Title: The Experienced Angler; or Angling Improved

Author: Robert Venables

Author of introduction, etc.: Izaak Walton

Release date: February 22, 2022 [eBook #67474]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Septimus Prowett and Thomas Gosden

Credits: Fiona Holmes and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

Hyphenation has been standardised.

The Contents list has been created by the Transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Changes made are noted at the end of the book.

J. Johnson, Printer, Brook Street, Holborn, London.

THE

EXPERIENCED ANGLER;

OR

Angling Improved.

IMPARTING MANY

OF THE

APTEST WAYS AND CHOICEST EXPERIMENTS

FOR THE

TAKING MOST SORTS OF FISH

IN

POND OR RIVER.

BY COL. ROBERT VENABLES.

“I have read and practised by many books of this kind, formerly made public; from which, although I received much advantage, yet without prejudice to their worthy Authors, I could never find in them that height of judgment and reason, manifested in this, as I may call it, Epitome of Angling.”

Isaac Walton.

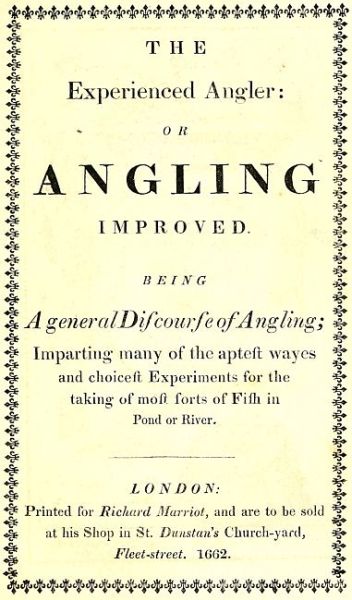

LONDON:

SEPTIMUS PROWETT, OLD BOND STREET,

AND

THOMAS GOSDEN, BEDFORD STREET,

COVENT GARDEN.

1825.

TO HIS INGENIOUS FRIEND THE AUTHOR,

ON HIS

ANGLING IMPROVED.

Honoured Sir,

Though I never, to my knowledge, had the happiness to see your face, yet accidentally coming to a view of this discourse before it went to the press; I held myself obliged in point of gratitude for the great advantage I received thereby, to tender you my particular acknowledgment, especially having been for thirty years past, not only a lover but a practiser of that innocent recreation, wherein by your judicious precepts I find myself fitted for a higher form; which expression I take the boldness to use, because I have read and practised by many books of this kind, formerly made public; from which, although I received much advantage in the practice, yet, without prejudice to their worthy Authors, I could never find in them that height of judgment and reason, which you have manifested in this, as I may call it, epitome of Angling; since my reading whereof I cannot look upon some notes of my own gathering, but methinks I do puerilia tractare. But lest I should be thought to go about to magnify my own judgment, in giving yours so small a portion of its due, I humbly take leave with no more ambition than to kiss your hand, and to be accounted

Your Humble and

Thankful Servant,

ISAAC WALTON.

MEMOIR

OF

COL. ROBERT VENABLES.

Of the author, Colonel Robert Venables, but little is known, and that little not very satisfactory. Among the Manuscripts in the Harleian Collection, are several Pedigrees of the Families of Venables: particularly in that marked ‘1393, f. 39,’ where the great ancestor of Venables is stated to have been Gabriel Venables, who came over with William the Conqueror, and afterwards received the Earldom of Kinderton, in Cheshire, from Hugh Lupus. Another Manuscript, No. 2059, recites a deed from one of the family, residing at Northwich, as early as anno 1260.

But reverting more immediately to the subject of this notice, the Harleian Manuscript ‘1993, f. 52.’ contains a paper, partly in the hand writing of Colonel Venables, which furnishes a detailed account of the time he served in the Parliament Army in Cheshire, and of the pay due to him from 1643 to 1646. From this authority it appears, that in 1644 he was made Governor of Chester; and from other sources we learn, that in 1645, he was Governor of Tarvin. In 1649, he was Commander in Chief of the Forces in Ulster, in Ireland, and had the towns of Lisnegarvy, Antrim, and[ii] Belfast delivered to him. His actions in the sister kingdom, are recited in an excessively rare book, entitled ‘A History, or Briefe Chronicle of the Chief Matters of the Irish Warres,’ printed at London, in 1650, 4to.

From this period no trace of him is discoverable, and it is probable that he was unemployed, until Cromwell, at the instigation of Cardinal Mazarine, fitted out a fleet for the conquest of Hispaniola, in 1654, when Colonel Venables, and Admiral Penn, were invested with the command of that armament. It appears however, to have been undertaken in an evil hour, and a contemporary manuscript in the Editor’s possession, and which has not been printed till now, furnishes the most valuable information respecting the disasters which they underwent. The manuscript is evidently addressed to some one, and it commences:—

Sir,

The opinion I was of, in that discourse we had at——, touching the Western Voyage of the English in 1654. I have been since abundantly confirmed in, by the perusal of some Papers and Memoirs of a Person of no mean character throughout that action, whose employment gave him opportunity to know all, at least the most considerable of its transactions, and I have reason to believe, by the account I have had of him, he was sufficiently able to take his measures of them aright. The substance of what I gathered from his notes, and [iii]from orders of the Councils of War, as well of the Commissioners, and from declarations of the Army, and letters from persons who held posts in that Army, all which I had the favour to inspect, I will here faithfully present you with. For indeed I am very desirous to beget in you the same sentiments of that affair, which I have, I think, with good reason entertained. And the rather, because the course you design to steer will give you opportunity of converse with those persons, who are most inquisitive after, as most concerned to know, matters of this nature; and yet, perhaps, under greater mistakes in this particular, than any others.

It was doubtless, none of the least ends which that fox, Oliver, had in that design; to rid himself of some persons whom he could neither securely employ, nor safely discard: which end seemed chiefly to influence the managery of the whole business, as you will perceive by the story.

It was pretended at first it should be carried on with great secrecy; but the delay was so great, and thereby the notice of it so public, as alarmed the Spaniards to provide for their reception. Venables moved to have had soldiers for this service drawn out of the Irish Army, which he had been well acquainted with; but it was peremptorily denied, and they were appointed to be drawn out of the army in England, whose officers generally gave out of their several companies the rawest and worst armed they had. And these being hastily shipped off at Portsmouth, the chief of the land [iv]officers, who were to go with them, were never suffered to rendezvous, or see together till they came to Barbadoes, where they arrived January 29, 1654-5. Here they found them to want 500 of the number promised, being but 2500 men in all, and not above half of those well armed. And though they had been assured they should find 1500 arms at Barbadoes, yet they could not there make up 200 arms; and all the help they had was to make half-pikes, wherein, and in fixing those arms they had, they met with some difficulty, their smith’s tools being on board their store ships, which were not yet come to them. For those ships took in their provisions at London, and they were promised should meet them at Portsmouth, and there they were told that they should reach them at Barbadoes; which yet they did not, nor till at least six months after. So that much of the provision, which was defective at first taking in, was by that time grown very corrupt.

While they staid at Barbadoes it was plainly discovered that not only the inhabitants there were against the general design, but that the seamen bandied against the land-men, and gave them not that assistance and furtherance which was in their power. Notwithstanding the land-soldiers great want of arms, Penn and the sea-officers would not be prevailed with to furnish them with any, nor so much as to lend them a pike or a lance; though he had above 1200 of the former to spare, and great numbers of the latter were put aboard on purpose for the army to kill cows with. At their leaving that place, the seamen had their full allow[v]ance of victuals and brandy on their fish-days; when the land-men had for four days in the week, but half their proportions, the other three fish-days, only bread and water.

In this condition they left Barbadoes, March the last, 1655. By the way they touched at St. Christopher’s, whence they took aboard a regiment of soldiers, who had been raised in that island; among whom they were pleased to find two Englishmen, Cox and Bounty, who had then lately come from Hispaniola, where the former had lived twelve years, and served as a gunner in the castle of St. Domingo.

Now when they were far out at sea, a dormant commission, not before discovered, was broken up, whereby two others, Winslow and Butler, were joined in commission, and equally empowered, with the two generals Venables and Penn; and nothing was to be done without their joint advice and orders: yea, when on shore, Venables, (though he had by his own commission a command of all the land forces in chief,) yet he was by this commission restrained from acting any thing without the concurrence of the commissioners, or such one, or more, of them as was present with him. A great debate now arose between these Commissioners about dividing the lion’s skin, before he was caught, which occasioned much heat among them, and gave great dissatisfaction to the soldiers. There was a clause in this joint commission, that all prizes and booties got by sea or land should be at the disposal of the commissioners, for the advance of the present service and design.[vi] This the greater part of the Commissioners judged was to be extended to all sorts of pillage. Venables thought it was meet to interpret it only of ships and their lading, and large quantities of treasure and goods in towns and forts: and that to extend it to all booty, by whomsoever got, would be both impossible to put in execution, and hugely disgustful to the soldier to attempt. When he could not prevail to have his sense of this hard clause pass, he propounded a middle way: that none should conceal or retain any arms, money, plate, jewels, or goods, to his private use, on pain of forfeiting his share in the whole, &c. but that all should be brought in unto officers, chosen by mutual consent, and sworn to be faithful therein; and then distribution to be made to each man according to his quality and desert. And agreeably thereto he framed both an order for the Commissioners to sign, and a declaration for the officers of the army to subscribe, testifying their submission to the order, and that they would endeavour that all under their respective commands should observe it; and further, that when their several pays should be discharged, they would acquiesce in the disposal of the surplus by the Commissioners, either in rewards to the deserving, or in necessaries for the public service, &c. This the Commissioners so far approved as to appoint it to be writ fair, and copies made, for each regiment one. The officers and soldiers were also content, and satisfied therewith; but when it came to the point, only Venables and Penn signed the order, and so the declaration [vii]fell too. Which surely was a great oversight in the Commissioners who refused, for by this means they would have soothed and pleased the army with a fair flourish, but in reality had by common consent obtained the whole to be at their own disposal.

Then the Commissioners propounding a fortnight’s pay to the soldiery instead of the pillage of St. Domingo, the chief city of Hispaniola, Venables prevailed with them to be content with six weeks pay. But when that would not be yielded to by the Commissioners, he requested the officers and soldiers, without standing on any terms, to venture their lives with him, and trust to Providence for the issue and reward; which they agreed unto for that time, but withal many of them declared they would never strike stroke more, where there should be commissioners thus to controul the general and soldiers, but would forthwith return for England.

By this time they drew near to Hispaniola; the land general and officers were for running the fleet into the harbour of St. Domingo, but they of the fleet opposed it, Penn assured them there was a bomb which would hinder their advance; though Cox, being called in, said he believed there was none, yea, declared among the soldiers, that he conceived the harbour was incapable of any thing of that kind. During the debate about this matter, Captain Crispin, who commanded a frigate, offered to venture the running in of his vessel into the harbour, and bore up so near as to fire on the castle of St. Domingo, and discovered nothing of any [viii]bomb, or other obstruction, as he after declared; yet was he commanded off by Penn. Then they of the army resolved at a council of war, among other things, that one regiment staying to land to the east of the city, which fell by lot to Col. Butler; the rest of the army should land some miles distant at the river Hine, the place where Drake landed, and force the fort which stood at the mouth of it: yet they of the fleet carried the army westward to Point Nizas, whence they had to march above thirty miles north to the city, through a strange, woody, and very hot country, where no water could be found, and many of them had but two days victuals delivered them from the fleet, none above three. The mean while Cox, who was designed to be guide to the land forces, had been sent by Penn a fishing, and was not returned, nor could be heard of at the landing; in the want of him, Venables desired to have had Bounty, or Fernes, who also was acquainted with the Island, but Penn would not part with either of them.

So soon as they were landed, the Commissioners appointed the publishing of an order against plundering, and that all pillage should be brought in unto a common store; but therein gave Venables liberty to promise the soldiers, in case the city should be taken by storm, six weeks pay, or a moiety of the pillage, excepting arms, ammunition, and such like: or in case it should be surrendered, three weeks pay, or a third of the pillage. This was signed by Penn, Winslow, and Butler.

The soldiers, who were before disgusted, were by [ix]this exasperated into mutiny. A sea regiment, which came ashore, was the first that laid down arms; and by their example all the rest. And much ado Venables had in any sort to pacify them; at last they were persuaded to march, though with much discontent: and in that unsatisfied, mutinying humour, they marched four days without any guide, tormented with heat, hunger and thirst, when they might have landed at the place best fitted for attack, fresh on the first day.

The mean while Col. Buller had, according to his order, essayed to land eastward of the city; but finding no place for it, was afterwards appointed by the Commissioners to land at Hine river, but with express order not to stir thence till the army came up. Accordingly he landed on Monday, April 17, and with him Col. Houldip, and 500 of his regiment, having Cox in their company. At their approaching, the Spaniards abandoned the fort near the river mouth, leaving two great guns dismounted, and the walls, as much as their haste would allow, dismantled. This encouraged Buller to pursue them towards the city; but in the narrow passes of the woods, he missed his way, and came to some plantations vacant and waterless, purposing there to expect the army: yet next morning sent out a party to descry the fort St. Hieronimo, who exposed themselves too much to view, and alarmed the Spaniards.

Soon after Buller had marched from the fort where he landed, the army came to the other side of the river Hine, but could not pass it, wanting a guide to shew them the ford, which induced them to march[x] five miles up the river, seeking one; and at last, the day being spent, they were forced to quarter that night without either food or good fresh water. Next day, after three miles march more, a ford was found, and the river passed, and they had not gone far, when a farm with water chancing in their way, gave them great refreshment. Where making a halt, and consulting what was meet for them to do, they resolved to go to the fleet at the harbour for provision for their hungry men; to which an Irishman, then brought in by some stratagem, offered to guide them the shortest way. And though Venables was jealous of him, and would not have heeded him, yet Commissioner Butler would have him followed, and charged them by virtue of their instructions so to do; and follow him they did, till a fruitless march three or four miles the contrary way, proved him a liar. At last, hearing Buller’s drums, they made towards him, and met with him near the strong fort, St. Hieronimo, a regular and well fortified pier, in the road to the city. Venables being at this time in the van, which he had led all their long march, went himself with the guide, for the officers being all very weary, were willing to be excused; to search the woods before the army, and discovered the Spaniards in ambush, before they stirred; who presently, thereupon advancing, the English forlorn immediately fired upon them too hastily and at too much distance, which gave the Spaniards advantage to fall in with them with their lances, before they could charge again, and so gave them some disorder, and killed some officers; among[xi] whom, to their great loss, Captain Cox perished; but the English quickly recovering themselves, beat the enemy back, and pursued them within cannon shot of the city.

These weary spent men, drawn on by their eagerness to this skirmish, forgot that thirst, which, so soon as the pursuit was over, they fainted under; many, both men and horse, dying on the place for very thirst. Venables, being much endangered at this action in the route of the forlorn, was earnestly entreated and pressed by the officers not to hazard himself so again, but to march with the body. This over, they called a council of war, where, considering their want of match, which was spent to three or four inches, and of provision, which all had been without two days, and some longer, and had no other sustenance but what fruits the woods afforded; they once again resolved to return to their ships, which the Irishman’s relation, and Commissioner Butler’s peremptory charge had diverted them from, and caused them to lose many men and horses with thirst and hunger in marching back that way, which otherwise had been saved.

Some four or five days were spent at the harbour in refreshing the tired, fainting soldiery, and taking new resolutions for a second march and charge. Wherein, they could not well be more speedy, for Penn and Winslow, two of the Commissioners, keeping at sea with the fleet, (which rode some leagues off from the fort by Hine river,) and refusing to come ashore, Venables, though then ill with the flux, was forced to make many[xii] dangerous passages to and from them in small Brigantines for their concurring counsel, which often differing, caused much delay, and gave the Spaniards time to gather heart and strength for better defence. The common soldiers this mean while, were but ill treated from the fleet. Those that by sickness or wounds in the last action, were disabled for further service, (they having no tents or carriages ashore to dispose of them in) were sent a ship board, and there they were kept forty-eight hours on the bare decks, without either meat, drink, or dressing; that worms bred in their wounds, which would soon be in that hot country, and some of them by that very usage perished, particularly one Captain Leverington, a brave man. The others ashore being furnished with the worst, and most mouldy of the biscuits; no beef, altogether unwatered, and no brandy to cheer their spirits; had their thirst greatly enraged, which that river, even where it was fresh, yet coming from copper, rather augmented than assuaged. And this usage and diet, together with the extraordinary rains that fell on their unsheltered bodies, cast them all into violent fluxes; sorry encouragements and preparatives for a second attempt, which yet was at last resolved on.

Tuesday, April 25. They had with them one mortar-piece, and two drakes, in the drawing whereof, and carrying of mattocks, spades, and calabashes of fresh water, the strongest men were employed till all were reduced to almost a like weakness; and the cruel sea-officers offered them no more brandy with them, than would be about a good spoonful to a man. One night[xiii] they lodged in the woods; the next day they advanced toward the fort of St. Hieronimo, which they resolved to attack, being in their way, about a mile from the town, and not fit to leave at their backs.

April 26. Adjutant-General Jackson had this day the command of the forlorn, consisting of four hundred men; in the van whereof, he put Captain Butler, and himself brought up the rear. Also he marched without any wings on either hand to search the woods, and discover ambushes, which was expressly contrary both to order, and their daily practice throughout their whole march from Point Nizas. With the forlorn thus managed, and all ready to faint with thirst, having marched eight miles without water, in a narrow pass in the thick woods, where but six could well march abreast, they fell into an ambuscado of the Spaniards, who suffered the forlorn all to march within them, and then charged them both in van and flank. Captain Butler with the van undauntedly received the charge, and in order, fired again, and all of them stood till he fell; but the rear ran away without abiding a charge, Jackson himself being the first man that turned his back. Venables, his regiment, with Ferguson his Lieutenant Colonel in the head of them, being next, charged their pikes on Jackson and his flying men; but they being too well resolved to be stopt, first routed that regiment, and then most of Heanes’s regiment. These all came violently upon the sea regiment, which was led by Venables and Goodson, then Vice-Admiral, who with their swords forced the runaways into the woods, choosing rather to kill, than[xiv] be routed by them. At the same time, which much advantaged them, the rear part of Heanes’s regiment having opened and drawn themselves on either side into the woods, counterflanked the Spaniards, and charged their ambuscadoes, which the Spaniards perceiving, and that the sea regiment advanced unrouted, retreated. The English then charged them afresh, pursued them, and beat them back beyond the fort, and so regained the bodies of the slain, and the place of fight, which ground they kept the rest of that day, and the night following, though the guns from the fort all that time, as well as during the skirmish, played hotly upon them, and killed sometimes eight or nine at a shot.

In this action, the valiant Heanes, major general, and Ferguson before mentioned, and such other officers of those regiments as knew not what it was to fly, fell by the swords and lances of the Spaniards; and many common soldiers with them.

The English now about the fort, Venables commanded to assault it, and that to that end, they should play the mortar-piece against it, and had it drawn up for that purpose. But he himself being before brought very low with his flux, the toil of the day had so far spent him, that he could not stand or go but as supported by two; and in that manner he moved from place to place, to encourage the men to stand, and to plant it. But the latter he could not prevail on, neither by commands, entreaties, or offers of rewards. At last, fainting among them, he was carried off, and Fortescue, who succeeded major general, in the stead of Heanes, took[xv] the command, who laboured much also to get the mortar-piece planted, but without any effect. For the spirits of the English soldiers were so sunk, by their want of water and provisions, the excessive heat, and their great sickness occasioned thereby, that not any one upon any account could be got to plant it. Night drawing on, whilst the soldiers buried the dead, they called a council of war of all the colonels, and field officers, where it was agreed, no man dissenting, that the difficulties of thirst were not to be overcome, and that if they staid there, though they beat the enemy, they must perish for want of water. Whereupon, it was resolved to retreat next morn at sun rise, if the mortar-piece could not play before. The morning came, and no place found to plant the mortar-piece, nor men that would work, the guns from the fort beating them off from every place, they buried their shells, drew off their mortar-piece, drakes, spades, &c. and making a strong rear-guard, retreated to their ships at the harbour.

In this attempt against the fort, the common soldiers shewed themselves so extremely heartless, that they only followed their officers to charge, and left them there to die, unless they were as nimble footed as themselves. And of all others, the planters, whom they had raised in those parts, were the worst, being only forward to do mischief; men so debauched as not to be kept under discipline, and so cowardly as not to be made to fight.

Being come to the harbour, they betook themselves to the examination and punishment of the cowardice of[xvi] some, and of divers miscarriages and disorders of others. Jackson was accused.

1. That contrary to express order, he had marched without any to search the woods.

2. That he took but few pikes, and those he placed in the rear, as if he feared only his own party.

3. That he put others in the van, and himself brought up his rear.

4. That he was the first man that run, and when there was a stop, he opened his way with both hands to get foremost.

These being proved before a council of war, he was sentenced to be cashiered: his sword broken over his head: and he made a swabber to keep the hospital ship clean, which was executed accordingly. And well it might, for sure it was much gentler than he deserved.[1]

[1] The Revolution in England, having necessarily raised great numbers of individuals to the rank of officers, from the lowest stations, a kind of equality reigned among the soldiery. The following instance of that equality is a curious fact, and displays equally the republican manners, and uncivilized spirit of that age.

Adjutant-General Jackson, who had been the first to run during the engagement, was tried by a court-martial, convicted of cowardice, cashiered with ignominy, and condemned to serve as a swabber on board the hospital ship!!—General Venables, with a naiveté common to the writers of that age, which, though seldom respectable, is always pleasing, makes the following observations on this sentence. After mentioning the terms of it, he adds, “And justly,—for the benefit of the sick and wounded, who owed their sufferings to his mis-behaviour. A sentence too gentle for so notorious an offender, against whom some of the Colonels made a complaint for whoring and drunkenness at Barbadoes; but not being able to prove the fact, he escaped; though considering his former course of life, the presumptions were strong, he and a woman lodging in one chamber, and not any other person with either, which was enough to induce a belief of his offence,[xvii] he, having two wives in England, and standing guilty of forgery; all which I desired Major-General Worsley in joining with me to acquaint his Highness (Cromwell) with, that he might be taken off, and not suffered to go with me, lest he should bring a curse on us, as I feared. But his Highness would not hear us.—After this, both perjury and forgery were proved against him, in the case of a Colonel or General, at Barbadoes, ruined by him, by that means. Upon the complaint, and with the advice of the said General, I rebuked him privately; which he took so distastely, that as it afterwards appeared, he studied and endeavoured nothing but mutiny; and found fit matter to work upon, as with an army that has neither pay nor pillage, arms nor ammunition, nor victuals, is not difficult: but this I came to understand afterwards.”—Venables’ Narrative.

A serjeant also, who in the skirmish threw down his arms, crying, “gentlemen, shift for yourselves, we are all lost;” and ran away, was hanged. Other offences met with meet punishments.

Now the business was, to consult what was next to be done. Commissioner Winslow came ashore to press for a third attempt, which the officers of the army would not be persuaded to undertake; for they all, with one consent, declared they would not lead on their men, saying, they would never be got to march up to that place again; or if they did, they would not follow them to a charge, but they freely offered to regiment themselves, and to live and die together. Whereupon, the Commissioners judging it needful to try to raise the soldiers by some success in a smaller exploit, resolved to attempt some other plantation, and at last Jamaica was pitched on to be the place.

During this debate, the soldiers on land were in great want and streights; for though all their provision was spent, yet Penn forbade any supply to be sent them [xviii]from the fleet, that their scarcity, yea, famine, grew so high, that they ate all the horses, asses, and dogs in the camp; yea, some ate such poisonous food, that they fell dead instantaneously. But beyond all this, a motion was made, that setting sail for England, the soldiers, whom they of the fleet usually called dogs, should be left ashore to the mercy of the enemy; which motion, Venables in behalf of the land-men, stiffly opposed, detesting so great inhumanity. Yet the soldiers were so apprehensive of such a trick, that when they came to go aboard, their officers would not suffer the sea regiment, which was on shore, to be first shipped, lest they should be so left in the lurch.

The fifth day after they set sail from Hispaniola, they came before Jamaica, where remembering the cowardice of the soldiers, which if not experienced, would scarce have been believed so great in Englishmen, they published an order against runaways, that the next man to any that offered to run, should kill him, or be tried for his own life. Which done, Penn and Venables placed themselves in the martin galley, and sailed up to the fort, and played upon it with their great guns, as it did upon them all the time that the soldiers were getting into the flat bottomed boats. Which so soon as they had done, a fresh gale of wind arose, which drove the boats directly upon the fort; this the Spaniards seeing, and a major, their best soldier, being disabled by a shot from the martin galley, they were so daunted that they took to their heels, and left the fort to the English. The army finding fresh water here, and fearing[xix] to advance further, lest (it being then three o’clock) they should in a strange country, and without guides, be inconveniently overtaken with night, in some place where they might be more exposed to the enemies assaults, and beating up their quarters, they resolved to stay at that fort, and landing place that night, and rest their weak and sick men. Next morning they marched early, and about noon, came to a Savanna near the chief town of the island, St. Jago, where two or three Spaniards appeared at a distance, making some signals of civility. The like number of English was sent to them, upon which they rode away, but making a stand, one was sent to them to know what they desired; they answered, ‘a treaty.’ The English, replied, they would treat when they saw any impowered thereunto. After some time, a priest and a major were sent from the town. The English as an introduction to the treaty, first demanded to have one hundred cows, with cassavia bread proportionably, sent them immediately; and so daily while the treaty lasted. Cows were sent in, but no bread; that being, as they said, scarce with them. Whereupon Commissioners were appointed on both sides to treat, and in conclusion, the Spaniards yielded to render the island and all in it, and all ships in the havens unto the English; the Spaniards and inhabitants having their lives granted them, and such as would, to be at liberty by a certain day to depart the island, but to take nothing, save their wearing apparel, and their books, and writings with them.

Articles of agreement to this purpose being signed on both sides, the English for their true performance, demanded and had the Governor of the island, and the Spanish Commissioners for hostages; and so they seemed to be in a fair way of settlement, with little ado. Yet after this, a colonel among the Spaniards, who had no good will to the governor, and was a man of interest among the commonalty, persuaded them to drive all the cattle away to the mountains, and thereby starve out the English. Which being understood, one of the Spanish Commissioners, Don Acosta, a Portuguese, sent his priest, an understanding negro, to dissuade them from their purpose. But they being resolute, and instigated by the colonel, hanged the negro, which enraged Acosta, and to be revenged on them for the death of his priest, whom he loved, advised the English that the cattle must necessarily, in a while, come down into the plains to drink. And by his direction, the English recovered the cattle, and prevented their mischief.

After this an order was published, that no private soldier should go out to shoot cows, which was done for two reasons; first, because the soldiers straggling about and going single, were often knocked on the head; and next, because they maimed and marred more than they killed; for it being a very woody country, unless a beast was shot dead, which was but seldom done, it escaped its pursuer, though it often died of its wounds; and many hundreds were found in the woods that had been so slain, and very many running about hurt and wounded. Thus great destruction was made of them, to no bodies advantage,[xxi] that in the end, they must need have smarted for the want of those which had been thus lavishly spoiled and lost. Besides, the cattle which at their first coming, were seen by great numbers, and so tame, that they might have been easily managed and driven up, were so affrighted by the soldiers disorderly chasing and shouting after them, that they were now grown wild and untractable. And therefore, commanded parties with their officers were thenceforwards ordered out to fetch in cattle as there was need; and by that means they were sufficiently supplied, and no waste made. But bread they still much wanted, for their own store ships not having yet reached them, they had no bread but what came from the fleet, whence it was very sparingly sent, and scarce any but what was bad and corrupt. I find it noted, that in seventeen days time, they had but three biscuits a man; that they could seldom get any thing from the fleet, unless the Commissioner would sign remittances for greater proportions than were indeed delivered; that of above a hundred tuns of brandy, which was put on board in England for this service, and above thirty tuns more taken in at Barbadoes, it could not be observed, that the land-men ever had ten tuns to their use, between the middle of April and the middle of July. So that the soldiers being put to feed wholly on fresh flesh and fruits, without either brandy, or any kind of bread; and that after they had been long at a scanty diet, upon salt meats, it hugely increased sickness among them, insomuch, that after their coming to Jamaica,[xxii] they died by fifty, sixty, and sometimes a hundred in a week, of fevers and fluxes.

Their streights and distresses being so great, put them on necessity of hastening to distribute the soldiers to plant for themselves, that they might have somewhat of their own to subsist on, without depending on the courtesy of others. And accordingly several of the regiment were dispersed into several places; but though such was their occasion, each for his particular private goods and necessaries, yet they could not without much difficulty, and many fruitless labours, obtain to have their trunks and stuff ashore to them; and many never had them at all, but they were carried back with the fleet into England.

Some discontents grew among the great ones. Venables telling Commissioner Butler of his drunkenness, which he was often guilty of, and in that condition, had discovered too much to the Spaniards, and reproving him for it, made him his enemy, and to practise against him, and thenceforwards he endeavoured to make factions, and raise disgusts in the army.

Penn gave notice of his intentions, suddenly to set sail for England, and would not be dissuaded.

Here the manuscript ends, but in continuation, Oldmixon[2] observes, that “they arrived in England in September, when they were both imprisoned for their scandalous conduct in this expedition, which would[xxiii] have been an irreparable dishonour to the English Nation, had not the island of Jamaica, which chance more than council, bestowed upon them, made amends for the loss at Hispaniola.” Their imprisonment would seem to have received general approbation, as in certain Passages of Every Dayes Intelligence, from Sept. 21 to 28, 1655, published by authority, it is said, “Gov. Penn and Gen. Venables, would be petitioning his Highnes, the Lord Protector for their enlargement out of the Tower again; but it is a little too soon yet; it were not amiss that they stayed till we hear again from the West Indies.” His subsequent liberation, and the particulars of his life after this period, with the time of his decease, and his residence when he quitted the cares of this world, are alike unknown to the writer, and have baffled all attempts at discovery.

[2] British Empire in America, 1740, 8vo.

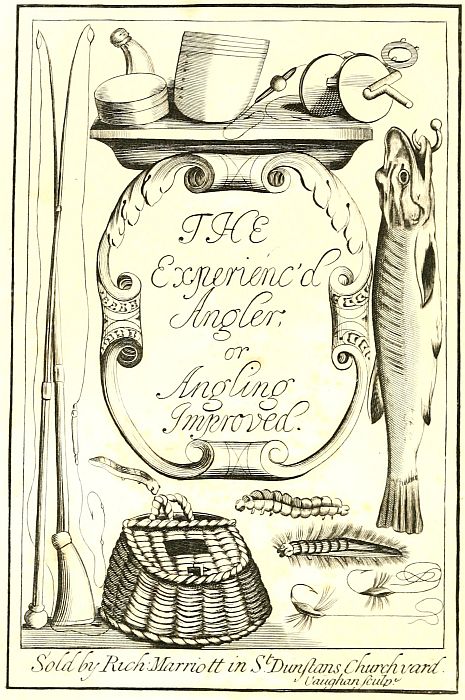

THE Experienc’d Angler, or Angling Improved.

Sold by Rich: Marriott in St Dunstans Church-yard.

Vaughan Sculp.

PREFATORY ADDRESS

TO

THE READER,

FROM

THE EDITION OF

MDCLXII.

Delight and Pleasure are so fast rivetted and firmly rooted in the heart of man, that I suppose there are none so morose or melancholy, that will not only pretend to, but plead for an interest in the same, most being so much enamoured therewith, that they judge that life but a living death, which is wholly deprived or abridged of all pleasure; and many pursue the same with so much eagerness and importunity, as though they had been born for no other end, as that they not only consume their most precious time, but also totally ruin their estates thereby: for in this loose and licentious age, when profuse prodigality passes for the characteristical mark of true generosity and frugality, I mean not niggardliness; is branded with the ignominious blot of baseness. I expect not that this under-valued subject, though it propound delight at an easy rate, will meet with any other entertainment than neglect, if not contempt, it being an art which few take pleasure in, nothing passing for noble or delightful which is not costly; as though men could not gratify their senses, but with the consumption of their fortunes.

Hawking and Hunting have had their excellencies celebrated with large encomiums by divers pens, and although I intend not any undervaluing to those noble recreations,[ii] so much famed in all ages and by all degrees, yet I must needs affirm, that they fall not within the compass of every ones ability to pursue, being as it were only entailed on great persons and vast estates; for if meaner fortunes seek to enjoy them, Actæon’s fable often proves a true story, and these birds of prey not seldom quarry upon their masters: besides those recreations are most subject to choler and passion, by how much those creatures exceed a hook or line in worth: and indeed in those exercises our pleasure depends much upon the will and humour of a sullen cur or kite, (as I have heard their own passions phrase them); which also require much attendance, care and skill to keep her serviceable to our ends. Further, these delights are often prejudicial to the husbandman in his corn, grass and fences; but in this pleasant and harmless Art of Angling a man hath none to quarrel with but himself, and we are usually so entirely our own friends, as not to retain an irreconcilable hatred against ourselves, but can in short time easily compose the enmity; and besides ourselves none are offended, none endamaged; and this recreation falleth within the capacity of the lowest fortune to compass, affording also profit as well as pleasure, in following of which exercise a man may employ his thoughts in the noblest studies, almost as freely as in his closet.

The minds of anglers being usually more calm and composed than many others, especially hunters and falconers, who too frequently lose their delight in their passion, and too often bring home more of melancholy[iii] and discontent than satisfaction in their thoughts; but the angler, when he hath the worst success, loseth but a hook or line, or perhaps, what he never possessed, a fish; and suppose he should take nothing, yet he enjoyeth a delightful walk by pleasant rivers in sweet pastures, amongst odoriferous flowers, which gratify his senses and delight his mind; which contentments induce many, who affect not angling, to choose those places of pleasure for their Summer’s recreation and health.

But, peradventure, some may alledge that this art is mean, melancholy, and insipid; I suppose the old answer, de gustibus non est disputandum, will hold as firmly in recreations as palates, many have supposed Angling void of delight, having never tried it, yet have afterwards experimented it so full of content, that they have quitted all other recreations, at least in its season, to pursue it; and I do pursuade myself, that whosoever shall associate himself with some honest expert angler, who will freely and candidly communicate his skill unto him, will in short time be convinced, that Ars non habet inimicum nisi ignorantem; and the more any experiment its harmless delight, not subject to passion or expence, he will probably be induced to relinquish those pleasures which being obnoxious to choler or contention so discompose the thoughts, that nothing during that unsettlement can relish or delight the mind; to pursue that recreation which composeth the soul to that calmness and serenity, which gives a man the fullest possession and fruition of himself and[iv] all his enjoyments; this clearness and equanimity of spirit being a matter of so high a concern and value in the judgments of many profound Philosophers, as any one may see that will bestow the pains to read, de Tranquilitate Animi, and Petrarch de Utriusque Conditionis Statu: Certainly he that lives Sibi et Deo, leads the most happy life; and if this art do not dispose and incline the mind of man to a quiet calm sedateness, I am confident it doth not, as many other delights; cast blocks and rubs before him to make his way more difficult and less pleasant. The cheapness of the recreation abates not its pleasure, but with rational persons heightens it; and if it be delightful the charge of melancholy falls upon that score, and if example, which is the best proof, may sway any thing, I know no sort of men less subject to melancholy than anglers; many have cast off other recreations and embraced it, but I never knew any angler wholly cast off, though occasions might interrupt, their affections to their beloved recreation; and if this art may prove a Noble brave rest to thy mind, it will be satisfaction to his, who is thy well-wishing Friend.

OR

PROFIT AND PLEASURE UNITED.

WHEN TO PROVIDE TOOLS, AND HOW TO MAKE THEM.

For the attaining of such ends which our desires propose to themselves, of necessity we must make use of such common mediums as have a natural tendency to the producing of such effects as are in our eye, and at which we aim; and as in any work, if one principal material be wanting, the whole is at a stand, neither can the same be perfected: so in Angling, the end being recreation, which consisteth in drawing the fish to bite, that we may take them; if you want tools, though you have baits, or baits, though you have tackle, yet you have no part of pleasure by either of these singly: nay, if you have both, yet want skill to use[2] them, all the rest is to little purpose. I shall therefore first begin with your tools, and so proceed in order with the rest.

1. In Autumn, when the leaves are almost or altogether fallen, which is usually about the Winter solstice, the sap being then in the root; which about the middle of January begins to ascend again, and then the time is past to provide yourself with stocks or tops: you need not be so exactly curious for your stocks as the tops, though I wish you to choose the neatest taper-grown you can for stocks, but let your tops be the most neat rush-grown shoots you can get, straight and smooth; and if for the ground-rod, near or full two yards long, the reason for that length shall be given presently; and if for the fly, of what length you please, because you must either choose them to fit the stock, or the stock to fit them in a most exact proportion; neither do they need to be so very much taper-grown as those for the ground, for if your rod be not most exactly proportionable, as well as slender, it will neither cast well, strike readily, or ply and bend equally, which will very much endanger your line. When you have fitted yourself with tops and stocks, for all must be gathered in one season, if any of them be crooked, bind them all together, and they will keep one another straight; or lay them on some even-boarded floor, with a weight on the crooked parts, or else bind them close to some straight staff or pole; but before you do this you must bathe them all, save the very top, in a gentle fire.

For the ground angle, I prefer the cane or reed before all other, both for its length and lightness: and whereas some object against its colour and stiffness, I answer, both these inconveniences are easily remedied; the colour by covering it with thin leather or parchment, and those dyed into what colour you please; or you may colour the cane itself, as you see daily done by those that sell them in London, especially if you scrape off the shining yellow outside, but that weakens the rod. The stiffness of the cane is helped by the length and strength of the top, which I would wish to be very much taper-grown, and of the full length I spoke of before, and so it will kill a very good fish without ever straining the cane, which will, as you may observe, yield and bend a little; neither would I advise any to use a reed that will not receive a top of the fore-mentioned length. Such who most commend the hazel-rod, (which I also value and praise, but for different reasons), above the cane; do it because, say they, the slender rod saveth the line; but my opinion is, that the equal bending of the rod chiefly, next to the skill of the Angler, saveth the line, and the slenderness I conceive principally serveth to make the fly-rod long and light, easy to be managed with one hand, and casteth the fly far, which are to me the considerations chiefly to be regarded in a fly-rod; for if you observe the slender part of the rod, if strained, shoots forth in length as if it were part of the line, so that the whole stress or strength of the fish is borne or sustained by the thicker part of the rod, which is no stronger than the stronger[4] end of such a top as I did before direct for the ground-rod, and you may prove what I say to be true, if you hang a weight at the top of the fly-rod, which you shall see ply and bend, in the stiff and thick part, more or less as the weight is heavy or light. Having made this digression for the cane, I return to the making up of the top, of which at the upper or small end, I would have you to cut off about two feet, or three quarters of a yard at most; and then piece neatly to the thick remaining part, a small shoot of black thorn or crab tree, gathered in due season as before, fitted in a most exact proportion to the hazel, and then cut off a small part of the slender end of the black thorn or crab tree, and lengthen out the same with a small piece of whale-bone, made round, smooth, and taper; all which will make your rod to be very long, gentle, and not so apt to break or stand bent as the hazel, both which are great inconveniences, especially breaking, which will force you from your sport to mend your top.

2. To teach the way or manner how to make a line, were time lost, it being so easy and ordinary; yet to make the line well, handsome, and to twist the hair even and neat, makes the line strong. For if one hair be long and another short, the short one receiveth no strength from the long one, and so breaketh, and then the other, as too weak, breaks also; therefore you must twist them slowly, and in the twisting, keep them from entangling together, which hinders their right plaiting or bedding. Further, I do not like the mixing of silk or thread with hair, but if you please, you may,[5] to make the line strong, make it all of silk, or thread, or hair, as strong as you please, and the lowest part of the smallest lute or viol strings, which I have proved to be very strong, but will quickly rot in the water, you may however help that in having new and strong ones to change for those that decay; but as to hair, the most usual matter whereof lines are made, I like sorrel, white, and grey best; sorrel in muddy and boggy rivers, and both the latter for clear waters. I never could find such virtue or worth in other colours, to give them so high praise as some do, yet if any other have worth in it, I must yield it to the pale or watery green, and if you fancy that, you may dye it thus. Take a pottle of allum water, and a large handful of marigolds, boil them until a yellow scum arise, then take half a pound of green copperas, and as much verde-grease, beat them into a fine powder, then put those with the hair into the allum water, set all to cool for twelve hours, then take out the hair and lay it to dry. Leave a bought, or bout, at both ends of the line, the one to put it to, and take it from your rod, the other to hang your lowest link upon, to which your hook is fastened, and so that you may change your hook as often as you please.

3. Let your hooks be long in the shank, and of a compass somewhat inclining to roundness, but the point must stand even and straight, and the bending must be in the shank; for if the shank be straight, the point will hang outward, though when set on it may stand right, yet it will after the taking of a few fish,[6] cause the hair at the end of the shank to stand bent, and so, consequently cause the point of the hook to lie or hang too much outward, whereas upon the same ground the bending shank will then cause the point of the hook to hang directly upwards.

When you set on your hook, do it with strong but small silk, and lay your hair upon the inside of the hook, for if on the outside the silk will cut and fret it asunder; and to avoid the fretting of the hair by the hook on the inside, smooth all your hooks upon a whetstone, from the inside to the back of the hook, slope ways.

4. Get the best cork you can without flaws or holes, as quills and pens are not of sufficient strength in strong streams; bore the cork through with a small hot iron, then put into it a quill of a fit proportion, neither too large to split it, or so small as to slip out, but so as it may stick in very closely; then pare your cork into the form of a pyramid, or small pear, and of what size you please, then on a smooth grindstone, or with pumice make it complete, for you cannot pare it so smooth as you may grind it: have corks of all sizes.

5. Get a musquet or carbine bullet, make a hole through it, and put in a strong twist, hang this on your hook to try the depth of river or pond.

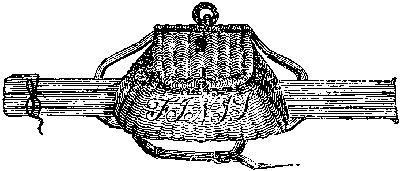

6. Take so much parchment as will be about four inches broad, and five long, make the longer end round, then take so many pieces more as will make five or six partitions, sew them all together, leaving the side of the longest square open, to put your lines, spare links,[7] hooks ready fastened, and flies ready made, into the several partitions; this will contain much, and will also lie flat and close in your pocket.

7. Have also a little whetstone about two inches long, and one quarter square; it’s much better to sharpen your hooks than a file, which either will not touch a well-tempered hook, or leave it rough but not sharp.

8. Have a piece of cane for the bob and palmer, with several boxes of divers sizes for your hooks, corks, silk, thread, lead, flies, &c.

9. Bags of linen and woollen, for all sorts of baits.

10. Have a small pole, made with a loop at the end, like that of your line, but much larger, to which must be fastened a small net, to land great fish, without which, should you want assistance, you will be in danger of losing.

11. Your pannier cannot be too light; I have seen some made of osiers, cleft into slender long splinters, and so wrought up, which is very neat, and exceeding light: you must ever carry with you store of hooks, lines, hair, silk, thread, lead, links, corks of all sizes, lest you should lose or break, as is usual, any of them, and be forced to leave your sport in quest of supplies.

DIVERS SORTS OF ANGLING; FIRST, OF THE FLY.

As there are many kinds and sorts of fish, so there are also various and different ways to take them; and, therefore, before we proceed to speak how to take each kind, we must say something in general of the several ways of angling, as necessary to the better order of our work.

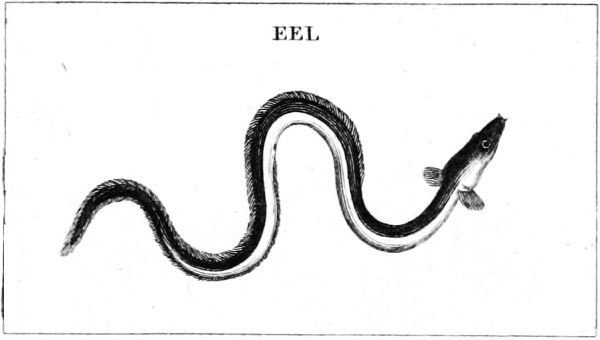

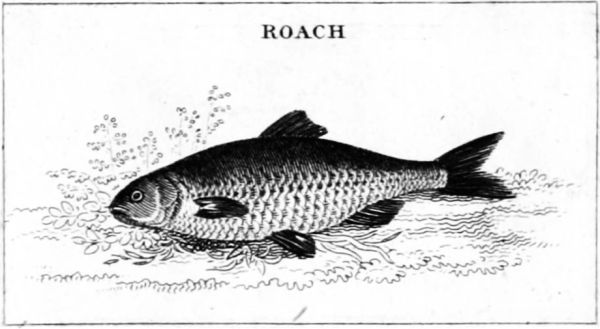

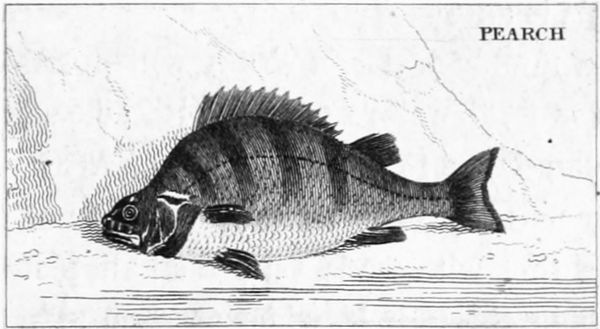

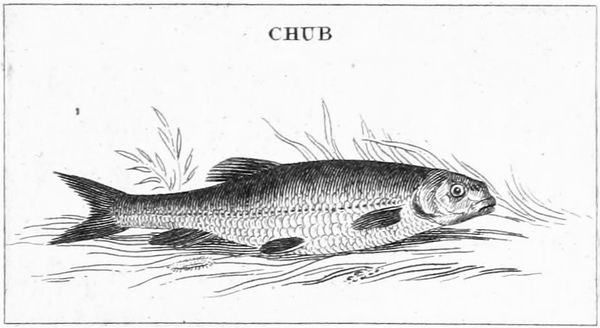

Angling, therefore, may be distinguished either into fishing by day, or, which some commend, but the cold and dews caused me to dis-relish that which impaired my health, by night; and these again are of two sorts, either upon the superficies of the water, or more or less under the surface thereof: of this sort is angling with the ground-line, with lead, but no float, for the Trout, or with lead and float for all sorts of fish, or near the surface of the water for Chub, Roach, &c. or with a troll for the Pike, or a minnow for the Trout; of which more in due place.

That way of angling upon or above the water, is with cankers, palmers, caterpillars, cad-bait, or any worm bred on herbs or trees, or with flies as well natural as artificial; of these last shall be our first discourse, as comprising much of the other last-named, and as being the most pleasant and delightful part of angling.

But I must here beg leave to dissent from the opinion of such who assign a certain fly to each month, whereas I am certain, scarce any one sort of fly continues[9] its colour and virtue one month; and generally all flies last a much shorter time, except the stone-fly, by some called the May-fly, which is bred of the water cricket, creeps out of the river, and getting under the stones by the water side, turns to a fly, and lies under the stones; the May-fly and the reddish fly with ashy grey wings. Besides the season of the year may much vary the time of their coming in; a forward Spring brings them in sooner, and a late Spring the later. Flies being creatures bred of putrefaction, take life as the heat furthers or disposes the seminal virtue by which they are generated into animation: and therefore all I can say as to time is, that your own observation must be your best instructor, when is the time that each fly comes in, and will be most acceptable to the fish, of which I shall speak more fully in the next section. Further also I have observed, that several rivers and soils produce several sorts of flies; as the mossy boggy soils have one sort peculiar to them; the clay soil, gravely and mountainous country and rivers; and a mellow light soil different from them all; yet some sorts are common to all these sorts of rivers and soils, but they are few, and differ somewhat in colour from those bred elsewhere in other soils.

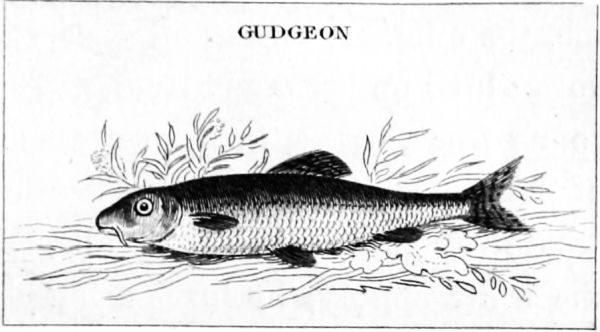

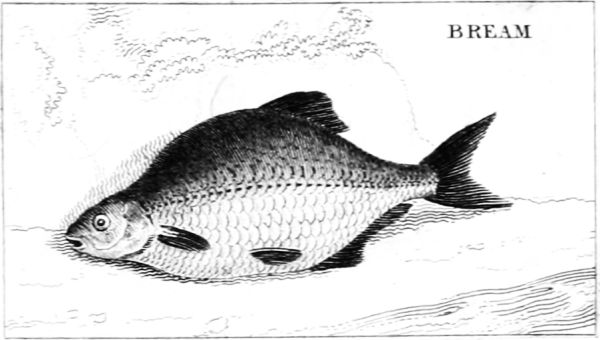

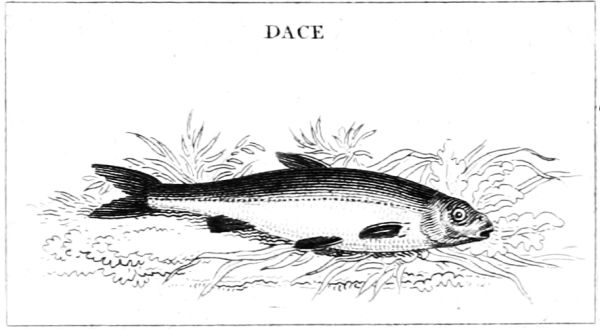

In general, all sorts of flies are very good in their season, for such fish as will rise at the fly, viz. Salmon, Trout, Umber, Grayling, Bleak, Chevin, Roach, Dace, &c. Though some of these fish do love some flies better than other, except the fish named, I know not any sort or kind that will ordinarily and freely rise at[10] the fly, though I know some who angle for Bream and Pike with artificial flies, but I judge the labour lost, and the knowledge a needless curiosity; those fish being taken much easier, especially the Pike, by other ways. All the fore-mentioned sorts of fish will sometimes take the fly much better at the top of the water, and at another time much better a little under the superficies of the water; and in this your own observation must be your constant and daily instructor; for if they will not rise to the top, try them under, it being impossible, in my opinion, to give any certain rule in this particular: also the five sorts of fish first named will take the artificial fly, so will not the other, except an oak-worm or cad-bait be put on the point of the hook, or some other worm suitable, as the fly must be, to the season.

You may also observe, what my own experience taught me, that the fish never rise eagerly and freely at any sort of fly, until that kind come to the water’s side; for though I have often, at the first coming in of some flies, which I judged they liked best got several of them, yet I could never find that they did much, if at all value them, until those sorts of flies began to flock to the rivers sides, and were to be found on the trees and bushes there in great numbers; for all sorts of flies, wherever bred, do, after a certain time, come to the banks of rivers, I suppose to moisten their bodies dried with the heat; and from the bushes and herbs there, skip and play upon the water, where the fish lie in wait for them, and after a short time die, and are not to be found: though of some kinds there come a second sort[11] afterwards, but much less, as the orange fly; and when they thus flock to the river, then is the best season to angle with that fly. And that thou may the better find what fly they covet most at that instant, do thus:

When you come first to the river in the morning, with your rod beat upon the bushes or boughs which hang over the water, and by their falling upon the water you will see what sorts of flies are there in greatest numbers; if divers sorts, and equal in number, try them all, and you will quickly find which they most desire. Sometimes they change their fly; though not very usual, twice or thrice in one day; but ordinarily they do not seek another sort of fly till they have for some days even glutted themselves with a former kind, which is commonly when those flies die and go out. Directly contrary to our London gallants, who must have the first of every thing, when hardly to be got, but scorn the same when kindly ripe, healthful, common, and cheap; but the fish despise the first, and covet when plenty, and when that sort grow old and decay, and another cometh in plentifully, then they change; as if nature taught them, that every thing is best in its own proper season, and not so desirable when not kindly ripe, or when through long continuance it begins to lose its native worth and goodness.

I shall add a few cautions and directions in the use of the natural fly, and then proceed:

1. When you angle for Chevin, Roach, or Dace, with the fly, you must not move your fly swiftly; when you see the fish coming towards it, but rather after one[12] or two short and slow removes, suffer the fly to glide gently with the stream towards the fish; or if in a standing or very slow water, draw the fly slowly, and not directly upon him, but sloping and sidewise by him, which will make him more eager lest it escape him; for, should you move it nimbly and quick, they will not, being fish of slow motion, follow as the Trout will.

2. When Chub, Roach, or Dace shew themselves in a sun-shiny day upon the top of the water, they are most easily caught with baits proper for them; and you may chuse from amongst them which you please to take.

3. They take an artificial fly with a cad-bait, or oak-worm, on the point of the hook; and the oak-worm, when they shew themselves is, better upon the water than under, or than the fly itself, and is more desired by them.

OF THE ARTIFICIAL FLY.

Having given these few directions for the use of the natural fly of all sorts, and shewed the time and season of their coming, and how to find them, and cautioned you in the use of them, I shall proceed to treat of the artificial fly. But here I must premise, that it is much better to learn how to make a fly by sight, than by any written direction that can possibly be expressed, in regard the terms of art do in most parts of England differ, and also several sorts of flies are called by different[13] names; some call the fly bred of the water cricket or creeper a May-fly, and some a stone-fly; some call the cad-bait fly a May, and some call a short fly, of a sad golden green colour, with short brown wings, a May-fly: and I see no reason but all flies bred in May, are properly enough called May-flies. Therefore, except some one that hath skill, would paint them, I can neither well give their names nor describe them, without too much trouble and prolixity; nor, as I alledged, in regard of the variety of soils and rivers, describe the flies that are bred and frequent each: but the angler, as before directed, having found the fly which the fish at present affect, let him make one as like it as possibly he can, in colour, shape, proportion; and for his better imitation let him lay the natural fly before him. All this premised and considered, let him go on to make his fly, which according to my own practice I thus advise.

First, I begin to set on my hook, placing the hair on the inside of its shank, with such coloured silk as I conceive most proper for the fly, beginning at the end of the hook, and when I come to that place which I conceive most proportionable for the wings, then I place such coloured feathers there, as I apprehend most resemble the wings of the fly, and set the points of the wings towards the head; or else I run the feathers, and those must be stripped from the quill or pen, with part of it still cleaving to the feathers, round the hook, and so make them fast, if I turn the feathers round the hook; then I clip away those that are upon the back of the hook, that so, if it be possible, the point of the hook[14] may be forced by the feathers left on the inside of the hook, to swim upwards; and by this means I conceive the stream will carry your flies’ wings in the posture of one flying; whereas if you set the points of the wings backwards, towards the bending of the hook, the stream, if the feathers be gentle as they ought, will fold the points of the wings in the bending of the hook, as I have often found by experience. After having set on the wing, I go on so far as I judge fit, till I fasten all, and then begin to make the body, and the head last; the body of the fly I make several ways; if the fly be one entire colour, then I take a worsted thread, or moccoda end, or twist wool or fur into a kind of thread, or wax a small slender silk thread, and lay wool, fur, &c. upon it, and then twist, and the material will stick to it, and then go on to make my fly small or large, as I please. If the fly, as most are, be of several colours, and those running in circles round the fly, then I either take two of these threads, fastening them first towards the bend of the hook, and so run them round, and fasten all at the wings, and then make the head; or else I lay upon the hook, wool, fur of hare, dog, fox, bear, cow, or hog, which, close to their bodies, have a fine fur, and with a silk of the other colour bind the same wool or fur down, and then fasten all: or instead of the silk running thus round the fly, you may pluck the feather from one side of those long feathers which grow about a cock or capon’s neck or tail, by some called hackle; then run the same round your fly, from head to tail, making both ends fast; but you must be sure to suit the feather an[15]swerable to the colour you are to imitate in the fly; and this way you may counterfeit those rough insects, which some call wool-beds, because of their wool-like outside and rings of divers colours, though I take them to be palmer worms, which the fish much delight in. Let me add this only, that some flies have forked tails, and some have horns, both which you must imitate with a slender hair fastened to the head or tail of your fly, when you first set on your hook, and in all things, as length, colour, as like the natural fly as possibly you can: the head is made after all the rest of the body, of silk or hair, as being of a more shining glossy colour than the other materials, as usually the head of the fly is more bright than the body, and is usually of a different colour from the body. Sometimes I make the body of the fly with a peacock’s feather, but that is only one sort of fly, whose colour nothing else that I could ever get would imitate, being the short, sad, golden, green fly I before mentioned, which I make thus: take one strain of a peacock’s feather, or if that be not sufficient, then another, wrap it about the hook, till the body be according to your mind; if your fly be of divers colours, and those lying long ways from head to tail, then I take my dubbing, and lay them on the hook long ways, one colour by another, as they are mixed in the natural fly, from head to tail, then bind all on, and fasten them with silk of the most predominant colour; and this I conceive is a more artificial way than is practised by many anglers, who use to make such a fly, all of one colour, and bind it on with silk, so that it looks like a fly with round[16] circles, but in nothing at all resembling the fly it is intended for: the head, horns, tail, are made as before. That you may the better counterfeit all sorts of flies, get furs of all sorts and colours you can possibly procure, as of bear’s hair, foxes, cows, hogs, dogs, which close to their bodies have a fine soft hair or fur, moccado ends, crewels, and dyed wool of all colours, with feathers of cocks, capons, hens, teals, mallards, widgeons, pheasants, partridges, the feather under the mallard, teal or widgeon’s wings, and about their tails, about a cock or capon’s neck and tail, of all colours; and generally of all birds, the kite, &c. that you may make yours exactly of the colour with the natural fly. And here I will give some cautions and directions, as for the natural fly, and so pass on to baits for angling at the ground.

1. When you angle with the artificial fly, you must either fish in a river not fully cleared from some rain lately fallen, that had discoloured it; or in a moorish river, discoloured by moss or bogs; or else in a dark cloudy day, when a gentle gale of wind moves the water; but if the wind be high, yet so as you may guide your tools with advantage, they will rise in the plain deeps, and then and there you will commonly kill the best fish; but if the wind be little or none at all, you must angle in the swift streams.

2. You must keep your artificial fly in continual motion, though the day be dark, the water muddy, and the wind blow, or else the fish will discern and refuse it.

3. If you angle in a river that is mudded by rain,[17] or passing through mosses or bogs, you must use a larger bodied fly than ordinary, which argues, that in clear rivers the fly must be smaller; and this not being observed by some, hinders their sport, and they impute their want of success to their want of the right fly, when perhaps they have it, but made too large.

4. If the water be clear and low, then use a small bodied fly with slender wings.

5. When the water begins to clear after rain, and is of a brownish colour, then a red or orange fly.

6. If the day be clear, then a light coloured fly, with slender body and wings.

7. In dark weather, as well as dark waters, your fly must be dark.

8. If the water be of a whey colour, or whitish, then use a black or brown fly: yet these six last rules do not always hold, though usually they do, or else I had omitted them.

9. Observe principally the belly of the fly, for that colour the fish observe most, as being most in their eye.

10. When you angle with an artificial fly, your line may be twice the length of your rod, except the river be much encumbered with wood and trees.

11. For every sort of fly have three; one of a lighter colour, another sadder than the natural fly, and a third of the exact colour with the fly, to suit all waters and weathers, as before.

12. I never could find, by any experience of mine own, or other man’s observation, that fish would freely[18] and eagerly rise at the artificial fly, in any slow muddy rivers: by muddy rivers, I mean such rivers, the bottom or ground of which is slime or mud; for such as are mudded by rain, as I have already, and shall afterwards further, shew at sometimes and seasons I would choose to angle, yet in standing meers or sloughs, I have known them, in a good wind, to rise very well, but not so in slimy rivers, either the Weever, in Cheshire, or the Sow, in Staffordshire, and others in Warwickshire, &c. and the Black-water in Ulster; in the last, after many trials, though in its best streams, I could never find almost any sport, save at its influx in Lough Neagh; but there the working of the Lough makes it sandy; and they will bite also near Tom Shane’s Castle, Mountjoy, Antrim, &c. even to admiration; yet sometimes they will rise in that river a little, but not comparable to what they will do in every little Lough, in any small gale of wind. And though I have often reasoned in my own thoughts, to search out the true cause of this, yet I could never so fully satisfy my own judgment, so as to conclude any thing positively; yet have taken up these two ensuing particulars as most probable.

1. I conjectured the depth of the loughs might hinder the force of the sun beams from operating upon, or heating the mud in those rivers, which though deep, yet are not so deep as the loughs; I apprehend that to be the cause, as in great droughts fish bite but little in any river, but not at all in slimy rivers, in regard the mud is not cooled by the constant and swift motion of the river, as in gravelly or sandy rivers, where, in fit[19] seasons, they rise most freely, and bite most eagerly, save as before in droughts, notwithstanding at that season some sport may be had, though not with the fly, whereas nothing at all will be done in muddy slow rivers.

2. My second supposition was, whether, according to that old received axiom, suo quæque, similima cœlo, the fish might not partake of the nature of the river, in which they are bred and live, as we see in men born in fenny, boggy, low, moist grounds, and thick air, who ordinarily want that present quickness, vivacity, and activity of body and mind, which persons born in dry, hilly, sandy soils and clear air, are usually endued withal. The fish participating of the nature of the muddy river, which is ever slow, for if they were swift, the stream would cleanse them from all mud, are not so quick, lively, and active, as those bred in swift, sandy, or stony rivers, and so coming to the fly with more deliberation, discern the same to be counterfeit, and forsake it; whereas, on the contrary, in stony, sandy, swift rivers, being colder, the fish are more active, and so more hungry and eager, the stream and hand keeping the fly in continual motion, they snap the same up without any pause, lest so desirable a morsel escape them.

You must have a very quick eye, a nimble rod and hand, and strike with the rising of the fish, or he instantly finds his mistake, and forces out the hook again: I could never, my eye-sight being weak, discern perfectly where my fly was, the wind and stream carrying it so to and again, that the line was never any certain direction or guide to me; but if I saw a fish rise, I[20] use to strike if I discerned it might be within the length of my line.

Be sure in casting, that your fly falls first into the water, for if the line falls first, it scares or frightens the fish; therefore draw it back, and cast it again, that the fly may fall first.

When you try how to fit your colour to the fly, wet your fur, hair, wool, or moccado, otherwise you will fail in your work; for though when they are dry, they exactly suit the colour of the fly, yet the water will alter most colours, and make them lighter or darker.

The best way to angle with the cad-bait, is to fish with it on the top of the water, as you do with the fly; it must stand upon the shank of the hook, in like manner with the artificial fly; if it come into the bend of the hook, the fish will little or not at all value it, nor if you pull the blue gut out of it; and to make it keep that place, you must, when you set on your hook, fasten a horse hair or two under the silk, with the ends standing a very little out from under the silk, and pointing towards the line; this will keep it from sliding back into the bend; and thus used, it is a most excellent bait for a Trout. You may imitate the cad-bait, by making the body of chamois, the head of black silk.

I might here notice several sorts of flies, with the colours that are used to make them; but for the reasons before given, that their colours alter in several rivers and soils, and also because, though I name the colours, yet it is not easy to choose that colour by any description, except so largely performed as would be[21] over large, and swell this small piece beyond my intended conciseness, which are easy and short, if rightly observed, are full enough, and sufficient for making and finding out all sorts of flies in all rivers. I shall only add, that the Salmon flies must be made with wings standing one behind the other, whether two or four; also he delights in the most gaudy and orient colours you can choose; the wings I mean chiefly, if not altogether, with long tails and wings.

OF ANGLING AT THE GROUND.

Now we are come to the second part of angling, viz. under the water, which if it be with the ground-line for the Trout, then you must not use any float at all, only a plumb of lead, which I would wish might be a small bullet, the better to roll on the ground; and it must also be lighter or heavier, as the stream runs swift or slow, and you must place it about nine inches or a foot from the hook; the lead must run upon the ground, and you must keep your line as straight as possible, yet by no means so as to raise the lead from the ground; your top must be very gentle, that the fish may more easily, and to himself insensibly, run away with the bait, and not be scared with the stiffness of the rod; and if you make your top of black thorn and whale-bone, as I before directed, it will conduce much to this purpose: neither must you strike so soon as you feel the fish bite,[22] but slack your line a little, that so he may more securely swallow the bait, and hook himself, which he will sometimes do, especially if he be a good one; the least jerk, however, hooks him, and indeed you can scarce strike too easily. Your tackle must be very fine and slender, and so you will have more sport than if you had strong lines, which frighten the fish, but the slender line is easily broke; with a small jerk. Morning and evening are the best times for the ground-line for a Trout, in clear weather and water, but in cloudy weather, or muddy water, you may angle at ground all day.

2. You may also in the night angle for the Trout with two great garden worms, hanging as equally in length as you can place them on your hook; cast them from you as you would cast the fly, and draw them to you again upon the top of the water, and not suffer them to sink; therefore you must use no lead this way of angling; when you hear the fish rise, give some time for him to gorge your bait, as at the ground, then strike gently. If he will not take them at the top, add some lead, and try at the ground, as in the day time; when you feel him bite, order yourself as in day angling at the ground. Usually the best Trouts bite in the night, and will rise in the still deeps, but not ordinarily in the stream.

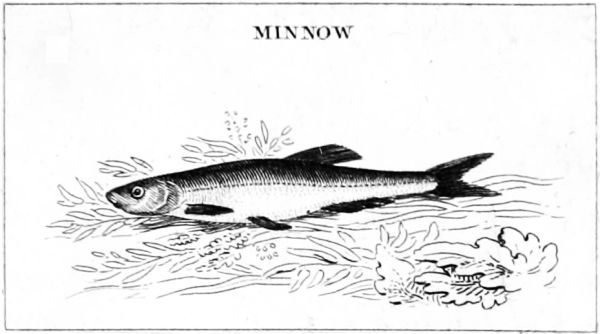

3. You may angle also with a minnow for the Trout, which you must put on your hook thus: first, put your hook through the very point of his lower chap, and draw it quite through; then put your hook in at his mouth, and bring the point to his tail, then draw[23] your line straight, and it will bring him into a round compass, and close his mouth that no water gets in, which you must avoid; or you may stitch up his mouth; or you may, when you have set on your hook, fasten some bristles under the silk, leaving the points about a straw’s breadth and half, or almost half an inch standing out towards the line, which will keep him from slipping back. You may also imitate the minnow as well as the fly, but it must be done by an artist with the needle.

You must also have a swivel or turn, placed about a yard or more from your hook, observing you need no lead on your line, for you must continually draw your bait up the stream, near the top of the water. If you strike a large Trout, and it should break either your hook or line, or get off, then near to her hole, if you can discover it, or the place you struck her, fix a short stick in the water, and with your knife loose a small piece of the rind, so as you may lay your line in it, and yet the bark be close enough to keep your line in, that it slip not out, nor the stream carry it away: bait your hook with a garden or lob-worm, your hook and line being very strong, let the bait hang a foot from the stick, then fasten the other end of your line to some stick or bough in the bank, and within one hour, you may be sure of her, if all your tackle hold.