Title: Origins of the 'Forty-five

and other papers relating to that rising

Editor: Walter Biggar Blaikie

Release date: October 1, 2023 [eBook #71772]

Language: English

Original publication: Edinburgh: Printed at the University press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society

Credits: MWS, Krista Zaleski and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

PUBLICATIONS

OF THE

SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY

SECOND SERIES

VOL.

II

ORIGINS OF THE ’FORTY-FIVE

March 1916

AND OTHER PAPERS RELATING TO THAT RISING

Edited by

WALTER BIGGAR BLAIKIE

LL.D.

EDINBURGH

Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society

1916

[Pg v]

I desire to express my thanks to the Government of the French Republic for permission to make transcripts and to print selections from State Papers preserved in the National Archives in Paris; to the Earl of Ancaster for permission to print the Drummond Castle Manuscript of Captain Daniel’s Progress; to the Earl of Galloway for Cardinal York’s Memorial to the Pope; to His Grace the Archbishop of St. Andrews for the use of papers elucidating the action of the Roman Catholic clergy in 1745; to Miss Grosett-Collins, who kindly lent me Grossett family papers; to Mrs. G. E. Forbes and Mr. Archibald Trotter of Colinton for private papers of the Lumisden family; to M. le Commandant Jean Colin of the French Army (author of Louis XV. et les Jacobites) for several valuable communications, and to Martin Haile for similar help.

To my cousin, Miss H. Tayler, joint author of The Book of the Duffs, I am indebted for transcripts of papers in the French Archives in Paris as well as for information from Duff family papers; to Miss Maria Lansdale for the transcript of the report of the Marquis d’Eguilles to Louis XV.; to Dr. W. A. Macnaughton, Stonehaven, for copies of the depositions referring to the evasion of Sir James Steuart; and to Miss Nairne, Salisbury, for the translation of Cardinal York’s Memorial.

I have also to acknowledge general help from the Hon. Evan Charteris; Mr. William Mackay, Inverness; Mr. J. K. Stewart, secretary of the Stewart Society; Mr. J. R. N. Macphail, K.C.; Mr. J. M. Bulloch, author of[Pg vi] The House of Gordon; Dr. Watson, Professor of Celtic History, Edinburgh; Mr. P. J. Anderson, Aberdeen University Library; Colonel Lachlan Forbes; the Rev. Archibald Macdonald of Kiltarlity; and the Rev. W. C. Flint of Fort Augustus.

I should be ungrateful if I did not make acknowledgment of the information I have received and made use of from five modern books—James Francis Edward, by Martin Haile; The King Over the Water, by A. Shield and Andrew Lang; The Jacobite Peerage, by the Marquis de Ruvigny; The History of Clan Gregor, by Miss Murray Macgregor; and The Clan Donald, by A. and A. Macdonald.

Lastly, I have to thank Mr. W. Forbes Gray for kindly reading and revising proofs and for other assistance; and Mr. Alex. Mill, who has most carefully prepared the Index and given me constant help in many ways.

W. B. B.

Colinton, March 1, 1916.

Page xxxix, lines 3 and 14, for ‘Excellency’ read ‘Eminence.’

Page 18, note 3, for see Appendix’ read ‘see Introduction, p. xxiii.’ [Transcriber’s note: found in footnote 140]

Page 47, note 1, for ‘John Butler’ read ‘John Boyle.’ [Transcriber’s note: found in footnote 180]

Page 113, note 3, last line, for ‘1745’ read ‘1746.’ [Transcriber’s note: found in footnote 323]

The Editor of ‘ORIGINS OF THE FORTY-FIVE’ requests members to make the following corrections:—

Page xviii, line 20, ‘September 3rd’ should be ‘September 1st.’

Page xxv, line 25, the age of Glenbucket should be ‘sixty-four,’ and at page lxi, line 6, his age should be ‘seventy-two.’

In a letter in the Stuart Papers (Windsor), from Glenbucket to Edgar, dated St. Ouen, 21 Aug. 1747, he states his age to be seventy-four.

Page 97, line 22 of note, ‘Clan Donald iii, 37,’ should be ‘iii, 337.’ [Transcriber’s note: found in footnote 301]

Page 164, note 1 [Transcriber’s note: found in footnote 388], and again in Genealogical Table, page 422, ‘Abercromby of Fettercairn’ should be ‘of Fetterneir.’

June 4, 1917.

[Pg vii]

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTION | ix |

| Papers of John Murray of Broughton | xlix |

| Memorial concerning the Highlands | liii |

| The late Rebellion in Ross and Sutherland | lv |

| The Rebellion in Aberdeen and Banff | lvii |

| Captain Daniel’s Progress | lxiv |

| Prince Charles’s Wanderings in the Hebrides | lxx |

| Narrative of Ludovick Grant of Grant | lxxiii |

| Rev. John Grant and the Grants of Sheugly | lxxvi |

| Grossett’s Memorial and Accounts | lxxviii |

| The Battles of Preston, Falkirk, and Culloden | lxxxiv |

| Papers of John Murray of Broughton found after Culloden | 3 |

| Memorial Concerning the Highlands, written by Alexander Macbean, A.M., Minister of Inverness | 71 |

| An Account of the Late Rebellion from Ross and Sutherland, written by Daniel Munro, Minister of Tain | 95 |

| Memoirs of the Rebellion in 1745 and 1746, so far as it Concerned the Counties of Aberdeen and Banff | 113 |

| A True Account of Mr. John Daniel’s Progress with Prince Charles Edward in the Years 1745 and 1746, written by himself | 167 |

| Neil Maceachain’s Narrative of the Wanderings of Prince Charles in the Hebrides | 227[Pg viii] |

| A Short Narrative of the Conduct of Ludovick Grant of Grant during the Rebellion | 269 |

| The Case of the Rev. John Grant, Minister of Urquhart; and of Alexander Grant of Sheugly in Urquhart, and James Grant, his Son | 313 |

| A Narrative of Sundry Services performed, together with an Account of Money disposed in the Service of Government during the late Rebellion, by Walter Grossett | 335 |

| Letters and Orders from the Correspondence of Walter Grossett | 379 |

| A Short Account of the Battles of Preston, Falkirk, and Culloden, by Andrew Lumisden, then Private Secretary to Prince Charles | 405 |

| APPENDICES— | |

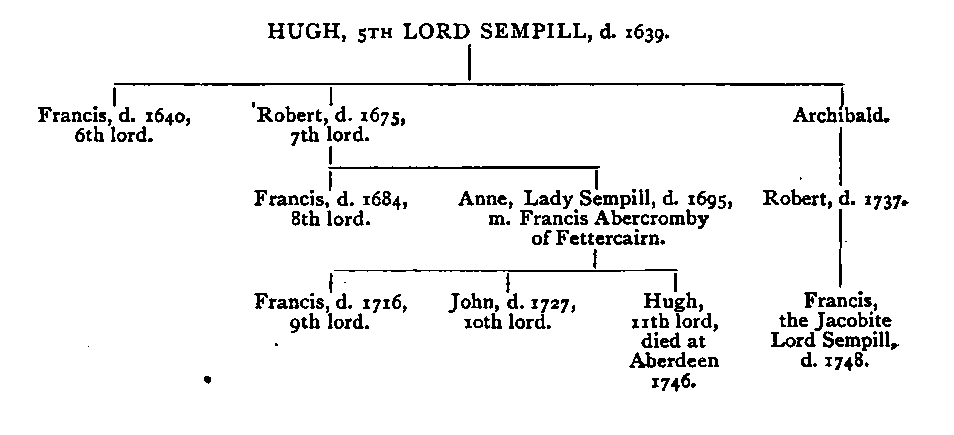

| I. The Jacobite Lord Sempill | 421 |

| II. Murray and the Bishopric of Edinburgh | 422 |

| III. Sir James Steuart | 423 |

| IV. The Guildhall Relief Fund | 429 |

| V. Cardinal York’s Memorial to the Pope | 434 |

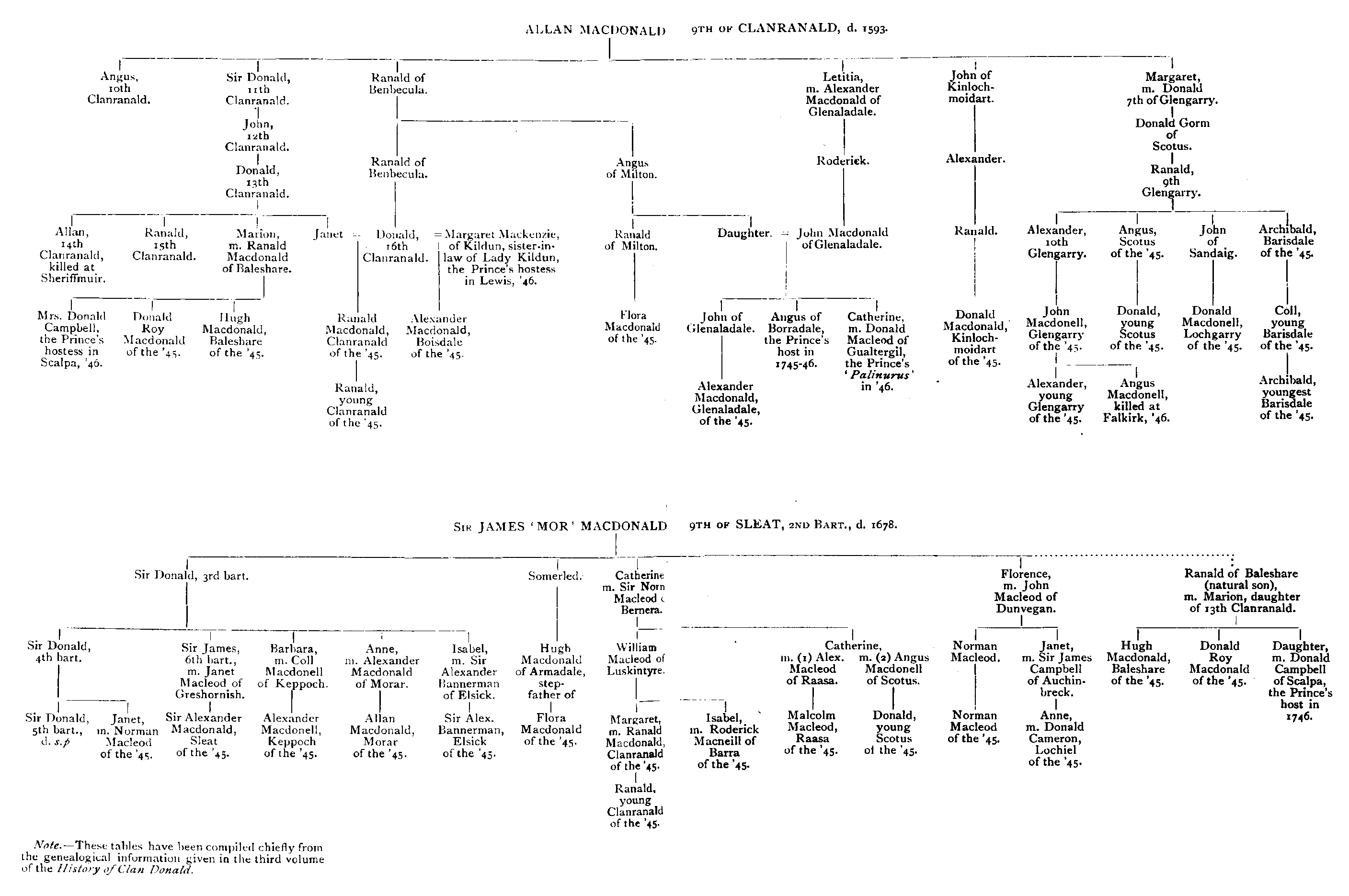

| VI. The Macdonalds | 449 |

| VII. Tables showing Kinship of Highland Chiefs | 451 |

| VIII. Lists of Highland Gentlemen who took part in the ’Forty-five | 454 |

| INDEX | 459 |

James Francis Edward, King James III. and VIII. of the Jacobites, the Old Pretender of his enemies, and the Chevalier de St. George of historians, was born at St. James’s Palace on 10th June 1688. On the landing of William of Orange and the outbreak of the Revolution, the young Prince and his mother were sent to France, arriving at Calais on 11th December (O.S.);[1] the King left England a fortnight later and landed at Ambleteuse on Christmas Day (O.S.). The château of St. Germain-en-Laye near Paris was assigned as a residence for the royal exiles, and this château was the home of the Chevalier de St. George for twenty-four years.

James II. and VII. died on 5th September 1701 (16th Sept. N.S.), and immediately on his death Louis XIV. acknowledged his son as king, and promised to further his interests to the best of his power.

The first opportunity of putting the altruistic intention of the King of France into operation occurred within a year of King James’s death, and the evil genius of the project was Simon Fraser, the notorious Lord Lovat.

Lovat, whose scandalous conduct had shocked the[Pg x] people of Scotland, was outlawed by the courts for a criminal outrage, and fled to France in the summer of 1702. There, in spite of the character he bore, he so ingratiated himself with the papal nuncio that he obtained a private audience with Louis XIV., an honour unprecedented for a foreigner. To him he unfolded a scheme for a Stuart Restoration. He had, he said, before leaving Scotland visited the principal chiefs of the Highland clans and a great number of the lords of the Lowlands along with the Earl Marischal. They were ready to take up arms and hazard their lives and fortunes for the Stuart cause, and had given him a commission to represent them in France. The foundation of his scheme was to rely on the Highlanders. They were the only inhabitants of Great Britain who had retained the habit of the use of arms, and they were ready to act at once. Lord Middleton and the Lowland Jacobites sneered at them as mere banditti and cattle-stealers, but Lovat knew that they, with an instinctive love of fighting, were capable of being formed into efficient and very hardy soldiers. He proposed that the King of France should furnish a force of 5000 French soldiers, 100,000 crowns in money, and arms and equipment for 20,000 men. The main body of troops would land at Dundee where it would be near the central Highlands, and a detachment would be sent to western Invernessshire, with the object of capturing Fort William, which overawed the western clans. The design was an excellent one, and was approved by King Louis. But before putting it into execution the ministry sent Lovat back to obtain further information, and with him they sent John Murray, a naturalised Frenchman, brother of the laird of Abercairney, who was to check Lovat’s reports.

It is characteristic of the state of the exiled Court, that it was rent with discord, and that Lord Middleton, Jacobite Secretary of State, who hated Lovat, privately[Pg xi] sent emissaries of his own to spy on him and to blight his prospects.

Lovat duly arrived in Scotland, but the history of his mission is pitiful and humiliating. He betrayed the project to the Duke of Queensberry, Queen Anne’s High Commissioner to the Scots Estates, and, by falsely suggesting the treason of Queensberry’s political enemies, the Dukes of Hamilton and Atholl, befooled that functionary into granting him a safe conduct to protect him from arrest for outlawry.

When Lovat returned to France he was arrested under a lettre de cachet and confined a close prisoner for many years, some records say in the Bastille, but Lovat himself says at Angoulême.

The whole affair had little effect in Scotland beyond compassing the disgrace of Queensberry and his temporary loss of office, but it had lasting influence in France and reacted on all future projects of Jacobite action. For, first, it instilled into the French king and his ministers the suspicious feeling that Jacobite adventurers were not entirely to be trusted. And second, Lovat’s account of the fighting quality of the Highlanders and of their devotion to the Stuarts so impressed itself on both the French Court and that of St. Germains that they felt that in the Highlands of Scotland they would ever find a point d’appui for a rising. Lovat’s report, in fact, identified the Highlanders with Jacobitism.

Scotland was the scene of the next design for a restoration, and the principal agent of the French Court was a certain Colonel Nathaniel Hooke. Hooke had been sent[Pg xii] to Scotland in the year 1705, to see if that country was in such a state as to afford a reasonable prospect of an expedition in favour of the exiled Stuart. In the year 1707, while the Union was being forced upon an unwilling population, and discontent was rife throughout the country on account of that unpopular measure, Hooke was again sent, and although not entirely satisfied with all he saw and heard, he returned with favourable accounts on the whole. Among other documents he brought with him was a Memorial of certain Scottish lords to the Chevalier, in which, among other things, it was stated that if James, under the protection of His Most Christian Majesty (Louis XIV.), would come and put himself at the head of his people in Scotland, ‘the whole nation will rise upon the arrival of its King, who will become master of Scotland without any opposition, and the present Government will be intirely abolished.’ It was some months before the French king gave any answer. St. Simon in his Memoires says that Louis XIV. was so disheartened by his previous failure that he would not at first listen to the suggestion of a French expedition; and it was only through the efforts of Madame de Maintenon that he was persuaded to sanction an invading force. Even then much time was wasted, and it was not until the spring of 1708 that a squadron was equipped under the command of the Admiral de Forbin, and a small army under the Comte de Gasse. Even when ready to sail, the constant and proverbial ill-luck of the Stuarts overtook the poor Chevalier. He caught measles, which still further delayed the expedition. By this time, naturally, the[Pg xiii] British Government had learned all about the scheme, and made their naval preparations accordingly. At last, on the 17th March, James, hardly convalescent, wrapped in blankets, was carried on board the flagship at Dunkirk. The squadron was to have proceeded to the Firth of Forth and to have landed the Chevalier at Leith, where his partisans were prepared to proclaim him king at Edinburgh. Possibly because of bad seamanship, possibly because of treachery,[4] the French admiral missed the Firth of Forth, and found himself off Montrose. He turned, and could proceed no nearer Edinburgh than the Isle of May, off which he anchored. There the British Fleet, which had followed him in close pursuit, discovered him. The admiral weighed anchor, and fought a naval action in which he lost one of his ships. He then retreated towards the north of Scotland. James implored to be set ashore even if it were only in a small boat by himself, but his solicitations were in vain. The admiral positively refused, saying that he had received instructions from the French king to be as careful of the Chevalier as if he were Louis himself; so Forbin carried him back to Dunkirk, where the heart-broken exile was landed on the 6th of April, having been absent only twenty days, and having lost one of the most likely opportunities that ever occurred for his restoration to his ancient kingdom of Scotland, if not to England.

After his return to France the Chevalier joined the French army. In 1708 he fought at Oudenarde and Lille, and the following year at Malplaquet. His gallant conduct won golden opinions from Marlborough and his troops. The[Pg xiv] British soldiers drank his health. James visited their outposts and they cheered him. What Thackeray puts into the mouth of a British officer well describes the situation: ‘If that young gentleman would but ride over to our camp, instead of Villars’s, toss up his hat and say, “Here am I, the King, who’ll follow me?” by the Lord the whole army would rise and carry him home again, and beat Villars, and take Paris by the way.’[5] But James stayed with the French, and the war ended with the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. This treaty gave the crown of Spain to the Bourbons, Gibraltar and the slave-trade to the British, and pronounced the expulsion of the Stuarts from France. A new asylum was found for the Chevalier in Lorraine, which, though an independent duchy, was largely under the domination of France. The Chevalier’s residence was fixed at Bar-le-Duc, and there he went in February 1713.

In August 1714, on the death of Queen Anne, James made a trip to Paris to be ready for action should his presence be required, but the French Government sent him back to Bar-le-Duc. The death of Louis XIV. on 1st September 1715 (N.S.) was the next blow the Jacobite cause sustained. The government of France passed to the Duke of Orleans as Regent, and his policy was friendship with the British Government.

Then came the Rising of 1715, which began at Braemar on 6th September, followed by the English rising in Northumberland under Forster. The movement in England was crushed at Preston on 13th November, the same day that the indecisive battle was fought at Sheriffmuir in Perthshire.

[Pg xv]

Lord Mar made Perth his headquarters, and invited James to join the Scottish army. The Chevalier, who had moved to Paris in October, in strict secrecy, and in disguise, being watched by both French and English agents, managed, after many remarkable adventures, checks, and disappointments, to get away from Dunkirk on 16th December (27th N.S.), and to reach Peterhead on the 22nd. Thence he went to Perth, where he established his Court at the ancient royal palace of Scone. He was proclaimed king and exercised regal functions; some authorities say that he was crowned.[7] But James had come too late; mutual disappointment was the result. He had been assured that the whole kingdom was on his side, but he found only dissension and discontent. His constant melancholy depressed his followers. No decisive action was taken; the project had failed even before he arrived, and Lord Mar persuaded him that he would serve the cause best by retiring and waiting for a happier occasion.

James was forced to leave Scotland on 5th February 1716 (O.S.). He landed at Gravelines on 10th February (21st N.S.), went secretly to Paris, and concealed himself for a week in the Bois de Boulogne. Thence he went to Lorraine, where he was sorrowfully told by the Duke that he could no longer give him shelter. The power of Britain was great; no country that gave the exile a home could avoid a quarrel with that nation. The Pope seemed to be the only possible host, and James made his way to Avignon, then papal territory. But even Avignon was too near home for the British Government, which, through the French regent, brought pressure to[Pg xvi] bear on the Pope; the Chevalier was forced to leave Avignon in February 1717, and to cross the Alps into Italy. Here for some months he wandered without a home, but in July 1717 he settled at Urbino in the Papal States.

For a time the cares of the Jacobite Court were centred on finding a wife of royal rank for the throneless king. After various unsuccessful proposals, the Chevalier became engaged to the Princess Clementina Sobieska, whose grandfather had been the warrior King of Poland. The Sobieski home was then at Ollau in Silesia; and in October 1718 James sent Colonel Hay to fetch his bride. The British Government determined to stop the marriage if possible. Pressure was put on the Emperor, who had Clementina arrested at Innsbruck while on her journey to Italy. Here the Princess remained a prisoner until the following April. The story of her rescue by Colonel Wogan is one of the romances of history, and has recently been the theme of an historical romance.[9] Wogan brought the princess safely to Bologna, and there she was married by proxy to James on 9th May 1719. While Wogan was executing his bridal mission, the Chevalier, who had almost given up hope of the marriage, had been called away to take his part in a project which seemed to augur a chance of success.

On the collapse of the rising of 1715, the Jacobite Court, despairing of assistance from France or Spain, had turned for aid to Charles XII. of Sweden. Charles had conceived a violent hatred for George I., who had acquired by purchase[Pg xvii] from the King of Denmark two secular bishoprics which had been taken from Sweden by the Danes, and which had been incorporated in the electorate of Hanover. As early as 1715 Charles listened to a project of the Duke of Berwick, by which he should send a force of Swedish troops to Scotland, but he was then too busy fighting the Danes to engage in the scheme. In 1717 the Jacobites renewed negotiations with Sweden, and a plan was formed for a general rising in England simultaneously with an invasion of Scotland by the Swedish king in person at the head of an army of 12,000 Swedes. The plot came to the knowledge of the British Government in time; the Swedish ambassador in London was arrested; the project came to nothing; but in the following year a more promising scheme for a Stuart restoration was formed.

Spain, smarting under the loss of her Italian possessions, ceded to Austria by the Peace of Utrecht, had declared war on the Emperor and had actually landed an army in Sicily. In compliance with treaty obligations, Great Britain had to defend the Emperor, and in August 1718 a British squadron engaged and destroyed a Spanish fleet off Cape Passaro. Alberoni, the Spanish minister, was furious and determined on reprisals. He entered into an alliance with the Swedish king; a plan for invading Great Britain was formed, and negotiations were opened with the Jacobite Court. The death of Charles XII. in December detached Sweden from the scheme, but Alberoni went on with his preparations. A great armada under Ormonde was to carry a Spanish army to the west of England, and a subsidiary expedition under the Earl Marischal was to land in north-western Scotland. The[Pg xviii] Chevalier was summoned to Spain to join the expedition, or failing that to follow it to England. The fleet sailed from Cadiz in March 1719. James had left Rome in February, travelling by sea to Catalonia and thence to Madrid and on to Corunna. He reached the latter port on 17th April, only to learn of the dispersal of the Spanish fleet by a storm and the complete collapse of the adventure.

The auxiliary Scottish expedition, unconscious of the disaster, landed in the north-western Highlands; but after some vicissitudes and much dissension the attempt ended with the Battle of Glenshiel on the 10th of June—the Chevalier’s thirty-first birthday—and the surrender next day of the remainder of the Spanish troops, originally three hundred and seven in number.

James returned from Corunna to Madrid, where he lingered for some time, a not very welcome guest. There he learned of the rescue of Princess Clementina and of his marriage by proxy. Returning to Italy in August, he met Clementina at Montefiascone, where he was married in person on September 1st, 1719.

From this time forward until the end of his life, forty-seven years later, the Chevalier’s home was in Rome, where the Pope assigned him the Muti Palace as a residence, along with a country house at Albano, some thirteen miles from Rome.

In 1720, on December 20th by British reckoning (Dec. 31st by the Gregorian calendar), Prince Charles Edward was born at Rome, and with the birth of an heir to the royal line, Jacobite hopes and activities revived.

At this time the Jacobite interests in England were in charge of a Council of five members, frequently termed ‘the Junta.’ The members of this Council were the Earl of Arran, brother of Ormonde, the Earl of Orrery, Lord[Pg xix] North, Lord Gower, and Francis Atterbury, Bishop of Rochester. Of these Atterbury was by far the ablest, and in England was the life and soul of Jacobite contriving. A great scheme was devised, which is known in history as the Atterbury Plot. The details are somewhat obscure, and the unravelling of them is complicated by the existence of another scheme contemporaneous with Atterbury’s, apparently at first independent, but which became merged in the larger design. The author of this plot was Christopher Layer, a barrister of the Middle Temple. Generally, his scheme was secretly to enlist broken and discharged soldiers. They were to seize the Tower, the Bank, and the Mint, and to secure the Hanoverian royal family, who were to be deported. The larger scheme of the Junta was to obtain a foreign force of 5000 troops to be landed in England under the Duke of Ormonde, and risings were to be organised in different parts of the kingdom. The signal for the outbreak was to be the departure of George I. for Hanover, which was expected to take place in the summer.

Layer, who does not seem to have been acting with Atterbury and the Junta until later, was in Rome in the early months of 1721, and there he unfolded his plan to the Jacobite Court. After he left, a plan of campaign was arranged which, however, seems to have been modified afterwards. The original intention was to begin the movement in Scotland, whither Lord Mar and General Dillon[12][Pg xx] were to proceed; and to accentuate the latter’s position as commander in Scotland he was created an earl in the Scottish peerage, although already an Irish (Jacobite) viscount. Lord Lansdowne was to command in Cornwall, Lord Strafford in the north, Lord North in London and Westminster, and Lord Arran was to go to Ireland. The Chevalier was to leave Rome when Mar and Dillon left Paris, and to make his way to Rotterdam via Frankfort, and there await events before deciding where it would be best to land. Things seemed to be prospering, but the English Jacobites did not sufficiently respond to the call for financial support. James, deeply disappointed, appealed to the Pope for help, only to be more bitterly mortified by his refusal. The Pope, in so many words, said that if the English Jacobites wanted a revolution they must pay for it themselves. The original orders for invasion were cancelled in April; but negotiations seem to have been continued with Spain through Cardinal Acquiviva, Spanish envoy at Rome, ever James’s friend. A revised plan of action was prepared. Wogan, who had been sent to Spain, had succeeded in procuring assistance from that country; ships had been prepared to carry a force of 5000 or 6000 men to Porto Longone, in the Isle of Elba, where James was to embark. In July, James was on the outlook for a Spanish fleet under Admiral Sorano.[13] But it was too late. The plot had been discovered, the demand for troops reaching the knowledge of the French ministers, who informed the British ambassador. Spain was compelled to prevent the embarkation, and King George did not go to Hanover that summer.

Mar had used the post office in spite of a warning by[Pg xxi] Atterbury not to do so; his correspondence was intercepted, and a letter was found which incriminated Atterbury and his associates. Government was not hasty in acting, and the first conspirator to be arrested was George Kelly, a Non-juring Irish clergyman who acted as Atterbury’s secretary. He was seized at his lodgings on May 21st; and he very nearly saved the situation. His papers and sword being placed in a window by his captors, Kelly managed during a moment of negligence to recover them. Holding his sword in his right hand he threatened to run through the first man who approached him, while all the time he held the incriminating papers to a candle with his left hand, and not till they were burned did he surrender. It was not until the end of August that Bishop Atterbury was taken into custody and committed to the Tower. His trial did not begin until the spring of the following year. Layer, who was betrayed by a mistress, was arrested in September and tried in November. He was condemned to death, but was respited from time to time in the hope that he would give evidence to incriminate Atterbury and his associates. Layer refused to reveal anything and was executed at Tyburn in May 1723, at the very time when the bishop’s trial was taking place in the House of Lords. Atterbury was found guilty: he was sentenced to be deprived of all his ecclesiastical benefices and functions, to be incapacitated from holding any civil offices, and to be banished from the kingdom for ever. His associates of the Junta escaped with comparatively light penalties. Kelly, sentenced to imprisonment during the King’s pleasure, was kept in the Tower until 1736, when he managed to escape, to reappear later in the drama. Atterbury went abroad and entered the Chevalier’s service. He died in exile at Paris in 1732, but he was buried in Westminster Abbey.

The failure of the schemes of Atterbury had a remarkable[Pg xxii] effect on the unfortunate Chevalier. Apparently weary of failure and longing for action, he wrote to the Pope on August 29th, 1722, offering to serve in a crusade against the Turks; but he was told it would not do, he must stick to his own task. To it he accordingly returned; and implicitly believing that his people were longing for his restoration, he issued a manifesto dated September 22nd, proposing ‘that if George I. will quietly deliver to him the throne of his fathers he will in return bestow upon George the title of king in his native dominions and invite all other states to confirm it.’[14] The manifesto was printed and circulated in England; it was ordered to be burned by the common hangman.

It is somewhat remarkable that although the Atterbury Expedition was to have been begun in Scotland, the records of the period make no mention of the project, nor do there seem to have been any preparations for a rising. The only suggestion of secret action being taken that I know of—and it is no more than a suggestion—is that in 1721, on the same day that General Dillon, who was to command in Scotland, was created a Scottish earl, a peerage was given to Sir James Grant of Grant by the Chevalier de St. George.[15] What the occasion of this honour may have been has never, so far as I know, been revealed.[16]

Jacobite affairs in Scotland at that time were administered by a Lanarkshire laird, George Lockhart of Carnwath. Lockhart had been a member of the old Scots Estates[Pg xxiii] before the Union of the kingdoms in 1707, and after the Union he sat in the Imperial Parliament until 1715. In that year he raised a troop of horse for the Jacobite cause, and after the rising he suffered a long imprisonment, but was eventually released without trial. From 1718 to 1727 he acted as the Chevalier’s chief confidential agent in Scotland. His system of Jacobite management was by a body of trustees, which was organised in 1722, and acted as a committee of regency for the exiled king. In 1727 Lockhart’s correspondence fell into the hands of Government and he had to fly the country. He was permitted to return in the following year, but lived for the rest of his life in retirement, and took no further part in Jacobite affairs.[17]

For some years after Lockhart’s flight, Scotland seems to have been without any official representative of the Jacobite Court. In May 1736, however, Colonel James Urquhart[18] was appointed, though under circumstances which have not yet been made known.

The proposed expedition connected with the Atterbury Plot was the last project for an active campaign of[Pg xxiv] restoration in which the Chevalier was personally to embark. Scheming, of course, went on, but only once after this did James leave Italy. In 1727, on the death of George I., he hurried to Nancy to be ready for any emergency, but the Duke of Lorraine had reluctantly to refuse him hospitality. He retired to Avignon, but, as before, the British Government brought pressure to bear, and he had to go back to Rome. Six years later, on the death of Augustus the Strong, he was offered the elective throne of Poland; but this he declined, saying that his own country engaged his whole heart and all his inclinations, though he regretted that his second son, Henry, then eight years old, was too young to be a candidate for the crown worn by his Sobieski ancestor.

Meanwhile his elder son, Charles Edward, was growing up, and the hopes of the party were fixed on his future. His father wished him to learn the art of war, so in August 1734 he was sent to join a Spanish army under his cousin, the Duke of Berwick,[19] who was engaged in the campaign against Austria, which brought the crown of Naples to the Spanish Bourbons. Charles, then not quite fourteen, took part in the siege and capture of Gaeta, a fortress in Campania, and accompanied Don Carlos in his triumphant entry into Naples as king on August 9th. The Prince won much credit for his conduct in the field, but this was the end of his experience of war, and his campaign had lasted only six days. His father was anxious to extend his military education, but France and Spain in turn declined to allow him to serve with their armies. Even the Emperor, about to make war on the Turks in 1737, refused to allow the young prince to accompany his army. European potentates were unwilling to receive Charles[Pg xxv] Edward even as a visitor. The Venetian minister in London was ordered to quit England on twenty-four hours’ notice, because his Government had shown civilities to the Prince on a visit to Venice. The British Government was too vigilant to hoodwink, too strong to offend. Peace reigned throughout Europe: Jacobite activity was dormant both in England and in Scotland: the royal exiles were isolated at Rome, and it seemed as if all hope of a Stuart Restoration had been abandoned.

The first to inspire the Jacobite Court with new life and hope, and set in motion the events which led up to the great adventure of ’Forty-five was John Gordon of Glenbucket. This remarkable man was no county magnate nor of any particular family. At this time he possessed no landed property; he was merely the tenant of a farm in Glenlivet, which he held from the Duke of Gordon. His designation ‘of Glenbucket’ was derived from a small property in the Don valley which had been purchased by his grandfather, and which he inherited from his father. He was not a Highlander, having been born in the Aberdeenshire lowland district of Strathbogie, but he had so thoroughly conformed himself to Highland spirit and manners that he had won the affection and confidence of the Highlanders of Banffshire and Strathspey. Glenbucket was at this time about sixty-four years old. In his younger days he had been factor or chamberlain to the Duke of Gordon, a position which conferred on him considerable influence and power, particularly over the Duke’s Highland vassals. In the ’Fifteen he had commanded a regiment of the Gordon retainers, and behaved with gallantry and discretion throughout the campaign.[20] About the year 1724 he had ceased[Pg xxvi] to be the Duke’s representative, but his connection with the Highlanders was continued by the marriages of his daughters. One of them was the wife of Forbes of Skellater, a considerable laird in the Highland district of Upper Strathdon; another was married to the great chief of Glengarry; and a third to Macdonell of Lochgarry.[21]

In the year 1737 Gordon sold Glenbucket, for which he realised twelve thousand marks (about £700); and he left Scotland to visit the Chevalier at Rome. On his way he passed through Paris, where he had an interview with Cardinal Fleury, the French prime minister. To the Cardinal he suggested a scheme of invasion, by which officers and men of the Irish regiments in the French service quartered near the coast could be suddenly and secretly transported to Scotland.[22] The Cardinal, whose general policy was peace at any price,[23] gave no encouragement to the scheme.

Glenbucket went on to Rome in January 1738: he delivered his message, was rewarded with a major-general’s commission,[24] and returned to Scotland. Immediately the Jacobite Court was filled with sanguine activity. What the terms of Glenbucket’s mission were, or whom he represented, have never been categorically stated. Murray[Pg xxvii] of Broughton hints that he only represented his son-in-law Glengarry and General Alexander Gordon.[25] Even if this limitation were true, it meant much. Glengarry was one of the greatest of Highland chiefs, while General Gordon was that Nestor of Scottish Jacobites who had been commander-in-chief after the Chevalier left Scotland in 1716, and whose opinions must have carried much weight. Although there is no direct statement of the terms of Glenbucket’s mission, its significance can readily be understood from the communication made to the English Jacobites. The Chevalier at once wrote off to Cecil, his official agent in London, informing him of the encouraging news he had received. The zeal of his Scottish subjects, he said, was so strong that he considered it possible to oppose the Scottish Highlanders to the greater part of the troops of the British Government then available, and there was good cause to hope for success even without foreign assistance, provided the English Jacobites acted rightly.[26]

At the time that the Chevalier’s message reached his adherents there happened to be in England a personage who bore the name and designation of Lord Sempill.[27] Though of Scots descent he was French by birth and residence. He was not familiar with English ways, and he did not understand English political agitation. Mingling for the most part with Jacobites avowed or secret, his ears were filled with execration of the reigning dynasty. On every side he heard the Whig Government denounced,[Pg xxviii] and he saw it tottering and vacillating. He mistook general political dissatisfaction for revolutionary discontent, and he came to the conclusion that the country longed for a restoration of the old royal line. Constituting himself an envoy from the English Jacobites,[28] he hurried off to Rome and reported to the Chevalier that the party was stronger than was generally believed, and that affairs in England were most favourable for action.

It is necessary here to relate how Glenbucket’s mission to Rome affected the Scottish Jacobites, and to introduce into the narrative the name of one who for five years was a mainstay of the Cause, though in the end he turned traitor.

John Murray of Broughton, a younger son of Sir David Murray of Stanhope (a Peeblesshire baronet of ancient family who in his day had been an ardent Jacobite), entered the University of Leyden in 1735, being then twenty years of age. In 1737 he had completed his studies and went on a visit to Rome, where he mixed in the Jacobite society of the place. Although he never had an interview with James himself, he frequently met the young princes, and he acquired the friendship of James Edgar, the Chevalier’s faithful secretary. Murray’s father had once been proposed as an official Jacobite agent in Scotland, and it seems highly probable that Edgar persuaded the son to look forward to assuming such a position. Murray left Rome to return to Scotland shortly before Glenbucket’s arrival in January 1738.

Glenbucket’s message had convinced James of the devotion of the Highlanders and the Jacobites of north-eastern Scotland, but he wished to know more of the spirit of the Scottish Lowlands. At the same time that he wrote to the English Jacobites, he despatched[Pg xxix] William Hay, a member of his household, to Scotland to make inquiries and to report. Hay overtook Murray who was lingering in Holland, and induced him to accompany him, as he was anxious to be introduced to Murray’s cousin, Lord Kenmure, an ardent Kirkcudbrightshire Jacobite. The acquaintance was duly made, and although no record is yet known of Hay’s actual transactions in Scotland, they can be conjectured with a fair amount of certainty from the results which followed them in spite of Murray’s disparaging remarks on his mission.[29] Hay visited the leading Jacobites, and it is difficult to doubt that he set in motion a scheme for concerted action. What is known is that he returned to Rome after three months’ absence greatly satisfied with what he had found. In the same year, presumably as the outcome of Hay’s mission, an Association of Jacobite leaders was formed, sometimes termed ‘the Concert,’ designed with the object of bringing together Highland chiefs and lowland nobles,[30] pledged to do everything in their power for the restoration of the exiled Stuarts. These Associators, as they were called, were: the Duke of Perth; his uncle, Lord John Drummond; Lord Lovat; Lord Linton, who in 1741 succeeded as fifth Earl of Traquair; his brother, the Hon. John Stuart; Donald Cameron, younger of Lochiel; and his father-in-law, Sir John Campbell of Auchenbreck, an Argyllshire laird. The position of manager was given to William Macgregor (or Drummond), the son of the Perthshire laird of Balhaldies.[31] In contemporary[Pg xxx] documents Macgregor[32] is generally termed ‘Balhaldy,’[33] and that designation has been used in this volume. Murray of Broughton did not belong to the Association, nor was he taken into its confidence until 1741. He, however, attached himself to Colonel Urquhart, the official Jacobite agent, and assisted him with his work. In 1740, when Urquhart was dying of cancer, Murray was appointed to succeed him.

In December 1739 Balhaldy was sent by the Associators to Paris, and from thence he went on to Rome. The Chevalier, greatly cheered by what he had to tell, instructed him to return to Paris and there to meet Sempill, who had become one of James’s most trusted agents. Sempill would introduce him to Cardinal Fleury, before whom they would lay the views of both the English and Scottish Jacobites.

Balhaldy returned to Paris, made the acquaintance of Sempill, an acquaintance which subsequently ripened into a strong political, perhaps personal, friendship. The interview with Fleury was obtained, and negotiations commenced in the beginning of 1740, about three months after the war with Spain, forced upon Walpole, had broken out.[34]

[Pg xxxi]

It is no part of my task to follow the intricacies of the negotiations between the French Ministry and the English Jacobites, except when they affect the affairs of the Scots, but here it is necessary to turn back for a moment to relate what took place after the English Jacobites received the Chevalier’s communication of Glenbucket’s message from Scotland.

Sempill, who had gone from England to Rome in the spring of 1738, was sent back in October with the Chevalier’s instructions to his English adherents to arrange for concerted action with the Scots. The English Jacobites formed a council of six members to serve as a directing nucleus. This council communicated the English views on the Scottish proposal to the Chevalier as follows. Although the Government, they said, had only 29,000 regular troops in the British Isles, of which 13,000 were in England, 12,000 in Ireland, and 4000 in Scotland, yet the rising of the Scots could not take place, as the King hoped, without foreign assistance. It would be a difficult matter to provide the Scots with sufficient arms and munitions, and even if this difficulty could be surmounted, it would take two months after they had been supplied before their army could assemble and establish the royal authority in Scotland; that it would take another month before the Scots could march into England. Meantime the English leaders would be at the mercy of the professional army of the Government which their volunteer followers, entirely ignorant of discipline, could never oppose alone. The principal royalists would be arrested in detail, and their overawed followers would hold back from joining the Scots. There were 13,000 regular soldiers in England. Government would probably transfer 6000 from Ireland, and the army would be further augmented by the importation of Dutch and Hanoverian troops. Probably 8000 men would be sent to the frontier[Pg xxxii] of Scotland. From this they concluded that a rising in Scotland without foreign assistance would involve possible failure and in any case a disastrous civil war, while, on the other hand, the landing of a body of regular troops would provide a rallying point for the insurgents. This force should be equal to the number of troops generally quartered about London and able to hold them, while the volunteer royalists would march straight to the capital which was ready to declare in their favour. They would then acquire the magazines and arsenals at the seat of government, and almost all the treasures of England (‘presque toutes les richesses d’Angleterre’). If at that juncture the Scots would rise, the Hanoverians would be driven to despair. No ally of the Elector, however powerful, would venture to attack Great Britain reunited under her legitimate sovereign. The requirement of the English would be 10,000 to 12,000 regular troops sent from abroad; without such a disciplined force the English Jacobites would not risk a rising.[35]

Sempill was sent by the Chevalier to Paris to lay these views before Cardinal Fleury. The Cardinal, peace lover though he was, felt that it would be absurd to neglect the assistance that the Jacobites might afford him in the complications which were certain to arise when the death of the Emperor Charles VI., then imminent, should occur.[36] When the English views of requirement were presented to him he received them sympathetically; said that the King of France would willingly grant the help the English Jacobites desired, but two things were absolutely necessary: he must have more exact information than had been given him with regard to what royalist adherents[Pg xxxiii] would join his troops on landing, and also as to those who would rise at the same time in the provinces. If the English leaders could satisfy His Majesty on these two points they might expect all they asked for.[37]

Such was the state of Jacobite affairs at the French Court when Sempill introduced Balhaldy to Fleury. I know of no categorical statement of the requirements that Balhaldy was to lay before the Cardinal, but from a memorandum he wrote[38] it may be inferred that the Associators had asked for 1500 men with arms, ammunition, and money. Fleury replied that his sovereign was greatly pleased with the proposals of the Scots, and that he approved of their arrangements on behalf of their legitimate king. France, however, was at peace with Great Britain, while Spain was at open war. King Louis would ask the Spanish Court to undertake an expedition in favour of King James to which he would give efficient support.[39] Shortly afterwards, the Cardinal was obliged to tell Balhaldy that Spain declined to entertain the proposal. The Spanish Court disliked the war with England, and was quite aware that it had been forced on Walpole by the Jacobites and the Opposition.[40] Spain was not going to embarrass the British Government by embarking on a Jacobite adventure.

Fleury then made a proposal that the Spanish Government should finance a scheme by which an army of 10,000 Swedish mercenaries should be engaged to invade Great Britain. While secret negotiation was going on between the French and Spanish Governments, knowledge[Pg xxxiv] of the proposal came to Elizabeth Farnese, Queen of Spain. Elizabeth, fearing that a successful movement for a Stuart restoration would put an end to the war with Great Britain which she strongly favoured, inspired a paragraph in the Amsterdam Gazette, which exploded the design before it could be accomplished.[41]

Driven at last from his hope of using Spain as a catspaw, Fleury informed Balhaldy that his master the King, touched with the zeal of the Scots, would willingly send them all the Irish troops in his service, with the arms, munitions, and the £20,000 asked for to assist the Highlanders.[42]

Balhaldy hurried back to Scotland with this promise and met the Associators in Edinburgh. Although the Jacobite leaders were disappointed that French troops were not to be sent, they gratefully accepted Fleury’s assurances, and in March 1741 they despatched the following letter to the Cardinal, which was carried back to Paris by Balhaldy.

Monseigneur,—Ayant appris de Monsieur le baron de Balhaldies l’heureux succès des représentations que nous l’avions chargé de faire à Votre Eminence sous le bon plaisir de notre souverain légitime, nous nous hâtons de renvoyer ce baron avec les témoignages de notre vive et respectueuse reconnaissance et avec les assurances les plus solennelles, tant de notre part que de la part de ceux qui se sont engagés avec nous à prendre les armes pour secouer le joug de l’usurpation, que nous sommes prêts à remplir fidèlement tout ce qui a été[Pg xxxv] avancé dans le mémoire que my lord Sempill et ledit sieur baron de Balhaldies eurent l’honneur de remettre, signé de leurs mains, entre celles de Votre Eminence au mois de mai dernier.

Les chefs de nos tribus des montagnes dont les noms lui ont été remis en même temps avec le nombre d’hommes que chacun d’eux s’est obligé de fournir,[44] persistent inviolablement dans leurs engagements et nous osons répondre à Votre Eminence qu’il y aura vingt mille hommes sur pied pour le service de notre véritable et unique seigneur, le Roi Jacques Huitième d’Ecosse aussitôt qu’il plaira à S.M.T.C. de nous envoyer des armes et des munitions avec les troupes qui sont nécessaires pour conserver ces armes jusqu’à ce que nous puissions nous assembler.

Ces vingt mille hommes pourront si facilement chasser ou détruire les troupes que le gouvernement présent entretient actuellement dans notre pays et même toutes celles qu’on y pourra faire marcher sur les premières alarmes que nous sommes assurément bien fondés d’espérer qu’avec l’assistance divine et sous les auspices du Roi Très Chrétien les fidèles Ecossais seront en état, non seulement de rétablir en très peu de temps l’autorité de leur Roi Légitime dans tout son royaume d’Ecosse et de l’y affermir contre les efforts des partisans d’Hannover, mais aussi de l’aider puissamment au recouvrement de ces autres Etats, ce qui sera d’autant plus facile que nos voisins de l’Angleterre ne sont pas moins fatigués que nous de la tyrannie odieuse sous laquelle nous gémissons tous également et que nous savons qu’ils sont très bien disposés à s’unir avec nous ou avec quelque puissance que ce soit qui voudra leur donner les recours dont ils out besoin pour se remettre sous un gouvernement légitime et naturel. Nous prenons actuellement des mesures pour agir de concert avec eux.

Quant au secours qui est nécessaire pour l’Ecosse en particulier, nous aurions souhaité que S.M.T.C. eût bien voulu nous accorder des troupes françaises qui eussent renouvelé parmi nous les leçons d’une valeur héroïque et d’une fidélité incorruptible que nos ancêtres ont tant de fois apprises dans la France même; mais puisque V.E. juge à propos de nous envoyer de sujets de notre Roi, nous les recevrons avec joie comme venant de sa part, et nous tâcherons de leur faire sentir[Pg xxxvi] le cas que nous faisons et de leur attachement à notre souverain légitime et de l’honneur qu’ils out acquis en marchant si longtemps sur les traces des meilleurs sujets et des plus braves troupes en l’Univers.

Monsieur le baron de Balhaldies connaît si parfaitement notre situation, les opérations que nous avons concertées, et tout ce qui nous regarde, qu’il serait inutile d’entrer ici dans aucun détail. Nous supplions V.E. de vouloir bien l’écouter favorablement et d’être persuadée qu’il aura l’honneur de lui tout rapporter dans la plus exacte vérité.

Si les ministres du gouvernement étaient moins jaloux de nos démarches ou moins vigilants, nous engagerions volontiers tous nos biens pour fournir aux frais de cette expédition; mais nuls contrats n’étant valables, suivant nos usages, sans être inscrits sur les registres publics, il nous est impossible de lever une somme tant soit peu considérable avec le secret qui convient dans les circonstances présentes. C’est uniquement cette considération qui nous empêche de faire un fond pour les dépenses nécessaires, [ce qui serait une preuve ultérieure que nous donnerions avec joie de notre zèle et de la confiance avec laquelle nous nous rangeons sous l’étendard de notre Roi naturel; mais le bien du service nous oblige de nous contenir et] d’avoir recours à la générosité de S.M.T.C. jusqu’à ce que l’on puisse lever les droits royaux dans notre pays d’une manière régulière.

Nous sommes persuadés que l’on pourra y parvenir dans l’espace de trois mois après l’arrivée des troupes irlandaises et nous ne doutons point que notre patrie, réunie alors sous le gouvernement de son Roi tant désiré ne fasse des efforts qui donneront lieu à V.E. de prouver à S.M.T.C. que les Ecossais modernes sont les vrais descendants de ceux qui ont eu l’honneur d’être comptés pendant tant de siècles les plus fidèles alliés des Rois, ses prédécesseurs.

Nous sommes bien sensiblement touchés des mouvements que V.E. s’est donnés et qu’elle veut bien continuer pour faire entendre au Roi Catholique les avantages qu’il y aurait à agir en faveur du Roi notre maître dans la conjoncture présente. Nous avions cru que ces avantages ne pouvaient échapper aux ministres Espagnols; mais quelque travers qu’ils prennent dans la conduite de cette guerre, V.E. prend une part qui ne saura manquer de les en tirer heureusement et de frustrer l’attente injuste des nations qui sont prêtes à fondre sur les trésors du nouveau monde.

[Pg xxxvii]

Nous en louons Dieu, Monseigneur, et nous le prions avec ferveur de vouloir bien conserver V.E. non seulement pour l’accomplissement du grand ouvrage que nous allons entreprendre sous sa protection mais aussi pour en voir les grands et heureux effets dans toute l’Europe aussi bien que dans les trois royaumes britanniques, auxquels son nom ne sera pas moins précieux dans tous les temps à venir qu’à la France même qui a pris de si beaux accroissements sous son ministère et dont la gloire va être élevée jusqu’au comble en faisant vigorer la justice chez ses voisins. Nous avons l’honneur d’être avec une profonde vénération et un parfait dévouement, Monseigneur, de votre Eminence, les très humbles et très obéissants serviteurs,

à Edimbourg, ce 13ème Mars 1741.

[Translation.]

Having learned from the Baron of Balhaldies of the happy success of the representations that we had instructed him to make to Your Eminence, with the approval of our legitimate Sovereign, we now hasten to send this Baron back with the proofs of our lively and respectful gratitude, and with the most solemn undertaking, both by ourselves and by those who are engaged along with us, to take up arms to throw off the yoke of the usurpation, that we are ready to fulfil faithfully all that was put forward in the Memorial, which my lord Sempill and the said Baron of Balhaldies signed with their own hands, and had the honour to place in the hands of Your Eminence last May.

The chiefs of our Highland clans, whose names we have sent at the same time with the number of men that each binds himself to furnish, will without fail keep their engagements, and we venture to be responsible to Your Eminence that there will be 20,000 men on foot for the service of our true and only lord, King James VIII. of Scotland, as soon as it will please His Most Christian Majesty to send us arms and munitions, and the troops that are necessary to guard those arms until we shall be able to assemble.

These 20,000 men will be able so easily to defeat or to destroy the troops that the Government employs at present in our country, and even all those that it may be able to despatch upon the first alarm, so[Pg xxxviii] that we feel entirely justified in hoping that with divine assistance and under the auspices of the most Christian King, the loyal Scots will be in a condition, not only in a short time to re-establish the authority of their legitimate King throughout the whole Kingdom of Scotland, and to sustain him there against the efforts of the partisans of Hanover, but also to aid powerfully in the recovery of these other States, which will be all the easier since our neighbours of England are not less wearied than we are of the odious tyranny under which we all equally groan; and we know that they are thoroughly determined to unite with us, and with any power whatever that would give them the opportunity they require to place themselves once more under a legitimate and natural Government. We are at present taking measures to act along with them.

As to the assistance that is necessary for Scotland in particular, we should have preferred that His Most Christian Majesty might have been willing to grant us French troops, who would have renewed among us the lessons of heroic bravery and incorruptible fidelity, that our ancestors have so often learned in France itself, but since Your Eminence thinks fit to send subjects of our King, we will receive them with joy as coming from him, and we will endeavour to make them feel the value that we attach to their devotion to our legitimate Sovereign, and the honour that they have acquired in treading so long in the footsteps of the best subjects and of the bravest troops in the Universe.

The Baron of Balhaldies knows so perfectly our situation, the plans that we have concerted, and everything that affects us, that it will be unnecessary to enter into any detail. We implore Your Eminence to listen to him favourably, and to be assured that he will have the honour of reporting to you with the utmost accuracy.

If the ministers of the Government were only less suspicious of our actions or less watchful, we would willingly pledge all our belongings to defray the cost of this expedition, but as no contracts (of loan or sale) are binding by our customs unless they have been inscribed in the public registers, it is not possible for us to raise a sum that would be sufficient, with the necessary secrecy that present circumstances require. It is this consideration alone that prevents us from raising a fund for the necessary expense, the raising of which would bear further proof of our zeal, which we should give with pleasure, and of the confidence with which we place ourselves under the standard of our natural King; but the good of the service obliges us to restrain our wishes and to have recourse to the generosity of His Most Christian Majesty until it is possible to establish the royal rights in our country in a regular manner.

We are persuaded that it would be possible to accomplish this three months after the arrival of the Irish troops, and we do not doubt that our country, reunited under the Government of its king, so much desired, would make such efforts as would enable Your Excellency to prove to His Most Christian Majesty that the modern Scots are the true[Pg xxxix] descendants of those who have had the honour of being counted during so many centuries the most faithful allies of the kings, his predecessors.

We are very sensibly touched by what Your Eminence has done, and will continue to do, to make the Catholic king understand the advantages that he would have in acting in favour of the King our master in the present juncture. We had believed that these advantages could not escape the notice of the Spanish Ministers, but whatever strange things they may have done in the conduct of this war, your Eminence is now acting in such a way as cannot fail happily to extricate them from the consequences of their mistakes, and to frustrate the unjust attitude of those nations who are ready to fall upon the treasures of the new world.

We praise God, Monseigneur, and we pray with fervour that He would preserve Your Eminence, not only for the accomplishment of the great work which we are going to undertake under your protection, but also that you may see the great and happy effects throughout Europe as well as in the three kingdoms of Britain in which your name will be not less precious in all time to come than in France itself, which has been enlarged so remarkably under your ministry; and that the glory of your name will be raised to the highest pitch by making justice flourish among your neighbours. We have the Honour to be, with profound veneration and perfect devotion, Monseigneur, Your Eminence’s very humble and obedient servants.

The promises of assistance from the French Court brought by Balhaldy, and the letter of acceptance by the lords of the Concert constituted the treaty between France and the Scottish Jacobites which formed the foundation of all subsequent schemes undertaken in Scotland. Even in the end it was detachments of the Irish regiments, whose use was originally suggested by Glenbucket, together with a Scottish regiment raised later than this by Lord John Drummond, that formed the meagre support that was actually sent over from France in 1745.

Balhaldy returned to France almost immediately, and in the winter of 1740-41, he went to England where he met the Jacobite leaders, of whom he particularly mentions the Earls of Orrery and Barrymore, Sir Watkin Williams Wynne, and Sir John Hinde Cotton. With them he endeavoured to form a scheme of concert between the[Pg xl] English and the Scottish Jacobites, but without much success.[45]

It was not until after the signing of the letter to Fleury that Murray was taken into the confidence of the Jacobite leaders, and it was at this time that he first met Lord Lovat. This was also the occasion of his first meeting with Balhaldy; their relations at this time were quite friendly; Balhaldy handed over to Murray the negotiation of a delicate ecclesiastical matter with which he had been entrusted by the Chevalier.[46]

Another early duty was to raise money for the Cause, but to Murray’s mortification, he had to give up the scheme of a loan, because all the sympathisers to whom he applied declined to subscribe; not, they said, because they objected to giving their money, but each and all refused to be the first to compromise himself by heading the subscription list. At this time Murray was not permitted to undertake any active propaganda for a rising, as the associated leaders feared that by increasing the numbers in the secret there would be too great danger of leakage. The Associators preferred to keep such work in their own hands, and each of them had a district assigned to him.

After Balhaldy’s departure the unfortunate Associators were kept in a state of agonising suspense, for nothing was heard from France until the end of 1742. In December of that year, Lord Traquair received a letter from Balhaldy couched in vague terms, assuring him that troops and all things necessary for a rising would be embarked early in the spring. The scheme, he wrote, was to make a landing near Aberdeen and another in Kintyre. The whole tone of the letter was so confident that the Associators[Pg xli] felt that a French expedition might be expected almost immediately, and they were profoundly conscious that Scotland was not ready. So alarmed were the leaders at the possibility of a premature landing, and so uncertain were they about the promises vaguely conveyed in Balhaldy’s letter, that they determined to send Murray over to Paris to find out what the actual French promises were, and how they were to be performed; and moreover to warn the Government of King Louis how matters stood in Scotland.

Murray set off in January 1743. On his way he visited the Duke of Perth, then residing at York, making what friends he could among the English Jacobites. When Murray got to London, he was informed of Cardinal Fleury’s death,[47] which somewhat staggered him, but he determined to go on to France to find out how matters stood.

On arriving in Paris, Murray met Balhaldy and Sempill. Balhaldy was surprised and not particularly glad to see him, but he treated him courteously, and discussing affairs with Murray, he patronisingly informed him that he had not been told everything. Sempill was very polite. He told Murray that a scheme had been prepared by Fleury, but that the Cardinal’s illness and death had interrupted it.[48] Sempill also told him that luckily he had persuaded the Cardinal to impart his schemes to Monsieur Amelot, the Minister for Foreign Affairs. An interview with the Minister was obtained at Versailles, and on Murray’s explaining the reason of his visit, Amelot frankly told him[Pg xlii] that the King of France had full confidence in the Scots, but that nothing could be done without co-operation with the English. He further warned the Scotsmen that an enterprise such as they proposed was dangerous and precarious. The King, he said, was quite willing to send ten thousand troops to help James his master, but the Jacobites must take care not to bring ruin on the Cause by a rash attempt. Murray was startled at Amelot’s answer after the assurances he had had from Sempill and Balhaldy of the minister’s keenness to help; he was further distressed that some arrangements, which Sempill had confidently mentioned to him as being made, were unknown to Amelot, while the minister owned that he had not read the Memorials, but promised to look into them.

It was on this occasion that Murray first became suspicious of the behaviour of Balhaldy and Sempill, a state of mind which grew later to absolute frenzy. When arranging for the interview with Amelot, they hinted very plainly to Murray that he must exaggerate any accounts he gave of preparations in Scotland. He came to the conclusion that they were deceiving the French minister by overstating Jacobite prospects at home, and after the interview he was further persuaded that Balhaldy and Sempill were similarly deceiving the Jacobite leaders with exaggerated accounts of French promises. He was further mortified to find that the Earl Marischal, who was much respected in Scotland, and to whom the Jacobite Scotsmen looked as their leader in any rising, would have nothing to do with Sempill and Balhaldy; while, on their part, they described the earl as a wrong-headed man, continually setting himself in opposition to his master and those employed by him, and applied to him the epithet of ‘honourable fool.’

Apparently about this time the preparations of the English Jacobites were languishing, and Balhaldy, proud[Pg xliii] of the Scottish Association which he looked upon as his own creation, volunteered to go over to England and arrange a similar Concert among the English leaders. He and Murray went to London together, and there Murray took the opportunity of privately seeing Cecil, the Jacobite agent for England. Cecil explained his difficulties, told him of the dissensions among the English Jacobites, and of their complaints about Sempill, who, he considered, was being imposed upon by the French Ministry. It is characteristic of Jacobite plotting to find that Murray concealed, on the one side, his interviews with Cecil from Balhaldy, and, on the other, he kept it a secret from Cecil that he had ever been in France.[49] Disappointed with his mission both in France and England, Murray returned to Edinburgh in March or April.

Meanwhile, Balhaldy was busy getting pledges in England and making lists of Jacobite adherents avowed and secret. Though they said they were willing to rise, he found they absolutely refused to give any pledge in writing, and he suggested, through Sempill, that the French minister should send over a man he could trust to see the state of matters for himself. Amelot selected an equerry of King Louis’s of the name of Butler, an Englishman by birth. Under pretence of purchasing horses, Butler visited racecourses in England, where he had the opportunity of meeting country gentlemen, and was astonished to find that at Lichfield, where he met three hundred lords and gentlemen, of whom, he said, the poorest possessed £3000 a year, he found only one who was not opposed to the Government. On his return to France, Butler sent in a long report on the possibilities of an English rising. He told the French Government that after going through part of England, a document had been placed in his hands giving an account of the whole country,[Pg xliv] from which it appeared that three-quarters of the well-to-do (‘qui avaient les biens-fonds’) were zealous adherents of their legitimate king, and that he had been enabled to verify this statement through men who could be trusted, some of whom indeed were partisans of the Government. He was amazed that the Government was able to exist at all where it was so generally hated. The secret, he said, was that all positions of authority—the army, the navy, the revenue offices—were in the hands of their mercenary partisans. The English noblesse were untrained to war, and a very small body of regular soldiers could easily crush large numbers of men unused to discipline. It would be necessary then to have a force of regular troops from abroad to make head against those of the Government.

Butler and Balhaldy returned to France in October. During their absence things had changed; the battle of Dettingen had been fought (June 27th, 1743), although Great Britain and France were technically at peace. King Louis was furious, and he took the matter up personally, and gave instructions to prepare an expeditionary force for the invasion of England. The main body was to consist of sixteen battalions of infantry and one regiment of dismounted dragoons, under Marshal Saxe, and was to land in the Thames. It was further suggested that two or three battalions should be sent to Scotland. Prince Charles Edward was invited to accompany the expedition, and was secretly brought from Rome, arriving in Paris at the end of January 1744. There was no affectation of altruism for the Stuart exile in King Louis’s mind, but the zeal of the Jacobites was to be exploited. He wrote his private views to his uncle, the King of Spain, communicating a project that he had formed, he said, in great secrecy, which was to destroy at one blow the foundations of the league of the enemies of the House of Bourbon. It might, perhaps, be hazardous, but from all that he could learn it[Pg xlv] was likely to be successful. He wished to act in concert with Spain. He sent a plan of campaign. Everything was ready for execution, and he proposed to begin the expedition on the 1st of January. It would be a very good thing that the British minister should see that the barrier of the sea did not entirely protect England from French enterprise.[50] It might be that the revolution to be promoted by the expedition would not be so quick as was expected, but in any case there would be a civil war which would necessitate the recall of the English troops in the Netherlands. The Courts of Vienna and Turin would no longer receive English subsidies, and these Courts, left to their own resources, would submit to terms provided they were not too rigorous.[51]

The story of the collapse of the proposed invasion is too well known to need description. Ten thousand troops were on board ship. Marshal Saxe and Prince Charles were ready to embark. On the night of the 6th of March a terrible storm arose which lasted some days. The protecting men-of-war were dispersed, many of the transports were sunk, a British fleet appeared in the Channel, and Saxe was ordered to tell the Prince first that the enterprise was postponed, and later that it was abandoned. Charles, nearly broken-hearted, remained on in France, living in great privacy, and hoping against hope that the French would renew their preparations. For a time he remained at Gravelines, where Lord Marischal was with him. He longed for action, and implored the earl to urge the French to renew the expedition to England, but Marischal only suggested difficulties. Charles proposed an expedition to Scotland, but his lordship said it would mean destruction. Then he desired to make a campaign with the French army, but Lord Marischal said it would only disgust the English.[Pg xlvi] Charles removed to Montmartre, near Paris, but he was ordered to maintain the strictest incognito. He asked to see King Louis, but he was refused any audience. His old tutor, Sir Thomas Sheridan, was sent from Rome to be with him; also George Kelly, Atterbury’s old secretary, who, since his escape from the Tower, had been living at Avignon. He took as his confessor a Cordelier friar of the name Kelly, a relative of the Protestant George Kelly, and, sad to say, a sorry drunkard, whose example did Charles no good. These Irish companions soon quarrelled with Balhaldy and Sempill, who wrote to the Chevalier complaining of their evil influence, while the Irishmen also wrote denouncing Balhaldy and Sempill.

Charles left Montmartre. His cousin, the Bishop of Soissons, son of the Marshal Duke of Berwick, kindly lent him his Château Fitzjames, a house seven posts from Paris on the Calais road, where he remained for a time. Another cousin, the Duke of Bouillon, a nephew of his mother, also was very kind, and entertained him at Navarre, a château near Evreux in Normandy. But his life was full of weary days. He could get nothing from the French, and ‘our friends in England,’ he wrote to his father, are ‘afraid of their own shadow, and think of little else than of diverting themselves.’ Things seemed very hopeless: the Scots alone remained faithful.

From the time that Murray left London in the spring of 1743, the Jacobite Associators had received no letters from Balhaldy. The suspense was very trying; indeed Lord Lovat felt for a time so hopeless that he proposed to retire with his son to France and end his days in a religious house.[52] Lovat’s spirits seem to have risen shortly after this owing to some success he had in persuading his neighbours to join the Cause, and he eventually resolved to remain in Scotland. It was only from the newspapers[Pg xlvii] the Jacobite leaders knew of the French preparations, but towards the end of December a letter was received from Balhaldy, which stated that the descent was to take place in the month of January. Other letters, however, threw some doubt on Lord Marischal’s part of the enterprise, which included an auxiliary landing in Scotland, and once more the Jacobite leaders were thrown into a state of suspense. They felt, however, that preparations must be made, and an active propaganda began among the Stuart adherents.

In due course news of the disaster to the French fleet reached Scotland, but no word came from Balhaldy or Sempill, and it was then determined to send John Murray to France to find out the state of matters. Murray tells the story of his mission in his Memorials. He met Prince Charles at Paris on several occasions, and told him that so far from there being 20,000 Highlanders ready to rise, as was the boast of Balhaldy, it would be unwise to depend on more than 4000, if so many. But in spite of this discouraging information, the Prince categorically informed Murray that whatever happened he was determined to go to Scotland the following summer, though with a single footman.[53]

Murray hastened home, and at once began an active canvass among the Jacobites; money and arms were collected, and arrangements were made in various parts of the country. Among other expedients was the establishment of Jacobite clubs, and the celebrated ‘Buck Club’ was founded in Edinburgh. The members of these clubs were not at one among themselves. Some of them said they were prepared to join Prince Charles whatever happened, but others only undertook to join if he were accompanied by a French expedition. At a meeting of the Club a document was drawn up by Murray representing[Pg xlviii] the views of the majority present, which insisted that unless the Prince could bring them 6000 regular troops, arms for 10,000 more, and 30,000 louis d’or, it would mean ruin to himself, to the Cause, and to his supporters.[54] This letter was handed to Lord Traquair, who undertook to take it to London and have it sent to Prince Charles in France. By Traquair it was delayed, possibly because he was busy paying court to the lady who about this time became Countess of Traquair,[55] but to the expectant Jacobites for no apparent reason save apathy. After keeping the letter for four months he returned it in April 1745, with the statement that he had been unable to find a proper messenger. Another letter was then sent by young Glengarry, who was about to proceed to France to join the Scottish regiment raised by Lord John Drummond for service in the French army. It was, however, too late; the Prince had left Paris before the letter could be delivered.

Distressed that the King of France would not admit him to his presence; wearied with the shuffling of the English Jacobites and the French ministers; depressed by Lord Marischal, who chilled his adventurous aspirations; plagued, as he tells his father, with the tracasseries of his own people, Charles determined to trust himself to the loyalty of the Scottish Highlanders. He ran heavily into debt; he purchased 40,000 livres’ worth of weapons and munitions,—muskets, broadswords, and twenty small field-pieces; he hired and fitted out two vessels. With 4000 louis d’or in his cassette he embarked with seven followers at Nantes on June 22nd (O.S.).

On July 25th he landed in Arisaig,—the ’Forty-five had begun.

[Pg xlix]

These papers, picked up after Culloden, are fragmentary and are not easy reading without a knowledge of their general historical setting, and this I have endeavoured to give in brief outline in the preceding pages. They are particularly interesting as throwing glimpses of light on the origins of the last Jacobite rising. They were written before the collapse of that rising and before Murray, after the great betrayal, had become a social outcast. Murray’s Memorials, edited for the Scottish History Society by the late Mr. Fitzroy Bell, were written thirteen years after Culloden as a history and a vindication. These papers may be considered as memoranda or records of the business Murray had been transacting, and they view the situation from a different angle.

Some of the events mentioned in the Memorials are told with fuller detail in these papers; they also contain thirteen hitherto unpublished letters, consisting for the most part of a correspondence between Murray and the Chevalier de St. George and his secretary James Edgar. But to my mind the chief interest of the papers lies in the fact that they present a clue to the origin of the Jacobite revival which led up to the ’Forty-five; that clue will be found in Murray’s note on page 25.

In 1901 the Headquarters Staff of the French Army issued a monograph based on French State Papers, giving in great detail the project for the invasion of Great Britain in 1744, and the negotiations which led up to it. The book is entitled Louis XV. et les Jacobites, the author being Captain Jean Colin of the French Staff. In his opening sentence Captain Colin tells how the Chevalier de St. George was living tranquilly in Rome, having abandoned all hope of a restoration, when about the end of 1737 he received a message from his subjects in Scotland informing him that the Scottish Highlanders[Pg l] would be able, successfully, to oppose the Government troops then in Scotland. In no English or Scottish history, so far as I am aware, has this message from Scotland been emphasised, but in the French records it is assumed as the starting-point of the movement on the part of the French Government to undertake an expedition in favour of the Stuarts. Murray refers to Glenbucket’s mission in the Memorials (p. 2), though very casually, and as if it were a matter of little moment, but the insistence in French State Papers of the importance of the Scottish message made it necessary to investigate the matter further.