Title: Aberdeenshire

Author: Alexander Mackie

Release date: April 5, 2024 [eBook #73335]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Cambridge University Press

Credits: Fiona Holmes and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The use of =L= around a letter indicates bold.

Hyphenations have been standardised.

Changes made are noted at the end of the book.

Because there are so many illustrations, it wasn't always possible to place them between paragraphs.

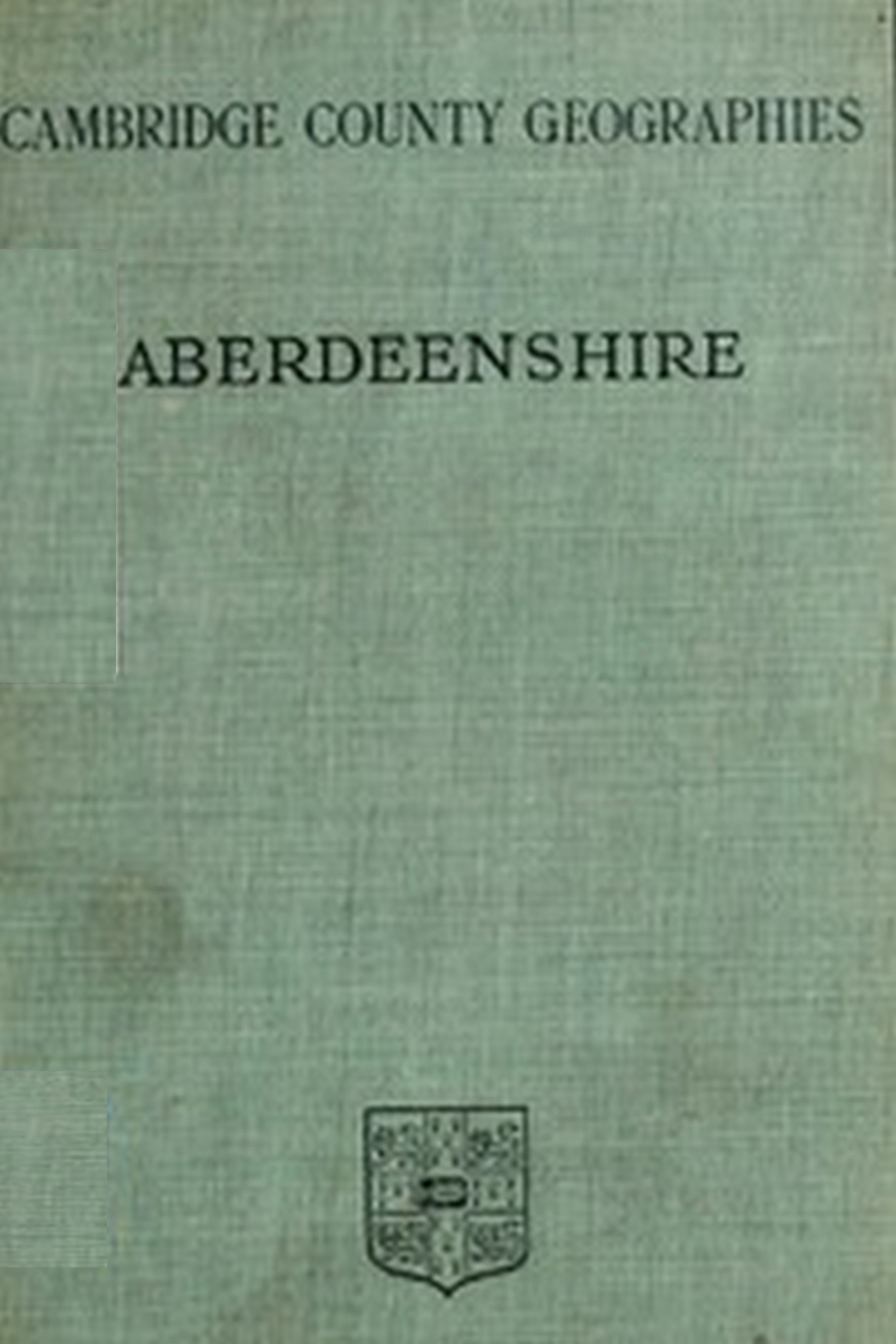

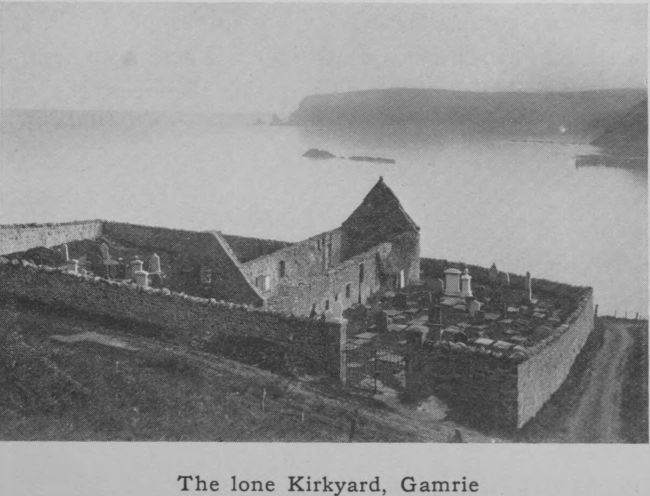

PHYSICAL MAP OF COUNTY OF

ABERDEEN

_Copyright. George Philip & Son L^{td}_

Click here for larger map CAMBRIDGE COUNTY GEOGRAPHIES

SCOTLAND

General Editor: W. MURISON, M.A.

ABERDEENSHIRE

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

London: FETTER LANE, E.C.

C. F. CLAY, MANAGER

Edinburgh: 100, PRINCES STREET

Berlin: A. ASHER AND CO.

Leipzig: F. A. BROCKHAUS

New York: G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Bombay and Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD.

All rights reserved

Cambridge County Geographies

ABERDEENSHIRE

by

ALEXANDER MACKIE, M.A.

Late Examiner in English, Aberdeen University, and

author of Nature Knowledge in Modern Poetry

With Maps, Diagrams and Illustrations

Cambridge:

at the University Press

1911

Cambridge:

PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A.

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS

[v]

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1. | County and Shire. The Origin of Aberdeenshire | 1 |

| 2. | General Characteristics | 4 |

| 3. | Size. Shape. Boundaries | 10 |

| 4. | Surface, Soil and General Features | 15 |

| 5. | Watershed. Rivers. Lochs | 20 |

| 6. | Geology | 35 |

| 7. | Natural History | 43 |

| 8. | Round the Coast | 52 |

| 9. | Weather and Climate. Temperature. Rainfall. Winds | 64 |

| 10. | The People—Race, Language, Population | 70 |

| 11. | Agriculture | 76 |

| 12. | The Granite Industry | 83 |

| 13. | Other Industries. Paper, Wool, Combs | 89 |

| 14. | Fisheries | 94 |

| 15. | Shipping and Trade | 102[vi] |

| 16. | History of the County | 105 |

| 17. | Antiquities—Circles, Sculptured Stones, Crannogs, Forts | 112 |

| 18. | Architecture—(_a_) Ecclesiastical | 121 |

| 19. | Architecture—(_b_) Castellated | 132 |

| 20. | Architecture—(_c_) Municipal | 145 |

| 21. | Architecture—(_d_) Domestic | 154 |

| 22. | Communications—Roads, Railways | 160 |

| 23. | Administration and Divisions | 166 |

| 24. | The Roll of Honour | 170 |

| 25. | The Chief Towns and Villages of Aberdeenshire | 178[vii] |

| PAGE | |

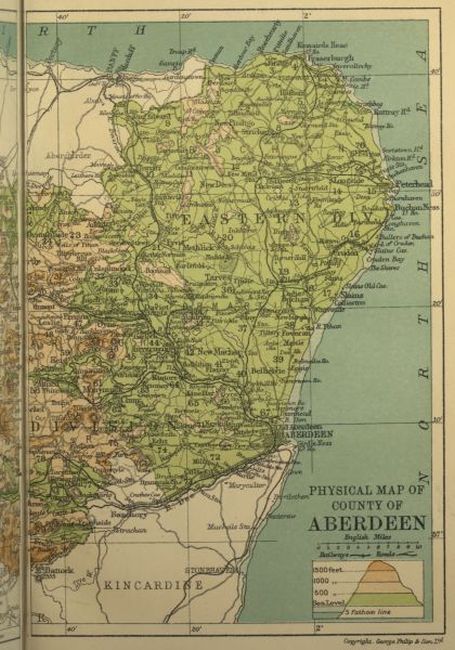

| The lone Kirkyard, Gamrie | 3 |

| Town House, Old Aberdeen | 5 |

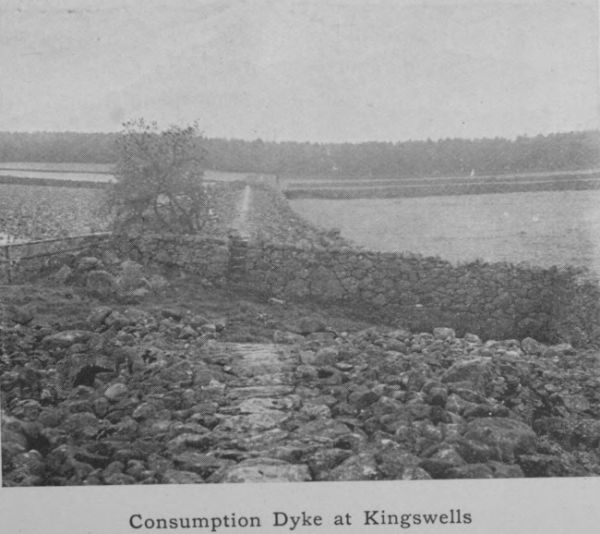

| Consumption Dyke at Kingswells | 7 |

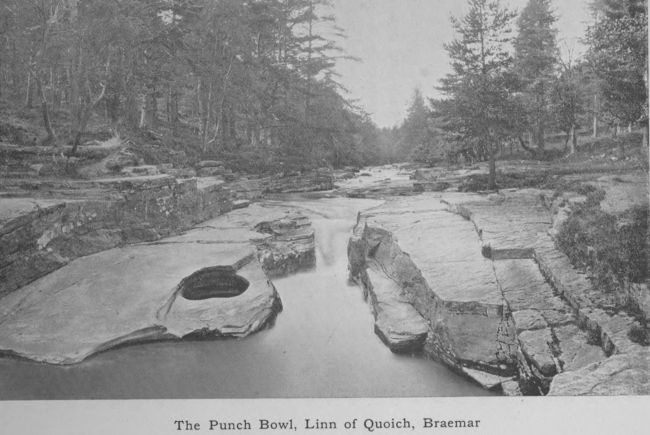

| The Punch Bowl, Linn of Quoich, Braemar | 9 |

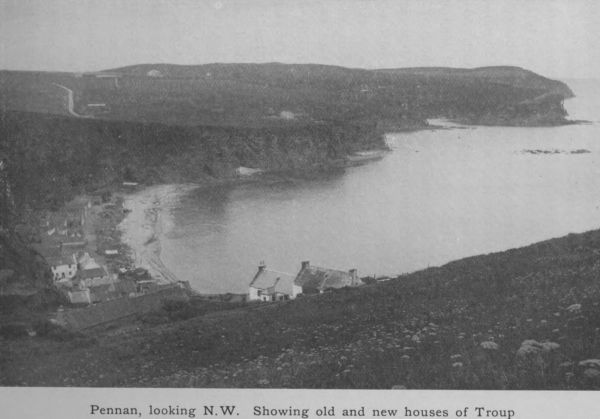

| Pennan, looking N.W. Showing old and new houses of Troup | 12 |

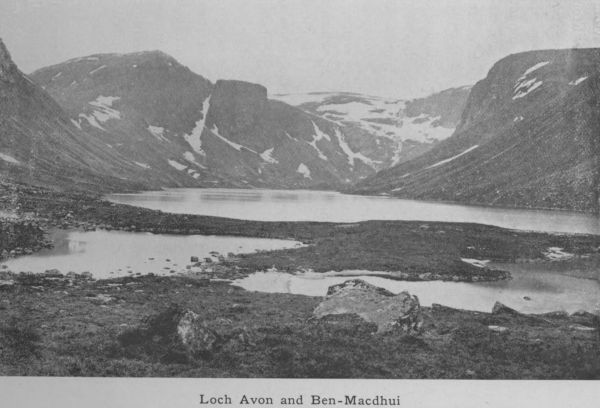

| Loch Avon and Ben-Macdhui | 14 |

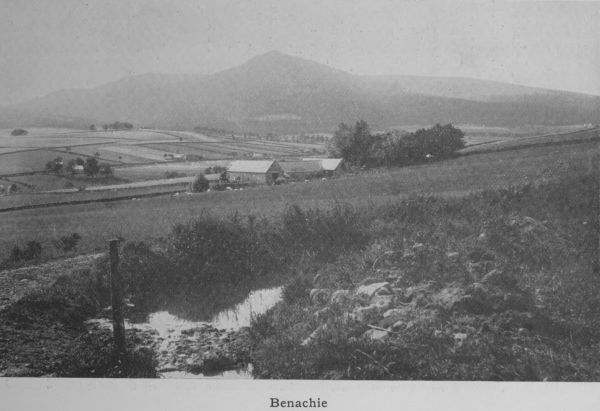

| Benachie | 19 |

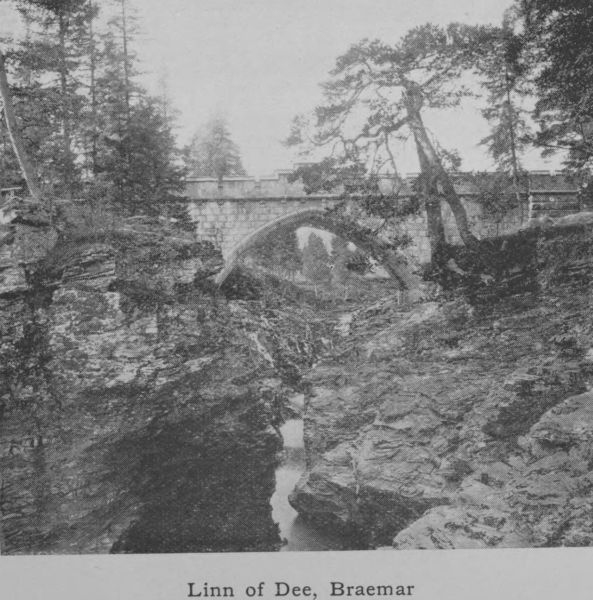

| Linn of Dee, Braemar | 21 |

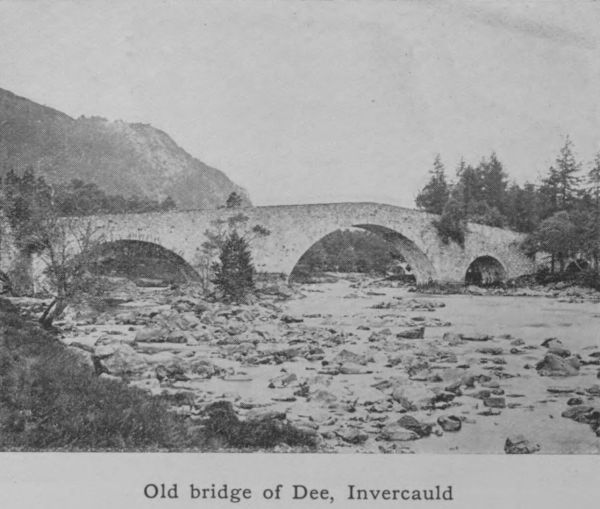

| Old bridge of Dee, Invercauld | 22 |

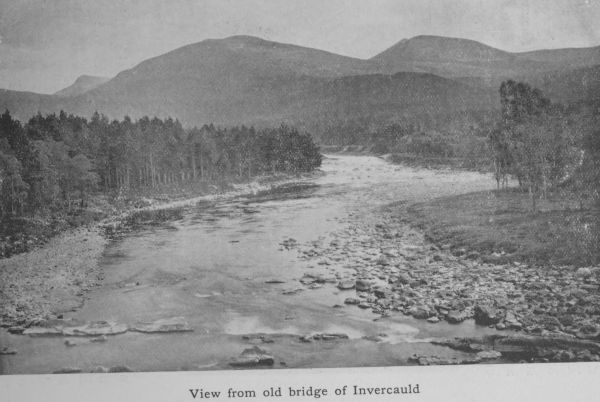

| View from old bridge of Invercauld | 23 |

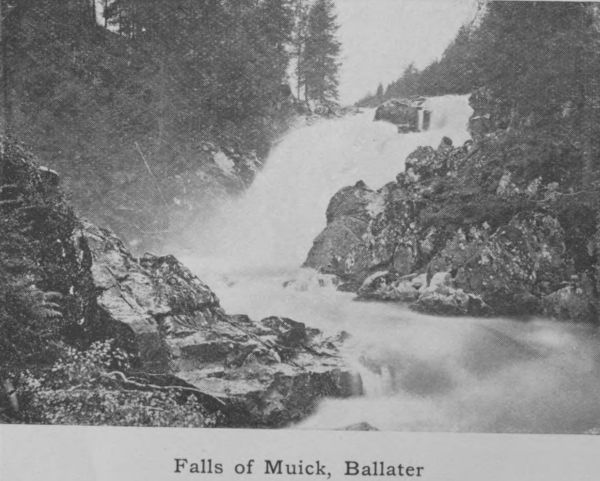

| Falls of Muick, Ballater | 24 |

| Birch Tree at Braemar | 26 |

| Fir Trees at Braemar | 28 |

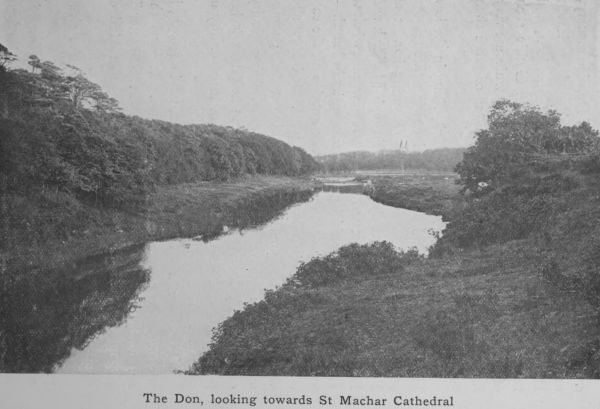

| The Don, looking towards St Machar Cathedral | 30 |

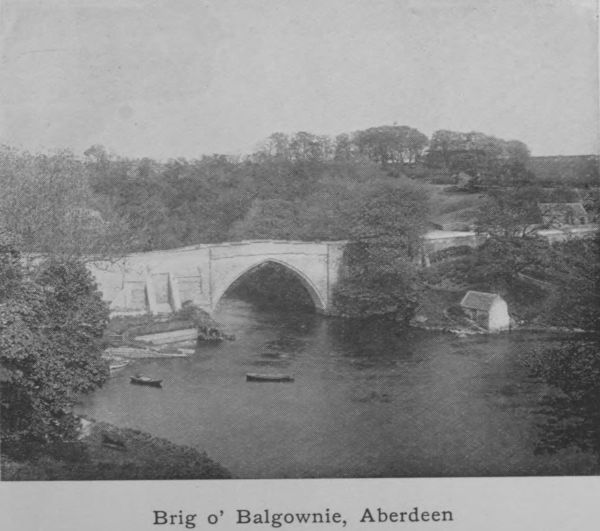

| Brig o’ Balgownie, Aberdeen | 31 |

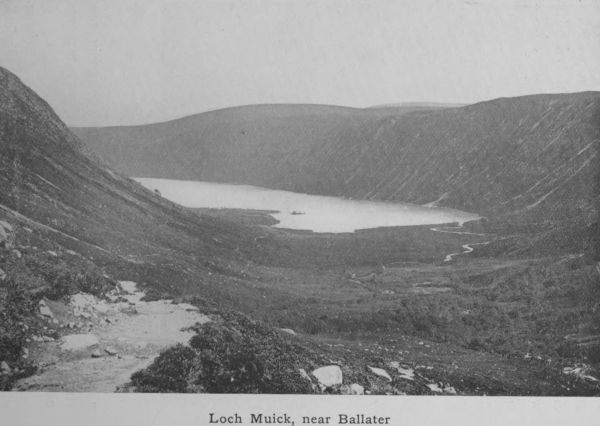

| Loch Muick, near Ballater | 32 |

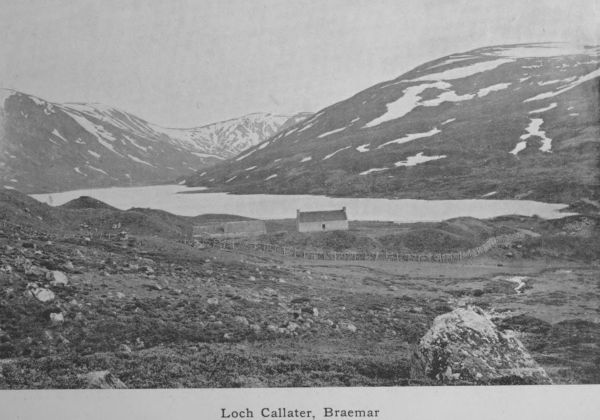

| Loch Callater, Braemar | 34 |

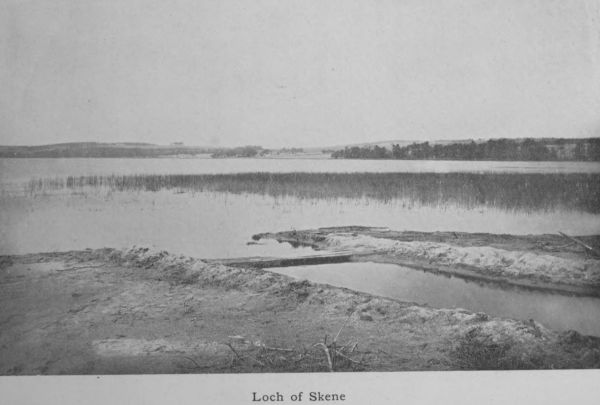

| Loch of Skene | 36 |

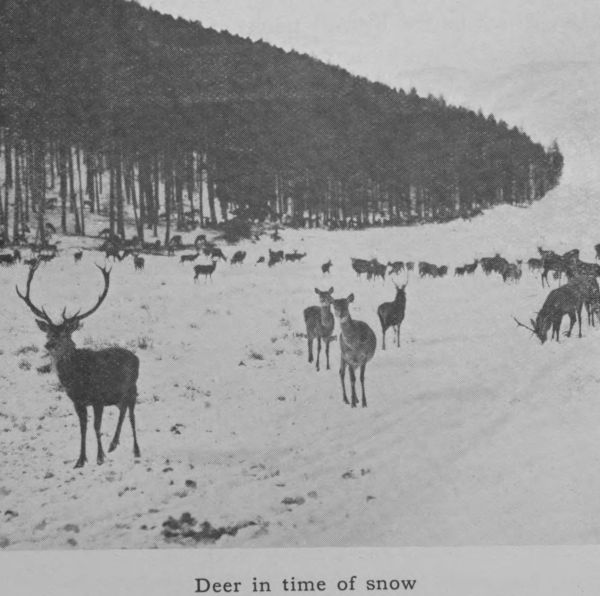

| Deer in time of snow | 47 |

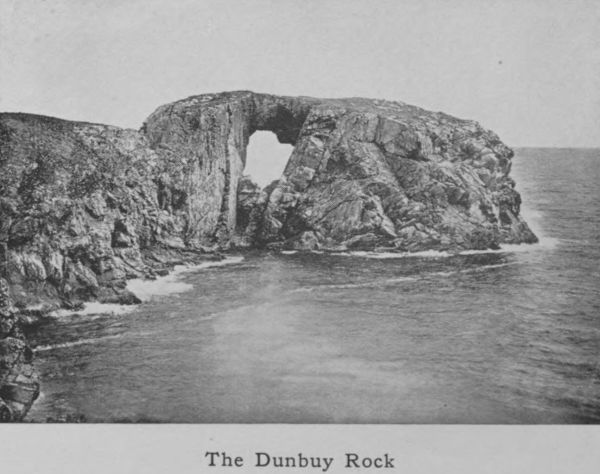

| The Dunbuy Rock | 48 |

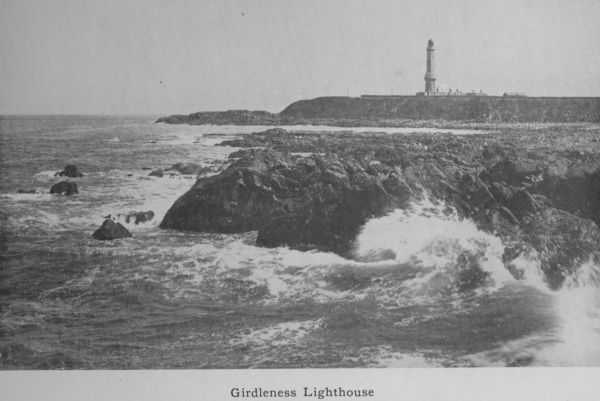

| Girdleness Lighthouse | 53[viii] |

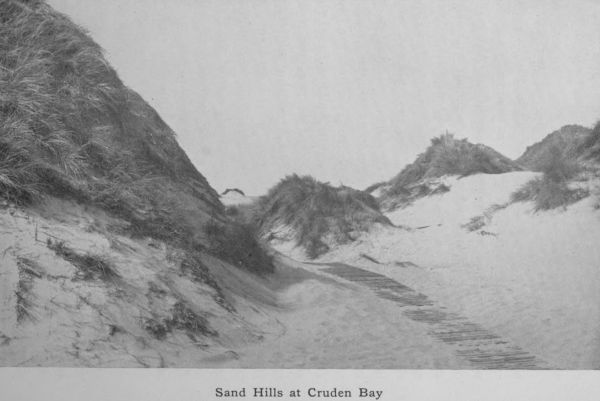

| Sand Hills at Cruden Bay | 56 |

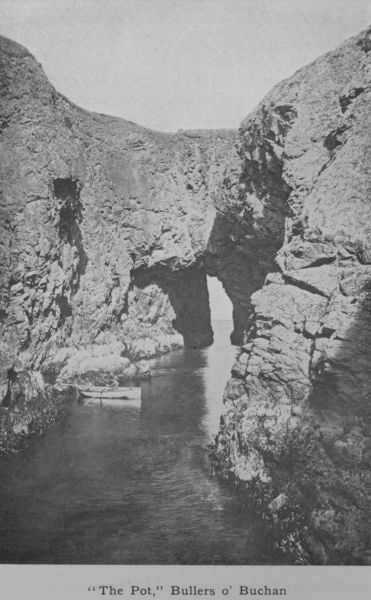

| “The Pot,” Bullers o’ Buchan | 58 |

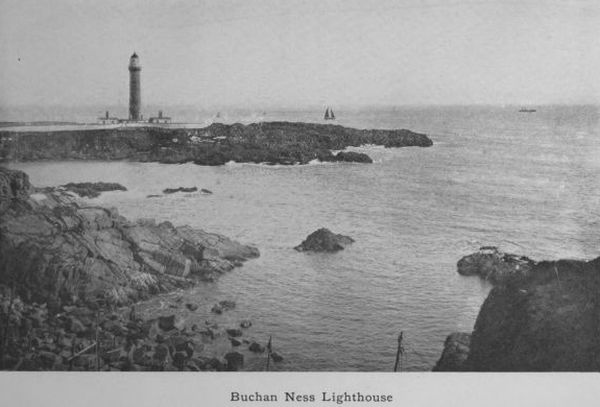

| Buchan Ness Lighthouse | 60 |

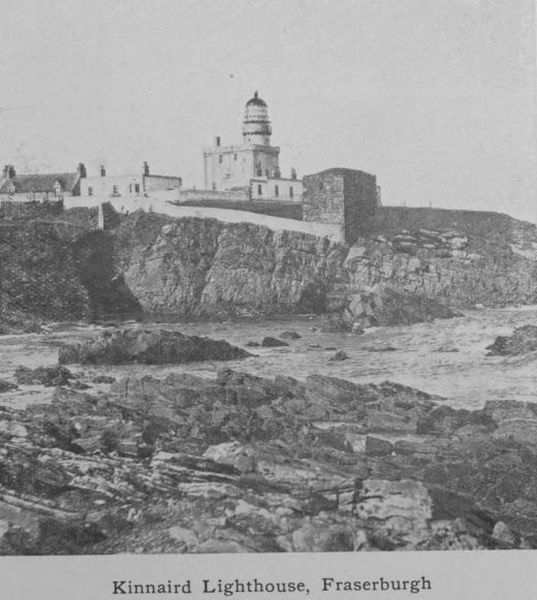

| Kinnaird Lighthouse, Fraserburgh | 61 |

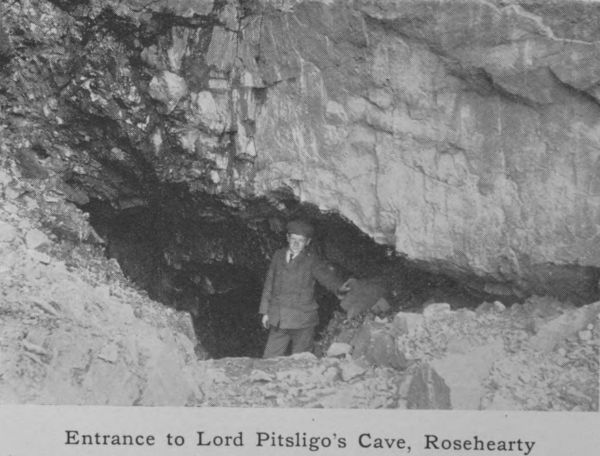

| Entrance to Lord Pitsligo’s Cave, Rosehearty | 62 |

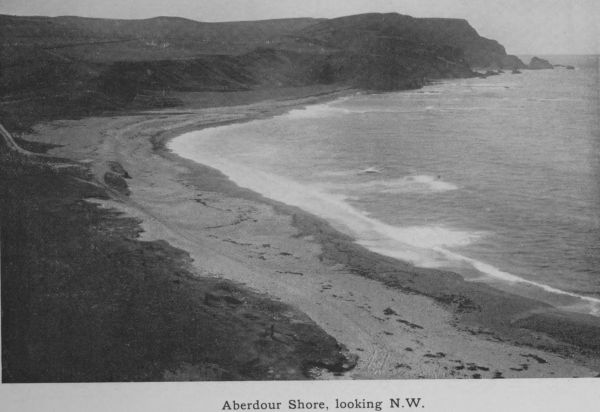

| Aberdour Shore, looking N.W. | 63 |

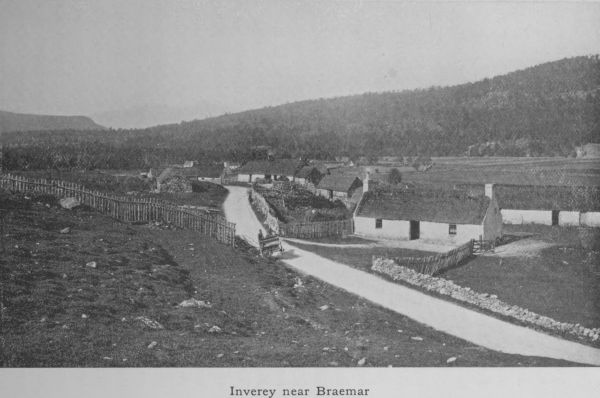

| Inverey near Braemar | 67 |

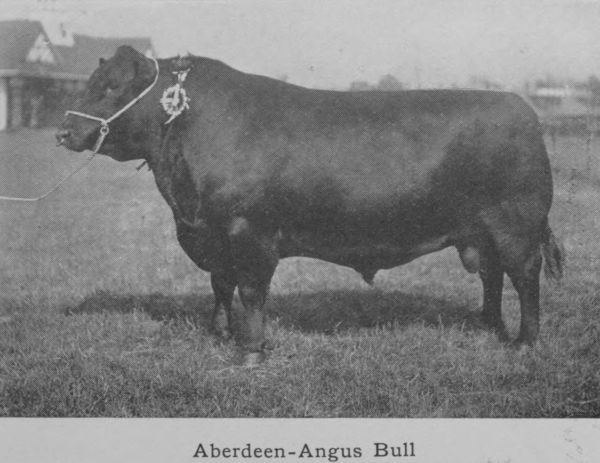

| Aberdeen-Angus Bull | 81 |

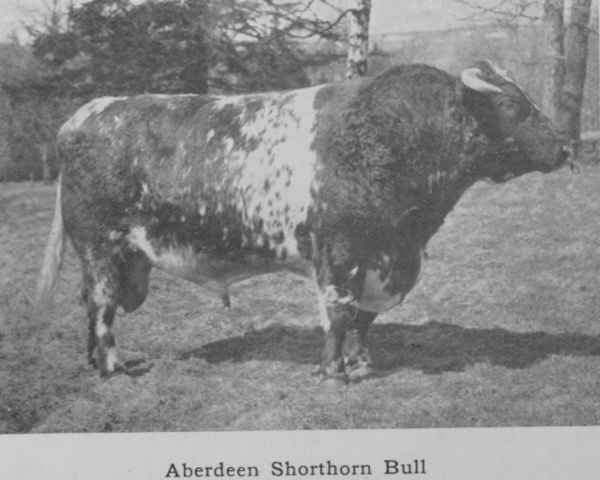

| Aberdeen Shorthorn Bull | 82 |

| Granite Quarry, Kemnay | 84 |

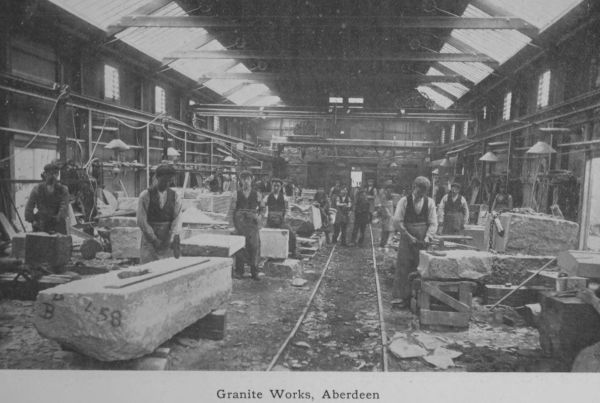

| Granite Works, Aberdeen | 86 |

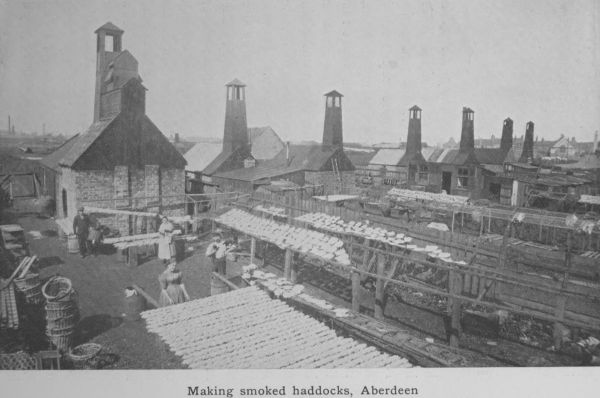

| Making smoked haddocks, Aberdeen | 93 |

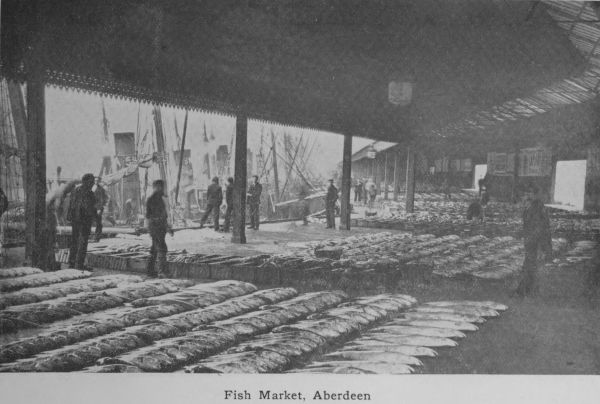

| Fish Market, Aberdeen | 97 |

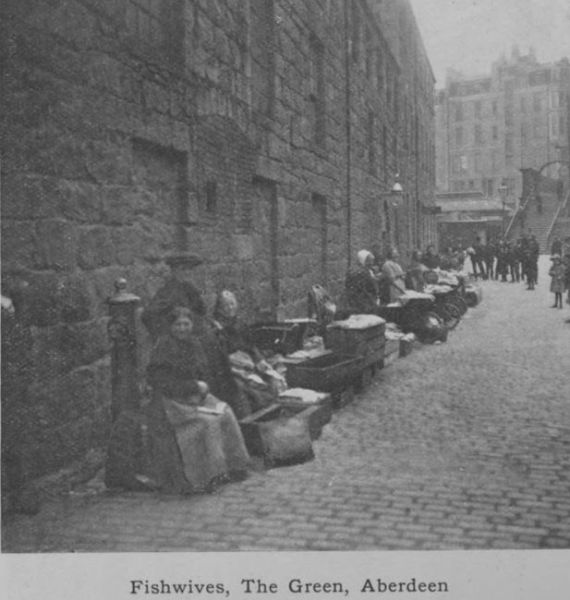

| Fishwives, The Green, Aberdeen | 98 |

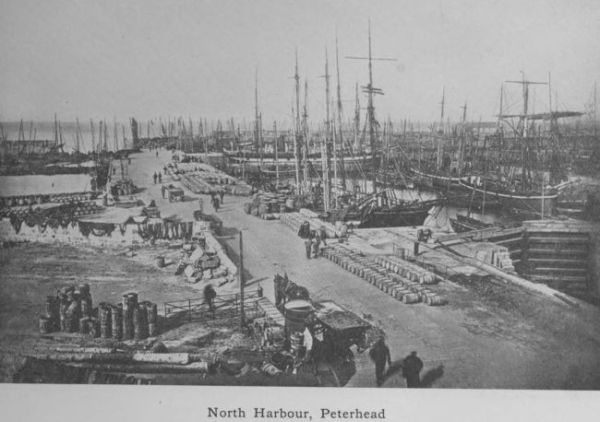

| North Harbour, Peterhead | 99 |

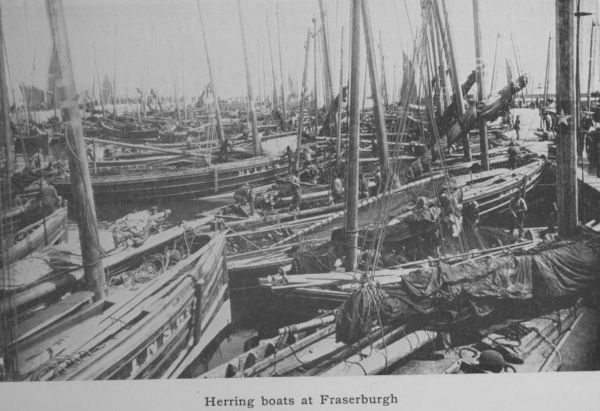

| Herring boats at Fraserburgh | 100 |

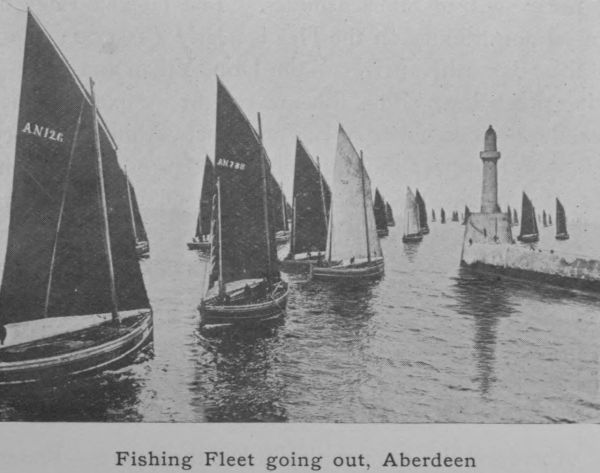

| Fishing Fleet going out, Aberdeen | 101 |

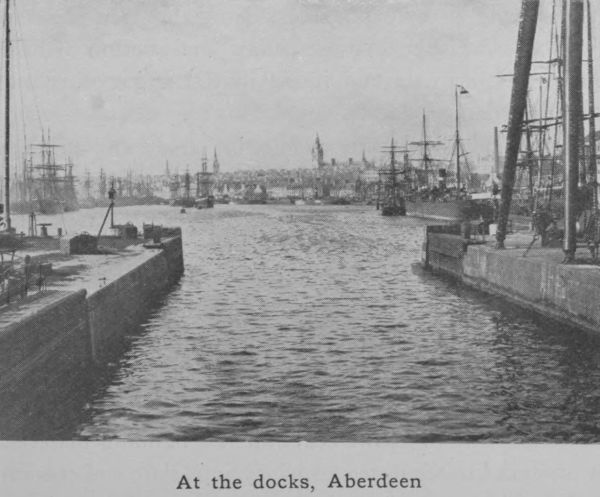

| At the docks, Aberdeen | 103 |

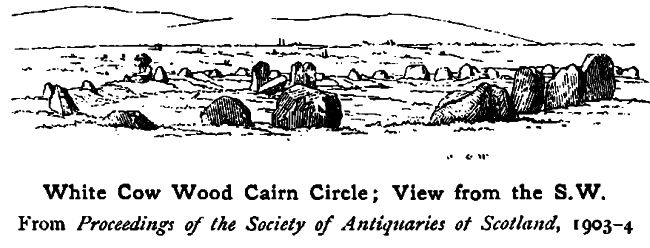

| White Cow Wood Cairn Circle; View from the S.W. | 113 |

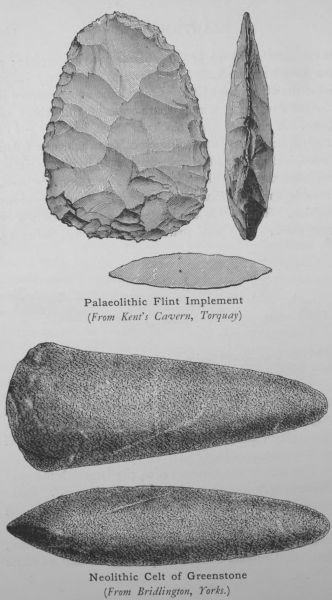

| Palaeolithic Flint Implement | 114 |

| Neolithic Celt of Greenstone | 114 |

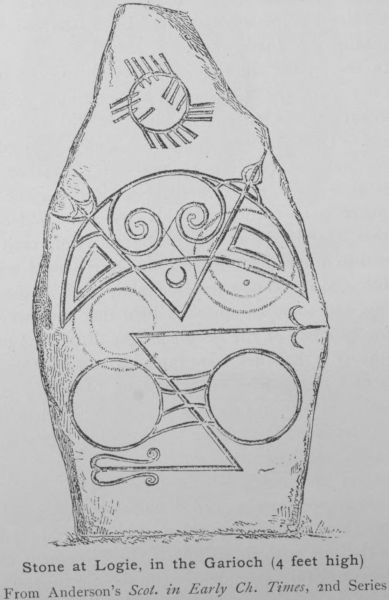

| Stone at Logie, in the Garioch | 116 |

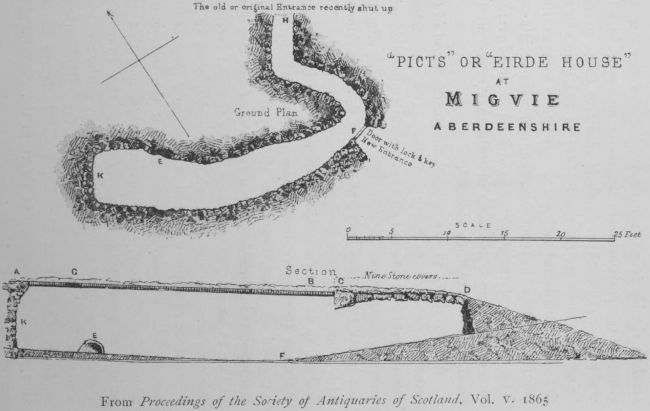

| “Picts” or “Eirde House” at Migvie, Aberdeenshire | 118 |

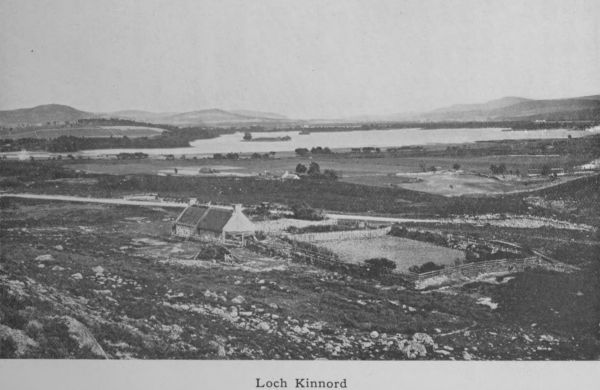

| Loch Kinnord | 120 |

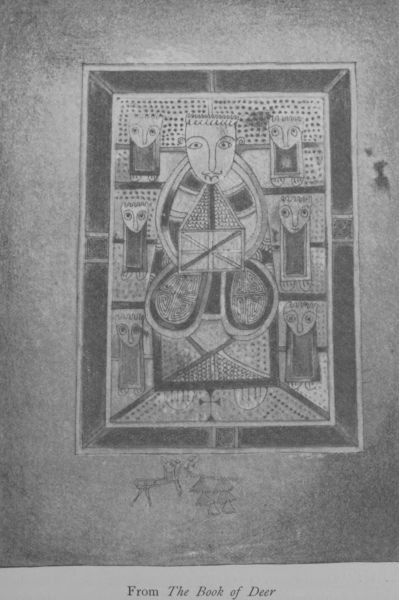

| From _The Book of Deer_ | 125 |

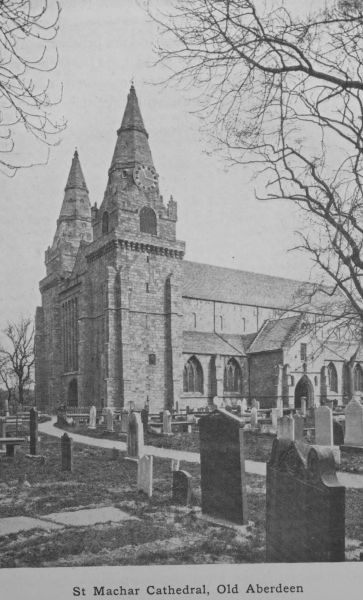

| St Machar Cathedral, Old Aberdeen | 127 |

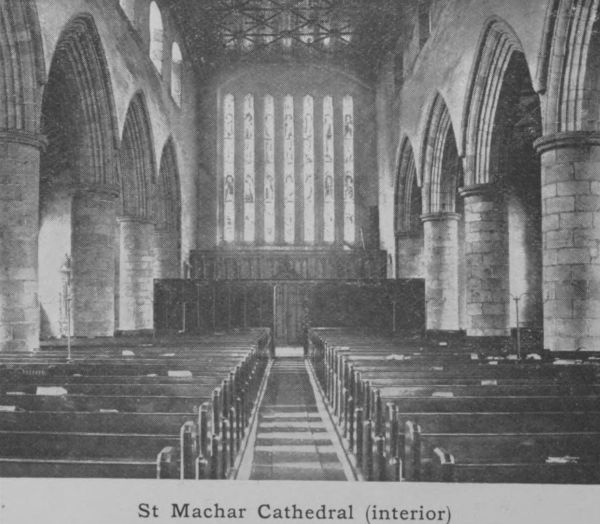

| St Machar Cathedral (interior) | 128 |

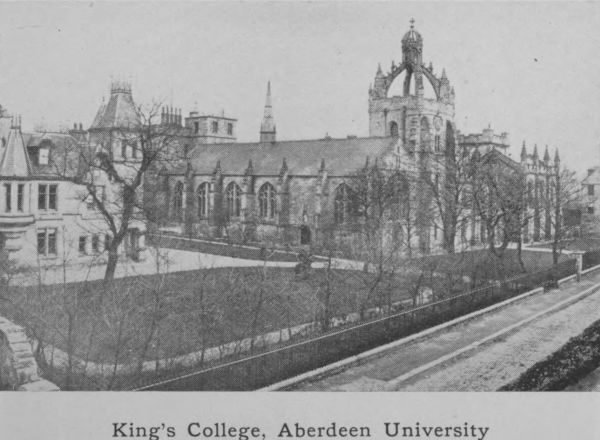

| King’s College, Aberdeen University | 129 |

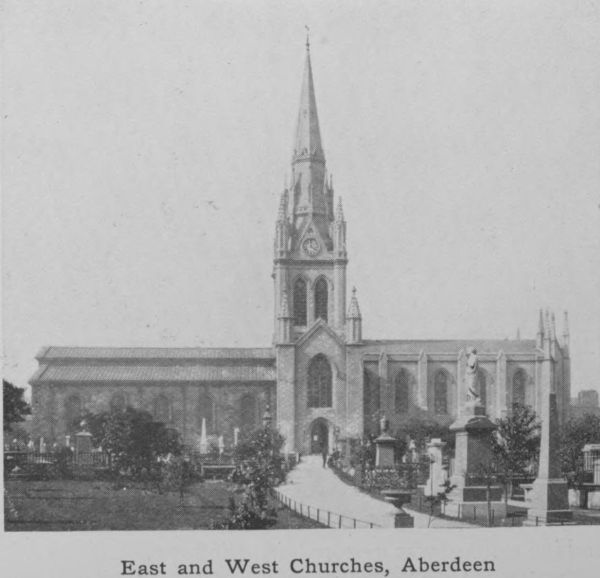

| East and West Churches, Aberdeen | 130 |

| Kildrummy Castle | 133 |

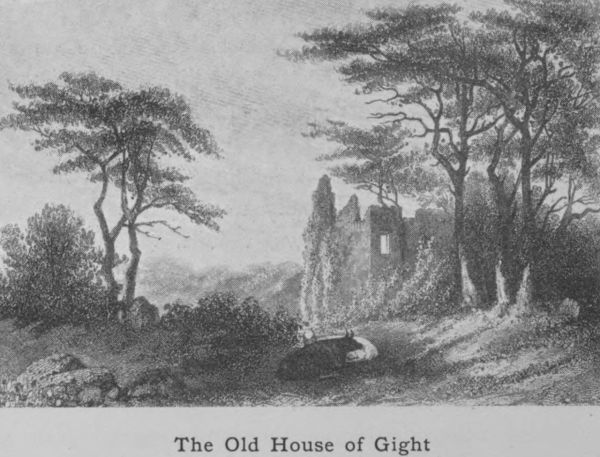

| The Old House of Gight | 138 |

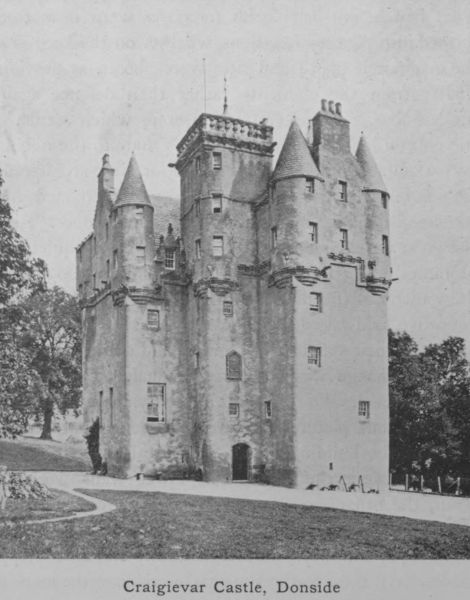

| Craigievar Castle, Donside | 140 |

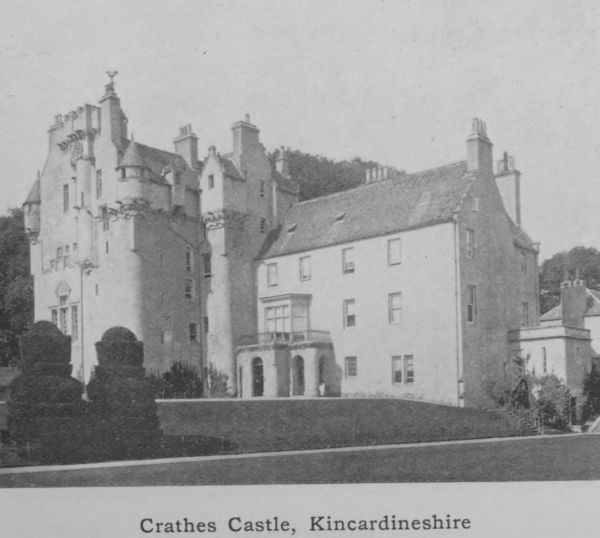

| Crathes Castle, Kincardineshire | 141 |

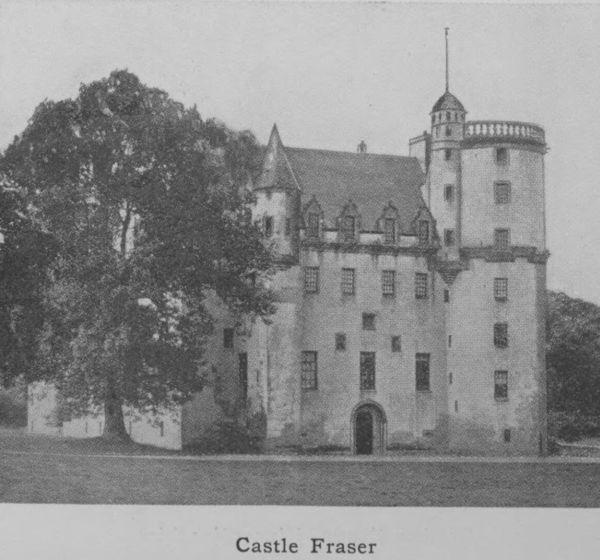

| Castle Fraser[ix] | 142 |

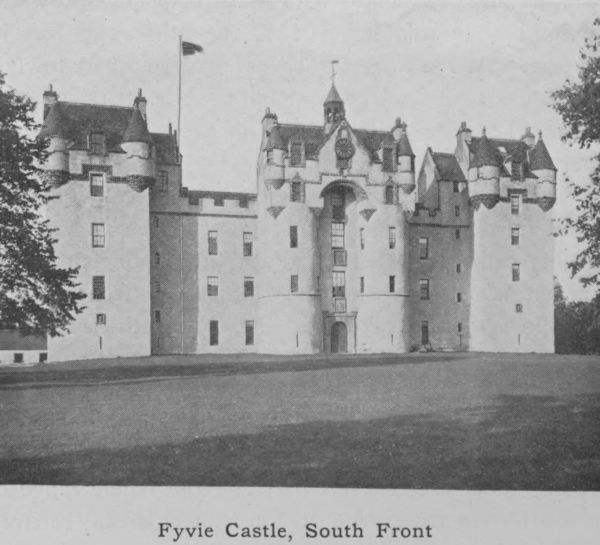

| Fyvie Castle, South Front | 144 |

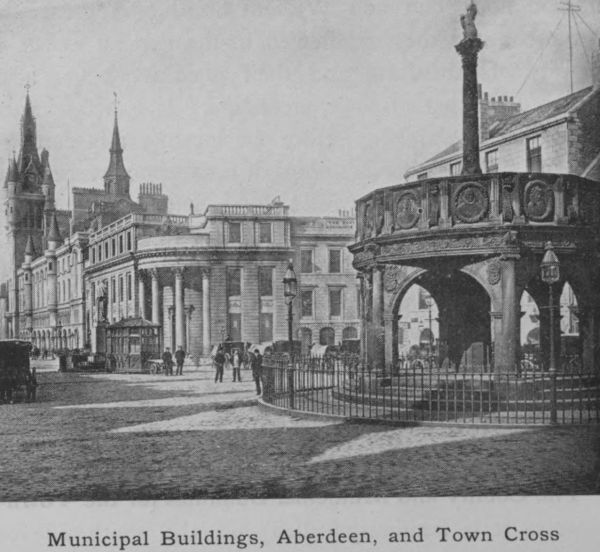

| Municipal Buildings, Aberdeen, and Town Cross | 146 |

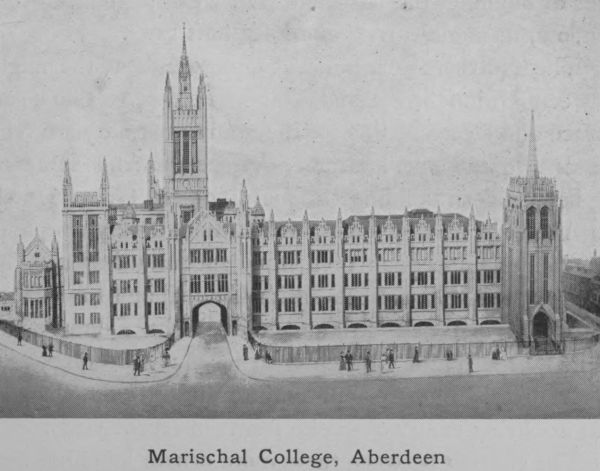

| Marischal College, Aberdeen | 147 |

| Union Terrace and Gardens, before widening of Bridge | 149 |

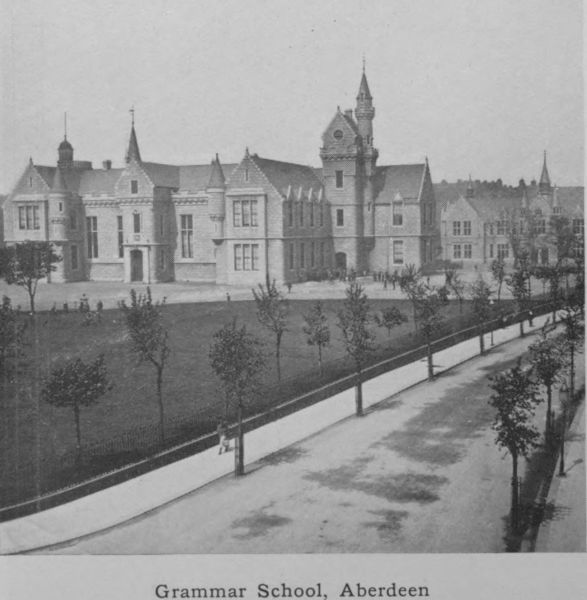

| Grammar School, Aberdeen | 150 |

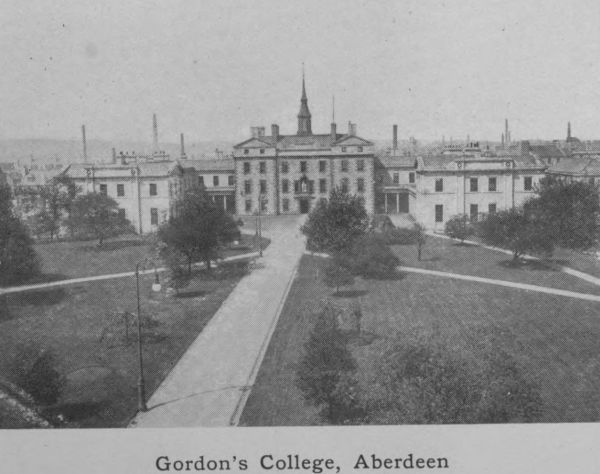

| Gordon’s College, Aberdeen | 151 |

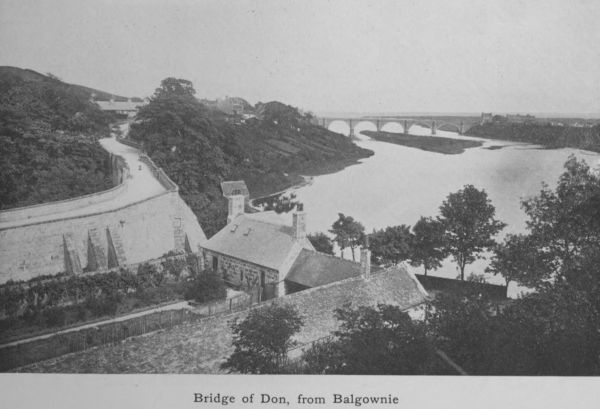

| Bridge of Don, from Balgownie | 152 |

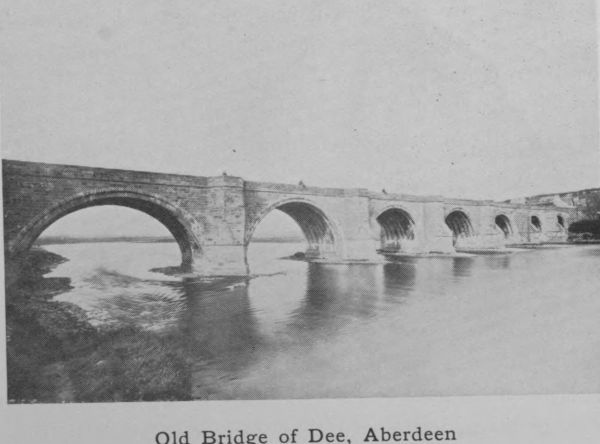

| Old Bridge of Dee, Aberdeen | 153 |

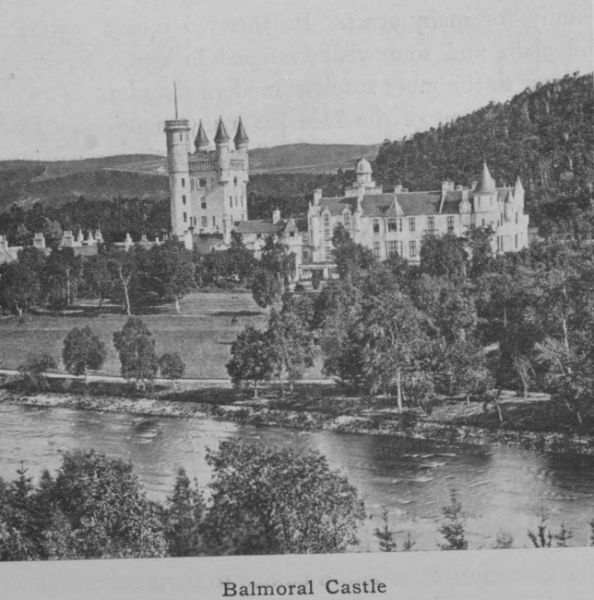

| Balmoral Castle | 155 |

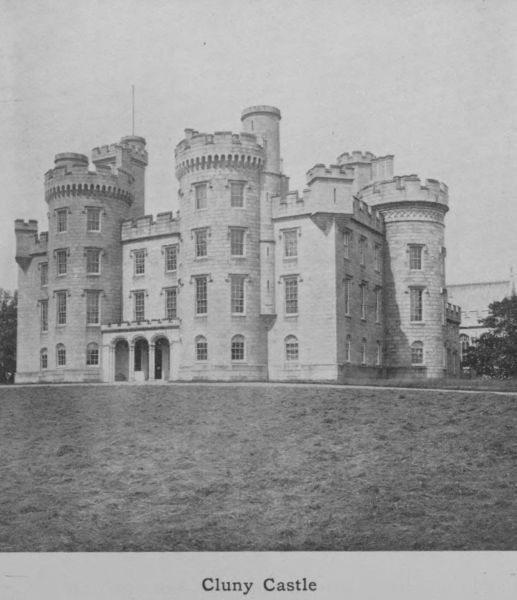

| Cluny Castle | 157 |

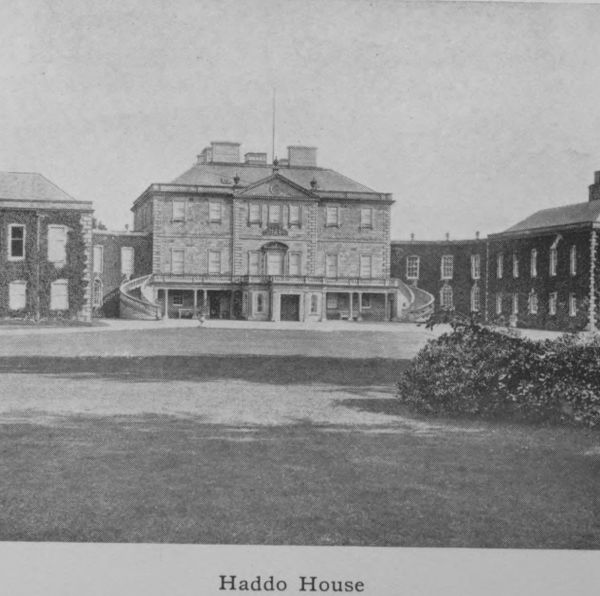

| Haddo House | 158 |

| Midmar Castle | 159 |

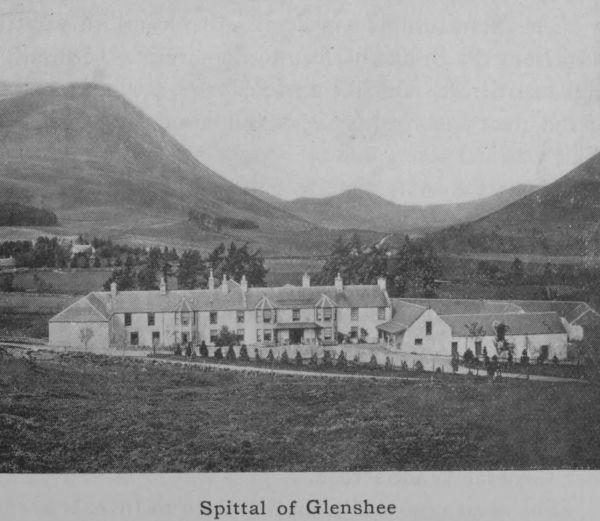

| Spittal of Glenshee | 161 |

| Professor Thomas Reid, D.D. | 175 |

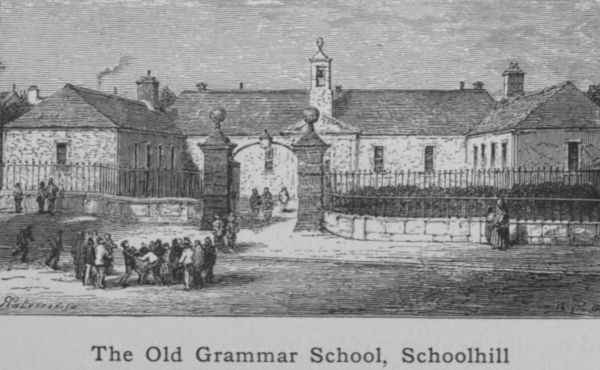

| The Old Grammar School, Schoolhill | 179 |

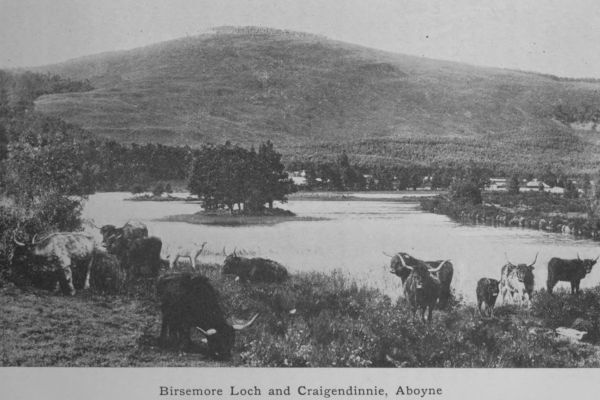

| Birsemore Loch and Craigendinnie, Aboyne | 182 |

| Mar Castle | 183 |

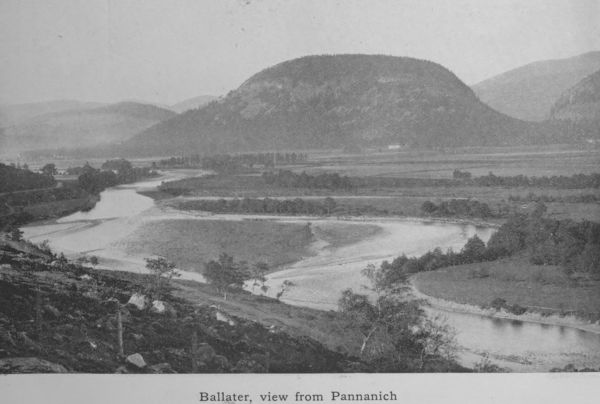

| Ballater, view from Pannanich | 184 |

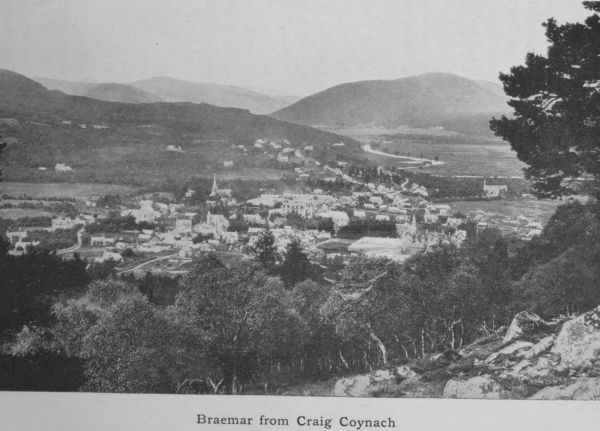

| Braemar from Craig Coynach | 186 |

| The Doorway, Huntly Castle | 188 |

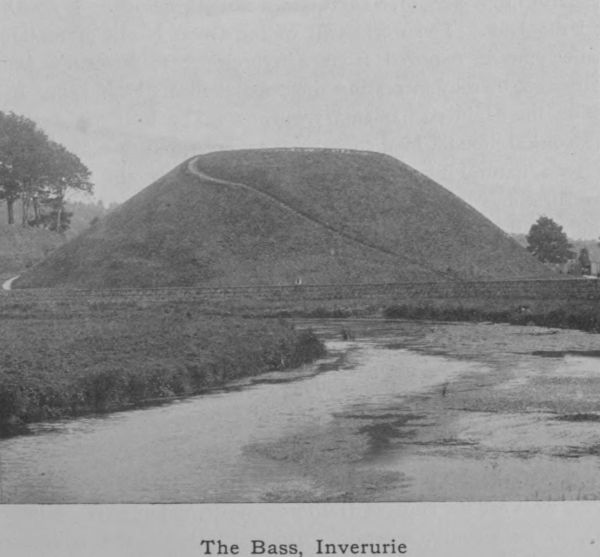

| The Bass, Inverurie | 189 |

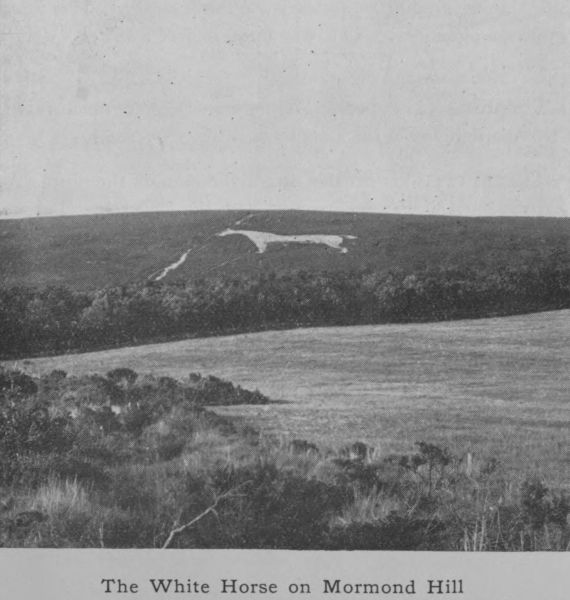

| The White Horse on Mormond Hill | 193 |

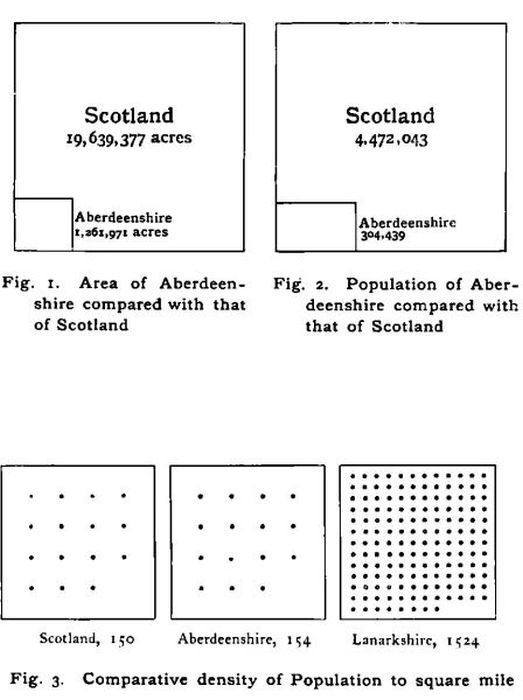

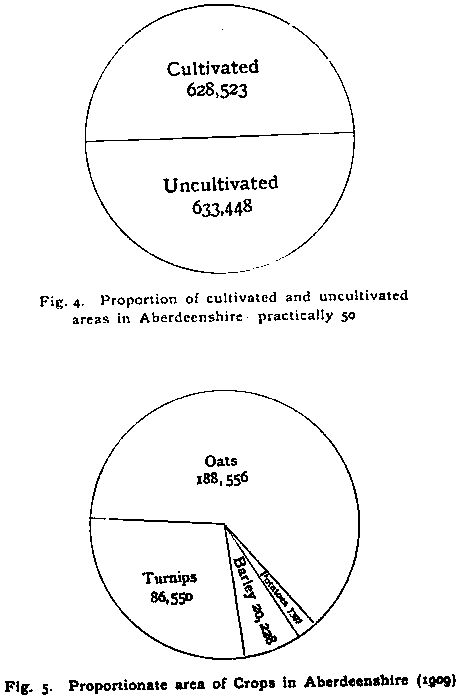

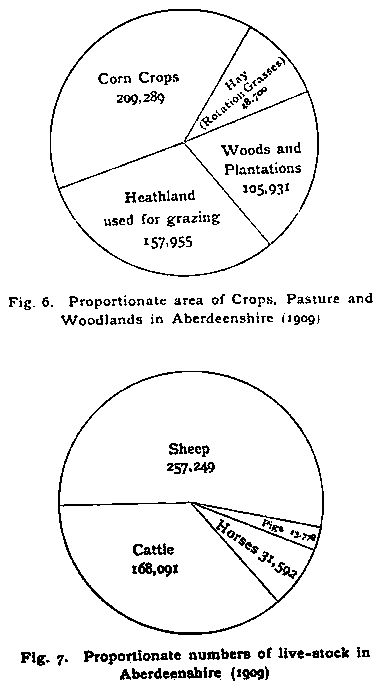

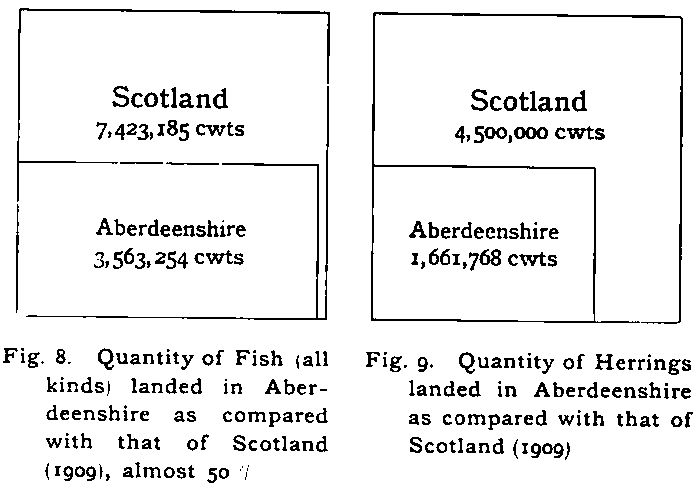

| Diagrams | 195 |

| Orographical Map of Aberdeenshire | Front Cover |

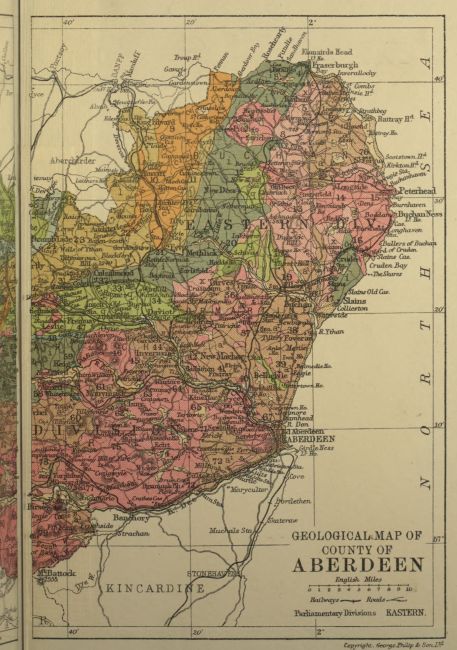

| Geological Map of Aberdeenshire | Back Cover |

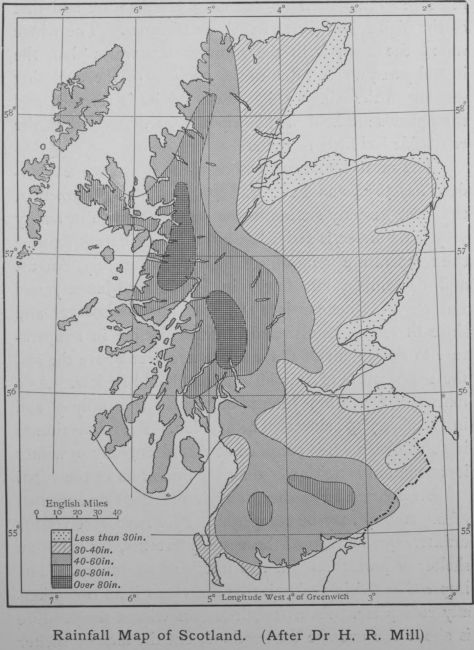

| Rainfall Map of Scotland | 65 |

The illustrations on pp. 3, 12, 62, 63 are from photographs by W. Norrie; those on pp. 5, 9, 14, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 28, 30, 31, 32, 34, 36, 48, 53, 56, 58, 60, 61, 67, 86, 93, 97, 98, 99,[x] 100, 101, 103, 120, 127, 128, 129, 130, 133, 140, 141, 144, 146, 147, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 155, 157, 158, 159, 161, 182, 183, 184, 186, 188 and 189, are from photographs by J. Valentine and Sons; that on p. 7 from a photograph by J. Watt; that on p. 47 from a photograph by Dr W. Brown; that on p. 84 from a photograph by A. Gordon; that on p. 193 from a photograph by A. Gray.

Thanks are due to W. Duthie, Esq., Collynie, for permission to reproduce the illustration on p. 82; to J. McG. Petrie, Esq., Glen-Logie, for permission to reproduce that on p. 81; to Messrs T. and R. Annan and Sons, for permission to reproduce that on p. 175; to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland for permission to reproduce those on pp. 113 and 118; and to Alexander Walker, Jr., Esq., Aberdeen, for permission to reproduce that on p. 179.

[1]

The term “shire,” which means a division (Anglo-Saxon sciran: to cut or divide), has in Scotland practically the same meaning as “county.” In most cases the two names are interchangeable. Yet we do not say Orkneyshire nor Kirkcudbrightshire. Kirkcudbright is a stewartry and not a county, but in regard to the others we call them with equal readiness shires or counties. County means originally the district ruled by a Count, the Norman equivalent of Earl. It is said that Aberdeenshire is the result of a combination of two counties, Buchan and Mar, representing the territory under the rule of the Earl of Buchan and the Earl of Mar. The distinction is in effect what we mean to-day by East Aberdeenshire and West Aberdeenshire; and the local students of Aberdeen University when voting for their Lord Rector by “nations” are still classified as belonging to either the Buchan nation or the Mar nation according to their place of birth.

The counties, then, are certain areas which it is convenient for political and administrative purposes to[2] divide the country into for the better and more convenient management of local and internal affairs. To-day Scotland has thirty-three of these divisions. In a public ordinance dated 1305, twenty-five counties are named. They would seem to have been first defined early in the twelfth century, but as a matter of fact nothing very definite is known, either as to the date of their origin or as to the principles which regulated the making of their geographical boundaries. It is certain, however, that the county divisions were in Scotland an introduction from England. The term came along with the people who were flocking into Scotland from the south. The lines were drawn for what seemed political convenience and no doubt they were suited to the times. To-day the boundaries seem on occasion somewhat erratic. Banchory, for example, is in Kincardineshire, while Aboyne and Ballater on the same river bank and on the same line of road and railway are in Aberdeenshire. If the carving were to be done over again in the twentieth century, more consideration would probably be given to the railway lines.

A commission of 1891 did actually rearrange the boundaries. Of the parishes partly in Aberdeen and partly in Banff, some were transferred wholly to Aberdeen (Gartly, Glass, New Machar, Old Deer and St Fergus), while others were placed in Banffshire (Cabrach, Gamrie, Inverkeithny, Alvah and Rothiemay). How it happened that certain parts of adjoining counties were planted like islands in the heart of Aberdeenshire may be understood by reference to such a case as that of[3] St Fergus. A large part of this parish belonged to the Cheynes, who being hereditary sheriffs of Banffshire were naturally desirous of having their patrimonial estates under their own legal jurisdiction, and were influential enough to be able to stereotype this anomaly. This explains the place of St Fergus in Banffshire; it is now very properly a part of Aberdeenshire.

The lone Kirkyard, Gamrie

The county took its name from the chief town—Aberdeen—which is clearly Celtic in origin and means the town at the mouth of either the Dee or the Don. Both interpretations are possible; but the fact that the Latin form of the word has always been Aberdonia and _Aberdonensis_, favours the Don as the naming river. As a matter of fact, Old Aberdeen, though lying at no great[4] distance from the bank of the Don, can hardly be said to be associated with Donmouth, whereas a considerable population must from a remote period have been located at the mouth of the Dee. Whatever interpretation is accepted, it was this city—the only town in the district conspicuous for population and resources—that gave its name to the county as a whole.

The whole region between the river Dee and the river Spey, comprising the two counties of Banff and Aberdeen, forms a natural province. There is no natural, or recognisable line of demarcation between the two counties. Their fortunes have been one. The river Deveron might conceivably have been chosen as the dividing line, but in practice it is so only to a limited extent. The whole district, which if invaded was never really conquered by the Romans, made one of the seven Provinces of what was called Pictland in the early middle ages, and it long continued to assert for itself a semi-independent political existence.

[5]

Town House, Old Aberdeen

The county is almost purely agricultural. It has always enjoyed a certain measure of maritime activity and of recent years the fishing industry, especially at Aberdeen, has made immense progress, but as a whole the area is a well-cultivated district. Round the coast and on all the lower levels tillage is the rule. In the interior the level of the land rises rapidly, and ploughed fields[6] give place to desolate moors and bare mountain heights in which agriculture is an impossible industry. The surface of the lowland parts, now in regular cultivation, was originally very rough and rock-strewn. It was covered with erratic blocks of stone, gneiss and granite (locally called “heathens”), left by the melting of the ice fields which overspread all the north-east of Scotland during the Ice Age. These stones have been cleared from the fields and utilised as boundary walls. Some idea of the extraordinary energy and excessive labour necessary to clear the land for tillage may be gathered from a glance at the “consumption” dyke at Kingswells, some five miles from Aberdeen. This solid rampart stretches like a great break-water across nearly half a mile of country, through a dip to the south of the Brimmond Hill. It is five or six feet in height and twenty to thirty in breadth and contains thousands of tons of troublesome boulders gathered from the surrounding slopes. The disposal of these blocks was a serious problem. It has been solved by this rampart. In other parts the stones were built up into enclosing walls and now serve the double purpose of enclosing the fields and providing a certain amount of shelter for crops and cattle. The slopes of the Brimmond Hill are in certain parts still uncleared and the appearance of these areas helps us to realise what this section of the country looked like before the enterprising agriculturist braced himself to prepare the surface for the use of the plough.

Consumption Dyke at Kingswells

The soil, except in the alluvial deposits on the banks of the Don and the Ythan, is not of great natural fertility,[7] yet by the exceptional industry of the inhabitants and their enterprise as a farming community it has been raised to a high degree of productiveness. The county now enjoys a well but hard earned reputation for progressive agriculture. Notably so in regard to cattle-breeding. It is the home of a breed of cattle called Aberdeenshire, black and polled, but it is just as famous for its strain of shorthorns which have been bred with skill and insight for more than a century. In spite, then, of its inferior soil, its wayward climate and its northern latitude, the inborn stubbornness and determination of its people have[8] made it a great and prosperous agricultural region and only those who on a September day have seen from the top of Benachie the undulating plains of Buchan glittering golden in the sun can realise what a transformation has been effected on a barren and stony land by the industry of man.

The most easterly of the Scottish counties, it abuts like a prominent shoulder into the North Sea. It has, therefore, a considerable sea-board partly flat and sandy, partly rocky and precipitous. The population of the numerous villages dotted along this coast used in time past to devote themselves to fishing, but the tendency of recent years has been to concentrate this industry in the larger towns, Fraserburgh, Peterhead and Aberdeen.

Other industries there are few. Next to agriculture and fishing comes granite, which is the only mineral worthy of mention found in the county. It is the prevailing rock of the district and is quarried to a considerable extent in various parts. A large part of the population earn their living by this industry, and Aberdeen granite, like Aberdeen beef and Aberdeen fish, is a well-known product and travels far. Paper and wool are also manufactured but only on a moderate scale.

There is only one other general feature of the county that deserves mention and that is its attractiveness as a health resort. The banks of the Dee, more especially in its upper regions, is a much frequented holiday haunt; and every summer and autumn Braemar, Ballater and Aboyne are crowded with visitors from all parts of the country. The late Queen Victoria no doubt gave the

[9]

The Punch Bowl, Linn of Quoich, Braemar

[10]

impetus to this fashion. Her majesty at an early period of her reign bought the estate of Balmoral, half-way between Ballater and Braemar, and having built a royal castle there made it her practice to reside for a large part of every year amongst the Deeside hills. Apart from this royal advertisement the high altitude of the district, and its dry, bracing climate, as well as its romantic mountain scenery, have proved permanently attractive. Here are Loch-na-gar (sung by Byron), Ben-Macdhui, Brae-riach, Ben-na-Buird, Ben-Avon and other Bens, all of them 4000, or nearly 4000, feet above sea-level, and all of them imposing and impressive in their bold and massive forms. These mountains supply elements of grandeur which exercise a fascination upon people who habitually live in a flat country, and Braemar is not likely to lose its merited popularity.

Aberdeenshire is one of the large counties in area, standing fifth in Scotland. Although Inverness contains more than twice the number of square miles in Aberdeenshire, its population is far behind that of Aberdeen, which in this respect is the third county in Scotland. Its greatest length from N.E. to S.W. is 102 miles; its greatest breadth from N.W. to S.E. is 50. The coast line measures 65 miles and is little indented. The whole area of the county is 1970 square miles, or 1,261,971 acres, of which 6400 are water.

[11]

In shape the county might be likened to a pear lying obliquely on its side, the narrow stalk-end being in the mountains, while the rounded bulging head is the north-eastern sea-board. The flattest portion is the region lying north of the Ythan, called Buchan, and even this can hardly be called flat, for the level is broken by Mormond Hill, near Strichen, rising to a height of 810 feet. All the way to Pennan Head the contour of the land is irregularly wavy. The narrower portion in the S.W., called Mar, is entirely mountainous, and midway between these two extremes lie the Garioch and Formartin—districts which are undulating in character. A crescent line drawn from Aberdeen to Turriff, the convex side being to the S.W., would divide the county into two parts, which might be described as lowland and highland. The lowland portion contains the lower valley of the Don as far up as Inverurie, the valley of the Ythan and all the remaining northern part of the county. South of this imaginary line the ground rises in ridge after ridge until it culminates in the lofty Grampian range of the Cairngorms. The bipartite character of the county, which is reflected in the occupation and pursuits as in the character and language of the two populations, is of some importance, and yet must not be pressed too far, because the population in the one half is practically insignificant as compared with that of the other. It follows that when Aberdeenshire men and Aberdeenshire ways are referred to, nine times out of ten it is the lowland part of the county that is in question.

[12]

Pennan, looking N.W. Showing old and new houses of Troup

The boundaries are, on the east, the North Sea, and[13] on the north as far west as Pennan Head, the Moray Firth. There Banffshire and Aberdeenshire meet. From that point inland a wavy boundary separates the two counties, the Deveron being for part of the way the dividing line. Above Rothiemay the boundary mounts the watershed between Deveronside and Speyside, and keeping irregularly to this line past the Buck of the Cabrach, and the upper waters of the Don, reaches Ben-Avon. Thence the line moves on to Ben-Macdhui with Loch Avon on the right, and at Brae-riach Banffshire ceases to be the boundary. For several miles, almost due south in direction, Inverness comes in as the county on the west. The southern boundary touches three counties, Perth, Forfar and Kincardine. At Cairn Ealar, which is the angle of turning and almost a right angle, the direction changes and runs east alongside of Perthshire to the Cairnwell Road, and crossing this leaves Perthshire at Glas Maol, where it touches Forfarshire. The line continues east but with a trend to the north, passing on the left Glenmuick, Glentanar and the Forest of Birse, in which the Feugh takes its rise. On the top of Mount Battock three counties meet, Forfar, Aberdeen and Kincardine. Henceforth we are alongside of Kincardineshire and the line bends north-west with a semi-circular sweep round Banchory-Ternan and the Hill of Fare to Crathes, from a little beyond which, the bed of the Dee becomes the boundary line all the way to Aberdeen. In all this area of high ground the line of march is practically the watershed throughout, marking off the drainage area[14] of the Don and the Dee from that of the Deveron and the Avon (a tributary of the Spey) on the one hand, and from that of the Tay and the two Esks (south and north)on the other.

Loch Avon and Ben-Macdhui

[15]

From what has been already said of the contour of the county it may be inferred that its surface is extremely varied. Every variety of highland and lowland country is to be found within its limits. Near the sea-board the land is gently undulating, never quite flat but not rising to any great height till Benachie (1440) is reached. From that point onwards, whether up Deveronside or Donside or Deeside, the mountains rise higher and higher till the Cairngorms, which comprise some of the loftiest mountains in the kingdom, are reached. At that point we are more than half-way across Scotland, and in reality are nearer to the Atlantic than to the North Sea. Less than half the land is under cultivation. Woods and plantations occupy barely a sixth part of the uncultivated area. The rest is mountain and moor, yielding a scanty pasturage for sheep and red-deer, and on the lower elevations for cattle.

In the fringe round the sea-board no trees will grow. It is only when several miles removed from exposure to the fierce blasts that come from the North Sea that they begin to thrive, but the whole Buchan district is conspicuously treeless. Almost every acre is cultivated and the succession of fields covered with oats, turnips and[16] grass, which fill up the landscape as with a great patchwork, is broken only here and there by belts of trees round some manor-house or farm-steading. Except in a few places the scenery of this lowland portion is devoid of picturesque interest, yet the woods of Pitfour and of Strichen, the policies of Haddo House near Methlick, the quiet silvan beauty of Fyvie, which more resembles an English than a Scotch village, the wooded ridge that overlooks the Ythan at the Castle of Gight, are charming spots that serve by contrast to accentuate the general tameness of this lower area.

In the higher region, the south-western portions of the county, agriculture is, to some extent, practised, but it is necessarily confined to narrow strips in the valleys of the rivers. The hills, which are rarely wooded, and that only up to fifteen hundred feet above sea-level, are rounded in shape, not sharp and jagged. They are, where composed of granite, invariably clothed in heather and are occasionally utilised for the grazing of sheep, but this is becoming less common, and year by year larger areas are depleted of sheep for the better protection of grouse. All the heathery hills up to 2000 feet are grouse moors. Throughout the summer these display the characteristic brown tint of the heather—a tint which gives place in early August to a rich purple when the heather breaks into flower. Long strips of the heather-mantle are systematically burned to the ground every spring. Such blackened patches scoring with their irregular outlines the sides of the hills in April and May give a certain amount of variety to the prevailing tint of brown. They serve a[17] very useful purpose. The young grouse shelter in the long and unburnt heather but frequent the cleared areas for the purpose of feeding on the tender young shoots which spring up from the blackened roots of the burned plants.

Further inland still, where the hills rise to a greater height, they become deer-forests. As a rule these forests are without trees and are often rockstrewn, bare and grassless. It is only in the sheltered corries or by the sides of some sparkling burn, that natural grasses spring up in sufficient breadth to provide summer pasturage for the red-deer, which are carefully protected for sporting purposes. Here too the ptarmigan breed in considerable numbers. The grouse moors command higher rents than would be profitable for a sheep-farmer to give for the grazing, and every year prior to the 12th of August, when grouse-shooting begins, there is an influx of sportsmen from the south, to enjoy this particular form of sport. The red grouse is indigenous to Scotland; it seems to find its natural habitat amongst the heather, where in spite of occasional failures in the nesting season, and in spite of many weeks’ incessant shooting, it thrives and multiplies. Deer-stalking begins somewhat later; in a warm and favourable summer, the stags are in condition early in September. This sport is confined to a comparative few.

The highest mountain in the Braemar district is Ben-Macdhui (4296 feet). A few others are over 4000—Brae-riach and Cairntoul. Ben-na-Buird and Ben-Avon, which last is notable for the numerous tors or warty knots[18] along its sky-line, are just under 4000 feet. Loch-na-gar, a few miles to the east and a conspicuous background to Balmoral Castle, is 3789. Byron called it “the most sublime and picturesque of the Caledonian Alps,” and Queen Victoria writing from Balmoral in 1850 described it as “the jewel of all the mountains here.” Its contour lines, which are somewhat more sharply curved than is usual in the Deeside hills, and the well-balanced distribution of its great mass make it easily recognised from a wide distance. This partly explains the pre-eminence which notwithstanding its inferiority of height it undoubtedly possesses. Due north from Ballater are Morven (2880) and Culblean, and due south is Mount Keen; a little east and on the boundary line of three counties is Mount Battock. Perhaps the most prominent hill, and the one most frequently visible to the great majority of Aberdeenshire folks, is Benachie, which stands as a fitting outpost of the vast regiment of hills. It stands apart and although only 1440 feet in height is an unfailing landmark from all parts of Buchan, from Aberdeen, from Donside, and even from Deveronside. Its well-defined outline and projecting “mither tap” render it an object of interest from far and near, while the presence or absence of cloud on its head and shoulders serves as a barometric index to the state of the weather.

[19]

Benachie

[20]

As we have already pointed out, the watershed coincides to a large extent with the boundary line of the county. The lean of Aberdeenshire is from west to east so that all the rivers flow in an easterly direction to the North Sea. On the west and north-west of the highest mountain ridges, the slope of the land is to the north-east, and the Spey with its several tributaries carries the rainfall to the heart of the Moray Firth.

The chief river of the county is the Dee. It is the longest, the fullest-bodied, the most picturesque of all Aberdeenshire waters. Taking its rise in two small streams which drain the slopes of Brae-riach, it grows in volume and breadth, till, after an easterly course of nearly 100 miles, it reaches the sea at Aberdeen. The head-stream is the Garrachorry burn, which flows through the cleft between Brae-riach and Cairntoul. A more romantic spot for the cradle of a mighty river could hardly be found. The mountain masses rise steep, grim and imposing—on one side Cairntoul conical in shape, on the other Brae-riach broad and massive, a picture of solidity and immobility. The Dee well is 4060 feet above sea-level and 1300 above the stream which drains the eastern side of the Larig—the high pass to Strathspey. As it emerges from the Larig, it is a mere mountain torrent but presently it is joined at right angles by the Geldie from the south-west, and the united waters move eastward through a wild glen of rough and rugged slopes

[21]

Linn of Dee, Braemar

and ragged, gnarled Scots firs to the Linn of Dee, 6-3/4 miles above Braemar. There is no great fall at the Linn, but here the channel of the river becomes suddenly contracted by great masses of rock and the water rushes through a narrow gorge only four feet wide. The pool below is deep and black and much overhung with rocks. For 300 yards stretches this natural sluice, formed by rocks with rugged sides and jagged bottom, the water racing past in small cascades. The river is here spanned by[22] a handsome granite bridge opened in 1857 by Queen Victoria.

Old bridge of Dee, Invercauld

As the river descends to Braemar, the glen gradually widens out, and the open, gravelly, and sinuous character of the bed, which is a feature from this point onwards, is very marked. Pool and stream, stream and pool succeed one another in shingly bends, clean, sparkling and beautiful. At Braemar the bed is 1066 feet above sea-level. Below Invercauld the river is crossed by the picturesque old bridge built by General Wade, when he made his well-known roads through the Highlands after the rebellion of 1745. Here the Garrawalt, a rough and obstructed

[23]

View from old bridge of Invercauld

[24]

Falls of Muick, Ballater

tributary, joins the main river. From Invercauld past Balmoral Castle to Ballater is sixteen miles. Here the bottom is at times rocky, at times filled with big rough stones, at other times shingly but never deep. The average depth is only four feet, and the normal pace under ordinary conditions 3-1/2 miles an hour. From Ballater, where the river is joined by the Gairn and the Muick, the Dee maintains the same character to Aboyne and Banchory, where it is joined by the Feugh from the forest of Birse. Just above Banchory is Cairnton, where the water supply for the town of Aberdeen, amounting on an average to 7 or 8 million gallons a day, is taken off. The course of the river near the mouth was diverted[25] some 40 years ago to the south, at great expense, by the Town Council, and in this way a considerable area of land was reclaimed for feuing purposes. The spanning of the river at this point by the Victoria bridge, which superseded a ferry-boat, has led to the rise of a moderately sized town (Torry) on the south or Kincardine side of the river.

The scenery of Deeside, all the way from the Cairngorms to the old Bridge of Dee, two miles west of the centre of the city, is varied and attractive. It is well-wooded throughout; in the upper parts the birch, which would seem to be indigenous in the district, adds to the beauty of the hill-sides, while the clean pebbly bed of the river and its swift, dashing flow delight the eyes of those who are familiar only with sluggish and mud-stained waters. It is not surprising therefore that the district has attained the vogue it now enjoys.

The Don runs parallel to the Dee for a great part of its course, but it is a much shorter river, measuring only 78 miles. It rises at the very edge of the county close to the point where the Avon emerges from Glen Avon and turns north to join the Spey. It drains a valley which is only ten or fifteen miles separated from the valley of the larger river. In its upper reaches it somewhat resembles Deeside, being quite highland in character; but lower down the river loses its rapidity, becoming sluggish and winding. Strathdon, as the upper area is called, is undoubtedly picturesque, but it lacks the bolder features of Deeside, being less wooded and graced with few hills on the grand scale. It has not, therefore, become a popular

[26]

Birch Tree at Braemar

[27]

summer resort, but its banks form the richest alluvial agricultural land in the county—

This old couplet is so far correct. The Dee is a great salmon river, providing more first-class salmon angling than any other river of Scotland, while the Don, though owing to its muddy bottom a stream excellent beyond measure and unsurpassed for brown trout, is not now, partly owing to obstruction and pollution, a great salmon river. But the agricultural land on Donside, which for the most part is rich deep loam, about Kintore, Inverurie and the vale of Alford is much more kindly to the farmer than the light gravelly soil of Deeside, which is so apt to be burnt up in a droughty summer. In the matter of stone, things have changed since the couplet took shape. The granite quarries of Donside are now superior to any on the Dee; but the trees of Deeside still hold their own, the Scots firs of Ballochbuie forest, west of Balmoral, being the finest specimens of their kind in the north.

The nether-Don has been utilised for more than a century as a driving power for paper and wool mills. Of these there is a regular succession for several miles of the river’s course, from Bucksburn to within a mile of Old Aberdeen. After heavy rains or a spring thaw the lower reaches of the river, especially from Kintore downwards, are apt to be flooded, and in spite of embankments which have been erected along the river’s course, few years pass without serious damage being done to the

[28]

Fir Trees at Braemar

[29]

crops in low-lying fields. Some parts of Donside scenery, notably at Monymusk (called Paradise), and at Seaton House just below the Cathedral of Old Aberdeen, and before the river passes through the single Gothic arch of the ancient and historical bridge of Balgownie, are very fine—wooded and picturesque, and beloved of more than one famous artist.

The next river is the Ythan, which, rising in the low hills of the Culsalmond district and flowing through the parish of Auchterless and past the charming hamlet of Fyvie, creeps somewhat sluggishly through Methlick and Lord Aberdeen’s estates to Ellon. A few miles below Ellon it forms a large tidal estuary four miles in length—a notable haunt of sea-trout, the most notable on the east coast. The river is only 37 miles long. It is slow and winding with deep pools and few rushing streams; moreover its waters have never the clear, sparkling quality of the silvery Dee. Yet at Fyvie and at Gight it has picturesque reaches that redeem it from a uniformity of tameness.

The Ugie, a small stream of 20 miles in length, is the only other river worthy of mention. It joins the sea north of the town of Peterhead. In character it closely resembles the Ythan, having the same kind of deep pools and the same sedge-grown banks.

The Deveron is more particularly a Banffshire river, yet in the Huntly district, it and its important tributary the Bogie (which gives its name to the well-known historic region called Strathbogie) are wholly in Aberdeenshire.

[30]

The Don, looking towards St Machar Cathedral

[31]

The Deveron partakes of the character of the Dee and the character of the Don. It is neither so sparkling and rapid as the one nor so slow and muddy as the other. Around Huntly and in the locality of Turriff and Eden, where it is the boundary between the counties, it has some charmingly beautiful reaches. Along its banks is a succession of stately manor-houses, embosomed in trees, and these highly embellished demesnes enhance its natural charms.

Brig o’ Balgownie, Aberdeen

[32]

Lakes are few in Aberdeenshire, and such as exist are not specially remarkable. The most interesting historically are the Deeside Lochs Kinnord and Davan which are [33] held by antiquarians to be the seat of an ancient city Devana—the town of the two lakes. In pre-historic times there dwelt on the shores of these lakes as also in the valleys that converge upon them a tribe of people who built forts, and lake retreats, made oak canoes, and by means of palisades of the same material created artificial islands. The canoes which have been recovered from the bed of the loch are hollowed logs thirty feet in length. Other relics—a bronze vessel and a bronze spearhead, together with many beams of oak—have been fished up, all proving the existence of an early Pictish settlement.

Loch Muick, near Ballater

Besides these, there is in the same district—but south-east of Loch-na-gar, another and larger lake called Loch Muick. From it flows the small river Muick—a tributary of the Dee, which it joins above Ballater. South-west of Loch-na-gar is Loch Callater, which drains into the Clunie, another Dee tributary, which joins the main river at Castleton of Braemar. On the lower reaches of the Dee are the Loch of Park or Drum, and the Loch of Skene, both of which drain into the Dee. Both are much frequented by water-fowl of various kinds.

The Loch of Strathbeg, which lies on the east coast not far from Rattray Head, is a brackish loch of some interest. Two hundred years ago, we are told, it was in direct communication with the sea and small vessels were able to enter it. In a single night a furious easterly gale blew away a sand-hill between the Castle-hill of Rattray and the sea, with the result that the wind-driven sand formed a sand-bar where formerly there was a clear

[34]

Loch Callater, Braemar

[35]

water-way. Since that day the loch has been land-locked and though still slightly brackish may be regarded as an inland loch.

Geology is the study of the rocks or the substances of which the earthy crust of a district is composed. Rocks are of two sorts: (1) those due to the action of heat, called igneous, (2) those formed and deposited by water, called aqueous. When the earth was a molten ball, it cooled at the surface, but every now and again liquid portions were ejected from cracks and weak places. The same process is seen in the eruptions of Mount Vesuvius, which sends out streams of liquid lava that gradually cools and forms hard rock. Such are igneous rocks. But all the forces of nature are constantly at work disintegrating the solid land; frost, rain, the action of rivers and the atmosphere wear down the rocks; and the tiny particles are carried during floods to the sea, where they are deposited as mud or sand-beds laid flat one on the top of the other like sheets of paper. These are _aqueous_ rocks. The layers are afterwards apt to be tilted up on end or at various angles owing to the contortions of the earth’s crust, through pressure in particular directions. When so tilted they may rise above water and immediately the same process that made them now begins to unmake them. They too may in time be so worn away that only fragments of them are left whereby we may interpret their history.

[36]

Loch of Skene

[37]

To these may be added a third kind of rock called metamorphic, or rocks so altered by the heat and pressure of other rocks intruding upon them, that they lose their original character and become metamorphosed. They may be either sedimentary, laid down originally by water, or they may be igneous, but in both cases they are entirely changed or modified in appearance and structure by the treatment they have suffered.

The geology of Aberdeenshire is almost entirely concerned with igneous and metamorphic rocks. The whole backbone of the county is granite which has to some extent been rubbed smooth by glacial action; but in a great part of the county the granite gives place to metamorphic rocks, gneiss, schist, and quartzite. A young geologist viewing a deep cutting in the soil about Aberdeen finds that the material consists of layers of sand, gravel, clay, which are loosely piled together all the way down to the solid granite. This is the glacial drift, or boulder clay, a much later formation than the granite and a legacy of what is called the great Ice Age. Far back in a time before the dawn of history all the north-east of Scotland was buried deep under a vast snow-sheet. The snow consolidated into glaciers just as in Switzerland to-day, and the glaciers thus formed worked their way down the valleys, carrying a great quantity of loose material along with them. When a warmer time came, the ice melted and all the sand and boulders mixed up in the ice were liberated and sank as loose deposits on the land. This is the boulder clay which in and around Aberdeen is the usual subsoil. It consists of rough,[38] half-rounded pebbles, large and small, of clay, sand, and shingle, and makes a very cold and unkindly soil, being difficult to drain properly and slow to take in warmth.

Below this boulder clay are the fundamental rocks. At Aberdeen these are pure granite; but in other parts of the county they are, as we have said, metamorphic, that is, they have been altered by powerful forces, heat and pressure. Whether they were originally sedimentary, before they were altered, is doubtful; some geologists think the crystalline rocks round Fraserburgh and Peterhead were aqueous. Mormond Hill was once a sandstone, and the schists of Cruden Bay and Collieston were clay. The same beds traced to the south are found to pass gradually into sedimentary rocks that are little altered. Whether they were aqueous or igneous originally, they have to-day lost all their original character. No fossils are found in them. These rocks are the oldest and lowest in Aberdeenshire. After their formation, they were invaded from below by intrusive masses of molten igneous rock, which in many parts of the county is now near the surface. This is the granite already referred to. Its presence throughout the county has materially influenced the character and the industry of the people.

Wherever granite enters, it tears its irregular way through the opposing rocks, and sends veins through cracks where such occur. The result of its forcible entrance in a molten condition is that the contiguous rocks are melted, blistered, and baked by the intrusive matter. Why granite should differ from the lava we[39] see exuding from active volcanoes is explained by the fact that it is formed deep below the surface where there is no outlet for its gases. It cools slowly and under great pressure and this gives it its special character. If found, therefore, at the surface, as it is in Aberdeen, this is because the rocks once high above it, concealing its presence have been worn away, which gives some idea of the great age of the district. One large granitic mass is at Peterhead, where it covers an area of 46 square miles, and forms the rocky coast for eight miles; but the whole valley of the Dee as far as Ben Macdhui, and a great part of Donside, consist of this intrusive granite. It varies in colour and quality, being in some districts reddish in tint as at Sterling Hill near Peterhead, at Hill of Fare, and Corennie; in other parts it is light grey in various shades.

The succession in the order of sedimentary rocks is definitely settled, and although this has little application to Aberdeenshire, an outline may be given. The oldest are the Palaeozoic which includes—in order of age—

Cambrian,

Silurian,

Old Red Sandstone or Devonian,

Carboniferous,

Permian.

Of these the only one represented in Aberdeenshire is the Old Red Sandstone, which occupies a considerable strip on the coast from Aberdour to Gardenstown, and runs inland to Fyvie and Auchterless and even as far as Kildrummy and Auchindoir. The deposit is 1300 feet[40] thick. A visitor to the town of Turriff is struck by the red colour of many of the houses there, a most unusual variant upon the blue-grey whinstone of the surrounding districts. The explanation is that a convenient quarry of Old Red Sandstone exists between Turriff and Cuminestown. Kildrummy Castle, one of the finest and most ancient ruins in the county, is not like the majority of the old castles built of granite but of a sandstone in the vicinity. The same band extends across country to Auchindoir, where it is still quarried.

The next geological group of Rocks, the Secondary or Mesozoic, includes—in order of age—

Triassic,

Jurassic,

Cretaceous.

These are not at all or but barely represented. A patch of clay at Plaidy, which was laid bare in cutting the railway track, belongs to the Jurassic system and contains ammonites and other fossils characteristic of that period. Over a ridge of high ground stretching from Sterling Hill south-eastwards are found numbers of rolled flints belonging to the Cretaceous or chalk period, but the probability is that they have been transported from elsewhere by moving ice and are not in their natural place.

The Tertiary epoch is just as meagrely represented as the Secondary. Yet this is the period which in other parts of the world possesses records of the most ample kind. The Alps, the Caucasus, the Himalayas were all upheaved in Tertiary times; but of any corresponding[41] activity in the north-east of Scotland, there is no trace. It is only when the Tertiary merges in the Quaternary period that the history is resumed. The deposits of the Ice Age, when Scotland was under the grip of an arctic climate, are much in evidence all over the county and have already been referred to. It is necessary to treat the subject in some detail.

During the glacial period, the snow and ice accumulated on the west side of the country, and overflowed into Aberdeenshire. There were several invasions owing to the recurrence of periods of more genial temperature when the ice-sheet dwindled. One of the earlier inroads probably brought with it the chalk flints now found west of Buchan Ness; another brought boulders from the district of Moray. South of Peterhead a drift of a different character took place. Most of Slains and Cruden as well as Ellon, Foveran, and Belhelvie are covered with a reddish clay with round red pebbles like those of the Old Red Sandstone. This points to an invasion of the ice-sheet from Kincardine, where such deposits are rife. Dark blue clay came from the west, red clay from the south, and in some parts they met and intermixed as at St Fergus. A probable third source of glacial remains is Scandinavia. In the Ice Age Britain was part of the continental mainland, the shallow North Sea having been formed at a subsequent period. The low-lying land at the north-east of the county was the hollow to which the glaciers gravitated from west and south and east, leaving their débris on the surface when the ice disappeared. So much is this a feature of Buchan that one well-known[42] geologist has humorously described it as the riddling heap of creation.

Both the red and the blue clay are often buried under the coarse earthy matter and rough stones that formed the residuum of the last sheet of ice. This has greatly increased the difficulty of clearing the land for cultivation. Moreover a clay subsoil of this kind, which forms a hard bottom pan that water cannot percolate through, is not conducive to successful farming. Drainage is difficult but absolutely necessary before good crops will be produced. Both difficulties have been successfully overcome by the Aberdeenshire agriculturist, but only by dint of great expenditure of time and labour and money.

The district of the clays is associated with peat beds. There is peat, or rather there was once peat all over Aberdeenshire, but the depth and extent of the beds are greatest where the clay bottom exists. A climate that is moist without being too cold favours the growth of peat and the Buchan district, projecting so far into the North Sea and being subject to somewhat less sunshine than other parts of the county, provides the favouring conditions. The rainfall is only moderate but it is distributed at frequent intervals, and the clay bottom helps to retain the moisture and thus promotes the growth of those mosses which after many years become beds of peat. These peat beds for long provided the fuel of the population. In recent years they are all but exhausted, and the facility with which coals are transported by sea and by rail is gradually putting an end to the “casting” and drying of peats.

[43]

Moraines of rough gravel—the wreckage of dwindling glaciers—are found in various parts of the Dee valley. The soil of Deeside has little intermixture of clay and is thin and highly porous. It follows that in a dry season the crops are short and meagre. The Scots fir, however, is partial to such a soil, and its ready growth helps with the aid of the natural birches to embellish the Deeside landscape.

In the Cairngorms brown and yellow varieties of quartz called “cairngorms” are found either embedded in cavities of the granite or in the detritus that accumulates from the decomposition of exposed rocks. The stones, which are really crystals, are much prized for jewellery, and are of various colours, pale yellow (citrine), brown or smoky, and black and almost opaque. When well cut and set in silver, either as brooches or as an adornment to the handles of dirks, they have a brilliant effect. Time was when they were systematically dug and searched for, and certain persons made a living by their finds on the hill-sides; but now they are more rare and come upon only by accident.

As we have seen in dealing with the glacial movements, Britain was at one time part of the continent and there was no North Sea. At the best it is a shallow sea, and a very trifling elevation of its floor would re-connect Scotland with Europe. It follows that our country was[44] inhabited by the same kind of animals as inhabited Western Europe. Many of them are now extinct, cave-bears, hyaenas and sabre-toothed tigers. All these were starved out of existence by the inroads of the ice. After the ice disappeared this country remained joined to the continent, and as long as the connection was maintained the land-animals of Europe were able to cross over and occupy the ground; if the connection had not been severed, there would have been no difference between our fauna and the animals of Northern France and Belgium. But the land sank, and the North Sea filled up the hollow, creating a barrier before all the species in Northern Europe had been able to effect a footing in our country. This applies both to plants and animals. While Germany has nearly ninety species of land animals, Great Britain has barely forty. All the mammals, reptiles and amphibians that we have, are found on the continent besides a great many that we do not possess. Still Scotland can boast of its red grouse, which is not seen on the continent.

With every variety of situation, from exposed sea-board to sheltered valley and lofty mountain, the flora of Aberdeenshire shows a pleasing and interesting variety. The plants of the sea-shore, of the waysides, of the river-banks, and of the lowland peat-mosses are necessarily different in many respects from those of the great mountain heights. It is impossible here to do more than indicate one or two of the leading features. The sandy tracts north of the Ythan mouth have characteristic plants, wild rue, sea-thrift, rock-rose, grass of Parnassus,[45] catch-fly (Silene maritima). The waysides are brilliant with blue-bells, speedwell, thistles, yarrow and violas. The peat-mosses show patches of louse-wort, sundew, St John’s wort, cotton-grass, butterwort and ragged robin. The pine-woods display an undergrowth of blae-berries, galliums, winter-green, veronicas and geraniums. The Linnaea borealis is exceedingly rare, but has a few localities known to enterprising botanists. The whin and the broom in May and June add conspicuous colouring to the landscape while a different tint of yellow shines in the oat-fields, which are throughout the county more or less crowded with wild mustard or charlock. The granitic hills are all mantled with heather (common ling, Calluna erica) up to 3000 feet, brown in winter and spring but taking on a rich purple hue when it breaks into flower in early August. The purple bell-heather does not rise beyond 2000 feet and flowers much earlier. Through the heather trails the stag-moss, and the pyrola and the genista thrust their blossoms above the sea of purple. The cranberry, the crow-berry and the whortle-berry, and more rarely the cloudberry or Avron (Rubus chamaemorus) are found on all the Cairngorms. The Alpine rock-cress is there also, as well as the mountain violet (Viola lutea), which takes the place of the hearts-ease of the lowlands. The moss-campion spreads its cushions on the highest mountains; saxifrages of various species haunt every moist spot of the hill-sides and the Alpine lady’s mantle, the Alpine scurvy-grass, the Alpine speedwell, the trailing azalea, the dwarf cornel (Cornus suecica), and many other varieties are to be found by those who care to look for them.

[46]

As we have said, no trees thrive near the coast. The easterly and northerly winds make their growth precarious, and where they have been planted they look as if shorn with a mighty scythe, so decisive is the slope of their branches away from the direction of the cold blasts. Their growth too in thickness of bole is painfully slow, even a period of twenty years making no appreciable addition to the circumference of the stem. Convincing evidence exists that in ancient times the county was closely wooded. In peat-bogs are found the root-stems of Scots fir and oak trees of much larger bulk than we are familiar with now. The resinous roots of the fir trees, dug up and split into long strips, were the fir-candles of a century ago, the only artificial light of the time.

The district is not exceptional or peculiar in its fauna. The grey or brown rat, which has entirely displaced the smaller black rat, is very common and proves destructive to farm crops—a result partially due to the eradication of birds of prey, as well as of stoats and weasels, by gamekeepers in the interest of game. The prolific rabbit is in certain districts far too numerous and plays havoc with the farmer’s turnips and other growing crops. Brown hares are fairly plentiful but less numerous than they were in the days of their protection. Every farmer has now the right to kill ground game (hares and rabbits) on his farm and this helps to keep the stock low. The white or Alpine hare is plentiful in the hilly tracts and is shot along with the grouse on the grouse moors. The otter is occasionally trapped on the rivers, and a few foxes

[47]

Deer in time of snow

are shot on the hills. The mole is in evidence everywhere up to the 1500 feet level, by the mole-heaps he leaves in every field, and the mole-catcher is a familiar character in most parishes. The squirrel has worked his way north during the last sixty years, and is now to be found in every fir-wood. The graceful roedeer is also a denizen of the pine-woods, whence he makes forays on the oat-fields. The red-deer is abundant on the higher and more remote hills, and deer-stalking is perhaps the most exciting[48] as it certainly is the most exacting of all forms of Scottish sport. The pole-cat is rarely seen; he is best known to the present generation in the half-domesticated breed called the ferret. The hedge-hog, the common shrew, and the water-vole are all common.

The Dunbuy Rock

The birds are numerous and full of interest. The coast is frequented by vast flocks of sea-gulls, guillemots, and cormorants, while the estuary of the Ythan has many visitants such as the ringed plover, the eider-duck, the shelduck, the oyster-catcher, redshank, and tern. On the north bank of this river the triangular area of sand-dunes between Newburgh and Collieston is a favourite nesting-place for eider-duck and terns. The nests of[49] the eider-duck, with their five large olive-green eggs embedded in the soft down drawn from the mother’s breast, are found in great numbers amongst the grassy bents. The eggs of the tern, on the other hand, are laid in a mere hollow of the open sand, but so numerous are they that it is almost impossible for a pedestrian to avoid treading upon them. Puffins or sea-parrots are conspicuous amongst the many sea-birds that frequent Dunbuy Rock. This island rock, half-way up the eastern coast, is a typical sea-bird haunt, where gulls, puffins, razorbills and guillemots are to be seen in a state of restless activity. A colony of black-headed gulls has for a number of years bred and multiplied in a small loch near Kintore. A vast number of migratory birds strike the shores of Aberdeenshire every year in their westward flight. The waxwing, the hoopoe, and the ruff are occasional visitors, the great northern diver and the snow-bunting being more frequent.

The game-birds of the district are the partridge and the pheasant in the agricultural region, and the red grouse on the moors. The higher hills, such as Loch-na-gar, have ptarmigan, while the wooded areas bordering on the highland line are frequented by black-cock and capercailzie. These last are a re-introduction of recent years and seem to be multiplying; but, like the squirrel, they are destructive to the growing shoots of the pine trees and are not encouraged by some proprietors. The lapwing or green plover’s wail is an unfailing sound throughout the county in the spring. These useful birds are said to be fewer than they were fifty years ago—a result probably due to[50] the demand for their eggs as a table delicacy. After the first of April it is illegal to take the eggs, and this partial protection serves to maintain the stock in fair numbers. The starling, which, like the squirrel, was unknown in this district sixty years ago, has increased so rapidly that flocks of them containing many thousands are now a common sight in the autumn. The kingfisher is met with, very, very rarely on the river-bank, but the dipper is never absent from the boulder-strewn beds of the streams. The plaintive note of the curlew and the shriller whistle of the golden plover break the silence of the lonely moors. The golden eagle nests in the solitudes of the mountains and may occasionally be seen, soaring high in the vicinity of his eyrie.

Of fresh-water fishes, the yellow or brown trout is plentiful in all the rivers, especially in the Don and the Ythan. The migratory sea-trout and the salmon are also caught in each, although the Dee is pre-eminently the most productive. The salmon fisheries round the coast and at the mouth of the rivers are a source of considerable revenue. The fish are caught by three species of net, bag-nets (floating nets) and stake-nets (fixed) in the sea, and by drag-nets or sweep-nets in the tidal reaches of the rivers. Time was when drag-nets plied as far inland as Banchory-Ternan (19 miles), but these have gradually been withdrawn and are now relegated to a short distance from the river mouth, the rights having been bought up by the riparian proprietors further up the river, who wish to obtain improved opportunities for successful angling. The Dee has, in this way, been[51] so improved that it is now perhaps the finest salmon-angling river in Scotland.

The insects of the district call for little remark. Butterflies are few in species and without variety. It is only in certain warm autumns that the red admiral puts in an appearance. The cabbage-white, the tortoise-shell, and an occasional meadow-brown and fritillary are the prevailing species.

The waters of the Ythan, the Ugie, and the Don are frequented by fresh-water mussels which produce pearls. These grow best on a pebbly bottom not too deep and are 3 to 7 inches long and 1-1/2 to 2-1/2 broad. The internal surface is bluish or with a shade of pink. The search for these mussels in order to secure the pearls they may and do sometimes contain was once a recognised industry. To-day it is spasmodic and mostly in the hands of vagrants. Many beds are destroyed before the mussels are mature and this lessens the chances of success. The pearl-fisher usually wades in the river, making observation of the bottom by means of a floating glass which removes the disturbing effect of the surface ripple. He thus obtains a clear view of the river-bed, and by means of a forked stick dislodges the mussels and brings them to bank, 150 making a good day’s work. He opens them at leisure and finds that the great majority of his pile are without pearls. If he be lucky enough, however, to come upon a batch of mature shells he may find a pearl worth £20. As a rule the price is not above ten or twenty shillings. Much depends on the size and the colouring. The most valuable are those of a pinkish hue.

[52]

The harbour-mouth, which is also the mouth of the Dee, is the beginning of the county on the sea-board. It is protected by two breakwaters, north and south, which shelter the entrance channel from the fury of easterly and north-easterly gales. To the south, in Kincardineshire, is the Girdleness lighthouse, 185 feet high, flashing a light every twenty seconds with a range of visibility stated at 19 miles. To the north of the harbour entrance are the links and the bathing station. The latter was erected in 1895 and has since been extended, every effort being made to add to the attractiveness of the beach as a recreation ground. A promenade, which will ultimately extend to Donmouth, is in great part complete; and all the other usual concomitants of a watering-place have been introduced with promising success so far, and likely to be greater in the near future.

From Donmouth the northward coast presents little of interest. All the way to the estuary of the Ythan is a region of sand-dunes bound together by marum grass and stunted whins, excellent for golf courses, but lacking in variety. In the sandy mounds in the vicinity of the Ythan have been found many flint chippings and amongst them leaf-shaped flint arrow-heads, chisels and cores, as well as the water-worn stones on which these implements were fashioned. These records of primitive man as he was in the later Stone Age are conspicuous here, and are

[53]

Girdleness Lighthouse

[54]

to be seen in other parts of the county. In the rabbit burrows, which are abundant in the dunes, the stock-dove rears her young. In 1888 a migratory flock of sand-grouse took possession of the dunes, and remained for one season.

Beyond the Ythan are the Forvie sands—a region of hummocks under which a whole parish is buried. The destruction of the parish took place several centuries ago, when a succession of north-easterly gales, continued for many days, whipped up the loose sand of the coast-dunes and blew it onward in clouds till the whole parish, including several valuable farms, was entirely submerged. The scanty ruins of the old church of Forvie is the only trace left of this sand-smothered hamlet.

Not far from the site of the Forvie church is a beautiful semi-lunar bay called Hackley Bay, where for the first time since Aberdeen was left behind, rocks appear, hornblende, slate, and gneiss. At Collieston, a village consisting of a medley of irregularly located cottages scrambling up the cliff sides, a thriving industry used to be practised, the making of Collieston “speldings.” These were small whitings, split, salted and dried on the rocks. Thirty years ago they were considered something of a delicacy and were disposed of in great quantities; now they have lost favour and are seldom to be had. At the north end of the village is St Catherine’s Dub, a deep pool between rocks, on which one of the ships of the Spanish Armada was wrecked in 1588. Two of the St Catherine’s cannon very much corroded have been brought up from the sea-floor. One of them[55] is still to be seen at Haddo House, the seat of the Earl of Aberdeen.

Northward we come upon a region of steep grassy braes, consisting of soft, loamy clay, 20 to 40 feet deep, and covered with luxuriant grasses in summer and ablaze with golden cowslips in the spring months. Along the coast are several villages which once populous with busy and hardy fishermen are now all but tenantless. Such are Slains and Whinnyfold crushed out of activity by the rise of the trawling industry. The next place of note is Cruden Bay Hotel built by the Great North of Scotland Railway Company, and intended to minister specially to the devotees of golf, for which the coast links are here eminently suitable. The fine granite building facing the sea is a conspicuous landmark. Just north of the Hotel is the thriving little town of Port Errol, through which runs the Cruden burn—a stream where sea-trout are plentifully caught at certain seasons. The next prominent object is Slains castle—the family seat of the Earls of Errol. It stands high and windy, presenting a bold front to the North Sea breezes. All its windows on the sea-face are duplicate, a necessary precaution in view of the fierceness of the easterly gales. Very few plants grow in this exposed locality, and these only in the hollow and sheltered ground behind the castle, where some stunted trees and a few garden flowers struggle along in a precarious existence. As we proceed, the rocky coast rises higher and bolder and presents variable forms of great beauty. [56]Beetling crags enclose circular bays with perpendicular walls on which the kittiwake, the guillemot, the jackdaw and the starling breed by the thousand. The rock of Dunbuy, a huge mass of granite, surrounded by the sea, and forming a grand rugged arch, is a summer haunt of sea-birds and rock-pigeons.[57]

Sand Hills at Cruden Bay

After this, we reach the picturesque and much visited Bullers of Buchan—a wide semi-circular sea cauldron, the sides of which are perpendicular cliffs. The pool has no entry except from the seaward side, and it is only in calm weather that a boat is safe to pass through the low, open archway in the cliff. In rough weather, the waves rush through the narrow archway with terrific force, sending clouds of spray far beyond the height of the cliffs. Under proper conditions the scene is one of the grandest in Aberdeenshire, and is a fitting contrast to the sublimely impressive scenes at the source of the Dee, right at the other end of the county. Beyond the Bullers, the coast consists of high granite rocks, behind which are windswept moors. Near Boddam is Sterling Hill quarry, the source of the red-hued Peterhead granite. Here too is Buchan Ness, the most easterly point on the Scottish coast, and a fitting place for a prominent lighthouse. The lantern of the circular tower (erected in 1827) stands 130 feet above high-water mark and flashes a white light once every five seconds. The light is visible at a distance of 16 nautical miles.

“The Pot,” Bullers o’ Buchan

At Peterhead, which is a prosperous fishing centre and the eastern terminus of the bifurcate Buchan line of railway, is a great convict prison, occupying an extensive range of buildings on the south side of the Peterhead bay. The convicts are employed in building a harbour[59] of refuge, which is being erected under the superintendence of the Admiralty at a cost of a million of money. The coast onwards to the Ugie mouth is still rocky, but from the river to Rattray Head, the rocks give place to sand-dunes similar in character to those further south. Alongside of the dunes is a raised sea beach. They form the links of St Fergus. Rattray Head is a rather low reef of rock running far out to sea and highly suitable as a lighthouse station. In the course of twelve years, the reef was responsible for 24 shipwrecks. The lighthouse erected in 1895 is 120 feet high and the light gives three flashes in quick succession every 30 seconds. It is visible 18 miles out to sea. Beyond this point is a region of bleak and desolate sands. Not a tree nor a shrub is to be seen. The inland parts are under cultivation, but the general aspect of the country is dismal and dreary, and the very hedgerows far from the sea-board lean landwards as if cowering from the scourges of the north wind’s whip. The country is undulatory without any conspicuous hill. Beyond Rattray Head is the Loch of Strathbeg already referred to. The tradition goes that the same gale as blighted Forvie silted up this loch and contracted its connection with the sea. On the left safely sheltered from the sea-breezes are Crimonmogate, Cairness and Philorth—all mansion-houses surrounded by wooded grounds. At the sea-edge stand St Combs (an echo of St Columba), Cairnbulg and Inverallochy. Here occurs another raised sea beach. Our course from Rattray Head has been north-west and thus we reach the last important town on the coast—Fraserburgh.

[60]

Buchan Ness Lighthouse

[61]

Kinnaird Lighthouse, Fraserburgh

Fraserburgh lies to the west of its bay. Founded by one of the Frasers of Philorth (now represented by Lord Saltoun), it is like Peterhead a thriving town. Like Peterhead too, it is the terminus of one fork of the Buchan Railway and a busy fishing centre. In the month of July, which is the height of the herring season, “the Broch,” as it is called locally, is astir with life from early morn.

[62]

Entrance to Lord Pitsligo’s Cave, Rosehearty

More herrings are handled at Fraserburgh than anywhere else on this coast, from Eyemouth to Wick. Between Fraserburgh and Broadsea is Kinnaird’s Head. Here we have another lighthouse which has served that purpose for more than a century, an old castle having been converted to this use in 1787. It was one of the first three lighthouses in Scotland. Kinnaird’s Head is believed to be the promontory of the Taixali mentioned by the Alexandrian geographer Ptolemy as being at the entrance of the Moray Firth. Here the rocks are of moderate height but further west they fall to sea-level and continue so past Sandhaven and Pittullie to Rosehearty. A low rocky coast carries us to Aberdour bay, where beds of Old Red Sandstone and conglomerate rise to an altitude of 300 feet.

[63]

Aberdour Shore, looking N.W.

[64]

The conglomerate extends to the Red Head of Pennan—once a quarry for mill-stones—where an attractive and picturesque little village nestles at the base of the cliff. The peregrine falcon breeds on the rocky fastnesses of these lofty cliffs, which continue to grow in height and grandeur till they reach their maximum (400 feet) at Troup Head. Troup Head makes a bold beginning for the county of Banff.

The climate of a county depends on a good many things, its latitude, its height above sea-level, its proximity to the sea, the prevailing winds, and especially as regards Scotland whether it is situated on the east coast or on the west. The latitude of Great Britain if the country were not surrounded by the sea would entitle it to a temperature only comparable to that of Greenland but its proximity to the Atlantic redeems it from such a fate. The Atlantic is 3° warmer than the air and the fact that the prevailing winds are westerly or south-westerly helps to raise the mean temperature of the western counties higher than that of those on the east. The North Sea is only 1° warmer than the air so that its influence is less marked.

Still, considering its latitude (57°-57° 40’), Aberdeenshire enjoys a comparatively moderate climate. It is neither very rigorous in winter nor very warm in

[65]

Rainfall Map of Scotland. (After Dr H. R. Mill)

[66]

summer. Of course in a large county a distinction must be drawn between the coast temperature and that of the high lying districts such as Braemar. The fringe round the coast is in the summer less warm than the inland parts, a result due to the coolness of the enclosing sea, but in the winter this state of affairs is reversed and the uplands are held in the grip of a hard frost while the coast-side has little or none.

The mean temperature of Scotland is 47°, while Aberdeen has 46°·4 and Peterhead 46°·8. That of Braemar, the most westerly station in the county, though in reality very little lower, is arrived at by entirely different figures; the temperature being much higher during July, August and September, but lower in December, January and February. Braemar is 1114 feet above sea-level and since there is a regular and uniform decline in temperature to the extent of 1° for every 270 feet above the sea, the temperature of this hill-station should be low. As a matter of fact, from June to September it is only 9° and in October 7°·5 below that of London. Yet its maximum is 10° higher than is recorded at Aberdeen, only in winter its minimum is 20° lower than the minimum of the coast.

Braemar and Peterhead as lying at the two extremes of the county may be compared. Peterhead receives the uninterrupted sweep of the easterly breezes, for it has no shelter or protection either of forests or mountains. The impression a visitor takes is that Peterhead is an exceptionally cold place. As a fact, its mean winter temperature is above the average for Scotland, but the lack of shelter and the constant motion of the air give an impression of[67] coldness. In the summer and autumn its mean falls below that of Scotland. It is therefore less cold in the cold months and less warm in the warm months than Braemar and has a seasonal variation of only 16°·3 between winter and summer, whereas Edinburgh has a range of 21° and London of 26°.

Inverey near Braemar

[68]The rainfall over the whole county is also moderate, ranging from less than 25 inches at Peterhead—the driest part of the area—to 40 inches at Braemar, and 32 at Aberdeen. This is a small rainfall compared with 60 or 70 inches on parts of the west coast. The driest months in Aberdeenshire are April and May, and generally speaking less rain falls in the early half of the year when the temperature is rising than in the later half when the temperature is on the decline. Two inches is about the average for each month from February to June, but October, November and December are each over three inches. The most of the rainfall of Scotland comes from the west and south. This explains why the west coast is so much wetter than the east. The westerly winds from the Atlantic, laden with moisture, strike upon the high lands of the west, but exhaust themselves before they reach the watershed and, having precipitated their moisture between that and the coast, they reach the east coast comparatively dry. Braemar just under the watershed is relatively dry. Its situation as an elevated valley, 1114 feet above sea-level and surrounded on three sides by hills of from three to four thousand feet, and the fact that it is 60 miles from the sea combine to make it one of the most bracing places and give it one of the finest summer climates in the British Isles.[69] This sufficiently accounts for its popularity as a health resort. May is its driest month, October its wettest.

Easterly winds bring rain to the coast, but as a rule the rain extends no further inland than 20 miles. Easterly winds prevail during March, April and May, which make this season the most trying part of the year for weakly people. In summer the winds are often northerly, but the prevailing winds of the year, active for 37 per cent. of the 365 days or little less than half, are west and south-west. East winds bring fog, and this is most prevalent in the early summer, June being perhaps the worst month. The greatest drawback to the climate from an agriculturist’s point of view is the lateness of the spring. The summer being short, a late spring means a late harvest, which is invariably unsatisfactory.

The low rainfall of the county is favourable to sunshine. Aberdeen has 1400 hours of sunshine during the year in spite of fogs and east winds; the more inland parts being beyond the reach of sea-fog have an even better record.

The great objection—an objection taken by folks who have spent part of their life in South Africa or Canada—is the variableness of the climate from day to day. There is not here any fixity for continued periods of weather such as obtains in these countries. The chief factor in this variability is our insular position on the eastern side of the Atlantic. When, on rare occasions, as sometimes happens in June or in September, the atmosphere is settled, Aberdeenshire enjoys for a few weeks weather of the most salubrious and delightful kind.

[70]

The blood of the people of Aberdeenshire, though in the main Teutonic, has combined with Celtic and other elements, and has evolved a distinctive type, somewhat different in appearance and character from what is found in other parts of Scotland. How this amalgamation came about must be explained at some length.

The earliest inhabitants of Britain must have crossed from Europe when as yet there was no dividing North Sea. They used rough stone weapons (see p. 114) and were hunters living upon the products of the chase, the mammoth, reindeer and other animals that roamed the country. Such were palaeolithic (ancient stone) men. Perhaps they never reached Scotland: at least there is no trace of them in Aberdeenshire. They were followed by neolithic (new stone) men, who used more delicately carved weapons, stone axes, and flint arrows. Traces of these are to be found in Aberdeenshire. A few short cists containing skeletal remains have been found in various parts of the county. In the last forty years some fifteen of these have been unearthed. From these anthropologists conclude that neolithic men lived here at the end of the stone age, men of a muscular type, of short stature and with broad short faces. They were mighty hunters hunting the wild ox, the wolf and the bear in the dense forests which, after the Ice Age passed, overspread the north-east. They clothed themselves against[71] the cold in the skins of the animals which they made their prey and were a rude, savage, hardy race toughened by their mode of life and their fierce struggle for existence. They did not live by hunting alone; they possessed herds of cattle, swine and sheep and cultivated the ground but probably only to a slight extent. Their weapons were rude arrow-heads, flint knives and flint axes; and a considerable number of these primitive weapons as well as the bones of red-deer and the primeval ox—bos primigenius—have been recovered from peat-mosses and elsewhere throughout the district. Such have been found at Barra, at Inverurie and at Alford.

Besides these remains, have been found urns made of boulder clay, burned by fire and rudely ornamented. These were very likely their original drinking vessels, afterwards somewhat modified as food vessels, and were, it is supposed, deposited in graves with a religious motive in accordance with the belief common among primitive peoples that paradise is a happy hunting-ground in which the activities of the present life will continue under more favourable conditions.