Title: The "City Guard": A History of Company "B" First Regiment Infantry, N. G. C. During the Sacremento Campaign, July 3 to 26, 1894

Creator: California. Infantry. First Regiment. Company B

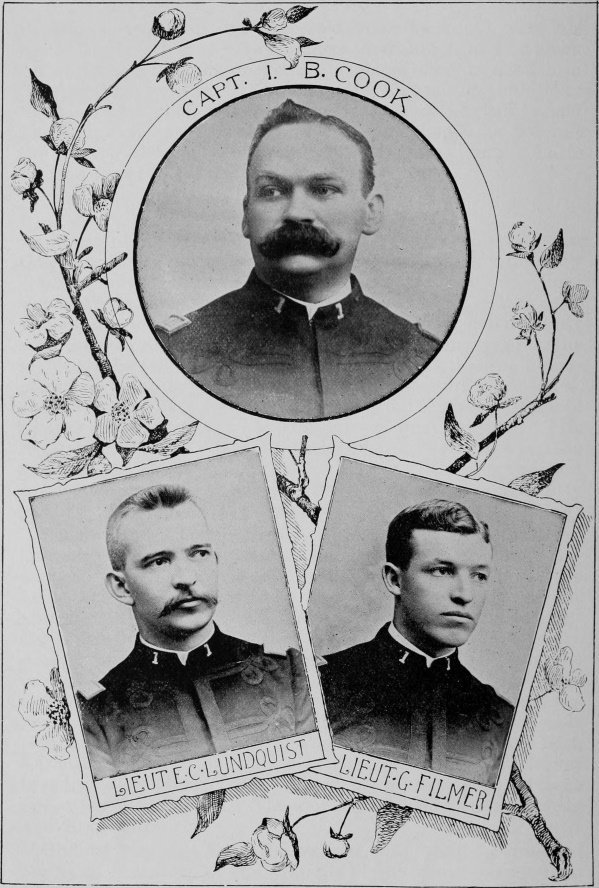

Author: Irving B. Cook

George Filmer

W. J. Hayes

A. McCulloch

William D. O'Brien

Release date: April 22, 2022 [eBook #67904]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: California infantry. 1st regt., 1861- Co. B

Credits: Alan & The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

DURING THE SACRAMENTO CAMPAIGN

July 3 to 26, 1894

INCLUDING

A Brief History of the Company since its Organization

March 31, 1854, to July 3, 1894

FILMER-ROLLINS ELECTROTYPE CO.

Typographers, Electrotypers and Stereotypers

424 SANSOME ST., SAN FRANCISCO

Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1895,

By Company B, “City Guard,” 1st Reg. N. G. C.,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

To the members of the “City Guard,” past, present, and to

come, this, our Company’s maiden effort, is

respectfully dedicated.

CONTENTS.

| THE STRIKE IN CALIFORNIA. | ||

| PAGE | ||

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| The Cause, | 9 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| The National Guard Called Out, | 15 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| Fourth of July at Sacramento, | 29 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| Camp on the Capitol Grounds, | 42 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| The Vigilantes at the Capitol Grounds, | 68 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| General Effects of the Strike, | 83 | |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| The Appearance of the Regulars and Its Effect Upon the Situation, | 93 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| The First Regiment at Ninth and D Streets, | 128 | |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| The American River Bridge, | 156 | |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| Off for Truckee. | 172 | |

| A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE COMPANY. | ||

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| “San Francisco City Guard,” | 219 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| “Independent City Guard,” | 224 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| “City Guard” from 1860 to 1870, | 229 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| From 1870 to 1880, | 237 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| From 1880 to 1894, | 244 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| Forty-one Years’ Target Practice, | 252 | |

[Pg v]

PREFACE.

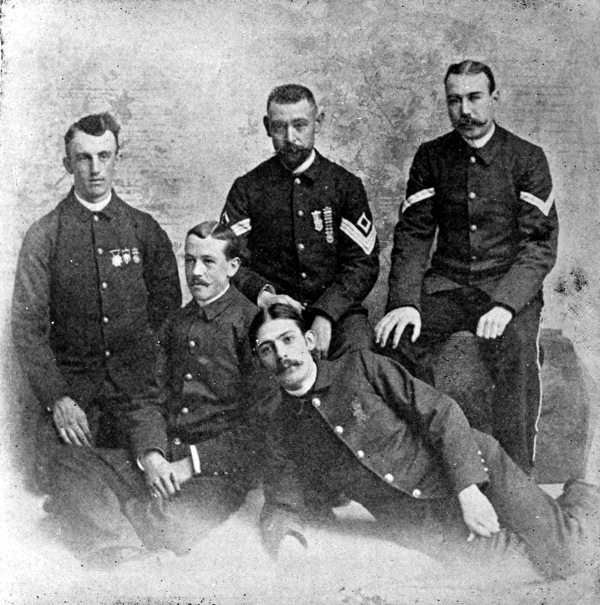

On September 1, 1894, shortly after the return of the company from its campaign at Sacramento, a committee of four was appointed, to be known as the history committee, to gather as much material concerning that campaign as possible, and to put it in a readable and concise form. The following were appointed: Lieutenant George Filmer, Corporal A. McCulloch, Privates W. J. Hayes and Wm. D. O’Brien.

The committee began its work enthusiastically and at once, as they believed that the most beneficial results could be attained by “striking while the iron is hot.” Their progress was necessarily slow; but when taken in connection with the circumstances, that the committee were engaged in earning their livelihood during the day, and thus limited in their work upon the history to their spare moments, and further, that they also took great care to prevent inaccuracies from creeping into their labors, the progress made, when viewed in this light, cannot be said to be unusually slow.

The idea of publishing a history was not an original idea, but rather it is the result of the gradual development of an incipient idea by a process of evolution containing three distinct steps. First it was only intended to have a short account written of the campaign and pasted in the company’s scrapbook; then, with this as a basis, the idea developed into the form of a printed pamphlet, and finally blossomed into the shape in which it now appears.

It was the intention of the committee to have the entire book set up by members of the company who were compositors by trade, and who had kindly volunteered their services. But, on account of the limited time that the volunteer compositors could bestow upon the work, it was found necessary, after about one-half the book had been thus set up, to give the[Pg vi] work to an outside publishing house, in order to present to the company a complete history of the campaign before the memory of this memorable event would be beyond the “time of which the mind of man doth not run.” And even though the members of the company were unable, through no fault of their own, to set up the entire work, the committee desires to acknowledge its appreciation of the kindness and the valuable assistance given by these members, viz: George Claussenius, W. L. Overstreet, Wm. McKaig, J. Brien, and R. E. Wilson.

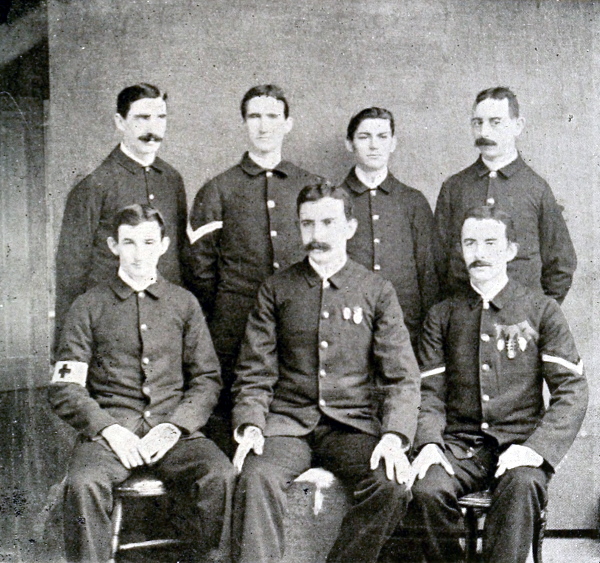

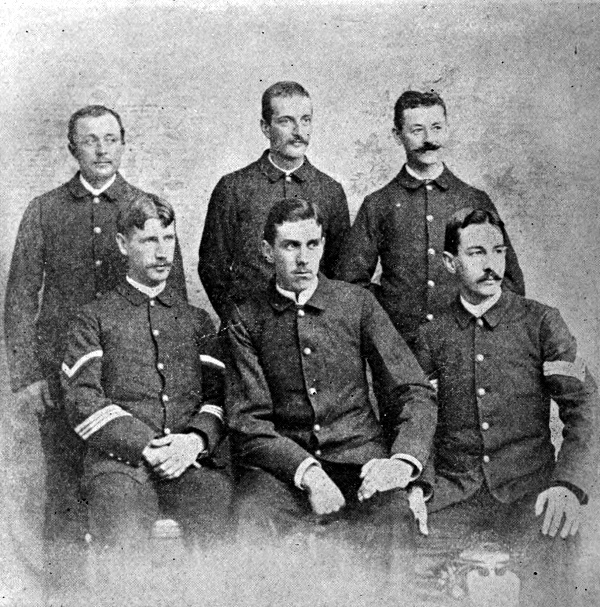

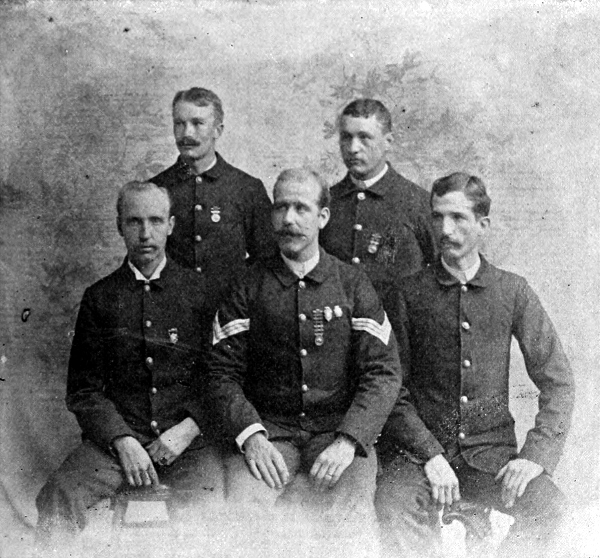

The committee further desires to thank Lieutenant Hosmer, Adjutant First Battalion, First Regiment Infantry, N. G. C., and Sergeant H. B. Sullivan, “of ours,” for the kind assistance they rendered the committee in making negatives of each tent crowd of the company.

It may be well here to mention the fact that at the request of the committee, Captain I. B. Cook consented to write the brief history of the Company. For this work and the thoroughness with which it is done, the committee extend to him its sincere thanks.

The committee do not pretend to uphold the book as a work of any great literary merit; and, while they do not propose to offer any excuses for the book, still they hope at least that it is free from any obvious signs of crudity or provincialism: it stands upon its own merits.

The work is largely of a personal nature, and, as such, has made the introduction of personalities unavoidable; but while this is so, the committee have tried to eliminate every thing of such a character which, in their judgment, would offend the most sensitive nature. In case, however, their judgment has erred at times, and things do appear which wound the feelings of some, the committee trust that the attempted witticism, for it is nothing more, will be received in the same spirit that it is offered, namely “peace, goodwill to all.”

In judging the results of their labor the committee beg that those judging will say, in the words of Miss Muloch:

[Pg vii]

[Pg viii]

[Pg 9]

THE CAUSE (?)

THE STRIKE AND ITS EFFECT.

AS the tiny stream that wends its course down the mountain slope on the way to the sea grows gradually larger and deeper by the successive uniting with it of similar streams until at last it becomes the mighty river in which its identity is completely lost, so a small labor movement springing up in a little town named Pullman in the vicinity of Chicago, and spreading out westward and southward, became larger and greater at each successive juncture with it of the employees of the railroad until at last, when its progress was stopped by the cool waves of the Pacific, it had grown to be a movement of gigantic proportions, stupendous in its effects, in which the primal cause of the movement was lost. California was particularly affected. Never before in the history of the State had she experienced such a movement as this. Traffic was completely stopped. Business was paralyzed. Goods could neither be received nor sent away. Merchants were laying off their employees and getting ready to close up their houses. Not a wheel of the Southern Pacific Company was turning in the State.

This movement had its source in a disagreement between the managers and the employees of the Pullman Car Manufacturing Company. By successive reductions the wages of the employees had become greatly reduced, far below that which the existing condition of affairs would seem to justify.[Pg 10] This, considered with certain other circumstances, caused a great deal of dissatisfaction among the men of the works. The accompanying circumstances, which served to intensify the dissatisfaction, were of a nature peculiar to the town of Pullman itself. A fair estimate would place the inhabitants of this town at about four thousand, all of whom are directly or indirectly dependent for subsistence upon the Pullman Car Manufacturing Company. Not only are they connected with the company by bond of employer and employee, but also are they related as landlord and tenant, and as creditor and debtor. Pullman has been nicknamed “the model town.” But there is more than one way of looking at this model town, just as there is more than one way of looking at a model jail. To a man like Carlyle, who had no sympathy for transgressors of the law, a jail like the famous Cherry Hill prison of Pennsylvania would be a model jail; for here a prisoner is confined in a single cell for the entire term of his confinement, with no other occupation than that of picking jute. But to the prisoner himself who is incarcerated there, it is a model jail, where he “who once enters leaves all hope behind.” So with the town of Pullman. To the stockholders of the Pullman Car Manufacturing Company, who see in its organization innumerable opportunities for enriching themselves at the expense of the workman, it is a model town. But to the poor employees, who encounter at every turn the grasping hand of the monopoly, it is a model town symbolical of all that characterizes slavery. In the hands of the Pullman Car Manufacturing Company resides the entire property of the town. They not only own the water and gas works, and the houses, but also sell to their employees the very necessities of life. All the inhabitants of the town are tenants; none are freeholders. From this it is easy to imagine the situation when a large cut was made in the wages. The corporation, you may be sure, never thought of making a corresponding reduction in the rent of the houses, or in the water and gas rates, or in the price of food. With greatly reduced wages, reduced to considerably less than what the artisans engaged in similar crafts were getting in the adjacent municipality of Chicago, and with rents and water, and gas rates correspondingly higher, the Pullman Car Manufacturing Company expected its employees to adjust themselves to the new condition of affairs. The chasm, however, was altogether too wide to be bridged. The men were compelled by the force of necessity to resist the reduction.

[Pg 11]

About the beginning of May, 1894, a committee of thirty-nine, representing every department in the works, waited upon Mr. Pullman, president of the company, and laid the case before him. They asked that the old rates, which were one-third higher than the present rates, be re-established. In spite of the fact, that at about the time the committee waited upon Mr. Pullman the company was paying large dividends, and had an enormous reserve fund, and further still, in spite of the fact, that Mr. Pullman had enough of spare cash to donate one hundred thousand dollars to a church, the petition was denied. The plea given was, that the state of business would not stand the increase of wages. The matter did not stop here. The car company was very indignant at the apparent intrusion of the workmen into the affairs of their business. How dare employees suggest to them how they shall conduct their business. The outcome of it was, that the men who formed the committee were individually discharged from their service. This was the straw that broke the camel’s back. The entire body of workmen struck. This was the direct strike.

A new element now enters into the strike. The employees of the Pullman Car Manufacturing Company, as a body, were affiliated with an organization known as the American Railway Union. The constitution of this latter organization was of such an elastic character as to be capable of being stretched so far as to include not only those who worked for the railroad proper, but also all who were employed upon any kind of railroad work whatsoever. The strike was referred by the workmen of Pullman to this higher body for settlement. The American Railway Union investigated the grievances of the men, and concluded that the strike was a just one; one worthy of their support. On June 23d, after having tried for a period of six weeks to adjust the difficulties between the men and their employers without success, the Executive Board of the Union gave notice to the Pullman Car Manufacturing Company, that, unless they agreed to the terms of settlement by the 27th of June, a boycott would be placed upon all Pullman cars. In other words the members of the union would refuse to handle any trains to which were attached Pullman cars. The 27th of June coming around with no signs of compliance on the part of the Pullman Company the threat of the union was put into execution. The entire Santa Fé System, comprising about seventeen different lines[Pg 12] and operating throughout that part of the country southward of Chicago to the Gulf and westward to the Pacific, was affected. This new phase of the strike, known as the sympathetic strike, was destined to be the greatest labor movement that America had ever experienced.

This is the method by which the American Railway Union undertook to bring the Pullman corporation to terms. In their letter to the public they stated that it was not their intention to tie up the railroads. They were willing to handle trains, provided Pullman cars were left off. This was, they said, the only means they had of striking the Pullman Car Manufacturing Company. In case a quarrel arose between them and the railroad companies it would be a quarrel that was forced upon them, and not one of their choosing. The railroad companies, on the other hand, were unable to separate their interests from the interests of the Pullman Car Manufacturing Company, so they took the quarrel upon their own shoulders. They were determined to send trains out with Pullman cars attached, or else they would not send any at all. On the 27th of June, the day that the boycott was placed upon Pullman cars, traffic over the entire Santa Fé system came to a standstill. The railroad employees, that is, those employees who were engaged in the strike—the firemen, switchtenders and switchmen—refused to move trains with Pullman cars attached, and the railroad companies refused to send out trains without them. And so began the sympathetic strike.

Every State, in which the lines of the above-mentioned system operated, was severely affected. In the East the unique position held by Chicago with regard to the different lines of railroads made it the hotbed of the strike. Seventeen different lines meet in Chicago. These being tied up, Chicago became the congregating point for many thousand strikers, some of whom were exceedingly desperate characters. Chicago, in the course of the strike, was the scene of many aggressive operations, and numerous were the conflicts between the troops and strikers, of which some resulted in fatalities. In the West the strike presented some features which were not manifested in the East. No State suffered more severely from the strike than did California. That the effect was so severe on California was due probably to its isolation; to its entire dependence upon railroad transportation, and to the fact that a great part of its produce consisted of fruit, which has[Pg 13] to find a ready market in the East. These facts, coupled with the fact that the tie-up came at that time in the year when the fruit was ripe and ready for shipping, and thus dependant upon rapid transportation for its value, are evidence enough of the injurious effects of the strike upon California. And yet, in spite of the ruinous consequences, it is strange to say that the sympathy of the people was almost unanimously with the strikers. The press of California has been severely criticised by the Eastern press for the manner in which it espoused the cause of the strikers. Yet the California press was only reflecting the opinions of the people.

The first scene of act one of the strike in California took place on the 27th of June. The overland trains, which are the only trains that carry Pullman cars with the exception of the Yosemite, did not leave the Oakland mole that day as usual. Throughout the 27th and part of the 28th all other trains ran as usual. But on the 28th President Debs of the American Railway Union telegraphed from Chicago to the heads of the local unions to tie up the entire Southern Pacific Company. The strike now began to operate in California with full force.

In such railroad centers of California as Los Angeles, Oakland, and Sacramento the strike assumed threatening aspects. In Sacramento the aspect was particularly alarming. Los Angeles and Sacramento are the two controlling centers for all lines that leave the State. The strike in neither Los Angeles nor Oakland reached the importance or received the attention that it did in Sacramento. This was due to the fact that in Los Angeles it was brought under control before it gained much headway. While in Oakland, though Oakland was invested by a large number of strikers who managed to do a good deal of mischief and damage, such as cutting the air-brakes on freight trains, and even going so far as to stop the entire local system, thus compelling the residents of the bay towns to resort to a provisional ferry; yet even while they did all this, it made little practical difference to the outcome of the strike whether the strikers reigned there or not as long as Sacramento or Los Angeles remained under their control. Sacramento and Los Angeles therefore were the backbone of the strike in California.

As the time wore on a peaceful settlement of the strike seemed to grow less. The railroad company, on the one hand, was determined not to yield. The strikers, on the[Pg 14] other hand, were getting impatient and angry at the rigidness of the railroad officials, and with this, growing more conscious of their power, seemed ready to set aside all legal restraints and resort to violent deeds to force an acquiescence to their will. Sacramento, where the strikers held forth in full sway, was the point toward which the attention of the people was directed. Speculation became rife as to what would be the outcome. That things could not continue in such a state much longer was universally conceded. The seriousness of the affair, however, kept rolling on. Complaints of people tied up at the different places in the State were increasing every day. Baggage and freight was accumulating with wondrous rapidity. Delayed mail—and here is where the strikers came in conflict with Uncle Sam—was piling up on every hand. It was only a question of time when the dam would break.

It was on June 29th that the first rumors were heard about calling out the State troops. A situation like this cannot fail to be other than closely related to the life of the National Guard. While California had been hitherto practically free from movements of this kind the Eastern States had not been so fortunate. It seems next to an impossibility for a railroad strike of any size to occur without its being accompanied by violence and crime. Time after time had the Eastern National Guard been called out to suppress strikers, who had finally deteriorated into rioters. The one seemed to follow the other as effect follows cause. As soon as a strike was inaugurated the people of the East looked for the effect, namely the calling out of the National Guard. This mode of thinking influenced the thought of California. The people now began to look to the State troops. The members of the National Guard were especially interested in the situation, for when they joined they little thought that they would be called upon to face any real danger. A sham battle at camp was about as near as they ever expected to get to an actual engagement. But as things began to look serious, their interest in affairs grew in intensity. “Great Heavens! we might be called out.” So they anxiously awaited further developments.

[Pg 15]

THE NATIONAL GUARD CALLED OUT.

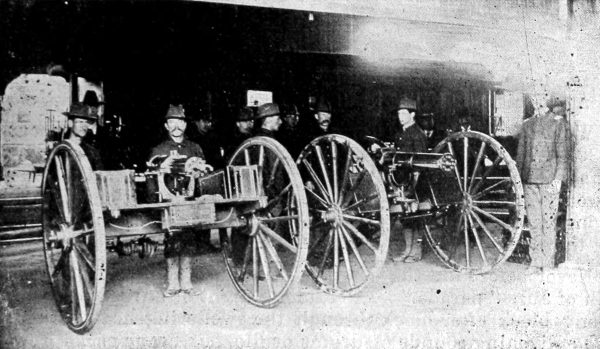

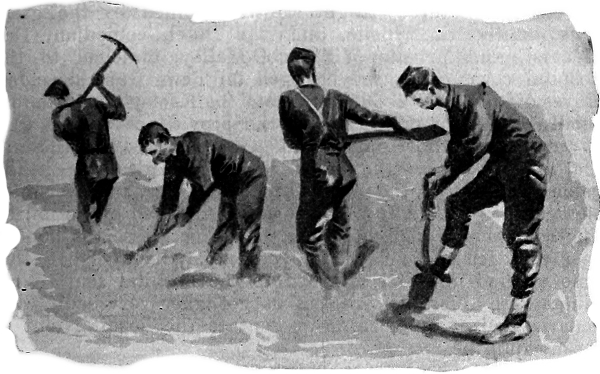

ON July 1st Uncle Sam took a hand in the game. Attorney General Olney sent instruction to the United States district marshals, whose jurisdiction was over that territory affected by the strike, to execute the process of the court, and prevent any hinderance to the free circulation of the mails. In accordance with these orders the United States marshal of the Southern District of California called upon General Ruger, commander of the western division of the Regular Army to furnish assistance at Los Angeles. Six companies, three hundred and twenty men, under the command of Colonel Shafter, were dispatched on July 2d for this place. They left San Francisco on the 10:30 P. M. train. To act in conjunction with the Regular Troops, Barry Baldwin, United States Marshal for the Northern District of California was at Sacramento with a large number of deputy United States marshals, sworn in for the occasion. The plan was to break, almost simultaneously, the blockade at these two places. The regulars experienced but little difficulty at Los Angeles. Not so, however, with the United States marshal and his deputies at Sacramento. The mob of strikers here was larger, more desperate, and better organized than at any other place in the State. On the afternoon of the 3d of July Baldwin attempted to open up the blockade. The operation of making-up the trains was calmly watched by the[Pg 16] strikers. Everything seemed to be going smoothly, when all of a sudden at a given signal the strikers rushed forward, and in a few minutes demolished what had been the result of several hours labor. At this the wrath of Marshal Baldwin knew no bounds. He attempted to force his way through the strikers, but was thrown several times to the ground. Regaining his feet after one of these falls he drew a revolver; but, before he could use it, he was seized and disarmed, and, were it not for the presence there of some cool heads, would have been severely handled. The marshal seeing the hopelessness of the situation withdrew, leaving the depot in possession of the strikers. That very afternoon, however, he called upon Governor Markham for military assistance to aid him in forcing and maintaining a free passage for the mails. In response to this call Major General Dimond of the National Guard of California was ordered to furnish the necessary assistance, using his discretion as to the number of men required. It was deemed advisable to call out a large force, as the experience of the Eastern militia in strike troubles showed that the display of a large force had a salutary effect. The following troops were ordered out: Of the Second Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Dickinson, the First Regiment Infantry, under the command of Colonel Sullivan, the Third Regiment Infantry, Colonel Barry commanding; one-half of the Signal Corps, under the command of Captain Hanks, and a section of the Light Battery, consisting of Lieutenant Holcombe, twelve men and a Gatling gun; of the Third Brigade, Companies A and B of the Sixth Regiment, under the command of Colonel Nunan; of the Fourth Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Sheehan, Companies A, E, and G; of the Second Infantry Regiment, Colonel Guthrie commanding, the Signal Corps and Light Battery B. In all about one thousand men. The following troops were ordered to hold themselves in readiness: The Fifth Regiment Infantry, Colonel Fairbanks commanding, consisting of two companies in Oakland, one in Alameda, one in San Rafael, one in Petaluma, one in Santa Rosa, and one in San Jose; the Second Artillery Regiment, Colonel Macdonald commanding, and the First Troop Cavalry, commanded by Captain Blumenberg. The San Francisco troops were ordered to be ready to leave that evening. Companies A and B of Stockton, under command of Colonel Nunan, were ordered to be ready to join the San Francisco troops as they passed through Stockton the[Pg 17] following morning. The Sacramento troops were to join the main body upon their arrival at the Capital City.

Colonel Sullivan received orders to assemble his troops at about 5:35 P. M. Colonel Barry was notified a little later. Both proceeded immediately to carry out their orders. The calling out of the troops had been anticipated by the officers of the National Guard. On Monday evening, July 2d, Colonel Sullivan called a meeting of the company commanding officers and arranged with them a plan that would insure the effective and rapid massing of the troops. The plan was this: The roll of each company was to be divided up into squads and a non-commissioned officer assigned to each squad, whose duty it would be, in case it became necessary, to see that the members of that squad were notified. Experience proved that the plan was exceedingly effective. Captain Cook lost no time in applying it to Company B. On the very same night he assembled the non-commissioned officers of the company, and assigned a squad of the company to each. Further, each non-commissioned officer, for the purpose of expediency, was given the following pre-emptory order:

“San Francisco, July 3d, 1894.

“Company Orders No. 8.

“You are hereby commanded to report at your armory immediately in service uniform upon reading this order. Bring your blankets, suit of underclothing, and two days’ rations to pack in your knapsack. Report without fail. Let B Company be the first in line for suppressing riot.

Irving B. Cook, Commanding Company.”

This was the plan by which the company was to be massed at short notice When the time came to test its effectiveness it had been so well applied to the company that it was like pressing the button and the entire machinery started in motion. Within an incredible short space of time after Captain Cook received orders to assemble his company, non-commissioned officers in charge of squads were speeding on their respective missions of notification. Many members, hearing that the militia were called out, reported without receiving any official notice. Company B was not the only company, nor was the First Regiment the only regiment, that had taken time by the forelock and laid plans for the rapid massing of their men. Subsequent developments showed that[Pg 18] arrangements had been made beforehand in all the companies of both regiments and that these arrangements had well fulfilled their end.

Thus far we have but considered one end of the action. Let us therefore transfer ourselves to the other end, namely the thresholds of the homes of the members. Here scenes occurred the memory and influence of which will never be forgotten. What a feeling of gloom and of sadness settled upon that household after the notifying officer had hurried up the steps, rang violently the door-bell and notified him, who was both a member of the family and a member of the National Guard, to report for duty at the armory. We may now talk lightly of the things we have done. We may now laugh heartily over the experiences of those campaigns. The public may sneer at the results which we have accomplished, but who could say on the night we were called out that the duty which we were ordered to perform was not such that we had no assurance of ever returning again to the bosom of our families. Is there a man who would speak lightly of the tear that glistened in the mother’s eye or the quivering of her lips? Who is there that would ridicule the sobbing of the sisters and of the wives, or sneer at the deep, heartfelt emotion of the father hidden beneath a gruff voice. Shame on him who has for these no thought but scorn! “Parting is such sweet sorrow,” the poet sings. Until the night of the 3d few of us however recognized this truth. Parting is sorrow, but ah! how sweet it is to know something of that great affection with which we are held. Thank God there come such times as these when the mist of humdrum life is lifted and we behold our position in the hearts of our family.

Many of us still remember how, while in our boyhood days, our souls used to thrill and how inspired we were when we read that after the battle of Lexington, old Israel Putnam left his plow yoked in the fields, mounted his fastest horse, hurried to Boston and offered his services to his country. But when we left those happy days behind us and went out into the cold, prosaic, and selfish world, and thought of Putnam’s noble and inspiring patriotism, a feeling of regret would arise within us to feel that there were no more Putnams. But during the late excitement we were undeceived. Right here among us we have such patriots. Patriots whose example ought to inspire and thrill every citizen. Like Old Putnam, they also paused in the midst of their toil and,[Pg 19] without waiting to be notified, hastened to offer their services to their State. Would that the grave could open up, so that Old Putnam might rest contented in the belief that the destinies of this Republic are presided over by young patriots worthy of their revolutionary sires.

To come back to the First Regiment Armory again. Throughout the evening it presented both inside and out an animated appearance. Fully five hundred people were gathered in front of the armory watching the course of developments. Inside of the armory men were hastening to and fro. Others were gathered into groups talking in an excited tone over the unusual event. In Company B’s rooms members were busily packing their knapsacks, rolling their blankets, and getting into their uniforms. Every now and again some member who was notified late in the evening would come running in and endeavor to make up for lost time. The experience of being called out was to them a novel one. Whoever thought that they—the National Guard, the “tin soldiers”—would ever be called upon to do anything more arduous or dangerous than to parade the streets on a holiday for the sake of eliciting admiration from the fair sex. Here was an opportunity for them of a lifetime to dissolve forever the charge of the contemptuous wretch, who stands upon the edge of the sidewalk during a parade of the National Guard and sneeringly remarks: “If they only smelt powder, how they would run.” Every member of the Guard determined that they would on this occasion establish a reputation far beyond the possibility of ever being open to the charge of being “sidewalk soldiers” again. They would—and many a noble resolve was made that night. To those standing upon the street watching the preparations of the militia to depart and who derisively jeered, the men said nothing, but to themselves said: “You just wait a few days my fine fellows and we will show you what we can do.” But alas, who can ever tell what the wheels of time will bring forth. At the same time everyone was more or less excited. Some were gay, others were thoughtful, and again some probably felt a peculiar sadness, feeling perhaps as though they were taking their last leave of those persons and things which were closely associated with their lives. Even the turning of the key of their locker was done with tenderness. For who knew that this would not be the last time. All, however, were ready for orders.

[Pg 20]

At 9:40 P. M. the command was given to “fall in.” Company B proceeded to the drill-hall, where they were formed by First Sergeant A. F. Ramm. On roll-call the following men answered to their names:

| Captain | I. B. Cook. | Private | Hayes, |

| 1st Lieut. | E. C. Lundquist | “ | Heeth, A., |

| 2d Lieut. | Geo. Filmer. | “ | Heizman, |

| 1st Sergt. | A. F. Ramm. | “ | Kennedy, |

| Sergt. | B. B. Sturdivant, | “ | Keane, |

| “ | A. H. Clifford, | “ | Lang, |

| “ | W. N. Kelly. | “ | Monahan, |

| Corp. | J. N. Wilson, | “ | McKaig, |

| “ | B. E. Burdick, | “ | O’Brien, |

| “ | E. R. Burtis, | “ | Overstreet, |

| “ | A. McCulloch. | “ | Perry, |

| Musician | Gilkyson, | “ | Powleson, |

| “ | Murphy, | “ | Radke, R., |

| “ | Rupp, | “ | Radke, G., |

| “ | Wilson. | “ | Sullivan, H. B. |

| “ | Stealy, | ||

| Private | Adams, | “ | Sieberst, V. |

| “ | Bannan, | “ | Shula, F., |

| “ | Baumgartner, | “ | Sindler, |

| “ | Claussenius, G., | “ | Tooker, |

| “ | Claussenius, M., | “ | Unger, |

| “ | Crowley, | “ | Wise, |

| “ | Flanagan, | “ | Wilson, R. E., |

| “ | Frech, | “ | Williams, |

| “ | Fetz, A., | “ | Warren, |

| “ | Gille, | “ | Wear, |

| “ | Gehret, A. C, | “ | Zimmerman. |

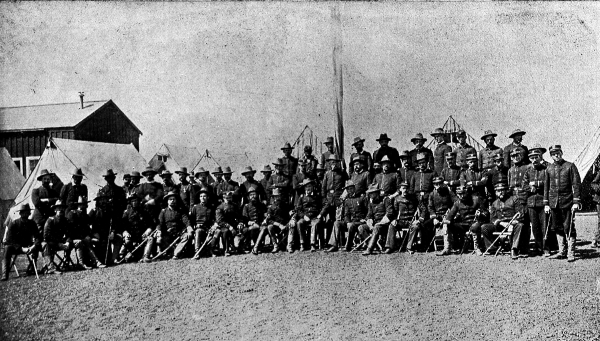

Upon the completion of the roll-call the company was turned over to the command of Captain Cook. In five minutes the entire regiment was mustered and formed in a hollow square. The size of the companies spoke volumes for the reputation of the regiment. It was now a little over three hours since the non-commissioned officers started on their tours of notification, and probably not more than an hour since some of the members were notified; still, here was almost the full regiment, thirty officers and three hundred and forty-six men, prepared to march. The zeal and alacrity with which the orders were obeyed is worthy of commendation. The men as they stood in ranks, attired in their campaign uniforms, their knapsacks and blankets strapped[Pg 21] to their backs, presented a striking appearance. May their appearance that night never fade from our memories. Colonel Sullivan stepped into the center of the square and made the following remarks:

“Men, we have been ordered to Sacramento to preserve the peace and dignity of the State. This is not a picnic trip; it is a serious duty. I have confidence that every man will do his full duty. I hope that our members will impress the enemy with the fact that we mean business, and I hope that no other recourse will be necessary. But if it becomes necessary to give orders to use ball and cartridge you must do it. You must remember that your own lives are at stake, and you will fire low, and fire to kill. These are hard words, but they are necessary words. I hope that we will return with the full number assembled here, and with honor and credit to the regiment. Fours right!”

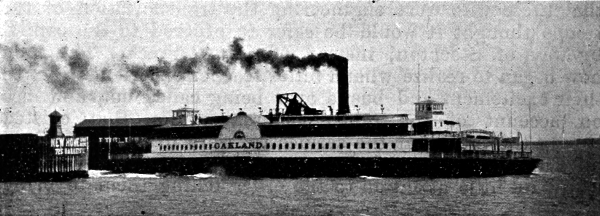

Each company executed the necessary movement, and marched out of the armory. The march was continued uninterrupted down Market street until Spear street was reached. Here a halt was made, and ammunition served out to the troops—twenty rounds to each man. The ammunition being distributed, the regiment marched upon the steamer Oakland, where they were joined shortly by the Third Regiment Infantry of twenty-six officers and two hundred and fifty-one men, and at ten minutes past eleven o’clock the troops bade farewell to San Francisco, and started for their destination.

The farewell reception the troops received from the public on their way down Market street, and while at the ferry, was one of a very mixed nature. Among the persons gathered to see us take our departure were a large number of men endowed with socialistic tendencies, whose view of the situation was so narrow that they viewed the calling out of the militia as an act of the Government’s to abet the railroad company in oppressing its employees, and not as an act necessary to maintain the laws of the land which guarantee to all equal rights in the protection of their property. These men jeered and cast all sorts of slurs at the men as they marched along. They sincerely wished that the strikers would give the troops their quietus. This was one extreme. The other extreme was made up of men of equally as narrow a view. These seemed to think that the workman had no rights whatever, and above all things, not even a shadow of a right to strike. They believed, or, if they did not believe it, they certainly[Pg 22] acted as if such were their belief, that the workingman should submit to all restrictions placed upon him, and that, if he attempted to rise above his conditions, then the Government should force him back again. These are the men who called upon us to blow the scoundrels to pieces. Between these two extremes there was a third element, made up of men who had a true insight into the condition of affairs: men who fully recognized the place that strikes hold in the development of the human race; men who detect in these visible presentations of discontent the conscious awakening of the workingman to a noble conception of his place in the history of civilization. It was from this stamp of men that the militia received its real encouragement; for they saw plainly that the ends of the workingman could not be attained through the disregard of the laws, but it was only by his developing with them and through them that he could even reach his true plane. Therefore, above all things, they desired to see the supremacy of the laws maintained. Viewing the calling forth of the militia as an instrument by which this was to be accomplished, they cheered and urged the troops to do that duty they had sworn to fulfill.

Upon the steamer Oakland reaching the other side the troops disembarked and marched up the mole. They were wheeled into line and halted. The command “Rest” was then given. Here the first of a series of provoking delays took place. The trains, which were to bear the troops to their destination were not fully made up; consequently the troops had to remain standing, at the time they most needed rest, upon the cold asphaltum for fully an hour. This does not speak well for those who were managing the transportation of the troops. It was extremely aggravating to the men, fatigued as they were after their march down Market street laden with baggage, to feel that, had a little foresight been exercised, they, instead of being compelled to stand upon the pavement for over an hour, might have passed that time in resting. A soldier, even though he is of the rank and file, is a human being, and needs as much rest as any other human being. At 1 A. M., July 4th, the troops were ordered aboard the train, and a start was made for Sacramento. The train was divided into two sections. The First Regiment was on board the first section, while the Third Regiment, together with the section of the Light Battery, occupied the second, and which followed after the first at about an interval of ten[Pg 23] minutes. Major General Dimond and staff accompanied the troops, and took passage on the second section. Brigadier General Dickinson and staff journeyed on the first section.

Each company had a separate car assigned to them. The members of Company B lost no time in relieving themselves of their knapsacks and blankets. Some of the men made up berths at once with the intention of getting as much rest and under as favorable conditions as possible. Others however thought it a waste of time to go to all this trouble for what they supposed would be but a few hours rest; so they simply stretched their legs upon the opposite seat and thus went to sleep. Here was another mistake. How much better it would have been had the men been informed that instead of a three hours’ journey before them they would be on the road eight or nine hours. The men then would have made due preparations for a good night’s rest. The Keeley Club, of which more will be related hereafter, appropriated a section of the sleeper to themselves, and, not knowing but what the days of some of them were numbered, proceeded to have a good time while they yet lived, for they knew that if any of their number did fall in the conflict with the strikers, that they would be a long time dead. All the early hours of the morning sounds of revelry could be heard coming from their apartment. Every now and again some tired individual, whose repose was broken by these revelers, would impatiently demand in language more forcible and expressive than can be represented here why it was they could not keep still. Ever and anon Captain Cook’s voice would be distinguished above the dim. “That will do now, let us have more quiet.” The effect of these commands was but temporary. A moment later they were at it again. And so passed the morning.

Precautions were taken to attract the least amount of attention possible. The window-shades were drawn so as to prevent the gleam of lights from tempting missiles from the strikers. In spite of these precautions, just after the train passed Sixteenth Street Station, a rock was hurled through the window of the cab of the second section narrowly missing the head of the engineer. Before the First Regiment left the armory, details were selected from each company to act as train guards, and placed under the command of Lieut. Thompson of Company G. Their special duty was to guard the[Pg 24] engine. Company B, Third Infantry, Captain Kennedy commanding, was detailed as train guard for the second section. Besides these guards sentinels were posted by the First Sergeants of each company at both ends of the cars. These men were stationed upon the platforms and relieved every hour. Their orders were of a twofold nature: First, they were to prevent anyone from leaving the car; Secondly, they were to alight whenever the train stopped and see that no one interfered in any way with it. Any person they saw approaching the train they were to call upon to “halt.” If the order was not obeyed they were to warn him, and finally if this proved ineffectual they were to fire upon him. Each sentinel loaded his piece as he went on duty. No sentinel had occasion to carry out literally his orders as the journey to Sacramento was practically uneventual. At Sixteenth street, Oakland, the train was delayed for a short time. Here it was found that the Block switch system would not work, the pipes containing the wires having been cut, thus rendering the entire system useless. The nature of the damage having been ascertained, the train proceeded on its way.

When the train stopped at Sixteenth Street Station the sentinels alighted in pursuance of their orders. There were a considerable number of people gathered at this place. Here it was that an unknown person, who was evidently a striker bent on mischief, but who claimed to be a deputy marshal, was given an opportunity of measuring the caliber of the men of the “City Guard” and of the National Guard in general. This person emerged from the crowd and was approaching the train, when Private George Claussenius, noticing him, called upon him to halt. The fellow, not a bit disturbed merely said: “Oh, that’s all right, I’m a deputy marshal.” This explanation might have been accepted in some quarters, but this time he knocked upon the wrong door. Claussenius quickly threw up his rifle, and forcibly said, “I don’t care who you are; Halt!” The man paused, undecided whether to advance or retreat. Lieut. Lundquist, who was standing upon the platform, took in the situation. “Claussenius,” he quietly said, “if that man advances a step further shoot him.” In an instant the man’s indecision vanished. He turned and slunk back into the crowd. The man’s identity was never ascertained. If he was a striker the reception he received was a proper one;[Pg 25] and if he was a deputy marshal he can thank his stars that his departure was not accelerated by the prod of a bayonet. These men, recruited in many instances from the scum of mankind gave themselves the airs of a Lucifer. But before the campaign was over more than one of them was taken down a peg or two by the different members of the National Guard.

At Tracy Private O’Brien had an amusing experience with a rustic. It was early in the morning. The sun had just begun to trace his westward course in the heavens. The fields, with one exception, seemed deserted, as far as the eye could stretch. The air held a deep stillness which was broken only by the sweet singing of the birds and disagreeable snoring of the soldiers. It was a beautiful opening of a Fourth of July morning. Crossing one of the fields at this time was a country rustic who, upon seeing the train, had his curiosity aroused; so, changing his direction, he advanced toward it. It so happened he approached the car that O’Brien was guarding. What a queer specimen! He was attired as the rustic is generally represented upon the stage. His trousers were drawn up almost to his neck by an abbreviated pair of suspenders. His head was covered by a well-battered straw hat, and his feet incased—O’Brien swears that they were number 14—in a cowhide pair of boots. O’Brien amusingly sized him up until he arrived within about four feet from the car, then suddenly stepping forward he brought his piece with a snap to the “charge bayonet,” and cried out sharply “halt.” Astonished at the unexpected sally, the rustic started involuntarily backward and exclaimed, “Why the gol darn thing’s got stickers on ’em.” A visible representation of the stickers was enough for the countryman. He did not approach closer.

The men as they awoke into consciousness that morning, but little refreshed by their short repose, were surprised to find that Sacramento was still a considerable distance off. It seems that those who were engineering the transportation of the troops thought it would be safer to proceed to the capital by way of Stockton, instead of going direct. The men now began to realize what a bitter teacher experience is. In their excitement and bustle over being called out, and also on account of the pretty general opinion that existed among the men that the service we were to perform would not last more than a day or two at the most, many of the men paid little attention to the order telling them to bring[Pg 26] rations and underclothing. As the morning gradually advanced unto noon their stomachs began to remind them that it was time to eat. They were ready to eat; but what? That was what troubled them. Fortunately the company is possessed of some far-sighted minds when the subject under consideration is the stomach. These men had brought with them a good supply of food. But even when these divided their supply in true Samaritan style, the quantity given to those that did not bring food was so small that it alleviated but slightly the pangs of hunger. Company B suffered less in this respect than did the other companies. A large number of B’s men love their stomach too well to run the smallest chance of having it suffer. Future developments will disclose what dreadful effects the misusing of their beloved organ had upon the men. The hungry mortals looked forward longingly for their arrival at Sacramento. For here surely they would be adequately supplied. But they were doomed to disappointment. Adjutant General Allen worked upon this hypothesis, that if the men did not bring the rations he ordered them to, they themselves were to blame and must therefore suffer the consequences. But how foolish is such reasoning. What if the men are to blame? Is it not the duty of a general to see that his men receive the proper subsistence. It is indeed a poor commander who hopes for success and at the same time allows his men to suffer hunger in the midst of plenty. Happily the men did not know what awaited them, they were content to live in hopes.

The train passed through Stockton at about 6:30 A. M. Here Companies A and B of the Sixth Regiment were standing in line ready to join the San Francisco regiments and proceed to the capital. They were taken on board the second section. The journey from Stockton was soon finished, and at 8:30 A. M. the first section arrived in Sacramento, and stopped at Twenty-first street.

[Pg 28]

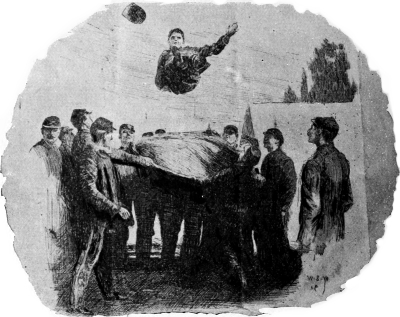

THE MOB IN FRONT OF THE DEPOT AT SACRAMENTO, JULY 4TH, 1894.

(BARRY BALDWIN HARANGUING THE STRIKERS FROM

THE TOP OF A PULLMAN CAR.)

[Pg 29]

FOURTH OF JULY AT SACRAMENTO.

“In war take all the time for thinking that the circumstances allow, but when the time for action comes, stop thinking.”

Andrew Jackson.

SACRAMENTO at last! Ah, boys, little did we think when our section pulled in at Twenty-first street, that we were now on the future field of the great and glorious, but bloodless battle of “The Depot.” The battle of strategic “co-operations” and still existing “truces,” in which we were destined to take such a prominent “standing” part.

Sacramento! The scene of our future troubles and joys (much of the former but how very few of the latter). Our troubles began when the order came to sling knapsacks and form in the street. That never to be forgotten 4th of July was a banner day for heat, even in the annals of sultry Sacramento; and as we stepped from our car, tired, hungry, and oh, my! how hot, we were inhumanely confronted by a large sign on the side of a brewery, “Ice Cold Buffalo 5cts.” The eye of many a brave comrade grew watery and his mouth dry as we stood there in the burning rays of the sun with our knapsacks and blankets on our backs facing that sign like a little band of modern Spartans and waiting patiently for the[Pg 30] order to march. Soon the “glittering staff,” armed to the teeth, passed “gorgeously” by; the order “forward” echoed along the line, and the “army of occupation” was in motion.

We had arrived and formed at 8:00 and marched at about 8:30. The train stopped at Twenty-first and R streets, and our line of march to the armory was as follows: North along Twenty-first to P, along P to Eleventh, along Eleventh to N, along N to Tenth, along Tenth to L and along L to the armory on the corner of Sixth, in all fully three miles.

Never before did the Old City Guard participate in such a 4th of July “parade.” After a long night of unrest, trudging along block after block through the sweltering heat, without the enlivening sounds of drums or fife, our heavy packs growing heavier at every step, the salt perspiration blinding our eyes, and looking up only to see the heat dancing along the road in front of us, we felt little inclination to joke or notice the open-mouthed wonder of many of the onlookers. Still we could hear the remarks of the bystanders, that they “guessed the strikers felt sick this morning,” or of the apparently less impressed small boy who “reckoned de strikers would pop off dat fatty fust.” The betting was even as to whether he meant Kennedy or Sieberst, but the rival claimants “co-operated” by rendering a decision.

Worn, weary, and hungry we arrived at the Armory at 9:15, and found the Sacramento troops, Companies E and G of the Second Infantry, already under arms. Stacking arms on L street, and a strong guard being left at the stacks, we were marched in column of twos into the armory drill-hall where the now world-renowned “ample breakfast” supplied by Adjutant General Allen, late Second Lieutenant Commissary Department Missouri State Volunteers, awaited us. This, according to General Allen, “ample breakfast,” consisted of coffee strong enough “to run for Congress,” and bread. Certainly a very “ample” breakfast for men who had been awake and traveling all night, many without dinner the evening before, and executed such a trying march that morning. Ample, too, when it is considered that this was intended to serve both as breakfast and lunch, and, it might be dinner.

Thus is a lesson in economy given by the military heads of this great State to the civil heads who may wish to profit thereby.

[Pg 31]

Thus is the frugality of our forefathers, in their great battle for home and freedom on the shores of the Atlantic, exemplified on the distant shores of the calm Pacific by our ever to be remembered Adjutant General, late Second Lieutenant Commissary Department Missouri State Volunteers.

However, despite our foolish doubts as to the amplitude and quality of our meal, the shade of the hall and the relaxation from the fatigue of the march were very welcome.

While we were regaling ourselves a shot was heard fired in the street in front of the armory; and the report quickly spread that the shot had been fired by a striker in the crowd, wounding a soldier on guard at the stacks. This, however, proved untrue, as it was found that a private of the Sixth, in loading, accidentally discharged his piece, the firing-pin of which seems to have been rusty, the cartridge exploding when he tried to force it home. The bullet struck the front rank man in the calf of the leg, wounding him severely. Passing through the guardsman’s leg, it struck on a rock in the street and split, both pieces glancing into the crowd of sightseers. In the crowd four persons in all were injured, more or less severely; one of them, Mr. O. H. Wing, a citizen of Sacramento, being struck in the abdomen and killed. His death was deeply regretted by the soldiers; especially so as Mrs. Wing, his gentle, high-minded widow, wrote to the soldier, the unfortunate cause of her bereavement, exonerating him from all blame and assuring him of her deepest sympathy.

Having finished our ample breakfast the City Guard was marched from the armory in column of twos, and allowed to rest in the shade of an awning on the corner of Sixth and M streets.

Now and all during the campaign which followed the absurdly childish way in which the press and many of the people looked on the citizen soldiery, and on the work which they were doing at the call of their country, was both surprising and irritating to the men who had left their homes and business to protect the lives and property of their fellow-citizens. It is true this was no wild unled mob. It was worse; as was proven later by the most cold-blooded train wreck and murder ever perpetrated in the West, that of the 12th of July. A murder far beyond the abilities of our[Pg 32] ignorant Eastern mobs, planned by the leaders and executed by some of the most important members of the A. R. U.

The absurd position of antagonism to the soldiers taken by the people was instanced on this first morning in what now seems a rather amusing incident, though it needed but little more to make it very serious at the time.

When arms were stacked in the street in front of the armory guards were posted round the building; L street at its crossing with Sixth and for a short distance towards Fifth and Seventh streets being most heavily guarded. This of course stopped the passage of all teams over this street for about the distance of a block. As “B” was leaving the armory to make room for the less fortunate companies which had not yet been introduced to General Allen’s breakfast, by this time reduced to bread and water, we saw an infuriated fool driving a wagon in which were seated two women and a child, lashing his horse at a furious pace through the line of sentries. He had passed several, but just at the crossing of Sixth street met men of sterner stuff. Two sentries, members of a Sacramento company, who happened to be close together and in the center of the street, decided to stop his mad career. One brought his piece to the “charge bayonets” while the other prepared to grasp the horse by the bridle. This he did, and did well, just as the horse reared at the pointed bayonet, carrying the soldier with him. Had he missed his leap for the bridle the horse would most undoubtedly have been impaled on the bayonet. The beast in the wagon became laughably furious when the beast in the shafts was stopped. He wasted his breath shouting out the usual jargon about “being a taxpayer,” etc., but it was of no avail; he was led ignominiously back over the route over which he had made his glorious charge for principle, greeted by the laughing jeers of the crowd that cheered him but a moment before as he made his mad rush to get through. Such is the uncertainty of public favor.

Here in the shade we waited, amusing ourselves as best we could, our guards at the company stacks being relieved every half hour until at 11:15 A. M., we received the order to fall in, preparatory, it seemed to the unconsulted enlisted man, to moving on the depot. This was confirmed in our minds when, having formed at the stacks, we were relieved of the heavy burden of our knapsacks; these being placed on wagons impressed for the purpose.

[Pg 33]

The division formation was made on Sixth street, the boys of “B” feeling greatly chagrined when they saw Brigadier General Sheehan’s four companies, “E” and “G,” of the Second Infantry, and “A” and “B,” of the Sixth Infantry of Stockton take the van; and surprise, too, thinking, as we did, that the lack of faith in the Sacramento companies at least was the real cause of our call for service. Later on that trying day our misgivings were justified.

The First Regiment under Colonel W. P. Sullivan fell in behind General Sheehan’s command. The First Battalion, under Major Geo. R. Burdick, consisting of companies “A,” Captain Marshall, “H,” Captain Eisen, “G,” Captain Sutliff, and “B,” Captain Cook; and the Second Battalion under Major Jansen, consisting of companies “F,” Captain Margo, “D,” Captain Baker, and “C” under Lieutenant Ruddick. The Third Regiment of Infantry, Colonel Barry commanding, brought up the rear, and acted as guard to the baggage. General Dimond and staff, and the Second Brigade Signal Corps, Captain Hanks, marched in rear of the First Regiment.

The movement toward the depot commenced at about 11:45 A. M., the companies of General Sheehan’s command marching in close column of company, and the San Francisco regiments falling almost immediately into street column formation; the Gatling gun section of Light Battery “A,” under 1st Lieutenant Holcombe, taking position in the hollow of the First Battalion of the First Regiment.

To those in the ranks it seemed as though the large crowds of gayly dressed sightseers which followed us, looked upon our march as a Fourth of July celebration. This, without doubt, was the cause of the remarkable sight which greeted us, as the Sacramento and Stockton companies fell away from our front later in the day, and exposed to our view a motley crowd of men, women, and children. It seemed more like a Saturday afternoon crowd on Market street than a mob resisting the authority of a United States marshal. Still it took but a second glance to tell us that the great majority were strikers.

What interesting studies were our comrades as we marched quietly along toward the depot; how truly were the feelings of each depicted on his face. Here and there fear was to be seen, plainly mingled however, with a determination not[Pg 34] to yield to the feelings. Some, too, seemed to feel an elation at the approaching conflict, while by far the greater number marched along with an indifference surprising in men who were answering their first call for actual service, and that, too, against men as well armed as they, angry and determined not to yield a foot. The militia well knew that this was no beer-drinking, stone-throwing, leaderless mob, to which the East is so well accustomed; but, on the contrary, that it was a well-organized and coolly led mob, holding the advantage of position and determined to fight rather than yield.

As the column debouched from Second street into the open ground before the depot, men wearing the A. R. U. badge could be seen rushing in from all directions, summoned, by furious blasts on a steam whistle, a preconcerted signal used by the strikers as soon as the intention of our officers became apparent.

When the head of our column had almost reached the open west end of the depot the command was halted, our battalion still keeping its street column formation. Then commenced a trial far more trying in the minds of most of us than even the hot fight we had so surely expected, would have been. It was now high noon and the sun had reached its zenith, the heat being remarkable even for Sacramento; the road was covered with a fine dust, which, stirred by the restless feet of the waiting soldiers, hung in clouds in the warm air, making breathing almost impossible.

As the column halted, the crowd which had been following us and which gathered at the blast of the steam whistle rushed in around the four foremost companies, completely shutting them off from our view, except for the line of bayonets which glistened above the heads of the mob. Then commenced a scene of confusion almost indescribable. Shouts, cheers and hoarse commands mingling in an uproar that at times was deafening. The strain on the San Francisco troops now became intense; the lack of sleep and food, combined with the terrific heat and the excitement and anxiety of the occasion, began to have its effect; many of the men tottered and fell. They were quickly borne off by their comrades in the ranks or by men of the fife and drum corps, who did efficient service on that trying day, to the hospital, established temporarily in the pipe house of the water company, where the Hospital Corps of the First did heroic work; gaining, as of course, no recognition thereof by the press.

[Pg 35]

The uproar in front continued. Suddenly the glittering line of bayonets fell and shouts from the mob of “Fall in there!” “Get in front!” “Don’t give a step!” resounded over the tumult. Anxiously we waited to hear the next order, which might ring the deathknell of many of our comrades, when shout after shout pealed out from the excited mob. A thrill ran along our ranks. “They had thrown down their arms.” We gritted our teeth and waited breathlessly for the order to charge. But that order was not to come during that whole trying day. Three times did the report run along the line that the Sacramento men had thrown down their arms and then taken them up again at the entreaty of their officers. The men in our ranks began to feel disgusted. Was this to be the performance gone through by each company in turn? Were they to be cheered and argued with, coddled and cajoled out of the ranks? Standing there in the dust, burning with thirst for water we dare not touch, with the thermometer above one hundred and five degrees in the shade, watching the farce in front, and looking off toward the vacant unprotected south front of the depot, knowing well that a corporal’s squad, if thrown in from the rear, could clear it, and yet powerless to move, it would have been little wonder if the best trained regular troops became disgusted. “Why do we not take the strikers in the rear while they palaver with the men in front?” “Where are our Generals, not a sign of whom have we seen since our arrival, and their staffs, numbering enough in themselves to clear the depot?” However,

We must stand there and await developments. They were certainly improving our tempers to fight, for we would have fought an European host for the chance to get into that shady depot and escape the burning heat of the dusty road. The men continued to fall on all sides exhausted, and it seemed as if the laurels of victory would deck the brow of a third party—Old Father Sol. The uproar of shouts, cheers, and yells continued in front. Suddenly a wave of surprise, then of satisfaction, passed over us. The Sacramento troops were marching off the ground, followed by a frantic mob of men and boys. Our chance would come soon. Speculation now became rife. Would the Stockton men do the same, or would they press forward against the mob? A few minutes of tumult, mingled yells and cheers for “Stock” settled the[Pg 36] question for us. We saw the flash of the bayonets as the pieces were brought to the right shoulder; fours right, column right, and the Stockton companies marched by, cheered to the echo by the strikers.

Our turn at last! A yell of “Three cheers for the San Francisco boys” was answered lustily by the mob. But we had gone beyond that; we wanted that depot, and meant to have it if the officers would only give the order. We grasped our pieces ready for the order, “Forward,” those who were growing sick and dizzy bracing themselves for a final rush. But the order never came. Cries for quiet and of “Baldwin” came from the mob nearest the Depot, and looking over the heads of the crowd we could see Marshal Baldwin mounting to the roof of the cab of one of a string of dead locomotives which stretched along the main line west. He was quickly followed by three or four leaders of the mob, who succeeded in quieting the crowd by assurances of “keep quiet”; “one at a time”; “you’re next”; etc. Now began a novel scene indeed. Imagine a United States marshal, with six hundred soldiers at his back, pleading with a mob with, as it seemed to us, tears in his eyes, to disperse, to surrender the Depot, to return to their homes. From that moment the strikers knew that the day was won, that no troops, no matter how willing, would enter that building while commanded by Marshal Baldwin, without the strikers’ own kind permission. How that mob enjoyed our humiliation and the scene of a United States marshal pleading with them like a child. We had been called from our homes for active service, and now stood, in all our useless bravery, the audience of a farce in real life.

The farce proceeded. The men on the cab draped the marshal’s head with small American flags, exchanged hats with him, and indulged in a few other pleasantries for the edification of their friends below.

Failing in his first purpose the marshal now began to plead for time that he might meet Mr. Knox or Mr. Compton and talk it over with them; methods which were supposed to have been tried before the call for military aid. He begged for a truce until 3 o’clock. Oh, the irony of it! He, the aggressor, begging for a truce at the hands of a mob until then plainly on the defensive. They refused the truce, the time was too short, they said. “Then 5, 6 o’clock,” appealingly spoke the marshal. Seeing plainly that the day was lost and that any [Pg 39]greater delay would now only be injurious to his own men, Col. Sullivan of the First, who, by the way, appeared to be the ranking officer present, though there had been at least four general officers with us in the morning, stepped upon the cab and told the mob, not in tones of pleading, but decidedly, that this truce must be entered into; that his men were not used to such extreme heat, and that he intended to move them into the shade. Suddenly Knox, the leader of the strikers, escorted by a large American flag, emerged from the depot, cheered loudly by the mob. Now, it appears a truce until 6 o’clock was quickly entered into, and the men who had marched confidently through the town that morning were, amid the hoots and jeers of the people, led away, sullen and dispirited, to a vacant lot by the side of the depot. Here the men of the First were allowed to rest and take advantage of such shade as they could find. B and the section of Light Battery A took possession of an old shed; C and G found another in rear of the first, which they appropriated to their own use; D was stretched on the ground a short distance farther on, and the other companies mingled together in the shade of some trees some distance to the right of B’s position. It could now be seen that, among the men, the disgust at the failure to accomplish what we had come such a distance to do, was very great. In B, at least, it was deep and genuine. All during that long sultry day the unprotected front entrance of that cool, shady building had stared us in the face, and yet, for some unaccountable reason, we did not get the order to enter. We felt that the strikers would retire if a company were thrown quietly in through that end, and were justified in our opinion, when, some days later, a corporal’s squad of regulars cleared the place in a few moments.

Under the influence of the rest and shade our excited feelings gradually became relieved. Talk as we might we could not improve our situation, so we soon resigned ourselves to circumstances, and waited as quietly as possible for 6 o’clock. The men of the Hospital Corps, under whose care 150 men had been placed during those three hours, now gradually drew ahead with their work, and soon had all their patients relieved. Out of the 150 soldiers prostrated we are glad to be able to say that only three were from B, and even these, after a few minutes’ rest, were able to lend their assistance to the Hospital Corps themselves.

[Pg 40]

Delegates from the strikers now made their appearance, with the evident intention of getting the soldiers drunk before six o’clock. Captain Cook, however, ordered his men to accept no invitations to drink. Not to be baffled, the strikers soon reappeared, carrying cases of bottled beer, which the captain quickly refused to allow his men to receive. Still persistent, a striker stepped into the shade of our shed carrying two quart bottles of whiskey, which he proceeded to toss amongst the men. The captain was still on the alert, however, and ordered the bottles returned, telling the overgenerous striker that he would not allow his men to receive liquor.

Lieutenant Filmer and Sergeant Kelly were then sent into town, with orders to purchase two cases of soda water, which, on its arrival, was quickly disposed of. Quartermaster Sergeant Clifford, ever watchful, procured at a coffee house close by a supply of buns, which he quickly manufactured into sandwiches, and distributed amongst his famished comrades.

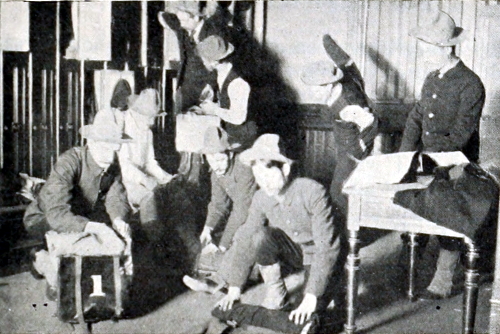

The scene had by this time become exceedingly picturesque. The tired, wearied men had quieted down, some stretched on the ground sleeping heavily, their heads pillowed on rolled blankets or on knapsacks; others resting in the same way, though chatting quietly, and still others were busily writing letters, using the head of a drum or the back of a knapsack placed on the knees as they sat on the ground as a desk.

It has been commonly reported that the soldiers became boisterously drunk, and fraternized freely with the very men they had come there to fight. If this be so, it was confined almost entirely to the other commands, no man of the First, to our knowledge, and most decidedly none of “B,” being even slightly intoxicated. The afternoon passed slowly by, no apparent preparations being made to resume hostilities at the expiration of the truce. Six o’clock came, but with it no change of position. Now we began to wonder whether or not our “ample breakfast” of the morning was intended to serve as supper, too. If that were so, we decided that man’s nature had changed since General Allen was young, for we certainly began to feel the pangs of hunger.

Our fears were allayed, however, when, at 6:30, the order “Fall in for supper” was given. Taking our arms with us, we were marched, under command of Lieutenant Filmer, to the State House Hotel, where our display of gastronomic powers completely dismayed the scurrying waiters.

[Pg 41]

Returning from supper our pace was an evidence of the good use we had made of this chance to appease our appetites.

Returned to our shed near the depot, it was evident the position remained unchanged. The different companies were either going to or returning from supper at the various hotels.

The evening passed quietly; many of the men sleeping on the ground where they had thrown their knapsacks.

At about 9:30 P. M. Captain Cook formed the company, and told us that the First would be removed to the Horticultural Hall, on the main floor of which we would be allowed to bivouac that night. The companies were already moving, and “B,” getting possession of an electric car, was the last company to leave. The car, as of course, proved to be the wrong one, and carried us less than half the desired distance. The rest of the way was covered on foot, the company arriving at the hall some little time after the other companies had settled down for the night. What a scene we would have presented to the eyes of a stranger! Every available foot of floor was covered with sleeping forms. The band stand and stage were utilized; even the steps, a very precarious bed indeed, were in demand; and every corner that appeared to offer security from draughts had its quota of men.

Thus ended that great and glorious Fourth of July, in the year of our Lord, 1894. Glorious, indeed, in the annals of this great Empire State of the West.

Thus, too, does history repeat itself. The Fourth of July! The anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, and of that greatest struggle of the Civil War of the Rebellion, the battle of Gettysburg; and now, for all future ages, to be trebly honored as the anniversary of the bloodless battle of the Sacramento Depot.

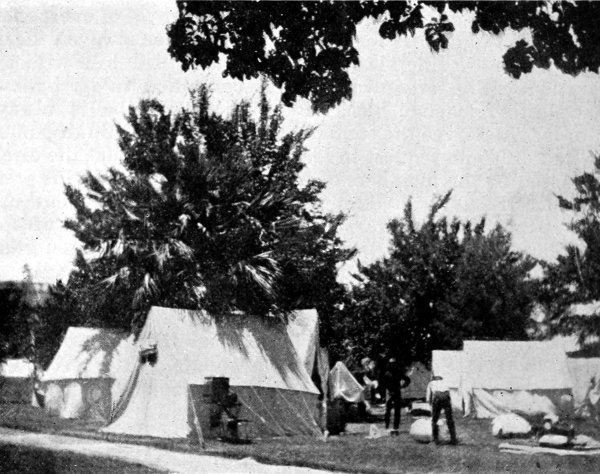

CAMP ON THE CAPITOL GROUNDS.

THURSDAY morning, July 5th, the weary members of the First Regiment were awakened from a comfortless sleep on the hard floor by the catcalls and shrieks of the early birds. Company F was quartered on the band-stand, and, from this point of vantage, sent up yells that would wake the dead; and clear and loud above all were heard the strident tones of Tommy Eggert. Sleep was out of the question, not to say dangerous, for soon bands of practical jokers were roaming around, like lions, seeking whom they might devour. Private Hayes discovered Sergeant Sturdivant in slumber sweet, his lengthy form enveloped in an immaculate and frilled nightgown, his tiny pink feet (he wears 10’s) incased in dainty worsted slippers fastened with pink ribbons; this was too much. Did he think he was at the Palace Hotel? If he even dreamed of such a thing he was soon to receive a rude awakening. Willing hands seized the blanket on which he lay, and he was yanked out into the middle of the floor. He awoke to find himself surrounded by a howling mob of men, while shouts of laughter filled the hall. What became of the nighty-nighty and those slippers is a mystery; for a number of the souvenir fiends of the company went on a still hunt[Pg 43] for those articles, but all in vain, they were never seen afterwards. Ben soon learned to sleep with his clothes on like the rest of the crowd.

Renewed confidence and security filled the rank and file when it was learned that we had received a strong reinforcement in the person of the old (young) Veteran Corporal Lew Townsend.[1]

[1] Corporal Lew R. Townsend is the veteran of the National Guard of California. He is 62 years of age, and has been in constant active duty for 40 years. He joined the First California Guard on July 12, 1854, and was transferred on January 30, 1857, to the City Guard. He remained a member of this organization until April, 1866, the date of the organization of the California National Guard, when it became Company B of the First Regiment Infantry, N. G. C. Lew continued his membership with this latter organization, and at present wears 13 service stripes, which show that he has served 39 years. On September 14th, 1894, he enlisted again, giving him credit for over 40 years of service.

Lew’s motto is “I’ll stay with the boys,” and he is the biggest boy in the crowd himself. Though his feet are going back on him a little, he manages to air his numerous medals, and bejeweled gun at all parades and military displays, and never misses a drill. He is still a good shot, and on Sunday morning, when his Palace Hotel breakfast agrees with him, makes the eyes of the youngsters over at the Shell Mound shooting range stick out of their heads at his remarkable shooting. May his kindly, jolly face be ever with us.

Soon the question of breakfast became of vital interest, and the faces of the boys grew very serious at the thought of a repetition of the heavy breakfast of the day before. But there were better things in store for us. The company received the order to “fall in,” and was marched to one of the downtown hotels, where a good meal was served. Thus fortified, we were ready for any thing, from playing marbles to killing a man. At this meal a nice large size linen napkin was placed at the plate of each man. Hereby hangs a tale. Handkerchiefs and towels were scarce. The boys had already been so well imbued with the principle of “taking,” by the illustrious and industrious example of Quartermaster Arthur Clifford, the great exponent of the art “of acquiring,” that seldom was a napkin seen again by any of the company on a Sacramento hotel dining-table. The honesty and rectitude of Van Sieberst must here receive special mention, his response to the call to serve his country was so hurried that he failed to supply himself with the necessary handkerchiefs and towels; but his fertile brain soon found a way out of this difficulty. He took a napkin, or, when such was not available, a roller towel from the hotel in the morning, used it all day as handkerchief and towel, but—here is where honesty became the best policy—returned the soiled article at supper, appropriated a clean one, and then, at night, slept that calm and peaceful sleep which the just alone enjoy.

After breakfast we were marched back to the hall, and there, for a few delightful hours, disported ourselves in its cool area.[Pg 44] This hall and the depot were the only cool spots in Sacramento. Scientists may rave about the spots on the sun, but a cool spot was the only spot that interested the ’Frisco boys while at Sacramento. The hope that we might continue to be quartered in this hall, was soon to be dispelled. The order came to fall in, and, after the usual ceremonies, the regiment was turned over to Colonel Sullivan, who made a short speech, in which he praised the conduct of the men the day before. The failure of the National Guard to accomplish its purpose could not, he said, be attributed to the lack of loyalty on the part of the First Regiment. He further stated that we would at once march over to the lawn of the Capitol where tents would be pitched, and camp established.

During the campaign the men were inflicted with all kinds of oratory. The number of speeches made would do credit to a political campaign, both as to quantity and quality. Colonel Sullivan started the flow of oratory at the armory with his dramatic and forcible “shoot to kill” speech. We had many speeches from him afterwards that ranged from the sublime to the pathetic. Who of us will ever forget the 4th of July, when we stood like Spartans under a blazing sun, listening to the oratory of Marshal Barry Baldwin and the strikers, who held forth from the top of an engine-cab. Major Burdick, many think, came next; but our boys say Captain Cook. We think they stand about even. Major Burdick’s speeches were longer; but, though Captain Cook spoke oftener (he gave us a rattle every morning before breakfast) and his speeches were just as long in point of time—he said less. A number expressed the opinion that these gentlemen were just practicing the art of spouting, to be in good condition to take an active part in the political campaign which would be inaugurated a few months later.

The regiment was then marched to the Capitol grounds, where tents were pitched on the nice, smooth, green lawn. It was afterwards rumored throughout the camp that this was done despite the objections of General Allen, who wanted the camp pitched on the plowed and broken ground just beyond the lawn. Our good General would not entertain the proposition; considering the comfort and welfare of his men of far more importance than the lawn. Hearing this rumor, the poet laureate of the company, after three days of close application, hard study, and great mental exertion produced the following poetic gem:

[Pg 47]