![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

![[Image unavailable.]](images/ill_017.jpg)

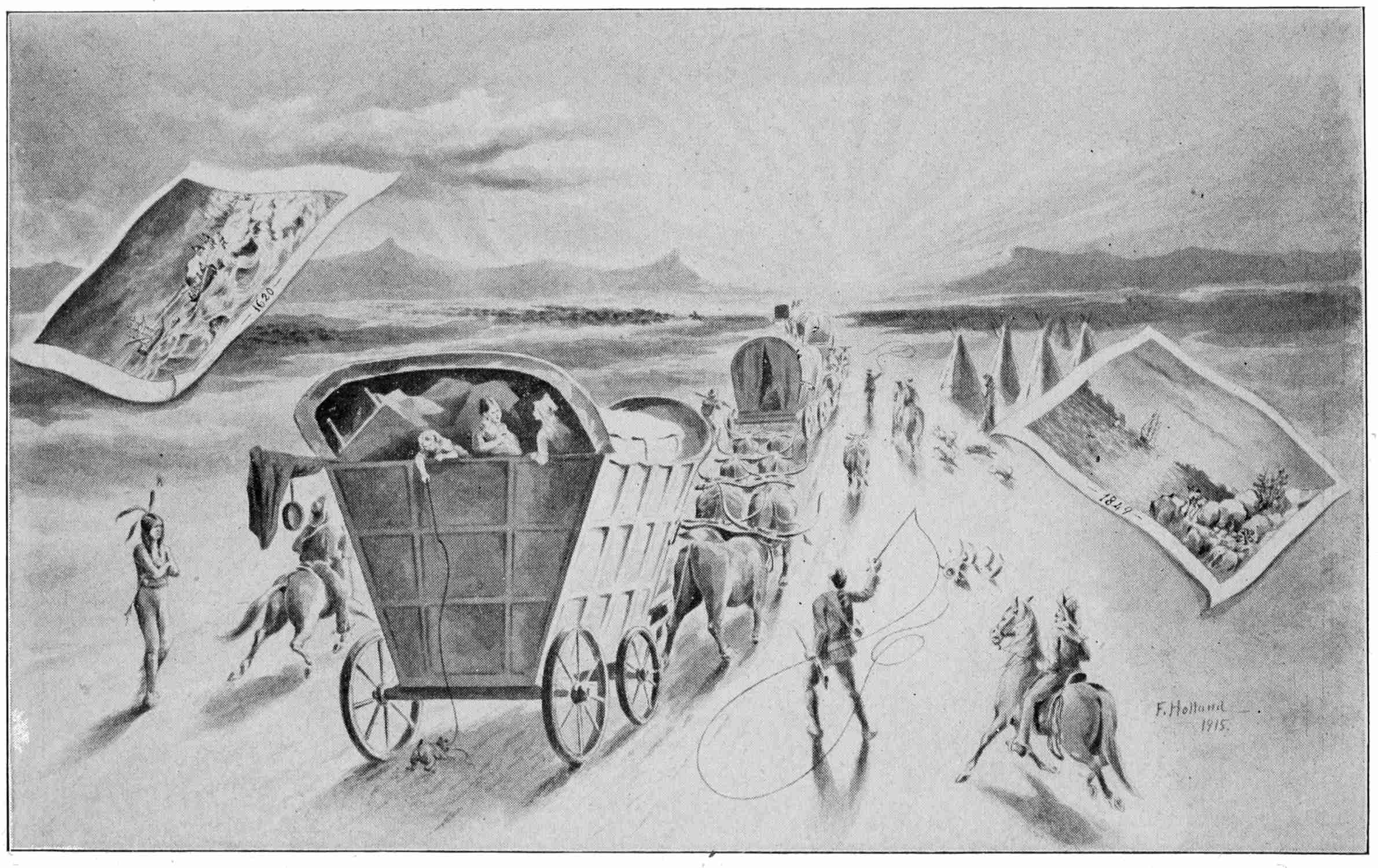

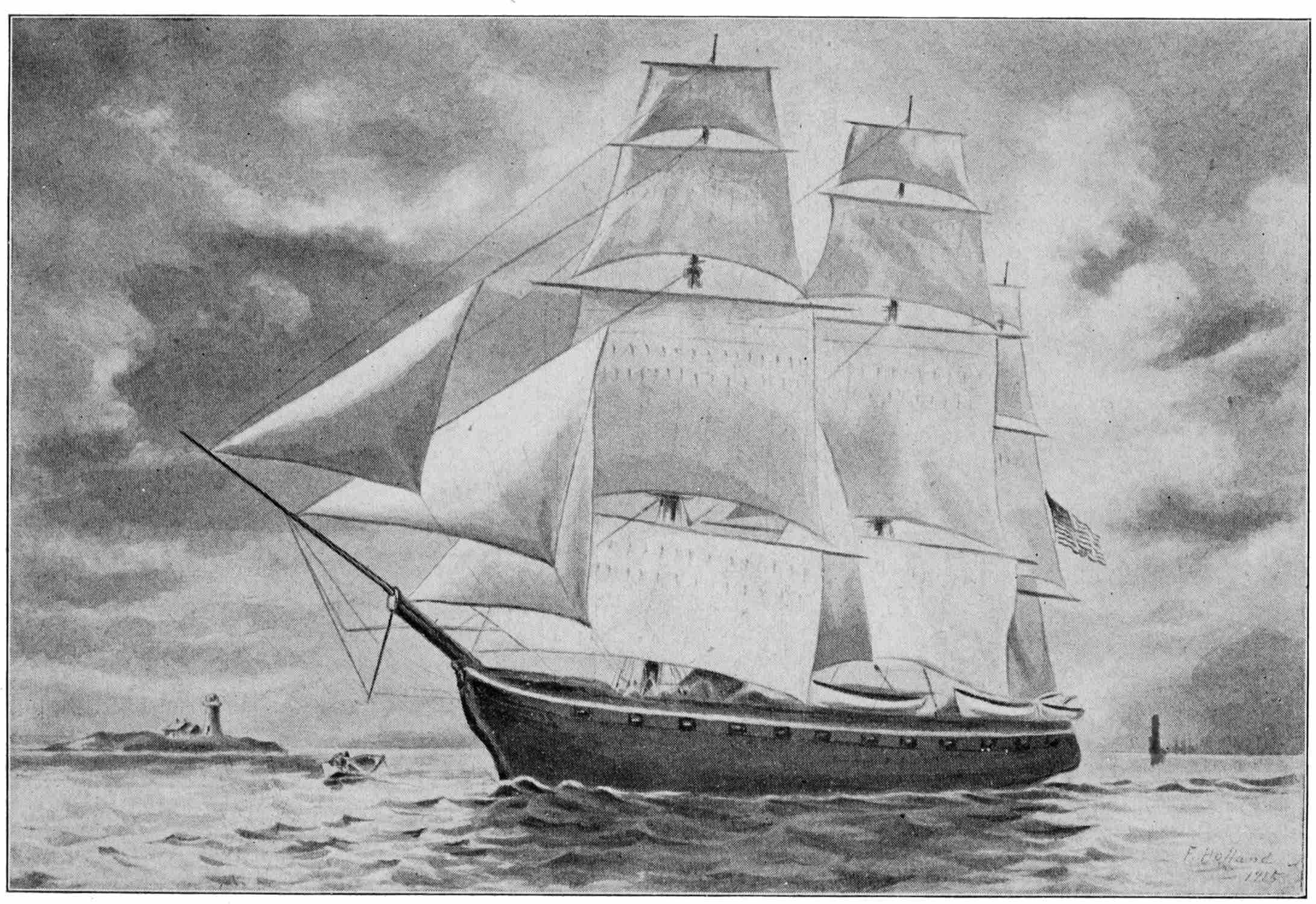

Title: The gold seekers of '49

a personal narrative of the overland trail and adventures in California and Oregon from 1849 to 1854

Author: Kimball Webster

Contributor: George Waldo Browne

Illustrator: Frank Holland

Release date: September 5, 2023 [eBook #71572]

Language: English

Original publication: Manchester: Standard Book Company

Credits: Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

CONTENTS

ERRATA

ILLUSTRATIONS

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

A Personal Narrative of the Overland Trail and Adventures in California and Oregon from 1849 to 1854.

BY KIMBALL WEBSTER A New England Forty-Niner

With an Introduction and Biographical Sketch

By George Waldo Browne

Illustrated By Frank Holland and Others

Manchester, N. H.

STANDARD BOOK COMPANY

1917

Copyrighted 1917

George W. Browne

To My Five Daughters, Mrs. Lizzie Jane Martin, Mrs. Eliza Ball Leslie, Mrs. Julia Anna Robinson, Mrs. Mary Newton Abbott, all of Hudson, N. H., and Mrs. Ella Frances Walch, of Nashua; and to the sweet memory of that loved Deceased Daughter, Latina Ray Webster, who quietly passed to the other side of the “Great Divide,” November 12, 1887, this narrative is most respectfully dedicated by the

Author

KIMBALL WEBSTER

It is with keen regret and sorrow that we are called upon to record the going out of the life of the author of the following pages, who has died since work was begun upon the book. Mr. Webster was born in Pelham, N. H., November 2, 1828, the seventh child and third son of John and Hannah (Cummings) Webster. His education was acquired in the schools of his native town and Hudson, N. H. He grew up inured to the hard work upon a New England farm, besides working in granite quarries in his 19th and 20th years. In April, 1849, a little over six months before he was twenty-one, with others scattered all over the country, he caught the gold fever. Characteristic of his methodical ways, he kept a journal of his journey across the country and of his experiences as a miner in California and land surveyor in Oregon. His experiences in the Land of Gold are told in his own vivid language in the following pages, and form one of the most interesting narratives of the days of the gold-seekers of the Pacific Slope.

In 1855, after leaving Oregon, he was employed as a surveyor and land examiner by the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad Company in the western part of Missouri. In 1858 he lived in Vinal Haven, Me., working in a granite quarry, but the following year took up his permanent residence in Hudson, N. H., where he lived the remainder of his long and useful life. Following his leading occupation as{10} surveyor and engineer, always active and capable in his duties as a citizen, Mr. Webster became a valuable and respected leader in public affairs, at one time or another holding all of the offices in the gift of his townsmen, while there were few important committees in which he did not figure prominently. Possessing an observing mind, a good memory and a logical discernment and summing up of local and general matters, he early began to compile a history of his town, and after fifty years of painstaking work he had collected the data for one of the most comprehensive town histories ever written. He was then past eighty, and it was the pleasure of the undersigned to be associated with him in the preparation of the manuscript for the printer and its publication. During work upon that, his “journal” of the days of ’49 were examined, and finally he consented to have it published.

He was a Justice of the Peace and had an extensive probate practice for nearly sixty years. He was a Mason and active in the order of Patrons of Husbandry. Mr. Webster retained his mental and physical powers, owing largely no doubt to a perfectly abstemious life, until within a short time of his decease, which occurred June 29, 1916, being 87 years, 7 months and 27 days of age. Noted for his sterling qualities, and having a wide acquaintance, he was mourned by a large circle of friends.

Mr. Webster married, January 29, 1857, Abiah, daughter of Seth and Deborah (Gage) Butler Cutter, of Pelham, N. H., who survives him, as well as five of their ten children, who have married and lived in Hudson.

G. W. B.

{11}

| Line | 16, | insert George W. Houston, Joseph B. Gage, and Calvin S. Fifield | 20 |

| 9, | read Moore, not moon | 39 | |

| 9, | read formed, not found | 45 | |

| 19, | erase of, and insert on, after mountains | 63 | |

| 19, | erase s at end of line, and insert r (Fort Bridger) | 65 | |

| 10, | read service berries, not summer berries | 74 | |

| Top, | Chapter IV | 83 | |

| 18, | spell Winnemucca | 83 | |

| 19, | correct spelling of principal | 96 | |

| 15, | read miners, not winers | 101 | |

| 18, | read weighed, not wished | 102 | |

| 17, | After promised, insert “to release to” | 127 | |

| Top, | also line 8, spell protractor | 151 | |

| 27 and 28, read the Pelham camp | 166 | ||

| 2, | after “The” erase following, and after morning insert before starting | 167 | |

| 3, | erase leaving and insert learning | 177 | |

| 8, | at end of line add ship, “Columbia” | 189 | |

| Top, | erase “the” between “to” and “commence” | 190 | |

| 4 and 7, | erase measured and insert meandered | 207 | |

| 7, | erase compassman and insert campman | 207 | |

| 22 and 23, name of river, “Callapooya” | 210 | ||

| 16, | erase “have” and insert “had” | 216 | |

The story of the pioneers of all times and all countries is one of great interest. In it is embodied the combined elements of adventure and patriotism; the certain forerunner of the coming greatness of the land quickened by the inspiring efforts of the newcomers, usually men of sterling qualities and unswerving purpose. The history of none of these adventurers is fraught with keener interest or more momentous results than that of the “Gold Seekers of ’49.”

The story of the men who dared and did so much in the early days of the discovery of GOLD on the Pacific Slope has never been fully told. In the pages of this remarkable book we are given in plain straightforward language without any attempt at embellishment, by one who participated in them, the trying experiences that comprised the adventures and achievements of the hardy volunteers forming the little army of gold seekers who crossed the plains immediately following the cry that awoke the land from ocean to ocean as no other word could have done.

With no Jason to lead them, no seer to prophesy success, no wizard to avert danger, these brave Argonauts pushed resolutely forward across a continent, traversing thousands of miles where the Greek heroes traveled hundreds, passing over long, weary stretches of pathless plains, under beetling crags, along frowning chasms and over alkaline deserts,{16} where the barest sustenance of life was denied them, constantly menaced by the Arabs of prairie and mountain flitting hither and thither across their way, enduring sickness and privations sufficient to have discouraged a less determined body, comrade after comrade falling from the ranks, the ever-decreasing band still resolutely marching onward into the Land of Gold, to become the creators of a mighty commonwealth, the builders of states. Through the flood of circulating coin that their pickaxes unloosened was advanced the prosperity of a nation whose progress since has been the wonder of the world.

In the midst of all of this, and much more that a glance at the scenes cannot even suggest, Mr. Webster bore a prominent part as pioneer, miner, prospector, and surveyor of the new country. With over half a century intervening since that far-away day his vivid narrative comes to the few now living who participated in the scenes like a voice in a dream, while imparting to others the inner story of an era in our country’s history that forms one of its most important chapters.

With nearly two-thirds of a century intervening since the days when the “gold fever” swept over the country, awakening steady-going New England as nothing else could have done, it is not strange we seldom meet now one of the veterans who answered the call and crossed a continent in a march as beset with dangers as many of a more warlike purpose, or rounded a world to pursue the phantom of fortune in a strange land. Very few of the Gold Seekers of ’49 are living to enjoy the halcyon days of a long and useful life.

G. W. B.

Late in the autumn of 1848 some reports began to be received from the new Territory of California, which had then lately been acquired by the United States from Mexico, that large deposits of gold had been discovered there, and that the small resident population had almost forsaken their former avocation and had repaired to the rich mines where they were reaping a golden harvest, in many instances making large fortunes in a brief period.

These reports were at first almost entirely discredited by the people of the United States. Many believed it to be some cunning device of interested persons to decoy thither immigrants and thereby stimulate the growth of that sparsely populated territory.

During the early part of the winter of 1848-49 these reports were in a great measure corroborated and confirmed by official statements from government officers, who were stationed on the Pacific coast; and as early as January, 1849, vessels were fitting up in Boston, New York and other Atlantic ports, in a manner suited to{18} convey passengers around Cape Horn to the New Eldorado, as it was then called.

The Pacific Mail Co. had at the time a line of steamers plying between New York and San Francisco, by the way of the Isthmus of Panama. These steamers made but one trip each way a month.

As soon as information of a reliable character was received in the Atlantic states regarding the mineral wealth of California, a large portion of the population became more or less excited, and many of an adventurous nature were at once determined to leave their homes and seek their fortunes on the western slope of the snowy mountains.

The query then arose, which was the cheapest, best and most expeditious route to reach San Francisco?

The long and tedious voyage of five or six months “around Cape Horn,” though perhaps the cheapest, was viewed by many as being almost beyond endurance.

The route by the Isthmus of Panama was attended by difficulties and dangers in crossing the Isthmus from Chagres to Panama, a distance of about fifty miles. This journey was performed in boats up the Chagres river, and thence by mules to Panama.

The journey by the latter route from New York to San Francisco had usually been performed in about thirty days and had usually been considered the better route.

So great was the rush to California by the way of the Isthmus in a short time, or as early as January, the tickets by that route were largely sold in advance for several trips, and thousands of passengers who had taken passage to Chagres were unable to get any conveyance{19} from there to California, and were compelled either to remain at Panama for weeks, and in many instances for months, or to return to New York or Boston.

This congested state of affairs rendered the Mail route extremely objectionable. While thousands were waiting for a passage at Panama, a large percentage of those waiting passengers were sick with the Panama fever or other tropical diseases, and many died from such diseases.

Numerous companies were organized during the winter with the intention of pursuing the land route across the extensive western plains and the Rocky Mountains, which was thought could be accomplished in from sixty to eighty days.

It will be remembered that all the country between the Missouri river and the Sacramento valley, which was called “The Great American Desert,” was almost an unbroken wilderness. No white people were then allowed to settle in that vast territory.

As soon as I had sufficient reasons for believing California to be what it had been represented to be as a gold bearing country, I was determined to go myself; and after taking a prospective view of the difficulties and dangers incident to a protracted detention on the Isthmus and the tediousness of a long, monotonous journey via Cape Horn, I finally concluded to cross the country by land; believing it would be an interesting and romantic journey and one not entirely free from difficulties and hardships.

The Granite State and California Mining and Trading Company was organized in Boston in March, 1849, as a{20} joint stock company, with a constitution and by-laws extremely strict and precise.

The above company numbered twenty-nine members, principally hale, hearty, strong men, who were then about to leave their homes and friends to seek their fortunes in the newly discovered gold mines of California. The names of these twenty-nine men were as follows:

Charles Hodgdon, Grovensor Allen, Dr. A. Haynes, John Lyon, Lafayette Allen, Samuel W. Gage, Joseph D. Gage, Thomas J. True, Alfred Williams, Cuthbert C. Barkley, Kimball Webster, Erastus Woodbury, James M. Butler, Alden B. Nutting, Benjamin Ellenwood, James W. Stewart, Jonathan Haynes, Charles W. Childs, Robert Thom, Jacob Morris, Austin W. Pinney, J. P. Hoyt, George Carlton, J. P. Lewis, Dr. Amos Batchelder and Edward Moore.

Ten of these men were from the town of Pelham, N. H., as follows: Capt. Joseph B. Gage, Samuel W. Gage, Joseph D. Gage, Dr. Amos Batchelder, George Carlton, James M. Butler, Austin W. Pinney, Robert Thom, Benjamin Ellenwood and Jacob Morris.

The majority of them were natives of Pelham and had always resided there as neighbors. Several of the others were from Boston, and a few from other towns of New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

Each member of the company was required to pay into the treasury the sum of three hundred dollars which, it was estimated, would be sufficient to furnish the necessary outfit and cover all traveling expenses.

It was the boast of the officers and many of the members that the Granite State Company would carry with{21} them and introduce into California New England principles. Pelham was my native town and although my home at that time was in Hudson I was acquainted with the larger number of the members from Pelham previous to the organization of the company. With the exception of the Pelham members they were all strangers to me. I was twenty years of age on November 2, 1848, five months before we started.

The officers at the time of starting were: George W. Houston, President; Joseph B. Gage, Vice President; Edward Moore, Secretary; Calvin S. Fifield, Treasurer; besides a Board of Directors. Another company similar to our own had been organized in Boston and numbered about forty members and was called the Mount Washington Company. These two companies mutually agreed to travel in company until they should reach California.

The president of the last mentioned company, Captain Thing, having several years previous traveled across the country from Independence, Missouri, to Fort Hall and Oregon, in company with some of the men of the American Fur Company, agreed to pilot the Granite State Company through to California for five dollars each.

Some two or three weeks previous to the time of the starting of the two companies, Captain Thing and Lafayette F. Allen of Boston were selected to go to Independence, Mo., in advance of the two companies, with sufficient funds to purchase mules and cattle in numbers adequate to supply the needs of the two companies in their embarkation on the broad plains at such time as they should arrive at the above mentioned place.

The necessary arrangements having all been matured{22} and the members having provided themselves with guns, pistols or revolvers, bowie-knives, and a plenty of powder, lead, caps, together with such other articles as they thought they might need on their long journey and after they should arrive at the “New Eldorado,” we started on our long journey.{23}

Tuesday, April 17, 1849.

We left Boston this morning at about 8 o’clock for Albany, by way of the Western Railroad.

After shaking hands and bidding such of our friends as had gathered at the station a good-bye, we seated ourselves in the cars, and as they began to move, the spectators that had gathered in and around the station sent up three most hearty cheers for the California adventurers; and they were very readily and heartily returned by us, while we were started on our way with railroad speed toward the land of gold.

We had a special car into which no intruder was allowed to trespass, and I believe a more jolly company of men has seldom been found. We arrived at Springfield, Mass., at about noon where we were fortunate in procuring a fine dinner, to which all did ample justice. After we had eaten we were soon on our way again.

We arrived at Greenbush, N. Y., before night, where we had some little trouble with the baggage master about procuring our trunks, which had been checked at Boston, as we had failed to procure the corresponding checks. However, after some little dispute he gave them up and we took the ferry boat for Albany on the opposite side of the Hudson.{24}

It will be remembered that at that time no railroad bridge spanned the Hudson River. Everything had to be ferried over. At Albany we took our quarters at the Mansion House.

I will here mention that on the road today we fell in with George W. Houston, our president, who had started in advance of the company for the purpose, as it was said, of evading some officers who were in pursuit of him for the object of detaining him until such time as he should be able to liquidate some obligations.

Wednesday, April 18.

We left Albany at 12:30 P.M. in an immigrant train for Buffalo. At Schenectady, about twenty miles from Albany, we were detained two or three hours, waiting for the passenger train to pass us. The fare by the immigrant train was considerably less but we soon discovered that it was a slow and tedious experience of travel, it being very slow. It was nearly night when we left Schenectady and proceeded slowly on our way. The night was cold and stormy—disagreeable in the extreme.

Some five or six inches of snow fell during the night, and there being no fires in the cars, or no place to lie down and nothing to eat, it was a very long, tedious night.

The night passed slowly away, and we arrived safely at Rochester at about 10 o’clock on the 19th; when, after refreshing ourselves with a good dinner, we crossed the Genesee River and took a view of the falls bearing the same name.

Near the middle of the channel is a high projecting{25} point of rocks, where the celebrated Sam Patch is said to have taken his last jump in presence of a large multitude of spectators; and it was said that he was never afterward seen. His motto was: “Some things may be done as well as others.”

Rochester has very excellent water power, and can boast of some of the best flouring mills in the world.

Left Rochester at one o’clock, by the express train, for Buffalo, at which place we arrived at five o’clock P.M., and put up at Bennett’s Temperance Hotel, where we found a very fine hotel and good accommodations.

Friday, April 20.

There being no steamers going west from Buffalo today, we were compelled to await another day for a passage.

A railroad had been built and opened from Buffalo to Niagara Falls, a distance of twenty-two miles. The larger number of the company took this trip and went to the celebrated Falls, as a pleasant manner of passing the few hours that we were compelled to wait. We left Buffalo at two o’clock and rode twenty-two miles over a very rough and uneven railroad, and arrived at the Falls at about three o’clock.

On my arrival at the cataract, I descended the lofty flight of stone steps numbering 290—crossed the river in a yawl boat to the Canada side—a short distance below the Falls; went under the sheet of water at Table Rock, where I found a very damp atmosphere caused by the rising spray—so very damp that I soon became completely saturated.{26}

I then went to the Suspension Bridge about two miles below the Falls, and there recrossed the river.

This bridge had been built the year previous, and was largely an experiment. It was a foot bridge suspended by wire cables and stood 230 feet above the water. It was about eight feet wide.

It seems useless for me to attempt a description of Niagara Falls. To be fully appreciated it must be seen. It is certainly one of Nature’s wonderful curiosities.

Saturday, April 21.

We left Buffalo at 11 o’clock, A.M., in the elegant, first-class steamer Canada, for Detroit, Michigan, with pleasant weather and a smooth lake.

The weather continued fine until about five o’clock, when it commenced raining, and the lake became somewhat rough.

Sunday, April 22.

The weather today has been very fine.

At 7 o’clock we landed at Amherstbury, Canada, near the mouth of the Detroit River; and at nine, landed at the wharf at Detroit.

Detroit is situated on the west bank of the river bearing the same name, about twenty miles above Lake Erie. It rises gradually from the river and is a very pleasantly situated city. In the forenoon I attended the Congregational Church, where we heard an eloquent sermon by an able divine.

In the afternoon I visited Windsor, Canada, situated on the east side of Detroit River. This place contains{27} an old Jesuit church said to be more than one hundred and fifty years old, and built by early French settlers.

In the evening a few of the Pelham boys visited Gen. Lewis W. Cass at his elegant residence. We found Mr. Cass at home, to whom we introduced ourselves. He was a native of New Hampshire, and formerly had his home there. He received us with the greatest cordiality and respect, wishing us the greatest success in our enterprise, and expressing a desire to accompany us himself.

We remain aboard the Canada tonight.

Monday, April 23.

We left Detroit at 7:30 this morning by the Michigan Central Railroad for New Buffalo, a small village on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan, near the line between the states of Michigan and Indiana. The country bordering on this road is principally very heavily timbered with oak, elm, hickory, ash, sycamore and other species. The houses are mostly small “log cabins.”

The soil is fertile but somewhat low and moist, and is said to be well adapted to the propagation of the “shakes.”

We arrived at New Buffalo at 7:30 in the evening, and we intended to have taken the steamer for Chicago immediately, but the harbor being so much exposed and the lake so very rough, it was impossible for the boat to make a landing at the wharf with safety. Consequently, we were compelled to await such time as the waters should become more calm. At that time the railroad had not been constructed around the south side of Lake Michigan into Chicago.

This was a newly constructed place and but a small{28} village at that; and as passengers usually embarked for Chicago almost immediately on their arrival here, the people had made no preparation to accommodate people over night. They had no accommodations to furnish lodgings or meals in so large numbers, and we were unable to obtain either. We were obliged to content ourselves in the cars during the night.

The night seemed long, cold and disagreeable, but at length it passed away.

Tuesday, April 24.

The weather this morning was very cold and windy. The steamer from Chicago landed at the wharf at about 9 o’clock this morning, but, owing to the rough state of the lake, she had not lain at the wharf over two or three minutes before she parted her large hawser, and immediately left for Chicago, without her passengers.

At about ten o’clock in the evening, the lake having become comparatively smooth, the steamer Detroit came in. We soon after got aboard and were on our way for Chicago.

This was an old vessel and had a very ungentlemanly list of officers.

It was not until after a long parley with the steward and captain, that we were successful in obtaining any refreshments. Immediately after supper, I lay down and soon fell asleep, and, on awaking the next morning, I found our boat moored at the wharf in Chicago. The past two days had been our first really bitter experience. Much of the same as bad or worse was in store for us.{29}

Wednesday, April 25.

Chicago at that time was a comparatively small city of about 25,000 inhabitants.

The Michigan and Illinois Canal from Lake Michigan at Chicago to the Illinois River at La Salle, which had been under construction for twelve years or more, had been finished the year previous, and was open for traffic.

We left Chicago at ten o’clock in the morning on a packet by the above mentioned canal for La Salle, a point situated at the head of navigation on the Illinois River.

The weather was fine and we found this to be a delightful mode of travel, but not very expeditious. The packet was drawn by mules or horses traveling on the tow-path.

The passengers had a good view of the broad Illinois prairies, as they passed leisurely through the country. A large percentage of those prairies were then unbroken and were the native home of the prairie hen. From Chicago westward the country is so nearly level that there are no locks in the canal for twenty-five miles.

At night we had the pleasure of seeing a burning prairie for the first time.

Thursday, April 26.

Owing to a leakage in the canal the packet ran aground about two o’clock this morning, where we were detained four hours—until six. We arrived at La Salle about two o’clock in the afternoon.

The canal passes along down a valley one mile or more broad, with bluffs on each side. This valley has the appearance of having been, at some remote period of the{30} past, the bed of a large river, and is thought by many to have once been the outlet and drainage of the Great Lakes, whose waters now form the great cataract of Niagara. I went out with my gun about one mile west of the city, where I found prairie chickens to be very numerous on the prairie. They are as large or larger than our New England partridge, which they very much resemble.

We left La Salle at 9 o’clock in the evening by the steamer Princeton for St. Louis, by way of the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers.

Friday, April 27.

The weather is fine today. The Illinois River is a stream about one-half mile wide, with low, timbered bottom lands on each side, which at this time are considerably inundated, the river being quite high.

The scenery along the river presents a very dreary appearance at this time. It is neither beautiful nor grand. We saw a few wild turkeys along near the shore, which to us was something new.

Saturday, April 28.

At ten o’clock we entered the Mississippi River, and at eleven, passed the junction of the Missouri with the Mississippi.

The river at this point is nearly two miles in width, and has a current of about four miles an hour.

The upper Mississippi is a deep, clear stream, while the Missouri has many shoals and sand bars, and whose{31} waters are always muddy, so very muddy that they color the Mississippi, from the junction to the Gulf of Mexico.

At one o’clock we arrived at St. Louis.

This flourishing city is situated on the west bank of the Mississippi, and, owing to its commanding position, will probably ever maintain a leading position among the great cities of the West.

The streets, at this time, are quite muddy and filthy, but they are of good width.

The population appears to be made up—as seems to us New Englanders—of a heterogeneous collection of almost every nation and tongue.

Tonight we engage passage to Independence, Missouri, and go aboard the steamer Bay State, which is to leave here tomorrow morning for St. Joseph, Mo.

Sunday, April 29.

We left St. Louis at ten o’clock and proceeded up the river. At twelve we entered the turbid waters of the Missouri.

The Bay State is a good vessel, but is very much crowded with Californians.

On her last voyage up the river she is said to have lost quite a large number of her passengers by cholera, which at present is quite prevalent on the western rivers.

At 4 o’clock we pass the beautiful city of St. Charles, situated on the north bank of the river.

The bottom lands along the river are low and subject to overflow; consequently the settlements in sight of the river are not very numerous, a few log cabins being seen on the banks.{32}

The channel of the river is very much obstructed by snags and sand bars and is constantly changing, which renders the navigation of the Missouri extremely difficult and dangerous.

Monday, April 30.

We made about ninety miles during the day yesterday, but moved slowly during the night.

Early this morning we passed the village of Hermon, noted for its extensive wine distilleries. A little later we passed Portland, situated on the north side of the river. At three we touched at Jefferson City, situated on the right bank of the Missouri River, 160 miles from St. Louis. This is the capital of Missouri, and is very pleasantly located on a high bank.

Tuesday, May 1.

At 12 o’clock we passed Glasgow; at 5, Brunswick; and at 7, Miami, all of which are apparently pleasant and thriving little villages.

The banks of the river are much higher than they are lower down, and consequently, we see more settlements.

Wednesday, May 2.

We saw a few small villages on the banks of the river.

At six o’clock P.M. we passed Lexington City, some forty or fifty miles below Independence, our destination.

Thursday, May 3.

At two o’clock this morning we arrived at Independence Landing, four miles from Independence.

This is the place where we are to be initiated into the beauties of camp life; and to fit out and start with our mule trains for California.

At 4 P.M. we had our tents pitched and, as we believed, were perfectly well prepared for the first night in camp, and partaking of a little supper—the first of our own cooking—we lay down, all seeming anxious to try our new manner of living.

We rested very comfortably for a time, but at length it began to rain quite rapidly, and we felt much pleased to find our tents so well adapted to shed water and protect us from a heavy shower.

Our joy, however, was soon after turned to disgust and chagrin when we felt the water between us and the ground, and on rising, we found our under blankets thoroughly drenched with water. Many of us were thoroughly wet to the skin.

This first mishap of the kind to happen must be attributed to our own innocent ignorance, as our tents were set on a slight declivity, and the necessity of trenching them on the upper sides to turn the water away, did not occur to us. However, we learned this part of camp life in such a manner as to never be forgotten.

It was learned in the same manner as we shall hereafter, probably, learn many other new things before our{34} journey is ended. A few of our party begin to believe that they have already seen almost enough of camp life to satisfy them.

The company held the monthly meeting today for the election of officers, for the month ensuing, at which Joseph B. Gage was elected president, his term of office to extend to June first. He seemed to feel very much pleased with his new position.

The rain descended in torrents today.

In the afternoon, nine of us took our saddles, a tent and some provisions and went about three miles in a southerly direction, where a large number of our mules were herded, for the purpose of trying our hand at breaking them.

These mules had been purchased by the agents of the two companies and were being kept by Mr. Sloan. We set our tent at the place of herding and made an ineffectual effort to kindle a fire; and after several like attempts, we were compelled to give it up and do without a fire, and put up with some raw ham and hard bread for our supper; after which we retired for a second night’s lodging in the tent.

Saturday, May 5.

The rain ceased last night, and it was fair and pleasant this morning. Five of our mules had broken out of their enclosure and gone astray. Some two or three of our party went in search of them, but returned tonight without success.

We tried our skill today at breaking mules, but having{35} heretofore had no experience or acquaintance with the long-eared animals, we found it to be a more difficult task than we had supposed it to be, and consequently did not make much progress.

They were young mules which had never been halter-broken, and were almost as wild as the deer on the prairie. A wild, unbroken mule is the most desperate animal that I have ever seen.

I will pass over the time intervening between now and May 26, or about three weeks, with the mention of a few incidents that occurred during our stay at Independence, and giving a slight description of the country surrounding this place.

This being one of the principal fitting-out places for California, it was crowded with immigrants from all parts of the United States. Hundreds of ox-teams and mule-teams were leaving here daily for California, besides many pack-trains, coaches and almost every kind of team or vehicle.

The Asiatic cholera was raging among the immigrants to a large extent.

Many were daily falling victims to this dreaded scourge, while many others were becoming disheartened and were turning back to their homes. Everything here was bustle and wild confusion. Much of the weather was rainy and disagreeable, with occasionally one of the most terrific thunder showers that I ever witnessed.

We tried in vain to break our mules by putting large packs of sand on their backs and leading them about, but it availed very little, as the second trial was as bad as the first; and they were nearly as wild and vicious when we{36} started on our journey as they were when they were first packed.

Several of our company were sick with the cholera, while a number of the Mount Washington company died with the same dread disease. These adverse circumstances detained us somewhat longer than we wished, and much longer than it was for our interest to remain; but as it seemed unavoidable, we were compelled to content ourselves as best we could. But we were looking for better days. Joseph B. Gage continued to fill the office of president.

The surrounding country is very beautiful with a rich, productive soil, much of it being a high, rolling prairie.

Timber is somewhat scarce, but it is of a superior quality.

There are some small plantations, principally cultivated by colored people, who in almost all cases appear to be well satisfied with their condition in life.

On May 26th, we had moved out about twenty miles from Independence and were prepared for a start. Independence is but a short distant from where Kansas City now stands. (Distance to here, 20 miles.)

Saturday, May 26.

We commenced packing our mules early in the morning, but owing to their wild and unbroken state, and being unacquainted with packing, we were not prepared to start until five o’clock in the evening, when we left our old camp-ground and travelled three miles and again camped. (Distance, 3 miles.){37}

This appeared like a very tedious way to get to California, a distance of more than 2,000 miles.

Sunday, May 27.

We commenced packing again this morning and were prepared to start at about noon. This is quite an improvement in point of time over yesterday.

It took as many men to pack a mule as could stand around it, and we were obliged to choke many of them, before we could get the saddle upon their backs.

They would kick, bite and strike with their fore feet, making it very dangerous to go about them. Several of our company were quite badly disabled by working with them, so that they were unable to assist in packing.

We started about noon and traveled about eight miles, over a high, rolling prairie, and camped. Today we crossed the western boundary of Missouri and entered the Indian Territory. (Distance, 8 miles.)

Monday, May 28.

This morning we started at 9 o’clock and traveled eighteen miles over a rolling prairie country, and camped near a small Indian village. Very little timber of any kind is found in this section, but we find plenty of grass and water.

The soil is deep and of first-rate quality; and at no distant day this must become one of the richest and most productive agricultural sections of the country. (Distance, 18 miles.){38}

Tuesday, May 29.

Leave camp at 10 o’clock and travel twelve miles across a prairie and camp in a very pleasant place, where we find plenty of good grass and water, and also a scanty supply of wood.

We saw about a dozen wild horses; but it was impossible to approach near them. Very little game is seen near the road. (Distance, 12 miles.)

Wednesday, May 30.

Owing to some of our horses and mules straying away last night and taking the road toward Missouri, we remained encamped today. The horses, mules and cattle belonging to the two companies number more than three hundred. It was necessary to guard them nights, and each member was obliged to take his turn on guard, regularly, a part of the night, once in two or three nights.

The cattle that we were driving were designed to furnish us with our principal dependence for provisions during our long journey. They were mostly young cattle and not very large. When we were in need of some provisions we would have one killed and dressed, and the meat was divided among the different messes.

We were fortunate enough to recover our mules and horses before night.

I went across about three miles to an Indian village. They have very comfortable log cabins, and were at work turning up the prairie with the plow; and apparently some of them have very good farms, and appear to be partially civilized, and seem to be in a fair way to give{39} up their former nomadic way of life in exchange for civilization, and gain their livelihood by tilling the soil, instead of pursuing the chase. This, probably, is one of the most civilized tribes, and the great majority of our wild Indians must be expected to cling to their ancient manners and customs for many years in the future.

Thursday, May 31.

The weather is fair and pleasant.

Edward Moon, Esq., secretary of our company, being very much out of health, turned back and left the company for Boston.

This is the second one of our company who has given up going to California and returned to his home.

Many are turning back with their teams, having become discouraged in anticipation of the long and tedious journey before them; large numbers are dying daily of cholera and other fatal diseases.

Leave camp at one o’clock and travel about four miles, where we cross a small river running south; and later, we cross a low, wet, swampy prairie about one and one-half miles in width, after which we travel six miles and camp.

Land today principally prairie, with some cottonwood timber along the streams. Soil excellent. (Distance traveled, 12 miles.)

Friday, June 1.

A beautiful morning. We leave camp at 9 o’clock this morning and travel about twenty miles, over a rolling{40} prairie, without wood or water. Camp in the afternoon about one-half miles west of the road.

We have lost four or five of our cattle, they having left the herd and strayed away. The mules are now becoming very tame and docile, but many of them have very sore backs.

Some of our mules are packed with more than two hundred pounds, which is much too heavy for so young animals. (Distance today, 20 miles.)

Saturday, June 2.

We delayed starting until 2 o’clock, for the reason that two of the Mount Washington men that are traveling with us were taken with the cholera during last night. We leave them with Dr. A. Haynes with assistants and travel twelve miles and camp on the north bend of a small stream, about fifteen miles from the Kansas River.

One of the cholera patients died at 5 o’clock this evening. The other seems some better and appears to be in a fair way to recover.

Sunday, June 3.

Fair and warm. Thermometer 86 degrees in the shade. The last of the two cholera patients died this morning at 9 o’clock. They both died at the camp where we left them, twelve miles east.

We remain here today where we find plenty of good wood, water and grass. The men of both companies are now in good health.

The two men that died of the cholera were large, heavy,{41} strong men in good health, and were taking their turn at driving cattle on Friday. They were stricken with cholera on Friday night. One of the men died Saturday afternoon, and the other died Sunday morning at 9 o’clock. They were buried on the wild prairie. There are hundreds of the immigrants dying constantly—more or less every day.

Monday, June 4.

Leave camp at 10 o’clock for the Kansas River. We cross two or three small streams and pass some Indian settlements, and arrive at the Kaw River ferry in season to cross our horses and mules and a part of our baggage before night.

The ferry-boat is made from hewn planks framed together, bearing a very strong resemblance to a raft.

The river is about 650 feet in width, with a rapid and muddy current. This is one of the three or four streams that contribute to render the waters of the Missouri so very muddy.

On the right bank of the river is situated a small Indian village, known as Uniontown, which, together with the Indian population, contains a few white men who have taken Indian women for their wives.

Two or three of the Mount Washington company are seriously attacked with cholera, but they recovered during the night. (Distance, 15 miles.)

Tuesday, June 5.

It was quite late in the afternoon before we had succeeded in getting all of our mules, horses, cattle and{42} baggage over the river, consequently we did not move our camp today.

The Pottawatomie tribe of Indians that inhabit this section of the country is quite numerous and is in a partial state of civilization. They are cultivating the soil to considerable extent and raise wheat, corn and potatoes in moderate quantities. We purchased of them some flour and two or three Indian ponies.

One or two of our company are talking some of leaving our company and joining some other party, but they concluded to continue with us.

Wednesday, June 6.

We leave camp at 12 o’clock and travel 18 miles. We passed a Catholic mission erected for the purpose of Christianizing the Indian tribes and converting them to the Catholic religion. Indian settlements are quite numerous here. Rattlesnakes are seen in large numbers.

We camped in the evening, after which a very violent shower came up.

The wind blew so violently that all of our tents were leveled to the earth over our heads, which was not very agreeable. However, we are compelled to make the best of all such misfortunes, and are becoming more accustomed to the endurance of hardships than at first. (Distance, 18 miles.)

Thursday, June 7.

We start at 9 o’clock this morning and after traveling four miles, cross the Little Vermillion River.{43}

We halt for dinner at 10 o’clock, and camp at 6 o’clock. The country through which we are traveling is very beautiful, it being a high, rolling prairie covered with a fine growth of grass, and watered by numerous cool springs of good water, with some small streams. (Distance, 16 miles.)

Friday, June 8.

Strike camp at 8 o’clock, travel until noon, when we unpack our mules and remain until 2 o’clock. Camp at 6 in the evening.

The road is dry and hard and almost as good as a turnpike.

The ox-teams make as good time as our mule train. (Distance traveled, 20 miles.)

Saturday, June 9.

Leave camp at 8:30, and soon after cross the Big Vermillion River, which is a stream of considerable size, with a very rapid current.

Halt for dinner at noon and camp at night without wood. The water is considerably impregnated with alkali, so very strong that it feels slippery.

There is said to be much of this kind of water on the plains. It is destructive to health and even life, both to man and animals. (Distance, 20 miles.)

Sunday, June 10.

Break camp before breakfast and travel twelve miles, where we find an abundance of wood and good water.{44}

Some returning Californians dined with us today, having traveled about 150 miles beyond this point, when they became discouraged and began to retrace their footsteps.

The prospects of reaching California certainly look somewhat discouraging at the present time.

The great bulk of the immigration, which is very large, is in advance of us. That very much dreaded scourge, the Asiatic cholera, is making such sad havoc among the Californians that almost every camp-ground is converted into a burial-ground, and at many places twelve or fifteen graves may be seen in a row.

Almost every traveler that we meet, who has ever been west of the Rocky Mountains, gives it as his opinion that there is not grass enough in that region of country to sustain one-half of the stock that is now on the California trail; and they are of the opinion that the present immigration cannot reach California this season.

Much trouble is also anticipated by many from some of the western tribes of Indians, who are said to be hostile to the whites. The Mormons who settled near the California trail, in the Great Lake valley, in 1847, are also much feared by a large number of those from Missouri.

All these circumstances and conditions combined are of sufficient weight to frighten many and cause them to banish the bright, golden visions which allured them from their homes, with the bright anticipations of soon becoming wealthy.

The principal anxiety that seems to fill the minds of such at the present time is to reach, as soon as possible, their former homes; and consequently, while the great{45} majority are moving west, a large number are traveling east.

To meet so many who have been farther westward on the trail, and who have turned backward, and are now seeking their former homes, has its influence upon a large number that would otherwise proceed and causes them to also reverse their course.

I have, myself, heard all these discouragements many times rehearsed, and weighed the matter, and have found conclusions as follows:

I started for California anticipating that we should meet many hardships, privations and dangers on our long journey, and, as yet, we have experienced nothing of a nature any more severe than we had reason to expect; and as for what we may find ahead of us we know but little of. I am fully determined to proceed as far in the direction of California as it is possible for me to go, and not to return until I have seen the place I set out to reach.

It seems to be a very curious fact that the immigrants from the state of Missouri—which by the way, were more numerous than from any other one state—seem to suffer more from the cholera than almost all the other immigration combined.

I know of no good reason why this should be so. They have had their homes on the frontier and, consequently, have been subjected to more exposure and hardships than any other class now on the California trail. (Distance traveled, 12 miles.){46}

Monday, June 11.

The first experience worthy of note this morning was a very heavy shower. This lasted two hours and was accompanied with a most terrific gale, which very soon levelled every tent in our camp, leaving us nothing under which we could shelter ourselves. Consequently, we were all most thoroughly drenched.

Start in the afternoon and travel fifteen miles over a smooth prairie, and camp. (Distance, 15 miles.)

Tuesday, June 12.

Weather very fine. Leave camp at 9 o’clock, and travel eight miles and camp until three, when we again move on nine miles farther, and camp for the night. (Distance traveled, 17 miles.)

Wednesday, June 13.

A shower with a heavy wind occurred at about midnight.

Our tents withstood the gale, but the rain was driven through in such large quantities as to drench us thoroughly.

At about 2 o’clock another shower occurred with a wind much stronger and more severe than the first, which levelled all our tents to the ground, notwithstanding the exertions of us all to keep them standing; and we were again left without a shelter, and compelled to pass the balance of the night as best we could—some standing in the open air with their backs to the storm, while others{47} were lying under their prostrate tents with water all around them two or three inches deep.

These showers are accompanied with very violent electrical displays and very heavy thunder. They are the most violent and terrifying of anything of the kind I have ever witnessed.

About daylight we managed to get fires started, and before noon dried ourselves and our camp equipage almost completely.

We started at noon and traveled eighteen miles. The land through which we passed is apparently very fertile, but is almost destitute of timber of any kind. Camp on a small stream of clear, pure water.

Thursday, June 14.

Leave camp at seven in the morning and travel until eleven o’clock. We take dinner on the bank of the Big Blue River—a fork of the Kansas. We start again at two o’clock and camp at six on the Big Blue. (Distance, 25 miles.)

Friday, June 15.

Weather fair and cool. Travel up the Blue River today. This is a most beautiful stream; has a rich and fertile soil, with considerable good timber. (Distance, 25 miles.)

Saturday, June 16.

Decamp at eight o’clock and travel ten miles to the point where the trail leaves the Blue River. We dine here.{48}

The road from this place to the Platte River is through prairie country destitute of wood. We travel fifteen miles in the afternoon and camp on the prairie, without wood, and with quite poor water.

Sunday, June 17.

Travel twelve miles in the forenoon to the Platte, or Nebraska River. In the afternoon we go up the river eight miles and camp near Fort Kearney, at the head of Grand Island. This island is 52 miles in length and appears to be well timbered.

The Platte is a large river, being from one to two miles wide, and has a very rapid current. Its waters are so very muddy that after a bucketful has settled, an inch of mud, or sediment will appear at the bottom. It has a bed of sand which is constantly in motion. (Distance traveled, 20 miles.)

Monday, June 18.

We remain here today.

The weather is fair and warm. Thermometer 86 degrees in the shade. Grass is not very abundant.

We repair our pack-saddles and other equipage which has become considerably out of repair. The backs and shoulders of many of our mules have become very sore and in a serious condition, many of them having lost large patches of skin, and the prospect, at present, seems to be that few of them will survive to reach California the present season.

We have made an inspection of our packs today in

view of trying to make them lighter, if possible, but could discover very little in them that the members were willing to discard.

We have, for one thing, a patent “filter,” the weight of which is about 30 pounds, which has been of no use to us, and the prospect now is that it will never be of any benefit whatever. We have some iron spades that probably will be of no benefit to any one.

We have also some large, heavy picks which we have brought all the way from Boston, and also shovels. These may be useful in the mines, but it does not seem to be feasible to pack them 2000 miles on the sore backs of mules.

There are, however, such a large number in the company that are so bitterly opposed to leaving any such article that they will defeat any such measure proposed; and even call all such foolish who believe it would be wise to lighten the loads of our poor mules in such a manner.

Tuesday, June 19.

Weather fair and very windy.

Remain here today. I visit Fort Kearney, which is about one and one-half miles distant from our camp.

The fort and other buildings are constructed of adobe, or sun-burned bricks, with one exception. The fort was established about two years since.

A large number of immigrants are encamped about the fort, at this time, and also a company of United States cavalry. It is said at Fort Kearney that the wagons passed here already this season, en route for California,{50} number 5,400, and also three pack trains. This point is about 350 miles from Independence, Mo.

Wednesday, June 20.

We packed in the afternoon and after traveling four miles, we encountered a very fierce shower, which thoroughly drenched every one of us. A little later another shower was encountered, which was much more severe than the first, and which was accompanied with some hail and a terrific wind.

Camp at the first good camping place after the showers. Blankets and all clothes thoroughly wet and no opportunity for drying them. It is certainly uncomfortable lodgings.

Since leaving Independence, until the last two or three days, my health has not been very good. (Distance, 10 miles.)

Thursday, June 21.

Travel nine miles in the forenoon and six in the afternoon. Our course is up the Platte River, the valley of which is nearly level and is several miles wide on either side. We camp tonight where there is no wood on the mainland, and we waded a branch of the river about twenty rods to an island to procure it. The water is not deep, but the current is quite rapid. There are numerous islands in the river.

Friday, June 22.

Travel 12 miles in the forenoon, halt two hours and dine. Travel eight miles in the afternoon and camp. All in good health.{51}

Saturday, June 23.

Travel up the River Platte today 20 miles, and camp without wood, but find plenty of “Buffalo chips,” which, if dry, are a very good substitute for fuel.

Sunday, June 24.

Weather fair and warm. Thermometer stands at 95 degrees, at noon, in the shade.

I traveled south, back from the river, about four miles to the bluffs, today. Owing to the very clear, transparent atmosphere, no one who was not acquainted with it could believe the distance was more than one mile at most. I did not believe it when I left camp, after having been told by those who had traveled the distance and back.

These bluffs are a succession of sand hills, rising abruptly from the level plain, along the Platte on both sides, and extend back from the river a long distance.

Antelopes are very plentiful, but are not easily killed on the level prairie. There is little timber or wood here. The soil is sandy, but produces a very good grass.

Monday, June 25.

Broke camp at 5 o’clock in the morning and traveled eight miles, where we halted until two in the afternoon. Travel three and one-half hours in the afternoon and camp on the bank of the river, where we found a good supply of wood. Mosquitoes are more plentiful here than I have ever seen before. I would judge there are more than forty bushels of these pests to the acre, and they are of a very large breed. (Distance, 20 miles.){52}

Tuesday, June 26.

Started at 5 o’clock this morning. We had traveled about ten miles, when the startling cry of “Buffalo ahead” was heard from those in advance.

This was the first buffalo herd seen by our company, and every one was anxious to gratify his curiosity by a sight of a real live American bison. On looking ahead about two miles, and not far from the immigrant trail, a herd of about one hundred buffaloes could be seen, quietly grazing.

A number of the company that could be spared from the train, immediately left the train and gave chase to the herd. The buffaloes on seeing their approach, immediately started toward the sand hills, and soon disappeared from sight. The men who were in pursuit followed them, and we soon after camped on the bank of the River Platte.

Soon after we had unpacked the mules, we saw four large buffaloes emerging from the brush, not more than 100 rods distant from our camp. Our horses were all unsaddled, and before we could catch and saddle them, the large animals were a long distance from us.

One of our men, Mr. Hodgdon, soon came in and stated that he had shot and killed a buffalo, about four miles distant from our camp, in the sand hills. After dinner, a party of four or five with two extra mules, went out to dress the slaughtered bison, and to bring the meat into our camp; and the balance of the company packed up the camp and started. During the afternoon, we killed a buffalo calf, four or five weeks old.{53}

We ate buffalo meat for supper, cooked with “Buffalo chips.” The meat is very coarse grained and of a dark color, and is very good, but in my estimation, is much inferior to good beefsteak. They are said not to be so good at this season of the year as they will be later, when they will be more fleshy. (Distance, 18 miles.)

Wednesday, June 27.

We started at 8 o’clock and traveled four miles in the forenoon. In the afternoon we go up the river to the South Platte.

I went up the river about three miles for some wood. Plenty of buffalo. (Distance, 17 miles.)

Thursday, June 28.

Fair weather. Packed in the morning and prepared to ford the south fork of the Platte River.

The stream is about three-fourths of a mile in width and from one foot to three feet deep. The current is rapid and water very muddy. From its appearance, any one might suppose the stream was 20 feet deep.

I crossed and recrossed it on horseback three times. We had no very bad luck in crossing. Some of our packs became wet and we unpacked on the west side of the stream and dried them. We started at one o’clock and traveled 12 miles in the afternoon and camped without wood, but found plenty of good, dry “Buffalo chips.” (Distance, 13 miles.){54}

Friday, June 29.

Start at 6.30 o’clock and finding neither wood nor water, we traveled seven hours, when we halt and make a search for water, and find a spring about one mile from camp.

This was good fortune. (Distance, 20 miles.)

Saturday, June 30.

Weather warm and dry. Travel ten miles in the forenoon and eight in the afternoon. One of our company killed a buffalo this afternoon, and after we had camped, Joseph B. Gage, with two or three others, with mules, went back to bring in the meat; but before they had arrived at the place where it was slain, they saw a band of Indians riding toward them, and they became frightened and returned to camp with all possible speed.

The next morning, a party of Sioux Indians came into our camp, and desired the doctor should give them some medicine, stating that their camp was on the opposite side of the Platte, and that the smallpox was raging among them.

They were perfectly friendly and said they had no intention of frightening our men away from the buffalo meat, but that they wished to talk with them and get some medicine; and also stated that they made all the friendly signs that they could think of to have them stop. The doctor supplied them with medicine and they left our camp. (Distance, 18 miles.){55}

Sunday, July 1.

We did not move camp today.

The land is not so level here as it is on the Lower Platte. Soil sandy; wood scarce; weather fair and dry.

Monday, July 2.

We started in the morning and soon passed through Ash Hollow, so-called. It derives its name from large quantities of red ash timber found here.

We dine at the foot of Castle Bluffs. These bluffs of sandstone rise abruptly several hundred feet, and having been exposed to the weather for many thousand years, have been transformed into shapes very much resembling ancient castles, hence the name. Camp on the Platte.

The road today has been very sandy. (Distance, 23 miles.)

Tuesday, July 3.

Break camp at half past six in the morning and travel four hours in the forenoon and eleven miles in the afternoon. Found the road sandy. Camp on the bank of the North Platte. (Distance, 25 miles.)

Wednesday, July 4.

The Fourth of July will remind an American of his home wherever he may be or however far he may be separated from it. Early in the morning we fired several rounds, and made as much noise as possible in honor of the day of Independence. We started in the morning and soon passed an encampment where we had the{56} pleasure of beholding the “Star Spangled Banner” floating in the cool breeze. We traveled a few miles farther and passed another camp with two large American flags waving above it.

We halted at noon within sight of Court House Rock. This rock is several hundred feet in length and at a distance bears a strong resemblance to a large building with a cupola. It is said to be about 12 miles from the road, but to measure the distance with the eye, a person would judge it to be not more than one mile distant. The name of J. J. Astor, with the date 1798, is said to have been carved there, and that it may still be seen. Mr. Astor was one of the American fur traders to cross the continent.

We camp seven miles south of Chimney Rock. This rock rises about 255 feet and in form very much resembles a chimney. Standing as it does on a level plain, it can be seen 25 or 30 miles away. Its material is sandstone and may easily be worked or cut. (Distance, 20 miles.)

Thursday, July 5.

Weather pleasant. Traveled 18 miles up the Platte and camped. Grass is quite scarce here.

Friday, July 6.

We passed “Scott’s Bluffs” in the forenoon which present a very peculiar appearance. We found plenty of wood at noon—the first we have had for four days.

Camp at a fine spring, where we also find an abundance of fuel but a scarcity of grass. In the afternoon{57} we have a view of “Laramie Peak,” distant more than 50 miles west. Camp at night on Horse Creek, where we find good grass and water. (Distance, 25 miles.)

Saturday, July 7.

Traveled 20 miles, principally over a barren country, and camped.

Sunday, July 8.

Weather fair with a high wind.

Start in the morning and after traveling three hours we reach Laramie River, which we ford with no other difficulty than to have some of our packs considerably wet. This stream, although small, is very rapid and has a gravelly bottom with clear water.

We soon after passed Fort Laramie and camp two miles above the fort on Laramie River. By recrossing the river we have good grass for our horses, mules and cattle. (Distance, 15 miles.)

Monday, July 9.

Remained here today.

Before leaving Boston we had light, strong trunks manufactured—two for each pack mule—in which to pack our clothing, provisions, etc. They were made as portable as was possible to insure sufficient strength. We now, after packing them about 700 miles, get a vote of the company to break them up and make bags from the leather coverings. This measure some of us have believed to be a wise plan for a month past, but those who{58} first favored the plan were laughed at by the majority. We have been packing thirty pounds of dead weight to each mule which can be dispensed with. The first thought of packing these trunks—two to each mule—to California, was a sad oversight by Captain Thing, who suggested them.

Tuesday, July 10.

Weather fair and warm; thermometer 98 degrees in the shade. Remained here today. In the evening I went down to the fort. The outside wall is built of adobe, or sun-burnt bricks, and encloses about one-half acre. The buildings are within the enclosure. The fort was established several years since by the American Fur Company for the purpose of trading with the Indians, and was sold a short time since by that company to the United States Government, and is now occupied by Colonel Sanderson with a regiment of United States Cavalry. He is now engaged in building a mill, house, barracks, etc.

Wednesday, July 11.

We still remain here.

All the camp grounds near the fort are literally covered with wagon irons, clothing, beans, bacon, pork and provisions of almost all kinds, which have been left by the advance immigration to lighten their loads and facilitate their speed.

Thursday, July 12.

Decamp at 9 o’clock and after traveling 21 miles, we camp on a small stream. Grass poor.{59}

Friday, July 13.

Weather cool. Started at seven in the morning and after 13 miles’ travel, we found a most excellent spring at which we dined.

In the afternoon we cross a small stream and camp on the Platte, where we find good grass. (Distance, 24 miles.)

Saturday, July 14.

Travel 13 miles in the forenoon and 12 in the afternoon and camped on a small river. Grass scarce.

Sunday, July 15.

Weather fair and warm. Remain in camp today. We have found plenty of wood since we left Laramie. The country through this part is hilly and broken; soil barren and sterile. The health of the company is good. The cholera followed the immigration to near Fort Laramie, making sad ravages in very many companies; but it seems at last to have slackened its hold and seems to have become extinct. For the last week we have seen but few graves by the roadside.

Many were the men who left their homes for California last spring, with bright prospects of reaping a golden harvest within a few months and returning to their home and friends. But alas! their hopes were blasted, and instead they have left their bones to bleach upon the great plains of Nebraska, with not even a stone to mark their resting place. Many, who one day have been in the enjoyment of perfect health, the next have been in their graves.{60}

Monday, July 16.

We started in the morning and in good season, and drove 17 miles before dinner, and eight more in the afternoon. The land over which we have traveled today is very barren and produces very little, excepting wild sage weeds with a very little grass, which at this time is perfectly dry.

Tuesday, July 17.

Started in the morning and traveled eight miles to the lower ferry on the North Platte, where we camped. Here we found a poor ferry boat in which we carried our packs to the opposite side of the stream, and caused all of our animals to swim over. We lost one mule by being drowned, with which exception we were very fortunate. The stream at this point is very rapid and deep. Travel 12 miles in the afternoon over a barren, sandy country and camp on the Platte.

Wednesday, July 18.

Travel 18 miles up the river and camp.

The land is poor and many of our mules are in poor condition; and some of the weakest appear as if they would be unable to proceed a great distance further.

Large quantities of bacon and other kinds of provisions have been left by immigrants by the side of the road when teams became exhausted, and may be seen in large heaps on almost every camp ground.

Farming and mining implements of all descriptions, mechanics’ tools, and wagons, all go to make up the list of abandoned property.{61}

Thursday, July 19.

Travel 12 miles and camp on the North Platte, two miles above the upper ferry, at a point where the road leaves the river.

In the afternoon we have very fine sport catching a sort of white fish from the river which are very plentiful at this place, and are a fine fish.

Friday, July 20.

We did not start today until noon.

The filter of which I have before spoken has been packed all these many miles from Independence on the mule of George Carlton. He has spoken in favor of leaving it several times, but the consent of some of the company could not be had. What could be done? The poor mule was getting weak and poor.

Mr. Carlton took the filter from the pack and put it into a thicket and informed two or three whom he well knew were in favor of leaving it behind, and said if we would “keep dark” he would let it remain there. So the filter was left behind when we started.

In the afternoon we traveled 11 miles and camped at a spring.

Saturday, July 21.

Start in the morning and in ten miles’ travel come to some very strong alkali water. Travel 5 miles farther and dine at a good spring.

Go 5 miles in the afternoon. Wild sage is the principal production here.{62}

Sunday, July 22.

Weather fine. Start in the morning and travel 20 miles. Camp on the Sweetwater River, a branch of the Platte, one mile above Independence Rock.

The country between the Platte and Sweetwater Rivers is very barren, destitute of timber, with very little grass or other vegetation, except wild sage. Much of the water is alkali, poisonous to cattle and horses and is entirely unfit for use. When water has evaporated here, a substance resembling saleratus may be gathered up in large quantities. In some cases it may be found on the surface three or four inches in thickness, white and pure as the finest pearlash manufactured; and on trial we found it equally as good for the purpose of making bread. We have seen large numbers of dead cattle by the roadside the past three days.

Monday, July 23.

Remain encamped here today for the benefit of our tired mules.

We had a fine shower in the afternoon. A buffalo was killed by one of our company yesterday which affords us plenty of meat.

Tuesday, July 24.

The majority of our company is not ready to advance, consequently we must remain here another day.

The excuse is made that it is necessary for the animals to recruit, but the grass is poor, and I believe the animals will gain very little. A short stop might be of some bene{63}fit, but to remain two or three days where there is very little grass seems like wasting time to no good purpose. The company is too large to travel in one body. Some are for going ahead, while others are in favor of resting. A company of ten men is quite large enough to travel expeditiously, but our company is so situated that it cannot well be dissolved at present.

Wednesday, July 25.

We break camp and travel up the Sweetwater River an hour, which brings us to the Devil’s Gate. This is a fissure in the rock in the Sweetwater River, thirty or forty feet wide, two or three hundred feet long, and perhaps two hundred feet high, through which the river passes, and is quite a natural curiosity.

Travel 20 miles and camp on the river.

Thursday, July 26.

Travel 10 miles in the forenoon and 10 in the afternoon, continuing up the Sweetwater. There is a range of mountains of each side of the valley. On the right they are composed almost entirely of barren rocks, destitute of vegetation. On the left they have some soil and some vegetation.

Friday, July 27.

Start in the morning and after six miles’ travel the road leaves the river and we travel 16 miles farther before we find either water or grass, when we reach the river again.{64}

We travel up the river two miles further and camp. Grass poor. The land along the Sweetwater is very poor, with the exception of a little bottom land. Today we had a view of the snow capped mountains—the Wind River Mountains.

Saturday, July 28.

Travel up the river 8 miles, where we find good grass, which we have not had the pleasure of seeing before for several days.

Sunday, July 29.

Weather fair and warm.

We remained encamped here today. I went out from camp a short distance into a small piece of timber and on my return a young deer ran out before me and I shot it with my pistol through the heart. This is the first deer that has been killed by the company. Mr. Lyon also killed a Mountain Sheep, or Bighorn.

Monday, July 30.

As we didn’t move our camp today some of us went deer hunting. Deer were quite plentiful, and J. B. Gage killed one, which we dressed and carried four miles to camp. I fired several shots with buckshot but did not succeed in killing any game.

The country in this vicinity is broken and mountainous; soil is rocky, sandy and not very productive.

Tuesday, July 31.

Weather fine—warm days and cool nights. Break camp at a late hour and leave the Sweetwater River, and in 16 miles’ travel we intersect it again, where we unpack our mules and dine. Grouse are very plentiful in this region. Remain two hours, after which we travel up the river six miles and camp where we find good grass. The Sweetwater is a fork of the Platte and derives its name from the peculiar taste of the water.

Wednesday, August 1.

We are now near the summit of the Rocky Mountains, at an elevation of about 7,000 feet above the Gulf of Mexico.

There was a heavy frost this morning.

Traveled up the river 11 miles in the forenoon. In the afternoon we traveled up the river five miles farther and camped on a small branch of the Sweetwater. We left the road today with the intention of taking a straight course through the mountains to Fort Hall, thereby avoiding the circuitous route by the way of Fort Bridges.

Captain Thing, our guide, states that he once traveled the route and in his opinion we shall find good grass and water, and that there is an Indian trail through which he thinks he can follow. The main road is now several miles to the south of us. This is known as the South Pass of the Rocky Mountains. Many suppose it to be a narrow, precipitous pass with high mountains on either side; but it is directly the reverse, it being almost a level plain, extending many miles to the north and to the{66} south; and were it not that the waters divide near this place, and a portion flow to the Gulf of Mexico, and another portion to the Pacific Ocean through the Colorado River and the Gulf of California, any one would not believe that they were standing on the summit of the Rocky Mountains.

The altitude of the South Pass is said to be 7,200 feet, as taken by Col. J. C. Fremont about two years since.

Thursday, August 2.

The weather was so cold last night that water in our buckets was frozen over this morning.

Traveled 13 miles over a sandy, barren country and intersect the Little Sandy River, a small stream coursing south. After camping I went out and shot a dozen grouse. Several others were out at the same time and killed as many as I did.

Friday, August 3.

Traveled 9 miles to the Big Sandy River and camped. Land poor and somewhat broken; destitute of timber with the exception of small willows near the streams.

Saturday, August 4.

Started this morning for Green River and traveled 30 miles over a barren desert, destitute of both grass and water. The country is not very broken, and we had no difficulty in traveling wherever we chose. We intersected Green River at a point where grass was abundant{67} and wood plentiful. Mr. Hodgdon, a prominent man of our company, was taken sick yesterday and was unable to travel this morning, consequently we left him behind together with eight other men, and we shall remain here until they arrive.

Sunday, August 5.

Remained in camp here today. Green River is a clear, rapid stream, ten to fifteen rods wide and is fordable in many places. It is one of the principal branches of the Colorado. Its waters are very cold, and its source is said to be Fremont’s Peak, a snow-capped mountain a considerable distance north, the altitude of which is about 13,000 feet.

Monday, August 6.

As we did not start today, some of us went deer hunting and killed one buck. At 9 o’clock in the evening the men whom we left behind with Mr. Hodgdon arrived safely, he having nearly recovered.

Tuesday, August 7.

Two or three of our company were not in very good health today and consequently we remained at the old camp ground.

Wednesday, August 8.

Our mules are in much better condition than they were when we camped on Green River. They had become so{68} wild that it was with considerable difficulty that we could catch them this morning.

Start this morning and travel down the river about one mile where we ford it without difficulty. We then followed down the river two miles farther to a branch that came from the west. We followed this branch up 15 miles and camped.

Thursday, August 9.

We left the stream this morning and commenced ascending a mountain. At noon we ate our dinner at a very fine mountain spring.

In the afternoon we continued to ascend and passed through a heavy growth of spruce timber. Our ascent was gradual until about 4 o’clock, when we found ourselves at the top of a peak of the Rocky Mountains. To the west and north the descent was steep—almost precipitous. We could see the stream that we had left in the morning many hundreds of feet below, but to reach it with our pack mules seemed almost an impossibility. There were but two ways from which to choose—either to descend to the stream, or retrace our steps. We were not long in deciding, and we chose the first and concluded to try to descend. In about two hours we reached the stream in a small pleasant valley. The descent made by us was about 2,000 feet and probably about one and one-half miles in length, the greater part being covered with a thick growth of standing and fallen timber.

Captain Thing says he was never before at this place and is at a loss to know what route to take to get out. (Distance, 15 miles.){69}

Friday, August 10.

We started in the morning and followed the stream up seven miles to its source. We then traveled one mile farther and halted, where we found neither water nor grass.

Captain Thing, with two or three men, went ahead to endeavor to find a passage through the mountains, which are heavily timbered and very rough and broken. They returned before night and we went on two miles farther through a dense growth of spruce, pine and fir and camped. Good grass and excellent water. This is in a small valley. (Distance, 10 miles.)

Saturday, August 11.