Title: "No. 101"

Author: Wymond Carey

Illustrator: Walter Paget

Release date: January 17, 2023 [eBook #69819]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: G. P. Putnam's Sons

Credits: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

By Wymond Carey

MONSIEUR MARTIN

A ROMANCE OF THE GREAT

SWEDISH WAR

Crown octavo. (By mail, $1.35.) Net, $1.20

| “NO. 101” |  |

| Illustrated. Crown octavo. $1.50. |

G. P. Putnam’s Sons

New York London

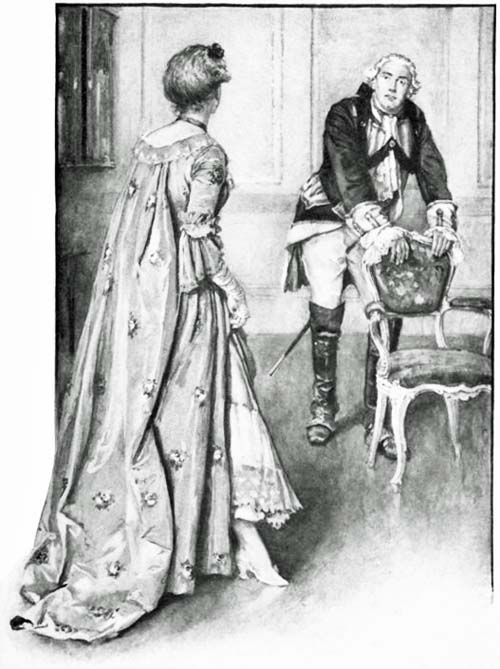

“The Vicomte henceforth cannot without harming himself

visit publicly a bourgeoise grisette.”

(See page 158.)

BY

Wymond Carey

Author of “Monsieur Martin,” “For the White Rose,” etc.

G. P. Putnam’s Sons

New York and London

The Knickerbocker Press

1905

Copyright, 1905

BY

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

TO

MY MOTHER

There was a real “No. 101.” Unpublished MS. despatches now in the Record Office of the British Museum reveal the interesting fact that on more than one occasion the British Government obtained important French state secrets through an agent known to the British ministers as “No. 101.” Who this mysterious agent was, whether it was a man or a woman, why and how he or she so successfully played the part of a traitor, have not, so far as is known to the present writer, been discovered by historians or archivists. The references in the confidential correspondences supply no answer to such questions. If the British ministers knew all the truth, they kept it to themselves, and it perished with them. Doubtless there were good reasons for strict secrecy. But it is more than possible that they themselves did not know, that throughout they simply dealt with a cipher whose secret they never penetrated. It is, however, clear that “No. 101” was in a position to discover some of the most intricate designs in the policy of the French Court, and that the British Government, through its[vi] agents, was satisfied of the genuineness of the secrets for which it paid handsomely.

On the undoubted existence of this mysterious cipher, and the riddles that that existence suggests, the writer has based his historical romance.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | “No. 101” | 1 |

| II. | One-Fourth of a Secret and Three-Fourths of a Mystery | 12 |

| III. | A Fair Huntress and the Girl with the Spotted Cow | 26 |

| IV. | A Lover’s Trick | 39 |

| V. | The Presumption of a Beardless Chevalier | 53 |

| VI. | The Wise Woman of “The Cock with the Spurs of Gold” | 66 |

| VII. | The King’s Handkerchief | 78 |

| VIII. | The Vivandière of Fontenoy | 95 |

| IX. | At the Charcoal-Burner’s Cabin in the Woods | 109 |

| X. | Fontenoy | 121 |

| XI. | In the Salon de la Paix at Versailles | 137 |

| XII. | A Royal Grisette | 149 |

| XIII. | What the Vicomte de Nérac Saw in the Secret Passage | 160 |

| XIV. | Two Pages in the Book of Life | 171 |

| XV. | André is Thrice Surprised | 182 |

| XVI. | The Fountain of Neptune | 196 |

| XVII. | Denise’s Answer | 207 |

| XVIII. | The heart of the Pompadour | 220[viii] |

| XIX. | The Flower Girl of “The Gallows and the Three Crows” | 231 |

| XX. | At Home with a Cipher | 244 |

| XXI. | The King’s Commission | 253 |

| XXII. | On Secret Service | 264 |

| XXIII. | The King Faints | 274 |

| XXIV. | A Wished-for Miracle | 285 |

| XXV. | The Fall of the Dice | 297 |

| XXVI. | The Thief of the Secret Despatch | 308 |

| XXVII. | The Chevalier Makes his Last Appearance | 319 |

| XXVIII. | The Carrefour de St. Antoine No. 3 | 330 |

| XXIX. | André Fails to Decide | 339 |

| XXX. | Denise Has to Decide for the Last Time | 354 |

| XXXI. | Fortune’s Banter | 366 |

| PAGE | |

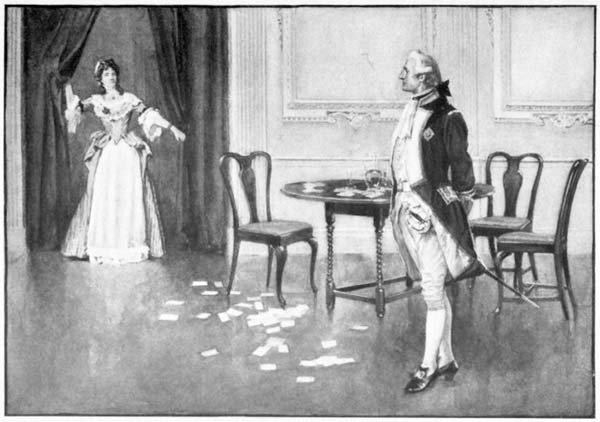

| “The Vicomte Henceforth Cannot without Harming Himself Visit Publicly a Bourgeoise Grisette” | Frontispiece |

| Statham Sat Pondering, His Eyes Riveted on the Crossed Daggers | 6 |

| “Is That Letter to the Comtesse des Forges, One of My Friends—My Friends, Mon Dieu!—Yours, or Is It not?” | 48 |

| “Fair Archeress,” He Said, “Surely the Shafts You Loose Are Mortal” | 88 |

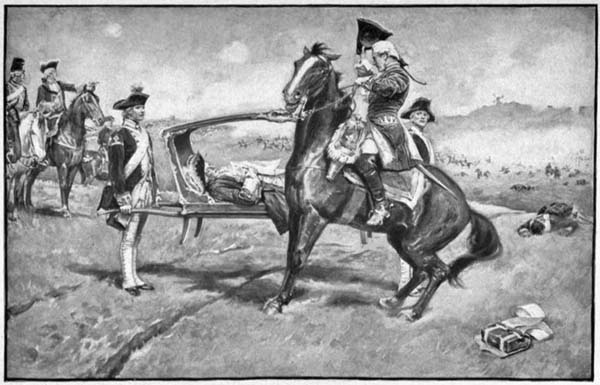

| Yes, that is Monseigneur le Maréchal de Saxe, Carried in a Wicker Litter, for He Cannot Sit His Horse | 124 |

| Madame de Pompadour | 188 |

| The Curtain Was Sharply Flung aside, and He Saw Denise | 204 |

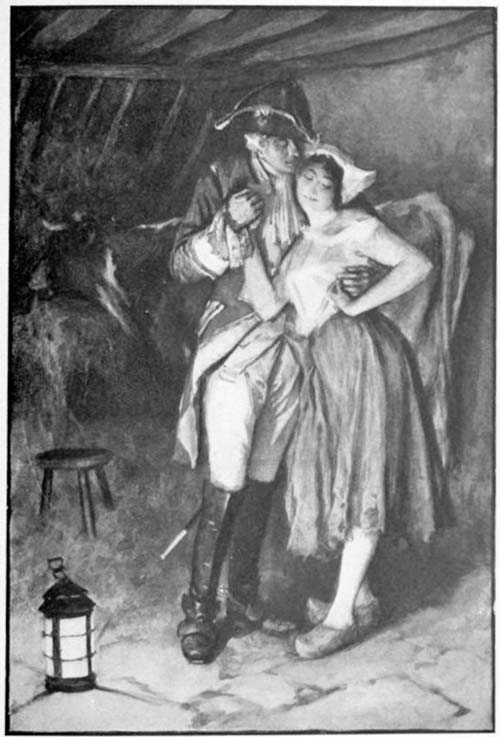

| Yvonne Very Modestly Disengaged the Arm which for the First Time He Had Slipped about Her Supple Waist | 234 |

| Yvonne with a Finger to Her Lips, Holding Her Petticoats off the Floor, Stole In, and behind Her a Stranger | 268[x] |

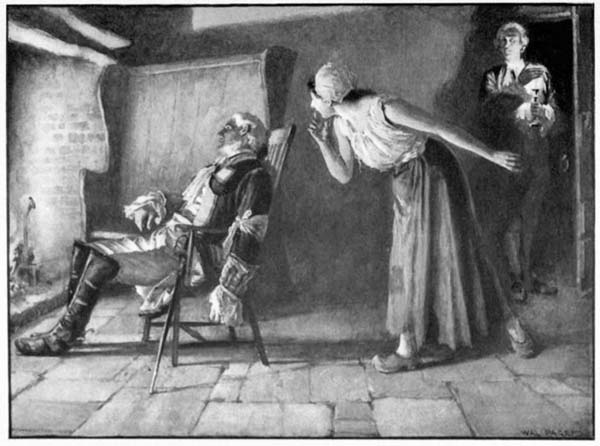

| The Candle Fell from Her Hand. “Gone!” She Muttered Feebly, “Gone!” | 320 |

| “Yvonne, of Course; Yvonne of the Spotless Ankles,” She Lifted Her Dress a Few Inches | 350 |

NO. 101.

NO. 101

One evening in the January of 1745, the critical year of Fontenoy and of the great Jacobite rising, a middle-aged gentleman, the private secretary of a Secretary of State, was working as usual in the room of a house in Cleveland Row. The table at which he sat was littered with papers, but at this precise moment he had leaned back in his chair with a puzzled expression and his left hand in perplexity pushed his wig awry.

“Extraordinary,” he muttered, “most extraordinary.” The remark was apparently caused by an official letter in his other hand—a letter marked “Most Private,” which came from The Hague, and the passage which he had just read ran:

“I have the honour to submit to you the following important communication in cipher, received, through our agent at Paris, from ‘No. 101,’” etc.

On the table lay the cipher communication together[2] with a decoded version which the secretary now studied for the third time. In explicit language the despatch supplied detailed information as to certain recent highly confidential negotiations between the Jacobite party in Paris and the French King, Louis XV., a revelation in short of the most weighty state secrets of the French Government.

“‘No. 101,’” the secretary murmured, scratching his head, “always ‘No. 101.’ It is marvellous, incredible. How the devil can it be done?”

But there was no answer to this question, save the fact which provoked it—that closely ciphered paper with its disquieting information so curiously and mysteriously obtained.

“Ah.” He jumped up and hurriedly straightened his wig. “Good-evening to you.”

The new-comer was a man of about five-and-thirty, tall, finely built, and of a muscular physique, with a face of considerable power. Most noticeable, perhaps, in his appearance was his air of disciplined reserve, emphasised in his strong mouth and chin, but almost belied by the glow in his large, dark eyes, which looked you through and through with a strangely watchful innocence.

“There is work to be done, sir?” he asked as he took the chair offered.

“Exactly. To-day we have received most gratifying and surprising information from our friend ‘No. 101’—and we have the promise of more.”

[3]“Yes.” The brief monosyllable was spoken almost softly, but the dark eyes gleamed, as they roamed over the room.

“The communications from ‘No. 101’ have begun again,” the secretary pursued; “that in itself is interesting. The Secretary of State therefore desired me to send at once for you, the most trustworthy secret agent we have. In a very few minutes Captain Statham of the First Foot Guards will be here—”

“Sent, I think, from the Low Countries at the request of our agents at The Hague?”

“Ah, I see you are as well informed as usual. You are quite right. Are you,” he laughed, “ever wrong?”

The spy paused. “The communications then from ‘No. 101’ concern the military operations?” was all he said.

“Not yet. But,” he almost laughed, “we have a promise they will. You know the situation. This will be a critical year in Flanders. Great Britain and her allies propose to make a great, an unprecedented effort; his Royal Highness the Duke of Cumberland will have the supreme command. Unhappily the French under the Maréchal de Saxe apparently propose to make even greater efforts. With such a general as the Maréchal against us we cannot afford to neglect any means, fair or foul, by which his Royal Highness can defeat the enemy.”

“Then you wish me to assist ‘No. 101’ in betraying[4] the French plans to our army under the Duke of Cumberland?”

“Not quite,” the other replied; “we cannot spare you as yet. But you have had dealings with this mysterious cipher, and we ask you to place all your experience at the disposal of Captain Statham.”

“I agree most willingly,” was the prompt answer.

“This curious ‘No. 101,’” continued the secretary slowly, “you do not know personally, I believe?”

The other was looking at him carefully but with a puzzled air.

“I ask because—because I am deeply curious.”

“I am as curious as yourself, sir. ‘No. 101’ is to me simply a cipher number,—nothing more, nothing less.”

“I feared so,” said the secretary. “But is it not incredible? The information sent always proves to be accurate, but there is never a trace of how, why, or by whom it is obtained.”

“That is so. Secrecy is the condition on which alone we get it. We pay handsomely—we obtain the truth—and we are left in the dark.”

“Shall we ever discover the secret, think you?”

“I am sure not.” The tone was conviction itself.

At this moment Captain Statham was ushered in, a typical English gentleman and officer, ruddy of countenance, blue-eyed, frankness and courage in every line of his handsome face and of his athletic figure.

“Captain Statham—Mr. George Onslow of the[5] Secret Service—” the secretary began promptly, adding with a laugh as the two shook hands: “Ah, I see you have met before. I am not surprised. Mr. Onslow knows everybody and everything worth knowing.” He gathered up a bundle of papers. “That is the communication from ‘No. 101’ and the covering letter. And now, gentlemen, I will leave you to your business.” He bowed and left the room.

Onslow took the chair he had vacated and for a quarter of an hour Captain Statham and he chatted earnestly on the position of affairs in the Low Countries, and the war then raging from the Mediterranean to the North Sea, on the vast efforts being made by the French for a great campaign in the coming spring, the military genius of the famous Maréchal de Saxe, the Austrian and Dutch allies of Great Britain, and the new English royal commander-in-chief who was shortly to leave to take over the work of saving Flanders from the arms of Louis XV. Onslow then briefly explained what the Secret Service agents of the Duke of Cumberland were to expect and why.

“Communications,” he wound up, “from this mysterious spy and traitor, ‘No. 101,’ invariably come like bolts from the blue. They are, of course, always in cipher and they will reach you by the most innocent hands—a peasant, a lackey, a tavern wench—sometimes you will simply find them, say, under your pillow, or in your boots. No one can tell how they get there. But never neglect them, however strange or unusual[6] their contents may be, for they are never wrong—never! The genuine ones you will recognise by this mark—” he took up the ciphered paper and put his fingers on a sign—“two crossed daggers and the figures 101 written in blood—you see—so”:

Captain Statham stared at the sign, entranced.

“A soldier,” Onslow remarked with his slow smile, “can always distinguish blood from red ink—is it not so?” Statham nodded. “Remember, then, those crossed daggers with the figures in blood are the only genuine mark. All others are forgeries—reject them unhesitatingly. Let me show it you again.” He produced from his pocket-book a paper with the design in the corner, which, when compared with the one on the table, corresponded exactly.

“I warn you,” Onslow added, “because the existence of this ‘No. 101’ is becoming known to the French—they suspect treachery—their Secret Service is clever and they may attempt to deceive you. As they do not know the countersign, though they may have guessed at the treachery of ‘No. 101’ they cannot really hoodwink you. Cipher papers which come in the name of ‘101’ without that remarkable signature are simply a nom de guerre, of politics, of love, of anything you like, but they are either a forgery or a trap; so put them in the fire.”

Statham sat pondering, his eyes riveted on the crossed daggers.

[7]Statham sat pondering, his eyes riveted on the crossed daggers. “You, sir,” he began, “have had dealings with this mysterious person. Is it a man or a woman?”

“Ah!” Onslow laughed gently. “Every one asks that, every man at least. I cannot answer; no one, indeed, can. My opinion? Well, I change it every month. But these are the facts: It is absolutely certain that the traitor insists on high, very high pay; absolutely certain that he or she has access to the very best society in Paris and at the Court, and is at home in the most confidential circles of the King and his ministers. We have even had documents from the private cabinet of Louis XV. Furthermore, the traitor can convey the information in such a way as to baffle detection. If it is a woman she is a very remarkable one; if it be a man he is one who controls important women. Perhaps it is both. Such knowledge, so peculiar, so accurate, so extensive, such skill and such ingenuity scarcely seem to be within the powers of any individual man or woman.”

“Every word you say sharpens my surprise and my curiosity.”

“Yes, and every transaction you will have with the cipher will sharpen it more and more. I have been fifteen years in the Secret Service, but this business is to-day as much a puzzle as it ever was, for ‘No. 101’ has taught me a very important secret, one unknown even to the French King’s ministers, which, so jealously guarded as it is, may never be discovered in the[8] King’s lifetime or at all. Can you really believe that Louis, while professing to act through his ministers, has stealthily built up a little secret service of his own whose work is to spy on those ministers, on his ambassadors, generals, and their agents, to receive privately instructions wholly different from what the King has officially sanctioned, and frequently directly to thwart, check, annul, and defeat by intrigue and diplomacy the official policy of their sovereign?”

“Is it possible?”

“It is a fact,” Onslow said, emphatically. “But the King, ‘No. 101,’ you and I and one or two others alone know it. Let me give you a proof. To-day officially Louis through his ministers has disavowed the Jacobites. The ministers believe their master is sincere; many of them regret it, but their instructions are explicit. In truth, through those private agents I spoke of, the King is encouraging the Jacobites in every way and is actually thwarting the steps and the policy which he has officially and publicly commanded.”

“And the ministers are ignorant of this?”

“Absolutely. But mark you, unless the King is very careful, some day there will come an awkward crisis. His Majesty will be threatened with the disclosure of this secret policy which has his royal authority, but which gives the lie to his public policy, equally authentic. And unless he can suppress the first he must be shown to be doubly a royal liar—not to dwell on the consequences to France.”

[9]“What a curious king!” Statham ejaculated.

“Curious!” Onslow laughed softly; “more than curious, because no one knows the real Louis. The world says he is an ignorant, superstitious, indolent, extravagant, heartless dullard in a crown who has only two passions—hunting and women. It is true; he is the prince of hunters and the emperor of rakes. But he is also a worker, cunning, impenetrable, obstinate, remorseless.”

“But why does he play such a dangerous game?”

“God knows. The real Louis no man has discovered, or woman either; he is known only to the Almighty or the devil. But you observe what chances this double life gives to our friend ‘No. 101.’”

Statham began to pace up and down. “What are the traitor’s motives?” he demanded, abruptly.

“Ah, there you beat me.” Onslow rose and confronted him. “My dear sir, a traitor’s motives may be gold, or madness, ambition, love, jealousy, revenge, singly or together, but above all love and revenge.”

Statham made an impatient gesture. “I would give my commission,” he exclaimed, “to know the meaning of this mystery.”

A sympathetic gleam lingered in Onslow’s eyes as he calmly scrutinised the young officer. “Ah,” he said, almost pityingly, “you begin to feel the spell of this mystery wrapped in a number, the spell of ‘No. 101,’ the fatal spell.”

“Fatal?” Statham took him up sharply.

[10]“Yes. I must warn you. Every single person who, in his dealings with this cipher, has got near to the heart of the truth has so far met with a violent end. It is not pleasant, but it is a fact. And the explanation is easy. Those who might betray the truth are removed by accident or design, some by this method, some by that. They pass into the silence of the grave, perhaps just when they could have revealed what they had discovered.” He paused, for Statham was visibly impressed. “Really there is no danger,” he added; “but I say as earnestly as I can, because you are young, and life is sweet for the young, for God’s sake stifle your curiosity, resist the spell—that fatal spell. Take the information as it comes, and ask no questions, push no inquiries, however tempting and easy the path to success seems, or, as sure as I stand here, His Majesty King George the Second will lose a promising and gallant officer.”

Statham walked away and resumed his seat. “And you, Mr. Onslow?” he demanded, looking up with the profoundest interest.

“Do I practise what I preach? Well, I am a spy by profession: to some men such a life is everything—it is, at least, to me. But I do not conceal from myself that if my curiosity overpowers me my hour for silence, too, will come—the silence of the unknown grave in an unknown land.”

“Then is no one ever to know?” Statham muttered with childish petulance.

[11]“Probably not. A hundred years hence the secret that baffles you and me will baffle our successors.”

Statham’s heels tapped on the floor. “Perhaps,” he pronounced, slowly, “perhaps the truth is well worth the price that is paid for it—death and the silence of the grave.”

Onslow stared at him. His eyes gleamed curiously as if they were fixed on visions known only to the inner mind. “Perhaps,” he repeated gravely. “But really,” he added, with a sudden lightness, “there is no one to persuade us it is so. Come, Captain Statham, you have not forgotten supper, I hope, and that I propose to introduce you to-night to the most seductive enchantress in London?”

“No, indeed. All day I have been hungering for that supper. In the Low Countries we do not get suppers presided over by ladies such as you have described to me.”

“In the French army they have both the ladies and the suppers,” Onslow replied, laughing. “And, my dear Captain, to the victors of the spring will fall the spoils. To-night shall be a foretaste, and if my enchantress does not make you forget ‘No. 101,’ I despair of the gallantry of British officers.”

He locked up the papers, chatting all the time, and then the two gentlemen went out together.

For some minutes the pair walked in silence, as if each was still brooding on the mysterious cipher whose treachery to France had brought them together. But presently Statham touched Onslow on the arm. “Tell me,” he said, “something of this enchantress. I am equally curious about her.”

“And I know very little,” Onslow replied. “Her mother, if you believe scandal, was a famous Paris flower girl, who was mistress in turn to half the young rakes of the noblesse; her father is supposed to have been an English gentleman. Your eyes will tell you she is gifted with a singular beauty, which is her only dowry. Gossip says that she makes that dowry go a long way, for she has two passions, flowers and jewels.”

“And she resides in London?”

“She resides nowhere,” Onslow answered with his slow smile; “she is here to-day and away to-morrow. I have met her in Paris, in Brussels, Vienna, Rome. She talks French as easily as she talks English, and[13] wherever she is her apartments are always haunted by the men of pleasure, and by the grand monde. Women you never meet there, for she is not a favourite with her own sex, which is not surprising.”

“Pardon,” Statham asked, “but is she—is she, too, in the Secret Service?”

“God bless my soul! No; we don’t employ ladies with a passion for jewels. It would expose them and us to too many temptations. And, besides, politics are the one thing this goddess abhors. Eating, drinking, the pleasures of the body, poetry, philosophy, romance, the arts, and the pleasures of the mind she adores; luxury and jewels she covets, but politics, no! They are a forbidden topic. For me her friendship is convenient, for the politicians are always in her company. When will statesmen learn,” he added, “that making love to a lady such as she is is more powerful in unlocking the heart and unsealing the lips than wine?” “And her name?”

“She has not got one. ‘Princess’ we call her and she deserves it, for she is fit to adorn the Palace of Versailles.”

“Perhaps,” said Statham, “she will some day.”

“Not a doubt of it—if Louis will only pay enough.”

They had reached the house. Statham noticed that Onslow neither gave his own nor asked for his hostess’s name. He showed the footman a card, which was returned, and immediately they were ushered into two handsome apartments with doors leading the one into[14] the other, and in the inner of the two they found some half-dozen gentlemen talking. Three of them wore stars and ribbons, but all unmistakably belonged to that grand monde of which Onslow had spoken. From behind the group the lady quietly walked forward and curtsied deferentially to Statham, who felt her eyes resting on his with no small interest as his companion kissed her hand. The secret agent had not exaggerated. This woman was indeed strikingly impressive. About the middle height, with a slight but exquisitely shaped figure, at first sight she seemed to flash on you a vision composed of dark masses of black hair, large and liquid blue eyes, and a dazzling skin, cream-tinted. Dressed in a flowing robe of dark red, she wore in her hair blood-red roses, while blood-red roses twined along her corsage, which was cut, not without justification, daringly open. Her bare arms, her theatrical manner, and the profusion of jewels which glittered in the candle-light suggested a curious vulgarity, which was emphasised by her speech, for her English, spoken with the ease of a native, betrayed in its accent rather than its words evidence of low birth. Yet all this was forgotten in the mysterious charm which clung about her like a subtle and intoxicating perfume, and as Statham in turn kissed her jewelled hand, a fleeting something in her eyes, at once pathetic and vindictive, shot with a thrill through him.

“An English officer and a friend of Mr. Onslow,” she remarked, “is always amongst my most welcome[15] guests,” and then she turned to the elderly fop in the star and ribbon and resumed her conversation.

Statham studied her carefully. Superb health, a superb body, and a reckless disregard of convention she certainly had, but the more he observed her the more certain he felt that that wonderful skin as well as those lustrous blue eyes and alluring eyebrows owed more to art than to nature. In fact every pose of her head, every line in her figure, the scandalous freedom of her attire were obviously intended to puzzle as much as to attract—and they succeeded. She was the incarnation of a fascination and of a puzzle.

Two more gentlemen had arrived, and Statham was an interested spectator of what followed.

“Princess,” the new-comer said, “I present to you my very good friend the Vicomte de Nérac.”

The lady turned sharply. Was it the visitor’s name or face which for the moment disturbed her equanimity?—yet apparently neither the Vicomte nor she had met before.

“Welcome, Vicomte,” she said, so swiftly recovering herself that Statham alone noticed her surprise, if it was surprise. “And may I ask how a Capitaine-Lieutenant of the Chevau-légers de la Garde de la Maison du Roi happens to be in England when his country is at war?”

“You know me, Madame!” the Vicomte stammered, looking at her in a confusion he could not conceal.

The lady laughed. “Every one who has been in[16] Paris,” she retorted, “knows the Chevau-légers de la Garde, and the most famous of their officers is Monsieur the Vicomte de Nérac, famous, I would have these gentlemen be aware, for his swordsmanship, for his gallantries—and for his military exploits which won him the Croix de St. Louis.”

“You do me too much honour, Madame,” the Vicomte replied.

“As a woman I fear you, as a lover of gallant deeds and as a fencer myself I adore you, as do all the ladies whether at Versailles or in Les Halles,” she laughed again. “But you have not answered my question. Why are you in England, Monsieur le Vicomte?”

“Nine months ago I had the misfortune to be taken prisoner, Madame, but in three weeks I return to my duty as a soldier and a noble of France.” He bowed to the company with that incomparable air of self-confidence tempered by the dulcet courtesy which was the pride of Versailles and the despair of the rest of the world.

“And here,” the lady answered, “is another gentleman who also shortly returns to his duty. Captain Statham of the First Foot Guards, Monsieur le Vicomte de Nérac of the Chevau-légers de la Garde. Perhaps before long you will meet again, and this time not in a woman’s salon.”

“When Captain Statham is taken prisoner,” the Vicomte remarked, smiling, “I can assure him Paris is not less pleasant than London, but till then he and I[17] must agree to cross swords in a friendly manner for the favours of yourself, Princess.”

“And you think you will win, Vicomte?”

“It is impossible we can lose,” the Vicomte replied. “Not even the gallantry of the First Foot Guards can save the allies from the genius of Monseigneur the Maréchal de Saxe.”

“We will see,” Statham responded gruffly.

“Without a doubt, sir.” The Vicomte bowed.

Statham stared at him stolidly. He could hardly have guessed that this exquisitely dressed gentleman with the slight figure and the innocently grand air was really a soldier, and above all an officer in perhaps the most famous cavalry regiment of all Europe, every trooper in which, like the Vicomte himself, was a noble of at least a hundred years’ standing, but he was reluctantly compelled to confess that the stranger was undeniably handsome, and his manner spoke of an ease and a distinction beyond criticism. His smile, too, was singularly seductive in its sweetness and strength, and his brown eyes could glitter with marvellous and unspeakable thoughts. From that minute he seemed to imagine that his hostess belonged to him: he placed himself next her at supper, he absorbed her conversation, and, still more annoying, she willingly consented. Statham in high dudgeon had to listen to the polite small talk of his English neighbour, conscious all the while that at his elbow the Vicomte was chattering away to “the princess” in the gayest French. And[18] after supper he along with the others was driven off to play cards while the pair sat in the other room alone and babbled ceaselessly in that infernal foreign tongue.

“The Vicomte,” Onslow said coolly, “has made another conquest.”

“It is true, then, that he is a fine swordsman as well as a rake?”

“Quite true. His victims amongst the ladies are as numerous as his victims of the sword. It is almost as great an honour for a man to be run through by André de Nérac as it is for a woman to succumb to his wooing. Do not forget he is a Chevau-léger de la Garde and a Croix de St. Louis.”

Statham grunted.

“It is not fair,” Onslow pursued, throwing down the dice-box. “You are not enjoying yourself,” and he rose and went into the other room. “Gentlemen,” he said, on his return, “I have persuaded our princess to add to our pleasure by dancing. In ten minutes she will be at your service.”

The cards were instantly abandoned and while they waited the Vicomte strolled in and walked up to Onslow.

“That is a strange lady,” he remarked, “a very strange lady. She knows Paris and all my friends as well as I do; yet I have never so much as seen her there.”

“Yes,” Onslow answered, looking him all over, “she is very strange.”

“And the English of Madame is, I think, not the[19] English of the quality?” Onslow nodded. “That, too, is curious, for her French is our French, the French of the noblesse. She says her father was an English gentleman, and her mother a Paris flower girl, which is still more curious, for the flower girls of Paris do not talk as we talk on the staircase Des Ambassadeurs at Versailles, or as my mother and the women of my race talk. Mon Dieu!” he broke off suddenly, for the princess had tripped into the room, turning it by the magic of her saucy costume into a flower booth in the market of Paris, and without ado she began to sing a gay chansonnette, waving gently to and fro her basket of flowers:

And the dance into which without a word of warning she broke was something to stir the blood of both English and French by its invincible mixture of coquetry, lithe grace, and audacious abandon, its swift transitions from a mocking stateliness and a tempting reserve to its intoxicating, almost devilish revelation of uncontrolled passion; and all the while that heartless, airy song twined itself into every pirouette, every pose, and was translated into the wickedest provocation by the twinkling flutter of her short skirt and the flashes[20] of the jewelled buckles in her saucy shoes. To Statham as to André de Nérac the princess had vanished, and all that remained was a witch in woman’s form, a witch with black hair crowned with crimson roses and a cream-tinted skin gleaming white against those roses at her breast.

“To the victor,” she cried, picking a nosegay from her basket, and kissing it, “to the victor of the spring!” and André and Statham found themselves hit in the face by the flowers. The salon rang with “Bravos” and “Huzzas” until every one woke to the discovery that the dancer had disappeared.

When she returned she was once more in her splendid robes and frigidly cynical as before.

“I am tired, gentlemen,” she said; “I must beg you to say good-night.” She held out her hand to the Vicomte. “Au revoir!” she said, permitting her eyes to study his olive-tinted cheeks and the homage of his gaze.

“Your prisoner, Madame,” he said, “your prisoner for always!”

“Or I yours?” she flashed back, swiftly.

And now she was speaking to Statham. “We shall meet again,” she said. “Yes, we shall meet again, Captain.”

“Not in London, Madame,” he answered.

“Oh, no! But I trust our meeting will be as pleasant for you as to-night has been for me.”

“It cannot fail to be.”

[21]“Ah, you never know. Women are ever fickle and cruel,” she answered, and once again as he kissed the jewelled fingers Statham was conscious of that pathetic, pantherish light in her great eyes, which made him at once joyous, sad, and fearful.

When they had all gone the woman stood gazing at her bare shoulders in the long mirror. “Fi, donc!” she muttered with a shrug of disgust, and she tore in two one of the cards with which the gamblers had been playing, allowing the fragments to trickle carelessly down as though the gust of passion which had moved her was already spent. Then she drew the curtains across the door between the two rooms, and remained staring into space. “André Pierre Auguste Marie, Vicomte de Nérac,” she murmured, “Seigneur des Fleurs de Lys, Vicomte de—” she smelled one of her roses, the fingers of her other hand tapping contemplatively on her breast. A faint sigh crept into the stillness of the empty, glittering room.

Then she flung herself on the low divan, put her arms behind her head, and lay gazing in front of her. The door was opening gently, but she did not stir. A man walked in noiselessly, halted on the threshold, and looked at her for fully two minutes. She never moved. It was George Onslow. He walked forward and stood beside her. She let her eyes rest on him with absolute indifference.

“There is your pass,” he said, in a low voice in which emotion vibrated.

[22]“I thank you.” She made no effort to take it, but simply turned her head as if to see him the better.

“Is that all my reward?” he demanded. “It was not easy to get that pass.”

“No?” She pulled a rose from her breast and sniffed it. “I believe you. I can only thank you again.”

He dropped the paper into her lap, where she let it lie.

“By God!” he broke out, “I wish I knew whether you are more adorable as you are now on that sofa, or as you were dancing in that flower girl’s costume.”

“Most men in London prefer the short petticoats,” she remarked, moving the diamond buckle on her shoe into the light, “but in Paris they have better taste, for only a real woman can make herself adorable in this”—she gave a little kick to indicate the long, full robe. “Think about it, mon ami, and let me know to-morrow which you really like the better.”

“And to-night?”

She stooped forward to adjust her slipper. “To-night,” she repeated, “I must decide whether I dislike you more as the lover of this afternoon, the man of pleasure of this evening, or the spy of to-morrow.”

He put a strong hand on her shoulder. In an instant she had sprung to her feet.

“No!” she cried, imperiously, “I have had enough for one day of men who would storm a citadel by insolence. Leave me!”

[23]“You are expecting some one?”

“And if I am?”

“Don’t torture me. Tell me who it is.”

“Perhaps you will have to wait till dawn or longer before you see him.”

“I will kill him, that is all,—kill him when he leaves this house.”

“I have no objection to that,” was the smiling answer. “One rake less in the world is a blessing for all women, honest or—” she fingered her rose caressingly.

“Is it one of those who were here to-night!” he demanded. “Perhaps that infernal libertine of a Vicomte de——”

“Pray, what have my secrets to do with you?” She faced him scornfully.

“This.” He came close to her. “You flatter yourself, ma mignonne, that you guard your secrets very well. So you do from all men but me. But I take leave to tell you that three-fourths of those secrets are already mine.” She sniffed at the rose in the most provoking way. “Yes, I have discovered three-fourths, and——”

“The one-fourth that remains you will never discover until I choose.”

“Do not be too sure.”

“And then——?”

“You, ma mignonne, you the guest of many men, will be in my power, and you will be glad to do what[24] I wish. Oh, I will not be your cur, your lackey, then, but you will——”

She dropped him a curtsey, and walked away to an escritoire, from a drawer in which she took out a piece of paper.

“The one-fourth that remains,” she said, holding it up, and offering it to him, “I give it to you, my cur and lackey.”

She watched him take it, unfold it, read it. His hand shook, the paper dropped from his fingers, and while he passed his handkerchief over his forehead she put the fragment in the fire.

They faced each other in dead silence. She was perfectly calm, but his mouth twitched and his eyes gleamed with an unhallowed fire and with fear.

“Are you mad?” he asked at last, “that you confess such a thing to me—me?”

“Better to you,” she retorted, “than to that infernal libertine, the Vicomte de Nérac, or that infernal simpleton, Captain Statham, eh? No, mon ami, my reason is this: Now, you, George Onslow, who profess to love me, who would make me your slave, are in my power, and the proof is that I order you to leave this room at once.”

“I shall return.”

“Then you certainly will be mad.”

“Ah!” He sprang forward. “Can you not believe that I love you more than ever? I——”

“Pshaw!”

[25]The door had slammed. Onslow was alone.

For a minute he stood, clenching his hands, frustrated passion glowing in his eyes. “Ah!” he exclaimed in a cry of pent-up anguish, and then the door slammed again as he strode out.

Two months later André, Vicomte de Nérac, was riding in the woods around Versailles, and, poverty-stricken, debt-loaded noble as he might be, his heart was gay, for was he not a Capitaine-Lieutenant in the Chevau-légers de la Garde, and a Croix de St. Louis; was he not presently about to fight again for honour and France, and was he not once more a free man and in his native land with Paris at his back? The leafless trees were just beginning to bud, though winter was still here, but the breath of spring was in the air and the gladness of summer shone in the March sun. Yes, the world bid fair to be kind and good, and André’s heart beat responsive to its call. Love and honour and France were his, and what more could a noble wish?

He let the reins drop and breathed with contentment the bracing breeze, while his eyes roamed to and fro. Clearly he was waiting for some one who, his anxious gaze up the road showed, might be expected to come[27] from that quarter—the quarter of the Palace of Versailles.

Along the path walked a peasant girl driving a splendid spotted cow. The bell at its fat throat tinkled merrily, the sun gleamed on its glossy spotted hide. The girl dropped a curtsey to the noble gentleman sitting there on his fine horse and himself so handsome a cavalier, and André nodded a smiling reply. She was not pretty, this peasant wench, with her shock of tumbled flaxen hair tossed over her smutty face, and her bodice and short skirt were soiled and tattered, but André, to whom all young women were interesting, in the sheer gaiety of his heart tossed her a coin and smiled again his captivating smile.

“May Monseigneur le Duc be happy in his love!” the wench said, as she bit the coin before she placed it in her bodice, and André remarked with approval the whiteness of her teeth. If her face was not pretty her body was both trim and sturdy, and she walked with the easy swing of perfect health. He could have kissed her smutty face then just because the world was so fair and he was free.

“You have a magnificent cow, my dear,” he remarked.

“But certainly,” she answered and her white teeth sparkled through her happy laugh, “better a fat cow for a wench than a lean husband. She carries me, does my spotted cow, which no husband would do,” and she scrambled on to the glossy back and laughed again,[28] throwing back her shock of flaxen hair. André observed, heedful by long experience of such trifles, that not even her clumsy sabots could spoil the dainty neatness of her feet.

“And what may your name be?” he demanded.

“Yvonne, Monsieur le Duc; they call me Yvonne of the Spotted Cow, and some,” she dimpled into a chuckle, “Yvonne of the Spotless Ankles. I am not pretty, moi, but that matters not. My fat cow or my ankles will get me a husband some day, and till then, like Monseigneur, I keep a gay heart.”

Whereupon she drove her heels into the cow’s flanks and the two slowly passed out of sight, though the merry tinkling of the bell continued to jingle through the leafless trees long after she had disappeared.

André waited patiently. An hour went by, still he waited. Twice he trotted up the road and peered this way and that, but there was not a soul to be seen, and with a muttered exclamation of disgust he was about to spur away when the notes of a hunting horn caused him to gather up the reins sharply. And now eager expectation was written on every line of his face.

A young lady in a beautiful riding dress of hunting green, and attended by a single lackey on horseback, came galloping down the forest track. At sight of him by the roadside she pulled up her horse in great astonishment.

“André—you—you are back?” she said, and the colour flooded into her cheeks.

[29]“Thank God, yes.”

“And well?”

“Perfectly. My wounds are healed. I am a prisoner no longer, and in a fortnight I return to the Low Countries to seek revenge from my enemies and yours, Denise, the English.”

Her grey eyes flashed, then dropped modestly. “You will find revenge, little doubt,” she said, “the Maison du Roi are soldiers worthy of the noblesse and of France. But do you not come to Versailles first?”

“No. My company is not on duty this month at the Palace and in April we shall all be with His Majesty in Flanders.”

“Yes,” she answered, “I forgot.”

She began to stroke her horse’s neck in some embarrassment. André gazed at her with the hungry eyes of a starved lover, and indeed this girl was worthy of a soldier’s homage. Neither a brunette nor a blonde, for her eyes were grey and their lashes almost black, though her hair was fair and the tint of her cheeks in the morning air delicate as the tint of a tender rose. Beautiful, yes! but something much more than beautiful. A great noble this lady surely, one who saw in kings and queens no more than an equal, and in palaces the only fit home of beauty nobly born, one to whom centuries of command had bequeathed a tone and quality which men and women can inherit but not acquire.

[30]“And when I return,” André said at last, “shall I find at Versailles what I desire more than revenge?”

“What is that?” she asked innocently.

“Can you not guess? Have you forgotten? Ah, Denise, twelve months ago you promised——”

“No, no,” she broke in, eagerly, “I said I would reflect.”

“There is only one thing that a poor Vicomte and a soldier of France can desire—your heart, Denise; your love, Denise; the heart and the love of the most beautiful and loyal woman in France, the heart of the Marquise de Beau Séjour. And André de Nérac loves the Marquise as he loves France. Can he say more?”

“I think not,” she said, averting her eyes, “and the Marquise de Beau Séjour thanks the Vicomte de Nérac for his words and his homage—to France.”

“I do not desire thanks—I——”

“Then go and do your duty as a noble and a soldier, and when peace and victory are ours perhaps I——”

“I cannot wait till then. Have pity, Denise, have pity on the man who was your playmate, who loved you then and who loves you now. Remember, remember, I beg you, that over there in England the one thought that consoled my prisoner’s lot was the hope that when I returned to you—you would——”

“But, André, I cannot give you an answer, here, now——”

[31]“Give it me then before I return to the war, that I may know whether I am to live in hope, or to die sword in hand and in despair.”

“There is more than one marquise in the world,” she said, quietly.

“Not for me.”

Denise looked at him, and he dropped his eyes, for he understood the calm reproach.

“Very well,” she said, with decision. “I go to my home to-morrow. You shall have my answer in four days at the Château de Beau Séjour if you care enough to come and hear it.”

“If—” he broke off. “Ah, Denise—!” he stretched out a passionate hand.

“Hush! There is some one coming.”

A young man was galloping towards them, a boy he seemed, saucy, insolent, handsome, fair, with great blue eyes sparkling with the gayest, wickedest, most careless joy of living. Removing his plumed hat with an airy sweep he kissed the lady’s fingers, bowed low in the saddle, and looked into her face:

“Marquise,” were his words, “the company and His Majesty await you.” His dare-devil eyes roved on to André’s face with a studied insouciance, but André gave him back the look, and more.

Denise made haste to present the young man. “Monsieur le Chevalier de St. Amant, secretary of the King’s Cabinet,” she said and her eyes pleaded for politeness from both.

[32]“Monsieur le Vicomte goes to the war?” the Chevalier asked, carelessly.

“As all true subjects of His Majesty ought to do,” André retorted.

“Except,” said the Chevalier, bowing to Denise, “those who find more pleasant pastime here at home.”

“It is curious,” André remarked, as if he had not heard, “that I who have known Versailles for ten years learn to-day for the first time of St. Amant. Where is St. Amant?”

“Ah,” answered the Chevalier, laughing, “in this life, Vicomte, we are always learning what is disagreeable. The dull philosophers of whom we hear so much in Paris at present say soldiers learn more than others—or ought to? Perhaps you differ from them?”

“Ma foi! no. For when it is necessary the soldiers teach what they have learned to the young men and the schoolboys, which is very good for the schoolboys. But perhaps you, sir, do not like lessons?”

“No, oh, no! my only regret at present is that I cannot stay now and have one at once. But Mademoiselle la Marquise will take your place and I can learn, as we ride together, something that she alone can teach. Monsieur le Vicomte, I have the honour to wish you good-morning and good-bye.” He raised his plumed hat and galloped away with Denise.

The flush in André’s cheek did not die out for some minutes. “Upstart! Puppy!” he continued to mutter while his eyes glittered and his fingers twitched involuntarily[33] on the handle of his sword. But his wrath and his scowls were suddenly dispelled in the most unexpected and agreeable way. A crisp tinkle of bells, the crack of a whip, and down the road came driving an ethereal phaeton, azure blue in colour, and in it sat an enchantress most bewitchingly clad in rose pink.

She too appeared to be waiting for somebody or something, for she pulled up ten yards off and gazed in the direction of the hunting horns which could be heard distinctly in the depths of the wood. To André she was most annoyingly indifferent, but the more he looked at her and marked her exquisite dress, her wonderful complexion, her seductive figure, and her entrancing equipage, the keener was his chagrin. Who was this airy sylph of the royal forest, this divinity floating in the rose of the queen of flowers through a leafless world as Venus might have floated on the sun-kissed foam at dawn? Gods! What a taste in dress, what a bust, and what amorous, saucy charm in her eye!

André fell back behind the trees and watched; nor did he have to wait long. In five minutes the royal hunting train swept by. The rose-pink lady curtsied to her sovereign. A cry of distress! Her hat caught by a sudden gust—surely it was very loosely set on that dainty head—flew off and fell almost under the hoofs of the horse of the King of France. Majesty looked up, coldly, caught her appealing eye, looked down at the hat, and galloped on as if he had seen[34] neither the hat nor its owner. The royal party behaved exactly as did their master, and the rose-pink goddess was left with disgust and indignation in her face and a tear trickling down her cheek.

André moved his horse forward, whereupon she threw a glance over her shoulder almost comic in its pathos and its amusement, as if she did not know whether to laugh or to cry; a glance which convinced his susceptible heart that she had been perfectly well aware of his presence all the while and now invited him to take what she had always intended he should have. In a second he was off his horse and was handing her the hat. Her bow and her smile were more than a reward, for if the rose-pink divinity was alluring seen from behind, she was positively bewitching at a distance of four feet in front. What wonderful eyes! They spoke at once of everything that could stir a soldier’s soul, and her blush was the blush of Aurora.

With the prettiest hesitation she inquired his name, which he only gave on condition that she should also tell hers. But this she laughingly refused. “My name is nothing,” she remarked, “for I am nobody. If you knew it you would despise yourself for having been polite to a bourgeoise.”

“Impossible!” André cried.

“But it is so,” she persisted, gravely, a challenge stealing from under her demure eyelashes.

“I shall find out,” André said, “I shall not rest till I find out.”

[35]“Then inquire,” she retorted gaily, “Rue Croix des Petits Champs—perhaps you will succeed,” and without more ado she flashed him a look of defiant modesty, whipped up her ponies, and the azure phaeton vanished as rapidly as it had appeared.

André stroked his chin meditatively. What did it mean? Who was the unknown and why did she come to the woods in that enchanting guise? A bourgeoise! Pah! it would be well if all the women of the bourgeoisie and some of the noblesse possessed but one of the secrets of her irresistible womanhood. But find out he must, and André, hot on this new quest, began to trot away. He was in a rare humour now, for he had noticed with unbounded satisfaction that, while Denise had been of the royal party, that boyish Chevalier had not.

But he had not ridden far when he was amazed to discover by the roadside Yvonne of the Spotless Ankles weeping as if her heart would break.

“What is the matter?” he demanded.

“Monseigneur—ah! it is the good Monseigneur—” she fell to crying again. “They have stolen my spotted cow,” she sobbed, “robbers have stolen my spotted cow.”

“Robbers?”

“But yes, three great robbers, and they have beaten me and taken Monseigneur’s piece too. My cow, my spotted cow!”

“See, Yvonne,” he said soothingly, “I am no monseigneur,[36] I am only a poor vicomte, but you shall have another cow, a spotted cow, too.”

But she would not believe it, whereupon he took all the money in his purse, four gold pieces and three silver ones, and thrust them into her hand.

She stared at the money incredulously.

“There, girl,” he urged, for a woman’s distress, even though she were only a peasant, hurt him, “be happy and buy a fat and spotted cow.”

She kneeled to kiss his hand. “Monseigneur,” she sobbed, “is kind to a poor wench. Surely the good God has sent him to me,” and she poured her hot tears of gratitude on the ruffles of his sleeve.

“I am happy again,” she murmured. “Yes, I will buy a cow and be happy,” and she began to sing, flinging the coarse matted hair out of her eyes.

André watched her contentedly; it was pleasant to see her joy.

“Monseigneur is not happy,” she surprised him by saying shyly.

“Can the poor be happy?” he asked, absently, for he was thinking of the goddess in pink.

“No,” she muttered, “not while there are robbers in the land, and the poor are taxed till they starve. Monseigneur is in love. Did I not see him talk with the great lady in green?” she added suddenly. “Ah, if Monseigneur would listen to a poor girl he too could be happy.”

“Peace!” he commanded, but he was much amused.

[37]“I too was in love,” she answered, “and women stole my lover from me as the robbers stole my cow, and I was sick. I wasted away, but the good God who sent me Monseigneur put it into my heart to go to the wise woman who lives at ‘The Cock with the Spurs of Gold’——”

“The Cock——?”

“’Tis a new tavern in the woods by the village yonder,” she replied earnestly, “and a wise woman lives there. For one piece of silver she brought me back my lover. They say she is a witch, but she is no witch, for with the help of the good God she cured my sickness and changed my lover’s heart so that once again he was as he had been.”

“Tush!” André interrupted, impatiently.

“But it is true,” she persisted. “And if Monseigneur is in distress, he, too, should go to the wise woman, and she will make him happy. It is so, it is so.”

“Adieu, my child, adieu!”

“Monseigneur will not forget. ‘The Cock with the Spurs of Gold,’ in the woods——”

He gave her matted head a pat. It was a pity she was not pretty, this wench, for she had a buxom figure. “A soldier,” he said lightly, “does not love wise women, Yvonne, he loves only the young and the fair and he wins them not by sorcery, but by his sword.”

“Monseigneur is a soldier?” she asked with grave interest.

[38]“Yes, a soldier of France.”

“My lover too is a soldier, but not as Monseigneur. Ah!” she whispered, “if all the nobles of France were as Monseigneur there would be no unhappy women, no robbers, and no poor.”

André left her there. His heart was gay again though his purse was empty, for he had made a woman happy. And as he rode through the woods he could hear her singing as she had sung when he had seen her first on the sleek back of her spotted cow. And all the way to Paris that song of a peasant wench softly caressed his spirit, for it clinked gaily to the echoes of the soul as might have clinked the golden spurs of the cock in the woods of Versailles, and it was fresh with the eternal freshness of spring and the immortal dreams of youth.

The March sun was setting on the hamlet of La Rivière, in the pleasant land of Touraine—Touraine the fit home of so many noble châteaux, the cradle of so many of the proudest traditions and the most inspiring memories of the romance of love and chivalry in the history of France.

André was standing in the churchyard of the hamlet, but it was not at the landscape that he knew so well that he was looking, nor even up the slope beyond, where the great Château de Beau Séjour shot its towers and pointed turrets through its encircling domain of wood. Ten leagues away in the dim distance lay Nérac, the poverty-stricken home from which he took his title, and whose meagre patrimony encumbered with the debts of his ancestors and his own barely sufficed to provide a living for the widowed mother to whom that morning he had said good-bye and whom the English in the Low Countries might decide he should never see again.

Yet it was not of his mother that he was thinking,[40] still less of the enchantress of the forest whose identity he had discovered—one Mademoiselle d’Étiolles she had proved to be, “La Petite d’Étiolles,” as that gay Lothario the Duc de Richelieu called her, the daughter of a Farmer-General, a bourgeoisie notorious for her beauty, her wit, and her friendship with the wits. Indeed he had forgotten the rose-pink divinity in the azure phaeton entirely. No, he was striving to pluck up courage to face Denise and receive her answer. For if that answer was not what he desired it would be better to ride straight down into the Loire and let the last male of the House of Nérac put an end to it for ever.

Twinkling lights began to shine in the great château; its towers and gables insolent in the majesty of their beauty, strong in the might of their antiquity, challenged and defied him in the dusk. That was the château of his Denise, the Marquise de Beau Séjour whom he, gallant fool, rich only in his noble pedigree, dared to love and hoped to win, Denise the richest heiress in France. Yet it had not been hers so long; its broad seignories were a thing of yesterday for her. Fifteen years ago she, as he, had been only the child of a vicomte as poor if as noble as himself. And Beau Séjour lay not here, but ten leagues away, a mile from Nérac, where that church spire hung its cross above the horizon.

The soft gloom of the growing dusk imaged for André at that moment the sombre pall of tragedy[41] which twelve years ago had fallen on the great château. An ancient house, a venerated name had been its owner’s; were not their achievements written in the chronicles of France? was not their origin lost in the twilight of dim ages far, so far away? Capets and Valois and Bourbons that house had seen coming and going on the throne, honour and fame and wealth and high endeavour had been theirs, and then shame and doom, swift, unexpected, irreversible. The story of their downfall had been his first lesson learned in budding manhood of the harshness of the world and the mystery of fate. Such a simple story, too. The wife of the Marquis had run away with a lover, a baseborn stranger gossip called him. The lover had deserted her, why and where no one knew, and disowned by her husband she had died miserably. Her husband, a soldier and ambassador of the great Louis Quatorze, had in despair or madness plunged into treason, and had paid the traitor’s penalty on the scaffold. His only son and heir, from remorse or consciousness of guilt, had perished by his own hand in Poland, whither he had gone to fight in the war. And here to-day at his feet a rough and stained tombstone marked the neglected grave of the only daughter who had remained. Had she lived she would to-night have been just two years older than Denise; had there been no treason, she and not Denise would have been mistress of that château now called De Beau Séjour.

Denise’s father for service to the state had been[42] awarded the lands of the traitor; the old name for centuries noted in this soil had been annulled in infamy; its blood was corrupted by the decree of the law, and by the King’s will the new Marquis had carried to his new possessions the title of his old, that Beau Séjour yonder so near to his own Nérac. The law and the King so far as in them lay had determined that the very name and memory of the ancient house should be blotted out for ever. But blot out the château they could not. There it stood haughty as of old, to tell to all what had once been, and the curious could still read here and there in its storied walls the arms and emblems, the scutcheons and shields of a family which had given nine Marshals to France, and in whose veins royal blood had flowed. What did that matter now? To-day it belonged to Denise, once poor as he was, and destined to be his bride before this sudden swoop upward on the ruins of another to the high places of France.

As André paced to and fro in the dusk the ghostly memories thickened. Twenty years ago as a boy he had ridden with his father to that château. He remembered but two things, but he remembered them as vividly as yesterday. Over the chief gateway a splendid coat of arms had caught his boyish fancy and he had asked what the motto “Dieu Le Vengeur” might mean. “Why, father, there it is again,” he had cried, for in the noble hall, above the famous sculptured chimney-piece, the first thing that caught the boy’s eye was[43] the scroll with those three words “Dieu Le Vengeur.” And the second memory was of a little girl playing with a huge wolf-hound in the dancing firelight under that motto, a little girl with blue eyes and fair hair, innocent of the evil to come, playing in her hall which had seen kings and queens for guests. “Dieu Le Vengeur” she had repeated—“God will protect me,” and they had all laughed. But had God protected her? Here was her grave at his feet. André now recalled his dying father’s remark five years later, when he had heard how his neighbour the Comte de Beau Séjour had been rewarded with the treason-tainted marquisate. “That would have been yours, André, my son,” he had said. And no one had understood, and he had died before he could explain, if explain he could. That, too, had been another bitter lesson in the cruelty of fate, in the bleak, bitter tragedy of baffled and unfulfilled ambitions.

Smitten with a sudden pity, a sharp anguish, André kneeled in the damp, tangled grass and peered at the tombstone which marked the humble resting-place of the dead, worse than dead, dishonoured and infamous. “Marie Angélique Jeanne Gabrielle ...” the rest was eaten away. But in the church close by lay the coffins of her ancestors, the crusaders and nobles, and Marshals of France. The names had been obliterated. But not even a wronged king had dared to remove the tombs with which that church was eloquent of the glories that had once been theirs. Yes, they lay[44] there of right, but she, little Marie, cradled in splendour, who had prattled of “Dieu Le Vengeur,” she, the daughter of a wanton and a traitor, lay here in the rain, and the sheep and the goats browsed over her, and the sabots of those once her serfs and tenants made an insulting path over her grave. And up there another reigned in her place.

A traitor! Yes, his daughter deserved her fate. There should be no mercy for traitors.

“What seek you, Monsieur le Vicomte?”

He started at the question. It was the Chevalier de St. Amant, boyish, insolent, though his tone was strangely soft.

“I was finding a lesson,” André replied quietly.

“In a tombstone?”

André explained. The Chevalier seemed impressed, for he went down on his knees and peered for some minutes at the weather-beaten stone.

“Poor child!” he muttered. “Poor child!”

André was thinking the Chevalier was better than he had supposed, but his next action jarred harshly. Standing carelessly on the stone he gathered his cloak about him. “Ah, well,” he remarked, with his dare-devil lightness, “it is perhaps more fortunate for you or me that little Marie is where she is.”

“For you or me?” André questioned, peering into his young face.

“The Marquise awaits you, Vicomte,” he twitched his thumb towards the château, “perhaps you will[45] understand better when you have seen her,” and with a careless tip of his saucy hat he strode away.

For one minute André burned to seize that cloak and speak to him very straightly. “Pah!” he muttered, “it will do later. Perhaps it will not be necessary at all.”

But it was with increased misgiving that he rode up to the château.

Denise received him in the great hall, unconsciously reproducing the picture which was burnt into André’s memory, for she stood with a certain sweet stateliness by the sculptured chimney-piece and a huge hound lay at her feet. Above her head the emblazoned scutcheon of the old house still adorned the noble carving—indeed you could not have destroyed the one without destroying the other—and the glad firelight which threw such subtly entrancing shadows on the dress and girlish figure of the young Marquise seemed to point with tongues of flame to that sublime motto, “Dieu Le Vengeur!” above her head.

André bowed and halted. Ambition, passion, and hope conspired to choke him for the moment. How fair and noble she was! yes, surpassingly fair and noble.

Denise said nothing. She stared at the buckle of her slipper.

“I have come for my answer,” he said, in a low voice.

She met his pleading eyes fearlessly. “The answer[46] is, ‘No,’” she replied, and her voice, too, was low, as if she could not trust it.

“No?” he repeated, half stunned.

She simply bowed her head.

“You mean it? Oh, Denise, you cannot mean it?”

“I have reflected and I mean it.”

“For always?”

“Yes.”

André stepped nearer. “I do not remind you, Denise,” he said, speaking with a composure won by a mighty mastery of himself, “that I love you, that I have loved you since I could love any woman. If you would not believe it before I was taken prisoner, when I spoke in the woods of Versailles, you would not believe it now. Nor do I remind you that twelve months ago you spoke very differently. A lover and a gentleman does not speak of these things when the answer has been ‘No.’ But I do ask you, before you say ‘No,’ always to remember that it was the wish of your dead father and of mine that the answer should be ‘Yes.’”

“My father died five years ago, yours even longer,” she answered.

“Do the years alter their wish?” he asked, with a touch of passion, “do they make a promise, good faith, honour, less a promise, less——”

“There was no promise,” she interrupted.

He bowed calmly. The gesture was better than speech.

[47]“And your reason, Denise?”

“I said I would give you an answer, I did not undertake to give reasons.”

“Certainly. May I plead, however, that perhaps, remembering the past, what you and I have been to each other since childhood, I have some right to ask?”

She placed her fan on the shelf of the chimney with sharp decision. The firelight flashed in her grey eyes. “I refuse,” she said, very distinctly, “to marry a man who does not love me.”

“Then you do not believe my words?” he questioned quickly.

“You are a noble, André,” she answered; “the courtesy of a noble and a gentleman requires that when he demands a woman’s hand in marriage he should profess to love her. For the honour you have done me I thank you, but a woman finds the proof not in words but in deeds. You are a brave soldier, but you do not love me. That is enough.”

“No, it is not enough for me,” he answered.

“Very well.” She took a step forward. “I had no desire to discuss things not fit for a girl to speak of to a man who has done her the honour to ask her hand in marriage, and I would have spared both myself and you unnecessary pain. Plainly then and briefly, when I take a husband I do not choose to share what he professes is his love with any other woman. That is my reason and my answer in one.”

[48]A flush darkened his sallow cheek. “It is not true,” he protested passionately, “it is not true.”

“You would deny it?” she cried, passion too leaping into her voice. “Is that letter to the Comtesse des Forges, one of my friends—my friends, mon Dieu!—yours, or is it not?” She handed it to him with hot scorn.

“It was written twelve months ago,” he said, somewhat lamely.

“And the duel which it caused is twelve months ago, too, I suppose? The right arm of her husband the Comte des Forges is healed, but the wound—my God! the wound in his heart and mine, that you can never heal. And she is not alone. Does not Paris ring with the gallantries of the Vicomte de Nérac? For aught I know there may be a dozen husbands in England who have lost their sword arm because André de Nérac professed to love their wives.” She checked herself and was calm again. “I thank you for the honour you have done me, but—” she offered him the stateliest, coldest curtsey, “Vicomte, I am your servant.”

She would have escaped by the door behind her, but André intercepted her. “No,” he said, “you do not leave me yet. I, too, have something to say and you, Marquise, will be pleased to hear it.”

Their eyes met and then Denise walked back to her place by the fireplace. She was trembling now, and she no longer looked him in the face.

“Is that letter to the Comtesse des Forges, one of my friends—my friends, Mon Dieu!—yours, or is it not?”

[49]“As to the past,” he said in a low voice, “I say nothing, for I deserve your reproaches. I have been foolish, wicked, unworthy of you. But there is no noble to-day at Versailles of whom the same could not be said. Men are men, and I have never concealed from you what I have been. But such things do not destroy love. They cannot and they never will, and every woman knows it. My past, I assert, is not your reason.”

“What then is?” she asked proudly.

“I am poor, you are rich, but that is not the reason, either. Do not think I would dishonour you by supposing that I believed that, though some whom you call your friends say it is. No, the reason is that while I have been away, a prisoner, defenceless, silent, some one—” he paused, “some one has been poisoning your mind, some one who hopes to take the place——”

“Take care——” she interrupted.

“You speak of the gossip of Paris. I will not tell you what the gossip of Paris and Versailles says, for you will hear it and more fitly from other lips than mine. But I say, that poisoner will answer to me.”

She was about to speak, but checked herself.

“And I will tell you why. First because I love you and I love no one else. You do not believe it. You ask for deeds, not words. In the future you shall have them. And second, because you, Denise, love me, yes, love me.”

[50]“Have done, have done with this mockery!” she cried.

“Tell me,” was his answer, “on your word of honour, that it is not so, tell me that you do not love me and never will, tell me that you love another and on my word as a gentleman I will never speak of love to you again.”

Dead silence. André waited quietly.

“I refuse,” she said, slowly, picking the words, “to be questioned in this manner. But as you insist, I repeat—I do not love you.”

André bowed. “One word more, Denise, if you please,” he said, “one word and I leave your presence for ever.”

She drew herself up. “Yes,” she said, “leave me for ever.” But for all that she, as he, seemed spellbound to the spot.

André deliberately drew from his pocket the letter that she had thrown in his teeth and faced her. “Thank you,” he said, very calmly. “Now that I know you mean what you said, I, too, know what I must do.” He walked away.

“Give me that letter,” she said with a swift flash of command. “It belongs to me.”

“Pardon,” he answered, quietly, “yesterday the Comte des Forges was killed by a friend of his whose honour he had betrayed. The letter belongs to the lady to whom it was written, the lady who will be the Vicomtesse de Nérac.”

[51]A faint cry escaped from Denise’s lips. For the moment she leaned faint against the chimney-piece, white and sick.

André looked at her, but he made no effort to offer her either sympathy or help. Then he walked back, Denise watching him, and flung the letter into the fire. Denise started, but she said nothing, though her great grey eyes were eloquent with half a dozen questions.

“The letter has served its purpose,” André said. “Adieu, Marquise!”

“What does this—this trickery mean?” she demanded, hotly.

“You must forgive one who loves you,” was the calm reply, “for love laughs at tricks. The Comte des Forges is alive and well: he has a wound in his shoulder which is only a scratch, for the poor Comte is always believing that some one is betraying his honour and Madame the Comtesse has a fickle heart. Yesterday I was his second, so I know.”

“Then—then—” she cried and stopped.

André bowed most courteously. “You refused to believe me, Mademoiselle: I returned the compliment and refused to believe you—and I proved it by a lover’s trick, if you choose to call it such. That is all, but it is enough.”

“Ah!” She crumpled up the fan in speechless indignation.

“No, Denise,” he said softly. “I shall not trouble you now or soon, but—” he had caught her hand—“you[52] shall yet be mine, I swear it. You think you do not love me, but you shall be convinced—you shall.”

He kissed her fingers with a tender reverence. “Adieu, Marquise! I go to my duty and revenge,” he said, and he left her there under the spell of his mastery, with her boar-hound at her feet, and the flames of fire pointing to the motto “Dieu Le Vengeur!”

André rode at a walking pace down the slope to the village, for he wanted to think. He had always prided himself on his knowledge of women; he had imagined he knew Denise as well as himself. She was of his class, lovely, high-spirited, proud, patriotic, and best of all a true woman. Hence it was a sore and surprising blow to his pride to discover that she should reject his love because he had lived the life of his and her class. He had gone to the château to confess everything, to swear that from this day onwards no other woman, be she beautiful as the dawn, as enchanting as Circe, could ever occupy five minutes of his thoughts. And he meant it. Those others, the shattered idols of a vanished past, had simply satisfied vanity, ambition, a physical craving. But Denise he really loved. She inspired a devotion, a passion which gripped and satisfied body, soul, and spirit; she was that without which life seemed unmeaning, empty, poor, despicable. But why could not she see this—the difference between a fleeting desire and the sincere[54] homage of manhood to an ideal, between the gallant and the lover? What more had a wife a right to expect than the love of a husband, brave, loyal, faithful? It was unreasonable, for men were men and women were women. Yet here was a woman who did.

But he would—must—win her. That was the adamantine resolution in his breast, all the stronger because she had scorned and defied him. Yet he would win her in his way, not hers. Yes, he would conquer her against herself. For him life now meant simply Denise—the heart and the soul and the spirit of Denise—the conquest of a woman’s will. The hot pulses of health and strength, of manhood, his noble blood and ambition throbbed responsive to the resolution. He thanked God that he was young and a soldier, that there was war and a prize to be won. Yet he also felt that this love meant something new, that it had transformed him into something that he had never dreamed of as possible. And victory would complete the change. So as he rode the fierce thoughts tumbled over each other in a foam of passion, in the sublime intoxication of a vision of a new heaven and a new earth—from which he was rudely awakened.

He had halted for the moment at the door of the village inn. In the dingy parlour sat the Chevalier, one leg thrown over the table, a beaker in his hand resting on his thigh, while his other hand was stroking the chin of the waiting wench, a strapping, tawdry slut.

[55]André kicked the door open. “Am I disturbing you?” he said, pitching his hat off as if the parlour were his own.

“Not in the least,” the Chevalier replied without stirring, though the girl began to giggle with an affectation of alarmed modesty. “My wine is just done”; he drained off the glass. “I will leave Toinette to you, Vicomte, for,” he put on his hat, “it is time I returned to the château.”

This studied insolence was exactly what André required. “I thank you,” he said, freezingly, “but before I take your place, you and I, Monsieur le Chevalier, will have a word first.”

“As you please, my dear Vicomte,” said the young man, swinging comfortably on to the table and peering at him from under his saucy plumes. “You will have much to say, I doubt not, for you must have said so little at the château. Run away, my child,” he added to the wench, who was now staring at them both with genuine alarm in her coarse eyes, “run away.”

André closed the door. “You will not return to the château,” he said quietly.

“My dear Vicomte, you suffer from the strangest hallucinations, stupid phantoms of the mind, if you——”

“Perhaps,” was the cold reply, “but the point of a sword is a reality which exorcises any and every phantom.”

The Chevalier laughed softly.

“Yes,” André continued, “I say it with infinite[56] regret, because you are young, you will not return to the château, for I am going to kill you, unless——”

“Unless?” The Chevalier slowly swung off the table.

“Unless you will give me your word of honour now that you will leave France to-morrow and never return.”

The young man reflectively put back one of his dainty love curls. “Ah, my dear Vicomte,” he answered, “I say it too with infinite regret, but that I cannot promise. So you must kill me I fear. Alas!” he added with dilatory derision, “alas! what have I done?”

“Very good”—André fastened his cloak—“in three days we will meet in Paris.”

“In Paris? Why not kill me here?”

“Here?” André stared at him in astonishment.

“Here and at once.” He walked to the door. “Two torches,” he called, “two torches.”

When he had lit them the Chevalier marched out. “This way,” he said politely; “permit me to show you, with infinite regret, where you can kill me.”

Half expecting a trick or foul play André followed him cautiously until he stopped in a deserted stable yard, paved and clean, and completely shut in by high walls. The young man gravely placed one torch in a ring on the north wall and the other on the wall opposite.

“That,” he said, in the pleasantest manner possible, “will make the lights fair. You”—he pointed to the[57] west—“will stand there, or here, if you prefer, to the east. You will agree, doubtless, that to a man who is to be killed it is a trifle where he stands.”

The torches flared smokily in the April dusk. He was mad, this boyish fool, stark, raving mad. But how prettily and elegantly he played the part.

“See,” the Chevalier said lightly, “there is no one to interrupt—the murder. Toinette knows neither my name nor yours; she will hold her tongue for money and in half an hour you will be gone—and I”—he shrugged his shoulders—“well, it is clean lying here, cleaner, anyway, than under the grass in that dirty churchyard.”

“You mean it?” André asked slowly.

The Chevalier took off his saucy hat and fine coat, hung them upon one of the rusty rings in the wall, and turned back his lace ruffles. A flash—his sword had cut a rainbow through the dusk across the yellow flare of the torches. “I am at your service, Vicomte,” he said with a low bow. “And I shall return to the château when and how I please, and I shall be welcome, eh?”

“By God!” André ripped out. “By God! I will kill you.”

He too had flung off his coat and cloak and took the position by the east wall. A strange duel this, assuredly not the first in which the Vicomte de Nérac had fought for a woman’s sake, but the strangest, maddest that man’s wit or a boy’s folly could have[58] devised. André was as cold as ice now, and he calmly surveyed his opponent as he tried the steel of his blade. How young and supple and insolently gay the beardless popinjay was; but he had the fencer’s figure, and the handling of his weapon revealed to the trained eye that this would be no affair of six passes and a coup de maître. Yet never did André feel so calmly confident of his own famed skill and rich experience. No, he would not kill him, but he would teach him a lesson that he would not forget.

For a brief minute both scanned the ground carefully, testing it with their feet, and marking the falling of the lights from those smoking torches, the flickering of the shadows in the raw chill of eve. All around was deathly still. Not so much as the cluck of a hen to break the misty silence.

“On guard!”