Title: Dorothea Beale: Principal of the Cheltenham Ladies' College, 1858-1906

Author: Elizabeth Helen Shillito

Release date: December 21, 2022 [eBook #69599]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1920

Credits: MWS and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

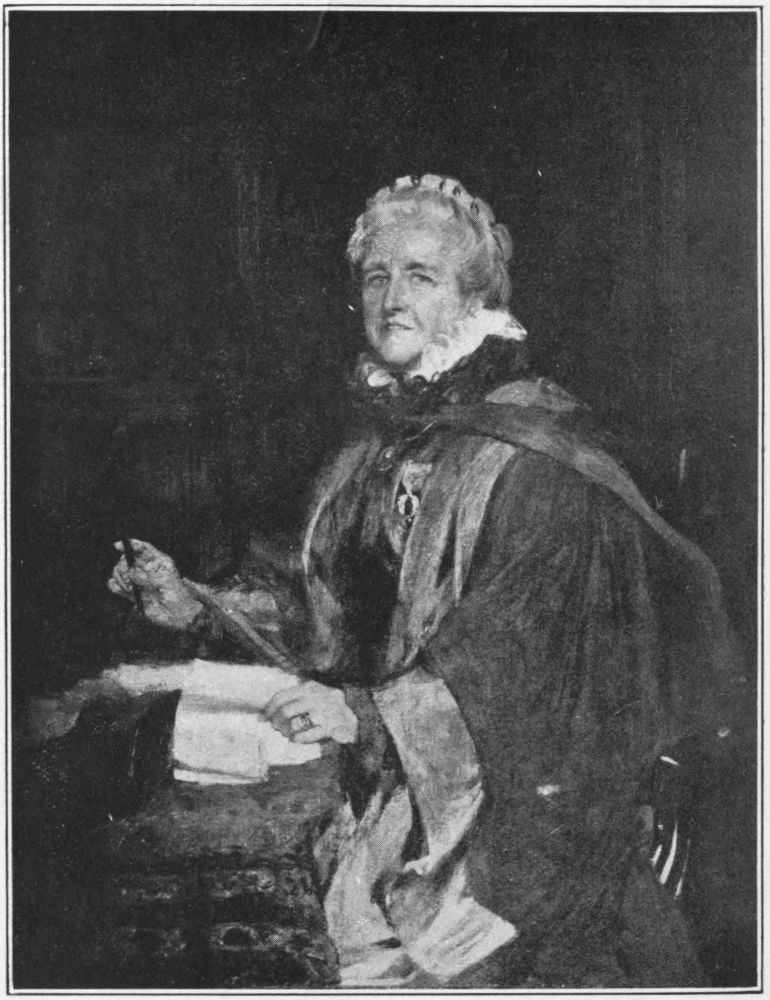

DOROTHEA BEALE

FROM A PAINTING BY J. J. SHANNON

Frontispiece

PIONEERS OF PROGRESS

WOMEN

Edited by ETHEL M. BARTON

PRINCIPAL OF THE CHELTENHAM LADIES’ COLLEGE

1858-1906

WITH TWO PORTRAITS

BY

ELIZABETH H. SHILLITO, B.A. (Lond.)

LONDON

SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE

NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1920

“Some there are who go forth to their own life-work with the holy hands of the dead who live laid on their hearts, who feel that they have a debt to repay, who see a ray of life from afar cast upon all they do, and bear about for ever a light within, which they must pass on for the sake of the dead who live.”

Edward Thring.

[Pg iii]

Great Souls who sail uncharted seas,

Battling with hostile winds and tide,—

Strong hands that forged forbidden keys,

And left the door behind them wide.

Diggers for gold where most had failed,

Smiling at deeds that brought them Fame,—

Lighters of lamps that have not failed—

Lend us your oil, and share your flame.

[Pg iv]

TO

Dr. ELSIE MAUD INGLIS

WHOSE CRIMEA WAS SERBIA,

BUT WHOSE POST-WAR WORK

IS IN ANOTHER WORLD

[Pg v]

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Discoveries and enterprises of the Nineteenth Century—Effect on the educational world—Girls’ education in age of Elizabeth and in Nineteenth Century—Protests against the latter—Pioneers of higher education—Our indebtedness to them | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Dorothea Beale—Parentage—Mrs. Cornwallis and her daughter—Their influence on Dorothea Beale—Home life—Early education—School life—Time of self-education—Attitude to games—Reading in early life—Euclid—School in France—Some personal characteristics—Religious and other influences of home | 4 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| History of Queen’s College—Early students—Rev. F. D. Maurice—His opening address—Dorothea Beale’s attitude to teaching—Study and friendship at Queen’s College—Appointment there—Difficulties—Resignation—Impetuosity of nature—Some inherent difficulties of women’s life | 10 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Clergy Daughters’ School at Casterton—Hasty acceptance of post there—Beautiful situation of school—Evils—Personal difficulties—Mr. Beale’s letters—Dorothea Beale’s dress and appearance—Thoughts of resignation—Father’s advice—Appeal to committee—Suspicions of High Church tendencies—Determination to resign—Notice from committee—Acknowledged indebtedness to the school—Appreciation—Work at home—History of England begun—Spartan habits—Some philanthropic work—Offer of service—Dawning conviction of real vocation—Her diary begun—Extracts—Time of waiting—Religious life and beliefs | 16[Pg vi] |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Cheltenham Ladies’ College—Early history—The first Principals—Advertisement for new Principal—Dorothea Beale candidate—Tributes to character and ability—Alleged High Church tendencies—Declaration of belief—Time of anxiety—Appointment as Principal—Work at Ladies’ College—Personal appearance at this time—Rule of silence—Precarious financial position of school—Practice of economy—Question of renewing lease of Cambray House—Mr. Brancker—His wise policy and administration—Some reminiscences—The Fight against ignorance and prejudice—Dorothea Beale’s inspiring leadership | 27 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Blue Book Report on condition of girls’ education—Dorothea Beale’s evidence and theories with regard to women as teachers; effects of higher education on health; idleness and health; the teaching of music—Modern ideas on the teaching of this subject | 38 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Rearrangement of school hours at the Ladies’ College—Opposition met and overcome—Gradual breaking down of prejudice—Gossip and disloyalty—Dorothea Beale’s gift of inspiring loyalty—Miss Belcher—Death of Dorothea Beale’s father—How she spent holidays—Singleness of aim—Idea of Sisterhood of Teachers—Expansion of Cheltenham College—Opposition to a new building—Dr. Jex Blake’s plea—Farewell to Cambray House—Continued growth—College incorporated under Companies’ Acts—Boarding houses made an intrinsic part of College—Defining of Principal’s powers—Cambray House again | 43 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Cheltenham College magazine started—Dorothea Beale, editor—Her “silver wedding”—“Old Girls’” Gift—Scheme of Guild put forward and carried out—Emblem—Opening address—Dorothea Beale’s remembrance of former pupils—Miss Newman’s work—Continued after her death—St. Hilda’s, Oxford—St. Hilda’s, East London—Dorothea Beale’s attitude to charitable enterprises | 51[Pg vii] |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| A time of darkness—Effect on outlook and character—Some general interests—Freshness of outlook—Pundita Ramabai—Interest in Indian widows—Women policemen—Balfour’s Education Act, 1902—Attitude to prizes—John Ruskin and the Ladies’ College—Paris Exhibitions—Another Royal Commission on Education—Visits of Empress Frederick and Princess Henry of Battenberg to College—Epidemic of smallpox—Dorothea Beale and vaccination—Personal honours—Officier d’Académie Française, Tutor in Letters of Durham University, Corresponding member of National Education Association, U.S.A., Freedom of Borough of Cheltenham, LL.D. Edinburgh—Robes presented by staff—Three weeks’ tour—A brief interval of ill-health—Story of the Shannon portrait—College Jubilee celebrations | 58 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Greatness of personality—Varied gifts—Prodigious power of work—Great organising capacity—Organisation of the Ladies’ College—Advice to teachers—Her sense of humour—The tricycle learnt at 67—Her extreme sensitiveness—Power of sympathy—Her outlook that of a religious poet—Her Scripture lessons—Her views on marriage—Tribute of the Bishop of Stepney | 70 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Signs of the end—The last Guild meeting—The last term—A journey to London—The doctor’s verdict—Operation—Waiting the call—A morning of suspense—Laid to rest—Tributes to her character and work | 75 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| The modern world—The need of work—Power of education—Supreme importance of home training—Responsibility of parents—Teaching as a vocation—Personal fitness—Different kinds of teaching—Elementary schools—Boarding schools—Demands of the work—Its joys and advantages—The need of devoted teachers | 79 |

[Pg viii]

I should like to acknowledge my indebtedness to all who have helped me in the writing of this short biography: especially to Mrs. Raikes for her kind permission to use her “Life of Dorothea Beale of Cheltenham,” without which this book could not have been written; also for her most generous help in many difficulties: and to Messrs. Constable, the publishers, for their kind consent. It is impossible to name all who have so willingly helped me, but I should like to mention Miss A. M. Andrews of Cheltenham; Lieut-Colonel J. F. Tarrant for his help in many ways; Mr. J. J. Shannon for kindly allowing a reproduction of Miss Beale’s portrait; Messrs. Martyn of Cheltenham for their photograph; “The Times,” Messrs. Macmillan, and other publishers, who have permitted me to quote extracts from works which are still copyright.

E. H. S.

[Pg 1]

“Tho’ they to-day are passed

They marched in that procession where is no first or last.”

—Austin Dobson.

The story of the nineteenth century is one of wonder: a story with Romance written large on every page. It is a tale of great discovery and enterprise in almost every sphere. Under the influence of its discoveries, material life became transformed and new mental and spiritual horizons appeared. The newly-acquired knowledge of forces like steam and electricity opened up to the world undreamed-of possibilities. Scientists at home and in distant places of the earth discovered truths that did much to reveal God’s ways to men. In the world of medicine new theories were applied to take from operations their dread, and fatality from many diseases. In literature it was a time of great riches: an age equal to any, not excepting the great Elizabethan; an age of prophets and seers, of men and women expressing in singleness of heart the truth as it was revealed to them. And those of us who already live at some distance can hardly imagine a time when Scott and Dickens, Browning and Tennyson, Ruskin and Carlyle, George Eliot and Charlotte Brontë will not be held in high esteem by those who love the great, the true, and the beautiful in literature.

Springing out of these discoveries and revelations there naturally arose a demand that the mind of man generally should be prepared to enjoy this new world. Dissatisfaction with existing methods of education began to be felt; and humble people who were unable to read and[Pg 2] write began to ask that they and their children should be taught.

The education of girls at this time was particularly unsatisfactory, though it had not always been so. In the age of Elizabeth, for example, girls of the higher classes had received an excellent education. It was customary then for girls to learn Greek, Latin, and Hebrew, and as Mrs. Stopes points out in her interesting book on “Sixteenth Century Women Students,” the number of really learned women was very great. I do not know when these ideals of education gave way to lower ones, but readers of Addison will remember that one of his aims in his Spectator essays was to rescue women from the utter frivolity and emptiness of their lives. How scathing he is in his description of the way in which ladies killed time! when the buying of a ribbon was held to be a good morning’s work!

In the early part of Queen Victoria’s reign, the education of girls was indeed deplorable. An excessive amount of time was given to accomplishments and to the study of deportment; the instruction consisted, for the most part, of a smattering of many subjects: and the whole process of education was shallow and superficial. If the women of that day developed—as many did—force of character and of intellect, it was rather in spite of their education than because of it. Numbers of girls rose in revolt against this mental and spiritual starvation: some managed to become well-educated without any outside help, but to a great number this system meant either an utterly frivolous or extremely dull grown-up life.

Many were the voices raised in protest against this lack of education. And as one reads the literature of this time one is greatly struck by the number of men who pleaded for a different régime: not only leaders of thought, like Tennyson and Ruskin, but ordinary men of the educated classes. Perhaps as lookers on they saw[Pg 3] most of the game, and into their souls there entered a deep bitterness that those who might count for so much counted for so little.

But although men by their writings and speeches and actual help in teaching, did much, it was on women that the real burden of this work was to fall. Neither sex can fully educate, though it may teach the other. In the main, the education of boys must be carried on by men; and the education of girls by women. It would be impossible to give a list of all the women who dedicated their powers to this work; who in a very real sense gave their lives that those after them might live. This little book is devoted to the story of one of the pioneers of educational work, and is necessarily limited to the part that Dorothea Beale played in this great enterprise. But Miss Beale, great as she was, was only one of many. Whilst she was working out her ideals at Cheltenham, other women in other schools and colleges were working out theirs: Frances Buss at the North London Collegiate, Emily Davies at Girton, Anne Clough at Newnham, Mrs. Reid at Bedford, Miss Pipe of Laleham, and many others. Nor is it possible to say which of these did the most important work. For we are dealing with that which cannot be measured,—the things of the mind and spirit.

Those of us who came late enough to enjoy some of the fruits of their work, can only acknowledge our deep sense of gratitude to this noble army of women who did so much. If the gates of knowledge are open to us, it was their hand which turned the key: if we can enter nearly every field of service, it was their feet which beat the track. If we hold in our hands a lamp that makes many of the dark places bright, it was they who kindled it and passed it on to us.

The part we must play is no passive one. If the lamp is to be kept burning, it must be fed by the oil of our devotion and our service.

[Pg 4]

“The pilgrim’s discovery is when he looks into his own heart and finds a picture of a city there. The pilgrim’s life is a journeying along the roads of the world seeking to find the city which corresponds to that picture.”—Stephen Graham.

Dorothea Beale, who was born on March 21, 1831, was fortunate in her parentage and early environment. Her father, Miles Beale, was a surgeon who had been trained at Guy’s Hospital. He came of a family of literary traditions, and he himself was a man of wide interests and learning. Her mother, Dorothea Margaret Complin, was of Huguenot extraction and belonged to a family distinguished for its ability, counting among its members several “advanced” women. Mrs. Beale’s aunt, Mrs. Cornwallis, the wife of a rector of Wittersham, Kent, was a woman of considerable intellect and great spiritual gifts. She wrote several books of a devotional character. One of these, “Preparation for the Lord’s Supper with a Companion to the Altar,” contains much excellent advice to ladies on the use and abuse of speech, the regulation of time, indolence, desire of admiration, sickness, etc., breathing a devout and earnest spirit, and revealing in the writer an attitude of great severity towards herself. This little book, with its old-fashioned appearance, seemed to me, as I read it, full of the spirit which animated Mrs. Cornwallis’s celebrated great-niece.

Her daughter, Caroline Frances Cornwallis, was a remarkable woman. Her published letters are extremely interesting, and deal with a variety of subjects, Italy, Education, Religion, Science, Philosophy. She wrote a number of books in the series called “Small Books on Great Subjects”. These were published anonymously, and were considered to be the work of a man, at a time when the known authorship of a woman would have damned any book. Miss Cornwallis often used to laugh[Pg 5] up her sleeve at the appreciation of critics who would undoubtedly have criticised her work unfavourably had they known it was that of a woman. She had a frail body, a courageous mind, and a devout spirit. At times she adopted a cynical attitude towards men’s low estimate of the intellectual powers of her sex. “Every man, you know, thinks he has a prescriptive right to be better informed than a woman, unless he has science enough to see that the said woman is up with him and therefore must know something.” This was, however, just a strain of bitterness bred in a brilliant, active mind handicapped by lack of facilities for real education, and restricted on every side by the bounds of custom and prejudice.

These two women undoubtedly influenced the future head of Cheltenham. Mrs. Beale’s sister, Elizabeth Complin, had lived for some time with the Cornwallises and was the medium through whom the young Beales came into contact with their ideas and ideals.

Dorothea Beale was also fortunate in being one of a large family. The spirit of the home seems to have been one of love and service. There was also a strong intellectual atmosphere, in which the children learnt early to love the best in literature. Her father would often read aloud to his children extracts from Shakespeare and other great writers, and from him and her mother Dorothea began early to imbibe a love of learning, and to find in literature some revelation of the great spiritual realities.

Dorothea’s education and that of the older members of the family was at first under the guidance of a governess. It must have been quite early in life that she received her first inkling of the incompetence of teachers of that day. She remembered a rapid succession of teachers whom Mrs. Beale was compelled to dismiss on account of their inability to teach. There appears to have been only one satisfactory governess, a Miss Wright, who was excellent: after she left, the girls were sent to school.

[Pg 6]

“It was a school,” says Dorothea Beale in her autobiography, “considered much above the average for sound instruction: our mistresses were women who had read and thought: they had taken pains to arrange various schemes of knowledge: yet what miserable teaching we had in many subjects: history was learned by committing to memory little manuals, rules of arithmetic were taught, but the principles were never explained. Instead of reading and learning the masterpieces of literature, we repeated week by week the Lamentations of King Hezekiah, the pretty, but somewhat weak, ‘Mother’s Picture’ of Cowper, and worse doggerel verses on the solar system.”

At the age of thirteen Dorothea was obliged to leave school on account of ill-health. She always considered this a fortunate circumstance as it enabled her to carry on her own education. No doubt a good deal of time was lost in following the circuitous routes of all self-educators, but the grit, determination, and power to overcome difficulties thereby developed, probably more than compensated for this. Libraries, notably those of the London Institute and Crosby Hall, at this time supplied her with many good books. The Medical Book Club circulated some books of general interest. She and her sisters were also able to attend excellent lectures given at the Literary Institution, Crosby Hall, and at the Gresham Institute.

“Miss Beale never learned to play,” said Mrs. Raikes in a speech on Foundress’ Day at the College after the beloved Principal had passed away. “During her girlhood there was no hockey, tennis, net-ball, swimming or other healthy exercise for girls; and Dorothea and her sisters were thrown back for their pleasure on the joys of the mind. Not only did Dorothea Beale never play herself, but she could never quite see the need for other people to play. The playgrounds, etc., which perforce grew up round Cheltenham Ladies’ College, were always rather a[Pg 7] stumbling-block to her, though she was wise enough to be led by those who were more in touch in this respect with the spirit of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

“Her reading always inclined to the solid type, and in her girlhood she came across few novels.

“Her love of reading was never allowed to dissipate itself on trivialities, and here she had a great advantage over girls of to-day, for the ephemeral literature of this age—the endless magazines and short stories—did not exist to tempt and gradually to fritter away a good literary taste.”

She was at this time very much interested in the life of Pascal who, prevented by his father from acquiring a knowledge of mathematics, discovered for himself the truths of Euclid. Perhaps, as Mrs. Raikes suggests, it was Pascal’s example which inspired her to work through the first six books of Euclid by herself. She plodded steadily through the fifth book, not knowing that even at that time a few simple algebraic principles were substituted for Euclid’s rather laborious methods. To Dorothea Beale, as to many boys and girls, mathematics came as a wonderful revelation; they opened up to her developing mind a new world. In her subsequent work as a teacher she seems to have been able to hand on to her pupils something of the thrill and wonder that she herself experienced in these early days.

In the year 1847 Dorothea was sent with two elder sisters to a Mrs. Bray’s school for English girls in the Champs Elysées. This school is perhaps best described in Miss Beale’s own words in the “History of Cheltenham Ladies’ College”.

“I was myself for a few months, in 1848, pupil in a school that was considered grand and expensive. Mrs. Trimmer’s was the English History used in the highest classes. We were taught to perform conjuring tricks with the globe by which we obtained answers to problems[Pg 8] without one principle being made intelligible. We were even compelled to learn from Lindley Murray lists of prepositions that we might be saved the trouble of thinking.”

She was glad, however, in later life of this and similar experiences. It gave her some idea of the enemies of education she had to fight. It made her realise how great was the need for the thorough training and education of teachers and how little could be accomplished without it.

In 1848 Mrs. Bray’s school came to an untimely end through the Revolution of that year and Dorothea returned home at the age of seventeen. Those who knew her at that time described her as “a grave and quiet girl, with a sweet serious expression and deliberate speech: also with a sunshiny smile and merry laugh on occasion. She was remarkable, even in a studious, sedentary family, for her love of reading and study.” According to one authority she was quite beautiful as a girl. One evening she and her sister Eliza went to a dance, Dorothea looking very lovely in a beautiful white dress. Eliza was dancing with a young man, who asked the name of that beautiful girl. “Oh!” said Eliza, delighted that he should admire Dorothea, “she’s my sister. Do you think she’s like me?”—“Good gracious, no!” blurted out the tactless young man. Eliza Beale used to tell this story with great zest, fully enjoying the reflection on her own looks.

In one part of her autobiography Dorothea Beale speaks of the influences of her early life.

“An aunt, my godmother, lived with us, and was often my friend in my childish troubles.... The strongest influence [on my inner life] was that of my sister Eliza. We were constantly together. She had a very lively imagination, and on most nights would tell me stories that she had invented. Early in the mornings she would transform our bedroom into some wild magic scene and[Pg 9] we would play at Alexander the Great and ride Pegasus on the foot of our four-post bedstead.”

Already she had begun to show some of the characteristics which were so marked in later life, her devotion to duty, her keen intellectual interests. She was prepared for Confirmation, in 1847, by the Rev. Charles Mackenzie, to whose teaching Dorothea felt she owed much. Of early religious influences and experiences she thus speaks in her MS. autobiography.

“There was the faith of my parents, the morning and evening prayer. There was the Bible picture-book and the Sunday lessons. The church we went to was an old one, St. Helen’s, and at the entrance were the words: ‘This is none other than the House of God, and this is the Gate of Heaven’. There were high pews and the service was almost a duet between clergyman and clerk, yet I realised, even more than I ever have in the most beautiful cathedral and perfect services, that the Lord was in that place, even as Jacob realised in the desert what he had failed to find at home.”

Religion with her was never allowed to be simply an affair of the emotions: it meant obedience, discipline, the rigid performance of duty, but it was also a source of the deepest emotions.

“I remember how, as the story of the Crucifixion was read, the church would grow dark, as it seemed.... I know nothing of the substance of the sermons now, but I remember the emotion they often called forth, and how I with difficulty restrained my tears.... The hymns were a great power in my life. I remember the joy with which I would sing, in my own room, Ken’s Evening Hymn, and the awful joy of the Trinity Hymn ‘Holy, Holy, Holy’.”

In later years she said that she could not remember a time when God was not an ever-present Friend, a knowledge which sustained her through the darkest periods of her life, and her many struggles.

[Pg 10]

Whether she had at this time realised what her life-work was to be, I cannot say, but it was at home that she began to enjoy her first experience of teaching. Her brothers at the Merchant Taylors’ School suffered much from the unintelligent teaching prevalent in the boys’ schools of that day, and received help in their Latin and Mathematics from their clever elder sister. All this work doubtless helped to develop in Dorothea that clear vigorous mentality that characterised the great Head Mistress of Cheltenham, and impressed still more definitely on her mind the need for reforms in education.

Duty seems to have been, even at this early age, the key-note of her life, and she apparently bore an older girl’s usual share in domestic affairs, helping with the mending and the usual work of the house.

But this time at home was just a quiet breathing space before wider opportunities of study were granted to her.

“Can you remember ... when the great things happened for which you seemed to be waiting? The boy, who is to be a soldier—one day he hears a distant bugle: at once he knows. A second glimpses a bellying sail: straightway the ocean path beckons to him. A third discovers a college and towards its kindly lamp of learning turns young eyes that have been kindled and will stay kindled to the end.”—James Lane Allen.

The opening of Queen’s College marked a great advance in the cause of girls’ and women’s education. It had its root in the Governesses’ Benevolent Institution, which was founded for the purpose of helping governesses in times of need. This was originated by the Rev. C. G. Nicolay, but in the year 1843 the Rev. David Laing, vicar of Holy Trinity Church, Kentish Town, was made honorary secretary. It was he who first saw that an institution[Pg 11] that existed merely to relieve distress was unsatisfactory, and sought to establish, rather, an organisation to prevent the need for relief. Accordingly, he established a Registry for Teachers, and set on foot a scheme for granting diplomas. The latter naturally led to the starting of examinations, which revealed such appalling depths of ignorance in those who were supposed to instruct others, that the need for their tuition was realised.

As is always the case in great movements many were thinking along the same lines, and Miss Murray, Maid of Honour to the Queen, was at this time meditating the starting of a College for Women, and was, as a matter of fact, collecting funds for this purpose. As soon, however, as she heard of Mr. Laing’s plans she handed over to him the money she had collected. He consulted with the government about the establishment of this college, and the Queen graciously allowed it to be named after herself. A house in Harley Street, next door to the Governesses’ Benevolent Institution, was taken. Professors from King’s College were asked to give lectures, and to many women for the first time higher education became a possibility.

The committee, as at first constituted, included such well-known people as Charles Kingsley, Sterndale Bennett, John Hullah, F. D. Maurice, and R. C. Trench. It is still possible to see in book form the lectures which inaugurated the work undertaken by Queen’s College. Though it originated with the idea of helping governesses who wished to qualify for their work, it numbered among its earliest students girls who were to play an important part in many ways in the life of the nation. Among the first pupils were Miss Buss, Adelaide Ann Proctor, Miss Jex-Blake, and Dorothea Beale. At first there were no women lecturers or women teachers, but many women offered their services as chaperones, and very faithful they were in carrying out their trying and exacting duties.

[Pg 12]

The name of the Rev. Frederick Denison Maurice will always be associated with the founding of Queen’s College. Perhaps the name means little to men and women of our generation, though he was not only a great thinker but one of the pioneers of those who apply Christian standards to social life. He founded a Working Men’s College, which is still in existence, and took a great part in the work of Queen’s College. He was compelled to resign his chair of theology at King’s College, on account of his unorthodox beliefs, especially on the question of eternal punishment. Throughout his life he suffered much from charges of heresy, but he exercised a great influence on the religious life of his day, and on that of subsequent generations. He denounced any political economy based on selfishness, declaring it to be false: the Cross, not self-interest, must be the ruling power of the Universe. His lecture at the opening of Queen’s College was a most inspiring one, and his words must have fallen on the ears of some of the girls who listened to him like a call to high and noble service.

“The vocation of a teacher,” said he, “is an awful one: you cannot do her real good, she will do others unspeakable harm, if she is not aware of its usefulness.” He spoke against the harm done by simply providing her with necessaries. “You may but confirm her in the notion that the training of an immortal spirit may be just as lawfully undertaken in a case of emergency as that of selling ribands.” He went on to speak with great decision about the need of a thorough education for those whose special work was “to watch closely the first utterances of infancy, the first dawnings of intelligence: how thoughts spring into acts, how acts pass into habits”.

It was probably about this time that Dorothea began to see what her life-work was to be, and the noble inspiring words of this great servant of God doubtless did much to strengthen in her mind the sense of being called[Pg 13] to high service. All through her career there is no thought more marked than that of the loftiness of a teacher’s work. From herself as well as from others of her calling she demanded that consecration of body, mind and spirit without which there can be no good work done. All who have read her “Addresses to Teachers,” and other works on teaching, realise the high level on which she placed the teacher’s calling, and the stress she laid on the need to pursue continuously impossible ideals of goodness and efficiency.

“All of us have to begin and we live in the intimate consciousness of this thought: Here is a child of God committed to my care, I am to help in so developing him in time that he may be a dweller in the eternal world here and hereafter. I, too, must live an eternal life, in order that I may draw forth that consciousness in him. I must behold the Face of the Father, and so become a light to my children that, seeing the light shine in me, they may glorify that Father.”[1]

[1] “Addresses to Teachers,” I, by Dorothea Beale.

Queen’s College was the greatest boon to Dorothea Beale. It gave her the chance of getting first-rate teaching in Mathematics and Greek. With Mr. Astley Cook she read, privately, Trigonometry, Conic Sections, and Differential Calculus. Soon after she was asked to teach Mathematics and became the first lady Mathematical tutor. As a teacher she could, ex officio, go to any class she liked, and attended at different times lectures on Latin, Greek, Mental Science, and German.

One of her chief friends at this time was a girl of her own age, Elizabeth Alston. The two used to study together, Elizabeth teaching Dorothea singing, whilst her friend taught her to read the New Testament in Greek. In later life she realised how much these singing lessons had done for her, enabling her to use her voice without fatigue for hours together.

Training colleges for elementary school teachers were[Pg 14] established before there was anything of the kind for the teachers of better class children, and it was the head of the Battersea Training College who examined the candidates and awarded the diplomas for knowledge of methods of teaching.

At Queen’s College Dorothea Beale began to show signs of where her power as a teacher would lie. Throughout life it was one of her leading ideas that a teacher should be primarily an inspirer of her pupils: that though she should never cease to prepare her work with the greatest care, her aim should be chiefly to kindle the enthusiasm that would make her pupils eager to learn for themselves. Even at this early age she seems to have possessed this faculty, and long after she left Queen’s College, she occasionally received letters from her former pupils, saying how much her teaching had meant to them.

Her time there, however, was not to be long. There arose difficulties which she felt could not be tolerated. These were, briefly, that one particular person had too much authority, while the women visitors had too little, and what they had was gradually diminishing. This led to many evils, notably the promotion of children into the upper section, or college, from the lower section, or school, long before they were able to derive any benefit from advanced tuition.

Dorothea Beale returned from a summer holiday abroad in 1856 to find these difficulties worse than ever. She and a friend thereupon sent in their resignations, hoping to be able to avoid giving any explanation. Dr. Plumptre, the Head, was, however, extremely anxious for her to reveal the reason for her withdrawal, which she did very reluctantly. After hearing her reasons for leaving, he acknowledged that she was acting in accordance with her conscience and was trying to do what she held to be her duty. Dorothea Beale throughout her life seems to have had to fight against an impetuosity of nature which was in curious opposition[Pg 15] to that greatness of mind that enabled her to wait for the carrying out of any great project. Her action in this connection was characteristically impetuous, for before the correspondence was concluded, she had accepted the post of Head Teacher at Casterton School.

Already we find that she had formulated some of the educational theories she held through life. One of these, which she mentioned in her letter to Dr. Plumptre, was that girls can be thoroughly educated only by women: that though some classes may be taken profitably by men, the education of girls as a whole must be in the hands of their own sex. She showed also her appreciation of the need for thorough groundwork, without which no advanced work can be well done.

Though her action in this matter was characteristically impetuous, and that of a young idealist, it revealed that strong sense of duty which would not allow her to shrink from any painful experience, if the doing of right was involved.

Dorothea Beale, probably because she was one of a big family of girls, was apparently spared one of the most perplexing problems of modern girls and women. From the moment when she felt herself called to the work of teaching she seems to have had no doubt that she was right to obey the call, and was thus saved the torment of the woman worker who is haunted by the thought of home needs unfulfilled. The only daughter in a home, who feels herself called to work outside it, has one of the most difficult of life’s problems to face. She has the knowledge that an ageing father and mother need her, that, perhaps, she will have by and by to earn her own living, and has in her heart the incessant call of the work that claims her. There is no one solution to a case of this kind: every case must be judged independently. It is a difficulty as inherent as sex or any other vital part of life, and needs to be honestly and frankly faced. To most girls in this position, I should say: Get your training early, whilst your parents are still strong and well,[Pg 16] so that if the opportunity of doing work comes you may be ready. Some girls who live in big towns are able to combine home duties with outside work: though on those who are not strong this life of twofold duty is often a great strain. Others, less fortunately placed, realise that the two are alternatives, the choice must be made, and the more imperative duty accepted. In this connection it is well to realise, I think, that the harder duty is not of necessity the right one. The work one dislikes is not necessarily the work one ought to undertake, though it may be. The attitude of many religious people in the past has, I think, been quite wrong in this respect. God has given to all of us special talents and aptitudes, in the exercise of which we find our greatest happiness and do our best work. To believe that the Creator always calls us to do the uncongenial task is, to my mind, to mock His plans. If, however, the beloved task has to be deferred, and the need of our loved ones claims us, there comes with the accepted duty peace and rest of mind, and the waiting time may be used for preparation of mind, heart, and character. To many men and more women, who have kept before them the vision of the work they would do, has often come in a quite unforeseen way an opportunity of doing it: and they have realised how much richer and better their life is for their wider experience during the time of waiting.

“Difficulties are the stones out of which all God’s houses are built.”—Archbishop Leighton.

All readers of “Jane Eyre” will remember the school, Lowood, to which Jane was sent, and her terrible experiences, especially at the beginning of her time there. The[Pg 17] foundation in actual life of this school of fiction, coloured by the Brontë temperament, with its evils exaggerated for the purposes of art, is known by all to be the Clergy Daughters’ School at Casterton. As we have seen in the last chapter, it was to this school that Dorothea Beale had somewhat hastily resolved to go after sending in her resignation to the Head of Queen’s College. Probably she looked upon the offer of this post as an indication that she was to sever her connection with the college in London. If in her decision she was to blame, she certainly paid the price of her mistake.

Casterton is near Kirkby Lonsdale, in a somewhat lonely district, within sight of the rounded height of Ingleborough. Dear to the heart of north-country people is this glorious wild country, but it must have seemed terribly out of the world to a girl accustomed to the life of London, to its libraries and lectures, and the many interests of the metropolis.

From the first Dorothea Beale felt herself oppressed and hindered by numbers of things which she did not approve, and could not alter. The girls wore a uniform which she found terribly depressing: the rules of the school were extremely rigid, and the restrictions so many that she felt the girls had no room for growth. To her, the whole organisation of the place seemed wrong in principle, and the effect on the character of the girls of a too rigid discipline appears to have been pernicious. To one whose views on education were already clearly defined, the having to “carry on” without any power to change what was wrong, must have been an extremely trying experience.

Nor was there much compensation in her own work of teaching: rather the opposite. She found herself compelled to teach many subjects, far more than she could do justice to: Scripture, Arithmetic, Mathematics, Ancient and Modern Church History, Physical and Political Geography, English Literature, Grammar and Composition,[Pg 18] French, German, Italian, and Latin. Holding such strong views as she did about the preparation of lessons and the careful correction of children’s work, she must have found this undue multiplication of subjects very unsatisfactory. There can be, I suppose, for natures like Dorothea Beale’s, few things so trying as circumstances which make a high standard of work impossible. Her father’s letters to her at this time reveal the strong friendship that existed between the two. She wrote home that she found the work hard and her father replied, evidently with the idea of cheering her:—

“Employment is a blessed state, it is to the body what sleep is to the mind.... I cannot be sorry when I hear that you are fully employed. I am sure it will be usefully.... I feel I can bear your being so far and so entirely away with some philosophy, and I am delighted that your letters bear the tone of content, and that you have been taken notice of by people who seem disposed to be kind to you.... Give an old man’s love to all your pupils and may they make their fathers as happy as you do.”

The difficulties at Casterton, however, did not grow less, but tended rather to increase. Her parents began to have some inkling of these, and to feel very doubtful whether she ought to stay at Casterton. On her birthday, March 21, her father wrote again:—

“God bless you and give you many birthdays. I fear the present is not one of the most agreeable: it is spent at least in the path of what you consider duty, and so will never be looked back upon but with pleasure.... Do not, however, my dear girl, think of remaining long in a position which may be irksome to you, for thus, I think, it will hardly be profitable to others, and indeed I question whether you would maintain your health where the employment was so great and duty the only stimulus to action. You have heard me often quote: ‘The hand’s best sinew ever is the heart’.”

[Pg 19]

Two months later Mr. Beale wrote:—

“I long to see you again very much. I cannot get reconciled to your position and feel satisfied that it is your place.... God bless you, my dear girl, and blunt your feelings for the rubs of the world, and quicken your vision for the beautiful and unseen of the world above you.”

The sensitiveness her father alludes to in this letter was one of Dorothea Beale’s leading characteristics to the end of her life. Though she welcomed and considered the criticism of competent people and often acted on it she had a curiously sensitive shrinking from adverse judgment: and this often cut her off from valuable advice. Her shyness, too, kept her from the friendship of those who, like herself, were too diffident to make advances. In it, however, lay one of her chief powers, the subtle perception that enabled her to see almost into the very souls of the girls she taught. Once, at Cheltenham, a child refused to admit that she had done wrong. One morning Dorothea Beale sent for the class teacher. “Send So-and-So to me,” she said, “I can see from her face this morning that she will tell me all.” And she was right.

It was at Casterton that she adopted the simple style of dress that she always preferred. One of her pupils thus describes her:—

“Her appearance, as I remember it then, was charming. Her figure was of medium height. The rather pale oval face, high, broad forehead, large, expressive grey eyes, all showed intellectual character. Her dress was remarkable in its neatness. She wore black cashmere in the week, and a pretty mouse-coloured grey dress on Sundays.”

Possibilities of making improvements at Casterton now began to weigh on her mind. Unless things were changed she felt she could not stay, but she was not inclined to give up without an effort at amelioration. She determined to take a very bold step and to appeal to the Committee. Her father was kept in touch with all her plans at this time and wrote:—

[Pg 20]

“I think we must be content to wait, at any rate for the present, and see if any good comes from your interview with the Committee. You notice two points chiefly—the low moral tone of the school and the absence of prizes [distinctions, responsibilities, etc.]. The want of sympathy and love (the great source of woman’s influence in every condition of life) was the prominent feature of the establishment in my mind after talking it over with you. But nothing can flourish if love be not the ruling incentive....”

He goes on to say that he realises how much love and devotion she puts into her work, but how useless it is when she is unsupported.

“Weigh the matter well before this Christmas,” he continues, “and if you find no changes are made, the same cold management continued, send in your resignation.”

Then the affectionate father concludes:—

“I cannot contemplate your not coming up at Christmas. As we grow older each year makes us more desirous of the company of those we love; perhaps, because we feel how soon we shall part with it altogether; perhaps, because we are become more selfish, but such is the fact.”

The six members of the Committee apparently consented with some reluctance to hear Dorothea, but she did get a hearing and brought her chief objections before them. The experience was not so trying as she had anticipated, and the Committee appeared fairly conciliatory. She explained—in speaking of the absence of prizes—that by this term she meant rather distinctions, privileges, and opportunities of doing good. She offered to resign, but the Committee said, “Oh, no, certainly not”. And she came away feeling that her efforts might have some good result.

Few people, whether individuals or collective bodies, can endure criticism, and Dorothea Beale’s complaints[Pg 21] seem to have caused a great deal of discomfort in her relationship with those connected with Casterton. This was increased very much by a suspicion that she was not orthodox according to the evangelical low-church point of view. She was considered “high,” and was suspected of holding extreme views about baptismal regeneration, one of the storm centres of religious controversy at this time. This caused even one of her chief friends on the Committee to wish her to leave.

With the tenacity of purpose that characterised her through life, she tried to believe that it was right for her to stay and fight the difficulties at Casterton. Gradually, however, the impossibility of doing so became evident, and she wrote to her father:—

“I do not see how it is possible to do much good. I may work upon a few individuals, but the whole tone of the school is unhealthy, and I never felt anything like the depression arising from the constant jar upon one’s feelings caused by seeing great girls professing not to care about religion.”

She suggested that she should send in her resignation, and her father replied at length, giving her advice as to how to approach the Committee, and again writing words of cheer:—

“Above all things take care of your health.... I am quite sure that you have a long course of usefulness before you. The flattering regard in which you are held at Queen’s College, and the constant means you always have in London of constantly improving yourself, must teach you somewhat of your own value. Though I would not indeed presume upon it further than to give you confidence to act rightly.”

It was near the end of November before Dorothea made her final decision to send in her resignation. She had not time to carry out this decision before she received the following note from the Committee:—

“On your last interview with the Committee you[Pg 22] implied an intention of resigning in case certain alterations should not be made by the Committee....

“The Committee are of opinion that, under the circumstances, it would be better that your connection with the school should cease after Christmas next, they paying you a quarter’s salary in advance.”

This note was received shortly before the Christmas holidays.

It is easier to imagine than to describe the effect of this summary dismissal on a highly sensitive girl, whose actions had throughout been prompted by a sincere desire for the good of the school. It is difficult to endure the sense of failure in youth before one has had assurance of one’s own powers. Again at this time her father’s sympathetic letters, reminding her of the high motives with which she had undertaken this work, were a great comfort to her. In after years Dorothea Beale acknowledged the value of this year at Casterton. No life is perhaps complete without its times of failure, as she must have felt her year at Casterton to be. For the world is full of men and women who fail, and it is only by personal knowledge of their experience that we can sympathise with them and help them to rise above it.

Many, however, appreciated the good work Dorothea Beale did at Casterton, and her quiet and steady persistence in what she felt to be right were not without their permanent influence on the school. Her remembrance of this school was a source of pain to her, and yet, as the years went on, she felt how much she owed to her experiences there. In The Times of November 19, 1906, there is an extract from a letter by Canon A. D. Burton, Casterton Vicarage, Kirkby Lonsdale.

“I have read with interest your account of Miss Beale’s life. I think, however, it is possible that it may give an erroneous impression with regard to her connection with Casterton, and it may be of interest if I mention that I happen to know something of the feelings she entertained[Pg 23] towards the school. Rather more than a year ago she wrote to say that it had long been in her mind to do something for the school in grateful remembrance of the benefit which her connection with it had been to her, and this wish finally took shape in the founding of a scholarship to Cheltenham, and the first Casterton-Beale Scholar is at the present time in residence at that college.

“The Casterton Clergy Daughters’ School, like most other schools of long standing, has a past which is not to be compared with its present. That is no disparagement to it, but the reverse. Its present state is one of high efficiency, but it is interesting that it was not on this account only that Miss Beale wished her name to be always connected with it, but because she felt herself in debt to it. ‘I owe much to it,’ were her words. A few months ago she also presented to the school an oil-painting of herself which was hung in the entrance hall.”

She did not leave Casterton, however, without some acknowledgment on the part of the authorities and others that her work and character had been appreciated. It must also have been a solace to her when Dr. Plumptre, hearing of her resignation, at once wrote and spoke of the possibility of a mathematical tutorship at Queen’s College.

It was characteristic of Dorothea Beale that after she returned home from Casterton with one part of her work finished and no other in view, she did not idly waste her time but began a definite piece of work—the writing of her history, “The Student’s Text-book of English and General History”. The need of such a book was felt very strongly at this time, partly because of the outcry against the papistical doctrine inserted into Ince’s history, one of the most popular text-books of the day. This book must have involved an enormous amount of work, though it dealt only in outline with this vast subject. In[Pg 24] the preface she makes it clear to the student that no real knowledge of history can be built upon such a slender foundation, and urges the need for filling in the outlines by wide and thorough reading. Her history was not her only occupation at this time; she did some visiting teaching—Latin and Mathematics—at Miss Elwell’s school at Barnes.

She realised the difficulty of working steadily at home, knowing the thousand distractions, social and domestic, that come to divert a girl from any definite pursuits. So she adopted the plan of writing her history in a large empty room at the top of the house. Here she would work without a fire on cold winter days. Whether this was an expression of the desire for Spartan simplicity of life which she always had, or was done simply to keep away members of the family who might wish to come and chat, one cannot say.

Dorothea Beale had evidently undertaken some work as secretary and collector for the Church Penitentiary Association and for a Diocesan Home at Highgate, working with Mrs. Lancaster. The latter greatly appreciated her and her conscientious work, and realised what a valuable helper she would be, if she could enlist her in this great service. She approached her with the suggestion that she should take the headship of the Home. Dorothea Beale considered the offer but refused. This must have been a great test of faith in her own judgment. Behind her were two experiences, both of which had ended in apparent failure because of her inability to agree with the authorities. No educational work was in view, and she must have questioned her own wisdom in refusing this opportunity of service which came to her. Yet it seems as if at this time there dawned on her mind the deep conviction that she was called to educational work among her own class: that with her temperament and ideas so much in advance of her own time a headship was the only post that[Pg 25] would give her the scope and freedom that she needed if she was to do her best work. And so she waited, not with idle hands and brain, but fully occupied with her history, her teaching, and home duties.

It was probably about this time that she began her Diary, which she kept with some intervals until the year 1901. The purpose of it seems to have been to keep a record not of outward events but rather of her moral and spiritual life. In it we have one of the many evidences of that sternness towards herself which she maintained in all circumstances of life, even in illness. Earlier, perhaps, than most people, she seems to have realised that her influence on others would depend entirely on what she herself was. One or two quotations from her journal will illustrate the purpose of it.

March 6.—History. Aunt E. came. Cross at not getting my own way. Some idleness. Impatient manner.

April 14.—History. Elizabeth. Called on the Blenkarnes. Dined at Chapter House. Idle. Indulgence in reading story at my time for evening prayer. Unpunctual in morning. Thoughtless about Mama.

April 20.—History, 16th Century. Felt terribly cross. O grant me calmness.

June 4.—Saw Mrs. Barret. Copied. Neglected prayer greatly. Very worldly.

June 7.—Wrote letters. A terrible blank of worldliness. Idle.

June 9.—Wrote to Miss Elwell. Letter from Cheltenham. Copied certificates. Worldly. Spoke angrily to A.

At this time there are many allusions in her journal to crossness. Probably it was the result of that supreme test of the active, energetic mind—the enduring of uncertainty. In 1901 she wrote to a friend about this period of her life:—

[Pg 26]

“Once I had an interval of work, and I thought perhaps God would not give it me again—but after that interval He called me here. I think now I can see better how I needed that time of comparative quiet and solitude, and a time to think over my failures, and a time to be more helpful to my family.”

Whilst still young, Dorothea Beale formed the habit of frequent attendance at early Communion, which she maintained all through her busy life. Like the saintly men and women of all ages, she felt that the more strenuous and exacting her work, the more she needed these hours of Communion. The Sacraments of the Church as generally necessary to salvation she believed to be two—Baptism and Holy Communion—but the whole of life to her was sacramental. More and more as years passed by did outward and visible things become to her the signs of inward and spiritual realities: to her, and to those of her school of thought, sacramentalism meant “the discovery of the river of the water of life flowing through the whole desert of human existence”.

But Dorothea Beale was no dreamy, unpractical mystic, holding herself aloof from the practical difficulties of life. She realised that there is little value in a religion that cannot find expression in the life of every day; and little strength in the soul that is not continually fortified by the struggle of work and the carrying out of duty.

“The religion of Dorothea Beale,” says Mrs. Raikes, “was far indeed from being a mere succession of beautiful and comforting thoughts. It meant authority. It involved all the difficulties of daily obedience, it meant the fatigue of watching, the pains of battle, sometimes the humiliation of defeat. Intense as was her feeling on religious subjects, it was never permitted to go off in steam, as she would term it, but became at once a practical matter for everyday life.”

[Pg 27]

O, I am sure they really came from Thee,

The urge, the ardour, the unconquerable will,

The potent, felt, interior command, stronger than words,

A message from the Heavens whispering to me even in sleep.

These speed me on.

—Walt Whitman, “Prayer of Columbus”.

Until about 1825, Cheltenham was simply a small market-town, famous for its mild climate and fertile soil, but at this time its medicinal springs were discovered, and it became the fashion for royalty and aristocracy to take the waters. Between 1801 and 1840 the population of Cheltenham increased tenfold. In 1843, Cheltenham College, a proprietary school for boys, was opened. Ten years later, on September 30, 1853, a meeting was held in the house of the Rev. H. Walford Bellairs, who was Her Majesty’s Inspector of Schools in Gloucestershire, and a prospectus was drawn up of “A College in Cheltenham for the education of young ladies and children under eight”.

The instruction was to include the Liturgy of the Church of England, grammar, geography, arithmetic, French, drawing, needlework. The fees were to range from 6 guineas to 20 guineas a year, and the capital was to consist of £2000 in £10 shares. The entire management and control were to be in the hands of the founders, the Rev. H. W. Bellairs; the Rev. W. Dobson, Principal of Cheltenham College; the Rev. H. A. Holden, Vice-Principal; Lieutenant-Colonel Fitzmaurice; Dr. S. E. Comyn; and Mr. Nathaniel Hartland.

They appointed as Principal Mrs. Procter, the widow of Colonel Procter, and as Vice-Principal her daughter, Miss Procter, who was understood to be the actual head. Mrs. Procter was to furnish the wisdom and stability of mature years, Miss Procter the youth and vigour[Pg 28] necessary for teaching. A younger sister held the post of secretary.

At first it was intended that the college should be restricted to day pupils, but it was soon found that this would limit its usefulness, and some months before the opening of the school the proprietors had arranged for three boarding-houses, the fees of which were extremely low, being only £40 a year.

Cheltenham Ladies’ College was laid on good foundations. The founders had an ardent desire for a thorough and liberal education, and their ideas were well carried out from the very beginning of the school’s career. The teaching appears to have been of a high order, the teachers were people of conscience and ability. In her “History of Cheltenham Ladies’ College,” Miss Beale quotes from old pupils who spoke most highly of the early days.

The school was opened on February 13, 1854, in Cambray House, where the great Duke of Wellington had once stayed for about six weeks. It was a fine square-built house with a beautiful garden. By the end of the first year the 100 pupils had increased to 150; the second year also marked an increase. But after that the numbers began to go down, until at the end of 1857 the numbers had fallen to 89, and the capital had begun to diminish.

Some disagreement on educational methods then arose between Miss Procter and the Committee, with the result that the former resigned and started another school in Cheltenham, which was continued for thirty years.

The Principal’s letter to the Committee on her departure shows her scrupulous care of the property of others:—

“My Dear Sir,

“I thank you much for your kind letter enclosing your cheque for £41 10s. 6d.

[Pg 29]

“I take this opportunity of sending you the keys of the college. The house has been cleaned throughout. The chimneys have all been swept.

“Some few stores—nearly ¹⁄₄ cwt. of soap, some dip candles, and two new scrubbing brushes—are in the closet in the pantry.

“The new zinc ventilator is in the press used for the drawing materials.

“Two cast-iron fenders, of mine, have been removed from two of the class-rooms.

“I remain, my dear Sir,

“Yours very sincerely,

“S. Anne Procter.”

It was in May, 1858, that the advertisement for a new Principal of Cheltenham College appeared in various papers.

Cheltenham Ladies’ College.

“A vacancy having occurred in the office of lady Principal, candidates for the appointment are requested to apply by letter (with references) before June 1 to J. P. Bell, Esq., Hon. Sec., Cheltenham.

“A well educated and experienced lady (between the ages of thirty-five and forty-five) is desired, capable of conducting an institution with not less than one hundred day pupils.

“A competent knowledge of German and French, and a good acquaintance with general English literature, arithmetic, and the common branches of female education, are expected.

“Salary, upwards of £200 a year, with furnished apartments and other advantages.

“No testimonials to be sent until applied for, and no answers will be returned except to candidates apparently eligible.”

Dorothea Beale applied for this post and was accepted[Pg 30] as a candidate for the headship. She had now to set about getting testimonials and recommendations. Some of these are interesting.

Miss Elwell, at whose school she had taught, wrote:—

“You have succeeded in making subjects usually styled dry, positively attractive, whilst your plan has been successful in forming not merely superficial scholars, even whilst producing results in a remarkably short period.”

Her friend, Elizabeth Ann Alston, wrote:—

“Of her power of teaching others and making them delight in their studies, there is no doubt. But you do not know her, as I do, in her home and daily life: there all look up to her and seek her counsel.”

Many testimonials were given as to her character and work, and these made such a favourable impression on the Cheltenham Committee that she was summoned for an interview on June 14.

She evidently had not any suitable clothes to wear on such a formidable occasion, and had to borrow a blue silk frock from her sister Eliza. Perhaps the work on her history had prevented her from attending to her wardrobe. She was appointed and everything seemed happily settled. One can imagine with what joy she looked forward to this opportunity of doing the work she longed to do untrammelled by bonds made by those of differing ideas. After all these months of waiting she had at last obtained her heart’s desire.

But the stigma of leaving Casterton was not easily removed, and a great blow awaited her.

On July 12 she received a letter from Mr. J. Penrice Bell, the Honorary Secretary of the Committee, saying that he had received from two gentlemen letters about her religious views, that might make it necessary for the Cheltenham Ladies’ College Committee to reconsider their decision. He quoted briefly their allegations:—

“‘She, Miss Beale, is very High Church, to say the least, and holds ultra views of baptismal regeneration.’[Pg 31] ... ‘She has also a serious and deep religious feeling, and a self-denying character. But she is decidedly High Church. Her opinions on the vital and critical question of sacramental grace are altogether those of the High Church or Tractarian school.’”

To a sensitive girl like Dorothea Beale this was indeed a shock, but she was determined not to lose the desired work through any misunderstanding, and replied at once to Mr. Bell explaining her views on baptism, which were said to be “extreme”:—

“If you understand by the opus operatum ‘efficacy’ of baptism that all who are baptized are therefore saved.... I explicitly state that I do not hold that doctrine. I believe baptism to be ‘an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace given unto us: to be the appointed means for admitting members into the Church of Christ’.”

The allegation that she belonged to the High Church party she dealt with:—

“Your second question [i.e. did she belong to the High Church?] ... cannot be categorically answered, since it has never been defined what are the opinions of the High Church party; I would say that I differ from some who assume that title.... I think no one could entertain a greater dread than I of those Romish opinions entertained by some ‘who went out from us, but were not of us’: indeed, during the last six months, I have been engaged in preparing an English history for the use of schools, because Ince’s “Outlines” (a book used in your college) inculcates Romish doctrines.”

The conclusion of her letter shows how clearly she realised the effect that might be produced if the Committee revoked their decision:—

“I have endeavoured to be perfectly candid: should the Council decide that my views are so unsound that I am unfit to occupy the position to which I have been appointed, I shall trust that they will allow me to make[Pg 32] as public a statement of my opinions as they are obliged to make of my dismissal, for I shall feel that after this no person of moderate views will trust me, and my own conscience would not allow me to work with the extreme party in either High or Low Church.”

The suspense whilst the Committee’s decision hung in the balance must have been great. Her diary indicates this:—

July 12.—Mr. Bell’s letter about High Church from Cheltenham, and my answer. Some vanity. (Prayer) for resignation.

July 14.—Letter from Cheltenham. Neglect of prayer. Several times rude.

The Committee, however, seem to have been satisfied with her letter to Mr. Bell, and another to Mr. Bellairs, in which she referred him to two friends who knew what her religious views were, sending him also two books, “which I have published without my name—not because I was ashamed of expressing what I thought right, but because one naturally shrinks from expressing without necessity one’s inner religious life”.

They still had one more question, which Mr. Bell asked in his next letter:—

“Holding the opinions you have expressed, should you consider it a duty and feel it incumbent on you to inculcate them in your Divinity instruction to the pupils?”

To this she replied:—

“I quite feel it to be a Christian duty, if it be possible, to live peaceably with all men, not giving heed to those things which minister questions rather than godly edifying, but I am sure you would feel I should be unworthy of your confidence could I through any fear of consequences resort to the least untruthfulness.”

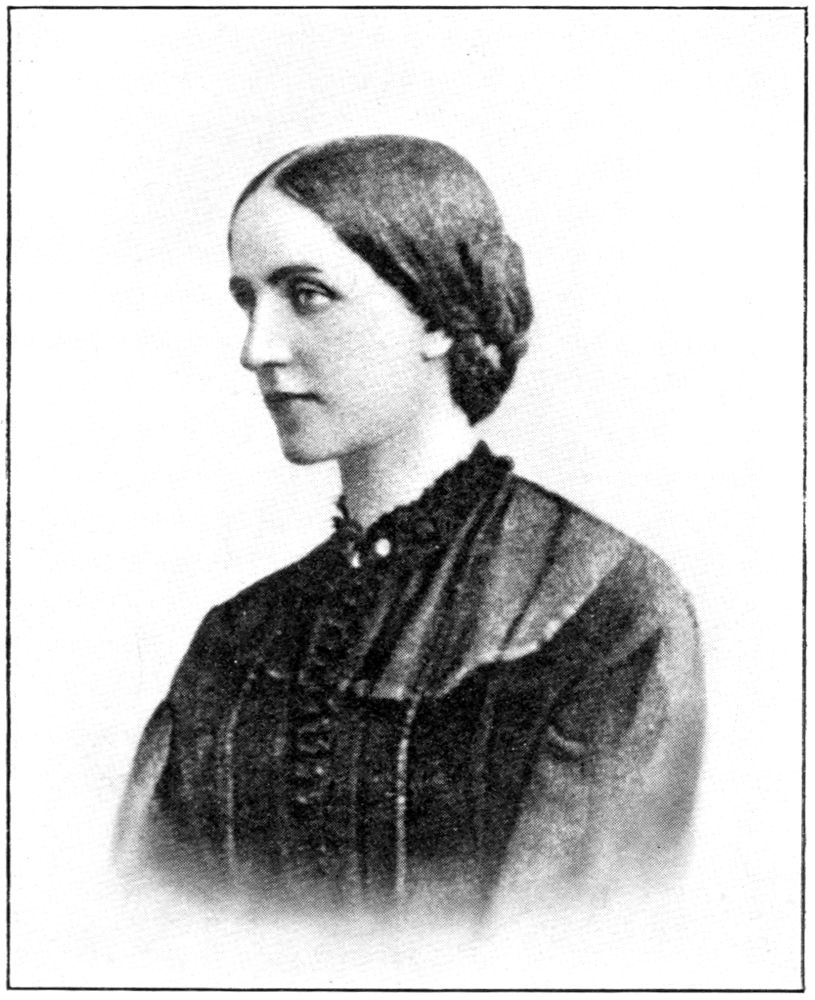

DOROTHEA BEALE IN 1859

p. 32

The difficulty was thus ended, and Dorothea Beale entered her kingdom. In spite of the many possibilities of giving offence, from the beginning she made the Scripture lessons the very centre of her teaching. To[Pg 33] these she went herself not only with her carefully prepared work but with her heart and soul equally equipped. She demanded equal reverence in her pupils, and during times of building at the college the noise of the hammer was suspended when these lessons were being given.

There is little record about the beginning of her work at Cheltenham. Twice Miss Brewer, who was to be Vice-Principal, called upon her: and there are one or two entries in her diary about “shopping” and “turning-out”. Even the date (August 4) on which she set out for Cheltenham with her mother is only known by deduction. One can imagine, however, the spirit in which Dorothea Beale set out into the unknown. Was it to be failure or success? Were her powers equal to the many difficulties that lay before her? Would the Committee turn out to be the kind of people with whom she could work? But we know enough to be sure that she looked to God as her guide in all things, and that in offering herself for this great work of education she laid her life and all her powers at His feet.

Dorothea Beale’s first two years at Cheltenham were a struggle from beginning to end. When she arrived the College had begun to go down, and many of the elder girls had left with Miss Procter, so that the oldest pupils were now only thirteen or fourteen years of age. Mrs. Raikes in her “Life,” quotes a description of her from a pupil who was at the school when she arrived:—

“I can see her now as she appeared in reality—the slight, young figure, the very gentle, gliding movements, the quiet face with the look of intense thoughtfulness and utter absence of all poor and common stress and turmoil, the intellectual brow, the wonderful eyes with their calm outlook and their expression of inner vision.”

One of her first decisions was to continue and make permanent the rule of silence, which Miss Procter had introduced at the beginning of the college. She was, at first, full of doubts as to the wisdom of this rule but was[Pg 34] so well satisfied with the results that she never saw any reason to alter it. Pupils were allowed to speak only with a teacher’s permission, which was always given when it was necessary. Her reasons for the ordaining of this rule were to inculcate habits of self-control, to prevent the making of friendships of which parents might not approve, to secure concentration and good discipline. It was very rigidly enforced, and if a girl broke it only a few times in the term a remark to that effect was inevitably put into her Report. One of the jokes frequently made against the Ladies’ College was that no Cheltenham girl could talk!

The history of these two years is given very graphically in Miss Beale’s History of the College, from which the following account is almost entirely taken. When Miss Beale was appointed there were only sixty-nine girls left, of whom fifteen had already given notice (of these only one actually left). Only £400 was left out of the original capital. The ladies who had kept boarding-houses gave up on account of the uncertainty, and several of the original shareholders sold their £10 shares for £5.

“Several birds of prey,” said Miss Beale, “were seen hovering about expecting the demise of the College, and it would probably have ceased to exist had there not remained two years of the Cambray lease, for the rent of which £200 a year had to be found. It is impossible to give an adequate idea of the hard struggle for existence maintained during the next two years, and of the minute economies which had to be practised. Haec nunc meminisse juvat. The Principal was blamed for ordering prospectuses without leave at the cost of fifteen shillings, and the second-hand furniture procured would not have delighted people of æsthetic taste. Curtains were dispensed with as far as possible, and it was questioned whether a carving-knife was required by the Principal in her furnished apartments.”

The teaching staff was reduced as far as possible and[Pg 35] the Principal and Vice-Principal gave up their half-holiday to chaperone those girls who took lessons from masters. The Principal did a great deal of teaching at this time including Scripture throughout the College.

Everything that could be done in those two years to curtail expenditure was done. The gain or loss of one pupil was considered an important event. One day Miss Beale was at dinner when a father called with two girls. The maid sent him away, saying that her mistress was at dinner. Miss Beale, however, sent her at once in pursuit after the departing visitors. She spoke to the maid afterwards about this matter and said, “I am never at dinner”.

At the end of these two years the lease of Cambray House expired, and, though the deficit was less at the end of 1860 than in 1859, there was not a single member of the Committee who was willing to take the responsibility of renewing the lease. Many causes conspired to make the school unpopular at this time, and the question of giving it up had to be seriously considered.

Just when things were at their worst a deliverer appeared in the person of Mr. J. Houghton Brancker, who was asked to audit the accounts. After a thorough investigation this gentleman gave his verdict that it was impossible for the school ever to pay its way with the then system of fees. Accordingly he drew up a scheme which he considered satisfactory, lowering the ordinary fees, but making music and drawing, which had hitherto been included in the ordinary curriculum, extra subjects. Mr. Brancker was asked to join the Council; under his able rule as chancellor of the exchequer, the College finances began to improve, and grinding anxiety about money matters soon became a thing of the past. Cambray House was taken by the year until things were in a more satisfactory state, but such a precaution was unnecessary, as the College after this had a career of almost unbroken progress and prosperity.

[Pg 36]

Financial difficulties were not, however, the only ones that Miss Beale had to fight, nor were they the hardest. Far greater foes to her peace of mind were those of ignorance, prejudice, and lack of ideals about girls’ education. Practical difficulties, too, stood in the way of high attainment. Dorothea Beale relates some of these in her “History of the Ladies’ College”. It was said that college life would “turn girls into boys”. Day schools for girls were unpopular, and the custom of having morning and afternoon school caused parents a great deal of trouble in sending maids with their children. Teachers were scarce and those to be had were very inferior.

“Do you prepare your lessons?” asked Dorothea Beale of a candidate.

“Oh no!” she replied, “I never teach anything I don’t understand.”

Parents looked with horror on the teaching of mathematics and even advanced arithmetic, in spite of the poverty to which ignorance of investments often reduced women.

Some reminiscences of former pupils give a little idea of what Dorothea Beale was like in her teaching and in her relationship to her children.

“I never remember her raising her voice, scolding us, being satirical or impatient with dullness or inattention. She was not satirical even when a small girl, on being asked what criticism might be passed on Milton’s treatment of “Paradise Lost,” ventured the audacious suggestion that the poet was ‘verbose’.”

Her methods were designed to encourage rather than to repress. A pupil recalls “an afternoon when she visited the needlework room and found me being most justly blamed for inefficiency. In kindly tones she said to the shy and clumsy culprit: ‘You ought to sew well, for your mother has such beautiful long fingers,’ and somehow I felt comforted and encouraged. Then there[Pg 37] was a day when I summoned up courage to go and tell her that I had been guilty of some small disobedience as well as others who had been detected and punished. She seized the opportunity of impressing upon me that as I was (though only fourteen) a teacher in my father’s Sunday School—a fact of which I did not know she was aware—I must surely see that obedience to rule was necessary. I can still hear the low, earnest tones in which she made her appeal to my sense of justice and right.”

At this period of her life her power was probably as great as it ever was, though the scope was comparatively narrow.

“It is my peculiar privilege,” writes one, “to have spent all my college career in her class, to go through years of her special personal teaching. In later days when the College assumed large dimensions, such an experience must have been rare; to those who could claim it, it meant a potent influence for life. How vividly can I recall her sitting on her little daïs, scanning the long schoolroom and discovering anything amiss at the far end of it; or making a tour of inspection to the various classes with a smiling countenance that banished terror.”

Her personal relationship to any of her children in sorrow was always a very tender one.

“When I was almost a child at College I lost my mother and shall never forget Miss Beale’s tender sympathy and help. She took such interest in my preparation for Confirmation and brought me herself to my first Communion—just she and I alone: a day I shall always remember. All through my girlhood she was a kind and ready adviser, and continued her interest throughout my married life. One always felt whatever happened to one, ‘Now I must tell Miss Beale’.”

So with the varied joys of teaching, and the difficulties of narrow means, and the opposition of supporters of the old régime, did Dorothea Beale’s life at Cheltenham begin.

[Pg 38]

Forty years later she wrote of this time:—

“How often I was full of discouragement. It was not so much the want of money as the want of ideals that depressed me. If I went into society I heard it said: ‘What is the good of education for our girls? They have not to earn their living.’ Those who spoke did not see that, for women as for men, it is a sin to bury the talents God has given: they seemed not to know that the baptismal right was the same for girls as for boys, alike enrolled in the army of light, soldiers of Jesus Christ.”

No knight of olden times who rode forth against the evils of his day needed greater courage than this woman who set out to destroy the evils of prejudice, custom, and ignorance. I have spoken sometimes with her “old girls,” who were with her in the early days, and were among the first to enter on paths untrodden by women’s feet. They were like men who seek a new land; no sacrifice seemed too great; no toil seemed too hard. Following their dauntless leader they knew themselves to be the vanguard of a great army of women infinite in number and of unknown power.

“Knowledge is now no more a fountain sealed.”—Tennyson, “The Princess”.

In order to understand Dorothea Beale’s work and that of her many contemporaries who were working towards the same end, it is necessary to know something of the depths to which girls’ education had sunk in that day. All readers of Ruskin’s “Sesame and Lilies” are familiar with his bitter invective against the attitude of parents towards this important question, and his passionate appeal[Pg 39] for reform. And Ruskin was only one of the many men who realised the pity of the paltry and superficial education that girls received, and the extent to which the whole world suffered on this account. So strong had public feeling become among the better educated on this burning question that, in the year 1864, a Schools’ Inquiry Commission was instituted; and as far as possible a thorough investigation was made of the subject. Reports on Girls’ Schools were given by Mr. Fitch, Mr. Bryce, and others.