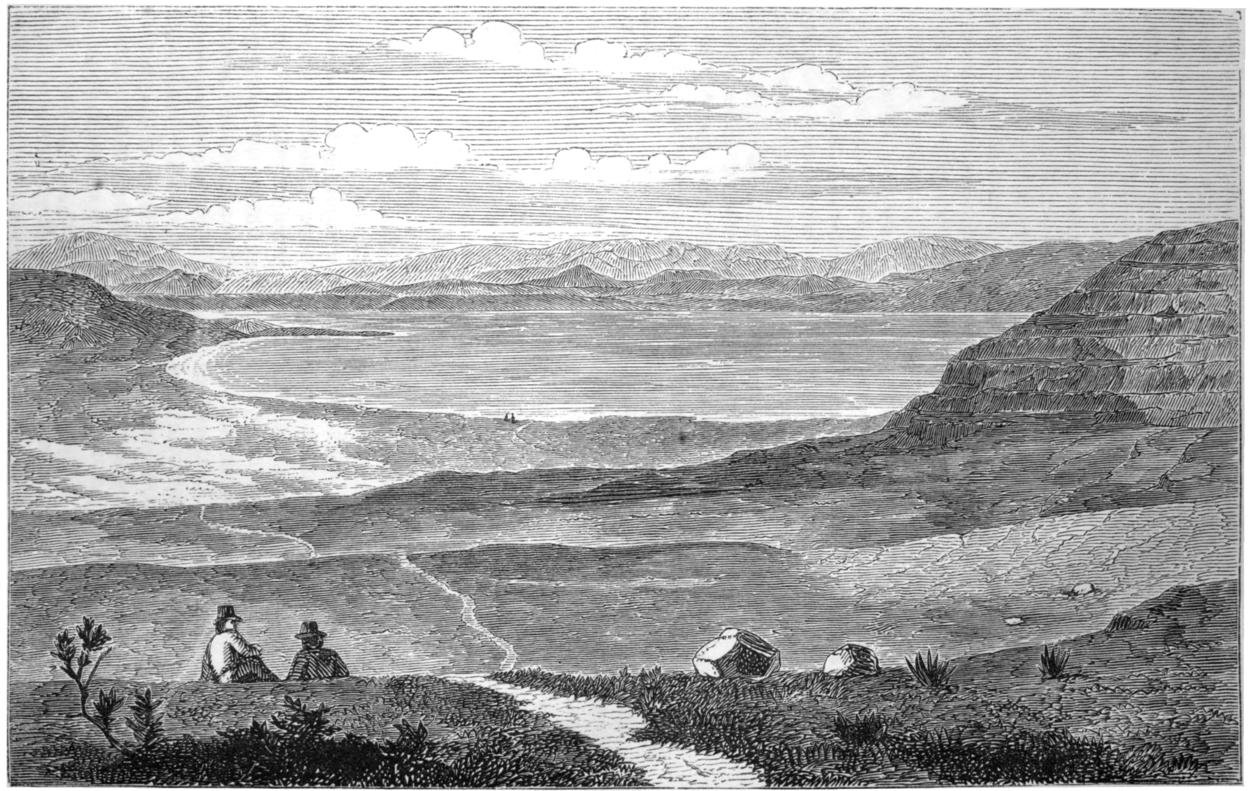

| 15. | THE DEAD SEA | 322 |

| 16. | ENSIGN PEAK | 358 |

| 17. | DESERÉT ALPHABET | 420 |

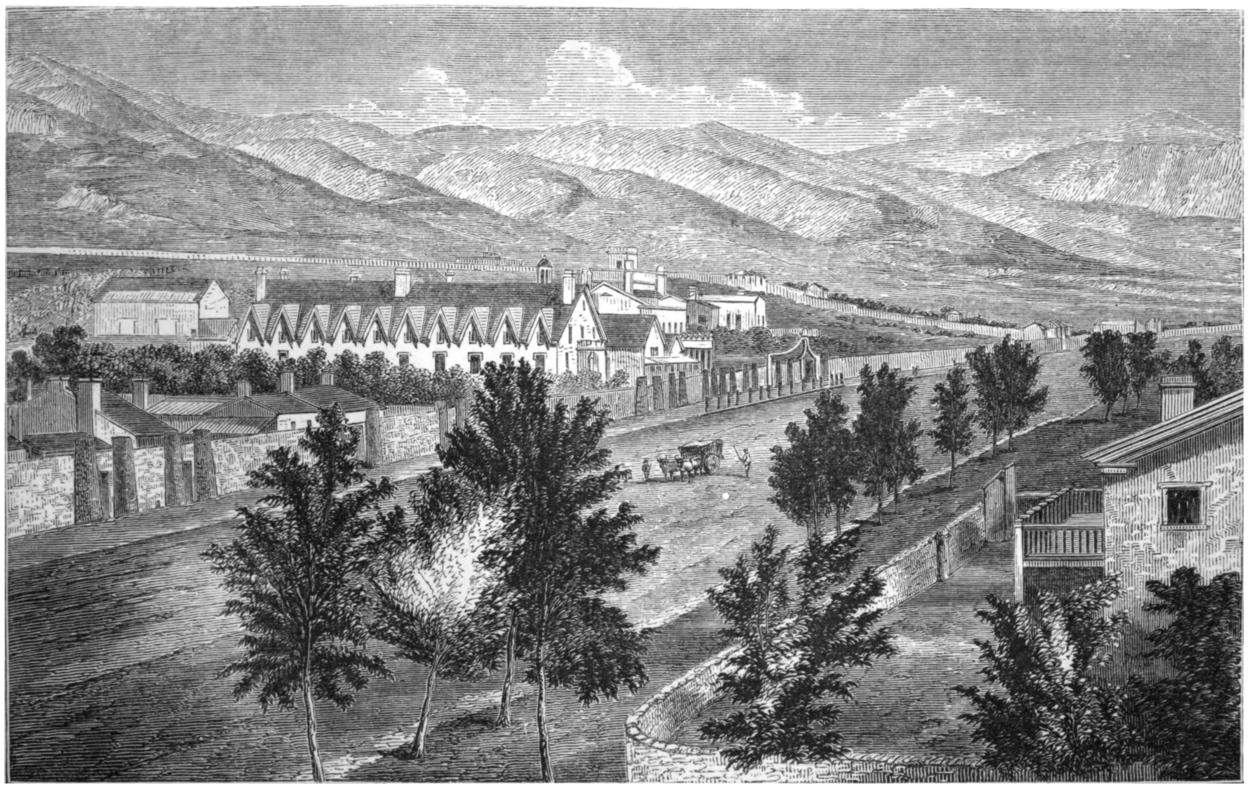

| 18. | MOUNT NEBO | 443 |

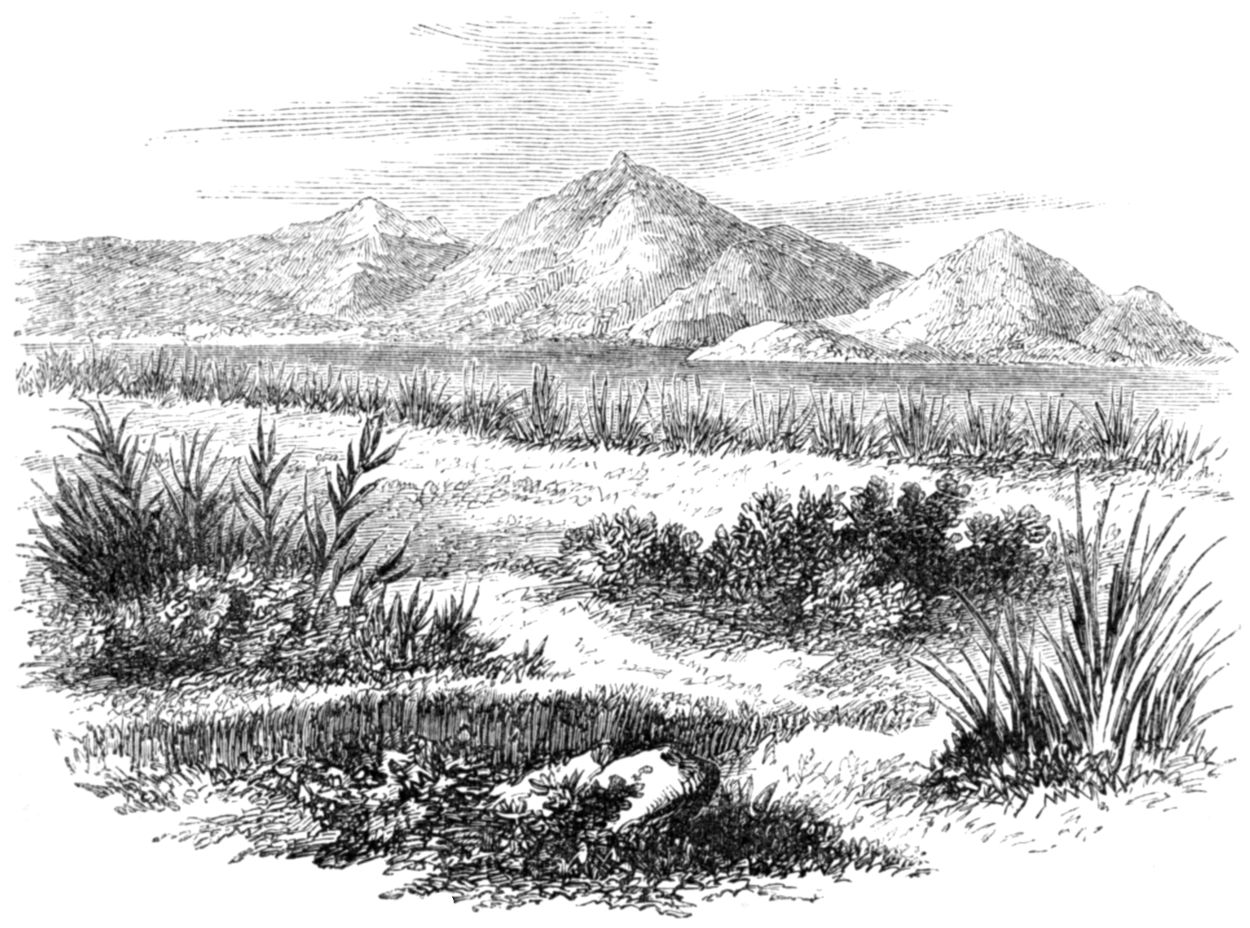

| 19. | FIRST VIEW OF CARSON LAKE | 490 |

| 20. | VIRGINIA CITY | 498 |

| 21. | IN THE SIERRA NEVADA | 502 |

Engraved by E. Weller 34. Red Lion Square.

London, Longman & Co.

Route from the

MISSOURI RIVER

to the

PACIFIC.

Route of Captn. Burton

The

Wahsatch Mountains

&

GREAT SALT LAKE

(from Captn. Stansbury)

NORTH

AMERICA.

[1]

THE CITY OF THE SAINTS.

A tour through the domains of Uncle Samuel without visiting the wide regions of the Far West would be, to use a novel simile, like seeing Hamlet with the part of Prince of Denmark, by desire, omitted. Moreover, I had long determined to add the last new name to the list of “Holy Cities;” to visit the young rival, soi-disant, of Memphis, Benares, Jerusalem, Rome, Meccah; and after having studied the beginnings of a mighty empire “in that New World which is the Old,” to observe the origin and the working of a regular go-ahead Western and Columbian revelation. Mingled with the wish of prospecting the City of the Great Salt Lake in a spiritual point of view, of seeing Utah as it is, not as it is said to be, was the mundane desire of enjoying a little skirmishing with the savages, who in the days of Harrison and Jackson had given the pale faces tough work to do, and that failing, of inspecting the line of route which Nature, according to the general consensus of guide-books, has pointed out as the proper, indeed the only practical direction for a railway between the Atlantic and the Pacific. The commerce of the world, the Occidental Press had assured me, is undergoing its grand climacteric: the resources of India and the nearer orient are now well-nigh cleared of “loot,” and our sons, if they would walk in the paths of their papas, must look to Cipangri and the parts about Cathay for their annexations.

The Man was ready, the Hour hardly appeared propitious for other than belligerent purposes. Throughout the summer of 1860 an Indian war was raging in Nebraska; the Comanches, Kiowas, and Cheyennes were “out;” the Federal government had dispatched three columns to the centres of confusion; intestine feuds among the aborigines were talked of; the Dakotah or Sioux had threatened to “wipe out” their old foe the Pawnee, both tribes being possessors of the soil over which the road ran. Horrible accounts of murdered post-boys and cannibal emigrants, greatly exaggerated, as usual, for private and public purposes,[2] filled the papers, and that nothing might be wanting, the following positive assertion (I afterward found it to be, as Sir Charles Napier characterized one of a Bombay editor’s saying, “a marked and emphatic lie”) was copied by full half the press:

“Utah has a population of some fifty-two or fifty-three thousand—more or less—rascals. Governor Cumming has informed the President exactly how matters stand in respect to them. Neither life nor property is safe, he says, and bands of depredators roam unpunished through the territory. The United States judges have abandoned their offices, and the law is boldly defied every where. He requests that 500 soldiers may be retained at Utah to afford some kind of protection to American citizens who are obliged to remain here.”

“Mormon” had in fact become a word of fear; the Gentiles looked upon the Latter-Day Saints much as our crusading ancestors regarded the “Hashshashiyun,” whose name, indeed, was almost enough to frighten them. Mr. Brigham Young was the Shaykh-el-Jebel, the Old Man of the Hill redivivus, Messrs. Kimball and Wells were the chief of his Fidawin, and “Zion on the tops of the mountains” formed a fair representation of Alamut.

“Going among the Mormons!” said Mr. M—— to me at New Orleans; “they are shooting and cutting one another in all directions; how can you expect to escape?”

Another general assertion was that “White Indians”—those Mormons again!—had assisted the “Washoes,” “Pah Utes,” and “Bannacks” in the fatal affair near Honey Lake, where Major Ormsby, of the militia, a military frontier-lawyer, and his forty men, lost the numbers of their mess.

But sagely thus reflecting that “dangers which loom large from afar generally lose size as one draws near;” that rumors of wars might have arisen, as they are wont to do, from the political necessity for another “Indian botheration,” as editors call it; that Governor Cumming’s name might have been used in vain; that even the President might not have been a Pope, infallible; and that the Mormons might turn out somewhat less black than they were painted; moreover, having so frequently and willfully risked the chances of an “I told you so” from the lips of friends, those “prophets of the past;” and, finally, having been so much struck with the discovery by some Western man of an enlarged truth, viz., that the bugbear approached has more affinity to the bug than to the bear, I resolved to risk the chance of the “red nightcap” from the bloodthirsty Indian and the poisoned bowie-dagger—without my Eleonora or Berengaria—from the jealous Latter-Day Saints. I forthwith applied myself to the audacious task with all the recklessness of a “party” from town precipitating himself for the first time into “foreign parts” about Calais.

And, first, a few words touching routes.

THE PACIFIC RAILROADAs all the world knows, there are three main lines proposed [3] for a “Pacific Railroad” between the Mississippi and the Western Ocean, the Northern, Central, and Southern.[2]

[2] The following table shows the lengths, comparative costs, etc., of the several routes explored for a railroad from the Mississippi to the Pacific, as extracted from the Speech of the Hon. Jefferson Davis, of Mississippi, on the Pacific Railway Bill in the United States Senate, January, 1859, and quoted by the Hon. Sylvester Maury in the “Geography and Resources of Arizona and Sonora.”

| Routes. | Distance by proposed railroad route. |

Sum of ascents and descents. |

Comparative cost of different routes. |

No. of miles of route through arable lands. |

No. of miles of route through land generally uncultivable, arable soil being found in small areas. |

Altitude above the sea of the highest point on the route. |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miles. | Feet. | Dollars. | Feet. | ||||

| Route near forty-seventh and forty-ninth parallels, from St. Paul to Seattle | 1955 | 18,654 | 135,871,000 | 535 | 1490 | 6,044 | |

| Route near forty-seventh and forty-ninth parallels, from St. Paul to Vancouver | 1800 | 17,645 | 425,781,000 | 374 | 1490 | 6,044 | |

| Route near forty-first and forty-second parallels, from Rock Island, viâ South Pass, to Benicia | 2299 | 29,120 | [3] | 122,770,000 | 899 | 1400 | 8,373 |

| Route near thirty-eighth and thirty-ninth parallels, from St. Louis, viâ Coo-che-to-pa and Tah-ee-chay-pah passes to San Francisco | 2325 | 49,985 | [4] | Imprac- ticable. |

865 | 1460 | 10,032 |

| Route near thirty-eighth and thirty-ninth parallels, from St. Louis, viâ Coo-chee-to-pa and Madeline Passes, to Benicia | 2535 | 56,514 | [5] | Imprac- ticable. |

915 | 1620 | 10,032 |

| Route near thirty-fifth parallel, from Memphis to San Francisco | 2366 | 48,521 | [4] | 113,000,000 | 916 | 1450 | 7,550 |

| Route near thirty-second parallel, from Memphis to San Pedro | 2090 | 48,862 | [4] | 99,000,000 | 690 | 1400 | 7,550 |

| Route near thirty-second parallel, near Gaines’ Landing, to San Francisco by coast route | 2174 | 38,200 | [6] | 94,000,000 | 984 | 1190 | 5,717 |

| Route near thirty-second parallel, from Gaines’ Landing to San Pedro | 1748 | 30,181 | [6] | 72,000,000 | 558 | 1190 | 5,717 |

| Route near thirty-second parallel, from Gaines’ Landing to San Diego | 1683 | 33,454 | [6] | 72,000,000 | 524 | 1159 | 5,717 |

[3] The ascents and descents between Rock Island and Council Bluffs are not known, and therefore not included in this sum.

[4] The ascents and descents between St. Louis and Westport are not known, and therefore not included in this sum.

[5] The ascents and descents between Memphis and Fort Smith are not known, and therefore not included in this sum.

[6] The ascents and descents between Gaines’ Landing and Fulton are not known, and therefore not included in this sum.

The first, or British, was in my case not to be thought of; it involves semi-starvation, possibly a thorough plundering by the Bedouins, and, what was far worse, five or six months of slow travel. The third, or Southern, known as the Butterfield or American Express, offered to start me in an ambulance from St. Louis, and to pass me through Arkansas, El Paso, Fort Yuma on the Gila River, in fact through the vilest and most desolate portion of the West. Twenty-four mortal days and nights—twenty-five being schedule time—must be spent in that ambulance; passengers becoming crazy by whisky, mixed with want of sleep, are often obliged to be strapped to their seats; their meals, dispatched during the ten-minute halts, are simply abominable, the heats are excessive, the climate malarious; lamps may not be used at night for fear of unexisting Indians: briefly, there is no end to[4] this Via Mala’s miseries. The line received from the United States government upward of half a million of dollars per annum for carrying the mails, and its contract had still nearly two years to run.

There remained, therefore, the central route, which has two branches. You may start by stage to the gold regions about Denver City or Pike’s Peak, and thence, if not accidentally or purposely shot, you may proceed by an uncertain ox-train to Great Salt Lake City, which latter part can not take less than thirty-five days. On the other hand, there is “the great emigration route” from Missouri to California and Oregon, over which so many thousands have traveled within the past few years. I quote from a useful little volume, “The Prairie Traveler,”[7] by Randolph B. Marcy, Captain U. S. Army. “The track is broad, well worn, and can not be mistaken. It has received the major part of the Mormon emigration, and was traversed by the army in its march to Utah in 1857.”

[7] Printed by Messrs. Harper & Brothers, New York, 1859, and Messrs. Sampson Low, Son, and Co., Ludgate Hill, and amply meriting the honors of a second edition.

The mail-coach on this line was established in 1850, by Colonel Samuel H. Woodson, an eminent lawyer, afterward an M. C., and right unpopular with Mormondom, because he sacrilegiously owned part of Temple Block, in Independence, Mo., which is the old original New Zion. The following are the rates of contract and the phases through which the line has passed.

1. Colonel Woodson received for carrying a monthly mail $19,500 (or $23,000?): length of contract 4 years.

2. Mr. F. McGraw, $13,500, besides certain considerable extras.

3. Messrs. Heber Kimball & Co. (Mormons), $23,000.

4. Messrs. Jones & Co., $30,000.

5. Mr. J. M. Hockaday, weekly mail, $190,000.

6. Messrs. Russell, Majors, & Waddell, army contractors; weekly mail, $190,000.[8]

[8] In the American Almanac for 1861 (p. 196), the length of routes in Utah Territory is 1450 miles, 533 of which have no specified mode of transportation, and the remainder, 977, in coaches; the total transportation is thus 170,872 miles, and the total cost $144,638.

Thus it will be seen that in 1856 the transit was in the hands of the Latter-Day Saints: they managed it well, but they lost the contracts during their troubles with the federal government in 1857, when it again fell into Gentile possession. In those early days it had but three changes of mules, at Forts Bridger, Laramie, and Kearney. In May, 1859, it was taken up by the present firm, which expects, by securing the monopoly of the whole line between the Missouri River and San Francisco, and by canvassing at head-quarters for a bi-weekly—which they have now obtained—and even a daily transit, which shall constitutionally extinguish the Mormon community, to insert the fine edge of that[5] wedge which is to open an aperture for the Pacific Railroad about to be. At Saint Joseph (Mo.), better known by the somewhat irreverent abbreviation of St. Jo, I was introduced to Mr. Alexander Majors, formerly one of the contractors for supplying the army in THE UTAH LINE.Utah—a veteran mountaineer, familiar with life on the prairies. His meritorious efforts to reform the morals of the land have not yet put forth even the bud of promise. He forbade his drivers and employés to drink, gamble, curse, and travel on Sundays; he desired them to peruse Bibles distributed to them gratis; and though he refrained from a lengthy proclamation commanding his lieges to be good boys and girls, he did not the less expect it of them. Results: I scarcely ever saw a sober driver; as for profanity—the Western equivalent for hard swearing—they would make the blush of shame crimson the cheek of the old Isis bargee; and, rare exceptions to the rule of the United States, they are not to be deterred from evil talking even by the dread presence of a “lady.” The conductors and road-agents are of a class superior to the drivers; they do their harm by an inordinate ambition to distinguish themselves. I met one gentleman who owned to three murders, and another individual who lately attempted to ration the mules with wild sage. The company was by no means rich; already the papers had prognosticated a failure, in consequence of the government withdrawing its supplies, and it seemed to have hit upon the happy expedient of badly entreating travelers that good may come to it of our evils. The hours and halting-places were equally vilely selected; for instance, at Forts Kearney, Laramie, and Bridger, the only points where supplies, comfort, society, are procurable, a few minutes of grumbling delay were granted as a favor, and the passengers were hurried on to some distant wretched ranch,[9] apparently for the sole purpose of putting a few dollars into the station-master’s pockets. The travel was unjustifiably slow, even in this land, where progress is mostly on paper. From St. Jo to Great Salt Lake City, the mails might easily be landed during the fine weather, without inconvenience to man or beast, in ten days; indeed, the agents have offered to place them at Placerville in fifteen. Yet the schedule time being twenty-one days, passengers seldom reached their destination before the nineteenth; the sole reason given was, that snow makes the road difficult in its season, and that if people were accustomed to fast travel, and if letters were received under schedule time, they would look upon the boon as a right.

[9] “Rancho” in Mexico means primarily a rude thatched hut where herdsmen pass the night; the “rancharia” is a sheep-walk or cattle-run, distinguished from a “hacienda,” which must contain cultivation. In California it is a large farm with grounds often measured by leagues, and it applies to any dirty hovel in the Mississippian Valley.

Before proceeding to our preparations for travel, it may be as well to cast a glance at the land to be traveled over.

[6]

The United States territory lying in direct line between the Mississippi River and the Pacific Ocean is now about 1200 miles long from north to south, by 1500 of breadth, in 49° and 32° N. lat., about equal to Equatorial Africa, and 1800 in N. lat. 38°. The great uncultivable belt of plain and mountain region through which the Pacific Railroad must run has a width of 1100 statute miles near the northern boundary; in the central line, 1200; and through the southern, 1000. Humboldt justly ridiculed the “maddest natural philosopher” who compared the American continent to a female figure—long, thin, watery, and freezing at the 58th°, the degrees being symbolic of the year at which woman grows old. Such description manifestly will not apply to the 2,000,000 of square miles in this section of the Great Republic—she is every where broader than she is long.

The meridian of 105° north longitude (G.)—Fort Laramie lies in 104° 31′ 26″—divides this vast expanse into two nearly equal parts. The eastern half is a basin or river valley rising gradually from the Mississippi to the Black Hills, and the other outlying ranges of the Rocky Mountains. The average elevation near the northern boundary (49°) is 2500 feet, in the middle latitude (38°) 6000 feet, and near the southern extremity (32°), about 4000 feet above sea level. These figures explain the complicated features of its water-shed. The western half is a mountain region whose chains extend, as far as they are known, in a general N. and S. direction.

The 99th meridian (G.)—Fort Kearney lies in 98° 58′ 11″—divides the western half of the Mississippian Valley into two unequal parts.

The eastern portion, from the Missouri to Fort Kearney—400 to 500 miles in breadth—may be called the “Prairie land.” It is true that passing westward of the 97° meridian, the mauvaises terres, or Bad Grounds, are here and there met with, especially near the 42d parallel, in which latitude they extend farther to the east, and that upward to 99° the land is rarely fit for cultivation, though fair for grazing. Yet along the course of the frequent streams there is valuable soil, and often sufficient wood to support settlements. This territory is still possessed by settled Indians, by semi-nomads, and by powerful tribes of equestrian and wandering savages, mixed with a few white men, who, as might be expected, excel them in cunning and ferocity.

The western portion of the valley, from Fort Kearney to the base of the Rocky Mountains—a breadth of 300 to 400 miles—is emphatically “the desert,” sterile and uncultivable, a dreary expanse of wild sage (artemisia) and saleratus. The surface is sandy, gravelly, and pebbly; cactus carduus and aloes abound; THE WESTERN GRAZING-GROUNDS.grass is found only in the rare river bottoms where the soils of the different strata are mixed, and the few trees along the borders of streams—fertile lines of wadis, which laborious irrigation and coal mining[7] might convert into oases—are the cotton-wood and willow, to which the mezquite[10] may be added in the southern latitudes. The desert is mostly uninhabited, unendurable even to the wildest Indian. But the people on its eastern and western frontiers, namely, those holding the extreme limits of the fertile prairie, and those occupying the desirable regions of the western mountains, are, to quote the words of Lieutenant Gouverneur K. Warren, U. S. Topographical Engineers, whose valuable reconnaissances and explanations of Nebraska in 1855, ’56, and ’57 were published in the Reports of the Secretary of War, “on the shore of a sea, up to which population and agriculture may advance and no farther. But this gives these outposts much of the value of places along the Atlantic frontier, in view of the future settlements to be formed in the mountains, between which and the present frontier a most valuable trade would exist. The western frontier has always been looking to the east for a market; but as soon as the wave of emigration has passed over the desert portion of the plains, to which the discoveries of gold have already given an impetus that will propel it to the fertile valleys of the Rocky Mountains, then will the present frontier of Kansas and Nebraska become the starting-point for all the products of the Mississippi Valley which the population of the mountains will require. We see the effects of it in the benefits which the western frontier of Missouri has received from the Santa Fé tract, and still more plainly in the impetus given to Leavenworth by the operations of the army of Utah in the interior region. This flow of products has, in the last instance, been only in one direction; but when those mountains become settled, as they eventually must, then there will be a reciprocal trade materially beneficial to both.”

[10] Often corrupted from the Spanish to muskeet (Algarobia glandulosa), a locust inhabiting Texas, New Mexico, California, etc., bearing, like the carob generally, a long pod full of sweet beans, which, pounded and mixed with flour, are a favorite food with the Southwestern Indians.

The mountain region westward of the sage and saleratus desert, extending between the 105th and 111th meridian (G.)—a little more than 400 miles—will in time become sparsely peopled. Though in many parts arid and sterile, dreary and desolate, the long bunch grass (Festuca), the short curly buffalo grass (Sisleria dactyloides), the mesquit grass (Stipa spata), and the Gramma, or rather, as it should be called, “Gamma” grass (Chondrosium fœnum),[11] which clothe the slopes west of Fort Laramie, will enable it to rear an abundance of stock. The fertile valleys, according to Lieutenant Warren, “furnish the means of raising sufficient quantities of grain and vegetables for the use of the inhabitants, and beautiful healthy and desirable locations for their homes. The remarkable freedom here from sickness is one of the attractive features of the region, and will in this respect go far to compensate[8] the settler from the Mississippi Valley for his loss in the smaller amount of products that can be taken from the soil. The great want of suitable building material, which now so seriously retards the growth of the West, will not be felt there.” The heights of the Rocky Mountains rise abruptly from 1000 to 6000 feet over the lowest known passes, computed by the Pacific Railroad surveyors to vary from 4000 to 10,000 feet above sea-level. The two chains forming the eastern and western rims of the Rocky Mountain basin have the greatest elevation, walling in, as it were, the other sub-ranges.

[11] Some of my informants derived the word from the Greek letter; others make it Hispano-Mexican.

There is a popular idea that the western slope of the Rocky Mountains is smooth and regular; on the contrary, the land is rougher, and the ground is more complicated than on the eastern declivities. From the summit of the Wasach range to the eastern foot of the Sierra Nevada, the whole region, with exceptions, is a howling wilderness, the sole or bed of an inland sweetwater sea, now shrunk into its remnants—the Great Salt and the Utah Lakes. Nothing can be more monotonous than its regular succession of high grisly hills, cut perpendicularly by rough and rocky ravines, and separating bare and barren plains. From the seaward base of the Sierra Nevada to the Pacific—California—the slope is easy, and the land is pleasant, fertile, and populous.

After this aperçu of the motives which sent me forth, once more a pilgrim, to young Meccah in the West, of the various routes, and of the style of country wandered over, I plunge at once into personal narrative.

Lieutenant Dana (U. S. Artillery), my future compagnon de voyage, left St. Louis,[12] “the turning-back place of English sportsmen,” for St. Jo on the 2d of August, preceding me by two days. Being accompanied by his wife and child, and bound on a weary voyage to Camp Floyd, Utah Territory, he naturally wanted a certain amount of precise information concerning the route, and one of the peculiarities of this line is that no one knows any thing about it. In the same railway car which carried me from St. Louis were five passengers, all bent upon making Utah with the least delay—an unexpected cargo of officials: Mr. F********, a federal judge with two sons; Mr. W*****, a state secretary; and Mr. G****, a state marshal. As the sequel may show, Dana was doubly fortunate in securing places before the list could be filled up by the unusual throng: all we thought of at the time was our good luck in escaping a septidium at St. Jo, whence the stage started on Tuesdays only. We hurried, therefore, to pay for our tickets—$175 each being the moderate sum—to reduce our luggage to its minimum approach toward 25 lbs., the price of transport for excess[9] being exorbitantly fixed at $1 per lb., and to lay in a few necessaries for the way, tea and sugar, tobacco and cognac. I will not take liberties with my company’s KIT.“kit;” my own, however, was represented as follows:

[12] St. Louis (Mo.) lies in N. lat. 28° 37′ and W. long. (G.) 90° 16′: its elevation above tide water is 461 feet: the latest frost is in the first week of March, the earliest is in the middle of November, giving some 115 days of cold. St. Joseph (Mo.) lies about N. lat. 39° 40′, and W. long. (G.) 34° 54′.

One India-rubber blanket, pierced in the centre for a poncho, and garnished along the longer side with buttons, and corresponding elastic loops with a strap at the short end, converting it into a carpet-bag—a “sine quâ non” from the equator to the pole. A buffalo robe ought to have been added as a bed: ignorance, however, prevented, and borrowing did the rest. With one’s coat as a pillow, a robe, and a blanket, one may defy the dangerous “bunks” of the stations.

For weapons I carried two revolvers: from the moment of leaving St. Jo to the time of reaching Placerville or Sacramento the pistol should never be absent from a man’s right side—remember, it is handier there than on the other—nor the bowie-knife from his left. Contingencies with Indians and others may happen, when the difference of a second saves life: the revolver should therefore be carried with its butt to the fore, and when drawn it should not be leveled as in target practice, but directed toward the object by means of the right fore finger laid flat along the cylinder while the medius draws the trigger. The instinctive consent between eye and hand, combined with a little practice, will soon enable the beginner to shoot correctly from the hip; all he has to do is to think that he is pointing at the mark, and pull. As a precaution, especially when mounted upon a kicking horse, it is wise to place the cock upon a capless nipple, rather than trust to the intermediate pins. In dangerous places the revolver should be discharged and reloaded every morning, both for the purpose of keeping the hand in, and to do the weapon justice. A revolver is an admirable tool when properly used; those, however, who are too idle or careless to attend to it, had better carry a pair of “Derringers.” For the benefit of buffalo and antelope, I had invested $25 at St. Louis in a “shooting-iron” of the “Hawkins” style—that enterprising individual now dwells in Denver City—it was a long, top-heavy rifle; it weighed 12 lbs., and it carried the smallest ball—75 to the pound—a combination highly conducive to good practice. Those, however, who can use light weapons, should prefer the Maynard breech-loader, with an extra barrel for small shot; and if Indian fighting is in prospect, the best tool, without any exception, is a ponderous double-barrel, 12 to the pound, and loaded as fully as it can bear with slugs. The last of the battery was an air-gun to astonish the natives, and a bag of various ammunition.

Captain Marcy outfits his prairie traveler with a “little blue mass, quinine, opium, and some cathartic medicine put up in doses for adults.” I limited myself to the opium, which is invaluable when one expects five consecutive days and nights in a prairie[10] wagon, quinine, and Warburg’s drops, without which no traveler should ever face fever, and a little citric acid, which, with green tea drawn off the moment the leaf has sunk, is perhaps the best substitute for milk and cream. The “holy weed Nicotian” was not forgotten; cigars must be bought in extraordinary quantities, as the driver either receives or takes the lion’s share: the most satisfactory outfit is a quantum sufficit of Louisiana Pirique and Lynchburg gold-leaf—cavendish without its abominations of rum and honey or molasses—and two pipes, a meerschaum for luxury, and a brier-root to fall back upon when the meerschaum shall have been stolen. The Indians will certainly pester for matches; the best lighting apparatus, therefore, is the Spanish mechero, the Oriental sukhtah—agate and cotton match—besides which, it offers a pleasing exercise, like billiards, and one at which the British soldier greatly excels, surpassed only by his exquisite skill in stuffing the pipe.

For literary purposes, I had, besides the two books above quoted, a few of the great guns of exploration, Frémont, Stansbury, and Gunnison, with a selection of the most violent Mormon and Anti-Mormon polemicals, sketching materials—I prefer the “improved metallics” five inches long, and serving for both diary and drawing-book—and a tourist’s writing-case of those sold by Mr. Field (Bible Warehouse, The Quadrant), with but one alteration, a snap lock, to obviate the use of that barbarous invention called a key. For instruments I carried a pocket sextant with a double face, invented by Mr. George, of the Royal Geographical Society, and beautifully made by Messrs. Cary, an artificial horizon of black glass, and bubble tubes to level it, night and day compasses, with a portable affair attached to a watch-chain—a traveler feels nervous till he can “orienter” himself—a pocket thermometer, and a B. P. ditto. The only safe form for the latter would be a strong neckless tube, the heavy pyriform bulbs in general use never failing to break at the first opportunity. A Stanhope lens, a railway whistle, and instead of the binocular, useful things of earth, a very valueless telescope—(warranted by the maker to show Jupiter’s satellites, and by utterly declining so to do, reading a lesson touching the non-advisability of believing an instrument-maker)—completed the outfit.

The prairie traveler is not particular about TOILET.toilet: the easiest dress is a dark flannel shirt, worn over the normal article; no braces—I say it, despite Mr. Galton—but broad leather belt for “six-shooter” and for “Arkansas tooth-pick,” a long clasp-knife, or for the rapier of the Western world, called after the hero who perished in the “red butchery of the Alamo.” The nether garments should be forked with good buckskin, or they will infallibly give out, and the lower end should be tucked into the boots, after the sensible fashion of our grandfathers, before those ridiculous Wellingtons were dreamed of by our sires. In warm weather,[11] a pair of moccasins will be found easy as slippers, but they are bad for wet places; they make the feet tender, they strain the back sinews, and they form the first symptom of the savage mania. Socks keep the feet cold; there are, however, those who should take six pair. The use of the pocket-handkerchief is unknown in the plains; some people, however, are uncomfortable without it, not liking “se emungere” after the fashion of Horace’s father.

In cold weather—and rarely are the nights warm—there is nothing better than the old English tweed shooting-jacket, made with pockets like a poacher’s, and its similar waistcoat, a “stomach warmer” without a roll collar, which prevents comfortable sleep, and with flaps as in the Year of Grace 1760, when men were too wise to wear our senseless vests, whose only property seems to be that of disclosing after exertions a lucid interval of linen or longcloth. For driving and riding, a large pair of buckskin gloves, or rather gauntlets, without which even the teamster will not travel, and leggins—the best are made in the country, only the straps should be passed through and sewn on to the leathers—are advisable, if at least the man at all regards his epidermis: it is almost unnecessary to bid you remember spurs, but it may be useful to warn you that they will, like riches, make to themselves wings. The head-covering by excellence is a brown felt, which, by a little ingenuity, boring, for instance, holes round the brim to admit a ribbon, you may convert into a riding-hat or night-cap, and wear alternately after the manly slouch of Cromwell and his Martyr, the funny three-cornered spittoon-like “shovel” of the Dutch Georges, and the ignoble cocked-hat, which completes the hideous metamorphosis.

And, above all things, as you value your nationality—this is written for the benefit of the home reader—let no false shame cause you to forget your hat-box and your umbrella. I purpose, when a moment of inspiration waits upon leisure and a mind at ease, to invent an elongated portmanteau, which shall be perfection—portable—solid leather of two colors, for easy distinguishment—snap lock—in length about three feet; in fact, long enough to contain without creasing “small clothes,” a lateral compartment destined for a hat, and a longitudinal space where the umbrella can repose: its depth—but I must reserve that part of the secret until this benefit to British humanity shall have been duly made by Messrs. Bengough Brothers, and patented by myself.

The dignitaries of the mail-coach, acting upon the principle “first come first served,” at first decided, maugre all our attempts at “moral suasion,” to divide the party by the interval of a week. Presently reflecting, I presume, upon the unadvisability of leaving at large five gentlemen, who, being really in no particular hurry, might purchase a private conveyance and start leisurely westward, they were favored with a revelation of “’cuteness.” On the day before departure, as, congregated in the Planter’s House[12] Hotel, we were lamenting over our “morning glory,” the necessity of parting—in the prairie the more the merrier, and the fewer the worse cheer—a youth from the office was introduced to tell, Hope-like, a flattering tale and a tremendous falsehood. This juvenile delinquent stated with unblushing front, over the hospitable cocktail, that three coaches instead of one had been newly and urgently applied for by the road-agent at Great Salt Lake City, and therefore that we could not only all travel together, but also all travel with the greatest comfort. We exulted. But on the morrow only two conveyances appeared, and not long afterward the two dwindled off to one. “The Prairie Traveler” doles out wisdom in these words: “Information concerning the route coming from strangers living or owning property near them, from agents of steam-boats and railways, or from other persons connected with transportation companies”—how carefully he piles up the heap of sorites—“should be received with great caution, and never without corroboratory evidence from disinterested sources.” The main difficulty is to find the latter—to catch your hare—to know whom to believe.

I now proceed to my Diary.

THE START.

Tuesday, 7th August, 1860.

Precisely at 8 A.M. appeared in front of the Patee House—the Fifth Avenue Hotel of St. Jo—the vehicle destined to be our home for the next three weeks. We scrutinized it curiously.

The mail is carried by a “Concord coach,” a spring wagon, comparing advantageously with the horrible vans which once dislocated the joints of men on the Suez route. MAIL-COACH.—MULES.The body is shaped somewhat like an English tax-cart considerably magnified. It is built to combine safety, strength, and lightness, without the slightest regard to appearances. The material is well-seasoned white oak—the Western regions, and especially Utah, are notoriously deficient in hard woods—and the manufacturers are the well-known coachwrights, Messrs. Abbott, of Concord, New Hampshire; the color is sometimes green, more usually red, causing the antelopes to stand and stretch their large eyes whenever the vehicle comes in sight. The wheels are five to six feet apart, affording security against capsising, with little “gather” and less “dish;” the larger have fourteen spokes and seven fellies; the smaller twelve and six. The tires are of unusual thickness, and polished like steel by the hard dry ground; and the hubs or naves and the metal nave-bands are in massive proportions. The latter not unfrequently fall off as the wood shrinks, unless the wheel is allowed to stand in water; attention must be paid to resetting them, or in the frequent and heavy “sidlins” the spokes may snap off all round like pipe-stems. The wagon-bed is supported by iron bands or perpendiculars abutting upon wooden rockers, which[13] rest on strong leather thoroughbraces: these are found to break the jolt better than the best steel springs, which, moreover, when injured, can not readily be repaired. The whole bed is covered with stout osnaburg supported by stiff bars of white oak; there is a sun-shade or hood in front, where the driver sits, a curtain behind which can be raised or lowered at discretion, and four flaps on each side, either folded up or fastened down with hooks and eyes. In heavy frost the passengers must be half dead with cold, but they care little for that if they can go fast. The accommodations are as follows: In front sits the driver, with usually a conductor or passenger by his side; a variety of packages, large and small, is stowed away under his leather cushion; when the brake must be put on, an operation often involving the safety of the vehicle, his right foot is planted upon an iron bar which presses by a leverage upon the rear wheels; and in hot weather a bucket for watering the animals hangs over one of the lamps, whose companion is usually found wanting. The inside has either two or three benches fronting to the fore or placed vis-à-vis; they are movable and reversible, with leather cushions and hinged padded backs; unstrapped and turned down, they convert the vehicle into a tolerable bed for two persons or two and a half. According to Cocker, the mail-bags should be safely stowed away under these seats, or if there be not room enough, the passengers should perch themselves upon the correspondence; the jolly driver, however, is usually induced to cram the light literature between the wagon-bed and the platform, or running-gear beneath, and thus, when ford-waters wash the hubs, the letters are pretty certain to endure ablution. Behind, instead of dicky, is a kind of boot where passengers’ boxes are stored beneath a stout canvas curtain with leather sides. The comfort of travel depends upon packing the wagon; if heavy in front or rear, or if the thoroughbraces be not properly “fixed,” the bumping will be likely to cause nasal hemorrhage. The description will apply to the private ambulance, or, as it is called in the West, “avalanche,” only the latter, as might be expected, is more convenient; it is the drosky in which the vast steppes of Central America are crossed by the government employés.

On this line mules are preferred to horses as being more enduring. They are all of legitimate race; the breed between the horse and the she-ass is never heard of, and the mysterious jumard is not believed to exist. In dry lands, where winter is not severe—they inherit the sire’s impatience of cold—they are invaluable animals; in swampy ground this American dromedary is the meanest of beasts, requiring, when stalled, to be hauled out of the mire before it will recover spirit to use its legs. For sureness of foot (during a journey of more than 1000 miles, I saw but one fall and two severe stumbles), sagacity in finding the road, apprehension of danger, and general cleverness, mules are superior[14] to their mothers: their main defect is an unhappy obstinacy derived from the other side of the house. They are great in hardihood, never sick nor sorry, never groomed nor shod, even where ice is on the ground; they have no grain, except five quarts per diem when snow conceals the grass; and they have no stable save the open corral. Moreover, a horse once broken down requires a long rest; the mule, if hitched up or ridden for short distances, with frequent intervals to roll and repose, may still, though “resté,” get over 300 miles in tolerable time. The rate of travel on an average is five miles an hour; six is good; between seven and eight is the maximum, which sinks in hilly countries to three or four. I have made behind a good pair, in a light wagon, forty consecutive miles at the rate of nine per hour, and in California a mule is little thought of if it can not accomplish 250 miles in forty-eight hours. The price varies from $100 to $130 per head when cheap, rising to $150 or $200, and for fancy animals from $250 to $400. The value, as in the case of the Arab, depends upon size; “rats,” or small mules, especially in California, are not esteemed. The “span”—the word used in America for beasts well matched—is of course much more expensive. At each station on this road, averaging twenty-five miles apart—beyond the forks of the Platte they lengthen out by one third—are three teams of four animals, with two extra, making a total of fourteen, besides two ponies for the express riders. In the East they work beautifully together, and are rarely mulish beyond a certain ticklishness of temper, which warns you not to meddle with their ears when in harness, or to attempt encouraging them by preceding them upon the road. In the West, where they run half wild and are lassoed for use once a week, they are fearfully handy with their heels; they flirt out with the hind legs, they rear like goats, breaking the harness and casting every strap and buckle clean off the body, and they bite their replies to the chorus of curses and blows: the wonder is that more men are not killed. Each fresh team must be ringed half a dozen times before it will start fairly; there is always some excitement in change; some George or Harry, some Julia or Sally disposed to shirk work or to play tricks, some Brigham Young or General Harney—the Trans-Vaal Republican calls his worst animal “England”—whose stubbornness is to be corrected by stone-throwing or the lash.

But the wagon still stands at the door. We ought to start at 8 30 A.M.; we are detained an hour while last words are said, and adieu—a long adieu—is bidden to joke and julep, to ice and idleness. Our “plunder”[13] is clapped on with little ceremony; a hat-case falls open—it was not mine, gentle reader—collars and other small gear cumber the ground, and the owner addresses to the clumsy-handed driver the universal G— d—, which in these lands changes from its expletive or chrysalis form to an adjectival[15] development. We try to stow away as much as possible; the minor officials, with all their little faults, are good fellows, civil and obliging; they wink at non-payment for bedding, stores, weapons, and they rather encourage than otherwise the multiplication of whisky-kegs and cigar-boxes. We now drive through the dusty roads of St. Jo, the observed of all observers, and presently find ourselves in the steam ferry which is to convey us from the right to the left bank of the Missouri River. The “Big Muddy,” as it is now called—the Yellow River of old writers—venerable sire of snag and sawyer, displays at this point the source whence it has drawn for ages the dirty brown silt which pollutes below their junction the pellucid waters of the “Big Drink.”[14] It runs, like the lower Indus, through deep walls of stiff clayey earth, and, like that river, its supplies, when filtered (they have been calculated to contain one eighth of solid matter), are sweet and wholesome as its brother streams. The Plata of this region, it is the great sewer of the prairies, the main channel and common issue of the water-courses and ravines which have carried on the work of denudation and degradation for days dating beyond the existence of Egypt.

[13] In Canada they call personal luggage butin.

[14] A “Drink” is any river: the Big Drink is the Mississippi.

According to Lieutenant Warren, who endorses the careful examinations of the parties under Governor Stevens in 1853, the THE MISSOURI RIVERMissouri is a superior river for navigation to any in the country, except the Mississippi below their junction. It has, however, serious obstacles in wind and frost. From the Yellow Stone to its mouth, the breadth, when full, varies from one third to half a mile; in low water the width shrinks, and bars appear. Where timber does not break the force of the winds, which are most violent in October, clouds of sand are seen for miles, forming banks, which, generally situated at the edges of trees on the islands and points, often so much resemble the Indian mounds in the Mississippi Valley, that some of them—for instance, those described by Lewis and Clarke at Bonhomme Island—have been figured as the works of the ancient Toltecs. It would hardly be feasible to correct the windage by foresting the land. The bluffs of the Missouri are often clothed with vegetation as far as the debouchure of the Platte River. Above that point the timber, which is chiefly cotton-wood, is confined to ravines and bottom lands, varying in width from ten to fifteen miles above Council Bluffs, which is almost continuous to the mouth of the James River. Every where, except between the mouth of the Little Cheyenne and the Cannon Ball rivers, there is a sufficiency of fuel for navigation; but, ascending above Council Bluffs, the protection afforded by forest growth on the banks is constantly diminishing. The trees also are injurious; imbedded in the channel by the “caving-in” of the banks, they form the well-known sawyers, or floating timbers, and snags, trunks standing like chevaux de frise at various[16] inclinations, pointing down the stream. From the mouth of the James River down to the Mississippi, it is a wonder how a steamer can run: she must lose half her time by laying to at night, and is often delayed for days, as the wind prevents her passing by bends filled with obstructions. The navigation is generally closed by ice at Sioux City on the 10th of November, and at Fort Leavenworth by the 1st of December. The rainy season of the spring and summer commences in the latitude of Kansas, Missouri, Iowa, and Southern Nebraska, between the 15th of May and the 30th of June, and continues about two months. The floods produced by the melting snows in the mountains come from the Platte, the Big Cheyenne, the Yellow Stone, and the Upper Missouri, reaching the lower river about the 1st of July, and lasting a month. Rivers like this, whose navigation depends upon temporary floods, are greatly inferior for ascent than for descent. The length of the inundation much depends upon the snow on the mountains: a steamer starting from St.Louis on the first indication of the rise would not generally reach the Yellow Stone before low water at the latter point, and if a miscalculation is made by taking the temporary rise for the real inundation, the boat must lay by in the middle of the river till the water deepens.

Some geographers have proposed to transfer to the Missouri, on account of its superior length, the honor of being the real head of the Mississippi; they neglect, however, to consider the direction and the course of the stream, an element which must enter largely in determining the channels of great rivers. It will, I hope, be long before this great ditch wins the day from the glorious Father of Waters.

The reader will find in Appendix No. I. a detailed itinerary, showing him the distances between camping-places, the several mail stations where mules are changed, the hours of travel, and the facilities for obtaining wood and water—in fact, all things required for the novice, hunter, or emigrant. In these pages I shall consider the route rather in its pictorial than in its geographical aspects, and give less of diary than of dissertation upon the subjects which each day’s route suggested.

Landing in Bleeding Kansas—she still bleeds[15]—we fell at once into “Emigration Road,” a great thoroughfare, broad and well worn as a European turnpike or a Roman military route, and undoubtedly the best and the longest natural highway in the world.[17] For five miles the line bisected a bottom formed by a bend in the river, with about a mile’s diameter at the neck. The scene was of a luxuriant vegetation. A deep tangled wood—rather a thicket or a jungle than a forest—of oaks and elms, hickory, basswood[16] and black walnut, poplar and hackberry (Celtis crassifolia), box elder, and the common willow (Salix longifolia), clad and festooned, bound and anchored by wild vines, creepers, and huge llianas, and sheltering an undergrowth of white alder and red sumach, whose pyramidal flowers were about to fall, rested upon a basis of deep black mire, strongly suggestive of chills—fever and ague. After an hour of burning sun and sickly damp, the effects of the late storms, we emerged from the waste of vegetation, passed through a straggling “neck o’ the woods,” whose yellow inmates reminded me of Mississippian descriptions in the days gone by, THE PRAIRIE.and after spanning some very rough ground we bade adieu to the valley of the Missouri, and emerged upon the region of the Grand Prairie,[17] which we will pronounce “perrairey.”

[15] And no wonder!

“I advise you, one and all, to enter every election district in Kansas and vote at the point of the bowie-knife and revolver. Neither give nor take quarter, as our case demands it.”

“I tell you, mark every scoundrel among you that is the least tainted with Free-soilism or Abolitionism, and exterminate him. Neither give nor take quarter from them.”

(Extracts from Speeches of General Stringfellow—happy name!—in the Kansas Legislature.)

[16] The basswood (Tilia Americana) resembles our linden: the trivial name is derived from “bast,” its inner bark being used for mats and cordage. From the pliability of the bark and wood, the name of the tree is made synonymous with “doughface” in the following extract from one of Mr. Brigham Young’s sermons: “I say, as the Lord lives, we are bound to become a sovereign state in the Union, or an independent nation by ourselves; and let them drive us from this place if they can—they can not do it. I do not throw this out as a banter. You Gentiles, and hickory and basswood Mormons, can write it down, if you please; but write it as I speak it.” The above has been extracted from a “Dictionary of Americanisms,” by John Russell Bartlett (London, Trübner and Co., 1859), a glossary which the author’s art has made amusing as a novel.

[17] The word is somewhat indefinite. Hunters apply it generally to the bare lands lying westward of the timbered course of the Mississippi; in fact, to the whole region from the southern Rio Grande to the Great Slave Lake.

Differing from the card-table surfaces of the formation in Illinois and the lands east of the Mississippi, the Western prairies are rarely flat ground. Their elevation above sea-level varies from 1000 to 2500 feet, and the plateau’s aspect impresses the eye with an exaggerated idea of elevation, there being no object of comparison—mountain, hill, or sometimes even a tree—to give a juster measure. Another peculiarity of the prairie is, in places, its seeming horizontality, whereas it is never level: on an open plain, apparently flat as a man’s palm, you cross a long groundswell which was not perceptible before, and on its farther incline you come upon a chasm wide and deep enough to contain a settlement. The aspect was by no means unprepossessing. Over the rolling surface, which, however, rarely breaks into hill and dale, lay a tapestry of thick grass already turning to a ruddy yellow under the influence of approaching autumn. The uniformity was relieved by streaks of livelier green in the rich soils of the slopes, hollows, and ravines, where the water gravitates, and, in the deeper “intervales” and bottom lands on the banks of streams and courses, by the graceful undulations and the waving lines of[18] mottes or prairie islands, thick clumps and patches simulating orchards by the side of cultivated fields. The silvery cirri and cumuli of the upper air flecked the surface of earth with spots of dark cool shade, surrounded by a blaze of sunshine, and by their motion, as they trooped and chased one another, gave a peculiar liveliness to the scene; while here and there a bit of hazy blue distance, a swell of the sea-like land upon the far horizon, gladdened the sight—every view is fair from afar. Nothing, I may remark, is more monotonous, except perhaps the African and Indian jungle, than those prairie tracts, where the circle of which you are the centre has but about a mile of radius; it is an ocean in which one loses sight of land. You see, as it were, the ends of the earth, and look around in vain for some object upon which the eye may rest: it wants the sublimity of repose so suggestive in the sandy deserts, and the perpetual motion so pleasing in the aspect of the sea. No animals appeared in sight where, thirty years ago, a band of countless bisons dotted the plains; they will, however, like the wild aborigines, their congeners, soon be followed by beings higher in the scale of creation. These prairies are preparing to become the great grazing-grounds which shall supply the unpopulated East with herds of civilized kine, and perhaps with the yak of Tibet, the llama of South America, and the koodoo and other African antelopes.

As we sped onward we soon made acquaintance with a traditionally familiar feature, the “pitch-holes,” or “chuck-holes”—the ugly word is not inappropriate—which render traveling over the prairies at times a sore task. They are gullies and gutters, not unlike the Canadian “cahues” of snow formation: varying from 10 to 50 feet in breadth, they are rivulets in spring and early summer, and—few of them remain perennial—they lie dry during the rest of the year. Their banks are slightly raised, upon the principle, in parvo, that causes mighty rivers, like the Po and the Indus, to run along the crests of ridges, and usually there is in the sole a dry or wet cunette, steep as a step, and not unfrequently stony; unless the break be attended to, it threatens destruction to wheel and axle-tree, to hound and tongue. The pitch-hole is more frequent where the prairies break into low hills; the inclines along which the roads run then become a net-work of these American nullahs.

Passing through a few wretched shanties[18] called Troy—last insult to the memory of hapless Pergamus—and Syracuse (here we are in the third, or classic stage of United States nomenclature), we made, at 3 P.M., Cold Springs, the junction of the Leavenworth route. Having taken the northern road to avoid rough ground and bad bridges, we arrived about two hours behind time.SQUALOR. The aspect of things at Cold Springs, where we were allowed an[19] hour’s halt to dine and to change mules, somewhat dismayed our fine-weather prairie travelers. The scene was the rale “Far West.” The widow body to whom the shanty belonged lay sick with fever. The aspect of her family was a “caution to snakes:” the ill-conditioned sons dawdled about, listless as Indians, in skin tunics and pantaloons fringed with lengthy tags such as the redoubtable “Billy Bowlegs” wears on tobacco labels; and the daughters, tall young women, whose sole attire was apparently a calico morning-wrapper, color invisible, waited upon us in a protesting way. Squalor and misery were imprinted upon the wretched log hut, which ignored the duster and the broom, and myriads of flies disputed with us a dinner consisting of dough-nuts, green and poisonous with saleratus, suspicious eggs in a massive greasy fritter, and rusty bacon, intolerably fat. It was our first sight of squatter life, and, except in two cases, it was our worst. We could not grudge 50 cents a head to these unhappies; at the same time, we thought it a dear price to pay—the sequel disabused us—for flies and bad bread, worse eggs and bacon.

[18] American authors derive the word from the Canadian chienté, a dog-kennel. It is, however, I believe, originally Irish.

The next settlement, Valley Home, was reached at 6 P.M. Here the long wave of the ocean land broke into shorter seas, and for the first time that day we saw stones, locally called rocks (a Western term embracing every thing between a pebble and a boulder), the produce of nullahs and ravines. A well 10 to 12 feet deep supplied excellent water. The ground was in places so far reclaimed as to be divided off by posts and rails; the scanty crops of corn (Indian corn), however, were wilted and withered by the drought, which this year had been unusually long. Without changing mules we advanced to Kennekuk, where we halted for an hour’s supper under the auspices of Major Baldwin, whilom Indian agent; the place was clean, and contained at least one charming face.

Kennekuk derives its name from a chief of the Kickapoos, in whose reservation we now are. This tribe, in the days of the Baron la Hontan (1689), a great traveler, but “aiblins,” as Sir Walter Scott said of his grandmither, “a prodigious story-teller,” then lived on the Rivière des Puants, or Fox River, upon the brink of a little lake supposed to be the Winnebago, near the Sakis (Osaki, Sawkis, Sauks, or Sacs),[19] and the Pouteoustamies (Potawotomies). They are still in the neighborhood of their[20] dreaded foes, the Sacs and Foxes,[20] who are described as stalwart and handsome bands, and they have been accompanied in their southern migration from the waters westward of the Mississippi, through Illinois, to their present southern seats by other allies of the Winnebagoes,[21] the Iowas, Nez Percés, Ottoes, Omahas, Kansas, and Osages. Like the great nations of the Indian Territory, the Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws, they form intermediate social links in the chain of civilization between the outer white settlements and the wild nomadic tribes to the west, the Dakotahs and Arapahoes, the Snakes and Cheyennes. They cultivate the soil, and rarely spend the winter in hunting buffalo upon the plains. Their reservation is twelve miles by twenty-four; as usual with land set apart for the savages, it is well watered and timbered, rich and fertile; it lies across the path and in the vicinity of civilization; consequently, the people are greatly demoralized. The men are addicted to intoxication, and the women to unchastity; both sexes and all ages are inveterate beggars, whose principal industry is horse-stealing. Those Scottish clans were the most savage that vexed the Lowlands; it is the case here: the tribes nearest the settlers are best described by Colonel B——’s phrase, “great liars and dirty dogs.” They have well-nigh cast off the Indian attire, and rejoice in the splendors of boiled and ruffled shirts, after the fashion of the whites. According to our host, a stalwart son of that soil which for generations has sent out her best blood westward, Kain-tuk-ee, the Land of the Cane, the Kickapoos number about 300 souls, of whom one fifth are braves. He quoted a specimen of their facetiousness: when they first saw a crinoline, they pointed to the wearer and cried, “There walks a wigwam.” Our “vertugardin” of the 19th century has run the gauntlet of the world’s jests, from the refined[21] impertinence of Mr. Punch to the rude grumble of the American Indian and the Kaffir of the Cape.

[19] In the days of Major Pike, who, in 1805-6-7, explored, by order of the government of the United States, the western territories of North America, the Sacs numbered 700 warriors and 750 women; they had four villages, and hunted on the Mississippi and its confluents from the Illinois to the Iowa River, and on the western plains that bordered on the Missouri. They were at peace with the Sioux, Osages, Potawotomies, Menomenes or Folles Avoines, Iowas, and other Missourian tribes, and were almost consolidated with the Foxes, with whose aid they nearly exterminated the Illinois, Cahokias, Kaskaskias, and Peorians. Their principal enemies were the Ojibwas. They raised a considerable quantity of maize, beans, and melons, and were celebrated for cunning in war rather than for courage.

[20] From the same source we learn that the Ottagamies, called by the French Les Renards, numbered 400 warriors and 500 women: they had three villages near the confluence of the Turkey River with the Mississippi, hunted on both sides of the Mississippi from the Iowa stream below the Prairie du Chien to a river of that name above the same village, and annually sold many hundred bushels of maize. Conjointly with the Sacs, the Foxes protected the Iowas, and the three people, since the first treaty of the two former with the United States, claimed the land from the entrance of the Jauflione on the western side of the Mississippi, up the latter river to the Iowa above the Prairie du Chien, and westward to the Missouri. In 1807 they had ceded their lands lying south of the Mississippi to the United States, reserving to themselves, however, the privileges of hunting and residing on them.

[21] The Winnebagoes, Winnipegs (turbid water), or Ochangras numbered, in 1807, 450 warriors and 500 women, and had seven villages on the Wisconsin, Rock, and Fox Rivers, and Green Bay: their proximity enabled the tribe to muster in force within four days. They then hunted on the Rock River, and the eastern side of the Mississippi, from Rock River to the Prairie du Chien, on Lake Michigan, on Black River, and in the countries between Lakes Michigan, Huron, and Superior. Lieutenant Pike is convinced, “from a tradition among themselves, and their speaking the same language as the Ottoes of the Platte River,” that they are a tribe who about 150 years before his time had fled from the oppression of the Mexican Spaniards, and had become clients of the Sioux. They have ever been distinguished for ferocity and treachery.

Beyond Kennekuk we crossed the first Grasshopper Creek. Creek, I must warn the English reader, is pronounced “CRIK.”“crik,” and in these lands, as in the jargon of Australia, means not “an arm of the sea,” but a small stream of sweet water, a rivulet; the rivers of Europe, according to the Anglo-American of the West, are “criks.” On our line there are many grasshopper creeks; they anastomose with, or debouch into, the Kansas River, and they reach the sea viâ the Missouri and the Mississippi. This particular Grasshopper was dry and dusty up to the ankles; timber clothed the banks, and slabs of sandstone cumbered the sole. Our next obstacle was the Walnut Creek, which we found, however, provided with a corduroy bridge; formerly it was a dangerous ford, rolling down heavy streams of melted snow, and then crossed by means of the “bouco” or coracle, two hides sewed together, distended like a leather tub with willow rods, and poled or paddled. At this point the country is unusually well populated; a house appears after every mile. Beyond Walnut Creek a dense nimbus, rising ghost-like from the northern horizon, furnished us with a spectacle of those perilous prairie storms which make the prudent lay aside their revolvers and disembarrass themselves of their cartridges. Gusts of raw, cold, and violent wind from the west whizzed overhead, thunder crashed and rattled closer and closer, and vivid lightning, flashing out of the murky depths around, made earth and air one blaze of living fire. Then the rain began to patter ominously upon the carriages; the canvas, however, by swelling, did its duty in becoming water-tight, and we rode out the storm dry. Those learned in the weather predicted a succession of such outbursts, but the prophecy was not fulfilled. The thermometer fell about 6° (F.), and a strong north wind set in, blowing dust or gravel, a fair specimen of “Kansas gales,” which are equally common in Nebraska, especially during the month of October. It subsided on the 9th of August.

Arriving about 1 A.M. at Locknan’s Station, a few log and timber huts near a creek well feathered with white oak and American elm, hickory and black walnut, we found beds and snatched an hourful of sleep.

8th August, to Rock Creek.

Resuming, through air refrigerated by rain, our now weary way, we reached at 6 A.M. a favorite camping-ground, the “Big Nemehaw” Creek, which, like its lesser neighbor, flows after rain into the Missouri River, viâ Turkey Creek, the Big Blue, and the Kansas. It is a fine bottom of rich black soil, whose green woods at that early hour were wet with heavy dew, and scattered over the surface lay pebbles and blocks of quartz and porphyritic granites. “Richland,” a town mentioned in guide-books, having disappeared, we drove for breakfast to Seneca, a city consisting of a few[22] shanties, mostly garnished with tall square lumber fronts, ineffectually, especially when the houses stand one by one, masking the diminutiveness of the buildings behind them. The land, probably in prospect of a Pacific Railroad, fetched the exaggerated price of $20 an acre, and already a lawyer has “hung out his shingle” there.