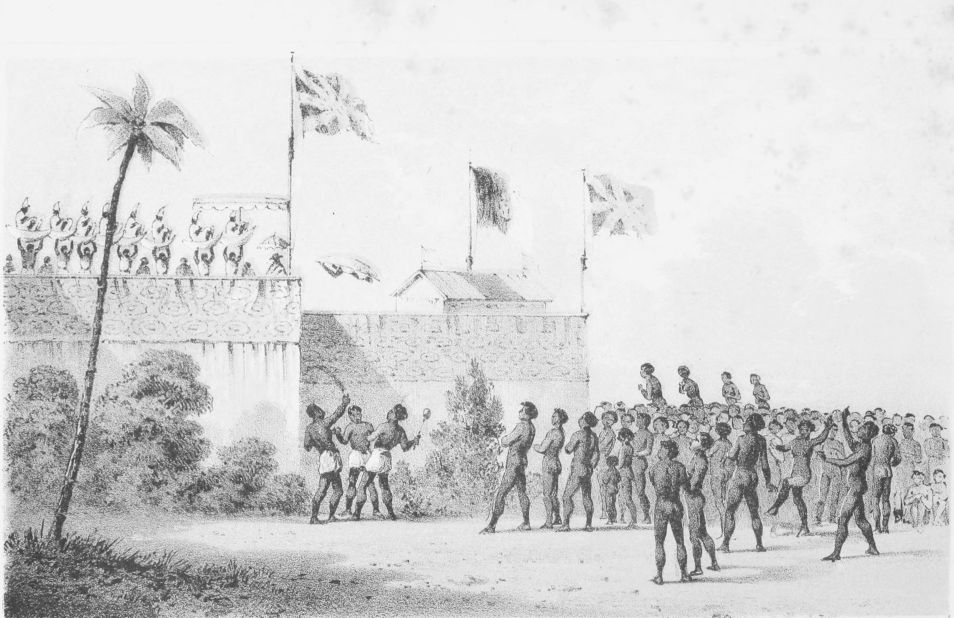

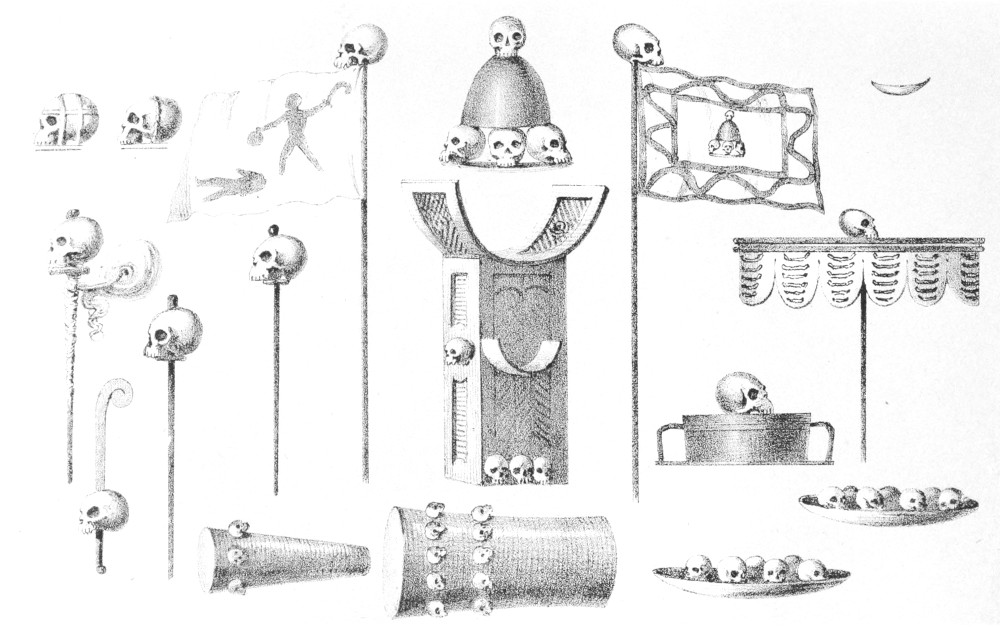

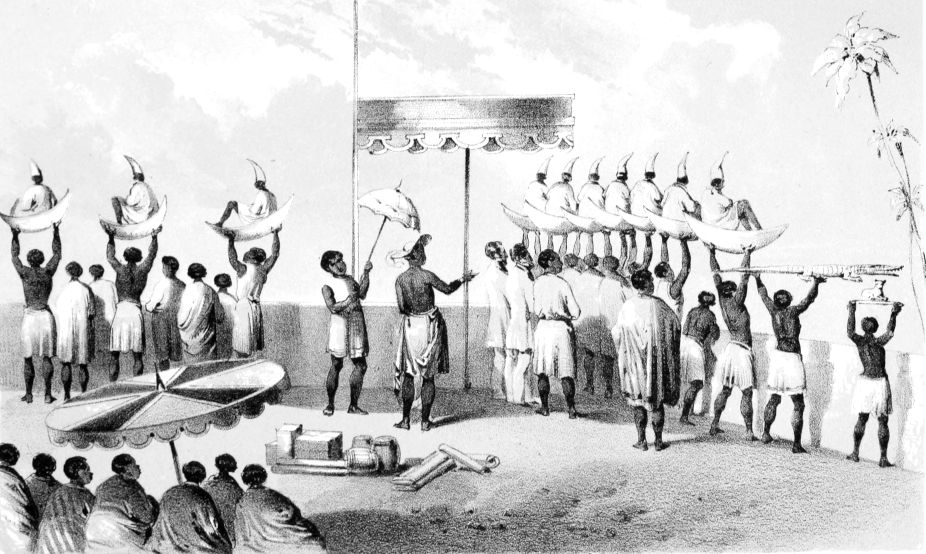

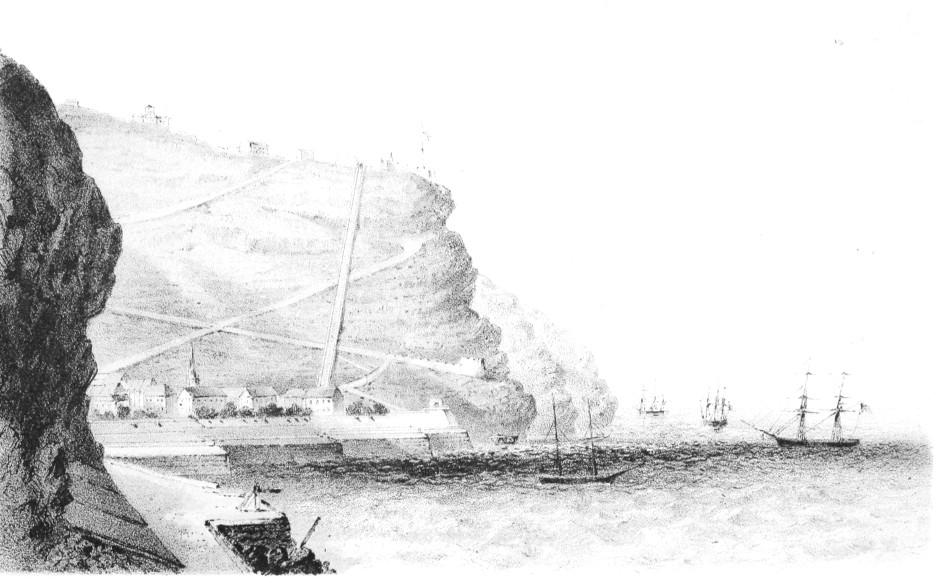

| F. E. Forbes, delt. | Lith. of Sarony & Co. N. Y. |

THE HUMAN SACRIFICES OF THE EK-GNEE-NOO-AH-TOH.

Title: Africa and the American Flag

Author: Andrew H. Foote

Release date: February 26, 2022 [eBook #67502]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: D. Appleton & Co

Credits: deaurider and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

[Pg 1]

The Great Work on Russia.

Fifth Edition now ready.

By Count A. de Gurowski.

One neat volume 12mo., pp. 328, well printed. Price $1, cloth.

CONTENTS.—Preface.—Introduction.—Czarism: its historical origin.—The Czar Nicholas.—The Organization of the Government.—The Army and Navy.—The Nobility.—The Clergy.—The Bourgeoisie.—The Cossacks.—The Real People, the Peasantry.—The Rights of Aliens and Strangers.—The Commoner.—Emancipation.—Manifest Destiny.—Appendix.—The Amazons.—The Fourteen Classes of the Russian Public Service; or, the Tschins.—The Political Testament of Peter the Great.—Extract from an Old Chronicle.

Notices of the Press.

“The author takes no superficial, empirical view of his subject, but collecting a rich variety of facts, brings the lights of a profound philosophy to their explanation. His work, indeed, neglects no essential detail—it is minute and accurate in its statistics—it abounds in lively pictures of society, manners and character. * * Whoever wishes to obtain an accurate notion of the internal condition of Russia, the nature and extent of her resources, and the practical influence of her institutions, will here find better materials for his purpose than in any single volume now extant.”—N. Y. Tribune.

“This is a powerfully-written book, and will prove of vast service to every one who desires to comprehend the real nature and bearings of the great contest in which Russia is now engaged.”—N. Y. Courier.

“It is original in its conclusions; it is striking in its revelations. Numerous as are the volumes that have been written about Russia, we really hitherto have known little of that immense territory—of that numerous people. Count Gurowski’s work sheds a light which at this time is most welcome and satisfactory.”—N. Y. Times.

“The book is well written, and as might be expected in a work by a writer so unusually conversant with all sides of Russian affairs, it contains so much important information respecting the Russian people, their government and religion.”—Com. Advertiser.

“This is a valuable work, explaining in a very satisfactory manner the internal conditions of the Russian people, and the construction of their political society. The institutions of Russia are presented as they exist in reality, and as they are determined by existing and obligatory laws.”—N. Y. Herald.

“A hasty glance over this handsome volume has satisfied us that it is one worthy of general perusal. * * * It is full of valuable historical information, with very interesting accounts of the various classes among the Russian people, their condition and aspirations.”—N. Y. Sun.

“This is a volume that can hardly fail to attract very general attention, and command a wide sale in view of the present juncture of European affairs, and the prominent part therein which Russia is to play.”—Utica Gazette.

“A timely book. It will be found all that it professes to be, though some may be startled at some of its conclusions.”—Boston Atlas.

“This is one of the best of all the books caused by the present excitement in relation to Russia. It is a very able publication—one that will do much to destroy the general belief in the infallibility of Russia. The writer shows himself master of his subject, and treats of the internal condition of Russia, her institutions and customs, society, laws, &c., in an enlightened and scholarly manner.”—City Item.

New Copyright Works, Adapted for Popular Reading.

JUST PUBLISHED.

BY D. APPLETON & CO.

I.

BY JOHN RUSSELL BARTLETT,

United States Commissioner during that period.

In 2 vols. 8vo, of nearly 600 pages each, printed with large type and on extra fine paper, to be illustrated with nearly 100 wood-cuts, sixteen tinted lithographs and a beautiful map, engraved on steel, of the extensive regions traversed. Price, $5.

II.

BY ANDREW H. FOOTE,

Lieutenant Commanding the U. S. Brig Porpoise, on the Coast of Africa, 1851-’53.

With tinted lithographic illustrations. One volume 12mo.

III.

EDITED BY BRANTZ MAYER.

With numerous illustrations. One vol. 12mo, cloth.

IV.

BY THE COUNT DE GUROWSKI.

One vol. 12mo, cloth.

V.

BY MRS. MARY J. HOLMES.

One vol. 12mo, paper cover or cloth.

VI.

A TALE BY CAROLINE THOMAS.

One vol. 12mo, paper cover or cloth.

“Excels in interest, and is quite equal in its delineation of character to The Wide, Wide World.”

VII.

BY T. B. THORPE.

With several illustrations. One vol. 12mo, cloth.

| F. E. Forbes, delt. | Lith. of Sarony & Co. N. Y. |

THE HUMAN SACRIFICES OF THE EK-GNEE-NOO-AH-TOH.

BY

COMMANDER ANDREW H. FOOTE,

U. S. NAVY,

LIEUT. COMMANDING U. S. BRIG PERRY ON THE COAST OF AFRICA,

A. D. 1850-1851.

NEW YORK:

D. APPLETON & CO., 346 & 348 BROADWAY,

AND 16 LITTLE BRITAIN, LONDON.

M DCCC LIV.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1854,

By D. APPLETON & COMPANY,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern

District of New York.

TO

COMMODORE JOSEPH SMITH, U. S. N.,

CHIEF OF THE NAVAL BUREAU OF YARDS AND DOCKS,

This Volume is Dedicated,

AS A SLIGHT TRIBUTE

OF RESPECT FOR HIS OFFICIAL CHARACTER,

AND AS AN ACKNOWLEDGMENT

OF HIS UNIFORM ATTACHMENT

AS A FRIEND.

[Pg 7]

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Subject and Arrangement—Area of Cruising-Ground—Distribution of Subjects. | 13 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Discoveries by French and Portuguese along the Coast—Cape of Good Hope—Results. | 17 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Pirates—Davis, Roberts, and others—British Cruisers—Slave-Trade systematized—Guineamen—“Horrors of the Middle Passage”. | 20 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Physical Geography—Climate—Geology—Zoology—Botany. | 31 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| African Nations—Distribution of Races—Arts—Manners and Character—Superstitions—Treatment of the Dead—Regard for the Spirits of the Departed—Witchcraft—Ordeal—Military Force—Amazons—Cannibalism. | 46 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Trade—Metals—Mines—Vegetable Productions—Gums—Oils—Cotton—Dye-Stuffs. | 65[Pg 8] |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| European Colonies—Portuguese—Remaining Influence of the Portuguese—Slave Factories—English Colonies—Treaties with the Native Chiefs—Influence of Sierra Leone—Destruction of Barracoons—Influence of England—Chiefs on the Coast—Ashantee—King of Dahomey. | 71 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Dahomey—Slavish Subjection of the People—Dependence of the King on the Slave-Trade—Exhibition of Human Skulls—Annual Human Sacrifices—Lagos—The Changes of Three Centuries. | 85 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| State of the Coast prior to the Foundation of Liberia—Native Tribes—Customs and Policy—Power of the Folgias—Kroomen, &c.—Conflicts. | 94 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| General Views on the Establishment of Colonies—Penal Colonies—Views of the People of the United States in reference to African Colonies—State of Slavery at the Revolutionary War—Negroes who joined the English—Disposal of them by Great Britain—Early Movements with respect to African Colonies—Plan matured by Dr. Finley—Formation of the American Colonization Society. | 101 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Foundation of the American Colony—Early Agents—Mills, Burgess, Bacon and others—U. S. Sloop-of-War “Cyane”—Arrival at the Island of Sherboro—Disposal of Recaptured Slaves by the U. S. Government—Fever—Slavers Captured—U. S. Schooner “Shark”—Sherboro partially abandoned—U. S. Schooner “Alligator”—Selection and Settlement of Cape Mesurado—Capt. Stockton—Dr. Ayres—King Peter—Arguments with the Natives—Conflicts—Dr. Ayres made Prisoner—King Boatswain—Completion of the Purchase. | 110 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Ashmun—Necessity of Defence—Fortifications—Assaults—Arrival of Major Laing—Condition of the Colonies—Sloops-of-War “Cyane” and “John Adams”—King Boatswain as a Slaver—Misconduct[Pg 9] of the Emigrants—Disinterestedness of Ashmun—U. S. Schooner “Porpoise”—Captain Skinner—Rev. R. R. Gurley—Purchase of Territory on the St. Paul’s River—Attack on Tradetown—Piracies—U. S. Schooner “Shark”—Sloop-of-War “Ontario”—Death of Ashmun—His Character by Rev. Dr. Bacon. | 123 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Lot Carey—Dr. Randall—Establishment of the Liberia Herald—Wars with the Deys—Sloop-of-War “John Adams”—Difficulties of the Government—Condition of the Settlers. | 141 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Commonwealth of Liberia—Thomas H. Buchanan—Views of different Parties—Detached Condition of the Colony—Necessity of Union—Establishment of a Commonwealth—Use of the American Flag in the Slave-Trade—“Euphrates”—Sloop “Campbell”—Slavers at Bassa—Expedition against them—Conflict—Gallinas. | 148 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Buchanan’s Administration continued—Death of King Boatswain—War with Gaytumba—Attack on Heddington—Expedition of Buchanan against Gaytumba—Death of Buchanan—His Character. | 159 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Roberts governor—Difficulties with English Traders—Position of Liberia in respect to England—Case of the “John Seyes”—Official Correspondence of Everett and Upshur—Trouble on the Coast—Reflections. | 166 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Roberts’ Administration—Efforts in Reference to English Traders—Internal Condition of Liberia—Insubordination—Treaties with the native Kings—Expedition to the Interior—Causes leading to a Declaration of Independence. | 173 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Independence of Liberia proclaimed and acknowledged by Great Britain, France, Belgium, Prussia, and Brazil—Treaties with England and France—Expedition against New Cesters—U. S. Sloop-of-War[Pg 10] “Yorktown”—English and French Cruisers—Disturbances among the native Chiefs—Financial Troubles—Recurring Difficulty with English Traders—Boombo, Will Buckle, Grando, King Boyer. | 180 |

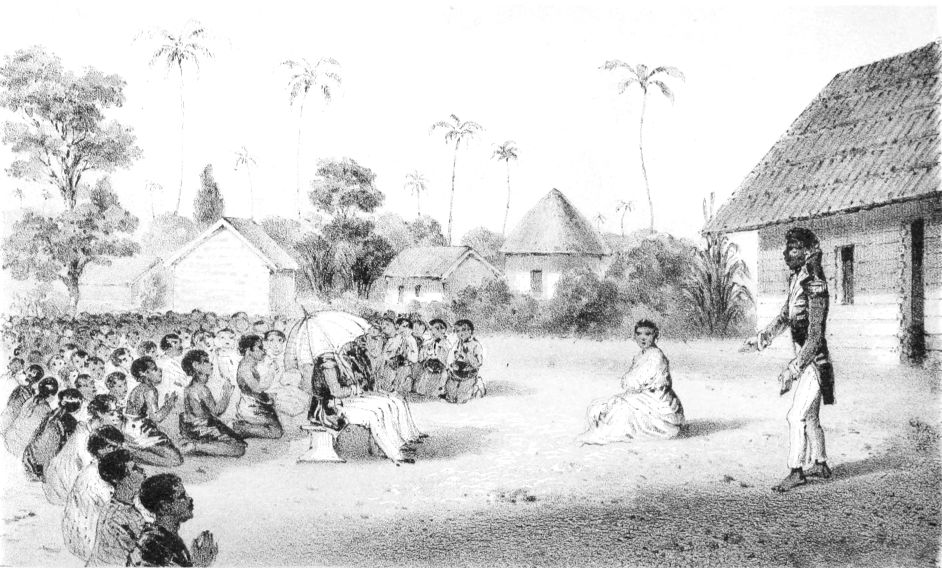

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Condition of Liberia as a Nation—Aspect of Liberia to a Visitor—Character of Monrovia—Soil, Productions and Labor—Harbor—Condition of the People compared with that of their Race in the United States—Schools. | 192 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Maryland in Liberia—Cape Palmas—Hall and Russwurm—Chastisement of the Natives at Berebee by the U. S. Squadron—Line of Packets—Proposal of Independence—Illustrations of the Colonization Scheme—Christian Missions. | 200 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Renewal of Piracy and the Slave-Trade at the close of the European War—British Squadron—Treaties with the Natives—Origin of Barracoons—Use of the American Flag in the Slave-Trade—Official Correspondence on the Subject—Condition of Slaves on board of the Slave-Vessels—Case of the “Veloz Passageira”—French Squadron. | 213 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| United States Squadron—Treaty of Washington. | 232 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Case of the “Mary Carver,” seized by the Natives—Measures of the Squadron in consequence—Destruction of Towns—Letter from U. S. Brig “Truxton” in relation to a captured Slaver. | 235 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Capture of the Slave-Barque “Pons”—Slaves landed at Monrovia—Capture of the Slave-equipped Vessels “Panther,” “Robert Wilson,” “Chancellor,” &c.—Letter from the “Jamestown” in reference to Liberia—Affair with the Natives near Cape Palmas—Seizure and Condemnation of the Slaver “H. N. Gambrill”. | 243[Pg 11] |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

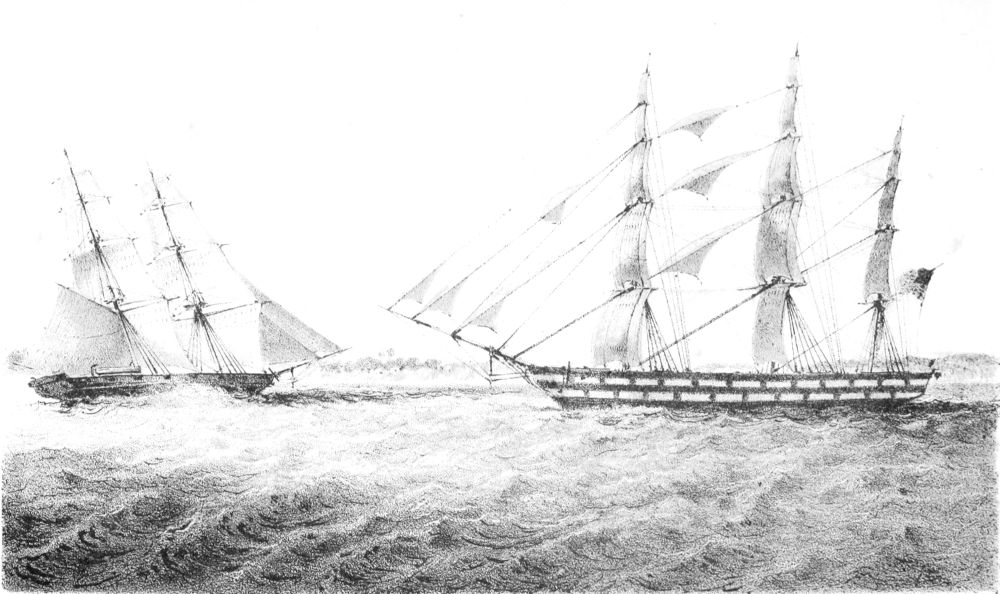

| Cruise of the “Perry”—Instructions—Dispatched to the South Coast—Benguela—Case of a Slaver which had changed her Nationality captured by an English Cruiser—St. Paul de Loanda—Abuse of the American Flag—Want of a Consul on the South Coast—Correspondence with British Officers in relation to Slavers under the American Flag—The Barque “Navarre”—Treaty with Portugal—Abatement of Custom-House Duties—Cruising off Ambriz—An Arrangement made with the British Commodore for the Joint Cruising of the “Perry” and Steamer “Cyclops”—Co-operation with the British Squadron for the Suppression of the Slave-Trade—Fitting out of American Slavers in Brazil. | 254 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| American Brigantine “Louisa Beaton” suspected—Correspondence with the Commander of the Southern Division of the British Squadron—Boat Cruising—Currents—Rollers on the Coast—Trade-Winds—Climate—Prince’s Island—Madame Fereira. | 272 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Return to the Southern Coast—Capture of the American Slave-Ship “Martha”—Claim to Brazilian Nationality—Letters found on board illustrative of the Slave-Trade—Loanda—French, English, and Portuguese Cruisers—Congo River—Boarding Foreign Merchant Vessels—Capture of the “Volusia” by a British Cruiser—She claims American Nationality—The Meeting of the Commodores at Loanda—Discussions in relation to Interference with Vessels ostensibly American—Seizure of the American Brigantine “Chatsworth,”—Claims by the Master of the “Volusia”. | 285 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| Another Cruise—Chatsworth again—Visit to the Queen near Ambrizette—Seizure of the American Brigantine “Louisa Beaton” by a British Cruiser—Correspondence—Proposal of Remuneration from the Captors—Seizure of the “Chatsworth” as a Slaver—Italian Supercargo—Master of the “Louisa Beaton”. | 306 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Prohibition of Visits to Vessels at Loanda—Correspondence—Restrictions removed—St. Helena—Appearance of the Island—Reception—Correspondence with the Chief-Justice—Departure. | 324[Pg 12] |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| Return to Loanda—“Cyclops” leaves the Coast—Hon. Captain Hastings—Discussion with the British Commodore in reference to the Visit at St. Helena—Commodore Fanshawe—Arrival at Monrovia—British Cruiser ashore—Arrival at Porto Praya—Wreck of a Hamburgh Ship. | 336 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| Return to the South Coast—Comparative Courses and Length of Passage—Country at the Mouth of the Congo—Correspondence with the British Commodore—State of the Slave-Trade—Communication to the Hydrographical Department—Elephants’ Bay—Crew on Shore—Zebras. | 344 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| The Condition of the Slave-Trade—Want of suitable Cruisers—Health of the Vessel—Navy Spirit-ration—Portuguese Commodore—French Commodore—Loanda—Letter from Sir George Jackson, British Commissioner, on the State of the Slave-Trade—Return to Porto Praya. | 357 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Island of Madeira—Porto Grande, Cape Verde Islands—Interference of the British Consul with the “Louisa Beaton”—Porto Praya—Brazilian Brigantine seized by the Authorities—Arrival at New York. | 369 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| Conclusion—Necessity of Squadrons for Protection of Commerce and Citizens abroad—Fever in Brazil, West Indies, and United States—Influence of Recaptured Slaves returning to the different regions of their own Country—Commercial Relations with Africa. | 379 |

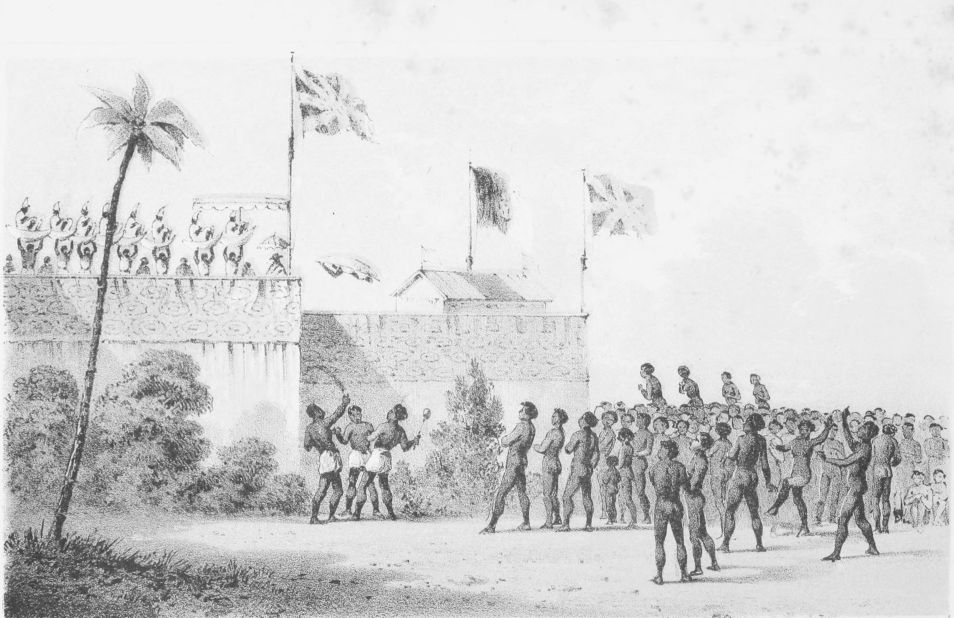

PROBABLE CONFIGURATION

of

AFRICA,

as represented by

Contouror Horizontal

Planes.

| J.J. Adamson, del. | Lith. of Sarony & Co. N. Y. |

SUBJECT AND ARRANGEMENT—AREA OF CRUISING-GROUND—DISTRIBUTION OF SUBJECTS.

On the 28th of November, 1849, the U. S. brig “Perry” sailed for the west coast of Africa, to join the American squadron there stationed.

A treaty with Great Britain, signed at Washington in the year 1842, stipulates that each nation shall maintain on the coast of Africa, a force of naval vessels “of suitable numbers and description, to carry in all not less than eighty guns, to enforce separately and respectively, the laws, rights, and obligations of each of the two countries, for the suppression of the slave-trade.”

Although this stipulation was limited to the term of five years from the date of the exchange of the ratifications of the treaty, “and afterwards until one or the[Pg 14] other party shall signify a wish to terminate it;” the United States have continued to maintain a squadron on that coast for the protection of its commerce, and for the suppression of the slave-trade, so far as it might be carried on in American vessels, or by American citizens.

To illustrate the importance of this squadron, the relations which its operations bear to American interests, and to the rights of the American flag; its effects upon the condition of Africa in checking crime, and preparing the way for the introduction of peace, prosperity, and civilization, is the primary object of this work.

A general view of the continent of Africa, comprising the past and present condition of its inhabitants; slavery in Africa and its foreign slave-trade; the piracies upon the coast before it was guarded and protected by naval squadrons; the geological structure of the country; its natural history, languages, and people; and the progress of colonization by the negro race returning to their own land with the light of religion, of sound policy, and of modern arts, will also be introduced as subjects appropriate to the general design.

If a chart of the Atlantic is spread out, and a line drawn from the Cape Verde Islands towards the southeastern coast of Brazil; if we then pass to the Cape of Good Hope and draw another from that point by the island of St. Helena, crossing the former north of the[Pg 15] equator, the great tracks of commerce will be traced. Vessels outward bound follow the track towards the South American shore, and the homeward bound are found on the other. Thus vessels often meet in the centre of the Atlantic; and the crossing of these lines off the projecting shores of central Africa renders the coasts of that region of great naval importance.

The wide triangular space of sea between the homeward bound line and the retiring African seaboard around the Gulf of Guinea, constituted the area on which the vigilance of the squadron was to be exercised. Here is the region of crime, suffering, cruelty and death, from the slave-trade; and here has been at different ages, when the police of the sea happened to be little cared for, the scene of the worst piracies which have ever disgraced human nature.

Vessels running out from the African coast fall here and there into these lines traced on the chart, or sometimes cross them. No one can tell what they contain from the graceful hull, well-proportioned masts, neatly trimmed yards, and gallant bearing of the vessel. This deceitful beauty may conceal wrong, violence, and crime—the theft of living men, the foulness and corruption of the steaming slave-deck, and the charnel-house of wretchedness and despair.

It is difficult in looking over the ship’s side to conceive the transparency of the sea. The reflection of the[Pg 16] blue sky in these tropic regions colors it like an opaque sapphire, till some fish startles one by suddenly appearing far beneath, seeming to carry daylight down with him into the depths below. One is then reminded that the vessel is suspended over a transparent abyss. There for ages has sunk the dark-skinned sufferer from “the horrors of the middle passage,” carrying that ghastly daylight down with him, to rest until “the sea shall give up its dead,” and the slaver and his merchant come from their places to be confronted with their victim.

The relation of the western nations to these shores present themselves under three phases, which claim more or less attention in order to a full understanding of the subject. These are,

I. Period of Discovery, Piracy and Slaving.

II. Period of Colonizing.

III. Period of Naval Cruising.

[Pg 17]

DISCOVERIES BY FRENCH AND PORTUGUESE ALONG THE COAST—CAPE OF GOOD HOPE—RESULTS.

The French of Normandy contested with the Portuguese the honor of first venturing into the Gulf of Guinea. It was, however, nearly a hundred years from the time when the latter first embarked in these discoveries, until, in 1487, they reached the Cape of Good Hope. For about eight centuries the Mohammedan in the interior had been shaping out an influence for himself by proselyting and commerce. The Portuguese discoverer met this influence on the African shores. The Venetians held a sort of partnership with the Mohammedans in the trade of the East: Portugal had then taken scarcely any share in the brilliant and exciting politics of the Levant; her vocation was to the seas of the West, but in that direction she was advancing to an overwhelming triumph over her Eastern competitor.

On the 3d of May, 1487, a boat left one of two small high-sterned vessels, of less tonnage than an ordinary river sloop of the present day, and landed a few weather-beaten men on a low island of rocks, on which[Pg 18] they proceeded to erect a cross. The sand which rustled across their footsteps, the sigh of the west wind among the waxberry bushes, and the croakings of the penguins as they waddled off,—these were the voices which hailed the opening of a new era for the world; for Bartholomew Diaz had then passed the southern point of Africa, and was listening to the surf of the Antarctic Sea.

This enterprising navigator had sailed from Lisbon in August, 1486, and seems to have reached Sierra Parda, north of the Orange River, in time to catch the last of the strong southeasterly winds, prevailing during the summer months on the southern coast of Africa, in the region of the Cape. He stood to the southwest, in vessels little calculated for holding a wind, and at length reached the region of the prevailing southwest winds. Then standing to the eastward he passed the Cape of Good Hope, of which he was in search, and bearing away to the northward, after running a distance of four hundred miles, brought up at the island of St. Croix above referred to. Coasting along on his return, the Cape was doubled, and named Cabo Tormentoso, or the Cape of Storms. The King of Portugal, on the discoverer’s return, gave it the more promising name of Cabo de buen Speranza, or Cape of Good Hope.

Africa thus fell into the grasp of Europe. Trade flowed with a full stream into this new channel. Portugal[Pg 19] conquered and settled its shores. Missionaries accompanied the Portuguese discoverers and conquerors to various parts of Africa, where the Portuguese dominion had been established, and for long periods influenced the condition of the country.

[Pg 20]

PIRATES—DAVIS, ROBERTS, AND OTHERS—BRITISH CRUISERS—SLAVE-TRADE SYSTEMATIZED—GUINEAMEN—“HORRORS OF THE MIDDLE PASSAGE.”

The second period is that of villany. More Africans seem to have been bought and sold, at all times of the world’s history, than of any other race of mankind. The early navigators were offered slaves as merchandise. It is not easy to conceive that the few which they then carried away, could serve any other purpose than to gratify curiosity, or add to the ostentatious greatness of kings and noblemen. It was the demands of the west which rendered this iniquity a trade. Every thing which could debase a man was thrust upon Africa from every shore. The old military skill of Europe raised on almost every accessible point embattled fortresses, which now picturesquely line the Gulf of Guinea. In the space between Cape Palmas and the Calabar River, there are to be counted, in the old charts, forts and factories by hundreds.

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were especially the era of woe to the African people. Crime against them on the part of European nations, had become[Pg 21] gross in cruelty and universal in extent. From the Cape of Good Hope to the Mediterranean, in respect to their lands or their persons, the European was seizing, slaying and enslaving. The mischief perpetrated by the white man, was the source of mischief to its author. The west coast became the haunt and nursery of pirates. In fact, the same class of men were the navigators of the pirate and the slaver; and sailors had little hesitation in betraying their own vessels occasionally into the hands of the buccaneer. Slave-trading afforded a pretext which covered all the preparations for robbery. The whole civilized world had begun to share in this guilt and in this retribution.

In 1692, a solitary Scotchman was found at Cape Mesurado, living among the negroes. He had reached the coast in a vessel, of which a man named Herbert had gotten possession in one of the American colonies, and had run off with on a buccaneering cruise; a mutiny and fight resulted in the death of most of the officers and crew. The vessel drifted on shore, and bilged in the heavy surf at Cape Mesurado.

The higher ranks of society in Christendom were then most grossly corrupt, and had a leading share in these crimes. There arrived at Barbadoes in 1694, a vessel from New England, which might then have been called a clipper, mounting twenty small guns. A company of merchants of the island bought her, and fitted her[Pg 22] out ostensibly as a slaver, bound to the island of Madagascar; but in reality for the purpose of pirating on the India merchantmen trading to the Red Sea. They induced Russell, the governor of the island, to join them in the adventure, and to give the ship an official character, so far as he was authorized to do so by his colonial commission.

A “sea solicitor” of this order, named Conklyn, arrived in 1719 at Sierra Leone in a state of great destitution, bringing with him twenty-five of the greatest villains that could be culled from the crews of two or three piratical vessels on the coast. A mutiny had taken place in one of these, on account of the chief’s assuming something of the character and habits of a gentleman, and Conklyn, after a severe contention, had left with his desperate associates. Had he remained, he might have become chief in command, as a second mutiny broke out soon after his departure, in which the chief was overpowered, placed on board one of the prize vessels, and never heard of afterwards. The pirates under a new commander followed Conklyn to Sierra Leone. They found there this worthy gentleman, rich, and in command of a fine ship with eighty men.

Davis, the notorious pirate, soon joined him with a well-armed ship manned with one hundred and fifty men. Here was collected as fruitful a nest of villany[Pg 23] as the world ever saw. They plundered and captured whatever came in their course. These vessels, with other pirates, soon destroyed more than one hundred trading vessels on the African coast. England entered into a kind of compromise, previously to sending a squadron against them, by offering pardon to all who should present themselves to the governor of any of her colonies before the first of July, 1719. This was equivalent to offering themselves to serve in the war which had commenced against Spain, or exchanging one kind of brigandage for another, by privateering against the Spanish commerce. But from the accounts of their prisoners very few of them could read, and thus the proclamation was almost a dead letter.

In 1720, Roberts, a hero of the same class, anchored in Sierra Leone, and sent a message to Plunket, the commander of the English fort, with a request for some gold dust and ammunition. The commander of the fort replied that he had no gold dust for them, but that he would serve them with a good allowance of shot if they ventured within the range of his guns; whereupon Roberts opened his fire upon the fort. Plunket soon expended all his ammunition, and abandoned his position. Being made prisoner he was taken before Roberts: the pirate assailed the poor commander with the most outrageous execrations for his audacity in resisting him. To his astonishment Plunket retorted upon him[Pg 24] with oaths and execrations yet more tremendous. This was quite to the taste of the scoundrels around them, who, with shouts of laughter, told their captain that he was only second best at that business, and Plunket, in consideration of his victory, was allowed to escape with life.

In 1721, England dispatched two men-of-war to the Gulf of Guinea for the purpose of exterminating the pirates who had there reached a formidable degree of power, and sometimes, as in the instance noted above, assailed the establishments on shore. They found that Roberts was in command of a squadron of three vessels, with about four hundred men under his command, and had been particularly active and successful in outrage. After cruising about the northern coast, and learning that Roberts had plundered many vessels, and that sailors were flocking to him from all quarters, they found him on the evening of the third of February, anchored with his three vessels in the bay north of Cape Lopez.

When entering the bay, light enough remained to let them see that they had caught the miscreants in their lair. Closing in with the land the cruisers quietly ran in and anchored close aboard the outer vessel belonging to the pirates. Having ascertained the character of the visitors, the pirate slipped his cables, and proceeded to make sail, but was boarded and secured just as the[Pg 25] rapid blackness of a tropical night buried every thing in obscurity. Every sound was watched during the darkness of the night, with scarcely the hope that the other two pirates would not take advantage of it to make their escape; but the short gray dawn showed them still at their anchors. The cruisers getting under way and closing in with the pirates produced no movement on their part, and some scheme of cunning or desperate resistance was prepared for. They had in fact made a draft from one vessel to man the other fully for defence. Into this vessel the smaller of the cruisers, the Swallow, threw her broadside, which was feebly returned. A grape-shot in the head had killed Roberts. This and the slaughter of the cruiser’s fire prepared the way for the boarders, without much further resistance, to take possession of the pirate. The third vessel was easily captured.

The cruisers suffered no loss in the fight, but had been fatally reduced by sickness. The larger vessel, the Weymouth, which left England with a crew of two hundred and forty men, had previously been reduced so greatly as scarcely to be able to weigh her anchors; and, although recruited often from merchant vessels, landed but one hundred and eighty men in England. This rendered the charge of their prisoners somewhat hazardous, and taking them as far as Cape Coast Castle, they there executed such justice as the place could[Pg 26] afford, or the demerits of their prey deserved. A great number of them ornamented the shore on gibbets—the well-known signs of civilization in that era—as long as the climate and the vultures would permit them to hang.

Consequent on these events such order was established as circumstances would admit, or rather the progress of maritime intercourse and naval power put an end to the system of daring and regulated piracy by which the tropical shores of Africa and the West Indies had been laid waste. This, however, was slight relief for Africa. It was to secure and systematize trade that piracy had been suppressed, and the slave-trade became accordingly cruelly and murderously systematic.

The question what nation should be most enriched by the guilty traffic was a subject of diplomacy. England secured the greater share of the criminality and of the profit, by gaining from her other competitors the right by contract to supply the colonies of Spain with negroes.

Men forget what they ought not to forget; and however startling, disgusting, and oppressive to the mind of man the horrors are which characterized that trade, it is well that since they did exist the memory of them should not perish. It is a fearfully dark chapter in the history of the world, but although terrific it has its value. It is more worthy of being remembered than[Pg 27] the historical routine of wars, defeats, or victories; for it is more illustrative of man’s proper history, and of a strange era in that history. The evidence taken by the Committee of the English House of Lords in 1850, has again thrust the subject into daylight.

The slave-trade is now carried on by comparatively small and ill-found vessels, watched by the cruisers incessantly. They are therefore induced, at any risk of loss by death, to crowd and pack their cargoes, so that a successful voyage may compensate for many captures. In olden times, there were vessels fitted expressly for the purpose—large Indiamen or whalers. It has been objected to the employment of squadrons to exterminate that trade, that their interference has increased its enormity. This, however, is doing honor to the old Guineamen, such as they by no means deserve. It is, in fact, an inference in favor of human nature, implying that a man who has impunity and leisure to do evil, cannot, in the nature of things, be so dreadfully heartless in doing it, as those in whose track the avenger follows to seize and punish. The fact, however, does not justify this surmise in favor of impunity and leisure. If ever there was any thing on earth which, for revolting, filthy, heartless atrocity, might make the devil wonder and hell recognize its own likeness, then it was on any one of the decks of an old slaver. The sordid cupidity of the older, as it is meaner, was also more callous[Pg 28] than the hurried ruffianism of the present age. In fact, a slaver now has but one deck; in the last century they had two or three. Any one of the decks of the larger vessels was rather worse, if this could be, than the single deck of the brigs and schooners now employed in the trade. Then, the number of decks rendered the suffocating and pestilential hold a scene of unparalleled wretchedness. Here are some instances of this, collected from evidence taken by the British House of Commons in 1792.

James Morley, gunner of the Medway, states: “He has seen them under great difficulty of breathing; the women, particularly, often got upon the beams, where the gratings are often raised with banisters, about four feet above the combings, to give air, but they are generally driven down, because they take the air from the rest. He has known rice held in the mouths of sea-sick slaves until they were almost strangled; he has seen the surgeon’s mate force the panniken between their teeth, and throw the medicine over them, so that not half of it went into their mouths—the poor wretches wallowing in their blood, hardly having life, and this with blows of the cat.”

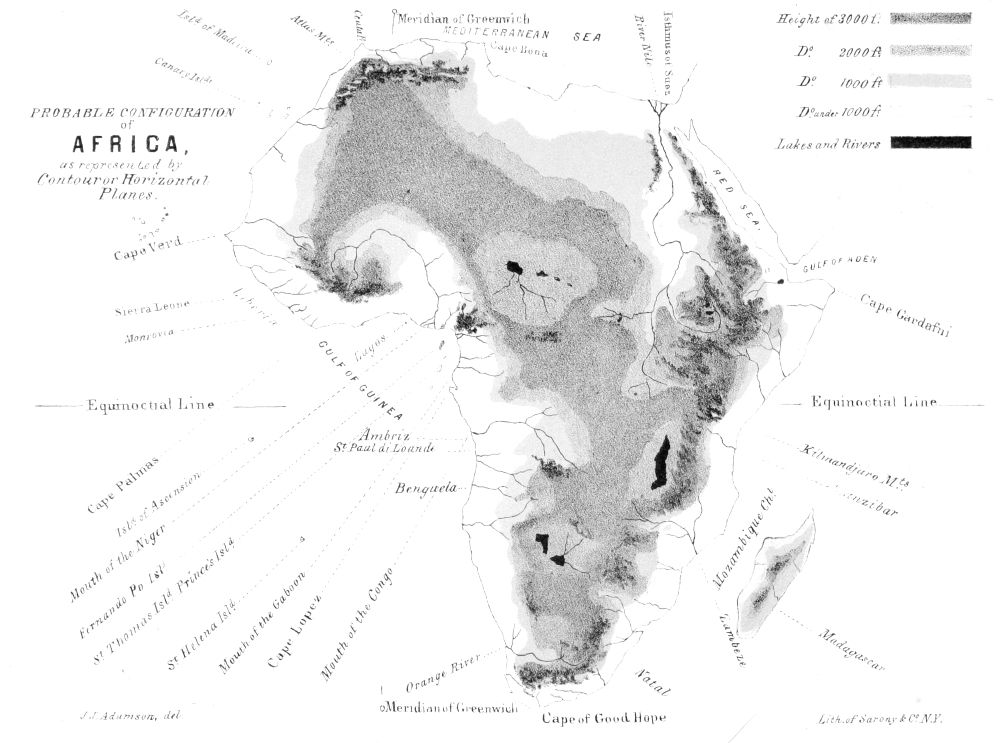

| F. E. Forbes, delt. | Lith. of Sarony & Co. N. Y. |

THE LOWER DECK OF A GUINEA-MAN IN THE LAST CENTURY.

Dr. Thomas Trotter, surgeon of the Brookes, says: “He has seen the slaves drawing their breath with all those laborious and anxious efforts for life which are observed in expiring animals, subjected, by experiment, to foul air, or in the exhausted receiver of an air-pump; has also seen them when the tarpaulins have inadvertently been thrown over the gratings, attempting to heave them up, crying out ‘kickeraboo! kickeraboo!’ i. e., We are dying. On removing the tarpaulin and gratings, they would fly to the hatchways with all the signs of terror and dread of suffocation; many whom he has seen in a dying state, have recovered by being brought on the deck; others, were irrevocably lost by suffocation, having had no previous signs of indisposition.”

In regard to the Garland’s voyage, 1788, the testimony is: “Some of the diseased were obliged to be kept on deck. The slaves, both when ill and well, were frequently forced to eat against their inclination; were whipped with a cat if they refused. The parts on which their shackles are fastened, are often excoriated by the violent exercise they are forced to take, and of this they made many grievous complaints to him. Fell in with the Hero, Wilson, which had lost, he thinks, three hundred and sixty slaves by death; he is certain more than half of her cargo; learnt this from the surgeon; they had died mostly of the smallpox; surgeon also told him, that when removed from one place to another, they left marks of their skin and blood upon the deck, and that it was the most horrid sight he had ever seen.”

The annexed sketch represents the lower deck of a[Pg 30] Guineaman, when the trade was under systematic regulations. The slaves were obliged to lie on their backs, and were shackled by their ankles, the left of one being fettered close to the right of the next; so that the whole number in one line formed a single living chain. When one died, the body remained during the night, or during bad weather, secured to the two between whom he was. The height between decks was so little, that a man of ordinary size could hardly sit upright. During good weather, a gang of slaves was taken on the spar-deck, and there remained for a short time. In bad weather, when the hatches were closed, death from suffocation would necessarily occur. It can, therefore, easily be understood, that the athletic strangled the weaker intentionally, in order to procure more space, and that, when striving to get near some aperture affording air to breathe, many would be injured or killed in the struggle.

Such were “the horrors of the middle passage.”

[Pg 31]

PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY—CLIMATE—GEOLOGY—ZOOLOGY—BOTANY.

Before proceeding to the colonizing era, it will be requisite to present an estimate of the value and importance of the African continent in relation to the rest of the world. This requires some preliminary notice of the physical condition of its territories, and the character and distribution of the tribes possessing them. Africa has not yet yielded to science the results which may be expected from it. Courage and hardihood, rather than knowledge and skill, have, from the circumstances of the case, been the characteristics of its successful explorers. We have, therefore, wonderful incidents and loose descriptions, without the accurate observation and statement of circumstances which can render them useful.

[Pg 32]

The vast radiator formed by the sun beating vertically on the plains of tropical Africa, heats and expands the air, and thus constitutes a sort of central trough into which gravitation brings compensating currents, by producing a lateral sliding inwards of the great trade-wind streams. Thus, as a general rule, winds which would normally diverge from the shores are drawn in towards them. They have been gathering moisture in their progress, and when pressed upwards, as they expand under the vertical sun, lose their heat in the upper regions, let go their moisture, and spread over the interior terraces and mountains a sheet of heavily depositing cloud. This constitutes the rainy season, which necessarily, from the causes producing it, accompanies the sun in its apparent oscillations across the equator.

The Gulf of Guinea has in its own bosom a system of hurricanes and squalls, of which little is known but their existence and their danger. A description of them, of rather an old date, specifies as a fact that they begin by the appearance of a small mass of clouds in the zenith, which widens and extends till the canopy covers the horizon. Now if this were true of any given spot, it would indicate that the hurricane always began there. The appearance of a patch of cloud in the zenith could be true of only one place out of all those which the hurricane influenced. If it is meant that[Pg 33] wherever the phenomenon originated, there a mass of cloud gradually formed in the zenith, this would be a most important particular in regard to the proximate cause of the phenomenon, for it would mark a rapid direction upwards of the atmosphere at that spot as the first observable incident of the series. That the movements produced would subsequently become whirling or circumvolant, is a mechanical necessity. But the force of the movement ought not to be strongest at the place where the mischief had its origin.

The squalls, with high towering clouds, which rise like a wall on the horizon, involve the same principles as to the formation of the vapor, and are easily explicable. They are not necessarily connected with circular hurricanes; but the principles of their formation may modify the intensity of the blasts in a circumvolant tornado. Since in the Gulf of Guinea they come from the eastward, it is to be inferred that they are ripples or undulations in an air current. In regard to all of this, it is necessary to speak doubtfully, for there is a great lack of accurate and detailed observation on these points.

Its position and physical characteristics give to this continent great influence over the rest of the earth. Africa, America, and Australia have nearly similar relations to the great oceans interposed respectively between them. Against the eastern sides of these regions[Pg 34] are carried from the ocean those strange, furious whirlings in the shallow film of the earth’s atmosphere, which constitute hurricanes. It is evident that these oceans are mainly the channels in which the surface winds move, which are drawn from colder regions towards the equator. The shores are the banks of these air streams. The return currents above flow over every thing. They are thus prevalent in the interior, so that the climatic conditions there are different from those on the seaboard. These circumstances in the southern extra-tropical regions are accompanied by corresponding differences in the character of the vegetable world.

These winds are sometimes drawn aside across the coast line—constituting the Mediterranean sirocco, and the African harmattan. Vessels far off at sea, sailing to the northward, are covered or stained on the weather side of their rigging (that next to the African coast), with a fine light-yellow powder. A reddish-brown dust sometimes tinges the sails and rigging. An instance of this occurred on board the “Perry” on her outward bound passage, when five hundred miles from the African coast.

The science of Ehrenberg has been searching amid the microscopic organisms contained in these substances, for tokens of their origin. In the red material he finds forms betraying not an African, but an American source, presumed to be in the great plains of the Amazon[Pg 35] and Orinoco. This suggests new views of the meteorology of the world; but the theories founded on it, are not clear of mechanical difficulties.

If we stand on almost any shore of the world as it exists at present, and consider the character of the land surface on the one hand, and of the ocean bottom on the other, we shall see that a very great difference in the nature of the beach line would be produced by a depression of the land towards the ocean, or by an elevation of it from the deep. The sea in its action on the bottom fills up hollows and obliterates precipices; but a land surface is worn into ravines and valleys. Hence a depression, so that the waters overflowed the land, would admit them into its recesses, and river courses, and winding gulleys—forming bays, islands, and secure harbors. Whereas elevation would bring up from the bottom its sand-banks and plains, forming an extent of slightly winding and unsheltered shore. The character of a coast will therefore depend very greatly upon its former history, before it became fixed. We have this contrast in the eastern and western sides of the Adriatic, or in the western and eastern sides of the British islands. These circumstances are to some degree controlled by the effects of partial volcanoes, or of powerful winds and currents. But on the whole, it may generally be inferred that a long unbroken shore indicates that the last change on the land level was one of[Pg 36] elevation; while a coast penetrated, broken, and defended by islands has received its conformation from being stopped in the process of subsiding.

The coast of Africa has over almost its whole circuit, that unbroken or slightly indented outline which would arise from upheaval. The only conspicuous exception to this, is in the eastern region, neighboring on the Mozambique Channel, where the Portuguese and the Arab possess the advantage, so rare in Africa, of having at their command convenient and sheltered harbors. There are centres of partial volcanic agency in the islands of the Atlantic, north of the equator, and in the distant spots settled by Europeans outside of Madagascar; but this action has not, as in the Mediterranean or Archipelago, modified the character of the continental shore. It is not known that there exists any active volcano on the continent.

Africa, therefore, if it could be seen on a great model of the world, would offer little, comparatively, that was varied in outline or in aspect. There would be great tawny deserts, with scanty specks of dusky green, or threads of sombre verdure tracing out its scant and temporary streams. There would be forests concealing or embracing the mouths of rivers, with brown mountains here and there penetrating through them, but rarely presenting a lofty wall to the sea. Interior plains would show some glittering lakes, begirt by the[Pg 37] jungle which they create. But it is a land nearly devoid of winter, either temporary or permanent. Only one or two specks, near the mouth of the Red Sea, and a short beaded line of the chain of Atlas, would throw abroad the silver splendor of perpetual snow. It is the great want of Africa, that so few mountains have on their heads these supplies for summer streams.

The sea-shore is generally low, except as influenced by Atlas, or the Abyssinian ranges, or the mountains of the southern extremity. There is, not uncommonly, a flat swampy plain, bordering on the sea, where the rivers push out their deltas, or form lagoons by their conflict with the fierce surge upon the shore. Generally at varying distances, there occur falls or rapids in the great rivers, showing that they are descending from interior plains of considerable elevation. The central regions seem, in fact, to form two, or perhaps three great elevated plateaux or terraced plains, having waters collected in their depressions, and joined by necks; such as are the prairies of Illinois, between the St. Lawrence and the Mississippi, or the llanos of South America between its great rivers. The southern one of these African plains approaches close to the Atlantic near the Orange River. Starting there at the height of three thousand feet, it proceeds round the sources of the river, and spreads centrally along by the lately visited, but long known lakes north of the[Pg 38] tropic. The equinoctial portion of it is probably drained by the Zambeze and the Zaire, flowing in opposite directions. It appears to be continuous as a neck westward of Kilmandjaro, the probable source of the Nile; till it spreads out into the vast space extending from Cape Verde to Suez, including in it the Niger and the Nile, the great desert, and the collections of waters forming Lake Tzad, and such others as there may be towards Fitre.

The mountains inclosing these spaces form a nearly continuous wall along the eastern side of Africa. The snows of Atlas form small streams, trickling down north and south; and, in the latter case, struggling almost in vain with the tropical heats, in short courses, towards the Desert of Sahara.

There are found separate groups of mountains, forming for the continent a broken margin on the west. There may also be an important one situated centrally between Lake Tzad and the Congo; but there appears no probability of a transverse chain, stretching continuously across this region, as has hitherto had a place on maps, under the title of the “Mountains of the Moon.”

No geological changes, except those due to the elevation of the oldest formations, appear to have taken place extensively in this continent. The shores of the Gulf of Guinea, and of the eastern regions, abound with gold, suggesting that their interior is not covered by[Pg 39] modern rocks. The two extremities at Egypt and Cape of Good Hope, have been depressed to receive secondary and tertiary deposits. There may be other such instances; but the continent seems, during a time, even geologically long, to have formed a great compact mass of land, bearing the same relations as now to the rest of the world.

The valleys and precipices of South Africa have been shaped by the mighty currents which circulate round the promontory of the Cape; and the flat summit of Table Mountain, at the height of three thousand six hundred feet, is a rocky reef, worn and fretted into strange projections by the surge, which the southeasters brought against it, when it was at the level of the sea.

The present state of organized life in Africa tells the same tale. It indicates a land never connected with polar regions, nor subjected to great variations of temperature. Our continent, America, is a land of extremes of temperature. Corresponding to that condition, it is a land characterized by plants, the leaves of which ripen and fall, so that vegetation has a pause, waiting for the breath of spring. All the plants of southern Africa are evergreens. The large browsing animals, such as the elephant and rhinoceros, which cannot stoop to gather grass, find continuous subsistence in the continuous foliage of shrubs. America abounds with stags[Pg 40] or deer—animals having deciduous horns or antlers. Southern Africa has none, but is rich in species of antelopes, which have true or permanent horns, and which nowhere sustain great variations of heat and cold. Its fossil plants correspond apparently in character to those which the country now bears.

Its fossil zoology offers very peculiar and interesting provinces of ancient life. These have been in positions not greatly unconformable to those of similar phenomena even now. Great inland fresh-water seas have abounded with new and strange types of organization, in character and office analogous to the amphibious forms occurring with profusion in similar localities of the present interior. These, and representatives of the secondary formations, rest chiefly on the old Silurian and Devonian series, the upheaving of which seems to have given the continent its place and outline. Coal is found at Natal, near the Mozambique Channel, but not hitherto known to be of value.

Africa still offers, and will long continue to offer, the most promising field of botanical discovery. Much novelty certainly remains to be elicited there, but it is very dilatory in finding its way abroad. Natal is the region most likely to be sedulously explored for some time. Vegetable ivory has been brought thence, and elastic, hard, useful timber abounds. Much lumber of good and varied character is taken to Europe from the[Pg 41] western regions of the continent; but so greatly has scientific inquiry been repelled by the deadly climate, that even the species affording it are unknown, or doubtfully guessed at.

The vegetation of the south is brilliant, but not greatly useful. It affords the type of that which covers the mountains, receding towards the northeast, until they reach perpetual snow near the equator. That which is of a more tropical character, stretches round their bases and through their valleys, with its profusion of palms, creepers, and dye-woods. These hereafter will form the commercial wealth of the country, affording oil, india-rubber, dye-stuffs, and other useful productions.

The wild animals of Africa belong to plains and to loose thickets, rather than to timbered forests. There is a gradation in the height of the head, among the larger quadrupeds, which indicates the sort of country and of vegetation suitable to them.

The musket, with its “villanous saltpetre,” in the hands of barbarians is everywhere expelling from the earth its bulkier creatures, so that the elephant is disappearing, and ivory will become scarce. Fear tames the wildest nature; even the lion is timid when he has to face the musket. The dull ox has learned a lesson with regard to him; for when the kingly brute prowls round an unyoked wagon resting at night, and his growl[Pg 42] or smell makes the oxen shake and struggle with terror, they are quieted by the discharge of firearms.

When Europeans first visited the shores of Africa, they were astonished at the tameness and abundance of unchecked animal life. The shallow bays and river lagoons were full of gigantic creatures; seals were found in great numbers, but of all animals these seem the most readily extirpated. The multitudes which covered the reefs of South Africa are nearly gone, and they seem to be no longer met with on the northern shores of the continent. The manatee, or sea-cow, and the hippopotamus, frequented the mouths of rivers, and were killed and eaten by the natives. They had never tamed and used the elephant: that this might have been done is inferred from the use of these animals by the Carthaginians. But as the Carthaginian territory was not African in the strict sense of the term, it may be doubted whether their species was that of Central Africa. This latter species is a larger, less intelligent looking, and probably a more stubborn creature than the Asiatic. The roundness of their foreheads and the size of their ears give them a duller and more brutal look; the magnitude of their tusks, and the occurrence of these formidable weapons in the female as well as in the male, are accommodated to the necessity of conflict with the lion, and indicate a wilder nature.

[Pg 43]

Lions of several species, abundance of panthers, cats, genets, and hyenas of many forms, mainly constitute the carnivorous province, having, as is suitable to the climate, a high proportion of the hyena form, or devourers of the dead. A foot of a pongo, or large ape, “as large as that of a man, and covered with hair an inch long,” astonished one of the earliest navigators. This animal, which indicates a zoological relationship to the Malayan islands, is known to afford the nearest approach to the human form. The monkey structure on the east coast of Africa tends to pass into the nocturnal or Lemurine forms of Madagascar, where the occurrence of an insulated Malayan language confirms the relationship indicated above.

The plains with bushy verdure nourish the ostrich and many species of bustards over the whole continent. Among the creatures which range far are the lammergeyer, or bearded eagle of the Alps, and the brown owl of Europe, extending to the extremity of the south. Among the parrots and the smaller birds, congregating species abound, forming a sort of arboreal villages, or joint-stock lodging-houses. Sometimes hundreds of such dwellings are under one thatch, the entrances being below. The weaving birds suspend their bottle-shaped habitations at the extremities of limber branches, where they wave in the wind. This affords security from monkeys and snakes; but they retain the instinct[Pg 44] of forming them so when there is no danger from either the one or the other.

Reptiles abound in Africa. The Pythons (or Boas) are formidable. Of the species of serpents probably between one-fourth and one-fifth are poisonous; but every thing relating to them in the central regions requires to be ascertained. The Natal crocodile is smaller than the Egyptian, but is greatly dreaded.

The following instance of its ferocity occurred to the Rev. J. A. Butler, missionary, in crossing the Umkomazi River, in February, 1853. “When about two-thirds of the way across, his horse suddenly kicked and plunged as if to disengage himself from the rider, and the next moment a crocodile seized Mr. Butler’s thigh with his horrible jaws. The river at this place is about one hundred and fifty yards wide, if measured at right angles to the current; but from the place we entered to the place we go out, the distance is three times as great. The water at high tide, and when the river is not swollen, is from four to eight or ten feet deep. On each side the banks are skirted with high grass and reeds. Mr. Butler, when he felt the sharp teeth of the crocodile, clung to the mane of his horse with a death hold. Instantly he was dragged from the saddle, and both he and the horse were floundering in the water, often dragged entirely under, and rapidly going down the stream. At first the crocodile drew them again to[Pg 45] the middle of the river, but at last the horse gained shallow water, and approached the shore. As soon as he was within reach natives ran to his assistance, and beat off the crocodile with spears and clubs. Mr. Butler was pierced with five deep gashes, and had lost much blood.”

[Pg 46]

[1] The author acknowledges his indebtedness for liberal and valuable contributions on the subject of Physical Geography, Geology, &c., to the Rev. Dr. Adamson, for twenty years a resident at the Cape of Good Hope, and government director and professor in the South African college. He wishes also to express his obligations for frequent suggestions from the same source on scientific subjects, during the preparation of this work.

AFRICAN NATIONS—DISTRIBUTION OF RACES—ARTS—MANNERS AND CHARACTER—SUPERSTITIONS—TREATMENT OF THE DEAD—REGARD FOR THE SPIRITS OF THE DEPARTED—WITCHCRAFT—ORDEAL—MILITARY FORCE—AMAZONS—CANNIBALISM.

Whence came the African races, and how did they get where they are? These are questions not easily answered, and are such as might have been put with the same hesitation, and in view of the same puzzling circumstances, three thousand years ago. On the monuments of Thebes, in Upper Egypt, of the times of Thothmes III., three varieties of the African form of man are distinctly portrayed. There is the ruling race of Egypt, red-skinned and massy-browed. There are captives not unlike them, but of a paler color, with their hair tinged blue; and there is the negro, bearing his tribute of skins, living animals, and ivory; with the white eyeball, reclining forehead, woolly hair, and other normal characteristics of his type.

Provided that these representations are correct, and that the colors have not changed, the Egyptian has[Pg 47] been greatly modified as to his tint of skin; whether we consider them as represented by the Copts, or the Fellahs of that country at present, the former bearing clearer traces of the more ancient form. The population of Africa, as it is at present, seems to be chiefly derivable from the other two races. There are, however, circumstances difficult to reconcile, in the present state of our knowledge, with any hypothesis as to the dispersion of man.

Southern and equatorial Africa includes tribes speaking dialects of two widely-spread tongues. One of them, the Zingian, or the Zambezan, is properly distinguished by the excess to which it carries repetition of certain signs of thought, giving to inflections a character different from what they exhibit in any other language. This tongue, however, bears, in other respects, a strong relationship to the many, but, perhaps, not mutually dissimilar dialects, of northern Africa. It may be considered as the form of speech belonging to the true or most normally developed African race.

The other of these two tongues offers also circumstances of peculiar interest. We may consider it, first, as it is found in use by the Hottentot or Bushman race, of South Africa. It has even among them regular and well-constructed forms of inflection, and as distinguishing it from the negro dialects, it has the sexual form of gender, or that which arises from the poetical or personifying[Pg 48] view of all objects—considering them as endowed with life, and dividing them into males and females. In this respect it is analogous to the Galla, the Abyssinian, and the Coptic. Nay, at this distant extremity of Africa, not only is the form of gender thus the same with that of the people who raised the wonderful monuments of Egypt, but that monumental tongue has its signs of gender, or the terminations indicating that relation, identical with those of the Hottentot race.

We have, therefore, the evidence of a race of men, striking through the other darker ones, on perhaps nearly a central line, from one end of the continent to the other. The poor despised Bushman, forming for himself, with sticks and grass, a lair among the low-spreading branches of a protea, or nestling at sunset in a shallow hole, amid the warm sand of the desert, with wife and little ones like a covey of birds, sheltered by some ragged sheepskins from the dew of the clear sky, has an ancestral and mental relationship to the builder of the pyramids and the colossal temples of Egypt, and to the artists who adorned them. He looks on nature with a like eye, and stereotypes in his language the same conclusions derived from it. He has in his words vivified external things, as they did, according to that form which, in our more logical tongues, we name poetical metaphor. The sun—“Soorees”—is to him a female, the productive mother of all organic life; and[Pg 49] rivers, as Kuis-eep, Gar-eep, are endowed with masculine activity and strength.

To this scattered family of man, which ought properly to be called the Ethiopic race, as distinguished from the negro, may probably be ascribed the fierce invasions from the centre, eastward and westward, under the names of Galla Giagas, and other appellations, which occasionally convulsed both sides of Africa; and, perhaps, by intermixture of races, gave occasion to much of the diversity found among native tribes, in disposition, manners, and language. The localities occupied by it have become insulated through the intrusion of the negro. Its southern division, or the Hottentot tribes, were being pressed off into an angle, and apparently in the process of extinction or absorption by the Zambezan Kaffirs from the north and east, when Europeans met and rolled them away into a small corner of desert.

Egypt was evidently the artery through which population poured into the broad expanse of Africa. That the progenitors of the negro race first entered there, and that another race followed subsequently, is one mode of disposing of the question, which, however, only removes its difficulties a little farther back.

This supposition is unnecessary. Any number of human families living together, comprises varieties of constitution, affording a source from which, by the force[Pg 50] of external circumstances, the extreme variations may be educed. If we examine critically the representations of the oldest inhabitants of Egypt, we shall see in the form of man which they exhibit, a combination of characteristics, or a provision for breaking into varieties corresponding to the conditions of external nature in the interior regions.

The dissatisfied, the turbulent, the defeated and the criminal would in these earliest times be thrown off from a settled community in Egypt, to penetrate into the southern and western regions. They would generally die there. Many ages of such attempts might pass before those individuals reached the marshes of the great central plateau, whose constitutions suited that position. Many of them, moreover, would die childless. Early death to the adult, and certain death to the immature, would sweep families off, as the streams bounding from southern Atlas intrude on the desert, and perish there. The many immigrants to whom all external things were adverse would be constantly weeded out; so it would be for generation after generation, until the few remained, whom heat, exposure, toil, marsh vapor, and fever left as an assorted and acclimated root of new nations.

Such seems to have been the process in Africa by which a declension of our nature took place from Egypt in two directions; one through the central plains down[Pg 51] to the marshes of the Gaboon or the Congo river, where the aberrant peculiarities of the negro seem most developed; and the other along the mountains, by the Nile and the Zambeze, until the Ethiopian sank into the Hottentot.

The sea does not deal kindly with Africa, for it wastes or guards the shores with an almost unconquerable surf. Tides are small, and rivers not safely penetrable. The ocean offered to the negro nothing but a little food, procured with some trouble and much danger. Hence ocean commerce was unknown to them. Only in the smallest and most wretched canoes did they venture forth to catch a few fish. If strangers sought for regions of prosperity, riches, or powerful government, their views were directed to the interior. Benin, in 1484, confessed its subordination to a great internal sovereign, who only gave responses from behind a curtain, or permitted one of his feet to be visible to his dependents, as a mark of gracious favor. It was European commerce in gold and slaves, received for the coveted goods and arms they bought, which ultimately gave these monarchs an interest in the sea-shore.

Cruelty and oppression were everywhere, as they still are. It is not easy for us to conceive how a living man can be moulded to the unhesitating submission in which a negro subject lives, so that it should be to him[Pg 52] a satisfaction to live and die, or suffer or rejoice, just as his sovereign wills. It can be accounted for only from the prevalence and the desolating fury of wars, which rendered perfect uniformity of will and movement indispensable for existence. It is not so easy to offer any probable reason for the eagerness to share in cruelty which glows in a negro’s bosom. Its appalling character consisted rather in the amount of bloodshed which gratified the negro, than in the studious prolongation of pain. He offers in this respect a contrast to the cold, demoniac vengeance of the North American Indian. Superstition probably excused or justified to him some of his worst practices. Human sacrifices have been common everywhere. There was no scruple at cruelty when it was convenient. The mouths of the victims were gagged by knives run through their cheeks; and captives among the southern tribes were beaten with clubs in order to prevent resistance, or “to take away their strength,” as the natives expressed it, that they might be more easily hurried to the “hill of death,” or authorized place of execution.

The negro arts are respectable, and would have been more so had not disturbance and waste come with the slave-trade. They weave coarse narrow cloths, and dye them. They work in wood and metals. The gold chains obtained at Wydah, of native manufacture, are well wrought. Nothing can be more correctly formed[Pg 53] for its purpose than the small barbed lancet-looking point of a Bushman’s arrow. Those who shave their heads or beards have a neat, small razor, double-edged, or shaped like a shovel. Arts improve from the coast towards the northeast.

Their normal form of a house is round, with a conical roof. The pastoral people of the south have it of a beehive form, covered with mats; the material is rods and flags. If the whole negro nations, however, were swept away, there would not remain a monument on the face of their continent to tell that such a race of men had occupied it.

One curious relation to external nature seems to have prevailed throughout all Africa, consisting in a special reverence, among different tribes, for certain selected objects. From one of these objects the tribe frequently derives its national appellation: if it is a living thing, they avoid killing it or using it as food. Serpents, particularly the gigantic pythons or boas, are everywhere reverenced. Some traces of adoration offered to the sun have been met with on the west coast; but, generally speaking, the superstitions of Africa are far less intellectual. These and many of their other practices have a common characteristic in the disappearance of all trace of their origin among the tribes observing them. To all inquiries they have the answer ready, that their fathers did so. There is in this, however,[Pg 54] no great assurance of real antiquity, for tradition extends but a short way back.

A reliance on grisgris, or amulets, worn about the person, belongs to Africa, perhaps from very ancient ages. Egypt was probably its source: a kind of literary character has been given to it by the Mohammedans. Throughout inland central Africa, sentences written on scraps of paper or parchment have a marketable value. An impostor or devotee may gain authority and profit in this way. As we pass southward we find this superstition sinking lower and lower in debasement: men there really cover or load themselves with all kinds of trumpery, and have a real and hearty confidence in bones, buttons, scraps, or almost any conceivable thing, as a security against any conceivable evil. The Kroomen, even, with their purser’s names, of Jack Crowbar, Head Man, and Flying-Jib, Bottle of Beer, Pea Soup, Poor Fellow, Prince Will, and others, taken on board the “Perry,” in Monrovia, were found now and then with their sharks’, tigers’ and panthers’ teeth, and small shells, on their ankles and wrists; although most of these people, from contact with the Liberians, have seen the folly of this practice, and dispensed with their charms.

The Africans also have stationary fetishes, consisting in sacred places and sacred things. They have practices to inspire terror, or gain reverence in respect to[Pg 55] which it is somewhat difficult to decide whether the actors in them are impostors or sincere. Idols in the forms of men, rude and frightful enough, are among these fetishes, but it cannot be said that idolatry of this kind prevails extensively in the country.

In two respects they look towards the invisible: they dread a superhuman power, and they fear and worship it as being a measureless source of evil. It is scarcely correct to call this Devil-worship, for this is a title of contrast, presuming that there has been a choice of the evil in preference to the good. The fact in their case seems to be, that good in will, or good in action, are ideas foreign to their minds. Selfishness cannot be more intense, nor more exclusive of all kindness and generosity or charitable affection, than it is generally found among these barbarians. The inconceivableness of such motives to action has often been found a strong obstacle to the influence of the Christian missionary. They can worship nothing good, because they have no expectation of good from any thing powerful. They have mysterious words or mutterings, equivalent to what we term incantations, which is the meaning of the Portuguese word from which originated the term fetish.

The other reference of their intellect to invisible things consists in acknowledging the continued existence of the dead, and paying reverence to the spirits of[Pg 56] their forefathers. This leads to great cruelty. Men of rank at their death are presumed to require attendance, and be gratified with companionship. This event, therefore, produces the murder of wives and slaves, to afford them suitable escort and service in the other world. From the strange mixture of the material and spiritual common to men in that barbarian condition, the bodies or the blood of the slain appear to be the essentials of these requirements. Thus, also, the utmost horror is felt at decapitation, or at the severing of limbs from the body after death. It is revenge, as much as desire to perpetuate the remembrance of victory, which makes them eager for the skulls and jaw-bones of their enemies, so that in a royal metropolis, walls, and floors, and thrones, and walking-sticks, are everywhere lowering with the hollow eyes of the dead. These sad, bare and whitened emblems of mortality and revenge present a curious and startling spectacle, cresting and festooning the red clay walls of Kumassi, the Ashantee capital.

Such belief leads to strange vagaries in practice. They sympathize with the departed, as subject still to common wants and ruled by common affections. A negro man of Tahou would show his regard for the desires of the dead by sitting patiently to hold a spread umbrella over the head of a corpse. The dead man’s mouth, too, was stuffed with rice and fowl, and in cold[Pg 57] weather a fire was kept burning in the hut for the benefit of their deceased friend. They consulted his love of ornament, also, for the top of his head and his brow were stained red, his nose and cheeks yellow, and the lower jaw white; and fantastic figures of different colors were daubed over his black body.

Dingaan, the Zulu chief, was exceedingly fond of ornament. He used to boast that the Zulus were the only people who understood dress. Sometimes he came forward painted with all kinds of stripes and crosses, in a very bizarre style. The people took all this gravely, saying that “he was king and could do what he pleased,” and they were content with his taste. It is this unreflecting character which astounds us in savages. They never made it a question whether the garniture of the king or of the corpse had any thing unsuitable.

All along the coasts, from the equator to the north of the Gulf of Guinea, they did not eat without throwing a portion on the ground for those who had died. Sometimes they dug a small hole for these purposes, or they had one in the hut, and into it they poured what they thought would be acceptable. They conceived that they had sensible evidence of the inclinations of the dead. In lifting up or carrying a corpse on their shoulders, men may not attend to the exact direction of their own muscular movements or those of their associates.[Pg 58] There are necessarily shocks, jolts and struggles, from the movements of their associates. People will, in some cases, pull different ways when hustled together. All these unconscious movements, not unlike the “table turnings” of the present era, were taken as expressive of the will of the dead man, as to how and whither he was to be carried.

Their belief, as we have seen, influenced their life: it was earnest and heartfelt. When the king of Wydah, in 1694, heard that Smith, the chief of the English factory, was dangerously ill with fever, he sent his fetishman to aid in the recovery. The priest went to the sick man, and solemnly announced that he came to save him. He then marched to the white man’s burial-ground with a provision of brandy, oil, and rice, and made a loud oration to those that slept there. “O you dead white people, you wish to have Smith among you; but our king likes him, and it is not his will to let him go to be among you.” Passing on to the grave of Wyburn, the founder of the factory, he addressed him, “You, captain of all the whites who are here! Smith’s sickness is a piece of your work. You want his company, for he is a good man; but our king does not want to lose him, and you can’t have him yet.” Then digging a hole over the grave, he poured into it the articles which he had brought, and told him that if he needed these things, he gave them with good-will, but[Pg 59] he must not expect to get Smith. The factor died, notwithstanding. The ideas here are not very dissimilar to those of the old Greeks.

It is remarkable, however, that in tracing this negro race along the continent towards the south, we find these notions and practices to fade away, and at last disappear. Southeast of the desert, along the Orange River, there is scarcely a trace of them.

The dread of witchcraft prevails universally. In general, the occurrence of disease is ascribed to this source. In the north they fear a supernatural influence; in the south this is traced to no superhuman origin, but is conceived to be a power which any one may possess and exercise. Among these tribes, the man presumed to be guilty of this crime is a public enemy (as were the witches occasionally found among our own venerated pious, and public-spirited puritan forefathers—a blemish in their character due to the general ignorance of the age), to be removed if possible, as a lion, tiger, or pestilence would be annihilated. Even the force of civilized law, when introduced among them, has not saved a man under this stigma from being secretly murdered by the terrified people. It has yielded only to the enlightening influence of Christian missionaries.

These delusions are often rendered the support of tyranny by the chiefs, for the property of the accused[Pg 60] is confiscated. Scenes sad and horrible are exhibited as the consequence of a chief’s illness. In order to force a discovery of the means employed, and to get the witchcraft counteracted, some native, who is generally rich enough to be worth plundering, is seized and tortured, until, as an old author expresses it, “he dies, or the chief recovers.” They extend the horror of the infliction, by calling in the aid of vermin life, destined in nature to devour corruption, by scattering handfuls of ants over the scorched skin and quivering flesh of their victim.

Generally among the Guinea negroes, the ordeal employed to detect this crime, is to compel the accused to drink a decoction of sassy-wood. This may be rendered harmless or destructive, according to the object of the fetishman. It is oftener his purpose to destroy than to save, and great cruelty has in almost all cases been found to accompany the trial.

Plunder is the reward of the soldier. In the central regions this was increased by the sale of captives. Captives of both sexes were the chief’s property. Thus the warriors looked to the acquisition of wives from the chief, as the recompense of successful wars. They announced this as their aim in their preparatory songs. The chief was, therefore, to them the source of every thing. Their whole thought responded to his movements, and sympathized with his greatness and success.

Women in Africa are everywhere slaves, or the[Pg 61] slaves of slaves. The burdens of agricultural labor fall on them. When a chief is announced as having hundreds or thousands of wives, it signifies really that he has so many female slaves. There does not appear to be any tribe in Africa, in which it is not the rule of society, that a man may have as many such wives as he can procure. The number is of course, except in the case of the supreme chief, but few. The female retinue of a sovereign partakes everywhere of the reverence due to its head. The chief and his household are a kind of divinity to the people. His name is the seal of their oath. The possibility of his dying must never be expressed, nor the name of death uttered in his presence. Names of things appearing to interfere with the sacredness of his, must be changed. His women must not be met or looked at.