JAMES CONNOLLY

Title: The Irish rebellion of 1916

or, the unbroken tradition

Author: Nora Connolly O'Brien

Release date: August 16, 2023 [eBook #71264]

Most recently updated: March 15, 2025

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Boni and Liveright, 1918

Credits: Al Haines

OR

THE UNBROKEN TRADITION

BY

NORA CONNOLLY

BONI AND LIVERIGHT

NEW YORK

Copyright, 1918,

Copyright, 1919,

By Boni & Liveright, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

James Connolly ...... Frontispiece

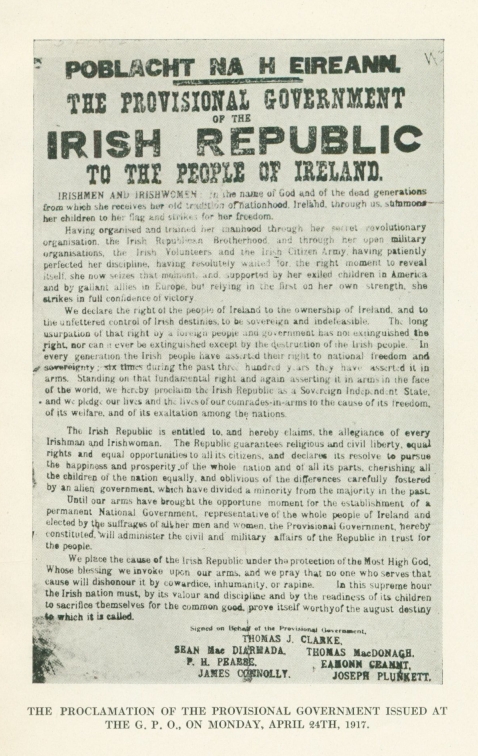

The Proclamation of the Provisional Government issued at the G.P.O. on Monday, April 24, 1917

MAPS

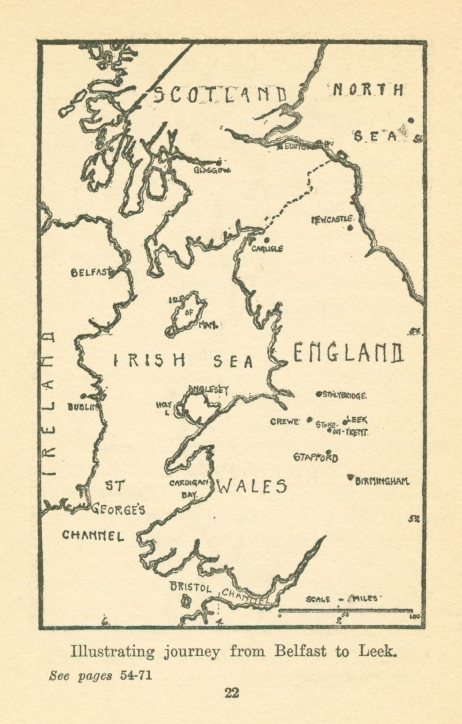

The Journey from Belfast to Leek

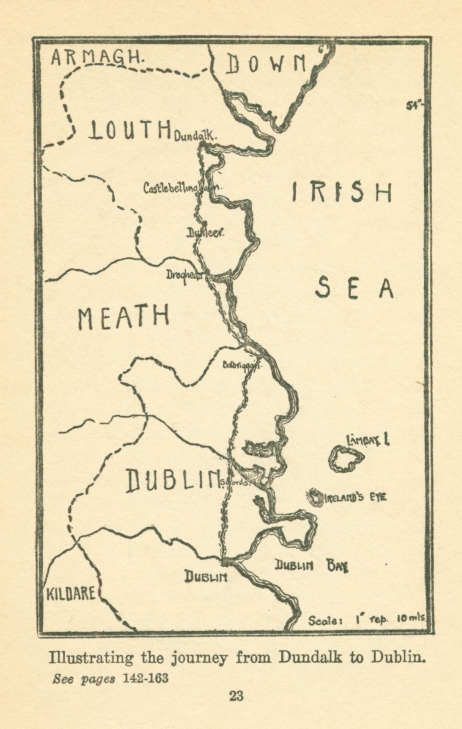

The Journey from Dundalk to Dublin

INTRODUCTION

There have been many attempts to explain the revolution which took place in Ireland during Easter Week, 1916. And all of them give different reasons. Some have it that it was caused by the resentment that grew out of the Dublin Strike of 1912-13; others, that it was the threatened Ulster rebellion, and there are many other equally wrong explanations. All these writers ignore the main fact that the Revolution was caused by the English occupation of Ireland.

So many people not conversant with Irish affairs ask: Why a revolution? Why was it necessary to appeal to arms? Why was it necessary to risk death and imprisonment for the self-government of Ireland? They say that there was already in existence an Act for the Self-government of Ireland, that it had been passed through the English House of Commons, and that if we had waited till the end of the war we would have been given an opportunity to govern ourselves. That they are not {viii} conversant with Irish affairs must be their excuse for thinking in that manner of our struggle for freedom.

To be able to think and to speak thus one must first recognize the right of the English to govern Ireland, for only by so doing can we logically accept any measure of self-government from England.

And we cannot do so, for, as a nation Ireland has never recognized England as her conqueror, but as her antagonist, as an enemy that must be fought. And this attitude has succeeded in keeping the soul of Ireland alive and free.

For the conquest of a nation is never complete till its soul submits, and the submission of the soul of a nation to the conqueror makes its slavery and subjection more sure. But the soul of Ireland has never submitted. And sometimes when the struggle seemed hopeless, and sacrifice useless, and there was thought to make truce with the foe, the voice of the soul of Ireland spoke and urged the nation once more to resist. And the voice of the soul of Ireland has the clangor of battle.

There have been many attempts to drown the voice of the soul of Ireland ever since the {ix} coming of the English into our country. There have been some who have had the God-given gift of leadership, but still sought to misinterpret the sound of the voice; who in shutting their ears to the call for battle have helped to fasten the shackles of slavery more securely on their country.

There was Daniel O'Connell who possessed the divine gift of leadership and oratory, and in whose tones the people recognized the voice of Ireland and flocked around him. During the agitation for the Repeal of the union between Ireland and England the people followed O'Connell and waited for him to give the word. Never for one moment did they believe that the movement was merely a constitutional one. Sensibly enough they knew that speeches, meetings and cheers would never win for them the freedom of their country. They knew that force alone would compel England to forego her hold upon any of her possessions.

So that when in 1844 O'Connell sent out the call bidding all the people of Ireland to muster at Clontarf, outside Dublin, they believed that the day had come, and from North, South, East and West they started on the journey. Those {x} who lived in the West and South traveled the distance in all sorts of conveyances, many of them, especially the poorer ones, walked the distance; but the trouble, the weariness, the hardship were all ignored by them in the knowledge that they were once more mustering to do battle for the freedom of their country.

But in the meantime, while the people were making all speed to obey the summons of O'Connell, the meeting had been proclaimed by the British Government; and the place of muster was lined with regiments of soldiers with artillery with orders to mow down the people if they attempted to approach the meeting place. Then it was that O'Connell failed the people of Ireland, and rung the knell for the belief of the Irish people in constitutionalism. He said, "All the freedom in the world is not worth one drop of human blood," and commanded the people to obey the order of the British Government and to return to their homes.

There are many pitiful, heart-breaking stories told of the manner in which this command of O'Connell reached the people. Many who had walked miles upon miles reached the outskirts of Dublin only to meet the people {xi} pouring out of it. When in return to their questions they were told that it was the request of O'Connell that they return to their homes, the heart within them broke for they knew that their idol had failed them, and their hopes of freeing Ireland were shattered.

Within the Repeal Association there was another organization called the Young Irelanders, which published a paper called The Nation. This paper was an immense factor in arousing and keeping alive a firm nationalist opinion in Ireland. The Young Irelanders were revolutionists, and by their writings counseled the people to adopt military uniforms, to study military tactics, to march to and from the meetings in military order. They made no secret of their belief that the freedom of Ireland must be won by force of arms.

During the famine in 1847, when the people were dying by the hundreds, although there was enough food to feed them, the Young Irelanders worked untiringly to save the people. At that time potatoes were the staple food of the people, everything else they raised, corn, pigs, cattle, etc., had to be sold to pay the terrible rackrents. The Young Irelanders called upon the people to keep the food in the country {xii} and save themselves; but day by day more food was shipped from the starving country to England; there to be turned into money to pay the grasping landlords. It was during this time that John Mitchell was arrested and transported for life to Van Diemen's land.

In 1848 there was an ill-fated attempt at insurrection. Even in the midst of famine and death, with the people dying daily by the roadside, there was still the belief that only by an appeal to force and arms could anything be wrung from England. In Tipperary, under Smith O'Brien, the attempt was made, more as a protest then, for famine, death, and misery had thinned the ranks, than with any hopes of winning anything. Most of the leaders were soon arrested and four of them were sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered; but this sentence was afterwards commuted to life imprisonment.

For many years after the famine the people were quiescent, and had grown quite uncaring about Parliamentary representation. And then was formed a revolutionary secret society calling itself the Fenians. The members of this organization were pledged to work for, and, when the time came, to fight for and }xiii} establish, an Irish Republic. James Stephens was the chief organizer. The organization spread through Ireland like wildfire. Even the English Army and Navy were honeycombed with it. Every means possible were taken by the English to cope with this new revolutionary movement—but they failed. The organization decided that a Rising would take place in February, 1867. This was later postponed; but unfortunately the word did not reach the South in time and Kerry rose. The word spread over Ireland that Kerry was up in arms. Measures were taken by the English to meet the insurrectionists, but before they reached the South the men had learned that the date of the rising had been postponed and had returned to their homes. Luby, O'Leary, Kickham, and O'Donovan Rossa were arrested. Still the Rising took place on the appointed date, although doomed to failure owing to the crippling of the organization by the arrest of its leaders, and the lack of arms. Even the elements were against the revolutionists, for a snowstorm, heavier than any of the oldest could remember having seen, fell and covered the country in great drifts.

They failed. But the teaching of the {xiv} Fenians and the organization they founded are alive to-day. It was the members of this organization that first started the Irish Volunteers. Ever on the watch for a ripe moment to come out and work openly, ever longing for the day when military instruction could be given to the nationalist youth, they seized upon the fact that if the Ulster Volunteers were permitted to drill and arm themselves to fight the English Government so could they. And in November, 1913, they called a meeting in the Rotunda, Dublin, and invited the men and women of Ireland to join the Irish Volunteers, and pledge themselves "to maintain and secure the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland."

So once more the people of Ireland heard the call to arms, and right royally they answered it. The Irish Volunteer Organization spread throughout the land, and the youth of Ireland were being trained in the art of soldiering.

Then it was that, like Daniel O'Connell and other constitutional leaders, Redmond proved himself of the body and not the soul of Ireland. He did not follow the example of Parnell, whose follower he was supposed to be, and use the threat of this large physical force party to {xv} gain his ends from the English Government. Parnell used to say to the British House of Commons: "If you do not listen to me, there is a large band of physical force men, with whom I have no influence, and upon whom I have no control, and they will compel you to listen to them." But Redmond, jealous of all parties outside his own (knowing well that when an Irishman had a rifle in his hands he no longer felt subservient to, or feared England; and that when the people of Ireland had the means to demand the freedom of their country they grew impatient of speech-making and petitioning), grew fearful for the loss of power of the Irish Parliamentary Party.

He knew also, that, as in the days of O'Connell, Butt, and Parnell, the people firmly believed that all the talk and show of constitutionalism was a blind, merely a throwing of dust in the eyes of the English Government, and to save himself and his Party he must approve this physical Force party. But not content with approval he needs must try to capture the Irish Volunteers. This attempt, I firmly believe, was made upon the advice, or the command of the British Government. He sent a demand to the Executive Committee {xvi} that a number of his appointees be received upon the Committee. This would enable him to know and obstruct all measures made by the Irish Volunteers and would prevent the loss of power of the Parliamentary Party.

By the votes of a small majority of the Committee these appointees were accepted. But the Committee soon found out that it was impossible to arm and prepare men for a revolution against a government, while the paid servants of that government were amongst them. They decided to part company even at the risk of a division in the ranks. They knew that every man who remained with them could be depended upon to do his part when the time for the Rising came.

Then England went to war. Shortly before this a Home Rule Bill had passed two readings in the House of Commons. England saw the stupidity of appealing to Irishmen to go to fight for the freedom of small nationalities, while any measure of freedom was denied to their own. So the Home Rule Bill passed the final reading in the House of Commons, and was put upon the Statute Book. Then fearful of the dissatisfaction of the Unionists an amendment was tacked on {xvii} that prevented its going into effect until after the war.

John Redmond dealt the final blow to his influence upon Ireland when he began to recruit for the English Army. Many of his followers, taking his word that Home Rule was now a fact entered the English Army at his request. They were, in the main, young, foolish, and ignorant fellows unable to analyze the Bill for themselves, and therefore could not know that the so-called Home Rule was a farce. They did not know that the Bill gave them no power over the revenue, over the Post Office, over the Royal Irish Constabulary, that they could not raise an army, or impose a tax, and that no law passed by the Irish Parliament could go into effect until the English House of Commons had given its approval. It was like telling a prisoner that he was free and keeping him in durance.

And from the beginning of the war the Irish Volunteers spent all the time they could in intensive drilling, not knowing at what time their hand might be forced, or the opportune moment for the Rising might arrive.

For in Ireland we have the unbroken tradition of struggle for our freedom. Every {xviii} generation has seen blood spilt, and sacrifice cheerfully made that the tradition might live.

Our songs call us to battle, or mourn the lost struggle; our stories are of glorious victory and glorious defeat. And it is through them the tradition has been handed down till an Irish man or woman has no greater dream of glory than that of dying

"A Soldier's death so Ireland's free."

THE IRISH REBELLION OF 1916

OR

THE UNBROKEN TRADITION

My first mingling with an actively, openly drilling revolutionary body took place during the Dublin strike of 1912-1913. I was living in Belfast then and had come to Dublin to see how things were managed, how the food was being distributed and the kitchens run; and, in fact, to feel the spirit of the people.

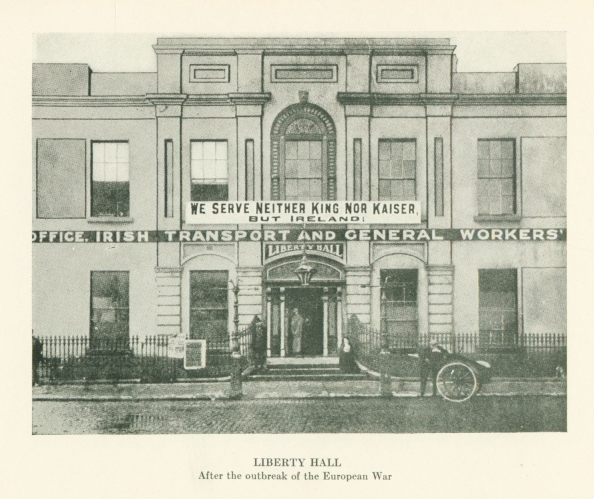

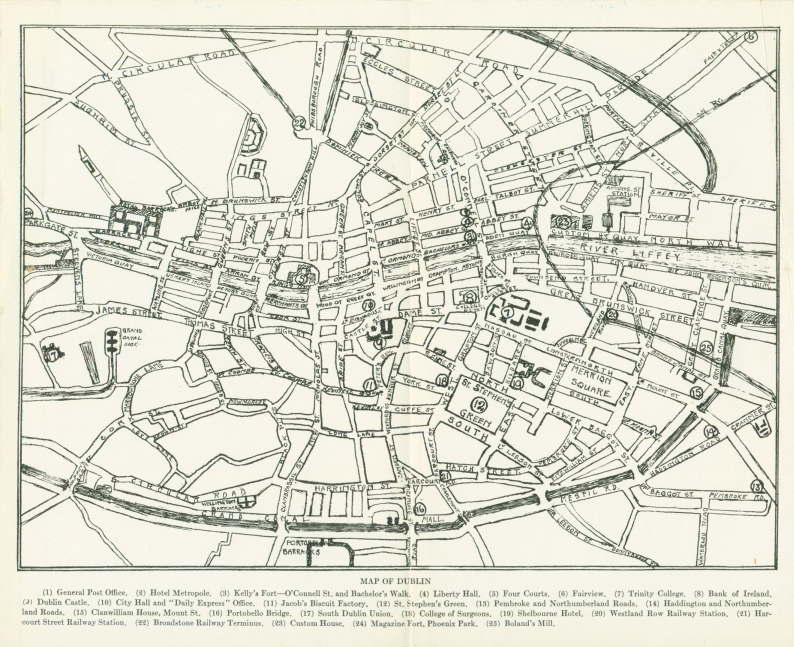

James Connolly, my father, was at that time in Dublin assisting James Larkin to direct the strike. He was my pilot. Liberty Hall, the headquarters of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, the members of which were on strike, was first visited. It is situated on Beresford Place facing the Custom House and the River Liffey. In the early part of the nineteenth century it had been a Chop House. Almost from the big front door a wide staircase starts. It ends at the second story. From there it branches out into {2} innumerable corridors thickly studded with doors. It took me a long time to master those corridors. Always I seemed to be finding new ones. Downstairs on the first floor were the theater and billiard rooms; and below them were the kitchens. During the strike these kitchens were used to prepare food for the strikers. It was to the kitchens my father first piloted me.

Here the Countess de Markieviez reigned supreme—all meals were prepared under her direction. There were big tubs on the floor; around each were about half a dozen girls peeling potatoes and other vegetables. There were more girls at tables cutting up meat. The Countess kept up a steady march around the boilers as she supervised the cooking. She took me to another kitchen where more delicate food was being prepared for nursing and expectant mothers.

"We used to give the food out at first," she said. "But in almost every case we found that it had been divided amongst the family. Now we have the women come here to eat. We are sure then that they are getting something sufficiently nourishing to keep up their strength." She showed me a hall with a long table in the {3} center and chairs around it. As it was near the "Mothers' dinner hour," as the girls called it, some of the striking women and girls were there to act as waitresses.

We came to the clothing shop next. Some persons had caught the idea of sending warm clothing for the wives and children of the strikers; accordingly one of the rooms of Liberty Hall was turned into an alteration room. Several women and girls were working from morning to night altering the clothes to fit the applicants. One of the girls said to me, "It was a wonder to us at first the number of strikers who had extra large families, until we found out that in many cases their wives had adopted a youngster or two for the day, and brought them along to get clothed." Not strictly honest, perhaps, but how human to wish to share their little bit of good fortune with those not so fortunate as themselves. How many little boys and girls knew for the first time in their lives the feel of warm stockings and shoes, and how many little girls had the delicious thrill of getting a new dress fitted on.

Thence to Croyden Park. Some time before the strike this immensely big place had {4} been taken over by the Union. I do not know how large it was but there were fields and fields, and long pathways edged with trees. It was used by the members as a football ground and for hurley and all sorts of sports and games. But this time the fields were ringed round with men and women watching the rows and rows of strikers who were in the fields, marching now to the right, now to the left at the commands of Captain White, who stood in the center, a tall soldierly figure blowing a whistle and gesticulating with great fervor.

Back and forth, right and left they marched with never a moment's rest; then round and round the fields they ran at the double; the Captain now at the head, now at the rear, now in the center shouting commands incessantly, sparing himself no more than the men. I remember once he stopped beside my father and myself; he was in a terrible rage, his hands were clenched and he was fairly gnashing his teeth. He had given a signal to one of the columns and they had misinterpreted it.

"Easy now, Captain," said my father, "remember they are only volunteers." Captain White turned like a flash.

"Yes," he said. "And aren't they great?" {5} And he forgot his rage in his admiration of the men of a few weeks' training. He gave an order, the men marched past and at a given place they received broom handles with which they practiced rifle drill.

After rifle drill came the line up for the march home. We waited till the last row was filing past and then fell in and marched back to the city with the Irish Citizen Army. It was exhilarating. At no period could I see the first part of the Army. The men and boys were whistling tunes to serve them in lieu of bands. On they swung to Beresford Place, where they lined up in front of Liberty Hall. Jim Larkin and my father spoke to them from the windows. When one man called out, "We'll stick by you to the end," he was loudly and heartily cheered. Captain White gave the order of dismissal and the men broke ranks but did not go away. When they were not drilling, or sleeping, or eating, they thronged round Liberty Hall, attesting that "where the heart lieth there turneth the feet."

When the strike was over and the men had won the right to organize, the membership of the Irish Citizen Army dwindled rapidly. When one takes into consideration the arduous {6} work and the long hours that comprised the daily round of these men, the wonder was that there were so many of them willing to meet after working hours to be drilled into perfect soldiers. But they knew that by so doing they were, in the words of my father, "signifying their adhesion to the principle that the freedom of a people must in the last analysis rest in the hands of that people—that there is no outside force capable of enforcing slavery upon a people really resolved to be free, and valuing freedom more than life." Also that "The Irish Citizen Army in its constitution pledges its members to fight for a Republican Freedom in Ireland. Its members are, therefore, of the number who believe that at the call of duty they may have to lay down their lives for Ireland, and have so trained themselves that at the worst the laying down of their lives shall constitute the starting point of another glorious tradition—a tradition that will keep alive the soul of the nation." And this was the knowledge that lightened all the labor of drilling and soldiering.

I was present at a lecture given to them by their Commandant, James Connolly. It was on the art of street fighting. I remember the {7} close attention every man paid to the lecture and the interest they displayed in the diagrams drawn on the board the better to explain his meaning. At the close of the lecture he asked, "Are there any questions?" There were many questions, all of them to the effect, whether it would not be better to do it this way, or could we not get better results that way. All in deadly earnestness, thinking only on how the best results might be achieved and not one man commenting on the danger to life the acts would surely entail. That one would have to risk death was taken for granted. Their one thought was how to get the most work done before death came.

A few months later there were maneuvers between one company of the Irish Citizen Army and a company of the Irish Volunteers. The Irish Volunteers had been formed after the Irish Citizen Army and by this time had spread over the length and breadth of Ireland. While the Irish Citizen Army admitted none but union men the Irish Volunteers made no such distinction. And as they both had the one ideal of a Republican Ireland there was much friendly rivalry between the two bodies. This time the maneuvers took the form of a {8} sham battle, which took place at Ticknock about six miles outside of Dublin. The Irish Citizen Army won the day. I particularly remember that afternoon. My father came into the house, tired but pleasantly excited—he had been an onlooker at the sham battle. "I've discovered a great military man," he said in high glee. "The way he handled his men positively amounted to genius. Do you know him—his name is Mallin?"

I did not know him then. I met him later when he was my father's Chief of Staff. During the rising he was Commandant in charge of the St. Stephen's Green Division of the Army of the Irish Republic, and he was executed during that dreadful time following the surrender of the Irish Republican Army.

During the month of July, 1914, I was camping out on the Dublin mountains. The annual convention of Na Fianna Eireann (Irish National Boy Scouts) had just been held, and I was a delegate to it from the Belfast Girls' Branch, of which I was the president. On the Sunday following the convention we were still camping out; but were suffering all the discomforts of blowy, rainy, stormy weather. Madame (the Countess de Markievicz) had a cottage beside the field where we were encamped, and it was thronged with us all that Sunday. Nothing would tempt us out in the field that night, and we kept putting off the retiring time, hour by hour, till it was nearly twelve o'clock. At that time we had just taken our courage in both hands, and were forcing ourselves to go out to our tents. We were standing near the door with our bedding in our arms when some of the Fianna boys halloed from outside. We {10} gladly opened the door—another excuse for putting off the evil moment—and about half a dozen boys came in to the cottage. They were in great spirits, although they had tramped some miles in the rain, and exhibited strange looking clubs to our curious eyes.

"Guess what we've been doing to-day, Madame," they said, but with an expression on their faces which said, "you'll never guess."

"It's too much trouble to guess," said Madame. "Tell us what it was and we will know all the quicker."

"We've been helping to run in three thousand rifles."

"Rifles—where—quick—tell me all about it. Quick."

"At Howth. But did you hear nothing about it?"

"Nothing. Tell me quick."

"Did you not hear that we had a brush with the soldiers; and that some were shot and some were killed?"

"No—no. Begin at the beginning and tell us the whole story."

"Well, during the week we were told to report at a certain place to-day—that there was important work to be done. This morning we {11} met as we were told, and we were shown these clubs. They were to be all the arms we were to have. We started out to march with the Volunteers to Howth. We knew, somehow or other, that we were going to get rifles but none of us knew for a fact how we were going to get them. As we marched we made all sorts of guesses as to how the rifles were coming. Of course, we did not carry the clubs in our hands; we brought them with us in the trek cart. But for a few others we were the only ones who knew what was in the cart. And do you know, Madame," he said with a veteran's pride, "we marched better than the Volunteers."

"When we came near Howth," said another boy as he took up the story, "two chaps came running towards us and told us to come on at the double. The Volunteers were rather tired but when they heard the word 'rifles' they simply raced. When we arrived at the harbor we saw the rifles being unloaded from a yacht. You ought to have heard the cheers when we saw them! Then it was that the clubs were distributed. They were given to a picked body of men and they were formed across the entrance to the pier. They were to use the clubs {12} if the police attempted to interfere with them. The rifles were handed out to the men, but there were more rifles than men so some had to be sent into the city in automobiles. Most of the ammunition was sent into the city in automobiles but quite a lot was put into the trek cart. But none was served out to the men."

"That was a nice thing to do," said the first boy, "to give rifles and no ammunition. And when we were attacked we couldn't shoot back. We had a fight with the soldiers and the police near the city. And when the soldiers and the police attacked us and might have taken the trek cart from us, we had only the butts of our rifles to defend it with. But we beat them off. Later on, though, they took their revenge when they shot down defenseless women and children. They just knelt down in the middle of Bachelor's Walk and fired into the crowd. I don't know how many were killed—some say five, some say more."

"But you brought the rifles safe," said Madame.

"The whole city is excited. The people are walking up and down the streets, they don't seem to think that they have any homes to go to."

When we heard that we wanted to dress and go down to Dublin. We wanted a share of the excitement, if we had not had any share in the fight. But Madame vetoed that suggestion almost as soon as it was mooted. We had to go to bed. But we had so much to talk about that we scarcely noticed the sogging wet tent when we were inside.

The next morning was gloriously fine. We breakfasted and were making plans to go into the city to hear some more about yesterday's exploit. Madame had already cycled in, and we were left to our own devices. We had not quite finished our work around the camp when we saw a taxi-cab stopping near the gate that was used as an entrance to the field. As we ran towards it we wondered what had brought it there. Before we reached it, however, one of the Fianna captains had jumped out of the taxi and was coming towards us.

"I have about twenty rifles in the car, and I want to get them to Madame's cottage," he said. "Will you help?"

We were glad of the opportunity. We jumped over the hedge into the next field where there were no houses, and had the rifles handed to us. We could only carry two at a time. The {14} captain stood at the car on the lookout, and also handed the rifles to us. We carried the rifles down to the window back of Madame's cottage, and when we had them all there one of us went inside to open the window to take the rifles from the other girls as they handed them through. We were delighted to handle the arms.

Later on one of the neighbors said that it was wrong to leave the rifles there. "There is a retired sergeant of the police who lives a little way up the road and he wouldn't be above telling about them."

This rather frightened us. If the police came and took them from us, what could we do? I decided to go in to Dublin and go to the Volunteer office and tell them about the rifles. When I had told about the rifles two of the men present accompanied me back to the camp to take the rifles from there.

We set off in another taxi and arrived at the camp before there was any sign of the police becoming active. All the rifles were carried out again and put in the taxi. When they were all in it, it was suggested that we should get into the taxi and sit on top of the rifles. The police would be less suspicious of a taxi {15} with girls in it. It was not a very comfortable seat that we had on that trip to Dublin. But the rifles were saved. When we got back to the office I offered to sit in any taxi with the rifles if they thought it would divert attention. I sat on quite a number of rifles that day. And at the end of the day I had a rifle of my own.

In the meantime, the bodies of those who had been shot by the soldiers were laid out and brought to the Cathedral. Preparations were made for a public funeral to honor the victims of English soldiery in Ireland. All the Volunteers were to march in honor of the dead, and the local trades unions, the Irish Citizen Army, the Cumami na mBan, the Fianna, and as many of the citizens of Dublin as desired to do so. The Fintan Lalor Pipe Band, connected with the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, were to play the Dead March. And there was to be a firing party of the Irish Volunteers who were to use the rifles that had so soon been the cause of bloodshed.

I spent all the day of the funeral making wreaths. The funeral was not to take place till the evening so as to permit all who wished to attend to do so. The Fianna boys went round to the different florists asking for {16} flowers to make wreaths to place on the graves of the dead. And they were richly rewarded. Every florist they went to gave bunches and bunches of their best flowers, and these the boys brought to Madame's house. Madame and I, and two or three other girls, worked continually all during the afternoon turning the flowers into wreaths. When we had finished we had seventeen glorious big wreaths. Just before six we piled into an automobile, some of the boys in Gaelic costume stood on the running board. The saffron and green of the kilts and the many wreaths made quite an artistic dash of color when we arrived at Beresford Place to have our place assigned to us.

The bodies of the five victims were removed from the Cathedral and placed in the hearses. Behind each one walked the chief mourners. Much interest was aroused by the sight of a soldier in the English uniform, who marched, weeping openly, after one of the hearses. He had joined the English Army and had promised to protect the English King, and now the soldiers of that king had shot and killed his innocent defenseless mother.

Dublin was profoundly moved as the funeral cortege passed through the city. Thousands {17} upon thousands marched to the cemetery after the hearses, and thousands more lined the streets. They were attesting their sympathy with the families of the dead, and their realization that England still intended to rule Ireland with the rifle and the bullet.

The firing party, as they marched after the hearses with their rifles reversed, excited much comment. The people contrasted the difference in the treatment accorded the Nationalists when they had a gun-running, with that accorded the Ulster gun-runners. And they knew once more that England would kill and destroy them rather than permit them to have the means to protect their lives and to fight for their liberties.

The authorities were aware of the feeling aroused in the people by the killing of the unarmed women and men, and to prevent any further disturbance they confined the soldiers to their barracks that evening. Still the feeling against "The King's Own Scottish Borderers" (the regiment that had done the shooting) ran so high that the entire regiment was secretly sent away from Dublin.

About one week later, while the people were still incensed at the shooting, England went to war. Almost immediately she issued an appeal to the Irish to join her army. Later she appealed to them to avenge the shooting of the citizens of Catholic Belgium. Because her memory was short, or perhaps because her need was so great she chose to ignore the fact that English soldiers had but shortly shot down and killed the unarmed citizens of Catholic Dublin. But Dublin did not forget.

The Irish Citizen Army distinguished itself when John Redmond and Mr. Asquith, who was then Prime Minister, came over to Dublin shortly after the outbreak of the war. They came to hold a recruiting meeting in the Mansion House. It was supposed to be a public meeting at which the Prime Minister and the Irish Parliamentary Leader would appeal to the citizens of Dublin to enlist in the British Army; yet no one was let in without a card of {19} admission. A cordon of soldiers were drawn across both ends of the street in which the Mansion House was situated, at Nassau Street and at St. Stephen's Green. No one could pass these cordons without presenting the card and being subjected to a close scrutiny by the local detectives. This was to make sure that no objectionable person could get in to the meeting and make a row. But the Nationalists of Dublin had no intention of going to the meeting; there was to be another one that would give them more pleasure.

A monster demonstration had been decided upon by the Irish Citizen Army to prove to Mr. Asquith, and through him to England, that the mass of the Dublin people were against recruiting for the British Army. They mustered outside of Liberty Hall. The speakers, amongst whom was Sean Mac Dermott who was there to represent the Irish Volunteers, were on a lorry guarded by members of the Irish Citizen Army armed with rifles and fixed bayonets; a squad similarly armed guarded the front and the rear. They were determined that there would be no arrest of anti-recruiters that night.

They marched around the city, the crowd {20} swelling as they went, and they stopped at the "Traitors' Arch" (the popular name for the Memorial to the Irish soldiers who fell in the Boer War), at St. Stephen's Green, two blocks away from where the recruiting meeting was being held. As speaker after speaker denounced recruiting, and denounced England, and Redmond, and Asquith, feeling surged higher and higher until it reached a climax when James Connolly called on those present to declare for an Irish Republic. Cheers burst from thousands of throats and a forest of hands appeared in the air as they declared for a Republic. We were told afterwards that the recruiting meeting had to stop till the anti-recruiters stayed their cheering.

The armed men of the Irish Citizen Army resumed the march first to make sure that none would be molested. Down Grafton Street they went and halted again beside the old House of Parliament, where Jim Larkin called on them to raise their right hands and pledge themselves never to join the British Army. Every one present did so. Then, whistling and singing Nationalist marching tunes and anti-recruiting songs, they marched back to Liberty Hall and dispersed. As a result of {21} Asquith's meeting, or because of the Irish Citizen Army meeting, only six men joined the British Army next day.

Midnight mobilizations were a feature of the Irish Citizen Army. They served a twofold purpose. They taught the men to be ready whenever called upon, and were a great source of annoyance to the police. At every mobilization of the Irish Citizen Army a squad of police and detectives were detailed by the authorities to follow and report all the movements. One midnight the men mobilized at Liberty Hall; they were divided into two bodies, the attacking and the defending. They marched to the North side of the city, one body going across the canal, and the other remaining behind to prevent the entrance of the attackers. The battle lasted two hours. It was a bitter winter's night and the police were on duty all the time as they did not dare to leave, for there was no telling what the Irish Citizen Army might be up to.

Illustrating journey from Belfast to Leek. See pages 54-71

Illustrating the journey from Dundalk to Dublin. See pages 142-163

After the men had completed their evolutions around the bridge they formed ranks and marched round the city, the police following them. They stopped at Emmet Hall, Inchicore, for refreshments. There they had a song {24} and dance, one chap remarking that the thought of the "peelers" (police) and the "G men" (detectives) outside in the cold added to the enjoyment. They broke up about six o'clock a.m. and marched back to Liberty Hall followed by the disheartened, miserable, frozen police.

There was another midnight mobilization later on. Announcements were made publicly that on this occasion the Irish Citizen Army would attack Dublin Castle, the center of English Government in Ireland for 600 years. The thought of such a deed never fails to fire the imagination of an Irish Nationalist. A favorite phrase of one of the officers of the Irish Citizen Army, Commandant Sean Connolly, was, "One more rush, boys, and the Castle is ours." He was in command of the body that attacked the Castle on Easter Monday. It was while calling on his men to rush the Castle that he received a bullet through his brain, thus achieving his lifelong dream of dying for Ireland while attacking the Castle.

One other mobilization which took place at midnight some time before the Rising was a disappointment, perhaps because it was unofficial. One of the Irish Citizen Army men {25} heard that a number of rifles were stored in a place near Finglass. He knew the whereabouts and whispered the news amongst his comrades. A number of them decided to make a raid on the place and capture the rifles. They started out at midnight, marched twenty miles before morning, but, unfortunately, the rifles had been removed before they arrived. They were disappointed but not downhearted; such things they considered part of the day's work.

They had another disappointment which was more amusing, at least our men could laugh at it when a few days were past. There was in Dublin a body of men called the Home Defense Corps. They wore a greenish gray uniform and on their sleeves an armlet with the letters "G.R." in red—abbreviations for Georgius Rex. They were called the "Gorgeous Wrecks" by the Dubliners. They were mainly men past the military age who had registered their willingness to fight the Germans when they invaded England, Scotland, or Ireland. These men paraded the streets of Dublin making a fine show with their uniforms and rifles, especially the rifles. Some of the Irish Citizen Army thought those rifles too {26} good to be left in the hands of "those old ones" and followed them on a march to find out where the rifles were kept. When our men came back they gathered a number of their friends together; after a short talk away they went for the rifles. It was done in quite a military manner; sentries and pickets were placed, the building surrounded and entered. Several made their way to the room where the rifles were kept and opened the windows to hand the rifles to the eager hands outside. Their plan was to march home with them quite openly as if returning from a route march.

The leader of the band was well known for his lurid and swift flow of language. Suddenly bursting out, he surpassed all his previous efforts and completely staggered the men around him—they beheld him examining one of the rifles. It was complete in every detail, just like an army rifle, but on lifting it it was easy to know that it was a very clever imitation. The men were heartbroken and disgusted, but they brought several of the rifles away with them to show their officers what the "Gorgeous Wrecks" were going to fight the Germans with. During a raid by the Dublin {27} police in a well-known house one of these rifles was taken away by them. How long it took them to realize its uselessness we do not know as it was never returned.

Towards the end of 1915 the hearts of the Irish Citizen Army beat high, when they were summoned one night for special business. One by one they were called into a room where their Commandant, James Connolly, and his Chief of Staff, Michael Mallin, were seated at a table. They were bound on their word not to reveal anything they should hear until the time came. Something like the following conversation took place:

"Are you willing to fight for Ireland?"

"Yes."

"It might mean your death."

"No matter."

"Are you ready to fight to-morrow if asked?"

"Whenever I'm wanted."

"Do you think we ought to fight with the few arms we've got?"

"Why wait? England can get millions to one."

"It might mean a massacre."

"In God's name let us fight, we've been waiting long enough."

"The Irish Volunteers might not come out with us. Are you still ready?"

"What matter? We can put up a good fight."

"Then in God's name hold yourself ready. The Day is very near."

To the eternal credit of the Irish Citizen Army be it recorded that only one man shirked that night.

Then on top of this glorious happening came the attempted raid on Liberty Hall by the police. That morning I was in the office with my father when a man came from the printer's shop and said, "Mr. Connolly, you're wanted downstairs." My father went downstairs. About five minutes later he came into the office again, took down a carbine, loaded it and filled his pockets with cartridges.

"What is it?" I asked. "Can I do anything?"

"Stay here, I'll need you," said my father and he left the office again. He was gone about five minutes when the door was banged {30} open and the Countess de Markievicz burst into the office.

"Where's Mr. Connolly?" she demanded excitedly. "Where's Mr. Connolly? They're raiding the Gaelic press—the place is surrounded with soldiers."

"He left here five minutes ago," I said. "He took his carbine with him and told me to remain here as he would need me."

She ran out again. In a few minutes I heard her and my father coming back along the corridor. She was talking excitedly and my father was laughing.

They came into the office—he took down a sheaf of papers and commenced signing them. They called for instant mobilization of the Irish Citizen Army. They were to report at Liberty Hall with full equipment at once.

"Well, Nora," said my father. "It looks as if we were in for it and as if they were going to force our hands. Fill up these orders as I sign them. I want two hundred and fifty."

I busied myself filling in these orders. The Countess began to help me—suddenly she stopped and cried out, "But, Mr. Connolly, I haven't my pistol on me."

"Never mind, Madame," said my father. "We'll give you one."

"Give it to me now," she said. "So my mind will be easy."

She was given a large Mauser pistol. Just then a picket came running in. He saluted and said, "They've left the barracks, sir." He was referring to the police. A line of our pickets had been stationed reaching from the barracks to Liberty Hall; their duty was to report any move they might see made by the police. In that way no sooner had a body of police left the barracks than word was sent along the line and in less than three minutes Liberty Hall was aware of it.

"Now, Madame," said my father when the picket had gone. "Come along, we'll be ready for them. Finish those, Nora, and come down to me with them."

I finished them and went down to the Co-operative shop. Behind the counter stood my father with his carbine laid along it; beside him Madame, and outside the counter was Miss Moloney taking the safety catch from off her automatic. I gave the batch of orders to my father; he called one of the men who stood in the doorway, and said, "Get these around at {32} once." The man saluted and went away. Just then another picket came in and said, "They will be here in a minute, sir, they've just crossed the bridge."

"Very well," said my father, and the men went away.

Miss Moloney then told me that some policemen had come in and had attempted to search the store, and that she had sent word to Mr. Connolly through the men in the printing shop, which was back of the Coöperative shop; and then busied herself resisting the search. One policeman had a batch of papers in his hands when my father came in. He saw at once what was going forward, drew his automatic pistol, pointed it at the policeman and said:

"Drop them or I'll drop you."

The policeman dropped them. My father then asked what he wanted. He said they had come to confiscate any copies of The Gael, The Gaelic Athlete, Honesty or The Spark that might be on the premises.

"Have you a search warrant?" asked my father. This was a bluff, because under the Defense of the Realm Act any house may be searched on suspicion; but it worked; the policeman said he had none.

"Go and get one," said my father, "or you'll not search here."

The police went away; and it was then that my father had come back to the office to sign the mobilization papers.

Shortly afterwards there came into the shop an Inspector of the police, four plain-clothes men and two policemen in uniform. I was behind the counter at this time.

"I am Inspector Banning," said the Inspector.

"What do you want?" asked my father.

"We have come to search for, and confiscate any, of the suppressed papers we may find here."

"Where's your warrant?" asked my father.

"I have it here," said the Inspector.

"Read it," said my father.

The Inspector read the warrant—it was to the effect that all shops and newsvendors were to be searched, and all copies of the suppressed newspapers confiscated.

"Well," said my father when the Inspector had finished reading. "This is the shop up to this door,"—pointing to one behind him,—"beyond this door is Liberty Hall, and through {34} this door you will not go. Go ahead and search."

"We have no desire to enter Liberty Hall," said the Inspector.

"I don't doubt you," said my father, whereat we all grinned.

At an order from the Inspector one of the policemen began to search around the place where the papers were kept. He looked at my father standing in the doorway with his carbine, and for a moment we thought he was going to rush him. Perhaps visions of stripes danced before him; but, at an order from his superior he went on with his work. It was a good thing for him that he did so, as there were the best of shots present, with less than ten paces between him and them.

"There is nothing here," he said at last to the Inspector. (We had made sure there would not be.) And then they all left the shop.

In the meantime, a series of strange sights were to be seen all over the city. The mobilization orders had gone forth and the men were answering them. Women in the fashionable shopping districts were startled by the sight of men, with their faces still grimed with the dust of their work, tearing along at a breakneck {35} speed, a rifle in one hand and a bandolier in the other.

Out from the ships where they were working; from the docks; out of the factories; in from the streets,—racing, panting, with eager faces and joyful eyes they trooped into Liberty Hall. Joyful because they believed the call had come at last.

No obstacle was great enough to prevent their answering the order. One batch were working in a yard overlooking a canal. A man appeared at the door, whistled to one of the men and gave him a sign.

"Come on, boys, we're needed," cried one and made for the door. The foreman, thinking it was a strike, closed the door. Nothing daunted they swarmed the walls, jumped into the canal, swam across, ran to their homes for their rifles and equipment and arrived at Liberty Hall, wet and happy. Another batch were busy with a concrete column and had just got it to the critical period, where one must not stop working or it hardens and cannot be used, when the mobilizer appeared at the door and gave them the news. Down went the tools and out they went through the gate in the twinkling of an eye.

All day long the men were arriving at Liberty Hall. Tense excitement prevailed amongst the crowds that came thronging outside the Hall. A guard was placed at the great front door, another at the head of the wide staircase and the rest were confined to the guard room. This guard room had a great fascination for me. The men were sitting on forms around an open fire; ranged along the walls were their rifles, and hanging above them their bandoliers; at the butts of the rifles were their haversacks containing the rest of their equipment; all was so arranged that when they received an order each man would be armed and equipped within a minute, and there would be no confusion or delay. When I first went in the men were singing, with great gusto, this Citizen Army marching tune:

We've got guns and ammunition, we know how to use them well,

And when we meet the Saxon we'll drive them all to Hell.

We've got to free our country, and avenge all those who fell,

And our cause is marching on.

Glory, glory to old Ireland,

Glory, glory to our sireland,

Glory to the memory of those who fought and fell,

And we still keep marching; on.

I knew then what was meant by sniffing a battle. I did not want to leave that room. The atmosphere thrilled me so that I regarded with impatience the men and women who were going about the Hall attending to the regular business of the Union, and not in the least perturbed by all the military display. "Business as usual," one chap remarked to me as I stood watching them all.

I did not stand long, for a Citizen Army man came to me and said, "You're wanted in No. 7 by Mr. Connolly." No. 7 was my father's office. When I got there my father said, "Nora, I have a carbine up at Surrey House and a bandolier. It is in my room." He then told me where. "I want you to get one of the scouts, who are always at Madame's house, to put the bandolier on and over it my heavy overcoat. Tell him to swing the rifle over his shoulder and come down here with it as if he were mobilizing. Get him here as soon as you can. I'll be staying here all night," he added.

I started off immediately for Rathmines where Surrey House, Countess de Markievicz's residence, is situated. On my way I met one of the scouts who was going there. When I told him my errand he offered to be the one {38} to bring the things back to Liberty Hall. When we reached the house, I went to the room, found the things which my father wanted and brought them down to the scout. He had just put them on when Madame called from the kitchen and asked me to have some tea. Of course I said I would have some. While I was waiting to be served she said to me, "What do you think is going to happen? I am going down to Liberty Hall immediately to take my turn of standing guard. By-the-way, what do you think of my uniform?"

She stepped out into the light where I could get a good view of her. She had on a dark green woolen blouse trimmed with brass buttons, dark green tweed knee breeches, black stockings and high heavy boots. As she stood she was a good advertisement for a small arms factory. Around her waist was a cartridge belt, suspended from it on one side was a small automatic pistol, and on the other a convertible Mauser pistol-rifle. Hanging from one shoulder was a bandolier containing the cartridges for the Mauser, and from the other was a haversack of brown canvas and leather which she had bought from a man, who had got it from a soldier, who in turn had brought it {39} back from the front; originally it had belonged to a German soldier. I admired her whole outfit immensely. She was a fine military figure.

"You look like a real soldier, Madame," I said, and she was as pleased as if she had received the greatest compliment.

"What is your uniform like?" she asked.

"Somewhat similar," I answered. "Only I have puttees and my boots have plenty of nails in the soles. I intend wearing my scout blouse and hat."

"This will be my hat," she said and showed me a black velour hat with a heavy trimming of coque feathers. When she put it on she looked like a Field Marshal; it was her best hat.

"What arms have you?" she then asked.

"A .32 revolver and a Howth rifle."

"Have you ammunition for them?"

"Some. Perhaps enough."

I then turned to the scout who was to carry my father's rifle and bandolier to Liberty Hall, and said, "We'd better go now." Saying "Slán libh" ("Health with ye") we left the room. On our way to the door we heard a heavy rap at it. I ran forward and opened {40} it. Judge of my surprise to see two detectives standing outside.

"What do you want?" I asked.

"The Countess de Markievicz."

"Wait," I said and closed the door.

Running back to the room I said, "Madame, there are two detectives at the door. They say they want you."

All the boys looked to their revolvers, and the boy who had my father's rifle said, "I hope I'll be able to get these down to Mr. Connolly."

Madame went into the hall and lit a small glimmer of light. The boys remained in the darkened background, and I opened the door.

The detectives came just inside of the door.

"What do you want with me?" asked Madame.

"We have an order to serve on you, Madame," said one of them.

"What is it about?" asked Madame.

"It is an order under one of the regulations of the Defense of the Realm Act, prohibiting you from entering that part of Ireland called Kerry."

"Well," said Madame. "Is that to prevent me from addressing the meeting to-morrow night in Tralee?" Madame was advertised to {41} at a meeting to organize a company of boy scouts the following day in the town of Tralee, County Kerry.

"I don't know, Madame," he answered.

"What will happen to me if I refuse to obey that order and go down to Kerry to-morrow?" asked Madame. "Will I be shot?"

"Ah, now, Madame, who'd want to shoot you? You wouldn't want to shoot one of us, would you, Madame?" said the detective who was doing all the talking.

"But I would," cried Madame. "I'm quite prepared to shoot and be shot at."

"Ah, now, Madame, you don't mean that. None of us want to die yet: we all want to live a little longer."

"If you want to live a little longer," said a voice from out of the darkness, "you'd better not be coming here. We're none of us very fond of you, and you make fine big targets."

"We'll be going now, Madame," said the detective. As he stepped out through the door he turned and said, "You'll not be thinking of going to Kerry, Madame, will you?"

"Good-by," said Madame cordially. "Remember, I'm quite prepared to shoot and be shot at."

"Well," she said as the door closed. "What am I going to do now? I want to go and defy them. How can I do it? I'm so well known—but I'm under orders. Perhaps Mr. Connolly wouldn't allow me to go anyway. I'll go down and talk it over with him. Wait a minute, Nora, and we'll all be down together."

On our way down a brilliant idea, as I thought, struck me. "Write your speech out, Madame, make it as seditious and treasonable as possible. Send some one down to Tralee to deliver it for you at the meeting. In that way, the meeting will be held, your speech delivered, and the authorities will not be able to arrest you on that charge."

"I was just thinking of that and who I could send down. But I'll decide nothing till I see Mr. Connolly," said Madame.

We met my father at the top of the staircase in Liberty Hall.

"What do you think, Mr. Connolly," cried Madame. "I've received an internment order or rather an order prohibiting me from going down to Tralee. What am I going to do about it? Shall I go or shall I obey the order."

"Did you bring the carbine and bandolier?" asked my father turning to me.

"Yes," I answered. "Harry has them."

"No, Madame," said my father. "You cannot go down to Tralee. If you make the attempt you will probably be arrested at some small station on the way, and sentenced to some months in jail. You are too valuable to be a prisoner at a time like this; I'll have need of you. If the authorities follow up their action of to-day we may be in the middle of things to-night or to-morrow; who knows? No, you must stay here. You are more important than the meeting."

"Should I send some one in my place, then?" asked Madame.

"That is for you to decide, though I think it would be a good thing."

"Whom will I send?" asked Madame.

"Send some one who cannot be victimized in case our hands are not forced; some one who is already victimized. Why not ask Mairé Perolz?"

"The very girl!" said Madame. "You can always pick out the right person."

"You had better get hold of Perolz, then," said my father. "Tell her what you want her to do and write out your speech. We'll relieve you of guard duty to-night, and promise you {44} that if things look lively we'll get word to you in time."

Madame left the Hall, and when I returned to her house a few hours later, she was busy writing out her speech. I sat down in the room and from time to time she read me out parts of it. It certainly was seditious and treasonable. She wrote on for quite some time after that and then with a sigh of satisfaction she said, "I have it finished. Perolz will come for it in the morning—she will take an early train."

Perolz had come and gone before I came down in the morning, but when she returned a few days later, I heard the whole story of her adventure, told in her own inimitable way.

She had traveled down to Limerick Junction accompanied by a very polite, attentive detective, whose company she dispensed with there by leaving the carriage she was in at the very last minute, and taking a seat in another. Hers was not a case of impersonation, for the Countess de Markievicz is very tall and rather fair while Mairé Perolz is of medium height and has red hair. She is very quick-witted and nimble of her tongue, never at a loss for what to do or for what to say.

THE PROCLAMATION OF THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT ISSUED AT

THE G.P.O. ON MONDAY, APRIL 24TH, 1917.

She was met at Tralee station by a guard of honor from the local Cumann na mBan (women's organization), Irish Volunteers, and intending boy scouts. They had never seen the Countess de Markievicz and consequently did not know that it was not she who had arrived. Although Mairé told me that she almost lost her composure when she heard one of the girls say, "She isn't a bit like her photograph."

She was escorted to the hotel. When she arrived there she said to the officers of the organization, "I am not Madame Markievicz. She received an order last night prohibiting her from entering Kerry. Things were looking lively in Dublin and Madame was needed. She wrote out her speech and I am to deliver it for her. In that way the meeting will be held and Madame's speech will be delivered, and Madame will still be able to do useful work. There is no need to let the public know till to-night."

The officers agreed that it would be best to keep the knowledge of the non-arrival of Madame from the public and the police. Just then the proprietor of the hotel came to the door and said, "Madame, there are two {46} policemen downstairs and they want your registration form at once." Under the Defense of the Realm Act every one entering an hotel, or boarding or lodging house is required to fill in a form declaring his name, address, occupation, and intended destination. This rule was most rigidly enforced by the police authorities.

"Can't they wait till I get a cup of tea?" asked Mairé.

"No. They said they would wait and take it back to the station with them."

"Very well," said Mairé. "Give it to me."

She filled out the form something like this, neglecting the minor details.

Name:—Mairé Perolz.

Address:—No fixed address—vagrant.

Age:—20?

Occupation:—None.

Nationality:—Irish.

She then gave it to the proprietor who took it away. From the window they watched the policemen carrying it to the police station, apparently very much absorbed in it. They returned shortly and asked to see the lady. When they came in to the room they still carried the registration form.

"You haven't filled in this form satisfactorily, {47} Madame," said one. "You must have some fixed address and some occupation."

"No indeed," said Mairé. "I live on my wits."

"And you are a Russian subject."

"How do you make that out, in the name of God?" asked Mairé.

"You are married to a Russian Count."

"First news I've heard of it," said Mairé. "Now listen here, I've filled that form out correctly and you'll have to be satisfied with it. I'll not fill out another."

They accepted the form at last. That night Mairé delivered Madame's speech, told why Madame could not be present, then added a little anti-recruiting speech of her own which evoked great applause. The next day she returned home in great spirits at having once more helped to outwit the police.

About this time the Executive of the Cumann na mBan (women's organization) in Dublin were having trouble in procuring First Aid and Hospital supplies. I suggested that being a Northerner and having a Northern accent, I could probably get them in Belfast. I knew that a number of loyalist nursing corps were in existence in that city, and thought that by letting it be inferred that I belonged to one of them, the loyalist shopkeepers would have no hesitation in selling me the supplies, and in all probability would let me have them at cost price. And that is exactly what happened. I purchased as many of the different articles as I needed and at less than half the price paid in Dublin.

While in Dublin I had visited the Employment Bureau in the Volunteer Headquarters. Its business was to find employment for Irishmen and boys who were liable for military service. Under the Military Service Act every {49} man or boy over eighteen, residing in England or Scotland since the preceding August, was required to report himself for service in the British Army. The Bureau found employment in most cases for those who preferred to serve in the Irish Republican Army and had come to Ireland to await the call. Of course, it was impossible to find jobs for them all; but those who had not received jobs were busy on the work of making ammunition and hand grenades for the Irish Republican Army. The greater number of them had to camp out during the miserable months of February and March, in the Dublin Mountains, so that too great a drain would not be placed on their slender resources.

On my return to Belfast at a meeting of the Cumann na mBan I suggested that we send hampers of foodstuffs down to those boys and men in Dublin. The suggestion was taken up with great gusto, and the members were divided into different squads; a butter squad, a bacon squad, a tea, a sugar, oatmeal, cheese, and tinned goods squad; and they were to solicit all their friends for these articles. They were then to be sent on to the different camps in Dublin to help on the fight. Since we had {50} done so well on the foodstuffs I thought it would be as well to ask the men and boys in Belfast for cigarettes and tobacco. I set about collecting on the Saturday on which we intended sending away the first hamper of food. I was so successful that I was unable to return home for lunch before half-past three.

When I arrived home my sister met me at the door and said there was a man in the parlor who wanted to see me, and that he had been waiting since noon. I went into the room and saw one of my Dublin friends.

"Why, hello, Barney," I said. "What brings you here?"

He told me that there was some work before me and that he had the instructions. With this he handed me a letter. I recognized my father's handwriting on the envelope. The letter merely said:

"Dear Nora, The bearer will tell you what we want you to do. I have every confidence in your ability.

"Your father,

"JAMES CONNOLLY."

"What are we to do?" I asked turning to Barney.

"Liam Mellowes is to be deported to-morrow {51} morning to England and we are to go there and bring him back."

"Sounds like a big job," I said. "What are the plans?"

"These are some of them," he answered showing me several pages closely written. "Some one will bring the final instructions from Dublin to-night."

The plan in the rough was that the messenger, being on the first glance uncommonly like Liam Mellowes, was to go to the place where he was interned and visit him. While he was visiting he was to change clothes with Liam Mellowes and stay behind, while Liam came out to me. We were then to make all speed to the station and lose no time in returning to Dublin.

Liam Mellowes had received, some time previously, an order from the military authorities to leave Ireland. This was because of his many activities as an organizer for the Irish Volunteers—as the order had it, because he was prejudicial to recruiting. He refused to obey and had been arrested. He was now to be forcibly deported. As Mellowes was absolutely essential to the plans for the Rising, being Officer in charge of the operations in the {52} West of Ireland, the attempt to bring him back from England was decided upon.

While waiting for the messenger to bring the final instructions from Dublin I sent out word to some of the Cumann na mBan girls that I should like to see them. When they came I told them that I had received an order that necessitated my going to Dublin; and that I should not be able to assist them in sending away the hampers. I gave them the money that I had collected for the cigarettes and tobacco, and they said they would see that everything went away all right. It was with great surprise and delight that the "refugees," as we called them, received the hampers a few days later.

After the girls left I fell to studying the instructions. The main idea was to go in as zig-zag a course as possible to our objective. My father had made out a list of the best possible places to break our journey. On one sheet of paper in Eamonn Ceannt's handwriting continued the plan; and on another, in Sean mac Diarmuida's, was a list of people with their addresses in England or Scotland, to whom we could go for safe hiding, if we found we were being followed by detectives.

Shortly after seven that evening Miss Moloney arrived at our house. She brought us a message from Dublin. It was to the effect that it was not yet known to what place Liam Mellowes was to be deported, but we were to go on our journey, and when we arrived at Birmingham, there would be a message waiting us there with the desired information. All that was known was that Liam Mellowes was to be deported to some town in the South of England.

There was a boat leaving for Glasgow that night at eleven forty-five. We decided to go on it; it was called the theatrical boat, because it was on this boat many theatrical companies left Belfast; we thought we would not be noticed among the throng. I was to ask for all the tickets at the railway stations, as my accent is not easily placed.

On Sunday morning I went up on deck expecting to be almost the first one there; Barney, however, was there before me. He said we would be in Glasgow shortly. I went below for my suitcase. When I came up on deck again I saw that we were nearer shore and that we were slowing up. I asked a steward if we should be off soon.

"No," he said. "We are slowing up here to put some cattle off."

"Will it take long?" I asked.

"About an hour."

"How far are we from Glasgow?" I then asked.

"Two or three miles."

"Can we get off here instead of waiting?"

"Nothing to prevent you," he said.

So Barney and I picked up our traps and, as soon as the gangway was fixed up for the {55} cattle to disembark, we went down it and on to the quay.

We walked along as if we had been born there, although as a matter of fact, neither Barney nor I had been in that place before. After a few minutes we came to a street with tramway lines on it and decided to wait for a car. We boarded the first car that came along. After riding in it for a long time we noticed that instead of approaching the city we seemed to be going farther away from it. We left the car at the next stop, and took another going in the opposite direction, and after riding for three-quarters of an hour arrived in Glasgow. We were more than pleased to think that if the police had noticed us when we went on the Glasgow boat at Belfast, and had sent on word for the Glasgow police to watch out for us, the boat would arrive without us.

Our next stop was to be Edinburgh. We went to the station and inquired when the Edinburgh train would be leaving. There was one leaving at eleven fifteen that would arrive in Edinburgh some time about one o'clock. We decided to go by it. Then we remembered that it was Sunday and that we had not been to Mass; also that if we went by that train {56} it would be too late when we arrived at Edinburgh to attend. It was not quite ten o'clock then; if we could find a church nearby, we could go to Mass and still be in time for the train. But where was there a church? "Look, Barney," I cried suddenly. "Here's an Irish-looking guard. We'll ask him to direct us." We asked him and he told us that there was a Catholic church five minutes' walk away from the station, and directed us to it. It took us more than five minutes to get there, but we arrived in time and were back at the station before the Edinburgh train left.

We arrived at Edinburgh about one o'clock. We were very tired as we had not slept on the boat; and we were hungry for we had not eaten in our excitement at leaving the boat before the time. Our first thought was to find a place to eat; but it was Sunday in Scotland and we found no place open. After wandering around for some time, looking all about us, we decided to ask a policeman. He directed us to the Waverley Hotel, where we were given a good dinner. And when we told the waiter that we were only waiting till our train came due, and that we wanted a place to rest, he told us that we could stay in the room we were {57} in. After dinner I found myself nodding and lay down on the couch. I must have fallen asleep almost instantly for it was dark when I awoke. Barney came in shortly afterwards. He had been looking up the trains he said and our train left at ten o'clock. It was about eight o'clock. We had something more to eat and left the hotel to go to the railway station. To my great surprise when we came outside everything was dark. Not a light showed from any of the buildings, or from the street cars. Cabs and motors went by, and only for the shouting of the drivers and the blowing of the motor-horns we would have been run down when crossing the streets. We have no such war regulation of darkness in Ireland. We arrived at the station at last. We had to go down a number of steps to get to the gate, and if it was dark in the streets it was pitch blackness down there. I was not surprised at the number of people I met on the steps, as I thought it might be a usual rallying place, but I was surprised to hear them talking in whispers. We went down till we came to the gate—it was closed and there was a man on guard at it.

"Can we not get in?" I asked.

"Where are you going?"

"To Carlisle."

"It's not time for the Carlisle train yet."

"But can't we go in and take our seats?" I asked.

"No," he answered, and after that I could get no further response.

We waited awhile at the gate. I noticed that quite a few were given the same answers although they were not going to the same place. More time passed and I began to feel anxious; I was afraid that we would miss the train.

"What time is it now?" I asked, turning to Barney. As he could not see in the dark he lit a match. Instantly, as with one voice, every one around and on the steps shouted, "Put out that light." And the man at the gate howled, "What the H—— does that fool mean!" We were more than surprised; we did not know why we could not light a match.

Just after that a couple of soldiers came towards the gate. I could hear the rattle of their hob-nailed boots and see the rifles swung on their shoulders. They talked with the man at the gate for a few minutes, then saying, "All right," went up the steps again. This happened more than once. My eyes were {59} accustomed to the darkness by now, and I could see a sergeant, with about twenty soldiers, coming down the steps. As they made for the gate I whispered to Barney, "Go close and listen to what the guard says to the sergeant." He went—and as the sergeant turned away, came back to me and picking up our bags said, "Come on." I followed without asking any questions. When we were out on the street Barney turned to me and said, "The guard told the sergeant to go to the other gate. We'll go too."

We followed the clacking sound of the soldiers' boots till we came to a big gate. It was evidently the gate used for vehicles. As we entered we were stopped by two guards who asked, "Where are you going?" "To Carlisle," I answered. They waved us inside. We walked down a long passageway. When we came to the train platforms, I asked a porter who was standing near:

"Where is the train for Carlisle?"

"There'll be no train to-night, Miss," he answered.

"But why?"

"Because, Miss," in a whisper, "the Zeppelins were seen only eight miles away, and {60} a moving train would be a good mark for them."

"But they will not come here, will they?" I asked.

"They are headed this way, Miss, they may be here in half an hour."

"Then we can't get to Carlisle?"

"To tell you the truth, Miss," he said, "I don't think any train will run to-night, except the military train. Make up your mind you'll not get to Carlisle to-night."

"When is there a train in the morning?" I asked him then.

"There's one at eight-fifteen."

"Well, I suppose we'll go by that one," I said.

And so we left the station.

We went back to the hotel. We were startled for a second when the registration forms were handed to us; we hadn't decided on a name or address. I took the forms and filled them with a Belfast address, put the one for Barney in front of him, placing the pencil on the name so that he would know what to sign. After signing we were shown to our rooms. I went to bed immediately as I was completely tired out. I was roused from a heavy sleep {61} by a knocking on the door, and a voice saying something I couldn't distinguish. I thought it was the "Boots" wakening me for breakfast, and turned over to finish my sleep. Some time later I was again wakened by a loud knocking on the door.

"Who is it?" I called out.

"Barney," was the answer.

"What is wrong?" I asked when I had opened the door.

"The manageress came to me," said Barney, "and said, 'Mr. Williams, go to your sister, I am afraid she is either dead or has fainted with the shock.'"

"What shock?" I asked, peering into the black darkness but failing to see anything.

"Nothing, only the Zeppelins have been dropping bombs all over the town."

"What!" I cried. "Zeppelins! You don't mean it. Have I slept through all their bombing?"

"You have," he said dryly. "The manageress wants all guests down in the parlor, so that in case this building is damaged, they'll all be near the street. Put something on and come down."

I put some clothes on me and went outside {62} the room. I could not see my own hand in front of me.

"Hold on to me," said Barney, "and I'll bring you downstairs. I know where the stairs are."

"All right," I said, making a clutch at where the voice was coming from.

"You'd better hold on to my back," said Barney. "That's the front of my shirt you've got."

I slid my hand around till I felt the suspenders at the back and held onto them. "Go ahead," I said, and we went. I tried to remember if the corridor was long or short, and if there were any turns from the stairs to my room, but I could not. Never have I walked along a corridor as long as that one seemed. After a bit I said, "Barney, are you sure you're going right? I don't remember it being as long as this." We were going very slowly, gingerly placing one foot after the other.

"We keep on," said Barney, "till we come to a turn and then between two windows are the stairs." And so we went on, but we came to no turning. We were feeling our way by placing our hands on the wall. At last, we felt an open space. "Ah," said Barney, "this {63} must be the stairs." And although we did not feel the windows we cautiously stepped towards it. It was not the stairs and I felt curiously familiar with it. I stumbled over something on the floor and stooped to pick up—my shoe. We were back at my room! We did not know whether to laugh or to be annoyed. We began to laugh and Barney said, "Come on, I know the way back to my room and from there we'll find the stairs."

"Couldn't you strike a match?" I asked.

"We were warned not to, when the 'Boots' knocked on the door," said Barney. We went along the corridor till Barney found his room. From there he knew the turns of the corridor, and at last we found the stairs. Going down I asked, "How is it that we are meeting none of the people?"

"Because," said Barney, "they've been down since the first knock and you had to be wakened twice."

"I thought they were wakening me for breakfast," I said.

The stairs seemed to twist and turn, and at one of the turns I saw a figure standing at a window, near a landing as I thought.

"Are we going the right way down to the {64} parlor?" I asked the figure, but received no reply.

"He's probably scared stiff and thinks he's in a safe place," said Barney. We reached the foot of the stairs and one of the men took us and led us towards the parlor. All the guests of the hotel were there huddled closely around the remains of the fire. I found a seat and sat down. There was very little talk. I could hear the guns going off very near. One of the women leaned toward me, and said, "You were rather long getting down. Did you faint—were you frightened?"

"No," I answered. "I slept through it all, until my brother came and wakened me."

"You lucky girl!" she exclaimed in heart-felt tones.