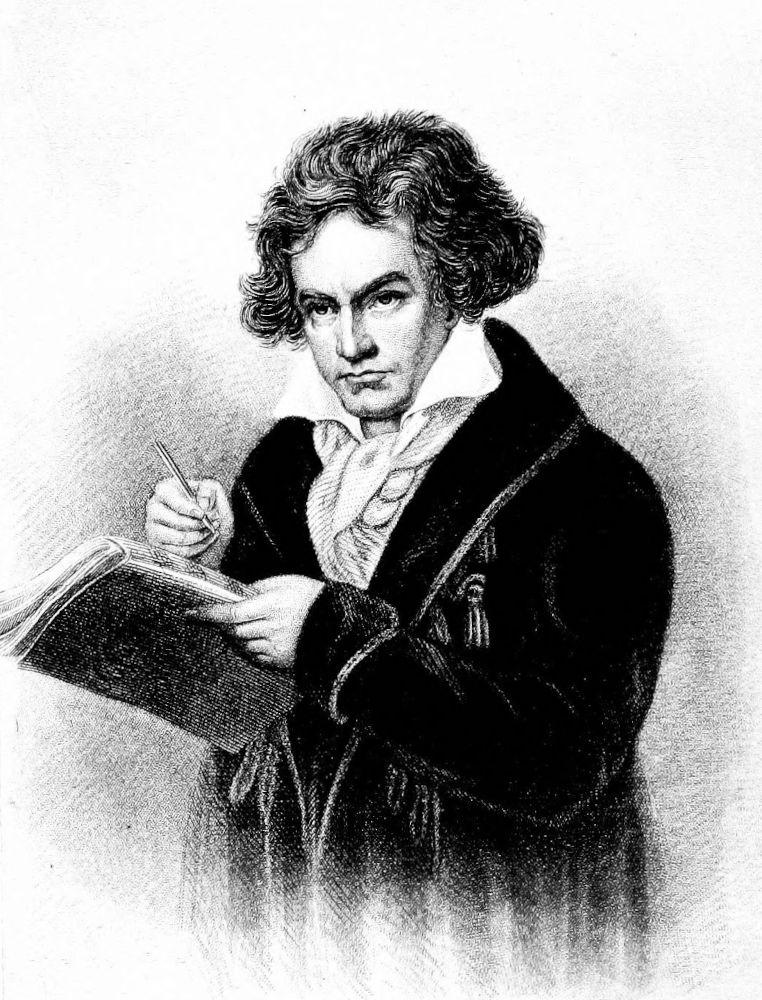

Mᶜ Rae, sc.

HANDEL.

Title: Nouvellettes of the musicians

Author: E. F. Ellet

Release date: August 4, 2023 [eBook #71344]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Cornish, Lamport & Co

Credits: The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Mᶜ Rae, sc.

HANDEL.

By MRS. E. F. ELLET,

AUTHOR OF “THE WOMEN OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION.”

NEW YORK:

CORNISH, LAMPORT & Co., PUBLISHERS.

ST. LOUIS:—Mc CARTNEY & LAMPORT.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1851,

By CORNISH, LAMPORT & Co.

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the United States, for the

Southern District of New York.

Stereotyped by Vincent Dill, Jr.,

Nos. 21 & 23 Ann Street, N. Y.

In the following series of Nouvellettes, something higher has been attempted than merely the production of amusing fictions. Each is founded on incidents that really occurred in the artist’s life, and presents an illustration of his character and the style of his works. The conversations introduced embody critical remarks on the musical compositions of great masters; the object being to convey valuable information on this subject—so little studied or known except among the few devoted to the art—in an attractive form. The view given of the scope and tendency of the works of different artists, and their relation to personal character, may also enforce a striking moral; showing the elevating influence of virtue, and the power of vice to distort even the loveliest gift of Heaven into a curse and reproach. Of the tales—“Tartini,” “Two Periods in the Life of Haydn,” “Mozart’s First Visit to Paris,” “The Artist’s Lesson,” “The Mission of Genius,” “The Young Tragedian,” and “Tamburini,” only are original; the others are adapted from the “Kunstnovellen” of Lyser and Rellstab. The sketch of the great pianist, Liszt, is translated from a memoir by Christern, a distinguished professor of music in Hamburg.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| HANDEL, | 7 |

| TARTINI, | 21 |

| HAYDN, | 39 |

| FRIEDEMANN BACH, | 75 |

| SEBASTIAN BACH, | 105 |

| THE OLD MUSICIAN, | 120 |

| MOZART, | 129 |

| THE ARTIST’S LESSON, | 169 |

| GLUCK IN PARIS, | 184 |

| BEETHOVEN, | 201 |

| THE MISSION OF GENIUS, | 227 |

| PALESTRINA, | 244 |

| THREE LEAVES FROM THE DIARY OF A TRAVELLER, | 251 |

| THE YOUNG TRAGEDIAN, | 261 |

| FRANCIS LISZT, | 271 |

| TAMBURINI, | 292 |

| BELLINI, | 311 |

| LOVE VERSUS TASTE, | 320 |

[Pg 7]

Nouvellettes of the Musicians.

In the parlor of the famous London tavern, “The Good Woman,” Fleet street, No. 77, sat Master John Farren, the host, in his arm-chair, his arms folded over his ample breast, ready to welcome his guests.

It was seven in the evening; the hour at which the members of the club were used to assemble, according to the good old custom in London, in 1741. Directly before John Farren, stood Mistress Bett, his wife, her withered arms akimbo, and an angry flush on her usually pale and sallow cheeks.

“Is it true, Master John,” she asked, in a shrill tone; “is it possible! do you really mean to throw our Ellen, our only child, into the arms of that vagabond German beggar?”

“Not exactly to throw her into his arms, Mistress Bett,” replied John, quietly; “but Ellen loves the lad, and he is a brave fellow—handsome, honest, gifted, industrious——”

“And poor as a church mouse!” interrupted Bett; “and nobody knows who or what he may be!”

“Yes! his countryman, Master Händel, says there is something great in him.”

“Pah! get away with your Master Händel! he is always your authority! What is he to us, now that it is all over with him in[Pg 8] the favor of His Majesty! While he could go in and out of Carlton House daily, I would have cared for his good word; but now that he is banished thence for his highflown insolent conduct, what is he, but an ordinary vagabond musician?”

“Hold your tongue!” cried John Farren, now really moved; “and hold Master Händel in honor! If he gives Joseph his good word, by my troth I have ground whereon I can build. Do you understand, Mistress Bett?”

The “good woman” seemed as though she would have replied at length; but before she could speak, the door opened, and two men of respectable appearance entered. Tom, the waiter, snatched up a porter-mug, filled and placed it on the round table in the middle of the room, and stood ready for further service; while Mistress Bett, flinging a scowl at both the visitors, silently left the apartment.

“Well,” cried the eldest of the two—a colossal figure, with a handsome and expressive countenance, and large flashing eyes—“well, Master John, how goes it?”

“So, so, Master Händel,” was the reply, “the better that you are just come in time to silence my good woman.”

Händel gave his hat and stick to the boy, and turned to his companion, a man about the middle height, simple and plain in his exterior; only in the corner of his laughing eye could the observer detect a world of shrewdness and waggery. His name was William Hogarth; and he was well esteemed as a portrait painter.

“You think, then,” asked Händel, keenly regarding his companion—“you think, then, Bedford would do something for my Messiah, if I got the right side of him?”

“You shall not trouble yourself to get the right side of him,” exclaimed Hogarth eagerly; “that I ask not of you; no honorable man would ask it. Speak to the point at once with him; and be sure, he will use all his influence to have your work suitably represented.”

“But is it not too bad,” cried Händel, “that I must flatter[Pg 9] such a shallow-pate as his Grace the Duke of Bedford, to get my best (Heaven knows, William, my best) work brought before the public? If his Grace but comprehended a note of it! but he knows no more of music than that lout of a linen-weaver in Yorkshire, who spoiled my Saul in such a manner, that I corrected him with my fist.”

Hogarth replied with vivacity—“You have been eight-and-twenty years in England; have you not yet found out that the patronage of a stupid great man does no harm to a work of art? You know me, Händel; and know that I abhor nothing so much as servility, be it to whom it may. Yet, I assure you, should I deal only with those who understand my labors, and have no good word from others, I should be glad if I obtained employment enough to keep wife and child from starving. As to luxuries, and my punch clubs, that have pleased you so well, I could not even think of them. You know as well as I, that talent, a true taste for art, and wealth to support both, are seldom or never found together. Let us thank God, if the unendowed are good-natured enough not to grudge us our glorious inheritance, while they deny us not a portion of the crumbs from their luxurious tables.”

Händel was leaning with both arms on the table, his head buried in his hands. Without looking up or changing his position, he murmured, “Must it ever be so; must the time never come, when the artist may taste the pure joy he prepares through his works for others! Hogarth,” he continued, with sudden energy, while he withdrew his hands from his face, and looked earnestly at his friend, “Hogarth, would you consent to leave your country, and exercise your art in other lands?”

“What a question! Not for the world,” replied the painter.

“There it is!” cried Händel, hastily: “you have held out, and begin now to reap the reward of your constancy; but I left my dear fatherland, just as new life in art began to be stirring. Oh, how nobly, how magnificently, is it now developed there! What could I not have done with the gifts bestowed upon me?[Pg 10] Have my countrymen achieved any thing great—they have done it without me, while I was here, tormenting myself in vain with your asses of singers and musicians, to drive a notion of what music is, into their heads. I have scarce yet numbered fifty years. I will return to my own country; better a cowherd there, than here again Director of the Haymarket Theatre, or Chapel-master to His Majesty, who, with all his court rabble, takes such delight in the sweet warblings of that Italian! Hogarth, you should paint the lambling, as the London women worship him as their idol, and bring him offerings?”

“I have already,” answered Hogarth, laughing; “but hush, our friends!”

Here the door opened, and there entered Master Tyers, then lessee of Vauxhall, the Abbe Dubos, and Doctor Benjamin Hualdy; they were followed by Joseph Wach, a young German, who had devoted himself to the study of music under Händel’s instruction, and Miss Ellen Farren, the young lady of the house. Master John arose; and Tom filled the empty porter mugs, and produced fresh ones.

Händel gave his pupil a friendly nod, and asked: “How come you on with your part? Can I hear you soon?”

“I am very industrious, Master Händel,” replied Joseph, “and will do my best, I assure you, to be perfect. You must only have a little patience with me.”

“Hem,” muttered Händel; “I have had it so long with the stupid asses in this country, it shall not so soon fail with you. Enough till to-morrow; to your prating with your little girl yonder.”

“Ah! Master Händel,” cried Ellen, pouting prettily, “you think, then, Joseph should only be my sweet-heart when he has nothing better to do?”

“That were, indeed, most prudent, little witch,” said Händel, laughing: “but ’tis ill preaching to lovers; that knows your father by experience, eh! old John?”

“Master Händel,” said the Abbe, taking the word, “do you[Pg 11] know I was not able to sleep last night, because your chorus—‘For the glory of the Lord shall be revealed,’—ran continually in my head, and sounded in my ears? I think, good Master Händel, your glory shall be revealed through your Messiah, when you can once get it brought out suitably. But the Lord Archbishop, it seems, is against it.”

Händel reddened violently, as he always did when anger stirred him: “A just Christian is the Lord Archbishop! He asked me if he should compose me a text for the Messiah; and when I asked him quietly if he thought me a heathen who knew nothing of the Bible, or if he thought to make it better than it stood in the Holy Scriptures, he turned his back on me, and represented me to the court as a rude, thankless boor.”

“It is not good to eat cherries with the great,” observed wise John Farren.

“I thought,” muttered Händel, “this proverb was only current on the continent; but I see, alas! that it is equally applicable in the land of freedom!”

“Good and bad are mingled all over the earth,” said Benjamin Hualdy, smiling: “and their proportion is everywhere the same. We must take the world, dear Händel, as it is, if we would not renounce all pleasure. Confess then: never felt you more joy—never were you more conscious of your own merit—never thanked you God more devoutly for his gifts to you, than when at last, after long struggle with ignorance and intrigue, you produced a work before the world, that charmed even enmity and envy to admiration!”

“And what care I for the admiration of fools and knaves?” interrupted Händel. Benjamin continued, in a conciliating tone—“Friend, he who can admire the beautiful and the good, is not so wholly depraved, as oft appears. There lives a something in the breast of every man, which, so long as it is not quite crushed and extinguished, lets not the worst fall utterly. I cannot name, nor describe it; but art, and music before all arts, is the surest test whereby you may know if that something yet exists.”

[Pg 12]

“Most surely,” cried Master Tyers. “I myself love music from my heart, and think with your great countryman, Doctor Luther, ‘He must be a brute who feels not pleasure in so lovely and wondrous an art.’ But, Master Händel, judge not my dear countrymen too harshly, if they have not accomplished so much as yours in that glorious art. Gifts are diverse; we have many that you have not.”

“You have been long in England,” observed the Abbe, “and have experienced many vexations and difficulties, particularly among those necessary to you in the production of your works. But tell me, Master Händel, supposing it true, that the court and nobles often do you injustice; that our musicians and singers are inferior to those in your own country; that we cannot grasp all the high spirit that dwells in your works; are you not, nevertheless, the darling of the people of Britain? Lives not the name of Händel in the mouth of honest John Bull, honored as the names of his most renowned statesmen? Well, sir, if that is true, give honest John Bull (he means well and truly, at least) a little indulgence. Let us hear your Messiah soon; your honor suffers nought, and you remain, after all, the free German you were before.”

“Aye!” cried Hogarth, “that is just what I have told him.” “And I,”—“And I,” exclaimed Tyers and Hualdy; while John added, coaxingly, “Only think, Master Händel, how often I have to give up to my good wife, without detriment to my authority as master of the house.”

Händel sat a few moments in silence, looking gloomily from one to another, around the circle. Suddenly he burst into a loud laugh, and cried in cheerful tone—“By my halidome, old fellow, you are right. Give us your hand; to-morrow early I go to the Duke of Bedford; and you shall hear the Messiah, were all the rascals in the three kingdoms and the continent against it. Tom, another mug!”

Loud and long applause followed his words: John Farren essayed a leap in his joy, which, ’spite of his corpulence, succeeded[Pg 13] beyond expectation, and moved the guests to renewed peals of laughter. Joseph whispered to the maiden at his side—“Oh, Ellen! if it prospers with him, our fortune is made; I have his word for it.”

The next morning Händel went, as he had promised his friends, to the Duke of Bedford. His Grace had given a grand breakfast, and half the court was assembled in his saloon. As soon as the servants saw Händel ascending the steps, they hastened to announce his arrival to their lord.

The Duke was not much of a connoisseur, but he loved the reputation of a patron of the arts, and took great pleasure in exhibiting himself in that light to the court and the king. It was his dearest wish to win the illustrious master to himself; particularly as he knew well that the absence of Händel from Carlton House was in no way owing to want of favor with the sovereign. The king, on the contrary, appreciated and highly valued his genius. But Händel’s energetic nature could not bend to the observance of the forms and ceremonies held indispensable, not only at Carlton House, but among all the London aristocracy; and it was natural that this peculiarity should gradually remove him from the circles of the nobility. His fame on this account, however, only rose the higher. His Oratorio of Saul, which the preceding year had been produced, first in London, then in the other large cities of England, had stamped him a composer whom none hitherto had surpassed. The king was delighted; the court and nobles professed, at least, to be no less so. Among the people, his name stood, as his friend had truly observed, with the proudest names of the age! When informed of his arrival, the Duke hastened out, shook the master cordially by the hand, and was about leading him, without ceremony, into the hall. But Händel, thanking him for the honor, informed him he was come to ask a favor of his Grace.

“Well, Master Händel,” said the Duke, smiling—“then come with me into my cabinet.” The master followed his noble host, and unfolded his petition in few words, to wit: that his Grace[Pg 14] would be pleased to set right the heads of the Lord Mayor and the Archbishop of London, so that they should cease laying hindrances in the way of the representation of his Messiah.

The Duke heard him out, and promised to use all his means and all his influence to prevent any further obstacle being interposed, and to remove those already in the way. Händel was pleased, more, perhaps, with the manner in which the polite but haughty Duke gave the promise, than with the promise itself.

“Now come in with me, Master Händel,” said the Duke; “you will see many faces that are not strangers to you; and moreover, a brave countryman of yours, whom I have taken into my service. His name is Kellermann, and he is an excellent flute player, as the connoisseurs say.”

“Alle tausend!” cried Händel, with joyful surprise; “is the brave fellow in London, and indeed in your Grace’s service? That is news indeed! I will go with you, were your hall filled besides with baboons.”

“Oh! no lack of them,” laughed the Duke, while he led his guest into the saloon; “and you will find a fat capon into the bargain.”

Great was the sensation among the assembled guests, when Bedford entered, introducing the celebrated composer. When he had presented Händel to the company, the Duke beckoned Kellermann to him; and Händel, without regarding the rest, greeted his old friend with all the warmth of his nature, and with childlike expressions of joy. Bedford seemed to enjoy his satisfaction, and let the two friends remain undisturbed; though the idol of the London world of fashion, Signor Farinelli, hemmed and cleared his throat many times over the piano, in token that he was about to sing, and wanted Kellermann to come back and accompany him. At length, Kellermann noticed his uneasiness; he pressed his friend’s hand with a smile, returned to his place, took up his flute, and Signor Farinelli, having once more cleared his throat, began a melting air with his sweet, clear voice.

Händel, a powerful man, austere in his life, vigorous in his works, abhorred nothing so much as the singing of these effeminate[Pg 15] creatures; and all the luxurious cultivation of Signor Farinelli seemed to him only a miserable mockery of nature, as of heaven-born art. But, however much displeased at the soft trilling of the Italian,—whom Kellermann dexterously accompanied and imitated on his flute,—he could not refrain from laughing inwardly at the effect produced on the whole company. The men rolled up their eyes, and sighed and moaned with delight; the ladies seemed to float in rapture, like Farinelli’s tones. “Sweet, sweet!” sighed one to another. “Yes, indeed!” lisped the fair in reply, drooping her eyelids, and inclining her head. Signor Farinelli ceased, and eager applause rewarded his exertions.

The Duke now introduced Händel to the Italian.

Farinelli, after some complimentary phrases, addressed the master in broken English.

“I have inteso,” he said, with a complacent smile, “that il Signor Aendel has composed una opera—il Messia. Is there in that opera a part to sing for il famous musico Farinelli—I mean, for me?”

Händel looked at the ornamented little figure from head to foot, and answered in his deepest bass tone, “No, Signora.”

The company burst out a laughing; the ladies covered their faces. Soon after, the German composer, with his friend Hogarth, took his leave. In the vestibule the artist showed Händel a sketch he had made of Farinelli singing, and his admirers lost in ecstasy. “By the Duke’s order,” whispered he.

“That is false of him!” exclaimed Händel, indignantly.

The satirical painter shrugged his shoulders.

Händel sat in his chamber, deep in composition. Once more he tried every note; now he would smile over a passage that pleased him; now pause earnestly upon something that did not satisfy him so well; pondering, striking out and altering to suit his judgment. At length his eyes rested on the last “Amen:” long—long—till a tear fell on the leaf.

[Pg 16]

“This note,” said he, solemnly, and looking upwards—“this note is perhaps my best! Receive, Oh benevolent Father, my best thanks for this work! Thou, Lord! hast given it me; and what comes forth from Thee—that endureth, though all things earthly perish:—Amen.”

He laid aside the notes, and walked a few times up and down the room. Then seating himself in his easy chair, and folding his arms, he indulged in happy dreams of his youth and his home. Thus he was found by Kellermann, who came at dusk to accompany him to the tavern. They discoursed long of their native land, of their art, and the excellent masters then living in Germany. At length they broke off from the theme, fearful of keeping their assembled friends waiting too long.

“Well, friend,” cried Hogarth gaily to the master as he entered; “was not my advice good? Has not Bedford helped you? and is your self-respect a whit injured?”

Händel nodded good-humoredly, and smiling, seated himself in his wonted place. “You remember, some time ago,” the painter continued, “when the Leda of the Italian painter Correggio was sold here at auction for ten thousand guineas, I said—‘If anybody will give me ten thousand guineas, I will paint something quite as good.’ Lord Grosvenor took me at my word; I went to work, and laid aside everything else. At last my picture is ready; I take it to his lordship; he calls his friends together, and, as I said, they all laugh at me; I have to take back my picture, and go home to quarrel with my wife!”

All laughed except Händel, who, after a few moments’ silence, said; “Hogarth, you are an honest fellow, but often wondrous dull! You cannot judge of the Italian painters. In the first place, their manner is entirely different from yours, and then you know nothing of their best works. Had you been, as I have, in Italy, and particularly in Rome, where live the glorious creations of Raphael and Michael Angelo, you would have respect for the old Italian painters; you would love and honor them, as I do the old Italian church composers. As to the modern[Pg 17] painters, they are like, more or less, in their way, to Signor Farinelli.”

“Well!” cried Hogarth; “we will not dispute thereupon. Tell us rather how you are pleased with your singers and performers, and if you think they will acquit themselves well to-morrow.”

“They cannot do very badly,” answered Händel; “I have drilled them diligently, and Joseph has helped me with assiduous study. Only the first soprano singer is dreadfully mediocre; I am sorry for it—for the sake of a few good notes—”

Here Joseph put his head in at the door, and said, “Master Händel, a word if you please.”

“Well, what do you want?” asked Händel: and rising, he came out of the room; his companions looked smiling at one another; and John Farren sent forth from his leathern chair a prolonged “ha! ha! ha!” Joseph took his master’s hand, and led him hastily across the passage and upstairs into his chamber, where Händel, to his no small astonishment, found the pretty Ellen.

“Ha! what may all this mean?” he asked, while his brow darkened; “what do you here, Miss Ellen, in the chamber of this young man—and so late too?”

“He may tell you that himself, Master Händel,” answered the damsel pettishly, and blushing while she turned away her face. But Joseph replied quickly and earnestly: “Think not ill of me and the good Ellen, my dear master; for what we do here, I am ready to answer before you.”

“Open your mouth, then, and speak,” said Händel.

Joseph went on: “For what I am, and what I can do, I thank you, my dear master. You befriended me when I came hither a stranger, without means of earning a support. To make me a good singer, you spent many an hour, in which you could have done something great.”

“Ho! ho! the fool!” cried Händel; “and do you think to make a good singer was not doing something great—eh?”

[Pg 18]

“You see, master, it has often grieved me to see you forced to vex yourself beyond reason with indifferent singers, because their education is far behind your works.”

“That is a pity, indeed,” sighed Händel.

“And I have tried,” continued Joseph, “to instruct a singer for you: I think I have so far succeeded, that she may venture before you. There she is!” and he pointed to Ellen.

Händel opened his eyes wide, looked astonished on the damsel, and asked, incredulously, “Ellen! what, Ellen there?”

“Yes, I!” cried Ellen, coming to him, and looking innocently in his face with her clear hazel eyes. “I, myself,” she repeated, smiling; “and now you know, Master Händel, what Joseph and I were about together.”

“Shall she sing before you, Master Händel?” asked Joseph.

“I am curious to see how your teaching has succeeded,” said Händel, while he seated himself: “Come, then, let her sing.” Joseph sprang joyfully to the harpsichord; Ellen went and stood beside him, and began.

How it was with the composer,—how he listened, when he heard the most splendid part in his forthcoming Messiah—the noble air, “I know that my Redeemer liveth;”—and how Ellen sang it, the reader may conjecture, when, after she had ceased, Händel still sat motionless, a happy smile on his lips, his large flashing eyes full of the tears of deep religious emotion. At length he drew a deep breath, arose, kissed the forehead of the maiden, kissed her eyes—in which likewise pure drops were glancing,—and asked in his mildest tone: “Ellen, my good—good child, you will sing this part to-morrow, at the representation, will you not?”

“Master Händel—Father Händel!” cried the maiden; and overcome with emotion, she threw herself sobbing on his neck. But Joseph sang—

[Pg 19]

“Amen!” resounded through the vast arches of the church, and died away in whispered melody in its remotest aisles. “Amen!” responded Händel, while he let fall slowly the staff with which he kept time. Successful beyond expectation was the first performance of his immortal master-piece. Immense was the impression it produced, as well on the performers as upon the audience. The fame of Händel stood now immovable.

When the composer left the church, he found a royal equipage in waiting for him, which, by the King’s command, conveyed him to Carlton House.

George the Second, surrounded by his whole household and many nobles of the court, received the illustrious German. “Well, Master Händel,” he cried, after a gracious welcome, “it must be owned, you have made us a noble present in your Messiah; it is a brave piece of work.”

“Is it?” asked Händel, and looked the monarch in the face, well pleased.

“It is, indeed,” replied George. “And now tell me what I can do, to express my thanks to you for it?”

“If your Majesty,” answered Händel, “will give a place to the young man who sang the tenor solo part so well, I shall be ever grateful to your Majesty. He is my pupil, Joseph Wach, and he would fain marry his pupil, the fair Ellen, daughter to old John Farren; the old man gives consent, but his dame is opposed, because Joseph has no place as yet. And your Majesty knows full well, that it is hard to carry a cause against the women.”

“You are mistaken, Master Händel,” said the King, with a forced smile; “I know nothing to that effect; but Joseph has from this day a place in our chapel as first tenor.”

“Indeed!” cried Händel, rubbing his hands with joy, “I thank your Majesty from the bottom of my heart!”

George was silent a few moments, expecting the master to ask some other favor. “But, Master Händel,” he said at length, “have you nothing to ask for yourself? I would willingly show[Pg 20] my gratitude to you in your own person, for the fair entertainment you have provided us all in your Messiah.”

The flush of anger suddenly mantled on Händel’s cheek, and he answered, in a disappointed tone—“Sire, I have endeavored not to entertain you—but to make you better.”

The whole court was astonished. King George stepped back a pace or two, and looked on the bold master with surprise. Then bursting into a hearty fit of laughter, and walking up to him—“Händel!” he cried—“you are, and will ever be, a rough old fellow, but”—and he slapped him good-naturedly on the shoulder—“a good fellow withal. Go—do what you will, we remain ever the best friends in the world.” He signed in token of dismission; Händel retired respectfully, and thanked Heaven as he turned his back on Carlton House, to hasten to his favorite haunt, the tavern.

We shall not attempt to describe the joy his news brought to the lovers, Joseph and Ellen, nor their unnumbered caresses and protestations of gratitude. John Farren took his good wife in his arms and hugged her, ’spite of her resistance and scolding, crying, “Nonsense, Bett! we must be friends to-day, though all the bells in old England ring a peal for it.”

For ten years more Händel travelled throughout England, and composed new and admirable works. When his sight failed him in the last years of his life, it was Ellen who nursed him as if she had been his child, while her husband Joseph wrote down his last compositions, as he dictated them.

Proud and magnificent is the marble monument erected in Westminster to the memory of Händel. Time may destroy it; but the monument he himself, in his high and holy inspiration, has left us—his Messiah—will last forever.

[Pg 21]

It was late one evening in the summer of 171-, that a party of wild young students at law in the University of Padua were at supper in the saloon of a restaurateur of that city. The revelry had been prolonged even beyond the usual time; much wine had been drunk; and the harmony and good feeling that generally prevailed during their convivial meetings had been interrupted by furious altercation between two of their number. As is almost always the case, the rest took sides with one or other of the disputants; all rose from table; high words were exchanged, and a scene of confusion and tumult was likely to ensue, when the offenders were imperiously called to order by one of their number. He was evidently young; but his slender limbs were firmly knit, and his form, though slight, so well proportioned as to give promise both of activity and strength beyond his years.

“For shame!” he cried, angrily, after producing a momentary silence by a vigorous thump on the table; “are you but a set of bullies, that you stand here pitching hard words at each other, and calling all the neighborhood to see how valiant we can be with our tongues? Fetch me him that can swear loudest, and give us space for our swords!”

Here the clamor was redoubled by all at once explaining, and contradicting each other.

The first speaker struck the table again till all the glasses rang.

“Have done,” he cried, “with this disgraceful uproar, or San Marco! I will fight you all myself—one by one!”

This threat was received with cries of “Not me—Giuseppe!”[Pg 22] and after a few moments, the two disputants stood forth, separated from their companions. A space was speedily cleared for the combat.

The combatants needed no urging; but scarcely was the clashing of their swords heard, when Pedrillo, the restaurateur, ran in, followed by his servants, and with a face pale with terror protested against his house being made the scene of riot and bloodshed. It would be his ruin, he averred; he should be indicted by the civil authorities; he should be banished the country; he could never again show his face in Padua! If young gentlemen would kill one another there were places enough for such a purpose besides a reputable establishment like his; and with ludicrous rapidity enumerating the localities resorted to by duellists of the city, he besought them with piteous entreaties to transfer themselves elsewhere, offering even to remain minus the expenses of their supper. But Pedrillo’s solicitations had little effect on the wilful young men, till backed by threats that he would call the guard. Most of them had known what it was to fall into the hands of the police for midnight disturbances, and duels were favorite pastimes among the students of the University; so that immediately on the disappearance of Pedrillo’s servant, the whole party precipitately left the house. First, however, Giuseppe, the one who had recommended a resort to the duel, laid the amount of the reckoning on the table.

As the party turned the corner of a narrow street, they came close upon a carriage, attended by several servants. At this sudden encounter with so many half intoxicated and noisy students, recognised by their dress and well known to be always ready for any deed of mischief, the attendants fled in every direction. The horses caught the alarm, and, wild with fright, plunged, reared, and set off at full speed down the street. A shout of laughter from the revellers, who thought it capital sport to see the dismay created at sight of them, greeted the ears of the terrified inmates of the carriage. But Giuseppe sprang forward, and at the peril of his life, threw himself upon the horses’ necks, pulling[Pg 23] the bits with such violence as to check them at once. The animals, quivering with fear, stood still; the coachman recovered his control over them; and Giuseppe, opening the door, assisted an elderly gentleman, very richly dressed, to alight, and inquired kindly if he had suffered injury.

“I have only been alarmed;” replied the gentleman, carefully adjusting his dress, and drawing his cloak about him. “But my daughter”—

Giuseppe had already lifted from the carriage the nearly lifeless form of a young girl. As the lamp-light fell upon her face, he could see it was one of matchless beauty.

“My Leonora!” exclaimed the father, in a tone of anxious apprehension. The young girl opened languidly a pair of beautiful dark eyes, started up, gazed with an expression of surprise upon the young student who had been supporting her, then threw herself into her father’s arms. With an expression of joy that she had recovered from her fright, the gentleman ordered his servants, who had returned when the danger was over, to procure another conveyance. This was immediately done; and turning to Giuseppe, he thanked him with lofty courtesy for the service he had rendered, and invited him to call next day at the house of the Count di Cornaro, in the Prado della Valle.

All night wild thoughts were busy in the brain of the young student. Never had such a vision of loveliness dawned upon him. And who was she? One elevated by fortune and rank so far above him that she would regard him but as the dust beneath her feet. As he had seen her in her delicate white drapery, like floating silver, her hair bound with pearls, she had moved, in some princely palace, among the nobles of the land. Many had worshipped; many had doubtless poured forth vows at her feet. How would she look upon one so poor and lowly? Giuseppe heaved a bitter sigh, but he resolved nevertheless to love her, and only her, for the rest of his life. A new sensation was born within him. He had hitherto cared only for frolic and revel and fighting; had been known only as Giuseppe, the mad student; the mover[Pg 24] and leader in all mischief; a perfect master of his weapon, and the most skilful fencer in Padua. So great was his passion for fencing, and so astonishing the skill he had acquired in the art, that the most finished adepts in that noble science were frequently known to resort to him for lessons. So fond was he, moreover, of exhibiting this accomplishment, that he shunned no opportunity of exercising it at the expense of his acquaintances. Many were the duels in which he had been engaged; whether on his own account or for the sake of his friends, it mattered little. His love of fighting was as well known as the fact that few could hope to come off victorious in a strife with him; and this may account for the ascendancy he evidently had over his companions, their unwillingness to chafe his humor, and submission to the imperious tone in which he was wont to address them.

Of late, disgusted with the study of law, to which he had been consigned by his parents as a last resort—their first wish having been that he should embrace a monastic life—he had adopted the resolution of leaving Padua, of taking up his abode in one of the great capitals, and pursuing the profession of a fencing-master. Thus he would have opportunity for the cultivation of his favorite science, and at the same time would be unfettered by the control of others, a yoke galling beyond measure to his impatient spirit. Already he had announced this determination to his fellow students, and waited only a favorable opportunity to effect his escape from the University.

How often are the plans of a human mind changed by the slightest accident! How many fortunes have been made or marred by occurrences so trivial that they would have passed unnoticed by ordinary observation! How many events of importance have depended on causes at the first view scarce worth the estimation of a hair! In the present instance, the Count di Cornaro’s horses taken fright cost a capital fencing-master, and gave the world—a Tartini!

In due time next day, Giuseppe appeared in the Prado della[Pg 25] Valle. As he was about to ascend the steps of the noble mansion belonging to the Count di Cornaro, a window above was hastily thrown open, and a rose fell at his feet. Glancing upward, he caught a glimpse of the bright face of Leonora; she smiled, and vanished from the window. The youth raised the flower, pressed it to his lips, and hid it in his bosom.

At the door, the porter received him as one who had been expected, and ushered him into a splendidly furnished apartment. The marble tables were covered with flowers; a lute lay on one of them; the visitor took it up, not doubting that it belonged to the beautiful Leonora, and while waiting for the Count, played several airs with exquisite skill.

“By my faith! you have some taste in music!” cried Cornaro, who had entered unperceived, as he finished one of the airs. The young man laid down the instrument, embarrassed, and blushing deeply, stammered an apology for the liberty he had taken.

“Nay, I excuse you readily, my young friend,” said the Count, cordially—extending his hand. Then motioning him to a seat, he asked his name.

“Giuseppe Tartini.”

“A native of Padua?”

“No; I was born at Pisano, in Istria.”

“Your business here?”

“I am a student at law, in the University.”

The speaker colored again; for he had suddenly become anxious to obtain the Count’s good opinion.

“And where,” asked Cornaro, after a pause, “did you acquire your knowledge in music?”

“You are pleased, Signor,” replied the youth, modestly, and bending his eyes to the ground, “to commend what is indeed not worthy—”

“Allow me judgment, if you please,” interrupted the Count, sharply. “I am myself skilled in the art. I ask, where did you receive instruction?”

“I took some lessons at Capo d’ Istria,” answered Giuseppe,[Pg 26] “when very young; my parents had placed me there to be educated for the church; and I found music a great solace in my seclusion.”

“The church! and why have you changed your pursuits?”

“I could not, Signor, conscientiously devote myself to a religious life—when I knew myself in no way fitted for it.”

“I understand; you wished to act a part in the world; you were right. Your parents were wrong to decide for you prematurely. I like your frankness and simplicity, Giuseppe. You may look upon me as a friend.”

This was said in the lofty tone of a patron. The young man bowed in apparent humility and gratitude.

“You rendered me a service last night, at great risk to yourself—ay, and some injury, too!” Here he noticed, for the first time, a slight wound on the cheek of his young visitor.

“Oh, it is nothing, Signor!” cried Giuseppe, really embarrassed that so slight a hurt should be alluded to.

“You may esteem it such, but I do not forget that I owe you thanks for your timely aid; nor do I fail to observe that you are modest as brave. I perceive, also, that you have talents, and lack, perhaps, the means of cultivating them. In such a case, you will not find me an ungenerous patron. In what way can I assist you now?”

Tartini made no reply, for his head was full of confused ideas. His former purposes and plans were wholly forgotten. The Count remarked his embarrassment, and graciously gave him permission to go home for the present and consider what he had said.

The young man lingered a moment before the door, and stole a glance upward, hoping to see once more the angelic face that had smiled upon him; but the window was closed and all was silent. He departed with a feeling of sadness and disappointment at his heart. He knew not how powerful an advocate he had in the bosom of the maiden herself. Under the sun of Italy love is a plant that springs up spontaneously; and the handsome face and form of the youth who had perilled his life to save her from harm[Pg 27] had already impressed deeply the fancy of the susceptible girl. Unseen herself, she watched his departure from her father’s house; and, impelled by something more than mere feminine curiosity, immediately descended to know the particulars of his visit. It was to be supposed that her woman’s wit could point out some way in which the haughty Count could discharge his obligation to the humble student. And she failed not to suggest such a way.

Two days after, Giuseppe was surprised by a message from the Count di Cornaro, proposing that he should become his daughter’s tutor in music, and offering a liberal salary. With what eagerness, with what trembling delight he accepted the offer! How did his heart beat, as he strove in the Count’s presence to conceal the wild rapture he felt, under a semblance of respect and downcast humility! How resolutely did he turn his eyes from the face of his beautiful pupil, lest he should become quite frantic with his new joy, and lest the passion that filled his breast should betray itself in his looks! As if it were possible long to conceal it from the bewitching object!

It was a day in spring. The soft air, laden with the fragrance of flowers, stole in at the draperied windows of Cornaro’s princely mansion, and rustled in the leaves of the choice plants ranged within. In the apartment to which we before introduced the reader, sat a fair girl, holding a book in her hand, but evidently too much absorbed in melancholy thought to notice its contents. She was reclining upon a couch in an attitude of the deepest dejection. Her face was very pale, and bore the traces of recent tears. As the bell rang, and the door was opened by the domestic, she started up and clasped her hands with an expression of the most lively alarm. But when a young man, apparently about twenty years of age, entered the room, she ran towards him, and throwing herself into his arms, wept and sobbed on his bosom.

[Pg 28]

“Leonora! my beloved!” cried the youth; “For heaven’s sake, tell me what has happened!”

“Oh, Giuseppe!” she answered, as soon as she could speak for weeping, “We are lost! My father has discovered all!”

“Alas! and his anger has not spared thee!”

“No—Giuseppe! He has pardoned me; thou art the destined victim! Stay—let me tell thee all—and quickly; for the moments are precious! The Marchese di Rossi, thou knowest, has sought my hand. He saw thee descend last night from my window.”

“He knows, then, of our secret marriage?”

“No—he knows nothing; but seeing thee leave my chamber at night, he gave information this morning to my uncle, the Bishop.”

“The villain! he shall rue this!” muttered Tartini, grasping the hilt of his weapon.

“Oh, think not of punishing him! it will but ruin all! Fly—fly—before my uncle——”

“Tell me all that has happened.”

“This only—the Bishop revealed what he knew to my father; I was summoned to his presence scarce an hour since. He reproached me with what he called the infamy I had brought upon his house. I could not bear his agony—Giuseppe! I confessed myself thy wedded wife!”

“Thou wast right—my Leonora! and then?”

“He refused to believe me! I called Beatrice, who witnessed our marriage, with her husband. My father softened; I knelt at his feet, and implored forgiveness.”

“And he?” asked Tartini, breathlessly.

“He pardoned me—he embraced me as his daughter; but required me to renounce thee forever.”

The young man dropped the hand he had held clasped in his.

“Wilt thou—Leonora?” he asked.

“Never—Giuseppe!”

“Beloved! let us go forth; I will claim thee in the face of the world.”

[Pg 29]

“Nay, my husband—listen to me! I have seen our friend, the good Father Antonio—and appealed to him in my distress. He counsels wisely. Thou must leave Padua, and that instantly! My father’s anger is not to be dreaded so much as that of my haughty uncle, who would urge him to all that is fearful. They would sacrifice thee—Giuseppe! Oh, thou knowest not the pride of our house! They would shrink from no deed—”

Here the speaker shuddered—and her fair cheek grew pale as death.

“I have no fears for myself—Leonora. They cannot sever the bonds of the church that united us; my own life I can defend.”

“Ah, thou knowest them not! the dungeon—the rack—the assassin’s knife—all will be prepared for thee. As thou lovest me, fly!” And gliding from his embrace, she sank down at his feet.

“Forsake thee—my wife! Abandon thee to the Cardinal’s vengeance—”

“I have naught to fear from him. Oh, hear Antonio’s advice! When thou art gone, the Bishop’s anger will abate. A few months may restore thee to me. Go—Giuseppe: there is safety in flight—to stay is certain death! Must Leonora entreat in vain?”

Their interview was interrupted by Beatrice, the nurse, who came in haste to warn Tartini that her master, with his brother the Bishop of Padua, was approaching the house, and that they were accompanied by several armed servants. There could now be no doubt of their intentions towards the offender. He comprehended at once, that even the forbearance the Count had shown his daughter had been dictated by a wish to secure his person. To stay would be utter madness; and yielding to the passionate entreaties of his young wife, he clasped her for the last time to his heart, pressed a farewell kiss on her forehead, and was gone before his pursuers entered the house.

That night, while the emissaries of the Bishop of Padua were searching the city, with orders to arrest the fugitive, and to cut[Pg 30] him down without mercy should he resist, Tartini, disguised in a pilgrim’s dress, was many miles on the way towards Rome.

More than two years after the occurrence of this scene, one evening in the winter of 1713, the Guardian of the Minors’ Convent at Assisi was conversing with the organist, Father Boëmo, on the subject of one of the inmates, whom Boëmo had taken under his peculiar care.

“The youth is a relative of mine,” continued the Guardian; “but considerations of humanity alone moved me to grant him an asylum, when, poor, persecuted and homeless, he threw himself on my compassion. Since then his conduct has been such as to secure my favor, and the respect of all the brethren.”

“In truth it has,” said Boëmo, warmly. “And believe me, brother, you will have as good reason to be proud of him as a kinsman, as I of my pupil. It is my knowledge of his worth that causes me such pain at his loss of health.”

“The wearing of grief, think you?”

“Not wholly. His anxiety for the safety of his wife was set at rest long ago by intelligence of her welfare. He knows well that the only daughter of so proud a house must be dear to her kinsmen—even by their unwearied efforts to discover his retreat. And I have taught him to solace the pains of absence.”

“Fears he still the Bishop’s resentment?”

“Oh, no; these convent walls are secure, and his secret well guarded, since only in your keeping and mine. His enemies may ransack Italy; they will never dream of finding him here.”

“What is the source, then, of his depression?”

“It is a mystery to me. I have marked it growing for weeks. And sure I am, it is not weariness of the solitude of this abode. Since his spirits rose from the sadness of his first misfortunes—since he breathed the air of comparative freedom, and joined in the exercises of our pious brethren, Giuseppe has been a changed man. Sorely hath he been tried in the furnace of affliction, and[Pg 31] he hath come forth pure gold. The religious calm of this retreat has taught him reflection and moderation. His past sorrow has chastened his spirit; the holy example of the brethren has nourished in his breast humility and resignation and piety. The ardent aspirations of his nature are now directed to the accomplishment of those great things for which Heaven has destined him. Never have I known so unwearied, so devoted a student.”

“With your training and good counsel, brother, he might well love study,” said the Guardian, with a smile.

“Nay, brother,” replied Boëmo, modestly, “I have but directed him in the cultivation of his surprising genius for music. And you know he excels on the violin. It is for that he seems to have a passion—a passion that I fear is consuming his very life.”

They were interrupted by one of the brethren, who had some business with the Guardian; and Father Boëmo proceeded to the cell of his pupil, whom he was to accompany to vespers.

He found the object of his care seated by his table, on which he leaned in a melancholy reverie. His form was emaciated; his face so pale that the good monk, who had seen him but a few hours before, was even startled at the increased evidence of indisposition. His violin was thrown aside neglected—strongest possible proof of the malady of one who had worshipped music with an idolatry bordering on madness.

Boëmo laid his hand kindly on his pupil’s shoulder, and said, in a tone of mild reproof—“Giuseppe!”

The young man made no reply.

“This is not well, my brother!” continued the worthy organist. “The gifts of God are not to be thus slighted; we offend Him by our despondency, which, save abuse of power, is the worst ingratitude.”

“It is your fault!” said the youth, bitterly, and looking up.

“Mine—and how?”

Giuseppe hesitated.

“How am I to blame for this sinful melancholy you indulge?”

[Pg 32]

“Your lessons have given me knowledge.”

“And does knowledge bring sorrow?”

“Saith not your creed thus? Since Adam tasted the fruit—”

“Of a knowledge forbidden.”

“So is all knowledge—of things higher than we can attain to. To aspire—and never reach—that is the misery of humanity.” And the speaker again buried his face in his hands.

“I understand you, my brother;” said Boëmo, after a pause. “I have been to blame in suffering you to pursue your studies in solitude. Knowing nothing of the outer world, you have wrought but in view of that ideal which, to every true artist, becomes more glorious and inaccessible as he gazes—as he advances. You despond, because you have labored in vain after perfection. Is it not so?”

“I have mistaken myself;” answered Tartini; “you have mistaken me. It was cruel in you to persuade me I was an artist.”

“And who tells you you are not?”

“My own judgment—my own heart.”

“It deceives you, then.”

“It does not,” cried Tartini, with sudden energy, and starting up with such violence that the worthy monk was alarmed. “It is you who have deceived me. You have taught me to flatter myself; to imagine I could accomplish something; to thirst for what was never to be mine. You have pointed me to a goal toward which I have toiled and panted—in vain—while it receded in mockery. You have given me wishes which are to prove my everlasting curse. Yes,”—he continued, striking his forehead, “my curse. What doom can be more horrible than mine?”

“You have but passed,” answered Boëmo, mildly, “though the trial of every soul gifted by Heaven with a true perception of the great and the beautiful.”

“It is not so,” exclaimed his pupil, passionately. “I have striven to soar—and fallen to the earth, never more to rise. I have dreamed myself the favorite of art—and awaked to find myself[Pg 33] outcast and scorned. My soul is dead within me. You must have foreseen this. Why prepare such anguish for one already the victim of misfortune?”

“Young man,” said the organist, impressively, “this feeling is morbid. I will not reason with you now; come with me, and let us see what change of subject——”

“Ay,” muttered Tartini, his face distorted, “to show the brethren what you have done; that they, too, may mock at me! I see them now—”

“Holy Mother! what ails you, my son?” cried Boëmo, much alarmed at the wild looks of his pupil.

“You will deem me mad, good father;” said Giuseppe in an altered voice, and grasping the monk’s arm; “but I swear to you—’tis the truth. I see them every night!”

“See whom?”

“The spirits—the demons, who come to mock at me! They range themselves around my cell—and grin and hiss at me in devilish scorn. As soon as it is dark they throng hither. See—they are coming now! stealing through the window——”

“My brother! my brother! is it come to this?” cried Boëmo in a tone of anguish.

“Sometimes,” said his pupil, “I have thought it but an evil dream. I strove against it till I knew too well it was no delusion of fancy.”

“Why—why did I not know of this before?”

“It was needless. I would not grieve you, father. Besides—I would not have the demons think I sought aid against them. That would have been cowardly! No—they do not even know how much their malice has made me suffer.”

“This must be looked to!” muttered the monk to himself; and drawing Giuseppe’s arm within his, he led him out of the cell and down to the chapel, intending after the evening service to confer with the Guardian respecting this new malady of his unfortunate friend.

They decided that it was best to leave Giuseppe no more alone[Pg 34] at night. The melancholy he had suffered to prey so long on his mind had impaired his reason; repose and cheerful conversation would restore him. Father Boëmo resolved to pass the first part of the night in his cell; but as he had to go before the hour of matins to pray with a poor invalid, he engaged a brother of the convent to take his place at midnight.

When the organist the next day saw his pupil, he was surprised at the change in his whole demeanor. Giuseppe received him in his cell with a face beaming with joy, but at the same time with an air of mystery, as if he almost feared to communicate some gratifying piece of intelligence.

“You passed a better night, my son,” said the benevolent monk. “I am truly rejoiced. I have prayed for you.”

“Listen, father!” said Giuseppe, eagerly. “I have conquered them. I have put them all to flight.”

“The evil one fleeth from those who resist him,” said Father Boëmo, solemnly.

“But I have done better; I have made a compact with him.”

“Giuseppe!” The monk crossed himself, in holy fear.

“Nay, father Boëmo! I have yielded nothing. The devil is my servant—the slave of my will. Last night the demons came again so soon as you were gone, and while brother Piero slept, to torment me. They mocked me more fiercely than ever. I was in despair. I cried to the saints for succor.”

“You did right.”

“The evil spirits vanished; but the mightiest of all, Satan himself, stood before me. I made a league with him. Do not grow pale, father! Satan has promised to serve me. All will go now according to my will.”[1]

Boëmo shook his head, mournfully.

“As a test of his obedience, I gave him my violin and commanded him to play something. What was my astonishment when he executed a sonata, so exquisite, so wonderful, that I had[Pg 35] never in my life imagined anything approaching it! I was bewildered—enchanted. I could hardly breathe from excess of rapture. Then the devil handed the violin back to me. “Take it, master,” said he, “you can do the same.” I took it, and succeeded. Never had I heard such music. You were right, father! I have done wrong to despair.”

The monk sighed, for he saw that his poor friend still labored under the excitement of a diseased imagination. He made, however, no effort to reason with him, but sought to divert his mind by speaking of other matters.

“You shall hear for yourself,” cried Tartini; and seizing his violin, he walked several times across the room, humming a tune, and at last began to play. The music was broken and irregular, though in the wild tones he drew from the instrument, the ear of an artist caught notes that were strangely beautiful. It seemed, in truth, the music of a half-remembered dream.

Again and again did Giuseppe strive to catch the melody; at length throwing down the instrument, he struck his forehead and wrung his hands in bitterness of disappointment.

“It is gone from me!” he cried, in a voice of agony. Father Boëmo sought in vain to lead his mind from this harrowing thought. Now he would snatch up the violin and play as if determined to conquer the difficulty; then fling it aside in despair, vowing that he would break it in pieces and renounce music forever.

After a consultation with the Guardian, Father Boëmo summoned medical assistance, and that night himself administered a composing draught to his young friend. He had the satisfaction of seeing him soon in a profound slumber; and having given him in charge once more to Piero, withdrew to spend an hour or two in prayer for his relief.

Just before matins the organist was aroused by a cry without. Being already dressed, he hastily descended to the court where the brother who had given the alarm stood gazing upward in speechless terror. Well might he shake with fear! Upon the[Pg 36] edge of the roof stood a figure, clearly visible in the moonlight, and easily recognized as that of the unhappy Giuseppe.

“Hush! not a word—or you are his murderer!” whispered Boëmo, grasping the arm of the affrighted monk. Both gazed on the strange figure; the one in superstitious fear—the other in breathless anxiety. Boëmo now perceived that Giuseppe held his violin. After a short prelude he played a sonata so admirable, so magnificent, that both listeners forgot their apprehensions and stood entranced, as if the melody floating on the night wind had indeed been wafted downward from the celestial spheres.[2]

A dead silence—a silence of awful suspense, followed this strange interruption. Neither dared to speak; for Boëmo well knew that a single false step would cost his friend’s life. And he was well aware that the sleep-walker often passes in safety over places where no waking man could tread. The great danger was that his slumber might be suddenly broken.

The sonata was not repeated. The figure turned and slowly retraced his steps along the roof, taking the way to Tartini’s cell. Father Boëmo breathed not till his pupil was in safety; then with a faint murmur of thanksgiving he sank on his knees, while the liberated monk hastened to communicate to the superior what he had seen. The worthy organist watched by the bed of his friend, after blaming severely the negligence of the brother who had been left to guard him. Giuseppe awoke feverish and disturbed—the workings of an unquiet imagination had worn out his strength and an illness of many weeks followed. During all this his faithful friend scarcely left him, but sought to minister to the diseased mind as well as the feeble frame. His care was rewarded. With returning health, reason and cheerfulness returned.

It was a holiday in Assisi. The inhabitants came in crowds to the church to join in the services; in fact so goodly an assemblage[Pg 37] had never been seen in that old place of worship. The fame of the admirable music to be heard there formed a powerful attraction. It is almost needless to say that the execution was that of the brothers of the Minors’ Convent.

Much curiosity had been excited among the people by the circumstance that a curtain was drawn across a part of the choir occupied by the musicians, during all parts of the service. As usual, general attention was fixed by the least appearance of mystery. The precaution had, in fact, been adopted for the sake of Tartini, who played the violin. He still stood in fear of the vengeance of the Cornaro family, who had spared no pains to discover his abode.

The service was nearly ended. While the music still sounded, the wind suddenly lifted the curtain and blew it aside for a moment. A suppressed cry was heard in the choir, and the violin-player ceased. He had recognized in the assembly a Paduan who knew him well.

The Guardian and Father Boëmo, when informed of this discovery, opposed Giuseppe’s resolution of quitting the convent. Both pledged themselves to protect him against the anger of the Bishop of Padua; besides, who knew that the same accident had discovered him? Even among the brethren he passed by an assumed name; it was probable that all was yet safe.

“Come, Giuseppe, you must play to-day in the chapel; the Guardian has guests, who have heard of our music, and we must do our best.”

The grateful pupil and the pleased instructor did their best. When the service was over, Father Boëmo took his young friend by the arm and led him into the parlor of the convent.

A lady of stately and graceful form, her face concealed by a veil, stood between two distinguished looking men, one in the robes of a cardinal. Tartini gave but one glance; the next instant—“Leonora!—my wife!” burst from his lips, and he clasped her, fainting, in his arms.

[Pg 38]

“Receive our blessing, children,” said the cardinal Cornaro. “Years of religious seclusion, Giuseppe, have rendered thee more worthy of the happiness thou art now to possess. Not to the wild disobedient youth, but to the man of tried worth, do I give my niece. Give him thy hand, Leonora.”

The young couple joined hands, and the cardinal pronounced over them a solemn benediction.

“In one thing, my son, thou art to blame,” he resumed—“in hiding thyself from us, instead of trusting our clemency. We have sought thee, not for the purpose of vengeance, but to restore thee to thy wife and country. But for a happy chance, we should still have been ignorant of the place of thy retreat. Yet Heaven orders all for the best. Sorrow has done a noble work with thee.”

“And it has made thee only more beautiful—my beloved!” whispered the happy artist, “my own Leonora—mine—mine forever!”

We do not question the sincerity of Tartini’s joy at his reunion with his lovely wife. But we must have our own opinion of his constancy, when, not long after, we find him leaving her side and flying from Venice for fear of the rivalship of Veracini, a celebrated violin-player from Florence. Perhaps this want of confidence was necessary to the development of his qualities as an artist. But we leave his after life with his biographer. One thing, however, is certain; of all his compositions, the most admirable and the most celebrated is “The Devil’s Sonata.”

[1] Lalande, to whom Tartini himself communicated this curious anecdote, relates it in his Travels in Italy.

[2] It may be seen by a reference to any detailed biography of Tartini, that nearly all the incidents recorded in this little tale are real facts.

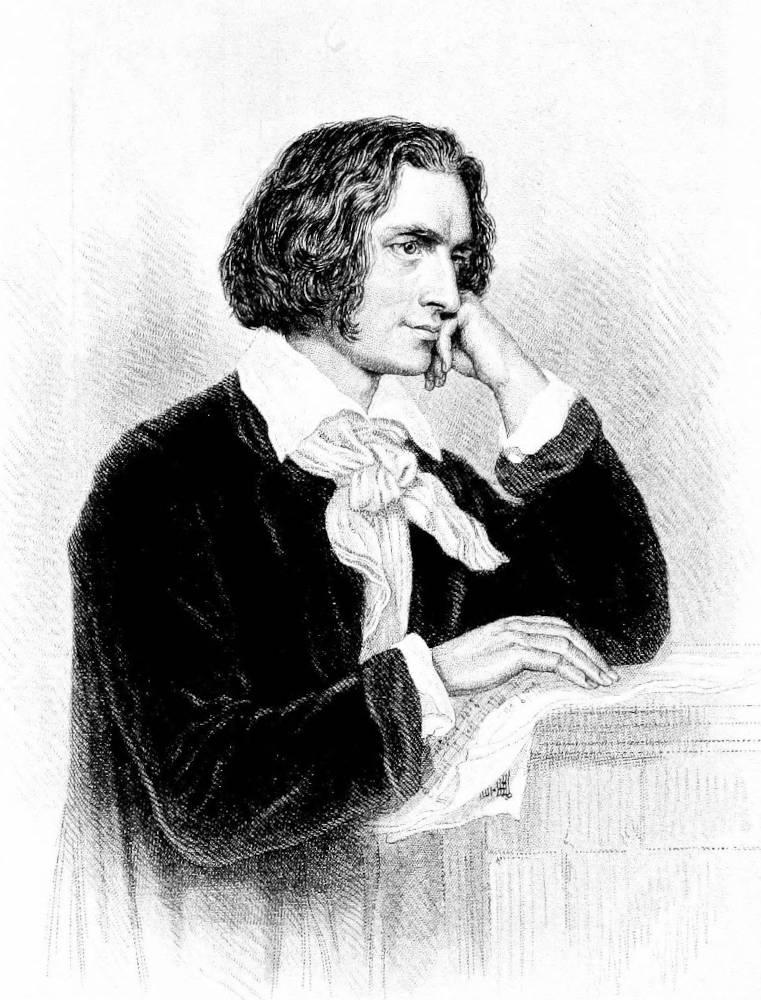

Mᶜ Rae, sc.

HAYDN.

[Pg 39]

In a small and insignificant dwelling in the village of Rohrau, on the borders of Hungary and Austria, lived, at the beginning of the last century, a young pair, faithful and industrious, plain and simple in their manners, yet esteemed by all their neighbors. The man, an honest wheelwright, was commonly called “merry Jobst,” on account of the jokes and gay stories with which he was always ready to entertain his friends and visitors, who, he well knew, relished such things. His wife was named Elizabeth, but no one in the village, and indeed many miles round it, ever called her any thing but “pretty Elschen.” Jobst and Elschen were indeed, to say truth, the handsomest couple in the country.

The Hungarians, like the Austrians and Bohemians, have great love for music. “Three fiddles and a dulcimer for two houses,” says the proverb; and it is a true one. It is not unusual, therefore, for some out of the poorer classes, when their regular business fails to bring them in sufficient for their wants, to take to the fiddle, the dulcimer, or the harp; playing on holidays on the highway or in the taverns. This employment is generally lucrative enough, if they are not spendthrifts, to enable them, not only to live, but to lay by something for future necessities.

“Merry Jobst” was already revolving in his own mind some means to be adopted for the bettering of his very humble fortunes, when Elschen one day said to him, “Jobst! it is time[Pg 40] to think of making something more for our increasing family!” Jobst gave a leap of joy, embraced pretty Elschen, and answered, “Come then! I will string anew my fiddle and your harp; every holiday we will take our place on the road side before the tavern, and play and sing merrily: we will give good wishes to those that listen to and reward us, and let the surly traveller, who stops not to hear us, go on his way!”

The next Sunday afternoon merry Jobst and pretty Elschen sat by the highway before the village inn; Jobst fiddled, and Elschen played the harp and sang to it with her sweet clear voice. Not one passed by without noticing them; every traveller stopped to listen, well pleased, and on resuming his journey threw at least a silver twopence into the lap of the pretty young woman. Jobst and his wife, on returning home in the evening, found their day’s work a good one.—They practised it regularly with the like success.

After the lapse of a few years, as the old cantor of the neighboring town of Haimburg passed along the road one afternoon, he could not help stopping, admiring and amused at what he saw. In the same arbor, opposite the tavern, sat merry Jobst fiddling as before, and beside him pretty Elschen, playing the harp and singing; and between them, on the ground, sat a little chubby-faced boy about three years old, who had a small board, shaped like a violin, hung about his neck, on which he played with a willow twig as with a genuine fiddle-bow. The most comical and surprising thing of all was, that the little man kept perfect time, pausing when his father paused and his mother had solo, then falling in with him again, and demeaning himself exactly like his father. Often too, he would lift up his clear voice, and join distinctly in the refrain of the song. The song pretty Elschen sang, ran somewhat in this way:

“Is that your boy—fiddler?” asked the teacher, when the song was at an end. Jobst answered,

“Yes, sir, that is my little Seperl.”[3]

“The little fellow seems to have a taste for music.”

“Why not? if it depends on me, I will take him, as soon as I can do so, to one who understands it well, and can teach him. But it will be some time yet, as with all his taste and love for it, he is very little and awkward.”

“We will speak further of it,” said the teacher, and went his way. Jobst and Elschen began their song anew, and the little Joseph imitated his father on his fiddle, and joined his infant voice with theirs when they sounded the ‘Hallelujah!’

The cantor came from this time twice a week to the house of merry Jobst to talk with him about his little son, and the youngster himself was soon the best of friends with the good-natured old man. So matters went on for two years, at the end of which, the cantor said to Jobst, “It is now the right time, and if you will trust your boy with me, I will take him, and teach him what he must learn, to become a brave lad and a skilful musician.”

Jobst did not hesitate long, for he saw clearly how great an advantage the instruction of Master Wolferl would be to his son. And though it went harder with pretty Elschen to part with Seperl, who was her favorite and only child, yet she gave up at last, when her husband observed—“The boy is still our own, and if he is our only child, we are—Heaven be praised!—both young, and love each other!”

[Pg 42]

So he said to Wolferl, the next time he came—“Agreed! here is the boy! treat him well—and remember that he is the apple of our eye.”

“I will treat him as my own!” replied the teacher. Elschen accordingly packed up the boy’s scanty wardrobe in a bundle, gave him a slice of bread and salt, and a cup of milk—embraced and blessed him, and accompanied him to the door of the cottage, where she signed him with the cross three times, and then returned to her chamber. Jobst went with them half the way to Haimburg, and then also returned, while Wolferl and Joseph pursued their way till they reached Wolferl’s house, the end of their journey.

Wolferl was an old bachelor, but one of the good sort, whose heart, despite his grey hairs, was still youthful and warm. He loved all good men, and was patient and forbearing even with those who had faults, for he knew how weak and fickle too often is the heart of man. But the wholly depraved and wicked he hated, as he esteemed the good, and shunned all companionship with them; for it was his opinion “that he who is thoroughly corrupt, remains so in this world at least; and his conversation with the good tends not to his improvement, but on the contrary, to the destruction of both.”

Such lessons he repeated daily to the little Joseph, and taught him good principles, as well as how to sing, and play on the horn and kettledrum; and Joseph profited thereby, as well as by the instruction he received in music, and cherished and cultivated them as long as he lived.

In the following year, 1737, a second son was bestowed on the happy parents, whom they christened Michael.

Years passed, and Joseph was a well instructed boy; he had a voice as clear and fine as his mother’s, and played the violin as well as his father; besides that, he blew the horn, and beat the kettledrum, in the sacred music prepared by Wolferl for church festivals. Better than all, Joseph had a true and honest heart, had the fear of God continually before his eyes, and was ever[Pg 43] contented, and wished well to all; for which everybody loved him in return, and Wolferl often said with tears of joy—“Mark what I tell you, God will show the world, by this boy Joseph, that not only the kingdom of heaven, but the kingdom of the science of music shall be given to those who are pure in heart!” The more Wolferl perceived the lad’s wonderful talent for art, the more earnestly he sought to find a patron, who might better forward the youthful aspirant towards the desired goal; for he felt that his own strength could reach little further, when he saw the zeal and ability with which his pupil devoted himself to his studies. Providence ordered it at length that Master von Reuter, chapel-master and music director in St. Stephen’s Church, Vienna, came to visit the Deacon at Haimburg. The Deacon told Master von Reuter of the extraordinary boy, the son of the wheelwright Jobst Haydn, the pupil of old Wolferl, and created in the chapel-master much desire to become acquainted with him.—The Deacon would have sent for him and his protector, but von Reuter prevented him with “No—no—most reverend Sir! I will not have the lad brought to me; I will seek him myself, and if possible, hear him when he is not conscious of my presence or my intentions; for if I find the boy what your reverence thinks him, I will do something, of course, to advance his interests.” The next morning, accordingly, von Reuter went to Wolferl’s house, which he entered quietly and unannounced. Joseph was sitting alone at the organ, playing a simple but sublime piece of sacred music from an old German master. Reuter, visibly moved, stood at the door and listened attentively. The boy was so deep in his music that he did not perceive the intruder till the piece was concluded, when accidentally turning round, he fixed upon the stranger his large dark eyes, expressive of astonishment indeed, but sparkling a friendly welcome.

“Very well, my son!” said von Reuter at last; “where is your foster-father?”

“In the garden,” said the boy; “shall I call him?”

“Call him, and say to him that the chapel-master, von Reuter,[Pg 44] wishes to speak with him. Stop a moment! you are Joseph Haydn; are you not?”

“Yes, I am Seperl.”

“Well then, go.”

Joseph went and brought his old master, Wolferl, who with uncovered head and low obeisance welcomed the chapel-master and music director at Saint Stephen’s, to his humble abode. Von Reuter, on his part, praised the musical skill of his protegé, enquired particularly into the lad’s attainments, and examined him formally himself. Joseph passed the examination in such a manner that Reuter’s satisfaction increased with every answer. After this he spent some time in close conference with old Wolferl; and it was near noon before he took his departure. Joseph was invited to accompany him and spend the rest of the day at the Deacon’s.

Eight days after, old Wolferl, Jobst and pretty Elschen, the little Michael on her lap, sat very dejectedly together, and talked of the good Joseph, who had gone that morning with Master von Reuter to Vienna, to take his place as chorister in St. Stephen’s church.

The clock struck eight, and all were awake in the Leopoldstadt. A busy multitude crowded the bridge—market women and mechanics’ boys, hucksters, pedlars, hackney coachmen and genteel horsemen, passing in and out of the city; and through the thickest of the throng might be seen winding his way quietly and inoffensively, the noted Wenzel Puderlein, hairdresser, burgher and house-proprietor in Leopoldstadt. Soon he passed over the space that divides Leopoldstadt from the city, and with rapid steps approached through streets and alleys, the place where resided his most distinguished customers, whom he came every morning to serve.

He stopped before one of the best looking houses; ascended the steps, rang the bell, and when the house-maid opened the[Pg 45] door, stepped boldly, and with apparent consciousness of dignity through the hall to a side door. Here he paused, placed his feet in due position, took off his hat modestly, and knocked gently three times.

“Come in!” said a powerful voice. Wenzel, however, started, and hung back a moment, then taking courage, he lifted the latch, opened the door and entered the apartment. An elderly man, of stately figure, wrapped in a flowered dressing-gown, sat at a writing table; he arose as the door opened, and said,

“’Tis well you are come, Puderlein! Do what you have to do, but quickly, I counsel you! for the Empress has sent for me, and I must be with her in half an hour.” He then seated himself, and Wenzel began his hairdressing without uttering a word, (how contrary to his nature!) well knowing that a strict silence was enjoined on him in the presence of the first physician to Her Imperial Majesty.

Yet he was not doomed long to suffer this greatest of all torments to him, the necessity of silence. The door of the chamber opened, and a youth of about sixteen or seventeen years of age came in, approached the elderly man, kissed his hand reverently, and bade him good morning.

The old gentleman thanked him briefly, and said, “What was it you were going to ask me yesterday evening, when it struck eleven and I sent you off to bed?”

The youth, with a modest smile, replied, “I was going to beg leave, my father, if your time permitted, to present to you the young man I would like to have for my teacher on the piano.”

“Very well; after noon I shall be at liberty; but who has recommended him to you?”

“An admirable piece which I was yesterday so fortunate as to hear him play at the house of Mlle. de Martinez.”

“Ah! your honor means young Haydn,” cried Puderlein, unwittingly, and then became suddenly silent, expecting nothing less than that his temerity would draw down a thunderbolt on his head. But contrary to his expectation, the old gentleman merely[Pg 46] looked at him a moment, as if in surprise, from head to foot, then said mildly, “You are acquainted with the young man then: what do you know of him?”

“I know him!” answered Puderlein; “Oh, very well, your honor; I know him well. What I know of him? Oh, much; for observe, your honor, I have had the honor to be hairdresser for many years to the chapel-master, von Reuter, in whose house Haydn has long been an inmate—it must now be ten or eleven years. I have known him, so to speak, from childhood. Besides I have heard him sing a hundred times at St. Stephen’s, where he was chorister, though it is now a couple of years since he was turned off.”

“Turned off? and wherefore?”

“Aye; observe, your honor, he had a fine clear voice, such as no female singer in the Opera; but getting a fright, and being seized with a fever—when he recovered, his fine soprano was gone! And because they had no more use for him at St. Stephen’s, they turned him off.”

“And what does young Haydn now?” asked the Baron.

“Ah, your honor, the poor fellow must find it hard to live by giving lessons, playing about, and picking up what he can; he also composes sometimes, or what do they call it? Well, what helps it him, that he torments himself? he lives in the house with Metastasio, not in the first story, like the court poet, but in the fifth; and when it is winter, he has to lie in bed and work, to keep himself from freezing; for, observe, he has indeed a fire-place in his chamber, but no money to buy wood to burn therein.”

“This must not be! this shall not be!” cried the Baron von Swieten, as he rose from his seat. “Am I ready?”

“A moment, your honor,—only the string around the hair-bag.”

“It is very good so; now begone about your business!” Puderlein vanished. “And you, help me on with my coat; give me my stick and hat, and bring me your young teacher this afternoon.” Therewith he departed, and young von Swieten, full of[Pg 47] joy, went to the writing-table to indite an invitation to Haydn to come to his father’s house.

Meanwhile, Joseph Haydn sat, sorrowful, and almost despairing, in his chamber. He had passed the morning, contrary to his usual custom, in idle brooding over his condition; now it appeared quite hopeless, and his cheerfulness seemed about to take leave of him forever, like his only friend and protectress, Mlle. de Martinez. That amiable young lady had left the city a few hours before. Haydn had instructed her in singing, and in playing the harpsichord, and by way of recompense, he enjoyed the privilege of board and lodging in the fifth story, in the house of Metastasio. Both now ceased with the lady’s departure; and Joseph was poorer than before, for all that he had earned besides, he had sent conscientiously to his parents, only keeping so much as sufficed to furnish him with decent, though plain clothing.