ARTHUR MACHEN

After the Hoppe photograph

Title: Arthur Machen: Weaver of Fantasy

Author: William F. Gekle

Release date: April 12, 2022 [eBook #67820]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Round Table Press

Credits: Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

ARTHUR MACHEN

After the Hoppe photograph

Weaver of Fantasy

William Francis Gekle

Millbrook, N. Y.

Round Table Press

1949

Copyright, 1949, by

William Francis Gekle

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except by a reviewer, without the permission of the author.

Round Table Press

MILLBROOK, N. Y.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

for

Verne

It was, I suppose, during the closing months of the First World War that an urbane and witty gentleman, writing in the Confederate city of Richmond, set down these words in the course of one of his interminable, and witty and urbane, monologues: “I wonder if you are familiar with that uncanny genius whom the London directory prosaically lists as Arthur Machen?”

Since there was no reply, as indeed none was expected, the amiable Charteris chatted on about Arthur Machen and, oddly enough, Robert W. Chambers, for some moments, and then he concluded with this statement.... “But here in a secluded library is no place to speak of the thirty years’ neglect that has been accorded Mr. Arthur Machen; it is the sort of crime that ought to be discussed in the Biblical manner, from the house-top....”

That thirty years’ neglect has almost doubled—and indeed one might say with perfect truth that Arthur Machen has suffered a lifetime of neglect, and, in perfect truth, it must be added that the loss has been the world’s which so blindly accorded neglect to the uncanny genius of Arthur Machen.

This is the sort of crime, as Mr. James Branch Cabell suggested back in 1918, that ought to be discussed in the Biblical manner—and it is my intention to do so.

At this point there will be voices raised in protest ... dim voices trained to the librarian’s whisper, voices that echo in the vaults of university libraries and in the reading rooms of Memorial Collections. There will be other voices—the amiable, all-inclusive voice of the anthologist and the rasping roar of the reprint editor. There will be the excited exclamations of the cultists and the happy burblings of the bibliographers as they pounce upon another Machen item. And of course we may expect to hear the calm and cultured tones of the collectors, the excavators and the discoverers, who have pointed with smug satisfaction to their rows of faded bindings and their “obscure little pamphlets.” As for the horror boys, happy with their harpies and hieroglyphs and wild hallucinations, they will probably croak and sibilate in unholy glee and rush down to start their presses—reprinting madly all they can find of the magical tales of that wonderful Welshman, Arthur Machen.

It will appear that I anticipate a renewed interest in the works of Arthur Machen. I do. It may even become apparent that I expect the publication of this book to work the miracle—to right the wrong of sixty years of neglect. I do. Nor is this to be attributed to egotism, nor to a vast respect for my powers of persuasion. A number of literary men, of small stature and great, have written well and passionately of Arthur Machen, only to have their effusions produce a magnificent calm. It is simply that there are signs and portents (of which more anon) that the time is now. And then of course there is always the bare hope that my admiration for Arthur Machen and my enthusiasm for his work may be contagious enough to result in another Arthurian revival. That would be an event to rival a genuine miracle at Glastonbury itself.

I spoke of the voices that will be raised in praise and recognition of Arthur Machen. It may occur to some that there was bitterness in what I said, and in the way I spoke of collectors and cultists, and of bibliographers and bibliophiles, and of anthologists and of the zealots of the pulp press. I daresay it is true that I am inclined to be bitter over the neglect accorded Arthur Machen. Of course the blame for that neglect cannot be fixed or fastened—but it must rest somewhere between the publishers of limited editions and the reprinters of almost unlimited editions, between the alpha and the omega, and the buying and reading public. That covers a lot of territory. One cannot indict the publishing world from top, literally, to bottom, literally. One cannot indict, to paraphrase a much quoted statement of Edmund Burke’s, an entire reading public. One can, to make a concrete proposal, attempt to do something about it.

The interest shown in the prospectus announcing this book has been gratifying, but it does not, to my mind at least, dismiss the charge of neglect. It merely indicates that there are others who bear witness to the crime and who wish to see justice done.

The book has been announced as a critical survey—and it will be that. Many of the stories, written in that decade of the delicate decadents, will be re-examined and re-evaluated. Mr. Machen will sometimes be spoken of as a “Gothick novelist”—a thing he has said he is not. The stories of the “Great War,” as he called it, are seen in a new perspective, as anyone must know who has re-read them, especially The Terror, in the past few years.

Many of Machen’s articles and essays, and such works as Hieroglyphics and Doctor Stiggins, offer food for thought to those who may think, for example, that Mr. James Farrell has settled literary criteria, once and for all, in his book, of a few years ago, The League of Frightened Philistines.

This book is, then, the result of some twenty years preparation; at least half of them spent in planning to “do something about it.” The book has grown slowly, with many interruptions before, during and since the war. The opening chapter or Prologue, called “Conversation Piece,” was written a dozen or so years ago. It was scheduled for publication in one of the ephemeral magazines of the day. This particular one proved to be more ephemeral than most ... to paraphrase a rather famous line, “it sank from sight before it was set.” However, the piece is here presented as it was written some twelve years back. I believe now, as I did then, that there was need for a book about Arthur Machen. I hope this book will fill that need.

At least one chapter, the ninth, may seem to some a philippic, a potpourri of purely personal preferences and prejudices, having little to do with Arthur Machen and his works. Needless to say, I believe it extremely relevant.

—W.F.G.

I cannot recall whether it was James Branch Cabell or Vincent Starrett who first directed me to the works of Arthur Machen. I am deeply grateful to both, not only for this, but for their encouraging letters concerning my book.

To Montgomery Evans and Paul Jordan-Smith for their enthusiasm and interest, their intimate sketches of Machen, and for facts not available elsewhere. To Carl Van Vechten and Robert Hillyer for their articles on Machen, parts of which are quoted herein.

To Joseph Kelly Vodrey and Paul Seybolt for their informative and helpful letters, and to Nathan Van Patten whose bibliographical labors lightened my own. To Meyer Berger for his notes on the Mons affair, and to Harper’s Bazaar for permission to quote from them. To the late Alfred Goldsmith and his delightful reminiscences of Machen. To all of these I am deeply grateful.

To Alfred A. Knopf for permission to quote from the Machen books bearing the Borzoi imprint, and for having published them in the first place. To Robert McBride & Co. for permission to quote from The Terror, and to Dodd, Mead & Co. for permission to quote from More Authors and I.

To Hilary Machen for his courtesy in handling my proofs at Amersham and, finally, to Arthur Machen for the ‘plenary blessing’ he gave this book.

| PREFACE | |

| PROLOGUE: Conversation Piece | 1 |

| CHAPTER | |

| One: Far Off Things | 14 |

| Two: The London Adventure | 37 |

| Three: The Weaver of Fantasy | 58 |

| Four: A Noble Profession | 72 |

| Five: The Legend of a Legend | 90 |

| Six: The Yellow Books | 112 |

| Seven: Machen’s Magic | 128 |

| Eight: The Pattern | 144 |

| Nine: The Veritable Realists | 161 |

| Ten: Things Near and Far | 178 |

| EPILOGUE | 197 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 199 |

| FRONTISPIECE | |

| Drawing made from the Hoppe Photograph | |

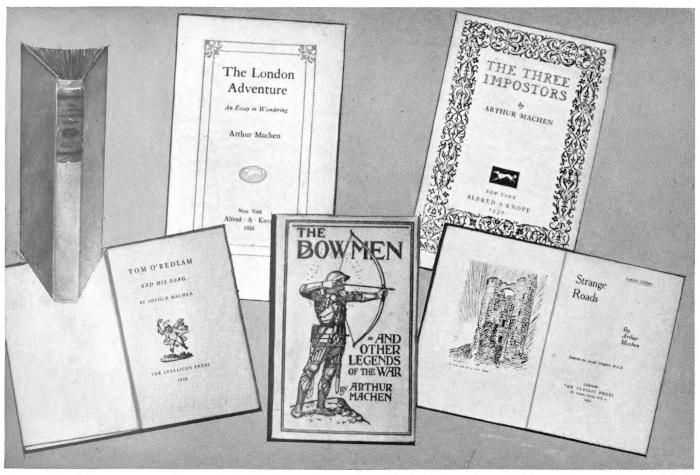

| SOME MACHEN ITEMS | |

| A photograph showing one of the famous Knopf Yellow Books and several title pages | facing page 112 |

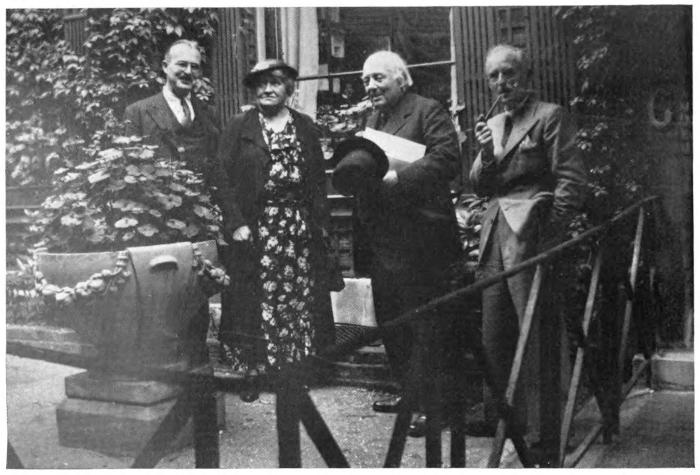

| THE MACHENS IN LONDON | |

| A photograph taken in London in 1937, Courtesy of Mr. Montgomery Evans | facing page 178 |

“And what,” asked the younger man, “are they?” He pointed to a long row of books plainly bound in yellow with faded blue and almost indecipherable titles. The Host felt a warmer glow than the brandy alone could have produced. “They are,” he said reverently, “my Machens.”

“Your whats?” asked the younger man absently. He had caught sight of a promising looking volume, enticingly entitled Aphrodite, on a lower shelf. The Host intercepted the glance, recognized the symptoms of failing interest and, with skill born of experience, drew his chair before the Aphrodite and pulled out a lapfull of the yellow books.

The younger man, not too obviously disappointed, concentrated on his small globular glass of Asbach Uralt. “Who,” he asked in tones that matched his look, “is Machen?”

“Arthur Machen,” began the Host in a voice that matched his look, “he is the ... he’s, well ... look!” He gestured to the shelves. “Fifteen books, and there are more, and you’ve never even heard of him. Fifteen of the most wonderful books in the English language, and you ask who he is!”

“Well,” said the young man with pardonable irritation, “just who is he?”

The Host settled back in his chair, fighting hard for[2] composure and coherence. “Arthur Machen,” he began again, and with every evidence of a strong determination to speak calmly, “is the man who has written more fine things than any dozen living authors you may care to mention. That may strike you as a rather broad and rash statement, but I am in a mood to shoot the works. And there are others, Highly Connected and Well Thought Of Persons, who have indicated much the same opinion. Arthur Machen has been appreciated by some of our best known composers of ‘literary appreciations.’ Unfortunately, this sort of praising is often akin to, and almost as effective as, burying. To the popular mind, a writer who has been appreciated by a duly accredited appreciator is a pet of the pedants, a delight of the dilettantes and nothing more. And, indeed, the titles found on some of the books containing these little essays in literary appreciation are often suggestive of archeological exploration rather than of due honor to a living author. I have in mind, specifically, two books whose titles seem to connote research into a particularly distant past. Buried Caesars and Excavations, those two books you see there; they would tell you in a much more literary style, and with considerable technical flourish, just who and what Arthur Machen was and is. But I am not minded to ask you to read them at present.

“I think,” resumed the Host generously gesturing toward the decanter and his friend’s glass, “that the time has come for a new and revised estimate of Arthur Machen. Would that I had the time, talent and/or the temerity to undertake the task! Let us, meanwhile, acknowledge but pass by these appreciators of Machen, at least for the moment.[3] He has attracted the attention and been subject to the discussion of Vincent Starrett, Carl Van Vechten, James Branch Cabell and others. He has even attracted the notice of such literary titans as Tiffany Thayer and Burton Rascoe. He has been crowned by that arbiter elegantiarum of American manners, morals and mentality, Walter Winchell, who once described Arthur Machen as ‘tops among the literati.’ This last, I fear, is not a critical estimate per se, but an indication of a vogue in certain quarters.

“Despite the fact that Mr. Machen has been ‘discovered’ by at least two of our most indefatigable bolster-uppers of literary reputations and revealers-of-lights-under-baskets; despite his having been exhumed and placed on exhibition upon a platform built for two, Machen remains yet to be properly appreciated and honored by a wider public. Perhaps he never will be, and perhaps it is best so. Machen once wrote that if a great book is really popular it is sure to owe its popularity to entirely wrong reasons. And I, for one, tremble to think of what Hollywood might do to Machen.” The Host paused briefly for replenishment.

“Far too often these appreciations have degenerated into what I have in my more bitter moments mentally called Match-Machen. An execrable pun, I grant you, but concerning a matter that is, to my mind, as offensive. I refer to the practice of certain appreciators who, in the execution of their self-appointed duties find it, for some reason or other, necessary to devise improbable genealogies to demonstrate their own wide literary knowledge and their conception of the subject of their labors. We find, for example, Mr. X in the act of appreciating a book by Mr. Y.

“How does he go about it? Why, he merely tells you that Mr. Y is the literary son of A out of B, whose maternal grandmother was C, and whose second-cousin is D. Another trick is to pretend that Mr. Y’s work is a play ... with music by R, scenery by S, costumes by T and lyrics by W. In short, you come away without the slightest notion about Mr. Y. But you have learned that Mr. X knows a great deal, apparently, about the doings of Messrs. A, B, C, D, R, S, T and W. Do you follow me?”

“But slightly,” confessed the younger man with that candor born of brandy.

“I will try to make myself clear,” said the Host selecting a volume from the shelves.

“Here we have an essay about a man called, let us say Blank. The author of this little essay will tell you that a passage of Blank’s prose suggests one of the more poignant episodes out of de Maupassant, set to music by Tchaikowski against a background of Gaugain’s Tahitian belles. Have you any idea what Blank’s prose is like?”

“No,” said the young man morosely.

“Good! Listen then to this. It is Vincent Starrett on Machen: ‘Joris Karl Huysmans, in a thoroughly good translation, perhaps remotely suggests Machen, both are debtors to Baudelaire.’ Now, does that tell you anything about Machen?”

“No, it does not!” said the young man. “But then, neither have you!”

“Quite true,” nodded the Host affably. “I am often carried away. But we have ably demonstrated my contention.” The younger man looked decidedly restless. “Um!”

“Know then,” said the Host relishing the sound of his voice, “that Arthur Machen, born in 1863, the son of a Welsh clergyman, first swam into the public ken early in the last decade of the last century—a fact which the public largely failed to appreciate until some years later. His earlier works were translations of the Heptameron, the Memoirs of Casanova, and several other large and, I should think, rather dull old works. But the most important were two remarkably unique books called The Anatomy of Tobacco and The Chronicle of Clemendy.

“Most of Machen’s best work was written before 1901—and in that year he temporarily deserted literature for the stage. Machen’s most productive period then, from 1890 to 1901, affords a curious and striking contrast with what was assumed to be the important literature and the important literary group of the time. The 1890’s in England were celebrated, although few people grow festive about it now, for the Yellow Book Boys, that delightful coterie of delicate decadents who glorified the carnation and the pansy. But after the maddest music had died away, and the reddest wine had been drunk, Cynara and Dorian fluttered to the shelves and Oscar and Hubert and Adelbert retired into a certain pastel-shaded obscurity from which they emerge from time to time as a new volume of memoirs is published. The period still commands a certain amount of academic attention—and yet the best books of that period were written not by these ‘Men of the Nineties,’ but by Arthur Machen. A chap named Muddiman, whose book you see there, wrote his history of these fellows and mentions Machen but briefly: ‘Arthur Machen, in those days, belonged to the short story[6] writers with Hubert Crackanthorpe, who was the great imaginative prose writer of the group.’ Alas, poor Hubert! Who knows him now! Holbrook Jackson and Richard Le Gallienne ignore Machen completely. And perhaps rightly so. Machen was not of the group, nor of the period. But here I wish to digress briefly....

“These delicate contemporaries of Machen derived from the French Symbolistes, who derived from Mallarme and Baudelaire, both of whom were admittedly influenced by Poe. It has been said that Machen was also influenced by Poe. The difference, if you will credit me, is that Poe’s influence, in as far as it exists, came to Machen direct. When it came to the others of the group it had been filtered through Gallic gravel and Symbolistic sand.

“So much for Machen’s literary history. No one could possibly tell it better than he has in Things Near and Far and Far Off Things—his two autobiographical collections. Nor is any literary history as simply told. It is not one of your tremendous collections of anecdotes concerning ‘literary figures of the day.’ It is the story of a lonely man who wanted, more than anything else, to write. And then—you must read Machen. All of him. I know of no other writer whose entire output can be so heartily recommended.

“You will realize, as you read, that when people use such names as Poe, Stevenson, Blackwood, and Henry James, they are but vaguely gesturing in the general direction of Machen’s own weird landscape. It is a land as strange as the misty mid-region of Weir where lies the dank tarn of Auber, the measureless caverns where runs the sacred river Alph. But it is like none of these. The young man of Gwent has[7] created his own landscape, a strange country spread out under a sky that glows as if great furnace doors had been opened, bordered by tall grey mountains, traversed by streams that coil their esses through silent woods. It is my fancy to think I have a picture of that country, painted by another genius. You see that Van Gogh hanging there?” The Host indicated a large framed print of writhing cypresses under a swirling sky. “On quiet November nights I sit here and look into it, half expecting to see young Meyrick or Lucian Taylor come down the hillside.

“It is curious to go over some of these former estimates of Arthur Machen. One first reads them through in a fine enthusiasm at finding someone else who has read Machen and found him good. But even those who praise him the most, fail to express, or even to hint at the ‘quiddity’ of Machen. They seem to find him so far beyond their powers to praise that they often resort to picayunish criticism. Thus we find Vincent Starrett mildly complaining about an absence of cloud descriptions in Machen. Or about a lack of humor. True, you’ll find no Maxfield Parrish sky castles, no James Gould Fletcher touches, no rotogravure alto-cirrus formations. But if ever a man could imply clouds without using the very word, Machen can. And although Machen has not yet introduced a pair of jolly grave-diggers to coax us back into our seats or cajole us into combing back our bristling hair, you will find he has humor.

“There does exist, however, a problem in classifying Machen—it seems to exist only a necessary evil. Essentially, I suppose, Machen is what might be called a Gothic novelist. He has been linked so often with the recognized practitioners[8] of the Gothic style and tradition. You’ll find no ivy-covered ruins, no deserted abbeys, no ravens, no baying mastiffs, not even a sinister monk—and we must rule out those jolly tosspots, the monks of Abergavenny. I daresay Machen would prefer to be known as a Silurist. His ruins are those of an older time, older even than the ruins of the golden city of the Roman legions.

“Vincent Starrett calls Machen the Novelist of Ecstasy and Sin—making him sound rather like a Messalinaen Lady Novelist. Mr. Van Vechten too, at least in his decadent novel Peter Whiffle, seizes upon Mr. Machen from much the same viewpoint, and makes Machen an asset in the character of his precious Peter. And all too frequently, in discussing Machen, the spirit of Baudelaire raises its ugly head. Novelist of Sin, forsooth! ‘Evil, be thou my good!’ What rot! And there are those, apparently, who would classify some of Machen’s tales as ‘erotica.’ Baudelaire, bosh! As well point out the resemblance between a lane in Gwent and a lupanar in Paris! No—Machen is neither a Gothic novelist nor a writer of delectable indelicacies. Machen’s tag must be sought for in hieroglyphics of his own devising.

“The ‘quiddity’ of Machen, the one quality that pervades all his work, is that of ‘ecstasy.’ It is not the ecstasy of the lyric lady-novelist. Mr. Starrett seems to think it is a technical device, since he finds it is ‘due in no small degree to his beautiful English style.’ Mr. Machen’s own idea of this quality is that it is ‘a removal from the common life.’ And that brings me to Hieroglyphics, a book that should be a text-book in all our Universities. But perhaps not—no, surely not. Because in this book of Machen’s you will find[9] set forth, once and for all, the difference between reading matter and fine literature. And such a book cannot fail to make enemies, nor to create false ideas even among its friends. Mr. Starrett says: ‘It is Arthur Machen’s theory of literature and life, brilliantly exposited by that cyclical mode of discoursing that was affected by Coleridge. In it he suggests the admirable doctrine of James Branch Cabell that fine literature must be, in effect, an allegory and not the careful history of particular persons.’ Mr. Cabell, who is, according to Mr. Starrett, Machen’s literary son, set forth his literary credo in Beyond Life some seventeen years after the publication of Hieroglyphics. In it, Mr. Cabell expresses admirably, and with his famed urbanity, many of the truths he learned at his father’s knee. One is as pleased with Cabell’s literary progenitor as with his prose.

“Just one more quotation. It is my favorite quotation to end quotations about literary credos or the mechanics of creation. Mr. Machen, in The Three Impostors says: ‘... I will give you the task of a literary man in a phrase. He has got to do simply this—to invent a wonderful story, and to tell it in a wonderful manner.’

“In his novels, The Three Impostors, The Hill of Dreams, The Secret Glory, The Terror, The Great Return, and in many of his shorter stories: The Great God Pan, The White People, in all his creative work, Machen has shown himself the master of his own precept. In Hieroglyphics Machen noted the difference between reading matter that related facts about a character or a group of characters, and fine literature that symbolizes certain eternal and essential elements in human nature by means of incidents. You will[10] find, then, that these wonderful stories are not merely startlingly original conceptions of heroes and heroines taking part in unusual events. That many of these plots and inventions are uncanny and fantastic does not place them in the ‘thriller’ class—having nothing more to say than the latest detective story. It would be absurd to think of The Great God Pan, for example, as merely a story about the discovery that Pan is not dead, or that Priapic cults may still flourish. No, it’s not so simple as that. There are other elements present, and chiefest of these is that quality of ecstasy. There are symbols and representations of a higher order, no cheap mysticism, no spiritualistic clap-trap. And finally there is in these stories an element of something that prompts belief.

“The Great God Pan is a story much more improbable, more fantastic than Frankenstein or The Strange Case of M. Valdemar. And it is not a mere pseudo-scientific story—it is believable. You do not believe that? Yet Machen wrote a story more fantastic still. A story with no possible explanation, scientific or otherwise, in short, nothing less than miraculous vision could have explained it. And that story was, and still is, widely accepted as true. The tale of the Bowmen at Mons, a simply written story, no flourishes, no elaborate atmosphere; yet with that quality of ecstasy, that quiddity of Machenism, has won belief. Quite recently, in a shop, I came across a volume that was an anthology of Myths, mysteries, visions and the like, and in it appeared the story of the Bowmen. It was not Machen’s story, however, and there was no mention whatever of Arthur Machen. It had been set down as an authentic legend, documented and sworn to by this one and that one who claimed to have been there. I daresay it[11] will, in time, join such distinguished company as the Walls of Jericho and Joshua’s obedient sun.

“Yes, you must read Machen. All of him. It has been implied that there is a sameness about Machen’s work. But do not imagine that you will read the same story, told and retold. You will come to realize that there is in Machen a definite pattern. He has said that most men, as well as writers, are men of one idea. And most writers create tales that are variations on one theme, that a common pattern, like the pattern of an Eastern carpet, runs through them all. And Machen’s pattern? You will see, when you read him, that literature ‘began with charms, incantations, spells, songs of mystery, chants of religious ecstasy, the Bacchic chorus, the Rune, the Mass.’ And Machen has taken as his symbol and pattern the devices and signs of ecstasy, of the removal from the common life. The dance—the maze—the spiral—the wheel—the vine, and wine, these are the outward signs of ecstasy, the patterns of Machen.

“One book in particular you must read—The Hill of Dreams, without a doubt one of the finest novels ever written. From the first grand sentence a spell is laid upon you. It has never failed to thrill me—it is like the master theme of a symphony—it is as magical as the opening notes of the Good Friday music in Parsifal. But there—I have fallen into the ways of those whom I have derided. And I have kept you quite later than I intended.”

The Host rose, stretched, and poured out a brace of nightcaps. The younger man, who had listened patiently to this lengthy monologue, gratefully accepted his brandy, sipped rather too avidly, for listening is also a thirsty business,[12] and said, “Why do you suppose Arthur Machen is so little known? I mean, he sounds marvelous—but, after all, people can’t help it if they don’t know about him.”

“That,” responded the Host sadly, “is one of the Mysteries of Mysteries. Perhaps Machen writes too ‘circumvolantly’ as Cabell says, for our critics. Or perhaps, as Van Vechten says, ‘one only takes from a work of art what one brings to it—and how few readers can bring to Machen the requisite qualities.’ Perhaps our critics are more apt to be impressed by clever young men who go about swimming classical streams, fishing for tarpon, or fighting in the fashionable war of the moment. The general public, unfortunately, knows Machen, if at all, through the inclusion of several of his stories in anthologies of mystery and horror stories. Which is about on a par with using Shelley’s Indian Serenade as a filler in a pulp confession magazine.

“A short time ago in London there was a dinner party in celebration of the seventy-fifth birthday of a writer. The guest of honor made the customary speech—but it was such a speech as has seldom been heard from a feted author. It was tragic, it could have been, and should have been, bitter—but all was gently said. After toiling in the fields of literature for over forty-two years, after having produced eighteen volumes of rare quality, he had earned but £635. That man was Arthur Machen.”

“He is still living?” asked the young man.

“Yes,” replied the Host gravely. “I should like to make a pilgrimage to his home. But you must go. Take these with you. Read them. I fear I have told you little about Arthur Machen. Nor am I the only one has confessed such a feeling[13] of inadequacy to cope with Machen. But I find comfort in what a very capable writer once said of another remarkable writer of Gothic Tales. It will be, I promise you, my final quotation of the evening. Dorothy Canfield once wrote, in a preface to Seven Gothic Tales: ‘The person who has set his teeth into a kind of fruit new to him is usually as eager as he is unable to tell you how it tastes. It is not enough for him to be munching away on it with relish. No, he must twist his tongue trying to get its strange new flavor into words, which never yet had any power to capture colors or tastes.’ And now, mind the step going out. It’s rather darkish.”

One might devote a great amount of time and give a great deal of thought to the opening paragraph of a book about Arthur Machen. It is not merely that one is faced with the usual problem of where to begin: in Caerleon or London, in Richmond, Virginia or Newark, New Jersey or, for that matter, wherever one first heard of or first read Arthur Machen. Nor is it simply a matter of how to begin: with a quotation—there are a number of very appropriate quotations—or with a review of a controversy raging in the London newspapers in 1915, or with a few paragraphs taken from Peter Whiffle, a rather outré novel published in New York some years ago. Nor is it even a matter of when to begin: with the Nineties, the Twenties, or only yesterday. The problem is one of selection, for one might pick up the line of the legend of Arthur Machen anywhere along the course of the last three quarters of a century. More than that, it is also a matter of the personal history of almost anyone who might attempt the task.

Most people will remember, I think, when it was and how it was, they first became acquainted with the work of Machen. And in most cases, I believe, it will be a rather[15] strong and vivid memory. Whether one was introduced to Machen by Cabell or Starrett or Van Vechten, or made the discovery for one’s self becomes a matter of some importance, at least to those who have come to know Machen and who regard him, as I do, as one of the greatest living writers in English literature. Yet it might seem that these personal recollections and this high regard, however deeply felt, are not quite reason enough for a book about such a man, nor significant enough to serve as an introduction to such a book.

Of course there are facts and figures. Many a book gets under way with an impressive array of figures, or with the clever juxtaposition of two facts which, by their very contrast, seem to promise an unrelenting interest and an unrelaxing grasp upon the reader, or it may start out with a simple statement of fact. Such figures as, for example, these: Arthur Machen’s works have appeared in anthologies which run to fabulous numbers of copies, and one of his stories has been published in an edition limited to two copies. Or a juxtaposition of facts, as for example: Arthur Machen has been praised by Oscar Wilde, the arbiter elegantiarum of the 1890’s, and by Walter Winchell, equally arbiter elegantiarum of the 1930’s.

Or a simple statement of fact, supplied, stiffly and on crackly paper by the British Ministry of Information: “Arthur Machen, the Welsh novelist, was born in Caerleon-on-Usk in 1863.” His Majesty’s Ministry or representative thereof, concludes with the intelligence that further information may be found in a certain book which may be obtained from a certain publisher.

Be it said, then, and to the everlasting glory of His[16] Majesty’s Ministry of Information, that Arthur Machen was born at Caerleon-on-Usk. And in the year 1863. A long time back.

Somerset Maugham once wrote something about the unhappy accidents of birth that often place a man amid scenes that must seem forever strange, and among men who must seem forever strangers. When such a person, after years of painful adolescence, dramatic conflict, moving tragedy and innumerable vicissitudes, finally arrives by some happy accident at some other spot upon this planet he feels, in the words of more than one sympathetic novelist, that he has “come home.” And then, presumably, the conflict and the tragedy and the vicissitudes begin all over again. In actual life writers, and artists of other sorts, are particularly susceptible to this form of cosmic accident—or at least many of them prefer to think so. It is, somehow, heartening to meet one who was pleased with the place of his birth.

“I shall always,” wrote Arthur Machen, “esteem it as the greatest piece of fortune that has fallen to me, that I was born in that noble, fallen Caerleon-on-Usk, in the heart of Gwent.... For the older I grow the more firmly am I convinced that anything which I may have accomplished in literature is due to the fact that when my eyes were first opened in earliest childhood they saw before them the vision of an enchanted land.”

There is no doubt that the simple fact that Arthur Machen was born in Caerleon-on-Usk has had a tremendous influence upon his style, his thinking, his writing, his philosophy and his life.

Caerleon-on-Usk, lying within the fabled land of Gwent and close to the Welsh border, would have fascinated Arthur Machen even if he had not been born there—just as it must fascinate everyone who has ever read Machen and anyone who ever will read him. “Little, white Caerleon,” he calls it, an island in the green meadows by the river, was once the headquarters of the Second Augustan Legion, one of the farthest outposts of the sprawling Roman Empire. The Romans originally called it Isca Silurum, evidently for its situation on the river Usk. Later Latin writers called it Urbs Legionem, a translation of the Welsh Caer-Leon.

Caerleon knew the hardened legionnaires, the men who crossed the Channel other conquerors failed to cross. It knew the tread of men who followed the eagles, and it knew the patricians who came with the Pax Romana in the wake of the legions. Caerleon knew also the gallant companions of the Round Table, for it was, in those times, a seat of Arthur the King, and many a summons brought the knightly riders within its walls and many a quest sent them off across the meadows where the river wound in great esses toward the dark forests hanging along the mountainside. Nennius places the scene of at least one of Arthur’s battles at Cairlion. As for Gwent, it is now called Monmouthshire, but in those days it formed the eastern division of the kingdom of South Wales, and some identify it as one of the three divisions of Essyllwg, the country of the Silures. Caerleon itself is the very stuff of legend, and yet it exists today, as it did in the middle nineteenth century, a small and sleepy town not far from the equally legendary Severn.

In this place and in the year 1863, Arthur Machen was[18] born—the son of a clergyman who had the poor “living” of Llanddewi Rectory. His father was John Edward Jones, who afterwards added his wife’s surname to his own, so that his son’s full signature became Arthur Llewelyn Jones Machen. Daniel Jones, Machen’s grandfather, was Vicar of Caerleon-on-Usk and his great grandfather was David Jones, Curate of St. Fagans, Glamorgan. It is not the present writer’s intention to compose a biography, “fictionized” or otherwise, of Arthur Machen. There will be none of your happy little phrases about what the “little Arthur” did, or what the “young Machen” or the “boy Machen” thought. Nor will the reader be asked to “imagine the young Arthur growing up amid the storied stones of Caerleon,” or to believe that “undoubtedly the young Arthur was influenced by the wild Welsh countryside,” or even to “assume that the boy Machen made many trips to the legendary shrines in and about Caerleon.”

Such a biography may one day be written, but one cannot refrain from hoping that it will not be. Machen has written his own biography in at least three of his books, and perhaps in all of them. The two frankly autobiographical books, Far Off Things and Things Near and Far tell most of the facts of his early life ... and they tell them with more meaning than even the most skilled and sympathetic biographer could. His novel, The Hill of Dreams, does more with the material suggested in these notes of a lifetime than the most gifted novelist of our day could attempt. The story of Lucian Taylor and his adventures, mental and physical, mystical and spiritual, in the invented town of Caermaen, is the story of Arthur Machen, beautifully told as no one else could tell it. To these books the reader is referred and, fair[19] warning, he will be referred to them again and again!

To be sure, Machen did make those little trips about the legendary town in which he lived; he was inspired by the storied stones of Caerleon and he was influenced by the wild Welsh countryside. He was an only child and he lived in that solitude which is so often the lot of an only child. He often accompanied his father on his “parish calls” and thus he came to know every farm and every lane, every hill and every valley in the heart of Gwent along the roads that led from the rectory at Llanddewi.

When he was eleven he went away to school, passing each term as a sort of “interlude among strangers” until he could come home again to Caerleon. Was he happy or unhappy at school? Was he fond of games or of mooning about—the two alternatives, apparently, of English public school life? That story is told in The Hill of Dreams and again in The Secret Glory. Machen’s schooldays were the schooldays of Lucian Taylor and Ambrose Meyrick ... to their stories we must again refer the reader. For conjecture and invention are beyond the scope of this study and Arthur Machen is seventeen when he really enters into our particular field.

For in his seventeenth year Arthur Machen went up to London. There was a very practical purpose behind this first visit to London—he was to come up before the examiners for entrance into the Royal College of Surgeons. Whether or not the actual purpose of this visit was of great importance to Machen is one of the conjectural matters upon which we shall not speculate. The matter had been arranged and decided by family and friends—it was the necessary preliminary[20] to a career in medicine or in surgery. Machen prepared for it by walking some three or four miles several times a week to the Pontypool Road Station to obtain copies of the London papers. These he studied with great care, devoting special attention to the theatrical pages. Not that he had ever given any particular thought to the stage or to the theater, or that he was, in the phrase of today, “stage-struck”; it was simply that the theater was typical of what London was, and of what Caerleon was not. At any rate, on a day in June 1880, he went up to London with his father. And thus began The London Adventure.

The examiners found something Machen already knew—he had no head for figures, either arithmetical or anatomical. And apparently Machen had not the interest or the ability to acquire, within a period of time agreeable to the examiners, a proficiency in either. It must not be assumed, however, that Arthur Machen had already decided upon a career in letters, to be pursued amid the pleasures of London. He had not. Years later Machen wrote that he had no idea, when first he went to London, of a career in literature. Indeed, he had never thought of it as a career, but as a destiny.

However, he had not been in London a month before he began to write. There is nothing particularly prophetic about this, nor anything especially startling. Most young men, at one time or another, try to write. And usually their creative efforts are turned in the direction of the epic, the heroic, the classic. A young man, trying to write, almost never permits himself to indulge in a fancy for the light[21] essay, the brief episode. It is epic or it is nothing, usually the latter. Doubtless the Freudians have an explanation for this. It would be, one supposes, a very long and very complicated explanation.

Machen had his own explanation—for his own case. He attributes it to his Celtic blood. Not that Machen thought the Celt, or the Welsh Celt at any rate, had contributed much to the world’s literature. Indeed, Machen had advanced the idea that “all impartial judges will allow that if Welsh literature were annihilated ... the loss to the world’s grand roll of masterpieces would be insignificant.” Yet he concedes a certain literary feeling that does not exist in the Anglo-Saxon ... an appreciative rather than creative faculty, lacking, perhaps, in the critical spirit but still, a delight in the noble phrase ... the music of words. And so—Machen tried, as a young man will, to write.

He wrote verses, of course. “Every literary career,” says Machen, “which is to be concerned with the imaginative side of literature begins with the writing of verses.” So Machen confirms, some sixty years before it was conceived, the opinion expressed above. He had written verses before, while still at the Hereford Cathedral School. They were concerned somewhat with matters derived from the Mabinogion and were probably composed in the heroic manner. This set of verses was, as is the custom, rejected.

He filled notebooks with “horrible rubbish—rubbish that had rhymes to it.” Much of what he wrote was greatly influenced by Swinburne’s Songs Before Sunrise. “Influenced” seems a mild sort of word to set alongside Machen’s own “cataclysmic.” At any rate, writing what he describes variously[22] as rubbish and drivel, Machen tried, at the same time, to pass his examinations for the Royal College of Surgeons. His examiners now arrived at their decision regarding Machen’s arithmetical ability and the career as a surgeon came to a close. Machen returned to Caerleon and the writing continued, mostly, of course, after the family had retired for the night.

A printer named Jones, who lived in the cathedral town of Hereford, one day received in the post a manuscript accompanied by a request to print one hundred copies of the poem. It was a poem. The title of the poem, Eleusinia, probably conveyed nothing to Mr. Jones, stationer, bookseller and printer of Hereford. As he struggled with the text, written in a large sprawling hand on both sides of ordinary letter paper, Mr. Jones might have wondered what our young people were coming to. Certainly the subject matter of the poem was vastly different from the Bibles, Prayer Books and Pitman’s Shorthand Manuals with which his shelves were stocked.

Fortunately for Mr. Jones, the poet pretended no knowledge of book-making. He specified no typographical niceties, he pleaded for no ornaments, he indicated no preference in paper or in binding. His one modest request, that the Greek phrase Oudeis Muomenos Odureta to appear on the title page, be set in Greek type, was withdrawn when Mr. Jones wrote him that Greek type would be extra. And so the phrase appeared in English, and with a typographical error, at no extra charge.

Mr. Jones presumably knew the young poet—remembered[23] him as a purchaser of letter paper and note books. The Llanddewi Rectory address was, in a way, reassuring. His bill would probably be paid, but Mr. Jones must have thought the usual thoughts about “minister’s sons.” As for the poet—he preferred anonymity, the comparative anonymity of “By a Former Member of the H.C.S.” For when a sixteen page pamphlet bearing the title Eleusinia and concerning itself with the Eleusian Mysteries, is published by a Former Member of the Hereford Cathedral School it must be admitted that such anonymity is, at best, comparative. Generations of readers of novels about English public schools will realize that every other former member of the H.C.S. would know at once that the book could have been written by none other than “old Machen.”

Of course the edition of one hundred copies guaranteed that the anonymity would still remain comparative—especially since it seemed unlikely that the former membership of the H.C.S. at large would be interested enough in poetry to purchase sixteen pages of it ... and without wrappers! It is not known, exactly, what happened to ninety-nine copies of Eleusinia. Henry Danielson in his Arthur Machen: A Bibliography (1923) says that his collation was taken from what is probably the only copy extant.

The text of this first work of Arthur Machen is, naturally, as little known to the general reader as a transcription of the Rosetta Stone ... and so it is likely to remain. What is it about? Machen says of it, “this is a horrible production.” He wrote it, he adds, by turning an encyclopedia article on Eleusis into verse, “some of it blank, some of it rhymed, all of it bad.” This is Machen’s estimate of it in the notes he[24] wrote for Danielson’s Bibliography. Nathan Van Patten lists, Beneath the Barley. A Note on the Origins of Eleusinia (1931). Whether this explains the poem or the mysteries is known only to those who have seen one of the twenty-five copies that were printed. However, in a letter written in 1945, Machen says: “It is less than nothing, but perhaps it might have suggested the entertaining question—‘Here is a boy of seventeen who is interested in the Eleusian Mysteries: what the devil will happen to him?’”

Well, Machen’s poem was published, and whatever he may have thought of it in 1923 or in 1945, his relations, in 1884, thought well enough of it to decide that journalism was the career for Arthur. It is amazing, in a way, that a pleasant little group in a country rectory should decide over a little pamphlet written “about” the pagan rites at Eleusis, that their youthful relative was destined for a career in journalism. Of course, relatives are proud of one’s books and equally proud of one’s pamphlets, even if they do not read them. And so, perhaps, the rector and his family never bothered too much about the contents of the rarest Machen item of them all. Doubtless more than one of the ninety-nine copies slowly disintegrates in a Welsh garret to this very day.

In the summer of 1881 Machen was back in London in quest of a career. This one too, although it had nothing to do with figures, did not quite come off. For some time he had thought about journalism as his relatives advised, but he did not actually follow their advice until some years later. Meanwhile, he lived in an old red-brick Georgian house in[25] Turnham Green where he wrote furiously in one manner or another. That Celtic appreciation of the fine phrase and the glorious sound of words was strong within him, for almost everything he read struck a responsive chord, and he would begin at once to compose an epic in the manner of the author or the book he was currently reading.

Thus there was a long heroic poem in the manner of William Morris, whose Earthly Paradise he had just purchased with his tea and tobacco money. Then there were innumerable verses in the manner of Robert Herrick. Now and then there would be a strong Swinburnian resurgence. And while all this furious creation was going on he worked in what was called the “editorial” department of a publishing house.

There are many tasks a literary man might do in serving his apprenticeship and Machen did most of them—or most of the ones current in the ’Eighties. He had assisted in the “grangerizing” of many old and odd volumes and he had composed “Shakespearean” calendars, selecting appropriate quotations from “The Bard” for each of the three hundred and sixty-five days. These and other more or less literary matters occupied his days and earned for him the sum of about a pound a week. At Turnham Green he wrote feverishly and planned prodigiously and read ravenously ... and almost every book he came upon set him off on another venture of his own.

There are some writers, and there are certain casts of mind, requiring exercises of this sort. It is rather odd that these should turn out to be the more imaginative writers after all. Yet it does seem that they have to work out for[26] themselves theories of composition and devote much of their time and talent and energy to perfecting the technicalities of the trade of writing. Poe, of course, comes to mind, and Coleridge and Hawthorne. They first developed theories, seemingly so rigid. They devised formulae, seemingly so mechanical. And then they created tales and poems, not from their observations and experience, based not on facts, but on fancy. And they composed them, apparently, with little regard for the formulae and systems of their own devising. They seem to leap from the frankly imitative to the fearlessly imaginative, without ever taking any of the intermediate steps they themselves had postulated, or calling into use any of the technical and mechanical aids with which they had practiced their trade.

Machen in 1881 might recognize and respond to a pattern or formula in Swinburne, in Burton, in Morris, in Herrick, in Stevenson, in Balzac, in Rabelais. This is not to imply that Machen merely developed a style “in the manner of Swinburne,” or of Stevenson or of any of them. To each of these he brought something of Machen—and as he learned his craft, the technical tricks, the automatic alliterations and the polished phrasing were fused into something, a way of writing, no one else has ever had, no one but Arthur Machen.

Meanwhile Machen discovered that he disliked his labours at the publishing house in Chandos Street. The business of composing cultural calendars to be hung in London kitchens and country parlours did not interest him, nor did he see why it should interest anyone. He therefore resigned his position—and in the face of a raise to twenty-four shillings a week! He then became, of all things, tutor to a[27] group of children, teaching them, of all things, mathematics! His head for figures seems to have improved considerably for, on going over the Euclid he was supposed to pass along to his charges, he found that it did make sense of a sort.

He had moved from Turnham Green to Clarendon Road—a street destined to become, one day, as well known as Baker Street, Cheyne Row and many another London street of literary fame. Machen was already existing on that famous and fantastic diet of “green tea, stale bread and great quantities of tobacco.” Fortunately, at first, his tutorial position entitled him to dinner with his pupils. Later his pupils changed, and with them his menu. The noon hour was spent in wandering about Turnham Green or Holland Park, with a pause for biscuit and beer at a convenient tavern.

These wanderings became a habit, and through the spring of 1883 Machen went further afield into the green suburbs to the north and west of the city. It was on these lonely outings that he first began to formulate one of his literary theories—that “in literature no imaginative effects are achieved through logical predetermination.” Now this theory—so demonstrably true in his own case—was arrived at by no logical predetermination but by sheer pedestrianism. It came about on these solitary walks when, as so often happened, the roads that led so invitingly to green and open country plunged suddenly into a row of horribly new brick houses or, more startling still, a vast and sprawling cemetery.

To the countryman, whose ideal landscape proceeds logically from valley to hill, from stream to pond, from crossroads to village, from fence to house and stile to pasture,[28] these monstrous outcroppings of civilization, these sudden and terrible interruptions of what was and should have continued to be a pleasant prospect, are more horrible even than a factory belching smoke from seven stacks.

And so these pleasant saunters that so often ended before a hideous row of red-brick houses, the quiet lanes that terminated abruptly before a vast pile of bricks and boards, created in Machen the beginnings of that doctrine of the strange and terrifying things that lie so close to the surface of the quiet and the commonplace. The hideous face at the window in a story written years later is but a reflection of the sudden apparition of a raw, new suburb at the end of a quiet lane leading north out of London.

For the present these were but things seen and felt, they sank quietly below the surface and floated deep down in the well of the unconscious. Tutoring and Turnham Green and the twisting roads of Notting Hill were sufficient unto the days. The nights in his small room in Clarendon Road were more urgent—more filled with magic. For here there was not the sudden sight of a street hastily hacked into a hillside, nor the mounds and monuments of a cemetery, but great books and greater magic flowing from the majesty of Gothic cathedrals or the Arthurian romances or the Divine Comedy. He read by night, lighting candles when the gas meter clicked off, and passed for a time into the “Middle Ages, walking in the silvery light with the Masters of the Sentences, with the Angelic Doctor, listening to the high interminable argument of the Schools.” Out of these books and studies, and a great deal out of Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy came a book that was to be called The Anatomy of Tobacco.

The book was sent to a publisher who, as it happened, liked it and who was prepared to publish it, after “certain preliminaries” were attended to. These preliminaries entailed a visit to Caerleon and called for another conference in the parlour at the Rectory. The family and the relations, remembering the pamphlet of a few years ago and encouraged by the news that the new book would contain many times more than sixteen pages, attended to the preliminaries.

In due course, in the year 1884, George Redway of London published The Anatomy of Tobacco. And a very handsome book it was, in its cream parchment boards and brick-red lettering on the spine. The author of this study of smoking, “Methodized, Divided, and Considered after a New Fashion” was one “Leolinus Silurensis, Professor of Fumical Philosophy in the University of Brentford,” in whom we may recognize our old friend, the former Member of the Hereford Cathedral School.

This is the book Machen calls “The Anatomy of Tankards” in his Far Off Things. There you may read the whys and the wherefores of this amazing composition, and the devious means by which Burton and tobacco and divers other curious books entered into its making. So convincing is his account of his investigations and research into the matter of taverns and tankards and such matters that quite a few collectors have spent considerable time, and were prepared to spend considerable sums, to acquire a copy of The Anatomy of Tankards. Meanwhile, Machen had quitted the six-by-ten room in the Clarendon Road and returned to Caerleon and a normal diet. Throughout the winter of 1884 he had worked on the proofs of the Anatomy and then[30] upon an assignment from Redway for another book. This was a translation of the Heptameron of Marguerite of Navarre. Machen blithely undertook the task, despite his own sworn statement that upon leaving Hereford School he could not have conjugated the simplest, and most popular, of French verbs.

The merrie and delightsome tales of the French Marguerite occupied him through winter and spring in Gwent. Once more he walked in the deep lanes about Caerleon and alternately missed London and revelled in the luxury of not being in Clarendon Road. By the time June came to Caerleon he had sent off the last batch of his translation and Redway had written him and offered him a job. It did not seem too hard a thing to return to Clarendon Road with a job, a real one, in the City. He was to catalogue books—and such books! There were books on Alchemy and Magic, on Mysteries and Ancient Worship, on the occult sciences and Rosicrucians and all sorts of wonderful and baleful and mystic and incredible matters.

Machen became the cataloguer of these curious volumes—and he came very close to being that wonderful phenomena of the twentieth century: a publisher’s advertising man! As a matter of fact, Machen did achieve something few, if any, publisher’s advertising men have accomplished—either before or since. Two of his catalogues have become highly prized collector’s items. They were published in 1887 and 1888 respectively.

Working in a book-filled garret in Catherine Street, Machen produced one catalogue which pops up from time to time in Machen bibliographies: The Literature of Occultism[31] and Archeology. Then it occurred to him to paraphrase a chapter in Don Quixote, the one in which the Curate and the Barber examine the Knight’s library. This chapter was written in a manner calculated to entice the wary or unwary book collector into buying the books discussed. The catalogue was issued under the title A Chapter from the Book Called The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote de la Mancha. The other catalogue, issued in the following year, bore the title Thesaurus Incantatus, The Enchanted Treasure or, The Spagyric Quest of Beroaldus Cosmopolita.

It will do little good to look for copies of these catalogues. Vincent Starret, the fortunate possessor of at least one of them, in his collection of Machen’s tales, The Shining Pyramid (Covici-Fried, Chicago, 1923) has included two pieces called The Priest and the Barber and The Spagyric Quest of Beroaldus Cosmopolita. These are taken, of course, from the catalogues in question. As to whether you will find the Starret volumes readily available—well, they are worth the search.

Well then, here was Machen in a hot-bed of the occult and the devilish, surrounded by books of all sorts, especially the strange, the weird and the curious. His room in the Clarendon Road held as many books as it could accommodate along with its occupant—the overflow was stacked between the rungs of a ladder on the landing outside. He was busy with notebooks once more, and writing furiously as ever—but in despair rather than the fine frenzy and high spirits of a few years before. For now he was deep in Rabelais and Balzac—and these books cast a spell upon him. They were warm, glowing books in which life was full[32] and rich and lusty—there were great eaters and drinkers and lovers in those days. They offered too great a contrast to the cold, lonely room in Clarendon Road and the diet of tea, tobacco and bread.

Machen was under the spell of a landscape bathed in a warm sun, with ruins standing close to roads, and wine flowing from vineyard to bottle to parched throats all within a few yards of enchanted space. This was a contrast indeed to the deep lanes of Gwent, the lonely ruins that stood in the shade and shadow of great hills and forests, and although Machen had spoken glowingly of the greenish-yellow cider of that land, still, he rather favored, in his mind at least, the wines of Touraine.

By night there was this magic of old books and by day there were the old books of magic, for the garret in Catherine Street was crowded with old and odd books of every sort, a collection that “represented that inclination of the human mind which may be a survival from the rites of the black swamp and the cave.” These studies did induce a frame of mind that might tend toward the strange and unusual. Living in this strange mixture of a glowing, gargantuan landscape and the dark labyrinths of the mediaeval mind, Machen tried, and sometimes desperately tried, to write.

“A man has no business to write,” said Machen many years later, “unless he has something in his heart, which, he feels cries out to be expressed.” And he had nothing to say—had only the urge to write, the vice of writing for writing’s sake—cacoethes scribendi—he called it! But then Machen has had time to reconsider his pronouncement of 1923, and[33] to revise his opinion regarding men who wrote—and why they write.

In a “London Letter” to the New York Times Book Section, Herbert W. Horwill wrote, in September 1935: “A curious literary problem is posed by that veteran author, Arthur Machen, in John o’ London’s Weekly. Imagine a man marooned on a desert island, and certain that he would remain there for the rest of his life. Imagine, moreover, that he possessed the literary faculty, and had salvaged pens, ink and paper from the wreck or else had devised home-made substitutes for them. Would such a man write, knowing that whatever he wrote would never be seen by any eye but his own?

“Mr. Machen tells us that he once heard this question discussed among a group of friends. Some answered yes and some no, and, when pipes were knocked out for the night, the problem was no nearer solution, though, to the best of his recollection, the ayes were in the majority. He voted with them himself, and, after further reflection, he still believes he was right. The hypothetical Crusoe might have no better implements available than quills of parrots’ feathers, paper made out of the bark of the guru tree and ink obtained by macerating the root of a certain plant. But, granted his possession of the literary faculty, he would possess also the literary impulse. He would write because he liked writing, apart from whatever fate might be in store for the thing written. The true spring of imaginative literature, Mr. Machen reminds us, is the delight of the creator in creation.”

In the desert island of Clarendon Road, all through the summer of 1885, Machen wrote. He wrote because he had to,[34] because he was under the spell of a master of gargantuan languages, because he was enamoured of the sound of words and because he had an ear for the rich and rolling phrase. And, of course, he wrote because he had the literary impulse. The pound a week he was paid by Redway could not afford him the rich living, the pleasures of Touraine. But then, after despair and after much almost pointless scribbling, he came at last upon the idea for the Great Romance.

It was to be a book in which Rabelais and Gwent were mingled ... and thus began the “History of the Nine Joyous Journeys ... in which were contained the amorous inventions and fanciful tales of Master Gervase Perrot, Gent.” Machen had prepared for this great undertaking by purchasing his ruled quarto paper, his pen points and his penholders. Quite possibly he envisioned a plaque on the door of his little cell at 23 Clarendon Road, announcing that Here Had the Great Romance been Written! There was, however, this difficulty—the vision of the great romance declined to be more specific. There were no hints as to plot, no guidance as to characters. He began, at any rate, a Prologue, written in a flowing and flowery 17th Century manner.

But now his cataloguing in Catherine Street had come to an end, and with it his pound or thereabouts per week. Nevertheless, he wrote on, even though he knew that his composition of the Great Romance might be abruptly terminated some three or four days in the future. Then, presumably, he would return to Caerleon, in all probability on foot. As it happened, he returned hurriedly by train. Just as he had come to the end of his tea and tobacco and rent money, he had word[35] that his mother was dying. Aunt Maria thoughtfully sent his fare with the summons.

Later, he returned to the “great romance,” writing once more in the familiar room in the rectory where the fire burned and the winds howled down from Twyn Barlwyn and tossed the branches and beat upon the door. He wrote late into the morning, long after his father had knocked out his last pipe and gone upstairs. So passed the winter of 1885. Through the days he walked in the lovely Gwentian hills and looked down upon the white farm houses standing in the midst of encircling trees. At night he worked in that room where he had, as a boy, first read de Quincy and Scott and the other writers who had helped to bring about the “renascence of wonder.” And in the following year he was alone. His father died that spring.

This was the John Edward Jones whose homecoming from Jesus College, Oxford, is described in the opening pages of Things Near and Far. Now Machen was more truly alone than ever. His father had been to him a good companion in his earliest rambles about the countryside. It had been his father’s hope that Arthur might one day return to Gwent to live, buy a small newspaper and settle down to a quiet career in country journalism.

There were certain inheritances that might help, when they came through. For Machen’s father seldom thought of the good these inheritances would do for him in his struggle to make ends meet at Llanddewi Rectory. But now he had gone and then, ironically, the long-lived Scottish relations went too, and the Scottish lawyers began to look through family Bibles for the next of kin.

Through these and other circumstances Machen at length came into money—smallish amounts which, shrewdly invested or even conservatively invested, might have stretched themselves out for a score or more years. This economic policy did not suggest itself or, if it did, was quietly ignored. The simple expedient of living modestly and comfortably, and dipping into a box for coins, when coins were required, seemed much the better plan.

In 1887 Machen returned to London, to live in Bedford Place, and to arrange for the publication of the Great Romance, now called The Chronicle of Clemendy. This was accomplished, with perhaps a deeper plunge into the box of coins, and the book was published that year. It was printed at Carbonnek, “for the society of Pantagruelists.” And it did, apparently, quite well. The nine joyous journeys and the merry monks of Abergavenny pleased Machen and his fellow Pantagruelists—which, in the year 1888 or 1948, is almost as much as can be asked of any book.

In the late 1880’s Arthur Machen had, as he said, “Rabelais on the brain.” He had been for some years under the spell of the gargantuan tales and of Balzac’s Contes Drolatiques—and perhaps even more under the spell, literarily if not literally, of the Holy Bottle and the magic of Touraine and whatever it is about the land of France that so beguiles the young of the Anglo-Saxon peoples.

It was under the Rabelaisian influence that Machen had written his “great Romance,” The Chronicle of Clemendy, and made his translation of the Heptameron. And finally he had undertaken to translate and publish an even more difficult and bizarre book—Le Moyen de Parvenir by Beroalde de Verville.

This book, rather highly prized by collectors of at least two sorts, is incredibly dull. No fault of Machen’s certainly, although he might have permitted it to remain untranslated. Still, he was at the stage and of an age when this sort of thing had an appeal. And so he translated and published it in not one, but two editions. There was a large paper edition and an “ordinary” edition—both preceded by a very small[38] edition (four copies) of a portion of the book under the title The Way to Attain.

Now of course every Machen bibliography lists this title, and many a Machenite has wished he might obtain a copy. Actually, it is one of the least important of Machen’s works. For this is merely a portion of Le Moyen de Parvenir—and very probably not an important part at that. Bibliographers, bibliophiles and bibliomaniacs are at liberty to go quietly mad in their quest for this queer little item. For queer it is—Machen himself cannot quite explain its existence. The four copies were issued in 1889, presumably by the Dryden Press who were to publish the complete work. A dispute over something or other arose and the project was dropped—at least by the Dryden Press. All four copies, apparently, are in the safe-keeping of Danielson, or they were at one time.

The other two editions were privately printed at Carbonnek in 1890 under the title of Fantastic Tales. There have been other editions, de luxe if not luxurious, for what is sometimes known as “the trade.” It may be assumed that the writer holds no very high opinion of this work. But then neither does Machen. He has described the book as being somewhat like a cathedral constructed entirely of gargoyles—as plain a warning as any ever given by an author regarding one of his works.

This fantastic collection of “discourses ... on Reformation politics ... many tales, some pointless, a few amusing” while it may provide puzzles, pleasure and profit for bibliophiles, is important only in that it marks the finish of the Rabelaisian influence upon Machen. Not that this influence was ever “Rabelaisian” in the usual sense ... it was[39] rather like that of various French poets and novelists of several generations over still other generations of English and American writers. During certain periods our younger writers and “intellectuals” would have Verlaine on the brain, or Baudelaire in their bonnets, but eventually they would go back to writing stark novels about Sussex or Sauk Center, or Wales or Wisconsin or the moors of the Missouri.

The extent of this enthusiasm and the depth of this influence may be estimated from the following rhapsody delivered by Ambrose Meyrick in The Secret Glory. “Let me celebrate, above all, the little red wine. Not in any mortal vineyard did its father grape ripen; it was not nourished by the warmth of the visible sun, nor were the rains that made it swell common waters from the skies above us. Not even in the Chinonnais, earth sacred though that be, was the press made that caused its juices to be poured into the cuve, nor was the humming of its fermentation heard in any of the good cellars of the lower Touraine. But in that region which Keats celebrates when he sings the ‘Mermaid Tavern’ was this juice engendered—the vineyard lay low down in the south, among the starry plains where is the Terra Turonensis Celestis, that unimaginable country which Rabelais beheld in his vision where mighty Gargantua drinks from inexhaustible vats eternally, where Pantagruel is athirst for evermore, though he be satisfied continually. There, in the land of the Crowned Immortal Tosspots was that wine of ours vintaged, red with the rays of the Dog-star, made magical by the influence of Venus, fertilised by the happy aspect of Mercury. O rare, super-abundant and most excellent juice, fruit of all fortunate stars, by thee were we translated, exalted into the[40] fellowship of that Tavern of which the old poet writes: Mihi est propositum in Taberna mori!”

Well, it was quite a thing while it lasted ... but the Rabelaisian vein petered out and Machen began to perceive that he was of Caerleon-on-Usk and not a townsman of Tours or a citizen of Chinon, and that the old grey manor-houses and the white farms of Gwent had their beauty and significance, though they were not castles in Touraine.

Meanwhile he was back at his old trade of cataloguing. He had switched employers for, when York Street would yield little more than a pound a week, Leicester Square would give thirty shillings. So back he went to cataloguing ancient books. Not that he was much good at it, nor that he preferred it above all other forms of employment. As a matter of fact he rather disapproved of the whole business and issued what almost amounts to a Manifesto to Collectors: “I don’t care two-pence,” he wrote, “whether a book is in the first edition or in the tenth; nay, if the tenth is the best edition, I would rather have it ... the only question being: is the book worth reading or not?”

Nevertheless, cataloguing seems to have been a rather flourishing trade at the time, and a profitable practice—for the publisher at any rate. For this was a remarkably literate era, and publishers pandered profitably to the popular taste ... they were busily at work discovering rare books, improving some with plates borrowed from others, issuing new and enlarged editions at the drop of a folio, and discovering the pleasures and profits to be derived from making translations—particularly from the French. In the same building occupied by Machen’s employers were the offices of Vizatelly,[41] the publisher who was even then bringing out translations of Zola’s works. At about the same time Machen was working there, Havelock Ellis was editing the Mermaid Tavern Series of Elizabethan Dramatists for Vizatelly. Ellis notes in his Autobiography that he was paid the sum of three guineas per volume—an amount he considered rather small. This may indeed have been a small amount—but he had a better deal of it than Machen who was asked, at about this time, to do a translation of the memoirs of Casanova.

The manner in which this undertaking came about was rather curious and very casual. One of the Brothers for whom he worked, and whom he does not otherwise identify in Things Near and Far, came to him one day with an old volume and asked Machen to translate from the place marked with a slip of paper. Machen set to work and about a year later he completed his translation of the twelve volumes of Casanova’s Memoirs. The place marked fell in about the fifth volume, and Machen simply translated through to the twelfth, began again at the first and worked through to the place in the fifth volume—which was “where he came in” as one says at the movies.

This monumental work, and the best translation to date of the Memoirs, was thrown in, as it were, with the cataloguing at thirty shillings a week. Machen simply remarks that he believes the cost to the firm to have been “strictly moderate.” Much more moderate than the three guineas per volume paid to Ellis for his editing. However, Machen was eventually offered an opportunity of profiting from his work. A few years later when the translation was about to be published, Machen was granted the privilege of[42] investing a thousand pounds in the venture. One of the Brothers suggested that, as he was now an interested party, he might wish to revise the manuscript.

Of course publishing was not quite the same game it is today ... there were publishers then who were, if not actually unscrupulous, a trifle careless in their accounting and possibly slightly unethical. Vizatelly was prosecuted and jailed as a result of his translations of Zola. Machen has remarked upon the irony of the situation—for even while Vizatelly was in jail, charged with circulating obscene literature, Zola was being well received on his trip through England. When Vizatelly died shortly thereafter the Mermaid Tavern series was taken over by another publisher without so much as a by-your-leave. Ellis’ name was removed from the volumes, and that, apparently, settled that. Ellis treated the affair with a silence he knew would not be taken as a sign of contempt. One gathers that publishers in those days were not very thin-skinned. However, in his autobiographical sketches describing these events, Machen offers not the slightest criticism of the Brothers but he did, shortly thereafter, quit the publishing business.

For almost a decade Machen had been in London, and for most of that time he had been writing. But he had written rather imitatively; he had, as he says, “been wearing costume in literature. The rich, figured English of the earlier 17th Century had a peculiar attraction....” Whether this was unnatural affectation or natural affinity, he wrote in this fashion—essays, verse, tales, epistols dedicatory. He even kept, for many years, a diary written in this manner. The[43] Anatomy of Tobacco was an “exercise in the antique,” the Chronicle tried to be mediaeval, Le Moyen was in the ancient mode, the Heptameron a mere finger-exercise in the composition of a period piece. At this point Machen decided to write in the modern manner.

In 1890 Machen began to make an approach to journalism. His Welsh relations were probably gratified when his pieces and stories began to appear in the Globe and the St. James Gazette. He was still a long way from adopting journalism as a profession or career, but he had decided to do some writing in “the modern manner” and the papers seemed to offer an outlet.

Journalism was then, as it is now, a wonderfully agitated world in which editors knew what their readers wanted and were determined to see that they got it—whether they liked it or not. Oddly enough, an editor’s staff never seems to have this happy faculty of knowing what the readers want, but they do know what their editors want—and so everyone is mildly unhappy about it excepting the editors—and it is questionable whether an editor is ever really happy, or ever deserves to be.

At any rate Machen wrote, on an average, about as much drivel as the average journalist must, and about as many silly stories as most journalists have to. Of course it was not as bad as it might have been, or as bad as it became later, for, according to Machen, editors in the 1890’s presumed a certain standard of education and culture in their readers. This tendency has been overcome, however, and along with certain other technical improvements the press as it existed during Machen’s time was much as it is today.

His success at writing for the Globe and an acceptance by the St. James Gazette started him on short stories. These appeared mostly in the Gazette whose rate of payment was commendably higher than the Globe’s. The connection did not last too long for one of the stories created quite a stir.

Reading it now one wonders at that, and when one remembers a few of the tales that were to flourish in the decade to follow, Machen’s little story of The Double Return seems harmless enough. The tale is rather reminiscent of The Guardsman—you will remember the success of the Lunts in that play on the stage and on the screen. Machen’s tale lacked the amorousness or even the intent of The Guardsman, it merely told of a man returning home after three weeks in the country.

“Back so soon?” asked his wife.

“I’ve been in the country for three weeks,” said he, rather put out.

“I know,” she said, “but you returned last night.”

“Indeed not, I spent last night at Plymouth on my way back from the country,” said the husband.