THISTLEDOWN

- New and Enlarged Edition, 1913

- Second Impression, 1914

- Third Impression, 1919

- Fourth Impression, 1921

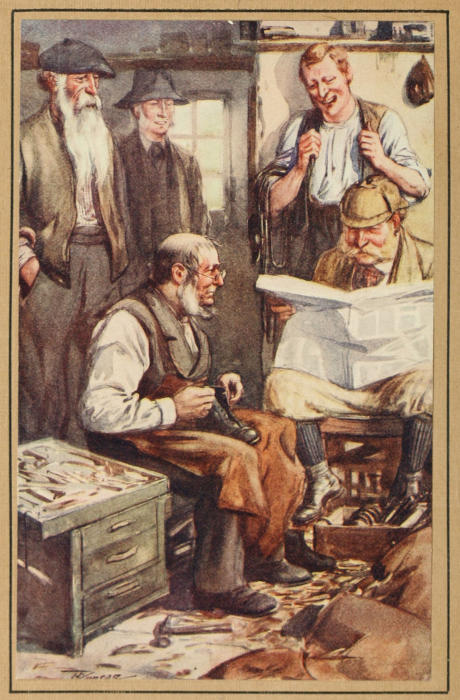

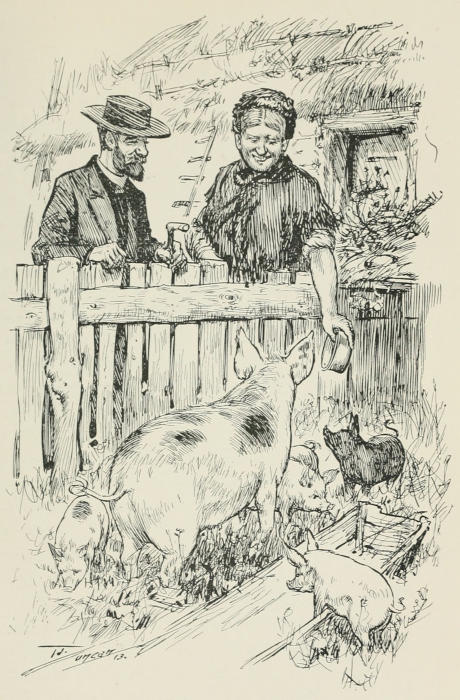

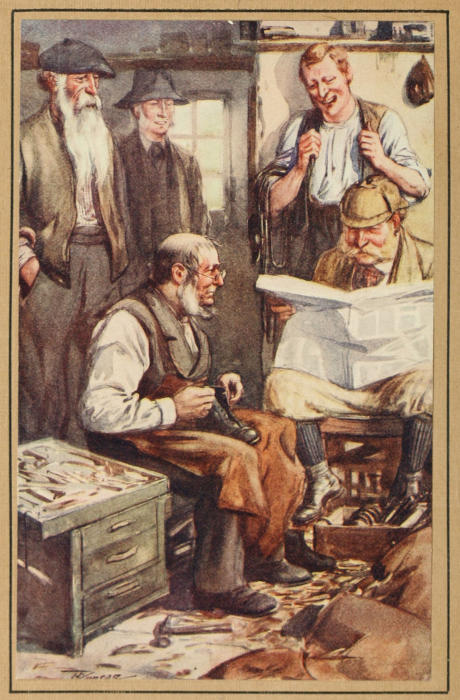

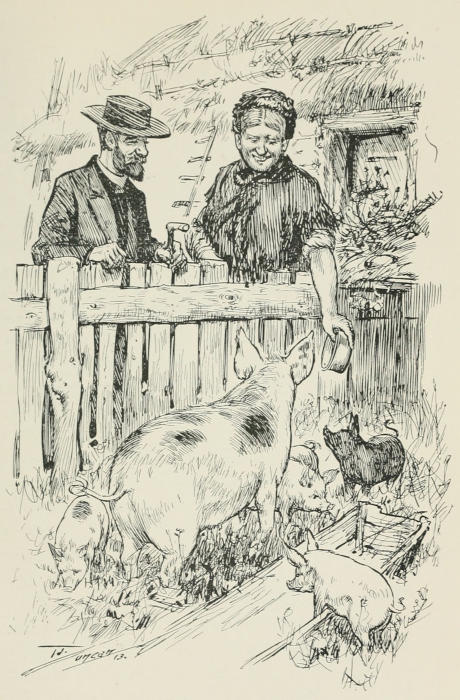

Scotch folks humour, being the common gift of Nature to all and

sundry in the land, differing only in degree, slips out most frequently

when and where least expected. Famous specimens of it come

down from our lonesome hillsides—from the cottage and farm

ingle-nooks.—Page 34.

Frontispiece.

[1]

THISTLEDOWN

A BOOK OF SCOTCH HUMOUR

CHARACTER, FOLK-LORE

STORY & ANECDOTE

BY

ROBERT FORD

EDITOR OF

“BALLADS OF BAIRNHOOD,” “AULD SCOTS BALLANTS”

“VAGABOND SONGS,” ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BY JOHN DUNCAN

PAISLEY: ALEXANDER GARDNER

Publisher by Appointment to the late Queen Victoria

[2]

An eminently learned and genial ex-Professor of

one of our Universities not long since pointed

out how Scotland was remarkable for three things—Songs,

Sermons, and Shillings. And whilst it may

not be disputed that she has enormous and ever-increasing

store of these three good things—and

that, moreover, she loves them all—there is a fourth

quality of her many-sided nature which is more

distinctly characteristic of Auld Caledonia and her

people, and that is the general possession of the

faculty of original humour. Not one in ten thousand

of the Scottish people may be able to produce a good

song, or a good sermon; not one in twenty thousand

of them may be able to “gather meikle gear and

haud it weel thegither;” but every second Scotsman

is a born humourist. Humour is part and parcel of

his very being. He may not live without it—may

not breathe. Consequently, it is found breaking

out amongst us in the most unlikely as well as in

the most likely places. It blossoms in the solemn[4]

assemblies of the people; at meetings of Kirk-Sessions;

in the City and Town Council Chambers; in our

Presbyteries; our Courts of Justice; and in the high

Parliament of the Kirk itself. Famous specimens of

it come down from the lonesome hillsides; from the

cottage, bothy, and farm ingle-nooks. It issues

from the village inn, the smiddy, the kirkyard; and

functions of fasting and sorrow give it birth as well

as occasions of feasting and mirth. It drops from

the lips of the learned and the unlearned in the land;

and is not more frequently revealed in the eloquence

of the University savant than in the gibberish of the

hobbling village and city natural.

Humorous Scottish anecdotes have been an abundant

crop; and collectors of them there have been

not a few. Dean Ramsay’s garrulous and entertaining

Reminiscences, and Dr. Charles Rogers’ Familiar

Illustrations of Scottish Life excepted, however, the

published collections of our floating facetiæ have

been “hotch-potch” affairs. Revelations each of

some little industry, no doubt, but few of them

affording any proof of the compiler’s familiarity with

the subject. And as none of them have reached

farther back than Dean Ramsay, and all have been

content to take the more familiar of Ramsay’s and

Rogers’ illustrations and anecdotes, and supplement[5]

these in hap-hazard fashion with random clippings

from the variety columns of the daily and weekly

newspapers, the individual result has been such as

Voltaire’s famous criticism eloquently describes:—They

have contained things both good and new;

but what was good was not new, and what was new

was not good.

To the present work the critical aphorism of

the “brilliant Frenchman” may not in fairness be

applied. In any attempt to afford an adequate

representation of the humours of the Scottish people,

illustrations must of necessity be drawn from widely

different sources, and I have, consequently, to confess

my indebtedness to various earlier gleaners in the

same field, chiefly to Dean Ramsay, Dr. Rogers, and

the genial trio, Carrick, Motherwell, and Henderson.

But for representative illustrations of Scottish life

and character I have gone further back and come

down to a later period than any previous writer on

the subject. And so, whilst the reader will discover

here much that is old and good, he will find very

much that is new, which, as illustrative of Scottish

humour and character, will compare with the best of

the old.

No pointless or dubiously nationalistic anecdote or

illustration has been admitted. The work has been[6]

carefully and elaborately classified under eighteen

distinct headings, each class, or section, being introduced

by an exposition of the phase or phases of life

and character to which it applies, and cemented from

first to last by reflective and expository comment.

Essentially a book of humour, it is hoped that

the reader will find it to be something more than a

merely funny book. If he does not, the writer will

have failed to realize fully his aim.

Robert Ford.

[1891.]

|

PAGE |

| CHAPTER I., |

11 |

| The Scottish Tongue—Its graphic force

and powers of pathos and humour. |

|

| CHAPTER II., |

32 |

| Characteristics of Scotch Humour. |

|

| CHAPTER III., |

56 |

| Humour of Old Scotch Divines. |

|

| CHAPTER IV., |

87 |

| The Pulpit and the Pew. |

|

| CHAPTER V., |

122 |

| The Old Scottish Beadle—His Character and Humour. |

|

| CHAPTER VI., |

149 |

| Humour of Scotch Precentors. |

|

| CHAPTER VII., |

169 |

| Humour of Dram-Drinking in Scotland. |

|

| CHAPTER VIII., |

195 |

| The Thistle and the Rose. |

[8] |

| CHAPTER IX., |

222 |

| Screeds o’ Tartan—A Chapter of Highland Humour. |

|

| CHAPTER X., |

247 |

| Humour of Scottish Poets. |

|

| CHAPTER XI., |

285 |

| ’Tween Bench and Bar—A Chapter of Legal Facetiæ. |

|

| CHAPTER XII., |

313 |

| Humour of Scottish Rural Life. |

|

| CHAPTER XIII., |

342 |

| Humours of Scottish Superstition. |

|

| CHAPTER XIV., |

367 |

| Humour of Scotch Naturals. |

|

| CHAPTER XV., |

386 |

| Jamie Fleeman, the Laird of Udny’s Fool. |

|

| CHAPTER XVI., |

401 |

| “Hawkie”—A Glasgow Street Character. |

|

| CHAPTER XVII., |

429 |

| The Laird o’ Macnab. |

|

| CHAPTER XVIII., |

440 |

| Kirkyard Humour. |

|

| INDEX, |

455 |

[9]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

|

PAGE |

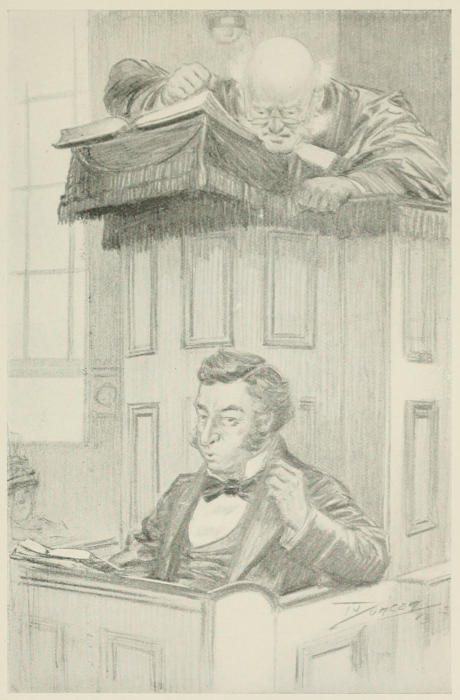

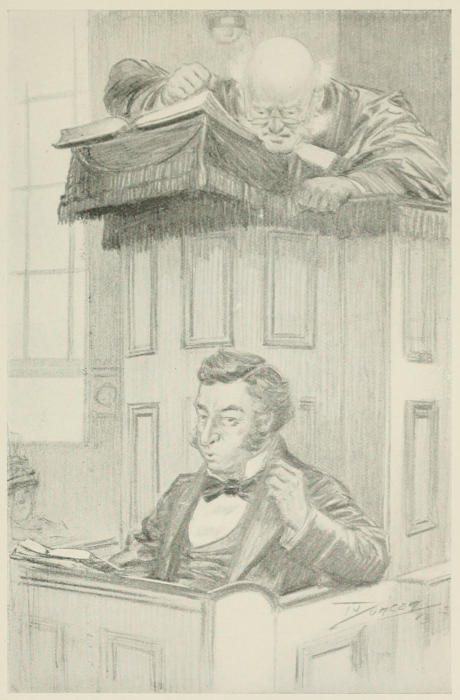

| Scotch folks’ humour, |

Frontispiece |

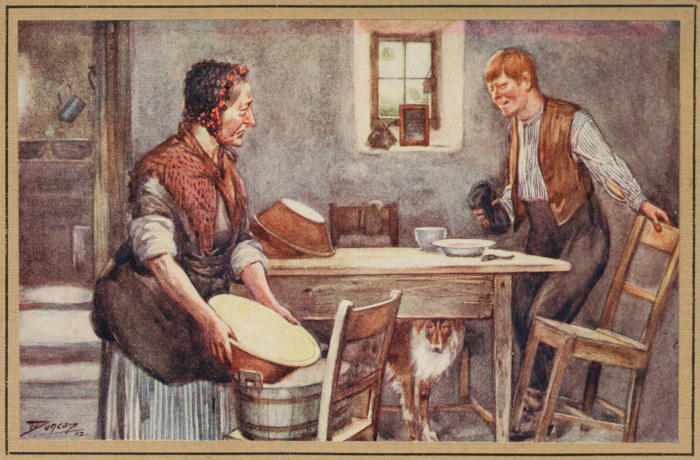

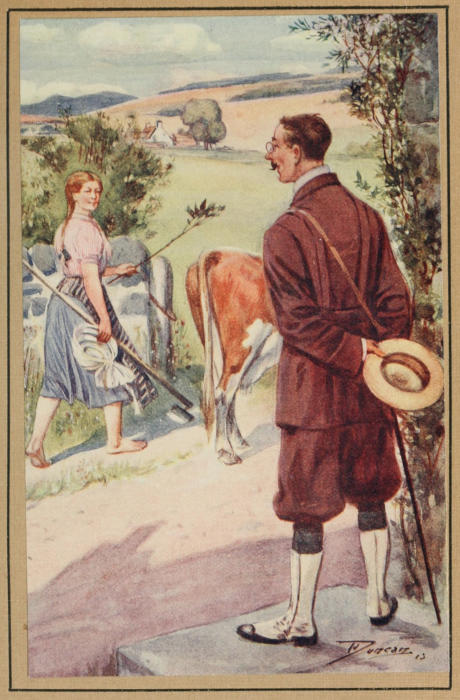

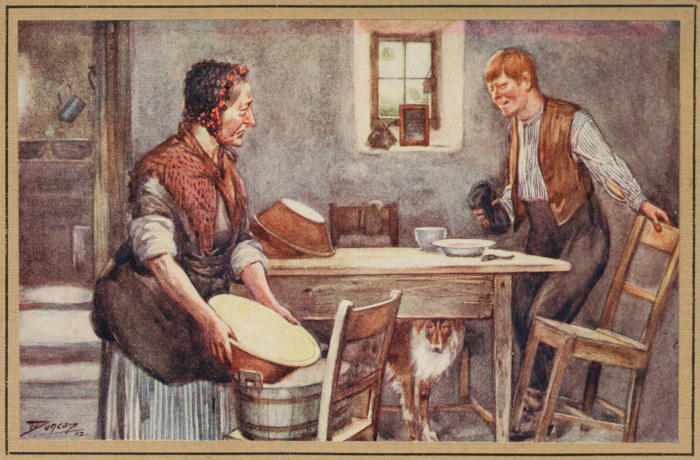

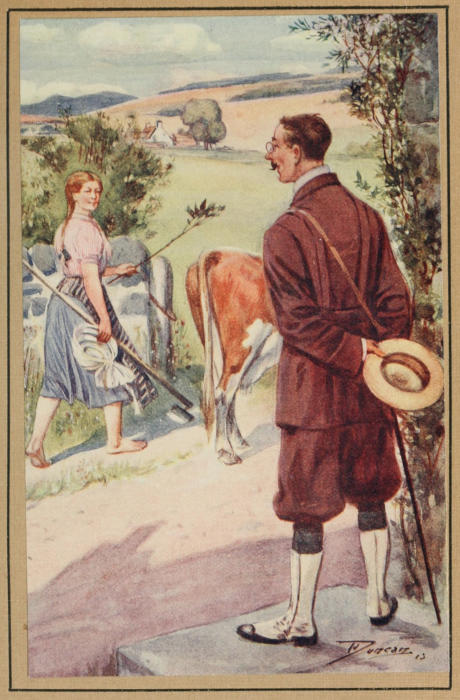

| “Plenty o’ milk for a’ the parritch,” |

35 |

| “Three fauts to his sermon,” |

91 |

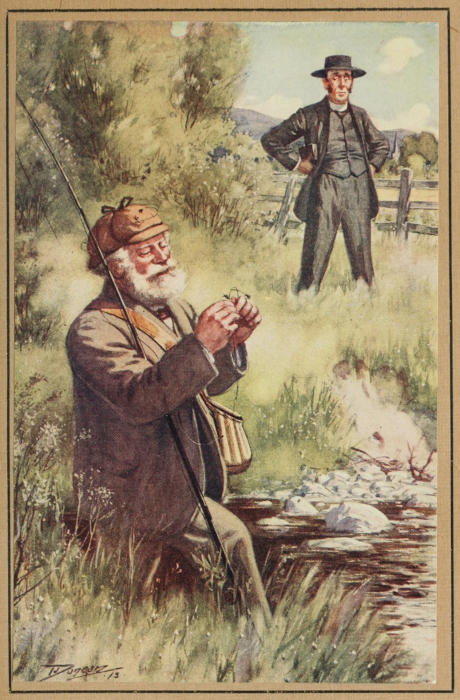

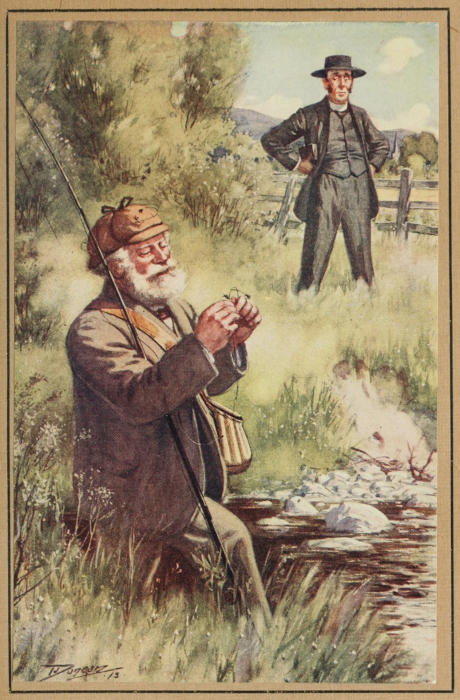

| “Ye didna seem to ha’e catch’d mony,” |

98 |

| “This wee black deev’luck, we ca’ Wee Macgregor o’ the Tron!” |

106 |

| “Can ye tell me how long Adam continued in a state of innocence?” |

120 |

| “I’m geyan weel on mysel’, sir,” |

131 |

| “I hae happit mony a faut o’ yours,” |

138 |

| “The foxes’ tails,” |

168 |

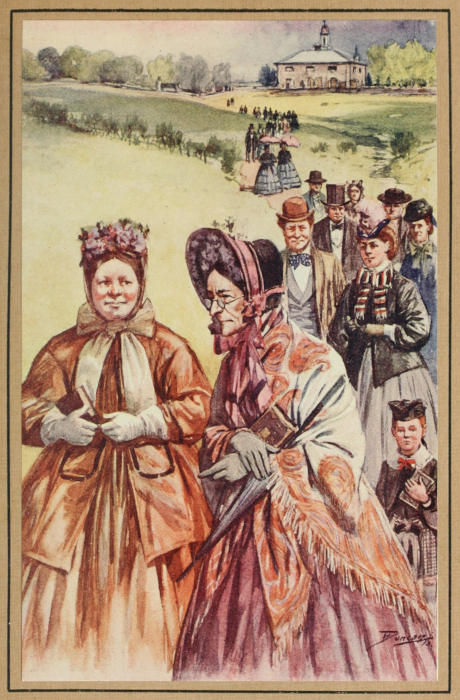

| “They mind their ain business,” |

215 |

| “Can ye no show him yer Government papers?” |

322 |

| “We do a’ oor ain whistlin’ here,” |

325 |

| “My—my faither’s below’t!” |

326 |

| “If ye was a sheep, ye wad hae mair sense,” |

328 |

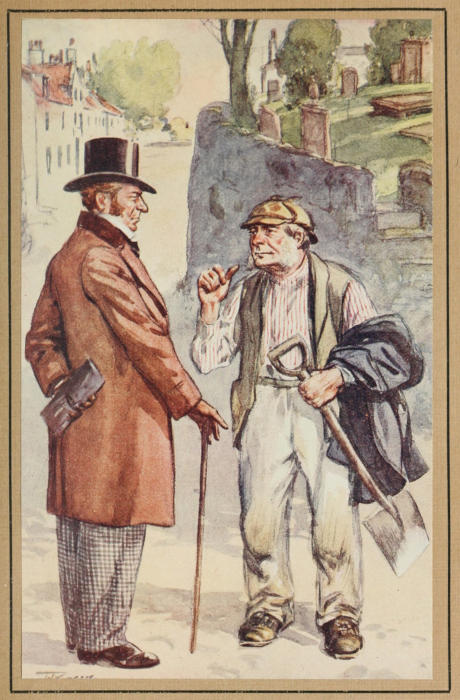

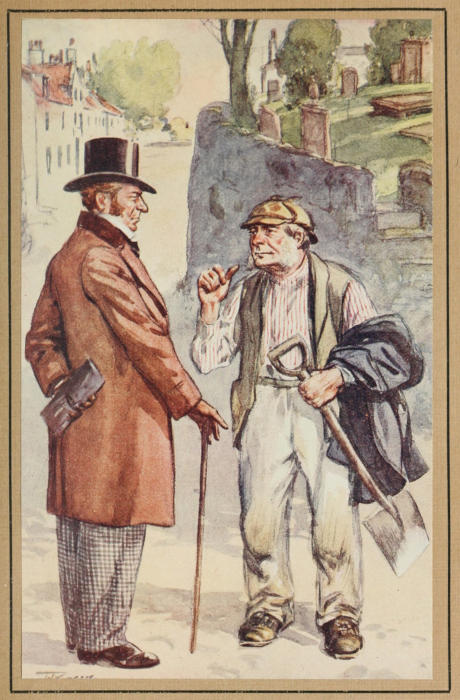

| “Jamie Carlyle, sir, feeds the best swine that come into Dumfries market,” |

335 |

| “Hoo the deil do you ken whether this be the road or no?” |

383 |

[10]

[11]

THISTLEDOWN

CHAPTER I

THE SCOTTISH TONGUE—ITS GRAPHIC FORCE AND POWERS OF PATHOS AND HUMOUR

We are frequently told—and now and again

receive unwelcome scraps of evidence in confirmation

of the scandal—that our dear old mother

tongue is falling into desuetude in our native land.

Already, it must be confessed, it has been abrogated

from the drawing-rooms of the ultra-refined upper

circles of Scottish society. The snobbish element

amongst the great middle-class, ever prone to imitate

their “betters,” affect not to understand it, and

blush (the sillier of them) when, in an unguarded

moment, a manifest Scotticism slips into their conversation.

There is a portion of the semi-educated

working population, again, who, imitating the snobbish

element of the middle grade, speak Scotch freely

only in their working clothes. On Sundays, and extra

occasions, when dressed in their very best, there is

just about as much Scotch in their talk as will show

one how poorly they can speak English, and just

about enough English to render their Scotch ridiculous.

Observing all this, and taking it in conjunction[12]

with the other denationalising tendencies of the age,

there are those who predict that the time is not far

distant when Burns’s poems, Scott’s novels, and

Hogg’s tales will be sealed books to the partially

educated Scotsman. That there is a growing tendency

in the direction indicated is quite true, but

the disease, I believe, is only skin deep as yet, and

the bone and sinew of the country remain quite

unaffected. That there will be a sudden reaction

in the patient must be the sincere desire of every

patriotic Scot. If the prediction of obsoletism is

ever to be realized, then, “the mair’s the pity.”

Scotland will not stand where she did. For very

much—oh, so much—of what has made her glorious

among the nations of the world will have passed

away, taking the sheen of her glory with it. What

Scotsmen, as Scotsmen, should ever prize most is

bound up inseparably with the native language.

Ours is a matured country, and the stirring scenes

of her history on which the mind of the individual

delights to dwell, are so frequently enshrined in

spirited ballad and song, couched in the pithy Scottish

vernacular, that, to suppose these latter dead—they

are not translatable into English—is to suppose

the best part of Scottish history dead and buried

beyond the hope of resurrection. For its own sake

alone the Scottish tongue is eminently deserving of

regard—of cultivation and preservation. Scotsmen

should be—and so all well-conditioned Scotsmen

surely are—as proud of their native tongue as they[13]

are of their far-famed native bens and glens. For

why, the rugged grandeur of the physical features

of our country are not more worthy of admiration

than the language in which their glories have been

most fittingly extolled. They have characteristics

in common; for rugged grandeur is as truly a feature

of the Scottish language as it is the dominant feature

of Scottish scenery. True, its various dialects are

somewhat tantalising. The Forfar man is vividly

identified by his “foo’s” and his “fa’s,” and his

“fat’s” and his “fans”; and the Renfrewshire man

by his “weans,” his “wee weans,” and his “yin

pound yin and yinpence,” etc. Taking a simple

phrase as an example—(Anglice):—“The spoon is

on the loom.” The Aberdonian will tell you that

“The speen’s on the leem.” The Perthshire man will

say “That spun’s on the luim”; and the Glasgow

citizen will inform you that “The spin’s on the lim.”

In a fuller example, a Renfrewshire person will vouchsafe

the information that he “Saw a seybo synd’t doon

the syvor till it sank in the stank.” A native of

Perthshire will only about half understand what the

speaker has said, and may threaten to “rax a rung

frae the boggars o’ the hoose and reeshil his rumple

wi’t,” without sending terror to the soul of his West

country confederate. Latterly, an Aberdonian may

come on the scene and ask, “Fa’ fuppit the loonie?”

and neither of the forenamed parties will at once

perceive the drift of his inquiry. To illustrate how

difficult it may be for the East and the West to[14]

understand each other, I will tell a little story. An

Aberdonian not long ago got work in Glasgow

where they used a quantity of tar, and was rather

annoyed to see his fellow-workmen wash the tar off

their hands while he washed and rubbed at his in

vain. His patience could stand it no longer, and

going up to the foreman, and, stretching out his

hands, he asked:—“Fat’ll tak’ it aff?” “Yes,”

replied the foreman, “fat’ll tak’ it aff.” “Fat’ll tak’

it aff?” “Yes, I said fat would tak’ it aff.” “But

fat’ll tak’ it aff?” persisted the Aberdonian. The

foreman pointed to a tub, and roared: “Grease,

you stupid eediot!” “Weel than,” retorted the

Aberdonian, “an’ fat for did you no say that at

first?”

There are, however, dialects and provincialisms in

the language of every country and people under the

sun, and the Scottish vernacular is not worse—not

nearly so bad as many are. Our dialects are mainly

the results of a narrowing and broadening of the vowel

sounds, as exemplified in the instance of the words

“spoon” and “loom.” I have spoken of the rugged

grandeur of the Scottish Doric, and its claims to preservation.

There are single words in Scotch which

cannot be adequately expressed in a whole sentence

in English. Think of “fushionless,” “eerie,” “wersh,”

“gloamin’,” “scunner,” “glower,” “cosie,” “bonnie,”

“thoweless,” “splairge,” and “plowter,” etc., and try

to find their equivalents in the language of the school.

Try and find a sentence that will fairly express some[15]

of the words. “A gowpen o’ glaur” is but weakly

expressed in “a handful of mud”; “stoure” is not

adequately defined by calling it “dust in motion”;

“flype yer stockin’, lassie,” is easier said than “turn

your stocking inside out, girl.” “Auld lang syne”

is not expressible in English. “A bonnie wee lassie”

is more euphonious and expressive by a long way than

“a pretty little girl.” “Hirsle yont,” “my cuit’s

yeukie,” “e’enin’s orts mak’ gude mornin’ fodder,”

“spak’ o’ lowpin’ ower a linn,” and “pree my mou’,”

are also good examples of expressive Scotch. Nowhere,

perhaps, is the singular beauty and rare

expressiveness of the Scottish national tongue seen

to better advantage than in the proverbial sayings—those

short, sharp, and shiny shafts of speech,

aptly defined as “the wit of one and the wisdom of

many,”—and of which the Scottish language has

been so prolific. “The genius, wit, and wisdom of

a nation are discovered by their proverbs,” says

Bacon; and, verily, while the proverbs of Scotland

are singularly expressive of the pith and beauty

of the vernacular in which they are couched, they

also reveal in very great measure the mental and

social characteristics of the people who have perpetuated

them. “A gangin’ fit’s aye gettin’, were’t

but a thorn;” “Burnt bairns dread the fire;” “A’e

bird in the hand’s worth twa in the bush;” “A

fool an’ his siller’s sune parted;” “Hang a thief

when he’s young an’ he’ll no steal when he’s auld;”

“There’s aye some water whaur the stirkie droons;”[16]

“Moudiwarts feedna on midges;” “When gossipin’

wives meet, the deil gangs to his dinner;” “Hungry

dogs are blythe o’ bursten puddin’s;” “He needs a

lang-shankit spune that wad sup wi’ the deil;” “A

blate cat maks a prood mouse;” “Better a toom house

than an ill tenant;” “Lippen to me, but look to

yoursel’;” “Jouk an’ lat the jaw gang by;” “Better

sma’ fish than nane;” “The tulziesome tyke comes

hirplin’ hame;” “Ha’ binks are sliddery;” “Ilka

cock craws best on his ain middenhead;” “Lazy

youth mak’s lowsy age;” “Next to nae wife, a guid

wife’s best;” “Lay your wame to your winnin’;”

“It’s nae lauchin’ to girn in a widdy;” “The

wife’s a’e dochter an’ the man’s a’e coo, the tane’s

ne’er weel, an’ the tither’s ne’er fu’.” These give

the evidence.

Ours is a language peculiarly powerful in its use

of vowels, and the following dialogue between a

shopman and a customer is a convincing example.

The conversation relates to a plaid hanging at a

shop door:—

Customer (inquiring the material)—“Oo?” (wool?).

Shopman—“Aye, oo.” (yes, wool).

Customer—“A’ oo?” (all wool?).

Shopman—“Ay, a’ oo” (yes, all wool).

Customer—“A’ a’e oo?” (all one wool?).

Shopman—“Ou, ay, a’ a’e oo” (oh, yes, all one

wool).

A dialogue in vowel sounds—surely a thing

unique in literature!

[17]

In his Scotch version of the Psalms—“frae

Hebrew intil Scottis”—the late Rev. Dr. Hately

Waddell, of Glasgow, gives many striking illustrations

of the force and beauty of idiomatic Scotch.

His language partakes rather much of the antique

form to be readily perceptible to the present generation,

but its purity is unquestionable, and its beauty

and power inexpressible in other words than his own.

Let us quote the familiar 23rd Psalm.

“The Lord is my herd; na want sal fa’ me.

“He louts me till lie amang green howes; He airts

me atowre by the lown waters.

“He waukens my wa’gaen saul; He weises me

roun for His ain name’s sake, intil richt roddins.

“Na! tho’ I gang thro’ the dead-mirk dail; e’en

thar sal I dread nae skaithin; for Yersel’ are nar-by

me; Yer stok an’ Yer stay haud me baith fu’ cheerie.

“My buird Ye ha’e hansell’d in face o’ my faes;

Ye ha’e drookit my head wi’ oyle; my bicker is fu’

an’ skailin’.

“E’en sae sal gude guidin’ an’ gude gree gang wi’

me ilk day o’ my livin’; an’ ever mair syne i’ the

Lord’s ain howff, at lang last, sal I mak bydan.”

Hear also Dr. Waddell’s translation of the last

four verses of the 52nd chapter of Isaiah, they are

inexpressibly beautiful:—

“Blythe and brak-out, lilt a’ like ane, ye bourocks

sae swak o’ Jerusalem; for the Lord He has hearten’d

His folk fu’ kin’; He has e’en boucht back

Jerusalem.

[18]

“The Lord He rax’d yont His hailie arm, in sight

o’ the nations mony, O; an’ ilk neuk o’ the yirth

sal tak tent an’ learn the health o’ our God sae

bonie, O!

“Awa, awa, clean but frae the toun: mak nor

meddle wi’ nought that’s roun’; awa frae her bosom;

haud ye soun’, wi’ the gear o’ the Lord forenent ye!

“For it’s no wi’ sic pingle ye’se gang the gate;

nor it’s no wi’ sic speed ye maun spang the spate;

for the Lord, He’s afore ye, ear’ an’ late; an’ Israel’s

God, He’s ahint ye!”

These suggest “The Lord’s Prayer intill Auld

Scottis,” as printed by Pinkerton, and which is cast

in more antique form still:—“Uor fader quhilk

beest i’ Hevin, Hallowit weird thyne nam. Cum

thyne kinrik. Be dune thyne wull as is i’ Hevin,

sva po yerd. Uor dailie breid gif us thilk day.

And forleit us our skaths, as we forfeit tham quha

skath us. And leed us na intill temtation. Butan

fre us fra evil. Amen.”

No writer of any time—Burns alone excepted—has

handled the native tongue to better purpose for

the expression of every feeling of the human heart

than has Sir Walter Scott; and in Jeanie Deans’

plea to the Queen for her sister’s life there is the

finest example of simple pathos, dashed with the

passion of hope struggling with despair, that is to

be met with anywhere in literature. It shows the

extent in this way of which the native speech is

capable.

[19]

“My sister—my puir sister Effie, still lives, though

her days and hours are numbered! She still lives,

and a word o’ the King’s mouth might restore her

to a heart-broken auld man, that never, in his daily

and nightly exercise, forgot to pray that His Majesty

might be blessed with a lang an’ a prosperous reign,

and that his throne, and the throne o’ his posterity,

might be established in righteousness. O,

madam, if ever ye kend what it was to sorrow for

and with a sinning and a suffering creature, whase

mind is sae tossed that she can be neither ca’d fit to

live or dee, hae some compassion on our misery!

Save an honest house from dishonour, and an unhappy

girl, not eighteen years of age, from an early

and dreadful death! Alas! it is not when we sleep

saft and wake merrily oursel’s that we think on other

people’s sufferings. Our hearts are waxed light within

us then, and we are for righting our ain wrangs

and fighting our ain battles. But when the hour of

trouble comes to the mind or to the body—and

seldom may it visit your leddyship—and when the

hour of death comes, that comes to high and low—lang

and late may it be yours!—oh, my leddy, then

it isna what we hae dune for oursel’s, but what we

hae done for others, that we think on maist pleasantly.

And the thought that ye hae intervened to

spare the puir thing’s life will be sweeter in that

hour, come when it may, than if a word o’ your

mouth could hang the haill Porteous mob at the

tail o’ a’e tow.”

[20]

Then the vigour and variety of the Scottish idiom

as a vehicle of description has perhaps never received

better illustration than in Andrew Fairservice’s account

of Glasgow Cathedral:—“Ay! it’s a brave

Kirk,” said Andrew. “Nane o’ yere whigmaleeries

and curliwurlies and open steek hems aboot it—a’

solid, weel-jointed mason wark, that will stand as

lang as the warld, keep hands and gunpowther aff

it. It had amaist a douncome lang syne at the

Reformation, when they pu’d doon the Kirks of

St. Andrews and Perth, and thereawa’, to cleanse

them o’ Papery, and idolatry, and image-worship,

and surplices, and sic like rags o’ the muckle hure

that sitteth on the seven hills, as if ane wasna braid

enough for her auld hinder end. Sae the commons

o’ Renfrew, and o’ the Barony, and the Gorbals, and

a’ aboot, they behoved to come into Glasgow a’e fair

morning, to try their hand on purging the High

Kirk o’ Popish nick-nackets. But the townsmen o’

Glasgow, they were feared their auld edifice might

slip the girths in gaun through siccan rough physic,

sae they rang the common bell, and assembled the

train-bands wi’ took o’ drum. By gude luck, the

worthy James Rabat was Dean o’ Guild that year

(and a gude mason he was himsell, made him keener

to keep up the auld bigging). And the trades

assembled, and offered downright battle to the commons,

rather than their Kirk should coup the crans,

as others had done elsewhere. It wasna for love o’

Papery—na, na!—nane could ever say that o’ the[21]

trades o’ Glasgow. Sae they sune came to an

agreement to tak a’ the idolatrous statues o’ sants

(sorrow be on them) out o’ their neuks—and sae

the bits o’ stone idols were broken in pieces by

Scripture warrant, and flung into the Molendiner

burn, and the Auld Kirk stood as crouse as a cat

when the flaes are kaimed aff her, and a’ body was

alike pleased. And I hae heard wise folk say that

if the same had been dune in ilka Kirk in Scotland,

the Reform wad just hae been as pure as it is e’en

now, and we wad hae mair Christianlike Kirks; for

I hae been sae lang in England, that naething

will drive out o’ my head, that the dog-kennel at

Osbaldistone-Hall is better than mony a house o’

God in Scotland.”

No man, it is well known, had ever more command

of the native vernacular than Robert Burns. In a

letter written at Carlisle, in June 1787, to his friend

William Nicol, Master of the High School, Edinburgh,

he has left a curious testimony at once to the

capabilities of the language and his own skill in it.

“Kind, honest-hearted Willie,” he writes, “I’m sitten

doon here, after seven-and-forty miles’ ridin’, e’en as

forjeskit and forniaw’d as a forfoughten cock, to gie

you some notion o’ my land-lowper-like stravaigin’

sin’ the sorrowfu’ hour that I sheuk hands and parted

wi’ Auld Reekie.

“My auld ga’d gleyde o’ a meere has huchyall’d

up hill and doun brae in Scotland and England, as

teuch and birnie as a vera deevil wi’ me. It’s true,[22]

she’s as puir’s a sang-maker, an’ as hard’s a kirk, and

tipper taipers when she tak’s the gate, jist like a

lady’s gentlewoman in a minuwae, or a hen on a het

girdle; but she’s a yauld, poutherie girran for a’ that,

and has a stamach like Willie Stalker’s meere, that

wad hae digeested tumbler-wheels, for she’ll whip me

aff her five stimparts o’ the best aits at a down-sitten’,

and ne’er fash her thoom. Whan ance her ring-banes

and spavies, her crucks and cramps, are fairly soupl’d,

she beets to, beets to, and aye the hindmost hour

the tightest. I could wager her price to a thretty

pennies, that for twa or three wooks, ridin’ at fifty

miles a day, the deil-stickit a five gallopers acqueesh

Clyde and Whithorn could cast saut on her tail.

“I hae dander’d owre a’ the country frae Dunbar

to Selcraig, and ha’e forgather’d wi’ mony a gude

fallow, and mony a weel-faur’d hizzie. I met wi’ twa

dink queynes in particular. Ane o’ them a sonsie,

fine, fodgel lass, baith braw and bonnie; the ither

was a clean-shankit, straught, tight, weel-faur’d

wench, as blythe’s a lintwhite on a flowerie thorn,

and as sweet and modest’s a new blawn plum-rose in

a hazel shaw. They were baith bred to mainers by

the beuk, and ony ane o’ them had as muckle smeddum

and rumblegumption as the half o’ some Presbytries

that you and I baith ken. They played me

sic a deil o’ a shavie, that I daur say if my harigals

were turn’d out ye wad see twa nicks i’ the heart o’

me like the mark o’ a kail-whittle in a castock.

“I was gaun to write you a lang pystle, but, Gude[23]

forgi’e me, I gat mysel’ sae noutourously bitchify’d

the day, after kail-time, than I can hardly stoiter

but and ben.

“My best respecks to the guidwife and a’ our

common friens, especiall Mr. and Mrs. Cruikshank,

and the honest guidman o’ Jock’s Lodge.

“I’ll be in Dumfries the morn gif the beast be to

the fore, and the branks bide hale.

“Gude be wi’ you, Willie! Amen!”

That letter might fairly be made the “Shibboleth”

in any case of doubt regarding one’s ability to read

Scotch. It would shiver the front teeth of some of

your counterlouper gentry. Yet it is not an overdone

example of the Scotch Doric as it was spoken

in Edinburgh drawing-rooms a hundred years ago—vide,

Henry Cockburn’s Memorials. Between it and

the “braid Scotch” of half a century earlier there

is a marked difference.

In the Scots Magazine for November, 1743, the

following proclamation is printed:—

“All brethren and sisters, I let you to witt that

there is a twa-year-auld lad littleane tint, that ist’

ere’en.

“It’s a’ scabbit i’ the how hole o’ the neck o’d,

and a cauler kail-blade and brunt butter at it, that

ist’er. It has a muckle maun blue pooch hingin’ at

the carr side o’d, fou o’ mullers and chucky-stanes,

and a spindle and a whorle, and it’s daddy’s ain jockteleg

in’t. It’s a’ black aneath the nails wi’ howkin’

o’ yird, that is’t. It has its daddy’s gravat tied about[24]

the craig o’d, and hingin’ down the back o’d. The

back o’ the hand o’d’s a’ brunt; it got it i’ the smiddy

ae day.

“Whae’er can find this said twa-year-auld lad littleane

may repair to M⸺o J⸺n’s, town-smith in

C⸺n, and he sall hae for reward twall bear scones,

and a ride o’ our ain auld beast to bear him hame,

and nae mair words about it, that wilt’r no.”

Hogg, in his “Shepherd’s Calendar,” referring to

the religious character of the shepherds of Scotland

in his day, tells that “the antiquated but delightful

exercise of family worship was never neglected,” and,

“formality being a thing despised, there are no

compositions I ever heard,” he continues, “so truly

original as those prayers occasionally were; sometimes

for rude eloquence and pathos, at other times

for an indescribable sort of pomp, and, not infrequently,

for a plain and somewhat unbecoming

familiarity.” He gives several illustrations, quite

justifying this description, from some with whom

he had himself served and herded. One of the most

notable men for this sort of family eloquence, he

thought, was a certain Adam Scott, in Upper

Dalgleish. Thus Scott prayed for a son who seemed

thoughtless—

“For Thy mercy’s sake—for the sake o’ Thy puir,

sinfu’ servants that are now addressing Thee in their

ain shilly-shally way, and for the sake o’ mair than

we daur weel name to Thee, hae mercy on Rab. Ye

ken fu’ weel he’s a wild, mischievous callant, and[25]

thinks nae mair o’ committin’ sin than a dog does o’

lickin’ a dish; but put Thy hook in his nose, and Thy

bridle in his gab, and gar him come back to Thee wi’

a jerk that he’ll no forget the langest day that he

has to live.” For another son he prayed:—“Dinna

forget puir Jamie, wha’s far awa’ frae us this nicht.

Keep Thy arm o’ power about him; and, oh, I wish

Ye wad endow him wi’ a little spunk and smeddum to

act for himsel’; for, if Ye dinna, he’ll be but a bauchle

i’ this warld, and a back-sitter i’ the neist.” Again:—“We’re

a’ like hawks, we’re a’ like snails, we’re a’

like slogie riddles; like hawks to do evil, like snails

to do good, and like slogie riddles to let through a’

the gude and keep a’ the bad.” When Napoleon I.

was filling Europe with alarm, he prayed—“Bring

doon the tyrant and his lang neb, for he has done

muckle ill this year, and gie him a cup o’ Thy wrath,

and gin he winna tak’ that, gie him kelty” [i.e.,

double, or two cups].

Very graphic, is it not! It reminds us of the

prayer of one Jamie Hamilton, a celebrated poacher

in the West country. As Jamie was reconnoitring a

lonely situation one morning, his mind more set on

hares than on prayers, a woman approached him from

the only house in the immediate district and requested

that he should “come owre and pray for auld Eppie,

for she’s just deein’.”

“Ye ken weel enough that I can pray nane,”

replied Jamie.

“But we haena time to rin for ony ither Jamie,”[26]

urged the woman, “Eppie’s just slippin’ awa’; and

oh! it wad be an awfu’ like thing to lat the puir bodie

dee without bein’ prayed for.”

“Weel, then,” said Jamie, “an I maun come, I

maun come; but I’m sure I kenna right what to

say.”

The occasion has ever so much to do with the

making of the man. Approaching the bed, Jamie

doffed his cap and proceeded:—“O Lord, Thou kens

best Thy nainsel’ how the case stands atween Thee

and auld Eppie; and sin’ Ye hae baith the heft and

the blade in Yer nain hand, just guide the gully as

best suits her guid and Yer nain glory. Amen.”

It was a poacher’s prayer in very truth, but a

bishop could not have said more in as few words.

But it is easy to be expressive in Scotch, for it is

peculiar to the native idiom that the simpler the language

employed the effect is the greater. Think how

this is manifested in the song and ballad literature of

the country. In popular ballads like “Gil Morrice,”

“Sir James the Rose,” “Barbara Allan,” and “The

Dowie Dens o’ Yarrow”; in Jane Elliot’s song of

“The Flowers of the Forest”; in Grizzel Baillie’s

“Werena my heart licht I wad dee”; in Lady Lindsay’s

“Auld Robin Gray”; in Lady Nairne’s “Land

o’ the Leal”; in Burns’s “Auld Lang Syne”; in

Tannahill’s “Gloomy Winter”; in Thom’s “Mitherless

Bairn”; and in Smibert’s “Widow’s Lament.”

I do not mean to say that the making of these songs

and ballads was a simple matter; but the verbal[27]

material is in each case of the simplest character,

and the effect such that the pieces are established

in the common heart of Scotland. Burns did not

go out of his way for either language or figures of

speech to describe Willie Wastle’s wife, yet see the

graphic picture we have presented to us by a few

strokes of the pen:—

“She has an e’e—she has but ane,

The cat has twa the very colour;

Five rusty teeth, forbye a stump,

A clapper-tongue wad deave a miller;

A whiskin’ beard about her mou’,

Her nose and chin they threaten ither—

Sic a wife as Willie has,

I wadna gie a button for her.

“She’s bow-houghed, she’s hein-shinn’d,

Ae limpin’ leg, a hand-breed shorter;

She’s twisted right, she’s twisted left

To balance fair in ilka quarter:

She has a hump upon her breast

The twin o’ that upon her shouther—

Sic a wife as Willie has,

I wadna gie a button for her.”

No idea there is strained. Every word is common.

The same may be said of Hew Ainshe’s lyric poem

in a different vein, “Dowie in the hint o’ Hairst,”

which I make no apology for quoting in full:—

“It’s dowie in the hint o’ hairst.

At the wa’-gang o’ the swallow,

When the wind grows cauld, and the burns grow bauld,

An’ the wuds are hingin’ yellow;

[28]

But oh, it’s dowier far to see

The wa’-gang o’ her the heart gangs wi’,

The dead-set o’ a shinin’ e’e.

That darkens the weary warld on thee.

“There was meikle love atween us twa—

Oh, twa could ne’er be fonder;

And the thing on yird was never made,

That could ha’e gart us sunder.

But the way o’ Heaven’s aboon a’ ken,

And we maun bear what it likes to sen’—

It’s comfort, though, to weary men,

That the warst o’ this warld’s waes maun en’.

“There’s mony things that come and gae,

Just kent, and just forgotten;

And the flowers that busk a bonnie brae,

Gin anither year lie rotten,

But the last look o’ yon lovely e’e,

And the deein’ grip she ga’e to me,

They’re settled like eternitie—

Oh, Mary; gin I were wi’ thee.”

By these illustrations I have endeavoured to shew

forth, to all whom it may concern, the verbal beauty,

the graphic force, and the powers for the expression

of pathos and humour there is in the vernacular speech

of Scotland. Like our national emblem—the thistle—it

is, of course, nothing in the mouth of an ass.

But well spoken, it is charming alike to the ear and

the intellect; and, for the reasons already urged in

this paper, is worthy of more general esteem and more

general cultivation than the current generation of

Scotch folk seem disposed to award it. Lord Cockburn

pronounced it “the sweetest and most expressive[29]

of living languages;” and no unprejudiced reader of

his Memorials will dispute the value of his opinion

on the subject. He wrote excellent Doric himself,

and made it the vehicle of his conversation in his

family, and casually throughout the day, as long as

he lived. Ho! for more such good old Scottish

gentlemen! Ho! for another Jean, Duchess of

Gordon, to teach our Scottish gentry how to speak

naturally! That we had more men in our midst,

with equal influence and education, and charged with

the fine spirit of patriotism which animates Scotland’s

ain “grand auld man”—Professor Blackie! It has

been the fashion for English journalists with pretensions

to wit, to animadvert by pen and pencil on what

they regard as the idiosyncracies of Scottish speech

and behaviour. Punch is a frequent offender in this

way. I say offender advisedly, for no Punch artist,

so far as I have seen—and I have scanned that journal

from the first number to the last—ever drew a Scotsman

in “his manner as he lived.” The originals of

the pictures may have appeared in London Christmas

pantomimes, but certainly nowhere else. Then the

language which in their guileless innocence they expect

will pass muster as Scotch, is a hash-up alike revolting

to the ears of gods and men. We don’t expect very

much from some folks, but surely even a London

journalist should know that a Scotsman does not say

“mon” when he means to say “man.” Charles

Macklin put it that way, and the London journalist

apparently can never get beyond Macklin. Don’t go[30]

to London for your Scotch, my reader! Listen to it

as it may still be spoken at your granny’s ingleside.

Familiarise yourself with it as it is to be found in its

full vigour and purity in the Waverley Novels; in

Burns’s Poems and Songs; in the “Noctes Ambrosianæ”

of Professor Wilson; in Galt’s Tales; in the

writings of the Ettrick Shepherd; in the stories of

George MacDonald, J. M. Barrie, and S. R. Crockett;

in the pages of “Mansie Wauch,” “Tammas Bodkin,”

and “Johnny Gibb.” Don’t learn English less;

but again, I say, read, write, and speak Scotch more

frequently. And, when doing so, remember you are

not indulging in a mere vulgar corruption of good

English, comparable with the barbarous dialects of

Yorkshire and Devon, but in a true and distinct, a

powerful and beautiful language of your own, “differing

not merely from modern English in pronunciation,

but in the possession of many beautiful words, which

have ceased to be English, and in the use of inflexions

unknown to literary and spoken English since the days

of Piers Ploughman and Chaucer.” “The Scotch,” as

the late Lord Jeffrey said, “is not to be considered as

a provincial dialect—the vehicle only of rustic vulgarity

and rude local humour. It is the language of

a whole country, long an independent kingdom, and

still separate in laws, character, and manners. It is

by no means peculiar to the vulgar, but is the common

speech of the whole nation in early life, and with

many of its most exalted and accomplished individuals

throughout their whole existence; and though it be[31]

true that, in later times, it has been in some measure

laid aside by the more ambitious and aspiring of the

present generation, it is still recollected even by them

as the familiar language of their childhood, and of

those who were the earliest objects of their love and

veneration. It is connected in their imagination not

only with that olden time which is uniformly conceived

as more pure, lofty, and simple than the present,

but also with all the soft and bright colours of

remembered childhood and domestic affection. All

its phrases conjure up images of school-day innocence

and sports, and friendships which have no pattern in

succeeding years.”

[32]

CHAPTER II

CHARACTERISTICS OF SCOTCH HUMOUR

Various writers have attempted to define

Scotch humour, but it is a difficult task, and

in all my reading of the subject I do not remember to

have ever seen a very satisfactory analysis of the subtle

quantity. The famous Sydney Smith did not admit

that such an element obtained in our “puir cauld

country.” “Their only idea of wit which prevails

occasionally in the North,” said he, “and which,

under the name of ‘wut,’ is so infinitely distressing

to people of good taste, is laughing immoderately at

stated intervals.” Further to this, the same sublime

authority declared that it would require a surgical

operation to get a joke well into a Scotch understanding.

It has been presumed that the witty Canon was

not serious in his remark; that it was a laboured effort

of his to make a joke. This may be true; and the

idea of a surgical operation was possibly suggested

by feeling its necessity on himself in order to get his

joke out. Be that as it may, but for the fact that

the genial Charles Lamb, curiously, entertained a

somewhat similar notion on the subject, the rude

apothegm of the Rev. Sydney Smith would never

have misguided even the most hopelessly opaque of[33]

his own countrymen. No humour in Scotch folk!

No humour in Scotland! There is no country in the

world that has produced so much of it. Of no other

country under the sun can it be so truly said that

humour is the common inheritance of the people.

Much of the kind of humour that drives an Englishman

into an ecstacy of delight, would, of course, only

tend to make a Scotsman sad; but that is no evidence

that the Scotch are lacking in their perceptions of

the humorous. It only shows that “some folks are

no ill to please.” “The Cockney must have his puns

and small jokes,” says Max O’Rell. “On the stage

he delights in jigs, and to really please him the best

of actors have to become rivals of the mountebanks

at a fair. A hornpipe delights his heart. An actor

who, for an hour together, pretends not to be able

to keep on his hat, sends him into the seventh heaven

of delight. Such performances make the Scotch smile—but

with pity. The Scotsman has no wit of this

sort. In the matter of wit he is an epicure, and only

appreciates dainty food.” In so far as the above

quotation applies to the denizens of the “North,” it

is perfectly true. In such circumstances the Scotch

will “laugh immoderately at stated intervals,” but

the laughs will be like angels’ visits, “few and far

between.”

Superficially regarded, Scotland is a hard-featured

land; yet Scotch folk are essentially humorous. Do

not go to the places of public amusement—to the

theatres and music halls—particularly in the larger[34]

towns, where the populations are so mixed; do not go

there to learn the Scottish taste and humour. This

practice has led to the proverbial saying that “a

Scotchman takes his amusement seriously.” In such

places you may learn something of the English character

and humour, but nothing of the Scotch. For

an Englishman’s wit (he has little or no humour)

being an acquired taste, comes out “on parade”—it

is a gay thing—while Scotch folks’ humour being the

common gift of Nature to all and sundry in the land,

differing only in degree, slips out most frequently

when and where least expected. Famous specimens

of it come down from our lonely hillsides—from the

cottage and farm ingle-nooks. It blossoms in the

solemn assemblies of the people—at meetings of Kirk

Sessions, in the City and Town Council Chambers, in

our Presbyteries, our Courts of Justice, and occasionally

in the high Parliament of the Kirk itself. In

testimony of this read the Reminiscences of Dean

Ramsay, Dr. Rodgers’ Century of Scottish Life,

The Laird of Logan, and other similar collections

of the national humour; or study the humours of

our Scottish life and character as they are abundantly

reflected in the immortal writings of Burns, and Scott,

and Galt, and Wilson.

One of the chief characteristics of Scotch humour,

as I have already indicated, is its spontaneity, or utter

want of effort to effect its production. Much of it

comes out just as a matter of course, and without the

slightest indication on the part of the creator that he[35]

is aware of the splendid part he is playing. Then it

has nearly always a strong practical basis. The Scotch

are characteristically practical people, and very much

of what is most enjoyable in humorous Scotch stories

and anecdotes, as Dean Ramsay truly says, arises

“from the simple and matter-of-fact references made

to circumstances which are unusual.”

There are others, of course, but these are the main

characteristics of Scotch humour. Our best anecdotes

illustrate this. Here is a good instance of the native

wit and humour:—

“Jock,” cried a farmer’s wife to her cowherd,

“come awa’ in to your parritch, or the flees ’ill be

droonin’ themsel’s in your milk bowl.”

“Nae fear o’ that,” was Jock’s roguish reply.

“They’ll wade through.”

“Ye scoondrel,” cried the mistress, indignantly,

“d’ye mean to say that ye dinna get eneuch milk?”

“Ou, ay,” said Jock, “I get plenty o’ milk for a’

the parritch.”

“Jock,” cried a farmer’s wife to her cowherd, “come awa’

in to your parritch, or the flees ’ill be droonin’ themsel’s in your

milk bowl.” “Nae fear o’ that,” was Jock’s roguish reply. “They’ll wade

through.” “Ye scoundrel,” cried the mistress, indignantly, “d’ye mean to

say that ye dinna get eneuch milk?” “Ou, ay,” said Jock, “I get plenty o’

milk for a’ the parritch.”—Page 35.

The colloquy was richly humorous, and at the

same time sublimely practical. The same may be

said of the following:—

During the time of the great Russian War a

countryman accepted the “Queen’s shilling,” and

very soon thereafter was sent to the front. But he

had scarcely time to have received his “baptism of

fire” when he turned his back on the scenes of

carnage, and immediately struck of in a bee line for

a distant haven of safety. A mounted officer, intercepting[36]

his retreat, demanded to know where he was

going.

“Whaur am I gaun?” said he. “Hame, of course;

man, this is awfu’ walk; they’re just killin’ ane anither

ower there.”

A brother countryman took a different view of the

same, or a similar situation. Just before his regiment

entered into an engagement with the enemy, he was

heard to pray in these terms:—“O, Lord! dinna be on

oor side, and dinna be on the tither side, but just stand

ajee frae baith o’ us for an oor or twa, an’ ye’ll see the

toosiest fecht that ever was fochen.” What a fine,

rough hero was there!

Speaking of praying prior to entering into engagements,

recalls another good and equally representative

anecdote. It is told of two old Scottish matrons.

They were discussing current events.

“Eh, woman!” said one, “I see by the papers

that oor sodgers have been victorious again.”

“Ah, nae fear o’ oor sodgers,” replied the other.

“They’ll aye be victorious, for they aye pray afore they

engage wi’ the enemy.”

“But do you no think the French ’ill pray too?”

questioned the first speaker.

“The French pray!” sneered her friend. “Yatterin’

craturs! Wha wad ken what they said?”

What a charmingly innocent auld wife! Surely

it was this same matron who once upon a time

entered the village grocery and asked for a pound

of candles, at the same time laying down the price[37]

at which the article in question had stood fixed for

some time.

“Anither bawbee, mistress,” said the grocer. “Cawnils

are up, on account o’ the war.”

“Eh, megstie me!” was the response. “An’ can

it be the case that they really fecht wi’ cawnil licht?”

A Scotch blacksmith, being asked the meaning of

metaphysics, explained as follows:—“Weel, Geordie,

ye see, it’s just like this. When the pairty that listens

disna ken what the pairty that speaks means, an’ when

the pairty that speaks disna ken what he means himsel’,

that’s metapheesics.” Many a lecture of an hour’s

length, I am thinking, has had no better results.

No anecdote can better illustrate the practical basis

of the Scotch mind than the following:—“John,”

said a minister to one of his congregation, “I hope

you hold family worship regularly.”

“Aye,” said John, “in the time o’ year o’t.”

“In the time o’ year o’t! What do you mean,

John?”

“Ye ken, sir, we canna see in the winter nichts.”

“But, John, can’t you buy candles?”

“Weel, I could,” replied John, “but in that case

I’m dootin’ the cost would owergang the profit.”

And practical in the management of their devotional

exercises, there is a practical side to the grief

of Scotch folk. “Dinna greet amang your parritch,

Geordie,” said one to another, “they’re thin eneuch

already.” And the story is told of an Aberdeenshire

woman who, when on the occasion of the death of[38]

her husband the minister’s wife came to condole with

her, and said—“It is a great loss you have sustained,

Janet.”

She replied, “Deed is’t, my lady. An’ I’ve just

been sittin’ here greetin’ a’ day, an’ as sune as I get

this bowliefu’ o’ kail suppit I’m gaun to begin an’ greet

again.”

“You have had a sore affliction, Margaret,” said a

minister once to a Scotch matron in circumstances

similar to the heroine of the above story. “A sore

affliction indeed; but I hope you are not altogether

without consolation.”

“Na,” said Margaret, “an’ I’m no that, sir; for gin

He has ta’en awa’ the saul, it’s a great consolation for

me to think that He’s ta’en awa’ the stammick as

weel.”

Ah, poor body! No doubt she gave expression to a

thought that had for some time been having a prominent

place in her mind. As Tom Moore reminds us,

in the midst of a serious poem, “We must all dine,”

and if the bread-winner has been laid aside for a time,

the means of subsistence are sometimes difficult to

obtain, and when “supply” is wholly cut off, a decrease

in “demand” is sometimes not unwelcome.

A splendid instance of the matter-of-fact view of

things celestial frequently taken by the Scotch mind

is in that story which Dean Ramsay tells of the old

woman who was dying at Hawick. In this Border

seat of tweed manufacture the people wear wooden-soled

boots—clogs—which make a clanking noise on[39]

the pavement. Several friends stood by the bedside

of the dying person, and one of them said to her—

“Weel, Jenny, ye’re deein’; but ye’ve done the

richt gaet here, an’ ye’ll gang to heaven; an’ when ye

gang there, should you see ony o’ oor fouk, ye micht

tell them that we’re a’ weel.”

“Ou,” said Jenny half-heartedly, “gin I see them

I’se tell them; but ye maunna expect that I’m to be

gaun clank, clankin’ about through heaven lookin’ for

your fouk.”

Of all the stories of this class, however, the following

death-bed conversation between a husband and wife

affords perhaps the very best specimen of the dry

humour peculiar to Scotch folk:—An old shoemaker

in Glasgow was sitting by the bedside of his wife,

who was dying. Taking her husband by the hand,

the old woman said, “Weel, John, we’re to pairt. I

hae been a gude wife to you, John.”

“Oh, middlin’, middlin’, Jenny,” said John, not

disposed to commit himself wholly.

“Ay, I’ve been a gude wife to you, John,” says she,

“an’ ye maun promise to bury me in the auld kirkyard

at Stra’von, beside my ain kith and kin, for I couldna

rest in peace among unoo fouk, in the dirt an’ smoke

o’ Gleska’.”

“Weel, weel, Jenny, my woman,” said John,

soothingly, “I’ll humour ye thus far. We’ll pit ye in

the Gorbals first, an’ gin ye dinna lie quiet there,

we’ll tak’ ye to Stra’von syne.”

And yet there is on record a retort of a Scotch[40]

beadle, which is almost equally moving. Saunders

was a victim to chronic asthma, and one day, whilst

in the act of opening a grave, was seized with a violent

fit of coughing. The minister, towards whom Saunders

bore little affection, at the same time entering

the kirkyard, came up to the old man as he was

leaning over his spade wiping the tears from his

eyes, and said, “That’s a very bad cough you’ve got,

Saunders.”

“Ay, it’s no very gude,” was the dry response, “but

there’s a hantle fouk lyin’ round aboot ye that wud be

gey glad o’t.”

Speaking of beadles reminds me of another good

illustration of the “practicality,” if I may dare to

coin a word, of the Scottish mind. A country beadle

had had repeated cause to complain to his minister

of interference with his duties on the part of his

superannuated predecessor. Coming up to the minister

one day, “John’s been interfeerin’ again,” said

he, “an’ I’ve come to see what’s to be dune?”

“Well, I’m sorry to hear it,” said the minister,

“but as I have told you before, David, John’s a silly

body, and you should try, I think, some other means

of getting rid of his annoyance than by openly resisting

him. Why not follow the Scriptural injunction given

for our guidance in such cases, and heap coals of fire

on your enemy’s head.”

“Dod, sir, that’s the very thing,” cried David,

taking the minister literally, and grinning and rubbing

his hands with glee at the prospect of an early[41]

and effectual settlement of the long-standing feud.

“Capital, minister; that’ll sort him; dod, ay—heap

lowin’ coals on his head, and burn the wratch!”

We are proverbially a cautious people. “The

canny Scot” is a world-wide term; but the Paisley

man who described Niagara Falls as “naething but a

perfect waste o’ water,” was canny to a fault. And

yet the Moffat man—his more inspiring native surroundings

notwithstanding—was scarcely more visibly

impressed by the same scene. “Did you ever see

anything so grand?” demanded his friend who had

taken him to see the mighty cataract.

“Weel,” said the Moffat man, “as for grand, I maybe

never saw onything better; but for queer, man, d’ye

ken, I ance saw a peacock wi’ a wooden leg.”

How naturally the one thing would suggest the

other will not readily appear to most folks.

He was more of a true Scot who, when the schoolmaster

in passing along one day said to him, “I see

you are to have a poor crop of potatoes this year,

Thomas,” replied—

“Ay, but there’s some consolation, sir; John Tamson’s

are no a bit better.”

“Hame’s aye hamely,”—some homes are more so

than others. The “Paisley bodies” have some reason

for being proud of their native burgh, as they are.

I have heard of one who was on a visit to Edinburgh

many years ago, and during his brief stay there was

discovered by one of the city guides lying on his

face on the Calton Hill, apparently asleep. The[42]

summer sun was scorching the back of his uncovered

head, and the guide thought it his duty to

rouse him up.

“I’m no sleepin’,” responded the Paisley man, to

the touch of the guide’s staff, “I’m just lyin’ here

thinkin’;” then turning himself round and looking

up, “Ay, freend,” continued he, “I was just lyin’

thinkin’ aboot Paisley.”

“Well,” responded the guide, “I don’t see why any

thought of Paisley should enter your head while you

can feast your eyes on fair ‘Edina, Scotia’s darling

Seat,’ as the Poet Burns has called our city here.”

“Maybe ay, an’ maybe no, freend; but it’s no easy

gettin’ the thocht o’ Paisley oot o’ a Paisley man’s

head, even although he is in the middle o’ Edinburgh.

Up in yer braw college there, the maist distinguished

professor in it is John Wilson, a Paisley man. In

St. George’s kirk, ower there, yer precentor, R. A.

Smith—an’ there’s no his marrow again in a’ Scotland—is

a Paisley man. In the jail ower by fornent us

there’s mair than a’e Paisley callan’ the noo. Syne,

ye see the Register House doon there, weel, the

woman that sweeps out the passages—an’ my ain

kissen to boot—is a Paisley woman. An’ so ye see,

freend, although ane’s in Edinburgh it’s no sae easy

gettin’ thochts o’ Paisley kept oot o’ his head.”

The next illustration is also truly Scotch. Two

Lowland crofters lived within a few hundred yards of

each other. One of them, Duncan by name, being

the possessor of “Willison’s Works,” a rarity in the[43]

district, his neighbour, Donald, sent his boy one day

to ask Duncan to favour him with a reading of the

book. “Tell your father,” said Duncan, “that I

canna lend oot my book, but he may come to my

hoose and read it there as lang as he likes.” Country

folk deal all more or less in “giff-gaff,” and in a few

days after, Duncan, having to go to the market, and

being minus a saddle, sent his boy to ask Donald to

give him the loan of his saddle for the occasion.

“Tell your father,” said Donald, “that I canna lend

oot my saddle; but it’s in the barn, an’ he can come

there an’ ride on it a’ day if he likes.”

The cannyness characteristic of our countrymen,

sometimes as a matter of course, is found manifesting

itself in ways which, to say the least of them, are

peculiar, as witness: A Forfar cobbler, described

briefly as “a notorious offender,” was not very long

ago brought up before the local magistrate, and being

found guilty as libelled, was sentenced to pay a fine

of half-a-crown, or endure twenty-four hours’ imprisonment.

If he chose the latter, he would, in accordance

with the police arrangements of the district,

be taken to the jail at Perth. Having his option,

the cobbler communed with himself. “I’ll go to

Perth,” said he; “I’ve business in the toon at ony

rate.” An official forthwith conveyed him by train

to the “Fair City”; but when the prisoner reached

the jail he said he would now pay the fine. The

Governor looked surprised, but found he would have

to take it. “And now,” said the canny cobbler, “I[44]

want my fare hame.” The Governor demurred, made

inquiries, and discovered that there was no alternative;

the prisoner must be sent at the public expense to the

place where he had been brought from. So the crafty

son of St. Crispin got the 2s. 8½d., which represented

his railway fare, transacted his business, and went

home triumphant, 2½d. and a railway journey the

better for his offence.

Our next specimen is cousin-german to the above.

It is of two elderly Scotch ladies—“twa auld maids,”

to use a more homely phrase—who, on a certain Sunday

not very long ago, set out to attend divine service

in the Auld Kirk, and discovered on the way thither

that they had left home without the usual small

subscription for the “plate.” They resolved not to

return for the money, but to ask a loan of the necessary

amount from a friend whose door they would pass

on the way. The friend was delighted to be able to

oblige them, and, producing her purse, spread out on

the table a number of coins of various values—halfpennies,

pennies, threepenny, and sixpenny pieces.

The ladies immediately selected a halfpenny each and

went away. Later in the course of the same day they

appeared to their friend again, and said they had

come to repay the loan.

“Toots, havers,” exclaimed old Janet, “ye needna

hae been in sic a hurry wi’ the bits o’ coppers; I could

hae gotten them frae you at ony time.”

“Ou, but,” said the thrifty pair, in subdued and

confidential tones, “it was nae trouble ava’, for there[45]

was naebody stannin’ at the plate, so we just slippit

in an’ saved the bawbees.”

Now that is just the sort of anecdote which an

Englishman delights to commit to memory and retail

in mixed companies of his Scotch and English friends;

and, lest he may have heard that one already—may

have worn it threadbare, indeed—I will tell another

which, if not quite so good, has the advantage of

being not so well known. A Scotchman was once

advised to take shower baths. A friend explained

to him how to fit up one by the use of a cistern and

colander, and Sandy accordingly set to work and had

the thing done at once. Subsequently he was met

by the friend who had given him the advice, and,

being asked how he enjoyed the bath—

“Man,” said he, “it was fine. I liked it rale weel,

and kept mysel’ quite dry, too.”

Being asked how he managed to take the shower

and yet remain quite dry, he replied—

“Dod, ye dinna surely think I was sae daft as

stand ablow the water without an umbrella.”

That’s truly Scotch. So is the next specimen, as

you will presently perceive. Two or three nights

before the advent of a recent Christmas, a Scotch

laddie of ten years old, or so, was sitting examining

very gravely a somewhat ugly hole in the heel of one

of his stockings. At length he looked towards his

mother and said—

“Mither, ye micht gie me a pair o’ new

stockin’s?”

[46]

“So I will, laddie, by and by; but ye’re no sair

needin’ new anes yet,” said his mother.

“Will I get them this week?”

“What mak’s ye sae anxious to hae them this

week?”

“Because, if Santa Claus pits onything into thir

anes it’ll fa’ oot.”

How naturally a Scotsman drops into poetry, too,

will be seen from the following:—

Mr. Dewar, a shopkeeper in Edinburgh, being in

want of silver for a bank note, went into the shop of

a neighbour of the name of Scott, whom he thus

addressed—

“I say, Master Scott,

Can you change me a note?”

Mr. Scott’s reply was—

“I’m no very sure, but I’ll see.”

Then going into the back-room, he immediately returned

and added—

“Indeed, Mr. Dewar,

It’s out o’ my power,

For my wife’s awa’ wi’ the key.”

It is by furnishing him with choice and representative

examples that one can best convey to a stranger

a knowledge of the characteristics of our national

humour. So much of it depends often on the quaintness

of the Scottish idiom, that it defies explanation,

and must be seen, or better still, be heard, to be[47]

understood. This course I have pursued in the present

paper; and the examples deduced, I think, fairly

demonstrate the strong substratum of practical common-sense

which underlies, and yet manifests itself

in, the lighter elements of the Scottish character,

frequently making humour where pathos was meant

to be. Take a few more:—

The wife of a small farmer in Perthshire some time

ago went to a chemist’s in the “Fair City” with two

prescriptions—one for her husband, the other for her

cow. Finding she had not enough of money to pay

for both, the chemist asked her which she would take.

“Gie me the stuff for the coo,” said she; “the morn

will do weel eneuch for him, puir body. Gin he were

to dee I could sune get another man, but I’m no sure

that I could sae sune get anither coo.”

The late Rev. Dr. Begg, was wont to tell of a Scotch

woman to whom a neighbour said, “Effie, I wonder

hoo ye can sleep wi’ sae muckle debt on your heid;”

to which Effie quietly answered, “I can sleep fu’ weel;

but I wonder hoo they can sleep that trust me.”

“Are you a native of this parish?” asked a sheriff

of a witness who was summoned to testify in a case

of distilling.

“Maistly, yer honour,” was the reply.

“I mean, were you born in this parish?”

“No, yer honour, I wisna born in this parish; but

I’m maistly a native for a’ that.”

“You came here when you were a child I suppose,

you mean?” said the sheriff.

[48]

“No, sir; I’m here just aboot sax year noo.”

“Then how do you come to be mostly a native of

the parish?”

“Weel, ye see, when I cam here, sax year syne, I

just weighed eight stane, an’ I’m fully seventeen stane

noo; so, ye see, that aboot nine stane o’ me belangs

to this parish, an’ I maun be maistly a native o’t.”

Not very long ago a countryman got married, and

soon after invited a friend to his house and introduced

him to his new wife, who, by the by, was a person of

remarkably plain appearance. “What do you think

o’ her John?” he asked his friend, when the good

lady had retired from the room for a little. “She’s

no’ very bonnie!” was the candid and discomforting

reply. “That’s true,” said the husband; “she’s no

muckle to look at, but she’s a rale gude-hearted

woman. Positeevly ugly outside, but a’ that’s lovely

inside.” “Lord, man, Tam,” said the friend gravely,

“it’s a peety ye couldna flype her!”

At a feeing market in Perth a boy was waiting to

be hired, when a farmer, who wanted such a servant,

accosted him, and after some conversation, enquired

if he had a written character. The lad replied that

he had, but it was at home. “Bring it with you

next Friday,” said the farmer, “and meet me here at

two o’clock.” When the parties met again, “Weel,

my man,” said the farmer, “ha’e ye got your character?”

“Na,” was the reply, “but I’ve gotten

yours, an’ I’m no comin’!”

“There’s anither row up at the Soutars’,” said[49]

Willie Wilson, as he shook the rain from his plaid

and took his accustomed seat by the inn parlour fire.

“I heard them at it as I cam’ by just noo.”

“Ay, ay; there’s aye some fun gaun’ on at the

Soutars’,” said another of the company, with a laugh.

“Fun? I shouldn’t think there’s much fun in those

disgraceful family disturbances,” said the schoolmaster.

“Aweel, it’s no’ so vera bad, after a’,” said the

other, who had his share of matrimonial strife. “Ye

see, when the wife gets in her tantrums she aye

throws a plate or brush, or maybe twa or three, at

Sandy’s head. Gin she hits him she’s gled, and gin

she misses him he’s gled; so, ye see, there’s aye some

pleasure to a’e side or the ither.”

The Laird of Balnamoon, riding past a high, steep

bank, stopped opposite a hole in it, and said, “John,

I saw a brock gang in there.”

“Did ye?” said John; “will ye haud my horse,

sir?”

“Certainly,” said the Laird, and away rushed John

for a spade.

After digging for half an hour, he came back nigh

speechless to the Laird, who had regarded him

musingly.

“I canna find him, sir,” said John.

“Deed,” said the Laird, very coolly, “I wad hae

wondered if ye had, for it’s ten years an’ mair sin’ I

saw him gang in.”

On one occasion, when the gallant Highlanders[50]

were stationed at Gibraltar, Sandy Macnab was sergeant

of the guard, and in due course of duty had

sent his corporal to make the last relief before four

o’clock in the morning. Whilst proceeding to one of

the outlying posts the corporal missed his footing, fell

over the cliff, and was killed. Meantime Sergeant

Macnab had been filling up the usual guard report,

preparatory to dismounting. Now, at the foot of

the form on which such reports are made out there

is a printed inquiry—“Anything extraordinary

occurred since mounting guard?”

Macnab, unaware of the accident to his corporal,

filled the query space up with the word “Nil,” and,

having no spare copy of the form, sent this in to the

orderly-room to take its chance. When the Colonel

and Adjutant attended in the orderly-room at ten

o’clock, learned of the mishap, and read Macnab’s

report, the latter was peremptorily ordered to appear

before them.

“Macnab,” cried the Colonel, in a rage, “what the

devil do you mean by filling up your guard report in

this way? You say ‘Nothing extraordinary occurred

since mounting guard,’ and yet your poor comrade

fell over the cliff and was killed.”

Sandy, finding himself in a fix, pulled himself

together, and after a moment or two of deliberation

answered, coolly, “Weel, sir, I dinna see onything

very extraordinar’ in that. It would hae been something

very extraordinar’ if he hadna been killed; he

fell fowr hunder feet!”

[51]

In Mr. Barrie’s Little Minister, a discussion takes

place in the village Parliament as to whether it is

possible for a woman to refuse to marry a minister.

“I once,” said Snecky Hobart, “knew a widow who

did. His name was Samson, and if it had been Tamson

she would hae ta’en him. Ay, you may look,

but it’s true. Her name was Turnbull, and she had

another gent after her, named Tibbets. She couldna

make up her mind atween them, and for a while she

just keeped them dangling on. Ay, but in the end

she took Tibbets. And what, think you, was her

reason? As you ken, thae grand folk hae their initials

on their spoons and nichtgowns. Ay, weel, she thocht

it would be mair handy to take Tibbets, because if

she had ta’en the minister, the T’s would have to be

changed to S’s. It was thochtfu’ o’ her.”

Our next two specimens show how waggish the

Scotch can be.

A farmer, returning from a Northern tryst, accompanied

by his servant Pate, not many years ago,

halted for refreshment at the Inn of Glamis, where,

meeting with a number of friends, a jolly party was

soon formed. Under the cheering hospitality of the

gude wife of the inn they cracked their jokes and told

their tales, till at length the farmer proposed that

his attendant, Pate, should enliven the meeting with

a song. One of the party, who professed to have an

estimate of the shepherd’s vocal abilities, sneeringly

replied, “Whaur can Pate sing?”

“What d’ye say?” answered the farmer. “Can[52]

Pate no sing? I’m thinkin’ he’s sung to as good fouk,

an’ better than you, in his time. I’ll tell ye o’ a’e

place whaur he has been kent to sing wi’ mair honour

to himsel’ than ye can brag o’, and that’s before the

Queen. Ay, an’ if it will heighten him ony in your

estimation, I’ll prove to you, for the wager o’a bottle

o’ brandy, that he even sleepit, an’ that no’ sae lang

syne, in the same hoose she was in.”

Thinking this latter assertion outstretched the

limits of all probability, the wager was immediately

taken by the party, when, to the satisfaction of all

the others present, the worthy farmer proved the

truth of his allegations by telling how, accompanied

by Pate, he had been to the Kirk of Crathie on the

Sunday previous, and that during the service, and in

presence of Her Royal Majesty, Pate had both sung

and slept. The farmer won the wager, and the bottle

circulated, amid continued outbursts of stentorian

laughter.

A worthy laird in a Perthshire village made the,

for him, wonderful journey to see the great Exhibition

of 1851. On his return, his banker, a man who

was well known to have the idea that he was by far

the most influential and potent power in the shire,

invited the laird, with some cronies, to a glass of

punch. The banker meant to amuse the company

at the old laird’s expense, to trot him out, and get

him to describe the sights of London. “An’ what,

laird, most of all impressed you at the great glass

house?” asked the banker, with a sly wink at the[53]

company. “Ah, weel, sir,” replied the laird, as he

emptied his glass, “I was muckle impressed wi’ a’ I

saw—muckle impressed! But the thing abune a’ that

impressed me maist was my ain insignificance. Losh,

banker, I wad strongly advise you to gang; it would

do you a vast amount o’ guid, sir!”

The next example affords the promise of an abundant

harvest of humour off the rising generation of

Scotsmen.

A little boy, whom we shall call Johnnie, just because

that is his name, was not very long since

employed as message-boy to a grocer in a small

country town in the west, said grocer being an ardent

advocate and supporter of the Conservative party in

the State. One morning Johnnie was an hour or so

late in turning out for duty, and on entering was

promptly interrogated by his master as to the cause.

“The cat’s had kittlins this mornin’,” asseverated

the lad, assuming a look of great earnestness; “four

o’ them, an’ they’re a’ Conservatives.”[1]

“Get in bye and tidy up that back shop,” said the

shopkeeper gruffly, not at the moment in a mood to

enquire fully into the extraordinary feline phenomenon.

One day, nearly a fortnight afterwards, the[54]

following sequel added itself, however, and there was

a perfect understanding established. A commercial

traveller, who is also a true-blue Tory, called at the

shop, and was discussing with the grocer the chances

of victory or failure to their party in an approaching

bye-election. Said the grocer, “Our party is gaining

strength in the country, of that I am convinced, and

with reason; why, my message-boy was telling me

recently that his mother’s cat has had kittens—four

of them—and they are all Conservatives.” The

traveller laughed, as only travellers who are anticipating

an order can laugh. When Johnnie entered

the premises with his basket on his arm and a tune

in his mouth.

“Hillo, Johnnie!” exclaimed the commercial,

“and so your cat has had kittens, has she? Eh?”

“Ay,” replied Johnnie, “four o’ them.”

“And all Conservatives, too, I believe?” remarked

the traveller.

“Na,” said Johnnie: “they’re Leeberals.”

“Liberals! you told me a fortnight ago they were

Conservatives,” interposed the master.

“Ou, ay; of course,” returned Johnnie, with the

utmost gravity. “They were Conservatives yon

time, but they’re seein’ noo!”

Just one more here. There is a cobbler in a little

town in the North—a worthy old soul, as it would

appear, whose custom has been for many years to

hammer and whistle from morn to night in his little

shop, and to discharge both functions so lustily as to[55]

be easily heard by the passers-by in the street. One

day not long since the minister, happening to pass,

missed the whistling accompaniment to the measured

click on the lapstone, and looked in to ascertain the

cause. “Is all well with you, Saunders?” he asked.

“Na, na, sir; it’s far frae bein’ a’ weel wi’ me. The

sweep’s gane an’ ta’en the shop ower my head.”

“Oh, that’s bad news, indeed,” responded the

minister, “but I think you might see your way

out of the difficulty soon if, as I always urge in

cases of emergency, you would make the matter a

subject of earnest prayer.” Saunders promised to

do this, and the preacher departed. In less than

a week he returned, and found the old cobbler

hammering and whistling away in his old familiar

“might and main” fashion. “Well, Saunders,

how is it now?” “Oh, it’s a’ richt, minister,”

was the reply. “I did as ye tell’d me, an’—the

sweep’s deid.”

[56]

CHAPTER III

HUMOUR OF OLD SCOTCH DIVINES

The late Lord Neaves, himself a man of a genial,

humorous nature, was wont to complain pleasantly

of his friend Dean Ramsay for having drawn

so many specimens of Scottish humour from the

sayings and doings of the native clergy. But the

worthy Dean, to employ a figure of his own recording,

simply “biggit’s dyke wi’ the feal at fit o’t;” in

other words, he gathered most grain from the field

which had produced the most abundant crop—the

field of clerical life and work. Your typical pastor,

it is true, has not to any extent been remarkable as

a humourist—the reverse may with more truth be

said of him. At the same time the Scottish pulpit

has contained many earnest, good men, who were

also genuine humourists. Yea, than the good old

Scotch divines, certainly no other class or section of

the community has laid up to its credit so many

witty and humorous sayings that are destined to live

with the language in which they are uttered. Every

parish in the land has stories to tell of such pastors.

It is only necessary to mention such prominent