PORTRAIT OF THE WIFE OF HICKS.

Title: The Life, Trial, Confession and Execution of Albert W. Hicks

Author: Albert W. Hicks

Contributor: L. N. Fowler

Release date: December 13, 2021 [eBook #66941]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Robert M. De Witt

Credits: Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

PORTRAIT OF THE WIFE OF HICKS.

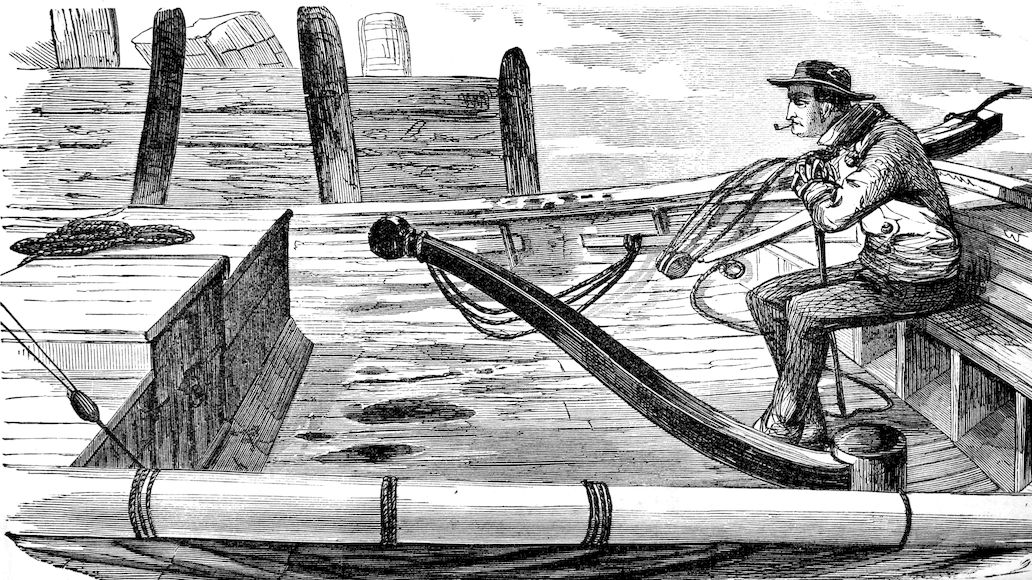

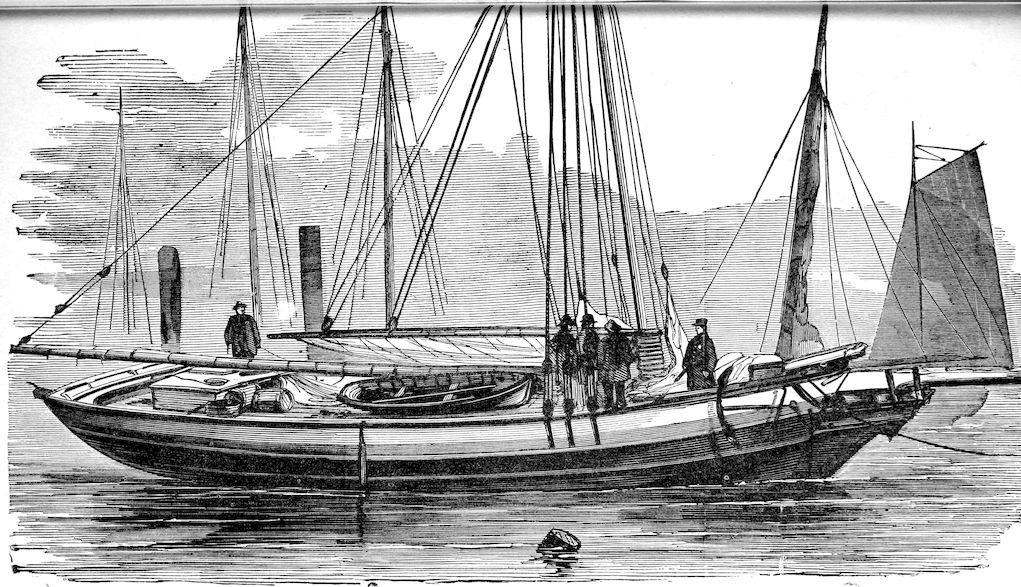

THE BOAT IN WHICH HICKS ESCAPED FROM THE OYSTER SLOOP.

PORTRAIT OF ALBERT W. HICKS, THE PIRATE.

I hereby certify that the within Confession of Albert W. Hicks was made by him to me, and that it is the only confession made by him.

On Thursday, March 16th, the sloop “E. A. Johnson,” sailed from the foot of Spring street, New York, for Deep Creek, Va., for a cargo of oysters.

The same sloop was ashore near Tottenville, S. I. on Friday, getting scrubbed, and having some carpenter work done. There she laid till Sunday morning, when she floated off, and proceeded down the Bay.

Again, she arrived in Gravesend Bay on Sunday afternoon, and remained there waiting for a fair wind until Tuesday at sunset, when she set out to sea, Captain Burr, a man by the name of Wm. Johnson, and two boys, named Smith and Oliver Watts, being on board.

The next morning, Wednesday the 22d of March, the sloop was picked up by the schooner “Telegraph” of New London, in the lower bay, between the West Bank and the Romer Shoals. On being boarded, she was found to have been abandoned, as also to bear the most unmistakable evidences of foul play having taken place at some time, not remote. It was also evident that a collision had taken place with some other vessel, as her bowsprit had been carried away, and was then floating alongside, attached to her by the stays. Upon further examination, her deck appeared to have been washed with human blood, and her cabin bore dire marks of a desperate struggle for life. 8The Telegraph made fast to her, and started for the city, but was failing in the effort (as both vessels were fast drifting ashore), when the towboat Ceres, Captain Stevens, being in the neighborhood, took them in tow, and brought them both up to the city, when they were moored in the Fulton Market slip.

The story of bloody traces was at once communicated to the Police Authorities, and soon it spread throughout the city that a terrible massacre had taken place. Speculation accused river pirates of the crime, but there was a doubt on the public mind. Throughout Wednesday, the circumstances connected with the case were canvassed thoroughly, but no new light could be obtained as to the mystery. The daily press served up the story to the public on Thursday morning. Scarcely had the papers been issued when two men, named John Burke and Andrew Kelly, residents of a low tenement house, No. 129 Cedar street, called at second ward station-house, and gave such information as led the officers to the conclusion that one of the hands who had sailed on board the sloop “Johnson” from the foot of Spring street, was implicated in the mysterious transaction. They said that a man, named Johnson, who had lived in the same house with them, had come home suddenly and unexpectedly the previous day, having with him an unusual amount of money, which he said he had received as prize money for picking up a sloop in the lower bay. They gave the man’s description, told which way he had gone with his wife and child. Immediately Officer Nevins and Captain Smith started on their way toward Providence, to which city they had reason to believe Johnson had gone.

Meantime, other facts came to light in connection with the mystery. The ill-fated sloop had run into the schooner “John B. Mathew,” Captain Nickerson, early on Wednesday morning, at which time only one man was seen on board, and this man was subsequently observed to lower the boat from the stern, and leave the sloop. This collision took place just off Staten Island, and was so severe as to render the “John B. Mathew” unfit for sea. Hence, she returned to the city for repairs.

On the same afternoon that the officers started after Johnson, officers Burdett and James, accompanied by our reporter, set out in search of the yawl belonging to the sloop, which was said to be adrift off Staten Island. This they succeeded in finding, and bringing to the city, after a tedious passage on a rough sea with a cold wind. The boat contained two oars, a right boot, a tiller, and part of an old broom. George Neidlinger, the hostler at Fort Richmond, south of which the boat was found, said that shortly before six o’clock the previous morning, he had seen a man land from the boat, whom he described in such a manner as to show that Johnson might be the individual.

It was next ascertained that a man answering the same description had made himself conspicuous at the Vanderbilt landing, where he had indulged freely in oysters, hot gins, and eggs. He was seen on the seven o’clock boat coming up to New York, by a deck hand, who had, by his own solicitation, counted a portion of his money, which he carried in two small bags, like 9shot-bags. Here the matter rested for a short time, while the people were waiting for news from the officers at Providence. It was during this interval that our artist succeeded in procuring the sketches herewith presented.

Meantime the sloop lying at the Fulton Market Slip was attended, day after day, by multitudes of the curious and the excited. The story of blood was the topic of conversation, and the spirit of revenge found a limited relief in verbal expressions of bitter desire for the punishment of the perpetrator, if he should be arrested.

Mr. Selah Howell, of Islip, L. I., part owner of the sloop, was on hand. He suspected William Johnson, the man who took supper with Captain Burr and himself in the cabin, on the evening before the sloop left the city. The theory that the murder had been committed by one of the crew favored this suspicion, and the idea floated from ear to ear until it became a settled conclusion in every mind. Mr. Howell viewed the boat, and identified it as belonging to the sloop.

The carman, who conveyed Johnson’s baggage to the Fall River steamboat, also described the man who had employed him, and the woman who was with him.

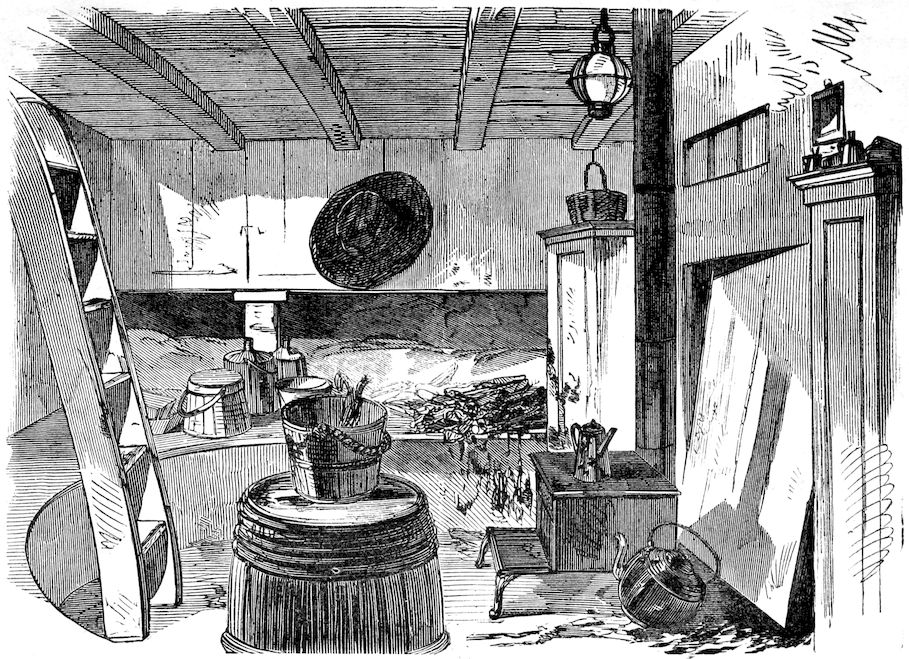

During Friday, Captain Weed and Mr. Howell searched the cabin of the sloop, and found in the captain’s berth a clean linen coat and a clean shirt, both neatly folded up, and each of them cut through the folds as if with a sharp knife. The coat had a sharp, clean cut, about seven inches long, through every fold; the shirt had some shorter cuts in it. They ascertained that an auger, which lay on the cabin floor, had been used to bore two holes immediately behind the stove, for the purpose of letting off the blood, which constituted a little sea. Instead of running off, it collected in the run beneath, where it remains. In brief, the cabin, the deck, and the starboard side of the vessel bore the most unmistakable evidences of a tremendous crime having been committed on board, and committed with the utmost regard to a previously arranged plan in the mind of the murderer, for three persons had been dispatched, two on deck and one in the cabin.

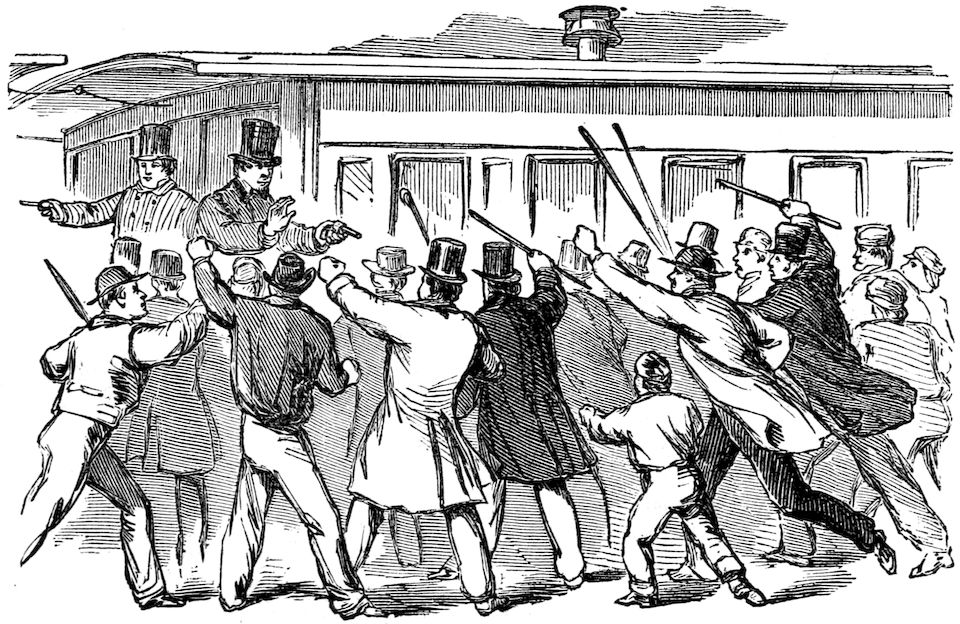

Public excitement continued on the increase; the public were waiting with all anxiety for a report from the pursuing officers, when, on Friday night, at a late hour, a dispatch was received from Providence, intimating that the murderer had been tracked to a private house, where he had taken lodgings, and would be arrested during the night. On Saturday, this news having been ventilated, the public excitement became greatly intensified, and it was anticipated that an effort would be made to lynch the prisoner on his arrival in the city. Crowds repaired to the railway depot, at Twenty-seventh street and Fourth avenue, also at Forty-second street, at the upper end of the Harlem Railroad. At 5 o’clock, P.M., the train arrived, containing the officers and their prisoner. But the multitudes who waited and looked for the prisoner were doomed to disappointment, for the officers had prepared themselves before reaching the city for avoiding any attack from infuriated mobs, by taking their places in the first or baggage car, thus avoiding suspicion. In this way they came down to the lower depot, and 10were transferred to an express wagon, and rolled down to the Second Ward station-house.

We give the account of the arrest in the words of Officer Nevins:

Captain Smith and myself left the city on Thursday, in the twelve o’clock train of the Long Shore Railroad, for Stonington and Providence. The same afternoon we arrived at Stonington, and went on board the Stonington boat Commonwealth, to make inquiries for a sailor man, his wife, and child. The boat arrived that morning about two o’clock, and of course our only chance of getting trace of the murderer was from the officers of the boat. We heard of several women and children, but they did not answer the description; so we waited until nine o’clock that night, when Mr. Howard, the baggage-master, arrived in the Boston night train. He gave us information of two or three different women who stopped on the route between Stonington and Boston. The description of one man, woman, and child, who stopped at Canton, Massachusetts, was so near, that on the arrival of the boat from New York, at two o’clock on Friday morning, we left in the train which carried forward her passengers. On arriving at Canton, however, we found that the woman was not the one we were in search of, so we immediately returned to Providence, being satisfied that the murderer could not have taken the Stonington route. In Providence we called upon Mr. George Billings, detective officer, who, with several other officers, cheerfully rendered us every assistance. We drove around the city to all the sailor boarding-houses, and to all the railroad depots, questioning baggage-masters and every one likely to give us information, but could get no satisfactory clew, so we concluded they had probably come by the Fall River route, and Captain Smith went down to the steamboat Bradford Durfee, to make inquiry there. The deck hand remembered that on the previous morning a sailor and a little sore-eyed woman and child came up with them, and asked him if he knew any quiet boarding-house, in a retired part of the city, where he could go for a few weeks. He told him he did not, but referred him to a hackman, who took him off to a distant part of the city. The hackman was soon found, and at once recollected the circumstances, and where he had taken the party. It was then arranged, to guard against accidents, that the hackman should go into the house, and inquire of the landlady if this man was in, pretending that two of the three quarter dollars which he had given him were counterfeit. He went there, and the landlady told him that the man was not in, but would be in that night. Arrangements were then made for a descent upon the house at two o’clock on Saturday morning. At this hour I knocked at the door, and at first the landlady did not seem inclined to let me in. I told her I was an officer who had arrested the hackman for passing counterfeit quarters, and as he had stated that he got them from the sailor, I had come to satisfy myself of the truth of the story. She opened the door, and we went up to this man’s room, some seven or eight 11of us, and found him in bed, apparently asleep. I woke him up, and he immediately began to sweat—God, how he did sweat! I charged him with passing counterfeit money, because I did not want his wife to know what the real charge was. We got his baggage together, and took him with it to the watch-house. I searched him, and found in his pocket the silver watch, since identified as Capt. Burr’s, also, his knife, pipe, and among the rest, two small canvas bags, which have since been identified as those used by the captain to carry his silver. In his pocket-book was $121, mostly in five and ten dollar bills of the Farmers’ and Citizens’ Bank of Brooklyn. There was no gold in his possession. I didn’t take his wife’s baggage, and I felt so bad for her that I gave her $10 of the money. Poor woman! as it was she cried bitterly, but if she had known what her husband was really charged with, it would have been awful. I took the $6 from the landlady that he had paid in advance, because I didn’t know but the money might be identified. When we got him to the watch-house, I told him to let me see his hands, for if he was a counterfeiter, and not a sailor, as he represented, I could tell. He turned up his palms, and said, “Those are sailor’s hands.” I said yes, and they are big ones, too; and then I told him I did not want him for counterfeiting, and he replied, “I thought as much.” So I up and told him what he was charged with, and he declared upon his soul that he was innocent, and knew nothing of the matter, and was never on the sloop. I don’t think his wife knew anything about it. Some time before he had picked up a yacht, and was to get $300 salvage, and when he came home so flush with money he told his wife he had got the prize money. I asked him if he would go on to New York quietly with us, or stay in jail ten or fifteen days for a requisition. He said he would go with us, and we started at 7 o’clock in the morning. He behaved so coolly and indifferently that I at one time almost concluded we had mistaken our man. At the New London depot there was an immense crowd of people waiting to see the prisoner, and, when we went through the crowd, they cried out, “There’s the murderer; lynch him—lynch him!” I told him that I would shoot the first man who touched him. At every station after that, as we came through there were large crowds curious to see the prisoner.

Soon after the arrival of the prisoner, the man John Burke, with whom he had lived in Cedar street, was confronted with the prisoner, whom he identified at once as William Johnson, the man who, with his wife and child, had left No. 129 Cedar street on Wednesday afternoon, and went on the Fall River boat. Mr. Simmons also stepped forward, and recognized the prisoner as one of the hands who sailed from this port with Captain Burr on board the sloop E. A. Johnson. Upon being asked if he knew Captain Burr, he said he did not, he never saw him, and never sailed in the vessel commanded by him.

On Sunday afternoon, an old man, named Charles La Coste, who keeps a 12coffee and cake stand near the East Broadway stage terminus at the South Ferry, identified Johnson as the man who, on Wednesday morning last, at about eight o’clock, stopped opposite to his stand, apparently looking to see what he sold thereat, when he asked him if he wanted some coffee. He afterward went into the booth and sat down, leaving what appeared to be his clothes-bag outside against the railings. He had coffee and cakes which amounted to the sum of six cents. When about to leave, he handed him a ten dollar gold piece in payment, when he asked him if he had no less change. He said he had, and pulled from his pocket a handful of gold, silver, and some cents, and, abstracting half a dime and a cent paid his bill. About this time some boot-blacks came round, and wanted to black his boots. He looked down at his feet, and said his boots were not worth the trouble. He then asked if he could get a carriage, when La Coste told him it was too early; he ought to get into an East Broadway stage, and ride up to French’s Hotel, as he had asked for the whereabouts of a respectable place to put up at. To this suggestion he demurred, when a newsboy came up to him, took hold of his bag, and implored him for the privilege of conveying his bag to any given point of the metropolis. The boy took the bag and followed the man.

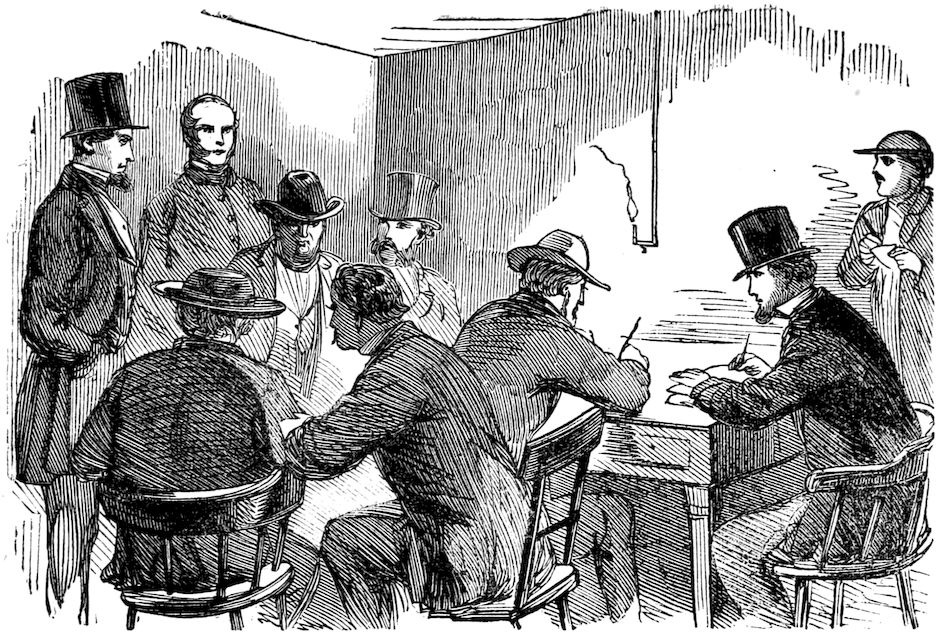

At a later hour the prisoner was brought from his cell and taken into the officers’ room in the back part of the station-house, where a promiscuous assemblage of men had gathered in. The prisoner took his place among them. The boy, Wm. Drum, was then brought into the room, and in a moment rested his finger upon the man whose clothes-bag he had carried from La Coste’s stand to the house No. 129 Cedar street, one morning last week, about eight o’clock; he did not recollect which morning. The man thus pointed out was the prisoner. The same boy immediately afterward saw the bag, and identified it as the one which he had carried from the South Ferry to Cedar street. He asked Johnson fifty cents for the job, but, on his refusal, he compromised, and took three shillings.

Abram Egbert was introduced in the same manner as the boy, and selected Johnson as the man who spoke to him on the bridge of the Vanderbilt landing, on Staten Island, last Wednesday morning, between six and seven o’clock. He was not certain, but he thought he was the man.

Augustus Gisler, the boy who sold Johnson the oyster stew, the eggs, and the numerous hot gins, was also introduced in the same manner. He at once pointed out Johnson, and said, “That is the man.”

Another little boy, who had asked to black Johnson’s boots, at the South Ferry, was introduced. He looked carefully through the crowd, repeatedly fastening his eyes upon Johnson. The boy at last stopped opposite Johnson again; the prisoner noticed this, made a contortion, and turned away his face, when the boy said he could not see the man. The prisoner was then taken back to his cell, and his baggage underwent an examination in one of the rooms of the station-house.

THE BLOOD-STAINED CABIN OF THE OYSTER SLOOP “E. A. JOHNSON”

13The first article identified was Capt. Burr’s watch, which was found in the prisoner’s possession by the detectives who arrested him. This watch the prisoner said he had had in his possession for 3 years. It was handed to Mr. Henry Seaman, an old friend of Captain Burr’s, who after looking at it for about half a minute, pronounced it to be Captain Burr’s watch; but to be certain, he would not open it until he had procured the necessary testimony to prove it. After a short absence he returned with a slip of paper from Mr. Seth P. Squire, watchmaker and jeweller, No. 182 Bowery, to whom it appears he had taken it to be cleaned nearly a year ago, at the request of Captain Burr. The following was the memorandum contained on the slip:

The watch was then opened, and the name of the maker and the number of the watch found to correspond exactly with the name and number on the slip. By this means the watch was fully identified. Two small bags, which Johnson said he had made himself, were also identified by Mr. Seaman, and Mr. Simmons, of Barnes & Simmons, as having been the property of Captain Burr.

Mr. Edward Watts, brother of Smith Watts, identified the daguerreotype found in the pocket of a coat belonging to Oliver Watts, which was found in Johnson’s clothes-bag, after his arrest, as that of a young lady friend of his brother, living in Islip, L. I.

Captain Baker, engaged in the oyster business in the Spring street market, recognized the prisoner as a man whom he had seen on board the sloop E. A. Johnson. He was certain of the man, as he had frequently seen him.

Mr. Selah Howell, taking a position right in front of the prisoner, as he stood in his cell, at once identified him as the man who took supper with Captain Burr and himself, on board the sloop, the night before she sailed.

Mr. George Neidlinger, the hostler who saw the man leave the yawl boat on the Staten Island beach, just south of Fort Richmond, identified the prisoner as that man. He also identified a glazed cap found in Hick’s baggage as the cap he had on that morning.

Mr. Michael Dunnan also identified Hicks as the man whom he had met on the road between Fort Richmond and the Vanderbilt landing, last Wednesday, about six o’clock.

The wife of Hicks arrived in this city from Providence, on Sunday morning, and in company with John Burk visited her husband at the station 14house. She stated that on Friday evening last she got a New York paper, and seeing in it the story of the “sloop murder,” proceeded to read it to her husband in their room, but before finishing it he said he was sleepy and wanted to go to bed, and she had better stop reading.

When taken down to the cell in which her husband was locked up, she broke out upon him in the most vituperative language, charging him with being a bloody villain. She held her child up in front of the cell door, and exclaimed, “Look at your offspring, you rascal, and think what you have brought on us. If I could get in at you I would pull your bloody heart out.” The prisoner looked at her very coolly, and quietly replied, “Why, my dear wife, I’ve done nothing—it will be all out in a day or two.” The poor woman was so overcome that she had to be taken away. She subsequently returned to her old quarters, No. 129 Cedar street.

On Monday, the prisoner Hicks, alias Johnson, was transferred to the custody of the U. S. Marshal Rynders, and upon the filling of several affidavits, he was committed for examination.

Such is a brief account of this horrible tragedy, than which nothing more calculated to excite public wrath has occurred in the neighborhood of this city for a number of years. That Hicks is the man who committed the triple murder on board the sloop E. A. Johnson, no doubt is entertained, and no one will regret his speedy satisfaction to the claims of public justice.

We have been favored by a gentleman with the following account of the family of Hicks: The father of the prisoner lives at Gloucester, a few miles from Chepatchet, Rhode Island. He used to be a collier in that neighborhood, and had the reputation of being an honest man. About fourteen or fifteen years ago he was employed by our informant. Simon Hicks, the brother of Albert W. Hicks, alias William Johnson, was several years ago sentenced to be executed for the murder of a man named Crossman, under the following circumstances: Mr. Crossman lived in Gloucester. He was an old bachelor, and lived alone. Simon Hicks and he were very friendly, and Simon used to visit him very often. One night, however, Simon went to Crossman’s house, broke in at the door while the old man was in bed, and beat him to death with a club. He then helped himself to several hundred dollars of the old man’s treasures, and in a few days left for Providence, a distance of sixteen or eighteen miles from Gloucester, taking with him a girl to whom he had been paying his addresses. In Providence he bought her a gold watch, and various other articles of finery. This lavish conduct caused suspicion, and he was arrested. He was examined in Chepatchet, and afterward acknowledged his guilt. He was subsequently tried in Providence, convicted of murder, and sentenced to be executed. While awaiting execution, one of the prisoners in the jail, whose time had almost expired, opened a number of the cells, and there was quite a stampede of prisoners, among whom was Simon Hicks. They were all recaptured within 15a few days, with the exception of Simon Hicks, who has never been heard of since. This escape was deemed a very strange circumstance, inasmuch as Simon was known to be imbecile and unwary. His simplicity created much sympathy in his behalf. In referring to Simon, our New York prisoner admitted that some strange stories had been told about him, but he guessed they never amounted to much. The last he had heard of his brother was that he had gone to California.

As everything connected with this mysterious and bloody affair must prove to be of public interest, we republish an extract from the last letter of Captain Burr, in which he speaks of William Johnson as a helmsman, written to his wife from Coney Island, previous to the departure of the E. A. Johnson on her ill-fated voyage:

“This man, William Johnson, who lives in New York, is a smart fellow. He went at the mast and scraped it while we were at Keyport, without telling, while I was ashore. He is a good hand; can turn his hand to almost anything. He is a ship-carpenter, he says, and has got quite a set of tools. He understands all about a boat, only is not a very good helmsman to steer the sloop nice when beating to windward; he understands steering well enough other ways. It requires a man that has been very much used to sailing a boat by the wind to steer fast. We often get in company with vessels that are smart, when it requires a nice helmsman; then it requires my skill more. Smith is a good helmsman close by the wind. I don’t think Oliver is quite so good. I will write the first chance after we get in Virginia. Should we have a chance, we are going to Pionkatonk to see if we can get a load there. That is about five miles short of the Rappahannock River. Selah knows where it is. I have nothing more at present. Would like to see you very much.

On his examination, the facts which have been related above were given in evidence, upon which he was committed, and the Grand Jury found a bill of indictment for robbery and piracy upon the high seas against him.

The trial commenced on the 18th of May, and lasted five days, during which time the prisoner maintained a show of cold indifference to the proceedings.

It being announced that this extraordinary and mysterious tragedy would be brought to trial this morning, the court-room was densely crowded. Judge Smalley said he was informed by the District Attorney, that there were a large number of witnesses for the prosecution, and as the District Court was larger than the Circuit room, the proceedings would be conducted in the District Court-room.

16There were several women in court who are to be examined as witnesses.

The prisoner stands charged with having, on the 21st of March last, made a violent assault on George H. Burr, on the high seas, on board the sloop Edwin A. Johnson, and there feloniously and piratically carried away the goods, effects, and personal property of the said George H. Burr, who was master of that vessel. The property consisted of about $150 in gold and silver coin, a watch and chain of the value of $26, a canvas bag, a coat, a vest, one pair of pantaloons, and a felt hat. The second indictment is the same as the first, but charges the felony to have been committed in the lower bay.

The prisoner was also indicted by the Grand Jury for the murder of George H. Burr, master of the Edwin A. Johnson, and two seamen (brothers) named Oliver Watts and Smith Watts. As robbery on the high seas is piracy, and punishable with death, the prisoner was placed on trial now for the robbery only.

The prosecution was conducted by ex-Judge Roosevelt, United States District Attorney, and Messrs. Charles H. Hunt and James F. Dwight, Assistant United States District Attorneys. Messrs. Graves and Sayles defended the prisoner, who was unchanged in appearance, and exhibited the same cool demeanor which had marked his conduct throughout the whole case.

The following Jurors were empannelled, after some challenges, and some being excused for having formed and expressed an opinion:

The following gentlemen were rendered ineligible, having formed and expressed an opinion in the matter: William A. Martin, Jos. J. B. Delvecchio, Dwight Johnson, Samuel Carson, Geo. Burbeck, John Latham, Thomas M. Clarke, and John Green.

The following gentlemen were challenged peremptorily by the prisoner’s counsel: Robert Goodenough, Geo. H. Nichols, A. B. Lawton, and Oscar Johnson. Daniel F. Leveridge was challenged for favor.

Mr. Dwight proceeded to open the case for the government.

Mr. Dwight said: You are empannelled, gentlemen of the jury, to try the issue between the United States and the prisoner at the bar, charged with robbery upon the high seas. Robbery committed upon the high seas, or in any basin or bay within the admiralty maritime jurisdiction of the United States, is declared by the act of Congress passed in 1820 to be piracy, and punishable with death. The indictment against the prisoner charges him in the first count with having on the 21st of March last, on the sloop Edwin A. Johnson, committed the crime of robbery upon George H. Burr, master and commander of that vessel, and with having feloniously and violently taken from him a watch, a large sum of money, and some wearing apparel. Robbery is the felonious and forcible taking the property of another from his person or in his presence against his will, by violence or by putting him in fear. It is larceny accompanied by violence. The punishment, as you will perceive, for the offence committed upon the high seas, is different from its punishment when committed upon land. It is to protect more effectually and punish more thoroughly offences occurring upon vessels upon the high seas, where the protection for person and property is not so great as it can 17be on land, where individuals are so much surrounded by the police regulations to protect them and their property. In this case, the prosecution will show to you, gentlemen, that on the morning of Wednesday, the 21st of March last, there was found floating in the Lower Bay of New York a deserted vessel. Her strange appearance attracted the attention of several vessels in that vicinity—among others the steam tug Ceres, which bore down to her, and the captain of which boarded this vessel. On reaching the deck there was presented a most unexpected and fearful sight. A state of great confusion appeared. The bowsprit of the vessel was broken off, and its rigging was trailing in the water. The sails were down, and the boom of the vessel, which had been set, was over the side of the vessel. There was no human being found on the vessel, and no light. Forward of the mast appeared a large pool of blood, which had run down to some cordage and sticks at the back of the mast, and also down the side of the vessel into the sea. This was just aft the forecastle hatch, on which, or near which was found some hair—a lock of hair. Amidships, and totally disconnected with this appearance of blood on the foredeck, there was another large patch of blood, showing signs as if a body had lain there; this also ran down the side of the vessel. Still further aft, just back of the small companionway, they found traces of blood again, also disconnected with that in the middle or forepart of the ship. Aft there appeared signs of a bloody body having been dragged from the entrance to the cabin. There was blood upon the rail and over the side, and it seemed as if an endeavor had been made to wash it off. On descending into the cabin, a state of still greater confusion appeared there. The few articles of furniture were disarranged. The companionway steps were pulled down, and some of the sails which lay on the companionway were pulled out. The floor was wet and bloody, and bore signs of having been covered in its entire extent with blood, which had been washed off with water, probably brought in the pail which was found there. Upon the handle of the pail there was found some hairs, where the hand would naturally hold it. These hairs were of a different color to those found in the other parts of the vessel.

The appearance on the floor and the disposition of the articles lying in the cabin, together with the two auger holes found bored in the lower part of the cabin, where the floor slanted down, showed that an endeavor had been made in washing the floor of the cabin to let the water run down. The auger with which these holes were bored was found there, and also some little chips which had been bored out of the floor. It seemed as if the attempt had been given up in the cabin, and the vessel had been abandoned afterwards. There were a small stove in the cabin and a pile of wood under which the blood had run. On the wood was lying a coffee-pot or a tea-pot with fresh tea leaves in it. The side of the tea-pot was indented and covered with human hair, which was likewise black like that found on the pail. There was nothing further than this to direct suspicion, and the vessel was taken in tow by the Ceres and brought up on the morning of Wednesday, the 21st of March, to the slip at the foot of Fulton Market. On the affair being noised about the town, the sloop was visited by a large number of persons; among others by persons acquainted with the vessel and those belonging upon her. It was found that this was the sloop E. A. Johnson, owned at Islip, Long Island—a vessel belonging in this district, and commanded by George H. Burr, who was also part owner. The sloop had been engaged in the oyster trade in Virginia, and had recently come in, and had on the 13th of March, a week previous, cleared from here to go to Virginia for another cargo of oysters. The crew consisted, when she cleared from here, on the 15th of March, of Geo. H. Burr, master, two sailors—Oliver Watts and Smith Watts—young men, brothers, residing at Islip, and the defendant, who, under the name of William Johnson, had shipped as first 18mate. During the day a great number of persons visited the vessel, and the daily press of the afternoon and the following morning scattered broadcast all over the city and its vicinity information concerning this affair. The attention of the public finally addressed to this fact was the cause of developing many slight circumstances, which gradually formed themselves into a chain of circumstantial proof directing the attention of the officers of justice to the offender, and resulting in the arrest of this prisoner. It was found that on Thursday, the 15th of March, the vessel sailed from here, being chartered by one Daniel Simmons, an oyster merchant of this place, living at Keyport, and one Edward Barnes, living at Keyport, to go to Virginia for a cargo of oysters; that it went out for a cargo as I have described, and that the captain had a large quantity of money in his possession to purchase oysters. The vessel went that week to Keyport, lay there some time, and in the last part of the week ran to Coney Island, and lay in Gravesend bay, waiting for a favorable tide and wind till Tuesday afternoon. During the Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday that the vessel lay there, the captain, crew, and others went on shore at different times, and one of the Watts boys had gone to Brooklyn on Monday or Tuesday, and returned on Tuesday, and on his return the vessel immediately proceeded to sea. The vessel had waited with its sails up, if I remember correctly, for the arrival of young Watts. He was taken off the beach in a yawl boat which was on board the vessel, and then she proceeded on her Virginia voyage. It was watched by persons who belonged to Coney Island, and also by two vessels lying at anchor at the same time, some distance from Coney Island. This was the close of the day—Tuesday about six or seven o’clock, if I remember rightly. From that time until the next morning only one thing is known of that vessel, and that by a connection of peculiar circumstances.

What was done upon that vessel during the night no mortal man save the prisoner knows. Oliver Watts and Smith Watts have never since that been seen in life. What became of them we can only judge by those circumstances which are thrown around by the appearance of the vessel and by the conduct of the prisoner, and other circumstances connected with him. Whether their bodies be in the sands of the lower bay, or floated out to sea, and are tossed by the waves there, we do not know. The prisoner fails to give an account of them, and we can only suppose that they were murdered by him and thrown into the sea. Next morning, Wednesday, the 21st, the prisoner appeared upon Staten Island, with the yawl boat of this sloop. Except, as I say, by implication, nothing is known in the meantime. The circumstances to which I refer are these: The schooner J. R. Mather, Captain Nickerson, was going from this city to Philadelphia, clearing from here March 20, and running down the bay. Some time during the night, between twelve and two o’clock, the vessel, then being down off Coney Island, had a collision with a vessel coming in. It appeared that the vessel going out saw this sloop coming in, and on going within three or four hundred feet, the course of that other vessel was changed, and she run down directly to this schooner, as if to run across its bow. That seemed to fail, and the course of that vessel was again changed; but instead of running across the bow of the schooner Mather, it seemed to fail, and struck the bow itself, cutting it down within six or eight inches of the water’s edge, and rendering the schooner incapable of proceeding to sea, and it returned for repairs. There was the finger of Providence again in that. On coming into this port the captain of the schooner J. R. Mather found that the sloop E. A. Johnson had come in, and by a comparison of the rigging of her bowsprit, found on the bow of his boat, with the rigging of the E. A. Johnson, that that was the vessel which caused the collision. Further than this, nothing is known of that night. There was no cry from the deck of the E. A. Johnson when it encountered the schooner; there was no hail, no attempt to disentangle themselves, and 19nothing was known of what was going on upon the deck of that vessel—whether there was a human being on it or not. The captain of the sloop saw a dark form aft, but could not say whether it was one man or two men. He knew that some person must have been on board, from the fact of her changing her course as I have described. On the morning of Wednesday, the 21st of March, about six o’clock, the prisoner came on shore at Staten Island, a little below Fort Richmond, which is in the Narrows, opposite Fort Hamilton. He was seen very soon afterward, coming on shore, by a Mr. Neildinger, whom he addressed, inquiring if his boat would be safe, designating where he had left her, to which Neildinger replied it would be all right, and the prisoner drew it upon shore, where it would be a little safer. The prisoner had with him a large canvas bag, which he carried upon his shoulders. After leaving Neildinger, he passed up Staten Island, encountering one or more persons, whom he addressed, and came to Vanderbilt’s landing, arriving there shortly before seven o’clock. He there inquired of the boat tender where he could procure some breakfast, and was directed to a shop, where he ate breakfast, and in payment offered to the boy who served him a $10 piece, which the boy could not and did not change, and he afterward gave him some silver. Afterward, in conversation with Mr. Egbert, in charge of the station there, he said he was a seafaring man; that he had been on the vessel William Tell in the lower bay; had had a collision with another vessel; that the captain had been killed against the mast, another person had been knocked overboard, and he had merely time to escape from the vessel with the money. He is described by that witness as being excited. He took the ferry-boat Southfield, left there at seven o’clock, and came up to the city. On the way up he entered into conversation with Francis McCaffrey, a deck hand. He produced before him a bag of money, and asked him to count it. It was a canvas bag, and contained $30 in silver, and a large quantity of gold. McCaffrey counted it, and the prisoner took possession of it again, and during the passage up had some more general conversation with him.

On the arrival of the Southfield at the Battery, between seven and eight o’clock, the prisoner took some refreshment—a cup of coffee, I think, and then hired a small boy to take his bag—a small canvas bag—filled with clothing and other articles, up to his house; it was taken up to his house in Cedar street, and left there. The prisoner lived at 129 Cedar street, with his wife; the other occupants of the house were Mr. and Mrs. Burke. They had various conversations with him during the day. During the morning the prisoner went out, and at the shop of Mr. James, on South street, exchanged the most of the money which he had (about $150), part gold and part silver, and received in exchange bills on the Farmers’ and Citizens’ Bank of Williamsburg. He made the remark to Mr. James at the time, that he came honestly by the money. Through the day he packed up his clothing, and in the afternoon, with his wife and child, took the Fall River boat, running from here up the Sound, and went up to Fall River, telling the carman who took his baggage, if any inquiries were made for him, to throw the inquirers off the scent. From Fall River he went to Providence. The whole or most of these facts coming to the knowledge of the officers of justice, two persons followed on his track, and very soon traced him from Fall River to Providence, and after some search were enabled to find him there. He was arrested on Friday night, the 22d or 23d March. They traced him to a small house in the outskirts of the city, and at one o’clock midnight obtained an entrance into the house, where they found him in a back room in bed. The windows and doors of the house were closed, and the defendant was found concealed under the clothes of the bed, with his head covered up. The officers withdrew the clothes, and found the defendant, there in a profuse perspiration and feigning sleep. He was awakened, or pretended to be 20awakened, by the officers. They said that they wanted to see him on a charge of passing counterfeit money on the hackman who had brought him to the house; he arose, and was asked to point out his baggage. He described two trunks, which they took with them. There were found on him a watch and a quantity of money—among the rest, about $120 in bills on the Farmers’ and Citizens’ Bank of Williamsburg, corresponding with those exchanged for him by Mr. James of this city. The clothes were returned to this city, and next morning the prisoner was brought here and lodged in the Second District station-house. On his arrival, he was told that the charge of counterfeit money was a mere feint, and that that was not the real charge against him; to which he very coolly replied that “he supposed so,” or something to that effect. To Mr. George Nevins and Mr. Elias Smith, the persons who pursued and discovered him, he said “he had no knowledge whatever of the sloop E. A. Johnson; had never known her or Captain Burr, and had not been on Staten Island for many months.” These statements he has maintained to the present time, constantly refusing to give any account of himself in connection with this vessel, or of anything which transpired on board of her after she left her anchor in Gravesend bay. That denial, contrary to the truth, that he had ever known Captain Burr, or ever been on the vessel E. A. Johnson, or had been on Staten Island when he was charged with being there, shows a full consciousness of the fatal effects of any evidence tending to establish that fact if uncontradicted, and in that contradiction he persisted. On being brought to this city, he was confronted with various persons that he had known before; with the man who carried his baggage; with the deck hand of the Southfield, and with various persons who saw him on the sloop Johnson; the watch found upon him was, through the hand of Providence, identified as the watch of Captain Burr, worn by him on the day of his leaving this port. That watch the prisoner stated he had had in his possession for a long time; that he bought it from his brother, and paid a certain sum of money for it; and as to the other articles, he claimed that they were his, and gave various accounts concerning them.

On the Monday following his being brought here he was examined before a United States magistrate, was indicted, and is now brought before you for the offence of robbery on the high seas. I have thus briefly gone over the various circumstances of this case as they will be produced to you by the evidence. I deemed it necessary to state to you the line of evidence that is intended to be pursued by the prosecution, that you may understand the bearing of each portion of the testimony toward the rest. You will perceive in this case one peculiarity. A great number of witnesses will be examined for the government, and among these witnesses there is a very slight connection, either with each other or with the individual himself—particularly with each other. Various witnesses will be produced before you from Islip, Gravesend, Staten Island, New York, and Brooklyn, who are unacquainted with each other, who each come up to add their little fibre to this strong cord of proof which is thrown round this defendant. Each little item of evidence is of no particular strength, of no decision in itself, but only forming a strong chain, a perfect chain, as claimed by the government, fixing without question and without doubt the guilt of this offence upon the prisoner. Your attention, gentlemen, is invited to this carefully and scrutinizingly, which scrutiny, I feel convinced, you will give to it. It is a question of great interest—it involves the punishment of a terrible crime. If this prisoner is the true offender, the result may be very serious to him. It involves a vindication of the law and the punishment of a crime which he thought he had covered up; for there is very little doubt he thought he had sunk the vessel by the collision in the Lower Bay; and I think you will say, as I have, in looking over the evidence, that the hand of Providence, in marking the track this man 21was to pursue, has placed upon that track the eyes of those who would come up afterward to identify him. It seems strange in this centre of swarming thousands, at such a time of the day as this prisoner escaped from that sloop, he could not have hidden himself. It seems as though there was but one eye to watch, and one instinct to follow and observe him. From the very time that he landed on Staten Island until he went to Providence, his whereabouts was known all the time. I cannot explain either to you or to myself what it was that caused him to be watched; that he was watched and observed will be shown. From the very commencement of his being seen on the E. A. Johnson till he was brought here, everything is known concerning him, save the twelve hours intervening from his sailing from Coney Island till the next morning. He has been called upon to give an account of the property of the Wattses and Captain Burr—but he claims it as his own. He has been called upon to give an account of those men with whom he was, and who are no doubt already dead; but he utterly disclaims any knowledge of them or of the vessel upon which they were. That, gentlemen, you will judge of on this trial. You will say whether he is guilty of the triple crime, the double, bloody, damning crime that occurred on the deck of that vessel; and if so, as jurors and citizens, whatever may be the result to him, and whatever the punishment, I have no doubt but that your verdict will be in accordance with the law and the facts.

Selah Cowell was the first witness called, and being examined by Mr. Dwight, deposed: I reside at Islip, Long Island; I know the sloop E. A. Johnson; I built her myself; I am an American citizen; I owned one half of her, and Captain George H. Burr owned the other half; he was an American citizen; I saw the prisoner at the bar on board the sloop E. A. Johnson, on the Wednesday evening before she left; she was at the Spring street dock; she had been lying there a week; she cleared on Thursday, 15th; Captain Burr told me he was going to Deep Creek, Virginia, for oysters; the crew consisted of Captain Burr, Oliver Watts, and Smith Watts, and the prisoner; Captain Burr told me he shipped the prisoner as mate; Captain Burr was about thirty-nine years of age, Oliver Watts was about twenty-four, and Smith Watts about nineteen; I knew Captain Burr for a long time; the color of his hair was dark; Oliver Watts had very light hair, and Smith Watts had dark brown hair; I don’t know the handwriting of the boys (Watts); I have seen considerable of Captain Burr’s writing; I saw the E. A. Johnson at the Battery when she was brought in by the harbor police; I saw the yawl boat of the Johnson with the harbor police; she had that yawl boat before she left; I took the Johnson to Islip; on examining the Johnson I found a valise—a square, black, canvas valise—and some clothes; I brought them here (identifies the valise); found the things now in it, and a knife in it; saw the prisoner in the sloop the night before she sailed; saw him next in court before the Commissioner.

Mr. Dwight to the Court—The examination before the Commissioner took place on the 28th and 29th of March.

Cross-examined by Mr. Graves—I had no conversation with the prisoner when I saw him on board the sloop on the Wednesday; I never saw Captain Burr since; Oliver Watts was a large man; he would weigh about 170 pounds; Smith Watts would weigh, perhaps, 180 pounds; he was very large for his age; Captain Burr was a small man; probably did not weigh more than 125 or 130 pounds; it was after the examination before the Commissioner—some four or five days—that I found the valise on board; I gave it to Henry Seaman; I took the sloop over to Hoboken, lay there a couple of 22days, and then took her to Islip; the Watts boys were on board the sloop the Wednesday evening before she sailed.

Re-direct.—I have seen Captain Burr write; I had business transactions with him for the last nine years; when the defendant was on board on Wednesday evening he was dressed with a blue shirt and overalls, like those I found in the vessel; I was on board about half an hour; I took supper there; the prisoner was at supper also; he sat at the table with us (shipping articles produced); I recognize the names, etc., here, to be in Captain Burr’s handwriting.

John A. Boyle deposed—I am enrollment and license clerk in the Custom House (produces a book); the E. A. Johnson was enrolled on 3d of December, 1858, as an American vessel (objected to by prisoner’s counsel; admitted; exception taken.)

Daniel Simmons deposed—I reside at Keyport, New Jersey; I am in the oyster business; I know the sloop Edwin A. Johnson; I had her chartered last spring from this port to Virginia for oysters; the last time I chartered her was on the 14th of March; I knew Capt. Burr for two years; I sailed once with him; I think she left here last on Thursday morning the 15th of March; I settled with Capt. Burr for his charter on Wednesday afternoon, 14th March; I gave him $200 in silver coin, quarters, halves, and ten and five cent pieces; I gave him other money.

Mr. Graves objected to any proof of the payment of coin to the captain, on the ground that the indictment did not warrant the allegation.

The Court was of opinion that the objection was not well founded, and overruled it.

Examination continued.—I paid him the balance of his charter money in gold; two tens, two fives, a two and a half, one dollar in gold and a half dollar; I gave it to him in a shot bag; it belonged to Capt. Burr, but I had it in my safe, with the money in it, for some days before; I did not know where the captain used to keep his money; there was a secret drawer in the sloop where I kept money when I sailed with him; I do not know that Capt. Burr ever kept his money there; I have seen that bag since, when it was taken out of the prisoner’s pocket at the Second precinct station-house; I saw it taken out of his pocket; there was nothing in the bag then; there were two bags—I only knew one of them; I saw the prisoner on board the sloop Edwin A. Johnson on the Wednesday before she sailed, at the foot of Spring street—(bag produced); to the best of my knowledge, this is the same bag that I gave the captain the two hundred dollars in; I saw the prisoner on board in the forenoon of Wednesday, and again in the evening; I think he had a monkey jacket on; I saw the prisoner again, I think, at Keyport, on board the sloop; I was about thirty yards from him; it was between daylight and dark; I could not swear positively to him being on board at Keyport; the next time I saw the prisoner was at the Second precinct station-house, when he was brought back from Providence; it was on a Saturday; I had some conversation with him; I asked him if he had ever seen me before; he said he had not; this was in the back room of the station-house; Captain Weed asked him if he knew me, and he said he did not; I told him I saw him on board the Edwin A. Johnson, at Spring street dock; he said he never was there, and did not know there was such a vessel; I asked him if he knew Capt. Burr; he said he did not; that he never saw him and never was on board the vessel; when I saw the prisoner on board the sloop his whiskers were red and full; when I saw him after, his whiskers were darker.

Cross-examined.—When I hailed the vessel at Keyport, I asked them where the captain was; and I think the prisoner is the man that answered me, but I am not certain; I had no conversation with the prisoner on board the sloop at Spring street; the first time I spoke to him was at the station-house; Captain 23Weed asked me if I knew him and I said I did; I identify the bag by the strings; I have no other marks to identify it; the bag was pretty nearly full; there was no hole in the bag I gave Captain Burr; there is a hole in this one produced.

David S. Baldwin deposed—I live at Islip; I know the prisoner; I saw him on board the sloop on the 13th March; he was helping to get out oysters; Captain Burr was not on board; the prisoner told me that he was going to Virginia with Captain Burr for a load of oysters; he told me that night, that if I wanted to go up town he would stay on board and mind the vessel; I was cook; this valise I saw before; the prisoner handed it to me when he came on board on the 13th; the prisoner did not stay on board that night (examines the contents of the valise); I saw this knife before with the prisoner, on board; he took it out to cut a piece of string; I know it by this piece of the handle being rough, and the rivet being bright; at that time the prisoner wore his whiskers as he does now; I saw the prisoner on Wednesday morning on board the sloop at breakfast; I did not see him again until to-day.

Cross-examined.—I had been cook with Captain Burr; I left the sloop on Wednesday; Smith Watts took my place as cook; the prisoner first came on board between six and seven o’clock on Tuesday morning; I never saw him before; I don’t know how he came to tell me he was going to Virginia with Captain Burr; the captain told Johnson if he wanted to go up town that night he could go; Johnson said to me if I wanted to go he would stay on board.

James H. Bacon deposed—I am in the oyster business; I know the prisoner at the bar; I saw him on board the E. A. Johnson on the 13th March; I was there two days getting out oysters; Johnson was there shovelling out oysters; he wore his whiskers same as he does now; he had a check shirt, short coat, and comforter about his neck; I next saw him after his arrest, when I was called on to identify him.

Cross-examined.—I reside at Port Richmond; I was examined before the Commissioner; he was working on board the boat helping me to fill out the oysters; I think he had a dark pair of pantaloons and a Kossuth hat; I think in the morning he had on a monkey coat, and when he went to work he pulled on a blue shirt; I had no conversation with him more than to tell him to fill the baskets a little fuller.

Reuben Keymer deposed—I am in the oyster and fish business; I knew of the sloop E. A. Johnson being at Gravesend in March last; I don’t recollect the date; she came there on Sunday and left on Tuesday night; the next day (Wednesday) I saw the sloop towed up by a steamer; I saw the prisoner the day the sloop sailed from Gravesend; he came ashore after one of the Wattses; it was just at sunset; he came ashore in the yawl boat; the sloop was about one hundred yards off; the prisoner was sculling the yawl; I was afraid he would run foul of me; the prisoner and Watts returned to the sloop in the yawl boat; the prisoner was dressed in a coat of the description of the one produced; I watched the sloop going out; she went southwest to clear Coney Island, and then she took a southerly course (a chart of the bay produced—the witness describes to the jury where the sloop lay, and her course); I saw her three miles out to the east of Sandy Hook; the wind was west northwest; the sloop was going about eight knots an hour; when she got out, she set her flying jib; at the rate she was going she would pass Sandy Hook in about an hour; when I saw Johnson come ashore from the sloop, I think I recognized the boy that went back with him as one I had seen on the sloop the day before.

Cross-examined.—I was not well acquainted with any of them except Capt. Burr. I am certain of the prisoner being the man who sculled the yawl; I told the man in my boat not to run into him; I turned to the prisoner and 24said to him, “Now I suppose you are going to give it to her;” I was in a row boat; we were rowing our boat; I next saw the prisoner in Court before the Commissioner; I think I stated before the Commissioner that the prisoner had a monkey jacket on when I saw him in the boat; I stood about five minutes on the shore and then went to my house; I saw from the house about three miles out; if she kept the southerly course I suppose she would have fetched up about the Highlands, below Sandy Hook; she made a straight wake. (Witness again described the course of the sloop on the chart.)

Charles Baker deposed—I live at Gravesend; I knew Capt. Burr; I know the sloop E. A. Johnson; I saw her in March last at Gravesend; I saw Capt. Burr come ashore at Gravesend bay; knew Smith and Oliver Watts by sight; I saw the prisoner Johnson come ashore and take away one of the hands; I saw the sloop go away in about eight or ten minutes after the prisoner and the young man got on board; Capt. Burr was on board; there were four on board altogether.

Cross-examined.—The young man had a small bundle under his arm; never saw the prisoner before that; had no conversation with him; he was a stranger and I took a little more notice of him than if I knew him; he had a kind of monkey coat on; he had whiskers; he had none on his upper lip then that I could see; I was not nearer to him than the length of this room; I did not see which of the Watts boys went along with him.

John S. Whitworth deposed—I live in Gravesend; I saw the prisoner at Gravesend beach on the 19th or 20th of March last; he came ashore in a yawl boat; I saw him raise the bow of the boat on the beach; I was painting a vessel at the time; the boat was not more than a few minutes there when I saw her go back again toward the E. A. Johnson, which was about 100 or 120 yards off; I saw the prisoner on the day following; he came ashore in the yawl boat; I did not see him go back to the sloop that day; I don’t think he had any coat on on Monday; I think he had a monkey coat on on Tuesday.

Cross-examined by Mr. Sayles.—The next yawl boat was coming ashore when I left off work on Tuesday; I went away before she came to the beach; the prisoner’s side was to me when he pulled the boat on the beach on Monday.

By the consent of counsel the jury were permitted to separate after suitable caution from the Court not to converse with any person on the subject of this trial.

Adjourned to Tuesday at ten o’clock.

Richard Eldridge, examined by Mr. Dwight, deposed that he saw the sloop E. A. Johnson at Gravesend on the Sunday morning and Monday; went on board of her; saw Captain Burr and the two Watts boys, and Johnson, the prisoner, on board; saw Johnson on board the sloop first on Sunday, Monday and Tuesday. I went out in the Sirocco, in company with the sloop, past Coney Island; we were bound up to the Health Office; it was about sunset when we went out; Captain Burr, the two Watts boys, and Johnson were on board when she left; she went on the usual course of southern vessels; I took a letter from Captain Burr to his home; Johnson wore a beard same as now, but no moustache on the upper lip; never saw the prisoner since until yesterday.

Cross-examined.—Knew Captain Burr well for years, and also knew the Watts boys; I did not know the prisoner before that time; I had no particular conversation with him; Captain Burr told me he was going to Virginia.

George Neidlinger deposed—I live on Staten Island, at Port Richmond; 25I saw Johnson, the prisoner, at six o’clock on the morning of the 21st of March; I was standing at the barn door; he came up to me and asked me if there was any one to interfere with his boat, and I said no; he left his boat on the south side of the fort, and he came from that direction; he told me he left the boat “back there;” I afterward went there and saw that the boat had been hauled up by some boys; the harbor police came for the boat and took it away the next evening; there was nothing in the boat that I could see but some sand, oyster shells, and oars; the prisoner went toward the Vanderbilt landing; he had on a monkey jacket and a Kossuth hat—(jacket produced)—it was like this; he had a bag, like a feed bag, which he carried on his shoulder—(witness described on the diagram where he saw the prisoner)—he landed on the point below Fort Tompkins; Vanderbilt’s landing is about two miles from Fort Tompkins; the prisoner wore his whiskers pretty much as they are now, only he had no hair on the upper lip; at the examination before the Commissioner he had no whiskers on the side.

Cross-examined.—Had never seen the man before; he had no conversation with me except to ask if any one would interfere with his boat; he had a monkey jacket and Kossuth hat, but I did not notice his pants; I made a mistake before the Commissioner in stating that the jacket came down below the knees; I meant to say that it came down to his hips; I corrected myself.

To the Court.—I think I changed my testimony before I left the Commissioner’s Court.

Cross-examination continued.—I saw the prisoner put on the coat before the Commissioner, and then I changed my mind.

To Mr. Dwight.—I am not an American; I am a German.

Michael Durnin deposed.—I live at Staten Island; I know Hicks, the prisoner; I saw him on the 21st of March; I was going down to Port Richmond, and met him with a bag on his shoulder; he bid me good morning, and I bid him the same; he asked something about his boat; he went toward Vanderbilt’s landing; he had a bag on his shoulder, like a feed bag.

This witness was not cross-examined.

Augustus Guisler deposed—I live at Stapleton, but attend bar at Vanderbilt’s Landing; I know the prisoner; I saw him on Wednesday morning, 21st March; he came to our shop, and said he wanted something to eat; he asked me if I had any coffee, and I said not, but told him where to get it; he went out and came back again, and said they were not up; he asked for eggs, and invited Mr. Hickbert to take a drink; he showed me a $10 gold piece, and asked me if I wanted it; I said, “No, sir, I have not change for it;” he then took some silver and paid me; I would not know the bag; the coat he had on was like that produced; it had patches on the elbows like this; Mr. Hickbert asked him if he was a seafaring man; he told Mr. Hickbert that he was captain of a sloop; that he had been run into, and one man was killed, and another knocked overboard; he said he was down stairs asleep at the time, and had only time to get his clothes and the “needful” (at the same time shaking the bag), and come ashore in the yawl boat; the bag in which he had his money was something like this one produced; he took the $10 gold piece out of the bag; he was about twenty minutes in our shop.

Cross-examined.—I didn’t count the money; Mr. Hickbert did not count it; I did not see the bag in his hand when he first came; he did not take it out of his pocket; he had a handkerchief in his hand; when he offered me the gold piece, he had the bag in his hands, leaning against the bar; he finally put his hand in his pocket and paid me; could not tell whether the bag was full or not; it looked like this bag; I have seen a good many shot-bags; I am seventeen years of age; I next saw the prisoner at the Second 26Ward station-house; Captain Weed sent for me; they told me they thought they had the man; I went there and identified him.

To the Court.—There were thirty or forty persons in the station-house at the time; I picked him out; no one pointed him out to me; I asked Captain Weed where he was; he said he would not tell me; that I was to point him out; there were others there; they all identified him but one little boy; the people were not mostly in policemen’s dress; there were all kinds of clothes.

Abraham S. Hickbert deposed that he saw the prisoner, on the 21st March, at the Vanderbilt ferry, at about half-past six o’clock; he asked me where he could get something good; I showed him; he went in and asked Augustus, the barkeeper. This witness corroborated the last witness as to the conversation with the prisoner, and further added that he told him that the vessel he was on was the William Tell; that he had been run into by a schooner, and one man was killed against the mast, and another knocked overboard. The prisoner shook a bag in his hand when he said he had only time to save the one thing needful.

Cross-examined.—I had never seen him before, to my knowledge; I cannot tell exactly how he was dressed, nor whether he had whiskers; I should think the man was about five feet eight inches; I did not take particular notice of his height; he said he was on the William Tell, and had been run into that morning in the lower bay.

To the Court.—Next saw the prisoner at the police station-house; identified him there by his face; he was not pointed out to me by any one.

To Mr. Graves.—To the best of my belief, he is the man I saw at Vanderbilt’s landing; I would not like to swear right up and down that he is the man.

Franklin E. Hawkins deposed that he is captain of the sloop Sirocco; I knew Captain Burr and the Watts boys; heard Captain Burr say he was going to write a letter home; saw the prisoner on board the sloop E. A. Johnson; my vessel was lying at Coney Island, and the sloop Johnson was lying at the same place; on the Sunday before she sailed I went out with her; Johnson came ashore in the yawl boat on the evening before the sloop sailed; Richard Eldridge took the letter from Captain Burr to his home in Islip; Captain Burr had dark hair; one of the Watts boys had light hair and the other a little darker; I do not know Captain Burr’s watch.

Cross-examined.—The prisoner met me when he came ashore on Tuesday, and asked me if I was Oliver; I had no conversation with the prisoner; heard him talk with the captain; I can swear positively that this is the man.

Patrick McCaffrey deposed—I am a deck hand on the Staten Island ferry-boat Southfield; I know the prisoner; I saw him in the gentlemen’s cabin about seven o’clock on the morning of the 21st of March; I was brooming off the cabin; he was sitting down, and he called me over and asked me if I was a judge of this country’s money; that he was afraid them fellows were cheating him; I said I was a pretty good judge of gold and silver, but did not know much of bills; he asked me to count the money; I counted out three or four gold pieces and told him what they were; the bag was a kind of a shot bag; he asked me where the water closet was and I showed him; he told me to mind his canvas bag and he would give me the price of my bitters (identifies the coat); my attention was particularly called to the coat by it being bare in some places and having patches on the elbow.

Mr. Dwight asked that the prisoner now put on the coat.

The Judge said that he could not compel the prisoner to do so, as it might aid other witnesses for the prosecution, who are now in court and have not yet been examined.

Examination continued.—Next saw the prisoner in the Second Ward 27station-house; he denied having ever seen me; I looked all around the station-house, and when I saw him I said, “There’s the man.”

To the Court.—There were forty or fifty in the station-house; my attention was not directed to him; no one pointed him out to me.

Cross-examined.—Had never seen him before I saw him on board the Southfield; he had whiskers up to his ears, but no moustache; his whiskers were blacker when I saw him in the station-house than they are now; I have not a doubt about the coat; I can swear positively to it and the man; I cannot swear positively to the shot bag; I was born in Ireland; I am only two years here; I have lived at Staten Island ever since; I have been a coachman, and have been now nearly eighteen months on the ferry-boat; I can’t tell how many passengers were in the ferry-boat that morning.

William Drumm, a lad, deposed that he met the prisoner on a Wednesday morning, about eight o’clock; can’t tell when; met him at the South ferry; it was about the 21st of March; I saw him at a coffee and cake stand at the ferry, kept by Charley McCosten; he got a cup of coffee and a piece of pie; he put down a gold piece, and the man said, “Oh, ——, have you no smaller change than that!” he then gave him something else. I carried Johnson’s bag to the corner of Cedar and Greenwich streets. I asked him fifty cents, and he gave me three shillings, and said if I did not go out of that he would kick me (laughter); there was a Dutchman there who told him two shillings were enough; I pointed out the prisoner on the following Sunday, in the station-house.

Cross-examined.—I testified before the commissioner that the bag was very heavy and cut my shoulder, and that it did not seem to be filled with clothes; I stated before the commissioner that the prisoner wore a greyish coat; I saw him first at the coffee stand; he wanted a carriage first.

Patrick Burke, deposed—I know the prisoner for about three years, by the name of William Johnson; he had a room from me in Cedar street, near Greenwich; the last time I saw him was on the Wednesday before his arrest; I did not remark his dress; he had nothing with him that I saw; I saw him again that day, in my house, about four o’clock; I saw some bills with him that day; I do not know how much; I do not know that he made any change in his clothes or his whiskers; he went away by the boat that evening; he took his wife and child with him; he took some things with him; he left a ship’s instrument (a compass, I think) behind at my house; I had no conversation with him that day more than to bid him the time of the day; he always paid me my rent like an honest man.

Cross-examined.—I think it was before noon I saw him with the bills in his hands; often saw bills with him before.

Catharine Burke, wife of the last witness, corroborated her husband’s testimony; Johnson did not say anything about what voyage he was going on the last time he went to sea.

Cross-examined.—I had seen the prisoner with money on previous occasions.

Albert S. James, broker, deposed—I saw the prisoner first on Wednesday, the 21st March, at my office in South street; he asked me to take some silver at as low a rate as possible; I had engaged to take some silver from the market, and asked him if he came from there; he said no; the “Cap” was sick; that he came honestly by the money; I changed about $135 in silver, and $35 in gold; it was in a bag and tied up in a handkerchief. (Handkerchief and bag produced.) I think that is like the bag but cannot identify the handkerchief; a man came into the office and the prisoner seemed to hesitate, and did not seem to want to open the bag before the man.

Q. What did you give him in exchange for the gold and silver.

A. I gave him $130 in Farmers’ and Citizens’ Bank of Williamsburg, Long Island; their denominations were tens, fives, threes and twos; I counted 28the money; the prisoner did not appear to count the money after me; he did not see how much there was.

Richard O’Conor, cartman, deposed—That he saw the prisoner on the 21st of March, and took his baggage to the Bay State (Fall River boat); the prisoner walked, and I saw him at the boat afterward. He told me if any one inquired where he was going, to tell them it was none of their business. When they were taking the luggage out, a woman asked him where they were going, and he said they were going to Albany to live on a farm.

Witness was not cross-examined.

George Nivens, officer of second precinct, deposed—That he understood that a man answering the prisoner’s description had left in the Stonington boat, but traced him to Providence, where he arrested him in a boarding-house. I found the hackman who had conveyed Johnson, and he took me to the house; I found him in bed with his wife; I shook him up and searched him; I found on him a watch; I took away two trunks, two bags, two handkerchiefs, and a knife, a pocket-book, and some bed-clothing, which he claimed to be his. (Identifies the watch, pocket-book, and bags; cannot identify the handkerchiefs.) I found in the pocket-book $121 in bills on the Farmers’ and Citizens’ Bank of Williamsburg, mostly fives and tens; there are some ones; there are also some on the Lee, Huguenot Bank, and City Bank of Brooklyn; when I arrested him first I told him I arrested him for passing counterfeit money; I did not make any statement to him at the station-house in Providence; I believe Mr. Smith did; I brought him to New York next day; he told me that the watch belonged to his brother; he said he had not been in New York or Staten Island during the month of March; that he had been speculating around the market, and had about $60; at another time he said he got the money from his brother; on counting over the money in the pocket-book I found there were $121 in it; when I informed him in the cars of the charge against him, he denied all knowledge of Capt. Burr and the sloop E. A. Johnson.

Cross-examined.—At the time I had the conversation with him in the cars he was in irons; he did not tell me that he could not read or write.

To Mr. Dwight.—When I arrested him in Providence he told me his name was Hicks—Albert W. Hicks.

Elias Smith deposed—That he was with Nivens when he made the arrest.

The Court.—Are you a police officer?

Witness.—No, sir; I am a reporter of the Times.

To Mr. Dwight.—The prisoner denied all knowledge of the sloop E. A. Johnson or Captain Burr; he said he had not been in New York for two months; I understood him to convey the idea that he had been in Providence for two months (identifies the watch and pocket-book as those taken from the prisoner in Providence); I cannot identify the clothing; I addressed the prisoner at the station-house, and said to him, “Hicks, you are charged with the murder of three men;” he said nothing; I then changed the language and said to him, “You are charged with imbruing your hands in the blood of three of your fellow men for money;” the prisoner shook his head and said, “I do not know anything about it;” I then said to him, “You have been on board the sloop Edwin A. Johnson;” he shook his head and said he did not know anything about it, and was never on it; Mr. Nivens read the newspaper accounts of the transaction to him; he said he did not care much about the arrest except for the interruption to his business, as he had purchased a place in Providence; I told him he would be identified when he got to New York; he said we might think what we liked; he seemed annoyed at our pressing the subject.

Cross-examined.—I never found out how much he had paid; I said to him, “If you are innocent, then you are willing to go back to New York?” after hesitating, he assented; Detective Billings, of Providence, was with me when he signed the agreement to come back.

SCENE OF THE FIRST CONFLICT ON BOARD THE SLOOP “E. A. JOHNSON,” WITH THE BLOOD-STAINS ON THE DECK.

PORTRAIT OF OLIVER WATTS.

PORTRAIT OF CAPT. GEORGE BURR.

29Samuel M. Downes deposed—I am captain and pilot of the steamtug Sirius; I picked up the sloop E. A. Johnson on the East Bank, near the Romer, about half-past six o’clock in the morning; I brought her to this city, and left her in the river at the foot of Fulton Market; the bowsprit of the sloop was broken off about midway; the jib hung overboard; there was no small boat on board; I boarded the sloop; one of the men of the schooner Telegraph had boarded her about the same time (witness describes the appearance of the sloop on a model produced in court); there were pools of blood on the deck, and the cabin appeared as if some one had been slaughtered there; there were marks of a hand, as if struggling, and then there appeared to be a blow of a hatchet where the hand mark was, as if it was cut; the blood flowed down to the scuppers; there were evidences of a scuffle; there was a mark of a foot in the blood, as if some person with a boot or a shoe had stepped in it; the appearance of the blood from the companionway seemed as if some person had been dragged from there and thrown overboard; there was some hair found in the pool of blood forward; it was dark brown hair; I did not remove the hair or anything on board; I brought her to New York; arrived about half-past ten o’clock at the foot of Fulton Market, and gave her up to Captain Weed of the Second Precinct.

Cross-examined, but nothing material was elicited.

Re-direct examination.—The wind was blowing north-northwest, which would bring the sloop out to sea.

Hart B. Weed, examined by Mr. Dwight, deposed—I am captain of the Second District police; I examined the clothes brought by Nivens from Providence; there were coat, pants, vest, and some flannel clothing contained in a bag used for feed; the clothes produced—coat, vest, and pantaloons—are those given to me by Officer Nivens; there was also a hat (several other articles of clothing produced); these were either found in the trunk or the bag; I recollect finding a daguerreotype in the trunk or bag (produces it); I sealed it up and gave it to the clerk of this court. (The daguerreotype is of a young lady, and is said to be that of the sweetheart of one of the Wattses.) I was at the station-house when the prisoner was brought there; he said he knew nothing about it; I asked him if he knew anything about the vessel or the murder, and he said “No; he knew nothing about it, and had not been in New York, Staten Island, or Long Island for some time; Dr. Bonton, the coroner’s assistant, accompanied me to the sloop; we found a lock of brown hair—human hair—lying partially in a pool of blood on the deck; I gave the hair to the Assistant District Attorney; it was sealed up in the manner of this package produced; I cannot now swear that this is the hair; it was then clotted with blood; I also found hair on the coffee-pot in the cabin; I gave that to you (Mr. Dwight); (another package produced) this is the hair found on the coffee-pot; the blood had the appearance as if a person lay down and the blood flowed at each side.”