ENGLAND

UNDER

THE ANGEVIN KINGS

BY

KATE NORGATE

IN TWO VOLUMES—VOL. II.

WITH MAPS AND PLANS

London

MACMILLAN AND CO.

AND NEW YORK

1887

All rights reserved

Title: England under the Angevin Kings, Volume II

Author: Kate Norgate

Release date: June 19, 2022 [eBook #68347]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Macmillan and Co, 1887

Credits: MWS, Fay Dunn, State Library of Western Australia and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber, and is placed in the public domain.

Please see the note at the end of the book.

ENGLAND

UNDER

THE ANGEVIN KINGS

ENGLAND

UNDER

THE ANGEVIN KINGS

BY

KATE NORGATE

IN TWO VOLUMES—VOL. II.

WITH MAPS AND PLANS

London

MACMILLAN AND CO.

AND NEW YORK

1887

All rights reserved

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| Archbishop Thomas, 1162–1164 | 1 |

| Note A.—The Council of Woodstock | 43 |

| Note B.—The Council of Clarendon | 44 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Henry and Rome, 1164–1172 | 46 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Conquest of Ireland, 795–1172 | 82 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Henry and the Barons, 1166–1175 | 120 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Angevin Empire, 1175–1183 | 169 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| The Last Years of Henry II., 1183–1189 | 229 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Richard and England, 1189–1194 | 273 |

| CHAPTER VIIIii.vi | |

| The Later Years of Richard, 1194–1199 | 332 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| The Fall of the Angevins, 1199–1206 | 388 |

| Note.—The Death of Arthur | 429 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| The New England, 1170–1206 | 431 |

LIST OF MAPS |

|||

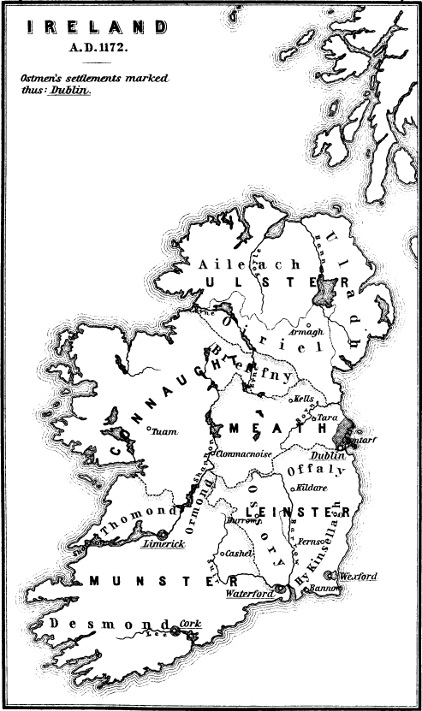

| III. | Ireland, A.D. 1172 | To face page | 82 |

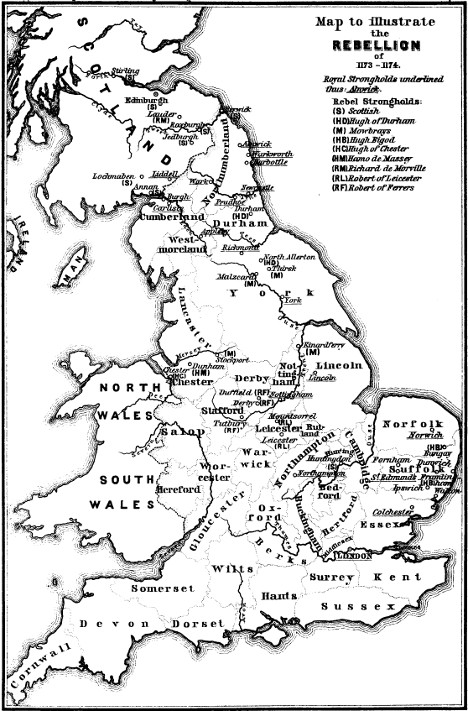

| IV. | Map to Illustrate the Rebellion of 1173–1174 | ” | 149 |

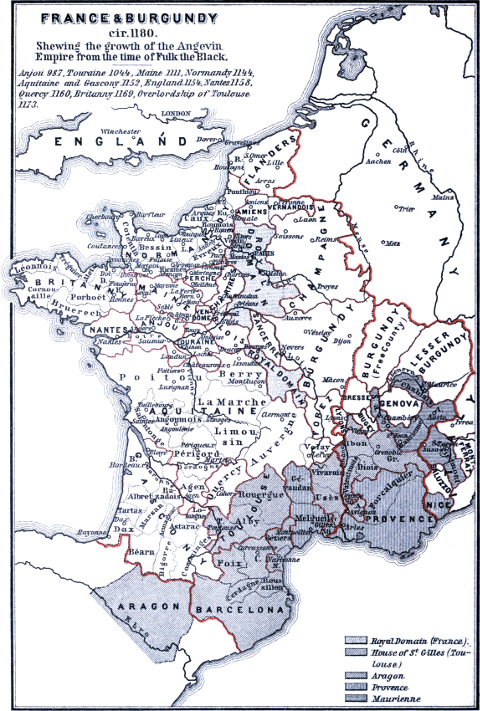

| V. | France and Burgundy c. 1180 | ” | 185 |

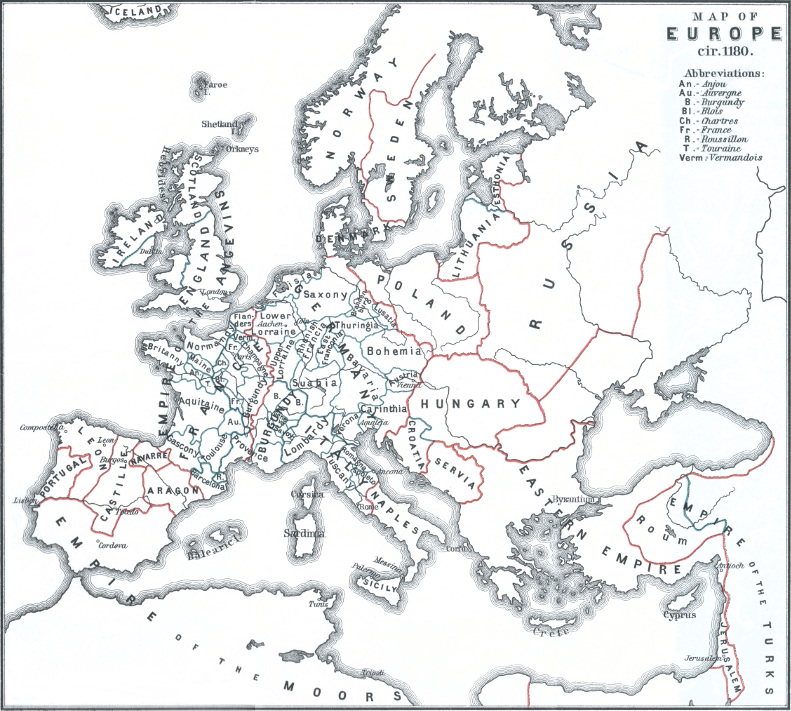

| VI. | Europe c. 1180 | ” | 189 |

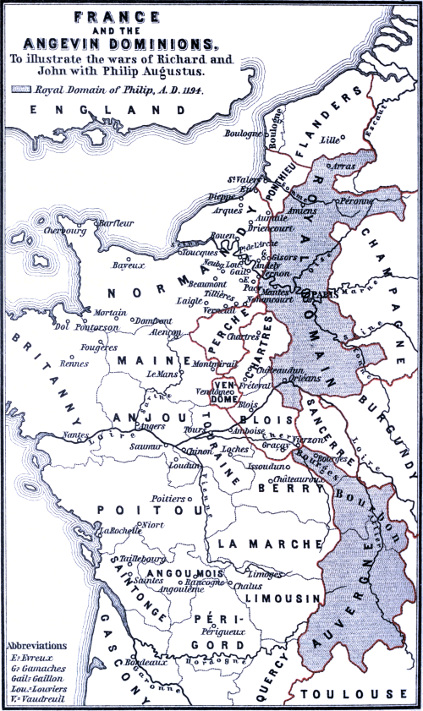

| VII. | France and the Angevin Dominions, 1194 | ” | 359 |

PLANS |

|||

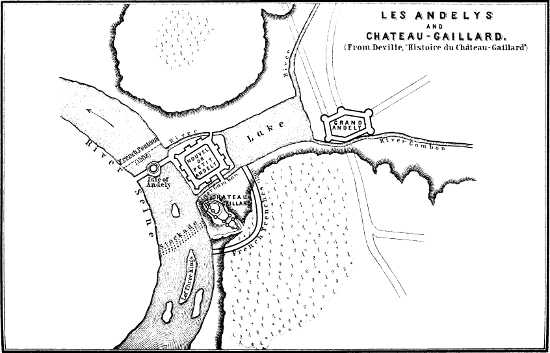

| VII. | Les Andelys and Château-Gaillard | To face page | 375 |

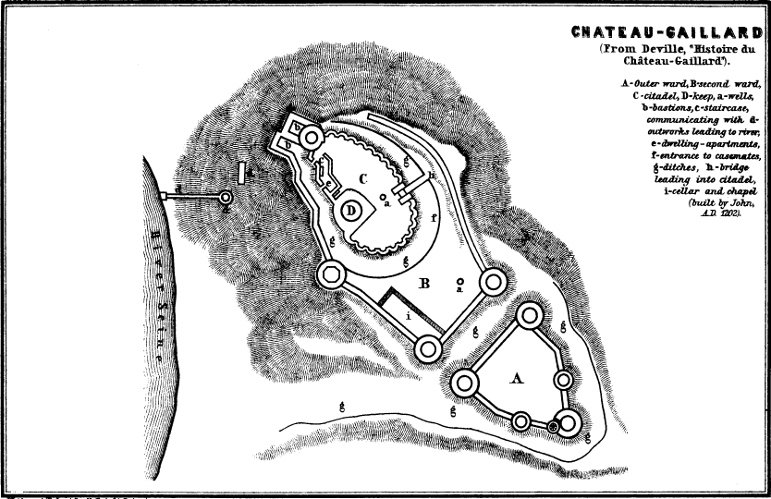

| VIII. | Château-Gaillard | ” | 378 |

Somewhat more than a year after the primate’s death, Thomas the chancellor returned to England. He came, as we have seen, at the king’s bidding, ostensibly for the purpose of securing the recognition of little Henry as heir to the crown. But this was not the sole nor even the chief object of his mission. On the eve of his departure—so the story was told by his friends in later days—Thomas had gone to take leave of the king at Falaise. Henry drew him aside: “You do not yet know to what you are going. I will have you to be archbishop of Canterbury.” The chancellor took, or tried to take, the words for a jest. “A saintly figure indeed,” he exclaimed with a smiling glance at his own gay attire, “you are choosing to sit in that holy seat and to head that venerable convent! No, no,” he added with sudden earnestness, “I warn you that if such a thing should be, our friendship would soon turn to bitter hate. I know your plans concerning the Church; you will assert claims which I as archbishop must needs oppose; and the breach once made, jealous hands would take care that it should never be healed again.” The words were prophetic; they sum up the whole history of the pontificate of Thomas Becket. Henry, however, in his turn passed them over as a mere jest, and at once proclaimed his intention to the chancellor’s fellow-envoys, one of whom was the justiciar, Richard de Lucy. “Richard,” said the king, ii.2“if I lay dead in my shroud, would you earnestly strive to secure my first-born on my throne?” “Indeed I would, my lord, with all my might.” “Then I charge you to strive no less earnestly to place my chancellor on the metropolitan chair of Canterbury.”[1]

Thomas was appalled. He could not be altogether taken by surprise; he knew what had been Theobald’s wishes and hopes; he knew that from the moment of Theobald’s death all eyes had turned instinctively upon himself with the belief that the future of the Church rested wholly in his all-powerful hands; he could not but suspect the king’s own intentions,[2] although the very suspicion would keep him silent, and all the more so because those intentions ran counter to his own desires. For twelve months he had known that the primacy was within his reach; he had counted the cost, and he had no mind to pay it. He was incapable of undertaking any office without throwing his whole energies into the fulfilment of its duties; his conception of the duties of the primate of all Britain would involve the sacrifice not only of those secular pursuits which he so keenly enjoyed, but also of that personal friendship and political co-operation with the king which seemed almost an indispensable part of the life of both; and neither sacrifice was he disposed to make. He had said as much to an English friend who had been the first to hint at his coming promotion,[3] and he repeated it now with passionate earnestness to Henry himself, but all in vain. The more he resisted, the more the king insisted—the very frankness of his warnings only strengthening Henry’s confidence in him; and when the legate Cardinal Henry of Pisa urged his acceptance as a sacred duty, Thomas at last gave way.[4]

The council in London was no sooner ended than Richard de Lucy and three of the bishops[5] hurried to Canterbury, byii.3 the king’s orders, to obtain from the cathedral chapter the election of a primate in accordance with his will. The monks of Christ Church were never very easy to manage; in the days of the elder King Henry they had firmly and successfully resisted the intrusion of a secular clerk into the monastic chair of S. Augustine; and a strong party among them now protested that to choose for pastor of the flock of Canterbury a man who was scarcely a clerk at all, who was wholly given to hawks and hounds and the worldly ways of the court, would be no better than setting a wolf to guard a sheepfold. But their scruples were silenced by the arguments of Richard de Lucy and by their dread of the royal wrath, and in the end Thomas was elected without a dissentient voice.[6] The election was repeated in the presence of a great council[7] held at Westminster on May 23,[8] and ratified by the bishops and clergy there assembled.[9] Only one voice was raised in protest; it was that of Gilbert Foliot,[10] who, alluding doubtless to the great scutage, declared that Thomas was utterly unfit for the primacy, because he had persecuted the Church of God.[11] The protest was answered by Henry of Winchester in words suggested by Gilbert’sii.4 own phrase: “My son,” said the ex-legate, addressing Thomas, “if thou hast been hitherto as Saul the persecutor, be thou henceforth as Paul the Apostle.”[12]

The election was confirmed by the great officers of state and the boy-king in his father’s name;[13] the consecration was fixed for the octave of Pentecost, and forthwith the bishops began to vie with each other for the honour of performing the ceremony. Roger of York, who till now had stood completely aloof, claimed it as a privilege due to the dignity of his see; but the primate-elect and the southern bishops declined to accept his services without a profession of canonical obedience to Canterbury, which he indignantly refused.[14] The bishop of London, on whom as dean of the province the duty according to ancient precedent should have devolved, was just dead;[15] Walter of Rochester momentarily put in a claim to supply his place,[16] but withdrew it in deference to Henry of Winchester, who had lately returned from Cluny, and whose royal blood, venerable character, and unique dignity as father of the whole English episcopate, marked him out beyond all question as the most fitting person to undertake the office.[17] By way of compensation, it was Walter who, on the Saturday in Whitsun-week, raised the newly-elected primate to the dignity of priesthood.[18]

Early next morning the consecration took place. Canterbury cathedral has been rebuilt from end to end since that day; it is only imagination which can picture the church of Lanfranc and Anselm and Theobald as it stood on that June morning, the scarce-risen sun gleaming faintly through its eastern windows upon the rich vestures of theii.5 fourteen bishops[19] and their attendant clergy and the dark robes of the monks who thronged the choir, while the nave was crowded with spectators, foremost among whom stood the group of ministers surrounding the little king.[20] From the vestry-door Thomas came forth, clad no longer in the brilliant attire at which he had been jesting a few weeks ago, but in the plain black cassock and white surplice of a clerk; through the lines of staring, wondering faces he passed into the choir, and there threw himself prostrate upon the altar-steps. Thence he was raised to go through a formality suggested by the prudence of his consecrator. To guard, as he hoped, against all risk of future difficulties which might arise from Thomas’s connexion with the court, Henry of Winchester led him down to the entrance of the choir, and in the name of the Church called upon the king’s representatives to deliver over the primate-elect fully and unreservedly to her holy service, freed from all secular obligations, actual or possible. A formal quit-claim was accordingly granted to Thomas by little Henry and the justiciars, in the king’s name;[21] after which the bishop of Winchester proceeded to consecrate him at once. A shout of applause rang through the church as the new primate of all Britain was led up to his patriarchal chair; but he mounted its steps with eyes downcast and full of tears.[22] To him the day was one of melancholy foreboding; yet he made its memory joyful in the Church for ever. He began his archiepiscopal career by ordaining a new festival to be kept every year on that day—the octave of Pentecost—in honour of the most Holy Trinity;[23] and in process of time the observance thus originatedii.6 spread from Canterbury throughout the whole of Christendom, which thus owes to an English archbishop the institution of Trinity Sunday.

“The king has wrought a miracle,” sneered the sarcastic bishop of Hereford, Gilbert Foliot; “out of a soldier and man of the world he has made an archbishop.”[24] The same royal power helped to smooth the new primate’s path a little further before him. He was not, like most of his predecessors, obliged to go in person to fetch his pallium from Rome; an embassy which he despatched immediately after his consecration obtained it for him without difficulty from Alexander III., who had just been driven by the Emperor’s hostility to seek a refuge in France, and was in no condition to venture upon any risk of thwarting King Henry’s favourite minister.[25] The next messenger whom Thomas sent over sea met with a less pleasant reception. He was charged to deliver up the great seal into the king’s hands with a request that Henry would provide himself with another chancellor, “as Thomas felt scarcely equal to the cares of one office, far less to those of two.”[26]

Henry was both surprised and vexed. It was customary for the chancellor to resign his office on promotion to a bishopric; but this sudden step on the part of Thomas was quite unexpected, and upset a cherished scheme of the king’s. He had planned to rival the Emperor by having an archbishop for his chancellor, as the archbishops of Mainz and Cöln were respectively arch-chancellors of Germany and Italy;[27] he had certainly never intended, in raising his favourite to the primacy, to deprive himself of such a valuable assistant in secular administration; his aim hadii.7 rather been to secure the services of Thomas in two departments instead of one.[28] To take away all ground of scandal, he had even procured a papal dispensation to sanction the union of the two offices in a single person.[29] Thomas, however, persisted in his resignation; and as there was no one whom Henry cared to put in his place, the chancellorship remained vacant, while the king brooded over his friend’s unexpected conduct and began to suspect that it was caused by weariness of his service.

Meanwhile Thomas had entered upon the second phase of his strangely varied career. He had “put off the deacon” for awhile; he was resolved now to “put off the old man” wholly and for ever. No sooner was he consecrated than he flung himself, body and soul, into his new life with an ardour more passionate, more absorbing, more exclusive than he had displayed in pursuit of the worldly tasks and pleasures of the court. On the morrow of his consecration, when some jongleurs came to him for the largesse which he had never been known to refuse, he gently but firmly dismissed them; he was no longer, he said, the chancellor whom they had known; his whole possessions were now a sacred trust, to be spent not on actors and jesters but in the service of the Church and the poor.[30] Theobald had doubled the amount of regular alms-givings established by his predecessors; Thomas immediately doubled those of Theobald.[31] To be diligent in providing for the sick and needy, to take care that no beggar should ever be sent empty away from his door,[32] was indeed nothing new in the son of the good dame Rohesia of Caen. The lavish hospitality of the chancellor’s household, too, was naturally transferred to that of the archbishop; but it took a different tone and colour. All and more than all the old grandeur and orderliness were there;ii.8 the palace still swarmed with men-at-arms, servants and retainers of all kinds, every one with his own appointed duty, whose fulfilment was still carefully watched by the master’s eyes; the bevy of high-born children had only increased, for by an ancient custom the second son of a baron could be claimed by the primate for his service—as the eldest by the king—until the age of knighthood; a claim which Thomas was not slow to enforce, and which the barons were delighted to admit. The train of clerks was of course more numerous than ever. The tables were still laden with delicate viands, served with the utmost perfection, and crowded with guests of all ranks; Thomas was still the most courteous and gracious of hosts. But the banquet wore a graver aspect than in the chancellor’s hall. The knights and other laymen occupied a table by themselves, where they talked and laughed as they listed; it was the clerks and religious who now sat nearest to Thomas. He himself was surrounded by a select group of clerks, his eruditi, his “learned men” as he called them: men versed in Scriptural and theological lore, his chosen companions in the study of Holy Writ into which he had plunged with characteristic energy; while instead of the minstrelsy which had been wont to accompany and inspire the gay talk at the chancellor’s table, there was only heard, according to ecclesiastical custom, the voice of the archbishop’s cross-bearer who sat close to his side reading from some holy book: the primate and his confidential companions meanwhile exchanging comments upon what was read, and discussing matters too deep and solemn to interest unlearned ears or to brook unlearned interruption.[33] Of the meal itself Thomas partook but sparingly;[34] its remainder was always given away;[35] and every day twenty-six poor men were brought into the hall and served with a dinner of the best, before Thomas would sit down to his own midday meal.[36]

The amount of work which he had got through by that time must have been quite as great as in the busiest days of his chancellorship. The day’s occupations ostensibly began about the hour of tierce, when the archbishop came forth from his chamber and went either to hear or to celebrate mass,[37] while a breakfast was given at his expense to a hundred persons who were called his “poor prebendaries.”[38] After mass he proceeded to his audience-chamber and there chiefly remained till the hour of nones, occupied in hearing suits and administering justice.[39] Nones were followed by dinner,[40] after which the primate shut himself up in his own apartments with his eruditi[41] and spent the rest of the day with them in business or study, interrupted only by the religious duties of the canonical hours, and sometimes by a little needful repose,[42] for his night’s rest was of the briefest. At cock-crow he rose for prime; immediately afterwards there were brought in to him secretly, under cover of the darkness, thirteen poor persons whose feet he washed and to whom he ministered at table with the utmost devotion and humility,[43] clad only in a hair-shirt which from the day of his consecration he always wore beneath the gorgeous robes in which he appeared in public.[44] He then returned to his bed, but only for a very short time; long before any one else was astir he was again up and doing, in company with one specially favoured disciple—the one who tells the tale, Herbert of Bosham. In the calm silent hours of dawn, while twelve other poor persons received a secret meal and had their feet washed by the primate’s almoner in his stead, the two friends sat eagerly searching the Scriptures together, till the archbishop chose to be left alone[45] for meditation and confession,ii.10 scourging and prayer,[46] in which he remained absorbed until the hour of tierce called him forth to his duties in the world.[47]

He was feverishly anxious to lose no opportunity of making up for his long neglect of the Scriptural and theological studies befitting his sacred calling. He openly confessed his grievous inferiority in this respect to many of his own clerks, and put himself under their teaching with child-like simplicity and earnestness. The one whom he specially chose for monitor and guide, Herbert of Bosham, was a man in whom, despite his immeasurable inferiority, one can yet see something of a temper sufficiently akin to that of Thomas himself to account for their mutual attraction, and perhaps for some of their joint errors. As they rode from London to Canterbury on the morrow of the primate’s election he had drawn Herbert aside and laid upon him a special charge to watch with careful eyes over his conduct as archbishop, and tell him without stint or scruple whatever he saw amiss in it or heard criticized by others.[48] Herbert, though he worshipped his primate with a perfect hero-worship, never hesitated to fulfil this injunction to the letter as far as his lights would permit; but unluckily his zeal was even less tempered by discretion than that of Thomas himself. He was a far less safe guide in the practical affairs of life than in the intricate paths of abstract and mystical interpretation of Holy Writ in which he and Thomas delighted to roam together. Often, when no other quiet time could be found, the archbishop would turn his horse aside as they travelled along the road, beckon to his friend, draw out a book from its hiding-place in one of his wide sleeves, and plunge into an eager discussion of its contents as they ambled slowly on.[49] When at Canterbury, his greatest pleasure was to betake himself to the cloister and sit reading like a lowly monk in one of its quiet nooks.[50]

But the eruditi of Thomas, like the disciples of Theobald, were the confidants and the sharers of far more than hisii.11 literary and doctrinal studies. It was in those evening hours which he spent in their midst, secluded from all outside interruption, that the plans of Church reform and Church revival, sketched long ago by other hands in the Curia Theobaldi, assumed a shape which might perhaps have startled Theobald himself. As the weeks wore quickly away from Trinity to Ember-tide, the new primate set himself to grapple at once with the ecclesiastical abuses of the time in the persons of his first candidates for ordination. On his theory the remedy for these abuses lay in the hands of the bishops, and especially of the metropolitans, who fostered simony, worldliness and immorality among the clergy by the facility with which they admitted unqualified persons into high orders, thus filling the ranks of the priesthood with unworthy, ignorant and needy clerks, who either traded upon their sacred profession as a means to secular advancement, or disgraced it by the idle wanderings and unbecoming shifts to which the lack of fit employment drove them to resort for a living. He was determined that no favour or persuasion should ever induce him to ordain any man whom he did not know to be of saintly life and ample learning, and provided with a benefice sufficient to furnish him with occupation and maintenance; and he proclaimed and acted upon his determination with the zeal of one who, as he openly avowed, felt that he was himself the most glaring example of the evils resulting from a less stringent system of discipline.[51]

His next undertaking was one which almost every new-made prelate in any degree alive to the rights and duties of his office found it needful to begin as soon as possible: the recovery of the alienated property of his see. Gilbert Foliot, the model English bishop of the day, had no sooner been consecrated than he wrote to beg the Pope’s support in this important and troublesome matter.[52] It may well be that even fourteen years later the metropolitan see had not yet received full restitution for the spoliations of the anarchy. Thomas however set to work in the most sweeping fashion, boldly laying claim to every estate which he could find toii.12 have been granted away by his predecessors on grounds which did not satisfy his exalted ideas of ecclesiastical right, or on terms which he held detrimental to the interest and dignity of his church, and enforcing his claims without respect of persons; summarily turning out those who held the archiepiscopal manors in ferm,[53] disputing with the earl of Clare for jurisdiction over the castle and district of Tunbridge, and reclaiming, on the strength of a charter of the Conqueror, the custody of Rochester castle from the Crown itself. Such a course naturally stirred up for him a crowd of enemies, and increased the jealousy, suspicion and resentment which his new position and altered mode of life had already excited among the companions and rivals of his earlier days. The archbishop however was still, like the chancellor, protected against them by the shield of the royal favour; they could only work against him by working upon the mind of Henry. One by one they carried over sea their complaints of the wrongs which they had suffered, or with which they were threatened, at the primate’s hands;[54] they reported all his daily doings and interpreted them in the worst sense:—his strictness of life was superstition, his zeal for justice was cruelty, his care for his church avarice, his pontifical splendour pride, his vigour rashness and self-conceit:[55]—if the king did not look to it speedily, he would find his laws and constitutions set at naught, his regal dignity trodden under foot, and himself and his heirs reduced to mere cyphers dependent on the will and pleasure of the archbishop of Canterbury.[56]

At the close of the year Henry determined to go and see for himself the truth of these strange rumours.[57] The negotiations concerning the papal question had detained him on the continent throughout the summer; in the end bothii.13 he and Louis gave a cordial welcome to Alexander, and a general pacification was effected in a meeting of the two kings and the Pope which took place late in the autumn at Chouzy on the Loire. Compelled by contrary winds to keep Christmas at Cherbourg instead of in England as he had hoped,[58] the king landed at Southampton on S. Paul’s day.[59] Thomas, still accompanied by the little Henry, was waiting to receive him; the two friends met with demonstrations of the warmest affection, and travelled to London together in the old intimate association.[60] One subject of disagreement indeed there was; Thomas had actually been holding for six months the archdeaconry of Canterbury together with the archbishopric, and this Henry, after several vain remonstrances, now compelled him to resign.[61] They parted however in undisturbed harmony, the archbishop again taking his little pupil with him.[62]

The first joint work of king and primate was the translation of Gilbert Foliot from Hereford to London. Some of those who saw its consequences in after-days declared that Henry had devised the scheme for the special purpose of securing Gilbert’s aid against the primate;[63] but it is abundantly clear that no such thought had yet entered his mind, and that the suggestion of Gilbert’s promotion really came from Thomas himself.[64] Like every one else, he looked upon Gilbert as the greatest living light of the English Church; he expected to find in him his own most zealous and efficient fellow-worker in the task which lay before him as metropolitan, as well as his best helper in influencing the king for good. Gilbert was in fact the man who in the natural fitness of things had seemed marked out for the primacy;ii.14 failing that, it was almost a matter of necessity that he should be placed in the see which stood next in dignity, and where both king and primate could benefit by his assistance ever at hand, instead of having to seek out their most useful adviser in the troubled depths of the Welsh marches. The chapter of London, to whom during the pecuniary troubles and long illness of their late bishop Gilbert had been an invaluable friend and protector, were only too glad to elect him; and his world-wide reputation combined with the pleadings of Henry to obtain the Pope’s consent to his translation,[65] which was completed by his enthronement in S. Paul’s cathedral on April 28, 1163.[66]

The king spent the early summer in subduing South-Wales; the primate, in attending a council held by Pope Alexander at Tours.[67] From the day of his departure to that of his return Thomas’s journey was one long triumphal progress; Pope and cardinals welcomed him with such honours as had never been given to any former archbishop of Canterbury, hardly even to S. Anselm himself;[68] and the request which he made to the Pope for Anselm’s canonization[69] may indicate the effect which they produced on his mind—confirming his resolve to stand boldly upon his right of opposition to the secular power whenever it clashed with ecclesiastical theories of liberty and justice. The first opportunity for putting his resolve in practice arose upon a question of purely temporal administration at a council held by Henry at Woodstock on July 31, after his return from Wales. The Welsh princes came to swear fealty to Henry and his heir; Malcolm of Scotland came to confirmii.15 his alliance with the English Crown by doing homage in like manner to the little king.[70] Before the council broke up, however, Henry met the sharpest constitutional defeat which had befallen any English sovereign since the Norman conquest, and that at the hands of his own familiar friend.

The king had devised a new financial project for increasing his own revenue at the expense of the sheriffs. According to current practice, a sum of two shillings annually from every hide of land in the shire was paid to those officers for their services to the community in its administration and defence. This payment, although described as customary rather than legal,[71] and called the “sheriff’s aid,”[72] seems really to have been nothing else than the Danegeld, which still occasionally made its appearance in the treasury rolls, but in such small amount that it is evident the sheriffs, if they collected it in full, paid only a fixed composition to the Crown and kept the greater part as a remuneration for their own labours. Henry now, it seems, proposed to transfer the whole of these sums from the sheriff’s income to his own, and have it enrolled in full among the royal dues. Whether he intended to make compensation to the sheriffs from some other source, or whether he already saw the need of curbing their influence and checking their avarice, we know not; but the archbishop of Canterbury started up to resist the proposed change as an injustice both to the receivers and to the payers of the aid. He seems to have looked upon it as an attempt to re-establish the Danegeld with all the odiousness attaching to its shameful origin and its unfair incidence, and to have held it his constitutional duty as representative and champion of the whole people to lift up his voice against it in their behalf. “My lord king,” he said, ii.16“saving your good pleasure, we will not give you this money as revenue, for it is not yours. To your officers, who receive it as a matter of grace rather than of right, we will give it willingly so long as they do their duty; but on no other terms will we be made to pay it at all.”—“By God’s Eyes!” swore the astonished and angry king, “what right have you to contradict me? I am doing no wrong to any man of yours. I say the moneys shall be enrolled among my royal revenues.”—“Then by those same Eyes,” swore Thomas in return, “not a penny shall you have from my lands, or from any lands of the Church!”[73]

How the debate ended we are not told; but one thing we know: from that time forth the hated name of “Danegeld” appeared in the Pipe Rolls no more. It seems therefore that, for the first time in English history since the Norman conquest, the right of the nation’s representatives to oppose the financial demands of the Crown was asserted in the council of Woodstock, and asserted with such success that the king was obliged not merely to abandon his project, but to obliterate the last trace of the tradition on which it was founded. And it is well to remember, too, that the first stand made by Thomas of Canterbury against the royal will was made in behalf not of himself or his order but of his whole flock;—in the cause not of ecclesiastical privilege but of constitutional right. The king’s policy may have been really sounder and wiser than the primate’s; but the ground taken by Thomas at Woodstock entitles him none the less to a place in the line of patriot-archbishops of which Dunstan stands at the head.[74]

The next few weeks were occupied with litigation over the alienated lands of the metropolitan see. A crowd of claims put in by Thomas and left to await the king’s return now came up for settlement, the most important case being that of Earl Roger of Clare, whom Thomas had summoned to perform his homage for Tunbridge at Westminster on July 22. Roger answered that he held the entire fief by knight-service, to be rendered in the shape of money-payment,[75] of the king and not of the primate.[76] As Roger wasii.17 connected with the noblest families in England,[77] king and barons were strongly on his side.[78] To settle the question, Henry ordered a general inquisition to be made throughout England to ascertain where the service of each land-holder was lawfully due. The investigation was of course made by the royal justiciars; and when they came to the archiepiscopal estates, one at least of the most important fiefs in dispute was adjudged by them to the Crown alone.[79]

Meanwhile a dispute on a question of church patronage arose between the primate and a tenant-in-chief of the Crown, named William of Eynesford. Thomas excommunicated his opponent without observing the custom which required him to give notice to the king before inflicting spiritual penalties on one of his tenants-in-chief.[80] Henry indignantly bade him withdraw the sentence; Thomas refused, saying “it was not for the king to dictate who should be bound or who loosed.”[81] The answer was indisputable in itself; but it pointed directly to the fatal subject on which the inevitable quarrel must turn: the relations and limits between the two powers of the keys and the sword.

Almost from his accession Henry seems to have been in some degree contemplating and preparing for those great schemes of legal reform which were to be the lasting glory of his reign. His earliest efforts in this direction were merely tentative; the young king was at once too inexperienced and too hard pressed with urgent business of all kinds, at home and abroad, to have either capacity or opportunity for great experiments in legislation. Throughout the past nine years, however, the projects which floated before his mind’s eye had been gradually taking shape; and now that he was at last freed for a while from theii.18 entanglements of politics and war, the time had come when he might begin to devote himself to that branch of his kingly duties for which he probably had the strongest inclination, as he certainly had the highest natural genius. He had by this time gained enough insight into the nature and causes of existing abuses to venture upon dealing with them systematically and in detail, and he had determined to begin with a question which was allowed on all hands to be one of the utmost gravity: the repression of crime in the clergy.

The origin of this difficulty was in the separation—needful perhaps, but none the less disastrous in some of its consequences—made by William the Conqueror between the temporal and ecclesiastical courts of justice. In William’s intention the two sets of tribunals were to work side by side without mutual interference save when the secular power was called in to enforce the decisions of the spiritual judge. But in practice the scheme was soon found to involve a crowd of difficulties. The two jurisdictions were constantly coming into contact, and it was a perpetual question where to draw the line between them. The struggle for the investitures, the religious revival which followed it, the vast and rapid developement of the canon law, with the increase of knowledge brought to bear upon its interpretation through the revived study of the civil law of Rome, gave the clergy a new sense of corporate importance and strength, and a new position as a distinct order in the state; the breakdown of all secular administration under Stephen tended still further to exalt the influence of the canonical system which alone retained some vestige of legal authority, and to throw into the Church-courts a mass of business with which they had hitherto had only an indirect concern, but which they alone now seemed capable of treating. Their proceedings were conducted on the principles of the canon law, which admitted of none but spiritual penalties; they refused to allow any lay interference with the persons over whom they claimed sole jurisdiction; and as these comprised the whole clerical body in the widest possible sense, extending to allii.19 who had received the lowest orders of the Church or who had taken monastic vows, the result was to place a considerable part of the population altogether outside the ordinary law of the land, and beyond the reach of adequate punishment for the most heinous crimes. Such crimes were only too common, and were necessarily fostered by this system of clerical immunities; for a man capable of staining his holy orders with theft or murder was not likely to be restrained by the fear of losing them, which a clerical criminal knew to be the worst punishment in store for him; and moreover, it was but too easy for the doers of such deeds to shelter themselves under the protection of a privilege to which often they had no real title. The king’s justiciars declared that in the nine years since Henry’s accession more than a hundred murders, besides innumerable robberies and lesser offences, had gone unpunished because they were committed by clerks, or men who represented themselves to be such.[82] The scandal was acknowledged on all hands; the spiritual party in the Church grieved over it quite as loudly and deeply as the lay reformers; but they hoped to remedy it in their own way, by a searching reformation and a stringent enforcement of spiritual discipline within the ranks of the clergy themselves. The subject had first come under Henry’s direct notice in the summer of 1158, when he received at York a complaint from a citizen of Scarborough that a certain dean had extorted money from him by unjust means. The case was tried, in the king’s presence, before the archbishop of the province, two bishops, and John of Canterbury the treasurer of York. The dean failed in his defence; and as it was proved that he had extorted the money by a libel, an offence against which Henry had made a special decree, some of the barons present were sent to see that the law had its course. John of Canterbury, however, rose and gave it as the decision of the spiritual judges that the money should be restored to the citizen and the criminal delivered over to the mercy of his metropolitan; and despite the justiciar’s remonstrances, they refused to allow the kingii.20 any rights in the matter. Henry indignantly ordered an appeal to the archbishop of Canterbury; but he was called over sea before it could be heard,[83] and had never returned to England until now, when another archbishop sat in Theobald’s place.

That it was Thomas of London who sat there was far from being an indication that Henry had forgotten the incident. It was precisely because Henry in these last four years had thought over the question of the clerical immunities and determined how to deal with it that he had sought to place on S. Augustine’s chair a man after his own heart. He aimed at reducing the position of the clergy, like all other doubtful matters, to the standard of his grandfather’s time. He held that he had a right to whatever his ancestors had enjoyed; he saw therein nothing derogatory to either the Church or the primate, whom he rather intended to exalt by making him his own inseparable colleague in temporal administration and the supreme authority within the realm in purely spiritual matters—thus avoiding the appeals to Rome which had led to so much mischief, and securing for himself a representative to whom he could safely intrust the whole work of government in England as guardian of the little king,[84] while he himself would be free to devote his whole energies to the management of his continental affairs. He seems in fact to have hoped tacitly to repeal the severance of the temporal and ecclesiastical jurisdictions, and bring back the golden age of William and Lanfranc, if not that of Eadgar and Dunstan; and for this he, not unnaturally, counted unreservedly upon Thomas. By slow degrees he discovered his miscalculation. Thomas had given him one direct warning which had been unheeded; he had warned him again indirectly by resigning the chancellorship; now, when the king unfolded his plans, he did not at once contradict him; he merely answered all his arguments and persuasions with one set phrase:—“I will render unto Cæsar the things that are Cæsar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.”[85]

In July occurred a typical case which brought matters to a crisis. A clerk named Philip de Broi had been tried in the bishop of Lincoln’s court for murder, had cleared himself by a legal compurgation, and had been acquitted. The king, not satisfied, commanded or permitted the charge to be revived, and the accused to be summoned to take his trial at Dunstable before Simon Fitz-Peter, then acting as justice-in-eyre in Bedfordshire, where Philip dwelt. Philip indignantly refused to plead again in answer to a charge of which he had been acquitted, and overwhelmed the judge with abuse, of which Simon on his return to London made formal complaint to the king. Henry was furious, swore his wonted oath “by God’s Eyes” that an insult to his minister was an insult to himself, and ordered the culprit to be brought to justice for the contempt of court and the homicide both at once. The primate insisted that the trial should take place in his own court at Canterbury, and to this Henry was compelled unwillingly to consent. The charge of homicide was quickly disposed of; Philip had been acquitted in a Church court, and his present judges had no wish to reverse its decision. On the charge of insulting a royal officer they sentenced him to undergo a public scourging at the hands of the offended person, and to forfeit the whole of his income for the next two years, to be distributed in alms according to the king’s pleasure. Henry declared the punishment insufficient, and bitterly reproached the bishops with having perverted justice out of favour to their order.[86] They denied it; but a story which came up from the diocese of Salisbury[87] and another from that of Worcester[88] tended still further to shew the helplessness of the royal justice against the ecclesiastical courts under the protection of the primate; and the latter’s blundering attempts to satisfy the king only increased his irritation. Not only did Thomas venture beyond theii.22 limits of punishment prescribed by the canon law by causing a clerk who had been convicted of theft to be branded as well as degraded,[89] but he actually took upon himself to condemn another to banishment.[90] He hoped by these severe sentences to appease the king’s wrath;[91] Henry, on the contrary, resented them as an interference with his rights; what he wanted was not severe punishment in isolated cases, but the power to inflict it in the regular course of his own royal justice. At last he laid the whole question before a great council which met at Westminster on October 1.[92]

The king’s first proposition, that the bishops should confirm the old customs observed in his grandfather’s days,[93] opened a discussion which lasted far into the night. Henry himself proceeded to explain his meaning more fully; he required, first, that the bishops should be more strict in the pursuit of criminal clerks;[94] secondly, that all such clerks, when convicted and degraded, should be handed over to the secular arm for temporal punishment like laymen, according to the practice usual under Henry I.;[95] and finally, that the bishops should renounce their claim to inflict any temporal punishment whatever, such as exile or imprisonment in a monastery, which he declared to be an infringement of his regal rights over the territory of his whole realm and the persons of all his subjects.[96] The primate, after vainly begging for an adjournment till the morrow, retired to consult with his suffragans.[97] When he returned, it was to set forth his view of the “two swords”—the two jurisdictions, spiritual and temporal—in terms which put an end to all hope ofii.23 agreement with the king. He declared the ministers of the Heavenly King exempt from all subjection to the judgement of an earthly sovereign; the utmost that he would concede was that a clerk once degraded should thenceforth be treated as a layman and punished as such if he offended again.[98] Henry, apparently too much astonished to argue further, simply repeated his first question—“Would the bishops obey the royal customs?” “Aye, saving our order,” was the answer given by the primate in the name and with the consent of all.[99] When appealed to singly they all made the same answer.[100] Henry bade them withdraw the qualifying phrase, and accept the customs unconditionally; they, through the mouth of their primate, refused;[101] the king raged and swore, but all in vain. At last he strode suddenly out of the hall without taking leave of the assembly;[102] and when morning broke they found that he had quitted London.[103] Before the day was over, Thomas received a summons to surrender some honours which he had held as chancellor and still retained;[104] and soon afterwards the little Henry was taken out of his care.[105]

The king’s wrath presently cooled so far that he invited the primate to a conference at Northampton. They met on horseback in a field near the town; high words passed between them; the king again demanded, and the archbishop again refused, unconditional acceptance of the customs; andii.24 in this determination they parted.[106] A private negotiation with some of the other prelates—suggested, it was said, by the diplomatist-bishop of Lisieux—was more successful; Roger of York and Robert of Lincoln met the king at Gloucester and agreed to accept his customs with no other qualification than a promise on his part to exact nothing contrary to the rights of their order. Hilary of Chichester not only did the same but undertook to persuade the primate himself. In this of course he failed.[107] Some time before Christmas, however, there came to the archbishop three commissioners who professed to be sent by the Pope to bid him withdraw his opposition; Henry having, according to their story, assured the Pope that he had no designs against the clergy or the Church, and required nothing beyond a verbal assent for the saving of his regal dignity.[108] On the faith of their word Thomas met the king at Oxford,[109] and there promised to accept the customs and obey the king “loyally and in good faith.” Henry then demanded that as the archbishop had withstood him publicly, so his submission should be repeated publicly too, in an assembly of barons and clergy to be convened for that purpose.[110] This was more than Thomas had been led to expect; but he made no objection, and the Christmas season passed over in peace. Henry kept the feast at Berkhampstead,[111] one of the castles lately taken from the archbishop; Thomas at Canterbury, where he had just been consecrating the great English scholar Robert of Melun—one of the three Papal commissioners—to succeed Gilbert Foliot as bishop of Hereford.[112]

On S. Hilary’s day the proposed council met at the royal hunting-seat of Clarendon near Salisbury.[113] Henry called upon the archbishop to fulfil the promise he had given at Oxford and publicly declare his assent to the customs. Thomas drew back. As he saw the mighty array of barons round the king—as he looked over the ranks of his own fellow-bishops—it flashed at last even upon his unsuspicious mind that all this anxiety to draw him into such a public repetition of a scene which he had thought to be final must cover something more than the supposed papal envoys had led him to expect, and that those “customs” which he had been assured were but a harmless word might yet become a terrible reality if he yielded another step. His hesitation threw the king into one of those paroxysms of Angevin fury which scared the English and Norman courtiers almost out of their senses. Thomas alone remained undaunted; the bishops stood “like a flock of sheep ready for slaughter,” and the king’s own ministers implored the primate to save them from the shame of having to lay violent hands upon him at their sovereign’s command. For two days he stood firm; on the third two knights of the Temple brought him a solemn assurance, on the honour of their order and the salvation of their souls, that his fears were groundless and that a verbal submission to the king’s will would end the quarrel and restore peace to the Church. He believed them; and though he still shrank from the formality, thus emptied of meaning, as little better than a lie, yet for the Church’s sake he gave way. He publicly promised to obey the king’s laws and customs loyally and in good faith, and made all the other bishops do likewise.[114]

The words were no sooner out of their mouths than Thomas learned how just his suspicions had been. A question was instantly raised—what were these customs? It was too late to discuss them that night; next morning theii.26 king bade the oldest and wisest of the barons go and make a recognition of the customs observed by his grandfather and bring up a written report of them for ratification by the council.[115] Nine days later[116] the report was presented. It comprised sixteen articles, known ever since as the Constitutions of Clarendon.[117] Some of them merely re-affirmed, in a more stringent and technical manner, the rules of William the Conqueror forbidding bishops and beneficed clerks to quit the realm or excommunicate the king’s tenants-in-chief without his leave, and the terms on which the temporal position of the bishops had been settled by the compromise between Henry I. and Anselm at the close of the struggle for the investitures. Another aimed at checking the abuse of appeals to Rome, by providing that no appeal should be carried further than the archbishop’s court without the assent of the king. The remainder dealt with the settlement of disputes concerning presentations and advowsons, which were transferred from the ecclesiastical courts to that of the king; the treatment of excommunicate persons; the limits of the right of sanctuary as regarding the goods of persons who had incurred forfeiture to the Crown; the ordination of villeins; the jurisdiction over clerks accused of crime; the protection of laymen cited before the Church courts against episcopal and archidiaconal injustice; and the method of procedure in suits concerning the tenure of Church lands.

The two articles last mentioned are especially remarkable. The former provided that if a layman was accused before a bishop on insufficient testimony, the sheriff should at the bishop’s request summon a jury of twelve lawful men of the neighbourhood to swear to the truth or falsehood of the charge.[118] The other clause decreed that when an estate was claimed by a clerk in frank-almoign and by a layman as a secular fief the question should be settled by the chiefii.27 justiciar in like manner on the recognition of twelve jurors.[119] The way in which these provisions are introduced implies that the principle contained in them was already well known in the country; it indicates that some steps had already been taken towards a general remodelling of legal procedure, intended to embrace all branches of judicial administration and bring them all into orderly and harmonious working. In this view the Constitutions of Clarendon were only part of a great scheme in whose complete developement they might have held an appropriate and useful place.[120] But the churchmen of the day, to whom they were thus suddenly presented as an isolated fragment, could hardly be expected to see in them anything but an engine of state tyranny for grinding down the Church. Almost every one of them assumed, in some way or other, the complete subordination of ecclesiastical to temporal authority; the right of lay jurisdiction over clerks was asserted in the most uncompromising terms; while the last clause of all, which forbade the ordination of villeins without the consent of their lords, stirred a nobler feeling than jealousy for mere class-privileges. Its real intention was probably not to hinder the enfranchisement of serfs, but simply to protect the landowners against the loss of services which, being attached to the soil, they had no means of replacing, and very possibly also to prevent the number of criminal clerks being further increased by the admission of villeins anxious to escape from the justice of their lords. But men who for ages had been trained to regard the Church as a divinely-appointed city of refuge for all the poor and needy, the oppressed and the enslaved, could only see the other side of the measure and feel their inmost hearts rise up in the cry of a contemporary poet—“Hath not God called us all, bond and free, to His service?”[121]

The discussion occupied six days;[122] as each clause was read out to the assembly, Thomas rose and set forth his reasons for opposing it.[123] When at last the end was reached, Henry called upon him and all the bishops to affix their seals to the constitutions. “Never,” burst out the primate—“never, while there is a breath left in my body!”[124] The king was obliged to content himself with the former verbal assent, gained on false pretences as it had been; a copy of the obnoxious document was handed to the primate, who took it, as he said, for a witness against its contrivers, and indignantly quitted the assembly.[125] In an agony of remorse for the credulity which had led him into such a trap he withdrew to Winchester and suspended himself from all priestly functions till he had received absolution from the Pope.[126]

It was to the Pope that both parties looked for a settlement of their dispute; but Alexander, ill acquainted both with the merits of the case and with the characters of the disputants, and beset on all sides with political difficulties, could only strive in vain to hold the balance evenly between them. Meanwhile the political quarrel of king and primate was embittered by an incident in which Henry’s personal feelings were stirred. His brother William—the favourite young brother whom he had once planned to establish as sovereign in Ireland—had set his heart upon a marriage with the widowed countess of Warren; the archbishop had forbidden the match on the ground of affinity, and his prohibition had put an end to the scheme.[127] Baffled and indignant, William returned to Normandy and poured the story of his grievance into the sympathizing ears first of his mother and then, as it seems, of the brotherhood at Bec.[128] On January 29, 1164—one day before the dissolution of the council of Clarendon—he died at Rouen;[129] and a writer who was himself at that time a monk at Bec not only implies his own belief that the young man actually died of disappointment, but declares that Henry shared that belief, and thenceforth looked upon the primate by whom the disappointment had been caused as little less than the murderer of his brother.[130] The king’s exasperation was at any rate plain toii.30 all eyes; and as the summer drew on Thomas found himself gradually deserted. His best friend, John of Salisbury, had already been taken from his side, and was soon driven into exile by the jealousy of the king;[131] another friend, John of Canterbury, had been removed out of the country early in 1163 by the ingenious device of making him bishop of Poitiers.[132] The old dispute concerning the relations between Canterbury and York had broken out afresh with intensified bitterness between Roger of Pont-l’Evêque and the former comrade of whom he had long been jealous, and who had now once again been promoted over his head; the king, hoping to turn it to account for his own purposes, was intriguing at the Papal court in Roger’s behalf, and one of his confidential agents there was Thomas’s own archdeacon, Geoffrey Ridel.[133] The bishops as yet were passive; in theii.31 York controversy Gilbert Foliot strongly supported his own metropolitan;[134] but between him and Thomas there was already a question, amicable indeed at present but ominous nevertheless, as to whether or not the profession of obedience made to Theobald by the bishop of Hereford should be repeated by the same man as bishop of London to Theobald’s successor.[135]

Thomas himself fully expected to meet the fate of Anselm; throughout the winter his friends had been endeavouring to secure him a refuge in France;[136] and early in the summer of 1164, having been refused an interview with the king,[137] he made two attempts to escape secretly from Romney. The first time he was repelled by a contrary wind; the second time the sailors put back ostensibly for the same reason, but really because they had recognized their passenger and dreaded the royal wrath;[138] and a servant who went on the following night to shut the gates of the deserted palace at Canterbury found the primate, worn out with fatigue and disappointment, sitting alone in the darkness like a beggar upon his own door-step.[139] Despairing of escape, he made another effort to see the king at Woodstock. Henry dreaded nothing so much as the archbishop’s flight, for he felt that it would probably be followed by a Papal interdict on his dominions,[140] and would certainly give an immense advantage against him to Louis of France, who was at that very moment threatening war in Auvergne.[141] He therefore received Thomas courteously, though with somewhat less than the usual honours,[142] and made no allusionii.32 to the past except by a playful question “whether the archbishop did not think the realm was wide enough to contain them both?” Thomas saw, however, that the old cordiality was gone; his enemies saw it too, and, as his biographer says, “they came about him like bees.”[143] Foremost among them was John the king’s marshal, who had a suit in the archbishop’s court concerning the manor of Pageham.[144] It was provided by one of Henry’s new rules of legal procedure that if a suitor saw no chance of obtaining justice in the court of his own lord he might, by taking an oath to that effect and bringing two witnesses to do the same, transfer the suit to a higher court.[145] John by this method removed his case from the court of the archbishop to that of the king; and thither Thomas was cited to answer his claim on the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross. When that day came the primate was too ill to move; he sent essoiners to excuse his absence in legal form, and also a written protest against the removal of the suit, on the ground that it had been obtained by perjury—John having taken the oath not upon the Gospel, but upon an old song-book which he had surreptitiously brought into court for the purpose.[146] Henry angrily refused to believe either Thomas or his essoiners,[147] and immediately issued orders for a great council to be held at Northampton.[148] It was customary to call the archbishops and the greater barons by a special writ addressed to each individually, while the lesser tenants-in-chief received a general summons through the sheriffs of the different counties. Roger of York was specially called in due form;[149] the metropolitan of all Britain, who ought to have been invitedii.33 first and most honourably of all, merely received through the sheriff of Kent a peremptory citation to be ready on the first day of the council with his defence against the claim of John the marshal.[150]

The council—an almost complete gathering of the tenants-in-chief, lay and spiritual, throughout the realm[151]—was summoned for Tuesday October 6.[152] The king however lingered hawking by the river-side till late at night,[153] and it was not till next morning after Mass that the archbishop could obtain an audience. He began by asking leave to go and consult the Pope on his dispute with Roger of York and divers other questions touching the interests of both Church and state; Henry angrily bade him be silent and retire to prepare his defence for his contempt of the royal summons in the matter of John the marshal.[154] The trial took place next day. John himself did not appear, being detained in the king’s service at the Michaelmas session of the Exchequerii.34 in London;[155] the charge of failure of justice was apparently withdrawn, but for the alleged contempt Thomas was sentenced to a fine of five hundred pounds.[156] Indignant as he was at the flagrant illegality of the trial, in which his own suffragans had been compelled to sit in judgement on their primate, Thomas was yet persuaded to submit, in the hope of avoiding further wrangling over what seemed now to have become a mere question of money.[157] But there were other questions to follow. Henry now demanded from the archbishop a sum of three hundred pounds, representing the revenue due from the honours of Eye and Berkhampstead for the time during which he had held them since his resignation of the chancellorship.[158] Thomas remarked that he had spent far more than that sum on the repair of the royal palaces, and protested against the unfairness of making such a demand without warning. Still, however, he disdained to resist for a matter of filthy lucre, and found sureties for the required amount.[159] Next morning Henry made a further demand for the repayment of a loan made to Thomas in his chancellor days.[160] In those days the two friends had virtually had but one purse as well as “one mind and one heart,” and Thomas was deeply wounded by this evident proof that their friendship was at an end. Once more he submitted; but this time it was no easy matter toii.35 find sureties;[161] and then, late on the Friday evening, there was reached the last and most overwhelming count in the long indictment thus gradually unrolled before the eyes of the astonished primate. He was called upon to render a complete statement of all the revenues of vacant sees, baronies and honours of which he had had the custody as chancellor—in short, of the whole accounts of the chancery during his tenure of office.[162]

At this crushing demand the archbishop’s courage gave way, and he threw himself at the king’s feet in despair. All the bishops did likewise, but in vain; Henry swore “by God’s Eyes” that he would have the accounts in full. He granted, however, a respite till the morrow,[163] and Thomas spent the next morning in consultation with his suffragans.[164] Gilbert of London advised unconditional surrender;[165] Henry of Winchester, who had already withstood the king to his face the night before,[166] strongly opposed this view,[167] and suggested that the matter should be compromised by an offer of two thousand marks. This the king rejected.[168] After long deliberation[169] it was decided—again at the suggestionii.36 of Bishop Henry—that Thomas should refuse to entertain the king’s demands on the ground of the release from all secular obligations granted to him at his consecration. This answer was carried by the bishops in a body to the king. He refused to accept it, declaring that the release had been given without his authority; and all that the bishops could wring from him was a further adjournment till the Monday morning.[170] In the middle of Sunday night the highly-strung nervous organization of Thomas broke down under the long cruel strain; the morning found him lying in helpless agony, and with great difficulty he obtained from the king another day’s delay.[171] Before it expired a warning reached him from the court that if he appeared there he must expect nothing short of imprisonment or death.[172] A like rumour spread through the council, and at dawn the bishops in a body implored their primate to give up the hopeless struggle and throw himself on the mercy of the king. He refused to betray his Church by accepting a sentence which he believed to be illegal as well as unjust, forbade the bishops to take any further part in his trial, gave them notice of an appeal to Rome if they should do so, and charged them on their canonical obedience to excommunicate at once whatever laymen should dare to sit in judgement upon him.[173] Against this last command the bishop of London instantly appealed.ii.37[174] All then returned to the court, except Henry of Winchester and Jocelyn of Salisbury, who lingered for a last word of pleading or of sympathy.[175] When they too were gone, Thomas went to the chapel of the monastery in which he was lodging—a small Benedictine house dedicated to S. Andrew, just outside the walls of Northampton—and with the utmost solemnity celebrated the mass of S. Stephen with its significant introit: “Princes have sat and spoken against me.” The mass ended, he mounted his horse, and escorted no longer by a brilliant train of clerks and knights, but by a crowd of poor folk full of sympathy and admiration, he rode straight to the castle where the council awaited him.[176]

At the gate he took his cross from the attendant who usually bore it, and went forward alone to the hall where the bishops and barons were assembled.[177] They fell back in amazement at the apparition of the tall solitary figure, robed in full pontificals, and carrying the crucifix like an uplifted banner prepared at once for defence and for defiance; friends and opponents were almost equally shocked, and it was not till he had passed through their midst and seated himself in a corner of the hall that the bishops recovered sufficiently to gather round him and intreat that he would give up his unbecoming burthen. Thomas refused; “he would not lay down his standard, he would not part with his shield.” “A fool you ever were, a fool I see you are still and will be to the end,” burst out Gilbert Foliot at last, as after a long argument he turned impatiently away.[178] The others followed him, and the primate was left with only two companions,ii.38 William Fitz-Stephen and his own especial friend, Herbert of Bosham.[179] The king had retired to an inner chamber and was there deliberating with his most intimate counsellors[180] when the story of the primate’s entrance reached his ears. He took it as an unpardonable insult, and caused Thomas to be proclaimed a traitor. Warnings and threats ran confusedly through the hall. The archbishop bent over the disciple sitting at his feet:—“For thee I fear—yet fear not thou; even now mayest thou share my crown.” The ardent encouragement with which Herbert answered him[181] provoked one of the king’s marshals to interfere and forbid that any one should speak to the “traitor.” William Fitz-Stephen, who had been vainly striving to put in a gentle word, caught his primate’s eyes and pointed to the crucifix, intrusting to its silent eloquence the lesson of patience and prayer which his lips were forbidden to utter. When he and Thomas, after long separation, met again in the land of exile, that speechless admonition seems to have been the first thing which recurred to the minds of both.[182]

In the chamber overhead, meanwhile, Henry had summoned the bishops to a conference.[183] On receiving from them an account of their morning’s interview with Thomas, he sent down to the latter his ultimatum, requiring him to withdraw his appeal to Rome and his commands to the bishops as contrary to the customs which he had sworn to observe, and to submit to the judgement of the king’s court on the chancery accounts. Seated, with eyes fixed on the cross, Thomas quietly but firmly refused. His refusal was reported to the king, who grew fiery-red with rage, caught eagerly at the barons’ proposal that the archbishop should be judged for contempt of his sovereign’s jurisdiction in appealing from it to another tribunal, and called upon theii.39 bishops to join in his condemnation.[184] York, London and Chichester proposed that they should cite him before the Pope instead, on the grounds of perjury at Clarendon and unjust demands on their obedience.[185] To this Henry consented; the appeal was uttered by Hilary of Chichester in the name of all, and in most insulting terms;[186] and the bishops sat down opposite their primate to await the sentence of the lay barons.[187]

What that sentence was no one outside the royal council-chamber ever really knew. It was one thing to determine it there and another to deliver it to its victim, sitting alone and unmoved with the sign of victory in his hand. With the utmost reluctance and hesitation the old justiciar, Earl Robert of Leicester, came to perform his odious task. At the word “judgement” Thomas started up, with uplifted crucifix and flashing eyes, forbade the speaker to proceed, and solemnly appealed to the protection of the court of Rome. The justiciar and his companions retired in silence.[188] “I too will go, for the hour is past,” said Thomas.[189] Cross in hand he strode past the speechless group of bishops into the outer hall; the courtiers followed him with a torrent of insults, which were taken up by the squires and serving-men outside; as he stumbled against a pile of faggots set ready for the fire, Ralf de Broc rushed upon him with aii.40 shout of “Traitor! traitor!”[190] The king’s half-brother, Count Hameline, echoed the cry;[191] but he shrank back at the primate’s retort—“Were I a knight instead of a priest, this hand should prove thee a liar!”[192] Amid a storm of abuse Thomas made his way into the court-yard and sprang upon his horse, taking up his faithful Herbert behind him.[193] The outer gate was locked, but a squire of the archbishop managed to find the keys.[194] Whether there was any real intention of stopping his egress it seems impossible to determine; the king and his counsellors were apparently too much puzzled to do anything but let matters take their course; Henry indeed sent down a herald to quell the disturbance and forbid all violence to the primate;[195] but the precaution came too late. Once outside the gates, Thomas had no need of such protection. From the mob of hooting enemies within he passed into the midst of a crowd of poor folk who pressed upon him with every demonstration of rapturous affection; in every street as he rode along the people came out to throw themselves at his feet and beg his blessing.

It was with these poor folk that he supped that night, for his own household, all save a chosen few, now hastened to take leave of him.[196] Through the bishops of Rochester, Hereford and Worcester he requested of the king a safe-conduct for his journey to Canterbury; the king declinedii.41 to answer till the morrow.[197] The primate’s suspicions were aroused. He caused his bed to be laid in the church, as if intending to spend the night in prayer.[198] At cock-crow the monks came and sang their matins in an under-tone for fear of disturbing their weary guest;[199] but his chamberlain was watching over an empty couch. At dead of night Thomas had made his escape with two canons of Sempringham and a faithful squire of his own, named Roger of Brai. A violent storm of rain helped to cover their flight,[200] and it was not till the middle of the next day that king and council discovered that the primate was gone.

“God’s blessing go with him!” murmured with a sigh of relief the aged Bishop Henry of Winchester. “We have not done with him yet!” cried the king. He at once issued orders that all the ports should be watched to prevent Thomas from leaving the country,[201] and that the temporalities of the metropolitan see should be left untouched pending an appeal to the Pope[202] which he despatched the archbishop of York and the bishops of London, Worcester, Exeter and Chichester to prosecute without delay.[203] They sailed from Dover on All Souls day;[204] that very night Thomas, after three weeks of adventurous wanderings, guarded with the most devoted vigilance by the brethren of Sempringham, embarked in a little boat from Sandwich; next day he landed in Flanders;[205] and afterii.42 another fortnight’s hiding he made his way safe to Soissons, where the king of France, disregarding an embassy sent by Henry to prevent him, welcomed him with open arms. He hurried on to Sens, where the Pope was now dwelling; the appellant bishops had preceded him, but Alexander was deaf to their arguments.[206] Thomas laid at the Pope’s feet his copy of the Constitutions of Clarendon; they were read, discussed and solemnly condemned in full consistory.[207] The exiled primate withdrew to a shelter which his friend Bishop John of Poitiers had secured for him in the Cistercian abbey of Pontigny in Burgundy.[208] On Christmas-eve, at Marlborough, Henry’s envoys reported to him the failure of their mission. On S. Stephen’s day Henry confiscated the whole possessions of the metropolitan see, of the primate himself and of all his clerks, and ordered all his kindred and dependents, clerical or lay, to be banished from the realm.[209]

The usual view of the council of Woodstock—a view founded on contemporary accounts and endorsed by Bishop Stubbs ( Constit. Hist., vol. i. p. 462)—has been disputed on the authority of the Icelandic Thomas Saga. This Saga represents the subject of the quarrel as being, not a general levy of so much per hide throughout the country, but a special tax upon the Church lands—nothing else, in fact, than the “ungeld” which William Rufus had imposed on them to raise the money paid to Duke Robert for his temporary cession of Normandy, and which had been continued ever since. “We have read afore how King William levied a due on all churches in the land, in order to repay him all the costs at which his brother Robert did depart from the land. This money the king said he had disbursed for the freedom of Jewry, and therefore it behoved well the learned folk to repay it to their king. But because the king’s court hath a mouth that holdeth fast, this due continued from year to year. At first it was called Jerusalem tax, but afterwards Warfare-due, for the king to keep up an army for the common peace of the country. But at this time matters have gone so far, that this due was exacted, as a king’s tax, from every house” [“monastery,” editor’s note], “small and great, throughout England, under no other name than an ancient tax payable into the royal treasury without any reason being shown for it.” Thomas Saga (Magnusson), vol. i. p. 139. Mr. Magnusson (ib. p. 138, note 7) thinks that this account “must be taken as representing the true history of” the tax in question. In his Preface (ib. vol. ii. pp. cvii–cviii) he argues that if the tax had been one upon the tax-payers in general, “evidently the primate had no right to interfere in such a matter, except so far as church lands were concerned;” and he concludes that the version in the Saga “gives a natural clue to the archbishop’s protest, which thus becomes a protest only on behalf of the Church.” This argument hardly takes sufficient account of the English primate’s constitutional position, which furnishes a perfectly “natural clue” to his protest, supposing that protest to have been made on behalf of the whole nation and not only of the Church:—or rather, to speak more accurately, in behalf of the Church in the true sense of that word—the sense which Theobald’s disciples were always striving to give to it—as representing the whole nation viewed in a spiritual aspect, and not only the clerical order. Mr. Magnusson adds: ii.44“We have no doubt that the source of the Icelandic Saga here is Robert of Cricklade, or ... Benedict of Peterborough, who has had a better information on the subject than the other authorities, which, it would seem, all have Garnier for a primary source; but he, a foreigner, might very well be supposed to have formed an erroneous view on a subject the history of which he did not know, except by hearsay evidence” (ib. pp. cviii, cix). It might be answered that the “hearsay evidence” on which Garnier founded his view must have been evidence which he heard in England, where he is known to have carefully collected the materials for his work (Garnier, ed. Hippeau, pp. 6, 205, 206), and that his view is entitled to just as much consideration as that of the Icelander, founded upon the evidence of Robert or Benedict;—that of the three writers who follow Garnier, two, William of Canterbury and Edward Grim, were English (William of Canterbury may have been Irish by birth, but he was English by education and domicile) and might therefore have been able to check any errors caused by the different nationality of their guide:—and that even if the case resolved itself into a question between the authority of Garnier and that of Benedict or Robert (which can hardly be admitted), they would be of at least equal weight, and the balance of intrinsic probability would be on Garnier’s side. For his story points directly to the Danegeld; and we have the indisputable witness of the Pipe Rolls that the Danegeld, in some shape or other, was levied at intervals throughout the Norman reigns and until the year 1163, when it vanished for ever. On the other hand, the Red King’s “ungeld” upon the Church lands, like all his other “ungelds,” certainly died with him; and nothing can well be more unlikely than that Henry II. in the very midst of his early reforms should have reintroduced, entirely without excuse and without necessity, one of the most obnoxious and unjust of the measures which had been expressly abolished in “the time of his grandfather King Henry.”

There is some difficulty as to both the date and the duration of this council. Gerv. Cant. (Stubbs, vol. i. p. 176) gives the date of meeting as January 13; R. Diceto (Stubbs, vol. i. p. 312) as January 25; while the official copy of the Constitutions (Summa Causæ, Robertson, Becket, vol. iv. p. 208; Stubbs, Select Charters, p. 140) gives the closing day as January 30 (“quartâ die ante Purificationem S. Mariæ”). As to the duration of the council, we learn from Herb. Bosh. (Robertson, Becket, vol. iii. p. 279) and Gerv. Cant.ii.45 (as above, p. 178) that there was an adjournment of at least one night; while Gilbert Foliot (Robertson, Becket, vol. v. Ep. ccxxv. pp. 527–529) says “Clarendonæ ... continuato triduo id solum actum est ut observandarum regni consuetudinum et dignitatum a nobis fieret absoluta promissio;” and that “die vero tertio,” after a most extraordinary scene, Thomas “antiquas regni consuetudines antiquorum memoriâ in commune propositas et scripto commendatas, de cætero domino nostro regi se fideliter observaturum in verbo veritatis absolute promittens, in vi nobis injunxit obedientiæ sponsione simili nos obligare.” This looks at first glance as if meant to describe the closing scene of the council, in which case its whole duration would be limited to three days. But it seems possible to find another interpretation which would enable us to reconcile all the discordant dates, by understanding Gilbert’s words as referring to the verbal discussion at the opening of the council, before the written Constitutions were produced at all. Gilbert does indeed expressly mention “customs committed to writing”; but this may very easily be a piece of confusion either accidental or intentional. On this supposition the chronology may be arranged as follows:—The council meets on January 13 (Gerv. Cant.). That day and the two following are spent in talking over the primate; towards evening of the third—which will be January 15—he yields, and the bishops with him (Gilb. Foliot). Then they begin to discuss what they have promised; the debate warms and lengthens; Thomas, worn out with his three days’ struggle and seeing the rocks ahead, begs for a respite till the morrow (Herb. Bosh.). On that morrow—i.e. January 16—Henry issues his commission to the “elders,” and the council remains in abeyance till they are ready with their report. None of our authorities tell us how long an interval elapsed between the issue of the royal commission and its report. Herbert, indeed, seems to imply that the discussion on the constitutions began one night and the written report was brought up next day. But this is only possible on the supposition that it had been prepared secretly beforehand, of which none of the other writers shew any suspicion. If the thing was not prepared beforehand, it must have taken some time to do; and even if it was, the king and the commissioners would surely, for the sake of appearances, make a few days’ delay to give a shew of reality to their investigations. Nine days is not too much to allow for preparation of the report. On January 25, then, it is brought up, and the real business of the council begins in earnest on the day named by R. Diceto. And if Thomas fought over every one of the sixteen constitutions in the way of which Herbert gives us a specimen, six days more may very well have been spent in the discussion, which would thus end, as the Summa Causæ says, on January 30.