Title: Weird Tales, Volume 1, Number 4, June, 1923: The unique magazine

Author: Various

Editor: Edwin Baird

Release date: December 22, 2022 [eBook #69608]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Rural Publishing Corporation

Credits: Wouter Franssen and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

FREE

$80 Drafting Course

There is such an urgent demand for practical, trained Draftsman that I am making this special offer in order to enable deserving, ambitious and bright men to get into this line of work. I will teach you to become a Draftsman and Designer, until you are drawing a salary up to $250.00 a month. You need not pay me for my personal instruction or for the complete set of instruments.

Draftsman’s Pocket

Rule Free—To Everyone Sending Sketch

To every person of 16 years or older sending a sketch I am going to mail free and prepaid the Draftsman’s Ivorine Pocket Rule shown here. This will come entirely with my compliments. With it I will send a 6 × 9 book on “Successful Draftsmanship”. If you are interested in becoming a draftsman, if you think you have or may attain drafting ability, sit down and copy this drawing, mailing it to me today, writing your name, and your address and your age plainly on the sheet of paper containing the drawing. There are no conditions requiring you to buy anything. You are under no obligations in sending in your sketch. What I want to know is how much you are interested in drawing and your sketch will tell me that.

Positions Paying Up to

$250 and $300 per Month

I am Chief Draftsman of the Engineers’ Equipment Co. and I know that there are thousands of ambitious men who would like to better themselves, make more money and secure faster advancement. Positions paying up to $250 and $300 per month, which ought to be filled by skilled draftsmen, are vacant. I want to find the men who with practical training and personal assistance will be qualified to fill these positions. No man can hope to share in the great coming prosperity in manufacturing and building unless he is properly trained and is able to do first class practical work.

I know that this is the time to get ready. That is why I am making the above offer. I can now take and train a limited number of students personally and I will give to those students a guarantee to give them by mail practical drawing room training until they are placed in a permanent position with a salary up to $250 and $300 per month. You should act promptly on this offer because it is my belief that even though you start now the great boom will be well on by the time you are ready to accept a position as a skilled draftsman. So write to me at once. Enclose sketch or not, as you choose, but find out about the opportunities ahead of you. Let me send you the book “Successful Draftsmanship” telling how you may take advantage of these opportunities by learning drafting at home.

FREE this $25 Draftsman’s

Working Outfit

These are regular working instruments—the kind I use myself. I give them free to you if you enroll at once. Don’t delay. Send for full information today.

Mail Your Drawing at Once—and Get Ivorine Pocket Rule Absolutely Free!

Ambitious men interested in drafting hurry! Don’t wait! This is your opportunity to get into this great profession. Accept the offer which I am making now. Send in your sketch or request for free book and free Ivorine Pocket Rule.

Chief Draftsman, Engineers’ Equipment Co.,

1951 Lawrence Av.

Div. 13-95 Chicago

The Unique Magazine

EDWIN BAIRD, Editor

Published monthly by THE RURAL PUBLISHING CORPORATION, 325 N. Capitol Ave., Indianapolis, Ind. Application made for entry as second-class matter at the postoffice at Indianapolis, Indiana. Single copies, 25 cents. Subscription, $3.00 a year in the United States; $3.50 in Canada. The publishers are not responsible for manuscripts lost in transit. Address all manuscripts and other editorial matters to WEIRD TALES, 854 N. Clark St., Chicago, Ill. The contents of this magazine are fully protected by copyright and publishers are cautioned against using the same, either wholly or in part.

Copyright, 1923, by The Rural Publishing Corporation.

VOLUME 1 25 Cents NUMBER 4

Sixteen Thrilling Short Stories

Two Complete Novelettes

Two Two-Part Stories

Interesting, Odd and Weird Happenings

| THE EVENING WOLVES | PAUL ELLSWORTH TRIEM | 5 |

| An Exciting Tale of Weird Events | ||

| DESERT MADNESS | HAROLD FREEMAN MINERS | 19 |

| A Fanciful Novel of the Red Desert | ||

| THE JAILER OF SOULS | HAMILTON CRAIGIE | 32 |

| A Powerful Novel of Sinister Madmen that Mounts to an Astounding Climax | ||

| JACK O’ MYSTERY | EDWIN MacLAREN | 49 |

| A Modern Ghost Story | ||

| OSIRIS | ADAM HULL SHIRK | 55 |

| A Weird Tale of an Egyptian Mummy | ||

| THE WELL | JULIAN KILMAN | 57 |

| A Short Story | ||

| THE PHANTOM WOLFHOUND | ADELBERT KLINE | 60 |

| A Spooky Yarn by the Author of “The Thing of a Thousand Shapes” | ||

| THE MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE | EDGAR ALLAN POE | 64 |

| A Masterpiece of Weird Fiction | ||

| THE MOON TERROR | A. G. BIRCH | 72 |

| Final Thrilling Installment of the Mysterious Chinese Moon Worshipers | ||

| THE MAN THE LAW FORGOT | WALTER NOBLE BURNS | 81 |

| A Remarkable Story of the Dead Returned to Life | ||

| THE BLADE OF VENGEANCE | GEORGE WARBURTON LEWIS | 86 |

| A Powerful, Gripping Story Well Told | ||

| THE GRAY DEATH | LOUAL B. SUGARMAN | 91 |

| Horrifying and Incredible Tale of the Amazon Valley | ||

| THE VOICE IN THE FOG | HENRY LEVERAGE | 95 |

| Another Thriller by the Author of “Whispering Wires” | ||

| THE INVISIBLE TERROR | HUGH THOMASON | 100 |

| An Uncanny Tale of the Jungle | ||

| THE ESCAPE | HELEN ROWE HENZE | 103 |

| A Short Story | ||

| THE SIREN | TARLETON COLLIER | 105 |

| A Storiette That Is “Different” | ||

| THE MADMAN | HERBERT HIPWELL | 107 |

| A Night of Horror in the Mortuary | ||

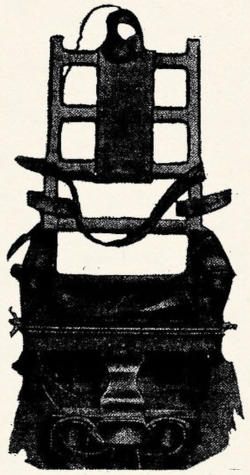

| THE CHAIR | DR. HARRY E. MERENESS | 109 |

| An Electrocution Vividly Described by an Eyewitness | ||

| THE CAULDRON | PRESTON LANGLEY HICKEY | 111 |

| True Adventures of Terror | ||

| THE EYRIE | BY THE EDITOR | 113 |

For Advertising Rates in WEIRD TALES apply to YOUNG & WARD, Advertising Managers, 168 North Michigan Blvd., Chicago, Ill.

Finding “The Fountain of Youth”

A Long-Sought Secret, Vital to Happiness, Has Been Discovered.

By H. M. Stunz

A secret vital to human happiness has been discovered. An ancient problem which, sooner or later, affects the welfare of virtually every man and woman, has been solved. As this problem undoubtedly will come to you eventually, if it has not come already, I urge you to read this article carefully. It may give you information of a value beyond all price.

This newly-revealed secret is not a new “philosophy” of financial success. It is not a political panacea. It has to do with something of far greater moment to the individual—success and happiness in love and marriage—and there is nothing theoretical, imaginative or fantastic about it, because it comes from the coldly exact realms of science and its value has been proved. It “works.” And because it does work—surely, speedily and most delightfully—it is one of the most important discoveries made in many years. Thousands already bless it for having rescued them from lives of disappointment and misery. Millions will rejoice because of it in years to come.

The peculiar value of this discovery is that it removes physical handicaps which, in the past, have been considered inevitable and irremediable. I refer to the loss of youthful animation and a waning of the vital forces. These difficulties have caused untold unhappiness—failures, shattered romances, mysterious divorces. True happiness does not depend on wealth, position or fame. Primarily, it is a matter of health. Not the inefficient, “half-alive” condition which ordinarily passes as “health,” but the abundant, vibrant, magnetic vitality of superb manhood and womanhood.

Unfortunately, this kind of health is rare. Our civilization, with its wear and tear, rapidly depletes the organism and, in a physical sense, old age comes on when life should be at its prime.

But this is not a tragedy of our era alone. Ages ago a Persian poet, in the world’s most melodious epic of pessimism, voiced humanity’s immemorial complaint that “spring should vanish with the rose” and the song of youth too soon come to an end. And for centuries before Omar Khayyam wrote his immortal verses, science had searched—and in the centuries that have passed since then has continued to search—without halt, for the fabled “fountain of youth,” an infallible method of renewing energy lost or depleted by disease, overwork, worry, excesses or advancing age.

Now the long search has been rewarded. A “fountain of youth” has been found! Science announces unconditionally that youthful vigor can be restored quickly and safely. Lives clouded by weakness can be illumined by the sunlight of health and joy. Old age, in a sense, can be kept at bay and youth made more glorious than ever. And the discovery which makes these amazing results possible is something any man or woman, young or old, can easily use in the privacy of the home, unknown to relative, friend or acquaintance.

The discovery had its origin in famous European laboratories. Brought to America, it was developed into a product that has given most remarkable results in thousands of cases, many of which had defied all other treatments. In scientific circles the discovery has been known and used for several years and has caused unbounded amazement by its quick, harmless, gratifying action. Now in convenient tablet form, under the name of Korex compound, it is available to the general public.

Any one who finds the youthful stamina ebbing, life losing its charm and color or the feebleness of old age coming on too soon, can obtain a double-strength treatment of this compound, sufficient for ordinary cases, under a positive guarantee that it costs nothing if it fails and only $2 if it produces prompt and gratifying results. In average cases, the compound often brings about amazing benefits in from twenty-four to forty-eight hours.

Simply write in confidence to the Melton Laboratories, 833 Massachusetts Bldg., Kansas City, Mo., and this wonder restorative will be mailed to you in a plain wrapper. You may enclose $2 or, if you prefer, just send your name without money and pay the postman $2 and postage when the parcel is delivered. In either case, if you report after a week that the Korex compound has not given satisfactory results, your money will be refunded immediately. The Melton Laboratories are nationally known and thoroughly reliable. Moreover, their offer is fully guaranteed, so no one need hesitate to accept it. If you need this remarkable scientific rejuvenator, write for it today.

The Cleanest, Yet Most Outspoken, Book Published

There is not a man or woman married or unmarried, who does not need to know every word contained in “Sex Conduct in Marriage.” The very numerous tragedies which occur every day, show the necessity for plain-spokenness and honest discussion of the most vital part of married life.

It is impossible to conceive of the value of the book; it must undoubtedly be read to be appreciated, and it is obviously impossible to give here a complete summary of its contents. The knowledge is not obtainable elsewhere; there is a conspiracy of silence on the essential matters concerning sex conduct, and the object of the author has been to break the barriers of convention in this respect, recognizing as he does that no marriage can be a truly happy one unless both partners are free to express the deepest feelings they have for each other without degrading themselves or bringing into the world undesired children.

The author is an idealist who recognizes the sacredness of the sex function and the right of children to be loved and desired before they are born. Very, very few of us can say truly that we were the outcome of the conscious desire of our parents to beget us. They, however, were not to blame because they had not the knowledge which would have enabled them to control conception.

Let us, then, see that our own marriage conduct brings us happiness and enjoyment in itself and for our children.

A Book for Idealists by an Idealist

The greatest necessity to insure happiness in the married condition is to know its obligations and privileges, and to have a sound understanding of sex conduct. This great book gives this information and is absolutely reliable throughout.

Dr. P. L. Clark, B. S., M. D., writing of this book says: “As regards sound principles and frank discussion I know no better book on this subject than Bernard Bernard’s ‘Sex Conduct in Marriage.’ I strongly advise all members of the Health School in need of reliable information to read this book.”

“I feel grateful but cheated,” writes one man. “Grateful for the new understanding and joy in living that has come to us, cheated that we have lived five years without it.”

SEX CONDUCT IN MARRIAGE

By BERNARD BERNARD

Editor-in-Chief of “Health and Life”

Answers simply and directly, those intimate questions which Mr. Bernard has been called upon to answer innumerable times before, both personally and by correspondence. It is a simple, straightforward explanation, unclouded by ancient fetish or superstition.

A few of the many headings are:—

Send your check or money order today for only $1.75 and this remarkable book will be sent postpaid immediately in a plain wrapper.

Health and Life Publications

Room 46-333 South Dearborn Street

CHICAGO

HEALTH AND LIFE PUBLICATIONS

Room 46-333 S. Dearborn St.,

Chicago, Illinois.

Please send me, in plain wrapper, postpaid, your book. “Sex Conduct in Marriage.” Enclosed $1.75.

The Unique |

WEIRD TALES |

Edited by |

VOLUME ONE |

25c a Copy |

JUNE, 1923 |

Subscription |

$3.00 A YEAR |

Paul Ellsworth Triem’s Latest Novel

An Exciting Tale of Weird Events

A taxicab stopped on the corner, and two people got out. They formed a decidedly incongruous pair; for the first to alight was a diminutive Chinese boy, scantily dressed, while his companion appeared to be a portly white man.

It was impossible to be sure of this fact, however, as this second passenger wore a long overcoat, with its ulster collar turned up around his face, and a dark cloth cap with the visor drawn down over his forehead and eyes.

Evidently the cab driver had been paid in advance, for he swung out from the curb as soon as his fares had dismounted, and was soon out of sight. The Chinese boy glanced at his companion, then set off silently up a street whose central portion was paved with cobblestones.

He seemed to know just where he was going. He paused only once, to cast a fleeting glance over his shoulder. Then he resumed his journey.

He had seen that the man in the ulster was following; and now, after traversing half a block of squalid, deserted street, the youngster turned abruptly into a pestilential-looking alley. This alley lay close to the top of a hill, and for a moment the man and the boy, who appeared to be his guide, could look down over the roofs to where the gay lights of Chinatown twinkled alluringly.

Presently the diminutive Oriental paused just outside a doorway. The man who had been following him came up, with a curious suggestion of eagerness and suspicion. Looking over the shoulder of the figure before him, he was able to make out the entrance to a narrow flight of unlighted stairs, which plunged steeply into the earth beneath a dilapidated building.

“Do we have to go down there, boy?” the man demanded.

“All a-same down here, master,” the youngster replied. “You come close—I show you!”

He began to descend as he spoke; and the man, after a moment of hesitation, plunged through the doorway after him. His manner was that of one who is taking a horribly unpleasant remedy, hoping to cure a still more horrible disease.

The diminutive Chinaman reached the bottom of the stairs and waited for his companion. When he felt the man’s heavy hand on his shoulder, he turned to his right, advancing cautiously through an almost impenetrable darkness.

There was a smell of dry rot in this basement, and around their feet rats scampered and squeaked. The man’s hand shook, and his breath came with a hissing sound through his clenched teeth.

“Now we go down again, master,” the boy announced presently. He had paused and turned again to the right. “You keep close—I show you!”

A step at a time, they descended a second flight of stairs. On either side were rough stone walls, powdery with mildew. The man discovered this with his free left hand. Strange odors came to him. Abruptly a bell rang, somewhere in the bowels of the darkness below them.

The boy stopped in his tracks.

“Now you go down, master,” he commanded. “Ah Wing waiting for you—you go slow. Goo’-by!”

He slipped out from under the heavy hand that would have detained him, and the man heard him go scampering like one of the rats up the stairs and away through the upper corridors.

Terror gripped the man left alone there on the stairs. He felt that he was in a trap—and he had been evading traps so long now that they had become an obsession with him.

He cried out, hoarsely, and as he did so a door opened below and a flood of light shone out.

“Pray continue your descent, Colonel Knight,” a cultured voice commanded from somewhere within the lighted room whose door had just opened. “The stairs are quite secure, and I am awaiting you!”

With a plunge that hinted at desperation, the man addressed as “Colonel Knight” reached the bottom of the stairs and crossed to the door. He paused there for a moment, till his eyes adjusted themselves to the change in illumination. Then he stepped inside, and heard the heavy door close behind him.

The room he had entered was of considerable extent, but was almost destitute of furniture. There were bare walls, dusty with green mildew; and bare floors, covered with layers of dust and litter. There were two chairs, one of which was already occupied.

And as the newcomer’s eyes rested on the occupant of that chair, all his doubts and fears returned to him. He had come to this unearthly spot to get away from almost certain death. Now he was not certain that the remedy would not prove worse than the disease.

The man sitting there, facing him, was dressed like a Chinaman, in silk trousers and coat, satin slippers, and black silk cap; but his eyes were of a metallic gray, and his high, thin-bridged nose spoke of Nordic blood. He would have been tall had he been standing. His hands were lying passive in his lap, but they were the hands of a man of great physical power.

And above all these details and beyond them was something the man in the ulster could not quite define—a radiation of power, as if the intellect and will of this strange being seated before him saturated the atmosphere of the empty room.

“Pray be seated, Colonel Knight!” the man in the chair said courteously. “I am glad to meet you. You have been recommended to me by a former student of mine—you know that I take only a few cases. It will be best for you to tell me your story, fully and accurately.”

Colonel Knight lowered himself into the empty chair. His eyes still peered out through the gap in his collar, and seemed to be fastened on the face of the man before him.

Then, slowly and grudgingly he removed his cap and turned down his collar, disclosing the pouchy face of a man well advanced into middle age. It was a face suggesting daring and resourcefulness, this face of Colonel Knight; and for a few moments the two sat staring curiously at each other.

“I think I can condense that statement I have to make,” the white man said finally. “I am a man of wealth. Five years ago, while traveling in Europe, I had the misfortune to attract the attention of the greatest gang of international thieves ever organized. Perhaps you have heard of them? They were called ‘The Evening Wolves,’ and were led by a man who called himself ‘Count von Hondon’.”

He paused for an instant to regard his companion curiously, but the Oriental merely bowed and sat impassively waiting.

“These men must have followed me about for some time before they struck. Finally they saw their chance. I was packed to leave Paris for Belgium, and they undoubtedly figured that I would have much of wealth with me.

“I did—but I had other things they had overlooked. I had my pistols, and I am a dead shot. I killed two of the robbers, and the rest fled. I supposed that would settle the matter, but I was mistaken. Five members of the gang were left alive, and they swore to be revenged upon me. They have followed me—”

A bell rang shrilly somewhere close at hand, and Colonel Knight leaped from his chair and looked wildly at his companion.

“What was that?” he cried. “That bell rang when I was descending the stairs—”

“Someone followed you here,” the other replied, “and is now trying to reach us. Pray continue!”

“But that man upon the stairs—”

“We will come to him presently. Let me ask you to finish!”

“There is nothing more! I have been followed for years, and now a physical trouble is added—my physician tells me I am going blind. I can’t see to run—”

The Chinaman eyed his companion deliberately.

“Why lie to me, my friend?” he demanded presently. “You come to me for help, and you wish to steal my ammunition! Now let me reconstruct your story for you. You yourself are ‘Count von Hondon.’ You were the leader of the master crooks called ‘The Evening Wolves.’ Five years ago you and your men made a rich haul, and you decided that a time had come to retire, or perhaps to go in by yourself. You departed,[7] taking with you the loot; and ever since it has been a running fight.

“Your old comrades could have shot you outright, but that would not restore to them the booty you stole. And you have not dared dispose of it, because it was the only thing that stood between you and death! You see, you can’t lie to me. Every lie carries its trade-mark with it, to those who have eyes to see. Now I shall ask you but one question, and let me warn you—if you lie now, you will never leave this place alive!”

He stood up and thrust an accusing finger toward the cowering thief.

“Tell me,” said the Chinaman, “the name of the person whom you and your men robbed!”

The beady eyes of Colonel Knight, or “Count von Hondon” as he had once been known in every capital in Europe, glittered with suspicion and fear. His breath caught in his throat, and he unfastened his collar with trembling fingers.

“The name,” he said hoarsely, “was—was—”

Ah Wing crossed toward the heavy door and laid his hand upon the knob. His metallic eyes blazed, and he looked down with fierce contempt upon the man trembling before him.

“Will you answer?” he cried. “Or shall I open this door?”

“It was a woman!” Knight whimpered. “Her name was—Madame Celia—”

He broke off and stared at the Chinaman, towering there before the door. Ah Wing had neither spoken nor moved; but there was in the room a disturbance as if a great voice had shouted out a curse.

Slowly the Chinaman came back toward his visitor. His face now was the impassive face of a carved Buddha.

“Colonel Knight,” he said gently, “the high gods have undoubtedly brought you to me. I am the only person in the world who can save you, for I work outside of the laws of men. And I will take your case, now that I fully understand it. But first I will ask you to show me the Resurrection Pendant which you stole from Madame Celia!”

The white man got slowly to his feet, his hands groping at his throat, his eyes protruding, his face the color of dough.

“The pendant!” he whispered through ashen lips. “The Resurrection Pendant! You know—you have heard?”

“Show me the Pendant,” repeated Ah Wing inexorably. “I know that you brought it with you tonight, just as I know that you intended, in case I refused to take your case, to try to disappear without returning to your hotel. Show me the Pendant!”

With faltering hands and without removing his fearful eyes from the face of his companion, the crook reached inside his ulster and drew forth a package wrapped in brown paper. This he slowly unfastened, disclosing a jewel case. More and more slowly his fingers fumbled with the catch.

There came a sound from the door—a voice that seemed to have difficulty in filtering through the heavy panels.

“Come out of that, Count! We got you over a barrel! Come out—”

The massive door shook under a terrific blow, as from a sledge. The man in the ulster seemed about to crumple to the floor.

Ah Wing spoke coldly.

“Show me the Pendant!” he repeated. “They cannot break down that door, but if you trifle with me I will open it!”

With hurried fingers the terror-stricken crook threw back the cover of the jewel case, disclosing a mass of diamonds, intricately and skilfully assembled into a great pendant.

Ah Wing took a long stride, which brought him close to the man who held the jewel case.

The Oriental’s steely eyes were fastened unwaveringly upon the pendant, whose history for half a century had been transcribed in suffering and death. Misfortune had followed this unique assemblage of perfect stones: death and insanity; the breaking of friendships; the treachery of children toward parents; the murder of lover by lover. And now the mysterious Chinaman seemed to have fallen under the spell of the gems, for he was taking in every detail of their perfection.

For a moment the assault upon the door had ceased, but now it was continued. Heavy blows fell, and the walls of the subterranean apartment shook.

“It will not take your friends long to discover that they cannot reach us by that route,” commented Ah Wing tranquilly, turning at last from his inspection of the Resurrection Pendant. “The door has a middle sheeting of boiler iron. It is bullet proof.”

He reseated himself, motioning for Colonel Knight to do the same. Absently he watched the white man close the jewel case, wrap it carefully in brown paper, and return it to his ulster pocket.

“And now,” continued the Chinaman, “I will ask you to tell me about these men. You say there are five of them? Please describe them to me, one at a time. Tell me all that you can remember as to physical and mental characteristics—I want every detail you can give me.”

Colonel Knight sat down heavily. It was obvious that the assault upon the door was shaking his nerves so that he could hardly command his voice. His eyes were the eyes of some hunted thing, which sees itself at the end of a blind alley.

With an evident effort, he tore his glance from the quivering panels and fastened it on his companion.

“Yes,” he said hollowly, “there are five of these men, and they have been chosen from the elite of the criminal world. I myself selected them and trained them. Each has his special ability. I will begin with the man whom I considered the brainiest of them all—the one who was almost my equal in planning and executing a really big robbery. His name is Monte Jerome.”

Suddenly the blows on the door ceased; and the room was so still, after the ferocious assault, that it seemed to press on the ear drums of the speaker. He winced and for a moment was silent. Then, resolutely he continued:

“Monte is thirty-five years old. He is less than five feet six, but is broad shouldered and powerful. He grew up in the alleys of a large city. He fought his way to the leadership of gang after gang, and at the time I picked him up was looking for new worlds to conquer. I chose him because of four qualities: his physical strength; his native cunning; his lack of sentiment—or, as it is usually called, ‘mercy’—and his absolute freedom from superstition. Monte believes in neither God, man, nor the devil. He was my right-hand man—and it is to his merciless pursuit that I owe my condition!”

Ah Wing had drawn a note-book from his pocket and was jotting down data. He glanced placidly toward the door, which was again shaking under a rain of heavy blows.

“Pray continue!” said he.

Something of the Chinaman’s imperturbability was beginning to influence the white man. He went on with greater assurance:

“Next to Monte Jerome in total ability, I always placed the man we called ‘Doc.’ I never knew his real name. That was not important, as he went under many aliases. Doc was my means of approach to the wealthy men and women—and particularly the latter—upon whom I specialized. He is a university man, and has lived among people of wealth and refinement much of his life.

“He has brains, but lacks the quality of ruthlessness so important in really successful commercial crime. He is utterly selfish, I believe, but certain necessary factors in his profession are revolting to him—and he has never made the effort to put down this weakness. Physically he is prepossessing: an inch or two over six feet in height, blue eyes, light brown hair, splendid carriage; and possessed of the manners of a Chesterfield.”

A thin, faint voice came through the door, upon which the tattoo had momentarily ceased:

“We’ve got you, Count! Open that door, or we’ll gouge your eyes out when we break in!”

Ah Wing waved his hand affably toward the source of this ominous promise.

“And our friend out there?” said he. “Is he one of those whom you have described?”

“I was just coming to him,” replied Colonel Knight, raising a shaking hand to his forehead and mopping off the beaded perspiration. “That is ‘Billy the Strangler,’ and I think the ‘Kid’ is with him. Those were my Apaches—my gun men—my killers. They are much alike. Both have cunning of a low order; and persistence—they are like bloodhounds, once they are put on the trail.

“They have been Monte’s most useful tools in his pursuit of me. But both are superstitious, and their native bloodthirstiness has grown on them till they are little better than homicidal maniacs. The Strangler is tall and slim, with high cheek bones and lean arms which seem to be threaded with steel wires. The Kid is of medium height, with grey eyes and sandy hair.”

The assault on the door had again been discontinued. Suddenly there came from directly overhead a sound of splintering boards, accompanied by a rain of dust and bits of plaster. Knight sprang up and retreated, snarling, toward a corner of the empty room.

“Ah, I have been waiting to see if your old comrades would think of that,” he commented. “It gives us a line on their resourcefulness.”

Colonel Knight regarded him with drawn lips, which exposed his yellow teeth.

“For God’s sake, what are we to do?” he cried. “Are you armed? You sit there like a statue—”

“Pray continue your very interesting description,” suggested Ah Wing. “There remains one of your band whom you have not described. I must know about him—and then I will deal with this other matter!”

For an instant the thief glared into the face of the man seated across from him. What he read there steadied him a little, although the crash of splintering boards from above told him that the men he had such good reason to fear were meeting with less resistance in this direction than they had encountered in their assault upon the door.

“There remains but one,” he said hoarsely. “That is Louie Martin, my gem expert. Martin is one of the best judges of diamonds and pearls in the world. He is an expert in recutting and remounting stolen jewelry. And he has a wide acquaintance among the crooked dealers of this country and Europe—”

An extensive area of plaster broke away suddenly and crashed down, tumbling about the heads and shoulders of the two occupants of the room. At the same instant the end of a heavy gas-pipe crashed through the laths, and the voices of the men on the floor above were raised in a shout of ferocious triumph.

Ah Wing stood up deliberately and looked toward the ceiling. He seemed to be measuring the progress of the men opposed to him. Then, without hurrying he crossed the room toward a dimly lighted corner, where he stooped and opened a small door in the wall. This door was built in segments, like that of a safe; and was hinged with metal plates of enormous strength.

Colonel Knight, who cowered directly behind the Chinaman, felt a breath of cool, moist air, smelling strongly of earthy decay, blowing up from this diminutive doorway.

“Kindly precede me, Colonel,” commanded Ah Wing. “Watch your step—the going is rather precipitous!”

Knight stooped and made his way through the opening. He found himself on a stairway which went steeply down into utter darkness.

A cloud of white dust filtered up into the light of the electric bulb; and, as Ah Wing stood watching, a lithe human figure landed with a crash on top of the heap of plaster and splintered boards and laths.

In the same instant the Chinaman passed silently through the small doorway, and his companion heard him slipping the bolts into place.

The darkness which had suddenly clutched them was so intense that it seemed to have physical substance. A squeaking sound from above brought Knight’s face swiftly up. Something cold and reptilian flapped into his eyes and, with another squeak, was gone.

“Only a bat!” said Ah Wing softly. “Rest your hand on my shoulder and feel your way a step at a time. I will turn on my flashlight!”

A conical beam of light drilled through the darkness below them, and Ah Wing’s companion saw that they were descending a narrow flight of stone steps that seemed to terminate in a panel of utter blackness. The walls on each side were damp; and pallid fungi had taken the place of the mildew of the cellars above.

“For God’s sake, where are we?” the white man demanded through chattering teeth. “This looks like the shaft of a mine!”

“This is part of the underground system which made Chinatown famous, before the disaster of 1906,” replied the Oriental. “Few white men have ever been down here—particularly of late years!”

He paused. They had reached a narrow landing, from which passages branched in half a dozen directions. Another descending stairway yawned ahead.

“If I were to leave you here,” smiled Ah Wing, “you would never find your way out! You could not go back the way you have come, for there are acute-angled branches which would confuse you. Most of them end in masses of rubbish, easily dislodged by the unwary! But with me you are safe!”

His voice had an ominous softness. Knight followed down along the second flight of stairs. His heart was pounding. Suppose these crumbling walls should collapse! Suppose this unearthly being, in whose hands his safety lay, decided to rob him!

Ah Wing spoke abruptly:

“We have been following down the face of a hill. Now we reach the level, and here we leave these catacombs!”

He turned sharply to the left and led the way along a short passage which terminated in a second diminutive door. Ah Wing shot back the bolts and motioned for his companion to proceed him into the room beyond.

Knight obeyed. Daylight was there—white, blazing daylight! He blinked as he crept through the opening.

Next moment he tried to cry out. An arm had passed in front of his body, pinioning him. In the same instant a sinewy hand came close to his face, and there was a little tinkle of broken glass—a diminutive globule had been broken under his nose.

The thief struggled to turn his head aside, fought to keep from breathing in the stupefying fumes; but with a smothering gasp he surrendered.

He breathed deeply, and as he did so a sudden feeling of lightness and of expansion came upon him. In the act of wondering stupidly what this substance was that the Chinaman had forced upon him, his mind went blank.

Ah Wing continued for a moment to hold his hand over the mouth and nostrils of his victim. Then he carried Knight across the room and laid him on a divan. Turning deliberately, he pressed an electric button.

Somewhere in the brooding silence of the building, beyond this room, a deep throated bell rang clamorously.

High in an apartment house, overlooking a street and something of the city, Monte Jerome, leader of the Evening Wolves, sat at his ease, a cigarette in the corner of his thin, merciless mouth, a telephone within reach.

From the back rooms of the apartment came the sound of heavy breathing, intermingled with an energetic and unmusical snore. Louie Martin, gem expert for the gang, and “Doc,” their society specialist, were sleeping.

Monte listened critically to the heavy breathing. He was an expert in such matters, and his seasoned judgment told him that neither of his comrades was faking sleep.

With a nod of satisfaction, he stood up and walked soundlessly into the corridor connecting the rooms, stopping first in that occupied by “Doc,” and then in the back room where Louie Martin was sleeping. In each room he paused long enough to make a thorough search of the clothing of the sleeping robber.

Monte went expeditiously through all the pockets, and even examined the linings. Just a little exhibition of the honor that obtains among thieves: Monte Jerome knew that his leadership depended on his ability to command his companions’ unwilling respect, and he was taking no chances.

“I got a hunch Doc is thinking of ditching the gang, and going it for himself,” Monte murmured as he returned toward the front room. “If he thinks—”

The ’phone bell rang suddenly, and the man on duty crossed to the instrument.

“Yes?” he said.... “Oh, hello, Billy.... What’s that—Hell’s bells! Got away! Get busy and find him—”

The voice of the Strangler came to him over the wire.

“Keep your shirt on, Chief!” it commanded. “You better come down here and see for yourself what we was up against!”

Two minutes later Monte was shaking Louie Martin awake.

“Come to life!” Monte grated. “The Count has made his getaway! You get into your clothes and tend ’phone! This is one hell of a mess!”

Martin climbed sluggishly and unwillingly out of bed.

“You’ve been running things,” he snarled. “If you’ve got ’em in a mess, it’s no one’s fault but your own!”

At a corner on the outskirts of Chinatown, Monte alighted from his taxi. This was a special machine, owned and operated by a crook who dealt indiscriminately in transportation, dope and bootleg whisky.

Monte commanded this worthy citizen to await his return, and plunged into a labyrinth of narrow streets and alleys.

A shrill whistle sounded presently, and he saw the Strangler beckoning him from a doorway. Crossing over, Monte followed his henchman into an alley, down a flight of narrow stairs, and into an unlighted basement. Here they were joined by the “Kid,” who carried an electric torch.

“Come on, Chief,” the “Kid” commanded. “We’ll show you first what we was up against—watch your step! If you stub your toe you’ll land in hell!”

They turned and went down another stairway, narrower and steeper than the first. At the bottom their way was barred by a heavy door, studded with great iron bolts. In one place the wood had been battered away, disclosing the gleaming surface of a steel panel.

“We followed the Count here, and thought we had him cornered,” the “Kid” drawled, rolling his cigarette from one corner of his mouth to the other and regarding Monte through lazy, sardonic eyes. “When we saw we couldn’t get through this way, we went up to the floor above and come at him through the ceiling. Come along—we’ll show you!”

They went back up one flight of stairs and entered a room which evidently had long been unused. Its walls were crumbling, and in the middle a great hole had been torn in the floor. The Strangler, who was leading the way, crossed over to this opening and unhesitatingly disappeared through it. Next moment a yellow light filtered up through the opening.

“Down you go, Chief,” commanded the “Kid.” “This was the door we made!”

Monte made his way down through the opening, landing on the upper of two chairs which had been piled precariously together to assist in the descent. He was followed by the “Kid,” and the three crooks stood examining the room in which Ah Wing and Colonel Knight had held their conference.

Monte spoke with a snarl.

“All right, you two!” he cried, “Here is where he was! Where is he now? Come across with your alibi!”

His two companions exchanged significant glances and the “Kid” took a slouching step closer to Monte.

“Look here, Chief,” said he, “it ain’t gonna be healthy for you to talk that way to me! I’m not spielin’ no alibi. What I’m givin’ you is straight goods, and you better get that twist out of your mush and act like a gentleman!”

He paused; and his two crumpled ears, which spoke of vicissitudes in the prize ring, grew red as a rooster’s comb. His glassy gray eyes glared unblinkingly at Monte.

The latter was not afraid of either of these men, or of both of them together. Monte had the unflinching courage of the perfect animal. But he had no notion of breaking up a gang which might prove useful to him.

“All right, boys,” he agreed, more pacifically, although his dark eyes continued to glow like coals. “If you can afford to take it easy, you got nothing on me! Tell me what happened.”

“That’s more like it,” the “Kid” growled. “Now you’re talking like a gentleman, Chief! Well, we follows the Count here, and thinks we has him holed up. We can’t bust down that door—this is an old Chink gambling hell, and everything is stacked against a fellow that wants to get in. But we comes down through the roof—”

Suddenly the “Kid” paused. From somewhere behind there had come a sound as of the opening of a door. The eyes of his two companions followed his and together they stood, rigid and alert.

Slowly the back wall of the room opened out toward them. Unconsciously, the crooks shrank closer together. Their faces were drawn, their figures rigid.

The panel swung fully open, and a figure appeared in it. It was the form of a tall man, clad in black silk.

The three crooks stood staring at him silently. So unexpected had been his appearance that it had affected them with a sort of paralysis. Their mouths gaped open and their eyes bulged.

Serenely, the intruder stood looking down upon them; and then, with a courteous wave of his hand, he spoke.

“Pardon my intrusion, gentlemen!” said he. “My little affairs can wait—I will return later!”

He turned, and next moment the panel had swung silently shut behind him.

Monte Jerome was the first of the three to recover.

“Come on—we’ve got to get him!” he cried.

“That was the Chink we saw spieling with the Count,” the “Kid” cried hoarsely. “But, for the love of cripe, how did he get here?”

Monte snarled wolfishly:

“Ask him that! We’ve got to bust through here—”

His compact body landed against the panel. It shook, but refused to yield.

“Come back here! Now, all together!” bellowed Monte.

The three leaped forward and struck the partition.

This time it swung inward, slowly and without a sound. The crooks leaped through the opening, and the “Kid” flashed his torch. They were standing just inside a vast, windowless room, at whose farther side they had a glimpse of sagging timbers and ruined walls. Nowhere was there a sign of the man who had eluded them.

“Get a move on!” Monte growled throatily. His lip drew up and he snarled at his companions. “A hell of a bunch of crooks, we are! Why didn’t you take a shot at him, when you saw he was going to make a getaway?”

The “Kid” glared back.

“Cut out that kind of talk, Chief! You got a gat, and two hands! He buffaloed you just like he did us! Be a sport and take your medicine!”

A determined search of the ruined chamber yielded no results. The “Kid” dropped to his stomach and wormed his way under the mass of timbers at the farther side. He found the beginning of a stone-lined tunnel, which dipped abruptly into the earth.

Damp, mouldy air fanned his cheeks; and as he crouched, motionless, listening, a distant reverberation came to him from the bowels of the earth. It sounded like the clanking of a great iron door.

“Let me out of this!” he growled, as he backed toward his companions. “We got a fat chance of following that yellow devil into his hole. You go, if you want to!”

Monte shook his head. He had regained his poise, and he had been thinking.

“No use trying to follow,” he admitted. “We got to comb Chinatown for the two of them. They can’t live down in that burrow forever. But why did this duck show himself? He must have known we were here—he could hear us talking!”

The “Kid” smiled craftily.

“Maybe him and the Count left something,” he suggested. “We better have a look!”

“No, they didn’t leave nothing. I would have seen it if they had. I got an idea the Chink wanted us to see him! He stood there with his face turned into the light. Well, we got to find him! That’s flat!”

The wolves shifted their quarters that night to a rooming-house on the edge of Chinatown, and the search for Colonel Knight and his mysterious companion, the tall Chinaman, began.

For three days they worked feverishly. Monte Jerome seemed never to sleep, and his temper was not at all improved by the ordeal. He drove his companions fiercely, and only the fact that they were playing for big stakes prevented open rebellion.

On the fourth day Monte and the “Kid,” who were loitering, alert but almost hopeless, in the entrance to a building in one of the narrow streets of the Oriental quarter, caught sight of a figure disappearing through a doorway. It was a tall figure, partly concealed by a light overcoat; but both of them leaped forward at the same instant.

“That was the Chink, sure as God made little red apples!” the “Kid” snapped.

They crossed the street. Several automobiles were drawn up close to the curb, among them a big blue limousine from which the Chinaman had stepped a moment before they identified him. Monte approached a well-dressed gentleman, who had just come out of the building, and asked him what was going on inside.

“This is the fall exhibition of the Iconoclasts,” the stranger explained good-naturedly.

He seemed to be sizing up the two crooks.

“I think you boys would enjoy it,” he added mischievously. “The admission is only fifty cents.”

Monte and the “Kid” bought tickets, and presently they entered a big room with a high ceiling, upon whose walls were hung a number of gaudy paintings. The newcomers stared round at the fifty or more spectators who were making the rounds of the gallery.

“Hell!” growled the “Kid,” “this ain’t no place for an honest strongarm man—Let’s beat it and send for Doc!”

Monte gripped his arm.

“Look!” he said under his breath. “Over there near the corner!”

The “Kid” looked stealthily as directed, and perceived the tall man in the gray topcoat. He was standing with his back to them, examining a red and yellow daub that looked like an omelette liberally seasoned with paprika.

“That’s him!” Monte whispered. “All right, Kid! You have Mike bring the cab down to the corner where we was waiting. Then, when this duck beats it out of here, I’ll hop in and we’ll follow him!”

Half an hour later the tall man in the gray coat—who in American garb looked more like an Oriental than he had when dressed as a Chinaman—paused to look deliberately at his watch, and then turned to the outer door.

By the time he stepped into the blue limousine, Monte had reached the corner and was climbing in beside the driver of the taxi. The “Kid” had the window down, and was kneeling with his head close to the driver’s.

“How ’bout it, Mike!” Monte demanded. “Can you keep ’em in sight?”

“Watch me!” snorted the driver. “There ain’t no Chink going can leave me behind. Did you see that chauffeur? Got a face like a monkey!”

There was no difficulty, for the present, in keeping the blue limousine in sight, however. It went sedately down a side street and took the turn toward the ferry. Five minutes later Monte and the Kid saw the cab in which they were seated draw in behind the larger car, and roll over the landing platform. The limousine was stationed on the right, and the cab on the left, of the big boat.

Monte scrambled down, and with a curt command to the other two made his way around to where he could see the enclosed car. The man in the gray overcoat was sealed inside, with a coffee-brown Chinaman in livery at the wheel. Monte kept them in sight till the ferry was approaching the slip. Then he hurried back and climbed in again beside the driver.

“Here’s where they’ll try to leave us behind, if they have any idea we’re following!” he predicted.

“Let ’em,” growled Mike. “If we don’t get took in by a speed cop, I won’t never let no Chink drive away from me! You boys just hang onto your bonnets, and watch us!”

The big blue car seemed to have accepted this challenge. The little man at the wheel swung out and passed half a dozen slower machines, then took the center of the road and held it.

With the coming of evening, a powdery fog swooped down over the ridges to the west, and suddenly the tail lights of the limousine shot up in the gloom[11] ahead. Notch by notch, the Chinese chauffeur was adding to his speed. The lighter car behind bounced and swayed, and Mike spat through his teeth.

“Say, that bird must be clear nuts!” he growled. “If we get took in, they’ll sentence us to about five life-times! What say, gents? Want to let him go?”

“You keep going!” snarled Monte, staring hardeyed into the fog. “If we get pinched, I pay for it, see? But don’t you let that bird get away, if you want to sleep in your little bed tonight!”

Mike glanced sideways at the man whose elbow touched his. Something he saw in the stony face of Monte Jerome caused him to turn all his attention to the task in hand.

The tail lights had been growing dim, but now, slowly, the cab began to gain. Other cars, headed for the ferry, shot out of the fog and into it, honking warning horns at the crazily lurching machine that burned the road in pursuit of the blue limousine. The stony faces of the three men in the cab never deviated from their straight glare into the gloom ahead.

The speed of the big car was slackening. The driver of the cab grinned wryly.

“He knows the ropes. Speed cop in this burg ahead lies awake nights thinking up new ways of raising hell for speedy drivers,” he explained. “Now we’ll creep up on ’em a little more!”

They passed through the little town and again were in the open country. The limousine continued its more leisurely progress, however, and presently turned to the right into a dirt road. The cab dropped farther behind, at Monte’s command.

“They can’t get away from us on this road. Probably aren’t going far, and we don’t want them to spot us. Take it easy!”

The road seemed to be leading gently down, and presently they caught the gleam of water on each side. Rushes grew up close to the track; and from somewhere in the dusk the cry of a gull sounded like the wailing of a lost soul.

Involuntarily, the “Kid” shivered.

“Hell of a country!” he mumbled. “Where you reckon he’s headed for?”

“Wait and see!” snapped Monte. “Hello!—he’s turning in! That must be a private road! Stop here!”

He slid from the seat and stood swinging his feet alternately, to restore the circulation in them. Then he jerked his head into the darkness.

“Come on, Kid! We got to see what he’s up to!”

The “Kid” clambered out, and the two crooks struck silently up the road. They reached the turn and found, as they had guessed, that they were at the entrance to a private road.

Instinctively, the two men paused and stared in through the trees. Night pressed thick and damp about them. A wind from the southeast brought to them the smell of the marshes, and once the booming whistle of a steamer sounded. In a lull of the wind, the gulls were screaming.

“This ain’t in my line, Chief!” snarled the “Kid,” glaring into the darkness. “I can bump a guy off under the city lights as nifty as the next one, but this nature stuff never did set right on my stomach. Let’s go back!”

“You go back if you want to!” Monte said menacingly. “But if you do, don’t come sniveling around me later on. I’m going in there!”

He struck off along the winding road, and in a moment the “Kid” fell into step at his side.

Without a word, the two advanced till suddenly the lights of a building shone upon them. They paused for a moment, then began to creep nearer, keeping in the shelter of clumps of bushes. In this way they came close enough to discern the outlines of a large and well-built house, with a broad frontage and two wings extending from the rear.

“For the love of cripe!” whispered the “Kid,” “would you look at them windows! Barred, every damn one of them!”

Monte nodded.

“Looks like a private foolish house to me,” he replied in the same cautious tone. “Come on—we’ll get around behind and see what we can make out!”

The musty darkness of the night, which had settled down around them, was now an advantage, as it made it easier for the two Wolves to get close to the house without being seen. They crept past the massive front, with its broad steps and wide porch, and continued till they came opposite the west wing. Most of the windows in this wing were dark, but toward the back they saw several lighted panels.

“Come on!” commanded Monte. “I hope that Chink doesn’t keep a dog, but plug him if one comes at you!”

On they crept till they were close to the windows. Massive and sinister against the light, stood the iron bars which had first caught their attention. They crept closer, and finally Monte hauled himself up into a gnarly pepper tree whose lacy branches almost touched the nearest of the lighted windows.

Next moment he reached down and grasped his companion’s shoulder.

“Come up here!” he grated, speaking half aloud in his excitement. “Don’t slip—catch that limb! There you are!”

He assisted the “Kid” to a foothold beside himself, and together they stared through the foliage and into the lighted room beyond.

The curtains were drawn aside and the shade rolled up. Seated in full view of the two crooks was the man they had been following for five years. He wore a dressing-gown, and beside his easy chair was a low table on which rested a leather covered box.

Suddenly he turned, raised the cover of the box—and Monte and the “Kid” held their breath and stared hungrily. The light was caught and split up into a cascade of vivid colors. The man in the dressing-gown seemed to have in his clutching hands a fountain of fire.

“The Resurrection Pendant!” snarled the “Kid,” reaching for his pistol. “Damn him!”

Monte gripped his companion by the wrist.

“None of that, you fool!” he hissed. “We’ve got to play safe—but the Count is caught in a trap! That Chink must have kidnapped him!”

Colonel Knight awoke and lay staring at the ceiling. It seemed a surprisingly long distance from him—and then his glance narrowed.

He turned his head, and suddenly sat up in bed. He had just remembered the events preceding his loss of consciousness.

Ponderingly, he examined his surroundings. He was in a big room, with a high ceiling. There were two windows at his right and one straight ahead, the latter partly open. Several easy chairs, a handsome mahogany house desk, and a row of bookcases flanking a fireplace came to him as successive details of his environment. A bar of yellow sunlight streamed through the end window.

A door behind him opened, and he turned to see a grinning, brown-faced Chinese boy approaching his bedside, bearing a breakfast tray.

“Ah Wing say he coming to see you by-m-by,” the newcomer commented placidly. “You hab breakfast now.”

He drew up a table and placed the tray in position, then skillfully arranged napkin and silverware—which were of the best quality—convenient to Colonel Knight’s hand. Afterward he withdrew.

Knight’s head felt clear enough, but, mentally and physically, he was relaxed[12] to the point of incoherence. He wanted to think, but couldn’t.

Mechanically, he lifted to his lips the cup of steaming coffee that the servant had poured for him. The taste of the hot, bitter fluid—he drank it without cream or sugar—helped him pull himself together. He remembered everything now: his visit to the mysterious Chinaman; the coming of his enemies, and their attack on the basement room; his flight with Ah Wing; and the latter’s ruse for bringing Knight fully within his power.

Sharply he turned his head and looked again at the end window; it was barred with heavy iron rods, and so were the two windows at the side. This room in which he lay was a luxurious prison!

The door opened again, softly, and Colonel Knight turned his head to find Ah Wing advancing toward him, dressed in white flannel trousers, silk shirt, and serge coat. In such a rig the newcomer looked every inch a Chinaman.

“Good morning, Colonel,” Ah Wing greeted his guest courteously. “I am glad to see you looking so fresh and rested this morning!”

Knight began to tremble.

“You yellow crook!” he croaked, his hands drawing up into knots. “So that was your scheme—to rob me, and then kidnap me? But don’t think you can get away with it—”

Ah Wing approached the bed and deftly reached under the nearer of the two pillows. From this place of concealment he drew two things: the morocco jewel case, and a revolver that Knight remembered having carried in his inside coat pocket.

“Here are the principle articles of your property, Colonel Knight,” said the master of the house. “The other things you will find after you are dressed.”

He paused to watch the man in the bed open the leather box and stare hungrily at the flashing jewels. Then he continued.

“There was an ordeal ahead of you, my friend, and you were in no condition to go through with it. You needed rest, but your nerves were screwed up to the snapping point. There was only one way to get you safely out of the city, and I used it.”

“You mean that the Wolves don’t know where I am?” Knight demanded.

“Not yet. I shall remedy that presently.”

Colonel Knight’s voice rose into a snarl:

“Remedy it? You mean you want them to know?”

“Of course I want them to know. I want them here, where I can deal with them. But never fear, my friend. Your old enemies will never be able to hurt you!”

He paused and looked around the apartment, then turned again to the man in the bed.

“These are your quarters. Adjoining your bedroom is the bath. This door opens into your sitting-room, and adjoining that is my conservatory, which you are at liberty to visit when you choose. There are no conditions placed upon your residence here except that you are not to try to leave the house without my permission—and you are to leave the end window exactly as it is. Don’t even lay your hand upon it, or upon the sill! This is important!”

Knight stared again at the single end window through which the sun was shining. He stared from it to the face of the strange being who continued to regard him with the impersonal interest of a Buddha. A sense of baffled curiosity arose within him, and he made a nervous, protesting movement with one of his puffy hands.

“Who the devil are you, anyway?” he broke out. “Ah Wing! That doesn’t mean anything to me—as well say ‘Mr. X!’ You are not a Chinaman. What and who are you?”

Ah Wing continued to stare imperturbably down at his guest, but the ghost of a smile showed at the corners of his usually expressionless mouth.

“No,” he agreed, “I am not a Chinaman. And I am not a Caucasian. You see that, dressed as I am today, I look unmistakably Oriental. Dressed like a man of Hong Kong, on the other hand, I look American or English. That has been my curse, and perhaps my blessing: the mixing of two irreconcilable blood lines has made me an outcast. I have no place in the government of any country, and therefore I have organized a government of my own.

“I am the emperor, the president, the king, of an invisible empire. I rule by right of intellect and will, and my first failure will be my death warrant; for, judged even by the standards of a thief like you, Colonel Knight, I am an outlaw—one who is outside the protection of the laws of men!”

He laughed, a short, mirthless laugh. As he crossed toward the door he said over his shoulder, “Remember about the window. I shall be going out from time to time, but if you carry out my instructions to the letter, no harm can come to you even in this house of hidden dangers.”

Try as he would, Colonel Knight could find nothing wrong with his situation as it had been outlined to him by Ah Wing. He spent most of the first day in the room in which he had awakened. From the windows in one direction he could see a landscaped lawn and hillside, dotted with shrubbery and intersected by winding gravel paths.

From the rear window concerning which he had been so curiously warned by the master of the house, he looked out over a bit of lawn bordering a kitchen garden. Beyond the garden lay a marshy field, and in the distance he made out a canal along which an occasional motor boat chugged industriously. No, there was nothing wrong here—he could hardly have hoped for a more peaceful place in which to rest and grow strong.

But—there was an air of brooding watchfulness over the silent house. He heard an occasional padded footstep passing the door of his sitting-room. Once he looked out. At the farther side of an extensive conservatory the brown-faced servant who had brought him his breakfast was spraying some snaky-looking vines bearing huge orange-colored flowers. Colonel Knight closed the door. Something about the place—the quiet and the isolation, perhaps, were getting on his nerves.

The second day passed as the first, but toward noon of the third day Ah Wing knocked at his door and entered noiselessly. He was dressed in his Oriental garb, and again looked like a poorly-disguised white man.

“I will be going out for a few hours this afternoon, Colonel,” he explained, regarding the man before him with his habitual unwinking stare. “I am taking Lim with me, and I think it will be best for you to remain in your quarters.”

Although his words had taken the form of a request, there was back of them the force of a command. The white man eyed him suspiciously, but presently nodded.

Some time later he heard the whir of a starting motor. Lim had brought him his luncheon, and now Knight figured the house would be deserted. He smiled. This would be his opportunity to look around a bit. The instincts of the crook were strong within him, and he was immensely curious with regard to the house of Ah Wing.

He waited an hour after he had heard the car leave the garage—from the back window he had caught a glimpse of it: a gray roadster of moderate size and power. Now he felt sure that he would not be interrupted.

Crossing to the door of the conservatory, he passed into it. Along one side were orchids, Colonel Knight realized vaguely that the collection must be priceless. Many of them were growing in diminutive glass rooms, upon whose walls he saw heavy drops of moisture.

One pale green blossom near him had weird markings in white and yellow, which gave it a disturbing resemblance to a grinning human face. The man thrust out a curious finger and touched it: the blossom drew itself together like a conscious thing, and he became aware of a sickening perfume which in an instant turned him dizzy.

He shrank back and continued his journey. The concrete floor narrowed, and at his left he saw a lily pond, upon whose surface great white blossoms showed their buttery yellow centers. Between the pads and blossoms of the lilies the water showed, deep and dark.

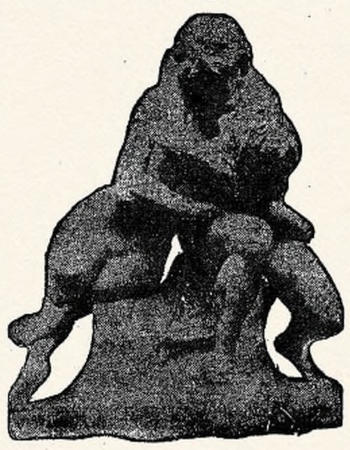

Colonel Knight leaned forward to peer into the pool; then, with a choking cry he staggered back, his face drained of blood: an ugly black snout had shot up out of the murky depths, and a huge lizard, with short, powerful forelegs armed with long claws, stared hungrily up at him.

He found his appetite for exploration losing its edge. He was tempted to turn back, but he wanted to settle one point: in case he should want to leave this house, how could he best do it? The windows were securely barred, but there must be plenty of doors.

A hall opened out from the conservatory, and on either side were rooms, variously furnished. He hurried on. Ahead, he saw a door which seemed to give upon the outer world. He grasped the knob. The door was locked, and the lock was one which a glance told him could be neither picked nor smashed.

Turning, he explored the rear of the house. In the east wing he found the kitchens and servants’ quarters, but a door which probably communicated with the kitchen gardens was locked.

Suddenly his wandering eyes caught the handle of a door in an angle of the pantry. He approached it and found that it opened upon a stair leading down. A gust of warm, damp air came up through the stairway, and for a moment Knight paused, sniffing curiously.

He found himself thinking of a certain sultry afternoon in India, when he had gone out into the simmering jungle. There was the same wild smell here—

He had his revolver in his hip pocket. That gave him confidence, and he must know if it would be possible for him to escape in this direction.

A phrase spoken by Ah Wing came to him—“Even in this house of hidden dangers!” But what dangers could there be?

Colonel Knight felt his way down into the basement. He found that it lay almost entirely below the level of the grounds, but presently his eyes became accustomed to the dusk and he could discern his surroundings.

He was in a broad and deep room, filled with a litter of packing cases, discarded articles of furniture, and a few garden tools. At its farther side was a door. Slowly and cautiously, the investigator made his way toward this.

It opened into a dark and narrow passage. He made his way along this, trying the handles of two locked doors, one on the right and the other on the left. Then he came to the end of the passage and to another door.

Cautiously, he opened it and looked inside: before him lay a room somewhat better lighted than the passage, but absolutely destitute of furniture. He crossed the threshold and stood for a long moment looking about him. The smell which he had associated with that hot afternoon in the jungle came to him almost overpoweringly now, but beyond he saw a door with an iron-barred transom. He wanted to try that door.

He had crossed halfway toward it when some subtle sense of danger brought him to a stop. He looked back. Nothing.

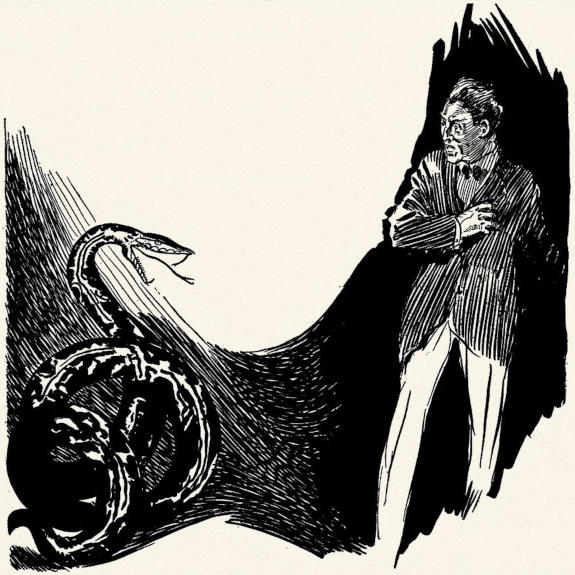

Then, with a start, he looked up, into the dusky ceiling. Something was moving there—he stepped back, drawing in his breath with a sharp hissing intake of terror. He backed toward the door. It was taking shape, up there among some uncovered beams and pipes—a huge column that seemed to have come alive! Slowly it swung down in a great curve.

Colonel Knight stood frozen in his tracks. It was a snake—but such a snake! He knew that this was no waking vision, but a horrible reality—

With a choking cry, he turned and ran as he had never run before in his life. Behind him he heard a hissing as of sand being poured from an elevation into a tin pail. A box was overturned. The thing was gaining on him—he turned, and with bulging eyes he saw the python strung out along the floor, its great body undulating, its flat head raised, its unblinking eyes burning through the dusk.

He could never make the stairs. At the left was a small door. He threw himself upon it and clutched the handle—it came open and, without looking before him, he threw himself forward. Something struck against the door as he jerked it shut, and he could hear that uncanny sand blast louder than before.

Groping about him in the utter darkness of this refuge, he found a metal contrivance—a wheel, with a metal stem connecting it with a large iron pipe. He was in the closet which housed the intake of the water system.

Then he remembered his revolver. It would be of little use to him against the horrible thing coiled outside.

When Ah Wing returned to the house, several hours later, he went quietly through the hall and conservatory to the door of Colonel Knight’s apartment.

Satisfied by a brief inspection that his “guest” was not in his rooms, the Chinaman turned and made his way to the basement door. His face was as serene as usual, but his eyes shone with a metallic gleam. He opened the door and for a moment stood listening.

An angry and prolonged hiss, which sounded like a great jet of steam, came plainly to him. He stepped into the hallway and deliberately closed the door behind him. Then he felt his way down the stairs, pausing within a few steps of the bottom to look unwinkingly about.

Something was moving in the dim shadows at the farther side of the room. It came slowly toward him, and he could make out the undulating length of the python. Ah Wing’s glowing eyes rested unwaveringly on the flat, evil head of the great snake, which came toward him more and more slowly.

With a final prolonged hiss, the python drew itself up into a huge coil. It was a tremendous creature, as large as a man’s body at its greatest diameter: but now it seemed to be turning slowly to stone. Its beady eyes grew dull, and its swaying head became rigid.

A muffled cry reached the ears of the motionless Chinaman. Without the flicker of an eyelid, he continued to stare down at the python.

Presently he descended to the foot of the stairs. The snake was still.

Ah Wing crossed to the closet door and threw it open.

“You can leave your retreat now, Colonel Knight,” he said. “My little playmate is temporarily in a condition of catalepsy—but I would not advise you to repeat this visit!”

Monte and the “Kid” went back to the city that same evening, but early next morning the leader of the Wolves returned to the neighborhood[14] where they had picked up the trail of Colonel Knight.

Monte had caught sight of a “For Rent” sign in the upper window of a cottage half a mile from the big house, and he wasted no time in hunting up the rental agent and signing a lease. By evening he had his men with him, and the battle lines were established for the final conflict.

“We got to get all the dope on this Chink and his layout we can,” Monte explained to his companions, as they sat smoking in the parlor of their new home. “We might try to rush the house, but I don’t like the looks of it. Chances are that Chink’s got a machine gun or a bunch of sawed-off pump guns there. We’ll have to size things up.”

He paused to stare at his men.

“Any kicks on that? All right, it’s settled. Louie, it’s your turn for sentry duty, and you better get over to the Chink’s castle now. At two o’clock I’ll send Doc over to relieve you. You might take a look at the windows, and see if any of them can be handled without a saw—there may be some loose bars!”

Louie Martin, the gem expert, was a little tallow-faced man with a straggling, peaked beard and shifty eyes. He had no real appetite for this sort of thing, but for personal reasons he was more willing than usual to go on duty tonight.

Slipping his automatic into the holster under his arm, he struck off along the road toward the house of Ah Wing, whose gables were visible from the cottage. A light wind was blowing from the southeast, and he could see the mist rising over the marshes. Somewhere from the steamy air above a night heron screamed raucously. Involuntarily, Louie shivered.

He was glad to turn his thoughts to his own immediate affairs. Louie Martin had made up his mind to strike out for himself. He had always admired Colonel Knight—or “Count von Hondon”—for the shrewd stroke of business he had done; and Louie was keen enough to perceive that Monte Jerome was not equal to the task of holding the Wolves together. At the present time there was open dissension among them. One of these days one of them would squeal on the others—that was the way this mob stuff usually ended.

No, Louie had made up his mind to watch his chance for a crack at the jewels—and then a clean getaway.

He reached the private road leading to the Chinaman’s house, paused for a moment to listen and reconnoiter, then stealthily struck into the grounds. Five minutes later he had skirted the west wing and was peering up through the shrubbery at the lighted windows of Colonel Knight’s apartment. Their location had been sketched for him by Monte.

“So that’s where the old devil is!” thought Louie. “Let’s just have a look-see!”

He climbed into a pepper tree—the same from which Monte and the “Kid” had seen Knight—and stared into the room. It was lighted, but there was no one in sight. Then, through a vista of open doors, he saw the man whom he had been sent to watch, walking slowly about with his hands clasped behind him, a cigar between his lips.

“Had a good supper, and now he’s enjoying a smoke!” Louie mumbled enviously. “Well, that’s good enough for me, too! Let’s have a look at that window!”

He slipped down from the tree and glanced about. At the corner of the house was a galvanized iron can, evidently used for lawn clippings. Louie lifted this cautiously and carried it over under the end window. Then he climbed upon it, raising his head cautiously till he was standing just beside the half-open window.

A silent inspection of the bars showed him that they were all securely fastened, with one possible exception: the bottom bar seemed to be loose in its niche. Louie climbed down, changed the can over to the opposite side, and examined the opposite end. Sure enough, it showed a crumble of concrete around the bolt which was supposed to hold it in place. With the utmost caution, fearing that the loose bar might be connected with an alarm system, the crook tested it.

A smile twisted his thin lips. It could be moved in and out of its niche.

A sound came from somewhere close at hand; and with the speed and silence of a wolf Louie Martin leaped to the ground, caught up the can, and replaced it where he had found it. Next instant he was hidden in a clump of flowering shrubs.

From this position he could see the top of a flight of steps leading down to the basement of the house of Ah Wing. He stood listening and watching, and presently he heard a door open and close, followed by steps ascending the stairs. Then some one came up out of the basement, and he saw the figure of a tall Chinaman walking deliberately toward the bush in which he was hiding. Louie reached under his coat for his pistol—

Ah Wing turned, and Louie saw that he was following a graveled path. And he was carrying something in one hand—a contrivance of twisted wires, like an iron basket.

As Ah Wing disappeared into the mist, Louie made up his mind. Tonight, after Knight had gone to bed, he would strike: he was not to be relieved till two o’clock, and that would give him time to put through his coup. But now he meant to follow Ah Wing. He needed all the information he could secure about the master of this silent house.

The Chinaman had disappeared into the eddying mist, but Louie struck into the path and soon came within hearing of the crisp footsteps. Ah Wing reached the edge of the grounds and crossed over into a marshy field.

Instinctively, the crook worked closer to the man he was shadowing. There was something oddly menacing about this night, with its mist and its fitful, salt-laden wind.

Suddenly through the swirling fog there appeared a light, which seemed to be suspended ten feet or so above the ground. It was moving slowly along in front of them—a murky light, like a blood-red mist.

Then Louie saw that it was the light suspended from the mast of a boat, and that the boat itself was moving slowly along before them, almost hidden by the banks of the canal. The tide must be out, he thought.

Ah Wing swung on through the night, and presently the man following him made out the silhouette of a building, perched above the canal. Louie slunk cautiously forward and saw that the boat, whose lantern he had previously observed, was making fast at that wharf.

Ah Wing leaped lightly to the sunken deck and disappeared down the companionway. Before Louie could decide what he was to do, the Chinaman reappeared and climbed back to the wharf. Louie had just time to slip into the shelter of a group of piling when the Chinaman passed the corner of the building.

And in his hand was another of the wire contrivances, filled with squirming, squeaking rats!

The white man felt his stomach doing queer antics. He had heard of Chinamen eating rats. Was that what this fellow was up to? What else could he want with them?

Ah Wing walked swiftly, and the man behind kept as close as he dared. Again they entered the grounds surrounding the big house, and the Oriental crossed to the basement stairs and went down. Louie paused in the bushes.

“I’m going to gamble,” he whispered suddenly to himself. “I’ll just sneak down those steps, and if he tries to come[15] out before I can duck, I’ll bean him! I want to know what he’s up to!”

Stealthily, he approached the steps. All that he could see was a murky hole, into which the cement stairs disappeared. A step at a time he made his way down—

And then he paused, holding himself bent forward, rigid as a man of stone. From beyond the door which opened out of this pit came a strange sound, the like of which he had never before heard. It was like a jet of steam, or like sand sifting into a tin pail from a considerable height.