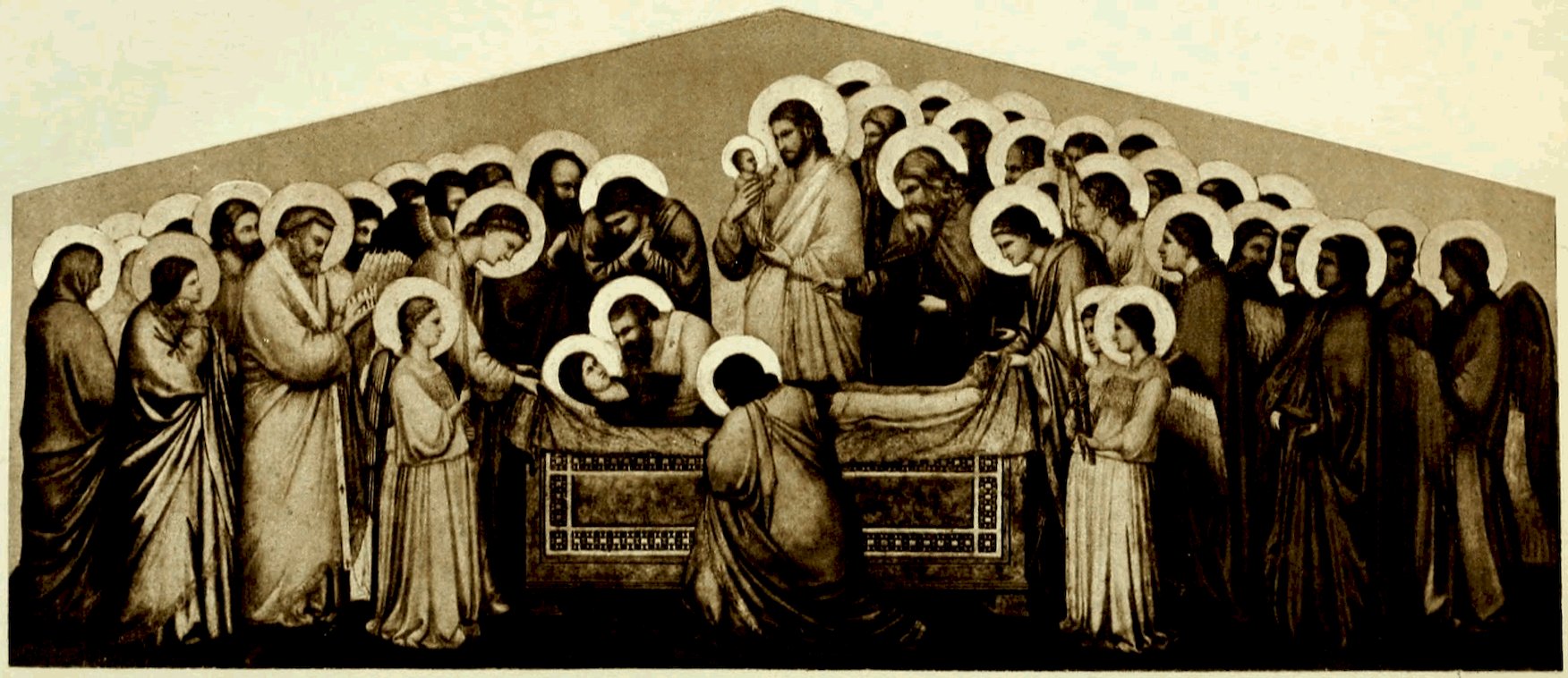

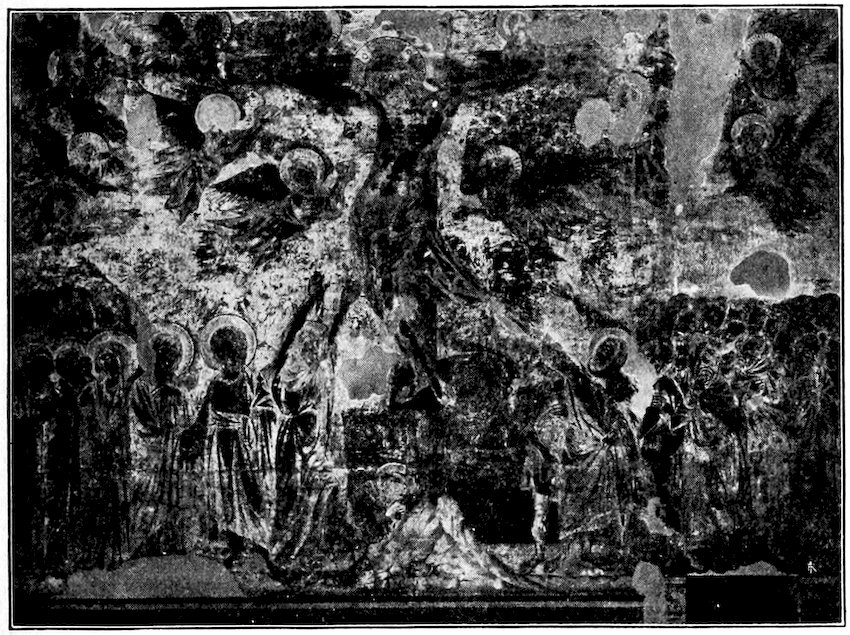

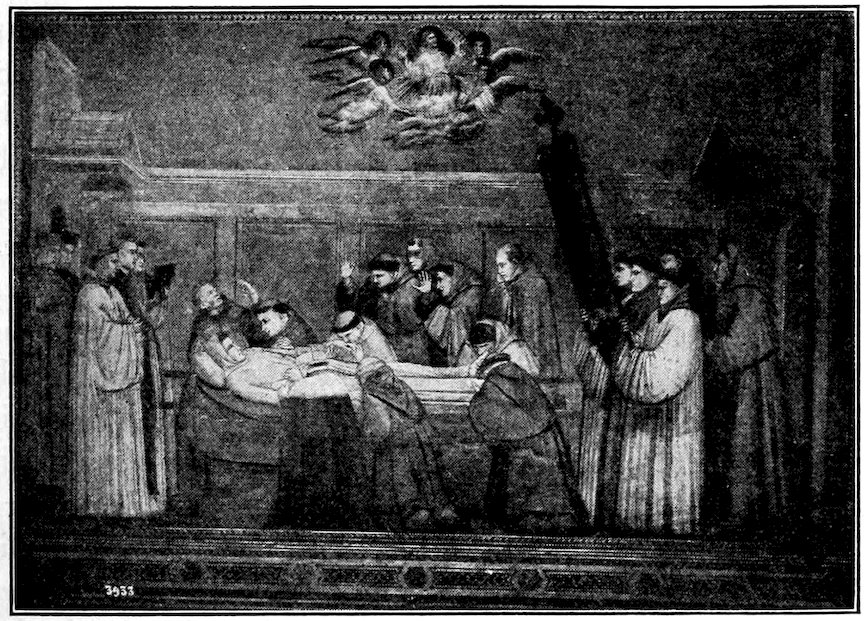

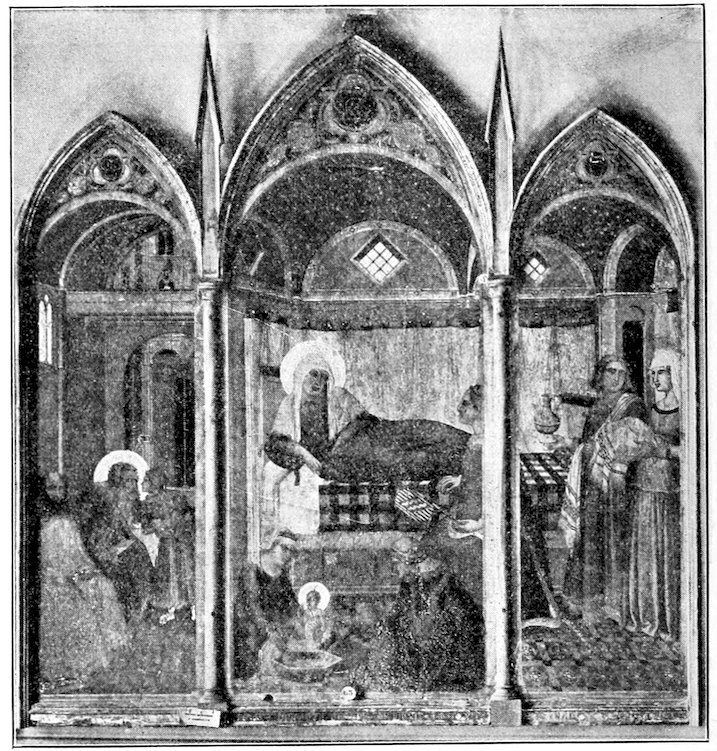

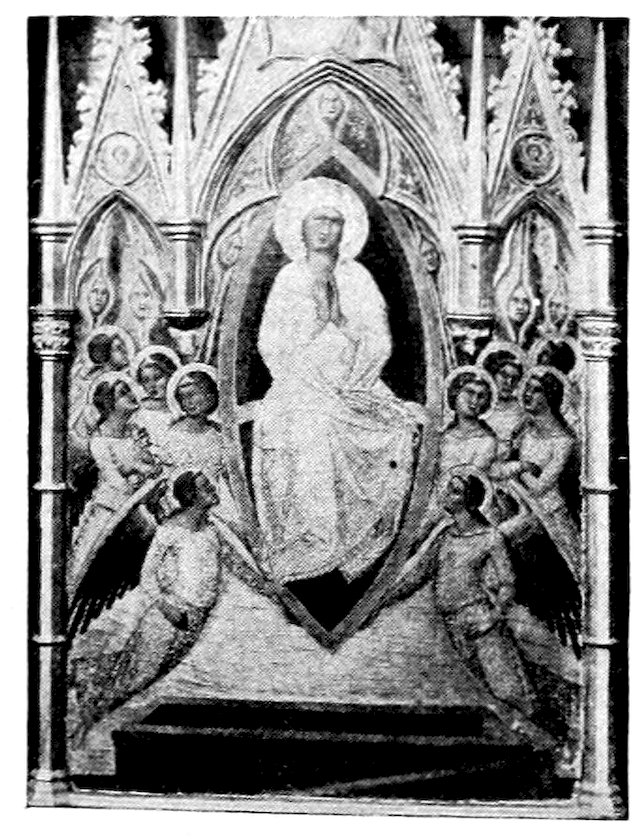

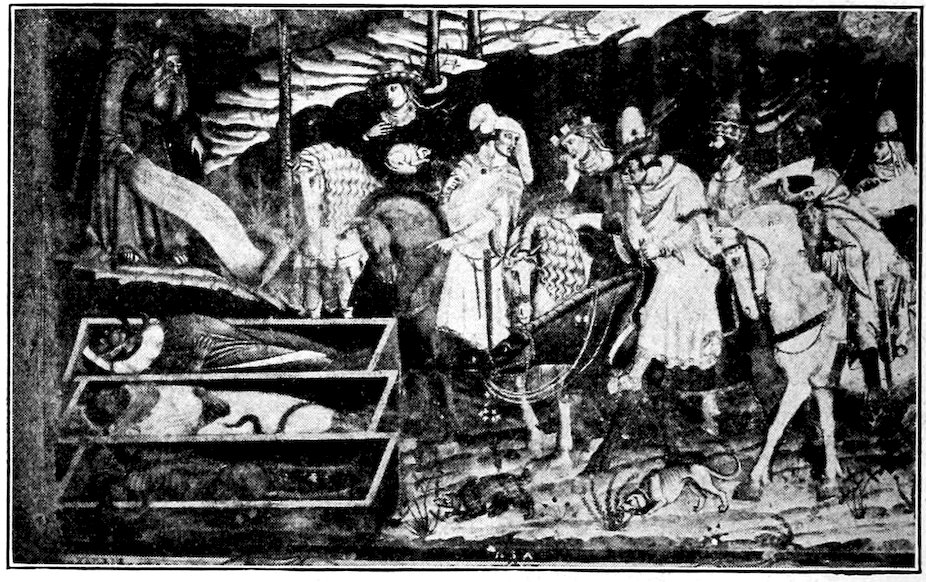

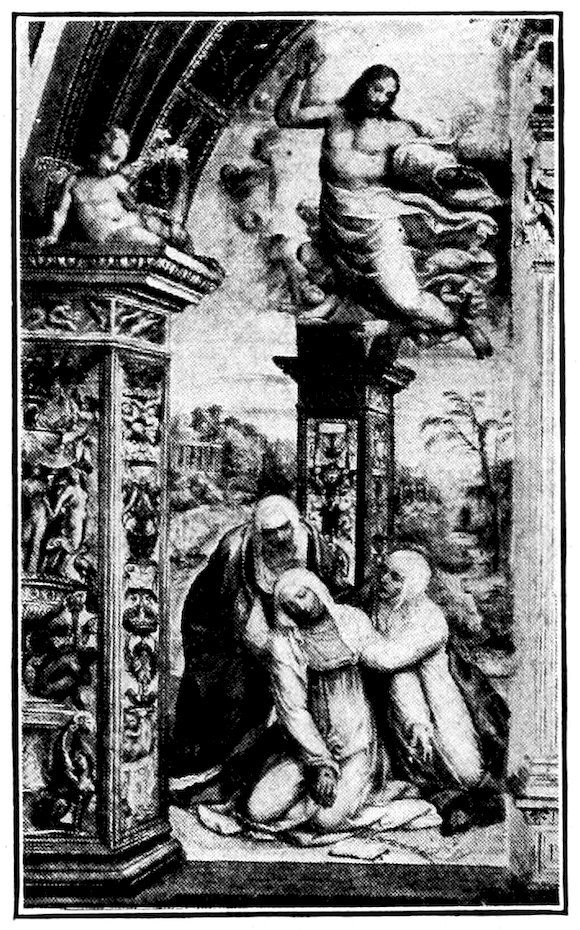

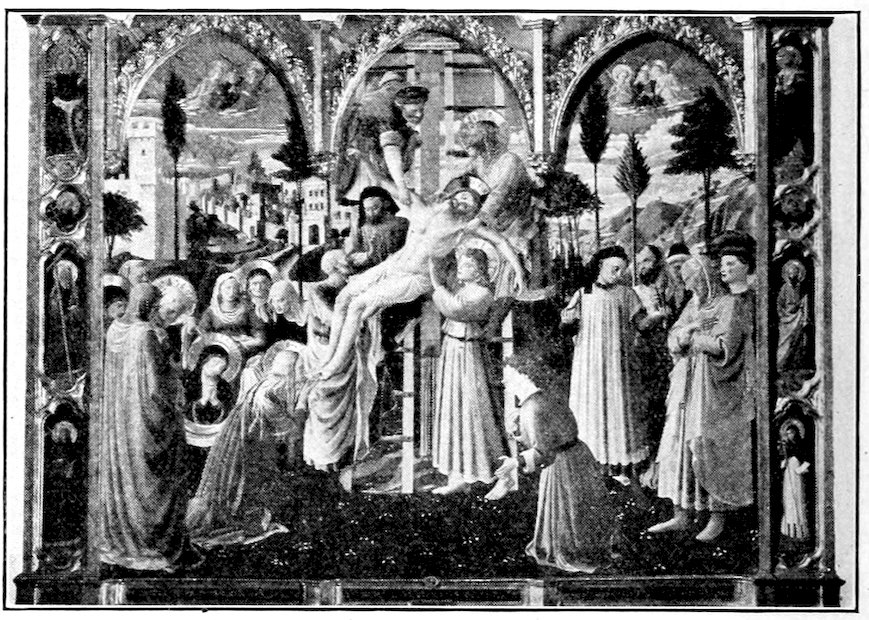

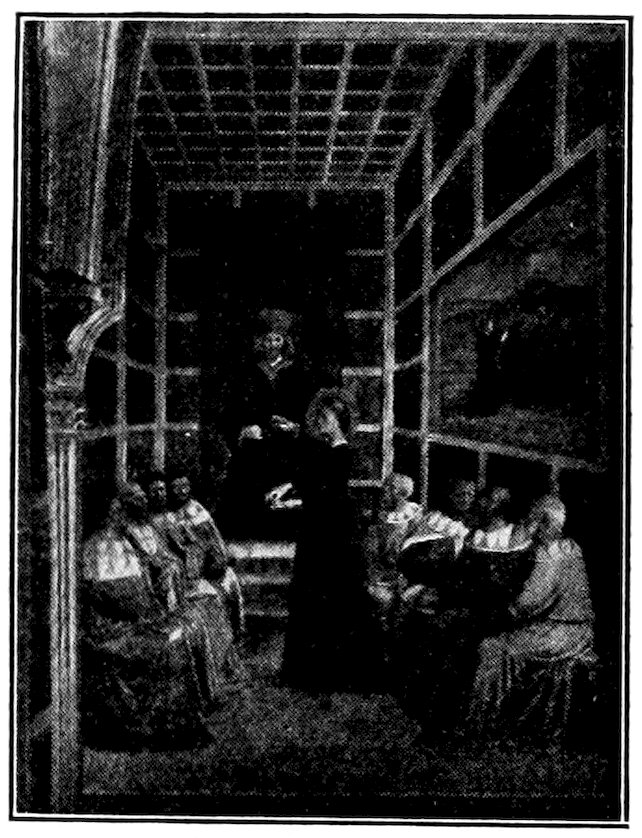

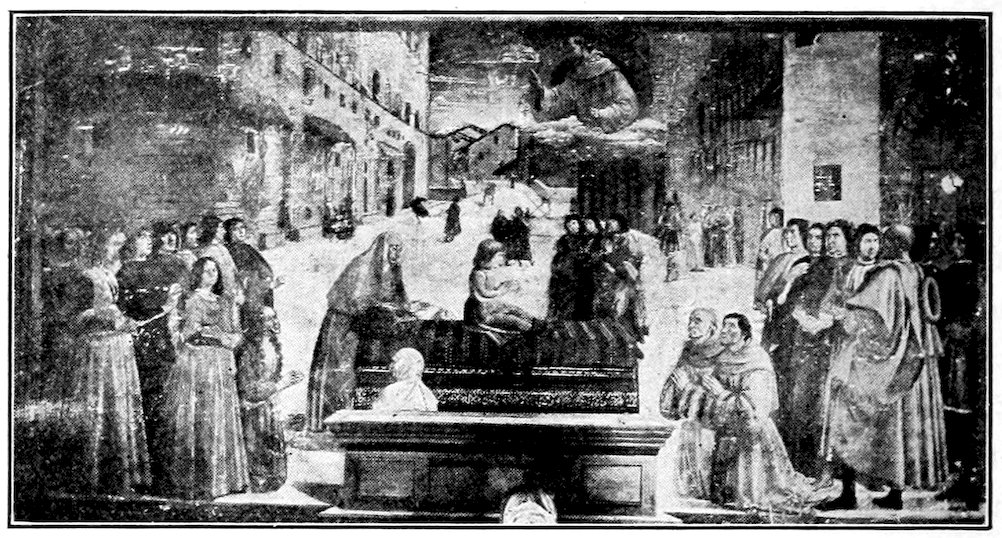

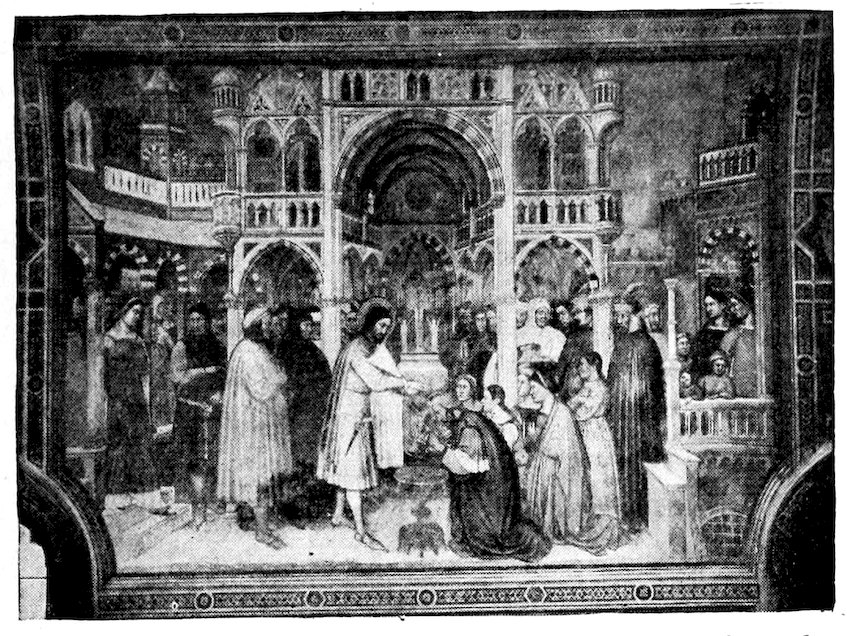

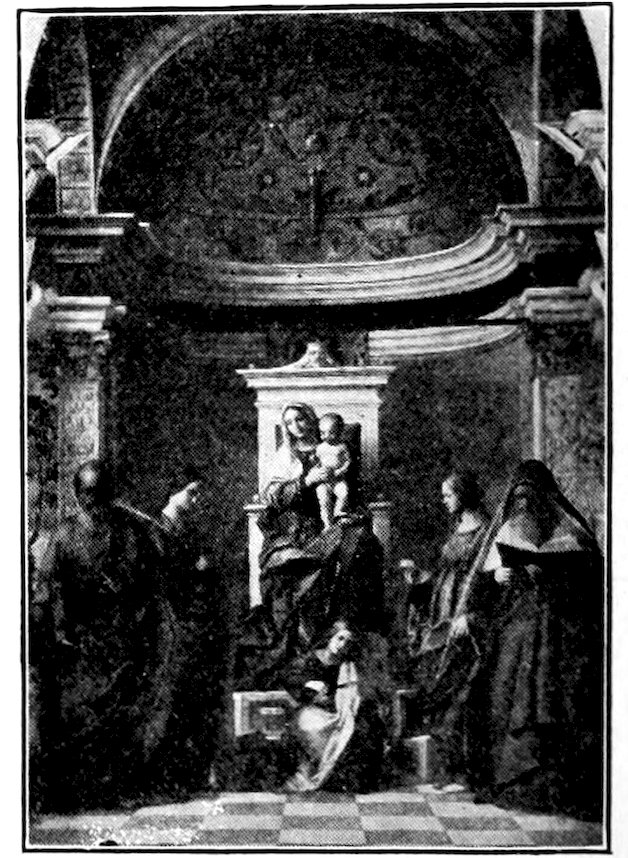

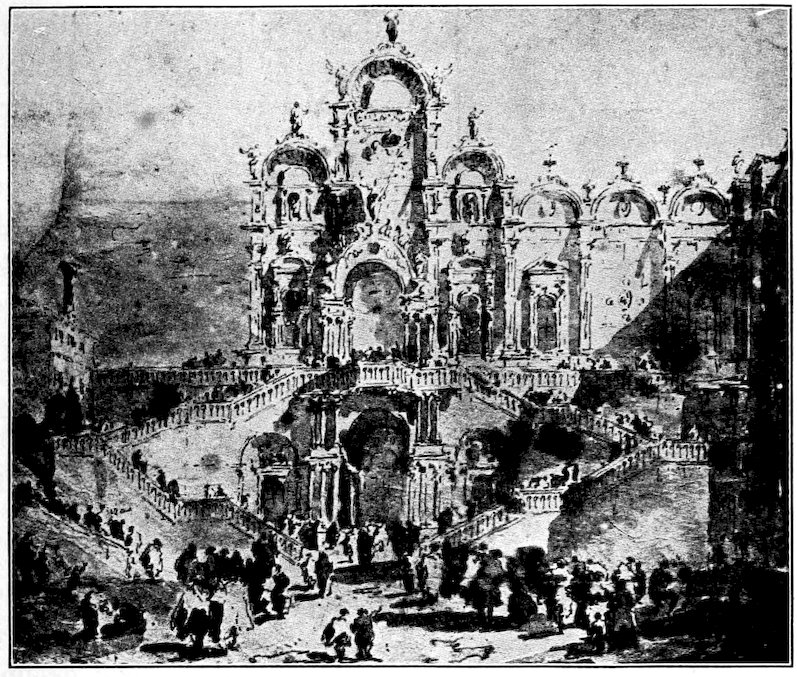

GIOTTO: DORMITION OF THE VIRGIN

Berlin

Title: A history of Italian painting

Author: Frank Jewett Mather

Release date: January 20, 2023 [eBook #69844]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Stanley Paul, 1923

Credits: Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

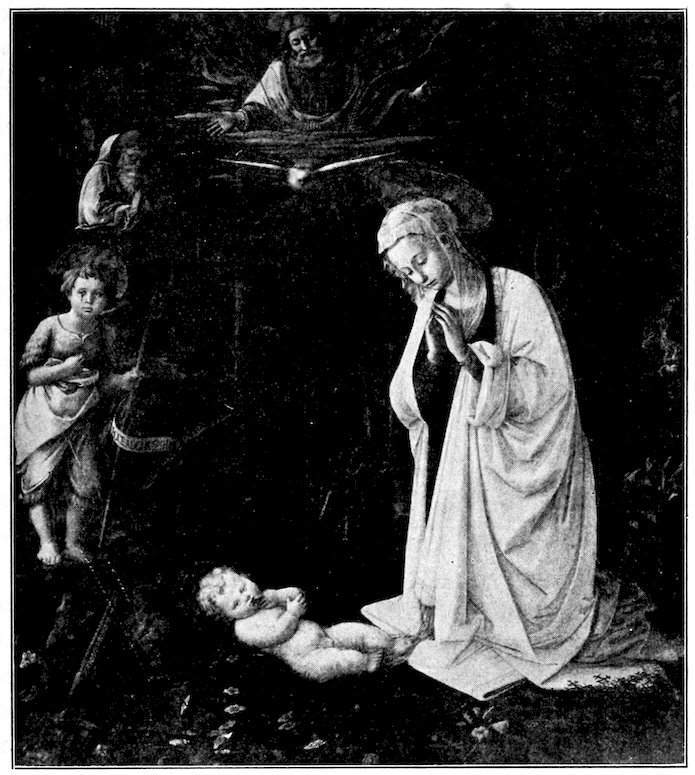

GIOTTO: DORMITION OF THE VIRGIN

Berlin

This book has grown out of lectures which were delivered at the Cleveland Art Museum in 1919–20. There I had ideal hearers, beginners who wanted to learn and were willing to follow a serious discussion. Since I aim at the same sort of a reader now, I have only slightly retouched and amplified the original manuscript. This is frankly a beginner’s book. I have had to omit whatever might confuse the novice, including many painters inherently delightful. Controversial problems for the same reason have been when possible avoided. When, however, I have had to cope with such, I have depended more on my own eyes and judgment than on the written words of others. But the latest literature has also been used, so that even the adept should here and there find something to his purpose.

For opinions on contested points, I have given my authority or personal reason in notes, which, in order not to clutter up the text, are printed at the end. By the same token, hints on reading and private study are tucked away in the last pages where they will not bother readers who do not need or want them. While I hope the book will be welcome in the classroom, I have had as much in mind the intelligent traveller in Europe and the private student. Throughout I have had before me the kind of introduction to Italian painting that would have been helpful to me thirty years ago in those days of bewildered enthusiasm when I was making my Grand Tour.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Giotto and the New Florentine Humanism | 1 |

| II. | Siena and the Continuing of the Mediaeval Style | 59 |

| III. | Masaccio and the New Realism | 109 |

| IV. | Fra Filippo Lippi and the New Narrative Style | 157 |

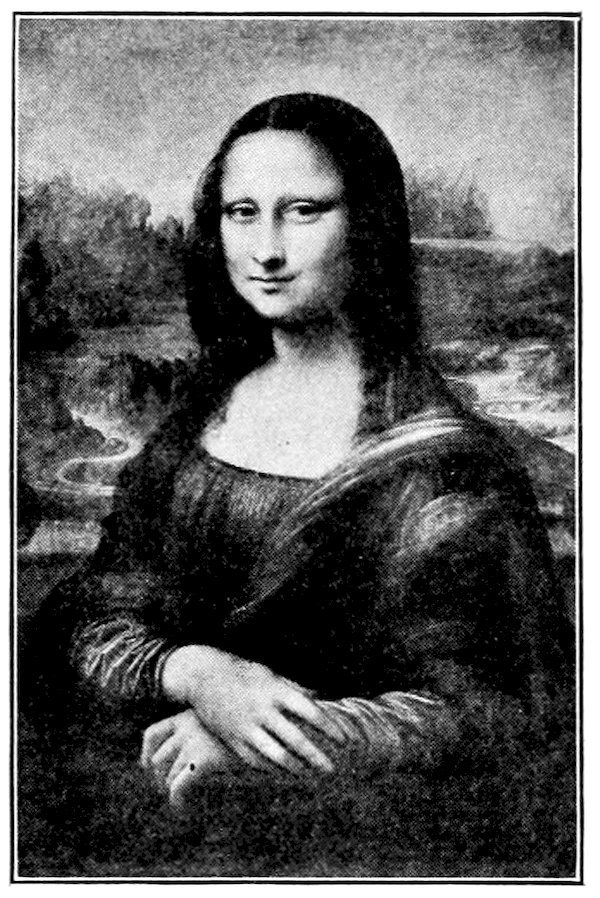

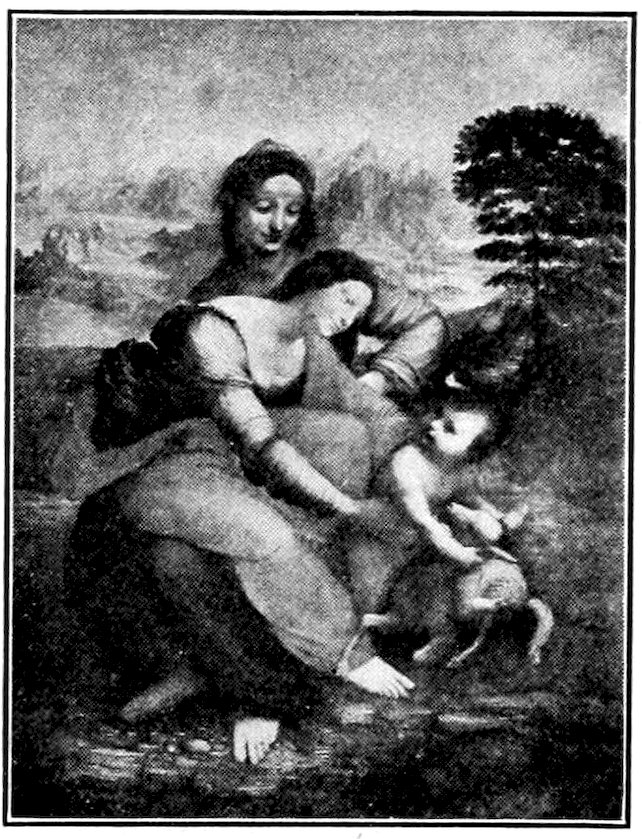

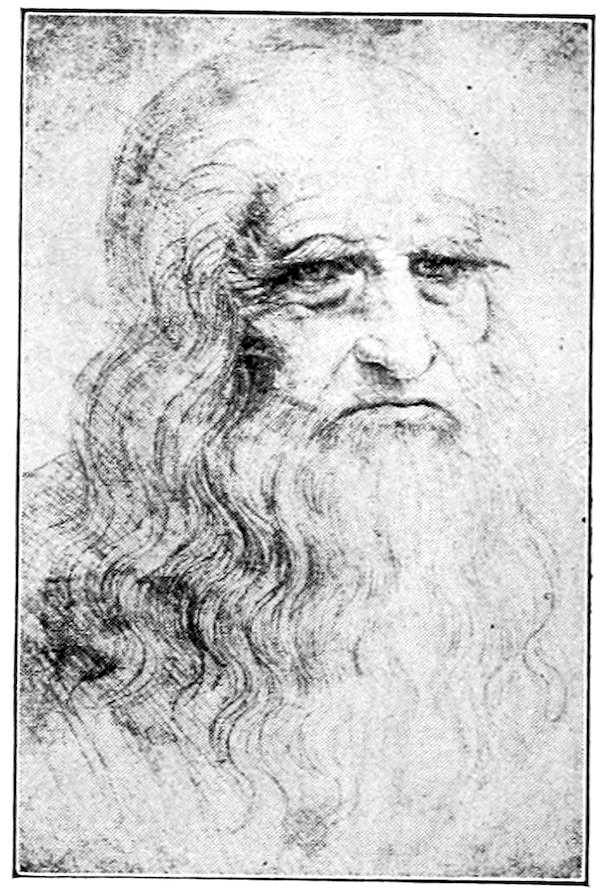

| V. | Dawn of the Golden Age: Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci | 201 |

| VI. | The Golden Age: Raphael and Michelangelo | 263 |

| VII. | Venetian Painting Before Titian | 323 |

| VIII. | Titian and Venetian Painting in the Renaissance | 389 |

| IX. | The Realists and Eclectics | 451 |

| Notes | 473 | |

| Hints for Reading | 489 | |

| Index | 491 |

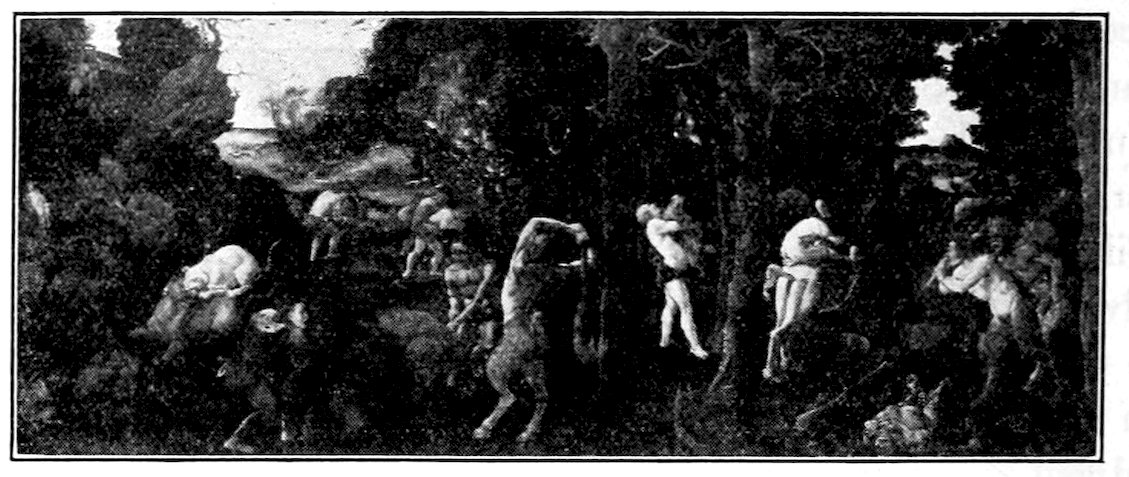

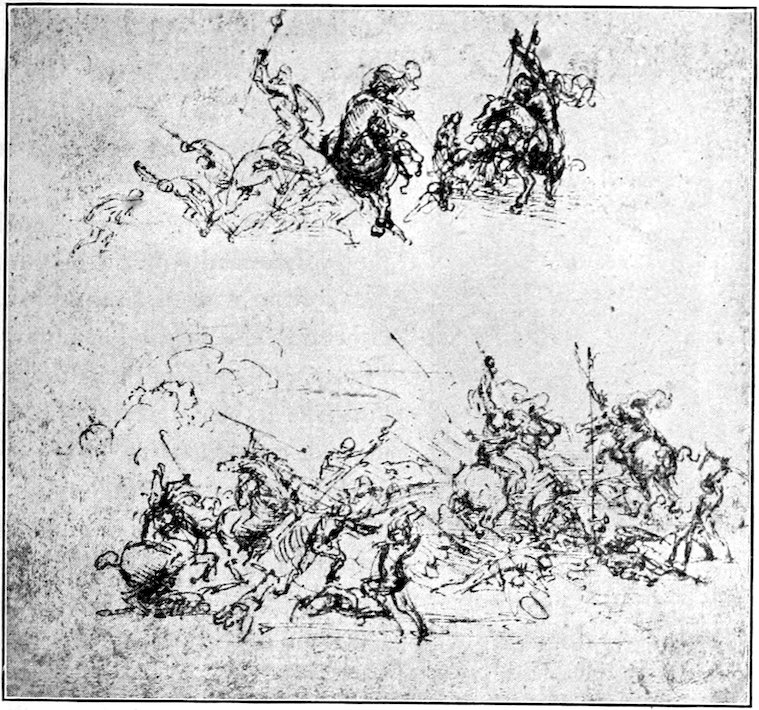

The Florentine ideal of Mass and Emotion—Its Humanism—The City of Florence about 1300—The Position and Methods of the Painter—The General demand for Religious Painting—Accelerated by the religious reforms of 1200, and changed in character—Insufficiency of the current Italo-Byzantine Style—Experiments towards a new manner: Duccio and the Sienese, Cimabue, Cavallini and the “Isaac Master”—Giotto—Immediate followers of Giotto, Andrea Orcagna and the return to sculptural methods—Later Panoramists, Andrea Bonaiuti and the Spanish Chapel.

Leonardo da Vinci, from the summit of Florentine art, has written “What should first be judged in seeing if a picture be good is whether the movements are appropriate to the mind of the figure that moves.” And again he has expressed somewhat differently the highest merits of painting as “the creation of relief (projection) where there is none.” For Florence, at least, these notions are authoritative, and they may well serve as text for most that I shall say about Florentine painting. To give significant emotion convincing mass—this was the problem of the Florentine painter from the moment when Giotto about the year 1300 began to find himself, to that day more than two centuries and a half later when Michelangelo died. No Florentine master of a strenuous sort ever failed to perceive this mission, and no unstrenuous artist was ever fully Florentine. This twofold aim—humanistic, in choice and mastery of emotion; scientific, in search for those indications which most vividly express mass where no mass is—this twofold endeavor Florence shared with the only 2greater city of art, Athens. Thus Florence is to the art of today what Athens was to that of classical antiquity.

In these two little communal republics were discovered and worked out to perfection all our ideals of humanistic beauty. Florence saw God, His Divine Son, the Blessed Virgin, and the saints quite as Athens had seen the gods of Olympus, the demi-gods, and the heroes simply as men and women of the noblest physical and moral type. Both agreed in magnifying and idealizing the people one ordinarily sees. For greater beauty, Athens represented them nude or lightly draped; for greater dignity, Florence chose the solemn garb of the Roman forum. Whether pagan or Christian, the guardians of a people’s morality were to be above haste, excitement, or any transient emotion. They were to express intensities of feeling, but a feeling more composed, permanent, and disciplined, than that of every day. Judgment and criticism count for as much in both arts as emotional inspiration. The great Florentine artist is a thinker; he is often poet and scientist, sculptor and architect, besides being a painter. Behind his painting lies always a problem of mind, and as sheer personalities the greatest painters of Siena, Venice, and Lombardy often seem mere nobodies when compared even with the minor Florentines. We should know something about a city that produced personality so generously, and before considering Giotto, the first great painter Florence bred, we shall do well to look at Florence as he saw it about the year 1300, being a man in the thirties.

Florence was then as now a little city, its population about 100,000 souls, but it was growing. The old second wall of about two miles’ circuit was already condemned in favor of a turreted circuit of over six. Up the Arno the forest-clad ridge of Vallombrosa was much as it is today; down the valley the jagged peaks of the Carrara mountains barred the way to the sea. The surrounding vineyards and olive orchards by reason of encroaching forest were less extensive than they are now, 3but through every gate and from every tower one could see smiling fields guarded by battlemented villas. In the city, the fortress towers of the old nobility, partizans mostly of the foreign Emperor, rose thickly, but already dismantled at their fighting tops, for the people, meaning strictly the ruling merchant and manufacturing classes, had lately taken the rule from the old nobles. Many of these had fled; some had been banished, as was soon to be that reckless advocate of the emperor, Dante Alighieri, an excellent poet of love foolishly dabbling in politics. Other patricians sulked in their fortress palaces. Some shrewdly got themselves demoted and joined the ruling trade guilds. Of these guilds a big four, five, or six, governed the city, while a minor dozen had political privilege. Only guild members voted for the city officers. The guilds combined the function of a trade union and an employer’s association, including all members of the craft from the youngest apprentice to the richest boss-contractor. Such a guild as the notaries, must have been much like a bar association, while the wholesale merchants’ guild must have resembled a chamber of commerce. The guild folk had early allied themselves with the Pope, the only permanent representative of the principle of order in Italy. The Pope was also the bulwark of the new free communes against the claims of the Teutonic Emperors. So in Florence piety, liberty, and prosperity were convertible terms.

Within the narrow walls was a bustling, neighborly, squabbling and making-up life. Everybody knew everybody else. The craftsman worked in the little open archways you may still see in the Via San Gallo, in sight and hearing of the passing world. Of weavers’ shops alone there were 300. No western city was ever prouder than Florence in those days. Her credit was good from the Urals to the Pentland Hills. Her gold florin was everywhere standard exchange. She had secret ways of finishing the fine cloths that came in ships and caravans 4from Ghent, Ypres, and Arras; she handled the silks of China and converted the raw pelts of the north into objects of fashion.

Her civic pride was actively expressing itself in building. Between 1294 and 1299 she had projected a new cathedral, the great Franciscan church of Santa Croce, a new town hall, and the massive walls we still see. For stately buildings she had earlier had only the Baptistry, in which every baby was promptly christened, and the new church of the Friars Preachers (Dominicans), Santa Maria Novella. In considering this Florence you must think of a hard-headed, full-blooded, ambitious community, frankly devoted to money-making, but desiring wealth chiefly as a step towards fame. Since the painter could provide fame in this world and advance one’s position in the next, his estate was a favored one.

The painter himself was just a fine craftsman. He kept a shop and called it such—a bottega. He worked only to order. There were no exhibitions, no museums, no academies, no art schools, no prizes, no dealers. The painters modestly joined the guild of the druggists (speziali), who were their color makers, quite as the up-to-date newspaper reporter affiliates himself with the typographical union. When a rich man wanted a picture, he simply went to a painter’s shop and ordered it, laying down as a matter of course the subject and everything about the treatment that interested him. If the work was of importance, a contract and specifications were drawn up. The kind of colors, pay by the job or by the day, the amount to be painted by the contracting artist himself, the time of completion, with or without penalty—all this was precisely nominated in the bond. Naturally the painter used his shop-assistants and apprentices as much as possible. Often he did little himself except heads and principal figures. But he made the designs and carefully supervised their execution on panel or wall. A Florentine painter’s bottega then had none of the preciousness of a modern painter’s studio. It was rather like 5a decorator’s shop of today, the master being merely the business head and guiding artistic taste. When we speak of a fresco by Giotto, we do not mean that Giotto painted much of it, any more than a La Farge window implies that our great American master of stained-glass design himself cut and set the glass. The painter of Florence had to be a jack-of-all-trades, a color grinder, a cabinet maker, and a wood carver; a gilder; to be capable of copying any design and of inventing fine decorative features himself. He must be equally competent in the delicate methods of tempera painting as in the resolute procedures of fresco.

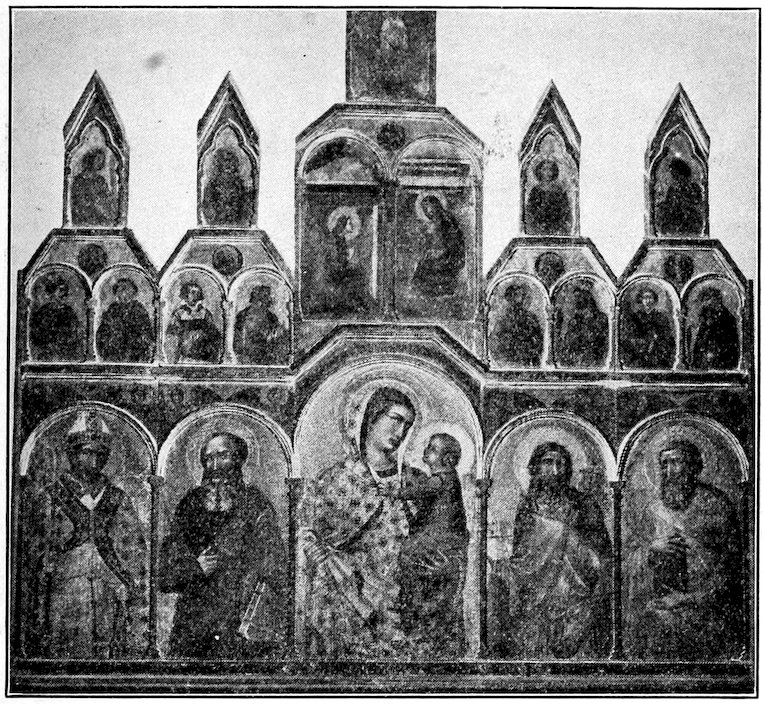

These two methods set distinct limits to the work and its effects. The colors were ground up day by day in the shop. Each had its little pot. There was no palette. Hence only a few colors were used, and with little mixing. For tempera painting a good wooden panel—preferably of poplar—was grounded with successive coats of finest plaster of Paris in glue and rubbed down to ivory smoothness. The composition was then copied in minutely from a working drawing. The gold background inherited from the workers in mosaic was laid on in pure leaf. The composition was first lightly shaded and modelled either in green or brown earth, and then finished up a bit at a time, in colors tempered with egg or vegetable albumen. The paints were thick and could not be swiftly manipulated; the whole surface set and so hardened that retouching was difficult. How so niggling a method produced so broad and harmonious effects will seem a mystery to the modern artist. It was due to system and sacrifice. Though the work was done piecemeal, everything was thought out in advance. Dark shadows and accidents of lighting which would mar the general blond effect were ignored. The beauty desired was not that of nature, but that of enamels and semi-precious stones. These panels are glorious in azures, cinnabars, crimsons, emerald-greens, and whites partaking of all of these hues. 6Their delicacy is enhanced by carved frames, at this moment, 1300, simply gabled and moulded; later built up and arched and fretted with the most fantastic gothic features.

If the painter in tempera required chiefly patience and delicacy, the painter in fresco must have resolution and audacity. He must calculate each day’s work exactly, and a whole day’s work could be spoiled by a single slip of the hand in the tired evening hour. For fresco, the working sketch was roughly copied in outline on a plaster wall. Then any part selected for a day’s work was covered with a new coat of fine plaster. The effaced part of the design must be rapidly redrawn on the wet ground. Then the colors were laid on from their little pots, and only the sound mineral colors which resist lime could be employed. The vehicle was simply water. The colors were sucked deep into the wet plaster, and united with it to form a surface as durable as the wall itself. Generally the colors were merely divided into three values,—light, pure colors, and dark. Everything was kept clear, rather flat, and blond, highly simple and beautifully decorative. One of the later painters, Cennino Cennini (active about 1400), tells us that a single head was a day’s work for a good frescante. The touch had to be sure, for a mis-stroke meant scraping the wet plaster off, relaying it, and starting all over again. The fresco painter accordingly needed discipline and method. Nothing could be farther from modern inspirational methods. Where everything was systematized and calculated in advance, you will see it was quite safe for a master to entrust his designs to pupils who knew his wishes. Every fresco when dry was more or less retouched in tempera, but the best artists did this sparingly, knowing that the retouches would soon blacken badly or flake off.

So much for the shop methods. Now for him who makes shops possible—the patron. A wealthy Florentine as naturally wanted to invest in a frescoed chapel as a wealthy American 7does in a fleet of motor cars. Considering the changed value of money, one indulgence was about as costly as the other. But the Florentine never quite regarded paintings as luxuries. They were necessary to him. He loved them. They enhanced his prestige in this world and improved his chances in the next. Then to beautify a church was really to magnify the liberty and prosperity of Florence, which largely derived from the Holy See. Recall that every Florentine was born a Catholic, baptized in the fair Church of St. John with the name of a saint. This saint, he believed, could aid him morally and materially, was in every sense his celestial patron. It paid to do the saint honor, and that could best be done through the painter’s art. The poorest man might have a small portrait of his patron, a rich man might endow a chapel and cause all his patron’s miracles to be pictured on the wall. Think also that every altar—a dozen or more in every large church—was a shrine[1], containing the bread and wine that by the never-ceasing miracle of the Mass became the Saviour’s body and blood; and was also a reliquary or tomb, containing in whole or part the body of some saint. Every altar then, and every chapel inclosing one, cried out for a twofold interpretation of its meaning. Everything about the Eucharist had to be explained (involving pretty nearly all of Biblical history), and the particular relic required similar illumination. Since many of the faithful could not read, and the Catholic Church has ever been merciful as regards sermonizing, these explanations of the altar as miracle shrine of Our Lord and as tomb of a particular saint were best made pictorially, and generally were so made.

Such motives for picture-making Florence of course shared with the entire Christian world. It remains to explain why she wanted more painting and better than any other mediæval city. She wanted more painting chiefly because of her exceptional civic pride and prosperity, she wanted better painting because she had moved ahead of the world towards finer, 8more passionate, and conscious experiences of life which the older painting was powerless to express. About the year 1200, a century before the time we are considering, there flourished two great religious leaders who gave to Christianity a new dignity and appeal. St. Dominic, with his disciple, St. Thomas Aquinas, endeavored to make Christianity more reasonable, St. Francis of Assisi endeavored to make it more heartfelt and compassionate. They founded two monastic orders with divergent yet harmonious aims. The Dominicans called men to a life of study and self-examination, enlisting the human reason to explain and justify the universe under the Christian scheme; the Franciscans called men to poverty, humility, and chastity, and service to the unfortunate. Between the two—one supplying the light of the reason and the other the light of the heart—they overcame heresies which had menaced both Christianity and civilization and roused the Church out of its dogmatic slumber. It was no longer enough for the Church to threaten. Men yielded to her now only on condition that their heads be convinced or their hearts touched. In Florence, where a rationalizing shrewdness and a real warm-heartedness singularly blended, the double appeal was irresistible. By and large the whole city either schematized with the Dominicans or slummed with the Franciscans. Here was urgent new matter requiring an art that could move and persuade.

Together with this religious revival and the political and commercial progress we have noted, came a literary revival. Before the end of the 13th century such poets as Guido Guinizelli, Guido Cavalcanti, and Dante Alighieri had so reshaped the rude vulgar tongue that it became worthy of its Latin succession. The refinements of chivalric love came to Florence in melodious verse, and what the poets called the “sweet new style,” il dolce stil nuovo, in diction presaged a similar sweet new style of painting. Alongside of the poets, Brunetto Latini in the Tesoro shows glimmerings of scientific interest, 9and Giovanni Villani lends substance and dignity to the work of the chronicler. Already the sculptors Nicola and Giovanni of neighboring Pisa had grasped the beauties respectively of classic sculpture and the noble intensity of that of the Gothic North. All this immensely increased that sum of fine thinking, feeling, and seeing which underlies all great art.

To express these new emotions the old painting was inadequate. Italy through the so-called Dark Ages produced art abundantly. Wherever power and order asserted themselves amid the welter of war and oppression, stately buildings rose and these were decorated. Thus at Rome, where the popes gradually added temporal to spiritual power, splendid basilicas grew over the tombs of the martyrs. At Ravenna, through the 6th and 7th centuries the seat of the Byzantine and Gothic sovereignties, magnificent churches and baptistries were covered with pictorial mosaics. In Sicily, at Messina, Cefalù and Palermo, the sway of the Norman kings in the eleventh and twelfth centuries expressed itself in churches and civic buildings of the utmost splendor, which were adorned with mosaics by Greek masters. When the fugitives from the valleys of the Po, Adige, and Piave, and Brenta fled from Attila to the Venetian fens, there again was a beginning of great building. Wherever there was a powerful primate as at Milan, Como, Parma, Pisa, or a wide ruling abbot as at Subiaco, Monte Cassino, Capua, you will find art.

But hardly, except perhaps in architecture, Italian art. We have sporadic provincial expressions dominated from afar by the prestige of the Eastern Roman Empire. At Constantinople there was a permanent court, a ceremonious civilization, an artistic blending of the traditions of old Greece and of the mysterious Levant. The merchants of the world sought from Byzantium, jewelry, enamels, embroideries, brocades, carved ivories, and pictured manuscripts. She was to the early Middle Ages what Paris is to ours—the æsthetic fashion 10maker of the world,—and her skilled artists went far afield as so many missionaries of the Byzantine style. We find them making the mosaics of Ravenna in the 6th and 7th centuries, of St. Mark’s at Venice from the 9th century, of many Roman churches from an even earlier date, of Palermo in the 12th, and of the Baptistry at Florence in the 13th. This Byzantine manner, as practiced by the travelling Greek artists and by their innumerable Italian imitators, is the real starting point and jump-off place for Italian painting. Hence in first studying the Byzantine style we do but imitate the Italian painters who immediately preceded Giotto.

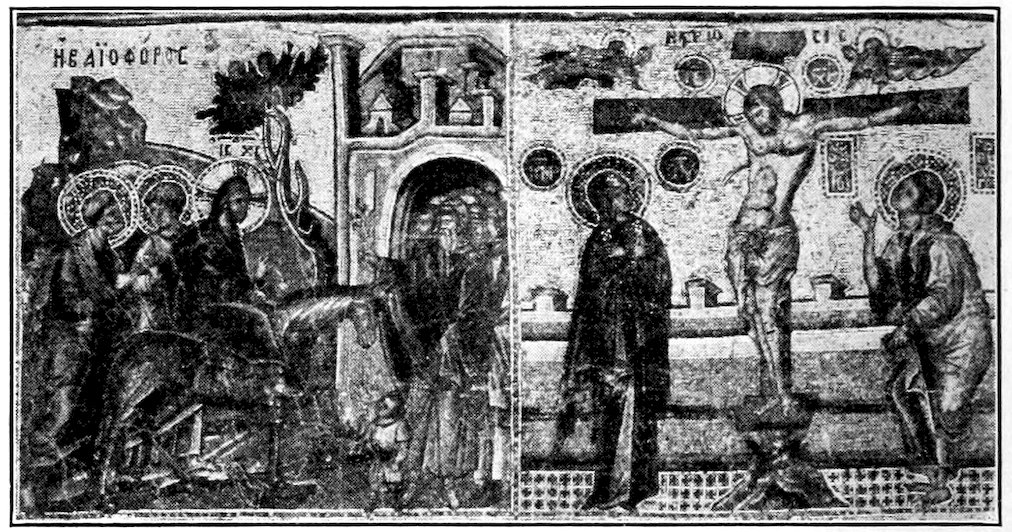

Fig. 1. Byzantine Narrative Style about 1300. Detail from Mosaic Book Covers in the Opera del Duomo.

Fig. 2. Mosaic in the Cathedral, Pisa. St. John, left, is by Cimabue, 1302; the Christ is in good Byzantine tradition; the Virgin, right, is some twenty years later.

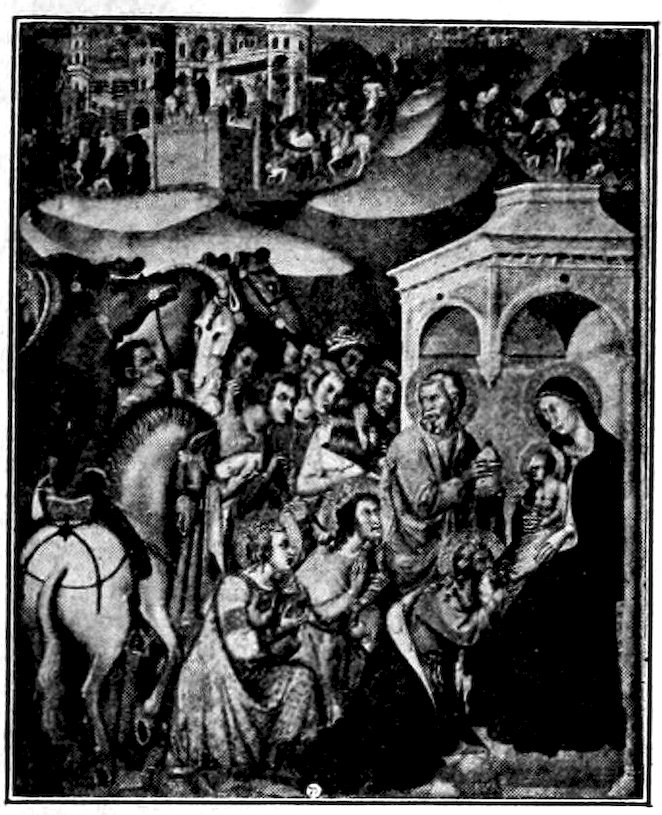

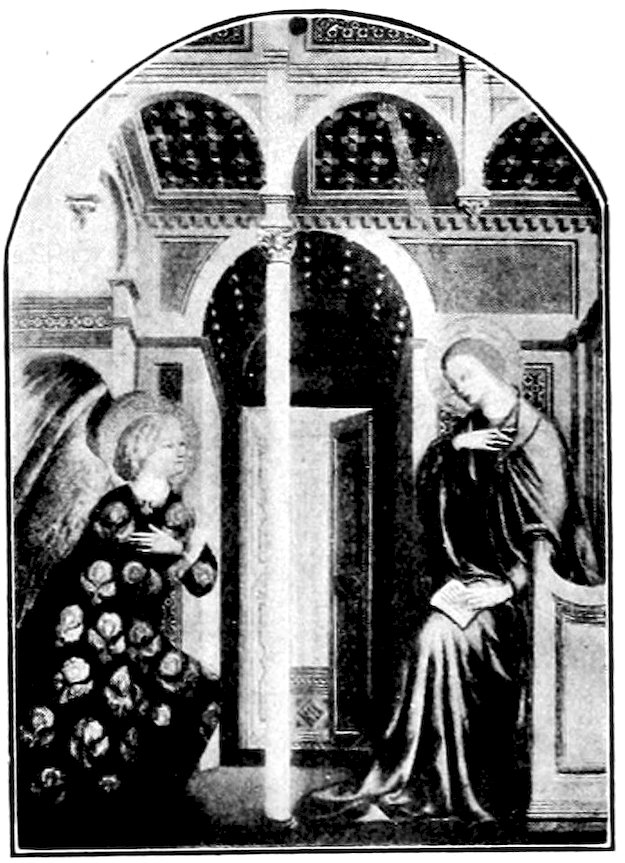

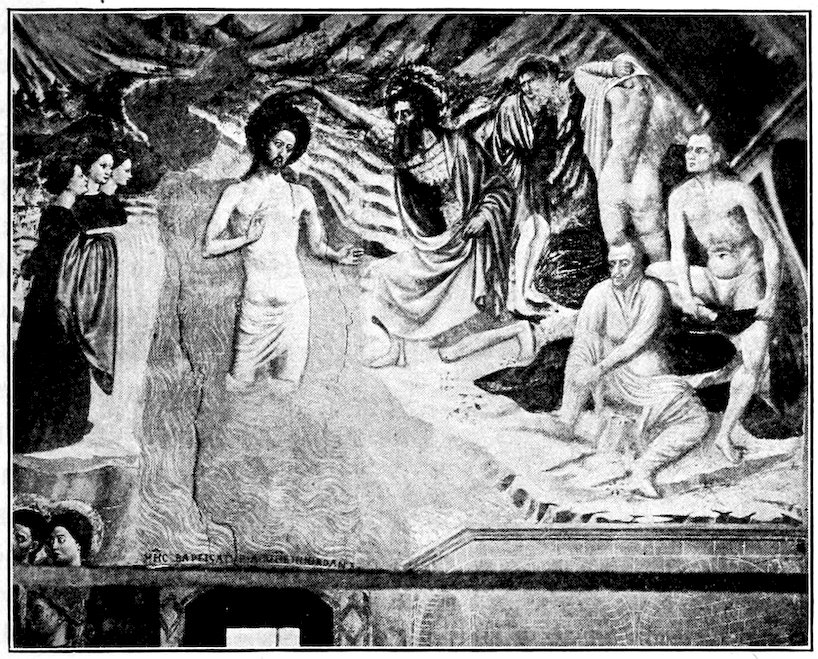

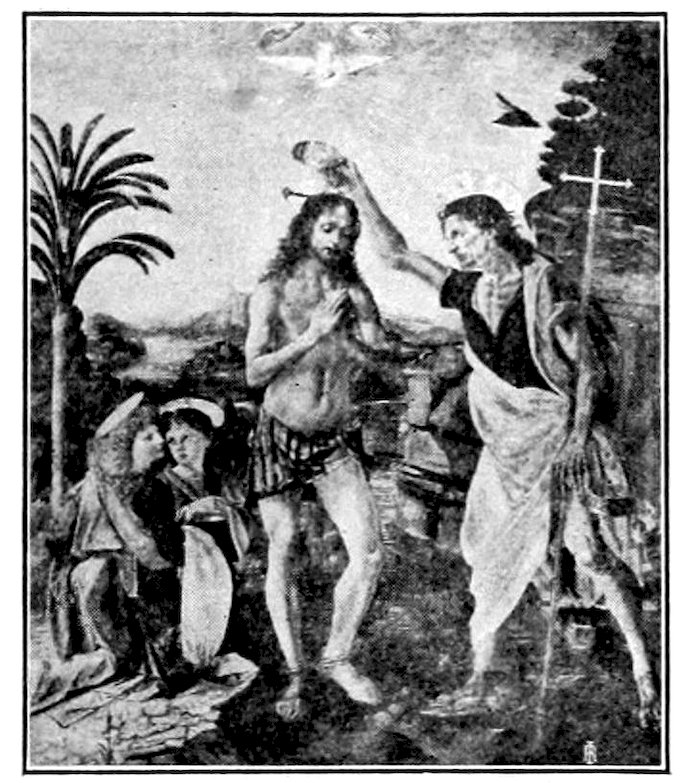

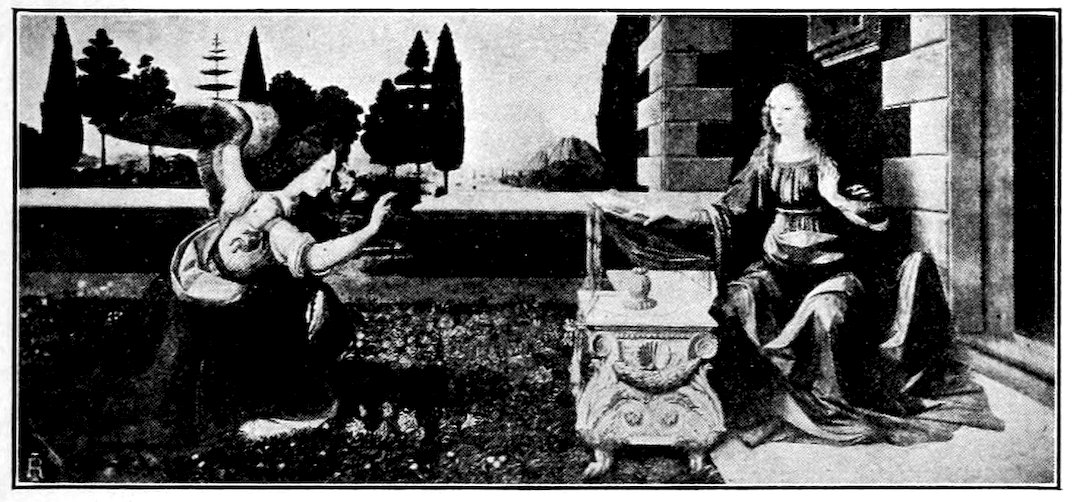

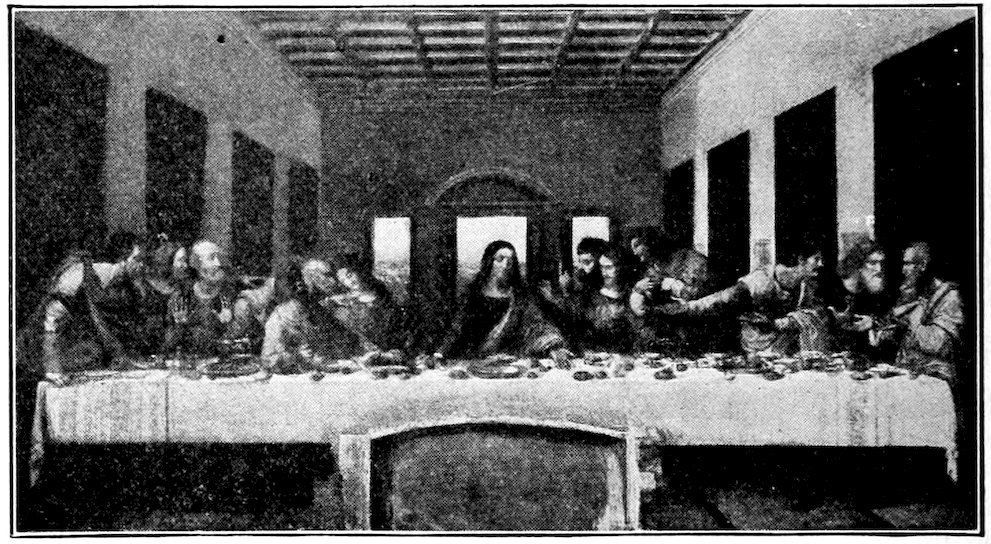

Byzantine pictures have come down to us on the largest and on the smallest scale—in the great mosaics and wall paintings, and as well on small panels and in the illustrated books used in the ritual of the church. Both are important. The mural decorations are what the early Italian painter had constantly before his eye; the miniatured psalters, Gospels, lectionaries, chorals and prayer books, afforded the patterns from which he drew with little alteration the standard compositions of the Annunciation to Mary, the Nativity of Christ, His Adoration by the Shepherds and Kings, His Baptism, the Raising of Lazarus, the Last Supper, Crucifixion, Descent into Hell, Resurrection, and Ascension. But Byzantine design is most imposing in its monumental phase. The most careless traveller still feels awe before those solemn figures of Christ supreme ruler (Pantokrator) and his Mother queen of heaven which are seen throned against a background of azure or gold and attended by solemn figures of apostles and martyrs, Figure 2. The forms are flat,—silhouettes enriched by interior tracery, the arrangement in the space formal, symmetrical, highly decorative. The smaller narrative compositions,[2] Figure 1, are clearly conceived but have small emotional appeal. For this reason the Italians of the Golden Age spoke of the Byzantine style as rude. This is an error. Rude in the hands of half-trained local imitators, the style as formulated in the 9th century 12at Constantinople was highly sophisticated and decoratively of great refinement. It was based on an admirable system of color spotting and a fine understanding of silhouette. The contours were cast in easy conventional curves. These were enriched within by hatchings and splintery angles of gold which contrasted effectively with the fluent outlines. Everything was done by precept and copybook. In four centuries before the year 1300, the style showed little change, indeed is still alive in the mountains of Macedonia and, until the Revolution, in Russia. The Byzantine artist seldom looked at a fellow mortal with artistic intent. He looked at some earlier picture or considered his own color preferences. Conventional and anæmic as the narrative style was, it did all that was required of it. Nothing better serves the purpose of an authoritative Church than the awe-inspiring Christs of the Lombard and Sicilian and Roman apses, and so long as the Church felt no duty beyond that of plain statement of her claims, the unfelt narratives from the Scriptures served every religious need.

It was different when under the leading of St. Dominic and St. Francis,[3] the Church eagerly wished to persuade men. Men may well have been frightened or even instructed by a Byzantine picture; nobody was ever persuaded by one. It took a century to work away from the Byzantine style, so deeply was it rooted. In fact, from the year 1226, that of St. Francis’s death, to about the end of the century, such artists as Guido of Siena, Coppo di Marcovaldo, Giunta of Pisa, Jacopo Torriti, Giovanni Cosma, Duccio, and Cimabue chiefly restudied the old Byzantine manner. They wished to learn how to build creditably before they began to tear down. Such reverent experiment extending over two generations only proved that the breach with Byzantine formalism was inevitable.

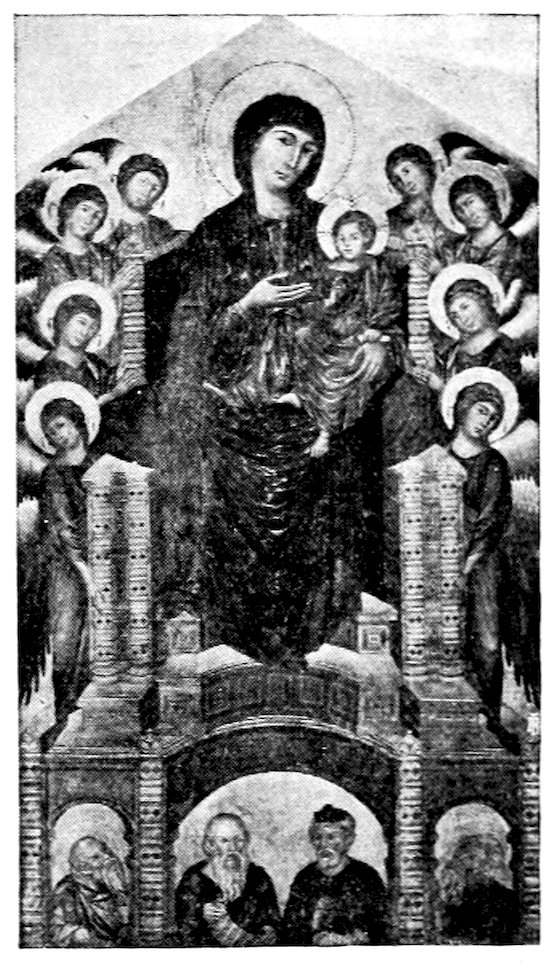

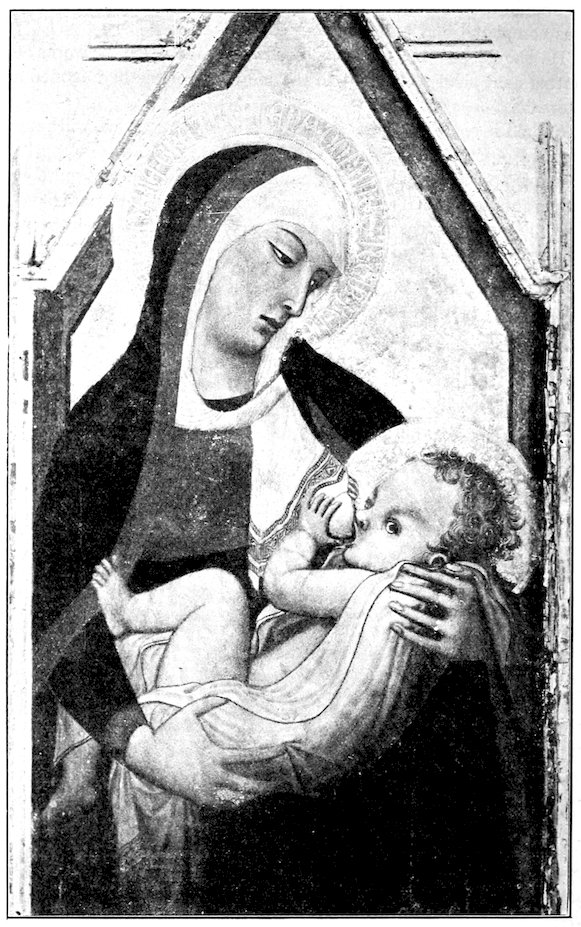

Fig. 3. Tuscan Master about 1285.—Otto Kahn, N.Y.

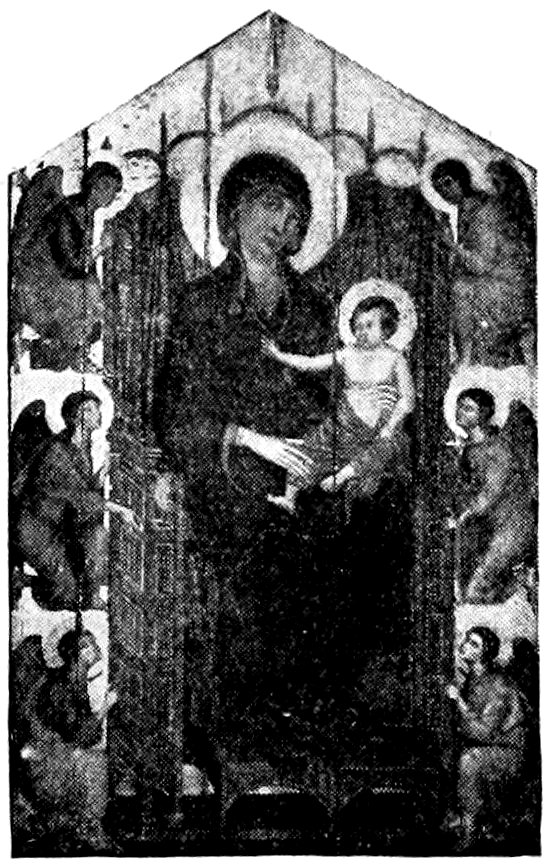

Fig. 4. Cimabue. Madonna in Majesty.—Uffizi.

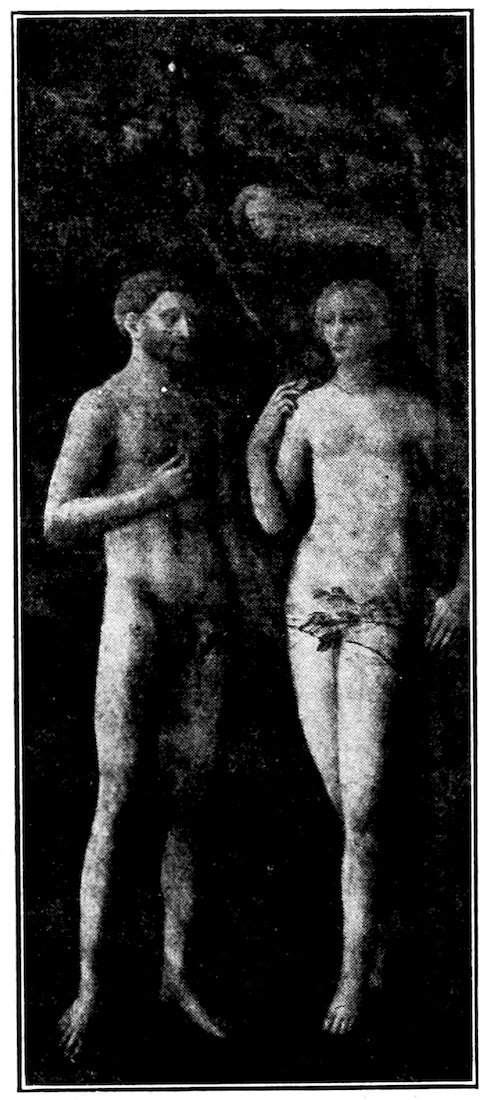

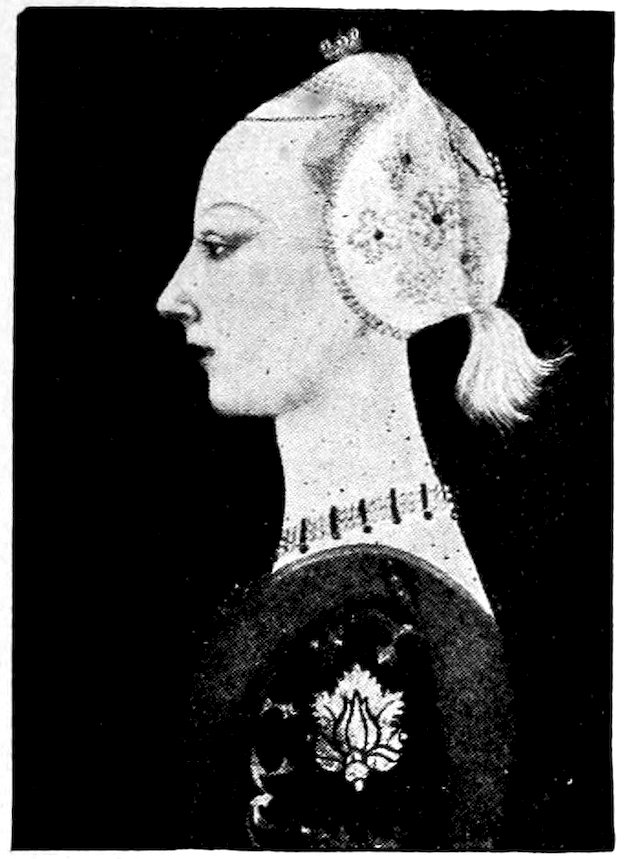

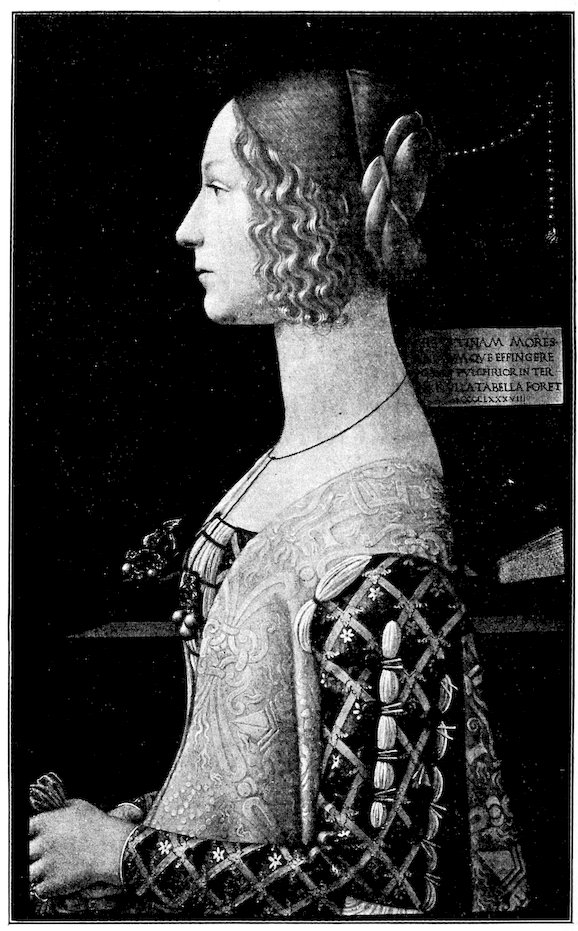

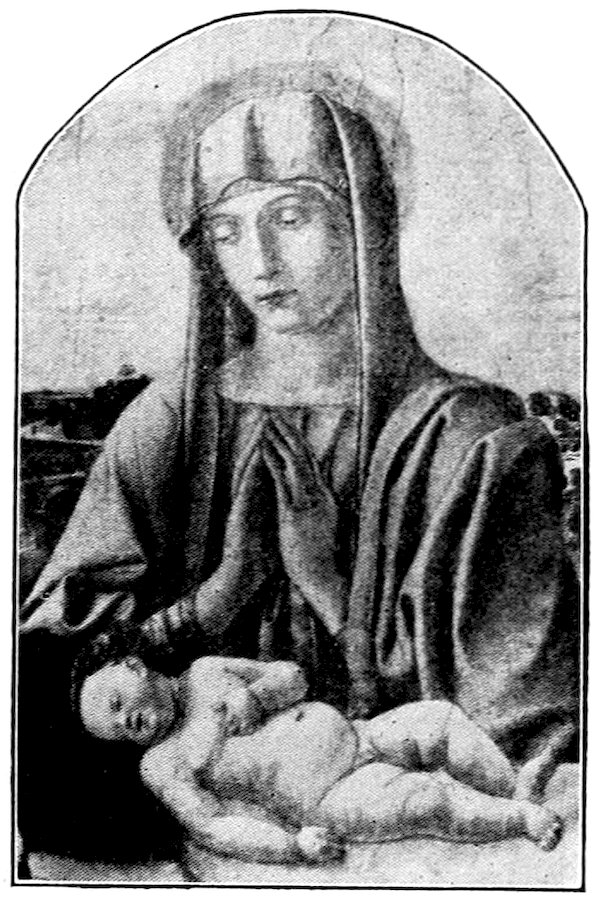

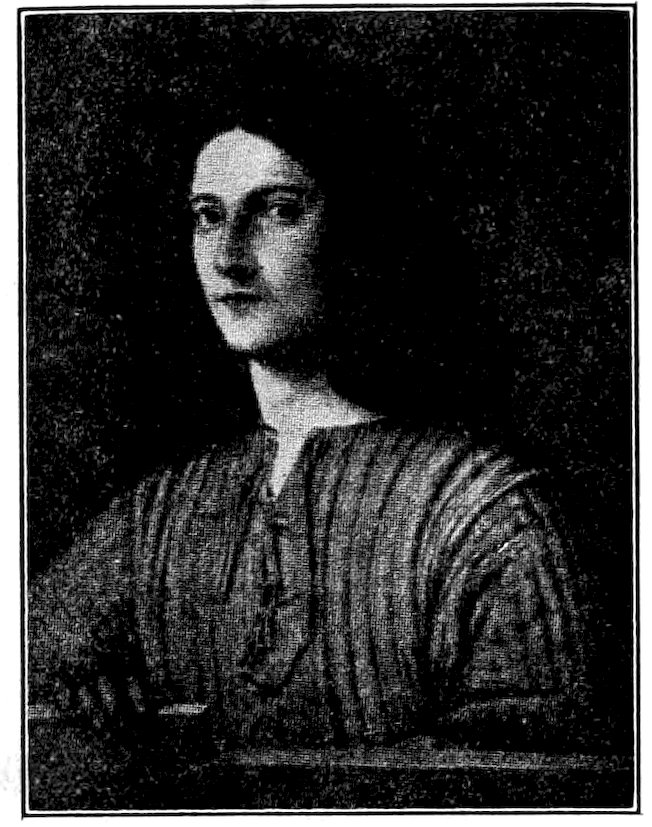

With the deepening and broadening of personal, civic, and religious emotions, the painter found new exactions laid upon him which the bloodless art of Byzantium could not satisfy. New life called for new forms to express it. We find in sculpture from about the year 1260, that of Giovanni Pisano’s first pulpit—wholly classical in its dignity—a kindred endeavor in advance of the art of painting. The renewal took three forms: the more conservative spirits accepted the Byzantine formulas but endeavored to refine on them in a realistic sense, to add grace to austerity. Such moderate development of the old style fixed the character of the school of Siena and was magnificently initiated by its greatest artist, Duccio, active about 1300. A very beautiful Madonna of this general tendency is in the collection of Mr. Otto Kahn at New York, Figure 3. It has been quite variously attributed.[4] It seems to me, however, a pure Tuscan work by Coppo or a painter akin to him. For the greater spirits such a reform was inadequate. Refine the Byzantine formulas to the utmost—there was no 14gain, rather loss in strength. Accordingly a vehement spirit like Cimabue,[1–5] acknowledgedly father of the Florentine school, accepts the Byzantine tradition loyally, but seeks to make its rigid mannerisms express the new religious passions. At times he is successful at this unlikely task of putting new wine into old bottles. His great enthroned Madonna at Florence, Figure 4, with solemn angels in attendance and grim patriarchs below her throne, may have been painted as early as 1285. It is faithful to the old monumental tradition—akin to the Christs and Marys of the mosaics—in its impressive richness is one of the most majestic things the century produced. It reveals the docility of its creator but only partially his power. We have hardly his hand but surely an echo of his influence in the tragic crucifix in the museum of Santa Croce. It is the moment of agony, and the powerful body writhes against the nails, while the head sinks in death. It may represent hundreds of similar crosses that stood high in air on the rood beam before the chancel, in sight both of the preacher and his public.

Somewhere about 1294, Cimabue was called to Assisi to decorate the church in which St. Francis was buried. His part was the choir and transepts of the upper church. In the cross vault he painted the four evangelists, on the walls he spread the stories of St. Peter and St. Paul, the legends of the Virgin scenes from the Apocalypse, the gigantic forms of the archangels and a Calvary, Figure 5, that is one of the most moving expressions of Christian art. Chipped and blackened, their lights become dark through chemical change, these wall paintings retain an immense power and veracity. The Byzantine forms gain a paradoxical solidity, like that of bronze. The convulsion of the figure of Christ is given back in the wild gestures of the mourning women and the terrified Jews. It is the moment of the earthquake and the opening of tombs; a cosmic terror and despair pervade the place. The work is hampered and rude but completely expressive. The sensitive 15Japanese critic and man of the world, Okakura Kakuzo, used to regard these sooty frescoes in the transepts of the Franciscan basilica as the high point of all European art, which should at least induce the tourist and the student to give a second look at these battered and fading masterpieces. Recently an inscribed date, 1296, has been discovered on the choir wall which settles a long vexed question of chronology. The upper part of the work in the transepts and choir must have been going on for some years earlier, and the entire decoration of the Upper Church should roughly be comprised between 1294 and 1300. Cimabue died about 1302 while working on the apsidal mosaic at Pisa, where the St. John is by his hand, Figure 2. He had brought life and passion into Italian painting, as his younger contemporary Giovanni Pisano had into Italian sculpture. Cimabue’s defect—that of a noble spirit—was the faith that the old pictorial form could contain the new surging emotions.

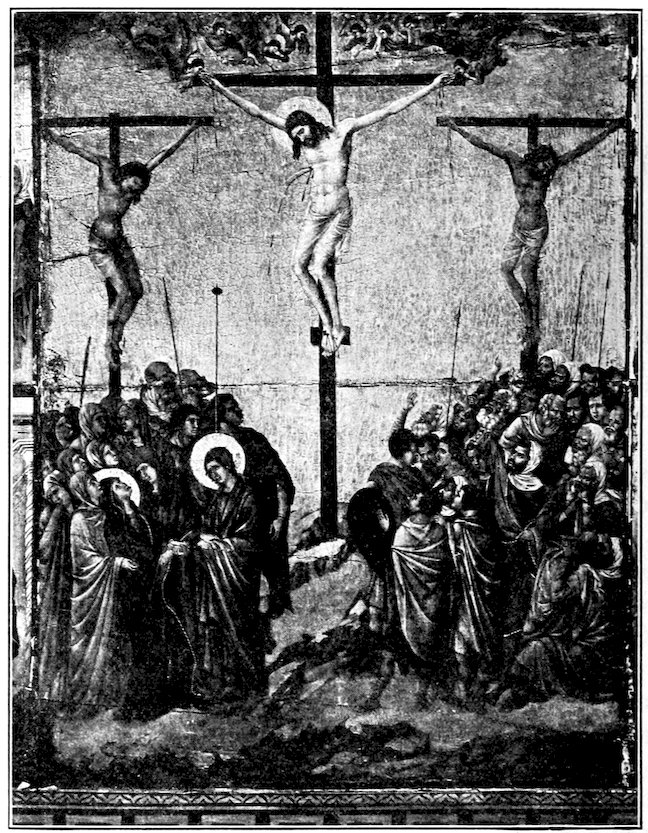

Fig. 5. Cimabue. Calvary. Fresco.—Upper Church, Assisi.

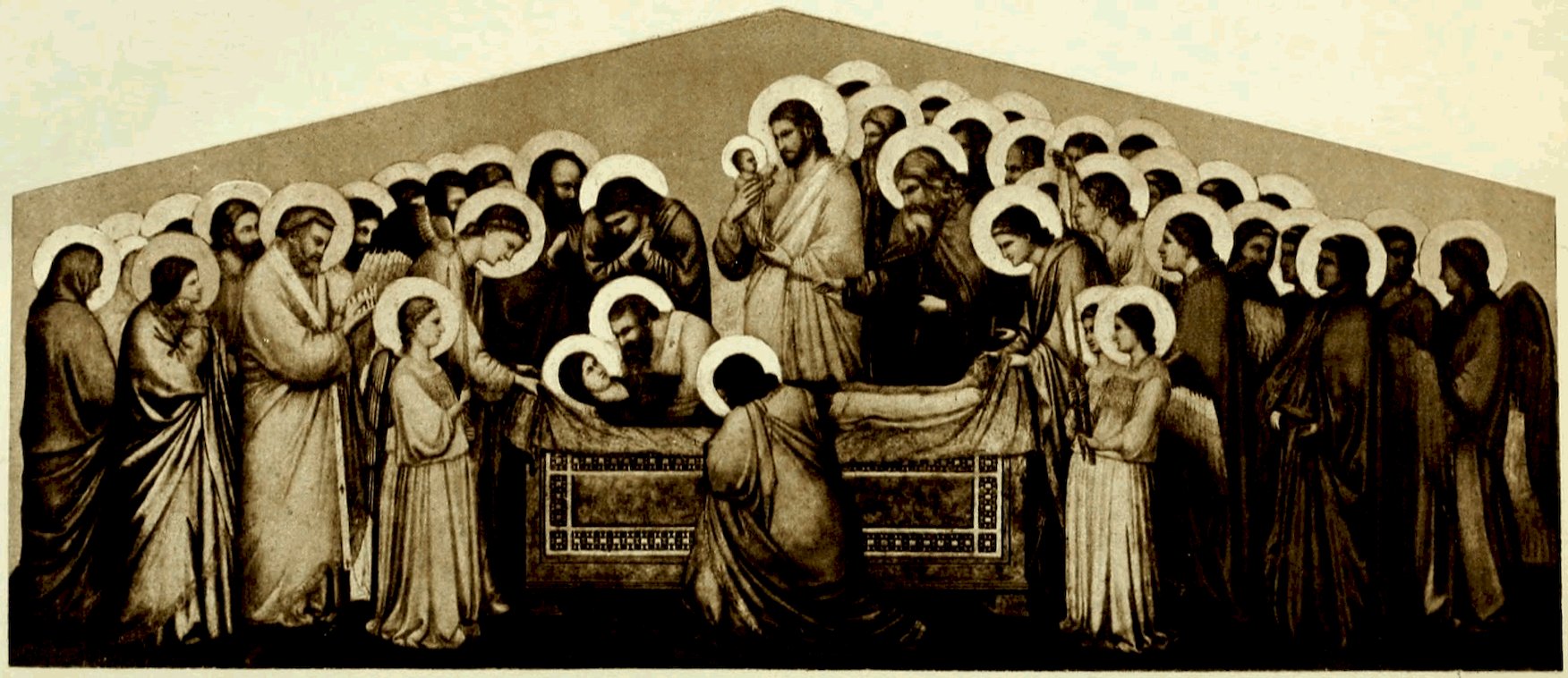

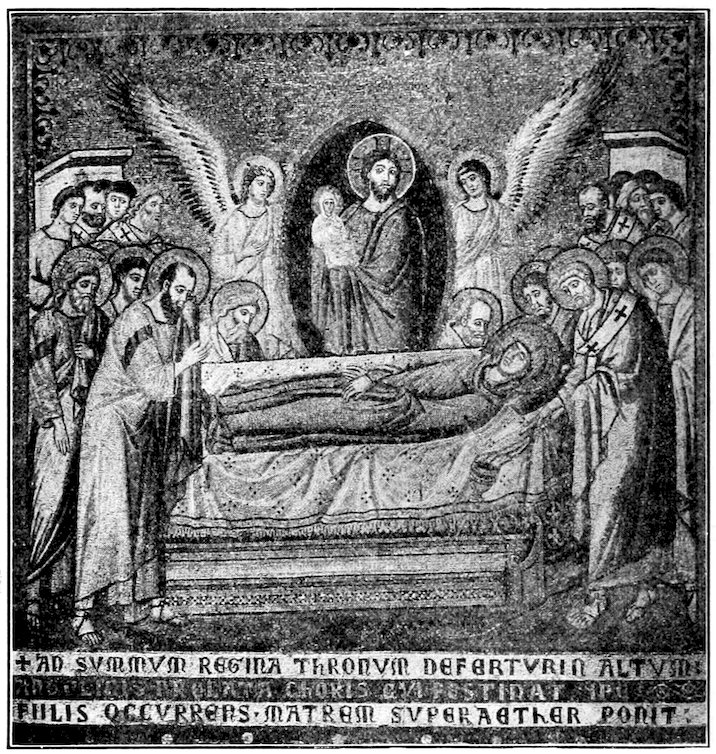

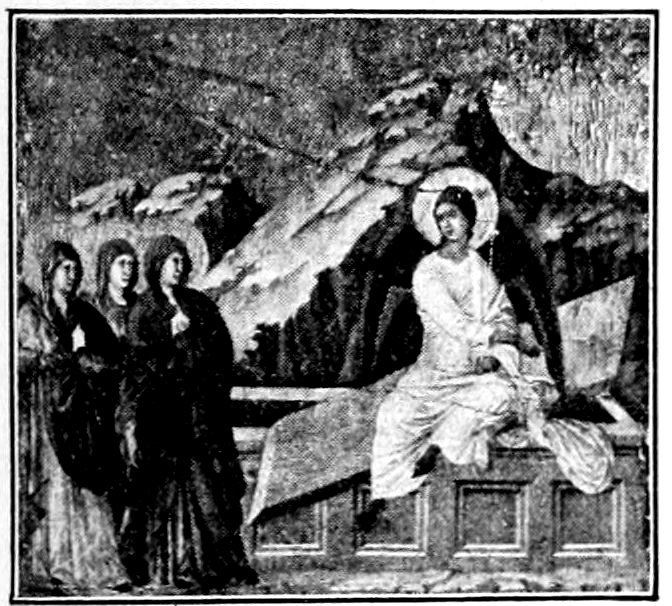

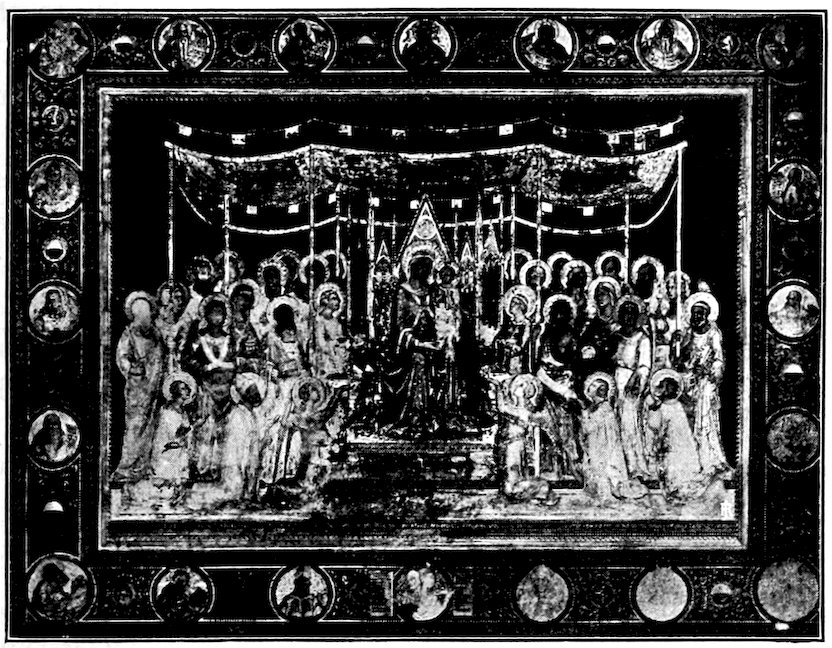

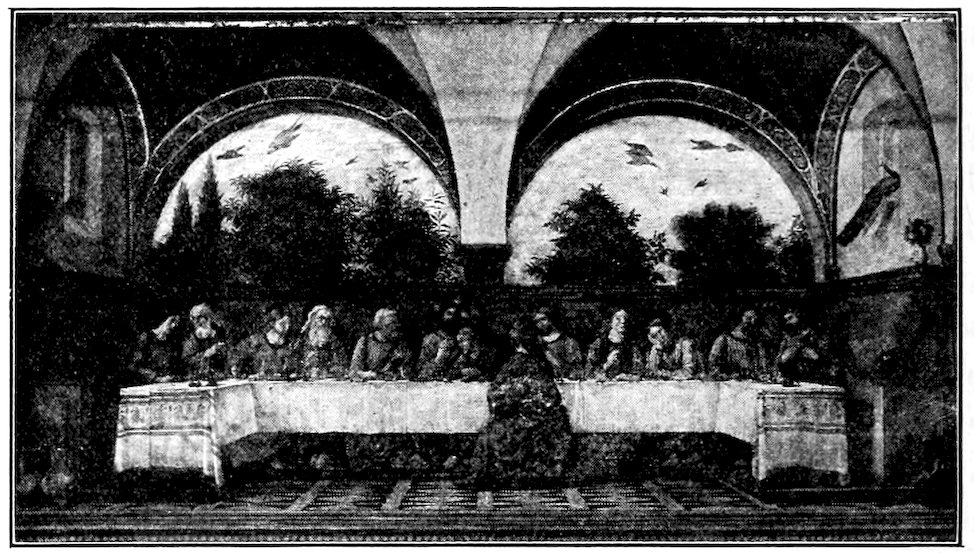

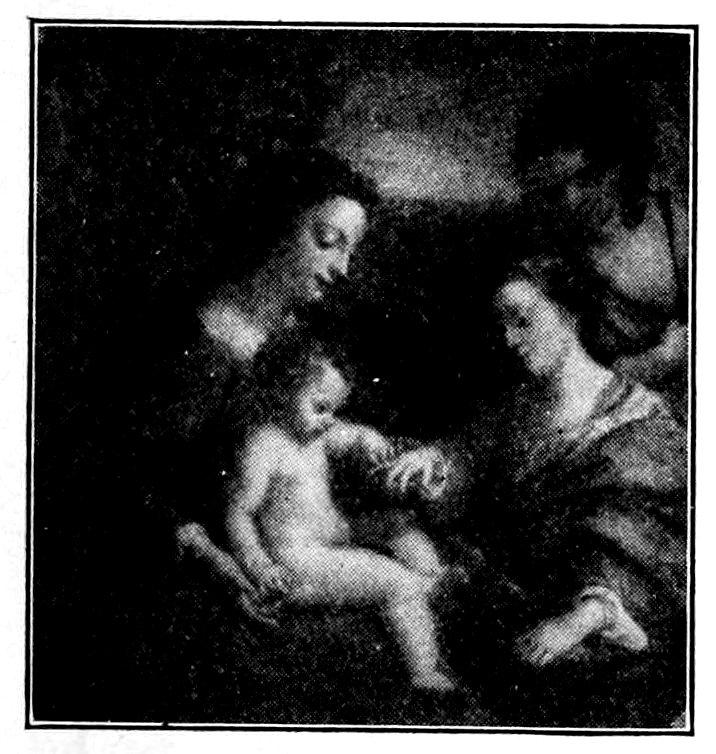

Fig. 6. Pietro Cavallini. Dormition of the Virgin. Mosaic.—S. M. in Trastevere, Rome.

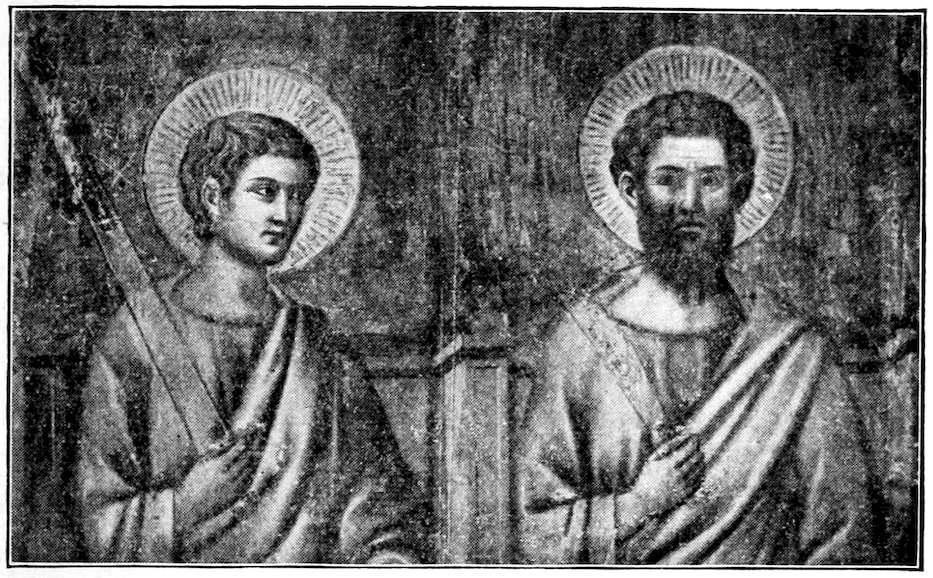

Fig. 7. Pietro Cavallini. Apostles, fresco, from Last Judgment.—Santa Cecelia in Trastevere.

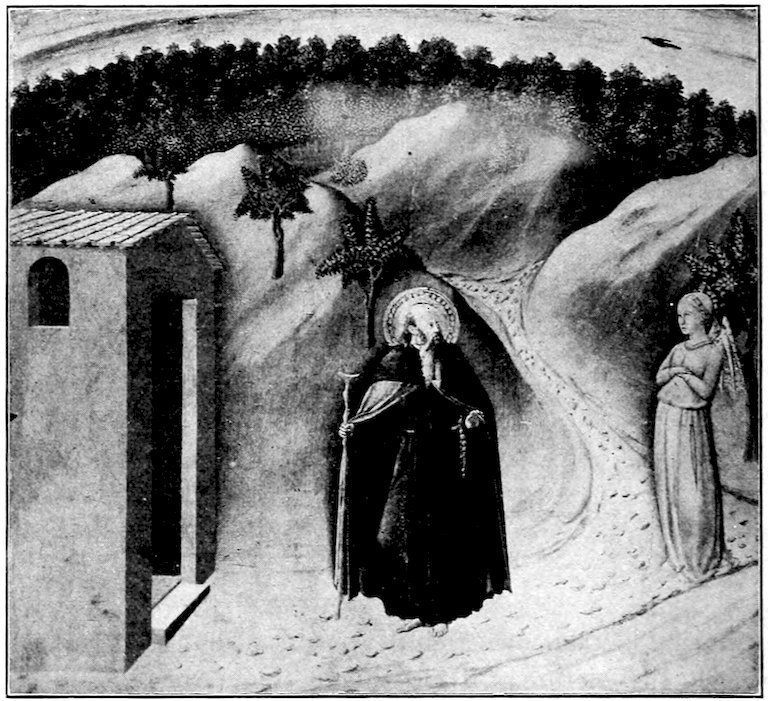

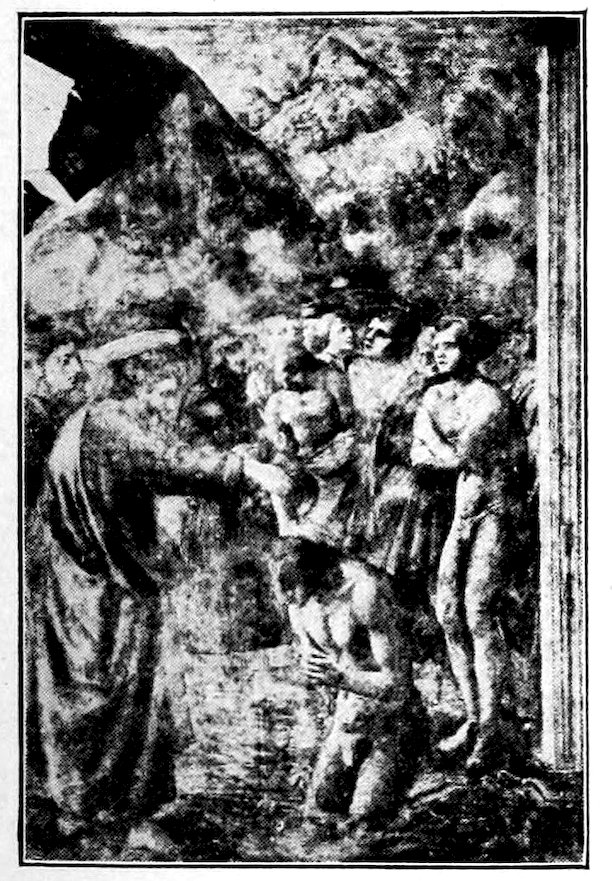

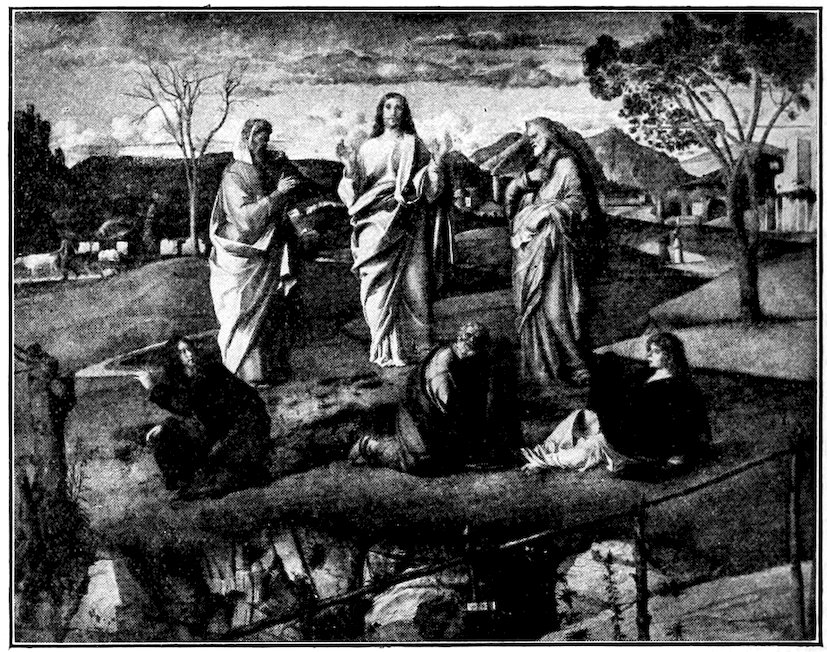

Colder spirits, as is often the case, more readily found the right way. And the discovery was made at Rome where the sculptured columns, arches, and sarcophagi, the pagan wall paintings and the earliest Christian mosaics combined to continue the lesson of classic humanism. A remarkable family of decorators, the Cosmati; with such contemporaries as Jacopo Torriti and Filippo Rusuti begin very cautiously to free themselves from Byzantine trammels. But it was a painter, Pietro Cavallini,[5] who more fully grasped that glory that had been Rome. In 1291 he designed for the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere a Madonna and four stories of the Christ Child in mosaic. Here we glimpse a new pictorial form, Figure 6. Those Byzantine hooks and hatchings which were quite false to form give way to a reasonable structure in light and dark, the hair no longer wild and ropy, is disposed in sculpturesque locks, the draperies are no longer a cobweb pattern, but cast in broad and classic folds. All these improvements may be noted in more complete form in the frescoed Last Judgment which has recently been uncovered in the church of Santa Cecilia, Figure 7. Here the heads of Christ and the Apostles are well built in carefully graduated light and shade, while the draperies suggest Hellenistic statuary. But the renovation is on the whole cold and academic. Cavallini has not much more to say than the Byzantines, but that little he says with far greater gravity and truthfulness. He was a lucid and industrious but not a fine or strong spirit. His work later at Naples—in the Church of the Donna Regina, about 1310—shows that when he will express strong emotions he becomes merely hectic. Yet he recovered for Italian painting more than a hint of the choice naturalism of old Rome, and 18that is his sufficient glory. There is greater power and knowledge than his in the work of such contemporaries as the unknown painters of the frescoed heads of prophets in Santa Maria Maggiore at Rome and of the stories of Isaac in the Upper Church at Assisi.[6] These show a resolute and intelligent effort to draw in masses of light and shade, and as well an ambition to recover the gravity of the early Christian mosaics. It is no wonder that some critics ascribe such dramatic and superbly constructed frescoes as The Betrayal of Esau to young Giotto, Figure 8, but the art is too mature for any young artist. We have rather to do with a great personality of Roman training who broke the way for Giotto. Cavalcaselle suggests, I think rightly, that the Florentine, Gaddo Gaddi, may have done some of this work. But we are safe only in calling this great painter “The Isaac Master.”

To recapitulate, there were three ways, all imperfect, open to a young and progressive painter who like Giotto di Bondone was forming a style about the year 1300. He might with the Sienese evade the issue of passion and naturalism, choosing for gracefulness, he might try over again the great adventure of his master Cimabue, endeavoring to bring emotion into the old unfit forms, or he might, like Pietro Cavallini, let emotion take care of itself and work academically towards better structure, drapery, light, and shade. His choice was absolutely momentous for modern painting, and I want you to feel that the issue was quite consciously and vividly before him, for he had spent much of his youth as a humble assistant in the basilica at Assisi, where frescoes in the vehement Tuscan manner of Cimabue and in the dignified Roman style of the Isaac Master were being painted side by side. His decision was to combine the merits of the two manners—to seek, like his master, sincerity and depth of emotion, but to embody it in the new and nobler forms of the Roman school. This decision virtually fixed the character of Christian art in Italy—it was 19to be warm and humanistic, but it was to revive much of that abstract nobility which old Rome had inherited from Greece. Thus Italian painting at the outset took a classic stamp which when true to itself it has never lost. In fundamental ideas of beauty, there is no real difference between Giotto, Masaccio, Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Titian, Michelangelo.

Fig. 8. “The Isaac Master.” Esau before Isaac. Fresco.—Upper Church, Assisi.

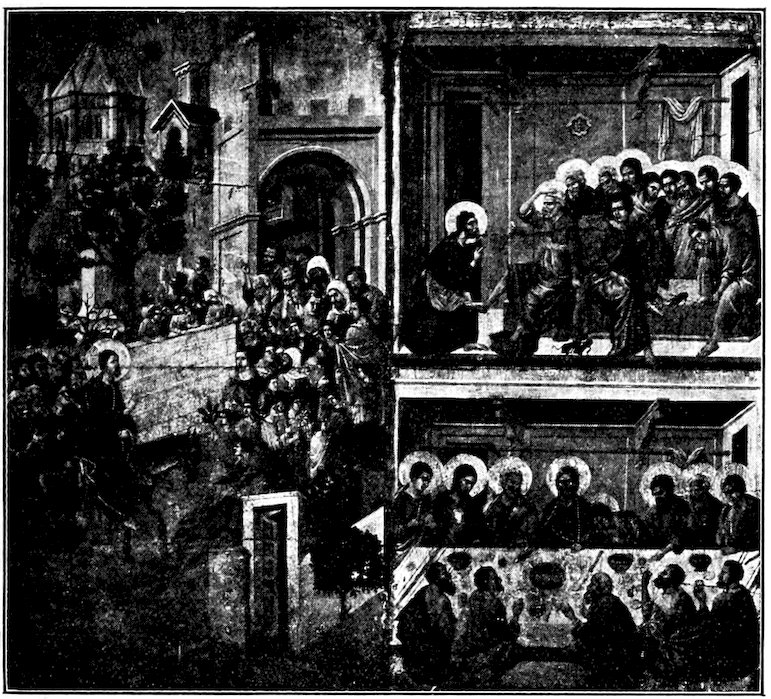

Giotto di Bondone,[7] according to the best information we 20have on a disputed point, was born in 1266, at the village of Colle, in the lovely valley of the Mugello. His people were prosperous and his way smooth. I see no reason for doubting the charming legend told by Ghiberti that Cimabue found the lad Giotto by the roadside diligently scratching the outlines of a sheep on a slate, and that that was the beginning of their association. In any case, we may surmise that he was early with Cimabue as apprentice and eventually went with the Master to Assisi to grind colors, clean brushes, and paint under direction. To be at that moment in the Franciscan Basilica was to be at the greatest creative center of the world. It seems to me likely that Giotto may have had a considerable part in the actual painting of the Old and New Testament stories in the nave, and I believe we may find his earliest designs in certain frescoes of the upper rows. The Lamenting over Christ’s Body, for example, singularly combines the energy of Cimabue with the dignity of Cavallini, and there are significant echoes of the composition in Giotto’s later version of the same theme at Padua. Tradition also ascribes to Giotto, maybe correctly, the Resurrection and Pentecost on the entrance wall.[8]

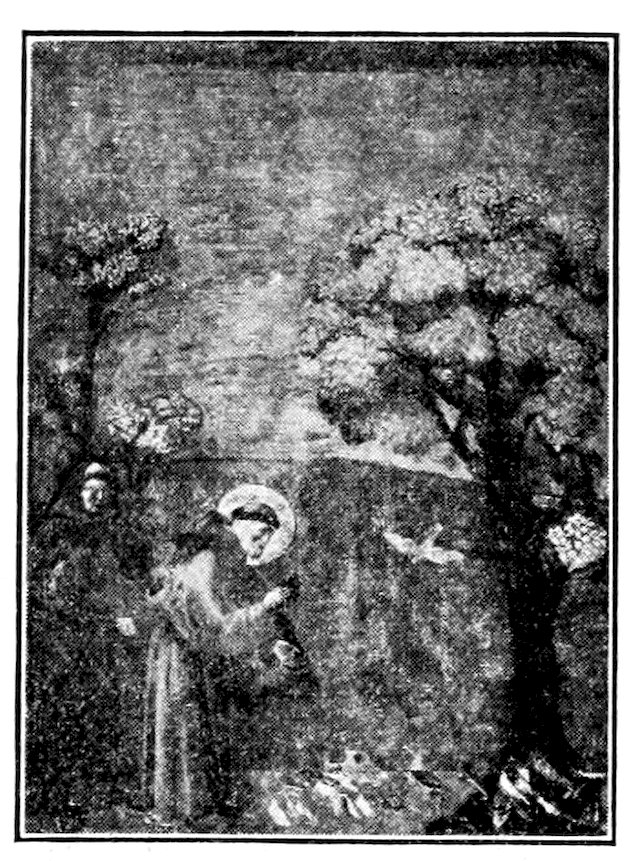

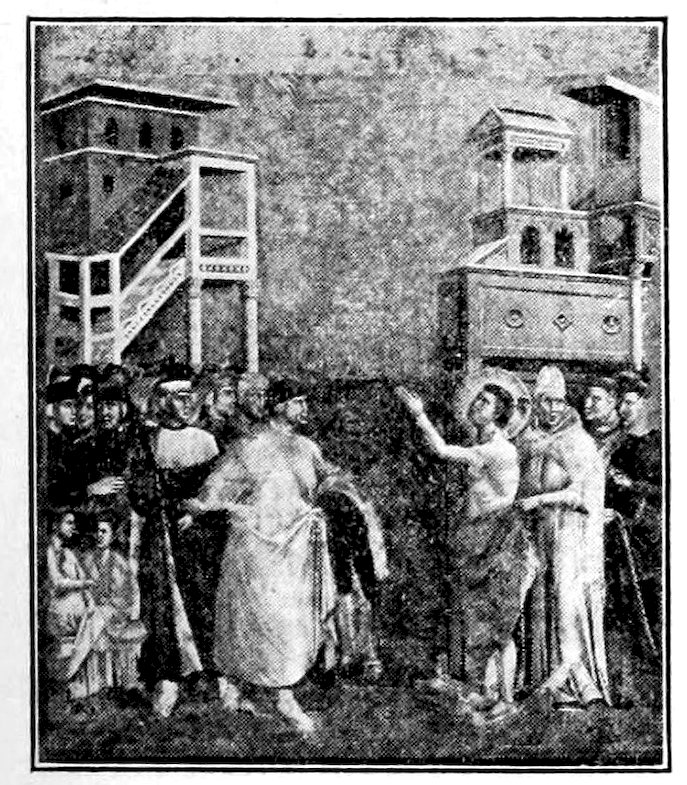

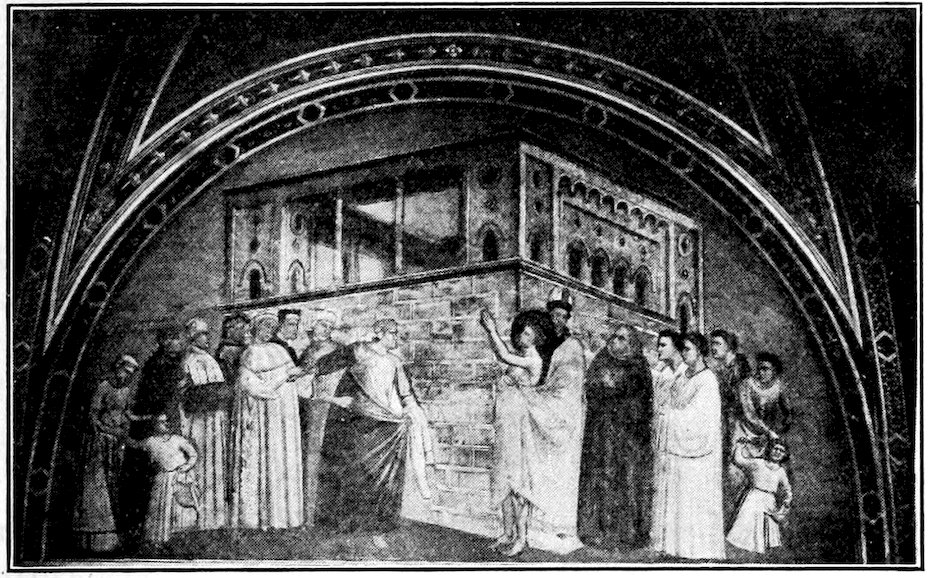

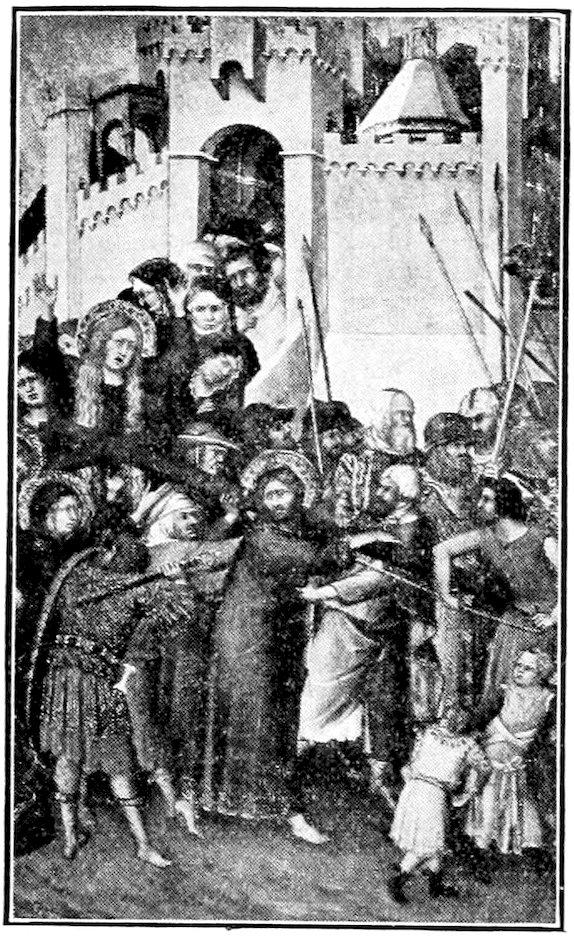

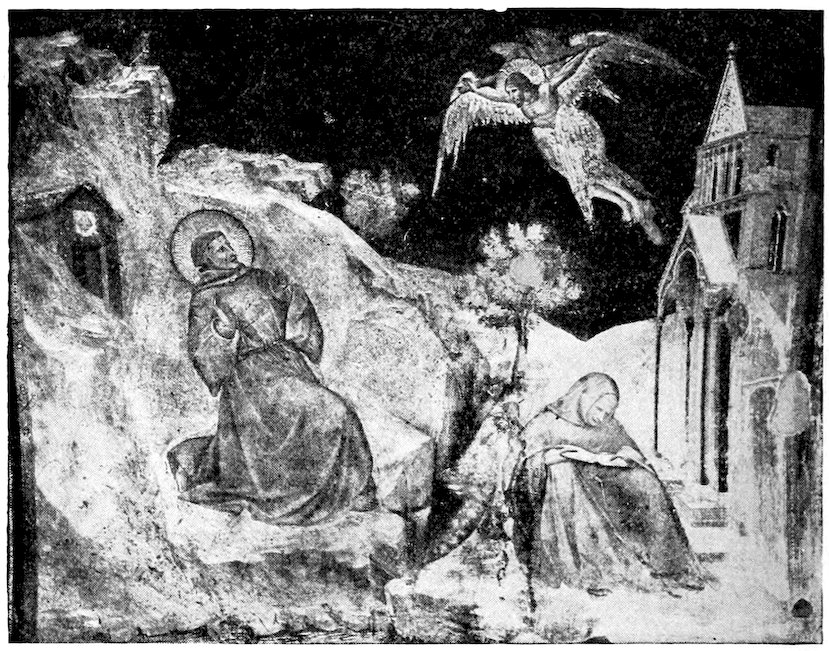

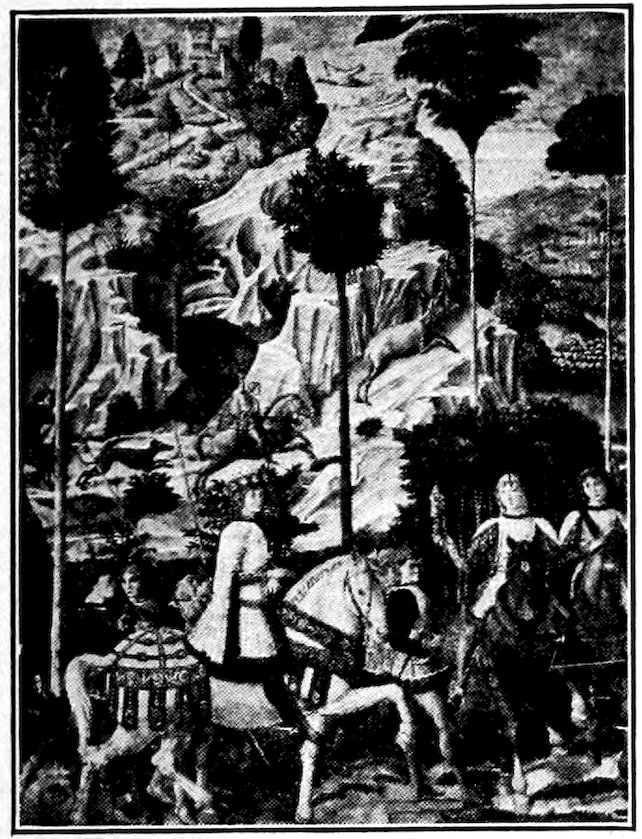

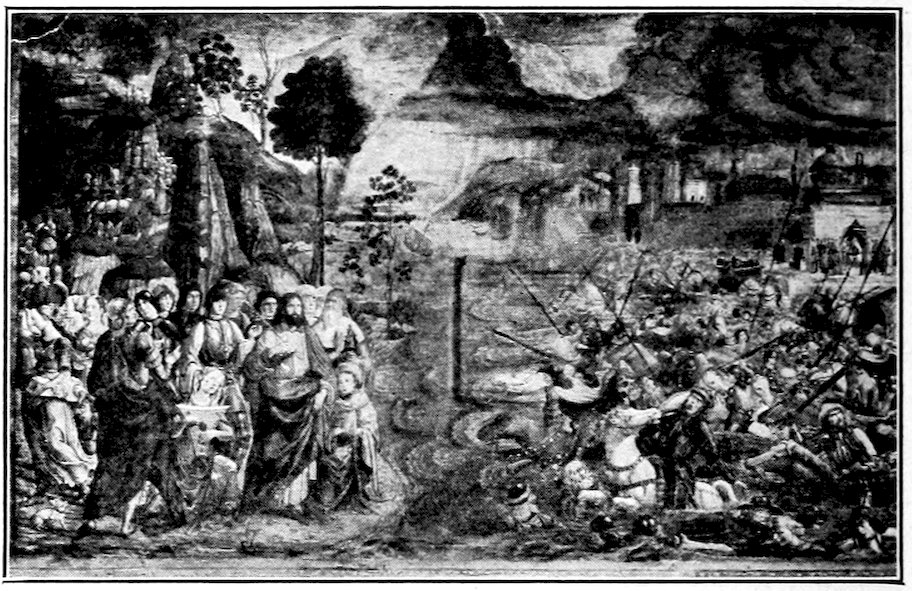

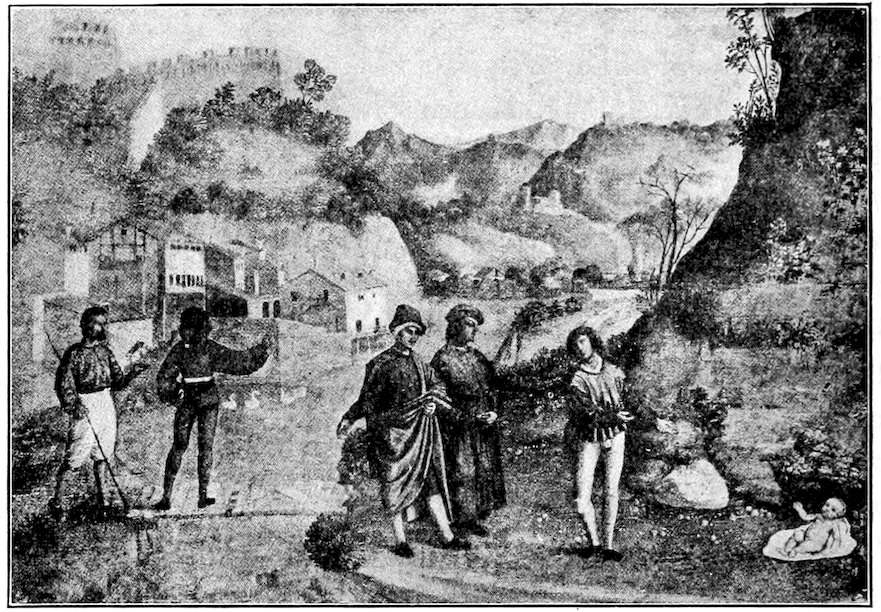

After 1296, according to Vasari’s entirely credible account, young Giotto took over the direction of the work for the newly elected Franciscan General, Giovanni dal Muro. What share he had in the vivacious and justly loved stories of St. Francis,[9] in the lower range of the nave, is greatly disputed. Of the twenty-eight frescoes involved, it seems clear to me that the first and the last three are by an artist more nearly in the Sienese tradition, that Nos. II to XVIII inclusive are designed by Giotto in the style of the Old Testament stories above and painted by him with a certain amount of assistance, and that the rest are largely inspired by Giotto but executed in his absence and without his final control. What is more important is the variety and vivacity of these narratives. Young Giotto is free to improvise, as he was not in the standard Bible subjects, and the mood shifts readily. We have charity, with St. Francis giving his cloak to a beggar, in an idyllic landscape; family strife in St. Francis renouncing his father, Figure 9; sorcery in the exorcism of the devils from Arezzo; an odd mixture of ogreishness and witchcraft, in St. Francis’s Fire Ordeal before the Soldan, Figure 11; a great pious intentness, in the choristers at the Cradle Rite; intense physical appetite, in the Miracle of the Spring; an entrancing blend of reverence and humor, in the Sermon to the Birds, Figure 10; stark tragedy in the Death of the Knight of Celano.

Fig. 10. The Sermon to the Birds.—Upper Church, Assisi.

Fig. 9.—St. Francis renounces His Father.—Upper Church, Assisi.

Fig. 11. St. Francis before the Soldan.—Upper Church, Assisi.

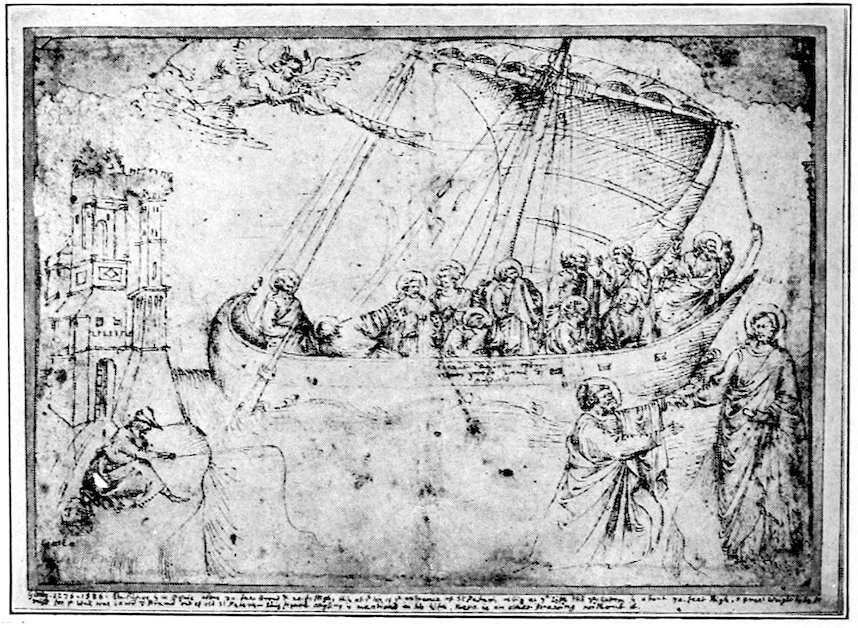

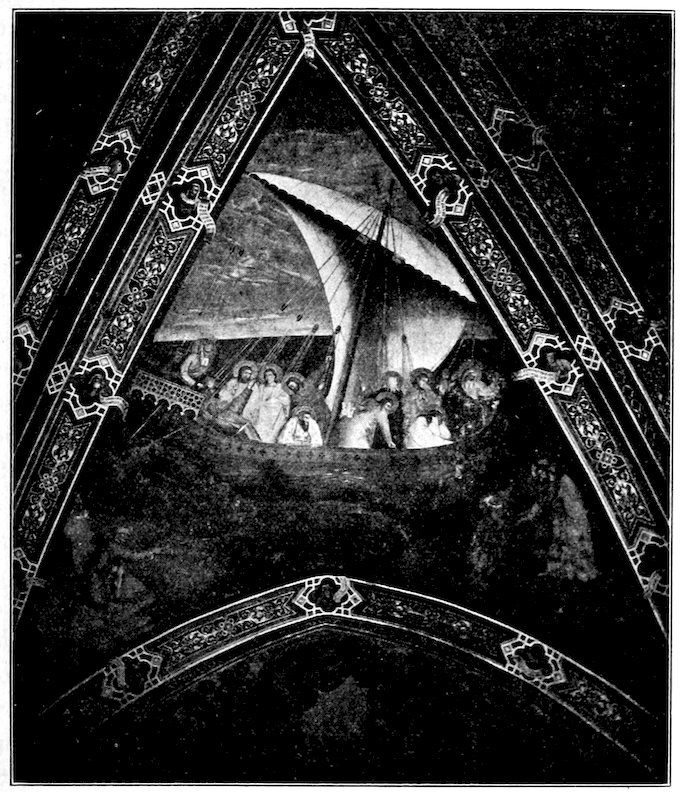

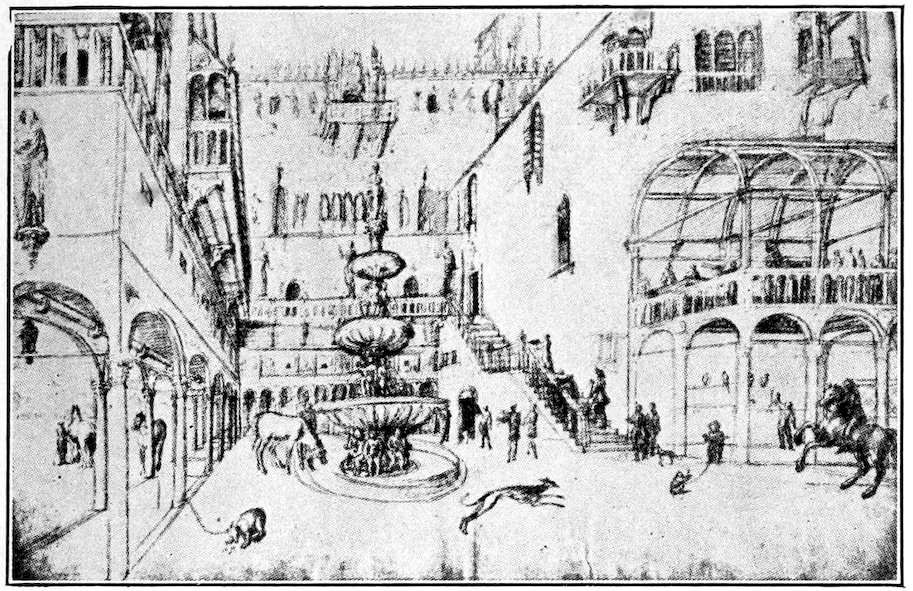

Fig. 12. Early Sketch Copy after Giotto’s Mosaic of the Navicella. Compare Fig. 31.—Metropolitan Museum, New York.

Giotto is still chiefly a sprightly illustrator. He is as yet insensitive to composition. He often perfunctorily splits his groups, giving each a landscape—or architectural back-screen quite in the Byzantine manner. His story-telling is brusque and without rhythm. His sense of form is already strong and growing, but there is little of the ease and style of 23the Isaac frescoes just above. In vitality the stories of St. Francis mark a great advance, but they lack the gravity and exquisiteness of balance proper to the best mural decoration.

It was at Rome that young Giotto was to broaden and refine his art. He was called thither before the year 1300 to design the great mosaic of Christ walking on the Sea of Galilee beside the tempest-tossed boat of the Apostles. It stood over the inside cloister-portal of old St. Peter’s, and has been many times moved in the rebuilding of the church, and with each move restored, so that what we now see in the porch is entirely remade. From certain fragments of the old mosaic, and old sketch copies, Figure 12, we may judge that the Navicella, as the Italians loved to call it, was an elaborate composition of great dramatic power, the logical consummation of the experiments at Assisi. Our best version of the Navicella is Andrea Bonaiuti’s adaptation, Figure 31, for the vault of the Spanish Chapel, 1365.

But Giotto was soon to renounce the facile method of diffuse and genial narrative in favor of a concise and massive style, akin to sculptured relief, and deeply influenced by the antique. The arches and the columns of Imperial Rome are teaching their silent lesson, the simple and noble forms of Cavallini and his nameless rivals show how painting may vie with sculpture in sense of mass and reality. With the problem of the representation of mass on a flat surface, Giotto wrestled eagerly and triumphantly. With a genius that few painters have equalled, he grasped the truth that the figure painter’s problem of representing space is chiefly that of emphatically suggesting mass. If you convince the eye of the tangibility of your objects, the mind will supply elbow room and air to breathe. It isn’t necessary to simulate a box, as the Sienese painters often did. The painter who can give a convincing sense of mass may handle accessories and perspective with the utmost freedom, according to the inner law of his design. The painter who thinks first of his space is in every way more 24bound to the smaller probabilities. Much thinking of this sort must have been done by Giotto before he worked out his new style at Padua.

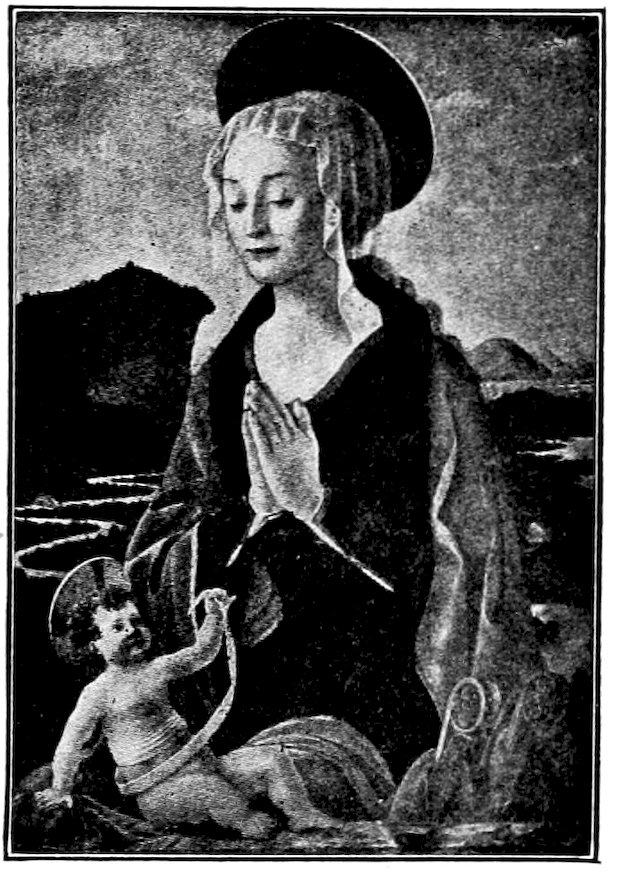

After his return from Rome, Giotto sojourned for a time in Florence, and in 1304 or thereabouts painted the gigantic Madonna formerly in the Trinità, Figure 13. It is impressive in mass, admirable in the intent expression of the attendant angels, rich in color, but the great figure is unhappily crowded by the canopy. Giotto is still a bit uncertain as to the rendering of space, and makes a good if unpleasing effort to suggest depth despite the limitations of a gold background. With all its nobility and tenderness, this is by no means so good a decoration as the great Madonna by Cimabue, Figure 4, which hangs nearby in the Uffizi.

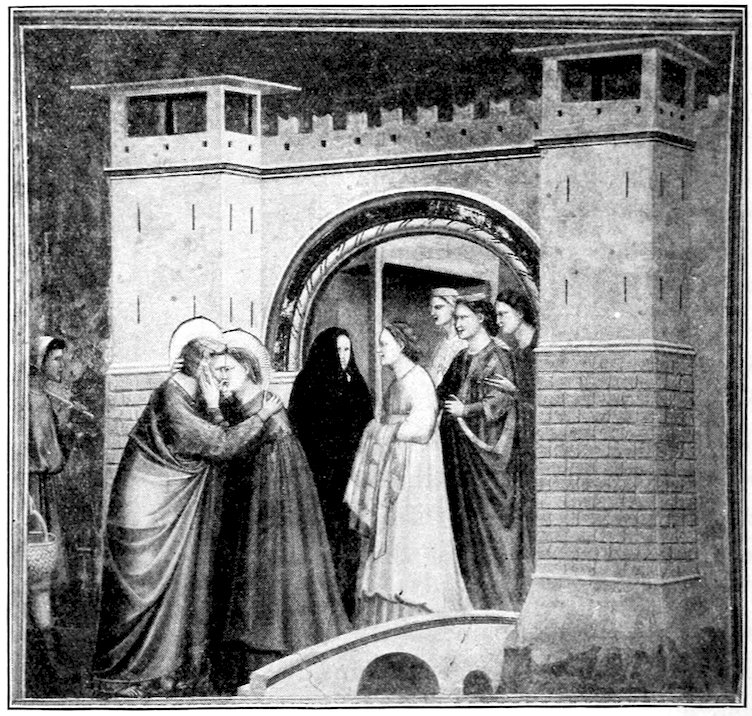

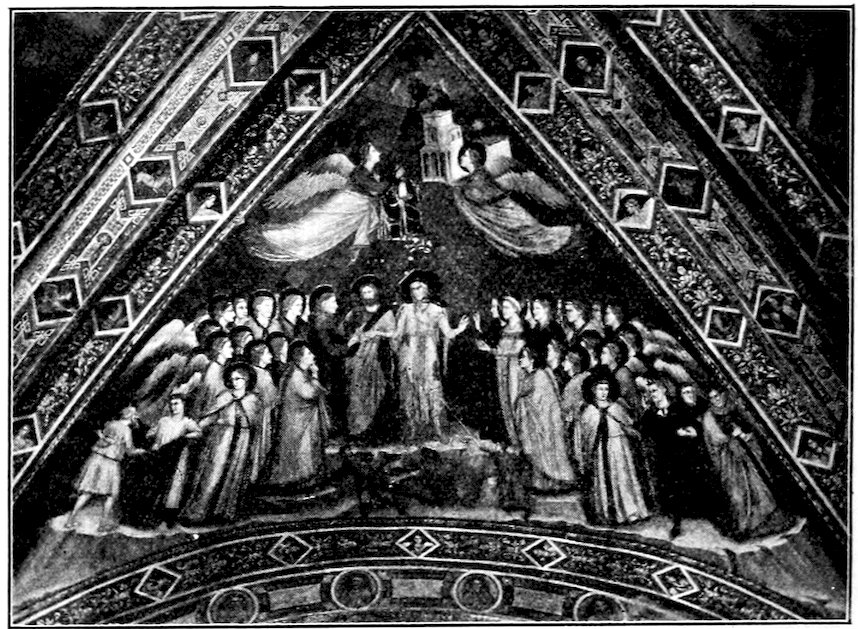

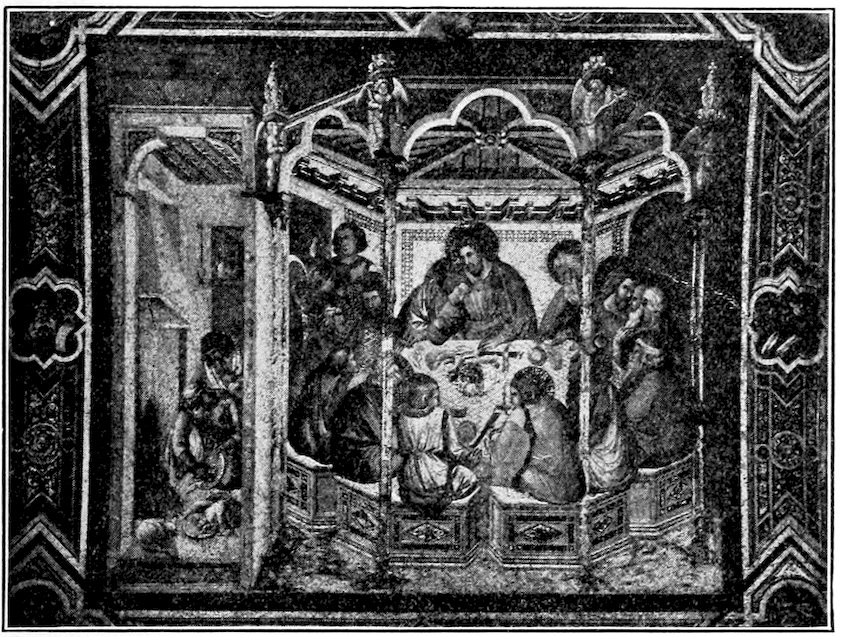

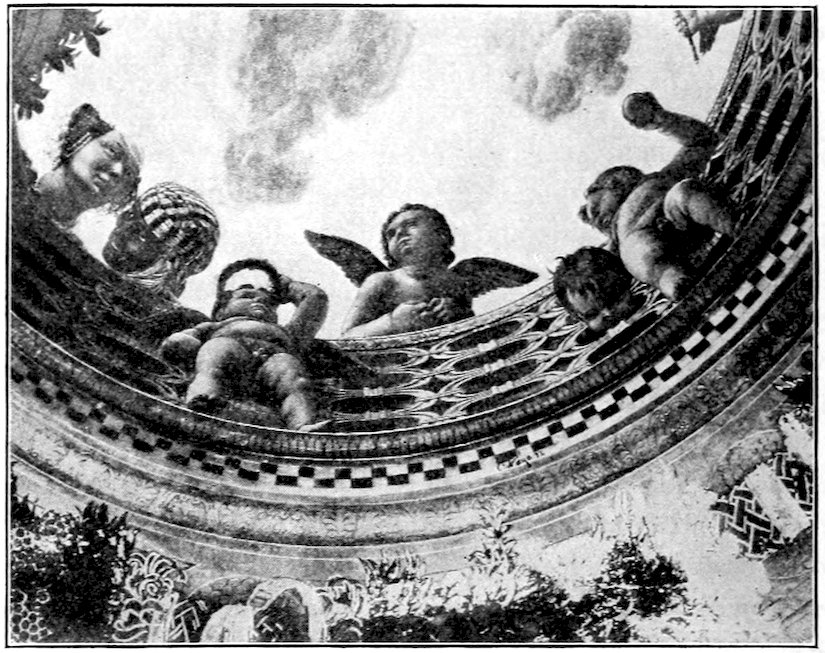

With the problems of space and mass, Giotto was soon to cope triumphantly. A wealthy citizen of Padua, Enrico Scrovegni, was planning a new chapel to the Virgin Annunciate. Doubtless he wished the repose of his father’s soul, for his father had been a notorious usurer. Dante incontinently puts him in hell with other profiteers. Enrico Scrovegni built his chapel near the ruins of a Roman arena and dedicated it March 25, 1305. The Arena Chapel was a brick box, barrel vaulted within—a magnificent space for a fresco painter. Giotto spread upon it the noblest cycle of pictures known to Christian art. Over the chancel arch he painted the Eternal, surrounded by swaying angels, and listening to the counter-pleas of Justice and Mercy concerning doomed mankind, with the Archangel Gabriel serenely awaiting the message that should bring Christ to Mary’s womb and salvation to earth. This is the Prologue. Opposite on the entrance wall is the Epilogue—a last judgment, with Christ enthroned as Supreme Judge amid the Apostles, and the just being parted from the wicked. Amid the just you may see Enrico Scrovegni presenting the chapel to three angels.

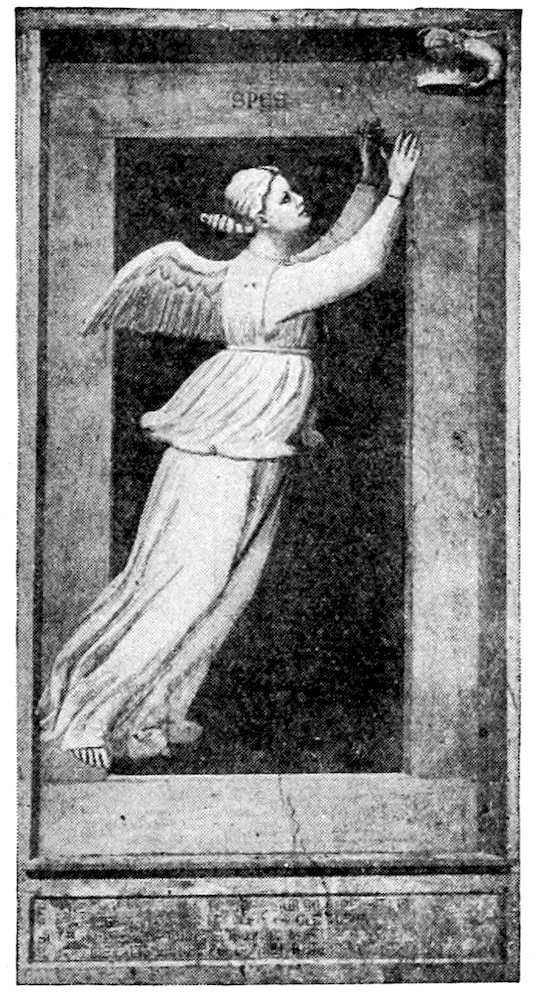

25The side walls are ruled off into three rows of pictures, with ornate border bands and a basement of sculpturesque figures symbolizing the seven virtues and vices. The story reads down from above. Below the azure vault and still a little in the curve are the stories of the Childhood of the Virgin—nothing in the chapel more simple and stately than these.[10] The middle course is devoted to the early deeds of Christ, from his birth to the expulsion of the money lenders from the temple. The lower row depicts His Passion ending with the Miracle of Pentecost. Much later a disciple of Giotto completed the story with the last days of the Virgin, in the Choir. Thus the narrative in its broadest sense is a life of the Virgin Mary, including that of her Divine Son, and both lives are brought into an eternal scheme of things by the prologue, which shows a relenting God, and the Epilogue which shows a now relentless Christ awarding bliss and woe to the race for all eternity.

Fig. 13. Giotto. Madonna Enthroned.—Uffizi.

The first impression of a visitor to the chapel will be a feeling of awe qualified by joy in the loveliest of colors. The whites of the classical draperies dominate. They are shot with rose, or pale blue, or grey green. Certain old enamels have the same quality of making the most splendid crimsons, blues, and greens seem merely foils to foreground masses of white which seem to include by implication all the positive colors. It is this bright and original color scheme balancing crimsons and azures with violets and greens which makes a 26thing of beauty out of what would otherwise be a stilted checkerboard arrangement.

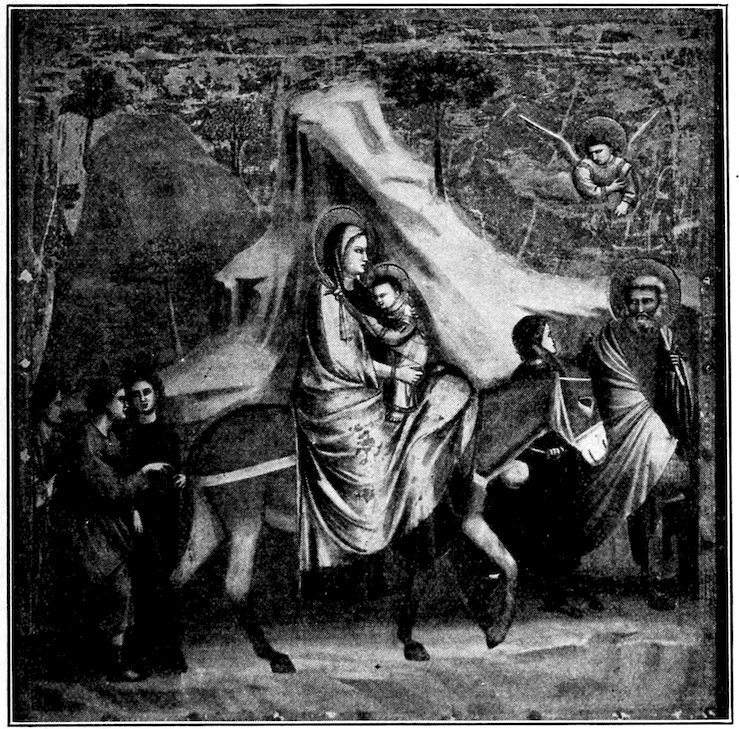

Fig. 13a. St. Joachim and St. Anna at the Beautiful Giotto Gate.—Arena, Padua.

Fig. 14. Giotto. The Flight into Egypt.—Arena, Padua.

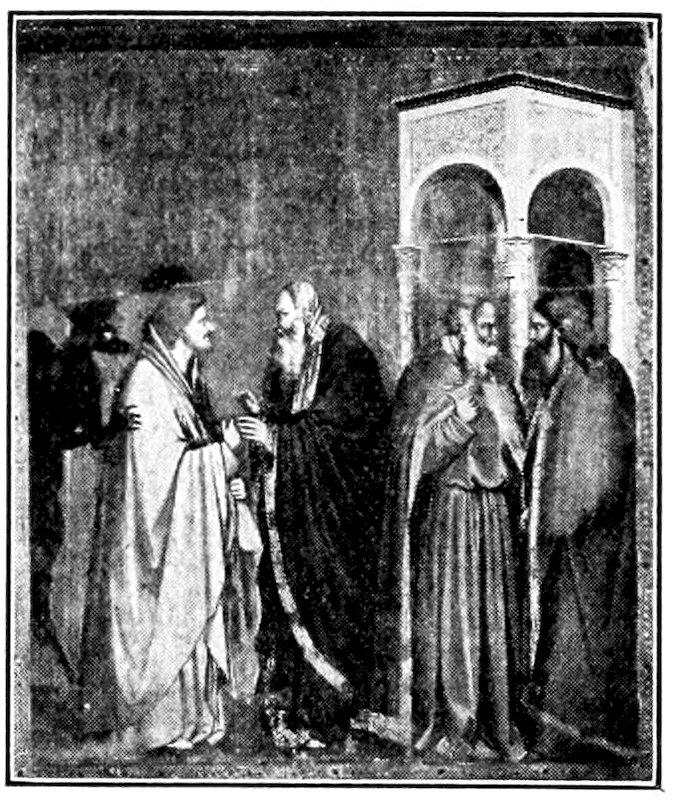

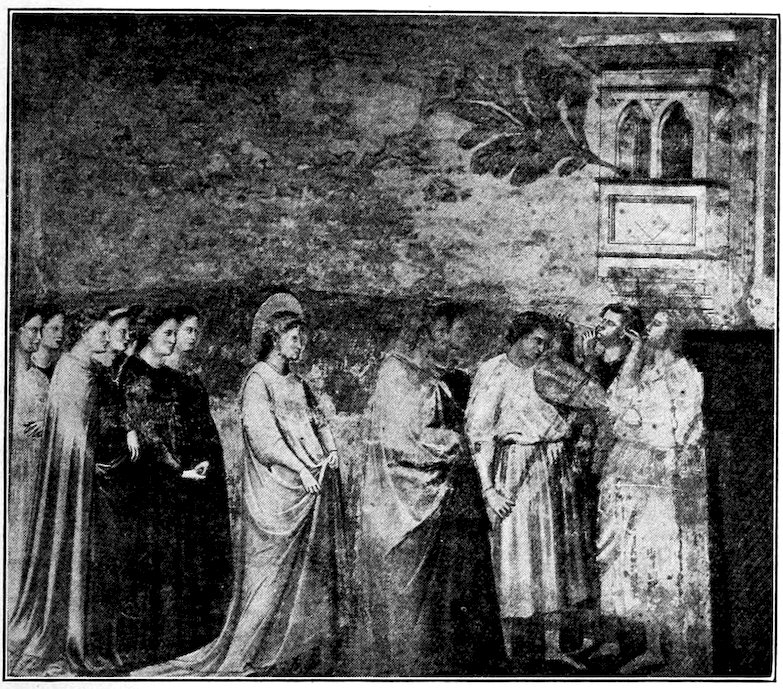

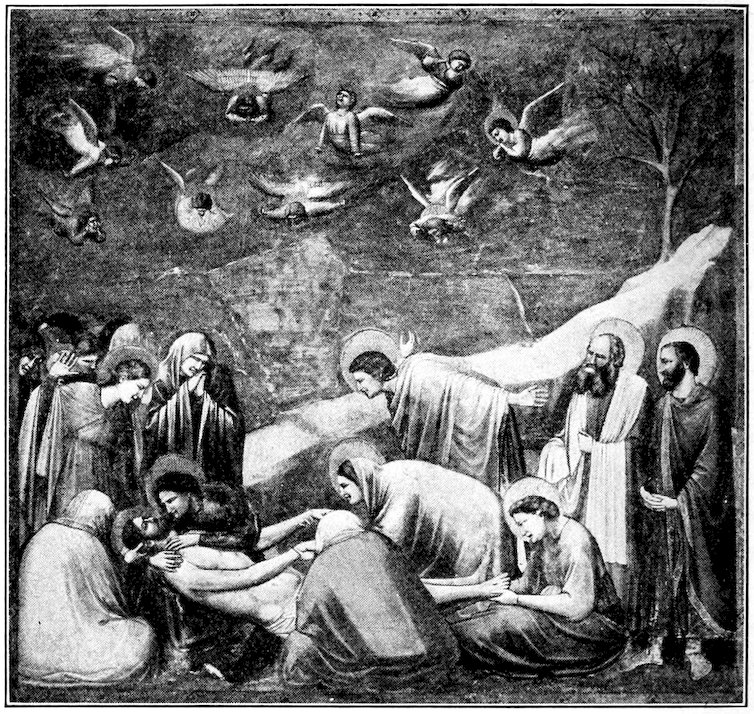

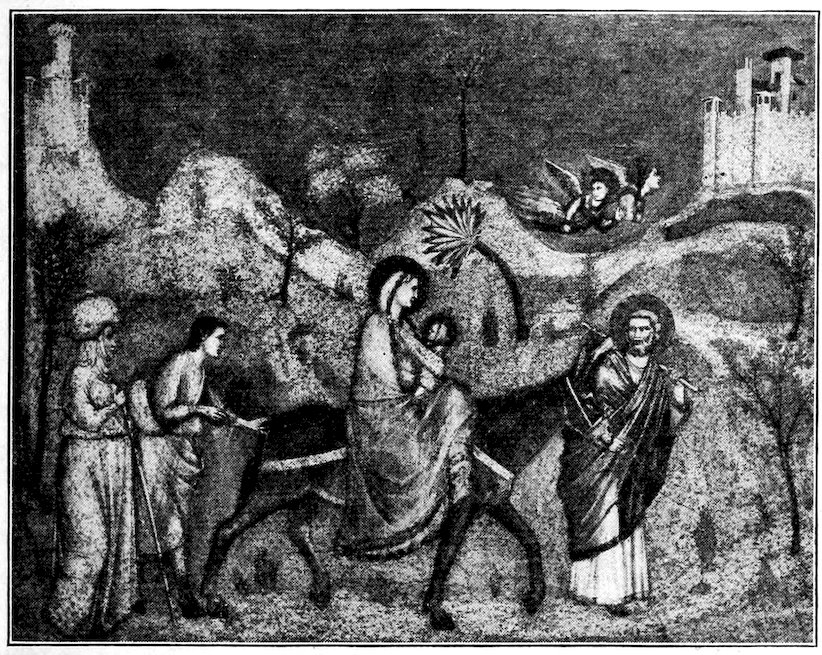

Next the eye will realize splendid people gravely occupied with solemn acts. There is the strangest blend of passion and decorum. See the eager old man who clutches his wife before a massive city gate while she caresses him tenderly, Figure 13a, note the firm gentleness of the bearded priest who handles a screaming baby before the altar, mark the sense of strain and hurry where a mother and child mounted on an ass, Figure 14, are pushed and dragged along by an old man and attendants. Or again, what sinister power in the scene where three Jewish magistrates press money upon a haggard, bearded, nervous man. You do not need the bat-like demon prompting him to know that it is the arch-traitor Judas, Figure 15. Then there is a strange, serene, processional composition, with the Virgin moving homeward among her friends to a solemn music, Figure 16. It has a rhythm like the frieze of the Parthenon. Perhaps your eye will fix longest on the scene where about the pale body of the dead Christ women wail with outstretched hands, or tend the broken body, while bearded men, accustomed to the hardness of life, stand in mute sympathy with folded hands, Figure 17. It is what the Gospel ought to look like. How Giotto shows every feeling, pushing its expression just to the verge, and there stopping, so 28that idyl and tragedy, devotion and wrath, treachery and fealty, fear and courage, each keeps its proper and distinguishing aspect, while all are invested in a common dignity and nobility. You will perhaps never have seen an art at once so varied and moving, and nevertheless so monumental, and you may well be curious as to the method.

Fig. 15. Giotto. Judas betraying Christ.—Arena, Padua.

You will see readily that these compositions are conceived sculpturally. Every one with the slightest change could be cut in marble. Indeed the seven Virtues, Figure 18, and seven Vices impersonated in monochrome on the dado of the chapel are direct imitations of sculpture. The figures throughout the life of Christ and the Virgin are of even size, and usually all on one plane. The landscapes and architectural features are arranged simply as frames or backgrounds for the figure groups. The figures are, whenever the subject permits, clad in drapery of a classic cast. Expression is conveyed not much by the faces, which have a uniform Gothic intentness, but by the action of the entire figure and especially of the hands. The forms are rather squat and massive, yet have a homely gracefulness. There is nothing like perspective, and small regard for distance, yet the figures have convincing bulk and move gravely in adequate space. All this is due to the most consummate draughtsmanship. Giotto simplifies his seeing; what he cares for is the thrust of the shoulder, or the poise of hip, the swing of the back from the pelvis, the projection of the chest, the balance of the head on the neck and its attachment to the shoulders. All these essential facts of mass he represents by 29the simplest lines of direction, by broad masses of light and shade, often merely by the tugging lines in drapery that tell of the form beneath. The cave men would have understood Giotto, and so would the post-impressionists of today. Conciseness, economy, force, mass—these are the technical qualities of the work, as human insight and tenderness are its grace. As the great analytical critic Bernard Berenson has well remarked, this painting makes the strongest possible appeal to our tactile sense, stirring powerfully all our memories of touch, and presenting the painted indications as so many swiftly grasped clues to reality. We have to do with a magnificently conceived shorthand. No artist before or since has made a greater expenditure of mind or achieved a more notable inventiveness than Giotto in the Arena Chapel.

Fig. 16. Giotto. The Virgin returning from her wedding.—Arena, Padua.

Fig. 17. Giotto. Lamentation over Christ.—Arena, Padua.

It was dedicated March 25, 1305, Giotto being nearly forty years old, and it was probably not completely painted on the day of dedication, since many draperies were borrowed from St. Mark’s, Venice, to cover, presumably, the still unpictured parts of the walls. Giotto lived some four years in Padua, brought his family there, received the exiled poet Dante and with him joked not too decorously about his own ugliness and that of his children. It seems likely enough, though not certain, that he followed the banished Pope to Avignon about 1309, and spent some years in Southern France. What is certain is that he was again in Florence by 1312, and that, having found his own solution of the problem of mass in the 31Arena Chapel, he thereafter rested comfortably on his discovery, never was quite as strenuous again, and spent his later years at a new problem—that of decorative symmetry.

Fig. 18. Giotto. Hope.—Arena, Padua.

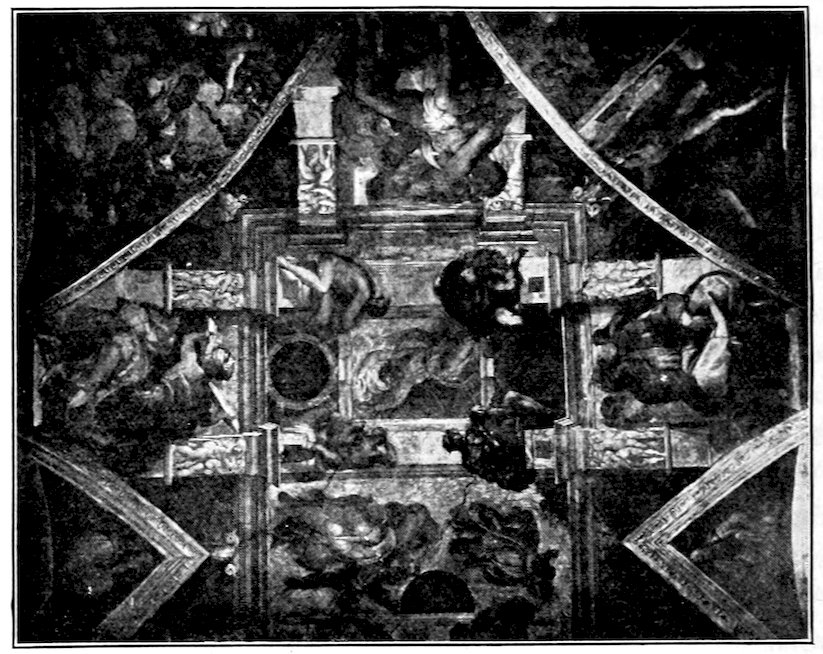

The first experiment towards a sweeter and more complex style was made in the cross vaults of the Lower Church of Assisi, immediately above the tomb of St. Francis. The subjects were the three virtues of the Franciscan vow—Poverty, Chastity, and Obedience—with a St. Francis in a glory of angels. In these great triangular compositions, allegory and symbolism run riot, and we do well to recall Hazlitt’s shrewd remark on Spenser’s “Faery Queene”—“the allegory will not bite.” Indeed one might forget it for the radiance of the azures, moss-greens, rose pinks, and deeper violets, for the delightful contrast of the freely composed groups with the intricate geometrical formality of the rich borders. Yet to ignore the allegory completely would be to forget the master’s intention. We may savor it best in the great composition: St. Francis Marries his Lady Poverty, Figure 18a. The bridal group stands on a central crag, Christ serving as priest, St. Francis slipping a ring on the gaunt hand of a haggard, yet strangely fascinating bride clothed in a single ragged garment. Her bare feet show through a crisply drawn and blossomless rose tree. Two urchins at the foot of the little cliff stand ready to stone so unseemly a bride. From the central group to right 32and left, earnest groups of angels spread in a descending curve. In the lower angle, left, a young man gives his rich cloak to an old beggar, while an angel points to the bridal: Poverty is accepted. At the lower right corner, another angel attempts to detain a young man who passes with a gesture of contempt in the company of two portly priests: Poverty is rejected by such. From the apex of the great triangle, the hands of God descend to welcome two angels, one of which offers the cloak given to the beggar, and the other a model of the church which is the splendid covering for the body of the Saint. The fantastic beauty of this and its companion pieces can only be appreciated on the spot. No frescoes of Italy surpass these for loveliness of color and perfection of condition. It is the most beautiful pictured Gothic ceiling in the world, perhaps the most fantastically beautiful of all figured ceilings whatever.

Fig. 18a. Giotto. St. Francis’ Mystic Marriage with Poverty.—Lower Church, Assisi.

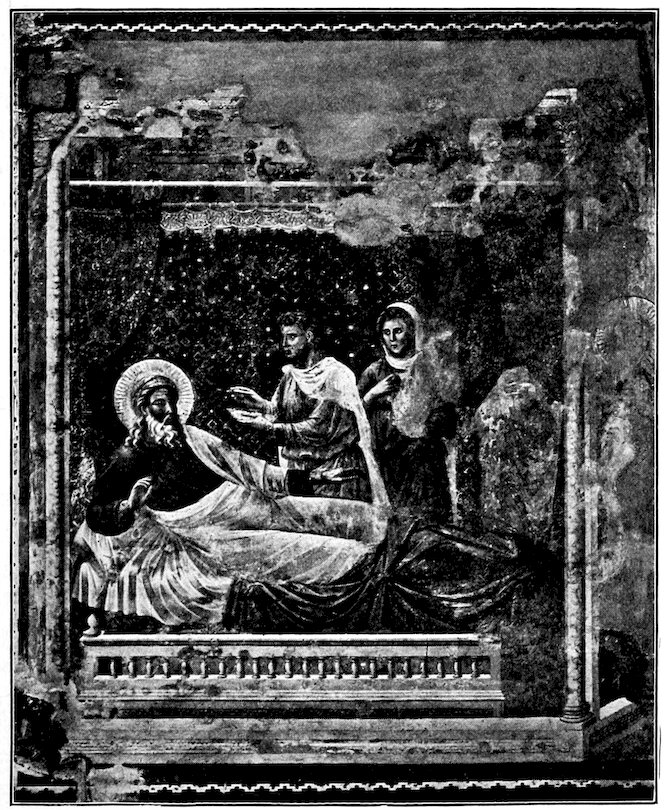

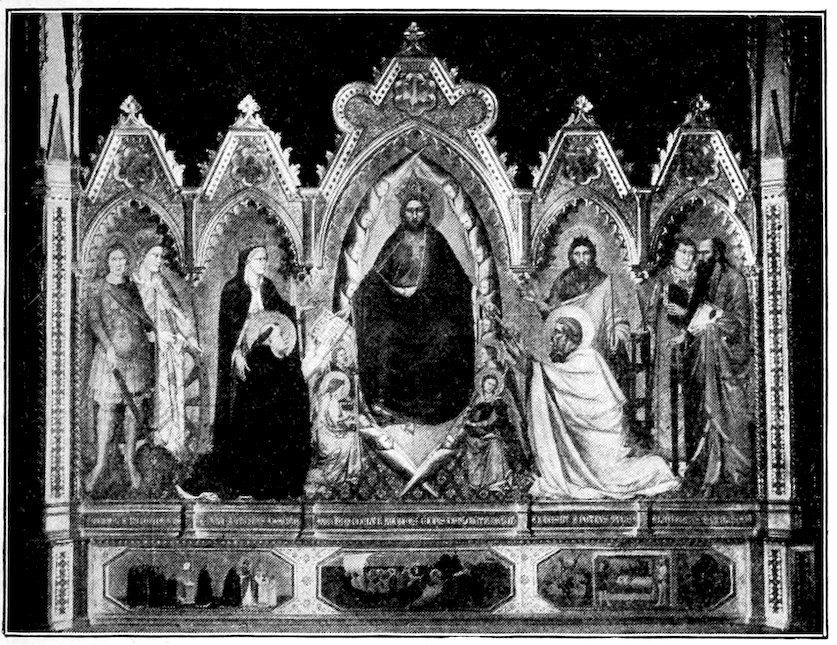

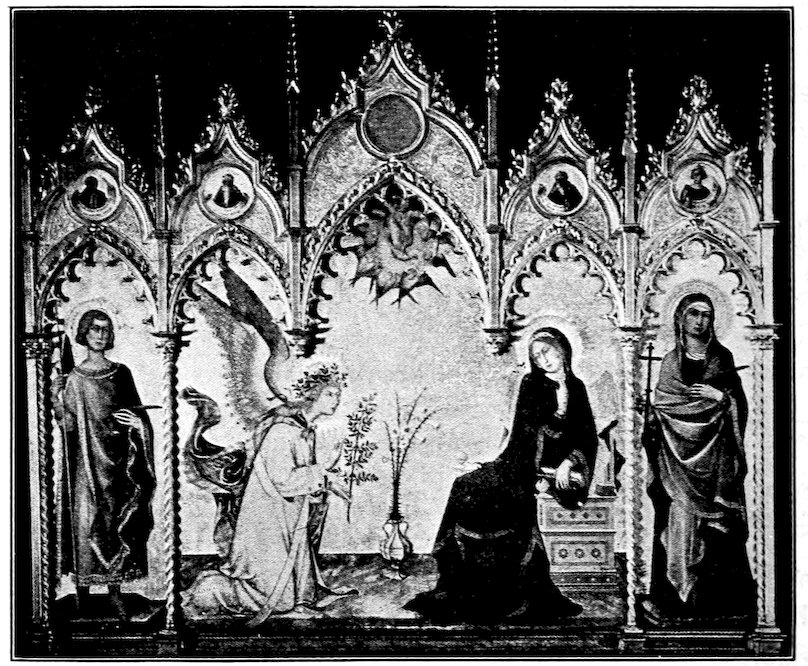

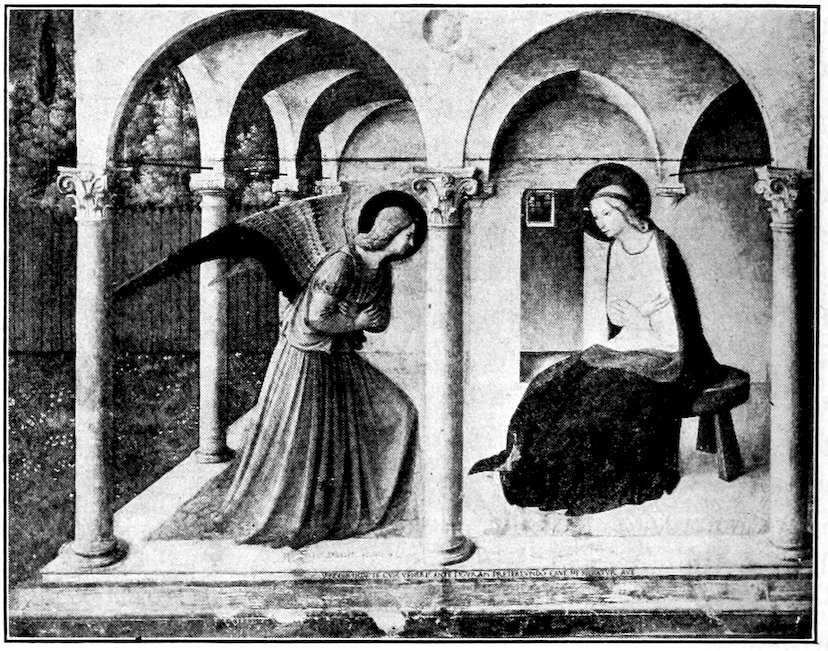

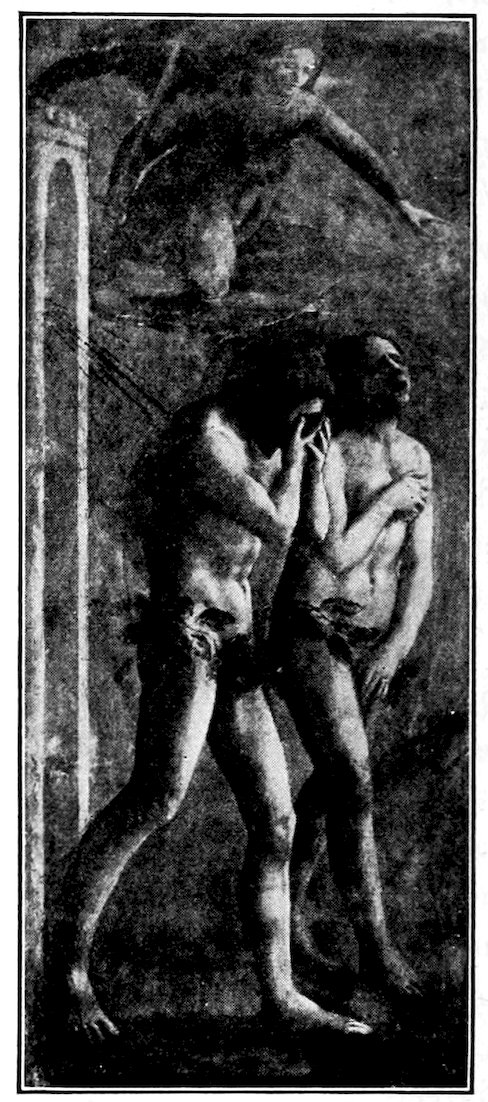

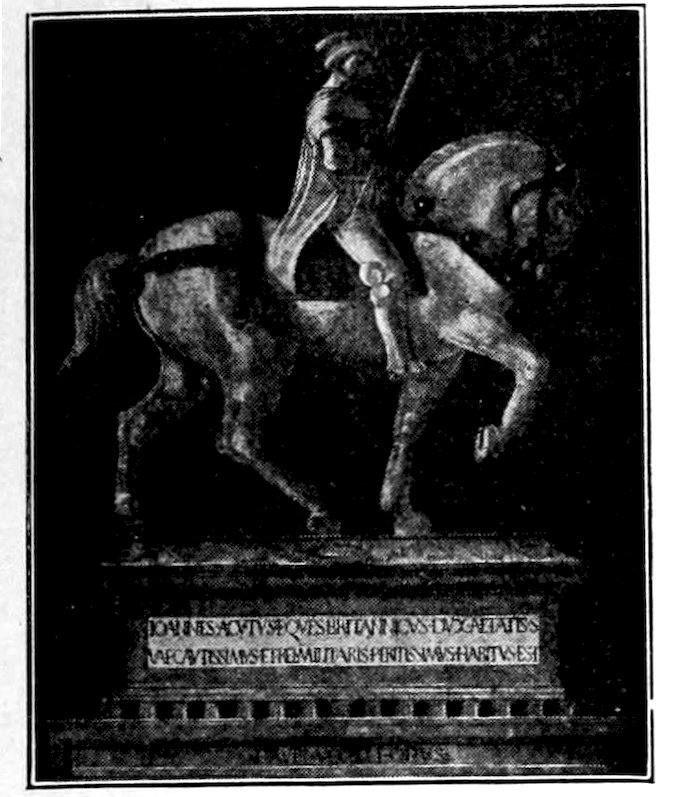

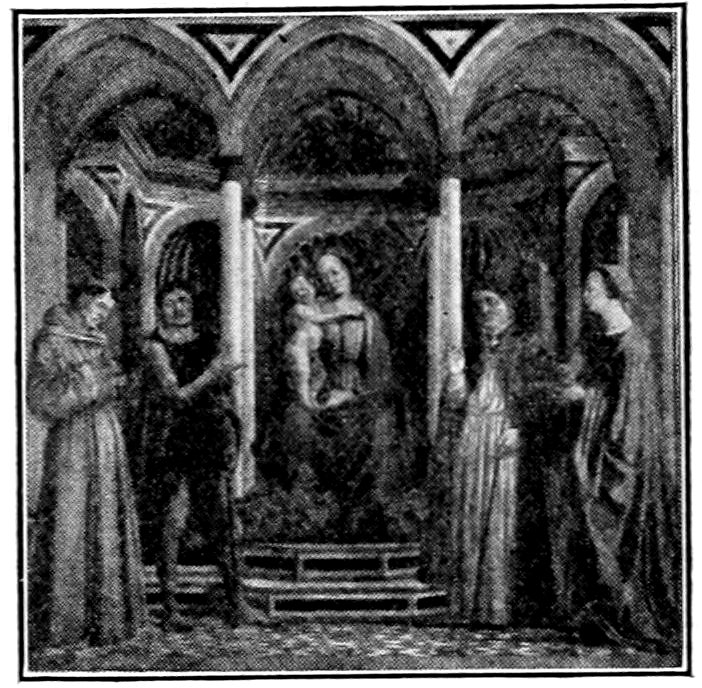

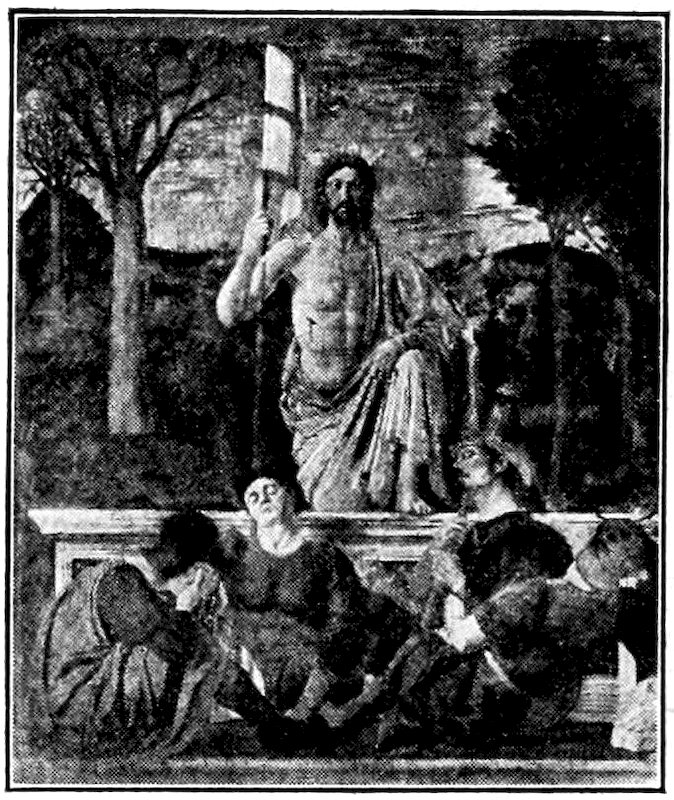

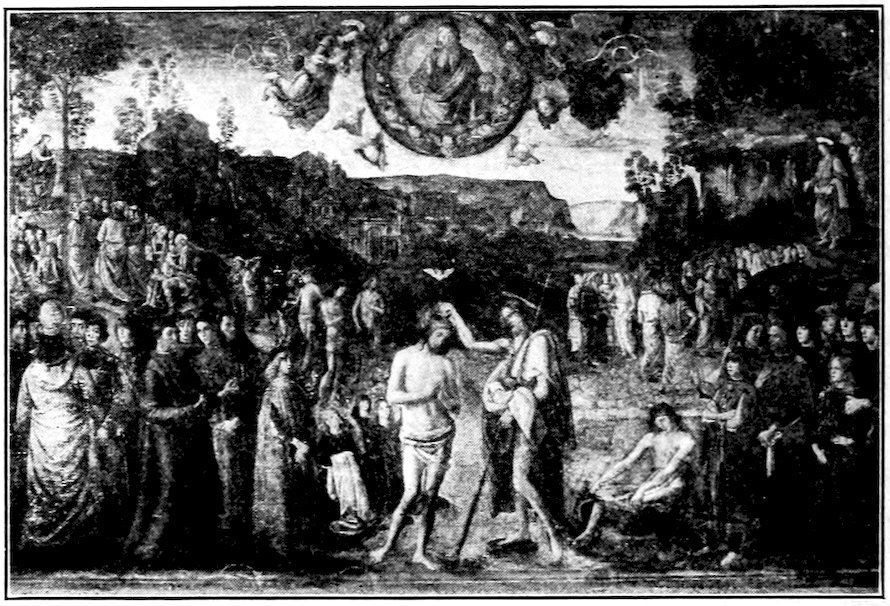

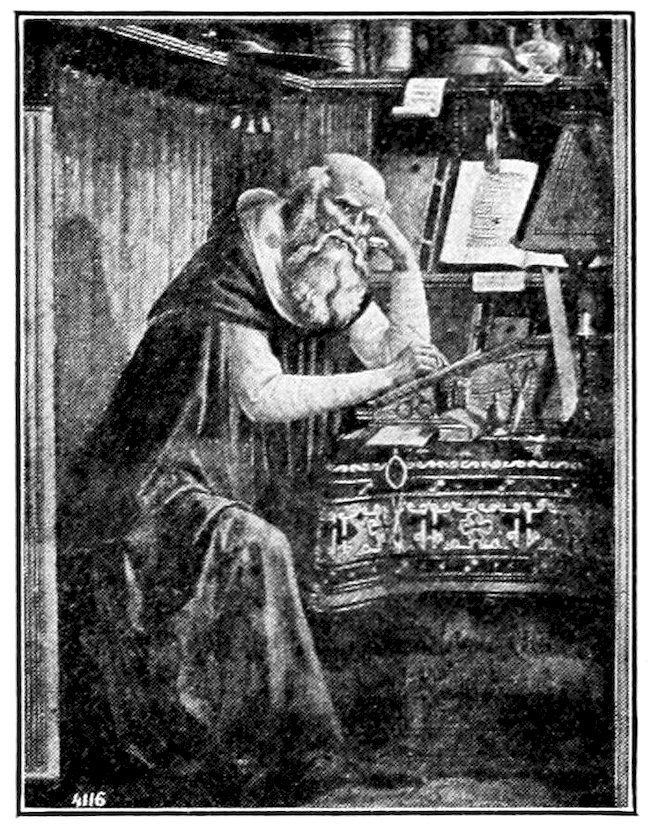

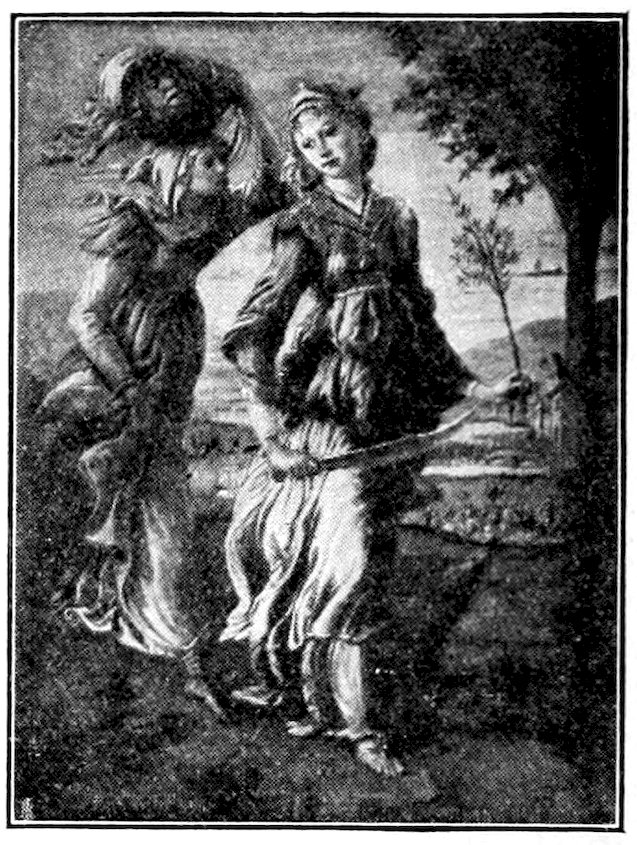

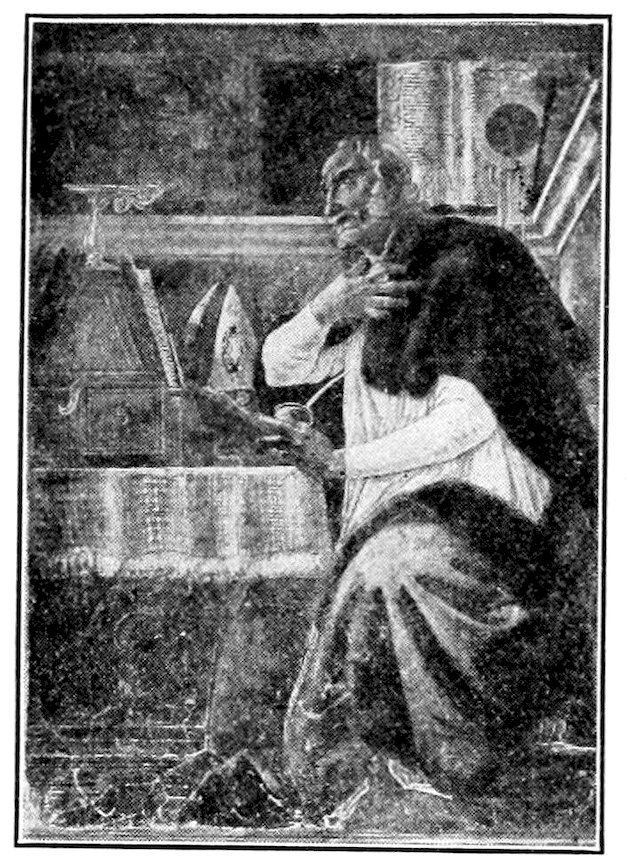

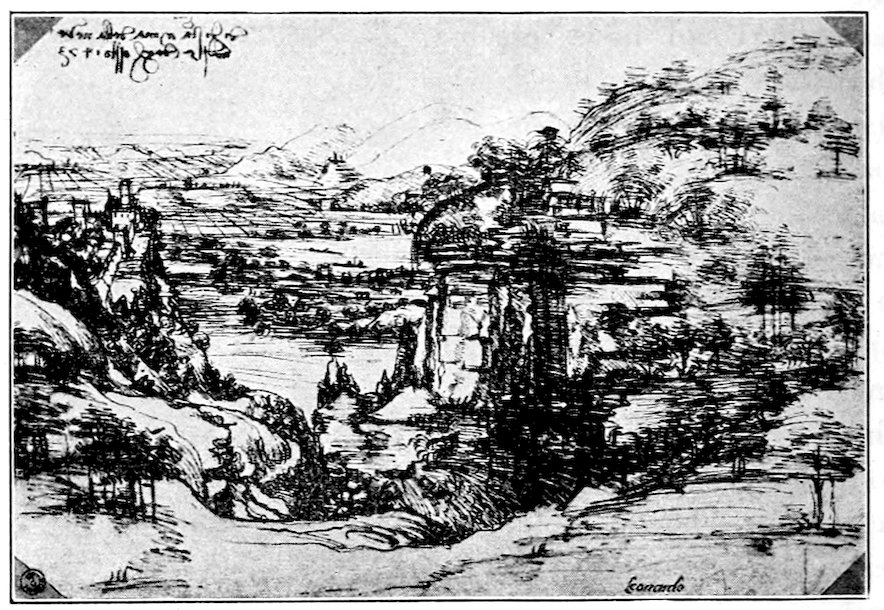

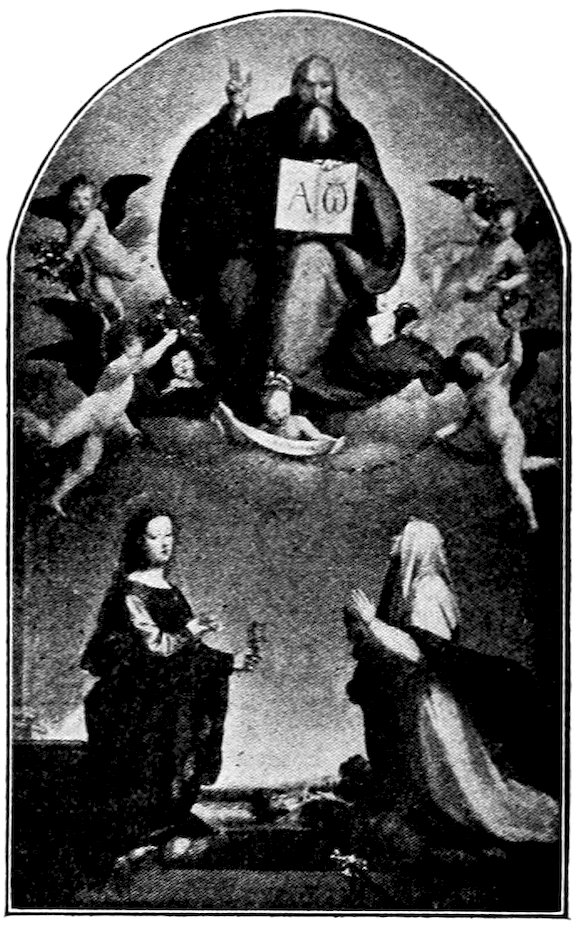

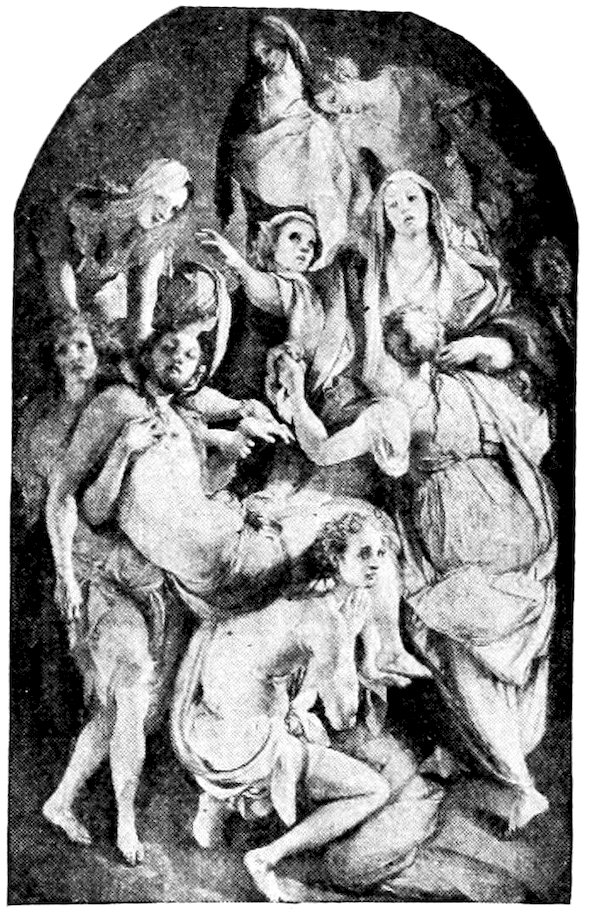

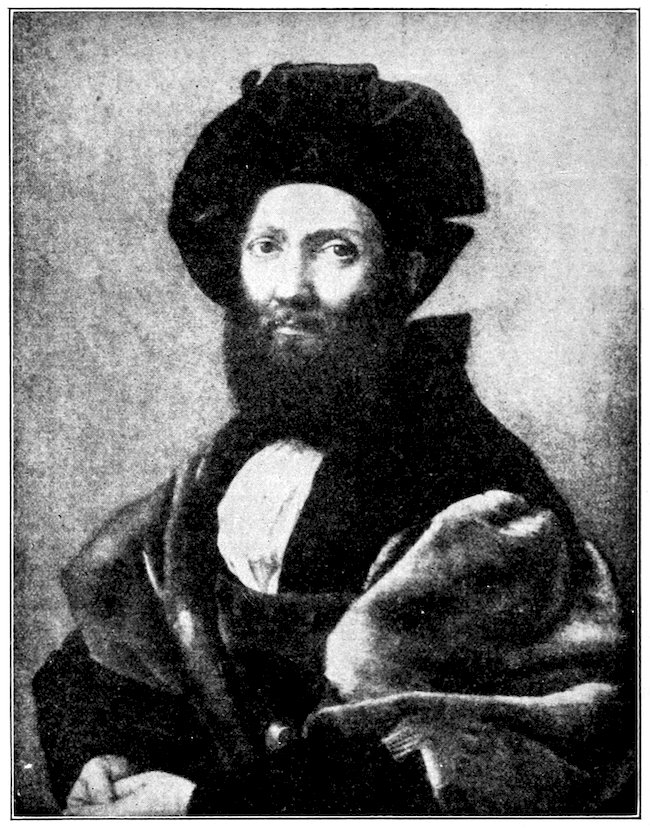

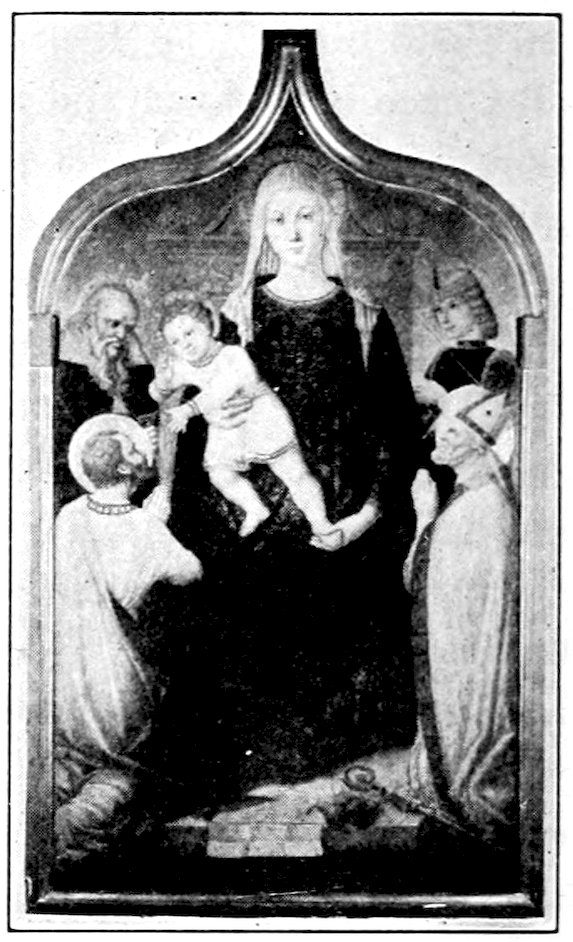

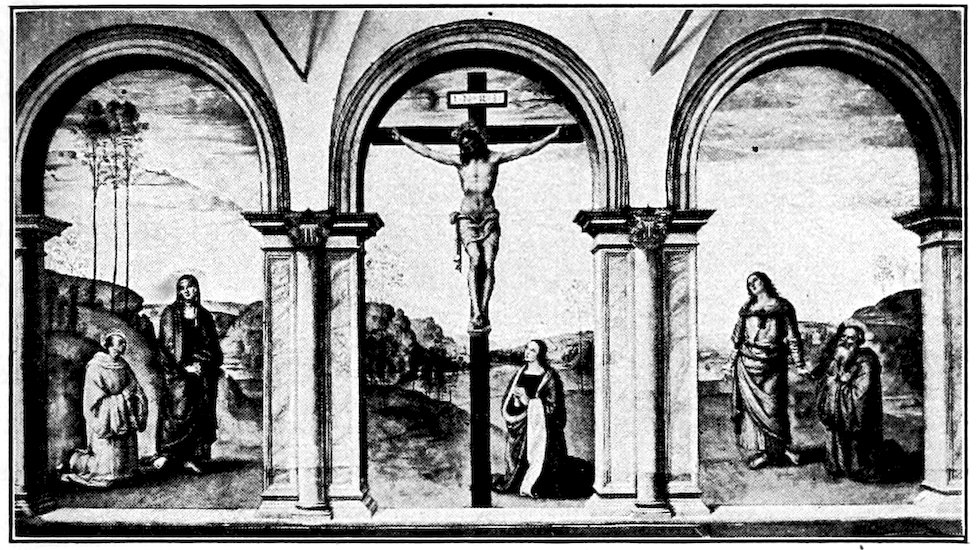

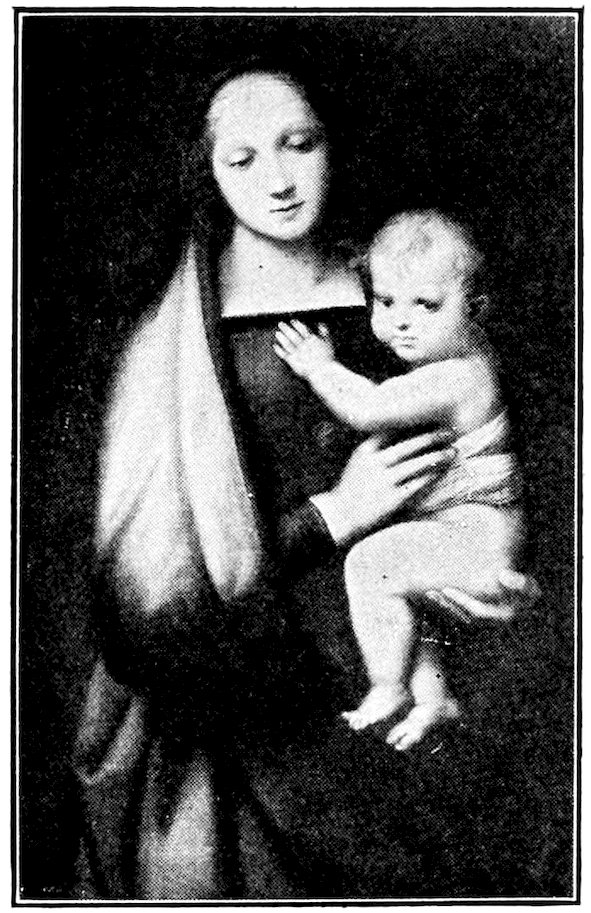

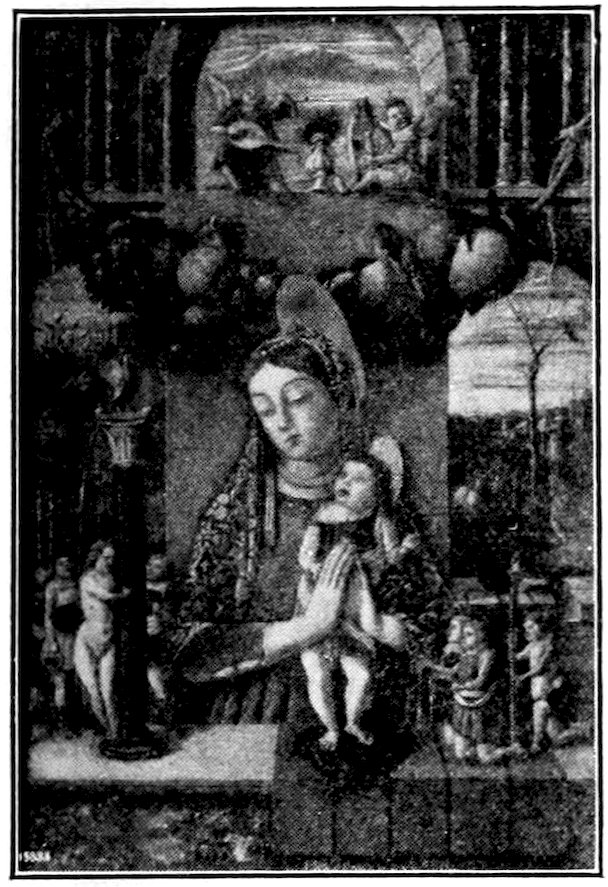

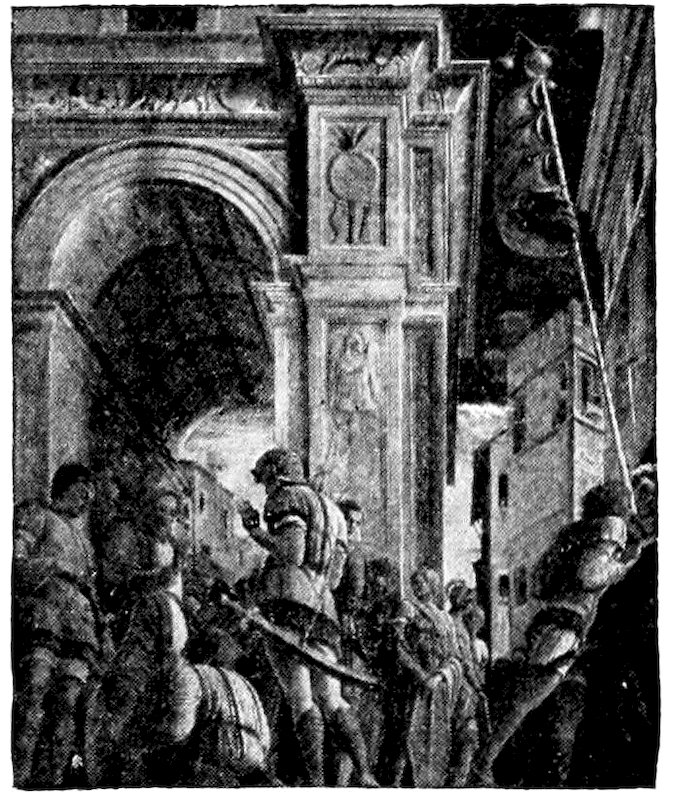

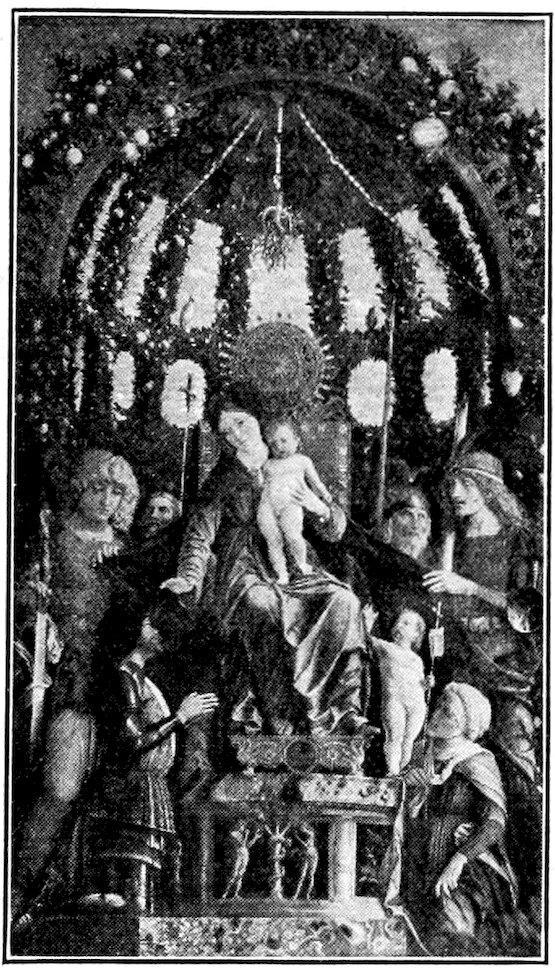

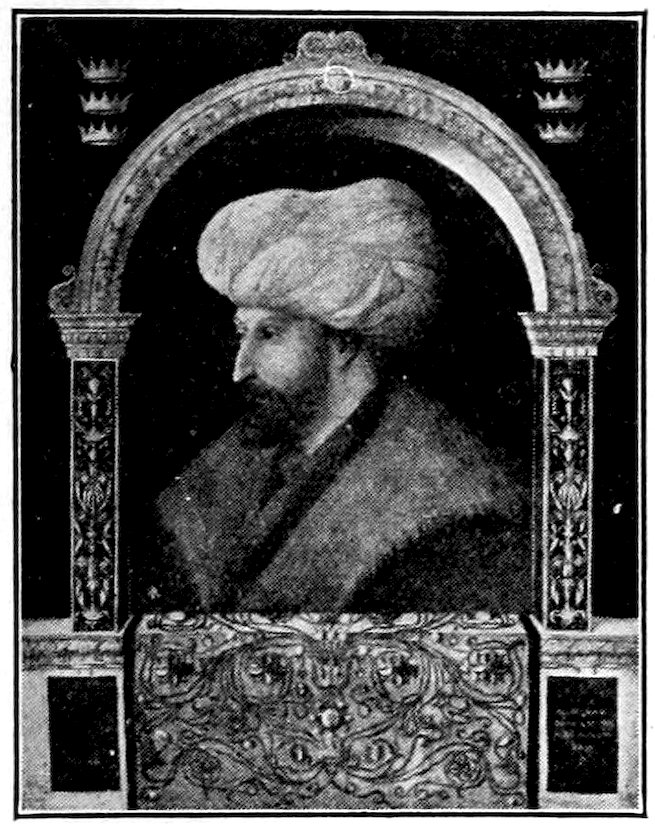

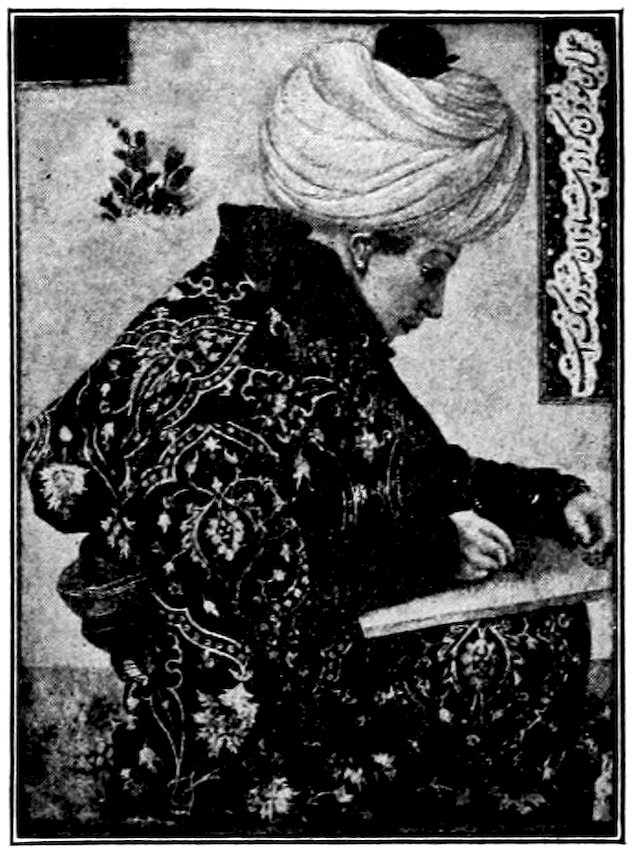

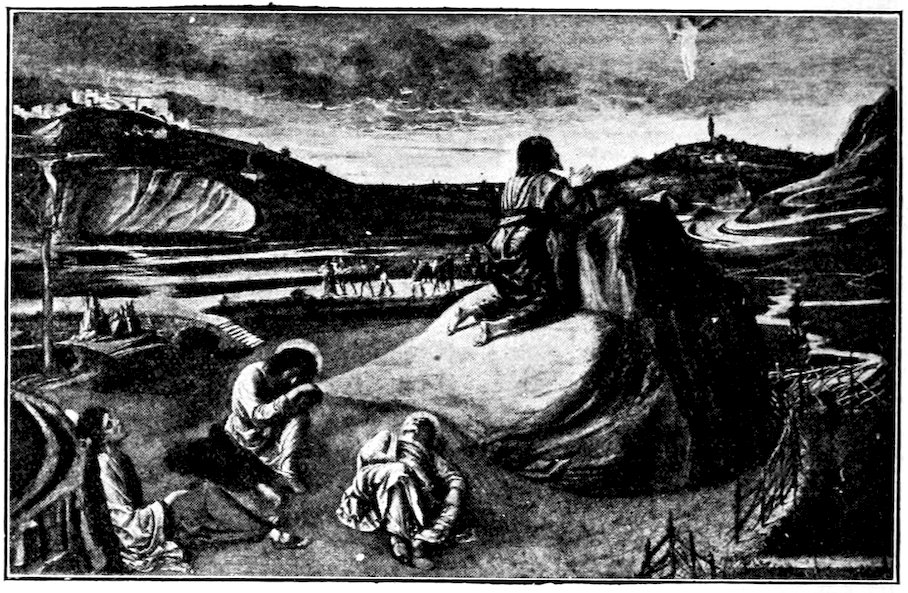

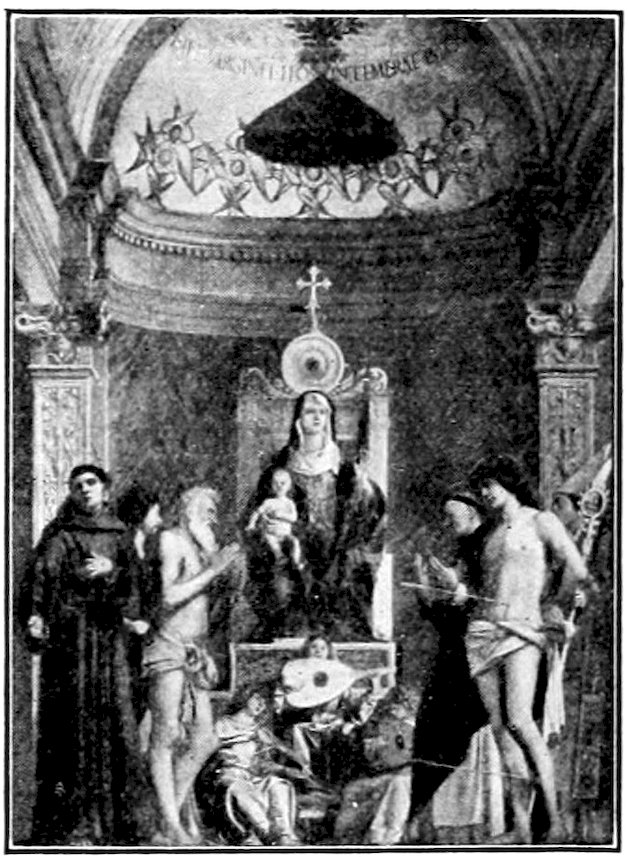

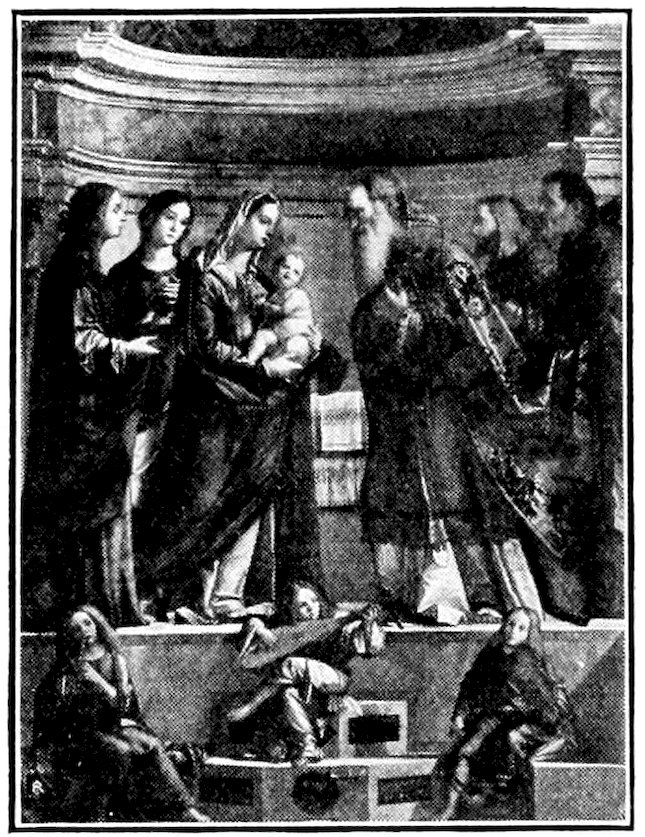

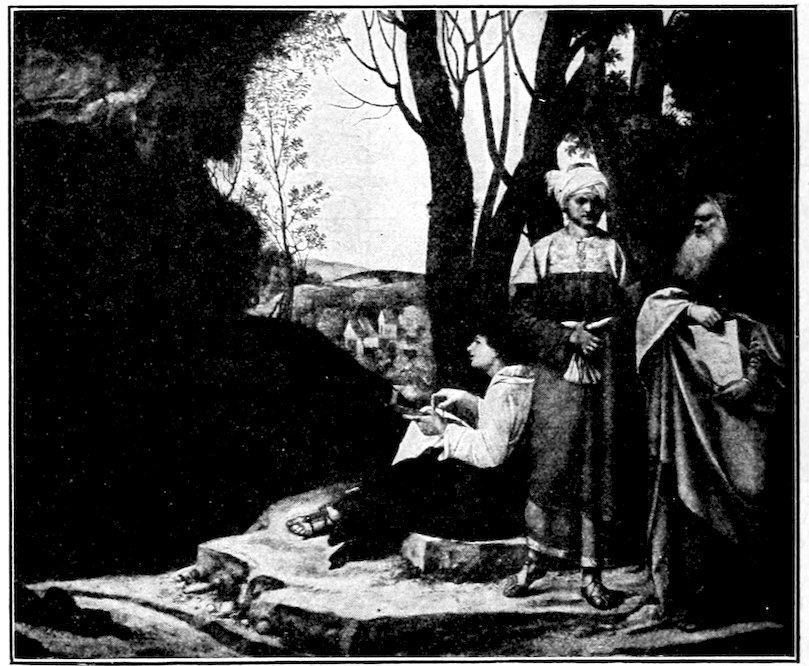

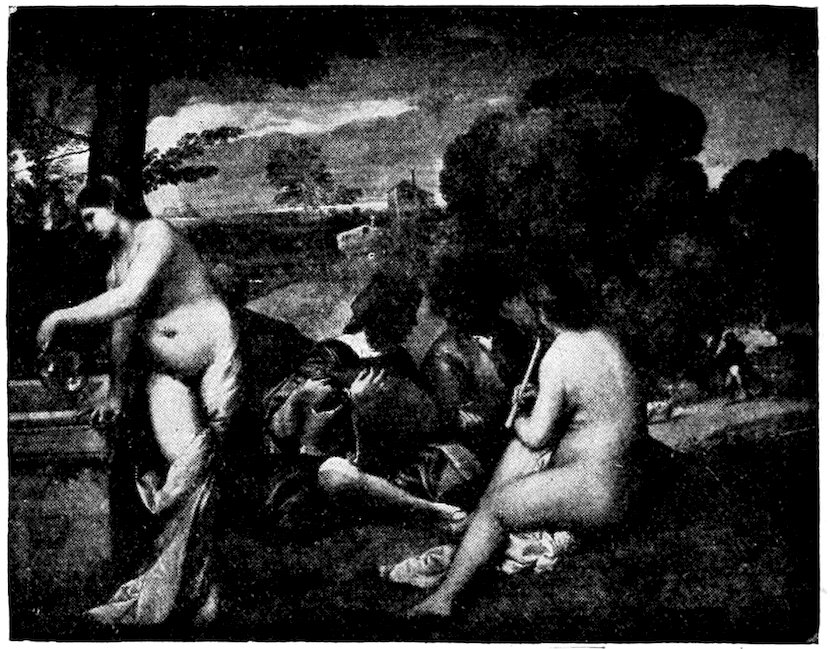

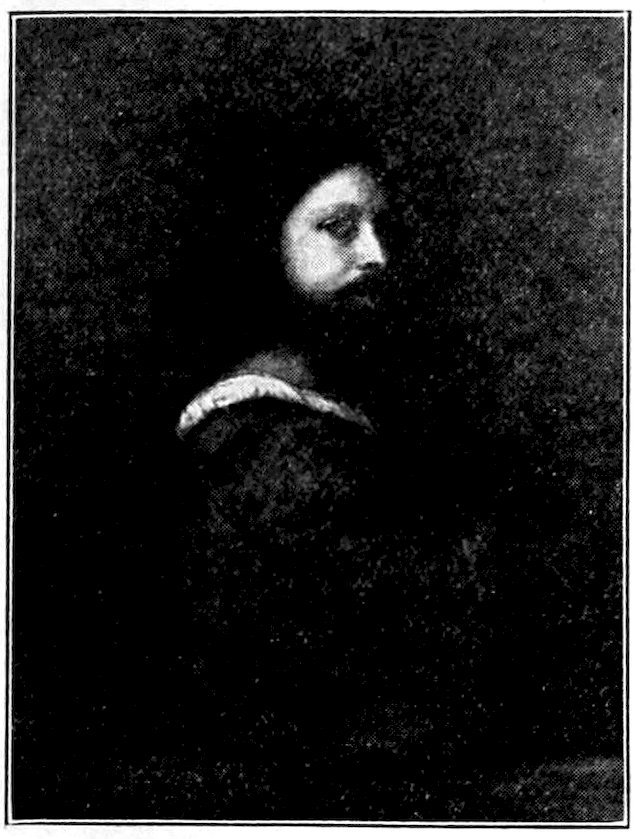

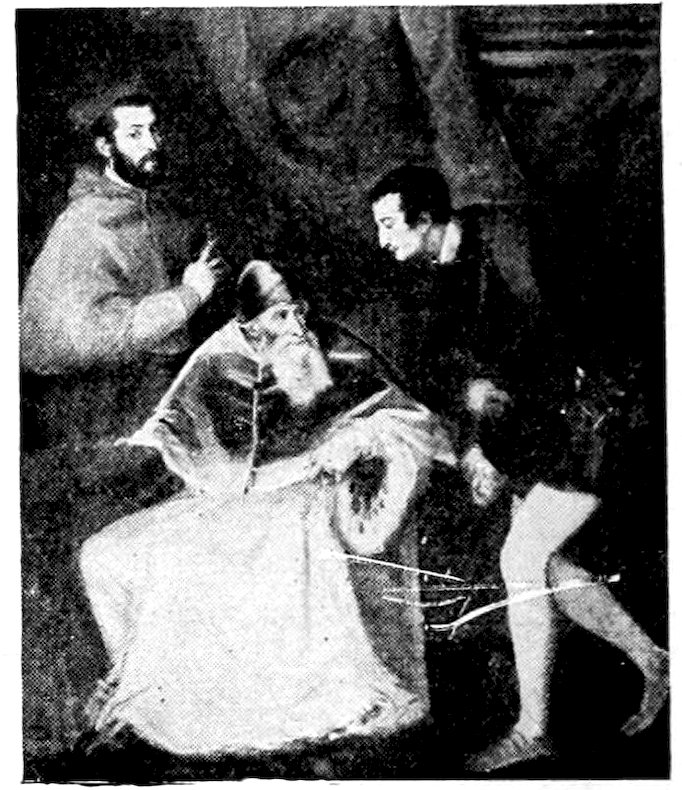

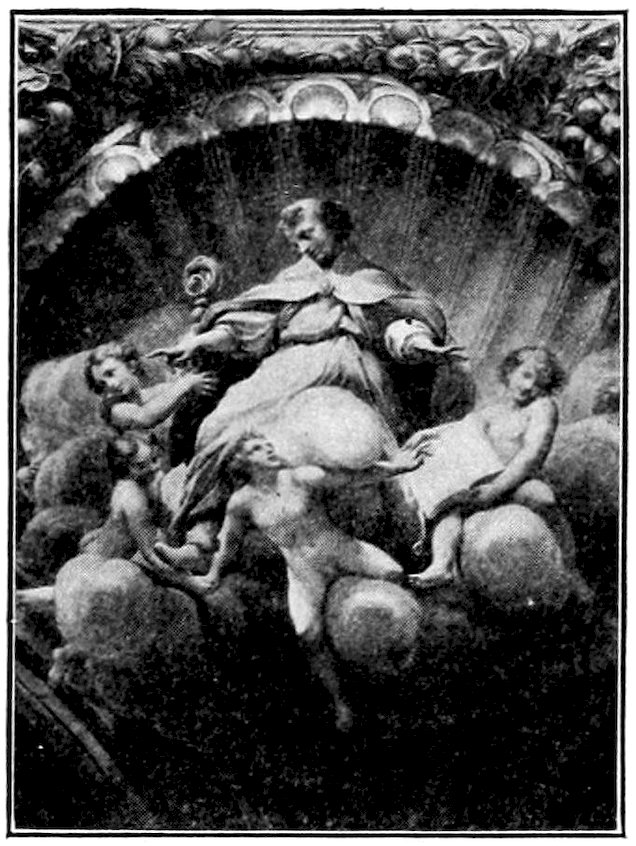

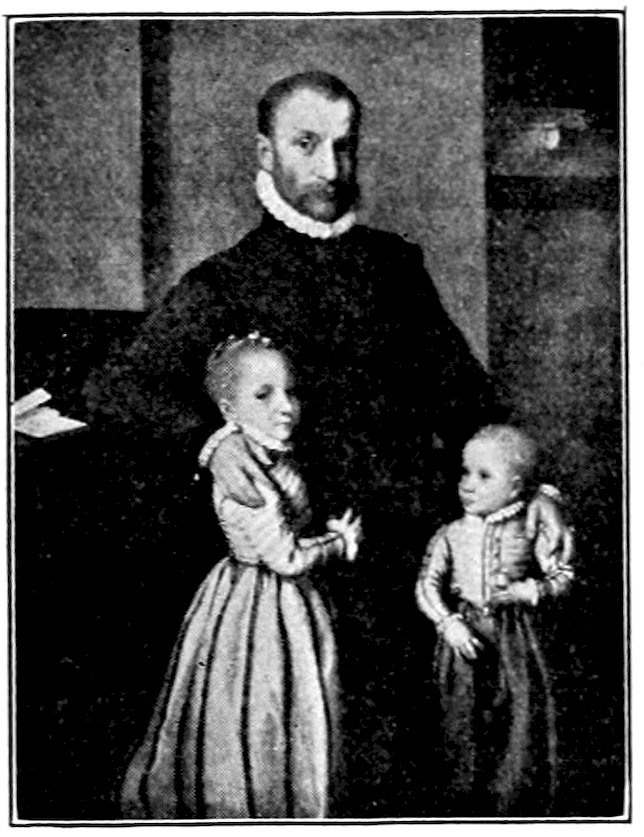

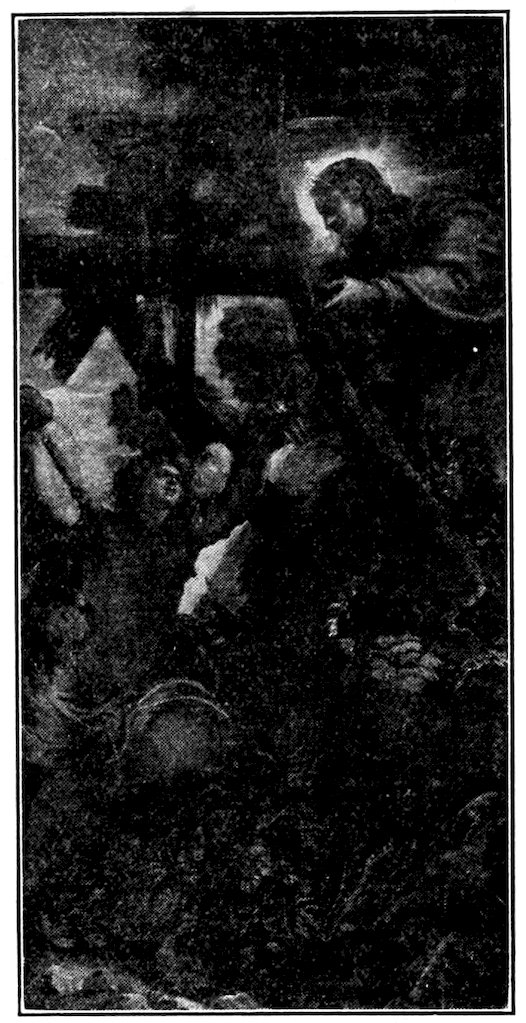

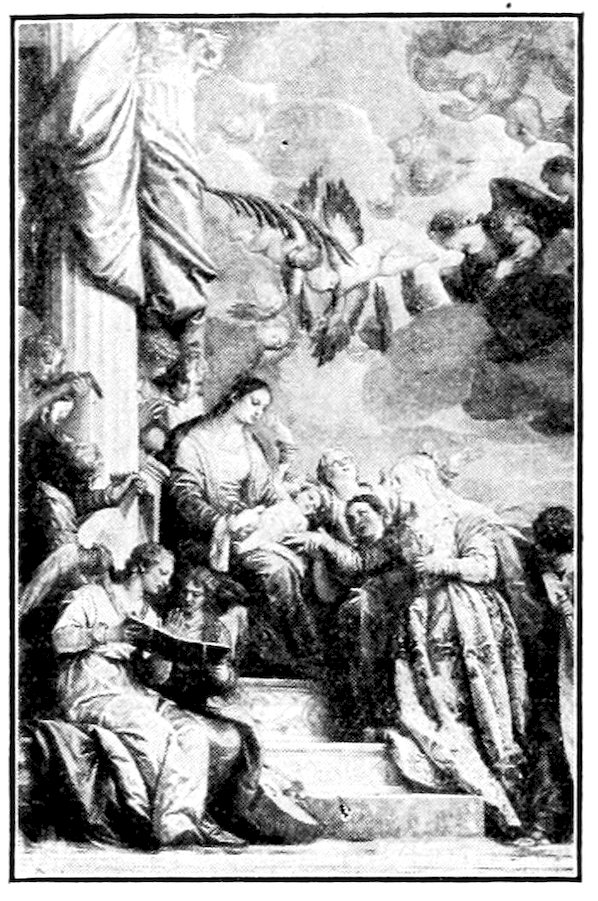

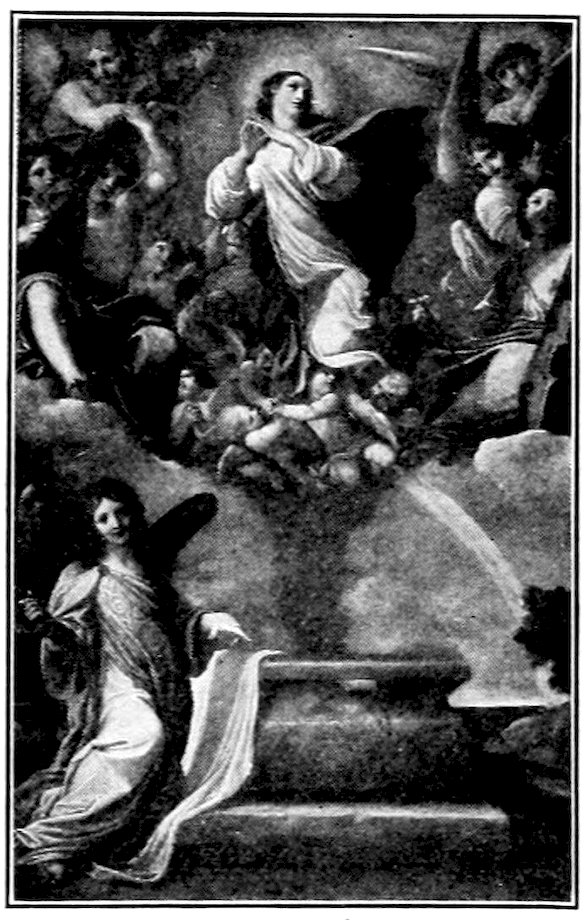

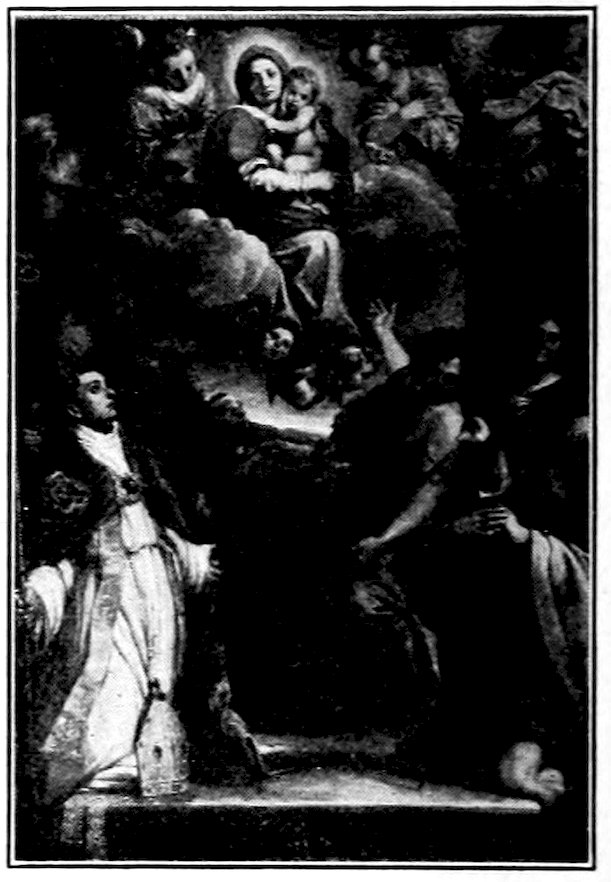

Because the figures are a little slight and the expression a 33bit sentimentalized, and the proportions rather arbitrarily handled to meet the exigencies of the curved spaces, many good critics, including Venturi and Berenson, deny these compositions to Giotto. One of them, the St. Francis in Glory, is clearly of inferior design and quality. For the others, it seems to me that the designs can only be by Giotto, while the execution is mostly by a charming assistant whose work in this ceiling and elsewhere in this church makes us wish we knew his name. No middle-aged painter of established repute was likely to undertake personally the dirty and fatiguing work of painting a ceiling in fresco. If we are right in supposing that Giotto may have designed this ceiling, shortly after his return from Avignon, say, after 1312, he would have been towards fifty years old, and provided with a shop-staff of well-trained assistants. From this time on, indeed, we may assume that he rather directed the work of others than painted himself. Such a view will permit us to accept as school works many fine pictures the design of which a too strict criticism has denied to Giotto. For example, the admirable Coronation of the Virgin, in Santa Croce, Florence, seems to me completely designed by Giotto, and the logical next step after the Franciscan allegories, though there can be little actual painting by the master on the panel, and his personal contribution may have been limited to a small working drawing. Indeed the only one of the later panels which seems to show throughout his actual handiwork is the lovely Dormition of the Virgin at Berlin, Frontispiece, which was painted for the Church of Ognissanti.

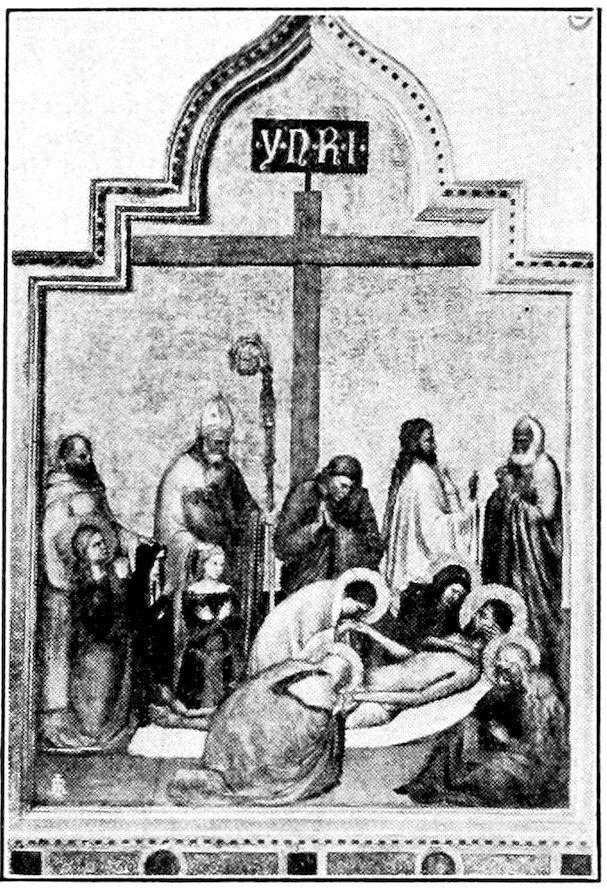

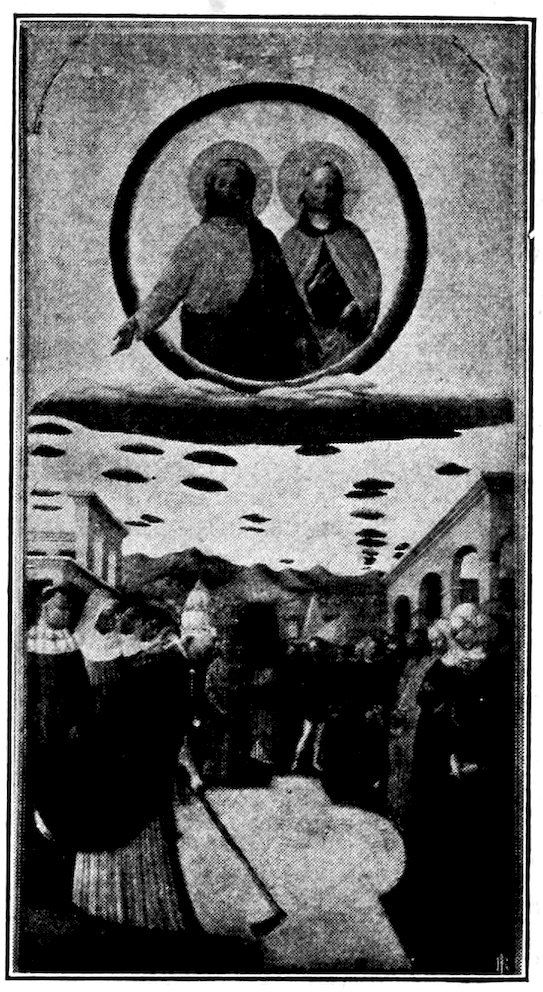

At about this period I think we may set the several crucifixes in Florentine churches, without inquiring too narrowly whether they are by the master or by scholars. Giotto has developed a singularly noble type. The Christ is no longer contorted in agony as in the crucifixes by Cimabue. He is dead, with his head quietly sunk on the powerful breast, and the body relaxed. The conception is humanistic. One feels 34chiefly the pity of stretching that glorious thing that is a man’s body on a cross. Probably the earliest of these crucifixes is that at Santa Maria Novella, while the finest is at San Felice. About 1320 we may set the dismembered ancona, painted for Cardinal Gaetano Stefaneschi, which originally stood on the high altar of St. Peter’s, Rome. The tarnished fragments which you may still see in the sacristy, are more splendid in color than any other tempera painting whatsoever. Probably only the central panels, Christ and St. Peter enthroned, are from Giotto’s hand, the side panels representing the martyrdom of Peter and Paul may well be both designed and executed by the accomplished assistant who carried out the allegories at Assisi.

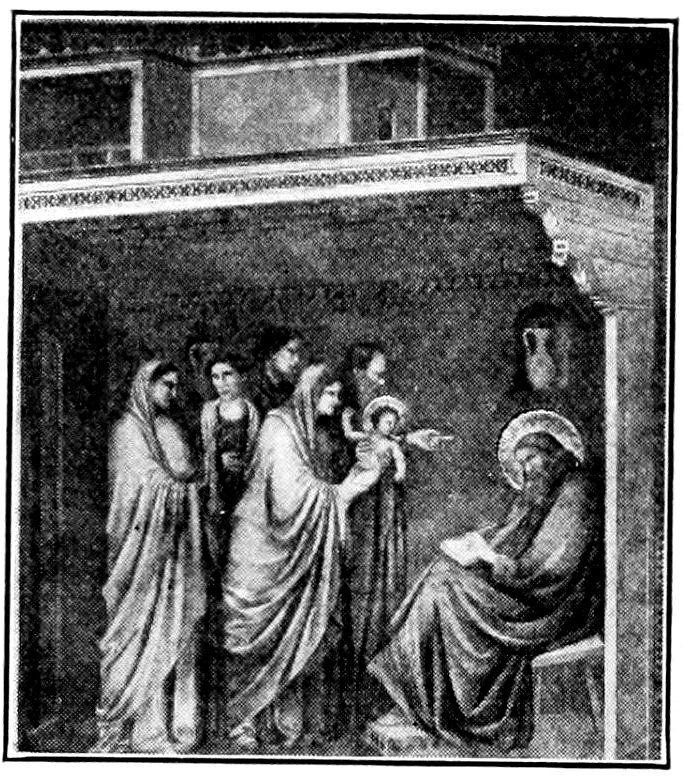

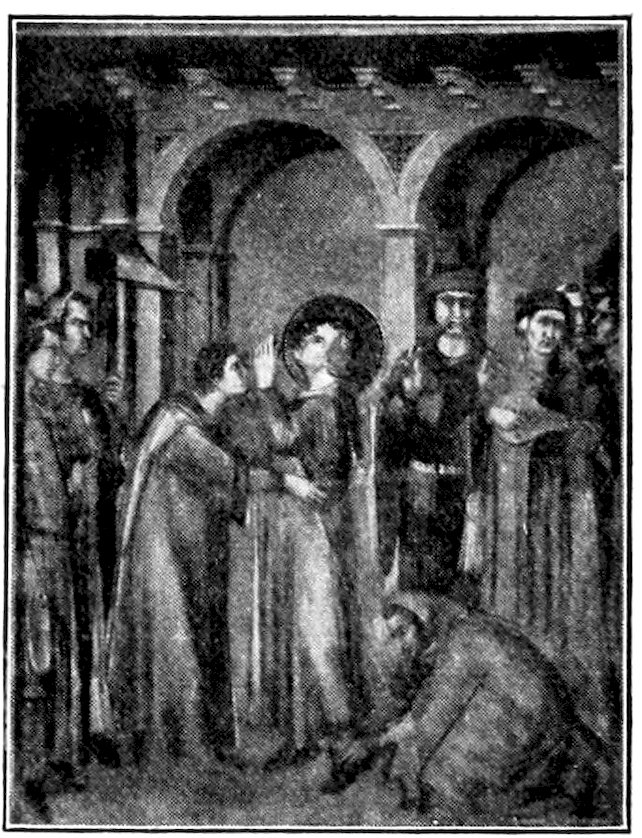

Fig. 19. Giotto. Naming of St. John the Baptist.—Peruzzi Chapel, Santa Croce.

So far we have seen Giotto a wanderer. Assisi, Rome, Padua, Rimini, delighted to do him honor, but apparently Florence had claimed few works from his hand. We have record of frescoes in the Badia which may have been early works. It was the decoration of Arnolfo’s great Franciscan church of Santa Croce that finally recalled Giotto and evoked his most accomplished work. He completed in the transepts of Santa Croce four chapels and as many altar-pieces. The frescoes were white-washed in the 16th century, and the panels broken up and lost. But in the last century the white-wash was scraped off from two of the chapels, and there we may see, so far as defacement and repainting permit, the masterpieces of the early Florentine school. We may reasonably guess the date of this work to be somewhere about 1320, Giotto being nearly sixty.

35In the chapel maintained by that noble family, the Peruzzi, Giotto spread on the side walls three stories from the life of St. John the Baptist, and as many more from that of St. John the Evangelist. The figures are superb, magisterial in pose; the draperies grand and ample after the classical fashion. Upon bulk and relief there is less insistence than at Padua. Giotto has passed the experimental stage as regards form, is less strenuous and more at his ease. Nothing is more stately in the chapel than the presentation of the infant Baptist to his father, who is temporarily stricken with dumbness, Figure 19. Simeon gravely writes the name John; Elizabeth with her adoring group of attendants carefully offers the vivacious child to his father’s gaze. The gestures are slow, definite, determined. The group beautifully fills the square space without crowding it. The composition, unlike the widely spaced Paduan designs, is drawn together into a mass.

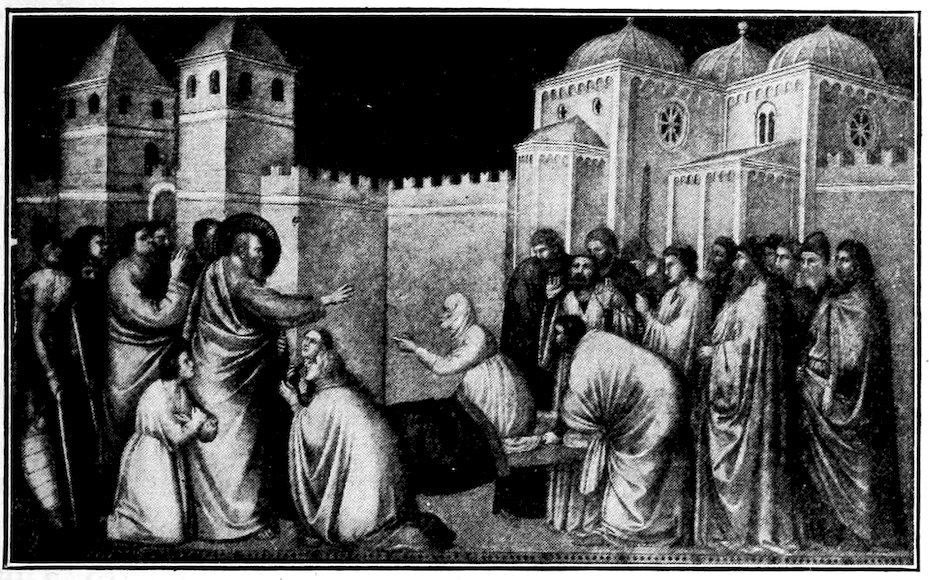

Fig. 20. Giotto. Resuscitation of Drusiana by St. John.—Peruzzi Chapel, Santa Croce.

Upon the Feast of Herod with Salome modestly dancing John Ruskin[11] has expended just eulogies in the petulant yet 36important little book “Mornings in Florence.” What is notable in the scene is its general decorum and the pathetic indecision of the weak King.

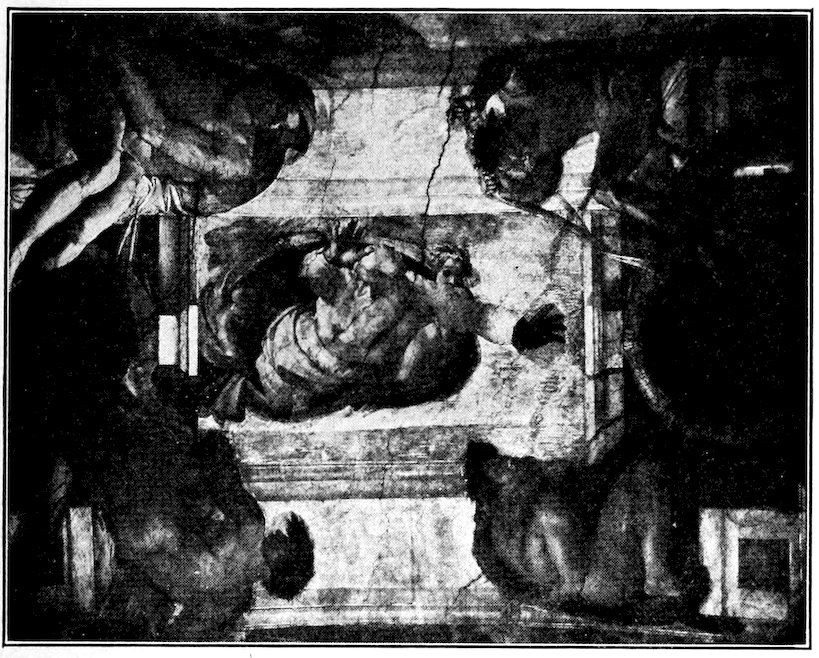

But the most accomplished design as such is the miracle of the Resuscitation of Drusiana by St. John the Evangelist, Figure 20. Even the inscenation before a fine Romanesque city is adequately, if very simply, realized. The gesture of the apostle is of majestic power, the contrast of the massive, upright, columnar forms of the elders, with the sharply bent forms of Drusiana, her mourners and bier bearers, is admirably invented, and the drastic portraiture of a cripple at the left adds a tang of reality while in no wise detracting from the dignity of the scene. We have a work in the grand style, massively conceived, warmly felt, wrought into an elaborate and satisfying symmetry. The Ascension of St. John has an even graver and more ample rhythm. The Golden Age of Raphael and Titian will have little to add to this except the minor graces.

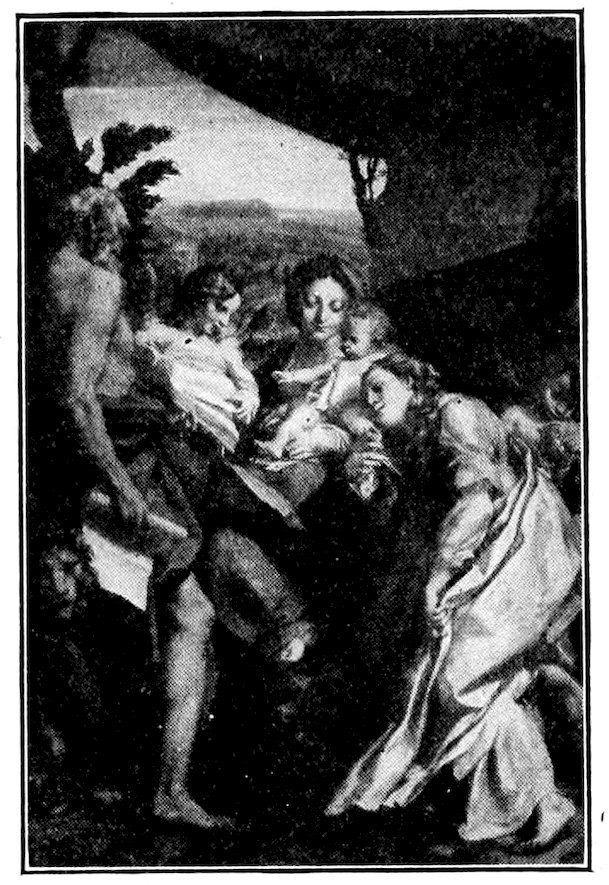

In the adjoining chapel of the Bardi family, Giotto, a little later, I believe, painted six stories of St. Francis, and four figures of the great Franciscan saints, St. Louis of France, St. Louis of Toulouse, St. Clare, and St. Elizabeth of Hungary. Over the entrance arch he set an animated picture of St. Francis receiving the stigmata, the wounds of the Saviour. Nearly thirty years earlier he had done this subject for the Church at Assisi, and in an altar-piece which has passed from Pisa to the Louvre. By comparing the rigid, angular figures of the earlier composition and their ill-adjusted accessories, with this easy and beautifully balanced arrangement, you may see how far Giotto had gone in the direction of grace, and you will not fail also to note how much more tragic the earlier and less calculated work is.

For the first time, in the Bardi chapel, Giotto conceives the decoration of the side walls as a whole. From the pointed lunettes above, through the three compositions on each wall, 37there is an architectural axis, sometimes arbitrarily imposed, about which the figures are symmetrically distributed. Often the scene is a screen with projecting wings as in the St. Francis before the Sultan of Morocco, or a similar fore-court, as in the Mourning for St. Francis. It will be well to compare the story of St. Francis renouncing his father, Figure 21, with the same subject at Assisi. You will recall that St. Francis, when rebuked by his father for a rash and impulsive act of charity, stripped off his clothes, then threw them at his father’s feet, and took refuge under the robe of the Bishop of Assisi. In the earlier version the architectural background splits the composition in two, adding to its intensity perhaps, but displeasing to the eye. Here in the late version a fine building seen in perspective both unifies the two groups and serves as apex for the decorative axis of the entire side wall.

Fig. 21. Giotto. St. Francis renounces his Father. Compare Fig. 9.—Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce.

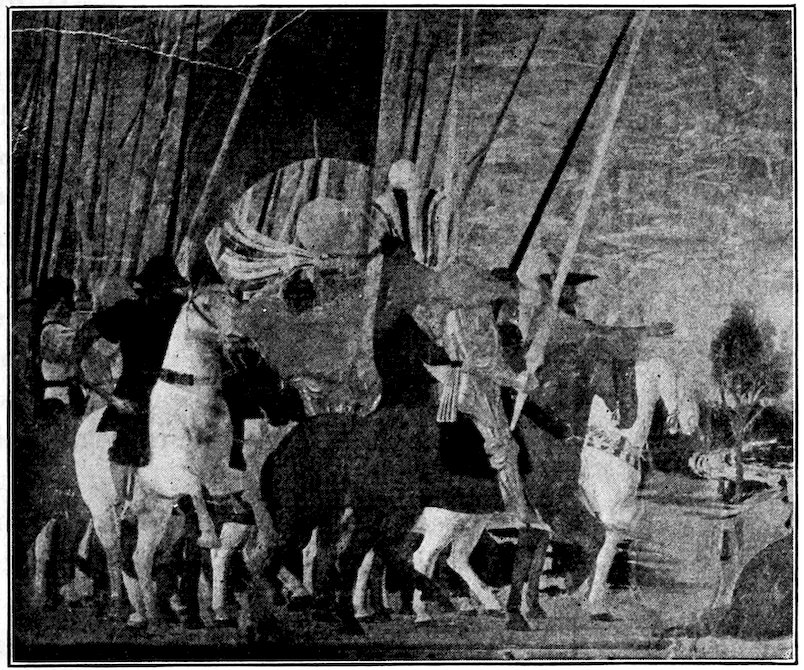

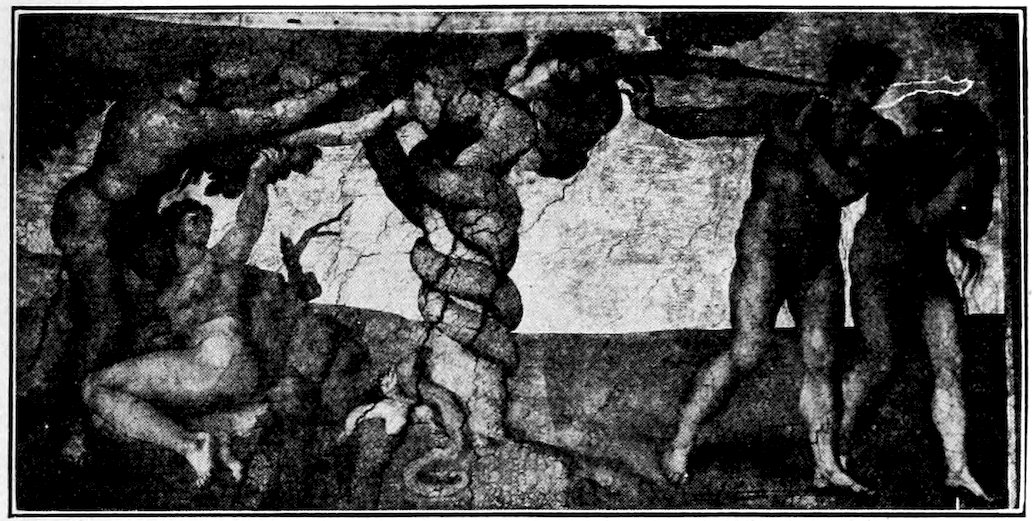

More remarkable still is the contrast between St. Francis Braving the Fire Ordeal before the Soldan, Figure 22, as depicted at Assisi and Florence. We have to do not merely with an immense 38advance in decorative composition, the accessories at Assisi being trivial and fantastic; not merely with progress towards a gracious symmetry and more massive and impressive form, but also with a complete change of moral point of view. At Assisi the Soldan is an ogre exacting a cruel test. The Moslem priests are a cowardly pack of magicians ignobly slinking away, St. Francis a grim fanatic. At Florence the Soldan is a noble and humane gentleman, amazed at an unreasonable ordeal forced upon his wise men. The Moslem doctors are splendid scholars grudgingly shrinking from an unfair test, St. Francis an alert little enthusiast half gloating over the confusion he has thrown into the enemy camp. With a by no means orthodox feeling, old Giotto, humanistic Giotto, almost seems to take, or at least to see, the pagans’ side of it. He who had written a manly poem against the excesses and hypocrisies of the Franciscan ideal of poverty, is now capable of criticizing the more extravagant propagandism of the saint himself.

It is a criticism that admits all tenderness and sympathy, as may be seen in the famous fresco representing the Mourning over the body of St. Francis while his soul is translated to heaven, Figure 23. Again John Ruskin is your best interpreter to this picture, which after all only needs to be seen. It combines all the qualities for which Giotto had striven—warmth, vivacity, ingenuity, unexpectedness in the narrative details; massiveness and dignity of the individual forms; and a decorative symmetry at once monumental, formal, and delightfully varied.

Fig. 23. Giotto. Death of St. Francis.—Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce.

40With this noble and deeply felt composition we virtually take leave of Giotto. For though he lived for many years yet, the works of his old age have largely perished. In the chapel at Assisi dedicated to St. Mary Magdalen are fine frescoes in which he surely had a leading part. From 1330 to 1333 he worked at Naples for King Robert of Anjou. Nothing remains from this visit except certain shrewd jests which the painter exchanged with the King. In 1334 Florence recalled him, and made him capomaestro of the Cathedral. Giotto designed the flower-like tower which rises lightly beside the temple of Our Lady of the Flower, invented and perhaps cut in marble certain reliefs on the base representing the crafts of men, but did not live to see the loveliest of bell towers finished. The task was completed by his pupil and artistic executor, Taddeo Gaddi. In the last years Giotto conceived vast compositions of a religious and political sort for the public buildings of the Commune. There were allegories of a strong and weak state, in the Bargello, the prison-fortress of the Captain of the People. These great symbolical designs are a kind of missing link between Giotto and the panoramic painters who followed him. We may find an echo of this lost work in the Civic Allegories in the Palazzo Pubblico of Siena. These were doing at the moment of Giotto’s death by a Sienese painter, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, who had studied the great Florentine master devoutly. Nothing of Giotto’s latest phase is left save a few figures in the battered frescoes in the Bargello which contain the idealized portrait of youthful Dante, Figure 24, and the gracious Dormition of the Virgin at Berlin, Frontispiece.

Fig. 24. Giotto. Dante, tracing from the ruined fresco in the Bargello.

Just before Giotto died, the tyrant of Milan borrowed him from Florence. Giotto soon returned, to die early in the year 1337, being seventy years old. Almost single-handed he had 41made Italian painting. He had lent life and warmth to the cold and academic reform of the Roman painters. He had expressed a maximum of feeling, without sacrifice of dignity. He had worked out beautiful and impressive forms of composition wherein symmetry and contrast met harmoniously. He had mastered the expression of mass on a plane surface with a certainty and energy no artist before had even imagined, and that few since have equalled. He had forecast and led the way in every manner of realistic figure painting.

Florence, when true to herself, could only repeat Giotto in one phase or another of his activity. In her casual and sprightly mood, she carries on the method of Giotto’s stories of St. Francis at Assisi, in mystical reflection and symbolism she must build on the allegories over St. Francis’ tomb and on the lost political frescoes; in her mood of strenuous search for reality she can but repeat the Paduan chapter of Giotto’s strivings, in rare moments of vision and fulfilment she will merely begin where the Santa Croce frescoes of Giotto ended.

However Giotto be ranked, and personally I see no greater artist on the rolls of history, his is indisputably the greatest single achievement; for no other artist who accomplished so much began with so little. It was no exaggeration that made Lorenzo Ghiberti regard the advent of Giotto as the coming to life of an art that had been buried for centuries. It is indeed the measured classicism of Giotto’s art that constitutes its greatness—its sweet and lucid reasonableness, its rugged yet disciplined strength. Seneca or Marcus Aurelius would have understood it perfectly, as Giotto himself, for his mellow wisdom and wit, would have been a welcome visitor at Horace’s Sabine farm. In his broad and flexible insight, his love of mankind, his clear perceptions of aims and ready acceptance of limitations, in his pathos without exaggeration, in his constructive skill without ostentation, in his simplicity without bareness, he is the authentic and indispensable link between 42the beauty of Greece and Rome and that of the Italian Golden Age. To know him is to know almost everything that is needful about older European painting, not to know him is to lack the very rudiments of an artistic education.

Giotto left many followers,[12] not one of whom at all understood his greatness. Like his friend Dante, he was distantly admired, but really loved only in bits. As perceptive a person as the artist biographer Vasari lavishes praise upon Giotto for his more trivial inventions—the Christ Child struggling out of the arms of the High Priest, for example. So Giotto’s followers picked unintelligently from his great accomplishment, choosing what the master himself would least have valued—his simple contours without his significant mass, his variety and vivacity without his warmth and restraint. On their own account they added complication. The sparse economy of Giotto’s best work could never have appealed to Florence at large. Something richer and gayer was wanted, more like Florentine life itself as it became after the general loosening up of manners and morals following the plague of 1348. Its chronicler, the author of the “Decameron,” fairly represents the new spirit. The best of the younger painters have indeed something of Boccaccio’s mentality—his light touch, his charm, his panoramic richness, his fluid and undisciplined grace. Thus arises what I may call the panoramic style of fresco painting—superficial, full of episodes and accessories, still religious in theme, but mundane in spirit, often cleverly conceived, and very superficially felt. These artists had grasped neither the meaning of Giotto’s drawing nor the beauty of his decorative formulas, they saw only his variety and energy. Meanwhile a great Sienese painter, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, a profound admirer of Giotto, had worked out a nobly spectacular form of painting in which the stage setting was elaborate and realistic. He painted much in Florence 43about 1334 and his novelties allured the new men. So we find fresco painting tending in a scenic direction, and panel painting following the same course more conservatively—not merely in Florence and Siena, but throughout Northern Italy as well.

Fig. 25. Giotto’s Assistant at Assisi. Flight into Egypt. Compare Figure 14.—Lower Church, Assisi.

Fig. 26. Taddeo Gaddi. St. Joachim Meets St. Anna. Compare Fig. 13a.—Baroncelli Chapel, Santa Croce.

Many of Giotto’s immediate pupils are mere names to us. Maso, whom the sculptor commentator Ghiberti praised for his sweetness, Stefano whom he dubbed the “ape of nature,” Puccio Capanna—their work must be at Assisi, but criticism has not succeeded in clearly disengaging it. The nameless master who executed the Franciscan allegories at Assisi and designed the stories of Christ’s youthful days, in the adjoining right transept, is the most accomplished and individual follower of Giotto. He works for grace, pathos, sumptuousness, and decorative breadth. He is a Giotto with the angles rubbed down. By comparing Giotto’s Flight of the Holy Family to Egypt, with the later version at Assisi, Figure 25, we may grasp the difference between master and scholar. Giotto is brusque, harsh, noble; the flight through a rocky defile gives a sense of urgency and peril; the composition carries forward like the ram of a battleship. In the version at Assisi the flight has become an attractive family excursion through a romantic valley; the mood is gentle, charming, unspecific. A moment in an epic has been attenuated into an idyl. This master never fails to express a dreamy sort of poetry, and in such compositions as the Massacre of the Innocents, and the Calvary, he commands a genuine pathos. He is exactly what Giotto might have been, had he skipped the strenuous Paduan 45phase, and become a decorator without the preliminary discipline of the draughtsman. There are reasons for thinking that this work was done by a shop assistant of Giotto’s, who for many years directed the decoration of the Lower Church at Assisi in Giotto’s stead. Some of the work in the Childhood of Christ, I believe, may be as late as 1330 to 1335.

Taddeo Gaddi is a more definite and less pleasing personality. He was Giotto’s godson and his assistant for twenty-four years, presumably from 1313 to 1337, as well as his artistic executor. Whether in panel or fresco, he was an admirable craftsman; in tempera, a fine colorist. His panels are widely scattered, some ten being in the United States; his frescoes, all that we need to note, are in Santa Croce. In the Baroncelli Chapel, just after Giotto’s death, Taddeo finished these frescoes of the early life of the Virgin, repeating themes which Giotto had used both in Padua and elsewhere in Santa Croce itself. His way of competing with Giotto is to stir and add and mix things up. Compare the meeting of Anna and Joachim at the Beautiful Gate in the two masters; Giotto at Padua is grave, noble, heartfelt; how he discriminates between the masculine clutch of the old husband and the tender embrace of the wife—how drastic the conception is, but also how clear and stately. Poor Taddeo on the other hand brings the sacred pair together with the bounce of a modern dance, Figure 26. He brings no brains to bear, and almost no feelings, just a sprightly and wholly casual inventiveness. Certain delightful little panels with stories of Christ and St. Francis which he did in Giotto’s shop for the doors of the sacristy wardrobes of Santa Croce remind us of the pity that he ever ceased to be an interpreter of a greater man’s designs. In the fresco of Job’s trials, in the Campo Santo, Pisa, he seems nearly a great artist. Conceivably he worked on designs of his late master. At least he had a certain critical sense, for at an artist’s reunion at San Miniato, about 1360, he told 46Andrea Orcagna and the rest of the company that painting had constantly declined since Giotto and was declining every day. He transmitted, his sound craftsmanship to a son, Agnolo, who decorated the Choir of Santa Croce with the legends of the Cross. He carried down the panoramic style to the end of the 14th century, practicing it with more taste than his father, achieving a grace without much inwardness or force.

A later contemporary of Giotto’s, Buonamico Buffalmacco,[13] seems to have inherited something of Giotto’s power, but the identification of his work is very uncertain, and he lives for us chiefly as an egregious wag in the pages of the Italian story writers.

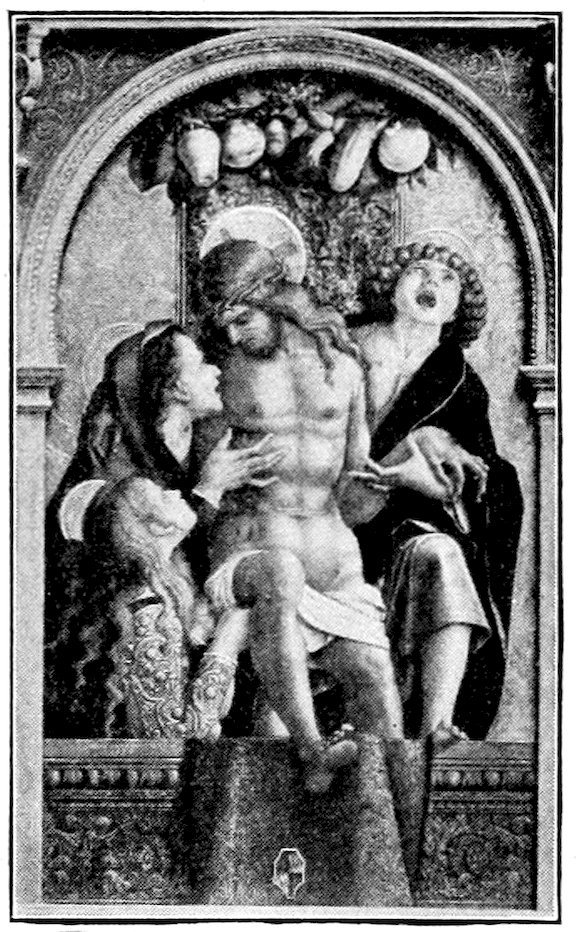

Fig. 27. Giottino. Deposition—Uffizi.

From another contemporary and possibly a scholar of Giotto, Bernardo Daddi, we have many panel pictures and a few frescoes at Santa Croce. He is an admirable craftsman, and a sincere illustrator, within his limitations, applying very competently to panel painting something of the panoramic realism of Ambrogio Lorenzetti. A prolific artist, his exquisitely finished little panels are quite common. In America are good examples in the New York Historical Society, in the Platt Collection, Englewood, and a more monumental piece in the Johnson Collection, Philadelphia. He lived well beyond the middle of the century.

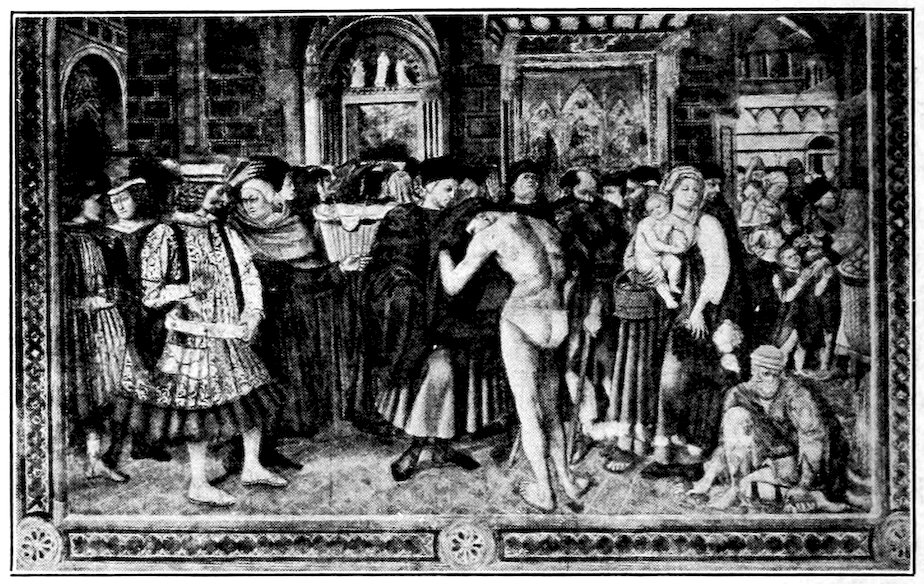

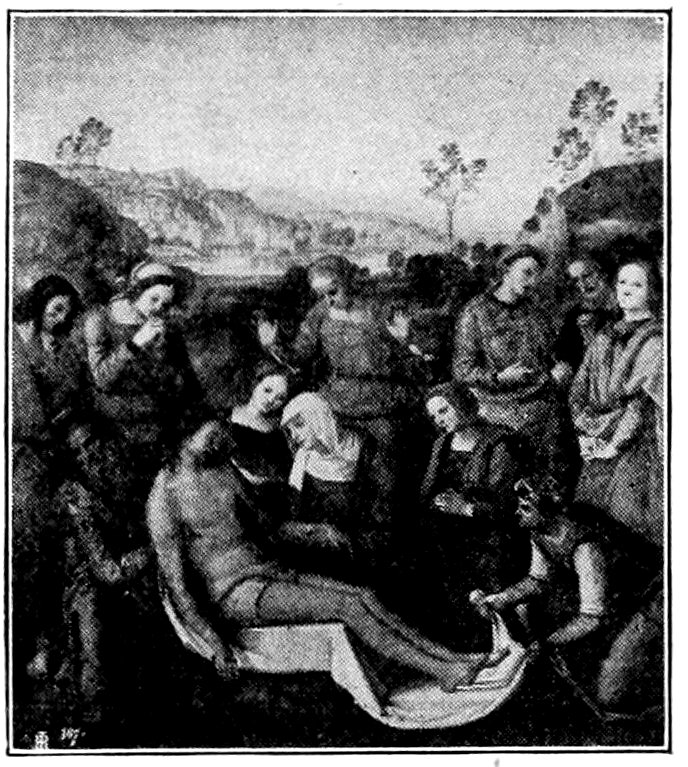

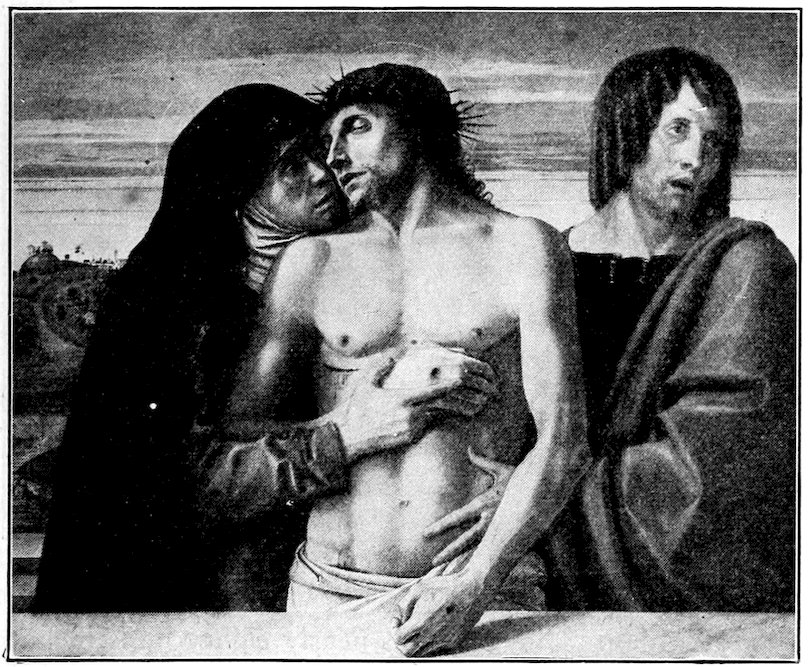

Giottino, who possibly is to be identified with Giotto’s pupil Maso, is a more delicate spirit with unusual resources of pathos. His best work is an altar-piece of the Deposition, Figure 27, 47painted about 1360 for the Church of San Remigio at Florence and now in the Uffizi. A preference for isolated figures and for vertical lines is noteworthy, as is the wistfulness of the attendant donors. Similar qualities of delicate precision as of dispersion are in the frescoes in Santa Croce which represent the Miracles of Pope Sylvester. The note is feminine and rather Sienese than genuinely Florentine.

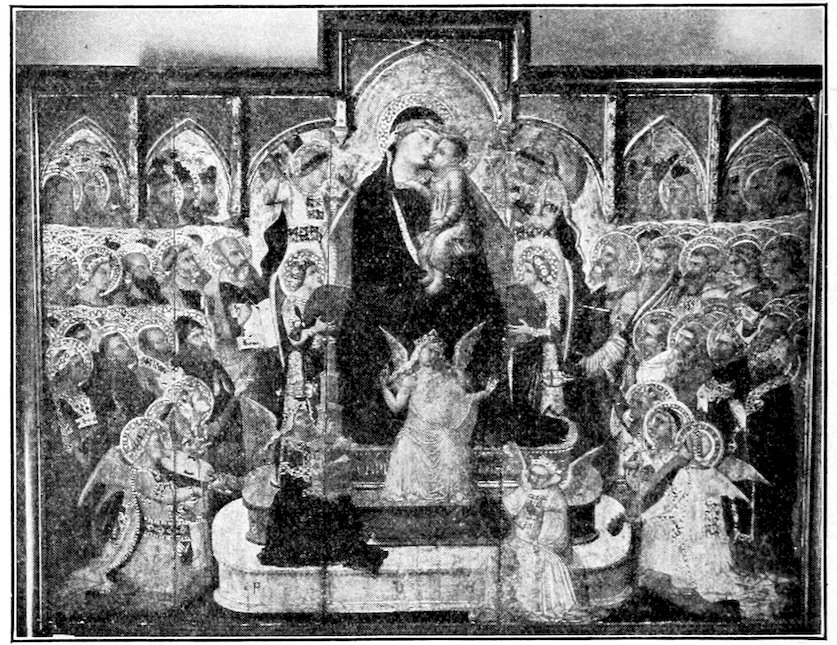

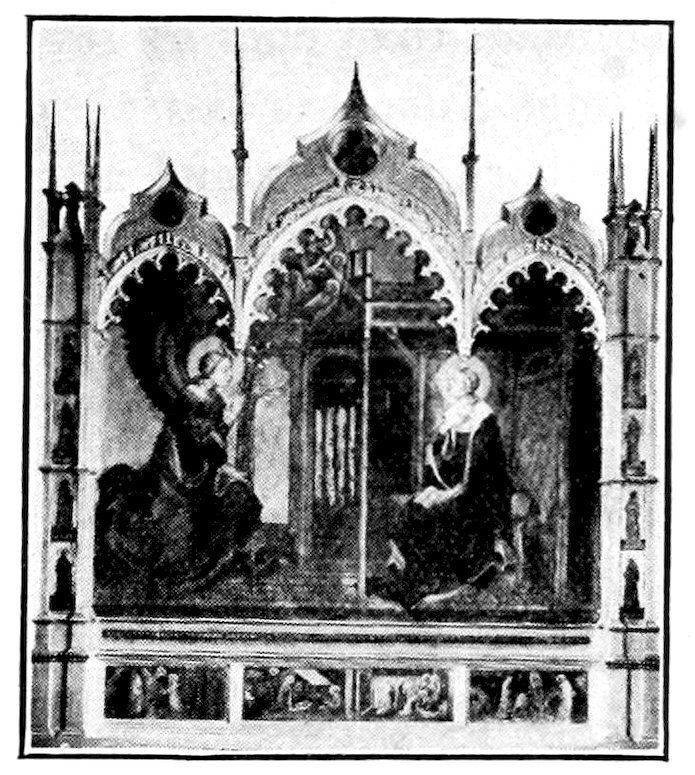

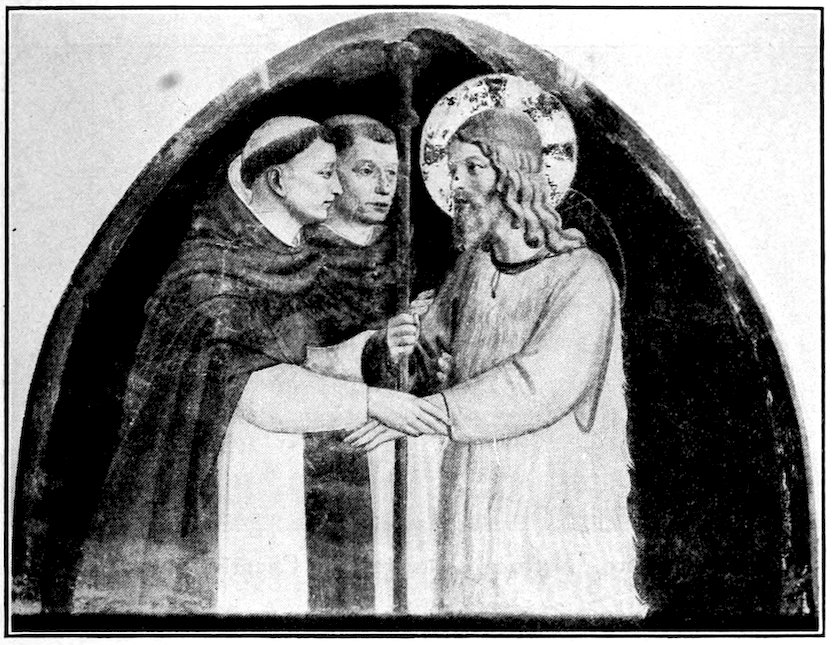

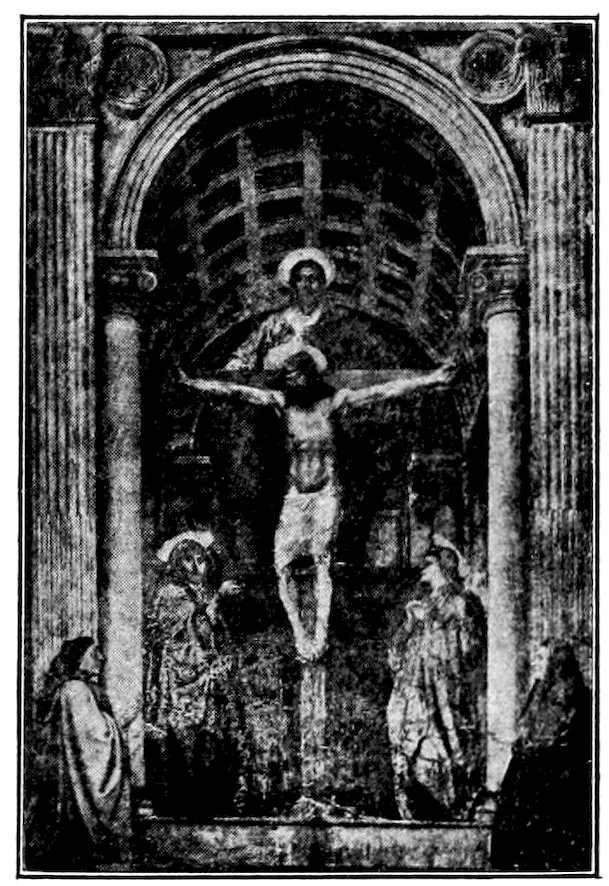

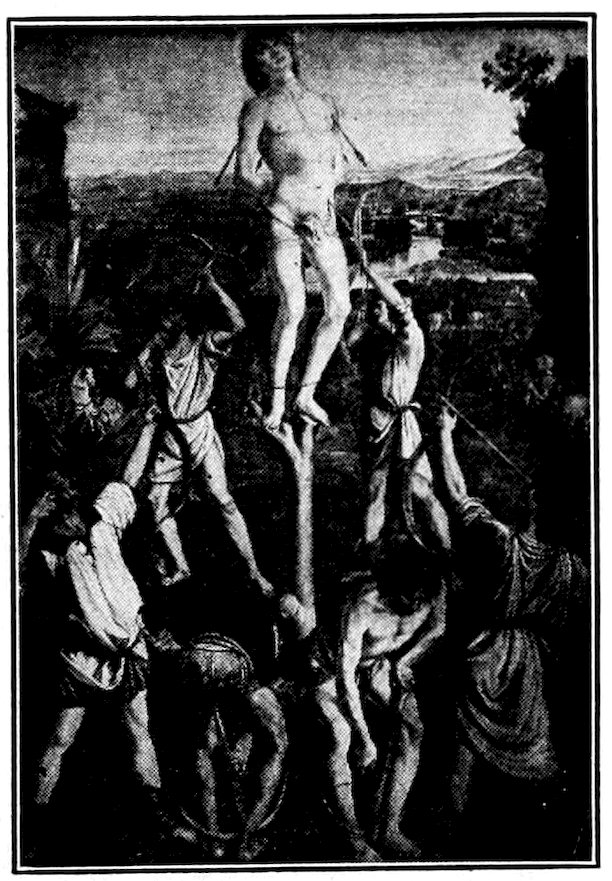

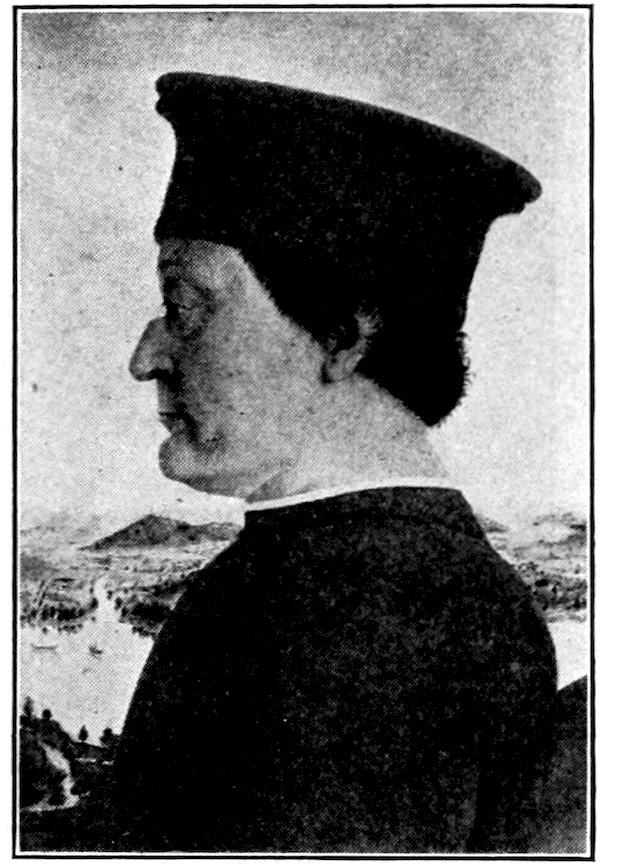

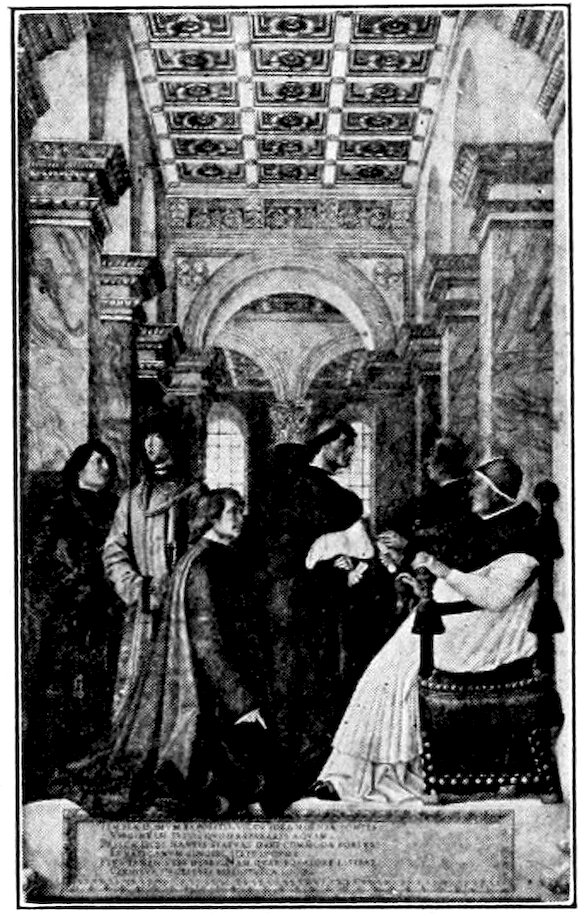

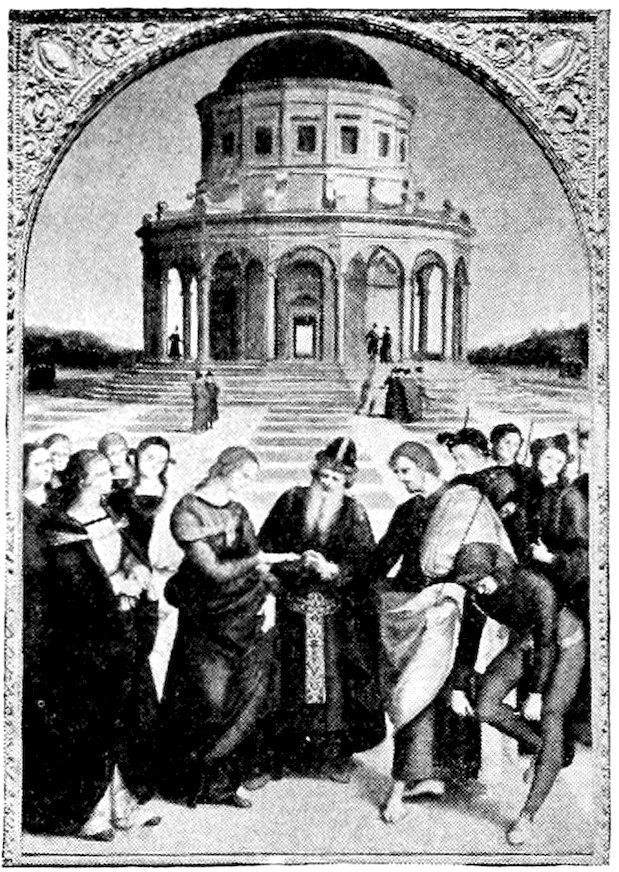

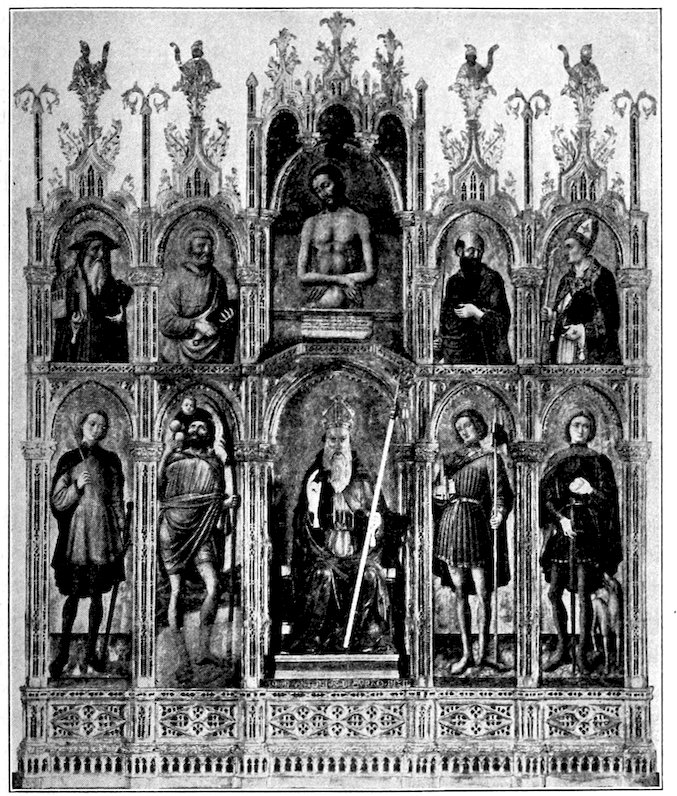

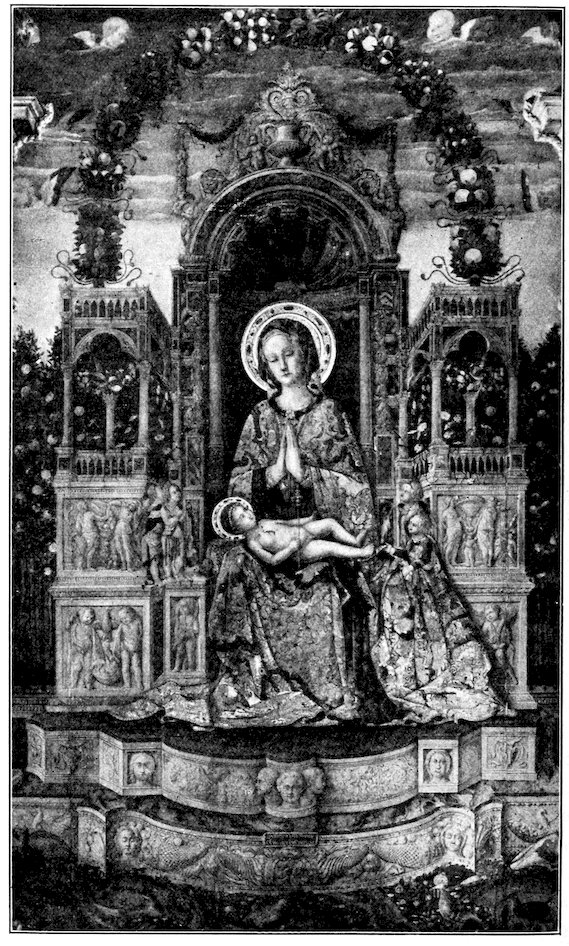

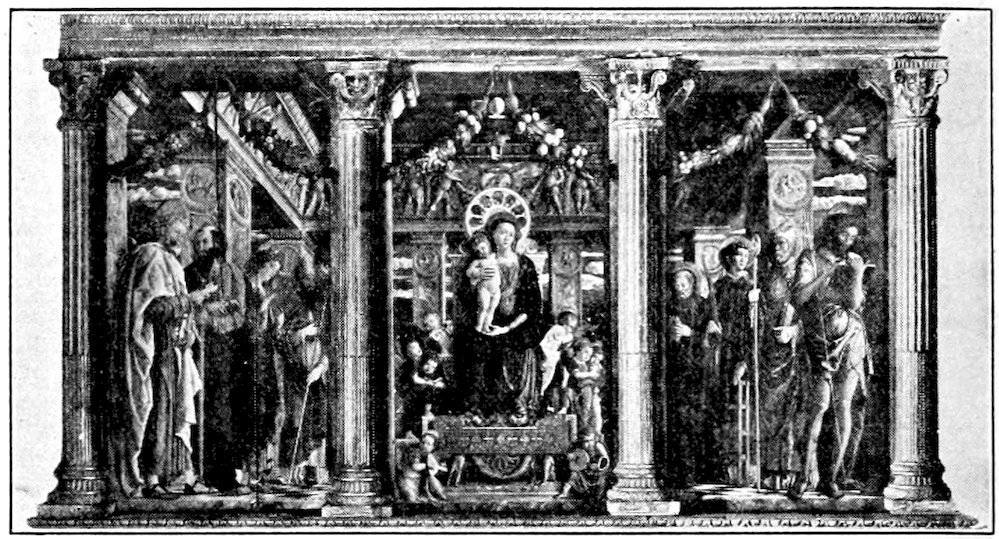

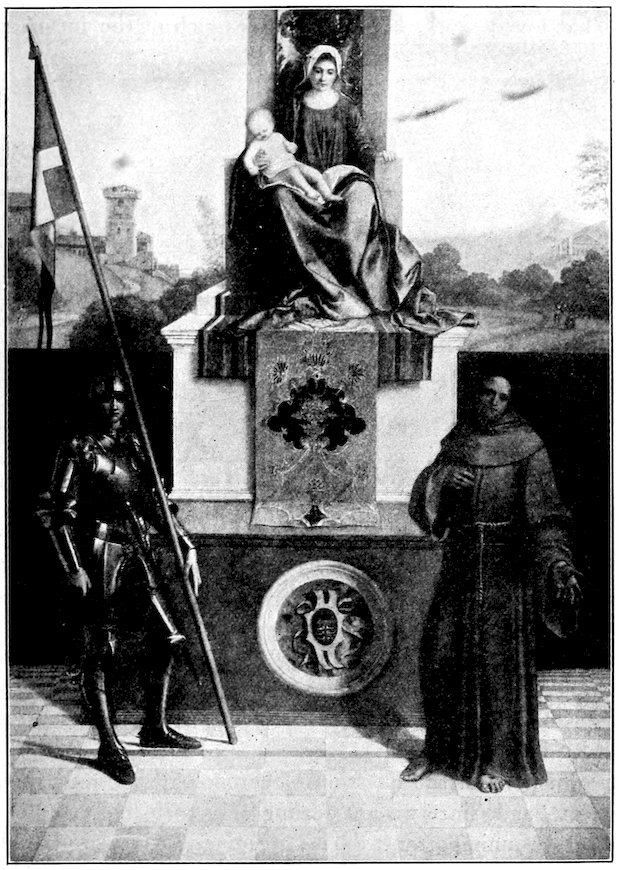

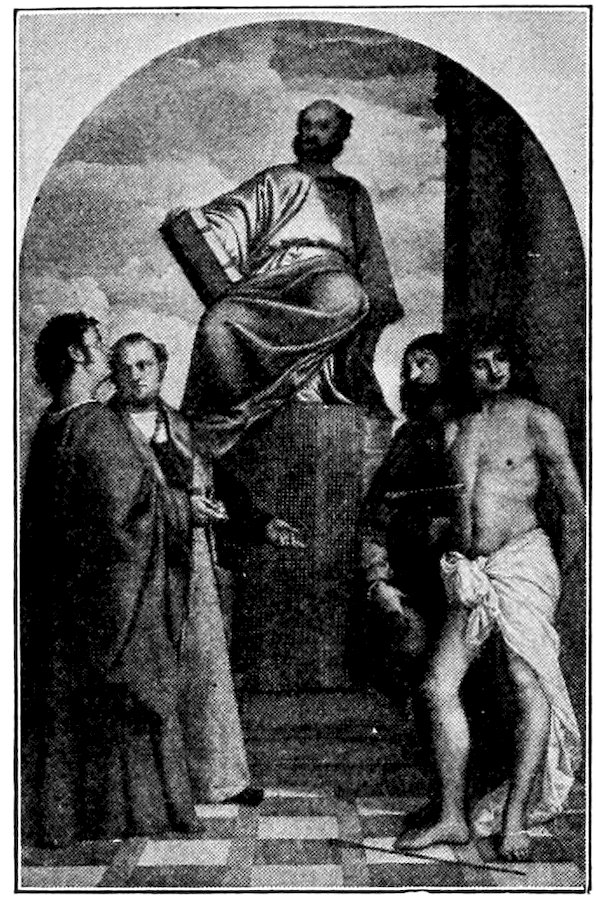

Fig. 28. Andrea Orcagna. Christ conferring authority upon St. Peter and St. Thomas Aquinas.—Strozzi Chapel, Santa Maria Novella.

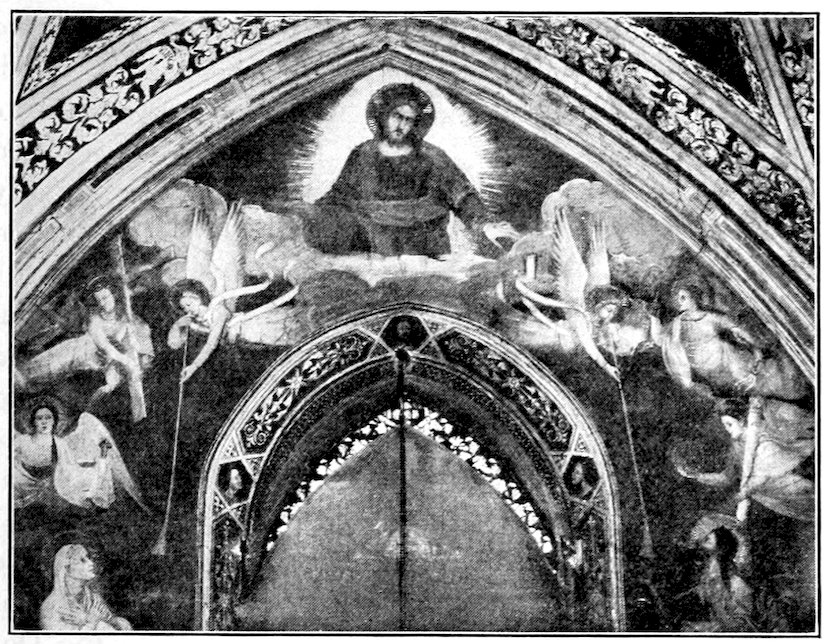

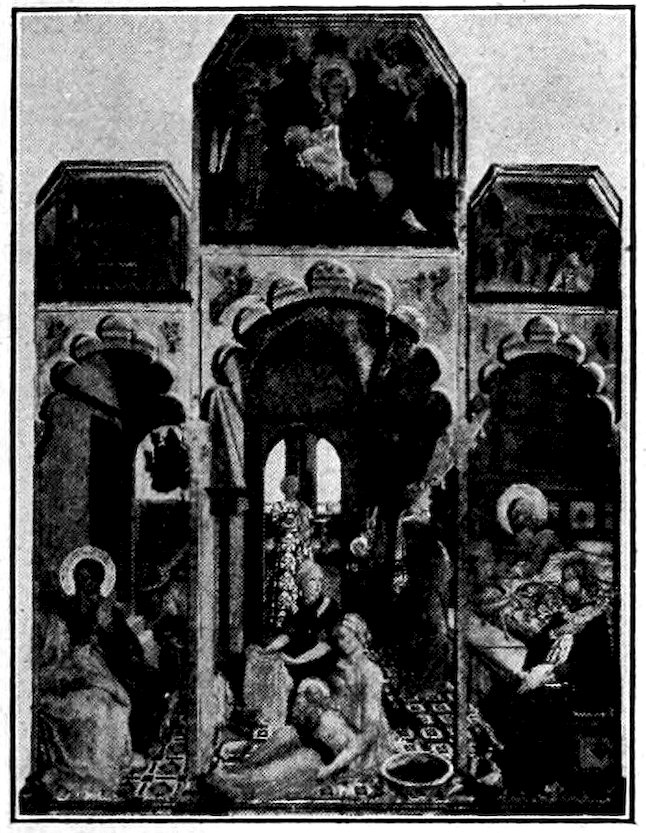

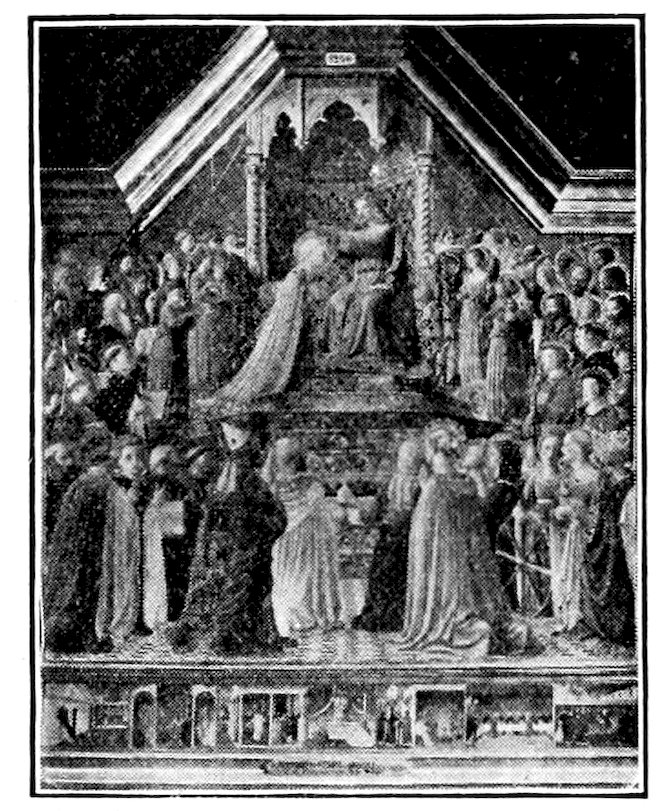

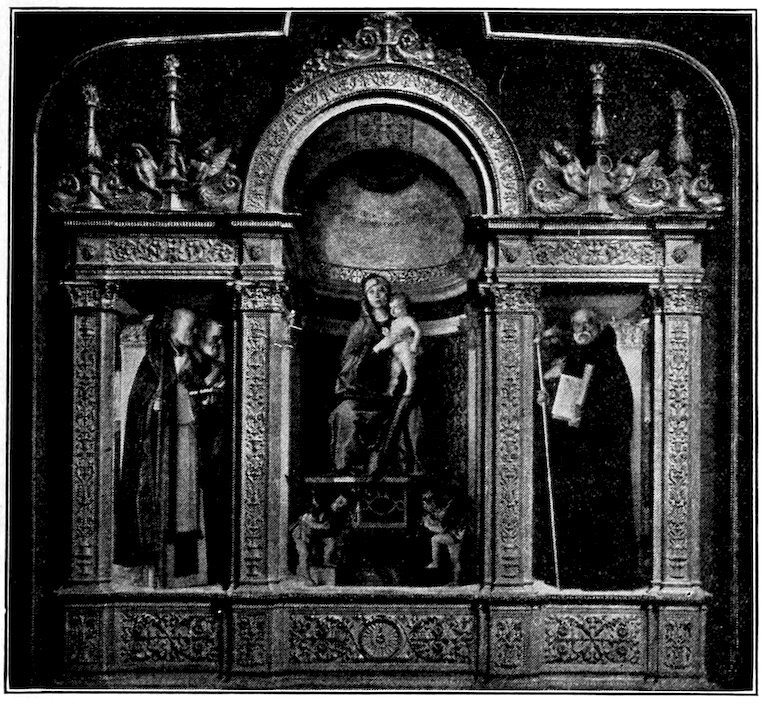

Outside of Giotto’s bottega arose the rare continuers of his tradition. Such an artist flourished about the middle of the century in the person of Andrea di Cione, better known by his nickname of Orcagna. He was more of a sculptor and architect than a painter, a man of dignity and force, a poet and thinker. Although not a pupil of Giotto, he studied that master’s work admiringly, and sought to reproduce its massiveness. Its brusqueness he largely rejected. Instead of sketching the draperies summarily, he drew the folds carefully 48after the model; he liked to treat the panel and wall as a whole, where Giotto had accepted the tradition of subdivision; he gave to his faces a greater sweetness and he occasionally attempted foreshortenings and impetuosities of gesture that Giotto would have avoided. Unluckily Orcagna’s most important frescoes have perished. We may grasp his nobility in the altar-piece which he finished and dated in 1357, Figure 28, for the chapel of the Strozzi family at Santa Maria Novella. The formality of the composition is noteworthy, as is the stately sweetness of the Madonna. The subject is Christ delegating his Power and Wisdom respectively to St. Peter and to St. Thomas Aquinas.

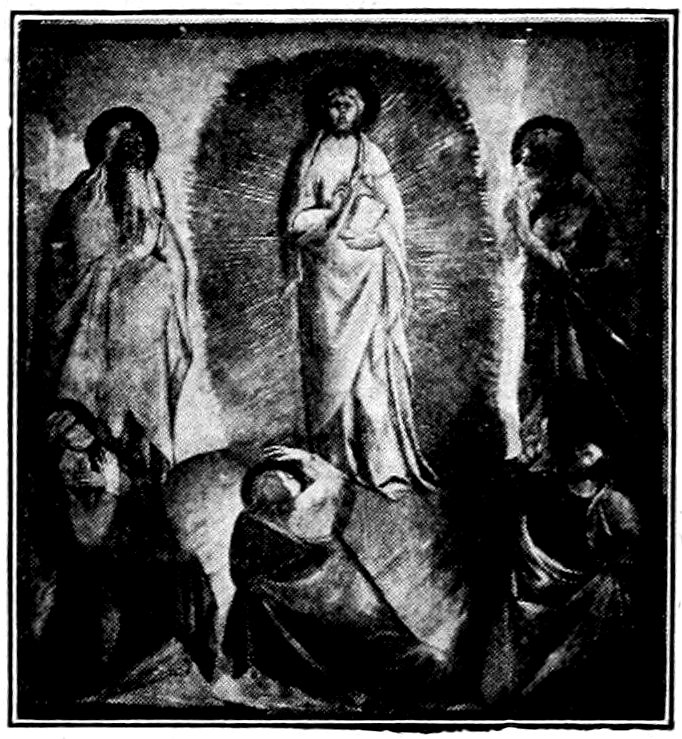

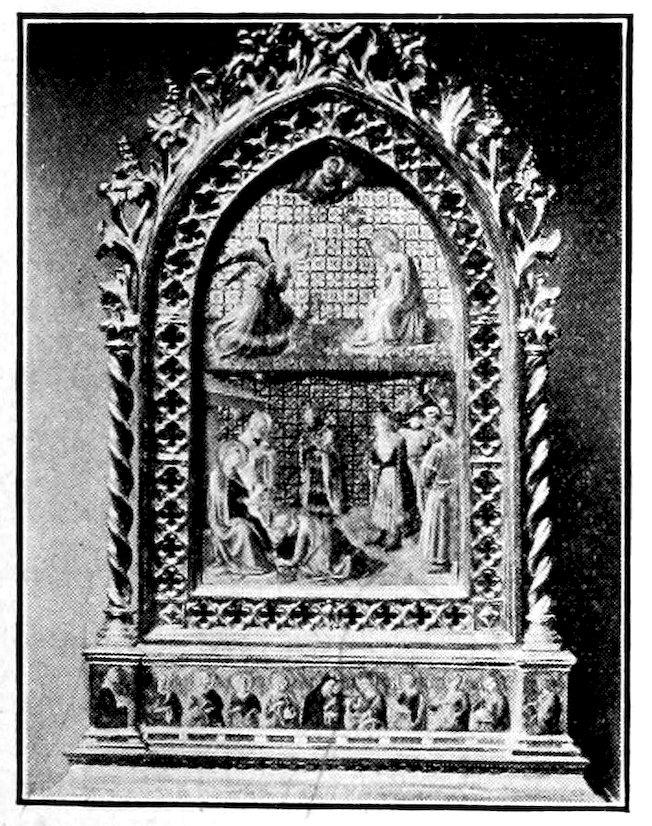

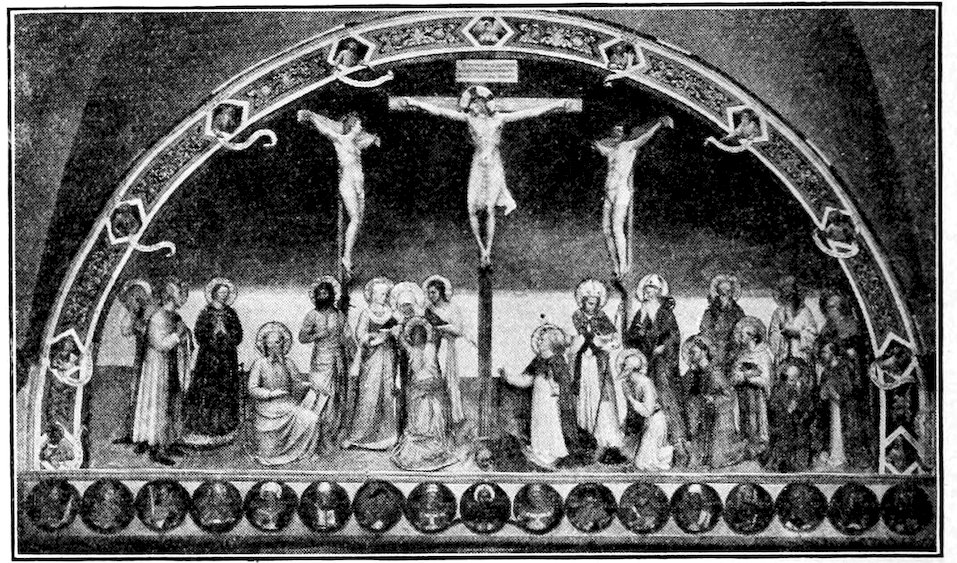

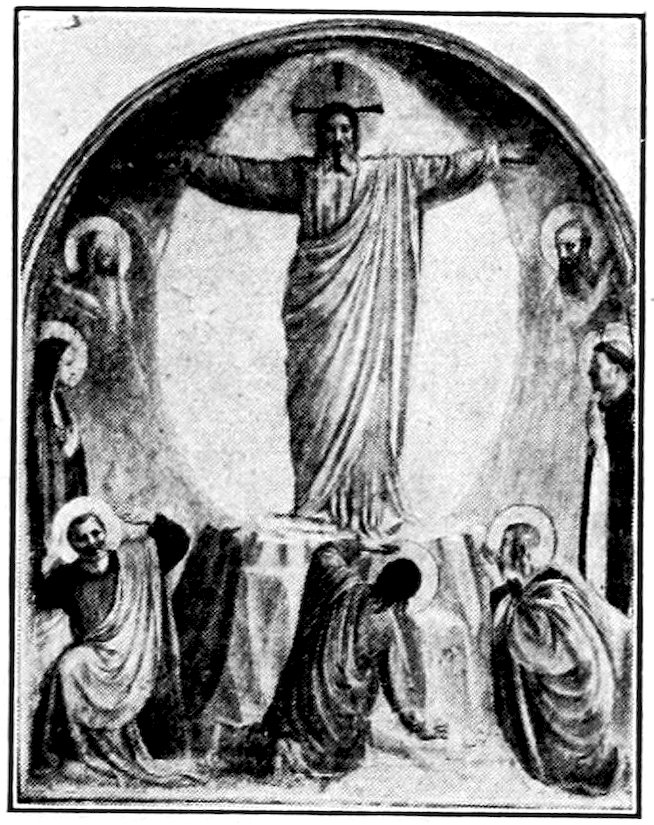

In the same chapel the figure of Christ leaning forward over a cloud and making the sublime gesture that decrees the end of the world and the Judgment Day, Figure 29, is probably designed by Orcagna, as are the larger figures below. We have here one of the freest and grandest conceptions of the period. The lovely garden-like heaven and the quaint and ingenious hell on the side walls are by Orcagna’s brother, Nardo di Cione. The mood is less grave than Orcagna’s, variety counts for more. The heads of the saints are of a most delicate beauty. Nardo has many of the qualities of the panoramic painters without their heedlessness. He represents a compromise between the severity of Giotto and the diffuseness of his own day. He worked indefatigably until 1366, and his younger brother, Jacopo, and his imitator, Mariotto, continued the manner almost into the new century.

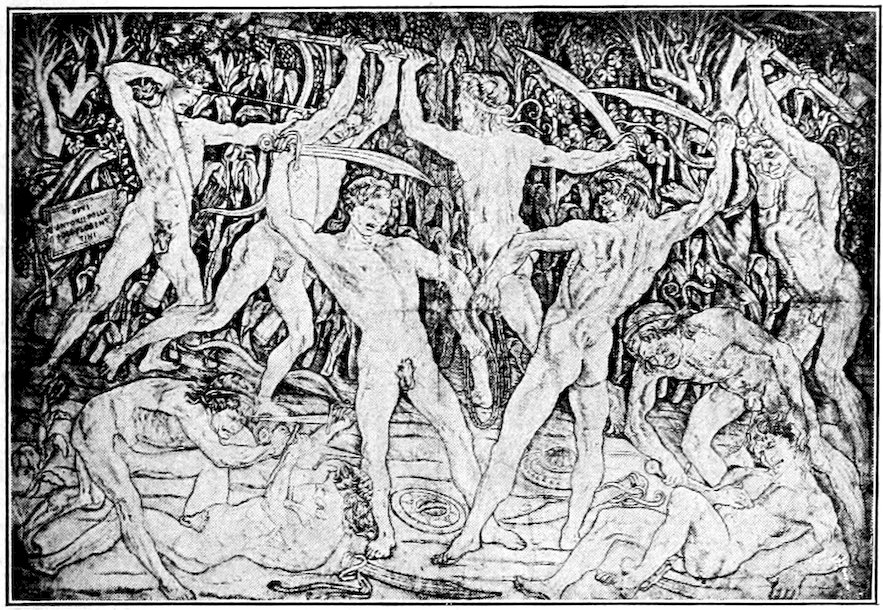

Orcagna was perhaps more versatile than critics have supposed. Recently discovered fragments of frescoes in Santa Croce, Figure 30, show a drastic power that no other Florentine possessed. The theme is miserable folk in time of pestilence crying out to Death to end their sorrows. The entire fresco would have shown Death passing them by and poising the scythe for prosperous and happy folk beyond. The whole scene exists in the famous frescoes of the Pisan Campo Santo which, while traditionally ascribed to Orcagna, are unquestionably of Sienese inspiration. They will occupy us later. Orcagna’s solitary position in Florence reminds us that artistic succession is rarely from master to pupil, but from great soul to great soul across intervening mediocrity.

Fig. 30. Andrea Orcagna. They call Death in Vain. Fragment from ruined fresco of the Triumph of Death.—Santa Croce.

Fig. 29. Andrea Orcagna. Upper part of Fresco of Last Judgment.—Strozzi Chapel, Santa Maria Novella.

50Giorgio Vasari regarded Gherardo Starnina (active before 1400) as an important link between Giotto and the Renaissance, and if Professor Suida is right in ascribing the frescoes of the legend of St. Nicholas in the Castellani Chapel, Santa Croce, to Starnina, Vasari was quite right. About this mysterious pupil of Antonio Veneziano who worked in Spain, we really know almost nothing. But the St. Nicholas frescoes have a grimness and gravity which points back to Giotto and withal a careful fusion of light and shade which anticipates Masolino and Masaccio. Meanwhile Giotto’s own great compositions in still undiminished splendor and impressiveness stood ready to give lessons to the eye and mind that could read them aright. Before such later panoramists as Niccolò di Pietro Gerini, Mariotto di Nardo, and Spinello Aretino were gone, that eye was already busy, in the person of a rugged little boy of San Giovanni in Valdarno. He may have already been called Masaccio for his untidiness. He was to rebuild on Giotto and create the grand style of the Renaissance.

A mere catalogue of those painters who pursued the panoramic method with ability can hardly be expected. One and all they followed the Sienese narrative style. Prominent would be certain incomers from other cities, Giovanni da Milano, Antonio Veneziano, and Spinello Aretino. These are typical decorators of the last quarter of the 14th century.

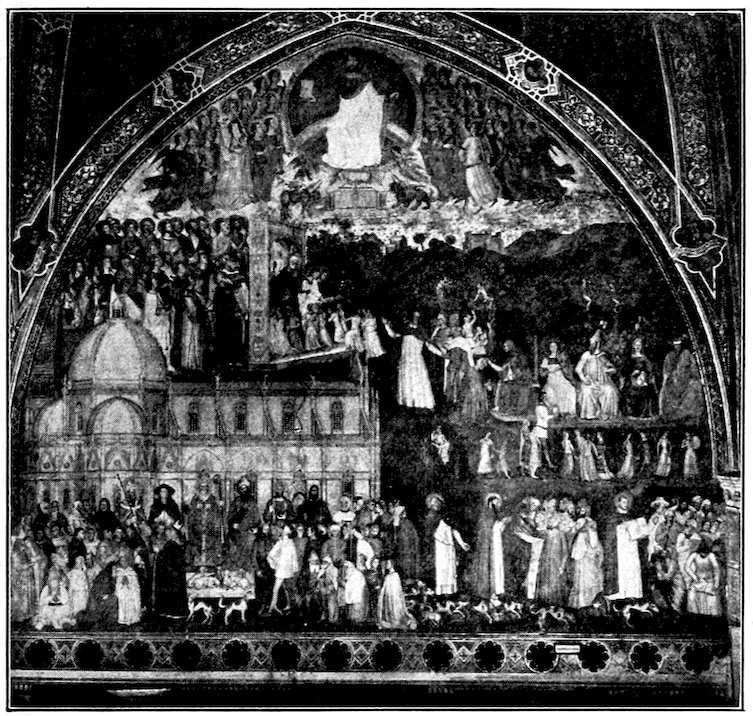

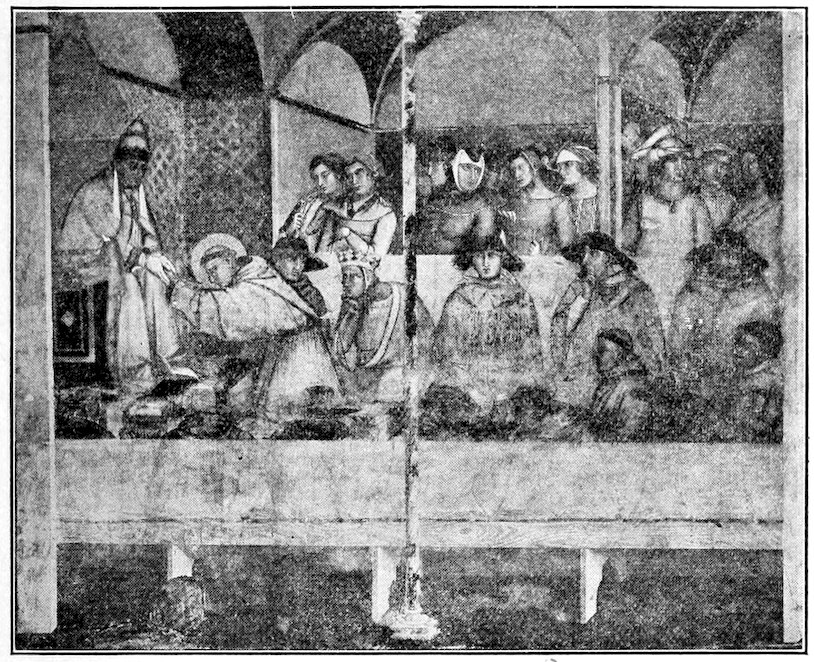

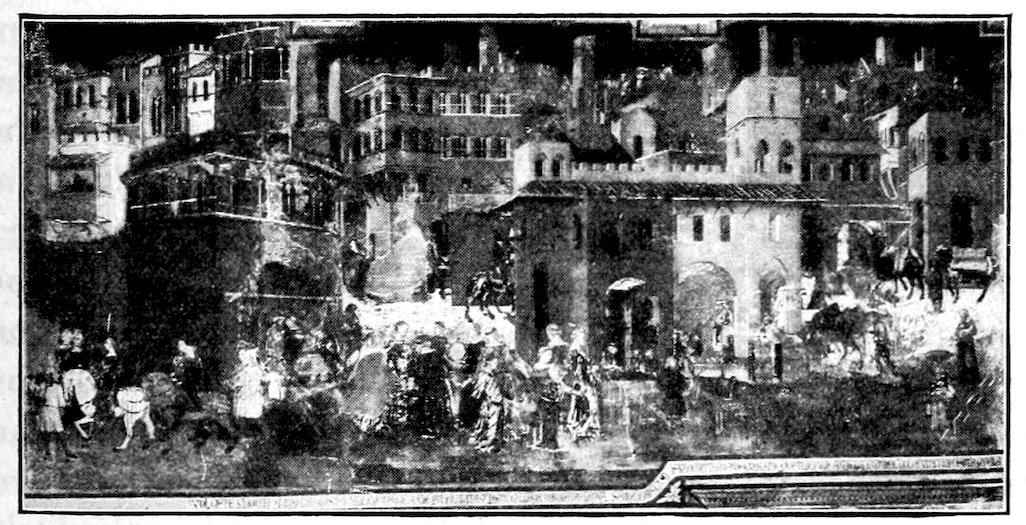

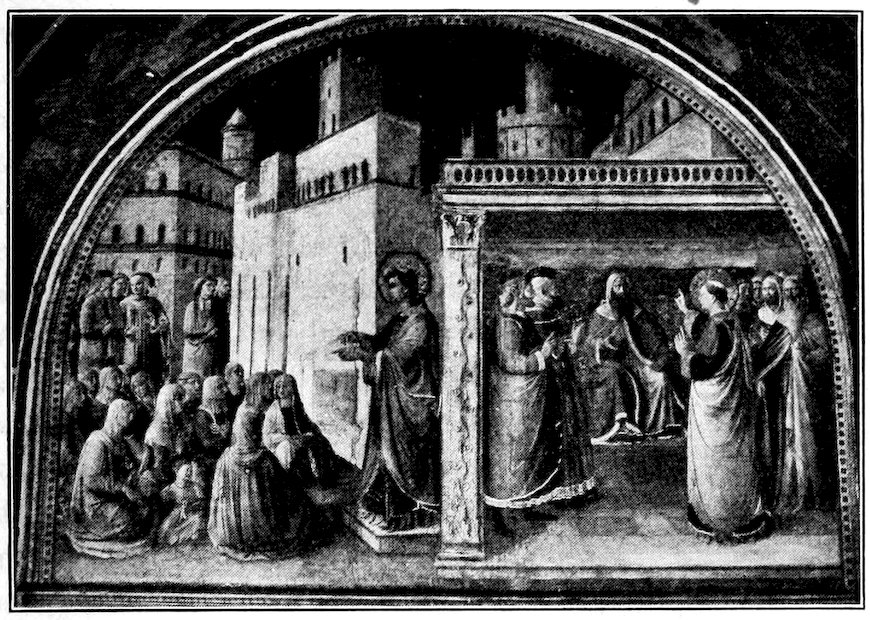

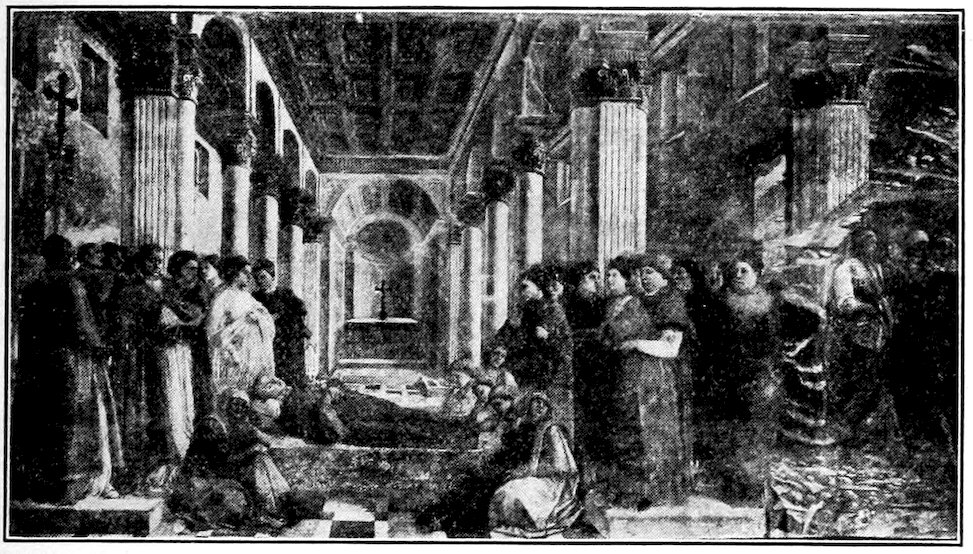

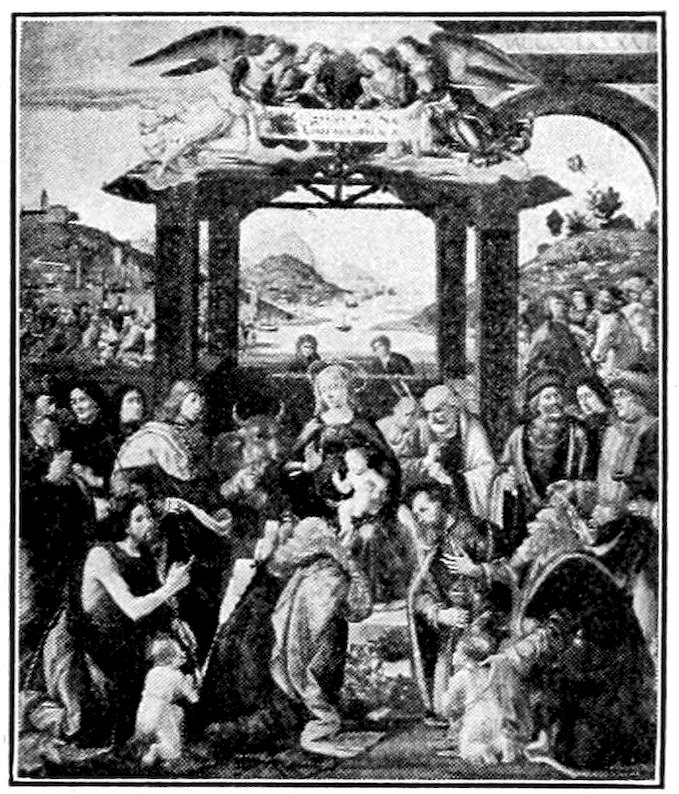

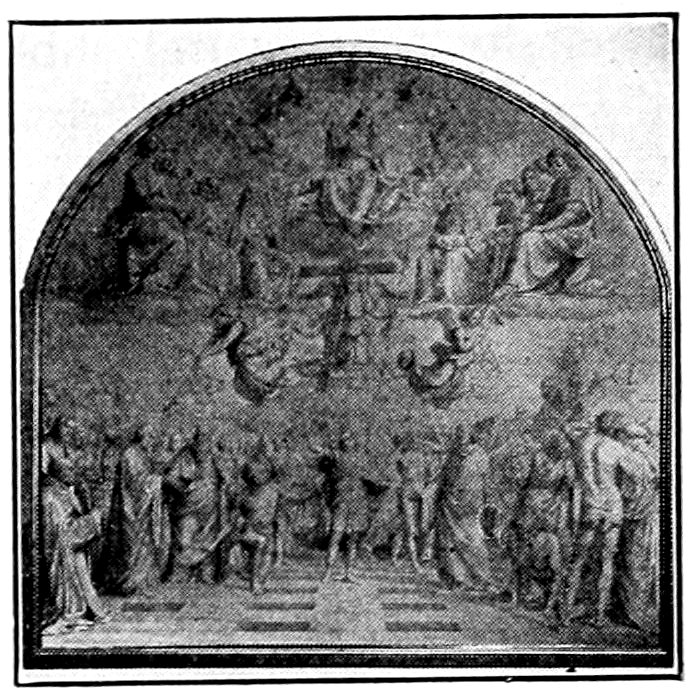

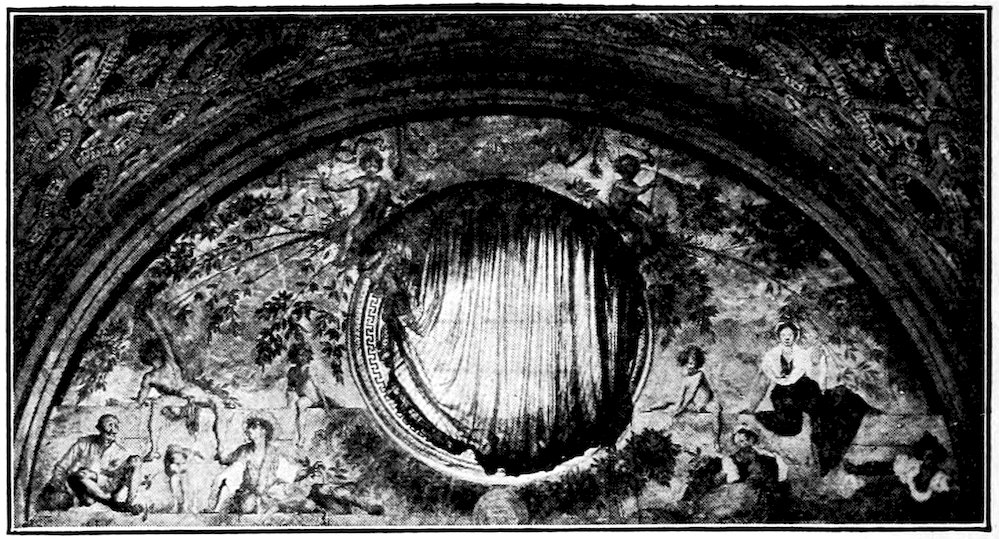

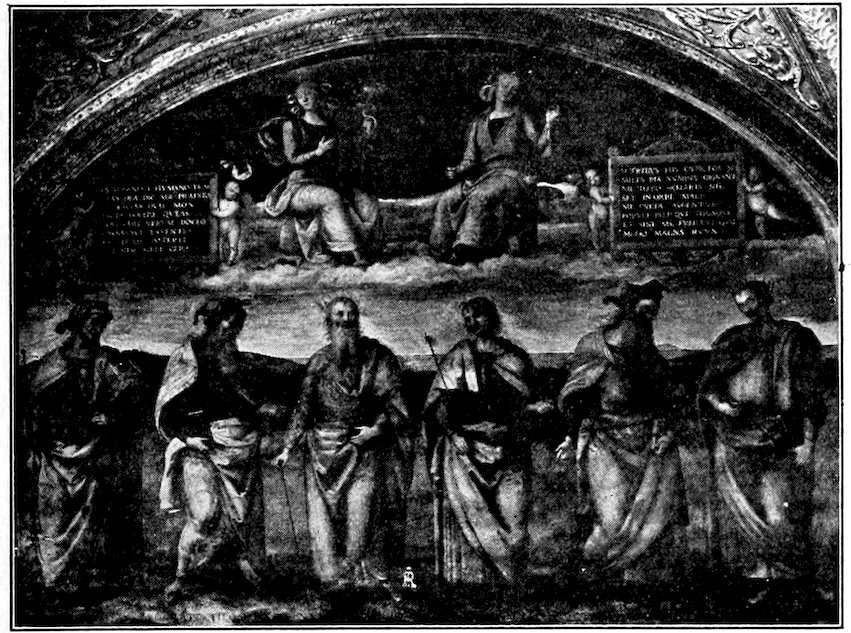

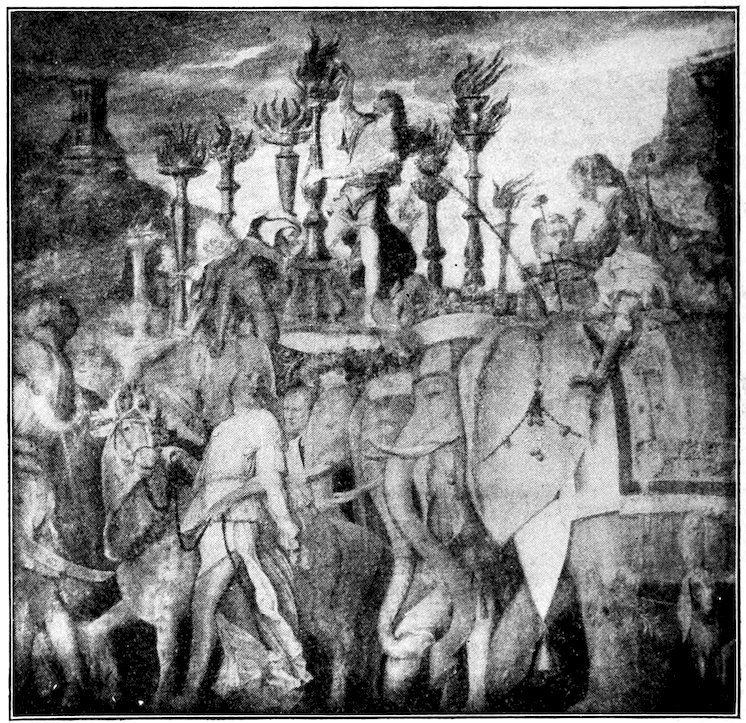

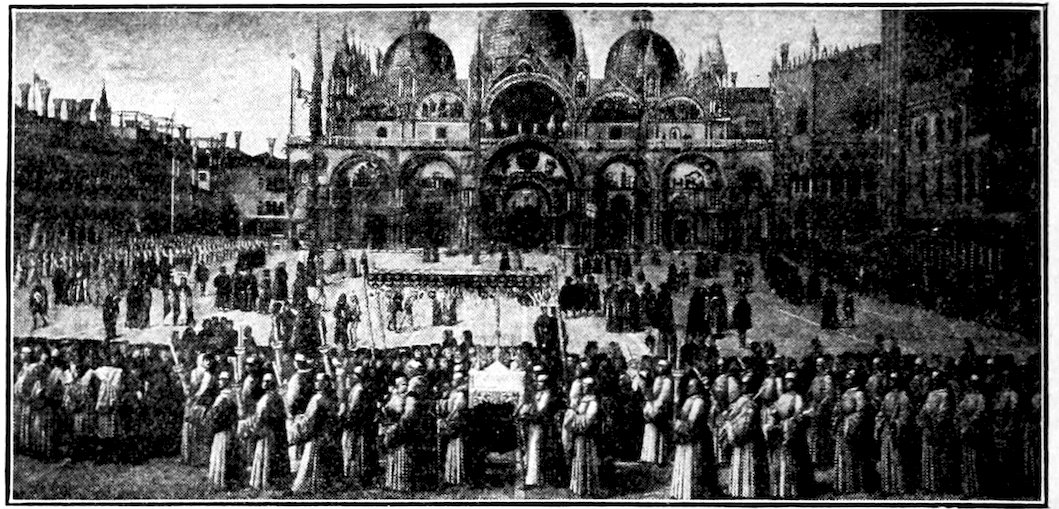

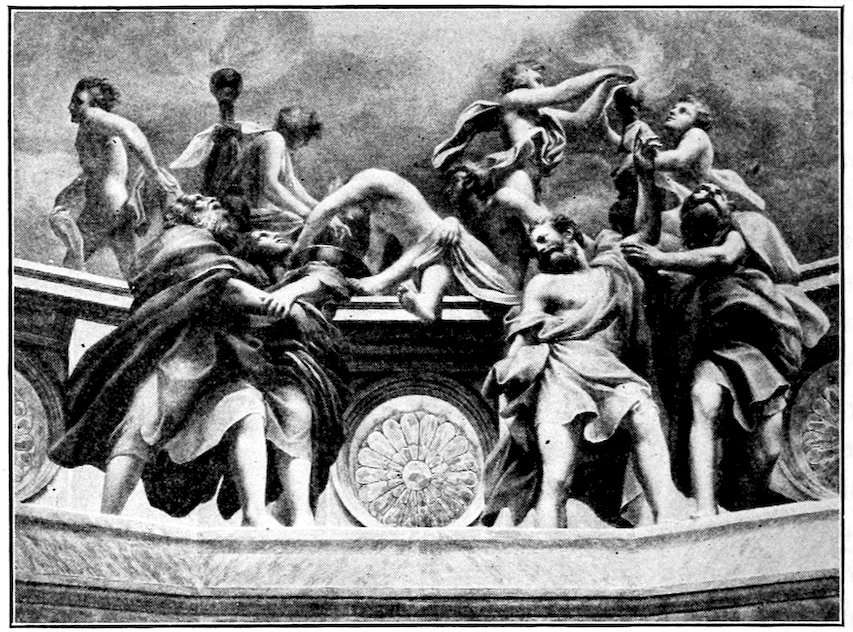

Fig. 31. Andrea Bonaiuti, The Navicella, fresco, closely imitated from Giotto’s Mosaic at St. Peter’s, Rome.—Spanish Chapel.

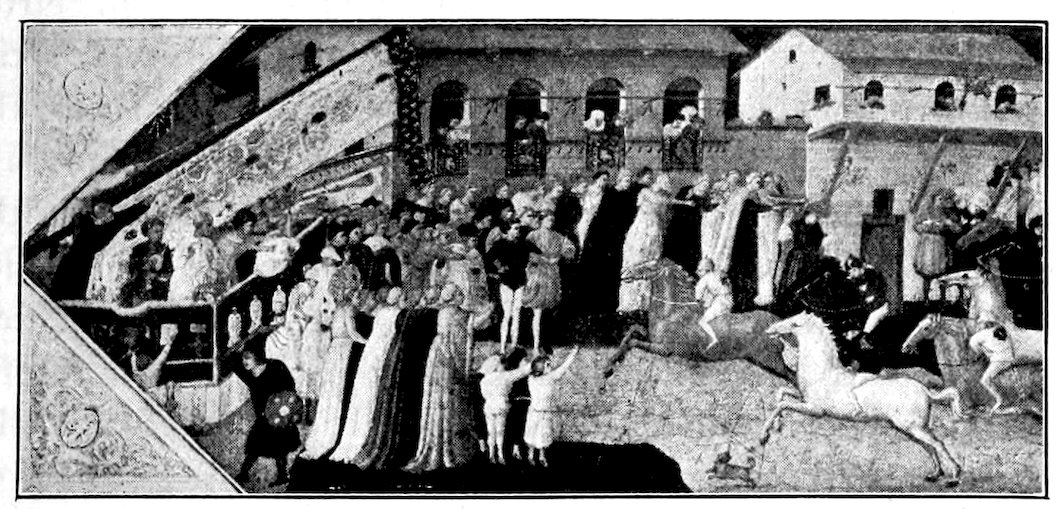

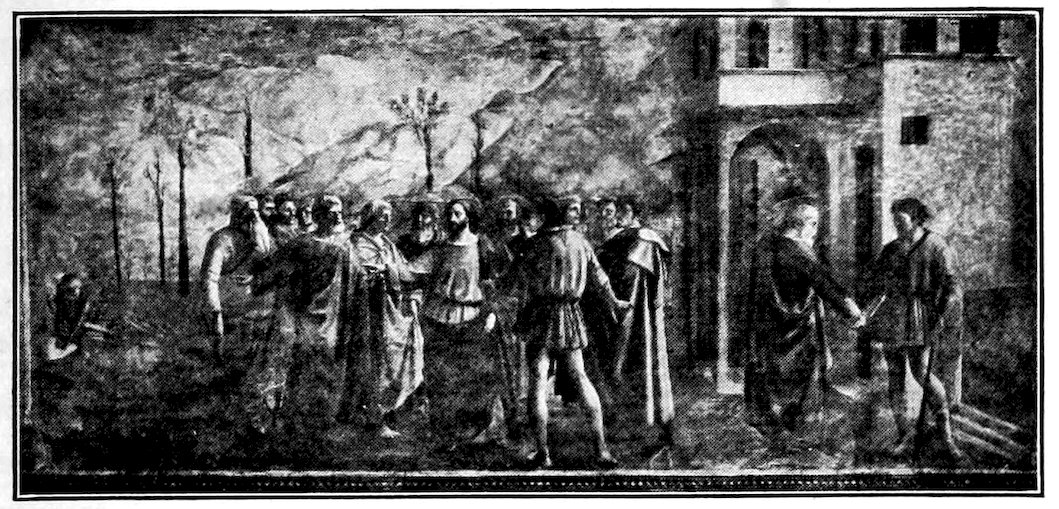

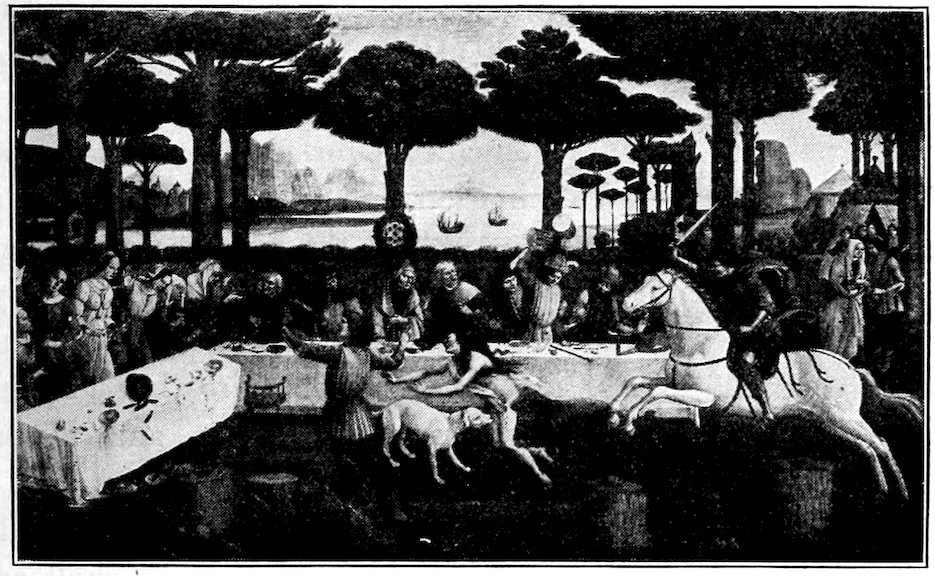

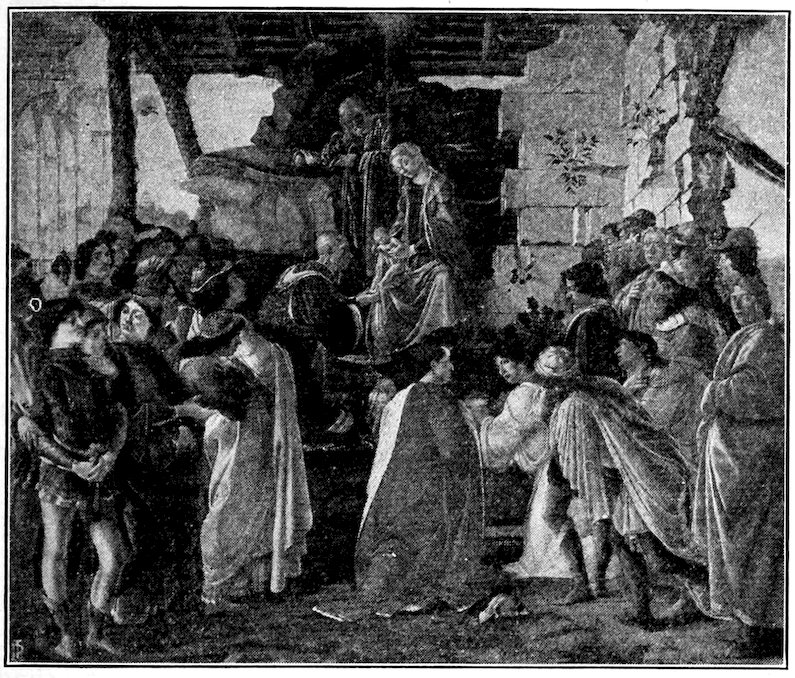

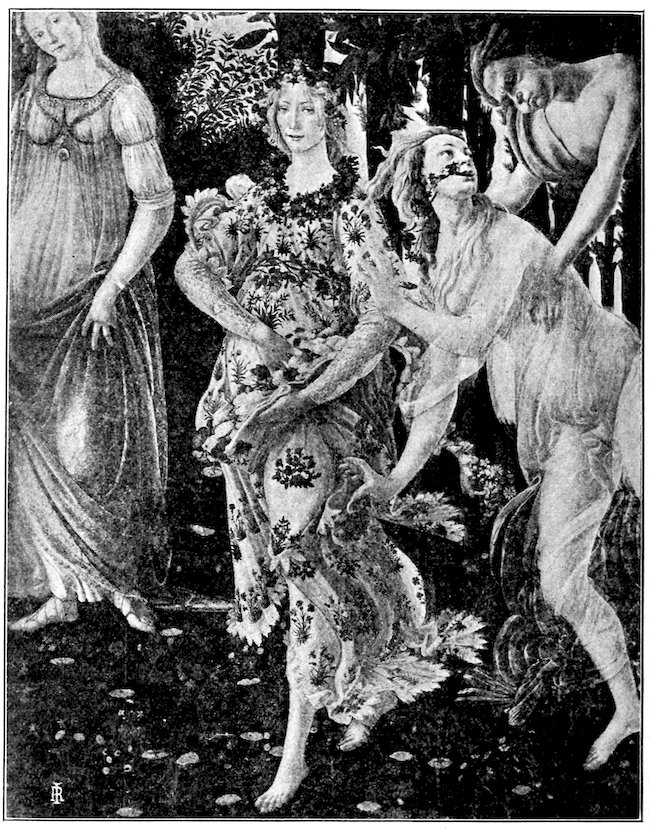

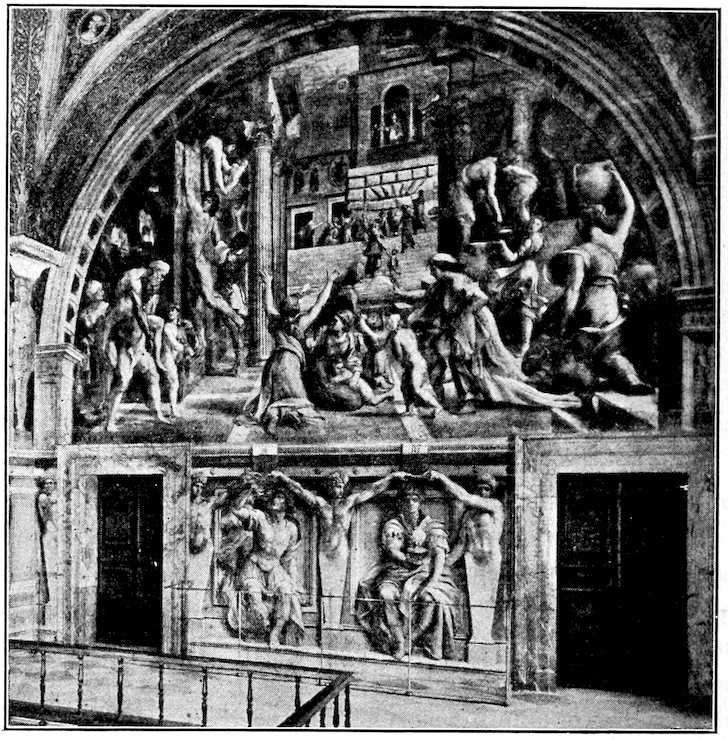

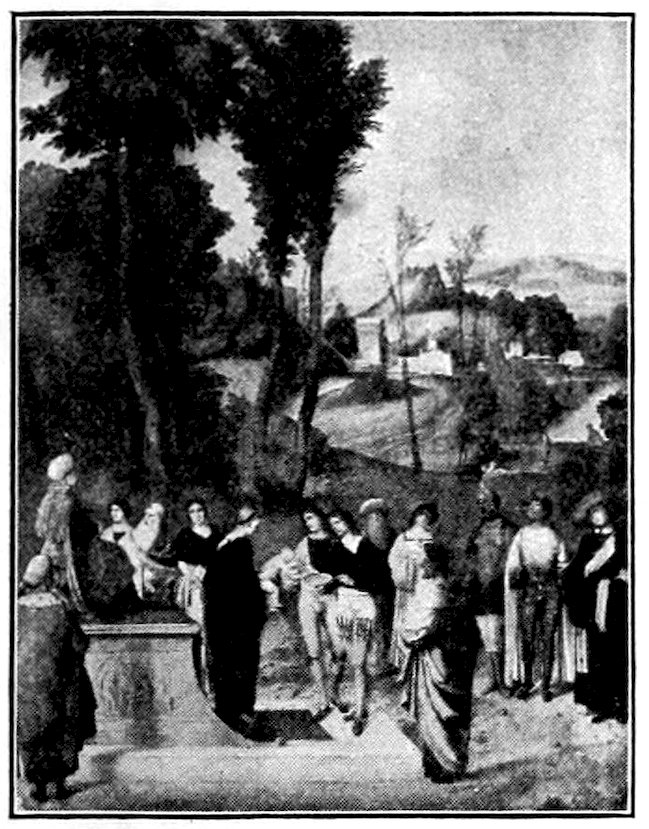

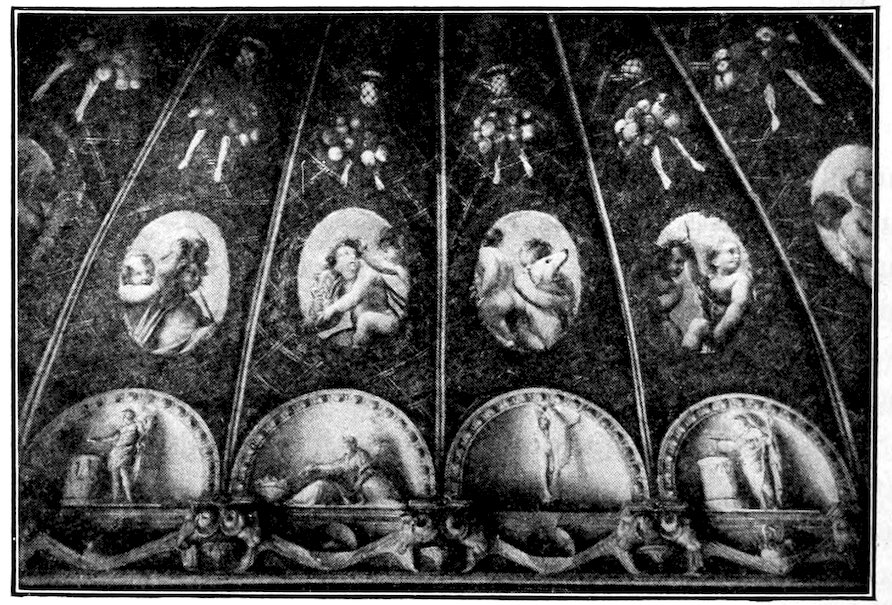

We do better to fix our attention upon the most remarkable example of the Florentine panoramic style, the decoration of the Spanish Chapel, the chapter house attached to the Dominican Church of Santa Maria Novella.[14] The work was begun by Andrea Bonaiuti in the year 1365, as we know from a recently discovered document. As decoration it is delightful, if rather superficially so. The artist treats his spaces as wholes, declining to cut them up into oblongs after the earlier fashion. He covers his great surfaces with ease and taste, has a knack at illustration, and a fine sense of color. The great Calvary over the triumphal arch imposes from its very vastness; the triangles of the cross vault, including a spirited 52transcript of Giotto’s Navicella, Figure 31, are composed with clarity and skill; the famous composition of the Dominican theologian, St. Thomas Aquinas, enthroned above the Liberal Arts and Sciences, and their representatives in history, combines an almost Byzantine formality and grandeur with prettiness and ingenuity in details. But the method is better shown in the decoration opposite, which represents the dual earthly powers, the Pope and the Emperor, enthroned equally, and supported by the representatives of the spiritual orders and secular estates, Figure 32. The group which symbolizes the right government of society, according to mediæval ideas, is set before a church which quite faithfully shows what the Cathedral of Florence was then intended to be. High up in the arch is the goal of all earthly endeavor—Heaven with Christ enthroned amid the angels; an altar with a lamb before Him, symbolizing His sacrifice; His Mother kneeling as intercessor for mankind. The Gate of Heaven with St. Peter in attendance, is naïvely set above the church on a sort of aerial raft. Below is a novel realistic touch, the villa-studded sky line of hills which encloses Florence. The real guide to St. Peter’s presence is always a Dominican monk, usually St. Dominic himself is intended—the founder and militant evangelist of the order, as St. Thomas Aquinas was its systematic theologian. In the lower range of the picture, St. Dominic confutes the heretics, who tear their wicked books in despair. Above he vainly beseeches careless gentlefolk at dalliance in an orange grove; still higher, he leads the truly penitent to Heaven’s gate. At the foot the Domini Canes (a bad pun for Dominicans) are vigilant. The moral of the fresco is, happy the world which trusts its worldly and religious business to the Emperor and the Pope, and its personal religious problems to the Dominicans. It is a kind of glorified poster for the order.

In its sprightliness, variety, complication and facile charm, it is a fine example of the panoramic style. It lacks every 53quality of seriousness whether as a composition or in the drawing of the figures. But its fairy tale profuseness and ease have made it ever since it was painted, one of the most popular decorations in Italy. Its success shows the kind of taste with which the few disciplined artists of the fourteenth century had to contend. Such obstacles have ever been the fate of the artist who cares enough for his art to practice it austerely.

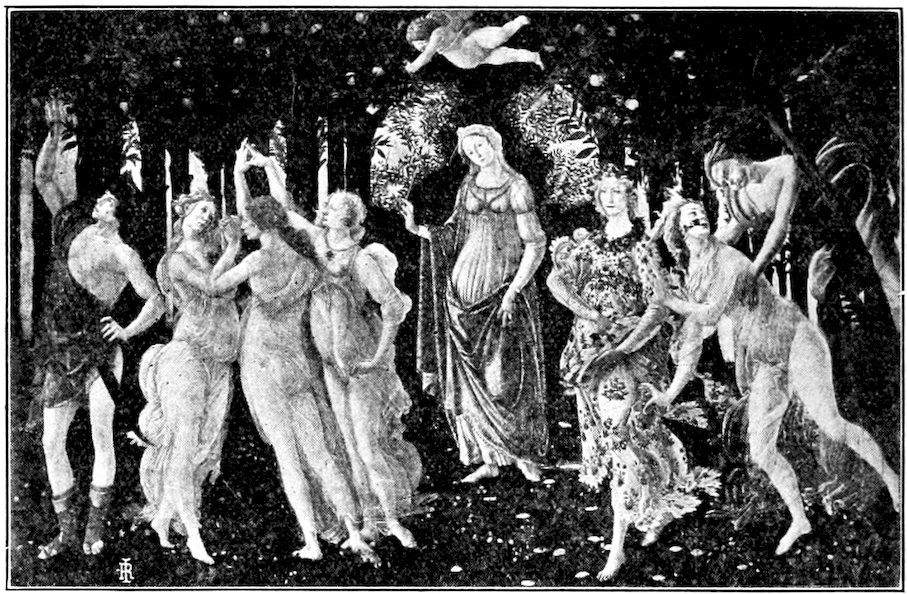

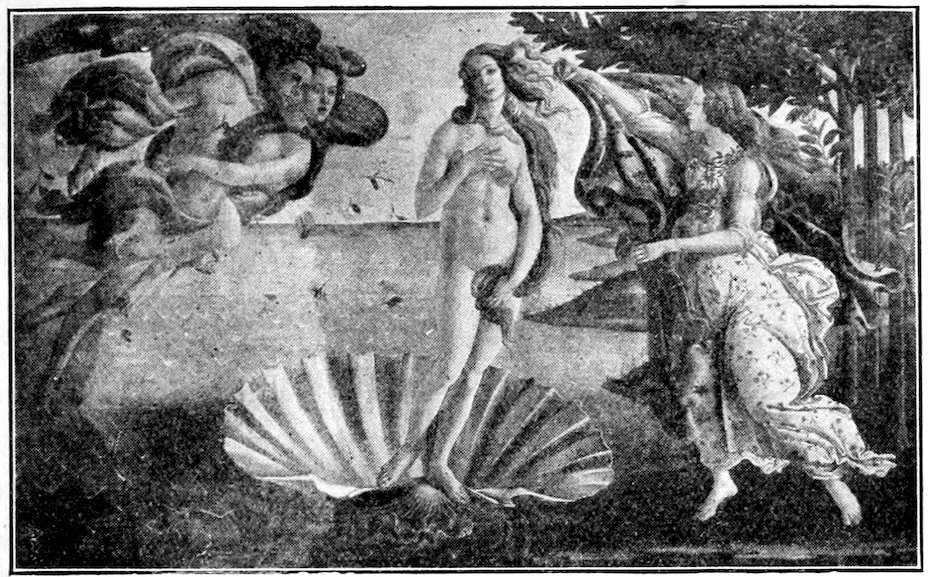

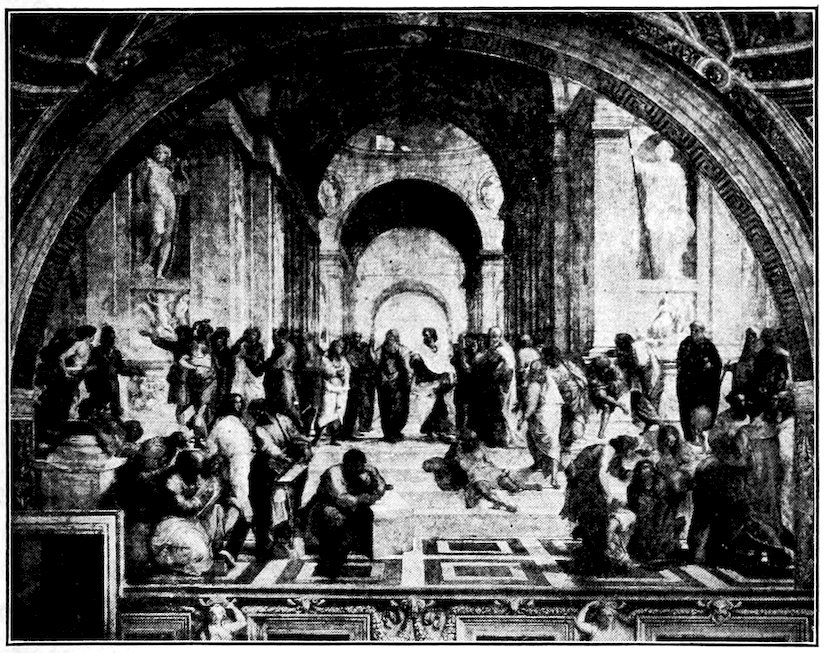

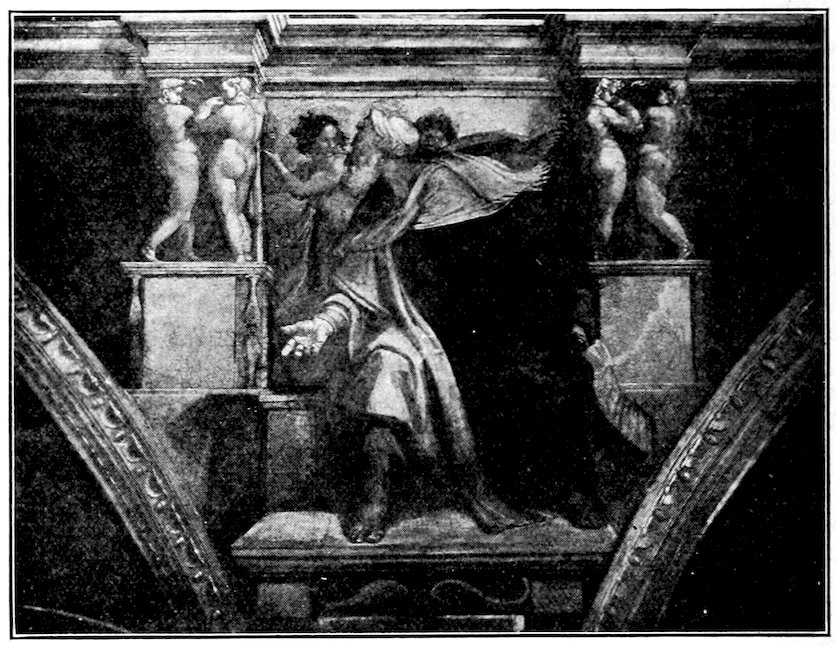

Fig. 32. Andrea Bonaiuti. Dominican Allegory of Church and State. Fresco.—Spanish Chapel.