Title: Naval battles of the world

Great and decisive contests on the sea ... with an account of the Japan-China war and the recent battle of the Yalu; the growth, power, and management of our new Navy.

Author: Edward Shippen

Release date: February 28, 2024 [eBook #73068]

Language: English

Original publication: Philadelphia: P. W. Ziegler Co

Credits: Brian Coe, Harry Lamé and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library with additional images from the Internet Archive.)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

The first part, Naval Battles of the World, starts here, the second part, Naval Battles of America, starts here.

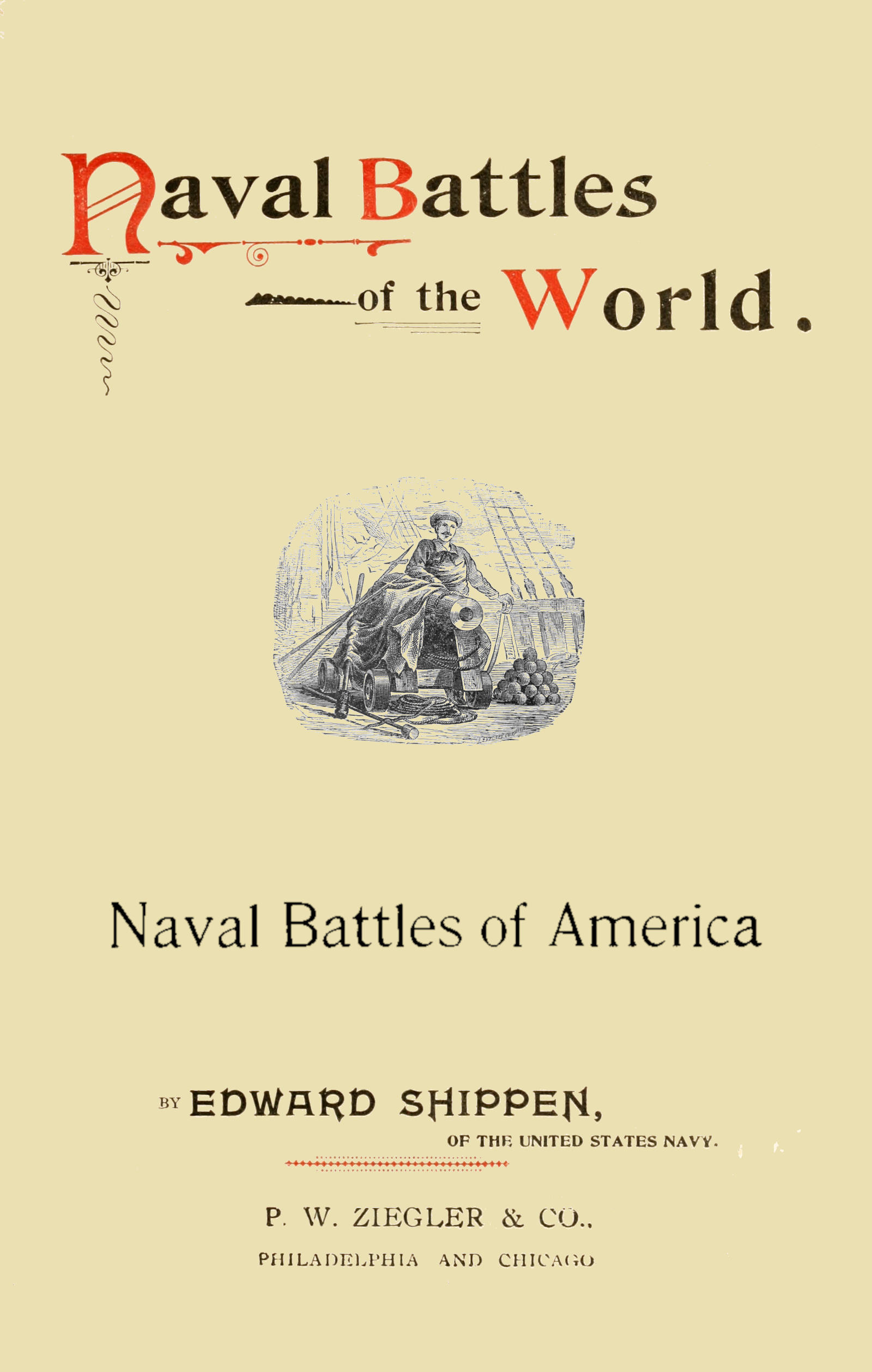

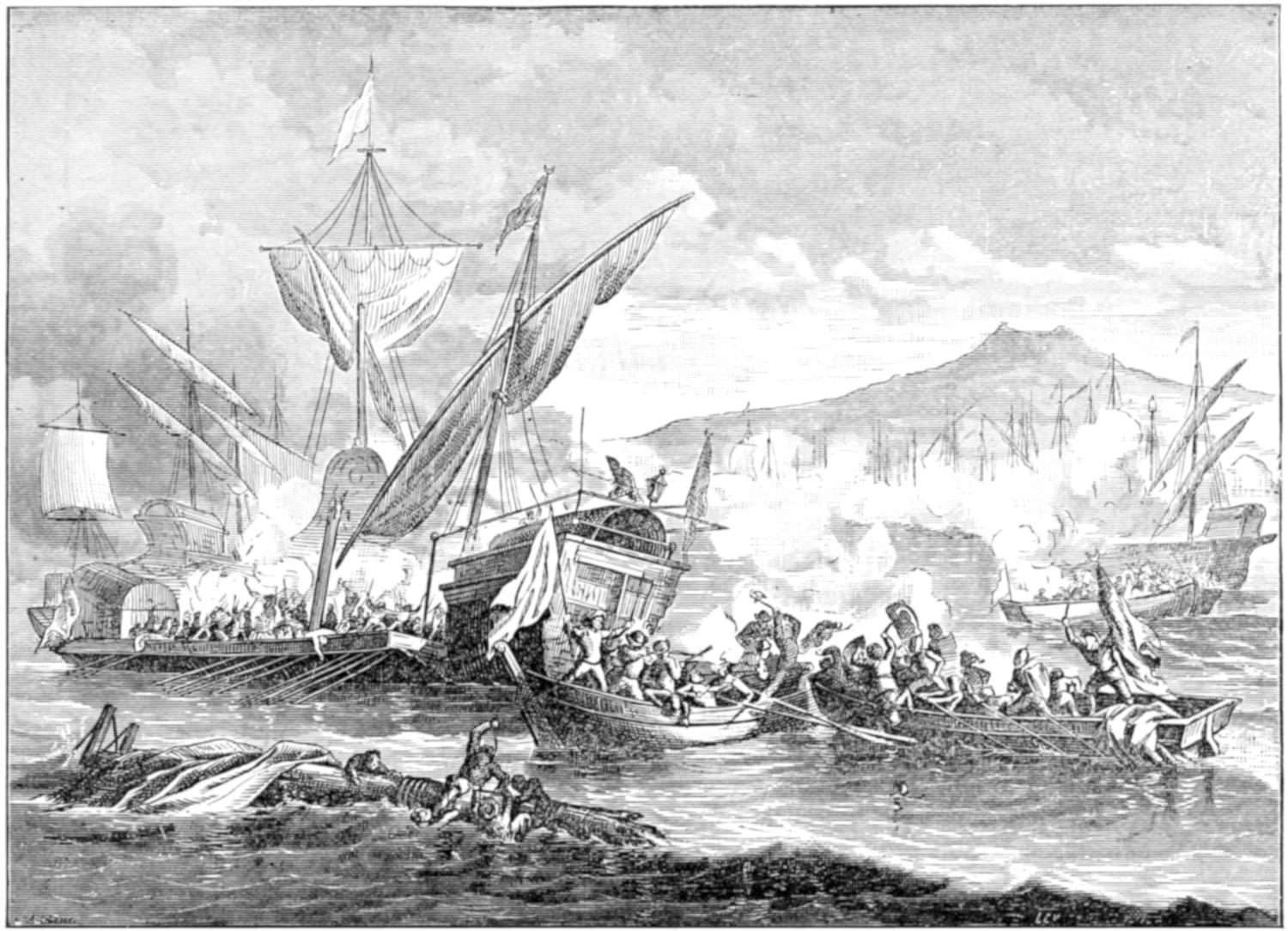

RETURN OF THE GREEKS FROM SALAMIS.

Great and Decisive

Contests on the Sea;

Causes and Results of

Ocean Victories and Defeats;

Marine Warfare and Armament

in all ages;

with an account of the

Japan-China War,

and the recent

Battle of the Yalu.

The Growth, Power and Management of

OUR NEW NAVY

in its Pride and Glory of Swift Cruiser, Impregnable Battleship, Ponderous

Engine, and Deadly Projectile;

Our Naval Academy, Training Ship, Hospital,

Revenue, Light House, and Life Saving Service.

BY EDWARD SHIPPEN,

OF THE UNITED STATES NAVY.

P. W. ZIEGLER & CO.,

PHILADELPHIA AND CHICAGO

COPYRIGHTED BY

JAMES C. McCURDY.

1883, 1894, 1898.

[I-V]

This collection is intended to present, in a popular form, an account of many of the important naval battles of all times, as well as of some combats of squadrons and single ships, which are interesting, from the nautical skill and bravery shown in them.

In most instances an endeavor has been made to give, in a concise manner, the causes which led to these encounters, as well as the results obtained.

As this book is not intended for professional men, technicalities have been, as far as possible, avoided. But it is often necessary to use the language and phraseology of those who fought these battles.

In all there has been a desire to give an unbiased account of each battle; and, especially, to make no statement for which authority cannot be found.

A study of naval history is of value, even in the most inland regions, by increasing a practical knowledge of geography, and by creating an interest in the great problems of government, instead of concentrating it upon local affairs. At the time that this volume was first[I-VI] issued, some people wondered why such a publication was necessary. The answer was that it was to inform the people of the great centre and West of the necessity of a navy, by showing them what navies had done and what influence they exercised in the world’s history.

That they are fully aware of this now is also not doubtful, and the probability is that those representatives of the people who oppose a sufficient navy for our country will be frowned down by their own constituents. Commonsense shows that, with our immense seacoast, both on the Atlantic and the Pacific, the navy, in the future, is to be the preponderant branch of our military force.

[I-VII]

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| INTRODUCTION. | |

| The Ancients’ Dread of the Sea; Homer’s Account of It; Slow Progress in Navigation before the Discovery of the Lode-stone; Early Egyptians; The Argonauts; The Phenicians and Greeks; Evidences of Sea-fights Thousands of Years before Christ; Naval Battle Fought by Rameses III; The Fleets of Sesostris; Description of Bas-relief at Thebes; Roman Galleys Described; Early Maritime Spirit of the Carthaginians; Herodotus’ Account of the Battle of Artemisium; The Greeks under Alexander; Romans and Carthaginians. | I-19 |

| I. SALAMIS. B. C. 480. | |

| The Island of Salamis; Xerxes; His Immense Power; His Fleet and Army; Events Preceding the Battle; The Contending Hosts Engage in Worship before the Fight Begins; The Greek Admiral Gives the Signal for Action; Many Persian Vessels Sunk at the First Onset; Fierce Hand-to-Hand Fighting; A Son of the Great Darius Falls; Dismay Among the Asiatics; Panic-stricken; Artifice of Queen Artemisia; She Escapes; Xerxes Powerless; He Rends his Robes and Bursts into Tears; Resolves to Return to Asia; Greece Wins her Freedom. | I-25 |

| II. NAVAL BATTLE AT SYRACUSE. B. C. 415. | |

| A Bloody Battle; Strength of the Athenians; The Fleet enters Syracuse Harbor in Fine Order; The Sicilians Blockade the Entrance and Imprison the Fleet; The Perils of Starvation Compel the Greeks to Attempt to Raise the Blockade; Both Fleets Meet at the Mouth of the Harbor; Confusion Among the Greeks; They are Finally Compelled to Turn Back and Take Refuge in their Docks; Another Attempt to Escape from the Harbor; Mutiny Among the Sailors; The Syracusans Appear in their Midst and Capture both Men and Ships; End of Athens as a Naval Power. | I-31 |

| III. ROMANS AND CARTHAGINIANS. | |

| Carthage a Place of Interest for Twenty Centuries; Romans and Carthaginians in Collision; First Punic War; Rome Begins the Construction of a Navy; A Stranded Carthaginian Vessel Serves as a Model; They Encounter the Carthaginians at Mylœ; Defeat of the Latter; Renewed Preparations of both Countries for the Mastery of the Mediterranean: A Great Battle Fought, 260 B. C.; The Romans Finally Victorious; They Land an Army in Africa and[I-VIII] Sail for Home; Encounter a “Sirocco” and Lose nearly all their Galleys on the Rocks; The Succeeding Punic Wars; Rome in Her Greatness; Antony and Octavius Appear Upon the Scene. | I-36 |

| IV. ACTIUM. B. C. 31. | |

| The Decisive Battle of Philippi, B. C. 42; Antony and Octavius Divide the Empire of the World Between Them; Trouble between Antony and Octavius; Antony’s Dissipations; His Passion for Egypt’s Queen; Octavius (the Future Augustus) Raises Fresh Legions to Oppose Antony; The Latter Proclaims Cleopatra Queen of Cyprus and Cilicia; The Republic Suspicious of Antony; Octavius Declares War Against Cleopatra; Crosses the Ionian Sea with his Fleet and Army, and Anchors at Actium, in Epirus; Meeting of the Roman and Antony’s Fleets; Preparation for Battle; A Grand Scene; Cleopatra’s Magnificent Galley; Discomfiture of Antony’s Centre; Cleopatra Panic-stricken; Flight of the Egyptian Contingent; Antony Follows Cleopatra; His Fleet Surrenders to Octavius; The Land Forces Refuse to Believe in Antony’s Defection; Despairing of His Return, they Accept Octavius’ Overtures and Pass Under his Banner; Octavius Master of the World; Suicide of Antony and Cleopatra. | I-48 |

| V. LEPANTO. A. D. 1571. | |

| A Momentous Battle that Decides the Sovereignty of Eastern Europe; Naval Events Preceding Lepanto; Turkish Encroachments; Pope Pius V Forms a League Against Them; Siege and Capture of Famagousta by the Turks; Barbarities of Mustapha; Christian Europe Aroused; Assembly of the Pontifical Fleet and Army; Don John, of the Spanish Squadron, Placed in Chief Command; Resolves to Seek and Attack the Ottoman Fleet; Encounters the Enemy in a Gulf on the Albanian Coast; Character of Don John; Preparations for Battle; Strength of his Fleet; A Magnificent Scene; The Turkish Fleet; Ali Pasha in Command; The Battle Opens; Desperate Fighting at all Points, Barberigo, of the Venetian Fleet, Badly Wounded; Two Renowned Seamen Face to Face; Uluch Ali Captures the Great “Capitana” of Malta; The Galley of Don John Encounters that of Ali Pasha; They Collide; Terrible Hand-to-Hand Fighting; Bravery of a Capuchin Friar; The Viceroy of Egypt Killed; Ali Pasha Killed; His Galley Captured; Dismay among the Turks; Uluch Ali Gives the Signal for Retreat; Terrible Loss of Life in the Battle; Christian Slaves Liberated; The Turkish Fleet Almost Annihilated; Alexander Farnese; Cervantes; Fierce Storm; Two Sons of Ali Prisoners; Don John and Veniero; Division of the Spoils; The Te Deum at Messina; Joy Throughout Christendom; Colonna in Rome; The Great Ottoman Standard; Decline of the Ottoman Empire. | I-56 |

| VI. THE INVINCIBLE ARMADA. A. D. 1588. | |

| Significance of the Term; Philip II; His Character; Determines to Invade England; The Duke of Parma; Foresight of Elizabeth; The Armada Ready; An Enormous Fleet; It Encounters a Tempest; Mutiny; The[I-IX] Armada reaches the English Channel in July; Lord Howard, Drake, Frobisher and Hawkins in Command of the English Fleet; Tactics of the English; Capture of the “Santa Anna” by Drake; The Spanish Reach Calais; Disappointment of the Spanish Commander; Another Storm Sets In; Distress in the Spanish Fleet; The English hang on its Rear and cut off Straggling Vessels; Shipwreck and Disaster Overtake the Armada on the Scottish and Irish Coast; A Fearful Loss of Life; Apparent Indifference of Philip II Concerning the Armada’s Failure; The Beginning of Spain’s Decline. | I-85 |

| VII. SOME NAVAL EVENTS OF ELIZABETH’S TIME, SUCCEEDING THE ARMADA. | |

| The Armada’s Discomfiture Encourages England to Attack Spain; Drake and Norris Unsuccessful at Lisbon; The Earl of Cumberland’s Expedition; Meets with a Bloody Repulse; League of Elizabeth with Henri Quatre, against the Duke of Parma; Sir Thomas Howard in Command of an English Fleet to the Azores; Frobisher and Raleigh’s Expedition of 1592; Prizes Taken on the Coast of Spain; Frobisher Wounded; His Death; Richard Hawkins; Walter Raleigh’s Expedition to Guiana; Expedition of Sir Francis Drake and Sir John Hawkins; Repulsed at Porto Rico; Death of Hawkins; England Anticipates Philip II in 1596 and Attacks Cadiz; The City Taken; The English Attack and Capture Fayal; Attempt to Intercept Spanish Merchantmen. | I-103 |

| VIII. NAVAL ACTIONS OF THE WAR BETWEEN ENGLAND AND HOLLAND. A. D. 1652-3. | |

| The Dutch Supreme on the Sea; The Commonwealth and the United Provinces; Negotiations for an Alliance Broken Off; An English Commodore Fires into a Dutch Fleet; Van Tromp sent to Avenge this Insult; Blake in Command of the English; The English Temporarily Masters in the Channel; Great Naval Preparations in Holland; The South of England at Van Tromp’s Mercy; Blake Collects his Fleet to meet Van Tromp; A Storm Scatters Both; The Dutch People Dissatisfied with Van Tromp; He Resigns; De Witt Assumes Chief Command; Blake Meets the French Fleet under Vendome; He Captures the Latter’s Fleet; Battle of North Foreland; De Witt Withdraws at Nightfall; Van Tromp to the Front Again; Denmark Declares Against the Commonwealth; The Dutch and English Meet in the English Channel; Blake Beaten; Van Tromp Sails Up and Down the Channel with a Broom at his Masthead; Battle off Portland; A Decisive Engagement; Van Tromp Escorts Dutch Merchantmen into Port; Discontent in the Dutch Fleet; Terrible Loss on Both Sides; Blake Learns of a New Fleet Fitted out by Van Tromp in April; They Meet Again; A Two Days’ Battle; Another Effort Two Months Later; The Brave Van Tromp Killed; The Power of Holland Broken: The States General Sues for Peace. | I-112 |

| IX. FRENCH AND DUTCH IN THE MEDITERRANEAN. A. D. 1676.[I-X] | |

| Revolt of Messina and Sicily; Louis XIV Sends Duquesne with a Fleet to Sustain the Insurgents; Sketch of Duquesne; England Makes Peace with Holland; Duquesne Repulses the Spanish Fleet and Captures the Town of Agosta; Learns of De Ruyter’s Presence in the Mediterranean; Meeting of the Hostile Fleets, Jan. 16, 1676; Splendid Manœuvres; The Advantage with the French; They Meet Again, in Spring, Near Syracuse; Sharp and Terrible Firing; De Ruyter Mortally Wounded; The Dutch Seek Shelter in Syracuse Harbor; The Sicilian and French Fleets Encounter the Dutch and Spanish Fleets Again, in May; Destruction of the Latter; Honors to the Remains of De Ruyter; Recompensing Duquesne; His Protestantism Distasteful to Louis XIV; Humiliates Genoa; Edict of Nantes; His Death and Private Burial; Subsequent Honors to his Memory. | I-146 |

| X. BATTLE OF CAPE LA HAGUE. A. D. 1692. | |

| Louis XIV Prepares to Attack England, to Seat James II on the Throne; Count de Tourville in Command of the French Fleet; Sketch of his Life; He is Ordered to Sail from Brest; Bad Weather; Arrogance of Pontchartrain, the Minister of Marine; Tourville meets a Powerful English and Dutch Fleet; Bravery of the Soleil Royal, the French Flag-ship; A Fog Ends the Fight; Louis XIV Compliments Tourville on his Gallant Defence Against Such Great Odds; Bestows the Title of Field Marshal on Him. | I-157 |

| XI. BENBOW, A. D. 1702. | |

| Benbow a Favorite of William III; Queen Anne Declares War Against France; Benbow Sent to the West Indies; He Falls in with a French Fleet; A Vigorous Attack Commenced; Disobedience of his Captains; He is Badly Wounded and Dies; The Captains Court-martialed; Detailed Account of the Capture and Destruction of the French and Spanish Fleets. | I-166 |

| XII. BYNG AND LA GALISSONIÈRE. A. D. 1756. | |

| Sketch of Admiral Byng; War between England and France; Capture of Minorca by the Latter; Byng sent to the Relief of the Island; La Galissonière in Command of the French; Failure to Engage the Latter’s Fleet, as Directed, by Byng; The English Driven Back to Gibraltar; Byng Superseded Without a Hearing; Tried by Court-martial and Sentenced to Death; The Sentence Considered Unjustly Severe by Pitt; Wrangling among the Officers of the Admiralty; Final Execution of the Sentence; Voltaire’s Sarcasm. | I-174 |

| XIII. SIR EDWARD HAWKE AND CONFLANS. A. D. 1759. | |

| Sketch of Hawke; Succeeds the Ill-fated Admiral Byng; In Command of a Blockading Squadron at Brest; Meets the French Fleet Under Admiral Conflans Near Belleisle; The Latter Inferior in Strength and Numbers; A Gale Arises During the Fight and Many Injured French Vessels Wrecked; The Latter Fleet Almost Entirely Disabled and Destroyed; Honors to Hawke. | I-183 |

| XIV. DE GRASSE AND RODNEY. A. D. 1782.[I-XI] | |

| Sketch of De Grasse; Earliest Exploits; Aids Washington in the Reduction of Yorktown; Recognition by Congress; Subsequent Events; Encounters an English Fleet, Under Rodney; De Grasse Loses Five Line-of Battle Ships; Exultation in England; De Grasse a Prisoner; Assists in Bringing About a Treaty of Peace Between the United States and England; Career of Rodney; Receives the Title of Baron and a Pension. | I-187 |

| LORD HOWE AND THE FRENCH FLEET. JUNE 1, A. D. 1794. | |

| The First of a Series of Memorable Engagements; Traits of Lord Howe; Anecdotes; Watching the French Fleet; The Latter Put to Sea; Skirmishing, May 28; A Great Battle, June 1; The French Open Fire First; Concentrated and Deadly Firing on Both Sides; The French Lose Six Line-of-Battle Ships; Howe’s Orders Not Obeyed by Some of the Captains; Some French Ships that Had Struck Escape in the Darkness; Anecdotes Concerning the Battle. | I-197 |

| BATTLE OF CAPE ST. VINCENT. A. D. 1797. | |

| Location of Cape St. Vincent; Admiral Sir John Jervis in Command of the English; Strength of His Fleet; Commodore Horatio Nelson; Chased by a Spanish Fleet; The Latter in Command of Don Joseph de Cordova; Feb. 14 a Disastrous Day for Spain; Surprised to See so Large an English Fleet; The Battle Opens; Boarding the San Nicolas; The Spanish Beaten at Every Point; The Battle over by 5 o’clock; Both Fleets Lay To to Repair Damages; Escape of the Spanish During the Night; Damages Sustained; Description of the Santissima Trinidada; The Cause of the Spanish Discomfiture; Great Rejoicing in Lisbon; Honors and Pensions Awarded to the English Commanders at Home; Admiral Cordova and His Captains. | I-217 |

| ENGLISH FLEET IN CANARY ISLANDS. A. D. 1797. | |

| English Expedition to the Canary Islands; Cutting Out a Brig in the Harbor of Santa Cruz; Attempt of the English to Capture the Town of Santa Cruz; An Expedition Under Rear Admiral Nelson Organized for the Purpose; The Garrison Apprised of Their Coming; Nelson Shot in the Arm and Disabled; The English Agree not to Molest the Canary Islands any Further if Allowed to Retire in Good Order; The Spanish Governor Finally Accepts this Offer; A Disastrous Defeat for Nelson. | I-236 |

| BATTLE OF CAMPERDOWN. 11TH OCTOBER, A. D. 1797. | |

| Viscount Duncan; His Early Life; The Mutiny of the Nore; Causes Leading to It; Disgraceful Practices of the English Admiralty of this Period; War with Holland; The Dutch Fleet Off the Texel under the Command of Vice-Admiral De Winter; The English Immediately Set Out to Intercept them; The Battle Opens about Noon of October 11th; Hard Fighting; The English[I-XII] Victorious; Accurate Firing of the Hollanders; The Losses Heavy on both Sides; Actual Strength of both Fleets; Duncan’s Admirable Plan of Attack; Nelson’s Memorandum. | I-243 |

| BATTLE OF THE NILE, 1ST AUGUST, 1798. | |

| Aboukir Bay; Its History; Learning that a Strong French Fleet Had Left Toulon, Nelson Seeks Them, He Finds the Fleet in Aboukir Bay; He Comes Upon Them at 6 o’clock in the Evening and Resolves to Attack Them at Once; A Terrible Battle; Misunderstanding of the French Admiral’s Instructions; Many Acts of Individual Heroism; Death of the French Admiral; Villeneuve Escapes with Four French Vessels; The Battle Over by 11 o’clock; The Most Disastrous Engagement the French Navy Ever Fought; Detailed Account of the Great Fight; The French Ship L’Orient Blown Up with a Terrific Explosion; Summary of the Losses on both sides; Masterly Tactics of Nelson; Gallant Behavior of the French; The Loss of This Battle of Immense Consequences to the Latter; Nelson Sails for Naples; Honors to Him Everywhere; His Official Report; French Officers of High Rank Killed; Anecdotes on Board the Vanguard on the Voyage to Naples. | I-259 |

| LEANDER AND GÉNÉREUX. 16TH AUG., A. D. 1798. | |

| Contest Between Single Ships; The Leander a Bearer of Dispatches from Nelson; Encounters the French Frigate Généreux; Attempts to Avoid the Latter; A Close and Bloody Fight of Six Hours; The Leander Surrenders; Captain Le Joille; Plundering the English Officers; Captain Thompson; Another Striking Incident; A French Cutter in Alexandria Harbor Abandoned on Being Attacked by Two English Frigates; The Officers and Crew of the Former, on Reaching the Shore, Massacred by the Arabs; General Carmin and Captain Vallette Among the Slain; Dispatches from Bonaparte Secured by the Arabs. | I-290 |

| ACTION BETWEEN THE AMBUSCADE AND BAYONNAISE A. D. 1798. | |

| Decisive Single Ship Actions; A Fruitful Source of Discussion; The British Account of It; History and Description of the Ambuscade; Unexpected Meeting with the Bayonnaise; The English Vessel the Fastest Sailer; A Battle Takes Place; Detailed Account of the Fight; The English Frigate Surrenders to the French Corvette; Causes of Discontent on Board the Former; Great Rejoicing in France; Promotion of the French Captain. | I-297 |

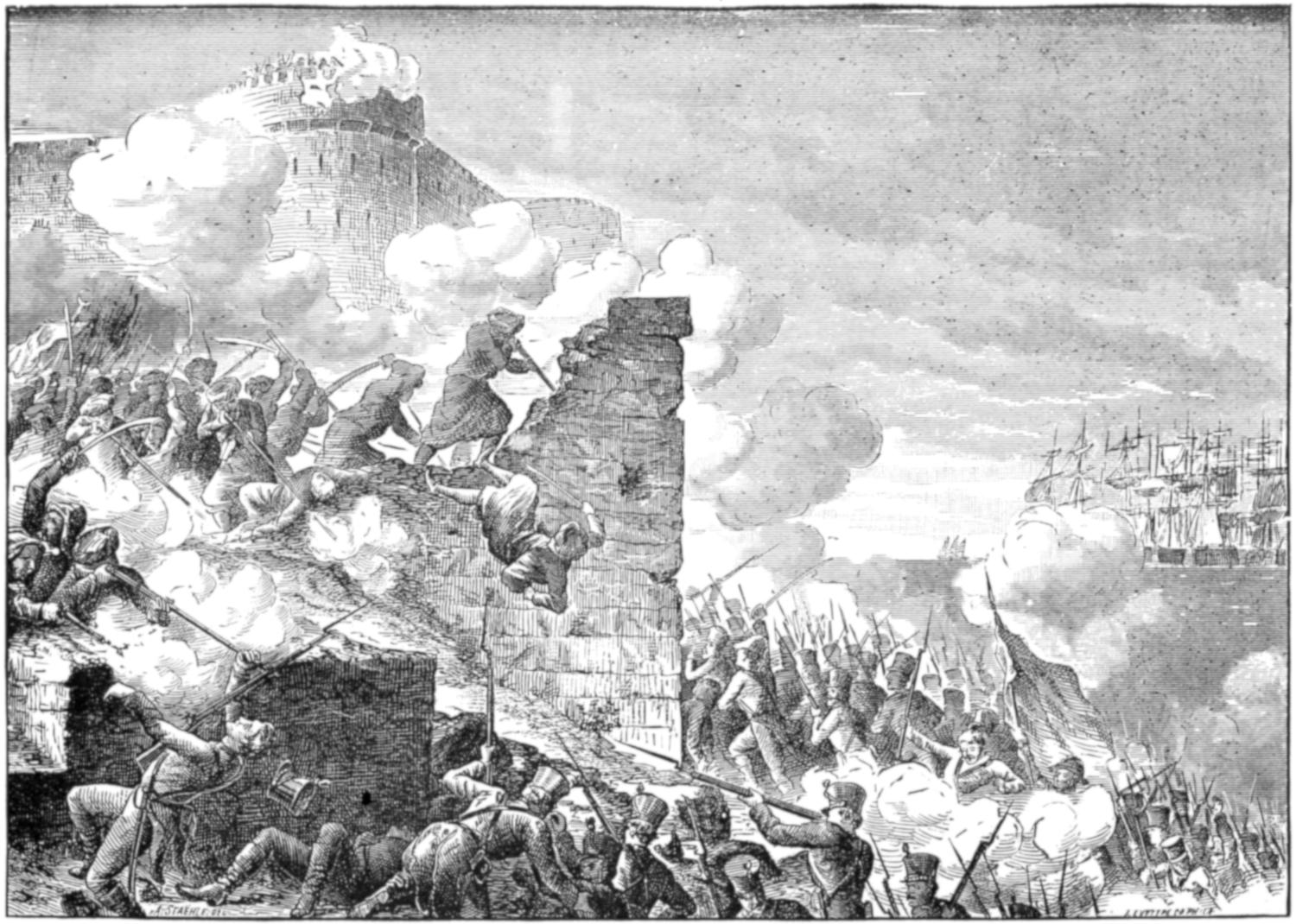

| SIR SIDNEY SMITH AND HIS SEAMEN AT ACRE. A. D. 1799. | |

| Minister to the Sublime Porte; Notified of Bonaparte’s Presence in Syria; The Latter Lays Siege to Acre; He Repairs Thither with a Fleet and Assists the Turks in Defending the Place; Admiral Perée, of the French Navy, Puts in an Appearance; Desperate Attempts to Storm the Place; Strength of Napoleon’s Army on Entering Syria; Kleber’s Grenadiers; Repeated and Desperate Assaults of the French; Unsuccessful Each Time; The Siege Abandoned After Sixty-one Days; Importance of the Place as Viewed by Napoleon. | I-304 |

| FOUDROYANT AND CONSORTS IN ACTION WITH THE GUILLAUME TELL. A. D. 1800.[I-XIII] | |

| Preliminary History; Rear Admiral Denis Décrès; Sketch of this Remarkable Man; His Tragic End; Engagement of the Guillaume Tell with the English Fleet Near Malta; Detailed Account of the Fight; Entirely Dismasted and Surrounded by English Vessels, the Guillaume Tell at last Surrenders; A More Heroic Defence Not To Be Found in the Record of Naval Actions; Taken to England, the Guillaume Tell is Refitted for the English Service, Under the Name of Malta; A Splendid Ship. | I-312 |

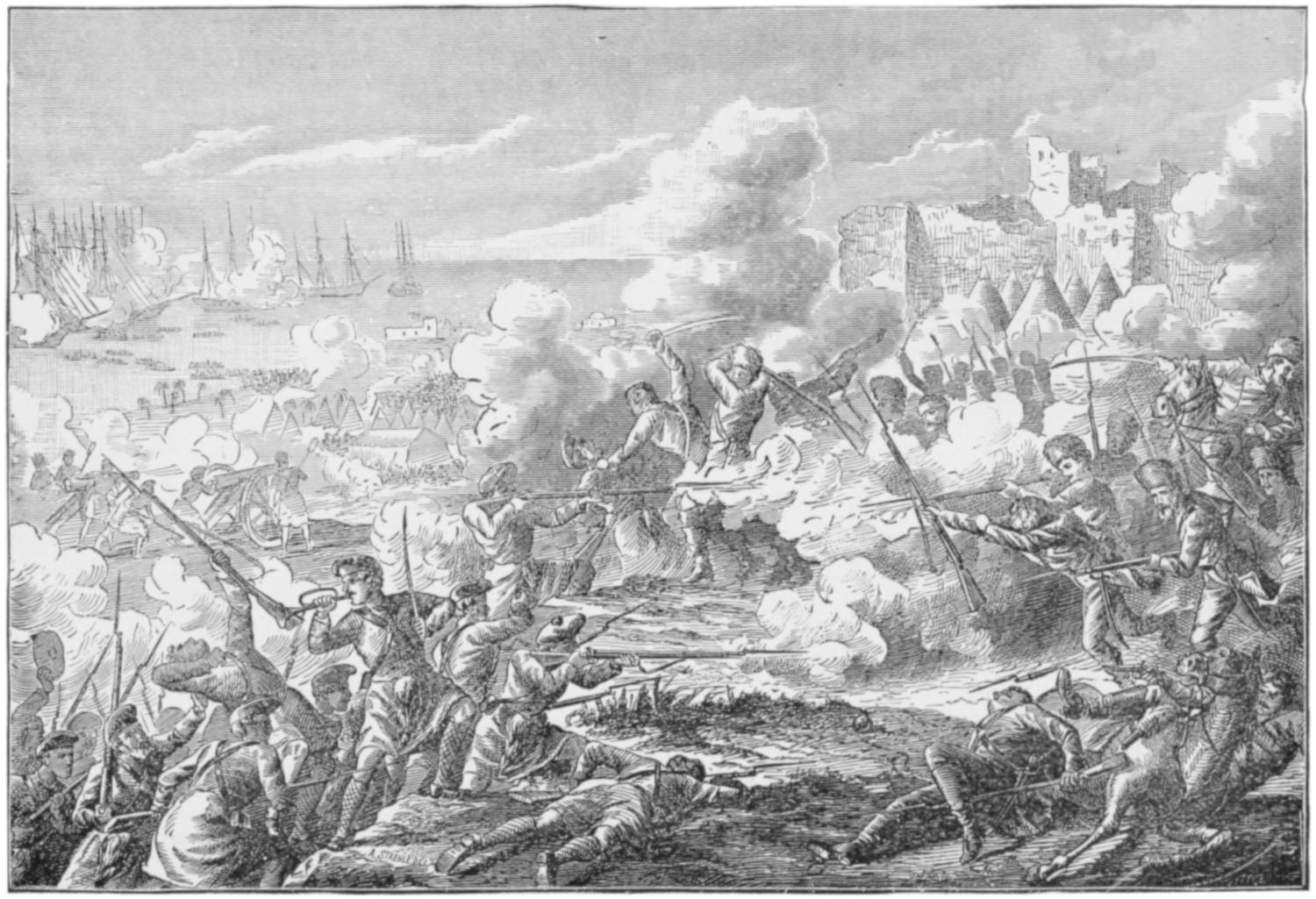

| NAVAL OPERATIONS AT ABOUKIR BAY AND CAPTURE OF ALEXANDRIA. A. D. 1801. | |

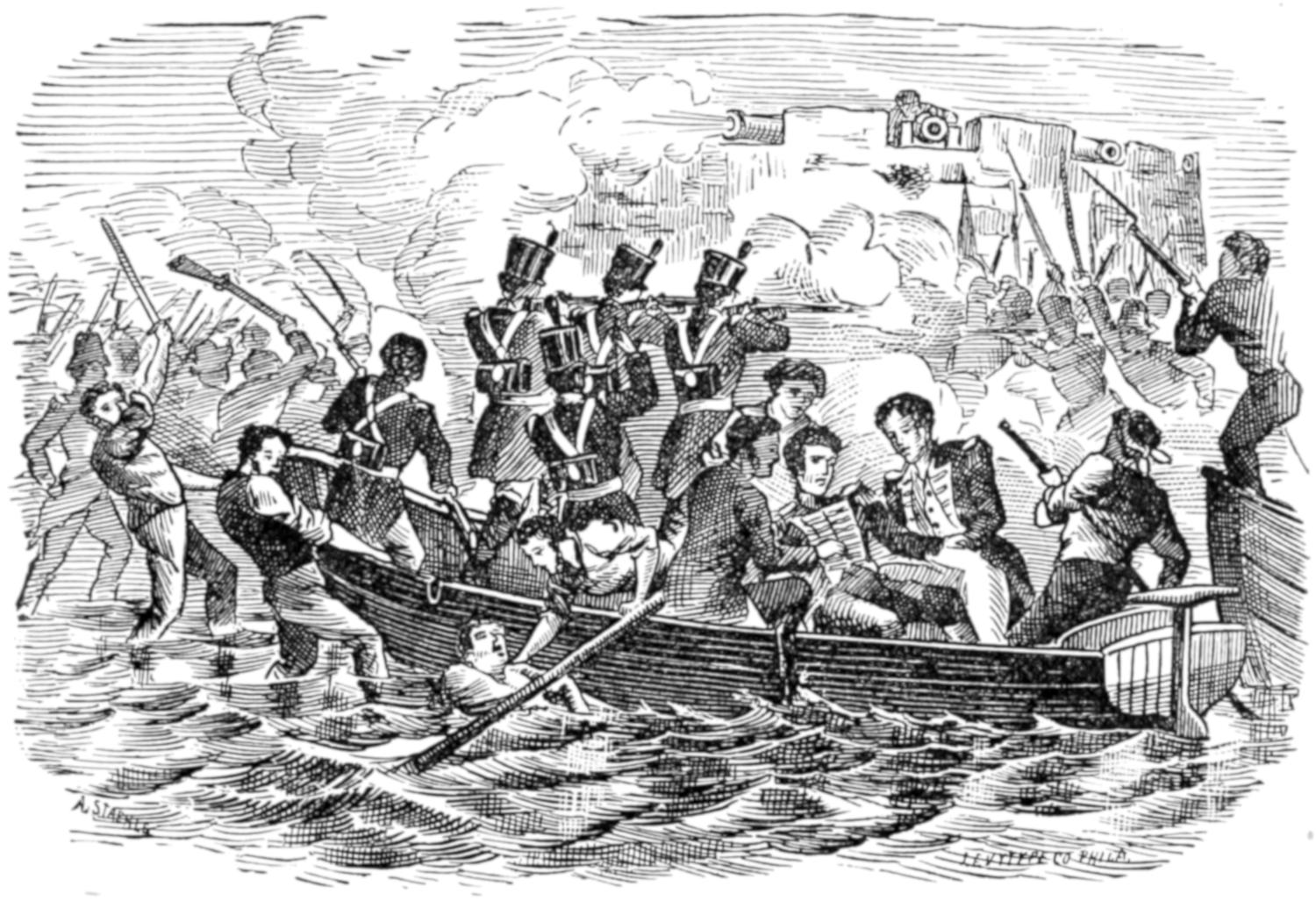

| Expulsion of the French Determined Upon; An English Fleet and Army Sent Thither Under Command of Lord Keith and Sir Ralph Abercrombie; The French Under Command of General Friant; The Former Land Troops Under a Galling Fire from Fort Aboukir and the Sand Hills; Sir Sidney Smith in Command of the Marines; A Heavy Battle Fought March 21; The French Forced to Retire; General Abercrombie Mortally Wounded; The French, Shut in at Alexandria, Finally Capitulate; Renewed Interest in this Campaign on Account of Recent Events; Points of Similarity. | I-318 |

| THE CUTTING OUT OF THE CHEVRETTE. JULY, A. D. 1801. | |

| An Example of a “Cutting-out Expedition”; The Combined French and Spanish Fleets at Anchor in Brest; The English Watching Them; The Chevrette at Anchor in Camaret Bay; The English Resolve to Cut Her Out; An Expedition Starts Out at Night, in Small Boats; They Board and Capture Her, in Spite of the Desperate Resistance of the French; Details of the Fight; The Losses on Both Sides. | I-322 |

| BOAT ATTACK UPON THE FRENCH FLOTILLA AT BOULOGNE. A. D. 1801. | |

| Another Boat Attack by the English, with Less Favorable Results; Lord Nelson in Command; Darkness and the Tides Against Them; They “Catch a Tartar”; The Affair a Triumph for the French. | I-328 |

| COPENHAGEN. A. D. 1801. | |

| Preliminary History; An English Fleet Under Sir Hyde Parker and Lord Nelson Ordered to the Cattegat; A Commissioner Empowered to Offer Peace or War Accompanies Them; Denmark Repels Their Insulting Ultimatum and Prepares for Defence; Strength of the English Fleet; They Attempt to Force the Passage of the Sound, and the Battle Begins; Early Incidents; Difficulties of the Large English Vessels in Entering the Shallow Waters; Strength of the Danish Fleet and Shore Batteries; Sir Hyde Parker Makes Signal to[I-XIV] Withdraw; Lord Nelson Disobeys and Keeps up the Fight; The Danish Adjutant General Finally Appears and an Armistice is Agreed Upon; A Characteristic Action of Lord Nelson; Death of the Emperor Paul, of Russia; Second Attack on Copenhagen, 1807; Observations Concerning England’s Conduct; A Powerful English Fleet Appears in the Sound; The Crown Prince Rejects England’s Humiliating Proposals; Copenhagen Bombarded and Set on Fire; Final Surrender; Plunder by the English. | I-331 |

| TRAFALGAR. OCTOBER 21ST, A. D. 1805. | |

| Napoleon’s Grand Schemes; Nelson in Search of the French Fleet; His Extensive Cruise; Napoleon’s Orders to His Admiral, Villeneuve; The English Discover the French and Spanish Fleets at Cadiz; Nelson’s Order of Battle a Master-piece of Naval Strategy; Strength of the English Fleet; Villeneuve Ordered to Sea; Strength of the Combined French and Spanish Fleets; The Hostile Forces Meet at Cape Trafalgar; The Battle; One of the Most Destructive Naval Engagements Ever Fought; The French Account of It; The Allied Fleet Almost Annihilated; Nelson Mortally Wounded; Further Particulars of the Battle; Estimate of Nelson’s Character; Honors to His Memory. | I-352 |

| LORD EXMOUTH AT ALGIERS. A.D. 1816. | |

| Biographical Sketch of Lord Exmouth; Atrocities of the Algerines Prompt the English to Send a Fleet, Under Lord Exmouth, Against Them; A Dutch Fleet Joins Them at Gibraltar; Strength of the Combined Fleet; Fruitless Negotiations with the Algerines; Strength of their Fortifications; The Allied Fleets Open Fire on the Forts and City; A Tremendous Cannonade; The Dey Comes to Terms; Capture of the Place by the French, Fourteen Years Later. | I-397 |

| NAVARINO. A. D. 1827. | |

| Assembly of the Allied English, French and Russian Fleets in the Mediterranean; Their Object; An Egyptian Fleet, with Troops, enters Navarino Harbor; History and Geographical Position of the Latter; Strength of the Opposing Fleets; Treachery of the Egyptians; The Battle Opens; Desperate Fighting; Bad Gunnery of the Turks; Destruction of Their Fleet. | I-407 |

| SINOPE. A. D. 1853. | |

| History of Sinope; An Abuse of Superior Force on the Part of the Russians; They Encounter the Turkish Fleet in Sinope Harbor and Demand the Latter’s Surrender; They Decline and the Battle Opens Furiously; The Turkish Fleet Totally Destroyed and That of the Russians rendered Comparatively Useless; Appearance of the Town of Sinope. | I-417 |

| LISSA. A. D. 1866. | |

| Position of the Island of Lissa; Its History; Attacked and Taken by the Italians; The Austrians Shortly After Come to its Relief; A Great Naval Battle Takes Place; Strength of the Opposing Fleets; The Ironclads That Took Part; Bad Management of the Italians Under Admiral Persano; They are Badly Beaten; Sketch of the Italian Admiral; His Court-Martial; William Baron Tegethoff, the Austrian Commander. | I-420 |

| SOME NAVAL ACTIONS BETWEEN BRAZIL, THE ARGENTINE CONFEDERATION AND PARAGUAY. A. D. 1865-68.[I-XV] | |

| Origin of the Long and Deadly Struggle; The Brazilian Fleet Starts Out on a Cruise; Lopez, Dictator of Paraguay, Determines to Capture this Fleet; His Preparations; The Hostile Fleets Encounter each other; Details of the Fight; Bad Management on both sides; The Paraguayans Forced to Retire; Another Battle in March, 1866, on the Parana River; Full Account of the Desultory Fighting; The Paraguayans Driven Out of their Earthworks; Two Unsuccessful Attacks, in 1868, on the Brazilian Monitors lying off Tayi; Interesting Account of one of these Attacks. | I-429 |

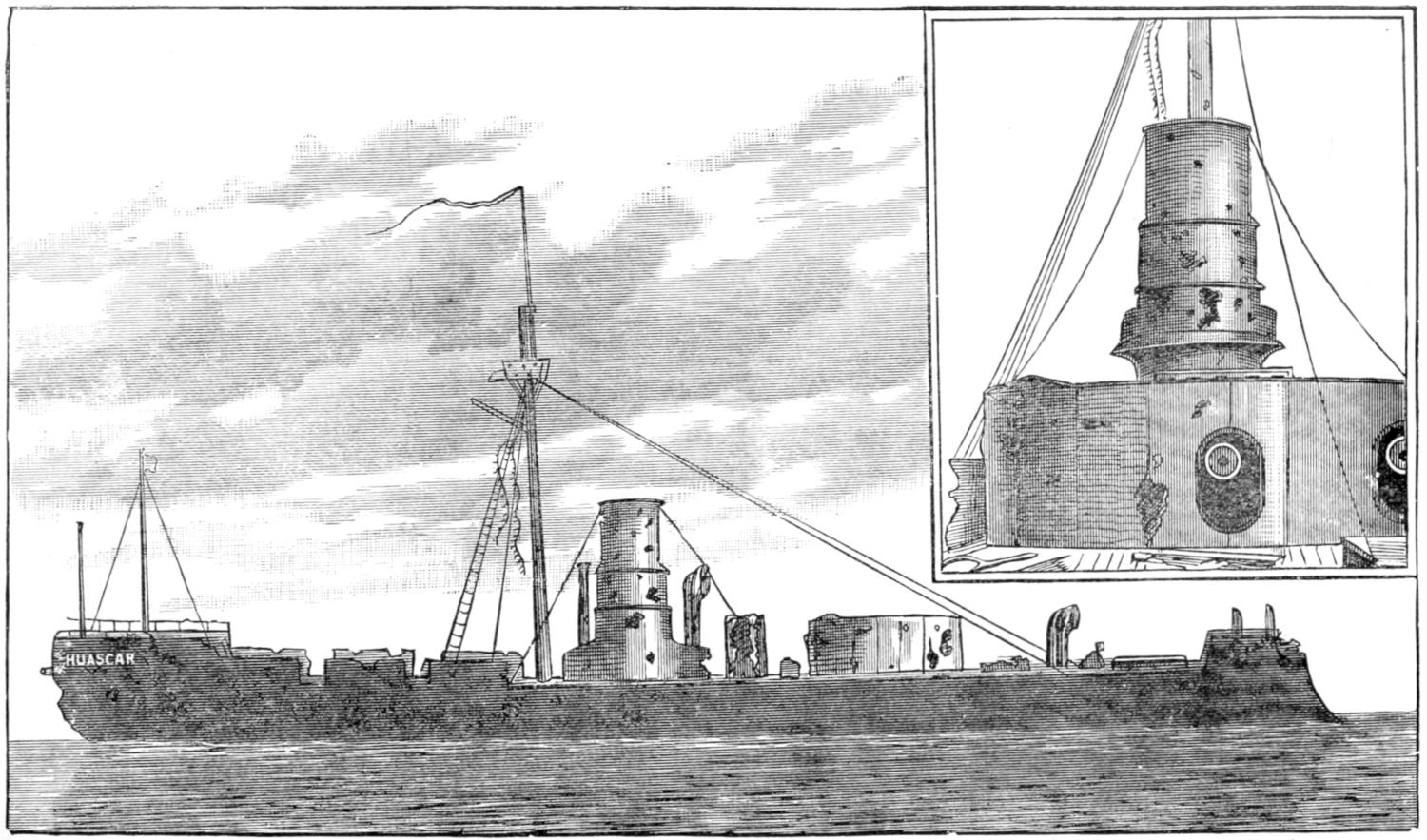

| THE CAPTURE OF THE HUASCAR. OCTOBER 8TH, A. D. 1879. | |

| Description of the Huascar; Her Earlier Exploits; Strength of the Chilian Squadron; The Latter Seek the Huascar; The Enemies Recognize each other; The Battle Begins at Long Range; Full Details of this Spirited Engagement; Terrible Loss of Life on Board the Huascar; She Finally Surrenders; Condition of the Chilian Fleet. | I-445 |

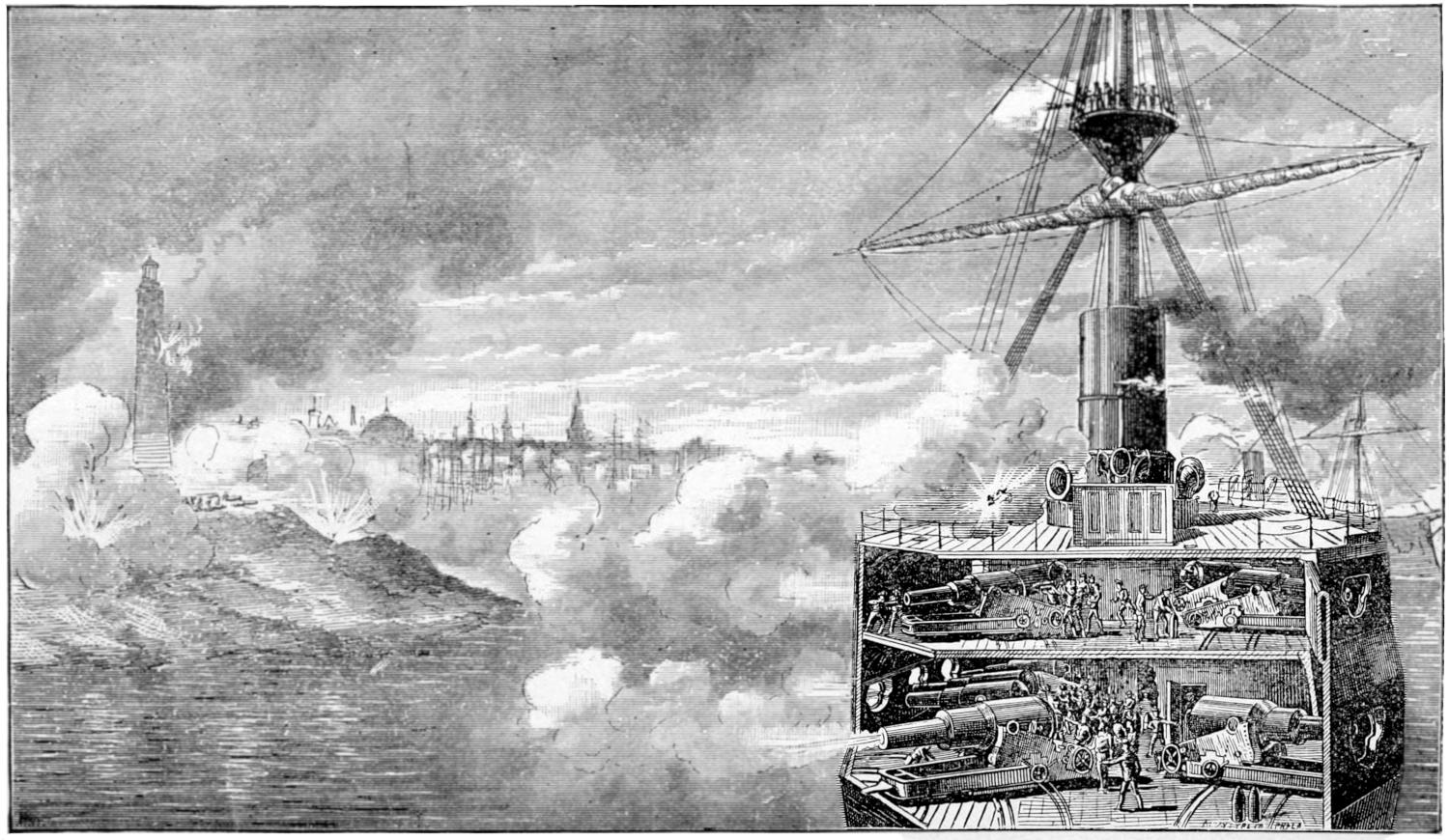

| BOMBARDMENT OF ALEXANDRIA. JULY 11TH, A. D. 1882. | |

| Political Complications; Arabi Pasha; Important Events Preceding the Bombardment; England Demands that Work on the Fortifications Cease; Arabi Promises to Desist, but Renews the Work Secretly; A Powerful English Fleet Opens Fire on the Defences; Silenced by the Fleet and Abandoned; Alexandria Set on Fire and Pillaged; Sailors and Marines from the American and German Fleets Landed to Protect the Consulates; Injury Sustained by the English Fleet. | I-458 |

| THE WAR BETWEEN CHINA AND JAPAN. | |

| The Opening of Japan to Foreign Nations; Japanese Geography and History; Early Explorers; Revolution of 1617; First American Efforts at Intercourse; Commander Glynn’s Attempt; Successful Expedition of Commodore Perry in 1852; First Treaty Signed; Subsequent Development of Japan; Outbreak of War with China; Sinking of the Kow-Shing; Historic Hostility between the Two Nations; Disputes over Korea; The Battle of the Yalu, September 17th, 1894; Details of the Fight; Results of this Battle; Importance to Naval Experts; Conclusions Derived; Succeeding Events of the War; Capture of Port Arthur; The Japanese Emperor; New Treaty with the United States. | I-467 |

| Page | ||

|---|---|---|

| 0. | Return of the Greeks from Salamis | Frontispiece |

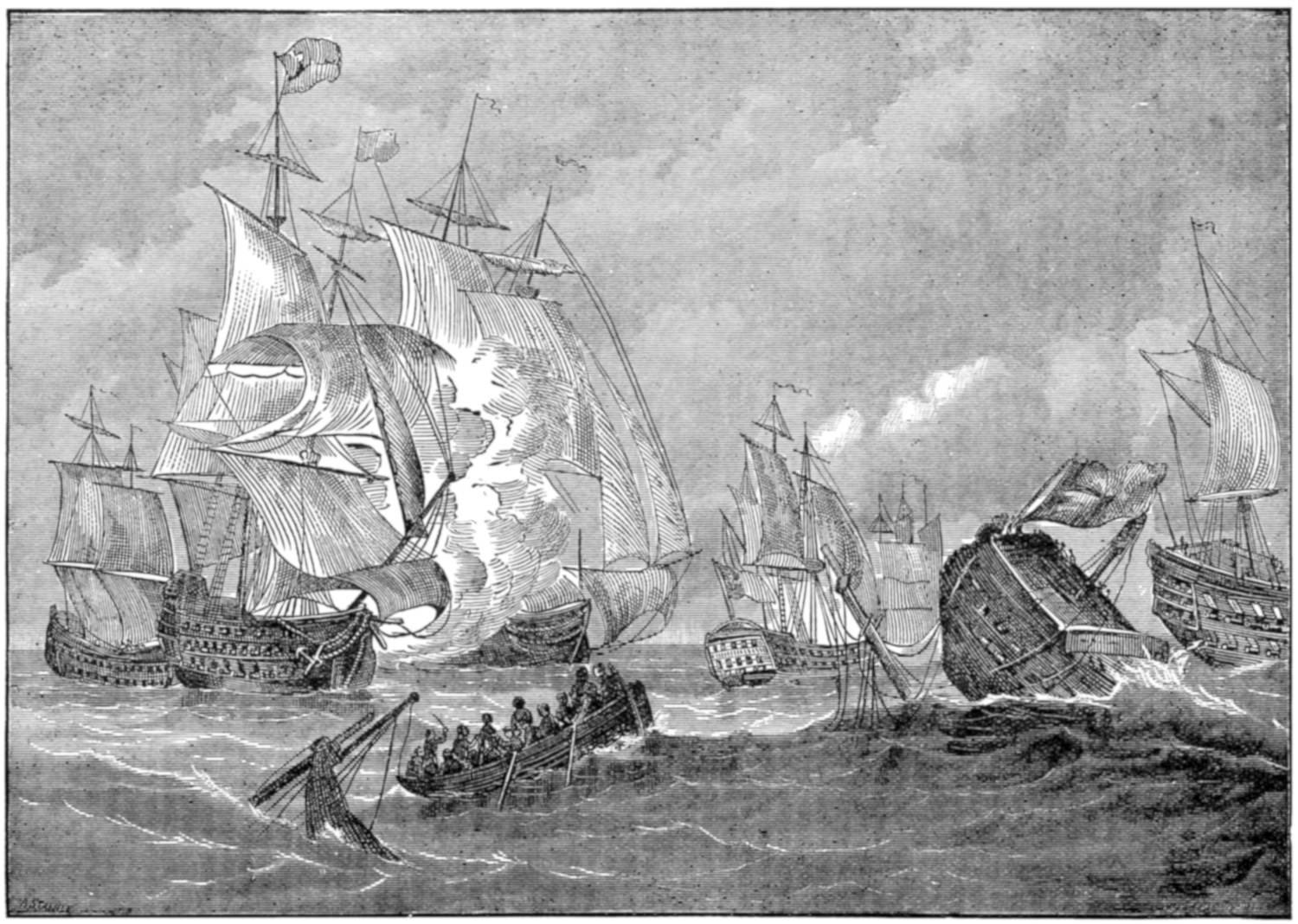

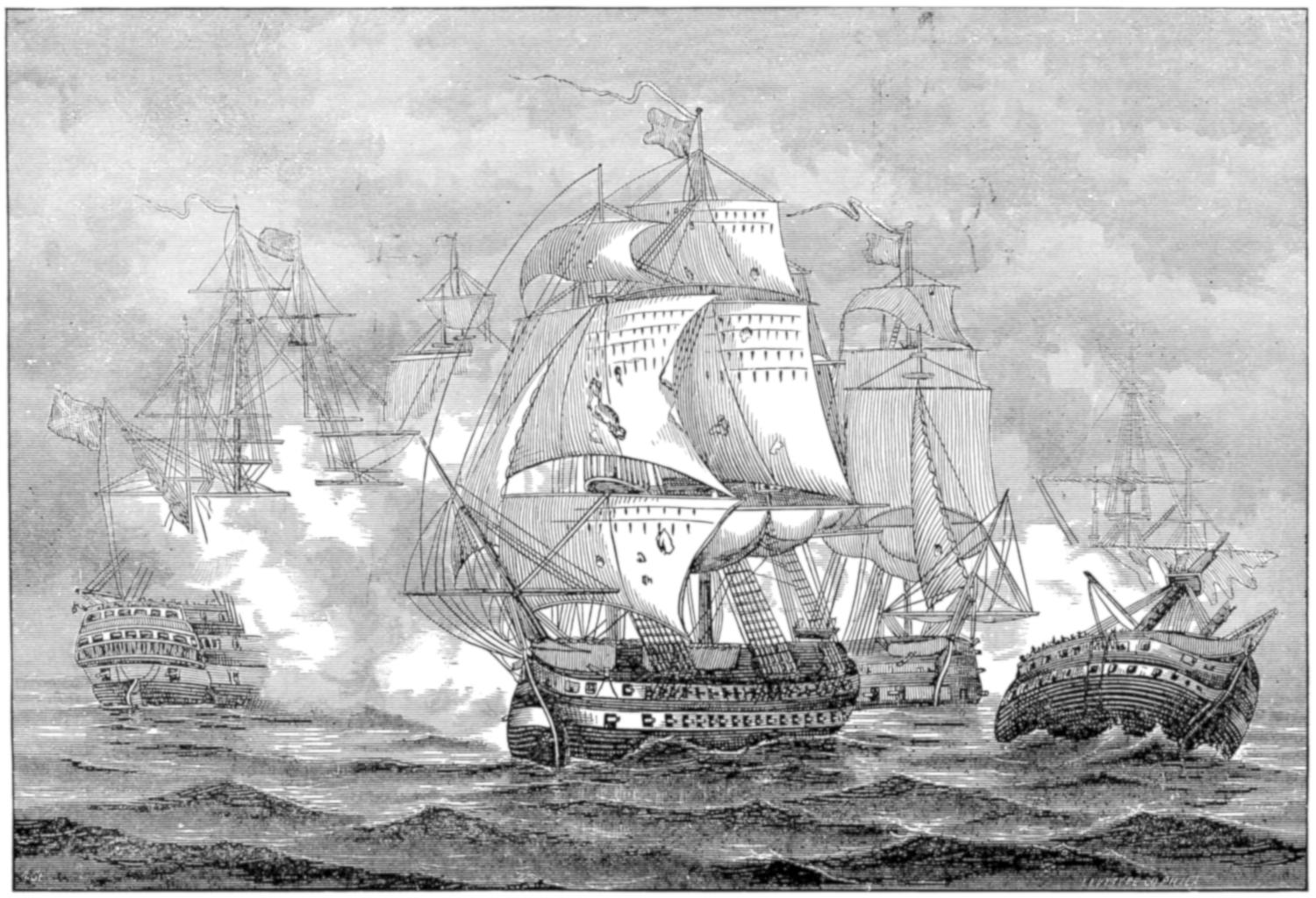

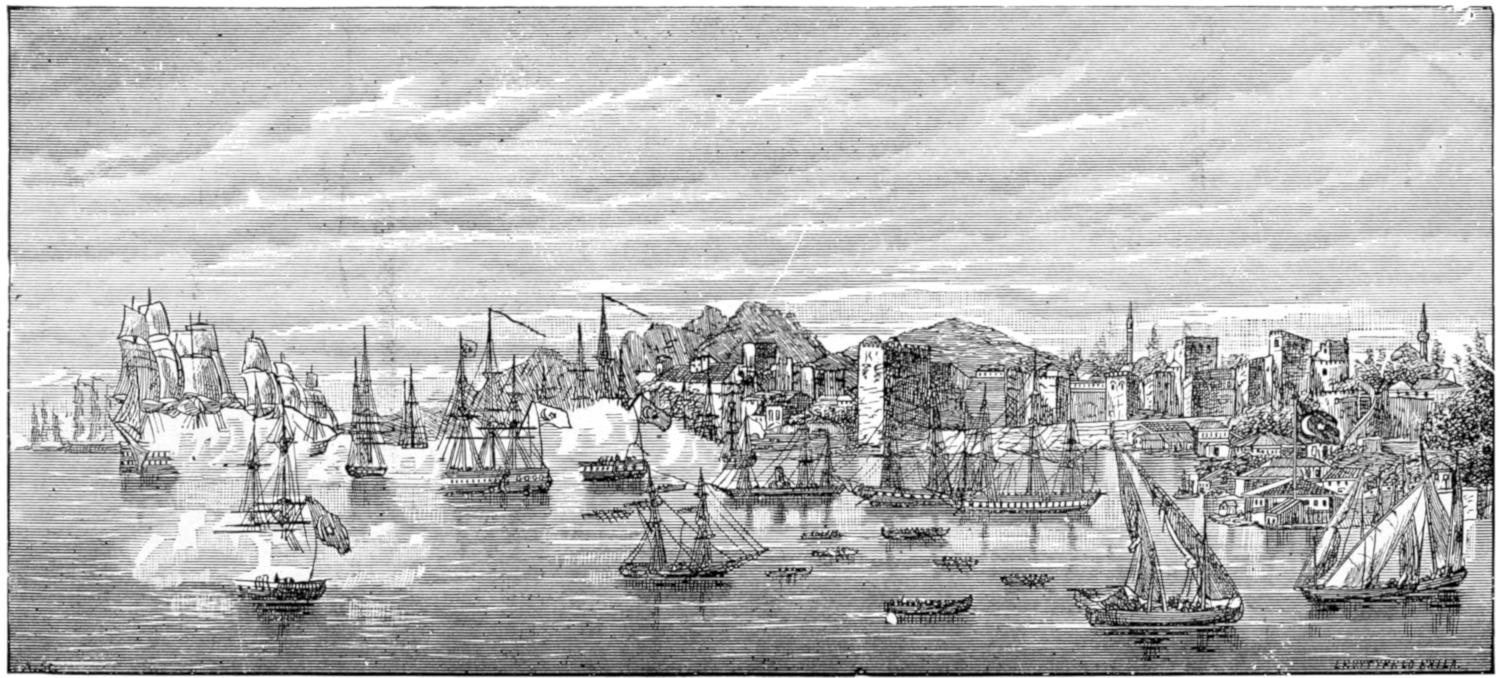

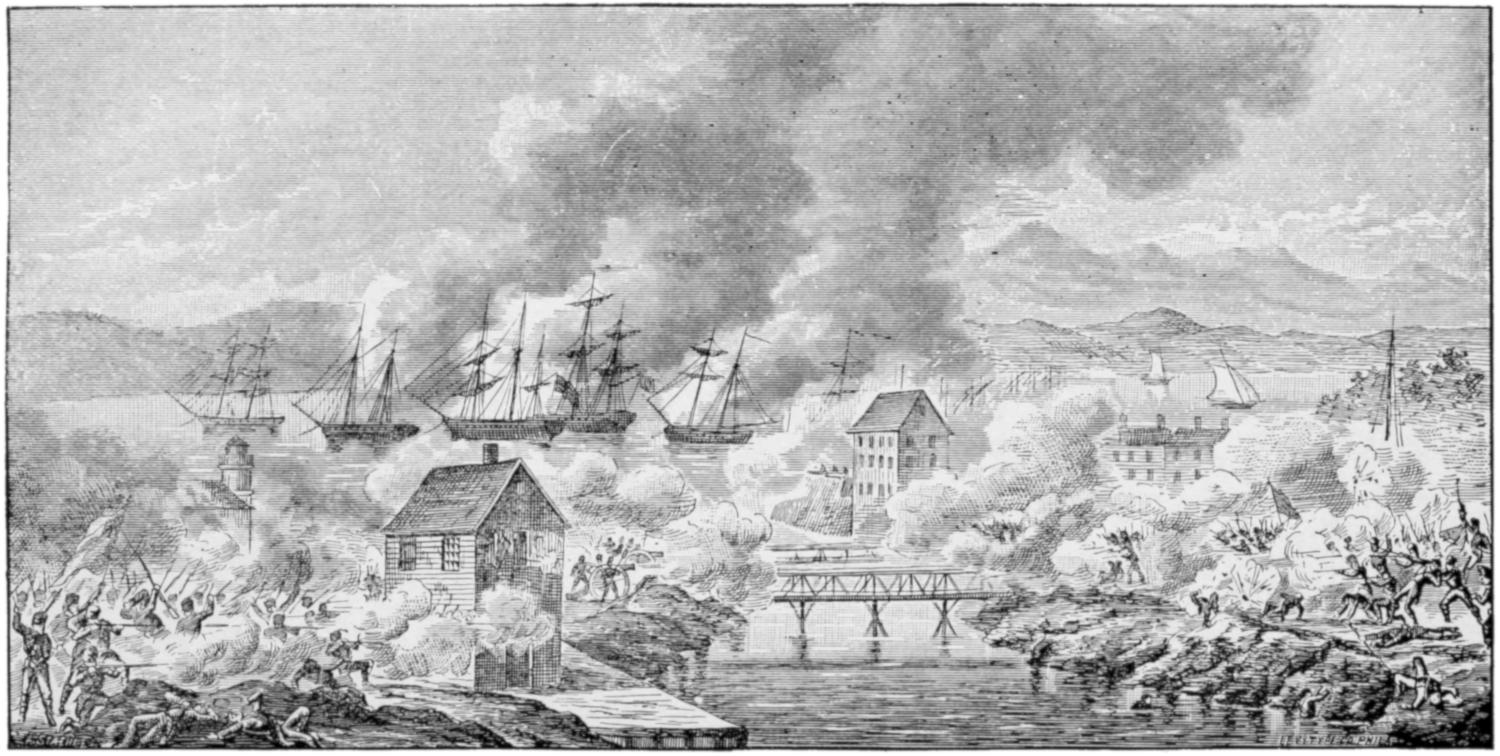

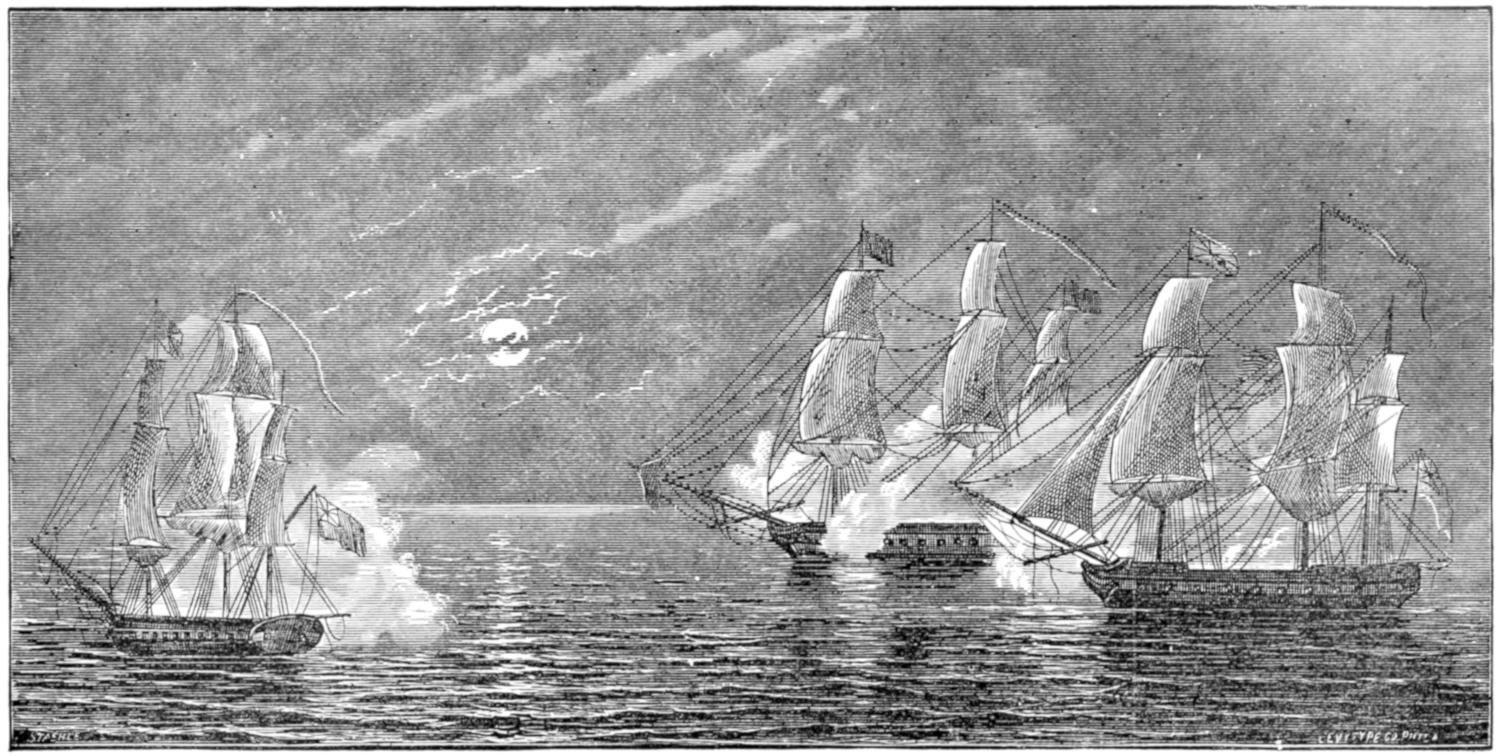

| 1. | Naval Battle, Eighteenth Century | I-20 |

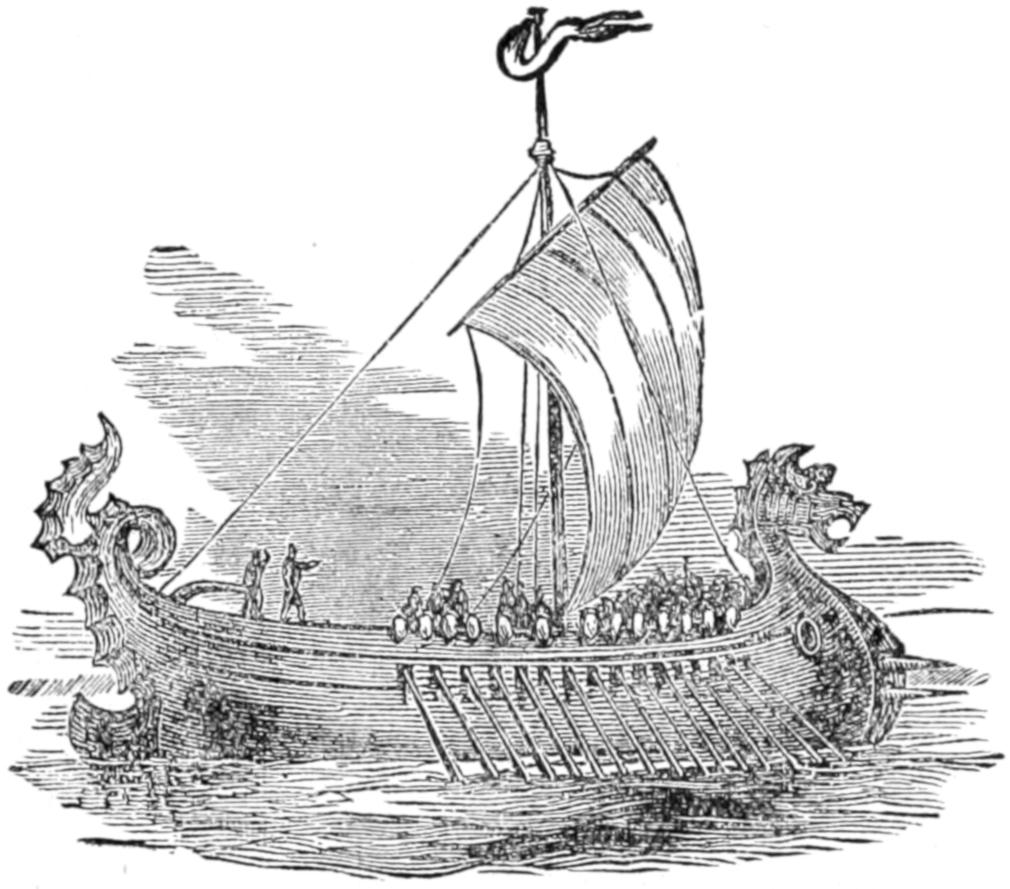

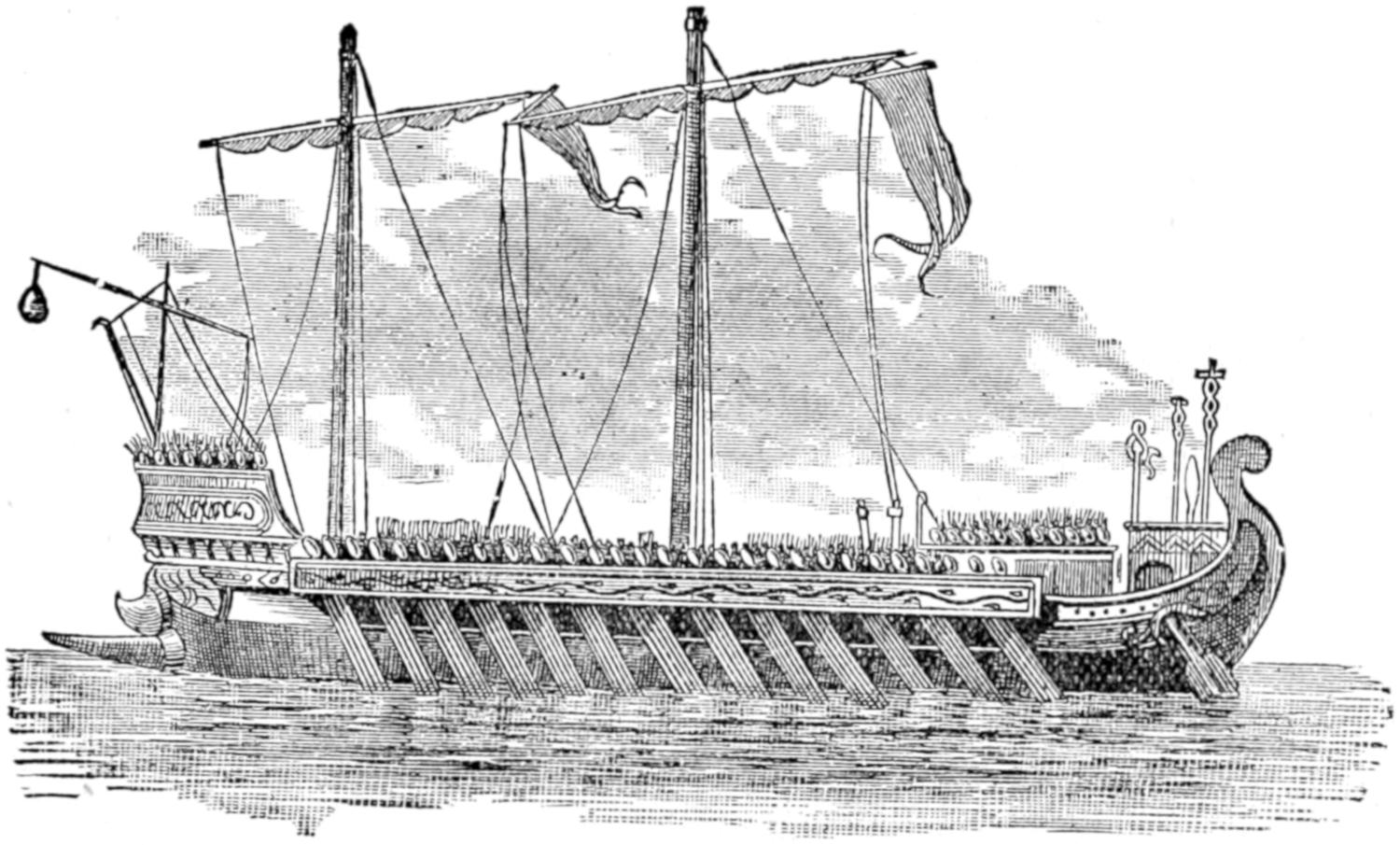

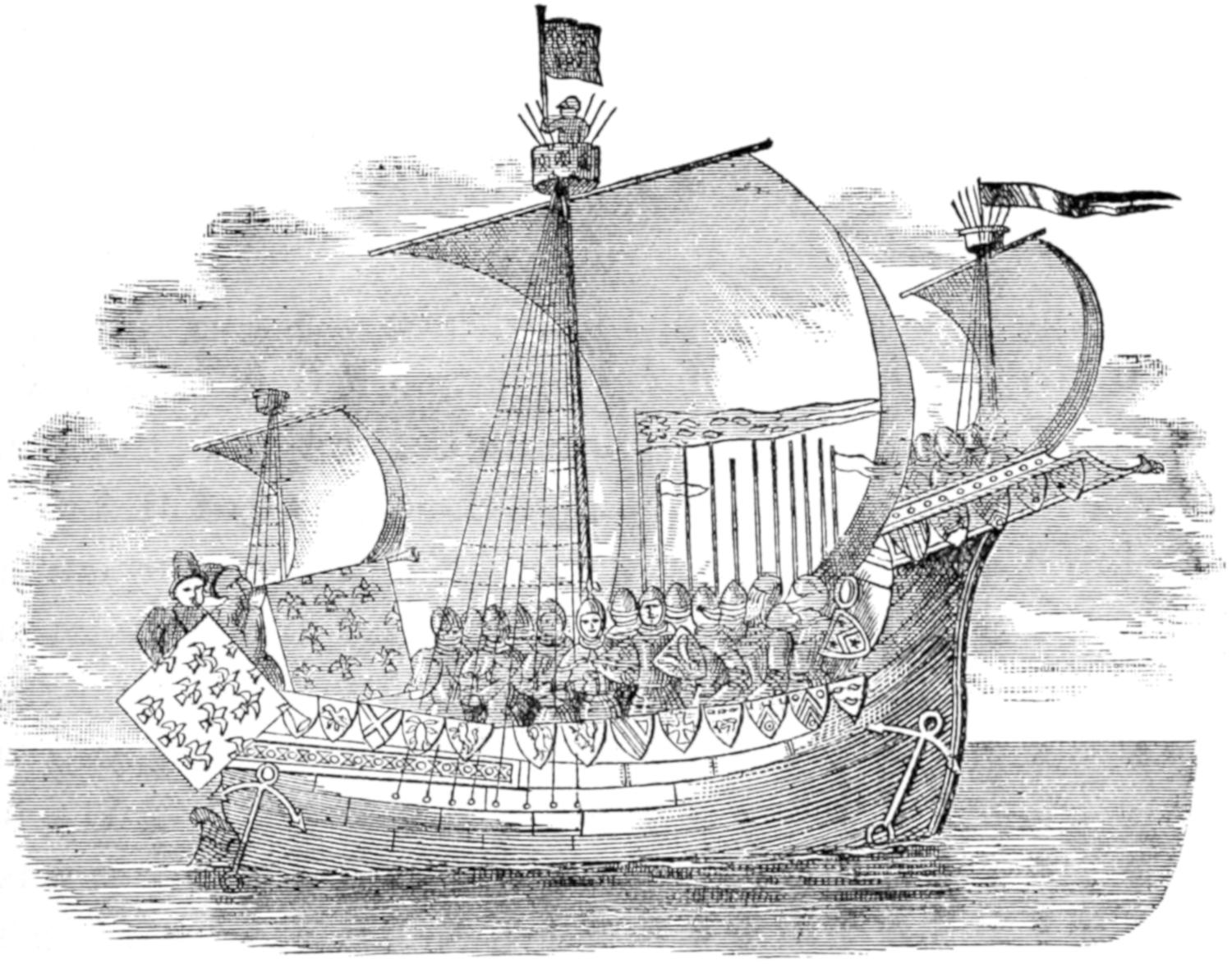

| 2. | A Norse Galley | I-35 |

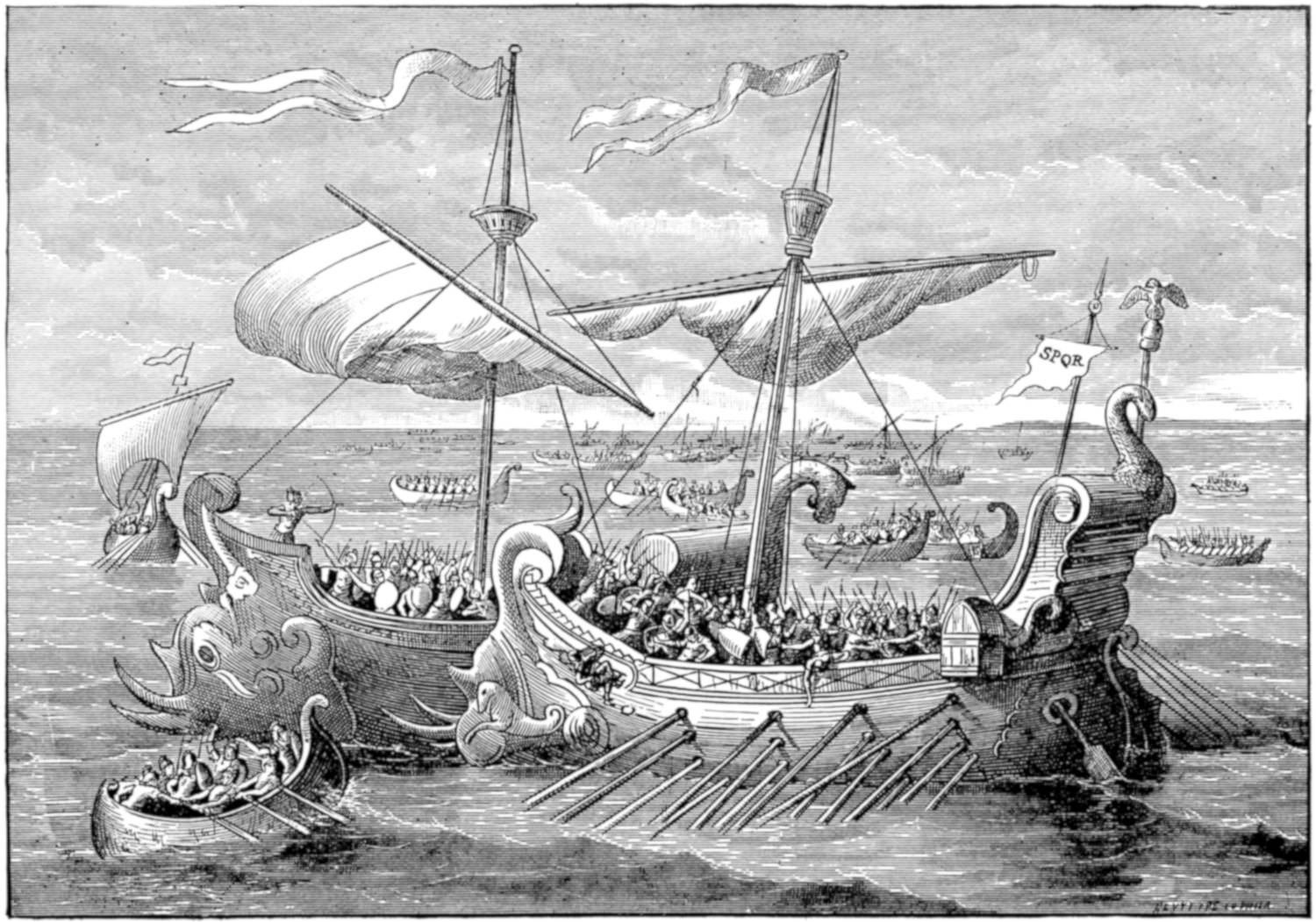

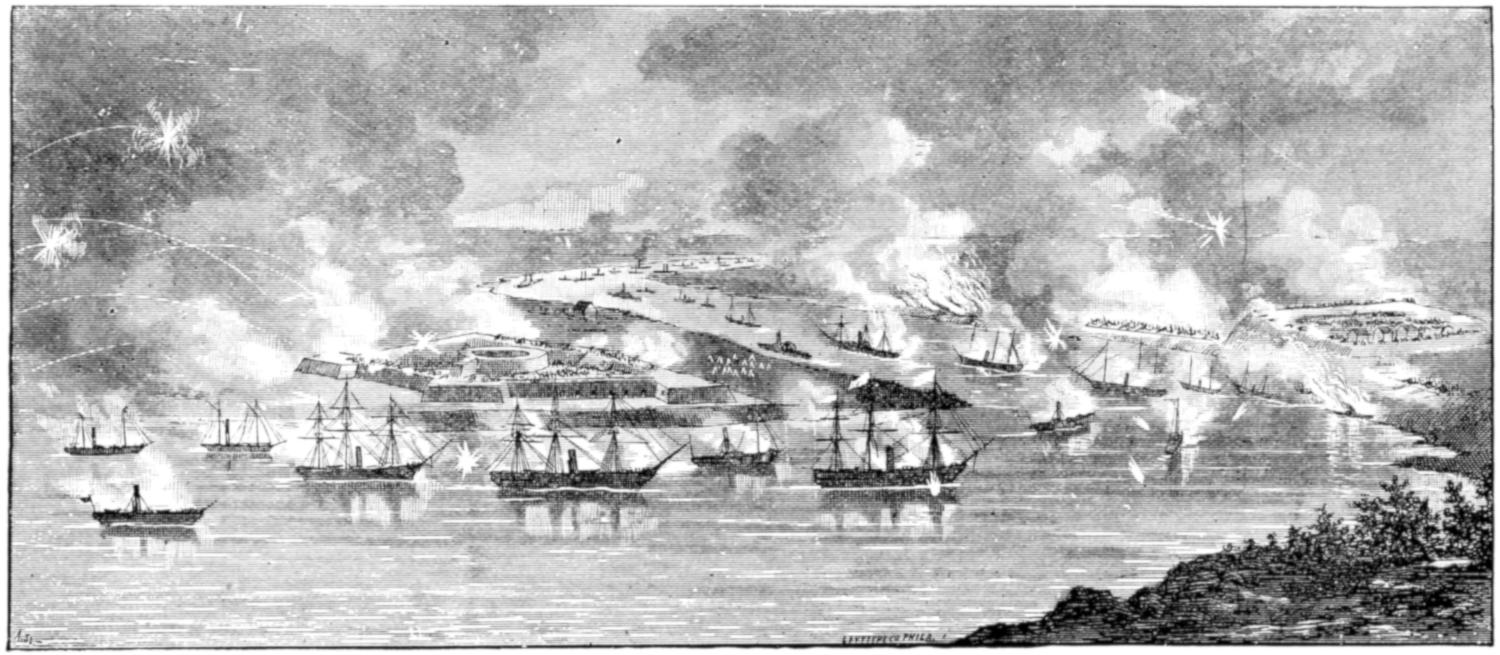

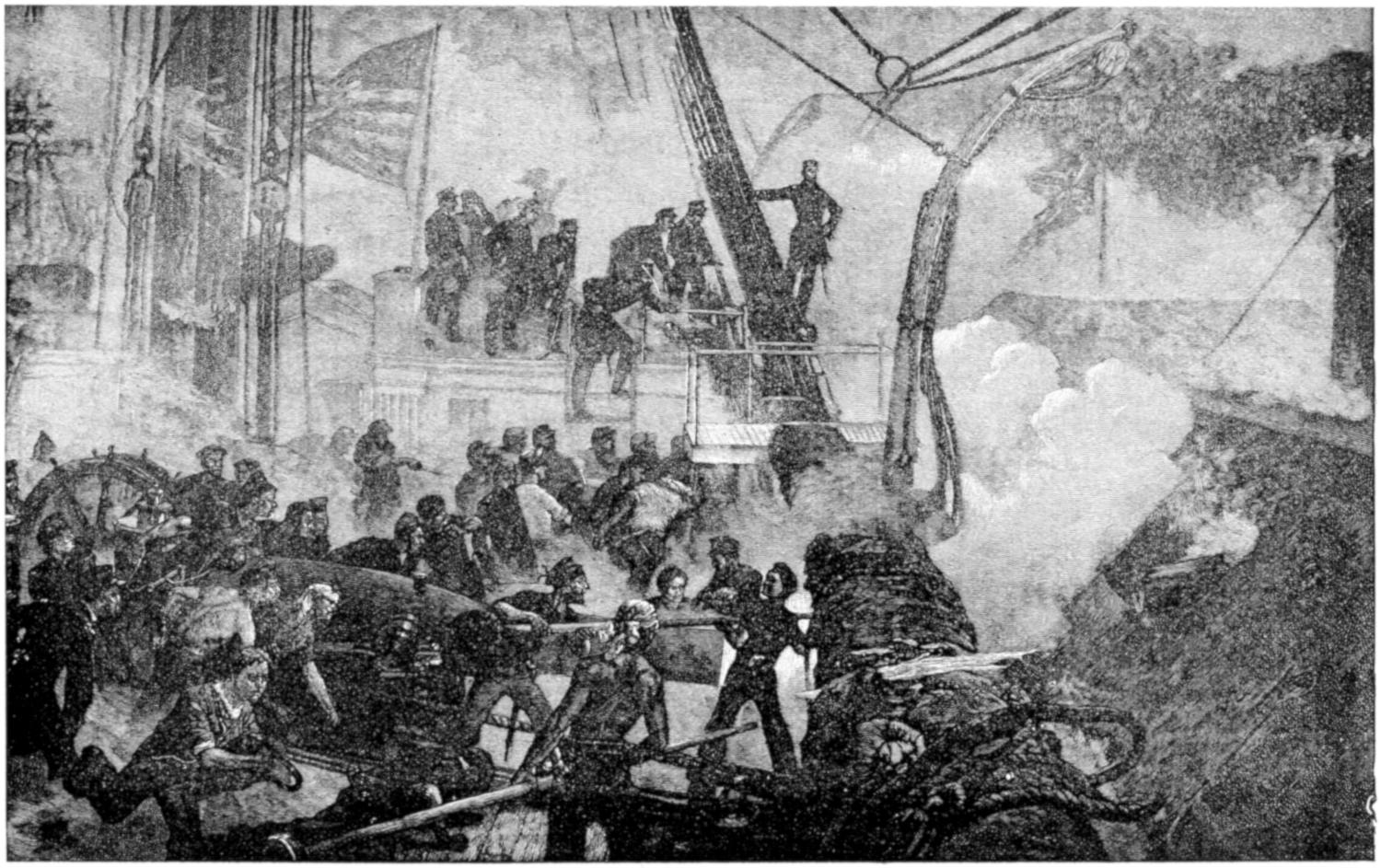

| 3. | Capture of the Carthaginian Fleet by the Romans | I-36 |

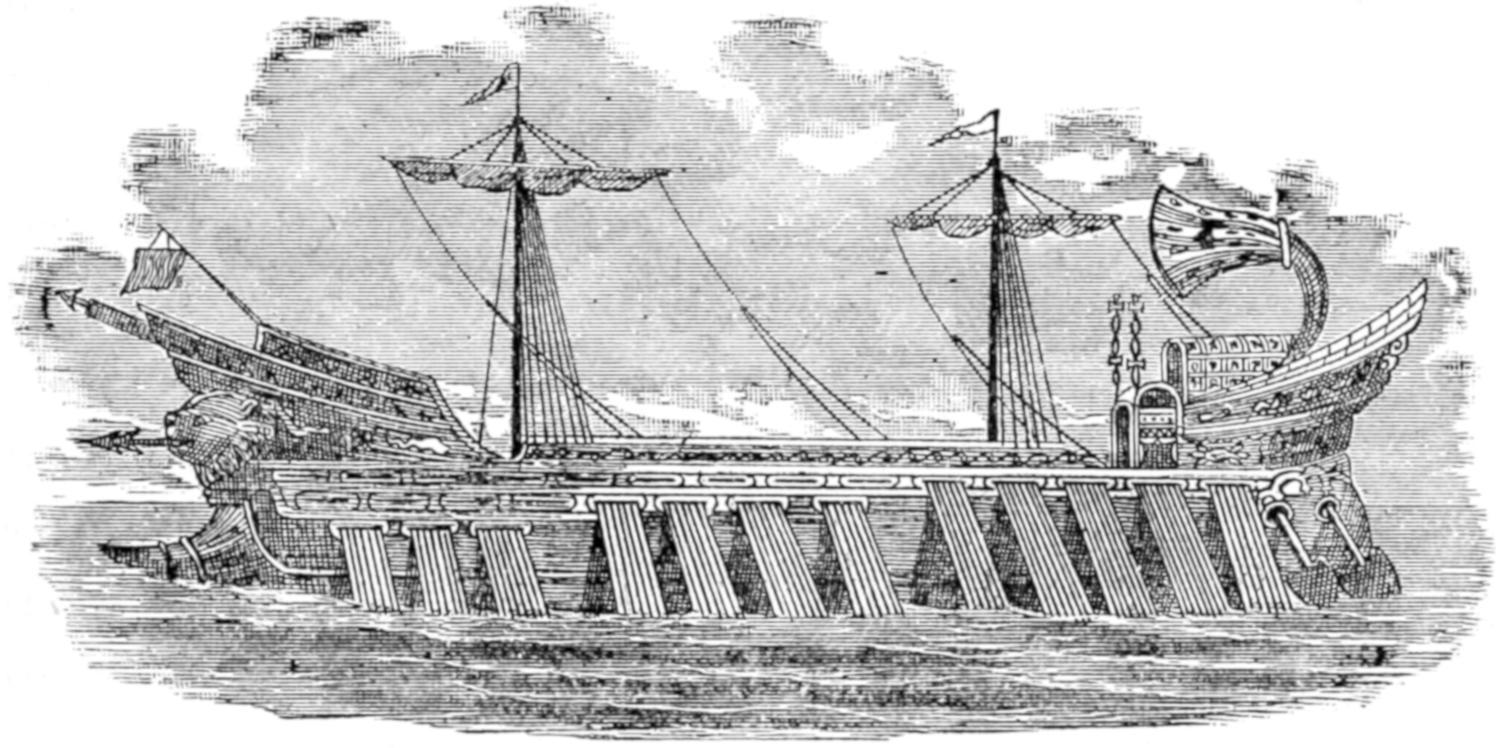

| 4. | Roman Galley | I-47 |

| 5. | Battle of Actium | I-53 |

| 6. | The Ptolemy Philopater | I-55 |

| 7. | Battle of Lepanto | I-68 |

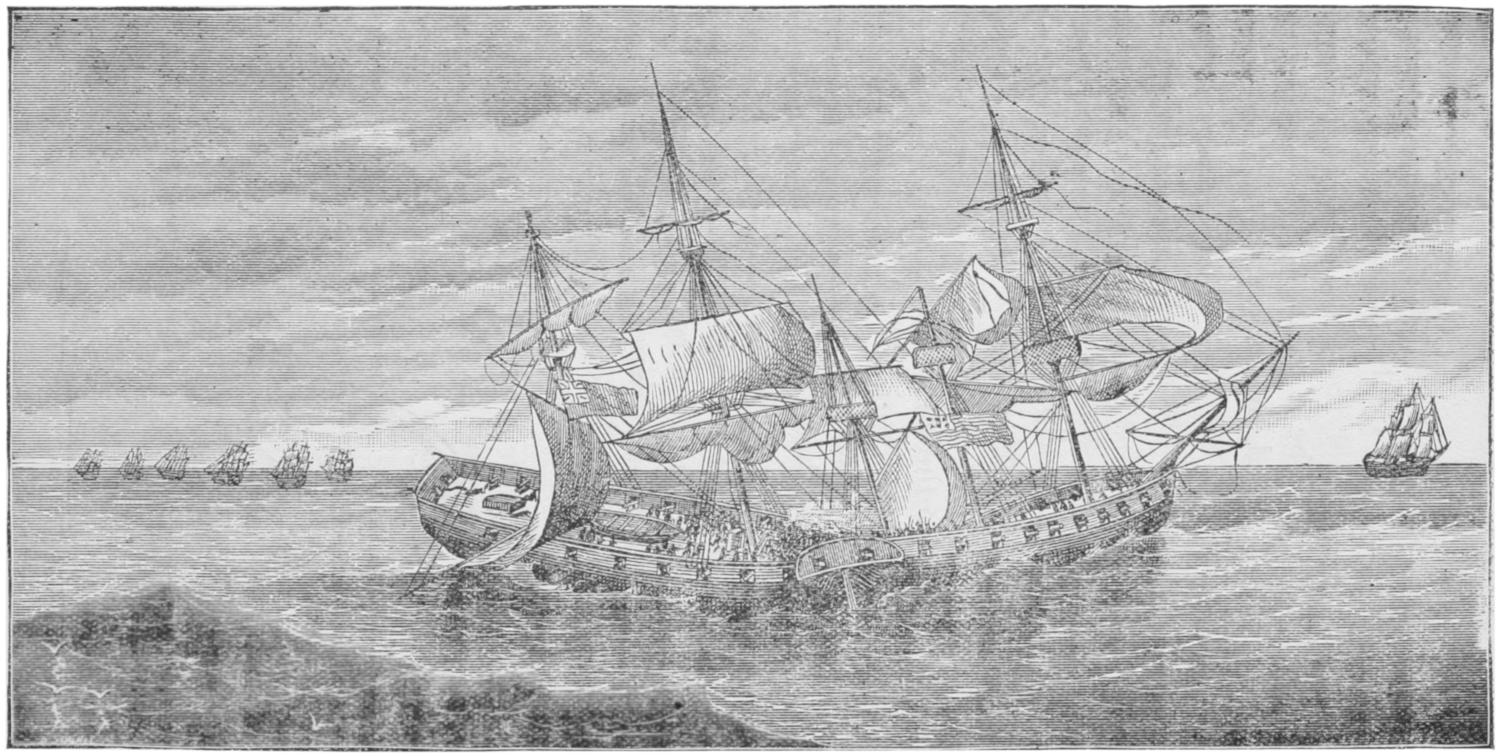

| 8. | The English Fleet following the Invincible Armada | I-85 |

| 9. | A Spanish Galeass of the Sixteenth Century | I-102 |

| 10. | Sir Francis Drake in Central America | I-103 |

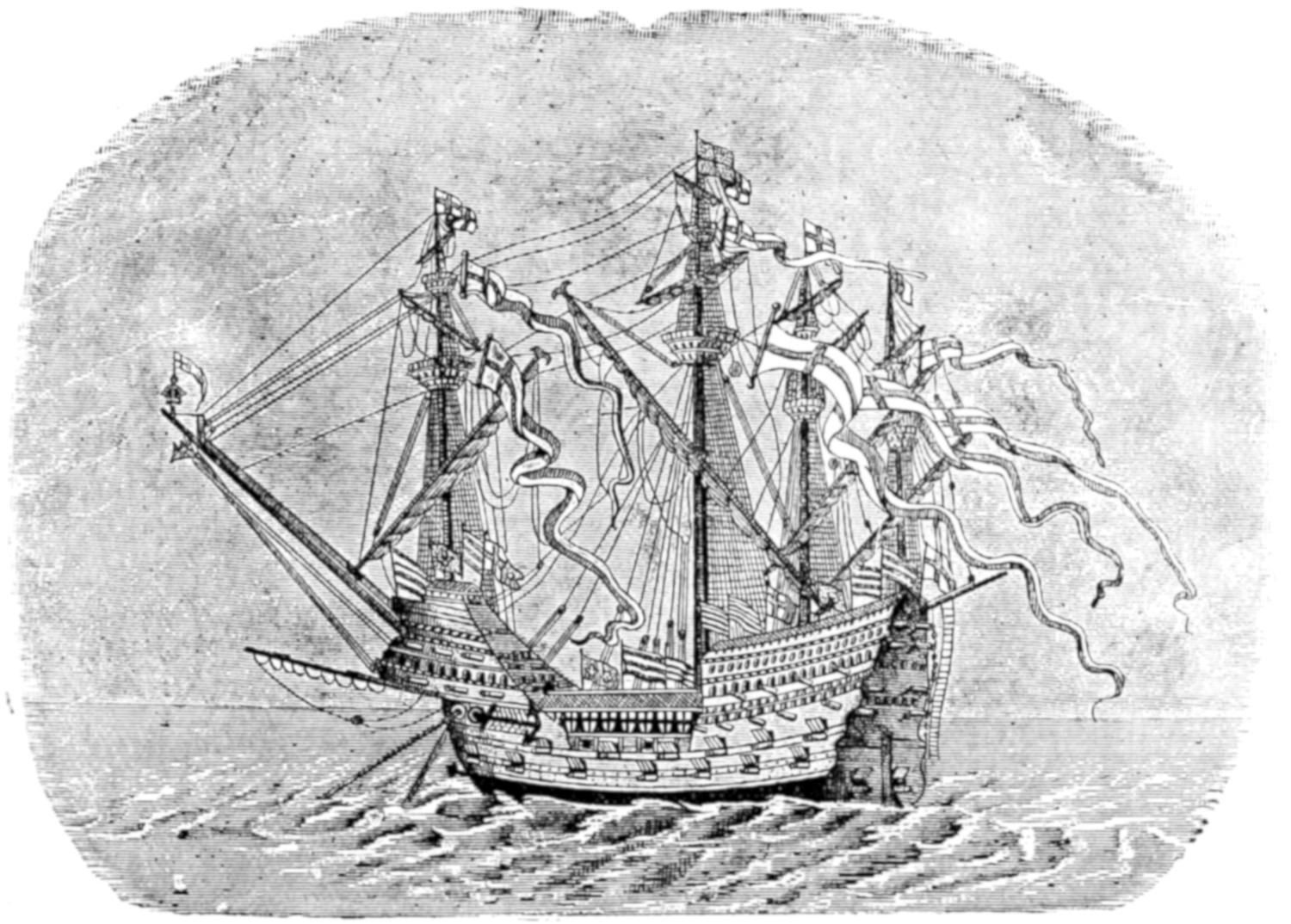

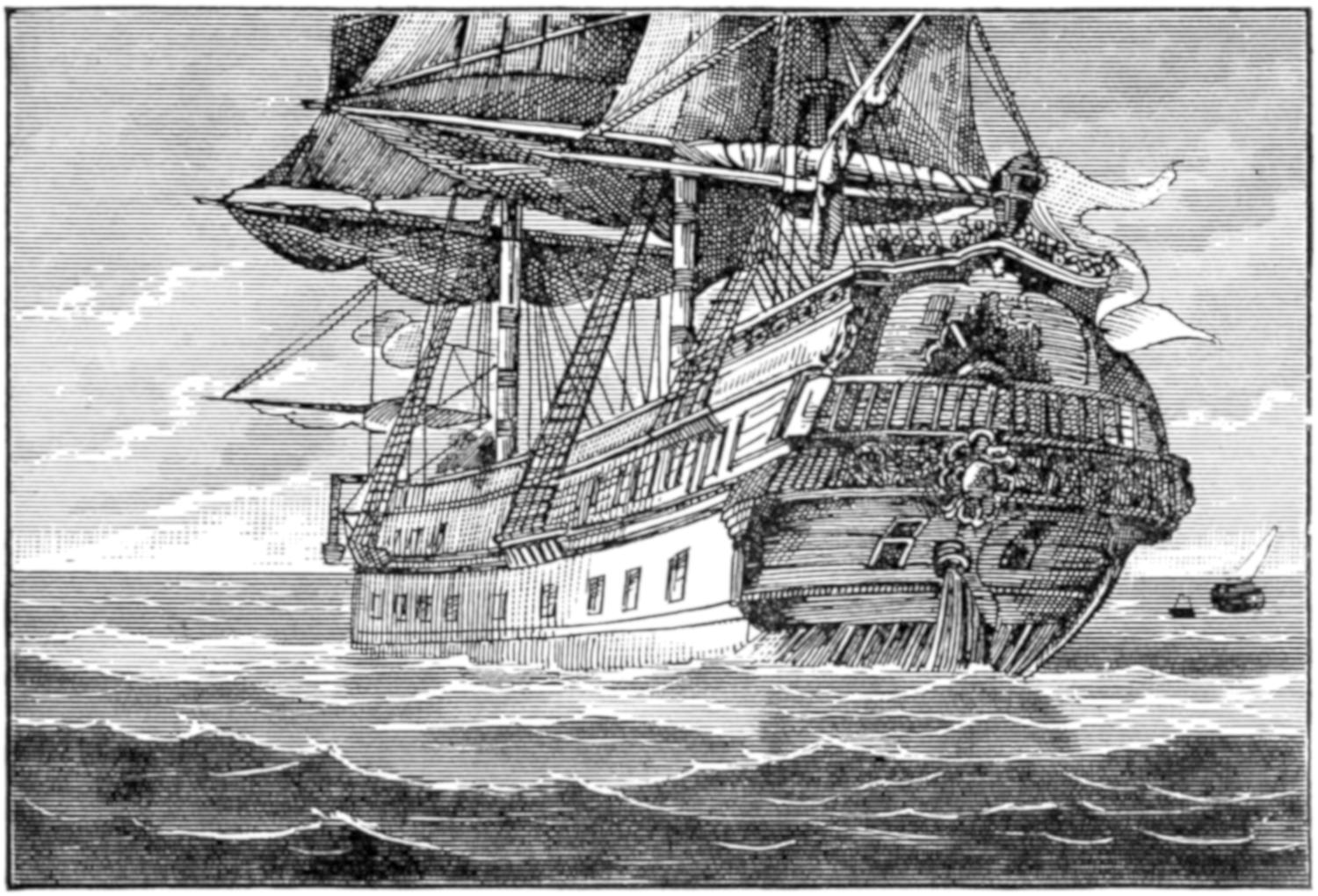

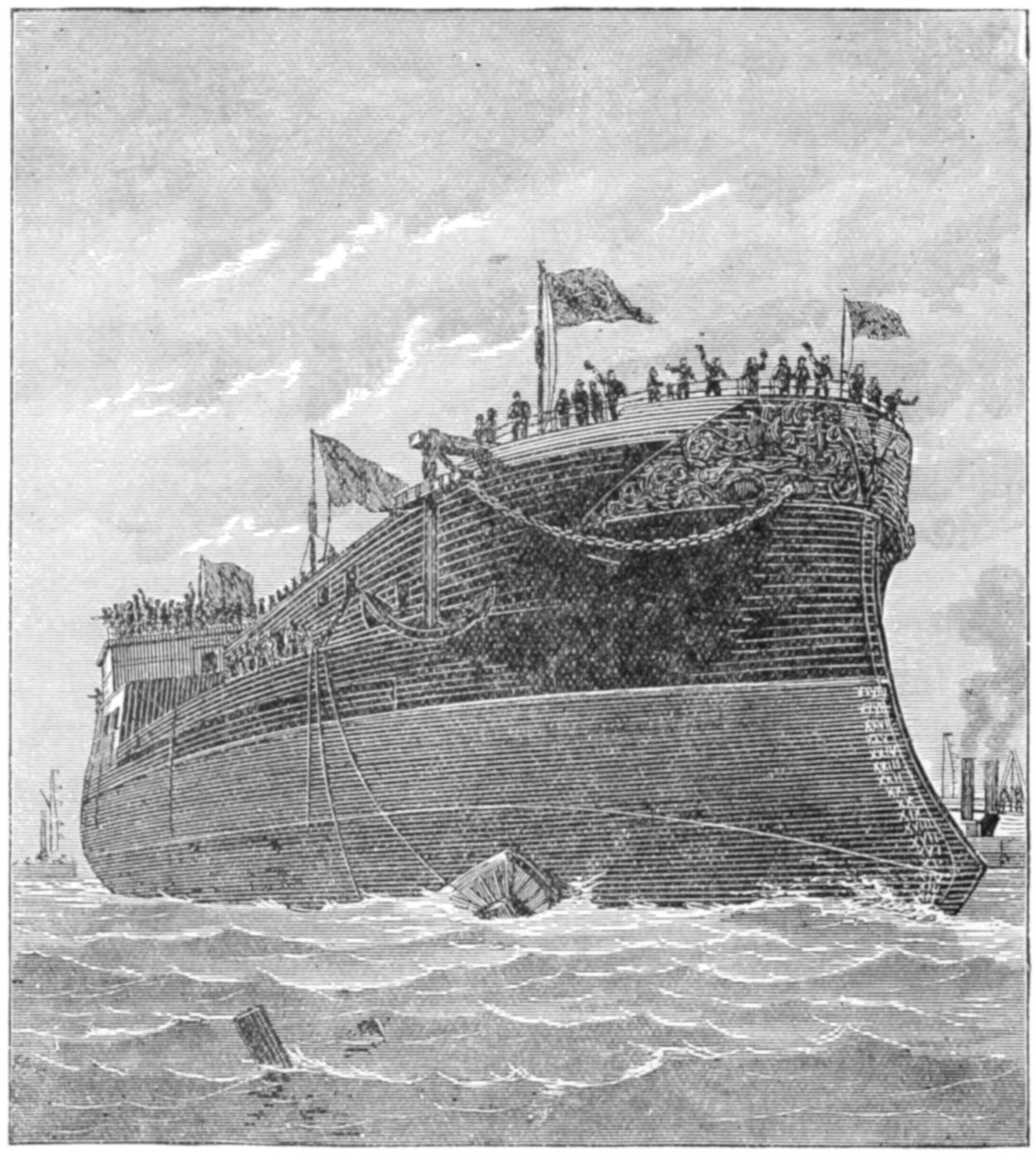

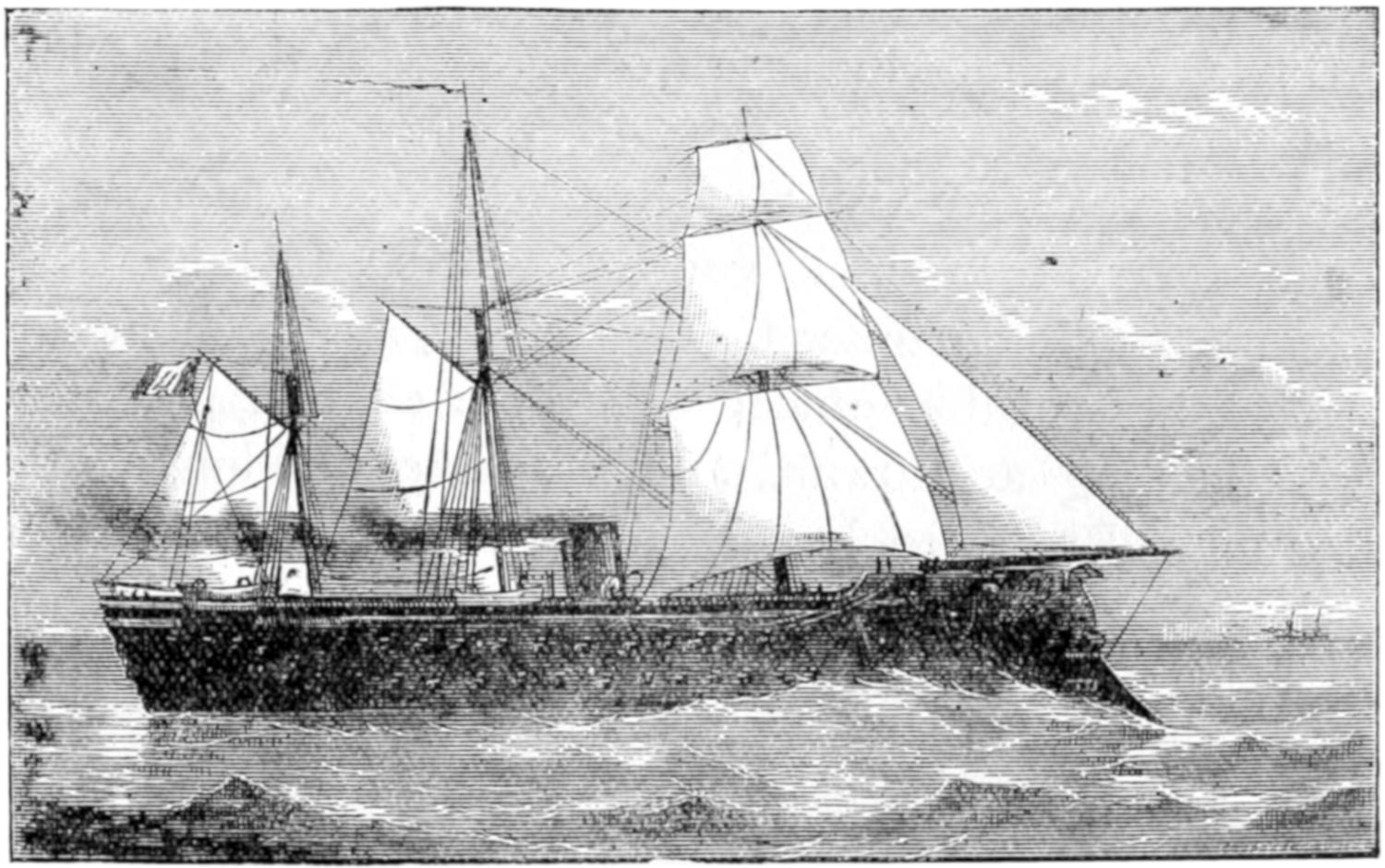

| 11. | Henry Grace DeDieu | I-111 |

| 12. | A Caravel of the time of Columbus | I-156 |

| 13. | Norman Ship of the Fourteenth Century | I-173 |

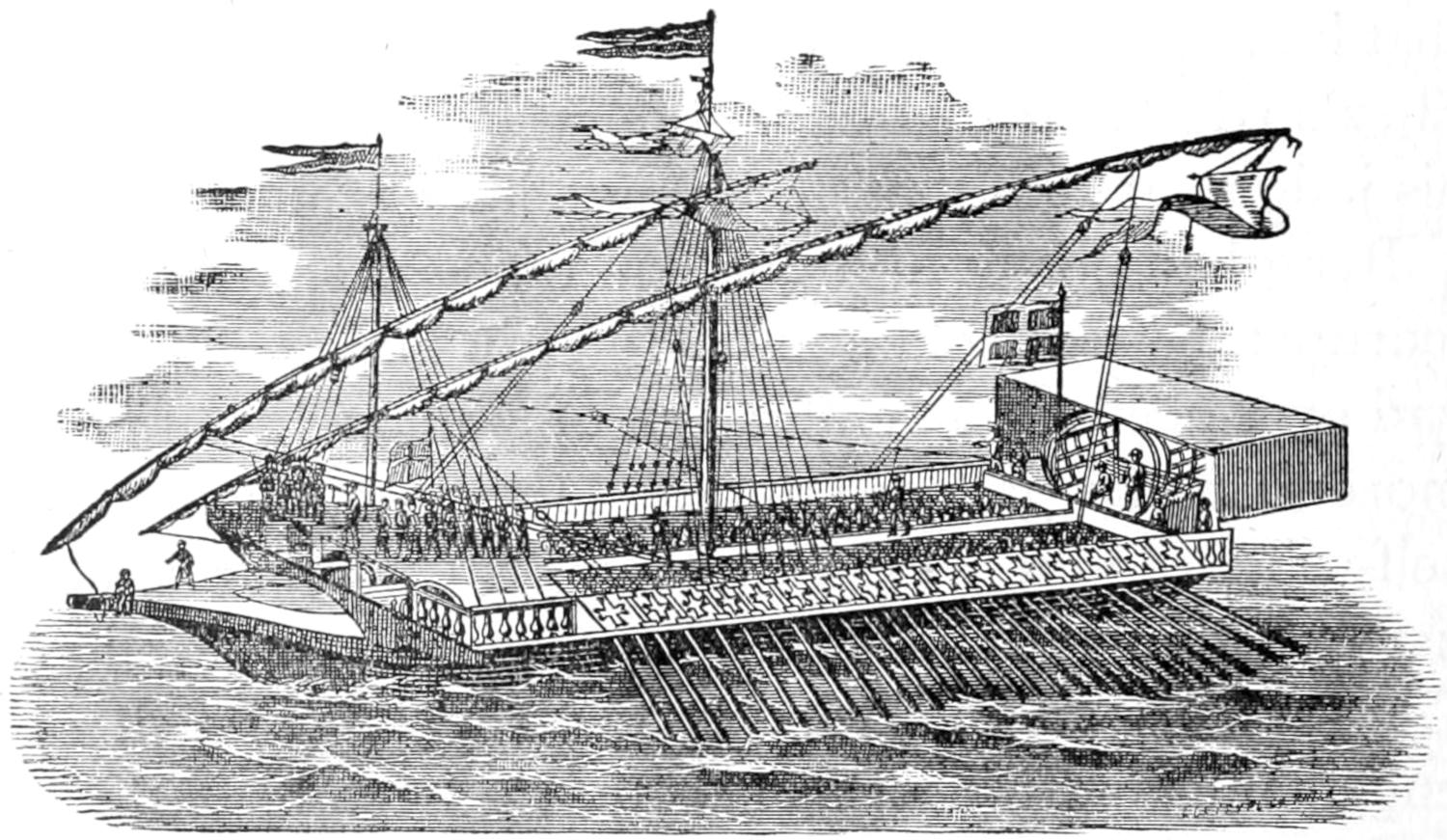

| 14. | Venetian Galley of the Sixteenth Century | I-182 |

| 15. | Bucentoro | I-186 |

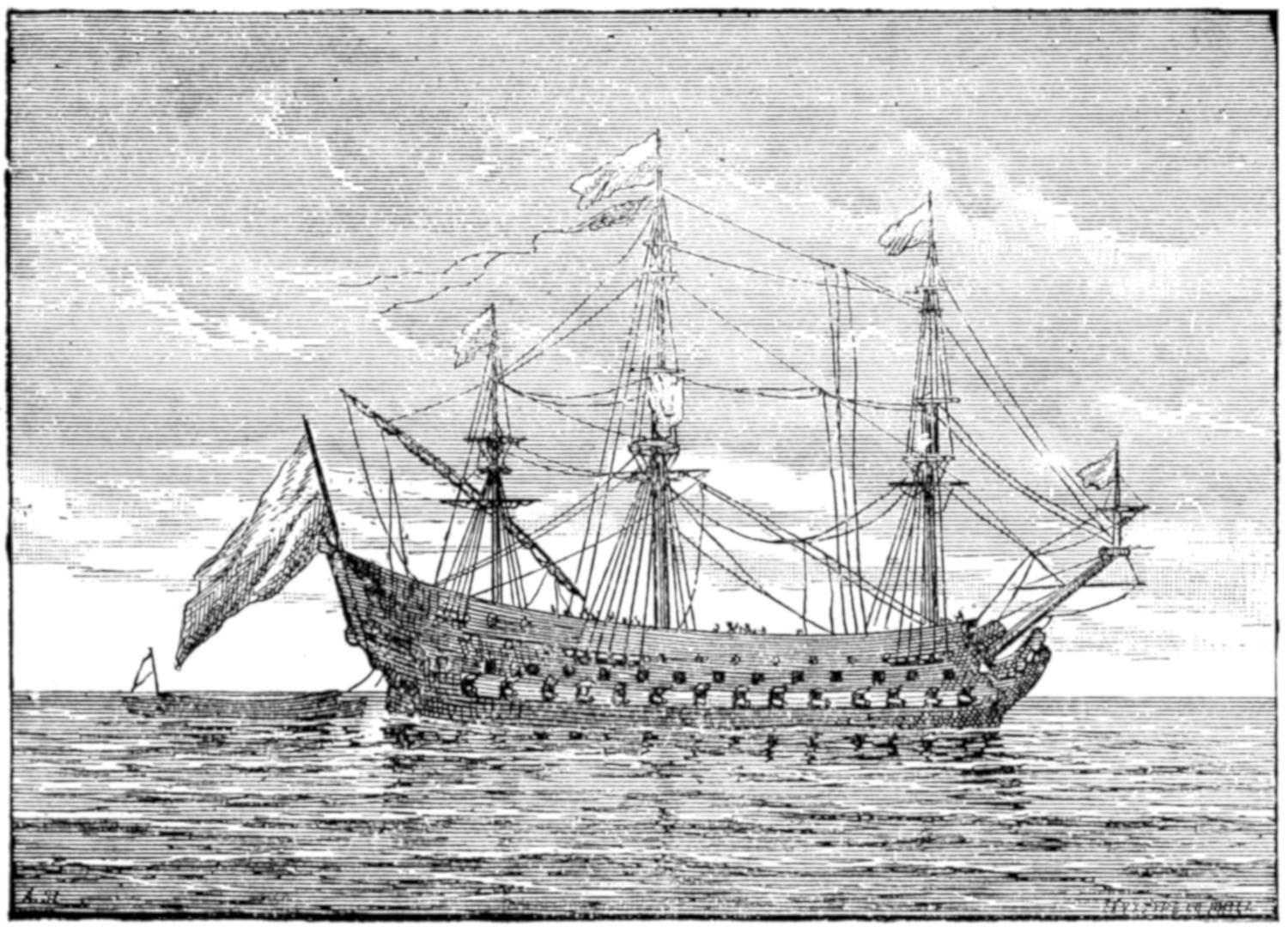

| 16. | Le Soleil Royal | I-195 |

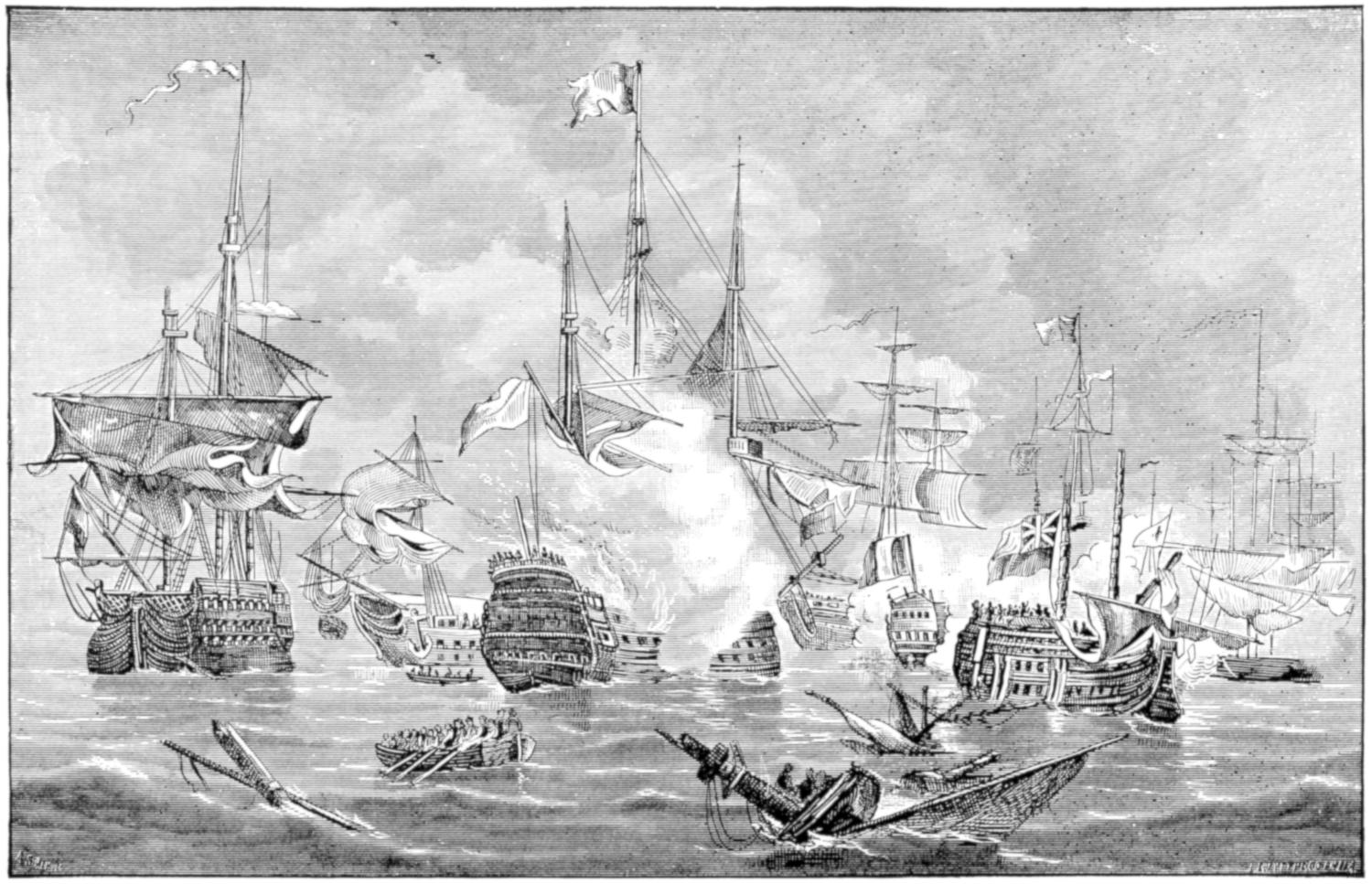

| 17. | Howe’s Action of June 1, 1794 | I-196 |

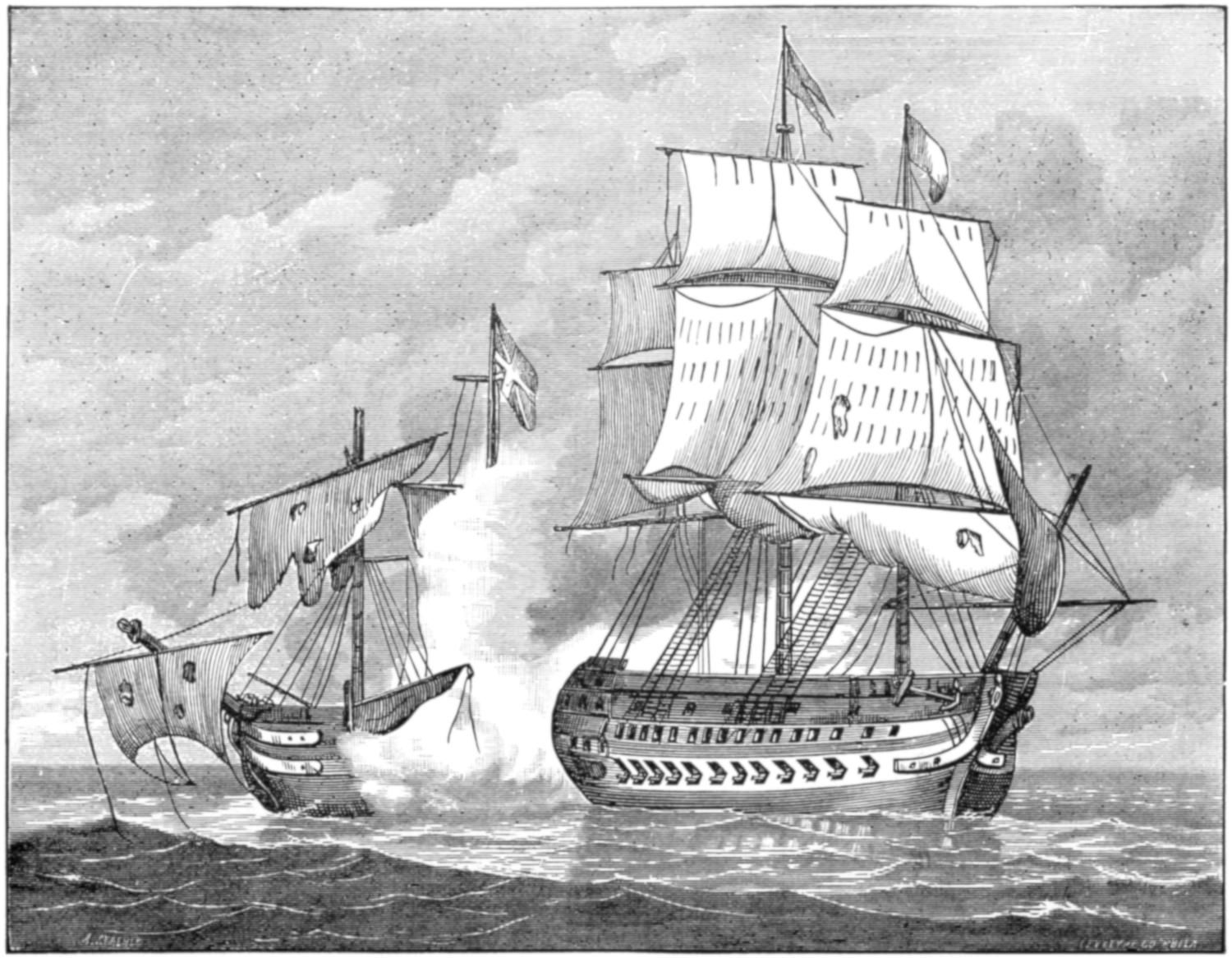

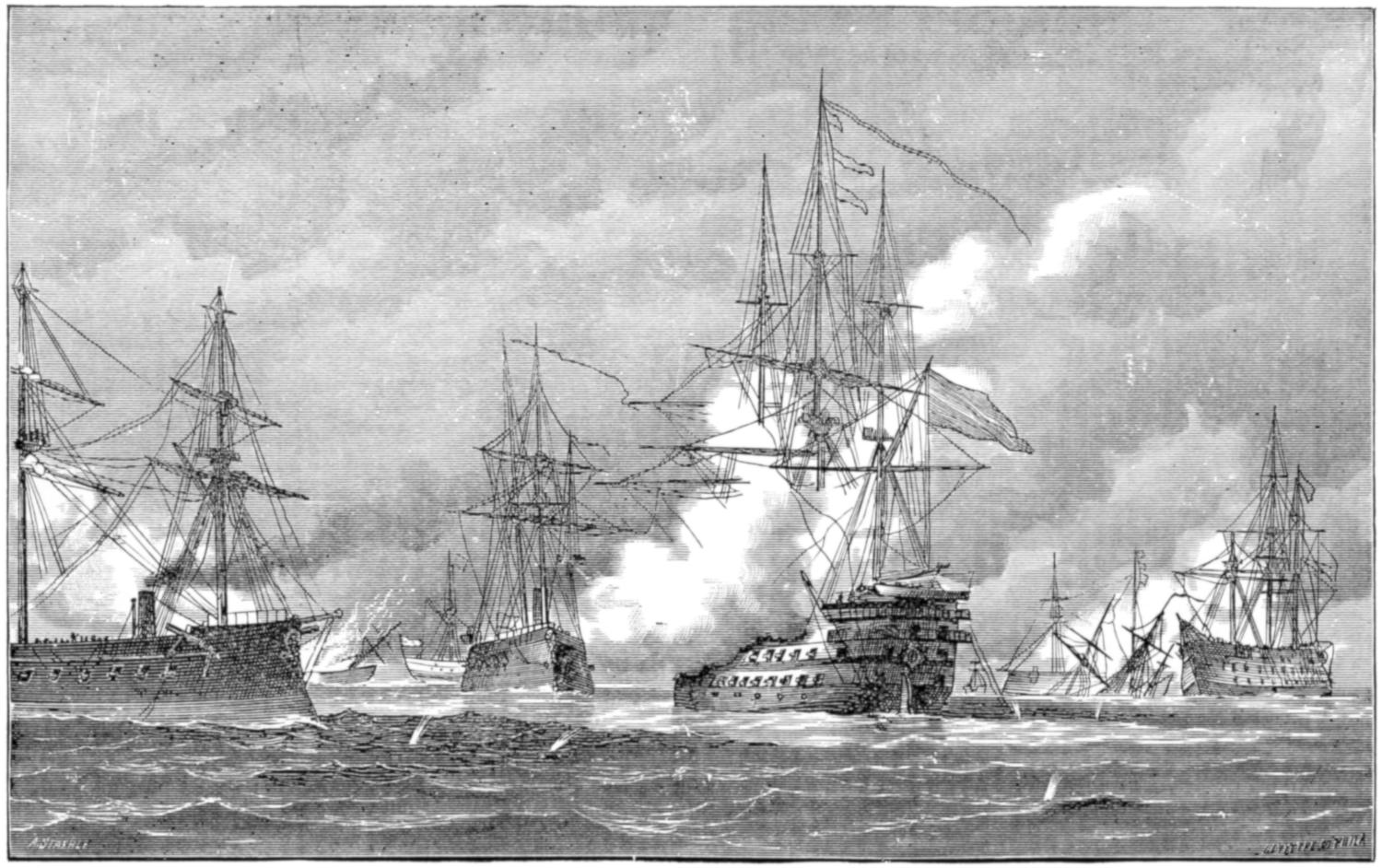

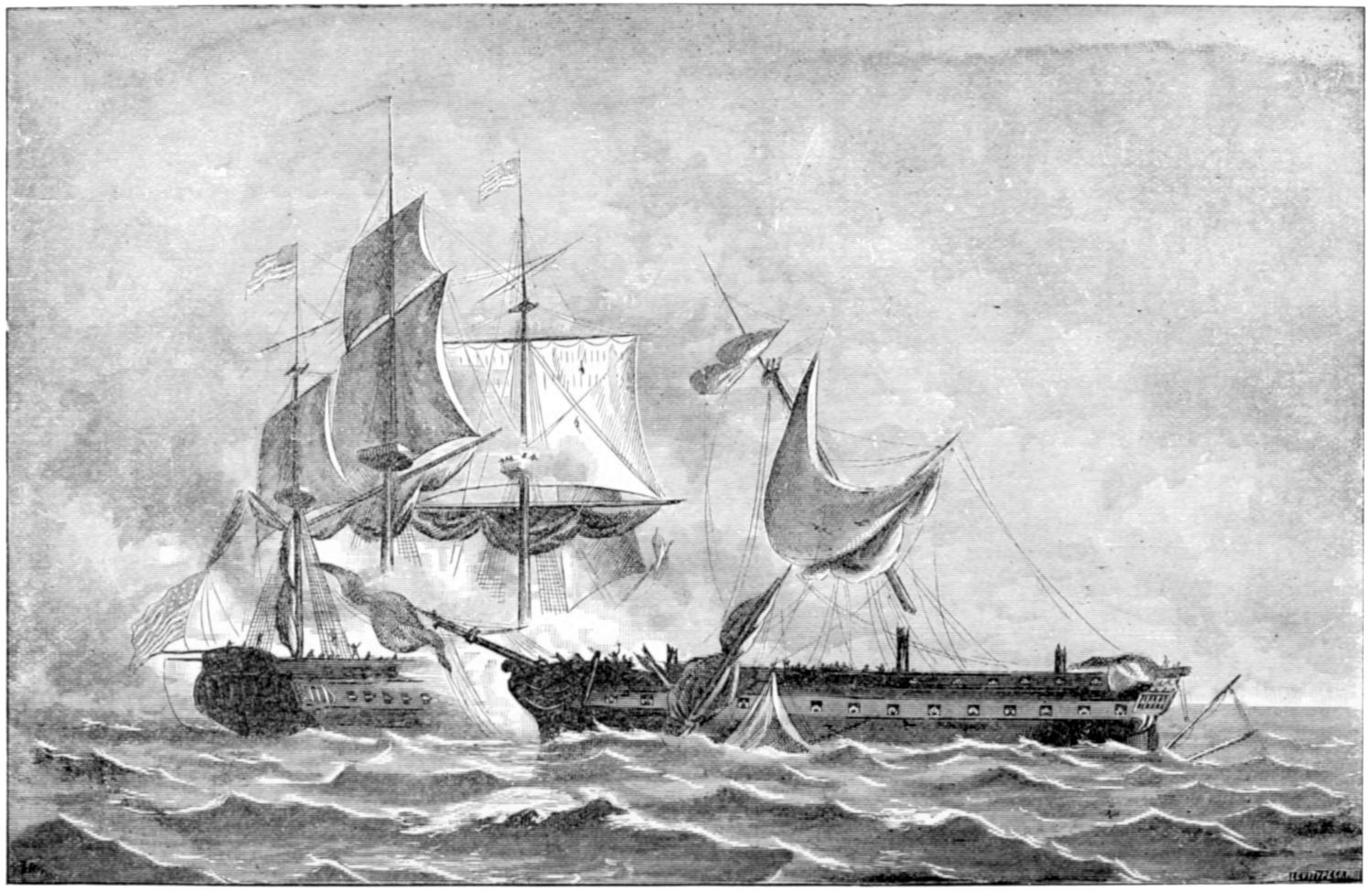

| 18. | Battle of Cape St. Vincent | I-229 |

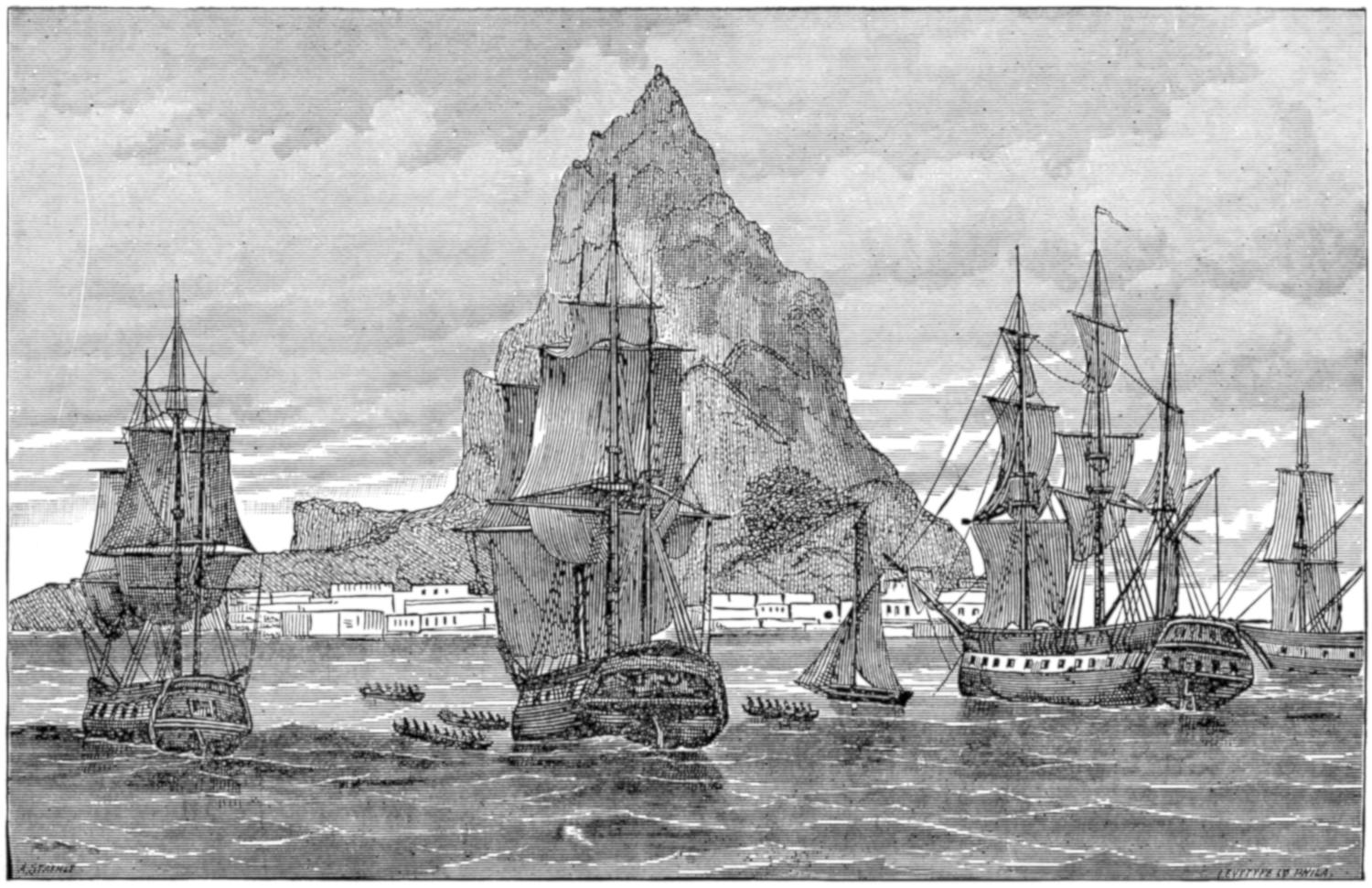

| 19. | English Fleet off Teneriffe | I-244 |

| 20. | Battle of the Nile | I-259 |

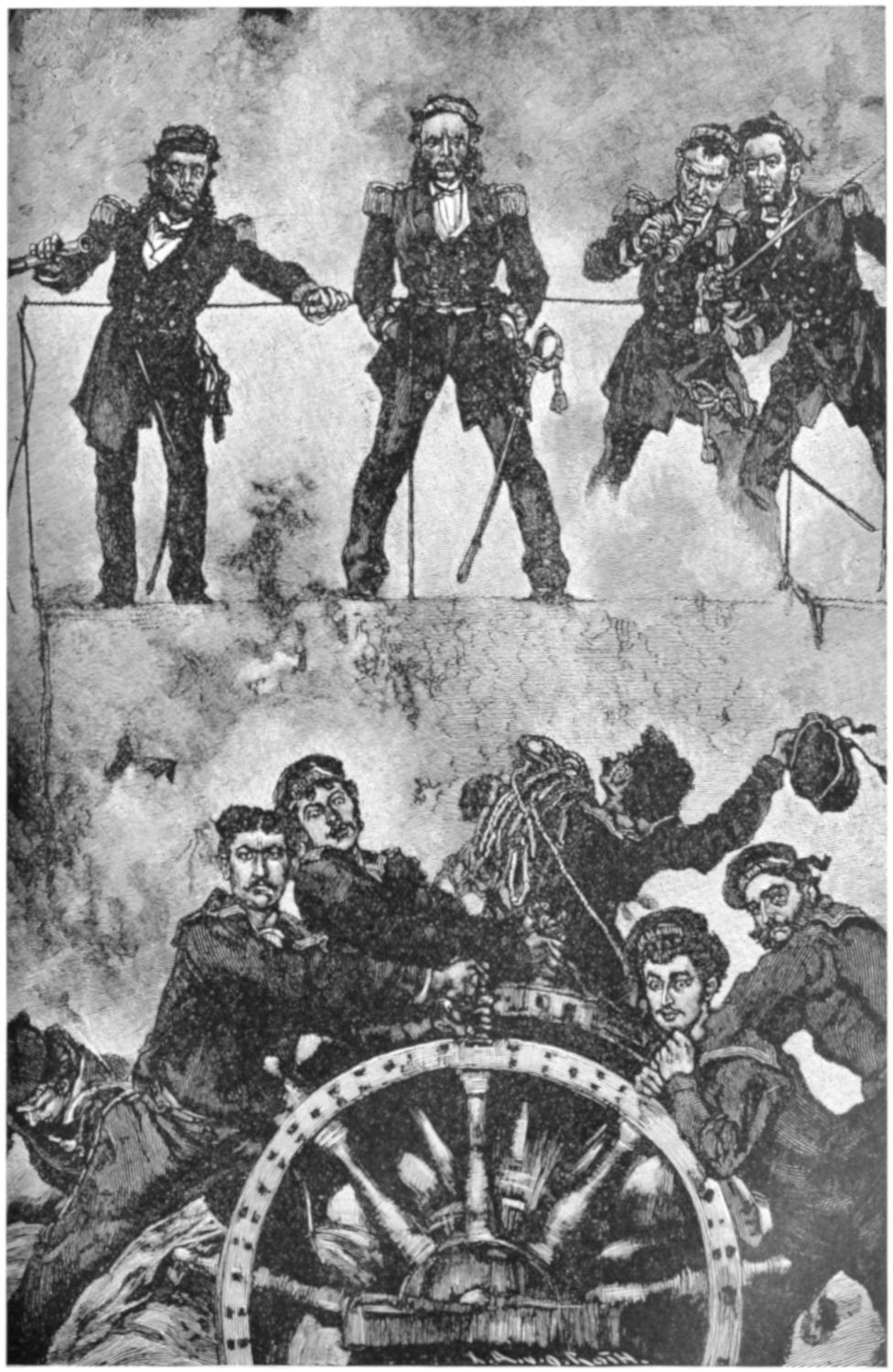

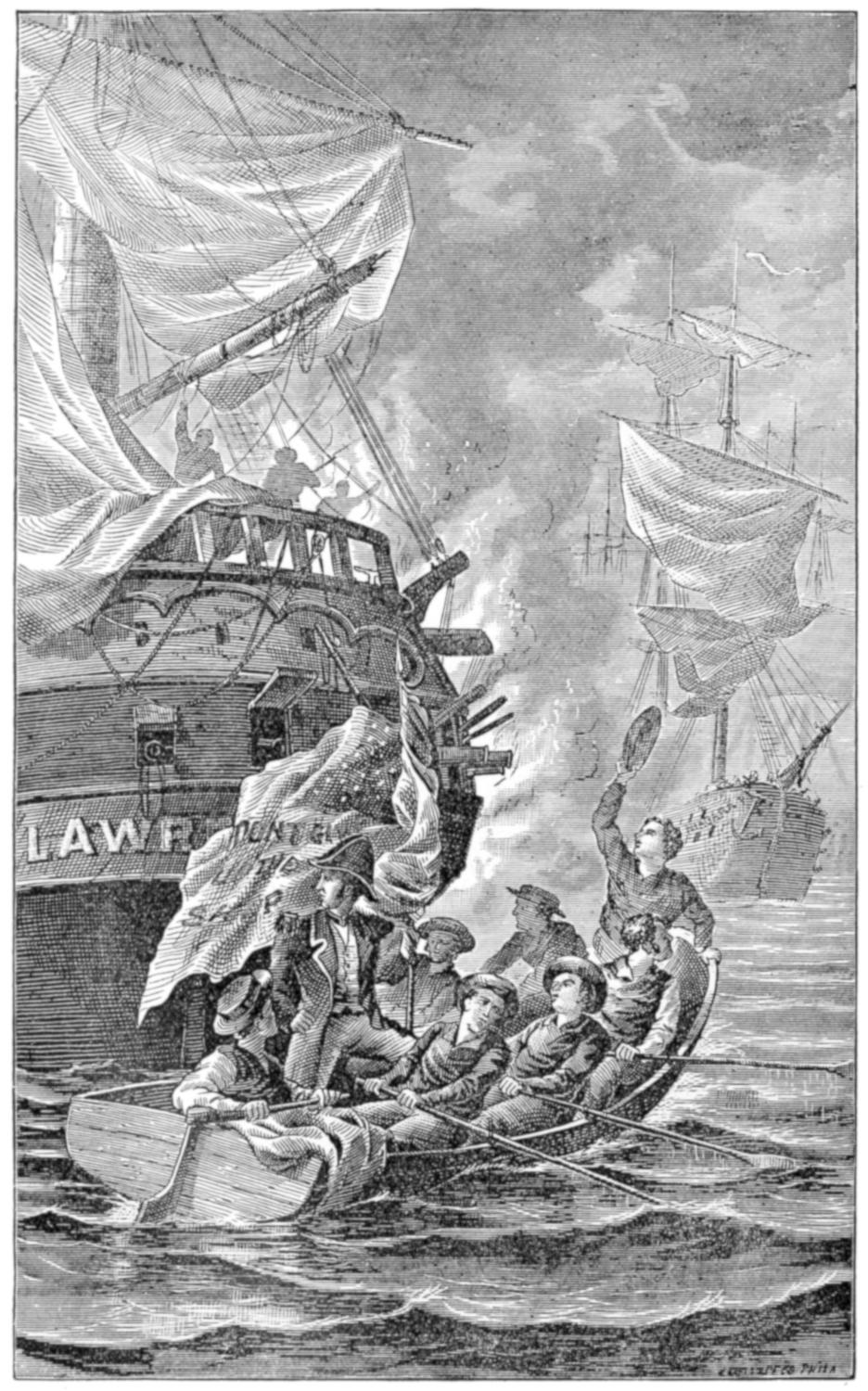

| 21. | Nelson Wounded at Teneriffe | I-270 |

| 21a. | Dutch Man-of-War, 17th Century. | I-270 |

| 22. | Capture of Admiral Nelson’s Dispatches | I-293 |

| 23. | Siege of Acre, 1799 | I-308 |

| 24. | Capture of Alexandria, 1801 | I-318 |

| 25. | Battle of Copenhagen | I-341 |

| 26. | Nelson’s Victory at Trafalgar | I-356 |

| 27. | Sinope, 1853 | I-417 |

| 28. | Battle of Lissa, 1866 | I-420 |

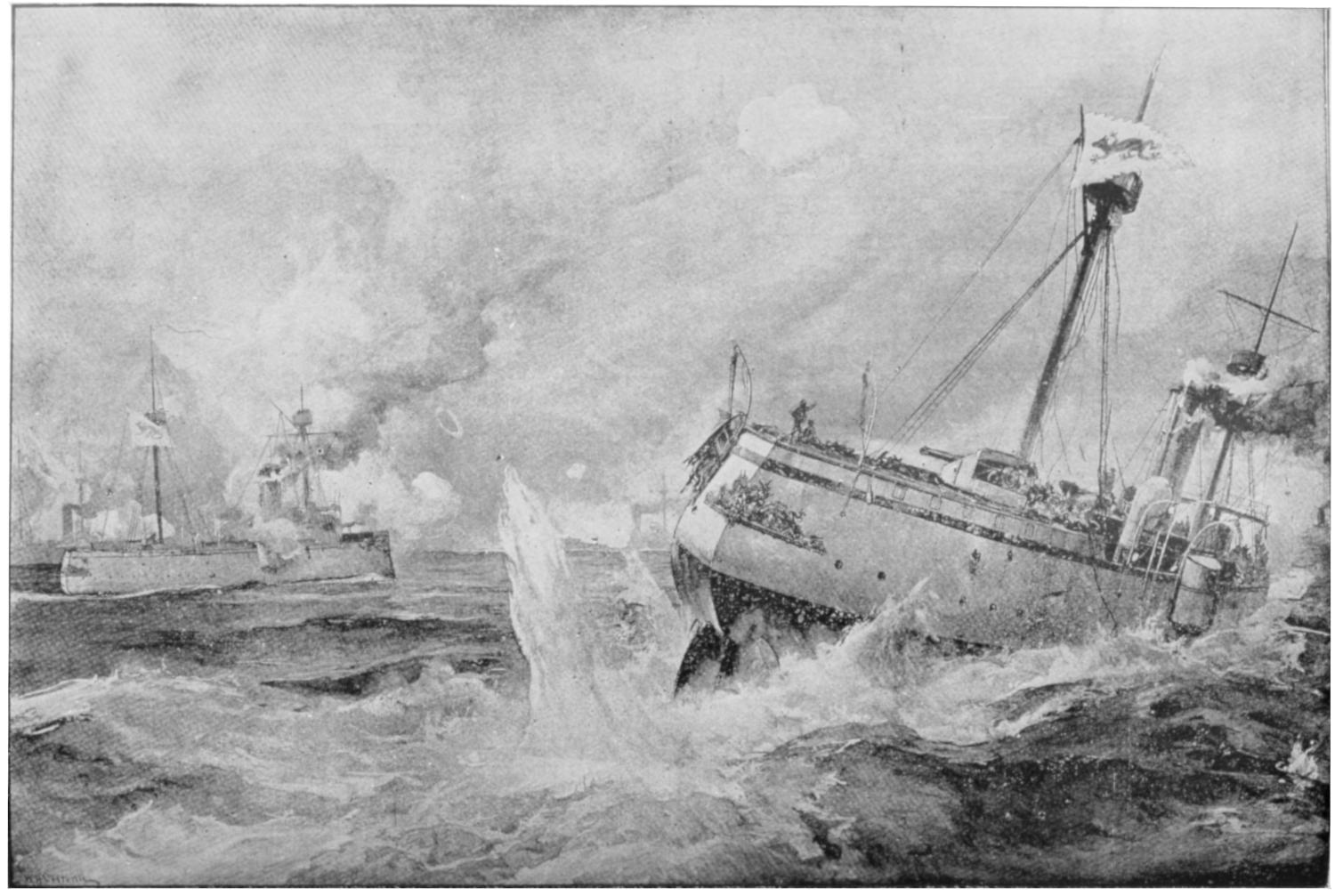

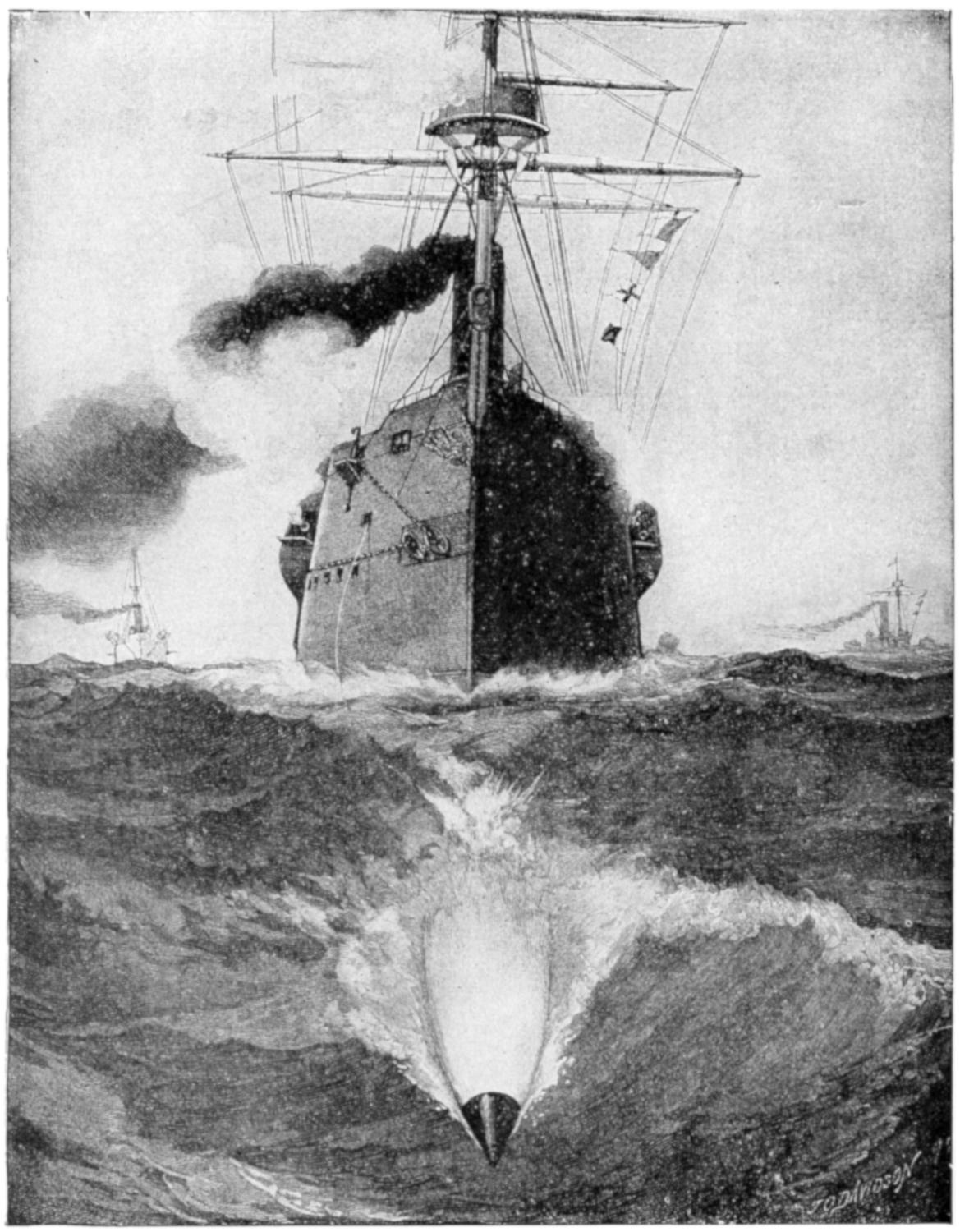

| 29. | Ferdinand Max Ramming the Re d’Italia | I-424 |

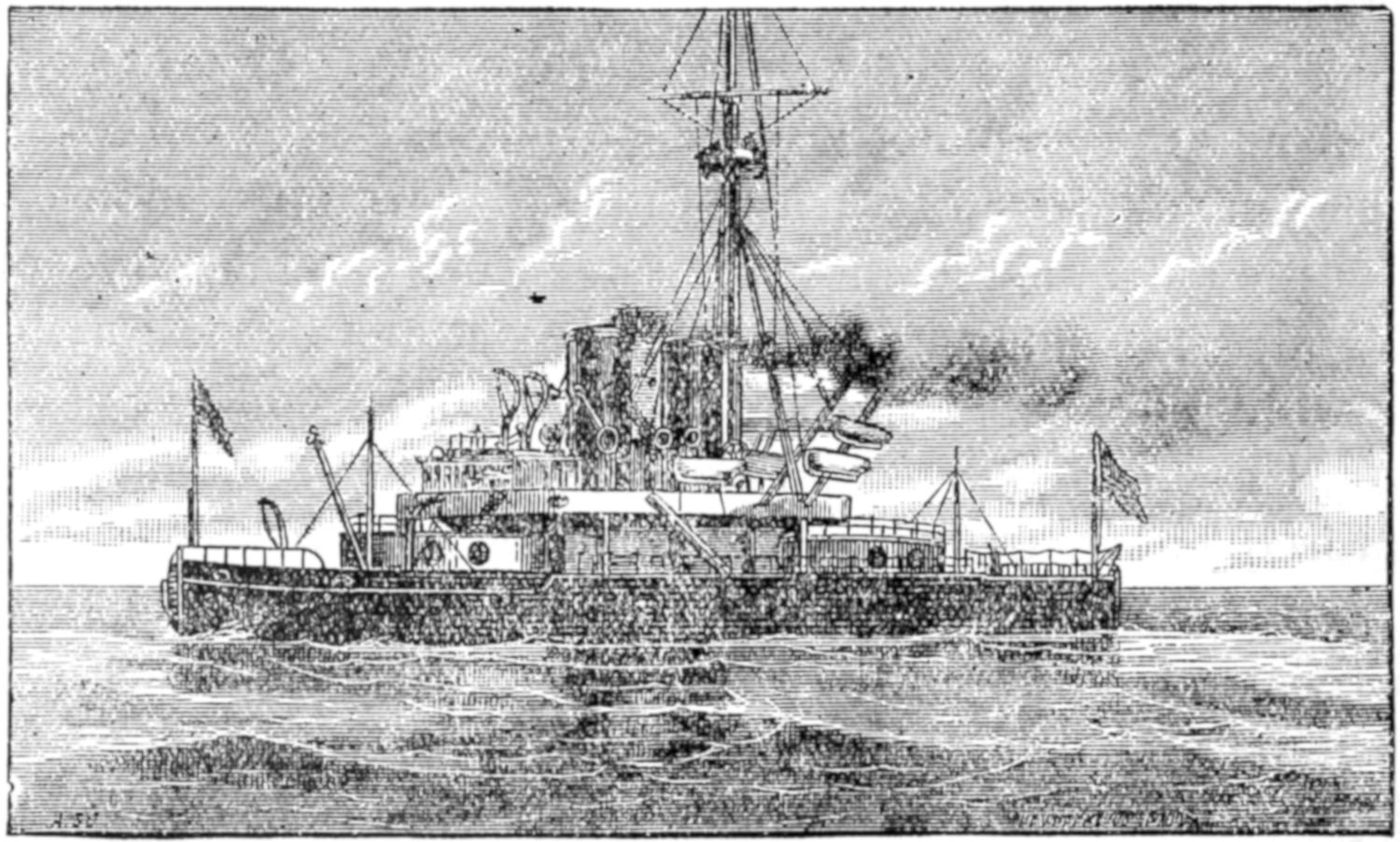

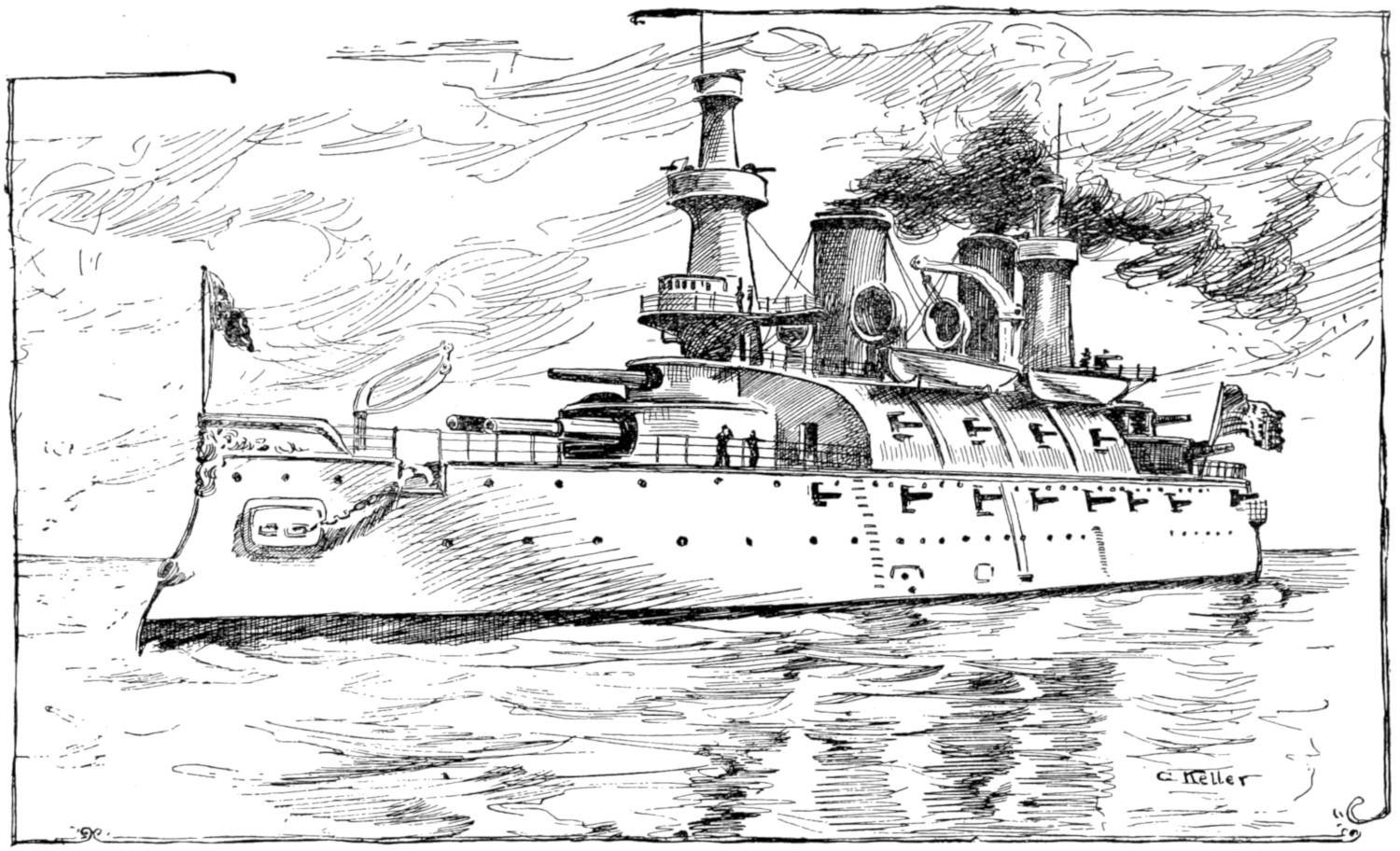

| 30. | The Dreadnaught[I-XVIII] | I-444 |

| 31. | Appearance of the Huascar after Capture | I-456 |

| 32. | Steel Torpedo Boat and Pole | I-457 |

| 33. | Bombardment of Alexandria | I-465 |

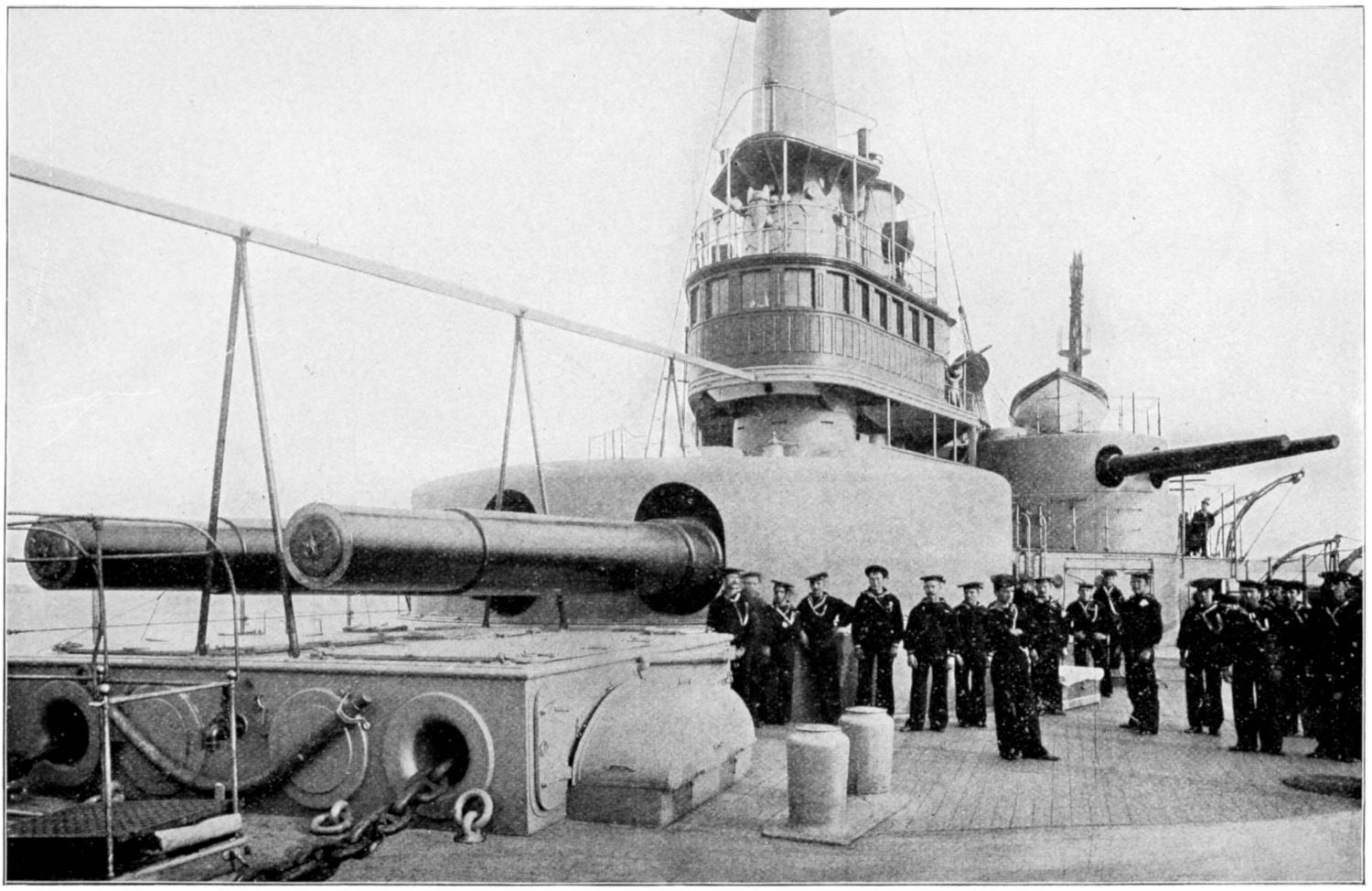

| 34. | The Alexandra | I-466 |

| 35. | Battle of the Yalu | I-482 |

[I-19]

The Ancients were full of horror of the mysterious Great Sea, which they deified; believing that man no longer belonged to himself when once embarked, but was liable to be sacrificed at any time to the anger of the Great Sea god; in which case no exertions of his own could be of any avail.

This belief was not calculated to make seamen of ability. Even Homer, who certainly was a great traveler, or voyager, and who had experience of many peoples, gives us but a poor idea of the progress of navigation, especially in the blind gropings and shipwrecks of Ulysses, which he appears to have thought the most natural things to occur.

A recent writer says, “Men had been slow to establish completely their dominion over the sea. They learned very early to build ships. They availed themselves very early of the surprising power which the helm exerts over the movements of a ship; but, during many ages, they found no surer guidance than that which the position of the sun and of the stars afforded. When clouds intervened to deprive them of this uncertain direction, they were helpless. They were thus obliged to keep the land in view, and content themselves with creeping timidly along the coasts. But at length there was discovered a stone which the wise Creator had endowed with strange properties. It was observed that a needle which had[I-20] been brought in contact with that stone ever afterwards pointed steadfastly to the north. Men saw that with a needle thus influenced they could guide themselves at sea as surely as on land. The Mariner’s compass loosed the bond which held sailors to the coast, and gave them liberty to push out into the sea.”

As regards early attempts at navigation, we must go back, for certain information, to the Egyptians. The expedition of the Argonauts, if not a fable, was an attempt at navigation by simple boatmen, who, in the infancy of the art, drew their little craft safely on shore every night of their coasting voyages. We learn from the Greek writers themselves, that that nation was in ignorance of navigation compared with the Phenicians, and the latter certainly acquired the art from the Egyptians.

We know that naval battles, that is, battles between bodies of men in ships, took place thousands of years before the Christian era. On the walls of very ancient Egyptian tombs are depicted such events, apparently accompanied with much slaughter.

History positively mentions prisoners, under the name of Tokhari, who were vanquished by the Egyptians in a naval battle fought by Rameses III, in the fifteenth century before our era. These Tokhari were thought to be Kelts, and to come from the West. According to some they were navigators who had inherited their skill from their ancestors of the lost Continent, Atlantis.

The Phenicians have often been popularly held to have been the first navigators upon the high seas; but the Carians, who preceded the Pelasgi in the Greek islands, undoubtedly antedated the Phenicians in the control of the sea and extended voyages. It is true that when the Phenicians did begin, they far exceeded their predecessors. Sidon dates from 1837 before Christ, and soon[I-21] after this date she had an extensive commerce, and made long voyages, some even beyond the Mediterranean.

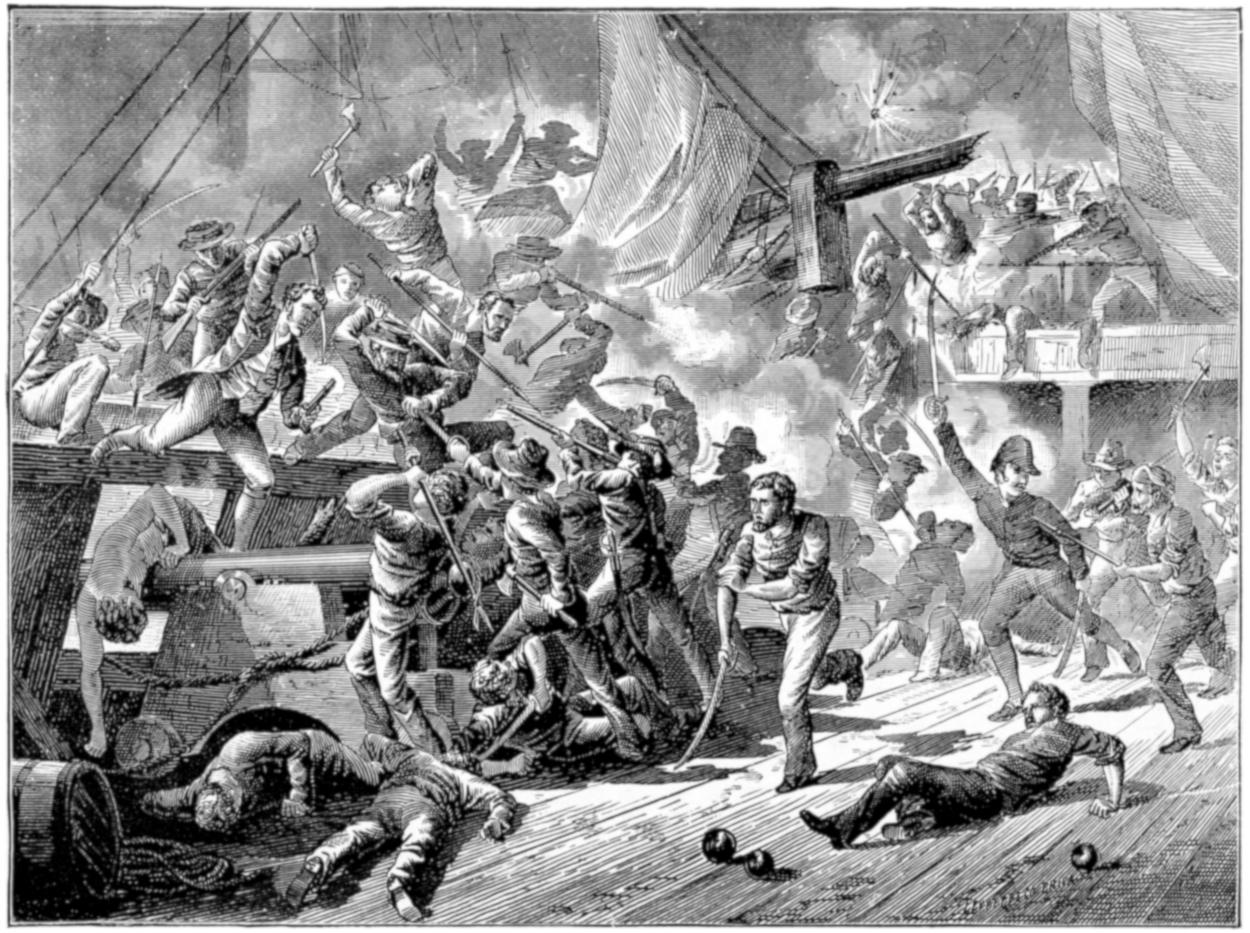

LINE OF BATTLE.

HOSTILE FRIGATES GRAPPLING.

NAVAL BATTLE, EIGHTEENTH CENTURY.

To return to the Egyptians. Sesostris had immense fleets 1437 years before Christ, and navigated not only the Mediterranean, but the Red Sea. The Egyptians had invaded, by means of veritable fleets, the country of the Pelasgi. Some of these ancient Egyptian ships were very large. Diodorus mentions one of cedar, built by Sesostris, which was 280 cubits (420 to 478 feet) long.

One built by Ptolemy was 478 feet long, and carried 400 sailors, 4000 rowers, and 3000 soldiers. Many other huge vessels are mentioned. A bas-relief at Thebes represents a naval victory gained by the Egyptians over some Indian nation, in the Red Sea, or the Persian Gulf, probably 1400 years before Christ.

The Egyptian fleet is in a crescent, and seems to be endeavoring to surround the Indian fleet, which, with oars boarded and sails furled, is calmly awaiting the approach of its antagonist. A lion’s head, of some metal, at the prow of each Egyptian galley, shows that ramming was then resorted to. These Egyptian men-of-war were manned by soldiers in helmets, and armed as those of the land forces.

The length of these vessels is conjectured to have been about 120 feet, and the breadth 16 feet. They had high raised poops and forecastles, filled with archers and slingers, while the rest of the fighting men were armed with pikes, javelins, and pole-axes, of most murderous appearance, to be used in boarding. Wooden bulwarks, rising considerably above the main-deck, protected the rowers. Some of the combatants had bronze coats of mail, in addition to helmets of the same, and some carried huge shields, covered, apparently, with tough bull’s hide.[I-22] These vessels had masts, with a large yard, and a huge square sail. They are said to have been built of acacia, so durable a wood that vessels built of it have lasted a century or more. They appear to have had but one rank of oars; although two or three tiers soon became common. None of the ancient Egyptian, Assyrian, Greek or Roman monuments represent galleys with more than two tiers of oars, except one Roman painting that gives one with three. Yet quinqueremes are spoken of as very common. It is not probable that more than three tiers were used; as seamen have never been able to explain how the greater number of tiers could have been worked; and they have come to the conclusion that scholars have been mistaken, and that the term quinquereme, or five ranks of oars, as translated, meant the arrangement of the oars, or of the men at them, and not the ranks, one above another, as usually understood.

Much learning and controversy has been expended upon this subject, and many essays written, and models and diagrams made, to clear up the matter, without satisfying practical seamen.

The Roman galleys with three rows of oars had the row ports in tiers. These ports were either round or oval, and were called columbaria, from their resemblance to the arrangement of a dove-cote. The lower oars could be taken in, in bad weather, and the ports closed.

The “long ships” or galleys of the ancient Mediterranean maritime nations—which were so called in opposition to the short, high and bulky merchant ships—carried square or triangular sails, often colored. The “long ships” themselves were painted in gay colors, carried flags and banners at different points, and images upon their prows, which were sacred to the tutelary divinities of their country. The “long ships” could make[I-23] with their oars, judging from descriptions of their voyages, perhaps a hundred miles in a day of twelve hours. In an emergency they could go much faster, for a short time. It is reliably stated that it took a single-decked galley, 130 feet long, with 52 oars, a fourth of an hour to describe a full circle in turning.

Carthage was founded by the Phenicians, 1137 years before our era; and not very long after the Carthaginians colonized Marseilles. Hanno accomplished his periplus, or great voyage round Africa, 800 years B. C., showing immense advance in nautical ability, in which the Greeks were again left far behind. Still later, the Carthaginians discovered the route to the British Islands, and traded there—especially in Cornish tin—while 330 years B. C. Ultima Thule, or Iceland, was discovered by the Marseillais Pitheas. Thus Carthage and her colonies not only freely navigated the Atlantic, but some have thought that they actually reached northern America.

Four hundred and eighty years before the Christian era the Grecian fleet defeated that of the Persians, at Salamis; and the next year another naval battle, that of Mycale (which was fought on the same day as that of Platæa on land), completely discomfited the Persian invaders, and the Greeks then became the aggressors.

Herodotus, who wrote about 450 years B. C., gives accounts of many naval actions, and even describes several different kinds of fighting vessels. He mentions the prophecy of the oracle at Delphi, when “wooden walls” were declared to be the great defence against Xerxes’ huge force—meaning the fleet—just as the “wooden walls of England” were spoken of, up to the time of ironclads. Herodotus says the Greek fleet at the battle of Artemisium, which was fought at the same time as Thermopylæ, consisted of 271 ships, which, by their very[I-24] skillful handling, defeated the much larger Persian armament, which latter, from its very numbers, was unwieldy.

At Artemisium, the Greeks “brought the sterns of their ships together in a small compass, and turned their prows towards the enemy.” And, although largely outnumbered, fought through the day, and captured thirty of the enemy’s ships. This manner of manœuvring was possible, from the use of oars; and they never fought except in calm weather.

After this, the Greeks, under Alexander, renewed their energies, and his fleet, under the command of Nearchus, explored the coast of India and the Persian Gulf. His fleets principally moved by the oar, although sails were sometimes used by them.

Among other well authenticated naval events of early times, was the defeat of the Carthaginian fleet, by Regulus, in the first Punic war, 335 years B. C. This victory, gained at sea, was the more creditable to the Romans, as they were not naturally a sea-going race, as the nations to the south and east of the Mediterranean were.

When they had rendered these nations tributary, they availed themselves of their nautical knowledge; just as the Austrians of to-day avail themselves of their nautical population upon the Adriatic coast, or the Turks of their Greek subjects, who are sailors.

Of naval battles which exercised any marked influence upon public events, or changed dynasties, or the fate of nations, the first of which we have a full and definite description is the battle of Actium. But before proceeding to describe that most important and memorable engagement, we may look at two or three earlier sea fights which had great results, some details of which have come down to us.

[I-25]

NAVAL BATTLES,

ANCIENT AND MODERN.

This great sea fight took place at the above date, between the fleet of Xerxes and that of the allied Greeks.

Salamis is an island in the Gulf of Ægina, ten miles west of Athens. Its modern name is Kolouri. It is of about thirty square miles surface; mountainous, wooded, and very irregular in shape.

It was in the channel between it and the main land that the great battle was fought.

Xerxes, in the flush of youth, wielding immense power, and having boundless resources in men and money, determined to revenge upon the Greeks the defeat of the Persians, so many of whom had fallen, ten years before, at Marathon. After years of preparation, using all his resources and enlisting tributary powers, he marched northward, in all the pomp and circumstance of war, and laid a bridge of boats at the Hellespont, over which it took seven days for his army to pass. His fleet consisted of over 1200 fighting vessels and transports, and carried 240,000 men.

Previous to the naval battle of which we are about to[I-26] speak, he lost four hundred of his galleys in a violent storm; but still his fleet was immensely superior in number to that of the Greeks, who had strained every nerve to get together the navies of their independent States. Such leaders as Aristides and Themistocles formed a host in themselves, while the independent Greeks were, man for man and ship for ship, superior to the Persians and their allies. Of the Greek fleet the Athenians composed the right wing; the Spartans the left, opposed respectively to the Phenicians and the Ionians; while the Æginetans and Corinthians, with others, formed the Greek reserve.

The day of the battle was a remarkably fair one, and we are told that, as the sun rose, the Persians, with one accord (both on sea and land, for there was a famous land battle as well on that day), prostrated themselves in worship of the orb of day. This was one of the oldest and greatest forms of worship ever known to man, and it still exists among the Parsees. It must have been a grand sight; for 240,000 men, in a thousand ships, and an immense force on the neighboring land, bowed down at once, in adoration.

The Greeks, with the “canniness” which distinguished them in their dealings with both gods and men, sacrificed to all the gods, and especially to Zeus, or Jupiter, and to Poseidon, or Neptune.

Everything was ready for the contest on both sides. Arms, offensive and defensive, were prepared. They were much the same as had been used for ages, by the Egyptians and others. Grappling irons were placed ready to fasten contending ships together; gangways or planks were arranged to afford sure footing to the boarders, while heavy weights were ready, triced up to the long yards, to be dropped upon the enemy’s deck,[I-27] crushing his rowers, and perhaps sinking the vessel. Catapults and balistæ (the first throwing large darts and javelins, the second immense rocks) were placed in order, like great guns of modern times. Archers and slingers occupied the poops and forecastles; while, as additional means of offence, the Rhodians carried long spars, fixed obliquely to the prows of their galleys, and reaching beyond their beaks, from which were suspended, by chains, large kettles, filled with live coals and combustibles. A chain at the bottom capsized these on the decks of the enemy, often setting them on fire. Greek fire, inextinguishable by water, is supposed, by many, to have been used thus early; while fire ships were certainly often employed.

Just as the Greeks had concluded their religious ceremonies, one of their triremes, which had been sent in advance to reconnoitre the Persian fleet, was seen returning, hotly pursued by the enemy.

An Athenian trireme, commanded by Ameinas, the brother of the poet Æschylus, dashed forward to her assistance. Upon this Eurybiades, the Greek admiral, seeing that everything was ready, gave the signal for general attack, which was the display of a brightly burnished brazen shield above his vessel. (This, and many other details may be found in Herodotus, but space prevents their insertion here.)

As soon as the shield was displayed the Grecian trumpets sounded the advance, which was made amid great enthusiasm, the mixed fleets, or contingents, from every state and city, vying with each other as to who should be first to strike the enemy. The right wing dashed forward, followed by the whole line, all sweeping down upon the Persians, or Barbarians, as the Greeks called them.

[I-28]

On this occasion the Greeks had a good cause, and were fighting to save their country and its liberties. Undaunted by the numbers of the opposing fleet, they bent to their long oars and came down in fine style. The Athenians became engaged first, then the Æginetans, and then the battle became general. The Greeks had the advantage of being in rapid motion when they struck the Persian fleet, most of which had not, at that critical moment, gathered way. The great effect of a mass in motion is exemplified in the act of a river steamboat running at speed into a wharf; the sharp, frail vessel is seldom much damaged, while cutting deep into a mass of timber, iron and stone. Many of the Persian vessels were sunk at once, and a great gap thereby made in their line. This was filled from their immense reserve, but not until after great panic and confusion, which contributed to the success of the Greeks. The Persian Admiral commanding the left wing, seeing that it was necessary to act promptly in order to effectually succor his people, bore down at full speed upon the flagship of Themistocles, intending to board her. A desperate hand-to-hand struggle ensued, and the vessel of Themistocles was soon in a terrible strait; but many Athenian galleys hastened to his rescue, and the large and magnificent Persian galley was sunk by repeated blows from the sharp beaks of the Greeks, while Ariamenes, the Admiral, was previously slain and thrown overboard. At this same moment the son of the great Darius, revered by all the Asiatics, fell, pierced by a javelin, at which sight the Persians set up a melancholy wailing cry, which the Greeks responded to with shouts of triumph and derision.

Still, the Persians, strong in numbers, renewed and maintained the battle with great fury; but the Athenian fleet cut through the Phenician line, and then, pulling[I-29] strong with starboard and backing port oars, turned short round and fell upon the Persian left flank and rear.

A universal panic now seized the Asiatics; and in spite of numbers, they broke and fled in disorder—all, that is, except the Dorians, who, led by their brave queen in person, fought for their new ally with desperate valor, in the vain hope of restoring order where all order was lost. The Dorian queen, Artemisia, at last forced to the conviction that the fugitives were not to be rallied, and seeing the waters covered with wreck, and strewn with the floating corpses of her friends and allies, reluctantly gave the signal for retreat.

She was making off in her own galley, when she found herself closely pursued by a Greek vessel, and, to divert his pursuit, as well as to punish one who had behaved badly, she ran her galley full speed into that of a Lycian commander, who had behaved in a cowardly manner during the engagement. The Lycian sank instantly, and the Greek, upon seeing this action, supposed that Artemisia’s galley was a friend, and at once relinquished pursuit; so that this brave woman and able naval commander succeeded in making her escape.

Ten thousand drachmas had been offered for her capture, and this, of course, was lost. Ameinas, who had pursued her, was afterwards named, by general suffrage, one of the “three valiants” who had most distinguished themselves in the hard fought battle against such odds. Polycritus and Eumenes were the two others.

The victory being complete at sea, Aristides, at the head of a large body of Athenians, landed at a point where many of the Persians were. The latter were divided from the main body of Xerxes’ army by a sheet of water, and were slain, almost to a man, by the Greeks, under the[I-30] very eyes of the Persian monarch and his main army, who could not reach them to afford assistance.

The discomfiture of his fleet rendered Xerxes powerless for the time; and, recognizing the extent of the misfortune which had befallen him, the mighty lord of so many nations, so many tributaries, and so many slaves, rent his robes, and burst into a flood of tears.

Thus ended the great battle of Salamis, which decided the fate of Greece.

The forces of the several independent Greek States returned to their homes, where their arrival was celebrated with great rejoicing, and sacrifices to the gods.

Xerxes, as soon as he realized the extent of the disaster which had befallen him, resolved at once to return with all possible expedition into Asia. His chief counsellor in vain advised him not to be downcast by the defeat of his fleet: “that he had come to fight against the Greeks, not with rafts of wood, but with soldiers and horses.” In spite of this, Xerxes sent the remnant of his fleet to the harbors of Asia Minor, and after a march of forty-five days, amidst great hardship and privation, arrived at the Hellespont with his army. Famine, pestilence and battle had reduced his army from a million or more to about 300,000.

The victory at Salamis terminated the second act of the great Persian expedition. The third, in the following year, was the conclusive land battle of Platæa, and subsequent operations. These secured not only the freedom of Greece and of adjoining European States, but the freedom and independence of the Asiatic Greeks, and their undisturbed possession of the Asiatic coast—an inestimable prize to the victors.

[I-31]

This battle was not only remarkable for its desperate fighting and bloody character, but for the fact that the complete and overwhelming defeat of the Athenians was the termination of their existence as a naval power.

An Athenian fleet had been despatched to the assistance of the small Greek Republic of Ægesta, near the western end of Sicily, then threatened by Syracuse.

The Athenian fleet numbered one hundred and thirty-four triremes, 25,000 seamen and soldiers, beside transports with 6000 spearmen and a proportionate force of archers and slingers. This considerable armament was designed to coöperate not only in the reduction of Syracuse, the implacable enemy of the Ægestans, but also to endeavor to subdue the whole of the large, rich and beautiful island of Sicily, at that time the granary and vineyard of the Mediterranean.

The Greek fleet drew near its destination in fine order, and approached and entered Syracuse with trumpets sounding and flags displayed, while the soldiers and sailors, accustomed to a long succession of victories, and regarding defeat as impossible, rent the air with glad shouts.

Syracuse is a large and perfect harbor; completely[I-32] landlocked, and with a narrow entrance. The Sicilians, entirely unprepared to meet the veteran host thus suddenly precipitated upon them, looked upon these demonstrations with gloomy forebodings. Fortunately for their independence, they had wise and brave leaders, while the commander of the great Athenian fleet was wanting in decision of character and in the ability to combine his forces and move quickly; a necessity in such an enterprise as his. It therefore happened that the tables were turned, and the proud invaders were eventually blockaded in the harbor of Syracuse, the people obstructing the narrow entrance so as to prevent escape, while the country swarmed with the levies raised to resist the invaders by land, and to cut them off from all supplies.

In the meantime the Greeks had seized a spot on the shores of the harbor, built a dock yard, and constructed a fortified camp.

Such being the state of affairs, a prompt and energetic movement on the part of the Athenians became necessary to save them from starvation. Nikias, their commander-in-chief, entrusted the fleet to Demosthenes, Menander, and Euthydemus, and prepared to fight a decisive battle.

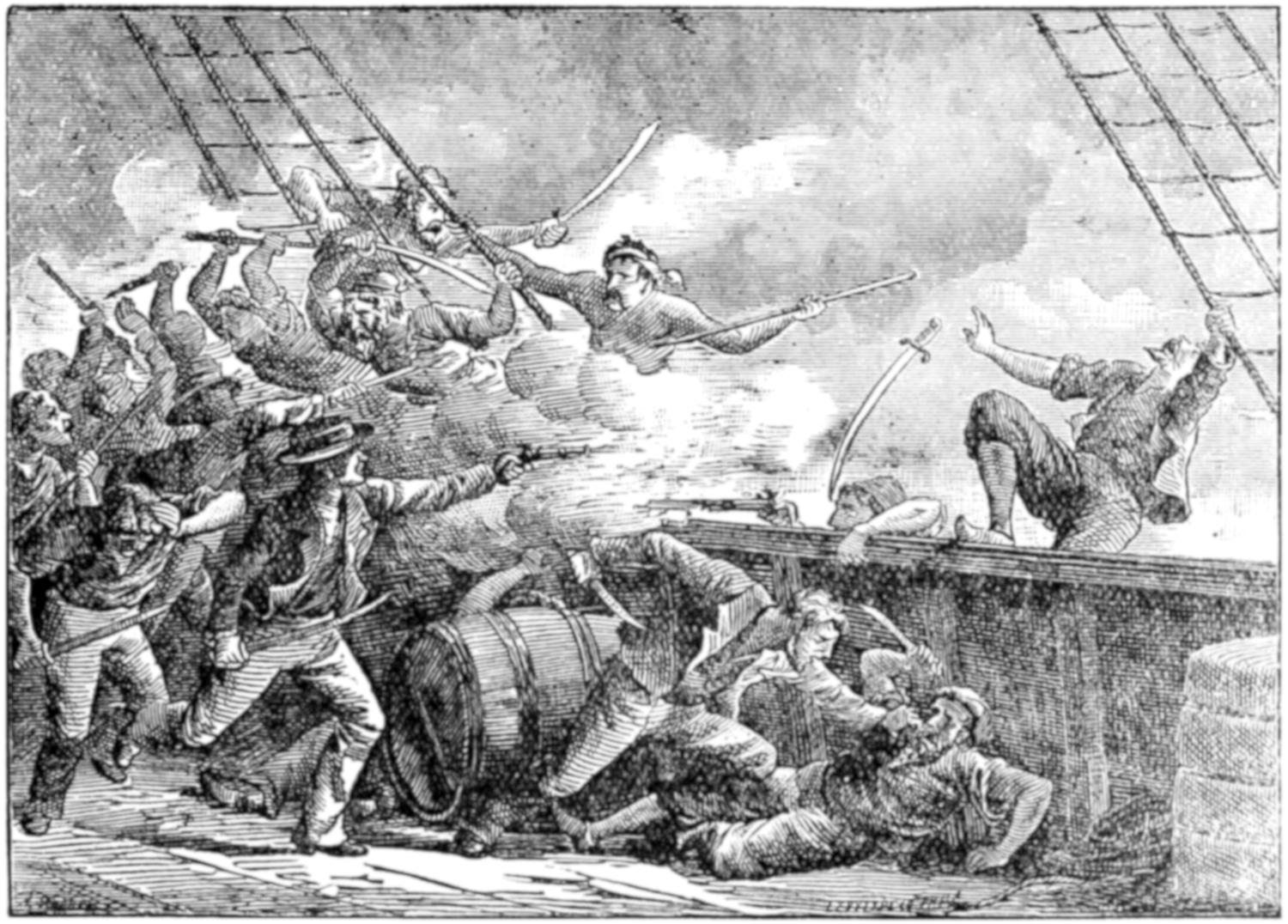

Taught by recent partial encounters that the beaks of the Syracusan triremes were more powerful and destructive than those of his own vessels, he instructed his captains to avoid ramming as much as possible, and to attack by boarding. His ships were provided with plenty of grappling irons, so that the Sicilians could be secured as soon as they rammed the Greek vessels, when a mass of veteran Greeks was to be thrown on board, and the islanders overcome in a hand-to-hand fight.

When all was ready the fleet of the Athenian triremes, reduced to one hundred and ten in number, but fully manned, moved in three grand divisions. Demosthenes[I-33] commanded the van division, and made directly for the mouth of the harbor, toward which the Syracusan fleet, only seventy-five in number, was also promptly converging.

The Athenians were cutting away and removing the obstructions at the narrow entrance, when their enemy came down rapidly, and forced them to desist from their labors, and form line of battle. This they did hurriedly, and as well as the narrow limits would permit. They were soon furiously attacked, on both wings at once, by Licanus and Agatharcus, who had moved down close to the shore, the one on the right and the other on the left hand of the harbor. The Syracusans, by this manœuvre, outflanked the Greeks, who, their flanks being turned, were necessarily driven in upon their centre, which point was at this critical moment vigorously attacked by the Corinthians, the faithful allies of the Syracusans. The Corinthian squadron, led by Python, had dashed down the middle of the harbor, and attacked, with loud shouts, as if assured of victory. Great confusion now ensued among the Athenian vessels, caught at a great disadvantage, and in each other’s way. Many of their triremes were at once stove and sunk, and those which remained afloat were so hemmed in by enemies that they could not use their oars. The strong point of the Athenian fleet had consisted in its ability to manœuvre, and they were here deprived of that advantage.

Hundreds of their drowning comrades were calling for assistance, while their countrymen on shore, belonging to the army, witnessed their position with despair, being unable to come to the rescue. Still, the Athenians fought as became their old renown. They often beat off the enemy by sheer force of arms, but without avail. The Syracusans had covered their forecastles with raw bulls’[I-34] hides, so that the grappling irons would not hold for boarding; but the Greeks watched for the moment of contact, and before they could recoil, leaped boldly on board the enemy’s triremes, sword in hand. They succeeded thus in capturing some Sicilian vessels; but their own loss was frightful, and, after some hours of most sanguinary contest, Demosthenes, seeing that a continuance of it would annihilate his force, took advantage of a temporary break in the enemy’s line to give the signal for retreat. This was at once begun; at first in good order, but the Syracusans pressing vigorously upon the Athenian rear, soon converted it into a disorderly flight, each trying to secure his own safety.

In this condition the Greeks reached the fortified docks, which they had built during their long stay, the entrance to which was securely guarded by merchant ships, which had huge rocks triced up, called “dolphins,” of sufficient size to sink any vessel upon which they might be dropped. Here the pursuit ended, and the defeated and harassed Athenians hastened to their fortified camp, where their land forces, with loud lamentations, deplored the event of the naval battle, which they had fondly hoped would have set them all at liberty.

The urgent question now was as to the preservation of both forces—and that alone.

That same night Demosthenes proposed that they should man their remaining triremes, reduced to sixty in number, and try again to force a way out of the harbor; alleging that they were still stronger than the enemy, who had also lost a number of ships. Nikias gave consent; but when the sailors were ordered to embark once more, they mutinied and flatly refused to do so; saying that their numbers were too much reduced by battle, sickness, and bad food, and that there were no seamen of experience[I-35] left to take the helm, or rowers in sufficient numbers for the benches. They also declared that the last had been a soldiers’ battle, and that such were better fought on land. They then set fire to the dock-yard and the fleet, and the Syracusan forces appearing, in the midst of this mutiny, captured both men and ships. Her fleet being thus totally destroyed, Athens never recovered from the disaster, and ceased from that day to be a naval power.

The subsequent events in this connection, though interesting and instructive, do not belong to naval history.

A NORSE GALLEY.

[I-36]

Carthage, the Phenician colony in Africa, which became so famous and powerful, was very near the site of the modern city of Tunis. It has been a point of interest for twenty centuries. Long after the Phenician sway had passed away, and the Arab and Saracen had become lords of the soil, Louis XI, of France, in the Crusade of 1270, took possession of the site of the ancient city, only to give up his last breath there, and add another to the many legends of the spot. The Spaniards afterwards conquered Tunis and held it for a time; and, in our own day, the French have again repossessed themselves of the country, and may retain it long after the events of our time have passed into history.

As soon as Rome rose to assured power, and began her course of conquest, trouble with the powerful State of Carthage ensued. Their clashing interests soon involved them in war, and Sicily and the Sicilian waters, being necessary to both, soon became their battle ground.

The Carthaginians had obtained a footing in Sicily, by assisting Roman renegades and freebooters of all nations who had taken refuge there. The Romans therefore passed a decree directing the Consul, Appius Claudius, to cross over to Messina and expel the Carthaginians who, from that strong point, controlled the passage of the great thoroughfare,[I-37] the strait of the same name. Thus commenced the first Punic war. The Romans were almost uniformly successful upon land, but the Carthaginians, deriving nautical skill from their Phenician ancestors, overawed, with their fleet, the whole coast of Sicily, and even made frequent and destructive descents upon the Italian shores themselves.

ROMAN GALLEY AND DRAW-BRIDGE.

CARTHAGINIAN GALLEY.

SMALLER ROMAN GALLEY.

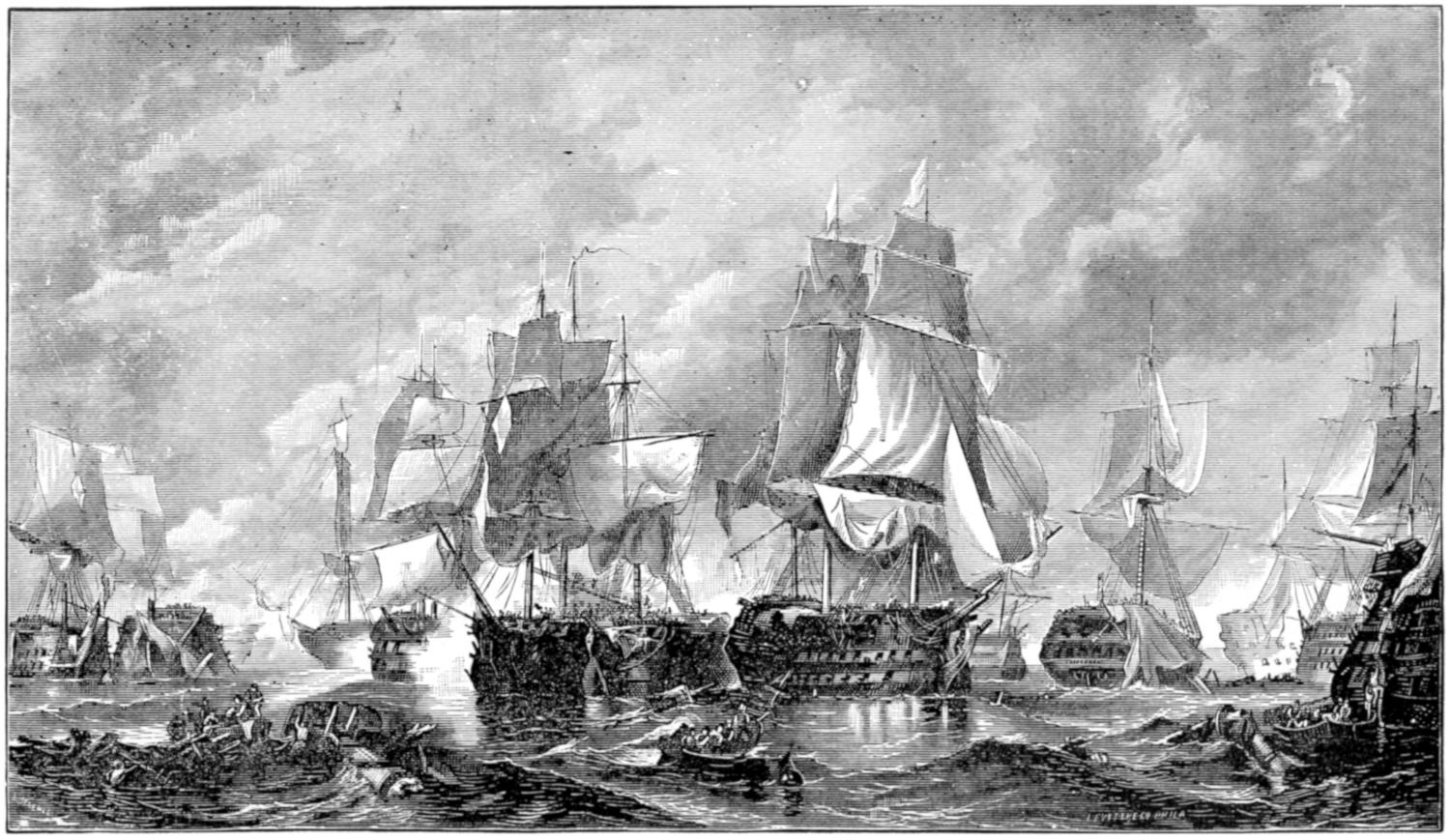

CAPTURE OF THE CARTHAGINIAN FLEET BY THE ROMANS.

The Romans at this time had no ships of war; but they began the construction of a fleet, to cope with their enemy, then the undisputed mistress of the seas.

Just at this time a Carthaginian ship of large size was stranded upon the Italian shores, and served as a model for the Romans, who, with characteristic energy, in a short time put afloat a hundred quinqueremes and twenty triremes. No particular description of these vessels is necessary, as they were the same in general plan as those already spoken of as in use among the Egyptians, Phenicians, and Greeks, for centuries. Able seamen were obtained from neighboring tributary maritime States, and bodies of landsmen were put in training, being exercised at the oar on shore; learning to begin and cease rowing at the signal. For this purpose platforms were erected, and benches placed, as in a galley.

It will here be necessary to give a short account of the Roman naval system, which was now rapidly becoming developed and established. As has been said, they had paid no attention, before this period, to naval affairs; and were only stirred up to do so by the necessity of meeting the Carthaginians upon their own element.

It is true that some authorities say that the first Roman ships of war were built upon the model of those of Antium, after the capture of that city, A. U. C. 417; but the Romans certainly made no figure at sea until the time of the first Punic war.

[I-38]

The Roman ships of war were much longer than their merchant vessels, and were principally driven by oars, while the merchant ships relied almost entirely upon sails.

It is a more difficult problem than one would at first sight suppose, to explain exactly how the oars were arranged in the quadriremes and quinqueremes of which we read. The Roman ships were substantial and heavy, and consequently slow in evolutions, however formidable in line. Augustus, at a much later period, was indebted to a number of fast, light vessels from the Dalmatian coast, for his victory over Antony’s heavy ships.

The ship of the commander of a Roman fleet was distinguished by a red flag, and also carried a light at night. These ships of war had prows armed with a sharp beak, of brass, usually divided into three teeth, or points. They also carried towers of timber, which were erected before an engagement, and whence missiles were discharged. They employed both freemen and slaves as rowers and sailors. The citizens and the allies of the State were obliged to furnish a certain quota of these; and sometimes to provide them with pay and provisions; but the wages of the men were usually provided by the State.

The regular soldiers of the Legions at first fought at sea as well as on land; but when Rome came to maintain a permanent fleet, there was a separate class of soldiers raised for the sea service, like the marines of modern navies. But this service was considered less honorable than that of the Legions, and was often performed by manumitted slaves. The rowers, a still lower class, were occasionally armed and aided in attack and defence, when boarding; but this was not usual.

Before a Roman fleet went to sea it was formally reviewed, like the land army. Prayers were offered to the gods, and victims sacrificed. The auspices were[I-39] consulted, and if any unlucky omen occurred (such as a person sneezing on the left of the Augur, or swallows alighting on the ships), the voyage was suspended.

Fleets about to engage were arranged in a manner similar to armies on land, with centre, right and left wings, and reserve. Sometimes they were arranged in the form of a wedge, or forceps, but most frequently in a half moon. The admiral sailed round the fleet, in a light galley, and exhorted the men, while invocations and sacrifices were again offered. They almost always fought in calm or mild weather, and with furled sails. The red flag was the signal to engage, which they did with trumpets sounding and the crews shouting. The combatants endeavored to disable the enemy by striking off the banks of oars on one side, or by striking the opposing hulls with the beak. They also employed fire-ships, and threw pots of combustibles on board the enemy. Many of Antony’s ships were destroyed by this means. When they returned from a successful engagement the prows of the victors were decorated with laurel wreaths; and it was their custom to tow the captured vessels stern foremost, to signify their utter confusion and helplessness. The admiral was honored with a triumph, after a signal victory, like a General or Consul who had won a decisive land battle; and columns were erected in their honor, which were called Rostral, from being decorated with the beaks of ships.

And now, to return to the imposing fleet which the Romans had equipped against the Carthaginians:—

When all was ready the Romans put to sea; at first clinging to their own shores, and practicing in fleet tactics. They found their vessels dull and unwieldy, and therefore resolved to board the enemy at the first opportunity, and avoid as much as possible all manœuvring.[I-40] They therefore carried plenty of grappling-irons, and had stages, or gangways, ingeniously arranged upon hinges, which fell on board of the enemy, and afforded secure bridges for boarding. By this means many victories were secured over a people who were much better seamen.

After various partial engagements with the Carthaginian fleet, productive of no definite results, Duilius assumed command of the Roman fleet, and steered for Mylœ, where the Carthaginians, under Hannibal, were lying at anchor.

The latter expected an easy victory, despising the pretensions of the Romans to seamanship, and they accordingly left their anchorage in a straggling way, not even thinking it worth while to form line of battle to engage landsmen.

Their one hundred and thirty quinqueremes approached in detachments, according to their speed, and Hannibal, with about thirty of the fastest, came in contact with the Roman line, while the rest of his fleet was far astern. Attacked on all sides, he soon began to repent of his rashness, and turned to fly—but the “corvi” fell, and the Roman soldiers, advancing over the gangways, put their enemies to the sword. The whole of the Carthaginian van division fell into the Roman hands, without a single ship being lost on the part of the latter. Hannibal had fortunately made his escape in time, in a small boat, and at once proceeded to form the rest of his fleet to resist the Roman shock. He then passed from vessel to vessel, exhorting his men to stand firm; but the novel mode of attack, and its great success, had demoralized the Carthaginians, and they fled before the Roman advance; fifty more of Hannibal’s fleet being captured.

So ended the first great naval engagement between Rome and Carthage; bringing to the former joy and[I-41] hope of future successes, and to the latter grief and despondency.

Duilius, the Consul, had a rostral column of marble erected in his honor, in the Roman forum, with his statue upon the top.

Hannibal was soon afterward crucified by his own seamen, in their rage and mortification at their shameful defeat.

Slight skirmishes and collisions continued to occur, and both nations became convinced that ultimate success could only be obtained by the one which should obtain complete mastery of the Mediterranean Sea. Both, therefore, made every effort; and the dock-yards were kept busily at work, while provisions, arms, and naval stores were accumulated upon a large scale.

The Romans fitted out three hundred and thirty, the Carthaginians three hundred and fifty quinqueremes; and in the spring of the year 260 B. C., the rivals took the sea, to fight out their quarrel to the bitter end.

The Roman Consuls Manlius and Regulus had their fleet splendidly equipped, and marshaled in divisions, with the first and second Legions on board. Following was a rear division, with more soldiers, which served as a reserve, and as a guard to the rear of the right and left flanks.

Hamilcar, the admiral of the opposing fleet, saw that the Roman rear was hampered by the transports which they were towing, and resolved to try to separate the leading divisions from them; hoping to capture the transports, and then the other divisions in detail; with this intention he formed in four divisions. Three were in line, at right angles to the course the Romans were steering, and the fourth in the order called “forceps.”

[I-42]

The last division was a little in the rear and well to the left of the main body.

Having made his dispositions, Hamilcar passed down the fleet in his barge, and reminded his countrymen of their ancestral renown at sea, and assured them that their former defeat was due, not to the nautical ability of the Romans, but to the rash valor of the Carthaginians against a warlike people not ever to be despised. “Avoid the prows of the Roman galleys,” he continued, “and strike them amidships, or on the quarter. Sink them, or disable their oars, and endeavor to render their military machines, on which they greatly rely, wholly inoperative.” Loud and continuous acclamations proclaimed the good disposition of his men, and Hamilcar forthwith ordered the advance to be sounded, signaling the vessels of the first division—which would be the first to engage—to retreat in apparent disorder when they came down close to the enemy. The Carthaginians obeyed his order to the letter, and, as if terrified by the Roman array, turned in well simulated flight, and were instantly pursued by both columns, which, as Hamilcar had foreseen, drew rapidly away from the rest of the fleet. When they were so far separated as to preclude the possibility of support, the Carthaginians, at a given signal, put about, and attacked with great ardor and resolution, making a desperate effort to force together the two sides of the “forceps” in which the Romans were formed. But these facing outward, and always presenting their prows to the Carthaginians, remained immovable and unbroken. If the Carthaginians succeeded in ramming one, those on each side of the attacked vessel came to her assistance, and thus outnumbered, the Carthaginians did not dare to board.

While the battle was thus progressing in the centre—without decided results—Hanno, who commanded the[I-43] Carthaginian right wing, instead of engaging the left Roman column in flank, stretched far out to sea, and bore down upon the Roman reserve, which carried the soldiers of the Triarii. The Carthaginian reserve, instead of attacking the Roman right column, as they evidently should have done, also bore down upon the Roman reserve. Thus three distinct and separate engagements were going on at once—all fought most valiantly. Just as the Roman reserve was overpowered, and about to yield, they saw that the Carthaginian centre was in full retreat, chased by the Roman van, while the Roman second division was hastening to the assistance of their sorely pressed reserve. This sight inspired the latter with new courage, and, although they had had many vessels sunk, and a few captured, they continued the fight until the arrival of their friends caused their assailant, Hanno, to hoist the signal for retreat. The Roman third division, embarrassed by its convoy, had been driven back until quite close to the land, and while sharp-pointed, surf-beaten rocks appeared under their sterns, it was attacked on both sides and in front, by the nimble Carthaginians. Vessel by vessel it was falling into the enemy’s hands, when Manlius, seeing its critical condition, relinquished his own pursuit, and hastened to its relief. His presence converted defeat into victory, and insured the complete triumph of the Roman arms; so that, while the Carthaginians scattered in flight, the Romans, towing their prizes stern foremost, as was their custom in victory, entered the harbor of Heraclea.

In this sanguinary and decisive battle thirty of the Carthaginian and twenty-four of the Roman quinqueremes were sent to the bottom, with all on board. Not a single Roman vessel was carried off by the enemy; while the Romans captured sixty-four ships and their crews.

[I-44]

Commodore Parker, of the U. S. Navy, in commenting upon this important naval action, says, “Had Hanno and the commander of the Carthaginian reserve done their duty faithfully and intelligently upon this occasion, the Roman van and centre must have been doubled up and defeated, almost instantly; after which it would have been an easy matter to get possession of the others, with the transports. Thus the Carthaginians would have gained a decisive victory, the effect of which would have been, perhaps, to deter the Romans from again making their appearance in force upon the sea; and then, with such leaders as Hamilcar, Hasdrubal and Hannibal to shape her policy and conduct her armaments, Carthage, instead of Rome, might have been the mistress of the world. Such are the great issues sometimes impending over contending armies and fleets.”

As soon as the Consuls had repaired damages they set sail from Heraclea for Africa, where they disembarked an army under Regulus; and most of the naval force, with the prisoners, then returned home. Regulus, however, soon suffered a defeat, and the Roman fleet had to be despatched to Africa again, in hot haste, to take off the scant remnant of his army. Before taking on board the defeated Legions the fleet had another great naval battle; and captured a Carthaginian fleet of one hundred and fourteen vessels. With the soldiers on board, and their prizes in tow, Marcus Emilius and Servius Fulvius, the Consuls then in command, determined to return to Rome by the south shore of Sicily. This was against the earnest remonstrances of the pilots, or sailing masters, “who wisely argued that, at the dangerous season when, the constellation of Orion being not quite past, and the Dog Star just ready to appear, it were far safer to go North about.”

[I-45]

The Consuls, who had no idea of being advised by mere sailors, were unfortunately not to be shaken in their determination; and so, when Sicily was sighted, a course was shaped from Lylybeum to the promontory of Pachymus. The fleet had accomplished about two-thirds of this distance, and was just opposite a coast where there were no ports, and where the shore was high and rocky, when, with the going down of the sun, the north wind, which had been blowing steadily for several days, suddenly died away, and as the Romans were engaged in furling their flapping sails they observed that they were heavy and wet with the falling dew, the sure precursor of the terrible “Scirocco.” Then the pilots urged the Consuls to pull directly to the southward, that they might have sea room sufficient to prevent them from being driven on shore when the storm should burst upon them. But this, with the dread of the sea natural to men unaccustomed to contend with it, they refused to do; not comprehending that, although their quinqueremes were illy adapted to buffet the waves, anything was better than a lee shore, with no harbor of refuge.

The north wind sprang up again after a little, cheering the hearts of the inexperienced, blew in fitful gusts for an hour or more, then died nearly away, again sprang up, and finally faded out as before. The seamen knew what this portended. “Next came a flash of lightning in the southern sky; then a line of foam upon the southern sea; the roaring of Heaven’s artillery in the air above, and of the breakers on the beach below—and the tempest was upon them!” From this time all order was lost, and the counsels and admonitions of the pilots unheeded. The Roman fleet was completely at the mercy of the hurricane, and the veterans who had borne themselves bravely in many a hard fought battle with their fellow man, now,[I-46] completely demoralized in the presence of this new danger, behaved more like maniacs than reasonable beings. Some advised one thing, some another; but nothing sensible was done—and when the gale broke, out of four hundred and sixty-four quinqueremes (an immense fleet) three hundred and eighty had been dashed upon the rocks and lost.

The whole coast was covered with fragments of wreck and dead bodies; and that which Rome had been so many years in acquiring, at the cost of so much blood, labor, and treasure, she lost in a few hours, through the want of experienced seamen in command.

During the succeeding Punic wars Rome and Carthage had many another well contested naval engagement.

Adherbal captured ninety-four Roman vessels off Drepanum, but the dogged courage of the Roman was usually successful.

We have few details of these engagements. What the Romans gained in battle was often lost by them in shipwreck; so that, at the end of the first Punic war, which lasted twenty-four years, they had lost seven hundred quinqueremes, and the vanquished Carthaginians only five hundred.

At the time spoken of, when the Romans were fighting the Carthaginians, the former were a free, virtuous and patriotic people. No reverses cast them down; no loss of life discouraged them.

After a lapse of two hundred years, Marcus Brutus and Cassius being dead, and public virtue scoffed at and fast expiring, an arbitrary government was in process of erection upon the ruins of the Republic.

The triumvirate had been dissolved, and Octavius and Antony, at the head of vast armies and fleets, were preparing,[I-47] on opposite sides of the Gulf of Ambracia, to submit their old quarrel to the arbitrament of the sword. In this emergency Antony’s old officers and soldiers, whom he had so often led to victory, naturally hoped that, assuming the offensive, he would draw out his legions, and, by his ability and superior strategy, force his adversary from the field. But, bewitched by a woman, the greatest captain of the age—now that Cæsar and Pompey were gone—had consented to abandon a faithful and devoted army, and to rely solely upon his fleet; which, equal to that of Octavius in numbers, was far inferior in discipline and drill, and in experience of actual combat.

ROMAN GALLEY.

[I-48]

Scene VII. Near Actium. Antony’s Camp.

Enter Antony and Canidius.

Ant.

Is it not strange, Canidius,

That from Tarentum and Brundusium

He could so quickly cut the Ionian Sea,

And taken in Toryne? you have heard on’t, sweet?

Cleo.

Celerity is never more admired

Than by the negligent.

Ant.

A good rebuke,

Which might have well becomed the best of men,

To taunt at slackness. Canidius, we

Will fight with him by sea.

Cleo.

By sea! What else?

Canid.

Why will my lord do so?

Ant.

For that he dares us to ’t.

Enob.

So hath my lord dared him to single fight.

Canid.

Ay, and to wage this battle at Pharsalia,

Where Cæsar fought with Pompey: but these offers

Which serve not for his vantage he shakes off;

And so should you.

Enob.

Your ships are not well mann’d;

Your mariners are muleteers, reapers, people

Ingrossed by swift impress; in Cæsar’s fleet

Are those that often have ’gainst Pompey fought;

Their ships are yare; yours, heavy; no disgrace

Shall fall you for refusing him at sea,

Being prepared for land.

Ant.

By sea, by sea.

Enob.

Most worthy sir, you therein throw away

The absolute soldiership you have by land;

Distract your army, which doth most consist

[I-49]

Of war-mark’d footmen; leave unexecuted

Your own renowned knowledge; quite forego

The way which promises assurance; and

Give up yourself merely to chance and hazard,

From firm security.

Ant.

I’ll fight at sea.

Cleo.

I have sixty sails, Cæsar none better.

Ant.

Our overplus of shipping will we burn;

And, with the rest full mann’d, from the head of Actium,

Beat the approaching Cæsar. But if we fail,

We then can do ’t at land.

Shakespeare—Antony and Cleopatra.