“Father of Plastic Surgery.”

Title: Plastic and cosmetic surgery

Author: Frederick Strange Kolle

Release date: April 23, 2024 [eBook #73452]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: D. Appleton and Company

Credits: deaurider and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

“Father of Plastic Surgery.”

PLASTIC AND

COSMETIC SURGERY

BY

FREDERICK STRANGE KOLLE, M.D.

FELLOW OF NEW YORK ACADEMY OF MEDICINE; MEMBER OF DEUTSCHE MEDEZINISCHE

GESELLSCHAFT, N. Y., KINGS COUNTY HOSPITAL ALUMNI SOCIETY,

AUTHORS’ COMMITTEE AMERICAN HEALTH LEAGUE, PHYSICIANS’

LEGISLATURE LEAGUE ETC.; AUTHOR OF “THE X-RAYS:

THEIR PRODUCTION AND APPLICATION,” “MEDICO-SURGICAL

RADIOGRAPHY,” “SUBCUTANEOUS

HYDROCARBON PROTHESES,” ETC.

WITH ONE COLORED PLATE AND FIVE HUNDRED AND

TWENTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT

NEW YORK AND LONDON

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

1911

Copyright, 1911, by

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

PRINTED AT THE APPLETON PRESS,

NEW YORK, U. S. A.

TO

ALPHONZO BENJAMIN BOWERS

WHO KINDLED THE FIRE OF MY AMBITION

AND KEPT IT BURNING BY

HIS INTEREST AND UNTIRING APPRECIATION

THIS WORK IS

WITH HEARTFELT GRATITUDE

INSCRIBED

The object of the author has been to place before the profession a thoroughly practical and concise treatise on plastic and cosmetic surgery. The importance of this branch of practice is at the present time undeniable, yet the literature on this subject is widely scattered and scanty. It consists mostly of small, detached papers or reports in different countries, with an occasional reference in text-books on general surgery.

The author feels, from the numerous inquiries made him by physicians from many parts of the world concerning methods herein described, that there is now an actual need for an authoritative work on this subject.

Great care has been taken to select the best matter and to present it with comprehensive illustrations every physician can readily and confidently refer to.

Skin-grafting has been particularly gone into, as well as electrolysis as applied to dermatology, with information as to the construction and scientific use of apparatus involved.

To the whole has been added the practical experience and criticism of the author, who has devoted many years to the scientific and faithful advancement of this specialty.

Frederick Strange Kolle.

12 East Thirty-first Street,

New York City.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I HISTORICAL |

|

| Historical | 1 |

| CHAPTER II REQUIREMENTS FOR OPERATING |

|

| The operating room: The walls; The floors; Skylight; Disinfection; Instrument cabinet; Operating table; Instrument table; Irrigator—Care of instruments—Preparation of the surgeon and assistants: Care of the hands; Gowns—Preparing the patient: General preparation; Preparation of the operative field | 9 |

| CHAPTER III REQUIREMENTS DURING OPERATION |

|

| Sponges and sponging—Sterilization of dressings: Wallace sterilizer; Sprague sterilizer; Sterilizing plant; Dressing cases; Waste cans—Sutures and sterilization: Silkworm gut and silk; Catgut | 22 |

| CHAPTER IV PREFERRED ANTISEPTICS |

|

| Antiseptic solutions—Antiseptic powders | 34 |

| CHAPTER V WOUND DRESSINGS |

|

| Sutured wounds—Sutureless coaptation—Granulation—Changing dressings—Wounds of the mucous membrane—Pedunculated flaps—Foreign bodies | 43 |

| CHAPTER VI SECONDARY ANTISEPSIS |

|

| Septicemia following wound infection—Gangrene—Erysipelatous infection | 52[x] |

| CHAPTER VII ANESTHETICS |

|

| General anesthesia: Preparation for general anesthesia; Chloroform; Ether; Combined anesthesia; Nitrous oxid; Ethyl bromid; Ethyl chlorid—Local anesthesia: Ethyl chlorid; Cocain; Beta eucain; Liquid air; Stovain | 58 |

| CHAPTER VIII PRINCIPLES OF PLASTIC SURGERY |

|

| Incisions—Sutures—Needles—Needle holders—Methods in plastic operations: Stretching method; Sliding method; Twisting method; Implantation of pedunculated flaps by bridging; Transplantation of nonpedunculated flaps or skin-grafting; Autodermic skin-grafting; Heterodermic skin-grafting; Zoödermic skin-grafting—Mucous-membrane-grafting—Bone-grafting—Hair-transplantation | 76 |

| CHAPTER IX BLEPHAROPLASTY |

|

| Ectropion: Partial ectropion; Complete ectropion; Ectropion of both lids—Epicanthus—Canthoplasty—Ptosis—Ankyloblepharon—Wrinkled eyelids—Xanthelasma palpebrarum | 103 |

| CHAPTER X OTOPLASTY |

|

| Restoration of the auricle—Auricular protheses—Coloboma—Malformation of the lobule: Enlargement of the lobule; Attachment of the lobe—Malformation of the auricle: Microtia—Auricular Appendages—Polyotia—Malposition of the auricle | 120 |

| CHAPTER XI CHEILOPLASTY |

|

| Harelip: Classification of harelip deformities; The operative correction of harelip; Of unilateral labial cleft; Of congenital bilateral labial cleft; Post-operative treatment of harelip—Superior cheiloplasty: Classification of deformities of the upper lip; Operative correction of deformities of the upper lip—Inferior cheiloplasty—Labial deficiency—Labial ectropion—Labial entropion—Vermilion deficiency | 145 |

| CHAPTER XII STOMATOPLASTY |

|

| The correction of macrostoma—The correction of microstoma | 192[xi] |

| CHAPTER XIII MELOPLASTY |

|

| Small and medium defects—Large defects—Employment of protheses | 198 |

| CHAPTER XIV SUBCUTANEOUS HYDROCARBON PROTHESES |

|

| Indications—Precautions—The advantage of the method—Untoward results: Intoxication; Reaction; Infection; Necrosis; Sloughing; Sloughing due to pressure; Subinjection; Hyperinjection; Air embolism; Paraffin embolism; Primary diffusion or extension of paraffin; Interference with muscular action of the wings of the nose; Escape of paraffin after withdrawal of needle; Solidification of paraffin in needle; Absorption or disintegration of the paraffin; The difficulty of procuring paraffin with proper melting point; Hypersensitiveness of skin; Redness of the skin; Secondary diffusion of the injected mass; Hyperplasia of the connective tissue following the organization of injected matter; Yellow appearance and thickening of the skin after organization of the injected mass has taken place; The breaking down of tissue and resultant abscess due to the pressure of the injected mass upon the adjacent tissue after the injection has become organized—The proper instruments for the subcutaneous injection of hydrocarbon protheses—Preparation of the site of operation—Preparation of the instruments for operation—The practical technique—Specific classification for the employment and indication of hydrocarbon protheses about the face—Specific classification for the employment and indication of hydrocarbon protheses about the shoulders, etc.—Specific technique for the correction of regional deformities about the face: Transverse depressions; Deficient or receding forehead; Unilateral deficiency; Interciliary furrow; Temporal muscular deficiency; Deformities of the nose; Deformities about the mouth; Deformities about the cheeks; Deformities about the orbit; Deformities about the chin; Deformities about the ear—Specific technique for the correction of deformities about the shoulders | 209 |

| CHAPTER XV RHINOPLASTY |

|

| The causes of nasal destruction—Classification of deformities—Surgical technique—Protheses—Nasal replanting—Nasal transplanting—Total rhinoplasty: Pedunculated flap method; The Indian or Hindu method; The French method; The Italian method; The combined flap method; Organic support of nasal flaps; Periostitic supports; Osteoperiostitic supports; Cartilaginous support of flap—Partial rhinoplasty; Restoration of base of nose; Restoration of lobule and alæ; Restoration of the alæ; Restoration of nasal lobule; Restoration of subseptum | 339[xii] |

| CHAPTER XVI COSMETIC RHINOPLASTY |

|

| Angular nasal deformity—Correction of elevated lobule—Correction of bulbous lobule—Angular excision to correct lobule—Correction of malformations about nasal lobule—Deficiency of nasal lobule—Correction of widened base of nose—Reduction of thickness of alæ—Correction of nasal deviation—Undue prominence of nasal process of the superior maxillary | 448 |

| CHAPTER XVII ELECTROLYSIS IN DERMATOLOGY |

|

| The electric battery—The voltage or electromotive force—Cell selector—Milliampèremeter—The electric current—Portable batteries—Electrodes—Removal of superfluous hair—Removal of moles or other facial growths—Telangiectasis—Removal of nævi—Removal of tattoo marks—The treatment of scars | 470 |

| CHAPTER XVIII CASE RECORDING METHODS |

|

| Photographs—Stencil record—The rubber stamp—The plaster cast—Preparation of photographs | 491 |

Transcriber’s Note: Some illustrations have been moved to where they fit best with the surrounding text. Links lead to the illustration, not to the page number.

| FIG. | PAGE |

| A. Cornelius Celsus (“Father of Plastic Surgery”). | Frontispiece |

| Historical | |

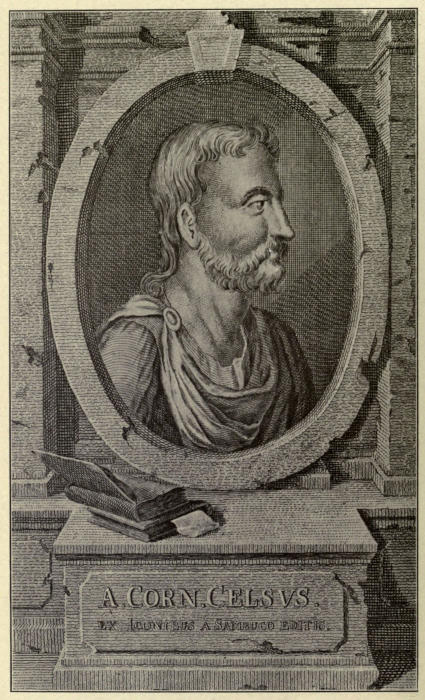

| 1.—Celsus incision for restoration of defect | 2 |

| 2.—Celsus incision to relieve tension | 2 |

| Requirements for Operating | |

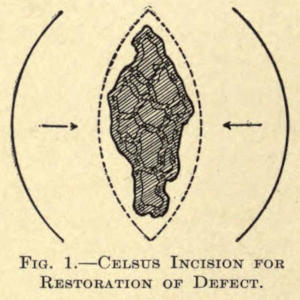

| 3.—Formaldehyd disinfecting apparatus | 11 |

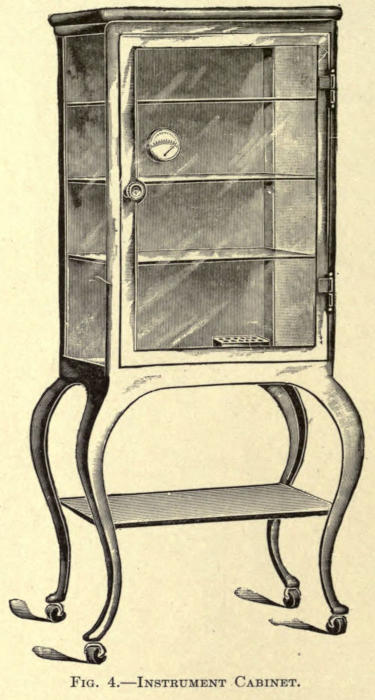

| 4.—Instrument cabinet | 12 |

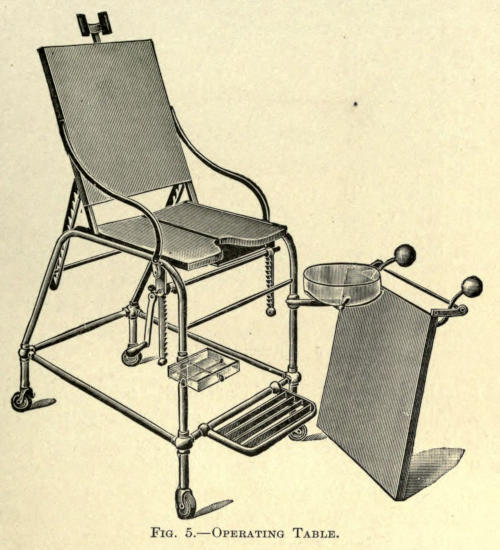

| 5.—Operating table | 13 |

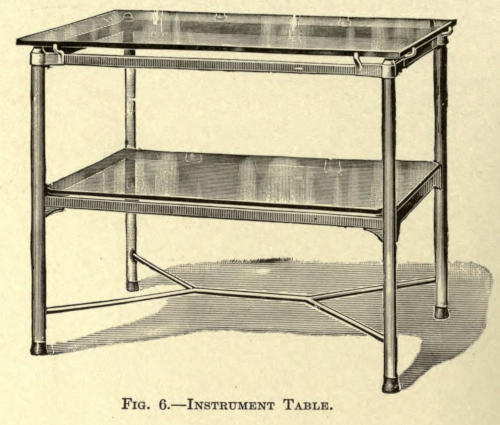

| 6.—Instrument table | 14 |

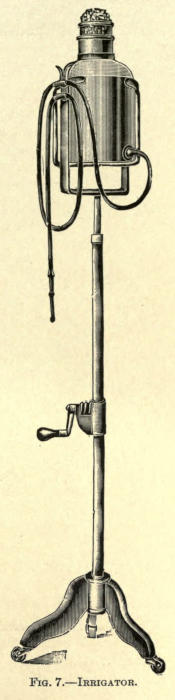

| 7.—Irrigator | 15 |

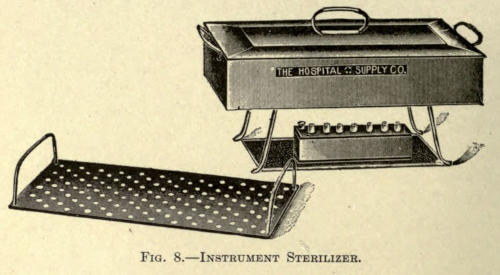

| 8.—Instrument sterilizer | 16 |

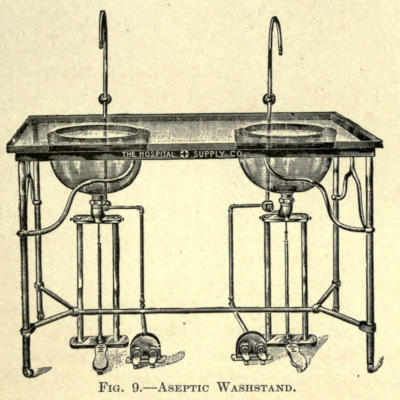

| 9.—Aseptic washstand | 17 |

| 10.—Von Bergman operating gown | 19 |

| 11.—Triffe rubber apron | 19 |

| Requirements during Operation | |

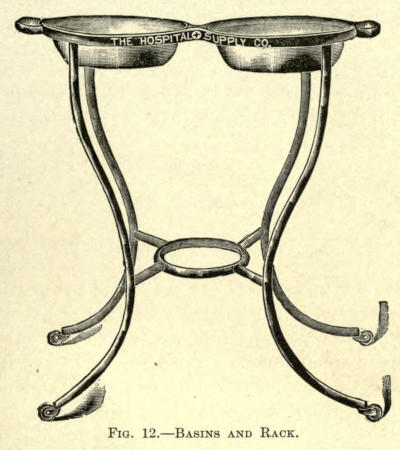

| 12.—Basins and rack | 23 |

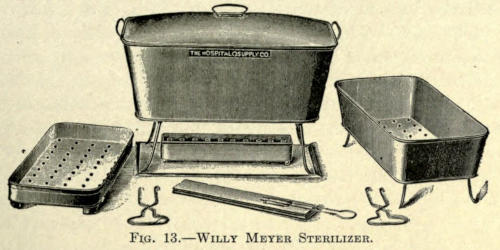

| 13.—Willy Meyer sterilizer | 25 |

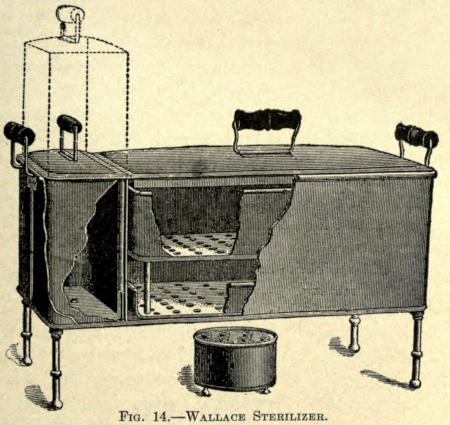

| 14.—Wallace sterilizer | 25 |

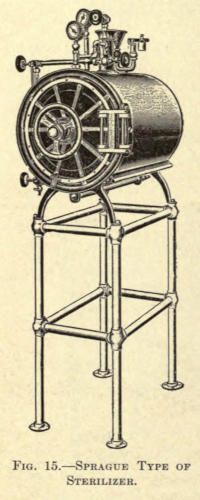

| 15.—Sprague type of sterilizer | 26 |

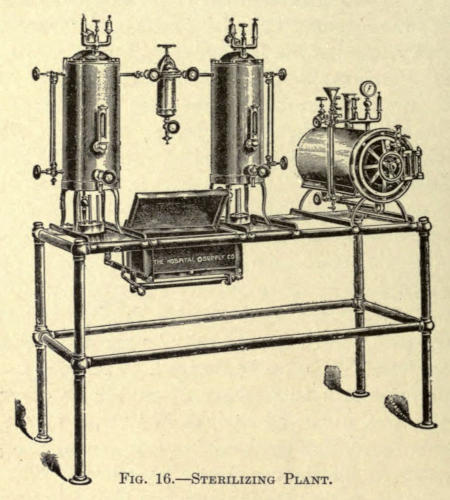

| 16.—Sterilizing plant | 28 |

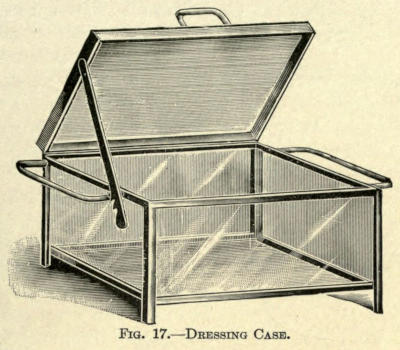

| 17.—Dressing case | 29 |

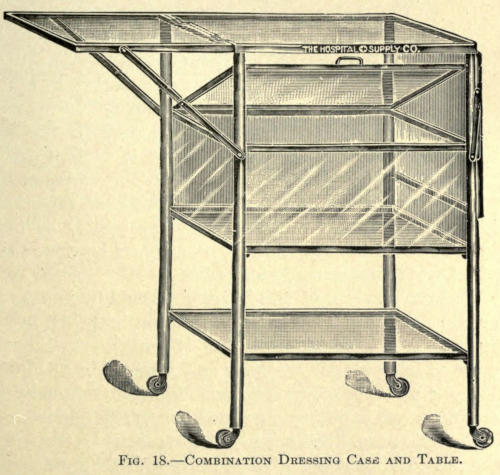

| 18.—Combination dressing case and table | 29 |

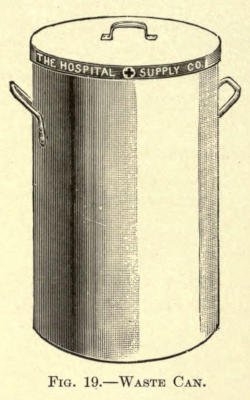

| 19.—Waste pail | 30 |

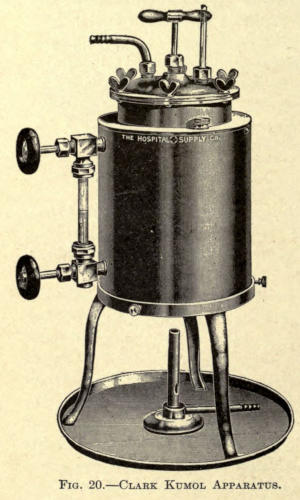

| 20.—Clark Kumol apparatus | 32 |

| Wound Dressing | |

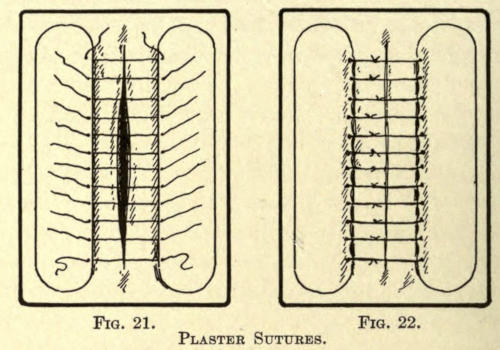

| 21, 22.—Plaster sutures | 46 |

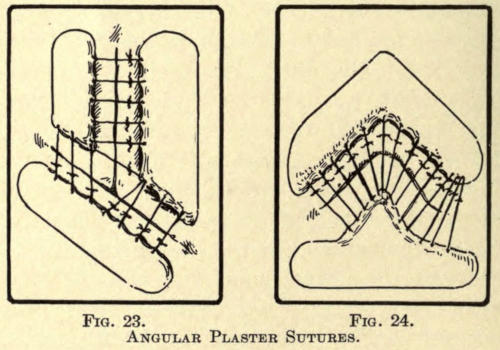

| 23, 24.—Angular plaster sutures | 46 |

| Secondary Antisepsis | |

| 25.—Walcher dressing forceps | 55 |

| 26.—Toothed seizing forceps | 55[xiv] |

| Anesthetics | |

| 27.—Schimmelbusch dropping bottle | 60 |

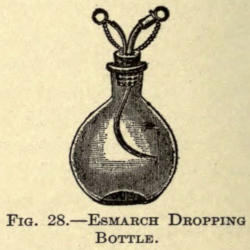

| 28.—Esmarch dropping bottle | 60 |

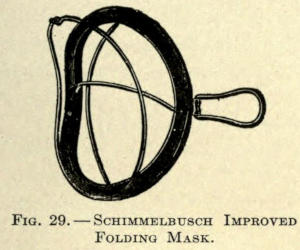

| 29.—Schimmelbusch folding mask | 61 |

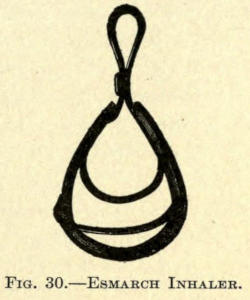

| 30.—Esmarch inhaler | 61 |

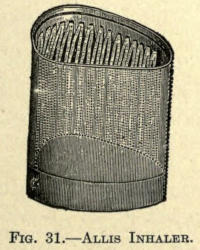

| 31.—Allis inhaler | 65 |

| 32.—Fowler inhaler | 65 |

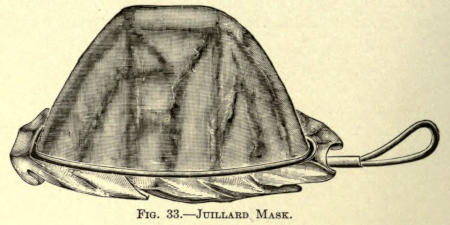

| 33.—Juillard mask | 66 |

| 34.—Simplex syringe | 72 |

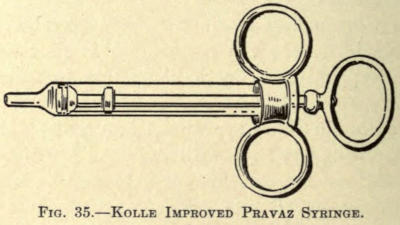

| 35.—Kolle improved Pravaz syringe | 72 |

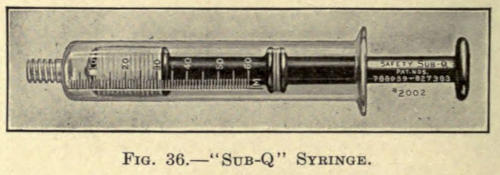

| 36.—“Sub-Q” syringe | 72 |

| Principles of Plastic Surgery | |

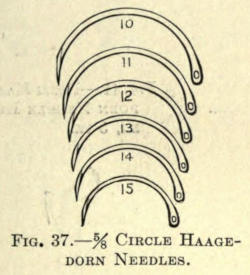

| 37.—⅝ circle Haagedorn needles | 77 |

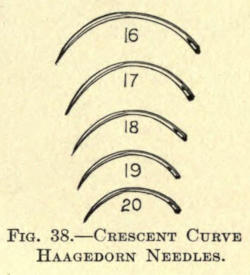

| 38.—Crescent curve Haagedorn needles | 77 |

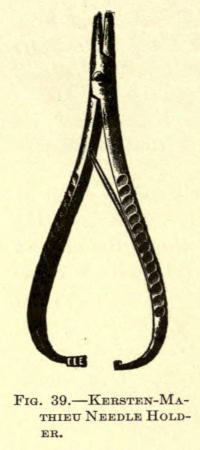

| 39.—Kersten-Mathieu needle holder | 78 |

| 40.—Haagedorn needle holder | 78 |

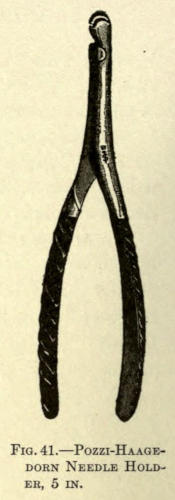

| 41.—Pozzi-Haagedorn needle holder | 78 |

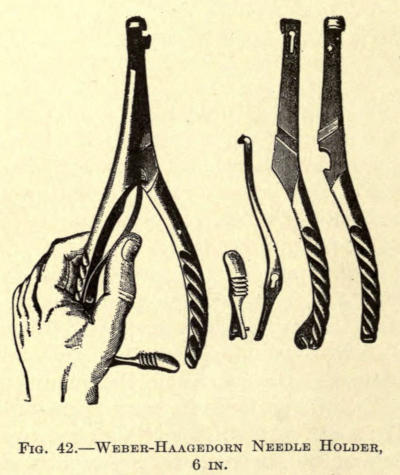

| 42.—Weber-Haagedorn needle holder | 78 |

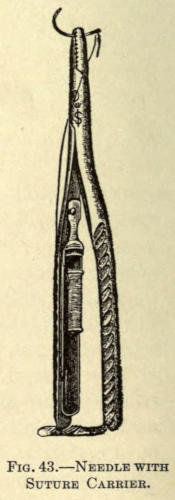

| 43.—Needleholder with suture carrier | 78 |

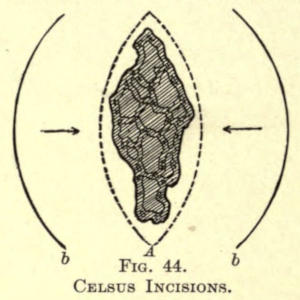

| 44.—Celsus skin incisions | 80 |

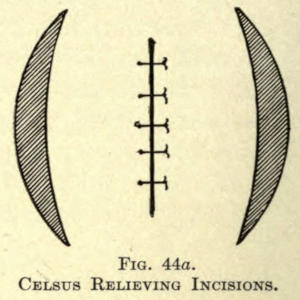

| 44 a.—Celsus relieving incisions | 80 |

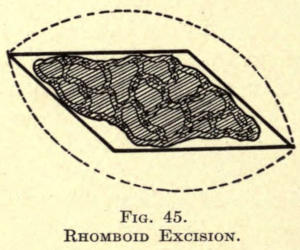

| 45.—Rhomboid excision | 80 |

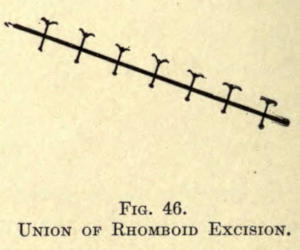

| 46.—Union of rhomboid excision | 80 |

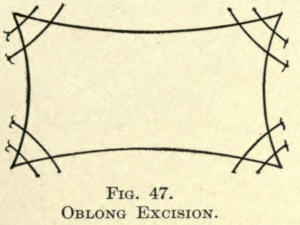

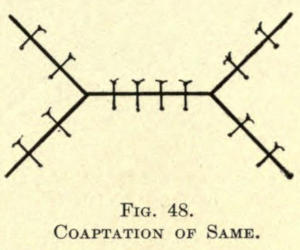

| 47.—Oblong excision | 81 |

| 48.—Coaptation of wound | 81 |

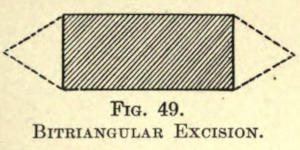

| 49.—Bitriangular excision | 81 |

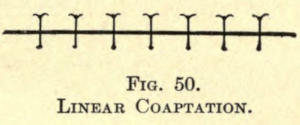

| 50.—Linear coaptation | 81 |

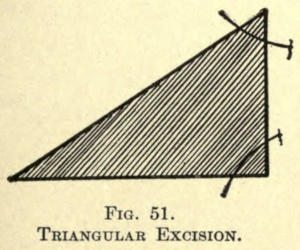

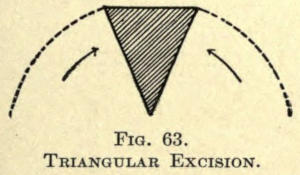

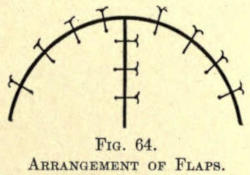

| 51.—Triangular excision | 81 |

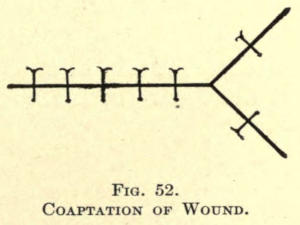

| 52.—Coaptation of wound | 81 |

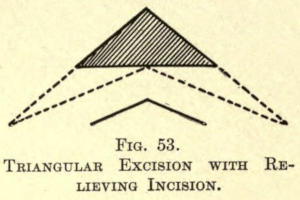

| 53.—Triangular excision with relieving incisions | 82 |

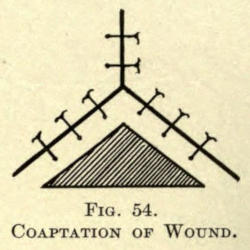

| 54.—Coaptation of wound | 82 |

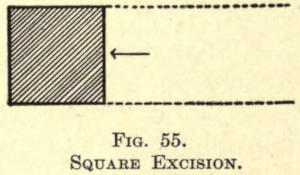

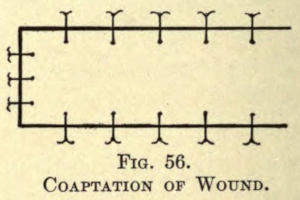

| 55.—Square excision | 82 |

| 56.—Coaptation of wound | 82 |

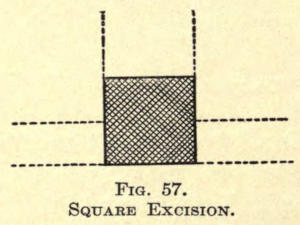

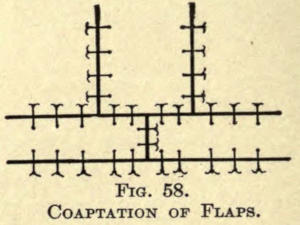

| 57.—Square excision | 82 |

| 58.—Coaptation of flaps | 82 |

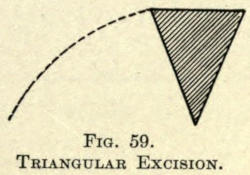

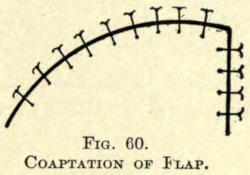

| 59.—Triangular excision | 83 |

| 60.—Coaptation of flap | 83 |

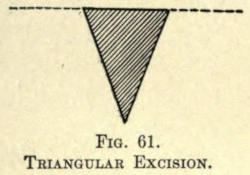

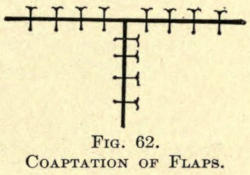

| 61.—Triangular excision | 83 |

| 62.—Coaptation of flaps | 83 |

| 63.—Triangular excision | 83 |

| 64.—Arrangement of flaps | 83 |

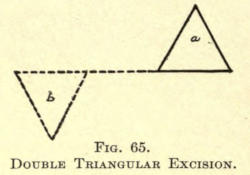

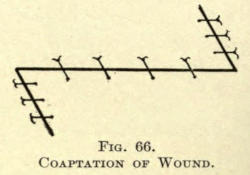

| 65.—Double triangular excision | 84 |

| 66.—Coaptation of wound | 84 |

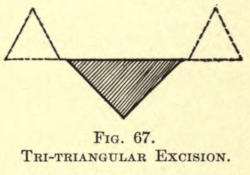

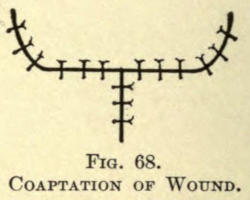

| 67.—Tri-triangular excision | 84 |

| 68.—Coaptation of wound | 84[xv] |

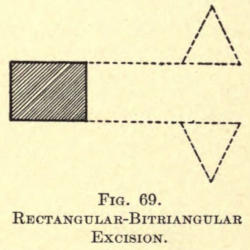

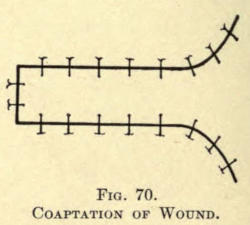

| 69.—Rectangular-bitriangular excision | 84 |

| 70.—Coaptation of wound | 84 |

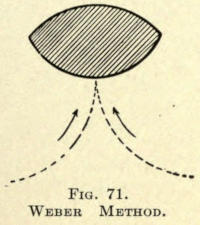

| 71.—Weber excision method | 85 |

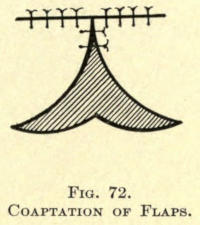

| 72.—Coaptation of flaps | 85 |

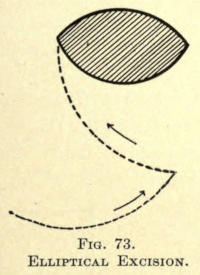

| 73.—Elliptical excision | 85 |

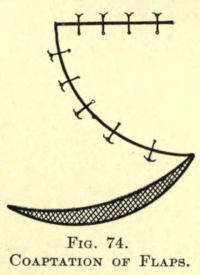

| 74.—Coaptation of flaps | 85 |

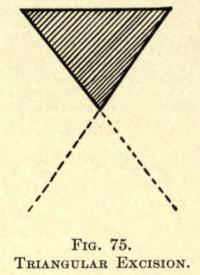

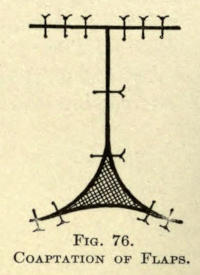

| 75.—Triangular excision | 86 |

| 76.—Coaptation of flaps | 86 |

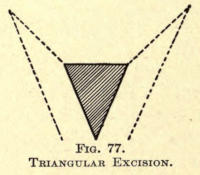

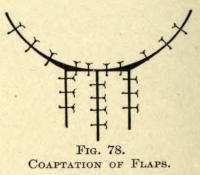

| 77.—Triangular excision | 86 |

| 78.—Coaptation of flaps | 86 |

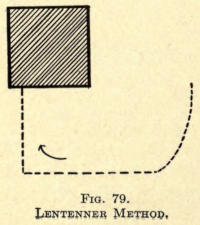

| 79.—Lentenner method of excision | 86 |

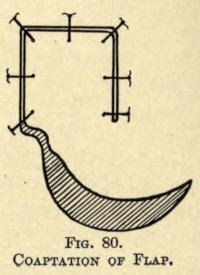

| 80.—Coaptation of flap | 86 |

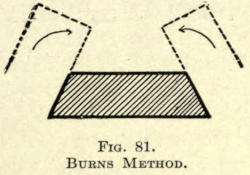

| 81.—Burns method of excision | 87 |

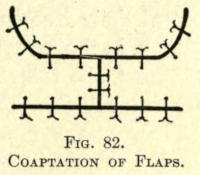

| 82.—Coaptation of flaps | 87 |

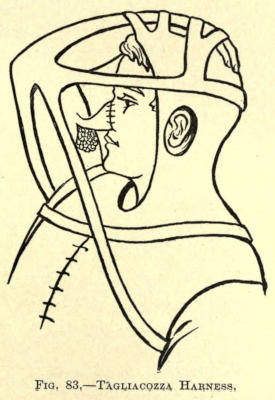

| 83.—Tagliacozza harness | 87 |

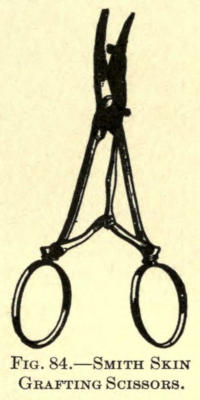

| 84.—Smith skin-grafting scissors | 89 |

| 85.—Thiersch skin-grafting razor | 93 |

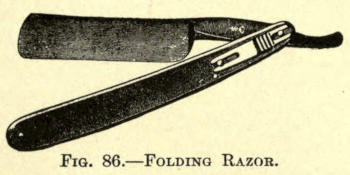

| 86.—Thiersch folding razor | 93 |

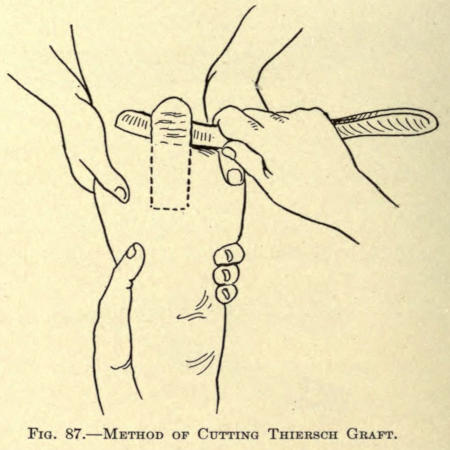

| 87.—Method of cutting Thiersch graft | 94 |

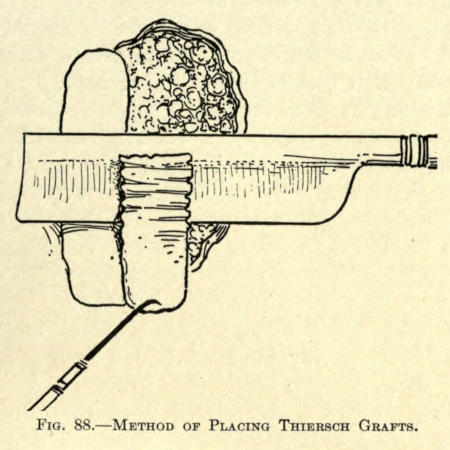

| 88.—Method of placing Thiersch graft | 95 |

| Blepharoplasty | |

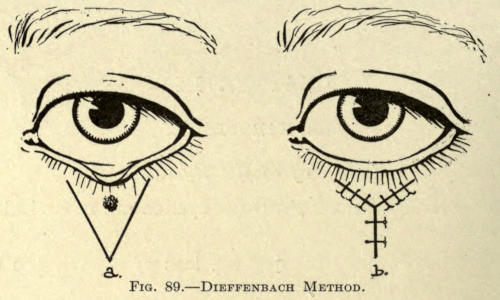

| 89.—Correction of ectropion, Dieffenbach method | 104 |

| 90 a and b.—Correction of partial ectropion (author’s case) | 104 |

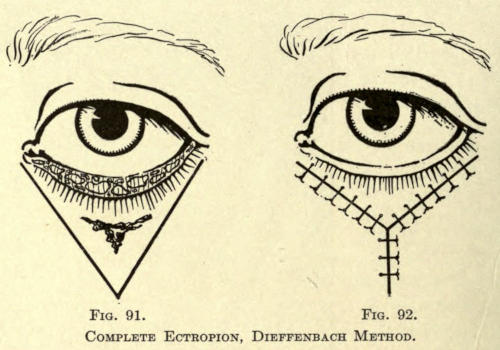

| 91, 92.—Complete ectropion, Dieffenbach method | 106 |

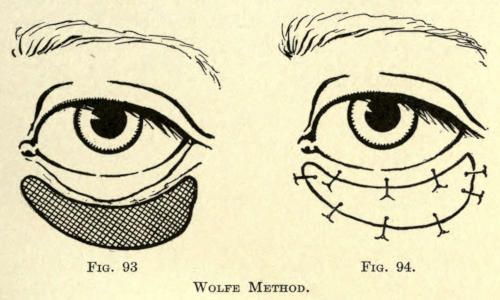

| 93, 94.—Complete ectropion, Wolfe method | 107 |

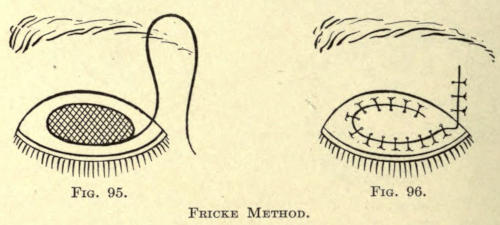

| 95, 96.—Complete ectropion, Fricke method | 108 |

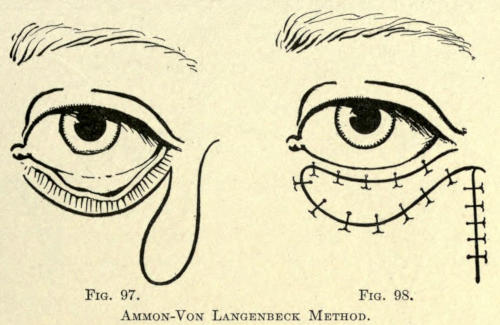

| 97, 98.—Complete ectropion, Ammon-Von Langenbeck method | 109 |

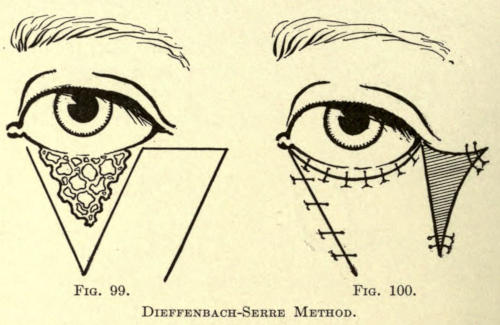

| 99, 100.—Complete ectropion, Dieffenbach-Serre method | 110 |

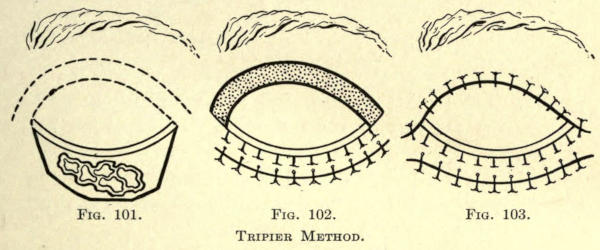

| 101, 102, 103.—Complete ectropion, Tripier method | 111 |

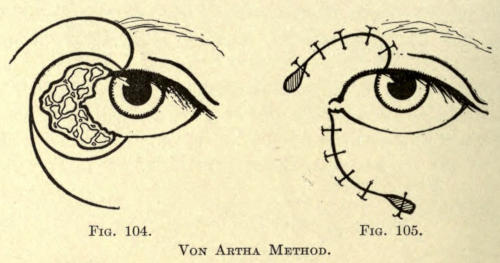

| 104, 105.—Complete ectropion, Von Artha method | 112 |

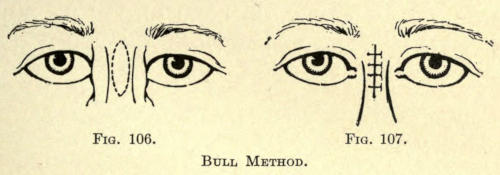

| 106, 107.—Epicanthus, Bull method | 113 |

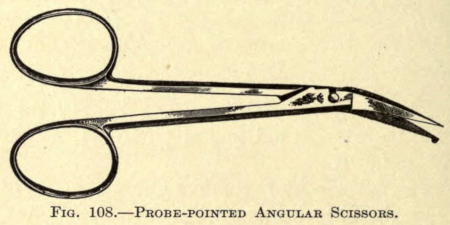

| 108.—Probe-pointer angular scissors | 114 |

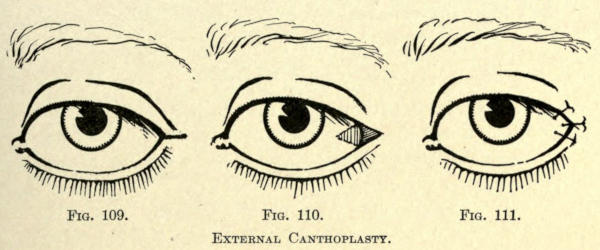

| 109, 110, 111.—External canthoplasty | 115 |

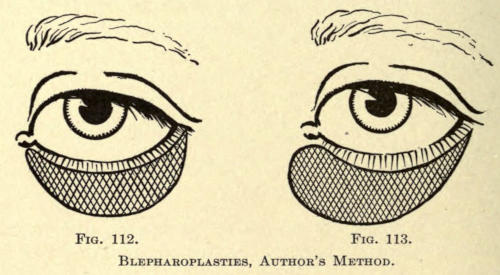

| 112, 113.—Blepharoplastics, author’s method | 116 |

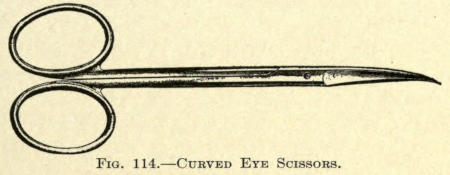

| 114.—Curved eye scissors | 117 |

| Otoplasty | |

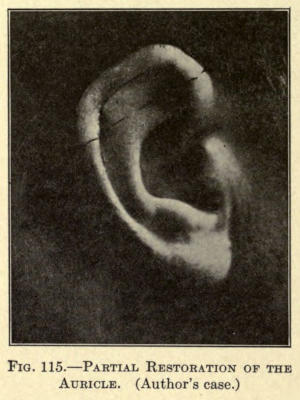

| 115.—Partial restoration of the auricle | 124 |

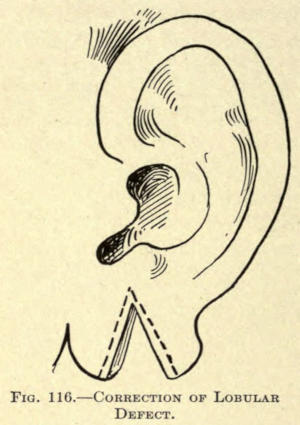

| 116.—Correction of lobular defect | 126 |

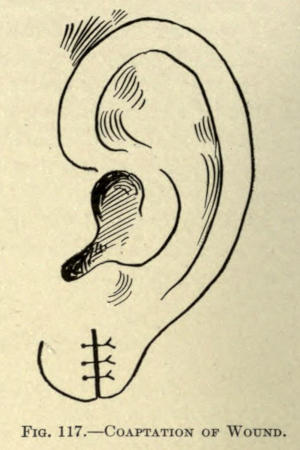

| 117.—Coaptation of wound | 126 |

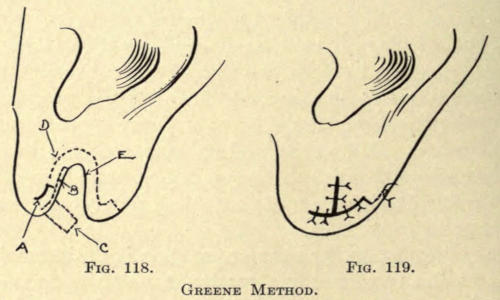

| 118, 119.—Greene method correcting coloboma | 126 |

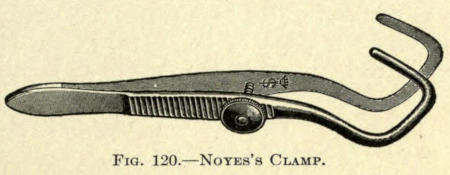

| 120.—Noyes’s clamp | 127 |

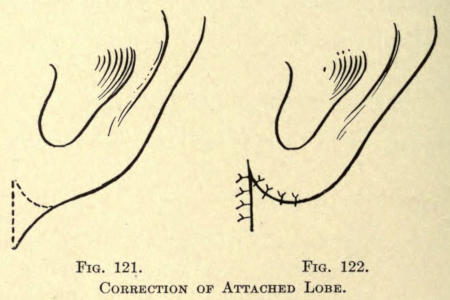

| 121, 122.—Correction of attached lobe | 128 |

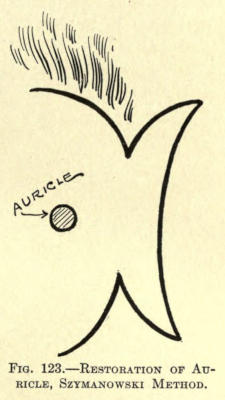

| 123.—Restoration of auricle, Szymanowski method | 129 |

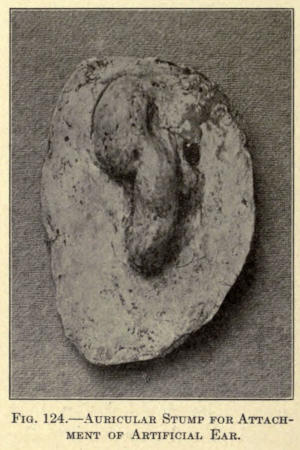

| 124.—Auricular stump for attachment of artificial ear | 130 |

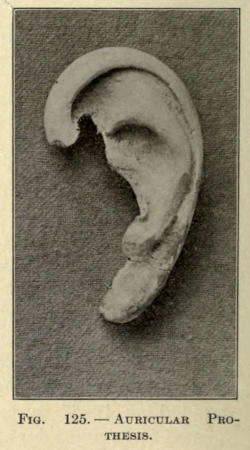

| 125.—Auricular prothesis | 130[xvi] |

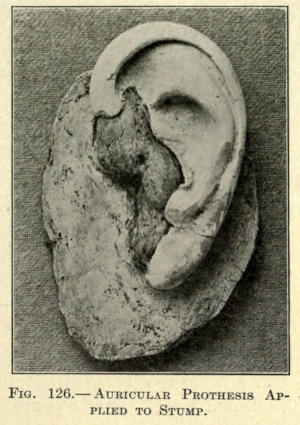

| 126.—Auricular prothesis applied to stump | 131 |

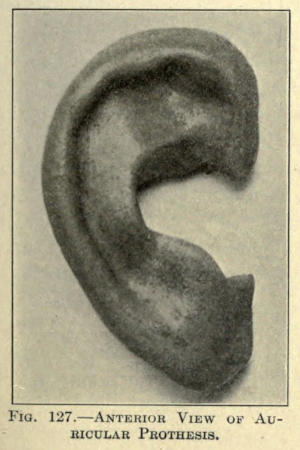

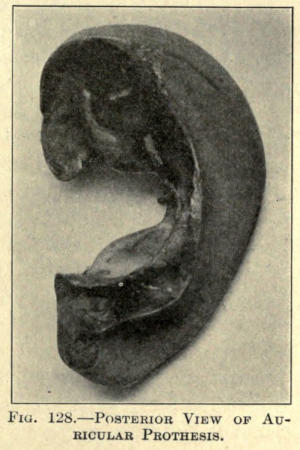

| 127.—Anterior view of auricular prothesis | 131 |

| 128.—Posterior view of auricular prothesis | 131 |

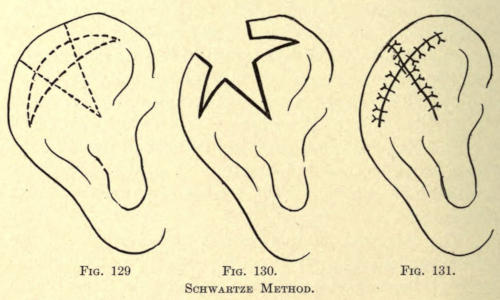

| 129, 130, 131.—Schwartze method of correction of macrotia | 134 |

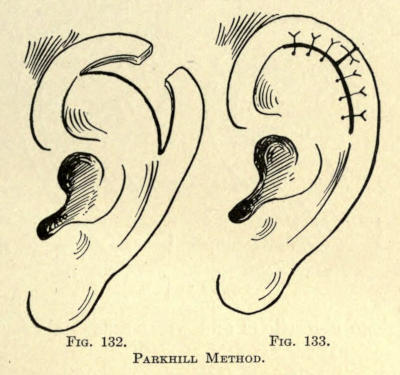

| 132, 133.—Parkhill method of correction of macrotia | 135 |

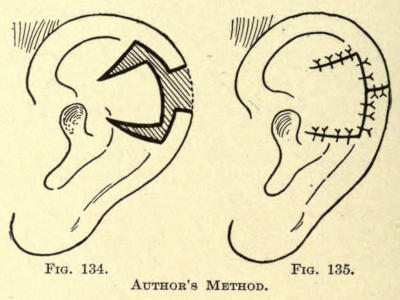

| 134, 135.—Author’s method of correction of macrotia | 137 |

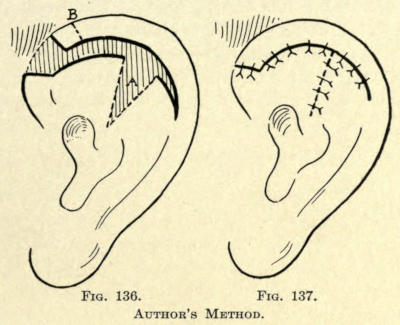

| 136, 137.—Author’s method of correction of macrotia | 137 |

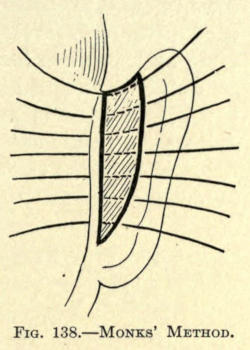

| 138.—Monks’ method of correction of malposed ear | 139 |

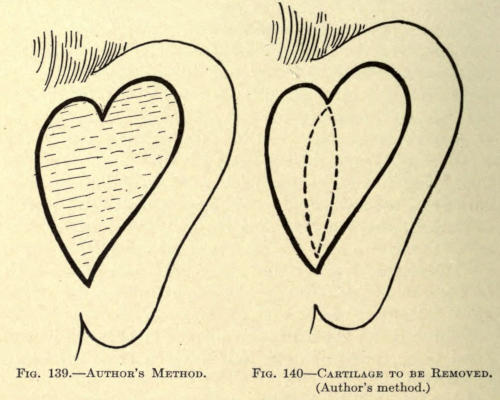

| 139, 140.—Author’s method of correction of malposed ear | 140 |

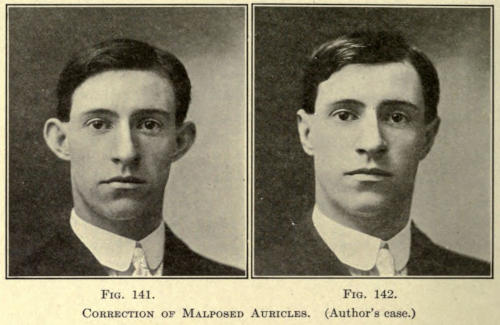

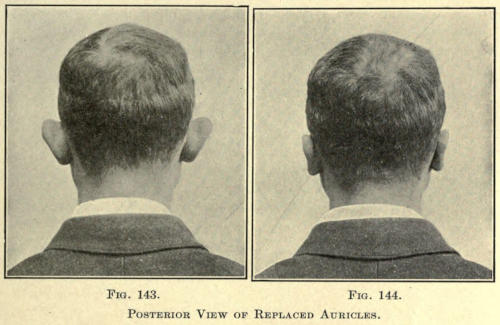

| 141, 142.—Correction of malposed auricles, author’s case (anterior view) | 142 |

| 143, 144.—Posterior view of replaced auricles | 143 |

| Cheiloplasty | |

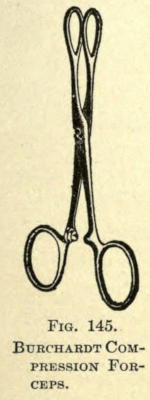

| 145.—Burchardt compression forceps | 145 |

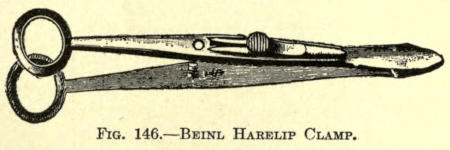

| 146.—Beinl harelip clamp | 145 |

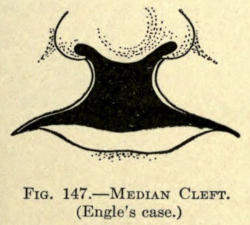

| 147.—Median cleft, Siegel’s case | 147 |

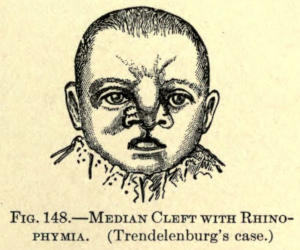

| 148.—Median cleft with rhinophyma, Trendelenburg’s case | 147 |

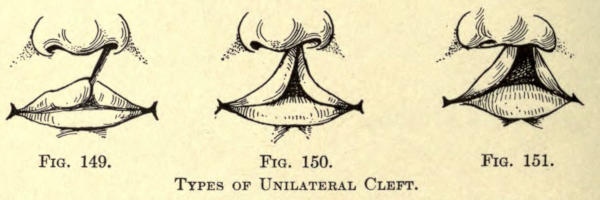

| 149, 150, 151.—Types of unilateral labial cleft | 148 |

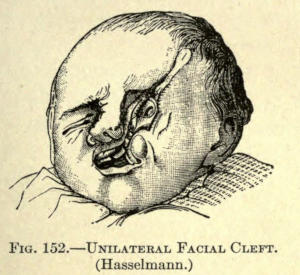

| 152.—Unilateral facial cleft, Hasselmann | 149 |

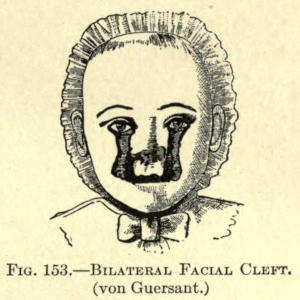

| 153.—Bilateral facial cleft, Guersant | 149 |

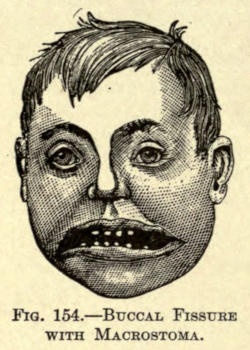

| 154.—Buccal fissure with macrostoma | 150 |

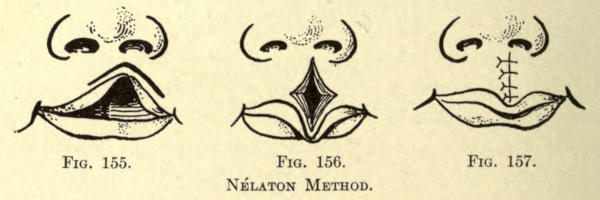

| 155, 156, 157.—Harelip correction, Nélaton method | 152 |

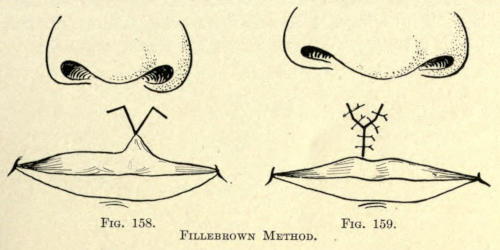

| 158, 159.—Harelip correction, Fillebrown method | 153 |

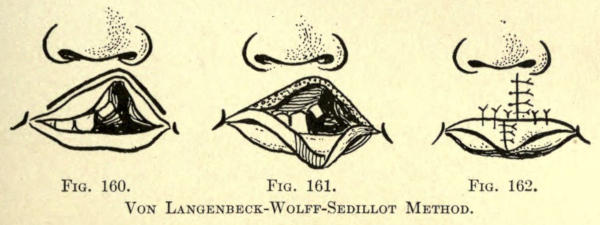

| 160, 161, 162.—Harelip correction, Von Langenbeck-Wolff-Sedillot method | 153 |

| 163, 164, 165.—Harelip correction, Malgaigne method | 154 |

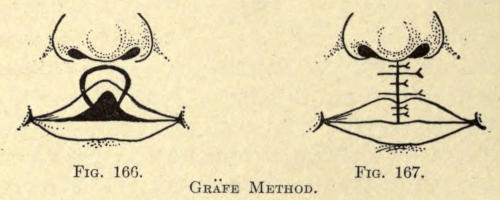

| 166, 167.—Harelip correction, Gräfe method | 154 |

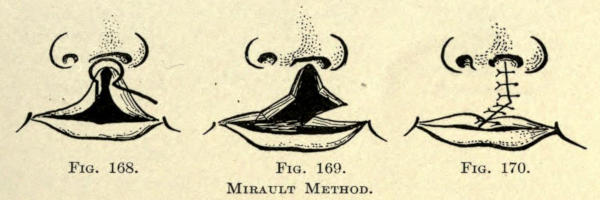

| 168, 169, 170.—Harelip correction, Mirault method | 155 |

| 171, 172, 173.—Harelip correction, Giralde method | 155 |

| 174, 175, 176.—Harelip correction, König method | 156 |

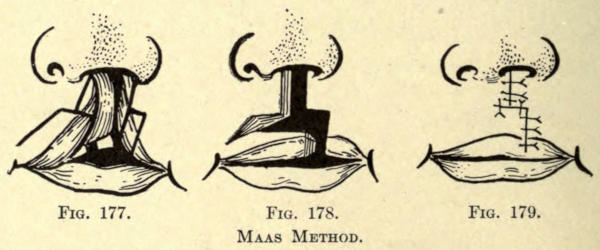

| 177, 178, 179.—Harelip correction, Maas method | 156 |

| 180, 181, 182.—Harelip correction, Haagedorn method | 157 |

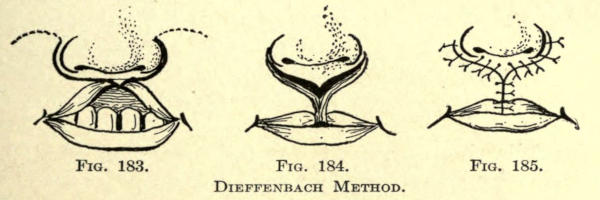

| 183, 184, 185.—Harelip correction, Dieffenbach method | 157 |

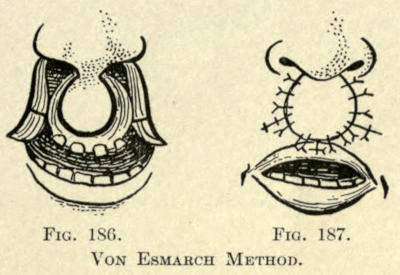

| 186, 187.—Correction bilateral cleft, Von Esmarch method | 159 |

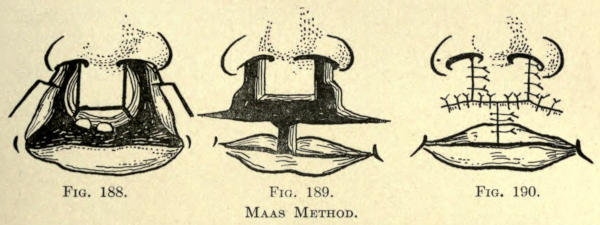

| 188, 189, 190.—Correction bilateral cleft, Maas method | 159 |

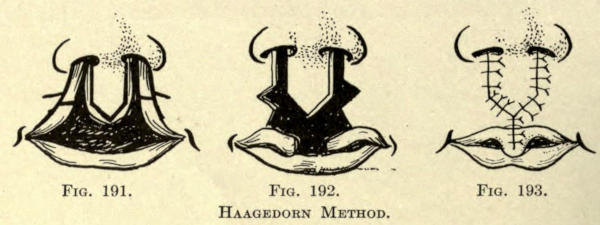

| 191, 192, 193.—Correction bilateral cleft, Haagedorn method | 160 |

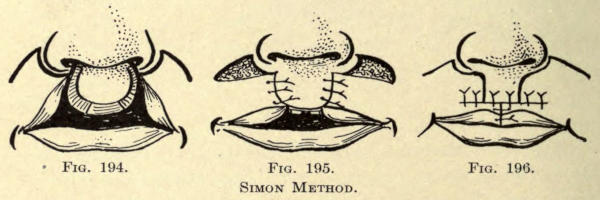

| 194, 195, 196.—Correction bilateral cleft, Simon method | 160 |

| 197.—Hainsley cheek compressor | 161 |

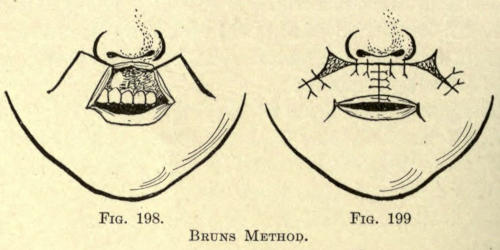

| 198, 199.—Superior cheiloplasty, Bruns method | 164 |

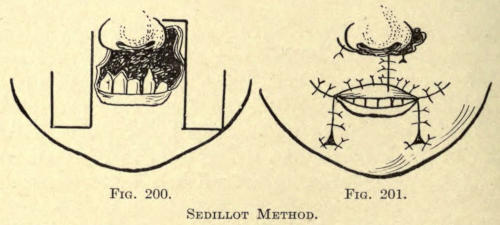

| 200, 201.—Superior cheiloplasty, Sedillot method | 165 |

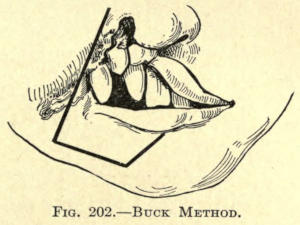

| 202.—Superior cheiloplasty, Buck method | 165 |

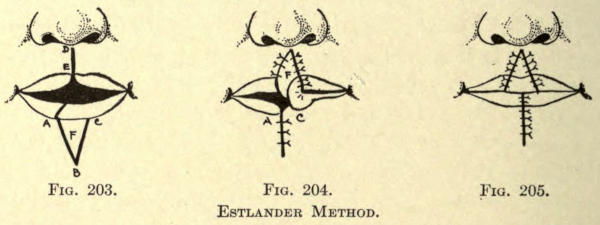

| 203, 204, 205.—Superior cheiloplasty, Estlander method | 166 |

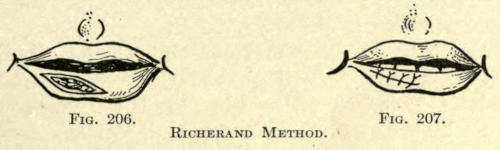

| 206, 207.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Richerand method | 169 |

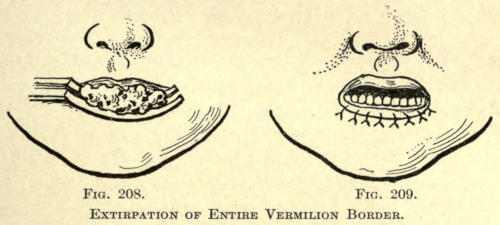

| 208, 209.—Extirpation of vermilion border | 169 |

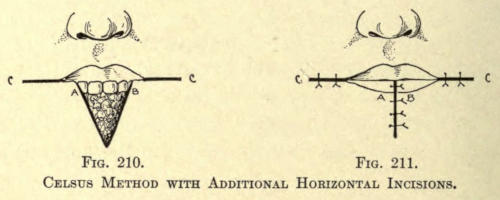

| 210, 211.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Celsus method with additional incisions | 170 |

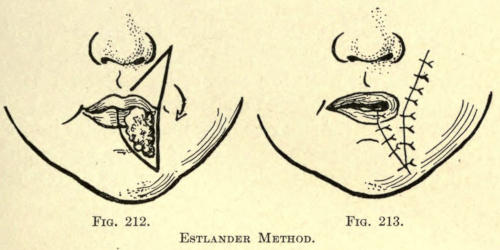

| 212, 213.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Estlander method | 171 |

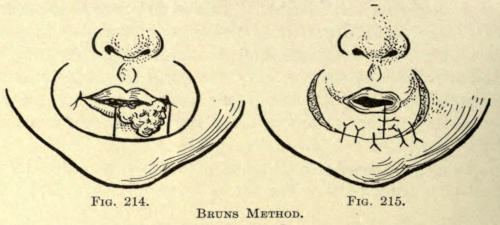

| 214, 215.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Bruns method | 172[xvii] |

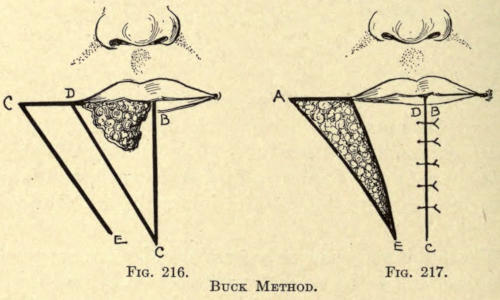

| 216, 217.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Buck method | 172 |

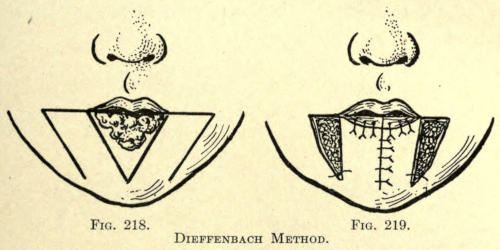

| 218, 219.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Dieffenbach method | 173 |

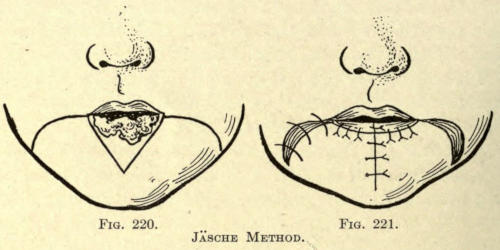

| 220, 221.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Jäsche method | 174 |

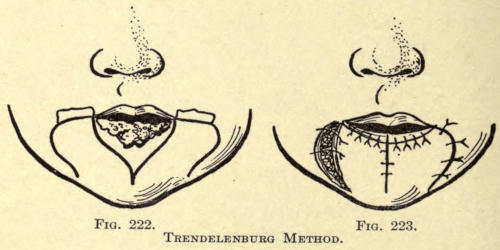

| 222, 223.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Trendelenburg method | 174 |

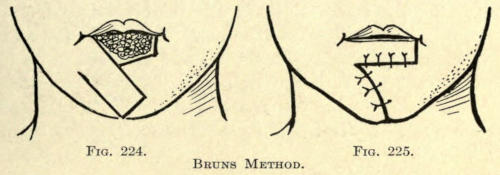

| 224, 225.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Bruns method | 175 |

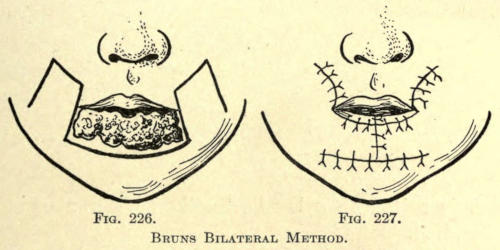

| 226, 227.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Bruns bilateral method | 175 |

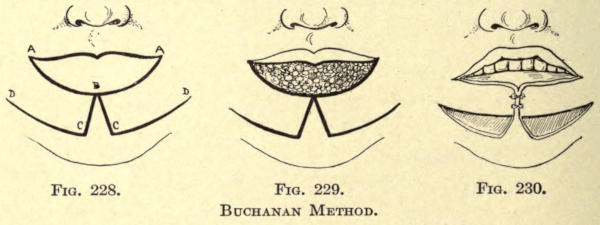

| 228, 229, 230.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Buchanan method | 176 |

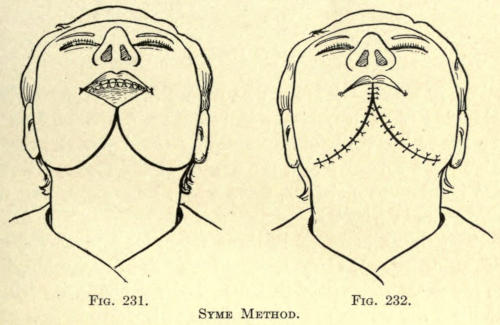

| 231, 232.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Syme method | 177 |

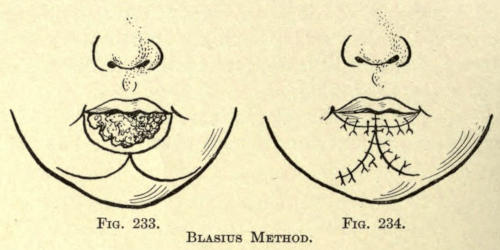

| 233, 234.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Blasius method | 178 |

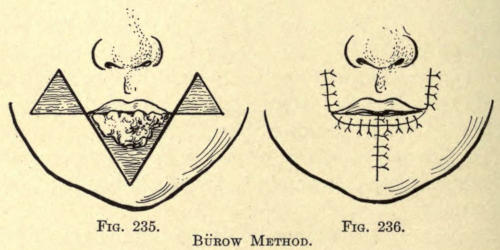

| 235, 236.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Bürow method | 178 |

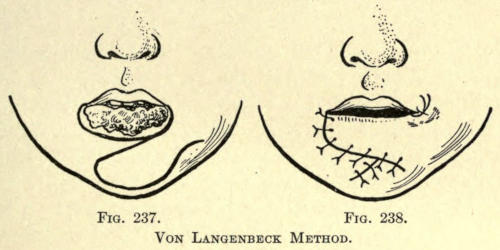

| 237, 238.—Inferior cheiloplasty, von Langenbeck | 179 |

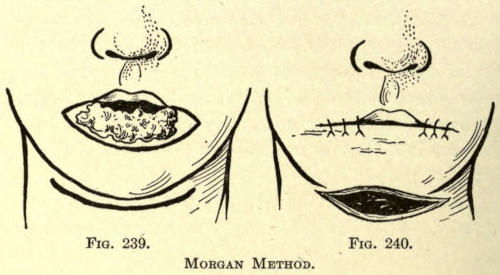

| 239, 240.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Morgan method | 180 |

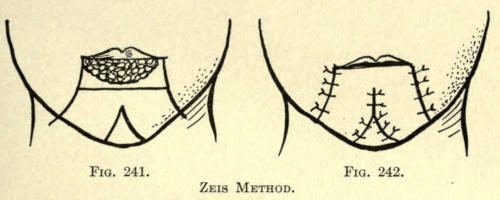

| 241, 242.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Zeis method | 181 |

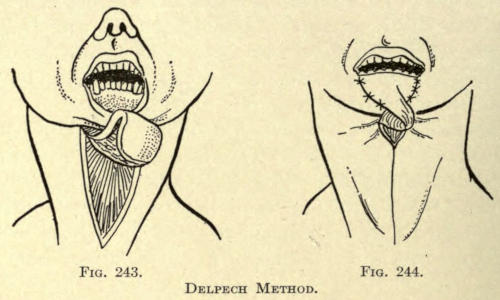

| 243, 244.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Delpech method | 182 |

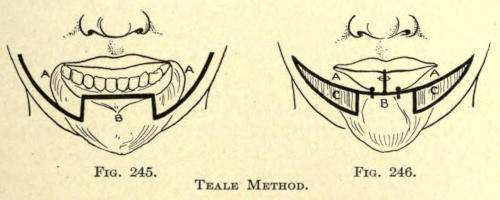

| 245, 246.—Inferior cheiloplasty, Teale method | 185 |

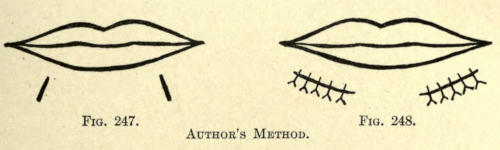

| 247, 248.—Labial ectropion, author’s method | 187 |

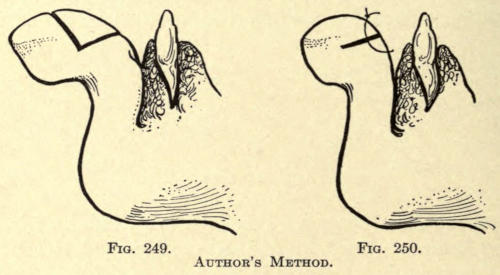

| 249, 250.—Labial ectropion, author’s method | 188 |

| Stomatoplasty | |

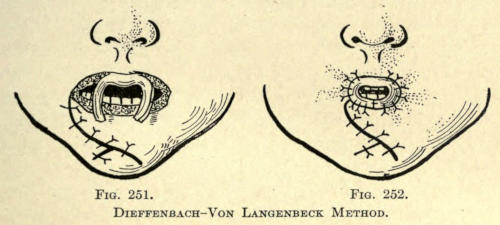

| 251, 252.—Correction of Macrostoma, Dieffenbach-Von Langenbeck method | 193 |

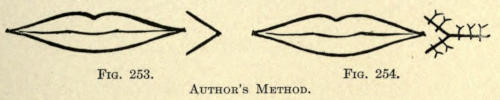

| 253, 254.—Correction of Macrostoma, author’s method | 195 |

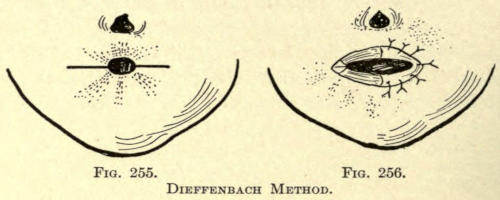

| 255, 256.—Correction of Microstoma, Dieffenbach method | 196 |

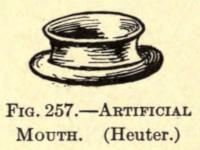

| 257.—Artificial mouth, Heuter | 196 |

| Meloplasty | |

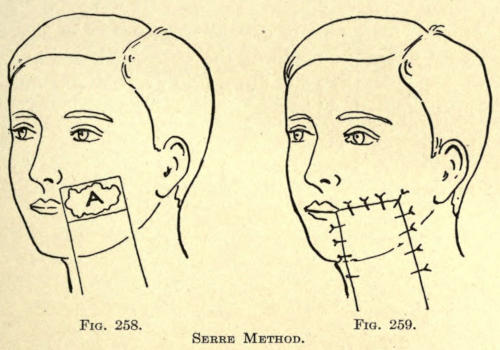

| 258, 259.—Meloplasty, Serre method | 199 |

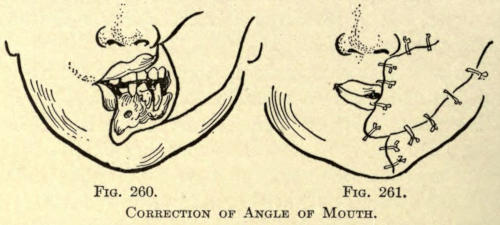

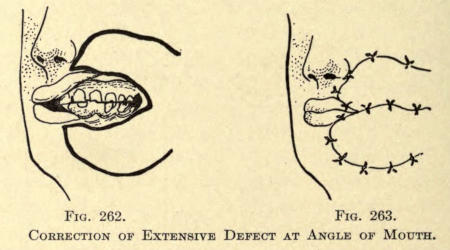

| 260, 261.—Correction of angle of mouth | 200 |

| 262, 263.—Correction of extensive angle of mouth | 200 |

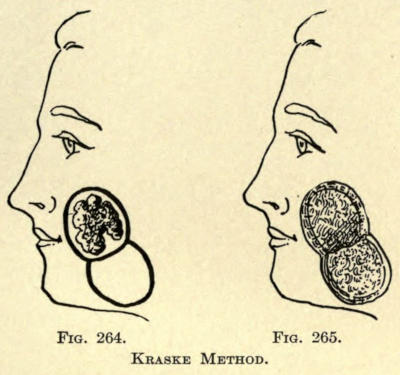

| 264, 265.—Meloplasty, Kraske method | 201 |

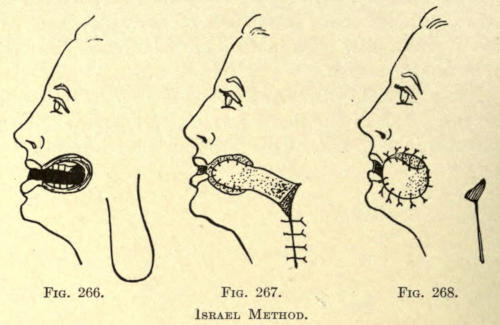

| 266, 267, 268.—Meloplasty, Israel method | 202 |

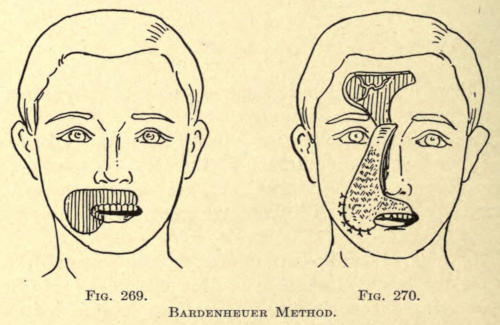

| 269, 270.—Meloplasty, Bardenheuer | 202 |

| 271, 272, 273, 274.—Meloplasty, Bardenheuer | 203 |

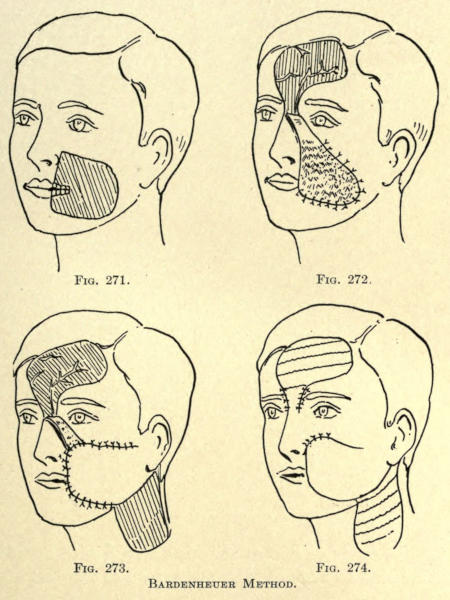

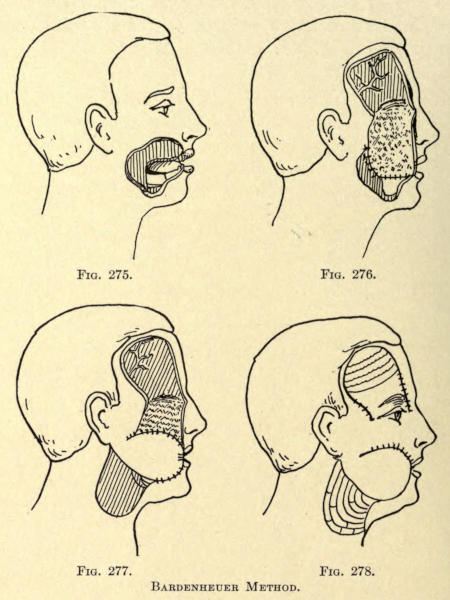

| 275, 276, 277, 278.—Meloplasty, Bardenheuer | 204 |

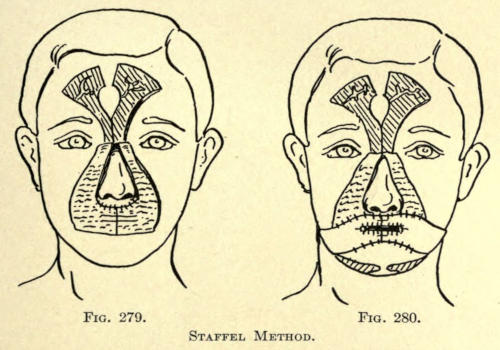

| 279, 280.—Meloplasty, Staffel | 205 |

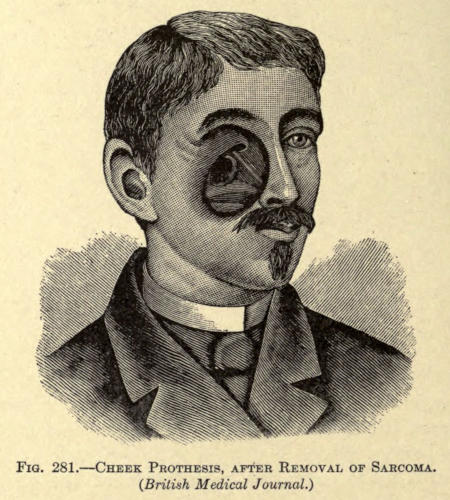

| 281.—Cheek prothesis after removal of sarcoma, Martin | 206 |

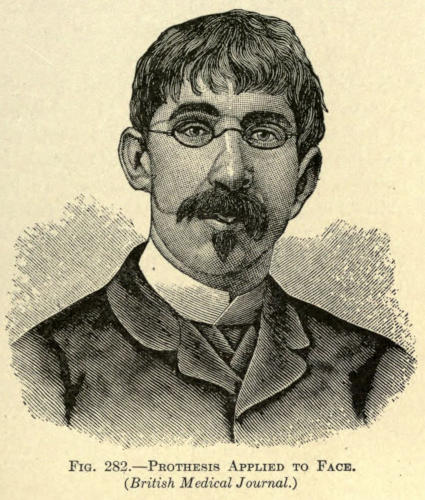

| 282.—Prothesis applied to face | 207 |

| Subcutaneous Hydrocarbon Protheses | |

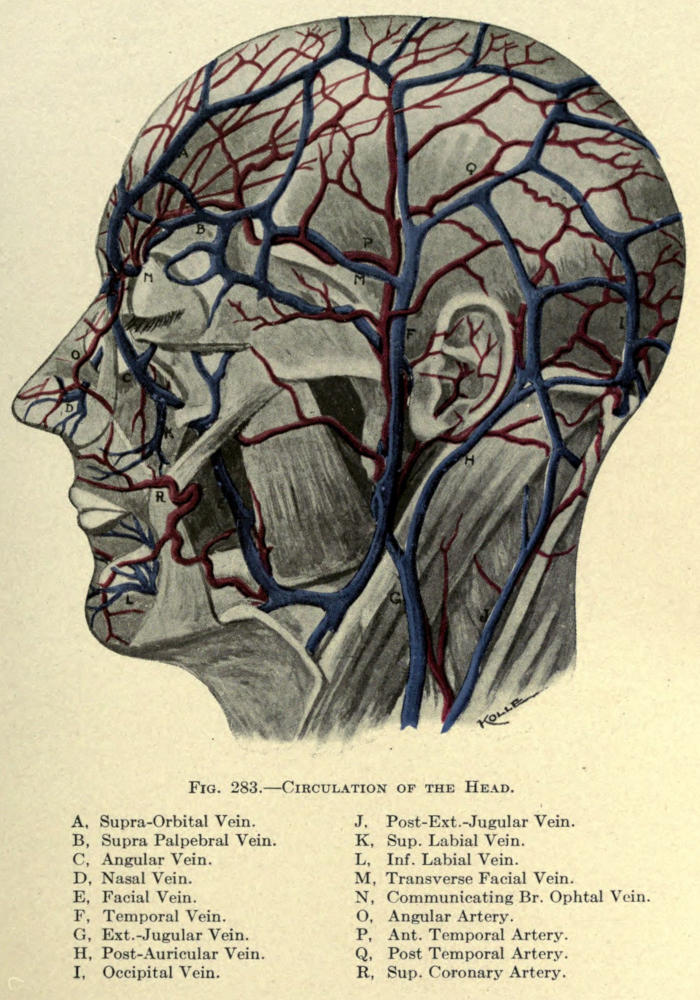

| 283.—Circulation of the head (author) | Facing 210 |

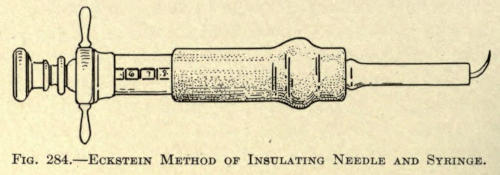

| 284.—Eckstein insulated syringe | 232 |

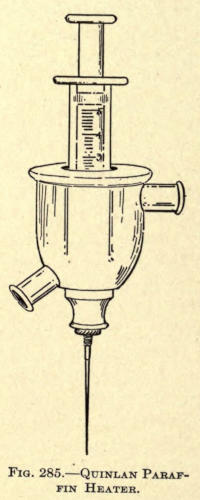

| 285.—Quinlan paraffin heater | 232 |

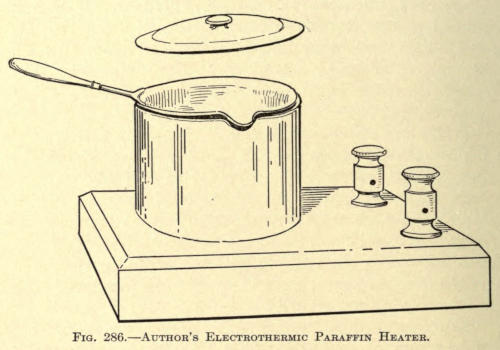

| 286.—Author’s electrothermic paraffin heater | 244 |

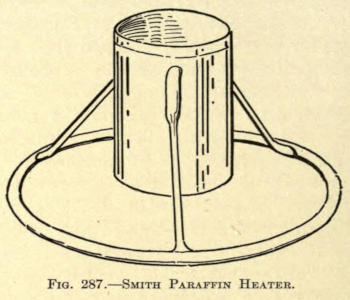

| 287.—Smith paraffin heater | 246 |

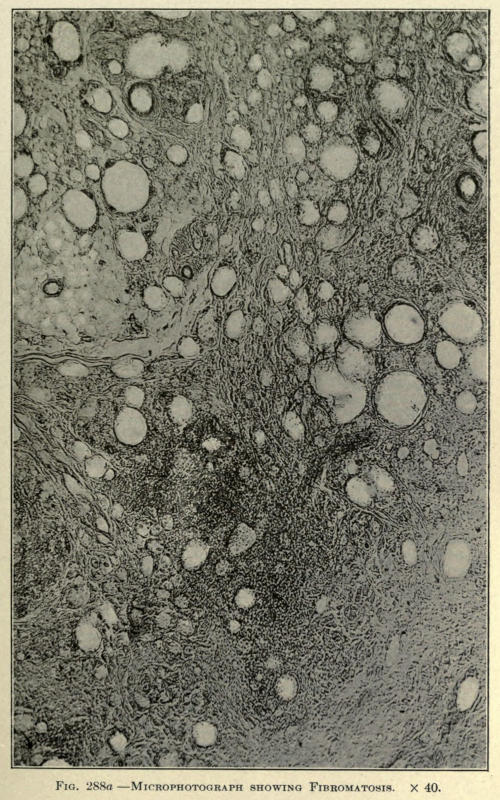

| 288 a, 288 b.—Microphotograph, showing fibromatosis | Facing 258 |

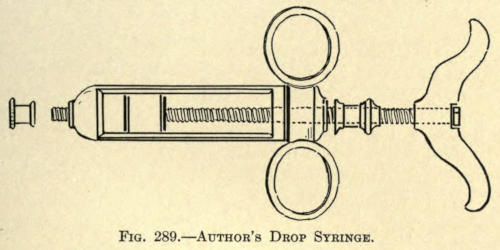

| 289.—Author’s drop syringe | 265 |

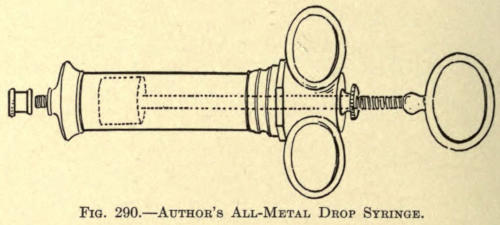

| 290.—Author’s all-metal syringe | 266[xviii] |

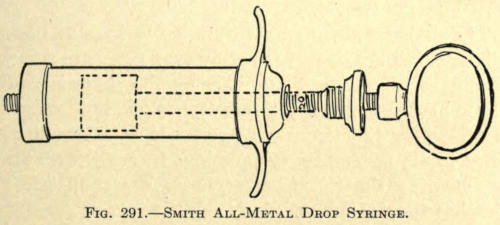

| 291.—Smith’s all-metal syringe | 267 |

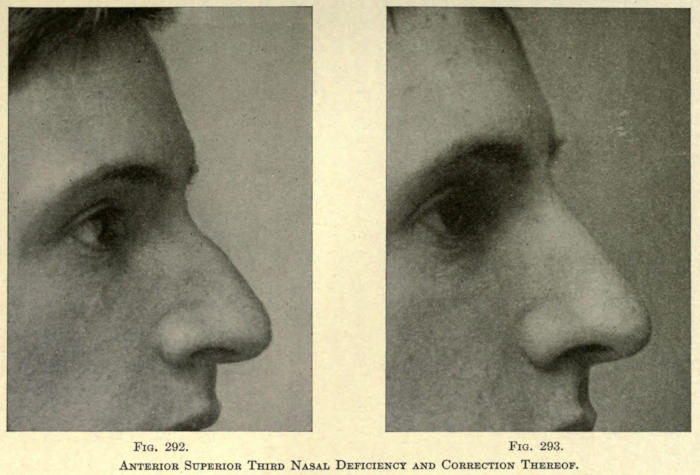

| 292, 293.—Anterior superior third nasal deficiency and correction thereof | 289 |

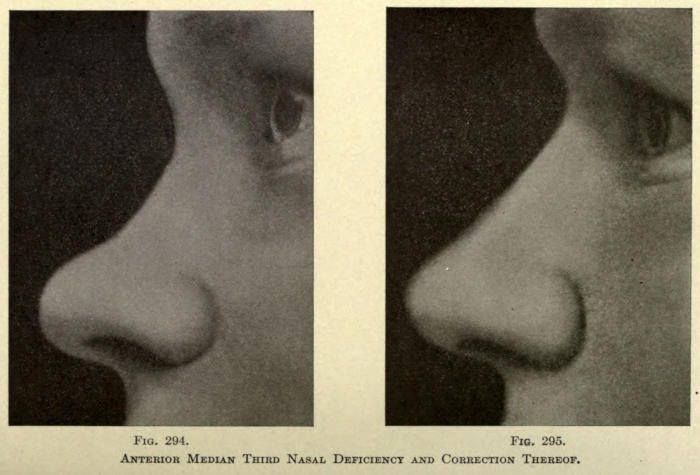

| 294, 295.—Anterior median third nasal deficiency and correction thereof | 292 |

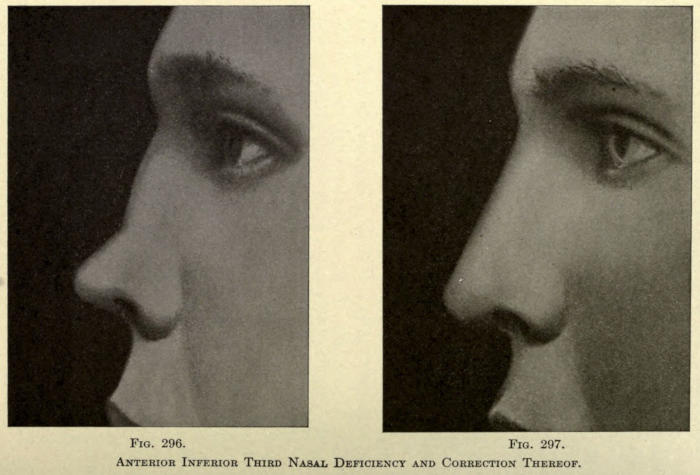

| 296, 297.—Anterior inferior third nasal deficiency and correction thereof | 294 |

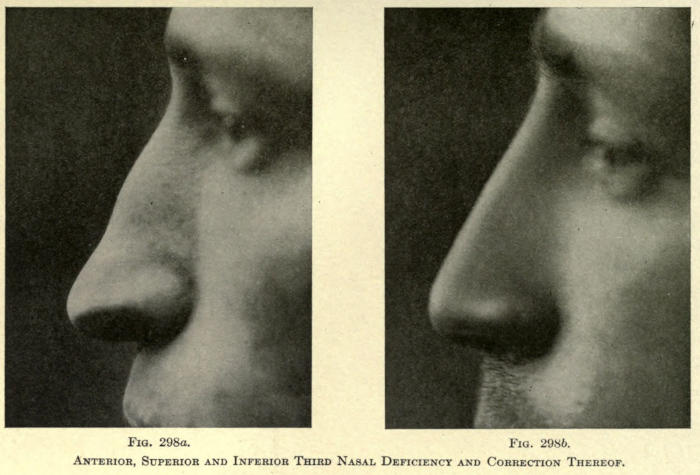

| 298 a, 298 b.—Anterior superior and inferior third nasal deficiency and correction thereof | 301 |

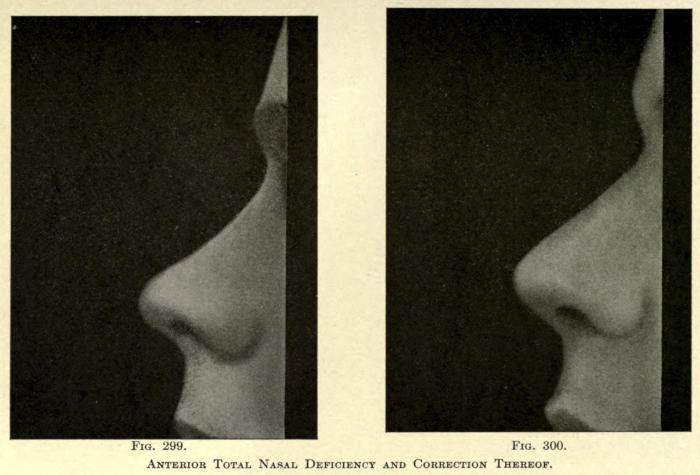

| 299, 300.—Anterior total nasal deficiency and corrections thereof | 303 |

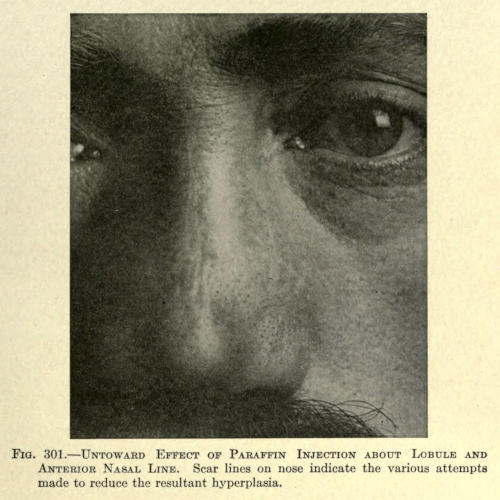

| 301.—Untoward effect of paraffin injection about lobule and anterior nasal line | 311 |

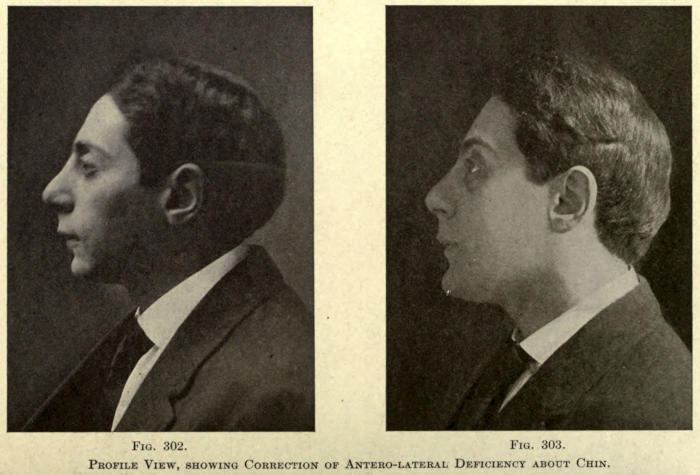

| 302, 303.—Profile view, showing correction of antero-lateral deficiency about chin | 330 |

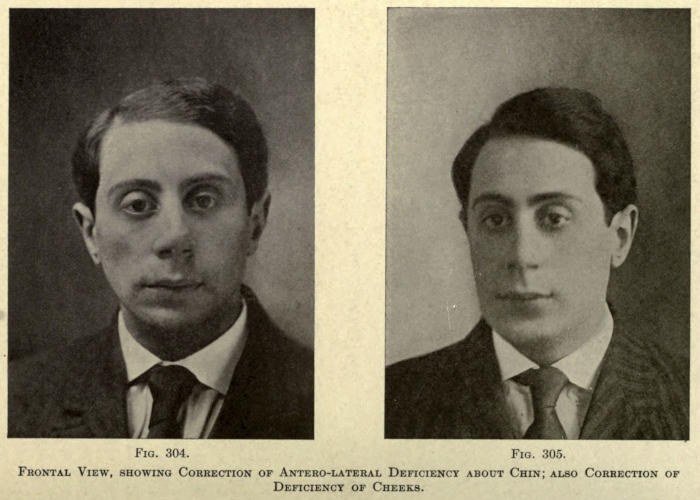

| 304, 305.—Frontal view, showing correction of antero-lateral deficiency about chin; also correction of deficiency of cheeks | 332 |

| Rhinoplasty | |

| 306.—Deficiency of superior and middle third of nose | 342 |

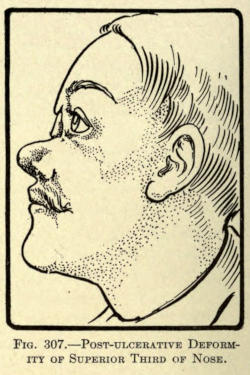

| 307.—Post-ulcerative deformity of superior third of nose | 342 |

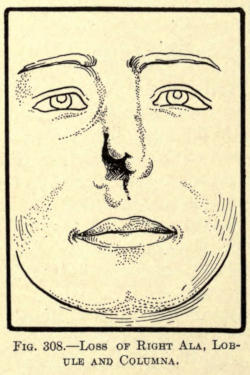

| 308.—Loss of right ala, lobule and columna | 342 |

| 309.—Loss of lobule, inferior septum and columna | 342 |

| 310.—Ulcerative loss of right median lateral skin of nose | 343 |

| 311.—Loss of nasal bones, partial dorsum, lobule and septum | 343 |

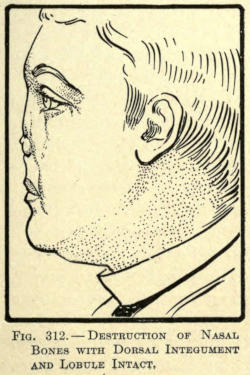

| 312.—Destruction of nasal bones with dorsum and lobule intact | 343 |

| 313.—Total loss of nose | 343 |

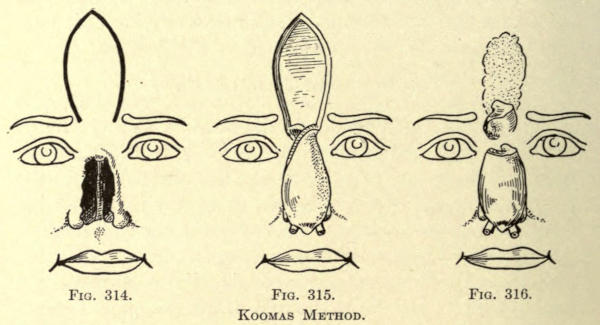

| 314, 315, 316.—Koomas method of rhinoplasty | 353 |

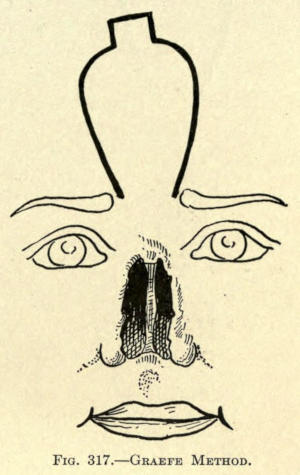

| 317.—Graefe method of rhinoplasty | 353 |

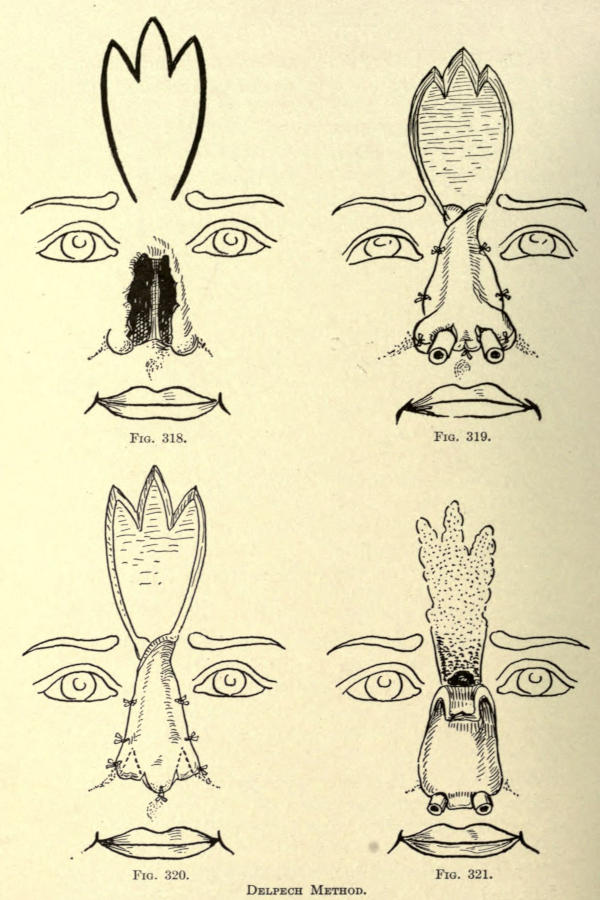

| 318, 319, 320, 321.—Delpech method of rhinoplasty | 354 |

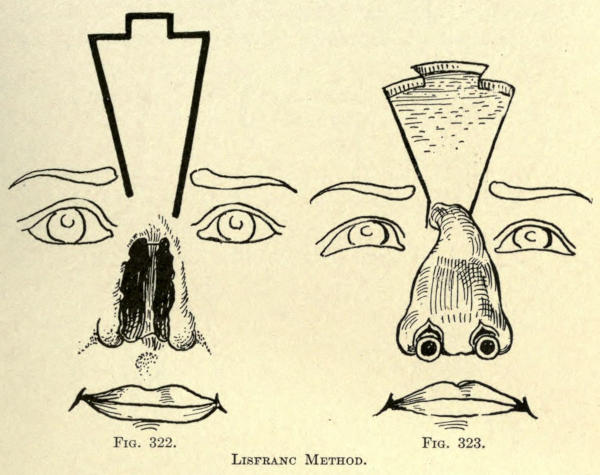

| 322, 323.—Lisfranc method of rhinoplasty | 355 |

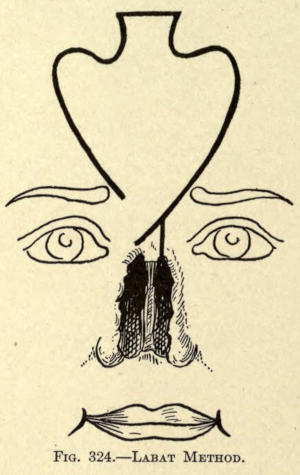

| 324.—Labat method of rhinoplasty | 356 |

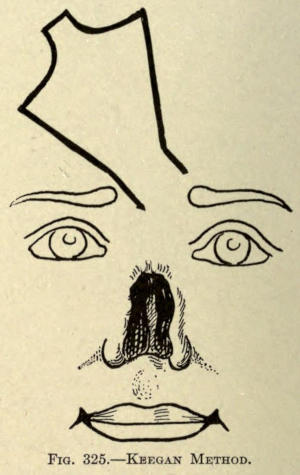

| 325.—Keegan method of rhinoplasty | 356 |

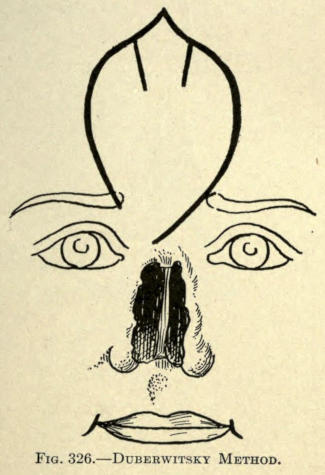

| 326.—Duberwitsky method of rhinoplasty | 357 |

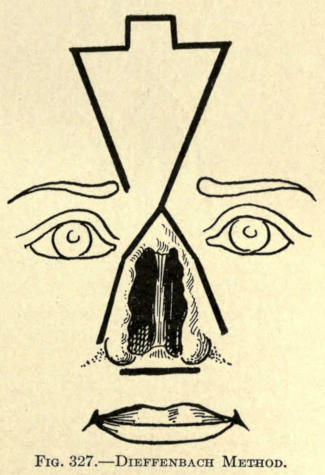

| 327.—Dieffenbach method of rhinoplasty | 357 |

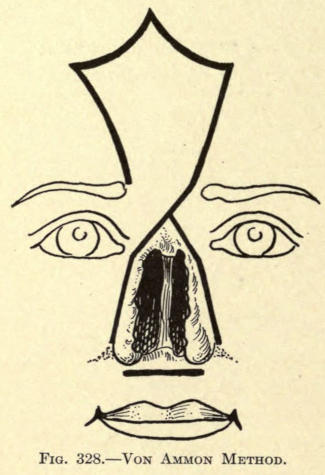

| 328.—Von Ammon method of rhinoplasty | 358 |

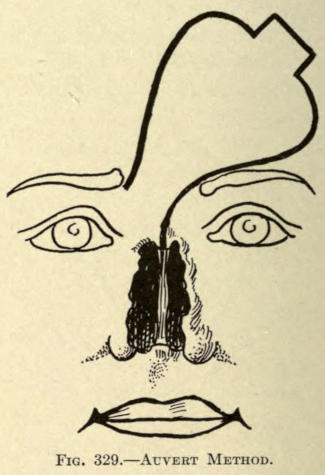

| 329.—Auvert method of rhinoplasty | 358 |

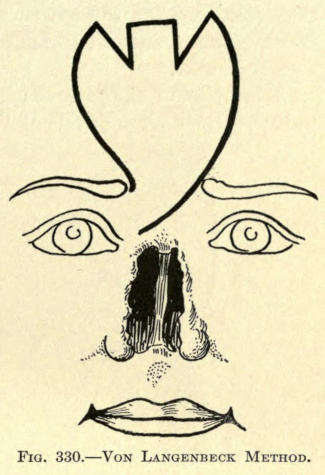

| 330.—Von Langenbeck method of rhinoplasty | 359 |

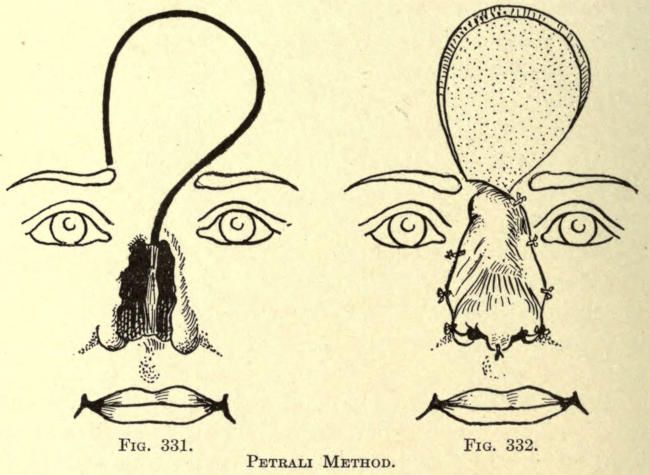

| 331, 332.—Petrali method of rhinoplasty | 360 |

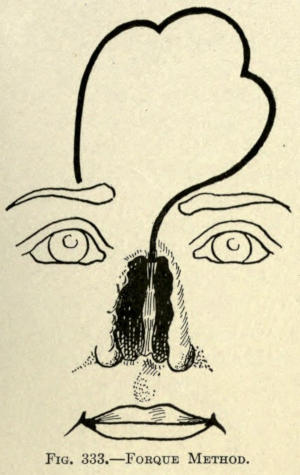

| 333.—Forque method of rhinoplasty | 361 |

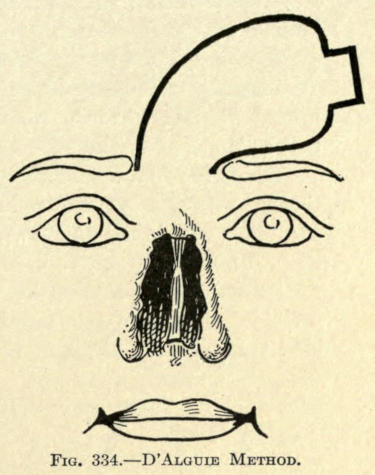

| 334.—D’Alguie method of rhinoplasty | 361 |

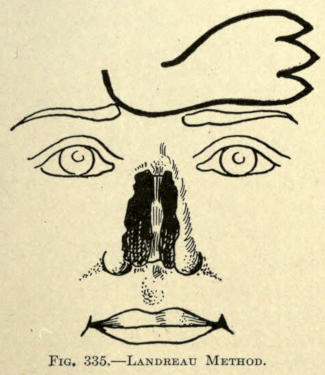

| 335.—Landreau method of rhinoplasty | 361 |

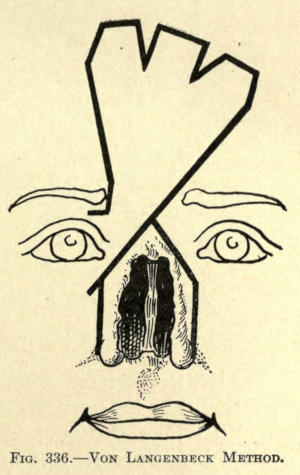

| 336.—Von Langenbeck method of rhinoplasty | 361 |

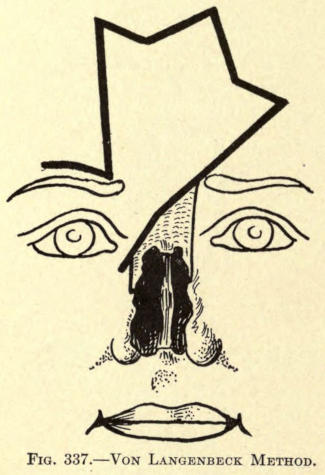

| 337.—Von Langenbeck method of rhinoplasty | 362 |

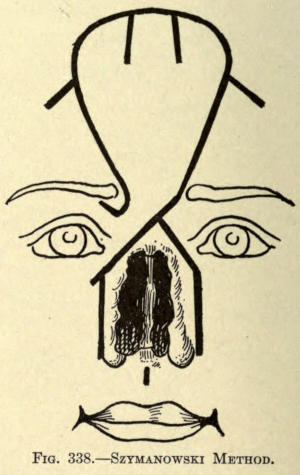

| 338.—Szymanowski method of rhinoplasty | 362 |

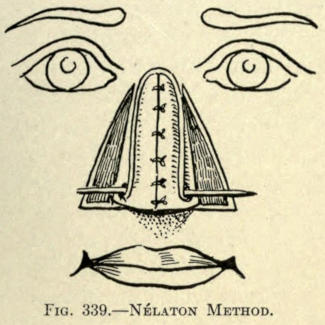

| 339.—Nélaton method of rhinoplasty | 365 |

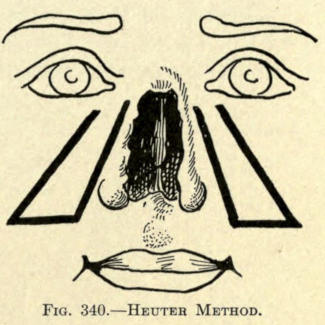

| 340.—Heuter method of rhinoplasty | 365 |

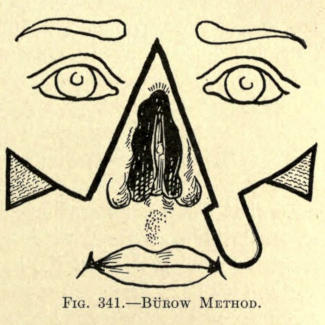

| 341.—Bürow method of rhinoplasty | 365 |

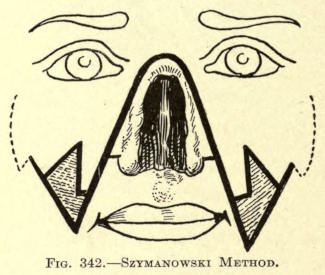

| 342.—Szymanowski method of rhinoplasty | 366 |

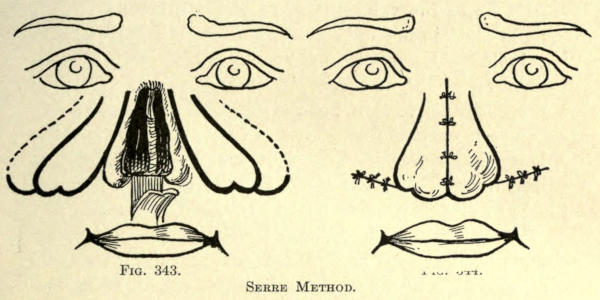

| 343, 344.—Serre method of rhinoplasty | 367 |

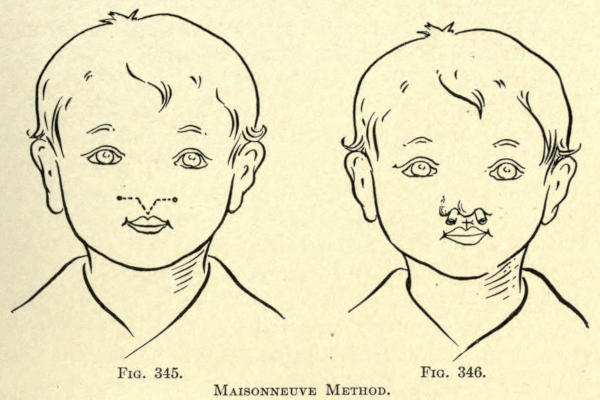

| 345, 346.—Maisonneuve method of rhinoplasty | 369[xix] |

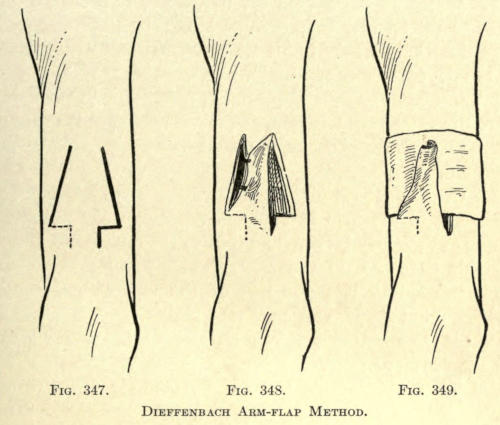

| 347, 348, 349.—Dieffenbach arm-flap method | 373 |

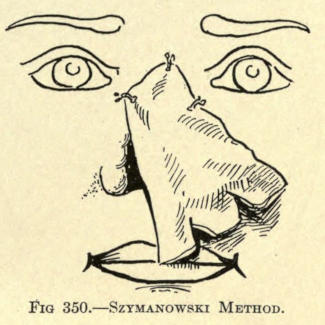

| 350.—Szymanowski arm-flap method | 375 |

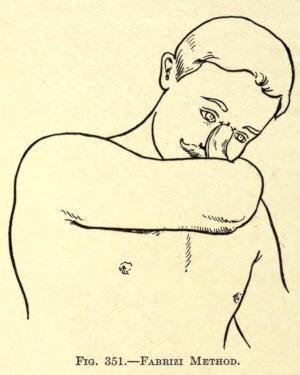

| 351.—Fabrizi arm-flap method | 376 |

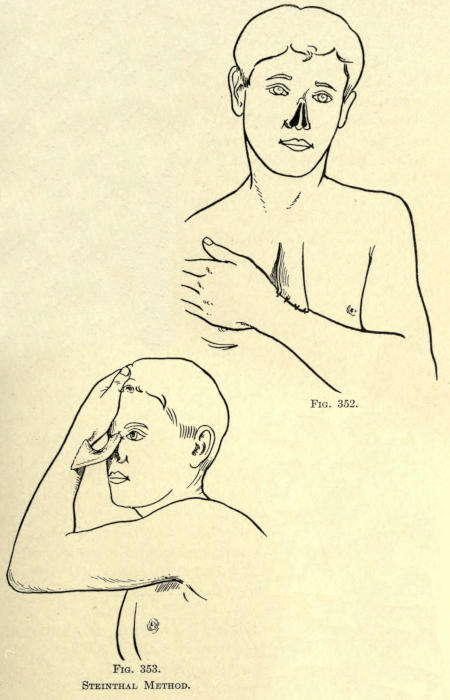

| 352, 353.—Steinthal thoracic flap method | 377 |

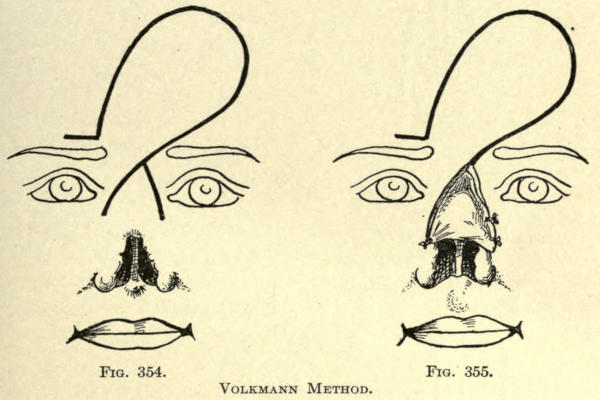

| 354, 355.—Volkman method of rhinoplasty | 379 |

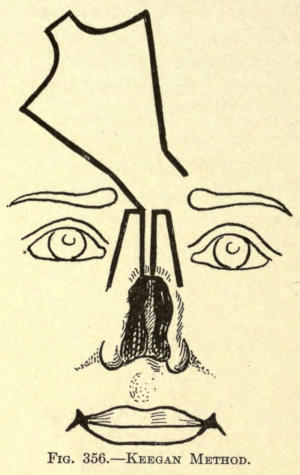

| 356.—Keegan method of rhinoplasty | 380 |

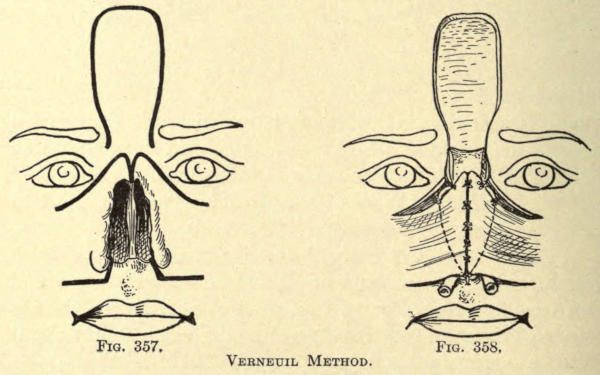

| 357, 358.—Verneuil method of rhinoplasty | 380 |

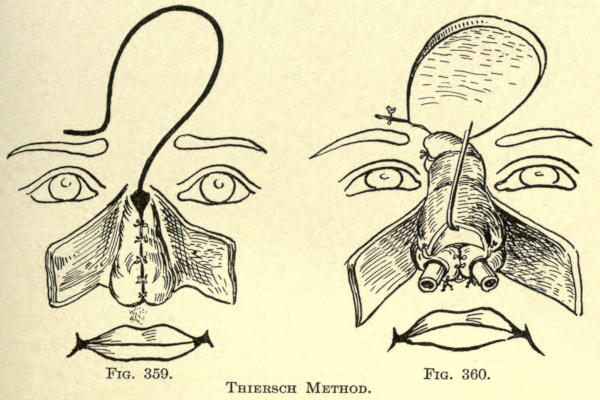

| 359, 360.—Thiersch method of rhinoplasty | 381 |

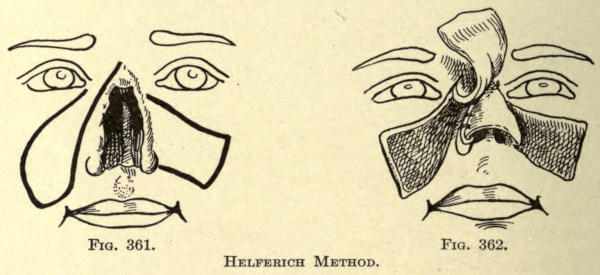

| 361, 362.—Helferich method of rhinoplasty | 382 |

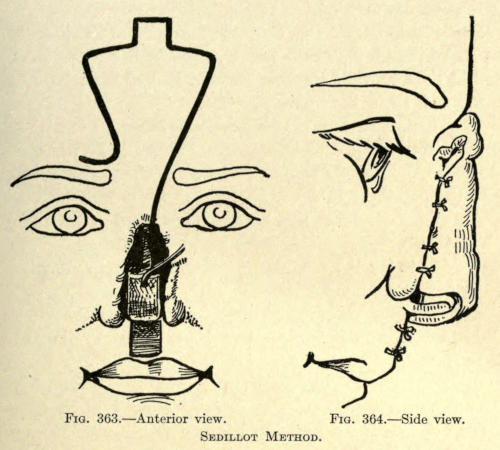

| 363, 364.—Sedillot method of rhinoplasty | 383 |

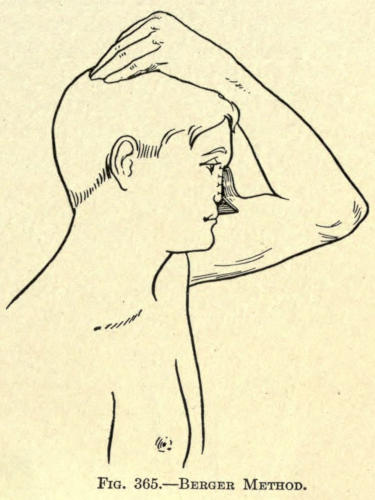

| 365.—Berger arm-flap method | 385 |

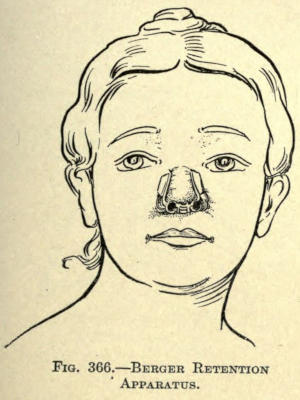

| 366.—Berger retention apparatus | 385 |

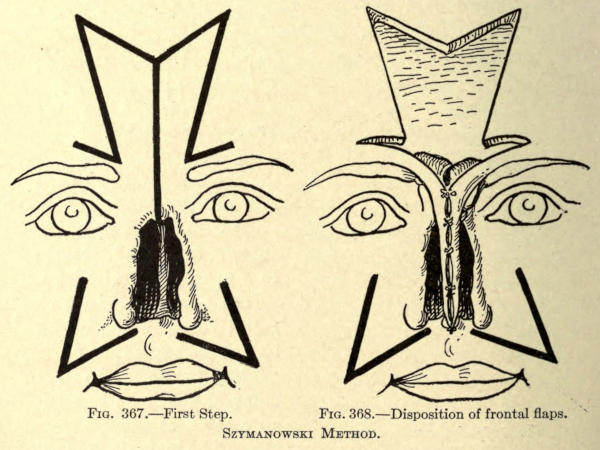

| 367, 368.—Szymanowski rhinoplasty method | 386 |

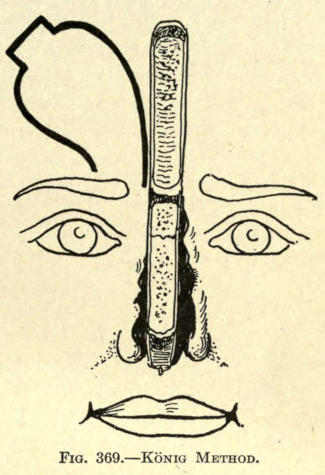

| 369.—König rhinoplasty method | 391 |

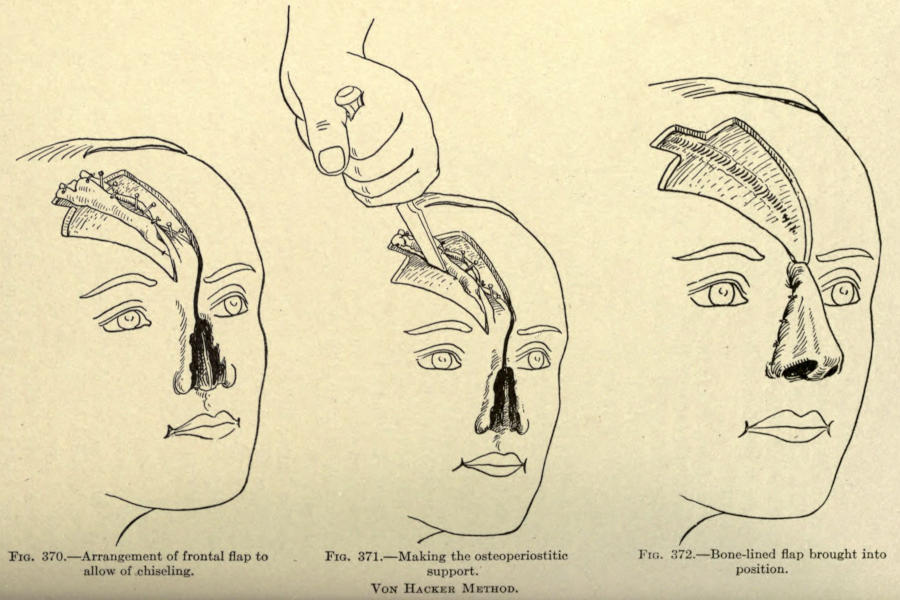

| 370.—Von Hacker rhinoplasty method, arrangement of frontal flap to allow chiseling | 392 |

| 371.—Von Hacker rhinoplasty method, making osteo-periostic support | 392 |

| 372.—Von Hacker rhinoplasty method, bone-lined flap in position | 392 |

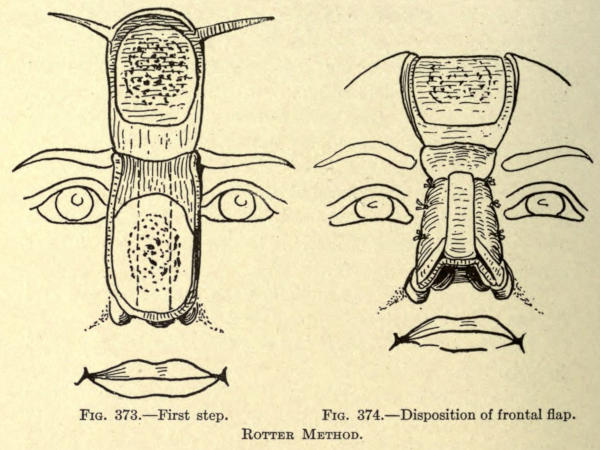

| 373, 374.—Rotter rhinoplastic method | 394 |

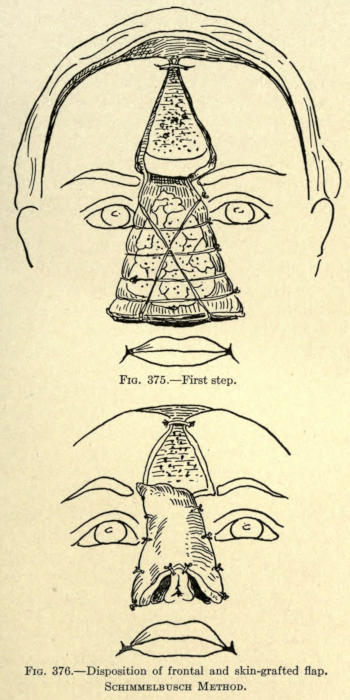

| 375, 376.—Schimmelbusch frontal flap method | 395 |

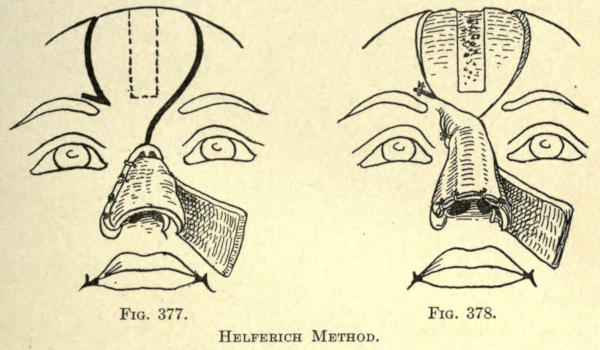

| 377, 378.—Helferich rhinoplasty method | 397 |

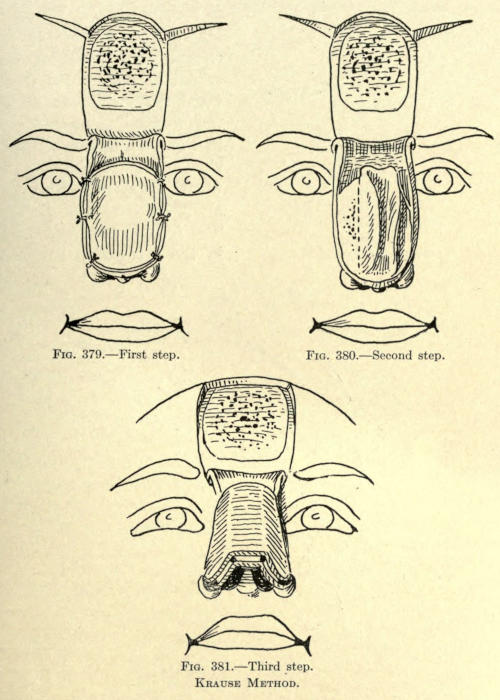

| 379, 380, 381.—Krause rhinoplasty method | 399 |

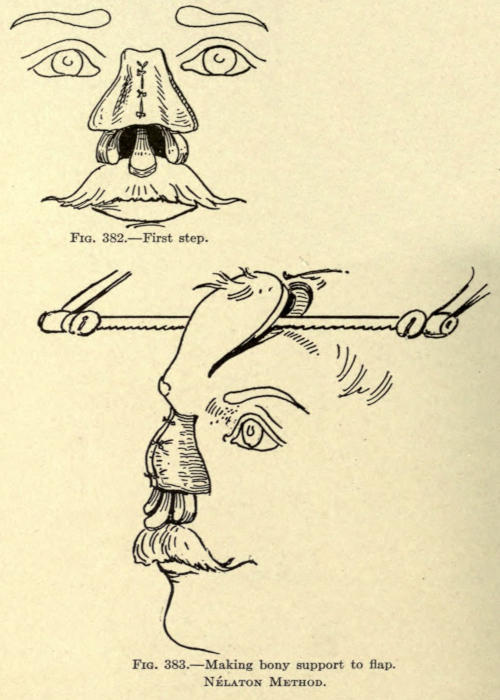

| 382.—Nélaton rhinoplasty method | 400 |

| 383.—Nélaton rhinoplasty method, making bony support | 400 |

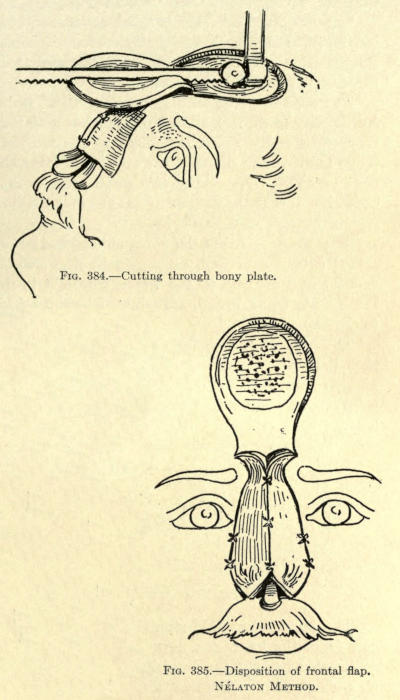

| 384.—Nélaton rhinoplasty method, cutting through bony plate | 401 |

| 385.—Nélaton rhinoplasty method, disposition of frontal flap | 401 |

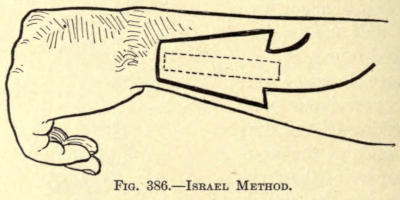

| 386.—Israel method, forearm flap | 402 |

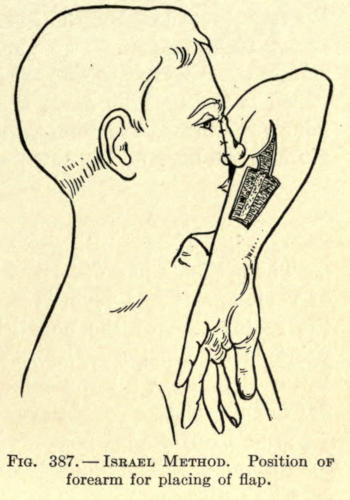

| 387.—Israel method, position of forearm to place flap | 403 |

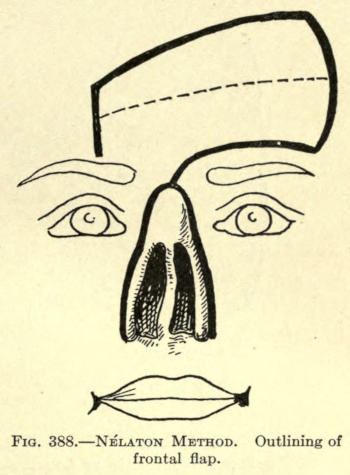

| 388.—Nélaton method, outlining frontal flap | 407 |

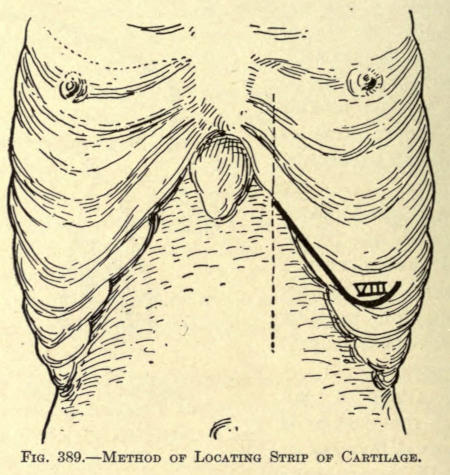

| 389.—Nélaton method, locating cartilage strip | 408 |

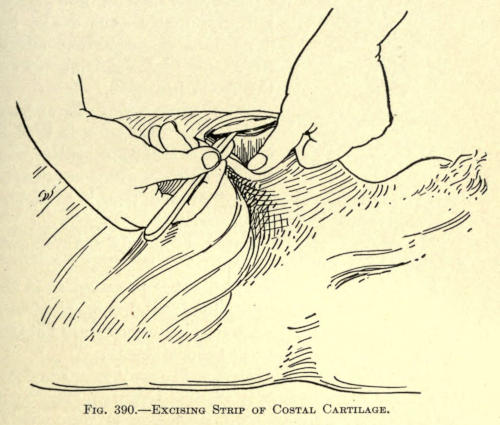

| 390.—Nélaton method, excision of cartilage strip | 409 |

| 391.—Nélaton method, placing of cartilage strip | 410 |

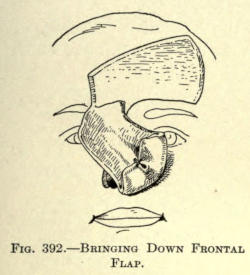

| 392.—Nélaton method, bringing down frontal flap | 411 |

| 393.—Nélaton method, placing frontal flap | 411 |

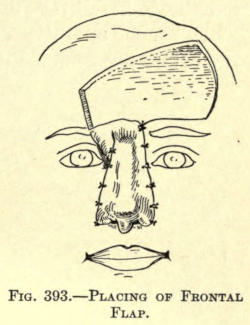

| 394, 395.—Steinhausen partial rhinoplasty method | 412 |

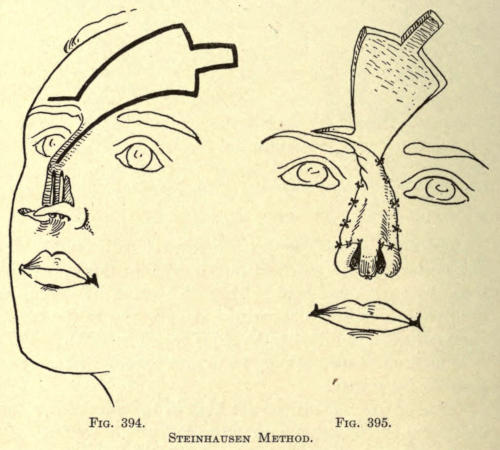

| 396, 397.—Neumann partial rhinoplasty method | 413 |

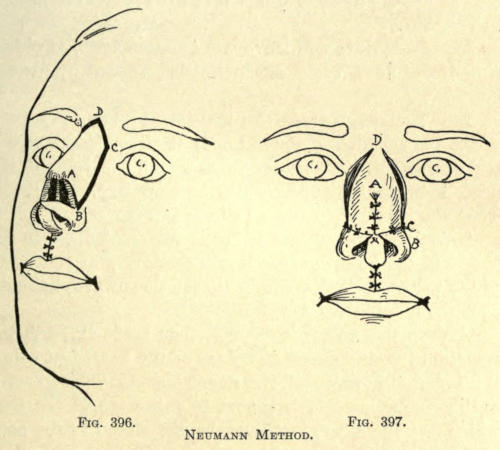

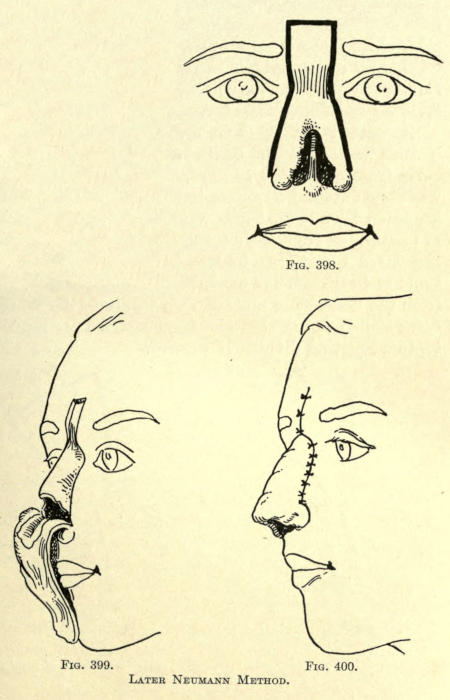

| 398, 399, 400.—Later Neumann partial rhinoplasty method | 415 |

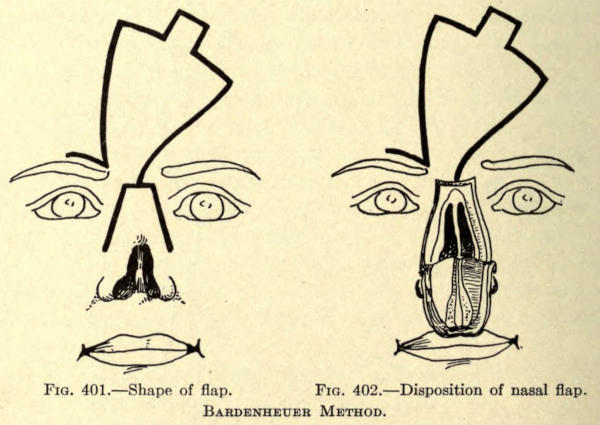

| 401.—Bardenheuer method, shape of flap | 416 |

| 402.—Bardenheuer method, disposition of flap | 416 |

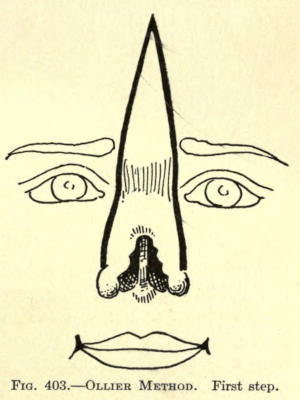

| 403.—Ollier method first step | 417 |

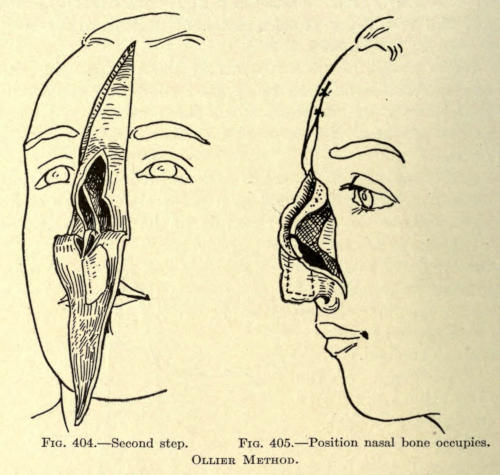

| 404.—Ollier method, second step | 418 |

| 405.—Ollier method, position nasal bone occupies | 418 |

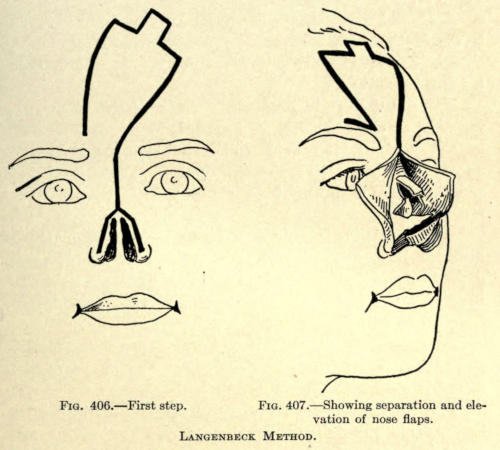

| 406.—Von Langenbeck method, first step | 419 |

| 407.—Von Langenbeck method, showing separation and elevation of nose flaps | 419 |

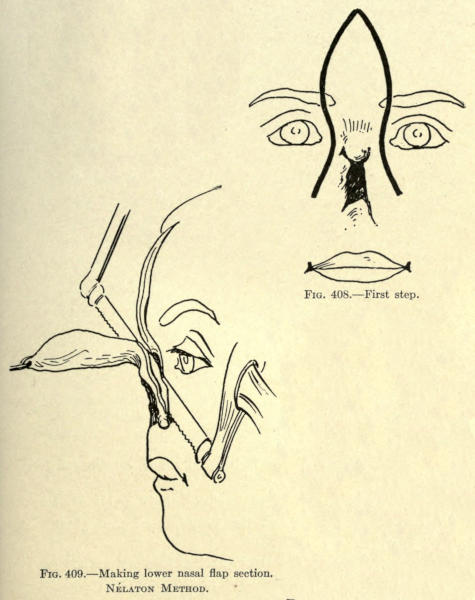

| 408.—Nélaton method, first step | 421 |

| 409.—Nélaton method, making lower nasal flap | 421 |

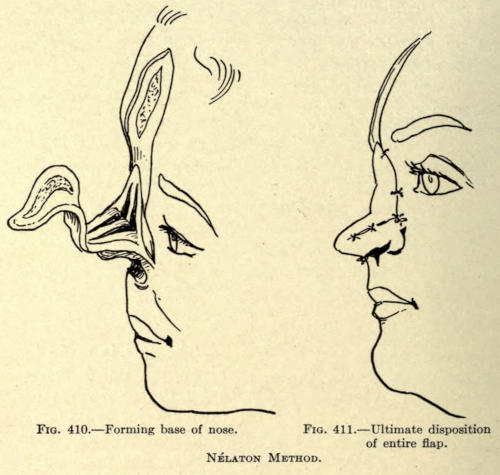

| 410.—Nélaton method, forming base of nose | 422[xx] |

| 411.—Nélaton method, ultimate disposition of flap | 422 |

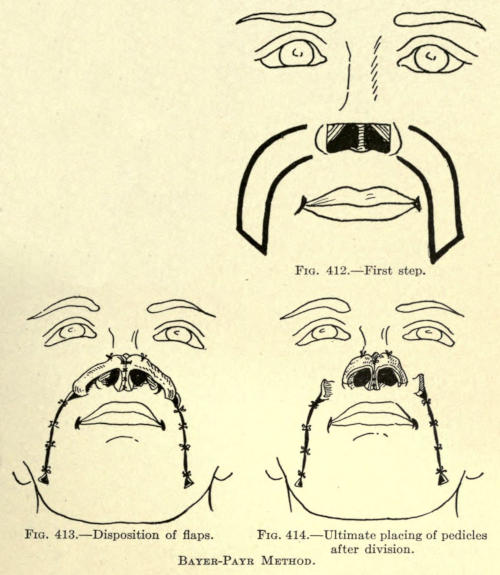

| 412.—Bayer-Payr restoration of lobule, first step | 425 |

| 413.—Bayer-Payr restoration of lobule, disposition of flaps | 425 |

| 414.—Bayer-Payr restoration of lobule, placing of pedicles after division | 425 |

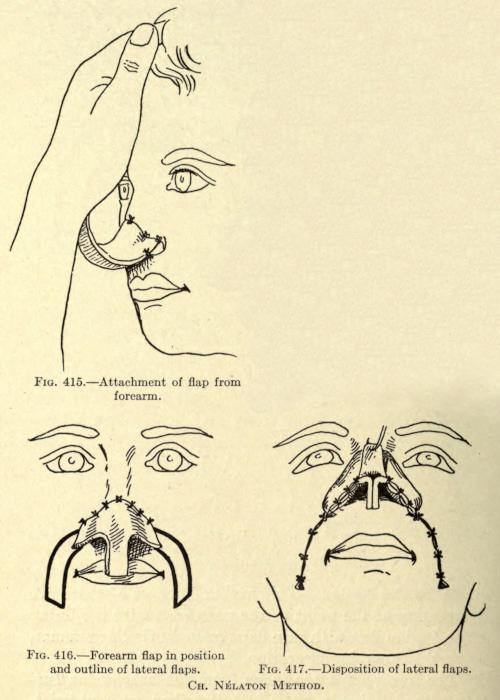

| 415.—Ch. Nélaton method, attachment of forearm flap | 426 |

| 416.—Ch. Nélaton method, forearm flap in position, lateral flaps | 426 |

| 417.—Ch. Nélaton method, disposition lateral flaps | 426 |

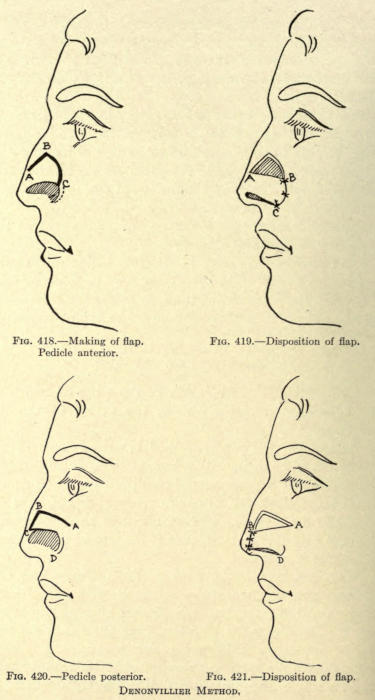

| 418.—Denonvillier method, making of flap for ala | 428 |

| 419.—Denonvillier method, disposition of flap for anterior pedicle ala | 428 |

| 420.—Denonvillier method, making of flap for ala, posterior pedicle | 428 |

| 421.—Denonvillier method, disposition of flap for ala, posterior pedicle | 428 |

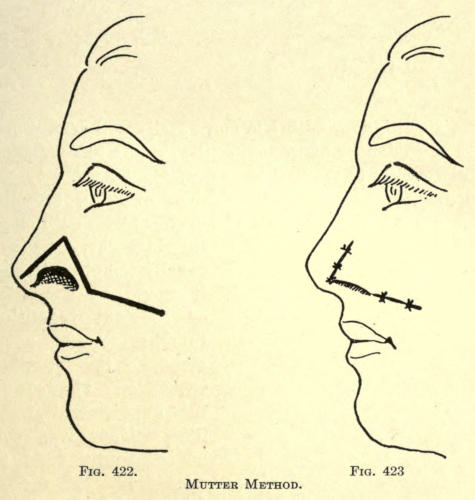

| 422, 423.—Mutter method of restoration of ala | 429 |

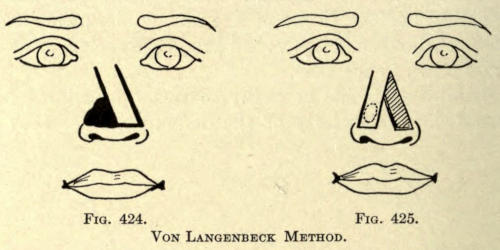

| 424, 425.—Von Langenbeck method of restoration of ala | 430 |

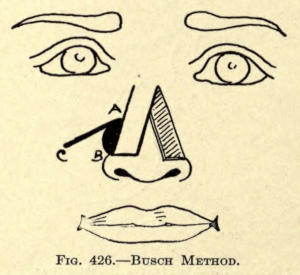

| 426.—Busch method of restoration of ala | 430 |

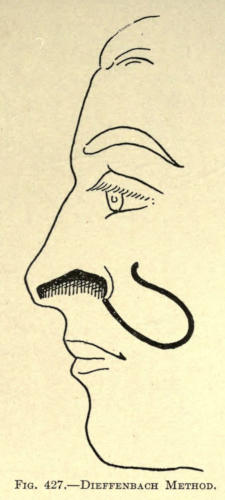

| 427.—Dieffenbach method of restoration of ala | 431 |

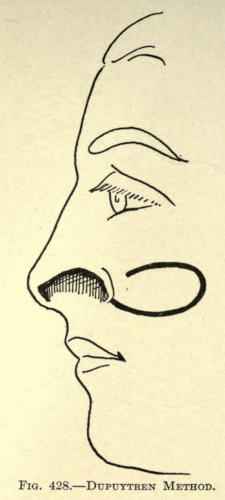

| 428.—Dupuytren method of restoration of ala | 431 |

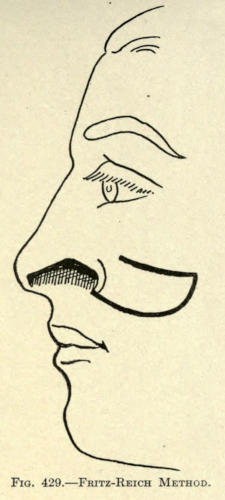

| 429.—Fritz-Reich method of restoration of ala | 431 |

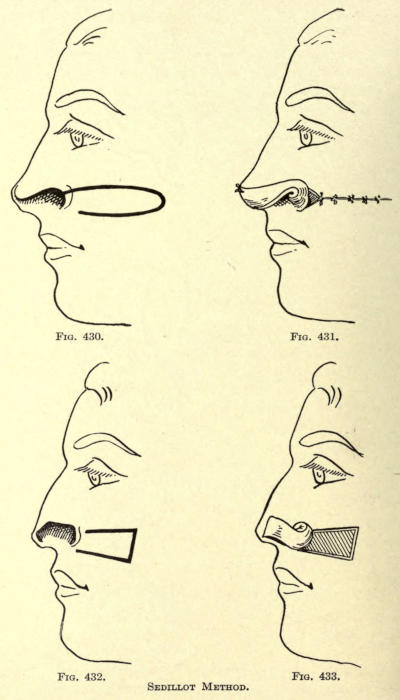

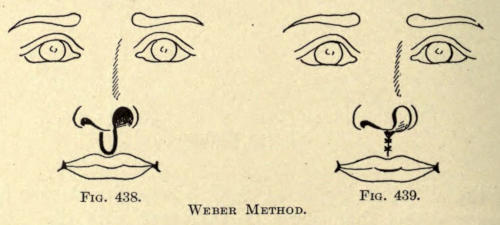

| 430, 431, 432, 433.—Sedillot method of restoration of ala | 432 |

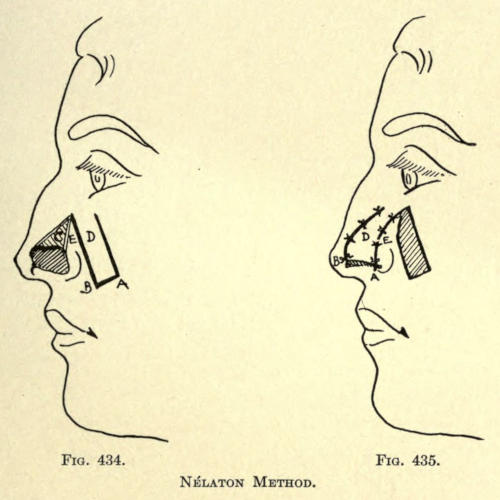

| 434, 435.—Nélaton method of restoration of ala | 433 |

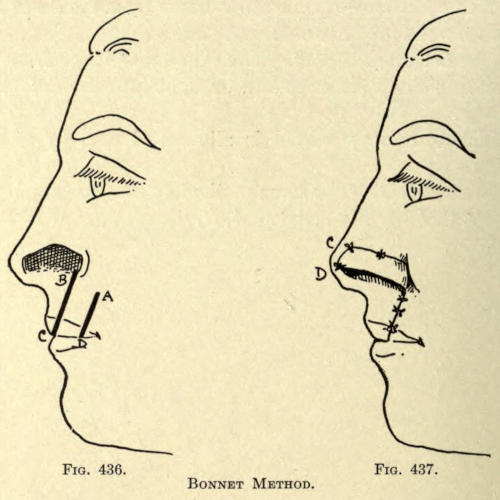

| 436, 437.—Bonnet method of restoration of ala | 434 |

| 438, 439.—Weber method of restoration of ala | 434 |

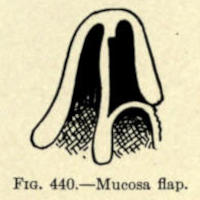

| 440.—Thompson mucosa flap | 435 |

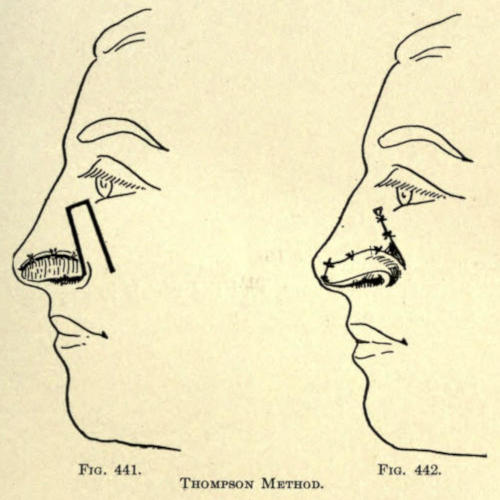

| 441, 442.—Thompson method of restoration of ala | 435 |

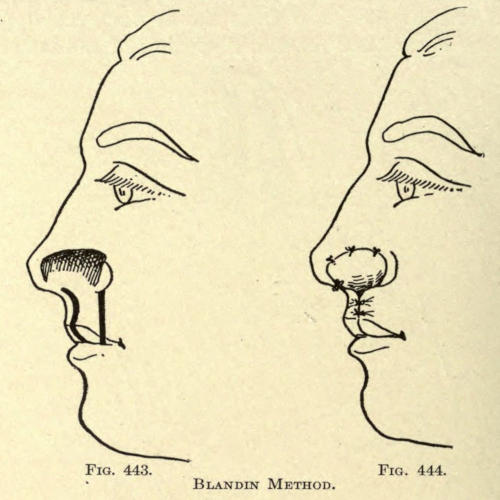

| 443, 444.—Blandin method of restoration of ala | 436 |

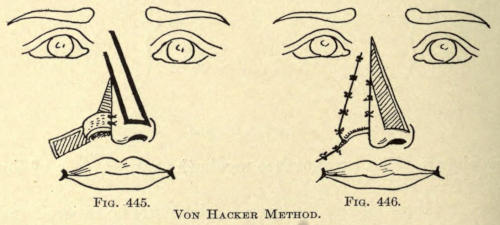

| 445, 446.—Von Hacker method of restoration of ala | 436 |

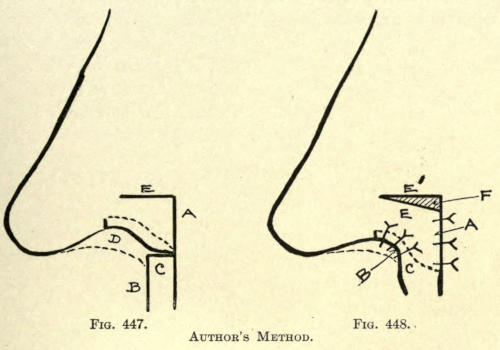

| 447, 448.—Kolle method of restoration of ala | 437 |

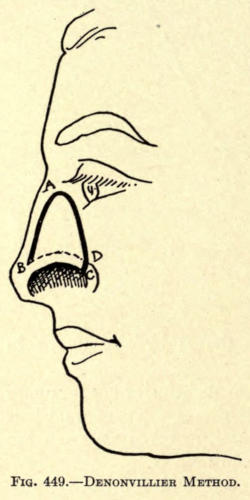

| 449.—Denonvillier method of restoration of ala | 438 |

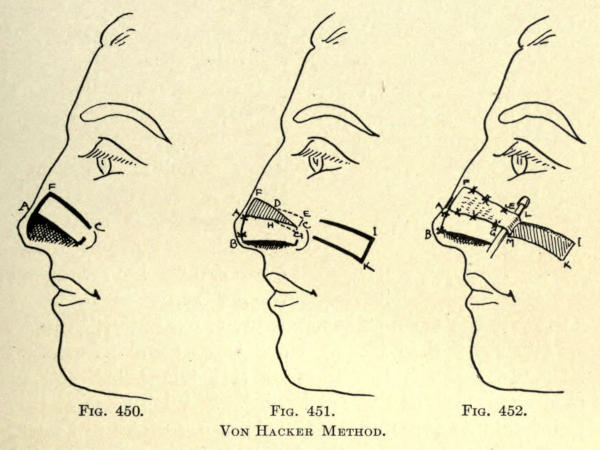

| 450, 451, 452.—Von Hacker method of restoration of ala | 439 |

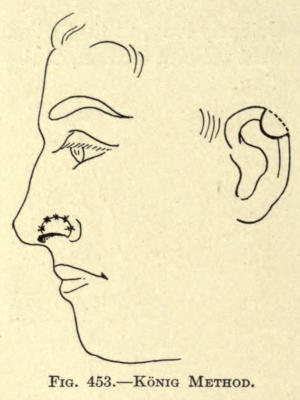

| 453.—König method of restoration of ala | 440 |

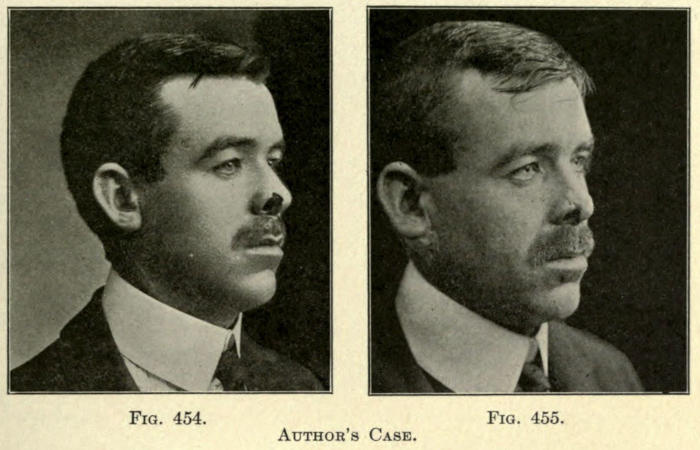

| 454, 455.—Kolle method of restoration of ala | 441 |

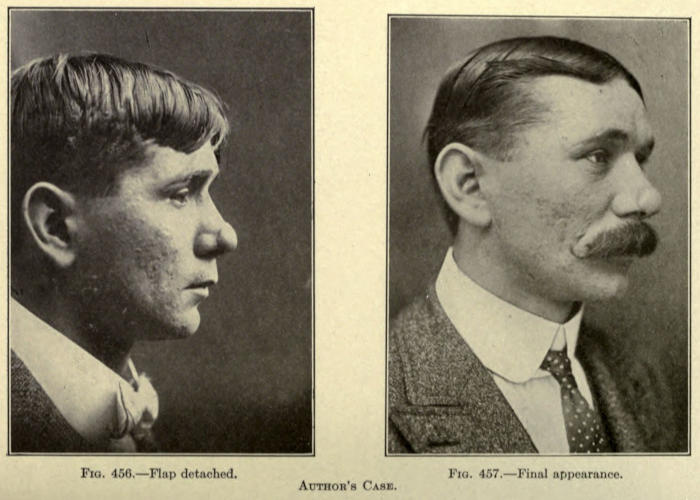

| 456, 457.—Kolle method of restoration of lobule | 442 |

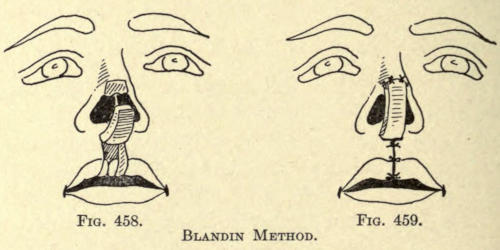

| 458, 459.—Blandin method of restoration of subseptum | 444 |

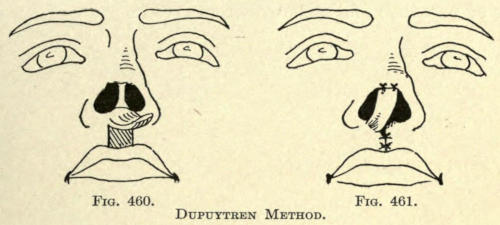

| 460, 461.—Dupuytren method of restoration of subseptum | 445 |

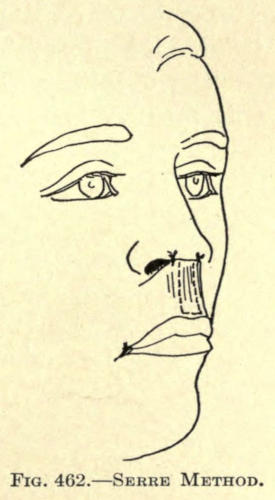

| 462.—Serre method of restoration of subseptum | 445 |

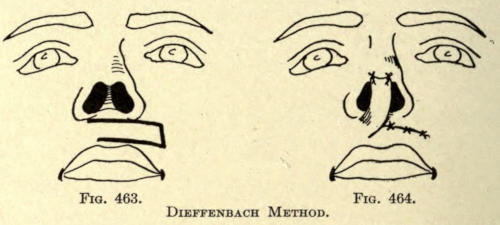

| 463, 464.—Dieffenbach method of restoration of subseptum | 446 |

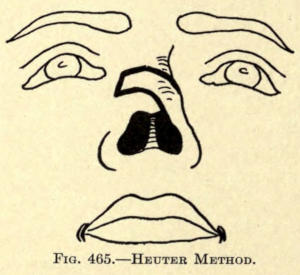

| 465.—Heuter method of restoration of subseptum | 446 |

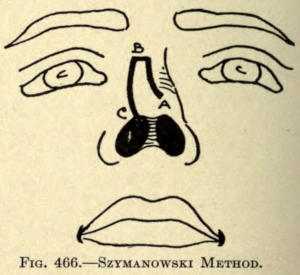

| 466.—Szymanowski method of restoration of subseptum | 446 |

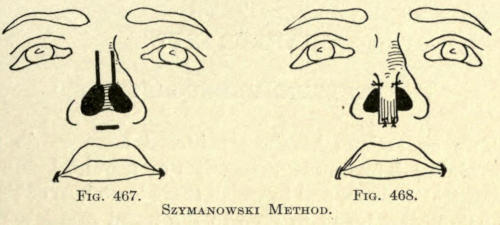

| 467, 468.—Szymanowski method of restoration of subseptum | 447 |

| Cosmetic Rhinoplasty | |

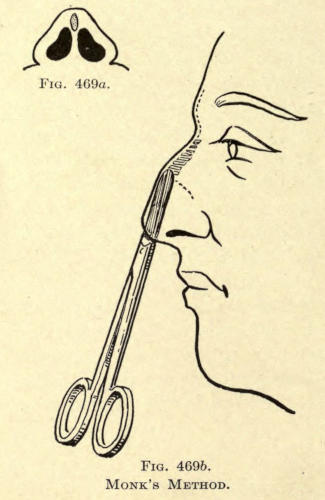

| 469 a, 469 b.—Monk method of correction of angular nose | 450 |

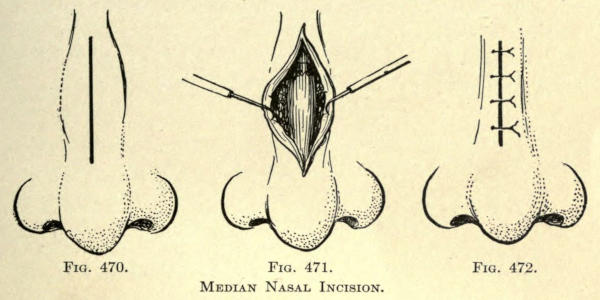

| 470, 471, 472.—Median nasal incision for angular nose | 451 |

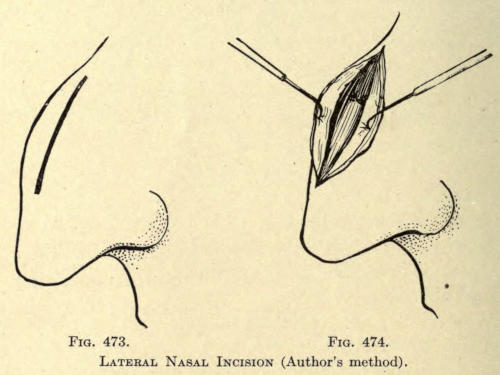

| 473, 474.—Kolle method of lateral incision for angular nose | 452 |

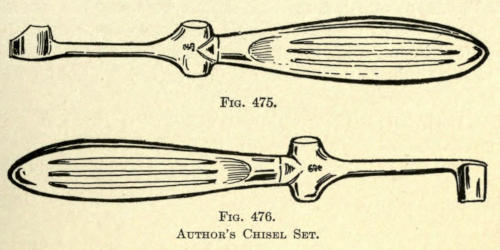

| 475, 476.—Kolle chisel set | 453 |

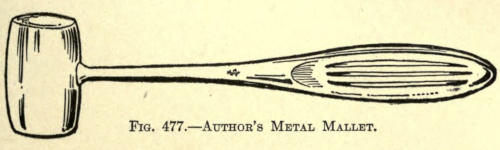

| 477.—Kolle metal mallet | 453 |

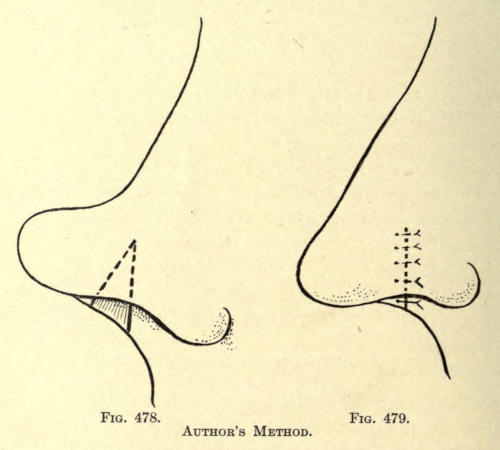

| 478, 479.—Kolle method of correction of retroussé nose | 454 |

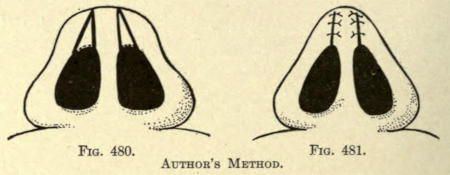

| 480, 481.—Kolle method of correction of broad lobule | 456[xxi] |

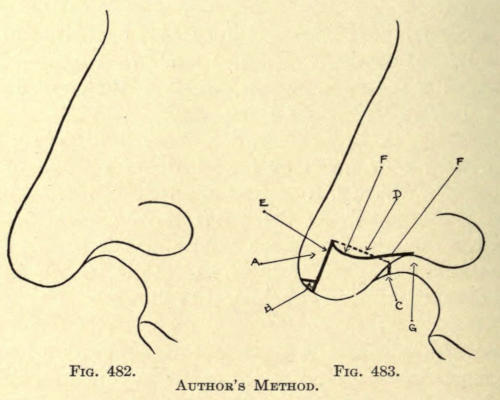

| 482, 483.—Kolle method of correction of elongated lobule | 458 |

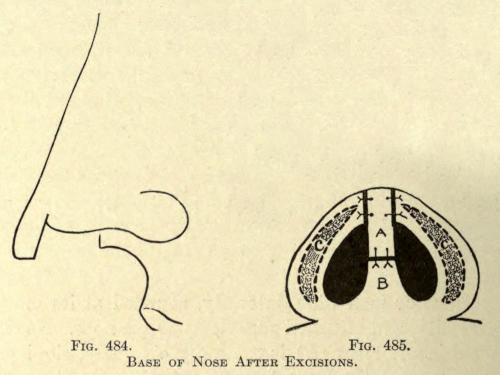

| 484.—Kolle method of correction of elongated lobule and base of nose after excision | 460 |

| 485.—Kolle method of correction of elongated lobule base of alæ and lobule | 460 |

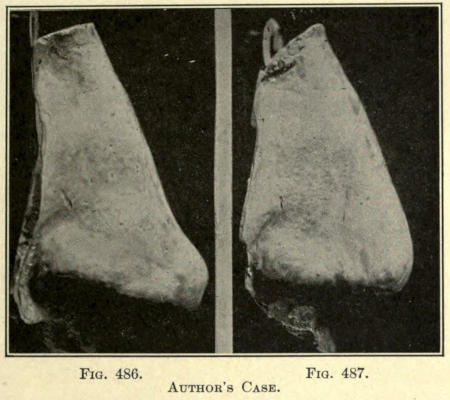

| 486, 487.—Kolle plaster cast of lobule operation | 461 |

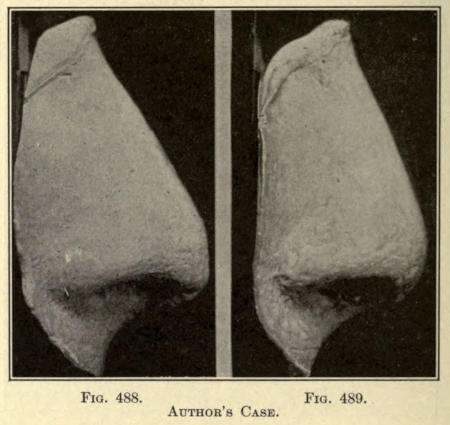

| 488, 489.—Kolle plaster cast of lobule operation | 462 |

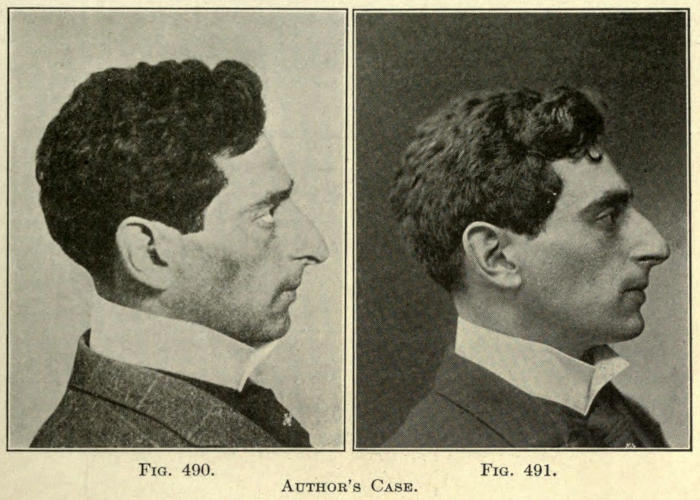

| 490, 491.—Kolle plaster cast of lobule operation | 463 |

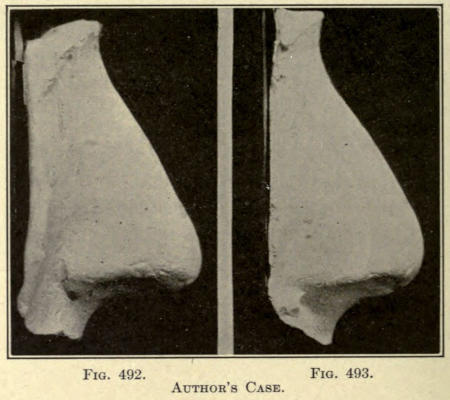

| 492, 493.—Kolle plaster cast of lobule operation | 464 |

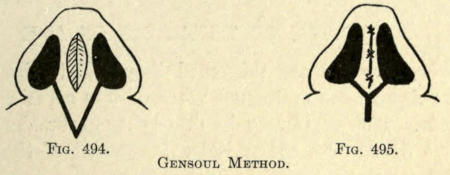

| 494, 495.—Gensoul method of correcting broad nasal base | 465 |

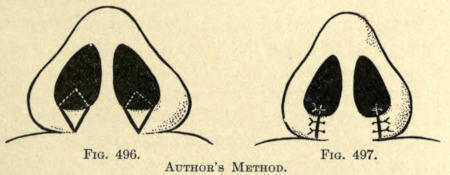

| 496, 497.—Kolle method of correction of broad nasal base | 465 |

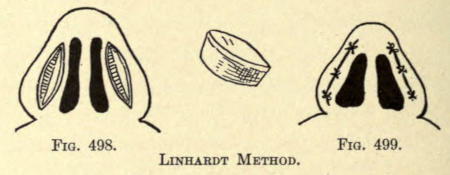

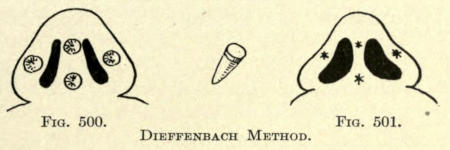

| 498, 499.—Linhardt method of reduction of thickened alæ | 466 |

| 500, 501.—Dieffenbach method of reduction of thickened nose | 467 |

| Electrolysis in Dermatology | |

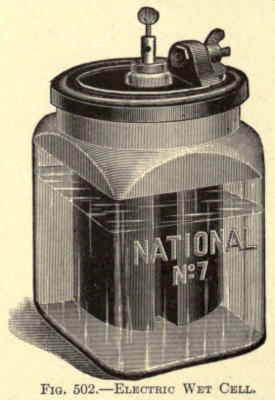

| 502.—Electric wet cell | 470 |

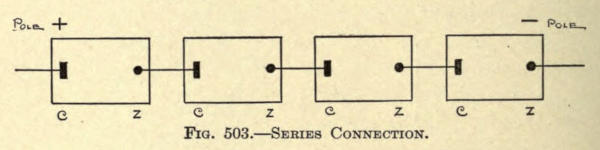

| 503.—Series connection of cells | 472 |

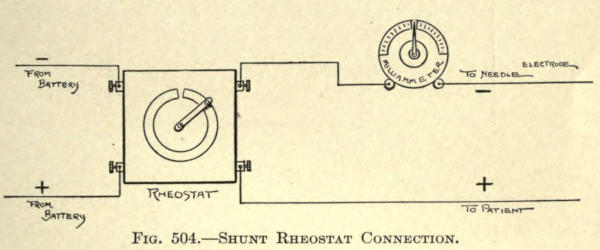

| 504.—Shunt rheostat connection | 473 |

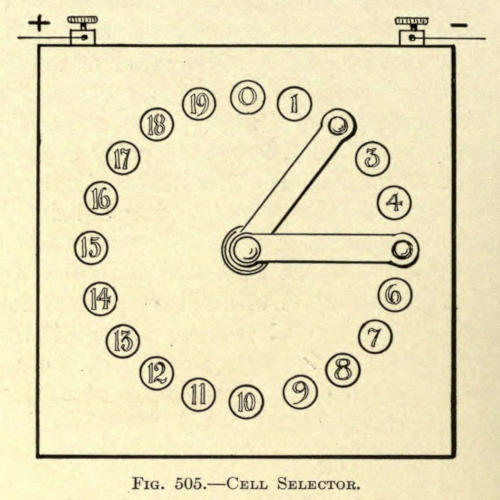

| 505.—Cell selector | 474 |

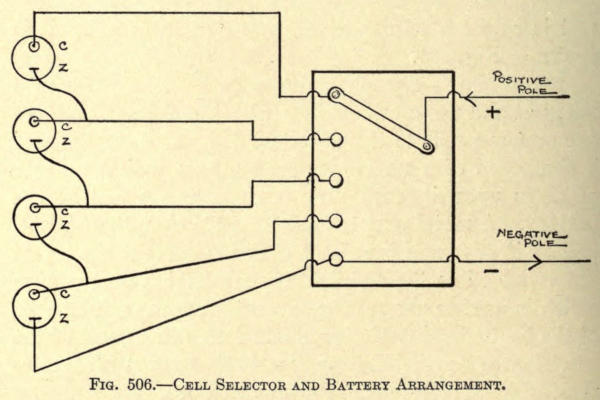

| 506.—Cell selector and battery connection | 474 |

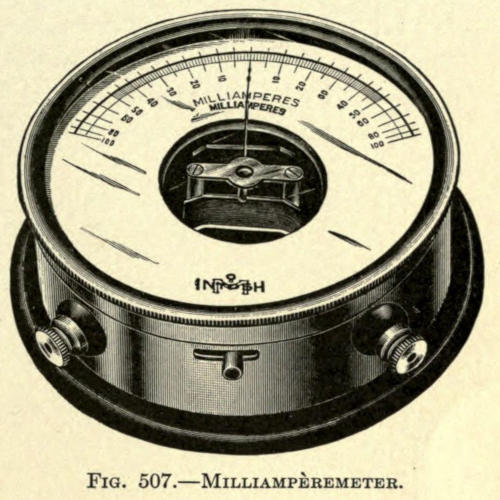

| 507.—Milliampèremeter | 475 |

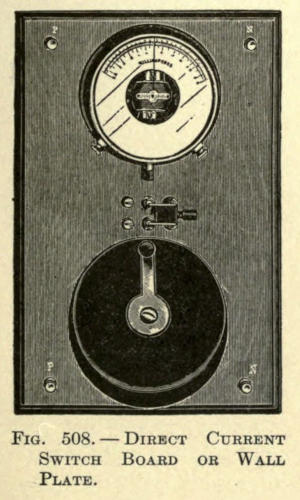

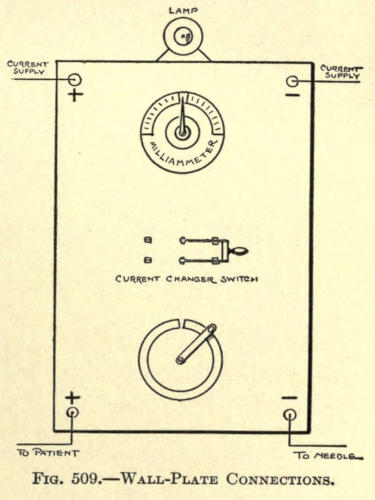

| 508.—Direct current wall plate | 475 |

| 509.—Wall-plate connections | 475 |

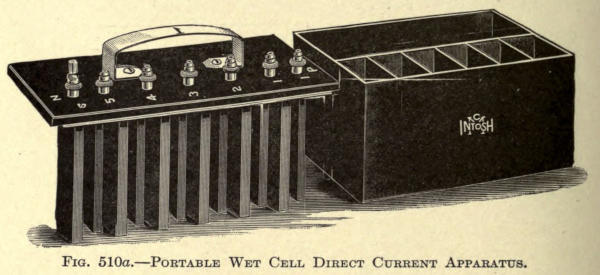

| 510 a.—Portable wet cell apparatus | 476 |

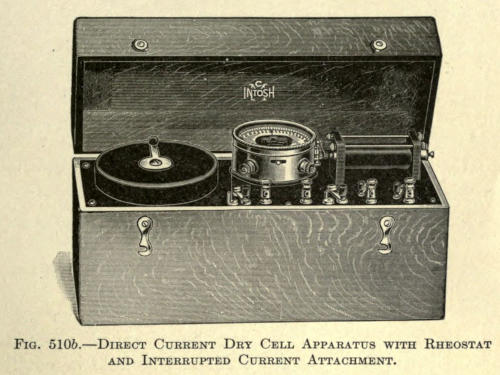

| 510 b.—Portable dry cell apparatus | 477 |

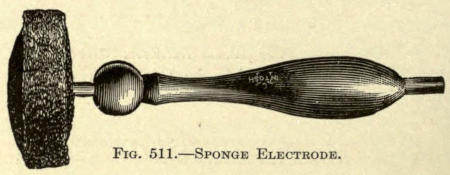

| 511.—Sponge electrode | 478 |

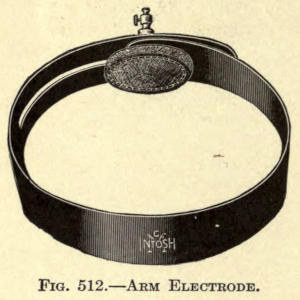

| 512.—Arm electrode | 478 |

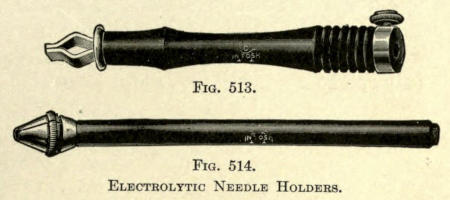

| 513, 514.—Electrolytic needle holders | 479 |

| 515.—Interrupting current needle holder | 479 |

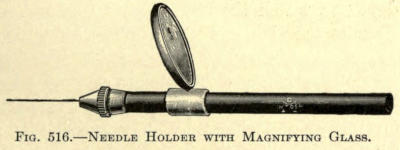

| 516.—Needle holder with magnifying glass | 479 |

| 517.—Epilating forceps | 481 |

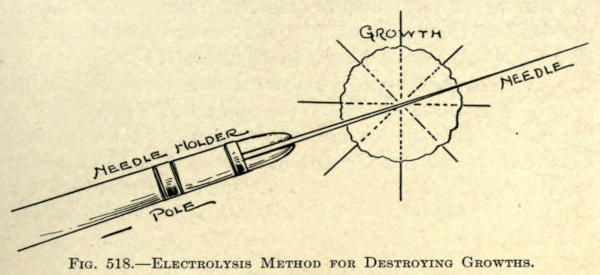

| 518.—Electrolysis method for destroying growths | 483 |

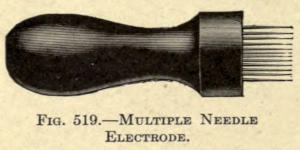

| 519.—Multiple needle electrode | 484 |

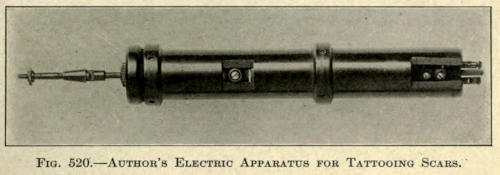

| 520.—Kolle electric apparatus for tattooing scars | 487 |

| Case Recording Methods | |

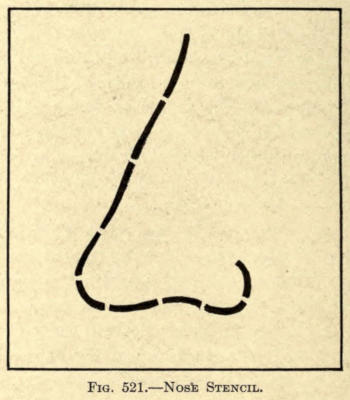

| 521.—Nose stencil | 492 |

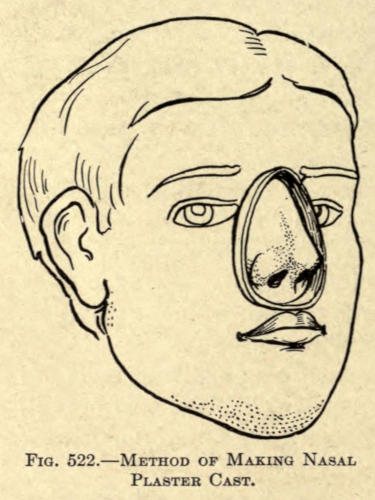

| 522.—Method of making nose plaster cast | 494 |

It seems almost incredible that at this late day so little is generally known to the surgical profession of the beautiful and practical, not to say grateful, art of plastic or restorative surgery, successfully practiced even by the ancients.

The progress of the art has been much interrupted. It is only the later methods of antisepsis, which have so greatly added to general surgery, that have placed it firmly upon the basis of a distinct and separate art in surgical science.

To Aulus Cornelius Celsus, a Latin physician and philosopher, supposed to have lived in the time of Augustus, we owe the first authentic principles of the science. He was a most prolific writer and an urgent worker. After having introduced the Hippocratic system to the Romans he became known as the Roman Hippocrates. His best-known work handed down to us is the “De Medicina,” the first edition of which, divided into eight books, appeared in Florence in 1478. The seventh and eighth volumes, designated the “Surgical Bible,” contain much valuable data in reference to opinions and observations of the Alexandrian School of Medicine.

In considering plastic operations about the face (Curta in auribus, labrisque ac naribus) he writes, “Ratio curationis ejus modi est; id quod curtatum est, in quadratum redigere; ab interoribus ejus angulis lineas transversas incidere, quæ citeriorem partem ab ulteriore[2] ex toto diducant; deinda ea quæ resolvimus, in unum adducere. Si non satis junguntur, ultra lineas, quas ante fecimus, alias dua lunatas et ad plagam conversas immittere, quibus summa tantum cutis diducatur, sic enim fit, ut facilius quod adducitur, segui possit, quod non vi cogendum est, sed ita adducendum ut ex facili subsequatur; et dimissum non multum recedat.”

Centuries elapsed before a clear understanding of the above was deduced. Several analyses have been advanced, those of O. Weber and Malgaigne being the most generally accepted.

As shown in Fig. 1 the method advanced is one for the restoration or repair of an irregular defect about the face in which two transverse incisions forming angular skin flaps, dissected from the underlying tissue, are advanced, joining the denuded free ends.

Should there be a lack of tissue to accomplish perfect coaptation a semilunar incision beyond either outer border is added, as shown in Fig. 2, which permits of greater traction, leaving two small quatrespheral areas to heal over by granulation:

Fig. 1.—Celsus Incision for Restoration of Defect.

Fig. 2.—Celsus Incision to Relieve Tension.

This is the oldest known reference to plastic surgery of times remote.

From the Orient, however, Susrata in his Ayur-Veda, the exact period of which is unknown, discloses the use of rhinoplastic methods.

For centuries following, and throughout the middle ages, the art seems to have waned and remained practically unknown, as far as is shown in the literature of that period.

A revivalist first appeared about the middle of the fifteenth century in the person of Branca, of Catania, a Sicilian surgeon, who about 1442 established a reputation of building up noses from the skin of the face (exore). His son Antonius enlarged upon his methods and is said to have utilized the integument of the arm to accomplish the same result, thus overcoming the extensive scarring of the face following the elder’s mode. He seems to have been the first authority employing the so-called Italian rhinoplastic method. He is also known to have ventured, more or less, successfully in operations about the lips and ears.

Balthazar Pavoni and Mongitore repeated these methods of operative procedure with more or less success and the brothers Bojanis acquired great celebrity at Naples in the art of remodeling noses.

Vincent Vianeo followed the work of the above.

But, somehow, the heroic efforts of these men dropped so much into oblivion that Fabricius ab Aquapende, in writing of the rhinoplastic work of the brothers Bojani, of Calabria, says: “Primi qui modum reparandi nasum coluere, fuerunt calabri; deinde devenit ad medicos Bononienses.”

That Germany was interested at an early date is shown in the admirable work of a chevalier of the Teutonic Order, Brother Heinrich Von Pfohlspundt, who wrote a book on the subject entitled “Buch der Brundth Ertznei,” with a subtitle, “Eynem eine nawe nasse zu mache.” His volume appeared in 1460, about the time of Antonio Branca, of whose methods he was ignorant, claiming to have learned the art from an Italian who succored many by his skill.

Between the years of 1546 and 1599 Kaspar Tagliacozzi,[4] Professor at Bologna, followed the art of rhinoplasty. His pupils published a book at Venice, describing his work in 1597, entitled “De Corturum chirurgia per insitionem,” which established the first authentic volume in restorative surgery. His operation for restoring the entire nose from a double pedicle flap taken from the arm was declared famous and the operation he then advocated still bears his name.

The great Ambroise Pare knew little of rhinoplasty except what he learned from hearsay. As an instance, he relates in 1575 that “A gentleman named Cadet de Saint-Thoan, who had lost his nose, for a long time wore a nose made of silver and while being much hurt by the criticisms and taunts of his acquaintances heard of a master in Italy who restored noses. He went there and had his facial organ restored, and returned to the great surprise of his friends, who marveled at the change in their formerly silver-nosed friend.”

Now again came a century of forgetfulness, the scientific world taking no cognizance of the work done until, suddenly, in 1794, a message came from Poonah, India, to the effect that an East Indian peasant named Cowasjee, a cowherd following the English army, was captured by Tippo Sahib, who ordered the prisoner’s nose to be amputated. His wounds were dressed and healed by English surgeons. Shortly after this the victim of this odd mode of punishment was befriended by the Koomas, a colony of potters, or, as others claim, a religious sect, who knew how to restore the nose by means of a flap taken from the forehead. They operated on him and restored his nose much to the surprise of Pennant, who reported the case in England.

Shortly following this, and in the same year, cases of similar nature are described in the Gentlemen’s Magazine (England), and Pennant’s “Views of Hindoostan.”

In 1811 Lynn successfully accomplished the operation in a case in England, and in 1814 Carpue published his[5] results in two cases successfully operated by him by the so-called Hindoo method.

France now took up the art of rhinoplasty. Delpech introduced a modification of the method of the Koomas in 1820, while Lisfranc performed the first operation of this nature in Paris in 1826.

In 1816 Graefe, of Germany, took up the work of Tagliacozzi but modified his method by diminishing the number of operations.

Bünger, of Marburg, thereupon, in 1823, successfully made a man’s nose by taking the necessary tegument from the patient’s thigh.

A still later modification in the art of rhinoplasty was that of Larrey, who in 1830 overcame a large loss about the lobule of the nose by taking the flaps to restore the same from the cheeks.

Among the better advocates of reparative chirurgery were Dieffenbach, v. Langenbeck, Ricard, v. Graefe (1816), Alliot, Blandin, Zeis, Serre, and Joberi, while Thomas D. Mutter, in 1831, published the results he obtained in America—his co-workers being Warren and Pancoast.

Although Le Monier, a French dentist, as early as 1764 originally proposed closure of the cleft in the soft palate, no one attempted to carry out his suggestion until in 1819 the elder Roux, of Paris, performed the operation. The following year Warren, of Boston, independently decided upon and successfully did an improved operation to the same end.

During the years 1865-70 Joseph Lister distinguished himself in the discovery and meritorious employment of carbolic acid as a means of destroying, or at least arresting, infectious germ life, the principle of which, now so fully developed, has advanced the obtainable surgical possibilities inestimably.

The credit of first collecting data of plastic operations belongs to Szymanowski, of Russia. In his magnificent[6] volume of surgery (1867), he embodies a somewhat thorough treatise on restorative surgery, leaving the subject to be treated more fully and independently, as it should be, to some other enthusiastic surgeon specialist. His work is the result of careful study of such operations on the cadaver, a method much to be recommended to the prospective or operating plastic surgeon.

Several years later, 1871, Reverdin added a valuable method to the still incomplete art, by introducing the now well-known circular epidermal skin grafts for covering granulating surfaces. Thiersch improved this method in 1886 by showing that comparatively large pieces of skin could be transplanted. Wolfe, of Glasgow, had also been successful in utilizing fairly large skin grafts.

Krause, however, improved upon all of these methods by transplanting large flaps of skin without detaching the subcutaneous tissue, a procedure which causes more or less injury to the graft in other methods, and by his method overcoming the subsequent contraction, heretofore a bad feature when the skin-grafted area had healed.

“The results of most plastic operations have been as satisfactory as the most sanguine could hope for or the most critical expect,” says John Eric Erichsen.

Many important additions have been made in the past few years—the outcome of untiring attempt and skill. Czerny replaces part of an amputated breast with a fatty tumor taken from the region of the thigh. Glück successfully repairs a defect in the carotid artery with the aid of a piece of the jugular vein. Glück, Helferich, and others have advocated implanting muscular tissue taken from the dog into muscular deficiencies in the human, due to whatever cause.

The transplantation of a zoöneural section into a defect of a nerve in the human was successfully accomplished by Phillippeaux and Vulpian.

Glück, who later restored a sciatic nerve in a rabbit by the transplantation of the same nerve taken from a hen, went so far as to restore a 5-cm. defect of the radial nerve of a patient by the employment of a bundle of catgut fibers, fully establishing the function of the nerve within a year’s time.

Guthrie has successfully replaced the organs and limbs of animals and has actually transplanted the heads of two dogs.

The transplantation of a toe, to make up a part of a lost finger, is proposed by Nicoladoni. Van Lair hints at the possibility of removing a part or a whole organ immediately before death to repair other living organs.

Von Hippel has successfully implanted a zoöcorneal graft from a rabbit upon the human eye, and Copeland has taken the corneal graft from one human and transplanted it upon the cornea of another to overcome opacity.

The transplantation of pieces of bone to overcome a defect of like tissue has been fully investigated by Ollier, v. Bergman, J. Wolff, MacEwen, Jakimowitsch, Riedinger, and others. They discovered that a graft of bone, with or without its periosteum, can be made to heal into a defect when strict antisepsis is maintained.

Von Nussbaum was the first to introduce the closing of an osseous defect by the use of a pedunculated flap of periosteum.

Poncet and Ollier employed small tubular sections of bone, while Senn has obtained excellent results from the use of chips of aseptic decalcified bone.

Hahn succeeded in implanting the fibula into a defect of the tibia.

On the other hand, cavities in the bones have been successfully filled by Dreesmann and Heydenreich with a paste of plaster made with a five-per-cent carbolic-acid solution, and at a later period by the employment of[8] paraffin (Gersuny) and iodoform wax, as advocated by Mosetig-Moorhof.

The thyroid glands taken from the sheep, it is claimed, have been successfully implanted in the abdomen of individuals whose thyroid glands had been lost by disease or otherwise.

Protheses of celluloid compound or gutta-percha and painted to resemble the nose or ear have been introduced with grateful result. Metal and glass forms have been used to replace extirpated testicles or to take the place of the vitreous humor of the eye (Mule).

Sunken noses have been raised with metal wire, metal plates, amber, and caoutchouc. Metal plates have been skillfully fitted into the broken bony vault of the cranium.

Lastly comes Gersuny’s most valuable method of injecting paraffin compounds subcutaneously for the restoration of the contour of facial surfaces and limbs, which is rapidly taking the place of extensive plastic transplantory and the much-objected-to metal and bone-plate operations for building up depressed noses and other abnormal cavities.

And the end of possibilities is not yet reached. The successful plastic surgeon has become an imitator of nature’s beauty to-day.

His skill permits of many almost unbelievable corrections of defects that would otherwise evoke the pity and too often the aversion of the onlooker, especially if these occur in the faces of those that have become marred in birth or age, by accident or disease. Withal, it is a noble, generous art, worthy of far more extensive use than it now enjoys.

The above fragmentary references include a number of plastic possibilities. They are introduced only in the sense of general interest to the cosmetic surgeon, the special and detailed subject matter herein given under the various divisions have to do only with plastic and cosmetic operations about the face.

The ideal operating room for the plastic surgeon need not necessarily be large, since it requires less work to render it aseptic. Furniture and possibly amphitheater accommodation are always a means of infection unless scrupulously cleansed, a task of time, difficult at best.

The room should be provided with large windows, with facilities for the introduction of the air from without. Two doors, and those well fitted, are all the room should have—but one being used, if possible.

The Walls.—The walls should be of plaster, smoothly laid and well painted, so that they may be readily washed down with antiseptic solutions—a daily morning rule. Glass or tiled walls are much used now and add considerably to the appearance and safety of the room, as plaster in time will crack, while the paint, owing to the heat of sterilizers or steam, often creeps and blisters, exposing an absorbing surface which readily wears down, exposing parts inaccessible for even acute cleanliness.

The Floors.—The floors of these rooms are now usually laid with tile mosaic or marble or a composition resembling linoleum. The base should be curved and all corners sloped off to improve drainage and to keep off dust and dirt.

Skylight.—A skylight of metal and glass is a valuable accessory. It should be fixed or never permitted to be opened during an operation.

Disinfection.—Spraying the room with an antiseptic is hardly necessary, since all germ life descends to the floor and can best be removed by washing with a 1-1000 bichlorid solution.

Should it be necessary to perform an unusually extensive operation in a private house, the room must be cleared of all furniture, pictures, drapery, and carpet. After plugging up the crevices in the windows and doors it should be well fumigated either with sulphur candles, as now commonly furnished, or, better, with formaldehyd.

The superiority of formaldehyd as a disinfecting agent is now well established. An illustration of an apparatus, largely doing away with the difficulties and dangers encountered in the use of the older and ordinary styles of the pressure or nonpressure type, is shown in Fig. 3. The main difficulty with these has always been their almost inaccessibility for cleansing purposes, and in such where this is not the case, the size of the aperture has been made so small that the inside could not be reached. In the pressure apparatus the tops are bolted on, making them exceedingly difficult to remove, with the result that the necessary cleaning was not properly attended to. The corrosive action of formaldehyd gas is such that under these conditions any apparatus would soon become useless.

In the type shown a single clamp arrangement is used (a). By the turning of the hand screw (b) two planed metal faces (the upper surface of the boiler and under surface of the cover) are brought together and sealed. When the cover (c) is removed the entire inside of the boiler is in sight and can be thoroughly cleansed, which should be done each time the apparatus is used. The pipes through which the formaldehyd gas passes after generation are arranged so that they can be taken off and cleaned.

Fig. 3.—Formaldehyd Disinfecting Apparatus.

The gas is generated in the boiler (d) and passes out from the top, down through the pipe (e), and from thence through a series of pipes (f) underneath the boiler, which are subjected to direct heat from the lamp (g). By this means the gas becomes superheated, the polymerization of the formaldehyd is almost entirely prevented, and a dry gas is insured and given off at the pipe (h).

The room should be left closed overnight and thoroughly aired thereafter. The bare floor must then be scrubbed with hot water and soda and flushed with a three-per-cent carbolic-acid solution.

As little furniture as possible should be found in an operating room, and this preferably of undecorated enameled iron.

Instrument Cabinet.—For the instruments and dressings there should be a dust-proof cabinet of iron and glass, such as is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.—Instrument Cabinet.

Operating Table.—The operating table should be of like construction and as plain as possible. Its top can be padded with sterilized felt, protected from moisture by rubber sheets. A surgical chair of plain construction might suffice, inasmuch as most plastic operations cover but a small area and are usually about the head and often performed under local anesthesia. A chair with head rest is much more comfortable, adding much to the moral and physical comfort of the then conscious patient. A very desirable chair is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.—Operating Table.

Instrument Table.—An instrument table, such as is shown in the next illustration, is quite necessary, upon which dressings and instruments are laid during operation.[14] In this the frame is of white enameled iron and the top and shelf of plate glass.

Fig. 6.—Instrument Table.

Irrigator.—An irrigator is often of service, especially in washing out the fine pieces of bone resulting from chiseling or drilling. In skin-grafting it may be used with sterilized three-per-cent salt solution as described later. The best irrigators are those of germ-proof or ground-glass stopper type. They are suspended from the wall by means of an iron bracket or pulley service or placed upon a movable enameled stand as shown in Fig. 7.

Irritating antiseptic solutions are to be avoided, their especial indication will be found under antiseptic care of wounds.

Fig. 7.—Irrigator.

All instruments should be of modern make, devoid of clefts or grooves, and having separating locks when possible. Wooden or ivory handles should be entirely discarded.[15] They should first be rendered free of dirt or dried blood by scrubbing briskly with a stiff nailbrush and hot water; then dried and placed in the sterilizer. The immersed instruments are boiled for five or ten minutes. There are many of such sterilizing apparatuses to be obtained, all made on the same plan, however, and consist of a copper or brass box and cover well nickel plated. Folding legs are placed beneath. A perforated tray is placed within for the immersion of instruments. An alcohol lamp with asbestos wick furnishes the heat.

One per cent of carbonate of soda added to the water prevents them from rusting. The simple subjection of instruments to carbolic-acid solutions or antiseptics of like nature is useless. (Gärtner, Kümmel, Gutch, Redard, and Davidsohn.)

From the sterilizer the instruments are placed in a glass tray containing a one-per-cent lysol solution. Knives, needles, and scissors should be immersed in a tray with alcohol, as a great number of antiseptics destroy their cutting edges. Glass or porcelain trays are best for this purpose. A sterilized towel being placed in the bottom of each for the better placing of instruments.

After operation all instruments should again be scrubbed with soap and hot water, immersed a moment in boiling water or a jet of live steam, dried with an aseptic cloth, and returned to the case.

A very effectual means of rendering instruments sterile is to place them in a metal box and bake them in the ordinary oven (200° F.) for one hour.

To preserve needles Dawbarn advises keeping them in a saturated solution of washing soda. Albolene has an unpleasant oiliness, but is otherwise good. Calcium chlorid in absolute alcohol is efficacious, but expensive. All rust accumulating on instruments must be carefully removed with fine emery cloth; this, however, is unnecessary if the soda solution is used as previously mentioned. It is well to occasionally dip the instruments (holding them with an artery forceps) into boiling water as they are used during operation.

Fig. 8.—Instrument Sterilizer.

The hands of the surgeon and his assistants must always be thoroughly prepared before operation or dressing a wound. The mere immersion of the hands into an antiseptic solution is not sufficient to remove[17] germ life. The oily secretions of the skin and its folds, as well as the cleft about the nails and the nails themselves, are common carriers of infection and are cleansed only by the vigorous method of scrubbing with soap and water and then rendered aseptic by the use of proper media.

The aseptic hospital washstand, as shown in Fig. 9, will be found an ideal piece of furniture; it has a frame constructed of wrought iron, white enameled. The top is of one-inch polished plate glass, with two twelve-inch holes.

Fig. 9.—Aseptic Washstand.

The entire stand can be moved away from the wall, to permit of thorough cleaning of basins, supply pipes, etc. The basins are the best annealed glass, and are supported by nickel-plated traps, with connections for vent pipes. The water supply is controlled by foot valves, which enable the operator to draw either cold, medium, or hot water at will. The waste is also controlled by a foot valve, as shown.

The systematic law of cleansing the hands should be insisted upon at all times. Rules for the method followed might be displayed in abbreviated form in the operating room by glass or enameled signs hung on the wall over the basin and reading as follows:

YOUR HANDS

| I. | Clean nails. |

| II. | Scrub with very hot water and soap for five minutes. |

| III. | Wipe in sterile towel. |

| IV. | Brush with eighty per cent alcohol. |

| V. | Dip into antiseptic solution. |

Green soap is commonly used and is to be preferred to powdered or cake soap. The powder cakes and clogs the container in damp weather, while the latter collects impurities from the air. Synol soap, also liquid, is perhaps the most ideal, a two per cent solution of which forms an excellent lavage for cleaning instruments, as well as washing down furniture in the operating room.

The brushes to be used are of the common wooden-back, hard-bristle make, which can be boiled without injury. There should be several of these, marked on their backs as desired, so that one brush can be used for the one purpose only. In cleansing the hands, the forearms, and even the elbows, should be similarly treated. After scrubbing with soap, as directed, they are to be rinsed, dried with a sterilized towel, again scrubbed with alcohol, and then dipped or flushed with a bichlorid solution.

No woolen garments should be allowed to come in contact with the site of the operation, nor is it well to allow such material in the operating room while working.

Freshly laundered linen gowns of Von Bergman’s pattern, reaching to the shoes, should be worn. They[19] should contain half sleeves and be buttoned on the back. See Fig. 10. These may be sterilized in the steam sterilizer or washed in one-per-cent soda solution. When soiled or blood-stained they should be relaundered.

The operator may substitute the gown with a rubber apron of the Triffe pattern, reaching as high as the collar, but continuous washing quickly ruins them. See Fig. 11.

Fig. 10.—Von Bergman Operating Gown.

Fig. 11.—Triffe Rubber Apron.

The patient for all plastic operations should be carefully examined as to general health and past history. His healing powers should be at their best, as much depends on primary union. If he presents a syphilitic history,[20] it is well to place him under treatment, for a time, at least, before an operation is undertaken. The bowels should be regular. Sulphate of magnesium should be given each morning, before breakfast, for at least two days prior to operating, while his general condition may be improved by the employment of bitter and alterative tonics. Nux vomica with tinct. cinchonæ com., associated with essence of pepsin aromat., or lactopeptone, are very useful. This treatment is also carried on for several days, post operatio.

The success of an operation depends, first, upon the selection of the case; second, the selection of the method employed, and, third, upon the hygiene under which the patient undergoes convalescence. The patient must be given to understand, in many cases, that it is often necessary to reoperate, even to the extent of seven or eight operations, to bring about the desired result. The first result obtained with many cosmetic operations is not at all gratifying to the patient, and unless this is explained to him beforehand he may become discouraged awaiting the next operation and disappear, thus losing the opportunity of being pleased finally, while the surgeon is misunderstood and underestimated by narrow-minded judges and the ever-willing friendly advisers and critics—a consummation much to be avoided.

The part to be operated upon should first be closely shaven. The oily secretions of the area are next rubbed off with an absorbent cotton sponge saturated with alcohol or ether. Next, the skin is washed with hot water and soap or three-per-cent synol suds, then rinsed, and finally rendered aseptic with a bichlorid solution.

If the operation is to be done about the face a rubber cap is so adjusted as to cover the hair. If this is not obtainable sterilized bandages can be employed.

In operations about mucous membranes, as in the nose and mouth, the parts must be cleaned at short intervals with a solution of permanganate of potash or boric acid. The teeth must be cleansed with antiseptic soap, tartar is scraped off, and the mouth rinsed with a proper disinfectant. The corrosive sublimate, or carbolated solutions, owing to their toxic qualities, cannot be used. The preparation of wounds for reoperation, or where an operation is secondary to injury, is referred to later.

All clothing about the site of operation should be removed and rubber cloth placed to surround the field and cover the clothing. This should be covered again with sterilized towels. Everything that touches the patient after this has been done should be aseptic; indeed, hands employed during operation must be immersed from time to time in 1-500 bichlorid solution, and allowed to remain wet.

Natural or sea sponges are now little used in surgery, owing to their peculiar cellular construction. They invite and readily retain spores and germs, are difficult to clean, and require almost constant attention to be at all safe.

Many methods for rendering these sponges aseptic have been proposed, but at best the life of such a sponge is short and hardly pays for the labor and time expended. The absorbing power of a sponge is, of course, its essential quality. For plastic operations sterilized absorbent cotton made into small balls answers every purpose. These puffs of cotton are covered with gauze to prevent the fraying out of the fibers. To further improve them, their centers may be made up of cellulose or wood fiber. When an absorbent cotton sponge is moistened and squeezed out it does not answer as well, since its absorbing qualities are much reduced; the addition of the other material overcomes this.

A much-used and inexpensive sponge having great absorbing power is made in the form of a small compress of sterilized gauze held together with one or two stitches of thread. All of the above sponges are sterilized with the needed dressings and are burned after use. When removed from the sterilizer they are placed in a suitable basin containing six per cent sterilized salt water. It is well to place the receptacle close by the assistant who is[23] to sponge. An enameled iron basin rack, as shown in Fig. 12, answers the purpose best.

Fig. 12.—Basins and Rack.

The soiled sponges are thrown into a lower empty basin or one placed at the operator’s feet. As they are removed from the solution they are squeezed as dry as possible and pressed upon, rather than wiped across, the operative field. It must be remembered that the surgeon’s work must not be hampered by slow or inefficient sponging, and that this procedure must be quick and timely. It is well for the assistant to become accustomed to the habit of the operator.

The best assistant is one who has acquired a methodical and regular manipulation, a result dependent upon constant individual association; such a one is practically invaluable for the skillful performance of plastic surgery. He becomes not only familiar with the one thing, but cultivates a ready knowledge of the arrest of hemorrhage[24] by digital compression when hemostatic forceps would hinder the ease of work, besides cultivating a happy manner of holding retractors or spreading the edges of the incisions with the free hand. As in most of these operations hemorrhage cannot be controlled by the so-called bloodless method. The assistant must control the constant oozing by the gentle pressure of the sponge quickly applied at short intervals. When the sponges are squeezed out in salt solution, as hot as the hand will bear comfortably, capillary oozing is more readily overcome.

All dressings to be used in covering wounds, post operatio, or otherwise, must be as scrupulously clean and free from infection as the hands and the instruments of the operator. This is done by means of sterilization by dry heat or steam under pressure. For all minor cases, small apparatuses only are needed. They are usually made of copper, often nickel-plated, and so constructed as to contain a lower perforated instrument tray and another, placed above it, for dressings. The two are fitted into an outer copper receptacle with snugly fitting cover. A folding stand is furnished upon which this arrangement is placed, and an alcohol lamp with asbestos wick furnishes the heating power. The lower tray is covered with water which, by boiling, fills the upper compartment with steam evenly distributed and with sufficient pressure to accomplish sterilization in from thirty to sixty minutes. Metal hooks are provided with which the trays can be removed. A complete and compact outfit, as designed by Willy Meyer, is shown in Fig. 13.

In the above sterilizer, or in those of similar type, there is naturally more or less saturation of the dressings and the possibility, in the event of the entire conversion of the water contained therein into steam, of[25] injuring the instruments by excessive heat. To overcome this defect the Wallace sterilizer may be advantageously employed.

Fig. 13.—Willy Meyer Sterilizer.

Fig. 14.—Wallace Sterilizer.

Wallace Sterilizer.—Its chief feature is the addition of a reservoir fitting with the separated sterilizer into the outer body. See Fig. 14. This reservoir automatically regulates the water and steam supply. It is filled with[26] water and inserted into the compartment provided for and adjoining the sterilizer. Through an opening in the bottom the water is permitted to escape into the sterilizer until the bottom of the latter is covered to a depth of ⅛ inch. As the heat is applied from the alcohol lamp this film of water is rapidly converted into steam.

The dressings arranged in the large tray are placed in the sterilizer and the supply of steam is maintained through the constant and steady flow of water from the reservoir, which compensates the evaporation in the sterilizer. In about twenty minutes the formation of steam in the top of the reservoir exerts sufficient pressure to force all the boiling water from the reservoir into the sterilizer to the depth of about 1½ inches. The tray of instruments is now inserted and the process continued for another ten minutes. Much less heat is required with this apparatus than with those of ordinary type, while sterilization can be continued uninterruptedly for one and one half hours, if need be.

Sprague Sterilizer.—The most perfect sterilizer is that of the Sprague type, in which a dry chamber is surrounded by steam under pressure. The apparatus is shown in Fig. 15.

Fig. 15.—Sprague Type of Sterilizer.

Its cylindrical chamber is surrounded by two heavy copper shells, the space between which is occupied by the water. This compartment is entirely shut off from the sterilizing chamber, and as the steam is generated, the inner, or sterilizing, chamber becomes heated to a degree[27] nearly equal to that of the steam in the surrounding cylinder; this prevents any condensation of steam taking place in the dressings. By opening the lever-handled valve at the bottom of the sterilizer in the rear, and the valve to the right, on top of the sterilizer, and allowing them to remain open for a space of four or five minutes, a vacuum is formed in the sterilizing chamber. These two valves are then closed, the lower one first, and the steam from the outer cylinder is allowed to enter the chamber, by opening the left valve on top.

The contents should be allowed to sterilize for twenty or twenty-five minutes under a pressure of fifteen pounds. Then close the steam-supply valve; open the vacuum valve (right) and the lever-handled valve at the bottom; leave these open about the same time as in creating a vacuum at the beginning of the process; close both valves, then open the air-filter valve on the door, in order to break the vacuum; the door can then be opened and the dressings be taken out dry and absolutely sterile.

The steam-safety valve on this sterilizer is set at seventeen pounds, but it can easily be regulated should a higher or lower pressure be desired. The door used on this apparatus has no packing of rubber or other soft material which wears or shrinks in time, a steam-tight joint being formed by the bringing together of two plane metal faces on the door and sterilizer head. The door hinge is so made that these parts are bound to come together properly, without the use of excessive caution. Springs on such doors are liable to get out of order or need replacing, and are avoided in this apparatus. All that is necessary to lock or unlock the door is to turn the large hand wheel on the front; the locking levers then work automatically. These sterilizers are arranged for both gas and steam heat.

Sterilizing Plant.—For the ideal operating room the entire sterilizing plant can be had in combined form, as shown in Fig. 16. It consists of a dry-heat dressing apparatus,[28] just described, water and instrument sterilizers, all mounted on a white enameled, tubular, wrought-iron frame. The chamber of the dressing sterilizer is 8½ by 19 inches. The water sterilizer has a capacity of six gallons in each tank and is fitted with natural stone filters, thermometer, water gauge, safety valve, etc. The size of the instrument sterilizer is 8 by 15 inches and 6 inches deep, with two trays. Each apparatus in the above can be used independently of the other, all being arranged for gas-heating.

Fig. 16.—Sterilizing Plant.

Dressing Cases.—All dressings should be sterilized immediately before operation, and not laid away for later use, as often done. As the aseptic material is taken from the sterilizer it is to be placed in glass cases provided therefor, from which they are removed, as needed, during the operation.

A simple glass case, as shown in Fig. 17, may be[29] used, or, better still, the same can be obtained in combination with an instrument table, as shown in Fig. 18.

Fig. 17.—Dressing Case.

Fig. 18.—Combination Dressing Case and Table.

Waste Cans.—All soiled dressings and sponges should be immediately thrown into an enameled iron pail furnished for the purpose. At no time must soiled dressings or sponges be thrown upon the floor, where they are walked over, soiling the floor and, by drying, contaminating the air of the room. Cans for this purpose are made of steel, enameled, of the form shown in Fig. 19.

The contents of the can must be taken from the room after each operation and burned. The can should be flushed with carbolic solution, and returned to the operating room.

Fig. 19.—Waste Can.

(Ligatures)

Silkworm Gut and Silk.—In plastic surgery silkworm gut and silk are used extensively. Rarely is ordinary catgut resorted to, because it is absorbed before thorough union takes place, besides being a source of infection, either primarily from imperfect sterilization or by taking it up from the secretions of the deeper layer of skin not affected by external antiseptics.

The sterilization of silk is accomplished by boiling it for one hour in a 1-20 carbolic solution and then keeping it in a 1-50 similar solution (Czerny). Or it may be boiled in water for one hour and retained in a 1-1,000 alcoholic solution of corrosive sublimate. Ordinarily it may, however, be simply subjected to boiling and steamed in the autocleve. Silkworm gut is treated in the same manner. It has greater tensile strength than silk, and[31] for that reason the thinner varieties are to be preferred to ordinary silk.

Catgut.—It is far more difficult to prepare catgut, but, since it is necessary for ligation, the following methods may be considered best:

The commercial catgut as made from the intestines of sheep, is wound snugly upon a rod of glass and thoroughly brushed with soft soap and hot water. It is then rinsed free of soap, wound upon small glass spools, and placed for forty-eight hours in a one-per-cent alcoholic bichlorid solution, composed of bichlorid of mercury, 10 parts; alcohol, 800 parts; distilled water, 200 parts. The turbid fluid produced by first immersion is changed. Before using, the spools are placed in a glass vessel contain containing a 1-2,000 sublimate alcohol (Schaffer), made up as follows:

| Bichlorid of mercury | gr. vj; |

| Alcohol | ℥x; |

| Distilled water | ℥iiss. |

These glass cases are obtainable for the purpose and contain a second perforated compartment for the ligatures passing through rubber valves placed into the openings (Haagedorn).

Catgut is generally prepared by soaking in oil of juniper for one week and then retaining it in absolute alcohol (Kocher), or a 1-1,000 alcoholic sublimate solution.

Another method for strengthening catgut, as well as to prevent its too rapid absorption, is to chromatize it. This is done as follows:

The catgut is placed in sulphuric ether for forty-eight hours, then treated for another forty-eight hours in a ten-per-cent solution of carbolized glycerin, followed by a five-hour subjection to a five-per-cent aqueous solution of chromic acid (Lister). It is allowed to remain in the latter forty-eight hours, then placed in an antiseptic, dry,[32] tightly closed receptacle, and finally soaked in 1-20 carbolic solution before using.

The formaldehyd method of Kossman is to immerse the gut in formaldehyd for twenty-four hours, then washing with a solution of chlorid and carbonate of sodium and retaining it in the same solution. The catgut in this procedure swells and its strength is much impaired in this way.

Any of the above methods are not above criticism, however, rigid as they may seem, bacterial growths having been obtained with nearly all of them.

The dry-air method (Boeckman, Reverdin) is reliable, but the subjection of catgut to dry air at a temperature of 303° F. for two hours results in making it tender and less pliable.

Fig. 20.—Clark Kumol Apparatus.

The Kumol method (Kronig) is considered the most reliable, even under the severest tests. This mode of sterilization is accomplished as follows: A specially devised apparatus of brass, with a cast-bronze top, both thoroughly nickel-plated, is used. The apparatus of J. G. Clark, as shown in Fig. 20, will be found excellent. The kumol is retained in a seamless cylinder, 8 by 8 inches, which is surrounded on the sides and bottom by a sand[33] bath; the flame, impinging on the bottom, heats the sand, thereby insuring an even heat to the inner or sterilizing cylinder. The catgut, in rings, is placed in a perforated basket hanging in the cylinder, which can be raised or lowered at will; after drying for two hours at 80° C., the basket is dropped, and the catgut immersed in the kumol, at 155° C., for one hour; the kumol is then drawn off through a long rubber tube, and the catgut dried at 100° C., for two hours; it is then transferred to sterile glass tubes plugged with cotton.

Prepared catgut of the various sizes can now, however, be purchased in the market, and that offered by the better firms of chemists is quite reliable and may be safely used for all plastic surgery about the face. It is supplied in glass tubes, either in given lengths, as in the Fowler type, in which the hermetically sealed tube is U-shaped or on glass spools placed in glass tubes, not sealed, but closed by a rubber cap, through which the desired length of ligature is drawn and then cut off.

These are solutions used for the destruction of and to arrest the progress of microörganisms that have found their way into wounds—the cause of sepsis, as exhibited by fever, suppuration, and putrefaction. These preparations are called antiseptics and are used to render parts aseptic. They vary much in their destructive power, effect on tissue, and toxic properties. The reader is referred to a work on bacteriology for the specific knowledge of such on germ life.

The antiseptic treatment of wounds was founded by Joseph Lister, 1865-70, then called Listerism. His one chemical agent to accomplish this was carbolic acid, but many such and more effective agents have been added since that time, all differing in their specific properties and each having, for the same reason, its particular use.

The following group of antiseptics has been chosen with a view of giving the best selection, to which the author has added a short description of each, so that the surgeon may choose one or the other, as the occasion may demand. As a rule, an operator cultivates the use of a certain line of antisepsis, especially in this branch of surgery, experience being the best guide; yet it is hoped he may find certain aid from those referred to, their particular use being pointed out from time to time, as the author has had occasion to prefer one or the other.

Alcohol (absolute).—This is a well-known antiseptic, but, because of its ready evaporation, is especially used for the hands, as described, and to cover sharp-edged instruments after sterilization.

Aluminum Acetate (Bürow, H. Maas).—A powerful, nontoxic antiseptic. Is used only in two- to five-per-cent solution. According to Primer, it arrests the development of schizomycetes, and in twenty-four hours destroys their propagation. It readily removes offensive odors of wounds; its great objections are that it injures the instruments, and, because of its astringent nature, roughens the skin of the hands. This, however, makes it particularly useful for sponging to arrest capillary oozing.

Boric Acid (Lister).—Not a powerful, but nonirritating, antiseptic. For this reason it is used extensively in cleansing mucous membranes, and, when associated with salicylic acid, as in the well-known Thiersch solutions, composed of salicylic acid, 2 gms.; boric acid, 12 gms.; water, 1,000 gms., is much used in skin-grafting operations. It is not very soluble in cold, but readily in hot, water and alcohol. The saturated solution is prepared by adding ℥j to the pint of boiling water.

Benzoic Acid.—Nonirritating, moderate antiseptic (Kraske); is prepared in 1-250 solutions. Soluble in hot water and alcohol, but sparingly in cold water.

Carbolic Acid (Phenylic Acid).—Not a powerful, but a much-used antiseptic. The purest acid should be used. It appears as a colorless crystalline solid, liquefied by the addition of five per cent water. If more water is added the solution becomes turbid, clearing when 1-2,000 is reached.

It is readily soluble in glycerin, alcohol, ether, and the fixed volatile oils. Solutions in alcohol and oils have no antiseptic effect (Koch). The 1-20 aqueous solution is recommended by Lister.

The aqueous solutions used in surgery are 1-20 and[36] 1-40. The weaker is used for the operator’s hands, to cover instruments, as already mentioned, and to impregnate sponges. The stronger solution is used for the carbolic spray, to cleanse the unbroken skin about the site of operation, and to disinfect wounds. Either solution, when applied to an open wound, whitens the raw surface, coagulates the albumen, and causes considerable irritation, which subsides quickly and is followed by numbness.

Such solutions, by virtue of their irritant nature, increase the serous discharge from a wound for about twenty-four hours, for which proper drainage must be provided, as by its collection it would add to the danger by increasing inflammation and suppuration, and, by absorption, even produce toxic effect generally.

When a cold solution is used it should be prepared by vigorous stirring to separate the globules of the acid. Hot water insures perfect distribution. After an infected wound is washed with it, the solution should not again be used, nor should any of the acid be permitted to remain in the spaces about the wound. It will be found that many patients cannot tolerate such dressings, and that others must be substituted.

Large surfaces should never be exposed to carbolic solutions, because the skin absorbs them readily, followed by untoward results. Dangerous symptoms have been known to result from the internal administration of seven drops of the acid, and fatal termination has followed its use as a surgical dressing (Bartley).

Mild acid poisoning is first noted in the urine, which turns olive green. If the agent is continued, the urine appears dark and turns almost black on standing. The coloring is due to the presence of indican. If the absorption is not prevented beyond this there is dull frontal aching, tinnitus aurium, dizziness, fainting, severe and uncontrollable vomiting. Untoward symptoms are noted by albuminuria, total absence of sulphates in the urine,[37] a contracted and inactive pupil, elevation of temperature, unconsciousness, muscular contraction, and death.

The treatment consists in immediately removing the cause and employing another antiseptic. Support the patient with stimulants, freely given. Cracked ice and brandy to allay the vomiting. Small doses of sodium sulphate, frequently repeated, as a means of converting the acid into nonpoisonous sulphocarbolate (Bauman). Albumen and milk internally. Magnesium sulphate, five per cent.

Chromic Anhydrid.—Improperly called chromic acid. Made by adding one and one half parts sulphuric acid, c. p., to one part of concentrated solution of dichromate of potash. Appears in saffron-colored crystals. It acts as a caustic upon tissue, and, although a splendid antiseptic, cannot be used for such purposes, but is well adapted for the preparation of catgut, as mentioned.

Creolin.—Is an antiseptic prepared from coal by dry distillation, and is used to stimulate granulations, being much more powerful than carbolic acid. It is nonirritant and practically nontoxic. Used in two-per-cent aqueous solutions, in which it appears as a turbid but effective mixture. It is well suited for cleansing the hands, a five-per-cent solution having none of the irritating or anesthetic effect of carbolic acid. Owing to the opacity of the aqueous solution, it is not suitable for the immersion of instruments for operation.