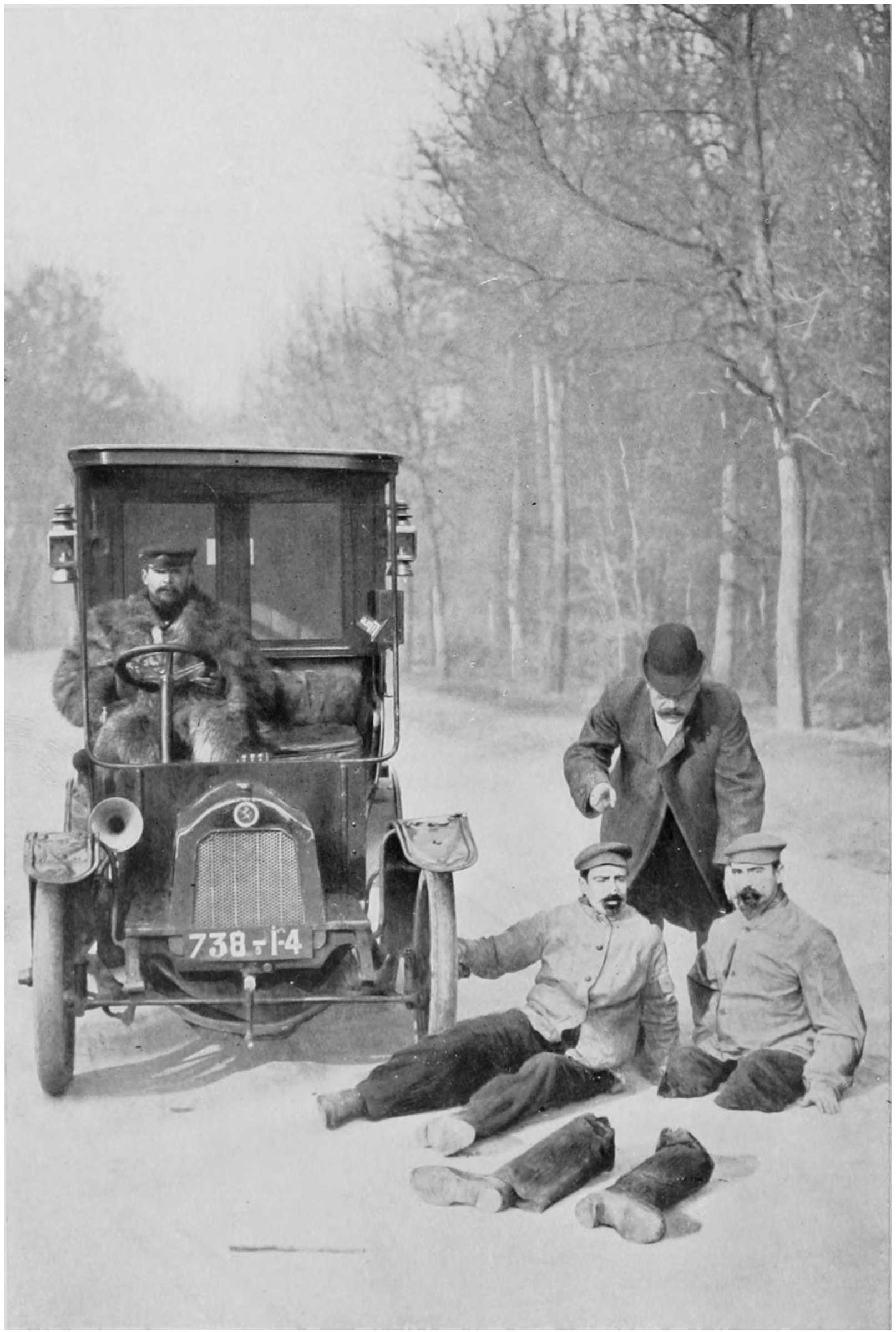

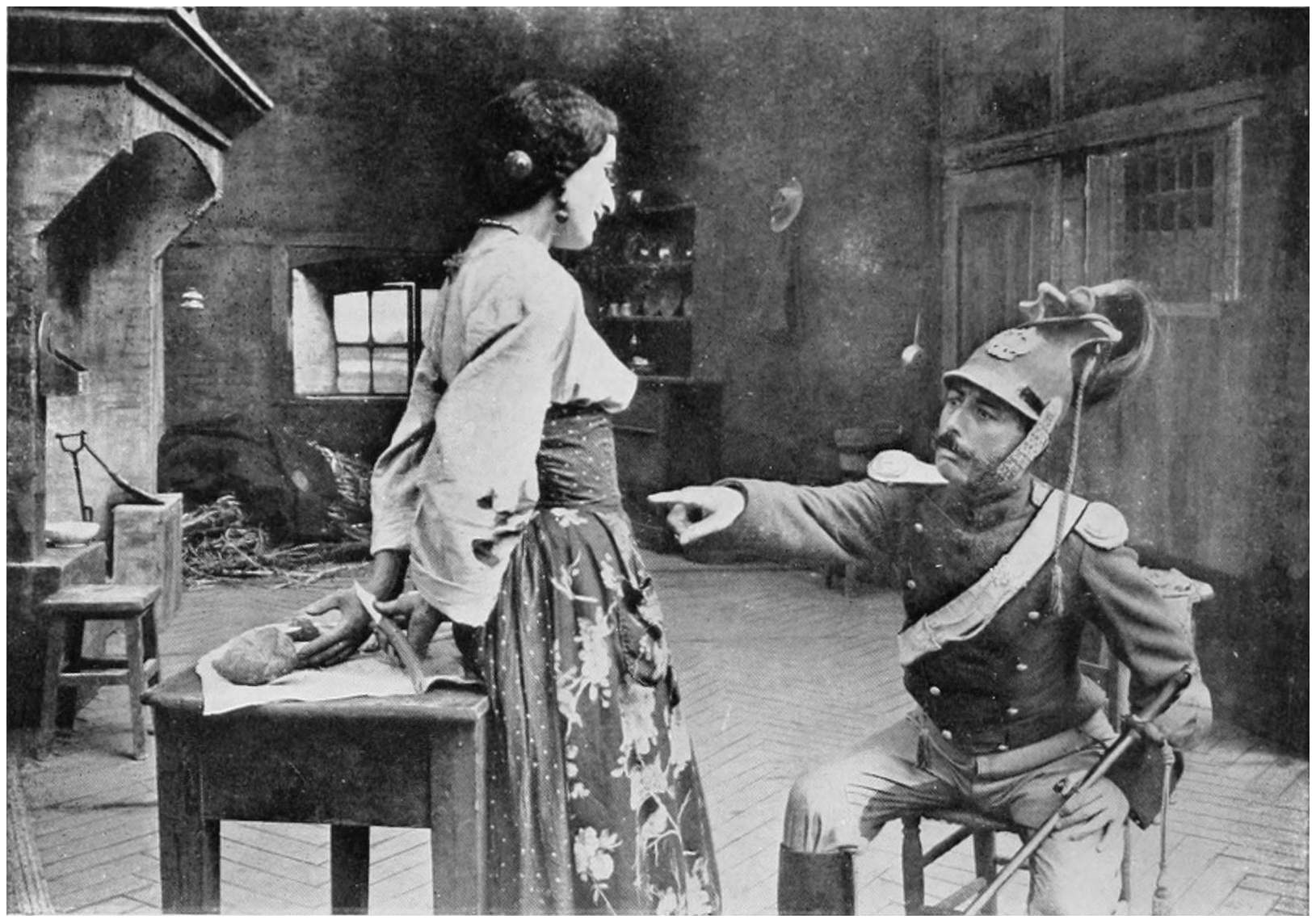

Frontispiece.

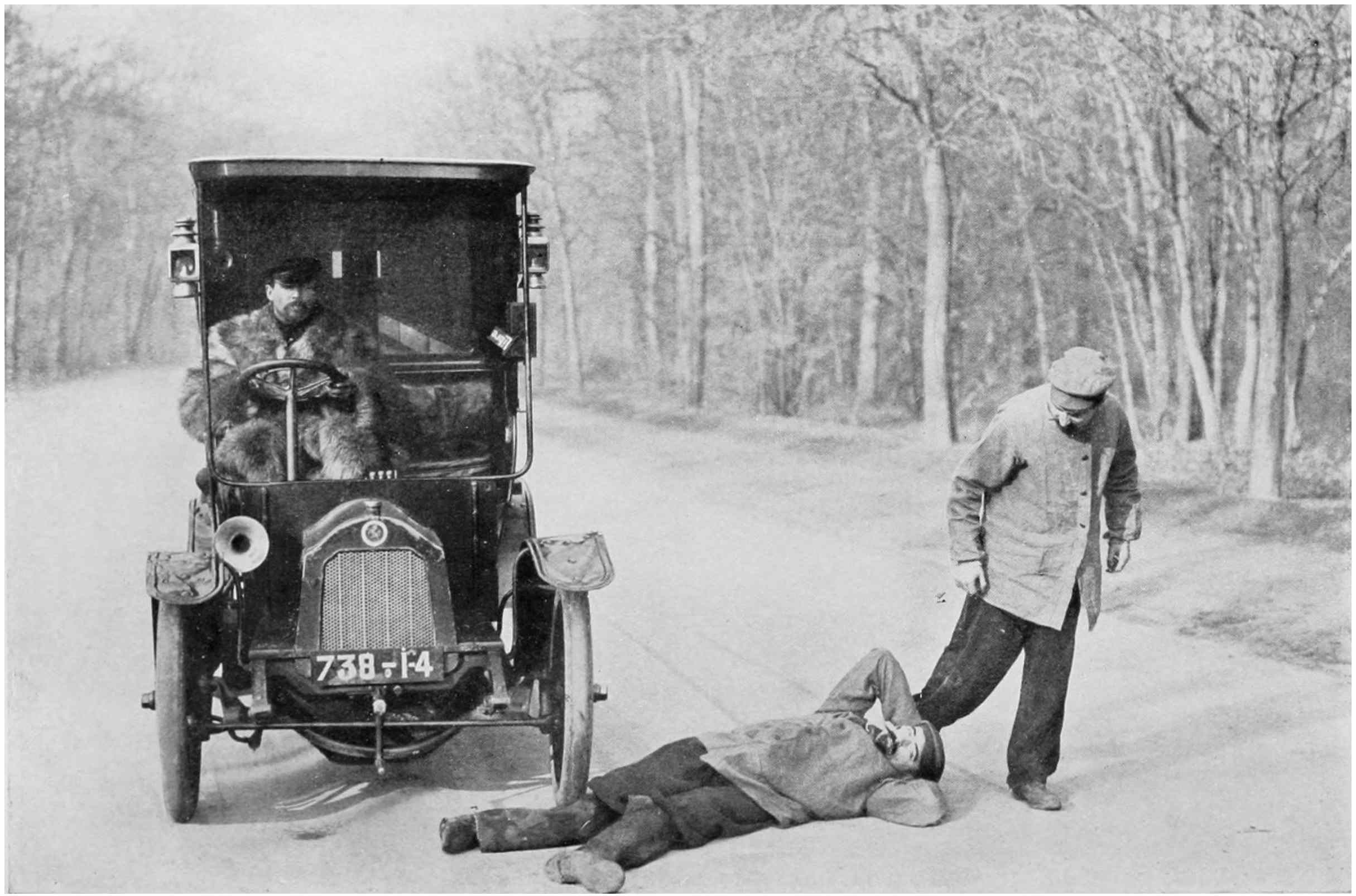

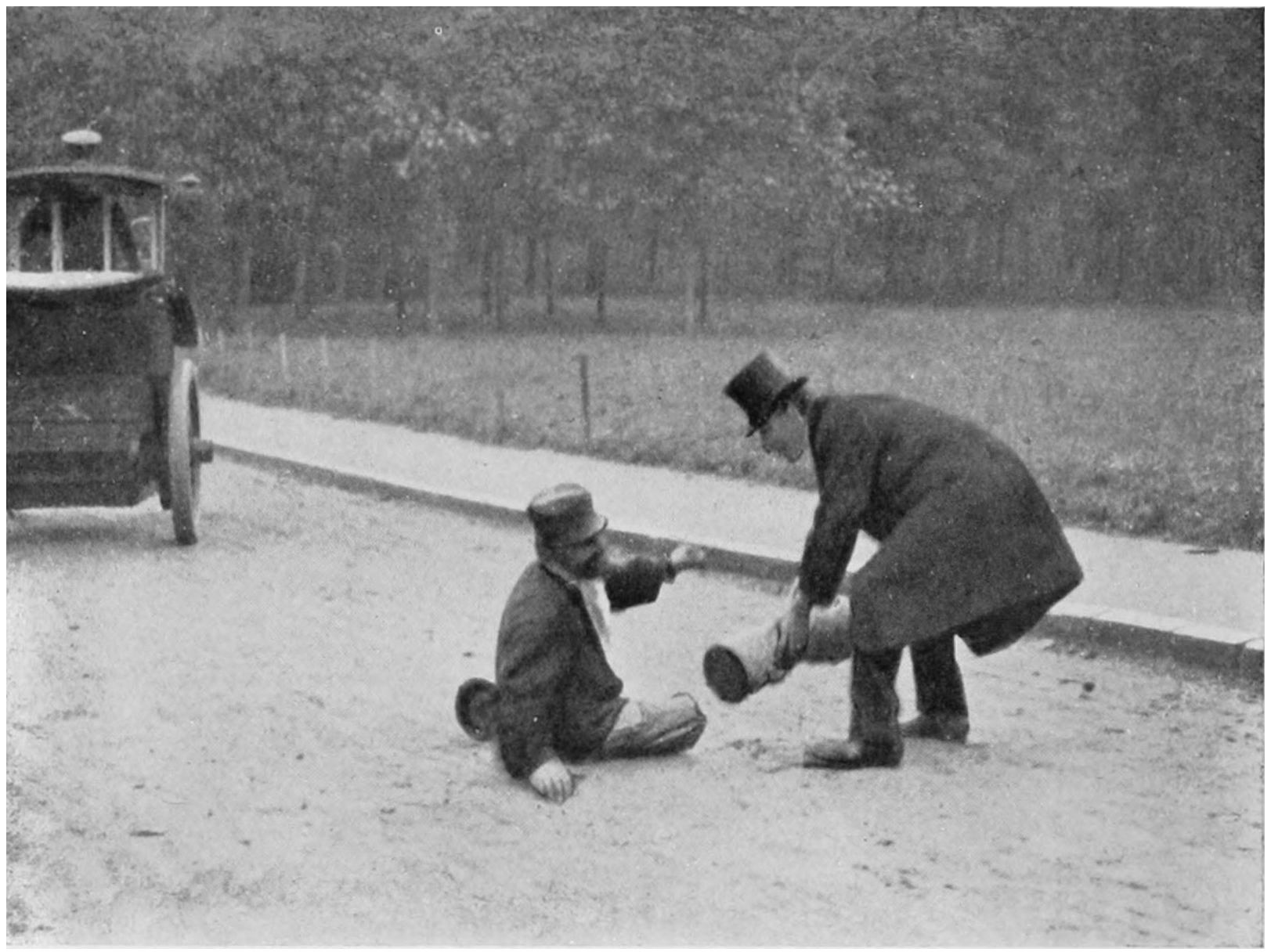

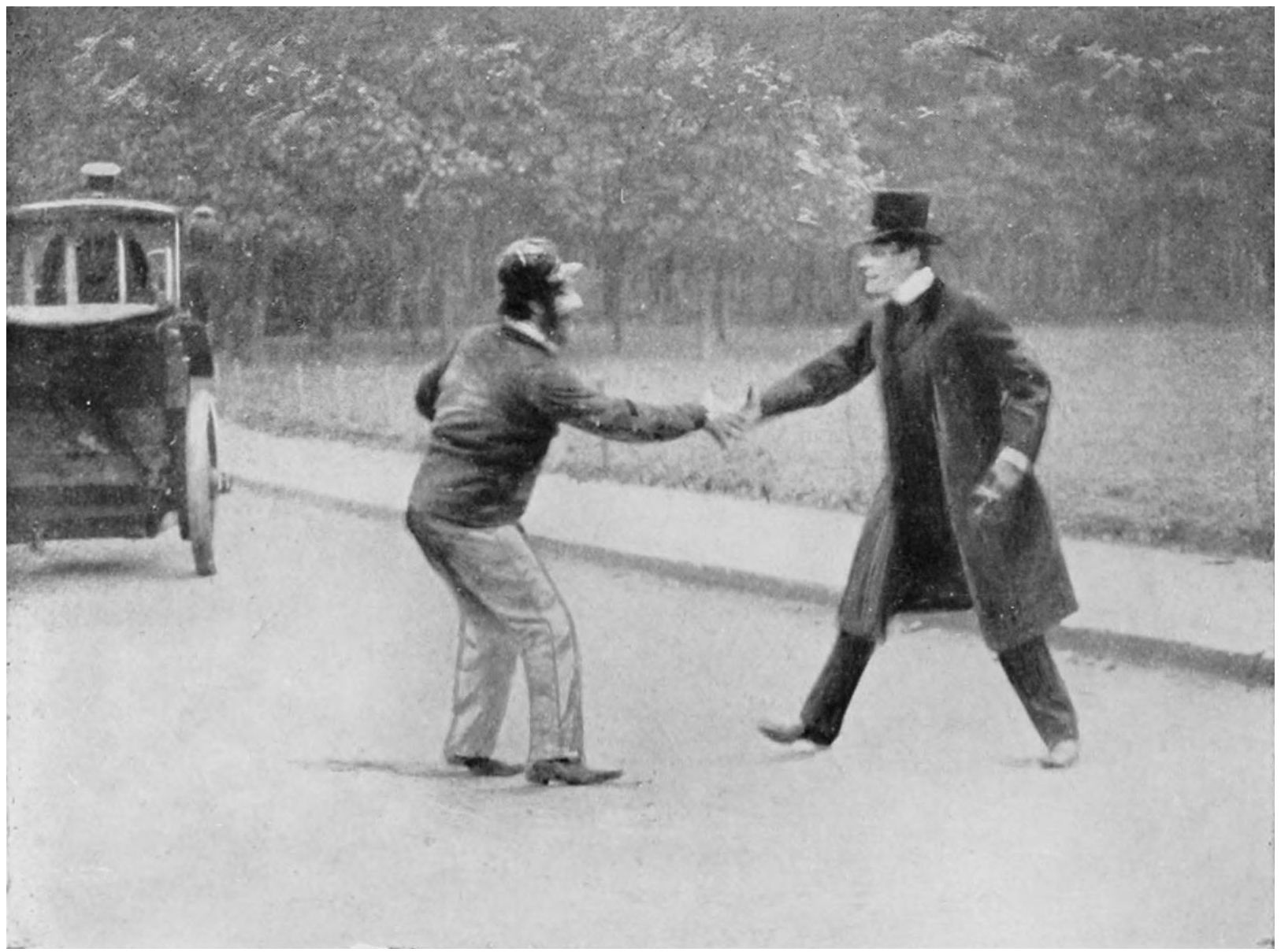

TRICK CINEMATOGRAPHY—THE AUTOMOBILE ACCIDENT.

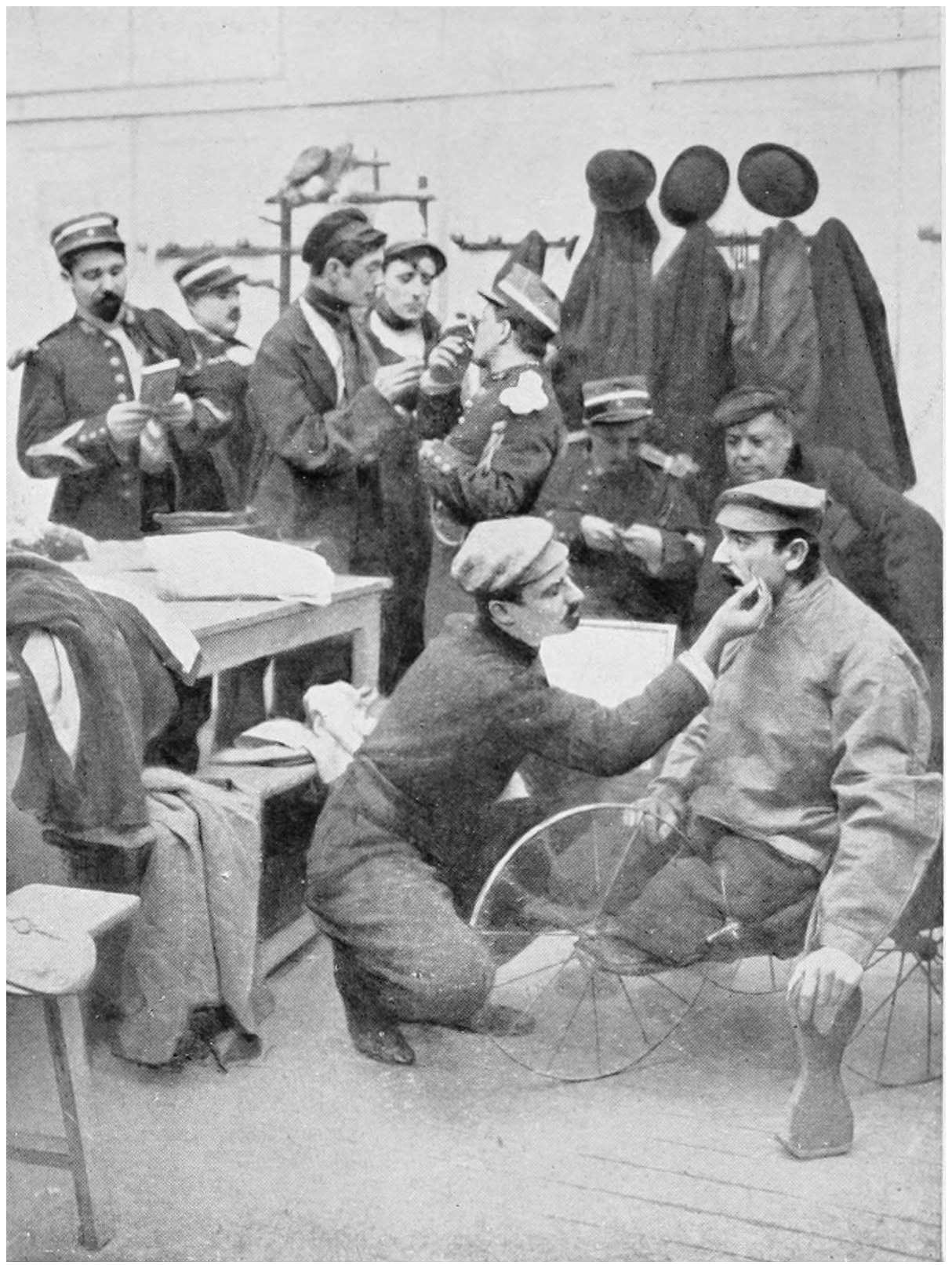

The producer giving instructions to the principal actor and his double, the legless cripple. The dummy legs in the foreground.—See page 211.

Title: Moving Pictures: How They Are Made and Worked

Author: Frederick Arthur Ambrose Talbot

Release date: May 2, 2022 [eBook #67972]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: J. B. Lippincott, 1914

Credits: deaurider, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

Cover created by Transcriber and placed into the Public Domain.

CONQUESTS OF SCIENCE

Uniform with this Volume.

BY FREDERICK A. TALBOT

THE OIL CONQUEST OF THE WORLD

LIGHTSHIPS AND LIGHTHOUSES

THE RAILWAY CONQUEST OF THE WORLD

STEAMSHIP CONQUEST OF THE WORLD

Philadelphia: J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

London: WILLIAM HEINEMANN

Frontispiece.

TRICK CINEMATOGRAPHY—THE AUTOMOBILE ACCIDENT.

The producer giving instructions to the principal actor and his double, the legless cripple. The dummy legs in the foreground.—See page 211.

CONQUESTS OF SCIENCE

MOVING PICTURES

HOW THEY ARE MADE AND WORKED

BY

FREDERICK A. TALBOT

NEW EDITION

ILLUSTRATED

Philadelphia: J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

London: WILLIAM HEINEMANN

1914

First Printed, January, 1912

Revised Edition, December, 1912

New Edition, November, 1914

Printed in England.

vii

The marvellous, universal popularity of moving pictures is my reason for writing this volume. A vast industry has been established of which the great majority of picture-palace patrons have no idea, and the moment appears timely to describe the many branches of the art.

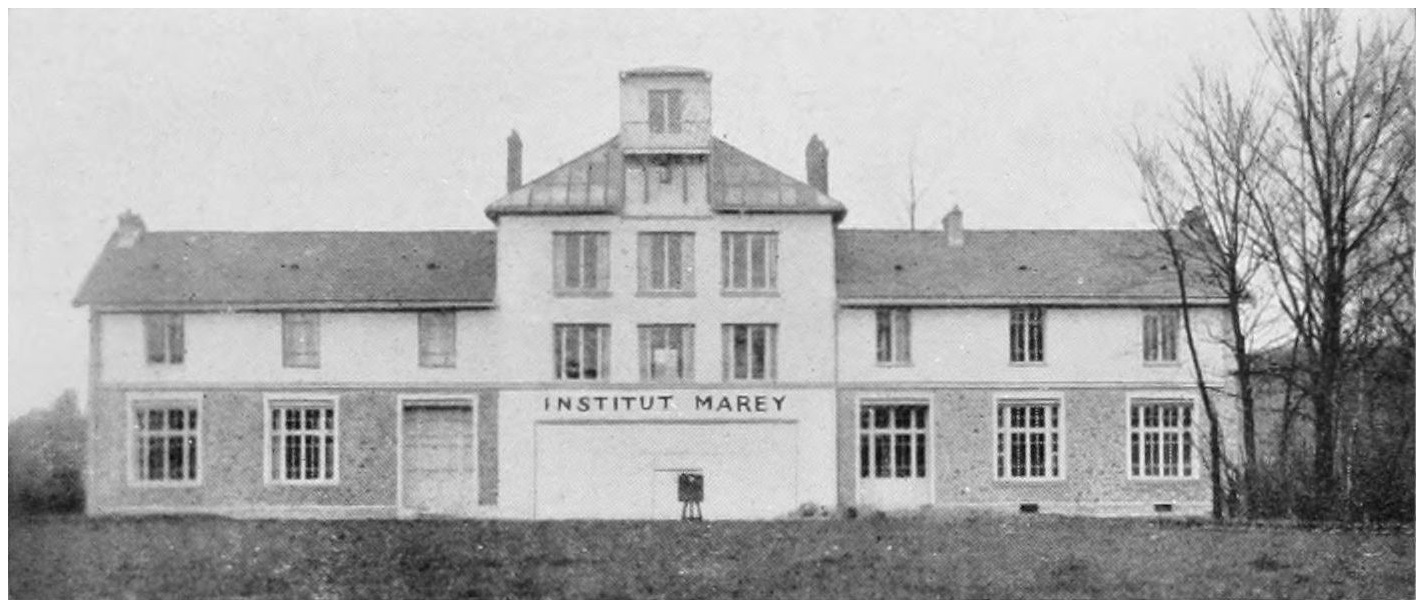

I have endeavoured to deal with the whole subject in a popular and comprehensive manner. I have been assisted by several friends, who have enabled me to throw considerable light upon the early history of motion photography and the many problems that had to be mastered before it met with public appreciation:—MM. Weiss and Bull, the Director and Assistant-Director respectively of the Marey Institute in Paris; M. Georges Demeny; Messrs. Frank L. Dyer, the President of Thomas A. Edison, Incorporated; W. F. Greene, Robert W. Paul, James Williamson, Lumière & Sons, Richard G. Hollaman, the Eastman Kodak Company, Dr. J. Comandon, F. Percy Smith, Albert Smith, and the numerous firms engaged in one or other of the various branches of the industry.

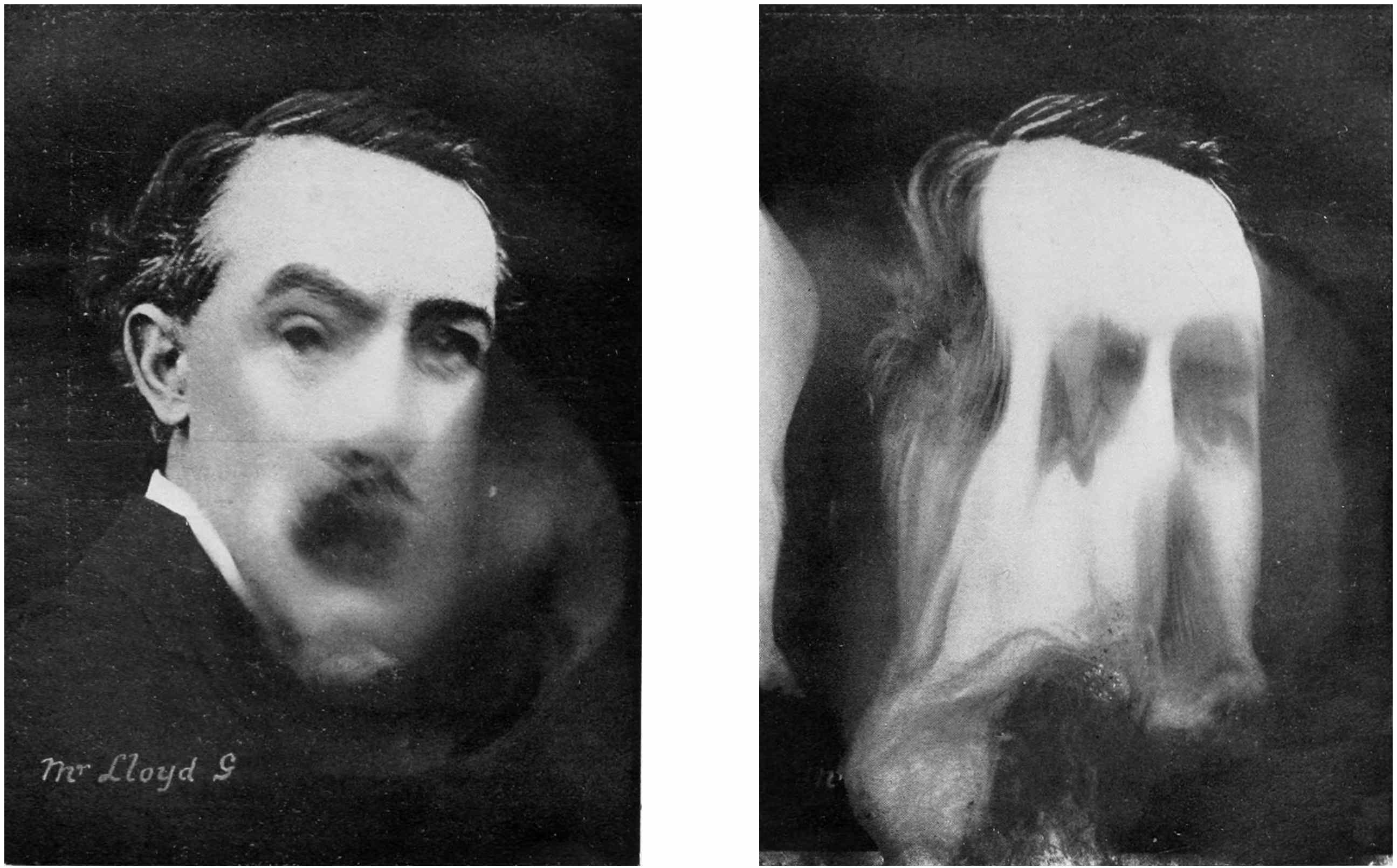

I am indebted especially to the editor of L’Illustration, the well-known Parisian illustrated weekly newspaper, in conjunction with the Société des Établissements Gaumont, for permission to publish the photographs illustrating Chapters XIX., XX., and XXI., as well as the frontispiece;viii also to Mr. A. A. Hopkins, the author of “Magic,” and to Messrs. Munn & Co., the proprietors of The Scientific American, of New York, U.S.A.

The book makes no claim to being a practical manual, because thereby intricate technicalities would have been unavoidable. The information respecting the various mechanical aspects of cinematography are set forth in a readable manner, so that the broad principles may be understood.

While the most popular features of motion photography are described fully, I have not omitted to introduce the reader to the educational and scientific developments, which are more wonderful and fascinating. Indeed, the cinematograph will probably achieve greater triumphs in these fields than it has accomplished already as a source of amusement.

FREDERICK A. TALBOT.

ix

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | WHAT IS ANIMATED PHOTOGRAPHY? | 1 |

| II. | THE FIRST ATTEMPTS TO PRODUCE MOVING PICTURES | 10 |

| III. | THE SEARCH FOR THE CELLULOID FILM | 23 |

| IV. | THE KINETOSCOPE: THE ANIMATOGRAPH: THE CINEMATOGRAPHE | 30 |

| V. | HOW THE CELLULOID FILM IS MADE | 50 |

| VI. | THE STORY OF THE PERFORATION GAUGE | 57 |

| VII. | THE MOVING PICTURE CAMERA, ITS CONSTRUCTION, AND OPERATION | 65 |

| VIII. | DEVELOPING AND PRINTING THE PICTURES | 76 |

| IX. | HOW THE PICTURES ARE SHOWN UPON THE SCREEN | 88 |

| X. | THE STUDIO FOR STAGING MOVING PICTURE PLAYS | 103 |

| XI. | THE CINEMATOGRAPH AS A RECORDER OF TOPICAL EVENTS: SCENIC FILMS | 116 |

| XII. | THE CINEMATOGRAPH THEATRE AND ITS EQUIPMENT | 130 |

| XIII. | HOW A CINEMATOGRAPH PLAY IS PRODUCED | 146 |

| XIV. | MOVING PICTURES OF MICROBES | 161 |

| XV. | SOME ELABORATE PICTURE PLAYS AND HOW THEY WERE STAGED | 169 |

| XVI. | PICTURES THAT MOVE, TALK, AND SING | 179 |

| XVII. | POPULAR SCIENCE AS REVEALED BY THE CINEMATOGRAPH | 190 |

| XVIII. | TRICK PICTURES AND HOW THEY ARE PRODUCED.— | |

| I. THE FIRST ATTEMPTS AT CINEMATOGRAPH MAGIC AND THE ARTIFICES ADOPTED | 197x | |

| XIX. | TRICK PICTURES AND HOW THEY ARE PRODUCED.— | |

| II. DANCING FURNITURE: STRINGS, CORDS, AND WIRES: “THE MAGNETIC GENTLEMAN”: THE “STOP AND SUBSTITUTION”: “THE AUTOMOBILE ACCIDENT”: REVERSAL OF ACTION | 207 | |

| XX. | TRICK PICTURES AND HOW THEY ARE PRODUCED.— | |

| III. MANIPULATION OF THE FILM: APPARITIONS AND GRADUAL DISAPPEARANCES BY OPENING AND CLOSING THE DIAPHRAGM OF THE LENS SLOWLY: “THE SIREN”: SUBMARINE EFFECTS | 218 | |

| XXI. | TRICK PICTURES AND HOW THEY ARE PRODUCED.— | |

| IV. LILLIPUTIAN FIGURES: “THE LITTLE MILLINER’S DREAM”: THE “ONE TURN ONE PICTURE” MOVEMENT: HOW SOME EXTRAORDINARY INCIDENTS ARE PRODUCED: “THE SKI RUNNER” | 231 | |

| XXII. | TRICK PICTURES AND HOW THEY ARE PRODUCED.— | |

| V. “PRINCESS NICOTINE” AND HER REMARKABLE CAPRICES | 242 | |

| XXIII. | TRICK PICTURES AND HOW THEY ARE PRODUCED.— | |

| VI. SOME UNUSUAL AND NOVEL EFFECTS | 254 | |

| XXIV. | ELECTRIC SPARK CINEMATOGRAPHY | 264 |

| XXV. | THE “ANIMATED” NEWSPAPER | 277 |

| XXVI. | ANIMATION IN NATURAL COLOURS | 287 |

| XXVII. | MOVING PICTURES IN THE HOME | 301 |

| XXVIII. | MOTION-PHOTOGRAPHY AS AN EDUCATIONAL FORCE | 312 |

| XXIX. | RECENT DEVELOPMENTS: THE GROWTH AND POPULARITY OF THE CINEMATOGRAPH: SOME FACTS AND FIGURES: CONCLUSION | 319 |

xi

| To face page | |

| Trick Cinematography—The Automobile Accident | Frontispiece |

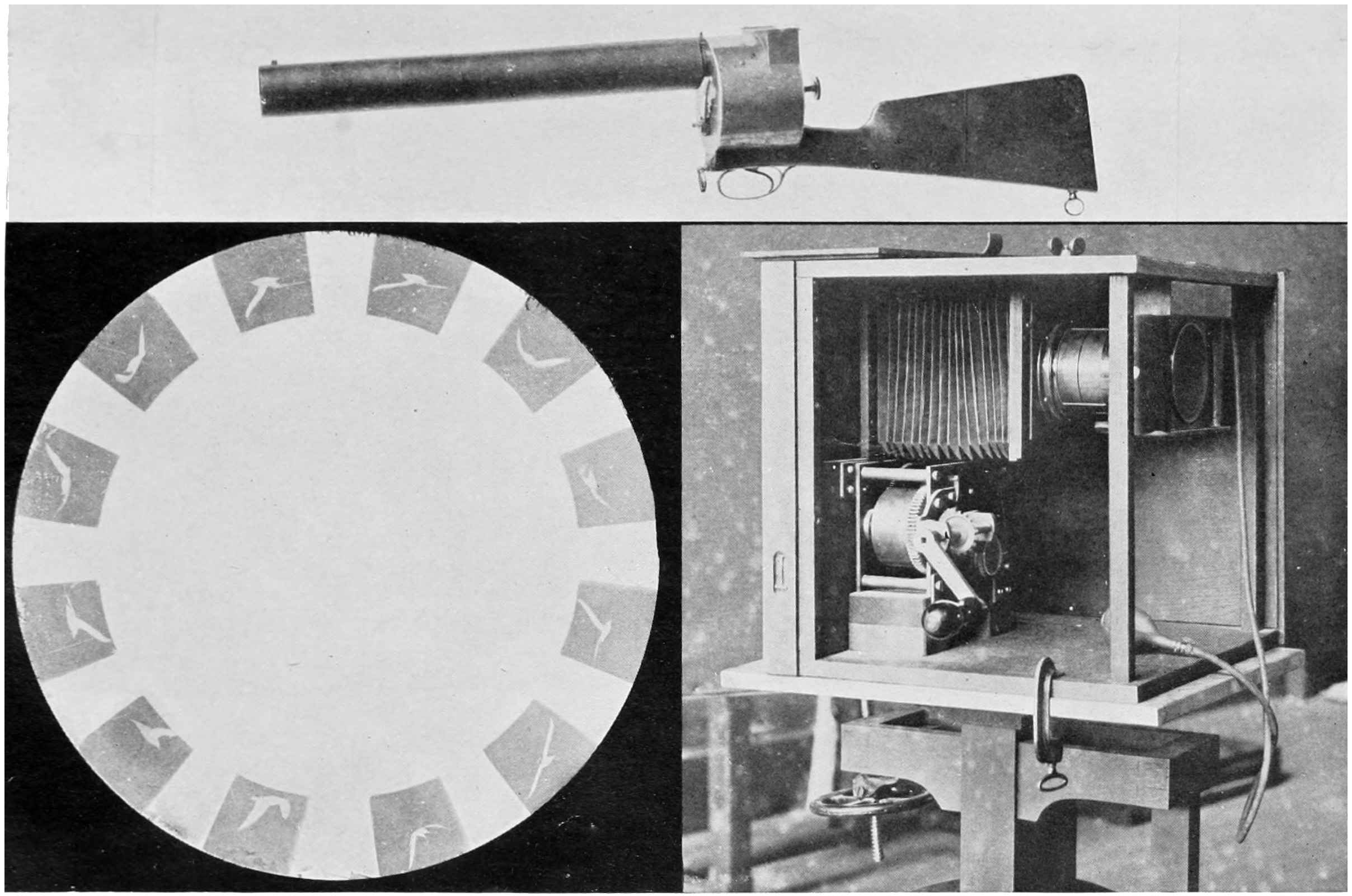

| Dr. E. J. Marey’s Famous Experiments—Photographic Gun of 1882 | 16 |

| Consecutive Pictures of a Gull Flying, taken with the Photographic Gun | 16 |

| Chronophotographic Apparatus for taking Consecutive Pictures upon a Single Glass Plate | 16 |

| Dr. Marey’s Animated Pictures made in 1884–6 for the Analysis of Motion | 17 |

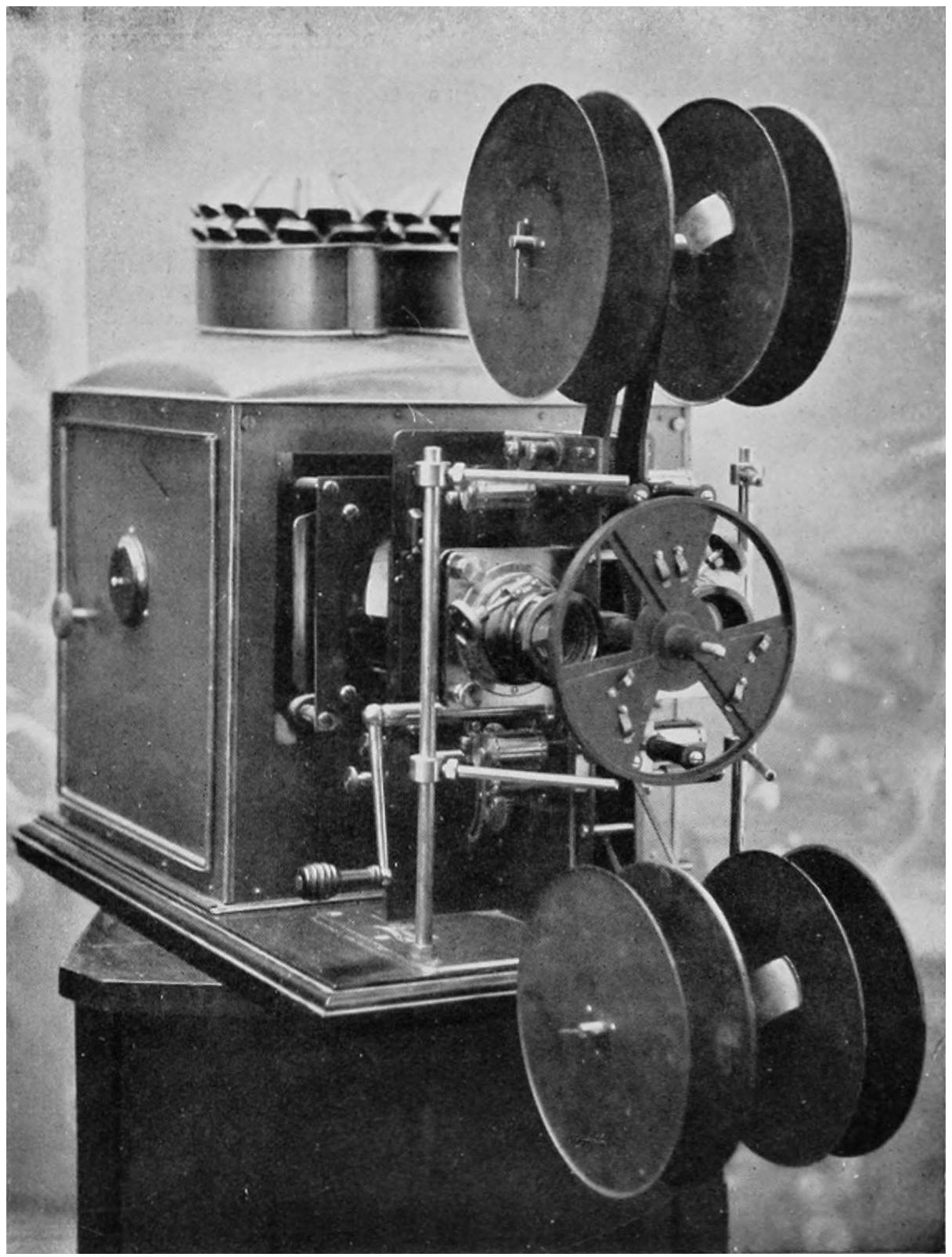

| Edison’s First Kinetoscope | 32 |

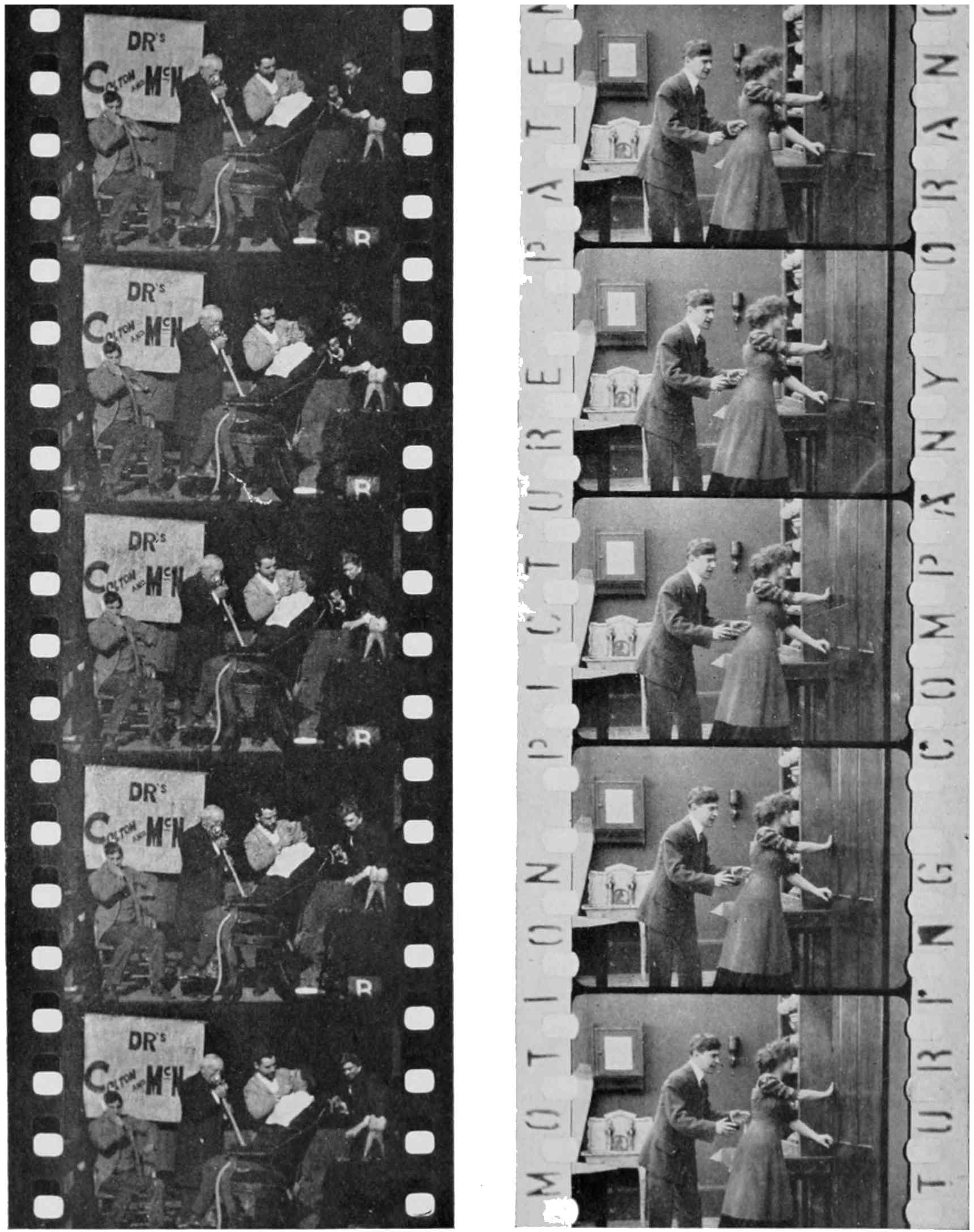

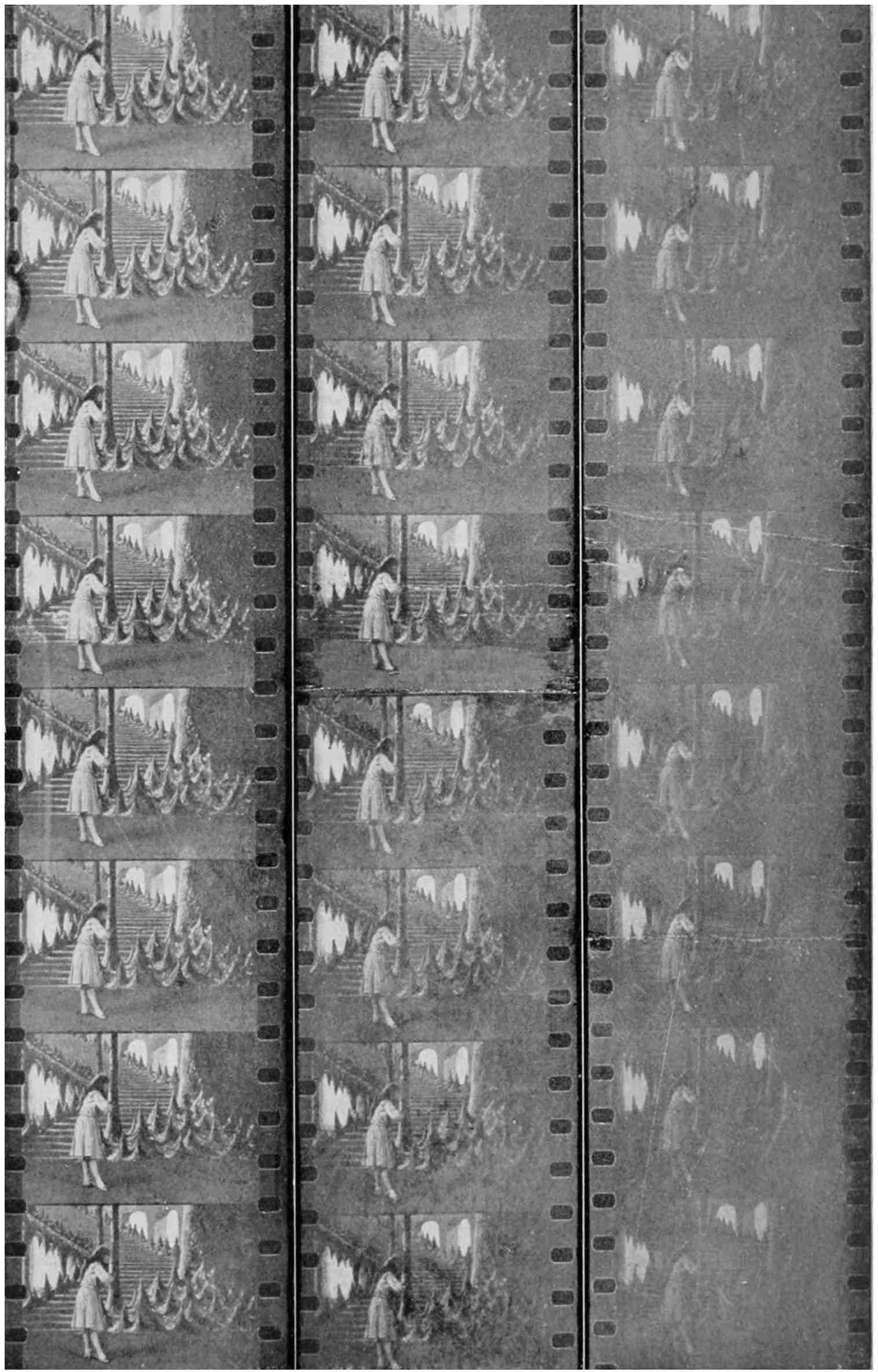

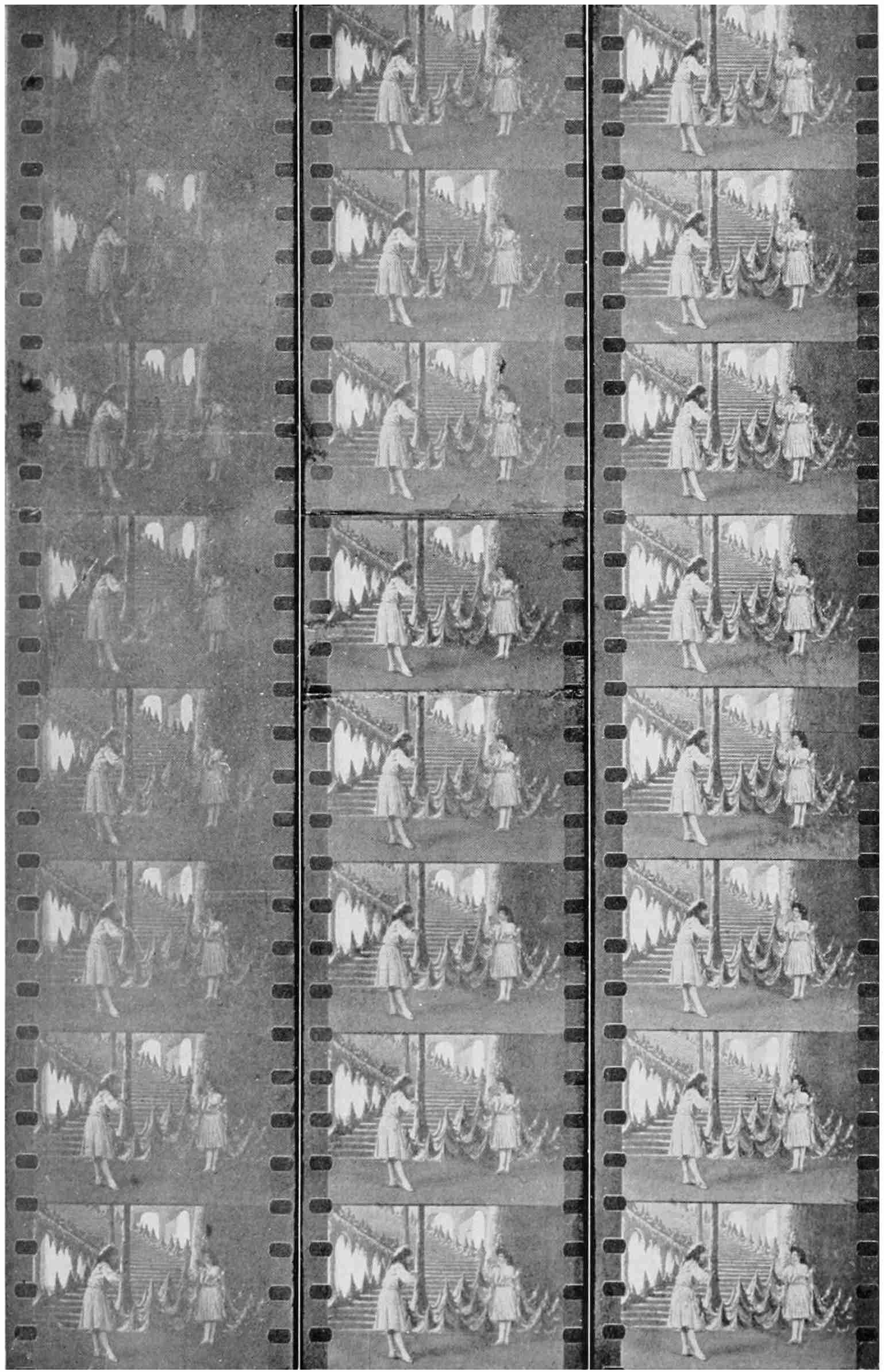

| Edison Film made about 1891 for the Kinetoscope | 33 |

| Edison Film made in 1911 for the Cinematograph | 33 |

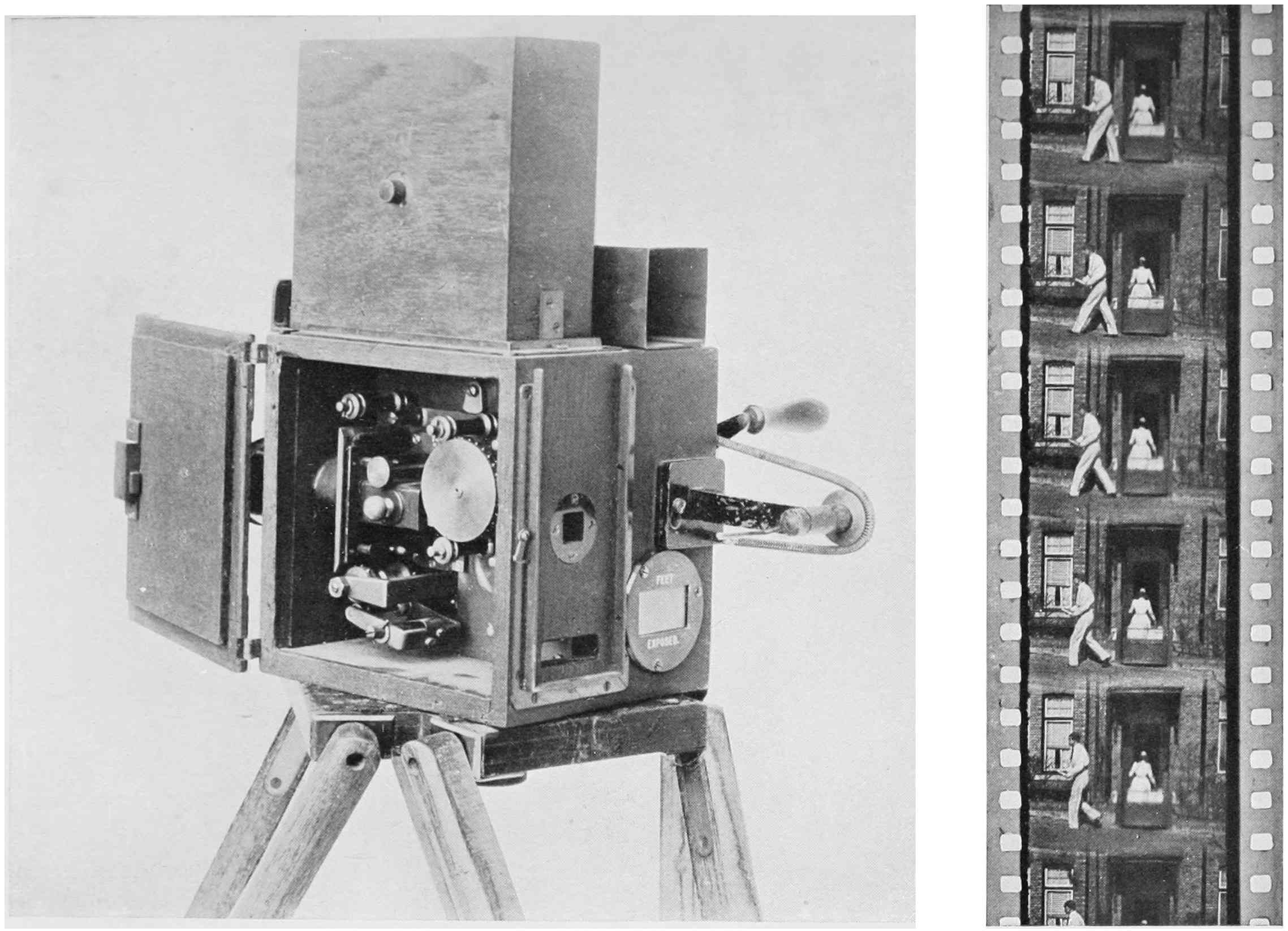

| Paul’s Camera showing Mechanism for moving the Film intermittently past the Lens | 36 |

| The First Kinetoscope Film made in England | 36 |

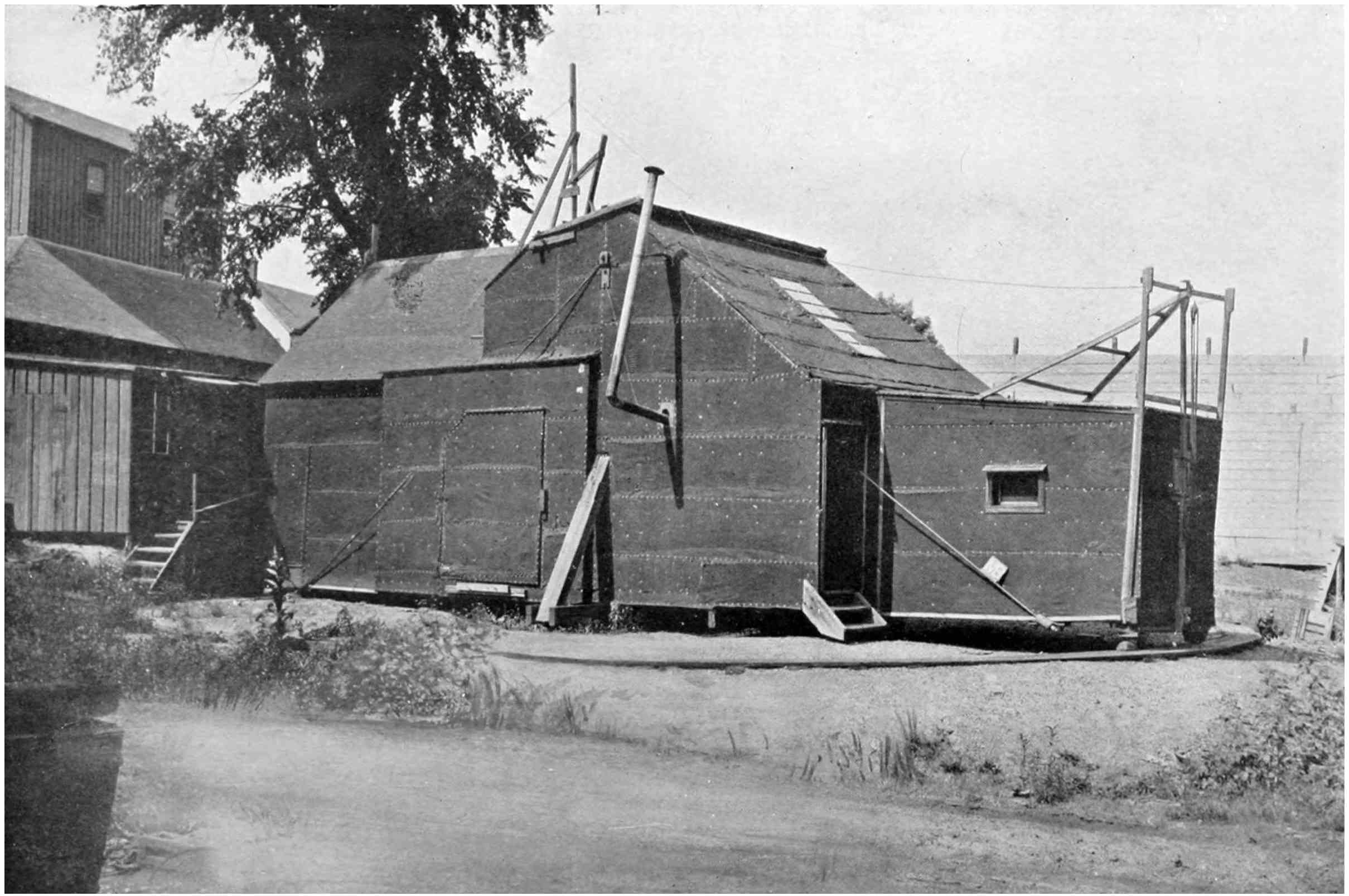

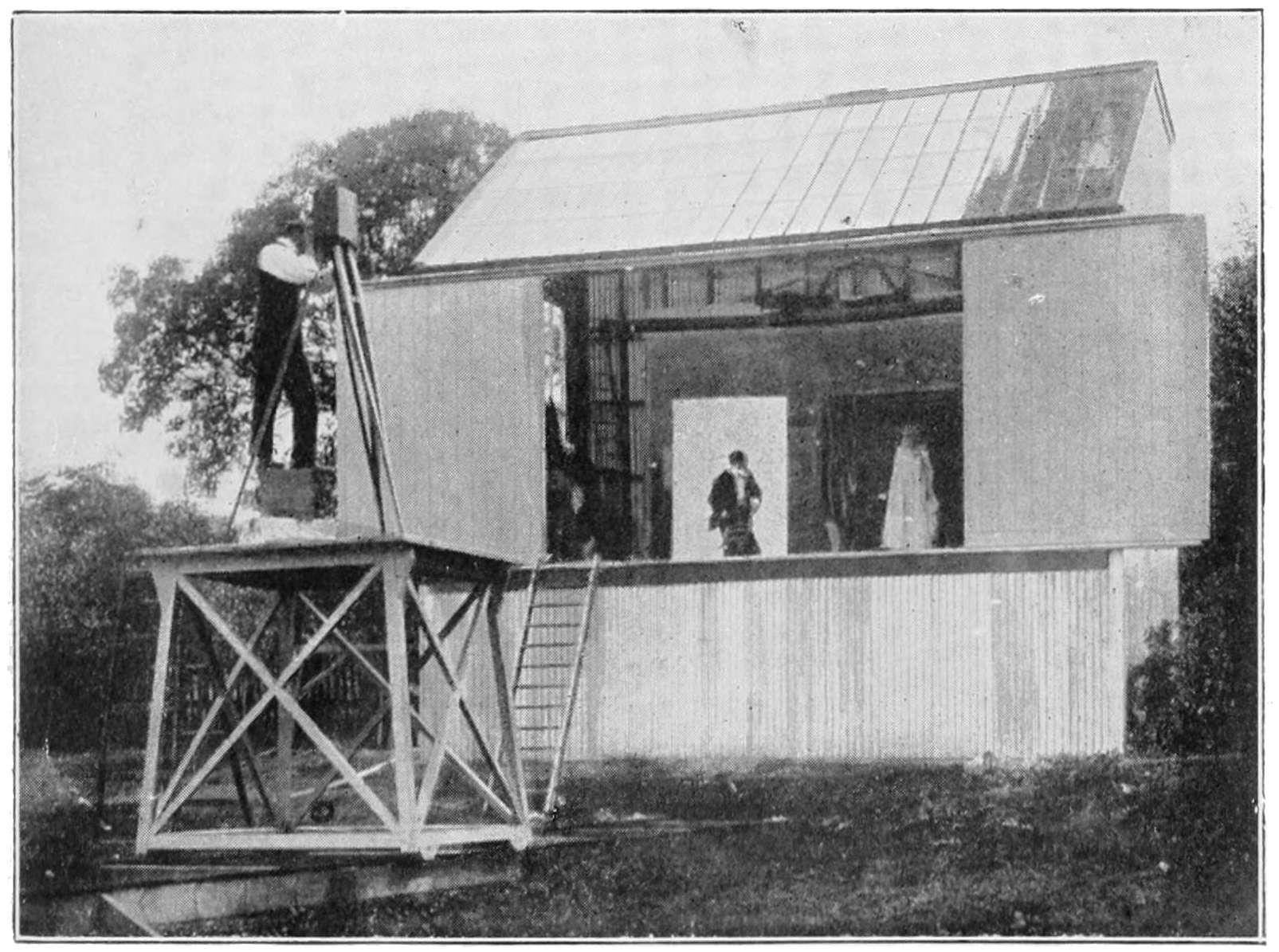

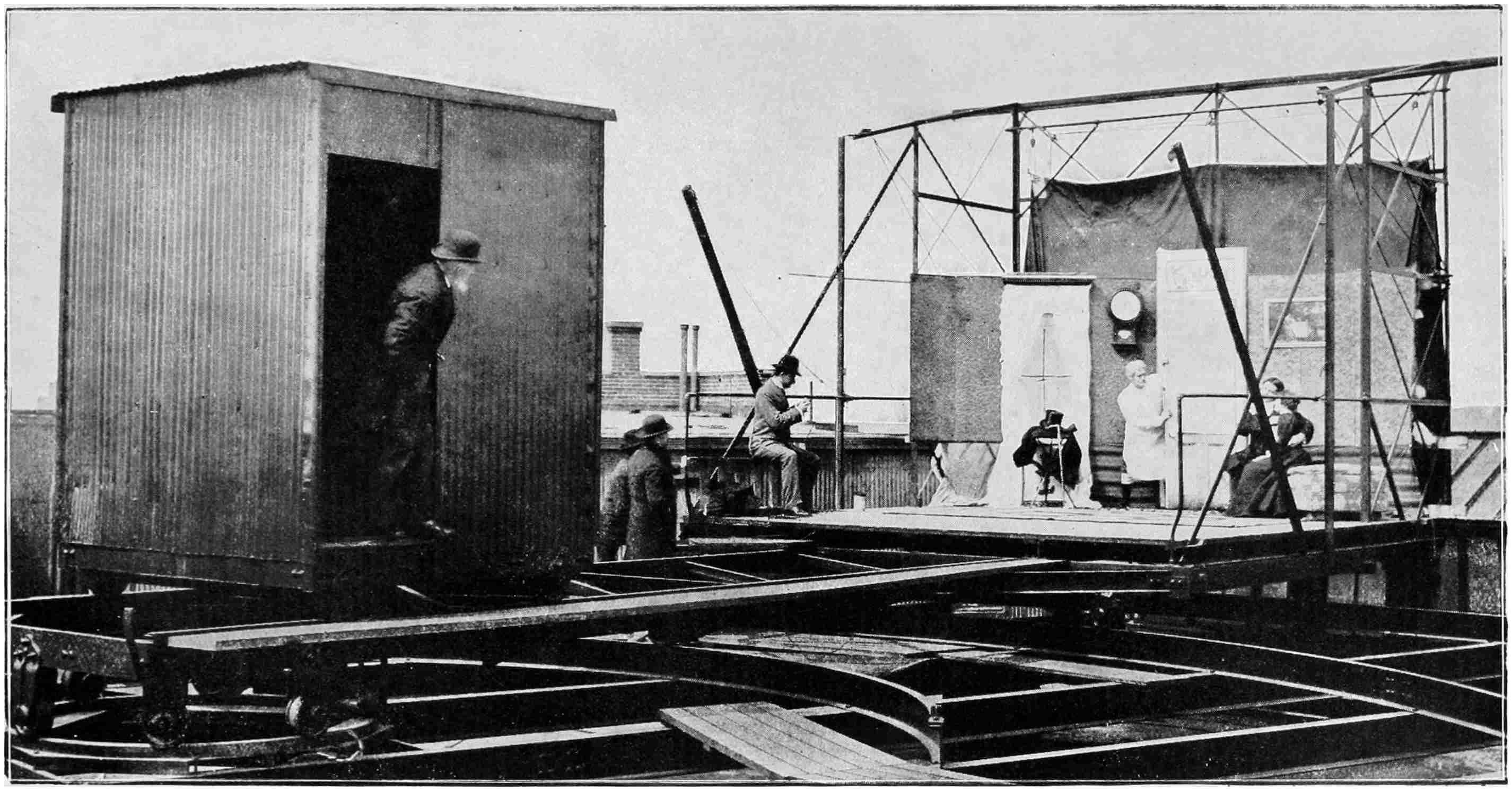

| The “Black Maria,” the First Edison Studio for making Kinetoscope Films | 37 |

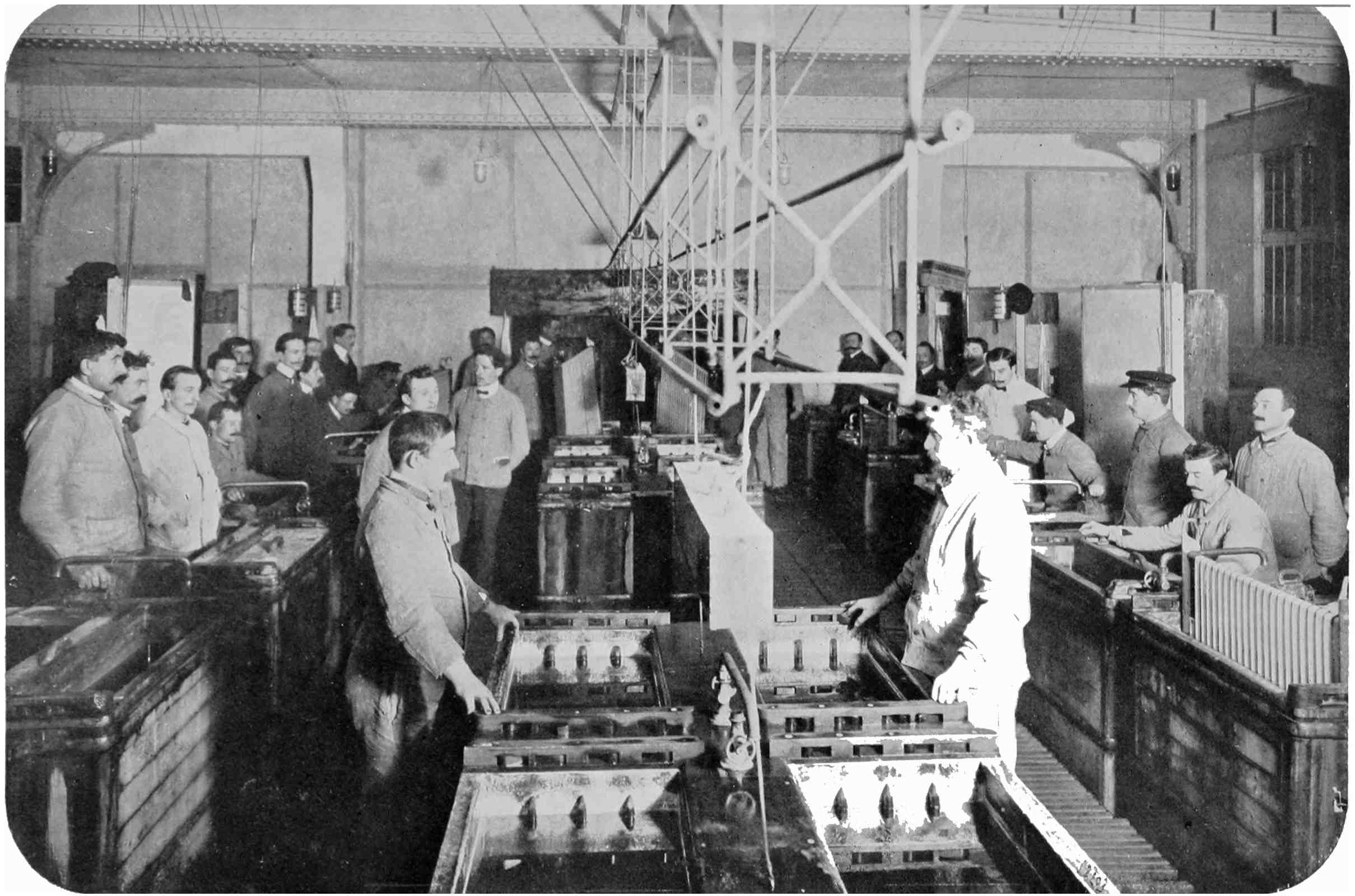

| The Dissolving Room | 52 |

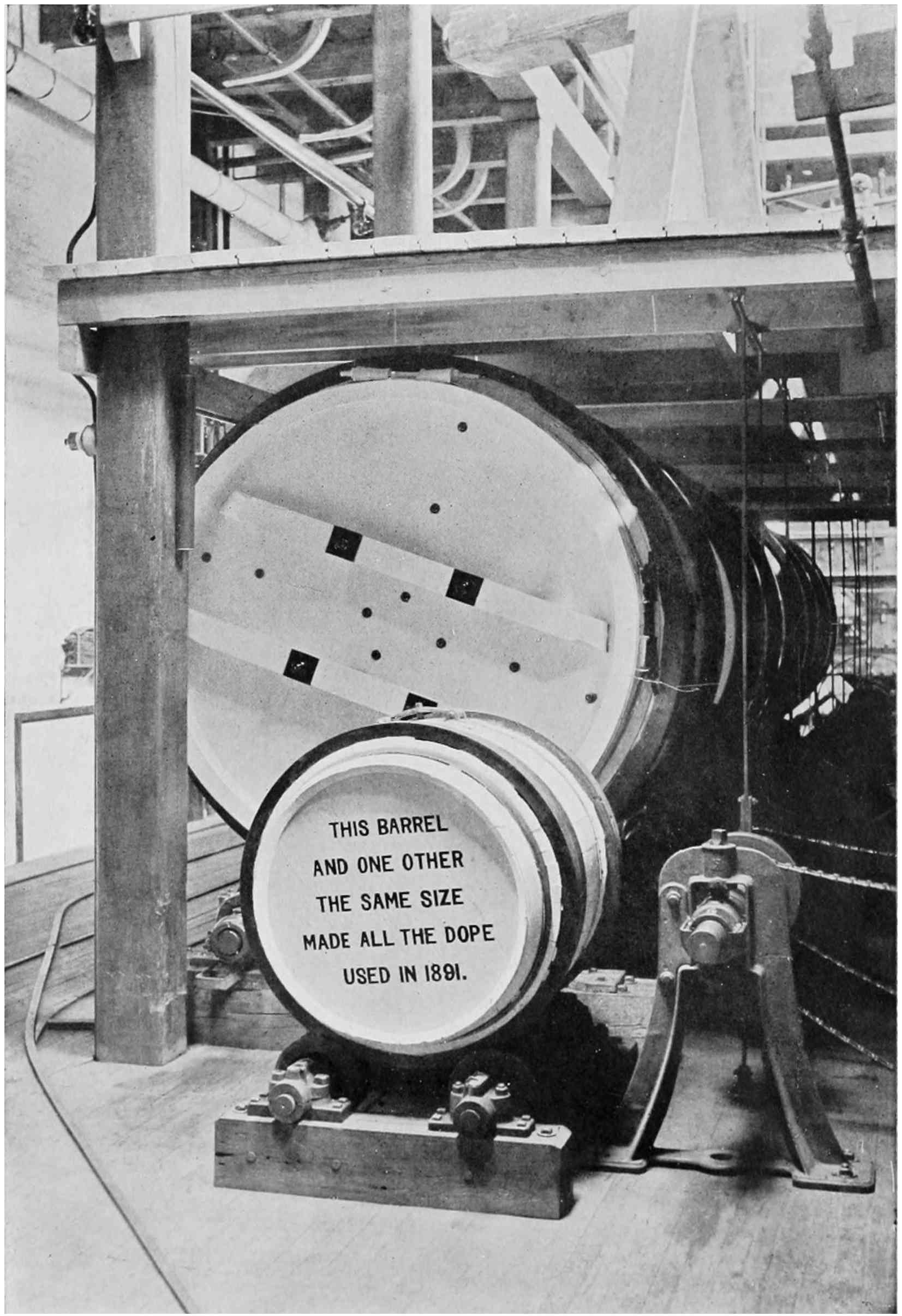

| The Mixing Barrel | 53 |

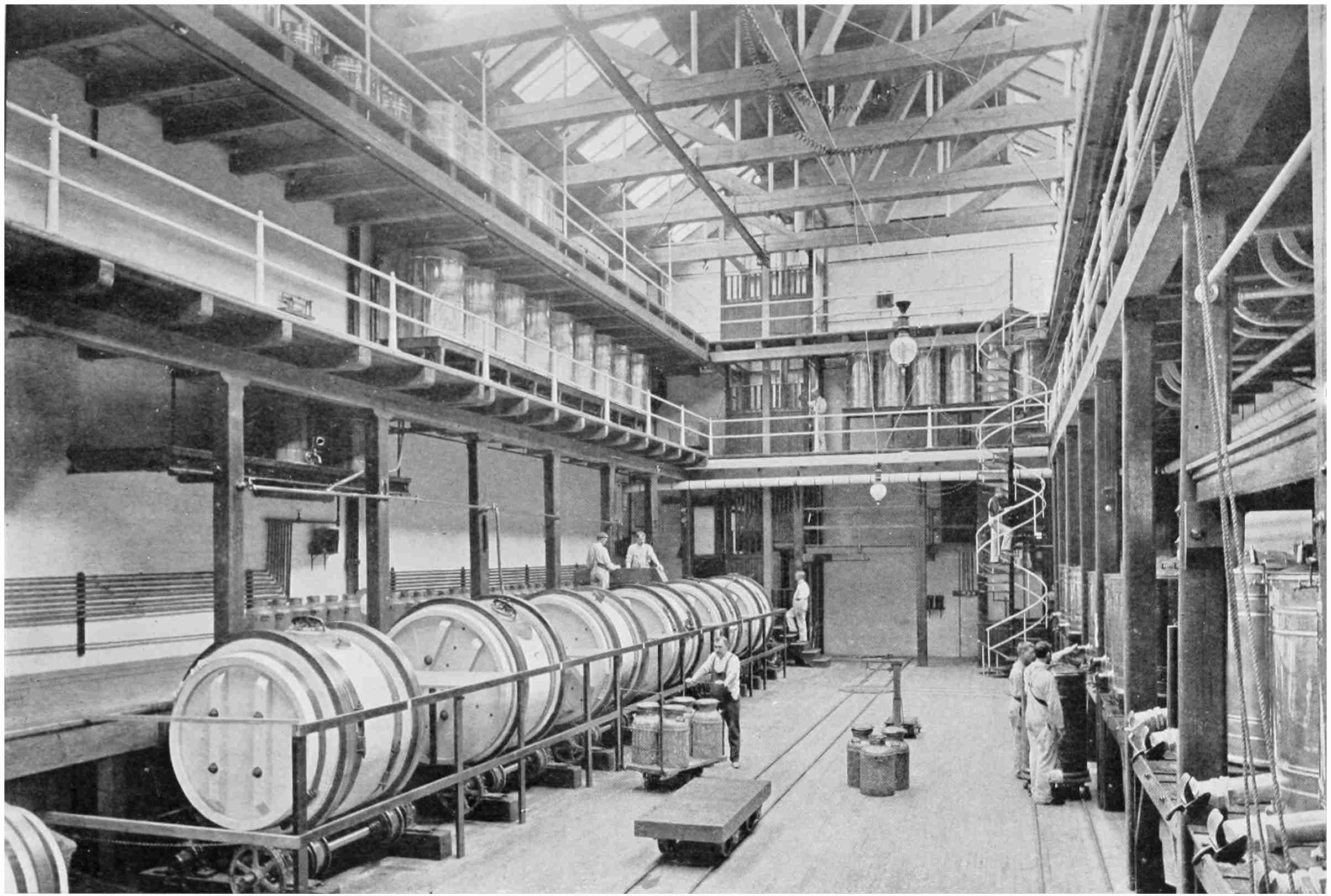

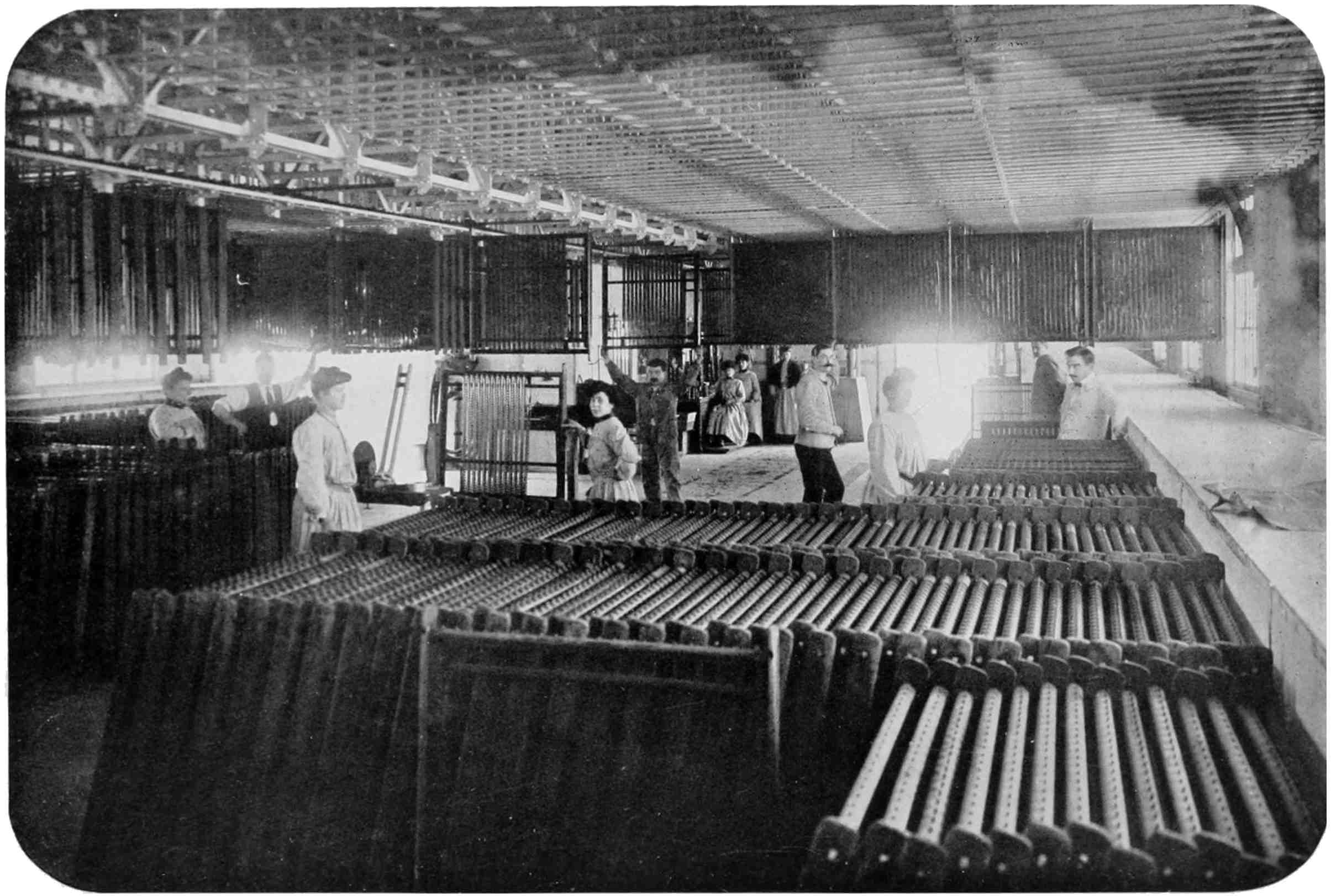

| A Battery of Celluloid Mixers | 54 |

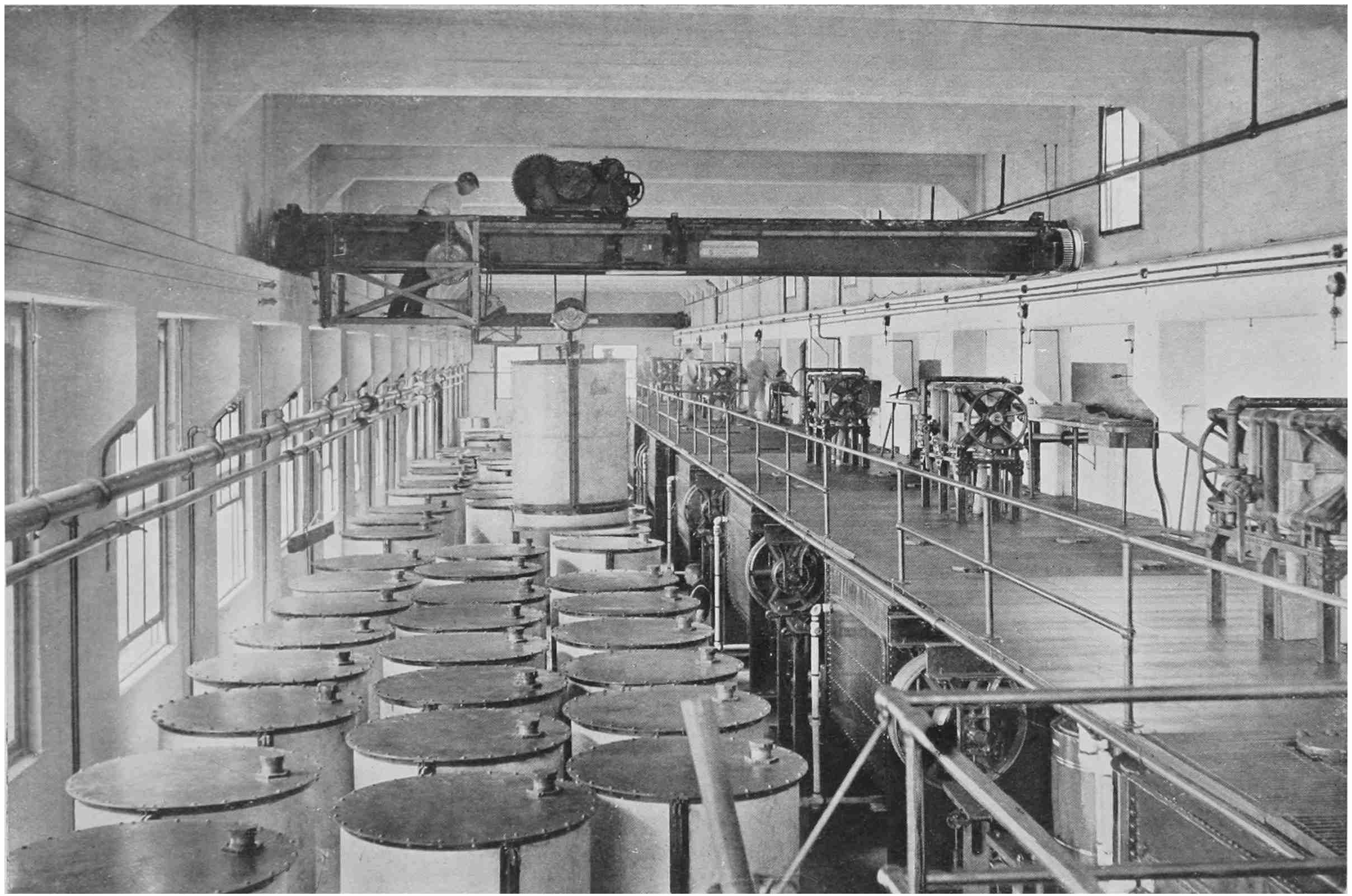

| The Liquid Celluloid Storage Room | 55 |

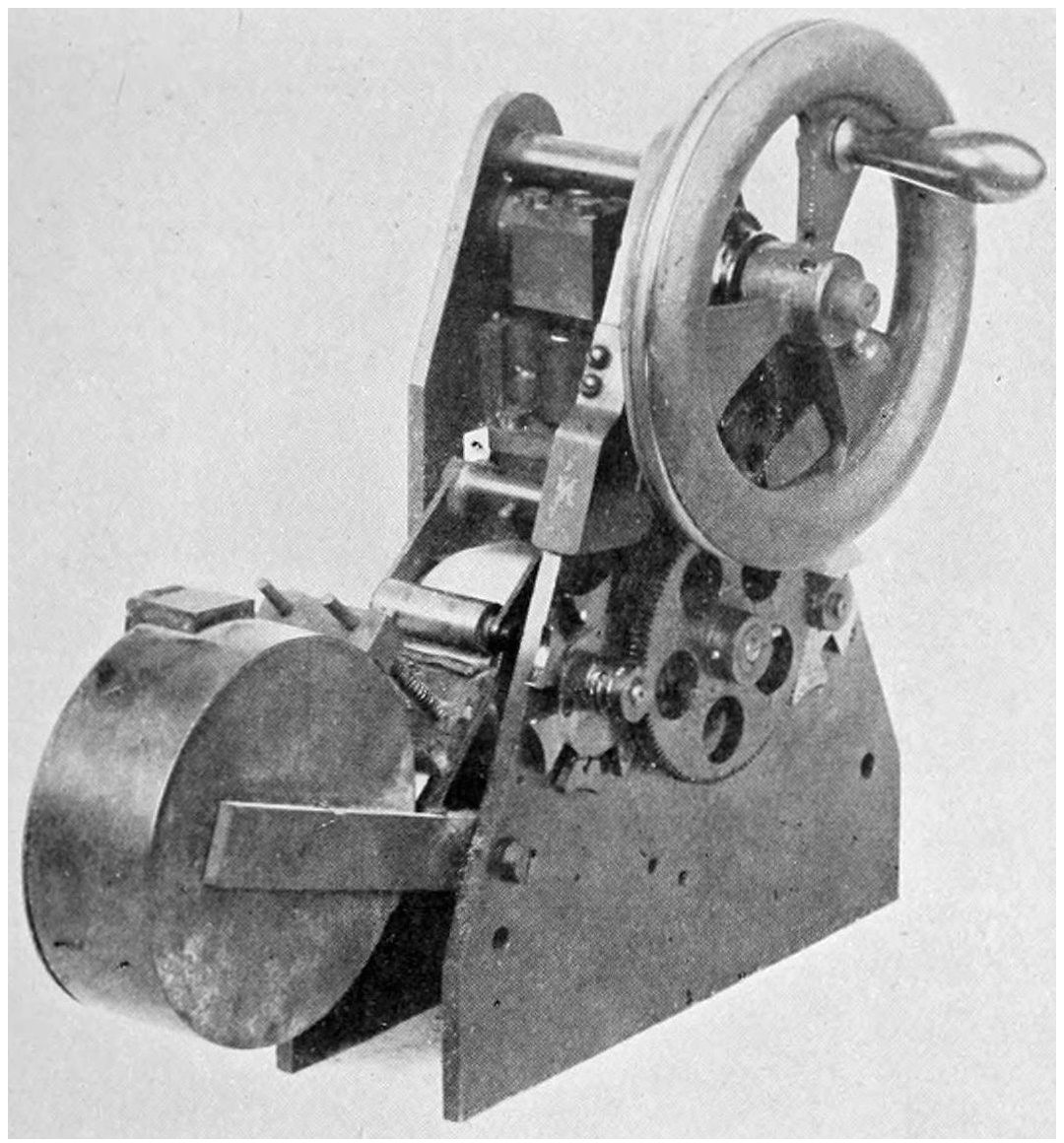

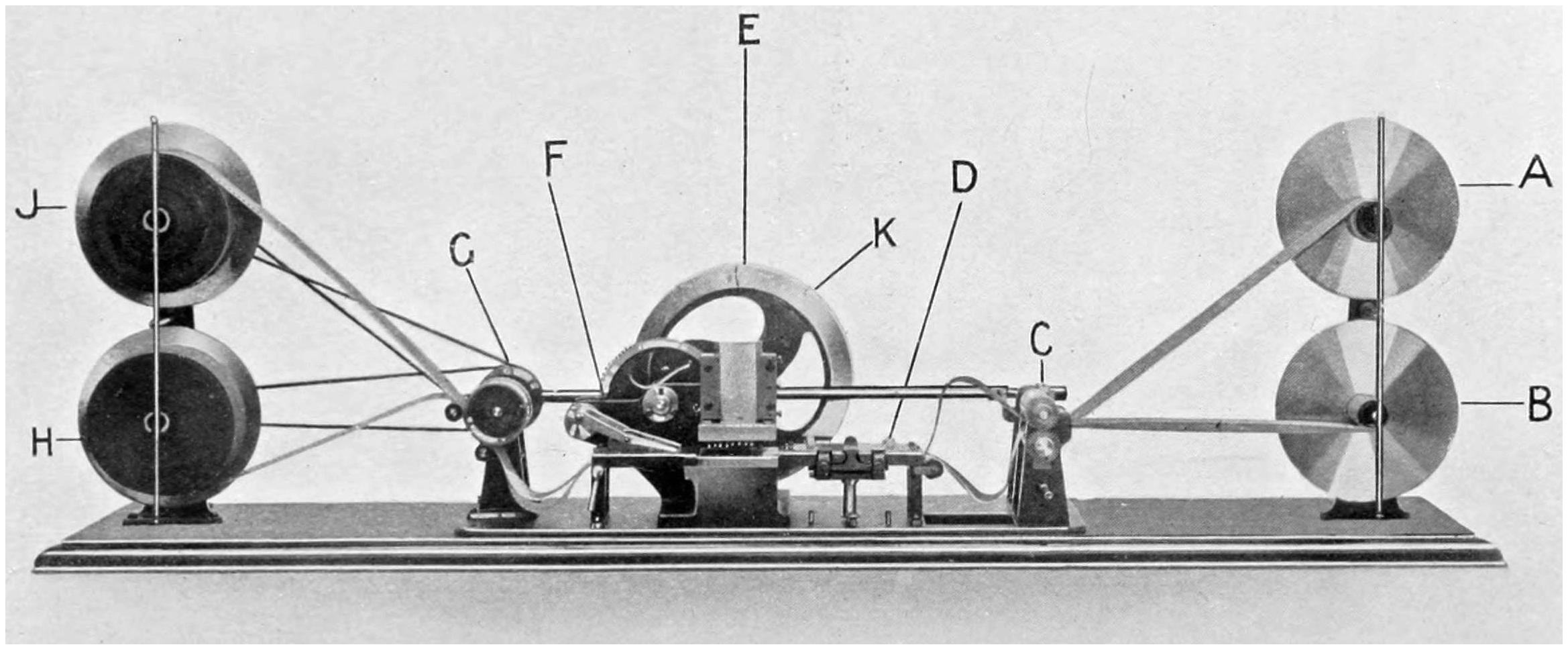

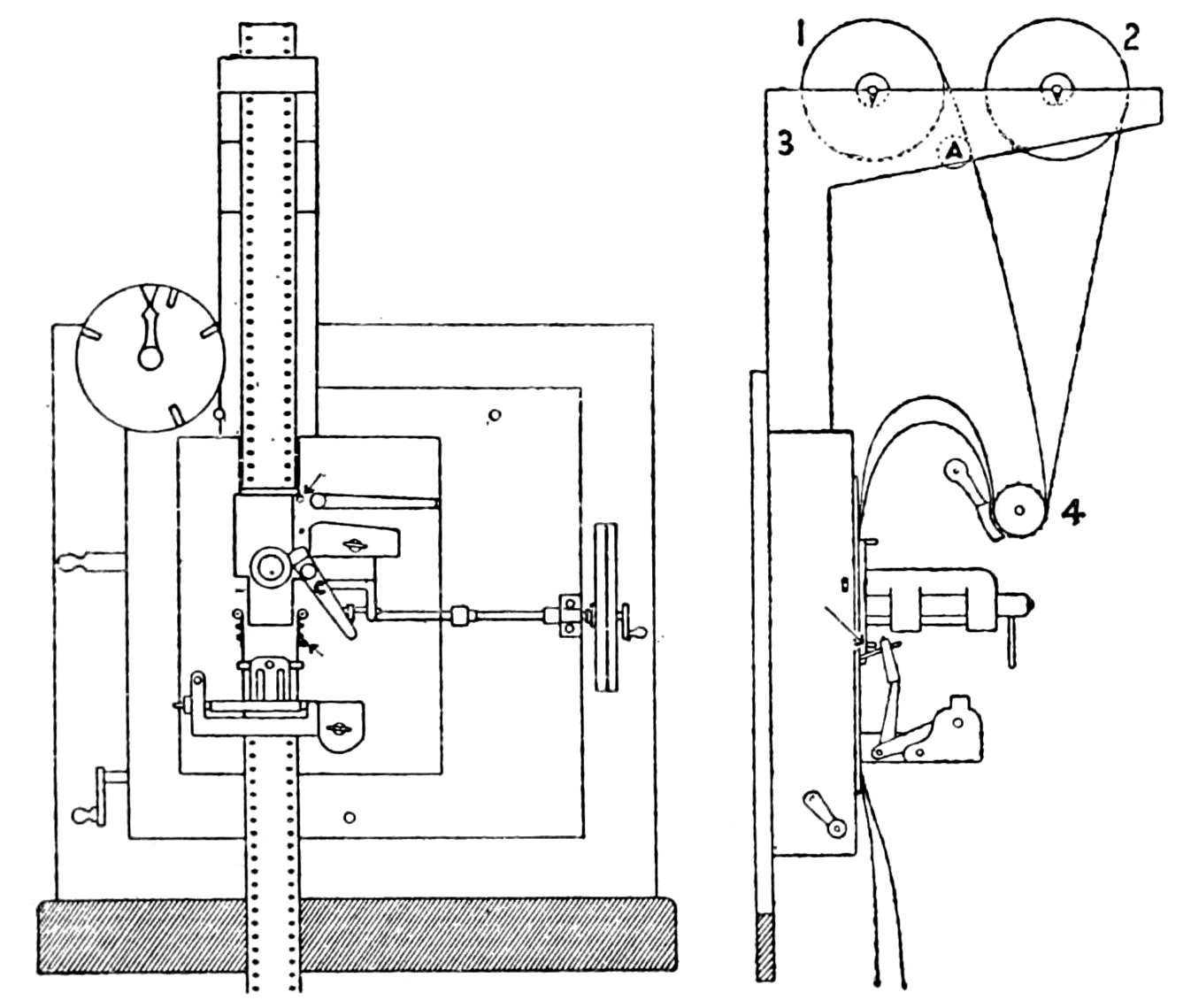

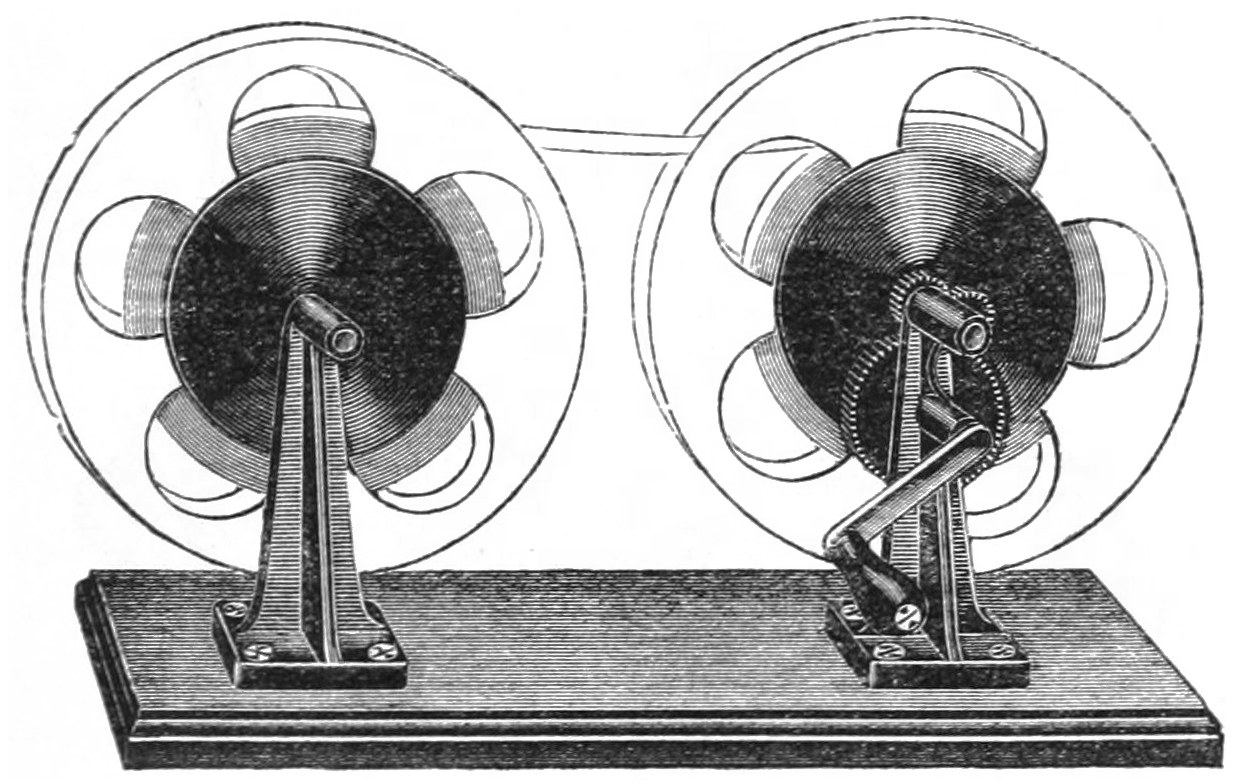

| Paul’s Rotary Perforator | 60 |

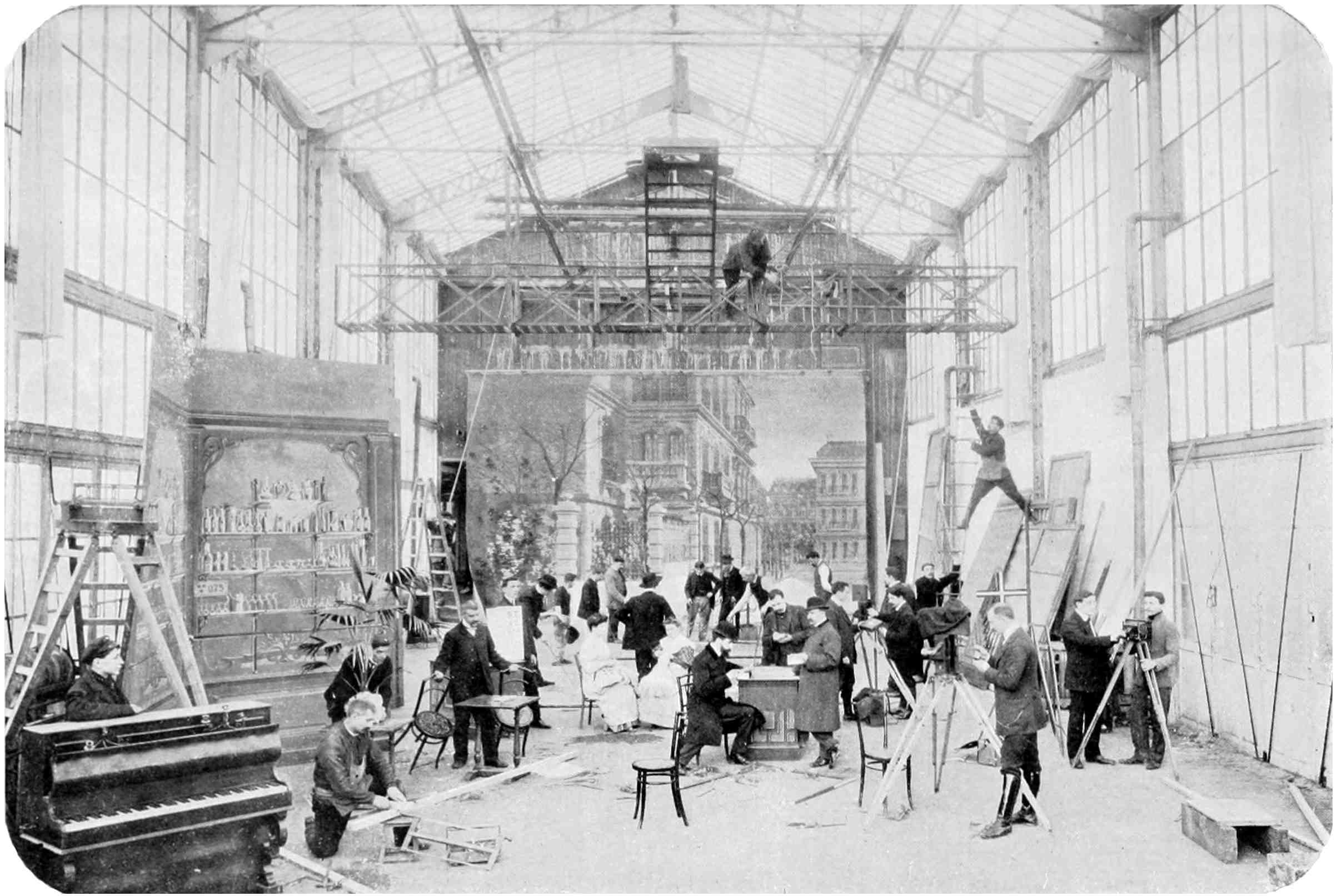

| The First Cinematograph Studio-Stage | 60 |

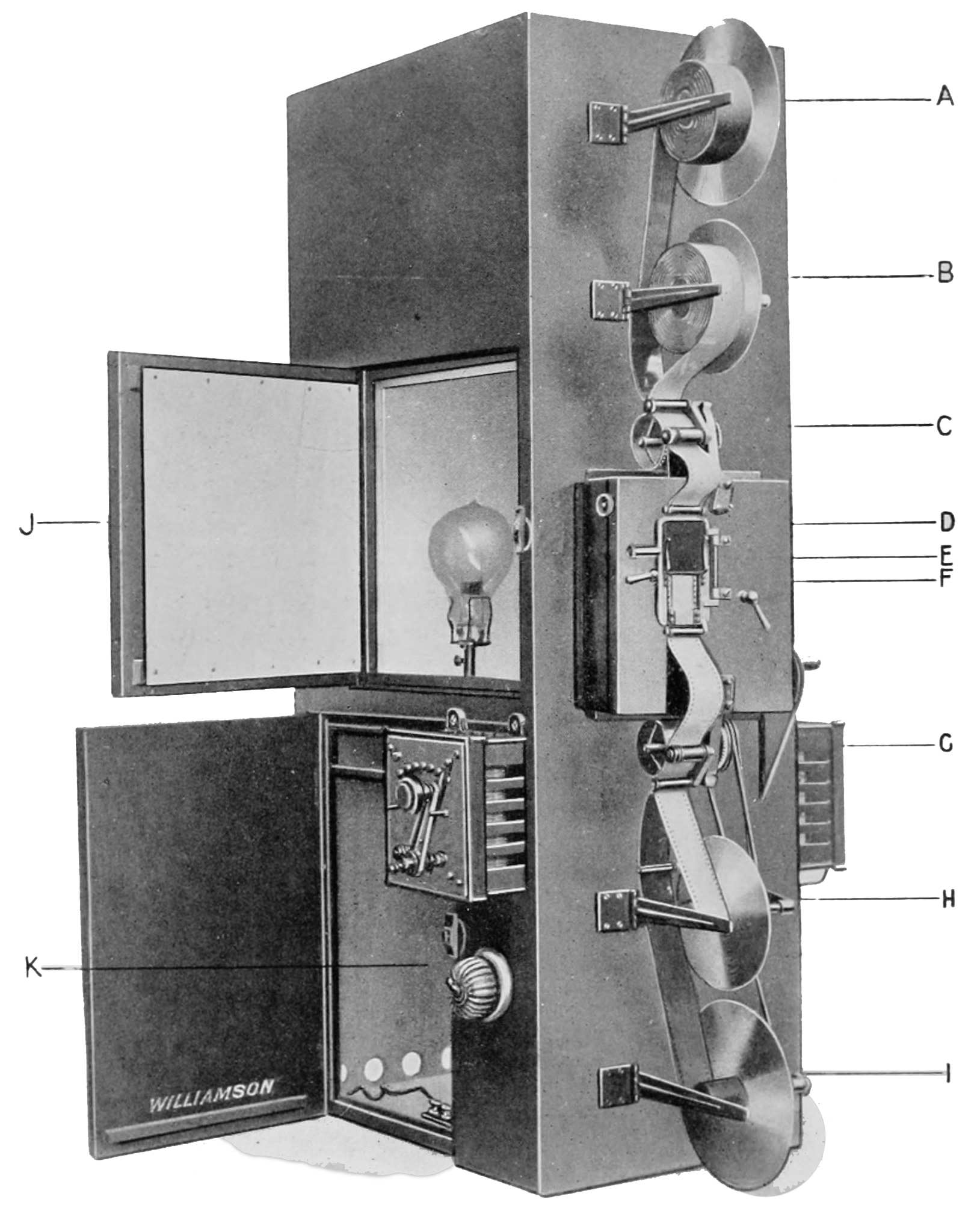

| The Williamson Film Perforator | 61 |

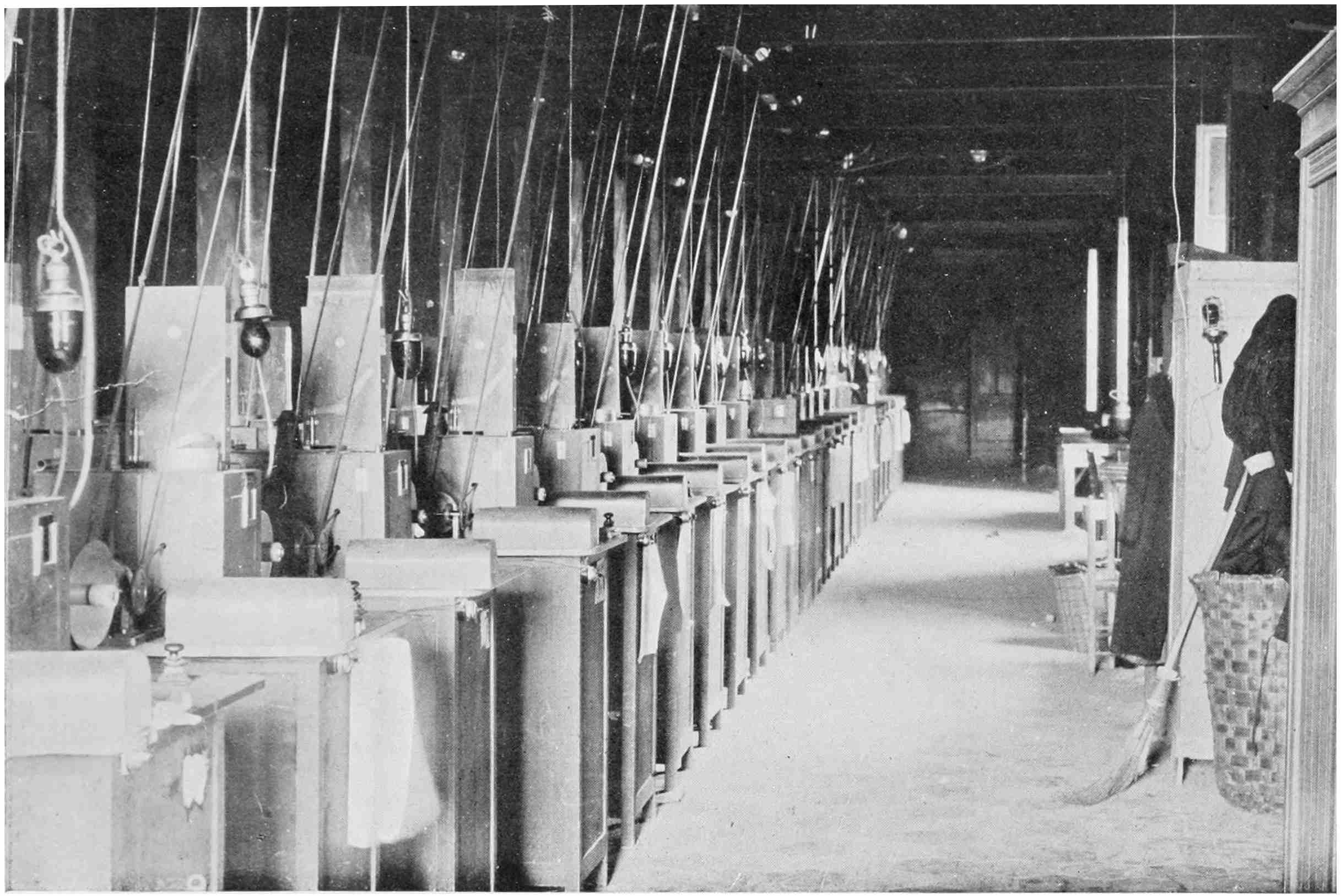

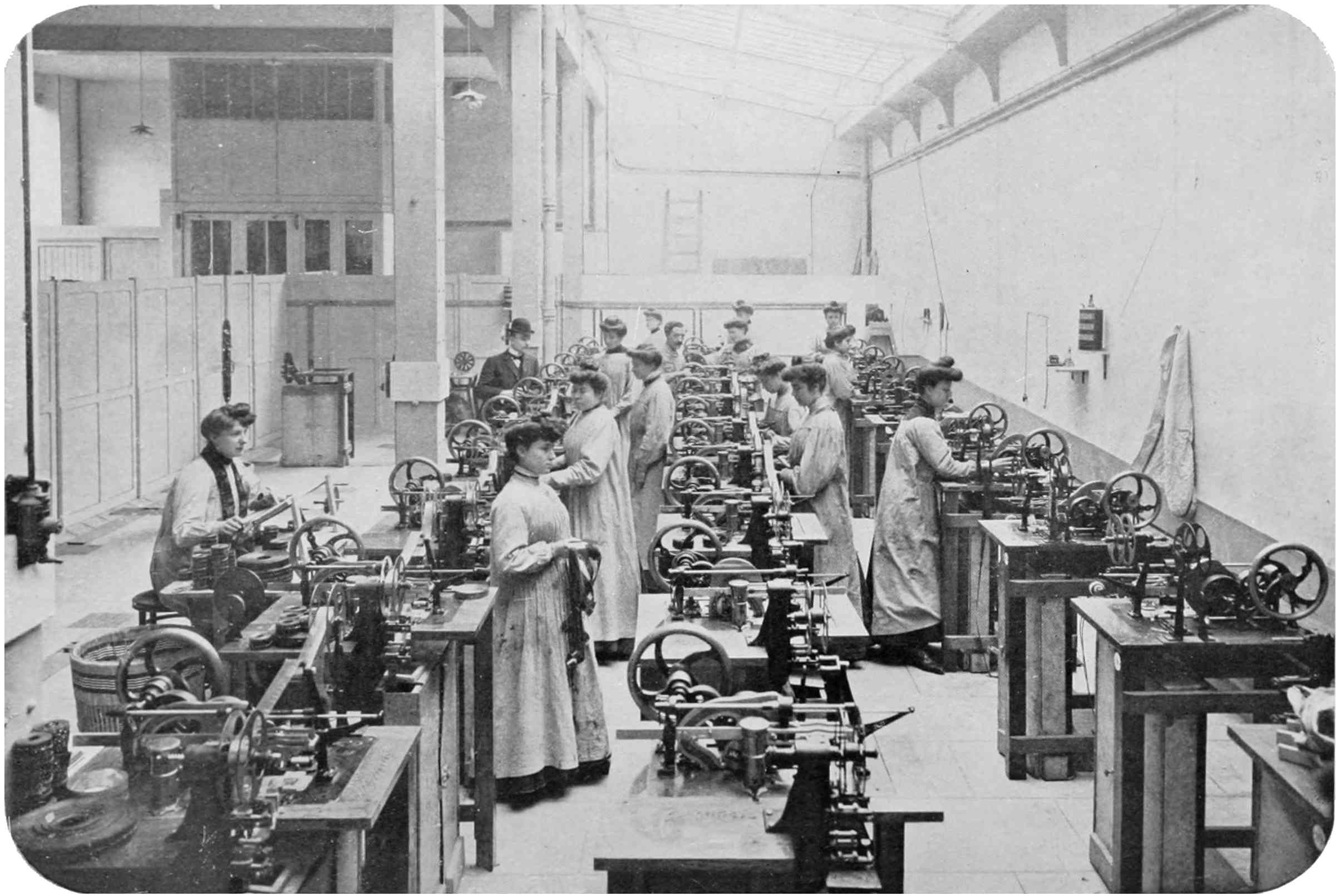

| The Perforating Room of the Cines Company in Rome | 66 |

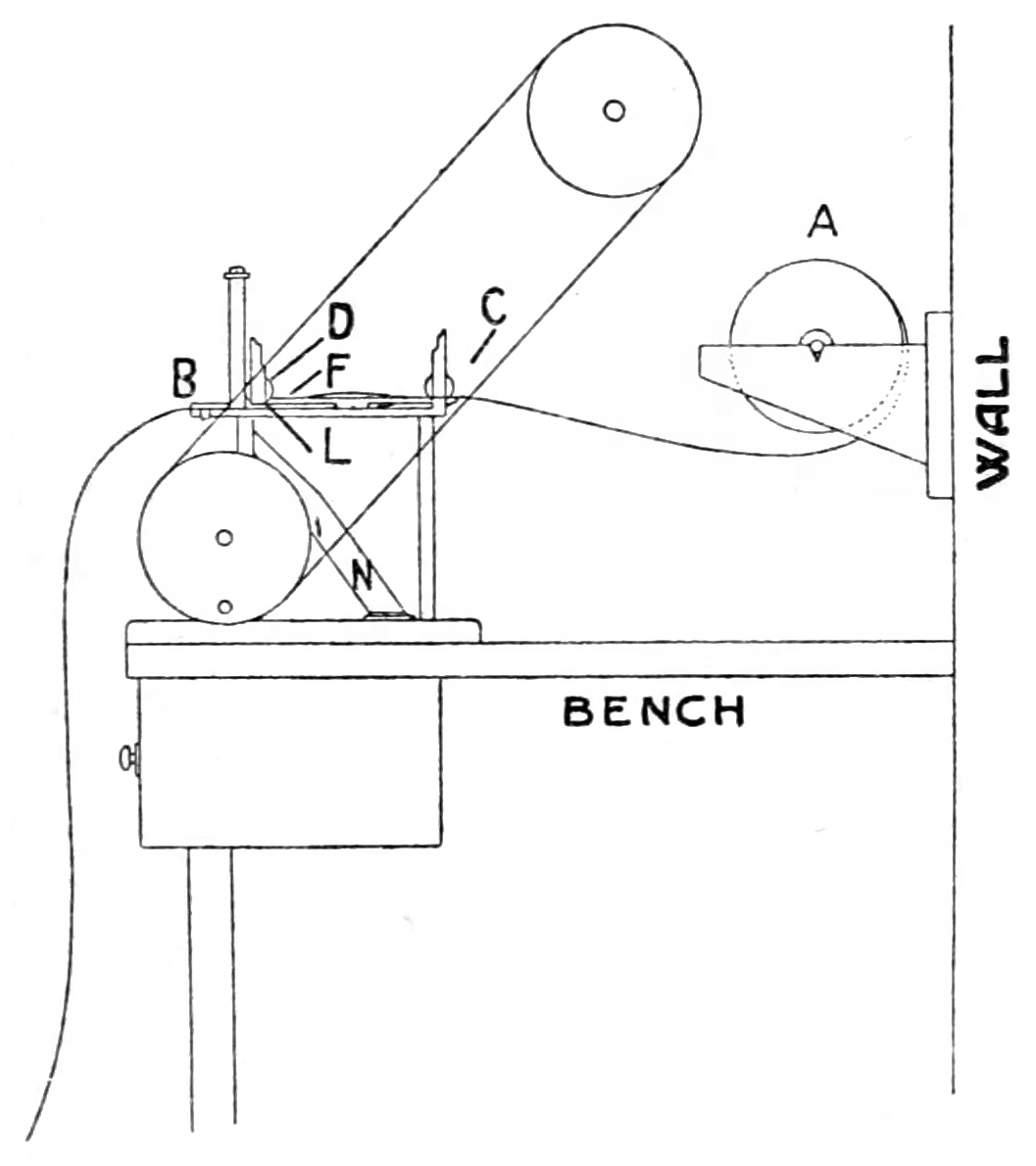

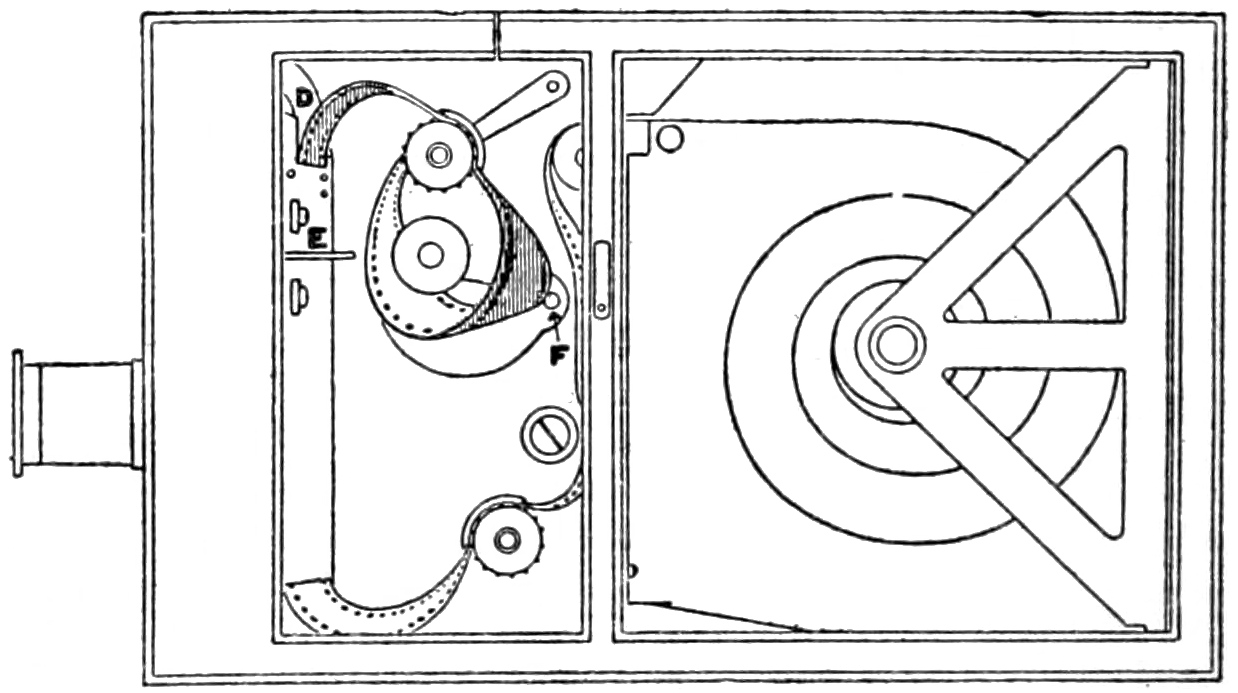

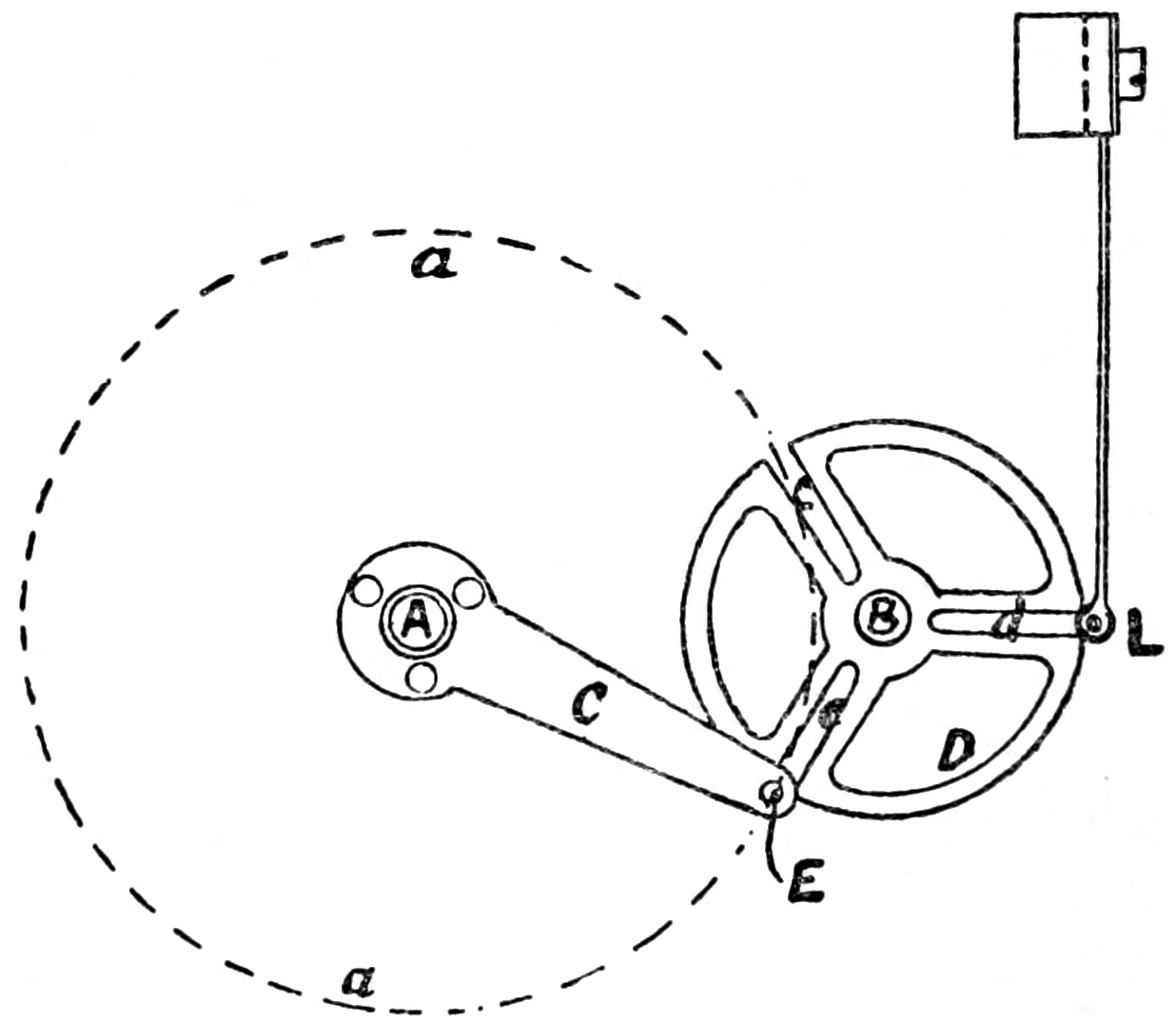

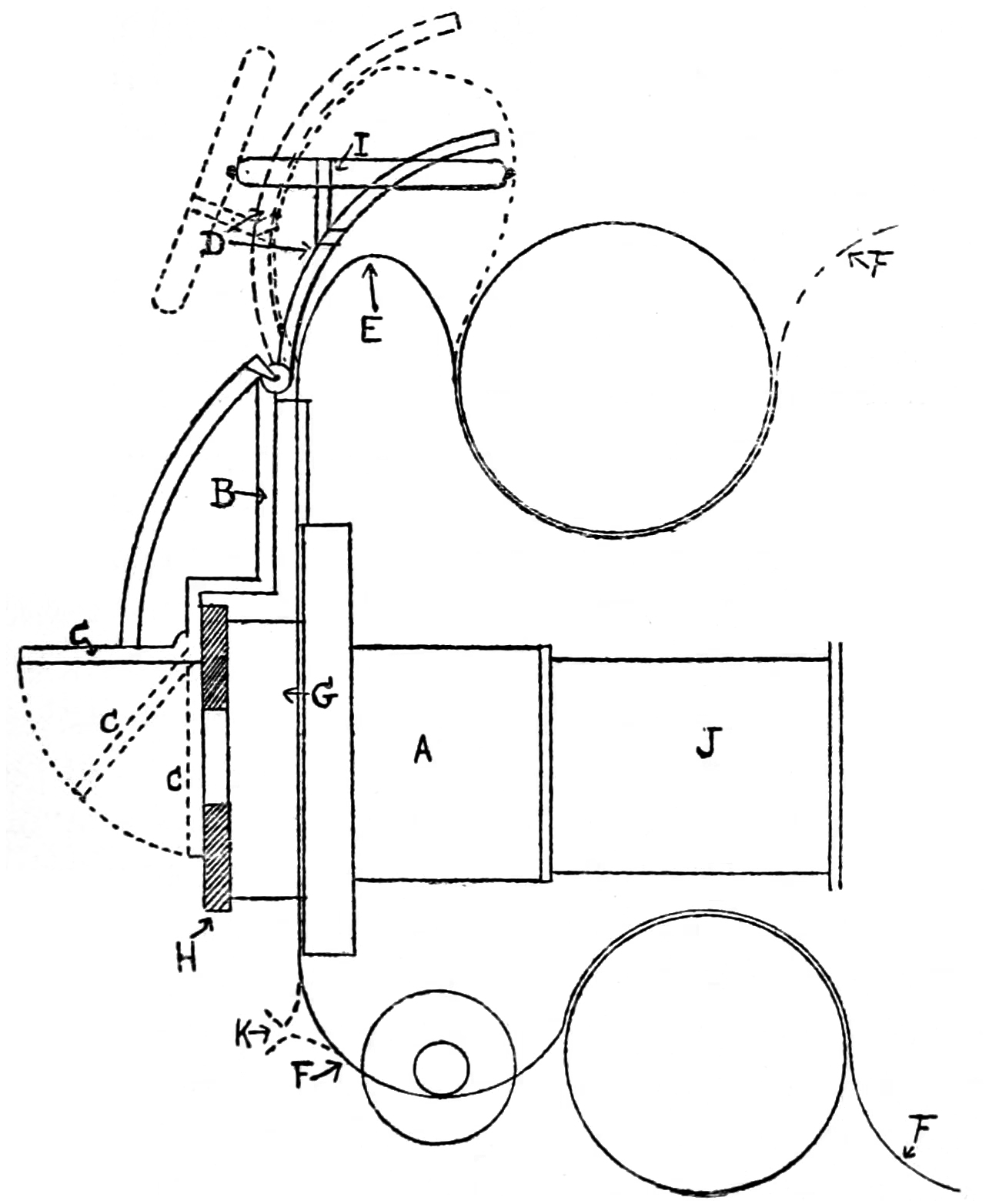

| The Film-moving Mechanism of a Cinematograph Camera | 67 |

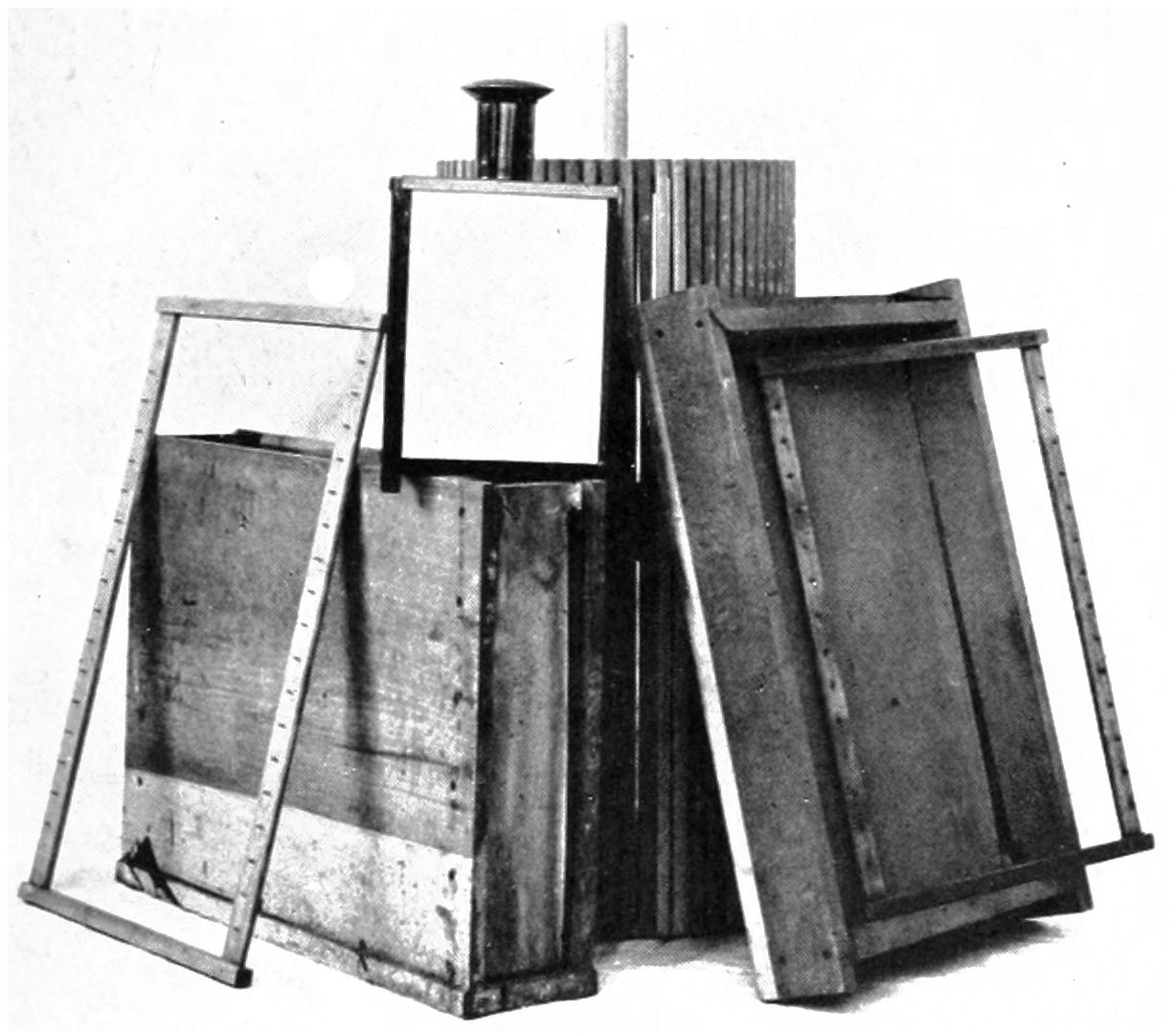

| Paul’s Complete Developing, Printing, and Drying Outfit | 70 |

| The First Developing Room in Great Britain, at Robert Paul’s Pioneer Film Factory | 70 |

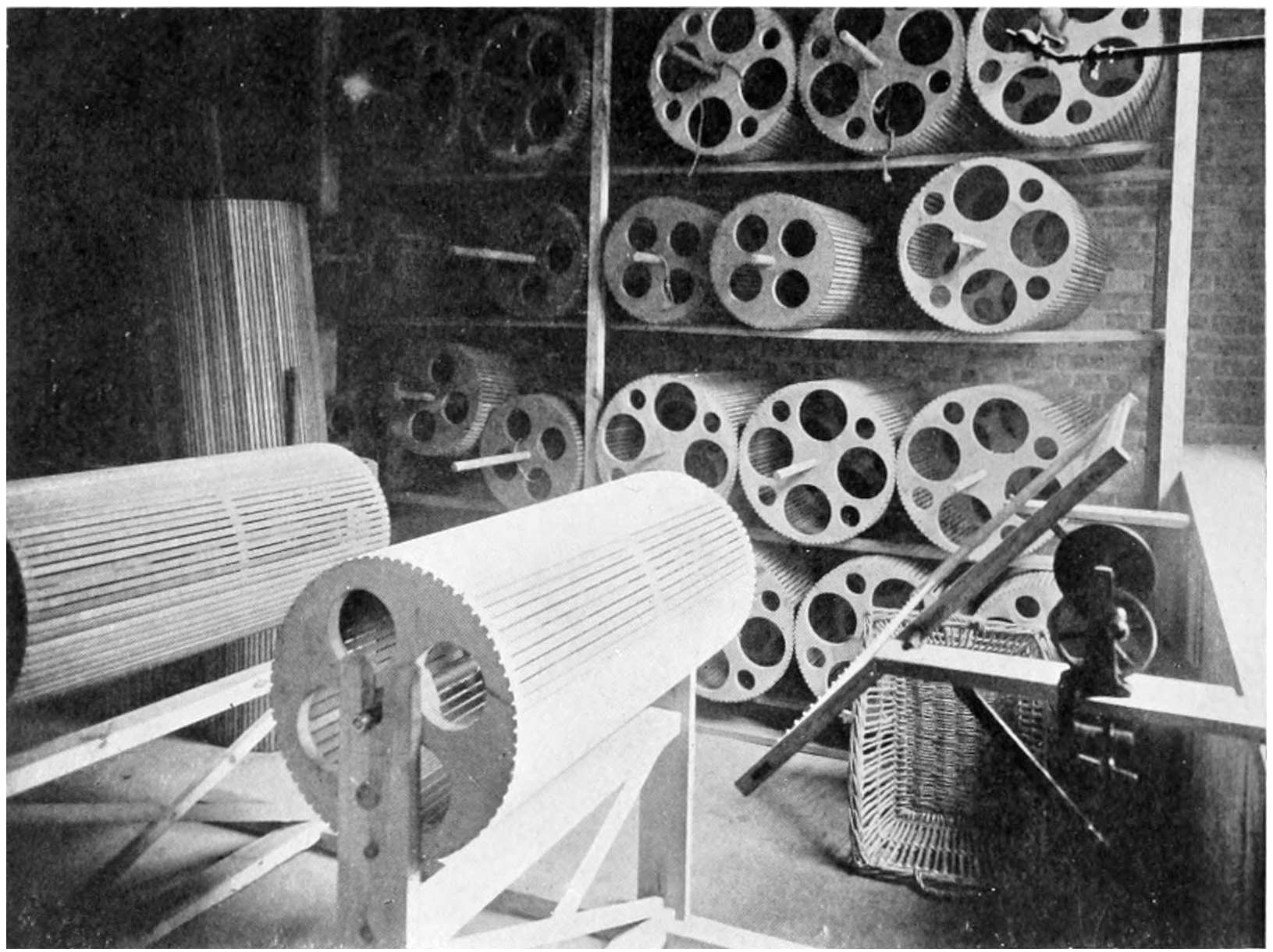

| After Development and Washing the Films were transferred from the Racks to the Cylinders | 71 |

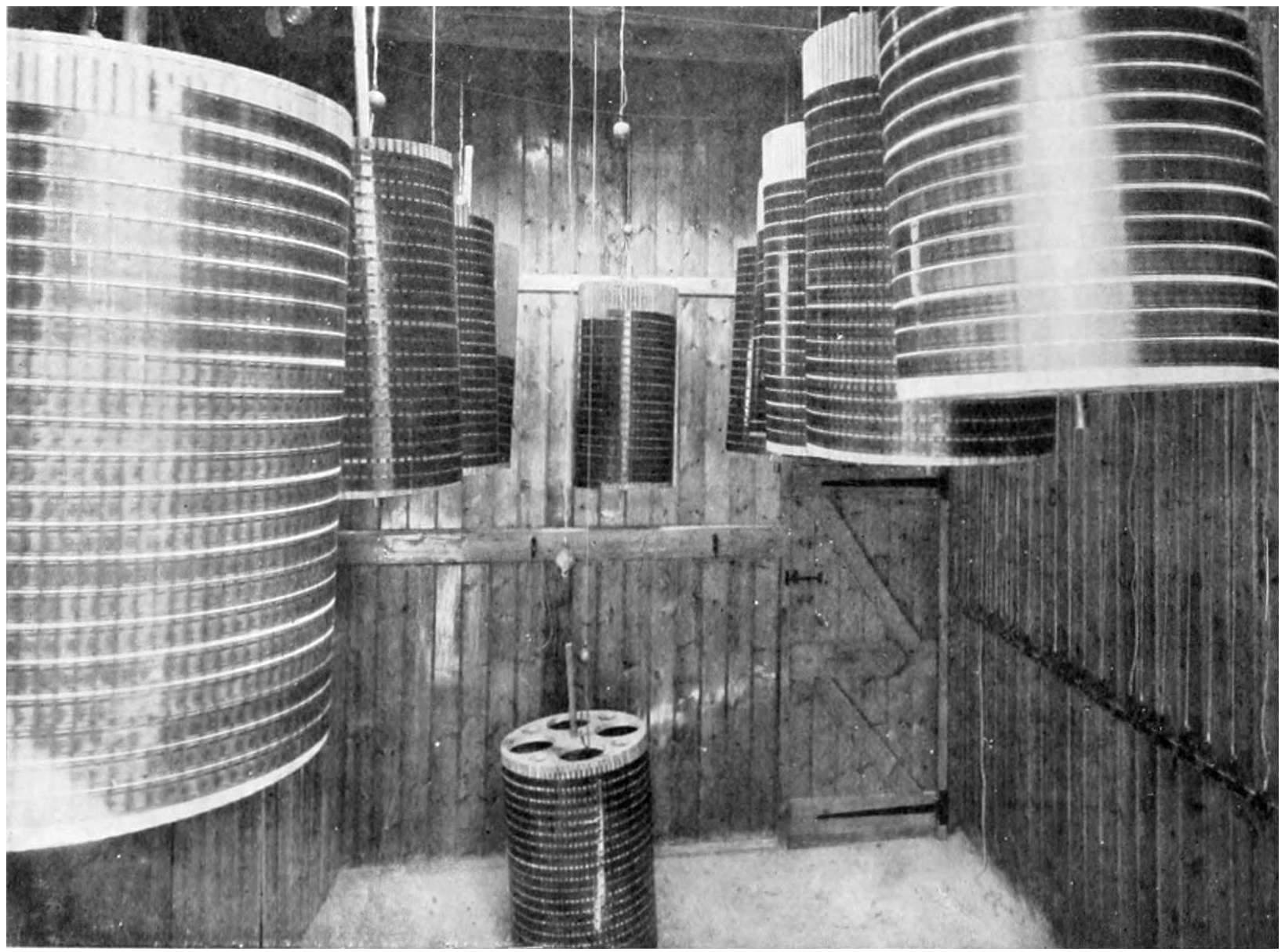

| The Drying Room, showing Films wound on the Drying Drums | 71xii |

| The Developing Room at the Pathé Works | 78 |

| The Drying Room at the Pathé Works | 79 |

| A Row of Printing Machines in the Rome Works of the Cines Company | 82 |

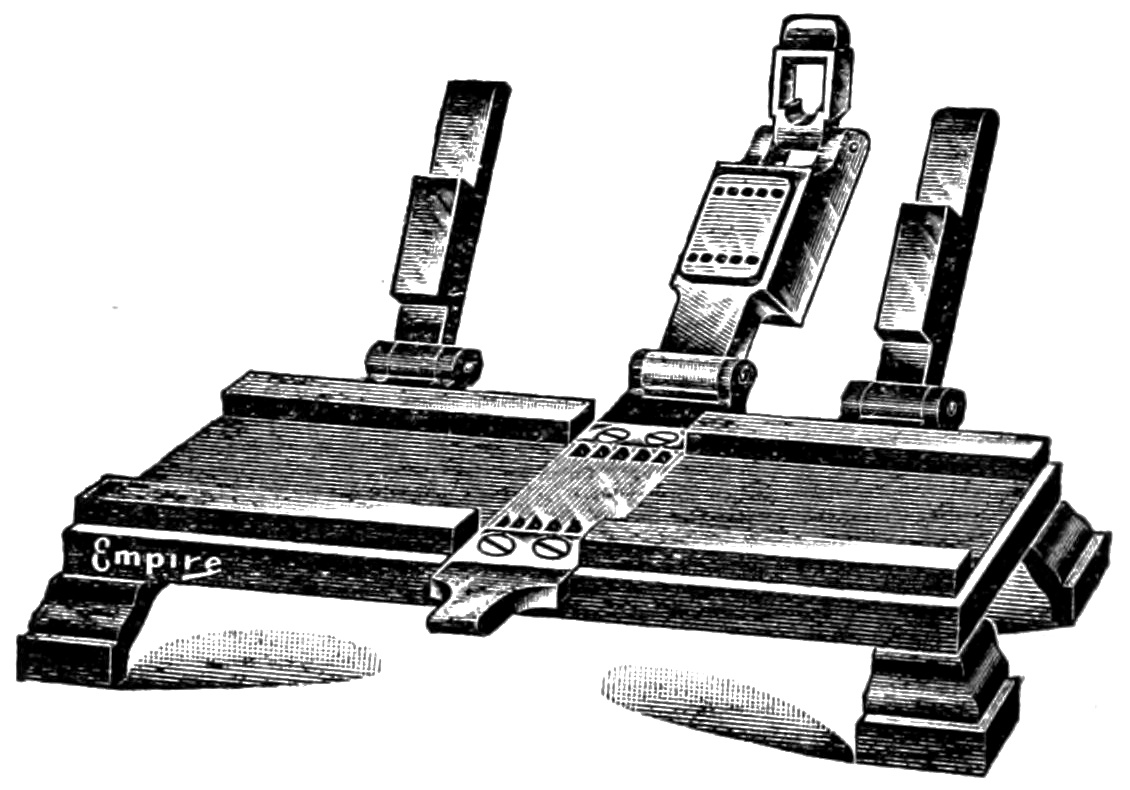

| The Williamson Printing Machine | 83 |

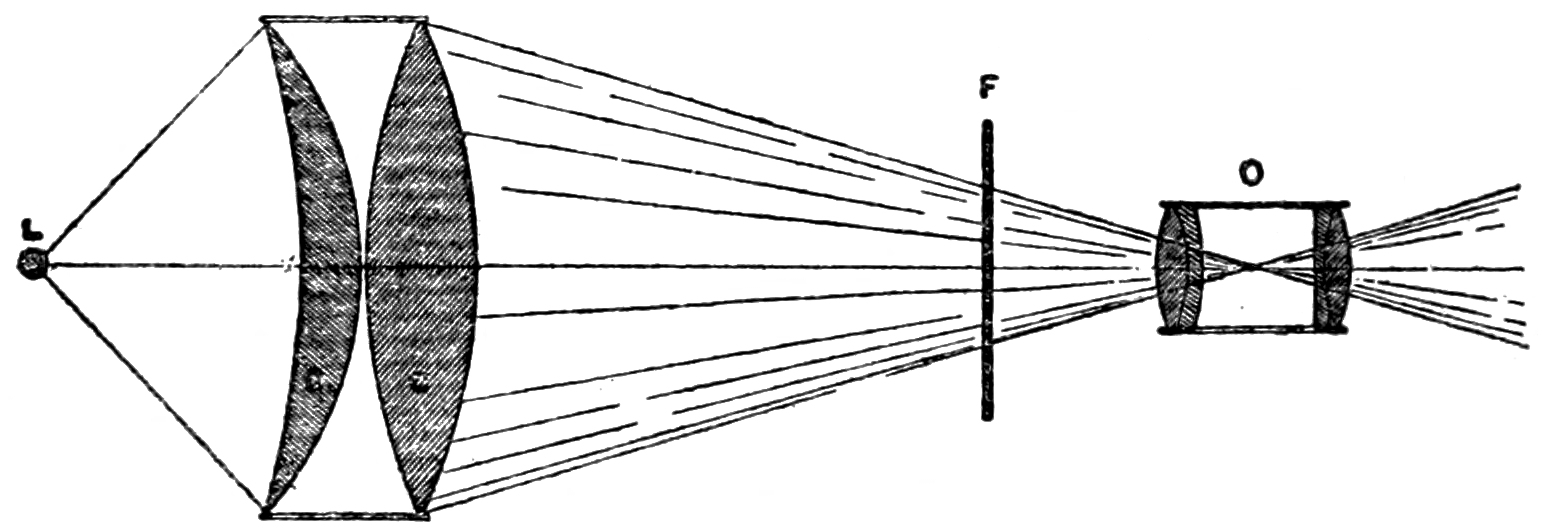

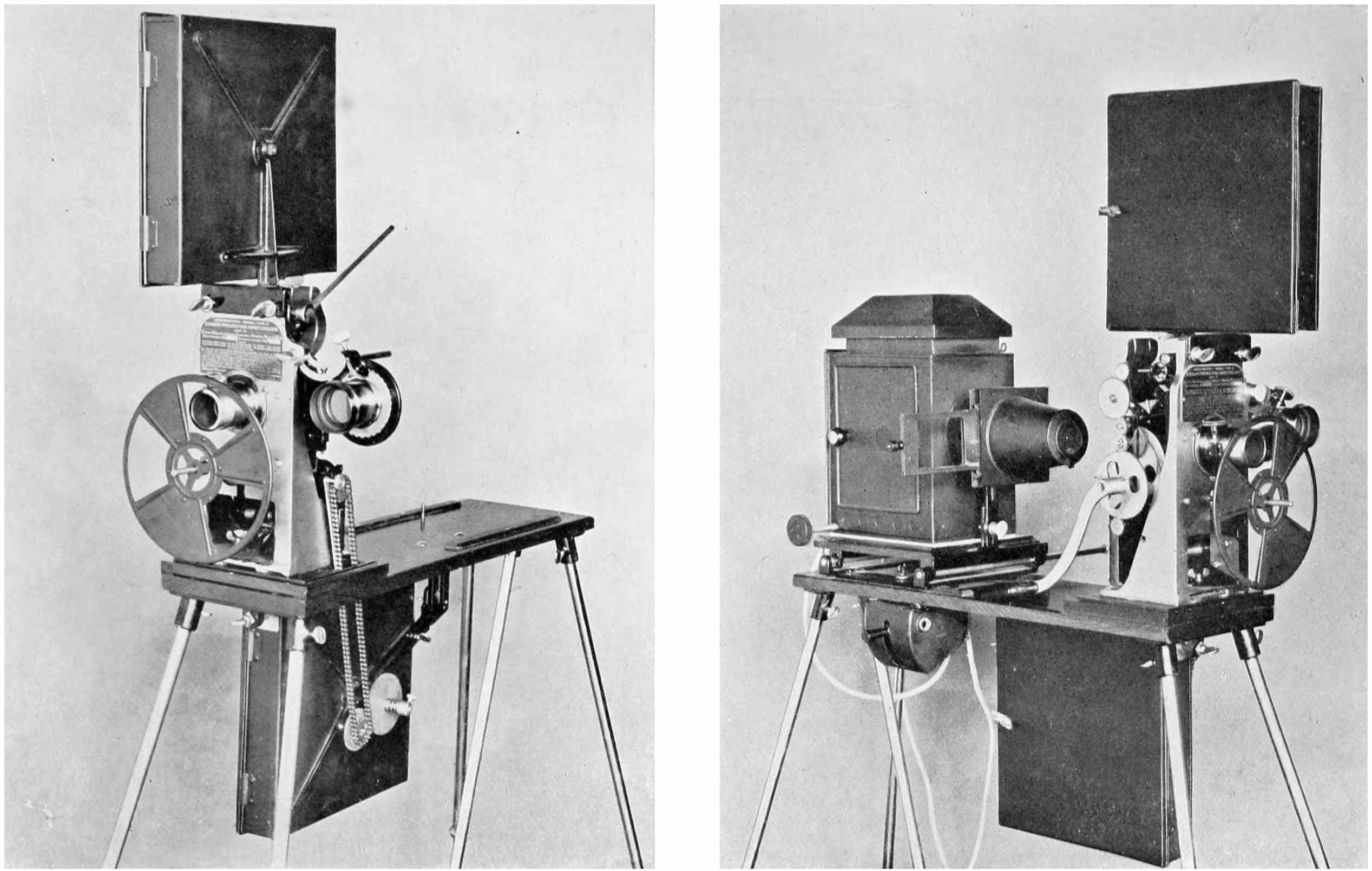

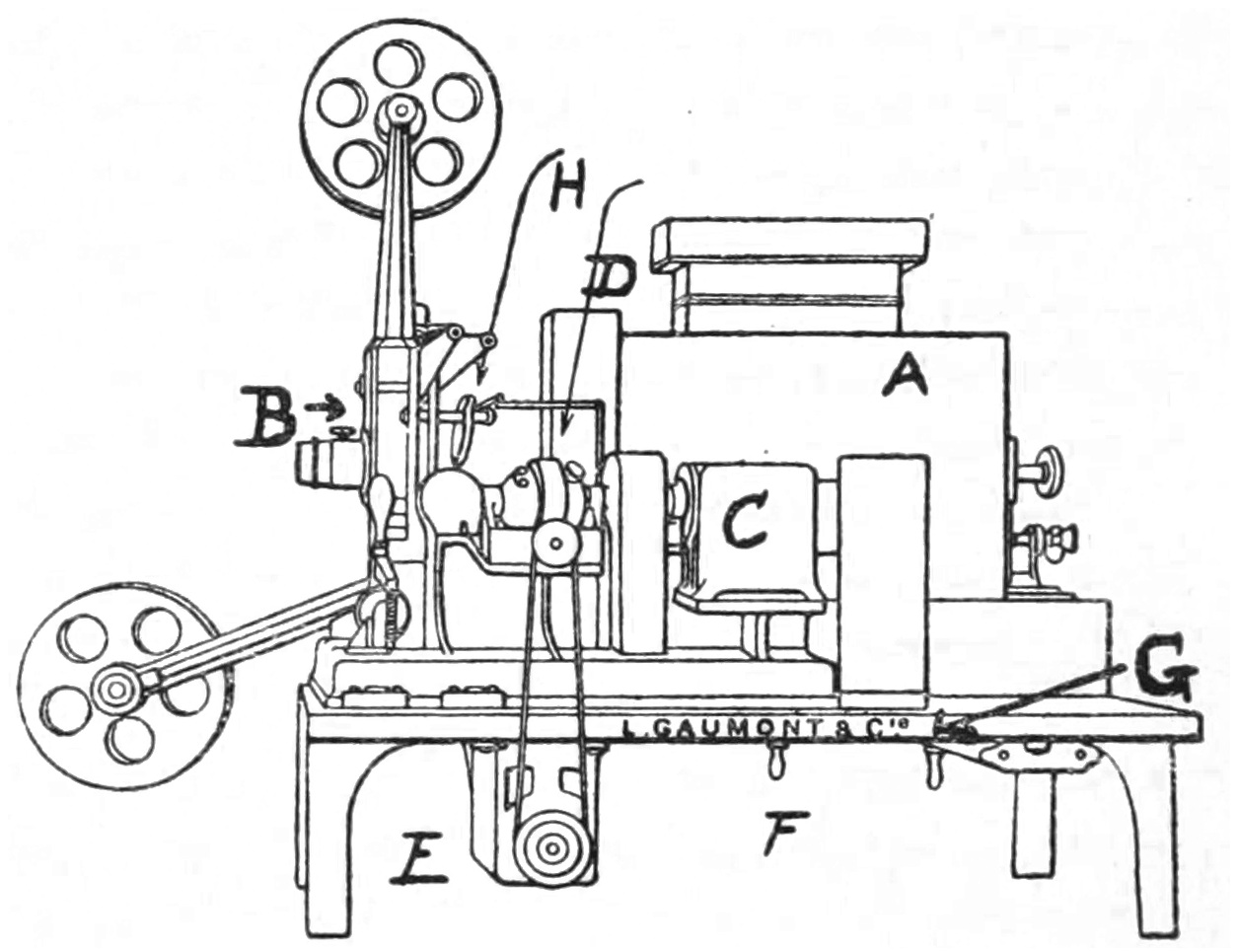

| The Projector and Mechanism | 100 |

| The Complete Projecting Installation | 100 |

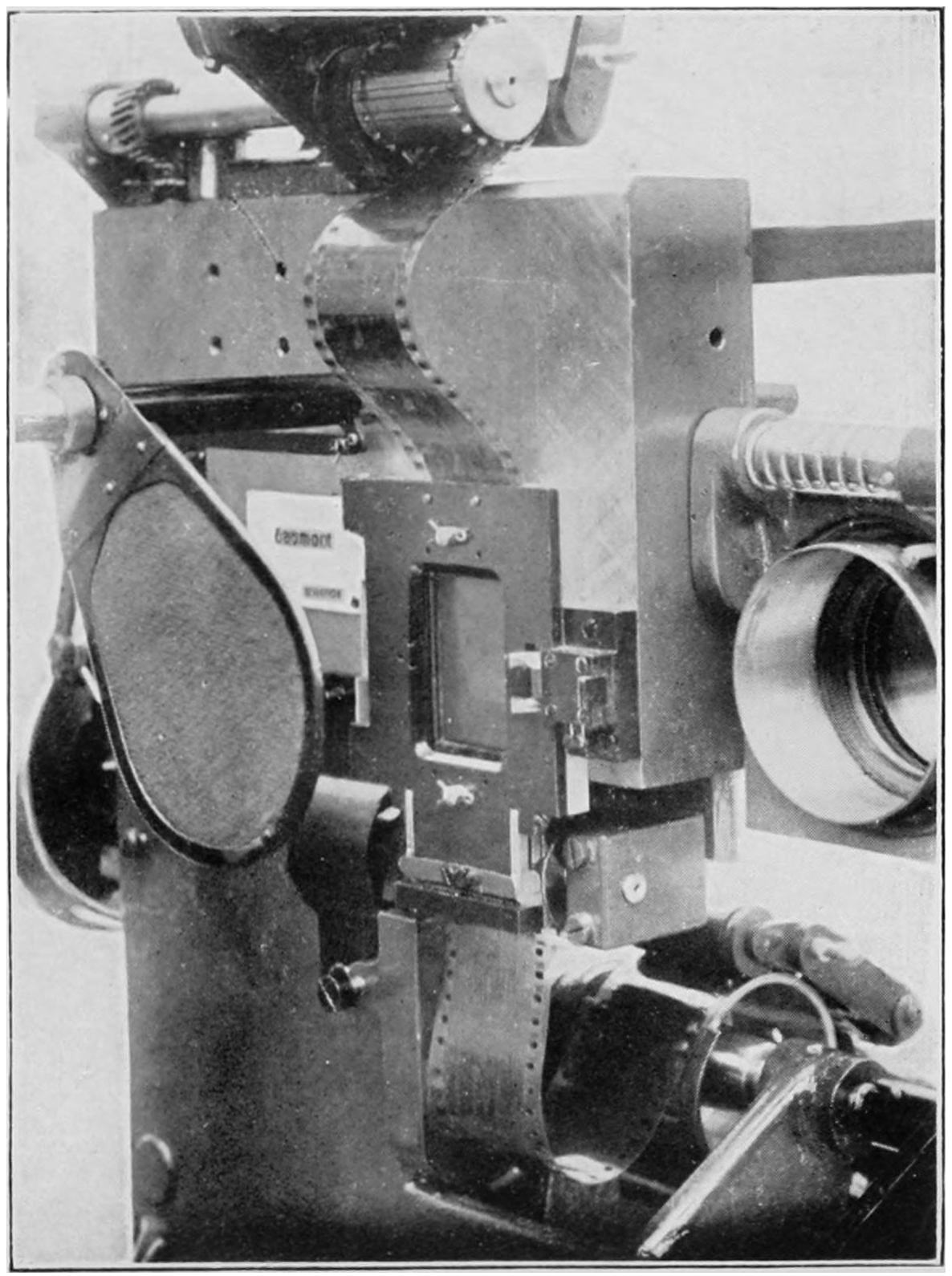

| The “Chrono” Projector | 101 |

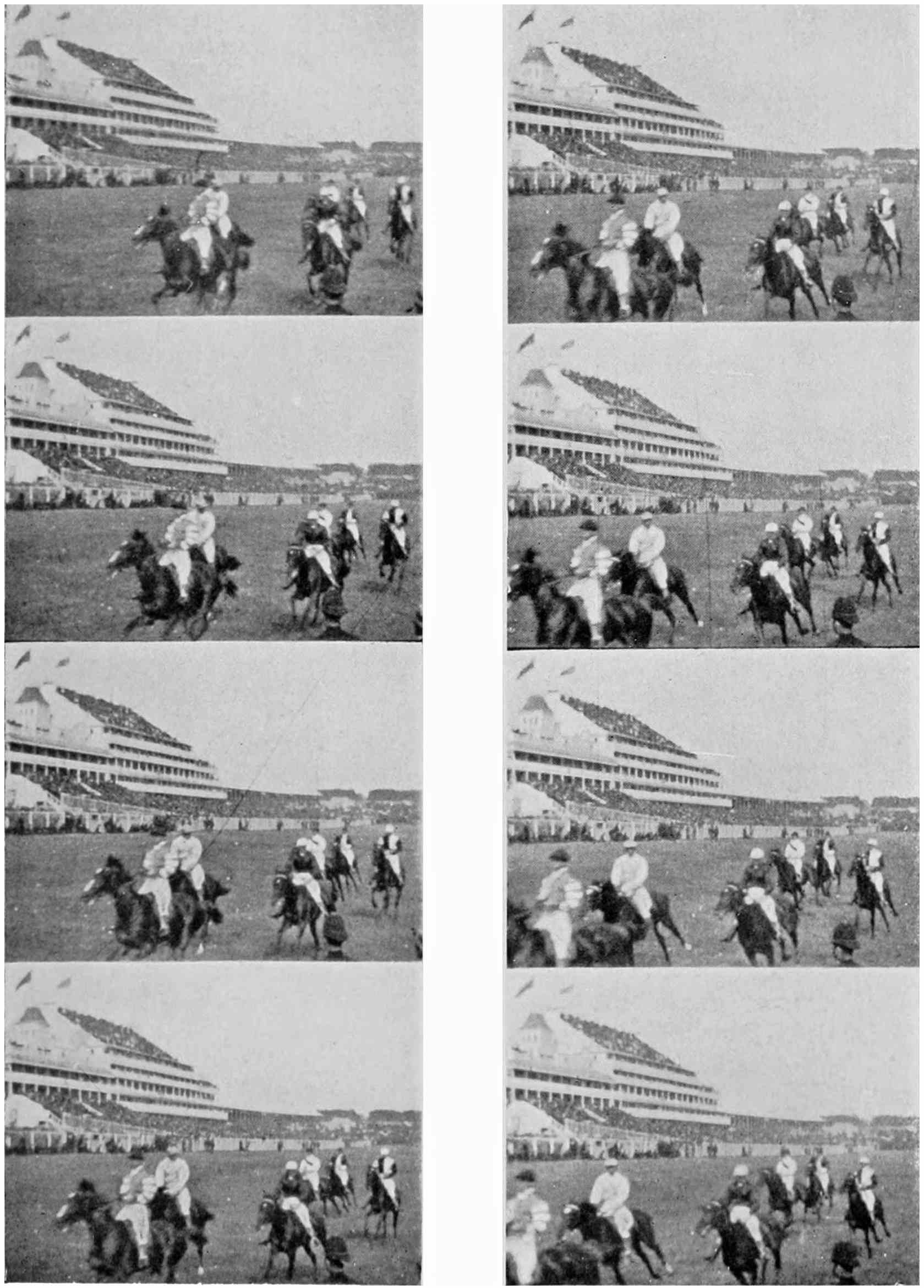

| Outstripping the Human Eye | 101 |

| An Early Open-Air Studio-Stage for producing Cinematograph Plays | 104 |

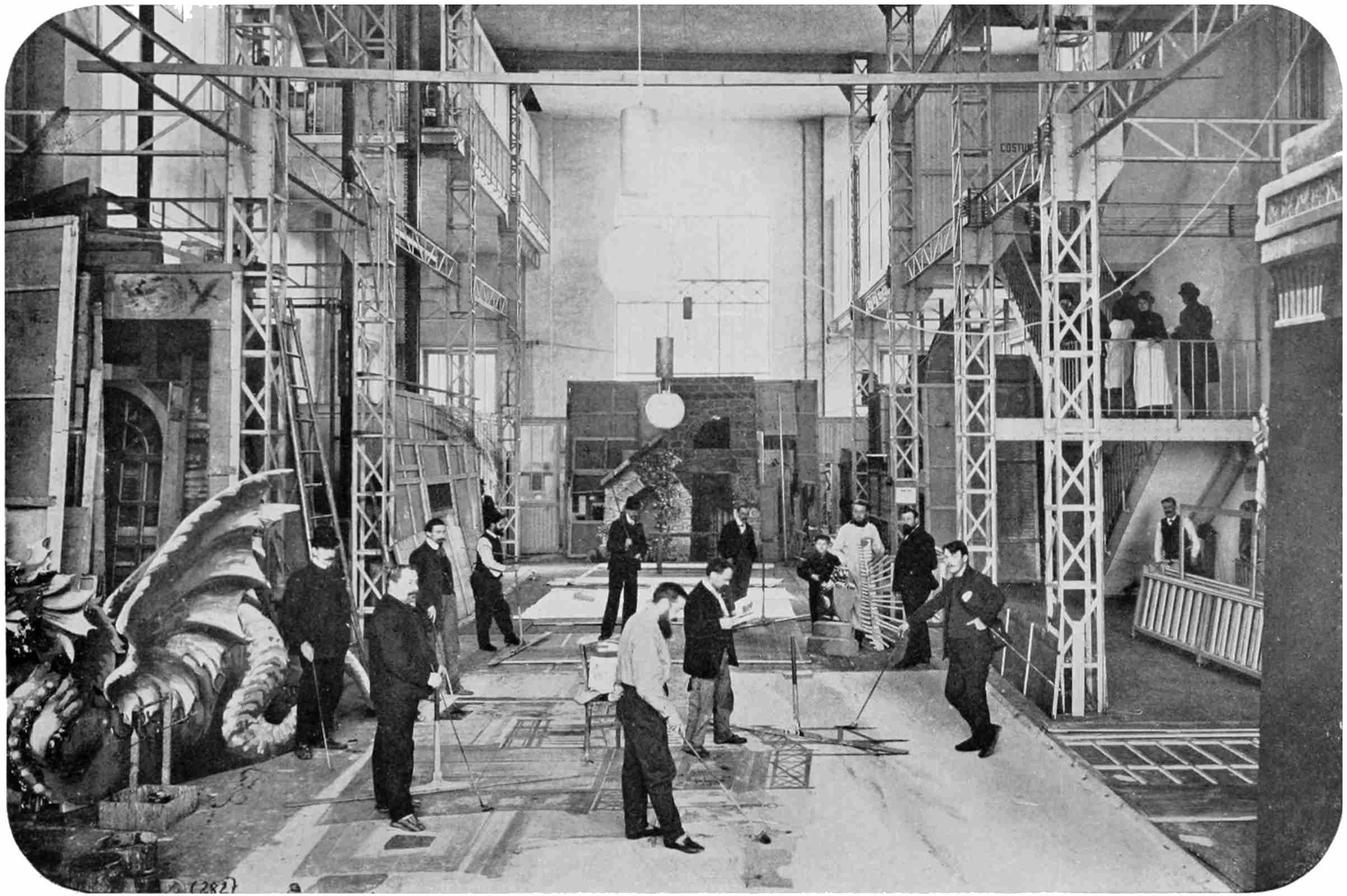

| The Scene-Painters’ Shop at a Pathé Studio | 105 |

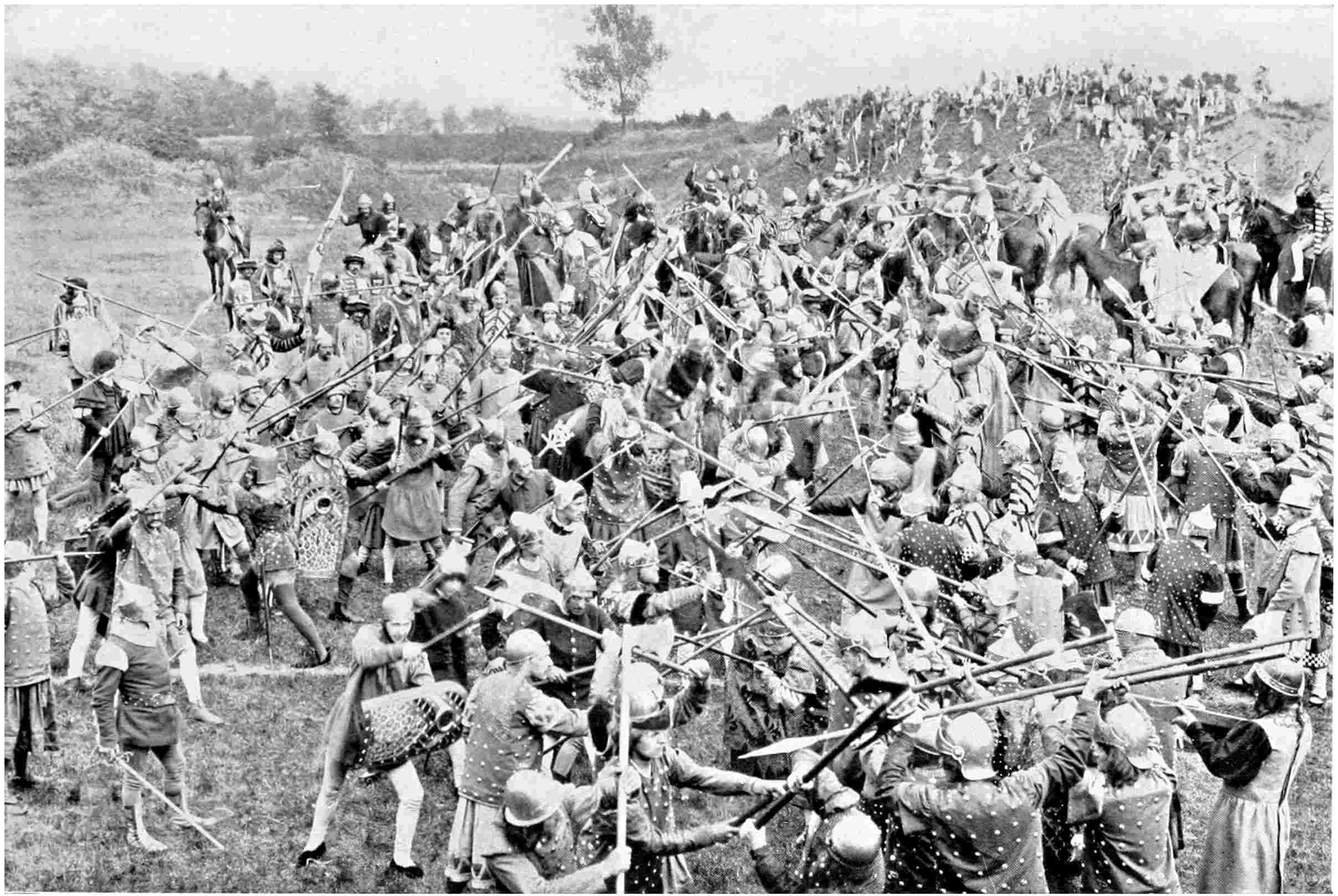

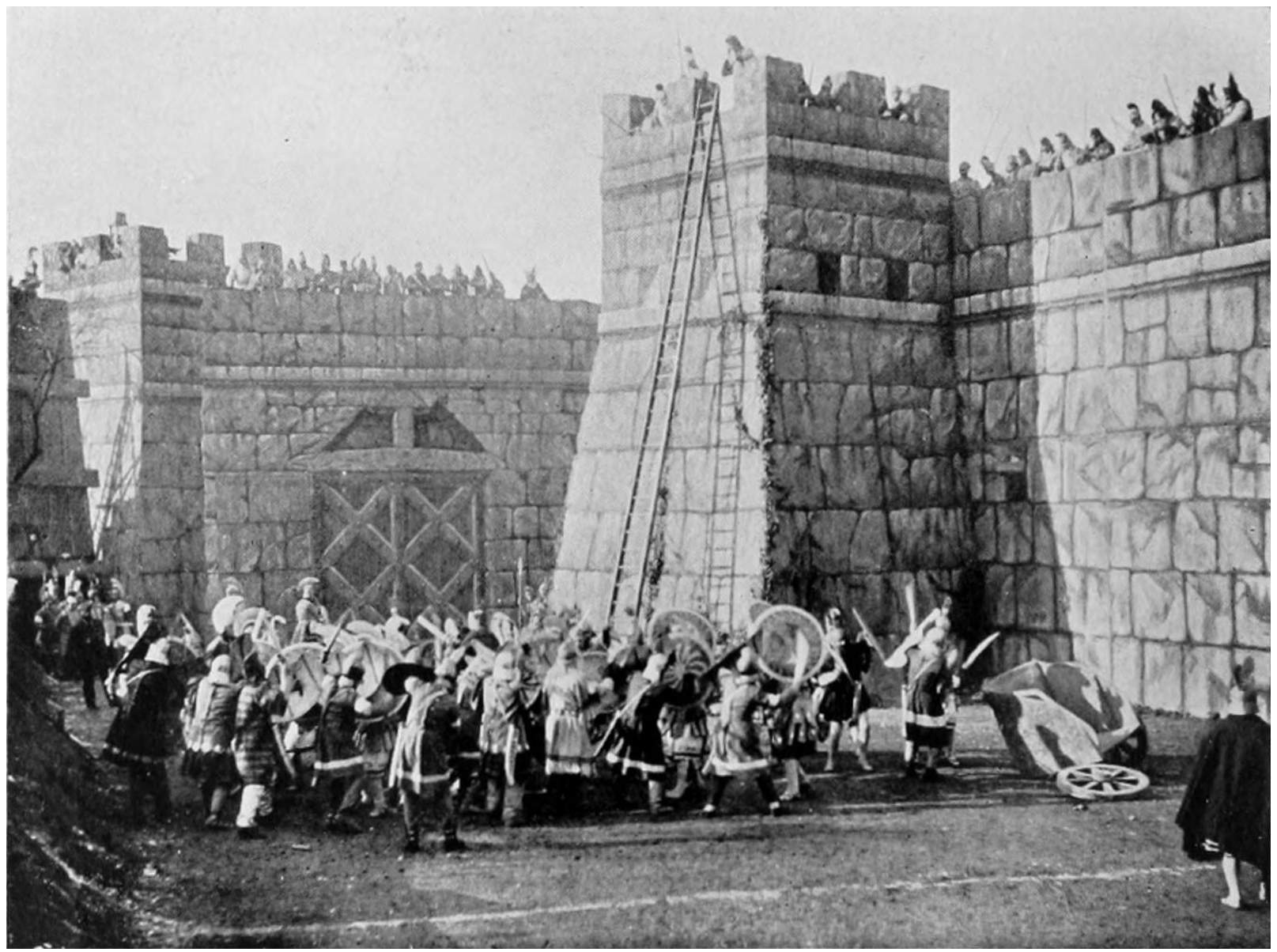

| Battle Scene from “The Siege of Calais” | 108 |

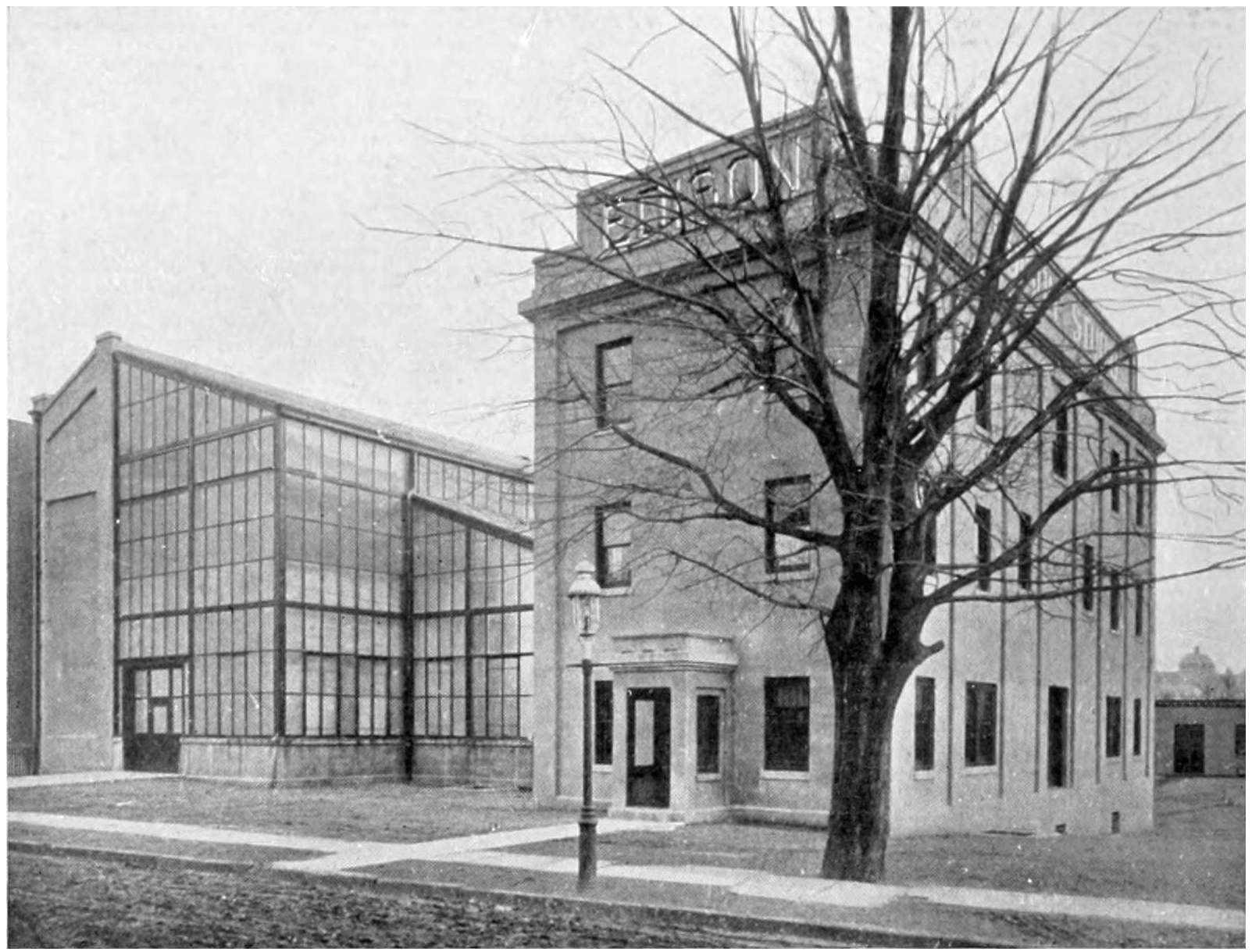

| Exterior of the Modern Edison Film-Play-Producing Theatre | 109 |

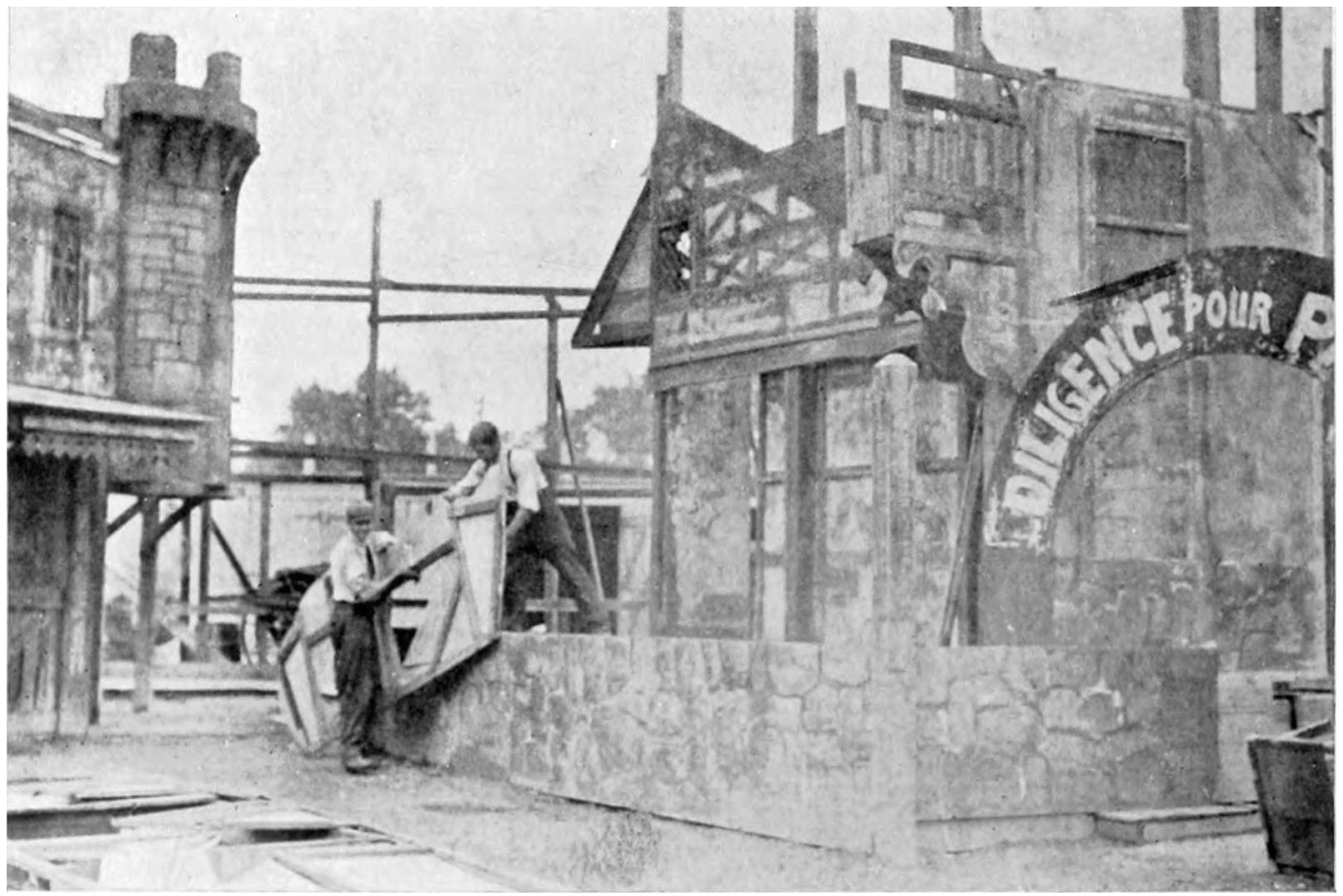

| Building a Solid Set for “The Two Orphans” | 109 |

| Building a Scene on one of the Pathé Studio-Stages for a Film Play | 112 |

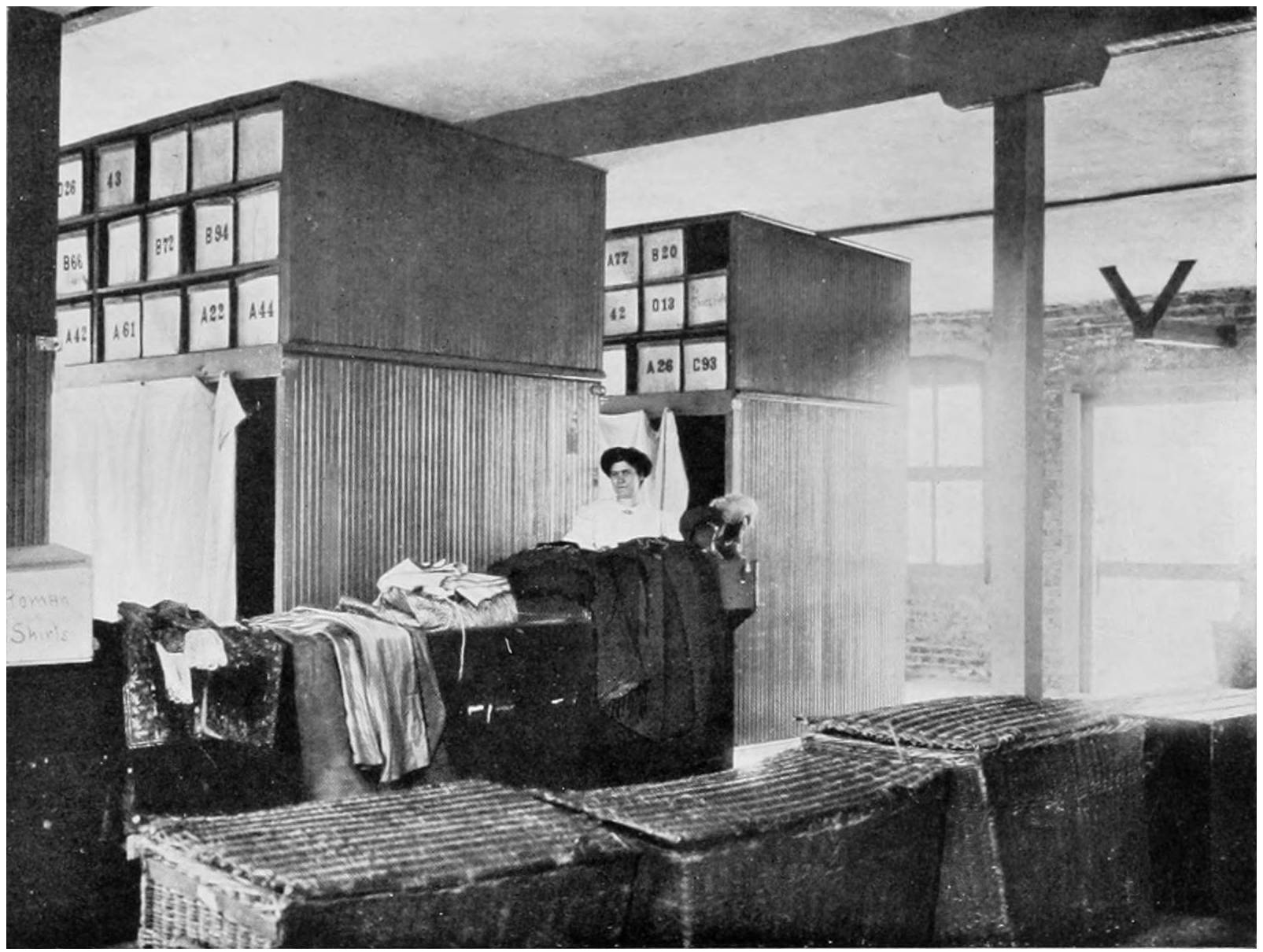

| The Wardrobe Room at the Selig Film Factory | 113 |

| The Selig Stock Company at Los Angeles | 113 |

| The First Topical Film | 118 |

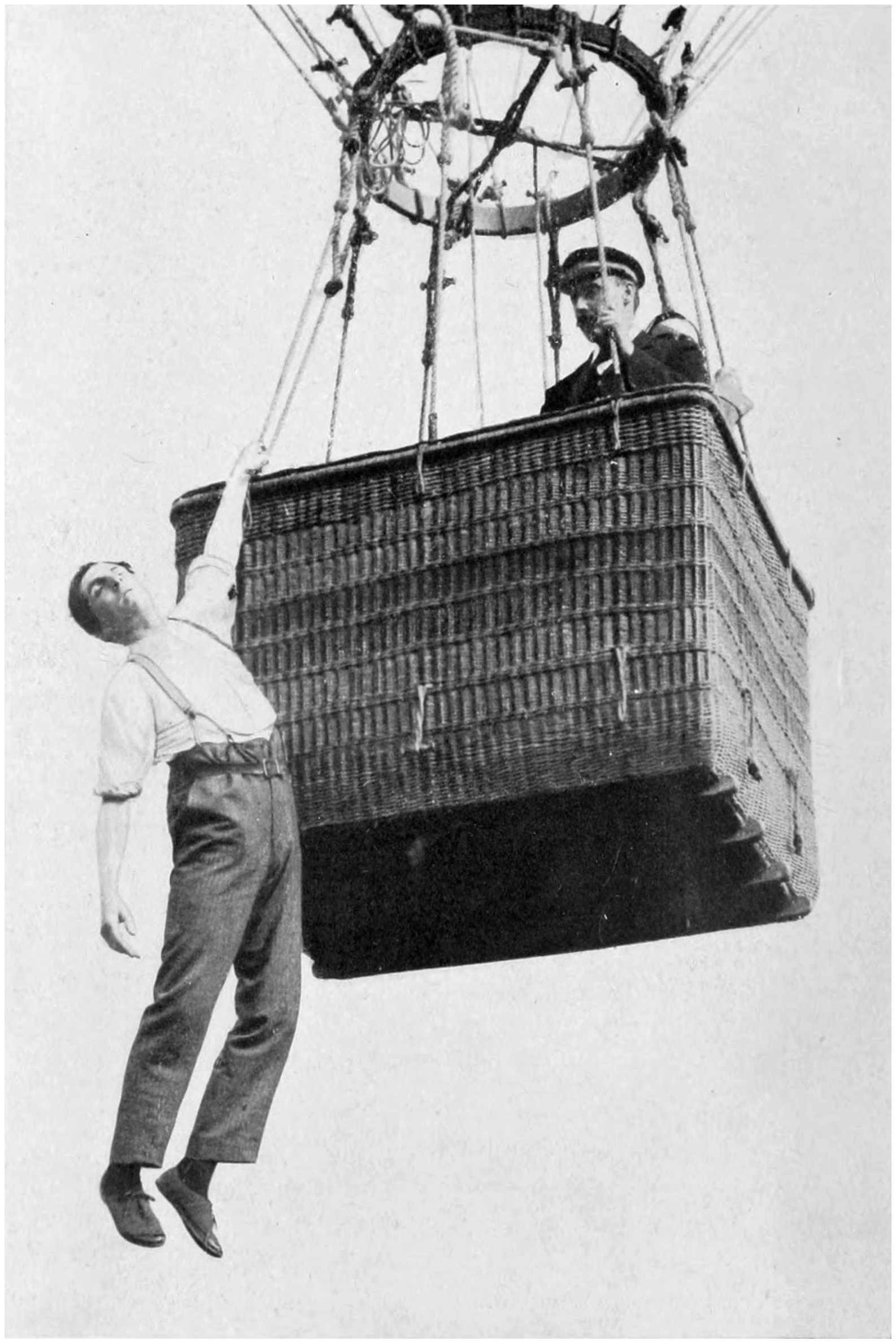

| The Fall from the Balloon | 119 |

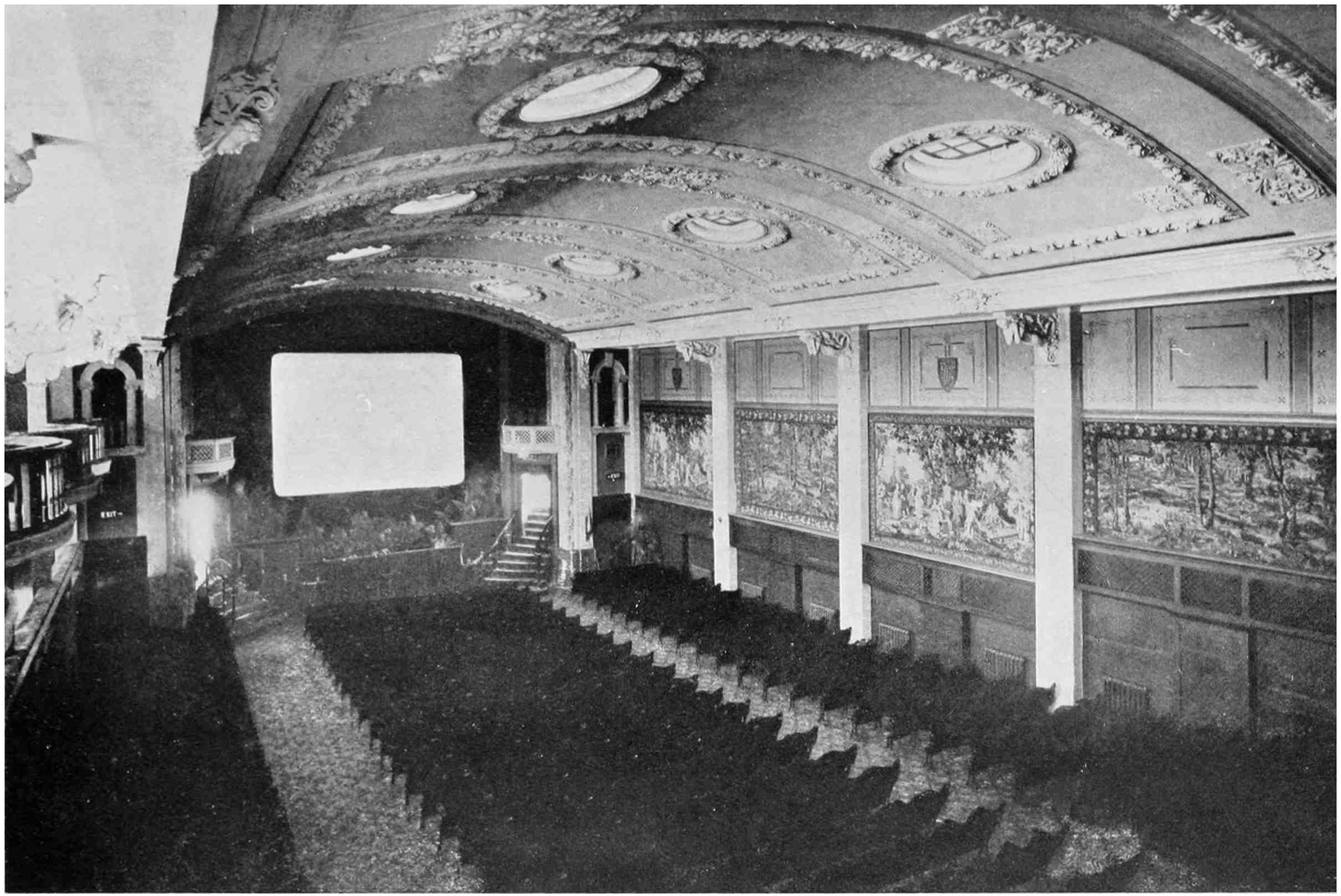

| The Luxury of the Modern Picture Palace | 134 |

| The Lantern Room of a Modern Cinematograph Theatre | 135 |

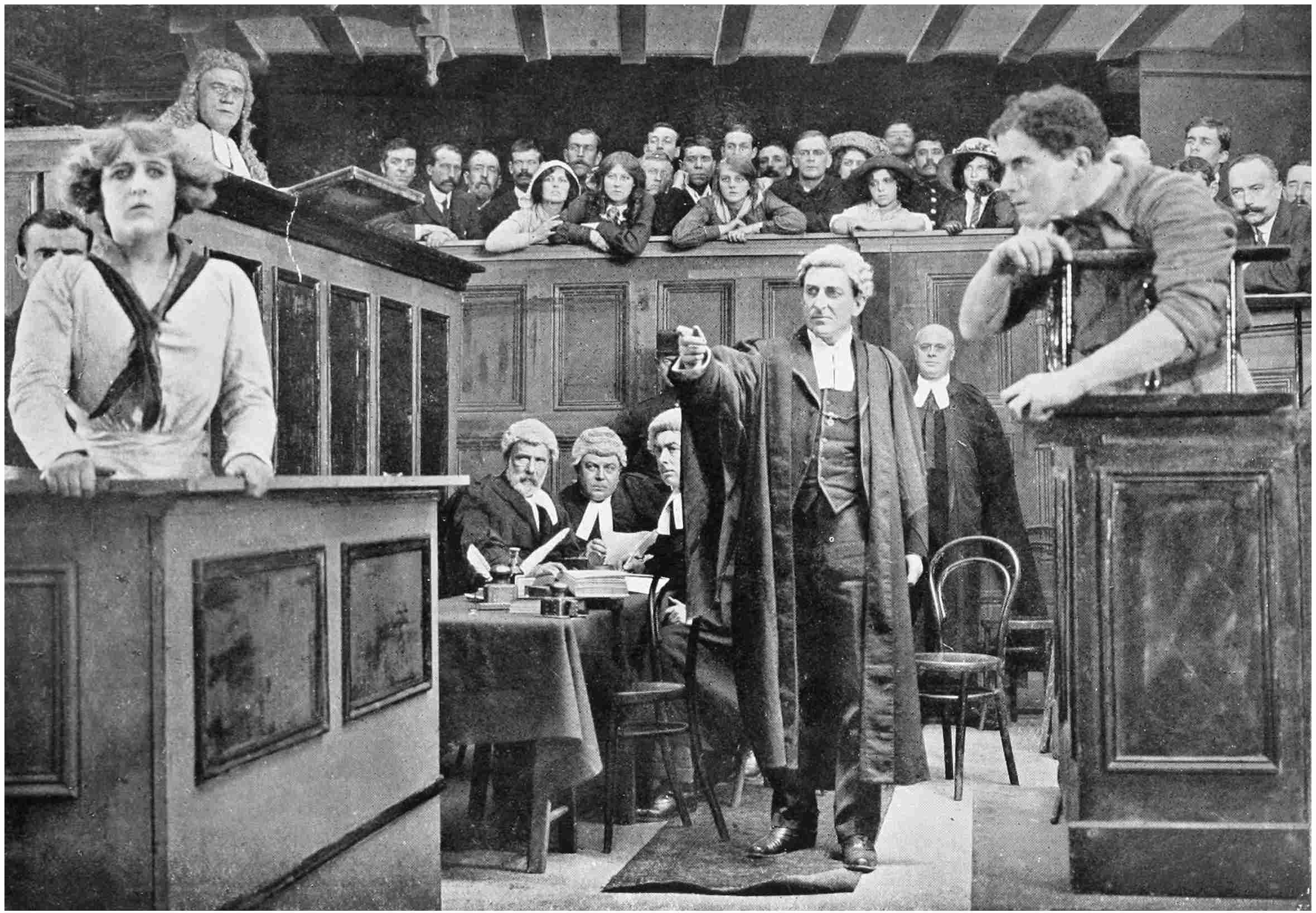

| The Trial Scene from “Rachel’s Sin” | 140 |

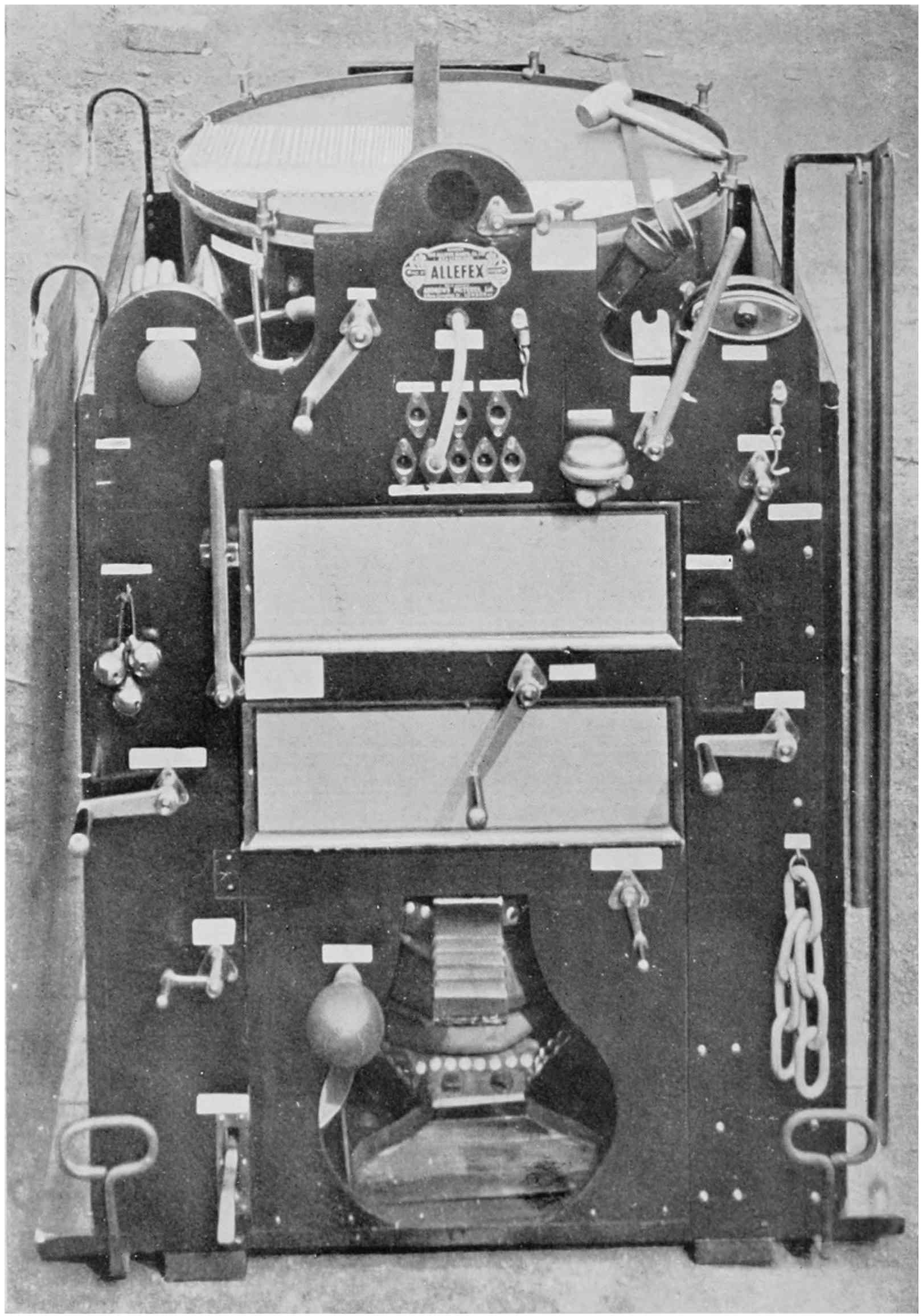

| How the Sound Accompaniments to Pictures are Produced | 141 |

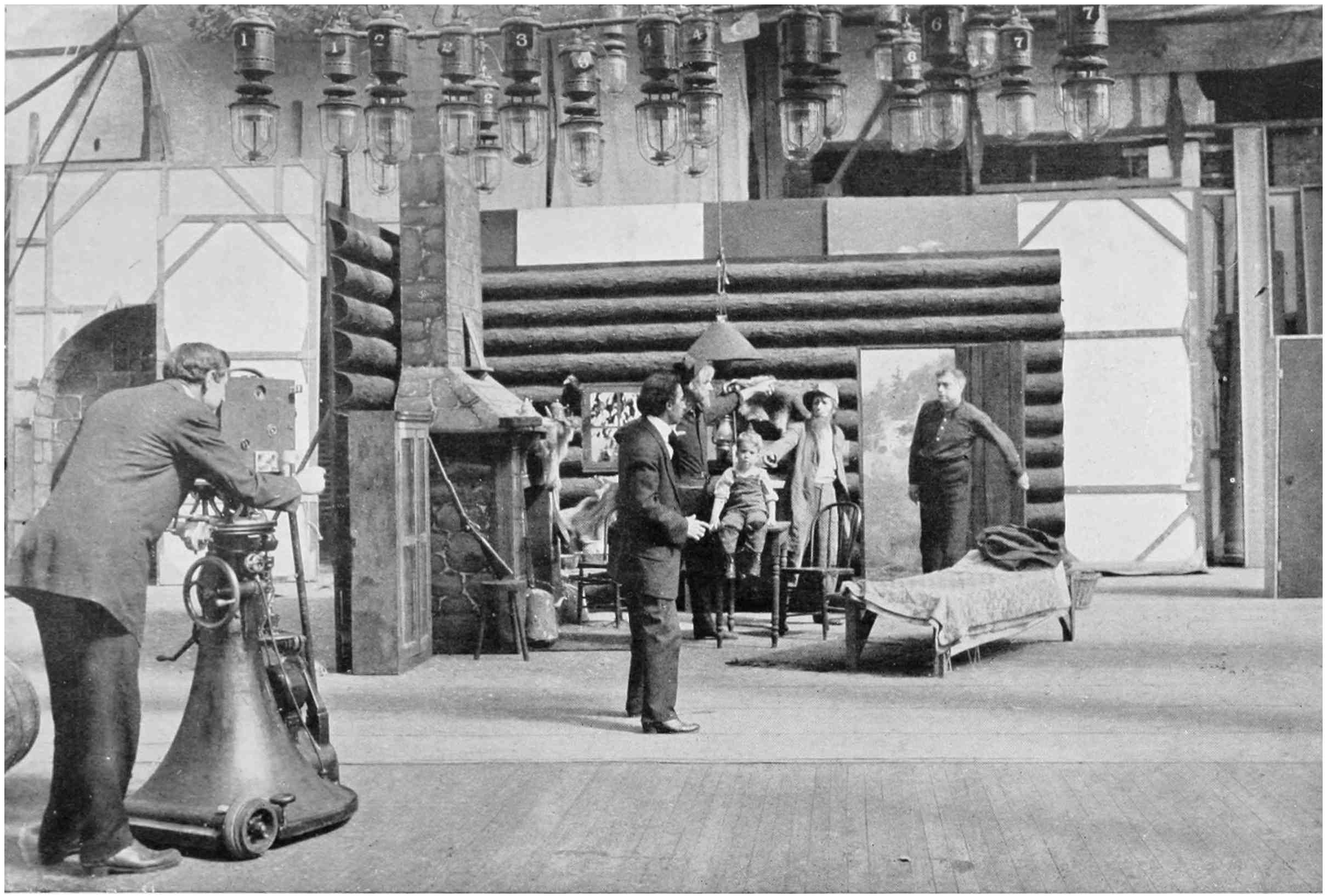

| The Film-Play Producer at Work | 148 |

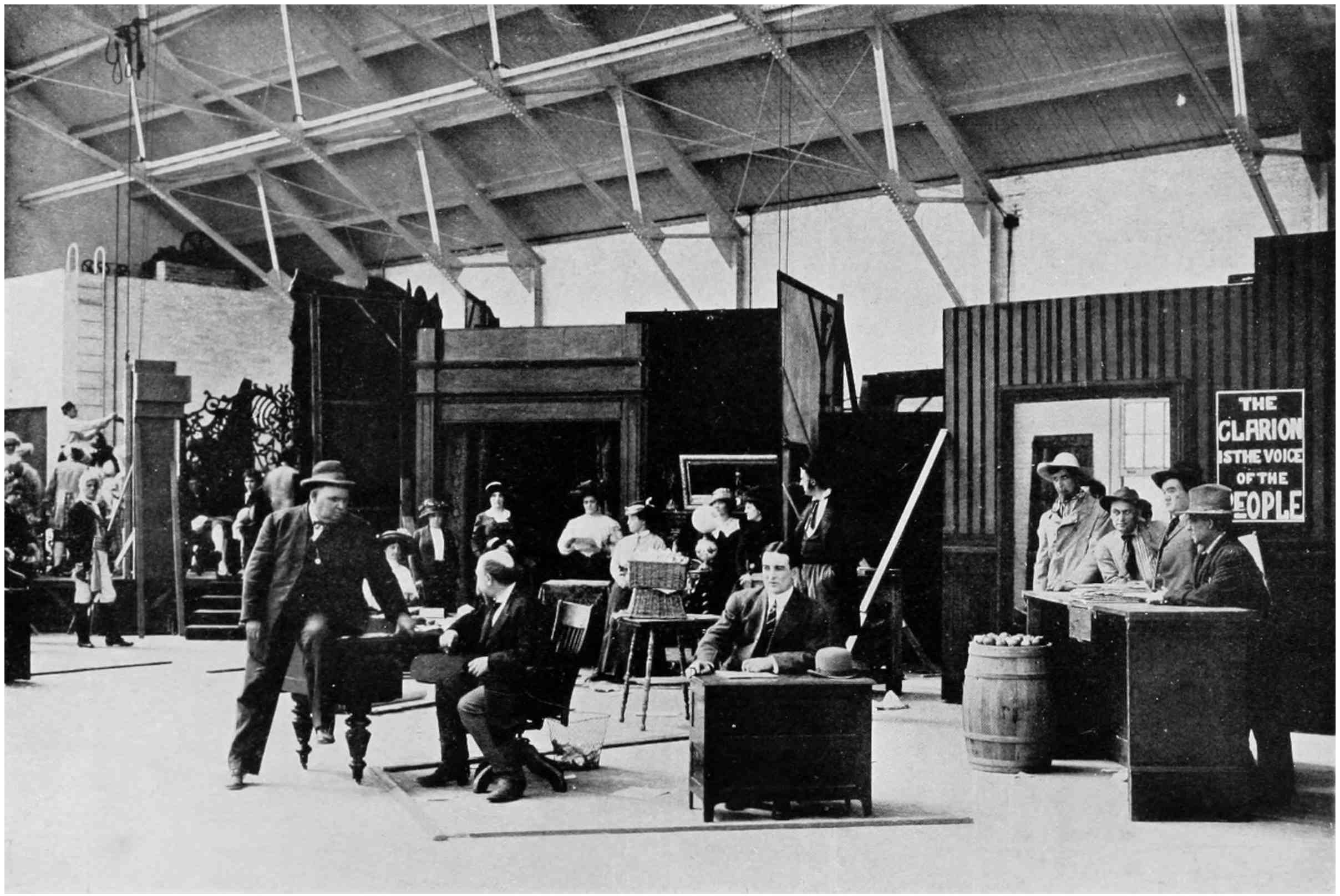

| Taking Three Picture-Plays Simultaneously | 149 |

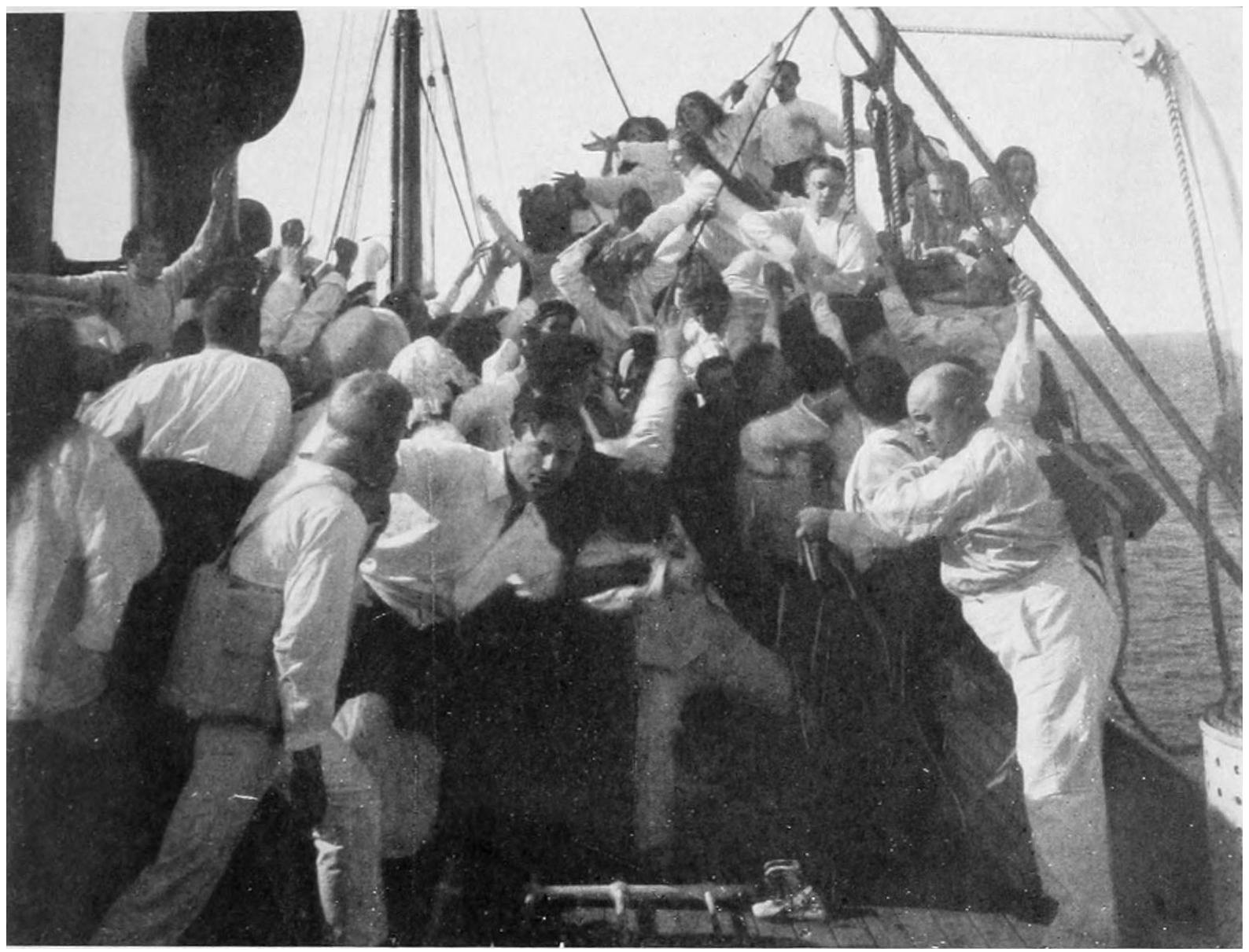

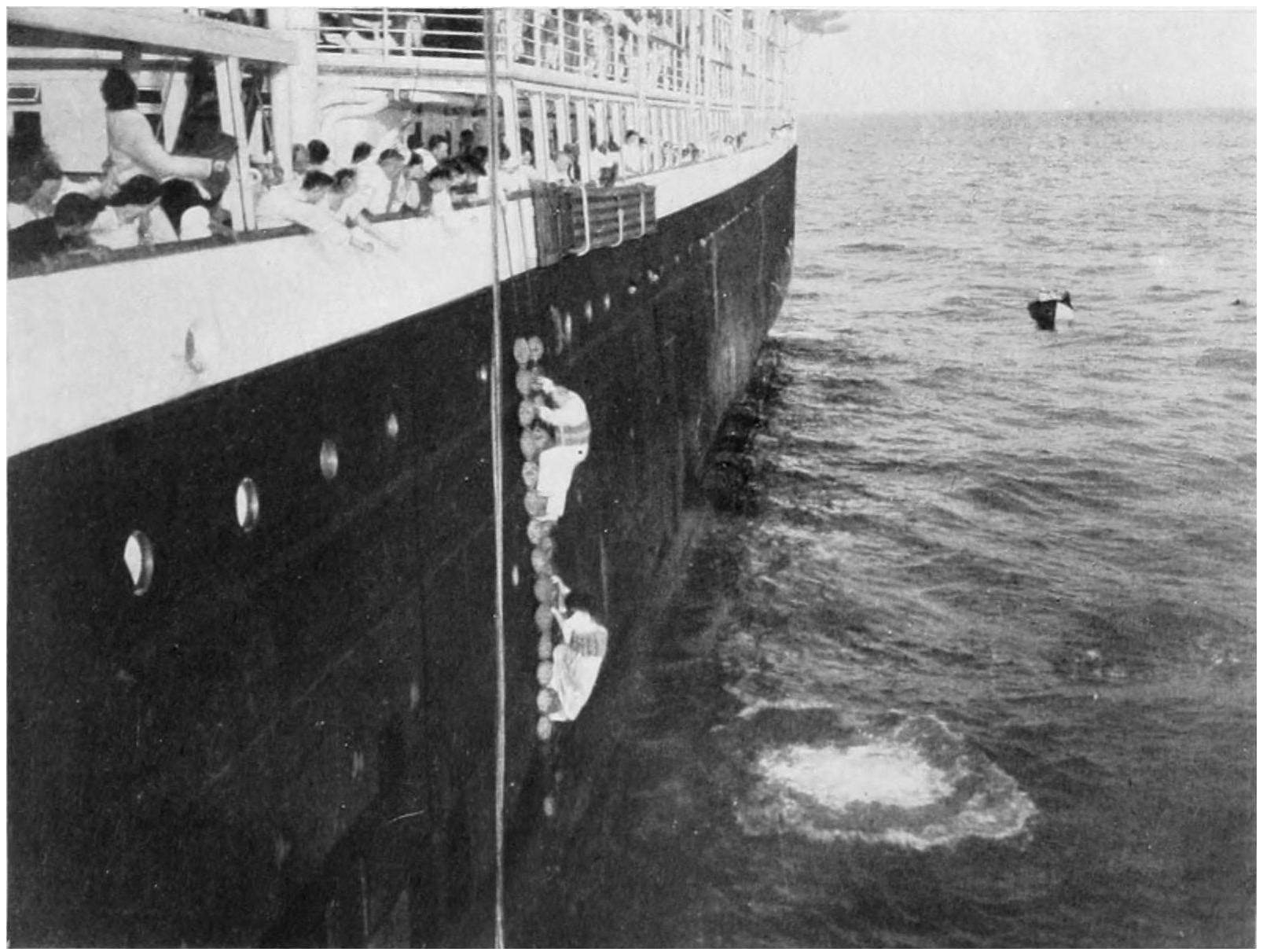

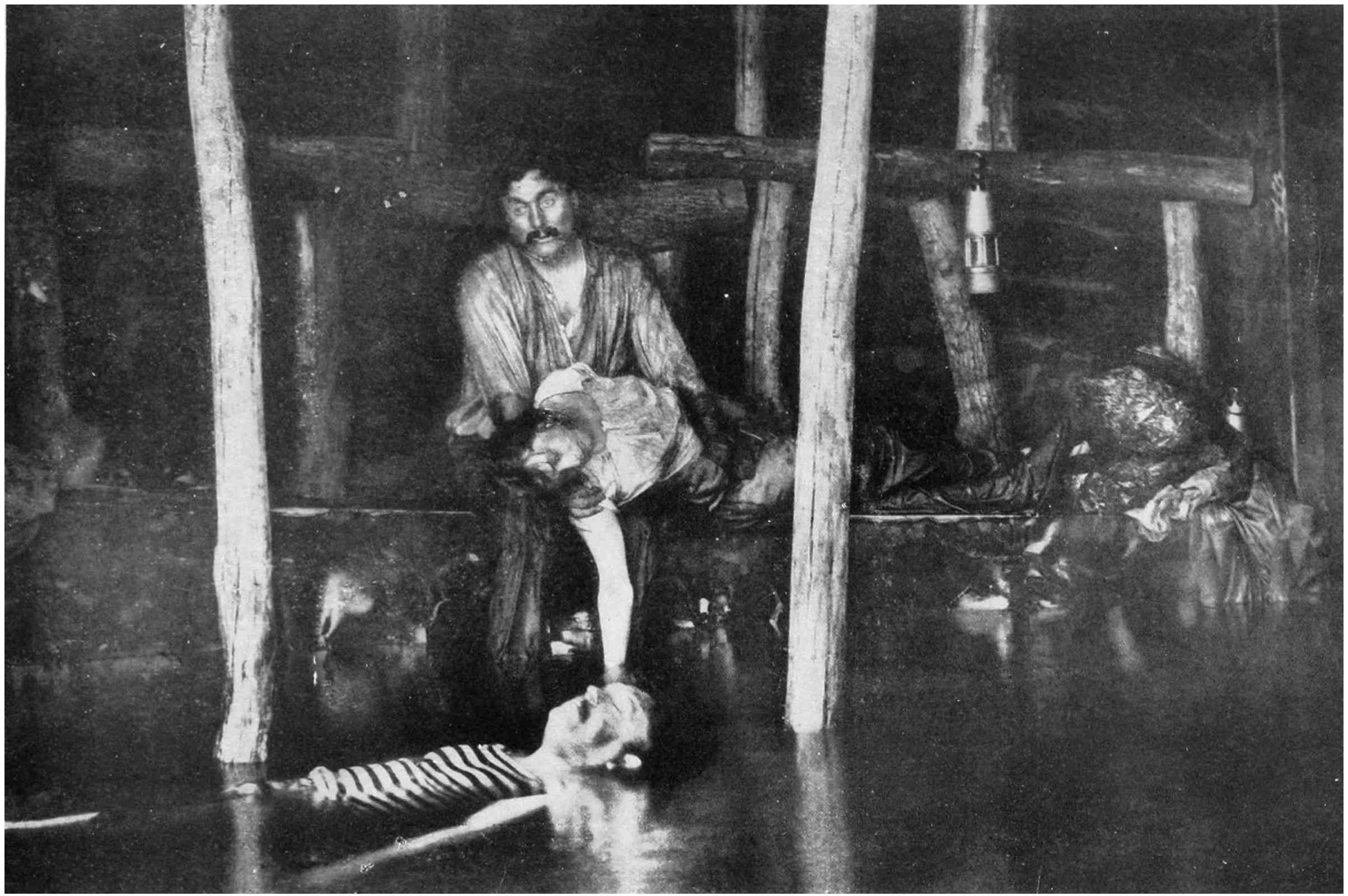

| The Fight for the Boats in “Atlantis” | 152 |

| “Sauve qui peut” at the Wreck of the Liner | 152 |

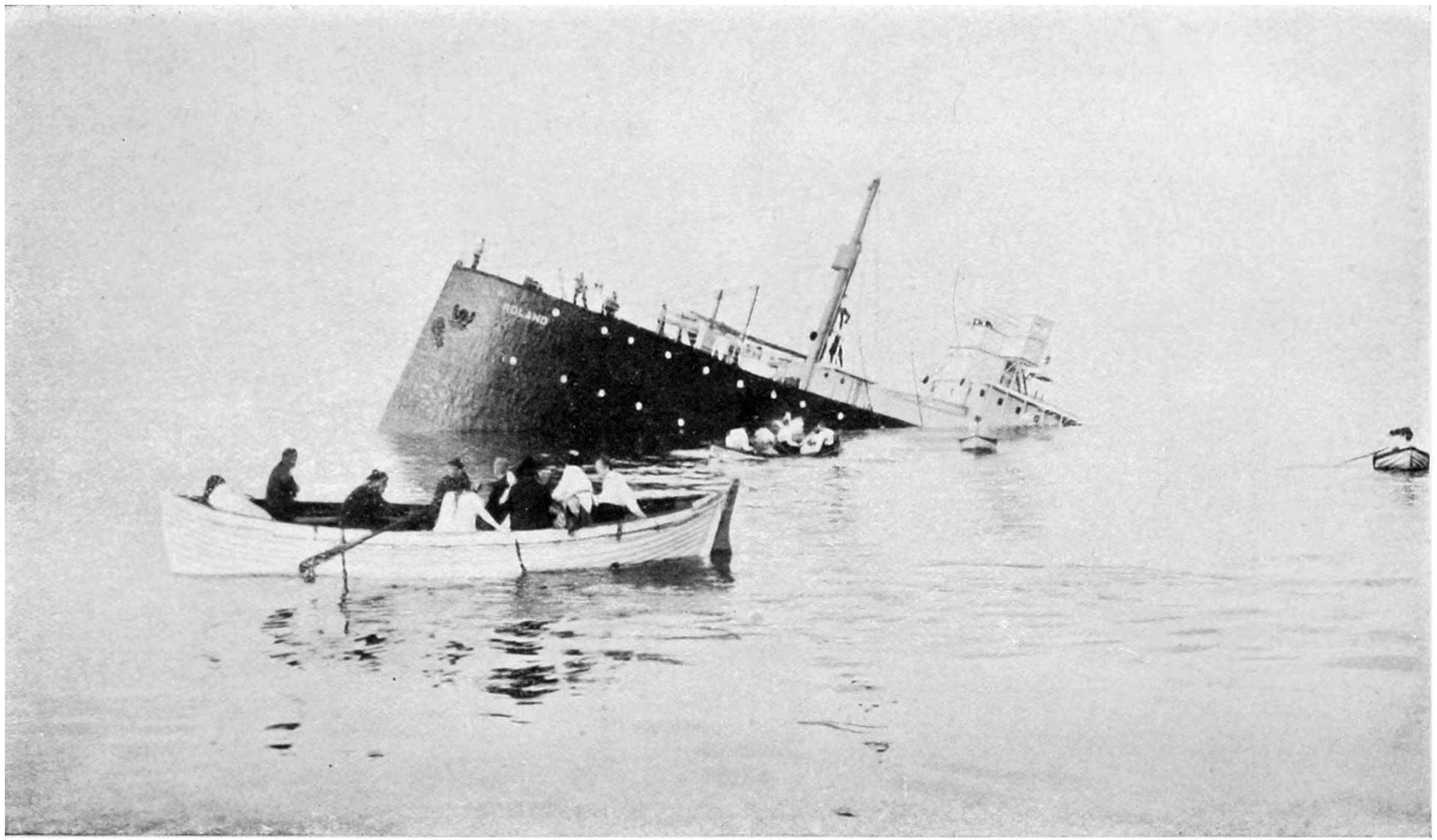

| The Sinking of the Liner “Roland” | 153 |

| Sorting, Examining, and Joining the Strips of Film | 156 |

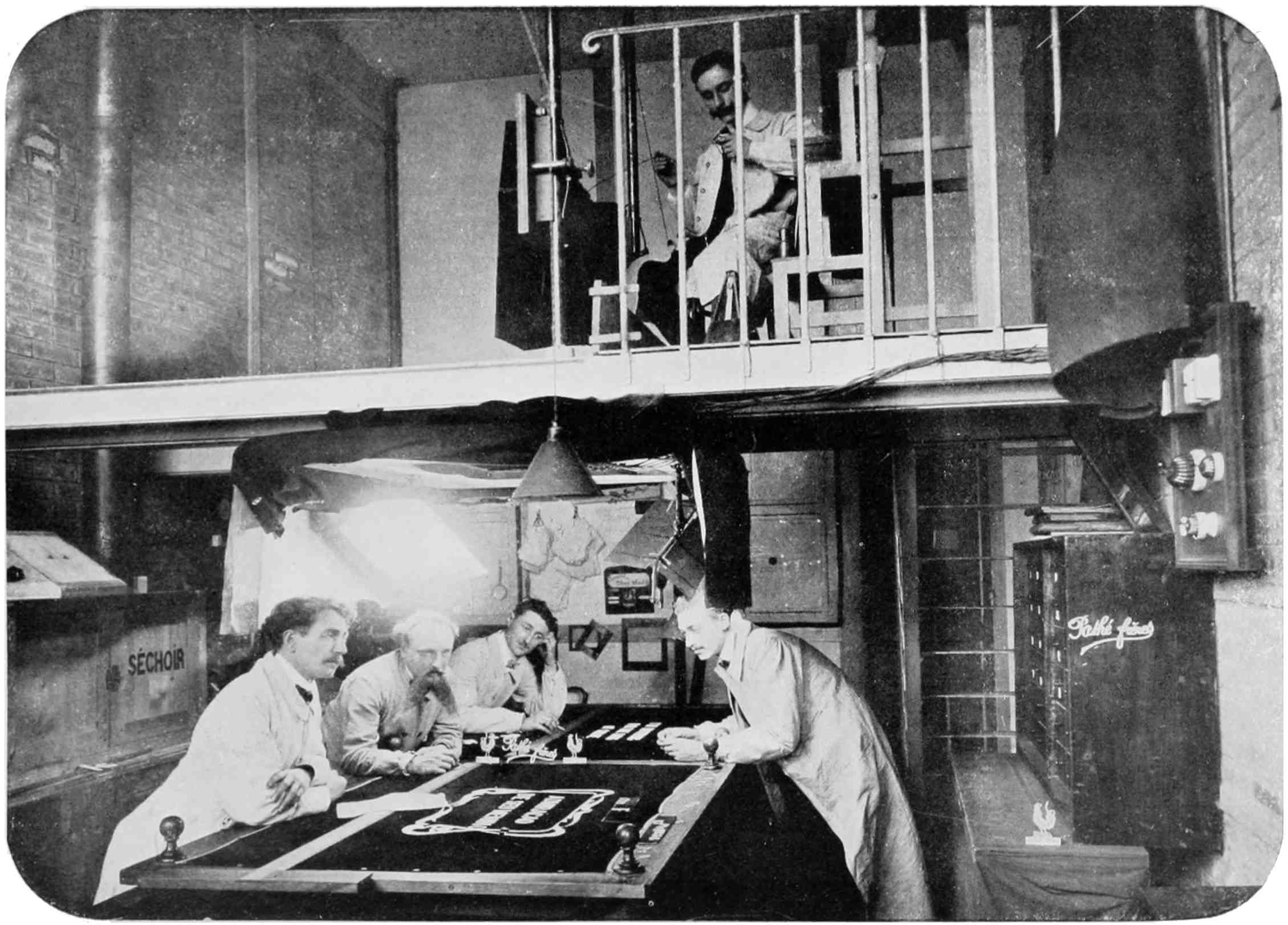

| Preparing the Titles | 157 |

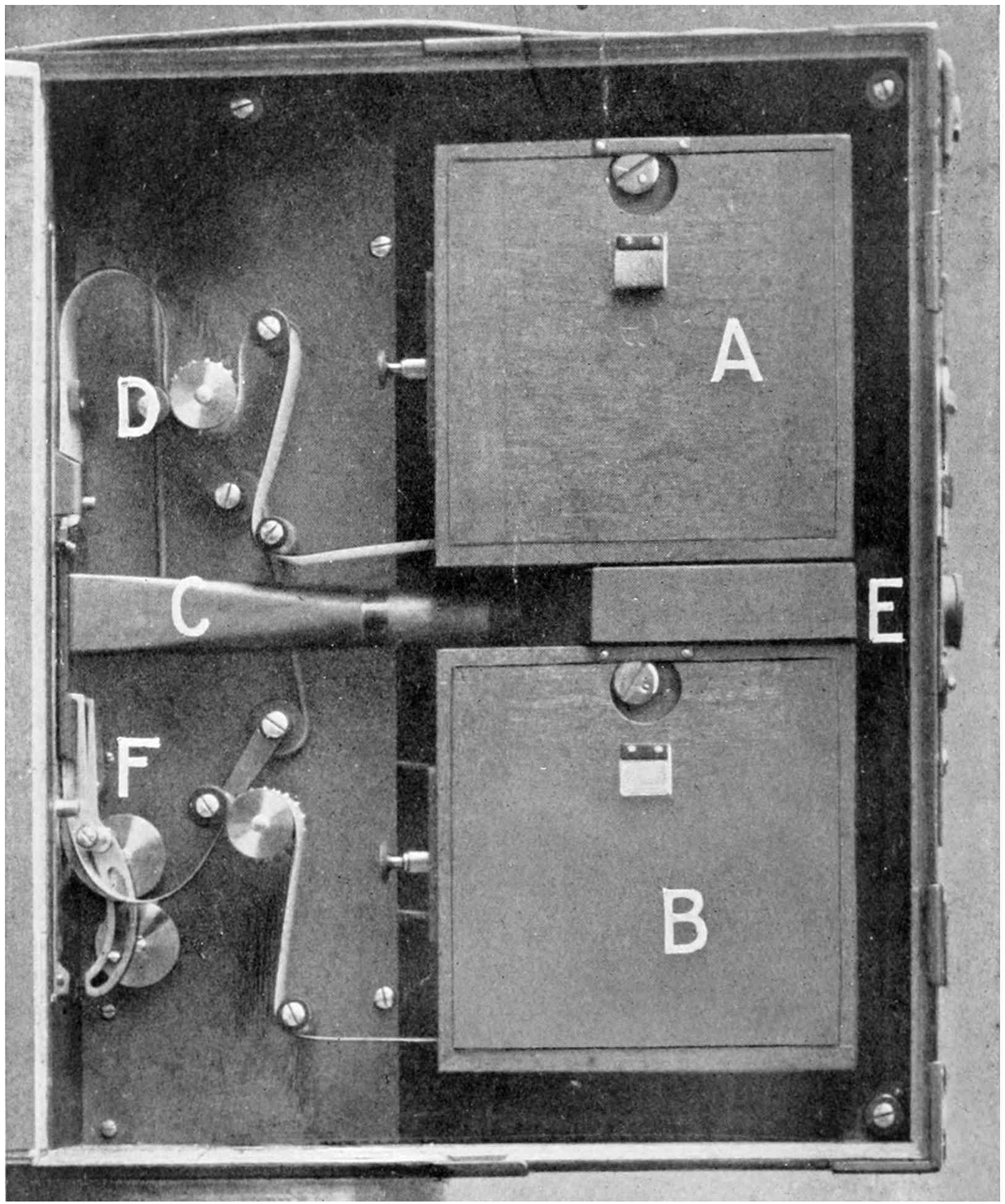

| Dr. Comandon’s Apparatus for taking Moving Pictures of Microbes | 164 |

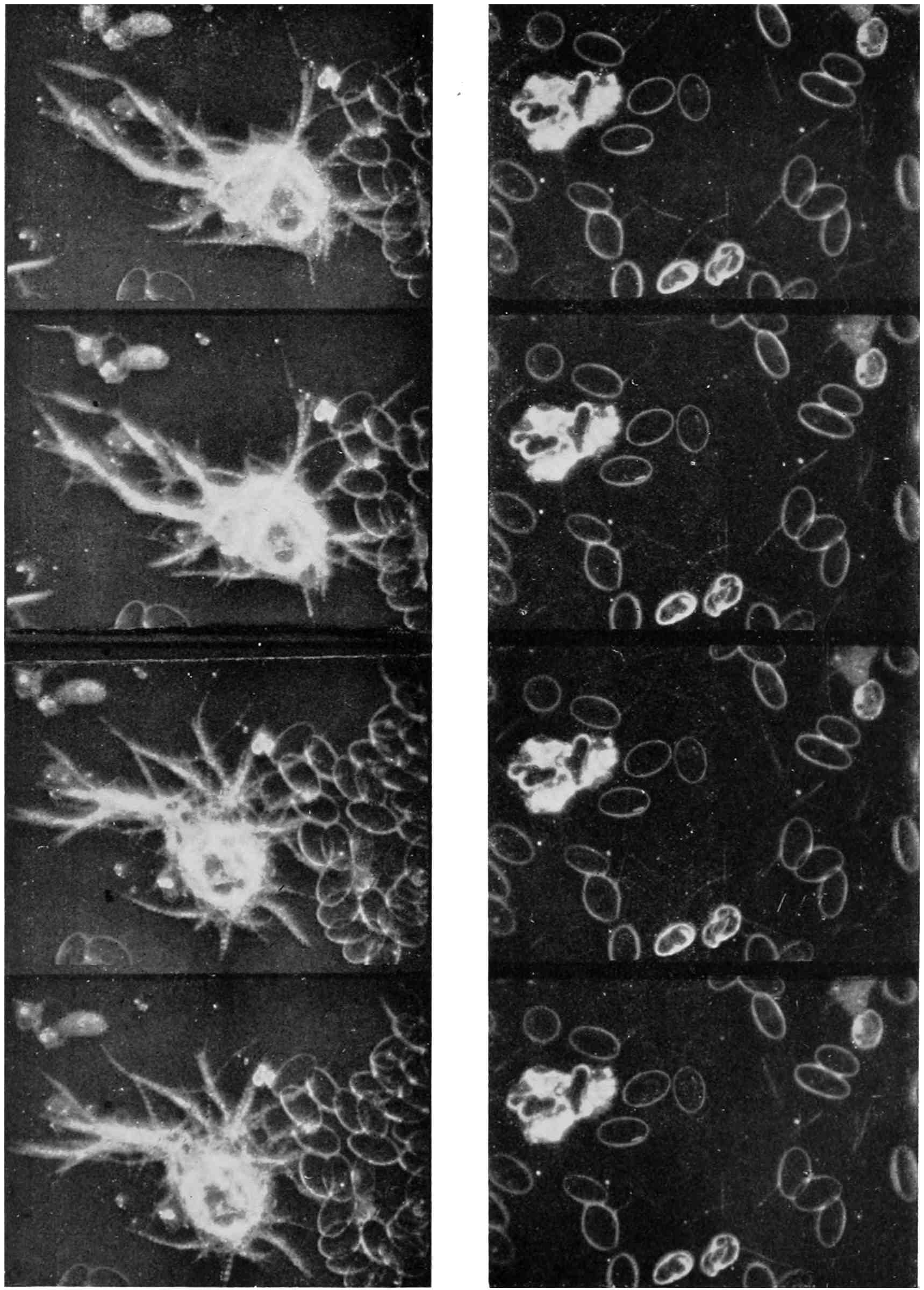

| The Phenomenon of Agglutination in a Fowl’s Blood | 165 |

| The Blood of a Fowl suffering from Spirochæta Gallinarum | 165 |

| A Triumph of the Cinematographer’s Art | 172 |

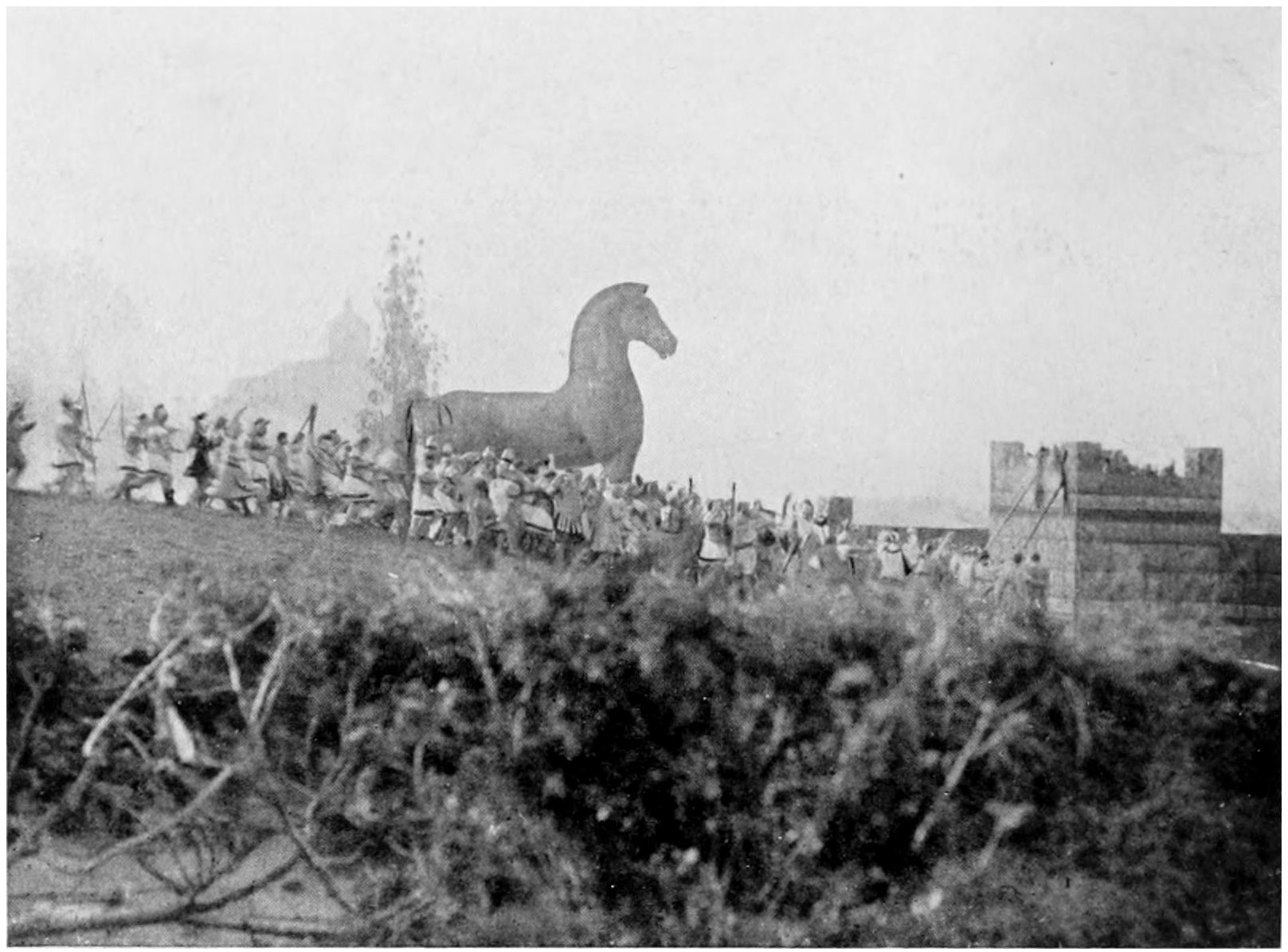

| The Gigantic Horse being Hauled by the Greeks under the Walls of Troy | 173 |

| “The Fall of Troy” | 173 |

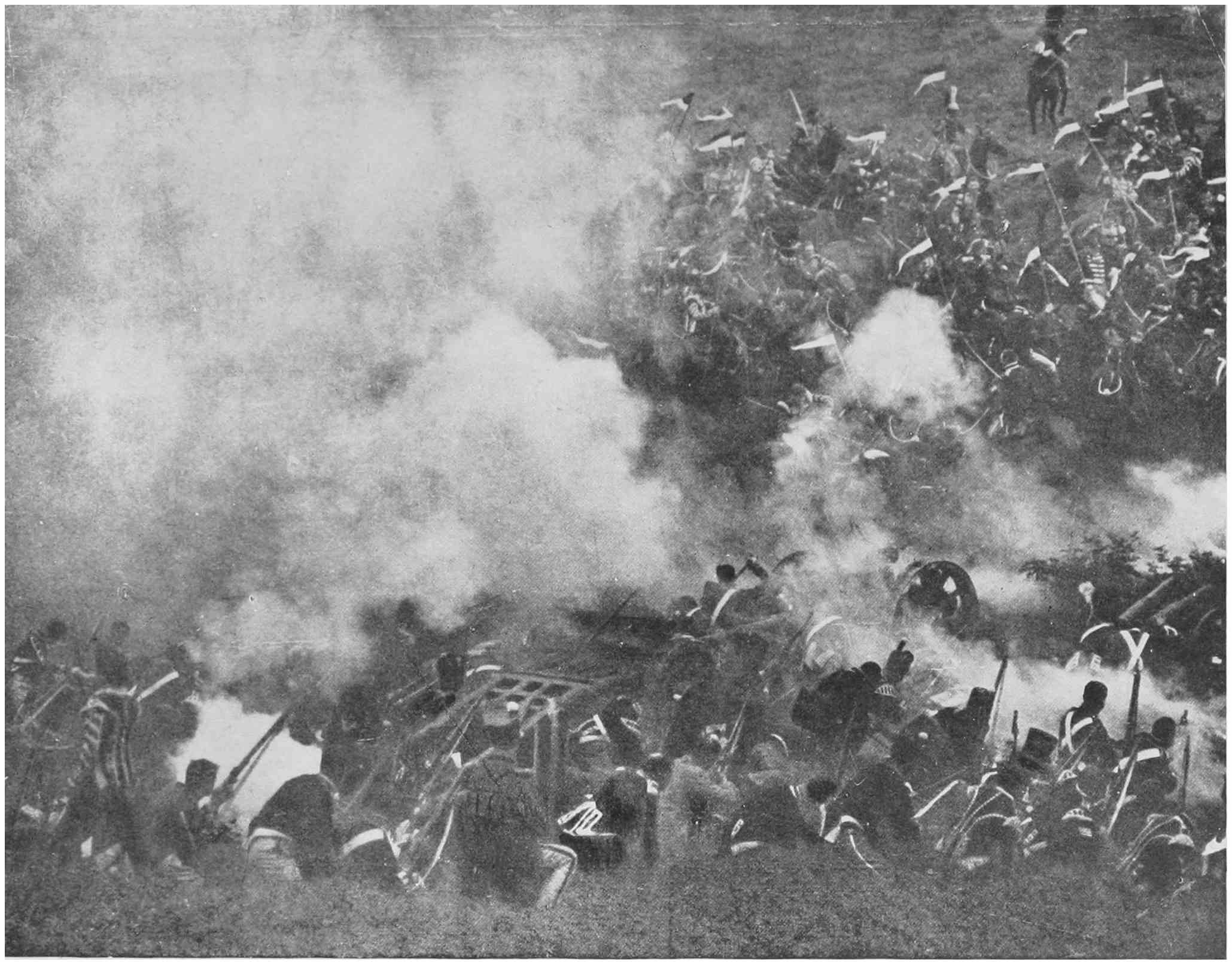

| The “Battle of Waterloo” upon the Film | 176xiii |

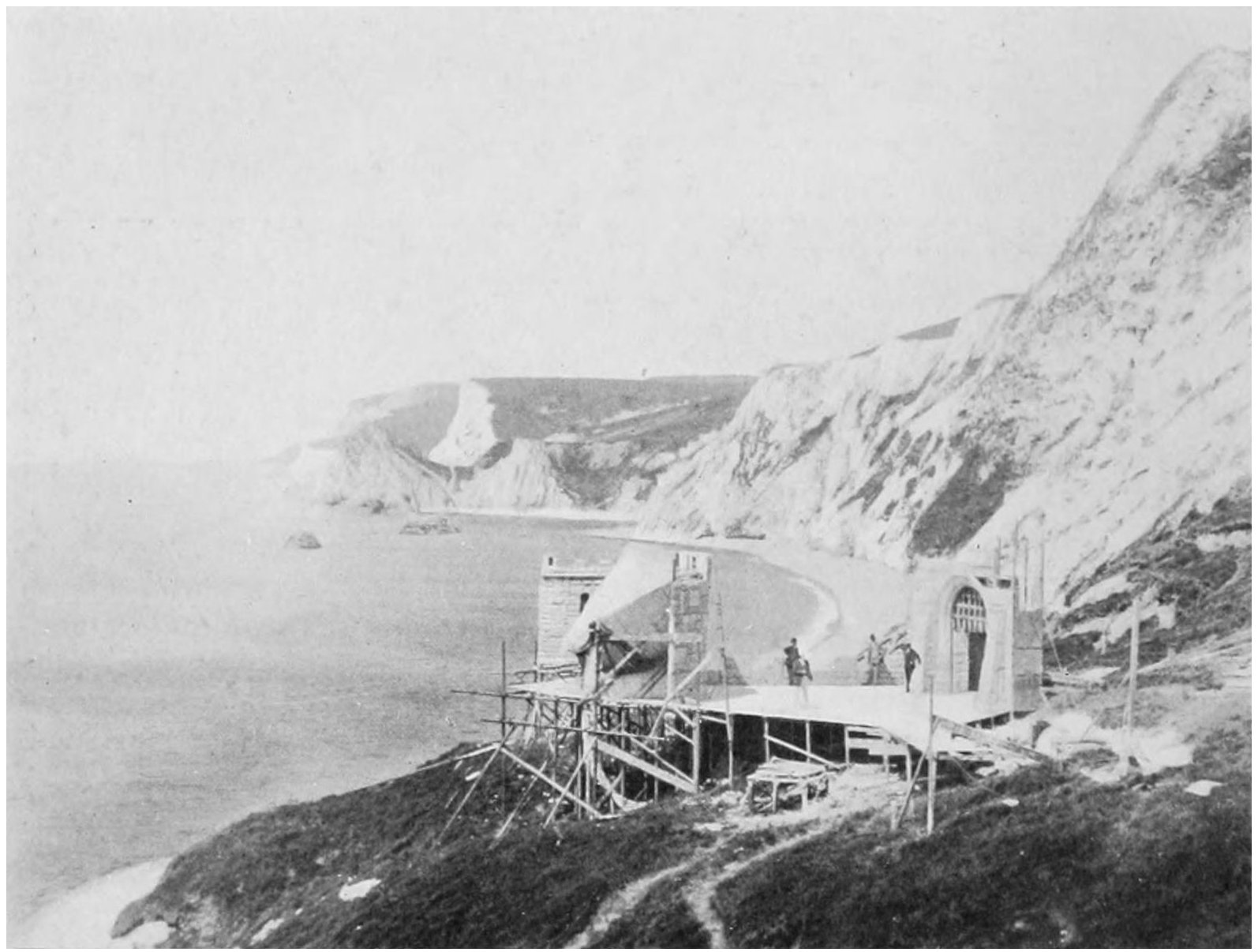

| Building the Scenery for the Film Performance of “Hamlet” | 177 |

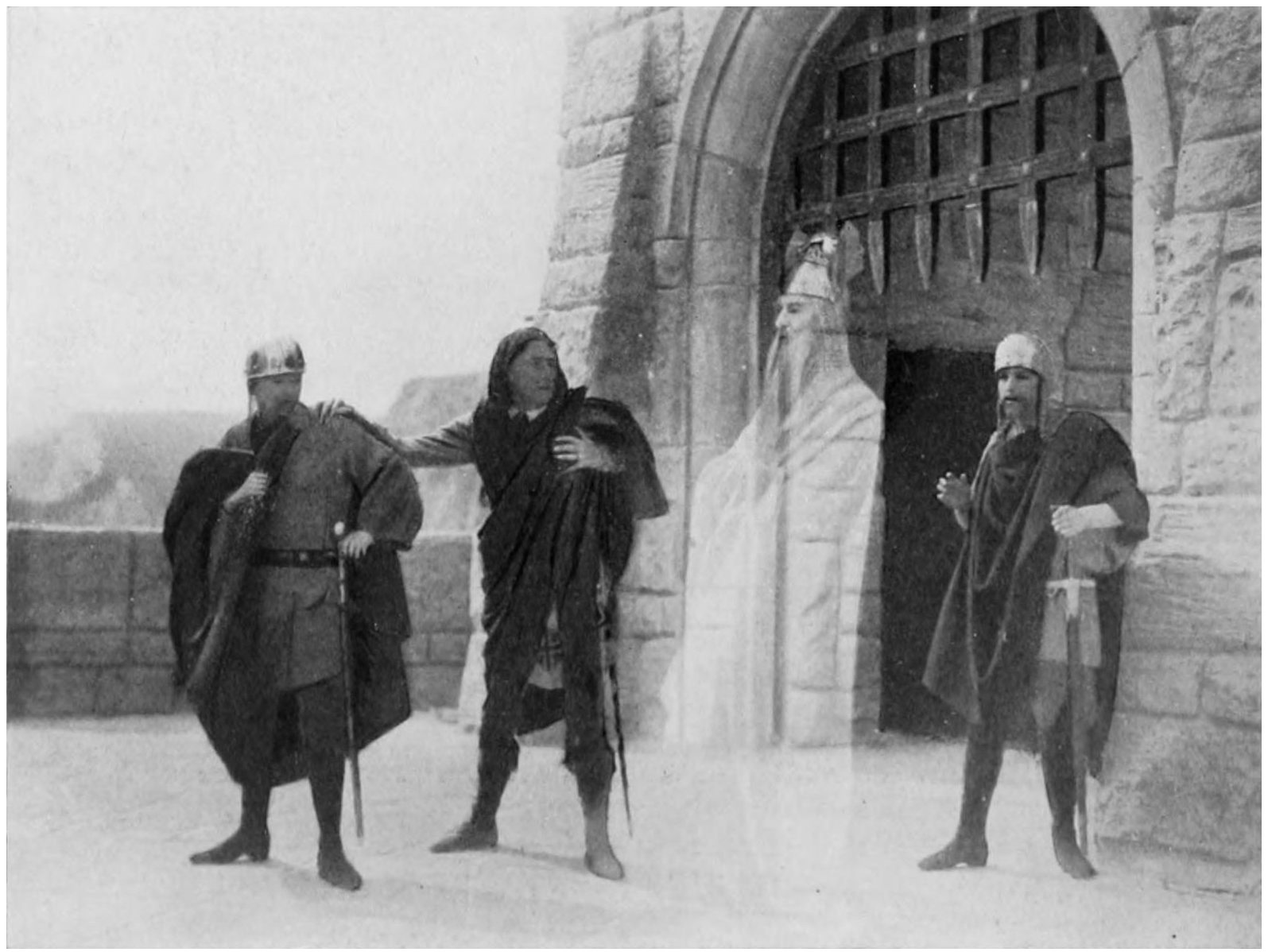

| The Ghost Scene from “Hamlet” | 177 |

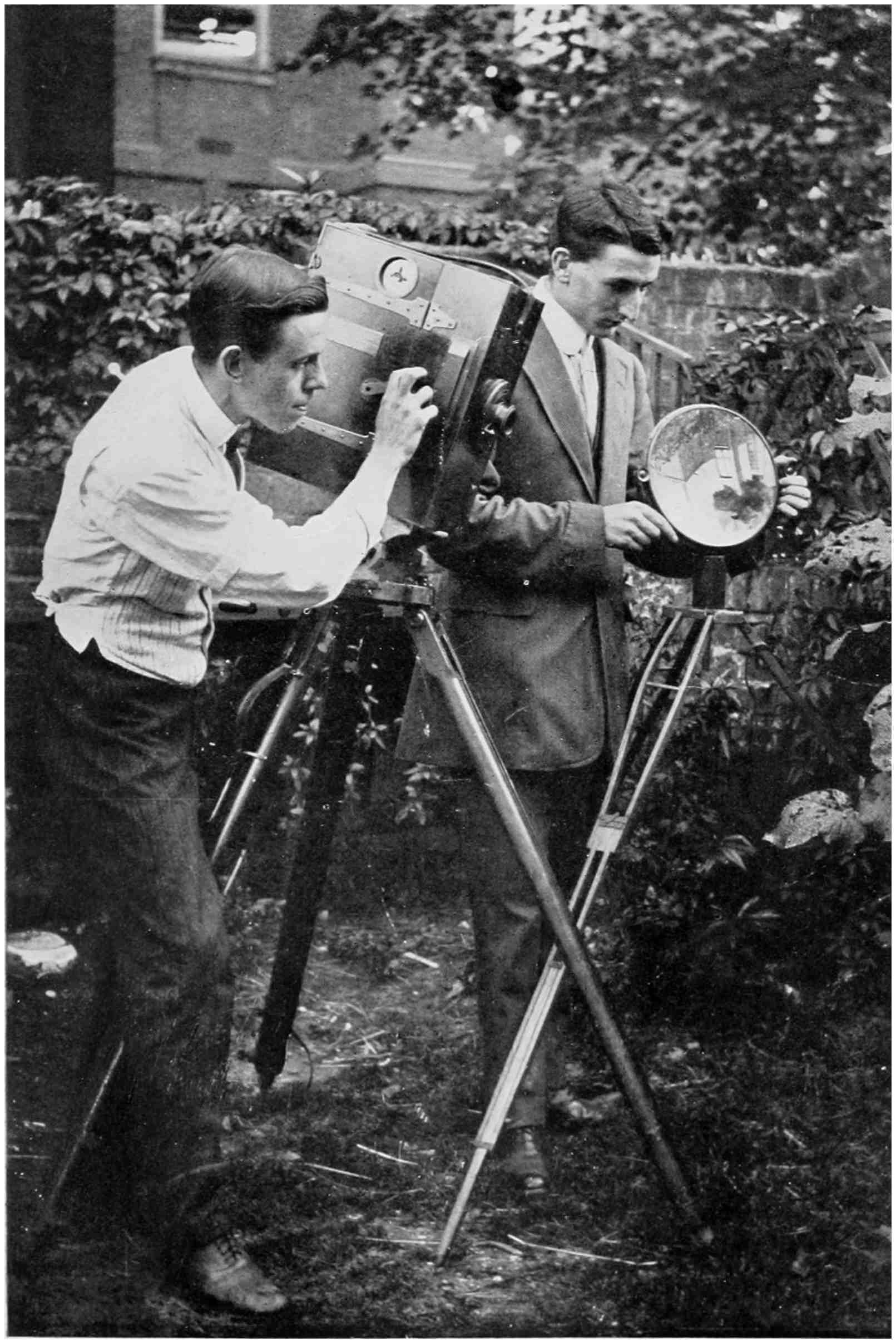

| Nature and the Cinematographer—Mr. Percy Smith at Work | 192 |

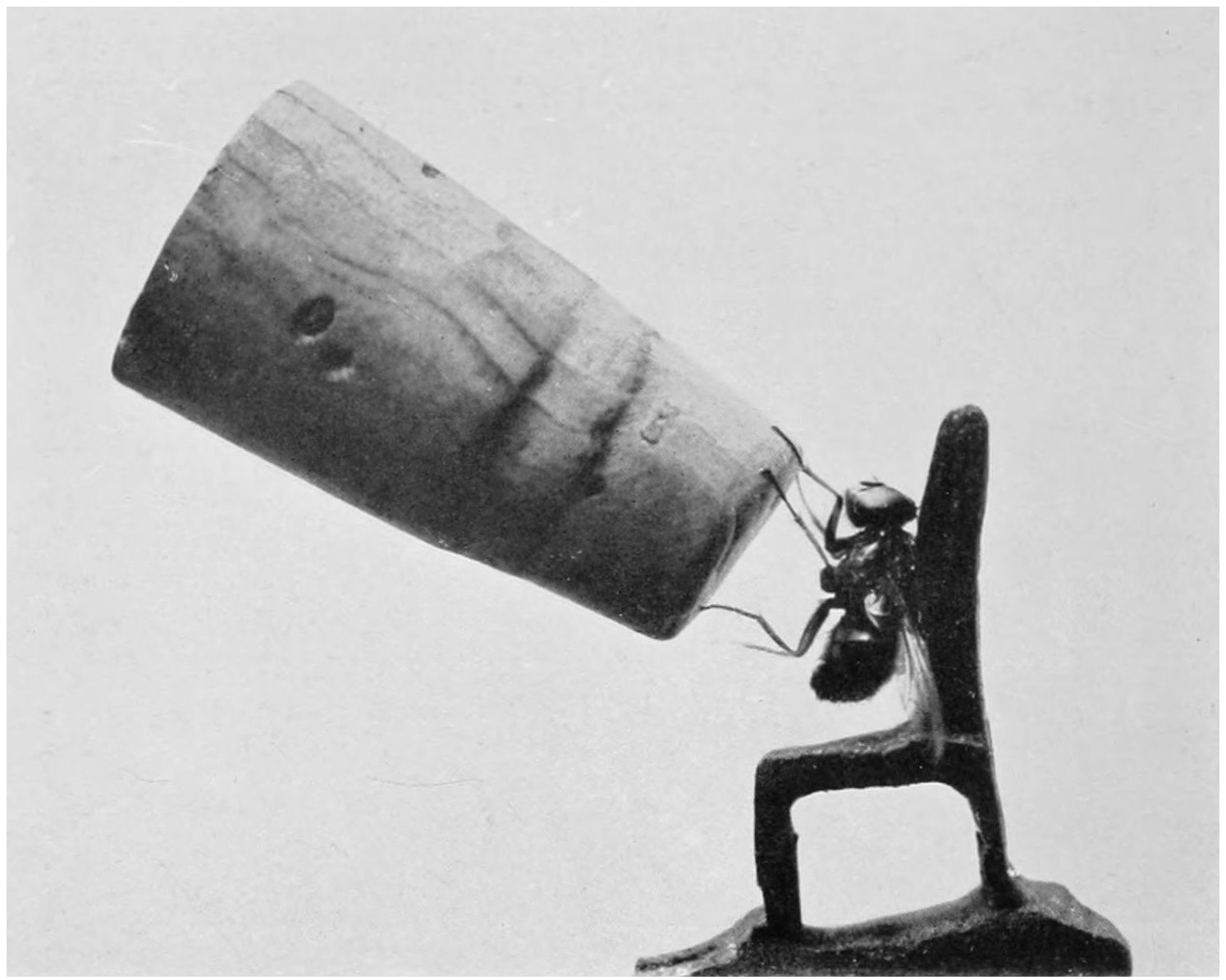

| Fly Seated in a Diminutive Chair Balancing a Cork | 193 |

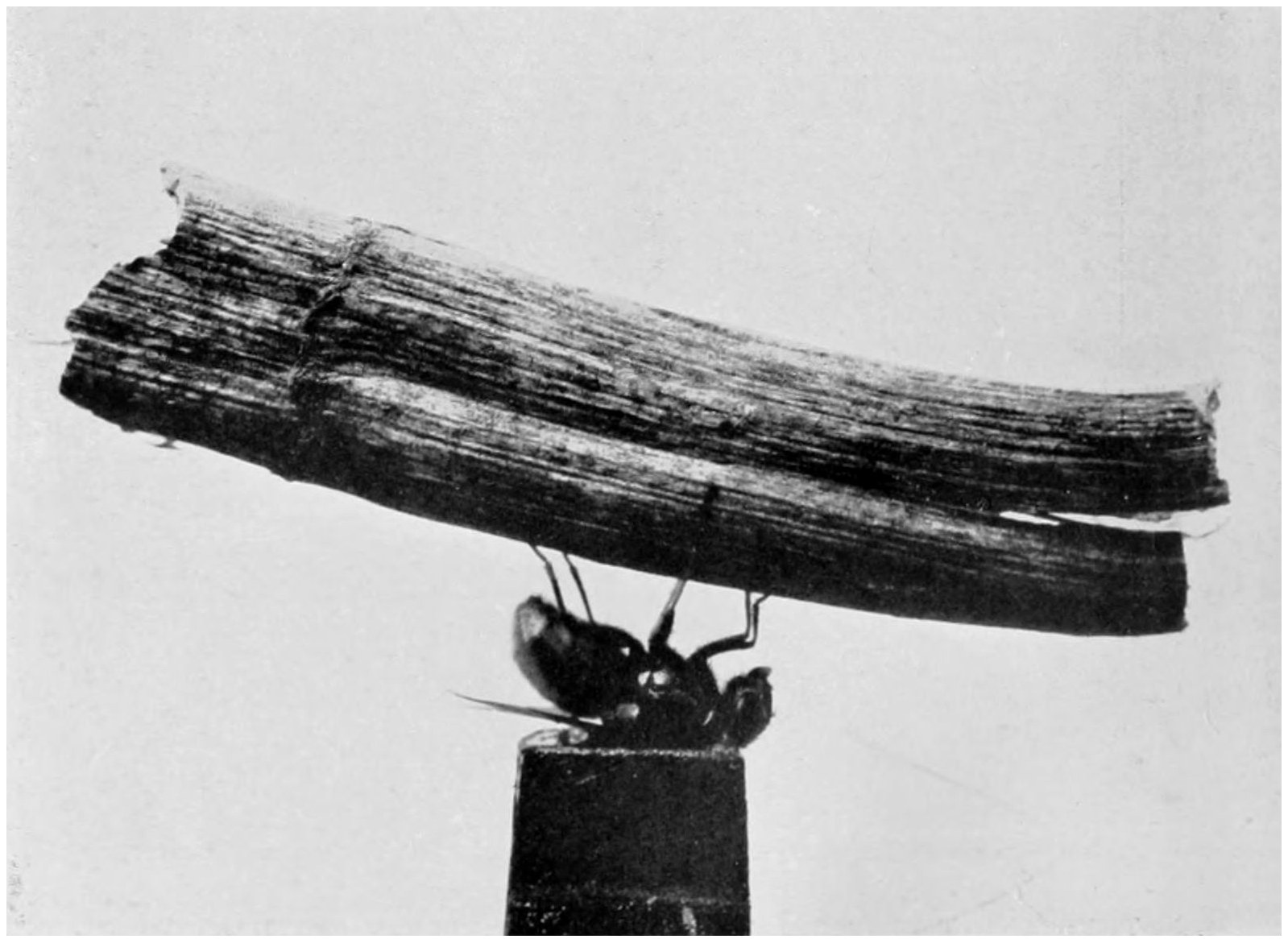

| An Unfamiliar Juggler—Bluebottle Balancing a Piece of Vegetable Stalk | 193 |

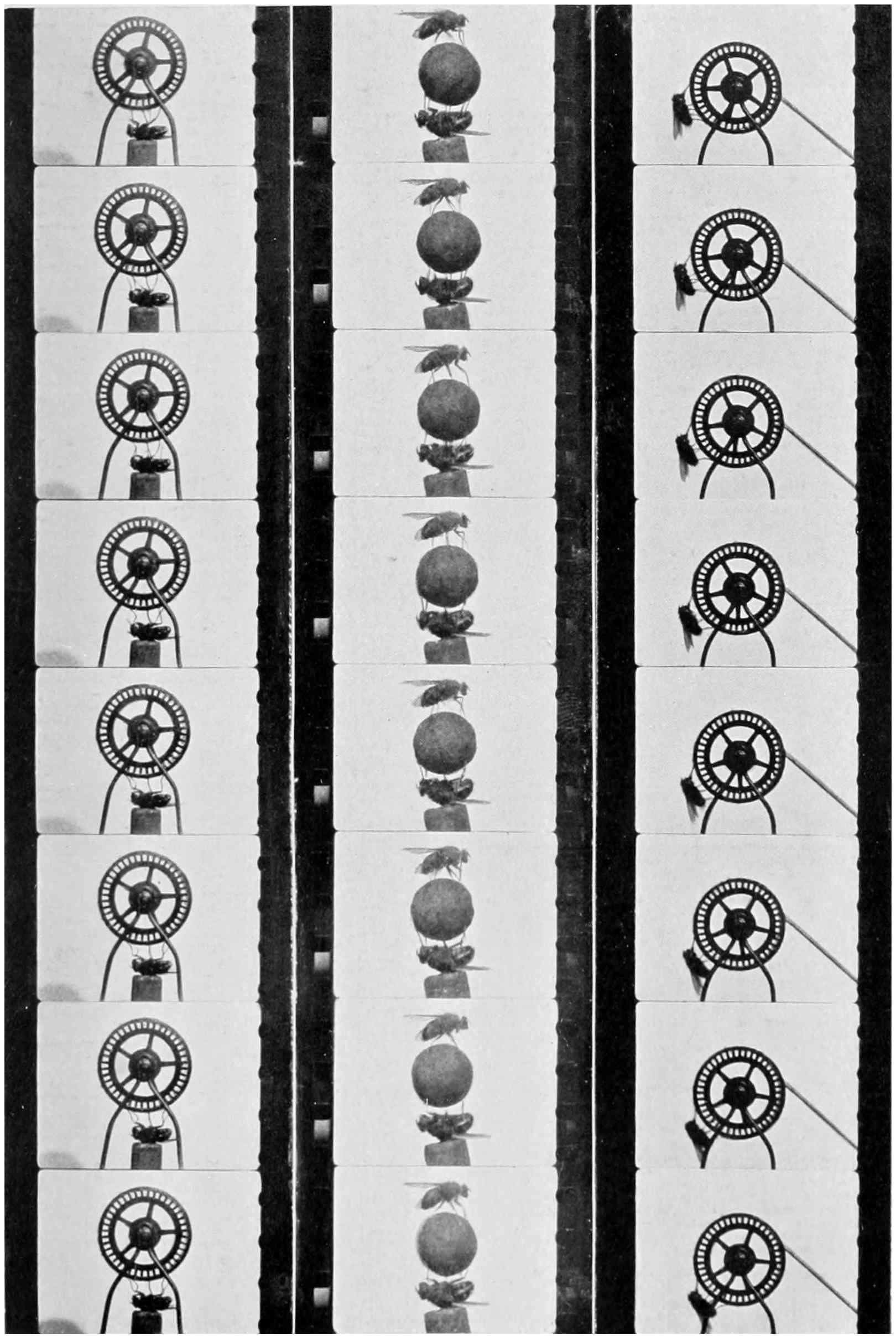

| Fly Lying on its Back Spinning a Wheel | 194 |

| Juggling Flies | 194 |

| The Fly Walking Up the Turning Wheel | 194 |

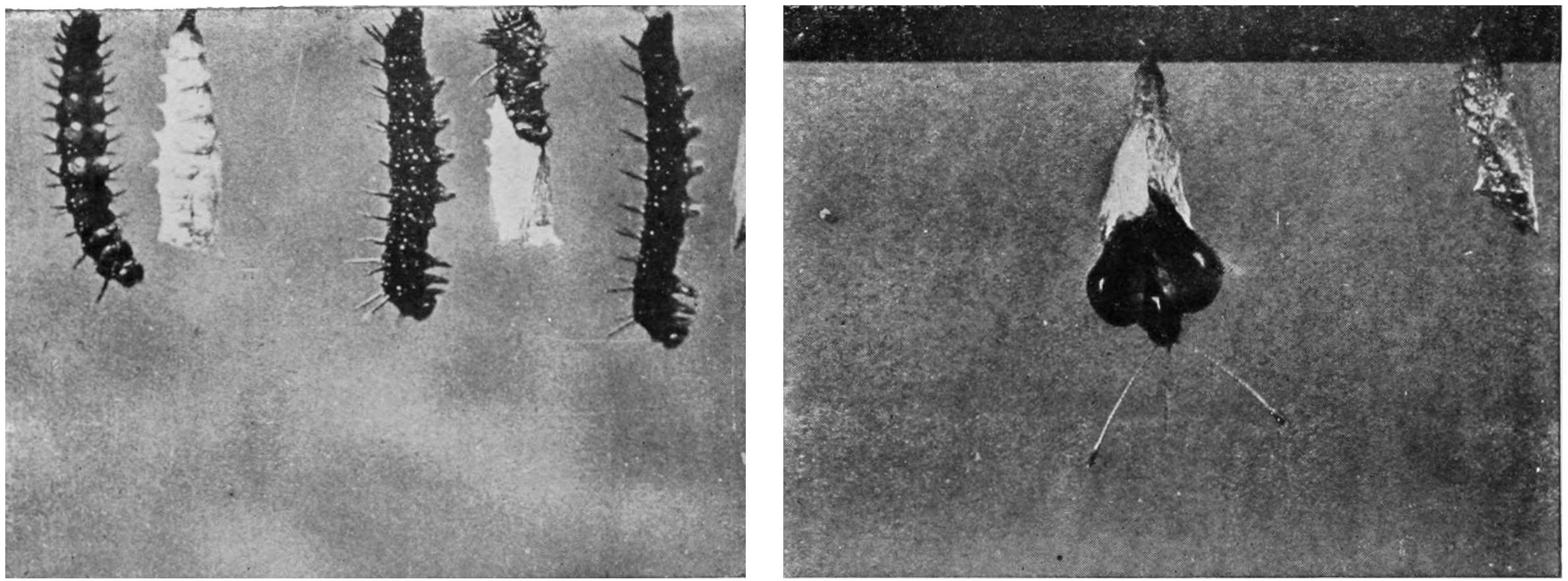

| The Life of the Butterfly | 195 |

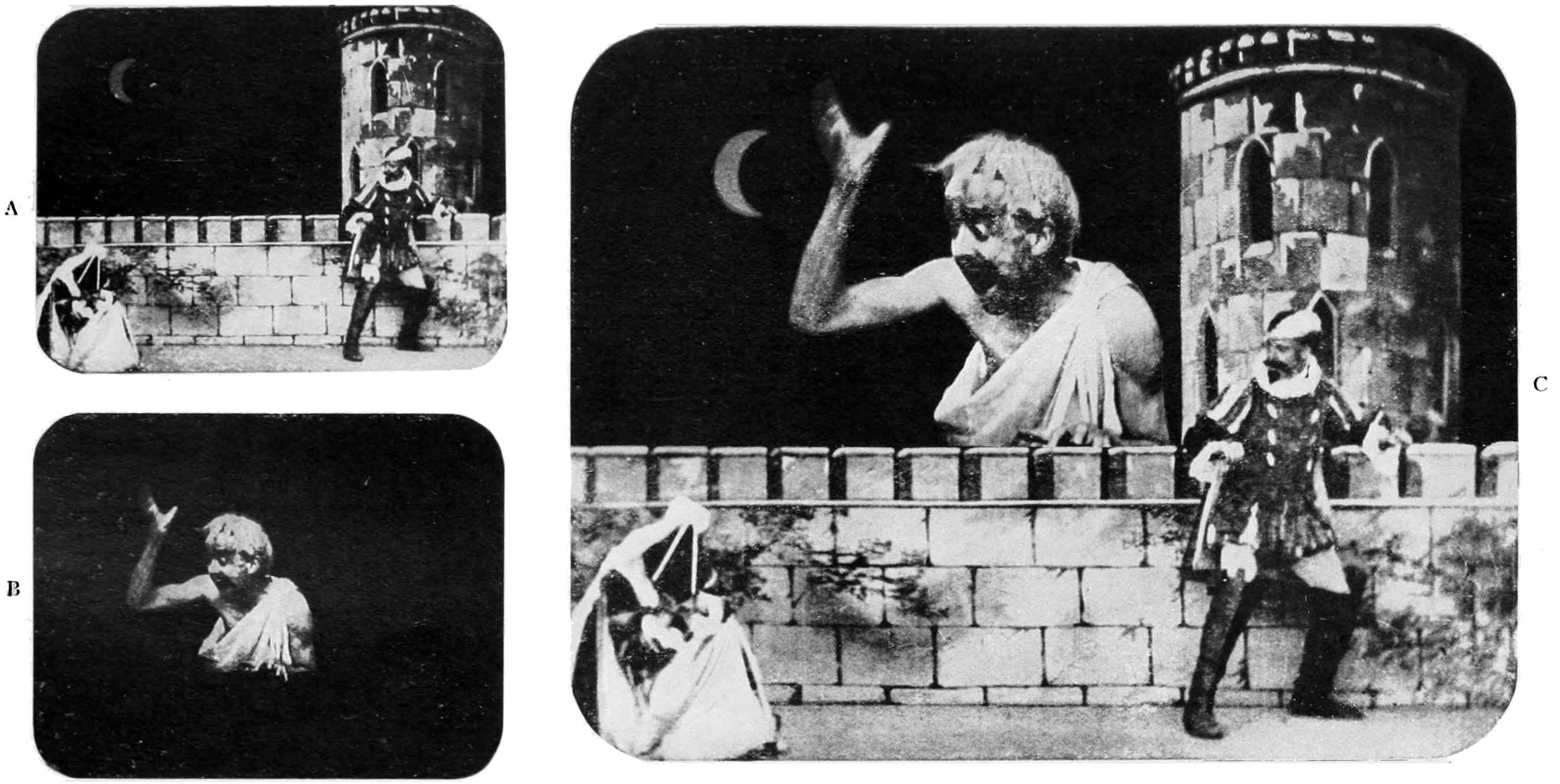

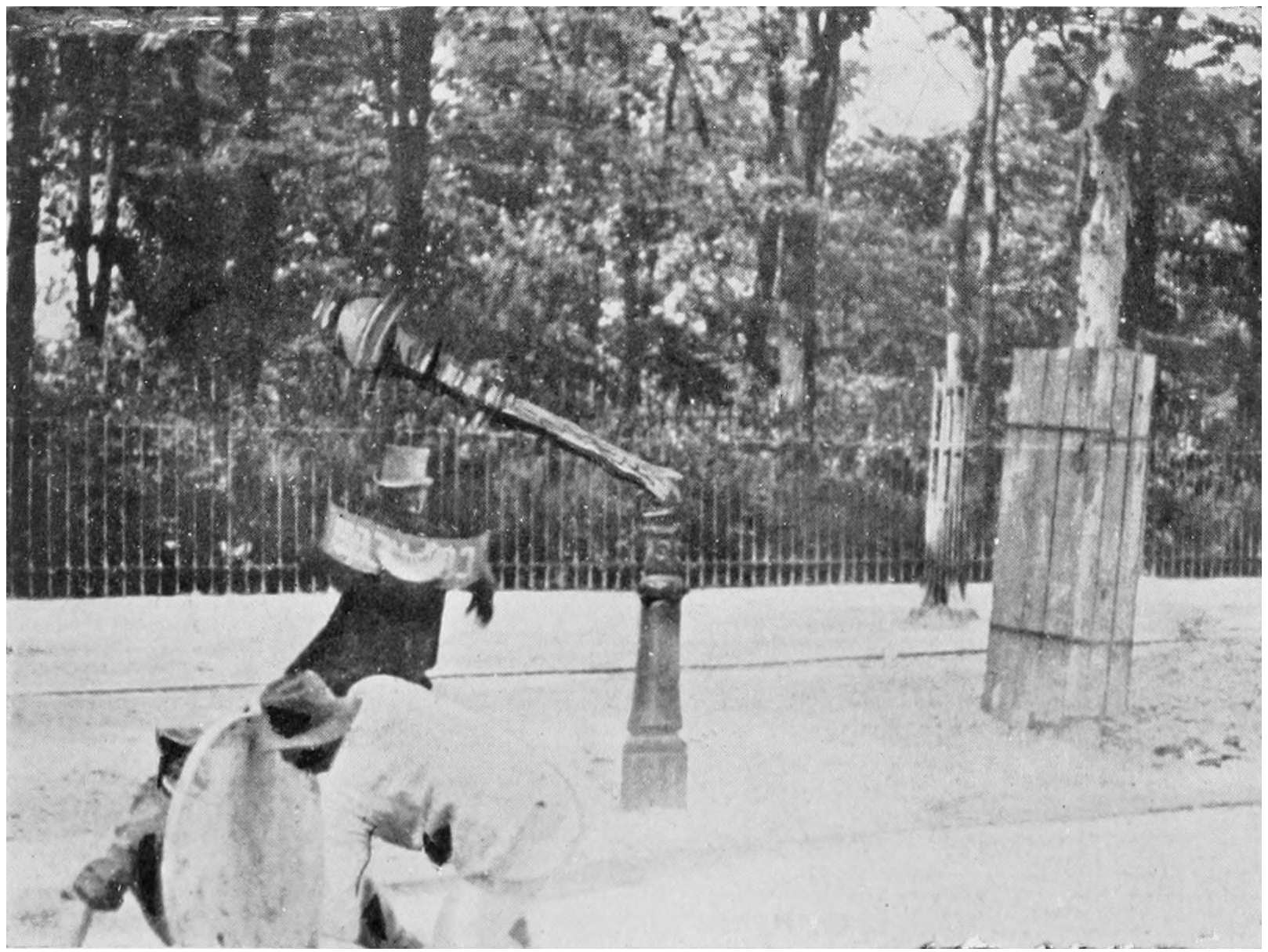

| The Magic Sword: A Mediæval Mystery Explained | 200 |

| A Christmas Carol: How Scrooge saw Bob Cratchit’s Home | 201 |

| “Ora Pro Nobis,” and How it was Produced | 202 |

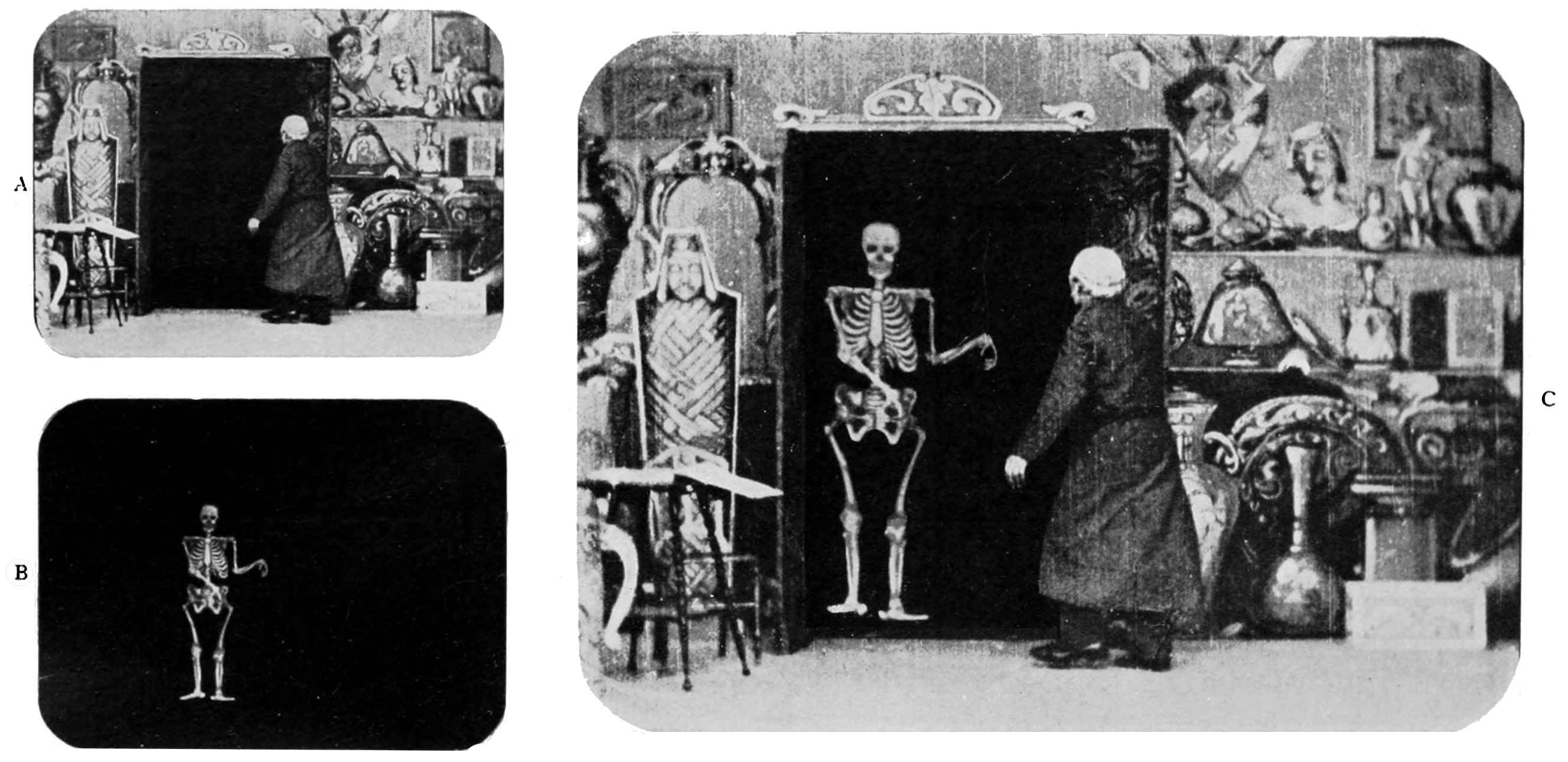

| The Secret of the Haunted Curiosity Shop | 203 |

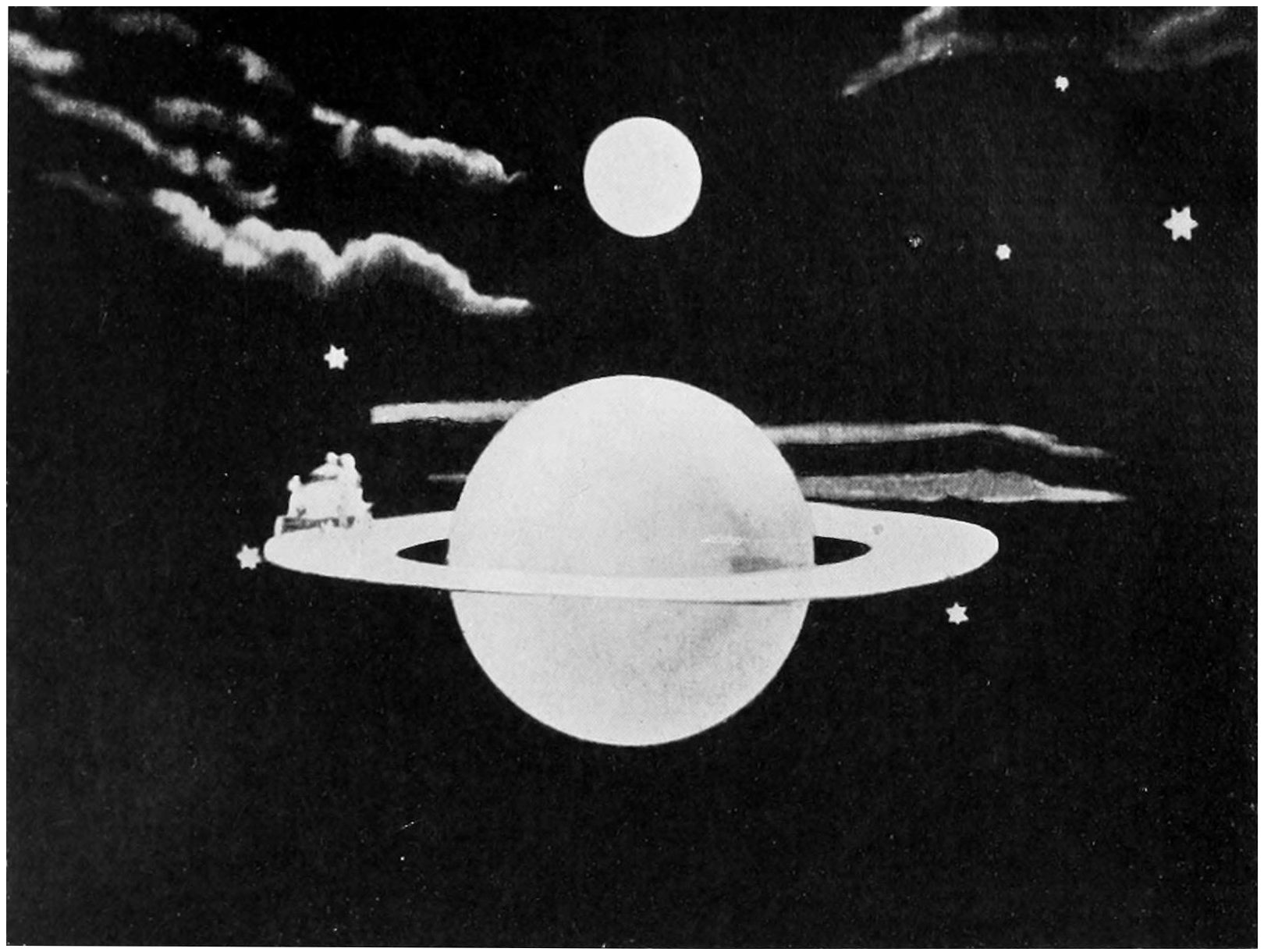

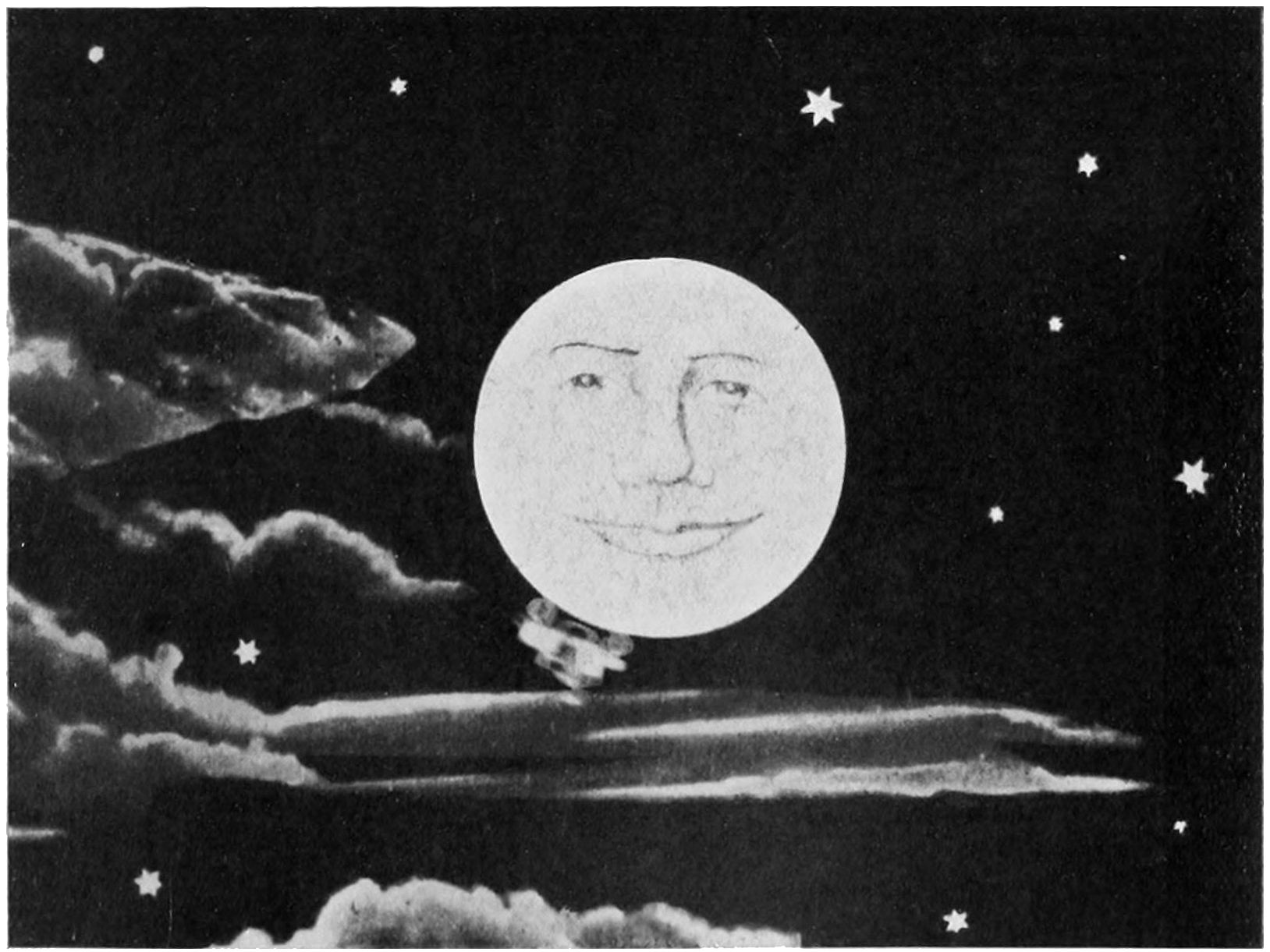

| Motoring Round the Ring of Saturn | 204 |

| The Car Circling the Sun | 204 |

| The Animated Swords | 205 |

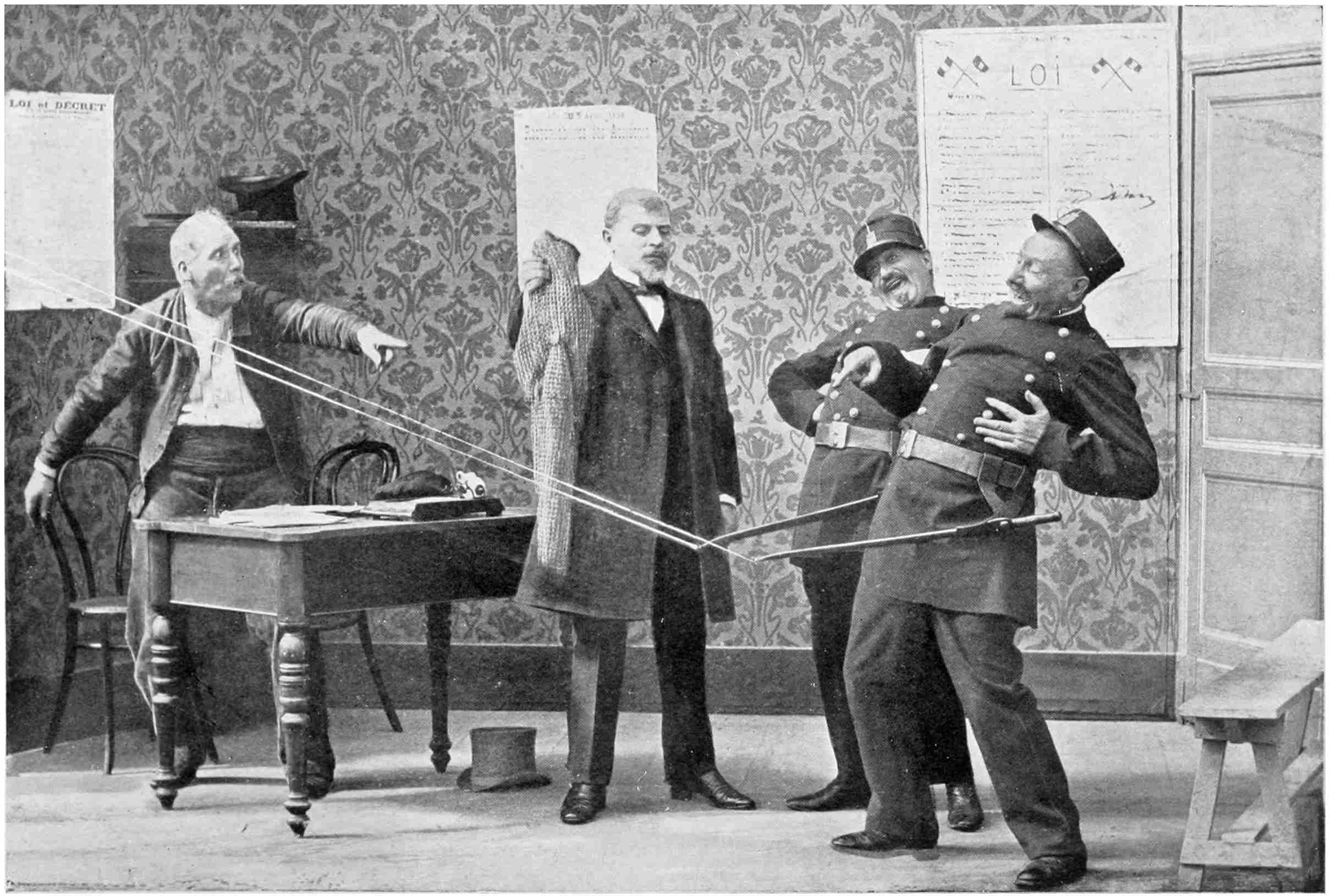

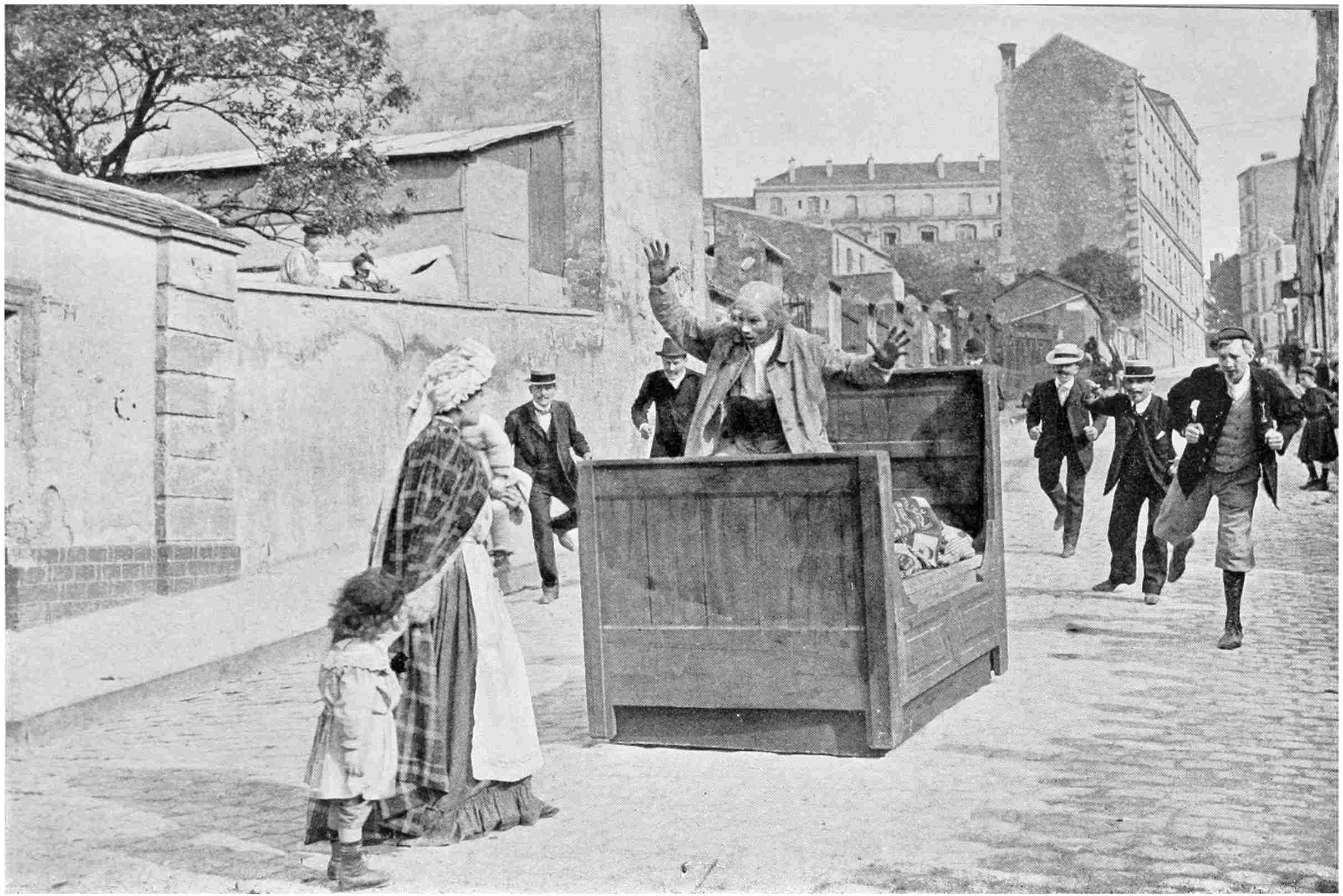

| The Travelling Bed | 208 |

| The Magnetic Gentleman | 209 |

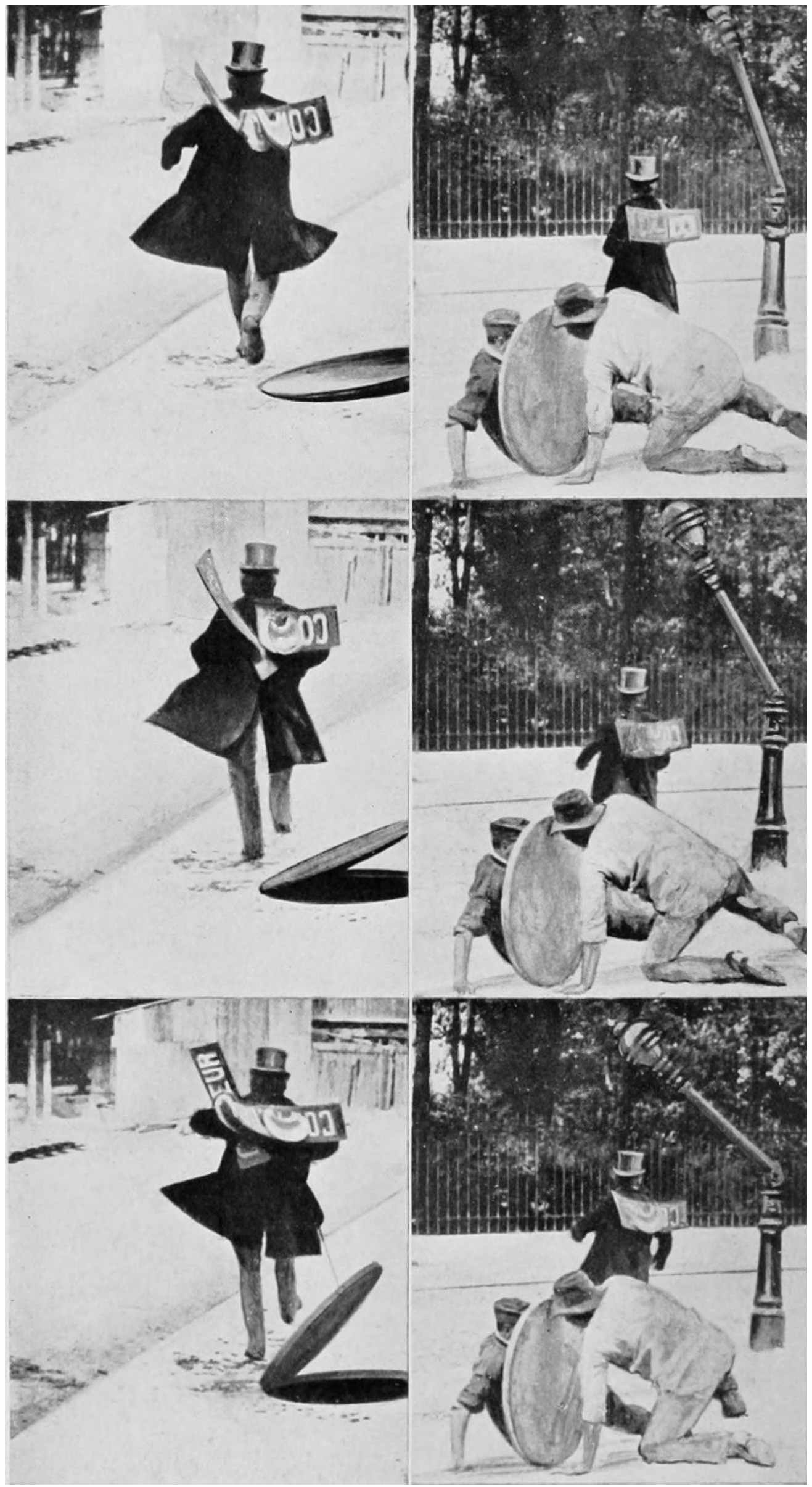

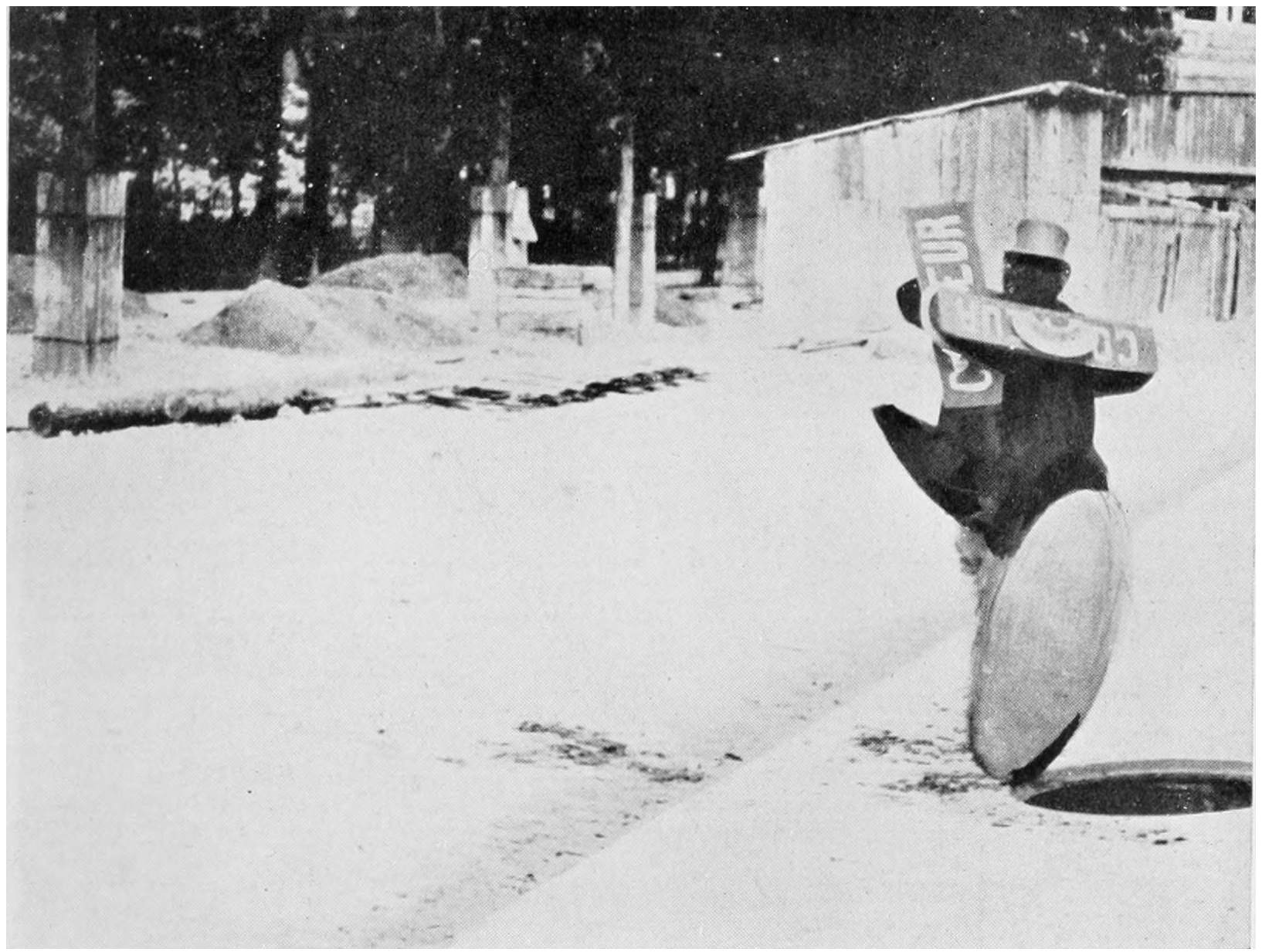

| The Pursuing Man-hole Cover is a Wooden Property | 210 |

| The Lamp-Post is a Stage Article Hinged in the Centre | 210 |

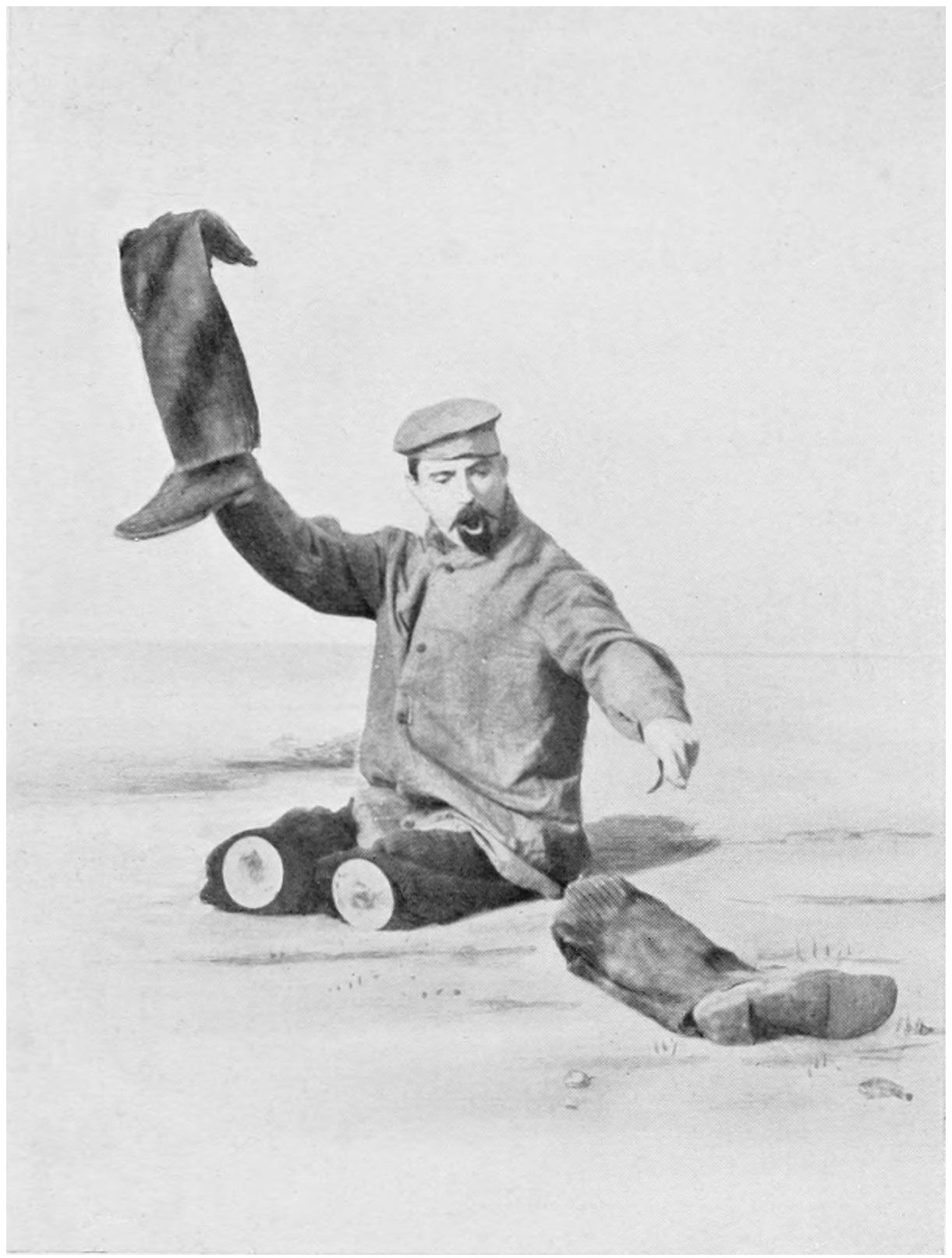

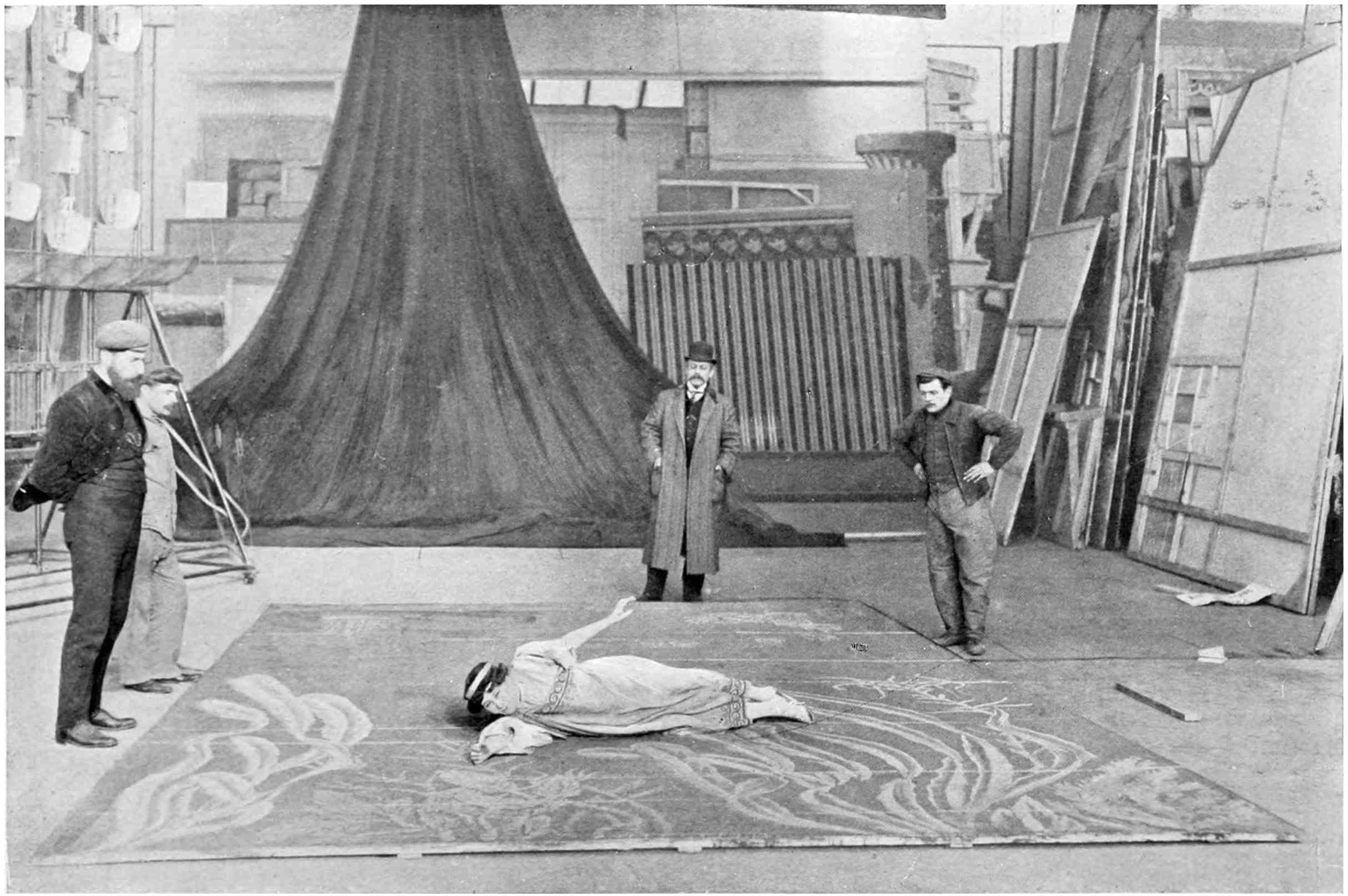

| The Trick Picture—The Automobile Accident: The Actor being replaced by the Legless Cripple with the Dummy Legs | 211 |

| The Taxi-cab Running over the Sleeper and Apparently Cutting off his Legs, but in Reality Displacing the Legless Cripple’s Property Limbs | 212 |

| Observing the Effects of the Disaster, the Doctor Proceeds to Replace the Severed Legs | 213 |

| The Limbs Replaced, the Patient and Doctor Shake Hands | 213 |

| The Roysterer, after being run over by the Taxi-cab, Sitting up and Brandishing his Severed Limbs | 214 |

| The Legless Cripple being Prepared for the Act | 214 |

| The Fountain of Youth | 215 |

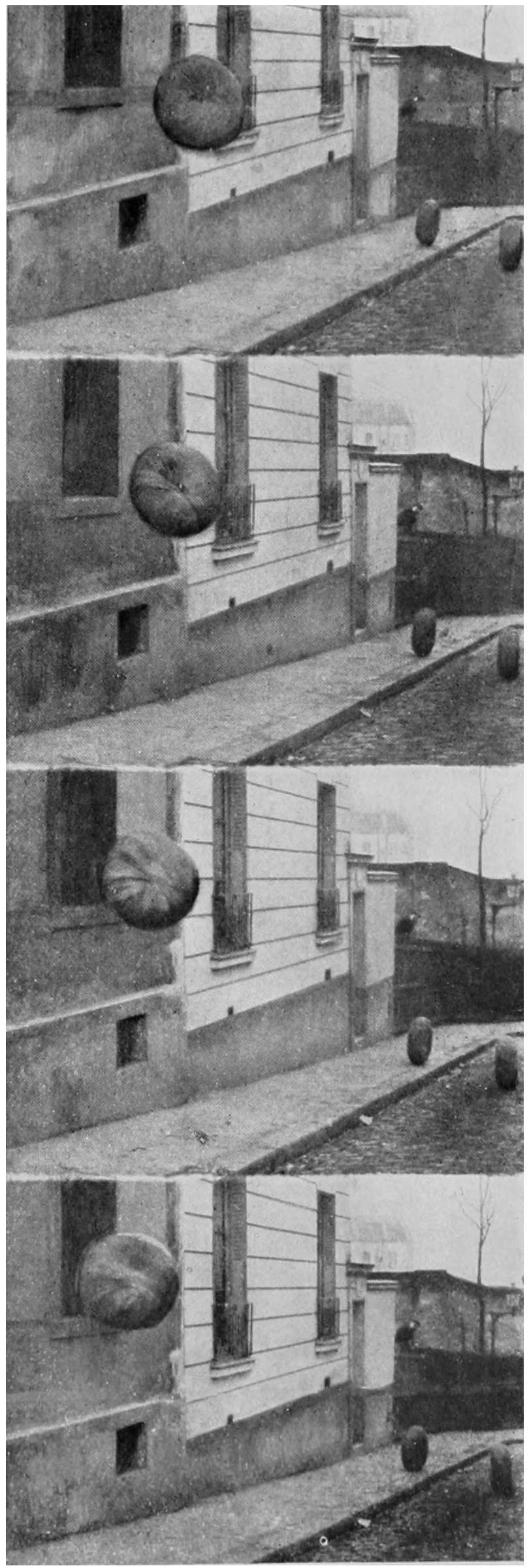

| Pumpkins Running Up-hill | 215 |

| The Revolving Table | 220 |

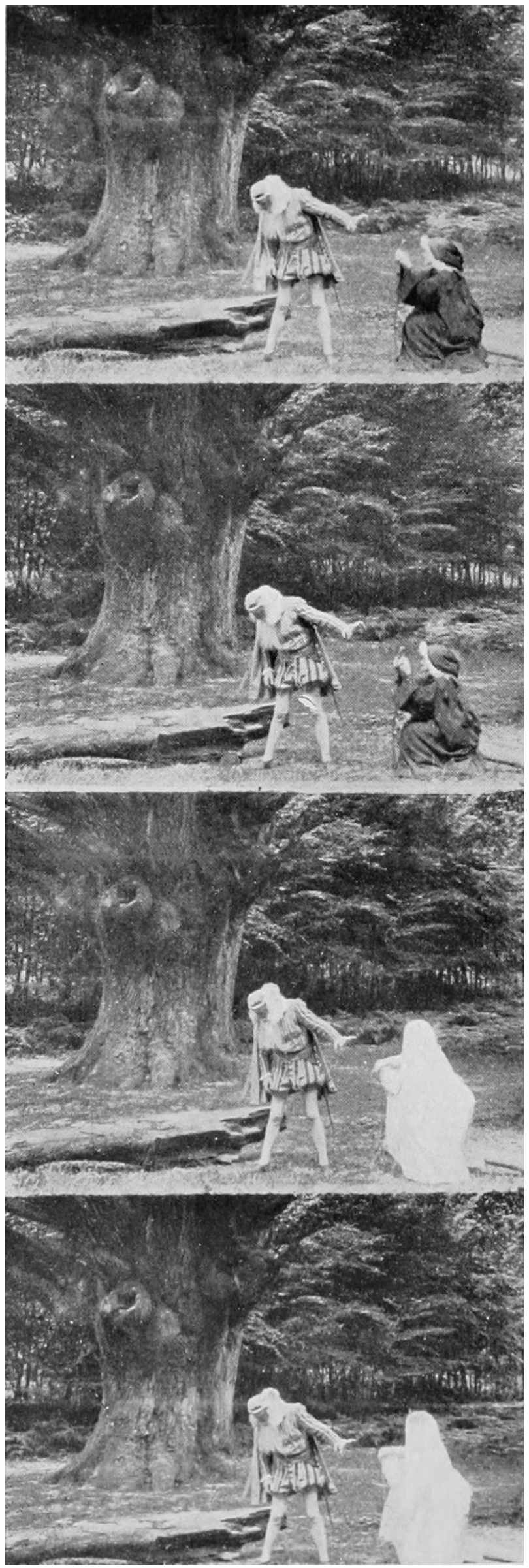

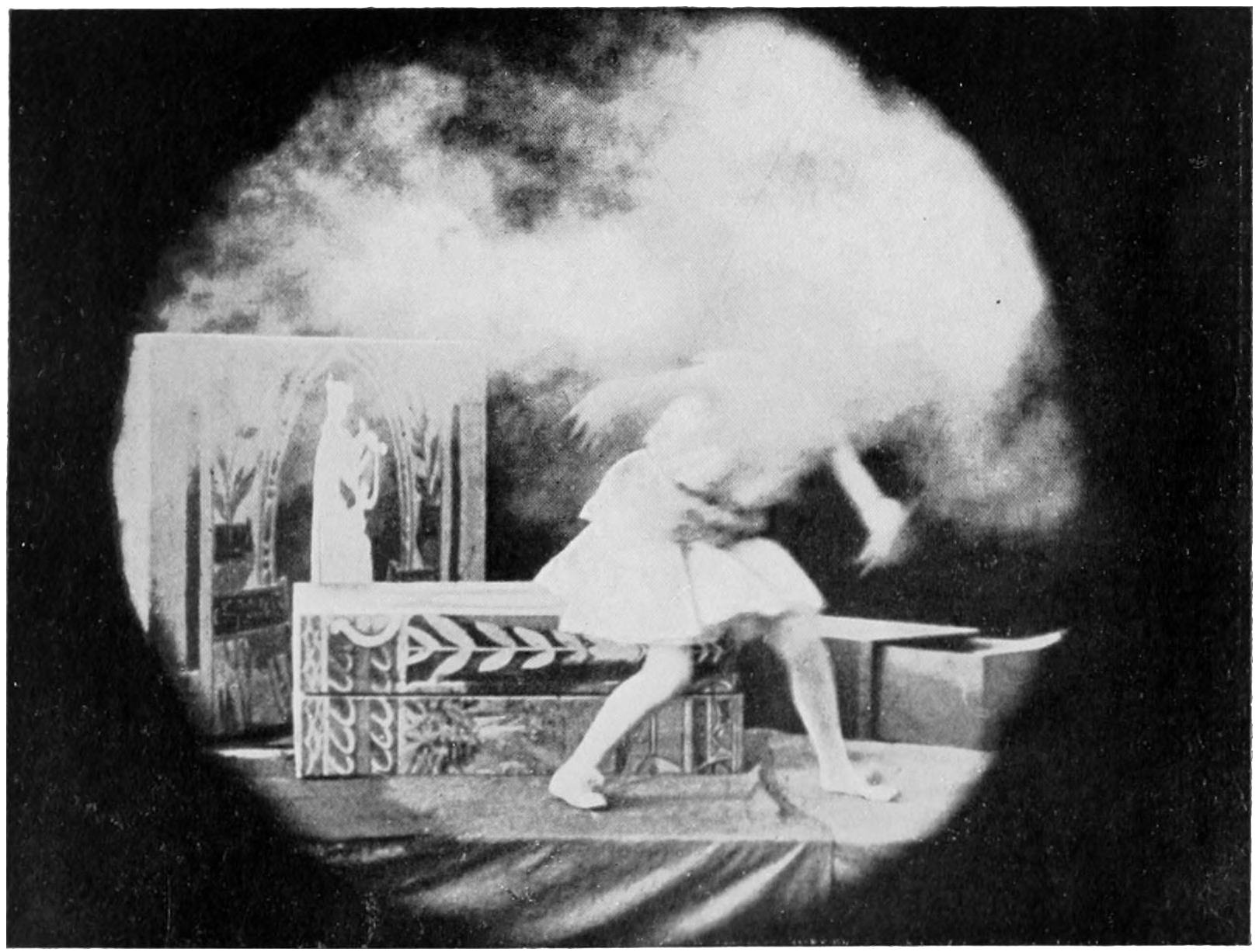

| The Secret of the Fairy’s Disappearance: While a Length of Film is being exposed the Diaphragm is closed slowly | 221 |

| The same Length of Film is re-exposed after the Fairy has entered the Picture, under a slowly opening Diaphragm | 222 |

| The Effect of Double Exposure under closing and opening Diaphragm | 223xiv |

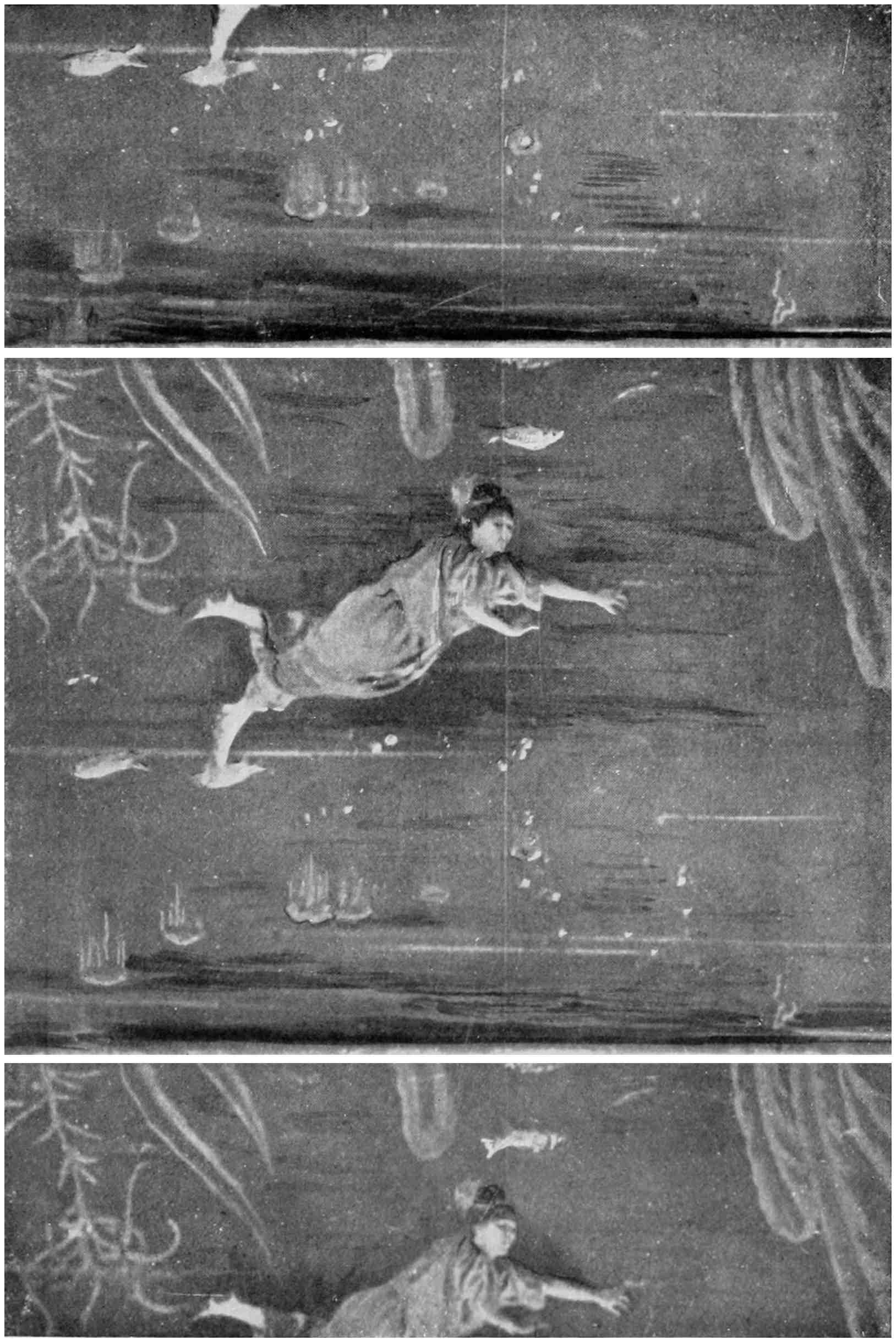

| The Mystery of “The Siren” | 226 |

| The Mystery of “The Siren” revealed | 227 |

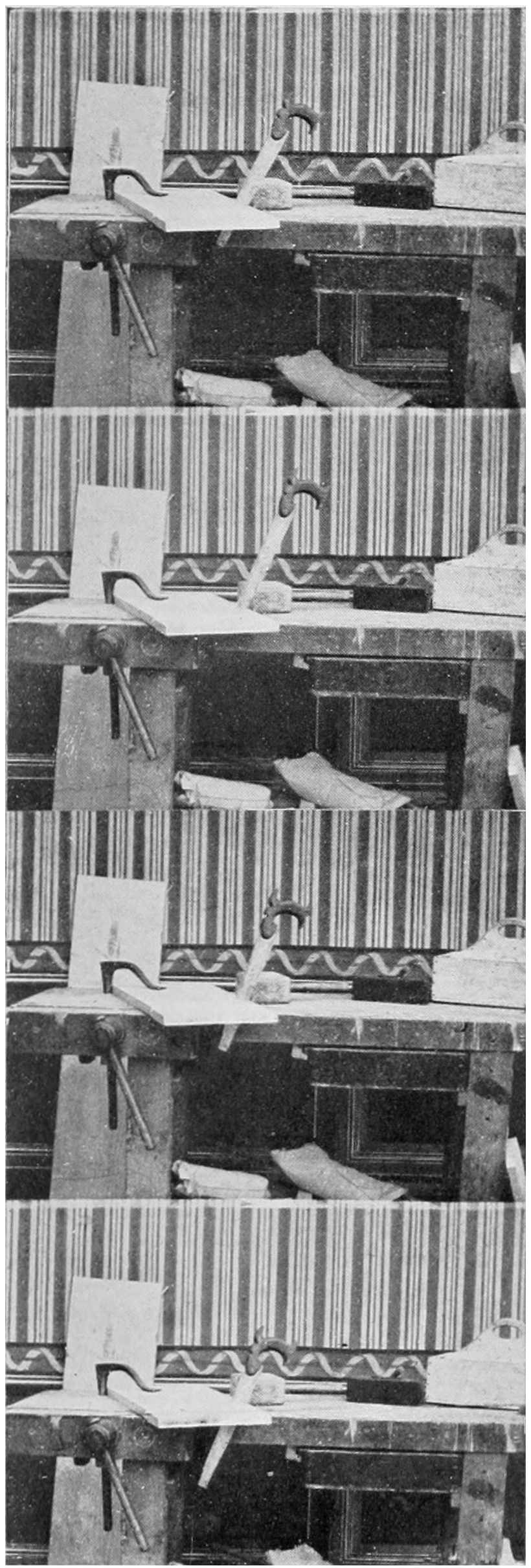

| A Workshop in which Tools move without Hands | 238 |

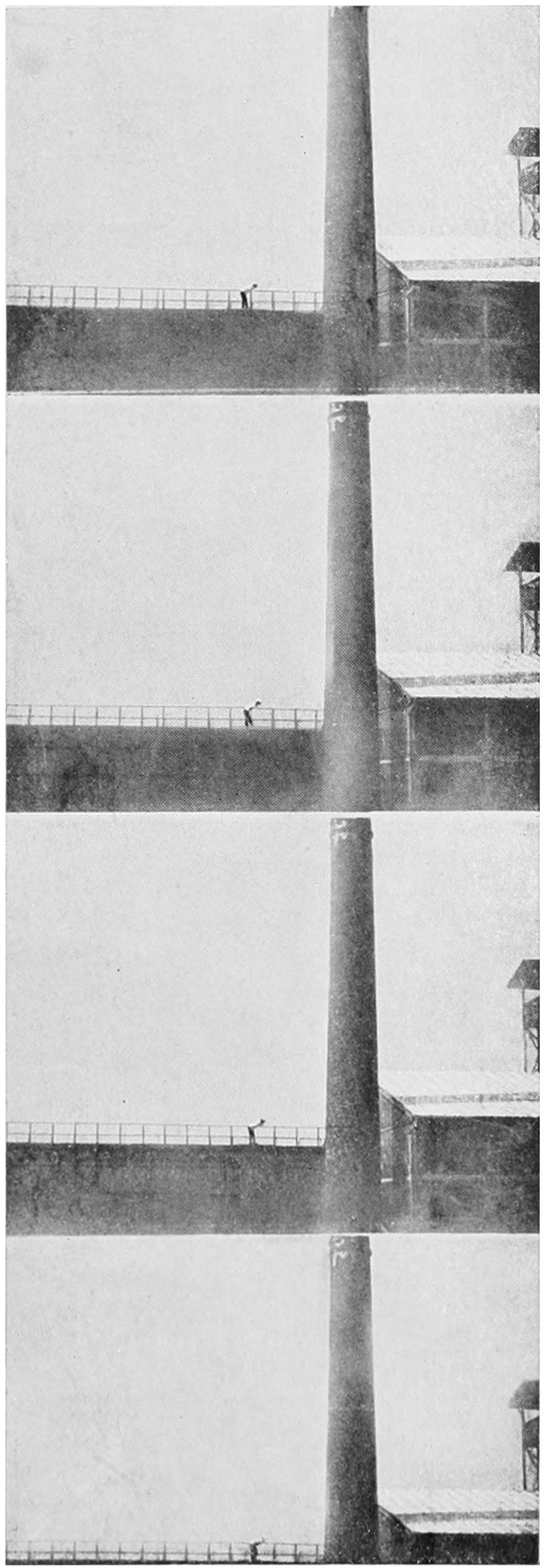

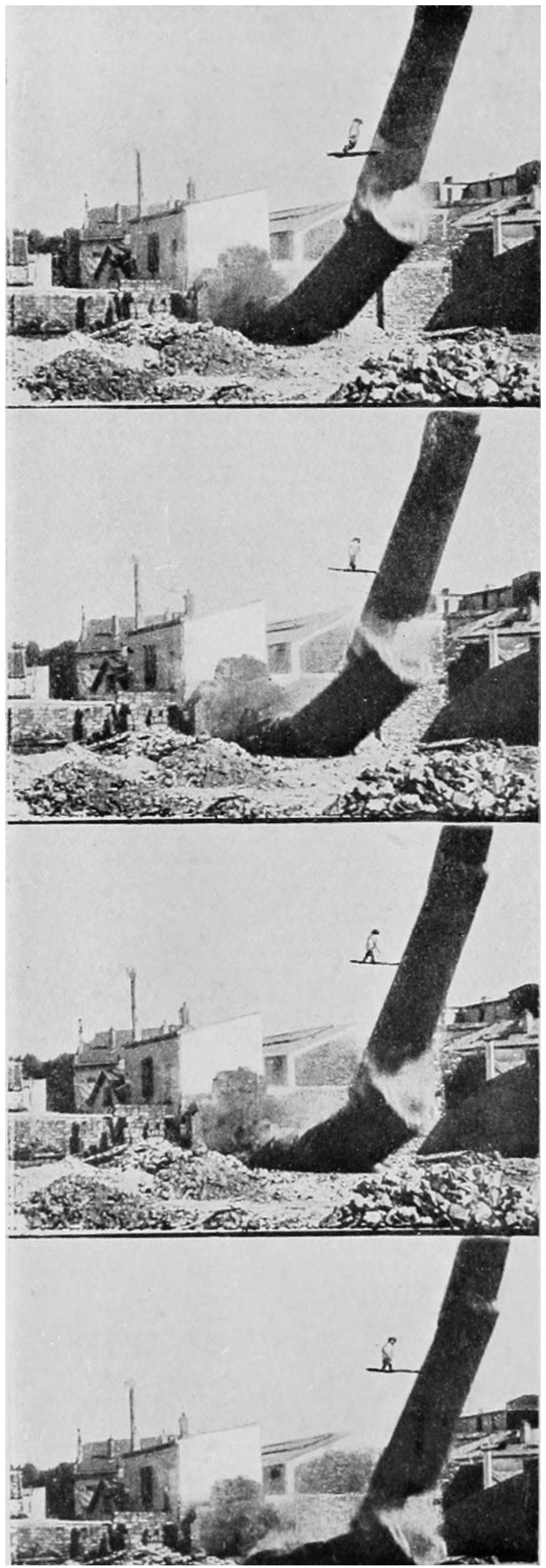

| The Skater approaching the Factory Chimney | 238 |

| The Result of the Collision with the Chimney | 239 |

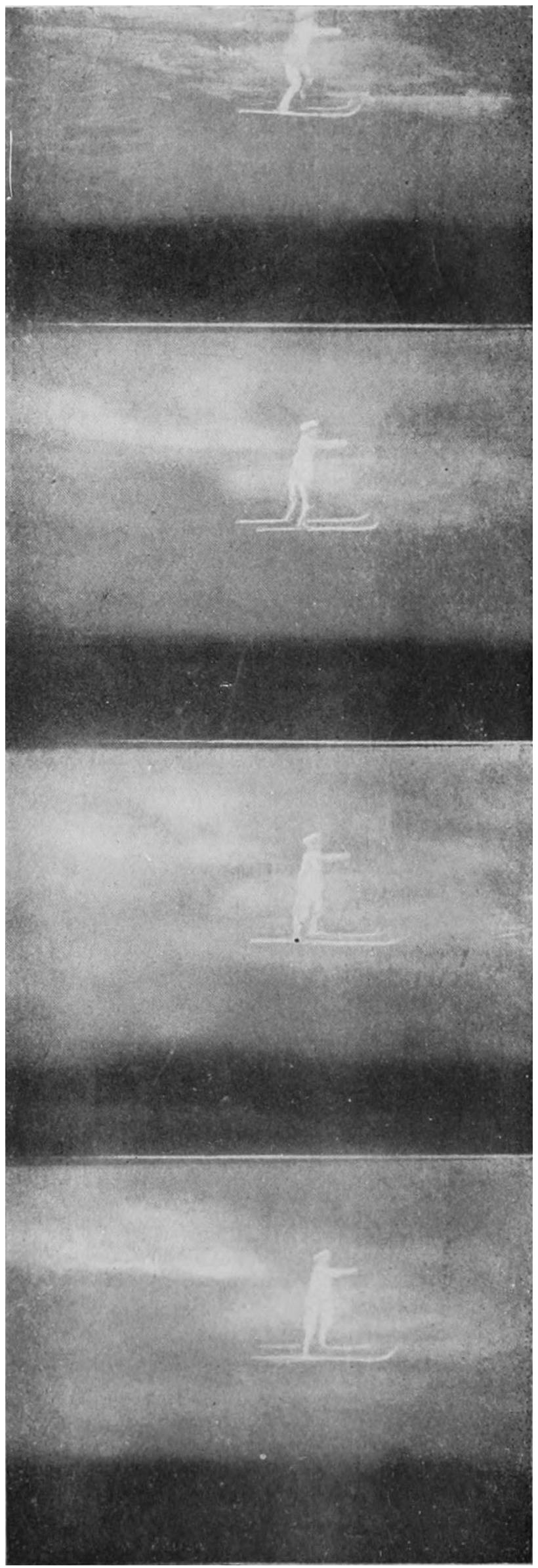

| The Ski-runner Disappears into Space | 239 |

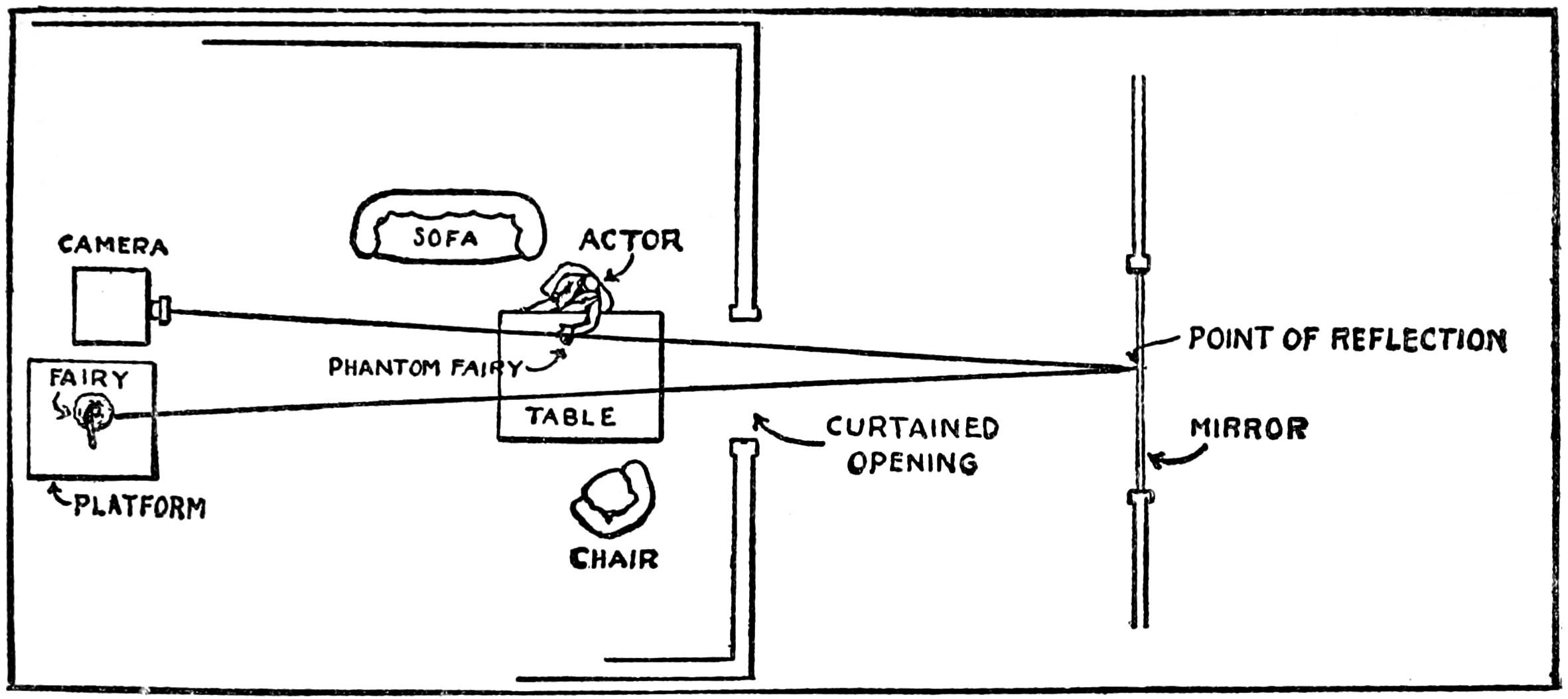

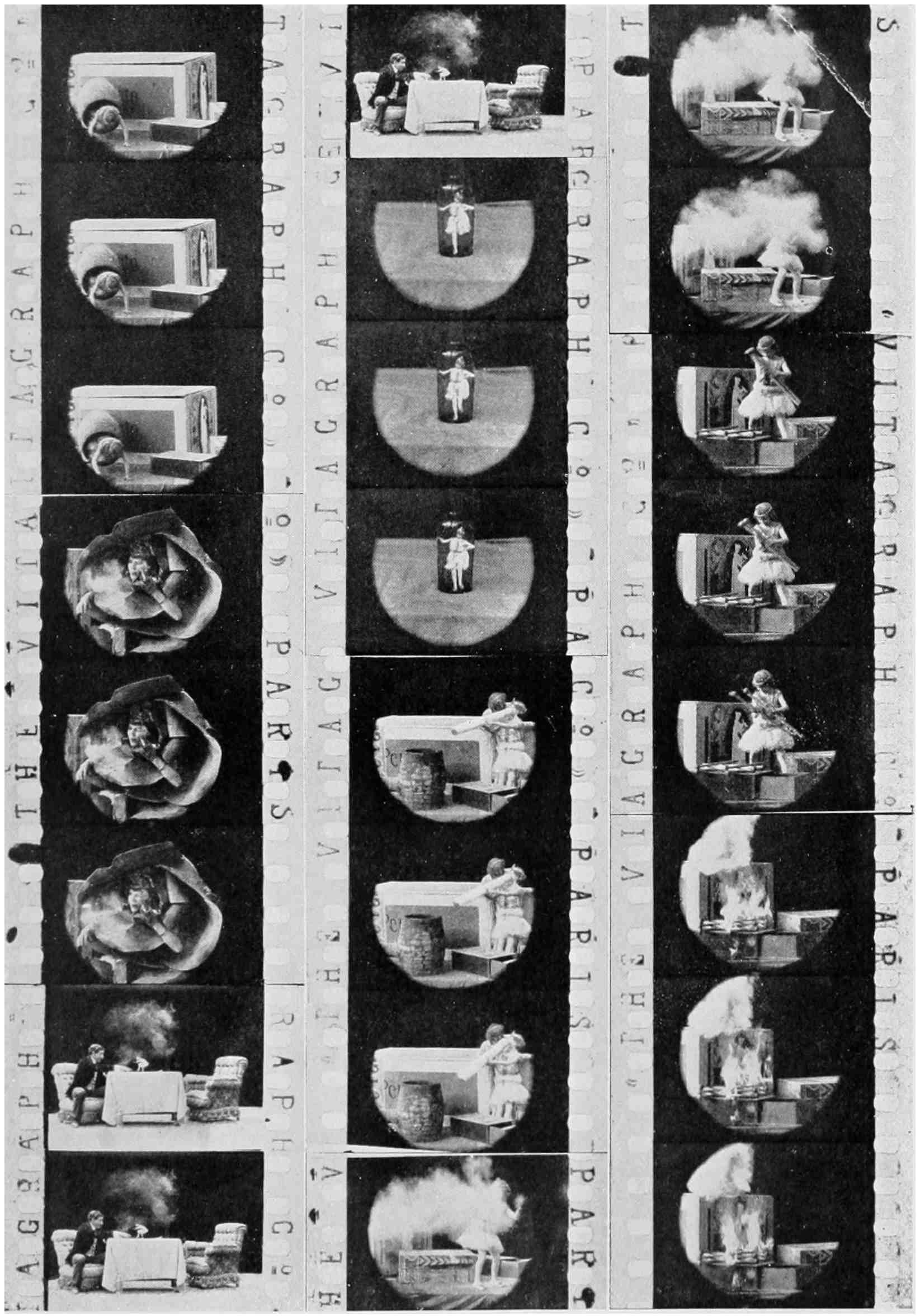

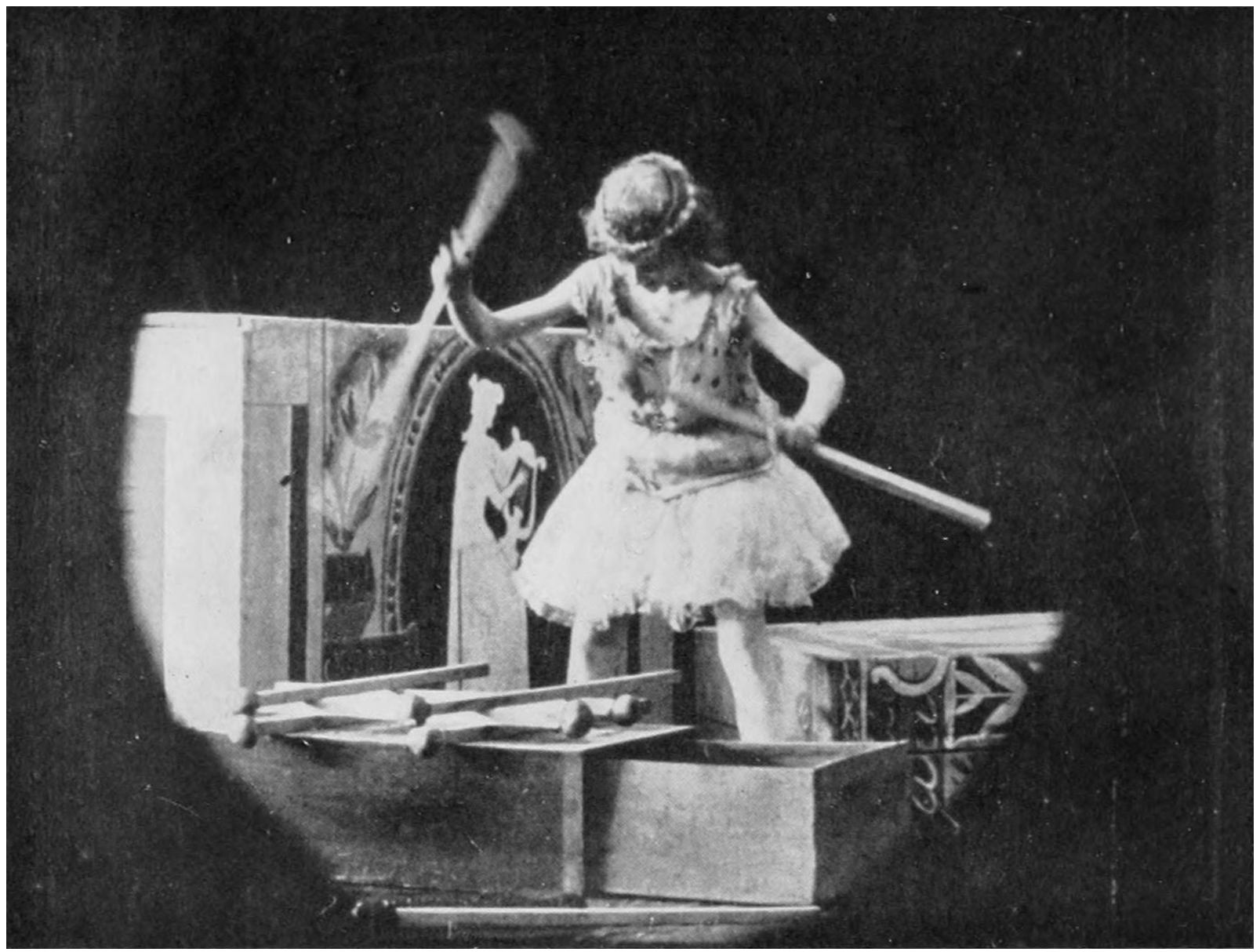

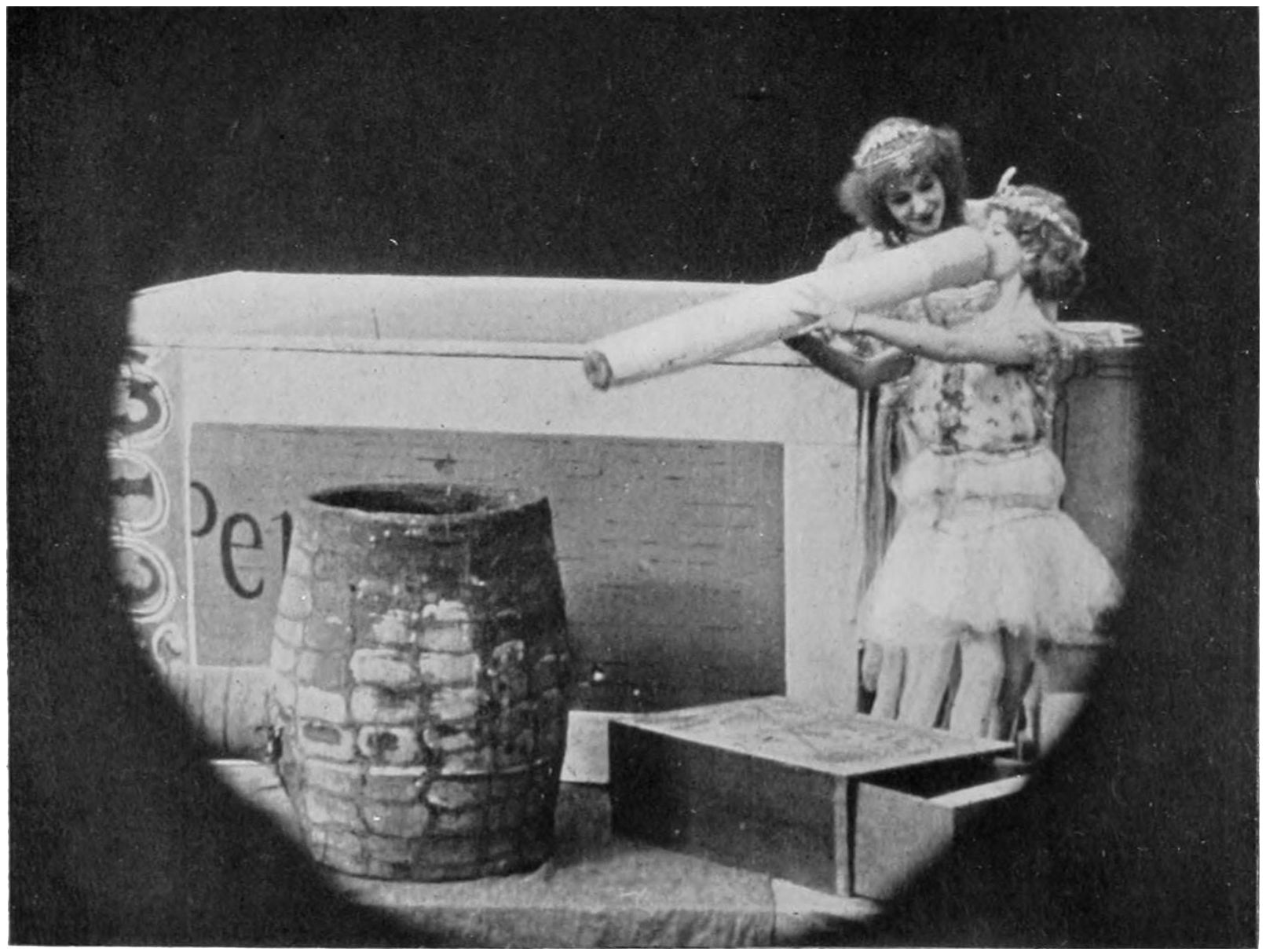

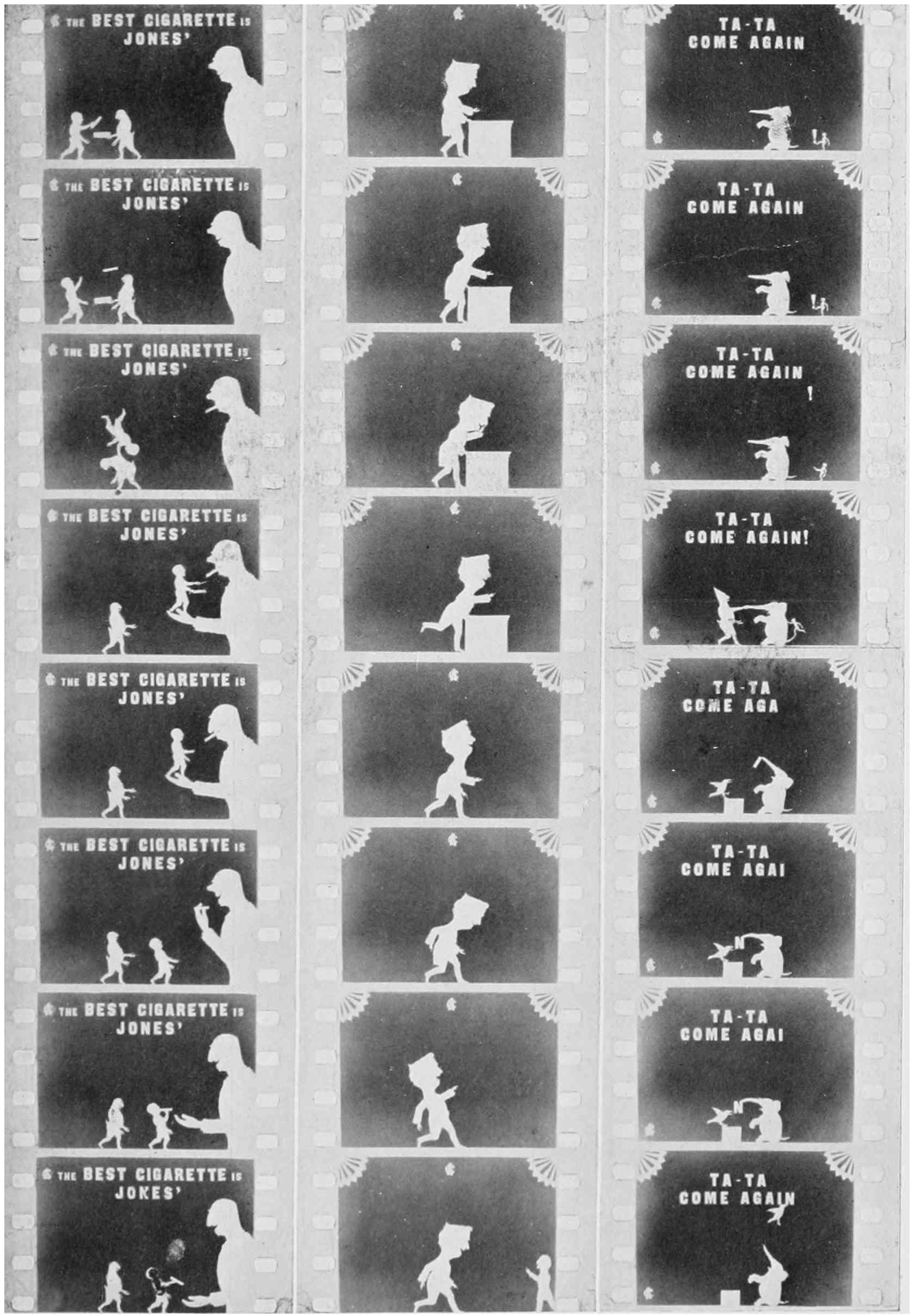

| Princess Nicotine—A Dainty Trick Film | 246 |

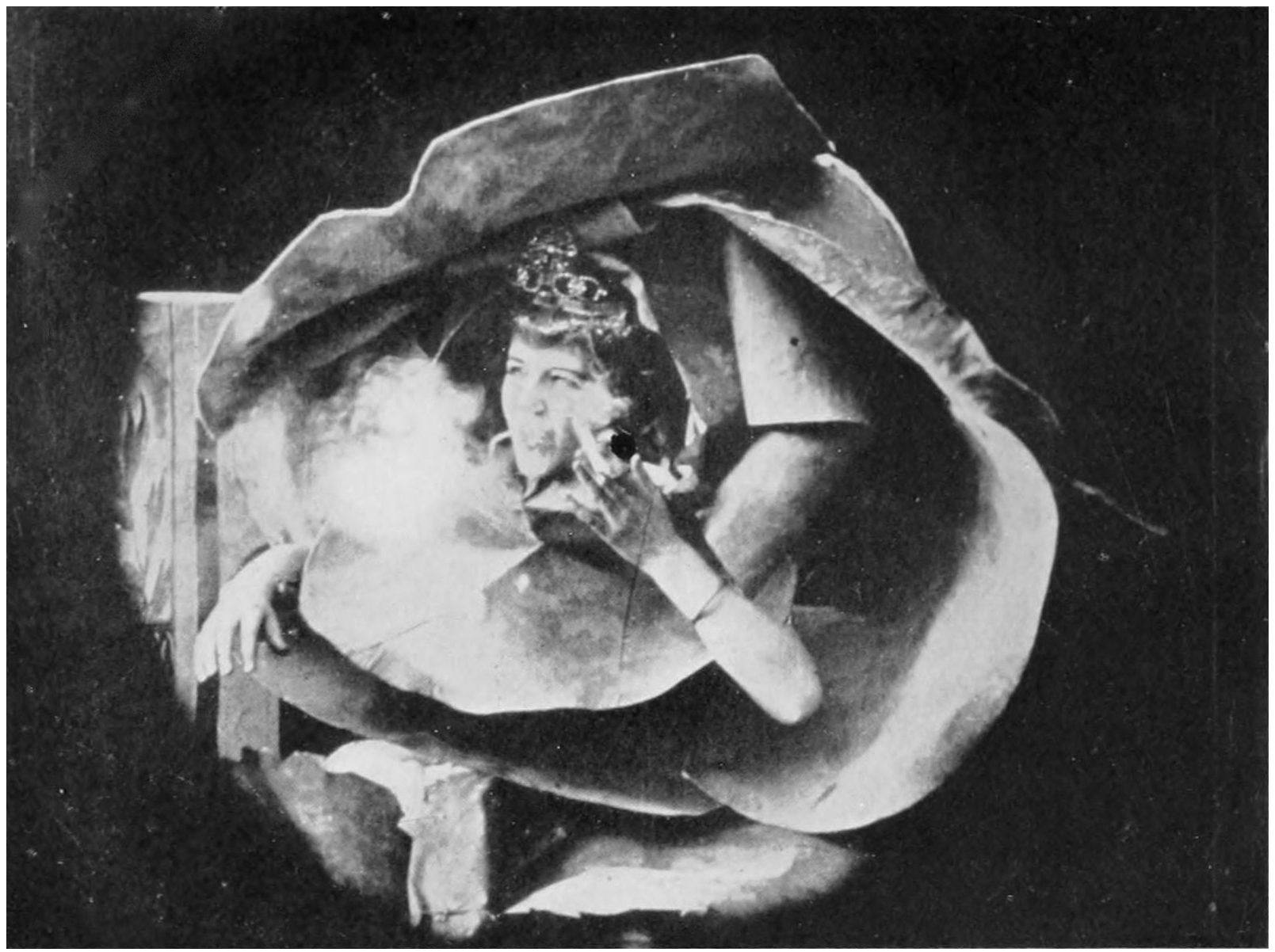

| The Fairy, Buried in the Heart of the Rose, Smoking a Cigarette | 247 |

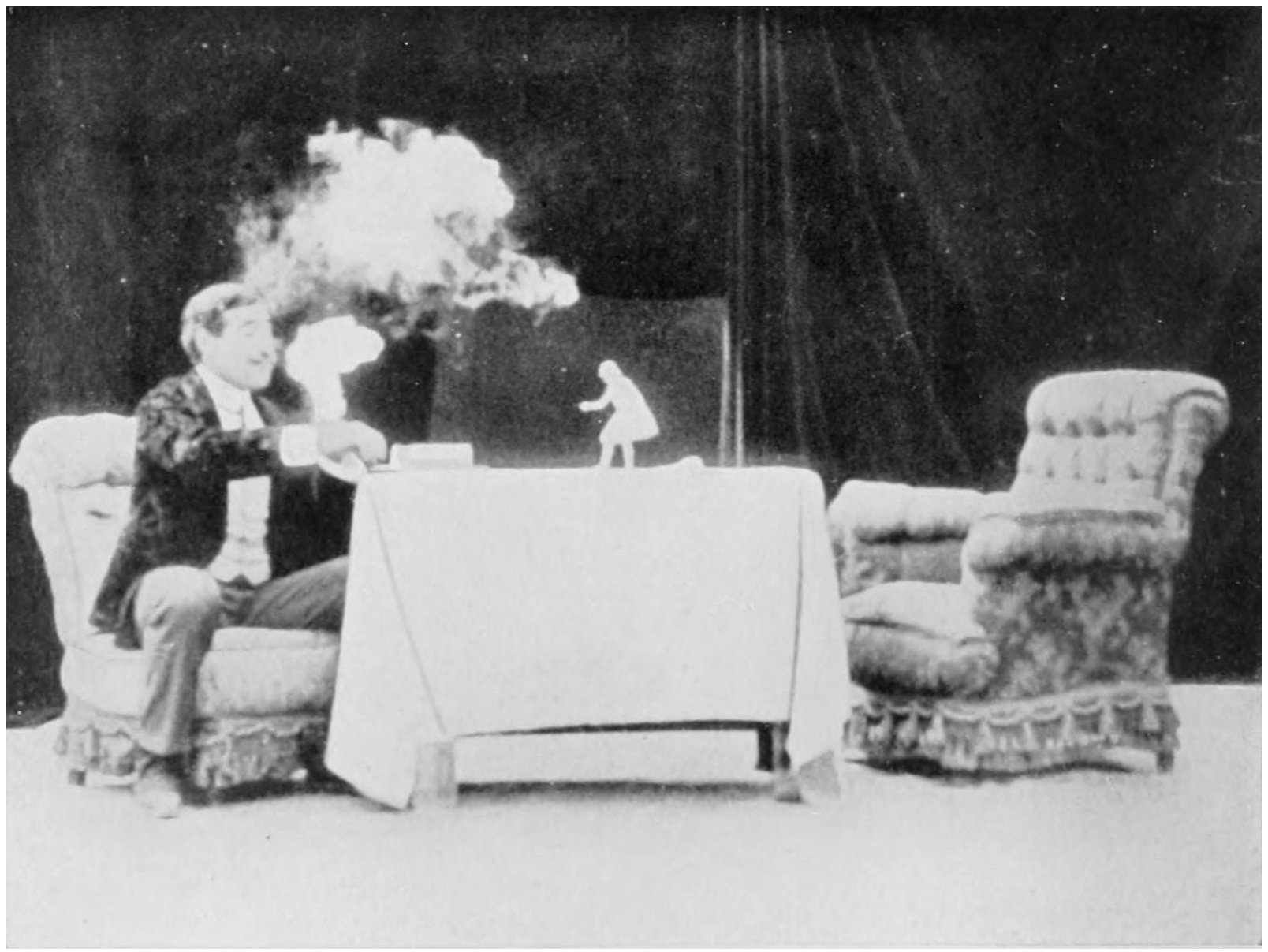

| The Diminutive Form of the Fairy on the Table | 247 |

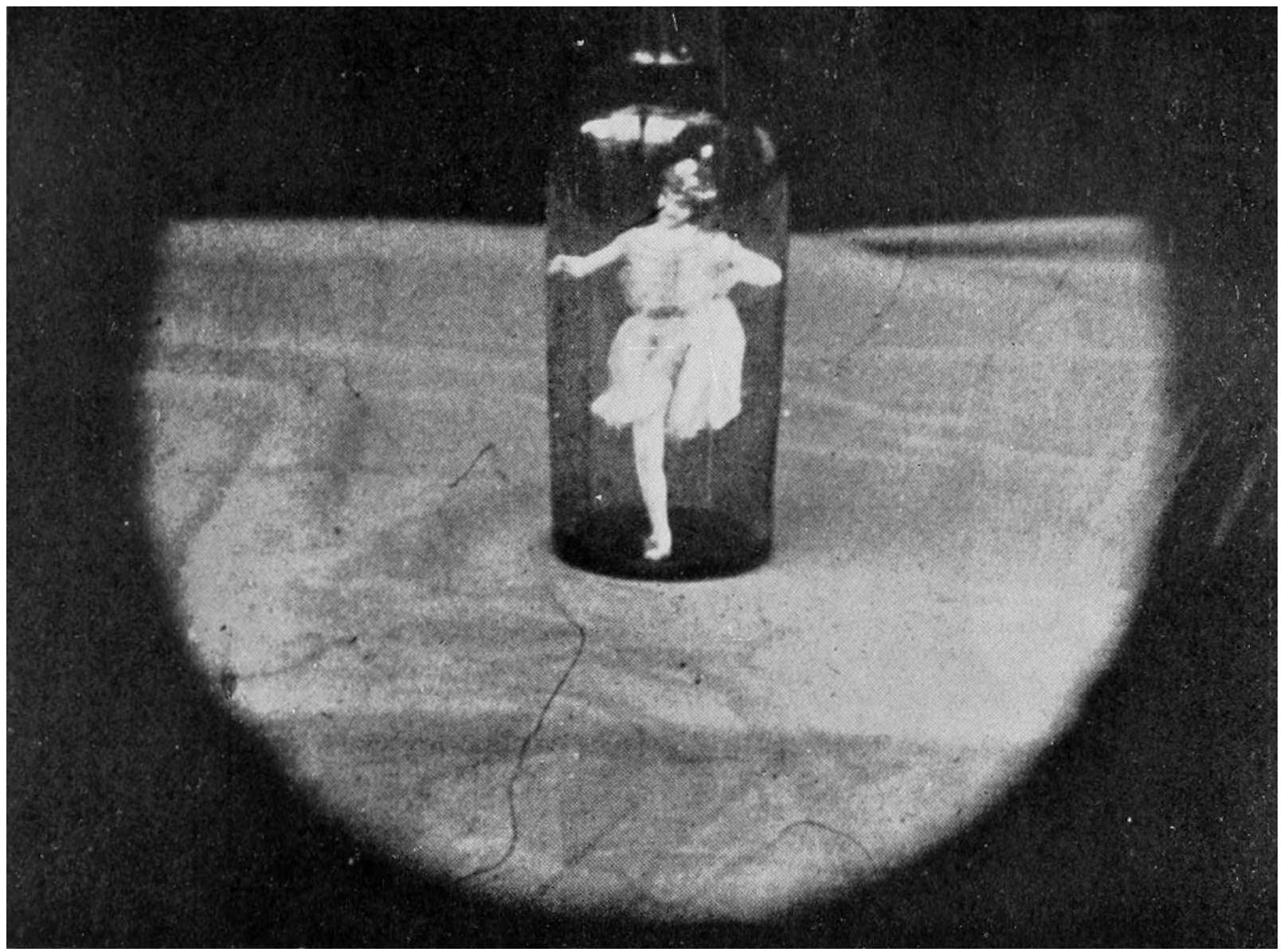

| The Fairy Imprisoned in the Bottle. This effect is obtained by double exposure | 250 |

| The Fairy, after Coquetting with the Bachelor, is driven away by the Smoke from his Cigarette | 250 |

| The Fairy proceeds to Build a Bonfire with Matches | 251 |

| The Fairy, her Accomplice, and Properties, which are Enlarged Reproductions of the Actual Articles | 251 |

| The Dissolution of the Government | 258 |

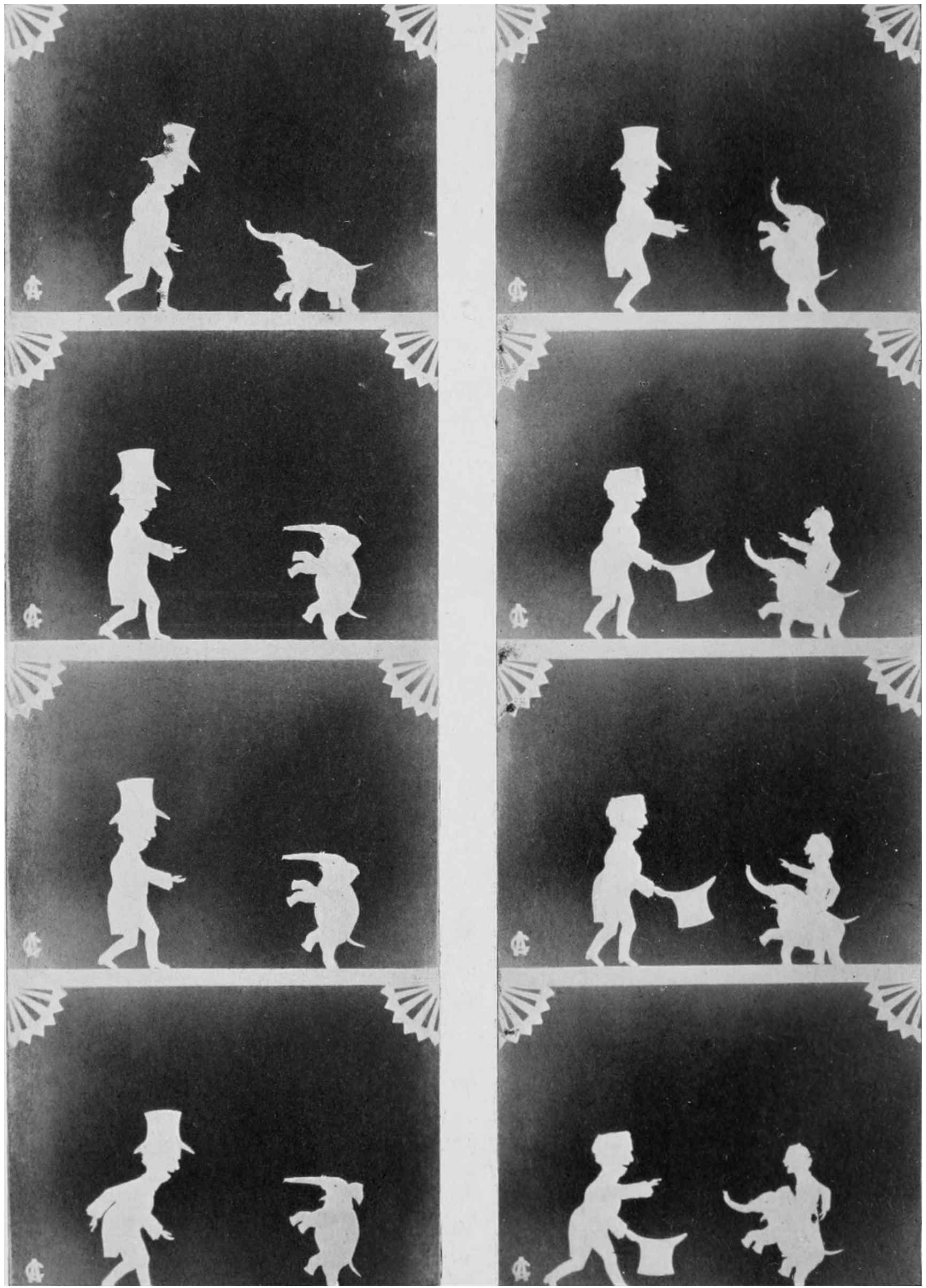

| The Latest Craze in Trick Cinematography: Silhouettes with Models | 259 |

| A Quaint Advertisement Film | 260 |

| Mr. Asquith in Cartoon | 260 |

| A Novel Curtain Idea | 260 |

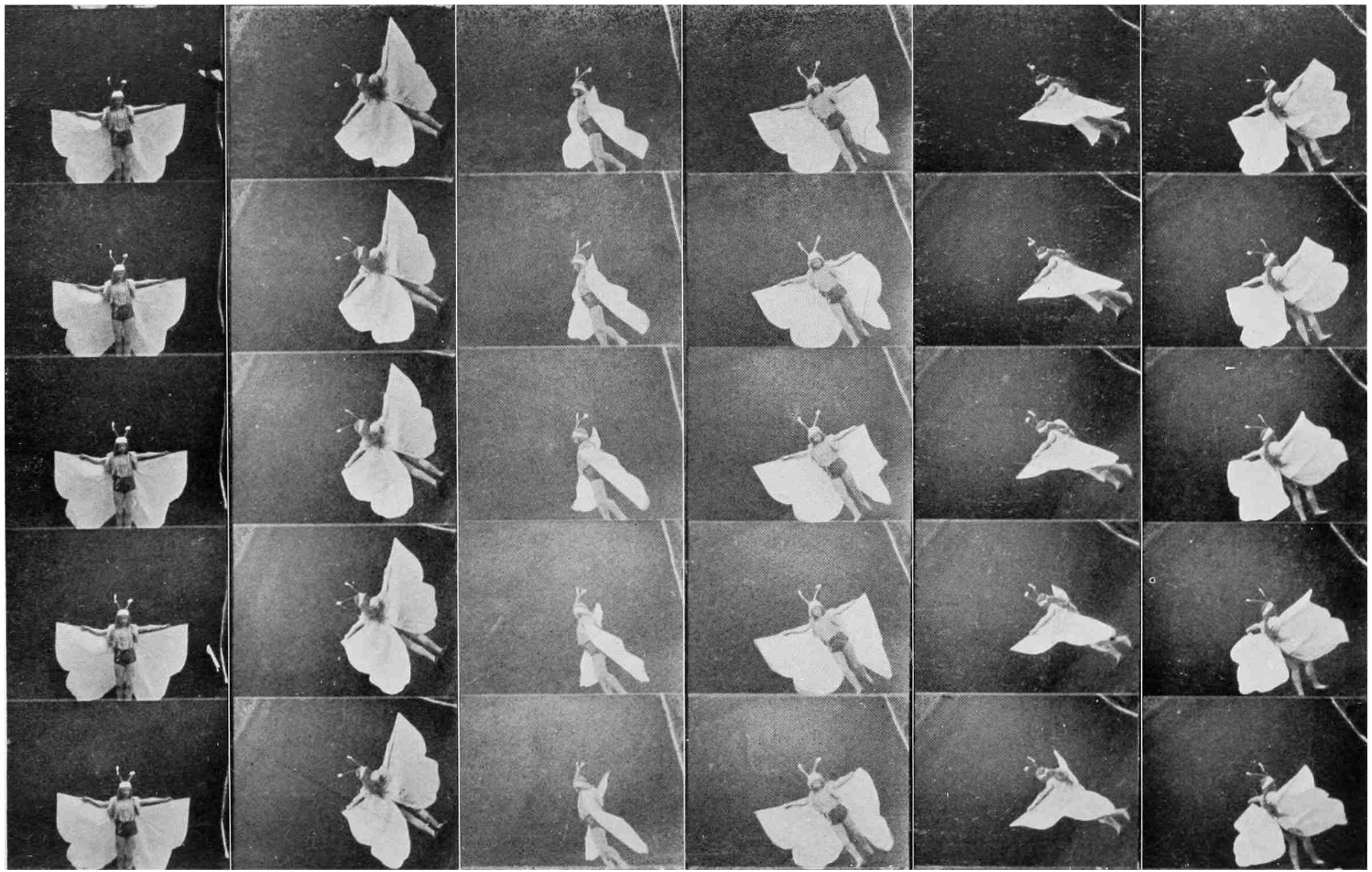

| The Human Butterfly: How are the Effects Obtained? | 261 |

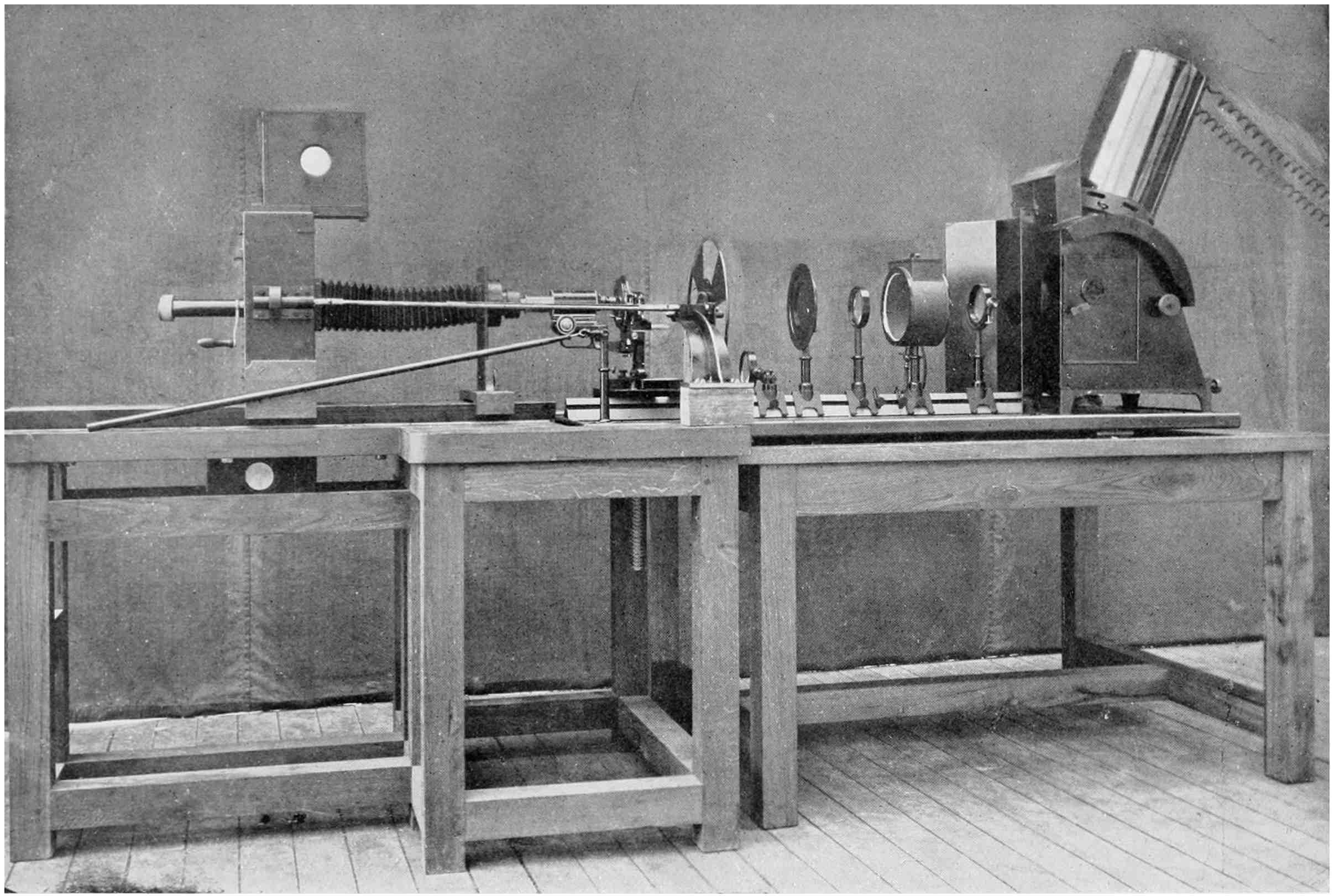

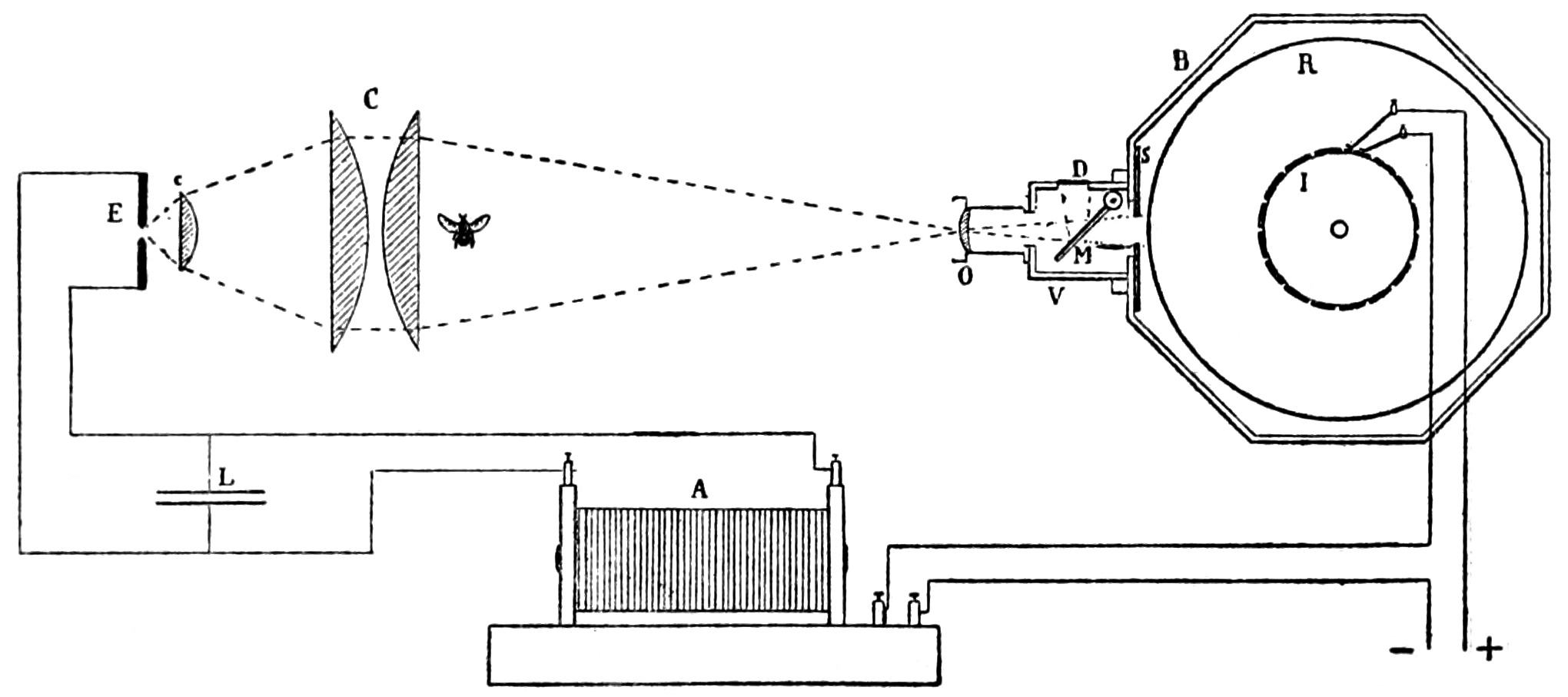

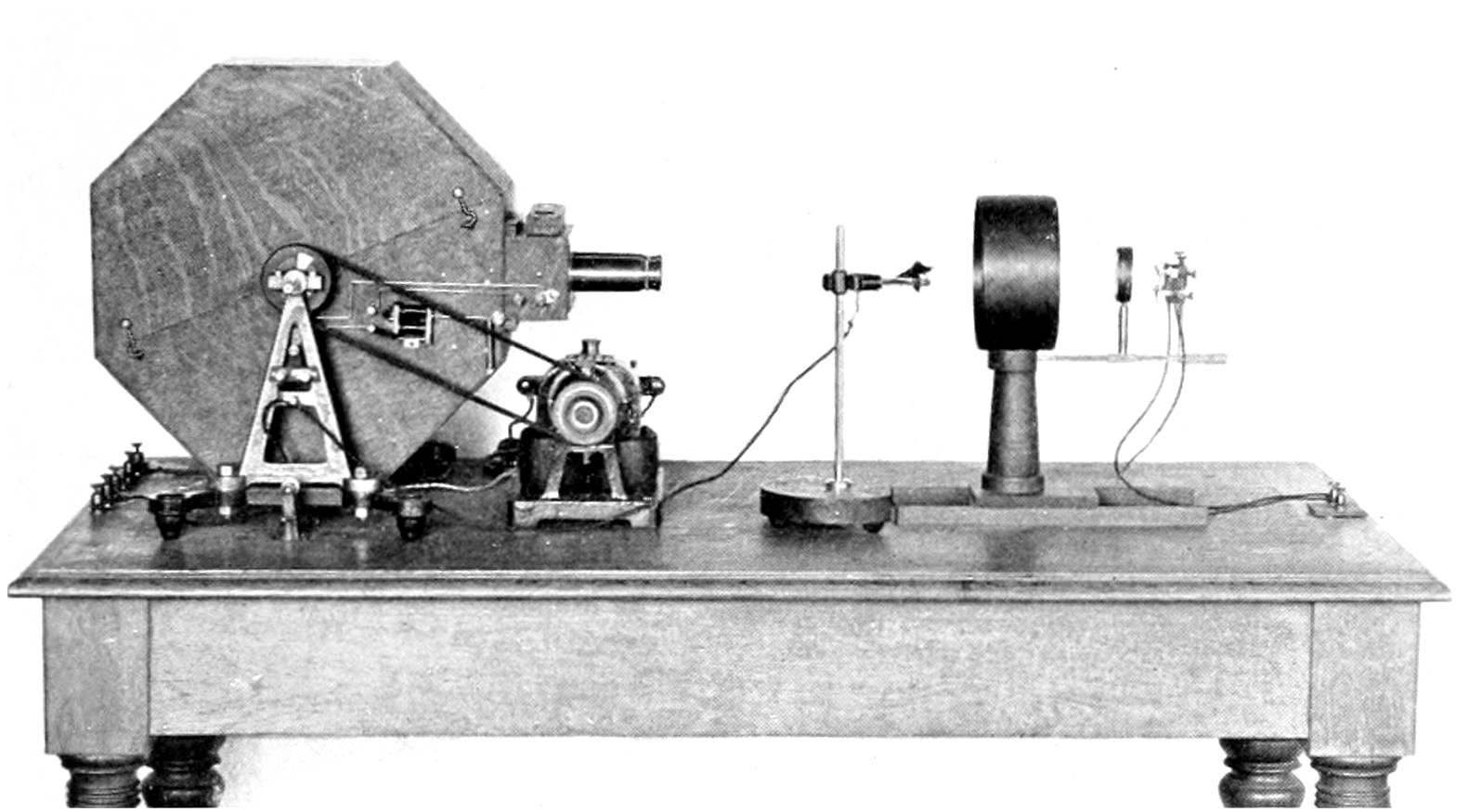

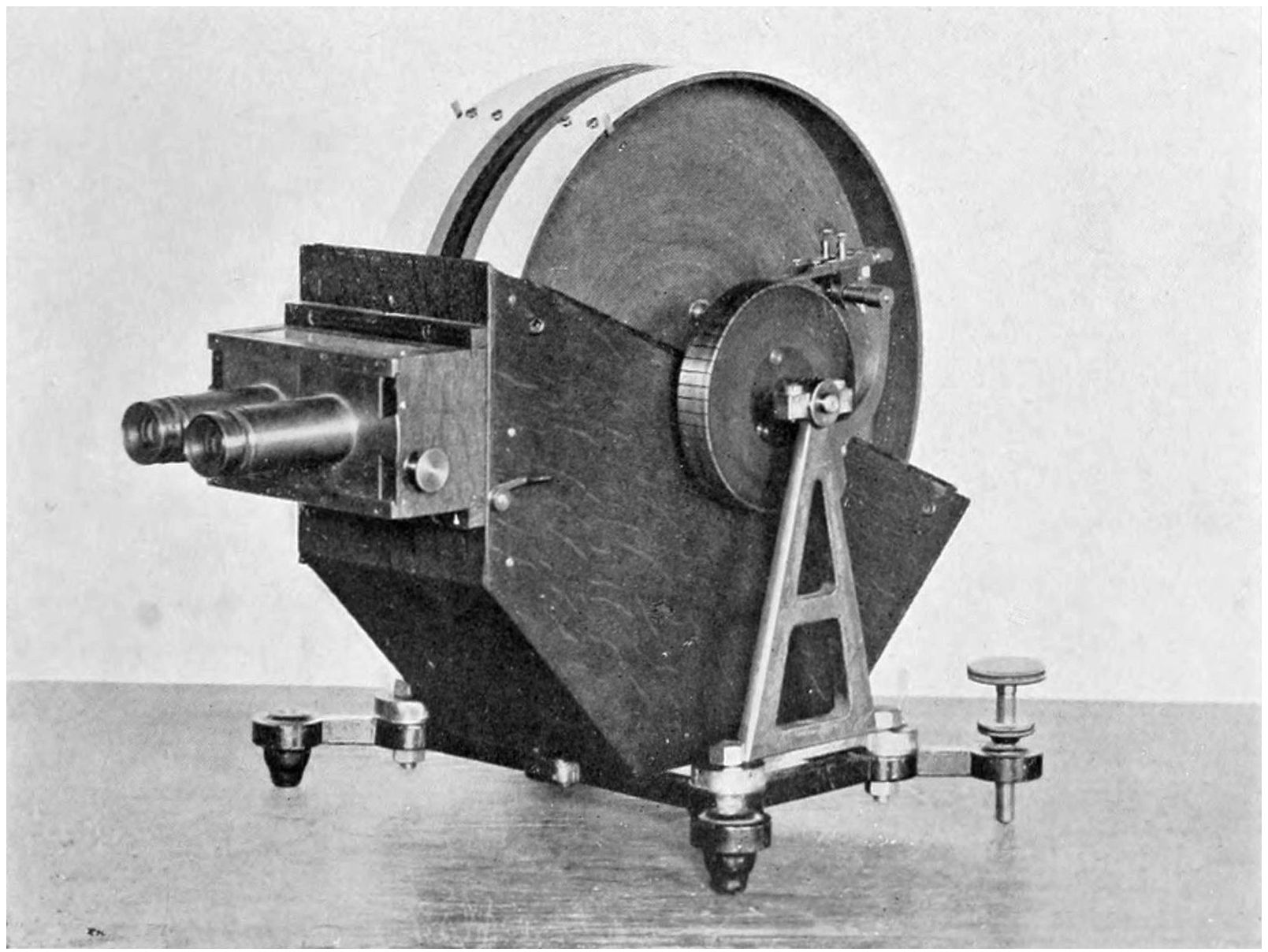

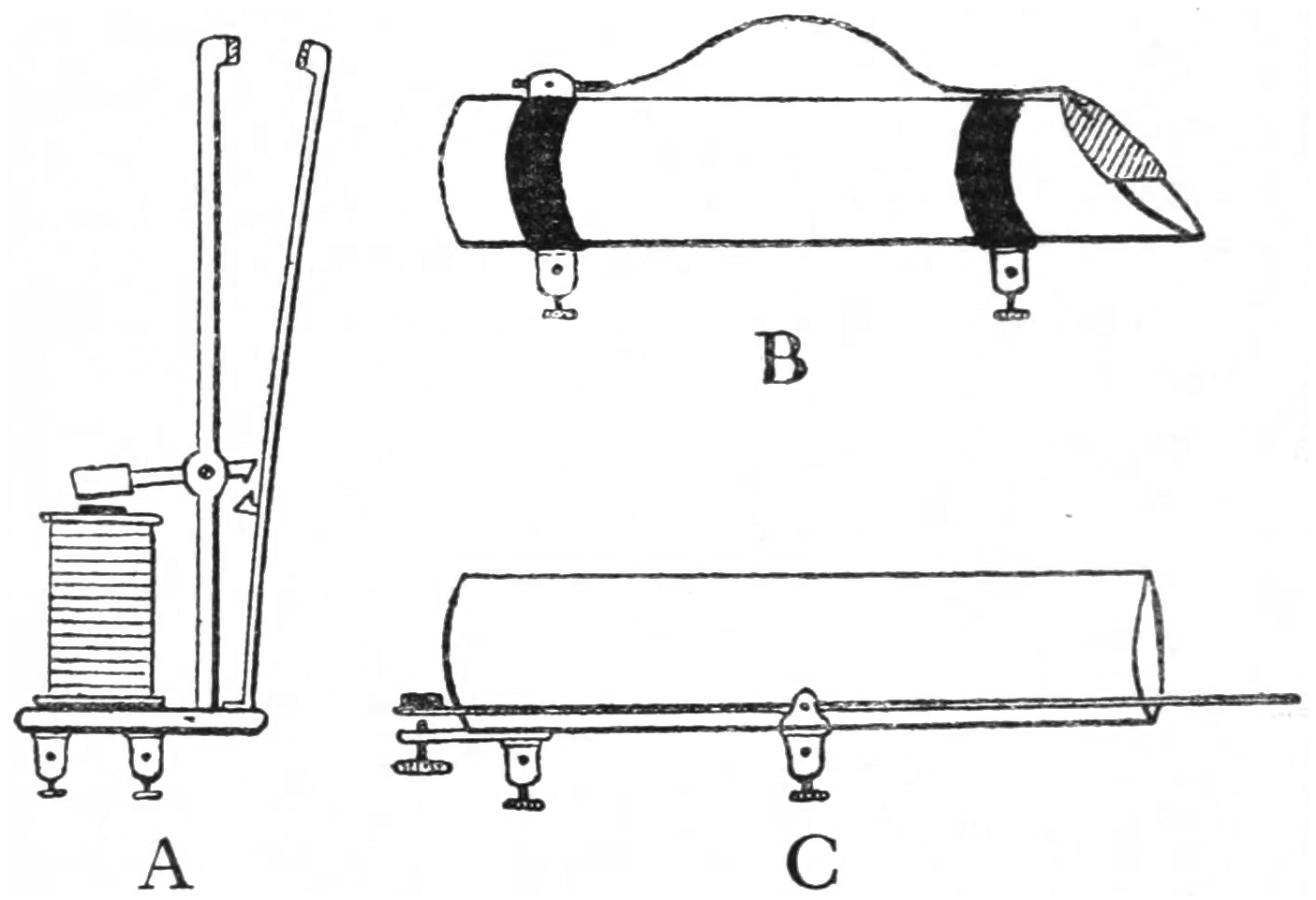

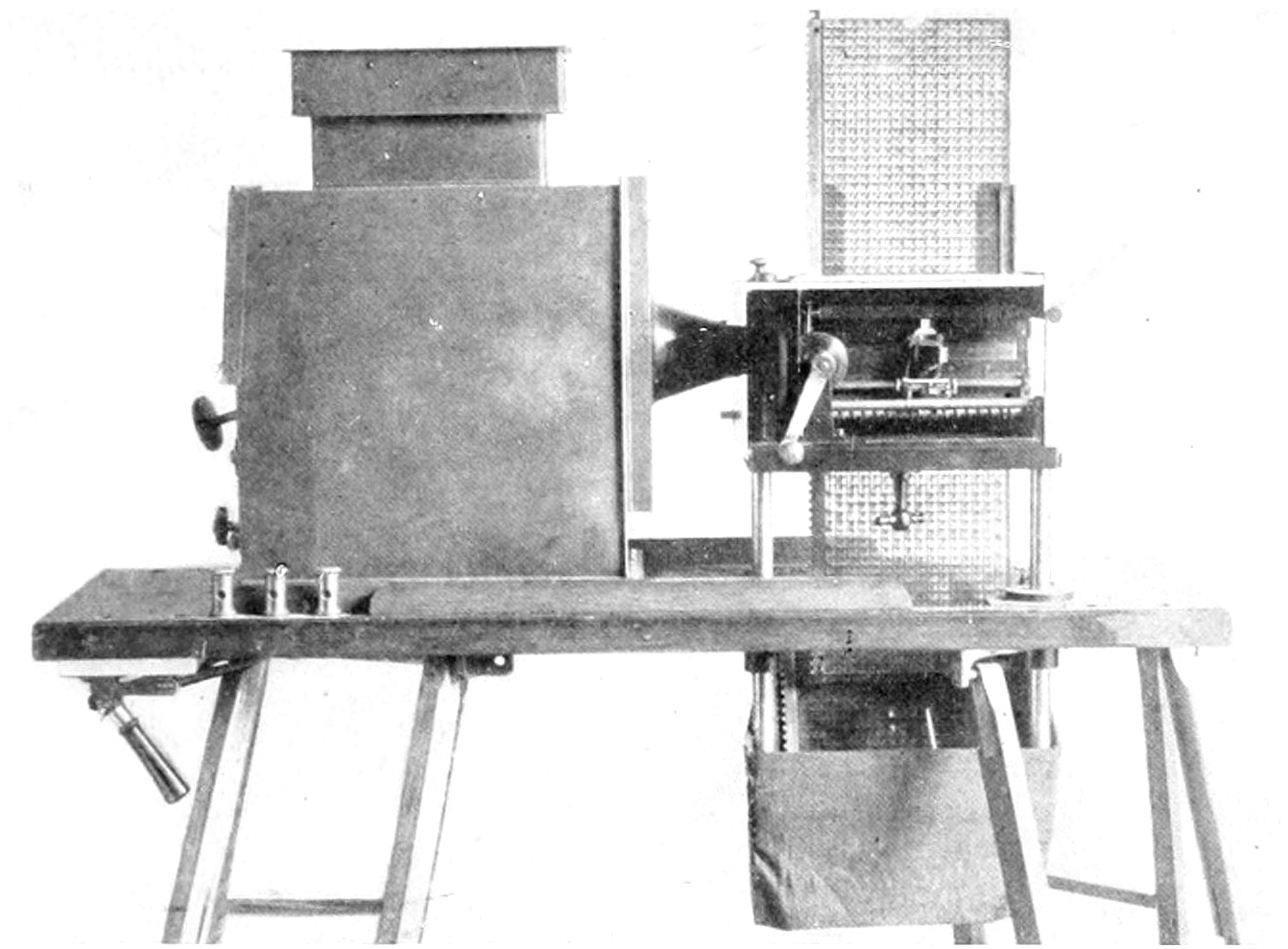

| M. Lucien Bull’s Complete Apparatus | 270 |

| The Novel Camera showing Stereoscopic Lens | 270 |

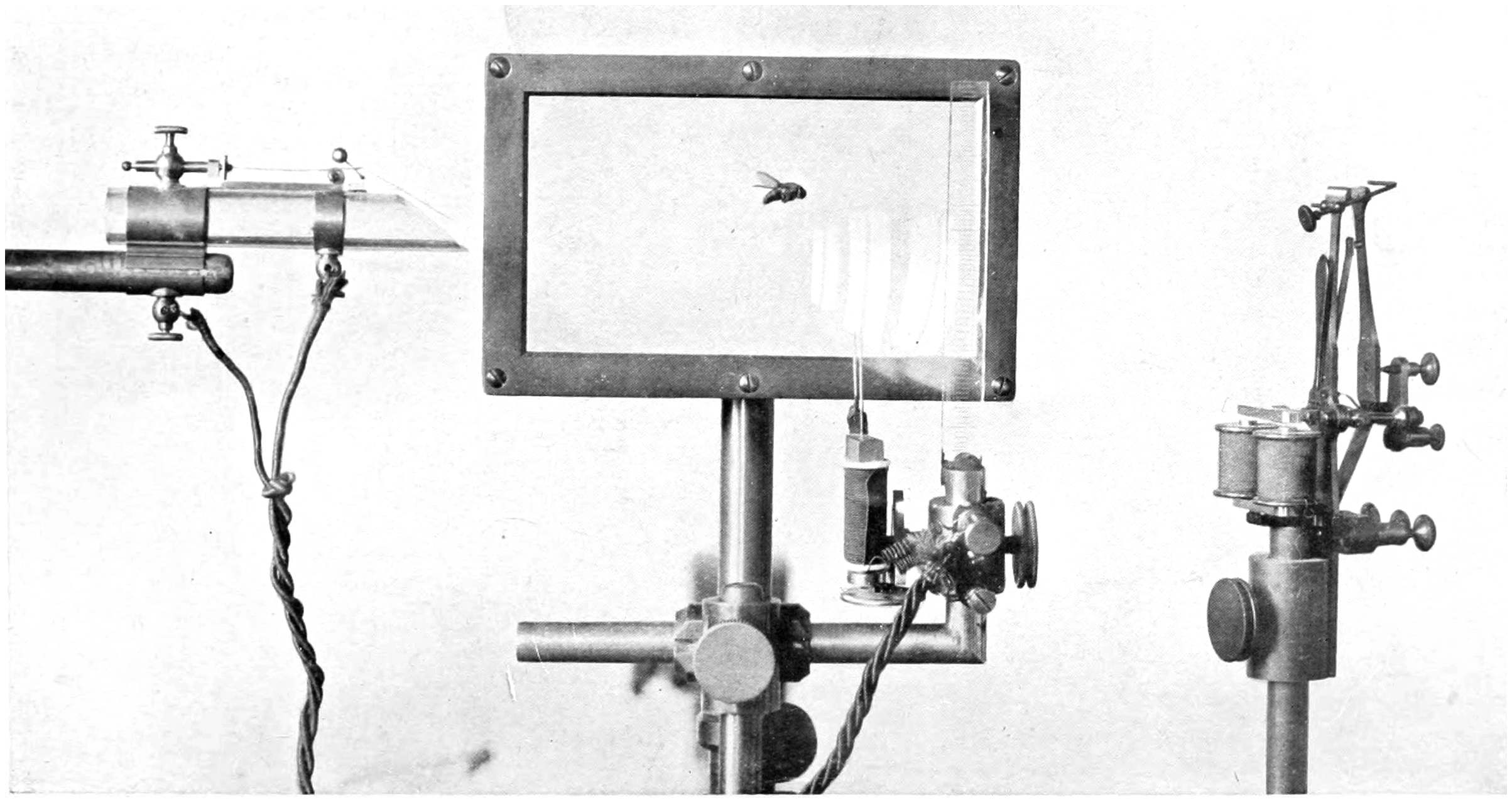

| A Bee Cinematographed in Full Flight | 271 |

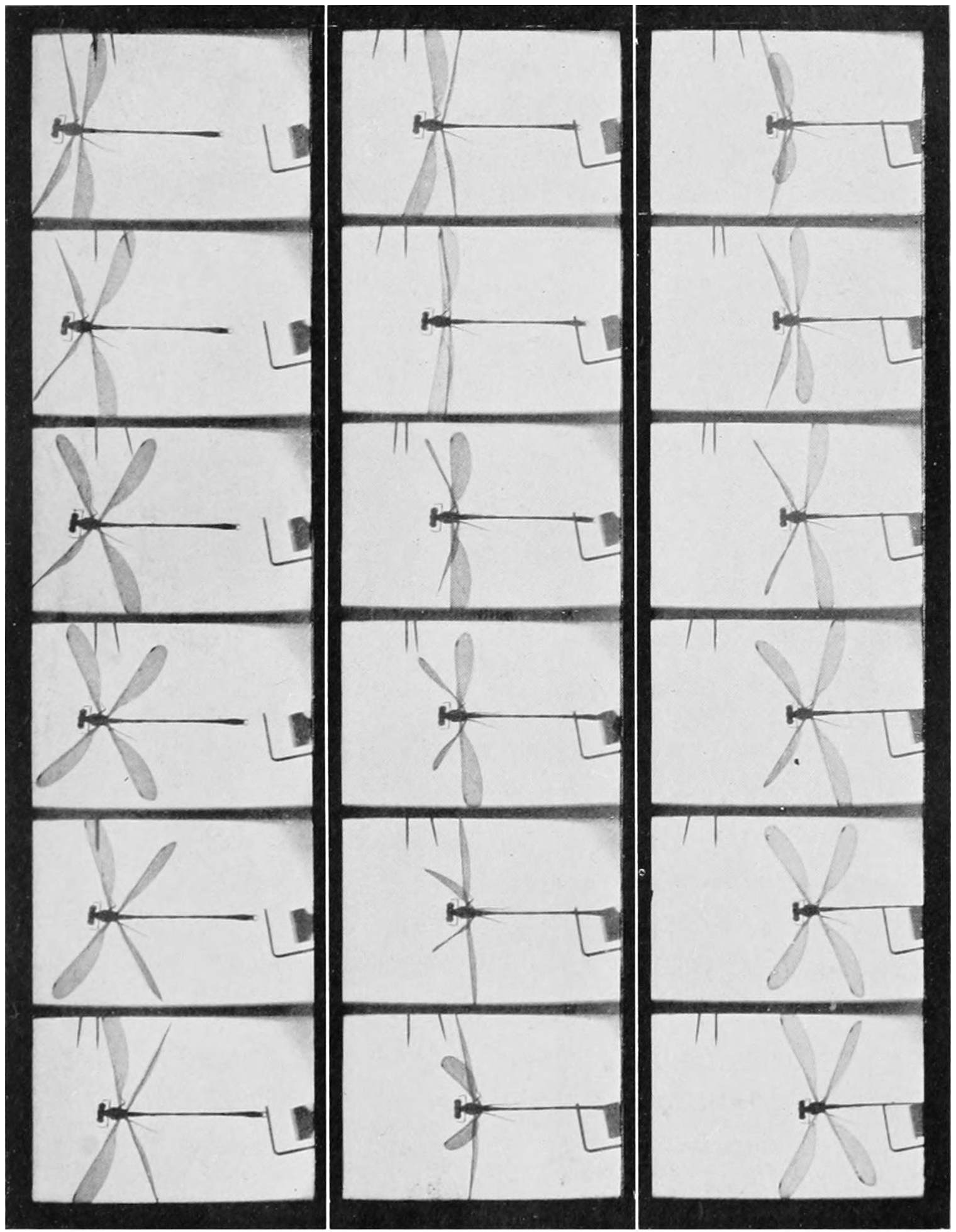

| A Dragon Fly in Flight | 274 |

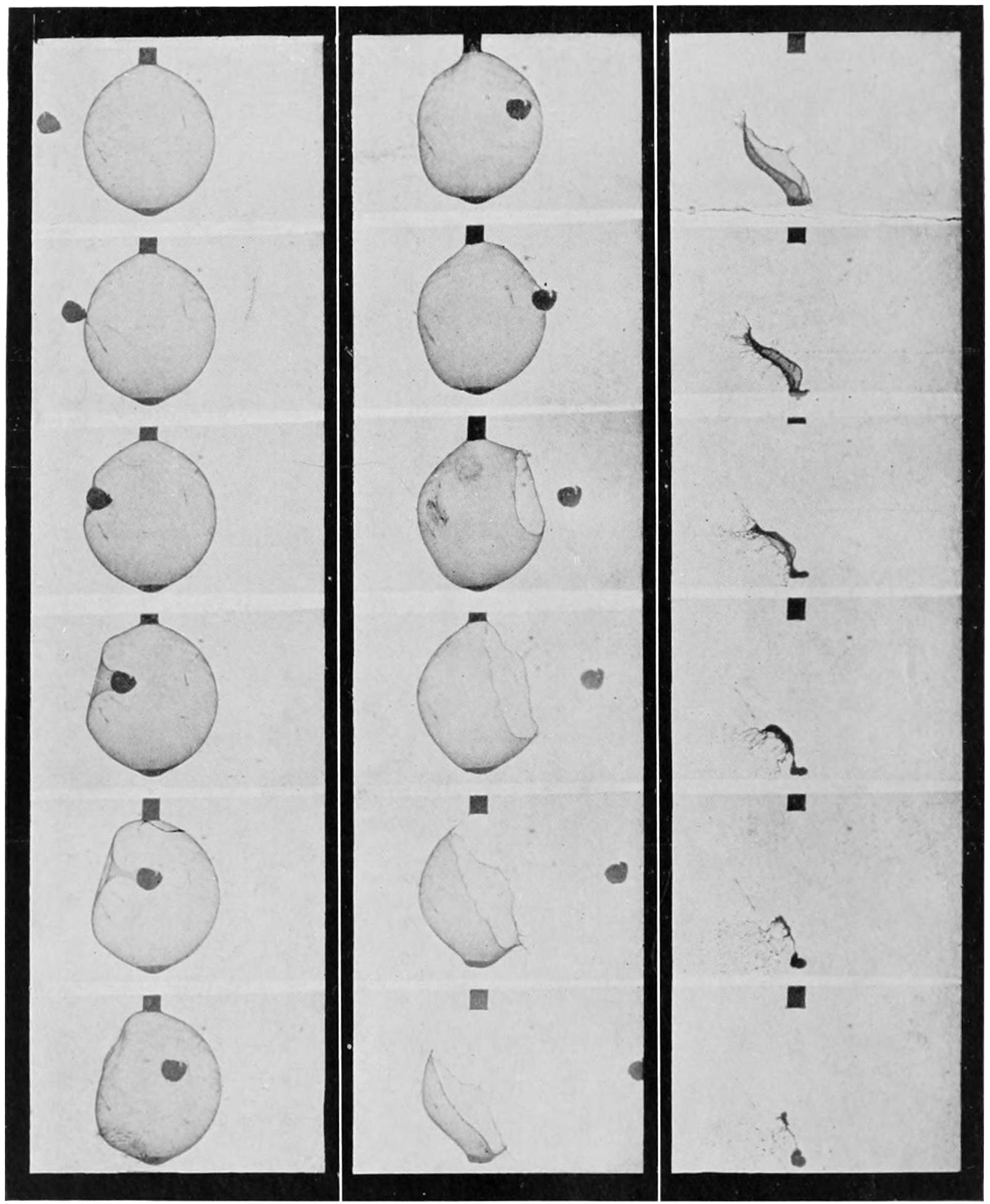

| Cinematograph Film of a Bullet Fired through a Soap Bubble | 275 |

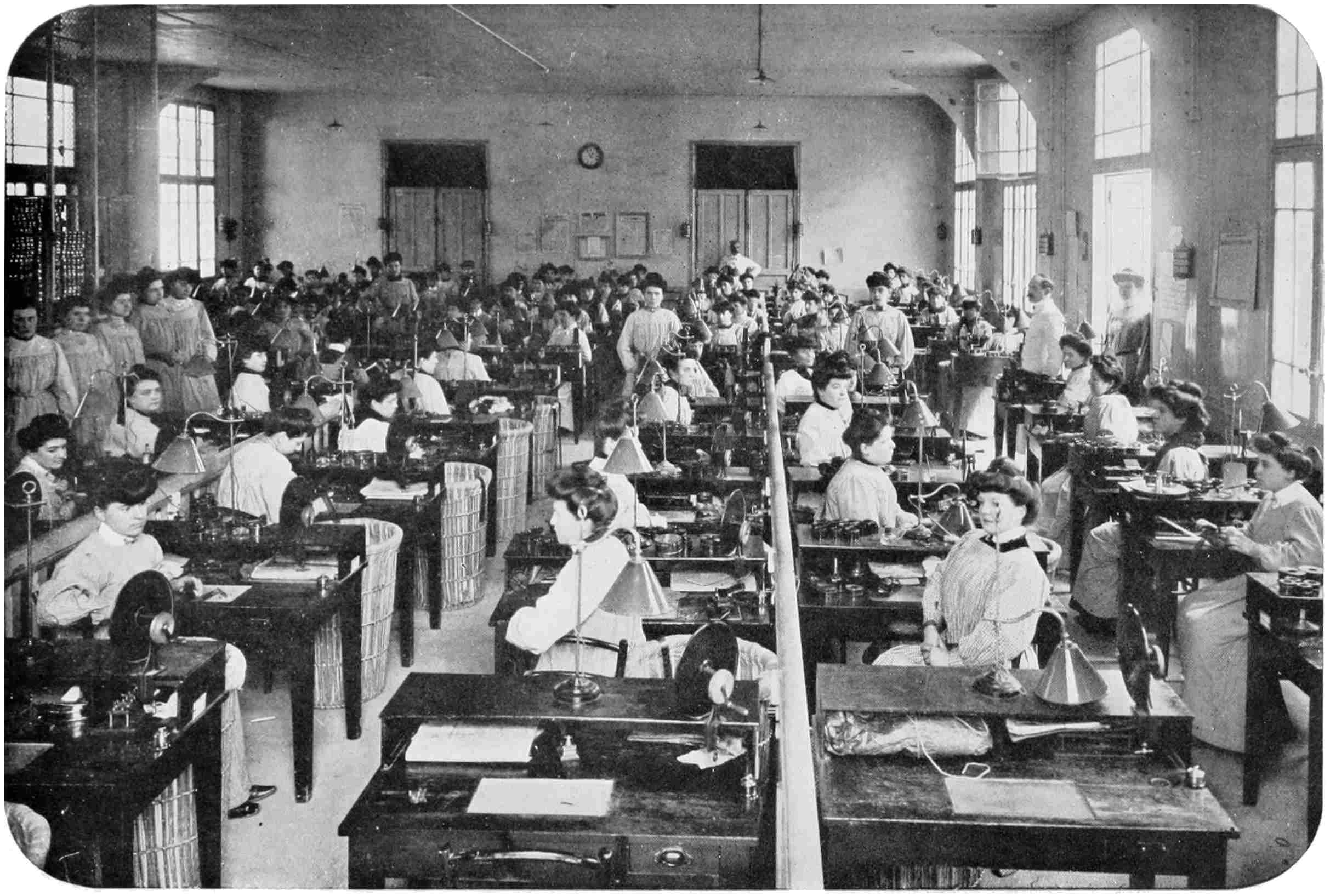

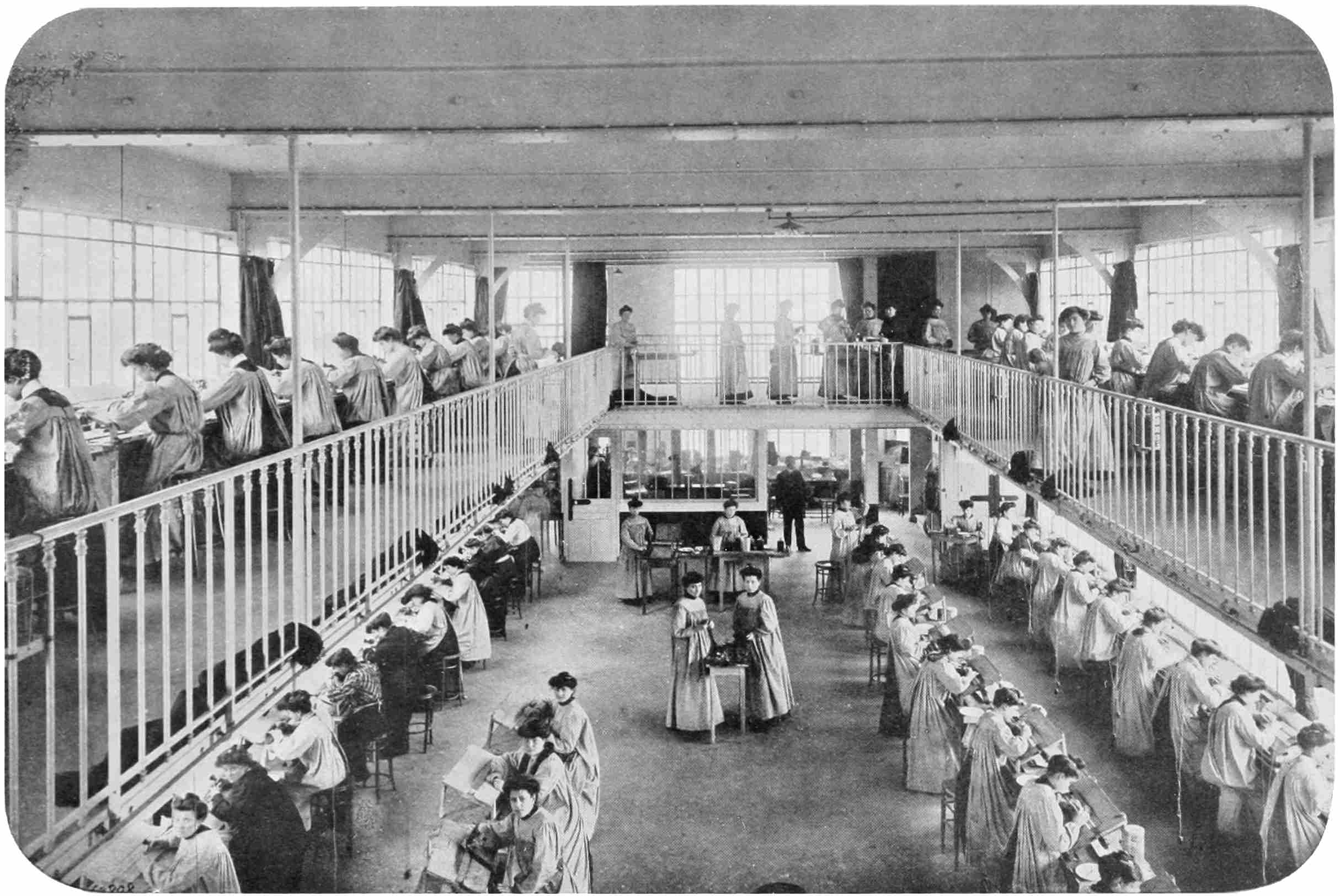

| Preparing the Pathé Colour Films | 288 |

| The Pathé Colour Machine-Printing Room | 289 |

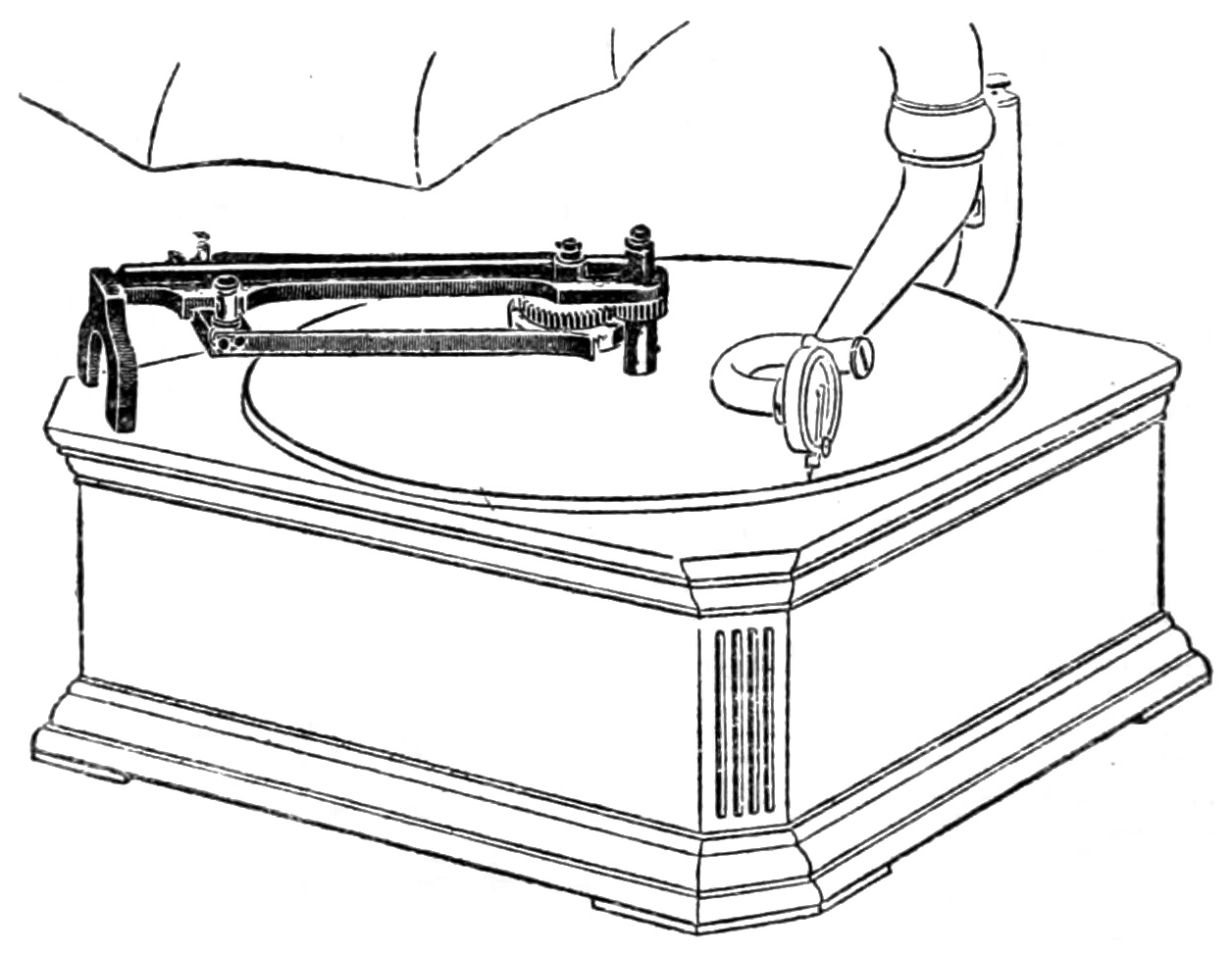

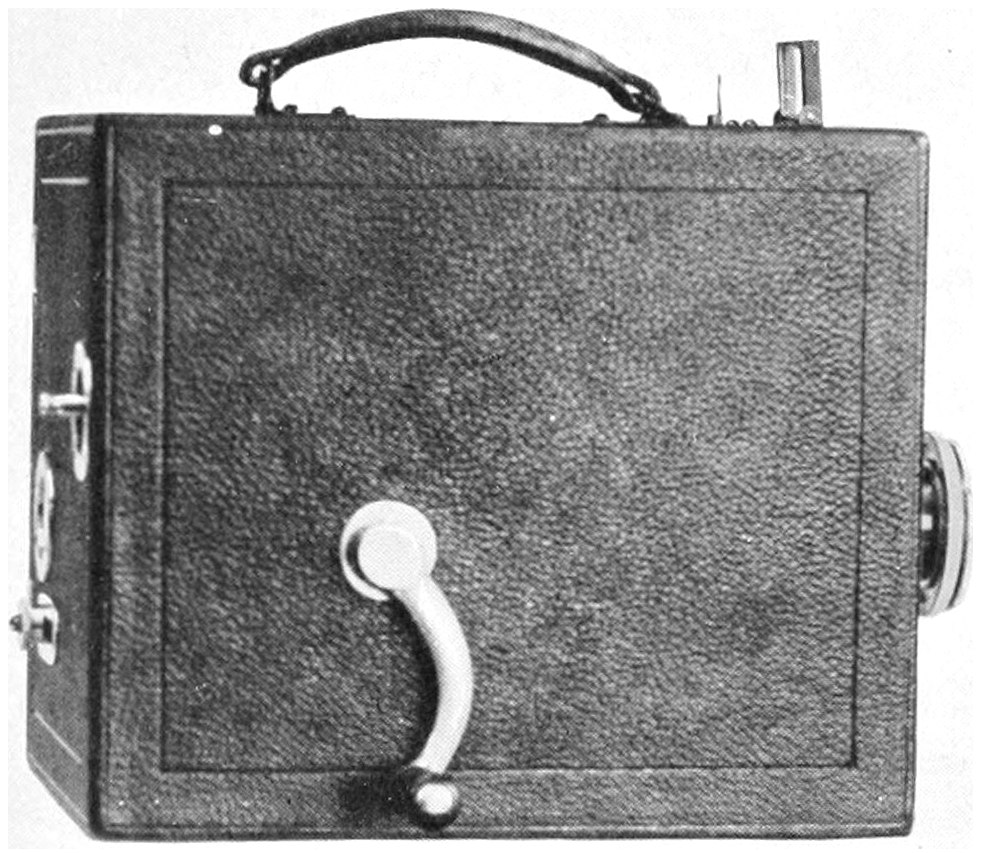

| The Kinora Camera | 302 |

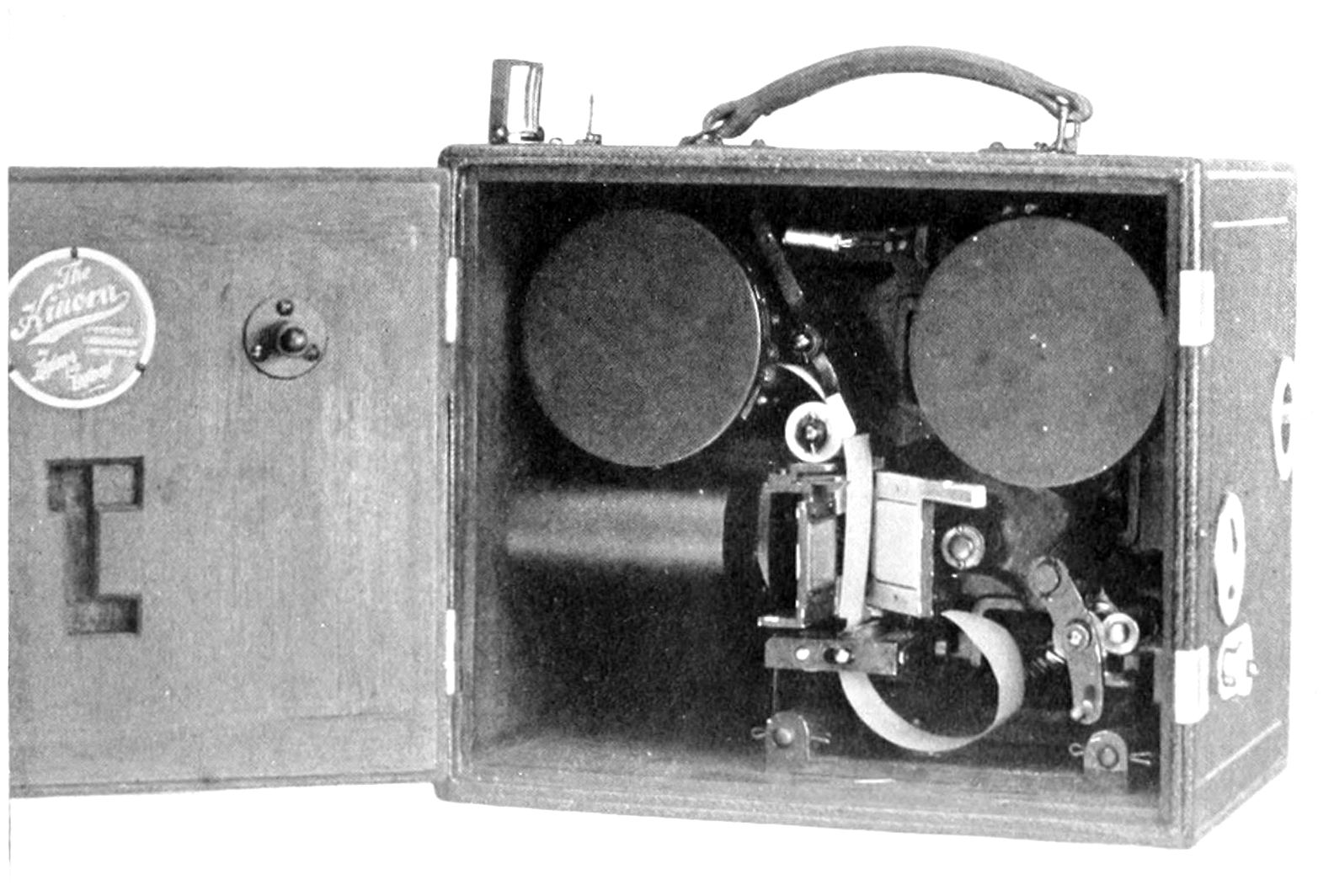

| The Mechanism of the Kinora Camera showing Paper Negative Film in position | 302 |

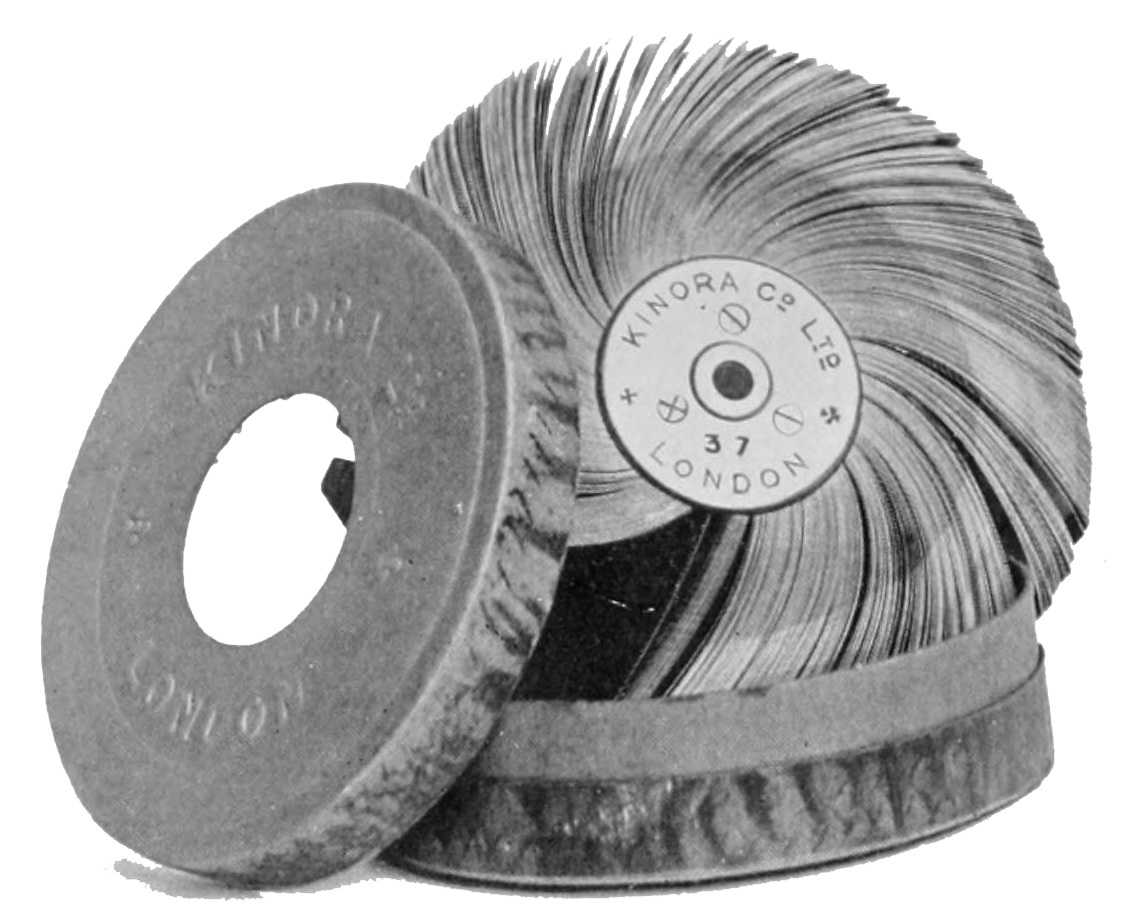

| The Reel of Positive Prints | 303 |

| The Kinora Reproduction Instrument | 303 |

| The Bettini Glass Plate Cinematograph | 308 |

| A Section of a Bettini Glass Plate Record | 308 |

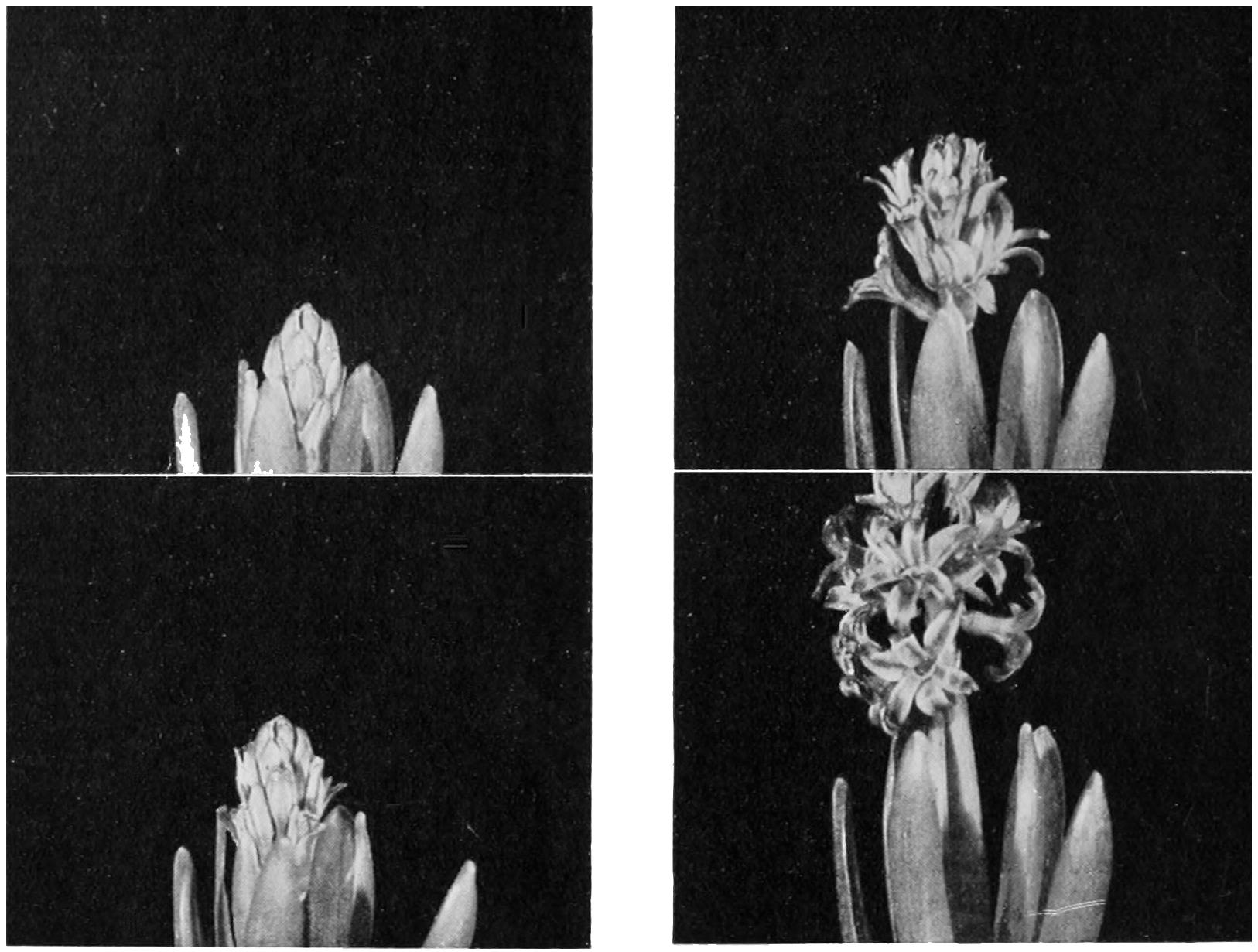

| The Birth of a Flower | 309 |

| Waging a Health Campaign by Moving Pictures | 309 |

| Cinematographing Africa from a Locomotive | 314 |

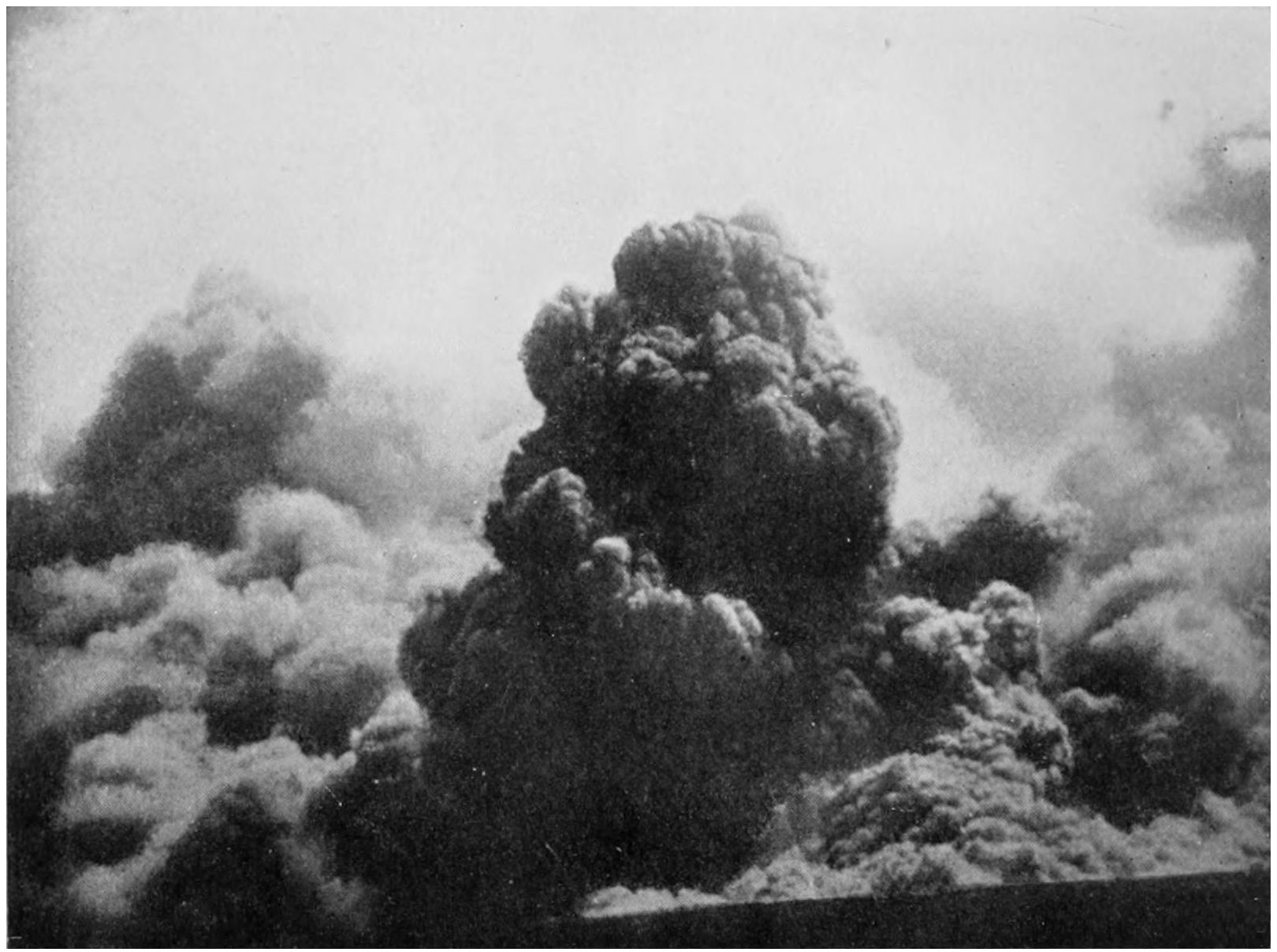

| Mount Etna in Eruption: Looking into the Crater of the Volcano | 315xv |

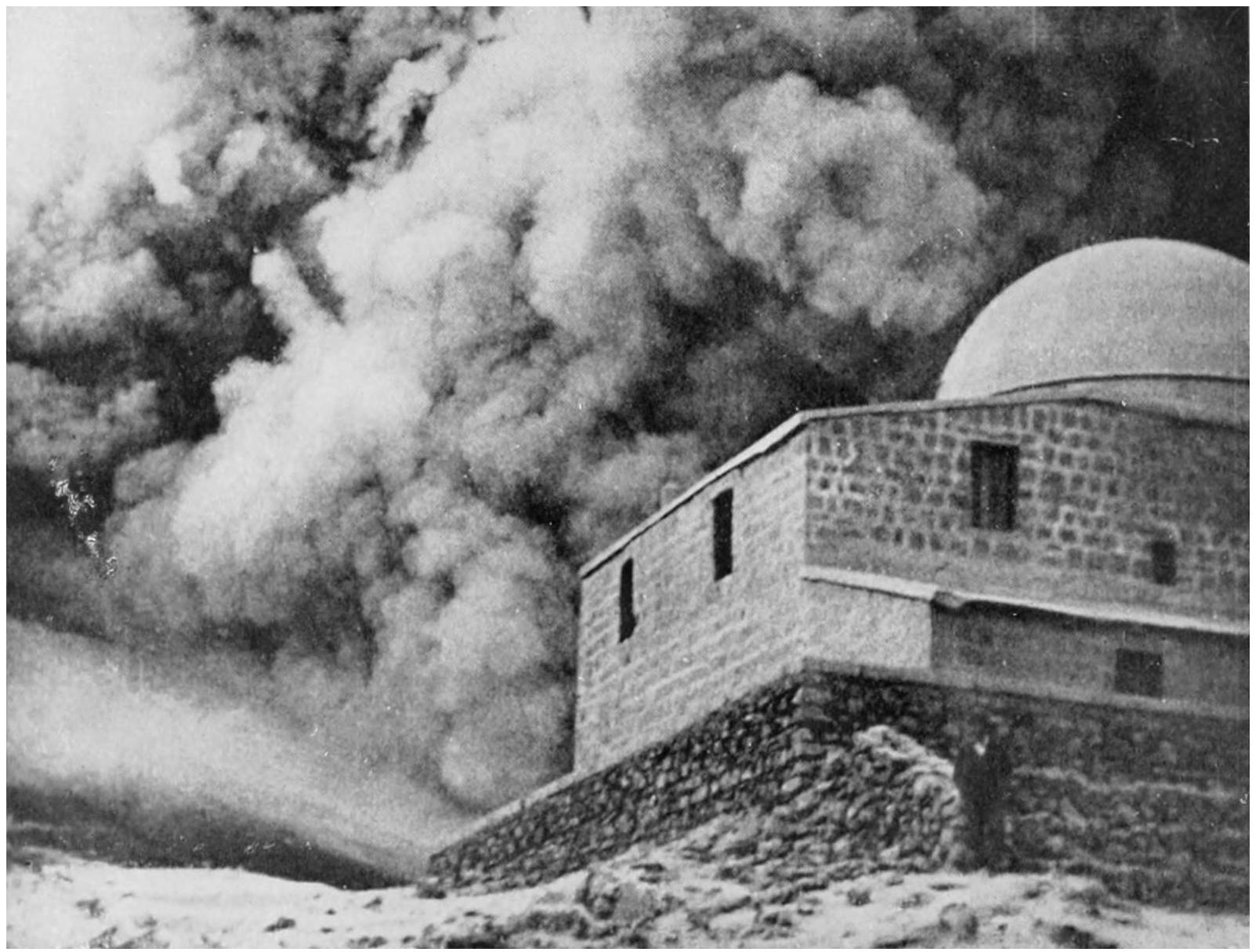

| The Plumes of Smoke as seen from the Observatory | 315 |

| The “Cradle of Cinematography”: The Marey Institute in Paris | 322 |

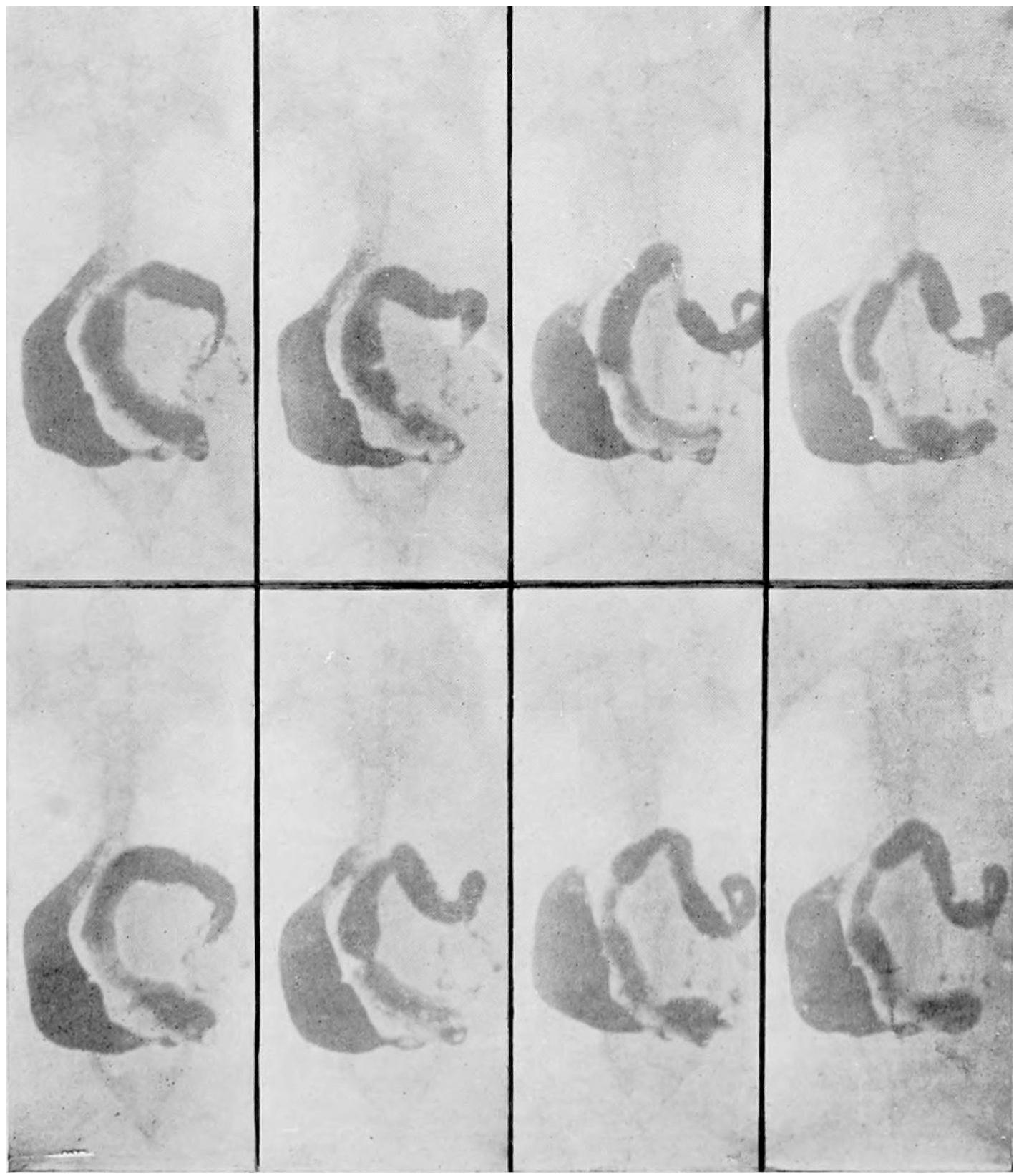

| The latest marvel in Moving Pictures: Combining the X-rays with the Cinematograph | 322 |

| After Fifty Years. This Film won the First Prize of 25,000 Francs at the recent Turin Exhibition | 323 |

1

From the day when it was found possible (by the aid of sunlight) to fix a permanent image of an object upon a sensitised surface, inventors steadily applied their ingenuity to the problem of instantaneous photography. In other words, they strove to realise the possibility of photographing an object in motion.

In our days the idea of “snap-shot” photography is such a commonplace that we can no longer realise the proportions of the task which confronted the early inventors. Probably most of us are unacquainted with the conditions under which the first photographs were taken. The writer has often heard a member of his family relate the amusing story of an ordeal which, as a lad, the latter underwent at the hands of the Frenchman, Daguerre. He was seized upon by the inventor as an experimental subject and was forced to sit in the brilliant sunlight for a long time. It seems incredible, but it is true, that when photography was in its infancy, an exposure of six hours was required to secure a recognisable impression of an object—a circumstance which left practically nothing but still life as feasible subjects for photography.

The problem which confronted the pioneers of instantaneous photography was the reduction of the period of exposure from about 20,000 seconds to a mere fraction of a second. Considering the magnitude of this difficulty, it is not surprising that the average person was sceptical as to its solution. The possibility of fixing a horse in the act of jumping, a bird in the act of flying, or an2 orator’s lips at the moment of uttering a word, must have seemed nearly as remote as the discovery of the Philosopher’s Stone. It is interesting to imagine the sensations of the sceptic of one hundred years ago, to whom instantaneous photography appeared a chimerical idea, should he be recalled to life to-day and be shown first a procession passing down the street, and a few hours afterward the same procession repeating itself before his eyes upon a screen in a darkened room, with all the semblance of reality in colour and animation.

In the end, it was the chemist who solved the problem of instantaneous photography, without which animated photography as we know it to-day would never have been even conceivable. He carried out innumerable laboratory experiments for the purpose of rendering the sensitised surface more and more susceptible to light—accelerating its actinic speed, as it is called—until at last he revolutionised photography, as he has changed nearly every other field of our modern industrial life. He succeeded in preparing a surface, or emulsion, so sensitive to light that it can take a picture clear, distinct, and full of detail, not merely in the space of one second, but in less than a thousandth part of a second—a picture equal, if not superior, to those which in the early days of photography required an exposure 20,000,000 times as long!

The wonderful achievement of instantaneous photography assumed at first a scientific rather than a commercial value. Many a “snap-shot” is taken which does not betray whether the plate has been exposed for six hours or only one-thousandth of a second; but, on the other hand, a “snap-shot” of a quickly moving subject may seize upon and fix an interesting or characteristic motion. It was this fact which led certain ingenious minds to perceive in instantaneous photography a valuable means of analysing motion. If a single photograph reproduced the exact posture of a moving subject at any given instant of time, they argued that a series of such photographs, if taken in sufficiently rapid succession, would form a complete record of the whole cycle of movements involved,3 for instance, in the jump of a horse or the flap of a bird’s wing.

Here, again, the inventor encountered a difficulty almost as great as the initial one of instantaneous photography. Not only had the chemist to devise a new sort of sensitised plate with a gelatine coating better and more convenient to handle than the medium before employed, but the mechanical engineer, the optical instrument maker, and the lens maker had to co-operate on a special sort of camera which should minimise the interval between successive exposures.

As earlier inventors had reduced the duration of the period of exposure, modern ones have succeeded in their turn in reducing the interval between exposures to a minute fraction of a second. When this result was achieved animated photography became a reality.

It was possible to secure a long series of consecutive snap-shots, or instantaneous pictures depicting motion, recorded at such brief intervals that when they were passed swiftly before the eyes they produced the illusion of movement.

At this point it is best to consider the physiological basis upon which animated photography rests. The word illusion, as used above, correctly describes what takes place. The eye sees a swift succession of instantaneous photographs; but it is deluded into believing that it sees actual movement.

We have all marvelled at the magician who causes bottles, eggs, birds, and animals to appear and disappear mysteriously before our very eyes. We know that it is trickery, pure and simple: that the eye is being deceived. The camera is a far more perfect trickster than the most accomplished illusionist that has ever lived, and moving pictures are the most cunning illusion that has ever been devised.

In order to convey this delusion, the photographer has taken advantage of one deficiency of the human eye. This wonderful organ of ours has a defect which is known as “visual persistence.” Briefly defined, this means that4 the brain persists in seeing an object after it is no longer visible to the eye. I will make this clear by further explanation.

The eye is in itself a wonderful camera. The imprint of an object is received upon a nervous membrane which is called the retina. This is connected with the brain, where the actual conception of the impression is formed, by the optic nerve. The picture therefore is photographed in the eye and transmitted from that point to the brain. Now a certain period of time must elapse in the conveyance of this picture from the retina along the optic nerve to the brain, in the same manner that an electric current flowing through a wire, or water passing through a pipe, must take a certain amount of time to travel from one point to another, although the movement may be so rapid that the time occupied on the journey is reduced to an infinitesimal point and might be considered instantaneous. When the picture reaches the brain a further length of time is required to bring about its construction, for the brain is something like the photographic plate, and the picture requires developing. In this respect the brain is somewhat sluggish, for when it has formulated the picture imprinted on the eye, it will retain that picture even after the reality has disappeared from sight.

This peculiarity can be tested very easily. Suppose the eye is focussed upon a white screen. A picture suddenly appears. The image is reflected upon the retina of the eye, and transmitted thence to the brain along the optic nerve. Before the impression reaches the brain the picture has vanished from the sight of the eye. Yet the image still lingers in the brain; the latter persists in seeing what is no longer apparent to the eye, just as plainly and as distinctly as if it were in full view. When the image does disappear, it fades away gradually from the brain.

True, the duration of this continued impression in the brain is very brief. In the average person it approximates about 2/48ths of a second, which appears so short as not to be worth consideration. Still, in a fraction of time a good deal may happen, and in the case of animated5 photography it suffices to bring a second picture before the eye ere the impression of the preceding image has faded from the brain. The result is that the second picture becomes superimposed in the brain upon the preceding image; and being stronger and more brilliant, it causes the disappearing impression to merge or dissolve into itself.

Indeed, one might go farther, and say that the brain acts in the same manner as a dissolving lantern. This apparatus is very familiar to us all, and in its most approved type one view is dissolved into another. For the purpose two lanterns are required, placed either side by side or one above the other, and both focussed upon the screen. For the purpose of illustrating our complex point we will consider that they are one above the other. A slide is projected brilliantly from the uppermost lantern. Presently the moment arrives to change the slide. If the operator withdrew it from the upper lantern and inserted another there would be a defined break or blank interval upon the screen betraying the change. So he inserts the new slide in the lower lantern, at the same time increasing the volume of light emitted from that lantern, and diminishing the volume thrown from the upper lantern. The result is that the picture projected from the upper lantern becomes fainter and fainter, while that shown by the lower lantern becomes stronger and stronger, until only the latter is seen upon the screen—the former has merged or dissolved into the latter.

The same action takes place in the brain in connection with cinematography. A picture is thrown upon the screen, and remains visible for 1/32nd part of a second. It is then eclipsed by the shutter, and—supposing that the photographs are taken at the rate of sixteen pictures per second—for the next 1/32nd part of a second the screen is darkened owing to the passage of the shutter. This division of time is not strictly correct, as we shall see later, but for present purposes I have considered the intervals of exposure and eclipse to be of equal duration.

Now as a picture will linger in the brain for 2/48ths of6 a second after it has vanished from the sight of the eye, the brain retains the impression during 1/32nd part of a second, while the shutter is passing across the lens. The second picture now comes before the eye, and although the previous picture still will remain in the brain for another 1/96th part of a second—the difference between 1/32nd and 2/48ths—the new picture, being the more brilliant, becomes superimposed upon that already obtained, and consequently causes the former dying image to merge into the later and brighter impression. This successive dissolution of one picture into the other continues until the whole string of snap-shots is exhausted. It will be noticed that every picture remains on the screen for 1/32nd of a second, followed by a period of darkness of nearly equal duration, the pictures thus being projected at the rate of sixteen per second.

The illusion of movement is enhanced by the fact that all fixed and stationary objects retain their relative positions in each succeeding image. Suppose, for instance, that a series of pictures, depicting a man walking along a street, are being shown upon a screen. In the first picture the man is shown with his left foot in the air. This remains in sight for 1/32nd of a second, and then disappears suddenly. Though the picture has vanished from the eye, the brain still persists in seeing the left foot slightly raised. One thirty-second part of a second later the next picture shows the man with his left foot on the ground. The shops, houses, and other stationary objects in the second image occupy the positions shown in the first picture, and consequently the dying impression of these objects is revived, while the brain receives the impression that the man has changed the position of his foot in relation to the stationary objects, and the left foot which was raised melts into the left foot upon the ground. The eye imagines that it sees the left foot descend. Another 1/32nd part of a second passes, and the right foot is seen elevated, but the fixed objects retain their positions still, and so on. The brain only notices the difference in the position of the moving objects, and thus secures an illusory idea that7 movement is taking place. I have taken a very simple example to illustrate the idea. As a matter of fact, moving pictures of men walking are seldom perfectly successful, generally having a jerky movement.

Thus we have seen what we describe as animated photography is not animation at all. All that happens is that a long string of snap-shot photographs, taken at intervals of 1/24th or 1/32nd part of a second, are passed at rapid speed before the eye. If the pictures are projected at the rate of one per second they resemble ordinary magic lantern projections. As the operator slowly and gradually increases the speed, the figures shown in the pictures assume a spasmodic motion, as if their limbs were moved jerkily by means of strings; this action becoming less and less pronounced as the speed is accelerated, until, at last, when the operator gains the requisite rate of projection, the jerky movement becomes resolved into steady rhythmic action.

In the early days it was difficult to convey the impression that motion was being shown, because the movement of the shutter cutting off the picture was so emphasised as to convey a distinct sense of blankness between the successive images. This regular intermittent occurrence of invisibility, described as “flicker,” caused tremendous strain to the eyes, and provoked nauseating headache. When the flicker was eliminated the strain ceased; the illusion was rendered more perfect as well.

In order to satisfy one’s self that the semblance of animation is an illusion, one has only to compare the projection of a moving object upon the screen, and its appearance in the camera obscura. In the latter case absolute continuous motion is shown. It may be said that complete animation by photography is quite out of the question with the single camera and projector. How it can be avoided and a more perfect camera obscura effect produced upon the screen is described later. Mechanical ingenuity has not succeeded yet in achieving such a result by means of a single lens.

As a matter of fact, only one-half or less of the movement8 that actually takes place is recorded upon the film. What is lost occurs during the period the shutter is closed after exposure, in order to permit a fresh area of sensitised surface to be brought into position behind the lens. However, the lapses are equal in point of time; and when sixteen pictures are taken per second, the interruption in the movement is not detected by the brain.

It may be asked why the operator confines himself to photographing at a speed of about sixteen pictures per second. This question is governed for the most part by economical motives. Film is expensive, and therefore the obvious point is to consume the minimum of material to secure the illusion. When Edison produced the kinetoscope, at least thirty pictures per second were necessary to bring about the illusion, but Messrs. Lumière and Paul, by means of their apparatuses, which were the first commercial cinematographs, reduced the number to sixteen pictures per second. If twenty-four photographs were taken and projected per second the result would be practically no better than when only sixteen pictures were made in the same period, so that the additional eight pictures and their requisite length of film represent so much wasted effort and material.

This law in regard to visual persistence concerning the number of pictures per second holds good only so long as pictures are taken and projected in monochrome or black and white. When animation in colour is introduced, the illusory effect produced upon the brain becomes disturbed, as is explained in the chapter dealing with this latter development of the art.

An interesting illustration of the fact that the eye is deceived may be narrated. A film of a train passing through a tunnel was required. Two trains were secured for the purpose, and at the rear of the leading train the camera was mounted in order to photograph the one following, care being observed to keep them an equal distance apart. In the darkness of the tunnel the question of illumination for the purposes of the exposures was somewhat perplexing. Various expedients were attempted, but9 all to no avail, and it appeared as if the task would have to be abandoned.

One of the party thereupon suggested a novel solution of the difficulty. A section of the track was marked off, and subdivided into short sections. The train was brought to the first mark and there stopped, when a flashlight photograph was made. It was then advanced to the next mark, and another flashlight instantaneous picture was secured. This process was repeated several times, the train being moved forward about eighteen inches between each exposure. About fifty exposures were made in this manner, and the length of exposed film thus obtained was multiplied to form a continuous picture of great length. When projected on the screen several hundred photographs were passed before the audience at the speed of sixteen pictures per second, and the semblance of motion was perfect, the train having the appearance of travelling through the tunnel at express speed.

This is one of the most interesting examples known to me of illusion by animated photography, and although it was not motion at all that was recorded, still it sufficed to convey the impression of movement to the public. In the course of the following chapters, however, various successful illusions caused by this means are described, especially in regard to “trick pictures.”

10

The idea of producing apparent animation by means of pictures is by no means new. The origin of the most primitive form of moving picture device is lost in the mists of antiquity; but it is certain that long before photography was conceived animated pictures were in vogue, and constituted a source of infinite amusement among children. The illusion was secured by a simple device known as the Zoetrope or the “Wheel of Life.” It consists of a small cylinder, mounted on a vertical spindle in such a way that it is free to revolve horizontally. A band of thin cardboard, or thick paper, on which is painted a series of pictures, generally in colour, depicting successive stages in a particular movement, such as a horse jumping, a child swinging, or two youngsters playing see-saw, is placed horizontally around the inside of the lower half of the cylinder. The upper half is pierced at regular intervals by long narrow slits or vertical openings, which come opposite the pictures and extend only about half-way down the length of the wall. When the cylinder is rotated sharply and one looks through the slits, the pictures portray apparent motion—the horse rises and falls in the jump, the swing moves to and fro, and the see-saw goes up and down—in accordance with the laws of visual persistence.

Each successive picture, it must be pointed out, is interrupted by the space in the surface of the wall between two consecutive slits through which one peeps into the cylinder. We have, in fact, a cinematograph in the most primitive11 form; the space between the apertures corresponding to the opaque sector of the shutter of the camera and the projector, whereby one picture is eclipsed from view on the screen to permit the next to be brought before the lens. Indeed, one can easily convert the zoetrope into a cinematograph if, instead of painted pictures, prints of a cinematograph film are mounted in the same way. As a matter of fact, some ingenious person followed this practice years ago, thus unconsciously producing the first animated pictures by photography, and in a crude way anticipating the kinetoscope.

From time to time the zoetrope was modified and revived in the praxinoscope, phenakistoscope, zoopraxinoscope, and a number of other forms with awe-inspiring names. In every instance, however, it was merely our old friend in a new guise. One of these modifications created a flutter of excitement in France in 1877. It was called the “praxinoscope,” and its creator, M. Reynaud, for the first time enabled a large audience to see animation upon the screen.

In this case projection was carried out in a highly novel manner. The front, or proscenium opening, of the stage was occupied by a large white screen, such as is used for magic lantern projection, the operator and his apparatus being on the stage behind, out of sight. Accordingly the audience saw the picture through the sheet. At the back of the stage a limelight lantern was set up, from which a still life picture was thrown, filling the greater part of the surface of the screen. The picture thus shown formed as it were the setting for the animated picture, in just the same way as the scenery comprises the environment for a stage play.

Below the level of the stage was a large rectangular table, at each corner of which were placed small vertical rollers. At one end of the table were two large spools, fitted with handles which were revolved horizontally. One spool carried a long band of transparent material, on which were painted at regular intervals silhouette figures in colour in successive stages of movement. The band led from this12 spool round the vertical roller immediately adjacent, then along the side of the table to the next corner, on to the next corner, on to the third corner, back to the fourth corner, and then to the empty reel, on which it was wound. By simultaneously rotating the loaded spool with the left hand, and the second reel with the right hand, the transparent picture band was passed round the table from one spool to the other.

Centrally with the sheet, and on a level with the table, there was a second limelight lantern, the back of which was towards the audience. This lantern threw its rays upward at an angle of forty-five degrees or so. As the band of pictures travelled along the table edge from the first to the second corner roller, it was passed through this second lantern, which projected the silhouette picture into a mirror hung overhead at the back of the stage, which in turn reflected the image on the screen. The figures on the band thrown from the second lantern appeared in the scene of the slide shown by the first lantern. As the band was moved forward, bringing successive phases of action upon the screen, apparent motion was produced. In fact, animated pictures were shown, and it was possible with a number of spools of painted bands to produce a comedy, tragedy, or other stage play in pictures. This crude apparatus was the first attempt to portray moving pictures upon a sheet before a large audience.

As instantaneous photography developed and efforts were made to adapt photographic records instead of painted pictures to the praxinoscope, great difficulty was experienced in securing the consecutive pictures sufficiently close to one another so as to reduce the loss of action between two successive pictures to the minimum. The cameras available were not suited to this work. Too much time was lost in removing the exposed sensitised surface to permit another unexposed area to be brought before the lens.

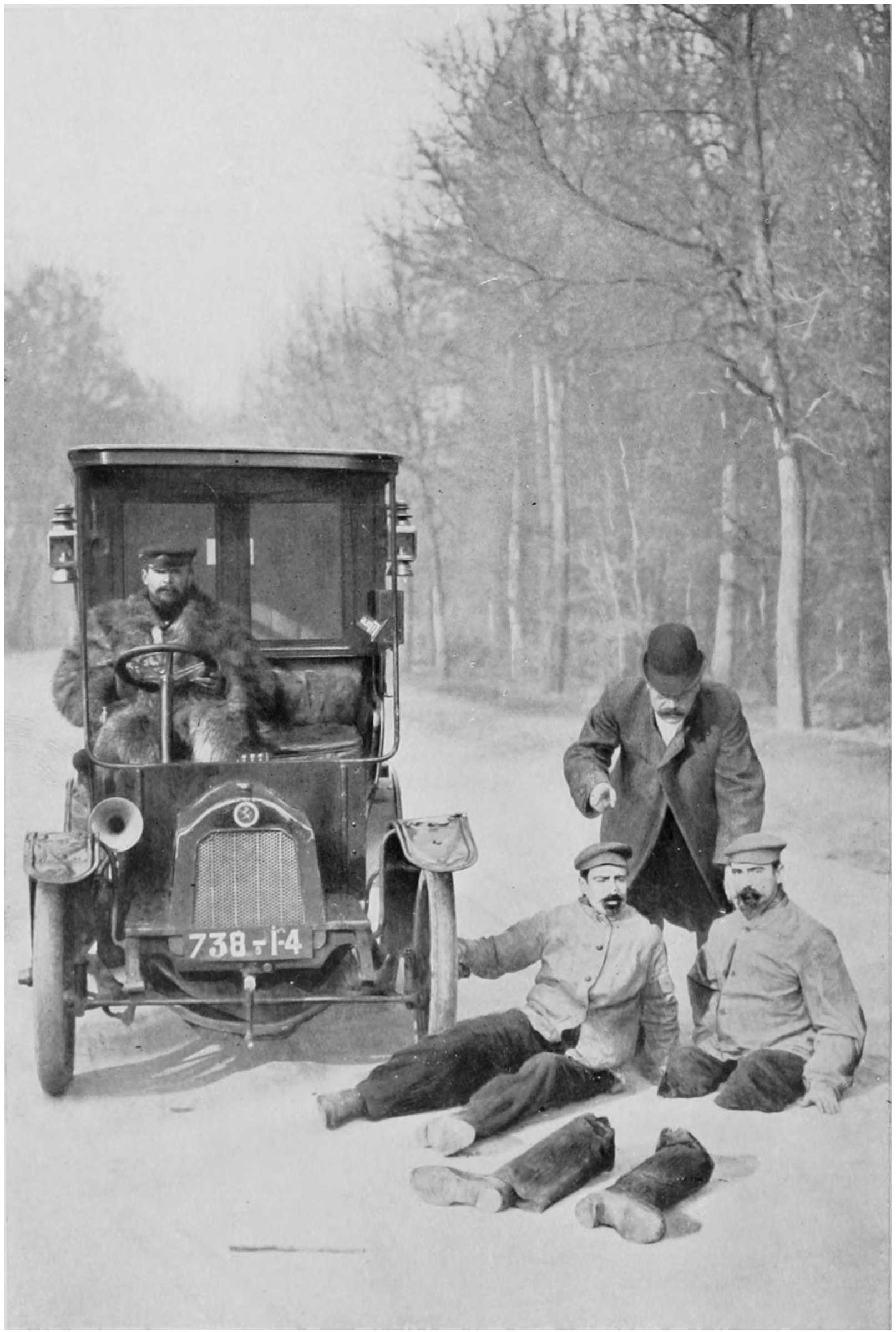

About 1872 Mr. Muybridge, an ingenious Englishman, resident in San Francisco, conceived a novel means of obtaining snap-shot photographs in rapid succession. He maintained that such photographs taken at regular13 intervals, reproduced in such a manner as to simulate natural animation, would reveal the peculiar attitudes of animals in motion and would prove of invaluable service to artists. He approached Governor Stanford and unfolded his scheme. Stanford was so impressed that he placed every facility at Muybridge’s disposal for the completion of the experiment, including the use of his valuable stud of horses and exercising track.

As it was impossible to secure the desired end with a single camera, Muybridge built a studio beside the track, in which twenty-four cameras were placed side by side in a row. On the opposite side of the track, facing the studio, he erected a high fence, painted white, while across the track between the studio and the screen twenty-four threads were stretched, each of which was connected with a powerful spring, which held in position the shutter of a camera.

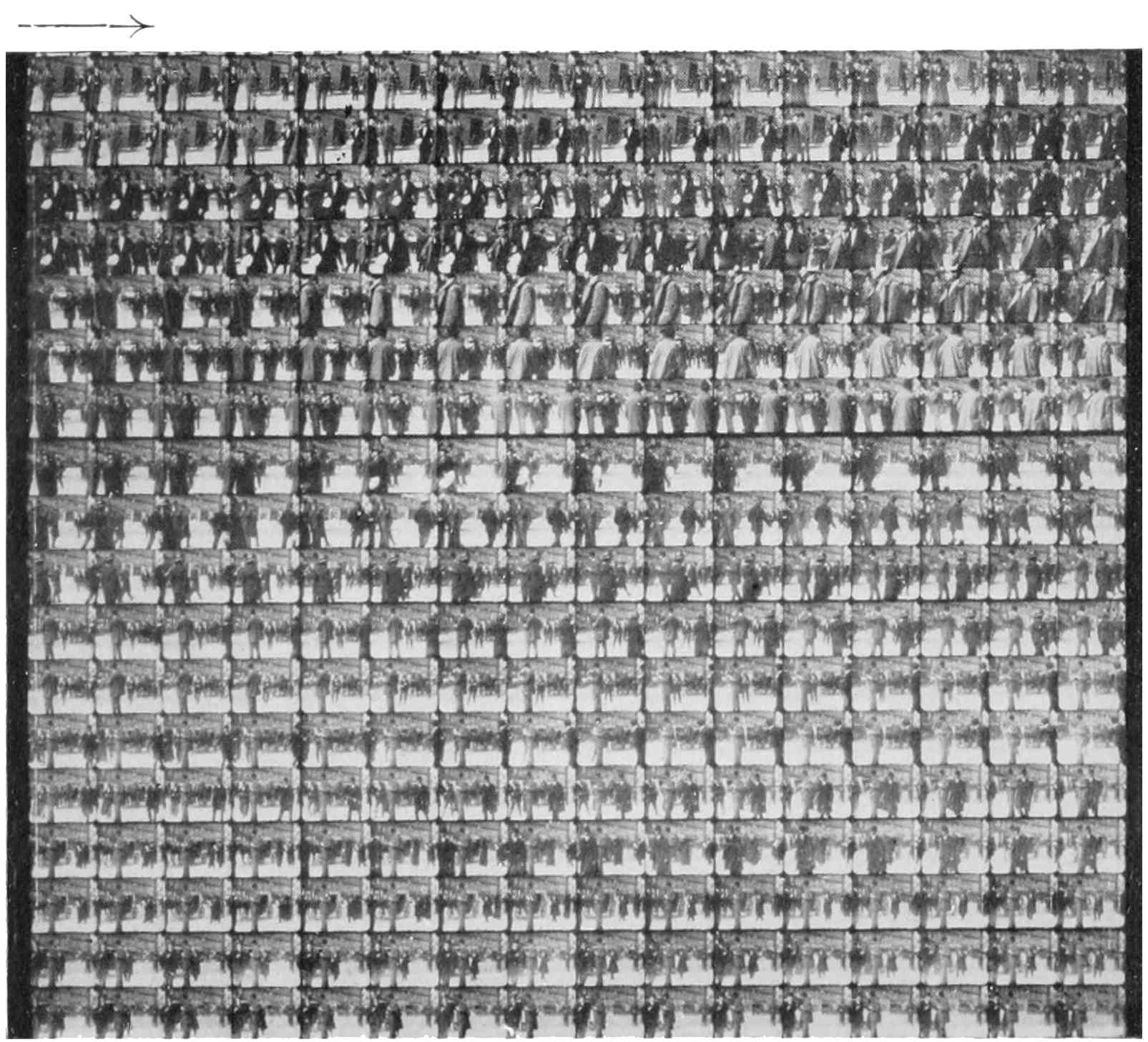

When all was ready, a horse was driven over this length of track at a canter, gallop, trot, or walk, as desired, and as the animal passed each camera, it broke the thread controlling its shutter, so that the horse photographed itself in its progress. In these experiments, however, Muybridge made no effort to secure detail. The photographs were taken in brilliant sunlight, and the white screen threw a dazzling reflection, causing the objects to stand out in bold relief, so that the record appeared in silhouette. As these photographs were taken for a specific purpose—the analysis of movement—the screen was subdivided into panels, whereby it was possible to determine the distance between each successive picture. (Fig. 1.)

[By Permission of “The Scientific American.”

Fig. 1.—The First Moving Pictures.

Twelve successive photographs, by Mr. Muybridge, of a horse in full gallop. In the last figure the horse is seen standing still. The speed of the horse was about 1,142 metres (3,746 feet) per minute.

As Muybridge’s experiments were carried out upon a somewhat private basis, the information about them that reached Europe was of a very meagre description. In France, however, they aroused a strong curiosity and peculiar interest, especially in artistic and scientific circles. They appealed especially to one man—Meissonier. The great artist, whose accuracy in the most minute detail was proverbial, was fascinated. He had observed very closely the curious attitudes that horses assume when in rapid motion, and had committed the observations to his canvases,15 only to meet with strenuous hostile criticism from his colleagues and the public. So when Governor Stanford, while visiting Paris, displayed some of Muybridge’s photographs, the great painter spent hours in studying them, and characterised them as an incalculable aid to art. Through Governor Stanford, he extended an invitation to Muybridge.

In the following year the Anglo-American experimenter—who might be described as the father of animated photography—visited the French capital, and received a warm greeting by Meissonier. The artist had been criticised for his views concerning muscular action, as displayed by the animals on his canvases, yet here was a man who could demonstrate, by the conclusive evidence of photography, that his views were correct. Meissonier arranged a private demonstration, which ranked as one of the most important social events of the year in Paris. Among those who accepted the invitation to witness the new wonder were Gerome, Goupil, Steinheil, Detaillé, Alexander Dumas, and Dr. Mallez. Muybridge had brought a representative collection of photographs with him, showing horses in movement, dogs, deer, and other animals running and jumping, as well as men wrestling, leaping, and performing other athletic exercises.

The pictures were examined at great length individually. Then by means of the zoopraxoscope, a form of the wheel of life, whereby pictures in action could be thrown upon the screen, they were displayed in animation, thereby conclusively demonstrating the fact that what appeared so incredibly singular an attitude in a painting or an individual photograph was in reality part of a graceful harmonious natural movement.

There was one feature of Muybridge’s work which must not be overlooked, and which decidedly restricted its application. A battery of cameras had to be employed, placed side by side. It was as if a number of photographers, standing in a row, pressed a button the instant the object in motion was opposite their respective cameras. All the photographs were broadside views, and16 taken from the same relative position. The results were not as the following eye of one person saw them, but as the eyes of twenty or thirty persons standing side by side grasped a glimpse of motion during the five-thousandth part of a second. If Muybridge had attempted to take 900 photographic impressions, such as the cinematograph camera records in the space of a minute to-day, he would have required nine hundred cameras for the purpose.

Of course, such a plan had no commercial possibilities. Its real value lay in the fact that it stimulated the ingenuity of a host of inventive brains towards the solution of animated photography. One and all were bent upon securing the same result that Muybridge had achieved, but with a single camera and from one point of view. Among these experimenters the names of Greene and Evans, Acres and Paul stand pre-eminent in Great Britain, while France and the United States had an equal number of contemporaneous investigators engaged upon the problem. Even Muybridge himself attempted its solution, for he realised only too well that a battery of cameras was impracticable to ensure the commercial success of animated photography.

It appears to be a sorry trick of fortune that every great invention, or development, should produce a bevy of claimants for the honour of being the “original inventor.” The word “original” is somewhat obscure and ambiguous, but it is employed frequently. As a matter of fact, it is a wise invention that can single out its creator. Animated photography has been no exception to the rule. Lawyers and the courts have reaped a rich harvest from protracted litigation in the effort to settle the question once and for all, with the inevitable result—the law has left the matter in a more hazy condition than ever.

The claim to the discovery of animated photography can scarcely be sustained by any one man. Desvignes devised an apparatus in 1860; Du Mont formulated the first tangible scheme of chronophotography, as it is called, in 1861, which Donisthorpe put into practice in 1876, while a host of other experimenters contributed to the problem in some particular detail. It was not invention, for the simple reason that there was nothing to invent; it was merely evolution and the perfection of details. As we have seen, what the experimenters had to accomplish was the reduction of the length of time occupied in bringing one sensitised surface before the lens after the preceding sensitised surface had been exposed. This was a matter of mechanical detail, for the chemist accelerated the speed of the sensitised surface more and more, and finally evolved the celluloid film. Various means of bringing successive sections of a sensitised surface before the lens were evolved, and produced a plethora of patents; but the perfection of details does not affect the fundamental principle of animated photography. In Great Britain many investigators were energetic in the quest, but the great majority never succeeded beyond the model stage; that is to say, their apparatuses never possessed any practical value, and only served to emphasise once more the truth of the well-worn axiom that there is a great gulf between the creative mind of the inventor and the commercial world with its enormous capacity for development and exploitation.

Among the early British experimenters was W. F. Greene, who, like others, was handicapped by having to make use of glass plates. In 1885 he displayed his first apparatus for taking and producing moving pictures, and two years later exhibited some pictures taken on glass in the window of his premises in Piccadilly. This unusual display created such interest, and the curiosity-provoked public so crowded the pavement that traffic was impeded, and the police called upon Greene to remove his pictures.

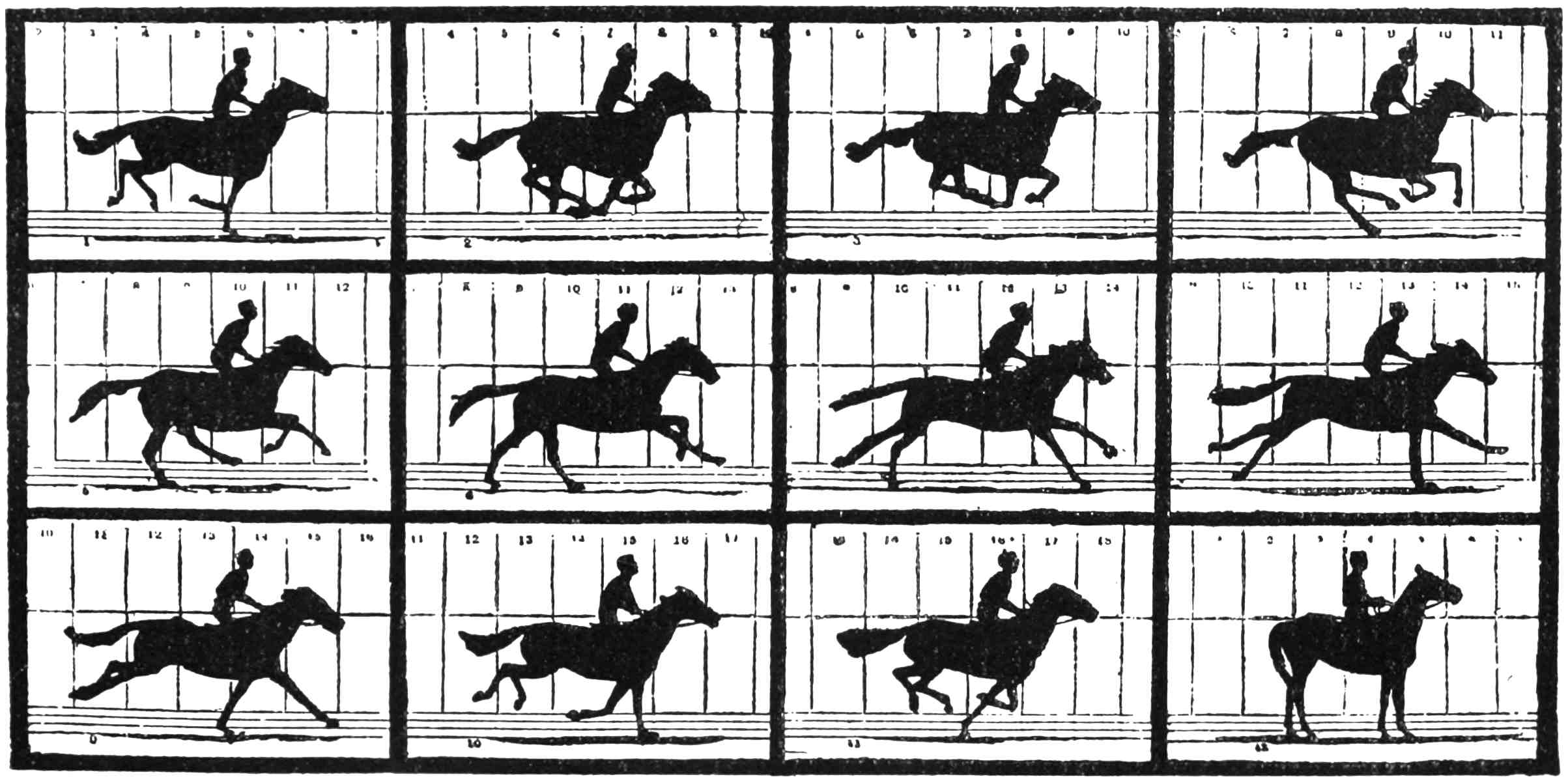

In France even greater things were being accomplished. Dr. E. J. Marey took up Muybridge’s work at the point where the Anglo-American abandoned it. Marey followed rather the lines laid down by the astronomical investigator Jansen, who in 1874 evolved a photographic revolver to secure records at short intervals of the transit of Venus across the sun’s disc. Marey constructed a photographic gun in 1882, with which he studied the flight of birds, and which worked on the principle elaborated by Jansen eight years before. The object of his quest was the analysis of18 motion. It will be seen, therefore, that in its very earliest stages the value of animated photography was conceded to be rather in the field of science than that of amusement. This celebrated French experimenter realised the inestimable value of “chronophotography” for the study and investigation of moving bodies, the rapidity in the changes of the position or form of which was impossible to follow otherwise. Marey, however, made no effort towards synthesis or reproduction of the motion thus obtained; he did not seek projection upon a huge scale upon the screen, but regarded chronophotography rather as a means of enabling photographic results to be resolved into diagrams for examining and elucidating obscure points incidental to motion.

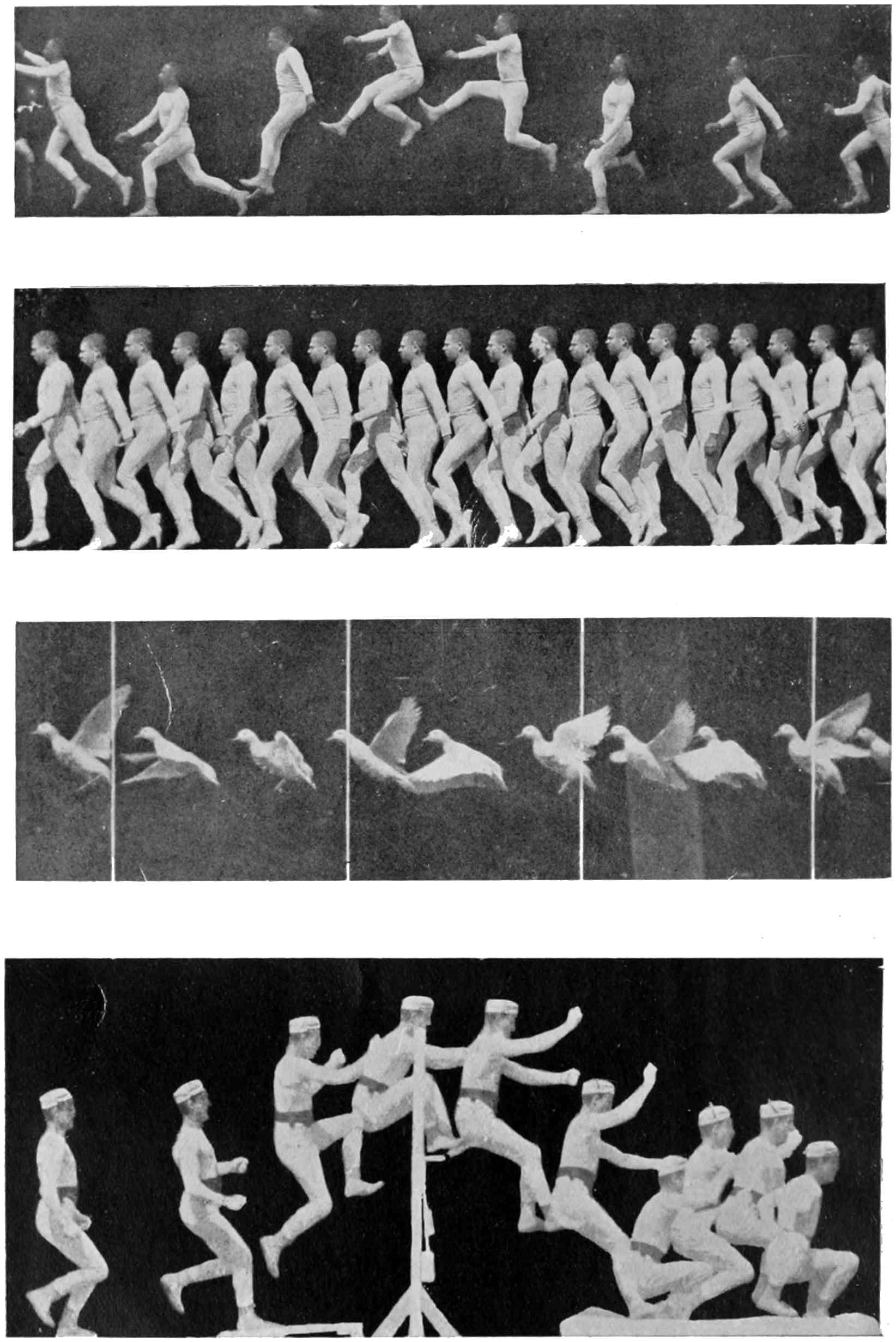

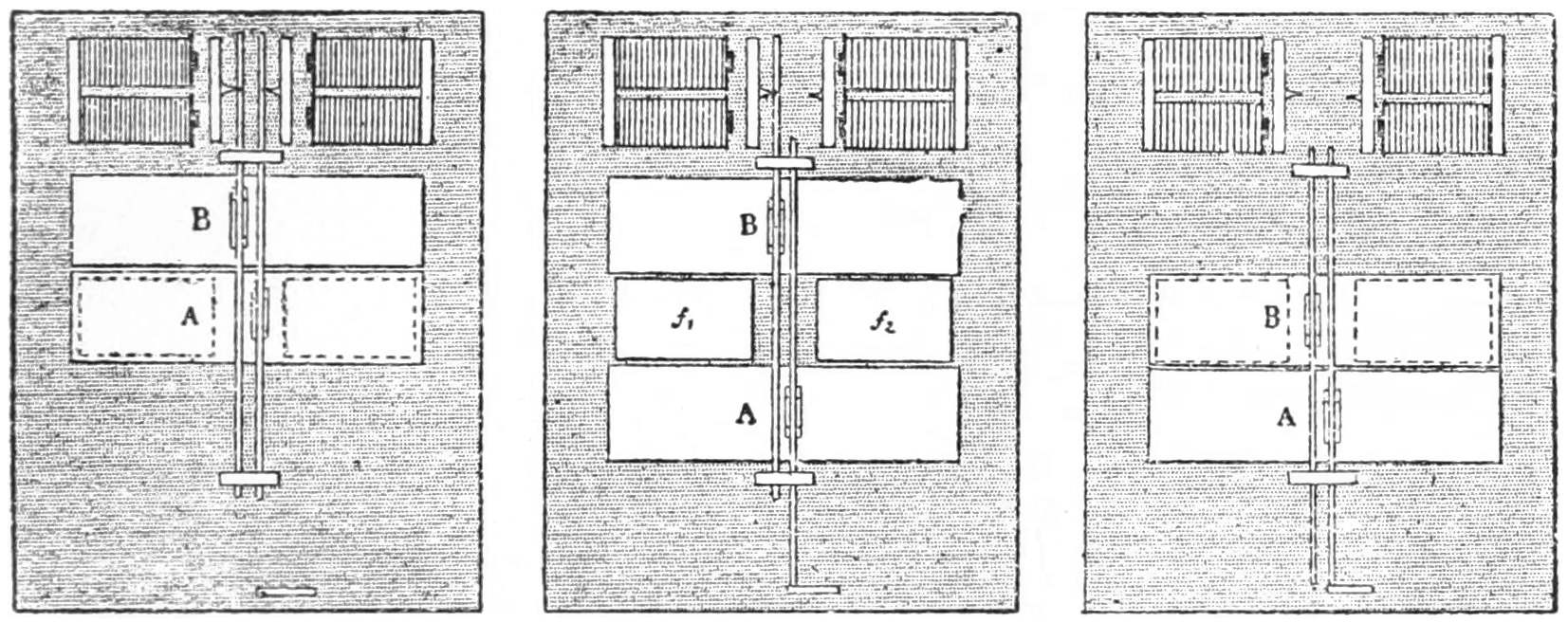

DR. E. J. MAREY’s FAMOUS EXPERIMENTS IN CINEMATOGRAPHY.

1. Photographic gun of 1882, to photograph birds in flight. 2. Consecutive pictures of a gull flying, taken with the photographic gun. 3. Chronophotographic apparatus for taking consecutive pictures upon a single glass plate, showing mechanism.

DR. MAREY’S ANIMATED PICTURES MADE IN 1884–86 FOR THE ANALYSIS OF MOTION.

1. A man jumping. 2. A man walking. 3. A duck flying. 4. A man leaping.

The objects, clothed in white, passed before a black screen, and the exposures averaged about 1/200 of a second.

Special apparatus was evolved and was set up at the Physiological Station in Paris, and some wonderful results were communicated by this industrious scientist to the French Association for the Advancement of Science at Nancy in 1886. Investigations were being carried out upon a large and advanced scale in France while the English were merely dabbling with the idea. Marey secured records of action intermittently from a single point of view by the revolution of a handle, and to a pronounced degree anticipated the present-day cinematograph.

Marey’s camera was successful in its details, especially considering the extreme difficulties attending the use of glass plates. He ascertained that in order to secure continuous motion it was imperative to cut off the light from the plate at regular intervals; and he accomplished this interruption by rotating an opaque disc, pierced with small radial slots, which permitted the light to reach the plate only intermittently. The general design of Marey’s camera is shown in Fig. 2. The camera, of the ordinary bellows type, was mounted in the upper part of a wooden frame clamped to a special support. Beneath was the handle, which rotated the shutter through gearing. This shutter moved at the back of the bellows, occupying the same position relatively as the focal plane shutter used in very rapid still-life instantaneous photography. By means of19 this shutter, the passage of a body across the field of the lens was split up into a number of consecutive units. The interval between two successive images, and the time of the exposure, could be altered merely by varying the revolving speed of the shutter. As a rule, the exposures were made at the rate of ten per second, but in some cases the length of the exposure was only 1/2,000th part of a second, with an interval of one-fifth second between two consecutive pictures. Marey used a black background, and his figures were clothed in white.

Fig. 2.—Marey’s Camera, Showing Shutter with Radial Slots.

There was an important reason for this reversal of Muybridge’s procedure. In the latter the shutter of each camera had to be opened as the horse or other object passed the lens. In Marey’s system the sensitised surface of the plate is directed against a dead black screen, and the lens may be left open without exercising any ill effect20 upon the photographic plate, because the latter receives no light. When a man clothed in white passed across this black surface in full sunlight, only his figure was recorded upon the sensitised surface, and thus was thrown in strong relief against the black background.

Special arrangements, however, had to be made to ensure the success of the result. A flat plane black background did not suffice, as a certain amount of light was reflected therefrom into the lens, resulting in the plate becoming fogged. The black screen employed was in reality a black cavity, known as “Chevreul’s black.” The cavity may be likened to a shed, the front wall of which is removed, and the whole interior blackened. In the screen used by Marey at the Physiological Station in Paris, the back of the shed was hung with black velvet, the floor was covered with pitch, while the sides and ceiling were treated with a dead black medium.

These arrangements enabled Marey to secure more useful results than were possible to Muybridge. From the scientific point of view they proved of incalculable value. His marvellous pictures widened our knowledge of animal motion to a remarkable extent, and provided incontrovertible records of action. Professor Marey ultimately recorded the sum of his experiments in a volume, Movement, which is now regarded universally as a classic in physiological science, and even to-day is consulted freely for the purpose of elucidating complex and obscure phases of motion.

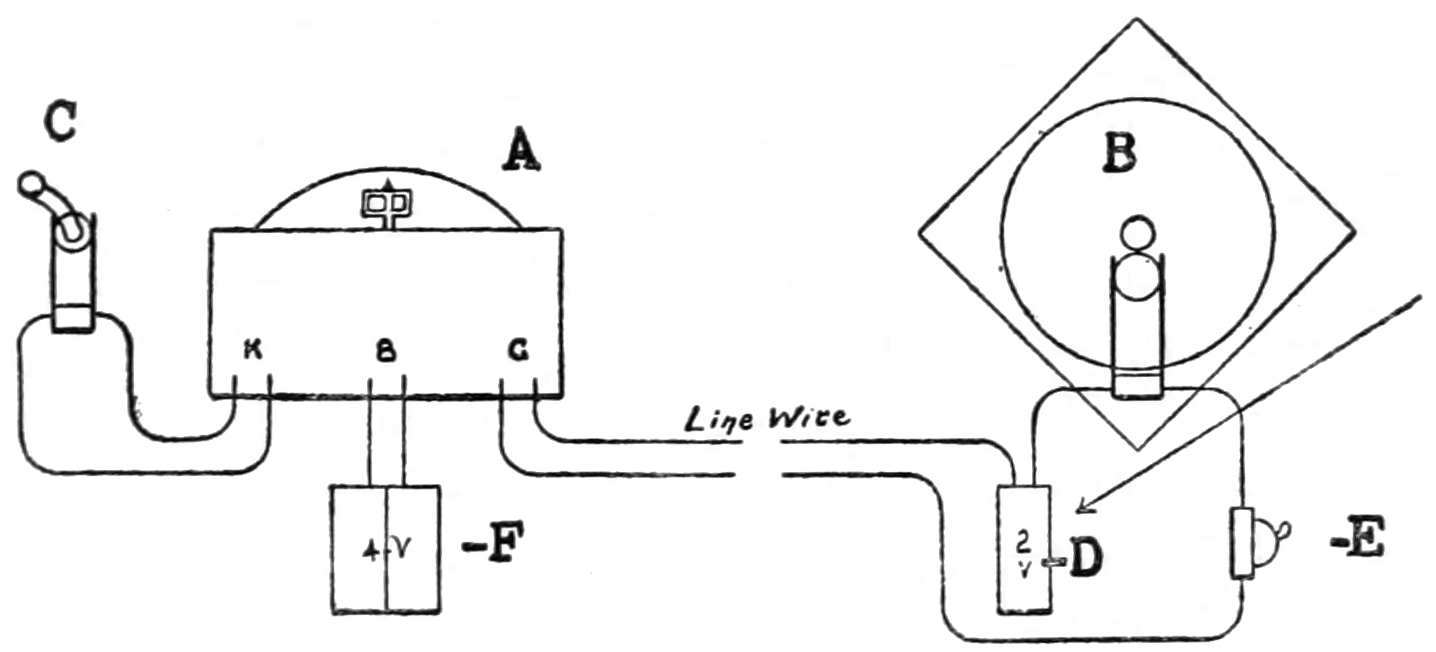

Other investigators at about this time were General Sebert, M. L. Soret of Geneva, and Ottomar Anschütz of Berlin. Soret succeeded in analysing some very intricate movements, while Anschütz produced a curious “wheel of life,” which was called the “electrical tachyscope.” A special camera was evolved whereby photographs were taken in rapid succession. From these negatives glass transparencies similar to lantern slides were produced, and mounted in sequence around the rim of a large wheel, which had to be of sufficient diameter to contain the whole series of pictures. It was mounted upon a massive iron pedestal,21 and was revolved from the rear by means of a handle.

Behind the wheel, and at the highest point, which corresponded to the level of the eyes of the average person while standing, a small box was placed. The front of this box was open, the size of this aperture corresponding exactly to the dimensions of the transparency. It was fitted with a small electric light—a Geissler tube, in fact, through which a current was passed from a Rhumkorff coil—and this light was switched on and off by each picture as it passed before the front of the lamp box. As each picture came into position before the aperture a contact was established, and an impulse of electricity was discharged through the lamp. It was a mere flash, but it served to illuminate the transparency immediately in front, so that the people gazing at the wheel received a brilliant and well-defined impression of the picture, which was shown in an apparently stationary position, though, in fact, the wheel was revolving continuously. When the wheel was rotated with sufficient speed, the flashes occurred in such rapid sequence that, in accordance with the phenomena of visual persistence, the illusion of animation was secured.

This was an extremely ingenious apparatus, but was too complicated, expensive, and elaborate to command any commercial value. It was regarded generally as a scientific toy. It was on view in London, in the Strand near Chancery Lane, for a little while, but failed to arouse very marked enthusiasm. However, the “inventor’s fiddle,” as the Anschütz tachyscope was popularly called, was adopted by several other inventors with certain modifications, but its application was naturally extremely limited. Comparatively speaking, only a very few pictures could be carried in the rim of the wheel, and as the travelling speed was somewhat high in order to convey a tangible impression of continuous motion, a subject was exhausted in a few seconds.

Associated with Dr. Marey in his experiments was another indefatigable spirit, M. Georges Demeny. He displayed considerable ingenuity in breaking down the22 peculiar difficulties associated with this work. Unfortunately the value of M. Demeny’s efforts have never been appreciated; but he brought his mind to bear upon the subject at a critical period, and devoted all his energies, time, and thought to the solution of complicated problems that defied contemporary experimenters. He proved an indispensable colleague to Professor Marey, which the author of Movement did not fail to acknowledge. So far as France is concerned, he rightly deserves to be regarded as the pioneer in cinematography. He not only photographed motion, but he reproduced it upon the screen, and devised an ingenious camera and projector to achieve his end.

M. Georges Demeny was forestalled in Great Britain by Messrs. Greene and Evans, who produced a chronophotographic apparatus which they patented in June, 1889, wherein the film was drawn intermittently before the lens for exposure. Two months previously, in April, 1889, another inventor, Stern, had filed a patent also, and these constitute the first intimation at the British Patent Office of the pending developments in cinematography. Neither issued beyond the experimental and model stage, for the simple reason that they were not reliable in their operation. There was no satisfactory mechanical means for moving the sensitised surfaces forward an equal distance after each exposure, and this omission of an indispensable feature proved fatal to their success.

23

In the struggle towards the perfection of animated photography the use of glass plates was a great hindrance. Investigators were hampered very seriously; they were thwarted at every turn. True, the appearance of the dry plate somewhat facilitated their efforts, but nevertheless the inevitable glass was bulky, heavy, fragile, and awkward to handle. Finally, the number of pictures obtainable upon a single surface was limited.

Realising the restrictions incidental to this sensitised medium, the energies of many investigators were devoted to the discovery of a less bulky, lighter, and more convenient substitute. Gelatine appeared promising at first sight, but failed to give the anticipated results because it lacked stability, and when immersed in the developing solution precipitated a variety of unexpected disasters which placed it out of court completely. The next expedient was the use of transparent paper, similar to what we call grease-proof paper, covered with the gelatine emulsion, invented by Morgan and Kidd, of Richmond. When the exposures were made, the paper was opaque and resembled ordinary bromide paper, the essential transparent effect being secured by an operation after development and fixing. This failed to give a clear, distinct positive, and the grain of the paper so broke up the resultant picture that this alternative was abandoned. A suggestion advocated by the Rev. W. Palmer also was attempted. The picture, after development and fixing, was stripped from its opaque support, and attached to a stiff sheet of insoluble24 gelatine. This gave a somewhat better effect, but it was a round-about method, and the stripping operation was one of great delicacy, involving extreme care, and uncertain in its results.

These substitutes failing one after another, the hopes of the experimenters became centred upon celluloid, which from every point of view appeared the most suitable medium. The application of celluloid to photographic purposes had been advocated many years previously, but there were many obstacles of a technical character which prevented its use at the time. The investigator, however, continued the struggle towards bringing the celluloid film into the realm of practicability.

He was baffled in one particular direction. Celluloid could not be employed with the collodion process, for the collodion which constituted the sensitive surface in the old wet process with glass plates, and which in itself is a solution of pyroxyline, a kind of gun-cotton—one of the basic constituents of celluloid—dissolved the celluloid which was coated with it. The perfection of the gelatino-bromide process removed this defect.

Then another difficulty loomed up. Celluloid at that time was not made in sheets sufficiently thin to render it applicable to photography, and the manufacturers of the commodity could not be prevailed upon to prepare the substance in this form. They argued that there was no promise of a sufficiently remunerative market to warrant the design of special machinery for the manufacture of such a product. Consequently, the experimenters were forced to prepare their own film bases.

The experiences of those who grappled with this question and faced trials and tribulations innumerable in this particular phase of operations make interesting reading. One reduced the celluloid to a liquid consistency and poured the plastic mass over large glass plates, rolling it out to form a thin skin. The surface of the glass previously was cleaned carefully to prevent the mixture adhering thereto. The pouring had to be carefully done so as to secure an even thickness, and to avoid the formation of air bubbles.25 In this way a thin sheet was secured—a decided forward step. In the dark room this “base,” as it is called, had next to be covered with a thin layer of sensitised emulsion, and the whole left to dry. Afterwards the sheet was cut into strips of the width required for the camera and apparatus. Unfortunately, in drying, the celluloid was found to play many sorry tricks. It buckled, twisted, and shrank into strange contortions, and the films thus produced were still somewhat too substantial, being, in fact, very similar to those used in the pack-film camera of to-day.

Another worker was more fortunate. By dint of importunity he succeeded in inducing one manufacturing firm to produce sheets of celluloid no thicker than drawing paper for his experiments. But when the sheets were delivered they were far from being satisfactory, being deficient in uniformity of thickness. Before the surface could be coated with sensitised emulsion a tedious task had to be performed. The inequalities had to be scraped and pared off, and finally the whole sheet had to be made thinner by being rubbed down with emery cloth and sandpaper. Hours were occupied in this process, and often a maddening accident happened in the final stages which irreparably injured the sheet and wasted not only time, but costly material. Even when sensitising was carried out successfully, it was found extremely difficult to keep the material flat. It is not surprising that after a prolonged experience of these disadvantages, this particular investigator abandoned his experiments for a time.

In the majority of these efforts the pictures obtained were about four inches in width by three inches deep, while the modern cinematograph film is only 1⅜ of an inch in width by three-quarters of an inch deep, and almost as thin as a shaving. The celluloid made at that time was not very transparent, and as the pictures were somewhat dense, the results were far from being satisfactory.

It began to look as though celluloid were doomed to follow in the wake of the other expedients that had been tested and found wanting. Such would have been the case but for the indefatigable efforts of one man who persevered26 with his experiments in the face of heartrending failures and disappointing results. This was Mr. Eastman, of Rochester, in the State of New York, who worked in conjunction with Mr. Walker. These two gentlemen had established a dry photographic plate manufacturing process, which had developed into a conspicuous success, and become known as the Eastman Dry Plate Company, now familiar as the Eastman Kodak Company.

The story of their innumerable experiments and ultimate success constitutes a fascinating chapter in the story of animated photography. As early as 1884 Mr. Eastman realised that a substitute for glass was in demand to facilitate ordinary photography. Accordingly he set out to discover a system of photographing on films. As he admits himself, it was by no means a new idea. From time to time spasmodic attempts in the same direction had been made by enterprising inventors, the earliest known dating back as far as 1854, a year or two before the invention of Parkesine, now known as celluloid, by Mr. A. Parkes, of Birmingham. All of these experimenters, however, had been baffled by the technical difficulties confronting their quest, and Mr. Eastman had no tangible assistance to aid him in his work of research. He was compelled to create the foundation upon which to carry out his developments, and to reap success from mortifying failures.

In 1884, when Messrs. Eastman and Walker commenced operations, the problem to be solved in the production of a suitable film, and the evolution of the means to handle it in the camera, were formidable obstacles. The mechanical part of the work proved the easier, and in 1885 roller photography, which has revolutionised the art of photography, at any rate from the amateur point of view, was invented and put on the market. This principle is now well known. A length of film, wound upon one roller, is passed behind the lens in sections for exposure, and then rolled up on a second roller, until the whole has been exposed. The device simplified the process very appreciably, and it may fairly be accused of being the parent of the modern “Kodak fiend.”

27

Though the mechanical part of the problem had thus been solved successfully, the film question was perfected only partially at this time. The film itself was far from satisfactory, but it sufficed to meet the requirements of the day, and to enable roller photography to come into vogue.

To meet the peculiar demands of roller photography, Mr. Eastman had set himself the task of producing a transparent base or support for the sensitised emulsion. That is to say, he sought and produced a stable substitute for the glass plate upon which the sensitised emulsion to record the image could be mounted. It was no easy search, as he speedily found to his cost, for it involved scores of experiments, one after the other, all of which resulted in heartrending failure. He sought to build up such a base as he had in mind by means of successive layers of collodion and rubber, but the result did not possess sufficient substance and strength.

Then he had recourse to paper, which he used merely as a temporary support. The roll of paper was first coated with soluble gelatine, and afterwards with the sensitised emulsion, which was rendered insoluble in itself by the addition of chrome alum. This produced a substantial film which was exposed by means of the roll holder attached to the ordinary camera. The image was developed and fixed. Then, still attached to the paper, the film was placed while wet, immediately after washing, upon a piece of glass coated with a thin solution of rubber.

As soon as the surface had dried, hot water was applied to the paper, which as the gelatine dissolved became detached, leaving the film adhering to the surface of the rubber-coated glass. In place of the paper a moistened thin sheet of gelatine was substituted. When the whole had dried thoroughly it was detached from the glass, and the result was a perfectly transparent negative.

The process was necessarily somewhat intricate and occupied some time, but the results obtained were sufficiently practicable to render it commercially exploitable. Mr. Eastman, however, soon recognised the fact that the28 trouble of transferring the image from the temporary paper base to the gelatine support decreased the practical value of the process. He decided to dispense with the paper support entirely, and in his search for a suitable substitute his thoughts turned toward celluloid. He communicated with the various manufacturers of that material, but not one was prepared to supply him with the substance in sheets of sufficient size and thinness. Consequently he was compelled to devise ways and means to supply the deficiency; and this was achieved partially by accident.

In the early part of 1889 some experiments were being made to discover a varnish to take the place of the gelatine sheets. One of his chemists drew Mr. Eastman’s attention to a thick solution of gun-cotton in wood alcohol. It was tested to prove its suitability to take the place of the gelatine, but was found wanting in practical efficiency. However, Mr. Eastman recognised the solution as one which might prove to be the film base for which he had been searching. He had had such a medium in mind when engaged in his first experiments in 1884, which resulted in the production of the stripping film. He decided to utilise this solution of gun-cotton in wood alcohol and to fashion it into the foundation for the sensitised emulsion, so that stripping and other troublesome operations of a like nature might be avoided. He was moved to this experiment because this solution could be made almost as transparent practically as glass. Accordingly he set to work to devise a machine to prepare thin sheets such as he required from this mixture. Success crowned his efforts, and in 1889 the first long strip of celluloid film suited to cinematograph work appeared in the United States.

Messrs. Eastman and Walker had not been alone in their quest. In England experiments were being carried out in the same field. Curiously enough, the main idea in this instance was to evolve a form of roller photography, the British experimenter being Mr. Blair. He likewise met with success; and the film was manufactured at St. Mary Cray in Kent. Though this film was far from being29 perfect, showing considerable variation in thickness, it served to assist the experiments in animated photography to a marked degree. The celluloid strip thus produced was about twice the width of that now used in cinematography, and as in the early attempts towards moving pictures, no effort was being made towards projection—the illusion was received by looking into an instrument through which the film travelled, and behind which a light was placed—it was made with a matt surface, so that it closely resembled ground glass, upon which the images stood out distinctly and brilliantly. The width of the film was gradually decreased; but this film-manufacturing industry never got a firm foothold in England. The Blair company was merged in that of the Eastman company in America, and it was not until many years had passed that another bid for participation in the manufacture of celluloid film for moving picture purposes was made by a British firm.

So soon as it leaked out in America in 1889 that Mr. Eastman had succeeded in his difficult search, and that a film with a transparent rigid support which was no more difficult to handle than a glass plate, and yet which was flexible and free from fragility, was commercially available, another experimenter appeared on the scene. He had been labouring in the field for some years, but, realising the futility of glass plates, had postponed his investigations until such time that a substitute could be obtained. His apparatus was ready, but the film was the missing link. Immediately it was available he secured some of the material and completed his apparatus. That man was Thomas Alva Edison, and his “Kinetoscope,” was the first commercial appliance to show pictures in natural movement. Animated photography was lifted from the realm of experiment into that of commercial practicability.

30

The World’s Fair at Chicago drew huge crowds from all parts of the world in 1893. The innumerable and varied side-shows evinced keen rivalry to obtain popular patronage. But there was one building sheltering a small instrument which made a particularly bold bid for public favour. It was a novelty, something that the man in the street had never seen before.

The announcement ran that “Edison’s Kinetoscope, showing photographs in motion, was to be seen for the first time.” It worked automatically, and to investigate the new wonder the curiosity-provoked sightseer dropped a nickel—a coin equal in value to 2½d.—into the slot, and applied his eye to the peep-hole, when he was treated to a new sensation for about 30 seconds. He saw photographic pictures flit before his gaze in such rapid succession that they appeared to be imbued with life. Children skipped, the lips of an orator moved in speaking, and so on. It certainly was a marvellous device, and those who availed themselves of the opportunity to see it in operation by means of the nimble nickel, expressed undisguised wonderment; to many it appeared uncanny.

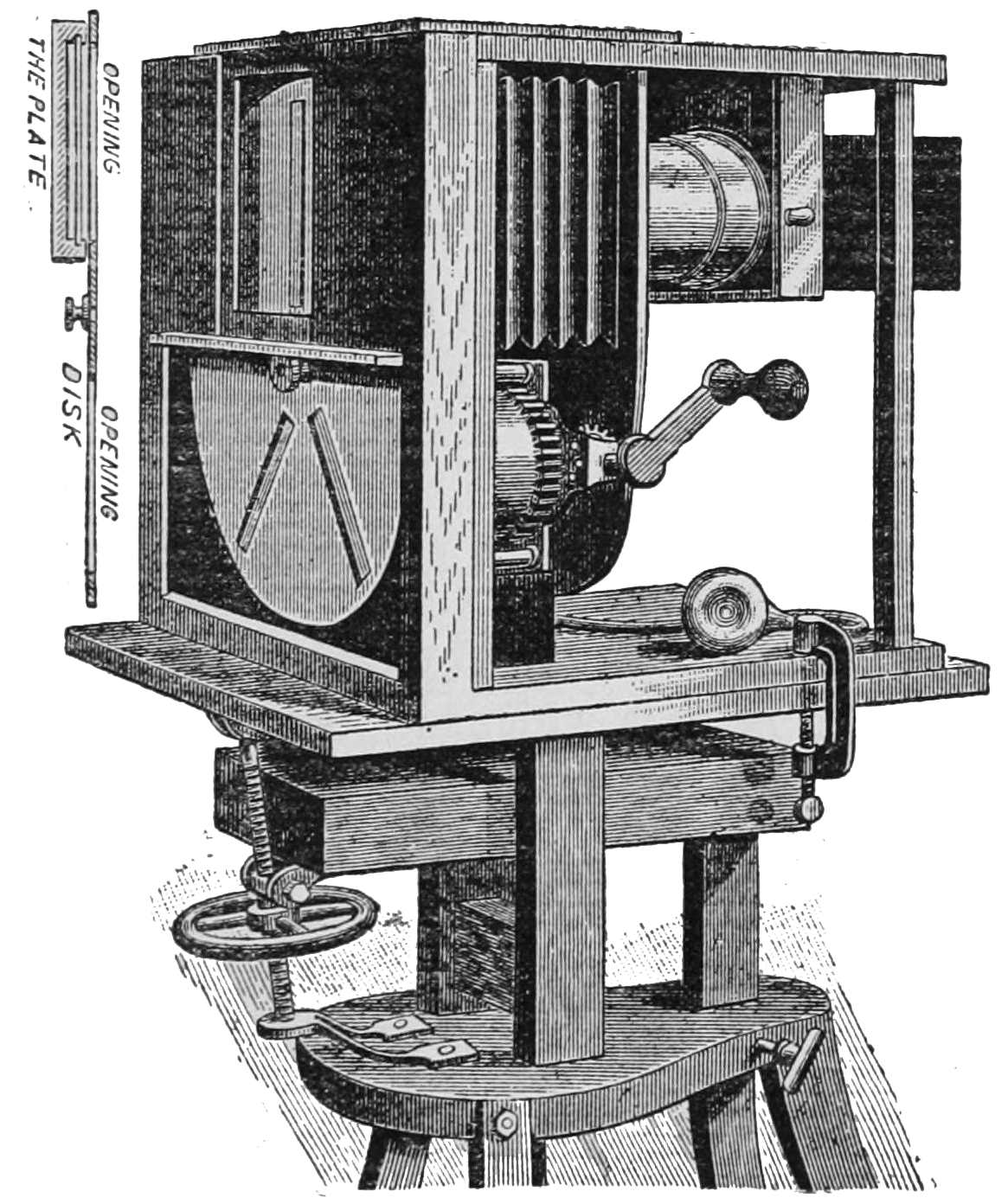

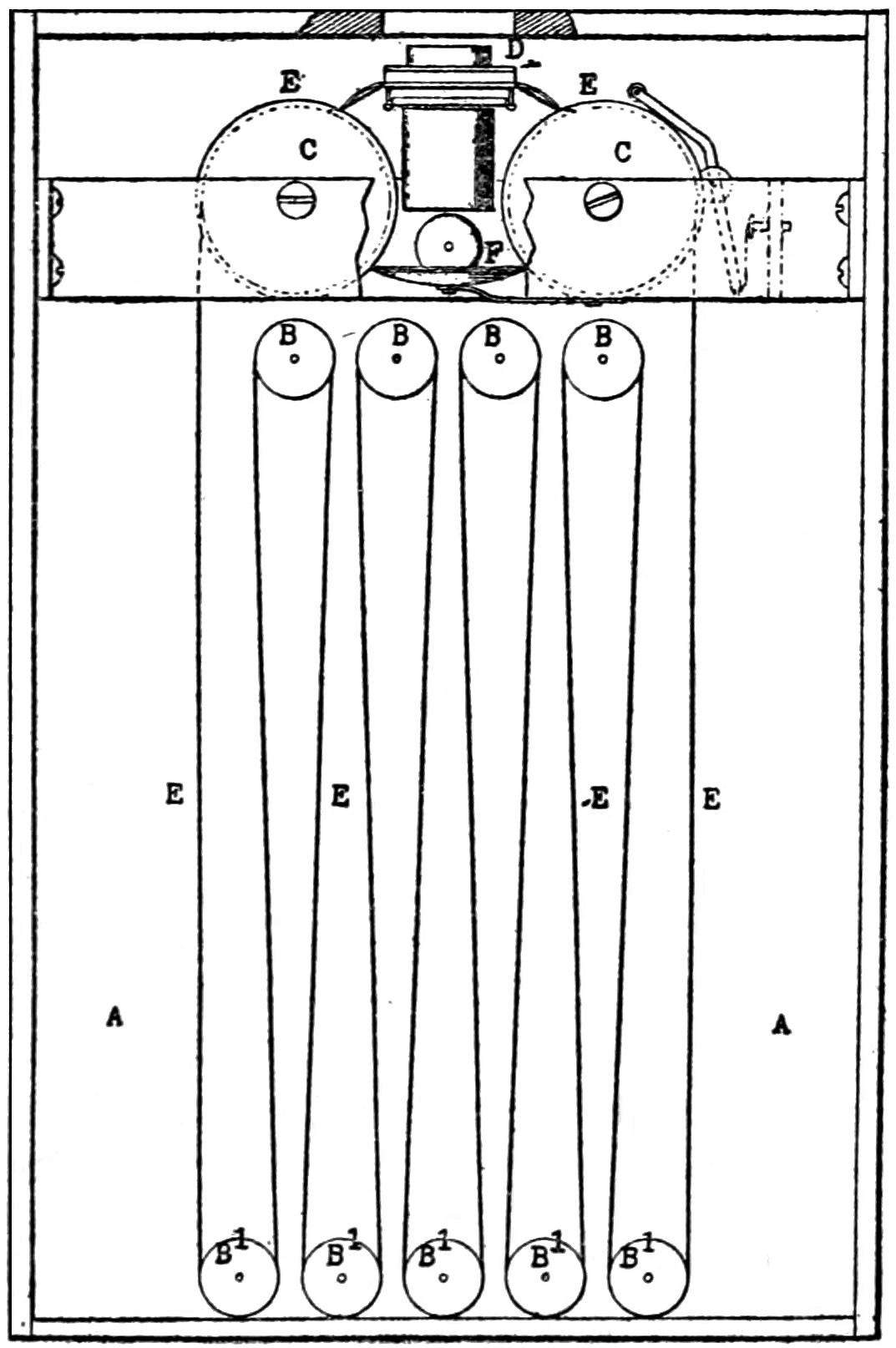

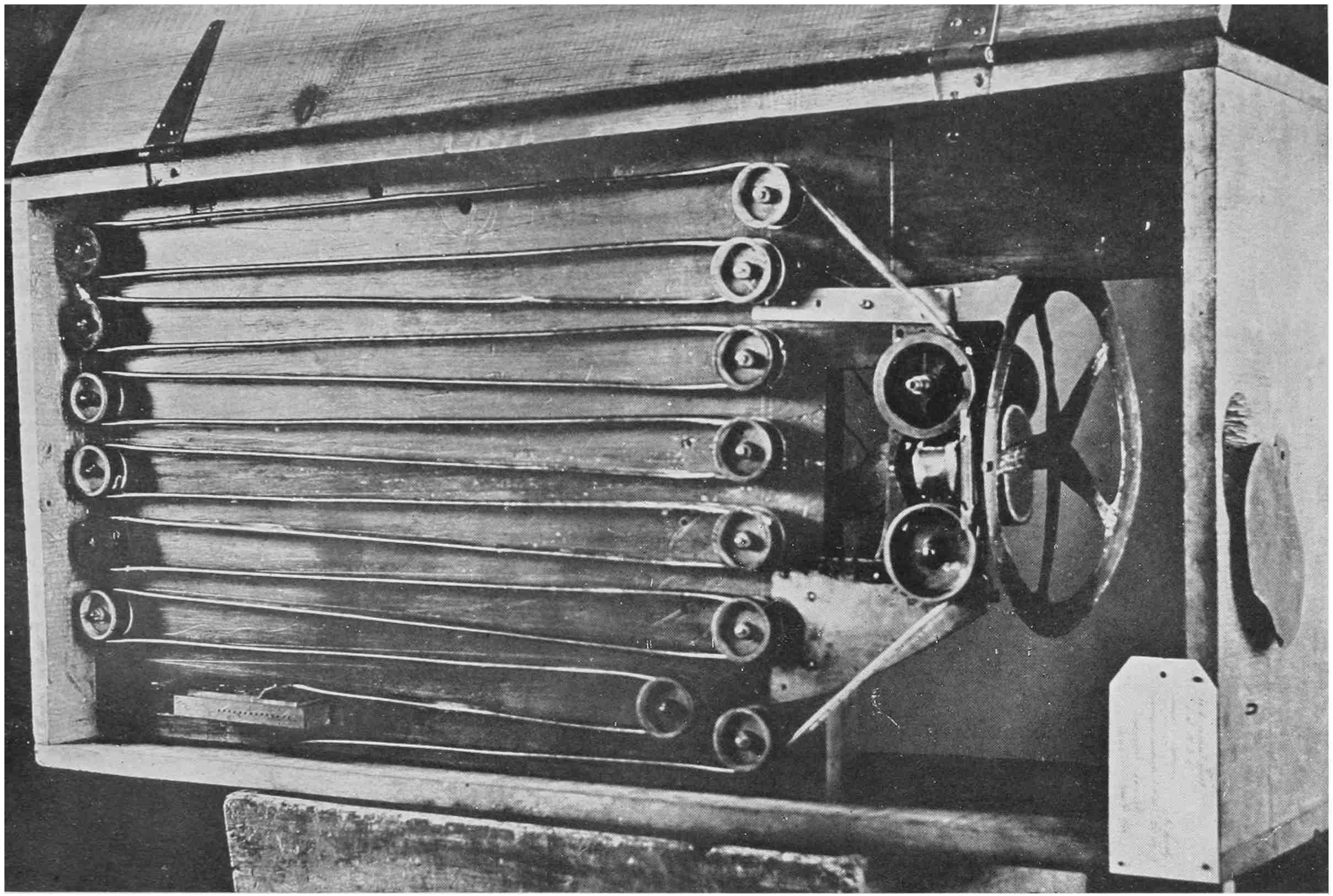

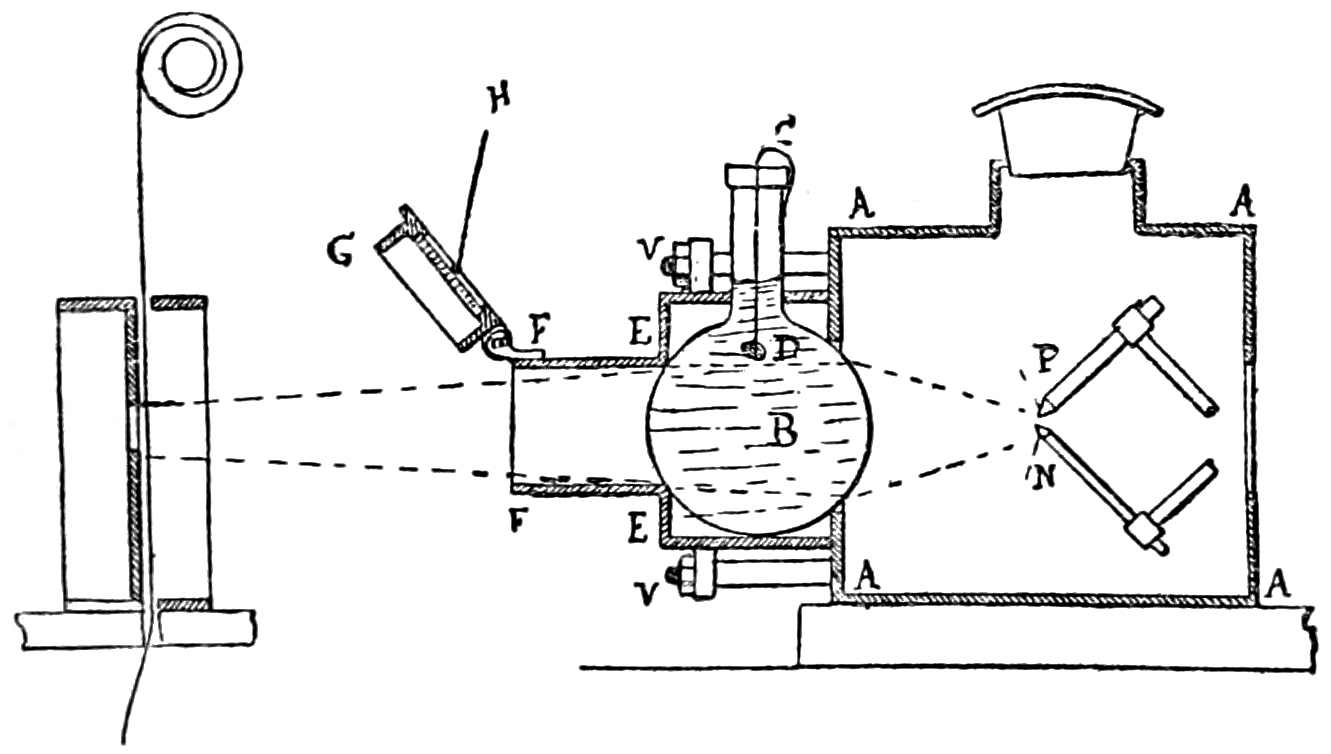

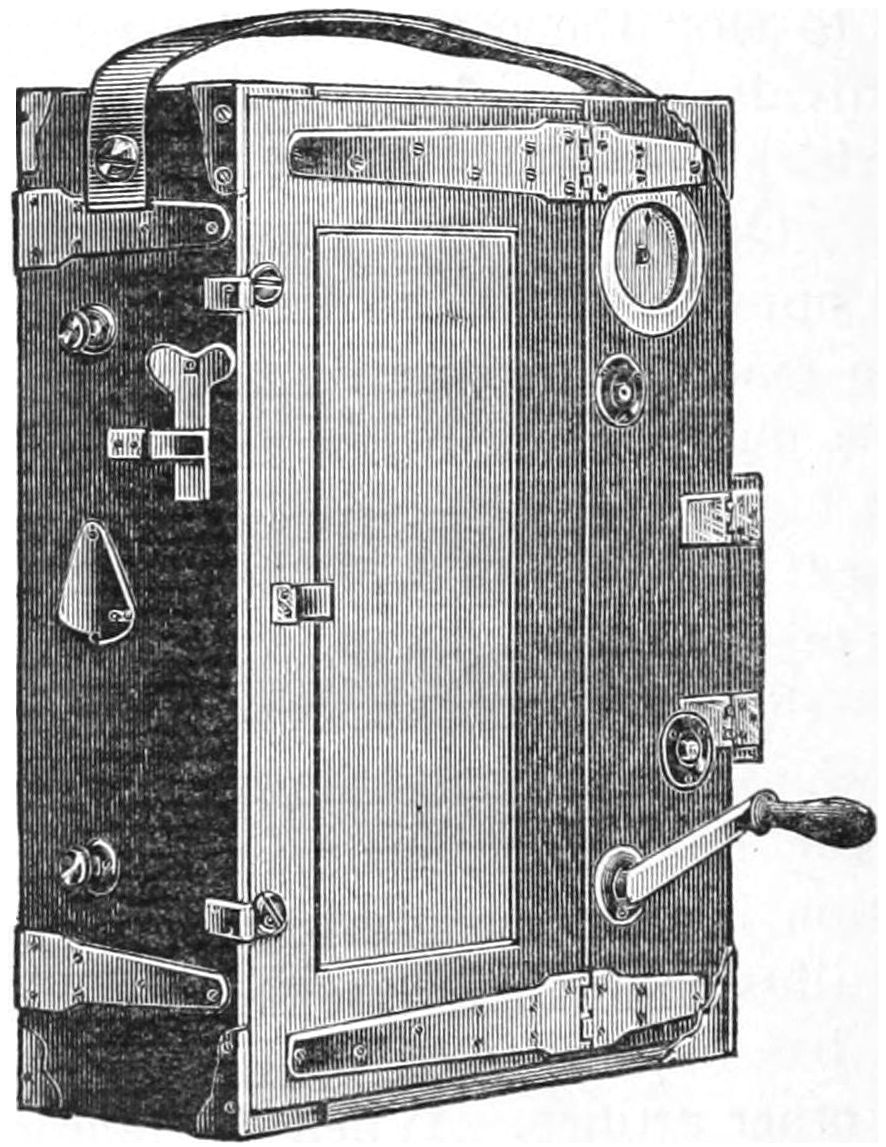

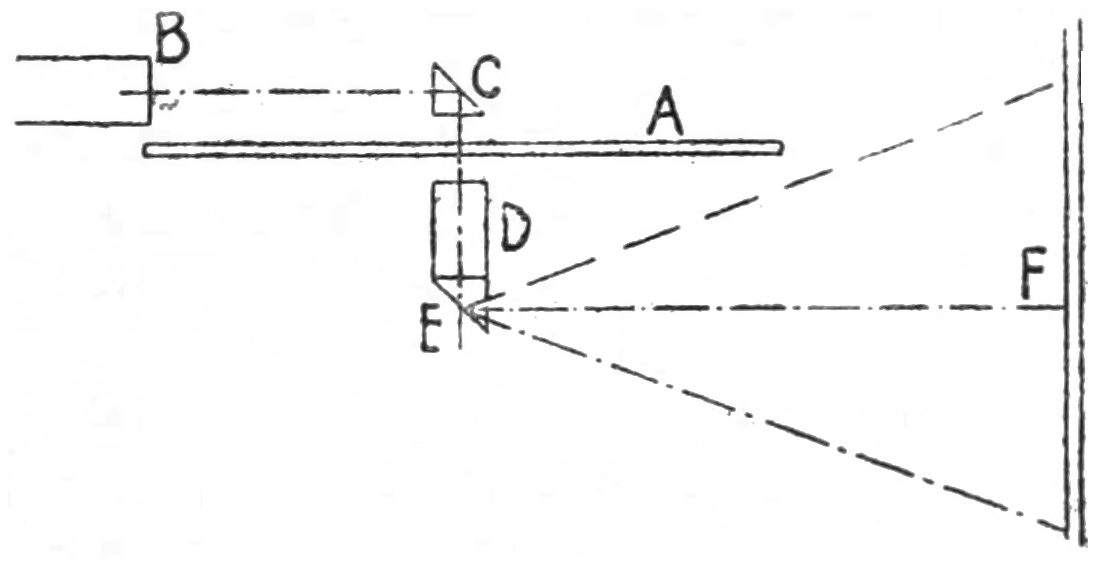

The Kinetoscope, Fig. 3, was housed in a wooden cabinet with a hinged door at one side. Within was a wooden frame A, which carried a series of small reels B and B¹ arranged in two horizontal rows at either edge of the frame. At the top of the frame there were two larger31 wheels C, between which was a magnifying lens D. Behind the latter there was a small electric lamp and reflector F. In front of the magnifying lens there was a disc having a narrow radial slot near its edge, which constituted the shutter. This was rotated continuously, and completed one revolution during the passage of each image across the eye-piece or magnifying lens.

Fig. 3.—Edison’s First Kinetoscope.

The ribbon of pictures, printed as transparencies upon a strip of celluloid film, somewhat dense so as to bring out the detail, formed an endless band E, 40 feet in length. This was threaded over the various reels in the manner shown in the illustration, and finally passed over the first large wheel C, thence to the second large wheel C, and back32 once more on to the reels B B¹. Though 40 feet constituted the average length of film employed, longer ones could be used within certain limits, by increasing the number of reels on the frame. As the film passed from one of the large wheels C to the other, it had to traverse the field of the magnifying lens, and the light, striking through the transparency, gave the person looking through the eye-piece a slightly magnified view of the picture.

The cabinet stood on end, so that one had to bend over the instrument to peer through the small eye-piece. When the coin dropped into the slot, an electric motor was started, setting the film and shutter in motion. The film travelled from left to right, while the shutter rotated in the opposite direction, cutting up the band of pictures into separate images, so that only one was seen at a time. The band travelled continuously, and each image was momentarily rendered visible by the light flashing through the radial slot in the shutter, the effect being the same as if the electric incandescent lamp were extinguished and relighted intermittently, at very brief intervals.

EDISON’S FIRST KINETOSCOPE.

This machine, completed about 1890, was very crude. It was known as the “peep-hole,” because one peered into the cabinet through the eye-piece at side.

The shutter had to be revolved at sufficient speed to bring the radial slot near its edge centrally over an image; in other words, the shutter had to complete its revolution with sufficient speed to bring the opening over the picture at the moment the latter on the travelling celluloid film came into the centre of the field of the lens. When this operation was carried out with sufficient velocity, the images were seen in such rapid succession as to convey the idea of continuous motion, by virtue of the principle of visual persistence.

One point must be borne in mind. The band of pictures travelled continuously. It did not, as in the machine of to-day, make a momentary pause as it came between the light and the lens. The movement to-day is intermittent, not continuous, though, curiously enough, all the early experimenters strove first towards the perfection of the latter arrangement. Continuous motion of the film has proved to be impossible, because the shutter must33 revolve at such a speed that the illumination is not sufficient to produce a bright impression upon the screen.

In order to prevent the film slipping in any way while travelling over the smooth reels by friction, a toothed sprocket was introduced to ensure the film being fed regularly and steadily before the lens; and to secure a purchase upon the film the latter was perforated uniformly along the margin to engage with the sprocket teeth. Edison found, as a result of his experiments, that four perforations per picture, on either side of the film, gave the best results, though in his earliest investigations he confined himself to perforating only one edge in this manner.

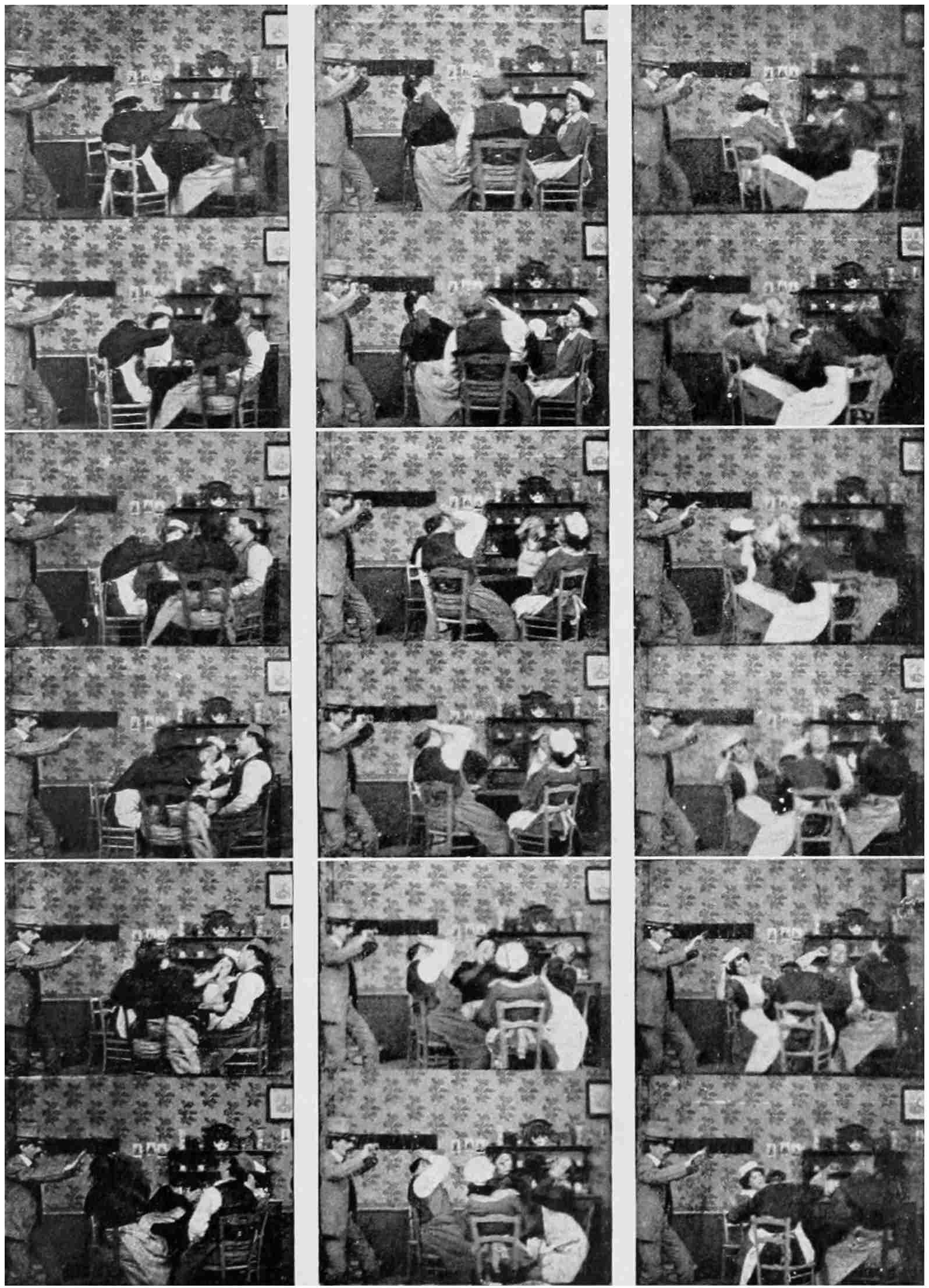

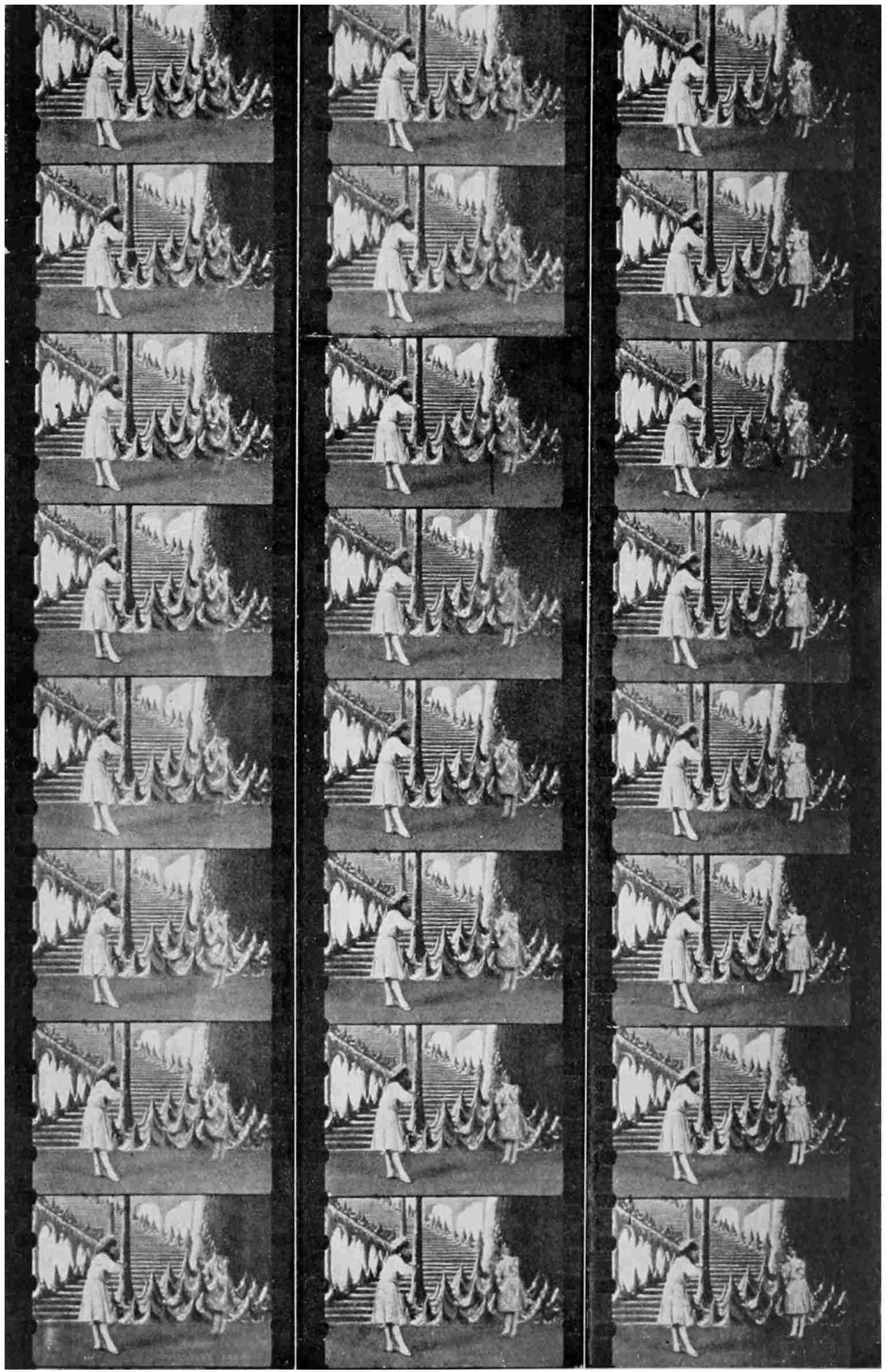

Edison Film made about 1891 for

the kinetoscope.

Edison Film made in 1911 for

the cinematograph.

TWENTY YEARS’ HISTORY OF MOVING PICTURES IN FILMS.

The only difference between the two films is that the kinetoscope film had to be made very dense. The size of the picture, 1-inch wide by ¾-inch deep, and perforation gauge, are identical.

Although many years have passed since the Kinetoscope first startled the public, the film has undergone but little change. The width remains the same; the dimensions of the picture are identical; and the perforation gauge has never been revised in regard to the number of holes per picture. The only salient difference between two Edison films, taken at intervals of twenty years, relates to the density of the picture, which nowadays, being projected upon a screen instead of being followed through a magnifying glass at short range, is thinner and lighter.

Brilliant as the Kinetoscope was, it made no great impression upon the public. It became known as the “peep-hole machine,” and was regarded, like the telephone in its early days, as a scientific toy. Edison appears to have failed to grasp its possibilities and the important part it was destined to play in our complex life, for he did not patent it in Great Britain.

Among those who saw the instrument at the World’s Fair were two Greek visitors from London. One was a greengrocer, the other a toy-maker. With shrewd business instinct they perceived here an opportunity to make a fortune in England. The Kinetoscope was known only by name in London, and the search for novelty in regard34 to new forms of amusement inevitably brings a rich reward to the ingenious exploiter. The two men acquired a machine and brought it home with them, their intention being to make duplicates and instal them in public places, to work upon the penny-in-the-slot principle.

The two Greeks evidently were not animated by very lofty ideas of business integrity, for they did not trouble to ascertain if the Kinetoscope were patented in Great Britain.

Upon arrival in London they sought for a man who could duplicate the machine they had brought with them; and they approached Mr. Robert W. Paul, an electrical engineer and scientific instrument maker, who at that time had his workshops in Hatton Garden. They brought the Kinetoscope to him. He had never seen it before, and was deeply interested in its operation. When, however, they suggested that he should produce copies of it to their order, he declined, for he felt sure that Edison never would have omitted to secure its protection in Great Britain. He pointed out to the Greeks that reproduction would probably be illegal, and that both he and they would expose themselves to litigation and heavy damages for infringing a patent.

His clients expressed dissatisfaction at this decision and departed with the instrument. After they had gone, Paul was prompted to make a search at the Patent Office, and to his intense surprise he found that Edison had not protected his invention by taking out British patents. He was thus at liberty to build as many machines as he desired, and forthwith he set to work, not only for his Greek visitors, but also for his own market.