Title: Travels in the footsteps of Bruce in Algeria and Tunis

Author: Sir R. Lambert Playfair

Release date: December 7, 2023 [eBook #72351]

Language: English

Original publication: London: C. Kegan Paul, 1877

Credits: Galo Flordelis (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TRAVELS

IN

THE FOOTSTEPS OF BRUCE

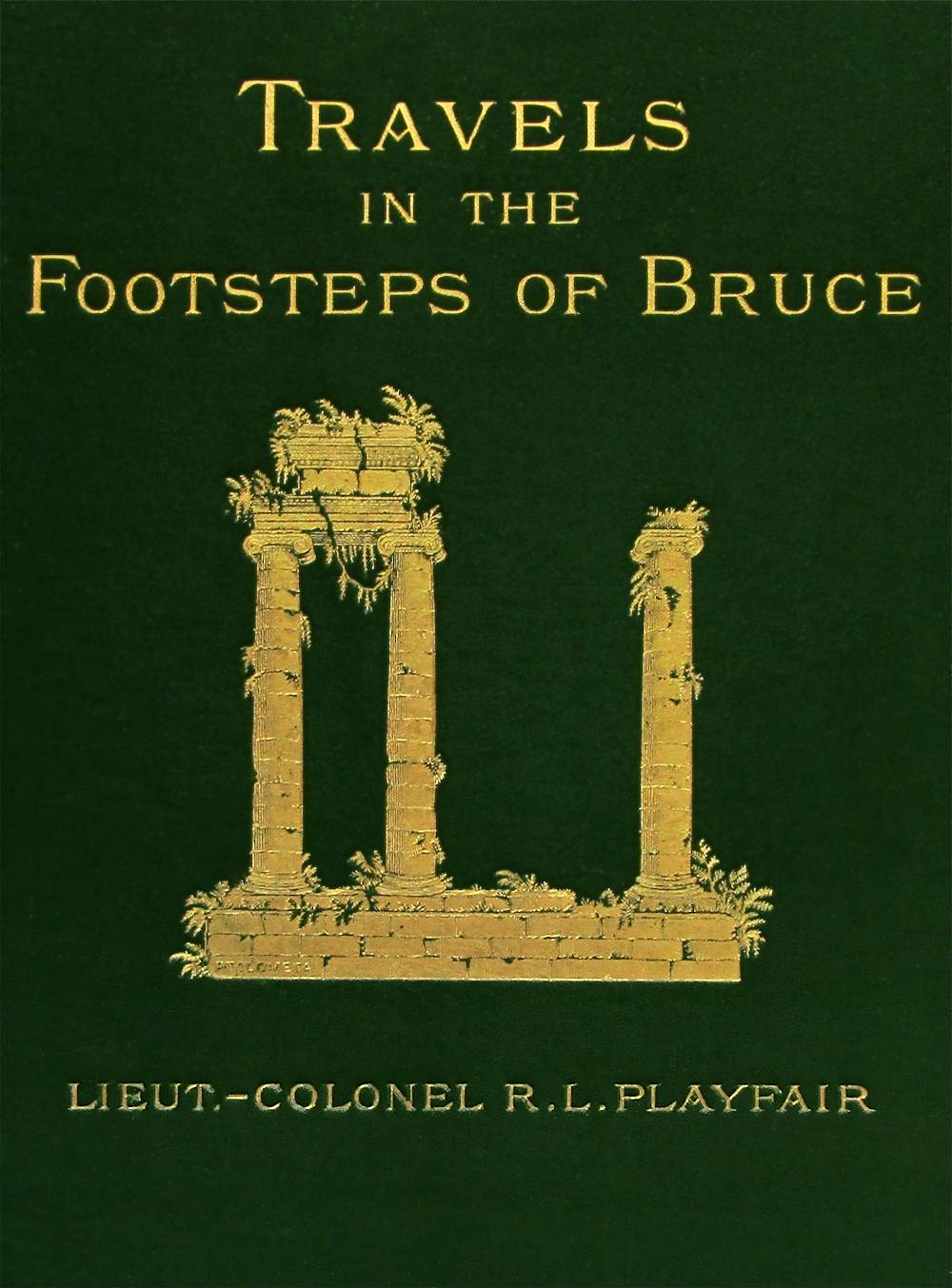

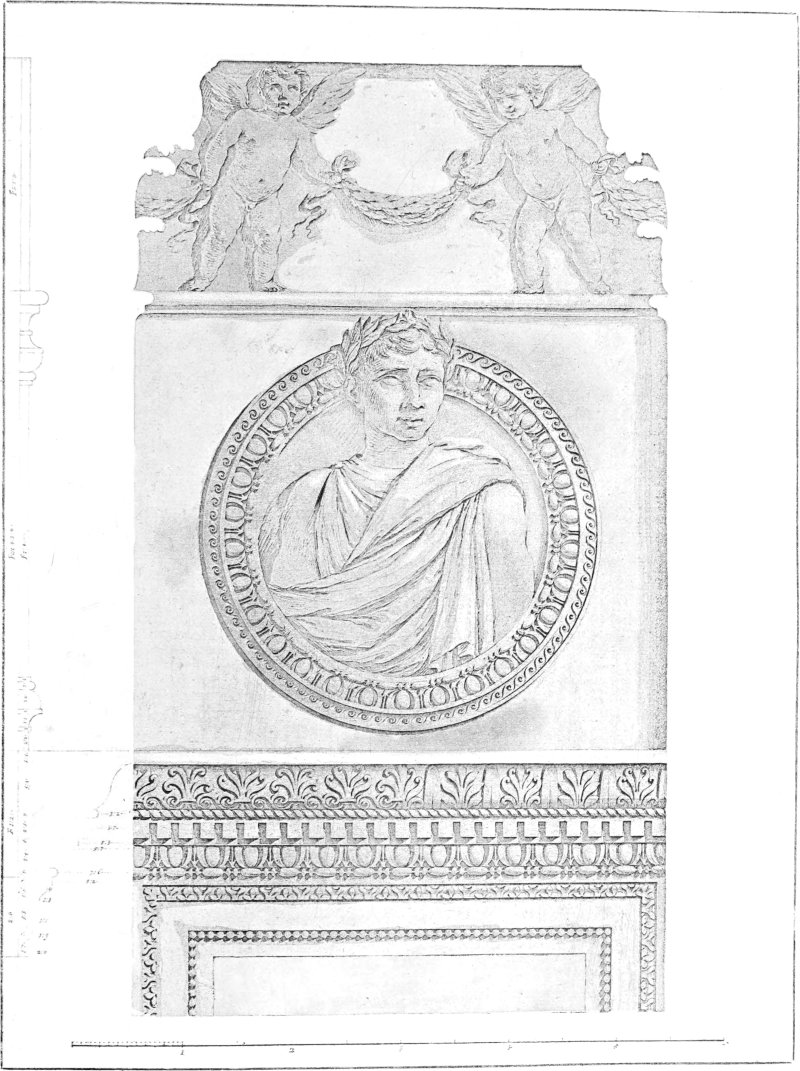

Plate I.

J. LEITCH & Co. Sc.

TOMBEAU DE LA CHRÉTIENNE, OR TOMB OF JUBA II.

FAC-SIMILE OF A WATER COLOR DRAWING BY BRUCE.

ILLUSTRATED BY FACSIMILES OF HIS ORIGINAL DRAWINGS

BY

LIEUT.-COLONEL R.

L. PLAYFAIR

H.B.M. CONSUL-GENERAL IN

ALGERIA

![[Illustration]](images/i02.jpg)

LONDON

C. KEGAN PAUL & CO., 1 PATERNOSTER

SQUARE

1877

(The rights of translation and of reproduction are reserved)

Dear Lady Thurlow,

May I dedicate to you the following pages, written to illustrate the earliest travels of your ancestor, James Bruce; and to make known a portion of that priceless collection of drawings, too long shut up in the muniment room of Kinnaird, which you have so kindly and so unreservedly placed at my disposal?

Although you are the sole heiress of the illustrious traveller, all the world are co-heirs with you in his fame and in the result of his explorations; and they will tender to you their sincerest thanks for restoring to them so important a part of their heritage.

Believe me, dear Lady Thurlow,

Yours most gratefully,

R. L. PLAYFAIR.

British Consulate General,

Algiers: October 1, 1877.

![[Decoration]](images/decor1.jpg)

| PAGE | ||

| INTRODUCTORY | 1 | |

| PART I. | ||

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | Bruce appointed Consul-General at Algiers | 15 |

| II. | Julia Cæsarea | 23 |

| III. | Start for Bone — Visit the Forest of Edough and Mines of Ain Barbar | 31 |

| IV. | Bone to Guelma — Ruins of Announa — Hammam Meskoutin — Roknia — Cave of Djebel Thaya — Mahadjiba — The Soumah | 36 |

| V. | Constantine | 47 |

| VI. | Bruce’s Route to Lambessa — Zana or Diana Veteranorum — The Medrassen — Bruce arrives at the Aures — Curious Meeting with a Chief of those Mountains | 52 |

| VII. | Our Arrival at Batna — History and Description of the Aures Mountains | 61 |

| VIII. | Start for the Aures — Lambessa — El-Arbäa — Menäa | 70 |

| IX. | Ascent of the Oued Abdi — Mines of Taghit — Arrival at Oued Taga | 77 |

| X. | Timegad | 83 |

| XI. | Leave Timegad — Foum Kosentina — Megalithic Remains — Oum el-Ashera — El-Wadhaha — Ascent of Chellia — Ain Meimoun — Lions | 91 |

| XII. | Ain Khenchla — Across the Plains of the Nememcha to Tebessa | 98 |

| XIII. | Tebessa — Return to Constantine | 103 |

| XIV. | Constantine to Algiers through Kabylia | 114 |

| [viii]PART II. | ||

| XV. | Start from Algiers on Second Expedition — Earl of Kingston undertakes Photographic Department — Arrival at Tunis — Sebkha es-Sedjouni — Mohammedia — Aqueduct of Carthage — Oudena — Zaghouan | 127 |

| XVI. | Es-Sabala — The Medjerda — Dragons of the Atlas — Bizerta — Immense Land-locked Harbour — Fish in Lake — Djebel Ishkul — Wild Buffaloes | 140 |

| XVII. | Visit to the Bey and General Kheir-ed-din — Difficulties attending Travel in Tunis — Improvement in the Government of the Country — Commencement of Bruce’s Journey by the Medjerda — Our Start for Susa by Sea — Susa | 147 |

| XVIII. | Departure from Susa — Es-Sahel — Effects of the Disforesting of Tunis — Olive-trees — El-Djem | 154 |

| XIX. | El-Djem to Kerouan | 163 |

| XX. | Kerouan to Djebel Trozza, Djilma and Sbeitla | 172 |

| XXI. | Sbeitla | 177 |

| XXII. | Bruce’s Journey from Sbeitla to Hydra | 188 |

| XXIII. | Leave Sbeitla — Sbiba — Er-Raheia — Hamada Oulad Ayar — Arrival at Mukther | 191 |

| XXIV. | Mukther | 197 |

| XXV. | Mukther to Zanfour — Bruce’s Route from Kef to Zanfour | 205 |

| XXVI. | Zanfour to Ain Edjah and Teboursouk — Dougga | 213 |

| XXVII. | Leave Teboursouk — Valley of Lions — Ain Tunga — Testour | 226 |

| XXVIII. | Testour to El-Badja by the Mountains — El-Badja | 231 |

| XXIX. | Route from El-Badja to Tabarca | 238 |

| XXX. | Tabarca | 247 |

| XXXI. | From Tabarca to La Calle | 251 |

| PART III. | ||

| XXXII. | Bruce’s Route from Tebessa to the Djerid and back to Tunis | 265 |

| XXXIII. | Bruce’s Route to Djerba, Tripoli, and back to Tunis | 275 |

| XXXIV. | Tripoli | 278 |

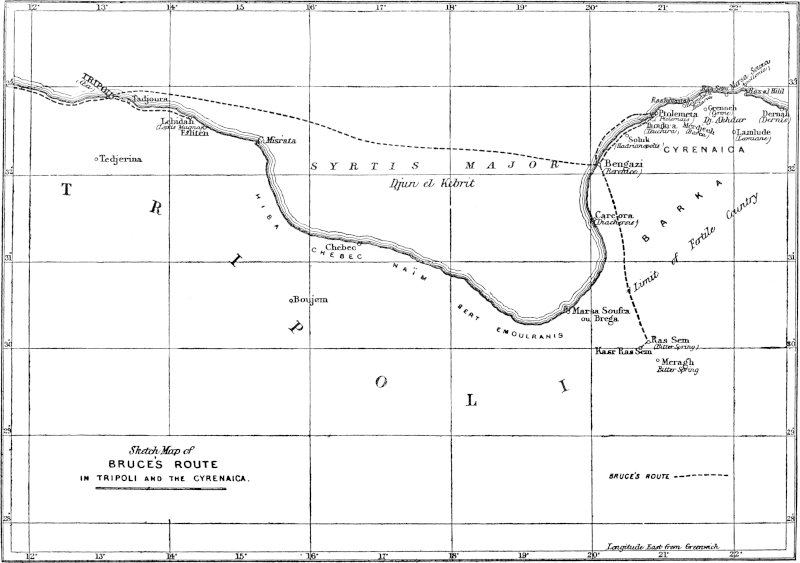

| XXXV. | Bruce’s Route continued — Lebidah — Bengazi — Teuchira — Ptolometa — Shipwreck at Bengazi — Departure for Canea | 283 |

| INDEX | 295 | |

![[Decoration]](images/decor1.jpg)

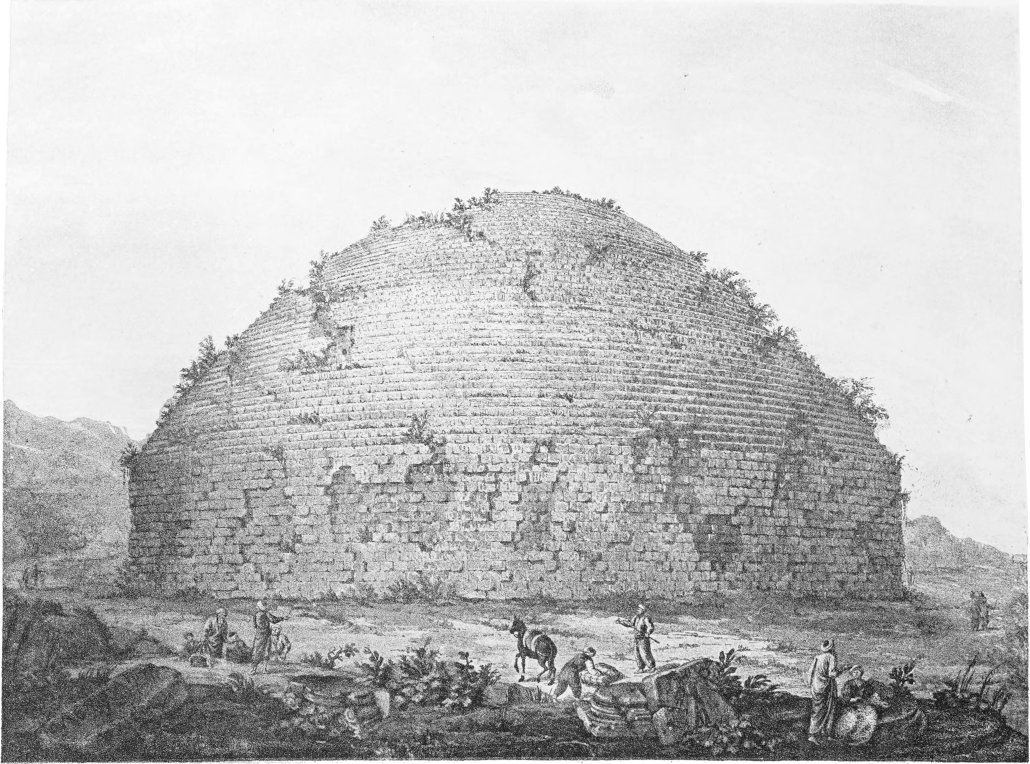

| PLATE | |||

| I. | Tombeau de la Chrétienne, or Tomb of Juba II. | Frontispiece | |

| Vase brought by Bruce from North Africa | Title Page | ||

| PAGE | |||

| Map of Part of Algeria and Tunis | to face | 1 | |

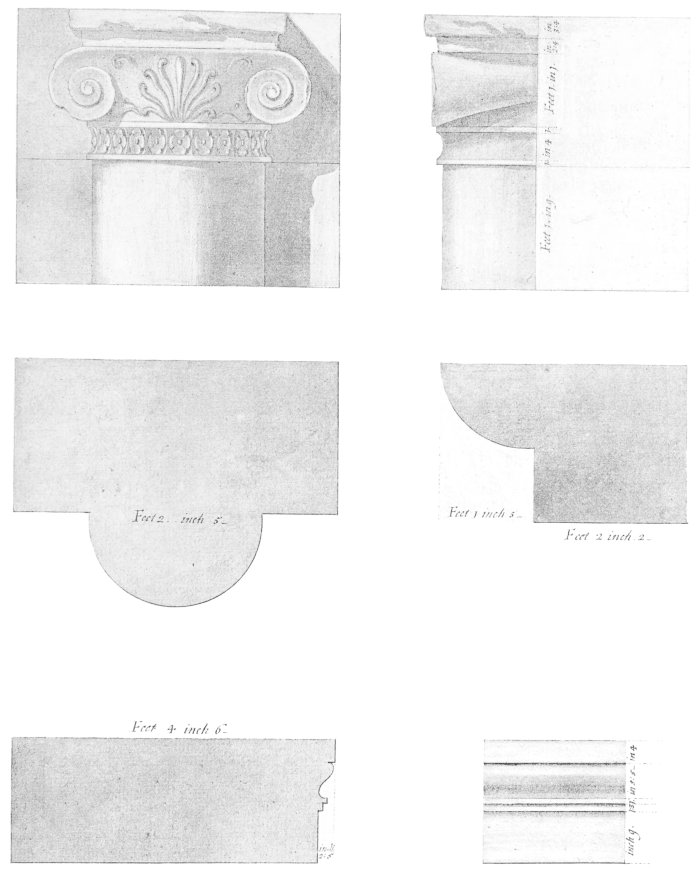

| II. | Tombeau de la Chrétienne, Details of Columnation | „ | 24 |

| False Door of Tombeau de la Chrétienne | 27 | ||

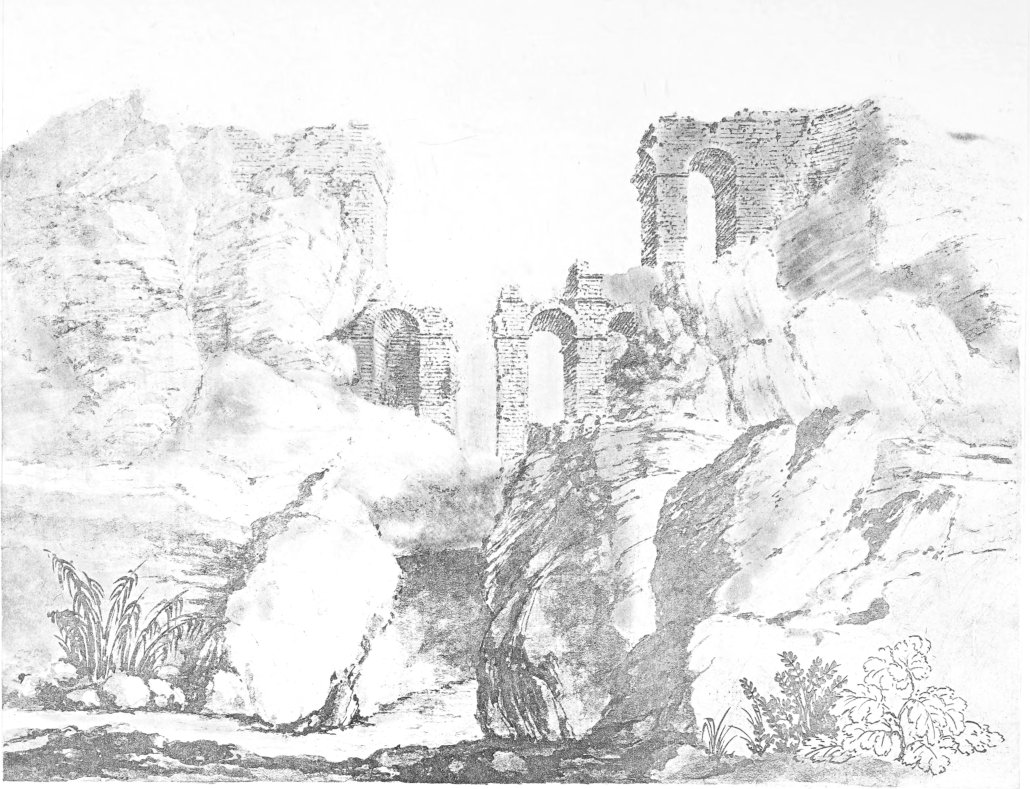

| III. | Aqueduct of Julia Cæsarea | to face | 28 |

| Portcullis at Seniore | 44 | ||

| IV. | El-Kantara of Constantine in 1765 | to face | 48 |

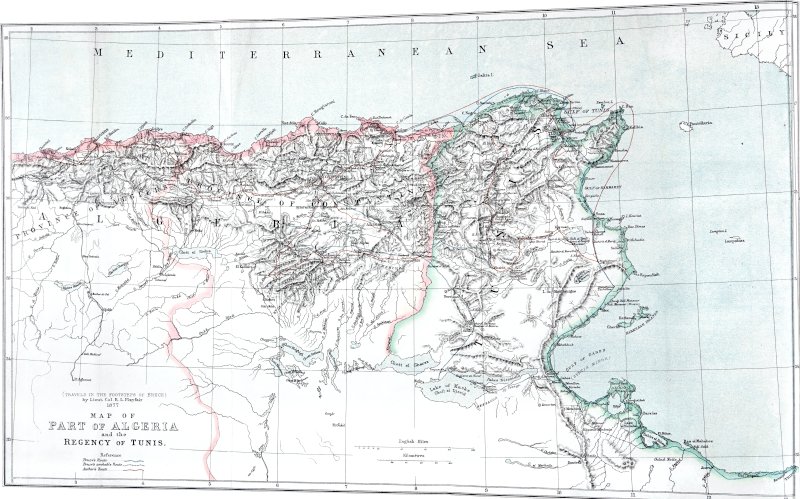

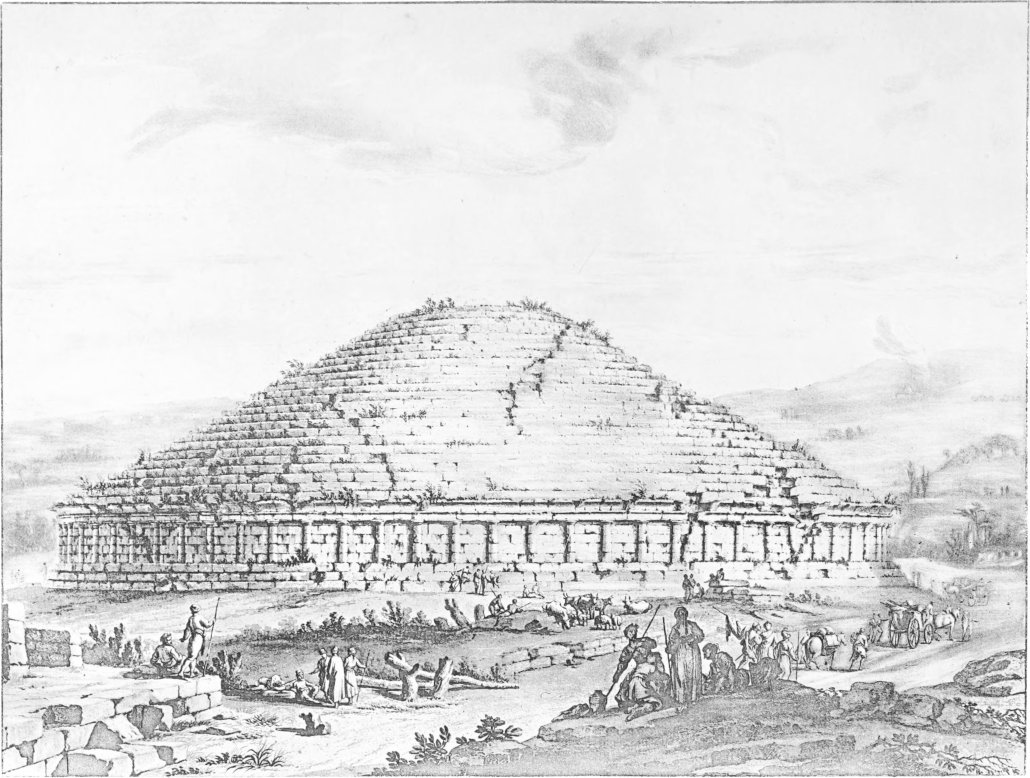

| V. | The Medrassen, or Tomb of the Numidian Kings | „ | 56 |

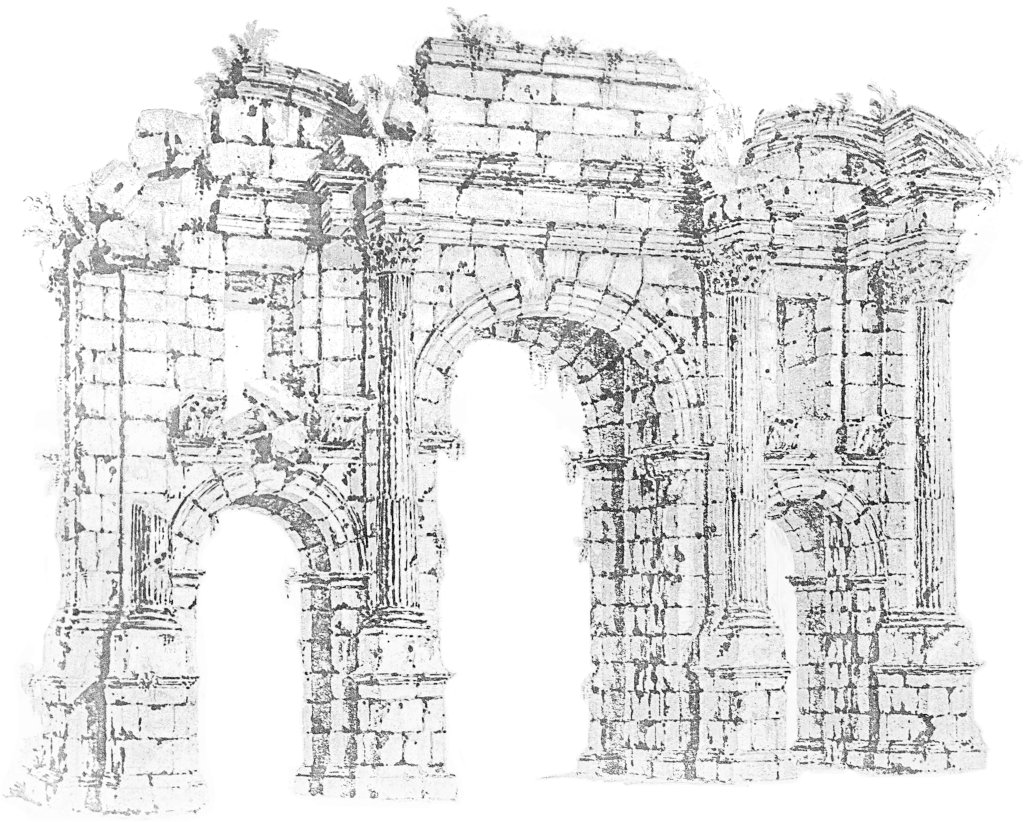

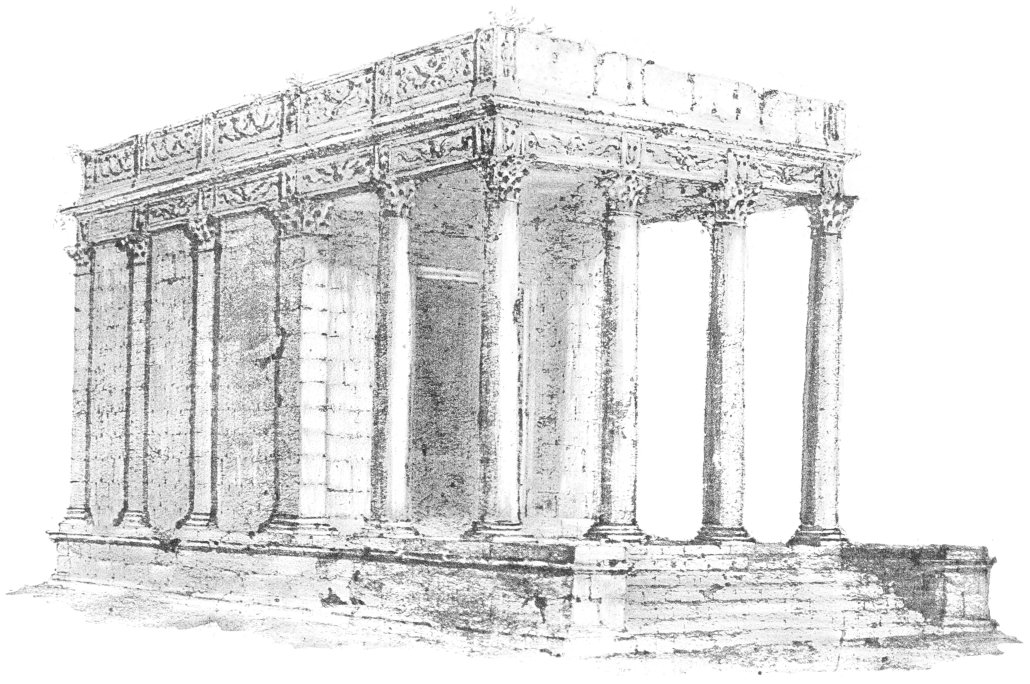

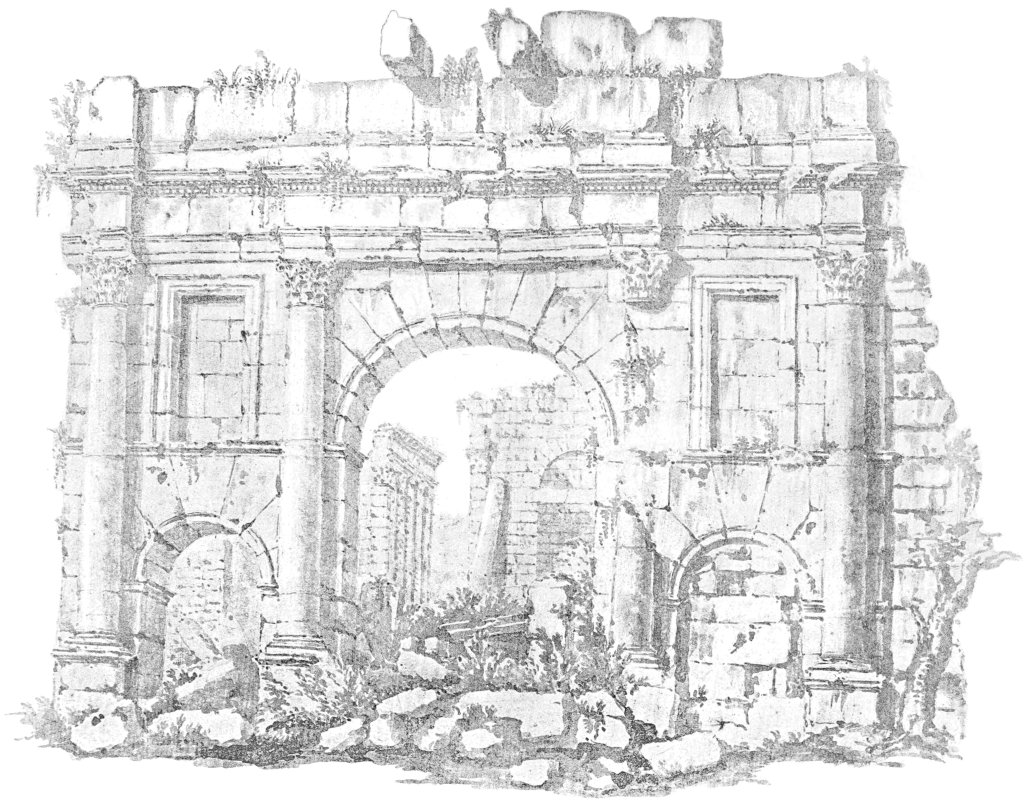

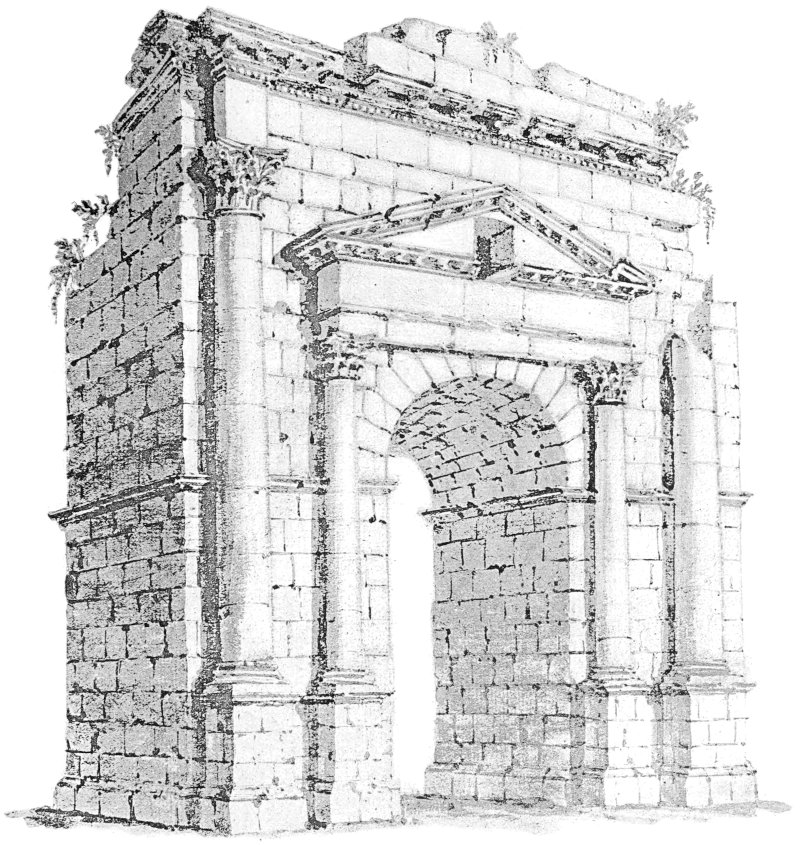

| VI. | Arch of the Gods, Timegad | „ | 88 |

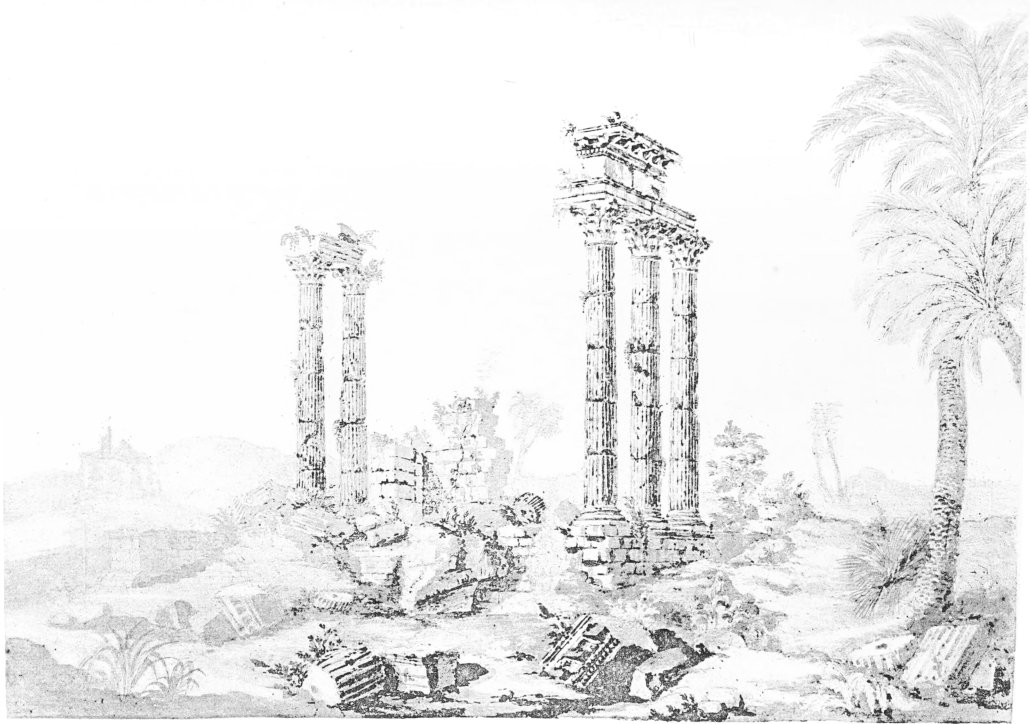

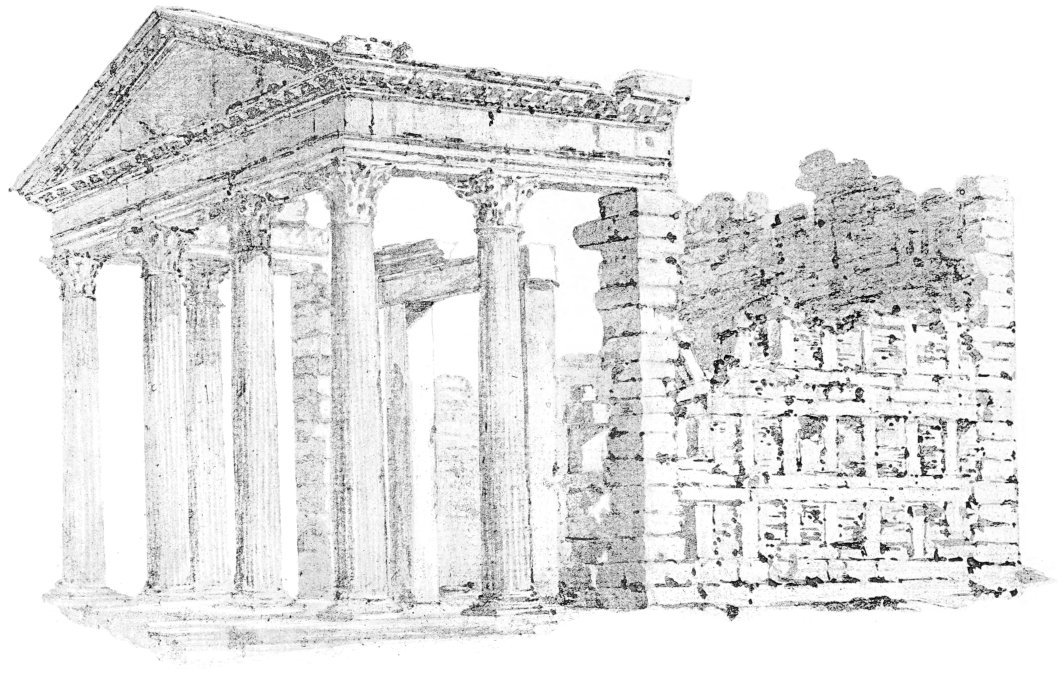

| VII. | The Capitol, Timegad | „ | 90 |

| VIII. | Temple of Jupiter, Tebessa | „ | 106 |

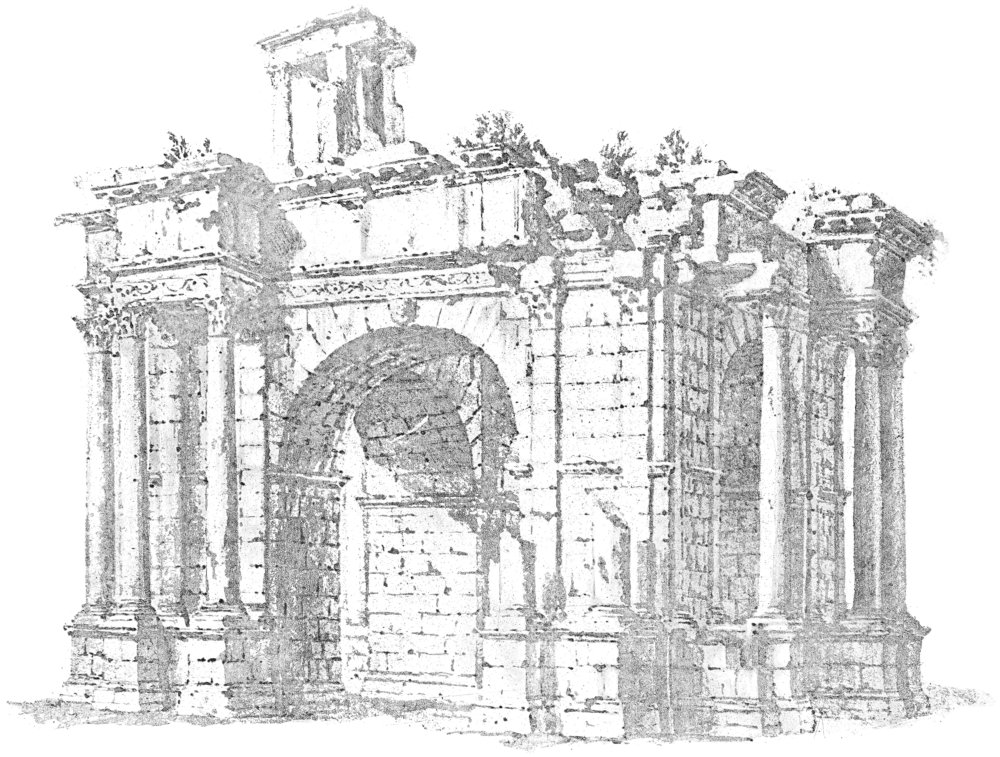

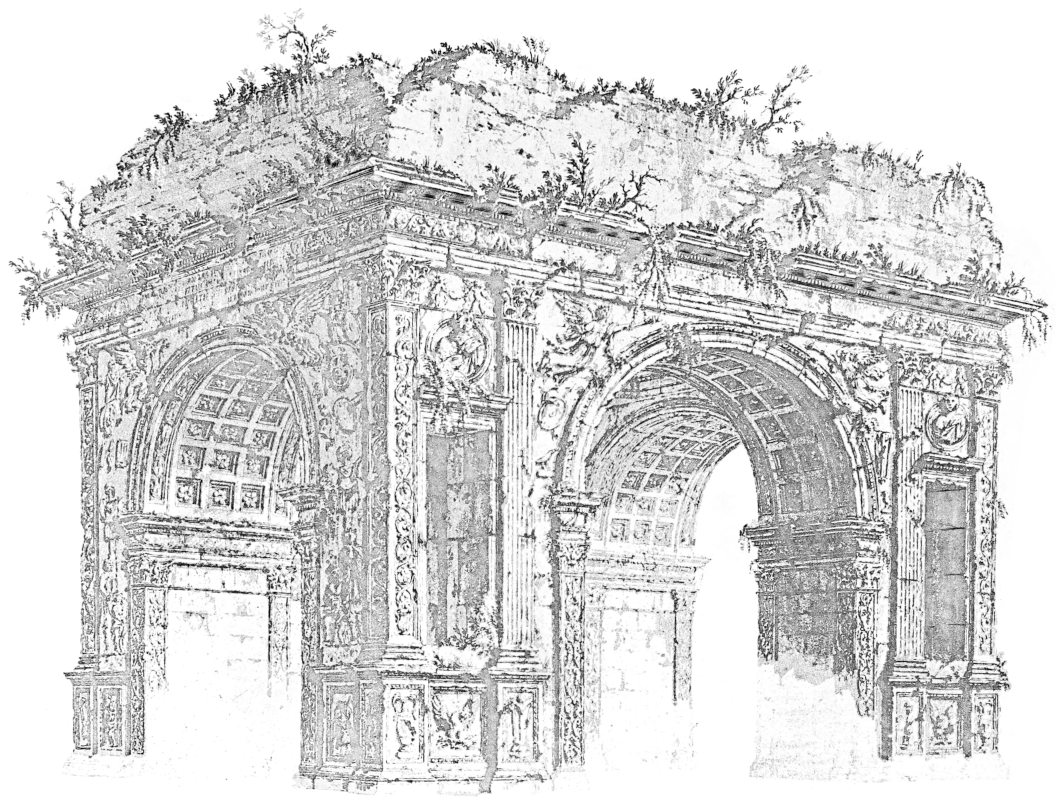

| IX. | Quadrifrontal Arch of Caracalla at Tebessa | „ | 108 |

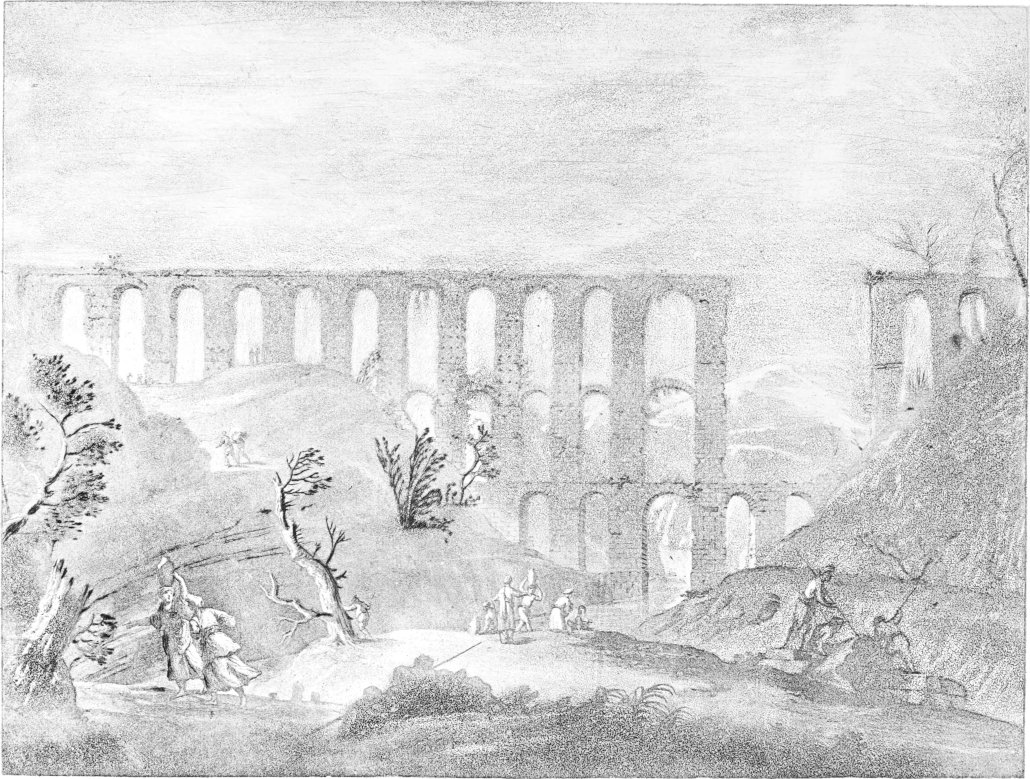

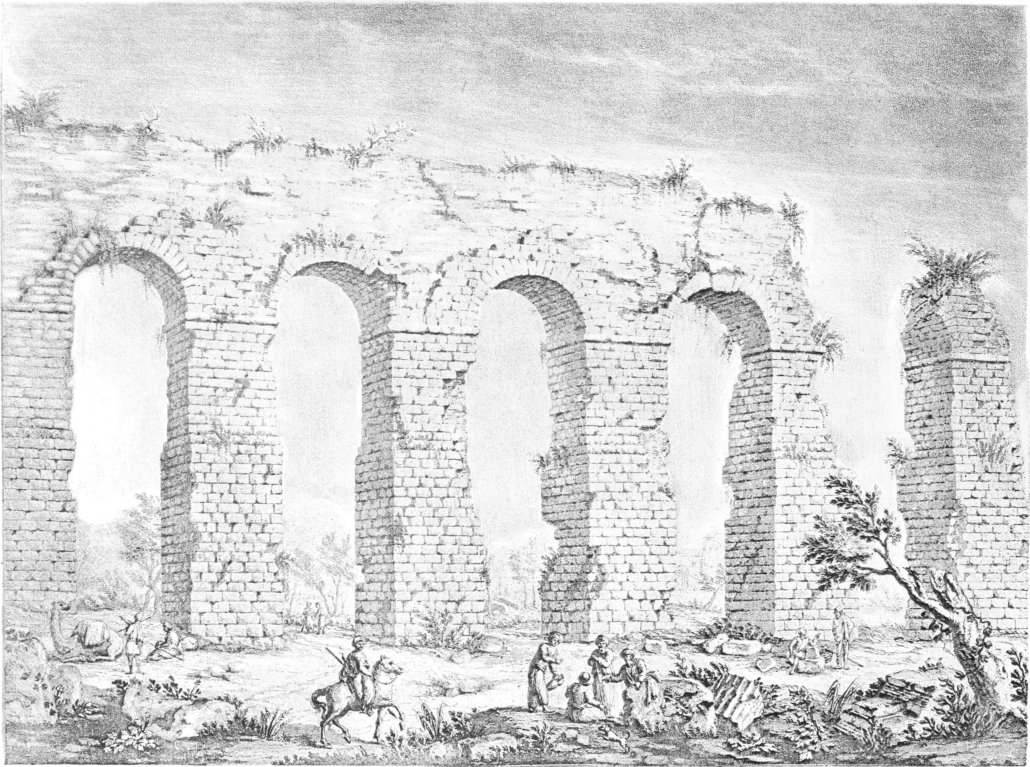

| X. | Aqueduct at Carthage | „ | 130 |

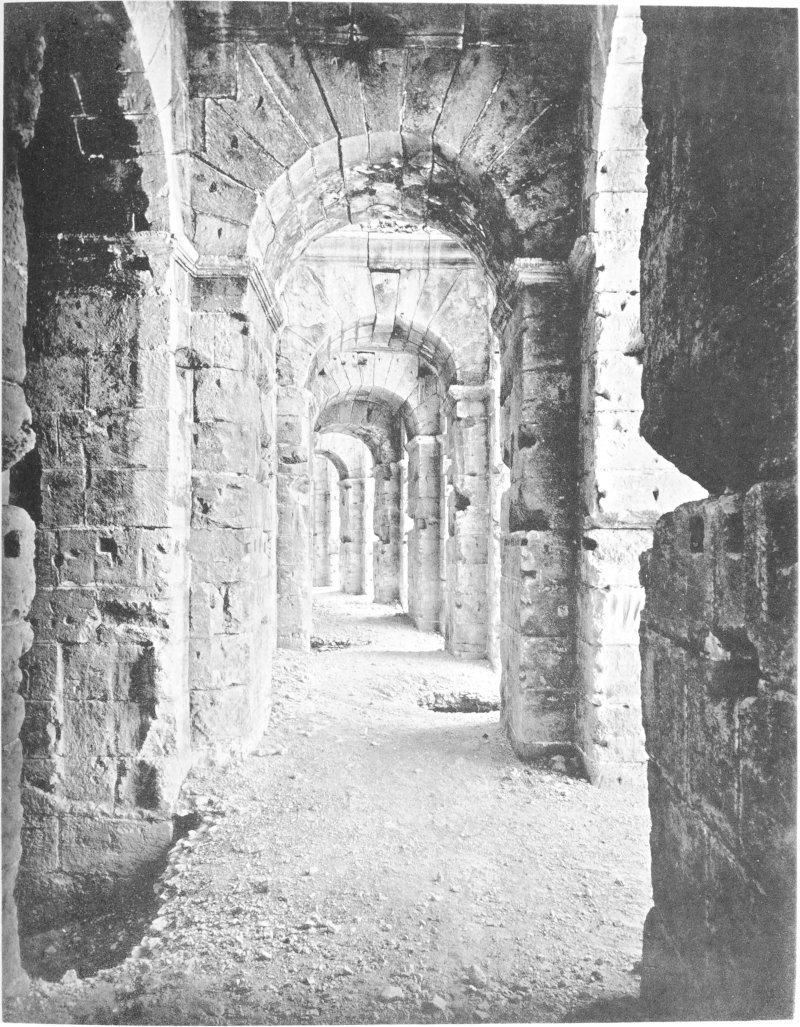

| XI. | Amphitheatre of El-Djem, Plan of Lower Storey | „ | 158 |

| XII. | Amphitheatre of El-Djem, General View | „ | 158 |

| XIII. | Amphitheatre of El-Djem, Interior of Lower Corridor | „ | 158 |

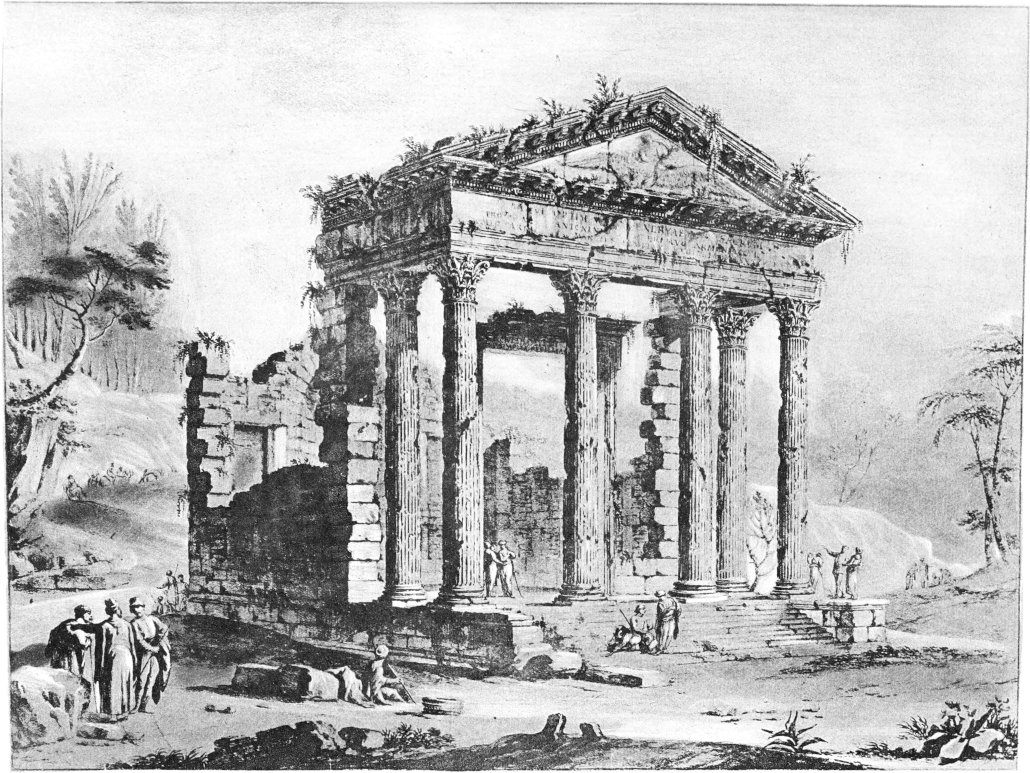

| XIV. | Entrance to Hieron of Temples at Sbeitla | „ | 184 |

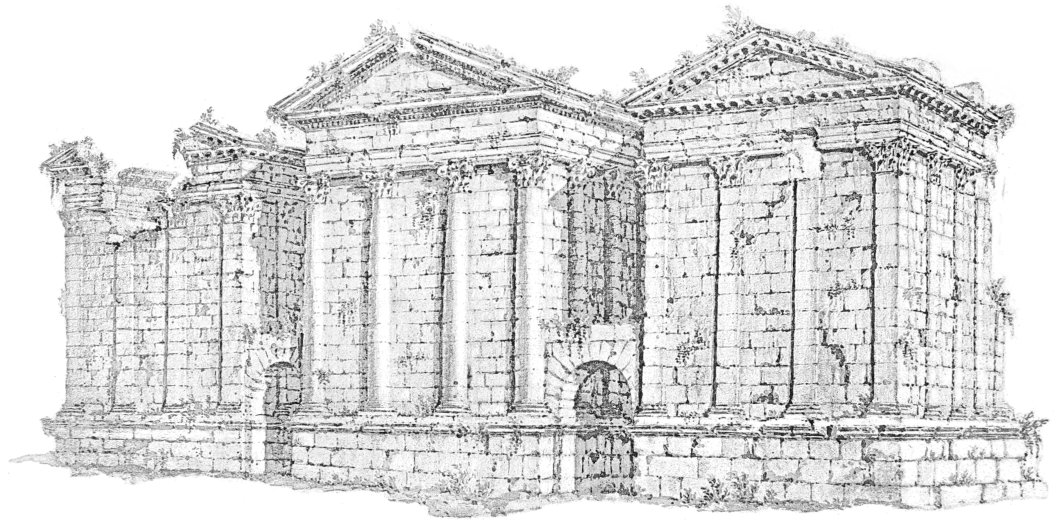

| XV. | Back View of Temples at Sbeitla | „ | 184 |

| XVI. | Triumphal Arch at Hydra | „ | 190 |

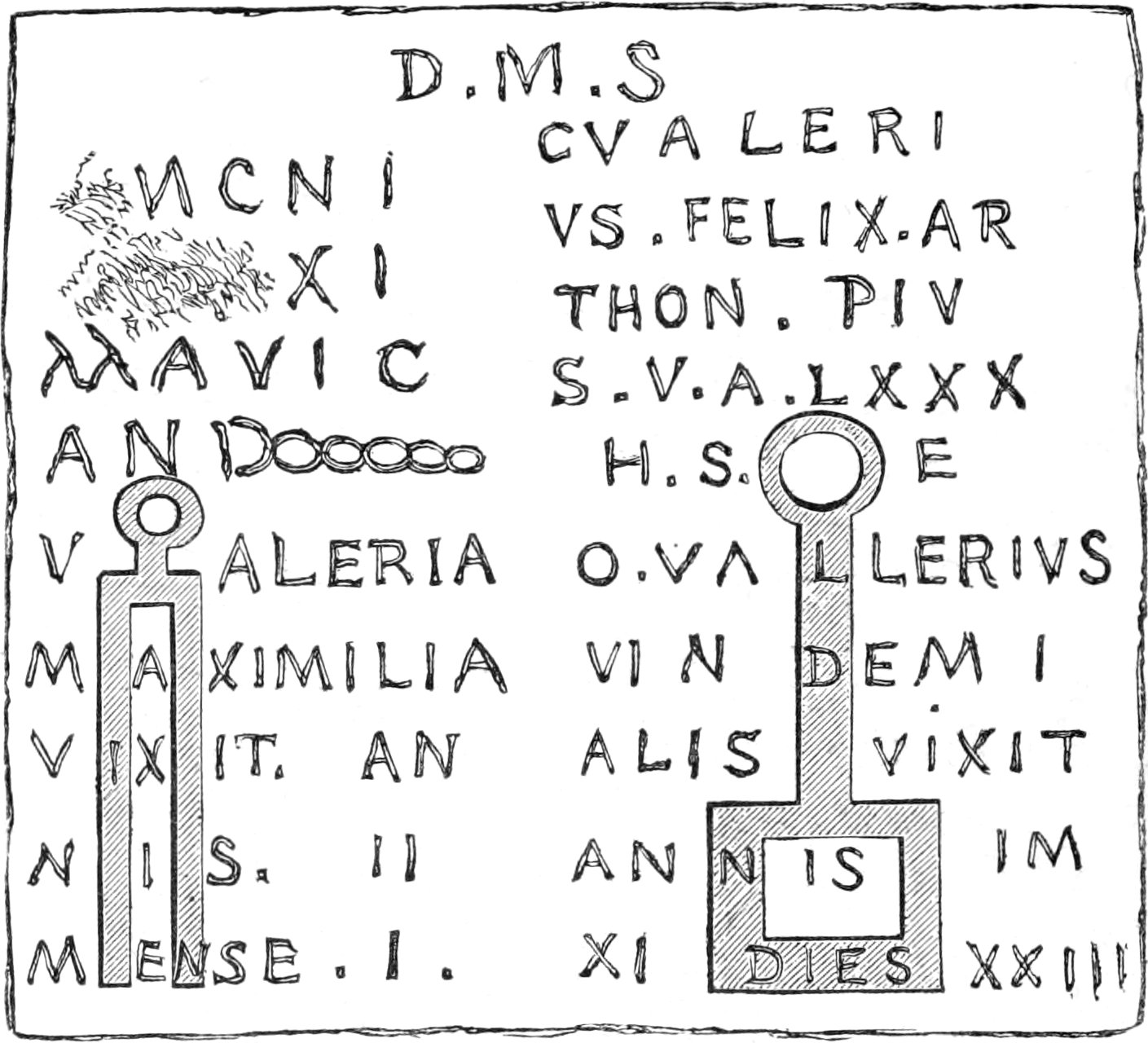

| Tombstone at Mukther | 198 | ||

| XVII. | Lower Triumphal Arch at Mukther, by Bruce | to face | 198 |

| XVIII. | Lower Arch at Mukther, Present Condition | „ | 198 |

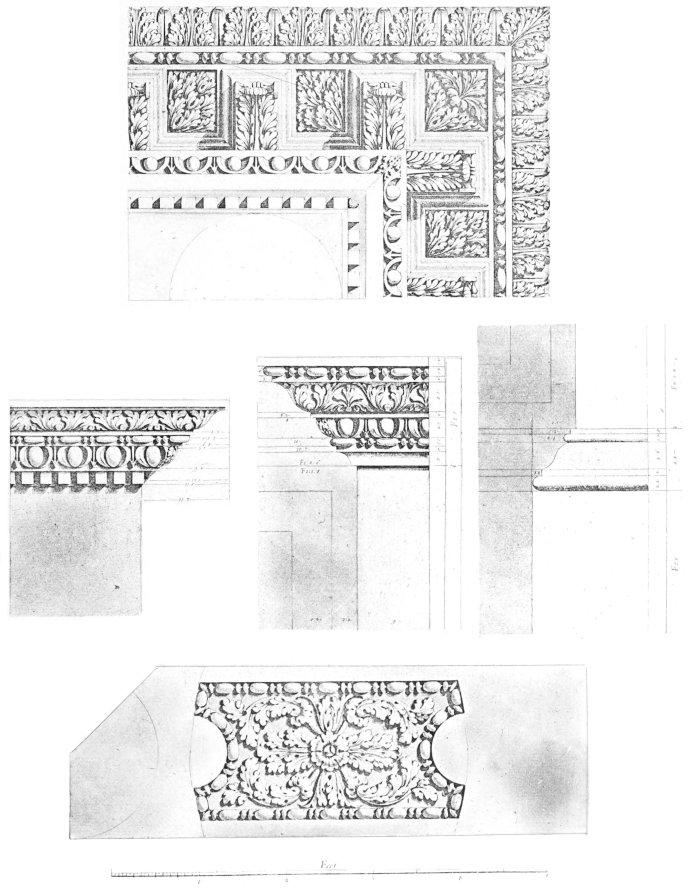

| XIX. | Lower Arch at Mukther, Architectural Details | „ | 198 |

| XX. | Arch of Trajan at Mukther | „ | 202 |

| [x]XXI. | Triumphal Arch and Temple at Zanfour | „ | 208 |

| XXII. | Temple of Jupiter and Minerva at Dougga, Side View | „ | 216 |

| XXIII. | Temple of Jupiter and Minerva at Dougga, Front View | „ | 216 |

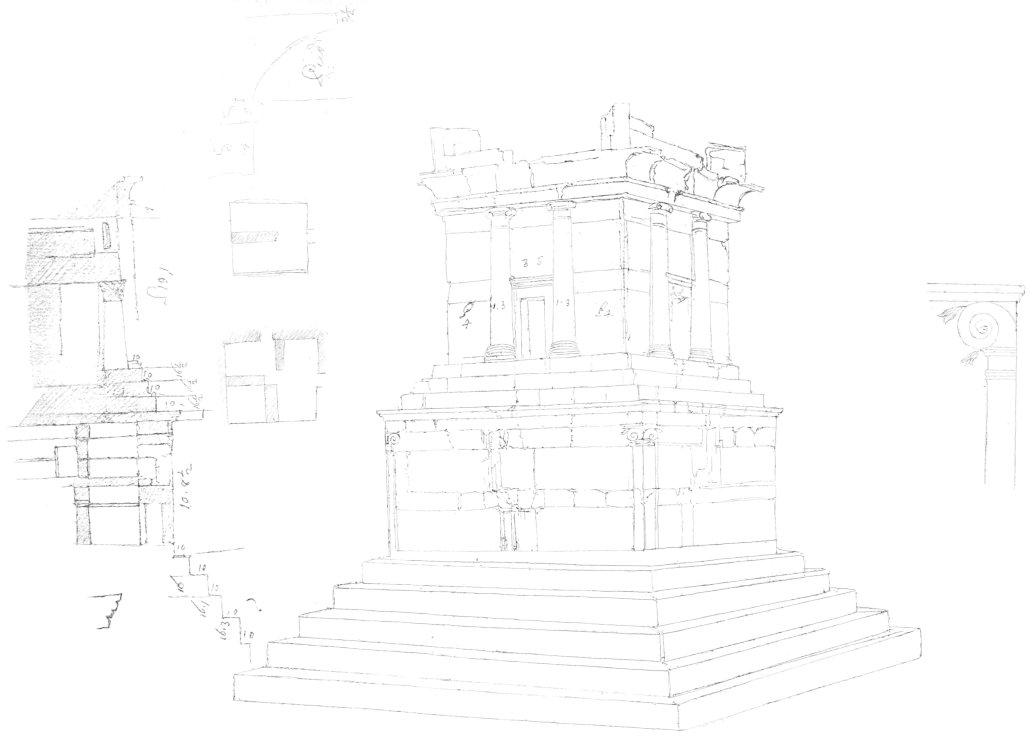

| XXIV. | Lybian Mausoleum at Dougga, Bruce’s Drawing | „ | 220 |

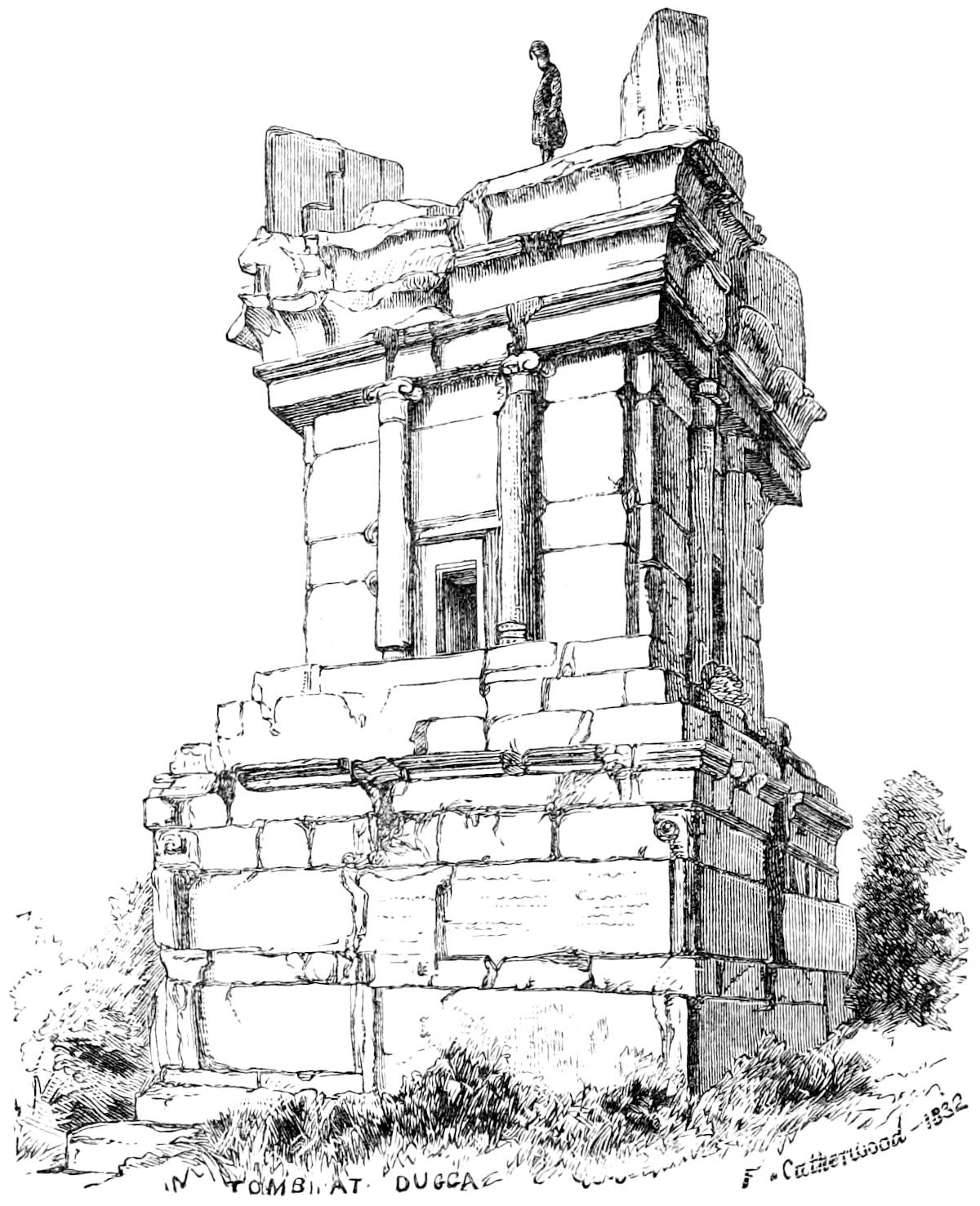

| Lybian Mausoleum at Dougga, Catherwood’s Drawing | 222 | ||

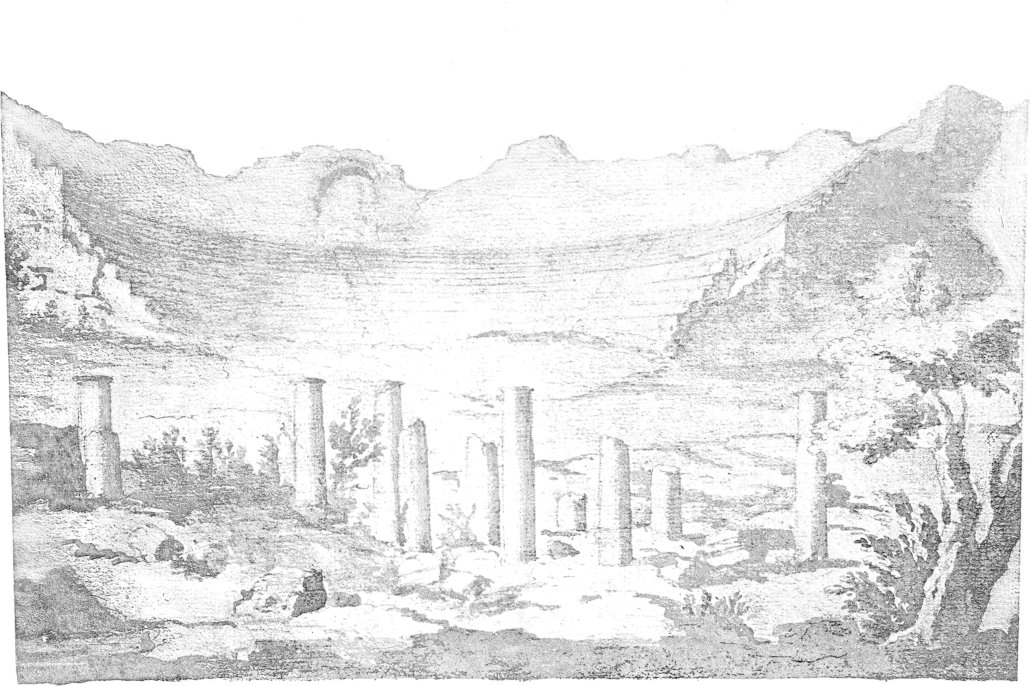

| XXV. | Theatre at Dougga | to face | 224 |

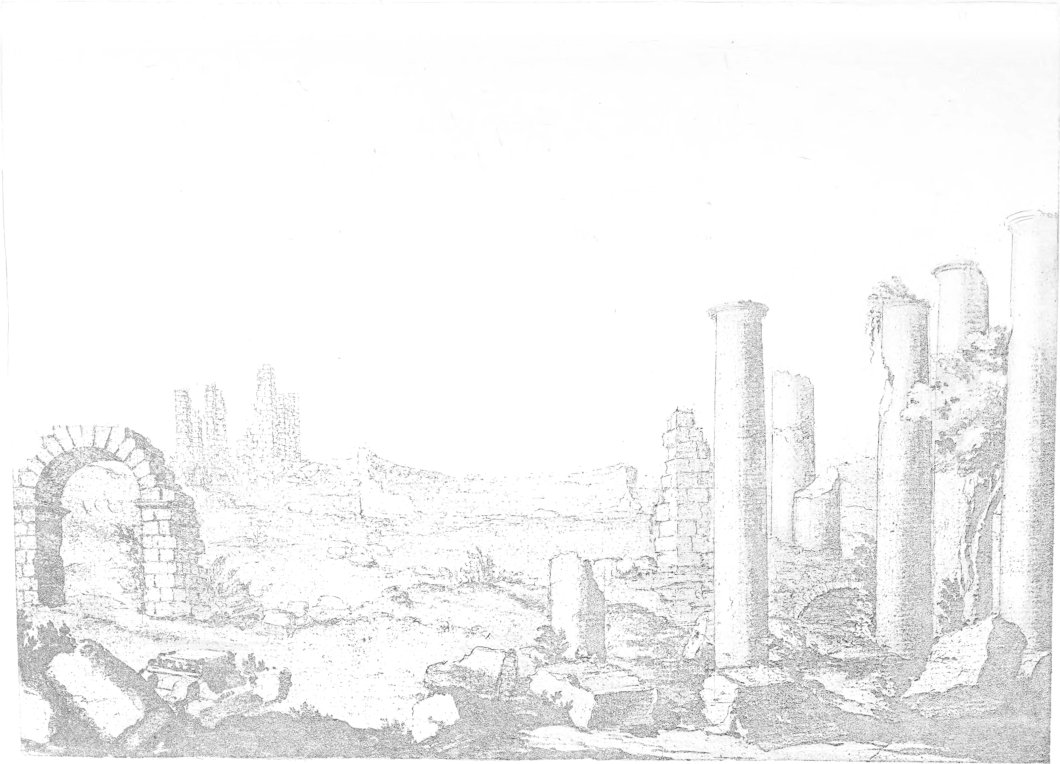

| XXVI. | Theatre at Ain Tunga | „ | 226 |

| XXVII. | Quadrifrontal Arch at Tripoli | „ | 280 |

| XXVIII. | Quadrifrontal Arch at Tripoli, Architectural Details | „ | 282 |

| Map of Bruce’s Route in Tripoli and the Cyrenaica | „ | 284 | |

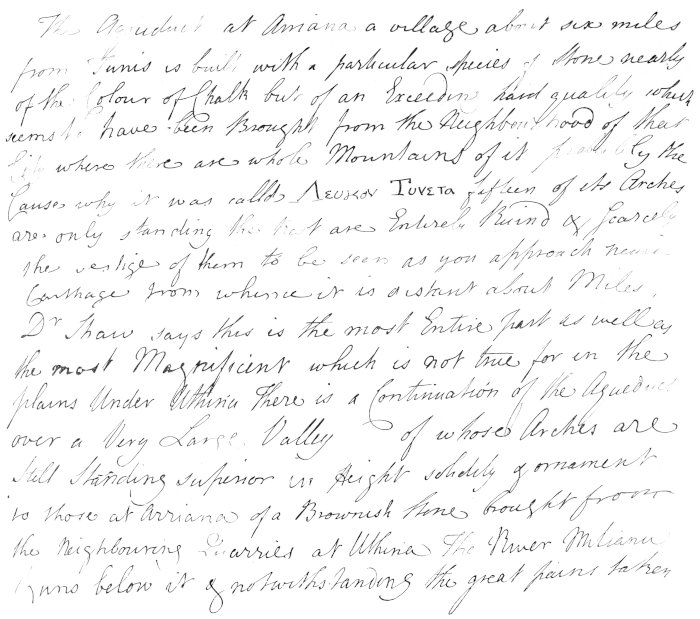

| XXIX. | Fac-simile of Bruce’s MS. | „ | 294 |

| Temple at Ptolemeta, Outer Covering of Volume. | |||

Map

of

PART OF ALGERIA

and the

Regency

of Tunis.

Edwd. Weller, Litho.

I must explain briefly how I came to travel in the footsteps of Bruce, and to illustrate the first works of this great father of African travel.

Many years of my life have been passed in and about the countries which he first opened out to geographical knowledge. When, therefore, I found myself at Algiers as Bruce’s successor in office, after the lapse of a century, my interest in him was redoubled. I read the unsatisfactory account of his Barbary explorations, prefixed to the first volume of his travels, with the greatest regret that it was not more detailed, and I resolved to ascertain whether some hitherto unpublished matter might not exist, tending to throw greater light on the subject.

I searched the records of the Consulate in vain; not a document of his time remained; all had been destroyed by fire before the French conquest. At the Record Office in London a series of his reports exists, containing many interesting details of the State of Algiers. They are bound up with Arabic documents relative to treaties of great historical value; but, naturally enough, there is not a word regarding his explorations, which only commenced after he had resigned his public duties in August 1765.

I then bethought me that Lady Thurlow, daughter of the late Lord Elgin, was great-great-granddaughter of the traveller, and heiress of Kinnaird. I applied to her, and was overjoyed to find that she possessed immense stores of his manuscripts, drawings, and collections. Lord Thurlow selected from amongst these everything relative to the first journey Bruce made in Africa before proceeding to Abyssinia, and these he most kindly placed at my disposal for publication, if I thought the subject sufficiently interesting. I went to Lord Thurlow’s, fully prepared to find much valuable matter, but I had no conception that a treasure of such magnitude and importance awaited me. I do not intend to allude to the great mass of drawings irrelevant to my present subject; what especially interested me was a collection of more than a hundred sheets, some having designs on both sides, completely illustrating[2] all the principal subjects of archæological interest in North Africa from Algiers to the Pentapolis, and executed in a style which an architectural artist of the present day could hardly excel.

Mr. Bruce frequently exhibited these drawings during his lifetime, and alluded to the desire he entertained of publishing a work on the antiquities of Africa. Ornamental title-pages for the various parts of this work actually exist, but he appears never to have commenced the letterpress necessary to illustrate the drawings. It is possible that the manner in which his book of travels had been received induced him to abandon the subject in disgust, but it is more probable that the enormous expense of engraving the drawings, estimated at from 3,000l. to 5,000l., rendered the project too costly to be realised.

After his death the increasing taste for the arts and the more general patronage of publications of that nature induced his son to think of making arrangements regarding such a work, but his designs were interrupted by his own death in 1810.

Major Cumming Bruce more than once entered into negotiations with the trustees of the British Museum for the transfer of the whole collection to the nation, but no arrangement satisfactory to both parties could be arrived at, and for the past thirty years they have remained unseen by the present generation, and almost forgotten, in the possession of the Bruce family.

With some of the monuments I was perfectly familiar, and I could judge of their extreme fidelity; others I found to be priceless records of structures which no longer exist; but the remainder, especially those situated in the Regency of Tunis, I could not identify at all, and I immediately formed the determination to follow him in his wanderings as far as it was possible for me to do so, and to ascertain the actual condition of those remarkable ruins, which the depredations of time and of barbarians have not been able to destroy.

To have followed in his footsteps exactly in the same order in which he made the journey would, for many reasons, have been inconvenient; and to have accompanied him throughout the whole extent of his explorations in the districts of the Djerid, Tripoli, and the Cyrenaica was more than I could accomplish. I determined, however, to visit every ruin in Algeria and Tunis which he had illustrated, and so to plan my route as to include all that was most picturesque and instructive in a country hardly at all known to the modern traveller.

No traveller has ever had to contend against a greater amount of ill-deserved obloquy than Bruce. There is hardly an act of his life or a statement in his writings that has not been questioned or received with incredulity; and yet, the more the countries in which he journeyed have been explored, the more his astonishing accuracy[3] and truthfulness have been recognised. I well remember, now nearly thirty years ago, meeting the brothers d’Abbadie at Cairo, on their return from a residence of many years in Abyssinia. I was on terms of intimacy with two of them, and our conversation naturally turned a good deal on Bruce’s travels. They assured me that, though they had occasion to consult his work as a daily text-book, they had never discovered a misstatement, and hardly even an error of any considerable importance in it.

It is not to be supposed that these drawings should have escaped criticism, and some people have even expressed grave doubts as to their having been, in any considerable degree, executed by Bruce himself.

On this point he ought to be allowed to state his own case, and I subjoin all the passages I have found in his MSS. bearing on the subject.

I had all my life applied unweariedly, perhaps with more love than talent, to drawing, the practice of mathematics, and especially that part necessary to astronomy.

· · · · · · ·

By the experiments I had made at Pæstum, and still later at an aqueduct about four-score miles from Algiers, where were the ruins of Jol or Cæsarea, the capital of the younger Juba and Cleopatra, I had found the immense time it would take a single hand to design the whole parts of any ancient fabric of ornamental architecture, so as to do it and the public justice. All the members of the Tuscan were plain, easily measured, and as easily drawn, but by the account I had from Shaw, and the inscriptions copied, and one awkward representation of three temples which he actually gives in his work, I found all here were ruins of architecture in the best time of Trajan, Hadrian, and the Antonines.

The description he gives of Jibbel Aures, Jemme, Hydra, and Spaitla sufficiently shows this. I found that without a number of assistants it was impossible even to do tolerable justice to such a multitude of objects, of greater consideration for taste, materials, and number than those at Rome, where all the orders of architecture, Composite, Corinthian, and Ionic, were to be found in their most perfect state. But where was that assistance to be obtained? and what encouragement was it in my power to give? that would induce a number of men of merit to dedicate so much of their time to the dangers of such an undertaking, unknown ways, sickly climates, and dangerous journeys. That I might not, however, be wanting to myself, I applied to Mr. Byres, Mr. Lumsden, and several other intelligent gentlemen then in Rome; several students were spoken to, but none would venture. A M. Chalgrin, a Frenchman, engaged himself, was terrified, and then drew back.

All the assistance I could get was a young man, a Bolognese, called Luigi, surnamed Balugani, which signifies short-sighted. This was very feeble help; but being of good disposition, in twenty-two months which he stayed with me at Algiers, by close application and direction he had greatly improved himself in what I chiefly wished him to apply to, foliage and ornaments in sculpture.

Assisted by him alone, the voyage to Africa and Asia was performed. He contracted an incurable distemper in Palestine, and died after a long sickness, after I entered Ethiopia, having suffered constant ill-health from the time he left Sidon. I had drawing instruments[4] a prodigious quantity of pencils, India ink, and colours. To these was added an instrument upon constructing whose parts great care was taken by Messrs. Nairne and Blunt, opposite to the Royal Exchange, under my constant direction and inspection; this was a large camera obscura,[1] upon whose specula great attention and pains had been shown, and many improvements and conveniences were added, which was all enclosed in a case representing a huge folio book, about four feet long and ten inches thick.

This, attentively used, and placed with taste and judgment, forwarded the work of drawing in a manner not easily conceivable; in a moment it fixed the proportion of every part to what size you pleased; it gave you in clear weather the sharpest, truest, and most beautiful projection of shade; every break that was in the building was truly represented upon the paper, every vignette, that nature had hung upon the summit or edges of the cornice, gave hints that could not be mistaken where the artist could place others with equal or superior advantage. It is true there were inconveniences in those lines at a distance from the focus, but those errors were mechanical and known, and easily redressed. A small one of these, an imperfect instrument, made at Rome, the young man Luigi had brought with him to Algiers, which afterwards served in good stead in saving my more excellent one.

I shall just name the quantity of work done.

First, thirteen large views of Palmyra, upon the largest imperial paper, the drawings twenty-two inches high, two of the same of Baalbec.[2]

On large imperial paper, of a smaller size—

Two views of the ruins of Carthage.

A temple over the fountain of Zowan.[3]

A noble triumphal arch at Tunga.[4]

A magnificent Corinthian arch and temple at Tipasa.[5]

Two views of a fine triumphal arch at Hydra, where are the Welled Sidi Boogannim, Dr. Shaw’s lion eaters, as bad to him as my raw beef to me.

Spaitla or Sufetula, vide Dr. Shaw, page 201, two Corinthian temples, one Composite temple; three views of these and one of a triumphal arch which serves as an approach to them.

Jibbel Aures, Aurasius Mons, a very fine ornamented building,[6] use unknown.

El Jemme, or Tisdrus, view of the amphitheatre there.

Taggou-zaina, the ancient Diana Veteranorum, triumphal arch of the Corinthian order there.[7]

Timgad olim Thamugadi, magnificent temple of white marble of the Corinthian order, though highly finished, and a triumphal arch with great particularities in architecture.

Medrashem, tomb of Syphax.

[5]Jol, Cæsarea, magnificent aqueduct of three rows of arches.

Cirta, Syphax’s capital, view of the aqueduct and cascade there.

Muctar, two triumphal arches of the Corinthian order.

Tripoli in Africa, a four-faced triumphal arch of white marble, the most ornamented of any building in the world; in parts of its details the most beautiful, never before known.

Assuras, triumphal arch and temple.

Ptolometa, old Ionic temple, the only one I know existing, built by Ptolemy Philadelphus, where my travels in Africa ended.

In order to conceive the number of pieces that each elevation or view was accompanied by, you may compute six to each elevation.

All these buildings, besides one or two perspective views, have geometrical elevations, and sections, with the whole detail of their ornaments and parts, all measured with the most indefatigable industry and strictest regard to truth. These sketches are most of them still by me, and you may still see how far every one was advanced in the desert.

I have now but one word to say as to what happened upon my coming home.

· · · · · · ·

When I carried my views of Palmyra to the King, he was exceedingly struck and pleased with them, and going to the window with the Prince of Mecklenburgh Strelitz, the Queen remained with me at the drawings, and I was a good deal surprised at her asking if I had not had help? I answered, ‘Undoubtedly, every help that I could get to make them worthy of the King’—yet I had desired Dr. Hunter to describe every part of my voyage and performance, and he told me he had done so.

· · · · · · ·

I will not be so hard as to expect that any one man shall be an excellent sky painter, an admirable figurist, a landscape, tree and water painter, a painter of ruined picturesque architecture, of ornaments and foliage, and of straight lines. Claude Lorraine was never capable of this, Clarisso cannot; Bartolozzi is not, and Cypriani far from being able; Mr. Robert Strange is capable of no part of it. I will give them leave to take all the help that they can get, and I will choose three drawings in the King’s collection and two of my own, and defy them to produce the equal in the term of two years.

Mr. Robert Strange, now Sir Robert Strange, knows well I have been at least an indifferent draughtsman in ruined architecture near these forty years, for about that time he himself recommended me my second drawing master, poor Bonneau, then teaching Lady Louisa Greville, daughter of my Lord Brock, afterwards Lord Warwick. Till then I had only been used to drawing military architecture; and with a ruler and compass I have ever since mostly drawn; I wish to make every part of my work as perfect as possible. You and Dr. Douglas will both testify how willingly I seek, and thankfully and openly I embrace every assistance. This I think doing justice to the public and to posterity, from whom, after ten days’ abuse from people that I despise, I shall receive the commendation or blame that appears ex facie of my work.

The famous Piranese, the best draughtsman of broken architecture that I know, is of another opinion; that perfection in every part he disdains; his figures are just untouched and[6] done with little, as he calls it; he knows he is no figurist, and therefore, in place of that agreeable ornament to design, he has placed figures in convulsions upon the points of stones and of rocks, with long legs and arms, and no bodies, but monstrous heads, and liker demons of another world than inhabitants of this. This the connoisseurs call freedom in design, masterly manner, and indeed it is so; it is freedom, just as great an one taken with the public as it would be for an individual in private life to walk in company with a long beard, nightgown and slippers.

The two great requisites in travelling are to see well and record faithfully what we have seen. I hope I may have succeeded in the first, but I am very certain I have done so in the last.

Thus, then, we see that according to Bruce’s own account the drawings were made by himself, with the aid of the camera obscura, and with such assistance as he could obtain from his young artist, Luigi Balugani. That they were done on the spot admits of no doubt whatever. During our late expedition my companion, the Earl of Kingston, took most successful photographs of every building drawn by Bruce throughout Tunis, with the single exception of Hydra; and though time, and the more destructive hand of man, have dealt hardly with some of the ancient monuments, others are almost unchanged, and a comparison of the original drawing and the photograph must satisfy the most sceptical on this point.

One of the most striking instances of accuracy of detail is in the case of the triumphal arch giving access to the Hieron of the three temples at Spaitla (Plate XIV.). In the attic of this building the first course of stones is entire; in the second only four stones are represented as remaining; two of these are in place, and two others have fallen on their sides, and are projecting beyond the surface of the façade. In our photograph these four stones now occupy exactly the same position as in Bruce’s sketch.

The drawings themselves furnish abundant proof, that two people worked simultaneously at delineating the ruins. Nearly every monument is drawn in duplicate, but no two sketches are ever from the same point of view. In some instances the difference of angle is very slight, as if the two companions had chosen positions sufficiently close to be able to converse together. A glance at the itinerary (page 21) will show that they never remained long enough in one place for either of them to have repeated his view of the object designed. Most of the measurements are written in Italian, as if Bruce had taken the actual dimensions and called them out to Balugani, who had recorded them. At the same time Bruce wrote Italian with as much facility as English, and many remarks in the former language occur in his own handwriting.

Sometimes, instead of only two copies of the same monument, there are several; but the same difference is always observable.

[7]One of these sketches, or sets of sketches, is done with the most perfect accuracy and good taste. Generally there is no attempt at accessories of any kind, but where such are inevitable they are always true to nature. The other, as far as its architecture is concerned, is also accurate, but it is marred by the introduction of grotesque figures and impossible landscapes, such as it was the custom of that age to consider, and which Bruce himself has described, as ‘that agreeable ornament to design.’ My impression is that the former are the production of Bruce himself, the latter perhaps in part his sketches, but finished up and ‘agreeably ornamented’ by Luigi Balugani.

There is still a third class of illustrations, finished architectural drawings done to scale; plans, sections, and elevations, with elaborate details of sculpture, columnation, &c. These could manifestly have been done better at home than abroad, and they are executed so beautifully, and with such a profound knowledge of architectural design that it is difficult to believe that they are the unaided work of Bruce himself. They were done during the retirement of the traveller at Kinnaird with a view to his intended publication, and it is just possible that he may have been aided by a professional draughtsman. It may be in allusion to this that he wrote to his friend the Hon. Daines Barrington, ‘You and Dr. Douglas will both testify how willingly I seek, and thankfully and openly I embrace, every assistance. This I think doing justice to the public and to posterity.’

These drawings were exhibited to the Institute of British Architects by Major Cumming Bruce, M.P., in 1837, and the following letter was addressed to him by Mr. Donaldson, their honorary secretary, under date May 17, 1837:—

‘By a special resolution passed at the ordinary meeting, held on Monday last, I am directed to convey to you the grateful acknowledgments of the members for the rich treat with which you favoured them on that occasion, by laying before them the highly interesting series of drawings prepared by Bruce, the traveller, in illustration of the antiquities existing in Northern Africa. The members were struck with that profusion of important edifices which embellished the provinces of the Romans; and they admired the perseverance and skill which enabled Bruce to procure such minute and highly wrought details of these monuments.

‘The members hope that these documents may ere long be published, and thus add another to the long list of obligations which not only this country, but all Europe, owes to his spirit of enterprise and research. These drawings prove that he added the acquirements of the naturalist, the geographer, and the philosopher, to those of the antiquarian, the scholar, and the artist.’

They were also shown at the Graphic Society about the same period, and the following is an extract from their proceedings, dated May 10.

[8]‘Distinguished as Bruce is for his researches in Abyssinia, these drawings furnish ground for an honourable and lasting reputation from a very distinct source. It has been said among some to whom their existence was known that they were not Bruce’s, but the work of a young Italian artist named Balugani, who was sent to him by Lumsden, the author of “Roman Antiquities.”

‘But among the drawings shown at the Graphic Society were some of Pæstum made by Bruce when he was alone, prior to his visit to Africa, where Balugani first joined him. The execution of these prove the same hand as appears in the greater part, and best, of those of the African cities,’—that is, according to my theory, of all those which were not ‘agreeably ornamented’ by Balugani.

They were submitted to several other eminent archæologists and architects of the day; amongst others to Mr. C. M. Cockerell, who, writing under date June 9, 1837, thus alludes to them:—

‘In an antiquarian point of view I consider them of the utmost importance . . . in a practical point of view they offer to the professor of architecture many motives of composition and ornament entirely new; and if not equal to the choicest remains of Greece are, perhaps, of more frequent use, and on both these grounds it is exceedingly to be regretted that they have been so long withheld from the public.’

Mr. W. Hamilton, the celebrated archæologist and diplomatist, who was one of the founders and first presidents of the Royal Geographical Society, and to whom we are indebted for the discovery of the Rosetta stone on board a French transport, writing on the same date, thus expresses himself: ‘They are indeed most interesting documents of his ability, fidelity, and perseverance. . . . I was particularly struck by his correct selection, amongst the many monuments he saw, of those only which were of a good time, and certainly they give a most favourable notion of the state of the arts under the first two centuries of the Roman Empire. We must not, of course, look to that quarter of the world for genuine specimens of Greek art, but these drawings afford the most convincing proofs that taste and judgment prevailed in these distant and flourishing colonies to at least as late a period as they did in Rome itself.’

No man is a better judge of architectural drawings than my esteemed friend Monsieur César Daly. I submitted two of them only for his inspection, and these by no means the most remarkable of the series—the Triumphal Arch and the Capitol of Timegad, which we had visited together. His opinion is worthy of being recorded:—‘The architectural conscience of Bruce exceeds that of most of the best architectural draughtsmen of his time, which nevertheless was rich in talent of this nature. You may remember with what care I myself designed the triumphal arch at Timegad. I intended to publish this drawing of a monument now accessible to everyone, and[9] having, as director of the Revue générale de l’Architecture, a reputation to keep up, my conscience as an artist was most particularly stimulated. Well, I have compared Bruce’s design with mine, and I repeat that I am much struck with his extreme exactness and the great conscientiousness of the man, so rigorous towards himself, regarding the design of a monument which in all probability none of his contemporaries would ever be called upon to verify.

‘During the thirty-five years that I have directed the Revue d’Architecture, that I have visited exhibitions of architecture, inspected the portfolios of architects, &c., &c., I have seen so much inexactness, which has inspired me with the most profound disgust, that I give, or rather I offer with eagerness, the tribute of my sympathy and respect wherever I find talent joined to honesty. I admired Bruce as a brave and intelligent traveller; now I love him as a serious and honest artist. I thank you once more. You will certainly find a means of publishing these treasures; they belong to science; they honour England in Bruce, and will serve most happily to teach us that which existed here and there in our Algeria, and which unfortunately exists no longer, or only in a state of débris.’

Bruce makes frequent allusion to drawings of his being ‘in the King’s collection,’ and in one place he remarks: ‘They composed three large volumes folio, two of which I presented to the King; one, not being then finished, remains in my custody to this day.’

These two volumes of drawings were exhibited by Her Majesty the Queen, through Mr. Woodward, the late Librarian at Windsor, to the Society of Antiquaries of London, on March 27, 1862.[8] I have not had an opportunity of inspecting these, and I am not aware of what the contents of the volumes in question may be: it is to be hoped that they contain drawings of the interesting monuments of which no sketches sufficiently finished to admit of reproduction exist in the Kinnaird collection, namely, the Amphitheatre of El-Djem and the Triumphal Arch of Diana Veteranorum.

All the relics and documents of this traveller have been preserved with scrupulous care; but I cannot resist expressing an opinion that his drawings, of which the Barbary sketches form only a portion, should not be allowed to remain in any private hands, but should be religiously enshrined in our national collection.

To reproduce the entire series would be a work of great magnitude and expense; nor is it necessary, either from an architectural or an archæological point of view. In Bruce’s own days they could only have been published by the costly process of[10] engraving. Photographic processes have now greatly facilitated the publication of such drawings, and permit us to lay them before the public as actual fac-similes.

In making my selection, I have as a rule preferred such drawings as I believe to have been done by Bruce himself on the spot; but I have included some of the more finished sketches to show the share that Balugani had in them, and specimens of those that I believe to have been subsequently executed in Scotland.

A few words are still necessary as to the manuscripts, which the traveller has left, and which are of the most fragmentary and unsatisfactory description.

They consist of the following documents:—

1. A carefully-written autobiography, intended for the Hon. Daines Barrington, Bruce’s intimate friend, after the publication of his travels. It is fantastically, perhaps conceitedly, entitled, ‘Memoirs of One Unknown.’ It alludes with some asperity to the reception his book met with, and professes great contempt of the doubts thrown on his veracity. It extends to about 86 pages of long folio, and bears date April 14, 1788.

2. A rough note-book of Arab manufacture, in which entries were evidently made from day to day immediately after each halt. On the first page is this memorandum:—

If I should die in this voyage, these notes are not to be published, as they are memoranda only for myself, and unintelligible, and designed to be so, to anybody else.

This contains a record of his journey from November 5, 1765, till December 30 in the same year. At the end are a few rough details of architecture, and copies of inscriptions.

3. A few sheets of native paper, as if torn out of a note-book similar to, but not exactly the same size as the preceding, containing a note on the Aqueduct at Arriana, and the records of his journey from December 29, 1765, till his arrival at Gabes about the middle of the following month. It is marked No. 7, which is erased, and No. 3 substituted. A fac-simile is given of one page of this manuscript (Plate XXV.).

4. A note-book, 12mo., of Arab paper, marked No. 2, containing notes on the Pentapolis, and of his subsequent journey in Syria and the Red Sea.

5. A similar book, marked No. 6, containing notes on the Pentapolis.

6. A volume containing, as its name indicates, ‘Basso-relievos, Statues, and Inscriptions, 1765.’

7. Draft of original letter, in Bruce’s handwriting, to Mr. Wood, author of the work on ‘Baalbec and Palmyra,’ dated Tunis, April 2, 1766, published in Vol. I. of ‘Bruce’s Travels,’ Appendix No. XXIII.

[11]8. A note on ‘Tripoly in Africa,’ certainly not written by Bruce.

9. An autograph memoir on the Island of Tabarca.

10. An autograph memoir on Tunis and Djerba, the island of the Lotophagi.

11. An original letter, dated London, June 16, 1775, to Mr. Seton (of Touch?), giving an account of his adventure with the Arab chief at Lambessa. This has been published in Major Cumming Bruce’s pamphlet, 1837.

In addition to these manuscripts and drawings, Bruce brought a very interesting collection of antiquities from North Africa, consisting of fragments of sculpture and inscriptions, including part of the frieze of the Temple of Hercules at Kef, a number of medals and coins, a small bronze statue of Mercury, and an exquisite bronze vase, which forms the design on the cover of this work. It has four faces, two of nymphs and two of satyrs, very beautifully executed, of a date probably not later than the second century. These are all in the possession of Lord Thurlow.

There is little doubt that Bruce transcribed his rough notes, and added many particulars, then fresh in his memory, which he did not think it necessary to record in his daily journal. This occurred during his residence at the island of Djerba. Probably this manuscript was not included amongst the books and drawings which he forwarded from Tripoli in Africa to Smyrna, or those which he despatched at Bengazi to Tripoli in Syria, in which case they would certainly have been lost during the shipwreck at Bengazi. His pocket-book was saved there, and may be the manuscript which I have numbered 2, into which 3 would naturally fit, but almost everything else he possessed was lost, especially

A book with many drawings, and a copy of M. de la Caille’s Ephemerides, having a great many manuscript marginal notes.

In addition to illustrating Bruce’s travels, I have had another object in view—to furnish an advanced hand-book of travel to those who, like myself, dislike diligence routes and French auberges, and revel in the delightful liberty of life on horseback and under canvas. I hope they will find many such suggestions as to routes here, as I should have been glad of myself, though they must not expect to be treated with the same amount of hospitality.

And here I think I ought, in justice to myself, to acknowledge the authorship of ‘Murray’s Handbook to Algeria.’ I have endeavoured, as far as possible, to avoid any allusion to the districts therein described; but this was not always possible, and passages will, no doubt, be found, which, but for this avowal, might lay me open to the charge of obtaining my information from a popular work in everybody’s hands.

Every word of these manuscripts relating to his Barbary journey I have embodied[12] in my text, either in the order in which I visited the places, or, where I was unable to do so, as a continuous narrative in his own words.

I have elsewhere acknowledged my deep obligations to Monsieur César Daly, with whom I had the pleasure of making the first part of my journey. I would also record how much I am indebted to Professor Donaldson, the Nestor of British architects, who, ever since he signed the letter to Major Cumming Bruce, before quoted, in 1837, has felt the deepest interest in Bruce’s work; he greatly aided me in making the best possible selection of the drawings for publication, and in many other respects he has given me the benefit of his great professional knowledge and experience.

I cannot conclude these introductory remarks without allusion to a letter which has reached me since the manuscript was in the publishers’ hands, and which has to me almost the solemnity of a voice from beyond the tomb. Mrs. Whitely Dundas, of Clifton, after stating that she had seen in the papers a paragraph to the effect that I had recently been instrumental in erecting a stained-glass window and memorial brass in the church at Algiers to Bruce, and that I was occupied on a work to illustrate his travels in this country, adds: ‘I can well imagine, even after the lapse of so many years, how proud and gratified my mother would have been could she have lived to see this day. She was Bruce’s only daughter, and died before her father’s fame and veracity were fully established.’

If what has been to me so great a labour of love shall have the effect of adding one leaf to the well-earned laurel-wreath of my favourite hero, I shall be amply repaid. My work has had no other object, although I have thought it advisable to combine the result of my own journeys with his, and thus to give the subject a wider interest, and make it useful for travellers in little-known parts of Algeria and Tunis.

However badly my share of the work may be performed, Bruce’s merits can hardly fail to ensure its success. Never was a trite old saying more aptly applied than that adopted by his biographer, and which I have engraved on his monument at Algiers: ‘Magna est veritas et prævalebit.’

FOOTNOTES:

[1]This instrument still exists at Kinnaird.

[2]In searching for Bruce’s Barbary drawings in Her Majesty’s Library at Windsor Castle, eighteen drawings of Palmyra and Baalbec were discovered; they bore no names or signature, and the authorship was unknown to the librarian until I identified them.

[3]Zaghouan.

[4]This is evidently a clerical error; there is no good arch at Ain Tunga. Bruce probably means Zanfour.

[5]Tebessa.

[6]The Prætorium of Lambessa.

[7]This does not exist in the Kinnaird collection.

[8]Proc. Soc. Antiq., 2nd series, vol. ii. p. 96.

[13]PART I.

BRUCE APPOINTED CONSUL-GENERAL AT ALGIERS.

The circumstances which induced Bruce to accept the post of Consul-General at Algiers are contained in the following extracts from his autobiography:—

My Lord Halifax, in many conversations, laughed at me for my intention of returning to Scotland. He said, the way of rising in this King’s reign was by enterprise and discovery; that all Africa, though just at our door, was yet unexplored; that every page of Doctor Shaw, a writer of undoubted credit, spoke of some magnificent ruins which he had seen in the kingdoms of Tunis and Algiers; that now was the age to recover these remains of architecture and add them to the King’s collection.

Fortune seemed to enter into this scheme. At the very instant, Mr. Aspinwall, very cruelly and ignominiously treated by the Dey of Algiers, had resigned his consulship, and Mr. Ford, a merchant, formerly the Dey’s acquaintance, was named in his place. Mr. Ford was appointed, and, dying a few days afterwards, the consulship became vacant. Lord Halifax pressed me to accept this, as containing all sorts of conveniences for making the proposed expedition. The appointment was a handsome one, the salary was 900l. a year, and a promise was added that a vice-consul of my own appointment would be allowed to keep my place while on the discovery, and that, if I made wide excursions into Africa, and any considerable additions to the King’s collection, my former conditions of being made a baronet were to be preserved, and either a pension if I chose to retire, or my rank and advancement in the diplomatique line, preserved to me on my return.

Many conversations passed about the then unknown and despaired of fountains of the Nile; but this was considered as an enterprise above the power of extraordinary men, presumption to think it was within the reach of an untried ordinary man like me, but agreed on all hands that he that should achieve it, if he was a Briton, should not in this age despair of any reward.

In passing through Holland, I had collected all the printed books in the Arabic language, and at the time when I was to go to Algiers I was as good an Arabian as these books and dictionaries and this manner of study could make me.

Thus prepared, I set out for Italy through France, and though it was in time of war, and some strong objections had been made to particular passports solicited by our Government from the French Secretary of State, Monsieur de Choiseul most obligingly waived all such exceptions with regard to me, and most politely assured me that those difficulties did not in any shape regard me, but that I was at perfect liberty to pass through or remain in France with those that accompanied me,[16] without limiting their number, as short or as long a time as should be agreeable to me.

On my arrival at Rome, I received orders to proceed to Naples, there to await His Majesty’s further commands.

While waiting at Naples for instructions to proceed to his post, Bruce visited Pæstum, the ruins of which were then but little known, and at the suggestion of Sir James Gray, the British Ambassador, made accurate drawings of those ruins, and conceived the idea of illustrating the history of that city from its various coins of different periods. This idea, which he was the first to originate, he executed with great learning and ingenuity. On proceeding to Africa, he entrusted these drawings to Sir Robert Strange, for the purpose of having them engraved; but, from circumstances which have never been explained, copies of them were surreptitiously obtained, and, on his return from Abyssinia, he found that his work had been pirated and published under another name. In his autograph memoir he expresses himself strongly on this subject, but his chief complaint is

That the bunglers did not know how to avail themselves of the materials for the history of Pæstum which, by whatever means, had fallen into their hands.

To resume, however, Bruce’s own narrative:—

The Government was so kind as to send the ‘Montreal’ frigate to carry me to Algiers.

I pursued my plan, studied hard, was become now a good Orientalist in general. I speedily spoke the Arabic fluently; among the natives and among the servants I exercised myself every day. I was also an adept in Geer, or Ethiopic, as far as Ludolph and Memmers and the few books I had could make me, but these were as yet very few.

It happened at St. Philip’s in Minorca, as it always, I believe, happens, that when a fortress is surrendered to an enemy, the papers, plans, and documents found therein are to be delivered up to the captors. The French, when they took Minorca, had found in that fortress a multitude of blank Mediterranean passes, a number of these being always lodged for common demand with the Secretary of the Governor of Minorca and Gibraltar. The French, upon finding these, had countersigned them, and sold them to Sardinians, Genoese, Neapolitans, and Spaniards, who navigated under their authority with English colours. They had not even taken the precaution of putting an English supercargo on board, so that English colours were found everywhere, with not a man on board but the enemies of Algiers.

This Regency soon were informed of this in all its circumstances by the French and Swedish Consuls residing in Algiers; they could not read, their only trial of the passport was by a countercheck delivered them by the Consul. When they applied this to these false passports they all checked and agreed; when the ships were, notwithstanding, brought into Algiers, the English Consul detected the fraud, disowned the signature, and the ship was made a legal prize.

This secret, however obvious to everyone skilled in business of that kind, was inscrutable to pirates who knew no other rule but the check; the cruisers were on the point of mutinying;[17] had I not been on good terms with the whole Regency, as well as with the common soldiers and merchants, I should have been burned in my house, or condemned to draw the stone cart in irons, as a short time before I had had the mortification to see the French Consul and all his nation do.

The event here alluded to is an extraordinary example of the terrorism which prevailed in Algiers at that epoch, and of the indignities to which even representatives of the most powerful nations were subjected, without provoking more than a passing remonstrance. The story is recorded in the private memorials of the Congrégation de la Mission, which have been obligingly placed at my disposal by the Superior-General in Paris. Well may he remark: ‘Nos confrères ont beaucoup travaillé et beaucoup souffert sur cette terre d’Afrique, où les Chrétiens avaient été si longtemps persécutés; maintenant la croix a heureusement triomphé, et puisque vous avez étudié l’histoire de ce pays, vous pouvez voir combien il a gagné à être délivré de la domination Mahométane.’

A French vessel had, through some mistake, fired upon an Algerian galliot, which made a prize of it, and brought it into the harbour of Algiers. Monsieur Vallière, the French Consul, went on the following day to request the Dey to restore the boat and its equipage, assuring his Highness that if the latter had been guilty of any infringement of the conventions between the two countries they would be severely punished in France. The Dey answered him that the French were only good at chicanery; they were liars, the greatest enemies of the country, and no better than spies of the Spaniards; he knew how to right himself, and would hear nothing more from the Consul, who might retire.

The Consul did retire, in company with his chancellor. In less than an hour he was again called to the palace, and, without further explanation, he was heavily chained, as were also the Vicar Apostolic, two other missionaries, the chancellor, the secretary, the Consul’s servants, and the crews of the four boats then in harbour, in all fifty-three persons. Every morning they were sent out to the hardest and most degrading labour, and exposed to the insults and jeers of the populace; harnessed two and two to stone carts and heavily ironed, they were compelled to drag their weary burden twice every day from the quarries at several miles’ distance to where the masons were at work, after which, though worn out with fatigue, the good priests’ first care was to console their fellow-captives, and to conduct public prayer in the Bagnio.

Our treaties, made and renewed by captains of men-of-war, from time to time, who know no more of the interest of their country in the Mediterranean than I know of directing a line-of-battle, afforded no sort of remedy for this grievance, which was new, because Port Mahon falling into the hands of the enemy was a new event not to be foreseen.

[18]These treaties were growing worse every day; they were a monstrous heap of confusion not understood either by the Turkish or the British Government. I wrote home repeated letters explanatory of the mischief and the causes of it. I either got no answers at all, or short ones, that showed me they did not attend to the subject. We were on the very eve of having all our Mediterranean and Straits trade carried into the Barbary ports as prizes, when letters were said to be expeded (sic) by the Secretary of State—I think the Duke of Grafton or Lord Shelburne—desiring the Governor of Mahon and Gibraltar (for Mahon was now restored to the English) to recall all these old irregular passports signed by the French, and in their place to issue what was called passavants, under the hand and seal of the Governor of those fortresses, importing the ship bearer thereof to be British property, and that this should serve as a passport during a limited time, after which new checks and new passports were to be issued by the Admiralty for the ships then in the Mediterranean and the Barbary cruisers that visited them. But no intimation was sent to the Consuls of this, nor was such passavant to be found in the treaty, nor did any new checks or passports come for a long time from the Admiralty.

In the meantime the Algerine cruisers were more exasperated than before; they had still no way of knowing an enemy from a friend but by the check the Consul gave them, and that had been declared as no longer of use, as covering fraud, and was issued no more.

· · · · · · ·

All Algiers was in arms, and to excuse our Government was impossible; they never did know Barbary politics in my time.

· · · · · · ·

British Consuls in the Straits, or in the Barbary States, are generally men that have failed in their own mercantile affairs; they are afraid to write the true situation of things to a Secretary of State, because they fear hurting their interest at Algiers and losing their posts at home. Government have for some years been afraid of Algiers, or so complaisant as to recal the British Consul upon a complaint they do not like him, and often for having done his duty.

I was no merchant, and afraid of neither; I had stated the thing as it was constantly, and one day when a few of these pirates had come home in disappointment at meeting nothing but what was covered by these passavants, crossing me in the street, one of them, drunk, I suppose, fired a large horse pistol directly in my face at the distance of sixteen yards. It was loaded with slugs, one of which cut the loop where my hat was buttoned, another cut the skin of my eyelid, and a third wounded me slightly in the left arm. Government seized the unhappy beast and would have put him to death, had I not saved him by the trouble of some application and interest, and even a little expense.

It was no vain boast on the part of Bruce that his intercession had saved this man’s life. Monsieur Laugier de Tassy, in his ‘Histoire du Royaume d’Alger,’ published at Amsterdam in 1727, gives the following account of what happened to another unhappy wretch who had insulted a British Consul, and there is little doubt that if Barbary justice had been left to take its course this man would have fared no better.

[19]‘In 1716 Mr. Thomas Thompson, British Consul, going to the Assembly Rooms of the ship captains, met on the pier a young Moor, who, it is generally believed, was drunk. The pier is very narrow, and much rain having fallen, the passage was by no means easy. The Moor would not make way for the Consul, but began to quarrel and even pushed him. The Consul asked him whether he wished to throw him off the pier, adding that he thought it rather impertinent of him not to turn aside. The Moor answered that it was well for a Christian to wish to pass before him, and at the same time seized the Consul, boxed his ears, tripped him over, threw him on the ground and placed his knee on his stomach. The Captain of the Port, having witnessed this scene from a distance, came forward and threatened the Moor, who thought it better not to wait for him and ran away. The Captain took the Consul to the house where the captains met, to console him and to repair the disorder he was in. The Admiral expressed his regret at what had happened. He told him he would report the matter to the Dey, and the Moor would soon be punished for his crime. The Admiral had great regard for the family of this young man, for his father was a friend of his and an honest merchant. When, therefore, he had laid the whole affair before the Dey, he begged him not to condemn the man to death, as he deserved, as he belonged to a respectable family, and that drink, to which he had been tempted by libertines, had been the cause of his crime. The Dey answered that he deserved to be hanged, but that out of regard for him he would be pardoned. As an example, however, and for the sake of the insulted Consul, it was necessary to punish the wretch; the Dey therefore asked the Admiral to choose the kind of punishment he liked. The Admiral chose the bastinado, and the Dey said to him, “Out of regard for thee I will spare him.” The Consul soon after arrived. The Dey, seeing him, said, “Consul, I am doing what you desire. I am sorry for what has happened to you, but you shall have justice; remain there.” He gave orders at the same time to the Moorish Bach-Chaouch to bring the accused before him. As he had not hidden himself, he was soon found and brought before the Dey, who, in great anger, said to him, “Wretch, what hast thou done?”—“I have beaten a Christian, a dog who wanted to be more than myself, and who insulted me.” The Dey, enraged at his arrogance, said, “Is it true that you have treated the British Consul in such and such a way?”—“Yes, my Lord,” he answered. “Is it worth sending for me for such a trifle?” Then the Dey, furious, cried out, “That is enough,” and pronounced sentence, which was that he should receive 2,200 stripes. This was done at once, in the presence of the Consul. He received 100 blows on the soles of the feet, so that his feet were taken off as far as the ankles, or held on by so little that Mehemed Effendi Khasnadar drew his knife and cut the skin by which they hung. As further blows[20] would have caused death, and as the Dey was anxious that he should suffer well before such a thing happened, he gave orders to conduct him to prison, so that he might regain strength. The following day, at nine in the morning, the Dey sent for the British Consul, and also for the prisoner, who there and then received the remaining 1,200 blows on his back, which was so cut up that he lost both speech and breath. But, as he was not yet dead, the Dey ordered him to be taken back to prison, and to be shut up there alone, and without help. This was done, and the poor wretch was suffered to die of pain, hunger, and thirst.’

To resume however Bruce’s narrative:—

This dispassionate behaviour reconciled all the soldiery to me, already well-inclined to a man as to personal friendship. I gave Government a long detail of the situation of their affairs, without fear or disguise; I begged them to send out a man of some knowledge and dignity in business, who with me might go through the treaties, renew them, and make them intelligible, who might bring out new Mediterranean passes, a thing to be done in a very short time, after which I was satisfied that things would be settled on a peaceable and permanent footing. I claimed the King’s promise to be allowed to appoint a man, who had nothing to do but to sign the passports, while I made the excursions into Africa, which were the object of my voyage, for which I was fully prepared, and wished to defer no longer.

I received an answer that His Majesty commanded me to stay, till an Ambassador should be sent, to explain and settle the matter and the disputes with the Dey of Algiers. At the same time it said, slightly enough, that it undoubtedly was the King’s wish I might continue at Algiers; but since I did not choose it, His Majesty was resolved, that these places should not be sinecures, and therefore another Consul would be sent over, unless I certified my resolution to stay in course.

This mandate, which was a direct breach of the faith of Government, filled me with indignation.

· · · · · · ·

A relative of my own, a Captain C———,[9] son to the Secretary of the Admiralty, a man that I knew much better than those that sent him, came as the King’s representative to Algiers, and brought with him a city attorney,[10] that had somehow or other connected himself by marriage with the family of Egerton, as Consul.

None of them understood a word of the language, none of them a word of sense; they quarrelled from the beginning, and the Ambassador privately engaged the Dey to send the Consul home again by the end of the year, when he would bring out another and new presents from the King.

· · · · · · ·

The Dey[11] continued my fast friend; he furnished me with all the necessary letters to his provinces. I told him I was going for some necessaries to Mahon. I should then go down the coast by Bona, to Tunis. I should then come back to Constantine and return again to Tunis by the foot of Mount Atlas.

[21]He assured me of every mark of friendship and protection, which he kept through the whole course of the voyage.

The Ambassador, in the Phœnix, man-of-war, and I in a small Mahonese barque, sailed together from Algiers for Mahon.[12]

In the night we were overtaken by a violent storm of wind, which lasted all the next day, broke our mainsail yard, and did us other considerable damage. We saw no more of the Phœnix; she had held her wind, which though violent was fair, and arrived at Gibraltar.

I put into Quarantine Island in Mahon, and announced my arrival there and the reason of it to General Townshend, desiring it might be entered in some book, where the authentic evidence of day and date might be referred to. Every sort of politeness was shown me by that officer, who ordered immediately to give me pratique. Having nothing to do in Mahon, I refused it, and set sail for Tunis.

As the first portion of Bruce’s journey is not given in the order in which he made it, I subjoin the dates of the various stages, as nearly as they can be made out.

1765.

FOOTNOTES:

[9]Captain Cleveland.

[10]Mr. Robert Kirke.

[11]Baba Ali, 1754-1766.

[12]Bruce’s passport for Tunis, signed by his successor, Robert Kirke, is dated August 19, 1765.

Julia Cæsarea.

There is no written account remaining of Bruce’s explorations to the west of Algiers, and the only allusion to them is the fact that he first used his camera obscura in delineating the Kubr-er-Rumiah, or Tombeau de la Chrétienne, as it is now called.

The illustrations he has left of Julia Cæsarea, which, doubtless, he visited while still Consul-General at Algiers, are as follows:

1. A perspective view in water-colours and distemper of the Kubr-er-Rumiah, or Tomb of Juba II. No architectural details are shown, as the débris around the base had not then been cleared away.

2. Finished drawing to scale, in Indian ink, of restored plan, and elevation of Tomb.

3. Perspective view in water-colours of the same building, taken from the S.E. In the foreground are architectural fragments, including Ionic capitals, frusta of columns, and portion of entablature. [Plate I.]

4. Finished drawing to scale, in Indian ink, of front and side elevation of capitals of Ionic order; plan of columns. Elevation and section of architrave. [Plate II.]

5. Duplicate of 2; dimensions not figured.

6. Duplicate of 4.

7. Pencil drawings of coins: six coins of Ptolemy, one of Juba II.

8. Pencil drawings of coins: eight coins of Juba, four of Juba and Cleopatra Selene, one of Cleopatra Selene.

9. Pencil sketch of Tomb, very similar to 3.

10. Perspective view of Aqueduct of Cherchel. [Plate III.]

11. A view of the same, in distemper.

12. Elevation and section of the same to scale.

13 to 15. Three ornamental titles of proposed work.

[24]The site of the ancient city of Jol, subsequently Julia Cæsarea, is marked by the modern town of Cherchel, about 72 miles west of Algiers.

After the surrender of Jugurtha to Marius by his son-in-law and ally, Bocchus King of Numidia, the latter reunited to his own kingdom the provinces, which extended from Saldae, the modern Bougie, to Molocath, the modern river Molouia, on the confines of Morocco. At his death, about 91 B.C., he left the western portion of his dominions to Bogud, and the newly annexed portions to his second son Bocchus.

Fifty years later we find these two divisions of Mauritania still existing, and governed by kings bearing the same names as before, but with this difference, that it was Bogud who was King of Eastern Mauritania, and Bocchus who governed the western portion or Tingitana.[13]

The former of these took part with Cæsar in the war, which terminated in the defeat of the Pompeian army at Thapsus, and the suicide of Juba I. King of Numidia. The infant son of that monarch was taken to Rome, where he graced the triumph of the great dictator; a part of the forfeited kingdom was given to Bogud, and subsequently the western province was added by Augustus, during the reign of his son Bocchus III. That prince reigned five years over the two Mauritanias, his capital being Jol, and died B.C. 33.

In the meantime the young Juba had been carefully educated at Rome, where he attained a high literary reputation, being frequently cited by Pliny, who describes him as more memorable for his erudition than for the crown he wore, glorious as it was. Plutarch also calls him the greatest historian amongst kings.

All his works have disappeared, though a long list of them has survived; they treated of a great diversity of subjects, including history, antiquities, arts, science, grammar and geography.

In the year 26 B.C. Augustus, desiring to give to the people of the late monarch a sovereign of their own race, fixed upon this son of Juba, and restored to him the western portion of his father’s dominions, trusting to his thorough Roman education to secure his submission, and on the prestige of his race and name to win the affections of the Numidian races, and to hasten their fusion with the conquering nation.

He removed his capital to the ancient Phœnician city of Jol, to which he gave the name of Julia Cæsarea.

He died in A.D. 19, leaving a son, Ptolemy, the last independent prince of Mauritania, who was far from sharing the high qualities of his father.

Plate II.

J. LEITCH &. Co. Sc.

TOMBEAU DE LA CHRÉTIENNE OR TOMB OF JUBA II.

FAC SIMILE OF PLATE OF ARCHITECTURAL DETAILS

EXECUTED BY BRUCE AFTER HIS RETURN TO SCOTLAND.

HENRY S. KING Co. LONDON.

[25]His reign was characterised by debauchery and misgovernment, and the Mauritanians were not slow to rise in revolt, under the leadership of Tacfarinas. This war lasted for seven years, shortly after which Tiberius died, and was succeeded by Caligula, who summoned Ptolemy to Rome, and, after having received him with great honour, caused him to be killed, as he thought that the splendour of his attire excited unduly the attention of the spectators. It is more likely that he desired to appropriate the wealth that Ptolemy was known to have accumulated. This murder was followed by a serious revolution in Mauritania, which lasted several years.

The Tombeau de la Chrétienne figured by Bruce is well known to all visitors to Algiers. It is one of three somewhat similar edifices, one of which is found in each province of Algeria, the other two being the Medrassen, or Tomb of the Numidian Kings in Constantine, and El-Djedar in Oran.

This, however, is the only one mentioned by any ancient author. Pomponius Mela, in his work ‘De Situ Orbis,’ written about the middle of the first century, after the death of Juba II., but before the murder of his son Ptolemy, mentions both Cæsarea (Cherchel) and Icosium (Algiers), and states that beyond the former is the monumentum commune regiæ gentis.

This at once decides the nature of the building, which, though intended to be seen far and near, is yet entirely concealed from view at Cherchel by the mountain of Chennoua, the presumption being that the king would not care to have constantly within sight of his royal residence, the tomb which he had caused to be constructed for himself.

The resemblance to the Medrassen, or Tomb of the Numidian Kings, from whom Juba was descended, is another presumption that it was erected by him in imitation of his ancestral mausoleum.

Bruce’s illustration (Plate I.) of this monument is the only inaccurate one in the whole series. Until long after his time the podium was so encumbered with débris that it was impossible to make out the architectural details, and he has represented this portion of the edifice rather as what he imagined it to be than as it actually existed.

Juba II. married Cleopatra Selene, daughter of the celebrated Egyptian queen by Marc Antony, and there is every probability that this monument served only as his tomb, and that of his wife, who died before him. It is hardly likely that the remains of his son Ptolemy, the last of his race, could have been transferred from Rome to Africa.

The tomb must have been violated at a very early period in the search for hidden[26] treasure. A careful examination of the accumulated earth and dust within revealed traces of successive races, who had visited the place, some of whom had even made it a place of residence, but none whatever of the bodies for whose reception it had been erected.

It is called by the Arabs Kubr er-Roumiah, tomb of the Roman, or rather Christian woman, the word Roumi (fem. Roumiah) being used commonly by Arabs all over the East to designate strangers of Christian origin.

Various explanations are given of this name. Marmol mentions a tradition, that under it were interred the mortal remains of the beautiful daughter of Count Julian, over the story of whose misfortunes the muse of Southey has shed so strong an interest.

Shaw[14] states that amongst the Turks it was known by the name Maltapasy, or Treasure of the Sugar Loaf; and the belief, that it covered some great accumulation of riches, has exposed it to attacks, by which it has been much ruined, and before which a less solid structure would have altogether disappeared. Marmol adds:

‘In the year 1555 Solharraes[15] attempted to pull it down, hoping to find some treasure in it; but when they lifted up the stones there came a sort of black poisonous wasps from under them, which caused immediate death wherever they stinged, and upon that Barbarossa dropped his design.’

Many other legends and traditions are connected with it, which it would be out of place here to reproduce.

The Tombeau de la Chrétienne is built on a hill forming part of the Sahel range, 756 feet above the level of the sea, covered with a brushwood of lentisk and tree heath, situated nearly midway between Tipasa and Koleah, and to the west of Algiers.

It is a circular, or rather polygonal, building, originally about 131 feet in height; the actual height at present is 100 ft. 8 in., of which the cylindrical portion is 36 ft. 6 in., and the pyramid 64 ft. 2 in. The base is 198 feet in diameter, and forms an encircling podium, or zone, of a decorative character, presenting a vertical wall, ornamented with sixty engaged Ionic columns, 2 ft. 5 in. in diameter, surmounted by a frieze or cornice of simple form. The capitals of the columns have entirely disappeared, but they are represented in Bruce’s drawings as having very small volutes, most of the space between which is occupied by a honeysuckle flower. There are two tendrils, one on each side of the flower, but growing out of the surface of the capital, and not continuous with the flower. The necking between the capital and the shaft[27] is composed of a succession of four small petalled flowers, flatly applied, contained between an upper and a lower fillet.

The series of the colonnade has at the cardinal points four false doors, the four panels of which, producing what may have been taken to represent a cross, probably contributed to fix the appellation of Christian to it.

Above the cornice rise a series of thirty-three steps, which gradually decrease in circular area, giving the building the appearance of a truncated cone.

The whole monument is placed on a low platform 210 feet square, the sides of which are tangents to the circular base.

During the Emperor Napoleon’s last visit to Africa he charged the well-known Algerian scholar, M. Berbrugger, and M. MacCarthy, the late and present directors of the library and museum, to explore this tomb, which had never been penetrated in modern times, spite of the attempt of Salah Rais, in 1555, and the efforts of Baba Mohammed in the end of the eighteenth century, to batter it down by means of artillery.

SKETCH SHOWING THE CROSS ON THE FALSE DOORS.

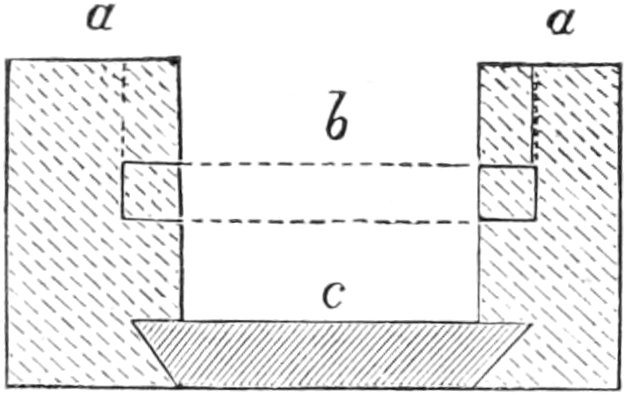

In May, 1866, a hole was drilled by an Artesian sound, which gave indications of an interior cavity, and shortly afterwards an opening was made from the exterior to the interior passage. Entering by this, both the central chamber and the regular door were easily found.

Below the false door, to the E., is a smaller one, giving access to a vaulted chamber, to the right of which was the door of the principal gallery. Above this are rudely sculptured the figures of a lion and a lioness.

From this passage a large gallery, about 6 ft. 7 in. in breadth, by 7 ft. 5 in. in height, is entered by a flight of steps. Along it are niches in the wall, intended to hold lamps. Its total length is 483 feet. This winds round in a spiral direction,[28] gradually approaching the centre, where are two sepulchral vaulted chambers, one 12 ft. 4 in. by 9 ft. 3 in., and the other 12 ft. 4 in. by 9 ft. 7 in., separated from each other by a short passage, and shut off from the winding passage by stone doors, consisting of a single slab capable of being moved up and down by levers like a portcullis.

Julia Cæsarea itself, corresponding to the charming little French town of Cherchel, is situated further on, at a distance of 71 miles from Algiers, and twenty from the nearest station, El-Afroun.

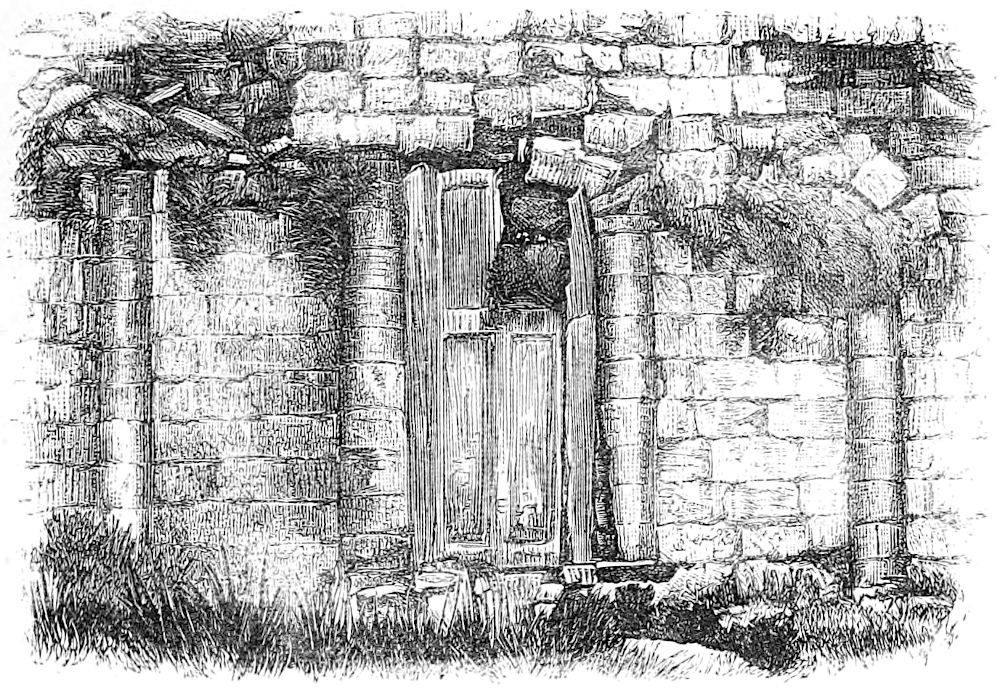

Close to the twenty-second kilometric stone, counting from where the Cherchel road branches off from the main one to Miliana at Bou-Rekika, and at a distance of between six and seven miles from Cherchel, is the subject of Bruce’s second illustration (Plate III.), part of the aqueduct which led the waters of the Oued el-Hachem, and the copious springs of Djebel Chennoua into Julia Cæsarea. This consisted of two converging branches, following the contour of the hills as open channels or traversing projecting spurs by means of galleries. In only two places was it necessary to carry the water over valleys on arches; the first was at the place here illustrated, and the second about three miles further on, at the junction of the two branches, where the united waters were carried over the valley of the Oued Billah on a single series of arches, of which five are still entire.

Many piers of the others remain, and the high road now passes between two of them.

Bruce has, as usual, left no names or indication of locality on his drawings of this structure, but its condition at the present day is hardly different from what it was a century ago. And amongst his MSS. I discovered a small scrap of paper containing a memorandum in pencil, which would have removed all doubts on the subject, had any existed.

‘Shershell arches. View is that of the east side. River Hashem. Shenoa on the east. The mountain of Beni Habeeb that seen through the broken arch.’

At this spot a small stream winds through a deep and narrow valley. The aqueduct is carried over this on a triple series of arches, nearly all of which are still entire, with the exception of the gap exhibited in the illustration.

The lower and middle series consisted each of seven arches, of which five are complete, and the upper one had sixteen, of which thirteen remain.

The construction of the building cannot compare with that of the great aqueduct of Carthage; the arches are irregular in form, where irregularity does not appear to have been necessary. The masonry is of cut stone only as far as the spring of the[29] middle arches, above which it is of rubble; all the superstructure above the bottom of the specus has disappeared, but at the south end there still remains a circular basin, intended, no doubt, to break the fall of the water, which descended at a steep incline, and to collect the stones and other substances which might be washed down by it, and thus allow only a stream of clear water to flow over into the duct beyond.

Plate III.

J. LEITCH &. Co. Sc.

AQUEDUCT OF JULIA CAESARIA (CHERCHEL)

FAC-SIMILE OF FINISHED INDIAN INK DRAWING BY BRUCE (AND BALUGANI?)

HENRY S. KING Co. LONDON.

The dimensions given by Bruce of this aqueduct are as follows:—

| Ft. | in. | lines. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height to keystone of lower arch | 39 | 9 | 0 |

| Thickness of keystone | 2 | 6 | 0 |

| Height to keystone of middle arch | 34 | 0 | 0 |

| Thickness of keystone | 1 | 9 | 0 |

| Thence to keystone of upper arch | 38 | 9 | 0 |

| Above intrados of upper arch | 5 | 9 | 0 |

| Total height | 116 | 6 | 4 |

| Breadth of first pier | 11 | 7 | 2 |

| Breadth of first arch | 11 | 5 | 0 |

| Breadth of second and third piers | 14 | 8 | 0 |

| Interval between them | 19 | 6 | 4 |

| Thickness of pier of first series | 14 | 7 | 3 |

Cherchel is easily reached in one day from Algiers by railway and omnibus, and is well worthy of a visit. It is pleasantly situated on the sea coast in a very picturesque plateau west of the Oued Billah, and between the mountains of the Beni Manasser and the sea. Ruins of former magnificence exist in every direction, and wherever excavations are made, columns and fragments of architectural details are found in abundance; unfortunately, little or no regard has been paid to the preservation of the numerous remains which existed even as late as the French conquest. Most of the portable objects of interest have been removed to museums elsewhere, and nearly all the monuments have been destroyed for the sake of their stones. The large amphitheatre outside the gate to the east still retains its outline, but the bottom is encumbered with twelve or fifteen feet of débris, and is at present a ploughed field; the steps, excepting in one small corner, have disappeared, and every block of cut stone has been removed. The theatre or hippodrome near the barracks is now a mere depression in the ground, though in 1840 it was in a nearly perfect state of preservation, and was surrounded by a portico supported by columns of granite and marble, to which access was obtained by a magnificent flight of steps. Here it is said that St. Arcadius suffered martyrdom by being cut in pieces. Magnificent baths existed both in the vicinity of the amphitheatre, where is now the Champs de Mars, and on the opposite side of the town overlooking the port. Even as late as my first visit to[30] Cherchel a curious old fort existed on the public place, built, as an inscription in the museum testifies, by the Caïd Mahmoud bin Fares Ez-zaki, under the government and by order of The Emir who executes the orders of God, who fights in the ways of God, Aroudj, the son of Yakoob, in the year of the Hejira 924. This was built out of older Roman materials found on the spot by the celebrated corsair Baba Aroudj, surnamed by Europeans Barbarossa.

Numerous columns of black diorite and the brèche of Djebel Chennoua lie scattered about the place, as well as magnificent fragments of what must once have been a white marble temple of singular beauty. In the museum a great variety of fragments are collected, many of which probably belonged to the same building, together with broken statues, tumulary and other inscriptions, capitals and bases of columns, amphoræ, etc., and in one corner, amongst a heap of rubbish, are some precious specimens illustrating curious facts connected with the state of industrial arts during the time of the Romans. For instance, a small section of a leaden pipe shows us that such implements were then made by rolling up a sheet of the metal, folding over the edges, and running molten lead along the joint. An ingot of the same metal exists, as perfect as when it left the foundry, with the maker’s name in basso relievo. There is a boat’s anchor much corroded, but still perfect in shape, a sundial of curious design, and, most interesting of all, the lower half of a seated Egyptian divinity, in black basalt, with a hieroglyphic inscription. This was found in the bed of the harbour, and may have been sent as a present to the fair Cleopatra, from her native land.