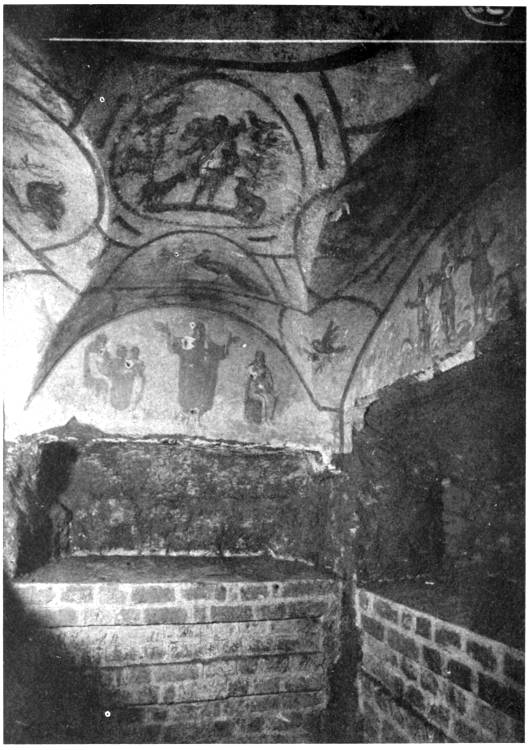

PAINTING IN THE CATACOMBS, CENTURY II OR III. THE GOOD SHEPHERD IN THE CENTRE. ON THE LEFT DANIEL IN THE DEN OF LIONS. ON THE RIGHT THE THREE CHILDREN IN THE FURNACE.

Title: The Early Christians in Rome

Author: H. D. M. Spence-Jones

Release date: January 3, 2022 [eBook #67095]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Methuen & co

Credits: Karin Spence, Turgut Dincer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE

EARLY CHRISTIANS IN ROME

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Dreamland in History

The White Robe of Churches

The Church of England: A History for the People (in Four Volumes)

Cloister Life in the Days of Cœur-de-Lion

Christianity and Paganism

The Golden Age of the Church

PAINTING IN THE CATACOMBS, CENTURY II OR III. THE GOOD SHEPHERD IN THE CENTRE. ON THE LEFT DANIEL IN THE DEN OF LIONS. ON THE RIGHT THE THREE CHILDREN IN THE FURNACE.

BY THE VERY REV.

H. D. M. SPENCE-JONES

M.A., D.D.

DEAN OF GLOUCESTER

PROFESSOR OF ANCIENT HISTORY IN THE ROYAL ACADEMY

WITH A FRONTISPIECE IN COLOUR AND

TWELVE OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS

SECOND EDITION

METHUEN & CO. LTD.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

| First Published | October 27th 1910 |

| Second Edition | 1911 |

TO

EDGAR SUMNER GIBSON, D.D.

LORD BISHOP OF GLOUCESTER

A GREAT SCHOLAR AND A WARM FRIEND

Of the five Books which make up this work, the First Book relates generally the history of the fortunes of the Church in Rome in the first days.

The foundation stories of the Roman congregations were laid largely by the Apostles Peter and Paul—Peter, so with one accord say the earliest contemporary writers,[1] being the first apostle who preached in Rome. Paul, who taught many years later in the Capital, was also reckoned as a founder of the Roman Church; for his teaching, especially his Christology, supplemented and explained in detail the teaching of S. Peter and the early founders.

The First Book relates how, after the great fire of Rome in the days of Nero, the Christians came into prominence, but apparently were looked on for a considerable period as a sect of dissenting Jews.

From A.D. 64 and onwards they were evidently regarded as enemies of the State, and were perpetually harassed and persecuted. No real period of “quietness” was again enjoyed by them until the famous edict of Constantine the Great, A.D. 313, had been issued. Although, through the favour of the reigning Emperor, a temporary suspension of the stern law of the State, sometimes lasting for several years, left the Christian sect for a time, comparatively speaking, at peace.

The Persecutions, which began in the days of Nero, with varying severity continued all through the reigns of the Flavians (Vespasian, Titus, Domitian).

Nerva, who succeeded Domitian, only reigned two years, and was followed by the great Trajan: still the persecution of the sect continued. This we learn from Pliny’s letter to Trajan, circa A.D. 111–113. Hadrian, who followed Trajan, virtually pursued the same policy.

In the latter years of Hadrian, from A.D. 134–5, the result of the great Jewish rebellion definitely and for ever separated, in the eyes of the government, the Christian from the Jew. Henceforth the Jew generally pursued his quiet way, and found new ideals, new hopes. The State feared the Jew no longer.

Not so the Christian. Rome saw clearly now that a new and influential sect had arisen in their midst; a sect absolutely opposed to the old Roman sacred traditions and worship, a sect, too, that evidently possessed some mighty secret power which enabled the Christians fearlessly to defy the magistracy of the Empire. This partly accounts for the greater severity of the persecution under the Antonine Emperors.

The policy of the Antonines (Pius and Marcus), which endeavoured to restore and to give fresh life to the old Roman traditions and worship, which they looked upon as indissolubly bound up with the greatness and power of Rome, was absolutely hostile to the spirit of Christian thought and teaching.

The First Book brings the history down to A.D. 180, the date of the death of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus.

The “Inner Life” of the Christian congregations is now dwelt on, and forms the subject-matter of Books II., III., IV.

The subject-matter of the Second Book is the everyday life of the Christian in the first, second, and third centuries, during which period the religion of Jesus of Nazareth was in the eyes of the Roman government an unlawful cult, and its adherents were ever liable to the severest punishment, such as confiscation of their goods, rigorous imprisonment, torture, and even death.

After dwelling on the question of the numbers of Christians in very early times, their public assemblies or meetings together are described with considerable detail in Book II. The importance of these “meetings” in early Christian life is dwelt upon. What took place at these gatherings is commented upon at considerable length. The position occupied by the slave at these “meetings,” and in Christian society generally, is examined briefly.

Some of the various difficulties which Christians in the age of persecution had to face, and the way by which these difficulties were combated, are described.

Instruction as to the way of meeting the difficulty of life for a Christian living in pagan Rome, was given by two different schools of thought. A sketch is given of (1) “Rigourists,” and (2) of the “gentler and more practical” schools which strove to accommodate the Christian life with the life of the ordinary Roman citizen.

The important part played by the “Rigourist” or ascetic school in the ultimate conversion of the Roman World to Christianity is examined.

Finally, some of the inducements are indicated which persuaded the Christian of the first three centuries to endure with brave patience the hard and dangerous life which was ever the earthly lot of the followers of Jesus.

The Third Book treats especially of the hard and painful nature of the “life” which, from A.D. 64, was the lot of the Christian in the Roman Empire. For the members of the community ever lived under the dark shadow of persecution. The severity of the persecution varied from time to time, but the dark shadow lay on them, and constantly brooded over all their works and days. We possess no direct detailed history of this state of things, but all the early contemporary writings of Christians, a good many of which, whole or in fragments, have come down to us, are literally honeycombed with notices bearing on this perpetual apprehension; and indeed so real, so constant was the danger, and so grave were the consequences to Christianity of any flinching in the hour of trial, that among the congregations of the first days, numerous schools existed for the purpose of training men and women to endure the sufferings of martyrdom.

The number of martyrs in these early years has been probably understated. Pagan contemporary writers of the highest authority, casually, but still definitely, allude to the great numbers of victims, while the tone of early Christian writings (already referred to) is deeply coloured with the pathetic memories of these blood-stained days.

Besides the references even of eminent pagan authorities and the perpetual allusions in early Christian writings to the great numbers of Martyrs and Confessors, a somewhat novel testimony to the vast number of martyrs is quoted here at some length from the history of the Catacombs, where the numbers of these Confessors are again and again dwelt on in the “handbooks” to the Roman subterranean cemeteries, compiled in the fifth and following centuries as “guides” for the crowds of pilgrims from foreign lands visiting Rome. These “Pilgrim Guides,” several of which have in later years come to light, have been recently made the subject of careful study.

The Fourth Book is devoted exclusively to the story of the Roman Catacombs. In the course of the second half of the nineteenth century, the vast subterranean City of the Dead, known as the Roman Catacombs, has been in parts patiently excavated, and carefully studied by eminent scholars. This study, which is still being actively pursued, has thrown much light upon the “life” lived among the early generations of Christians. The inscriptions and epitaphs graved and painted, the various symbols carved upon the countless tombs in the Catacombs, have told us very much of the relations between the rich and the poor. They have disclosed to us something of the secret of the intense faith of these early believers on the “Name,” and have shown us what was the sure and certain hope which inspired their wonderful endurance of pain and agony, and their marvellous courage in the hour of trial.

All this and much more the inscriptions on the thousand thousand graves, the dim fading pictures, the rough carvings, speak of in a language none can mistake. It is, indeed, a voice from the dead, bearing its strange, weird testimony which none can gainsay or doubt.

The work of excavation and the patient study of these Catacombs are yet slowly proceeding, but from what has been already discovered we have learned much of the “Inner Life” of this early Christian folk.

The history of these wonderful Catacombs, this subterranean city of the dead beneath the suburbs of ancient Rome, is told at some length and with considerable detail in the Fourth Book.

The Fifth Book may be considered as a supplement to the work, which in the first four Books has dwelt on (1) the very early history, and (2) on the “Inner Life” of the Christian Church in the first three centuries, especially in Rome.

Christianity sprang from the heart of the Chosen People, the Jews. The Divine Founder in His earthly life was pleased to be a Son of the Chosen People, and His disciples, who laid the early stories of the Faith, were all Jews, as were the earliest converts to the religion of Jesus.

The history of the Jews—their past and present condition—is indissolubly bound up with the records of Christianity. It constitutes the most important confirmation which we possess of the truth of early Christian history. It is the weightiest of all evidential arguments here, and it cannot be refuted or disproved.

The general account of the Chosen People before the coming of Messiah is well known, and the historical accuracy of the Old Testament records is generally admitted. But the memories of the fortunes of the Jewish race after A.D. 70, when the Temple and City were destroyed, and when the heart of Judaism, as it were, ceased to beat, are comparatively little known.

The Fifth Book tells something of that eventful history. It sketches first, very briefly, the last fatal wars of the Jews. Then it tells how directly after the Temple was burnt a remarkable group of Rabbis arose, who, undismayed by what seemed the hopeless ruin of their race, at once proceeded to the reconstruction of Judaism upon totally new foundation stories.

These strange and wonderful scholars gathered together a mass of memories, traditions, and precepts which from the days of Moses had gradually been grouped round the sacred Torah,—the Law of the Lord,—and which had formed the subject-matter of the teaching of the Rabbinic schools of the Holy Law during the five centuries which had elapsed since the Return from the Captivity.

All these memories—traditions—comments, the great scholar Rabbis and their disciples arranged, codified, amplified. This work went on for some three hundred years or more; their labours resulted in the production of the Talmud.

The great object of this marvellous book, or rather collection of books, the Talmud, was the glorification of Israel; but no longer as a separate, a distinct nation, but what was far greater, as a separate People, a People specially beloved of God, for whom a glorious destiny was reserved in a remote future, a destiny which only belonged to the Jews.

In the several sections of this Fifth Book the Talmud is described:—the materials out of which it was composed, the method of the composition, the marvellous power which it exercised upon the sad Remnant of the Jewish people, how it bound them, exiles though they were in many lands, and kept them together,—all this is told at some length.

The ten or twelve millions of Jews, scattered through many hostile nations, living in the world of to-day, more powerful, more influential by far than they were in the golden age of David and Solomon, linked together by a bond which has never snapped, are indeed an ever-present evidence of the truth of the story of the early Christians dwelt on in the first four Books of this work.

| BOOK I | |

| THE BEGINNINGS OF CHRISTIANITY IN ROME | |

| PART I | |

| INTRODUCTORY | |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| A sketch of the early Jewish colony in Rome—Allusion to Jews by Cicero—Favour shown them by Julius Cæsar—Mention of Jews by the great poets of the Augustine age—Characteristic features and moral power of Jews—Their numbers in the days of Nero | 3 |

| I | |

| (a) FOUNDATION OF THE CHURCH IN ROME—INFLUENCE OF S. PETER | |

| Into this colony of Jews came the news of the story of Jesus Christ—Was S. Peter among the first preachers of Christianity in Rome?—Quotations from early Christian writers on this subject—Traditional memories of S. Peter in Rome | 7 |

| II | |

| EARLY REFERENCES | |

| Quotations from patristic writers of the first three centuries, bearing on the foundation of the Church in Rome, including the oldest Catalogues of the Bishops of Rome—Deduction from these quotations | 13 |

| PART II | |

| I | |

| (b) FOUNDATION OF THE CHURCH IN ROME—INFLUENCE OF S. PAUL | |

| S. Paul in Rome—His share in laying the foundation stories in the Capital—Paul’s Christology more detailed than that contained in S. Mark’s Gospel, which represents S. Peter’s teaching | 21 |

| II | |

| POSITION OF CHRISTIANS AFTER A.D. 64 | |

| The great fire of Rome in the days of Nero brought the unnoticed sect of Christians into prominence—The games of Nero—Never again after A.D. 64 did Christians enjoy “stillness”—The policy of the State towards them from this time was practically unaltered | 25 |

| III | |

| THE VEILED SHADOW OF PERSECUTION—POLICY OF THE FLAVIAN EMPERORS | |

| Silence respecting details of persecutions in pagan and in Christian writings—Reason for this—These writings contain little history; but the Christian writings are coloured with the daily expectation of death and suffering—In spite of persecution the numbers of Christians increased rapidly—What was the strange attraction of Christianity?—Persecution of the sect under the Flavian Emperors Vespasian, Titus, Domitian | 35 |

| PART III | |

| INTRODUCTORY | |

| The correspondence between Trajan and Pliny, and the Imperial Rescript—Genuineness of this piece in Pliny’s Letters | 45 |

| I | |

| THE LETTERS OF PLINY | |

| Nerva—Character of Trajan—Story of correspondence here referred to—Pliny’s Letters—Reply of Trajan, which contained the famous Rescript—Tertullian’s criticism of Rescript—Pliny’s Letters—They were no ordinary letters, but were intended for public reading—Pliny’s character—The vogue of writing letters as literary pieces for public reading—Pliny’s Letters briefly examined—The letter here under special consideration—Its great importance in early Christian history | 48 |

| II | |

| VOGUE OF EPISTOLARY FORM OF LITERATURE | |

| Letters of public men considered as pieces of literature—After Trajan there were very few Latin writings until the close of the fourth century—In that period some celebrated letters again appear (written by Symmachus and by Sidonius Apollinaris a few years later)—These letters were evidently written as pieces of literature intended for public circulation | 63 |

| III | |

| THE NEW TESTAMENT EPISTLES, AND LETTERS OF APOSTOLIC FATHERS | |

| Adoption of favourite letter-form as literary pieces—in Epistles of the New Testament, and in letters of Apostolic Fathers | 69 |

| PART IV | |

| I | |

| (a) HADRIAN—HIS POLICY TOWARDS CHRISTIANITY | |

| Hadrian—His life of travel—His character—Early policy towards Christians—He insults Christianity in his building of Aelia Capitolina on site of Jerusalem—The great Jewish war—Its two results—(a) Complete change in the spirit of the Jews—(b) A new conception of the Christian sect on part of Roman Government—It was now recognized that the Christian was no mere Jewish dissenter, but a member of a distinct sect, dangerous to Roman policy | 75 |

| II | |

| (b) HADRIAN—HIS ENMITY TOWARDS CHRISTIANITY GRADUALLY INCREASED | |

| Last years of Hadrian—Persecution of Christians more pronounced—Undoubted authorities for this graver position of Christians throughout the Empire—Table showing succession of Antonines to the Empire | 81 |

| III | |

| ANTONINUS PIUS AND MARCUS ANTONINUS—THEIR IDEALS | |

| Character of Antoninus Pius—His intense love for Rome—His determination to restore the old simple life to which Rome owed her greatness—His devotion to ancient Roman traditions, and to the old Roman religion—Antoninus Pius and his successor Marcus lived themselves the simple austere life they taught to their court and subjects | 84 |

| IV | |

| INTENSE ANTIPATHY OF THE ANTONINES TO CHRISTIANITY | |

| Reason of the Antonines’ marked hostility to the Christian sect—The Christians stood resolutely aloof from the ancient religion which these two great sovereigns believed was indissolubly bound up with the greatness of Rome—With such views of the sources of Roman power and prosperity, only a stern policy of persecution was possible—This policy, pursued in days of Pius, was intensified by his yet greater successor Marcus—The common idea that the Christians were tolerated in the days of the Antonines must be abandoned—Their sufferings under the rule of these great Emperors, especially in the days of Marcus, can scarcely be exaggerated | 91 |

| BOOK II | |

| THE LIFE OF A CHRISTIAN IN THE EARLY DAYS OF THE FAITH | |

| INTRODUCTORY | 101 |

| I | |

| NUMBERS OF CHRISTIANS IN THE EARLY DAYS | |

| Certain reasons to which the rapid acceptance of Christianity was owing—The great numbers of the early converts is borne witness to by pagan authors, such as Tacitus and Pliny, and by Christian contemporary writers such as Clement of Rome, Hermas, Irenæus, and others—The testimony of the Roman catacombs described in detail in Fourth Book is also referred to | 102 |

| II | |

| THE ASSEMBLIES OF CHRISTIANS | |

| These “assemblies” constituted a powerful factor in the acceptance and organization of the religion of Jesus—Their high importance is recognized by the great teachers of the first days—Quotations from these are given | 107 |

| III | |

| OF WHOM THESE PRIMITIVE “ASSEMBLIES” WERE COMPOSED | |

| Information respecting these early meetings of Believers is supplied by leading Christian teachers—Quotations from these are given | 110 |

| IV | |

| WHAT WAS TAUGHT AND DONE IN THESE “ASSEMBLIES” | |

| A general picture of one of them by Justin Martyr—(A) Dogmatic teaching given in these meetings—(B) Almsgiving—Is shown to be an inescapable duty—Is pressed home by early masters of Christianity on the faithful—All offerings made were, however, purely voluntary—No communism was ever taught or hinted at in the early Church—(C) Special dogmatic instruction respecting the value of almsgiving was given by some early teachers—Several of these instructions are given here—(D) Apart from this somewhat strange dogmatic teaching on the value of almsgiving, the general duty of almsgiving was most strongly impressed on the faithful—Passages emphasizing this from very early writers are here quoted—(E) Special recipients of these alms are particularized; amongst these, in the first place, widows and orphans, and the sick, appear—(F) These alms in some cases were not to be confined to the Household of Faith—(G) Hospitality to strangers is enjoined—References here are given from several prominent early teachers—Help to prisoners for the Name’s sake enjoined—Assistance to be given to poorer Churches is recommended—(H) Burial expenses for the dead among the poorer brethren are to be partly defrayed from the “alms” contributed at the assemblies, partly from private sources—Lactantius, in his summary of Christian duties, dwells markedly on this duty—Important witness of the Roman catacombs here | 113 |

| V | |

| THE SLAVE IN EARLY CHRISTIAN LIFE | |

| Position in Christian society—How the slave was regarded in the “assemblies”—Paulinus of Nola quoted on the general Christian estimate of a slave—How this novel view of the slave was looked on by pagans | 134 |

| A general summary of the effect which all this teaching current in the primitive “assemblies” had on the policy and work of the Church in subsequent ages | 137 |

| VI | |

| DIFFICULTIES IN ORDINARY LIFE AMONG THE EARLY CHRISTIANS | |

| Difficulties in common life for the Christian who endeavoured to carry out the precepts and teaching given in the “assemblies” are sketched—In family life—In trades—In the amusements of the people—In civil employments—In the army—In matters of education—A general summary of such difficulties is quoted from De Broglie (l’Église et l’Empire) | 140 |

| VII | |

| THE ASCETIC AND THE MORE PRACTICAL SCHOOLS OF TEACHING | |

| Two schools of teaching, showing how these difficulties were to be met, evidently existed in the early Church—(A) The school of Rigourists—Tertullian is a good example of a teacher of this school—Effect of this school on artisans—On popular amusements—On soldiers of the Legions—On slaves—On family life—From this stern school came the majority of the martyrs—(B) The gentler and more practical school—exemplified in such writings as the Dialogue of Minucius Felix and in writings of Clement of Alexandria, etc.—Results of the teaching of the gentler school—Art was still possible among Christians, although permeated with heathen symbols—The Christian might still continue to live in the Imperial court—might remain in the civil service—in the army, etc.—Examples for such allowances found in Old Testament writings—(C) The Rigourist school again dwelt on—Its great influence on the pagan empire—The final victory of Christianity was largely owing to the popular impression of the life and conduct of followers of this school—This impression was voiced by fourth century writers such as Prudentius and Paulinus of Nola, and is shown in the work of Pope Damasus in the catacombs | 144 |

| VIII | |

| WHAT THE RELIGION OF JESUS OFFERED IN RETURN FOR THIS HARD LIFE TO RIGOURISTS, AND IN A SLIGHTLY LESS DEGREE TO ALL FOLLOWERS OF THE SECOND SCHOOL | |

| (A) Freedom from ever-present fear of death—S. Paul, Ignatius, and especially epitaphs in the Roman catacombs are referred to here—(B) New terminology for death, burial, etc., used—(C) The ever-present consciousness of forgiveness of sins—(D) Hope of immediate bliss after death—The power of the revelation of S. John in early Christian life—(E) Was Christian life in the early centuries after all a dreary existence, as the pagans considered it? | 153 |

| BOOK III | |

| THE INNER LIFE OF THE CHURCH | |

| PART I | |

| A.D. 64–A.D. 180 | |

| INTRODUCTORY | |

| The early Church remained continually under the veiled shadow of persecution—This state of things we learn, not from the “Acts of the Martyrs,” which, save in a certain number of instances, are of questionable authority, but from fragments which have come down to us of contemporary writings—Extracts from two groups of the more important of these are quoted | 163 |

| I | |

| QUOTATIONS FROM APOSTLES, ETC. | |

| First Group.—From writings of apostles and apostolic men, including the Epistle to the Hebrews—1 Peter—Revelation of S. John—First letter of S. Clement of Rome—The seven genuine letters of S. Ignatius | 166 |

| II | |

| QUOTATIONS FROM WRITINGS OF THE SECOND CENTURY | |

| Second Group.—Early writings, dating from the time of Trajan to the death of Marcus Antoninus (A.D. 180); including—“Letters of Pliny and Trajan”—“Letter to Diognetus”—“The Shepherd of Hermas”—“1st Apology of Justin Martyr”—“Minucius Felix”—“Writings of Melito of Sardis”—“Writings of Athenagoras”—“Writings of Theophilus of Antioch”—“Writings of Tertullian”—the last-named a very few years later, but bearing on same period | 177 |

| PART II | |

| TRAINING FOR MARTYRDOM | |

| INTRODUCTORY | |

| The sight of the martyrs’ endurance under suffering had a marked effect on the pagan population. This was noticed and dreaded by the Roman magistracy. Efforts were constantly made by the Government to arrest or at least to limit the number of martyrs | 193 |

| I | |

| OF THE SPECIAL TRAINING FOR MARTYRDOM | |

| The Church conscious of the powerful effect of a public martyrdom upon the pagan crowds—established a training for—a preparation in view of a possible martyrdom—This training included: (a) A public recitation in the congregations of Christians of the “Acts,” “Visions,” and “Dreams” of confessors—(b) The preparation of special manuals prepared for the study of Christians—In these manuals our Lord’s words were dwelt on—(c) A prolonged practice of austerities, with the view of hardening the body for the endurance of pain | 197 |

| II | |

| QUOTATIONS FROM TERTULLIAN, ETC. | |

| Certain of Tertullian’s references to this preparation, and to the austerities practised with this view, are quoted. (His words, written circa A.D. 200, indicate what was in the second century a common practice in the Church.) S. Ignatius’s words in his letter to the Roman Church are a good example of what was the use of the Church in the early years of the second century—Some of the words in question are quoted | 202 |

| PART III | |

| THE GREAT NUMBERS OF MARTYRS IN THE FIRST TWO HUNDRED AND FIFTY YEARS | |

| INTRODUCTORY | |

| Christian tradition by no means exaggerates the number of martyrs—the contrary, indeed, is the case—In the first two hundred and fifty years the general tone of the early Christian writings (above quoted) dwells on those blood-stained days—But the great pagan authors of the second century, Tacitus and Pliny, are the most definite on the question of the vast number of martyrs—Here is cited a new piece of evidence concerning these great numbers from notices in the “Pilgrim Itineraries” or “Guides” to the catacombs of the sixth and following centuries—These tell us what the pilgrims visited—The vast numbers of martyrs in the different cemeteries again and again are dwelt upon | 207 |

| I | |

| List of the various cemeteries and their locality, with special notice of numbers of martyrs buried in each | 210 |

| II | |

| SPECIAL REFERENCE IN THE “MONZA” PAPYRUS, ETC. | |

| The “Monza” Catalogue—made for Queen Theodolinda by Gregory the Great, with notices of number of martyrs from the catalogue in question—Inscriptions of Pope Damasus—References by the poet Prudentius on the number of martyrs | 214 |

| III | |

| DEDUCTIONS FROM THE “MONZA” CATALOGUE AND “PILGRIM” GUIDES | |

| General summary, allowing for some exaggeration in the “Pilgrim” Guides and in the “Monza” Catalogue, on the great numbers of these confessors and martyrs | 215 |

| BOOK IV | |

| THE ROMAN CATACOMBS | |

| PART I | |

| INTRODUCTORY | |

| The nature of the catacombs’ witness to the secret of the “Inner Life” of the Church—A brief sketch of the contents of the Fourth Book | 219 |

| I | |

| THE ROMAN CATACOMBS—THEIR PLACE IN ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY | |

| Early researches—Their disastrous character—De Rossi—His view of the importance of the testimony of the catacombs in early Christian history—Much that has been considered legendary is really historic—Witness of catacombs to the faith of the earliest Christians | 223 |

| II | |

| DE ROSSI’S WAY OF WORKING IN HIS INVESTIGATIONS | |

| Among the materials with which De Rossi worked may be cited: Acta Martyrum of S. Jerome, Liber Pontificalis, the “Pilgrim Itineraries,” and the “Monza” Catalogue, which is specially described—Decoration of certain crypts—Basilica (ruins) above ground—Luminaria—Graffiti of pilgrims—Inscriptions of Pope Damasus in situ, and also preserved in ancient syllogæ | 226 |

| Certain of his more important discoveries in the cemeteries of SS. Domitilla, Priscilla, Callistus—The yet later discoveries of Marucchi and others | 230 |

| III | |

| GENERAL ACCOUNT OF THE VASTNESS AND SITUATION OF THE CATACOMBS | |

| (1) The Vatican cemetery and the groups of catacombs on the right bank of the Tiber | 232 |

| IV | |

| (2) On the Via Ostiensis—Basilica of S. Paul—Cemeteries on the Via Ardeatina—Grandeur of cemetery of S. Domitilla—The small basilica of S. Petronilla | 236 |

| V | |

| (3) Groups of cemeteries on the Via Appia—S. Sebastian (ad Catacumbas)—Group of S. Callistus—The Papal crypt—S. Soteris—Catacomb of Prætextatus on left hand of the Via Appia—Tomb of S. Januarius in this catacomb | 242 |

| VI | |

| (4) Cemeteries on the Via Latina and Via Tiburtina—S. Hippolytus—S. Laurence—S. Agnes’ cemetery on the Via Nomentana | 248 |

| VII | |

| (5) Cemeteries on the Via Salaria Nova—S. Felicitas; the great cemetery of S. Priscilla, and the ancient Roman churches connected with it—Legends—Remains of basilica of S. Sylvester over the cemetery of S. Priscilla—Memories of S. Peter in this cemetery—Its waters—Recent discoveries—Popes buried in the basilica of S. Sylvester | 258 |

| VIII | |

| (6) Unimportant cemeteries on the Via Salaria Vetus—S. Pamphylus—S. Hermes—S. Valentinus, etc. | 274 |

| APPENDIX I.—S. PETRONILLA | |

| Suggested derivation of Petronilla—De Rossi and other scholars still hold to the ancient Petrine tradition—Reasons for maintaining it—Early mediæval testimony here—Traces of the early cult of this Saint | 277 |

| APPENDIX II.—TOMB OF S. PETER | |

| Probable situation of the tomb in present basilica of S. Peter—Account of what was found in the course of the excavations in the seventeenth century, by Ubaldi, Canon of S. Peter’s, who was an eye-witness of the discoveries made in A.D. 1626, when the works required for the great bronze Baldacchino of Bernini were being carried out | 279 |

| PART II | |

| TWO EXAMPLES OF RECENT DISCOVERIES | |

| I | |

| THE CRYPT OF S. CECILIA | |

| The old story of the famous Saint no longer a mere legend—Reconstruction of S. Cecilia’s life—The crypt is described—Her basilica in the Trastevere quarter—once S. Cecilia’s house | 289 |

| II | |

| REMOVAL OF S. CECILIA TO HER BASILICA | |

| Discovery of remains of S. Cecilia by Paschal I., A.D. 821—Appearance of the body, which he translated from the crypt in the catacomb of Callistus to her basilica—Her tomb in the basilica opened in A.D. 1599 by Clement VIII.—Appearance of the body—Maderno copied it in marble—How De Rossi discovered and identified in the original catacomb the crypt of S. Cecilia | 292 |

| III | |

| THE TOMB OF S. FELICITAS, AND OF HER SONS | |

| Discovery and identification of the burial-places of S. Felicitas, of S. Januarius, and of her other sons—Reconstruction of her story—Tomb of S. Januarius found in cemetery of Prætextatus on the Via Appia—Original tomb of S. Felicitas found in the cemetery bearing her name (Via Salaria Nova)—Identification of the burial-places of her other sons | 298 |

| PART III | |

| TEACHING OF THE INSCRIPTIONS AND CARVINGS ON THE TOMBS | |

| I | |

| EPITAPHS IN THE CATACOMBS—THEIR SIMPLICITY | |

| Uncounted numbers of graves in this silent city of the dead; computed at three, four, or five millions—belonging to all ranks—Some of these were elaborately adorned—Greek often the language of very early epitaphs—Great simplicity as a rule in inscriptions—No panegyric of dead—just a name—a prayer—an emblem of faith and hope—Communion of saints everywhere asserted | 307 |

| II | |

| EPITAPHS IN THE CATACOMBS CONTRASTED WITH PAGAN INSCRIPTIONS | |

| A few of these epitaphs quoted—never a word of sorrow for the departed found in them—Question of the catacomb teaching on efficacy of prayers of the dead for the living—S. Cyprian quoted here—Desire of being interred close to a famous martyr—Marked difference in the pagan conception of the dead—Some pagan epitaphs quoted | 310 |

| III | |

| EPITAPHS IN THE CATACOMBS—THEIR DOGMATIC TEACHING | |

| The epitaphs on the catacomb graves tell us with no uncertain voice how intensely real among the Christian folk was the conviction of the future life—They talk, as it were, with the dead as with living ones—Dogmatic allusions in these short epitaphs necessarily are very brief, but yet are quite definite—The supreme divinity of Jesus Christ constantly asserted—The catacombs are full of Christ—Of the emblems carved on the graves—Jesus Christ as “the Good Shepherd” most frequent—The “Crucifixion” became a favourite subject of representation only in later years | 314 |

| APPENDIX | |

| On the wish to be interred close to a saint or martyr—Quotation from S. Augustine here | 321 |

| BOOK V | |

| THE JEW AND THE TALMUD | |

| INTRODUCTORY | |

| The story of the Jew—his past—his condition now, is the weightiest argument that can be adduced in support of the truth of Christianity—What happened to the “sad remnant” of the people after the exterminating wars of Titus and Hadrian, A.D. 70 and 134–5, is little known; yet the wonderful story of the Jew, especially in the second and third centuries, is a piece of supreme importance—How Rabbinic study and the putting out of the Talmud have influenced the general estimate of the Old Testament among Christian peoples | 325 |

| I | |

| THE LAST THREE GREAT WARS OF THE JEWS | |

| The First War, A.D. 66–70—Revolt of the Jews—The dangerous revolt was eventually crushed by Vespasian, and when he succeeded to the Empire his son Titus completed the conquest—Fate of the city of Jerusalem, A.D. 70—Why was the Temple burned?—The recital of Sulpicius Severus gives the probable answer—The account in question was apparently quoted from a lost book of Tacitus—The Roman triumph of Titus—The memories of the conquered Jews on the Arch of Titus in the Forum—The great change in Judaism after A.D. 70, when the Temple and city were destroyed—The change was completed after the war of Hadrian in A.D. 134–5 (the third war)—Brief account of the second and third wars—The bitter persecution after the third war soon ceased, and the sad Jewish remnant was left virtually to itself | 329 |

| II | |

| RABBINISM (a) | |

| The conservation of the remnant of the Jews was owing to the development of Rabbinism—Rabbinism, however, existed before A.D. 70—Traditional story of the rise of Rabbinism contained in the “Mishnah” treatise Pirke Aboth—Effect of the great catastrophe of A.D. 70—Mosaism was destroyed, and was replaced by Rabbinism | 338 |

| III | |

| RABBINISM (b) | |

| Extraordinary group of eminent Rabbis who arose after the catastrophe of A.D. 70—Their new conception of the future of Israel—The Torah (Law of Moses) and other writings of the Old Testament from the days of Ezra had been esteemed ever more and more highly—The “Halachah” or (Rules round the Torah) gradually multiplied—The elaboration of these “Halachah” and “Haggadah” (traditions) formed the “Mishnah”—this work roughly occupied the new Jewish schools during the whole of the second century—Explanation of term “Mishnah”—The next two or three centuries were occupied by the Rabbis in their schools of Palestine and Babylonia in a further commentary on the “Mishnah”—This second work of the Rabbis was termed the “Gemara” | 342 |

| IV | |

| THE TALMUD | |

| Portions of the “Talmud” had existed before A.D. 70—probably some few of the “Halachah” and “Haggadah” even dating from the days of Moses—some from the times of the Judges, and others belonging to the schools of the Prophets—In the times of Ezra arose the strange and unique “Guild of Scribes,” devoted to the study and interpretation of the sacred writings and the traditions which had gathered round them in past ages—R. Hillel a little before the Christian era began the task of arranging the results of the labours of the scribes—R. Akiba after A.D. 70 continued the work of arrangement, but was interrupted—His fame and story—R. Meir further worked at the same task, which was finally completed by R. Judah the Holy, who generally arranged the Mishnah in the form in which it has come down to us—This “Mishnah” served as the text for the great academies of Palestine and Babylonia to work on in the third and two following centuries—Their writings are known as the “Gemara”—The Mishnah and Gemara together form the Talmud—A picture of the great Rabbinic academies of Palestine and Babylonia—Their methods of study | 347 |

| V | |

| HOW THE TEXT OF THE BOOKS OF THE OLD TESTAMENT WAS PRESERVED | |

| Description of the Massorah—The work of the Massorites in the preservation of the text of the sacred books—Present condition of the Massorah | 361 |

| VI | |

| CONCLUDING MEMORANDA | |

| Inspiration of the Old Testament Scriptures, according to the Talmud account | 364 |

| The story of the Talmud through the ages | 365 |

| The Talmud and the New Testament | 366 |

| Influence of the Talmud on Judaism | 368 |

| Influence of the Talmud on Christianity | 370 |

| VII | |

| (A) AN APPENDIX ON THE “HAGGADAH” | |

| “Haggadah” in the Talmud and in other ancient Rabbinical writings—Signification of the “Haggadah”—Its great importance—Its enduring popularity | 371 |

| Examples of “Haggadah” quoted from the Palestinian Targum on Deuteronomy | 373 |

| VIII | |

| (B) ON THE “HALACHAH” AND “HAGGADAH” | |

| The general purport of the “Halachah”—Some illustrations—Further details connected with the “Haggadah”—It is not confined to the later Books of the Old Testament—The “Haggadah” also belongs to the Pentateuch—Examples of this quoted—Instances of the influence of “Haggadah” in the New Testament Books | 376 |

| IX | |

| Women’s Disabilities | 380 |

| Index | 381 |

| Painting in the Catacombs, Second and Third Centuries. The Good Shepherd in the centre. On the left, Daniel in the Den of Lions. On the right, the Three Children in the Furnace | Frontispiece |

| From Palmer’s Early Christian Symbolism. By permission of Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. | |

| FACING PAGE | |

|---|---|

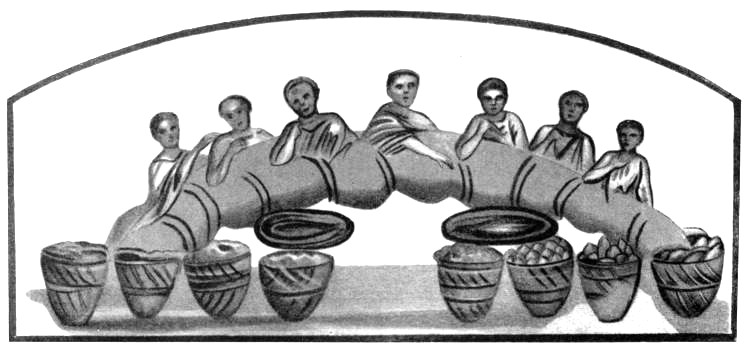

| The “Come and Dine” of the Last Chapter of St. John’s Gospel—The Mystic Repast of the Seven Disciples (Cemetery of Callistus, Second Century. A Favourite Picture in the Catacombs) | 219 |

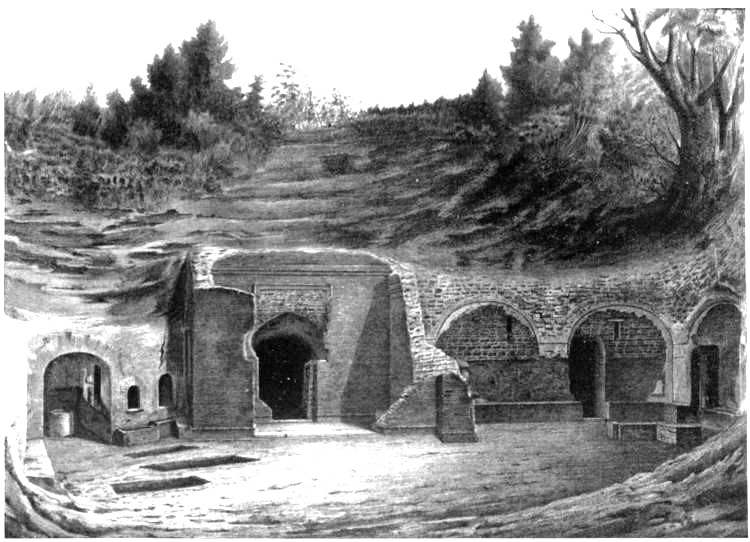

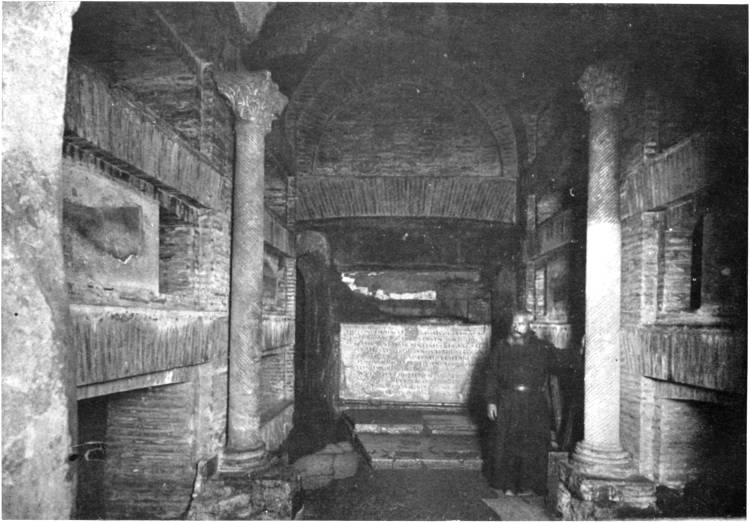

| Entrance to the Cemetery of S. Domitilla (Crypt of the Flavians, First Century) | 240 |

| From Roma Sotterranea Cristiana. By permission of the Author, Orazio Marucchi | |

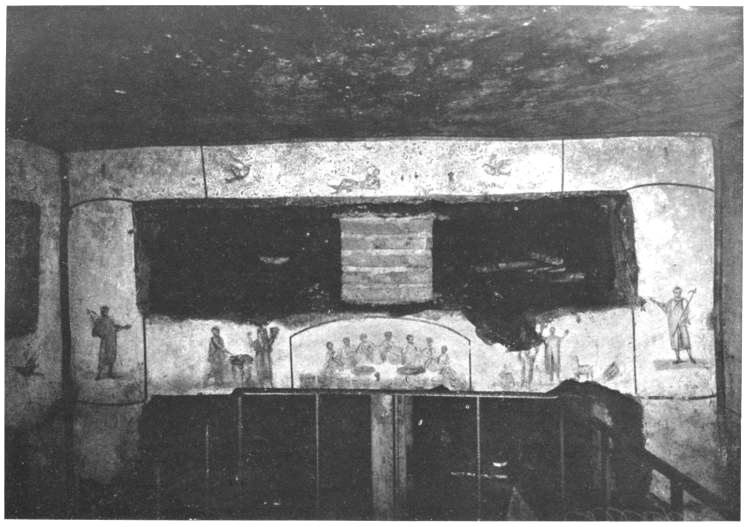

| Paintings in a Chapel of Catacomb of S. Callistus, showing a Tomb subsequently excavated above the Original Tomb of the Saint | 245 |

| Photo, S. J. Beckett | |

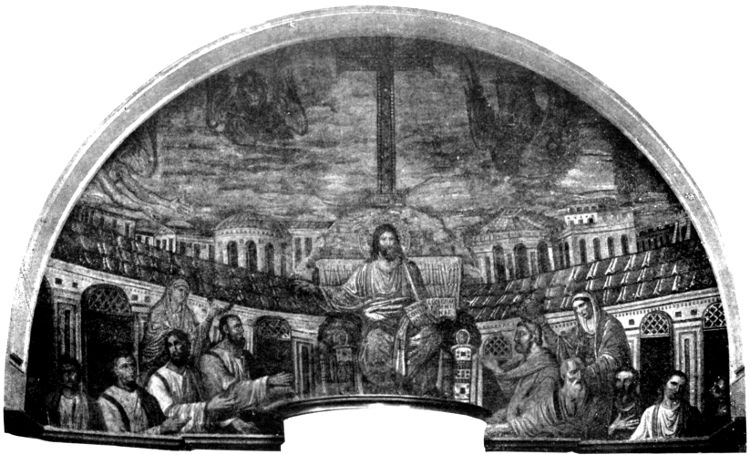

| Mosaic in the Apse of the Church of Sta. Pudenziana, Rome | 263 |

| Photo, Moscioni | |

| In the Catacomb of S. Priscilla (Second or Third Century) | 267 |

| Photo, S. J. Beckett | |

| Chapel of the Tombs of the Third-Century Bishops of Rome, partly restored—Catacomb of S. Callistus | 273 |

| Photo, S. J. Beckett | |

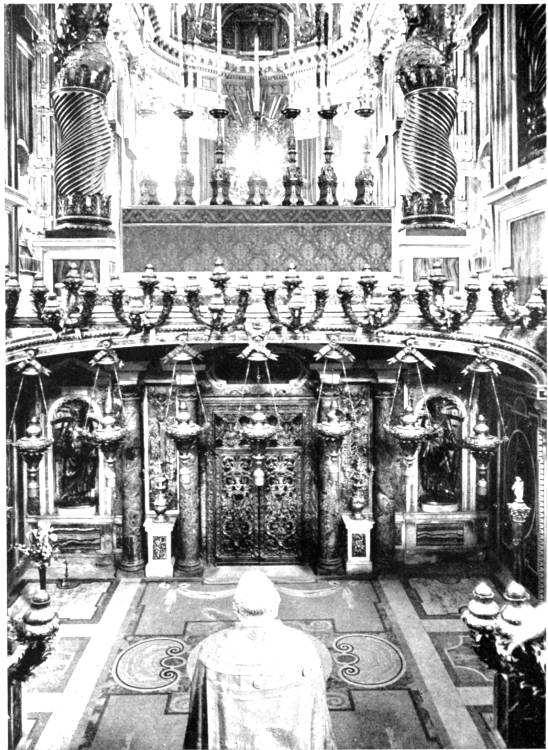

| S. Peter’s, Rome—The Confession | 281 |

| Photo, S. J. Beckett | |

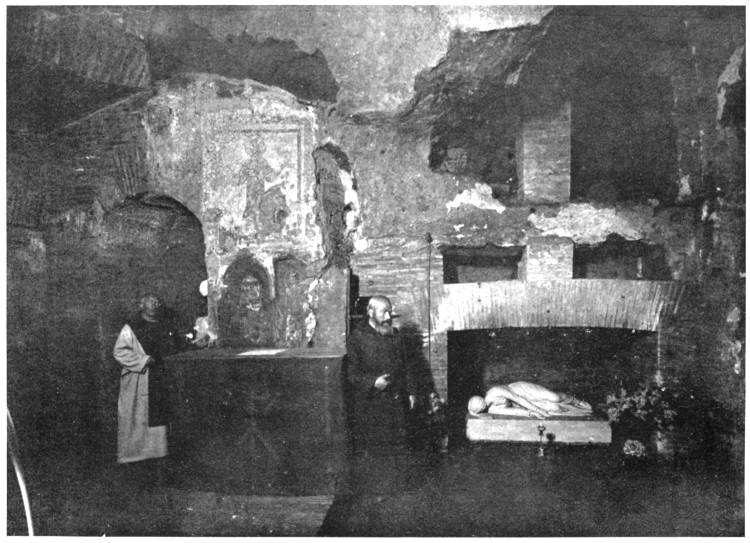

| A Replica of Maderno’s Effigy of S. Cecilia—as she was found—is in the Niche of the S. Callistus Chamber, where the Body originally was deposited | 293 |

| Photo, S. J. Beckett | |

| Sepulchral Inscriptions from the Roman Catacombs | 310 |

| Photo, S. J. Beckett | |

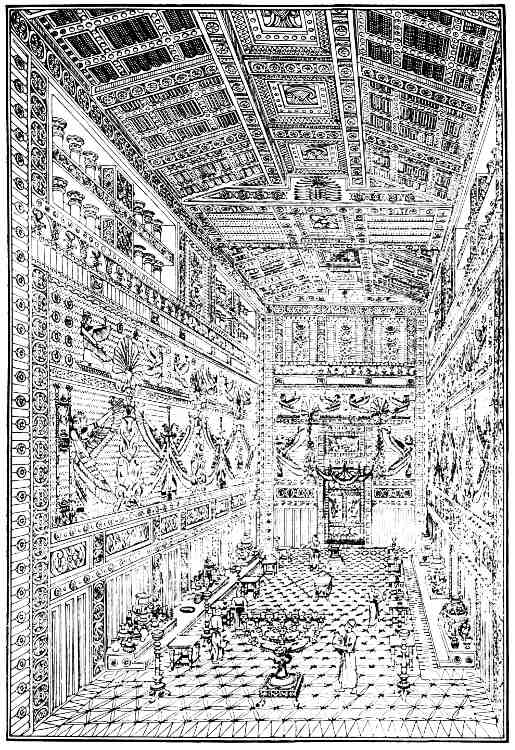

| The Temple—Jerusalem—The Holy Place | 330 |

| From the Jewish Encyclopædia. By permission of Funk & Wagnalls Co. | |

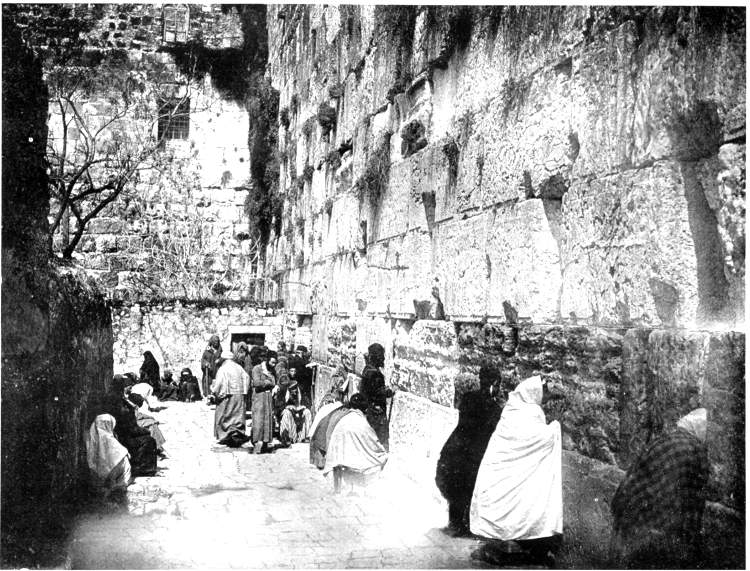

| The “Wailing-Place” of the Jews, before the Ruined Walls of the Temple | 332 |

| Photo, The Photochrom Co. | |

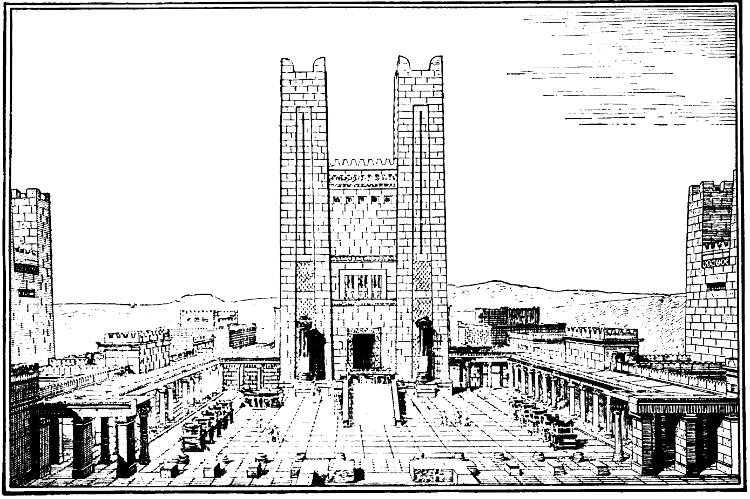

| The Temple, Jerusalem, before its Destruction by Titus, a.d. 70 | 340 |

| From a drawing in the Jewish Encyclopædia. By permission. |

At the beginning of the first century of the Christian era the Jewish colony in Rome had attained large dimensions. As early as B.C. 162 we hear of agreements—we can scarcely call them treaties—concluded between the Jews under the Maccabean dynasty and the Republic. After the capture of Jerusalem by Pompey, B.C. 63, a number more of Jewish exiles swelled the number of the chosen people who had settled in the capital. Cicero when pleading for Flaccus, who was their enemy, publicly alludes to their numbers and influence. Their ranks were still further recruited in B.C. 51, when a lieutenant of Crassus brought some thousands of Jewish prisoners to Rome. During the civil wars, Julius Cæsar showed marked favour to the chosen people. After his murder they were prominent among those who mourned him.

Augustus continued the policy of Julius Cæsar, and showed them much favour; their influence in Roman society during the earlier years of the Empire seems to have been considerable. They are mentioned by the great poets who flourished in the Augustan age. The Jewish Sabbath is especially alluded to by Roman writers as positively becoming a fashionable observance in the capital.

A few distinguished families, who really possessed little of the Hebrew character and nationality beyond the name, such as the Herods, adopted the manners and ways of life[4] of the Roman patrician families; but as a rule the Jews in foreign lands preferred the obscurity to which the reputation of poverty condemned them. Some of them were doubtless possessors of wealth, but they carefully concealed it; the majority, however, were poor, and they even gloried in their poverty; they haunted the lowest and poorest quarters of the great city. Restlessly industrious, they made their livelihood, many of them, out of the most worthless objects of merchandise; but they obtained in the famous capital a curious celebrity. There was something peculiar in this strange people at once attractive and repellent. The French writer Allard, in the exhaustive and striking volumes in which he tells the story of the persecutions in his own novel and brilliant way, epigrammatically writes of the Jew in the golden age of Augustus as “one who was known to pray and to pore over his holy national literature in Rome which never prayed and which possessed no religious books” (“Il prie et il étudie ses livres saintes, dans Rome qui n’a pas de théologie et qui ne prie pas”).

They lived their solitary life alone in the midst of the crowded city—by themselves in life, by themselves, too, in death; for they possessed their own cemeteries in the suburbs,—catacombs we now term them,—strange God’s acres where they buried, for they never burned, their dead, carefully avoiding the practice of cremation, a practice then generally in vogue in pagan Rome. Upon these Jewish cemeteries the Christians, as they increased in numbers, largely modelled those vast cities of the dead of which we shall speak presently.

They watched over and tenderly succoured their own poor and needy, the widow and the orphan; on the whole living pure self-denying lives, chiefly disfigured by the restless spirit, which ever dwelt in the Jewish race, of greed and avarice. They were happy, however, in their own way, living on the sacred memories of a glorious past, believing with an intense belief that they were still, as in the glorious days of David and Solomon, the people beloved of God—and that ever beneath them, in spite of their many confessed backslidings, were the Everlasting Arms; trusting, with a faith which[5] never paled or faltered, that the day would surely come when out of their own people a mighty Deliverer would arise, who would restore them to their loved sacred city and country; would invest His own, His chosen nation, with a glory and power grander, greater than the world had ever seen.

There is no doubt but that the Jew of Rome in Rome’s golden days, in spite of his seeming poverty and degradation, possessed a peculiar moral power in the great empire, unknown among pagan nations.[2]

In the reign of Nero, when the disciples of Jesus in Rome first emerged from the clouds and mists which envelop the earliest days of Roman Christianity, the number of Jews in the capital is variously computed as amounting to from 30,000 to 50,000 persons.

The Jewish colony in Rome was a thoroughly representative body of Jews. They were gathered from many centres of population, Palestine and Jerusalem itself contributing a considerable contingent. They evidently were distinguished for the various qualities, good and bad, which generally characterized this strange, wonderful people. They were restless, at times turbulent, proud and disdainful, avaricious and grasping; but at the same time they were tender and compassionate in a very high degree to the sad-eyed unfortunate ones among their own people,—most reverent, as we have remarked, in the matter of disposing of their dead,—on the whole giving an example of a morality far higher than that which, as a rule, prevailed among the citizens of the mighty capital in the midst of whom they dwelt.

The nobler qualities which emphatically distinguished the race were no doubt fostered by the intense religious spirit[6] which lived and breathed in every Jewish household. The fear of the eternal God, who they believed with an intense and changeless faith loved them, was ever before the eyes alike of the humblest, poorest little trader, as of the wealthiest merchant in their company.

Into this mass of Jewish strangers dwelling in the great city came the news of the wonderful work of Jesus Christ. As among the Jews at Jerusalem, so too in Rome, the story of the Cross attracted many—repelled many. The glorious news of salvation, of redemption, sank quietly into many a sick and weary heart; these hearts were kindled into a passionate love for Him who had redeemed them—into a love such as had never before been kindled in any human heart. While, on the other hand, with many, the thought that the treasured privileges of the chosen people were henceforward to be shared on equal terms by the despised Gentile world, excited a bitter and uncompromising opposition—an opposition which oftentimes shaded into an intense hate.

The question as to who first preached the gospel of Jesus Christ to this great Jewish colony will probably never be answered. There is a high probability that the “story of the Cross” was told very soon after the Resurrection by some of those pilgrims to the Holy City who had been eye-witnesses of the miracle of the first Pentecost.

There is, however, a question connected with the beginnings of Christianity in Rome which is of the deepest interest to the student of ecclesiastical history, a question upon which much that has happened since largely hangs.

Was S. Peter in any way connected with the laying of the foundation of the great Christian community in Rome; can he really be considered as one of the founders of that most important Church? An immemorial tradition persists in so connecting him; upon what grounds is this most ancient tradition based?

Scholars of all religious schools of thought now generally[8] allow that S. Peter visited Rome and spent some time in the capital city; wrote his great First Epistle from it, in which Epistle he called “Rome” by the not unusual mystic name of “Babylon,” and eventually suffered martyrdom there on a spot hard by the mighty basilica called by his name.

The only point at issue is, did he—as the favourite tradition asserts—pay his first visit to Rome quite early in the Christian story, circa A.D. 42, remaining there for some seven or eight years preaching and teaching, laying the foundations of the great Church which rapidly sprang up in the capital?

Then when the decree of the Emperor Claudius banished the Jews, A.D. 49–50, the tradition asserts that the apostle returned to the East, was present at the Apostolic Council held at Jerusalem A.D. 50, only returning to Rome circa A.D. 63. Somewhere about A.D. 64 the First Epistle of Peter was probably written from Rome.[3] His martyrdom there is best dated about A.D. 67.

A careful examination of the most ancient “Notices” bearing especially on the question of the laying of the early stories of the Roman Church, determines the writer of this little study to adopt the above rough statement of S. Peter’s work at Rome. Some of the principal portions of these “notices” will now be quoted, that it may be seen upon what basis the conclusion in question is adopted. The quotations will be followed by a sketch of the traditional and other evidence specially drawn from the testimony of the very early Roman catacomb of S. Priscilla. This sketch, which is here termed the “traditional evidence,” it will be seen, powerfully supports the deduction derived from the notices quoted from very early Christian literature.

Clemens Romanus, A.D. 95–6. In the fifth chapter of the well-known and undoubtedly authentic Letter of Clement of Rome to the Corinthians, the writer calls the attention of the Corinthians to the examples of the Christian “athletes” who “lived very near to our own time.” He speaks of the apostles who were persecuted, and who were faithful to death. “There was Peter, who after undergoing many sufferings, and having borne his testimony, went to his appointed place of glory. There was Paul, who after enduring chains, imprisonments, stonings, again and again, and sufferings of all kinds ... likewise endured martyrdom, and so departed from this world.”

The reason why Clement of Rome mentions these two special apostles (other apostles had already suffered martyrdom) is obvious. Clement was referring to examples of which they themselves had been eye-witnesses. Paul, it is universally acknowledged, was martyred in Rome; is not the inference from the words of Clement, that Peter suffered martyrdom in this same city also, overwhelming?

Ignatius, circa A.D. 108–9, some twelve or thirteen years after Clement had written his Epistle to the Corinthians, on his journey to his martyrdom at Rome, thus writes to the Roman Church: “I do not command you like Peter and Paul: they were apostles; I am a condemned criminal.” Why now did Ignatius single out Peter and Paul? So Bishop Lightfoot, commenting on this passage, forcibly says: “Ignatius was writing from Asia Minor. He was a guest of a disciple of John at the time. He was sojourning in a country where John was the one prominent name. The only conceivable reason why he specially named Peter and Paul was that these two apostles had both visited Rome and were remembered by the Roman Church.”

Papias of Hierapolis, born circa A.D. 60–70. His writings probably date somewhat late in the first quarter of the second century. On the authority of Presbyter John, a personal disciple of the Lord, Papias tells us about Mark: he was a friend and interpreter of S. Peter, and wrote down what he heard[10] his master teach, and there (in Rome) composed his “record.” This notice seems to have been connected by Papias with 1 Pet. v. 13, where Mark is alluded to in connexion with the fellow-elect in Babylon (Rome).

“It seems,” concludes Bishop Lightfoot, referring to Irenæus (S. Clement of Rome, ii. 494), “a tolerably safe inference, therefore, that Papias represented S. Peter as being in Rome, that he stated Mark to have been with him there, and that he assigned to the latter a Gospel record (the second Gospel) which was committed to writing for the instruction of the Romans.”

Dionysius of Corinth, A.D. 170, quoted by Eusebius (H. E. II. xxv.), wrote to Soter, bishop of Rome, as follows: “Herein by such instructions (to us) ye have united the trees of the Romans and Corinthians (trees) planted by Peter and Paul. For they both alike came also to our Corinth, and taught us; and both alike came together to Italy, and having taught there, suffered martyrdom at the same time.”

Irenæus, circa A.D. 177–90, writes: “Matthew published also a written Gospel among the Hebrews in their own language, while Peter and Paul were preaching and founding the Church in Rome. Again after their departure, Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, himself also handed down to us in writing the lessons preached by Peter.”—H. E. III. i. 1.

Clement of Alexandria, circa A.D. 193–217 (Hypotyposes, quoted by Eusebius, H. E. vi. 14) tells us how, “when Peter had preached the word publicly in Rome, and declared the gospel by the Spirit, the bystanders, being many in number, exhorted Mark as having accompanied him for a long time, and remembering what he had said, to write out his statements, and having thus composed his Gospel, to communicate it to them; and that when Peter learnt this, he used no pressure either to prevent him or to urge him forwards.”

Tertullian, circa A.D. 200, adds his testimony thus: “We read in the lives of the Cæsars, Nero was the first to stain the rising faith with blood. Thus Peter is girt by another (quoting the Lord’s words) when he is bound to the Cross. Thus Paul obtains his birthright of Roman citizenship when he is born again there by the nobility of Martyrdom.”—Scorpiace, 15.

Tertullian again writes: “Nor does it matter whether they are among those whom John baptized in the Jordan, or those whom Peter baptized in the Tiber.”—De Baptismo, 4.

Tertullian once more tells us: “The Church of the Romans reports that Clement was ordained by Peter.”—De Præscriptione Hær. 36.

Tertullian again bears similar testimony: “If thou art near to Italy, thou hast Rome.... How happy is that Church on whom the apostles shed all their teaching with their blood, where Peter is conformed to the passion of the Lord, where Paul is crowned with the death of John (the Baptist), where the Apostle John after having been plunged in boiling oil, without suffering any harm, is banished to an island!”—De Præscriptione, 36.

Caius (or Gaius) the Roman presbyter, circa A.D. 200–20, who lived in the days of Pope Zephyrinus, and was a contemporary of Hippolytus, if not (as Lightfoot suspects) identical with him (Hippolytus of Portus), gives us the following detail: “I can show you the trophies (the Memoriæ or Chapel-Tombs) of the apostles. For if you will go to the Vatican or to the Ostian Way, thou wilt find (there) the trophies (the Memoriæ) of those who founded the Church.”

Caius is here claiming for his own Church of Rome the authority of the Apostles SS. Peter and Paul, whose martyred bodies rest in Rome.—Quoted by Eusebius, H. E. II. xxv.

Thus at that early date when Caius wrote, the localities of the graves of the two apostles were reputed to have been the spots where now stand the great basilicas of SS. Peter and Paul.

Eusebius, H. E. II. xiv., gives a definite date for the first coming of Peter to Rome, and his preaching there. The historian was describing the influence of Simon Magus at Rome. This, he adds, did not long continue, “for immediately under the reign of Claudius, by the benign and gracious providence of God, Peter, that powerful and great apostle who by his courage took the lead of all the rest, was conducted to Rome against this pest of mankind. He (S. Peter) bore the precious merchandise of the revealed light from the East to those in the West, announcing this light itself, and salutary[12] doctrine of the soul, the proclamation of the kingdom of God.”

Eusebius also writes that “Linus, whom he (Paul) has mentioned in his Second Epistle to Timothy as his companion at Rome, has been before shown to have been the first after Peter that obtained the Episcopate at Rome.”—Eusebius, H. E. III. iv.

The traditional memories of Peter’s residence in Rome and his prolonged teaching there are very numerous. De Rossi while quoting certain of these as legendary, adds that an historical basis underlies these notices. Some of the more interesting of these are connected with the house and family of Pudens on the Aventine, and with the cemetery of Saint Priscilla on the Via Salaria.

To the pilgrims of the fifth and following centuries were pointed out the chair in which Peter used to sit and teach (Sedes ubi prius sedit S. Petrus), and also the cemeterium fontis S. Petri—cemeterium ubi Petrus baptizaverat. Marucchi, the pupil and successor of De Rossi, believes that this cemetery where it was said S. Peter used to baptize, is identical with parts of the vast and ancient catacomb of Priscilla. These and further traditional notices are dwelt on with greater detail presently when the general evidence is summed up.[4]

And now to sum up the evidence we have been quoting:

The Literary Notices have been gathered from all parts of the Roman world where Christianity had made a lodgment.

From Rome (Clement of Rome) in the first and second centuries and early in the third century.

From Antioch (Ignatius, Papias) (including Syria and Asia Minor) very early in the second century.

From Corinth (Greece) (Dionysius) in the second half of the second century.

From Lyons (Gaul) (Irenæus) in the second half of the second century.

From Alexandria (Egypt) (Clement of Alexandria) in the second half of the second century.

From Carthage (North Africa) (Tertullian) in the close of the second century.

These and other literary notices, more or less definitely, all ascribe the laying of the foundation stories of the Church of Rome to the preaching and teaching of the Apostles Peter and Paul. All without exception in their notices of this foundation work place the name of Peter first. It is hardly conceivable that these very early writers would have done this had Peter only made his appearance in Rome for the first time in A.D. 63 or 64, after Paul’s residence in the capital for some two years, when he was awaiting the trial which resulted in his acquittal.

Then again, the repeated mention of the two great apostles as the Founders of the Roman Church would have been singularly inaccurate if neither of them had visited the capital before A.D. 60–1, the date of Paul’s arrival, and A.D. 63–4, the[14] date of S. Peter’s coming, supposing we assume the later date for S. Peter’s coming and preaching.

When we examine the literary notices in question we find in several of them a more circumstantial account of Peter’s work than Paul’s; for instance:

Papias and Irenæus give us special details of S. Mark’s position as the interpreter of S. Peter, and tell us particularly how the friend and disciple of S. Peter took down his master’s words, which he subsequently moulded into what is known as the second Gospel.

Tertullian relates that S. Peter baptized in the Tiber, and mentions, too, how this apostle ordained Clement.

Eusebius, the great Church historian to whom we owe so much of our knowledge of early Church history, writing in the early years of Constantine’s reign, in the first quarter of the fourth century, goes still more into detail, and gives us approximately the date of S. Peter’s first coming, which he states to have been in the reign of Claudius, who was Emperor from A.D. 41 to A.D. 54 (Eusebius, H. E. II. xiv.). The same historian also repeats the account above referred to of Mark’s work as Peter’s companion and scribe in Rome (H. E. II. xv.), adding that the “Church in Babylon” referred to by S. Peter (1 Ep. v. 13) signified the Church of Rome.

Jerome, writing in the latter years of the same century (the fourth), is very definite on the question of the early arrival of S. Peter at Rome—“Romam mittitur,” says the great scholar, “ubi evangelium prædicans XXV annis ejusdem urbis episcopus perseverat.” Now, reckoning back the twenty-five years of S. Peter’s supervision of the Roman Church would bring S. Peter’s first presence in Rome to A.D. 42–3; for Jerome tells us how “Post Petrum primus Romanam ecclesiam tenuit Linus,” and the early catalogues of the Roman Bishops—the Eusebian (Armenian version), the catalogue of Jerome, and the catalogue called the Liberian—give the date of Linus’ accession respectively as A.D. 66, A.D. 68, A.D. 67.

The early lists or catalogues of the Bishops of Rome, just casually referred to, are another important and weighty witness to the ancient and generally received tradition of the early visit and prolonged presence of S. Peter at Rome.

The first of these in the middle of the second century was drawn up, as far as Eleutherius, A.D. 177–90 by Hegesippus, a Hebrew Christian. Eusebius is our authority for this. This list, however, has not come down to us. It is, however, probable that it was the basis, as far as it went, of the list drawn up by Irenæus circa A.D. 180–90. This is the earliest catalogue of the Roman Bishops which we possess. Irenæus, after stating that the Roman Church was founded by the Apostles Peter and Paul, adds that they entrusted the office of the Episcopate to Linus.

In the Armenian version of the Chronicles of Eusebius, the only version in which we possess this Eusebian Chronicle, Peter appears at the head of the list of Roman Bishops, and twenty years is given as the duration of his government of the Church. Linus is stated to have been his successor. In the list of S. Jerome a similar order is preserved—with the slight difference of twenty-five years instead of twenty as the duration of S. Peter’s rule. The deduction which naturally follows these entries in the two lists has been already suggested. The Liberian Catalogue, compiled circa A.D. 354, places S. Peter at the head of the Roman Bishops—giving twenty-five years as the duration of his government. Linus follows here.

The Liberian Catalogue was the basis of the great historical work now generally known as the “Liber Pontificalis,” which in its notices of the early Popes embodies the whole of the Liberian Catalogue—only giving fresh details. The “Liber Pontificalis” in its first portion in its present form is traced back to the earlier years of the sixth century.

The traditional notices of the early presence of S. Peter in Rome are many and various. Taken by themselves they are, no doubt, not convincing—some of them ranking as purely legendary—though we recognize even in these “purely legendary” notices an historical foundation; but taken together they constitute an argument of no little weight.

Among the “purely legendary” we have touched upon the memories which hang round the house of Pudens, and the church which in very early times arose on its site.[5] Of far[16] greater historical value are the memories which belong to the Catacomb of Priscilla, memories which recent discoveries in that most ancient cemetery go far to lift many of the old traditions into the realm of serious history.

The historical fact of the burial (depositio) of some ten or eleven of the first Bishops round the sacred tomb of the Apostle S. Peter (juxta corpus beati Petri in Vaticano), gives additional colour to the tradition of the immemorial reverence which from the earliest times of the Church of Rome encircles the memory of S. Peter.

From the third century onward we find the Roman Bishops claiming as their proudest title to honour their position as successors of S. Peter. In all the controversies which subsequently arose between Rome and the East this position was never questioned. Duchesne, in his last great work,[6] ever careful and scholarly, does not hesitate to term the “Church of Rome” (he is dwelling on its historical aspect) the “Church of S. Peter.”

This study on the work of S. Peter in the matter of laying the early stories of the great Church which after the fall of Jerusalem in A.D. 70 indisputably became the metropolis of Christianity, has been necessarily somewhat long—the question is one of the highest importance to the historian of ecclesiastical history. Was this lofty claim of the long line of Bishops of Rome to be the successors of S. Peter, ever one of their chief titles to honour, based on historic evidence, or was it simply an invention of a later age?

All serious historians now are agreed that S. Peter taught in Rome, wrote his Epistle from Rome, and subsequently suffered martyrdom there.

But historians, as we have stated, are not agreed upon the date of his first appearance in the queen city. Now the sum of the evidence massed together in the foregoing brief study, leads to the indisputable conclusion that the date of his coming to Rome must be placed very early in the story of Christianity, somewhere about A.D. 41–3.

Everything points to this conclusion. How could Peter be, with any accuracy, styled the “Founder of the Church of[17] Rome” if he never appeared in Rome before A.D. 64? Long before this date the Church of the metropolis had been “founded,” had had time to become a large and flourishing Christian community. This estimate of the signal importance of the Church of Rome is based on various testimonies, among which may be ranked the long list of salutations in S. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, written circa A.D. 58.

All the various notices of the leading Christian writers of the first and second centuries in all lands carefully style him as such. Paul, it is true, in most, not in all these early writings, is associated with him as a joint founder: this in a real sense can also be understood; for although Paul came at a later date to Rome and dwelt there some two years, the presence of one of the greatest of the early Christian teachers would surely add enormously to the stability of the foundations laid years before. The teaching of the great Apostle of the Gentiles, continued for two years, was, of course, a very important factor in the “foundation work,” and was evidently always reckoned as such.

But even then, as we have seen, while the two apostles are frequently joined together as founders in the writings of the early Christian teachers, in several notable instances Peter’s work is especially dwelt upon by them.

Then again in the traditional “Memories” preserved to us, some of them of the highest historical value, it is Peter, not Paul, who is ever the principal figure. Paul rarely, if ever, appears in them. Great though undoubtedly Paul was as a teacher of the Christian mysteries and as an expounder of Christian doctrine, it is emphatically Peter, not Paul, who lives in the “memories” of the Roman Christian community.

The place which the two basilicas of S. Peter and S. Paul on the Vatican Hill and on the Ostian Way have ever occupied in the minds and hearts not only of the Roman people, but of all the innumerable pilgrims in all ages to the sacred shrines of Rome, seems accurately to measure the respective places which the two apostles hold in the estimate of the Roman Church.

The comparative neglect of S. Paul’s basilica in Rome when measured with the undying reverence shown to, and with the enormous pains and cost bestowed on the sister[18] basilica of S. Peter, is due not to any want of reverence or respect for the noble Apostle of the Gentiles, but solely because Rome and the pilgrims to Rome were deeply conscious of the special debt of Rome to S. Peter, who was evidently the real founder of the mighty Church of the capital.

The writer of this work is fully conscious that the conclusion to which he has come after massing together all the available evidence, is not the usual conclusion arrived at by one great and influential school of thought in our midst; nor does it accord with the conclusion of that eminently just scholar-Bishop Lightfoot, who while positively affirming the presence of S. Peter in Rome, whence, as he allows, he wrote his First Epistle, and where through pain and agony he passed to his longed-for rest in his Master’s Paradise, yet cannot accept the tradition of his early presence in the metropolis.

The writer of this study has no doubt whatever that the teaching of the vast majority of the Roman Catholic writers on this point is strictly accurate, and that S. Peter at a comparatively early date, probably somewhere about the year of grace 42–3, came to Rome confirmed in the faith—taught—strengthened with his own blessed memories of his adored Master—the little band of Christians already dwelling in the capital of the Empire. Under his pious training the little band, in the six, seven, or eight years of his residence in their midst, became the strong nucleus of the powerful Church of Rome.

Then, most probably, he left Rome when the decree of the Emperor Claudius, A.D. 49, was promulgated: the decree which was the result of the disturbances among the turbulent Jewish colony,—disturbances no doubt owing to bitter and relentless opposition to the fast spreading of the Christian faith in their midst. As Suetonius (Claudius, 25) tersely but clearly tells us: “Judæos, impulsore Christo assidue tumultuantes Roma expulit.”

From the year 49, when he left the Queen City, S. Peter apparently was absent from the Church in which for some seven or eight years he had laboured so well and so successfully, continuing his work, however, in other lands. Then in A.D. 63–4 he returned, resumed his Roman work, wrote the First[19] Epistle which bears his name, and eventually suffered martyrdom.

This conclusion, of such deep importance in early ecclesiastical history, has been arrived at—as the student of the foregoing pages will see—from no one statement, from no whole class, so to speak, of evidences, but from the cumulative evidence afforded by the massing together the statements of early writers, the testimony of the catacombs, the witness of tradition, and the voice of what may almost be accurately termed immemorial history.[7]

The Roman Church in the year of grace 61 was evidently already a powerful and influential congregation: everything points to this conclusion: its traditions, we might even say its history, and, above all, the notices contained in S. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans written not later than A.D. 58.

Virtually alone among the Churches of the first thirty years of Christianity does S. Paul give to this congregation unstinting, unqualified praise—very different to his words addressed to the Church in Corinth in both of his Epistles to that notable Christian centre, or to the Galatian congregation in his letter to the Church of that province; or even to the Thessalonians, the Church which he loved well, where reproach and grave warnings are mingled with and colour his loving words.

But to the Church of Rome, in which in its many early years of struggle and combat he bore no part whatever, his praise is quite unmingled with rebuke or warning. As regards this congregation (Rom. i. 8), Paul thanks God for them all that their faith is spoken of throughout the whole world. In the concluding chapter of the Epistle, some twenty-five specially distinguished members of the Roman congregation are saluted by name, though it by no means follows that S. Paul was personally acquainted with all of those who were named by him.

About three years after writing his famous letter to the Romans,—just referred to,—Paul came as a prisoner to the[22] capital city. But although a prisoner awaiting a public trial, the imperial government gave him free liberty to receive in his own hired house members of the Christian Church, and indeed any who chose to come and listen to his teaching; and this liberty of free access to him was continued all through the two years of his waiting for the public trial. The words of the “Acts of the Apostles,” a writing universally received as authentic, are singularly definite here: “And Paul dwelt two whole years in his own hired house (in Rome), and received all that came unto him, preaching the kingdom of God, and teaching those things which concern the Lord Jesus Christ, with all confidence, no man forbidding him” (Acts xxviii. 30–31).

It was during these two years of the imprisonment that the great teacher justified his subsequent title, accorded him by so many of the early Christian writers, of joint founder with S. Peter of the Roman Church. The foundations of the Church of the metropolis we believe certainly to have been laid by another leading member of the apostolic band, S. Peter.[8] But S. Paul’s share in strengthening and in building up this Church, the most important congregation in the first days of Christianity, was without doubt very great.

At a very early period, certainly after the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple, Rome became the acknowledged centre and the metropolis of Christendom. The great world-capital was the meeting-place of the followers of the Name from all lands. Thither, too, naturally flocked the teachers of the principal heresies in doctrinal truth which very soon sprang up among Christian converts. Under these conditions something more, in such a centre as Rome, was imperatively needed than the simple direct Gospel teaching, however fervid: something additional to the recital of the wondrous Gospel story as told by S. Peter and repeated possibly verbatim by his disciple S. Mark. A deeper and fuller instruction was surely required in such a centre as Rome quickly became. Men would ask, Who and what was the Divine Founder of the religion,—what was His relation to the Father, what to the angel-world? What was known of His pre[23]existence? These and such-like questions would speedily press for a reply in such a cosmopolitan centre as imperial Rome. Inspired teaching bearing on such points as these required to be welded into the original foundation stories of the leading Church which Rome speedily became, and this was supplied by the great master S. Paul, to whom the Holy Ghost had vouchsafed what may be justly termed a double portion of the Spirit. The Christology of Paul, to use a later theological term, was, in view of all that was about to come to pass in the immediate future, a most necessary part of the equipment of the Church of God in Rome.

The keynote of the famous master’s teaching during those two years of his Roman imprisonment may be doubtless found in the letters written by him at that time. Three of these, the “Ephesian,” “Colossian,” and “Philippian” Epistles, were emphatically massive expositions of doctrine—especially that addressed to the Colossians. From these we can gather what was the principal subject-matter of the Pauline teaching at Rome. His thoughts were largely taken up with the great doctrinal questions bearing on the person of the Founder of Christianity.

We will quote one or two passages from the great doctrinal Epistle to the Colossians as examples of the Pauline teaching at this juncture of his life when he was engaged in building up the Roman Church, and furnishing it with an arsenal of weapons which would soon be needed in their life and death contest with the dangerous heresies[9] which so soon made their appearance in the city which was at once the metropolis of the Church and the Empire.

“The Father, ... who hath translated us into the kingdom of His dear Son, ... who is the image of the invisible God, the first-born of every creature: for by Him were all things created, that are in heaven, and that are in earth, visible and invisible, whether they be thrones, or dominions, or principalities, or powers: all things were created by Him, and for Him: and He is before all things, and by Him all things consist. And He is the head of the body, the Church: who[24] is the beginning, the first-born from the dead; that in all things he might have the pre-eminence. For it pleased the Father that in Him should all fulness dwell; and, having made peace through the blood of His Cross, by Him to reconcile all things unto Himself; by Him (I say), whether they be things in earth, or things in heaven” (Col. i. 12–20).

And once more: “Beware lest any man spoil you through philosophy and vain deceit, after the tradition of men, ... and not after Christ. For in Him dwelleth all the fullness of the Godhead bodily. And ye are complete in Him, which is the head of all principality and power.”

Preaching on such texts, which contain those tremendous truths which just at this time he embodied in his Colossian letter, did S. Paul lay the foundation of the “Christology” of the Church of Rome. With justice, then, was he ranked by the early Christian writers as one of the founders of the Roman Church, for he was without doubt the principal teacher of the famous congregation in the all-important doctrinal truths bearing on the person and office of Jesus Christ.

S. Peter, whose yet earlier work at Rome, we believe, stretching over some eight or nine years, we have already dwelt on, was evidently absent from the capital when S. Paul in A.D. 58 wrote his famous Letter to the Romans; nor had he returned in A.D. 61, when Paul was brought to the metropolis as a prisoner; but that he returned to Rome somewhere about A.D. 63–4 is fairly certain.

For a little more than thirty years, dating back to the Resurrection morning, with the exception of the occasion of that temporary and partial banishment of the Jews and Christians from Rome in the days of the Emperor Claudius, had the Christian propaganda gone on apparently unnoticed, certainly unheeded by the imperial government.

The banishment decree of Claudius, the outcome of a local disturbance in the Jewish quarter of the capital, was after a brief interval apparently rescinded, or at least ignored by the ruling powers; but in the middle of the year 64, only a few months after S. Paul’s long-delayed trial and acquittal and subsequent departure from Rome, a startling event happened which brought the Christians into a sad notoriety, and put an end to the attitude of contemptuous indifference with which they had been generally regarded by the magistrates both in the provinces and in the capital.