Title: Proceedings [of the] fourth National Conservation Congress [at] Indianapolis, October 1-4, 1912

Creator: United States. National Conservation Congress

Release date: January 4, 2023 [eBook #69706]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: National Conservation Congress

Credits: Bob Taylor, Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Books project.)

[Pg 1]

Indianapolis

OCTOBER 1–4, INCLUSIVE, 1912

“Let us conserve the foundations of our prosperity”

(Declaration of the Governors, 1908)

INDIANAPOLIS

NATIONAL CONSERVATION CONGRESS

1912

[Pg 2]

Wm. B. Burford Press

INDIANAPOLIS,—IND.

[Pg 3]

| PAGE | |

| Officers and Committees, 1912 | 9 |

| Standing Committees, 1912 | 10 |

| Officers and Committees, 1913 | 11 |

| Constitution | 13–17 |

| Resolutions | 18–23 |

| OPENING SESSION— | |

| Invocation—Rev. F. S. C. Wicks | 24 |

| Address of Welcome for the State of Indiana, Hon. Charles Warren Fairbanks | 24–31 |

| Address for the City of Indianapolis, Mr. Richard Lieber | 31–33 |

| Address on Behalf of the Local Business Organizations, Mr. Winfield Miller | 33–37 |

| President’s Address, Hon. J. B. White | 37–40 |

| Message from the President of the United States | 41 |

| Address, Hon. Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of War, Personal Representative of the President of the United States | 41–46 |

| Announcements | 47 |

| SECOND SESSION— | |

| Invocation, Rev. Dr. A. B. Storms | 47 |

| Address, “What the States are Doing,” Dr. George E. Condra | 48–61 |

| Address, “Conservation Redefined,” Mr. E. T. Allen | 61–66 |

| Report, Dr. C. E. Bessey, Chairman, Committee on Education | 66–71 |

| Illustrated Address, “Bird Slaughter and the Cost of Living,” Dr. T. Gilbert Pearson. | 71 |

| Address and Illustrated Lecture, “Federal Protection of Migratory Birds,” Dr. W. T. Hornaday | 72–73 |

| THIRD SESSION— | |

| Invocation, Rev. Dr. Allan B. Philputt | 74 |

| Communication from Mr. Gifford Pinchot | 74 |

| Address, “The Conservation of Man.” Dr. Harvey W. Wiley | 75–91 |

| FOURTH SESSION— | |

| Invocation, Rev. Harry G. Hill | 91 |

| Address, “Human Life as a National Asset,” Mr. E. E. Rittenhouse | 92–102 |

| Address, “Public Health Movement,” Prof. Irving Fisher | 103–111 |

| Announcement by the President | 111 |

| Committee on Resolutions | 111 |

| Address, “Authority in Health Control,” Dr. L. E. Cofer | 111–122 |

| Address, “Land Frauds,” Dr. George E. Condra | 123–130 |

| Address, “Conservation of Land and the Man,” Mrs. Haviland H. Lund | 131–132 |

| Address, “Farmers’ Union,” Mr. Charles S. Barrett | 132–134 |

| FIFTH SESSION— | |

| Address, “A Plea for More Educational Opportunities,” Prof. E. T. Fairchild | 134–139 |

| Address, “Hygiene in Relation to Public Health,” Dr. Oscar Dowling | 139–144 |

| Address, “The Duty of the Employer,” Dr. Edward Rumely | 144–147 |

| Letter from Mr. Charles A. Doremus, of New York | 147 |

| Address, “Conservation of the Human Race,” Dr. J. N. Hurty | 148–154 |

| Address, “The Rescue of the Fit,” Mr. Harrington Emerson | 154–160 |

| SIXTH SESSION— | |

| Address, “Human Efficiency,” Dr. Henry Wallace | 161–170 |

| Address, “Is the Child Worth Conserving?” Judge Ben B. Lindsey | 170–181 |

| Remarks, Miss Adeline Denny | 181 |

| SEVENTH SESSION— | |

| Reading of Telegrams | 182 |

| Report from Col. M. H. Crump | 182–183 |

| Address, “The Lumberman’s Viewpoint,” Major E. G. Griggs | 183–195 |

| Nominating Committee | 196 |

| Report, Mrs. Orville T. Bright | 196–200 |

| Address, “Saving Miners’ Lives,” Dr. Joseph A. Holmes | 200–205 |

| Address, “The Prevention of Railroad Accidents,” Mr. Thomas H. Johnson | 205–214 |

| Address, “Vital Statistics and the Conservation of Human Life, a National Concern,” Mr. A. B. Farquhar | 214–223 |

| Address, “The Prevention of Elevator Accidents,” Mr. Reginald Pelham Bolton | 223–230 |

| Resolution, Mr. R. P. Bolton | 231 |

| Resolution, Mr. Frederick Kelsey | 231 |

| EIGHTH SESSION— | |

| Address, Honorable Woodrow Wilson | 232–240 |

| NINTH SESSION— | |

| Remarks, Mrs. Philip N. Moore | 241 |

| Address, Miss Julia Clifford Lathrop | 242–249 |

| Address, Mrs. Matthew T. Scott | 250–254 |

| Address, Mrs. John R. Walker | 255–258 |

| Address, Mrs. Marion A. Crocker | 258–262 |

| Paper, Mrs. Elmer Black (See Supplementary Proceedings) | 262 |

| Remarks, Colonel John I. Martin, Sergeant-at-Arms | 262–263 |

| TENTH SESSION— | |

| Address, “The Problem of Tuberculosis,” Dr. Livingston Farrand | 264–271 |

| Address, “The Conservation of Navigable Streams,” Mr. Jacob P. Dunn (See Supplementary Proceedings) | 271 |

| Address, “Social, Industrial and Civic Progress,” Mr. Ralph M. Easley | 272–281 |

| Address, “Disposition of Sewage,” Dr. Burton J. Ashley | 281–286 |

| Remarks, Mr. J. B. Baumgartner | 286 |

| Report, Executive Committee, Presented by Mr. E. Lee Worsham, Chairman | 286–287 |

| Remarks, Mr. E. Lee Worsham | 287 |

| Report, Committee on Nominations | 288 |

| Remarks, Mr. Charles Lathrop Pack | 289 |

| Address, “The Investigations of Flood Commission of Pittsburgh,” Mr. George M. Lehman | 289–296 |

| ELEVENTH SESSION— | |

| Remarks, Hon. J. B. White | 296 |

| Address, “The Story of the Soil,” Mr. H. H. Gross | 297–302 |

| Address, “The Story of the Air,” Prof. Willis L. Moore | 303–305 |

| Report, Committee on Resolutions | 306 |

| Resolution, Mr. John B. Hammond | 306 |

| Presentation of Invitations from Cities Desiring the Next Congress | 306 |

| Address, Mr. Don Carlos Ellis | 307–310 |

| SUPPLEMENTARY PROCEEDINGS | 312 |

| FORESTRY SECTION | 312 |

| Remarks, Mr. D. Page Simons | 312 |

| Remarks, Mr. T. B. Wyman | 312 |

| Remarks, Maj. E. G. Griggs | 313 |

| Remarks, Mr. Charles Lathrop Pack | 313 |

| Remarks, Mr. I. C. Williams | 313 |

| Remarks, Dr. Henry S. Drinker | 313 |

| Remarks, Mr. E. A. Sterling | 313 |

| Remarks, Hon. John M. Woods | 313 |

| Remarks, Mr. Henry E. Hardtner | 313 |

| Remarks, Prof. F. W. Rane | 313 |

| Remarks, Col. W. R. Brown | 313–314 |

| Remarks, Mr. F. A. Elliott | 314 |

| Remarks, Mr. Hugh P. Baker | 314 |

| Remarks, Mr. P. S. Ridsdale | 314 |

| Appointment of Committees on Resolutions | 314 |

| Co-operation with other agencies, permanent organizations and resolutions. | |

| THIRD SESSION— | |

| Remarks, Mr. H. E. Hardtner | 314 |

| Remarks, Mr. T. B. Wyman | 314 |

| Remarks, Col. W. R. Brown | 314 |

| Remarks, Mr. F. A. Elliott | 315 |

| Remarks, Mr. N. P. Wheeler | 315 |

| Remarks, Mr. D. Page Simons | 315 |

| Report, Committee on Resolutions | 315 |

| FOURTH SESSION— | |

| Committee on Permanent Organizations— | |

| Report, Mr. E. T. Allen | 315–316 |

| Remarks, Mr. Z. D. Scott | 316 |

| Remarks, Mr. F. A. Elliott | 316 |

| Remarks, Mr. H. D. Langille | 316 |

| Remarks, Mr. W. H. Shippen | 316 |

| Register, Forestry Section | 317 |

| Address, “The Present Situation of Forestry,” Prof. Henry S. Graves, United States Forester | 318–325 |

| FOOD SECTION | 326–327 |

| Address, “Food Conservation by Cold Storage,” Mr. F. G. Urner | 327–334 |

| National Association of Conservation Commissioners | 334–335 |

| Accident Prevention Section | 335 |

| Review of Progress in the Conservation of Waters | 335 |

| Report, Standing Committee on Waters, by Mr. W. C. Mendenhall | 335–344 |

| WILD LIFE PROTECTION | 344 |

| Report, Standing Committee on Wild Life Protection, by Dr. W. T. Hornaday | 344–347 |

| Address, “The Vital Resources of the Nation,” Dr. Henry Sturgis Drinker | 347 |

| Paper, “Conservation of the Soil,” Hon. James J. Hill | 349–352 |

| Paper, “War is the Policy of Waste—Peace, the Policy of Conservation,” Mrs. Elmer Black | 352–356 |

| Address, “The Conservation of Navigable Streams,” Mr. Jacob P. Dunn | 357–362 |

| Report from the National Fertilizer Association, presented by Mr. John D. Toll and Mr. Charles S. Rauh | 363–365 |

| Dr. W. J. McGee: An Appreciation of His Services for Conservation, Mr. W. C. Mendenhall | 365–367 |

[Pg 9]

President,

John B. White, Kansas City, Mo.

Executive Secretary,

Thomas R. Shipp, Washington, D. C.

Treasurer,

D. Austin Latchaw, Kansas City, Mo.

Recording Secretary,

James C. Gipe, Indianapolis, Ind.

Executive Committee.

E. Lee Worsham, Atlanta, Ga., Chairman.

| J. Lewis Thompson, Houston, Texas. | Dr. H. E. Barnard, Indianapolis, Ind. |

| W. A. Fleming Jones, Las Cruces, N.M. | Mrs. Philip N. Moore, St. Louis, Mo. |

| Walter H. Page, New York. | Bernard N. Baker, Baltimore, Md. |

| George C. Pardee, Oakland, Cal. | Henry C. Wallace, Des Moines, Iowa. |

| Gifford Pinchot, Washington, D. C. | |

Local Board of Managers, Indianapolis.

Richard Lieber, Chairman.

| Joseph C. Schaf, Vice-Chairman. | James W. Lilly, Treasurer. |

L. H. Lewis, Secretary.

| Frederic M. Ayres. | O. D. Haskett. |

| George L. Denny. | Albert E. Metzger. |

| Edgar H. Evans. | William J. Mooney. |

| Carl G. Fisher. | W. H. O’Brien. |

| C. G. Hanch. |

Vice-Presidents.

| Arkansas—E. N. Plank, Decatur. | Nebraska—Prof. E. A. Burnett, Lincoln. |

| California—Francis Cuttle, Riverside. | |

| Colorado—I. S. T. Gregg, Golden. | New Jersey—E. A. Stevens, Hoboken. |

| Connecticut—Prof. J. W. Toumey, Hartford. | New York—Dr. W. T. Hornaday, New York City. |

| District of Columbia—Dr. Harvey W. Wiley, Washington. | Ohio—J. C. Rodgers, Mechanicsburg. |

| Florida—T. J. Campbell, Palm Beach. | Oklahoma—T. C. Harrice, Wagoner. |

| Georgia—L. R. Akin. | South Carolina—Prof. M. W. Twitchell, Columbia. |

| Illinois—Ballard Dunn, Chicago. | South Dakota—Gov. R. S. Vessey, Pierre. |

| Iowa—Prof. P. G. Holden, Ames. | Texas—W. Goodrich Jones, Temple. |

| Louisiana—Henry E. Hardtner, Urania. | Washington—A. L. Flewelling, Spokane. |

| Massachusetts—Prof. F. W. Rane, Boston. | Wisconsin—Herbert Quick, Madison. |

| Missouri—Herman Von Schrenk, St. Louis. |

[Pg 10]

STANDING COMMITTEES, 1912.

Forests—H. S. Graves, Washington, D. C., Chairman; E. T. Allen, Portland, Ore.; Major E. G. Griggs, Tacoma, Wash.; William Irvine, Chippewa Falls, Wis.; George K. Smith, St. Louis.

Minerals—Dr. Joseph A. Holmes, Washington, D. C., Chairman; Dr. Charles R. Van Hise, Madison, Wis.; Dr. I. C. White, Morgantown, W. Va.; C. W. Brunton, Denver, Col.; John Mitchell, New York City.

Lands and Agriculture—Prof. L. H. Bailey, Cornell University, Chairman; Prof. George E. Condra, Nebraska; Prof. J. L. Snyder, Lansing, Mich.; F. D. Coburn, Kansas; Charles S. Barrett, Union City, Ga.

Education—Dr. C. E. Bessey, Lincoln, Neb., Chairman; Dr. David Starr Jordan, Leland Stanford University, Oakland, Cal.; Dr. Edward E. Alderman, University of Virginia, Charlottesville; Dr. E. C. Craighead, Tulane University, New Orleans, La.; Prof. E. T. Fairchild, Topeka, Kas.

Vital Resources—Dr. William H. Welch, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md., Chairman; Prof. Irving Fisher, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.; Dr. J. N. Hurty, Indianapolis, Ind.; Hon. A. B. Farquhar, York, Pa.; Dr. Oscar Dowling, Shreveport, La.

Homes—Mrs. Matthew T. Scott, Washington, Chairman; Mrs. Harriet Wallace-Ashby, Des Moines, Iowa; Mrs. J. E. Rhodes, St. Paul, Minn.; Mrs. Sarah S. Platt-Decker,[1] Denver, Col.; Mrs. Amos F. Draper, Washington, D. C.

Child Life—Hon. Ben B. Lindsay, Denver, Col., Chairman; Dr. Samuel M. Lindsay, New York City; Judge Henry L. McCune, Kansas City, Mo.; Mrs. Carl Vrooman, Bloomington, Ill.; Dr. Anna Louise Strong, Seattle, Wash.

Food—Dr. Harvey W. Wiley, Washington, D. C., Chairman; F. G. Urner, New York; Prof. F. Spencer Baldwin, Boston, Mass.; J. F. Nickerson, Chicago, Ill.; Lucius P. Brown, Nashville, Tenn.; E. H. Jenkins, New Haven, Conn.; M. A. Scovelle, Lexington, Ky.; Prof. Geo. A. Loveland, Lincoln, Neb.

Civics—Ralph Easley, New York, Chairman; Albert Hall Whitfield, Jackson, Miss.; B. A. Fowler, Phœnix, Ariz.; H. M. Beardsley, Kansas City, Mo.; Francis J. Heney, San Francisco, Cal.

General (including Domesticated Animals and Wild Life)—Dr. W. T. Hornaday, New York, Chairman; Dr. L. O. Howard, Washington, D. C.; Mrs. Minnie Maddern Fiske, New York City; Dr. John Muir, Martinez, Cal.; D. Austin Latchaw, Kansas City, Mo.; Prof. Geo. A. Loveland, Lincoln, Neb.

Waters—Hon. J. N. Teal, Portland, Ore., Chairman; Hon. Joseph E. Ransdell, Lake Providence, La.; Walter S. Dickey, Kansas City, Mo.; Hon. Herbert Knox Smith, Washington, D. C.; W. K. Kavanaugh, St. Louis, Mo.; Dr. W. J. McGee, Washington, D. C.; Prof. Geo. F. Swain, Harvard University.

National Parks (including Mammoth Cave, Ky., and Adjacent Lands)—Dr. W. J. McGee,[1] Washington, D. C.; Dr. Henry F. Drinker, South Bethlehem, Pa.; Hon. William P. Borland, Kansas City, Mo.; Hon. Gifford Pinchot, Washington, D. C.; M. H. Crump, Bowling Green, Ky.

[1] Deceased.

[Pg 11]

President,

Charles Lathrop Pack, Lakewood, N. J.

Vice-President,

Mrs. Philip N. Moore, St. Louis, Mo.

Executive Secretary,

Thomas B. Shipp, Indianapolis, Ind.

Treasurer,

D. A. Latchaw, Kansas City, Mo.

Recording Secretary,

James C. Gipe, Indianapolis, Ind.

Executive Committee,

E. Lee Worsham, Atlanta, Ga., Chairman.

| Walter H. Page, New York City. | Joseph N. Teal, Portland, Oregon. |

| J. B. White, Kansas City, Missouri. | Dr. Henry Wallace, Des Moines, Iowa. |

| B. N. Baker, Baltimore, Maryland. | Dr. George C. Pardee, Oakland, Cal. |

| Dr. Henry S. Drinker, S. Bethlehem, Pa. | Thomas Nelson Page, Washington, D. C. |

| George E. Condra, Lincoln, Neb. | Gifford Pinchot, Washington, D. C. |

| Mrs. Emmons Crocker, Fitchburg, Mass. | |

[2]Standing Committees.

Forestry—Henry S. Graves, Chairman, Forest Service, Washington, D. C.; E. T. Allen, Yeon Portland, Ore.; J. B. White, Long Building, Kansas City, Mo.; W. R. Brown, Berlin, New Hampshire; E. A. Sterling, Secretary, Real Estate Building, Philadelphia, Pa.

[2] At the time the Proceedings went to press the other standing committees had not been appointed.

[Pg 13]

OF THE

NATIONAL CONSERVATION CONGRESS

As Amended by the Fourth Congress.

Article 1—Name.

This organization shall be known as the National Conservation Congress.

Article 2—Object.

The object of the National Conservation Congress shall be: (1) to provide a forum for discussion of the resources of the United States as the foundation for the prosperity of the people, (2) to furnish definite information concerning the resources and their utilization, and (3) to afford an agency through which the people of the country may frame policies and principles affecting the wise and practical development, conservation and utilization of the resources to be put into effect by their representatives in State and Federal Governments.

Article 3—Meetings.

Section 1. Regular annual meetings shall be held at such time and place as may be determined by the Executive Committee.

Section 2. Special meetings of the Congress, or its officers, committees or boards, may be held subject to the call of the President of the Congress or the Chairman of the Executive Committee.

Section 3. After a call of the Executive Committee by the Chairman, and after all members of the Committee have been notified of the meeting in sufficient time to be present, three members shall constitute a quorum for the transaction of business.

Article 4—Officers.

Section 1. The officers of the Congress shall consist of a President, to be elected by the Congress; a Vice-President to be elected by the Congress;[Pg 14] a Vice-President from each State, to be chosen by the respective State delegations; one from the National Conservation Association and one from the National Association of Conservation Commissioners; an Executive Secretary, a Recording Secretary, and a Treasurer, all to be elected by the Congress.

Section 2. The duties of these officers may at any time be prescribed by formal action of the Congress or Executive Committee. In the absence of such action their duties shall be those implied by their designations and established by custom. In addition, it shall be the duty of the Vice-Presidents to receive from the State Conservation Commissions, and other organizations concerned in Conservation, suggestions and recommendations and report them to the Executive Committee of the Congress.

Section 3. The officers shall serve for one year, or until their successors are elected and qualify.

Article 5—Committees and Boards.

Section 1. An Executive Committee of seven, in addition to which the President of the National Conservation Association, the President of the National Association of State Conservation Commissioners, and all ex-Presidents of the Congress shall be members, ex officio, shall be appointed by the President to act for the ensuing year; its membership shall be drawn from different States, and not more than one of the appointed members shall be from any one State. The Executive Committee shall act for the Congress and shall be empowered to initiate action and meet emergencies. It shall report to each regular annual session.

Section 2. A Board of Managers shall be created in each city in which the next ensuing session of the Congress is to be held, preferably by leading organizations of citizens. The Board of Managers shall have power to raise and expend funds, to incur obligations of its own responsibility, to appoint subordinate boards and committees, all with the approval of the Executive Committee of the Congress. It shall report to the Executive Committee at least two days before the opening of the ensuing session, and at such other times as the Congress or the Executive Committee may direct.

Section 3. An Advisory Board, consisting of one person from each national organization having a conservation committee, shall be created to serve during that Congress and during the interval before the next succeeding Congress. The board shall report to and co-operate with the Executive Committee.

Section 4. The President shall appoint a Finance Committee of five, three from the members of the Executive Committee and two from the[Pg 15] Advisory Board, whose duty it shall be to plan ways and means of increasing the revenue of the Congress, and to prepare a budget of expenditures. The Chairman shall be a member of the Executive Committee.

Section 5. The Executive Committee shall appoint, in consultation with the Vice-President from the State, a State Secretary whose duty shall be to work with the State organizations for the special interests of the Congress. Such Secretary shall report progress to the Executive Committee.

Section 6. A Committee on Credentials shall be appointed, consisting of five (5) members, by the President of the Congress not later than on the second day of each session of the Congress. It shall determine all questions raised by delegates as to representation, and shall report to the Congress from time to time as required by the President of the Congress.

Section 7. A Committee on Resolutions shall be created for each annual meeting of the Congress. A Chairman shall be appointed by the President. One member of the committee shall be selected by each State represented in the Congress. The committee shall report to the Congress not later than the morning of the last day of each annual meeting.

Section 8. Permanent committees, consisting of five members each, on each of the following five divisions of Conservation: Forests, waters, lands, minerals and vital resources, shall be appointed by the President of the Congress. The Committee on Vital Resources is to consist of six subordinate committees as follows: Food, homes, child life, education, civics, and general (including wild life, domesticated animals, and cultivated plants). These committees shall, during the intervals between the annual meetings of the Congress, inquire into these respective subjects and prepare reports to be submitted on the request of the Executive Committee, and render such other assistance to the Congress as the Executive Committee may direct.

Section 9. By direction of the Congress, standing and special committees may be appointed by the President.

Section 10. The President shall be a member, ex officio, of every committee of the Congress.

Article 6—Arrangements for Sessions.

Section 1. The program for the session of each annual meeting of the Congress, including a list of speakers, shall be arranged by the Executive Committee. The entire program, including allotments of time to speakers and hours for daily sessions and all other arrangements concerning the program, shall be made by the Executive Committee.

Section 2. Unless otherwise ordered, the rules adopted for the guidance of the preceding Congress shall continue in force.

[Pg 16]

Article 7—Membership.

Section 1. The personnel of the National Conservation Congress shall be as follows:

Officers and Delegates.

Officers of the National Conservation Congress.

Fifteen delegates appointed by the Governor of each State and Territory.

Five delegates appointed by the mayor of each city with a population of 25,000 or more.

Two delegates appointed by the mayor of each city with a population of less than 25,000.

Two delegates appointed by each board of county commissioners.

Five delegates appointed by each national organization concerned in the work of Conservation.

Five delegates appointed by each State or interstate organization concerned in the work of Conservation.

Three delegates appointed by each chamber of commerce, board of trade, commercial club, or other local organization concerned in the work of Conservation.

Two delegates appointed by each State, or other university, or college, and by each agricultural college, or experiment station.

Honorary Members.

The President of the United States.

The Vice-President of the United States.

The Speaker of the House of Representatives.

The Cabinet.

The United States Senate and House of Representatives.

The Supreme Court of the United States.

The representatives of foreign countries.

The Governors of the States and Territories.

The Lieutenant-Governors of the States and Territories.

The Speakers of State Houses of Representatives.

The State officers.

The mayors of cities.

The county commissioners.

The presidents of State and other universities and colleges.

The officers and members of the National Conservation Association.

The officers and members of the National Conservation Commission.

The officers and members of the State Conservation Commissions and associations.

Section 2. Membership in the National Conservation Congress shall be as follows:

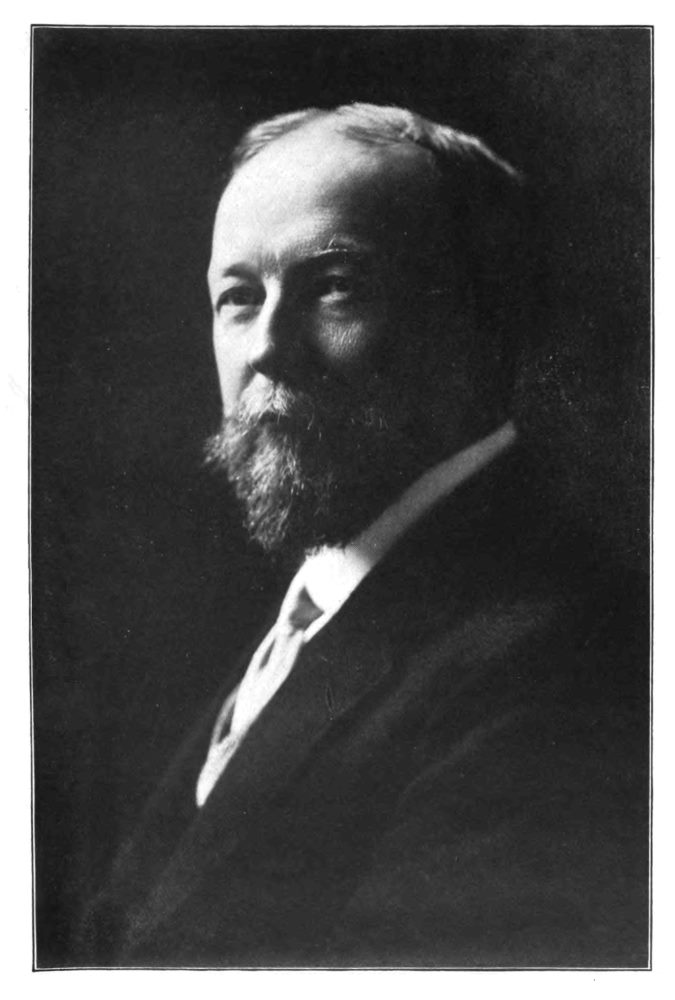

J. B. White (signature)

OF KANSAS CITY, MO.,

PRESIDENT, FOURTH NATIONAL CONSERVATION CONGRESS

[Pg 17]

Individual membership: One dollar a year, entitling the member to a copy of the Proceedings and an invitation to the next year’s Congress, without further appointment from any organization.

Individual permanent, or life membership: Twenty-five dollars, entitling the member to a certificate of membership and a copy of the Proceedings and invitations to all succeeding annual Congresses.

Individual supporting membership: One hundred dollars, or more, entitling the member to a certificate of membership, a copy of the Proceedings, and an invitation to all succeeding Congresses.

Organization membership: Twenty-five dollars, entitling its delegates to the Proceedings, and an invitation to the organization to appoint delegates to the next Congress.

Organization supporting membership: One hundred dollars, or more, entitling the organization to appoint one delegate from each State, each of whom shall receive a copy of the Proceedings.

Article 8—Delegations and State Officers.

Section 1. The several delegates from each State in attendance at any Congress shall assemble at the earliest practicable time and organize by choosing a Chairman and a Secretary. These delegates, when approved by the Committee on Credentials, shall constitute the delegation from that State.

Article 9—Voting.

Section 1. Each member of the Congress shall be entitled to one vote on all actions taken viva voce.

Section 2. A division or call of States may be demanded on any action, by a State delegation. On division, each delegate shall be entitled to one vote; provided (1) that no State shall have more than twenty votes; and provided (2) that when a State is represented by less than ten delegates, said delegates may cast ten votes for each State.

Section 3. The term “State” as used herein is to be construed to mean either State, Territory, or insular possession.

Article 10—Amendments.

This Constitution may be amended by a two-thirds vote of the Congress during any regular session, provided notice of the proposed amendment has been given from the Chair not less than one day or more than two days preceding; or by unanimous vote without such notice.

[Pg 18]

FOURTH NATIONAL CONSERVATION CONGRESS.

The Fourth National Conservation Congress, made up of delegates from all sections and from thirty-five States of the Union, met in the City of Indianapolis, do hereby make the following declarations:

Recognizing the natural resources of the country as the prime basis of property and opportunity, we reaffirm the declaration of the preceding Congress, that the rights of the people in these resources are natural, inherent, and inalienable; and we insist that these resources shall be developed, used and conserved in ways consistent both with the current and future welfare of our people.

We put chief emphasis on vital resources and the health of the people; and since health and brains are the first and most important factors of efficient life, we urge the adoption of all rational and scientific methods which will lead to their building-up.

To be well born is the primal requirement, and the first step to make sure that children shall be well born is to stop the multiplication of those bearing hereditary defects of body and mind. We believe that science is capable of solving the problem satisfactorily and that improvement is possible under existing conditions. We earnestly urge its consideration by the public.

We believe that every State should have wisely ordered health laws, with officers empowered to enforce them, and also that a National Department of Health should be created, comporting with the dignity and importance of the cause. This department should work effectively for the promotion of the physical and hence the moral and intellectual health of the people.

The accurate registration of births and deaths, which has been called the ‘Bookkeeping of Humanity,’ is a fundamental necessity for a study and knowledge of disease, and for all public health work. Therefore, we affirm our belief in the importance of vital statistics registration, and recommend that all States now without proper vital statistics adopt as early as possible the model bill for the registration of vital statistics indorsed by the United States Bureau of the Census, and by many prominent professional and scientific bodies.

We urge the strengthening of laws safeguarding the health and the lives of workers in industrial establishments; and we commend to the[Pg 19] employers of labor all practicable safety devices and proved preventive measures against illness and injury and physical inefficiency; and we urge upon the other States the investigation of accidents by elevators and the enactment of laws similar to those on the statute books of Pennsylvania and Rhode Island.

We commend the activity of all individuals and organizations and governmental agencies to put an end to such work by children and women as impairs the health of the race. Childhood is our greatest resource, and its right to protection in growing to a normal maturity is inalienable. We deplore the ignorant use of medicines; and we call upon all humane and educational agencies to teach the waste and danger of any drug-habit.

We earnestly advocate the employment by communities and manufacturing concerns of such methods of sewage disposal as will render their waste products harmless to health and utilize them in the restoration of soil fertility; and we urge the enactment by States of laws prohibiting stream pollution and by the Federal Government of such legislation as will prevent the pollution of interstate and coastal waters.

Uniform State legislation regulating the refrigeration of perishable food stuffs is advisable, therefore this Congress recommends that its Food Committee be requested to study the questions involved in the production, collection, sanitary preparation, transportation, preservation and marketing of perishable foods and to report its findings to the succeeding Congress as a basis for uniform legislation.

In view of the enormous losses annually sustained by the agricultural interests of the United States on account of the ravages of injurious insects, which might be kept more under control by an increase of insect-eating birds, we urge the passage of Federal laws for the protection of all migratory birds; and the passage of State laws for the prohibition of spring shooting and of the sale of game.

We reaffirm the great importance of our fishery resources, which are threatened with serious diminution. We urge upon Congress and the States to provide more liberally for the propagation and preservation of food fishes.

LANDS.

We keenly recognize the need of the people of the country for more complete and accurate knowledge of their land and its conditions than is now available, in order to promote their economic, social and intellectual well-being and to conserve scattered individual energy;

We recognize that such data should be collected by a general series of State and National surveys arranged in the order in which they will be most accurate and effective and that many of these are already in progress;

[Pg 20]

This Congress earnestly points out the following kinds of data of which the people have need and the approximate order in which it should be collected, namely:

1. A thorough geographical survey of public boundaries and cultural features.

2. Of the form or topography of the earth’s surface.

3. Of the geology, including the structure and economic deposits of the earth’s crust.

4. Of the kinds and distribution of soils in their relation to agricultural operations.

5. Of the climate in its local variations and relation to crops and industry.

6. Of the surface and underground water supply of the country in its local and regional relation, including flood and storage problems.

7. Of various biological, crop and forestry conditions and relations.

8. And of many other surveys of a more specialized character and local application which may be adequately carried forward on the basis outlined above.

We urge the several States and the Federal Government to examine their existing agencies to determine whether they are completely and effectively fulfilling these functions.

Further, we reaffirm the action of the last Conservation Congress in approving the withdrawal of the public lands pending classification, and the separation of surface rights from mineral, forest and water rights, including water-power sites, and we recommend legislation for the classification and leasing for grazing purposes all unreserved lands suitable chiefly for this purpose, subject to the rights of homesteaders and settlers, on the acquisition thereof under the land laws of the United States; and we hold that arid and non-irrigable public grazing lands should be administered by the Government in the interest of small stockmen and home-seekers until they have passed into the possession of actual settlers.

FORESTS.

Believing that the necessity of preserving our forests and forest industries is so generally realized that it calls only for constructive support along specific lines—

We commend the work of the Federal Forest Service, and urge our constituent bodies and all citizens to insist upon more adequate appropriations for this work and to combat any attempt to break down the integrity of the national forest system by reductions in area, or transfer to State authority.

[Pg 21]

Since Federal co-operation under the Weeks law is stimulating better forest protection by the States, and since the appropriation for such co-operative work is nearly exhausted, we urge appropriation by Congress for its continuance.

We recommend that the Federal troops be made systematically available for controlling forest fires.

Deploring the lack of uniform State activity in forest work, we emphatically urge the crystallization of effort in the lagging States toward securing the creation of forest departments with definite and ample appropriations, in no case of less than ten thousand dollars per annum, to enable the organization of forest fire work, publicity propaganda, surveys of forest resources and general investigations upon which to base the earliest possible development of perfected and liberally financed forest policies.

We recommend in all States more liberal appropriation for forest fire prevention, especially for patrol to obviate expenditure for fighting neglected fires, and the expenditure of such effort in the closest possible co-operation with Federal and private protective agencies; and also urge such special legislation and appropriation as may be necessary to stamp out insect and fungus attacks which threaten to spread to other States. We cite for emulation the expenditure by Pennsylvania of $275,000 to combat the chestnut blight, and the large appropriation by Massachusetts to control insect depredation, and urge greater Congressional appropriation for similar work by the Bureau of Entomology.

Holding that conservative forest management and reforestation by private owners are very generally discouraged or prevented by our methods of forest taxation, we recommend State legislation to secure the most moderate taxation of forest land consistent with justice and the taxation of the forest crop upon such land only when the crop is harvested and returns revenue wherewith to pay the tax.

We appreciate the increasing support by lumbermen of forestry reforms and suggest particularly to forest owners the study and emulation of the many co-operative patrol associations which are doing extensive and efficient forest fire work and also securing closer relations between private, State and Federal forest agencies. Believing that lumbermen and the public have a common object in perpetuating the use of forests, we indorse every means of bringing them together in mutual aid and confidence to this end.

MINERALS.

We reaffirm the opinion of the last Conservation Congress that mineral deposits underlying public lands should be transferred to private ownership only by long-time leases with revaluation at stated periods,[Pg 22] such leases to be in such amounts and subject to such regulations as to prevent monopoly and needless waste; and that in case of doubt as to availability of such mineral deposits, or while they are waiting exploration, surface rights to the land should be transferred by lease only under such conditions as to promote development and protect the public interest. Natural and manufactured fertilizing materials should be limited and regulated by law.

Since present conditions in the mining industry result in heavy and unnecessary loss of life and great waste of natural gas, coal and other mineral resources, we call to public attention the need of specific and uniform laws for the betterment of these conditions—laws as rigid and comprehensive as we enact for the protection of life and for the right use of property in any other fundamental industry.

WATER POWER.

We reaffirm the previously expressed belief of the Conservation Congress than all parts of every drainage basin are related and inter-dependent, and that each stream should be regarded and treated as a unit from its source to its mouth.

Recognizing the vast economic benefits to the people of water power derived largely from interstate and navigable rivers, we favor public control of their water power development; and we demand that the use of their water rights be permitted only for limited periods, with just compensation in the interests of the people.

COUNTRY LIFE.

We applaud the betterment of conditions affecting country life, such as good roads, and organizations for co-operative buying and selling; and we urge the study of rural credit systems whereby the farmer may more easily borrow capital at a reasonable rate of interest.

We applaud the work of making rural schools fit rural needs.

DR. W. J. McGEE.

We here place on record our sense of the deep loss by the country through the untimely death of Dr. W. J. McGee, a member of a Committee of this Congress, a scientific man of broad attainment, and of the widest human sympathy, whose helpfulness in these Congresses and many similar meetings will be sadly missed.

THE EXHIBIT.

We mention with appreciation the work of the Committee on Exhibits, Mrs. Philip N. Moore, Chairman, which made the instructive health exhibit under the management of Dr. Winthrop Talbot.

[Pg 23]

We record our grateful appreciation of the hospitality and helpfulness of the State Government of Indiana, and of the City Government of Indianapolis; and of the Local Board of Managers, Mr. Richard Lieber, Chairman; of the Reception Committee, Mr. Albert E. Metzger, Chairman; of the Commercial and Industrial organizations which, through the Commercial Club, made the Congress here possible; of the State Board of Agriculture, and of the Claypool Hotel, for their helpful courtesies and generous co-operation; and we thank the newspapers of Indianapolis for their unusually generous and accurate reports.

We wish to assure the retiring President, Captain White, of the heartiest appreciation of the Congress and of the country for his generous and efficient administration of the complicated business of the Congress; and Mr. Thomas R. Shipp, the Executive Secretary, for his zealous labor and good judgment and skilful management; and Mr. James C. Gipe, the Recording Secretary, for his energy and efficiency; and Colonel John I. Martin, the Sergeant-at-arms, must add one more vote of thanks to his ever-lengthening collection.

[Pg 24]

FOURTH NATIONAL CONSERVATION CONGRESS.

OPENING SESSION.

The Congress convened in the Murat Theater, Indianapolis, Indiana, on the morning of October 1, 1912, President J. B. White in the chair.

President White—The Fourth National Conservation Congress will now come to order, and the audience will please rise while the Rev. Dr. F. S. C. Wicks invokes Divine blessing.

Invocation.

Infinite and Eternal One, we would open our Congress with an acknowledgment of Thee as the Giver of every good and perfect gift. Thou hast placed us in a rich and fertile land, teeming with the things needful for Thy children, and Thou hast laid upon us the great responsibility of conserving these resources so that these blessings will extend to our children’s children and to all generations forevermore. To Thee be all the praise and the glory. Amen.

ADDRESSES OF WELCOME.

President White—On behalf of the State of Indiana, your fellow citizen, the Honorable Charles Warren Fairbanks, will address the Congress in words of welcome. (Applause.)

Mr. Fairbanks—Mr. President, Ladies and Gentlemen: Indiana has frequently been honored by the presence of conventions of national importance. Our countrymen, engaged in various and vast pursuits and in the consideration of a large variety of questions, religious, social, fraternal, economic and political in their character, have assembled here from time to time to take counsel together with respect to the subjects engaging their particular attention, and to the advancement of our common welfare.

Our State has a hospitality for all who are engaged in promoting the moral, material and political well-being of our rapidly multiplying millions. I will not be misunderstood, I know, when I say that we have never more heartily welcomed to our midst any body of men than we now welcome the Fourth National Conservation Congress. (Applause.)

[Pg 25]

We recognize in this great assembly one of the most beneficent agencies for good which has taken on the form of systematic organization, national in its scope. It is not sectional, but is as comprehensive in its purpose as the ample limits of the Republic. It takes thought, not of the few, but embraces within its generous purpose one hundred millions of people of all conditions and without suggestion or partiality for white or black, native or alien born. How vast and how vital the field of its activities!

How full of promise such an assembly as this is! It is, Mr. Chairman, a complete answer to the pessimist. No thought of commercial gain has brought you here; a spirit of altruism, love of country and of mankind has been the impelling motive which has caused you, at your own expense, to leave the comforts of your homes and firesides and your daily vocations to come here and deliberate upon great themes of larger interest to the great community of which you are a part than to yourselves.

You hold no commission from the government, yet your service is of profound importance to it. You are not public servants in a narrow sense, but in a broad sense you freely serve the public in the best possible way.

The lesson of men voluntarily devoting themselves to the betterment of their fellows without the thought of sordid gain is a fine one and must impress itself in a very vivid and beneficial way upon the minds of others and tend to elevate the entire mass. What tends to impress us with our interdependence and to stimulate a feeling of homogeneity among us as this movement does is of incalculable benefit. It is a splendid thing for people to fellowship together in this manner, to take counsel of each other with reference to questions concerning the common good. It shows that we are interested more in what concerns the great body of the community than in what concerns ourselves.

General Harrison, gifted statesman and our fellow citizen, once very happily expressed the fact of the strength of confederated numbers in a good cause. He told of an engagement during the great Civil War when he was colonel of an Indiana regiment that was fighting in the midst of a woods and thicket. The enemy was pressing hard in front and fighting every inch of ground with a desperation that was unsurpassed. The Indiana regiment was feeling the shock of war in an extreme degree, and was almost on the point of discouragement. They felt they were fighting the battle alone. But in the course of time, as they emerged into a savannah, they saw a New York regiment, with its battle flags flying to the breeze; and over there another regiment from Kansas, and a shout of victory went up all along the line, for they found they were not a mere detachment, but part of a great army fighting for a common cause.

[Pg 26]

So it is a fine thing to feel that we are part of a great army fighting for a common cause—for home and country, rather than detached units fighting for ourselves. (Applause.)

Conservation is comparatively new in the vocabulary of our modern domestic economy, but it is a great word. It has come to be one of the greatest words of the human language from a practical standpoint. It is a continent-wide word in America. Conservation in some aspect of the subject touches every community, every city, every State and every individual. In other words, in a vital degree, it touches the welfare of one hundred millions of American citizens. Its importance is just beginning to be appreciated. Great today, but greater tomorrow in the progress of affairs. (Applause.)

A good Providence endowed us so abundantly with the prime necessities of our being that we have not fully realized the fact that there was either a possibility or danger of dissipating them. We were wont to boast of our inexhaustible resources. Nature has been prodigal, and we have been prodigal in the use and abuse of what she had so generously placed at our hands.

The forests—how vast and how majestic! We were obliged to fell them for the plow and the harvest, and for homes and cities. We came to look upon them as in our way—obstructions to our progress, as in a certain sense they were, but in a large way they were not. And we carried the work of demolition to the danger point before we realized our mistake. What nature had been centuries creating for us we frequently recklessly destroyed in a day.

The soil, the primary source of human life and strength, was rich beyond compare. In the laboratory of nature the chemical elements had been so nicely compounded that, to use a familiar simile, the farmer had only to tickle the land with a hoe and it laughed with the harvest. In time, Mother Earth began to resent neglect and abuse, and the crop yield diminished; but that mattered little to the unthinking, for there were still vast areas of virgin soil and the food supply was adequate to our needs. In the course of time, however, there were no unoccupied lands to be pre-empted, no fresh soil for the asking.

MILLIONS COME TO OUR SHORES.

Millions of men and women flocked to our shores every ten years from every land beyond the seas, seeking home and opportunity; millions every decade were added to our population at home by natural increase. Students of statistics came to realize that in the face of an increasing demand for food supply at home, regardless of the millions in the Old World dependent upon our granaries, soil exhaustion was a subject of very vital importance, a crime, if you please, not by the[Pg 27] statute, but by moral law; and this may be said with respect to the reckless or ignorant dissipation of all our natural resources.

We are in a very real sense trustees of the fields and forests, mines and other sources of wealth, not to use and abuse at our will, but rather to use for our own reasonable necessities and then to transmit them unimpaired, so far as possible, and if possible increased in life-sustaining power, to our children. (Applause.)

By no other method can our civilization be perpetually maintained upon the highest level and the Republic kept in the forefront of the nations of the world. The man who owns and tills the soil, who owns and fells the forest, who owns and mines the coal, has no moral right to abuse his ownership; no one has a moral right to waste patrimony which must support not only the owner but the man who is not the owner, and whose continued comfort and existence must depend upon the wisdom with which the owner of the soil and forest and mine uses them.

The importance of Conservation derives emphasis from the rapidity with which our population grows. Our cities will not only multiply in number, but their inhabitants will increase, population will become congested everywhere, and the demand upon our natural resources will be greatly increased. We have added nearly ninety millions to our population in one hundred years. One hundred years ago we were small in numbers compared with the older countries. We have outstripped all but the older empires and republics of Continental Europe. Take Russia, with her 172,000,000; take India, with 325,000,000, and China, where they are building a republic upon the ruins of an empire, with her 400,000,000, and the United States stands fourth in magnitude of population among the nations of the world, having outstripped all but these, and with the present ratio of increase, in one hundred and fifty or two hundred years we will stand not the last of these great populous countries. And what does this signify? It signifies that the great subject of Conservation that you are taking hold of with such intelligent, patriotic interest, will be the overmastering question then as it is today. (Applause.)

Who can put a practical limitation upon a definition of Conservation? Conservation of our natural resources does not go far enough. The public health falls within the subject of Conservation in the fullest and best sense, and that is susceptible of many subdivisions. Conservation of the minds and morals, Conservation of our political institutions—all of these and many more subjects of but little less importance engage the attention of such men as are assembled here.

I understand, Mr. Chairman, that the human side of Conservation is to receive particular emphasis in this Congress. I am glad it is so. We have been so long concerned with the physical resources that we have[Pg 28] failed to give proper credit to really a larger aspect of Conservation. As important as is the conservation of our natural resources, far more important is the question of conserving the health, conserving the intellect, conserving the morality of the one hundred millions of people we have. (Applause.) I have known men who were more solicitous regarding the health of a fine horse or dog than the health of the family. I have sometimes seen (but not in any of the States from which any of you come) ladies that had a more affectionate solicitude for a fine cat or a fine poodle than for the members of her household. (Laughter.) We are getting beyond that. We are coming to appreciate that that greatest assets in the United States today are men and women, and we must know how to conserve them.

There is manifest and gratifying awakening upon this subject throughout the country. We have not begun to appreciate the possibilities in this field. Men of science, the microscope, the laboratory and carefully gathered and well-digested statistics have opened up a new world to our vision. Physicians and surgeons have been exploring the mysteries of the physical man and familiarizing themselves with the perils of his environment and learning how to arrest the work of his destroyer.

They have learned how to locate his worst enemies by the use of the searching eye of the microscope, enemies who destroy more thousands than those enemies who come with fleets and armies and flaunting banners. It was not the Chagres river and Culebra cut which defeated the French Company in the construction of the Panama Canal, but the mosquito.

An American physician opened up the way to the completion of this work of world-wide moment by destroying the insect which had successfully defeated the French. The white plague, which takes such tremendous toll annually, is now under siege from every quarter, and science will in due time win a new victory in removing this scourge. Better sanitation in cities, villages, schoolhouses, workshops, homes, on farms and in cities, guarding our water supply against pollution, insuring pure food and pure drugs and their better preparation, are a few of the imperative requirements of the day. And when I speak of pure food and drugs, Dr. Wiley comes to my mind. (Applause.) He has to do with an aspect of practical Conservation that will entitle him and his associates to perpetual remembrance in the United States. (Applause.)

These are all practical questions, the importance of which cannot be over-emphasized. They concern the health and happiness of many millions of people and the destiny of the Republic itself.

[Pg 29]

INDIANA NOT INDIFFERENT.

Indiana has not been indifferent to this great movement. It has taken up the work of Conservation with full appreciation of its magnitude and its direct bearing upon the present and future of the State. Our interests are so diversified that our conservationists in all branches of the movement find full opportunity for the exercise of their activities.

We have an agricultural college which is doing much to advance agriculture, horticulture, stock raising and the like along advanced lines. Farmers are being interested in the necessity of cultivation of the soil and the importance of seed selection, drainage and the like. We have farmers’ short courses instituted by the college which are proving of immense value. We are conserving the health of the livestock upon the farms. Sanitation has played an important part in this branch of work, as it has upon the human side.

We have a board of forestry supported by the State, and a Forestry Association organized by the people; also a commission to protect the food supply of our lakes and streams. These are only a few of the evidences of our progress in Conservation.

We are conserving with particular care the health of our school children with admirable results. We have learned, somewhat slowly perhaps, that sound bodies and sound minds should and can go together, and that to educate the mind and allow the body to become diseased is false economy on the part of the State and is nothing short of a crime, committed through either our ignorance or indifference.

We have sought to guard against and cure occupational diseases which impair and disqualify so many wage earners. We have more and more sought to throw around them such safeguards as well protect them against injury and death, and then to provide an adequate measure of compensation in case of accident as one of the legitimate burdens upon industry of the community which ultimately rests upon the public.

HAVE REDUCED ACCIDENTS.

During the last fifteen years we have made much advance in the conservation of the health of our people. By rigid factory inspection we have reduced accidents to our workmen from machinery and by improved sanitation we have protected their health. We have also rigidly inspected our mines with like results.

In fifteen years diphtheria has decreased sixty per cent., consumption has decreased in this same period six to eight per cent.; deaths from typhoid fever have fallen in the last two years from almost two thousand to 936 in 1911. Education, better living, improved sanitation, and an efficient State Board of Health, with its excellent organization of health officers in every locality, the co-operation of the press in the education of the people and support of our health officers, have accomplished[Pg 30] a great work in increasing in a very considerable degree the health, vigor and happiness of our people.

The net result of it all is told in the vital statistics of the State. In the last fifteen years the duration of life has been increased from 38.7 years to 44.6 years.

We are advocating the creation of a State Conservation Board with supervisory power over all subjects of Conservation now committed to separate and independent boards or commissions, so as to more effectively co-ordinate their efforts in a scientific manner, avoiding duplication and intensifying the work. It is suggested that a building be erected by the State for the proper accommodation of the entire Conservation service.

We regard this as a matter of great importance, and there is no doubt whatever that the State will liberally respond to the prevailing sentiment in favor of broadening the work of Conservation. It never pursues any parsimonious policy in supporting whatever concerns the education, health, moral safety and welfare of our people, so far as this may be appropriately accomplished under the law.

It is not inappropriate in this presence to observe that the Conservation of our political fabric must not be left out of consideration. This is a matter we must always hold uppermost in our minds, lest we allow harm to come to our priceless heritage.

Partisan utterance would, of course, contravene good taste, and I shall not offend against it; but I may suggest with propriety that we should hold fast to the fundamental principles of republican government, which have been our guaranty of liberty and human rights and of orderly progress for a century and a quarter.

The political wisdom of our forefathers has been abundantly vindicated in our experience. Older countries in continental Europe and in the Orient are turning toward us more and more and fashioning their political institutions after ours.

We need not be quick to surrender the present well-tried guaranties we have of justice and the rights of men for theories which neither upon good reason nor upon experience are commended to our best judgement.

The program which lies before you is full of the promise of entertainment and instruction. Men of wide experience, students of our economic and social needs, will lay before you the rich fruit gathered by them in the fields of their activities. Specialists in many branches of the great work of Conservation will make you their debtors. I shall not, of course, attempt to anticipate the subjects upon which they will enlighten you.

Custom, my friends, alone has led me to make the observations in which I have indulged in extending you welcome on behalf of the State[Pg 31] of Indiana. It is quite unnecessary to occupy your time in discharge of this pleasant duty, which but for his enforced absence would have been performed by the distinguished Governor of the State.

You would understand me, I know, if I merely said “Welcome.” You would know that it was no perfunctory utterance, but that it came from the bottom of the Hoosier heart. In a sense we do not look upon you as our guests; we prefer to regard you as members of our household. (Applause.)

President White—The thanks of the delegates, the thanks of the visitors, and the thanks of the people of the United States are due and will be given to the Hon. Charles W. Fairbanks for this most intelligent address, this statement of the principles that lie at the heart of every true conservationist. (Applause.) He has taken a forward step, he has led in the great movement in his own State, and he is now president of the Indiana Forestry Association.

I want to say that it is very fortunate for the people of the country that this address, and others that will follow, will be published and sent broadcast over this great land. We are going to teach the principles of conservation in every home.

It is now fitting that the next speaker should be also a conservationist—a conservationist of a different type, but no less a true conservationist, for at his hands, through his work, has come to the City of Indianapolis a reduction in fire loss from $600,000 to $300,000 annually. He is President of the Merchants’ and Manufacturers’ Insurance Bureau, and has practiced conservation in a most practical manner by reducing the fire loss and saving money to the people. We who have investigated that subject in Germany and other countries know how necessary it is that it should be brought home to us here in our cities and our homes. I now have the pleasure of introducing to you the Chairman of the Local Board of Managers, Mr. Richard Lieber. (Applause.)

Mr. Lieber—Mr. President, Ladies and Gentlemen: It is a very great pleasure and a distinguished honor to welcome you to our city upon this auspicious occasion. The City of Indianapolis deeply appreciates your coming and knows that through participation in your assemblages and deliberations it will materially profit in those matters which are of such vast and comprehensive benefit to its citizens. From here, through your able and learned speakers, potential knowledge will be disseminated throughout the length and breadth of our beloved country, which, in its application, will increase the happiness, contentment and usefulness of our people.

You have come here to consider most serious problems regarding the conservation of national wealth, more particularly that of vital resources, and above all, the conservation of human life.

[Pg 32]

For that reason, coupled with our welcome, is our expression of thanks for your coming, for “your worth is warrant of your welcome.”

The thought of conservation is comparatively new. It marks a new era in the development of the country, and nowhere are its lessons more intensely needed than in a country like ours, vast in its expanse, relatively sparsely populated and apparently inexhaustible in its natural riches.

But are these riches inexhaustible? Can we go on in the manner of our fathers and forefathers, who frequently had to destroy in self defense?

Not since the days of the migration of nations, not even since the legendary days of the fall of Troy has the world witnessed anything like this stupendous conquest of a virgin continent. It is an intensified Iliad of modern days. No comparison with former ages can suffice. What are even the wondrous tales of Moses’ messengers of the great land where “floweth milk and honey” compared with the gigantic proportions and abounding riches of this modern promised land?

That the pioneer, coming to this land was destructive before he could be constructive is a matter of historical truth. It could not have been otherwise. He fought civilization’s battle, that civilization may enjoy peace and prosperity. But some of these destructive habits of the settler have taken root in our being and destruction has continued where construction was needed. What have the American people not wasted! Land and water, fish and game, coal, natural gas and too many other riches. Above all, how many useful and dear lives are drawn into the surging maelstrom of our national waste through indifference, carelessness and greed!

We find ourselves confronted here with the anamorphosis of civilization.

Human sacrifice belongs to a dark and unenlightened day, but the human sacrifice in mills and mines, in railroads and sweatshops in our time is a dark blot upon our civilization. (Applause.)

In this mad chase after things material at any cost, we must pause, for a nation will become unbalanced in its natural progress if its spiritual and intellectual advance be retarded.

Conservation wishes to bring about a more harmonious blending of these national needs. It teaches a wholesome regard for created values, it preaches the sanctity of a child’s life and the economic value of our boys’ and girls’ health, and aside from general consideration where is an application of conservation ideals and principles more needed than in our cities. We must learn that a good man’s or woman’s example in the community is more beneficial and of greater force than a mere ordinance. Virtue, righteousness and high principle spring from the [Pg 33]seen of teaching that has fallen in mind and heart; they are inculcated but cannot be legislated. (Applause.)

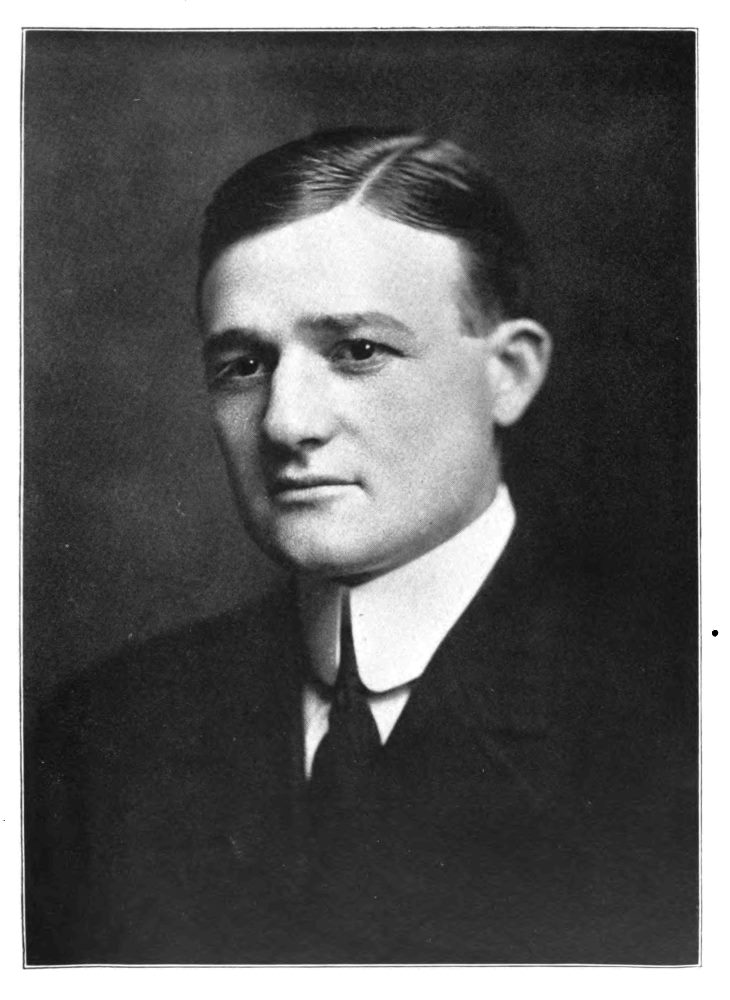

CHARLES LATHROP PACK

PRESIDENT, FIFTH NATIONAL CONSERVATION CONGRESS

Would it not in this connection be braver for us fathers and mothers to speak openly to our boys and girls concerning the dangers that beset them in their course of life end thus turn the energies of their lives into the board avenues of light, strength and usefulness than to let them be drawn into the abysmal chasm of a veritable hell of human waste. Would it not be better to save, to lessen the inflow, than to clog the mouth of this human sewer by police orders after prudery, hypocrisy and cowardice have filled it? (Applause.) We are everlastingly treating symptoms instead of diseases, attacking effects instead of causes, and we persistently thereby aggravate the malady.

Let us have more light of thought, more air of true freedom and a deeper and more sympathetic understanding of our own needs and those of our fellow man that we may be enabled to show the folly of vice, the contentment of virtue; that we may alleviate pain and want, and that the warmth of human sympathy may send hope to the hopeless, courage to the faltering and faith to the despondent.

With these fervent wishes the City of Indianapolis welcomes the Fourth National Conservation Congress. (Applause.)

President White—These words of welcome, coming from a different point of view, are felt deeply by us all. We feel the spur of duty still greater.

It is very fitting that another side of conservation should be heard from. The business men, the local business organizations of a city have done a good work for conservation. Human efficiency is one of the greatest forces that move the world, and systematic organization is one of the greatest powers towards efficient conservation of life and of all material progress. A business man knows that his success depends upon perfect organization, and that perfect organization is just as necessary to the conservation of every natural resource.

I have the pleasure of introducing to you Mr. Winfield Miller, of Indianapolis, who speaks on behalf of the local business organizations. (Applause.)

Mr. Miller—Mr. President, Ladies and Gentlemen: When I was honored by the commercial organizations of Indianapolis with the invitation to extend for them a few words of greeting and welcome to this National Conservation Congress, I looked into the biggest book, the Dictionary, for a definition of the word “Conservation.” I found the word concisely defined to mean “the art of preserving from decay, loss or injury.” While the definition is not extended, it is comprehensive and can be readily amplified to cover every phase of the question.

[Pg 34]

I then turned to the greatest book, the Bible, and read that early edict which still holds good, “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread.” Over this ancient decree and its cause, there have been volumes of theological commiseration, but in the light of subsequent history, it is now generally agreed that man has been a greater force in the garden of the world that if he had remained in the Garden of Eden.

The thought occurs, however, that resting under the edict of life-long toil man would, from an early period, have practiced conservation in all things. But he soon discovered that “the earth and the fulness thereof” were his, and, as ever, has been injuriously careless of results.

Again, he was not left without hope. The same great authority, in language and grandeur of thought unsurpassed, gives a promise of perpetual inspiration, in this, that “While the earth remaineth, seed time and harvest, and cold and heat, and summer and winter, and day and night shall not cease.” This promise, according to accepted chronology, has the confirmation of forty centuries of time and gives man the assurance of a continued field in which to do his work. The earth, the air, the waters are his environment; they are immutable, unchangeable. The animal, vegetable and mineral kingdoms furnish him food, clothing, shelter, life. Their best use should be his first and highest consideration.

Nature has been prodigal in her gifts to man. Her kingdoms have been his to rightfully exploit. But too long and too often has selfish and neglectful exploitation been his purpose and practice.

There is abundance for all if nature’s forces are properly conserved and her products fairly distributed. But some men, in their greed and haste, have grabbed a thousand-fold more than their necessities or happiness required. They eat their bread in the sweat of the other man’s face. On the other hand, the many have been ignorantly neglectful of the opportunities of their environments—so that life presses hard, too hard. Avarice, ignorance, waste, have linked arms to the detriment of civilization.

We must strive for the necessities of food, clothing and shelter. These sustain animal life, which is worth while; but animal life, endowed with the highest moral and mental strength, is the goal to be reached, for the summit of man’s ambitions should shine with human comfort and happiness. Conservation is the road to that summit and this National Congress has convened to further blaze the path and light the road. (Applause.)

Inventions of the last century, mostly within the half century, have injected into the field of travel and communication means that excite profound admiration; chemical analysis of the air and soil have shown that the food supply of the world, if nature’s forces are properly conserved, is without limit; while the mighty strides made in the better[Pg 35] understanding of the physical needs of man himself insure the race at large improved health and longer life.

May I briefly indulge in a few common illustrations? The telegraph, the telephone, the automobile, steam and electric power save time and shorten distance. In that part of commerce relating to traffic we have caught the spirit of conservation. The railroad builder no longer takes the route of the least resistance in construction, but applies the geometric proposition that the straightest line is the shortest distance between two given points, works to that end, meets the difficulties of engineering, reduces gradients, and practically builds his road along the line of least resistance, conserves time, saves energy, increases efficiency and lessens rates.

The school books tell us of the “Seven Wonders” of the ancient world—the Pyramids, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and so on; all to gratify the vanity of kings and queens; not one for the advancement of civilization.

In a little more than two years the dream of four centuries will be realized—the Panama Canal will be completed. The distance from the Occident to the Orient will be shortened seven thousand miles—the truly modern wonder in advancing civilization and practical conservation. (Applause.)

While the physical aspects of this mighty work, as they relate to the traffic and commerce of the world, stand out in bold relief, but little less, if any, in achievement, is the practical demonstration that scientific sanitary methods can clean the plague spots of the world and make them healthy and habitable for man.

Who can compute the saving of time and energy this mighty work will bestow on the generations to come. Long after the passions of this generation have ceased, history will record the names of the strong men who have brought to full consummation this great waterway, as true benefactors of mankind.

At this time, our public press is ecstatic over the great harvests of 1912 that promise such abounding prosperity. Some writers are so extravagant as to say that the bountiful yields from our soil make an epoch in history. To speak of one crop only, the corn, or Indian maize crop, spreads over 108,000,000 acres, and is estimated to be 3,000,000,000 bushels. How enormous! At fifty cents a bushel, its money value would be $1,500,000,000, or $16.00 to every man, woman and child in the United States. Measured in bread, there would be enough to give to each of our 93,000,000 of people a five-cent loaf for more than 320 days, or nearly one full year. As gratifying as this is, the average yield is only twenty-seven bushels per acre; while it is shown that, by proper selection of seed, cultivation and fertilization of the soil, easily twice the yield could be produced, which would double the benefits enumerated.

[Pg 36]

How often do we pass a barren field, the soil too impoverished to grow wire grass, nettles, or thistles. The every-day farmer will tell you that a crop or two of clover will restore the necessary plant life to the soil of that field, and again make it blossom like the rose. He knows from practical observation and experience the cure, if he cannot scientifically trace the cause of the transformation.

Truly truth is stranger than fiction. Back of the restoration of a thousand barren fields restored to productiveness in the simply way named, lies one of the world’s greatest romances in patient scientific investigation that will continue to bring untold benefits to mankind. You know the story of Professor Nobbe, of Forest Academy, Germany. He also knew that clover and other legumens of the plant family would restore fertility to the soil. But why? After long and exhaustive study, labor and experiment, he found that the clover family were nature’s chemist of the soil; that by an invisible, intangible cord of attraction they drew from the inexhaustible reservoir of the air nitrogen so necessary to plant and animal life.

We are told that “nitrogen is what makes the muscles and brain of man; that it is the essential element of all elements in the growth of animals and plants, and, significantly enough, it is also the chief constituent of the gunpowder and other explosives with which the wars of the world are waged. The single discharge of a 13-inch gun liberates enough nitrogen to produce scores of bushels of wheat.”

Some day, through this agency, man may turn his attention entirely from war to the production of food, and in that hour true conservation of life will have reached its triumph.

We are further told that four-fifths of the air we breath is nitrogen, and that four-fifths of the atmosphere around us is nitrogen, so that if mankind dies of nitrogen starvation, it will die with food everywhere in and about it.

So that, while the human race may be but from three to six months behind abject starvation, the fact begins to appear that through science “mankind has just begun to sound the world’s capacity for food production and that it is practically limitless.”

The proper conservation of the soil by the application of the research of scientific discovery means increased yields of all plant crops, with but little greater expenditure of energy. This would enable the producer of food and clothing to sell more pounds, bushels and yards at less cost, and still reap as great reward for his labor as at present. This would forestall the Malthusian doctrine that population increases faster than the means of subsistence and, still better, would help to solve the high cost of living that presses so sorely upon the millions throughout the world today. Man is a productive machine; so the more machines of the highest type the world possesses the better for the world.

[Pg 37]

This conservation movement that is so strongly taking hold of the minds of thinking men and women, is so big, so broad and so comprehensive that it covers every phase of human thought and activity in what is best and highest for the individual as well as organized society. It is education in the broadest sense.

The Golden Rule is not only a statement but a living principle. To teach that a just distribution of nature’s gifts to each individual who is willing to earn and conserve his share is a recognition of that principle.

The City of Indianapolis esteems it a high honor to have this Congress with us. To all of its members, and especially to the distinguished men from other lands who have come to give us their best thought upon the various questions affecting this great movement, we extend our most cordial welcome and greeting, and our deep appreciation of your presence.

Our commercial organizations also cordially join in holding the door of welcome and hospitality open to you, and bespeak for your deliberations their kindest sympathy and deepest interest.

President White—This is a proud day for the officers of this Congress, for its delegates from the different States, and for the friends of Conservation everywhere, to be welcomed so hospitably, not only for ourselves who are strangers within your gates, but generously because of your sympathy in the great cause for which we stand. The citizens of your great city are noted for their public spirit, for their broad culture, and as being always found in the van with the army of those of progressive ideas. It is very fitting that the State of Indiana should have this Congress within its borders because of the immense interest shown and all the valuable help given by its citizens in the conservation of all natural resources, especially of human life and soil fertility.

To become the best, to do the best for all in a community, we must each develop the best within us, and must find our greatest reward in something far beyond the mere accumulation of dollars. Our community of interests recognizes a reciprocity of duty each to and for the other. Our title to the regard of our fellow men must come from our devotion to them and our love of humanity and its highest ideals, and not from selfish zeal in accumulating monetary wealth, which only represents the toil, the waste, and the necessities of human lives. This has been and is the age of commercialism. The measure of success has been gauged by the amount of money accumulated. In the language of Goldsmith, our country was in danger of descending to a condition “where wealth accumulates and men decay.” But I believe a turning point has been reached; and that we are entering upon a new era, a more glorious conception of higher duties for mankind; so that it shall not be asked: “What hath he taken from others in the competitive struggle for existence,”[Pg 38] but rather: “What hath he given to others of himself for their advancement and development?” He who lives only for himself and does not plant for those that are to come after him, lives in vain. I believe the time is near at hand when a man shall be regarded with pity and as very poor indeed, who has nothing but money selfishly gained for selfish use.

The Conservation Congress of the United States has a great field to occupy. Its labors are for the betterment of its citizens in every way. Its work is to seek for the best methods to do the greatest good to all for this and for future generations. And in this there is no partisan politics; but it is such good national politics, that each party will strive only in seeking for the best methods for the common good.