Vol. LXXXVIII No. 8

The

Yale Literary Magazine

Conducted by the

Students of Yale University.

“Dum mens grata manet, nomen laudesque Yalenses

Cantabunt Soboles, unanimique Patres.”

May, 1923.

New Haven: Published by the Editors.

Printed at the Van Dyck Press, 121-123 Olive St., New Haven.

Price: Thirty-five Cents.

Entered as second-class matter at the New Haven Post Office.

ESTABLISHED 1818

MADISON AVENUE COR. FORTY-FOURTH STREET

NEW YORK

Clothing for the Tennis Player and the Golfer

- Flannel Trousers, Knickers, Special Shirts, Hosiery, Shoes

- Hats, Caps

- Shetland Sweaters, Personal Luggage

- Men’s and Boys’ Garments for

- Every requirement of Dress or Sporting Wear

- Ready made or to Measure

The next visit of our Representative

to the HOTEL TAFT

will be on May 30 and 31

BOSTON

Tremont cor. Boylston

NEWPORT

220 Bellevue Avenue

THE YALE CO-OP.

A Story of Progress

At the close of the fiscal year, July, 1921, the

total membership was 1187.

For the same period ending July, 1922, the

membership was 1696.

On May 1st, 1923, the membership was 1922,

and men are still joining.

Why stay out when a membership will save

you manifold times the cost of the fee.

THE YALE LITERARY MAGAZINE

Contents

MAY, 1923

| Leader |

Laird Shields Goldsborough |

245 |

| The Acolyte |

Herbert W. Hartman, Jr. |

249 |

| Chopin |

Arthur Milliken |

250 |

| The Bells of Antwerp |

Morris Tyler |

251 |

| Rhapsody |

Arthur Milliken |

253 |

| Offering |

D. G. Carter |

254 |

| Gabrielle Bartholow |

Lewis P. Curtis |

255 |

| A Little Learning |

Laird Goldsborough |

268 |

| Notabilia: On the Francis Bergen Medal |

Maxwell E. Foster |

273 |

| Book Reviews |

|

274 |

| Editor’s Table |

|

277 |

[245]

The Yale Literary Magazine

Leader

There be two handles to all things in this world,

one called the good, and one the bad. But a man

may lay hold of anything by whichever handle shall

please him best.—Old Stoic Maxim.

It has been usual, in the past, for Editors of The Yale Literary

Magazine to express themselves as strongly opposed to something,

when engaged in writing a leader. Two recent leaders have

varied this procedure to the extent of declaring the opposition of

their authors to opposition, but the principle of being opposed to

something remains. At the present moment, it occurs to us that

it might be interesting to suppose correct a few of the pessimistic

opinions held by that rather noisy group whom we shall call The

Troubled Spirits. On the basis of these suppositions, we shall

then try to show that, bad as things are, there still remain a few

bright spots lurking in unsuspected corners of the very evils whose

existence we are admitting, for the sake of argument.

A convenient starting point may perhaps be found in the Compulsory

Sunday Chapel question. It can be urged that the two

services now provided prevent anyone from claiming that he is[246]

forced to listen to propaganda in the form of a sermon, on Sunday.

But The Troubled Spirits, whose positions we are now admitting,

regard the matter differently. If we are correctly informed, they

consider it a fact, however unpleasant, that the average Yale

student feels a very real, if unofficial, compulsion to attend whichever

Sunday service is held at a later hour than the other. The

Troubled Spirits defy the University to hold the short service at

eleven o’clock, and the long one at ten—believing that their position

would be more than vindicated by the lack of attendance at

the earlier service. In short, so far as The Troubled Spirits are

concerned, Sunday service is at eleven o’clock, and contains a

sermon varying in length from twenty minutes to half an hour.

But after allowing all that, and allowing, too, that the visiting

clergymen are attempting to foist opinions of their own upon the

undergraduate body, there is still something to be said. In the

first place, we imagine that The Troubled Spirits, on leaving

college, will perform their undoubted duty of attacking Christianity

with every resource in their power. Hence, were we in their

place, we should ask nothing better than to have all the foremost

of our enemies brought before us, at great expense, and exposed

in such a manner that we could most easily detect the flaws in

their armor, which we were later to pierce.

Secondly, there will be certain of The Troubled Spirits whose

ardor will evaporate on leaving college, and who will allow the

public opinion of their friends and relatives to force them to

church again every Sunday. To these we should like to say that

observations upon the sermons of more than one pitifully underpaid

clergyman have convinced us, from The Troubled Spirits’

point of view, that in this respect “the worst is yet to come”.

However stupid and unthinking The Troubled Spirits may find

the highly cultured, and in many cases highly paid, gentlemen

who speak at Yale, they will find the less highly paid, and not

infrequently less cultured, type of man to whom they are destined,

infinitely more stupid, and perhaps positively unpalatable. The

flowers of rhetoric, when blended skillfully into a delicately fragrant

and perfumed discourse, are, indeed, far more expensive

than a bouquet of orchids—few of us will ever be able to afford

them again. And so, after a lapse of years, I can imagine an old[247]

and embittered Troubled Spirit attempting a Drydonian paraphrase

to this effect:—

Battell to some faint meaning made pretense,

Elsewhere, they never deviate into sense.

That, of course, would happen to very few Troubled Spirits, but

it is not impossible.

Having attempted to prove, let us hope with some slight measure

of success, that even the most troubled of The Troubled Spirits

may find some crumb of consolation in present-day Sunday Chapel

conditions, let us pass on to another example. Perhaps, by way

of trivial digression, it might be interesting to speak of the feeling

among The Troubled Spirits that Osborn Hall should be summarily

destroyed as a relic of a past and barbarous age. Here,

though we might admit the contentions of The Troubled Spirits

as before, we think it more serviceable merely to recommend that

The Troubled Spirits go and look at Osborn Hall. If our own

spirits were troubled, we can imagine nothing more soothing than

to look at Osborn Hall for the first time. Around the front of

the main entrance runs a band of stonework carved with animals

and foliage exactly resembling the woodcuts in The Troubled

Spirits’ favorite magazines. One of the beavers, in particular, is

gnawing away at a capitalistic grapevine with a communistic fury

only to be called prophetic. Again, we have never seen anything

more “advanced” than the exquisite mosaiced representation of a

steamboat complete with paddle-wheels, which adorns the under

surface of one of the arches. It is exactly the same thing as the

“Painting Of A Train of Gear Wheels” sold recently in Paris as

the latest example of Da Da. It seems, then, that this matter

might very well rest by allowing The Troubled Spirits to admire

Osborn Hall as a sample of the latest phase in unrepressed art,

while the rest of us respect it as an example of what our grandfathers

were fond of, and of what our grandsons will treat with

veneration. But to return to things less trivial—

As this is written, the Senior class have voted that the most

important thing needed by Yale is football victories, and we are,

for once, in accord with The Troubled Spirits in thinking that our

gridiron defeats are dreadful things. They may not go so far as[248]

to admit, with The Troubled Spirits, that football at Yale has

become not the most manly but the most sentimental of sports,

yet they do attach great weight to the matter. The Troubled

Spirits, I understand, go much further, and assert that year after

year the University is expected to have confidence, trust, or perhaps

blind faith in the team. They would have us believe that

Yale has been taught to accept defeat with a pious resignation that

savors of slave morality. And then they point to other fields of

endeavor. Is the student given a long cheer by his parents before

going into an examination, and assured that it won’t matter anyhow

if he fails? Does the greatest of generals receive the same

amount of encouragement from his people no matter if his success

be large or small? The Troubled Spirits have put these questions

to many of us, and, without waiting for reply, answered them

almost vulgarly in the negative. They remark that it is fundamentally

self-evident that one must spur one’s charger, not feed

him lumps of sugar, before going into battle. And therefore they

would attempt to excite the student body to such a pitch that to

be a member of a team defeated by Harvard would not be an

wholly enviable post.

But, even supposing there was a word of truth in these extreme

views, it seems to us that, while The Senior Class, The Troubled

Spirits, and ourselves are agreed in desiring a football victory as

soon as possible, we may as well take pleasure in a certain aspect

of these defeats which is very desirable in a quiet way. It has

always been held that football victories help to stimulate enrollment,

and it is universally admitted that the enrollment of the

University is far too large as it is. Likewise, victorious Harvard

is swamped with “race problems” and what not, which do not

trouble us. We are permitted to jog along without attacks from

“degraded races, who are trying to cast off the yoke of oppression

with the key of learning”, and want a look through our keyhole.

That, at least, is a consoling thought. May it bring a little peace

to The Troubled Spirits.

LAIRD SHIELDS GOLDSBOROUGH.

Shall we then consecrate those things we know,

Clinging to patterns with complacent ease,—

Or, tired with feigning meekness on our knees,

Rise up in might and confidently go,

Leaving the rest to kneel? The candles glow

Whether or not we speak our litanies.

Yet wiser men say hope cannot appease

The lasting voice that chants, “God wills it so!”

Rather I think our fitful prayers ascend

To Him who lights the candles of our Love,

Knowing we seek in Him our human best:

Thus does the worth of God in man defend

Our emulation, make us walk above

Man’s world with Him while kneeling with the rest.

Ethereal and pale, pure melody,

Was Shelley’s song, while Keats could never sing

Without more warmth and depth of coloring:

But Chopin soars unshackled, truly free,

For music is a higher poetry,

Not bound by clumsy words, so it may wing

Its way through groves celestial or cling

To the warm couch of wine and revelry.

I hear the sea wind crooning; far below

The cold stars shiver on the ocean floor.

What nation is that rising ’gainst the foe

In revolution fierce? What antique lore

Do those bells toll? Whence comes this overflow

Of tones so sweet that we can bear no more?

[251]

The Bells of Antwerp

Why do you call to me,

Bells of the centuries, mellowed with yearning and joy o’er the ages?

What is your secret that charms each new listener back to life’s pages

Men scrawled out in blood and carousel, love and the brine of the north wind?

“We are the keepers of secrets, sighed to us out of the darkness;

Guardians of clandestine loves that will burn past all human remembrance,

Told by our tongues that rejoice in the undying ardor of telling.

Ancient conspiracy ran to our doors, we appointing the hour,

Passed through the arras and knelt for the gesture that spelt absolution,

Forgetting that we spied the drama to curse and proclaim at our pleasure.

We are the tyrants that reigned in the city of mantle and doublet

And hose; when the gem-crusted baldric that sheltered the dagger was slung

’Cross a heart that beat steadfast and calm with a faith most eternally constant.

Each of us carols an air that was born of a vision-mad organist,

Preaches the infinite word that God whispered to man when his uplifted

Eyes caught a flash of eternity granted as part of the covenant.

Joyful our voices and kind to the heart that is sad with contrition,

Bringing a hope in the good that is past with the quieter ages,

Soothing humanity’s fears with our message that tells of a future.

[252]

Harsh and unmeaning and cruel is our song to the souls that are stiff

With a pride that turns faith in the mind to a stone in the heart of the thinker,

Blinded by twilight within, which shuts out all sunshine and laughter.

Ever unchanging our call, to the winds, the clouds and the rainbow,

Rings forth in song at the moments that God as His sentinels ordered;

Now we are one with the jet-wingéd night and the cloud-mantled sunrise.”

“Thus do we call to you,

Bells of the centuries, mellowed with yearning and joy o’er the ages.

These be our secrets that charm each new listener back to life’s pages

Men scrawled out in blood and carousel, love and the brine of the north wind.”

Moon-lit sea coast, wild rose blowing,

Smack of salt, and gray gull’s cry:

Night that is wild with the exultation

Of the bellowing breath from a cool, clear sky:

Green waves swinging down the moon-path

Pause and lean and break and roar,

Making full majestic music,

As they pound the sounding shore.

Oh, to forget! half-mad with moon-light,

And toss with the cold waves where they go,

Cedar green and molten silver,

Tireless tumult of ebb and flow,

Rapturous, wild, eternal rhythm,

To and fro.

I will go into the city of tired eyes,

And tell my thoughts to each pedestrian,

And on its towers, beneath its leaden skies,

Inscribe a little message for all men.

And few shall read its modest letters there,

And none of them shall ever understand,

Yet all I will perform, nor greatly care,

For I may not be long within the land.

[255]

Gabrielle Bartholow

When Miss Amy Lowell, in an essay upon the poetry of

Edwin Arlington Robinson, expressed a doubt whether

Mr. Robinson’s recent popularity had not gone to his head and

would for the future endanger his work, no one then reading

could fully comprehend the ineptitude of her fear. Perhaps the

reader severely questioned her, but he could not be convinced

until Roman Bartholow appeared to prove that any such statements

as Miss Lowell’s were erroneous. Miss Lowell has based

her fear, curiously enough, upon the melodramatic poem Avon’s

Harvest, in which, though the poet was but playing with dime

novel effects, his verse was more masterfully composed than in

any of his earlier poems. Avon’s Harvest in its technique alone

revealed a tightening of the poet’s art. His cadences were more

definite, his vocabulary less elaborate, his construction certain and

replete with the artlessness of art. There was to be seen no

machinery in this poem, for it had vanished in the poet’s change

to an objective method. The faults of Merlin and of Lancelot

were due only to construction and that construction itself to an

intensely subjective method. In these poems Mr. Robinson did

not let the story tell itself as he was wont to do in the now famous

short poems, but he must, for Merlin and Lancelot are essentially

lyric dramas, sing for himself the love motifs, the tragedies as he

himself experienced them. For this reason he must weave the

story according to the whispering of his own moods. And in so

doing he must lay himself open to attack on the grounds of

incoherence of form. Miss Lowell was indeed one of the first

of his critics to notice this, yet it is surprising that she should

have refused to see in Avon’s Harvest the correction of the faults

she censured in the lyrics; to wit, the change of treatment, the

growth of sureness that the poet’s objective manner was displaying.

That essential objectivity which distinguishes Flammonde,

Richard Cory, and Zola, which previously was employed

only to etch a character in a paucity of strokes,—that objectivity,[256]

with the publication of Avon’s Harvest, Mr. Robinson announced

to be the latest of his secrets for the writing of narrative poetry.

Though he followed this poem with others in the objective

manner, the most remarkable of which is the little known Avenel

Gray, no complete study has appeared until his last narrative

poem, Roman Bartholow, a work that is dramatic, expressive, and

yet holds about it more folds of dignity and power than even the

elegiac The Man Against the Sky. Roman Bartholow, because of

its complete and extensive objectivity, impresses one most signally

with its inevitability, a characteristic which Mathew Arnold termed

the basis for all great poetry. From the opening lines where

Bartholow gazes down upon “a yellow dusk of trees” to the close

of the last canto there is never a moment when the story does not

move silently ahead, dynamically, inevitably, since the author has

been able to withhold comment, and since he has purposely avoided

an obvious climax. Mr. Robinson can no longer see climax in

life, for to him destinies are decided well in advance of any

catastrophe, so that the climax that does appear in the poem is

one miraculously cast in overtones. No word comes from the

poet that it is at hand. No word comes from the characters. The

word is found in the reader’s mind, forcing him to believe its

presence. He knows that Gabrielle, though she would “shrivel

to deny it”, is come to the end of all her hopes. He knows she

can only accept her fate. There is nothing more to say. The poet

has only set down the theme, for the story has of its own force

driven itself to its conclusion with the majestic restraint of an

Aeschylean tragedy.

Mr. Robinson has discovered that to take Nature as she is is

not necessarily to say to the player that he may sit on the piano.

Yet this taking of Nature as she is, despite the fact that Mr.

Robinson calls the theme a “good deal of a mix up”, in no wise

complicates the bare plot. Roman Bartholow, an ailing descendant

of an old Maine family, is brought to know again the joy of life

by acquaintance with a man that comes to visit him and forgets

to go away. This Penn-Raven, though he works a cure for

Bartholow, succeeds in doing the opposite for Roman’s wife. He

falls in love with her and, before the opening of the poem, has

for some time possessed her adequately. Gabrielle is a peculiar[257]

character, but let it suffice here to say that the liaison with Penn-Raven

is no answer to her problem. In Bartholow she married

the wrong man, and the Raven she comes to find intolerable. She

is one who has always suffered disappointments. It is no wonder,

therefore, that, realizing she cannot fully enter into Bartholow’s

renascence as he would have her do, in an effort to save for him

his new-found light she drowns herself. Thenceforward the

solution is cruelly plain. Bartholow, unaware of Gabrielle’s act

and provoked by Penn-Raven, pays him to leave the house. Word

is then brought that Gabrielle is drowned. That is in midsummer.

It is fall when Bartholow himself leaves the house forever to go

whither he will, cherishing the light of his regeneration the while

he thinks of Gabrielle who couldn’t follow his rebirth, not being

reborn in his manner, and who threw herself away.

These men and this one woman are the persons around whom

the whole power of Mr. Robinson’s poetry abides. Yet there is

one of whom I have not spoken, a fisherman who, though playing

a minor part, frets his useful time upon the stage. He makes his

appearance in the two opening cantos and again in the last two.

Once in the final scene between Penn-Raven and Gabrielle he is

referred to as one who knows more of their relation than even

Bartholow. Thus his function is immediately evident. He is the

chorus that gives its warning and advice. More than that, he is

the mouthpiece to Mr. Robinson’s own thoughts.

That spring when, out of a winter steeped in night, Bartholow

was

reborn to breathe again

Insatiably the morning of new life,

there came to him from across the river this prophet-fisherman,

this hobo scholiast with his face “to frighten Hogarth” who was

at once

Socratic, unforgettable, grotesque,

Inscrutable, and alone.

He came to Bartholow dressed in “a checkered inflammation of

myriad hues” and bearing as a peace-offering for his appearance

a catch of trout for breakfast. Presumably he came to bring the

fish and drink a glass, but incidentally he was curious to investigate

this new birth of Roman’s and to discover if it blinded his eyes[258]

so that he saw nothing further than acquaintance between Penn-Raven

and his wife. Wherefore he sat with Roman and heard

recounted the glory of being alive once more. But Umfraville

was wise. He was in the eyes of the world “irremediably defeated”

and for that reason had hid himself back in the woods

where he

lived again the past

In books, where there were none to laugh at him

And where—to him, at least—a world was kind

That is no more a world.

Hence from this distance he was able to understand the flood of

human nature and capable of pronouncing judgment upon it. He

was gifted, as he said, with an “ingenuous right of utterance”

which gave him full license to speak his mind. He knew that

Gabrielle’s unfaithfulness must come to Roman’s ears. He knew

the tragedy that it would be to this proud, sensitive friend of his,

and, knowing it, offered his aid if ever Roman’s light should be

obscured.

It is in brilliant contrast to this “unhappy turtle” that Penn-Raven

appears, Penn-Raven, the bounder, archguest, corruptor

and healer in one breath. He it is, with his solid face, thick lips

and violet eyes, upon whom “one may not wholly look and live”,

for in Penn-Raven there is more of the devil than is safe to

investigate. The devil only knows why he came to Bartholow,

why he possessed those violet eyes withal, and, after he had met

Gabrielle, why the devil he ever went away. He was large and

muscular and imbued with a healthy-mindedness which could

purge the soul of Roman. Not only was he able to change this

man’s outlook upon life, bringing him light where only darkness

had lain, but he could worm his way to the heart of Gabrielle

and make her his for as long as he chose. He loved her with all

the force of his animal self, yet he could hint to her that she was

insufficient to Bartholow’s present needs. Callous Penn-Raven!

He never understood Gabrielle, though he later called her “flower

and weed together”. In her he saw mostly the weed, the woman

who had forsaken her husband and who might be expecting him

to take her away. So he thought and so he said to her, not

noticing the agony he caused. He did not know the woman he[259]

later called the flower who, though she had surrendered herself to

his affections, yet saved for Roman a far transcending love. Thus

to hint that she go with him was perhaps insulting her. At any

rate it was a brutal intimation, a selfish one—and Penn-Raven was

always brutal and always selfish. He could cry aloud of his

tragedies and disillusions, the while the woman by his side was

preparing herself to die. He could confront the husband with

a nasty truth, looking upon him with those violet eyes, half

triumphant and half sad. “Setting it rather sharply,” he could

say, “you married the wrong woman.”

Poor Bartholow and proud! Stung with the malevolent implications

with which Penn-Raven sought to gain Gabrielle,

Bartholow once leaped upon him, feeling his “thick neck luxuriously

yielding to his fingers”, and in his absurd pride thought to

throttle him. At that time he was experiencing more pain than

ever he had through the long winter before. He as a proud idealist

was waking up to the fact that to be bathed in a new light is not

to be external to sorrow.

Imagine his position. During the months previous to the spring

when he “ached with renovation”, Bartholow had suffered from

the malady of the sick-soul. His hopes were dulled, his ideals

gone crashing. In his wife, for whom he cherished a desire to

bring her closer to his thoughts, he found a woman cold and

bitter from the disappointments she had suffered. Plainly she

knew she had married the wrong man, plainly he did not know it.

For to him life meant no more than disillusion, until one day,

perhaps in April, life brought Penn-Raven with his zest for living,

with his red-corpuscular religion of healthy-mindedness. To

Bartholow, ready to catch at anything, this formidable spirit was

the light. He grasped and claimed it. The light was his remaking.

He was of the elect of earth, the twice-born. With joy gleaming

in his eyes, he was up at dawn that spring morning,

Affirming his emergence to the Power

That filled him as light fills a buried room

When earth is lifted and the light comes in.

Penn-Raven was the Friend! Blessed Penn-Raven! He had

given him gold with which to build the city of his desires. There

was Gabrielle. How glad she would be to help him build that[260]

city, that house of gold in particular where he and she should

live! She should be partner to his every mood. Gabrielle too

should receive rebirth and with him build that house. Poor

Bartholow!

Bartholow is a man upon whom the Light has fallen. What

he will do with it is the subject of the poem. Where Lancelot

was the study of a man in pursuit of the Light, Roman Bartholow

is the study of a man after the Light had come. If both men were

heroes in the sense that Galahad was a hero, no suffering would be

entailed. But these are mortal men and mortal men are plagued

with ignorance and frailty. Each has to learn that when the Light

gleams before him he must follow it alone. Alone he must live in

the Light. Alone he must fight for it. Few men know this and

of all men Bartholow was the most unaware.

Bartholow then, because he did not know that his new position

demanded the leaving of the old, still clung, but with added eagerness,

to the hope of entering into spiritual communion with his

wife. He was ever besieging her with his hopes and reproving

her for delinquency, but by degrees he came to perceive that she

would never erect that house with him. Gabrielle had two reasons,

neither of which he knew. She was no longer his wife and she

alone realized that the Light for him might mean the night for her.

Roman was too wrapt up in himself to discover the first, the

second he could learn, as Gabrielle had learned, only through

suffering. So on he hoped and thought about it. Then Gabrielle,

revealing that weakness, that was so peculiarly hers, of telling

preferably the wrong and obvious reason for her delinquency to

the right and subtle one, made it out to him that she could not

share his light because Penn-Raven was hers too intimately.

Anon came the Raven himself and forced the truth upon the

husband, making a darkness to cover him that was far more

agonizing than any he had known. When Bartholow saw this

and would abandon the Light to seek again a less tormented existence,

Penn-Raven said to him, “There is no going back”. He

said, with an insight and eloquence unusual to him,

Your doom is to be free. The seed of truth

Is rooted in you, and the seed is yours

For you to eat alone. You cannot share it

[261]

Though you may give it, and a few thereby

May take of it and so not wholly starve.

...

Your dawn is coming where a dark horizon hides it,

And where a new day comes with a new world.

The old place that was a place for you to play in

Will be remembered as a man remembers

A field at school where many victories

Were lost in one defeat that was itself

A triumph over triumph—now disowned

In afterthought. You know as well as I

That you are the inheritor to-night

Of more than all the pottage or the gold

Of time would ever buy. You cannot lose it

By gift or sale or prodigality

Nor any more by scorn. It is yours now,

And you must have it with you in all places,

Even as the wind must blow.

Like Job, when Jehovah spoke to him out of the heavens, Bartholow

listened to the sentence placed upon him by one who had

brought him light only to obscure it darkly. He listened and

behold he was like a man that understands. He was quickly to

know what Gabrielle in her suicide had done for him, and it was

well he understood, before he learned of her, that he was free to

live a life of knowledge and of sympathy with man, that he was

alone, and that not even Gabrielle could build a golden house with

him. Sadly he replied,

When a man’s last illusion, like a bubble,

Covered with moonshine, breaks and goes to nothing,

And after that is less than nothing,

The bubble had then better be forgotten

And the poor fool that blew it be content

With knowing he was born to be a fool.

Poor Bartholow! It was a hard road along which he forced

himself to go, proud, defiant, hopeful, until the night when he

found the Raven, like a reproving older child, pinning him to his

chair lest he again try to annihilate him. After that he knew what

was before him, for he was no longer hopeful, defiant, or proud.

He had learned as Lancelot and like him

[262]

in the darkness he rode on

Alone; and in the darkness came the Light.

Penn-Raven had brought the Light and showed Bartholow how

it must be followed. But it was Gabrielle who was “too beautiful

to be alive” that revealed to him its incessant worth. It was

Roman’s wife who failed and died, Gabrielle whom Penn-Raven

loved, for whom Roman hungered, Gabrielle, whose

dark morning beauty

Was like an armor for the darts of time

Where they fell yet for nothing and were lost

Against the magic of her slenderness,

Gabrielle in whom there was much of spring, much of chilly fall,

much of Botticelli—a shadowed mingling of violets and wintergreen.

Bartholow saw this and that morning, when she stood in

the doorway, half awake, watching his springtime antics of adoration

of his new self in his looking-glass, he found her irresistible

and

crushed

The fragrant elements of mingled wool

And beauty in his arms and pressed with his

A cool silk mouth, which made a quick escape,

Leaving an ear—to which he told unheard

The story of his life intensively.

“He told unheard”. There, there was the cloud that must bring

him darkness. Gabrielle did not heed him.

For the sake of an explanation, let us first attribute her listlessness

to a dislike of physical affections from her husband. Let us

say, along with Penn-Raven, that she retreated from Roman

because she was an adultress, that she told him she would never

build that house because that house would be founded on a lie.

Infidelity must out. How great then would be the tumbling down

of Roman’s house! A woman guilty as she could never hope to

build a spiritual house.

Such an explanation of Gabrielle’s lack of enthusiasm is at first

glance somewhat superficial. The Gabrielle of the poem who has

moved us so profoundly is not the woman Penn-Raven describes

in this manner. Gabrielle was not motivated by selfishness and

cowardice. She did not die because she feared her husband.[263]

Yet, however one interpret Gabrielle, this judgment of her, which

Penn-Raven voiced, remains partially correct. Gabrielle was

essentially “flower and weed together”. In the eyes of the men

the weed was uppermost and, provokingly at that, discouragingly

beautiful. Wintergreen and violets! This weed to Bartholow

was just a bit shallow and colder than any fish in any ocean. She

mocked his renascent gestures, his Greek, and even mistook Apollo

for Narcissus when she found him looking in his mirror. She

even had a cursed habit of innuendo, so it seemed, for after a

pretty speech of his about a soul groping in its loneliness, out she

came with a furtive remark that the fish upon her plate was

“beautiful, even in death”.

Shallow Gabrielle! Selfish, faithless, beautiful Gabrielle! Thus

men saw her until it was too late to see her again. Like Flammonde,

what was she and what was she not?

Gabrielle’s superficiality, at first so evident, appears to be explained

by her later actions. In cantos IV and V Gabrielle is very

far from any taint of superficiality. It is only at the outset that

she gives the impression. This is done by Mr. Robinson in order

that the reader may understand the attitudes of Bartholow and

Penn-Raven toward her. What Gabrielle really is the reader will

shortly discover. But the touch of the weed, nevertheless, remains.

It was part of Gabrielle and she employed it as a protection against

her lovers. Fearing lest Penn-Raven find her suffering, she preferred

to be tortured by him rather than reveal herself. Against

Bartholow she adopted it because, knowing herself to be totally

outside his mystical experience, she hoped to ease his desires of

building impossible houses.

Gabrielle, indeed, is worthy of infinite pity. Beset at once by

the Raven’s exhortations that she go away with him, and by her

husband with his mysticism, her situation was precarious. No

light had come to her, but since it had fallen blessedly upon her

husband, to aid him in his holding it was her duty. That she

might desert him to sink again into the night she refused to consider.

That she might do nothing but remain with him she

pondered carefully. If so she stayed she could not save him. She

was not worthy, as he himself had bitterly reproached her, of his

mysteries. Yet how he prayed she might be! Without her all[264]

would be as it had been, though Gabrielle knew differently. She

knew he must follow the Light alone. Such was the law. It was

decreed that she look with “tired and indolent indifference” upon

the spring that was for Roman the beginning of a new life. “I

am not worthy of your mysteries”, she had said with an insight at

once supreme. Afterwards she told him,

You understand it

You and your new-born wisdom, but I can’t;

And there’s where our disaster like a rat,

Lives hidden in our walls.

...

Even a phantom house if made unwisely

May fall down on us and hurt horribly.

A different light was come to Gabrielle. As she spoke these

words, a “pale fire” descended upon her, shriveling the weed,

giving luxuriance to the flower. A miracle alone could have

revealed to her the truth, and if it was not a miracle, it was the

light from her own tragedy. She had failed, in marrying Bartholow,

to find the being she sought. Likewise Penn-Raven had

disappointed her. But she loved her husband for the light that

had come to him. The Light was greater than herself. Wherefore

of Bartholow she thought,

If my life would save him,

And make him happy till he died in peace,

I’m not so sure he mightn’t have it.

No one had known the flower that grew within the weed. No

one had cared to search beyond a certain libidinous examination.

She, however, was aware. The command was come that she save

Bartholow. She accepted. With her determination made she

resisted two trying interviews with Penn-Raven and her husband,

who successively tried to wound her sensitivity more deeply. The

Raven groaned about his tragedies and disillusions, while Gabrielle

was going out to die. There was nothing more in life for her

than an austere duty, implacable and dark.

Where the Light falls, death falls;

And in the darkness comes the Light.

But a cruel farewell to her husband and the faces were for her

no more. This woman, greater in every way than Vivian or[265]

Guinevere, Gabrielle, the one complete and incisive expression of

a poet’s ideal, the crowning achievement to a brilliant tier of

characters, Gabrielle who stepped above the broken ruins of her

life to save a weak man, this Gabrielle crept stilly from the house

and, before descending, paused a moment in the night.

Now she could see the moon and stars again

Over the silvered earth, where the night rang

With a small shrillness of a smaller world,

If not a less inexorable one,

Than hers had been; and after a few steps

Made cautiously along the singing grass,

She saw the falling lawn that lay before her,

The shining path where she must not be seen,

The still trees in the moonlight, and the river.

Yes, she was surely dead before she died. Tragedies had been

her secret playthings and there was nothing left, nothing but to

follow her peculiar light. Like Juliet her dismal scene she must

act alone. She must go—forever. But the going was not difficult,

for she was dead before she died.

Truly if one lingers over this pitiable death of Gabrielle’s, protesting

against a destiny that will enact such evil, there is bound

to rise in one’s mind the many instances in Mr. Robinson’s poetry

where the same story is told. It is in The Children of the Night

that this judgment of the world found its earliest expression,

thenceforward developing until it has now reached its culmination.

Here, in Roman Bartholow, in the magic loveliness of Gabrielle

it has come to a noble conclusion.

Previous to this poem Mr. Robinson’s philosophy has expressed

itself negatively. It is his belief that evil is the result of moral

choice. He does not call disease, accident, or war by the name of

evil, because it is possible to look forward to a day when such

excrescences will be removed. Evil, to Mr. Robinson, is that

which is ineradicable and the ineradicable is the situation resulting

from moral choice. Man has little free will. He is continuously

obliged to make a choice against his wish, a choice that will bring

disappointment. We have seen how Orestes was locked in evil

perplexity when the alternative was presented: either to obey

heaven, slay his mother, and be damned by earth, or to obey earth,

forgive his mother, and be damned by heaven. Whichever[266]

road he followed evil overtook him. Whichever road we choose,

says Mr. Robinson, evil must overtake us—with this one exception,

however, that whereas Aeschylus believed the gods brought man

to his doom, Mr. Robinson maintains that it is man’s own frailty.

Take Lancelot for an example. Lancelot has come to a point

where he must make a moral choice. Either he can accept the

Light and forsake Guinevere, or he can retain the Queen and

lose the Light. The alternative is implacable. The one or the

other, it says. There is no middle way nor any synthesis. To

accept the new situation and leave the old, that is the way of truth.

Only by that way can man hope to achieve happiness. If he

attempt to mediate, then he will lash himself and cry in Lancelot’s

words,

God, what a rain of ashes falls on him

Who sees the new and cannot leave the old!

Thus, previous to Roman Bartholow, Mr. Robinson, believing

that man can rarely leave his old surroundings for the new, has

developed his philosophy from the negative side. He has not

treated of the attainment of the Light, but has showed the struggle

of the man who is making the choice. He has been interested in

the man’s failure and in consequence he has written of Merlin,

Lancelot, and of Seneca Sprague.

With Roman Bartholow, however, he has represented in

Gabrielle a complete and final expression of the positive side of

his philosophy. Many years ago in an exquisite lyric, Bon

Voyage, he wrote fleetingly of a man who saw his light and

claimed it. But the poem was only a scherzo, a dash down the

hill. Mocking the “little archive men” who tried to extract therefrom

a “system” of thought, it raced away. Yet it contained a

seed that to-day has burst into a flower that Gabrielle is, or was.

It told of a man who had left the old. He had been as courageous

as Galahad. To-day Gabrielle is such.

Roman, of course, in finding the Light, was obliged to abandon

his earlier hopes of building that house with Gabrielle. Roman

like Lancelot was unable to meet that requirement. He failed,

and would have perished had it not been for Gabrielle. She was

to reveal to him her incessant worth. The Light for Gabrielle

demanded a mad sacrifice. There was no happiness entailed.[267]

There was alone the recompense of that cold, resistless river.

Leaving an inexorable world as she followed the light, she was, to

complete the list of the poet’s figures, the one

who had seen and died,

And was alive now in a mist of gold.

Thus, after the tale is told, comes the realization of the ultimate

isolation of man. Gabrielle had gone away alone. Penn-Raven

too had disappeared. Each was bound from the other by ineradicable

law. There never could have been a golden house with

two to build it. It is not thus we are made. Bartholow was to

come to understand that he could not build but by himself, that

his renascence was a gift to him alone. It was Umfraville, who

saw what he could see and was accordingly alone, who summed

it up when he said,

There were you two in the dark together

And there her story ends. The leaves you turn

Are blank; and where a story ends it ends.

So Bartholow left him there on the steps of the old house that

he had sold after the others had disappeared. Umfraville was

free and Bartholow, with his memories before him, was alone and

free. A cold fire was his light to prove, but he knew it never

would go out. There would always be with him the memories of

Gabrielle, the cool fragrance of her body, the silent beauty of her

deed. The key he held in his hand was the key to the ivied house.

The key he held was his no longer. For the last time it had locked

for him a door that once had opened to so much pain. But a tide

was come and there were no more sand castles. All was as it had

been and was to be.

They are all gone away,

The House is shut and still,

There is nothing more to say.

LEWIS P. CURTIS.

I.

It was one of those blistering July afternoons that sometimes

descend upon people who have traveled a long way in the

palatial discomfort of a Pullman, only to find themselves completing

the last leg of their journey amid the democratic rattle-ty-bang

of an antique, plush-lined day-coach. Several cars in

advance, the energetic branch line locomotive was belching clouds

of smoke and whistling shrilly at each spralling crossroad; while

within the day-coach itself, a faded sign proclaimed that persons

of color would only be tolerated on the last three seats of each

car, and thus localized the scene to one of those down at the heel

Southern railroads that have not yet recovered from the Civil

War.

The greater part of the passengers were negroes, prosperously

dressed, and covertly taking pains to be as obnoxious as possible

to the little group of whites entrenched in a compact and strategic

position among the last three seats of the car. Of the latter, one

was a grey-haired gentlewoman of the old South, her expression

combining with the pride of blood a certain indefinable mellow

sweetness. A blue-eyed child of six sat by her side, and perhaps

he too was conscious of his descent, but he kept his nose glued

close to the window for all that. Behind these two, in a little

compartment formed by turning two seats together, sat three

ruddy farm girls in uncomfortable attitudes of acute self-consciousness.

They had been giggling and overflowing with spirits

during most of the trip, but the appearance of a young man in the

seat opposite, at the last junction, had reduced their exuberance

and heightened their curiosity. For, on one side of the neatly

strapped suitcase which he had erected beside him as a sort of

barrier from the negroes, appeared the legend, “P. R. Melton,

N. Y. C.”

[269]

II.

Thought Philip Melton, “Niggers ... niggers and heat ... the

Devil putting collars of mustard plaster on damned souls....

“Common, common, common sort of girls ... perfectly decent,

but not my class ... too muscular, or maybe it’s fat....

“Nice little chap ... eyes, hair, skin ... football some day ...

wonder if his grandmother’s a Carroll ... aristocrat....

“Hot ... gosh....

“Marion ... letters ... letters in my pocket ... mush, but not common

... my class ... glad I’m a gentleman ... ‘known by what he

does not do’ ... clickety clack, clickety clack, clickety clack....

“Marion ... never wrote a girl stuff like that before ... laps it

up all right ... must practice on some one ... my class, not common

at all....

“‘The man who seduces a pure country girl because he fears

the diseases of the city deserves to be flayed alive’ ... funny ...

seduce is such a nasty word....

“Clickety clack, clickety clack, clack, click.... Fool train had to

get here some time....”

[270]

III.

As he clattered down the precipitous steps of the day-coach,

the last of which was a clear jump of at least two feet, Philip

saw the tall, still vigorous figure of his uncle detach itself from

the crowd and come forward with its perpetually surprising grace.

“Glad to see you, boy.” The words had something soothingly

restful about them that betrayed the unhurried country gentleman.

“A very long, hot ride, I’m afraid, and the train late as usual.

Your mother well? And Don’ld?” The last name was slurred

with the paternal carelessness of the man who has lived to ask

his youngest brother’s son whether that brother is well.

“I brought Marion over in the car.” The clear eyes twinkled

mischievously. “She was sitting on the porch as I drove by, and

it seemed to me you rather liked her last summer. Mind she

doesn’t wind you around her little finger before your two weeks

are over. These ministers’ daughters—” The phrase melted

away, and his uncle turned to direct the chauffeur. But Philip

smiled inwardly. He knew his favorite uncle had once been “a

bad man among the ladies”, as they put it in the South.

[271]

IV.

That night Philip lay half smothered in his enormous feather

bed, and thought again, this time in retrospect. He was a boy

whom a nagging illness had kept secluded during most of his

early life, and the previous Freshman year at college had filled

him with restless new ideas. Adolescence, too long delayed, was

upon him with a vengeance, at last.

“Good move, coming here ... she’s certainly one of the most

naturally beautiful girls I ever saw ... skin a little off, perhaps....

Lord, how can people stand to eat sausages the way they do here

... we’ll have them to-morrow ... in July!

“Somehow I feel too overconfident.... God help us if she ever

really falls in love with me ... still, I don’t quite see why that’s

my lookout ... Don Juan....”

“See here, Philip Melton, you’re an ass!” (That was the voice

of common sense, speaking in crisp periods.) “You’ve never kissed

a girl in your life, and you’ve thought too much about it lately.

You’ve always been too bashful to even flirt with sub-debs. And

now that curiosity, not romance, has gotten hold of you, and

you’ve achieved the enormous conquest of receiving a few sloppy

letters from a country clergyman’s daughter, you think—! Don

Juan, blaah!” (And common sense disgustedly retired.)

But Philip’s thoughts soon began to drift in the old channel.

And egotism, which lies crushed into its corner during waking

hours, came out and sported in the land of demi-dreams.

“She blushed once, really.... I saw her do it ... and she let me

take her hand practically as long as I wanted to, to look at her

ring.

“Oh Phil, you’re not so bad ... you’ll learn ... learn ... lllle....”

Sleep.

[272]

V.

The river was not very broad. It curved and twisted between

ranks of weeping willows, and, just as Philip grew tired of rowing,

a perfect grotto of a cove beckoned them to come in and rest.

Marion had taken off her ugly rubber bathing cap while Philip

rowed, and as they slid among the green and golden shadows of

the willows, he was almost startled at the beauty of her hair. It

seemed to flow about her shoulders in a leaping cascade of light

and shadow, and Philip’s throat tightened as he watched it. Then

he remembered that he was in search of love, not beauty, and

that with a girl one must “shoot a line”. The boat touched the

bank with a soft plash, and Philip summoned courage to mention

one of his poems, which he said had come to him while he was

rowing her up the river.

It began:

“Oh, how I wish I might transmute the arts,

And make of poetry a long caress—”

and, aside from the questionable novelty of addressing a short

poem to one’s love in Elizabethan blank verse, it was neither

better nor worse than the efforts of many young poets, not as yet

nipped in the bud.

[273]

VI.

A week later, Philip could lie out on the terrace of his uncle’s

garden, sunning himself, and muse somewhat as follows:

“I’m getting the hang ... not a doubt in the world ... last night,

now ... her hair is awfully nice when you feel it on your cheek....

“I think I’d better not try poetry ... again ... maybe ... it sounds

too well ... too as if I weren’t really feeling deeply....

“Still I’ve got her going mighty well ... last night she said,

‘Maybe, just one before you go’.... I’ve thought of an awfully

romantic way to do it....

“Poor Marion.... I wonder if I could really break her heart....

I mean I hope she’ll soon get over it when I’m gone....

“Anyhow I’ll never be afraid of Peggy Armitage again.... I’ve

got the hang ... damn it ... got the hang....”

[274]

VII.

The Gods seemed to have conspired with Philip to make his

last night in the South all that he could have wished. He and

Marion had been rowing again in the moonlight, and now that it

had really grown very late, they were sitting in a secluded arbor

at the far end of the garden, which looked out over the river.

The moon, which had been waxing ever since Philip’s arrival,

was now full. And great trailing strands of the weeping willows

shut them up alone, in a little secret lattice of moon shadows.

Her head was resting lightly against his shoulder, and they were

speaking only now and then in whispers. She was very lovely, a

pale lady of the moon, and he felt himself yearn strangely toward

her. The note in his voice was not forced now. She seemed to

feel it, and as his eager lips bent down to hers she met them firmly

with her own, warm and yielding. For a long, long minute the

kiss lasted. Philip’s sensations seemed to ebb and fuse together.

Then suddenly the moment passed. Habit reasserted itself, and

Philip thought, “Lord! The trapper trapped! Another minute

and I’d have proposed!”

[275]

VIII.

It was afternoon on the broad, cool veranda. Philip had departed

northward by the morning train, and a twinkling-eyed old

gentleman was sipping great cooling sips of julep through a straw.

He had once been a bad man among the ladies, and perhaps a

casual observer might have thought he was so still. At least, the

laughing girl at his side seemed not to lack for entertainment.

“Ah but, my dear Maid Marion, you forget that after all

Philip is my nephew.”

“And that should make him quite invincible to my poor

charms?”

“Invincible! And you say he kissed you! Really, my dear,

these minsters’ daughters—”

“And you a vestryman! But seriously, Mr. Melton, Philip got

to making love awfully well toward the last—except the poetry—that

was always terrible! You are to be congratulated, sir! With

my aid you have started your nephew on the road to ruin!”

“Dear child! And have you never heard me say he is my

favorite nephew?”

LAIRD GOLDSBOROUGH.

[276]

Notabilia

On the Francis Bergen Medal

One of the most charming of all the intellectual traditions of

Yale is the group of Francis Bergen Memorial lectures

delivered each year gratis to the University. Mr. Frank Bergen

has lately added another memorial to his son. It takes the form

of a gold medal to be awarded each year at the Lit. dinner by the

outgoing board to the author of the most creditable contribution

to the Lit. during their term of office. The editors themselves

are ineligible.

Francis Bergen was in the Class of 1914, and a member of the

Lit. board of that year. He was a college poet of distinction and

promise. Had it not been for his tragic death on his way to

Plattsburg, and with a few more years of lyric inspiration, it is

likely that his poetry would have served itself as his own commanding

memorial.

As it is, he is a traditional character of the Renaissance. You

will meet no graduates of his generation who do not remember

in greater or less degree Bergen’s extraordinary Turkish water

pipe, and his long conversations with imaginary personages in his

own room, unconscious of the attentive and astonished ears of

his classmates about him. And the miracle is that in the Yale of

then, still smacking of the Y-sweatered bulldog ideal, he should

have been universally loved and admired, in spite of eccentricity.

Such tales are indeed the romance of the beginning of wisdom

at Yale.

This medal, this awarded piece of gold, this honor in the eyes

of the literati of each winner’s generation at Yale, has about it

a glamor of remembrance, a glory peculiar to itself. It is in

memory of a poet whom the Gods loved too well, and did not allow

to sing his fill. By its own name it is an inspiration more precious

than gold.

M. E. F.

The Captain’s Doll. By D. H. Lawrence. (Thomas Seltzer.)

There is, in all living literature, a kind of between-the-lines

expression of the atmosphere belonging to the described

period and the described place. With the advent of literary

interest in thought as well as action, the point of view peculiar to

the time, the race, and the situation has been present also. To

create these mysterious things by connotation from the written

word, so that the reader becomes, temporarily, contemporary and

incident with the characters of the story, is at least one of the

essentials of a permanent novel. And while I am not at all prepared

to predict permanency for The Captain’s Doll, I feel that

Mr. Lawrence has been particularly happy in this strange business

of evoking environmental atmosphere.

For instance, there is a moment in the first “novelette”—the

volume contains three—when the German Countess-heroine and

the Scotch Captain-hero are climbing a Tyrol Alp in a motorbus.

The Alps and a motorbus! Everywhere, against the naked looming

rocks and great glaciers, the blue sky and the blown clouds, are

bulky trucks, picknickers, and “the wrong kind of rich Jews”.

There are wild mosses and berry bushes among the rocks, but

“the many hundreds of tourists who passed up and down did not

leave much to pick”. Yet the exhilaration and the spell that

belong to climbing even a civilized mountain are there; the civilized

climbers get out of their lorry and feel it. The German Countess

feels it in a glad, pagan abandonment: she likes the wind in her

face, and she likes to see “away beyond, the lake lying far off and

small, the wall of those other rocks like a curtain of stone, dim

and diminished to the horizon. And the sky with curdling clouds

and blue sunshine intermittent”. She “breathes deep breaths”,

and says, “Wonderful, wonderful to be high up!” The English-Scot

feels it, but in a different way. “His eyes were dilated with

excitement that was ordeal or mystic battle rather than the

Bergheil ecstacy.” He looks soulfully out, out of the world,[278]

hating the mountains for their excitement, and their “uplift” that

takes him beyond himself, and he feels bigger than the mountains.

All that, as Mr. Lawrence tells it, comes pretty close to “getting”

these races in a phase of our era, a phase which is important

because man in relation to nature is man at his best. And anyone

who has climbed mountains of late years will appreciate the realism

of the picture, and of the story’s atmosphere.

But I said I could not predict the future for The Captain’s Doll.

To me, Mr. Lawrence seems supremely able in handling the psychology

of the moment, but less effective with the dynamic

psychology necessary for his drama. I am not sure his characters

would act as they do; I think no others would. Through a series

of individual snapshots which are real to the life, Captain Hepburn

and Countess Hannele move in a manner I cannot take for

granted. More decidedly I should apply this criticism to the

principals in the second story, The Fox. Over time, these people

are all a little queer: it is the fault in most of this “new” kind

of writing.

D. G. C.

Members of the Family. By Owen Wister. (The MacMillan

Company.)

When the cauldron of contemporary American literature has

boiled down and the dross been skimmed off by the years,

there will be a special and enduring mold set aside for the works

of Owen Wister. In his writings and in the pictures of Frederick

Remington a richly romantic period of our national life will be

long preserved. The Virginia, Lin McLean, and Scipio Le Moyne,

even as the nightingale, were not born for death. As Scipio

himself remarked, “I ain’t going to die for years and years.”

The eight short stories included in Members of the Family are

typical of Mr. Wister’s most delightful and vivid manner. Those

who enjoyed The Virginian or Red Men and White will wax

happy over such tales as The Gift Horse and Where It Was.

Owen Wister’s characters are unusual to us, but like that most[279]

fanciful of characters, Long John Silver, they live. For humor,

strength of plot, characterization, and general worth this collection

takes rank with the very highest.

F. D. A.

A Book of British and American Verse. Edited by Henry Van

Dyke. (Doubleday, Page & Co.)

As a general rule anthologies are of a distinct sameness. The

most noticeable thing, therefore, in regard to this collection

of verse by Henry Van Dyke is his novel method of arrangement.

Instead of fitting the poems in chronologically he segregates them

according to their poetical form. The volume is divided into six

sections, devoted respectively to: ballads; idylls or stories in verse;

lyrics; odes; sonnets and epigrams; and elegies and epitaphs.

As to the selection, it is as judicious as one would expect coming

from Mr. Van Dyke. An attractive feature is the inclusion of a

considerable number of modern poems. In quantity the collection

lies between the Oxford Book of English Verse and Burton

Stevenson’s Home Book of Verse, being nearer to the former.

It is especially adapted for use in class-room work and is a valuable

addition to a small library, from a utilitarian as well as an aesthetic

viewpoint.

F. D. A.

The Goose Step. By Upton Sinclair. (Paine Book Co.)

Thorough discussion of this latest book by Upton Sinclair

is a task that would require many pages. A brief dissertation

upon his remarks about Yale, however, will suffice to shed considerable

light upon the book as a whole.

Commenting upon the University in general, Mr. Sinclair remarks:

“But the secret societies come in, and now Yale is just

what Princeton is, a place where the sons of millionaires draw

apart and lead exclusive lives.” Disregarding for the moment

the innuendo cast upon the societies here, it seemed best to interview

the millionaire we know in order to ascertain whether he was[280]

really being secretly exclusive. The cause of research suffered

when he proved to be out for the evening wearing the dress suit

of his neighbor, who was working his way through college and

could not use it himself.

Concerning societies Mr. Sinclair further opines that they encourage

intoxication and venereal disease, but dictate the choice

of clothing, slang, and tobacco, while preventing originality of

cogitation. It is a sad thought, and the woeful plight of the

American college lad is typified by the brazen indifference with

which he bears his shame.

Mr. Sinclair certainly exaggerates—we are now speaking constrainedly,

ourself—but his sincerity no one can doubt, as no one

can sweepingly deny all his charges. He may irritate or he may

distress or he may merely edify, but he always gets a reaction.

F. D. A.

Han and Cherrywold came across the campus together.

“What do you think of our first issue?” asked Han.

“Well,” replied Cherrywold, “a little thin, to be sure, but very fine goods—and

mostly home-made, at that.”

“Yes,” mused Han, “and this one shall be better. I look forward to a

short and pleasant evening.”

So saying, they approached the luxurious and delicately heated office

confidently and in the best of spirits. But oh, what enemies lurk in the dark

places ever eager to strike a treacherous blow at the Muse! In the window

of her palace hung a filthy, yellow sheet advertising that altogether despicable

sport of debating. With a mighty oath both jammed their keys into the

lock, tore to the window, and stamped upon this latest outrage. That done,

with spirits not altogether as calm as before, they sat down to wait for the

others, who were, of course, late. In a short while they were joined by

ante-moral, pro-subjective Rabnon. The conversation turned, purely by

chance, upon bastard sons. The question before the house was: Whose

was the greater—Aaron Burr’s or Elihu Yale’s? So rife became the argument

that Cherrywold was dispatched to follow up certain clues and obtain

further information upon the question. In a short while he returned

greatly excited and out of breath. A number of prominent men

had been interviewed—one of whom, though it may be hard to believe, was

a professor. It was, however, decided to withhold the verdict on this remarkable

case until the following month. As we go to press, new evidence

is pouring into the office, owing to our expert secret service department, and

we fully expect to startle the world by an announcement of momentous

import at a near date.

In spite of this coup, our spirits were sorely tried by the sudden entrance

of Mr. and Mrs. Stevens—one hour late! Due to the latter’s persuasive

smile, we controlled our language. Beside, one must be cautious in the

presence of three aliases. Cherrywold re-read Han’s poem for the tenth

time.

“On reading this more and more,” he remarked, “I like it less and less.”

“Then read it less and less,” suggested Mr. Stevens. His wife tittered

approvingly.

After that there was comparative silence, broken only by the muttered

threats of Cherrywold each time he pulled out his watch. Another half-hour

smoked by. Suddenly out of the darkness there appeared in the doorway

a halo. With badly shaken nerves, all stared wildly at the light. Suddenly

the hushed expectancy was broken.

[282]

“Well, if it isn’t little sunshine,” cried Rabnon. “And two hours late

at that!”

“Then he’s the cause of all this daylight saving muddle,” asserted Mrs.

Stevens. “Land sakes! Who’d think it to look at him?”

“My gosh!” yelled Cherrywold. “Aren’t we ever going to get down to

work? If the rest of you don’t stop your giggling there won’t be any May

issue. Now, Han, what do you want after this title; I suppose dashes?”

“No, thank you,” replied Han sweetly. “I’ll take dots.”

Eventually something was done, but no one knew exactly what nor cared

much, for by that time it was far into the night and we were all three-quarters

asleep. Some unknown person by the name of Briggs likes to tell

people how to ruin a perfectly good day. He better look to his laurels, for

he’ll have to go some to beat a new series, entitled “How to ruin a perfectly

good evening,” by

CHERRYWOLD.

Yale Lit. Advertiser.

Compliments

of

The Chase National Bank

HARRY RAPOPORT

University Tailor

Established 1884

Every Wednesday at Park Avenue Hotel,

Park Ave. and 33rd St., New York

1073 CHAPEL STREET NEW HAVEN, CONN.

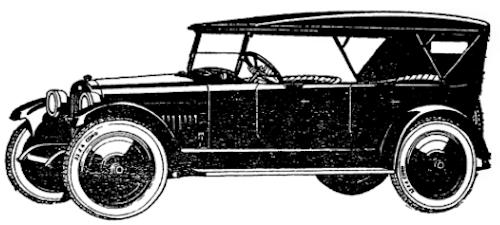

DORT SIX

Quality Goes Clear Through

$990 to $1495

Dort Motor Car Co.

Flint, Michigan

$1495

The Knox-Ray

Company

Jewelers, Silversmiths,

Stationers

- Novelties of Merit

- Handsome and Useful

- Cigarette Cases

- Vanity Cases

- Photo Cases

- Powder Boxes

- Match Safes

- Belt Buckles

- Pocket Knives

970 CHAPEL STREET

(Formerly with the Ford Co.)

Steamship

Booking

Office

Steamship lines in all parts

of the world are combined

in maintaining a booking

agent at New Haven for

the convenience of Yale

men.

H. C. Magnus

at

WHITLOCK’S

accepts booking as their direct

agent at no extra cost to

the traveler. Book Early

Top-Hole Approval

New golf suits. Ripping,

rakish, rugged

distinction! For men

of taste. Knickers for links

and field! And, of course,

trousers for town! Three

piece sport suits for good

sports.

- SPORT SWEATERS

- GOLF HOSE

- GOLF CAPS “KNOX”

- “KNOX” COMFIT STRAWS

SHOP OF JENKINS

940 Chapel Street New Haven, Conn.

The Nonpareil Laundry Co.

The Oldest Established

Laundry to Yale

We darn your socks, sew

your buttons on, and make

all repairs without extra

charge.

PACH BROS.

College

Photographers

1024 CHAPEL STREET

NEW HAVEN, CONN.

CHAS. MEURISSE & CO.

4638 Cottage Grove Ave., Chicago, Ill.

POLO MALLETS, POLO BALLS, POLO SADDLES and

POLO EQUIPMENT of every kind

Catalog with book of rules on request

CHASE AND COMPANY

Clothing

GENTLEMEN’S FURNISHING GOODS

1018-1020 Chapel St., New Haven, Conn.

Complete Outfittings for Every Occasion. For Day or Evening

Wear. For Travel, Motor or Outdoor Sport. Shirts, Neckwear,

Hosiery, Hats and Caps. Rugs, Bags, Leather Goods, Etc.

Tailors to College Men of Good Discrimination

1123 CHAPEL STREET NEW HAVEN, CONN.

Established 1852

I. KLEINER & SON

TAILORS

1098 Chapel Street

NEW HAVEN, CONN.

Up Stairs

Only a small

measure of thought will bring the decision

that it is not so strange after all

that Roger Sherman photographs seem

to live.

Guaranteed—“Always a Better Portrait.”

Hugh M. Beirne

227 Elm Street

Men’s Furnishings

“Next to the Gym.”

Foreign Sweaters, Golf

Hose, Wool Half Hose, all

of exclusive and a great

many original designs.

Our motto: “You must

be pleased.”

John F. Fitzgerald

Hotel Taft Bldg.

NEW HAVEN, CONN.

Motor Mart

Garage

OLIVE AND WOOSTER STS.

Oils and Gasoline

Turn-auto Repair Service

The Yale

Literary Magazine

has trade at 10% discount

with local

stores

Address Business Manager

Yale Station

“Costs less per

mile of service”

The new Vesta in

handsome hard rubber

case, showing

how plates are separated

by isolators.

Vesta

STORAGE BATTERY

VESTA BATTERY CORPORATION

CHICAGO

The Brick Row Book Shop, Inc.

Booksellers—Importers—Print Dealers

DR. JOHNSON

A PLAY

by A. Edward Newton, Author of The Amenities of

Book-collecting, and A Magnificent Farce.

We suggest that Mr. Newton’s play would look well

on your shelf of 18th Century books,—and more than

that, it reads well.

Lovers of Johnson will welcome this newest addition

to the Johnson family.

The Brick Row Book Shop, Inc.

New York, 19 East 47th St. New Haven, 104 High St.

Princeton, 68½ Nassau Street

THE NASH SIX TOURING CAR

Five Disc Wheels and Nash Self-Mounting Carrier, $25 additional

NASH

Compare the Nash Six Touring, unit for

unit, with any other car of similar price

and you will be immediately impressed

with its outstanding superiority. In every

feature of construction and every phase of

performance the Nash Six leads the field.

THE NASH MOTORS COMPANY

KENOSHA, WISCONSIN

FOURS and SIXES

Prices range from $915 to $2190, f.o.b. factory

NEW HAVEN

CONNECTICUT |

522 FIFTH AVENUE

NEW YORK CITY |

L’Ile Percée

The Finial of the St. Lawrence or

Gaspé Flaneries

Being a Blend of Reveries and Realities of History and Science

of Description and Narrative as also

A Signpost to the Traveler

By John M. Clarke

Author of “The Heart of Gaspé”; D.Sc., Colgate, Chicago,

Princeton; LL.D., Amherst, Johns Hopkins; member of

the National Academy of Sciences; New York

State Paleontologist.

Here is a book—the first for many years, so far as our knowledge

goes—which can legitimately be compared with that classic

of regional literature, Thoreau’s “Cape Cod.” Its author’s subject,

like Thoreau’s, is one of the quaintest and most fascinating

provincial districts of the continent; a district which has the

literary advantage of being to this day less known than Cape

Cod was, even at the time when Thoreau tramped its length.

Illustrated, Price $3.00.

Poems of Giovanni Pascoli

Translated by Evaleen Stein

A generous selection from work of the most permanently

significant of modern Italian poets.

Price $1.50

Wind In The Pines

By Victor S. Starbuck

A volume of verse expressing the call of the open.

Price about $1.50