Title: The deformities of the fingers and toes

Author: William Anderson

Release date: March 15, 2023 [eBook #70298]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: J. & A. Churchill

Credits: Charlene Taylor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

THE DEFORMITIES OF THE

FINGERS AND TOES

BY

WILLIAM ANDERSON, F.R.C.S.

SURGEON TO ST. THOMAS’S HOSPITAL; EXAMINER IN SURGERY AT THE

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON, AND ROYAL COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

OF ENGLAND; PROFESSOR OF ANATOMY IN THE ROYAL

ACADEMY OF ARTS, ETC.; FORMERLY HUNTERIAN

PROFESSOR OF SURGERY AND PATHOLOGY IN

THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

LONDON

J. & A. CHURCHILL

7 GREAT MARLBOROUGH STREET

1897

The following pages are developed from a course of Hunterian Lectures delivered by the Author in the theatre of the Royal College of Surgeons, in 1891. The matter has been revised and brought up to date, and augmented by a section upon the congenital deformities of the hands and feet.

WILLIAM ANDERSON.

2 Harley Street, W.

March 1897.

| Section I CONTRACTIONS OF THE FINGERS |

|

| PAGE | |

| INVOLVING THE DIGITAL AND PALMAR FASCIÆ (DUPUYTREN’S CONTRACTION) | 4 |

| FROM DEVELOPMENTAL IRREGULARITIES IN THE BONY AND LIGAMENTOUS ELEMENTS OF THE ARTICULATIONS | 44 |

| FROM UNBALANCED ACTION OF THE FLEXOR MUSCLES AFTER RUPTURE, DIVISION, OR DESTRUCTION OF THE EXTENSOR TENDON | 63 |

| FROM NUTRITIVE CHANGES IN THE MOTOR APPARATUS | 65 |

| FROM TENDO-VAGINITIS OF THE BURSAL SHEATH OF THE FLEXOR TENDONS | 67 |

| FROM INFLAMMATORY AND DEGENERATIVE CHANGES IN THE ARTICULAR STRUCTURES | 68 |

| PARALYTIC AND SPASTIC CONTRACTIONS FOLLOWING LOCAL INJURY | 70 |

| CONGENITAL AND INFANTILE CONTRACTIONS | 77 |

| TRIGGER FINGER | 78[viii] |

| Section II CONTRACTION OF THE TOES |

|

| FROM PATHOLOGICAL LESIONS IN THE CUTANEOUS AND FASCIAL STRUCTURES | 86 |

| FROM DEVELOPMENTAL IRREGULARITIES IN THE ARTICULAR STRUCTURES AND COMPRESSION BY MISSHAPEN SHOES | 87 |

| HAMMER TOE | 88 |

| HALLUX FLEXUS | 104 |

| HALLUX VALGUS | 115 |

| HALLUX VARUS | 120 |

| LATERAL DEVIATION OF THE LESSER TOES | 122 |

| ARTHRITIC CONTRACTIONS | 124 |

| PARALYTIC CONTRACTIONS | 127 |

| Section III CONGENITAL DEFORMITIES OF THE HANDS AND FEET |

|

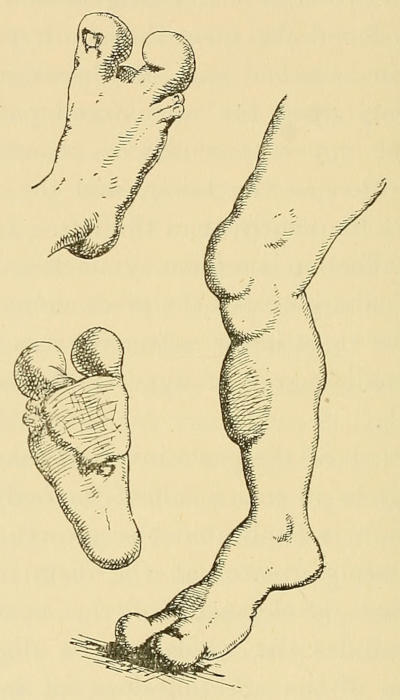

| MAKRODACTYLY | 128 |

| SUPERNUMERARY FINGERS AND TOES | 144 |

| SYNDACTYLY | 145 |

| ECTRODACTYLY | 147 |

| BRACHYDACTYLY | 149 |

The section of surgical disease treated in the following pages is unambitious in its scope, but it is, nevertheless, one that deserves the attention of every surgeon and pathologist, because it comprises a group of ailments which are the source of much pain and crippling, and because it offers many problems of causation that are still unsolved. It is true that none of these affections threaten life, but in medicine, as in law, it is often the value of the principle involved rather than the magnitude of the interests immediately at stake that invests the case with importance.

There is a material advantage to be gained by studying the deformities of the hands together with those of the feet, for it will be found that nearly all the forms of contraction that appear in the one are represented in the other, and a comparison of the conditions under which the two sets of affections arise may throw light upon the pathogeny of both. At the same time, if we glance at the structural and functional differences[2] in the hand and foot, and at the fact that civilised life imposes artificial restraints upon the freedom of action of the one, while it cultivates to a marvellous degree of perfection the variety and precision of movement in the other, we shall understand that although certain deformities of the fingers may have a strict pathological analogy with those of the toes, the effects produced, and the treatment required may differ essentially in the two sets of cases.

It will be seen that our knowledge of some of the affections to be described is of very recent date, and that certain diseases, frequent in occurrence, obvious in character, and very inconvenient or painful in results, have only found a place in our text-books within recent years. Even the most ancient in point of literary existence scarcely dates beyond the third decade of the present century; while the youngest, when regarded in the same aspect, is merely a child of a few winters; and yet both the one and the other may be nearly as old as mankind.

These may be grouped as follows: 1. Contractions due to pathological processes taking place in the cutaneous and fascial structures of the palm and palmar surface of the fingers. This includes the so-called “contraction of the palmar fascia,” with which the name of the great surgeon Dupuytren is inseparably connected, as well as another affection of similar character, but different pathological origin. 2. Contractions due to developmental irregularities in the bony and ligamentous elements of the articulations. Under this heading come the deformity which may be termed “hammer finger” and the closely allied lateral distortions of the digits—affections which are chiefly of importance in their bearing upon analogous conditions of the toes. 3. Contractions arising from shortening of the finger flexors, without paralytic or spastic complications. 4. Contractions due to unbalanced action of the flexor muscles after accidental solution of continuity of the extensor tendons. 5. Contractions arising from nutritive changes in[4] the motor apparatus consequent upon long immobilisation of the part, with pressure; or from inflammatory processes in the inter-muscular planes, or in the muscles themselves. 6. Contractions dependent upon inflammatory articular disease of traumatic or constitutional origin. 7. Contractions of neuropathic origin, paralytic or spastic. Under this denomination, as under the last, only those questions which concern the surgeon will be taken into consideration. 8. Trigger finger; a condition not yet susceptible of scientific classification. 9. Congenital deformities not included under any of the preceding headings.

The clinical features of the disease called Dupuytren’s “contraction of the palmar fascia” were well known before the true seat of the morbid process was surmised; but the Greek and Arab writers, and their European followers down to the end of the last century, make no reference to it. The first accessible descriptions are those of Sir Astley Cooper in his “Treatise on Fractures and Dislocations” published in 1822, and of Boyer in the eleventh and last volume of his “Maladies Chirurgicales,” issued in 1826. The latter is really a very correct account from the clinical aspect; and although the author could suggest no[5] better pathological explanation than that implied by the name “crispatura tendinum,” which he found already given to the disease by previous writers, in works that cannot now be traced, he accepts it with commendable hesitation.[1] Sir Astley Cooper, on the other hand, supplies a less detailed description, but recognises the non-tendinous origin of the disease. The classical essay, however, was that of Dupuytren (1831), which, partly from its intrinsic merits and partly from the fame of the writer, attracted wide attention, and called forth within the next few years a number of eminently scientific observations upon the pathology of the complaint. More recently the affection has received close attention from many distinguished surgeons in France, Germany, America, and England.

Symptomatology.—Before entering into the symptomatology, I ought to premise that there are to be distinguished two forms of the so-called contraction of the palmar fascia: one in which the condition occurs independently of any definite traumatism and tends to multiplicity of lesion, the other appearing as a result of an ordinary wound, and confined to the parts in direct relation to the injury. The first of these I propose to speak of as[6] true Dupuytren’s contraction, the second as traumatic contraction. The characteristics of the latter will be referred to later.

The symptoms of the true form have been so often and so graphically described that little can be added to the current accounts. I shall, then, limit my clinical picture to a simple outline, filled in with a few details taken from the series of examples which have been under my own observation. In a typical case, a middle-aged or elderly man notices in the course of the distal furrow, and directly over the head of the metacarpal bone of the ring or little finger, a small nodule in the skin, or perhaps only a puckering and exaggeration of the flexion line. By-and-by a ridge appears running proximally from this point towards the wrist, and distally along the central axis of the finger. The ridge is prominent, round, and very hard, especially between the flexion fold and the root of the digit, and the skin is usually drawn to it tightly at the seat of the initial sign. It passes on to the front of the first phalanx, nearly always preserving the central position, but spreading out and usually sending processes to the deep surface of the integument as it reaches the first joint of the finger, and as it contracts, draws down the metacarpal phalanx towards the palm. After a while the second phalanx may become bent in like manner, and by exception even the distal bone. The articular structures[7] show no trace of disease, the tendons are normal, the finger retains all its strength within the progressively narrowing range of motion left to it by the disease, and the utility of the hand may for a long while be little impaired. Sooner or later other fingers may become involved, and the affection may appear in the opposite hand, to follow a like course. The process of contraction is slow in progress, perhaps extending over ten or twenty years; it is painless, and is uncomplicated by any signs of active inflammation. At length, after a more or less protracted period, it may terminate spontaneously in any of its stages, but the mischief wrought is permanent, and unless the surgeon intervenes, the patient carries it to his grave.

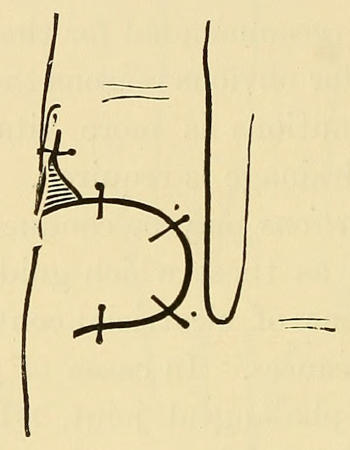

This is the more ordinary course, but the signs show great variety in different cases. 1. The disease may remain limited to the palm, not giving rise to flexion of the finger; this is especially frequent in women. 2. Any or all of the fingers may be attacked, and the rigid bands may implicate also the thenar and hypothenar eminences. 3. Either or both inter-phalangeal joints may become flexed, while the metacarpo-phalangeal joint remains free. 4. The palmar cord may remain single and central, or it may send off a lateral branch on either or both sides in the inter-digital web, and so implicate two or three fingers. 5. A central band, after reaching the root of the finger, may bifurcate, sending a branch to either[8] side of the digit; this, in my experience, is the least common variety. 6. The cord, instead of running along the central axis of the finger, may pass towards the inter-digital cleft and then divide, giving branches to two digits; a band of this kind would be in dangerous relation to the digital vessels and nerves in the event of operation by excision. (Fig. 1.)

The statistics as to fingers affected in my series of cases correspond closely to those already published by Adams, Keen, and others. They are as follows: Thumb, four times; index finger, three times; middle finger, twenty-two times; ring finger, thirty-nine times; little finger, twenty-eight times (these numbers include the purely palmar bands where they were placed over the metacarpo-phalangeal articulation, but had not yet led to contraction of the digit; traumatic cases are excluded). The most common association where more than one digit was affected was that of the ring and little fingers; when a single finger was attacked, it was most frequently the fourth. The flexion involved in almost equal proportions the metacarpo-phalangeal joint alone, and this together with the first inter-phalangeal joint. In four cases the first inter-phalangeal joint was contracted, while the metacarpo-phalangeal articulation was free, and in one case the distal joint alone was flexed, although the band extended from the palm. In only two cases were all the[9] fingers implicated. The condition was bilateral in twenty-four cases out of thirty-nine, right-handed in ten, and left-handed in five. Thus the right hand was attacked thirty-four times, and the left twenty-nine times. Of the twenty-four bilateral[10] cases, nine were worse in the right hand, six in the left; in the rest the severity differed little on the two sides. Nearly one-third were unsymmetrical as to the fingers attacked. In eight patients, six of whom were women, the band was purely palmar, and did not cause any contraction of the fingers.

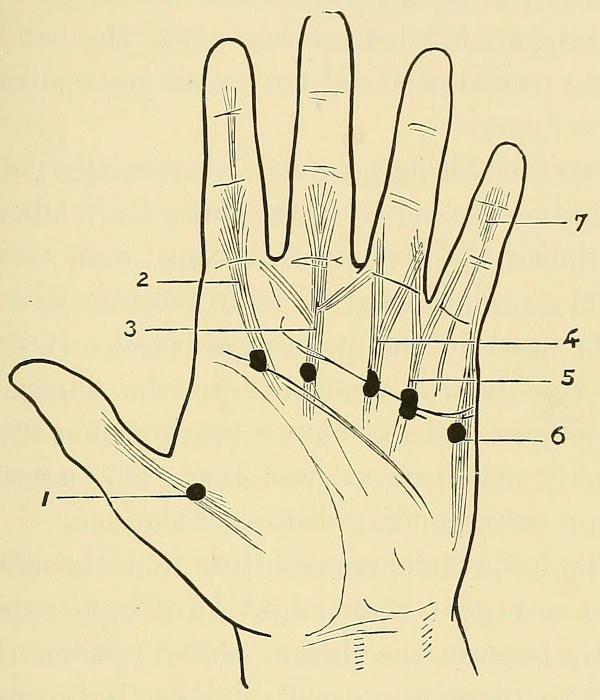

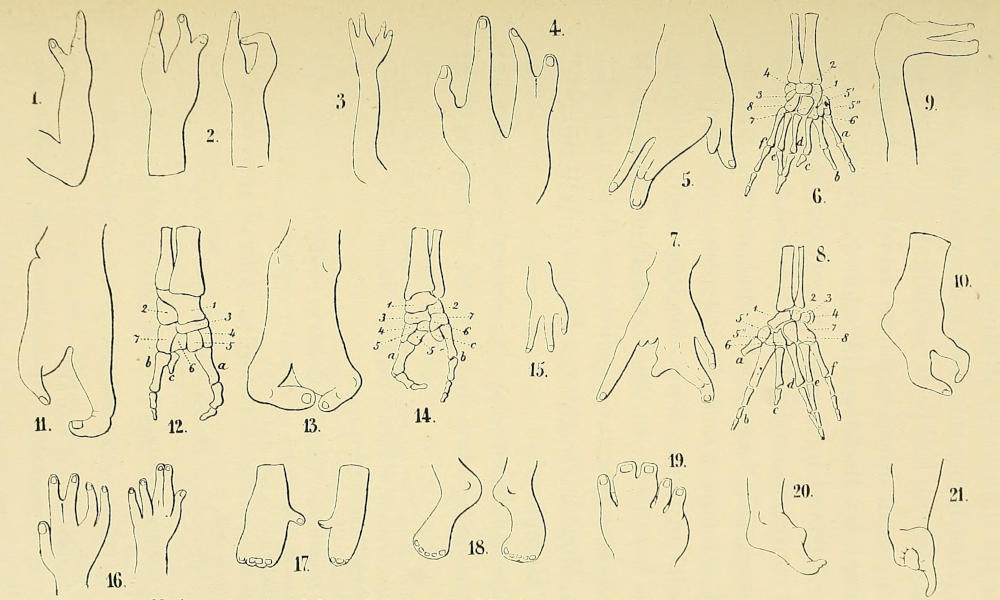

Fig. 1.

Diagram showing the various types of the abnormal bands in Dupuytren’s contraction. The position of the initial lesions over the heads of the metacarpal bones and opposite the flexion lines is indicated by the black spots. 1. Thenar band; 2. Axial band extending to distal joint; 3. Axial band giving off lateral branches to adjoining fingers; 4. Axial band bifurcating to send branches to sides of finger; 5. “Interosseous” band bifurcating to join two adjacent digits; 6. Hypothenar band; 7. Band more developed at distal than at proximal extremity, and leading to contraction of first or second inter-phalangeal joint, the metacarpo-phalangeal joint remaining free.

Two interesting points to be especially noted in reviewing the series were—first, the tendency to multiplicity of the initial lesions; and, secondly, the close coincidence of their position with that of the heads of the metacarpal bones. In no case did the disease commence in the finger itself. These facts probably have a bearing upon etiology. In only one instance was there any association with a corresponding disease of the sole.

The inconveniences resulting from the affection are less urgent than might have been expected, partly because the flexion power remains, partly because there is no pain, and partly because the contraction seldom attains an aggravated form until an age when æsthetic considerations are of minor importance and the more active period of working life is drawing to a close. In some extreme cases, however, the nail of the contracted finger may press against the palm, and cause ulceration, and in one instance brought under my notice by a friend the deformity was nearly the cause of a fatal accident, the bent finger becoming hooked in the handle of a moving railway carriage in such a[11] manner that it could not be disengaged. The patient saved himself by seizing a pillar, while the traction force tore asunder the diseased fibrous bands and set the straightened finger free. It is needless to say that the benefit of the impromptu operation was limited to the immediate service rendered.

The frequency of the complaint is difficult to estimate. With a view to forming some opinion as to its prevalence in the poorer classes I took advantage of the kindness of Mr. J. Lunn of the Marylebone Infirmary, Mr. Percy Potter of the Kensington Infirmary, Dr. A. H. Robinson of the Mile End Infirmary, and Dr. S. G. Litteljohn of the Central District Schools at Hanwell, to select cases from the large body of patients in the institutions under their control; and in the cases of Kensington and Mile End I had also the privilege of access to the workhouses in connection with the infirmaries. The total numbers of the persons thus open to investigation were 2600 adults, and 800 children under the age of sixteen. All of these were carefully examined, and every example of Dupuytren’s contraction (as well as of the other conditions included in these lectures) was systematically recorded. Of the 2600 adults, of whom about five-sixths were over middle age, 33, or 1·27 per cent., were found to be suffering from various stages of the affection, while in the 800 children no trace of the disease was to be[12] detected. This proportion is very much smaller than that discovered by Mr. Noble Smith, who was fortunate enough to detect no fewer than 70 examples in 700 persons. His facts and deductions have been fully discussed at the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society and in the medical papers.

Sex.—The influence of sex is very noteworthy, but much less than was formerly conjectured. Cases of any degree of severity in the female are rare, but the slighter forms are fairly common. Of thirty-nine non-traumatic cases, twenty-five were in men and fourteen in women, but of the latter number in only eight was there any contraction of the fingers. This proportion is larger on the side of the female sex than that given by Dr. Keen in the valuable series analysed by him in 1882 (20 females to 106 males); but it must be pointed out that most of the cases in my list would have escaped notice altogether without a close examination of the palm.

Age.—True Dupuytren’s contraction is almost essentially a disease of middle or later life at its onset. It was estimated by Dr. Keen that about five-sixths of the cases began after the age of thirty, but his examples included some of the traumatic form, which may of course originate at any period of life. In my own series only one, a man of thirty-two, was below the age of forty when the disease first appeared, and in the number[13] seen in hospital practice before I began to keep notes of the cases, I do not recollect one in which the symptoms commenced in youth or early adult life. My friend Surgeon-Captain A. H. De Lom, has kindly obtained for me some statistics that bear very directly upon this point. He finds by reference to the Army Reports that in a force averaging 203,000 soldiers, between the ages of seventeen and thirty-five, only three cases of contraction of the fingers came under treatment in five years (1885-89), and it is not certain whether these were of the traumatic or of the specific variety. It is of course possible that some incipient cases escaped attention, but the magnitude of the figures gives a value to the record in spite of this source of fallacy. It is stated, however, that exceptions to the rule do occur, and that conditions bearing a resemblance to true Dupuytren’s contraction have been seen in childhood, and some of these are even believed to be congenital; but it is probable that a closer examination of such cases would prove them to be of a different pathological nature. There appears to be no limit to the period of onset in the other direction. In eighteen cases in my list the disease was unnoticed until after the age of sixty, and in six of these it did not appear until the eighth decade; and it is significant that the majority of these patients, a portion of whom were women, had given up laborious employment before the symptoms appeared.

Class and occupation.—It is very difficult to obtain any information of statistical value as to the proportionate distribution of the complaint in the “classes” and “masses,” and there is great difference of opinion upon the question amongst our best authorities. It is at any rate certain that our workhouses contain a considerable number of examples, and that the disease is also very often found in men and women of the educated ranks. The same doubt exists with reference to the influence of occupation, but there is no question that the earlier observers greatly exaggerated the importance of this factor. It appears, indeed, that in various callings which involve much rough treatment of the palm the affection is even less common than in the rest of the community. Its infrequency amongst soldiers has been already remarked, and Mr. Johnson Smith informs me that it is very rare amongst sailors. In about two hundred patients at the Seamen’s Hospital, whom he was kind enough to examine in order to put the question to the test, only one example of the disease was found, and this was probably of traumatic origin. Shoemakers have been said to suffer frequently, and for mechanical reasons, but there seems to be no substantial foundation for the belief. I have only met with one of the craft so affected, and by a somewhat curious coincidence the disease was of older date, and more severe in the left hand than in the right. This man told me that he had never[15] seen or heard of the complaint amongst his fellow workmen. Two of the worst cases in my own series were in clerks. With reference to the question of occupation, it may be remembered that the affection is bilateral in nearly two-thirds of the cases, and that the left hand is affected almost as frequently as the right—in my own cases in the proportion of six to seven. This and the other facts named would appear to negative the view that mere friction and pressure of the palm by tools or other objects habitually held within the hands can account for the disease. On the contrary, it is possible that habitual rough usage of the hands, by leading to epidermic thickening, protects the deeper structures; and that the horny-handed toiler is proportionately less liable to the disease than his more fortunate and more tender-palmed fellow citizen. Nevertheless, when the condition has once started it is likely that its progress would be hastened by any external source of irritation, and hence the strong conviction of the sufferers as to the mechanical origin of their deformity.

Constitutional condition.—If a generalisation would be permissible solely upon the cases in my own list, I should be inclined to think that the patients were rather above than below the average in health. Twenty-six out of the thirty-nine had passed threescore and ten when they came under my notice, and with four exceptions all were in[16] good physical condition, and one (a woman with fairly well-marked contraction in both hands) had reached the span of ninety-three years. In each case careful inquiries were made with reference to the inheritance or past or present existence of gout, rheumatism, and rheumatoid arthritis, and the result, confirmed as far as possible by direct examination of the patients, was altogether contrary to my preconceived notions on the subject. Of the whole number, only one had suffered from gout, one from rheumatic fever, three from rheumatoid arthritis (all in women, whose Dupuytren’s disease was limited to slight palmar lesion), and six from mild subacute or chronic rheumatism. A possible gouty inheritance was traced in three cases. All were free from nervous disorders except two of the women, who were subject to neuralgias of an ordinary kind, and one (aged seventy-three) with a double contraction of thirty years’ standing, who was suffering from hemiplegia of three years’ duration. No complaint as to the digestive functions was made in any case.

The evidence brought forward by different observers with regard to constitutional tendency appears to be extremely conflicting. Thus, Dr. Keen, whose contribution is one of the most careful records we possess, found no fewer than forty-two gouty patients out of forty-eight cases; and Mr. Adams expresses his opinion that the disease is a gouty thickening of the palmar fascia.[17] Dr. Abbe of New York, on the other hand, has noticed a remarkable frequency of nervous symptoms in connection with Dupuytren’s contraction, and believes that the complaint is of neuropathic origin, while other surgeons have in like manner assigned to rheumatism, rheumatoid arthritis, alcoholism, and other conditions an important causative relation with the disease. There is, of course, no doubt that such widespread affections as gout and rheumatism, neuroses and alcoholism are present in certain cases—it would be strange were it not so; but it is noticeable that the writer who gives a prominent place in the causation to any one of these conditions always holds the claims of the rest in very low esteem; and it appears probable that the associated constitutional tendencies noticed in the different groups of cases depended rather upon the particular class or set from which the observer drew his patients than upon any essential connection between the local and internal affections. My own experience of the disease has been based principally upon cases in hospitals, and hence the remarkable absence in my series of the neurotic or gouty predispositions that might have appeared in persons whose worldly circumstances favoured either of those conditions.

Habits.—In my inquiries as to habits, the usual difficulty of obtaining trustworthy replies was experienced. Three of the more severe cases pleaded guilty to long-standing intemperance, but[18] the rest all regarded themselves as moderate drinkers—an elastic term. There was, however, nothing in their general condition to indicate that alcoholism had exercised any material influence in favouring the palmar lesion.

Race and climate.—We have at present no statistics with regard to the effects of race and climate upon the disease; but so far as we are at present informed it must be rare, if not altogether absent, in certain countries. During my own residence of six years in Japan I did not meet with a single instance; and the far larger experience of my friend Surgeon-General Takaki has been equally negative as to this particular affection. My friend Surgeon-Colonel Owen tells me that in an extensive experience amongst the natives of Bengal, Central Asia, and Afghanistan, he does not recollect more than one or two cases, and that these may have been traumatic. At any rate, the condition is extremely rare.

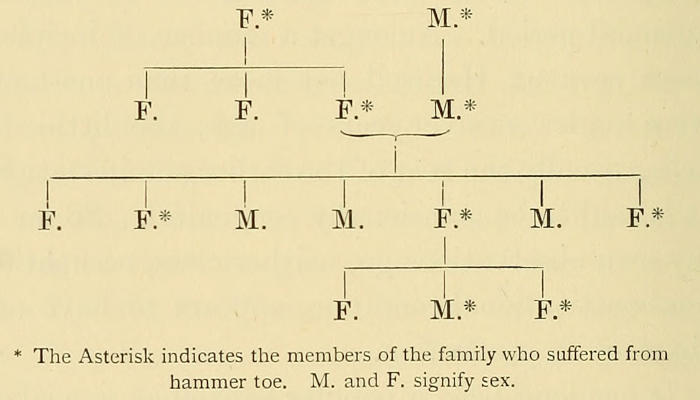

Inheritance.—There is unquestionably a strong predisposition to the disease in certain individuals and families, and so many examples of hereditary transmission of the tendency have been related that it is useless to add further to the list. We can no more explain the cause of this special predisposition than we can account for the idiosyncrasy which renders certain persons inordinately liable to erysipelas and some other affections; and although Dupuytren’s contraction is often associated[19] with such widespread complaints as gout, rheumatism, and various neuroses, its relation to these is probably to be regarded as a coincidence.

Morbid anatomy.—It has long been a subject of dispute whether the complaint is or is not a contraction of the palmar fascia. There is, of course, no doubt that the palmar fascia is always implicated to some extent, but its exact relation to the morbid tissue that constitutes the essence of Dupuytren’s disease can only be decided by a consideration of the anatomy of the healthy structure.

It is perhaps not easy to say what is meant by the expression “palmar fascia,” since the text-books are by no means agreed upon the point. We have really to notice four palmar structures which may claim a share in the title. These are (1) the radiating fascia, spreading towards the fingers from the palmaris longus and annular ligament; (2) the aponeuroses investing the muscles of the thumb and fingers; (3) a delicate connective tissue blending with 1 and 2 and forming sheaths for the flexor tendons, the lumbricales, and the digital vessels and nerves; (4) the fascia of Gerdy, which runs transversely across the bases of the second, third, fourth, and fifth fingers and in the inter-digital webs, and is continuous with the superficial fascia of the digits and dorsal surface of the hand. Lastly, in addition to these,[20] we might regard the ligamenta vaginalia and the transverse ligaments connecting the metacarpo-phalangeal articulations as specialisations of the family. We are, however, mainly concerned with the radiating fascia and fibres of Gerdy.

The radiating fascia consists of a strong fibrous expansion extending subcutaneously from the anterior annular ligament and palmaris longus tendon, and consisting of an outer or thenar portion, spreading over the muscles of the thumb and blending with the muscular aponeurosis; an inner or hypothenar portion similarly related to the muscles of the little finger; and a central digital expansion which is derived almost entirely from the palmaris longus when this is present, but is well developed even when the muscle is wanting. The central portion spreads out in a fan-like manner as it approaches the fingers, giving off some strong fibres from its anterior surface through the palmar fat to the connective tissue of the superjacent corium, especially in the situation of the palmar folds, and attached by its deep surface to the delicate fascial investment surrounding the tendons, vessels, and nerves; finally, a little beyond the middle of the palm it divides into four segments, one for each digit, each of which soon breaks up into two lateral bands that embrace the sides of the metacarpo-phalangeal joint to blend with its ligaments and the periosteum of the first phalanx, and running on become similarly[21] connected with the first inter-phalangeal joint and middle phalanx. Where the four digital bands diverge they are joined together by deep transverse fibres which pass from the inner to the outer border of the hand, blending in these situations with the muscular aponeurosis. (Fig. 2.)

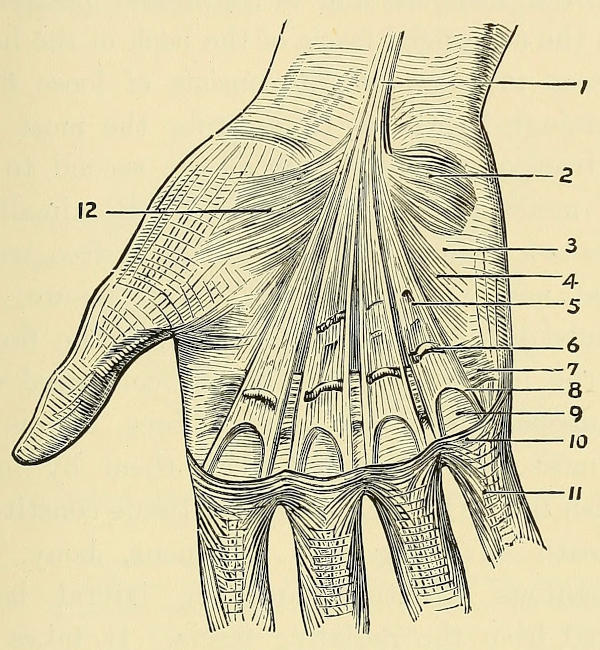

Fig. 2.

The Palmar Fasciæ.

1. Palmaris longus tendon; 2. Palmaris brevis; 3. Muscular aponeurosis of hypothenar eminence; 4. Fibres from radiating fascia to hypothenar eminence; 5. Innermost digital portion of central segment of radiating fascia; 6. Fibrous band passing to integumental fold; 7. Transverse fibres appended to radiating fascia; 8. Lateral digital branches of radiating fascia; 9. Portion of vaginal fascia exposed between 5 and 10, Fibres of Gerdy; 11. Superficial digital fascia continuous with fibres of Gerdy; 12. Thenar portion of radiating fascia blending with muscular aponeurosis.

The transverse fibres of Gerdy are really the proximal portion of a superficial fascia which invests the whole of the four inner digits immediately under the skin, forms the subcutaneous web of the fingers, and is continuous posteriorly with the superficial fascia of the back of the hand. As seen in the palm, it consists of loose fibres intermingled with fat, running for the most part in a transverse direction from the second to the fifth metacarpo-phalangeal joint. Proximally it presents a somewhat sharply defined free border placed nearly opposite the joint fissure, and extends distally, as before stated, to the fingers and the inter-digital web, and is connected with the deeper tissues by a few fibres, but is for the most part separated from them by loose, whitish fat. On the fingers the tissue constitutes a sheath investing the tendinous, bony, and ligamentous structures and the lateral bands derived from the radiating fascia. It takes the form of a distinctly membranous sheet dorsally and at the sides, but in front it appears as a coarse irregular network supporting the digital vessels and nerves, and containing a large quantity of fat in its meshes. It is connected strongly with the corium, especially at the palmar folds, and more loosely with the deeper structures by fine fibres.

Fig. 3.

Transverse Section of Hand through the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Metacarpal Bones.

1. Palmar integument; 2. Fat transversed by fibres from 3; 3. Radiating fascia; 4. Vaginal fascia, superficial portion; 5. Palmar vessels and nerve; 6. Flexor tendons and lumbricales; 7. Vaginal sheath blending with fascia of interossei; 8. Septal fibres from vaginal fascia to bone; 9. Interossei; 10. Middle metacarpal bone; 11. Extensor tendon and sheath; 12. Superficial fascia beneath dorsal integument; 13. Fascia of hypothenar eminence; 14. Muscles of little finger.

Between the proximal border of the fibres of Gerdy and the point of bifurcation of the digital[23] bands of the radiating fascia is a space about half an inch in length, in which is seen a portion of the vaginal fascia that invests the tendons, vessels, and nerves in the palm. (Fig. 3.) The connective-tissue fibres in this latter are for the most part transversely arranged. They are connected superficially with the deep surface of the radiating fascia, where they lie beneath it, and deeply with the aponeuroses of the interossei, transverse metacarpal ligament, and glenoid plates, and form septa between the flexor tendons of the four fingers. Where they ensheath the tendons[24] above the ligamenta vaginalia they are separated from them by a kind of lymph space.

If we examine a case of Dupuytren’s contraction in the light of our anatomical knowledge, we shall be struck by the circumstance that the morbid structure which causes the permanent flexion of the fingers bears no resemblance in position or character to the normal fibrous tissues of the part, although it is apparently continuous in the proximal direction with the digital bands of the radiating fascia. The band is best developed beyond the point where the radiating fascia normally ceases, and maintains its longitudinal fibrillation while crossing the vaginal fascia and the transverse fibres of Gerdy. The varieties and modes of branching already described are only to a limited extent related to the anatomical arrangements—that is, where the morbid tissue spreads proximally over the radiating fascia, and sends lateral branches along the course of Gerdy’s fibres; but it is certain that the tendon-like cords are of entirely new formation, and that they exist at the expense of the normal structures. The well-known preparation in St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, which has been figured by Mr. Adams, affords a demonstration of this, as the band, instead of following the direction of the radiating fascia, runs towards the inter-digital cleft and there bifurcates, sending branches to the adjacent sides of two fingers. In a specimen of my own the band runs axially to the little[25] finger and spreads out in front of the first phalanx as a fatless fan-like expansion, that differs altogether in character and arrangement from the normal subcutaneous tissue and becomes closely connected with the skin, the structure of which, however, remains unchanged. The firmest point of integumental adhesion is opposite the distal flexion fold over the head of the fifth metacarpal bone. The first phalanx is flexed to about 90°, and over the metacarpo-phalangeal joint the contracted cord lies in a plane considerably anterior to the tendons, vessels, and nerves, all of which maintain their normal relation to the bones and muscles. There is no tendency on the part of the morbid growth to follow the deep connections of the fascia in the palm.

The radiating fascia, and perhaps even the tendon of the palmaris longus, are made tense and prominent by the shrinking of the new material, but the palmaris longus has no primary share in the production of the deformity, and in fact the disease may be present where the muscle is undeveloped. Repeated experience in operations has proved that the flexor tendons are not affected, and that even in long-standing cases the joints may be fully extended immediately after the division of the morbid fibrous bands. It may be accepted as a principle that the development of a tendon once completed, the tissue has little or no disposition to retrograde changes in[26] the direction of its length. When the most prominent parts of the contracted cords are exposed for excision they bear much resemblance to tendon in contour and striation, but they are less bluish and lustrous in aspect. On dissecting them away from the radiating fascia the transverse fibres interlocking the digital segments of the latter may often be seen unchanged, and in one case in which the disease had attacked the sole the new fibrous tissue could easily be detached from the fascial fibres, which retained all their lustre.

The histological appearances of the new growth are those of fibrous tissue. If the disease is spreading, the fibrous strands are intermingled with nuclear proliferation, which extends especially along the course of the vessels.

Pathology.—The study of the character and relations of the diseased structure indicates that it is an inflammatory hyperplasia commencing in the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the palm, involving the fascia secondarily, and replacing the adipose connective tissue which normally serves as an elastic cushion for the palmar surface of the hand and fingers. It must now be considered what is the cause of the morbid process. The view of Dupuytren has already been referred to. He believed that the affection was provoked by repeated injuries of the palmar fascia by pressure and friction from implements used habitually in different mechanical callings; but the facts I have[27] adduced in the discussion of the etiology conflict strongly with the hypothesis. It has been shown that in artisans both hands may be equally affected where only one is brought in contact with the tool, that aggravated forms of contractions may appear in persons who are not at all exposed to any such habitual source of irritation, and, moreover, that the disease appears to be of less than average frequency in certain employments in which the palms are subject to an unusual degree of friction.

Some source of irritation, however, must be present, and it has been suggested that this is to be found in gouty deposits. In one case recently brought forward by Mr. Lockwood, uric acid crystals were actually present in connection with the bands; but this experience is exceptional. That the new tissue might become the seat of such a deposit in gouty subjects is more than probable, but in the majority of cases of Dupuytren’s contraction seen in this country the patients are not, and have not been, subject to gout. It would, moreover, be difficult to find any condition that presents less resemblance in its course and tendencies to known manifestations of the gouty poison. The changes, indeed, are much more suggestive of chronic rheumatism than gout, but even the probability of this source of origin is not supported by observed facts. The situation of the initial lesions, and the peculiar tendency of the new growth to feed like a parasite upon the[28] tissues in which it spreads and which it replaces have led me to believe strongly that the active cause of the disease is a chronic inflammation probably set up by a micro-organism, which gains access to the subcutaneous tissue through accidental lesions of the epidermis overlying the bony prominences formed by the heads of the metacarpal bones. This would explain better than any existing hypothesis the persistent course of the disease and its proneness to recur after the most skillfully devised operation, while the almost constant limitation of the disease to the declining years of life corresponds mainly to lessened resistance in the bodily organism, and partly perhaps to senile absorption of the palmar fat cushion and atrophy of the protective thickening of the epidermis. The almost complete immunity of the foot is accounted for by the protection afforded by the shoes and stockings. Individual and inherited susceptibilities are exemplified here as in other complaints of known bacterial origin. To determine the question I have sought the experienced aid of my colleague, Mr. Shattock, in carrying out a series of bacteriological researches.

In a patient in whom it was decided to excise the contracted tissue in two hands the more recently affected member was selected for experiment. The skin was incised under strict antiseptic precautions, portions of the growing tissue were cut away with the aid of a knife and forceps,[29] sterilised by heat immediately before use, and the fragments excised were at once placed in cultivating tubes of agar-agar and gelatine. In a second case a commencing nodule upon the plantar fascia of a patient, suffering also from Dupuytren’s contraction of the hands, was treated in a similar manner. In Case 1 two of the three fragments quickly showed a growth obviously due to contamination. On the third and fourth days a yellow nodule appeared in all three specimens, and on cultivation assumed a form which led us to believe that a specific organism had been isolated; but on making a cover-glass preparation of this it proved to be merely a form of yellow sarcina. In the jelly tube containing one of the original pieces of tissue, and in the agar tube a second growth, micrococcus candidans, subsequently developed, and a like growth appeared in Case 2. It is desirable that these experiments should be repeated; but it must not be assumed that negative evidence necessarily disproves the agency of organisms; partly because our present means of detection are not yet perfected, and partly because the tissue examined may merely offer the result of a morbid process that has already come to a natural termination. Sections from Case 1 stained with fuchsin and by Gram’s method showed no organisms as viewed under 1/12 homogeneous immersion.

False Dupuytren’s contraction.—There is a[30] form of digital contraction usually classed with that just described, but differing from it in origin and several other respects. It is always due to obvious traumatisms, such as incised or lacerated wounds, involving the palmar or digital fascia. The age at which the lesion begins is governed by the period of injury, and hence the condition is as common in childhood and early adult life as in middle or old age. The seat of initial lesion is single, and the affection is confined to the injured hand, not tending to appear subsequently in other parts of the same hand or in the opposite member, as in most examples of the ordinary form. The contraction progresses rapidly to a certain point, and then ceases to get worse. It rarely becomes so strongly marked as in the worst cases of the true Dupuytren’s disease. The contracted band, starting from the point of injury (which is indicated by an ordinary scar) has seldom the tendon-like form of the well-marked “Dupuytren,” the characteristic puckers in the skin are represented only by ordinary cicatricial adhesions, and the digital extensions are usually in the form of one or two lateral bands following the bifurcation of the digital process of the radiating fascia. Lastly, the effect of operation is different. Subcutaneous division is less efficacious when the skin is extensively implicated in the cicatrix, and the excision of the band or the transplantation of a flap after division of the cicatrix is not followed by[31] the strong tendency to recurrence observable after similar proceedings in the true form. In all the seven cases in my list the nature and traumatic origin of the disease could be recognised without difficulty.

A subcutaneous cicatricial contraction of the finger may also result from violent and sudden super-extension of the joint. The lateral bands extending from the radiating fascia are ruptured, and if the finger is not kept straight by mechanical appliances a contraction of the joint is liable to occur. In such cases the resistance to extension is felt to depend upon two tense lateral bands, while the movements of the articulation in the direction of flexion remain strong and normal.

Treatment.—Some eighty years ago Baron Boyer, speaking of the disease now under consideration, said that it had been advised to expose and divide the contracted tendon, and even to excise a portion, afterwards keeping the hand extended upon a splint; but, he remarks, “Le succès d’une telle opération est trop incertain; elle n’a probablement jamais été pratiquée et un chirurgeon prudent devra toujours s’en abstenir.” It was he who expressed the congratulatory belief that surgery had already in his day reached its final limits, and all that had then not been accomplished could scarcely be regarded as attainable. For many years after his time it cannot be said that the treatment made any real progress. It is[32] true that Sir Astley Cooper advised subcutaneous section of the contracted bands, but the suggestion was not carried into practice till much later, when Dupuytren, having decided that the tendons were not affected, did what Boyer considered unpermissible, cut the contracted cords and superjacent integument, and straightened the hand upon a splint. The results appeared to fully justify the remarks of his predecessor, for under this treatment the gaping wound suppurated; and if the patient recovered without loss of the hand the process of cicatrisation at length restored the deformity in a more hopeless and distressing form than before. A few years afterwards Goyrand recommended an improved method: that of exposing the tense bridle of morbid tissue by a longitudinal incision, dividing it, and then reuniting the edges of the cutaneous wound; and this plan was adopted with various modifications by other surgeons. The absence of antiseptic precautions, however, exposed the wound to all the dangers of infection, and as the treatment mostly failed to secure the advantage hoped for it fell into disrepute, and patients were usually dissuaded by their friends, and even by their medical attendants, from submitting to any operative measures. It is to Jules Guérin that we are indebted for the first demonstration of the value of the subcutaneous method proposed by Sir Astley Cooper, and the practice was carried out in[33] this country by Messrs. Tamplin and Lonsdale, and perfected by Mr. William Adams. For a time the subcutaneous operation held its ground without a rival, but the introduction of the antiseptic principle in surgery rendered it possible to reconsider the discredited open method, and the plan was revived with various modifications by Kocher, Busch, Hardie, and others, with encouraging though variable results.

The therapeutical measures now eligible may be briefly enumerated:

Non-operative treatment.—There is no doubt that in the milder cases and when the morbid process has come to a standstill, a considerable improvement may be effected by massage and persevering extension. I have seen in a patient of seventy the fourth and fifth fingers brought from an angle of 90° with the palm nearly to a straight line within a year, but the contraction relapsed completely in three months, when a severe illness made it necessary to suspend the treatment.

We have heard much of the wonders effected by hypnotism during the latter days, but the surgeon hardly expected to be told that Dupuytren’s contraction, of all diseases, could be cured by “suggestion.” Yet in a recent volume of one of our medical journals we find a practitioner gravely claiming a successful result for this treatment in a case of the kind; a curious demonstration[34] of the survival, at the end of the nineteenth century, of the peculiar mental condition that brought patients to the feet of Greatrakes and Perkins in a bygone generation.

The Operative measures may be divided into three classes: subcutaneous, open, and plastic.

The Subcutaneous method deserves the first place. Mr. Adams’s operation consists in the subcutaneous division of all the contracted bands of fascia which can be felt; “the bands to be divided by several punctures with the smallest fascia knife passed under the skin and cutting from above downwards, followed by immediate extension to the full extent required for the complete straightening of the fingers when this is possible, and the application of a retentive, well-padded, metal splint from the wrist along the palm of the hand and fingers; the fingers and hand to be bandaged to the splint. When the full extension cannot be safely made, it must be carried as far as possible without tearing the skin.” This plan I have followed, with slight variations, but I have found it easier, after making the preliminary puncture (which should be longitudinal in direction to prevent gaping during the subsequent extension), to pass the knife beneath the band and to cut from within outwards, except in places where the deep surface of the skin is very tightly adherent, and the little wounds are sealed with cotton wool impregnated with collodion and[35] dusted over with iodoform. The sensation conveyed to the operator by the division of the round palmar cords is very similar to that experienced in tenotomy, and the effect of each section is immediate and encouraging. In some examples, however, the morbid tissue has become so firmly blended with the corium, especially over the proximal phalanx, that a satisfactory division is difficult, or even impossible; and if the extension be carried too far ominous fissures begin to appear in the rigid integument. When this happens the surgeon, if wise, will be satisfied with whatever he has been able to achieve, without proceeding further at the time. The splint extension may be immediate or deferred. Where the skin has held good there is no reason why the fingers should not be put in position at once and fixed in place by a splint of plaster of Paris or other material; but if it be evident that the integument at any point has been severely strained, it is desirable to wait for a few days before the parts are put on the stretch, and there is no reason to believe that the delay will be attended by any disadvantage. The operation may with benefit be preceded by careful washing of the hand and packing with a weak solution of perchloride of mercury solution or other antiseptic, and antiseptic dressings should be applied until the incisions are completely healed.

The after-treatment consists in the use of[36] splints of various forms. The palmar splints of Mr. Adams are very convenient, but in the early periods plaster of Paris is equally satisfactory, and renders the intervention of the instrument-maker unnecessary. Whatever form be adopted it should be worn day and night for two or three weeks, and then be replaced by a well-moulded front splint of sheet iron, to be applied at night only, and kept in use for several months. The hand once set free during the day the patient is to be urged to practise friction, with passive extension and active movements of the joint, at every possible opportunity; and it is only by strict attention to these rules that permanency of the improvement can be ensured. In private practice the instructions are usually carried out with a good will, and hence relapses are exceptional. Mr. Adams and Mr. Macready estimate them as less than ten per cent. But in hospital practice the case is different. The artisan has seldom much leisure or inclination for unpleasant manipulations for which, despite the assurances of the surgeon, he sees little immediate necessity, and he frequently allows the hand to drift into a condition, which, if not worse, is at least little better than before.

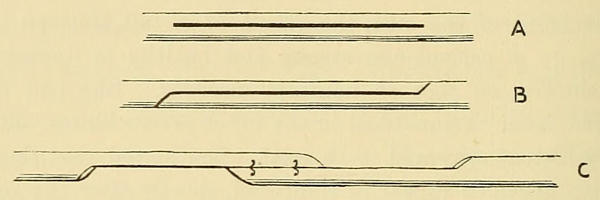

The Open operations may be placed under two separate headings—one in which the bands are merely divided in one or two places, and the other in which the morbid tissue is excised as far[37] as possible. The first of these, however—the original method of Goyrand—may now be held as superseded, since it has neither the safety of the subcutaneous method nor the thoroughness of the more radical measure. We need therefore only discuss the latter. The cutaneous incision may be either longitudinal and linear, as practised by Goyrand, Kocher, and others, or V- or Y-shaped, after the method of Busch, Madelung, and Richer. In any case the reflected skin should be very gently dealt with, and the wound carefully closed after the removal of the diseased bands. In most instances the simple linear incision gives all that is required, but the other varieties are useful when the distal end of the band branches or expands. The isosceles flap of Busch is made with the base opposite the metacarpo-phalangeal joint, the apex at the distal extremity of the hollow of the palm. (Fig. 4.) When the hand is extended after section or excision of the contracted tissue the apex of the flap is drawn away from the angle of the incision, and the wound when closed assumes a Y-shape. A Y-incision, with the fork over the first phalanx, and the stem corresponding to the palmar cord, is of advantage where the fibrous band spreads out broadly and becomes adherent to the skin beyond the metacarpo-phalangeal joint, the reflection of the angular flap within the fork allowing the safe removal of the diseased tissue. In any of these operations the anatomical[38] relations of the vessels and nerves should be carefully borne in mind. Fortunately the morbid tissue seldom encroaches upon the nerve tracts in such a way as to expose them to danger. The best rule for the surgeon is to confine his dissection as far as possible to the tissue overlying the axes of the flexor tendons, and not to make any further lateral excursion than is absolutely necessary.[39] Extreme care, however, will always be needed in excising cords which run towards the inter-digital web, as these lie directly over the nerves. The tendons are quite safe in the palmar incisions, as they lie much deeper than the fibrous cords, but the diseased tissue is closely related to the thecæ in the fingers. The after-treatment is similar to that recommended for the subcutaneous operation, but for obvious reasons the necessity for antiseptic precautions is more vital in the open method. No drainage is required.

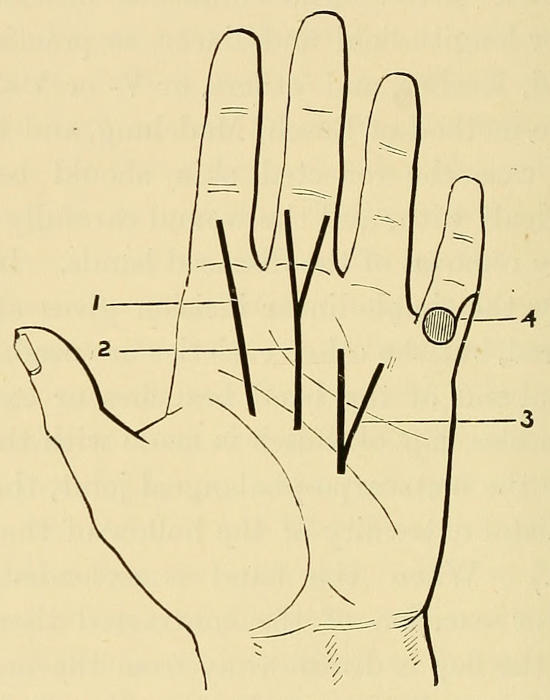

Fig. 4.

Diagram showing Incisions for Open and Smaller Plastic Operations.

1. Straight incision (Goyrand); 2. Y-incision modified to allow incision of digital expansion of band; 3. V-incision of Busch; 4. Position of flap to fill gap left by section of contracted band and superjacent integument (Author’s method).

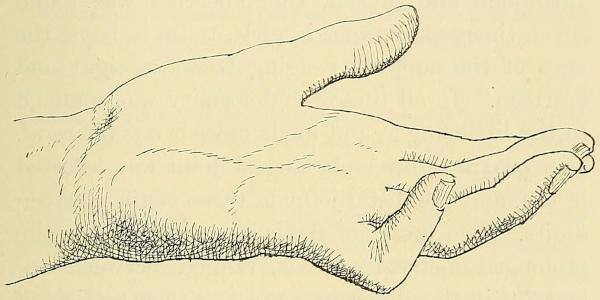

Plastic operations may be conducted under the same principles as those which guide the surgeon in the treatment of cicatricial contractions from burns or other causes. In cases of contraction at the metacarpo-phalangeal joint, where the skin is greatly involved, I have made a transverse incision through the integument and fibrous cord at the root of the finger and filled up the wide gap left on extending the joint by the transplantation of a flap from the side of the digit. (Fig. 5.) The dissection of the flap must be carefully conducted in order to avoid injury to the digital nerves. The result is usually good and permanent. In some cases it might be permissible to carry the plastic principle still further by the transplantation of a flap on the Tagliacotian principle from the chest or upper arm or any other convenient point; or the more simple resource of grafting, after the manner of Thiersch, may be employed with advantage,[40] as it has been proved to have a remarkable effect in lessening cicatricial contraction.

Fig. 5.

Diagram showing lateral flap transplanted into gap left by division of the contracted band, with the superjacent integument at the level of the inter-digital web.

Of these various procedures I believe that the best operation in most cases is the subcutaneous plan. It is speedy and safe, the immediate results are very satisfactory, the risks of relapse are in my experience less than in the open method, and in the event of a recurrence the other lines of treatment are still available. The open operation involves a more extensive surgical injury, and although it will usually do well under antiseptic precautions, there is a greater risk of casualties. It is perhaps most applicable to the slighter cases, in which the whole of the disease can be removed, but it may also be employed where the subcutaneous plan has failed. The plastic operations[41] are most useful in the traumatic forms, and in those cases of true Dupuytren’s contraction where the skin is so far involved that full or satisfactory extension is impossible. The method I have suggested produces an immediate result, and under ordinary circumstances a long after-treatment is unnecessary, because the flap of integument does not tend to contract. The larger operation can only be called for in very severe cases, where all other measures have failed.

It is not certain in any given example whether the surgeon will be successful in giving lasting relief to the patient. Were it simply a question of dividing or excising a common cicatricial band, there is no reason why the result of every well-devised operation should not be permanent; but experience shows that even with the greatest care it is occasionally difficult to prevent a return of the condition which gave rise to the deformity in the first place—that is, a growth of new fibrous tissue which tends to contract.

The main conclusions arrived at may be stated as follows:

1. There are two forms of disease comprised under the name “contraction of the palmar fascia,” the one traumatic in origin, occurring at all ages, and not tending to spread far beyond the seat of injury; the other unassociated with obvious traumatism, tending to multiplicity of lesion, and almost confined to middle and advanced life.

2. The latter condition, the true “Dupuytren’s contraction,” is not, strictly speaking, a contraction of the palmar fascia, but consists of a chronic inflammatory hyperplasia, commencing in the corium and subcutaneous connective tissue, involving secondarily the palmar fasciæ, and tending to the formation of dense bands of cicatricial tissue which replace the normal structure.

3. It does not appear to be especially connected with pressure or friction of the palm by tools or other objects employed in manual occupations, but is probably caused by infective organisms which gain admission through epidermic lesions, usually located over the prominent heads of the metacarpal bones.

4. It is almost essentially a disease of middle and advanced age, more common in men than in women, occurring in all classes, tending to progress slowly through a long course of years, and liable to recurrence after operation.

5. It is connected with a special susceptibility, inherited or acquired, which cannot yet be accounted for or expressed in any known terms; but neither gout, rheumatism, rheumatoid arthritis, nor any other of the ordinary constitutional ailments has been proved to have any causative relation to the disease.

6. Cicatricial deformities of the digits resulting from burns and other severe injuries are often of a very distressing character, and especially those[43] which prevent opposition of the thumb to the fingers. When the joints are not destroyed, the utility of the member may generally be restored by well-devised plastic measures, the new material being either an epidermic graft, or a skin flap taken from a convenient portion of the surface; but it is useless to lay down laws in detail for the treatment of these conditions, as the variations in the extent and position of the loss of substance are so great that only the ingenuity of the operator can guide him in the application of the general principles of plastic surgery.

There are certain affections of the fingers which have hitherto attracted little notice, but are interesting on account of their relationship to deformities of much greater frequency in the lower extremity. These are conditions of abnormal flexion and of lateral deviation of the phalanges at the inter-phalangeal articulations, the first of which corresponds exactly to the well-known deformity of the foot called “hammer toe.”

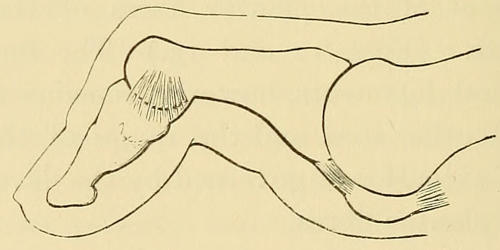

Fig. 6.

“Hammer Finger.”

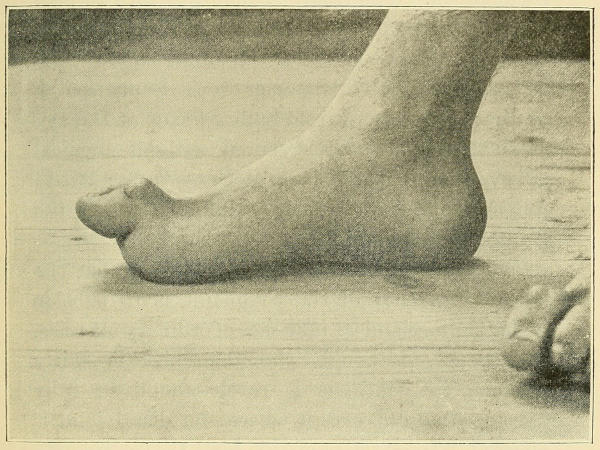

“Hammer finger” (Fig. 6) is not a rare complaint, although much less familiar, possibly because much less troublesome, than hammer toe. It may be defined as a permanent flexure of one or more digits, nearly always at the first or second inter-phalangeal joint, and unassociated with inflammatory or degenerative disease in the articular structures, or with any evidence of paralytic or spastic phenomena in the muscles. It is strictly limited in onset to the developmental period, and may manifest itself at any time between birth and adult life, possibly even before birth in some instances. It is more common in girls than in boys. The digit most frequently attacked is the little finger, and the proximal[45] inter-phalangeal joint is more often affected than the distal joint. It is usually symmetrical. The contraction is slow, progressive, and painless, and becomes arrested spontaneously at any degree of flexion, but seldom goes beyond an angle of 90°. The joint cannot be extended by any ordinary force except in the earliest stage, and even then the bent position is immediately resumed after the cessation of the effort. Flexion, on the other hand, is complete and of fair power. No alteration is produced in the deformity by flexion of the wrist, a fact which proves that the main obstacle to extension does not lie in the tendons. There are no contracted fascial bands, and, as a rule, the skin is normal, but occasionally a small longitudinal fold may be present in the angle of flexion. In rare instances the resistance to extension is capable of yielding suddenly with a spring-like action, and[46] a similar movement recurs as the joint is replaced in the position of flexion. These cases are usually classed with the condition known as “trigger finger.” The contraction also occurs in the metacarpo-phalangeal joint, but very rarely attains a degree marked enough to attract the attention of patient or surgeon. In 800 children examined at the Central District School at Hanwell by Dr. Litteljohn and myself, this affection was found seven times—five times in girls, twice in boys, the ages of the subjects ranging between eight and fourteen. In all these the deformity was confined to the little finger, and in six cases it was bilateral. The proximal inter-phalangeal joint was affected in ten, and the distal joint in three of the thirteen digits. The angle of flexion measured from the prolonged metacarpal axis, ranged between 20° and 80° in the different cases. A contraction of less than 20° was frequent, but the deformity was so slight that the cases were not recorded as pathological. Besides these examples, I have met with several cases in adult women, in whom the defect is said to have originated in early childhood. The little finger was affected in all, but in one the ring finger, and in another the ring and middle fingers were also involved. Only the last was unilateral. The following case may serve as a type of the more troublesome forms:

G. B., a domestic servant, aged twenty-two, was admitted into St. Thomas’s Hospital in June 1889, with contraction of[47] the third, fourth, and fifth fingers of the right hand at the first inter-phalangeal joints. The patient, a strong, healthy girl, quite free from neurotic tendencies, stated that her little and ring fingers had been contracted from early childhood, and that the condition had increased slowly but progressively to the present time. The middle finger became similarly affected about five months before admission. She had never suffered from pain, and the parts had been free from all sign of inflammation; the deformity, however, caused very great inconvenience in her occupation. Two months before admission an attempt had been made to relieve the flexion of the little finger by subcutaneous section of the fascia, with the result of inducing a traumatic contraction of the metacarpo-phalangeal joint. The family history was negative. On examination the little finger was found to be flexed at an angle of 90° at the first inter-phalangeal joint, and the metacarpo-phalangeal joint was bent at an angle of 120° by cicatricial contraction of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (the result of the operation alluded to). The ring finger was flexed at the first inter-phalangeal joint to about 110°, and the middle finger at the corresponding articulation to about 150°. In the case of the inter-phalangeal joints, the movements in the direction of flexion were quite free and of normal power, but extension was strongly resisted by ligamentous tension at the points named. No increase in the range of movement was gained by flexion of the wrist. A first operation was undertaken for the relief of the cicatricial contraction at the proximal joint of the little finger. The tense integumental band was divided, and after straightening the joint a flap was dissected from the ulnar side of the digit opposite the point of incision and twisted into the gap. (Fig. 4.) The wound united by first intention, and the result was permanent. A week later an operation was performed upon the first inter-phalangeal articulation of the same finger. The lateral ligaments were divided subcutaneously near their proximal attachment, and it was found that the joint could then be straightened by the use of moderate force; but on the discontinuance of the extension the contraction was reproduced by the elastic tension of the flexor, except during flexion of the wrist. The hand was placed upon a splint. The patient,[48] who did not bear restraint well, left the hospital, and has since been lost sight of.

There is little doubt that in this case the primary contraction was due to imperfect evolution of the ligaments, and that the shortening of the tendons was secondary. The reason for accepting this order of phenomena is that a pure myogenic contraction does not readily lead to changes in the joint structures, because the articulations are capable of full extension while the flexor tendons are relaxed by bending the wrist, and hence the limitation of movement is not constant. (See Case recorded on page 58.) On the other hand, in a permanent contraction of a finger-joint occurring during the period of active growth the flexors are never stretched to their full extent, and consequently do not undergo their normal longitudinal development; but should such a contraction originate in an adult the case is different, as muscle and tendon show very little disposition to undergo active involution in the direction of their length after their complete development is attained; and hence after division of the abnormal bands in true Dupuytren’s disease the tendons do not impede the complete extension of the digit. This law, that joint contractions commencing in youth lead to shortness of muscle tendon, while those beginning in adult life do not, is worthy of the attention of the surgeon.

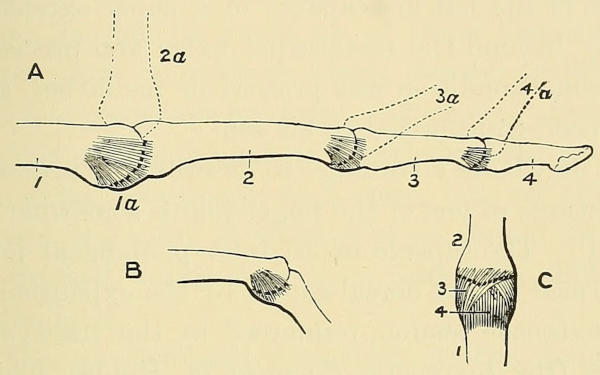

Pathology.—The affection is of some pathological[49] importance, because it affords a simple test case by which many other questions of larger moment may be decided. It has been demonstrated that the permanent obstacle to extension of the contracted joint is to be found in the ligaments, there is no evidence of either muscular or nervous impairment or of any inflammatory changes in or about the joint, the process of contraction is slow and painless, and the condition always originates and progresses to its maximum during the term of active growth. In order to understand the significance of the complaint, it is necessary to dwell upon some facts in digital anatomy and physiology that have not received the consideration they deserve. If we examine a number of hands, it will be found that there is a remarkable wide physiological variation in the range of movement at the phalangeal articulations in different individuals, and it requires but a small departure outside the physiological limits of variation to constitute the pathological deformity under consideration. The results of my own observations are as follows: (1) At each of the digital joints the distal bone, starting from the position of extreme flexion, passes through a variable number of degrees before it reaches the point at which it is arrested by tension of the ligaments. In the metacarpo-phalangeal joint the angle formed between the two bones during extreme flexion is usually about 80°, and the entire extending movement from this point[50] may be represented in the healthy hand by any number of degrees between 90 and 190. That is, in one person the motion is arrested a little before the axis of the phalanx reaches a line with that of the metacarpal bone; in another it may be possible to continue the extension until the two bones form an angle with a dorsal opening of 90°. At the first inter-phalangeal joint there is a similar but less extensive variation. The extreme flexion angle is 60° or 70°, and the full extension may be checked as soon as the axes of the two bones are in the same line (frequently a little before this point is reached), or may be carried on 30° beyond. In the distal joint the flexion angle is about 80°, and extension may be checked when the two bones are in the same line, or may be capable of continuation for 40° or more. In the thumb the range of movement at the metacarpo-phalangeal joint varies from 80° to 170°, and at the inter-phalangeal joint from 90° to 120°, in different persons—i.e., the physiological variation in the two articulations is 90° and 30° respectively. The diagram (Fig. 7) may help to render this clear. It is not only in different individuals that such variations are apparent, but the fingers of the same hand and corresponding fingers in opposite hands may differ from each other to a marked degree in range of extension. The super-extension is usually greatest in childhood, and undergoes great diminution as adult life is approached,[51] although in many cases it is persistent; as a rule, however, the limitation is in direct proportion to the strength of the hand, and is hence nearly always greater in the left hand than in the right. These peculiarities are matters of common observation, and popular expressions have ever been coined to represent the extremes in the range of variation. Thus a person who is able to bend his joints backwards to a conspicuous degree is said to be “double-jointed,” and one who cannot extend them beyond the straight line is called “stiff-jointed”;[52] and it is well known that “double-jointedness” and “stiff-jointedness” run in families, and in some cases may be traced through several generations. In the author, for example, the metacarpo-phalangeal joints of the index and middle fingers of the right hand are “stiff,” while those of the left are capable of a super-extension of 45° beyond the metacarpal axis; and precisely the same condition was present in his father, and has been transmitted to his son.

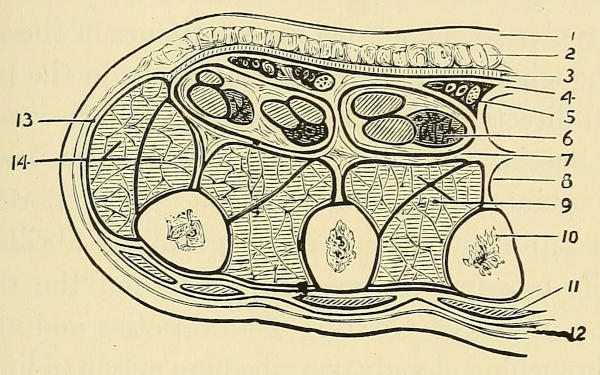

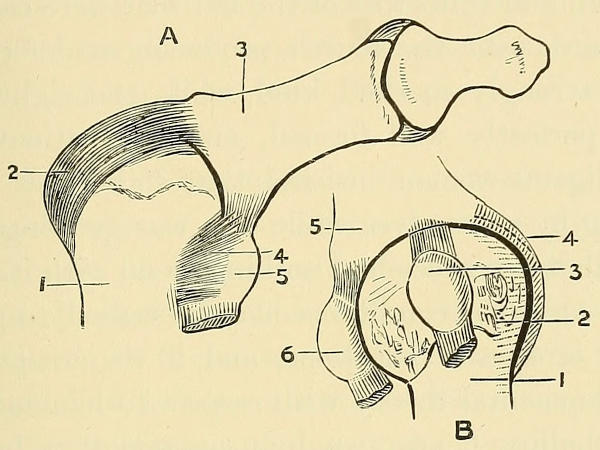

Fig. 7.

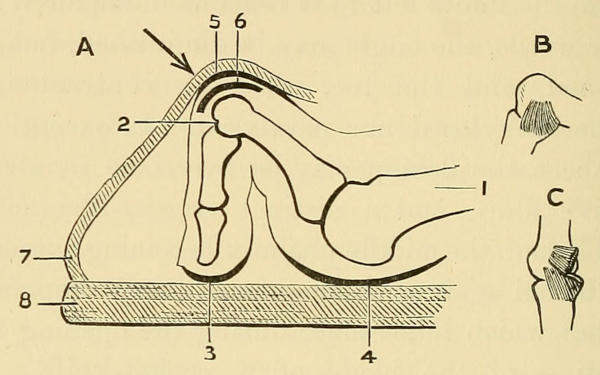

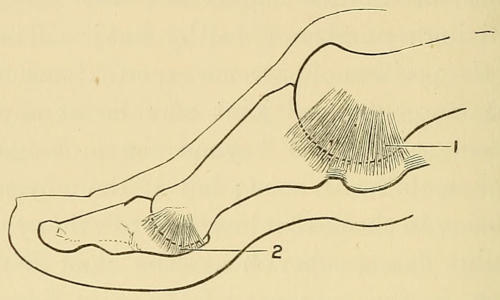

A. Skeleton of finger with lateral ligaments; 1. Metacarpal bone; 1a. Anterior fibres of lateral ligament blending with glenoid plate; 2. Metacarpal phalanx; extension checked by short anterior fibres of lateral ligament (1a) at line of metacarpal axis; 2a. Super-extension permitted when 1a long; 3 and 3a. Middle phalanx under conditions similar to 2 and 2a; 4 and 4a. Ungual phalanx.—B. Hammer finger; extension at first inter-phalangeal joint arrested by imperfect longitudinal development of anterior fibres of lateral ligament.—C. Palmar aspect of first inter-phalangeal joint (left middle finger); 1. Metacarpal phalanx; 2. Middle phalanx; 3. Anterior fibres of lateral ligament decussating with those of the opposite side; 4. Glenoid plate.

It may be of advantage to describe the articular structures of one of the finger-joints somewhat in detail. The capsule of an inter-phalangeal joint is formed on the dorsal aspect by the expansion of the extensor tendon, reinforced by the transverse fibres (the ligamenta dorsalia of Henle), which bind the tendon to the bone and lateral ligaments; on the palmar surface of the articulation is a glenoid plate of fibro-cartilage firmly attached to the anterior border of the distal bone, but very feebly connected with the neck of the proximal bone, and fused intimately with the anterior fibres of the lateral ligaments; lastly, at the sides of the joints are the radial and ulnar lateral ligaments, the attachment of which it is important to study closely, as they are often imperfectly described in anatomical text-books. The fibres of each lateral ligament are attached above to a little tubercle at the side of the head of the first phalanx, and from this point they radiate in a fan-like manner—the[53] more posterior passing to the side of the base of the second phalanx, the rest blending with the glenoid plate, and through the intermediation of this are connected with the anterior border of the base of the distal bone, decussating to some extent with fibres of the opposite ligament. (Fig. 7, C.) The strongest part of the glenoid plate, in fact, is made up of these ligamentous fibres; and it is these which, relaxed in flexion, become progressively more and more stretched during extension, and at length by their tension bring the movement to a close, but, as already shown, the point at which the maximum tension is reached varies to a large extent in different individuals.

The physiological variations in the range of movements are thus to be explained by variations in the relative length of the anterior fibres of the lateral ligaments. The ideal constitution of a joint depends upon the existence of a certain ratio between the growth of bone and that of ligament. Should the ligaments grow in excess, their redundant length will permit great super-extension, and may even cease to check the movement; but if the bone grow relatively faster than the ligaments, the anterior portion of the latter will the sooner become tense during extension, and where this disproportion is exceptionally great the motion may be checked before it attains physiological completeness, the result being a[54] “hammer finger.” Irregularities of development are most likely to occur in those joints which, for one or other reason, have the least functional activity. In the hand the little finger is much less powerful than its fellows; and in association with this it may often be noticed that the fourth tendon of the flexor sublimis is reduced to a mere thread; in the foot the same thing is observed in the corresponding digit, but in a more marked degree, and it is the degenerate little toe which is most liable to the “hammer deformity.”

We may then define hammer finger as the result of a developmental irregularity of the first or second inter-phalangeal joint (rarely of the metacarpo-phalangeal joint) by which the anterior fibres of the lateral ligaments become prematurely tense during extension, and so check that movement before it attains its normal physiological limit. It is precisely analogous to hammer toe; but it is of less frequency than the latter affection, because while civilisation sedulously cultivates the freedom and precision of action in the fingers, it devises foot-coverings to repress the natural play of the toes. The tendency to the deformity may be transmitted by descent through an indefinite number of generations.

Diagnosis.—Spurious hammer finger, like false hammer toe, may occur from—(1) articular lesions due to rheumatism, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, tuberculosis, and inflammations of traumatic[55] origin; or (2) from interference with the muscular functions by paralysis of the extensors or by spastic contraction of the flexors. In the first group the joint will be found in a more or less complete state of ankylosis, movements in all directions being impeded. In the second group the articulation, although contracted, is freely mobile under passive force, unless, as in some congenital paralyses, irregularities of development in the articulations be superadded.

Treatment.—The treatment of hammer finger is a far less simple problem than that of hammer toe, because in the toe the sacrifice of the movement of the affected articulation does not sensibly impair the utility of the digit, while in the fingers an ankylosis of the first inter-phalangeal joint in the position of either flexion or extension would be even more inconvenient than the ligamentous contraction. The measures available are (1) passive movement; (2) subcutaneous section of lateral ligaments, with or without tendon lengthening; and (3) amputation. In the milder cases a persevering use of passive motion will in time effect a cure; but when the contraction has reached an advanced degree it may be impossible to make an impression by this means. We may then divide the lateral ligaments, and keep the fingers straight by means of an extension splint while the tendons are relaxed by flexion of the wrist, trusting to subsequent massage and passive motion, or, failing[56] this, to tendon lengthening (by a process to be described later), to overcome the resistance of the shortened muscles. Section of tendons within the theca is useless, because no uniting material is thrown out between the divided ends. As a last resource, amputation may be demanded to remove a useless and inconvenient member.

Lateral versions of the phalangeal joints.—Lateral versions of the fingers are intimately associated with hammer finger in pathology, and the two distortions are sometimes combined. The lateral inclination, which seldom exceeds 25°, may affect either of the inter-phalangeal joints, but is more frequently in the distal phalanx. Like the “hammer” deformity, it is usually found in the little finger, and is symmetrical. The version is nearly always towards the radial side, and the movements of the joint are a little impaired. Amongst eight hundred children in the Hanwell School were found six cases, of which five were double and affected the little fingers, the sixth being in the fourth digit and unilateral; in two the version was associated with slight hammer flexion. It is occasionally seen in the index finger, and the version is then towards the ulnar side. The condition is rather unbecoming than inconvenient, and cases are seldom brought to the surgeon for relief. It is a result of irregularity of development, the condyle growing a little more rapidly on one side than on the other. The constancy[57] of the radial direction of the version of the little finger is probably explained by the fact that any lateral pressure to which this digit is subjected is from the ulnar side, while in the index finger the pressure is more often from the radial side, and hence an ulnar distortion is here the more usual. The deflected joint may be straightened by the use for a few weeks of a narrow metallic side splint, jointed opposite the articulations. No operation is required.

Exaggerated forms of distortion of the fingers may occur in rheumatoid arthritis, gout, or chronic rheumatism, and in various nervous affections,[2] but these rarely call for surgical treatment.