Title: A history of English literature

A practical text-book

Author: Edward Albert

Release date: May 10, 2023 [eBook #70731]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1923

Credits: Tim Lindell, Karin Spence. Barger Richardson Library (Oakland City University) and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Transcriber’s Note:

This work features some large and wide tables. These are best viewed

with a wide screen.

A HISTORY OF

ENGLISH LITERATURE

A PRACTICAL TEXT-BOOK

BY

EDWARD ALBERT, M.A.

GEORGE WATSON’S COLLEGE, EDINBURGH, AUTHOR OF

“A PRACTICAL COURSE IN ENGLISH”

NEW YORK

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1923

By THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

Third Printing

Printed in the United States of America

[v]

It may be of use to explain briefly the principles underlying the construction of this book.

In the first place the aim has been to make the book comprehensive. All first-class and nearly all second-class authors (so far as such classification is generally accepted) have been included. Due proportion between the two groups has been attempted by giving the more important authors greater space. The complete index should assist in making the book a handy volume of reference as well as a historical sketch.

In accordance with the plan of making the volume as comprehensive as possible, a chapter has been added dealing with modern writers. An attempt of this kind has certain obvious drawbacks; but it has at least the double advantage of demonstrating the living nature of our literature, and of setting modern authors to scale against the larger historical background.

Secondly, the endeavor has been to make the book practical. Discussion has been avoided; facts, so far as they are known and verifiable, are simply stated; dates are quoted whenever it is possible to do so, and where any doubt exists as to these the general opinion of the best authorities has been taken; there are frequent tabulated summaries to assist the mind and eye; and, lastly, there are the exercises.

It would be as easy to overpraise as it is to underestimate the value of the exercises. But in their favor one can at least point out that they enable the student to work out for himself some simple literary and historical problems; that they supply a collection of obiter dicta by famous critics; and that they are a storehouse of many[vi] additional extracts. The index to all the extracts in the book should assist the student in locating every quotation from any writer he may have in view.

While he has never neglected the practical aspect of his task, the writer of the present work has never been content with a bleak summary of our literary history. It has been his ambition to set out the facts with clearness, vivacity, and some kind of literary elegance. How far he has succeeded the reader must judge.

The use of the Bibliography (Appendix II) is strongly urged upon all readers. Such a book as the present cannot avoid being fragmentary and incomplete. The student should therefore pursue his inquiries into the volumes mentioned in the Appendix. Owing to the restrictions of space, the Bibliography is small. But all the books given are of moderate price or easily accessible. Moreover, they have been tested by repeated personal use, and can be recommended with some confidence.

There remains to set on record the author’s gratitude to his colleagues and good friends, for their skill and good-nature in revising the manuscript and in making many excellent suggestions.

E. A.

Edinburgh

[vii]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | The Old English Period | 1 |

| II. | The Middle English Period | 15 |

| III. | The Age of Chaucer | 32 |

| IV. | From Chaucer to Spenser | 57 |

| V. | The Age of Elizabeth | 87 |

| VI. | The Age of Milton | 159 |

| VII. | The Age of Dryden | 190 |

| VIII. | The Age of Pope | 231 |

| IX. | The Age of Transition | 281 |

| X. | The Return to Nature | 362 |

| XI. | The Victorian Age | 451 |

| XII. | The Post-Victorian Age | 518 |

| General Questions and Exercises | 562 | |

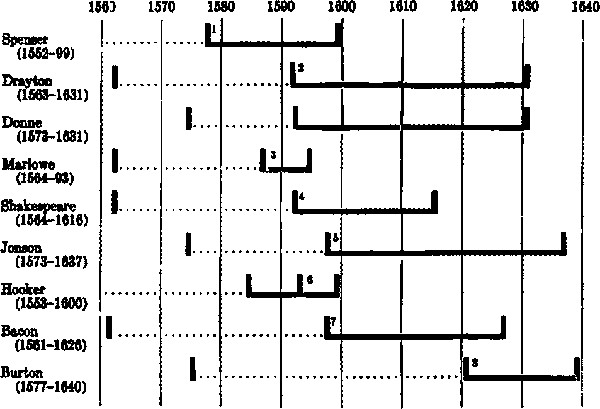

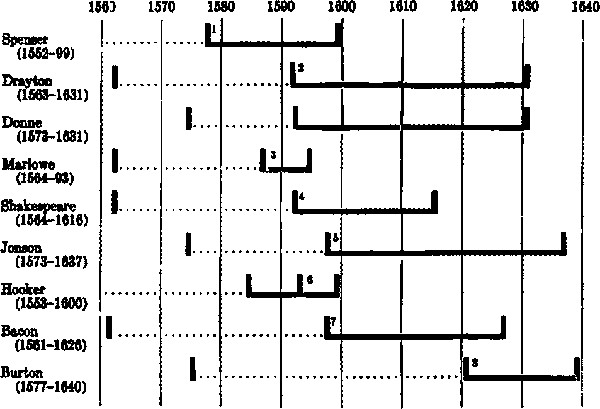

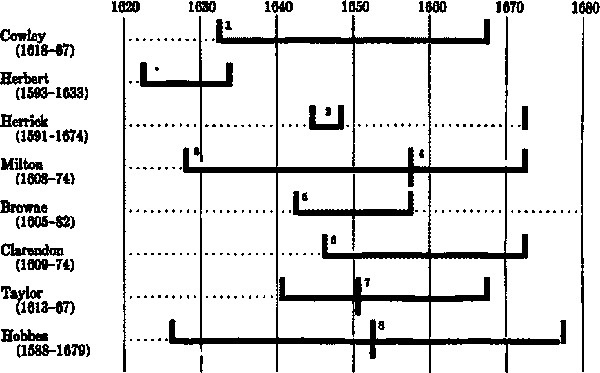

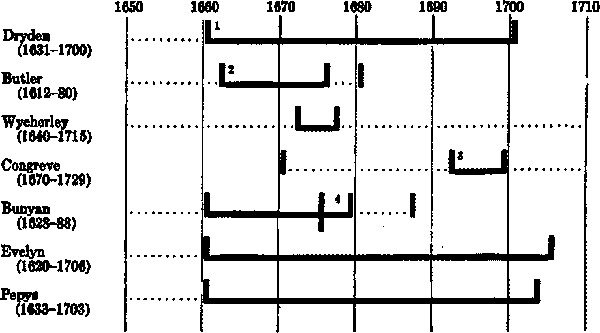

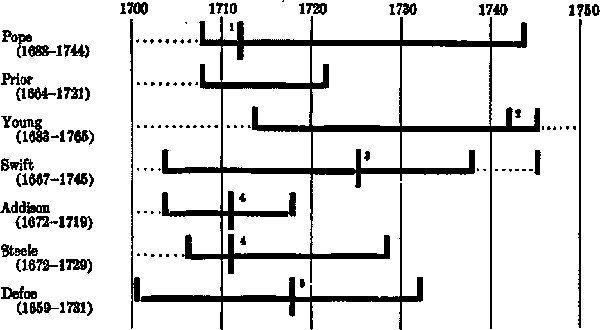

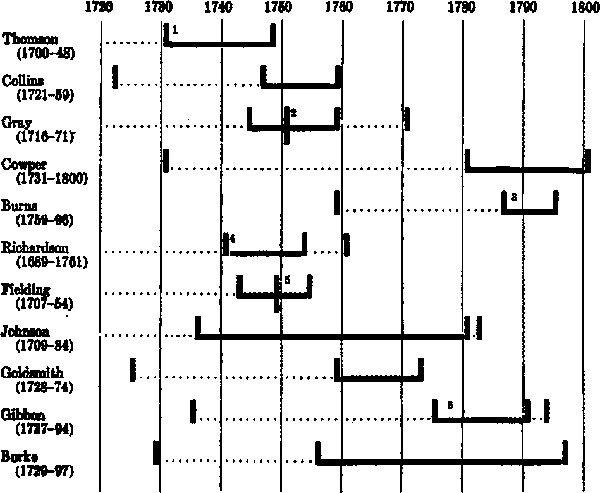

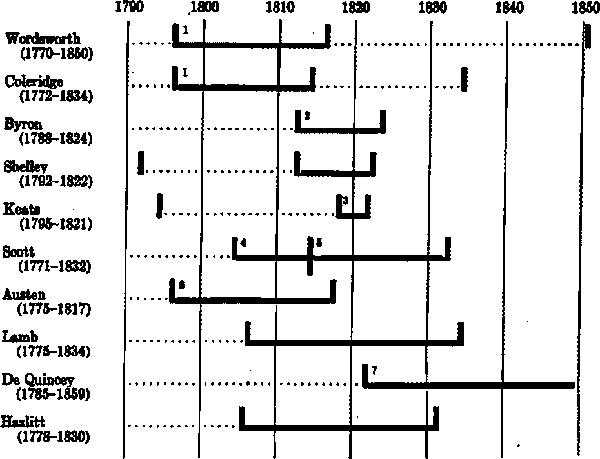

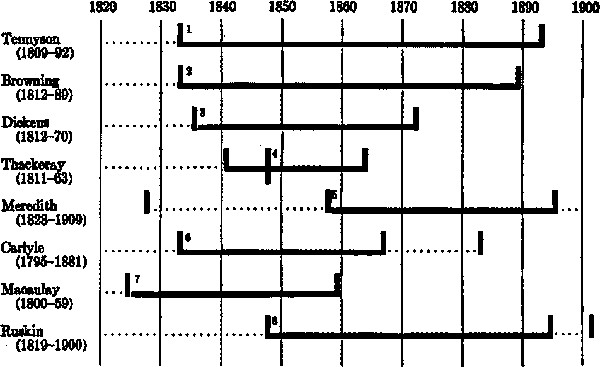

| Appendix I: General Tables | 581 | |

| Appendix II: Bibliography | 591 | |

| Index to Extracts | 601 | |

| General Index | 607 |

[viii]

Permissions to use copyrighted material have been courteously granted by the following American publishers:

Brentano’s, Inc. for the right to print extracts from the works of Bernard Shaw; E. P. Dutton & Company for Siegfried Sassoon; Duffield & Company for H. G. Wells; Dodd Mead & Company for Rupert Brooke; Harper & Brothers for Thomas Hardy; John W. Luce & Company for J. M. Synge; and Charles Scribner’s Sons for John Galsworthy, and R. L. Stevenson.

We have also obtained from the literary agents of Rudyard Kipling, Joseph Conrad, and J. E. Flecker, permission to use the selections included from these authors. To all the above we wish to express our acknowledgment and thanks.

[1]

A HISTORY OF ENGLISH LITERATURE

Of the actual facts concerning the origin of English literature we know little indeed. Nearly all the literary history of the period, as far as it concerns the lives of actual writers, is a series of skillful reconstructions based on the texts, fortified by some scanty contemporary references (such as those of Bede), and topped with a mass of conjecture. The results, however, are astonishing and fruitful, as will be seen even in the meager summary that appears in the following pages.

The period is a long one, for it starts with the fifth century and concludes with the Norman Conquest of 1066. The events, however, must be dismissed very quickly. We may begin in 410 with the departure of the Romans, who left behind them a race of semi-civilized Celts. The latter, harassed by the inroads of the savage Caledonians, appealed for help to the adventurous English. The English, coming at first as saviors, remained as conquerors (450–600). In the course of time they gained possession of nearly all the land from the English Channel to the Firth of Forth. Then followed the Christianizing of the pagan English, beginning in Kent (597), a movement that affected very[2] deeply all phases of English life. In succession followed the inroads of the Danes in the ninth century; the rise of Wessex among the early English kingdoms, due in great measure to the personality of King Alfred, who compromised with the Danes by sharing England with them (878); the accession of a Danish dynasty in England (1017); and the Gallicizing of the English Court, a process that was begun before the Conquest of 1066. All these events had their effect on the literature of the period.

1. Pagan Origins. The earliest poems, such as Widsith and Beowulf, present few Christian features, and those that do appear are clearly clumsy additions by later hands. It is fairly certain, therefore, that the earliest poems came over with the pagan conquerors. They were probably the common property of the bards or gleemen, who sang them at the feasts of the warriors. As time went on Christian ideas were imposed upon the heathen poetry, which retained much of its primitive phraseology.

2. Anonymous Origins. Of all the Old English poets, we have direct mention of only one, Cædmon. The name of another poet, Cynewulf, obscurely hinted at in three separate runic or riddling verses. Of the other Old English poets we do not know even the names. Prose came much later, and, as it was used for practical purposes, its authorship is in each case established.

3. The Imitative Quality. Nearly all the prose, and the larger part of the poetry, consists of translations and adaptations from the Latin. The favorite works for translation were the lives of saints, the books of the Bible, and various works of a practical nature. The clergy, who were almost the sole authors, had such text-books at hand, and were rarely capable of reaching beyond them. This secondhand nature of Old English is certainly its most disappointing feature. In most cases the translations are feebly imitative; in a few cases the poets (such as Cynewulf) or the prose-writers (such as Alfred) alter, expand, or comment[3] upon their Latin originals, and then the material is of much greater literary importance.

4. The Manuscripts. It is very likely that only a portion of Old English poetry has survived, though the surviving material is quite representative. The manuscripts that preserve the poetical texts are comparatively late in their discovery, are unique of their kind, and are only four in number. They are (a) the Beowulf manuscript (containing also a portion of a poem Judith), discovered in 1705, and said to have been written about the year 1000; (b) the Junian manuscript, discovered in 1681 by the famous scholar Junius, and now in the Bodleian Library, containing the Cædmon poems; (c) the Exeter Book, in the Exeter Cathedral library (to which it was given by Leofric about 1050, being brought to light again in 1705), which preserves most of the Cynewulf poems; and (d) the Vercelli Book, discovered at Vercelli, near Milan, in 1832, which contains, along with some prose homilies, six Old English poems, including Andreas and Elene.

The Old English language was that of a simple and semi-barbarous people: limited in vocabulary, concrete in ideas, and rude and forcible in expression. In the later stages of their literature we see the crudeness being softened into something more cultured. In grammar the language was fairly complicated, possessing declinable nouns, pronouns, and adjectives, and a rather elaborate verb-system. There were three chief dialects: the Northern or Northumbrian, which was the first to produce a literature, and which was overwhelmed by the Danes; the West Saxon, a form of the Mercian or Midland, which grew to be the standard, as nearly all the texts are preserved in it; and the Kentish or Jutish, which is of little literary importance.

1. Origin of the Poem. It is almost certain that the poem originated before the English invasions. There is[4] no mention of England; Beowulf himself is the king of the “Geatas.” The poem, moreover, is pagan in conception, and so antedates the Christian conversion. With regard to the actual authorship of the work there is no evidence. It is very likely that it is a collection of the tales sung by the bards, strung together by one hand, and written in the West Saxon dialect.

2. The Story. There are so many episodes, digressions, and reversions in the story of Beowulf that it is almost impossible to set it down as a detailed consecutive narrative. Putting it in its very briefest form, we may say that Beowulf, son of Ecgtheow, and king of the Geatas, sails to Denmark with a band of heroes, and rids the Danish King Hrothgar of a horrible mere-monster called Grendel. The mother of Grendel meets with the same fate, and Beowulf, having been duly feasted and rewarded, returns to his native land. After a prosperous reign of forty years Beowulf slays the dragon that ravishes his land, but himself receives a mortal wound. The poem concludes with the funeral of the old hero.

3. The Style. We give a short extract, along with a literal translation, to illustrate the style. The short lines of the poem are really half-lines, and in most editions they are printed in pairs across the page. The extract deals with Beowulf’s funeral rites:

| Him ðá ge-giredan | For him then did the people of the |

| Geáta leóde | Geáts prepare |

| Âd on eorðan | Upon the earth |

| Un-wác-lícne | A funeral pile, strong, |

| Helm-be-hongen | Hung round with helmets, |

| Hilde-bordū | With war-boards and |

| Beorhtū byrnū | Bright byrnies[1] |

| Swá he béna wæs | As he had requested. |

| Ā-legdon ðá to-middes | Weeping the heroes |

| Máerne þeóden | Then laid down |

| Hæleð hiófende | In the midst |

| Hláf-ord leófne | Their dear lord; |

| On-gunnon ðá on beorge | Then began the warriors[5] |

| Bæl-fýra mæst | To wake upon the hill |

| Wigend weccan | The mightiest of bale-fires; |

| Wu [du-r] êc á-stáh | The wood smoke rose aloft, |

| Sweart of swicðole | Dark from the wood-devourer;[2] |

| Swógende let | Noisily it went, mingled |

| [Wópe] be-wunden | With weeping; the mixture |

| Wind-blond ğ-læg | Of the wind lay on it |

| Oð that he tha bàn-hús | Till it the bone-house |

| Ge-brocen hæfd[e] | Had broken, |

| Hat on hreðre | Hot in his breast: |

| Higū un-róte | Sad in mind, |

| Mód-ceare mændon | Sorry of mood they moaned |

| Mod-dryhtnes [cwealm]. | The death of their lord. |

It will be observed that the language is abruptly and rudely phrased. The half-lines very frequently consist of mere tags or, as they are called, kennings. Such conventional phrases were the stock-in-trade of the gleemen, and they were employed to keep the narrative in some kind of motion while the invention of the minstrel flagged. At least half of the lines in the extract are kennings—beorhtū byrnū, hláf-ord leófne, higū un-róte, and so on. Such phrases occur again and again in Old English poetry. It will also be observed that the lines are strongly rhythmical, but not metrical; and that there is a system of alliteration, consisting as a rule of two alliterated sounds in the first half-line and one in the second half-line.

With regard to the general narrative style of the poem, there is much primitive vigor in the fighting, sailing, and feasting; a deep appreciation of the terrors of the sea and of other elemental forces; and a fair amount of rather tedious repetition and digression. Beowulf, in short, may be justly regarded as the expression of a hardy, primitive, seafaring folk, reflecting their limitations as well as their virtues.

1. The Pagan Poems. The bulk of Old English poetry is of a religious cast, but a few pieces are distinctly secular.

[6]

(a) Widsith (i.e., “the far traveler”) is usually considered to be the oldest poem in the language. It consists of more than a hundred lines of verse, in which a traveler, real or imaginary, recounts the places and persons he has visited. Since he mentions several historical personages, the poem is of much interest, but as pure poetry it has little merit.

(b) Waldhere (or Walter) consists of two fragments, sixty-eight lines in all, giving some of the exploits of a famous Burgundian hero. There is much real vigor in the poem, which ranks high among its fellows.

(c) The Fight at Finnesburgh, a fragment of fifty lines, contains a finely told description of the fighting at Finnesburgh.

(d) The Battle of Brunanburgh is a spirited piece on this famous fight, which took place in 937. The poem has much more spirit and originality than usual, contains some fine descriptions, and forces the narrative along at a comparatively fast pace.

(e) The Battle of Maldon is a fragment, but of uncommon freshness and vivacity. The battle occurred in 993, and the poem seems to be contemporary with the event.

2. The Dramatic Monologues. These poems, which are called The Wanderer, The Seafarer, Deor’s Complaint, The Wife’s Complaint, The Husband’s Message, and Wulf and Eadwacer, appear in the Exeter Book. It is unlikely that they were composed at the same time, but they are alike in a curious meditative pathos. In Old English literature they come nearest to the lyric. As poetry, they possess the merit of being both original and personal, qualities not common in the poems of the period.

3. The Cædmon Group. In his Historia Ecclesiastica Bede tells the story of a herdsman Cædmon, who by divine inspiration was transformed from a state of tongue-tied ineffectiveness into that of poetical ecstasy. He was summoned into the presence of Hilda of Whitby, who was abbess during the years 658–80. He was created a monk,[7] and thereafter sang of many Biblical events. On a blank page of one of the Bede manuscripts there is quoted the first divinely inspired hymn of Cædmon, a rude and distinctly uninspired fragment of poetry, nine lines in all, composed in the ancient Northumbrian dialect.

That is all we know of the life and works of Cædmon; but in the Junian manuscript a series of religious paraphrases was unearthed in the year 1651. In subject they corresponded rather closely to the list set out by Bede, and in a short time they were ascribed to Cædmon. The poems consist of paraphrases of Genesis, Exodus, and Daniel and three shorter poems, the chief of which is the Harrowing of Hell. Modern scholarship now recognizes that the poems are by different hands, but the works can be conveniently lumped together under the name of the shadowy Northumbrian. The poems appear in the West Saxon dialect, in spite of the fact that Cædmon must have written in his own dialect; but the difficulty is overcome by pointing out that a West Saxon scribe might have copied the poems.

In merit the poems are unequal. At their best they are not sublime poetry, but they are strong and spirited pieces with some aptitude in description. On the average they are trudging mediocrities which are frequently prosaic and dull.

4. The Cynewulf Group. In 1840 the scholar Kemble lighted upon three runic (or pre-Roman) signatures which appeared respectively in the course of the poems called Christ and Juliana (in the Exeter Book) and Elene (in the Vercelli Book). The signatures read “Cynewulf” or “Cynwulf.” In 1888 a signature “Fwulcyn” was discovered in The Fates of the Apostles. This is all we know of Cynewulf, if we accept the quite general personalities that appear in the course of the poems. Yet an elaborate life has been built up for the poet, and other poems, similar in style to the signed pieces, have been attributed to him. The Phœnix, The Dream of the Rood, and the Riddles of the Exeter Book are the most considerable of the additional poems.

[8]

The Cynewulfian poems are much more scholarly compositions than the Beowulf or even the Cædmon poems. There is a greater power of expression, less reliance on the feeble kenning, and some real expertness in description. The ideas expressed in the poems are broader and deeper, and a certain lyrical fervor is not wanting. The date is probably the tenth century.

1. Alfred (848–900). Though there were some prose writings of an official nature (such as the laws of Ine, who died about 730) before the time of Alfred, there can be little objection to the claim frequently made for him, that he is “the father of English prose.” As he tells us himself in his preface to the Pastoral Care, he was driven into authorship by the lamentable state of English learning, due in large measure to the depredations of the Danes. Even the knowledge of Latin was evaporating, so the King, in order to preserve some show of learning among the clergy, was compelled to translate some popular monastic handbooks into his own tongue. These works are his contribution to our literature. As he says, they were often “interpreted word for word, and meaning for meaning”; but they are made much more valuable by reason of the original passages freely introduced into them. The books, four in number, are an able selection from the popular treatises of the day: the Universal History of Orosius; the Ecclesiastical History of Bede; the Pastoral Care of Pope Gregory; and the Consolation of Philosophy of Boëthius. His claim to the translation of Bede is sometimes disputed; and there is a fifth work, a Handbook or commonplace book, which has been lost. The chronological order of the translations cannot be determined, but they were all written during the last years of the reign.

We add a brief extract to illustrate his prose style. It is not a highly polished style; it is rather that of an earnest but somewhat unpracticed writer. When it is simplest[9] it is best; in its more complicated passages it is confusing and involved. The vocabulary is simple and unforced.

| Swa clæne heo wæs oðfeallen on Angelcynne [-þ] swiðe feawa wæron be-heonan Humbre þe hira þe-nunge cuðon understanden on Englisc, oððe furðon an ærend-ge-writ of Ledene on Englisc areccan; and ic wene [-þ] naht monige be-geondan Humbre næron. Swa feawa heora wæron [-þ] ic furbon anne ænlepne ne mæg geþencan be-suðan Thamise þa þa ic to rice feng. Gode Ælmightigum sy þanc, [-þ] we nu ænigne an steal habbað lareowa. For þam ic þe beode, [-þ] þu do swa ic gelyfe [-þ] þu wille. | So clean [completely] has ruin fallen on the English nation, that very few were there this side the Humber that could understand their service in English or declare forth an Epistle [an errand-writing] out of Latin into English; and I think that not many beyond Humber were there. So few such were there, that I cannot think of a single one to the south of the Thames when I began to reign. To God Almighty be thanks, that we now have any to teach in stall [any place]. Therefore I bid thee that thou do as I believe that thou wilt. |

| Preface to “Pastoral Care” |

2. Ælfric (955–1020) is known as “the Grammarian.” Of his life little is known. It is probable that he lived near Winchester, and he was certainly the first abbot of Eynsham, near Oxford, in 1006. A fair number of his works, both in Latin and English, have come down to us. Of his English books, two series of homilies, adapted from the Latin, seem to have been composed about the year 990. A third series of homilies, called The Lives of the Saints, is dated approximately at 996. Several of his pastoral letters survive, as well as a translation of Bede’s De Temporibus and some English translations of Biblical passages.

Ælfric’s style is interesting, for it is representative of the scholarly prose of his time, a century after Alfred. It is flowing and vigorous, showing an almost excessive use of alliteration. In many cases it suggests a curious hybrid between the poetry and prose of the period.

3. Wulfstan was Archbishop of York from 1003 till his death in 1023. In his prose, which survives in more than[10] fifty homilies and in his famous Letter to the English People (Lupi Sermo ad Anglos), he shows the effects of “style” to a marked degree. His Letter in particular is a fervid epistle, detailing with considerable power and fluency the dreadful plight of the English nation in the year 1014. The alliteration and rhythm are exceedingly well marked, much more so than in the case of Ælfric.

4. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was probably inspired by King Alfred, who is said even to have dictated the entries dealing with his own campaigns. The Chronicle has come down to us in four versions, all of which seem to have sprung from a common stock. The four versions are preserved in seven manuscripts, of which the most notable are those connected with Canterbury and Peterborough. From the period of the English invasions till the year 892 the books are fairly in accord. At the latter year they diverge. Each introduces its local events and miscellaneous items of news, and they finish at different dates. The last date of all is about the middle of the twelfth century.

The style of the Chronicle varies greatly; it ranges from the baldest notes and summaries to quite ambitious passages of narrative and description. Of the latter class the well-known passage on the horrors of Stephen’s reign is a worthy example. We give a brief extract, dated 1100, just at the close of the Old English period, which is a fair average of the different methods:

| On þisum geare aras seo ungeþwærnes on Glæstinga byrig betwyx þam abbode Ðurstane and his munecan. Ærest hit com of þæs abbotes unwisdome [-þ] he misbead his munecan on fela thingan, and þa munecas hit mændon lufelice to him and beadon hine [-þ] he [`s]ceolde healdan hi rihtlice beon and lufian hi, and hi woldon him beon holde and gehyrsume. | In the year arose the discord in Glastonbury betwixt the Abbot Thurstan and his monks. First it came from the Abbot’s unwisdom: In that he mis-bade [ruled] his monks in many things and the monks meant it lovingly to him and bade him that he should hold [treat] them rightly and love them and they would be faithful to him and hearsome [obedient]. |

[11]

From the time when it first appears till it is swamped by the Norman Conquest Old English literature undergoes a quite noticeable development. In the mass the advance appears to be considerable, but when we reflect that it represents the growth of some five hundred years, we see that the rate of progress is undoubtedly slow. We shall take the poetical and prose forms separately.

1. Poetry. Poetry is much earlier in the field, and its development is the greater. It begins with the rude forms of Beowulf and concludes with the more scholarly paraphrases of Cynewulf.

(a) The epic in its untutored form exists in Beowulf. This poem lacks the finer qualities of the epic: it is deficient in the strict unity, the high dignity, and the broad motive of the great classical epic; but a crude vigor and a certain rude majesty are not wanting. It is no mean beginning for the English epic. The later poems of the Cædmon and Cynewulf types are too discursive and didactic to be epics, though in places they are like The Battle of Maldon and The Fight at Finnesburgh in their narrative force.

(b) The lyric—that is, the short and passionate expression of a personal feeling—hardly exists at all. The nearest approach to it lies in the dramatic monologues, such as Deor’s Complaint. These poems are too long and diffuse to be real lyrics, but they have some of the expressive melancholy and personal emotion of the lyric.

2. Prose. The great bulk of Old English prose consists of translation; and in its various shapes English prose adopts the methods of its originals. We have many homilies, some history, and a few pastoral letters, all based strictly upon Latin works. There are very few passages of real originality, and they are short and disjointed. Of historical writing we have the rudiments in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. On the whole, the development is very small, for the prose is bound by the curse of imitativeness.

[12]

1. Poetry. We have once more to distinguish between the earlier Beowulf stage and the later Cynewulf stage. In the earlier period the style is more disjointed, abrupt, and digressive, and is weighted down by the reliance upon the kenning. In the later stage there is greater passion and insight, less reliance upon the stock phrases, and a greater desire for stylistic effects.

2. Prose. In spite of its limited scope, Old English prose shows quite an advance in style. The earlier style, represented by the prose of Alfred, is rather halting and unformed, the sentences are loosely knit, the vocabulary is meager, and there is an absence of the finer qualities of rhythm and cadence. By the time of Wulfstan the prose has gained in fluency. It is much more animated and confident, and it freely employs alliteration and the commoner rhetorical figures.

But within this development both of prose and poetry there was already the seed of decay. During the last century of the period the poetical impulse was weakening; there is little verse after the time of Cynewulf. The prose too was failing, and the language was showing symptoms of weakness. The inflections were loosening even before the Norman Conquest, and the Old English vocabulary was being subtly Gallicized. The Norman Conquest was in time to put an abrupt finish to a process already well advanced.

1. Examine the style of the following poetical passages. Point out examples of kennings, and mention the purposes they serve. Comment upon the type of sentence, the use of alliteration, and the nature of the vocabulary. Compare the style with that of the Beowulf extract given on page 4.

| (1) Us is riht micel, | For us it is much right |

| That we rodera weard, | That we the Guardian of the skies, |

| Wereda wuldor-cining, | The glory-King of hosts,[13] |

| Wordum herigen | With our words praise, |

| Modum lufien. | In our minds love. |

| He is mægna sped, | He is of power the essence, |

| Heofod ealra | The head of all |

| Heah-gesceafta, | Exalted creatures, |

| Fréa Ælmīhtig. | The Lord Almighty. |

| Næs him fruma æfre | To him has beginning never |

| Ór geworden | Origin been, |

| Ne nu ende cymth | Nor now cometh end |

| Écean drihtnes, | To the eternal Lord, |

| Ac he bíth á ríce | But he is ever powerful |

| Ofer heofen-stolas. | Over the heavenly thrones. |

| Cædmon. |

| (2) Nis tháer on thám lande | There in that land is not |

| Láth geníthle, | Harmful enmity, |

| Ne wop ne wracu, | Nor wail nor vengeance, |

| Weá-tácen nán, | Evil-token none, |

| Yldu ne yrmthu, | Old age nor poverty, |

| Ne se enga death, | Nor the narrow death, |

| Ne lífes lyre, | Nor loss of life, |

| Ne láthes cyme, | Nor coming of harm, |

| Ne syn ne sacu, | Nor sin nor strife, |

| Ne sár-wracu, | Nor sore revenge, |

| Ne wædle gewin, | Nor toil of want, |

| Ne wélan ansýn, | Nor desire of wealth, |

| Ne sorg ne sláep, | Nor care nor sleep, |

| Ne swar leger, | Nor sore sickness, |

| Ne winter-geweorp, | Nor winter-dart, |

| Ne weder-gebregd | Nor dread of tempest |

| Hreóh under heofonum. | Rough under the heavens. |

| The Phœnix. |

2. Comment briefly upon the style of the following prose extract. How does it compare with modern English prose?

| Ðu bæde me for oft engliscera gewritena. And ic þe ne getiðode ealles swa timlice ær ðam þe þu mid weorcum þæs gewilnodest æt me þa ða þu me bæde for Godes lufon georne [-þ] ic þe æt ham æt þinum huse gespræce. And pu ða swiðe mændest þa þa ic mid þe wæs [-þ] þu mine gewrita begitan ne mihtest. Nu wille ic [-þ] þu hæbbe huru þis litle nu ðe wisdom gelicað. And pu hine habban wilt [-þ] þu ealles ne beo minra boca bedæled. God luvað pa godan weorce and he wyle big habban æt us. | Thou hast oft entreated me for English Scripture, and I gave it thee not so soon, but thou first with deeds hast importuned me thereto; at what time thou didst so earnestly pray me for God’s love that I should speak to thee at thy house at home, and when I was with thee great moan thou madest that thou couldst get none of my writings. Now will I that thou have at least this little, sith knowledge is so acceptable unto thee: and thou wilt have it rather than be altogether without my books. God loveth good deeds and will have them at our hands [of us].[14] |

| Ælfric, Introduction to the Old Testament | |

3. What appears to you to be the reasons why in Old English poetry appears before prose?

4. Mention some of the effects of translation upon both the poetry and the prose of the Old English.

5. “Old English prose is much nearer modern English prose than Old English poetry is to modern English poetry.” Discuss this statement.

[15]

The extensive period covered by this chapter saw many developments in the history of England: the establishment of Norman and Angevin dynasties; the class-struggle between king, nobles, clergy, and people; and the numerous wars against France, Scotland, and Wales. But, from the literary point of view, much more important than definite events were the general movements of the times: the rise of the religious orders, their early enthusiasm, and their subsequent decay; the blossoming of chivalry and the spirit of romance, bringing new sympathy for the poor and for womankind; the Crusades, and the widening of the European outlook which was gradually to expand into the rebirth of the intellect known as the Renaissance. All these were only symptoms of a growing intelligence that was strongly reflected in the literature of the time.

This period witnesses the disappearance of the pure Old English language and the emergence of the mixed Anglo-French or Middle English speech that was to be the parent of modern English. As a written language Old English disappears about 1050, and, also as a written language, Middle English first appears about the year 1200. With the appearance of the Brut about 1200 we have the beginning of the numerous Middle English texts, amply illustrating the changes that have been wrought in the interval: the loss of a great part of the Old English vocabulary; a great and growing inrush of French words; the confusion, crumbling, and ultimate loss of most of the old inflections;[16] and the development of the dialects. There are three main dialects in Middle English: the Northern, corresponding to the older Northumbrian; the Midland, corresponding to Mercian; and the Southern, corresponding to the Old English Kentish or Southern. None of the three can claim the superiority until late in the period, when the Midland gradually assumes a slight predominance that is strongly accentuated in the period following.

The latter part of the three hundred years now under review provides a large amount of interesting, important, and sometimes delightful works. It is, however, the general features that count for most, for there is hardly anything of outstanding individual importance.

1. The Transition. The period is one of transition and experiment. The old poetical methods are vanishing, and the poets are groping after a new system. English poets had two models to follow—the French and the Latin, which were not entirely independent of each other. For a time, early in the period, the French and Latin methods weighed heavily upon English literature; but gradually the more typically native features, such as the systematic use of alliteration, emerge. It is likely that all the while oral tradition had preserved the ancient methods in popular songs, but that influence was slight for a long period after the Norman Conquest.

2. The anonymous nature of the writing is still strongly in evidence. A large proportion of the works are entirely without known authors; most of the authors whose names appear are names only; there is indeed only one, the Hermit of Hampole, about whom we have any definite biographical detail. There is an entire absence of any outstanding literary personality.

3. The Domination of Poetry. The great bulk of the surviving material is poetry, which is used for many kinds of miscellaneous work, such as history, geography, divinity,[17] and rudimentary science. Most of the work is monastic hack-work, and much of it is in consequence of little merit.

Compared with poetry of the period, the prose is meager in quantity and undeveloped in style. The common medium of the time was Latin and French, and English prose was starved. Nearly all the prose consists of homilies, of the nature of the Ancren Riwle; and most of them are servile translations from Latin, and destitute of individual style.

For the sake of convenience we can classify the different poems into three groups, according to the nature of their subjects.

1. The Rhyming Chronicles. During this period there is an unusual abundance of chronicles in verse. They are distinguished by their ingenuous use of incredible stories, the copiousness of their invention, and in no small number of cases by the vivacity of their style.

(a) The Brut. This poem was written by a certain Layamon about the year 1205. We gather a few details about the author in a brief prologue to the poem itself. He seems to have been a monk in Gloucestershire; his language certainly is of a nature that corresponds closely to the dialect of that district. The work, thirty thousand lines in length, is a paraphrase and expansion of the Anglo-Norman Brut d’Angleterre of Wace, who in turn simply translated from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Latin history of Britain. In the Brut the founder of the British race is Brutus, great-grandson of Æneas of Troy. Brutus lands in England, founds London, and becomes the progenitor of the earliest line of British kings. In style the poem is often lifeless, though it has a naïve simplicity that is attractive. The form of the work, however, is invaluable as marking the transition from the Old English to the Middle English method.

Alliteration, the basis of the earlier types, survives in a casual manner; at irregular intervals there are rudely[18] rhyming couplets, suggesting the newer methods; the lines themselves, though they are of fairly uniform length, can rarely be scanned; the basis of the line seems to be four accents, occurring with fair regularity. The following extract should be scrutinized carefully to bring out these features:

| To niht a mine slepe, | At night in my slepe |

| Their ich læi on bure, | Where I lay in bower [chamber] |

| Me imæette a sweuen; | I dreamt a dream— |

| Ther oure ich full sari æm. | Therefore I full sorry am. |

| Me imætte that mon me hof | I dreamt that men lifted me |

| Uppen are halle. | Up on a hall; |

| Tha halle ich gon bestriden, | The hall I gan bestride, |

| Swulc ich wolde riden | As if I would ride; |

| Alle tha lond tha ich ah | All the lands that I owned, |

| Alle ich ther ouer sah. | All I there overlooked. |

| And Walwain sat biuoren me; | And Walwain sate before me; |

| Mi sweord he bar an honde. | My sword he bare in hand. |

| Tha com Moddred faren ther | Then approached Modred there, |

| Mid unimete uolke. | With innumerable folk. |

(b) Robert of Gloucester is known only through his rhyming history. From internal evidence it is considered likely that he wrote about 1300. From his dialect, and from local details that he introduces into the poem, it is probable that he belonged to Gloucestershire. Drawing largely upon Layamon, Geoffrey of Monmouth, and other chroniclers, he begins his history of England with Brutus and carries it down to the year 1270. The style of the poem is often lively enough; and the meter, though rough and irregular, often suggests the later “fourteener.” As a rule the lines are longer than those of the Brut, and the number of accents is greater.

(c) Robert Manning (1264–1340) is sometimes known as Robert of Brunne, or Bourne, in Lincolnshire. In 1288 he entered a Gilbertine monastery near his native town. His Story of Ingelond (1338) begins with the Deluge, and traces the descent of the English kings back to Noah. The latter portion of the book is based upon the work of[19] Pierre de Langtoft, and the first part upon Wace’s Brut. The meter is a kind of chaotic alexandrine verse; but an interesting feature is that the couplet rhymes are carefully executed, with the addition of occasional middle rhymes.

Manning’s Handlyng Synne (1303) is a religious manual based on a French work, Manuel des Pechiez. The poem, which is thirteen thousand lines in length, is a series of metrical sermons on the Ten Commandments, the Seven Deadly Sins, and the Seven Sacraments. The author knows how to enliven the work with agreeable anecdotes, and there are signs of a keen observation. The meter is an approximation to the octosyllabic couplet.

Manning’s language is of importance because it marks a close approach to that of Chaucer: a comparative absence of old words and inflections, a copious use of the later French terms, and the adoption of new phrases.

(d) Laurence Minot, who probably flourished about 1350, appears as the author of eleven political songs, which were first published in 1795. The pieces, which sing of the exploits of Edward III, are violently patriotic in temper, and have a rudely poetical vigor. Their meters are often highly developed.

2. Religious and Didactic Poetry. Like most of the other poetry of the period, this kind was strongly imitative, piously credulous, and enormous in length.

(a) The Ormulum, by a certain Orm, or Ormin, is usually dated at 1200. As it survives it is an enormous fragment, twenty thousand lines in length, and composed in the East Midland dialect. It consists of a large number of religious homilies addressed to a person called Walter. Of poetical merit the poem is destitute; but it is unique in the immense care shown over a curious and complicated system of spelling, into which we have not the space to enter. Its metrical form is noteworthy: a rigidly iambic measure, rhymeless, arranged in alternate lines of eight and seven syllables respectively. This regularity of meter is another unique feature of the poem, which we illustrate by an extract:

[20]

| An Romanisshe Kaserrking | A Roman Kaiser-king |

| Wass Augusstuss [gh]ehatenn | Was called Augustus |

| And he wass wurrthenn Kaserrking | And he became Kaiser-king |

| Off all mannkinn onn eorthe, | Of all mankind on earth, |

| And he gann thenkenn off himmsellf | And he gan think of himself |

| And off hiss micle riche. | And of his muckle kingdom, |

| And he bigann to thenkenn tha, | And he began to think |

| Swa summ the goddspell kithethth | Just as the gospel tells |

| Off thatt he wollde witenn wel | Of what he would well know |

| Hu mikell fehh himm come, | How much money [fee] would come to him |

| [GH]iff himm off all hiss kinedom. | If to him of all his kingdom |

| Illc mann an penning [gh]æfe. | Each man a penny gave. |

(b) The Owl and the Nightingale, the date of which is commonly given as 1250, is attributed to Nicholas of Guildford. The poem consists of a long argument between the nightingale, representing the lighter joys of life, and the owl, which stands for wisdom and sobriety. The poem is among the most lively of its kind, and the argument tends to become heated. In meter it is rhyming octosyllabic couplets, much more regular than was common at the time.

(c) The Orison to Our Lady, Genesis and Exodus, the Bestiary, the Moral Ode, the Proverbs of Alfred, and the Proverbs of Hendyng are usually placed about the middle of the thirteenth century. Of originality there is little to comment upon; but as metrical experiments they are of great importance. The Proverbs show some regular stanza-formation, and the Moral Ode is remarkable for the steadiness and maturity of its measure, a long line coming very close to the fourteener.

(d) The Cursor Mundi was composed about 1320. It is a kind of religious epic, twenty-four thousand lines long, composed in the Northern dialect. The author, who divides his history into seven stages, draws upon both the Old and the New Testaments. The meter shows a distinct advance in its grip of the octosyllabic couplet.

[21]

(e) Richard Rolle of Hampole, who died in 1349, is one of the few contemporary figures about whom definite personal facts are recorded. He was born in Yorkshire, educated at Oxford, and ran away from home to become a hermit. Subsequently he removed to Hampole, near Doncaster, where he enjoyed a great reputation for sanctity and good works.

He wrote some miscellaneous prose and a few short poems, but his chief importance lies in his authorship of the long poem The Pricke of Conscience. This work, which is based upon the writings of the early Christian Fathers, describes the joys and sorrows of a man’s life as he is affected in turn by good and evil. The meter is a close approximation to the octosyllabic couplet, which shows extensions and variations that often resemble the heroic measure. It has been suggested that Hampole is the first English writer to use the heroic couplet; but it is almost certain that his heroic couplets are accidental.

(f) The Alliterative Poems. In a unique manuscript, now preserved in the British Museum, are found four remarkably fine poems in the West Midland dialect: Pearl, Cleannesse, Patience, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. There is no indication of the authorship, but judging from the similarity of the style it is considered likely that they are by the same poet. The date is about 1300. The first three poems are religious in theme, and of them Pearl is undoubtedly the best. This poem, half allegorical in nature, tells of a vision in which the poet seeks his precious pearl that has slipped away from him. In his quest he spies his pearl, which seems to be the symbol of a dead maiden, and obtains a glimpse of the Eternal Jerusalem. The poem, which contains long discussions between the poet and the pearl, has some passages of real, moving beauty, and there is a sweet melancholy inflection in some of the verses that is rare indeed among the fumbling poetasters of the time. The meter is extraordinarily complicated: heavily alliterated twelve-lined stanzas, with intricate rhymes arranged on a triple basis (see p.[22] 149). Cleannesse and Patience, more didactic in theme, are of less interest and beauty, but they have an exultation and stern energy that make them conspicuous among the poems of the period. They are composed in a kind of alliterative blank verse. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is one of the most captivating of the romances. Its meter also is freely alliterated and built into irregular rhyming stanzas which sometimes run into twenty lines.

3. The Metrical Romances. The great number of the romances that now appear in our literature can be classified according to subject.

(a) The romances dealing with early English history and its heroes were very numerous. Of these the lively Horn and Havelock the Dane and the popular Guy of Warwick and Bevis of Hampton were among the best. Even contemporary history was sometimes drawn upon, as in the well-known Richard Cœur-de-Lion.

(b) Allied to the last group are the immense number of Arthurian romances, which are closely related and often of high merit. Sir Tristrem, one of the earliest, is by no means one of the worst; to it we may add the famous Arthur and Merlin, Ywain and Gawain, the Morte d’Arthure, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

(c) There was also a large number of classical themes, such as the exploits of Alexander the Great and the siege of Troy. King Alisaunder is very long, but of more than average merit. Further examples are Sir Orpheo and The Destruction of Troy.

(d) The group dealing with the feats of Charlemagne is smaller, and the quality is lower. Rauf Coilyear, an alliterative romance, is probably the best of them, and to it we may add Sir Ferumbras.

(e) A large number of the romances deal with events which are to some extent contemporary with the composition. They are miscellaneous in subject, but they are of much interest and some of them of great beauty. Amis and Amiloun is a touching love-story; William of Palerne is on the familiar “missing heir” theme; and The Squire[23] of Low Degree, who loved the king’s daughter of Hungary, is among the best known of all the romances.

It would take a volume to comment in detail upon the romances. The variety of their meter and style is very great; but in general terms we may say that the prevailing subject is of a martial and amatory nature; there is the additional interest of the supernatural, which enters freely into the story; and one of the most attractive features to the modern reader of this delightful class of fiction is the frequent glimpses obtainable into the habits of the time.

1. The Ancren Riwle, or Rule of Anchoresses, is one of the earliest of Middle English prose texts, for it dates from about 1200. The book, which is written in a simple, matter-of-fact style, is a manual composed for the guidance of a small religious community of women which then existed in Somersetshire. Nothing certain is known regarding the author. Its Southern dialect shows some traces of Midland. As in some respects the text is the forerunner of modern prose, we give an extract:

| Uorþi was ihoten a Godes half iðen olde lawe þet put were euer iwrien; & [gh]if eni unwrie put were, & best feolle þerinne, he hit schulde [gh]elden þet þene put unwrieh. Ðis is a swuðe dredlich word to wummen þet scheaweð her to wep-monnes eien. Heo is bitocned bi þe þet unwrieð þene put: þe put is hire veire neb, & hire hwite swire, & hire hond, [gh]if hes halt forð in his eihsihðe. | Therefore it was ordered on the part of God in the old law that a pit should be ever covered, and if there were any uncovered pit, and a beast fell therein, he should pay for it, that uncovered the pit. This is a very dreadful saying for a woman that shows herself to a man’s eyes. She is betokened by the person that uncovers the pit; the pit is her fair face, and her white neck, and her hand, if she holds it forth in his eyesight. |

2. The Ayenbite of Inwyt was written by Dan Michel of Northgate, who flourished about 1340. The book is a servile translation of a French work, and is of little literary importance. To the philologist it is very useful as an example of the Southern dialect of the period.

[24]

1. Poetry. (a) Meter. The most interesting feature of this period is the development of the modern system of rhymed meters, which displaced the Old English alliterative measures. Between the Old English poems of Cynewulf (about 950) and the Middle English Brut (about 1205) there is a considerable gap both in time and in development. This gap is only slightly bridged by the few pieces which we proceed to quote.

A quatrain dated at about 1100 is as follows:

In this example we have two rough couplets. The first pair rhyme, and in the second pair there is a fair example of assonance. The meter, as far as it exists at all, is a cross between octosyllables and decasyllables.

A few brief fragments by Godric, who died in 1170, carry the process still further. The following lines may be taken as typical:

These lines are almost regular, and the rhyme in the second couplet is perfect.

The Brut, with its ragged four-accented and nearly rhymeless lines, shows no further advance; but the Ormulum, though it does without rhyme, is remarkable for the regularity of its meter. Then during the thirteenth century there comes a large number of poems, chiefly romances and homilies. Much of the verse, such as in Horn, Havelock the Dane, and the works of Manning, is in couplet[25] form. It is nearly doggerel very often, and hesitates between four and five feet. This is the rough work that Chaucer is to make perfect. The following example of this traditional verse should be carefully scanned:

During the fourteenth century, with the increase of dexterity, came the desire for experiment. Stanzas in the manner of the French were developed, and the short or bobbed line was introduced. The expansion of the lyric helped the development of the stanza. Thus we pass through the fairly elaborate meters of Minot, the Proverbs of Hendyng, and the romances (like The King of Tars) in the Romance sestette, to the extremely complicated verses of Sir Tristrem, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and Pearl. We add a specimen of the popular Romance sestette, and a verse from a popular song of the period.

[26]

(b) The Lyric. The most delightful feature of the period is the appearance of the lyric. There can be little doubt that from Old English times popular songs were common, but it is not till the thirteenth century that they receive a permanent place in the manuscripts. We then obtain several specimens that for sweetness and lyrical power are most satisfying.

Apart from its native element, the lyric of the time drew its main inspiration from the songs of the French jongleurs and the magnificent, rhymed Latin hymns (such as Dies Iræ and Stabat Mater) of the Church. These hymns, nobly phrased and rhymed, were splendid models to follow. Many of the early English lyrics were devoutly religious in theme, especially those addressed to the Virgin Mary; a large number, such as the charming Alysoun, are love-lyrics; and many more, such as the cuckoo song quoted below (one of the oldest of all), are nature-lyrics. In the song below note the regularity of the meter:

| Sumer is i-cumen in, | Summer is coming, |

| Lhude sing cuccu: | Loud sing cuckoo: |

| Groweth sed, and bloweth med, | Groweth seed and bloweth mead, |

| And springth the wde nu. | And springeth the wood now. |

| Sing cuccu, cuccu. | Sing cuckoo, cuckoo. |

| Awe bleteth after lombe, | Ewe bleateth after lamb, |

| Lhouth after calue cu; | Loweth after calf the cow; |

| Bulluc sterteth, bucke verteth; | Bullock starteth, buck verteth[12] |

| Murie sing cuccu, | Merry sing cuckoo: |

| Cuccu, cuccu. | Cuckoo, cuckoo. |

| Wel singes thu, cuccu; | Well sing’st thou, cuckoo; |

| Ne swik thu nauer nu. | Nor cease thou ever now. |

| Sing cuccu nu, | Sing cuckoo now, |

| Sing, cuccu. | Sing, cuckoo. |

(c) The Metrical Romances. A romance was originally a composition in the Romance tongue, but the meaning was narrowed into that of a tale of the kind described in the next paragraph. Romances were brought into England by[27] the French minstrels, who as early as the eleventh century had amassed a large quantity of material. By the beginning of the fourteenth century the romance appears in English, and from that point the rate of production is great. Romantic tales are the main feature of the literature of the time.

TABLE TO ILLUSTRATE THE DEVELOPMENT OF LITERARY FORMS

| YEAR | POETRY | PROSE | |||

| Lyrical | Narrative | Didactic | Narrative | Didactic | |

| Beowulf | |||||

| 700 | Cædmon | ||||

| 800 | |||||

| 900 | Alfred | ||||

| A.S. | |||||

| Cynewulf | CHRONICLE | ||||

| 1000 | Ælfric | ||||

| Wulfstan | |||||

| 1100 | |||||

| Ormulum | |||||

| 1200 | |||||

| Brut | AncrenRiwle | ||||

| 1300 | Manning | ||||

| Alysoun, | THE | Hampole | |||

| etc. | ROMANCES | ||||

| 1400 | Cursor Mundi | ||||

[28]

The chief features of the romance were: a long story, cumulative in construction, chiefly of a journey or a quest; a strong martial element, with an infusion of the supernatural and wonderful; characters, usually of high social rank, and of fixed type and rudimentary workmanship, such as the knightly hero, the distressed damsel, and the wicked enchanter; and a style that was simple to quaintness, but in the better specimens was spirited and suggestive of mystery and wonder. In meter it ranged from the simple couplet of The Squire of Low Degree to the twenty-lined stanza of Sir Tristrem. In its later stages, as Chaucer satirized it in Sir Thopas, the romance became extravagant and ridiculous, but at its best it was a rich treasure-house of marvelous tales.

2. Prose. The small amount of prose is strictly practical in purpose, and its development as a species of literature is to come later.

With poetry in such an immature condition, it can be easily understood that style is of secondary importance. The prevailing, almost the universal, style is one of artless simplicity. Very often, owing chiefly to lack of practice on the part of the poet, the style becomes obscure; and when more ambitious schemes of meter are attempted (as in Pearl) the same cause leads to the same result. Humor is rarely found in Middle English, but quaint touches are not entirely lacking, as facts revealed in the life of Hampole show. Pathos of a solemn and elevated kind appears in the Moral Ode, and the romance called The Pistyl of Susan and the Pearl, already mentioned, have passages of simple pathos.

1. The following extracts show the development of English poetry from Old English to Chaucerian times. Trace the changes in meter (scansion, rhyme, and stanza-formation), alliteration, and style. Are there any[29] traces of refinements such as melody and vowel-music?

| (1) Swá íú wætres thrym | When of old the water’s mass |

| Ealne middan-geard, | All mid-earth, |

| Mére-flód, theáhte | When the sea-flood covered |

| Eorthan ymb-hwyrft, | The earth’s circumference, |

| Thá [`s]e æthela wong | Then that noble plain |

| Æg-hwæs án-súnd | In everything entire |

| With yth-fare | Against the billowy course |

| Gehealden stód, | Stood preserved, |

| Hreóhra wæga | Of the rough waves |

| Eádig unwemmed, | Happy, inviolate, |

| Thurh áest Godes; | Through favour of God. |

| Bídeth swá geblówen | It shall abide thus in bloom, |

| Oth bæles cyme | Until the coming of the funeral fire |

| Dryhtnes dómes. | Of the Lord’s judgment. |

| The Phœnix, 900 |

| (2) And ich isæh thæ vthen | And I saw the waves |

| I there sæ driuen; | In the sea drive; |

| And the leo i than ulode | And the lion in the flood |

| Iwende with me seolue. | Went with myself. |

| Tha wit I sæ comen, | When we two came in the sea, |

| Tha vthen me hire binomen. | The waves took her from me; |

| Com ther an fisc lithe, | But there came swimming a fish; |

| And fereden me to londe. | And brought me to land. |

| Tha wes ich al wet, | Then was I all wet |

| And weri of soryen, and seoc. | And weary from sorrow, and sick. |

| Tha gon ich iwakien | When I gan wake |

| Swithe ich gon to quakien. | Greatly I gan quake. |

| Layamon, Brut, 1200 |

[30]

| (6) In Nauerne be [gh]unde the see | In Avergne beyond the sea |

| In Venyse a gode cyte, | In Venice a good city |

| Duellyde a prest of Ynglonde, | Dwelled a priest of England, |

| And was auaunsede, y understonde. | And was advanced I understand. |

| Every [gh]ere at the florysyngge | Every year at the flourishing |

| When the vynys shulde spryngge | When the vines should spring |

| A tempest that tyme began to falle | A tempest then began to fall |

| And fordede here vynys alle; | And ruined all their vines.[31] |

| Every [gh]ere withouten fayle | Every year without fail |

| And fordyde here grete trauayle. | And ruined their great labour. |

| Therfor the folk were alle sory | Therefore the folk were all sorry |

| Thurghe the cyte comunly: | Through the city commonly. |

| Thys prest seyde, y shal [gh]ou telle | This priest said, “I shall you tell |

| What shall best thys tempest felle; | What shall best this tempest fell; |

| On Satyrday shal [gh]e ryngge noun | On Saturday shall ye ring noon |

| And late ne longer ne werke be doun. | And let no longer work be done.” |

| Handlyng Synne, 1350 |

2. Account for the poor quality of English prose during this period.

3. What were the effects of the Norman Conquest upon English literature?

4. Describe the main features of the romance.

[32]

Compared with the periods covered by the last two chapters, the period now under review is quite short. It includes the greater part of the reign of Edward III and the long French wars associated with his name; the accession of his grandson Richard II (1377); and the revolution of 1399, the deposition of Richard, and the foundation of the Lancastrian dynasty. From the literary point of view, of greater importance are the social and intellectual movements of the period: the terrible plague called the Black Death, bringing poverty, unrest, and revolt among the peasants, and the growth of the spirit of inquiry, which was strongly critical of the ways of the Church, and found expression in the teachings of Wyclif and the Lollards, and in the stern denunciations of Langland.

1. The Standardizing of English. The period of transition is now nearly over. The English language has shaken down to a kind of average—to the standard of the East Midland speech, the language of the capital city and of the universities. The other dialects, with the exception of the Scottish branch, rapidly melt away from literature, till they become quite exiguous. French and English have amalgamated to form the standard English tongue, which attains to its first full expression in the works of Chaucer.

2. A curious “modern” note begins to be apparent at this period. There is a sharper spirit of criticism, a more searching interest in man’s affairs, and a less childlike faith in, and a less complacent acceptance of, the established[33] order. The vogue of the romance, though it has by no means gone, is passing, and in Chaucer it is derided. The freshness of the romantic ideal is being superseded by the more acute spirit of the drama, which even at this early time is faintly foreshadowed. Another more modern feature that at once strikes the observer is that the age of anonymity is passing away. Though many of the texts still lack named authors, the greater number of the books can be definitely ascribed. Moreover, we have for the first time a figure of outstanding literary importance, who gives to the age the form and pressure of his genius.

3. Prose. This era sees the foundation of an English prose style. Earlier specimens have been experimental or purely imitative; now, in the works of Mandeville and Malory, we have prose that is both original and individual. The English tongue is now ripe for a prose style. The language is settling to a standard; Latin and French are losing grip as popular prose mediums; and the growing desire for an English Bible exercises a steady pressure in favor of a standard English prose.

4. Scottish Literature. For the first time in our literature, in the person of Barbour (died 1395), Scotland supplies a writer worthy of note. This is only the beginning; for the tradition is handed on to the powerful group of poets who are mentioned in the next chapter.

1. His Life. In many of the documents of the time Chaucer’s name is mentioned with some frequency; and these references, in addition to some remarks he makes regarding himself in the course of his poems, are the sum of what we know about his life. The date of his birth is uncertain, but it is now generally accepted as being 1340. He was born in London, entered the household of the wife of the Duke of Clarence (1357), and saw military service abroad, where he was captured. Next he seems to have entered the royal household, for he is frequently mentioned as the recipient of royal pensions and bounties. When[34] Richard II succeeded to the crown (1377) Chaucer was confirmed in his offices and pensions, and shortly afterward (1378) he was sent to Italy on one of his several diplomatic missions. More pecuniary blessings followed; then ensued a period of depression, due probably to the departure to Spain (1387) of his patron John of Gaunt; but his life closed with a revival of his prosperity. He was the first poet to be buried in what is now known as Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey.

2. His Poems. The order of Chaucer’s poems cannot be ascertained with certitude, but from internal evidence they can as a rule be approximately dated.

It is now customary to divide the Chaucerian poems into three stages: the French, the Italian, and the English, of which the last is a development of the first two.

(a) The poems of the earliest or French group are closely modeled upon French originals, and the style is clumsy and immature. Of such poems the longest is The Romaunt of the Rose, a lengthy allegorical poem, written in octosyllabic couplets, and based upon Jean de Meung’s Le Roman de la Rose. This poem, which, though it extends to eight thousand lines, is only a fragment, was once entirely ascribed to Chaucer, but recent research, based upon a scrutiny of Chaucerian style, has decided that only the first part, amounting to seventeen hundred lines, is his work. Other poems of this period include The Dethe of the Duchesse, probably his earliest, and dated 1369, the date of the Duchess’s death, The Compleynte unto Pité, Chaucer’s ABC, The Compleynte of Mars, The Compleynte of Faire Anelida, and The Parlement of Foules. Of these the last is the longest; it has a fine opening, but, as so often happens at this time, the work diffuses into long speeches and descriptions.

(b) The second or Italian stage shows a decided advance upon the first. In the handling of the meters the technical ability is greater, and there is a growing keenness of perception and a greater stretch of originality. Troilus and Cressida is a long poem adapted from Boccaccio. By far[35] the greater part of the poem is original, and the rhyme royal stanzas, of much dexterity and beauty, abound in excellent lines that often suggest the sonnets of Shakespeare. The poem suffers from the prevailing diffuseness; but the pathos of the story is touched upon with a passionate intensity.

The Hous of Fame, a shorter poem in octosyllabic couplets, is of the dream-allegory type, as most of Chaucer’s poems of this period are; and it is of special importance because it shows gleams of the genuine Chaucerian humor. In this group is also included The Legende of Good Women, in which Chaucer, starting with the intention of telling nineteen affecting tales of virtuous women of antiquity, finishes with eight accomplished and the ninth only begun. After a charming introduction on the daisy, there is some masterly narrative, particularly in the portion dealing with Cleopatra. The meter is the heroic couplet, with which Chaucer was to familiarize us in The Canterbury Tales.

(c) The third or English group contains work of the greatest individual accomplishment. The achievement of this period is The Canterbury Tales, though one or two of the separate tales may be of slightly earlier composition. For the general idea of the tales Chaucer may be indebted to Boccaccio, but in nearly every important feature[36] the work is essentially English. For the purposes of his poem Chaucer draws together twenty-nine pilgrims, including himself. They meet at the Tabard Inn, in Southwark, in order to go on a pilgrimage to the tomb of Thomas à Becket at Canterbury. The twenty-nine are carefully chosen types, of both sexes, and of all ranks, from a knight to a humble plowman; their occupations and personal peculiarities are many and diverse; and, as they are depicted in the masterly Prologue to the main work, they are interesting, alive, and thoroughly human. At the suggestion of the host of the Tabard, and to relieve the tedium of the journey, each of the pilgrims is to tell two tales on the outward journey, and two on the return. In its entirety the scheme would have resulted in an immense collection of over a hundred tales. But as it happens Chaucer finished only twenty, and left four partly complete. The separate tales are linked with their individual prologues, and with dialogues and scraps of narrative. Even in its incomplete state the work is a small literature in itself, an almost unmeasured abundance and variety of humor and pathos, of narrative and description, and of dialogue and digression. There are two prose tales, Chaucer’s own Tale of Melibœus and The Parson’s Tale; and nearly all the others are composed in a powerful and versatile species of the heroic couplet.

To this last stage of Chaucer’s work several short poems are ascribed, including The Lack of Stedfastness and the serio-comic Compleynte of Chaucer to his Purse.

There is also mention of a few short early poems, such as Origines upon the Maudeleyne, which have been lost.

During his lifetime Chaucer built up such a reputation as a poet that many works were at a later date ascribed to him without sufficient evidence. Of this group the best examples are The Flower and the Leaf, quite an excellent example of the dream-allegory type, and The Court of Love. It has now been settled that these poems are not truly his.

3. His Prose. The two prose tales cannot be regarded as among Chaucer’s successful efforts. Both of them—that[37] is, The Tale of Melibœus and The Parson’s Tale on Penitence—are lifeless in style and full of tedious moralizings. Compared with earlier prose works they nevertheless mark an advance. They have a stronger grasp of sentence-construction, and in vocabulary they are copious and accurate. The other prose works of Chaucer are an early translation of Boëthius, and a treatise, composed for the instruction of his little son Lewis, on the astrolabe, then a popular astronomical instrument.

The following extract is a fair example of his prose:

“Now, sirs,” saith dame Prudence, “sith ye vouche saufe to be gouerned by my counceyll, I will enforme yow how ye shal gouerne yow in chesing of your counceyll. First tofore alle workes ye shall beseche the hyghe God, that he be your counceyll; and shape yow to suche entente that he yeue you counceyll and comforte as Thobye taught his sone. ‘At alle tymes thou shall plese and praye him to dresse thy weyes; and loke that alle thy counceylls be in hym for euermore.’ Saynt James eke saith: ‘Yf ony of yow haue nede of sapience, axe it of God.’ And after that than shall ye take counceyll in yourself, and examyne well your thoughtys of suche thynges as ye thynke that ben beste for your profyt. And than shall ye dryue away from your hertes the thynges that ben contraryous to good counceyl: this is to saye—ire, couetyse, and hastynes.”

The Tale of Melibœus

4. Features of his Poetry. (a) The first thing that strikes the eye is the unique position that Chaucer’s work occupies in the literature of the age. He is first, with no competitor for hundreds of years to challenge his position. He is, moreover, the forerunner in the race of great literary figures that henceforth, in fairly regular succession, dominate the ages they live in.

(b) His Observation. Among Chaucer’s literary virtues his acute faculty of observation is very prominent. He was a man of the world, mixing freely with all types of mankind; and he used his opportunities to observe the little peculiarities of human nature. He had the seeing eye, the retentive memory, the judgment to select, and the capacity to expound; hence the brilliance of his descriptions, which we shall note in the next paragraph.

[38]

(c) His Descriptions. Success in descriptive passages depends on vivacity and skill in presentation, as well as on the judgment shown in the selection of details. Chaucer’s best descriptions, of men, manners, and places, are of the first rank in their beauty, impressiveness, and humor. Even when he follows the common example of the time, as when giving details of conventional spring mornings and flowery gardens, he has a vivacity that makes his poetry unique. Many poets before him had described the break of day, but never with the real inspiration that appears in the following lines:

The Prologue contains ample material to illustrate Chaucer’s power in describing his fellow-men. We shall add an extract to show him in another vein. Observe the selection of detail, the terseness and adequacy of epithet, and the masterly handling of the couplet.

[39]

(d) His Humor and Pathos. In the literature of his time, when so few poets seem to have any perception of the fun in life, the humor of Chaucer is invigorating and delightful. The humor, which steeps nearly all his poetry, has great variety: kindly and patronizing, as in the case of the Clerk of Oxenford; broad and semi-farcical, as in the Wife of Bath; pointedly satirical, as in the Pardoner and the Summoner; or coarse, as happens in the tales of the Miller, the Reeve, and the Pardoner. It is seldom that the satirical intent is wholly lacking, as it is in the case of the Good Parson, but, except in rare cases, the satire is good-humored and well-meant. The prevailing feature of Chaucer’s humor is its urbanity: the man of the world’s kindly tolerance of the weaknesses of his erring fellow-mortals.

Chaucer lays less emphasis on pathos, but it is not overlooked. In the poetry of Chaucer the sentiment is humane and unforced. We have excellent examples of pathos in the tale of the Prioress and in The Legende of Good Women.

We give a short extract from the long conversation between Chaucer and the eagle (“with fethres all of gold”) which carried him off to the House of Fame. The bird, with its cool acceptance of things, is an appropriate symbol of Chaucer himself in his attitude toward the world.

(e) His Narrative Power. As a story-teller Chaucer employs somewhat tortuous methods, but his narrative possesses a curious stealthy speed. His stories, viewed strictly as stories, have most of the weaknesses of his generation: a fondness for long speeches, for pedantic digressions on such subjects as dreams and ethical problems, and for long explanations when none are necessary. Troilus and Cressida, heavy with long speeches, is an example of his prolixity, and The Knight’s Tale, of baffling complexity and overabundant in detail, reveals his haphazard and dawdling methods; yet both contain many admirable narrative passages. But when he rises above the weaknesses common to the time he is terse, direct, and vivacious. The extract given below will illustrate the briskness with which his story can move.

(f) His Metrical Skill. In the matter of poetical technique English literature owes much to Chaucer. He is not an innovator, for he employs the meters in common use. In his hands, however, they take on new powers. The octosyllabic and heroic couplets, which previously were slack and inartistic measures, now acquire a new strength, suppleness, and melody. Chaucer, who is no great lyrical poet, takes little interest in the more complicated meters common in the lyric; but in some of his shorter poems he shows a skill that is as good as the very best apparent in the contemporary poems.

(g) Summary. We may summarize Chaucer’s achievement by saying that he is the earliest of the great moderns. In comparison with the poets of his own time, and with those of the succeeding century, the advance he makes is almost startling. For example, Manning, Hampole, and the romancers are of another age and of another way of thinking from ours; but, apart from the superficial archaisms of spelling, the modern reader finds in Chaucer something closely akin. All the Chaucerian features help to create this modern atmosphere: the shrewd and placidly humorous observation, the wide humanity, the quick aptness of phrase, the dexterous touch upon the meter, and, above all, the fresh and formative spirit—the genius turning dross into gold. Chaucer is indeed a genius; he stands alone, and for nearly two hundred years none dare claim equality with him.

1. William Langland, or Langley (1332–1400), is one of the early writers with whom modern research has dealt adversely. All we know about him appears on the manuscripts of his poem, or is based upon the remarks he makes[42] regarding himself in the course of the poem. This poem, the full title of which is The Vision of William concerning Piers the Plowman, appears in its many manuscripts in three forms, called respectively the A, B, and C texts. The A text is the shortest, being about 2500 lines long; the B is more than 7200 lines; and the C, which is clearly based upon B, is more than 7300 lines. Until quite recently it has always been assumed that the three forms were all the work of Langland; but the latest theory is that the A form is the genuine composition of Langland, whereas both B and C have been composed by a later and inferior poet.

From the personal passages in the poem it appears that the author was born in Shropshire about 1332. The vision in which he saw Piers the Plowman probably took place in 1362.

The poem itself tells of the poet’s vision on the Malvern Hills. In this trance he beholds a fair “feld ful of folk.” The first vision, by subtle and baffling changes, merges into a series of dissolving scenes which deal with the adventures of allegorical beings, human like Do-wel, Do-bet, and Do-betst, or of abstract significance like the Lady Meed, Wit, Study, and Faith. During the many incidents of the poem the virtuous powers generally suffer most, till the advent of Piers the Plowman—the Messianic deliverer—restores the balance to the right side. The underlying motive of the work is to expose the sloth and vice of the Church, and to set on record the struggles and virtues of common folks. Langland’s frequent sketches of homely life are done with sympathy and knowledge, and often suggest the best scenes of Bunyan.

The style has a somber energy, an intense but crabbed seriousness, and an austere simplicity of treatment. The form of the poem is curious. It is a revival of the Old English rhymeless measure, having alliteration as the basis of the line. The lines themselves are fairly uniform in length, and there is the middle pause, with (as a rule) two alliterations in the first half-line and one in the second. Yet in spite of the Old English meter the vocabulary draws[43] freely upon the French, to an extent equal to that of Chaucer himself.

We quote the familiar opening lines of the poem. The reader should note the strong rhythm of the lines—which in some cases almost amounts to actual meter—the fairly regular system of alliteration, and the sober undertone of resignation.

2. John Gower, the date of whose birth is uncertain, died in 1408. He was a man of means, and a member of a good Kentish family; he took a fairly active part in the politics and literary activity of the time, and was buried in London.

The three chief works of Gower are noteworthy, for they illustrate the unstable state of contemporary English literature. His first poem, Speculum Meditantis, is written in French, and for a long time was lost, being discovered as late as 1895; the second, Vox Clamantis, is composed in Latin; and the third, Confessio Amantis, is written in English, at the King’s command according to Gower himself. In this last poem we have the conventional allegorical setting, with the disquisition of the seven deadly sins, illustrated by many anecdotes. These anecdotes reveal Gower’s capacity as a story-teller. He has a diffuse and watery style of narrative, but occasionally he is brisk and competent. The meter is the octosyllabic couplet, of great smoothness and fluency.

[44]

3. John Barbour (1316–95) is the first of the Scottish poets to claim our attention. He was born in Aberdeenshire, and studied both at Oxford and Paris. His great work is The Brus (1375), a lengthy poem of twenty books and thirteen thousand lines. The work is really a history of Scotland from the death of Alexander III (1286) till the death of Bruce and the burial of his heart (1332). The heroic theme is the rise of Bruce, and the central incident of the poem is the battle of Bannockburn. The poem, often rudely but pithily expressed, contains much absurd legend and a good deal of inaccuracy, but it is no mean beginning to the long series of Scottish heroic poems. The spirited beginning is often quoted: