Title: Library of the best American literature

Editor: William W. Birdsall

Rufus M. Jones

Release date: December 23, 2022 [eBook #69620]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Monarch Book Company

Credits: Richard Hulse and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

The cover image was provided by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Punctuation has been standardized.

Most abbreviations have been expanded in tool-tips for screen-readers and may be seen by hovering the mouse over the abbreviation.

The text may show quotations within quotations, all set off by similar quote marks. The inner quotations have been changed to alternate quote marks for improved readability.

This book has illustrated drop-caps at the start of each chapter. These illustrations may adversely affect the pronunciation of the word with screen-readers or not display properly in some handheld devices.

This book was written in a period when many words had not become standardized in their spelling. Words may have multiple spelling variations or inconsistent hyphenation in the text. These have been left unchanged unless indicated with a Transcriber’s Note.

The symbol ‘‡’ indicates the description in parenthesis has been added to an illustration. This may be needed if there is no caption or if the caption does not describe the image adequately.

Footnotes are identified in the text with a superscript number and are shown immediately below the paragraph in which they appear.

Transcriber’s Notes are used when making corrections to the text or to provide additional information for the modern reader. These notes are identified by ♦♠♥♣ symbols in the text and are shown immediately below the paragraph in which they appear.

LIBRARY

OF THE

Best American Literature

CONTAINING

The Lives of our Authors in Story Form

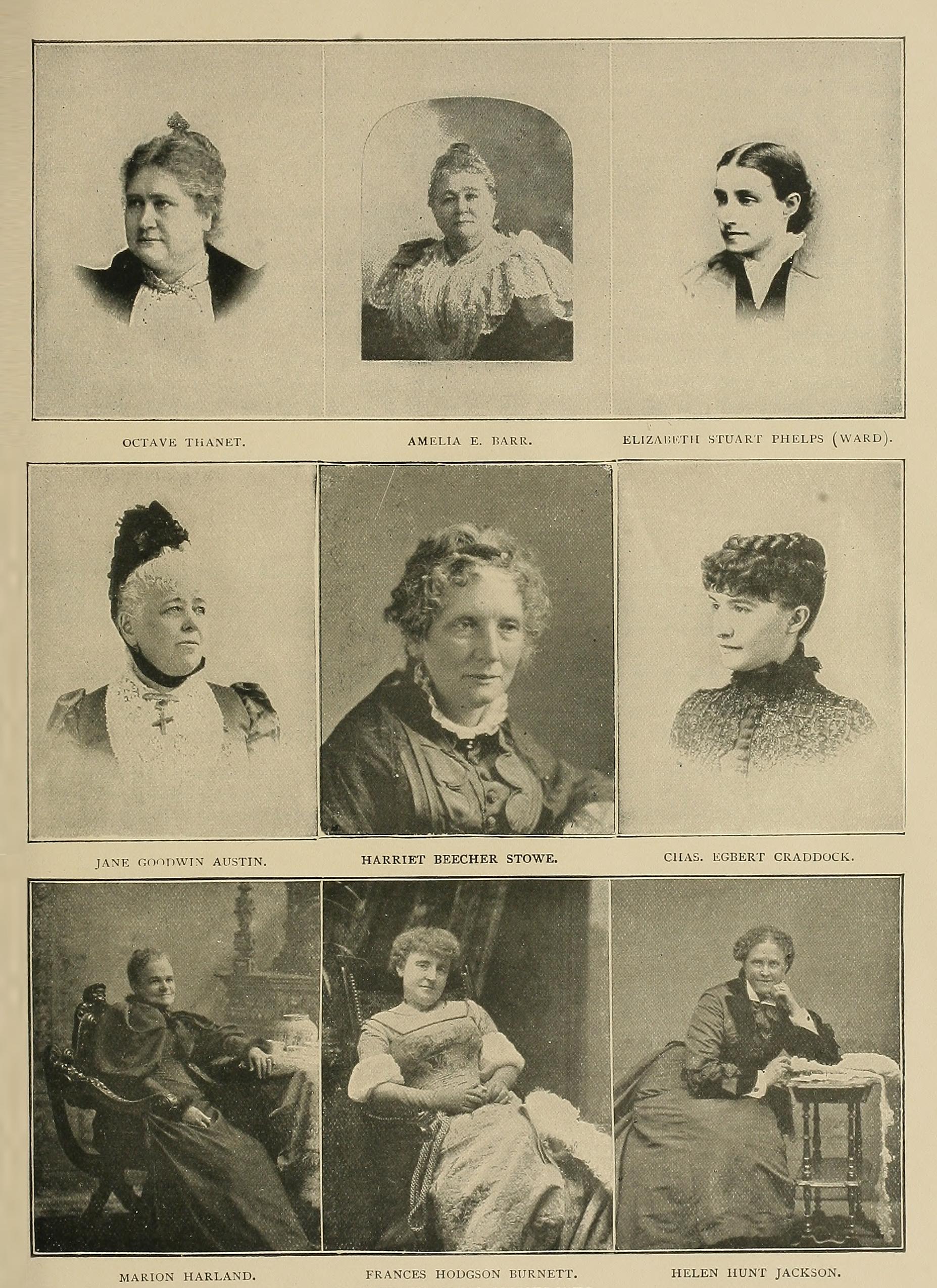

Their Portraits, their Homes, and their Personal Traits

How they Worked and What they Wrote

Choice Selections from Eminent Writers

EMBRACING

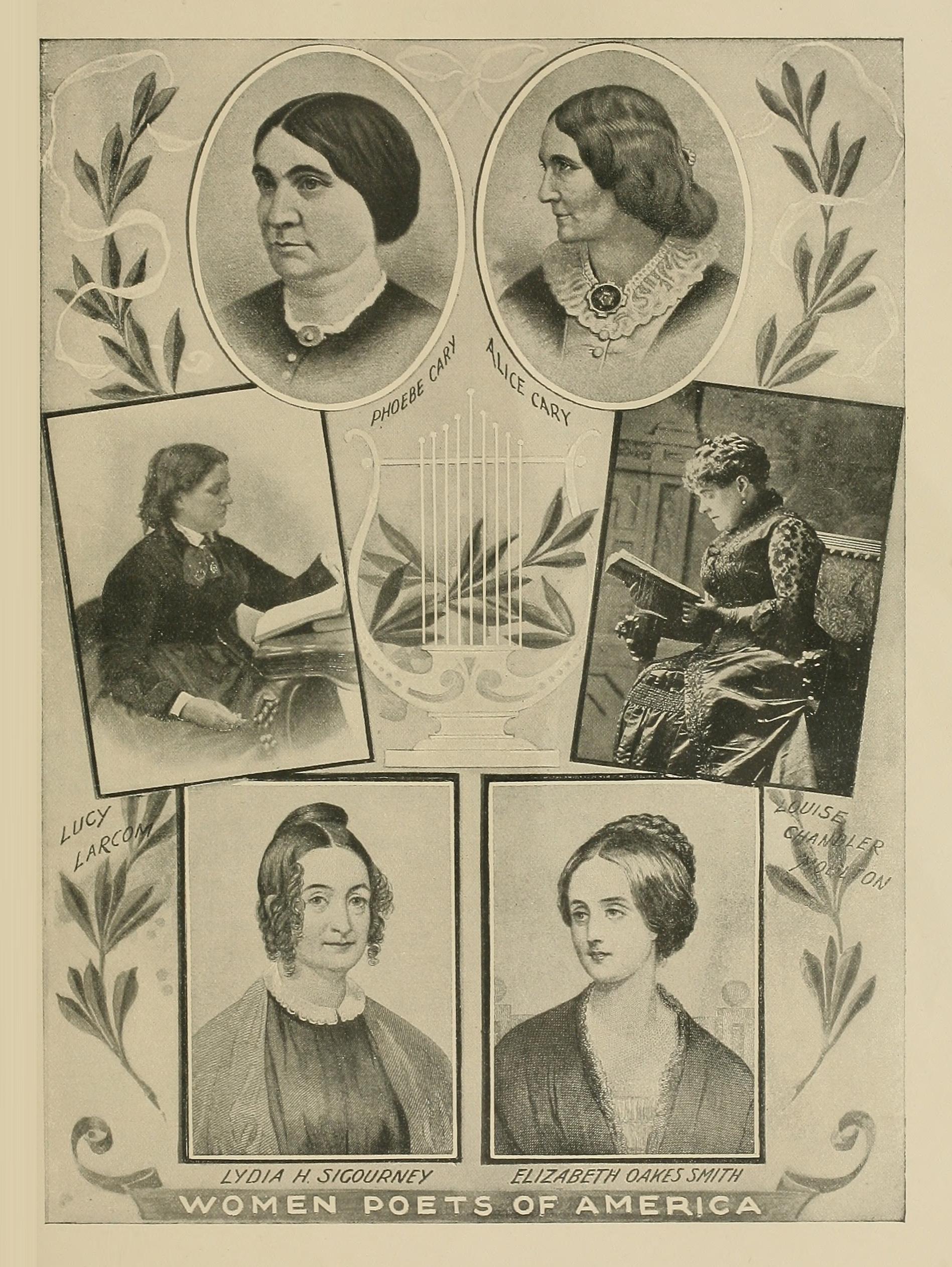

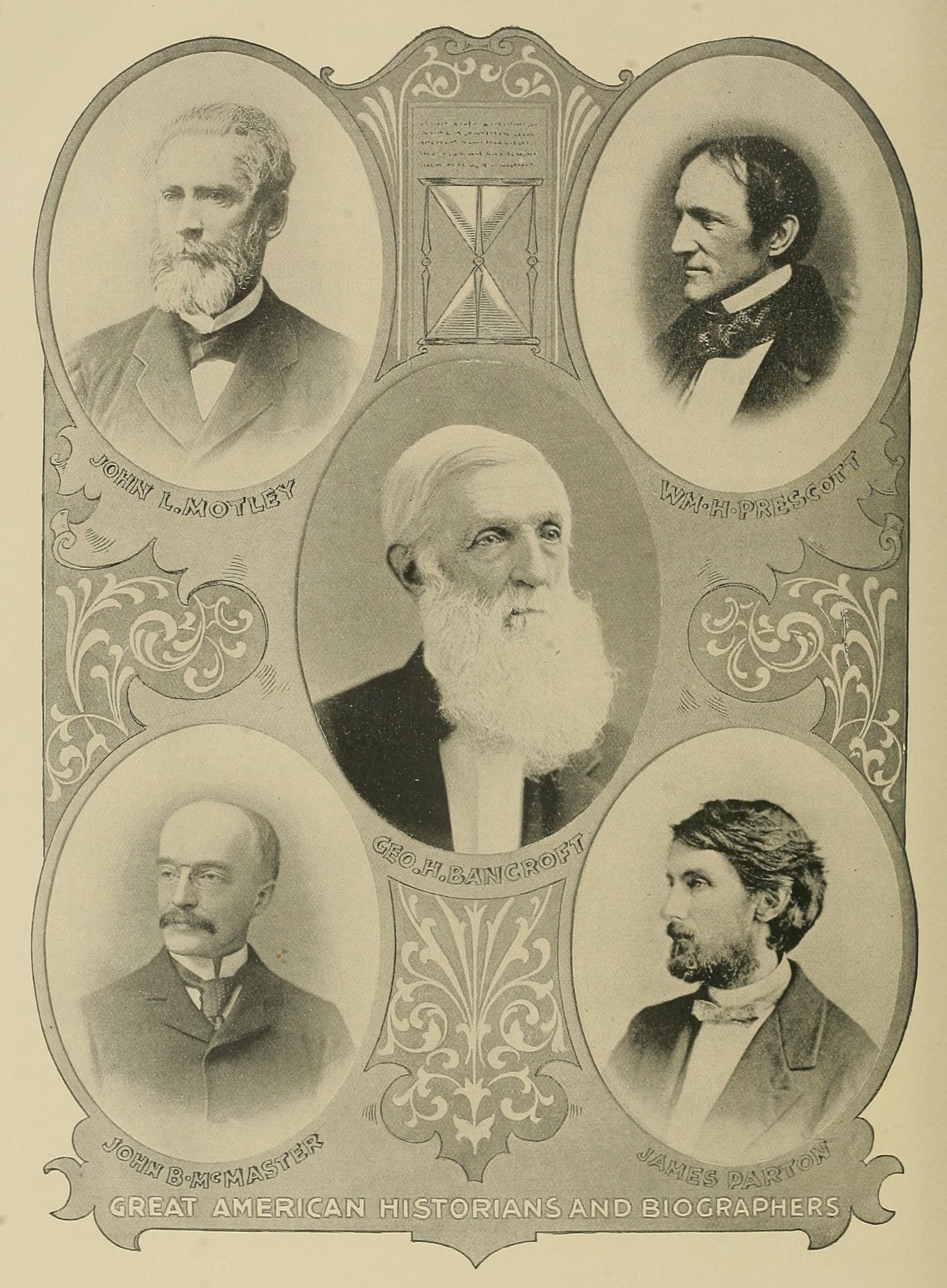

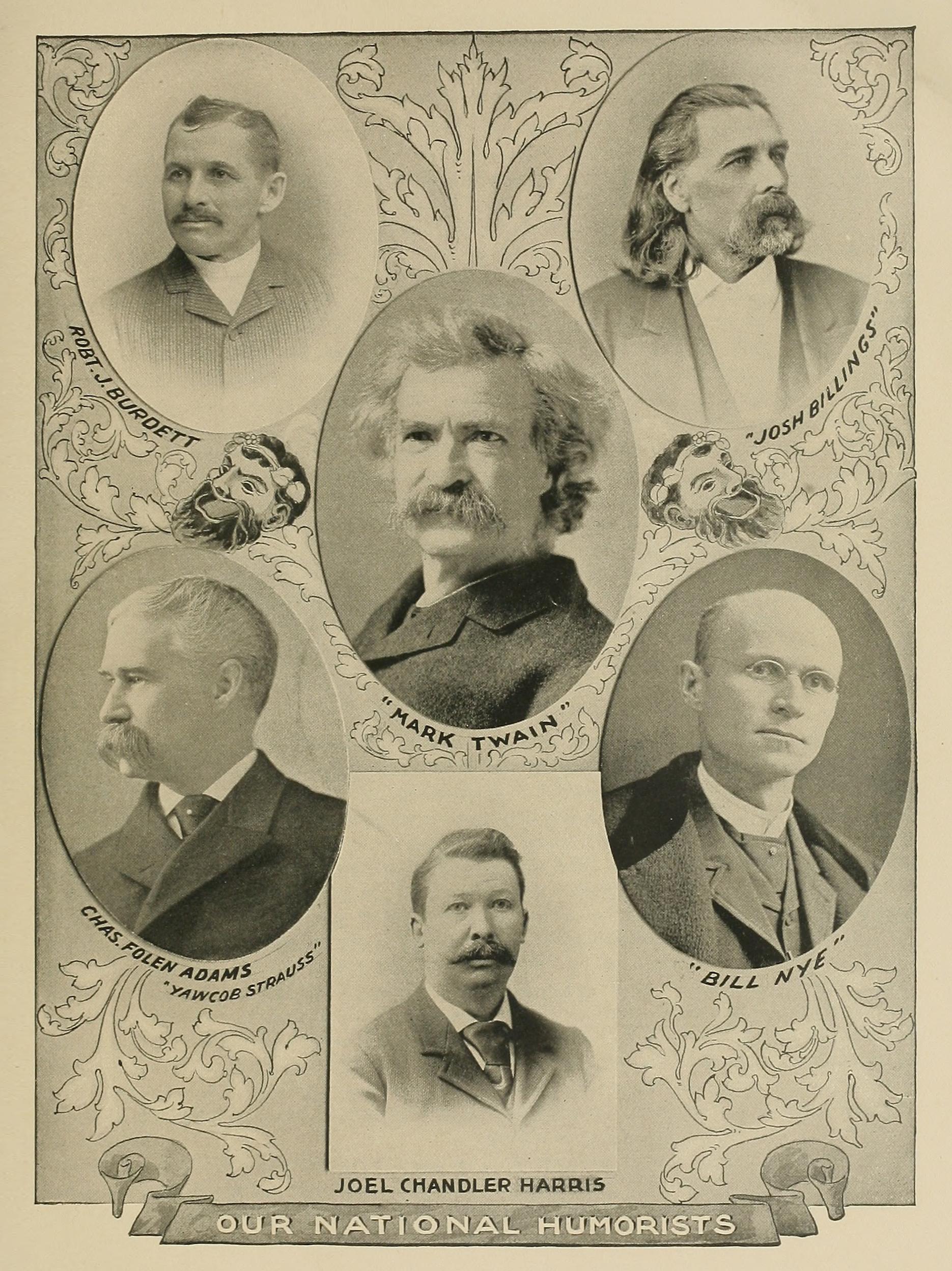

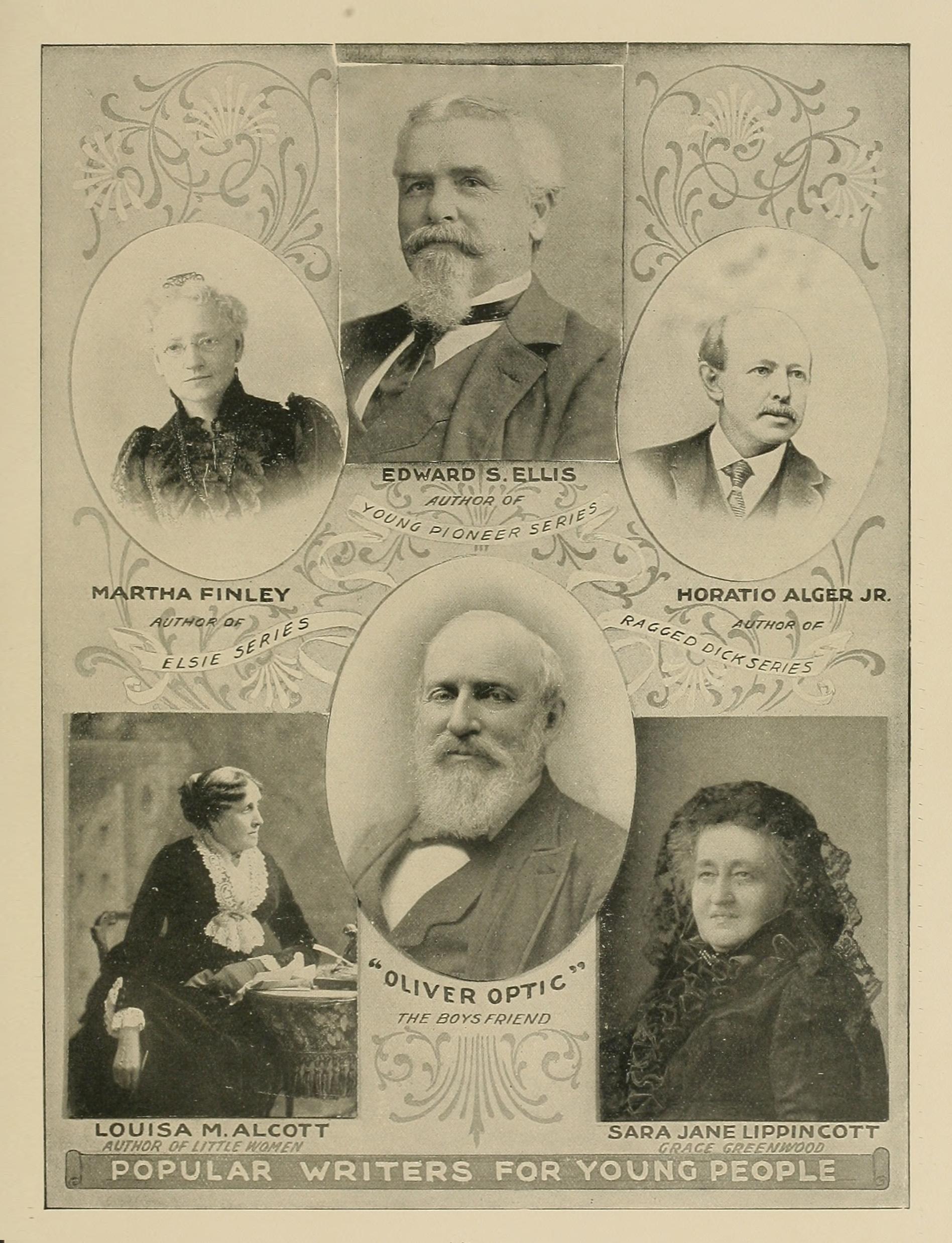

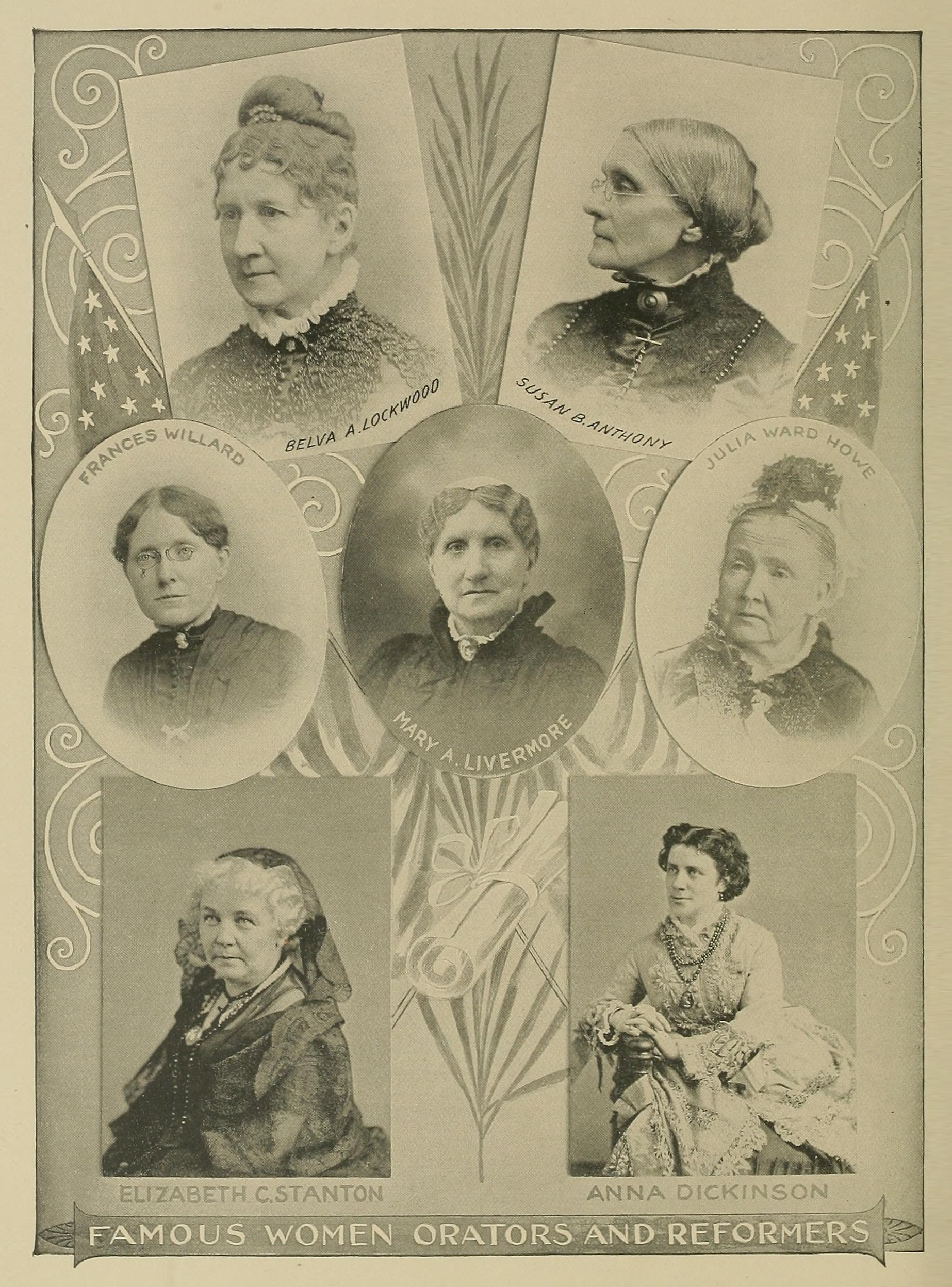

GREAT AMERICAN POETS AND NOVELISTS, FOREMOST WOMEN IN AMERICAN LETTERS, DISTINGUISHED CRITICS AND ESSAYISTS, OUR NATIONAL HUMORISTS, NOTED JOURNALISTS AND MAGAZINE CONTRIBUTORS, POPULAR WRITERS FOR YOUNG PEOPLE, GREAT ORATORS AND PUBLIC LECTURERS

ELEGANTLY ILLUSTRATED WITH HALF TONE PORTRAITS

And Photographs of Authors’ Homes, together with Many Other Illustrations in the Text

MONARCH BOOK COMPANY,

Successors to and formerly L. P. Miller & Co.,

CHICAGO, ILL. PHILADELPHIA, PA.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1897, by

W. E. SCULL,

in the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

All rights reserved.

ALL PERSONS ARE WARNED NOT TO INFRINGE UPON OUR COPYRIGHT BY USING EITHER THE MATTER OR THE PICTURES IN THIS VOLUME.

LITERATURE OF AMERICA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

Our obligation to the following publishers is respectfully and gratefully acknowledged, since, without the courtesies and assistance of these publishers and a number of the living authors, it would have been impossible to issue this volume.

Copyright selections from the following authors are used by the permission of and special arrangement with MESSRS. HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO., their authorized publishers:—Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry W. Longfellow, Oliver Wendell Holmes, James Russell Lowell, Bayard Taylor, Maurice Thompson, Colonel John Hay, Bret Harte, William Dean Howells, Edward Bellamy, Charles Egbert Craddock (Miss Murfree), Elizabeth Stuart Phelps (Ward), Octave Thanet (Miss French), Alice Cary, Phœbe Cary, Charles Dudley Warner, E. C. Stedman, James Parton, John Fiske and Sarah Jane Lippincott.

TO THE CENTURY CO., we are indebted for selections from Richard Watson Gilder, James Whitcomb Riley and Francis Richard Stockton.

TO CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS, for extracts from Eugene Field.

TO HARPER & BROTHERS, for selections from Will Carleton, General Lew Wallace, W. D. Howells, Thomas Nelson Page, John L. Motley, Charles Follen Adams and Lyman Abbott.

TO ROBERTS BROTHERS, for selections from Edward Everett Hale, Helen Hunt Jackson, Louise Chandler Moulton and Louisa M. Alcott.

TO ORANGE, JUDD & CO., for extracts from Edward Eggleston.

TO DODD, MEAD & CO., for selections from E. P. Roe, Marion Harland (Mrs. Terhune), Amelia E. Barr and Martha Finley.

TO D. APPLETON & CO., for Wm. Cullen Bryant and John Bach McMaster.

TO MACMILLAN & CO., for F. Marion Crawford.

TO HORACE L. TRAUBEL, Executor, for Walt Whitman.

TO ESTES & LAURIAT, for Gail Hamilton (Mary Abigail Dodge).

TO LITTLE, BROWN & CO., for Francis Parkman.

TO FUNK & WAGNALLS, for Josiah Allen’s Wife (Miss Holley).

TO LEE & SHEPARD, for Yawcob Strauss (Charles Follen Adams), Oliver Optic (William T. Adams) and Mary A. Livermore.

TO J. B. LIPPINCOTT & CO., for Bill Nye (Edgar Wilson Nye).

TO GEORGE ROUTLEDGE & SONS, for Uncle Remus (Joel C. Harris).

TO TICKNOR & CO., for Julian Hawthorne.

TO PORTER & COATES, for Edward Ellis and Horatio Alger.

TO WILLIAM F. GILL & CO., for Whitelaw Reid.

TO C. H. HUDGINS & CO., for Henry W. Grady.

TO THE “COSMOPOLITAN MAGAZINE,” for Julian Hawthorne.

TO T. B. PETERSON & BROS., for Frances Hodgson Burnett.

TO JAS. R. OSGOOD & CO., for Jane Goodwin Austin.

TO GEO. R. SHEPARD, for Thomas Wentworth Higginson.

TO J. LEWIS STACKPOLE, for John L. Motley.

Besides the above, we are under special obligation to a number of authors who kindly furnished, in answer to our request, selections which they considered representative of their writings.

HE

ink of a Nation’s Scholars is more sacred than the blood of its martyrs,”—declares Mohammed. It is with this sentence in mind, and a desire to impress upon our fellow countrymen the excellence, scope and volume of American literature, and the dignity and personality of American authorship, that this work has been prepared and is now offered to the public.

HE

ink of a Nation’s Scholars is more sacred than the blood of its martyrs,”—declares Mohammed. It is with this sentence in mind, and a desire to impress upon our fellow countrymen the excellence, scope and volume of American literature, and the dignity and personality of American authorship, that this work has been prepared and is now offered to the public.

The volume is distinctly American, and, as such it naturally appeals to the patriotism of Americans. Every selection which it contains was written by an American. Its perusal, we feel confident, will both entertain the reader and quicken the pride of every lover of his country in the accomplishments of her authors.

European nations had already the best of their literature before ours began. It is less than three hundred years since the landing of the Mayflower at Plymouth Rock, and the planting of a colony at Jamestown, marked the first permanent settlements on these shores. Two hundred years were almost entirely consumed in the foundation work of exploring the country, settling new colonies, in conflicts with the Indians, and in contentions with the mother country. Finally—after two centuries—open war with England served the purpose of bringing the jealous colonists together, throwing off our allegiance to Europe, and, under an independent constitution, of introducing the united colonists—now the United States of America—into the sisterhood of nations.

Thus, it was not until the twilight of the eighteenth century that we had an organized nationality, and it was not until the dawn of the nineteenth that we began to have a literature. Prior to this we looked abroad for everything except the products of our soil. Neither manufacturing nor literature sought to raise its head among us. The former was largely prohibited by our generous mother, who wanted to make our clothes and furnish us with all manufactured articles; literature was frowned upon with the old interrogation, “Who reads an American book?” But simultaneously with the advent of liberty upon our shores was born the spirit of progress—at once enthroned and established as the guardian saint of American energy and enterprise. She touched the mechanic and the hum of his machinery was heard and the smoke of his factory arose as an incense to her, while our exhaustless stores of raw materials were transformed into things of use and beauty; she touched the merchant and the wings of commerce were spread over our seas; she touched the scholar and the few institutions of learning along the Atlantic seaboard took on new life and colleges and universities multiplied and followed rapidly the course of civilization across the mountains and plains of the West.

But the spirit of progress did not stop here. Long before that time Dr. Johnson had declared, “The chief glory of every people arises from its authors,” and our people had begun to realize the force of the truth, which Carlyle afterwards expressed, that “A country which has no national literature, or a literature too insignificant to force its way abroad, must always be to its neighbors, at least in every important spiritual respect, an unknown and unesteemed country.” The infant nation had now begun its independent history. Should it also have an independent literature; and if so, what were the bases for it? The few writers who had dared to venture into print had dealt with European themes, and laid their scenes and published their books in foreign lands. What had America, to inspire their genius?

The answer to this question was of vital importance. Upon it depended our destiny in literature. It came clear and strong. To go elsewhere were to imitate the discontented and foolish farmer who became possessed of a passion for hunting diamonds, and, selling his farm for a song, spent his days in wandering over the earth in search of them. The man who bought this farm found diamonds in the yard around the house, and developed that farm into the famous Golconda mines. The poor man who wandered away had acres of diamonds at home. They were his if he had but been wise enough to gather them.

So was America a rich field for her authors. Nature nowhere else offered such inspiration to the poet, the descriptive and the scientific writer as was found in America. Its mountains were the grandest; its plains the broadest; its rivers the longest; its lakes were inland seas; its water-falls were the most sublime; its caves were the largest and most wonderful in the world; its forests bore every variety of vegetable life and stretched themselves from ocean to ocean; it had a soil and a climate diversified and varied beyond that of any other nation; birds sang for us whose notes were heard on no other shores; we had a fauna and a flora of our own. For the historian there was the aboriginal red man, with his unwritten past preserved only in tradition awaiting the pen of the faithful chronicler; the Colonial period was a study fraught with American life and tradition and no foreigner could gather its true story from the musty tomes of a European library; the Revolutionary period must be recorded by an American historian. For the novelist and the sketch writer our magnificent land had a rich legendary lore, and a peculiarity of manners and customs possessed by no other continent. The story of its frontier, with a peculiar type of life found nowhere else, was all its own.

It was to this magnificent prospect, with its inspiring possibilities that Progress,—the first child of liberty—stood and pointed as she awoke the slumbering genius of independent American Authorship, and, placing the pen in her hand bade her write what she would. Thus the youngest aspirant in literature stood forth with the freest hand, in a country with its treasures of the past unused, and a prospective view of the most magnificent future of the nations of earth.

What a field for literature! What an opportunity it offered! How well it has been occupied, how attractive the personality, how high the aims, and how admirable the methods of those who have done so, it is the province of this volume to demonstrate. With this end in view, the volume has been prepared. It has been inspired by a patriotic pride in the wonderful achievement of our men and women in literature, in making America, at the beginning of her second century as a nation, the fair and powerful rival of England and Continental Europe in the field of letters.

Wonderful have been the achievements of Americans as inventors, mechanics, merchants—indeed, in every field in which they have contended—but we are prepared to agree with Dr. Johnson that “The chief glory of a nation is its authors;” and, with Carlyle, that they entitle us to our greatest respect among other nations. The reading of the biographies and extracts herein contained should impress the reader with the debt of gratitude we as a people owe to those illustrious men and women, who, while wreathing their own brows with chaplets of fame, have written the name, “America,” high up on the literary roll of honor among the greatest nations of the world.

HIS

work has been designed and prepared with a view to presenting an outline of American literature in such a manner as to stimulate a love for good reading and especially to encourage the study of the lives and writings of our American authors. The plan of this work is unique and original, and possesses certain helpful and interesting features, which—so far as we are aware—have been contemplated by no other single volume.

HIS

work has been designed and prepared with a view to presenting an outline of American literature in such a manner as to stimulate a love for good reading and especially to encourage the study of the lives and writings of our American authors. The plan of this work is unique and original, and possesses certain helpful and interesting features, which—so far as we are aware—have been contemplated by no other single volume.

The first and main purpose of the work is to present to our American homes a mass of wholesome, varied and well-selected reading matter. In this respect it is substantially a volume for the family. America is pre-eminently a country of homes. These homes are the schools of citizenship, and—next to the Bible, which is the foundation of our morals and laws—we need those books which at once entertain and instruct, and, at the same time, stimulate patriotism and pride for our native land.

This book seeks to meet this demand. Four-fifths of our space is devoted exclusively to American literature. Nearly all other volumes of selections are made up chiefly from foreign authors. The reason for this is obvious. Foreign publications until within the last few years have been free of copyright restrictions. Anything might be chosen and copied from them while American authors were protected by law from such outrages. Consequently, American material under forty-two years of age could not be used without the consent of the owner of the copyright. The expense and the difficulty of obtaining these permissions were too great to warrant compilers and publishers in using American material. The constantly growing demand, however, for a work of this class has encouraged the publishers of this volume to undertake the task. The publishers of the works from which these selections are made and many living authors represented have been corresponded with, and it is only through the joint courtesy and co-operation of these many publishers and authors that the production of this volume has been made possible. Due acknowledgment will be found elsewhere. In a number of instances the selections have been made by the authors themselves, who have also rendered other valuable assistance in supplying data and photographs.

The second distinctive point of merit in the plan of the work is the biographical feature, which gives the story of each author’s life separately, treating them both personally and as writers. Longfellow remarked in “Hyperion”—“If you once understand the character of an author the comprehension of his writings becomes easy.” He might have gone further and stated that when we have once read the life of an author his writings become the more interesting. Goethe assures us that “Every author portrays himself in his works even though it be against his will.” The patriarch in the Scriptures had the same thought in his mind when he exclaimed “Oh! that mine enemy had written a book.” Human nature remains the same. Any book takes on a new phase of value and interest to us the moment we know the story of the writer, whether we agree with his statements and theories or not. These biographical sketches, which in every case are placed immediately before the selections from an author, give, in addition to the story of his life, a list of the principal books he has written, and the dates of publication, together with comments on his literary style and in many instances reviews of his best known works. This, with the selections which follow, established that necessary bond of sympathy and relationship which should exist in the mind of the reader between every author and his writings. Furthermore, under this arrangement the biography of each author and the selections from his works compose a complete and independent chapter in the volume, so that the writer may be taken up and studied or read alone, or in connection with others in the particular class to which he belongs.

This brings us to the third point of classification. Other volumes of selections—where they have been classified at all—have usually placed selections of similar character together under the various heads of Narrative and Descriptive, Moral and Religious, Historical, etc. On the contrary, it has appeared to us the better plan in the construction of this volume to classify the authors, rather than, by dividing their selections, scatter the children of one parent in many different quarters. There has been no small difficulty in doing this in the cases of some of our versatile writers. Emerson, for instance, with his poetry, philosophy and essays, and Holmes, with his wit and humor, his essays, his novels and his poetry. Where should they be placed? Summing them up, we find their writings—whether written in stanzas of metred lines or all the way across the page, and whether they talked philosophy or indulged in humor—were predominated by the spirit of poetry. Therefore, with their varied brood, Emerson and Holmes were taken off to the “Poet’s Corner,” which is made all the richer and more enjoyable by the variety of their gems of prose. Hence our classifications and groupings are as Poets, Novelists, Historians, Journalists, Humorists, Essayists, Critics, Orators, etc., placing each author in the department to which he most belongs, enabling the reader to read and compare him in his best element with others of the same class.

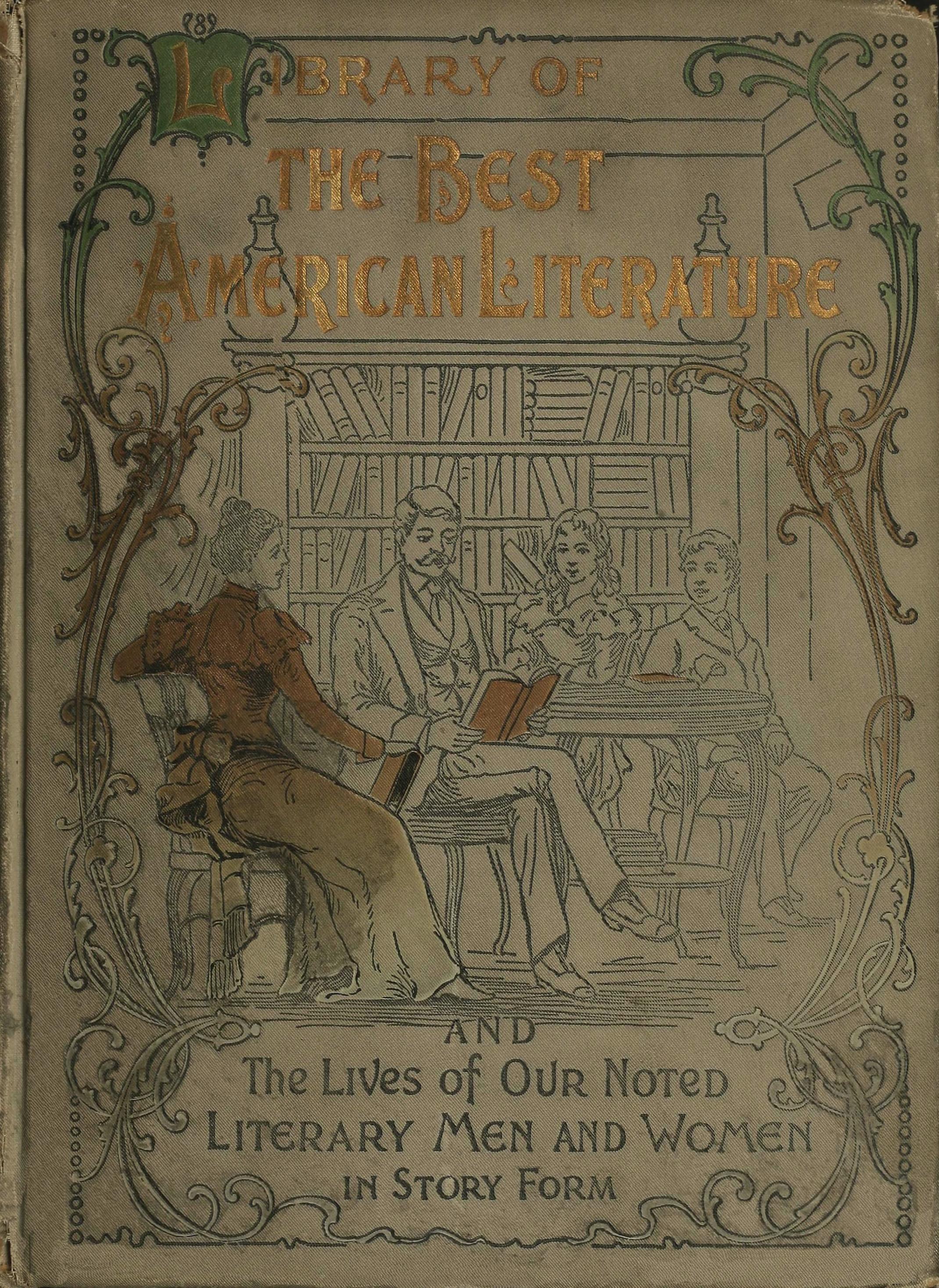

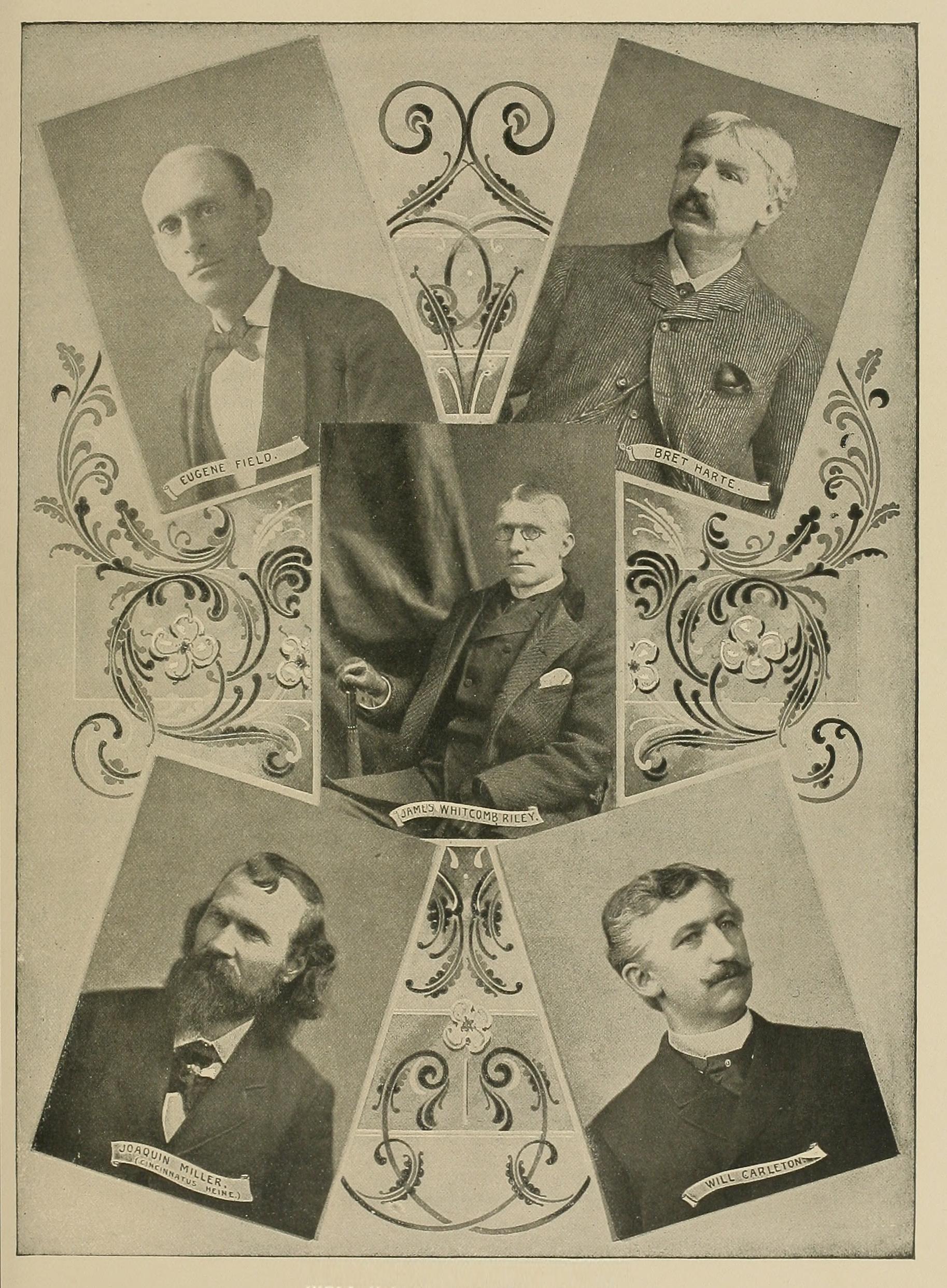

Part I., “Great Poets of America,” comprises twenty of our most famous and popular writers of verse. The work necessarily begins with that immortal “Seven Stars” of poesy in the galaxy of our literary heavens—Bryant, Poe, Longfellow, Emerson, Whittier, Holmes and Lowell. Succeeding these are those of lesser magnitude, many of whom are still living and some who have won fame in other fields of literature which divides honors with their poetry. Among these are Bayard Taylor, the noted traveler and poet; N. P. Willis, the most accomplished magazinist of his day; R. H. Stoddard, the critic; Walt Whitman; Maurice Thompson, the scientist; Thomas Bailey Aldrich and Richard Watson Gilder, editors, and Colonel John Hay, politician and statesman. The list closes with that notable group of well-known Western poets, James Whitcomb Riley, Bret Harte, Eugene Field, Will Carleton, and Joaquin Miller.

The remaining nine parts of the book treat in similar manner about seventy-five additional authors, embracing noted novelists, representative women poets of America; essayists, critics and sketch writers; great American historians and biographers; our national humorists; popular writers for young people; noted journalists and magazine contributors; great orators and popular lecturers. Thus, it will be seen that in this volume the whole field of American letters has been gleaned to make the work the best and most representative of our literature possible within the scope of a single volume.

In making a list of authors in whom the public were sufficiently interested to entitle them to a place in a work like this, naturally they were found to be entirely too numerous to be all included in one book. The absence of many good names from the volume is, therefore, explained by the fact that the editor has been driven to the necessity of selecting, first, those whom he deemed pre-eminently prominent, and, after that, making room for those who best represent a certain class or particular phase of our literature.

To those authors who have so kindly responded to our requests for courtesies, and whose names do not appear, the above explanation is offered. The omission was imperative in order that those treated might be allowed sufficient space to make the work as complete and representative as might be reasonably expected.

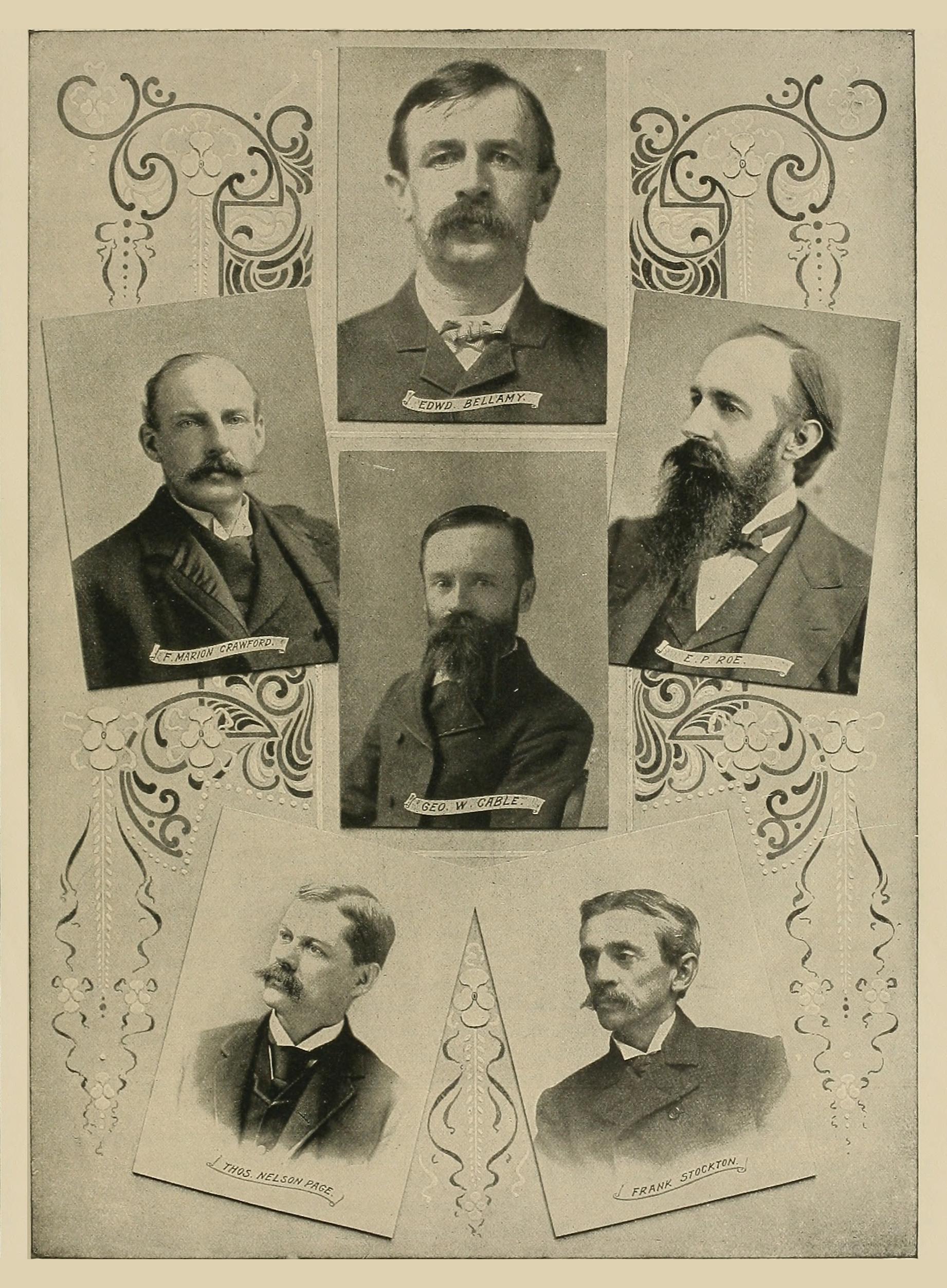

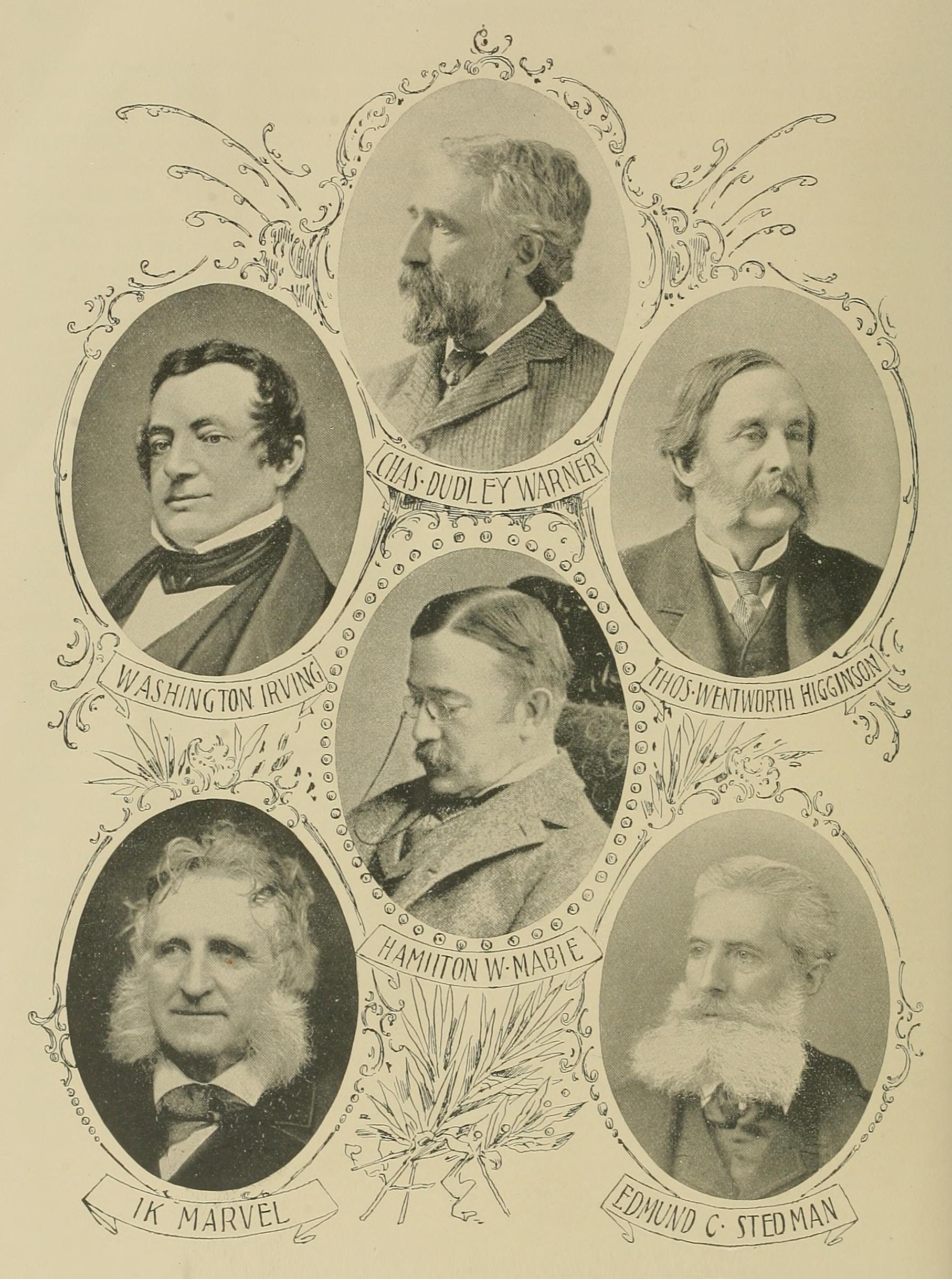

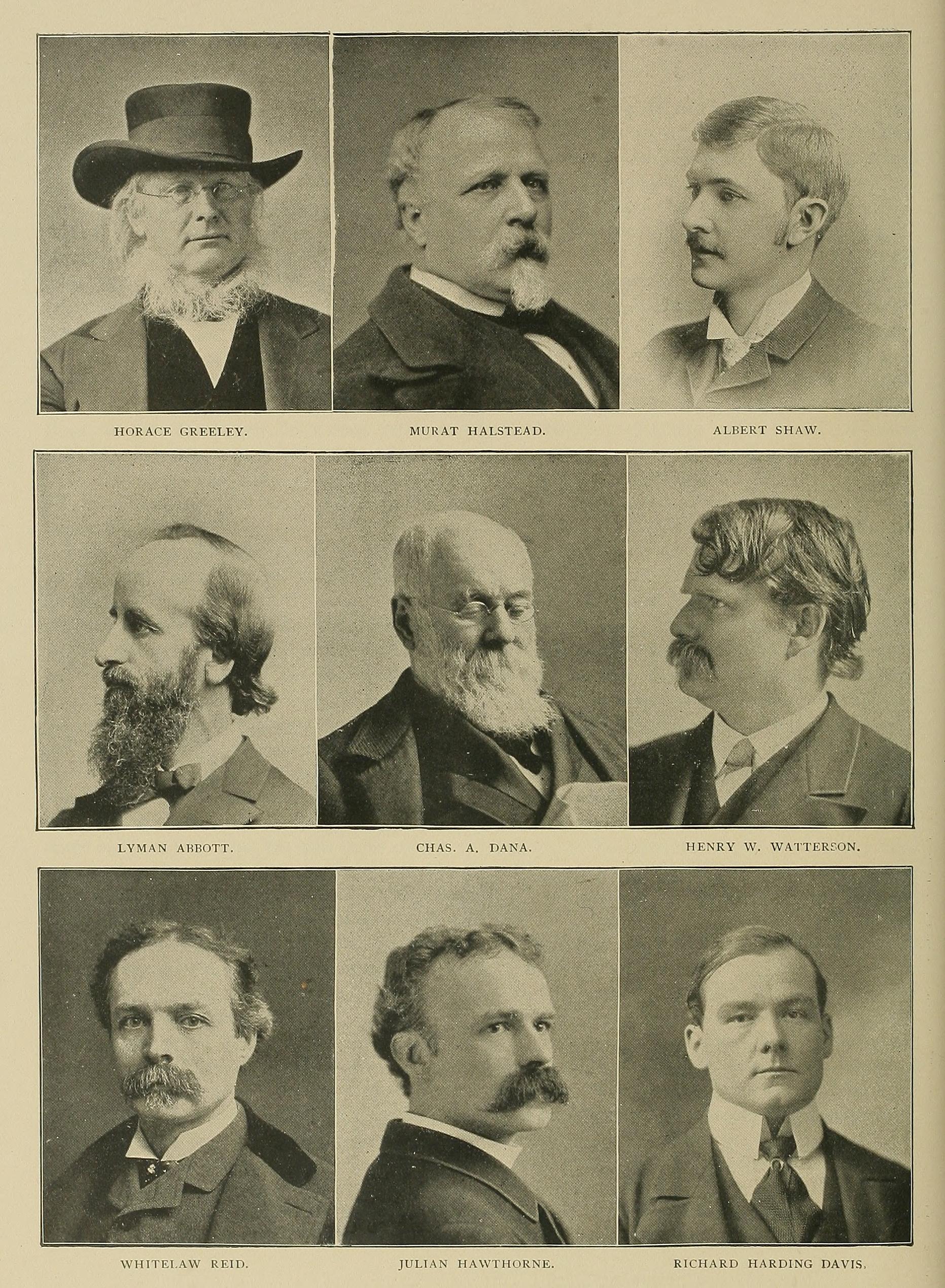

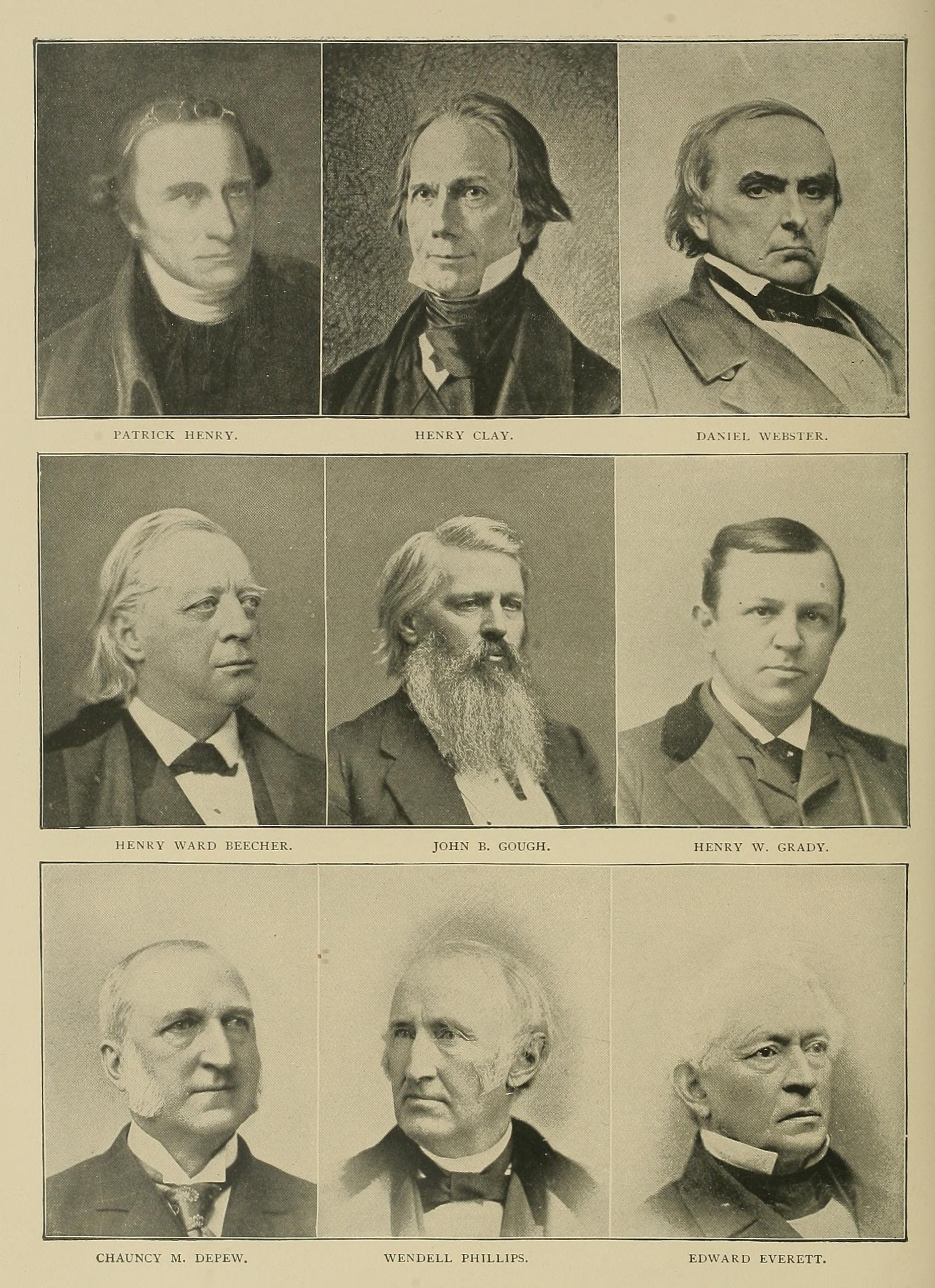

Special attention has been given to illustrations. We have inserted portraits of all the authors whose photographs we could obtain, and have, also, given views of the homes and studies of many. A large number of special drawings have also been made to illustrate the text of selections. The whole number of portraits and other illustrations amount to nearly one hundred and fifty, all of which are strictly illustrative of the authors or their writings. None are put in as mere ornaments. We have, furthermore, taken particular care to arrange a number of special groups, placing those authors which belong in one class or division of a class together on a page. One group on a page represents our greatest poets; another, well-known western poets; another, famous historians; another, writers for young people; another, American humorists, etc. These groups are all arranged by artists in various designs of ornamental setting. In many cases we have also had special designs made by artists for commemorative and historic pictures of famous authors. These drawings set forth in a pictorial form leading scenes in the life and labors of the author represented.

♦ ‘Duyckink’ replaced with ‘Duyckinck’

♦ ‘Workskip’ replaced with ‘Worship’

♦ ‘Hours’ replaced with ‘Days’

♦ ‘Belamy’s’ replaced with ‘Bellamy’s’

♦ ‘Dakotah’ replaced with ‘Dacotah’

♦ added work omitted from the TOC

♦ ‘Rebublic’ replaced with ‘Republic’

WHOSE WRITINGS, BIOGRAPHIES AND PORTRAITS APPEAR IN THIS VOLUME.

Abbott, Lyman.

Adams, Charles Follen, (Yawcob Strauss).

Adams, Wm. T., (Oliver Optic).

Alcott, Louisa May.

Aldrich, Thomas Bailey.

Alger, Horatio, Jr.

Anthony, Susan B.

Artemus Ward, (Charles F. Browne).

Austin, Jane Goodwin.

Bancroft, George H.

Barr, Amelia E.

Beecher, Henry Ward.

Bellamy, Edward.

Bill Nye (Edgar Wilson Nye).

Browne, Charles F., (Artemus Ward).¹

Bryant, William Cullen.

♦Burdette, Robert J.

♦ ‘Burdett’ replaced with ‘Burdette’

Burnett, Frances Hodgson.

Cable, George W.

Carleton, Will.

Cary, Alice.

Cary, Phoebe.

Child, Lydia Maria.¹

Clay, Henry.

Clemens, Samuel L., (Mark Twain).

Cooper, James Fenimore.

Craddock, Charles Egbert, (Mary N. Murfree).

Crawford, Francis Marion.

Dana, Charles A.

Davis, Richard Harding.

Depew, Chauncey M.

Dickinson, Anna Elizabeth.

Dodge, Mary Abigail, (Gail Hamilton).¹

Dodge, Mary Mapes.¹

Eggleston, Edward.

Ellis, Edward.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo.

Everett, Edward.

Field, Eugene.

Finley, Martha.

Fiske, John.¹

French, Alice, (Octave Thanet).

Gail Hamilton, (Mary Abigail Dodge).¹

Gilder, Richard Watson.

Gough, John B.

Grady, Henry W.

Greeley, Horace.

Grace Greenwood, (Sarah J. Lippincott).

Hale, Edward Everett.

Halstead, Murat.

Harris, Joel Chandler, (Uncle Remus).

Harte, Bret.

Hawthorne, Julian.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel.

Hay, John.

Henry, Patrick.

Higginson, Thomas Wentworth.

Holley, Marietta, (Josiah Allen’s Wife).¹

Holmes, Oliver Wendell.

Howe, Julia Ward.

Howells, William Dean.

Ik Marvel, (Donald G. Mitchell).

Irving, Washington.

Jackson, Helen Hunt.

Joaquin Miller (Cincinnatus Heine Miller).

Josiah Allen’s Wife, (Marietta Holly).¹

Josh Billings, (Henry W. Shaw).¹

Larcom, Lucy.

Lippincott, Sarah Jane, (Grace Greenwood).

Livermore, Mary A.

Lockwood, Belva Ann.

Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth.

Lowell, James Russell.

Mabie, Hamilton W.

Mark Twain, (Samuel L. Clemens).

Marion Harland, (Mary V. Terhune).

McMaster, John B.

Miller, Cincinnatus Heine, (Joaquin).

Mitchell, Donald Grant (Ik Marvel).

Motley, John L.

Moulton, Louise Chandler.

Murfree, Mary N., (Chas. Egbert Craddock).

Nye, Edgar Wilson, (Bill Nye).

Oliver Optic, (William T. Adams).

Octave Thanet, (Alice French).

Page, Thomas Nelson.

Parkman, Francis.¹

Parton, James.

Phillips, Wendell.

Poe, Edgar Allen.¹

Prescott, William.

Reid, Whitelaw.

Riley, James Whitcomb.

Roe, Edward Payson.

Shaw, Albert.

Shaw, Henry W., (Josh Billings).

Sigourney, Lydia H.

Smith, Elizabeth Oakes.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady.

Stedman, Edmund Clarence.

Stockton, Frank.

Stoddard, Richard Henry.

Stowe, Harriet Beecher.

Taylor, Bayard.¹

Terhune, Mary Virginia.

Thompson, Maurice.¹

Wallace, General Lew.¹

Ward, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps.

Warner, Charles Dudley.

Watterson, Henry.

Webster, Daniel.

Whitman, Walt.

Whittier, John Greenleaf.

Willard, Frances E.

Willis, Nathaniel Parker.

Whitcher, Mrs. (The Widow Bedott).¹

¹ No Portrait.

WELL KNOWN AMERICAN POETS

N. P. WILLIS

THOMAS BAILEY ALDRICH • WALT WHITMAN

RICHARD HENRY STODDARD

RICHARD WATSON GILDER • COL. JOHN HAY

THE POET OF NATURE.

T

is said that “genius always manifests itself before its possessor reaches manhood.” Perhaps in no case is this more true than in that of the poet, and William Cullen Bryant was no exception to the general rule. The poetical fancy was early displayed in him. He began to write verses at nine, and at ten composed a little poem to be spoken at a public school, which was published in a newspaper. At fourteen a collection of his poems was published in 12 mo. form by E. G. House of Boston. Strange to say the longest one of these, entitled “The Embargo” was political in its character setting forth his reflections on the Anti-Jeffersonian Federalism prevalent in New England at that time. But it is said that never after that effort did the poet employ his muse upon the politics of the day, though the general topics of liberty and independence have given occasion to some of his finest efforts. Bryant was a great lover of nature. In the Juvenile Collection above referred to were published an “Ode to Connecticut River” and also the lines entitled “Drought” which show the characteristic observation as well as the style in which his youthful muse found expression. It was written July, 1807, when the author was thirteen years of age, and will be found among the succeeding selections.

T

is said that “genius always manifests itself before its possessor reaches manhood.” Perhaps in no case is this more true than in that of the poet, and William Cullen Bryant was no exception to the general rule. The poetical fancy was early displayed in him. He began to write verses at nine, and at ten composed a little poem to be spoken at a public school, which was published in a newspaper. At fourteen a collection of his poems was published in 12 mo. form by E. G. House of Boston. Strange to say the longest one of these, entitled “The Embargo” was political in its character setting forth his reflections on the Anti-Jeffersonian Federalism prevalent in New England at that time. But it is said that never after that effort did the poet employ his muse upon the politics of the day, though the general topics of liberty and independence have given occasion to some of his finest efforts. Bryant was a great lover of nature. In the Juvenile Collection above referred to were published an “Ode to Connecticut River” and also the lines entitled “Drought” which show the characteristic observation as well as the style in which his youthful muse found expression. It was written July, 1807, when the author was thirteen years of age, and will be found among the succeeding selections.

“Thanatopsis,” one of his most popular poems, (though he himself marked it low) was written when the poet was but little more than eighteen years of age. This production is called the beginning of American poetry.

William Cullen Bryant was born at Cummington, Hampshire Co., Mass., November 3rd, 1784. His father was a physician, and a man of literary culture who encouraged his son’s early ability, and taught him the value of correctness and compression, and enabled him to distinguish between true poetic enthusiasm and the bombast into which young poets are apt to fall. The feeling and reverence with which Bryant cherished the memory of his father whose life was

“Marked with some act of goodness every day,”

is touchingly alluded to in several of his poems and directly spoken of with pathetic eloquence in the “Hymn to Death” written in 1825:

Alas! I little thought that the stern power

Whose fearful praise I sung, would try me thus

Before the strain was ended. It must cease—

For he is in his grave who taught my youth

The art of verse, and in the bud of life

Offered me to the Muses. Oh, cut off

Untimely! when thy reason in its strength,

Ripened by years of toil and studious search

And watch of Nature’s silent lessons, taught

Thy hand to practise best the lenient art

To which thou gavest thy laborious days,

And, last, thy life. And, therefore, when the earth

Received thee, tears were in unyielding eyes,

And on hard cheeks, and they who deemed thy skill

Delayed their death-hour, shuddered and turned pale

When thou wert gone. This faltering verse, which thou

Shalt not, as wont, o’erlook, is all I have

To offer at thy grave—this—and the hope

To copy thy example.

Bryant was educated at Williams College, but left with an honorable discharge before graduation to take up the study of law, which he practiced one year at Plainfield and nine years at Great Barrington, but in 1825 he abandoned law for literature, and removed to New York where in 1826 he began to edit the “Evening Post,” which position he continued to occupy from that time until the day of his death. William Cullen Bryant and the “Evening Post” were almost as conspicuous and permanent features of the city as the Battery and Trinity Church.

In 1821 Mr. Bryant married Frances Fairchild, the loveliness of whose character is hinted in some of his sweetest productions. The one beginning

“O fairest of the rural maids,”

was written some years before their marriage; and “The Future Life,” one of the noblest and most pathetic of his poems, is addressed to her:—

“In meadows fanned by Heaven’s life-breathing wind,

In the resplendence of that glorious sphere

And larger movements of the unfettered mind,

Wilt thou forget the love that joined us here?

“Will not thy own meek heart demand me there,—

That heart whose fondest throbs to me were given?

My name on earth was ever in thy prayer,

And wilt thou never utter it in heaven?”

Among his best-known poems are “A Forest Hymn,” “The Death of the Flowers,” “Lines to a Waterfowl,” and “The Planting of the Apple-Tree.” One of the greatest of his works, though not among the most popular, is his translation of Homer, which he completed when seventy-seven years of age.

Bryant had a marvellous memory. His familiarity with the English poets was such that when at sea, where he was always too ill to read much, he would beguile the time by reciting page after page from favorite authors. However long the voyage, he never exhausted his resources. “I once proposed,” says a friend, “to send for a copy of a magazine in which a new poem of his was announced to appear. ‘You need not send for it,’ said he, ‘I can give it to you.’ ‘Then you have a copy with you?’ said I. ‘No,’ he replied, ‘but I can recall it,’ and thereupon proceeded immediately to write it out. I congratulated him upon having such a faithful memory. ‘If allowed a little time,’ he replied, ‘I could recall every line of poetry I have ever written.’”

His tenderness of the feelings of others, and his earnest desire always to avoid the giving of unnecessary pain, were very marked. “Soon after I began to do the duties of literary editor,” writes an associate, “Mr. Bryant, who was reading a review of a little book of wretchedly halting verse, said to me: ‘I wish you would deal very gently with poets, especially the weaker ones.’”

Bryant was a man of very striking appearance, especially in age. “It is a fine sight,” says one writer, “to see a man full of years, clear in mind, sober in judgment, refined in taste, and handsome in person.... I remember once to have been at a lecture where Mr. Bryant sat several seats in front of me, and his finely-sized head was especially noticeable.... The observer of Bryant’s capacious skull and most refined expression of face cannot fail to read therein the history of a noble manhood.”

The grand old veteran of verse died in New York in 1878 at the age of eighty-four, universally known and honored. He was in his sixth year when George Washington died, and lived under the administration of twenty presidents and had seen his own writings in print for seventy years. During this long life—though editor for fifty years of a political daily paper, and continually before the public—he had kept his reputation unspotted from the world, as if he had, throughout the decades, continually before his mind the admonition of the closing lines of “Thanatopsis” written by himself seventy years before.

THANATOPSIS.¹

The following production is called the beginning of American poetry.

That a young man not yet 19 should have produced a poem so lofty in conception, so full of chaste language and delicate and striking imagery, and, above all, so pervaded by a noble and cheerful religious philosophy, may well be regarded as one of the most remarkable examples of early maturity in literary history.

¹ The following copyrighted selections from Wm. Cullen Bryant are inserted by permission of D. Appleton & Co., the publishers of his works.

O him who, in the love of Nature, holds

Communion with her visible forms, she speaks

A various language; for his gayer hours

She has a voice of gladness, and a smile

And eloquence of beauty, and she glides

Into his darker musings with a mild

And healing sympathy, that steals away

Their sharpness, ere he is aware. When thoughts

Of the last bitter hour come like a blight

Over thy spirit, and sad images

Of the stern agony, and shroud, and pall,

And breathless darkness, and the narrow house,

Make thee to shudder, and grow sick at heart;—

Go forth, under the open sky, and list

To Nature’s teachings, while from all around—

Earth and her waters, and the depths of air—

Comes a still voice.—Yet a few days, and thee

The all-beholding sun shall see no more

In all his course; nor yet in the cold ground,

Where thy pale form was laid, with many tears,

Nor in the embrace of ocean, shall exist

Thy image. Earth, that nourish’d thee, shall claim

Thy growth, to be resolved to earth again;

And, lost each human trace, surrendering up

Thine individual being, shalt thou go

To mix forever with the elements,

To be a brother to the insensible rock

And to the sluggish clod, which the rude swain

Turns with his share, and treads upon. The oak

Shall send his roots abroad, and pierce thy mould.

Yet not to thine eternal resting-place

Shalt thou retire alone,—nor couldst thou wish

Couch more magnificent. Thou shalt lie down

With patriarchs of the infant world,—with kings,

The powerful of the earth—the wise, the good,

Fair forms, and hoary seers of ages past,

All in one mighty sepulchre. The hills

Rock-ribb’d and ancient as the sun,—the vales

Stretching in pensive quietness between;

The venerable woods,—rivers that move

In majesty, and the complaining brooks

That make the meadows green; and, pour’d round all,

Old ocean’s gray and melancholy waste,—

Are but the solemn decorations all

Of the great tomb of man. The golden sun,

The planets, all the infinite host of heaven,

Are shining on the sad abodes of death,

Through the still lapse of ages. All that tread

The globe are but a handful to the tribes

That slumber in its bosom. Take the wings

Of morning, traverse Barca’s desert sands,

Or lose thyself in the continuous woods

Where rolls the Oregon, and hears no sound

Save its own dashings,—yet—the dead are there,

And millions in those solitudes, since first

The flight of years began, have laid them down

In their last sleep,—the dead reign there alone.

So shalt thou rest; and what if thou withdraw

In silence from the living, and no friend

Take note of thy departure? All that breathe

Will share thy destiny. The gay will laugh

When thou art gone, the solemn brood of care

Plod on, and each one, as before, will chase

His favorite phantom; yet all these shall leave

Their mirth and their employments, and shall come

And make their bed with thee. As the long train

Of ages glides away, the sons of men—

The youth in life’s green spring, and he who goes

In the full strength of years, matron and maid,

And the sweet babe, and the gray-headed man—

Shall, one by one, be gather’d to thy side,

By those who in their turn shall follow them.

So live that, when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, which moves

To that mysterious realm where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon; but, sustain’d and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.

WAITING BY THE GATE.

ESIDES the massive gateway built up in years gone by,

Upon whose top the clouds in eternal shadow lie,

While streams the evening sunshine on the quiet wood and lea,

I stand and calmly wait until the hinges turn for me.

The tree tops faintly rustle beneath the breeze’s flight,

A soft soothing sound, yet it whispers of the night;

I hear the woodthrush piping one mellow descant more,

And scent the flowers that blow when the heat of day is o’er.

Behold the portals open and o’er the threshold, now,

There steps a wearied one with pale and furrowed brow;

His count of years is full, his ♦allotted task is wrought;

He passes to his rest from a place that needs him not.

In sadness, then, I ponder how quickly fleets the hour

Of human strength and action, man’s courage and his power.

I muse while still the woodthrush sings down the golden day,

And as I look and listen the sadness wears away.

Again the hinges turn, and a youth, departing throws

A look of longing backward, and sorrowfully goes;

A blooming maid, unbinding the roses from her hair,

Moves wonderfully away from amid the young and fair.

Oh, glory of our race that so suddenly decays!

Oh, crimson flush of morning, that darkens as we gaze!

Oh, breath of summer blossoms that on the restless air

Scatters a moment’s sweetness and flies we know not where.

I grieve for life’s bright promise, just shown and then withdrawn;

But still the sun shines round me; the evening birds sing on;

And I again am soothed, and beside the ancient gate,

In this soft evening sunlight, I calmly stand and wait.

Once more the gates are opened, an infant group go out,

The sweet smile quenched forever, and stilled the sprightly shout.

Oh, frail, frail tree of life, that upon the greensward strews

Its fair young buds unopened, with every wind that blows!

So from every region, so enter side by side,

The strong and faint of spirit, the meek and men of pride,

Steps of earth’s greatest, mightiest, between those pillars gray,

And prints of little feet, that mark the dust away.

And some approach the threshold whose looks are blank with fear,

And some whose temples brighten with joy are drawing near,

As if they saw dear faces, and caught the gracious eye

Of Him, the Sinless Teacher, who came for us to die.

I mark the joy, the terrors; yet these, within my heart,

Can neither wake the dread nor the longing to depart;

And, in the sunshine streaming of quiet wood and lea,

I stand and calmly wait until the hinges turn for me.

♦ ‘alloted’ replaced with ‘allotted’

“BLESSED ARE THEY THAT MOURN.”

DEEM not they are blest alone

Whose lives a peaceful tenor keep;

The Power who pities man has shown

A blessing for the eyes that weep.

The light of smiles shall fill again

The lids that overflow with tears;

And weary hours of woe and pain

Are promises of happier years.

There is a day of sunny rest

For every dark and troubled night;

And grief may bide an evening guest,

But joy shall come with early light.

And thou, who, o’er thy friend’s low bier,

Sheddest the bitter drops like rain,

Hope that a brighter, happier sphere

Will give him to thy arms again.

Nor let the good man’s trust depart,

Though life its common gifts deny,—

Though with a pierced and bleeding heart,

And spurned of men, he goes to die.

For God hath marked each sorrowing day,

And numbered every secret tear,

And heaven’s long age of bliss shall pay

For all his children suffer here.

THE ANTIQUITY OF FREEDOM.

ERE are old trees, tall oaks, and gnarled pines,

That stream with gray-green mosses; here the ground

Was never touch’d by spade, and flowers spring up

Unsown, and die ungather’d. It is sweet

To linger here, among the flitting birds

And leaping squirrels, wandering brooks and winds

That shake the leaves, and scatter as they pass

A fragrance from the cedars thickly set

With pale blue berries. In these peaceful shades—

Peaceful, unpruned, immeasurably old—

My thoughts go up the long dim path of years,

Back to the earliest days of Liberty.

O Freedom! thou art not, as poets dream,

A fair young girl, with light and delicate limbs,

And wavy tresses gushing from the cap

With which the Roman master crown’d his slave,

When he took off the gyves. A bearded man,

Arm’d to the teeth, art thou: one mailed hand

Grasps the broad shield, and one the sword; thy brow,

Glorious in beauty though it be, is scarr’d

With tokens of old wars; thy massive limbs

Are strong and struggling. Power at thee has launch’d

His bolts, and with his lightnings smitten thee;

They could not quench the life thou hast from Heaven.

Merciless Power has dug thy dungeon deep,

And his swart armorers, by a thousand fires,

Have forged thy chain; yet while he deems thee bound,

The links are shiver’d, and the prison walls

Fall outward; terribly thou springest forth,

As springs the flame above a burning pile,

And shoutest to the nations, who return

Thy shoutings, while the pale oppressor flies.

Thy birth-right was not given by human hands:

Thou wert twin-born with man. In pleasant fields,

While yet our race was few, thou sat’st with him,

To tend the quiet flock and watch the stars,

And teach the reed to utter simple airs.

Thou by his side, amid the tangled wood,

Didst war upon the panther and the wolf,

His only foes: and thou with him didst draw

The earliest furrows on the mountain side,

Soft with the Deluge. Tyranny himself,

The enemy, although of reverend look,

Hoary with many years, and far obey’d,

Is later born than thou; and as he meets

The grave defiance of thine elder eye,

The usurper trembles in his fastnesses.

Thou shalt wax stronger with the lapse of years,

But he shall fade into a feebler age;

Feebler, yet subtler; he shall weave his snares,

And spring them on thy careless steps, and clap

His wither’d hands, and from their ambush call

His hordes to fall upon thee. He shall send

Quaint maskers, forms of fair and gallant mien,

To catch thy gaze, and uttering graceful words

To charm thy ear; while his sly imps, by stealth,

Twine round thee threads of steel, light thread on thread,

That grow to fetters; or bind down thy arms

With chains conceal’d in chaplets. Oh! not yet

Mayst thou unbrace thy corslet, nor lay by

Thy sword, nor yet, O Freedom! close thy lids

In slumber; for thine enemy never sleeps.

And thou must watch and combat, till the day

Of the new Earth and Heaven. But wouldst thou rest

Awhile from tumult and the frauds of men,

These old and friendly solitudes invite

Thy visit. They, while yet the forest trees

Were young upon the unviolated earth,

And yet the moss-stains on the rock were new,

Beheld thy glorious childhood, and rejoiced.

TO A WATERFOWL.

HITHER, ’midst falling dew,

While glow the heavens with the last steps of day,

Far, through their rosy depths, dost thou pursue

Thy solitary way?

Vainly the fowler’s eye

Might mark thy distant flight to do thee wrong,

As, darkly limn’d upon the crimson sky,

Thy figure floats along.

Seek’st thou the plashy brink

Of weedy lake, or marge of river wide,

Or where the rocking billows rise and sink

On the chafed ocean side?

There is a Power whose care

Teaches thy way along that pathless coast,—

The desert and illimitable air,—

Lone wandering, but not lost.

All day thy wings have fann’d,

At that far height, the cold, thin atmosphere,

Yet stoop not, weary, to the welcome land,

Though the dark night is near.

And soon that toil shall end;

Soon shalt thou find a summer home, and rest,

And scream among thy fellows; reeds shall bend,

Soon, o’er thy shelter’d nest.

Thou’rt gone; the abyss of heaven

Hath swallow’d up thy form; yet on my heart

Deeply hath sunk the lesson thou hast given,

And shall not soon depart.

He who, from zone to zone,

Guides through the boundless sky thy certain flight,

In the long way that I must tread alone,

Will lead my steps aright.

ROBERT OF LINCOLN.

ERRILY swinging on brier and weed,

Near to the nest of his little dame,

Over the mountain-side or mead,

Robert of Lincoln is telling his name:

Bob-o’-link, bob-o’-link,

Spink, spank, spink;

Snug and safe is that nest of ours,

Hidden among the summer flowers.

Chee, chee, chee.

Robert of Lincoln is gayly dressed,

Wearing a bright black wedding coat;

White are his shoulders and white his crest,

Hear him call in his merry note:

Bob-o’-link, bob-o’-link,

Spink, spank, spink;

Look what a nice new coat is mine,

Sure there was never a bird so fine.

Chee, chee, chee.

Robert of Lincoln’s Quaker wife,

Pretty and quiet, with plain brown wings,

Passing at home a patient life,

Broods in the grass while her husband sings,

Bob-o’-link, bob-o’-link,

Spink, spank, spink;

Brood, kind creature; you need not fear

Thieves and robbers, while I am here.

Chee, chee, chee.

Modest and shy as a nun is she,

One weak chirp is her only note,

Braggart and prince of braggarts is he,

Pouring boasts from his little throat:

Bob-o’-link, bob-o’-link,

Spink, spank, spink;

Never was I afraid of man;

Catch me, cowardly knaves if you can.

Chee, chee, chee.

Six white eggs on a bed of hay,

Flecked with purple, a pretty sight

There as the mother sits all day,

Robert is singing with all his might:

Bob-o’-link, bob-o’-link,

Spink, spank, spink;

Nice good wife, that never goes out,

Keeping house while I frolic about.

Chee, chee, chee.

Soon as the little ones chip the shell

Six wide mouths are open for food;

Robert of Lincoln bestirs him well,

Gathering seed for the hungry brood.

Bob-o’-link, bob-o’-link,

Spink, spank, spink;

This new life is likely to be

Hard for a gay young fellow like me.

Chee, chee, chee.

Robert of Lincoln at length is made

Sober with work and silent with care;

Off is his holiday garment laid,

Half-forgotten that merry air,

Bob-o’-link, bob-o’-link,

Spink, spank, spink;

Nobody knows but my mate and I

Where our nest and our nestlings lie.

Chee, chee, chee.

Summer wanes; the children are grown;

Fun and frolic no more he knows;

Robert of Lincoln’s a humdrum crone;

Off he flies, and we sing as he goes:

Bob-o’-link, bob-o’-link,

Spink, spank, spink;

When you can pipe that merry old strain,

Robert of Lincoln, come back again.

Chee, chee, chee.

DROUGHT.

LUNGED amid the limpid waters,

Or the cooling shade beneath,

Let me fly the scorching sunbeams,

And the southwind’s sickly breath!

Sirius burns the parching meadows,

Flames upon the embrowning hill,

Dries the foliage of the forest,

And evaporates the rill.

Scarce is seen the lonely floweret,

Save amid the embowering wood;

O’er the prospect dim and dreary,

Drought presides in sullen mood!

Murky vapours hung in ether,

Wrap in gloom, the sky serene;

Nature pants distressful—silence

Reigns o’er all the sultry scene.

Then amid the limpid waters,

Or beneath the cooling shade,

Let me shun the scorching sunbeams

And the sickly breeze evade.

THE PAST.

No poet, perhaps, in the world is so exquisite in rhythm, or classically pure and accurate in language, so appropriate in diction, phrase or metaphor as Bryant.

He dips his pen in words as an inspired painter his pencil in colors. The following poem is a fair specimen of his deep vein in his chosen serious themes. Pathos is pre-eminently his endowment but the tinge of melancholy in his treatment is always pleasing.

HOU unrelenting Past!

Strong are the barriers round thy dark domain,

And fetters, sure and fast,

Hold all that enter thy unbreathing reign.

Far in thy realm withdrawn

Old empires sit in sullenness and gloom,

And glorious ages gone

Lie deep within the shadow of thy womb.

Childhood, with all its mirth,

Youth, Manhood, Age that draws us to the ground,

And, last, Man’s Life on earth,

Glide to thy dim dominions, and are bound.

Thou hast my better years,

Thou hast my earlier friends—the good—the kind,

Yielded to thee with tears,—

The venerable form—the exalted mind.

My spirit yearns to bring

The lost ones back;—yearns with desire intense,

And struggles hard to wring

Thy bolts apart, and pluck thy captives thence.

In vain:—thy gates deny

All passage save to those who hence depart;

Nor to the streaming eye

Thou giv’st them back,—nor to the broken heart.

In thy abysses hide

Beauty and excellence unknown;—to thee

Earth’s wonder and her pride

Are gather’d, as the waters to the sea;

Labors of good to man,

Unpublish’d charity, unbroken faith,—

Love, that midst grief began,

And grew with years, and falter’d not in death.

Full many a mighty name

Lurks in thy depths, unutter’d, unrevered;

With thee are silent fame,

Forgotten arts, and wisdom disappear’d.

Thine for a space are they:—

Yet shalt thou yield thy treasures up at last;

Thy gates shall yet give way,

Thy bolts shall fall, inexorable Past!

All that of good and fair

Has gone into thy womb from earliest time,

Shall then come forth, to wear

The glory and the beauty of its prime.

They have not perish’d—no!

Kind words, remember’d voices once so sweet,

Smiles, radiant long ago,

And features, the great soul’s apparent seat,

All shall come back; each tie

Of pure affection shall be knit again;

Alone shall Evil die,

And Sorrow dwell a prisoner in thy reign.

And then shall I behold

Him by whose kind paternal side I sprung,

And her who, still and cold,

Fills the next grave,—the beautiful and young.

THE MURDERED TRAVELER.

HEN spring, to woods and wastes around,

Brought bloom and joy again;

The murdered traveler’s bones were found,

Far down a narrow glen.

The fragrant birch, above him, hung

Her tassels in the sky;

And many a vernal blossom sprung,

And nodded careless by.

The red bird warbled, as he wrought

His hanging nest o’erhead;

And fearless, near the fatal spot,

Her young the partridge led.

But there was weeping far away,

And gentle eyes, for him,

With watching many an anxious day,

Were sorrowful and dim.

They little knew, who loved him so,

The fearful death he met,

When shouting o’er the desert snow,

Unarmed and hard beset;

Nor how, when round the frosty pole,

The northern dawn was red,

The mountain-wolf and wild-cat stole

To banquet on the dead;

Nor how, when strangers found his bones,

They dressed the hasty bier,

And marked his grave with nameless stones,

Unmoistened by a tear.

But long they looked, and feared, and wept,

Within his distant home;

And dreamed, and started as they slept,

For joy that he was come.

Long, long they looked—but never spied

His welcome step again.

Nor knew the fearful death he died

Far down that narrow glen.

THE BATTLEFIELD.

Soon after the following poem was written, an English critic, referring to the stanza ♦beginning—“Truth crushed to earth shall rise again,”—said: “Mr. Bryant has certainly a rare merit for having written a stanza which will bear comparison with any four lines as one of the noblest in the English language. The thought is complete, the expression perfect. A poem of a dozen such verses would be like a row of pearls, each beyond a king’s ransom.”

♦ ‘begining’ replaced with ‘beginning’

NCE this soft turf, this rivulet’s sands,

Were trampled by a hurrying crowd,

And fiery hearts and armed hands

Encounter’d in the battle-cloud.

Ah! never shall the land forget

How gush’d the life-blood of her brave,—

Gush’d, warm with hope and courage yet,

Upon the soil they fought to save.

Now all is calm, and fresh, and still,

Alone the chirp of flitting bird,

And talk of children on the hill,

And bell of wandering kine, are heard.

No solemn host goes trailing by

The black-mouth’d gun and staggering wain;

Men start not at the battle-cry:

Oh, be it never heard again!

Soon rested those who fought; but thou

Who minglest in the harder strife

For truths which men receive not now,

Thy warfare only ends with life.

A friendless warfare! lingering long

Through weary day and weary year;

A wild and many-weapon’d throng

Hang on thy front, and flank, and rear.

Yet nerve thy spirit to the proof,

And blench not at thy chosen lot;

The timid good may stand aloof,

The sage may frown—yet faint thou not,

Nor heed the shaft too surely cast,

The foul and hissing bolt of scorn;

For with thy side shall dwell, at last,

The victory of endurance born.

Truth, crush’d to earth, shall rise again;

The eternal years of God are hers;

But Error, wounded, writhes in pain,

And dies among his worshippers.

Yea, though thou lie upon the dust,

When they who help’d thee flee in fear,

Die full of hope and manly trust,

Like those who fell in battle here.

Another hand thy sword shall wield,

Another hand the standard wave,

Till from the trumpet’s mouth is peal’d

The blast of triumph o’er thy grave.

THE CROWDED STREETS.

ET me move slowly through the street,

Filled with an ever-shifting train,

Amid the sound of steps that beat

The murmuring walks like autumn rain.

How fast the flitting figures come;

The mild, the fierce, the stony face—

Some bright, with thoughtless smiles, and some

Where secret tears have left their trace.

They pass to toil, to strife, to rest—

To halls in which the feast is spread—

To chambers where the funeral guest

In silence sits beside the bed.

And some to happy homes repair,

Where children pressing cheek to cheek,

With mute caresses shall declare

The tenderness they cannot speak.

And some who walk in calmness here,

Shall shudder as they reach the door

Where one who made their dwelling dear,

Its flower, its light, is seen no more.

Youth, with pale cheek and tender frame,

And dreams of greatness in thine eye,

Go’st thou to build an early name,

Or early in the task to die?

Keen son of trade, with eager brow,

Who is now fluttering in thy snare,

Thy golden fortunes tower they now,

Or melt the glittering spires in air?

Who of this crowd to-night shall tread

The dance till daylight gleams again?

To sorrow o’er the untimely dead?

Who writhe in throes of mortal pain?

Some, famine struck, shall think how long

The cold, dark hours, how slow the light;

And some, who flaunt amid the throng,

Shall hide in dens of shame to night.

Each where his tasks or pleasure call,

They pass and heed each other not;

There is one who heeds, who holds them all

In His large love and boundless thought.

These struggling tides of life that seem

In wayward, aimless course to tend,

Are eddies of the mighty stream

That rolls to its appointed end.

NOTICE OF FITZ-GREEN HALLECK.

As a specimen of Mr. Bryant’s prose, of which he wrote much, and also as a sample of his criticism, we reprint the following extract from a Commemorative Address which he delivered before the New York Historical Society in February 1869. This selection is also valuable as a character sketch and a literary estimate of Mr. Halleck.

HEN

I look back upon Halleck’s literary life, I cannot help thinking that if his death had happened forty years earlier, his life would have been regarded as a bright morning prematurely overcast. Yet Halleck’s literary career may be said to have ended then. All that will hand down his name to future years had already been produced. Who shall say to what cause his subsequent literary inaction was owing? It was not the decline of his powers; his brilliant conversation showed that it was not. Was it then indifference to fame? Was it because he put an humble estimate on what he had written, and therefore resolved to write no more? Was it because he feared lest what he might write would be unworthy of the reputation he had been so fortunate as to acquire?

HEN

I look back upon Halleck’s literary life, I cannot help thinking that if his death had happened forty years earlier, his life would have been regarded as a bright morning prematurely overcast. Yet Halleck’s literary career may be said to have ended then. All that will hand down his name to future years had already been produced. Who shall say to what cause his subsequent literary inaction was owing? It was not the decline of his powers; his brilliant conversation showed that it was not. Was it then indifference to fame? Was it because he put an humble estimate on what he had written, and therefore resolved to write no more? Was it because he feared lest what he might write would be unworthy of the reputation he had been so fortunate as to acquire?

“I have my own way of accounting for his literary silence in the latter half of his life. One of the resemblances which he bore to Horace consisted in the length of time for which he kept his poems by him, that he might give them the last and happiest touches. Having composed his poems without committing them to paper, and retaining them in his faithful memory, he revised them in the same manner, murmuring them to himself in his solitary moments, recovering the enthusiasm with which they were first conceived, and in this state of mind heightening the beauty of the thought or of the expression....

“In this way I suppose Halleck to have attained the gracefulness of his diction, and the airy melody of his numbers. In this way I believe that he wrought up his verses to that transparent clearness of expression which causes the thought to be seen through them without any interposing dimness, so that the thought and the phrase seem one, and the thought enters the mind like a beam of light. I suppose that Halleck’s time being taken up by the tasks of his vocation, he naturally lost by degrees the habit of composing in this manner, and that he found it so necessary to the perfection of what he wrote that he adopted no other in its place.”

A CORN-SHUCKING IN SOUTH CAROLINA.

From “The Letters of a Traveler.”

In 1843, during Mr. Bryant’s visit to the South, he had the pleasure of witnessing one of those antebellum southern institutions known as a Corn-Shucking—one of the ideal occasions of the colored man’s life, to which both men and women were invited. They were free to tell all the jokes, sing all the songs and have all the fun they desired as they rapidly shucked the corn. Two leaders were usually chosen and the company divided into two parties which competed for a prize awarded to the first party which finished shucking the allotted pile of corn. Mr. Bryant thus graphically describes one of these novel occasions:

Barnwell District,

South Carolina, March 29, 1843.

UT

you must hear of the corn-shucking. The one at which I was present was given on purpose that I might witness the humors of the Carolina negroes. A huge fire of light-wood was made near the corn-house. Light-wood is the wood of the long-leaved pine, and is so called, not because it is light, for it is almost the heaviest wood in the world, but because it gives more light than any other fuel.

UT

you must hear of the corn-shucking. The one at which I was present was given on purpose that I might witness the humors of the Carolina negroes. A huge fire of light-wood was made near the corn-house. Light-wood is the wood of the long-leaved pine, and is so called, not because it is light, for it is almost the heaviest wood in the world, but because it gives more light than any other fuel.

The light-wood-fire was made, and the negroes dropped in from the neighboring plantations, singing as they came. The driver of the plantation, a colored man, brought out baskets of corn in the husk, and piled it in a heap; and the negroes began to strip the husks from the ears, singing with great glee as they worked, keeping time to the music, and now and then throwing in a joke and an extravagant burst of laughter. The songs were generally of a comic character; but one of them was set to a singularly wild and plaintive air, which some of our musicians would do well to reduce to notation. These are the words:

Johnny come down de hollow.

Oh hollow!

Johnny come down de hollow.

Oh hollow!

De nigger-trader got me.

Oh hollow!

De speculator bought me.

Oh hollow!

I’m sold for silver dollars.

Oh hollow!

Boys, go catch the pony.

Oh hollow!

Bring him round the corner.

Oh hollow!

I’m goin’ away to Georgia.

Oh hollow!

Boys, good-by forever!

Oh hollow!

The song of “Jenny gone away,” was also given, and another, called the monkey-song, probably of African origin, in which the principal singer personated a monkey, with all sorts of odd gesticulations, and the other negroes bore part in the chorus, “Dan, dan, who’s the dandy?” One of the songs commonly sung on these occasions, represents the various animals of the woods as belonging to some profession or trade. For example—

De cooter is de boatman—

The cooter is the terrapin, and a very expert boatman he is.

De cooter is de boatman.

John John Crow.

De red-bird de soger.

John John Crow.

De mocking-bird de lawyer.

John John Crow.

De alligator sawyer.

John John Crow.

The alligator’s back is furnished with a toothed ridge, like the edge of a saw, which explains the last line.

When the work of the evening was over the negroes adjourned to a spacious kitchen. One of them took his place as musician, whistling, and beating time with two sticks upon the floor. Several of the men came forward and executed various dances, capering, prancing, and drumming with heel and toe upon the floor, with astonishing agility and perseverance, though all of them had performed their daily tasks and had worked all the evening, and some had walked from four to seven miles to attend the corn-shucking. From the dances a transition was made to a mock military parade, a sort of burlesque of our militia trainings, in which the words of command and the evolutions were extremely ludicrous. It became necessary for the commander to make a speech, and confessing his incapacity for public speaking, he called upon a huge black man named Toby to address the company in his stead. Toby, a man of powerful frame, six feet high, his face ornamented with a beard of fashionable cut, had hitherto stood leaning against the wall, looking upon the frolic with an air of superiority. He consented, came forward, demanded a bit of paper to hold in his hand, and harangued the soldiery. It was evident that Toby had listened to stump-speeches in his day. He spoke of “de majority of Sous Carolina,” “de interests of de state,” “de honor of ole Ba’nwell district,” and these phrases he connected by various expletives, and sounds of which we could make nothing. At length he began to falter, when the captain with admirable presence of mind came to his relief, and interrupted and closed the harangue with an hurrah from the company. Toby was allowed by all the spectators, black and white, to have made an excellent speech.

THE WEIRD AND MYSTERIOUS GENIUS.

DGAR

Allen Poe, the author of “The Raven,” “Annabel Lee,” “The Haunted Palace,” “To One in Paradise,” “Israfel” and “Lenore,” was in his peculiar sphere, the most brilliant writer, perhaps, who ever lived. His writings, however, belong to a different world of thought from that in which Bryant, Longfellow, Emerson, Whittier and Lowell lived and labored. Theirs was the realm of nature, of light, of human joy, of happiness, ease, hope and cheer. Poe spoke from the dungeon of depression. He was in a constant struggle with poverty. His whole life was a tragedy in which sombre shades played an unceasing role, and yet from out these weird depths came forth things so beautiful that their very sadness is charming and holds us in a spell of bewitching enchantment. Edgar Fawcett says of him:—

DGAR

Allen Poe, the author of “The Raven,” “Annabel Lee,” “The Haunted Palace,” “To One in Paradise,” “Israfel” and “Lenore,” was in his peculiar sphere, the most brilliant writer, perhaps, who ever lived. His writings, however, belong to a different world of thought from that in which Bryant, Longfellow, Emerson, Whittier and Lowell lived and labored. Theirs was the realm of nature, of light, of human joy, of happiness, ease, hope and cheer. Poe spoke from the dungeon of depression. He was in a constant struggle with poverty. His whole life was a tragedy in which sombre shades played an unceasing role, and yet from out these weird depths came forth things so beautiful that their very sadness is charming and holds us in a spell of bewitching enchantment. Edgar Fawcett says of him:—

“He loved all shadowy spots, all seasons drear;

All ways of darkness lured his ghastly whim;

Strange fellowships he held with goblins grim,

At whose demoniac eyes he felt no fear.

By desolate paths of dream where fancy’s owl

Sent long lugubrious hoots through sombre air,

Amid thought’s gloomiest caves he went to prowl

And met delirium in her awful lair.”

Edgar Poe was born in Boston February 19th, 1809. His father was a Marylander, as was also his grandfather, who was a distinguished Revolutionary soldier and a friend of General Lafayette. The parents of Poe were both actors who toured the country in the ordinary manner, and this perhaps accounts for his birth in Boston. Their home was in Baltimore, Maryland.

When Poe was only a few years old both parents died, within two weeks, in Richmond, Virginia. Their three children, two daughters, one older and one younger than the subject of this sketch, were all adopted by friends of the family. Mr. John Allen, a rich tobacco merchant of Richmond, Virginia, adopted Edgar (who was henceforth called Edgar Allen Poe), and had him carefully educated, first in England, afterwards at the Richmond Academy and the University of Virginia, and subsequently at West Point. He always distinguished himself in his studies, but from West Point he was dismissed after one year, it is said because he refused to submit to the discipline of the institution.

In common with the custom in the University of Virginia at that time, Poe acquired the habits of drinking and gambling, and the gambling debts which he contracted incensed Mr. Allen, who refused to pay them. This brought on the beginning of a series of quarrels which finally led to Poe’s disinheritance and permanent separation from his benefactor. Thus turned out upon the cold, unsympathetic world, without business training, without friends, without money, knowing not how to make money—yet, with a proud, imperious, aristocratic nature,—we have the beginning of the saddest story of any life in literature—struggling for nearly twenty years in gloom and poverty, with here and there a ray of sunshine, and closing with delirium tremens in Baltimore, October 7th, 1849, at forty years of age.

To those who know the full details of the sad story of Poe’s life it is little wonder that his sensitive, passionate nature sought surcease from disappointment in the nepenthe of the intoxicating cup. It was but natural for a man of his nervous temperament and delicacy of feeling to fall into that melancholy moroseness which would chide even the angels for taking away his beautiful “Annabel Lee;” or that he should wail over the “Lost Lenore,” or declare that his soul should “nevermore” be lifted from the shadow of the “Raven” upon the floor. These poems and others are but the expressions of disappointment and despair of a soul alienated from happy human relations. While we admire their power and beauty, we should remember at what cost of pain and suffering and disappointment they were produced. They are powerful illustrations of the prodigal expense of human strength, of broken hopes and bitter experiences through which rare specimens of our literature are often grown.

To treat the life of Edgar Allen Poe, with its lessons, fully, would require the scope of a volume. Both as a man and an author there is a sad fascination which belongs to no other writer, perhaps, in the world. His personal character has been represented as pronouncedly double. It is said that Stevenson, who was a great admirer of Poe, received the inspiration for his novel, “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” from the contemplation of his double character. Paul Hamilton Hayne has also written a poem entitled, “Poe,” which presents in a double shape the angel and demon in one body. The first two stanzas of which we quote:—

“Two mighty spirits dwelt in him:

One, a wild demon, weird and dim,

The darkness of whose ebon wings

Did shroud unutterable things:

One, a fair angel, in the skies

Of whose serene, unshadowed eyes

Were seen the lights of Paradise.

To these, in turn, he gave the whole

Vast empire of his brooding soul;

Now, filled with strains of heavenly swell,

Now thrilled with awful tones of hell:

Wide were his being’s strange extremes,

’Twixt nether glooms, and Eden gleams

Of tender, or majestic dreams.”

It must be said in justice to Poe’s memory, however, that the above idea of his being both demon and angel became prevalent through the first biography published of him, by Dr. Rufus Griswold, who no doubt sought to avenge himself on the dead poet for the severe but unanswerable criticisms which the latter had passed upon his and other contemporaneous authors’ writings. Later biographies, notably those of J. H. Ingram and Mrs. Sarah Ellen Whitman, as well as published statements from his business associates, have disproved many of Griswold’s damaging statements, and placed the private character of Poe in a far more favorable light before the world. He left off gambling in his youth, and the appetite for drink, which followed him to the close of his life, was no doubt inherited from his father who, before him, was a drunkard.

It is natural for admirers of Poe’s genius to contemplate with regret akin to sorrow those circumstances and characteristics which made him so unhappy, and yet the serious question arises, was not that character and his unhappy life necessary to the productions of his marvelous pen? Let us suppose it was, and in charity draw the mantle of forgetfulness over his misguided ways, covering the sad picture of his personal life from view, and hang in its place the matchless portrait of his splendid genius, before which, with true American pride, we may summon all the world to stand with uncovered heads.

As a writer of short stories Poe had no equal in America. He is said to have been the originator of the modern detective story. The artful ingenuity with which he works up the details of his plot, and minute attention to the smallest illustrative particular, give his tales a vivid interest from which no reader can escape. His skill in analysis is as marked as his power of word painting. The scenes of gloom and terror which he loves to depict, the forms of horror to which he gives almost actual life, render his mastery over the reader most exciting and absorbing.

As a poet Poe ranks among the most original in the world. He is pre-eminently a poet of the imagination. It is useless to seek in his verses for philosophy or preaching. He brings into his poetry all the weirdness, subtlety, artistic detail and facility in coloring which give the charm to his prose stories, and to these he adds a musical flow of language which has never been equalled. To him poetry was music, and there was no poetry that was not musical. For poetic harmony he has had no equal certainly in America, if, indeed, in the world. Admirers of his poems are almost sure to read them over and over again, each time finding new forms of beauty or charm in them, and the reader abandons himself to a current of melodious fancy that soothes and charms like distant music at night, or the rippling of a nearby, but unseen, brook. The images which he creates are vague and illusive. As one of his biographers has written, “He heard in his dreams the tinkling footfalls of angels and seraphim and subordinated everything in his verse to the delicious effect of musical sound.” As a literary critic Poe’s capacities were of the greatest. “In that large part of the critic’s perceptions,” says Duyckinck, “in knowledge of the mechanism of composition, he has been unsurpassed by any writer in America.”

Poe was also a fine reader and elocutionist. A writer who attended a lecture by him in Richmond says: “I never heard a voice so musical as his. It was full of the sweetest melody. No one who heard his recitation of the ‘Raven’ will ever forget the beauty and pathos with which this recitation was rendered. The audience was still as death, and as his weird, musical voice filled the hall its effect was simply indescribable. It seems to me that I can yet hear that long, plaintive ‘nevermore.’”