THE RADIO GUNNER

IN THE LABORATORY

Title: The Radio Gunner

Author: Alexander Forbes

Illustrator: Jr. Heman Fay

Release date: December 29, 2021 [eBook #67038]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Houghton Mifflin Company

Credits: Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

IN THE LABORATORY

“Certainly they give men rewards for doing such things, but what reward can there be in any gift of Kings or peoples to match the enduring satisfaction of having done them, not alone, but with and through and by trusty and proven companions?”

Kipling; Sea Warfare

Early in the twentieth century the annual Memorial Day parade was passing through a New England town. The sun shone hotly down till the tarvia of the road felt soft and sticky underfoot. At the head of the procession the usual brass band led the way with martial music. Every one in the town was out, the older citizens for the most part standing reverently with uncovered heads, while the children, in anything but a solemn mood, tagged along on the flanks of the band.

Jim Evans, a boy of six years, stood by the sidewalk in front of the little white house in which he lived, his mother beside him, holding him by the hand. At the rhythmic crescendo of the approaching music, his pulse throbbed, and as the band swept by his eyes sparkled with delight. Then came the aged veterans of the Civil War in their faded blue uniforms, their grizzled white beards and wrinkled features giving them a quaintness in the child’s eyes that made him want to call his mother’s attention. He tugged at her hand and looked up at her. The look in her face struck wonder to his childish soul; there were tears in her eyes. He gazed at her in amazement. Tears had always been to him the expression of childish grievance—nothing more. He had never seen them shed by a grown-up. To his inquiring mind a mystery had now presented itself. More than that, deep down within him there was an awakening of something he had never felt before. His mother looked down and saw the expression of wonder in the child’s serious face. Her only answer was a tightening of her grip on his hand and a quiver of the lip.

The sound of the beating drum died away down the street; the procession was gone. The mother and child returned to the little garden behind the house. Seating herself in a garden chair, she took him in her lap.

“Jim,” she said in a low tender voice, “my father would have been marching with those old men if he had lived. I remember so well when he said ‘good-bye.’ I was a little girl about as big as you are, and he picked me up in his arms and kissed me. Then he went away and never came back. He died fighting bravely for all of us who stayed behind.”

Thus with the vision of the parade fresh in his eyes and the sound of martial music still ringing in his ears, and with the wonder of this new meaning of his mother’s tears stirring his soul, the tradition of an heroic life and death, the most precious heritage of the mother, was handed on to Jim, the small boy. In after years he never saw a Memorial Day parade but the memory of that day rose vividly before him, and he never forgot what the day stood for.

Eleven years after this incident, one October afternoon, Jim Evans, now at boarding-school, had gone up into the laboratory in the top of the schoolhouse to finish an experiment with a new radio hook-up before putting on his football clothes. He had just become absorbed in his task when he heard the ringing of a bell which sounded the fire alarm. Every boy in the school had his duty in the fire brigade assigned him, and all knew that this summons took precedence over everything.

Evans dropped his tools and ran to a window overlooking the school grounds. From his high position he could see the situation at a glance. The school grounds comprised a superb grove of stately white pines, the pride of the neighborhood. Within this grove, by its western border, was a pond, and north of the pond the grove was bounded for a short distance at its northwest corner by a small swamp, choked with dense vegetation, a place frequented by a great variety of bird life. West of the grove lay a wide expanse of low meadowland overgrown with tall grass and thick bushes. After weeks of drought the ground was parched and dry. A strong northwest wind was blowing, and a brush fire burning in the meadow was sweeping rapidly toward the pine grove, imminently threatening its destruction. Evans saw the boys dash into a building and then, emerging with buckets and brooms, start on a run, led by Sam Mortimer, chief of the fire brigade, to the south side of the pond. Here lay the greater part of the boundary between the meadow and the grove, and here it was that the shore of the pond was most easily approached, for on the north it was lined with the dense swamp vegetation. Evidently the plan of campaign was to form a bucket line from the pond along the western edge of the grove to its southern extremity. Evans could see that no one was detailed to deal with the fire north of the pond; apparently it was assumed that the natural moisture there would stop the fire. Now Evans had frequently haunted this swamp in search of birds, and knew that the drought had reduced it to a highly inflammable state. After a brief survey of the situation, he ran downstairs and out toward the grove. By the time he was out on the grounds the entire school, boys and masters, had disappeared into the grove to the south of the pond. Evans ran for the swamp where the smoke told him the fire was already entering the dense growth of brush.

Into the thicket he plunged and clawed his way through the tall bushes till, half-suffocated with smoke, he reached the advancing line of the fire. Down he went on his hands and knees and began scraping away the dried leaves from the surface of the mud, now and again jumping to his feet and uprooting bushes where the density of the growth required it, then dropping again to his knees and working among the leaves like a terrier. Thus he made across the path of the fire a swath where the flames were stopped except in the strongest gusts of wind. Now and then one of these would blow a burning leaf across the swath and start the fire anew on the other side. Then Evans would jump back and stamp out the fresh blaze. Once, when a runaway blaze threatened to spread too fast to be stopped in this way, he threw himself on it and smothered it with his body.

With feverish effort he struggled against the advancing flames, fearful lest they should get beyond his control in the larger bushes and trees by the edge of the pond and thus set fire to the entire pine grove. But now he saw the water of the pond gleaming through the smoke not far ahead, and redoubled his efforts to carry his swath of bare earth to the water’s edge. Half-blinded with smoke he dug and clawed and kicked away the leaves till at last he reached the muddy shore of the pond, and with vast relief saw the last of the flames expend themselves in the dried leaves west of the line.

He turned and walked back over the swath he had made, searching carefully for embers that might start the fire anew. Only smouldering embers did he find, and, stamping these out, he returned to the edge of the pond satisfied that no more danger lay in this quarter. He then skirted the shore of the pond and came to the south side where the rest of the boys, having put out the fire in that quarter with their bucket line, were assembling.

Evans approached the others, picking the thorns out of his fingers as he came.

When Mortimer saw him he said, “Well, Jim, where in thunder have you been?”

“In the swamp,” was the answer.

“What, looking for birds? There’s no fire there, is there?”

Evans looked at him a second before answering, then said quietly, “No.”

“Didn’t you hear the fire bell?” said Mortimer.

“Yes,” said Evans.

“That’s a nice example to set the younger boys!” said Mortimer. “How can we make anything of the fire brigade if the fellows in the graduating class quit in an emergency like that? You ought to be put in the jug.”

The eyes of half a dozen boys standing near were on Evans, but he said nothing. The fire brigade was formally dismissed, and the boys repaired to the gymnasium where they dressed for football practice. As they were dressing, Evans spoke to no one, and no one spoke to him. In the line-up between the first and second teams, Evans, being one of the smallest on the squad, played quarterback on the second. Usually his game was not remarkable; he was criticized for too much deliberation in the choice of plays. To-day he seemed possessed; he was all over the field at once, picking up the ball on fumbles, darting through the line and gaining ground, till Mortimer, captain of the first eleven, coached his team to watch Evans and stop him. In spite of all he could do to rally his team, Evans made a touchdown which resulted in the defeat of the first eleven by the second, a humiliation it had hitherto been spared.

As the boys were walking back to the locker building in their reeking football clothes, the head-master drew Mortimer aside and said to him: “Didn’t you have your whole fire brigade on the south side of the pond?”

“Yes, sir,” said Mortimer.

“I suppose you thought the swamp on the north side would be too wet to burn, and the fire would stop there anyway,” said the head-master.

“Surely.”

“I should have thought so, too,” said the head-master; “there’s usually standing water all through there. Fortunately some one who knew better than you or I went in there and saved the pine grove. I’ve just been looking over the ground and found that the fire had gone right into the middle of the swamp to where some one had scraped away the leaves and stopped it. It was dry as tinder everywhere. Have you any idea who could have done it?”

Mortimer was staggered.

“Jim Evans was in the swamp,” he said. “It must have been he. And I called him down for not being on the job. Why didn’t he tell me?”

Mortimer hastened to find Evans and ascertain the truth.

“Why didn’t you tell me, you great chump?” he said.

“You seemed to take it for granted that I’d been making a fool of myself, and I suppose that made me sore. Anyway, I didn’t feel like going into explanations with those other fellows looking on.”

“Well, I’m going into explanations just as quick as I can,” said Mortimer warmly.

“That’s mighty white of you, Sam,” said Evans, “but don’t make too much fuss over it.”

Mortimer lost no time in telling all who had heard his sharp rebuke—and more too—the truth of the matter.

The next year Evans and Mortimer were freshmen together in college. The friendship between them was firmly established, but in the larger number of boys with whom they were thrown the divergence of their tastes caused them to see less and less of each other. Mortimer was universally liked and socially prominent. Altogether he was a distinguished figure in his class. Evans devoted himself assiduously to scientific study, and in his leisure time his strong love of outdoor life usually led him away from, rather than toward, the haunts of men. For this reason, as well as because of his reserved and retiring disposition, he was socially comparatively obscure, though respected and beloved by the few with whom he became intimate.

Few would have supposed that one so obviously a leader as Mortimer could ever want to lean for support in any exigency of life on one younger than himself. Yet there were times when he felt depressed or when his philosophy of life seemed clouded with doubts. At such times he was apt to stroll over to Evans’s room where the two friends would have a “heart-to-heart” talk, often lasting well into the night; and always the clouds of confusion or doubt would disappear.

The spring following their entrance into college came that great turning-point in history, when in April, 1917, America entered the war. Mortimer enrolled in the first Plattsburg Camp where he applied himself so well to his training for the army that, in spite of being only twenty years old, he won the commission of first lieutenant. After many months in a training camp he was promoted to captain and sent overseas. His company continued in training in France till the last two months of the war when it was sent into action in the Argonne. Mortimer served with distinction and won an enviable citation.

Evans, being a proficient radio operator, enlisted at once in the navy and was put through the intensive course for radio electricians, and then sent abroad on a destroyer.

When he left his home the parting was not easy. His mother was a widow, and he her only child; he was all she had. But in the spirit with which the Spartan mothers gave to their sons the shields they were to carry into battle, saying as they did so, “Return with it, or on it,” Jim Evans’s mother bade him Godspeed with a brave smile on her lips. He had a tradition to live up to, and she thanked God he was able to do it.

During the last months of the war the destroyer to which Evans was attached was among those basing on Queenstown and performing the arduous duty of meeting the great convoys from the States, far out at sea, and escorting them through the danger zone to safety.

The life on these slim fighting ships was a strange one indeed. As they slid silently out of the harbor past Haulbowline, three, four, or five in column, they never knew what might be in store for them. Then as they passed Daunt Rock and, forming their scouting line, plunged into the head seas that swept their narrow decks, there came the test of the sailor’s morale. To learn to live and carry on in their cramped quarters, rolling, pitching, and thrashing about till it seemed as if neither flesh and blood nor steel could stand it any longer, while the cold, gray rollers, washing over the ship from stem to stern, chilled the very soul, was a feat that seemed to call for even more than human powers of adaptation.

But it was not always rough and dreary. There were days of sparkling sunshine and calm seas, days when Evans’s spirit expanded and he rejoiced in the grandeur of the ocean. And as he became more and more accustomed to the life, his love of the sea, born at first in his childhood acquaintance with it on the New England coast, became deeper, till it was woven into every fiber of his being.

Soon after the Armistice, Evans went to London on leave. He now wore the uniform of a Chief Petty Officer, having risen through the successive grades of radio electrician to chief. In London he met Sam Mortimer, and they had a happy evening together. Mortimer told of the days and nights at the front in mud, rain, shell-fire, and gas.

“How was it on the destroyers?” he asked of Evans.

“Pretty hard to stick it at first,” was the answer. “In those early days when we first started bucking the head seas going out to seventeen degrees west to look for convoys, I’d just want to curl up in the lee of a stack where I could breathe fresh air and still not be drenched to the skin with the spray and green seas washing over the decks. I didn’t care a hang half the time if I made good or not. And I was just crazy for the sight of the green hills of Ireland and the spires of Queenstown, the snug berth at the mooring buoy and the liberty party ashore. Then I waked up to the fact that the messages I had to copy in those tedious watches in the radio room were very close to the heart of our naval strategy; handling them mechanically like an automaton, I was losing a golden opportunity to read the controlling mind. I began to notice things, and I saw a wonderful evolution going on. Sailing orders which at first required long messages were later transmitted in a few brief signals. Every month saw new growth of efficiency in handling communications and disposing the forces. We have the British chiefly to thank for that—especially Admiral Bayly.

“Toward the end I got to feel more like part of the ship; I got so I didn’t mind, no matter how rough it was, and then the real spirit of the sea got hold of me. As an old sailor said, life at sea clears the corruption of the beach right out of your system. I’ve got now so that when the old ship leaves Corkbeg Light astern and puts her nose into the Atlantic, I feel that I’m getting back into my native element.”

“I like the ocean on a nice calm day,” said Mortimer, “but I’d never feel like that.”

“What I want to do now more than anything,” said Evans, “is to go for a good long cruise in my own boat when I can go where I want, turn in when I want, and get up when I want.”

“I’ll do that with you when we get home,” said Mortimer.

“That’s a go,” echoed Evans warmly. “Don’t forget it.”

“You bet I won’t,” said Mortimer.

Before the end of the winter these two young men were back in college, finishing the courses they had begun. The summer vacations were for Mortimer so well occupied with house parties and travel that the promised cruise was forgotten.

After college Mortimer studied law. As a student of this profession, though of average thoroughness, he was more especially characterized by brilliance; he could take in the “headlines” of a subject quickly and well. After a short apprenticeship as a lawyer, he turned his attention to politics in which he made for himself a brilliant and successful career.

Evans took up research in physics as his life-work, and after a year in the great Cavendish Laboratory of Cambridge, England, he found a place in the physics department of one of the leading American universities. His researches dealt with the problems of atomic structure and dynamics, and in this work he was deeply absorbed, giving little time to anything else, except during his vacations when he made a point each year of taking a substantial allowance of outdoor life, usually cruising in a small sailboat along the New England coast and often as far as Nova Scotia or the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Thus he kept the elasticity of youth, and with it an ever-increasing self-reliance, so that no problem presented to him by wind or tide or fog could catch him without adequate resource.

Three years after graduation the class of which Evans and Mortimer were members held a reunion at their Alma Mater in June. Mortimer, now as always the leader in his class, was the central figure, usually surrounded by groups of warm friends chatting about old times and war times, or discussing questions of the day. Once during the reunion he contrived to get off in a corner with Evans.

“What about that cruise we planned in London?” he said. “Six years have gone by and we don’t seem to have pulled it off yet.”

“Name your day this summer,” said Evans, “and I’ll take you on.”

“I’m scheduled for a vacation the first of August. How would that suit you?”

“That suits me fine. My boat will be in the harbor; just come to my laboratory and we’ll go aboard.”

“That’s a date,” said Mortimer; “don’t forget.”

On August first Mortimer appeared at the Physics Building and asked for Evans. A crotchety diener in faded overalls showed him to a room in the basement far removed from the light of day. Within, the sight which met his eye was what appeared to be a hopeless snarl of junk. There was a maze of glass tubing bent into all sorts of bizarre shapes, some of it covered with crumpled bits of sheet lead or tinfoil from the wrapping of a cake of chocolate; there were wires leading every which way with no apparent vestige of order; there were old wooden packing-boxes serving as supports, rusty nails bent upward for hooks, nondescript objects tied together with twine or stuck together with wax. Yet within this crazy jumble were instruments whose construction required the highest refinement of manual skill that can be found in all the world. The entire set-up was the culmination of years of patient planning, designing, and assembling. Crude as it appeared, it was in reality the key to some of the profoundest secrets of Nature; and no man on earth save Evans knew how to use it. In the midst of this strange assortment of matter, Evans sat on an empty packing-box, his eye glued to the eye-piece of an optical instrument.

“Well, Jim, are you coming sailing?”

Before answering, Evans scribbled some figures on a scrap of paper. Then he turned to Mortimer.

“Good Lord, Sam, is it the first of August already? I’d clean lost track of time.”

“That’s what it is; and there’s a fine sailing breeze.”

“Sailing breeze or no, I can’t knock off now. I’ve been sweating all summer to get this experiment going right, and it’s going at last to the Queen’s taste.”

“Well, where do I come in? I’ve come all the way from New York to go cruising with you.”

“I tell you what,” said Evans, after a moment’s reflection, “you go down to the harbor and find Jones’s store. Get whatever looks good in the way of fresh food; I’ve got plenty of canned goods and staple groceries on board. Get the stuff delivered at Salter’s Landing. I can finish up this experiment by midnight, and I guess after that it won’t hurt me to get it out of my system for a while. Go to the movies or anything you like, and then come here with a taxi about midnight, and we’ll get aboard as quick as we can.”

Clearly the man of science could no more be budged till his cherished experiment had yielded its golden fruit of knowledge than can the moon be diverted from her course in the skies. No exploration of new continents, no searching for hidden gold can lure the spirit on with so strong an appeal as the unknown law of Nature awaiting the crucial experiment, planned and prepared for months, and then appearing at last like the light of day when the experiment is done and the measurements construed with the power of reason.

Mortimer obeyed, and wandered off to spend the afternoon and evening on the water-front of the harbor. The next day the two friends sailed a sparkling sea together in a tiny cruising knockabout—boys once more.

The next act of our story opens in the year 1937. An international crisis of the most momentous nature had just come to a head in Europe.

For some years past a group of powerful men in Constantinople, intriguing diplomatists and financial magnates, had been quietly developing a scheme for world domination. By a process of peaceful penetration, aided liberally by the adroit use of secret agents, they had obtained complete control of the Balkan Peninsula and Asia Minor, and for the first time in history reaped the harvest of a proper development of the rich natural resources of these areas. Thus enriched, the coalition had spread its tentacles all around the Mediterranean till it held Italy and Spain firmly in its grip; and yet by respecting the nominal independence of these countries the power which it had over them was cleverly concealed from the world.

Much of Russia was entangled in the snare. Being once more promised a realization of the fools’ dream of communism, the adherents of Bolshevism were won over into an alliance. By propaganda promising the dawn of a new day of freedom, the enthusiastic support of the peasants, long oppressed by the sinister strangle-hold of the Soviets, was enlisted in behalf of the new combination.

The old Pan-Islam spirit of the Moslems was vigorously exploited, and thus a powerful underlying motive force was brought to bear on the furtherance of the scheme.

A substantial Turkish navy was built, and with money furnished by the coalition, Greece, Italy, and Spain were encouraged to build strong navies, too. No one of these navies was big enough to excite much suspicion in England or America, and no one but the coalition and its secret agents knew that these three navies were planned with a view to forming parts of one great whole. With diabolical cunning the gigantic plot against the world had been laid, and no exigency had been overlooked. Then suddenly in the early summer of 1937, the fruits of this vast intrigue appeared. Italy and Spain found themselves committed to an alliance with Constantinople with a view to obtaining complete control of the Mediterranean Sea. Through the work of a body of spies, unique in preparedness and efficiency, France suddenly found her Mediterranean fleet paralyzed, and before she could make a move to defend them, her ships were seized without a blow. With astonishing rapidity the various navies, thus reinforced, were mobilized and operated as a coördinated fleet. England had but few ships in the Mediterranean at the time, and these were soon engaged in battle by overwhelming numbers, and sunk, after putting up the stiffest resistance imaginable against fearful odds. Then Malta and Egypt were attacked and seized. The south coast of France was occupied with an invading force; all important points on the north coast of Africa were taken, and the control of the Mediterranean became complete, with the exception of Gibraltar.

The British Navy was rushed to the defense of this stronghold, and had they passed the strait a naval action would have ensued which might have saved Europe then and there from the specter of the new Byzantine Empire. But this exigency, like others, had been anticipated. As the great navy steamed into the straits, supposedly under the protection of Gibraltar, a vast battery of sixteen-inch guns mounted on railway cars opened a withering fire from the Spanish shore at Tarifa. Less than half of the capital ships passed through this barrage, and most of those, before they were well out of range, ran into a mine-field stretching across the strait, laid at night some weeks before by enemy submarines and made ready for action by wire from Tarifa as the fleet approached.

A handful of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers escaped the trap, and bravely faced their fate in the defense of Gibraltar. But the waiting enemy had now such an overwhelming advantage in numbers that their doom was sealed. Cut off by land and sea, it was of course only a matter of time before Gibraltar fell.

And now England was left with her mighty navy gone, all but the few ships that were in dry-dock and couldn’t be sent in time, and a few obsolete vessels purposely left at home.

All Northern Europe rose to fight the Constantinople Coalition. England, France, Belgium, Holland, Germany, Poland, and the Scandinavian nations placed troops in the field. And soon two giant armies faced each other entrenched in a battle-line extending from the Pyrenees to the Alps and thence along mountain barriers where such existed, eastward to the Caspian Sea. In the development of land warfare, defensive measures had outstripped offensive measures, and especially strong were the defensive methods used by the Mediterranean forces. Consequently ground could be gained by the northern armies only at the cost of prohibitive losses. A military deadlock ensued, and the problem became one of attrition. In natural resources in the Eastern Hemisphere the Mediterranean group had slightly the better situation, but what counted still more was control of the Atlantic Ocean, and through it, access to the resources of the Western Hemisphere.

This control by the Mediterranean Powers being undisputed, virtually all commerce between North America and Northern Europe was cut off. The resources of Northern Europe sufficed to maintain the war for the present, but clearly materials from the Western Hemisphere would in time be a necessity if the war was to go on.

Through the summer months America maintained neutrality, although it was daily becoming clearer to those whose vision extended beyond the balance-sheet of the current month that, as in 1917, civilization was at stake, and the sooner America shouldered her share of the fight the better it would be for all the world, herself included.

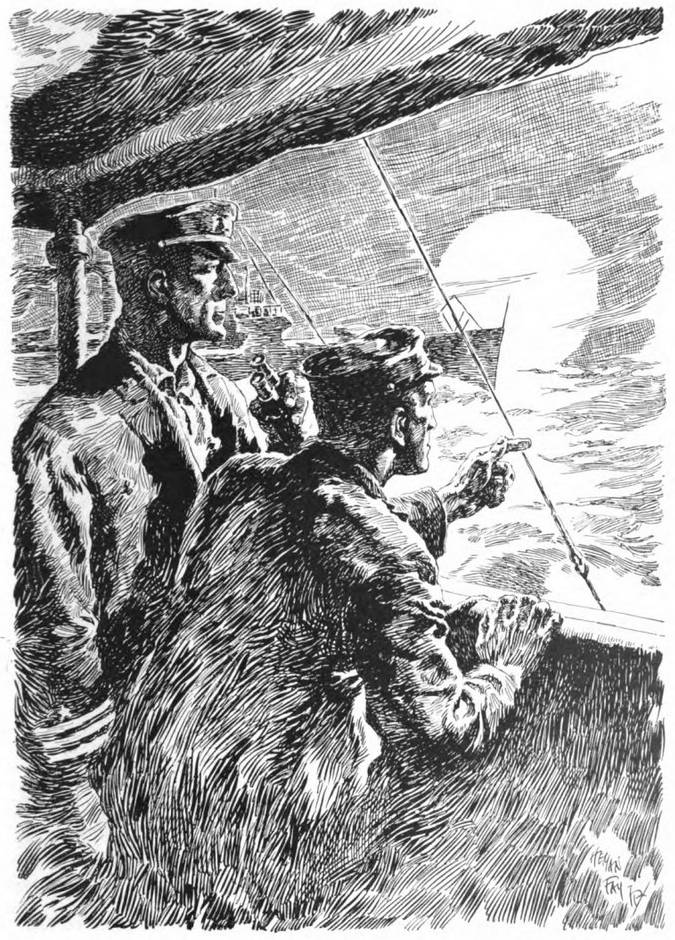

This was the situation when on a warm sunny morning in September one of America’s newest destroyers crossed Cape Cod Bay at a thirty-knot speed, and, gliding smoothly into Provincetown Harbor, dropped anchor. As the chain rattled down, a tall, well-built man in civilian clothes stood on the bridge beside the skipper and surveyed the harbor. Presently his eye rested on a small sailboat, ketch-rigged, of some thirty-six feet over-all length, making toward them about a quarter of a mile away.

“I guess that’s my boat, skipper,” said the civilian.

“Going round the Cape in that, are you? She’s not over-roomy, but she looks like a good sea boat,” was the answer.

A boat was lowered; the civilian left the bridge, shook hands with the skipper, and was soon on his way toward the sailboat which presently shot up into the wind and, with her sails flapping, gradually lost headway as the motor-boat from the destroyer came up on her starboard quarter. The passenger clambered over the side and into the cockpit of the little ketch, a sailor handed him his suitcase, and with a parting word of thanks to the crew of the motor-boat he sat down to look about him.

At the wheel was a man not over middle height, compact and strong-looking, with a clear, ruddy complexion, dressed in a pair of khaki trousers and gray flannel shirt, a striking contrast to the officers of the destroyer. The new skipper wasted no time in greetings, but with eyes intent on the movements of the motor-boat just shoving off, reached for the starboard jib sheet, pulled it in and held it till the sailboat payed off to port and gathered steerageway. Then, trimming the jib over, he settled back comfortably and said, “Well, how are you? Had a nice trip across the Bay, didn’t you?”

“Beautiful; those destroyers glide along like a dream. This is a cozy little boat you’ve got, Jim; where’s your crew?”

“You’re my crew to-day,” said the skipper. “Lord! I don’t want a crew killing time about the deck. That’s the advantage of this size and rig; I can handle her alone, and yet she’s big enough for comfortable cruising, and safe in any sea there is. I couldn’t afford a crew if I wanted one; so I’m glad I don’t. Take your valise below and have a look round, don’t you want to? Take the port bunk, my gear’s on the starboard.”

His friend acted on the suggestion and with a landsman’s clumsiness engineered himself and his valise down the hatch into the coziest, snuggest little cabin he had ever seen. Presently he returned to the cockpit.

“Looks like a nice little place to duck in out of the wet.”

“It is rather a nice little cabin,” said the skipper. “To tell the truth, this boat just suits me, and I feel as much at home on her as I do anywhere in the world. I used to fancy something fast and racy as my ideal of a sailboat, but as I get older I incline more to this sort of thing, seaworthy and comfortable, fit to ride out any gale that blows.”

“You don’t look so awfully old yet,” said the other.

“I don’t suppose I do,” said the skipper, “but if I remember rightly I’m only a year younger than you.”

“That’s so,” said the other. “I’m forty, and they tell me I look five years older than I am. But you don’t look any older than you did in college.”

“I’m generally supposed to be still in the twenties. I judge that my sheltered and quiet existence in the laboratory, together with lots of outdoor life, camping, cruising, etc., has kept me young, while battling with the storms of a busy world has been ageing you.”

The skipper of the sailboat was Jim Evans; his passenger, Sam Mortimer. Through the years since college their friendship had endured, yet their lives led them so far apart that they seldom came together. Evans’s career as a scientist had brought him happiness, but no fame. His reputation for work of the highest quality was known only to a handful of experts competent to judge.

Mortimer’s career in politics had, on the other hand, placed him increasingly in the limelight, till in the spring of 1937 he found himself shouldering no less a responsibility than that of Secretary of the Navy, just as the European crisis was coming to a head. His predecessor had been none too competent, and in consequence his six months in office had been almost wholly taken up with reorganization in the Department, and little time had been left him to study the principles of naval policy, strategy, and tactics. His knowledge of naval affairs was small, and indeed he knew little of seafaring lore in any form. In years gone by he had made one or two short cruises in a small boat with Evans, but since then his recreations had been golf and tennis, and all his professional attention had been focused on politics. As yet no action had been taken by the American Government toward joining in the war, and the public had little idea whether any was to be expected; but to the Cabinet it was evident that action must come soon. Now Mortimer was keenly aware that the question of naval control of the Atlantic Ocean would soon be resting on his shoulders more directly than on those of any other man living; small wonder, then, that he felt overwhelmed by the responsibility he saw approaching. The American Navy was large and powerful, and, reinforced by such French ships as had been outside the Mediterranean and such British ships as had escaped disaster, it was about an even match for the consolidated navy of the Mediterranean Powers. On its efficiency rested the control of the Atlantic.

Early in September Secretary Mortimer left Washington for Boston to spend three days examining the resources of the First Naval District. He had spent a harassed and busy summer struggling to get the navy ready for the task which each week made it seem more probable was to devolve upon it. Every week the consciousness of his inability to see with an expert’s eye the large problems of naval strategy distressed him more. His brain was in a whirl, and he felt that he must for one day at least get off and give himself over to relaxation.

In this crisis the old desire to see Evans came over him; the sense of reliance on his friend, though often forgotten, was still there. He had telegraphed Evans asking if he could spare a day when they might get off by themselves and have a good talk. Evans had replied, suggesting a sail round Cape Cod as the most complete escape from the interruptions which would pursue them were they to remain in the haunts of men. Evans had his boat at Provincetown, and Mortimer, on completing his business in Boston, boarded a destroyer at the Navy Yard in the early morning and joined his friend in time to make a good start round the Cape.

The wind was west, and a little beating to windward brought the boat clear of Provincetown Harbor and around Race Point, where they started their sheets, then jibed and began the long reach down the Cape, by Highland Light, keeping close in shore where the sandy and pebbly beach and the bluffs behind presented a pleasing if somewhat monotonous picture.

As these two stanch friends sat chatting together in the cockpit of the Petrel, as Evans called his boat, dropping Highland Light astern and picking up Nauset, their talk drifted toward the topic that was harassing Mortimer by day and night.

“How much have you kept up with navy affairs since you left the service after the war?” he asked of Evans.

“Enough to know that the engineering men of the service have made wonderful strides in development in various fields, especially in communications, opening possibilities undreamed of in 1918, and that through the perennial difficulties of personnel, these developments are not utilized to anything like the extent they might be. To tell the truth, the navy has always interested me intensely; it has been a hobby of mine to read Mahan and other standard writers during my spare time, as well as the Naval Institute Proceedings. I’ve also kept in touch with some of the radio men I knew in the war who have stayed in the service, and I have watched with great interest the progress in radio communication that has taken place.”

“My God, I wish I had your knowledge of the subject,” said Mortimer. “Law and politics have taught me some things, but they haven’t taught me the principles of naval policy and naval operations, and those are the things I want to know now.

“I suppose you realize,” he went on, “that we may not be able to stay out of the European vortex much longer.”

“On the face of it,” answered Evans, “I should say we were due in it right now. I haven’t heard the ‘inside dope,’ but I can’t conceive of our staying out much longer, all things considered.”

“Well, I trust your discretion enough to say that you have sized it up about right. There won’t be many weeks more of neutrality; and then a big load comes on our Department.”

“I should say it was a clear case,” said Evans, “that the whole game hung on our navy. While the enemy keep their fleet intact and maintain the complete control of the Mediterranean, the Northern armies can never score a decisive victory; and if the Turks are left in control of the Atlantic the attrition will all come on our side. We must establish and keep up a steady flow of supplies from both North and South America to maintain even the present status; and we must destroy their navy to win the war.”

Thus the conversation progressed to a discussion of the basic principles of naval policy and strategy, in which Mortimer, as more than once before, found himself marveling at Evans’s clearness and breadth of vision. None of the admirals at the heads of bureaus in Washington had seemed able to see things in so large a perspective; none had helped him to grasp the fundamental principles of the problem before him as this man, trained in science, yet versed in naval affairs as well.

The small cabin clock struck two-bells.

“Let’s have some lunch, Sam,” said Evans. “Take the wheel, steer as you’re going, due south, while I get the stuff out.”

He disappeared down the hatch with the nimbleness of a boy in his teens, and began to prepare a simple lunch over an alcohol stove. As Mortimer sat at the wheel with the warm wind off the Cape Cod shore fanning his cheek, he pondered over this simple child of Nature, to all appearances a college boy on a vacation, whose characterization of the crisis offered so much food for thought.

Soon Evans reappeared in the cockpit with an appetizing meal which they ate in camp style, Evans steering and eating at the same time, not appreciably to the detriment of either task. Again he left Mortimer at the wheel while he addressed himself to the task of cleaning up. When next he came on deck, he found Mortimer manifestly drowsy and a good two points off the course. The warm shore wind, the peace and quiet and the relaxation from constant strain, conspired to overcome him. Evans reached below for a pillow and placed it on the lee side.

“Here, stretch out on the cockpit seat and take a good nap,” he said.

Mortimer relinquished the wheel, and soon was fast asleep.

When next he waked the afternoon was well advanced. The air felt rather close and muggy, and so hazy was it that the sun shone dimly, and the land, only three or four miles away, was scarcely visible.

“Where are we?” he asked.

“There’s Chatham nearly abeam,” said Evans. “The barometer’s falling; I think we may get a squall.”

“Your boat will stand it, I trust?”

“She’ll stand it, all right,” said Evans with a laugh. “She’ll stand anything that blows. The only practical question is whether to take the short cut between Bearse Shoal and Monomoy. It saves two or three miles, and if it’s going to be rotten weather it’ll be more comfortable for old men like us to get into some sheltered water before dark.”

“What is there against the short cut?”

“Well, if it should get thick with rain it would be a little hard to see where we were, and there are shoals on both sides; also it’s all so shoal there that a heavy squall from the northeast would kick up an infernal rip with the tide running the way it will be when we get there. But then, a rip can’t hurt us unless it’s bad enough to let her touch bottom in the trough, and it would take a first-class hurricane to do that.”

“Well, all I ask is that you avoid a serious shipwreck, for I’ve responsibilities ahead that I really ought not to sidestep.”

“You can trust the Petrel to get you through,” said Evans.

“Not to mention her skipper,” answered Mortimer.

Still the west wind held and the little boat stood on till Chatham was on the starboard quarter and no longer visible through the haze. The air still felt warm and heavy; in the northeast, through the haze, dark clouds could be dimly seen gathering. Evans trimmed in his sheets and luffed toward the point of Monomoy. Pollock Rip Slue Lightship was visible, and on that Evans took a careful bearing and wrote it down, together with the time. Monomoy could barely be seen as a faint white line of sand to the westward. No landmark there could be identified, but Evans noted the bearings of as much of it as he could see, then studied the chart. He took a look round at the sky, left the wheel, and glanced at the barometer.

“Glass is falling fast,” he said. “Take the wheel a minute while I put on rubber boots and oilers; then you can do the same.”

He dived below and soon came up dressed in oilskins and sou’wester, took the wheel, and sent Mortimer down to put on his spare set. Suddenly a chill wind struck from the northeast; the sails went over and fetched up on the sheets to starboard.

“What’s up?” called Mortimer from below.

“Wind’s shifted; nothing much yet,” answered Evans as he trimmed over the jib and slacked the main sheet.

Mortimer came on deck. Evans was looking now at the compass and now at the clouds in the northeast, already looking murky and ominous.

“I’m heading for that short cut,” said Evans. “I could still go out round Pollock Rip, but it would waste a lot of time and we’ll be all right in here. I know where we are well enough to hit the channel; if it blows hard the rip will be rather sensational at the shallowest point, but won’t do us any harm. She’s built so strong that even if she did touch the sand in the trough of a wave, it wouldn’t hurt her.”

The wind was now blowing freshly from the northeast and the Petrel was driving along before it at a good speed.

“Isn’t it about time to reef?” asked Mortimer.

“We shan’t need to. That’s the beauty of this rig; you can shorten sail to your heart’s content without reefing.”

The clouds grew darker and the wind increased till whitecaps appeared and dotted the sea, and the little boat sped on before it with increasing speed.

“Time to get in the mainsail,” said Evans; “take the wheel; steer southwest by west, and hold your course as close as you know how.”

Then he let go the halyards, and running forward with a couple of stops in his hand, had the sail down and roughly furled in a few seconds.

“Now,” he said, taking the wheel again, “she’ll stand a whole lot of wind this way. Hold the chart for me. This channel isn’t buoyed, and the chart helps.”

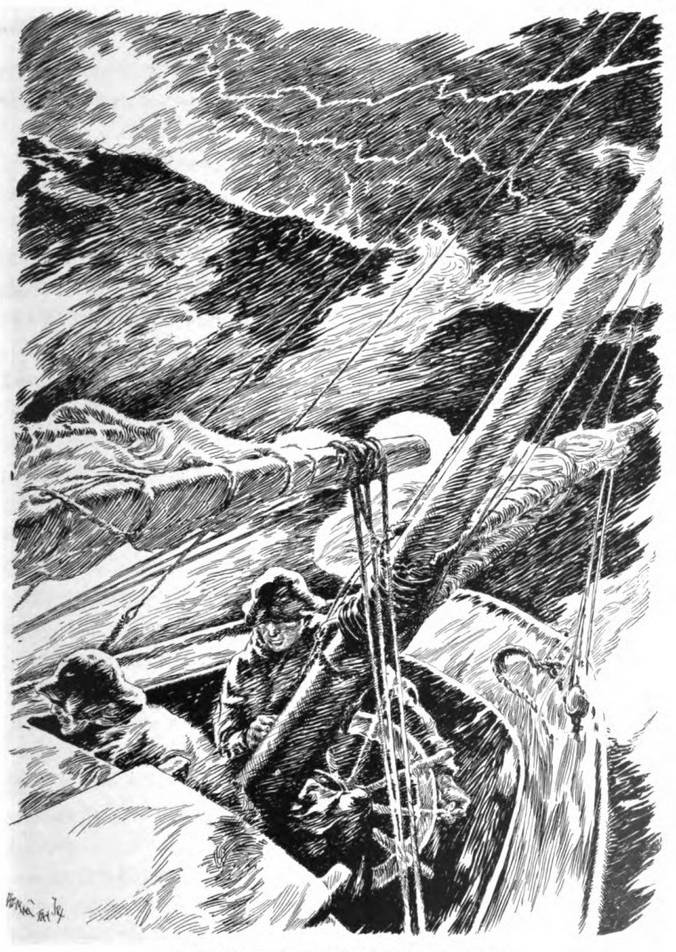

Even with only the mizzen and jib the Petrel made good speed; and now with the stiff wind and east-running tide, the whitecaps were increasing to good-sized breakers. Then the dark clouds to windward gathered themselves into a huge black knot, black as ink and roughly funnel-shaped. Like a giant projectile this black mass approached, coming at an astounding speed.

“This is going to be a good one,” said Evans. “It’ll be thick in a minute, I wouldn’t mind seeing a landmark ahead. Ah! there’s Monomoy Light.”

Straining his eyes he could barely make out the lighthouse and get an approximate bearing on it. But Mortimer’s eyes were riveted on the colossal black storm-cloud whirling through space toward him in a way that fairly took his breath away.

“The jib’s all we’ll want when this hits,” said Evans, and in another second or two he had the mizzen down and a stop around it.

AND THEN THE THING STRUCK

And then the thing struck. So violent was the blow that it seemed as if the boat might be lifted from the water and carried through space. The air was full of flying water—sheets of spray blown from the tops of the waves, while overhead a darkness almost like the night closed in. Rain came driving horizontally in sheets, and lightning flashed round half the horizon. It was impossible to see a quarter of a mile.

Mortimer looked at Evans whose eyes scarcely left the compass, and saw in his face alertness, steadiness, and strength; and the fear which such an overwhelming outburst of the fury of the elements had naturally aroused in him was effectually quelled.

Almost as quickly as it had come the black cloud blew over, leaving a sense of dazzling brightness by contrast, although the sky was still heavily clouded. For three or four minutes the wind blew with almost unabated fury, the little boat scudding bravely before it under her jib. Then the wind moderated enough to relax the tension, but still blew hard enough to make them glad of shortened sail.

“Eighty miles an hour, I’ll bet, during the height of that,” said Evans. “All of forty, still.”

And now the waves had become high and steep and short.

“We’re getting into that tide rip I spoke of; the water’s getting shoal. The sand’s so white it looks shoaler than it really is.”

Mortimer looked ahead and saw through the rain great whitecaps forming an almost solid line like the breakers on a beach, and in the troughs of the waves the white sand bottom gleamed alarmingly near.

“Lord! are we going into that?” he asked.

“She won’t touch, and the waves can’t hurt her. They may come aboard now and then, but they’ll drain right out through the cockpit scuppers. You might close the cabin hatch.”

The waves grew higher and steeper, and now they were in a mass of breaking whitecaps. Each wave lifted the little boat up, and with her nose deep down in the trough, she would dash forward with amazing speed till the wave broke all around her and she came to a stop in a smother of foam. Looking back, it often seemed as though the waves, towering high and curling over the stern, would swamp the boat completely, but each time the stern rose gracefully, and at most a few gallons of water would splash into the cockpit.

“I didn’t suppose any boat could live in this,” said Mortimer.

“It sometimes surprises me to see how well she rides these things,” answered Evans. “I’d like to see that lighthouse again to make sure we’re in the channel. We should in a minute, as the rain’s letting up, and we’re getting near to it. There it is. We’ll be through most of it in a minute now.”

Then, with series of plunges, in each of which it seemed as if she must drive her bow into the white sand, so close below the surface it appeared, the Petrel passed through the roaring breakers into the deeper water beyond, where, rough as it was, it seemed like a haven of refuge compared with the rip they had come through.

Mortimer breathed more freely. “I don’t mind saying I felt scared coming through that,” he said. “I’m glad you know this game as well as you do.”

“I’m not sorry to be through it myself,” said Evans. “It was quite rough enough for a bit. I don’t think I ever saw such an ugly squall, and I’ve seen some bad ones. Still, as long as I had that bearing on Monomoy Light we were in no danger. Quarter of a mile out of the channel, it’s so shoal she might have hit.”

“What would you have done if you hadn’t got that bearing?”

“I guess I’d have stood off and waited till it cleared enough to see the lighthouse, or else beat out round Bearse Shoal, and that would have been a hell of a rough thrash to windward; still, it wouldn’t have hurt us any.”

“It looks to me as if the gods had a way of fighting on your side,” said Mortimer. “Do you always get away with it when you take a chance like that?”

Evans looked serious. “I don’t know as I can claim that,” he said, “but Fortune has been pretty good to me in her own way. Maybe I was rather foolish to go through that. It will be smoother from now on; there’ll be some small rips, but nothing like that one. I think we’d better make for Hyannis. We could anchor in Chatham Roads, but that would be exposed if the wind turned southwest. Hyannis is a good harbor in any wind, and it will be easy getting in after dark with Bishop and Clerk’s and the harbor range lights to steer by. It’ll be handier for you in the morning, too. Take her while I hoist the mizzen; we may as well have that now.”

In another minute the little boat was speeding on before the gale under mizzen and jib. The rain had subsided, but a leaden twilight was closing in. Monomoy appeared as a low white streak of sand on the starboard beam. Hugging it close, they rounded Monomoy Point and luffed to clear the north end of Handkerchief Shoal. Evans went below and lit the running lights, then, starting a fire in the small coal stove in the galley, put some potatoes and rice on to boil. Then he came on deck with some pilot biscuit and chocolate, and the two friends settled down in the snug little cockpit to enjoy their sail through the shoals in the gathering darkness.

Soon their talk drifted back to the all-important topic of the coming crisis.

“It always seemed to me,” said Evans, “that a navy could conveniently be likened to a living organism, a man, for instance. A man has senses—sight, hearing, etc.—which tell him what’s happening about him. Nerves carry the impressions from the sense organs to the central station, the brain, where information is sorted into the springs of action; other nerves carry messages from the brain to the muscles that work the arms and legs—and incidentally the teeth. Now in the navy your patrols, scouts, planes, drifters, etc., with their observers and hydrophones, and all forms of radio receiving apparatus, are the senses, and I should include under that head, spies. In place of the muscles, fists, and teeth you have the ships’ engines and the guns, torpedoes, bombs, and such like. The nervous system is the general staff which determines policy, the admirals who execute it, and communications which are the nerves that bring information into the navy’s brain, and in turn give the word for action. Communications, of course, comprise flag signals, blinkers, semaphores, couriers, postal service, telephones, telegraph, radio, and the newer methods, such as infra-red rays.

“Now it seems to me the importance of communications hasn’t been emphasized half enough. The methods available are highly developed, but their value isn’t clearly enough appreciated. You can hardly find a finer, keener, better-trained bunch of men anywhere than the officers of our navy, but the profession has grown so complex and the duties to be learned so manifold that it takes an exceptional man to grasp all the possibilities science has developed and to see them in a proper perspective. The average naval officer takes far more interest in ordnance and gunnery than he does in communications. The difference between an athlete and a lummox is not in the muscles, but in the nervous system which coördinates their action. Provided the muscles are not atrophied or diseased, they’ll do what the nerves tell ’em to. Now gunnery is obviously important—so obviously that the personnel tends to look on it as the whole thing. Of course it must be efficient, but it has been ever since Sims made it so; it must be kept up to the mark, but it is a strong tradition in the navy to keep it so, and I don’t think you’ll have any trouble on that score. It is intelligence and coördination, and communication in particular that you must look out for in order to make your fighting strength effective. Just as the skill and wisdom of the gunnery officer direct the titanic force of the guns to the point where it is most telling, so the controlling mind, acting through communications, directs the force of the entire fleet; that’s the field where the minimum energy will yield the largest return; put your best efforts in there.”

“Don’t forget morale,” said Mortimer.

“Quite right,” said Evans; “morale is more than half the fight; without it no amount of skill or intelligence will avail; but without the aid of the mind morale is flung helpless at the mercy of superior skill in an opponent. I am inclined to assume morale; and I believe it is a justified assumption, for to stress and foster it is a tradition well maintained in our service.”

Evans went on to explain to Mortimer some of the methods of communication which had been developed: the internal communications in a ship, the dual use of a single antenna to receive two messages simultaneously on different wave-lengths, the use of infra-red rays for secret messages between ships in a fleet, and many other things which Mortimer had never had time to learn.

“I wish I could make you Director of Naval Communications,” said Mortimer. “Unfortunately the rank that goes with that position is rear admiral. Under the existing regulations the highest rank I could give you is lieutenant-commander. If you were a captain, I could make you a temporary rear admiral in order to hold that position, but I don’t know of any way that it could be done straight from civil life.”

“If I were you I wouldn’t try to make me an admiral or even a lieutenant-commander,” answered Evans. “Professional naval officers are apt to resent having men out of civil life put over them with superior naval rank. They’d feel that I was ‘striped way up,’ even as lieutenant-commander, and that I hadn’t earned my rank. I should encounter friction and difficulties in consequence. I sure want to help you in any capacity I can, but my suggestion is that you make me a warrant officer, say radio gunner.”

“Radio gunner!” exclaimed Mortimer; “that’s a pretty small job for you. You’d be subordinate to a lot of ensigns just out of Annapolis.”

“It’s not necessarily such a small job; officers of high rank are apt to heed the advice of a dependable warrant officer, regarding him as a technical expert. Often they respect a warrant officer who knows his business a good deal more than they do ensigns and lieutenants. If he works his opportunities right, he may put over more than purely technical ideas. A man who doesn’t use his opportunities right won’t get very far in warfare though he wears the gold braid of an admiral.”

The night had closed in dark as pitch, and the wind swept on furiously from the stormy sky. Evans steered his little boat over the waves, guided by the familiar lights in the distance. To the south the lights of a tow of barges and a coasting schooner, threading the ship channel through the shoals, grew dimmer and finally were lost in the murk.

The conversation drifted on to the question of the use of scientists in war. Evans summed up his views on this point as follows:

“Make free use of scientists, but use them with skill. A scientist in war, if he hasn’t engineering sense as well as scientific spirit, is apt to be like a drunken man trying to make a speech; his mind is so discursive he can never get to the point. In peace the best measure of a scientist’s merit is the patience with which he can seek truth for its own sake, and his indifference to the application of his work to tangible results. In war this point of view is out of season; the man’s value then depends on his impatience to apply all he knows to getting results of the most tangible kind. At the dinner hour we sit down to eat our food and digest it; the dinner hour over, eating becomes unseasonable, and we must absorb what we have eaten and utilize it in the performance of the day’s work.

“In the war with Germany a vast amount of time was wasted by scientists who couldn’t adapt their points of view to war-time conditions. They insisted on laying their foundations with the same painstaking thoroughness and patience with which they would pave the way to a new theory of light; they kept before them the same ideal of perfection which the highest standards of peace-time scholarship demand. The Armistice found them still laying their foundations, and their efforts all wasted, as far as winning the war was concerned. Of course it pays to keep some fundamental work going on the chance of the war lasting a good many years, but there’s such a thing as sense of proportion about it; and that’s what lots of scientists lack.”

“How is the non-scientific head of a big department to know whether a line of research promises to bring results in a finite time or not?” asked Mortimer.

“That’s difficult,” said Evans. “The best thing is to have on hand some men of large caliber whom you can trust to have engineering sense as well as scientific vision, and make them keep the others in the paths of reason.”

Among other things Evans pointed out the great importance of weather forecasting in naval warfare.

“It doesn’t take much imagination to see that it might come in handy to know a little beforehand when something like what hit us to-day is coming. Imagine trying to carry out some kinds of naval operations during the worst of that squall. Then the direction of the wind may affect the visibility in different directions, so as to make it a decisive factor in a naval action.”

“Weather prediction is still pretty much a matter of guesswork, isn’t it?” asked Mortimer.

“No, there’s a good deal of science to it,” said Evans, “and there’s more coming to fruition than is generally known. Professor Jeremy is probably the ablest meteorologist in the world. He has been doing some wonderful research on the causes of weather changes, and I believe he’s in a way to reach some very important conclusions before long. You couldn’t do better than put him in charge of your Naval Weather Service, with a free hand to do things his own way. He’d have a sense of proportion, and go at the most practical kind of research which would in a few months give our navy so much better knowledge of weather prediction than the enemy as to be a really important military advantage. Then the trouble would be to make the admirals appreciate what they had, and use it.”

They had now crossed the open sheet of water between Monomoy and Point Gammon, and had passed Bishop and Clerk’s lighthouse a mile to leeward, till it was already receding on the port quarter. The outline of Point Gammon showed dimly to windward. Taking a bearing on Hyannisport Light, Evans luffed and trimmed in the sheets a bit. Soon they were in the lee of Point Gammon where the water was smoother, and steering north-northwest picked up the spindle on Great Rock on the weather bow. Passing this they luffed close on the wind till they sighted the breakwater to leeward just before they brought the range lights in line. Inside the breakwater, Evans kept off and steered for the lights in the cottages that line the harbor shore, while the dark line of the land ahead loomed nearer and nearer, and its outline grew more distinct. The riding lights of some of the larger boats at anchor were now quite distinguishable from the cottage lights beyond. Evans went forward, cleared the anchor, and hauled down the jib, then returning to the wheel he picked his way in past some of the larger vessels to a snug anchorage near a group of Cape Cod catboats. The gale was still blowing hard and showed no signs of moderating, so he let go both anchors and gave them a generous allowance of scope. He made all snug on deck in spite of the darkness, with an alacrity born of long experience and the most intimate familiarity with every rope and cleat on his boat; then put up the riding light. With a careful look around he went aft into the cockpit, saying:

“Well, we’re all snug here. The holding ground’s good, so it can blow all it’s a mind to, and we shan’t drag. Let’s go below, get out of these wet oilers, and have something to eat.”

The hour was late for supper—a fact which did not militate against their appetites. In the cabin there was warmth from the little galley stove where the potatoes and rice were now done. Evans opened a tin of canned chicken and stirred the contents into the rice.

“Supper’s ready,” he said, putting some plates and bread on the table. “This chicken-rice mixture is about the easiest thing to get ready on a rough day, and it makes a pretty good meal in itself.”

They fell to like a pair of wolves, and Mortimer declared he had never found a meal more to his liking.

After supper Evans tumbled the débris into a big dishpan and began a hasty but effective dish-washing.

“Can I help?” asked Mortimer.

“You can wipe,” answered Evans, and tossed him a dish towel.

Before turning in, Evans took another look at the weather which still showed no signs of changing, and then the tired men took to their bunks, and darkness reigned in the little cabin except for a glimmer from the riding light through a porthole forward.

Tired as he was, it was some time before Mortimer fell asleep. The excitement of the squall and the novelty of his surroundings kept him awake, listening to the wind shrieking in the rigging. But the gentle rocking of the boat in her sheltered anchorage lulled him off at last to a deep sleep.

Next morning he waked to hear Evans shaking the ashes out of the galley stove. The wind had moderated and the sky showed signs of clearing. After a plunge overboard and a good breakfast, Mortimer felt better than he had for months. Evans rowed him ashore in his dinghy in time to catch the train, and before they parted it was settled that Evans should go to Washington in a fortnight’s time and be enrolled as a radio gunner in the navy.

Evans took advantage of the northeast wind which was still blowing strong to make the run to New Bedford. With a single-reefed mainsail, for comfort in handling, as he was alone, he made the run through Wood’s Hole and across Buzzard’s Bay in six hours or so, and dropped anchor in New Bedford Harbor some time before sunset. As he sailed across the bay he pondered the problem confronting his friend.

“It’s strange,” he said to himself, “on what capricious things the great affairs of the world sometimes depend. But Sam will make good, even if he does seem to know less about the navy than I do. He’s able, he’s dead in earnest, and he’s open-minded; damn few secretaries have been more than that.”

He racked his brains to think how he could help his friend, and in his mind there grew the framework of a strong organization of engineering men so mobilized as to place at the disposal of the navy the efficient use of the best that science could offer.

At New Bedford he arranged to have his boat hauled out for the winter.

“I don’t expect to put her in commission next summer,” he said to the man at the shipyard; “you’d better be prepared to store her for a second winter.”

Early in October, about four weeks after Mortimer’s sail around Cape Cod with Evans, the United States declared war against the Constantinople Coalition, otherwise known as “The Mediterranean Powers.”

Like a great conflagration, a new wave of idealism swept over the land. To every one was offered the opportunity to come forward and give the best that was in him, and few but accepted it gladly.

Washington became the scene of turmoil. Flocks of people poured in. The “swivel-chair warrior” reappeared in all his glory, and the “efficiency expert” added the finishing touch to the orgy of organization and reorganization in which the War Department became engulfed.

In the Navy Department a comparative quiet reigned; the atmosphere was almost that of an efficiently organized and smoothly running business. Until two or three days before the declaration of war Secretary Mortimer was daily in conference for an hour or more with a certain civilian, but so large was the department and so many were the new faces that no one noticed him to be the same individual as the warrant officer, Radio Gunner Evans, who, the day before war was declared, was assigned to duty in the Radio Division of the Bureau of Engineering. Here Evans was given a room to himself. On his desk were two telephones, one connected with the department exchange, the other with the Secretary’s room by a special wire. Evans had himself completed the laying of these wires into his own room and made the terminal connection with the telephone on his desk. No one but he and Mortimer knew where this line led.

Nominally Evans’s duty was the direction and supervision of a group of civilian experts engaged in designing new radio apparatus for installation on ships and shore stations. He was also frequently seen at the office of the Director of Naval Communications.

It behooves the personnel of this office to coöperate cordially with the personnel of the Bureau of Engineering, since the latter makes the apparatus for the former to use, though some people don’t understand this fact. In general, the personnel of the D.N.C. office did not know why this warrant officer should appear from time to time, and some said, “Who’s this guy, anyway, and what’s he doing round here?”

To which query the answer was, as like as not, “Dunno; maybe he’s using this office as an alibi for dodging his work where he belongs.”

Before a state of war had existed two days, letters had been received from Mortimer by half a dozen of the best radio engineers in the country and a number of eminent investigators in various fields of physical science, asking them to come to Washington to confer with him. Within a week nearly all of these men had come, and a comprehensive plan had been laid for the coöperative work whereby their brains could be utilized to the best advantage of the navy. At these conferences Commander Rich, head of the Radio Division of the Bureau of Engineering, was present, and the impression which he made on the scientists for his rapid grasp of what was essential in the great problem before them was such that more than one took occasion to congratulate Mortimer on having such a man in his organization, especially on having him in charge of so important a branch of the service as radio. About this time, also, Professor Jeremy, with rank of lieutenant-commander, was placed in charge of the naval weather service, and with a group of able young assistants began to attack his problem with energy and resource.

The public mind turned rather to the army than to the navy; to most people entry into the war meant the sending of troops to reinforce the armies of Northern Europe in the line of trenches stretching across the continent; the thought of the happenings on the sea scarcely figured in their minds. The popular hue and cry was, “Join the Army.” Congress began agitating the question of conscription for the army. But the navy needed enormous additions to its personnel.

Mortimer paid a visit to the Bureau of Engineering and, after discussing progress with the Bureau Chief and Commander Rich, he slipped into Evans’s room to discuss matters with him.

“It looks as if this conscription business might fill up the army and leave the navy high and dry,” he said. “I don’t think Congress understands that the main task is up to the navy, and we’ve got to have men to do it.”

“People don’t understand that, as a rule,” answered Evans. “They look at the battle-line across Europe, and think that’s the war. They don’t understand that the war can be carried on only by means of certain commodities some of which can be produced only in the Western Hemisphere; that the vast resources of South America are of vital importance to whichever side controls them; that the control of the sea has thus far given the enemy access to these resources and denied it to our allies; and that the one way to checkmate them is to secure complete control of the seas for ourselves. Welcome as our army would be to reinforce those of Northern Europe, even if we got it safely across, it could do nothing decisive against the present defensive methods in use along the enemy’s line. No, the game is up to us; you’re dead right, we’ve got to have our share of the men.”

“I believe the President could do something about it by executive action,” said Mortimer. “But I’m not sure if he’s quite alive to the importance of the navy himself. Military affairs are not his long suit. If I urge on him the importance of it, the danger is that, unless I can give him convincing reasons, he may assume that it’s just the usual thing—each man wants his own particular show to be the biggest. I want to get the essential points down in convincing and unanswerable form, and I’d like to have you help me prepare the case.”

Evans then enumerated the salient points, indicating wherein the problem devolved upon the navy, while Mortimer questioned him and took notes. Evans showed how, through the progress of science and invention during the last twenty years, new methods had become available in warfare, and how the devilish cunning of the Constantinople plotters had utilized these and had taken advantage of their maritime control of the Mediterranean to establish a powerful grip on the south of France and make their defenses virtually impregnable, new inventions in offensive warfare having been more than countered by new methods of defense. He then enumerated the raw materials essential to maintaining the intricate structure of their military system and showed how a large percentage of these could be got only from the tropical regions of the Western Hemisphere—South America, Central America, and the West Indies. During the summer, when they held undisputed control of the Atlantic, the enemy had been transporting enormous stores of those things which they most needed across from Brazil. Now that the American Navy had entered the field to dispute the control of the Atlantic, it became a question of naval power which side should keep its own source of supplies open and cut off that of the opponents.

The enemy now had control of Portugal, the Azores, Madeira, Teneriffe, and the Cape Verde Islands, and, with submarine and seaplane bases at Lisbon and the islands, they were continuing to harass the shipping in the North Atlantic in defiance of international law. Furthermore, under protection from these bases they could maintain an almost uninterrupted flow of commerce with South America, their ships passing close to the African coast where American surface craft could not safely attack them.

During their conversation Evans revealed a knowledge of raw materials, their places of origin and their uses, at which Mortimer was amazed.

“I don’t see how you ever learned and remembered all these facts,” he said.

“I forget lots of things I hear,” answered Evans, “but these facts are so relevant to the crisis at hand that I had good reason to remember them. After all, the facts are open to any one; it’s just a matter of taking the trouble to put them together and see what they mean.”

In discussing the submarine situation, Evans urged the importance of getting possession of the Azores as soon as possible. He believed that a blow struck with the entire naval strength available would encounter no very serious opposition from the enemy.

“My guess is that, much as they want to keep the Azores, they are so much keener about keeping their navy intact and holding their control of the Mediterranean that they wouldn’t risk their fleet in a major naval action for the sake of the islands. Of course, we must first effect a consolidation of our fleet with what’s left of the British and French navies, in order to have the maximum strength available.”

“That’s one of the first things we’ve got to get after,” said Mortimer. “Well, first of all there’s this matter of personnel to start right, and I must be about it. Many thanks for these points you’ve given me; they’ll come in handy.” With that he left the room.

The next day Evans was called by Mortimer on the telephone connected directly with the Secretary’s room. The President had listened attentively to his recital of cogent facts and had been much impressed. He was almost certain the draft bill would go through, and had virtually assured Mortimer that the navy would not suffer in the choice of men.

Not many days passed before Evans and Mortimer were again closeted together discussing the coördination of naval effort. The British Navy was still able, in spite of the disaster, to furnish an appreciable addition to the force, and, above all, to furnish the wisdom and indomitable spirit bred of centuries of maritime greatness. Coöperation with it was now in Mortimer’s mind as a foremost consideration. To this end he was about to dispatch a commission of liaison officers to London. On this occasion Evans emphasized especially the need of a well-organized intelligence service with agents permeating the enemy’s country.

“At sea it is universally admitted that by virtue of our great preponderance of available power, we must take command,” said Evans. “But in the matter of intelligence service there is none on earth that can touch the British, and I believe we had better play that game under their lead. Their organization is marvelous, and the best we can do is to fit our machinery to theirs.

“You know, I think there’s something in the temperament of a certain type of Englishman that fits him extraordinarily well for the hazardous game of secret service in enemy country. It’s his faculty of keeping his thoughts and feelings to himself, his impenetrable exterior, together with his coolness in danger.”

“Haven’t we plenty of men with those same faculties?” Mortimer asked.

“It’s rare to find them so well developed in an American. Then, too, there’s a thoroughness in the education of the British scholar that helps him grasp new and difficult problems. What I’m driving at is this:—there ought to be some one in Constantinople who is not only a damn clever spy, but who also understands what you can do with radio.”

“You’re trying to combine too much in one man,” said Mortimer. “You don’t want to have your secret agent for intelligence bother his head with technical stuff like radio; he should rely on others for that.”

“Of course he should, as far as handling the apparatus is concerned. But he must grasp the basic principles, so that he’ll understand the kind of thing modern apparatus will do for him.

“Both in regard to secret service and to coördination in general, we must get together with the British communication experts and come to an understanding about codes and apparatus. Science has given us such a wealth of new methods in radio engineering that much depends on a clear understanding of what your apparatus will do. The British have developed it along their lines, and we along ours. There should be consultation to determine the best way of standardizing procedure in the fleet, and still more important at the moment is to consult with them as to how recent developments in both countries may be made to help the business of communicating with our spies.”

“I wonder if it wouldn’t be a good plan for you to go with the commission we are sending to England, and confer with their radio men on the matter of apparatus and communication methods in general,” said Mortimer.

“I believe it would,” answered Evans. “I should like to discuss those points with them, and I should like particularly to see some man in their intelligence service who understands radio methods, or at least their possibilities, and who could get into Constantinople; together we could work out codes and ciphers and other matters of procedure that would facilitate the transmission of intelligence to us from that interesting spot.”

“All right; I’ll send you along with the bunch,” said Mortimer. “I think the party will be ready to go in four or five days.”

“I’ve been thinking,” said Evans, still following his previous train of thought, “that an old friend of mine in England would be the ideal person for that job; I mean, to undertake to keep us posted from enemy headquarters. He’s an archaeologist by profession, and the most versatile man I know. He has spent a lot of time in Greece and Asia Minor, knows Constantinople and the Balkans like a book; he’s a wonderful linguist, and the best actor you ever saw. His name is Heringham. I used to play chess with him when I was studying in the Cavendish in Cambridge, and I never knew a man who could fool you more adroitly as to his real plan of campaign. He used to take every kind of part in student theatricals, from a Buddhist to a buffoon, and to realize that the same man did them all would tax your powers of belief to the limit. I don’t think he knows much radio, but he has a good scientific foundation, and he’s so confoundedly clever that he’d learn what he needed for that job in no time. I’d give a lot to have him in Constantinople and to have had a chance to plan things a bit with him first.”

“What’s he doing now?” asked Mortimer.

“Nothing important,” was the answer. “I got a letter from him saying he offered his services to the army, and was rejected because of his age and a slight defect in his eyes; he’s forty-one or forty-two. He’s still living at his rooms in Trinity, trying to make himself useful at odd jobs.”

“Do you suppose there’s any way of getting your wish realized?”

“I don’t know. I’d like to get over there and see what can be done.”

“I’ll give you letters to any one you want,” said Mortimer.

“I think I’d better keep away from the mighty men at the top, and have my business talks with their technical radio men. Send over Barton who is right-hand man to the Chief of Naval Intelligence, and the real brains of the Bureau, and tell him how much you want me to dip into his line of business; he’s no red-tape artist. Between us we may find a way to the sort of collaboration we want.”

A few days later a scout cruiser capable of forty knots slipped out of the Navy Yard at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and headed south, passing between the Isles of Shoals and Cape Ann; but when well out of sight of land she changed her course to east, and sped rapidly out to sea, making several knots better than her economical cruising speed. On board of her was a group of liaison officers of high rank. Commander Barton, of the Bureau of Naval Intelligence, and a number of experts on naval specialties—ordnance, aircraft, and the like, including Evans and a certain Lieutenant Brown representing the Director of Naval Communications.