Lin McLean

Title: A journey in search of Christmas

Author: Owen Wister

Illustrator: Frederic Remington

Release date: September 2, 2023 [eBook #71547]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Harper & Brothers

Credits: Richard Tonsing, Charlene Taylor, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Lin McLean

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Lin’s Money Talks Joy | 1 |

| II. | Lin’s Money is Dumb | 13 |

| III. | A Transaction in Boot-Blacking | 37 |

| IV. | Turkey and Responsibility | 50 |

| V. | Santa Claus Lin | 75 |

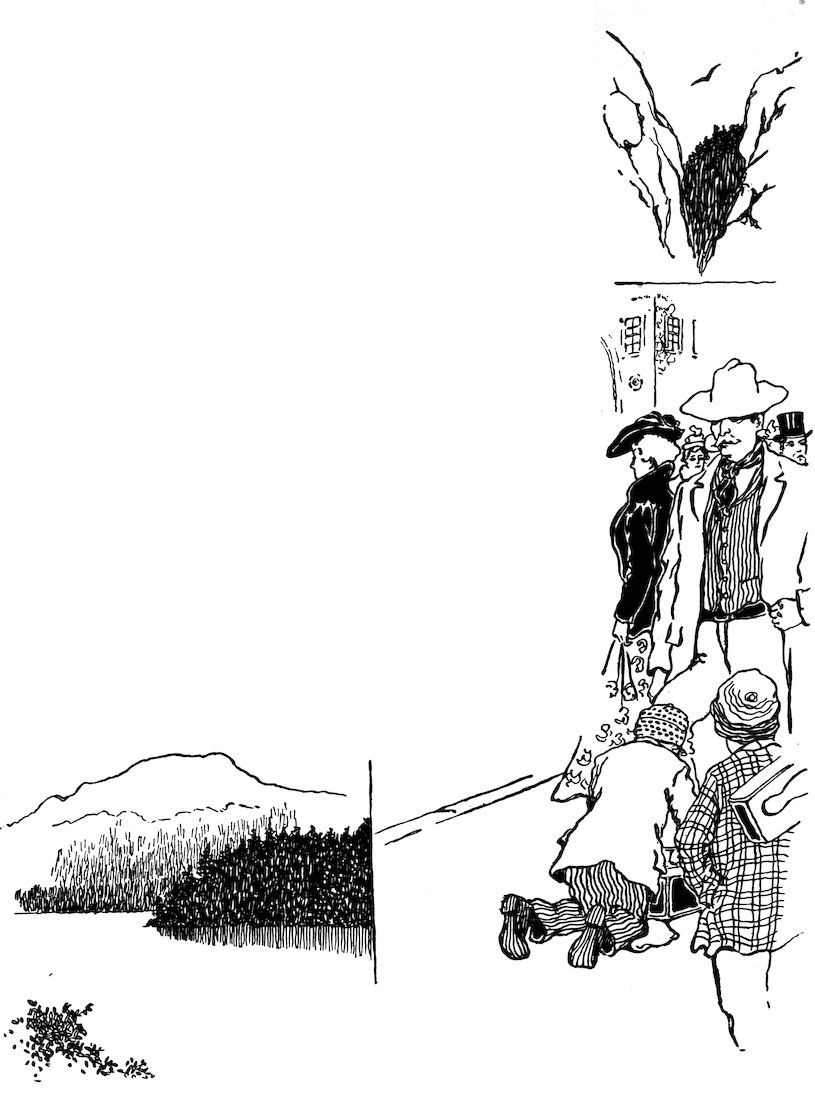

| Lin McLean | Frontispiece | |

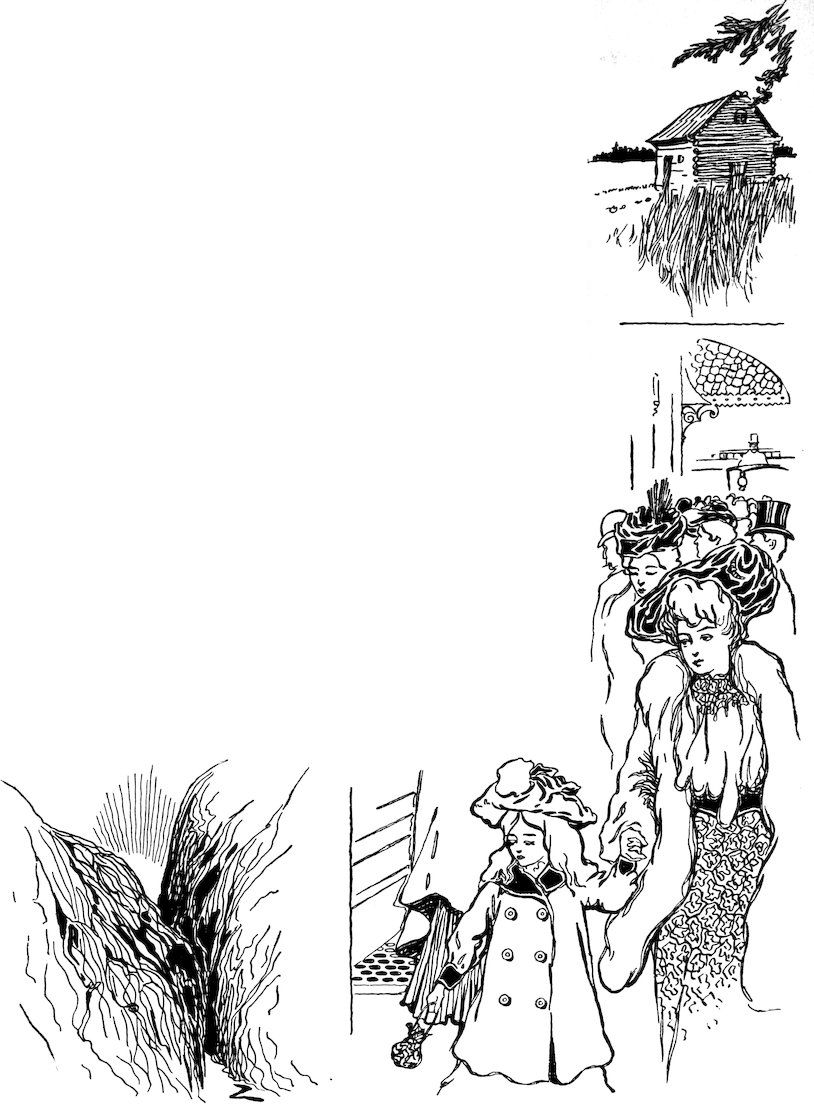

| “Lin walked in their charge, they leading the way” | Facing p. | 52 |

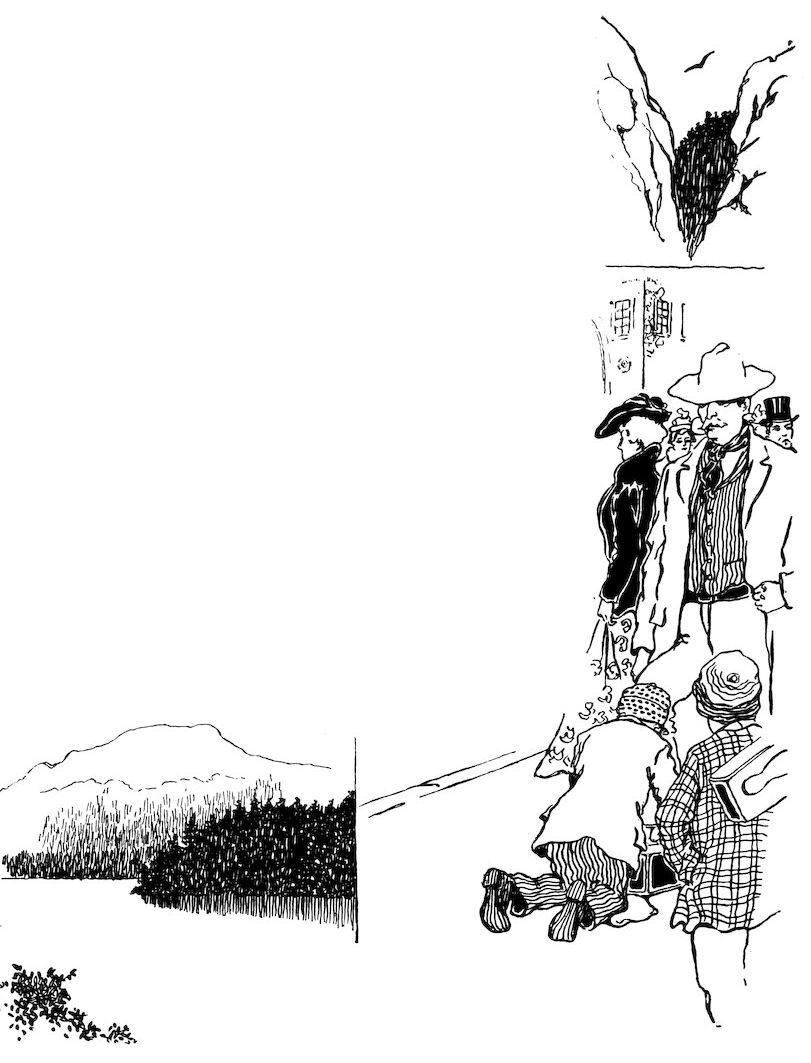

| “‘This is Mister Billy Lusk’” | „ | 90 |

The Governor descended the steps of the Capitol slowly and with pauses, lifting a list frequently to his eye. He had intermittently pencilled it between stages of the forenoon’s public business, and his gait grew absent as he recurred now to his jottings in their accumulation, with a slight pain at their number, and the definite fear that they would be more in seasons to come. They were the names of his friends’ children to whom his excellent heart moved him to give Christmas presents. He had put off this regenerating evil until the latest day, as was his custom, and now he was setting forth to do the whole thing at a blow, entirely planless among the guns and rocking-horses that would presently surround him. As he reached the highway he heard himself familiarly addressed from a distance, and, turning, saw four sons of the alkali jogging into town from the plain. One who had shouted to him galloped out from the others, rounded the Capitol’s enclosure, and, approaching with radiant countenance, leaned to reach the hand of the Governor, and once again greeted him with a hilarious “Hello, Doc!”

Governor Barker, M.D., seeing Mr. McLean unexpectedly after several years, hailed the horseman with frank and lively pleasure, and, inquiring who might be the other riders behind, was told that they were Shorty, Chalkeye, and Dollar Bill, come for Christmas. “And dandies to hit town with,” Mr. McLean added. “Redhot.”

“I am acquainted with them,” assented his Excellency.

“We’ve been ridin’ trail for twelve weeks,” the cow-puncher continued, “and the money in our pants is talkin’ joy to us right out loud.”

Then Mr. McLean overflowed with talk and pungent confidences, for the holidays already rioted in his spirit, and his tongue was loosed over their coming rites.

“We’ve soured on scenery,” he finished, in his drastic idiom. “We’re heeled for a big time.”

“Call on me,” remarked the Governor, cheerily, “when you’re ready for bromides and sulphates.”

“I ain’t box-headed no more,” protested Mr. McLean; “I’ve got maturity, Doc, since I seen yu’ at the rain-making, and I’m a heap older than them hospital days when I bust my leg on yu’. Three or four glasses and quit. That’s my rule.”

“That your rule, too?” inquired the Governor of Shorty, Chalkeye, and Dollar Bill. These gentlemen of the saddle were sitting quite expressionless upon their horses.

“We ain’t talkin’, we’re waitin’,” observed Chalkeye; and the three cynics smiled amiably.

“Well, Doc, see yu’ again,” said Mr. McLean. He turned to accompany his brother cow-punchers, but in that particular moment Fate descended, or came up, from whatever place she dwells in, and entered the body of the unsuspecting Governor.

“What’s your hurry?” said Fate, speaking in the official’s hearty manner. “Come along with me.”

“Can’t do it. Where’re yu’ goin’?”

“Christmasing,” replied Fate.

“Well, I’ve got to feed my horse. Christmasing, yu’ say?”

“Yes; I’m buying toys.”

“Toys! You? What for?”

“Oh, some kids.”

“Yourn?” screeched Lin, precipitately.

His Excellency the jovial Governor opened 6his teeth in pleasure at this, for he was a bachelor, and there were fifteen upon his list, which he held up for the edification of the hasty McLean. “Not mine, I’m happy to say. My friends keep marrying and settling, and their kids call me uncle, and climb around and bother, and I forget their names, and think it’s a girl, and the mother gets mad. Why, if I didn’t remember these little folks at Christmas they’d be wondering—not the kids, they just break your toys and don’t notice; but the mother would wonder—‘What’s the matter with Dr. Barker? Has Governor Barker gone back on us?’—that’s where the strain comes!” he broke off, facing Mr. McLean with another spacious laugh.

But the cow-puncher had ceased to smile, and now, while Barker ran on exuberantly 7McLean’s wide-open eyes rested upon him, singular and intent, and in their hazel depths the last gleam of jocularity went out.

“That’s where the strain comes, you see. Two sets of acquaintances—grateful patients and loyal voters—and I’ve got to keep solid with both outfits, especially the wives and mothers. They’re the people. So it’s drums, and dolls, and sheep on wheels, and games, and monkeys on a stick, and the saleslady shows you a mechanical bear, and it costs too much, and you forget whether the Judge’s second girl is Nellie or Susie, and—well, I’m just in for my annual circus this afternoon! You’re in luck. Christmas don’t trouble a chap fixed like you.”

Lin McLean prolonged the sentence like a distant echo.

“A chap fixed like you!” The cow-puncher said it slowly to himself. “No, sure.” He seemed to be watching Shorty, and Chalkeye, and Dollar Bill going down the road. “That’s a new idea—Christmas,” he murmured, for it was one of his oldest, and he was recalling the Christmas when he wore his first long trousers.

“Comes once a year pretty regular,” remarked the prosperous Governor. “Seems often when you pay the bill.”

“I haven’t made a Christmas gift,” pursued the cow-puncher, dreamily, “not for—for—Lord! it’s a hundred years, I guess. I don’t know anybody that has any right to look for such a thing from me.” This was indeed a new idea, and it did not stop the chill that was spreading in his heart.

“Gee whiz!” said Barker, briskly, “there goes twelve o’clock. I’ve got to make a start. Sorry you can’t come and help me. Good-bye!”

His Excellency left the rider sitting motionless, and forgot him at once in his own preoccupation. He hastened upon his journey to the shops with the list, not in his pocket, but held firmly, like a plank in the imminence of shipwreck. The Nellies and Susies pervaded his mind, and he struggled with the presentiment that in a day or two he would recall some omitted and wretchedly important child. Quick hoof-beats made him look up, and Mr. McLean passed like a wind. The Governor absently watched him go, and saw the pony hunch and stiffen in the check of his speed when Lin overtook his 10companions. Down there in the distance they took a side street, and Barker rejoicingly remembered one more name and wrote it as he walked. In a few minutes he had come to the shops, and met face to face with Mr. McLean.

“The boys are seein’ after my horse,” Lin rapidly began, “and I’ve got to meet ’em sharp at one. We’re twelve weeks shy on a square meal, yu’ see, and this first has been a date from ’way back. I’d like to—” Here Mr. McLean cleared his throat, and his speech went less smoothly. “Doc, I’d like just for a while to watch yu’ gettin’—them monkeys, yu’ know.”

The Governor expressed his agreeable surprise at this change of mind, and was glad of McLean’s company and judgment during the impending selections. A picture of a cow-puncher and himself discussing a couple of dolls rose nimbly in Barker’s mental eye, and it was with an imperfect honesty that he said, “You’ll help me a heap.”

And Lin, quite sincere, replied, “Thank yu’.”

So together these two went Christmasing in the throng. Wyoming’s Chief Executive knocked elbows with the spurred and jingling waif, one man as good as another in that raw, hopeful, full-blooded cattle era which now the sobered West remembers as the days of its fond youth. For one man has been as good as another in three places—Paradise before the Fall; the Rocky Mountains before the wire fence; and the Declaration of Independence. And then this Governor, besides being young, almost as young as Lin McLean or the Chief-Justice (who lately had celebrated his thirty-second birthday), had in his doctoring days at Drybone known the cow-puncher with that familiarity which lasts a lifetime without breeding contempt; accordingly, he now laid a hand on Lin’s tall shoulder and drew him among the petticoats and toys.

Christmas filled the windows and Christmas stirred in mankind. Cheyenne, not over-zealous in doctrine or litanies, and with the opinion that a world in the hand is worth two in the bush, nevertheless was flocking together, neighbor to think of neighbor, and every one to remember the children; a sacred assembly, after all, gathered to rehearse unwittingly the articles of its belief, the Creed and Doctrine of the Child. Lin saw them hurry and smile among the paper fairies; they questioned and hesitated, crowded and made decisions, failed utterly to find the right thing, forgot and hastened back, suffered all the various desperations of the eleventh hour, and turned homeward, dropping their parcels with that undimmed good-will that once a year makes gracious the universal human face. This brotherhood swam and beamed before the cow-puncher’s brooding eyes, and in his ears the greeting of the season sang. Children escaped from their mothers and ran chirping behind the counters to touch and meddle in places forbidden. Friends dashed against each other with rabbits and magic lanterns, greeted in haste, and were gone, amid the sound of musical boxes.

Through this tinkle and bleating of little machinery the murmur of the human heart drifted in and out of McLean’s hearing; fragments of home talk, tendernesses, economies, intimate first names, and dinner hours; and whether it was joy or sadness, it was in common; the world seemed knit in a single skein of home ties. Two or three came by whose purses must have been slender, and whose purchases were humble and chosen after much nice adjustment; and when one plain man dropped a word about both ends meeting, and the woman with him laid a hand on his arm, saying that his children must not feel this year was different, Lin made a step towards them. There were hours and spots where he could readily have descended upon them at that, played the rôle of clinking affluence, waved thanks aside with competent blasphemy, and, tossing off some infamous whiskey, cantered away in the full, self-conscious strut of the frontier. But here was not the moment; the abashed cow-puncher could make no such parade in this place. The people brushed by him back and forth, busy upon their errands, and aware of him scarcely more than if he had been a spirit looking on from the helpless dead; and so, while these weaving needs and kindnesses of man were within arm’s touch of him, he was locked outside with his impulses. Barker had, in the natural press of customers, long parted from him, to become immersed in choosing and rejecting; and now, with a fair part of his mission accomplished, he was ready to go on to the next place, and turned to beckon McLean. He found him obliterated in a corner beside a life-sized image of Santa Claus, standing as still as the frosty saint.

“He looks livelier than you do,” said the hearty Governor. “’Fraid it’s been slow waiting.”

“No,” replied the cow-puncher, thoughtfully. “No, I guess not.”

This uncertainty was expressed with such gentleness that Barker roared. “You never did lie to me,” he said, “long as I’ve known you. Well, never mind. I’ve got some real advice to ask you now.”

At this Mr. McLean’s face grew more alert. “Say, Doc,” said he, “what do yu’ want for Christmas that nobody’s likely to give yu’?”

“A big practice—big enough to interfere with my politics.”

“What else? Things and truck, I mean.”

“Oh—nothing I’ll get. People don’t give things much to fellows like me.”

“Don’t they? Don’t they?”

“Why, you and Santa Claus weren’t putting up any scheme on my stocking?”

“Well—”

“I believe you’re in earnest!” cried his Excellency. “That’s simply rich!” Here was a thing to relish! The Frontier comes to town “heeled for a big time,” finds that presents are all the rage, and must immediately give somebody something. Oh, childlike, miscellaneous Frontier! So thought the good-hearted Governor; and it seems a venial misconception. “My dear fellow,” he added, meaning as well as possible, “I don’t want you to spend your money on me.”

“I’ve got plenty all right,” said Lin, shortly.

“Plenty’s not the point. I’ll take as many drinks as you please with you. You didn’t expect anything from me?”

“That ain’t—that don’t—”

“There! Of course you didn’t. Then, what are you getting proud about? Here’s our shop.” They stepped in from the street to new crowds and counters. “Now,” pursued the Governor, “this is for a very particular friend of mine. Here they are. Now, which of those do you like best?”

They were sets of Tennyson in cases holding little volumes equal in number, but the binding various, and Mr. McLean reached his decision after one look. “That,” said he, and laid a large, muscular hand upon the Laureate. The young lady behind the counter spoke out acidly, and Lin pulled the abject hand away. His taste, however, happened to be sound, or, at least, it was at one with the Governor’s; but now they learned that there was a distressing variance in the matter of price.

The Governor stared at the delicate article of his choice. “I know that Tennyson is what she—is what’s wanted,” he muttered; and, feeling himself nudged, looked around and saw Lin’s extended fist. This gesture he took for a facetious sympathy, and, dolorously grasping the hand, found himself holding a lump of bills. Sheer amazement relaxed him, and the cow-puncher’s matted wealth tumbled on the floor in sight of all people. Barker picked it up and gave it back. “No, no, no!” he said, mirthful over his own inclination to be annoyed; “you can’t do that. I’m just as much obliged, Lin,” he added.

“Just as a loan. Doc—some of it. I’m grass-bellied with spot-cash.”

A giggle behind the counter disturbed them both, but the sharp young lady was only dusting. The Governor at once paid haughtily for Tennyson’s expensive works, and the cow-puncher pushed his discountenanced savings back into his clothes. Making haste to leave the book department of this shop, they regained a mutual ease, and the Governor became waggish over Lin’s concern at being too rich. He suggested to him the list of delinquent taxpayers and the latest census from which to select indigent persons. He had patients, too, whose inveterate pennilessness he could swear cheerfully to—“since you want to bolt from your own money,” he remarked.

“Yes, I’m a green horse,” assented Mr. McLean, gallantly; “ain’t used to the looks of a twenty-dollar bill, and I shy at ’em.”

From his face—that jocular mask—one might have counted him the most serene and careless of vagrants, and in his words only the ordinary voice of banter spoke to the Governor. A good woman, it may well be, would have guessed before this the sensitive soul in the blundering body; but Barker saw just the familiar, whimsical, happy-go-lucky McLean of old days, and so he went gayly and innocently on, treading upon holy ground. “I’ve got it!” he exclaimed; “give your wife something.”

The ruddy cow-puncher grinned. He had passed through the world of woman with but few delays, rejoicing in informal and transient entanglements, and he welcomed the turn which the conversation seemed now to be taking. “If you’ll give me her name and address,” said he, with the future entirely in his mind.

“Why, Laramie!” and the Governor feigned surprise.

“Say, Doc,” said Lin, uneasily, “none of ’em ’ain’t married me since I saw you last.”

“Then she hasn’t written from Laramie?” said the hilarious Governor; and Mr. McLean understood and winced in his spirit deep down. “Gee whiz!” went on Barker. “I’ll never forget you and Lusk that day!”

But the mask fell now. “You’re talking of his wife, not mine,” said the cow-puncher, very quietly, and smiling no more; “and, Doc, I’m going to say a word to yu’, for I know yu’ve always been my good friend. I’ll never forget that day myself—but I don’t want to be reminded of it.”

“I’m a fool, Lin,” said the Governor, generous instantly. “I never supposed—”

“I know yu’ didn’t. Doc. It ain’t you that’s the fool. And in a way—in a way—” Lin’s speech ended among his crowding memories, and Barker, seeing how wistful his face had turned, waited. “But I ain’t quite the same fool I was before that happened to me,” the cow-puncher resumed, “though maybe my actions don’t show to be wiser. I know that there was better luck than a man like me had any call to look for.”

The sobered Barker said, simply, “Yes, Lin.” He was set to thinking by these words from the unsuspected inner man.

Out in the Bow-Leg country Lin McLean had met a woman with thick, red cheeks, calling herself by a maiden name; and this was his whole knowledge of her when he put her one morning astride a Mexican saddle and took her fifty miles to a magistrate and made her his lawful wife to the best of his ability and belief. His sage-brush intimates were confident he would never have done it but for a rival. Racing the rival and beating him had swept Mr. McLean past his own intentions, and the marriage was an inadvertence. “He jest bumped into it before he could pull up,” they explained; and this casualty, resulting from Mr. McLean’s sporting blood, had entertained several hundred square miles of alkali. For the new-made husband the joke soon died. In the immediate weeks that came upon him he tasted a bitterness worse than in all his life before, and learned also how deep the woman, when once she begins, can sink beneath the man in baseness. That was a knowledge of which he had lived innocent until this time. But he carried his outward self serenely, so that citizens in Cheyenne who saw the cow-puncher with his bride argued shrewdly that men of that sort liked women of that sort; and before the strain had broken his endurance an unexpected first husband, named Lusk, had appeared one Sunday in the street, prosperous, forgiving, and exceedingly drunk. To the arms of Lusk she went back in the public street, deserting McLean in the presence of Cheyenne; and when Cheyenne saw this, and learned how she had been Mrs. Lusk for eight long, if intermittent, years, Cheyenne laughed loudly. Lin McLean laughed, too, and went about his business, ready to swagger at the necessary moment, and with the necessary kind of joke always ready to shield his hurt spirit. And soon, of course, the matter grew stale, seldom raked up in the Bow-Leg country where Lin had been at work; so lately he had begun to remember other things besides the smouldering humiliation.

“Is she with him?” he asked Barker, and musingly listened while Barker told him. The Governor had thought to make it a racy story, with the moral that the joke was now on Lusk; but that inner man had spoken and revealed the cow-puncher to him in a new and complicated light; hence he quieted the proposed lively cadence and vocabulary of his anecdote about the house of Lusk, and instead of narrating how Mrs. beat Mr. on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, and Mr. took his turn the odd days, thus getting one ahead of his lady, while the kid Lusk had outlined his opinion of the family by recently skipping to parts unknown. Barker detailed these incidents more gravely, adding that Laramie believed Mrs. Lusk addicted to opium.

“I don’t guess I’ll leave my card on ’em,” said McLean, grimly, “if I strike Laramie.”

“You don’t mind my saying I think you’re well out of that scrape?” Barker ventured.

“Shucks, no! That’s all right, Doc. Only—yu’ see now. A man gets tired pretending—onced in a while.”

Time had gone while they were in talk, and it was now half after one and Mr. McLean late for that long-plotted first square meal. So the friends shook hands, wishing each other Merry Christmas, and the cow-puncher hastened towards his chosen companions through the stirring cheerfulness of the season. His play-hour had made a dull beginning among the toys. He had come upon people engaged in a pleasant game, and waited, shy and well-disposed, for some bidding to join, but they had gone on playing with one another and left him out. And now he went along in a sort of hurry to escape from that loneliness where his human promptings had been lodged with him useless. Here was Cheyenne, full of holiday for sale, and he with his pockets full of money to buy; and when he thought of Shorty and Chalkeye and Dollar Bill, those dandies to hit town with, he stepped out with a brisk, false hope. It was with a mental hurrah and a foretaste of a good time coming that he put on his town clothes, after shaving and admiring himself, and sat down to the square meal. He ate away and drank with a robust imitation of enjoyment that took in even himself at first. But the sorrowful 31process of his spirit went on, for all he could do. As he groped for the contentment which he saw around him he began to receive the jokes with counterfeit mirth. Memories took the place of anticipation, and through their moody shiftings he began to feel a distaste for the company of his friends and a shrinking from their lively voices. He blamed them for this at once. He was surprised to think he had never recognized before how light a weight was Shorty, and here was Chalkeye, who knew better, talking religion after two glasses. Presently this attack of noticing his friends’ shortcomings mastered him, and his mind, according to its wont, changed at a stroke. “I’m celebrating no Christmas with this crowd,” said the inner man; and when they had next remembered Lin McLean in their hilarity he was gone.

Governor Barker, finishing his purchases at half-past three, went to meet a friend come from Evanston. Mr. McLean was at the railway station buying a ticket for Denver.

“Denver!” exclaimed the amazed Governor.

“That’s what I said,” stated Mr. McLean, doggedly.

“Suffering Moses!” said his Excellency. “What are you going to do there?”

“Get good and drunk.”

“Can’t you find enough whiskey in Cheyenne?”

“I’m drinking champagne this trip.”

The cow-puncher went out on the platform and got aboard, and the train moved off. Barker had walked out, too, in his surprise, and as he stared after the last car Mr. McLean waved his wide hat defiantly and went inside the door.

“And he says he’s got maturity,” Barker muttered. “I’ve known him since seventy-nine, and he’s kept about eight years old right along.” The Governor was cross and sorry, and presently crosser. His jokes about Lin’s marriage came back to him and put him in a rage with the departed fool. “Yes, about eight. Or six,” said his Excellency, justifying himself by the past. For he had first known Lin, the boy of nineteen, supreme in length of limb and recklessness, breaking horses and feeling for an early mustache. Next, when the mustache was nearly accomplished, he had mended the boy’s badly broken thigh at Drybone. His skill (and Lin’s spotless health) had wrought so swift a healing that the surgeon overflowed with the pride of science, and over the bandages would explain the human body technically to his wild-eyed and flattered patient. Thus young Lin heard all about tibia, and comminuted, and other glorious new words, and when sleepless would rehearse them. Then, with the bone so nearly knit that the patient might leave the ward on crutches to sit each morning in Barker’s room as a privilege, the disobedient child of twenty-one had slipped out of the hospital and hobbled hastily to the hog ranch, where whiskey and variety waited for a languishing convalescent. Here he grew gay, and was soon carried back with the leg refractured. Yet Barker’s surgical rage was disarmed, the patient was so forlorn over his doctor’s professional chagrin.

“I suppose it ain’t no better this morning, Doc?” he had said, humbly, after a new week of bed and weights.

“Your right leg’s going to be shorter. That’s all.”

“Oh, gosh! I’ve been and spoiled your comminuted fee-mur! Ain’t I a son-of-a-gun?”

You could not chide such a boy as this; and in time’s due course he had walked jauntily out into the world with legs of equal length, after all, and in his stride the slightest halt possible. And Doctor Barker had missed the child’s conversation. To-day his mustache was a perfected thing, and he in the late end of his twenties.

“He’ll wake up about noon to-morrow in a dive, without a cent,” said Barker. “Then he’ll come back on a freight and begin over again.”

At the Denver station Lin McLean passed through the shoutings and omnibuses, and came to the beginning of Seventeenth Street, where is the first saloon. A customer was ordering Hot Scotch; and because he liked the smell and had not thought of the mixture for a number of years, Lin took Hot Scotch. Coming out upon the pavement, he looked across and saw a saloon opposite with brighter globes and windows more prosperous. That should have been his choice; lemon-peel would undoubtedly be fresher over there; and over he went at once, to begin the whole thing properly. In such frozen weather no drink could be more timely, and he sat, to enjoy without haste its mellow fitness. Once again on the pavement, he looked along the street towards up-town beneath the crisp, cold electric lights, and three little bootblacks gathered where he stood, and cried, “Shine? Shine?” at him. Remembering that you took the third turn to the right to get the best dinner in Denver, Lin hit on the skilful plan of stopping at all Hot Scotches between; but the next occurred within a few yards, and it was across the street. This one being attained and appreciated, he found that he must cross back again or skip number four. At this rate he would not be dining in time to see much of the theatre, and he stopped to consider. It was a German place he had just quitted, and a huge light poured out on him from its window, which the proprietor’s fatherland sentiment had made into a show. Lights shone among a well-set pine forest, where beery, jovial gnomes sat on roots and reached upward to Santa Claus; he, grinning, fat, and Teutonic, held in his right hand forever a foaming glass, and forever in his left a string of sausages that dangled down among the gnomes. With his American back to this, the cow-puncher, wearing the same serious, absent face he had not changed since he ran away from himself at Cheyenne, considered carefully the Hot Scotch question and which side of the road to take and stick to, while the little bootblacks found him once more, and 40cried, “Shine? Shine?” monotonous as snowbirds. He settled to stay over here with the southside Scotches, and, the little, one-note song reaching his attention, he suddenly shoved his foot at the nearest boy, who lightly sprang away.

“Dare you to touch him!” piped a snowbird, dangerously. They were in short trousers, and the eldest enemy, it may be, was ten.

“Don’t hit me,” said Mr. McLean. “I’m innocent.”

“Well, you leave him be,” said one.

“What’s he layin’ to kick you for, Billy? ’Tain’t yer pop, is it?”

“Naw!” said Billy, in scorn. “Father never kicked me. Don’t know who he is.”

“He’s a special!” shrilled the leading bird, sensationally. “He’s got a badge, and he’s going to arrest yer.”

Two of them hopped instantly to the safe middle of the street, and scattered with practised strategy; but Billy stood his ground. “Dare you to arrest me!” said he.

“What’ll you give me not to?” inquired Lin, and he put his hands in his pockets, arms akimbo.

“Nothing; I’ve done nothing,” announced Billy, firmly. But even in the last syllable his voice suddenly failed, a terror filled his eyes, and he, too, sped into the middle of the street.

“What’s he claim you lifted?” inquired the leader, with eagerness. “Tell him you haven’t been inside a store to-day. We can prove it!” they screamed to the special officer.

“Say,” said the slow-spoken Lin from the pavement, “you’re poor judges of a badge, you fellows.”

His tone pleased them where they stood, wide apart from each other.

Mr. McLean also remained stationary in the bluish illumination of the window. “Why, if any policeman was caught wearin’ this here,” said he, following his sprightly invention, “he’d get arrested himself.”

This struck them extremely. They began to draw together, Billy lingering the last.

“If it’s your idea,” pursued Mr. McLean, alluringly, as the three took cautious steps nearer the curb, “that blue, clasped hands in a circle of red stars gives the bearer the right to put folks in the jug—why, I’ll get somebody else to black my boots for a dollar.”

The three made a swift rush, fell on simultaneous knees, and, clattering their boxes down, began to spit in an industrious circle.

“Easy!” wheedled Mr. McLean, and they looked up at him, staring and fascinated. “Not having three feet,” said the cow-puncher, always grave and slow, “I can only give two this here job.”

“He’s got a big pistol and a belt!” exulted the leader, who had precociously felt beneath Lin’s coat.

“You’re a smart boy,” said Lin, considering him, “and yu’ find a man out right away. Now you stand off and tell me all about myself while they fix the boots—and a dollar goes to the quickest through.”

Young Billy and his tow-headed competitor flattened down, each to a boot, with all their might, while the leader ruefully contemplated Mr. McLean.

“That’s a Colt forty-five you’ve got,” ventured he.

“Right again. Some day, maybe, you’ll be wearing one of your own, if the angels don’t pull yu’ before you’re ripe.”

“I’m through!” sang out Towhead, rising in haste.

Small Billy was struggling still, but leaped at that, the two heads bobbing to a level together; and Mr. McLean, looking down, saw that the arrangement had not been a good one for the boots.

“Will you kindly referee,” said he, forgivingly, to the leader, “and decide which of them smears is the awfulest?”

But the leader looked the other way and played upon a mouth-organ.

“Well, that saves me money,” said Mr. McLean, jingling his pocket. “I guess you’ve both won.” He handed each of them a dollar. “Now,” he continued, “I just dassent show these boots up-town; so this time it’s a dollar for the best shine.”

The two went palpitating at their brushes again, and the leader played his mouth-organ with brilliant unconcern. Lin, tall and brooding, leaned against the jutting sill of the window, a figure somehow plainly strange in town, while through the bright plate-glass Santa Claus, holding out his beer and sausages, perpetually beamed.

Billy was laboring gallantly, but it was labor, the cow-puncher perceived, and Billy no seasoned expert. “See here,” said Lin, stooping, “I’ll show yu’ how it’s done. He’s playin’ that toon cross-eyed enough to steer anybody crooked. There. Keep your blacking soft and work with a dry brush.”

“Lemme,” said Billy. “I’ve got to learn.” So he finished the boot his own way with wiry determination, breathing and repolishing; and this event was also adjudged a dead heat, with results gratifying to both parties. So here was their work done, and more money in their pockets than from all the other boots and shoes of this day; and Towhead and Billy did not wish for further trade, but to spend this handsome fortune as soon as might be. Yet they delayed in the brightness of the window, drawn by curiosity near this new kind of man whose voice held them and whose remarks dropped them into constant uncertainty. Even the omitted leader had been unable to go away and nurse his pride alone.

“Is that a secret society?” inquired Towhead, lifting a finger at the badge.

Mr. McLean nodded. “Turruble,” said he.

“You’re a Wells Fargo detective,” asserted the leader.

“Play your harp,” said Lin.

“Are you a—a desperaydo?” whispered Towhead.

“Oh, my!” observed Mr. McLean, sadly; “what has our Jack been readin’?”

“He’s a cattle-man!” cried Billy. “I seen his heels.”

“That’s you!” said the discovered puncher, with approval. “You’ll do. But I bet you can’t tell me what we wearers of this badge have sworn to do this night.”

At this they craned their necks and glared at him.

“We—are—sworn (don’t yu’ jump, now, and give me away)—sworn—to—blow off three bootblacks to a dinner.”

“Ah, pshaw!” They backed away, bristling with distrust.

“That’s the oath, fellows. Yu’ may as well make your minds up—for I have it to do!”

“Dare you to! Ah!”

“And after dinner it’s the Opera-house, to see ‘The Children of Captain Grant’!”

They screamed shrilly at him, keeping off beyond the curb.

“I can’t waste my time on such, smart boys,” said Mr. McLean, rising to his full height from the window-sill. “I am going somewhere to find boys that ain’t so turruble quick stampeded by a roast turkey.”

He began to lounge slowly away, serious as he had been throughout, and they, stopping their noise short, swiftly picked up their boxes and followed him. Some change in the current of electricity that fed the window disturbed its sparkling light, so that Santa Claus, with his arms stretched out behind the departing cow-puncher, seemed to be smiling more broadly from the midst of his flickering brilliance.

On their way to turkey, the host and his guests exchanged but few remarks. He was full of good-will, and threw off a comment or two that would have led to conversation under almost any circumstances save these; but the minds of the guests were too distracted by this whole state of things for them to be capable of more than keeping after Mr. McLean in silence, at a wary interval, and with their mouths, during most of the journey, open. The badge, the pistol, their patron’s talk, and the unusual dollars wakened wide their bent for the unexpected, their street affinity for the spur of the moment; they believed slimly in the turkey part of it, but what this man might do next, to be there when he did it, and not to be trapped, kept their wits jumping deliciously; so when they saw him stop they stopped instantly, too, ten feet out of reach. This was Denver’s most civilized restaurant—that one which Mr. McLean had remembered, with foreign dishes and private rooms, where he had promised himself, among other things, champagne. Mr. McLean had never been inside it, but heard a tale from a friend; and now he caught a sudden sight of people among geraniums, with plumes and white shirtfronts, very elegant. It must have been several minutes that he stood contemplating the entrance and the luxurious couples who went in.

“Plumb French!” he observed, at length; and then, “Shucks!” in a key less confident, while his guests ten feet away watched him narrowly. “They’re eatin’ patty de parley-voo in there,” he muttered, and the three bootblacks came beside him. “Say, fellows,” said Lin, confidingly, “I wasn’t raised good enough for them dude dishes. What do yu’ say! I’m after a place where yu’ can mention oyster stoo without givin’ anybody a fit. What do yu’ say, boys?”

That lighted the divine spark of brotherhood!

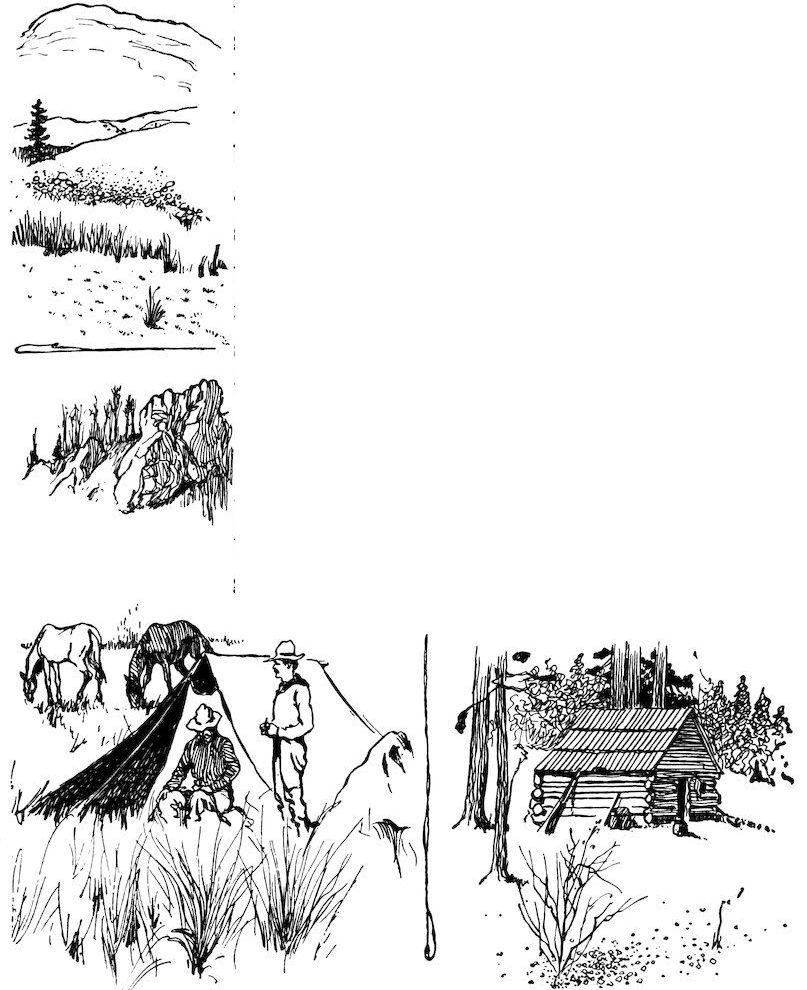

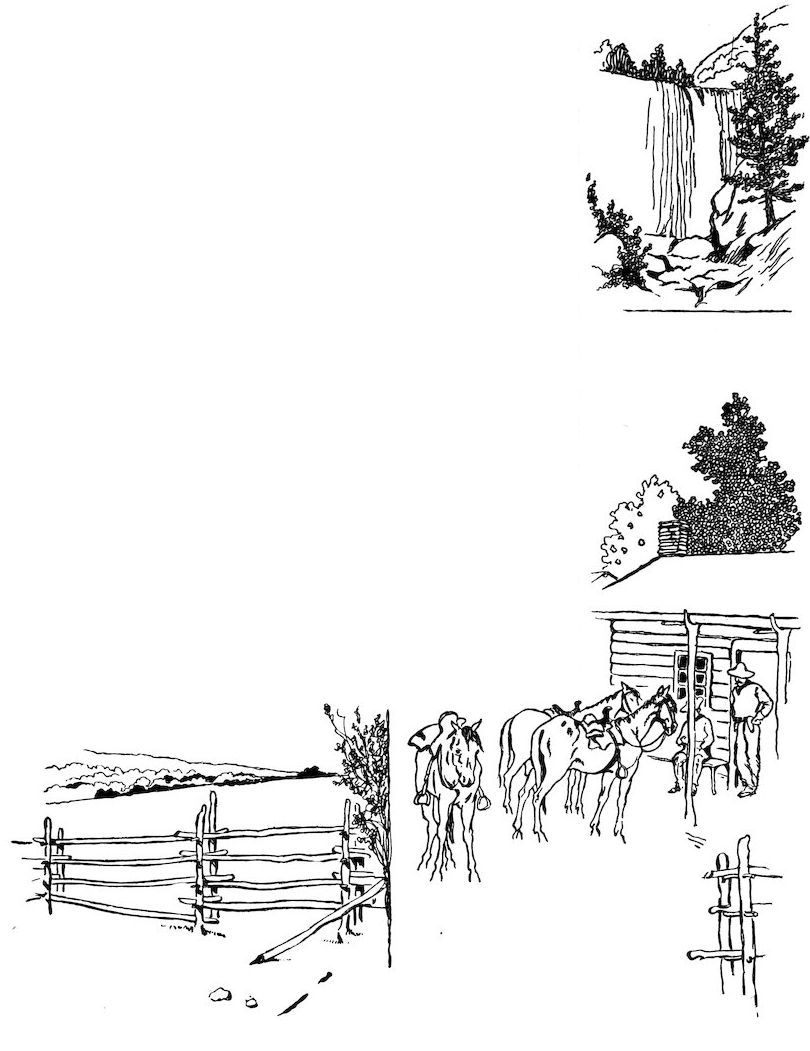

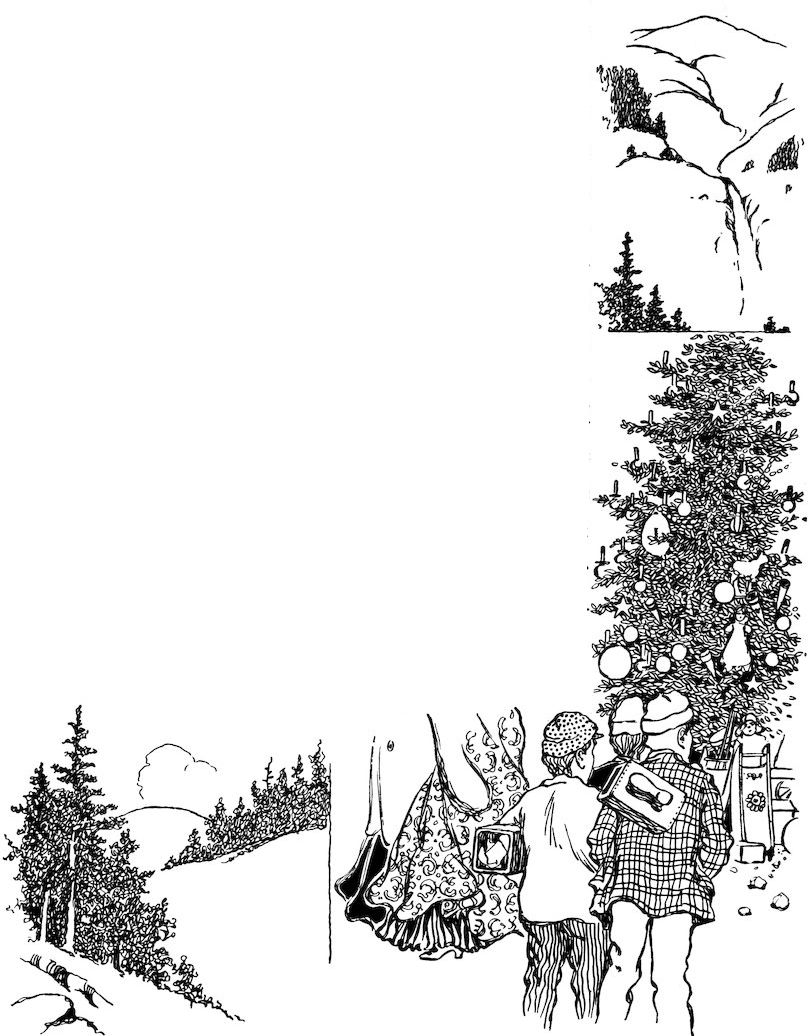

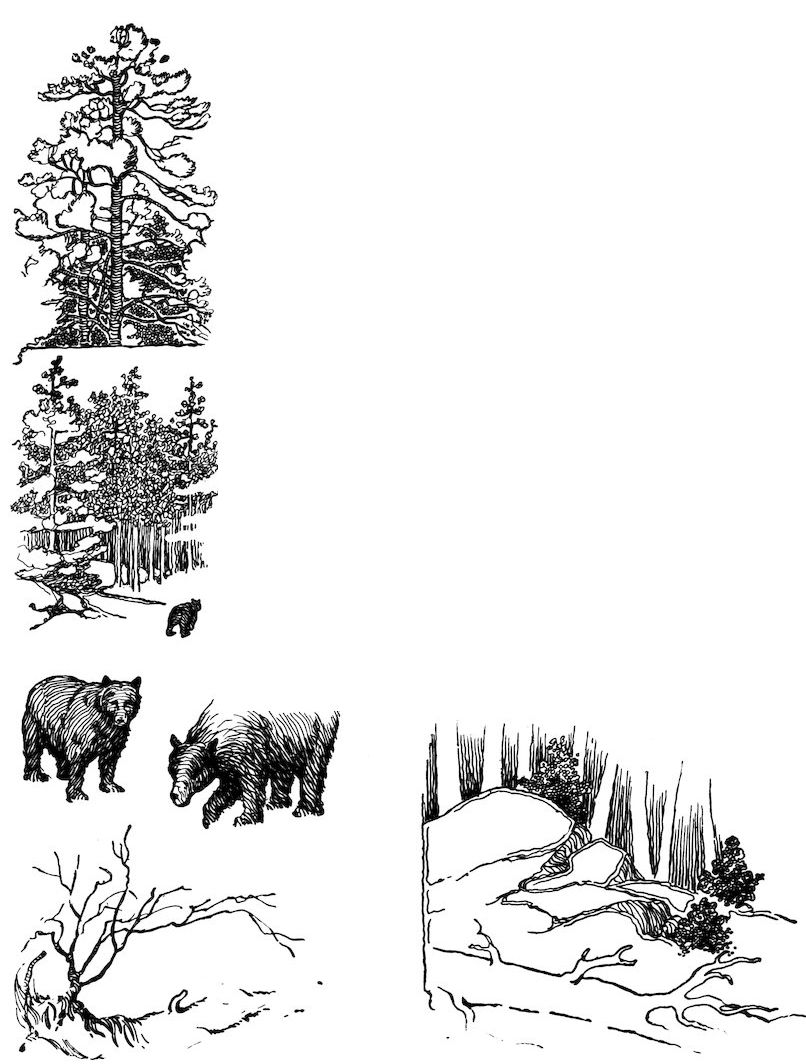

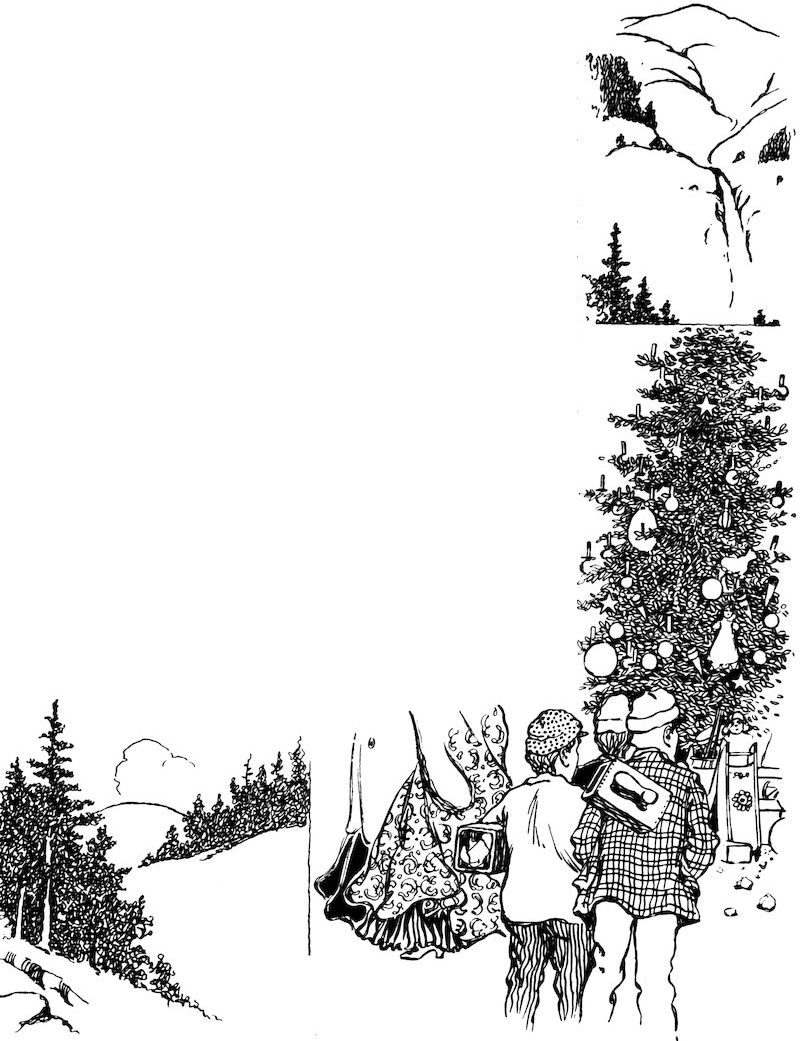

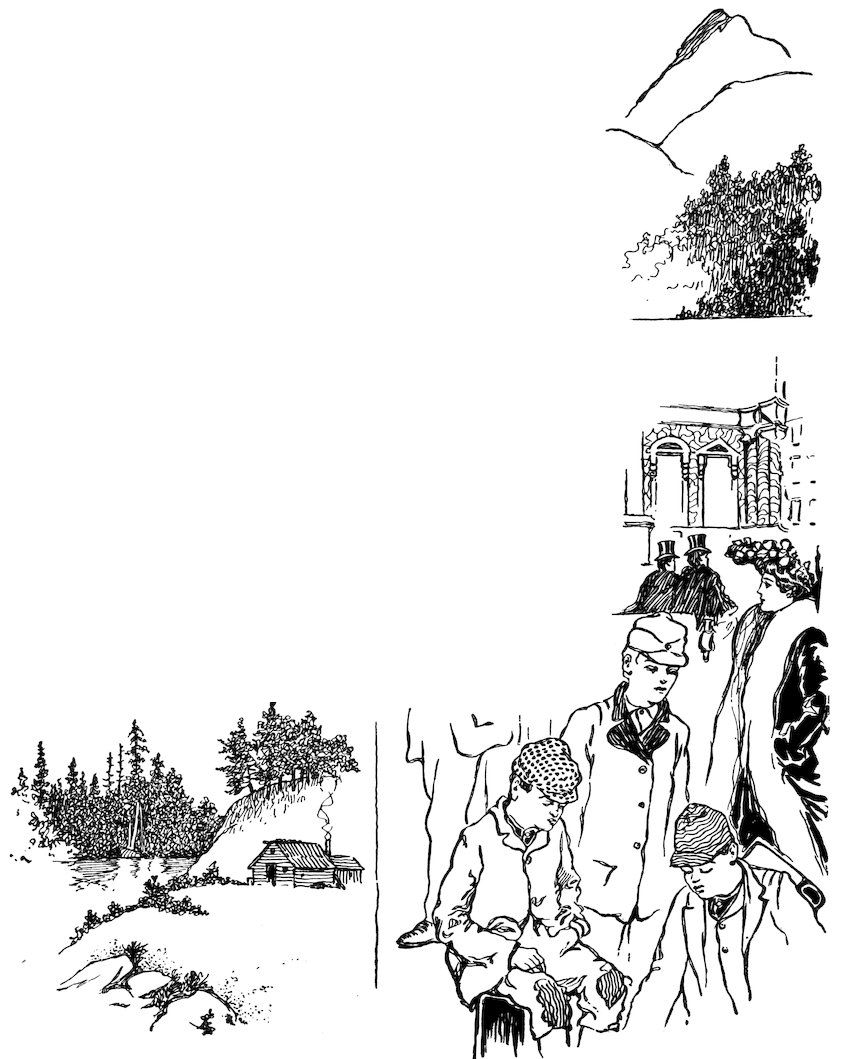

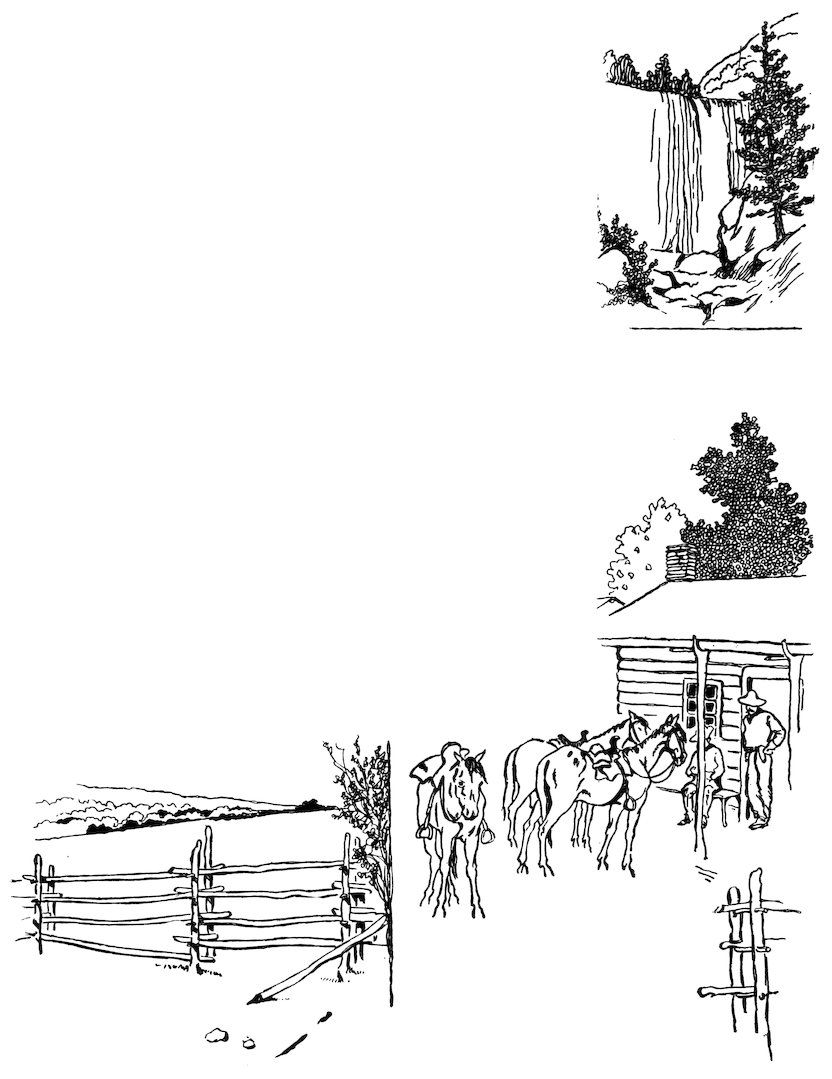

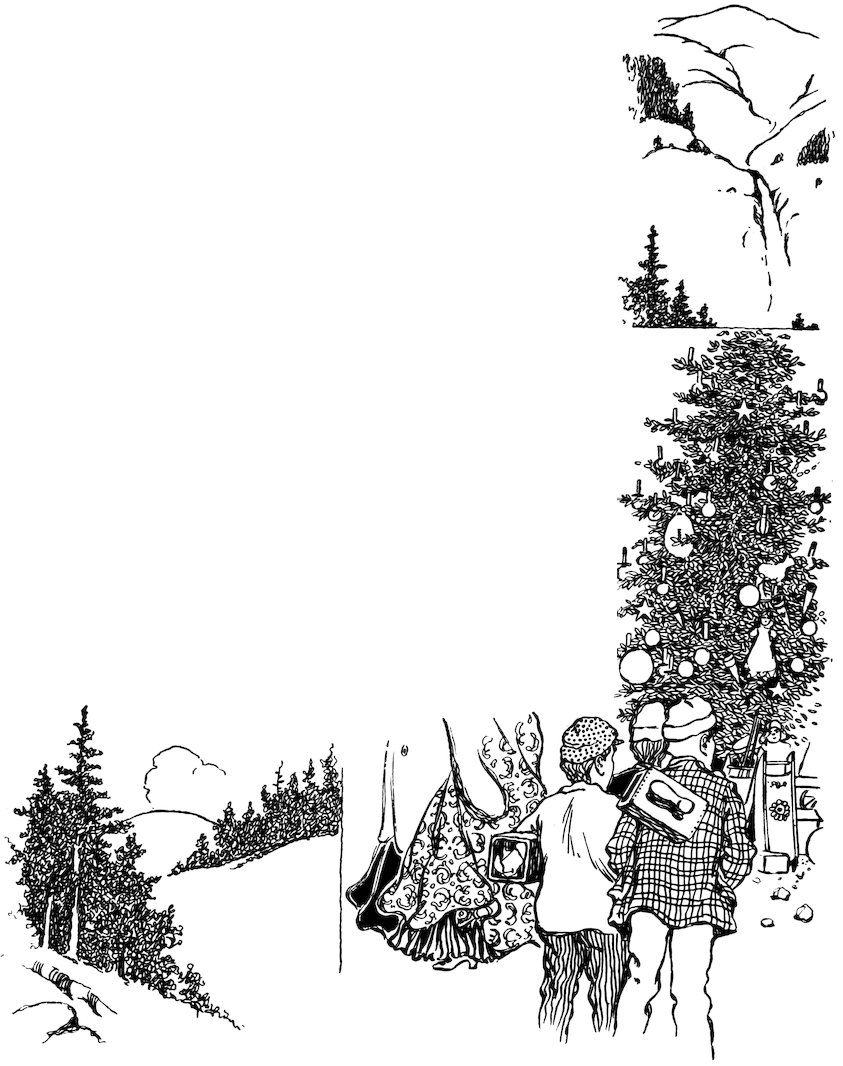

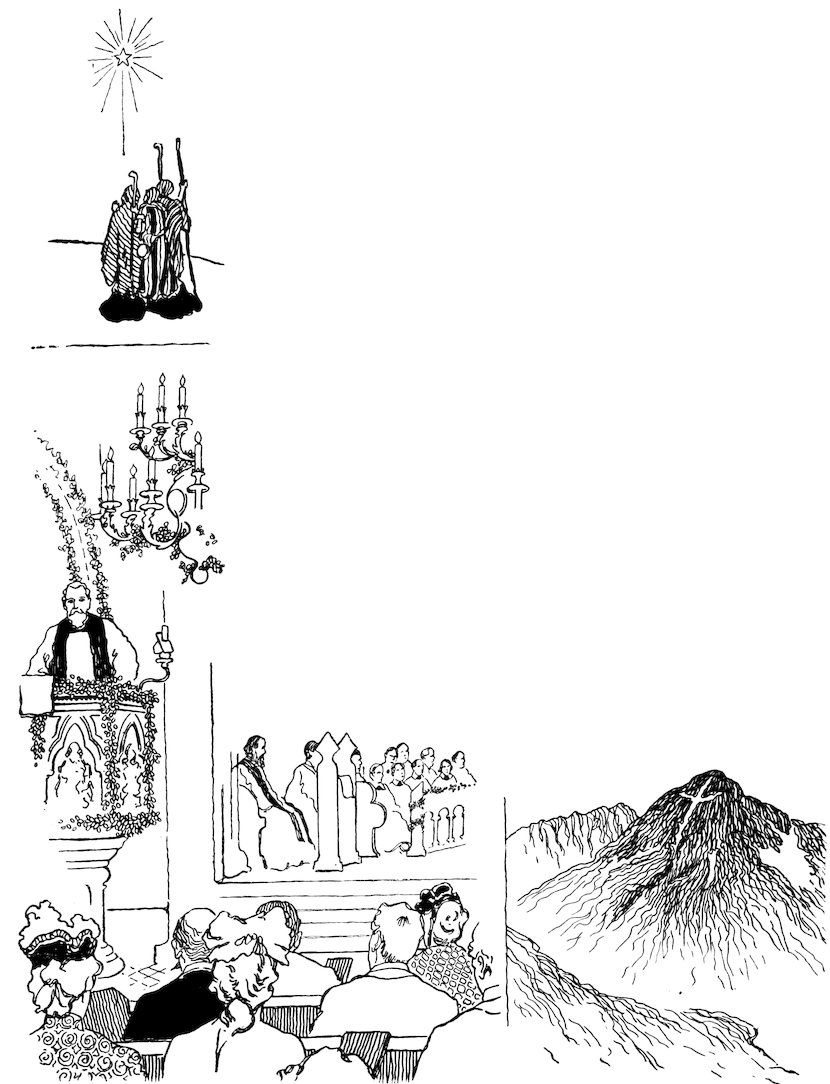

“Lin walked in their charge, they leading the way”

“Ah, you come along with us—we’ll take yer! You don’t want to go in there. We’ll show yer the boss place in Market Street. We won’t lose yer.” So, shouting together in their shrill little city trebles, they clustered about him, and one pulled at his coat to start him. He started obediently, and walked in their charge, they leading the way.

“Christmas is comin’ now, sure,” said Lin, grinning to himself. “It ain’t exactly what I figured on.” It was the first time he had laughed since Cheyenne, and he brushed a hand over his eyes, that were dim with the new warmth in his heart.

Believing at length in him and his turkey, the alert street faces, so suspicious of the unknown, looked at him with ready intimacy as they went along; and soon, in the friendly desire to make him acquainted with Denver, the three were patronizing him. Only Billy, perhaps, now and then stole at him a doubtful look.

The large Country Mouse listened solemnly to his three Town Mice, who presently introduced him to the place in Market Street. It was not boss, precisely, and Denver knows better neighborhoods; but the turkey and the oyster-stew were there, with catsup and vegetables in season, and several choices of pie. Here the Country Mouse became again efficient; and to witness his liberal mastery of ordering and imagine his pocket and its wealth, which they had heard and partly seen, renewed in the guests a transient awe. As they dined, however, and found the host as frankly ravenous as themselves, this reticence evaporated, and they all grew fluent with oaths and opinions. At one or two words, indeed, Mr. McLean stared and had a slight sense of blushing.

“Have a cigarette?” said the leader, over his pie.

“Thank yu’,” said Lin. “I won’t smoke, if you’ll excuse me.” He had devised a wholesome meal with water to drink.

“Chewin’s no good at meals,” continued the boy. “Don’t you use tobacker?”

“Onced in a while.”

The leader spat brightly. “He ’ain’t learned yet,” said he, slanting his elbows at Billy and sliding a match over his rump. “But beer, now—I never seen anything in it.” He and Towhead soon left Billy and his callow profanities behind, and engaged in a town conversation that silenced him, and set him listening with all his admiring young might. Nor did Mr. McLean join in the talk, but sat embarrassed by this knowledge, which seemed about as much as he knew himself.

“I’ll be goshed,” he thought, “if I’d caught on to half that when I was streakin’ around in short pants! Maybe they grow up quicker now.” But now the Country Mouse perceived Billy’s eager and attentive apprenticeship. “Hello, boys!” he said, “that theatre’s got a big start on us.”

They had all forgotten he had said anything about theatre; and other topics left their impatient minds while the Country Mouse paid the bill and asked to be guided to the Opera-house. “This man here will look out for your blackin’ and truck, and let yu’ have it in the morning.”

They were very late. The spectacle had advanced far into passages of the highest thrill, and Denver’s eyes were riveted upon a ship and some icebergs. The party found its seats during several beautiful lime-light effects, and that remarkable fly-buzzing of violins which is pronounced so helpful in times of peril and sentiment. The children of Captain Grant had been tracking their father all over the equator and other scenic spots, and now the north pole was about to impale them. The Captain’s youngest child, perceiving a hummock rushing at them with a sudden motion, loudly shouted, “Sister, the ice is closing in!” and Sister replied, chastely, “Then let us pray.” It was a superb tableau: the ice split, and the sun rose and joggled at once to the zenith. The act-drop fell, and male Denver, wrung to its religious deeps, went out to the rum-shop.

Of course Mr. McLean and his party did not do this. The party had applauded exceedingly the defeat of the elements, and the leader, with Towhead, discussed the probable chances of the ship’s getting farther south in the next act. Until lately Billy’s doubt of the cow-puncher had lingered; but during this intermission whatever had been holding out in him seemed won, and in his eyes, that he turned stealthily upon his unconscious, quiet neighbor, shone the beginnings of hero-worship.

“Don’t you think this is splendid?” said he.

“Splendid,” Lin replied, a trifle remotely.

“Don’t you like it when they all get balled up and get out that way?”

“Humming,” said Lin.

“Don’t you guess it’s just girls, though, that do that?”

“What, young fellow?”

“Why, all that prayer-saying an’ stuff.”

“I guess it must be.”

“She said to do it when the ice scared her, an’ of course a man had to do what she wanted him.”

“Sure.”

“Well, do you believe they’d ’a’ done it if she hadn’t been on that boat, an’ clung around an’ cried an’ everything, an’ made her friends feel bad?”

“I hardly expect they would,” replied the honest Lin, and then, suddenly mindful of Billy, “except there wasn’t nothin’ else they could think of,” he added, wishing to speak favorably of the custom.

“Why, that chunk of ice weren’t so awful big, anyhow. I’d ’a’ shoved her off with a pole. Wouldn’t you?”

“Butted her like a ram,” exclaimed Mr. McLean.

“Well, I don’t say my prayers any more. I told Mr. Perkins I wasn’t a-going to, an’ he—I think he’s a flubdub, anyway.”

“I’ll bet he is!” said Lin, sympathetically. He was scarcely a prudent guardian.

“I told him straight, an’ he looked at me, an’ down he flops on his knees. An’ he made ’em all flop, but I told him I didn’t care for them putting up any camp-meeting over me; an’ he says, ‘I’ll lick you,’ an’ I says, ‘Dare you to!’ I told him mother kep’ a-licking me for nothing, an’ I’d not pray for her, not in Sunday-school or anywheres else. Do you pray much?”

“No,” replied Lin, uneasily.

“There! I told him a man didn’t, an’ he said then a man went to hell. ‘You lie; father ain’t going to hell,’ I says, and you’d ought to heard the first class laugh right out loud, girls an’ boys. An’ he was that mad! But I didn’t care. I came here with fifty cents.”

“Yu’ must have felt like a millionaire.”

“Ah, I felt all right! I bought papers an’ sold ’em, an’ got more an’ saved, an’ got my box an’ blacking outfit. I weren’t going to be licked by her just because she felt like it, an’ she feeling like it most any time. Lemme see your pistol.”

“You wait,” said Lin. “After this show is through I’ll put it on you.”

“Will you, honest? Belt an’ everything? Did you ever shoot a bear?”

“Lord! lots.”

“Honest? Silver-tips?”

“Silver-tips, cinnamon, black; and I roped a cab onced.”

“O-h! I never shot a bear.”

“You’d ought to try it.”

“I’m a-going to. I’m a-going to camp out in the mountains. I’d like to see you when you camp. I’d like to camp with you. Mightn’t I some time?” Billy had drawn nearer to Lin, and was looking up at him adoringly.

“You bet!” said Lin; and though he did not, perhaps, entirely mean this, it was with a curiously softened face that he began to look at Billy. As with dogs and his horse, so always he played with what children he met—the few in his sage-brush world; but this was ceasing to be quite play for him, and his hand went to the boy’s shoulder.

“Father took me camping with him once, the time mother was off. Father gets awful drunk, too. I’ve quit Laramie for good.”

Lin sat up, and his hand gripped the boy. “Laramie!” said he, almost shouting it. “Yu’—yu’—is your name Lusk?”

But the boy had shrunk from him instantly. “You’re not going to take me home?” he piteously wailed.

“Heavens and heavens!” murmured Lin McLean. “So yu’re her kid!”

He relaxed again, down in his chair, his legs stretched their straight length below the chair in front. He was waked from his bewilderment by a brushing under him, and there was young Billy diving for escape to the aisle, like the cornered City Mouse that he was. Lin nipped that poor little attempt and had the limp Billy seated inside again before the two in discussion beyond had seen anything. He had said not a word to the boy, and now watched his unhappy eyes seizing upon the various exits and dispositions of the theatre; nor could he imagine anything to tell him that should restore the perished confidence. “Why did yu’ head him off?” he asked himself, unexpectedly, and found that he did not seem to know; but as he watched the restless and estranged runaway he grew more and more sorrowful. “I just hate him to think that of me,” he reflected. The curtain rose, and he saw Billy make up his mind to wait until they should all be going out in the crowd. While the children of Captain Grant grew hotter and hotter upon their father’s geographic trail, Lin sat saying to himself a number of contradictions. “He’s nothin’ to me. What’s any of them to me?” Driven to bay by his bewilderment, he restated the facts of the past. “Why, she’d deserted him and Lusk before she’d ever laid eyes on me. I needn’t to bother myself. He wasn’t never even my step-kid.” The past, however, brought no guidance. “Lord, what’s the thing to do about this? If I had any home— This is a stinkin’ world in some respects,” said Mr. McLean, aloud, unknowingly. The lady in the chair beneath which the cow-puncher had his legs nudged her husband. They took it for emotion over the sad fortunes of Captain Grant, and their backs shook. Presently each turned, and saw the singular man with untamed, wide-open eyes glowing at the stage, and both backs shook again.

Once more his hand was laid on Billy. “Say!”

The boy glanced at him, and quickly away.

“Look at me, and listen.”

Billy swervingly obeyed.

“I ain’t after yu’, and never was. This here’s your business, not mine. Are yu’ listenin’ good?”

The boy made a nod, and Lin proceeded, whispering: “You’ve got no call to believe what I say to yu’—yu’ve been lied to, I guess, pretty often. So I’ll not stop yu’ runnin’ and hidin’, and I’ll never give it away I saw yu’, but yu’ keep doin’ what yu’ please. I’ll just go now. I’ve saw all I want, but you and your friends stay with it till it quits. If yu’ happen to wish to speak to me about that pistol or bears, yu’ come around to Smith’s Palace—that’s the boss hotel here, ain’t it?—and if yu’ don’t come too late I’ll not be gone to bed. By this time of night I’m liable to get sleepy. Tell your friends good-bye for me, and be good to yourself. I’ve appreciated your company.”

Mr. McLean entered Smith’s Palace, and, engaging a room with two beds in it, did a little delicate lying by means of the truth. “It’s a lost boy—a runaway,” he told the clerk. “He’ll not be extra clean, I expect, if he does come. Maybe he’ll give me the slip, and I’ll have a job cut out to-morrow. I’ll thank yu’ to put my money in your safe.”

The clerk placed himself at the disposal of the secret service, and Lin walked up and down, looking at the railroad photographs for some ten minutes, when Master Billy peered in from the street.

“Hello!” said Mr. McLean, casually, and returned to a fine picture of Pike’s Peak.

Billy observed him for a space, and, receiving no further attention, came stepping along. “I’m not a-going back to Laramie,” he stated, warningly.

“I wouldn’t,” said Lin. “It ain’t half the town Denver is. Well, good-night. Sorry yu’ couldn’t call sooner—I’m dead sleepy.”

“O-h!” Billy stood blank. “I wish I’d shook the darned old show. Say, lemme black your boots in the morning?”

“Not sure my train don’t go too early.”

“I’m up! I’m up! I get around to all of ’em.”

“Where do yu’ sleep?”

“Sleeping with the engine-man now. Why can’t you put that on me to-night?”

“Goin’ up-stairs. This gentleman wouldn’t let yu’ go up-stairs.”

But the earnestly petitioned clerk consented, and Billy was the first to hasten into the room. He stood rapturous while Lin buckled the belt round his scanty stomach, and ingeniously buttoned the suspenders outside the accoutrement to retard its immediate descent to earth.

“Did it ever kill a man?” asked Billy, touching the six-shooter.

“No. It ’ain’t never had to do that, but I expect maybe it’s stopped some killin’ me.”

“Oh, leave me wear it just a minute! Do you collect arrow-heads? I think they’re bully. There’s the finest one you ever seen.” He brought out the relic, tightly wrapped in paper, several pieces. “I foun’ it myself, camping with father. It was sticking in a crack right on top of a rock, but nobody’d seen it till I came along. Ain’t it fine?”

Mr. McLean pronounced it a gem.

“Father an’ me found a lot, an’ they made mother mad lying around, an’ she throwed ’em out. She takes stuff from Kelley’s.”

“Who’s Kelley?”

“He keeps the drug-store at Laramie. Mother gets awful funny. That’s how she was when I came home. For I told Mr. Perkins he lied, an’ I ran then. An’ I knowed well enough she’d lick me when she got through her spell—an’ father can’t stop her, an’ I—ah, I was sick of it! She’s lamed me up twice beating me—an’ Perkins wanting me to say ‘God bless my mother!’ a-getting up and a-going to bed—he’s a flubdub! An’ so I cleared out. But I’d just as leaves said for God to bless father—an’ you. I’ll do it now if you say it’s any sense.”

Mr. McLean sat down in a chair. “Don’t yu’ do it now,” said he.

“You wouldn’t like mother,” Billy continued. “You can keep that.” He came to Lin and placed the arrow-head in his hands, standing beside him. “Do you like birds’ eggs? I collect them. I got twenty-five kinds—sage-hen, an’ blue grouse, an’ willow-grouse, an’ lots more kinds harder—but I couldn’t bring all them from Laramie. I brought the magpie’s, though. D’you care to see a magpie egg? Well, you stay to-morrow an’ I’ll show you that an’ some other things I got the engine-man lets me keep there, for there’s boys that would steal an egg. An’ I could take you where we could fire that pistol. Bet you don’t know what that is!”

He brought out a small tin box shaped like a thimble, in which were things that rattled.

Mr. McLean gave it up.

“That’s kinni-kinnic seed. You can have that, for I got some more with the engine-man.”

Lin received this second token also, and thanked the giver for it. His first feeling had been to prevent the boy’s parting with his treasures, but something that came not from the polish of manners and experience made him know that he should take them. Billy talked away, laying bare his little soul; the street boy that was not quite come made place for the child that was not quite gone, and unimportant words and confidences dropped from him disjointed as he climbed to the knee of Mr. McLean, and inadvertently took that cow-puncher for some sort of parent he had not hitherto met. It lasted but a short while, however, for he went to sleep in the middle of a sentence, with his head upon Lin’s breast. The man held him perfectly still, because he had not the faintest notion that Billy would be impossible to disturb. At length he spoke to him, suggesting that bed might prove more comfortable; and, finding how it was, rose and undressed the boy and laid him between the sheets. The arms and legs seemed aware of the moves required of them, and stirred conveniently; and directly the head was upon the pillow the whole small frame burrowed down, without the opening of an eye or a change in the breathing. Lin stood some time by the bedside, with his eyes on the long, curling lashes and the curly hair. Then he glanced craftily at the door of the room, and at himself in the looking-glass. He stooped and kissed Billy on the forehead, and, rising from that, gave himself a hangdog stare in the mirror, and soon in his own bed was sleeping the sound sleep of health.

He was faintly roused by the churchbells, and lay still, lingering with his sleep, his eyes closed and his thoughts unshaped. As he became slowly aware of the morning, the ringing and the light reached him, and he waked wholly, and, still lying quiet, considered the strange room filled with the bells and the sun of the winter’s day. “Where have I struck now?” he inquired; and as last night returned abruptly upon his mind, he raised himself on his arm.

There sat Responsibility in a chair, washed clean and dressed, watching him.

“You’re awful late,” said Responsibility. “But I weren’t a-going without telling you good-bye.”

“Go?” exclaimed Lin. “Go where? Yu’ surely ain’t leavin’ me to eat breakfast alone?” The cow-puncher made his voice very plaintive. Set Responsibility free after all his trouble to catch him? This was more than he could do!

“I’ve got to go. If I’d thought you’d want for me to stay—why, you said you was a-going by the early train.”

“But the durned thing’s got away on me,” said Lin, smiling sweetly from the bed.

“If I hadn’t a-promised them—”

“Who?”

“Sidney Ellis and Pete Goode. Why, you know them; you grubbed with them.”

“Shucks!”

“We’re a-going to have fun to-day.”

“Oh!”

“For it’s Christmas, an’ we’ve bought some good cigars, an’ Pete says he’ll learn me sure. O’ course I’ve smoked some, you know. But I’d just as leaves stayed with you if I’d only knowed sooner. I wish you lived here. Did you smoke whole big cigars when you was beginning?”

“Do yu’ like flapjacks and maple syrup?” inquired the artful McLean. “That’s what I’m figuring on inside twenty minutes.”

“Twenty minutes! If they’d wait—”

“See here, Bill. They’ve quit expectin’ yu’, don’t yu’ think? I’d ought to waked, yu’ see, but I slep’ and slep’, and kep’ yu’ from meetin’ your engagements, yu’ see—for you couldn’t go, of course. A man couldn’t treat a man that way now, could he?”

“Course he couldn’t,” said Billy, brightening.

“And they wouldn’t wait, yu’ see. They wouldn’t fool away Christmas, that only comes onced a year, kickin’ their heels, and sayin’ ‘Where’s Billy?’ They’d say, ‘Bill has sure made other arrangements, which he’ll explain to us at his leesyure.’ And they’d skip with the cigars.”

The advocate paused, effectively, and from his bolster regarded Billy with a convincing eye.

“That’s so,” said Billy.

“And where would yu’ be then, Bill? In the street, out of friends, out of Christmas, and left both ways, no tobacker and no flapjacks. Now, Bill, what do yu’ say to us puttin’ up a Christmas deal together? Just you and me?”

“I’d like that,” said Billy. “Is it all day?”

“I was thinkin’ of all day,’ said Lin. “I’ll not make yu’ do anything yu’d rather not.”

“Ah, they can smoke without me,” said Billy, with sudden acrimony. “I’ll see ’em to-morro’.”

“That’s yu’!” cried Mr. McLean. “Now, Bill, you hustle down and tell them to keep a table for us. I’ll get my clothes on and follow yu’.”

The boy went, and Mr. McLean procured hot water and dressed himself, tying his scarf with great care. “Wished I’d a clean shirt,” said he. “But I don’t look very bad. Shavin’ yesterday afternoon was a good move.” He picked up the arrow-head and the kinni-kinnic, and was particular to store them in his safest pocket. “I ain’t sure whether you’re crazy or not,” said he to the man in the looking-glass. “I ’ain’t never been sure.” And he slammed the door and went down-stairs.

He found young Bill on guard over a table for four, with all the chairs tilted against it as a warning to strangers. No one sat at any other table or came into the room, for it was late, and the place quite emptied of breakfasters, and the several entertained waiters had gathered behind Billy’s important-looking back. Lin provided a thorough meal, and Billy pronounced the flannel cakes superior to flapjacks, which were not upon the bill of fare.

“I’d like to see you often,” said he. “I’ll come and see you if you don’t live too far.”

“That’s the trouble,” said the cow-puncher. “I do. Awful far.” He stared out of the window.

“Well, I might come some time. I wish you’d write me a letter. Can you write?”

“What’s that? Can I write? Oh yes.”

“I can write, an’ I can read, too. I’ve been to school in Sidney, Nebraska, an’ Magaw, Kansas, an’ Salt Lake—that’s the finest town except Denver.”

Billy fell into that cheerful strain of comment which, unreplied to, yet goes on content and self-sustaining, while Mr. McLean gave amiable signs of assent, but chiefly looked out of the window; and when the now interested waiter said, respectfully, that he desired to close the room, they went out to the office, where the money was got out of the safe and the bill paid.

The streets were full of the bright sun, and seemingly at Denver’s gates stood the mountains; an air crisp and pleasant wafted from their peaks; no smoke hung among the roofs, and the sky spread wide over the city without a stain; it was holiday up among the chimneys and tall buildings, and down among the quiet ground-stories below as well; and presently from their scattered pinnacles through the town the bells broke out against the jocund silence of the morning.

“Don’t you like music?” inquired Billy.

“Yes,” said Lin.

Ladies with their husbands and children were passing and meeting, orderly yet gayer than if it were only Sunday, and the salutations of Christmas came now and again to the cow-puncher’s ears; but to-day, possessor of his own share in this, Lin looked at every one with a sort of friendly challenge, and young Billy talked along beside him.

“Don’t you think we could go in here?” Billy asked. A church door was open, and the rich organ sounded through to the pavement. “They’ve good music here, an’ they keep it up without much talking between. I’ve been in lots of times.”

They went in and sat to hear the music. Better than the organ, it seemed to them, were the harmonious voices raised from somewhere outside, like unexpected visitants; and the pair sat in their back seat, too deep in listening to the processional hymn to think of rising in decent imitation of those around them. The crystal melody of the refrain especially reached their understandings, and when for the fourth time “Shout the glad tidings, exultingly sing,” pealed forth and ceased, both the delighted faces fell.

“Don’t you wish there was more?” Billy whispered.

“Wish there was a hundred verses,” answered Lin.

But canticles and responses followed, with so little talking between them they were held spellbound, seldom thinking to rise or kneel. Lin’s eyes roved over the church, dwelling upon the pillars in their evergreen, the flowers and leafy wreaths, the texts of white and gold. “‘Peace, good-will towards men,’” he read. “That’s so. Peace and good-will. Yes, that’s so. I expect they got that somewheres in the Bible. It’s awful good, and you’d never think of it yourself.”

There was a touch on his arm, and a woman handed a book to him. “This is the hymn we have now,” she whispered, gently; and Lin, blushing scarlet, took it passively without a word. He and Billy stood up and held the book together, dutifully reading the words:

This tune was more beautiful than all, and Lin lost himself in it, until he found Billy recalling him with a finger upon the words, the concluding ones:

The music rose and descended to its lovely and simple end; and, for a second time in Denver, Lin brushed a hand across his eyes. He turned his face from his neighbor, frowning crossly; and since the heart has reasons which Reason does not know, he seemed to himself a fool; but when the service was over and he came out, he repeated again, “‘Peace and good-will.’ When I run on to the Bishop of Wyoming I’ll tell him if he’ll preach on them words I’ll be there.”

“Couldn’t we shoot your pistol now?” asked Billy.

“Sure, boy. Ain’t yu’ hungry, though?”

“No. I wish we were away off up there. Don’t you?”

“The mountains? They look pretty—so white! A heap better ’n houses. Why, we’ll go there! There’s trains to Golden. We’ll shoot around among the foot-hills.”

To Golden they immediately went, and, after a meal there, wandered in the open country until the cartridges were gone, the sun was low, and Billy was walked off his young heels—a truth he learned complete in one horrid moment and battled to conceal.

“Lame!” he echoed, angrily. “I ain’t.”

“Shucks!” said Lin, after the next ten steps. “You are, and both feet.”

“Tell you, there’s stones here, an’ I’m just a-skipping them.”

Lin, briefly, took the boy in his arms and carried him to Golden. “I’m played out myself,” he said, sitting in the hotel and looking lugubriously at Billy on a bed. “And I ain’t fit to have charge of a hog.” He came and put his hand on the boy’s head.

“I’m not sick,” said the cripple. “I tell you I’m bully. You wait an’ see me eat dinner.”

But Lin had hot water and cold water and salt, and was an hour upon his knees bathing the hot feet. And then Billy could not eat dinner.

There was a doctor in Golden; but in spite of his light prescription and most reasonable observations, Mr. McLean passed a foolish night of vigil, while Billy slept, quite well at first, and, as the hours passed, better and better. In the morning he was entirely brisk, though stiff.

“I couldn’t work quick to-day,” he said. “But I guess one day won’t lose me my trade.”

“How d’ yu’ mean?” asked Lin.

“Why, I’ve got regulars, you know. Sidney Ellis an’ Pete Goode has theirs, an’ we don’t cut each other. I’ve got Mr. Daniels an’ Mr. Fisher an’ lots, an’ if you lived in Denver I’d shine your boots every day for nothing. I wished you lived in Denver.”

“Shine my boots? Yu’ll never! And yu’ don’t black Daniels or Fisher, or any of the outfit.”

“Why, I’m doing first-rate,” said Billy, surprised at the swearing into which Mr. McLean now burst. “An’ I ain’t big enough to get to make money at any other job.

“I want to see that engine-man,” muttered Lin. “I don’t like your smokin’ friend.”

“Pete Goode? Why, he’s awful smart. Don’t you think he’s smart?”

“Smart’s nothin’,” observed Mr. McLean.

“Pete has learned me and Sidney a lot,” pursued Billy, engagingly.

“I’ll bet he has!” growled the cow-puncher; and again Billy was taken aback at his language.

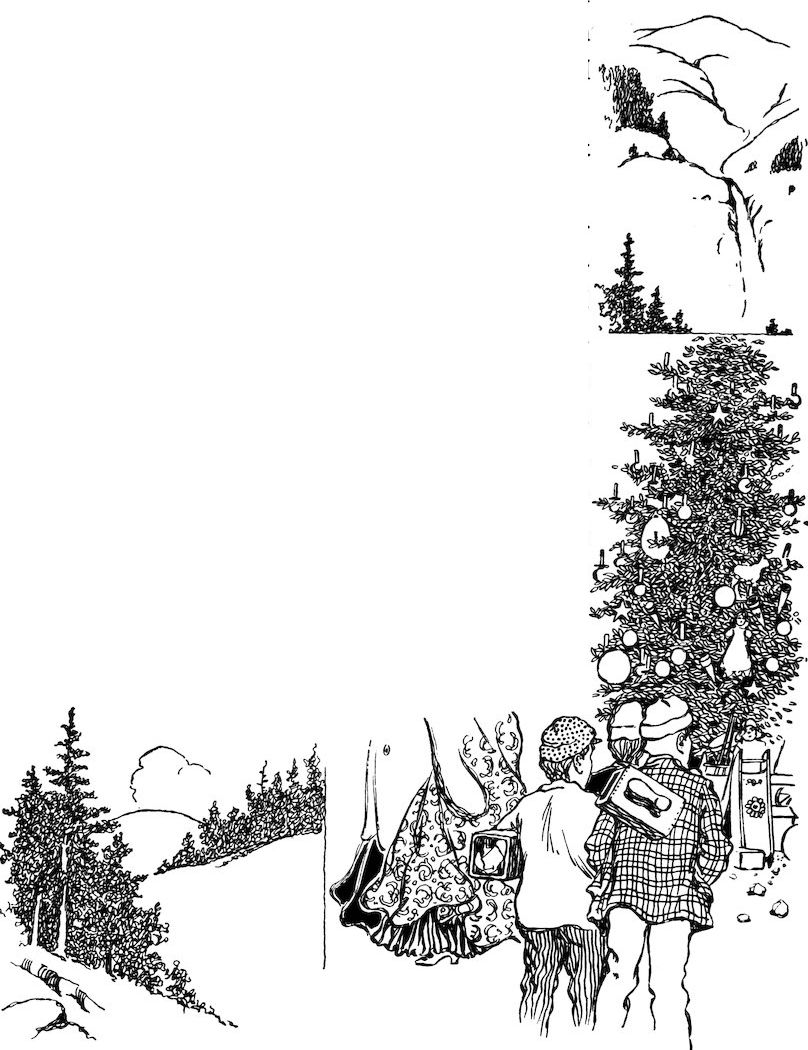

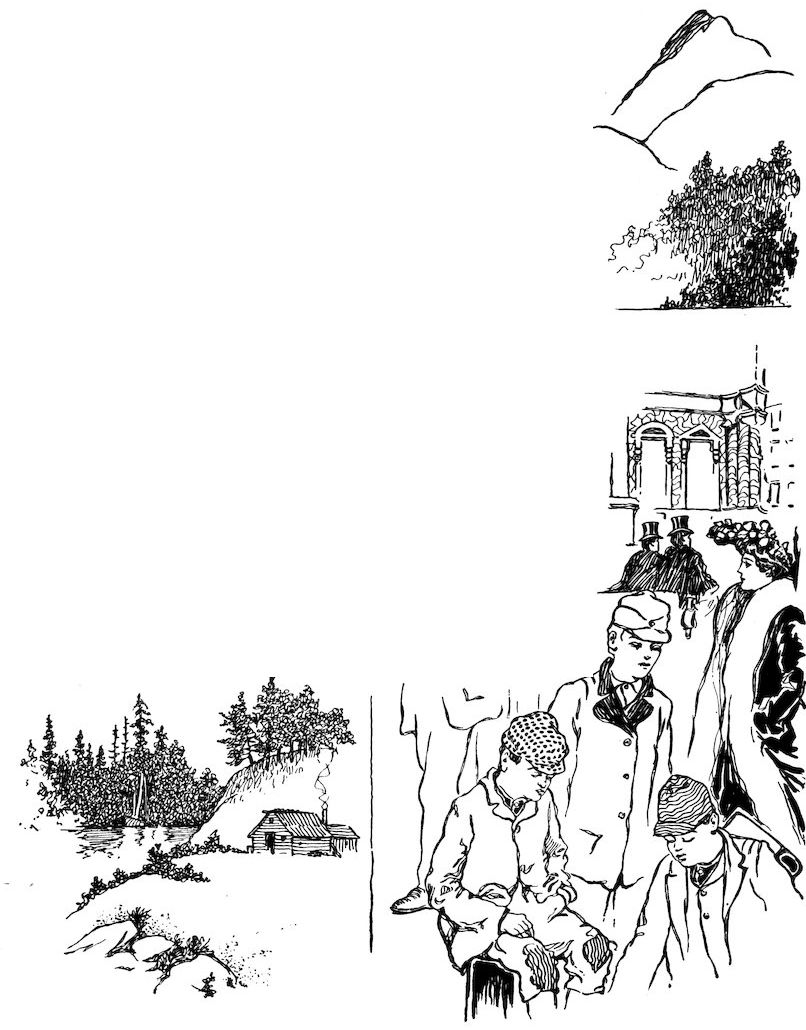

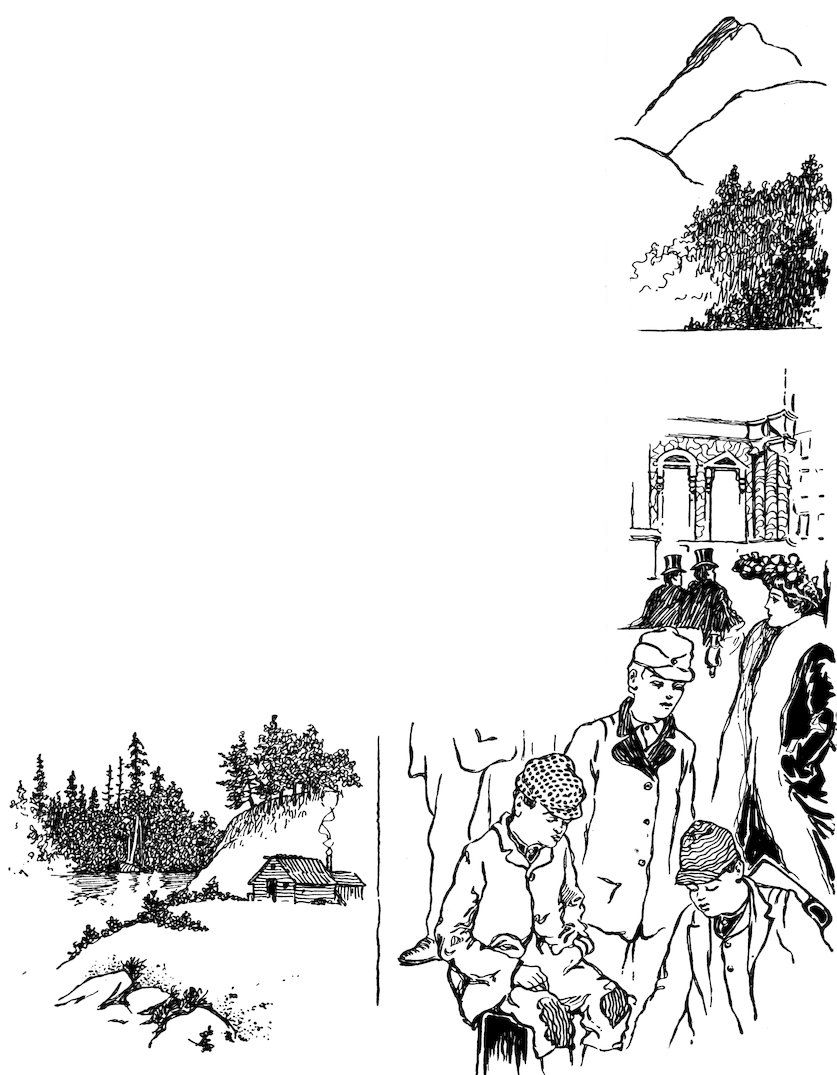

“‘This is Mister Billy Lusk’”

It was not so simple, this case. To the perturbed mind of Mr. McLean it grew less simple during that day at Golden, while Billy recovered, and talked, and ate his innocent meals. The cow-puncher was far too wise to think for a single moment of restoring the runaway to his debauched and shiftless parents. Possessed of some imagination, he went through a scene in which he appeared at the Lusk threshold with Billy and forgiveness, and intruded upon a conjugal assault and battery. “Shucks!” said he. “The kid would be off again inside a week. And I don’t want him there, anyway.”

Denver, upon the following day, saw the little bootblack again at his corner, with his trade not lost; but near him stood a tall, singular man, with hazel eyes and a sulky expression. And citizens during that week noticed, as a new sight in the streets, the tall man and the little boy walking together. Sometimes they would be in shops. The boy seemed as happy as possible, talking constantly, while the man seldom said a word, and his face was serious.

Upon New Year’s Eve Governor Barker was overtaken by Mr. McLean riding a horse up Hill Street, Cheyenne.

“Hello!” said Barker, staring humorously through his glasses. “Have a good drunk?”

“Changed my mind,” said Lin, grinning. “Proves I’ve got one. Struck Christmas all right, though.”

“Who’s your friend?” inquired his Excellency.

“This is Mister Billy Lusk. Him and me have agreed that towns ain’t nice to live in. If Judge Henry’s foreman and his wife won’t board him at Sunk Creek—why, I’ll fix it somehow.”

The cow-puncher and his Responsibility rode on together towards the open plain.

“Suffering Moses!” remarked his Excellency.