[Pg i]

Title: The heart of Africa, Vol. 2 (of 2)

Author: Georg August Schweinfurth

Translator: Ellen E. Frewer

Release date: September 12, 2023 [eBook #71622]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low, and Searle

Credits: Carol Brown, Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE

THREE YEARS’ TRAVELS AND ADVENTURES

IN THE UNEXPLORED REGIONS OF CENTRAL AFRICA.

FROM 1868 TO 1871.

BY

TRANSLATED BY ELLEN E. FREWER.

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY WINWOOD READE.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

Vol. II.

WITH MAPS AND WOODCUT ILLUSTRATIONS.

LONDON:

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, LOW, AND SEARLE.

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188, FLEET STREET.

1873.

All rights reserved.

[Pg ii]

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS,

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING CROSS.

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Niam-niam—Signification of the name—General characteristics—Distinct nationality—Complexion and tattooing—Time spent on hair-dressing—Frisure à la gloire—Favourite adornments—Weapons—Soldierly bearing—A nation of hunters—Women agriculturists—The best beer in Africa—Cultivated plants—Domestic animals—Dogs—Preparation of maize—Cannibalism—Analogy with the Fans of the West Coast—Architecture—Power of the princes—Their households—Events during war—Immunity of the white man—Wanton destruction of elephants—Bait for wild-fowl—Arts and manufactures—Forms of greeting—Position of the women—An African pastime—Musical taste—Professional jesters and minstrels—Praying-machine—Auguries—Mourning for the dead—Disposal of the dead—Genealogical table of Niam-niam princes | Page 1 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Mohammed’s friendship for Munza—Invitation to an audience—Solemn escort to the royal halls—Waiting for the king—Architecture of the halls—Grand display of ornamental weapons—Fantastic attire of the sovereign—Features and expression—Stolid composure—Offering gifts—Toilette of Munza’s wives—The king’s mode of smoking—Use of the cola-nut—Musical performances—Court fool—Court eunuch—Munza’s oration—Monbuttoo hymn—Munza’s gratitude—A present of a house—Curiosity of natives—Skull-market—Niam-niam envoys—Fair complexion of natives—Visit from Munza’s wives—Triumphal procession—A bath under surveillance—Discovery of the sword-bean—Munza’s castle and private apartments—Reserve on geographical subjects—Non-existence of Piaggia’s lake—My dog exchanged for a pygmy—Goats of the Momvoo—Extract of meat—Khartoomers’ stations in Monbuttoo country—Mohammed’s plan for proceeding southwards—Temptation to penetrate farther towards interior—Money and good fortune—Great festival—Cæsar dances—Munza’s visits—The Guinea-hog—My washing-tub | 37 |

| CHAPTER XV.[Pg iv] | |

| The Monbuttoo—Previous accounts of the Monbuttoo—Population—Surrounding nations—Neglect of agriculture—Products of the soil—Produce of the chase—Forms of greeting—Preparation of food—Universal cannibalism—National pride and warlike spirit—Power of the sovereign—His habits—The royal household—Advanced culture of the Monbuttoo—Peculiarities of race—Fair hair and complexion—Analogy to the Fulbe—Preparation of bark—Nudity of the women—Painting of the body—Coiffure of men and women—Mutilation not practised—Equipment of warriors—Manipulation of iron—Early knowledge of copper—Probable knowledge of platinum—Tools—Wood-carving—Stools and benches—Symmetry of water-bottles—Large halls—Love of ornamental trees—Conception of Supreme Being | 80 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The Pygmies—Nubian stories—Ancient classical allusions—Homer, Herodotus, Aristotle—My introduction to Pygmies—Adimokoo the Akka—Close questioning—War-dance—Visits from many Akka—Mummery’s Pygmy corps—My adopted Pygmy—Nsewue’s life and death—Dwarf races of Africa—Accounts of previous authors: Battel, Dapper, Kölle—Analogy of Akka with Bushmen—Height and complexion—Hair and beards—Shape of the body—Awkward gait—Graceful hands—Form of skull—Size of eyes and ears—Lips—Gesticulations—Dialect inarticulate—Dexterity and cunning—Munza’s protection of the race | 122 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Return to the North—Tikkitikki’s reluctance to start—Passage of the Gadda—Sounding the Keebaly—The river Kahpily—Cataracts of the Keebaly—Kubby’s refusal of boats—Our impatience—Crowds of hippopotamuses—Possibility of fording the river—Origin and connection of the Keebaly—Division of highland and lowland—Geographical expressions of Arabs and Nubians—Mohammedan perversions—Return to Nembey—Bivouac in the border-wilderness—Eating wax—The Niam-niam declare war—Parley with the enemy—My mistrust of the guides—Treacherous attack on Mohammed—Mohammed’s dangerous wound—Open war—Detruncated heads—Effect[Pg v] of arrows—Mohammed’s defiance—Attack on the abattis—Pursuit of the enemy—Inexplicable appearance of 10,000 men—Waudo’s unpropitious omen—My Niam-niam and their oracle—Mohammed’s speedy cure—Solar phenomenon—Dogs barbarously speared—Women captured—Niam-niam affection for their wives—Calamus—Upper course of the Mbrwole—Fresh captive—Her composure—Alteration in scenery—Arrival at the Nabambisso | 147 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Solitary days and short provisions—Productive ant-hill—Ideal plenty and actual necessity—Attempt at epicurism—Expedition to the east—Papyrus swamp—Disgusting food of the Niam-niam—Merdyan’s Seriba—Hyæna as beast of prey—Losing the way—Reception in Tuhamy’s Seriba—Scenery of Mondoo—Gyabir’s marriage—Discovery of the source of the Dyoor—Mount Baginze—Vegetation of mountain—Cyanite gneiss—Mohammed’s campaign against Mbeeoh—Three Bongo missing—Skulls Nos. 36, 37, and 38—Indifference of Nubians to cannibalism—Horrible scene—Change in mode of living—Invasion of ants—Peculiar method of crossing the Sway—Bad tidings—Successful chase—Extract of meat—Return of long absent friends—Adventures of Mohammed’s detachment—Route from Rikkete to Kanna—Disappointment with Niam-niam dog—Limited authority of Nganye—Suspension-bridge over the Tondy | 194 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Division of the caravan—Trip to the east—African elk—Bamboo-forests—Seriba Mbomo on the Lehssy—Abundance of corn—Route between Kuddoo and Mbomo—Maize-culture—Harness-bushbock—Leopard carried in triumph—Leopards and panthers—The Babuckur—Lips of the Babuckur women—Surprised by buffaloes—Accident in crossing the Lehssy—Tracts of wilderness—Buffaloes in the bush—The Mashirr hills—Tamarinds again—Wild dates—Tikkitikki and the cows—The Viceroy’s scheme—Hunger on the march—Passage of the Tondy—Suggestion for a ferry—Prosperity of Ghattas’s establishments—Arrival of expected stores—A dream realised—Trip to Kurkur—Hyæna dogs—Dislike of the Nubians to pure water—Two soldiers killed by Dinka—Attempt to rear an elephant—My menagerie—Accident from an arrow—Cattle plagues—Meteorology—Trip to the Dyoor—Gyabir’s delusion—Bad news of Mohammed—Preparations for a second Niam-niam journey | 246 |

| CHAPTER XX.[Pg vi] | |

| A disastrous day—Failure to rescue my effects—Burnt Seriba by night—Comfortless bed—A wintry aspect—Rebuilding the Seriba—Cause of the fire—Idrees’s apathy—An exceptionally wet day—Bad news of Niam-niam expedition—Measuring distance by footsteps—Start to the Dyoor—Khalil’s kind reception—A restricted wardrobe—Temperature at its minimum—Corn requisitions of Egyptian troops—Slave trade carried on by soldiers—Suggestions for improved transport—Chinese hand-barrows—Defeat of Khartoomers by Ndoruma—Nubians’ fear of bullets—A lion shot—Nocturnal disturbance—Measurements of the river Dyoor—Hippopotamus hunt—Habits of hippopotamus—Hippopotamus fat—Nile whips—Recovery of a manuscript—Character of the Nubians—Nubian superstitions—Strife in the Egyptian camp | 289 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Fresh wanderings—Dyoor remedy for wounds—Crocodiles in the Ghetty—Former residence of Miss Tinné—Dirt and disorder—The Baggara-Rizegat—An enraged fanatic—The Pongo—Frontiers of the Bongo and Golo—A buffalo-calf shot—Idrees Wod Defter’s Seriba—Golo dialect—Corn magazines of the Golo—The Kooroo—The goats’ brook—Increasing level of land—Seebehr’s Seriba Dehm Nduggoo—Discontent of the Turks—Visit to an invalid—Ibrahim Effendi—Establishment of the Dehms—Nubians rivals to the slave-dealers—Population of Dar Ferteet—The Kredy—Overland route to Kordofan—Shekka—Copper mines of Darfoor—Raw copper | 332 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Underwood of Cycadeæ—Peculiar mills of the Kredy—Wanderings in the wilderness—Crossing the Beery—Inhospitable reception at Mangoor—Numerous brooks—Huge emporium of slave-trade—Highest point of my travels—Western limit—Gallery-woods near Dehm Gudyoo—Scorbutic attack—Dreams and their fulfilment—Courtesy of Yumma—Remnants of ancient mountain ridges—Upper course of the Pongo—Information about the far west—Great river of Dar Aboo Dinga—Barth’s investigations—Primogeniture of the Bahr-el-Arab—First giving of the weather—Elephant-hunters from Darfoor—The Sehre—Wild game around Dehm Adlan—Cultivated plants of the Sehre—Magic tuber—Deficiency of water—A night without a roof—Irrepressible good spirits of the Sehre—Lower level of the land—A[Pg vii] miniature mountain-range—Norway rats—Gigantic fig-tree in Moody—The “evil eye”—Little steppe-burning—Return to Khalil’s quarters | 373 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Katherine II.’s villages—Goods bartered by slave-traders—Agents of slave-traders—Baseness of Fakis—Horrible scene—Enthusiasm of slave-dealers—Hospitality shown to slave-dealers—Three classes of Gellahbas—Intercourse with Mofio—Price of slaves—Relative value of races—Private slaves of the Nubians—Voluntary slaves—Slave-women—The murhaga—Agricultural slave-labour—Population of the district—Five sources of the slave-trade—Repressive measures of the Government—Slave-raids of Mehemet Ali—Slow progress of humanity—Accomplishment of half the work—Egypt’s mission—No co-operation from Islamism—Regeneration of the East—Depopulation of Africa—Indignation of the traveller—Means for suppressing the slave-trade—Commissioners of slaves—Chinese immigration—Foundation and protection of great States | 410 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Tidings of war—Two months’ hunting—Yolo antelopes—Reed-rats—Habits of the Aulacodus—River-oysters—Soliman’s arrival—Advancing season—Execution of a rebel—Return to Ghattas’s Seriba—Disgusting population—Allagabo—Alarm of fire—Strange evolutions of hartebeests—Nubian cattle-raids—Traitors among the natives—Remains of Shol’s huts—Lepers and slaves—Ambiguous slave-trading—Down the Gazelle—The Balæniceps again—Dying hippopotamus—Invocation of saints—Disturbance at night—False alarm—Taken in tow—The Mudir’s camp—Crowded boats—Confiscation of slaves—Surprise in Fashoda—Slave-caravans on the bank—Arrival in Khartoom—Telegram to Berlin—Seizure of my servants—Remonstrance with the Pasha—Mortality in the fever season—Tikkitikki’s death—Θάλαττα. θάλαττα. | 443 |

[Pg viii]

[Pg ix]

(ENGRAVED BY J. D. COOPER.)

| PAGE | |

| King Munza in full dress | Frontispiece |

| Remarkable head-dress of the Niam-niam | 7 |

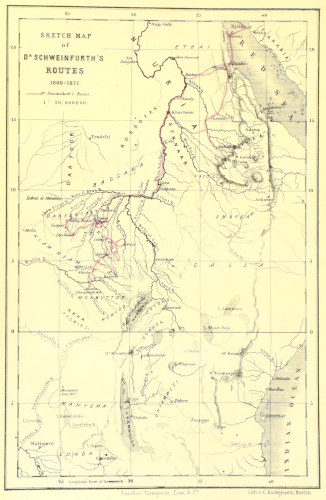

| Knives, scimitars, trumbashes, and shield of the Niam-niam | 10 |

| Niam-niam warrior | 11 |

| Niam-niam warriors | to face 12 |

| Clay pipes of the Niam-niam | 14 |

| Niam-niam dog | 15 |

| Niam-niam granary | 20 |

| Bamogee: or hut for the boys | 21 |

| Niam-niam handicraft | 26 |

| Munza’s residence | to face 63 |

| Breed of cattle from the Maoggoo country | 64 |

| Goat of the Momvoo | 69 |

| King Munza dancing before his wives | to face 74 |

| King Munza’s dish | 79 |

| Monbuttoo warriors | 103 |

| Monbuttoo woman | 105 |

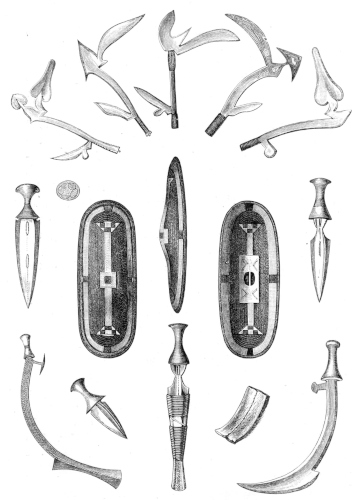

| Weapons of the Monbuttoo | 107 |

| Spear-heads | 111 |

| Hatchet, spade, and adze, of the Monbuttoo | 112 |

| Wooden kettle-drum | 113 |

| Single seat used by the women | 114 |

| Seat-rest | 115 |

| Water-bottles | 116 |

| Bomby the Akka | 130 |

| Nsewue the Akka | 134 |

| Dinka pipe | 146 |

| View on the Keebaly, near Kubby | to face 158 |

| A gallery-forest | to face 166[Pg x] |

| Mohammed defies his enemies | to face 177 |

| Our daily life in camp | to face 194 |

| Suspension-bridge over the Tondy | to face 244 |

| Horns of Central African Eland | 249 |

| Golo woman | 350 |

| Corn-magazine of the Golo | 352 |

| Kredy hut | 375 |

| Interior of Kredy hut | 376 |

| “Karra,” the magic tuber | 399 |

| A Bongo concert | 404 |

| Slave-traders from Kordofan | to face 410 |

| Babuckur slave | 420 |

| Slave at work | 424 |

| Hunting reed-rats | 447 |

| Far-el-boos. (Aulacodus Swinderianus) | 449 |

| Bongo village, near Geer | to face 461 |

[double-click image to enlarge]

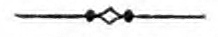

SKETCH MAP OF Dᴿ SCHWEINFURTH’S ROUTES 1868-1871.

London. Sampson Low & Cᵒ. Lith. v. C. Korbgeweit, Berlin.

[Pg 1]

The Niam-niam. Signification of the name. General characteristics. Distinct nationality. Complexion and tattooing. Time spent on hair-dressing. Frisure à la gloire. Favourite adornments. Weapons. Soldierly bearing. A nation of hunters. Women agriculturists. The best beer in Africa. Cultivated plants. Domestic animals. Dogs. Preparation of maize. Cannibalism. Analogy with the Fans of the West Coast. Architecture. Power of the princes. Their households. Events during war. Immunity of the white man. Wanton destruction of elephants. Bait for wild-fowl. Arts and manufactures. Forms of greeting. Position of the women. An African pastime. Musical taste. Professional jesters and minstrels. Praying machine. Auguries. Mourning for the dead. Disposal of the dead. Genealogical table of Niam-niam princes.

Long before Mehemet Ali, by despatching his expeditions up the White Nile, had made any important advance into the interior of the unknown continent—before even a single sailing vessel had ever penetrated the grass-barriers of the Gazelle—at a time when European travellers had never ventured to pass the frontiers of that portion of Central Africa which is subject to Islamism—whilst the heathen negro countries of the Soudan were only beginning to dawn like remote nebulæ on the undefined horizon of our geographical knowledge—tradition had already been circulated about the existence of a people with whose name the Mohammedans of the Soudan were accustomed to associate all the savagery which could be conjured up by a fertile imagination. The comparison might be suggested that just as[Pg 2] at the present day, in civilised Europe, questions concerning the descent of men from apes form a subject of ordinary conversation, so at that time in the Soudan did the Niam-niam (under the supposition that they were graced with tails) serve as common ground for all ideas that pertained to the origin of man. This people, whose existence was evoked from the mysterious hordes of witches and goblins, might have vanished amidst the dim obscurity of the primeval forests if it had not been that Alexandre Dumas, in his tale of ‘l’Homme à Queue,’ so rich in its charming simplicity, had, exactly at the right moment, raised a small memorial which contributed to its preservation.

To lift in a measure the veil which had enveloped the Niam-niam with this legendary and magic mystery fell to the lot of my predecessor Piaggia, that straightforward and intrepid Italian who, animated by the desire of opening up some reliable insight into their real habits, had resided alone for a whole year amongst them.[1]

I reckon it my own good fortune that I was so soon to follow him into the very midst of this cannibal population. It was indeed a period of transition from the age of tradition to that of positive knowledge, but I have no hesitation in asserting that these Niam-niam, apart from some specialities which will always appertain to the human race so long as it hangs unconsciously upon the breast of its great mother Nature, are men of like passions with ourselves, equally subject to the same sentiments of grief and joy. I have interchanged with them many a jest, and I have participated in their child-like sports, enlivened by the animating beating of their war-drums or by the simple strains of their mandolins.

[Pg 3]

The name Niam-niam[2] is borrowed from the dialect of the Dinka, and means “eaters,” or rather “great eaters,” manifestly betokening a reference to the cannibal propensities of the people. This designation has been so universally incorporated into the Arabic of the Soudan, that it seems unadvisable to substitute for it the word “Zandey,” the name by which the people are known amongst themselves. Since among the Mohammedans of the Soudan the term Niam-niam (plur. Niamah-niam) is principally associated with the idea of cannibalism, the same designation is sometimes applied by them to other nations who have nothing in common with the true Niam-niam, or “Zandey,” except the one characteristic of a predilection for eating human flesh. The neighbouring nations have a variety of appellations to denote them. The Bongo on the north sometimes call them Mundo, and sometimes Manyanya; in the country behind these are the Dyoor, who uniformly speak of them as the O-Madyaka; the tribe of the Mittoo on the east give them the name of the Makkarakka, or Kakkarakka; the Golo style them Kunda; whilst among the Monbuttoo they are known as Babungera.

The greater part of the Niam-niam country lies between the fourth and sixth parallels of north latitude, and a line drawn across the centre from east to west would correspond with the watershed between the basins of the Nile and Tsad. My own travels were confined exclusively to the eastern portion of the country, which, as far as I could understand, is bounded in that direction by the upper course of the Tondy; but in that district alone I became acquainted with as many as thirty-five independent chieftains who rule over the portion of Niam-niam territory that is traversed by the trading companies from Khartoom.

Of the extent of the country towards the west I was unable[Pg 4] to gain any definite information; but as far as the land is known to the Nubians it would appear to cover between five and six degrees of longitude, and must embrace an area of about 48,000 square miles. The population of the known regions is at least two millions, an estimate based upon the number of armed men at the disposal of the chieftains through whose territory I travelled, and upon the corresponding reports of the fighting force in the western districts.

No traveller could possibly find himself for the first time surrounded by a group of true Niam-niam without being almost forced to confess that all he had hitherto witnessed amongst the various races of Africa was comparatively tame and uninteresting, so remarkable is the aspect of this savage people. No one, after observing the promiscuous intermingling of races which (in singular contrast to the uniformity of the soil) prevails throughout the entire district of the Gazelle, could fail to be struck by the pronounced characteristics of the Niam-niam, which make them capable of being identified at the first glance amidst the whole series of African races. As a proof of this, I may introduce a case in point. I was engaged one day in taking the measurements of a troop of Bongo bearers, when at once I detected that the leader of the band had all the characteristics of the Niam-niam type. I asked him how it happened that he was a “nyare,” i.e., a local overseer, among the Bongo, when the mere shape of his head declared him, beyond a doubt, to be a Niam-niam. To the amazement of all who were present he replied that he was born of Niam-niam parents, but that it had been his fate when a child to be conveyed into the country of the Bongo. This is an example which serves to demonstrate how striking are the distinctions which enable an observer to carry out the diagnosis of a negro with such certainty, and to arrive at conclusions which ordinarily could only be conjectured by noticing his apparel or some external and accidental adornments.

[Pg 5]

I propose in the present chapter to give a brief summary of the characteristics of this Niam-niam people, and shall hope so to explain the general features of their physiological and osteological aspect, and so to describe the details of their costume and ornaments, that I may not fail in my desire to convey a tolerably correct impression of this most striking race.

The round broad heads of the Niam-niam, of which the proportions may be ranked among the lowest rank of brachycephaly, are covered with the thick frizzly hair of what are termed the true negroes; this is of an extraordinary length, and arranged in long plaits and tufts flowing over the shoulders and sometimes falling as low as the waist. The eyes, almond-shaped and somewhat sloping, are shaded with thick, sharply-defined brows, and are of remarkable size and fulness; the wide space between them testifies to the unusual width of the skull, and contributes a mingled expression of animal ferocity, warlike resolution, and ingenuous candour. A flat square nose, a mouth of about the same width as the nose, with very thick lips, a round chin, and full plump cheeks, complete the countenance, which may be described as circular in its general contour.

The body of the Niam-niam is ordinarily inclined to be fat, but it does not commonly exhibit much muscular strength. The average height does not exceed that of Europeans, a stature of 5 feet 10½ inches being the tallest that I measured. The upper part of the figure is long in proportion to the legs, and this peculiarity gives a strange character to their movements, although it does not impede their agility in their war dances.

The skin in colour is in no way remarkable. Like that of the Bongo, it may be compared to the dull hue of a cake of chocolate. Among the women, detached instances may be found of various shades of a copper-coloured complexion, but the ground-tint is always the same—an earthy red, in contrast to the bronze tint of the true Ethiopian (Kushitic)[Pg 6] races of Nubia. As marks of nationality, all the “Zandey” score themselves with three or four tattooed squares filled up with dots; they place these indiscriminately upon the forehead, the temples, or the cheeks. They have, moreover, a figure like the letter X under the breasts; and in some exceptional cases they tattoo the bosom and upper parts of the arm with a variety of patterns, either stripes, or dotted lines, or zigzags. No mutilation of the body is practised by either sex, but this remark must be subject to the one exception that they fall in with the custom, common to the whole of Central Africa, of filing the incisor teeth to a point, for the purpose of effectually griping the arm of an adversary either in wrestling or in single combat.

On rare occasions, a piece of material made from the bark of the Urostigma is worn as clothing; but, as a general rule, the entire costume is composed of skins, which are fastened to a girdle and form a picturesque drapery about the loins. The finest and most variegated skins are chosen for this purpose, those of the genet and colobus being held in the highest estimation; the long black tail of the quereza monkey (Colobus) is also fastened to the dress. Only chieftains and members of royal blood have the privilege of covering the head with a skin, that of the serval being most generally designated for this honour. In crossing the dewy steppes in the early morning during the rainy season, the men are accustomed to wear a large antelope hide, which is fastened round the neck, and, falling to the knees, effectually protects the body from the cold moisture of the long grass. A covering, which always struck me as very graceful, was formed from the skin of the harness bush-bock (A. scripta), of which the dazzling white stripes on a yellowish ground never fail to be very effective. The sons of chieftains wear their dress looped up on one side, so that one leg is left entirely bare.

The men take an amount of trouble in arranging their hair which is almost incredible, whilst nothing could be more[Pg 7] simple and unpretending than the ordinary head-gear of the women. It would, indeed, be a matter of some difficulty to discover any kind of plaits, tufts, or top-knots which has not already been tried by the Niam-niam men. The hair is usually parted right down the middle; towards the forehead it branches off, so as to leave a kind of triangle; from the fork which is thus formed a tuft is raised, and carried back to be fastened behind; on either side of this tuft the hair is arranged in rolls, like the ridges and crevices of a melon. Over the temples separate rolls are gathered up into knots, from which hang more tufts, twisted like cord, that fall in bunches all round the neck, three or four of the longest tresses being allowed to go free over the breast and shoulders. The women dress their hair in a simpler but somewhat similar manner, omitting the long plaits and tufts. The most peculiar head-gear that I saw was upon some men who[Pg 8] came from the territory of Keefa, and of this a representation is given in the accompanying portrait. These people reminded me very much of the description given by Livingstone of the Balonda, that people of Londa, on the Zambesi, which he came across during his first journey. The head is encircled by a series of rays like the glory which adorns the likeness of a saint. This circle is composed entirely of the man’s own hair, single tresses being taken from all parts of the head and stretched tightly over a hoop, which is ornamented with cowries. The hoop is fastened to the lower rim of a straw hat by means of four wires, which are drawn out before the men lie down to sleep, when the whole arrangement admits of being folded back. This elaborate coiffure demands great attention, and much time must be devoted to it every day. It is only the men who wear any covering at all upon their head: they use a cylindrical hat without any brim, square at the top and always ornamented with a waving plume of feathers; the hat is fastened on by large hair-pins, made either of iron, copper, or ivory, and tipped with crescents, tridents, knobs, and various other devices.

A very favourite decoration is formed out of the incisor teeth of a dog strung together under the hair, and hanging along the forehead like a fringe. The teeth of different rodentia likewise are arranged as ornaments that resemble strings of coral. Another ornament, far from uncommon, is cut out of ivory in imitation of lions’ teeth, and arranged in a radial fashion all over the breast, the effect of the white substance in contrast with the dark skin being very striking. Altogether the decoration may be considered as imposing as the pointed collar of the days of chivalry, and is quite in character with the warlike nation who find their pastime in hunting. Glass beads are held in far less estimation by the Niam-niam than by the neighbouring races; and only that lazuli blue sort which I have mentioned[Pg 9] as known in the Khartoom market by the name of “mandyoor” finds any favour at all amongst them. Cowries are often used to trim the girdles as well as the head-gear.

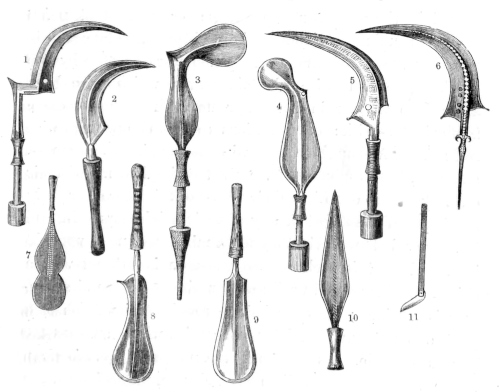

The principal weapons of the Niam-niam are their lances and their trumbashes. The word “trumbash,” which has been incorporated into the Arabic of the Soudan, is the term employed in Sennaar to denote generally all the varieties of missiles that are used by the negro races; it should, however, properly be applied solely to that sharp flat projectile of wood, a kind of boomerang, which is used for killing birds or hares, or any small game: when the weapon is made of iron, it is called “kulbeda.” The trumbash of the Niam-niam[3] consists ordinarily of several limbs of iron, with pointed prongs and sharp edges. Iron missiles very similar in their shape are found among the tribes of the Tsad basin; and a weapon constructed on the same principle, the “changer manger,” is in use among the Marghy and the Musgoo.

The trumbashes are always attached to the inside of the shields, which are woven from the Spanish reed, and are of a long oval form, covering two-thirds of the body; they are ornamented with black and white crosses or other devices, and are so light that they do not in the least impede the combatants in their wild leaps. An expert Niam-niam, by jumping up for a moment, can protect his feet from the flying missiles of his adversary. Bows and arrows, which, as handled by the Bongo, give them a certain advantage, are not in common use among the Niam-niam, who possess a peculiar weapon of attack in their singular knives, that have blades like sickles. The Monbuttoo, who are far more skilful smiths than the Niam-niam, supply them with most of these weapons, receiving[Pg 10] in return a heavy kind of lance, that is adapted for the elephant and buffalo chase.

Knives, scimitars, trumbashes, and shield of the Niam-niam.

(The shield is represented in three different positions.)

[Pg 11]

Such are the details with which I present the reader with my portrait of the Niam-niam in his full accoutrement of war. With his lance in one hand, his woven shield and trumbash in the other—with his scimitar in his girdle, and his loins encircled by a skin, to which are attached the tails of several animals—adorned on his breast and on his forehead by strings of teeth, the trophies of war or of the chase—his long hair floating freely over his neck and shoulders—his large keen eyes gleaming from beneath his[Pg 12] heavy brow—his white and pointed teeth shining from between his parted lips—he advances with a firm and defiant bearing, so that the stranger as he gazes upon him may well behold, in this true son of the African wilderness, every attribute of the wildest savagery that may be conjured up by the boldest flight of fancy. It is therefore by no means difficult to account for the deep impression made by the Niam-niam on the fantastic imagination of the Soudan Arabs. I have seen the wild Bishareen and other Bedouins of the Nubian deserts; I have gazed with admiration upon the stately war-dress of the Abyssinians; I have been riveted with surprise at the supple forms of the mounted Baggara: but nowhere, in any part of Africa, have I ever come across a people that in every attitude and every motion exhibited so thorough a mastery over all the circumstances of war or of the chase as these Niam-niam. Other nations in comparison seemed to me to fall short in the perfect ease—I might almost say, in the dramatic grace—that characterised their every movement.

In describing this people, it is hard to determine how far they ought to be designated as a nation of hunters, or one of agriculturists, the two occupations apparently being equally distributed between the two sexes. The men most studiously devote themselves to their hunting, and leave the culture of the soil to be carried on exclusively by the women. Occasionally, indeed, the men may bring home a supply of fruits, tubers and funguses from their excursions through the forests, but practically they do nothing for the support of their families beyond providing them with game. The agriculture of the Niam-niam, in contrast with that of the Bongo, involves but a small outlay of labour. The more limited area of the arable land, the larger number of inhabitants that are settled on every square mile, the greater productiveness of the soil, of which in some districts the exuberance is unsurpassed—all combine to make the[Pg 13] cultivation of the country supremely easy. The entire land is pre-eminently rich in many spontaneous products, animal and vegetable alike, that conduce to the direct maintenance of human life.

The Eleusine coracana (the “raggi” of the East Indies), a cereal which I had found only scantily propagated among the people that I have hitherto described, is here the staple of cultivation; sorghum in most districts is quite unknown, and maize is only grown in inconsiderable quantities.

Here, as in Abyssinia (where its product is called tocusso), eleusine affords a material for a very palatable beer.[4] In the Mohammedan Soudan the inhabitants, from cold fermented sorghum-dough, extract the well-known merissa; and by first warming the dough, and exercising more care and patience in the process, is made the bilbil of the Takareer; neither of these beverages, however, to our palate would be much superior to sour pap: even the booza of Egypt, made though it is from wheat, is hardly in any respect superior in quality. But the drink which by the Niam-niam is prepared from their eleusine is really capable, from the skill with which it is manipulated, of laying a fair claim to be known as beer. It is quite bright; it is of a reddish-pale brown colour, and it is regularly brewed from the malted grain, without the addition of any extraneous ingredient; it has a pleasant, bitter flavour, derived from the dark husks, which, if they were mixed in their natural condition with the dough, would impart a twang that would be exceedingly unpalatable. How large is the proportion of beer consumed by the Niam-niam may be estimated by simply observing the ordinary way in which they store their corn. As a regular rule, there are three granaries allotted to each dwelling, of which two are made [Pg 14]to suffice for the supply which is to contribute the meal necessary for the household; the other is entirely devoted to the grain that has been malted.

Manioc, sweet potatoes, yams, and colocasiæ are cultivated with little trouble, and rarely fail to yield excellent crops. Plantains are only occasionally seen in the east, and from the districts in which I travelled, I should judge that they are not a main support of life at any latitude higher than 4° N. Sugar-canes and oil-palms entirely failed in this part of the land, but I was informed that they were as plentiful in Keefa’s territory as they are among the Monbuttoo.

All the Niam-niam are tobacco-smokers. Their name for the Nicotiana tabacum is “gundey,” and they are the only people of the Bahr-el-Ghazal district that have a special designation for the plant. The other sort, N. rustica, which, on the contrary, has a local appellation in nearly every dialect of the neighbouring nations (apparently denoting[Pg 15] that the plant is indigenous to Central Africa) is utterly unknown throughout the country. The people smoke from clay pipes of peculiar form, consisting of elongated bowls without stems. Like other negro races that remain untainted by Islamism, they abstain from ever chewing the tobacco.

In broad terms, it may be stated that no cattle at all exists in the land; the only domestic animals are poultry and dogs. The dogs belong to a small breed resembling the wolfdog, but with short sleek hair; they have ears that are large and always erect, and a short curly tail like that of a young pig. They are usually of a bright yellowish tan colour, and very often have a white stripe upon the neck; their lanky[Pg 16] muzzle projects somewhat abruptly from an arched forehead; their legs are short and straight, thus demonstrating that the animals have nothing in common with the terrier breed depicted upon the walls of Egyptian temples, and of which the African origin has never been proved. Like dogs generally in the Nile district, they are deficient in the dewclaws of the hind-feet. They are made to wear little wooden bells round their necks, so that they should not be lost in the long steppe grass. After the pattern of their masters, they are inclined to be corpulent, and this propensity is encouraged as much as possible, dogs’ flesh being esteemed one of the choicest delicacies of the Niam-niam.

Cows and goats are familiar only by report, although it may happen occasionally that some are brought in as the result of raids that have been perpetrated upon the adjacent territories of the Babuckur and the Mittoo. There would hardly seem to be any specific words in the language to denote either sheep, donkeys, horses, or camels, which, according to common conception, would all come very much under the category of fabulous animals.

Although the Niam-niam have a few carefully-prepared dishes of which they partake, in a general way they exhibit as little nicety or choice in their diet as is shown by all the tribes (with the remarkable exception of the Dinka) of the Bahr-el-Ghazal district. The most palatable mess that I found amongst them was composed of the pulp of fresh maize, ground while the grain is still soft and milky, cleansed from the bran, and prepared carefully so that it was not burnt to the bottom of the pot. The mode of preparation is rather ingenious. A little water having been put over the fire till it is just beginning to boil, the raw meal, which has previously been rolled into small lumps, is very gently shaken in, and, having been allowed to simmer for a time, the whole is finally stirred up together.

The acme, however, of all earthly enjoyments would seem[Pg 17] to be meat. “Meat! meat!” is the watchword that resounds in all their campaigns. In certain places and at particular seasons the abundance of game is very large, and it might readily be imagined that the one prevailing and permanent idea of this people would be how to chase and secure their booty; but, as I have remarked before, there is no greater evidence of the real difference between the disposition of nations than that which is afforded by their general expression for food. As, for example, the Bongo verb “to eat” is “mony,” which is their ordinary designation of sorghum, their corn; so the Niam-niam word is identical with “pushyoh,” which is their common name for meat.

Just as in his investigation of the animal and vegetable kingdoms the naturalist is attracted to the very lowest organizations because they contain the germs of the higher and more complicated, in the same degree does the interest of the traveller centre upon the simplest development of culture, because he knows that it is the embryo of the most advanced civilization.

The accuracy of the report of the cannibalism which has uniformly been attributed to the Niam-niam by every nation which has had any knowledge at all of their existence, would be questioned by no one who had a fair opportunity of investigating the origin of my collection of skulls. To a general rule, of course, there may be exceptions here as elsewhere; and I own that I have heard of other travellers to the Niam-niam lands who have visited the territories of Tombo and Bazimbey, lying to the west of my route, and who have returned without having witnessed any proof of the practice. Piaggia, moreover, resided for a considerable time in those very districts, and yet was only once a witness of anything of the kind; and that, as he records, was upon the occasion of a campaign, when a slaughtered foe was devoured from actual bloodthirstiness and hatred. From my own knowledge, too, I can mention chiefs, like Wando, who[Pg 18] vehemently repudiated the idea of eating human flesh, although their constant engagement in war furnished them with ample opportunity for gratifying their taste if they desired. But still, taking all things into account, as well what I heard as what I saw, I can have no hesitation in asserting that the Niam-niam are anthropophagi; that they make no secret of their savage craving, but ostentatiously string the teeth of their victims around their necks, adorning the stakes erected beside their dwellings for the exhibition of their trophies with the skulls of the men whom they have devoured. Human fat is universally sold. When eaten in considerable quantity, this fat is presumed to have an intoxicating effect; but although I heard this stated as a fact by a number of the people, I never could discover the foundation upon which they based this strange belief.

In times of war, people of all ages, it is reported, are eaten up, more especially the aged, as forming by their helplessness an easier prey to the rapacity of a conqueror; or at any time should any lone and solitary individual die, uncared for and unheeded by relatives, he would be sure to be devoured in the very district in which he lived. In short, all who with ourselves would be consigned to the knife of the anatomist would here be disposed of by this melancholy destiny.

I have already had occasion to mention how the Nubians asserted that they knew cases in which Bongo bearers who had died from fatigue had been dug out from the graves in which they had been buried, and, according to the statements of Niam-niam themselves—who did not disown their cannibalism—there were no bodies rejected as unfit for food except those which had died from some loathsome cutaneous disease. In opposition to all this, I feel bound to record that there are some Niam-niam who turn with such aversion from any consumption of human flesh that they would[Pg 19] peremptorily refuse to eat out of the same dish with any one who was a cannibal. The Niam-niam may be said to be generally particular at their meals, and when several are drinking together they may each be observed to wipe the rim of the drinking vessel before passing it on.

Of late years our knowledge of Central Africa has been in many ways enlarged, and various well-authenticated reports of the cannibalism of some of its inhabitants have been circulated; but no explanation which can be offered for this unsolved problem of psychology (whether it be considered as a vestige of heathen worship, or whether it be regarded as a resource for supplying a deficiency of animal food) can mitigate the horror that thrills through us at every repetition of the account of the hideous and revolting custom. Among all the nations of Africa upon whom the imputation of this odious custom notoriously rests, the Fan, who dwell upon the equatorial coasts of the west, have the repute of being the greatest rivals of the Niam-niam. Eye-witnesses agree in affirming that the Fan barter their dead among themselves, and that cases have been known where corpses already buried have been disinterred in order that they might be devoured. According to their own accounts, the Fan migrated from the north-east to the western coast. In various particulars they evidently have a strong affinity with the Niam-niam. Both nations have many points of resemblance in dress and customs: alike they file their teeth to sharp points; they dress themselves in a material made from bark, and stain their bodies with red wood; the chiefs wear leopard skins as an emblem of their rank; and all the people lavish the same elaborate care upon the arrangement of their tresses. The complexion of the Fan is of the same copper-brown as that of the Niam-niam, and they indulge in similar orgies and wild dances at the period of every full moon; they moreover pursue the same restless hunter life. They would appear to be the same of whom the old[Pg 20] Portuguese writers have spoken under the name of “Yagas,” and who are said, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, to have laid waste the kingdom of Loango.

No regular towns or villages exist throughout the Niam-niam country. The huts, grouped into little hamlets, are scattered about the cultivated districts, which are separated from one another by large tracts of wilderness many miles in extent. The residence of a prince differs in no respect from that of ordinary subjects, except in the larger number of huts provided for himself and his wives. The hareem collectively is called a “bodimoh.”[5]

The architecture of the eastern Niam-niam corresponds very nearly with what may be seen in many other parts of Central Africa. The conical roofs are higher and more pointed than those of the Bongo and Dinka, having a projection beyond the clay walls of the hut, which affords a good shelter from the rain. This projection is supported by posts, which give the whole building the semblance of being surrounded by a verandah. The huts that are used for cooking have roofs still more pointed than those which serve for sleeping. Other little huts, with bell-shaped roofs, erected in a goblet-shape upon a substructure of clay, and furnished with only one[Pg 21] small aperture, are called “bamogee,” and are set apart, as being secure from the attacks of wild beasts, for sleeping-places of the boys, as soon as they are of an age to be separated from the adults.

Every sovereign prince bears the title of “Bya,” which is pronounced very much like the French word bien. His power is limited to the calling together of the men who are capable of bearing arms, to the execution in person of those condemned to death, and to determining whether there shall be peace or war. Except the ivory and the moiety of elephant’s flesh, he enjoys no other revenue; for his means of subsistence he depends upon his farms, which are worked either by his slaves or more generally by his numerous wives. Towards the west, where a flourishing slave-trade is driven to the cost of the oppressed inhabitants who are not true Zandey, a portion of the tribute is raised by a conscription of young girls and boys, a part of the purchase-money paid by the Darfoor traders to the chief being handed over to the parents who are thus robbed of their children.

Although a Niam-niam chieftain disdains external pomp and repudiates any ostentatious display, his authority in one respect is quite supreme. Without his orders no one would for a moment entertain a thought either of opening war or concluding peace. The defiant imperious bearing of the chiefs alone constitutes their outward dignity, and there are[Pg 22] some who in majestic deportment and gesture might vie with any potentate of the earth. The dread with which they inspire their subjects is incredible: it is said that for the purpose of exhibiting their power over life and death they will occasionally feign fits of passion, and that, singling out a victim from the crowd, they will throw a rope about his neck, and with their own hands cut his throat with one stroke of their jagged scimitar. This species of African “Cæsarism” vividly recalls the last days of Theodore, King of Abyssinia.

The eldest son of a chief is considered to be the heir to his title and dignity, all the other sons being entrusted with the command of the fighting forces in separate districts, and generally being assigned a certain share of the hunting booty. At the death of a chief, however, the firstborn is frequently not acknowledged by all his brothers; some of them perchance will support him, whilst others will insist upon their right to become independent rulers in the districts where they have been acting as “behnky.” Contentions of this character are continually giving rise to every kind of aggression and repeated deeds of violence.[6]

Notwithstanding the general warlike spirit displayed by the Niam-niam, it is a very singular fact that the chieftains very rarely lead their own people into actual engagement, but are accustomed, in anxious suspense, to linger about the environs of the “mbanga,” ready, in the event of tidings of defeat, to decamp with their wives and treasures into the most inaccessible swamps, or to betake themselves for concealment to the long grass of the steppes. In the heat of combat each discharge of lances is accompanied by the loudest and wildest of battle-cries, every man as he hurls his[Pg 23] weapon shouting aloud the name of his chief. In the intervals between successive attacks the combatants retire to a safe distance, and mounting any eminence that may present itself, or climbing to the summit of the hills of the white ants, which sometimes rise to a height of 12 or 15 feet, they proceed to assail their adversaries, for the hour together, in the most ludicrous manner, with every invective and every epithet of contempt and defiance they can command. During the few days that we were obliged to defend ourselves by an abattis against the attacks of the natives in Wando’s southern territory, we had ample opportunity of hearing these accumulated opprobriums. We could hear them vow that the “Turks” should perish, and declare that not one of them should quit the country alive; and then we recognised the repeated shout, “To the caldron with the Turks!” rising to the eager climax, “Meat! meat!” It was emphatically announced that there was no intention to do any injury to the white man, because he was a stranger and a new-comer to the land; but I need hardly say that, under the circumstances, I felt little inclination to throw myself upon their mercy.

It is in a measure anticipating the order of events, but I may here allude to the remarkable symbolism by which war was declared against us on the frontiers of Wando’s territory when we were upon our return journey. Close on the path, and in full view of every passenger, three objects were suspended from the branch of a tree, viz. an ear of maize, the feather of a fowl, and an arrow. The sight seemed to recall the defiant message sent to the great King of Persia, when he would penetrate to the heart of Scythia. Our guides readily comprehended, and as readily explained, the meaning of the emblems, which were designed to signify that whoever touched an ear of maize or laid his grasp upon a single fowl would assuredly be the victim of the arrow. Without waiting, however, for any depredations on our part,[Pg 24] the Niam-niam, with the basest treachery, attacked us on the following day.

In hunting, the Niam-niam employ very much the same contrivances of traps, pits, and snares as the Bongo; but their battues for securing the larger animals are conducted both more systematically and on a more extensive scale.

In close proximity to each separate group of hamlets, and more frequently than not at the threshold of the abodes of the local chieftains known as the “borrumbanga,” or “chief court,” there is always a huge wooden kettledrum, made of a hollow stem mounted upon four feet. The sides of this are of unequal thickness, so that when the drum is struck it is capable of giving two perfectly distinct sounds. According to the mode or time in which these sounds are rendered, three different signals are denoted, the first being the signal for war, another that for hunting, and the third a summons to a festival. Sounded originally in the mbanga of the chief, these signals are in a few minutes repeated on the kettledrums of the “borrumbangas” of the district, and in an incredibly short space of time some thousands of men, armed if need be, are gathered together.

Perhaps the most frequent occasions on which these assemblages are made arise from some elephants having been seen in the adjacent country. As soon as the force is collected, the elephants are driven towards some tracts of dense grass that have been purposely spared from the steppe burning. Provided with firebrands, the crowd surrounds the spot; the conflagration soon extends on all sides, until the poor brutes, choked and scorched, fall a helpless prey to their destroyers, who despatch them with their lances. Since not only the males, with their large and valuable tusks, but the females also with the young, are included in this wholesale and indiscriminate slaughter, it may easily be imagined how year by year the noble animal is fast being exterminated. The avarice of the chiefs, ever desirous of[Pg 25] copper, and the greediness of the people, ever anxious for flesh, make them all alike eager for the chase. I constantly saw the natives returning to their huts with a large bundle of what at first I imagined was firewood, but which in reality was their share of elephant-meat, which after being cut into strips and dried over a fire had all the appearance of a log of wood.

The thickets along the river-banks abound in many kinds of wild fowl, which the natives catch by means of snares. The most common are guinea-fowl and francolins, which are caught by a bait that is rather unusual in other places. Instead of scattering common corn in the neighbourhood of the traps, the people make use of fragments of a fleshy Stapelia. This little succulent grows on the dry parts of the steppe, and is frequently found about the white anthills; it is likewise naturalised in Arabia and Nubia, and in a raw condition is sometimes eaten as human food. Birds are very fond of it, and so approved is it as a bait that I not unfrequently found it growing beside the huts, where it was planted for this particular purpose.

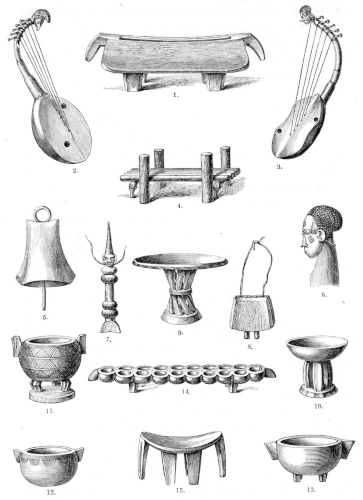

The handicraft of the Niam-niam exhibits itself chiefly in ironwork, pottery, wood carving, domestic architecture, and basket-work; of leather-dressing they know no more than others in this part of Central Africa. Their earthenware vessels may be described as of blameless symmetry. They make water-flasks of an enormous size, and manufacture pretty little drinking-cups. They lavish extraordinary care on the embellishment of their tobacco-pipes, but they have no idea of the method of giving their clay a proper consistency by washing out the particles of mica and by adding a small quantity of sand. From the soft wood of several of the Rubiaceæ they carve stools and benches, and produce great dishes and bowls, of which the stems and pedestals are very diversified in pattern. I saw specimens of these which were admirable works of art, and the designs[Pg 26] of which were so complicated that they must have cost the inventor considerable thought.

Niam-niam handicraft.

| 1. Wooden signal drum. | 6. Carved head for the neck of | 9, 10, 11, 12, 13. Wooden dishes. |

| 2 and 3. Mandolins. | a mandolin. | 14. Mungala-board. |

| 4. Bedstead. | 7. Carved signal-pipe. | 15. Wooden stool. |

| 5. Iron bell. | 8. Wooden dog-bell. |

[Pg 27] As every Niam-niam soldier carries a lance, trumbash, and dagger, the manufacture of these weapons necessarily employs a large number of smiths, who vie with each other in producing the greatest variety of form. The dagger is worn in a sheath of skin attached to the girdle. The lance-tips differ from those of the Bongo in having a hastate shape, to use once more the botanical term which distinguishes the folia hastata from the folia lanceolata. Every weapon bears so decidedly the stamp of its nationality that its origin is discoverable at a glance. All the lances, knives, and dagger-blades are distinguished by blood-grooves, which are not to be observed upon the corresponding weapons of either the Bongo or Dyoor.

Mutual greetings among the Niam-niam may be said to be almost stereotyped in phrase. Any one meeting another on the way would be sure to say “muiyette;” but if they were indoors, they would salute each other by saying “mookenote” or “mookenow.” Their expression for farewell is “minahpatiroh;” and when, under any suspicious circumstances, they wish to give assurance of a friendly intention, they make use of the expression “badya, badya, muie” (friend, good friend, come hither). They always extend their right hands on meeting, and join them in such a way that the two middle fingers crack again; and while they are shaking hands they nod at each other with a strange movement, which to our Western ideas looks like a gesture of repulse. The women, ever retiring in their habits, are not accustomed to be greeted on the road by any with whom they are not previously intimate.

No wooing in this country is dependent, as elsewhere in Africa, upon a payment exacted from the suitor by the father of the intended bride. When a man resolves upon matrimony, the ordinary rule would be for him to apply to[Pg 28] the reigning prince, or to the sub-chieftain, who would at once endeavour to procure him such a wife as might appear suitable. In spite of the prosaic and matter-of-fact proceeding, and notwithstanding the unlimited polygamy which prevails throughout the land, the marriage-bond loses nothing of the sacredness of its liabilities, and unfaithfulness is generally punished with immediate death. A family of children is reckoned as the best evidence and seal of conjugal affection, and to be the mother of many children is always recognised as a claim to distinction and honour. It is one of the fine traits of this people that they exhibit a deep and consistent affection for their wives, and I shall have occasion in a future chapter to refer to some touching instances of this feature in their character.

The festivities that are observed on the occasion of a marriage are on a very limited scale. There is a simple procession of the bride, who is conducted to the home of her future lord by the chieftain, accompanied by musicians, minstrels, and jesters.[7] A feast ensues, at which all partake in common, although, as a general rule, the women are accustomed to eat alone in their own huts. The domestic duties of a housewife consist mainly in cultivating the homestead, preparing the daily meals, painting her husband’s body, and dressing his hair. In this genial climate children require comparatively little care or attention, infants being carried about everywhere in a kind of band or scarf.

The Niam-niam have one recreation which is common to nearly the whole of Africa. A game, known by the Nubians as “mungala,” is constantly played by all the people of the entire Gazelle districts, and although perhaps it is not known by the Monbuttoo, it is quite naturalised among all the negroes as far as the West Coast. It is singular that this[Pg 29] pastime should be so familiar to the Mohammedan Nubians, who only within the last twenty years have had any intercourse at all with the negroes of the south; but in all likelihood they received it in the same way as the guitar,[8] as a legacy from their original home in Central Africa. The Peulhs devote many successive hours to the amusement, which requires a considerable facility in ready reckoning; they call it “wuri.” The game is played likewise by the Foolahs, the Yolofs, and the Mandingo, on the Senegal. It is found again among the Kadje, between the Tsad and the Benwe. The recurrence of an object even trivial as this is an evidence, in its degree, indirect and collateral, of the essential unity that underlies all African nations.

The “mungala” itself[9] is a long piece of wood, in which two parallel rows of holes are scooped out. Nubian boards have sixteen holes, the Niam-niam have eighteen. Each player has about two dozen stones, and the skill of the game consists in adroitly transferring the stones from one hole to another. In default of a board the game is frequently played upon the bare ground, in which little cavities are made for the purpose.

Having thus detailed their warlike demeanour, their domestic industry, and their common pastime, I would not omit to mention that the Niam-niam are no strangers to enjoyments of a more refined and ideal character than battles and elephant-hunts. They have an instinctive love of art. Music rejoices their very soul. The harmonies they elicit from their favourite instrument, the mandolin, seem almost to thrill through the chords of their inmost nature. The prolonged duration of some of their musical productions is very surprising. Piaggia, before me, has remarked that he believed a Niam-niam would go on playing all day and all night, without thinking to leave off either to eat or to drink;[Pg 30] and although I am quite aware of the voracious propensities of the people, I am half-inclined to believe that Piaggia was right.

One favourite instrument there is, which is something between a harp and a mandolin. It resembles the former in the vertical arrangement of its strings, whilst in common with the mandolin it has a sounding-board, a neck, and screws for tightening the strings. The sounding-board is constructed on strict acoustic principles. It has two apertures; it is carved out of wood, and on the upper side is covered by a piece of skin; the strings are tightly stretched by means of pegs, and are sometimes made of fine threads of bast, and sometimes of the wiry hairs from the tail of the giraffe. The music is very monotonous, and it is very difficult to distinguish any actual melody in it. It invariably is an accompaniment to a moaning kind of recitative, which is rendered with a decided nasal intonation. I have not unfrequently seen friends marching about arm-in-arm, wrapt in the mutual enjoyment of their performance, and beating time to every note by nodding their heads.

There is a singular class of professional musicians, who make their appearance decked out in the most fantastic way with feathers, and covered with a promiscuous array of bits of wood and roots and all the pretentious emblems of magical art, the feet of earth-pigs, the shells of tortoises, the beaks of eagles, the claws of birds, and teeth in every variety. Whenever one of this fraternity presents himself, he at once begins to recite all the details of his travels and experiences in an emphatic recitative, and never forgets to conclude by an appeal to the liberality of his audience, and to remind them that he looks for a reward either of rings of copper or of beads. Under minor differences of aspect, these men may be found nearly everywhere in Africa. Baker and some other travellers have dignified them with the romantic name of “minne-singers,” but the designation of “hashash” (buffoons)[Pg 31] bestowed upon them by the Arabs of the Soudan would more fairly describe their true character. The Niam-niam themselves exhibit the despicable light in which they regard them by calling them “nzangah,”[10] which is the same term as that by which they designate those abandoned women who pollute Africa no less than every civilized country.

The language of the Niam-niam (or, to speak more properly, the Zandey dialect), as entirely as any of the dialects which prevail throughout the Babr-el-Ghazal district, is an upshoot from the great root which is the original of every tongue in Africa north of the equator, and is especially allied to the Nubio-Lybian group. Although the pronunciation is upon the whole marked and distinct, there are still certain sounds which are subject to a considerable modification, even when uttered by the same individual. The nasal tone which is given to the open sounds of a and e as they rise from the throat fix a character upon the articulation that is quite distinct from that of the Bongo, and altogether the dialect is poorer in etymological construction, being deficient in any separate tenses for the verbs; it is, moreover, far less vocalised, and has a cumbrousness which arises from the preponderance of its consonants.

The language is undoubtedly very wanting in expressions for abstract ideas. For the Divinity I found that many interpreters would employ the word “gumbah,” which signifies “lightning,” whilst, in contrast with this, other interpreters would make use of the term “bongbottumu;” but I imagine that this latter expression is only a kind of a periphrasis of the Mohammedan “rasool” (a prophet, or messenger of God), because “mbottumu” is their ordinary term by which they would designate any common messenger or envoy.

[Pg 32]

Although none of the natives of the Gazelle district may be credited with the faintest conception of true religion, the Niam-niam have an expression of their own for “prayer” as an act of worship, such as they see it practised by the Mohammedans. This word is “borru.” When, however, the expression is examined, it is found really to relate to the augury which it is the habit of the people to consult before they enter upon any important undertaking.

The augury to which I have thus been led to refer is consulted in the following way. From the wood of the Sarcocephalus Russegeri, which they call “damma,” a little four-legged stool is made, like the benches used by the women. The upper surface of this is rendered perfectly smooth. A block of wood of the same kind is then cut, of which one end is also made quite smooth. After having wetted the top of the stool with a drop or two of water, they grasp the block and rub its smooth part backwards and forwards over the level surface with the same motion as if they were using a plane. If the wood should glide easily along, the conclusion is drawn that the undertaking in question will assuredly prosper; but if, on the other hand, the motion is obstructed and the surfaces adhere together—if, according to the Niam-niam expression, a score of men could not give free movement to the block—the warning is unmistakable that the adventure will prove a failure.

Now, since they also use this term “borru” to describe the prayers of the Mohammedans, there seems some reasonable evidence for supposing that they actually regard this rubbing as akin to a form of worship. As often as I asked any of the Niam-niam what they called prayers, they invariably replied by referring to this practice and by making the gesture which I compare to working with a plane. This praying-machine is concealed as carefully as may be from the eyes of the Mohammedans. It was, however, frequently resorted to during the subsequent brief period of warfare,[Pg 33] when my own Niam-niam attendants diligently consulted the oracle, and, as the result was uniformly satisfactory, it contributed not a little to confirm their confidence in my reputation for good luck.

There are other ordeals common to the Niam-niam with various negro nations, and which are considered as of equal or still greater importance. An oily fluid, concocted from a red wood called “bengye,” is administered to a hen. If the bird dies, there will be misfortune in war; if the bird survives, there will be victory. Another mode of trying their fortune consists in seizing a cock, and ducking its head repeatedly under water until the creature is stiff and senseless. They then leave it to itself. If it should rally, they draw an omen that is favourable to their design; whilst if it should succumb, they look for an adverse issue.

A Niam-niam could hardly be induced to go to war without first consulting the auguries, and his reliance upon their revelations is very complete. For instance, Wando, our inveterate antagonist, although he had succeeded in rousing two districts to open enmity against us, yet personally abstained from attacking our caravan, and that for no other reason than that his fowl had died after swallowing the “bengye” that had been administered. We awaited his threatened attack, and were full of surprise that he did not appear. Shortly afterwards, we were informed that he had withdrawn in fear and trembling to an inaccessible retreat in the wilderness. Our relief was considerable. It might have fared very badly with us, as all our magazines were established on his route; but, happily, he had gone, and the Niam-niam with whom we were brought in contact stoutly maintained that it was the death of his fowl alone which had deterred him from an assault and had rescued us from entire destruction.

These auguries are consulted likewise in order to ascertain[Pg 34] the guilt or innocence of any that are accused, and suspected witches are tried by the same ordeal.

The same belief in evil spirits and goblins which prevails among the Bongo and other people of Central Africa is found here. The forest is uniformly supposed to be the abode of the hostile agencies, and the rustling of the foliage is imagined to be their mysterious dialogue. Superstition, like natural religion, is a child of the soil, and germinating like the flowers of the field it unfolds its inmost secrets. Beneath the dull leaden skies of the distant North there are believed to be structures haunted by ghosts and spectres. Here the forest, with its tenantry of owls and bats, is held to be the abode of malignant spirits; whilst betwixt both are the Oriental nations, who, without forests, and exposed to the full strength of a blazing sun, fear nothing so much as “the evil eye.” Truly it may be averred that the development of superstition is dependent upon geographical position.

In thus recapitulating the general characteristics of the Niam-niam, this chapter necessarily has exhibited some measure of repetition. I will proceed to conclude it, in the same manner as the record of the Bongo, by a few remarks upon the customs of this people with regard to their dead.

Whenever a Niam-niam has lost any very near relative the first token of his bereavement is shown by his shaving his head. His elaborate coiffure—that which had been his pride and his delight, the labour of devoted conjugal hands—is all ruthlessly destroyed, the tufts, the braids, the tresses being scattered far and wide about the roads in the recesses of the wilderness.

A corpse is ordinarily adorned, as if for a festival, with skins and feathers. It is usually dyed with red wood. Men of rank, after being attired with their common aprons, are interred either sitting on their benches, or are enclosed in a kind of coffin, which is made from a hollow tree.

According to the prescriptions of the law of Islam, the[Pg 35] earth is not thrown upon the corpse, which is placed in a cavity that has been partitioned off at the side of the grave. This is a practice mentioned before, and which is followed in many heathen parts of Africa.

Like the Bongo, the Niam-niam bury their dead with a scrupulous regard to the points of the compass; but it is remarkable that they reverse the rule, the men in their sepulture being deposited with their faces towards the east, the women towards the west.

A grave is covered in with clay, which is thoroughly stamped down. Over the spot a hut is erected, in no respect differing externally from the huts of the living, and being equally perishable in its construction, it very soon either rots away through neglect or is destroyed in the annual conflagration of the steppe-burning.

[Pg 36]

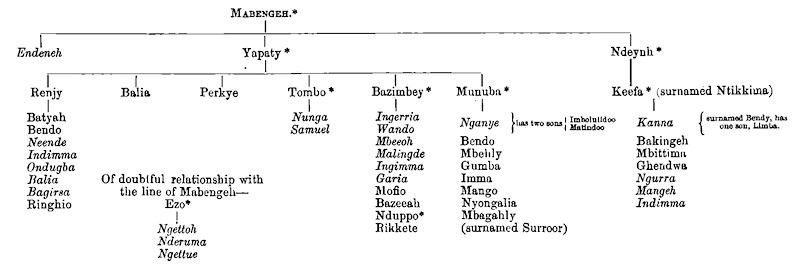

Genealogical Table of the Reigning Niam-niam Princes in 1870.

Note.—The names of reigning princes are printed in italics. The names of deceased princes are marked thus *.

[1] In the ‘Bolletino della Soc. Geogr. Italiana,’ 1868, pp. 91-168, the Marquis O. Antinori has, from the verbal communications of the traveller himself, most conscientiously collected Piaggia’s experiences and observations in the country of the Niam-niam during his residence.

[2] It should again be mentioned that the word Niam-niam is a dissyllable, and has the Italian pronunciation of Gnam-gnam.

[3] The accompanying illustration (page 10) gives examples of five different forms of trumbash.

[4] The brewing of beer from malted eleusine is practised in many of the heathen negro countries; and in South Africa the Makalaka, a branch of the great Bantoo race, are said to devote a considerable attention to it.

[5] “Bodimoh,” in the Zandey dialect, has also the meaning of “papyrus.”

[6] Of the thirty-five chieftains who rule over these 48,000 square miles of territory, comparatively few in any way merit the designation of king. The most powerful are Kanna and Mofio, whose dominions are in extent equal to about a dozen of the others.

[7] Among the Kaffirs the ceremony of conducting a bride to her new home is observed with much formality.

[8] Vide vol. i. chap. ix.

[9] A mungala board is represented in Fig. 14 of the plate illustrating Niam-niam handicraft.

[10] In Loango all exorcists and conjurors are called “ganga,” an appellation which would appear to have the same derivation as this Zandey word “nzangah.” The “Griots” in Senegambia are held in the same contempt as the Niam-niam minstrels.

Mohammed’s friendship for Munza. Invitation to an audience. Solemn escort to the royal halls. Waiting for the King. Architecture of the halls. Grand display of ornamental weapons. Fantastic attire of the sovereign. Features and expression. Stolid composure. Offering gifts. Toilette of Munza’s wives. The king’s mode of smoking. Use of the cola-nut. Musical performances, Court fool. Court eunuch. Munza’s oration. Monbuttoo hymn. Munza’s gratitude. A present of a house. Curiosity of natives. Skull-market. Niam-niam envoys. Fair complexion of natives. Visit from Munza’s wives. Triumphal procession. A bath under surveillance. Discovery of the sword-bean. Munza’s castle and private apartments. Reserve on geographical subjects. Non-existence of Piaggia’s lake. My dog exchanged for a pygmy. Goats of the Momvoo. Extract of meat. Khartoomers’ stations in Monbuttoo country. Mohammed’s plan for proceeding southwards. Temptation to penetrate farther towards interior. Money and good fortune. Great festival. Cæsar dances, Munza’s visits. The Guinea-hog. My washing-tub.

Munza was impatiently awaiting the arrival of the Khartoomers. His storehouses were piled to the full with ivory, the hunting booty of an entire year, which he was eager to exchange for the produce of the north or to see replaced by new supplies of the red ringing metal which should flow into his treasury.

This was Mohammed’s third visit to the country, and not only interested motives prompted the king to receive him warmly, but real attachment; for the two had mutually pledged their friendship in their blood, and called each other by the name of brother. During his absence in Khartoom, Mohammed had entrusted the command of the expedition of the previous year to his brother Abd-el-fetah, a Mussulman of the purest water and a hypocritical fanatic, who had greatly offended[Pg 38] the king by his arrogance and unsympathetic reserve. He considered himself defiled by contact with a “Kaffir,” and would not allow a nigger to approach within ten steps of his person; he refused to acknowledge either African king or prince, and always designated the ladies of the court as slaves. But Mohammed was entirely different. By all the natives he was known by his unassuming title of “Mbahly,” i.e., the little one, and in all his dealings with them he was urbanity itself. He won every heart by adopting the national costume, and attired in his native rokko-coat and scarlet plume, he would sit for hours together over the brimming beer-flasks by the side of his royal confrère, recounting to him all the wonders of the world and twitting him with his cannibal propensities. No wonder then that Munza’s daily question to Mohammed’s people had been: “When will Mbahly come?” and no wonder that, as we were preparing to cross the great river, his envoys had met us with a cordial greeting for his friend. Nor was the attachment all on Munza’s side. Immediately on our arrival, Mohammed, leaving the organization of our encampment entirely to the discretion of his lieutenants, had gathered up his store of presents, and hastened to convey them to the king. The greater part of these offerings consisted of huge copper dishes, not destined, however, in this remote corner of the globe to be relegated to the kitchen, but to be employed for the far more dignified office of furnishing music for the royal halls. The interview was long, and our large encampment was complete and night was rapidly approaching before Mohammed returned to his quarters. He came accompanied by the triumphal strain of horns and kettle-drums, and attended by thousands of natives bearing the ample store of provisions which, at the king’s commands, had been instantly forthcoming. He announced that I was invited to an audience of the king on the following morning, and that a state reception was to be prepared in honour of my visit. It need[Pg 39] hardly be said that it was with feelings of wonder and curiosity that I lay down that night to rest.

The 22nd of March, 1870, was the memorable date on which my introduction to the king occurred. Long before I was stirring, Mohammed had once more betaken himself to the royal quarters. On leaving my tent, my attention was immediately attracted to the opposite slopes, and a glance at the wide space between the king’s palace and the houses of his retinue was sufficient to assure me that unusual animation prevailed. Crowds of swarthy negroes were surging to and fro; others were hurrying along in groups, and ever and anon the wild tones of the kettle-drum could be heard even where I was standing. Munza was assembling his courtiers and inspecting his elephant-hunters, whilst from far and near streamed in the heads of households to open the ivory-mart with Mohammed, and to negotiate with him for the supply of his provisions.

Somewhat impatiently I stood awaiting my summons to the king, but it was already noon before I was informed that all arrangements were complete, and that I was at liberty to start. Mohammed’s black body-guard was sent to escort me, and his trumpeters had orders to usher me into the royal presence with a flourish of the Turkish reveille. For the occasion I had donned a solemn suit of black. I wore my unfamiliar cloth-coat, and laced up the heavy Alpine boots, that should give importance to the movements of my light figure; watch and chain were left behind, that no metal ornament might be worn about my person. With all the solemnity I could I marched along; three black squires bore my rifles and revolver, followed by a fourth with my inevitable cane-chair. Next in order, and in awestruck silence, came my Nubian servants, clad in festive garments of unspotted whiteness, and bearing in their hand the offerings that had been so long and carefully reserved for his Monbuttoo majesty.

[Pg 40]

It took us half an hour to reach the royal residence. The path descended in a gentle slope to the wooded depression of the brook, then twisted itself for a time amid the thickets of the valley, and finally once more ascended, through extensive plantain-groves, to the open court that was bounded by a wide semicircle of motley dwellings. On arrival at the low parts of the valley we found the swampy jungle-path bestrewn with the stems of fresh-hewn trees and a bridge of the same thrown across the water itself. The king could hardly have been expected to suggest such peculiar attention of his own accord, but this provisionary arrangement for keeping my feet dry was made in compliance with a kindly hint from Mohammed, who, knowing the nature of my boots, and the time expended in taking them off and on, had thus thoughtfully insured my ease and comfort; moreover, these boots were unique in the African world, and must be preserved from mud and moisture. Unfortunately all these arrangements tended to confirm the Monbuttoo in one or other of their infatuated convictions, either that my feet were like goats’ hoofs, or, according to another version, that the firm leather covering was itself an integral part of my body. The idea of goats’ feet had probably arisen from the comparison of my hair and that of a goat; and doubtless the stubbornness with which I always refused to uncover my feet for their inspection strengthened them in their suspicion.