Title: Venice

The queen of the Adriatic

Author: Clara Erskine Clement Waters

Release date: October 19, 2023 [eBook #71915]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: Dana Estes and Company

Credits: Al Haines

THE QUEEN OF THE ADRIATIC

By

CLARA ERSKINE CLEMENT

Author of "Naples, the City of Partbenope," "Constantinople,

the City of the Sultans," etc.

Illustrated

BOSTON

Dana Estes and Company

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1893

BY ESTES AND LAURIAT

All rights reserved

COLONIAL PRESS

Printed by C. H. Simonds & Co.

Boston, U.S.A.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

II. A Summer Day

III. The Doges: their Power and their Achievements

IV. The Venetians at Constantinople

V. Modern Processions and Festivals

VI. Gradenigo, Tiepolo, and the Council of Ten

VII. Murano and the Glass-Makers

VIII. Marino Faliero; Vettore Pisani and Carlo Zeno

X. The Two Foscari; Carmagnola and Colleoni

XI. An Autumn Ramble

XII. Venetian Women: Caterina Cornaro, Rosalba Carriera

XIII. The Archives of Venice

XIV. The Treasures of the Piazza

XV. Glory, Humiliation, Freedom

XVI. Saints and Others

XVII. Historians and Scholars

XVIII. Palaces and Pictures

XIX. The Accademia; Churches and Scuole

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

The Bridge of Sighs (Photogravure) ... Frontispiece

Festival Scene, Bridge of the Rialto

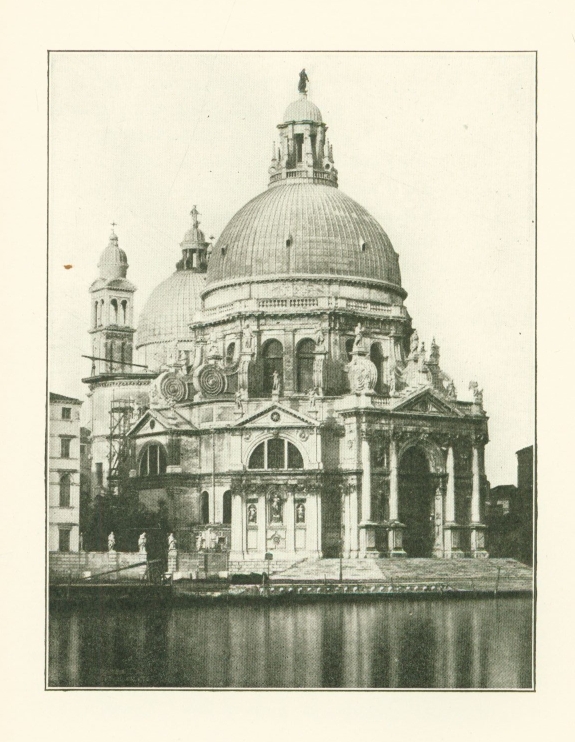

Church of Santa Maria Della Salute

Molo of San Marco; Columns of Execution

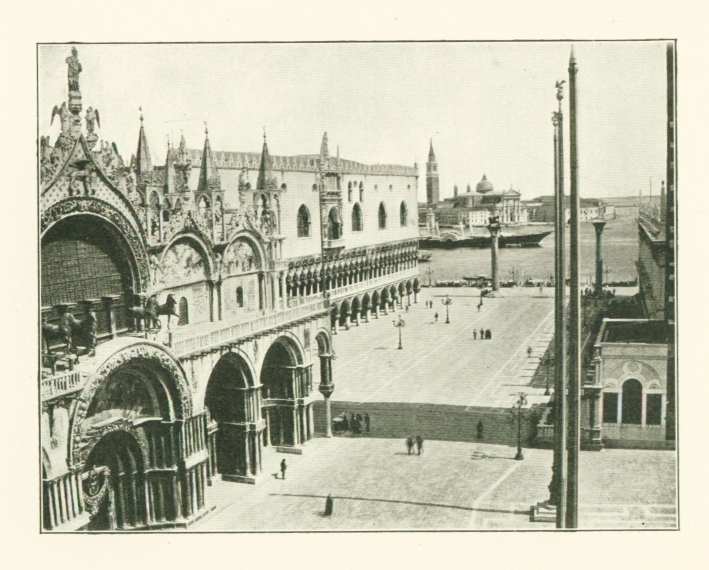

The Piazzetta; Ducal Palace; San Marco

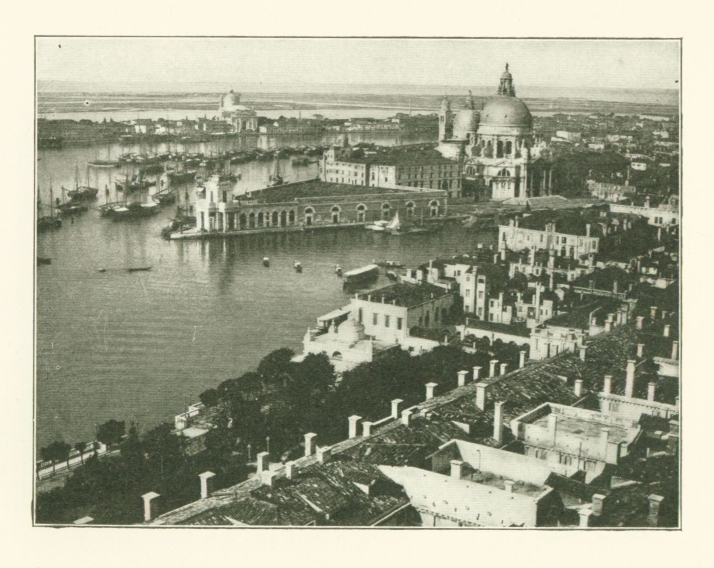

Panorama from the Campanile of St. Mark

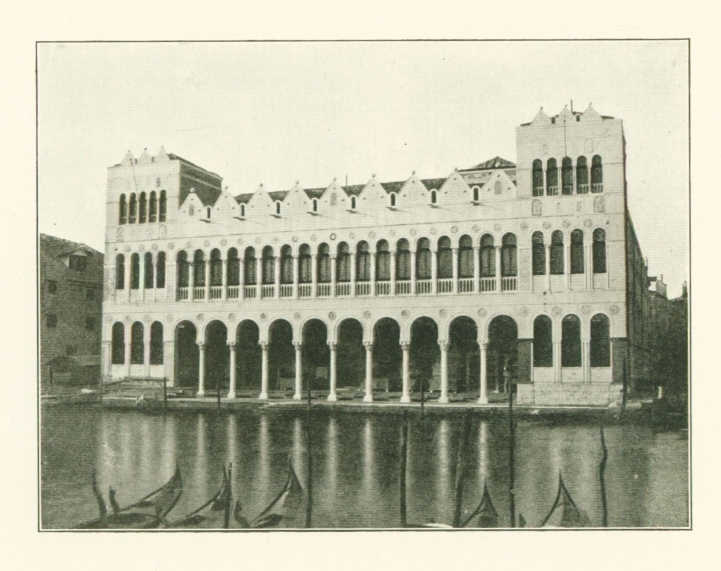

Museo Civico; formerly Palazzo Ferrara, later Fondaco dei Turchi

Torre dell' Orologio; Clock Tower

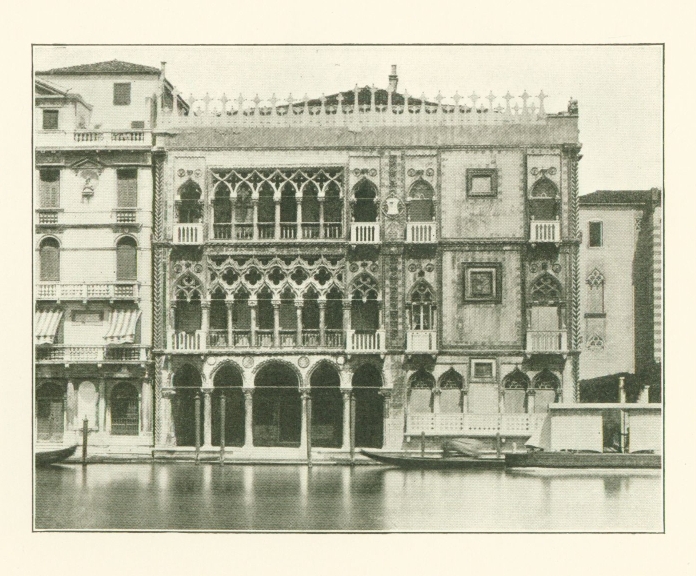

Ca' d' Oro, on the Grand Canal

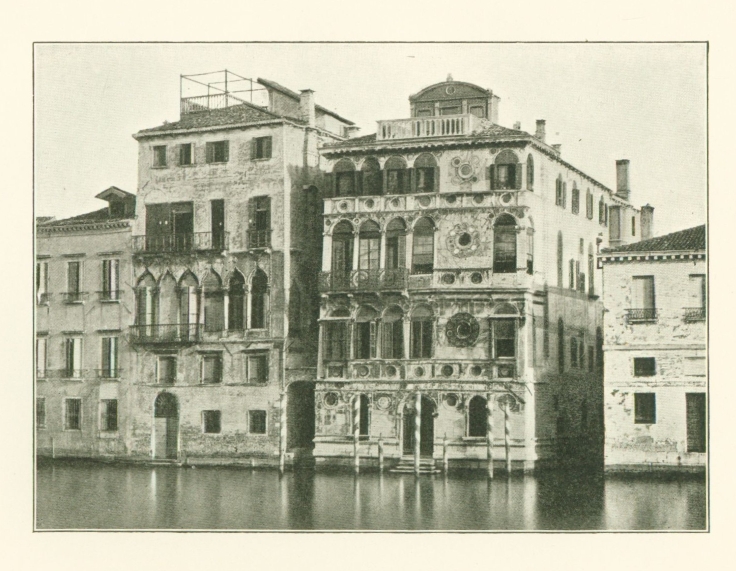

Dario Palace, on the Grand Canal

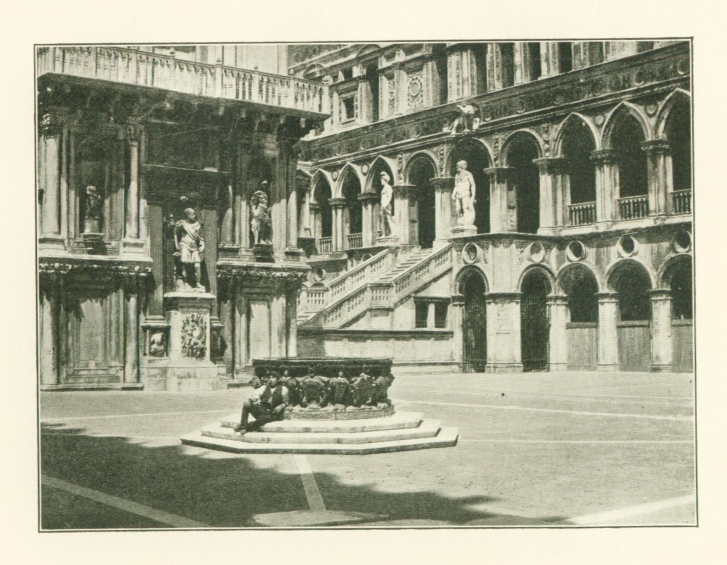

Court of the Ducal Palace; Giants' Staircase

THE QUEEN OF THE ADRIATIC;

OR,

VENICE, MEDIÆVAL AND MODERN.

The Venice which one visits to-day is so curiously a part and not a part of the ancient Venice of which we dream, that one feels, when in that sea-enveloped and fairy-like city, a strange sense of duality,—of being a veritable antique and an equally veritable modern. He has a genuine sympathy with the past, and regrets that he has not the enchanter's wand to bring it all back again,—long enough, at least, for him to revel in its magnificence.

If he believes in reincarnation, he is speedily convinced that he was once a Venetian indeed; else how could he feel so much at home, and how love Venice as he does! And yet, alas! he cannot quite lose his modern point of view.

The first emotion is all delight, and a delight that never loses its thrill; for until the time comes for reflection, we are under the charm of a perfect atmosphere, of skies of liquid blue, tinged at times with crimsons, gold, and violets, such as come only from Nature's loom; of music and soft, fascinating speech; of mysterious labyrinths and sunlit spaces,—in a word, under the spell of Venice. And if {2} Time brings to us the thought of the other side of the picture,—the decay which is stealthily doing its sad work, the grayness when it is gray, and all the pathos which ever attends a queen uncrowned,—yet through all and above all is the joy and pleasure which having once been ours, we are resolved to keep.

To sail from Trieste in an evening of the spring, and make one's first approach to Venice in the early morning, affords an experience that one should not forego. With the clear sun rising behind, surrounded by the marvellous waters blushing in every color of the rainbow beneath his rays, and the pearly tinted city lifting itself from this many-colored sea, as if in welcome, every poetic and artistic sense is filled to overflowing.

Can this coloring be described in words? Alas! no. For when the sea is likened to liquid fire, broken into scintillations and spread over a quivering background of sea-blue and sea-green waves, the half has not been said. When the eye rests on some far-away sand, dun and sombre in the distance, what vividness of flaming red and glorious orange comes out in the middle ground, while nearer the blues and greens are mingled with a shimmering silver! The atmosphere itself seems tinted by reflections from Aurora's garlands, and the strangely luminous blue sky smiles over all.

"Then lances and spangles and spars and bars

Are broken and shivered and strewn on the sea;

And around and about me tower and spire

Start from the billows like tongues of fire."

To the south stretches the long island reaching from the Porto di Lido to Malamocco, its sands now sparkling like gems. The fort of San Niccolo guards the entrance to the Lagoon; the little island of St. Elena is passed, and Murano is seen to the north. But glances only can be spared for these; for Venice itself, with its towers and domes, its {3} belfries, spires, and crosses, its palaces all lacework and arabesques, rises above, while all around, on the canal, numbers of light, curiously shaped boats and sombre gondolas are gathering,—their boatmen clamoring for news and customers.

Descending, as in a dream, we enter a gondola for the first time. The Giardini Pubblici is passed, and soon one stands on the Piazzetta and enters the Piazza of St. Mark, feeling as if he had passed through a living, moving transformation scene, and been dropped into the middle of the twelfth century. And why not? For at this early hour the Piazza seems consecrated to the Past. The few boatmen, fruit-sellers, and lazzaroni who are there might belong to the Middle Ages as well as to the nineteenth century.

Why might they not have seen that grave procession which in 1177 passed into the Chapel of San Marco to celebrate the reconciliation of a Pope and an Emperor,—that day when proud Frederick Barbarossa so nobly proved his greatness?

He had struggled against the Church on the one hand, and the spirit of independent government on the other, with a determination and bravery such as few men in all history have shown.

Threatened with excommunication by Pope Adrian IV., and actually laid under the ban by Alexander III., Frederick refused to recognize him as Pope, and set up four anti-popes, one after another, who died, as if their position brought its own fatal curse. During sixteen years he carried matters with so high a hand that he successfully defied Alexander and Italy; and the much humiliated Pope wandered from court to court, seeking the aid of one kingdom after another, always in vain.

Some States frankly acknowledged their fear of Barbarossa; others dared not meet the sure vengeance of the {4} Ghibellines which would follow the espousal of his cause; Sicily could give him a home, but could not seat him firmly on his throne; and all eyes began to turn to the Republic of the Sea.

The Barbarossa scarcely gave Italy time to rise from beneath his tread and recover herself from one of his disastrous marches through her territory, marking his route by flames and ruin, before he again appeared with his barbaric army, pillaging and destroying all that had escaped his last visitation, and returning to his Northern throne in triumph. At last he turned his face towards the Eternal City for the fifth time, only to find that the Confederacy of the Lombards had raised a barrier against which he beat himself in vain. He was repulsed in repeated engagements; and after the battle of Legnano, May, 1176, he saw the beginning of the end of the audacious policy by which he had so long dominated at home and abroad.

Soon after this first humiliation of his arch enemy, Alexander decided to appeal to the Venetians for succor; and early in 1177 he sailed from Goro, attended by five cardinals and ambassadors from the King of Sicily, who had fitted out a papal squadron of eleven galleys.

After some disasters and perils, his Holiness reached Venice at evening on March 23, and was lodged in the Abbey of San Niccolo. The Doge, the nobles, and the clergy made haste next day to welcome the Holy Father to Venice; and after a service in San Marco, where he gave his benediction to the people, the Doge Sebastiano Ziani escorted him to a palace at San Silvestro, which was his home so long as he remained at Venice.

The Venetians now sent two ambassadors to Frederick at Naples to arrange, if possible, a peace between the Pope and the Emperor. The bare mention of Alexander as the true successor of Saint Peter so enraged Frederick that he could scarcely speak his words of defiance:—

"Go and tell your Prince and his people that Frederick, King of the Romans, demands at their hands a fugitive and a foe; that if they refuse to deliver him to me, I shall deem and declare them the enemies of my empire; and that I will pursue them by land and by sea until I have planted my victorious eagles on the gates of St. Mark."

Whatever regret the Venetians may have had at being thus forced to protect their guest and punish so insulting a foe, they immediately prepared thirty-four galleys, commanded by the flower of their nobility, among whom was the son of the Doge Ziani; and Ziani himself assumed the chief command.

Barbarossa's fleet was more than double in number, and under the command of his son Otho. On the 26th of May, on the stairs of the Piazzetta, Alexander girded upon Ziani a splendid sword, and gave him his blessing. Feeling the great responsibility they had assumed,—for not only the holy cause, but the glory of Venice was in their keeping,—the Venetians fiercely contested the day. Not less desperate the army of the German prince, and not less bravely did he fight. But after six hours of dreadful slaughter, he found himself a prisoner, with forty of his ships in the hands of the enemy, and his whole following completely routed.

Otho was at once released, having solemnly sworn to persuade his father to a reconciliation with Alexander. A promise faithfully kept; for although this dreadful defeat at Salboro must have largely contributed to the repentance of Barbarossa, he never again attempted to rebel against his Holiness.

The Pontiff met Ziani at the spot on which they had parted, and all who had survived the battle followed them to San Marco in triumph and thankfulness; and there Alexander gave the Doge a ring, saying, "Take this, my son, as a token of the true and perpetual dominion of the {6} ocean, which thou and thy successors shall wed every year, on this Day of the Ascension, in order that posterity may know that the sea belongs to Venice by right of conquest, and that it is subject to her, as a bride is to her husband."

And now began the somewhat difficult arrangement of a meeting between Frederick and the Pope, which was at last appointed at Venice, where the Emperor arrived on Saturday evening, July 23. Six cardinals met him at San Niccolo Del Lido, and formally absolved him from the papal curse, that he might not enter the city while under the ban.

On Sunday morning the Pope, in his pontifical robes, sat enthroned at San Marco. (In the vestibule, by the centre portal, a lozenge of red marble in the pavement marks the historic spot.) On his right hand was the Doge, and on his left the Patriarch of Grado; while the ambassadors of England, France, and Sicily, the delegates from the free cities, and a throng of nobles and cardinals and other ecclesiastical dignitaries, all in splendid attire, gave dignity and brilliancy to the scene.

And now trumpets are heard, and the tread of the procession conducting Barbarossa across the Piazza. The doors of San Marco are wide open, and guards are at each portal to hold back the pressing crowds of citizens eager to see the grand ceremony. The procession is passing in; and from out the multitude of armed warriors, with glistening helmets and shining lances, nobles in richly flowing togas, and wealthy commoners in brilliant, graceful draperies, one figure stands out alone.

The Emperor advances with a martial step, and his whole bearing bespeaks a man great even in submission. His serious face is calm, his crowned helmet is on his head, and his red beard falls far down on his breast. His armor is not concealed by his flowing mantle, and his slashed surcoat of dark, rich velvet, bordered with gold {7} embroidery, discloses a tunic of more delicate tint and stuff. On his breast and partly hidden by his beard is embroidered a large Crusader's cross. In his splendid jewelled baldric, on the right, is a large sheathed knife, while, on the left, his heavy long sword reaches almost to the ground. Well may the historian Hazlitt say:—

"It was certainly a grand and imposing spectacle, and one which was apt to raise in the breasts of the spectators many strange and conflicting emotions; and while the greater part of those present looked on such a consummation perhaps as the triumph of a great man, the latter solemnly declared that to God alone was the glory.

"Assuming a lowly attitude, Barbarossa approached the steps of the throne on which Ranuci (Alexander) was seated, and, casting aside his purple mantle, he prostrated himself before the Pope.

"The sufferings and persecutions of eighteen years recurred at that moment to the memory of his Holiness; and a sincere and profound conviction that he was the instrument chosen of Heaven to proclaim the predestined triumph of Right might have actuated the Pontiff, as he planted his foot on the neck of the Emperor, and borrowing the words of David, cried:

"'Thou shalt go on the lion and the adder; the young lion and the dragon shalt thou tread under thy feet.'

"'It is not to thee, but to Saint Peter, that I kneel,' muttered the fallen tyrant.

"'Both to me and to Saint Peter,' insisted Ranuci, pressing his heel still more firmly on the neck of Frederick; and it was not until the latter appeared to acquiesce that the Pope relaxed his hold, and suffered his Majesty to rise.

"A Te Deum closed this remarkable ceremony; and on quitting the cathedral, the Emperor held the sacred stirrup and assisted his tormentor to mount."

How the recollection of this narrative incites the fancy, and how the Piazza, but just now so empty, is crowded to {8} overflowing with representatives from East and West and the Isles of the Sea!

From the different stories of the Ducal Palace, and extending quite around the square, from every possible projection, float the standards and banners that have been taken from the enemies of the Venetians; while the great scarlet banner, with its embroidered Lion of St. Mark, waves gently above the principal entrance to San Marco, where the bronze horses now stand. Rich stuffs in the brilliant coloring of Eastern looms, and cloths of gold and silver fall from the balconies thronged with ladies pressing eagerly forward to watch all that happens in the square below.

On the roofs are hundreds of human beings, and every corner that affords a view of San Marco and the Piazza is fully occupied. Men perch like birds on such slight and insecure footholds that they seem like colored statues made fast to the edifices themselves. Here and there a few proud chargers champ their bits and strive to free themselves from their grooms, who wait impatiently, as we do, for the sound of the trumpets to proclaim the rising of this august conclave.

Just here a soft, musical voice deprecatingly suggests: "The Signior has not chosen his lodgings, and one knows not where to take his luggage."

THE FEAST OF LA SENSA.

Pope Alexander, as indeed he ought, wished to confer all the benefits in his power upon the Venetians, and gave the papal sanction, rather unnecessarily as it would seem, to certain customs which this independent people had for some time followed without authority. They were now duly authorized to seal their letters and despatches with lead rather than with wax; to use tapers and trumpets, {9} and even to display the silken canopy and sword of state when ceremony made them fitting. This silken canopy is disagreeably contracted into an umbrella by some over-careful writers, but there is good reason to believe that long before this time the Doges had indulged in this luxury.

Before the departure of the Pontiff he celebrated a High Mass and preached a sermon in San Marco, and at the end conferred upon the Doge the highest and most flattering favor that could be bestowed upon a temporal ruler, by descending from the pulpit and presenting him with a consecrated Golden Rose, in token of friendship for Ziani and for Venice.

These seals and umbrellas and trumpets and tapers made little difference to the people; the Golden Rose gratified their pride and love of their idolized Republic; but it was with the Marriage of the Adriatic—the Andata alii Due Castelli, as it was called by the Venetians—that they were principally concerned; that characteristic Venetian fête, which soon became famous in all the world. Alexander had comprehended their love of pageants, their luxuriousness, and pride of wealth.

And now, as if by magic, the Bucentaur appears; and the dignity and splendor of this galley vastly increased the magnificence and effectiveness of state occasions. It was about twenty-one feet wide in the broadest part, and nearly five times as long. The lower deck was manned by one hundred and sixty-eight rowers, who rowed with gilded oars, while forty other mariners managed the evolutions of the ship. The outside was covered with carvings, and decorated in gold and purple. The prow bore figures emblematic of the Republic, and the beak was shaped into a Lion of St. Mark.

The upper deck, devoted to the illustrious strangers and guests of the Republic, and to the Dogaressa and other {10} patrician ladies, was finished in a grand cabin, with a splendid carved ceiling, and divided by rows of graceful pillars. On the outside this saloon was covered with the richest velvet, and furnished within with luxurious cushions. The Doge had an equally splendid cabin in the stern, encircled by a balcony from which the whole fête could be seen; and from a second balcony outside the prow he dropped the ring into the sea, proudly repeating the form of words given him by the Pontiff. Sails there were none, but from the top of a huge mast floated the scarlet banner of Saint Mark, with an image of the lion on one side, and of the Virgin Mary on the other,—as it may still be seen in the Municipal Museum,—and beside this sacred standard hung the white flag, the gift of the Pope.

The old pictures of the Bucentaur represent her as crowded with ladies in splendid attire, all intent upon the varied and curious spectacle around them. Here was a throng of boats, galleys, feluccas, gondolas, and the small, swift boats which always covered the canals and lagoons wherever there was anything of interest to be seen, as quickly as a crowd on foot now gathers in the streets of a modern city.

There were the patrician gondolas, each vying with the other in the costliness and brilliancy of its carving and decorations. The houses in the centre, with curtains drawn, revealed the lovely women in their gorgeous and picturesque costumes, and the music of fifes and lutes added to the joyousness of all; while the sound of the church bells, as they grew more and more indistinct, served to emphasize the deeper meaning of the day and ceremony, which was almost forgotten in this dazzling scene.

Then, too, the "Anti-Doge" was always there,—the representative of the poor people, chosen by them, and usually the best gondolier among them. On some half-ruined {11} boat he held a court of his fellows, all wearing masks. He had his own fifers, who fifed anything but well, and surrounded by hundreds of little boats he performed all sorts of buffoonish tricks,—now offering to tow the Bucentaur, again begging for a seat on the Ship of State, and all with most ridiculous gestures and in apparent good faith. Whatever he did was received with laughter and merriment, not only by his friends but by the patricians as well.

At length the castles of San Andrea and San Niccolo were reached; and just outside them the ring was dropped into the majestic Gulf of Venice. At this moment every sound was hushed. Each one of the vast throng desired to hear the words of the Sposalizio (marriage); and immediately following it the Patriarch of Venice returned thanks to the sea for all its blessings, and prayed for their continuance.

With the first buzz that indicated the close of these solemnities, the "Anti-Doge" cast an iron hoop into the water, and in a moment gayety reasserted itself. The return to Venice was in some sense a race for the smaller craft; the Bucentaur and the patrician boats were enlivened by songs and witty persiflage; and the whole evening was given up to merry-makings of various sorts.

Doubtless, in the earliest celebrations of this marriage there were those who shook their heads, looked solemn, and tried to be serious and even sad in the midst of the festivity, recalling and regretting the more simple celebration of Ascension Day, which had been good enough for their fathers, and was consequently fine enough for them. Such people exist everywhere and at all periods; but what was the difference?

At the end of the tenth century, and almost two hundred years before the visit of Pope Alexander, when, as the record says, "there was no custom of triumphs," {12} Pietro Orseolo returned from his victorious expedition against the pirates and corsairs of Africa, who had been the scourge of all the coasts of the Adriatic. He had cleared the sea of robbers, and greatly extended the dominion of Venice.

For the first time a triumphal entrance was involuntarily made. The grateful populace surrounded the victor and attended him to the Great Council, where the most flattering praises were addressed to him, couched in magnificent words.

Orseolo had set out on his expedition on Ascension Day, and on its first anniversary the Feast of La Sensa was inaugurated. In a large barge, quite concealed by its covering of cloth of gold, the clergy in their richest vestments, wearing all the sacred jewels and ornaments, left the olive-groves of San Pietro in Castello, and at the Lido met the still more magnificent barge of the Doge. Then, as in later days, every sort of boat that could be used in all Venice was there, filled with all conditions of people.

The ceremony began with litanies and psalms, after which the Bishop rose and prayed aloud: "Grant, O Lord, that this sea may be to us and to all who sail upon it tranquil and quiet. To this end we pray. Hear us, good Lord." Then the singers intoned, Aspergi me, O Signor (Cleanse thou me, O Lord), while the two barges approached each other, and the Bishop sprinkled the Doge and the Court with holy water, and what remained was poured into the sea.

This simple religious rite, celebrated in the enchanting atmosphere of the lovely, blooming season of the year, must have deeply moved the hearts of those who went down to the sea in ships, as who did not in Venice? It was perfectly adapted to the initial years of a Republic when aristocratic rule was in its infancy; but two centuries later all was changed, and the Sposalizio was in accord {13} with Ziani and his aims as truly as La Sensa represented Orseolo.

There are those who question all the story of the romantic incidents of Pope Alexander's visit to Venice. To them we would give the customary and most satisfactory answer of the Venetians: "Is it not depicted in the Hall of the Great Council? If it had not been true, our good Venetians would never have painted it."

THE BOATS OF MODERN VENICE.

Most of the craft one sees in Venice now are vastly different from those we have been thinking of. The gondolas, alas! all look as if ready for a funeral,—black, only sombre black. This seems an unnecessary extension of the time when the sins of the fathers shall be visited on the children; for many more than three or four generations have perambulated these fascinating waters in these dismal boats. Why should the undue extravagance of the past, which was curbed by this monotonous gloom, forbid a bit of cheerfulness now, hundreds of years later?

It may be fortunate that the Bucentaur went up in fervent heat, for it is more than possible that it might not have realized our ideal of what it should be; and now each one can gaze in imagination at just what he would have made it if he could. But we would like to have some galleys remaining, and rowed by slaves or prisoners. It would afford an outlet for sympathy and pity, the exercise of which virtues is good for us, and which are so often, even in Venice, bestowed on those who neither merit nor need them.

But we have the felucca, the sandolo, the bissone, and innumerable little boats to add life to the canals and lagoons. If we can see numbers of these, with their variously colored sails, running the gamut from white to {14} brilliant orange and tawny red, with here and there those that are striped, and many that are deliciously patched and resemble Joseph's coat in their variety of tones,—if we can but get all these between the Riva degli Schiavoni and the Isola di San Giorgio Maggiore at the sunset hour, we need not regret not having lived under the Doges.

Never were colors more picturesquely mingled; and as they pass to and fro, out from and into the Giudecca, we almost forgive the gloom of the gondolas, especially if now and then one adds its effect in contrast with the brilliancy of the other boats. That marvellous Venetian sunset! It is an unending subject. One talks of it, writes about it, tries to exaggerate it and fails to do so, and can never think of Venice without recalling it. It is like a vast conflagration, and its flames seem likely to lap up the water it blazes over, together with all the boats and men who dare to row or sail into its fiery circle.

But we must not omit the steamboats that now traverse Venetian waters. What can we say of them? There are two views, each having strong supporters. Perhaps the larger number cry out, "Desecration and deterioration;" but others find them more in the spirit of Venice at its best than anything that is equally prominent in the modern city.

How eagerly did the old "makers of Venice" seize on everything that could advance her commerce and her trade! Would they have hesitated to use any power that could save their ducats and their time? Ah, no; and the glorious new impulse which this age has brought to United Italy finds expression in the revival of her industries, and her adoption of ideas evolved by others while she slept the dreamless sleep from which she now awakens.

Venice in summer with a marine artist for a companion,—could anything be better? An artist from early dawn to dark, from the top of his curly head to the soles of his feet; an artist who indeed appreciates—no, perhaps approves would be more nearly true—the pictures of Titian and Tintoretto on a rainy day, but will have none of them in any kind of weather when the sea can be studied and painted.

The summer is the only season when one can really know modern Venice; the only time when one can in any good degree separate himself from the long ago and live in the present; the time when he will, in spite of himself, turn his back on the works of man and live out in the world that God created before palaces and churches, arsenals and towers, had been invented.

The most delicious of days is that when in the cool morning we take to our gondola, with our artist and his traps, the books that we think we shall read but rarely do, the fancy work which soon loses its interest, the rugs on which to lie for the afternoon siesta, the basket with the solid luncheon, a second with fruit and sweets, and a third with wine. And when our little maid Anita, so busy in the house that she can scarcely leave it, comes with her gay handkerchief but half arranged about her shoulders, begging pardon for her tardiness and smiling at our gondolier, Giacomo, whom she calls her cousin (?), all is ready.

We pass into a side canal to do a necessary housekeeping errand; for we live not in hotels,—not we,—and sometimes, we will admit, our furniture requires repairs, and frequently we must buy some needful article which we fail to find in our "completely furnished lodgings." But the effect of the historic name of our palace is to make us feel so wealthy that we do not regret the lire that we spend with the proper amount of haggling, and our spacious quarters and carved balconies are so inexpensive to our American minds that our padrone hears no complaints.

Few gondolas are yet moving. Cooing pigeons, pert sparrows, and swiftly circling swallows are searching here and there for any stray crumbs that will afford a morning meal. We stop at a traghetto (gondola stand), and Anita darts away and disappears on her errand. We meanwhile watch a great water-barge which has just arrived with its cargo of "sweet water" from the mainland. How weary the men look, and no wonder; for to Giacomo's questions they reply that two days have passed since they set sail. The winds have held them back, but they hope that the same weather may send them home before night; and as they are safely here, why complain? The small boats are there ready to receive the water; and the wheezy little engine soon fills them, and they go off to replenish the public wells by means of their long hose.

All this time, as we watch these proceedings with interest, the artist has been sketching like mad. Theoretically he disdains anything inside the Grand Canal; but we think that "all is fish that comes to his net" in the way of novelties in Venetian life; and it is wonderful how many such despised "pot-boilers" he sells.

And now Anita comes tripping down with the coveted coffee-pot she had begged us to buy now, knowing from experience that we may be too late home to have it ready for the morning. As we move off, we ask the bargemen {17} how much they get for their cargo, and are much excited by their answer, "Cinque lire, signor." One dollar for all that! One loves Venice with a well-filled purse in his pocket, but he would not like to earn his living at Venetian prices for labor.

Now, our business ended, we are really ready to start, and we settle ourselves comfortably to enjoy the sights on either hand. As we come into the Grand Canal, some rosy sunrise colors still linger in the east and remind us of Poussin, who declared when flying from Venice, "If I stay here, I shall become a colorist!" With this reminder of the glorious canvases on which we turn our backs day after day, and, to be frank, now rarely think of, we wonder at the spell that is over us.

It is an enchanting spirit of do-nothing that possesses us; our thoughts wander lazily from one subject to another, but never rouse us to energy of action. We think complacently of the artistic treasures of every kind which are within our reach,—for which when in Boston we long with an energy of desire that would keep us going from San Marco to the Ducal Palace, on to the Frari and other churches, and so through the whole list of "sights" with zealous industry; and yet, now we are here, we will have none of them, at least not to-day. October will come, and bring another spirit to us. But now Venice is enough. Its changing aspect, its clouds, its islands, its people,—in a word, its boat life is enough.

Leaving thus behind us that great Past which at other times holds us with its wondrous power, we find full compensation in the Venice that still lives; and of this Venice the best part is the water class (if one may use this term), the robust, frank, joyous survival of the old Republic, bubbling and growing into the new Italy of our day.

A good gondolier, like our Giacomo, is a treasure,—the sort of man that helps one to respect the human race and {18} forget how many of another sort one has seen. If you allow him to feel himself to be a part of your life, he will identify himself with your interests, sympathize in your joys and sorrows, and tell you all his own. We must admit, however, that there is another kind, and that a bad gondolier is like a certain little girl whom we all know,—from bad he rapidly goes to horrid.

As Giacomo makes us his confidant,—I had almost said confessor,—we find the gondolier's life to be a happy one, in spite of its surface seeming of hardship and poverty. They see the sun whenever it shines, and breathe the fresh air; their exercise develops a fine physique; polenta, bread, and wine are delicious with the sauce of a good appetite; and being a most conservative race, they desire only to be what their ancestors were in past centuries. They go rarely to church. Custom is their religion, and at each traghetto there is an image of the Virgin ready to grant their prayers; and all their good or ill is promptly referred to "Our Blessed Madonna."

A country-flitting for a few days in the summer, with half a dozen or more companions, and their little suppers in the winter content them for amusements, while an extra treat of theatre or opera makes them supremely happy. And on festal days who sees more than the gondolier? If a rowing-match occurs, with what excitement does he defend his favorite champion! Curiously enough, each contrada, or district, has its own customs and festivals, even its own dialect to some extent; and while each one knows intimately the affairs of his own contrada, outside that quarter he knows little, and little is known of him. All this has Giacomo taught us; and we admire his honest face as he touches his cap and asks the artist where we are to go.

"Are any large vessels lying off the Riva, Giacomo?"

"Si, signor" (another touch of the cap), "an Austrian Lloyd came in last evening."

"Then let as lie in her shade awhile."

Coming to our vantage-ground, where even the extra canopy on our gondola could not have sufficiently lessened the heat of the sun, we prepare for a long stay.

The water is magnificent. The sands on the Lido have been stirred by the wind, and the opaque green sea is mottled with yellow stains. The fishing-boats are always fascinating, and claim our first attention; some are already at their anchorage near the public gardens, unloading the "catch" of the night; others, still some distance out, are tacking and crossing each other's bows in a confusing fashion, led by a procession coming nearer in; the many-hued sails with their curious designs—full-blown roses, stars or crescent moons, hearts blood-red and pierced by arrows—absorb our attention as imperatively as when we first saw them long years ago; and our artist still puts them on his canvas as eagerly as if he had not done it a hundred times before, and others of his sort a hundred thousand. "New every morning and fresh every evening" can be repeated in Venice with rare truthfulness.

The gondola is moored, and the artist hastily sets up his easel and begins his work. The rowers watch him until they see him quite absorbed, and then by signs ask permission of Giacomo to leave us awhile. A little signal-flag soon brings a row-boat alongside, and takes them off. Anita's fingers are already flying over a piece of pretty lace which is always in her hands when she has a moment of leisure. It is at such times as this that we learn from Giacomo many things that we have not read in books, and question him about the customs we observe.

To-day a steamboat passing at the moment reminded us that we had heard a reference to a strike of the gondoliers when the vaporetti first appeared at Venice. At a sign Giacomo comes near enough to talk to us in a quiet tone; and as he advances, cap in hand, Anita cannot refrain from {20} darting a glance at his handsome face, and as quickly looking down at the never-ending lace.

"Do the gondoliers like the steamers, Giacomo?"

"As the devil loves holy water, signora."

"Have you ever made any opposition to their being here?"

"Undoubtedly, signora. When first they began to run between the station and the public gardens, we made a strike."

"A strike of gondoliers in Venice? How dreadful! How did it end? Tell me all about it, Giacomo."

"Con piacere, signora. It was on the Monday before All Soul's Day that we determined on the strike; and some loose-tongued fellows told our plans, so that the Syndic heard the tale and sent for some leading gondoliers and tried to have them give it up. But we held fast, and on Tuesday morning not a man nor a gondola was found at the traghetti. But at each one the image of Our Lady was decked as for a festival, and the Italian flag was flying to show that we were true to Italy.

"The Grand Canal was deserted and quiet as the grave, except when a steamer passed loaded with passengers. There were no gondolas at the ferries; and when the Syndic had done his best, there was but one boat to each one of them. Crowds of women waited angrily to go to market, and all who wished to pass for any reason were scolding and cursing the vaporetti on every side.

"The gondoliers were walking about in slouched hats, and gathering in knots on the bridges and at the street-corners. The wine-shops were full, for the air was keen, and a warm corner was needed when one had no exercise to stir the blood. But there were no riots."

"But the gondolas, Giacomo, where were they?"

"In the little canals, madama, and so closely packed that one could walk a long way on them in some places {21} and never see the water. It was a sad, sad sight,—so many good Venetian boats idle, and those foreign 'puffers' full of people! And so Tuesday passed; and that evening no songs were heard, no stories told, and every gondolier in Venice was as sad as if his mother lay dead."

"Were there no quarrels, Giacomo? Did not the women tell the gondoliers that they were wrong?"

"The women, signora, were firmer than the men. They hated the vaporetti and cursed them. But on Wednesday, as had been thought, the trouble increased. At every traghetto the Syndic posted a mild appeal to the boatmen, and bade them remember what pride Venice had in her gondoliers. It persuaded them and flattered them as if they were naughty children, and invited them to meet the town council. They went; but only talk came of it. The gondoliers demanded the dismissal of the steamers; the council refused, and the meeting dissolved quietly.

"But what a confusion there was! You know, madama, that everybody goes on All Soul's Day to San Michele to lay a wreath on the family graves. Not to do this would make them unhappy all the year. And how to do it on this day was the question; for not one gondolier in all Venice was tempted, not even by the offer of twenty times his usual fare.

"Every boat of every sort that was not a gondola passed and repassed many times to the cemetery and back; and all were full. No doubt the boatmen made a good day's wage; but the gondoliers had never seen, not even in the carnival, anything so ridiculous; and that evening when they described to each other the boats and the rowers they had seen, and acted out all these absurdities, you would have thought them the merriest souls alive."

"But were they so, Giacomo?"

"No, indeed, signora: they were miserable. They could not sleep, or if they did they dreamed that they were rowing {22} over the lagoons, and only woke in wretchedness to find it was not true."

"And on Thursday what happened?"

"The gondoliers then took an advocate, and sent him to the Syndic to plead their cause. But the Syndic would not listen; he would only deal with the gondoliers themselves, and he began to be severe and to talk of many steamboats running everywhere; and the gondoliers were told of 'launches' that could thread the smallest canals better than gondolas! Alas! signora, what could be done if this were true?

"Just then the military and customs officers who had loaned their boats to the ferries sent word that they must have them again; and an old gondolier whom all the others respected, took his boat out and began to serve a ferry. Instantly the strike was ended. The gondolas were untied, cleaned, and dressed as for a gala-day. The canals and lagoons were soon alive with them, and we had our Venice back again."

It was the old story. The gondoliers could not be allowed to stand in the way of progress, nor could they lay down the law to Venice. But their simple way of going on a strike, and absolute simplicity in ending it, was almost pathetic; such children did they seem in comparison with strikers and strikes that we know.

By this time midday has come, and our very early breakfast calls for an early luncheon. The artist is so absorbed in his work that it seems almost a sin to disturb him; but in his ardor to-day he has painted so rapidly as quite to satisfy us, and half to content himself,—a true artist rarely does more than this.

After luncheon we try to read; but the many changing sights and sounds are too distracting for anything that requires thought, and when we read a story on the lagoon we are never able to remember whether the lovers married {23} or were separated by a cruel fate. A sentence is well begun, when a deeper shadow puts a new color on everything, and we drop our book to look; the same sentence is half read a second time, when a fruit-boat laden with piles of green and golden melons and luscious peaches comes so near us that Anita calls out to Giacomo to buy what will be needed on the morrow, and we listen to the chattering and bargaining until that is over; the third time that particular sentence is finished, but just then drowsiness overcomes our brain, and we are asleep.

We wake to find our rowers in their places, and the day so far spent that we must decide where we will dine,—at home, at the Lido, or at our favorite trattoria. To-day we favor the Lido, although we are hungry and the dinner is not so good as on the Zattere; but the exquisite outlook at sea and sky, and the mystery of the bit of distant coast, minister to that Venetian appetite of eyes which is never satisfied, and the home coming at night sends us to sleep with such a heavenly vision in our thought.

Landing rather late at Sant' Elisabetta, we have only time for a quick stroll around our favorite promenade, while Giacomo orders our dinner. The fresh sea-breeze is delicious, and the dim blue line of hills above Trieste seems very near in the clear atmosphere; we gather a large bunch of poppies and a dainty nosegay of primroses, and then seek the little osteria.

When we turn our gondola homeward, the afterglow is fading, and the gloaming with its quiet leads the thoughts far, far away. The stars come out, and the rising moon gives just that light that changes all objects into ghostly apparitions. The schooners are phantom-ships; everything that is moving is indistinct and spirit-like, seeming as if suspended and floating in mid-air, until we come nearer to the city and the lights give a new aspect to the evening.

The pyramids of lamps on San Marco are all ablaze. Gondolas are hastening to the Piazzetta. The band is playing, and we know how gay it all is. But to-night we turn into the Grand Canal, where we catch glimpses into lighted rooms with richly ornamented ceilings, while from the overhanging balconies come gay voices and musical laughs, such as are in harmony with the pearly city the moon is now revealing; and the artist recites from Longfellow,—

"White swan of cities, slumbering in thy nest

So wonderfully built among the reeds

Of the lagoon, that fences thee and feeds,

As sayest the old historian and thy guest!

White water-lily, cradled and caressed

By ocean streams, and from the silt and weeds

Lifting thy golden pistils with their seeds,

Thy sun-illumined spires, thy crown and crest!

White phantom city, whose untrodden streets

Are rivers, and whose pavements are the shifting

Shadows of palaces and strips of sky;

I wait to see thee vanish like the fleets

Seen in mirage, or towers of cloud uplifting

In air their unsubstantial masonry."

There is a wonderful fulness and magnificence of sound in the title of the Doge of Venice! It has only been paralleled by that of the Stadtholder of the United Provinces, and excelled by that of the President of the United States.

Why is this? Partly because it is a less generic title than emperor, king, sultan, and so on; and then it was the gift of the people, not a mere accident of birth. A man was already known for strength of character or for great deeds before he received the Beretta. He had attained an influence over other men in such a degree that they were willing to elevate him above themselves.

In the accounts of the achievements and acts of the Doges, it would seem that their power was absolute; but the truth shows this appearance to be most deceitful. For while the earliest of these dukes were autocratic, the democracy soon feared the effect of such rulers, and gradually the Doge was hedged in until, in one way and another, he who appeared to govern was more governed himself than were many who surrounded him.

But when, in 697, Luca Anafesto was elected the first Doge of Venice, and in the church of his own parish was seated in an impromptu chair of state, and invested with a crown of gold and a sceptre of ivory, he thereby acquired vast power. He was not only the head of civil and military affairs, but of the Church as well, since the purely {26} spiritual matters only were controlled by the clergy. His Serenity alone could convoke the church assemblies; and no deacon, bishop, or patriarch could be chosen or confirmed in office without his sanction.

In fact, he was a Sovereign, for the Tribunes were subordinate to the Doge; and for twenty years Anafesto reigned supreme. But in that time the public vacillated curiously as to how they would be governed. Theoretically they were a democracy, and monarchy was an experiment; and for centuries a semi-civil war existed in Venice, degenerating at times into actual anarchy.

The name of Doge was given up, and that of Magister (Master) was adopted; again Doge was in favor, and not infrequently those who bore the dignity of that office were blinded, insulted, exiled, and even murdered. To change the Doge seemed to be the only panacea which occurred to the Venetians in times of difficulty; and erelong what at the first glance seems an honor came to be, in fact, a serious danger,—a position subject to suspicions, jealousies, and conspiracies.

Like the stories of the early days of other nations, that of Venice is largely mythical, confusing, and confused; and not until Giovanni Sagornino (John of Venice, and Deacon John, as he is called) wrote a connected and trustworthy story of his own time, can we clearly trace the course of events.

From 976 on through the dogates of the Orseoli and the Michieli, the external history of Venice is told by recounting the fightings with Dalmatians and other neighbors, and even with the Normans at Naples, and the story of the earlier crusades; while its internal history is a strange mixture of plots and counterplots on the one hand, and the endeavors of those who had learned the value of law and order, on the other, to bring about some conditions on which all could rest with confidence.

The manner of electing the Doge during three centuries was very curious, but after all not unlike the methods of politics almost everywhere. There are always bold, enterprising men who seem born to be leaders, and others who, through family tradition or great wealth, appropriate to themselves prominent positions. These classes existed in Venice, and they held what we should call caucuses, and decided who suited them best for Doge. Of course there were compromises to be made before these leaders could agree; but at last a sort of mass-meeting was called in San Marco, and the people were advised as to who they should elect. Naturally, he who was thus easily exalted could be as easily destroyed; and the inspiriting cries of Provato, Provato (Approved), which arose like thunder-tones to announce the will of the people, must have had an undertone on a purely minor key, in spite of the honor and dignity they conferred.

Vitale Michieli II., who came into power in 1117, was the last Doge elected by this dubious form of universal suffrage. The people had grown in experience and intelligence, and demanded more real power for themselves.

A century had now passed since Venice had begun to replace the mud huts and primitive houses of her founders and their descendants with marble palaces; and the churches and monasteries of the tenth and eleventh centuries show full well the riches of the Republic at that period, and foreshadow the abounding magnificence which followed so rapidly. But this wealth was not distributed among the people, as the privileges of salt-gathering and fishing had been among the primeval dwellers on these islands.

The fact that San Marco, the Ducal Palace, and the first Public Hospital were all founded by one Doge, Orseolo I., from his private fortune at the close of the tenth century, and even the wills of the Patriarch Fortunate in 825, and {28} of other wealthy patricians, prove how riches were massed in certain families; and these families also absorbed the honors of the Republic.

The names of the Orseoli, Michieli, Dandolos, Contarinis, Morosinis, Tiepolos, and others occur ad infinitum, alternating in the story of the glories and riches of Mediæval Venice. They were all patricians (Maggiori), and a wide chasm now separated them from the lower classes (Mediocri and Minori). The former had sufficient means to stay at home, while the two latter were forced to follow various maritime occupations; and it soon came about that all the larger ships were owned by Patricians, were fitted out by them, and brought back to them the gold which gave them their power. In short, Venice, calling herself a Republic, was governed by an Oligarchy,—by a few families who now owned almost all the soil outside of that in possession of ecclesiastical establishments.

One custom which had greatly furthered the establishment of the aristocracy was discontinued in 1033; this was the association of the son of the Doge with his father in the power and responsibility of the office, which directly tended to making it hereditary. But in spite of reforms, only patricians held the civil, military, naval, or ecclesiastical offices; only patricians governed the provinces; the judicial and episcopal benches were filled by the same class, and to them alone had the Beretta and the Pallium been given. In five centuries, as frequently as the Doges had succeeded each other, but nineteen families had been honored with this office, which had now assumed a power as independent and a magnificence as imposing as those of the rulers of Germany or France.

After reading of the power, wealth, and influence of the Venetian Republic in 1172, we are surprised to learn that its population was but sixty-five thousand; and yet, even with this small number, the Arrengo (General Assembly), {29} consisting of all male inhabitants, had become a troublesome body, and hitherto no measure was valid that had not been passed by it.

The Patricians found themselves between two fires,—the Arrengo on the one hand, where the poorest and most ignorant of the Minori had equal rights with themselves, and on the other hand the Doge, who was elected for life, and whose power was only modified by two Councillors, who might easily be entirely in his control.

The assassination of Michieli III. in 1172 afforded an opportunity for changes, and the increasing dissatisfaction of the aristocracy now culminated in a reform of the Constitution, which ended in a division of Venice into six wards, from each of which two deputies appointed forty members of a Great Council (Consiglio Grande), which was to be the general legislature, elected annually on September 29. The Arrengo was not abolished, but would be convened only on occasions of vast importance, such as a Declaration of War, the Election of a Doge, or the making of a Treaty of Peace.

This measure seemed very harmless, as there were no limitations to the rank of a Councillor; but the Patricians well knew that the Deputies would be of their order, and each of these could appoint four members of his own family; and as almost from the first the meetings of the Council were held with closed doors, it soon became anything but a democratic body.

Having thus largely extinguished the power of the people, the Patricians proceeded to limit that of the Doge. The Council of Two was replaced by one with six members, who were to advise his Serenity on all matters, and without their approval no act of his could be legal. These Privy Councillors retained their office through the entire Dogate to which they were elected. From the four hundred and eighty members of the Grand Council, sixty {30} Senators were annually elected to attend to many matters which did not require to be brought before the whole council, and to overlook the machinery of the government.

All this being done, a new Doge was elected in an entirely novel manner. Thirty-four of the Grand Council were appointed to choose eleven from their number as an Electoral Conclave; these eleven were bound by a solemn oath to impartiality, and any candidate who received nine of their votes was declared to be the Doge.

On Jan. 11, 1173, the eleven met in San Marco with open doors, and in the presence of a vast conclave elected Orio Malipiero, one of their own number. But he diffidently declined the office, and begged permission to nominate Sebastiano Ziani, as better qualified for this exalted station.

This nomination was accepted, and from the high altar of San Marco the Procurator announced to the people, using the new formula, "This is your Doge, if it pleases you" (Questo e vostro doge, se m piacera), and the people responded with shouts and acclamations.

That all this was not as spontaneous as it appeared, was soon demonstrated; for when Ziani was carried around the Piazza in a wooden chair by some workmen from the Arsenal, he distributed liberally to the people money stamped with his own name, which had been expressly prepared for the purpose. This unusual liberality alarmed the jealous Patricians, and at once a law was made that only a newly elected doge should be permitted to distribute largesse, and he not less than one hundred nor more than one hundred and fifty ducats. This money was called Oselle, and was specially coined for the purpose.

Returning to the cathedral, Ziani was solemnly invested with the crown and sceptre. Thus began his important reign, which lasted but five years and a quarter, and ended in his voluntary abdication. The enormous wealth of {31} his family was said to have been founded by the good fortune of an ancestor who found in the ruins of Altino a golden cow which had been dedicated to the service of Juno. However it may have been, this tradition gave rise to the saying, "He has the cow of Ziani," when speaking of a wealthy man.

By the advice of Ziani, the Bank of Venice was established, and was the first institution of its kind in Europe. During his reign Venice bore her part in the siege of Ancona, which so alarmed the Greek Emperor that he, so to speak, bought back his former ally by a treaty which bound him to pay Venice one thousand and five hundred solid pounds of gold; but his most important political acts were those already recounted in the reconciliation of Alexander III. and Frederick Barbarossa.

Ziani did much for the improvement of the Piazza, and extended it by removing buildings which were falling into ruin. He embellished the whole city by the construction of elegant bridges; but tradition teaches that his greatest architectural achievement was the taking down of the Church of San Geminiano, in order to enlarge San Marco, which he did at his own cost.

Before demolishing the sanctuary, Ziani applied to the Pope for his sanction of the act. The Pope answered that he could not authorize a sacrilege, but he could be very indulgent after it had been committed. The church soon disappeared, and its destruction gave rise to a curious custom. For many succeeding years, on an appointed day, the Doge, attended by a brilliant retinue, repaired to the Piazza, where he was met by the curé of the parish with his clergy. The curé asked, "When will your Serenity be pleased to restore my church on its former site?"

"Next year," the Doge annually replied, and broke the promise as often.

ENRICO DANDOLO.

From the abdication of Ziani to the election of Dandolo, in 1193, there were no incidents in the story of Venice that do not fade before the tremendous achievements of the fiery old man, eighty-six years old when elected, who for twelve years labored to exalt Venice and humble the Greeks, and, finally dying at Constantinople, which he had twice conquered, was buried in St. Sophia, far from his beloved San Marco, and the city for which he gave his life.

The oath taken by Dandolo at his institution in the Dogate is the first promissione which has been preserved. By it he was bound, by all possible pledges, faithfully to execute the laws of the Republic, to submit his private affairs to the common courts, to write no personal letters to the Pope nor any ruler, and to maintain at his own cost two ships of war. To such lengths had the jealousy of the Patricians already reached that the Doge was little more than the figure-head of the Republic.

The reign of Dandolo opened with the usual conflicts with the Pisans, Dalmatians, and any other neighbors who were troublesome to the Venetians at that time, none being of unusual importance. But when, in 1195, Innocent III. ascended the papal throne, he initiated the preaching of a Crusade destined to result in the glory of Dandolo and Venice, but not in the conquest of the Saracens nor the possession of Palestine.

Innocent, but thirty-six years old, ambitious and energetic, soon brought to his allegiance all the powers of Europe except the Republics of Pisa and Venice. Dandolo, with his bravery and inflexibility of purpose, was a formidable opponent, and when at last his concurrence was sought, he was asked to aid the Crusade for gain and not as a subject of the Pope.

In France the preaching of Foulkes of Neuilly attracted thousands to his standard. Hazlitt says:—

"The streets of Paris, the banks of the Marne, and the plains of Champagne were deserted. Doctors left their patients; lovers forsook their mistresses. The usurer crept from his hoard; the thief emerged from his hiding-place. All joined the holy phalanx. The joust and the tourney, the love of ladies, the guerdon of valor, were alike forgotten in the excitement, the tilters taking the vow and assuming the emblem of sanctity; in a short time the flower of French chivalry, from Boulogne to the Pyrenees, was assembled under the banners of Theobald, Count of Champagne, and his cousin Louis, Count of Blois and Chartres."

Remembering the terrible disasters that had attended the former Crusades in reaching the Holy Land, these leaders resolved to invite the Venetians to furnish shipping to transport soldiers and horses to Palestine.

An embassy of six French noblemen was sent to Venice, which city they reached on Feb. 15, 1201. Among them was one gratefully remembered by us for his record of events which tells us much that the Venetian writers quite ignored; in fact, some of them make no pretence of regarding the whole affair as anything but an opportunity to increase the glory of the Venetians.

The French ambassadors did not attempt to ignore the vast power of the Venetians to aid or hinder them in the prosecution of the Crusade. Men and money they had in plenty, but with prayers and tears they entreated Venice to furnish them with ships. Indeed, according to Villehardouin, the Crusaders were accomplished in weeping, and shed tears copiously on all occasions of joy, sorrow, or devotion.

There were repeated assemblies of the various councils, and after each of these Dandolo required some days for {34} reflection; but at length it was agreed that the Crusaders should assemble at Venice on the 22d of June in the following year, when they should be provided with transports for thirty-five thousand men and forty-five hundred horses; it was also promised that these men and horses should be supplied with provisions for a year, and be taken wheresoever the service of God required. Then, with true Venetian magnificence, the armament was to be increased by fifty galleys at the expense of the Republic. For all this the French promised to pay eighty-five thousand marks (£170,000) in four instalments.

These conditions being settled, a grand convocation was called in San Marco, where ten thousand of the people, after the Mass, were humbly entreated to assent to the wishes of the ambassadors,—a harmless deceit of these so-called Republicans. Villehardouin made a moving appeal, watered with tears, and declared that the ambassadors would not rise from their knees until they had obtained consent to their wishes.

"With this the six ambassadors knelt down, weeping. The Doge and the people then cried out with one voice, 'We grant it, we grant it!' And so great was the sound that nothing ever equalled it. The good Doge of Venice, who was most wise and brave, then ascended the pulpit and spoke to the people. 'Signori,' he said, 'you see the honor which God has done you, that the greatest nation on earth has left all other peoples in order to ask your company, that you should share with them this great undertaking, which is the conquest of Jerusalem.'"

Let us for a moment picture this scene, one of the most unusual in history. It was a winter afternoon, when the choir and altars alone could have light enough to relieve the gloom of the cathedral, filled by an excited crowd, each man of which felt the responsibility (we know with how little reason) of the "Yes" or "No" he was to speak. {35} There was no humility here, such as the foreign nobles were accustomed to; these sea-faring, weather-beaten men looked on them as equals.

Before the high altar, where the silvery hair and ducal robes of Dandolo were glistening in the light, knelt these splendidly attired nobles, weeping and begging for what these poor vassals believed that they could grant or withhold. We cannot imagine the varied and overpowering emotions that ascended with that shout of "Concediamo," nor the echoes of the great dome that hung so gloomily over all.

The treaty, written on parchment, and strengthened with oaths and seals, was despatched to Innocent for his approval, and all Venice began to hum with the unusual preparations for the expedition. The small coins were found insufficient to pay the necessary workmen at the arsenal; and a new silver coin, stamped with the effigy of Dandolo, was issued for their payment.

Besides the many ships to be built, there was armor to be furnished for a host; catapults and battering-rams must be made ready; the Venetian galleys were to be provided with lofty towers to be used in attacking fortresses on the seashore; while an enormous amount of grain, food, wine, swords, daggers, and battle-axes, thousands of bows and tens of thousands of arrows with metal tips, as well as supplies of cordage, oars, sails, anchors, and chains, and many other things, must be made ready to load one hundred and ten large store-ships. And for all this but sixteen months of hand labor!

The vast amount of stores always kept in Venice were insufficient, and men and ships must be spared to go in search of materials. The laborers were divided and subdivided, and employed both day and night. The whole work went on as if by magic. As soon as a transport or galley was completed, it was launched, and another rose in {36} its place; Venice bustled with labor and bristled with its results, and seemed a vast Babel for noise.

At San Niccolo and elsewhere on the Lido, barracks for troops, stables, and storehouses were built, provisions were abundantly supplied; and the skilful and generous manner in which Venice fulfilled her great contract would have made her famous, had this not been eclipsed by greater deeds.

As it became known in all Europe that Venice had undertaken the transport of the Crusaders, adventurers began to pour into the city. They came singly and in bands, until early in 1202 fifteen thousand had gathered; and this number was nearly doubled by June. These strangers added greatly to the gayety of life in Venice; for, bent upon dangerous adventures, they were determined to amuse themselves while they could. They explored the lagoons in the fascinating barchette by day, and by night told stories of love and war, and woke the echoes to the unusual sound of the national airs of many nations and tribes, all more or less martial and inspiriting as heard from one island to another.

But alas! as month followed month and the expedition did not move, when it began to be whispered that the barons could not fulfil their engagements, these harmless amusements changed to drinking and gambling and such other license of behavior as often led to fatal quarrels.

The leaders who had come at the appointed time were shocked by the absence of numbers of those who should have brought their share of men and money. There had been great discouragements; young Thibault of Champagne, their chosen leader, had died; and in the long time that had elapsed since the treaty was made, many impatient spirits had embarked from other ports and taken various routes to Palestine.

Boniface, Marquis of Monteferrato, was now the leader {37} of the Crusade; and he and the other nobles, after stripping themselves of money, jewels, and other valuables, were still unable to pay the last thirty-two thousand marks of their debt. The situation was deplorable; the crowded barracks were full of disease, and many were dying daily, and no one could see any prospect of relief. Even Dandolo was touched by the troubles and the devotion of the barons; and now came his temptation,—for it is not probable, as some authors seem to believe, that he could have seen the end from the beginning; but his patriotism, which we must allow to have been a refined sort of selfishness, suggested to him a compromise which was finally made.

Dandolo proposed that in consideration of the debt still due, the Crusaders should join with the Venetians in subduing Zara, that ever-turbulent and ever-rebelling city. The larger part of the Crusaders made no objection to this plan; a smaller number thought it wrong for soldiers of the cross to turn their arms against Christians, and feared the disapproval of the Pope. No telegraphs nor submarine cables existed; to consult his Holiness would require months, and meantime the debt could be paid by taking Zara, and they might be landed in Palestine. The condition of the idle soldiers became more and more alarming; and when the Venetians answered the objections of the Cardinal-legate, Peter of Capua, in abrupt fashion, and he left the Crusaders to their fate, the bargain was soon closed and all arrangements completed.

But one thing remained to be settled,—the choice of a commander of the fleet; and this was accomplished on a Sunday, in San Marco. The importance of the occasion drew all the inhabitants, and indeed, all strangers who could find a place, to the Cathedral and the Piazza. Patricians, barons, statesmen, soldiers, and the people, all were there, as well as ladies in rich brocades, with necklaces of pearls and precious stones and priceless jewels in their hair.

The crimson, scarlet, and purple robes of the statesmen with their diamond or gold buttons, the full armor of the barons and knights, almost as brilliant as jewels, the helmets and shields held by the pages, all served to render it a scene of dazzling brilliancy; while the splendid hangings and decorations of San Marco, the costly vessels of gold upon its altars, and the gorgeous vestments of the priests served to impress the strangers with the dignity and wealth of the Republic.

The silks ceased to rustle, and the swords and battle-axes to clink, as the acolytes took their places; and the service seemed about to begin, when suddenly the Doge arose and majestically ascended the pulpit. He was ninety-five years old, and erect as in youth; his ruddy face and large blue eyes, which did not show their dimness of sight, spoke not half his age; the furrows across his brow alone indicated the experiences and the years that he had passed through, and the ducal crown was never worn with more majestic dignity. Every sound was hushed, and in the farthest corner of San Marco could his words be heard:

"'Signori, you are associated with the greatest nation in the world in the most important matter which can be undertaken by men. I am old and weak, and need rest, having many troubles in the body; but I perceive that none can so well guide and govern you as I who am your lord. If you will consent that I should take the sign of the cross to care for you and direct you, and that my son should, in my stead, regulate the affairs of the city, I will go to live and die with you and the pilgrims.'

"When they heard this, they cried with one voice, 'Yes, we pray you, in the name of God, take it and come with us.'

"Then the people of the country and the pilgrims were greatly moved and shed many tears, because this heroic man had so many reasons for remaining at home, being old. But he was strong and of a great heart. He then descended from the pulpit, and knelt before the altar weeping; and the cross was sewn upon the front of his great cap, so that all might see it. And the Venetians that day in great numbers took the cross."

THE CRUSADERS AND DANDOLO AT ZARA.

All preliminaries being settled, and Raniero Dandolo made Vice-Doge during his father's absence, the embarkation of the army was begun. This furnished one of those spectacles so frequent in mediæval Venice, and was watched for days by all the city.

As yet no restraint had been put upon the luxury of dress and display of wealth which the Venetians loved; and the guilds of the city, each in its appropriate costume, presented a brilliant and picturesque assembly whenever the pageants of which they were so fond brought them together in large numbers. And where do the conditions afford so beautiful a setting to artistic display as in this wonderful city of the sea? Where else would silks and velvets, precious stones, and gold and silver work seem so suitable as in this "Queen of the Adriatic," rising from its many-tinted waters sparkling beneath a southern sun?

The noble war-horses of the Frenchmen, led unwillingly upon the vessels, were an astonishing spectacle to the Venetians, and would be so still, since recently a single horse at San Lazaro was mentioned as one of the sights of Venice by our landlord!

To the French, German, and Flemish Crusaders the Venetian war-ships, huge in size, with deck upon deck and above all great towers, were equally marvellous. So heavy were they that in addition to sails each one required fifty oars with four men to each oar. The finest of these, called "The World," was venerated by the Venetians; for not only was it the largest ship afloat, but it had proved invincible in former battles.

As the four hundred and eighty vessels were filled, one by one they proceeded down the Grand Canal and anchored off the Castle, until the galleys, transports, and long boats extended for miles on the Venetian waters. The excitement {40} can scarcely be described. "Bound for Palestine! To deliver Jerusalem! To exterminate the Infidels!" These cries aroused the people to the greatest enthusiasm, and helped the Venetian women, though not without tears and anguish, to bid God-speed to those they held most dear.

A part of the vessels were sent off in advance; and a week later, on a brilliant October day, the remaining fleet departed. From the masts fluttered the standards of Venice and of all the chief countries of Europe, as well as the rich gonfalons and banners of the nobles; while above every mast arose the sacred cross. The ships were filled to their summits with soldiers, their armor glistening in the sun; while the sides of the principal vessels were hung with the emblazoned shields of the nobles they carried.

Early in the morning the Doge and the barons heard Mass in San Marco, and from there, in grand procession, marched to the quay to the music of silver trumpets and cymbals. Barges were waiting to convey them to the ships; and as they embarked, hundreds of barchette and other small boats filled with ladies and children surrounded them, and followed to witness the departure of the fleet, and wave their final farewells to husbands and fathers, sons and lovers.

Each noble had his own ship, and an attendant transport for horses. Dandolo's galley was vermilion-colored, as if he were an imperial potentate, and his pavilion when on shore was of the same royal hue. The signal for sailing was given by a hundred trumpets, and in the castles at the crosstrees of the ships the priests and monks chanted the "Veni Creator Spiritus."

As ship after ship left its moorings, as sail after sail swelled before the wind, and the rowers bent to their oars, it seemed as if the whole sea were covered; and the hearts {41} of those who were left behind were comforted by the feeling that no power could withstand so goodly and brave a host. The fleet was watched with straining eyes until but a few white specks could be discerned in the dim distance, and the people returned to their beloved Venezia, seeming now like a vast house of mourning upon which the silence of the tomb had fallen.

In the Ducal Palace the Marquis of Monteferrato, the commander-in-chief of the army, lay ill, or made a pretence of being so. He was attended by the Baron de Montmorency and other nobles, all strict churchmen, of whom it was more than suspected that their delay was caused by fear of the disapproval of the Pope. Two months passed before they joined the Crusade; and as they moved about the city and sailed on the lagoons, they seemed like the last link between Venice and all that had gone from her.

The lovely weather which attended the fleet brought it, in spite of some delays, before the fortress of Zara on Saint Martin's eve (November 10). No stronghold in the dominions of Venice could compare with this for strength, and a girdle of lofty watch-towers secured it against surprise. It was garrisoned by Hungarian soldiers under fine discipline, and the Zaratines were a brave people. Seventeen years had elapsed since they had expelled the last Venetian Podestà from their territory, and they had full faith in their ability to repulse an enemy.

But the Zaratines had not counted on such a force as now besieged them, and on the second day offers of surrender were made to Dandolo, on condition that the lives of the people were spared. The Doge left the emissaries in order to consult with the barons, and returning to his pavilion found the Zaratines gone, and in their stead the Pope's envoy, Abbot Guy of Vaux-Cernay, who advanced with an open letter in his hand, exclaiming, "Sir, I {42} prohibit you, in the name of the Apostle, from attacking this city; for it belongs to Christians, and you are a pilgrim!"

Dandolo was furious, and none the less so when he learned that Abbot Guy had persuaded the Zaratines not to surrender to the Venetians. But a council was called, and the barons agreed with the Doge to resume the siege at once. The abbot had led the Zaratines to believe that under no circumstances would their lives be spared, and the second siege was fiercely contested. On the sixth day the city fell, and was given up to pillage. Fierce quarrels ensued between the French and the Venetians over the division of the spoil; and this uproar was scarcely calmed before an emissary from his Holiness arrived, calling the Crusaders to account for their present occupation and commanding them to retain no booty.

The French nobles were greatly disturbed, while the old Doge and his councillors were indifferent to the curses or blessings of the Pontiff, who had directed the barons to hold no intercourse with the Venetians, "except by necessity, and then with bitterness of heart." Innocent expected the Crusaders to proceed at once to Constantinople, and suggested that if the Emperor, to whom he had already written, did not supply them generously with provisions, they might, "in the name and for the sake of the Redeemer," seize such things as they needed, wherever they could be had. He concluded by commanding them to proceed at once to Palestine, "turning neither to the right nor to the left." This in no wise affected the Venetians. They were excommunicated; but what of that? They had demanded their pound of flesh from the Crusaders, which was the taking of Zara, to which the barons had agreed; and Dandolo, by his addition to the fleet and the army, at his own cost or that of Venice, had left them little cause of complaint of their bargain, since without him they could not even start for Palestine. Whatever future {43} causes of dissatisfaction might arise against him, thus far it had been purely a business transaction between the Doge and the barons. Of the present condition Gibbon says:—

"The conquest of Zara had scattered the seeds of discord and scandal; the arms of the allies had been stained in their outset with the blood, not of infidels, but of Christians; the King of Hungary and his new subjects were themselves enlisted under the banner of the cross; and the scruples of the devout were magnified by the fear or lassitude of the reluctant pilgrims. The Pope had excommunicated the false Crusaders who had pillaged and massacred their brethren, and only the Marquis Boniface and Simon of Montfort escaped these spiritual thunders,—the one by his absence from the siege, the other by his final departure from the camp."

The soldiers became so turbulent as to give constant anxiety to the barons; and the Zaratines were happy at the enmities among the invaders, and encouraged by the Pope's care for their interests.

The Crusaders sent humble apologies to the Pontiff, so depicting to him the uncontrollable circumstances which had surrounded them, as in a net, that the heart of Innocent was touched, and he sent to Monteferrato his blessing and pardon for himself and the Crusaders.

But Dandolo told the Nuncio that in the affairs of Venice the Pope could scarcely be interested, since his Holiness had no concern in them, and he neither asked nor desired any communication with the Holy See.