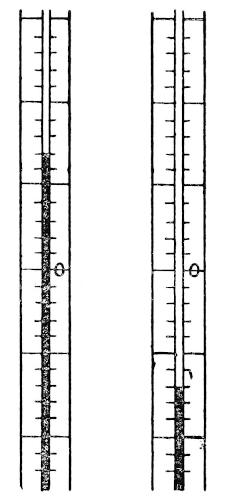

Fig. 1.—Reading Thermometer Scale above and below Zero.

Title: Hints to Travellers, Scientific and General, Vol. 2

Creator: Royal Geographical Society

Editor: Edward Ayearst Reeves

Release date: March 20, 2022 [eBook #67668]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Royal Geographical Society

Credits: Michael Ciesielski and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

HINTS TO TRAVELLERS

SCIENTIFIC AND GENERAL

TENTH EDITION

REVISED AND CORRECTED

FROM THE NINTH EDITION EDITED FOR THE

Council of the Royal Geographical Society

BY

E. A. REEVES, F.R.A.S., F.R.G.S.

Map Curator and Instructor in Surveying to the Royal

Geographical Society.

Vol. II.

METEOROLOGY, PHOTOGRAPHY, GEOLOGY, NATURAL

HISTORY, ANTHROPOLOGY, INDUSTRY AND

COMMERCE, ARCHÆOLOGY, MEDICAL, ETC.

LONDON

THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY

KENSINGTON GORE, S.W. 7

AND AT ALL BOOKSELLERS

1921

Price of the two Volumes, 21s. net.

To Fellows, at the Office of the Society, 15s. net.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED,

DUKE STREET, STAMFORD STREET, S.E. 1, AND GREAT WINDMILL STREET, W. 1.

The first seven sections of this volume have been carefully revised, but required no serious alteration. The eighth section required very extensive changes and additions, due to the great progress of Tropical Medicine in the last fourteen years. The Society is much indebted to Dr. Andrew Balfour, C.B., C.M.G., Director-in-Chief of the Wellcome Bureau of Scientific Research, who has very kindly revised and extended the Medical Hints in the light of his wide experience in the Sudan and in the East during the War.

In the instructions for the use of drugs the word “tablet” has been used to denote products compressed in the form usually described by a proprietary word that belongs in law only to the products of a particular firm.

A. R. H.

| PAGE | |

| SECTION I. | |

| Meteorology and Climatology (by Hugh Robert Mill, D.SC., LL.D., F.R.S.E., formerly President Royal Meteorological Society and Director British Rainfall Organization) | 1-50 |

| General Remarks, 1—A Record of Weather, 2—Non-Instrumental Observations, 3—Instrumental Observations, 11—Observations for Forecasting the Weather, 32—Extra-European Weather Services, 42—Table of Relative Humidity, 44—Table showing Pressure of Saturated Aqueous Vapour in Inches of Mercury at Lat. 45° for each degree Fahr. from -30° to 119°, 50—Isothermal, Isobaric, and Rainfall Maps, 50. | |

| SECTION II. | |

| Photography (by J. Thomson, formerly Instructor in Photography, R.G.S. Revised by the late J. McIntosh, Secretary Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain) | 51-62 |

| The Camera, 51—Selecting a Camera, 51—The Hand Camera, 52—Camera Stand, 54—Lenses, 54—Exposure Tables, 56—Sensitive Plates or Films, 57—How to keep Plates and Films Dry, 58—Apparatus and Chemicals for Development, 58—Photography in Natural Colours, 61. | |

| SECTION III. | |

| Geology (by the late W. T. Blanford, F.R.S. Revised by Prof. E. J. Garwood, F.R.S.) | 63-78 |

| General Remarks, 63—Outfit, 64—Collections, 65—Mountain Chains, 70—Coasts, 71—Rivers and River-Plains, 72—Lakes and[vi] Tarns, 73—Evidence of Glacial Action, 74—Deserts, 75—Early History of Man in Tropical Climates, 76—Permanence of Ocean Basins, 76—Atolls or Coral-Islands, 77. | |

| Memorandum on Glacier Observations. (Revised by Alan G. Ogilvie) | 78-81 |

| SECTION IV. | |

| Natural History (by the late H. W. Bates, F.R.S. Revised by W. R. Ogilvie-Grant, British Museum, Natural History) | 82-105 |

| Outfit, 82—Where and What to Collect, 89—Mammals and Birds, 91—Preserving Mammals, &c., in Alcohol, 92—Preparation of Skeletons of Animals, 94—Reptiles and Fishes, 96—Land and Freshwater Mollusca, 97—Insects, 99—Botanical Collecting, 99—Fossils, 104—General Remarks, 104—Observations of Habits, &c., 104. | |

| SECTION V. | |

| Anthropology (by the late E. B. Tylor, D.C.L., F.R.S.) | 106-129 |

| Physical Characters, 106—Language, 110—Arts and Sciences, 113—Society, 118—Religion and Mythology, 124—Customs, 126. | |

| Note by Professor R. R. Marett | 129 |

| Queries of Anthropology (by the late Sir A. W. Franks, K.C.B., F.R.S.) | 129-132 |

| Anthropological Notes (by W. L. H. Duckworth, M.D., SC.D., M.A.) | 132-137 |

| SECTION VI. | |

| Industry and Commerce (by Sir John Scott Keltie, LL.D., formerly Secretary R.G.S.) | 138-147 |

| General Remarks, 138—Minerals and Metals, 140—Vegetable Products, 141—Agriculture, 143—Animal Products, 144—Trade, 144—Climate, 145—Facilities and Hindrances to Commercial Development, 146. | |

| [vii]SECTION VII. | |

| Archæology (by D. G. Hogarth, C.M.G., D.LITT.) | 148-159 |

| Recording, 148—Cleaning and Conservation, 156. | |

| SECTION VIII. | |

| Medical Hints (by the late William Henry Cross, M.D. Revised by Andrew Balfour, C.B., G.M.G., M.D.) | 160-292 |

| Introduction, 160—General Hints, 168—Diseases and their Prevention and Treatment, 169—Medicines, Medical Appliances, &c., 252—Treatment of Wounds and Injuries, 275. | |

| Canoeing and Boating (by the late J. Coles) | 293-297 |

| Orthography of Geographical Names (by Maj.-General Lord Edward Gleichen, K.C.V.O.) | 298-305 |

| On the Giving of Names to Newly-Discovered Places | 306 |

| INDEX | 307-318 |

| PAGE | |

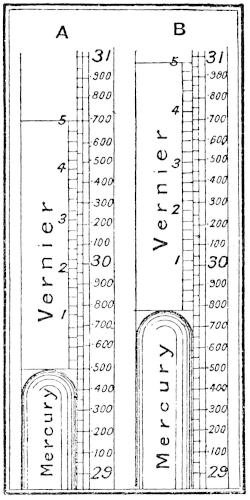

| Diagram showing how to read Thermometer Scale | 13 |

| Mr. H. F. Blanford’s Portable Thermometer Screen | 15 |

| Hut for Sheltering Thermometers | 16 |

| Section of Assmann’s Aspiration Psychrometer | 20 |

| Diagram showing how to read Barometer Vernier | 27 |

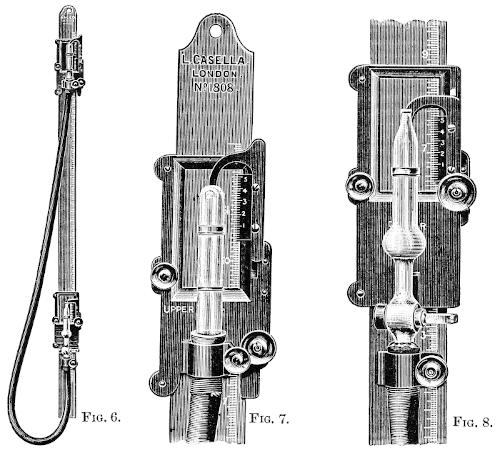

| The Collie Barometer, with the Deasy Mounting | 30 |

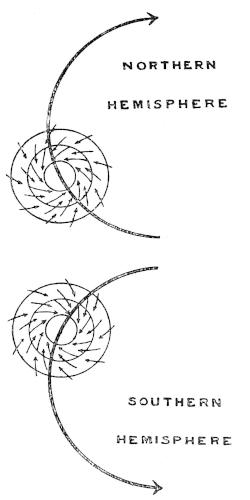

| Diagram showing Cyclone Paths and Circulation of Winds in Cyclones | 33 |

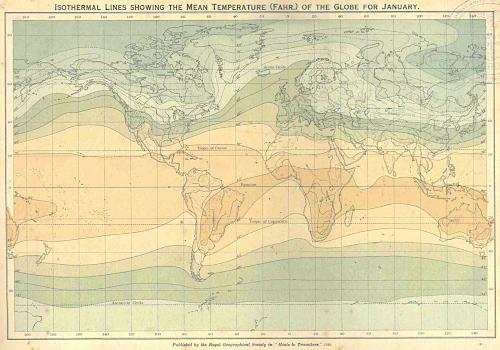

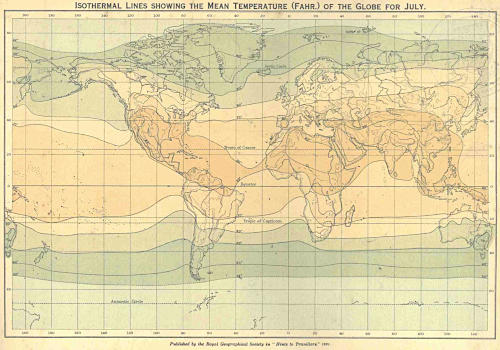

| Charts of the World showing Isothermal Lines for January and July | 50 |

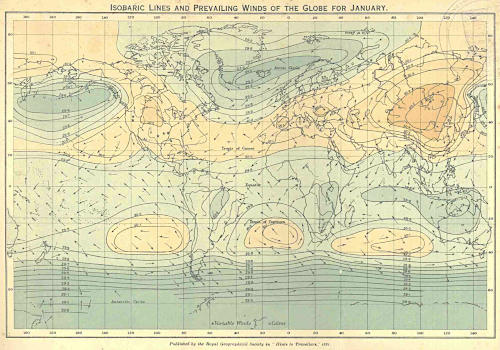

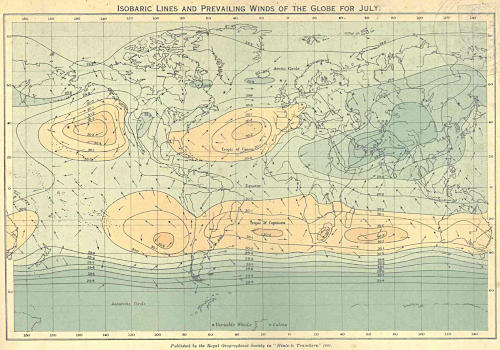

| Charts of the World showing Isobaric Lines for January and July | 50 |

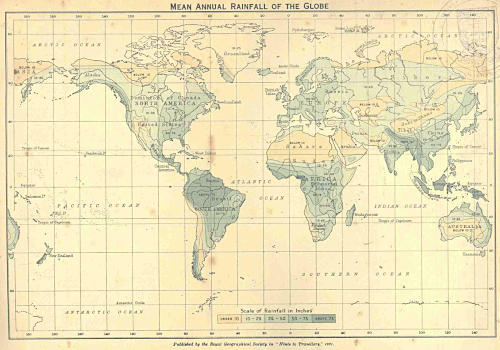

| Rainfall Chart of the World | 50 |

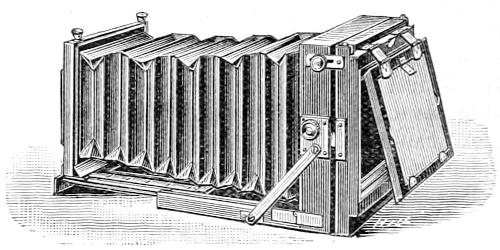

| Bellows Camera | 52 |

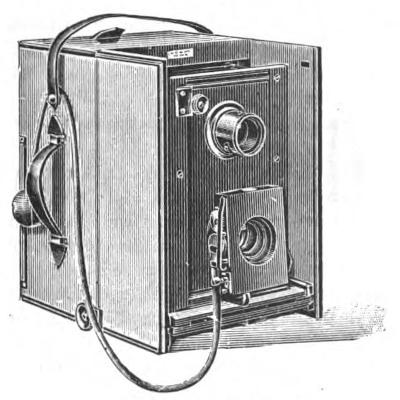

| Twin-Lens Camera | 53 |

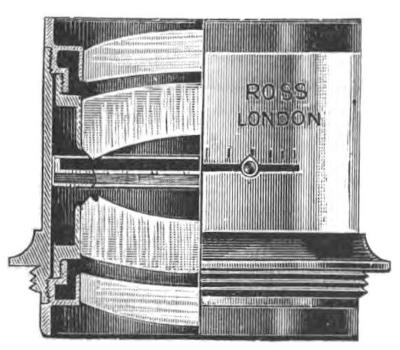

| Homocentric Lens | 55 |

| General Collecting Case for Natural History Specimens | 93 |

| Drying Press for Botanical Specimens | 100-101 |

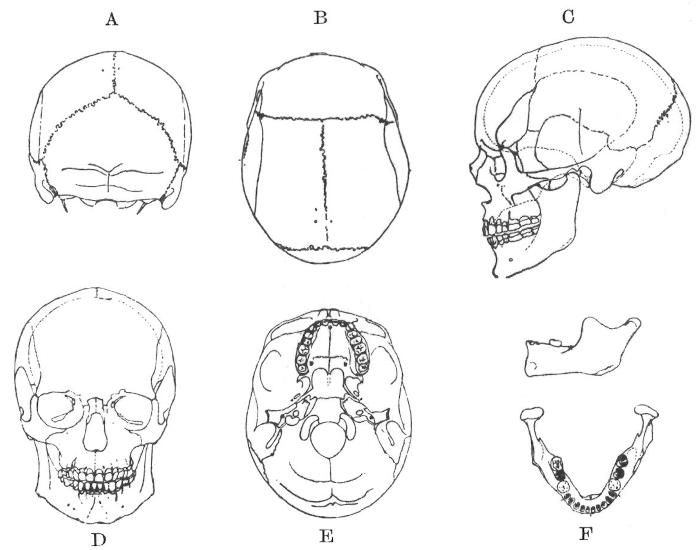

| Diagrams of the Human Skull illustrating Craniological Descriptions | 134 |

| Diagrams of the Human Skull illustrating Cranial Measurements | 135 |

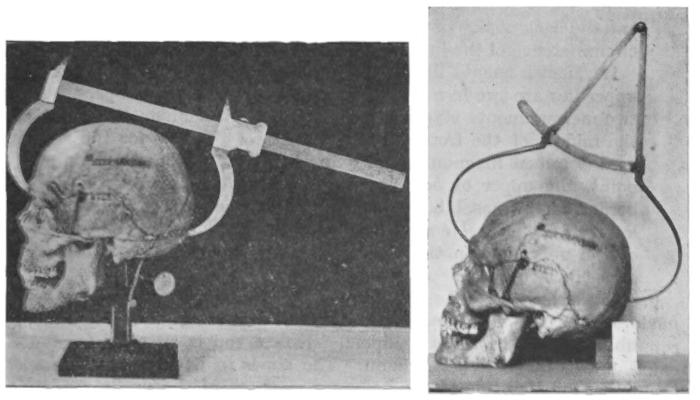

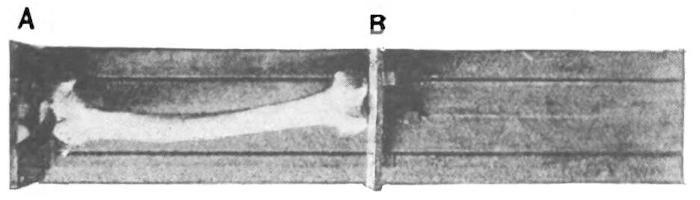

| Diagram of Portion of the Thigh-Bone for Measurement of its length | 137 |

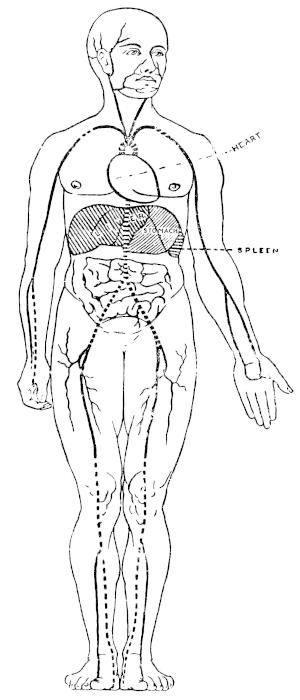

| Diagram showing some of the Principal Organs of the Body, and the Course of the Main Blood-Vessels | 162 |

| Spectacles for Preventing Snow-Blindness | 199 |

| Diagram illustrating method of compressing the Main Artery of the Thigh | 278 |

| Diagrams illustrating methods of Restoring Breathing in cases of Drowning | 284 |

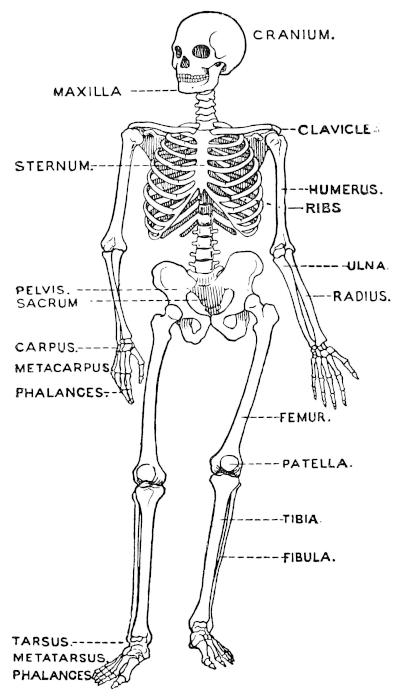

| Diagram of the Human Skeleton, giving the Names and Positions of the Chief Bones | 285 |

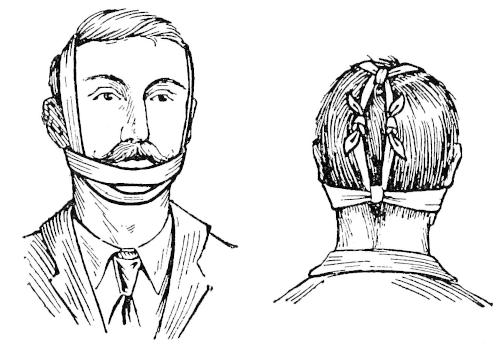

| Diagrams showing Bandaging of Broken Jaw | 289 |

By Hugh Robert Mill, D.SC, LL.D., F.R.S.E.,

Formerly President Royal Meteorological Society, and Director

of the British Rainfall Organization.

The nature of the meteorological observations made by a traveller or by a resident in regions where there is no organised meteorological service will necessarily depend on the object which he has in view, the time he is able to devote to meteorological work, his knowledge of meteorology as a science, and his interest in it.

Of the many ways in which a traveller may add to the knowledge of atmospheric conditions, five may be specially mentioned:—

1. A record of the weather, observed day by day with regard both to non-instrumental observations and the readings of instruments. This may be taken as the minimum incumbent on all travellers.

2. Observations for forecasting the weather and obtaining warning of storms. This is sometimes of vital importance; it is always valuable at the time, and occasionally the results are worth recording. It may, however be looked upon as a practical application of the systematic observations.

3. Observations with a view to determining the character of the local climate. The traveller passing through a country can do little in this way, as long continued uniform observations in one place are necessary to fix the annual variations. Still, the recording of such data as may be obtained is always important in a little-known region, and the work of several travellers at different seasons will allow some fair deductions to be drawn. When a day is spent in camp, much importance attaches to regular observations made every two hours, from which the diurnal changes of climate may be ascertained.

4. Special meteorological researches. These usually demand special instruments and skilled observers. Observations in the upper air by kites or balloons in particular, must be an end in themselves. Exact measures of radiation in deserts, of rainfall in forests and on adjacent open ground, of temperature during land and sea breezes, or of fogs, thunderstorms, tornadoes, etc., in places subject to those visitations, are always of value. As a rule, however, the traveller cannot devote much time to these matters, unless the study of physical geography is the object of his journey.

5. The collection of existing meteorological records. It sometimes happens that at outlying stations meteorological observations have been taken and recorded for a considerable time. If they have not been already communicated to some meteorological centre, the traveller should obtain a copy of them, and also compare the instruments in use with his own. He might in some cases aid in securing a knowledge of local climate by inducing residents at outlying stations to start regular observations.

The first two ways of advancing meteorology need alone be considered in detail; but with regard to all, it must be clearly understood that the value of the work is greater the more carefully the observations are made and recorded, and the more remote and less known the region.

1. A Record of Weather.—The traveller who makes his journey for any other purpose than the study of physical geography would be wise to burden himself as little as possible with instruments, but to understand thoroughly and use faithfully the few he carries. In a rapid march many different climates may be traversed in a few weeks, and the[3] records of variation of weather so obtained could not have much value; but when a halt of a few days or of a week or two is made, systematic observations become valuable.

The first place must be given to non-instrumental observations, which may be made at any time on the march or in camp, and should always be noted at the time they are made in the rough note-book, and copied carefully into the journal each evening. These observations in the rough note-book will necessarily be mixed up with others on various subjects; but the meteorological facts should have a place reserved for themselves in the journal, say at the end of each day’s work.

Wind.—Observations of the direction and force of the wind at several fixed hours in the day are advisable for comparison with instrumental readings; but on the march every decided change should be recorded if the nature of the country permits. In the depths of a forest, or in a narrow valley, the wind, if felt at all by the traveller, gives scarcely any clue to the movement of the air over the open country, but in most cases the movements of low clouds, when any are in sight, may be taken as a fairly satisfactory test. The direction is to be observed by means of the compass, and it will be sufficient to estimate it by the eight principal points—North, North-east, East, South-east, South, South-west, West, and North-west. Any sudden changes in direction so pronounced as to be noticeable should be recorded, for, taken in conjunction with the barometer readings, if the journey is along a route of nearly constant level, they are valuable aids in predicting the weather. In some places the direction of the wind undergoes a well-marked regular diurnal change in perfectly settled weather.

Wind is always named by the direction from which it blows. The force of the wind is best estimated on the scale Calm, Light, Moderate, Fresh, Strong, and Gale. It is impossible, without long experience and the tuition of a trained observer, to assign relative numbers to these forces which should have any permanent value for comparison with the observations of others. Travelling on foot in a strong wind is always uncomfortable, and in a gale very difficult. If it is impossible to make way against the wind at all, or to pitch tents, the force may be put down[4] as Hurricane after it has passed, the traveller bearing in mind that if he can write in his note-book at all, while unsheltered, a hurricane is not blowing. If a lake or a river without appreciable current is in sight, wind just sufficient to produce white crests on the waves may be called fresh, and that sufficient to blow away spray from the crests deserves to be termed strong. At sea, in a sailing-vessel, it is possible to acquire great skill in estimating wind-force; hence Beaufort’s scale, originally devised with reference to the amount of sail a well-equipped frigate could carry, has come into extensive use, and it is as well to know it. By comparison with anemometers, the approximate velocity in miles per hour corresponding to the numbers on the scale has been estimated:—

Beaufort’s Scale of Wind Force.[1]

| No. | Name. | Mean Velocity in miles per hour. |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Calm | 0 |

| 1 | Light air | 1 |

| 2 | Light breeze | 4 |

| 3 | Gentle breeze | 9 |

| 4 | Moderate breeze | 14 |

| 5 | Fresh breeze | 20 |

| 6 | Strong breeze | 26 |

| 7 | Moderate gale | 33 |

| 8 | Fresh gale | 42 |

| 9 | Strong gale | 51 |

| 10 | Whole gale | 62 |

| 11 | Storm | 75 |

| 12 | Hurricane | 92 |

The duration of strong wind should be noted, as well as the time of any marked change of strength. The land and sea winds of tropical coasts show a well-marked relation to the position of the sun and the hour of sunset, and in places where these winds blow the hours of calm and change should be noted. On mountain slopes a similar diurnal effect may be noticed; the wind usually blows uphill during the day and downhill[5] at night, while in valleys it usually blows either with or against the direction of the river. Local winds of peculiar character are sometimes met with in association with mountains such as the Föhn of the Alps, the Chinook wind of the Rocky Mountains, and the Helm wind of the Eden Valley in England and Adam’s Peak in Ceylon.

Whirlwinds and tornadoes are rare phenomena, but if met with, it is worth while to take some trouble to put on record at least the hour of their appearance (local time), the direction in which the whirl moves onward, and the breadth of the path of destruction it leaves behind. When a storm of wind has passed over a wooded region and blown down many trees, the direction in which most of the trunks lie is worth observing. The top of the tree usually falls in the direction in which the wind was blowing, hence the root usually points to the direction of the wind. Waterspouts are closely allied to whirlwinds, and in any of those phenomena of revolving columns of air it is of much theoretical importance to determine the direction of the whirl about the axis, i.e., whether the rotation is in the direction of the hands of a watch or the opposite. The prevailing wind of a district may often be discovered by the slope of trees growing on open ground, or still better, by the difference in the degree of wave erosion on small lakes. If the banks are of the same material all round, the side against which the prevailing wind drives the waves will always be the most worn away.

Cloud and Sunshine.—It would be impossible to keep a record of the countless changes in the cloud-covering of an English sky, but in many parts of the world the absence or presence of cloud is a function of latitude, altitude, and season, of great stability, and worthy of being attentively studied. The amount of cloud is usually estimated as the number of tenths of the sky covered; but it is a very difficult thing indeed to compare a tenth of the visible sky near the horizon with a tenth near the zenith. There is no difficulty, however, in observing when the sky is completely overcast or quite free of cloud, and as a matter of convenience the belt round the horizon to the height of thirty degrees may be neglected, i.e., the lower third of the distance from the horizon to the zenith. Very often it will be found that clouds form and disappear at certain hours of the morning or evening, and it is useful to get exact information on the subject.

Of more importance than the amount of cloud is its nature, elevation, and movement. Distinct species of cloud have been recognised for a[6] long time, and from more recent studies it would appear that they owe their distinctive appearance to the altitude at which they float in the air. Meteorologists distinguish a number of classes and transitional forms of cloud; it is enough for the traveller to be able to recognise the most definite types, viz., Cirrus, Cumulus, Stratus, and Nimbus. Cirrus clouds are the small tufts or wisps of cloud which float very high in the atmosphere, and to which the popular name of “mare’s tails” is applied. The transitional form, Cirro-Cumulus, popularly known as “mackerel scales” or “mackerel sky,” is equally easy to identify. Cumulus clouds are great woolly-looking heaps of cloud, the lower surface of which is often nearly horizontal, while above they well into an exuberant variety of rounded forms. They represent the condensation of moisture in ascending columns of heated air. Stratus clouds are low-lying sheets of condensed moisture, which, being usually seen at a low angle, appear like thin layers parallel to the horizon. The transitional type Cirro-Stratus is usually seen in the form of great feather-like clouds stretching across nearly the whole sky. Nimbus is a rather low-lying cloud from which rain is falling even if the rain is re-evaporated before reaching the ground. The lowest clouds of all, those resting on the surface of the ground and enveloping the observer, are called mist and fog. The two are distinguished by the fact that a mist wets objects immersed in it, while a fog does not. All clouds, except Cirrus, are physically the same, consisting of minute globules of liquid water falling through a portion of air saturated with moisture. The globules being small offer a relatively great surface to friction, and so fall very slowly, and in the higher clouds they evaporate on the lower surface before they have time to agglomerate into raindrops. In the highest of all clouds, the cirrus type, the particles are spicules of ice and not globules of water. It is a common error to suppose that black clouds differ from white clouds. All clouds are white when they reflect the light of the sun, and all are black when they come between the eye and the sun in sufficient thickness to cut off a considerable portion of its light.

The sudden appearance of a particular kind of cloud is important as a weather sign. It shows that changes are going on in the vertical circulation of the atmosphere. Hence if cirrus or cumulus cloud should be observed to be increasing the fact should be noted, and the direction in which the clouds are moving should be noted also.

In observing cloud-motion attention should be given only to the sky overhead; at any lower angle the parallax due to viewing the clouds obliquely deprives the observation of value. It is also necessary to distinguish between the movement of the upper and of the lower clouds, as these are floating in very different parts of the atmosphere. It is comparatively rarely that the motion, say of nimbus and cirrus, is in the same direction. On a lofty mountain, strata of cloud which from below were seen to be cumulus may be passed through as layers of mist, and on emerging from them their upper surface may be seen below one. In many mountains the cloud-belt is as sharply defined as the snow-line, and its variations should be carefully observed.

Clouds should occasionally be photographed as a record. This should be done especially when a type of cloud comes to be recognised as a usual one, for while exceptional forms may prove interesting, a record of the usual forms is certain to be valuable. In this connection a protest may be made against the horrible custom of some amateur and of many professional photographers of printing in clouds from some stock negative in their pictures of scenery. The cloud is an essential part of a picture, and it is better to leave an over-exposed sky of natural cloud than to insert a beautiful representation of a cloud-form which may be one never visible in the particular place or at the particular season.

Mist, Fog and Haze.—Mist or fog at low levels will of course be recorded whenever observed, and its density and duration noted. A good way to define the density of thick fog is to measure the number of yards at which an object becomes indistinguishable, and the most convenient object for the purpose is a person. Light mists lie over water or marshes at certain hours in particular seasons, and their behaviour should always be observed. It often happens that the distant view from a height is obscured by a haze not due to moisture, and this appearance should be noticed with a view to discovering its cause. The smoke from forest or prairie fires in Canada sometimes produces so thick a haze as to put a stop to surveying operations for weeks at a time. Haze is often due to dust blown from deserts, or ejected from volcanoes, and sometimes to swarms of insects.

Rain and Dew.—The journals of most travellers fail to give a clear idea of the prevalence of rain during their journeys, and it is much to be desired that something more explicit than “a showery day” or[8] “fairly dry” should be recorded. The hour of commencement and cessation of rain during a march should be noted, and some indication given as to whether the rain fell heavily or lightly. In this way any tendency to a diurnal periodicity of rain would be detected, and some definite meaning would be given to the terms rainy season and dry season. If rain occurs during the night it should also be recorded, and the amount of night rains should always be measured by means of a rain gauge in the manner to be described later.

The general condition of a country with regard to rain may often be judged from the appearance of vegetation or the marks of former levels of high-water in lakes or rivers. Thus on mountain slopes or the sides of a valley any difference in the luxuriance of vegetation according to exposure probably indicates the influence of rainfall as guided by the prevailing wind. So, too, the appearance of lines of drifted débris on the banks some distance from the edge of a lake or river may be taken as indications of the height to which the waters sometimes rise; and conversely the appearance of rows of trees in the middle of a wide shallow lake may indicate the line of a river which has temporarily flooded the surrounding meadows. Such observations have an important bearing on climate.

The appearance and amount of dew are also to be recorded. The most important points to notice are the hour in the evening when the deposit commences, and the hour in the morning when the dew disappears. It should be noted also whether the deposit of dew is in the form of small globules standing apart on exposed surfaces, or if it is heavy enough to run together into drops and drip from vegetation to the ground.

Thunderstorms and Hail.—The occurrence of thunderstorms should of course be noted, and here the hour of occurrence is of very great importance, for thunderstorms frequently show a marked diurnal period. The appearance of lightning without thunder should be recorded when it is observed, but this will naturally be almost always after sunset. Hailstorms usually accompany thunderstorms, and sometimes take the place of them. The occurrence of hail is most frequent in summer, and records of the size of hailstones are important. If possible they should, when very large, be photographed along with some object of known size, and their structure described. It might at least be noticed whether they are hard and clear, like pure ice, or opaque like compacted snow, or made up of concentric layers of clear and opaque ice alternately.

Snow.—Snow falls in all parts of the world, although in tropical or sub-tropical latitudes only at great elevations above sea-level. The actual limits of snowfall at sea-level are as yet imperfectly known, and any observations of snow showers in the neighbourhood of the tropics are of importance. It is essential in such a case to record also the approximate elevation of the land. On mountains in all latitudes the position of the snow-line should be noted at every opportunity. This is the line above which snow lies permanently all the year round, or below which snow completely melts in summer; and it is a climatic factor of some importance. It may be remarked, for instance, that if the traveller finds snow lying on grass, moss, or other vegetation, he is certainly not above the snow-line. It is necessary also to notice that glaciers may descend unmelted a long distance below the level of perpetual snow. While the conditions of snow lying on the ground in the Arctic regions and above the snow-line in any part of the world are matters pertaining more to geology and mountaineering than to meteorology, the duration of snow-showers, the character of the snow, and the depth to which it lies on ground below the snow-line are too important from their bearing on climatology to be overlooked.

The character of the snow as it falls varies from the sleety, half-melted drops common in warm air to the fine dust of hard, separate ice-crystals found in the intense cold of a Polar or Continental winter. The feathery appearance of lightly-felted flakes is an intermediate type between the two extremes. In measuring the depth of snow as it lies, care should be taken to select open ground where there is no drifting, and when the snow is not too deep the measurement can usually be best made with a walking-stick on which a scale of feet and inches (or of centimetres) has been cut. Such a stick is useful for measuring the depth of shallow streams, and for many other purposes. The result should be entered as “depth of fallen snow,” so that there may be no risk of confusing the figures with the amount of snowfall estimated as rain. Speaking roughly, a foot of snow is usually held to represent an inch of rain. A violent storm of wind, accompanied with falling or driving snow, is termed a blizzard in the western United States, and a buran in Siberia. The name blizzard has been naturalized in the Antarctic, but it is not known that this phenomenon is identical with the American storm.

Frost.—The appearance of frost in the form of hoar-frost (the way in[10] which atmospheric water-vapour is deposited in air below the freezing-point), or of thin ice formed on exposed water, should always be carefully looked for and noted. In hot, dry countries the intense radiation from the ground at night often reduces the temperature below the freezing-point, although, during the day, the ground may be very hot. The appearance of frost at sunrise is a valuable check on the readings of a minimum thermometer, and in most cases is a more trustworthy datum. Similarly in cold countries, where snow is lying on the ground or ice covering the rivers, the appearance of thaw, especially in cloudy weather, is a delicate test of the rise of the air temperature to the freezing-point. The traveller should never fail to record cases of melting and solidifying of any substances due to changes of temperature. The softening of candles and the freezing of mercury or of spirits give information regarding temperature at least as valuable as the readings of thermometers.

Other Observations.—Any peculiar atmospheric phenomena, such as the appearance of the zodiacal light after sunset, the aurora, the electrical lights seen on pointed objects, and known as St. Elmo’s fire, rainbows, especially lunar rainbows, haloes, the appearance of mock-suns or moons, meteors or shooting stars, should be noted on their occurrence, as many of them are valuable weather prognostics. Attention should also be given to any appearances of mirage, or other effects of irregular distribution of atmospheric density. A mirage is only rarely so perfect as to show ships inverted in the air, palm-grown islands in the sea, or distant oases in the desert. The common form is an unusual intensification of refraction, raising land below the horizon into sight, or apparently cutting off the edges of headlands or islands at sea or on large lakes. It is worth while observing the temperature of the air and of the water or ground when an unusually clear mirage effect is visible.

Another interesting series of observations may be made on the colours of the sky and clouds at sunrise and sunset. A phenomenon often observed at sunset, but the existence of which is still sometimes denied, should be looked for. This is the appearance of a gleam of coloured light at the moment when the upper edge of the sun dips below a cloudless horizon. A note should be made of the nature of the horizon, whether land or sea, and of the colour of the light if it should be observed. When opportunity offers, the first ray of the rising sun might be similarly observed.

The traveller should, at the end of each day, give his opinion of the nature of the weather, saying whether he felt it hot or cold, relaxing or bracing, close or fresh. Such observations have no necessary relation to degree of temperature or humidity as recorded by instruments; but the human body is the most important of all instruments, and everything which affects it should be studied. By paying attention to the foregoing instructions, an observant traveller will bring home a far better meteorological log without instruments than a more careless person could produce by the diligent reading of many scales. Yet, in enforcing the importance of non-instrumental observations, we must not leave the impression that the readings of instruments are of little value. It is, in ordinary circumstances, only by the readings of instruments that the climate of one place can be compared with that of another, and only the best results of instrumental work are precise enough to form a basis for climatological maps.

The minimum requirement of instrumental observations by a traveller is the reading twice daily of the barometer and of the dry and wet bulb thermometers, to ascertain the temperature and humidity of the air, also the reading once daily, in the morning, of the minimum thermometer which has been exposed all night, and on days in camp of the maximum thermometer also. It is very desirable to expose a rain gauge whenever it is practicable to do so. Unless special meteorological researches are to be carried out, nothing farther in the way of observations need be attempted. A very useful supplement to the necessary observations is the use of a self-recording barograph or thermograph; but these are delicate instruments, liable to get out of order unless very carefully handled, and it will not always be possible to make use of them.

The observer must understand what his instruments are intended to measure, how they act, and how they should be exposed, read, and the reading recorded. He must know enough about all these things to be able to dispense with unnecessary precautions only possible at fixed observatories, and, at the same time, to neglect nothing that is necessary to secure accuracy in the results.

Thermometer Corrections.—All thermometers, without exception, should have the degree marks engraved on the stem, or on a slip of enamel within the outer tube, and be supplied with a certificate from the National Physical Laboratory showing the error of the scale at different points. This certificate should be in duplicate, and a copy ought to be left in a safe place at home. After a long journey the thermometers which have been in use should be sent to have their errors re-determined. The corrections are not, however, to be applied by the observer unless he is working out his observations for some special purpose. No thermometer is passed at the National Physical Laboratory if its error approaches one degree, so that for all ordinary purposes of description a certificated thermometer may be looked on as correct. But when the readings are being critically discussed and compared with the observations of other people, the correction is of the greatest importance. It cannot be too strongly impressed upon an observer that, in reading meteorological instruments, he must read exactly what they mark, and record that figure in his observation-book on the spot. The corrections can be applied afterwards by the specialist who discusses the work. For subsequent reference it is necessary to note in the observation-book the registered N.P.L. number of the thermometer in use, and if a thermometer should get broken and another be used instead, the number of the new instrument must be noted at the date where it is first employed. Care should be taken to use the same thermometer for one purpose all the time if possible, and only an accident to the instrument should necessitate a change being made.

Thermometers are either direct-reading or self-registering. The former are used for obtaining the temperature at any given moment, the latter for ascertaining the highest or the lowest temperature in a certain interval of time. They are filled either with mercury, or a light fluid which freezes less readily, such as alcohol or creosote.

Thermometer Scales.—The particular system on which the thermometers are graduated is of no importance, but merely a matter of convenience. The Fahrenheit scale is used for meteorological purposes in English-speaking countries; but for all other scientific purposes the Centigrade scale is used everywhere. One can be translated into the other very[13] simply by calculation[2]; but it is convenient for a traveller to have all his thermometers graduated in accordance with one scale only.

The graduation, as marked on the stem of the thermometer, is usually to single degrees, but anyone can learn to read to tenths of a degree by a little practice. Care must be taken to have the eye opposite the top of the mercury column. Suppose it to be between 50 and 51, the exact number of tenths above 50 is to be estimated thus: If the mercury is just visible above the degree mark it is 50°.1, if distinctly above the mark 50°.2, if nearly one-third of the way to the next mark 50°.3, if almost half-way 50°.4, exactly half-way 50°.5, a little more than half-way 50°.6, about two-thirds of the way 50°.7, if nearly up to the next mark 50°.8, and if just lower than the mark of 51° it is 50°.9. The eye soon becomes accustomed to estimating these distances.

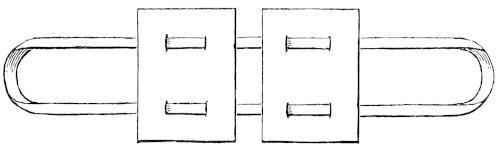

Fig. 1.—Reading Thermometer Scale above and below Zero.

In using a thermometer below zero, the observer must pay attention to the change in the direction of reading the scale, the fractions of a degree counting downward from the degree mark instead of upward from it, as in readings above zero. Readings below the zero of the scale are distinguished in recording them by prefixing the minus sign. The annexed figure shows the reading of two thermometers graduated to fifths of a degree, one showing a temperature of 1°.4, the other of -1°.4. The British Meteorological Office now recommends the use of the Centigrade thermometer graduated from the absolute zero, i.e., the freezing point is shown by 273°, the boiling point as 373°.

Care of Thermometers.—Mercurial thermometers will always be employed for ordinary purposes in places where the temperature is not likely to fall to -40°: i.e., everywhere except in[14] the polar regions and the interior of continents north of 50° N. These thermometers are very strong and are not easily broken except by violence. The one vulnerable part is the bulb, which is of thin glass and filled with heavy mercury. Hence, in carrying thermometers, care has to be taken to protect the bulb from coming in contact with any hard object. The best way to carry an unmounted thermometer is in a closed brass or vulcanite tube with a screw top, the inside of the tube being lined with india-rubber and provided with a cushion of cotton-wool for the bulb to rest on. If the thermometer is mounted in a wooden frame it should be secured in a box so that the frame is firmly held and the bulb projects into a vacant part of the box, which may be lightly filled with cotton-wool or provided with a deep and well-padded recess. Every thermometer which is not graduated above 120° should have an expansion at the top of the tube which the mercury that may be driven beyond the scale by over-heating will not fill; otherwise any accidental over-heating will break the bulb.

The unavoidable shaking or any sudden shock during travelling is apt to cause the mercury column to separate, and a portion of it may be driven to the top of the tube, where it may remain unless looked for and brought back. Hence it is important to see that the top of the bore of the tube is visible, and not covered by any attachment holding the tube to a wooden frame. Thermometer readings are absolutely valueless unless the whole of the mercury fills the bulb and forms a continuous column in the stem. To bring a broken column together the best plan is to invert the thermometer, if necessary shaking it gently, until the mercury flows from the bulb and entirely fills the tube, leaving a little vacant dimple in the mass of mercury in the bulb. When this is done, the thermometer should be brought into its normal position bulb downwards, and the column will usually be found to have united. If this method does not succeed the thermometer may be held in the hand by the upper end, raised to the full stretch of the arm, and swung downwards through a wide arc with a steady sweep. I have never known this method to fail.

Thermometer Screens.—It is usual at fixed stations to expose the thermometer to the air by hanging it in a screen made of louvre-boards so arranged that the air penetrates it freely while the direct rays of the sun are cut off. The Stevenson screen, constructed on this plan with a[15] door opening on the side away from the sun, is well adapted for use in temperate countries; but it is too cumbrous to carry on a journey and does not afford sufficient ventilation for use in tropical countries. An excellent substitute is the canvas screen devised by the late Mr. H. F. Blanford, which consists of a bamboo frame carrying the thermometers (with their bulbs four feet from the ground). The whole structure is five feet high, and is sufficient for any places where the wind is moderate. It is constructed of bamboos or rods of light wood, cords, and canvas, which may readily be made up before starting, and it is easily renewed or repaired. The canvas roof should be triple or quadruple according to the thickness of the material. Such a screen will afford sufficient protection at night, or even in the day, if set up in the shade, and it will throw off rain; but in the sun it will require a thick mat as an additional protection on or preferably stretched above the roof.

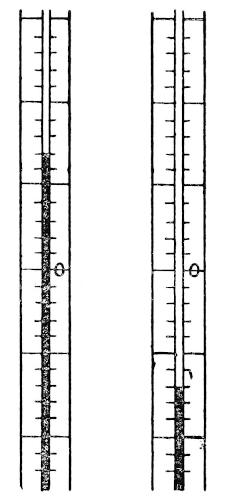

Fig. 2.—Mr. H. F. Blanford’s Portable Thermometer Screen.

For a more permanent station the form of exposure recommended by a committee of the British Association for use in tropical Africa will be found very suitable in hot countries.

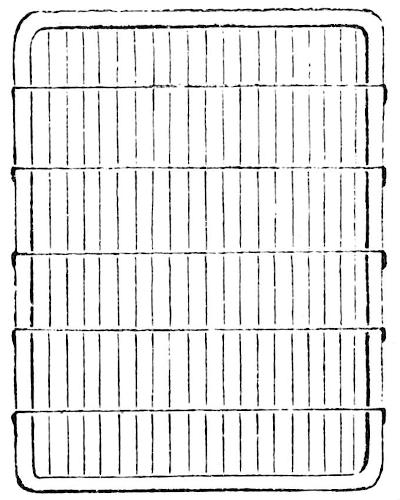

Fig. 3.—Hut for Sheltering Thermometers.

The thermometers are placed in a galvanised iron cage, which is kept locked for safety. This cage is suspended under a thatched shelter,[16] which should be situated in an open spot at some distance from buildings. It must be well ventilated, and protect the instruments from being exposed to sunshine or rain, or to radiation from the ground. A simple hut, made of materials available on the spot, would answer this purpose. Such a hut is shown in the drawing (Fig. 2). A gabled roof with broad eaves, the ridge of which runs from north to south, is fixed upon four posts, standing four feet apart. Two additional posts may be introduced to support the ends of the ridge beam. The roof at each end projects about eighteen inches; in it are two ventilating holes. The tops of the posts are connected by bars or rails, and on a cross bar is suspended the cage with the instruments. These will then be at a height of six feet above the ground. The gable-ends may be permanently covered in with mats or louvre-work, not interfering with the free circulation[17] of the air, or the hut may be circular. The roof may be covered with palm-fronds, grass, or any other material locally used by the natives for building. The floor should not be bare but covered with grass or low shrubs.

The great object of these precautions is to obtain the true temperature of the air, and avoid the excessive heating due to the direct rays or reflected heat of the sun falling on the thermometers, and the excessive cooling due to the radiation of heat from the thermometers to a clear sky at night. Such a shelter is absolutely necessary when maximum and minimum thermometers are used; but can be dispensed with for the simple observation of the temperature of the air at a given time. This may be effected by securing a rapid flow of air over the thermometer, either by causing the air to flow past the instrument or by causing the instrument to move rapidly through the air. It has been found by experiment that the true temperature of the air is obtainable in this way whether the operation is performed in sunshine or in shade; but it is preferable to do so in the shade.

Sling Thermometer.—The sling thermometer is the most simple and convenient of all instruments for ascertaining the temperature of the air. It is an unmounted thermometer with a cylindrical bulb, and the degree-marks engraved on the glass stem. The upper end terminates in a ring to which a silk cord about two feet long is attached. As a precaution it is as well to secure the cord by a couple of clove hitches round the top of the thermometer stem as well as to the ring, as the thermometer would then be held securely even if the ring broke. The thermometer is used by whirling it in a vertical circle about a dozen times, the observer taking care, by having a loop of the string round the wrist or finger, that it is not allowed to fly off. Then the thermometer is read, swung once more, and read again. This process is repeated until two consecutive readings are identical; when this is the case the instrument shows the true temperature of the air. It is sufficient to note the final temperature in the observing book.

The risk of breaking a sling thermometer is the only drawback to its use. Only a silk cord should be used, and it should be examined frequently to see that it has not got chafed. In swinging the thermometer, an open place must be selected where it is not likely to come in contact with a branch or any other object.

Hygrometers.—As the humidity or degree of moisture in the atmosphere is a very important climatic factor it is necessary to measure it as carefully and as frequently as the temperature of the air. There are many instruments, called psychrometers or hygrometers, for doing this; but few of them are simple enough for the use of a traveller. The proportion of water-vapour in air is a little difficult to understand at first, because it is not a constant quantity as in the case of the other constituents of air, but varies according to the amount of water-surface exposed to the air and according to the temperature. The maximum amount of water-vapour which can be present in air varies with the temperature, being greater as the temperature is higher and less as the temperature is lower. Thus, if air at 50° F. contains the maximum amount of water-vapour which it can contain at that temperature, it is said to be saturated, for it will take up no more and evaporation stops; and if the temperature were to fall ever so little there would be more water-vapour present in the air than it could hold and some would separate out and condense into dew or rain, hence the temperature of saturation is called the dew-point. But if air saturated at 50° is warmed up say to 60° it can then contain more water-vapour than it has, and the temperature would require to fall 10° before dew or rain could form. When the air is not saturated water exposed to it evaporates rapidly until the maximum quantity of water-vapour is again present, a larger quantity corresponding to the higher temperature. At any given temperature the essential thing to know about the humidity of the air is the additional amount of water-vapour it could take up before becoming saturated, or in other words the humidity relative to the maximum humidity possible at the existing temperature. The relative humidity is expressed in percentages of the maximum humidity possible (saturation) at the actual temperature of observation. It may be measured by two methods, (1) finding the dew-point or temperature at which the amount of vapour present saturates the air; (2) by finding the rate at which the air allows evaporation to proceed; the farther the air is from saturation the more rapid is the rate.

The dew-point may be found directly by means of an instrument by which the air is cooled down until it begins to deposit moisture on a polished surface, but such an instrument is inconvenient to handle when travelling. It may also be found indirectly by calculation from the relative humidity.

The relative humidity is most easily calculated from the rate of evaporation. It is one of the laws of evaporation that heat is required to change liquid into vapour, and when evaporation is going on heat is being abstracted from surrounding bodies, and they are growing colder. By allowing evaporation to take place from the bulb of a thermometer the rate of evaporation may be measured by the fall of temperature produced, and tables have been constructed to convert the differences between the wet and dry bulb readings into relative humidities.

The wet-bulb thermometer consists of an ordinary thermometer, the bulb of which is covered with clean muslin and kept moist by means of a piece of cotton lamp-wick dipping into a small vessel of pure water. Care must be taken to have the water quite pure and free from salt, otherwise the true reduction of temperature will not be observed. Hence special precautions are necessary when observing at sea or in an arid country where the ground is covered with incrustations of salt.

In any form of wet bulb thermometer when the air is much below the freezing point, it will usually be found most satisfactory to remove the muslin covering and allow the bulb to become covered with a coating of ice, by dipping it into water and allowing the water to freeze upon it. Evaporation takes place from solid ice sufficiently rapidly to give the true wet-bulb readings at least with a sling thermometer.

When the air is saturated, i.e., relative humidity = 100 per cent., there is no difference in the reading of the wet and dry bulb thermometers, and the greater the difference between the readings at a given air temperature the smaller is the relative humidity of the air.

The wet-bulb thermometer has to be exposed to the air with the same precautions as are taken in the case of the dry bulb. The two may be hung side by side—but at least six inches apart—in the screen or cage described on p. 15; or the wet bulb may be employed as a sling thermometer. One way to do this is to tie a muslin cap on the bulb of the sling thermometer with a piece of wet lamp-wick coiled round the upper part of the bulb, and then whirl it until the reading becomes constant, taking care to moisten the bulb again if it should become dry. Another way is simply to twist a piece of filter-paper or blotting-paper round the bulb, and dip it in water before swinging.

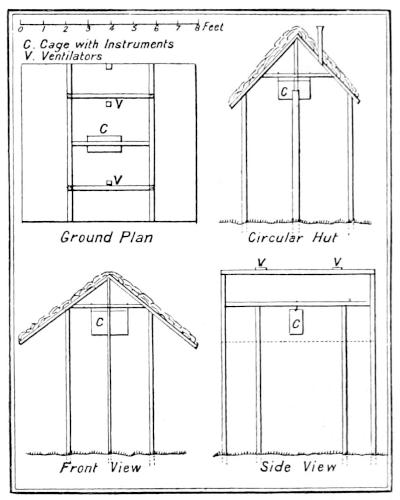

Aspiration Psychrometer.—Perhaps the most convenient form of wet and dry bulb thermometer for use by a traveller is that known as[20] Assmann’s Aspiration Psychrometer. It requires no protecting screen, is not subject to the risk attending the use of the sling thermometer, and gives an extremely close approximation to the true temperature and humidity. The principle of the instrument is very simple. The wet and dry bulb thermometers are enclosed separately each in an open tube (see Fig. 4) through which a current of air is drawn by means of a fan, actuated by clockwork in the upper part of the case. In making an observation, all that is required is to see that the water vessel for the wet bulb is filled and the bulb properly moist, and that the dry bulb is free from any condensed moisture. The instrument is then hung to a branch or other support placed in the open air (or even held in the hand), preferably in the shade, although this is not essential, and the clockwork wound up. Air will then be drawn over the bulbs for five minutes or more, and if the temperature of each thermometer has not become steady by the time the clockwork has run down, it must be wound up again.

Fig. 4.—Section of Assmann’s Aspiration Psychrometer.

The thermometers in Assmann’s Psychrometer are graduated according to the Centigrade scale, and each degree is subdivided into fifths on a slip of porcelain enclosed in the outer tube of the thermometer (see p. 13).

Minimum Thermometer.—The minimum temperature of the night can usually be ascertained by a traveller exposing a minimum thermometer when the camp is set up and reading it in the morning before starting on his way. There are several forms of minimum thermometer, but the only one likely to be used is that known as Rutherford’s. It is very delicate and liable[21] to go out of order. The instrument should be of full size, as used in meteorological stations at home; it must be packed so as to be as free as possible from shock or vibration, and ought to be carried in a horizontal position. The bulb is filled with alcohol or some similar clear fluid, and within the column of spirit in the stem there is included a little piece of dark glass shaped like a double-headed pin. This is the index which continues pointing to the lowest temperature until the instrument is disturbed or re-set. The thermometer has to be hung in a horizontal position. When the temperature rises, the column of spirit moves along the tube, flowing past the index without disturbing it. When the temperature falls, the spirit returns towards the bulb, flowing past the index until the end of the column touches the end of the index. The phenomenon known as surface-tension gives to the free surface of any liquid the properties of a tough film, and the smaller the area of a free surface is, the greater is this effect of surface-tension. Hence it is that the inner surface of the column of alcohol is not penetrated by the glass index, but draws the index with it backwards towards the bulb. As soon as the temperature begins to rise, the alcohol once more flows past the index towards the farther end of the tube. The end of the index farthest from the bulb remains opposite the mark on the stem indicating the lowest temperature which had occurred since it was last set, and this reading must be taken without touching the thermometer.

To set the index it is only necessary to tilt the bulb end of the tube upwards, when the index will slide down by its own weight until it comes in contact with the inner surface of the end of the column of alcohol.

Care of a Minimum Thermometer.—The chief dangers to which a minimum thermometer are liable are three—(1) the index being shaken into the bulb, (2) the index being shaken partly or wholly out of the column of spirit, and sticking in the tube, and (3) the column of spirit becoming separated or a portion of the spirit evaporating into the upper end of the tube.

The thermometer should be so constructed as to make it impossible for the index to get into the bulb, or with an index so long as not wholly to leave the tube, and this should be seen to before purchasing. When any of the other derangements occurs the natural instinct of[22] an observer is to immerse the thermometer in warm water until the spirit entirely fills the tube, and then allow it to cool. The only drawback to this simple method is the almost inevitable bursting of the bulb and destruction of the thermometer. This method should never be attempted; but if the warning were not given, the idea would be sure to occur to the observer some time or other, and he would proceed to destroy his thermometer with all the fervour of a discoverer. The only satisfactory way to rectify a deranged minimum thermometer is as follows:

If the column is separated, but the index remains in the spirit, grasp the instrument firmly by the upper end and swing it downwards with a jerk (as in the case of the mercurial thermometer mentioned on p. 23). If the index has been shaken out of the spirit and remains sticking in the upper part of the tube, or if a little spirit has volatilised into the top of the tube and cannot be shaken down by the first method, a quantity of spirit should be passed into the upper end of the tube by grasping the thermometer by the bulb end of the frame and swinging in the same way. When the index is immersed or the drop of volatilised spirit joined on to the column, the first process of swinging by grasping the upper end of the tube will bring the instrument into working order. After any operation of this kind the thermometer should be kept in a vertical position bulb downwards, to allow the spirit adhering to the sides of the tube to drain back completely. Then the thermometer should be brought into the horizontal position and set by allowing the index to slide down to the end of the column of spirit. The end of the column of spirit farther from the bulb should always show the same temperature as the dry-bulb thermometer. If it should be observed to read a degree or two lower, it will be found that some of the spirit has volatilized and condensed at the end of the tube.

The minimum thermometer should be exposed to the air four or six feet from the ground under a screen or roof, like that described on p. 15, so that it is not exposed to the open sky, and the ground under the shelter should be covered with grass or leaves, not on any account left bare. The loss of heat by radiation of the ground to the open sky will produce a night temperature much lower than that of the air a few feet above the ground, and a radiation thermometer is often employed, laid on the grass and exposed to the sky to measure this effect.[23] Travellers, however, can rarely be expected to make observations of such a kind, as the instrument is one of extreme delicacy.

Maximum Thermometers.—Maximum registering thermometers are filled with mercury, and are less liable to get out of order than spirit-thermometers. The simplest and best form for use by travellers is Negretti and Zambra’s. Its principle is very simple. When the temperature rises and the mercury in the bulb expands, it forces its way along the stem in the usual manner; but there is a little constriction in the tube just outside the bulb which breaks the column as the temperature begins to fall, and so prevents the mercury in the bulb from drawing back the thread of mercury from the tube. The thermometer is hung horizontally, and the end of the mercury farthest from the bulb always shows the highest temperature since it was last set. Before reading the thermometer, it is well to take the precaution of seeing that the inner end of the thread of mercury is in contact with the constriction in the tube, and if, by the shaking of the instrument or otherwise, the mercury has slipped away from this position, it should be brought back to it by tilting the thermometer bulb downwards very gently, then returning it to the horizontal position and reading.

To set this thermometer, it is only necessary to hold it vertically bulb downwards and shake it slightly, if necessary striking the lower end of the frame carrying the instrument, gently against the palm of the hand. This causes the mercury to pass the constriction and re-enter the bulb. When set, the end of the column farther from the bulb should indicate the same temperature as the ordinary dry-bulb thermometer.

Another form of maximum thermometer is known as Phillips’. It is an ordinary mercurial thermometer, but a short length of the upper part of the column in the tube is separated from the rest by a little bubble of air. It is used in the horizontal position, and as the temperature rises the whole column moves forward, while, when the temperature falls, only that portion behind the air-bubble retires towards the bulb. The tip of the column thus remains to mark the maximum temperature to which its farther end points. The instrument is set by gently tilting the bulb end downwards, when the detached portion of the column at once runs back until stopped by the air-bubble. This is the most convenient instrument to use at a fixed station; but in travelling it is apt to get out of order as shaking may have the effect of allowing the air-bubble to escape into[24] the upper part of the tube, or into the bulb, and the instrument cannot easily be brought into working order again.

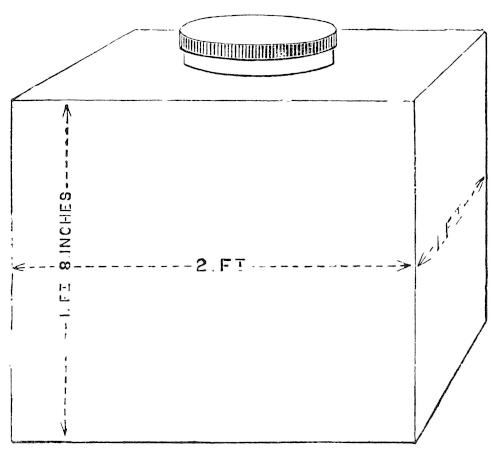

Rain-Gauge.—While measurements of rainfall can possess no climatological value unless they are carried on continuously at a fixed station, some very interesting observations may be made by the traveller both during the night when in camp, and during heavy showers when compelled to stop on the march. The rain-gauge is in itself the most simple of all scientific instruments, for it consists essentially of a copper funnel to collect the rain as it falls, and a bottle to contain what has been collected. A graduated measuring glass is the only accessory required. Rain is measured by the depth to which the water would lie on level ground if none soaked in, evaporated or flowed away. On an emergency, a rain-gauge can be improvised out of a biscuit tin, or any vessel with vertical sides and an unobstructed mouth. Such a vessel standing level would collect the rain, the depth of which might be measured by an ordinary inch-rule. It is rare, however, to find rain so heavy as to give any appreciable depth when collected in a vessel freely open to evaporation, and in order to estimate the amount of rainfall to small fractions of an inch, the device is employed of measuring the water collected in the receiver of the gauge in a glass jar of much smaller diameter than the mouth of the collecting funnel. Thus, if the funnel exposes a surface of fifty square inches, and the measuring glass has a cross-section of one square inch, the fall of 1/50 of an inch of rain on the funnel will give a quantity of water sufficient to fill the measuring glass to the depth of an inch. In this way the actual rainfall may be read to the thousandth part of an inch without trouble. The smallest diameter for a serviceable rain-gauge is five inches, and this size is well adapted for the traveller. A three-inch rain-gauge might be employed, but the results obtained with it are not so satisfactory. The rain-gauge should be placed in an open situation, so that it is not sheltered by any surrounding trees or buildings, and it ought to be firmly fixed by placing it between three wooden pegs driven securely into the ground. The mouth of the gauge should be level, and when the instrument is fixed, the rim of the funnel ought to be one foot above the ground. A spare measuring glass should be carried, but as there is always a considerable risk of breaking such fragile objects, it is well to carry also one or two small brass measures of the capacity of half an inch, two-tenths of an inch, and one-tenth of an inch of measured rainfall. In this way,[25] although no satisfactory record could be kept of light rainfall, a very fair estimate may be made of any torrential showers, the half-inch measure being used first, and then the smaller measures, finally estimating by eye the fraction of the tenth of an inch that remains over. It must, however, be distinctly borne in mind that an estimate formed in this way is not an accurate measurement, and the fact of using the rough method must be stated in the note-book.

When snow falls along with rain, the melted snow is measured as equivalent to rainfall, and if the funnel of the rain-gauge should contain some unmelted snow at the time of observation, it should be warmed until the snow melts before a measurement is taken. When snow falls in a strong wind the drift that occurs makes it almost impossible to measure the amount accurately, but an effort should be made to estimate the average depth of the snow over a considerable area.

If the receiving bottle of the rain-gauge should be broken by frost or accident, any other bottle may be used, or in default of a bottle, the copper case itself will act as a receiver, although the risk of loss by evaporation, and by the wetting of a large surface in pouring out the water, is considerably increased.

At a fixed station the rain-gauge should be read every morning. The traveller who only exposes his rain-gauge during a halt should be careful to state the hours when it was exposed and when it was read.

Barometers.—The barometer is the most delicate, and at the same time the most important, instrument which a meteorologist has to employ. It requires particular care in transport, and must be very carefully mounted and read, while several accessory observations have to be made at each reading in order to ascertain the corrections required for the subsequent calculation of the results. The function of the barometer is to measure the pressure of the air at the time of observation, and this purpose may be carried out by the use of two different principles. The oldest and best method is to measure the height at which a column of heavy fluid is maintained in a tube entirely free from air. The weight of this column is equal to the weight of a column of the atmosphere of the same sectional area. Mercury being the densest fluid is the only one usually employed, because the column balancing a column of the atmosphere of equal sectional area is the shortest that can be obtained, and, consequently, a mercurial barometer is the most portable that can be[26] constructed on this principle. The mercurial barometer has come to be recognised as the standard in all parts of the world.

The average height of the column of mercury in a barometer is about thirty inches, and, consequently, the whole instrument cannot well be made less than three feet long, so that when account is taken of the glass tube, and the amount of mercury it contains, it is long, fragile and heavy. To avoid the disadvantages inherent in such an instrument, the method of measuring the pressure of the air by the compression of a spring holding apart the sides of an air-free flexible metallic box was devised, and the aneroid barometer invented. The aneroid is graduated on the dial in “inches,” i.e., divisions each of which corresponds to a change of atmospheric pressure, equal to that measured by one inch of mercury in a standard barometer. Although a carefully constructed aneroid is a very useful instrument indeed, it is not to be trusted like a mercurial barometer kept in a proper place. But a good aneroid is likely to be much more serviceable to the ordinary traveller on the march than a standard mercurial barometer, every packing and unpacking of which exposes it to the risk of breakage, or to the equally fatal risk of air obtaining access to the vacuous space at the top of the tube. The scale of a barometer may be divided into millimetres, or, as now recommended by the British Meteorological Office, into millibars or thousandths of a hypothetical “atmosphere.” We shall describe the Fortin barometer, which is best adapted for use at a fixed station, and one devised by Prof. Collie and Capt. Deasy, which is portable enough for the use of travellers.

The Fortin Barometer.—The barometer must be kept in a room with as equable a temperature as possible; the instrument must be absolutely vertical—hence it should be hung freely and not touched while it is being read; it must be in a good light, and yet be sheltered from the direct rays of the sun. The measurement of the height of any mercurial barometer is that of the difference of level between the surface of the mercury in the tube and the surface of the mercury in the cistern. When the mercury rises in the tube it falls in the cistern, and vice versâ, although when the cistern is much wider than the tube the changes of level there are much less than those in the tube. In most barometers an arbitrary correction is made to allow for this change, the “inches” engraved on the scale not being true inches. In the Fortin barometer, however, the lower end of the measuring rod is brought in contact with[27] the mercury in the cistern before every reading, and then the scale of inches engraved on the upper part of the measuring rod gives the true height of the column of mercury. In calculating the barometric pressure for purposes of comparison, five corrections have to be applied: (1) for temperature, which requires the temperature of the barometer at the time of reading to be observed, (2) for altitude, which necessitates knowing the elevation of the place of observation above sea-level, (3) for the force of gravity at sea-level, which requires the latitude to be known, (4) for the capillary attraction between the mercury and the glass tube, which is a constant for each barometer, (5) for the slight imperfection in engraving the scale (index error), which is also a constant for each instrument.

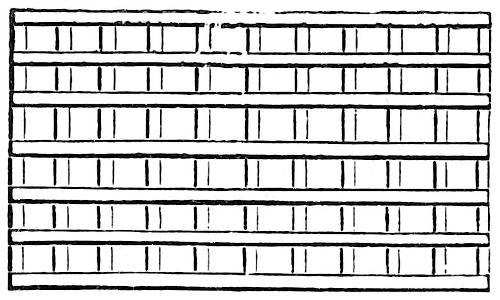

Fig. 5.—Two Readings of the Barometer Vernier.

It is enough for the observer at a fixed station, and to such alone can the use of a Fortin barometer be recommended, to read the temperature on the thermometer attached to the barometer and to read the height of the mercury in the barometer tube. These two figures he is to enter in his note-book, and unless he is himself discussing the results, he should apply no correction whatever to them. The rules for observing, then, are:—

1. Read the attached thermometer and note the reading.

2. Bring the surface of the mercury in the cistern into contact with the ivory point which forms the extremity of the measuring rod by turning the screw at the bottom of the cistern. The ivory point and its reflected image in the mercury should appear just to touch each other and form a double cone.

3. Adjust the vernier scale so that its two lower edges shall form a tangent to the convex surface of the mercury. The front and back edges of the vernier, the top of the mercury, and the eye of the observer are then in the same straight line.

4. Take the reading, and enter the observation as read without either correcting it to freezing point or reducing it to the sea-level.

The scale fixed to the barometer is divided into inches, tenths, and half-tenths, so that each division on this scale is equal to 0.050 inch.

The small movable scale or vernier attached to the instrument enables the observer to take more accurate readings; it is moved by a rack and pinion. Twenty-four spaces on the fixed scale correspond to twenty-five spaces on the vernier; hence each space on the fixed scale is larger than a space on the vernier by the twenty-fifth part of 0.050 inch, which is 0.002. Every long line on the vernier (marked 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) thus corresponds to 0.010 inch. If the lower edge of the vernier coincides with a line on the fixed scale, and the upper edge with the twenty-fourth division of the latter higher up, the reading is at once supplied by the fixed scale as in A (Fig. 5), where it is 29.500 inches. If this coincidence does not take place, then read off the division on the fixed scale, above which the lower edge of the vernier stands. In B (Fig. 5) this is 29.750 inches. Next look along the vernier until one of its lines is found to coincide with a line on the fixed scale. In B this will be found to be the case with the second line above the figure “2.” The reading of the barometer is therefore:—

| On fixed scale | 29.750 |

| On vernier (12 × .002) | .024 |

| Correct reading | 29.774 |

Should two lines on the vernier be in equally near agreement with two on the fixed scale, then the intermediate value should be adopted.

5. Lower the mercury in the cistern by turning the screw at the bottom until the surface is well below the ivory point; this is done to prevent the collection of impurities on the surface about the point.

The transport of barometers requires very great care in order to prevent the introduction of air into the tube or the fracture of the tube by the impact of the mercury against the top. To reduce the risk of these accidents, the barometer must be carried with the tube quite full of mercury, and in an inverted position, at least with the cistern end kept higher than the top of the tube. The flexible cistern of the Fortin type of barometer allows of it being screwed up tight so as to fill the tube and close the lower end of it. In case of breakage, the operation of fitting a new tube is not very difficult, but unless the tube has been[29] carried out ready filled with mercury, this cannot well be attempted. In order to drive out the film of air adhering to the glass on the inside, it is necessary, after filling the tube, to raise its temperature to the boiling-point of mercury. No one should attempt either to fill or to change a barometer tube unless he has had practice in doing so under expert supervision beforehand.

The Collie Portable Mercurial Barometer.—This instrument is not likely to be broken in travelling. It is quickly set up, and from such tests as have been applied, it appears to give excellent results. The cistern and vacuum tube at the top are of equal diameter, and are connected by a flexible tube, and the difference in level of the mercury may be measured directly by means of a graduated rod, or as in Deasy’s mounting by means of a vernier. There is no attached thermometer, but if the instrument be used in the open air, and is exposed for ten minutes or a quarter of an hour before using, it will be sufficient to note the temperature of the air in the usual way.

The upper end (Fig. 7) is about 2.5 inches long, and contains an air-trap, into which all the air that may accidentally enter the barometer, either by the tap leaking, through the rubber tubing, or through either of the joints, must find its way. The lower or reservoir end (Fig. 8) is about 4.5 inches long, and has an air-tight glass tap about an inch below the broad part. These ends are forced into the rubber tubing, and, as an additional precaution against leakage, copper wire is bound round the joints. The scale is cut on an aluminium bar, along which two carriages, to which the barometer is attached, move up and down, and they can be clamped to the bar at any place (Fig. 6). By means of the verniers attached to the carriages, which are divided to 0.002 of an inch, it is easy to estimate the height of the mercury to 0.001.

To use the barometer, the carriages are put on the scale bar; the lower one is clamped at the bottom of the bar, and the upper one some inches higher up; the barometer is attached to the carriages by clamps which fit over the joints; the rubber cap is removed from the reservoir end, the tap opened, the verniers put in the middle of their runs, and the upper carriage moved up the bar until there is a vacuum. By means of the screws on the right of the carriages the verniers are moved up or down until the top of the mercury at each end is in line with the edges of the rings attached to the verniers, which fit round the glass ends. Both verniers are then read, and the difference gives the height of the barometer.[30] The rubber cap on the reservoir end is merely to prevent the small quantity of mercury, which should be left above the tap when it is closed, from being shaken out when travelling.

Fig. 6. The Collie Barometer, with the Deasy Mounting, in its Normal Working Position.

Fig. 7. The Upper Carriage and Vernier on a larger scale, with Barometer Attached.

Fig. 8. The Lower Carriage and Vernier, with Reservoir End of Barometer Attached. (Same scale as Fig. 7.)

To pack up the barometer, lower the upper carriage very slowly until the mercury has touched the top of the glass; then detach the barometer[31] from this carriage, and either let the upper end hang vertically below the reservoir, or detach the reservoir end from its carriage and raise it till the barometer hangs vertically. By this means the barometer is completely filled with mercury, and then the tap must be closed. The tube is then to be coiled away in its padded box. When too much air is found in the trap, it must be extracted by means of the air-pump.

The Aneroid Barometer.—The aneroid barometer is so convenient on account of its portability that, although much less trustworthy than a mercurial barometer, it is much more likely to be used by a traveller. Care should be taken in using it to see that the pointer has come to a position of equilibrium, and it should be tapped gently before reading. The eye must be brought directly over the end of the pointer, and the reading made to one-hundredth of an inch, the barometer being held in a horizontal position. Every opportunity of comparing the aneroid with a standard mercurial barometer should be taken, and a note made of the readings of both. The mercurial barometer will require to be corrected for temperature before its indications can be used for correcting the aneroid, as all good aneroids are compensated for changes of temperature. The readings of an aneroid give a very fair idea of the changes of atmospheric pressure, and are very much better than none at all, although they cannot in any case be accepted as of the highest order of accuracy.

The Watkin mountain aneroid, which is so constructed as to be thrown into gear at the moment when it is read, appears to be free from the worst errors of the ordinary aneroid.

For climatological purposes, it is impossible to make barometric observations of value while travelling unless the altitude of each camping-place is accurately known. This is practically never the case except when travelling along the sea-shore or the margin of a great lake the elevation of which has been determined. But, meteorology apart, barometric readings in any little known country are of value, because by comparing them with simultaneous readings taken at a neighbouring fixed station, new data as to the altitude of the country may be obtained. While in camp, it would be an extremely useful thing to make barometer readings, even with an aneroid, every two hours, in order to get some information as to the normal daily range of atmospheric pressure.

The Boiling-point Thermometer.—The temperature at which water boils depends on the pressure of the atmosphere, so that an accurate observation[32] of the boiling-point of water enables the pressure of the atmosphere at the moment of observation to be determined with the utmost accuracy. This method of determining atmospheric pressure having been used hitherto almost solely for the purpose of measuring altitudes, the boiling-point thermometer is usually known as the Hypsometer, but its records are quite as valuable for use at fixed stations as in mountain climbing. Mr. J. Y. Buchanan recommends the use of a boiling-point thermometer with a very open scale graduated to fiftieths of a degree Centigrade and entirely enclosed in a wide glass tube through which steam from water boiling in a copper vessel is passing. On a thermometer of this kind change of pressure can be measured by the change of boiling-point more accurately than with the aid of a mercurial barometer. See Table, Vol. I., p. 293.

2. Observations for Forecasting the Weather.—The familiar name of “weather-glass” is appropriately applied to the barometer, for in most parts of the world it is the surest indicator of any approaching storm.

The scientific prediction of the weather by means of the barometer involves the comparison of the simultaneous readings of barometers over as wide an area as possible, and can only be carried out where there is a complete telegraph system and a public department charged with the work. The storms of wind and rain which break the more usual steady weather are usually associated with the formation of centres of low atmospheric pressure towards which wind blows in from every side. These atmospheric depressions move, as a rule, in fairly regular tracks, the rate of movement of the centre of the depression having no relation to the rate at which the wind blows or to the direction of the wind. The term cyclone is usually applied to such a moving depression, because of the rotating winds round the centre; but the size of a cyclone may vary from a vast atmospheric eddy extending across the whole breadth of the Atlantic to one only a few miles in diameter. The strength of the wind in a cyclone depends on the barometric gradient; in other words, the greater the difference in atmospheric pressure between two neighbouring points the stronger is the wind that blows between them. Or, when a cyclone is passing over an observer, the more rapidly the barometer falls or rises the stronger may the wind be expected to blow.

In direct contrast to the cyclone or depression is the system of high pressure rising to a centre from which the wind blows out on every side.[33] This is called an anticyclone, and is a condition which, once established, may last for many days, or even weeks, without change. It is the typical condition for dry calm weather in all parts of the world.

Fig. 9.—Cyclone Paths and Circulation of Winds in Cyclones in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.