SYDENHAM

Title: The seven books of Paulus Ægineta, volume 3 (of 3)

translated from the Greek: with a commentary embracing a complete view of the knowledge possessed by the Greeks, Romans, and Arabians on all subjects connected with medicine and surgery

Author: Aegineta Paulus

Translator: Francis Adams

Release date: April 13, 2023 [eBook #70533]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Printed for the Sydenham Society

Credits: Tim Lindell, Turgut Dincer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Transcriber’s Note: This book, in particular the Index, contains links to page references across all three volumes. Whether the links to Volumes I and II will work for you will depend on the device you’re reading this on, and your internet connectivity.

You’ll also need a font that can display characters such as 𐆖 (U+10196 ROMAN DENARIUS SIGN) and 𐆐 (U+10190 ROMAN SEXTANS SIGN).

THE

SYDENHAM SOCIETY

INSTITUTED

MDCCCXLIII

SYDENHAM

LONDON

MDCCCXLVII.

THE

SEVEN BOOKS

OF

PAULUS ÆGINETA.

TRANSLATED FROM THE GREEK.

WITH

A COMMENTARY

EMBRACING A COMPLETE VIEW OF THE KNOWLEDGE

POSSESSED BY THE

GREEKS, ROMANS, AND ARABIANS

ON

ALL SUBJECTS CONNECTED WITH MEDICINE AND SURGERY.

BY FRANCIS ADAMS.

IN THREE VOLUMES.

VOL. III.

LONDON

PRINTED FOR THE SYDENHAM SOCIETY

MDCCCXLVII.

PRINTED BY C. AND J. ADLARD,

BARTHOLOMEW CLOSE.

I think it necessary to say a few words in explanation of the reason why the reader will find in the Commentary contained in this, my concluding volume, some deviation from the plan upon which the Commentaries in the two preceding volumes were executed.

In the Advertisement to the First Volume it is stated that, by the advice of the Council of the Sydenham Society, I had restricted the history which I gave of professional opinions on the various subjects treated of in the course of my work to what is properly called the period of ancient literature, and to this rule it will accordingly be observed that I have generally adhered, except in a few instances, where a departure from it seemed to be demanded for the sake of illustration, or for some other special object. But in dealing with the subject-matter of the present volume, namely, the Materia Medica and Pharmacy of the ancients, it became apparent to me from the first that a different plan of proceeding was indispensable, otherwise the usefulness of the whole work to the ordinary reader would be very much impaired. It is well known how frequently the nomenclature of the sciences connected with these subjects has changed, and what differences of opinion have prevailed with regard to many of the substances used in the practice of medicine by the ancients. In order, therefore, to render the information contained in this and the preceding volumes of ready access for practical purposes, it appeared to me necessary to bring down the annotations to modern times, so that one might see at once what is the exact import of the ancient terms of art, and what the medicinal substances mentioned in the course of the work actually were, according to the nomenclature[vi] of the present age. Accordingly it will be found that the Commentary in this volume abounds in references to modern authorities, and contains a variety of materials collected, not only from the earlier herbalists and commentators on Dioscorides, Theophrastus, and other ancient authors, but likewise from recent writers on Botany, Mineralogy, and the Materia Medica, in illustration of the various articles which are treated of in this work. And I have much satisfaction in having it in my power to state that the plan now described has the authority and sanction of the Council, who gave it their entire approval. To Dr. Pereira I owe my grateful acknowledgment for much valuable advice and assistance received from him on this part of my work; but at the same time it is fair to him to state I have no right to make him in anywise responsible for opinions herein advanced which may turn out to be erroneous.

And now, having brought my laborious undertaking to a conclusion, I would embrace the present opportunity of returning my most sincere expression of thanks to the Council for the honour which they conferred upon me in selecting my work for publication, and for the very flattering terms in which they speak of the first volume in the Annual Report of their proceedings for 1845. I trust that whatever degree of merit they discovered in it will be found not to be wanting in the succeeding parts, and that, taken together, the three volumes will be acknowledged to constitute a more copious repertory of ancient opinions on professional subjects than is to be found elsewhere. If such be the judgment which the intelligent members of the Sydenham Society shall generally pronounce on my work, I shall certainly never regret the time and exertions which I have bestowed upon it.

F. A.

Banchory, June 21st, 1847.

| SEVENTH BOOK. | ||

| SECT. | PAGE | |

| 1. | On the Temperaments of Substances as indicated by their Tastes | 1 |

| 2. | On the Order and Degrees of the Temperaments | 2 |

| On the powers of simple medicines | 6 | |

| 3. | On the Powers of Simples individually | 17 |

| Appendix to the Third Section—On the Substances introduced into the Materia Medica by the Arabians | 424 | |

| 4. | On Simple Purgative Medicines | 480 |

| On those things which evacuate bile | 481 | |

| Medicines which evacuate black bile | 483 | |

| Medicines which evacuate phlegm | ib. | |

| Medicines which evacuate water | 484 | |

| On cholagogues | 489 | |

| On melanogogues | 491 | |

| On phlegmagogues | 492 | |

| On hydragogues | ib. | |

| 5. | On Compound Purgatives | 493 |

| 6. | On the Management of those who take Purgative Medicines; and what is to be done to those who are not purged by a proper dose of Purgatives | 497 |

| 7. | On the Treatment of Hypercatharsis | 499 |

| 8. | On the Antidotes called Hieræ | 500 |

| 9. | On Liniments to be applied to the Anus, and purgative Applications to the Navel | 502 |

| 10. | On Emetics | 503[viii] |

| Modes of administering hellebore | 504 | |

| 11. | On the different kinds of Antidotes | 510 |

| 12. | On Trochisks, or Troches | 528 |

| 13. | On Dry Applications and Abstergents (Smegmata) | 536 |

| 14. | On Liniments to the Mouth and Throat | 541 |

| 15. | On Delicious and Officinal Potions | 544 |

| 16. | On Collyria and Agglutinative Applications | 548 |

| 17. | On Plasters, and those things which are added to the boiling of them, from the Works of Antyllus, and on the proportion of wax to oil | 558 |

| 18. | On Emollient Plasters and Epithemes | 576 |

| 19. | On Restorative Ointments (Acopa), Liniments, Calefacient Plasters (Dropaces), and Sinapisms | 581 |

| 20. | On Different Preparations of Oil and Ointments | 589 |

| 21. | On Œnantharia | 598 |

| 22. | On Perfumes and Cyphi | 599 |

| 23. | On the Preparations of Masucha, which some call Masuaphium | 601 |

| 24. | On Pessaries, from the Works of Antyllus | ib. |

| 25. | On Medicines which may be substituted for one another, from the Works of Galen | 604 |

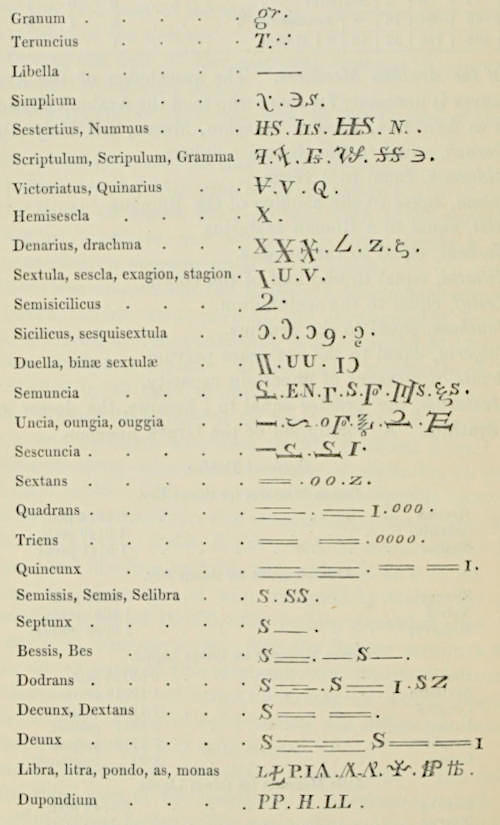

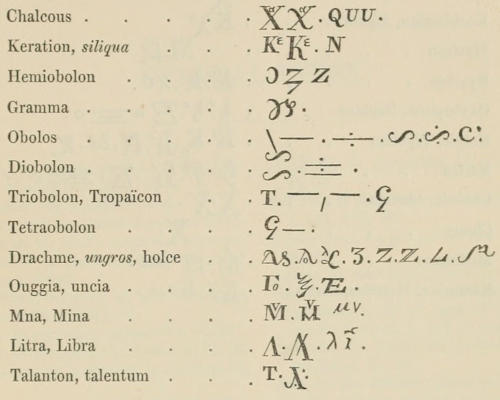

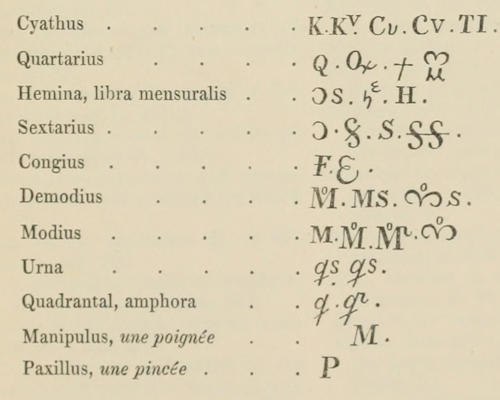

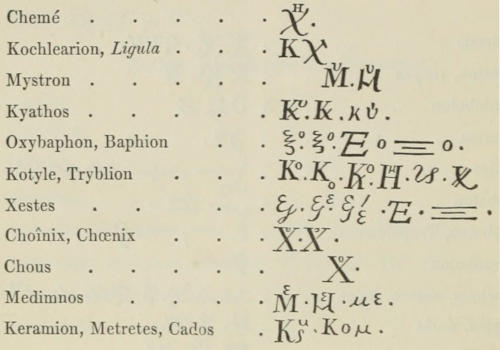

| 26. | On Weights and Measures | 609 |

| General Index | 629 | |

In this book, being the seventh and last of the whole work, we are to treat of the properties of all Medicines, both Simple and Compound, and more especially of those mentioned in the six preceding books.

It is not safe to judge from the smell with regard to the temperament of sensible objects; for inodorous substances consist indeed of thick particles, but it is not clear whether they are of a hot or cold nature; and odorous substances, to a certain extent, consist of fine particles and are hot; but the degree of the tenuity of their parts, or of their hotness, is not indicated, because of the inequality of their substance. And still more impracticable is it to judge of them from their colours, for of every colour are found hot, cold, drying, and moistening substances. But in tasting, all parts of the bodies subjected to it come in contact with the tongue and excite the sense, so that thereby one may judge clearly of their powers in their temperaments. Astringents, then, contract, obstruct, condense, dispel, and incrassate; and, in addition to all these properties, they are of a cold and desiccative nature. That which is acid, cuts, divides, attenuates, removes obstructions, and cleanses[2] without heating; but that which is acrid, resembles the acid in being attenuant and purging, but differs from it in this, that the acid is cold, and the acrid hot; and, further, in this, that the acid repels, but the acrid attracts, discusses, breaks down, and is escharotic. In like manner, that which is bitter cleanses the pores, is detergent and attenuant, and cuts the thick humours without sensible heat. What is watery is cold, incrassate, condenses, contracts, obstructs, mortifies, and stupefies. But that which is salt contracts, braces, preserves as a pickle, dries, without decided heat or cold. What is sweet relaxes, concocts, softens, and rarefies: but what is oily humectates, softens, and relaxes.

A moderate medicine which is of the same temperament as that to which it is applied, so as neither to dry, moisten, cool, nor heat, must not be called either dry, moist, cold, or hot; but whatever is drier, moister, hotter, or colder, is so called from its prevailing power. It will be sufficient for every useful purpose to make four ranks according to the prevailing temperament, calling that substance hot, according to the first rank, when it heats, indeed, but not manifestly, requiring reflection to demonstrate its existence: and in like manner with regard to cold, dry, and moist, when the prevailing temperament requires demonstration, and has no strong nor manifest virtue. Such things as are manifestly possessed of drying, moistening, heating or cooling properties, may be said to be of the second rank. Such things as have these properties to a strong, but not an extreme degree, may be said to be of the third rank. But such things as are naturally so hot as to form eschars and burn, are of the fourth. In like manner such things as are so cold as to occasion the death of a part are also of the fourth. But nothing is of so drying a nature as to be of the fourth rank, without burning, for that which dries in a great degree burns also; such are misy, chalcitis, and quicklime. But a substance may be of the third rank of desiccants without being caustic, such as all those things which are strongly astringent, of which kind are the unripe juice of grapes, sumach, and alum.

Commentary. The following is a list of the ancient authorities on the Materia Medica and Pharmacy: Hippocrates (pluries); Dioscorides (de Materia Medica); Celsus (v); Scribonius Largus (pluries); Marcellus Empiricus; Pliny (H. N. pluries); Rei Rusticæ Scriptores; Apuleius (de Herbis); Antonius Musa (de Herba Betonica); Macer Floridus; Galenus (de Simpl.; de Comp. Med. sec. loc.; de Comp. Med. sec. gen.); Aëtius (i and ii); Oribasius (Med. Collect. xi et seq.); Sextus Platonicus (de Med. ex animal.); Zosimus Panopolita (de Zythorum confectione); Actuarius (Meth. Med.); Myrepsus (pluries); Psellus (de Lapidibus); Rhases (Contin. liber ult.; ad Mansor. iii); Avicenna (ii, et alibi); Serapion (de Simpl.; de Antidot.); Mesue (de Simpl.); Haly Abbas (Pract. ii and x); Averrhoes (Collig. v); Albengnefit (Libellus de Simpl. med. virt.); Geber (Chemia); Servitor (de Præpar. Med. i. e. xxviii Albucasis); Baitharis Præfatio ap. Casiri Biblioth. Arab. Hisp. p. 276; Ebn Baithar (Uebersetz von Sontheimer); Rei Rusticæ Scriptores Arabici ap. Casiri B. A. H.; Alchindus (Libellus de Med. compos. grad.)

Hippocrates, although he appears to have been familiarly acquainted with the properties of most of the vegetable substances of the Old World, still employed in the practice of medicine, has left no regular treatise on the Materia Medica and pharmacy of his time. Theophrastus has treated more fully and ingeniously of botany and vegetable physiology than any other Greek writer; but except in two or three instances he scarcely alludes to the medicinal powers of the articles which he describes. In short, Dioscorides is the first and great authority on the Materia Medica,—his contributions to which can never be too highly appreciated; for, as Alston justly remarks, the science in ancient times remained ever after in nearly the same state as he left it. The genius of Galen, it is true, shed a considerable degree of lustre over the subject by his philosophical theory regarding the general actions of medicines; but his descriptions of particular substances, and even his detail of their properties, are mostly borrowed from Dioscorides. The Greek authors, subsequent to his time, can scarcely be said to have added one single article to the list of medicinal substances described by him. Aëtius, however, although he[4] can advance no great claim to originality, has given, as we shall see presently, a remarkably lucid exposition of the Galenical principles of therapeutics. Of Pliny’s great work, so replete with the most rare and curious information on almost every department of ancient literature, we feel reluctant to speak otherwise than in terms of unqualified eulogy, and yet candour obliges us to admit that on all medical subjects this writer is but a very indifferent authority. For, being evidently possessed of no practical acquaintance with professional matters, he appears to have been wholly incapable of discriminating real from pretended facts in medicine, and has accordingly jumbled important and useless matter together in many instances with very little judgment, nor can his opinions be much relied upon except when he copies closely from Dioscorides. The same objection cannot be made to his countryman Celsus; but the plan of his work being limited, the account which he gives of these matters is confined to a classification of simple substances, and a few formulæ for the formation of the more important pharmaceutical compounds. The Arabians added camphor, senna, musk, nux vomica, myrobalans, tamarinds, and a good many other articles to the Materia Medica; but, upon the whole, they transmitted the science to us in much the same shape as regards arrangement and general principles as they received it from their Grecian masters. At the same time it is impossible to take even a cursory view of the great work of Ebn Baithar, now fortunately rendered accessible to many European scholars by Dr. Sontheimer’s translation of it into German, without being struck with the amazing industry, enterprise, and talent displayed by that wonderful people in this department of medical science. In this collection, more than 1400 medicinal and dietetical articles are described, many of them no doubt in nearly the same terms as they had been noticed by Dioscorides and Galen, but of original matter relative to substances then for the first time introduced into the practice of medicine, there is no lack; and it is only to be regretted that a proper key to these stores is still a desideratum which it is to be feared will not soon be supplied. Ebn Baithar’s list of medicinal substances, however, is far more copious than[5] those of the other Arabians, who in general follow closely in the footsteps of the Greek authorities, and seldom supply anything very original of their own. For example, the Materia Medica of Rhases contains only 765 articles, and that of Avicenna only 747, which it is to be remarked, is a smaller number than is contained in the work of Dioscorides, wherein Alston states that he counted above 90 minerals, 700 plants, and 168 animal substances, making 958 in all. This is nearly triple the number of simples contained in the Materia Medica of the Edinburgh Dispensatory at the present day, which amount only to 341 articles; so that if this branch of medical science has received any material improvement in modern times, it must arise principally from our superior accuracy in estimating the virtues of the substances now in use, or in making more ingenious compositions of their elementary ingredients. At all events, it is quite clear that the Greek, Roman, and Arabian physicians were amply provided with medicines of every possible character, and there is no reason to suppose that they were in anywise behind us in the skilful management of them. It has been affirmed, indeed, in some late publications which we have seen, that the ancients had never classified the articles in the Materia Medica according to the nature of their actions; but this we need scarcely assure the reader is a very erroneous account of the matter: and in proof of this we could have wished, if our limits had permitted us, to have introduced here some of the classified lists of medicinal substances as given by the ancient authorities, and more especially those of Aëtius and Serapion.

We have mentioned above that Aëtius’s account of the general principles of the Materia Medica is particularly excellent, and we have now to add, that as it is sufficiently explicit to convey a distinct idea of the Galenical system, and is contained within moderate limits when compared with the full and lengthy exposition of it given by Galen himself, we shall give that of Aëtius entire, and confine our annotations almost solely to it in the present instance:—

“There are differences in the particular actions of medicines, arising from each of them being to a certain degree hot, or cold, or dry, or humid, or consisting of subtile or of gross particles, but the degree in which each of them is possessed of the above-mentioned properties cannot be truly and accurately determined. We have endeavoured, however, to define them in such a manner as will be sufficient for all practical purposes, laying it down that there is one class of medicines possessed of a similar temperament to our bodies, when they have received a certain principle of change and aliation from the heat in them, and that there is another which is of a hotter temperament than we. Of this temperament I have thought it right to make four orders, the first being imperceptible to the senses, and only to be inferred from reflection; the second being perceptible to the senses; the third strongly heating but not burning; and the fourth, or last, caustic. In like manner of frigorific or cooling things, the first order requires reflection to demonstrate its coldness: the second consists of such things as are perceptibly cold; the third is perceptibly cold, but does not occasion mortification; the fourth produces mortification. So it is in like manner with humectating and desiccant articles. Let such an order of degrees be laid down to render clearer the course of instruction, rose oil or the rose itself being placed in the first order of cooling things; the juice of roses in the second, and in the third and fourth those things which are extremely cold, such as cicuta, meconium, mandragora, and hyoscyamus. In regard to hot things, dill and fenugreek belong to the first order; those which are next to them, to the second; and so of the third and fourth, until we come to the caustic. In like manner, respecting moistening and desiccant medicines, beginning with those of a moderate degree, we may arrange them until we come to their extremes. Such knowledge is of no small importance for the purpose of medical instruction. One ought also to exercise the sense of taste, and remember the peculiar qualities of juices; as, for example, that such a substance when[7] applied to the tongue dries strongly, contracts, and roughens it to a considerable depth, such as unripe wild pears, cornels, and the like; every such thing that is intensely austere is called sour. Such things, as when applied to the tongue, do not constringe and contract it like astringents, but, on the contrary, appear to be detergent and cleansing, are called salt. Such things as are more detergent and also rougher in a painful degree, are called bitter. Those things which are biting and corrosive with a strong heat, are called acrid; and such as are biting without heat, are called acid, and these have the power of causing a fermentation when poured upon earth. Of those which lubricate, fill, remove asperities, and, as it were, erosions of the tongue, such as do so with sensible delight, are called sweet; but such as do this without sensible delight, are called fat. If, then, you wish to form a judgment of acrimony, you may learn to do so from garlic, onions, and the like, which are to be frequently tasted and long masticated, in order that the sensation thereby imparted may be fixed in the memory. But if you wish to acquire the perception of astringency, you may do so from galls, sumach, and the like; if of bitterness, from natron and bile; and if of sweetness, from rob and honey. Further, if you would wish to judge of such things as are devoid of all qualities, or of an intermediate quality as to taste, take water, and having tasted it, retain the perception in your memory; but see that it be the purest water, and that it contain none of the aforesaid qualities; neither sweetness, acidity, acrimony, nor bitterness; and, in addition, that it be neither very hot nor very cold. Proceeding from this, you may the more readily perceive the obscure taste of certain juices which I call moderately sweet, but which others call watery; such as the juice of green reeds and of grass, of wheat and of barley, and of moderately sweet things, as resembling what I have described to be of all other things the most devoid of qualities, I mean water, which is in an intermediate state between heat and cold, or inclines a little to cold. If being endowed with such a taste, it have not a liquid but a dry consistence, it must necessarily be terrene and desiccative without pungency. These things are called emplastic, such as starch, and most of the thoroughly-washed metals, as pompholyx, ceruse, calamine, Cimolian earth, Samian earth, and[8] the like. Some are not only terrene, but also watery in their nature; and some contain no little air in them: such are viscid and therefore emplastic. There are two kind of emplastic medicines, the one very terrene and dry, and the other altogether viscid, being composed of water, earth, and, for the most part, of air, such as sweet oil. The white of an egg is similar to oil, but more terrene. The cheesy part of milk is emplastic, and so also the fat of swine. The fat and suet of a bull and a buck-goat are acrid, and more terrene than that of swine. That of a goose or a cock is hotter and drier than that of swine; but of subtile parts, and by no means terrene. The fats then, if they have no acrimony, are emplastic, or obstruent of the pores, more especially if of a drier and more terrene nature, such as well-washed wax. Emplastic medicines then are of such a nature. But astringents are terrene, and with regard to the composition of their particles are thick; but in their qualities they are cold. Acids in composition are attenuating, but cold, like astringents. The terrene particles contained in the juices, which, when melted, contract and dry the humidity of the sentient parts of the tongue, if particularly rough, are called sour; but if less so, austere; and we properly call the temperament of such juices cold. But since they are unequally desiccative—for in this consists their asperity—they are likewise terrene; for every watery substance permeates the body evenly, and when removed it easily coalesces; but what is terrene when removed does not readily coalesce again. And the peculiarity of the sensation, if you will recollect the impression, will testify to the same effect; for the passage of acid juices, in the organs of sensation, appears quick; but that of sour, slow; and acids exert their actions more on the deep-seated parts, whereas sour substances act more superficially. When you wish to ascertain the action of a truly sour substance, if that which is made trial of appear at the same time sour and pungent, I would recommend you to lay that species aside, and to have recourse to something which is sour without being pungent, and neither acid, sweet, nor bitter, but as much as possible having no one quality or power mixed up with its astringency; for it is useless and foolish to make trial of such a medicine, as it cannot be ascertained whether it be by its astringency, or by[9] any of the qualities mixed with it, or by a combination of both, that the substance which is made trial of exerts its action. Therefore, chalcitis, misy, copperas, the flakes of copper, sori, and, in addition to them, the armeniacum pictorium (Armenian pigment), mercury, and other astringent substances which are also at the same time pungent, act by both their properties upon the bodies to which they are applied; but we are not thereby informed whether they burn by their astringency or by their acrimony; for such substances, when taken into the body, being composed of gross particles, and rather hot in their powers, having become ignited in the course of time, according to the change which they undergo in the body of the animal, ulcerate and burn the parts about the stomach like heated stones or irons; and owing to their weight they are incapable of being distributed over the body. It is better, therefore, after much observation, to look out for something that is purely astringent, and when you have found such a substance, make haste to try it in the manner you have formerly heard described; such as having tasted the flowers of the wild pomegranate, galls, or the flowers of the cultivated pomegranate, hypocistis, acacia, sumach, or the like, if the substance appear intensely sour, and it is manifest that it contains no other quality, you must prove the action of astringency from it. A sour substance then is terrene and cold, and its quality may necessarily be removed in three ways; either by being heated, or moistened, or by undergoing both these changes at the same time. If only heated, it will neither become more humid nor softer; but becoming harder it will have acquired sweetness, as is the case with acorns and chesnuts, as they are called. But if only moistened, and if the humidity is of a thick nature and watery, it becomes austere; for the astringent part being dissolved renders the juice austere, it being the property of a watery fluid to obtund the powers of every juice. If a subtile and airy fluid be superadded, it will become acid, for coldness being attenuating will render the former quality acid. When moistened and heated at the same time, if with a watery humidity, it will occasion a change to sweetness; but if with an airy, to fatness; for the fruits of such trees as appear sweet to us when ripened, are, when newly formed, sour and dry in their consistence,[10] each according to the nature of the tree which produced it; but in process of time, they become more humid or juicy; and some get acidity superadded to their sourness, which latter quality when they have laid aside they become again sweet as they arrive at maturity. Some do not acquire sweetness at all while upon the trees, but after a time, when separated from them. Some without the intermediate acidity pass from sourness to sweetness, as the fruit of the olive. All things are concocted by heat, which is of a twofold nature, the one proper and innate, and the other supplied from without by the sun. But, since being sour at first, they become sweet when ripe, their sweetness is occasioned by heat; but their acidity and sourness by cold. And it has already become obvious that as fruits being sour at first, in process of time become, some sweet, some acid, some austere, and some remain sour, that great variety will arise from a mixture of these qualities. Wherefore, the fruit of the ilex, the cornel, and other such things, are sour to the last, because they remain cold and dry as at the beginning, being only increased in size, but acquiring no other internal change. The fruits of the myrtle, the wild pear, and the oak are sweet and sour at the same time; but the fruit of Aminæan vines, wine, and such like things, are only austere. The fruit of the palm tree, and of wines, the Surrentine, and such as have sweetness joined to astringency, are at the same time austere and sweet. The Theræan wine, the Scybelitic, boiled must called rob, and other such like things, are only sweet. The fruit and juice of the olive in particular, but also of all other such things from which oil is formed, are fatty. And as a sour juice in process of time, becoming at first sweeter, and afterward turning more acrid and bitter, ends in becoming wholly bitter; so in like manner, a cold juice becomes at first more acid, and if wholly congealed it turns entirely acid; and such fruits as at gathering are filled with much humidity, and such as otherwise acquire much water, readily become acid from very slight causes. For if the unripe grape is acid, but the ripe sweet, and if all fruits are ripened by the solar heat, it is obvious that what is more imperfect and colder is acid; whereas, what is more perfect and hotter is sweet. When wine, therefore, from refrigeration becomes acid, it is clear that it returns[11] again to the same juice from which it was formed, I mean that of the unripe grape. But vinegar differs thus far in power from the juice of the unripe grape, that the vinegar has acquired a certain degree of acrimony from the putrefactive heat (”fermentation?“); but the juice of the unripe grape has no acquired heat, and therefore none of the acrimony of vinegar; wherefore, vinegar is more attenuating than the juice of the unripe grape, as the sensation bears testimony to the truth of what has been said; but the acrimony of the vinegar is not sufficient to overcome the coldness arising from its acidity; it serves, however, to make it more penetrating; for inasmuch as heat is more penetrating than cold, so does the acrimony of vinegar the more readily pass the pores of sensible bodies, and thus acrimony takes the lead, but coldness follows at no great interval. And it is this mixed and almost indescribable sensation which prevents us from calling vinegar simply cold; for we perceive in it a certain fiery acrimony. But the coldness, from the accompanying acidity, straightway obtunds and extinguishes the acrimony, and therefore there is a much greater sensation from the coldness than from the heat; for some persons by drinking oxycrate in the summer season are sensibly cooled, and remain free from thirst. But since thirst arises from two distinct causes, either from a deficiency of moisture or an excess of heat, that arising from dryness is not cured, but that occasioned by heat is removed by it; for vinegar by itself does not moisten, but is decidedly refrigerant. Thirst, therefore, arising from a hot intemperament, or from a hot and dry one, is not to be cured by drinking vinegar; but when humidity and heat meet together, the proper cure of such a kind of thirst is vinegar; but otherwise in the case of those who are thirsty in ardent fevers and all other hot diseases, and in those during summer and hot weather, their state is a compound of heat and dryness, so that the proper cure for it is a composition of vinegar and water; for the vinegar is decidedly refrigerant, and by its tenuity readily diffusible, and the water, in addition to its property of cooling, is the most moistening of all substances, for nothing is more moistening than water. But as an external application for heat of the hypochondrium, the juice of unripe grapes is preferable to vinegar, because it has no violent and offensive[12] coldness, nor any pungent heat mixed with it; for in such affections persons require to be soothed without violence by an application which will not induce externally any pungent acrimony. The juice of the unripe grape, then, is not only acid but sour; for, as mentioned before, almost all the fruits of trees are at first sour to the taste; and not only are acids cold, but so also are sour and austere things. And if any one will taste quinces, myrtles, or medlars, he will perceive clearly that there is one sensation from acids, and another from sour and austere things; for sour things seem to propel inwards the part which they touch, everywhere equally squeezing, constricting, and contracting, as it were; but the austere seem to penetrate deeply, and to induce a rough and unequable sensation, so that by drying they expel the humidity of the parts of sensation. Thus, between sour and austere juices, there is a certain peculiar difference of sensation not easily to be described, but which everybody must understand from what has been said. Every sour substance, then, when free from all other qualities, I have upon trial always found to be cold; but every sweet substance is hot, and does not greatly exceed the heat in us; and as we are delighted, more especially if we are cold, with the touch of warm water, until it expand the parts congealed by the cold, and as it heats us, and does not dissolve nor break the continuity of the parts, it is very pleasant and useful; so all sweet food is hot, and yet it is not possessed of such a degree of heat as to be unpleasant, but remains within the limits of those things which expand, soften, and are demulcent: for all nutritive food is allied to, and agrees with, the whole substance of the bodies which it nourishes; it requires, therefore, to be moderately hot, so as to agree with the bodies which are nourished; and hence one kind of food and medicine does not agree with all men; for according to his peculiar substance and affection is every one delighted and benefited. And such being the nature of things those kinds of food which are less sweet are less hot, and their heat is proportionate to their sweetness; but these things, when they get to an immoderate degree of heat, are no longer sweet, but appear bitter, such as honey which is old and much boiled, and so also with all other sweet things; for such things as without boiling or preparation are allied to the[13] temperaments of the bodies which they nourish, appear already sweet; but all such as are not allied appear unsavoury until prepared, for those which are hot require to be corrected by cold, and those which are sufficiently cold by the mixture of calefacient food and by heat. In like manner such things as are terrene and drier than proper, are to be corrected by humidity; and those things which are humid and watery, by drying; that which is sweet therefore, in addition to being more or less hot, is necessarily more or less humid. But when this bitterness arises from being over-roasted, as in lime and ashes, it is necessarily rendered dry and hot. For this reason every bitter thing is of such a nature as to prove detergent, and is calculated to break down and to cut viscid and thick humours, and such are ashes and natron; but that bitter sap is dry and terrene, may be collected from the circumstance, that bitter things are of all others the least prone to putrefaction, and do not engender worms nor other animals such as are usually formed in roots, herbs, and fruits when they become putrid; for we see that such animals and putrefactions take place in humid bodies. Those things which are intensely bitter (I call those things such which have no other manifest quality) are uneatable, not only by men, but by almost all animals, because every living creature is more or less humid, and bitter things are dry in like manner as ashes and cinders. As, therefore, that which is truly sweet is nutritive, and that which is purely bitter innutritive, so those things which are intermediate are nutritive indeed, but less so than the sweet. The salt juice is allied to the bitter, for both are terrene and hot; but they differ from one another perceptibly in this, that the bitter is more attenuated and wrought by the heat and dryness; and thus, too, of salts, such as are hard, denser, and more terrene (as are almost all the fossils), are less calefacient and attenuating; but such as are brittle and porous are at the same time more attenuating and hotter; and some of them are bitterish, being intermediate between the hard salts and aphronitrum; and if you will warm any saltish thing to a great degree it will straightway become bitter. Thus, the water of the Lake Asphaltitis, which they call the Dead Sea, being contained within a hollow and hot place, and overheated by the sun, becomes bitter, and for this reason it becomes more[14] bitter in summer than in winter. And if you will draw some of it, and put it into a hollow vessel in a place exposed to the sun during the summer season it will straightway become more bitter than it generally is. For no animals appear to be found in such water, neither plants; and although the rivers which fall into it contain many large fishes, more especially the river near Jericho called Jordan, none of the fishes pass the mouth of the river, and if you will catch some and throw them into the Lake, you will see that they die immediately, and hence it is called the Dead Lake or Sea. Thus, that which is intensely bitter is inimical to all plants and animals, and is of a parched and dry nature, becoming like soot from roasting. Having, therefore, settled the powers of bitter juices, and said that they are cutting, detergent, attenuant, and decidedly hot, to such a degree only as not to burn, we shall next proceed to the acrid; and first we may say of them that they are truly hot, then corrosive, caustic, escharotic, and of a dissolvent nature, when applied externally to the skin; but when taken internally, those which, in their whole substance are adverse to certain animals, are all septic and destructive to them, as the cantharis and buprestis are to men. But such as are distinguished only by excess of their heating powers, if thicker and terrene, as arsenic, sandarach, and the like, we call ulcerative of the internal parts; but if they consist of subtile parts, such as the common seeds, carrot, anise, and the like, they are diuretic, diaphoretic, and, in a word, cutting and discutient; and some are also useful in expectorations from the chest and menstrual discharges. But acrid juices would seem to differ from bitter, not only in possessing strong heat, but also in this, that all bitter things are not only hot but of a dry temperament like ashes, while in such acrid substances as are not bitter, there is often much humidity mixed, and therefore we use no few acrid things as articles of food. But since enough has been said respecting all the juices, it still remains to treat of the vapours. Most of the vapours, then, affect us similarly to the juices; for all acids, and likewise vinegar itself, move the senses of smell and taste in like manner; and acrid things, as garlic, onions, and the like, are pungent and offensive to the smell, no less than to the taste; so that, without tasting certain things, such as dung, we are confident that we know its[15] quality, and therefore at once we abstain from them, because we repose confidence in the sense of smell. And of fragrant things, such as have become putrid and offend the smell, we straightway throw away, and do not attempt to taste; and in short, with regard to almost all things, the smell and taste are found to agree; and we refer each of them to two classes, calling the most of those substances which have smell, odorous, and fetid, and considering the odorous analogous to sweet things, and the fetid to such as are not sweet to the tongue, it would appear that from bodies which have no smell there is but little emitted, or at least that it is disproportionate to their bulk, as is the case with salt and sour things in particular; for the substance of sour things is of a dense and cold nature, so that it is natural that what is emitted from them should be small in quantity, thick, and terrene in its parts, so as not to reach the brain in respiration. Hence it is not safe to judge of their temperament from the smell as it is from the taste: for we know that things which are inodorous consist of thick particles, but it is not apparent how they are as to heat and cold; and that fragrant things consist of subtile particles, and are hot in their nature; but it is not shown by the smell but by the taste what is the degree of their tenuity and heat. The inequality of their substance is the cause why fragrant things give no certain indication of temperament; and therefore it is not safe to judge of all the qualities of the rose from its smell; but in taste all the parts of the bodies which are tasted fall equably upon the tongue, and each excites a sensation agreeably to its nature, namely, the sour part in it which is terrene consists of thick particles and is cold; the bitter, which consists of subtile parts and is hot; and third, the watery, which is necessarily cold. It is not safe then, as has been said, to form a judgment of all the powers of simple substances from the smell; but it is still more impracticable to estimate simple medicines from their colours; for hot, cold, dry, and humid substances are found of every colour. And yet from the colour of every kind of seeds, roots, or juices it is possible to derive a certain indication of their temperament. For example, onions, squills, and wine, the whiter they are, are the less hot; but such as are of a yellowish and intermediate colour are hotter. And wheat, vetches, and kidney-beans,[16] and chick-peas, the root of iris, that of kingspear, and many others, are similarly affected. In each genus, for the most part, such things as are gold coloured, red, and of a bright yellow, are hotter than the white, so that if any conjecture can be formed therefrom of the powers of medicines, it is so far well. It is best then, as has been often said and demonstrated, to determine the powers of each by exact experiment, for by this you cannot be deceived; but before ascertaining their powers by experiment, the taste will give many indications, in which it will be assisted in a small degree by the smell.” (Præfatio in Aëtium.)

For a fuller account of the subject, the reader is referred to the first five books of Galen’s work ‘On the Powers of Simples;’ to the first tractate of the Second Book of Avicenna; and to the introductory part of Serapion’s work ‘On Simples.’ A useful abstract of the ancient opinions is given in the small tract of Albengnefit. The nature of the tastes is ingeniously discussed in the ‘Timæus’ of Plato, and by Theophrastus (de Causis Plantarum, vi.) Alkhendi’s theory of the action of compound medicines appears to be ingenious; but it is complex and difficult to explain, being founded upon the principles of geometrical properties and musical harmony. The ‘Chemia’ of Geber contains a very interesting abstract of the knowledge possessed by the ancients regarding the recondite nature of substances, that is to say, on alchemy, but supplies little or no information on the Materia Medica or Pharmacy.

Before concluding our present commentary, it may be proper to remark, as tending to show the importance of the Galenical theory of the action of medicines in the literature of medicine, that not only was it generally adopted by most of the Greek and Arabian authorities subsequent to Galen, but it prevails in the works of all our old herbalists, as, for example, Gerarde, Parkinson, Culpeper, and of the other writers on the Materia Medica, down to the days of Quincy. We may also take the present opportunity to state that in the works of the ancient authorities, we have detected a few traces of the singular doctrine of signatures, as it has been called, but that with the exception of Geber, who can scarcely be held to be a medical writer, we have[17] found no allusion to alchemy or astral influence, as having anything to do with the operation of medicines. The first ancient writer who notices alchemy, we believe, is Firmicus (iii.) Though the Arabians were much given to this superstitious conceit, it would appear from what we have mentioned that their medical authorities had kept their minds free from the contamination of it.

Commentary. The part of our task upon which we are now entering is at once so arduous and important, that we cannot but feel diffident of our abilities to execute it properly. We may venture, however, to assure the reader that we have spared no pains as far as lay in our power to unravel the intricacies with which this department of ancient science is involved, and that, with this intention, upon every article we have carefully compared the descriptions of the ancient authors, and have likewise availed ourselves of the learned labours of modern commentators on Theophrastus, Pliny, and Dioscorides. We may mention that those we have generally reposed most confidence in are Matthiolus, Dodonæus, Harduin, Stackhouse, Schneider, Sprengel, and Sibthorp. It will also be seen that we have paid a good deal of attention to the works of our English herbalists, the study of whose works we consider highly important, as reflecting much light on the ancient literature of this subject. We have further culled freely from a variety of other sources. As our limits prevent us from entering into the discussion of controverted points, we are under the necessity of merely giving the result of our own investigations in each case. Those who wish to see the commentator’s opinions more fully on these matters are referred to the Appendix to Dunbar’s ‘Greek Lexicon,’ which was written exclusively by him.

Abrotonum, Southernwood, warms and dries in the third degree, being of a discutient and cutting nature, for it is possessed of a very small degree of sourness, and if rubbed with oil over the whole body, it cures periodical rigors. But it is prejudicial to the stomach; and the burnt being more desiccative than the unburnt, cures alopecia, along with some of the finer oils.

Commentary. Dioscorides and most of the subsequent authorities, with the exception of Paulus, describe two species, the mas. and the femina. The one without doubt is the Artemisia Abrotanum; the other probably the Santolina Chamæcyparissus. The use of southernwood is as ancient as Hippocrates, but Galen is the ancient author who has treated of its faculties most elaborately. He recommends it strongly both externally in fomentations, and internally as an anthelminthic. For the latter purpose it is praised by the natural historian Ælian (H. A. ix, 33), and by most of the medical authorities on the Materia Medica, both ancient and modern. As an application in ophthalmy, along with the pulp of a roasted quince, it is highly spoken of by Galen and the others. Galen says, that friction with the oil of southernwood is useful in intermittents, and this character of it is confirmed by all the authorities down to recent times. Avicenna joins Dioscorides in praising it as an emmenagogue, and says, that it produces abortion. (ii, 266.) Aëtius is fuller than the others on the virtues of the lixivial ashes of southernwood, recommending them particularly in diseases of the anus and in alopecia. Celsus ranks it among the cleansing medicines (v, 5.) Pliny makes mention of a vinous tincture (xiv, 19.) See also Dioscorides (v, 49.) Macer Floridus, a comparatively modern authority, joins the more ancient authorities in commending it as an antidote to narcotic poisons. He also says, that a vinous tincture of it is useful in sea-sickness. Serapion, after quoting freely from Dioscorides and Galen, under this head adds, upon “an unknown authority,” that, when boiled with oil and rubbed over the stomach, it cures coldness of the same. (De Simpl. 317.) In the modern Greek Pharmacopœia (Athens, 1837), the two species of wormwood are described by the names of Artemisia Abrotonum and Artemisia contra. See further Pereira (M. M. 1356.)

Agallochum, is an Indian wood resembling the thyia, of an aromatic nature. When chewed it contributes to the fragrance of the mouth. It is also a perfume. Its root, when drunk to the amount of a drachm weight, cures waterbrash and loss of tone in the stomach, and agrees with hepatic, dysenteric, and pleuritic complaints.

Commentary. It is probably the lignum aloes or Aloexylon Agallochum, Lour., although there has been considerable difference of opinion on this point. See Gerarde’s ‘Herbal’ and the commentators on Dioscorides and Mesue. Our author’s description of it is taken from Dioscorides (i, 21.) The Arabian authorities and Simeon Seth describe several varieties of it; the most excellent of which is said to be the Indian. At all times it has been much used in India as a perfume. See in particular Avicenna, who gives an elaborate dissertation on the different kinds of agallochum or xylaloe, found in India, and the modes of preparing it (ii, 2, 733.) See also Serapion (De Simpl. 197); Ebn Baithar (ii, 224); and Rhases (Cont. l. ult. i, 27.) It does not occur in the Hippocratic treatises, nor in the works of Celsus. Although not retained in our Dispensatory, it is still kept in the shops of the apothecaries, and has the reputation of being cordial and alexiterial. See Gray (Suppl. to Pharmacop. p. 91.)

Agaricum, Agaric, is a root or an excrescence from the trunk of a tree, of a porous consistence, and composed of aerial and terrene particles. It is of a discutient nature, cuts thick humours, and clears away obstructions, of the viscera particularly.

Commentary. It appears to have been the same as the Boletus igniarius (touchwood or spunk), which is still retained in our modern Dispensatories. It is a fungous excrescence which grows on the trunk of the oak, larch, cherry, and plum. Dioscorides and most of the ancient authorities speak highly of it as a styptic. Dioscorides also commends it in stomach complaints, but Aëtius maintains that it is prejudicial to the stomach. Galen calls it cathartic, and speaks highly of its virtues in the cure of jaundice and other hepatic affections. (De Simpl. v.) For the Arabians, see Avicenna (ii, 2); Serapion (De Simpl. 78); Rhases (Contin. l. ult. i, 28.) They recommend it in jaundice, like Galen, and in complaints of the lungs, melancholy, protracted fevers, and in other cases. It is now seldom used, being found to act harshly both as an emetic and a cathartic. We have treated of the poisonous agarici in another place (v, 64.) The Boletus Laricis occurs in the modern Greek Pharmacopœia. (Athens, 1837.)

Ageratum, Maudlin, is possessed of discutient and slightly anti-inflammatory powers.

Commentary. Our modern herbalists are generally agreed that this is our maudlin, that is to say, the Achillea Ageratum, and the commentators on Mesue hold that it is his eupatorium. From Dioscorides down to modern times it has been commended as a diuretic medicine and an emollient of the uterus. Dioscorides, however, seems to say that it is heating, whereas Galen represents it as mildly anti-inflammatory. Perhaps there is some error in the text of the former. (iv, 59.) We do not find it in the works of Hippocrates, nor in those of Celsus, nor have we found it treated of by any of the Arabians, except Ebn Baithar, who merely gives extracts from Dioscorides and Galen (ii, 57.)

Vitex, the Chaste-tree, heats and dries in the third rank. It consists of fine particles and dispels flatulence, whence it is believed to contribute to chastity, not only when eaten and drunk, but also when strewed under one. Its seed also, when drunk, acts as a deobstruent of the liver and spleen. When toasted it is less flatulent and more distributable.

Commentary. The anaphrodisiacal powers of the Vitex Agnus Castus, or chaste-tree, are noticed by most of the medical authorities, and by Ælian (H. A. ix, 36.) But modern authorities question its claims to this character. Until lately, however, it held a place in our Pharmacopœia. Our author abridges Dioscorides (1, 134), and Galen (De Simpl.) For the Arabians, see particularly Avicenna (ii, 2, 43), and Rhases (Cont. l. ult. 31.) It occurs in the works of Hippocrates.

Gramen, Grass, that of Parnassus is particularly useful; it is desiccative, moderately cooling, consists of fine particles, and is somewhat sour; it, therefore, is an agglutinant of bloody wounds, and its decoction is lithontriptic.

Commentary. Dioscorides treats separately of the agrostis, which probably is our couch-grass, or Triticum repens, and of the agrostis in Parnasso, which has been very doubtfully referred[21] to the Parnassia palustris. (iv, 30.) Our author would appear to have confounded these two articles together, and to have applied to the latter the characters which Dioscorides gives to the other. The modern herbalists agree with the ancients in commending the couch-grass as being diuretic and lithontriptic. None of the commentators or herbalists have given a satisfactory account of the esculent grass of Galen. The Arabians treat of the grasses very confusedly. See in particular Avicenna (ii, 2, 704); Rhases (Contin. l. ult. iii, 50); Serapion (c. 119.) In the modern Greek Pharmacopœia the Triticum repens stands for the ἀ. (p. 72.) Apuleius says “Græci agrostem Latini gramen appellant.”

Anchusæ, Alkanet; there are four varieties, all of which are not possessed of the same powers. For that which is called onoclea has a root which is astringent and somewhat bitter; whence it is useful in splenitic and nephritic cases. It is a suitable remedy for erysipelas when applied with polenta. The leaves are less cooling and desiccative than the root, and, therefore, they are also drunk for diarrhœa. The lycapsos being more astringent, agrees in like manner with erysipelas. The onochilos (or alcibiadios) being possessed of stronger medicinal properties than these, is beneficial for the bites of vipers, when applied as a cataplasm, as an amulet, and when eaten. The fourth variety being smaller than the others, has scarcely got a name: but being more bitter than the alcibiadios, it is applicable in cases of the broad lumbricus when taken in a draught to the extent of an acetabulum.

Commentary. The first species is either the Anchusa tinctoria L., or the Lithospermum tinctorium; the lycapsos, the Echium italicum L.; the alcibiadios, the Echium diffusum, and the fourth species the Lithospermum fruticosum. There is considerable difficulty, however, in determining the alkanets of the ancients. Our author, in his account of them, follows Galen, who, in his turn, copies from Dioscorides. Avicenna, Rhases, and Haly Abbas borrow all they say of them from Dioscorides and Galen. The only one of these substances that is retained in our modern Pharmacopœias is the Anchusa tinctoria, and it is used only for colouring. The medicinal virtues of the[22] Lithospermum, or of any species of Echium, are scarcely recognized. Indeed, as the Anchusa tinctoria is retained in the modern Greek Pharmacopœia, and as it is there stated to be a common plant in Greece, we need have no hesitation in admitting it to be the common anchusa of the ancients.

Adarce is a sort of froth of salt water, collecting about rubbish and weeds. It is very acrid, and heating almost to burning when applied externally with other things; for it cannot be taken internally.

Commentary. The description of this substance given by Dioscorides, Galen, and the other authorities is substantially the same as our author’s, from which all we can gather is that it was a saline concretion formed about reeds and herbs in salt lakes. But even Matthiolus confesses that he never could satisfy himself that he had found the substance in question, and no modern authority on the Materia Medica has treated of it. Dioscorides compares it to the alcyonium, from which we think it probable that the adarce may have been applied to some species of this zoophyte. See Alcyonium. Dioscorides recommends it for the cure of lepra and sciatica (v, 136.) The Arabians borrow from him under this head. See in particular Avicenna (ii, 2, 17); Serapion (c. 378.) It is not mentioned by Celsus.

Adiantum, Maiden-hair, is desiccative, attenuant, and moderately discutient; and with regard to heat and cold, it holds an intermediate place. It, therefore, cures alopecia, discusses swellings, proves lithontriptic when taken in a draught, dries up expectorations from the lungs, and stops defluxions of the belly.

Commentary. Theophrastus says that it derives its name from its property of not being wet in rain. He adds, that it promotes the growth of the hair. (H. P. vii, 13.) Nicander says the same of it. (Ther. 846.) According to Apuleius, it is the same as the callitrichon, polytrichon, and asplenon. There can be no doubt that it is the A. Capillus Veneris L. Dioscorides describes another species by the name of τριχόμανες, which[23] Sprengel and Schneider agree in referring it to the Asplenium Trichomanes L. Stackhouse agrees with them respecting both these species. The syrup of capillaire, which still holds its place in the shops as a favorite domestic medicine, is prepared from the Adiantum.

Sempervivum, Wall-pepper (or House-leek?), of which there are two varieties. It cools in the third degree, is moderately desiccative and astringent, and is applicable for erysipelas, herpes, and inflammations from a defluxion.

Commentary. Our author, copying from Galen and Aëtius, describes two species which seem to be the Sempervivum arboreum and Sedum rupestre. Dr. Lindley, however, refers the latter to S. ochroleucum. Dioscorides has a third species, which may be referred to the Sedum stellatum. The greater house-leek is praised by Dioscorides as an application for headache, for the bites of venomous spiders, diarrhœa, and dysentery; as an anthelminthic when drunk with wine; for stopping the fluor of women in a pessary, and as an application to the eyes in ophthalmy (iv, 88, 89.) Macer Floridus commends it in menorrhagia. He calls it acidula. Serapion, Avicenna, Rhases, and Haly Abbas merely copy from the Greeks. Even Ebn Baithar has nothing original under this head. These plants, although not retained in our Dispensatory, are still allowed to possess medicinal properties. See Lindley (Veg. Kingd. 345.) It is still retained in some of the foreign Dispensatories, and is held to be refrigerant and astringent.

Ætonychon will be treated of under the head of Stones.

Pulticula, Pap, is a kind of puls fit for being supped, which is prepared from ground spelt or from any corn, and agrees with children. It answers also for cataplasms.

Commentary. Dioscorides gives the same account of it. It is the Puls fritilla of Pliny. Matthiolus says it is called bouillie in French, i. e. pap. Hesychius speaks of its being prepared from wheat, and Pliny from rice.

Ægilops, Cockle, is possessed of discutient powers, whence it cures indurated inflammations and ægilops (fistula lachrymalis.)

Commentary. There is great difficulty in determining the grasses of the ancients. This may be seen by consulting the ‘Herbal’ of Gerarde on this subject. The present article was probably the Ægilops ovata. Dioscorides gives nearly the same account of it as our author, who copies Galen. He further mentions that the juice of it, mixed up with flour and dried, was laid up for use (iv, 136.) The Arabians borrow closely from Dioscorides. See in particular Avicenna (ii, 2, 211), and Serapion (c. 25.)

Populus nigra, the Black Poplar; it is heating in the first degree, moderately desiccative, and consists of fine particles. Its leaves, when applied with vinegar, remove gouty pains; but the resin of it being hotter than the leaves, is mixed with restorative ointments and emollient plasters. But its fruit, when drunk with vinegar, is beneficial to epileptics.

Commentary. There can be no doubt that it is the Populus nigra. Our author and all the other authorities, both Greek and Arabian, copy closely from Dioscorides (i, 110.) We will have occasion to treat of its gum or resin afterwards. See Karabe. Celsus does not mention the black poplar. The αἴγειρος κρητικὴ of Hippocrates was no doubt a variety of Populus nigra. For the Arabians, consult in particular Avicenna (ii, 2, 333, 340, 364); Serapion (c. 266); and Rhases (Cont. l. ult. i, 165.)

Testiculus, the testicle of a stag, when dried and triturated with wine and drunk, is a remedy to those who have been bitten by vipers. It is also mixed with compound medicines.

Commentary. Sextus Platonicus in like manner recommends the privy parts of a stag as an antidote for poisons. All copy from Dioscorides (ii, 46.)

Salvia Æthiopis, Ethiopian Sage, has leaves like the petty-mullein; and the decoction of its root, when drunk, relieves ischiatic and pleuritic diseases, hæmoptysis, and asperity of the trachea, when taken with honey.

Commentary. It may be set down as being the Salvia Æthiopis, to which our English herbalist Gerarde gives the English name of mullein of Æthiopia. Neither Galen nor Aëtius has treated of it. Our author has borrowed from Dioscorides (iv, 193.) We do not find it in the Materia Medica of the Arabians, with the exception of Ebn Baithar, who merely gives an extract from Dioscorides under this head.

Sanguis, Blood; no kind of it is of a cold nature, but that of swine is liquid and less hot, being very like the human in temperament. That of common pigeons, the wood pigeons, and the turtle, being of a moderate temperament, if injected hot, removes extravasated blood about the eyes from a blow; and when poured upon the dura mater, in cases of trephining, it is anti-inflammatory. That of the owl, when drunk with wine or water, relieves dyspnœa. The blood of bats, it is said, is a preservative to the breasts of virgins, and, if rubbed in, it keeps the hair from growing; and in like manner also that of frogs, and the blood of the chamæleon and the dog-tick. But Galen, having made trial of all these remedies, says that they disappointed him. But that of goats, owing to its dryness, if drunk with milk, is beneficial in cases of dropsy, and breaks down stones in the kidneys. That of domestic fowls stops hemorrhages of the membranes of the brain, and that of lambs cures epilepsies. The recently coagulated blood of kids, if drunk with an equal quantity of vinegar, to the amount of half a hemina, cures vomiting of blood from the chest. The blood of bears, of wild goats, of buck goats, and of bulls, is said to ripen apostemes. That of the land crocodile produces acuteness of vision. The blood of stallions is mixed with septic medicines. The antidote from bloods is given for deadly poisons, and contains the blood of the duck, of the stag, and of the goose.

Commentary. Our author abridges this article from Galen. See also in particular Serapion (De Simpl. ex Animalibus.)

Lolium, Darnel, is heating and drying, almost in the third degree, being equal in power to the iris.

Commentary. This, which is the Zizanien of the Arabians, may be set down as the Lolium temulentum. Dioscorides gives the fullest account of its medicinal faculties; he recommends it along with radishes and salt as an application to gangrenous and spreading sores, and with sulphur and vinegar for lichen and lepra; when boiled with pigeon’s dung and linseed in wine for discussing strumous and indolent tumours; for ischiatic disease boiled with mulse and applied as a cataplasm; and used in a fumigation with myrrh, saffron, and frankincense, he says it promotes conception (ii, 122.) Aëtius says, it is more acrid but less attenuant than iris. We have not been able to find it noticed in the works of Hippocrates nor in those of Celsus. The Arabians merely copy Dioscorides and Galen. See Serapion (c. 70); and Avicenna (ii, 2, 658.) Our old English herbalists repeat the ancient characters of this plant.

is the fruit of a shrub growing in Egypt, the decoction of which is an ingredient in the Collyria, for promoting acuteness of vision.

Commentary. Galen and Aëtius have not treated of this article. Our author copies from Dioscorides, who, under the name of ἀκακαλὶς, describes it as an Egyptian plant, resembling the myrica (i, 118.) We may therefore conjecture, with considerable probability, that it is merely some species or variety of the tamarix. It does not appear that it is treated of by the Arabians, nor have we found it in the works of Hippocrates or Celsus.

Acacia is of the third order of desiccants, and of the first of cooling medicines; but if washed, of the second. It is sour and terrene.

Commentary. Dioscorides describes the acacia as being a thorny tree or shrub, not erect, having a white flower and fruit like lupine, inclosed in pods, from which is expressed the juice that is afterwards dried in the shade (i, 133.) It was much disputed among the older commentators on Dioscorides whether or not this description applies to the Acacia vera; but since the time of Prosper Alpinus, it has been generally decided in the affirmative by all scholars, with the exception of Dierbach, who contends in favour of the A. Senegal, without any good reason, as far as we can see. This gum was used medicinally by the authors of the Hippocratic collection, who prescribe it as an astringent in hemorrhages, for which purpose it is also recommended by Celsus (v. 1.) Serapion and the others merely copy from Dioscorides and Galen. See in particular Avicenna (ii, 2, 3.)

Urtica, the Nettle; the fruit and leaves are composed of fine particles, and are desiccative without pungency; they dispel and cleanse swellings, loosen the bowels, are moderately flatulent, and therefore incite to venery.

Commentary. This article is either the Urtica dioica, or the pilulifera; or both species were comprehended under it. In the modern Greek Pharmacopœia, the pilulifera stands first (p. 164.) Galen, like our author, calls it aphrodisiacal. Macer Floridus recommends it strongly as being calefacient and stimulant. Both Dioscorides and Galen agree in commending it as an expectorant when the chest is loaded with thick humours. The Arabians treat of it at considerable length. See Avicenna (ii, 2, 714); Serapion (c. 150); Rhases (Cont. l. ult.; 152.)

Acanthus, Bears-breech (called also Melamphyllon and Pæderos), has discutient and desiccative powers.

Commentary. It is the plant which our English herbalists describe by the name of Bears-breech, now called the Acanthus mollis by botanists. Dioscorides recommends it as being diuretic, and astringent of the bowels (iii, 17.) Our author follows Galen. Whether “gummi acanthinum” of[28] Celsus (v, 2) belong to this place, or not rather to the acacia, as Milligan suggests, we cannot determine for certain. Modern authorities have confirmed the characters which the ancients ascribed to it. (See Rutty, M. M. p. 70); Gray (Suppl. to Pharmacop. p. 45.)

Acanthium, is composed of fine particles, and has heating powers, therefore it is a remedy for convulsions.

Commentary. Gerarde and our other herbalists delineate and describe this plant under the name of the cotton-thistle, meaning either the Onopordon acanthium or O. Illyricum, cotton-thistle. Dioscorides affirms that it is of service to persons affected with tetanus, and upon his authority all the others, both ancient and modern, ascribe virtues to it in this case. The reader may be amused by comparing what Gerarde and Culpeper have written of it with the ancient descriptions of Dioscorides and Pliny. The cotton-thistle was long used as a potherb. See Beckmann (History of Inventions, under Artichoke); and Loudon (Encycl. of Garden, p. 736.)

Spina alba, the White-thorn. Its root is desiccative and moderately astringent, therefore it relieves stomachic complaints, hæmoptysis, and toothache; but its seed, consisting of fine particles, and being of a hot nature, when drunk relieves convulsions. Acantha Ægyptia, or Arabica, the Egyptian or Arabic thorn, is possessed of very astringent and desiccative powers. Whence it restrains a flow of blood and other discharges.

Commentary. Respecting the two thistles here described, we may refer the former, with Sibthorp, to the Cirsium Acarna, and the latter, or Arabian, to the Onopordon acanthium. All the authorities follow Dioscorides in giving its characters. (iii, 12.) See Avicenna (ii, 2, 671-3); Serapion (c. 130); Averrhoes (Collig. v, 42); Rhases (Cont. l. ult. i, 670.)

Acinus; it resembles basil, and is moderately astringent, therefore it restrains alvine and uterine discharges, when[29] taken in a draught; and when applied as a cataplasm, is of use for erysipelas and phygethlon.

Commentary. Our old herbalists describe it under the name of wild basil, meaning perhaps the Ocimum pilosum, and there seems little reason to question their authority in this instance. Neither Galen nor Serapion has described it. Indeed we are not aware that any of the Arabians has described it except Ebn Baithar (ii, 254); neither have we found it in the Hippocratic collection, nor in the works of Celsus.

Aconitum, Wolfsbane, is possessed of septic and deleterious properties; it is, therefore, not to be taken internally, but externally it may be applied to flesh requiring erosion. The lycoctonon, being possessed of the same properties as the former, is particularly fatal to wolves, as the other is to panthers.

Commentary. The two species of aconite described by Dioscorides (iv, 77), and the other authorities, are generally supposed to be the Doronicum Pardalianches and the Aconitum Napellus. In the modern Greek Pharmacopœia, the Neomontanum is substituted for the former of these. The κάμμαρον of Hippocrates would seem to be the latter. It has been already treated of among the poisonous substances in the Fifth Book (§ 45.) It was used only as an anodyne, and principally in complaints of the eyes. Avicenna in treating of the aconites, borrows closely from Dioscorides (ii, 2, 361, 676.) He says of the lycoctonon, that it is not administered either internally or externally. Rhases says of the aconite, that it was used to relieve pains of the eyes. (Cont. l. ult. i, 20.)

Acorum, Sweet Flag, heats and dries in the third degree. We use its root for a diuretic, and for scirrhus of the spleen. It also attenuates a thickened cornea.

Commentary. It appears indisputably to be the Acorus pseudacorus, as even Gerarde the old herbalist has clearly stated, and not the Acorus verus, as Dr. Hill and others have maintained. All the ancient authorities ascribe much the[30] same virtues to it as our author. See particularly Dioscorides (i, 2); Avicenna (ii, 2, 45); Rhases (Cont. l. ult. 21); Serapion (c. 269.) In the modern Greek Pharmacopœia it is identified with the κάλαμος ἁρωματικός (p. 32.)

Locustæ, Grasshoppers, in fumigations relieve dysuria, especially of women. The wingless grasshopper, when drunk in wine, relieves the bite of scorpions.

Commentary. It is quite certain that the Ἀκρὶς of the Greeks, and the Locusta of the Romans was a species of locust or grasshopper. See Harduin (ad Plin. H. N. xi, 35.) Without doubt, then, it was the Gryllus migratorius L. The wingless locusta mentioned by our author is the insect in its larvous state. Our author copies from, and abridges, Dioscorides (ii, 56); and Avicenna does the same (ii, 2, 388.) Celsus treats of the locusta only as an article of food (ii, 28.) In this way, as is well known, the locusts were much used by the ancients. They are not noticed, however, either as an article of food or of medicine in the modern Greek Pharmacopœia.

Sambucus, the Elder-tree, and Χαμαιάκτη, Sambucus humilis vel Ebulus, Dwarf-elder, are possessed of desiccative, moderately discutient and agglutinative powers. When eaten or drunk they occasion a discharge of water from the bowels.

Commentary. The two species of elder, namely, the Sambucus nigra and Ebulus, are much commended by the ancients for the cure of dropsy. As Dioscorides states, the elder is hydragogue, but disagrees with the stomach. He further recommends a hip-bath made of water in which elder has been boiled, for obstructions and hardness of the uterus (iv, 161.) Galen and the other Greek authorities treat of it in general terms like Paulus. The Arabians in treating of it generally borrow from Dioscorides and Galen. See particularly Serapion (c. 284.) It appears to be the acte of Rhases (Cont. l. ult. i, 23); and is the aktha of Ebn Baithar, according to his German translator, Dr. Sontheimer, in which opinion we fully agree with him. The Sambucus of Avicenna (ii, 2, 611) is[31] not the elder, but the jasmine. We have not been able to detect the other in his Book on the Mat. Med., but can scarcely suppose that he has entirely overlooked it.

Sales, Salts, have desiccant and astringent powers. Wherefore they consume whatever humours are in the body, and also contract by their astringency. Whence they form pickles, and preserve substances from putrefaction. Roasted salts are more discutient.

Commentary. For an account of the factitious salts of the ancients, see in particular Pliny (H. N. xxxi, 39.) Sprengel remarks that the ἅλος ἄχνη, or spuma maris, is merely the skum or down of salt, which sticks to rocks in such situations as salt is usually formed in. The ἅλος ἂνθος, or flos salis, he adds, is a very different substance, being a native, impure carbonate of soda; containing also magnesia, lime, and some terrene admixture, to which it owes its colour. When deprived of its carbonic acid it becomes caustic, and was then called ἄφρος νίτρου by the ancients (v. ἀφρόνιτρον.) The sal ammoniac of the Greeks was a native fossil salt, and considerably different from ours. Geoffroy seems to agree with Salmasius, that it was the sal gem. Dr. Hill also maintains that it was only a peculiar form of the sal gem. See also Jameson’s ‘Mineral.’ (iii, 15.) In fact, from Dioscorides’ description of the ammoniac salt, nobody can avoid seeing that it was merely a variety of the common fossil salt. He treats of the medicinal faculties of the salts at so great length that we dare not venture to copy his account of them. It is literally translated by Pliny (xxxi, 45.) He recommends them internally by the mouth and in clysters, and externally in fomentations, baths, and fumigations. Serapion quotes the whole of Dioscorides’ chapter on Salts without supplying much additional information of his own. He describes minutely the process of roasting salts in an earthen vessel, and covering them up with coals, and thus applying heat to them. The sal ammoniac he describes, from Arabian authorities, as being a white red salt, extracted from hard clear stones, and being saltish, with much pungency (c. 409.) We never could altogether satisfy ourselves whether or not this be the same as the sal[32] ammoniac of the Greeks. Rhases (Cont. l. ult. 600) and Avicenna (ii, 2, 608) are brief and indistinct in describing the sal ammoniac, but probably refer to the true sal ammoniac. Ebn Baithar minutely describes several kinds of it. Pliny also has a description of a factitious salt, which it would appear could be nothing else than our sal ammoniac. (N. H. xxxvi, 45.) Still, however, we need have no hesitation in setting down the ammoniac salt of the Greek medical authors as being a variety of the sal gem. This is the conclusion which Beckmann arrives at regarding it: he holds, however, that Geber and Avicenna were certainly acquainted with our ammoniac salt. (History of Inventions.)

Althæa or Ebiscus, Marsh-mallows, is a species of wild mallows. It is discutient, relaxant, anti-inflammatory, soothing, and ripens tumours (phymata). But the root and seed have all the other properties in a more intense degree, and are also detergent of alphos. The seed is lithontriptic.

Commentary. This must either be the Lavatera arborea or Althæa officinalis. Dioscorides is much fuller than our author in enumerating its properties, but upon the whole they agree very well as to its general character. Besides the cases in which our author recommends it, Dioscorides speaks highly of the decoction of it when drunk with wine in dysuria, the grievous pains of calculus, dysentery, and other acute affections. He also advises the mouth to be rinsed with it in cases of toothache (iii, 153.) It would be useless to go over the other authorities, who supply no new views. Even our modern herbalists all agree in repeating the praises of the marsh-mallow as delivered by Dioscorides. For the Arabians, see Avicenna (ii, 2, 72); Serapion (c. 76); Rhases (Cont. l. ult. i, 26); Averrhoes (Collig. v, 42.) This genus of the Malvaceæ does not seem to be noticed either by Hippocrates or Celsus. The Althæa officinalis occurs in the modern Greek Pharmacopœia, published at Athens in 1837.

Halimon consists of heterogeneous particles, being saltish and sub-astringent. But the greater part of it is of a hot[33] temperament, with an undigested sap. It therefore promotes the formation of milk and semen.

Commentary. Our author abridges the characters of this substance, which probably is the Atriplex Halimus, from Galen or Dioscorides (i, 126.) It is the sea-purslane of our English herbalists. For the Arabians, see particularly Avicenna (ii, 2, 470.)

Alcæa, Vervain-mallow, is a species of wild mallows. When drunk with wine it removes dysenteries and gnawing pains of the belly, more particularly its root.

Commentary. All the authorities agree in giving this article, which evidently is the Malva Alcæa, Vervain-mallow, the general characters of the mallow. See particularly Dioscorides (iii, 154.) It does not occur in the works either of Hippocrates or Celsus, nor, as far as we know, in those of the Arabians.

Alcyonia; they are detergent and discutient of all matters, being possessed of an acrid quality; but the kind called milesium (it is vermiform and purple) is the best: wherefore, when burnt, it cures alopecia, and cleanses lichen and alphos. That which has a smooth surface is most acrid, proving not only detergent, but likewise excoriating; but that which resembles unwashed wool is the weakest of all.