Title: Domestic Annals of Scotland from the Reformation to the Revolution, Volume 2 (of 2)

Author: Robert Chambers

Release date: May 25, 2024 [eBook #73695]

Language: English

Original publication: Edinburgh: W. & R. Chambers

Credits: Susan Skinner, Mr David Mowatt, Brian Wilcox and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

DOMESTIC

ANNALS OF SCOTLAND.

From the Reformation to the Revolution.

SECOND EDITION.

VOLUME II.

W. & R. CHAMBERS, EDINBURGH AND LONDON.

MDCCCLIX.

Edinburgh:

Printed by W. and R. Chambers.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| REIGN OF CHARLES I.: 1625-1637, | 1 |

| REIGN OF CHARLES I.: 1637-1649, | 105 |

| INTERREGNUM: 1649-1660, | 174 |

| REIGN OF CHARLES II.: 1660-1673, | 255 |

| REIGN OF CHARLES II.: 1673-1685, | 349 |

| REIGN OF JAMES VII.: 1685-1688, | 469 |

| GENERAL INDEX, | 503 |

VOL. II.

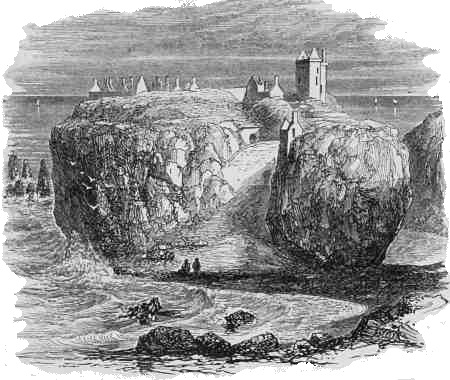

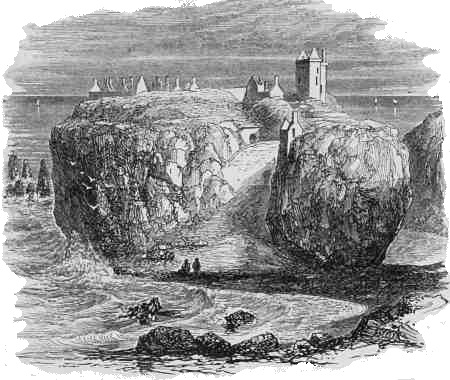

| Frontispiece Vignette.—DUNNOTTAR CASTLE. | |

| PAGE | |

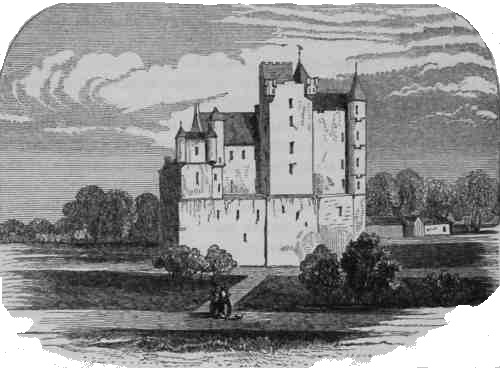

| BOG AN GICHT CASTLE, | 46 |

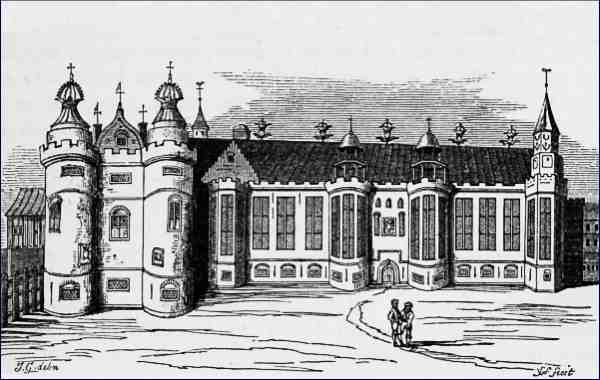

| HOLYROOD PALACE, AS BEFORE THE FIRE OF 1650, | 205 |

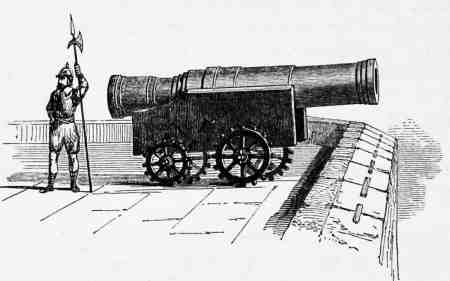

| MONS MEG, | 468 |

| THE JOUGS—AT DUDDINGSTON CHURCH, | 501 |

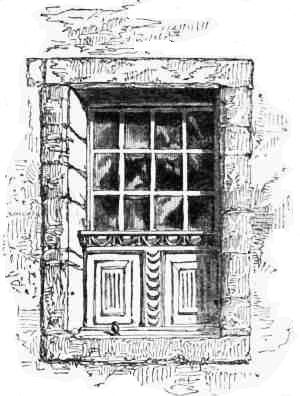

| HALF-GLAZED WINDOW OF SEVENTEENTH CENTURY, | 524 |

1

James I. was peaceably succeeded on the throne by his son Charles I., then in the twenty-fifth year of his age. The administration of Scottish affairs continued to be conducted by the Privy Council in Edinburgh. For the endowment of the Episcopal Church now established, the king (1625) attempted a revocation of the church-lands from the lay nobles and others into whose hands they had fallen; but this excited so strong a spirit of resistance, that he was obliged to give it up. He ended by issuing (1627) a commission to receive the surrender of impropriated tithes and benefices, and out of these, and the superiorities of the church-lands, to increase the provisions of the clergy. These proceedings, though legal, were unpopular. The nobles, alarmed for their property, began to lean towards the middle and humbler classes, who objected to a hierarchy on religious grounds solely. While all was smooth on the surface, while the lords of the Privy Council were full of expressions of servile obedience, while they, as well as all judges and magistrates, gave most loyal and regular attendance at church, and duly knelt at the communion—a strong spirit of discontent ran through society. The more zealous Presbyterians formed the habit of meeting in private houses for prayer and worship. They beheld with apprehension the tendency to medieval ceremonies which Charles, and his favourite councillor, Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, were manifesting in England. That leaning to Arminianism which the English Church was also accused of—modifying Calvinism so far as to say that the perdition of sinners had been only foreseen, not decreed, and that God’s wrath against them was not to last for ever—was viewed with the utmost alarm in Scotland. The only means the king had of giving reassurance was to make a loud profession of horror for popery, and to practise all possible severities upon its adherents. That the2 king and his Council availed themselves of this chance, will be found abundantly evidenced in our chronicle.

It is rather remarkable, that the adjustment of the tithes by King Charles in 1627 has proved a most useful practical measure, in annulling a certain class of disputes between the clergy and their flocks; anticipating, in short, the valuable commutation acts of England and Ireland by upwards of two centuries.

During the first few years of the reign, large bodies of troops were raised in Scotland, and conducted by native officers to serve the Protestant powers of the continent, engaged in the great thirty years’ struggle with Catholic Germany.

The king paid a visit to Scotland in 1633, in order to be crowned as its sovereign, and to see what further could be done for perfecting the Episcopal system. His reception was respectful, but not so affectionate as that experienced by his father. He wanted the good-humour of James; he treated all difficulties in a stern and imperious manner. The people were overborne by his power and his obduracy, but left unconvinced, unreconciled. In the subsequent year, he lost additional ground by a tyrannical and unjust trial of the Lord Balmerino on a charge of treason, for merely having in his possession the scroll of a petition against the royal measures. At the same time, the Scotch people knew of the king’s quarrels with the English patriots Elliot, Pym, and others; they knew that he had resolved on calling no more parliaments; they heard of Strafford’s despotic government in Ireland; they sympathised with the Puritans who were now and then pilloried and cropped of their ears, or driven in multitudes to Holland and America. Although, then, there was a strong prepossession for the institution of monarchy, there was also a steady muster of irritation and fear against the government of this particular monarch. It might have been evident to any dispassionate observer, that, if the present system were persevered in, an explosion would sooner or later take place.

There was this further difference between the late and present king, that while James was only anxious for a church polity which would work harmoniously with his doctrines of state, Charles—who, unlike his father, was an earnestly religious man—deemed Episcopacy a necessary part of faith. The struggle was now, therefore, between a people fanatic for one system, and a king fanatic for another. One thing Charles had long considered as necessary to complete his favourite project in Scotland—the introduction of a liturgy into the ordinary worship. He thought the proper time was now come, because he everywhere saw external obedience. A service-book being accordingly prepared by Laud, on the basis of that commonly used in England, but with a few innovations relishing of popery and Arminianism, an order of Privy Council was given for its being read in the churches. This was precisely what was necessary to exhaust the popular powers3 of endurance. It seemed to the multitude as if popery, almost undisguised, were once more about to be introduced. When the dreaded book was opened in St Giles’s Church (July 1637), the congregation rose in violent agitation to protest against it. It was hooted as a mass in disguise, and a stool was thrown at the head of the reader. Similar scenes occurred elsewhere; but the clergy in general had declined to bring the book forward. The state-officers and bishops now found themselves objects of popular hate to such an extent that they could not present themselves in public. The service-book was not merely a failure in itself, but it had produced a kind of rebellion. Charles discovered, when too late, that, as usually happens with men of headstrong temper, the truth had been concealed from him. The general obedience had been a hypocrisy. Nineteen-twentieths of the people were in their hearts opposed to his measures, and now he had given them occasion to declare themselves and enter at all hazards upon a course of resistance.

This is the date of the patent of Charles I., conferring on Sir Robert Gordon of Gordonstown the dignity of a baronet of Nova Scotia, being the first patent of the kind granted. Gordon of Cluny and Gordon of Lesmoir also got similar patents during the same year, and Lesmoir’s eldest son, being of full age, was at the same time made a knight; such being the original design regarding this honour. The order of baronets of Nova Scotia, which still holds an honourable place in Scottish society, was projected by King James, as an encouragement to gentlemen of property in his native kingdom to enter into the scheme of Sir William Alexander (subsequently Earl of Stirling) to plant Nova Scotia. In the patent of each, a certain portion of land in that country is assigned along with the honour, the infeoffment being executed on the Castle Hill of Edinburgh; but this, as is well known, has never been otherwise than an ideal advantage. ‘His majesty, the more to encourage the baronets in that heroic enterprise [of planting Nova Scotia], besides other privileges, did augment every one of their coats of arms by joining thereto a saltire azure, or a blue St Andrew’s cross, set in a white field, with another scutcheon in the middle of the blue cross, comprehending a red rampant lion in a yellow field, with a red tressure of fleur-de-luces about the lion, with an imperial crown above the scutcheon, being the arms of New Scotland. The crest of the arms of New Scotland is two hands joined together, the one armed, the other unarmed, holding a laurel and4 a thistle twisted, issuing out of them, with this motto, “Munit hæc, et altera vincit.” The supporters are a unicorn upon the right side, and a savage man upon the left.’—G. H. S.

The town-council of Aberdeen at this time anticipated the wisdom and good manners of a later age, by ordaining that ‘no person should, at any public or private meeting, presume to compel his neighbour, at table with him, to drink more wine or beer than what he pleased, under the penalty of forty pounds.’1

Thomas Crombie, burgess of Perth, was ‘summoned to underlie the law, for the alleged slaughter of ane William Blair, a westland gentleman, wha notwithstanding had done the same negligently to himself. Being of intention to have struck the said Thomas with ane whinger, he hurt himself in the arm, whereof he died twenty days after. The said Thomas compeared with eighty burgesses of Perth, besides five earls, six lords, and twenty-six barons, upon the burgh of Perth’s desire to back him, [and] was clengit and freed therefrae.’—Chron. Perth.

By the royal command, a fast was held throughout Scotland, in consequence of the heavy rains which had prevailed since the middle of May, threatening the destruction of the fruits of the earth. It was a time of calamity. The marriage of the king to the Princess Henrietta Maria of France (June 16th), had of course brought the mass into London, and ‘no sooner was the queen’s mass, the plague of the soul, received, than a raging pestilence broke out in the city of London and parts adjoining, which in a short time cut off above 40,000 persons.’—Stevenson’s Hist. C. Scot.

The government was incensed by bruits set in circulation by a set of ‘restless and unquiet spirits,’ to the effect that the king designed some change in the kirk and its canons. The king issued a proclamation denouncing these injurious rumours as troublesome to the commonwealth, and protesting that so well was he pleased with the existing arrangements, that, if he had not found them established by his late dear father, he would himself have never rested till they were perfected as they now stood. It may be suspected that this proclamation did not put an end to5 the bruits, for in October the king discovered that a number of Catholic noblemen and gentlemen were bringing up their children in popish seminaries abroad, and at the same time entertaining popish priests at home; wherefore it had become necessary that some suitable anti-papist edicts should be published. The parents of children educated abroad were ordered to have them brought home before a certain day, under severe penalties. Great pains were threatened against those who should give entertainment or shelter to popish priests after a certain day. Finally, the proclamation charged ‘all our subjects, of whatsoever rank or degree, to conform themselves to the publict profession of the true religion, prohibiting the exercise of ony contrary profession, under the pains conteinit in the laws made thereanent.’—P. C. R.

A proclamation was resolved on for a strict execution of the laws against the selling of tallow out of the country. Contrary to the views of modern mercantile men, there was a general fear and dislike in those days regarding export trade. It was always thought to have a bad effect in making things scarce and dear at home. No one seems ever to have dreamed of the profitable quid pro quo without which the trade could not have been carried on. We require to have a full conception of this universal delusion, before we can understand the frame of mind under which the Privy Council of the day could speak of the transport of tallow as ‘a crime most pernicious and wicked,’ perpetrated by a set of ‘godless and avaritious persons,’ acting ‘without regard of honesty or of those common duties of civil conversation whilk in a good conscience they ought to carry in the estate.’

It was, to all appearance, under a sincere horror for ‘this mischeant and wicked trade,’ which threatened to leave not enough of tallow to supply the needs of the population, that the lords announced their resolution to punish it with confiscation of all the remaining movable goods of the guilty parties.—P. C. R.

John Gordon of Enbo, having suffered some injury at the hands of Sutherland of Duffus, longed for revenge, but for some time in vain. At length, riding with a single friend between Sideray and Skibo, he encountered Duffus’s brother, the Laird of Clyne, also attended by a single friend on horseback. Gordon, with a cudgel in his hand, assaulted Clyne, and gave him many blows. ‘Then they drew their swords, and, with their seconds, fell to it eagerly.’

6

Clyne, after being sorely wounded in the head and hand, was suffered by Eubo to escape with his life.

The curious part of the affair is to come. Enbo was prosecuted by Duffus before the Privy Council, and committed to the Castle of Edinburgh. The Duffus party were full of triumph, making sure of ample retribution. At that crisis arrives the sage and courteous Sir Robert Gordon of Gordonstown, who had heretofore made so many rough matters smooth in the north. He first dealt with Duffus, to induce him to withdraw the prosecution, which he apparently looked on in no other light than as a species of unrighteous revenge. Duffus proved obdurate, ‘thinking to get great sums of money decerned to him by the lords from John Gordon, for satisfaction of the wrong done to his brother, whereby he might undo John Gordon’s estate.’ Feeling now relieved from all ties towards Duffus, Sir Robert ‘dealt by all means for John Gordon’s relief and mitigation of his fine.’ Very much by the interest of the Lord Gordon, then in Edinburgh with the French commissioners, he succeeded in inducing the Privy Council to let John Gordon off with a fine of a hundred pounds Scots, equal to £8, 6s. 8d. sterling!—‘and nothing to the party.’ Duffus left Edinburgh in sad discomfiture, to meet the blame of his friends for not having accepted the better conditions offered at first by Sir Robert Gordon. The proto-baronet at the same time returned to the north, bringing John Gordon of Enbo along with him, ‘beyond the expectation of all his friends and foes in those parts, who thought that he should not have been released so soon, nor fined at so small a rate, wherein Sir Robert purchased himself great credit and commendation.’ So Sir Robert calmly assures us in his own narrative of the transaction.—G. H. S.

A convention of Estates was held, under the Earl of Nithsdale as commissioner, to treat regarding the revocation of the church-lands. Those whose fortunes were thus threatened were greatly alarmed and incensed by the urgency of the king. The suspicion of the Earl of Nithsdale being a papist must have added to the unpopularity of the affair. If we are to believe a story which Burnet reports from Sir Archibald Primrose, they held a private meeting to consult how they might best protect their own interests, and it was agreed by them that, when assembled, ‘if no other argument did prevail to make the Earl of Nithsdale desist, they would fall upon him and all his party in the old Scots manner, and knock them on the head.... One of these lords, Belhaven, of the7 name of Douglas, who was blind, bid them set him by one of the party, and he would make sure of one. So he was set next the Earl of Dumfries. He was all the while holding him fast. And when the other asked him what he meant by that, he said, ever since the blindness was come on him, he was in such fear of falling, that he could not help the holding fast to those who were next to him. He had all the while a poniard in his other hand, with which he had certainly stabbed Dumfries, if any disorder had happened. The appearance at that time was so great, and so much heat was raised upon it, that the Earl of Nithsdale would not open all his instructions, but came back to court, looking on the service as desperate.’

It is much to be desired for this anecdote that it had some support in other authority. The Lord Belhaven pointed to was then a man little over fifty, and his epitaph in Holyrood Abbey describes him as kind to his relations, charitable to the poor, moderate in prosperity, and constant under adversity—though, to be sure, posthumous certificates of that kind do not generally rank as evidence of the first class.2

A taxation was granted to the king by the Scottish parliament, amounting to £40,000 Scots. Some of the burghs came to an agreement with the lords of the Privy Council for certain proportions of this taxation, to be paid annually while it continued; and we are thus supplied with a means of estimating the comparative importance and wealth of some of the principal towns in the kingdom. We find the following towns set down, with the annexed sums at their names: Glasgow, £815, 12s. 6d.; Linlithgow, £163, 2s. 6d.; Stirling, £422, 17s. 9d.; St Andrews, £490; Dunbar, £90, 15s.; Culross, £84, 10s.; Canongate, £100; Hamilton, 100 merks.

Paisley, now a huge city of the industrious, was, in the reign of Charles I., only a village surrounding the ruins of an ancient abbey. The dominant personage of the place was the Earl of Abercorn, a cadet of the Hamilton family, enriched by the possession of the abbey-lands. Through the influence of the earl’s mother, who had become a Catholic, the town was described as ‘a nest of papists.’ Nevertheless, the interest of Lady8 Abercorn’s relative, Lord Boyd, had procured a presentation to the parish church in favour of Mr Robert Boyd of Trochrig, recently principal of the Edinburgh University—one of a group of men deep in theological learning, adepts in Latin versifying, who then threw a lustre upon Scotland—but at the same time a zealous protester against the late Episcopalian innovations in the church. Being thus obnoxious to Lady Abercorn, albeit her ladyship’s relation, his settling in Paisley was viewed by her, her sons, and her friends, with great disrelish, and the consequence was a material resistance to the presentee, being perhaps the first occurrence of the kind in our country, the precursor of many.

‘He was ordained to have his manse in the fore-house of the abbey, as the most convenient place for that use. And having put his books and a bed thereintill; one Sunday, he being preaching, in the afternoon, the Master of Paisley,3 being the Earl of Abercorn’s brother, with some others, came to the minister’s house, none being thereintill, and cast all his books on the ground, and thereafter locked the door.’ On a complaint from Boyd to the Privy Council, the Master was brought to penitence for this outrage, and it was then hoped that matters would go on smoothly. On his returning, however, to his manse, he found the locks of the doors stopped up with stones, so that he could not get in without force, which he was not permitted to use. As he was going away, ‘the rascally women of the town, coming to see the matter—for the men purposely absented themselves—not only upbraided Mr Robert with opprobrious speeches, and shouted and hoyed him, but likewise cast dirt and stones at him; so that he was forced to leave the town and go to Glasgow.’

Being a man of a gentle nature, Boyd withdrew to his house of Trochrig in Ayrshire, without making any complaint as to his late ill-usage. The case, however, being taken up by the Archbishop of Glasgow, and brought before the Privy Council, Lady Abercorn, the earl her son, and the Master her second son, all came to Edinburgh in the earl’s ‘gilded carroch,’ accompanied in the usual manner with their friends, to answer for the outrages which had been committed. An order was given for the replacement of Boyd in his parish; but, meanwhile, he sunk under a weakly and reduced constitution, and died, January 5, 1627, at the age of forty-nine.4

9

‘Betwixt the hours of eight and nine in the morning, there appeared a phenomenon in the open firmament, which was looked on by many as a presage of some future calamity. The sun shining bright, there appeared, to the view of all people, as it were three suns; one be-east, and the other south-be-west the true sun, and in appearance not far from it. From that which lay south-west, there proceeded a luminary in the form of a horn, that pointed north-west, and carried as it were a rainbow, in colour gray, but clearer than the rest of the sky. Whether these signs were ominous or not, manifold were the calamities which then prevailed.5

Just before this time, a large body of men, variously stated at 3000 and 4400, was raised in Scotland by Sir Donald M‘Kay of Strathnaver, ‘a gentleman of a stirring spirit,’ and Sir James Leslie—supposed to have been of the Lindores family—to assist Ernest Count Mansfeldt in the Bohemian army against the Emperor of Germany. This being the Protestant cause, and likewise the cause of the king’s brother-in-law, the Elector Palatine, who had accepted the crown of Bohemia, the enlistment received the royal sanction and patronage, £2000 being disbursed to Sir Donald, and £600 to Sir James, while a further sum of £400 was promised to be at the service of the troops on their landing in Hamburg.6 The movement harmonised with the feelings of the people of Scotland, to many of whom an honourable military service with pay was convenient and agreeable on less exalted considerations than that of religious sympathy, as the industry of the country was then too little advanced to hold out a gainful occupation to all who were anxious for it. The estates and influence of Sir Donald being in Sutherlandshire, it naturally fell out that a large portion of the officers of the corps were from that county and the adjacent districts of Ross and Caithness—Monroes, Mackenzies, Rosses, Gordons, Sinclairs, and Gunns. The greater number of the recruits embarked at Cromarty in October, and had a prosperous voyage to the Elbe; but their commander, Sir Donald, was detained by sickness till the spring of the ensuing year. Owing to the death of Count Mansfeldt, the corps took a new destination, though adhering to the same cause, for they entered the service of the King of Denmark, their own king’s uncle, who had engaged in the war against the emperor.

10

The exploits of these Scottish levies have been recorded in a curious but confused narrative, the production of one of the officers, and now a great rarity, entitled Monro his Expedition, with the worthy Scots Regiment called M‘Kay’s Regiment, &c.7 The author, Colonel Robert Monro, states that he composed it at his spare hours, ‘for the use of all worthy cavaliers favouring the laudable profession of arms.’ He gives a long list of officers, all bearing familiar Scottish names—as Forbes, Monro, M‘Kay, Sinclair, Ross, Gordon, Stewart, Innes, Seton, Dunbar, Hay, and Gunn. In the ranks were included a small band of Macgregors, who had been lying for some time in the Tolbooth of Edinburgh, on account of their irregularities, and who are said to have proved good soldiers under regular discipline and with a legitimate outlet for their inherent turbulence and courage.

One portion of the Scots Regiment was sent to join the English auxiliaries under General Morgan. Another was put to a severe duty in defending the Pass of Oldenburg against Tilly’s army. The latter are described as shewing a remarkable degree of firmness and gallantry in that trying situation, from which they had to retire, after a loss of four hundred men. Another party, of four companies, under Major Dunbar, defended the Castle of Brandenburg in Holstein against 10,000 men under Tilly, with such desperate and sanguinary pertinacity, that, on the place being ultimately taken, they were all put to the sword. On many other occasions, these valiant Scotsmen distinguished themselves greatly, insomuch that they came to be called the Invincible Regiment. It was greatly owing to them that Stralsund made such an obstinate defence against Wallenstein. Here they lost 500 men in seven weeks, only about 400 being now left. When the Danish king was forced to evacuate Pomerania, the Scots defended the bridge at Wolgast, till he was safe. So early as January 1628, Sir Donald M‘Kay had to go home for fresh levies. He returned in July with as many as raised the corps to 1400 effective men. But before any further remarkable service had been performed by the regiment, the King of Denmark was glad to make peace.

The regiment then transferred itself to the service of Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, who had now put himself at the head of the Protestant interest against Catholic Germany. Throughout his11 remarkable campaign in Pomerania and Mecklenburg, our brave Scots were on incessant service, and were usually employed on posts of peculiar difficulty or danger. The waste of men was enormous; and in February 1631, Lord Reay—for so Sir Donald M‘Kay was now styled—returned home once more for fresh levies. He was detained in England by some circumstances of an unpleasant nature, which enter into our national history; but the levies were sent out notwithstanding, and the efficiency of the Scots Regiment, or rather regiments, never for a moment flagged. At the brilliant capture of Frankfort-on-the-Oder, when so many of the imperialists perished, and so much of their wealth fell into the hands of the Swedish king, our countrymen had a distinguished part. In the subsequent transactions ending with the splendid victory of Leipsic, by which the Protestant world was for the time liberated, they were ever in the front, doing and suffering much. And so it went on, even after the death of the king at Lutzen in 1633, their great losses being continually made up again by the arrival of fresh levies from Scotland. Amongst many gallant officers who received their training in these wars, were two men destined to take prominent parts in the history of their country—namely, Colonels Alexander and David Leslie.8

Amongst the preparations for war at this time, the Privy Council, reflecting on the inconveniences of being wholly dependent on foreign countries for gunpowder, empowered Sir James Baillie of Lochend, knight, to see if he could induce some Englishmen to come and settle in Scotland for the manufacture of that article.—P. C. R.

Mr Thomas Ramsay, minister of Dumfries, was unusually zealous against popery, probably by reason of its peculiar abundance within the bounds of his cure. One day, as he and some co-presbyters were passing along the bridge over the Nith, they encountered a person on horseback whom they recognised to be ‘ane mess priest by whom numbers of the country people are pervertit not only in their religion, but in their allegiance to the king’s majesty.’ ‘Having used their best endeavours to have apprehendit the priest, it fell out that, by the help of some12 excommunicat papists, who was in company with him, he escaped.’ They, however, secured ‘his horse and cloak-bag, wherein there was a number of oisties, superstitious pictures, priests’ vestments, altar, chalice, plate-boxes with oils and ointments, with such other trash as priests carry about with them for popish uses.’

Mr Thomas Ramsay and his friends immediately came to Edinburgh, and presented themselves before the Privy Council, who, according to their wishes, passed an act of approbation in their favour, and ordered them to make a bonfire at the market-cross of Dumfries, and there burn all the popish ‘trash’ excepting the silver articles, which were to be melted down for the benefit of the poor.—P. C. R.

Four of the bishops, and a number of commissioners from presbyteries, met in Edinburgh to deliberate on church matters, being the nearest approach to a General Assembly which could now be permitted. Amongst the matters discussed were the increase of papistry and sin, the persecutions of the Protestants in Germany, and the war against France. Anxiety was also expressed regarding the prospects of the harvest. ‘Because of the extraordinar rains, which now threaten rotting of the fruits of the ground before they be ripe, and so a fearful famine upon this land in so dangerous a time, when the seas are closed by the enemies, and no hope of help from other countries if God shall send a famine, [it was resolved] to entreat the Lord that he wold cause the heaven answer the earth, and the earth answer the corn, and the corns to answer our necessity, and us to answer His will, in faith, repentance, and obedience.’9

At this time, Great Britain might be said to be drifting towards a war with France. The king having offended Louis XIII. by turning off all the Catholic priests who had come over in attendance upon his queen, the French monarch retaliated by ordering the seizure of British vessels within his ports. There were a hundred and twenty English and Scottish ships in those ports, chiefly loading with wine, and the whole were seized. The Scotch, however, contrived to make themselves appear as still connected with France by an ancient league—a league which, it is to be feared, only existed as a friendly illusion common to the two nations. Out of deference to this13 notion, the Scotch vessels were all dismissed, while the English were retained.—Bal.

‘There was a warrant from the king’s majesty and his Council, for listing in Scotland 9000 men, to go to serve under the king of Denmark, in the German wars for renewing the palatinate and Bohemia.... There was many forcit, as beggars, idle men, and [those wanting] competent means to live upon, under the conduct of the Earl of Nithsdale, my Lord Spynie, and the Laird of Murkle (Sinclair), as colonels.

‘There was the same year 2000 gentlemen, landed men, barons, lords, and others of guid sort, levanted from Scotland under the Earl of Morton, for helping to take the Isle of [Ré] in France. But the isle was recovered by the French frae the English.’—Chron. Perth.

The recruiting of these German legions does not appear to have been conducted in a very scrupulous manner. Some of the circumstances afford a rich illustration of the social condition of Scotland at that time. On the 1st of November 1627, Robert Scott, bailie of Hawick, reported to the Privy Council a number of ‘idle and masterless men, fit to be employed in the wars’—namely, ‘Allan Deans, miller; Allan Wilson; George Dickson, callit the Wran; John Rowcastle; Walter Scott, maltman; John Tait, piper; William Beatison; Robert Lidderdale, callit the Corbie; Robert Langlands; James Waugh, officiar; James Towdop; William Scott, callit Young Gillie; John Laing, piper; William M‘Vitie; Walter Fowler; and Andrew Deans.’ This proceeding of Bailie Scott was in obedience to an act of Estates. The lords, having narrowly examined these men, liberated seven as ‘not fit persons to be employed in the wars.’ Two were set free, under surety to appear again when called upon. The remaining persons they ordained to be delivered to the Earl of Nithsdale, ‘to be sent by him with the rest of his company to the wars in Germany.’ Seeing, however, that ‘the said persons are men and servants to William Douglas of Drumlanrig, and that reason and equity craves that they sould be rather delivered to Sir James Douglas of Mowsill, brother to the said Laird, nor to any other colonel or captain whatsoever,’ they ordained accordingly, provided that Sir James should satisfy the Earl for his expenses. The men thus dealt with were to be lodged in the Tolbooth, until the ship should be ready to carry them abroad, the Earl undertaking to satisfy Andrew White the jailer, ‘for their expenses during the time of their remaining in ward.’—P. C. R.

14

In the exigencies of the unfortunate wars in which the king became involved with Spain and France, he was led to the strange idea of raising a small troop of Highland bowmen. This weapon, which had long since declined in most European countries before the advance of firearms, was still in use in the north of Scotland—indeed, continued partially so for sixty years yet to come. Most probably it was the chief of the MacNaughtans, now a gentleman of the Privy Chamber, who had suggested such a levy to the king, for he it was who undertook to raise and command the corps. At the date noted, Charles wrote to the Privy Council of Scotland, to the Earl of Morton, and the Laird of Glenurchy, asking assistance and co-operation for MacNaughtan in his endeavours to raise the men, it being declared that they should have ‘as large privileges as any has had heretofore in the like kind.’

It appears that MacNaughtan came to the Highlands in the course of the autumn, and engaged upwards of one hundred men for this extraordinary service. ‘George Mason’s ship’ was placed at Lochkilcheran, to receive the men as they were engaged, and carry them to their field of action. It seems to have been designed that they should join a regiment commanded by the Earl of Morton, which was now lying at the Isle of Wight, designed to support the Duke of Buckingham in the dismally unfortunate expedition he had made for the relief of Rochelle. It was not till some weeks after that affair was concluded by his Grace’s evacuation of the Isle of Ré, that the bowmen, to the stinted number of one hundred, left their native shores. Departing in the very middle of winter, the ship encountered weather unusually tempestuous, was chased by the enemy, and obliged to put into Falmouth. There MacNaughtan wrote to the Earl of Morton—‘Our bagpipers and marlit plaids served us to guid wise in the pursuit of ane man-of-war that hetly followit us.’ He told his lordship he would come on with his men to the Isle of Wight as soon as possible, being afraid of a lack of victuals where he was; and meanwhile he entreated that his lordship would prepare clothes for the corps, ‘for your lordship knows, although they be men of personages, they cannot muster before your lordship in their plaids and blue caps.’

What came of these ‘poor sojours, quho ar far from thair owin countrie,’ we nowhere learn.10

15

‘... there being upon the coast of Zetland about the number of 250 Fleming busses at the herring-fishing, attended with nine waughters ... there cam upon them fourteen great Biscayen Spanish ships, in whilk there were 4000 soldiers, with ane great sum of money for the payment of the Spanish army in Germany; whilk ships, being bound for Dunkirk, cam that north way for their safest passage, till keep themselves free from the harm of Flemish or English ships. But, approaching to the said coast, they set upon the Hollanders, and, sinking three of the waughters, the haill busses took the flight, some till little creeks in Zetland, where the Spaniard did sink a number of their busses, and taking their master, did put the rest of their company to the edge of the sword, with some also of the country people, inhabitants thereof, resisting their tyranny.’

The Privy Council, duly apprised of these outrages on the 13th of the month, were taking measures for their correction, when, on the 16th, ‘there arase a great fray in the town of Edinburgh, for, the busses having left the waughters combating with the Dunkirkers, and having fled away therefrae, there cam of them the number of threescore all together in form of ane half-moon, up the Firth of Forth; where, at the first perceiving afar off of such a number of ships in the form foresaid, as if they had been in battle or onset thereof, the haill people thought they had been ane army of Spaniards and Dunkirkers assuredly. Whereupon the Privy Council caused mak a proclamation, that all manner of men, offensive and defensive, under the pain of death, should all in arms to the sea-shore, upon the first touk of the drum. All this day, the Lords of Council held their council at Leith, where also David Aikenhead, provost of Edinburgh, with some of the bailies and council thereof, attended the event of the said ships, till advertise the people of the town what they sould do thereanent. About eight hours at night, by command of the Privy Council, the cannons were trailed down with furnishing thereto from the Castle of Edinburgh till Leith, and the town of Edinburgh were put in arms under ten handseignies, every man better resolved than another to abide the worst till death, or they to put the enemies to destruction.... About ten hours at night certain word cam, by two boats that was sent from Leith, to the effect that they were our friends and only a number of busses fled from the tyranny of the Dunkirkers ... and then the cannons were trailed back again to the Castle, and the people were commanded to their rest.’—Jo. H.

16

As the Privy Council was sitting in its chamber in Holyrood Palace, an outrage took place, recalling the wild acts of thirty years since. One John Young, poultry-man, attacked Mr Richard Bannatyne, bailie-depute of the regality of Broughton, at the council-room door, and struck him in the back with a whinger, to the peril of his life. The Council, in great indignation, immediately sent off Young to be tried on the morrow at the Tolbooth, with orders, ‘if he be convict, that his majesty’s justice and his depute cause doom to be pronounced against him, ordaining him to be drawn upon ane cart backward frae the Tolbooth to the place of execution at the Mercat Cross of Edinburgh, and there hangit to the deid and quartered, and his head to be set upon the Nether Bow, and his hand to be set upon the Water Yett.’—P. C. R.

A warrant was granted by the Privy Council regarding Alexander Robison, a Jesuit lately taken and put into the Tolbooth of Edinburgh, ‘where he has remained divers months bygane’ [since the 20th September of preceding year]. As his staying in the country could not but lead to the corruption of the people in their religious opinions and their allegiance to the king, the Council deemed it expedient that Robison be ‘sent away out of the country nor unnecessarily halden within the same.’ He was therefore to be called before a justice court in the Tolbooth, where, ‘after acknowledging of his offence in transgressing of his majesty’s laws made against the resorting and remaining of Jesuits within this kingdom,’ they were to ‘take him solemnly sworn and judicially acted, that he sall depairt and pass furth of this kingdom with the first commodity of a ship going toward the Low Countries, and that he sall not return again within the same without his majesty’s licence ... under pain of deid.’—P. C. R.

Two days after, the Council took into consideration certain petitions of Alexander Robison, ‘heavily regretting the want of means to entertein him in ward and satisfy his bypast charges therein.’ ‘Seeing it accords not with Christian charity to suffer him to starve for hunger, he being his majesty’s prisoner,’ the lords agreed that he should have 13s. 4d. [that is, 1s. 1-1/3d. sterling] per day, counting from the 20th of September last.

The latter part of this year, marked by a military disaster and17 disgrace nearly unexampled in British annals11, was made further memorable by a tempest of extraordinary violence, which destroyed a vast quantity of mercantile shipping, including many collier vessels carrying their commodity to the Thames. At one part of the coast of Scotland, a high tide, assisted by the storm, produced an inundation over a large tract of low land. It came upon the Blackshaw in Carlaverock parish, and upon certain parts of the parish of Ruthwell ‘in such a fearful manner as none then living had ever seen the like. It went at least half a mile beyond the ordinary course, and threw down a number of houses and bulwarks in its way, and many cattle and other bestial were swept away with its rapidity; and, what was still more melancholy, of the poor people who lived by making salt on Ruthwell sands seventeen perished; thirteen of these were found next day, and were all buried together in the churchyard of Ruthwell, which no doubt was an affecting sight to their relations, widows, and children, &c., and even to all that beheld it. One circumstance more ought not to be omitted. The house of Old Cockpool being environed on all hands, the people fled to the top of it for safety; and so sudden was the inundation upon them, that, in their confusion, they left a young child in a cradle exposed to the flood, which very speedily carried away the cradle; nor could the tender-hearted beholders save the child’s life without the manifest danger of their own. But, by the good providence of God, as the cradle, now afloat, was going forth of the outer door, a corner of it struck against the door-post, by which the other end was turned about; and, going across the door, it stuck there till the waters were assuaged.

‘Upon the whole, that inundation made a most surprising devastation in those parts; and the ruin occasioned by it had an agreeable influence on the surviving inhabitants, convincing them, more than ever, of what they owed to divine Providence; and for ten years thereafter, they had the holy communion about that time, and thereby called to mind even that bodily deliverance.’12

There now being much anxiety about foreign invasion, some care18 was taken to ascertain the state of the national defences, and there was also a proposal to fortify various places, of which, it may be remarked, Leith was one. Sir John Stewart of Traquair had been sent to inquire into the condition of Dumbarton Castle, and now reported as follows: ‘At his entry within the castle, he found only three men and a boy in ordinar guarding the same. The walls in the chief and most important parts were ruinous and decayed; the house wanting doors, locks, or bolts, and nather wind nor water tight; the ordnance unmounted, and little or no provision of victuals and munition (except some few rusty muskets) within the same.’

The description, it is to be feared, was generally characteristic. In those days, which we look back upon as so romantic, there was one thing wanting—revenue. In Scotland, owing to the poverty of the government, national buildings alternated between long periods of neglect and decay, and abrupt attempts at repair when there was a pressing need. As to the case of Dumbarton, Sir John Stewart was empowered to get it put into proper order, with a promise of reimbursement.—P. C. R.

The Privy Council took energetic measures against certain persons of the south-western province, including Herbert Maxwell of Kirkconnel, Charles Brown in New Abbey, Barbara Maxwell Lady Mabie, John Little, master of household to the Earl of Nithsdale, John Allan in Kirkgunzeon, John Williamson in Lochrutton, and many others, all apparently people in respectable circumstances. It was found that these individuals proudly and contemptuously disregarded both the excommunication and the horning which they had brought upon themselves by persisting in their ‘obdured and popish opinions and errors,’ haunted and frequented all public parts of the country, ‘as if they were free and lawful subjects,’ and were ‘reset, supplied, and furnished with all things necessar and comfortable unto them,’ a great encouragement to them to continue in their erroneous opinions, ‘whereas if this reset, supply, and comfort were refused unto them, they might be reclaimed from their opinions, to the acknowledgment of their bypast misdemeanours.’ As if to mark more effectually the infamy of these recusants, a pair who had been excommunicated for adultery were classed with them. A commission was issued for the apprehension and trial of all persons ‘who are suspect guilty of the reset and supply of the said excommunicat rebels.’

Two of the commissioners—Sir William Grier of Lag and Sir19 John Charteris of Amisfield—went very promptly to that peculiar nest of papists, New Abbey, and there apprehended Charles and Gilbert Brown, two of the ‘excommunicat rebels.’ Enraged by this act, the wife of Charles Brown, and a number of other women, raised a mob against the minister and schoolmaster of the parish, ‘whose wives and servants they shamefully and mischantly abused, and pursued with rungs [sticks] and casting of stones.’ This being held as a great insolency, and likely to prove an evil example if unpunished, the Council ordered the commissioners to hold a court at Dumfries for the trial and punishment of the offenders.—P. C. R.

A few weeks afterwards, one of the excommunicated ladies, Janet Johnston, spouse of Brown of Lochhill, was taken into custody; but being in a delicate state, she was allowed (June 26) to go home till the time of her accouchement, on condition that she gave caution for her living during the interval ‘without offence and scandal to the kirk,’ and ‘conform with the ministry for giving unto them satisfaction regarding her religion;’ failing which, immediately after her recovery, ‘she sall depairt furth of the kingdom, and not return again within the same without his majesty’s licence, under pain of ane thousand merks.’—P. C. R.

These proceedings were followed up by some sharp handling of the papists of Aberdeenshire and the priests trafficking there.

The clergy of the city of Edinburgh, eight in number, were now disposed to sympathise in and support their flocks in the general repugnance to the new arrangements at the celebration of the communion. They had become sensible of the great inconvenience of dissent, and wished to bring the people back to the churches. There was, however, but a faint hope of prevailing with the king to sanction a return to the old simple forms. At the approach of the Easter celebration of the communion, ‘there was in the Little East Kirk a private meeting of the ministers of Edinburgh, and a certain number of the citizens of the said town, to the end they might reconceil the hearts of the people to their pastors, to the end, if it might be possible, they might have acquired ane dispensation from the king to celebrate the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper without kneeling, after the ancient form of the discipline of the Kirk of Scotland.... The conveners, having met three or four times thereupon, thought best to send Mr William Livingstone to the king’s majesty to deal for obteining the said dispensation; but before he cam to court, his majesty was informed of his message,20 and absolutely refused the same until he were further advised.’—Jo. H. The king afterwards sent an imperious order to the Archbishop of St Andrews, desiring him to see to the condign punishment of the authors of this movement. The people were silenced, but soured; and the course of things that led to the Civil War went on.

George Lauder of the Bass, and his mother, ‘Dame Isobel Hepburn Lady Bass,’ were at this time in embarrassed circumstances, ‘standing at the horn at the instance of divers of their creditors.’ Nevertheless, as was complained of them, ‘they peaceably bruik and enjoy some of their rents, and remain within the craig of the Bass, presuming to keep and maintein themselves, so to elude justice and execution of the law.’ A Scotch laird and his mother holding out against creditors in a tower on that inaccessible sea-rock, form rather a striking picture to the imagination. But debt even then had its power of exorcising romance. The Lords of Council issued a proclamation, threatening George Lauder and his mother with the highest pains if they did not submit to the laws. A friend then came forward and represented to the lords ‘the hard and desolate estate’ of the two rebels, and obtained a protection for them, enabling them to come to Edinburgh to make arrangements for the settlement of their affairs.—P. C. R.

Under encouragement, as was supposed, from the Duke of Buckingham, the Scottish Catholics had for some time been raising their heads in a manner not known for many years before. They began to indulge a hope that possibly a certain degree of toleration might be extended to them. Some impetuous spirits amongst them went so far in ‘insolency’ as to write pasquinades upon the Bishop of Aberdeen, and post them upon his own church doors. The Privy Council were too well aware of the unpopularity of the king on account of the episcopal innovations which he loved, to allow him to remain under any additional odium on account of a faith about which he was, at the best, indifferent. Besides, ‘taking order’ with popery was always a cheap and ready means of making political capital against Presbyterian opponents. We accordingly find the Council at this date issuing orders regarding a number of persons of consideration in the north, as well as the priests whom they entertained, but particularly against the Marquis of Huntly, whose protection they deemed21 to be the chief cause why popery was not better repressed in that quarter.

There was first a recital regarding a host of men who acted as officers, or lived as tenants, upon the extensive estates of the marquis—‘Mr Robert Bisset of Lessendrum, bailie of Strabogie; Alexander Gordon of Drumquhaill, chamberlain of Strabogie; Patrick Gordon of Tilliesoul; John Gordon, in Little-mill; Adam Smith, chamberlain of the Enzie; Robert Gordon, in Haddo; Barbara Law, spouse to the said Adam Smith; Margaret Gordon, good wife of Cornmellat; Malcolm Laing, in Gulburn; and Mr Adam Strachan, chamberlain to the Earl of Aboyne.’ It was stated of them, that they had remained indifferent under the ‘fearful sentence of excommunication,’ and the consequent process of horning—that is, rebellion—frequenting all parts of the country ‘as if they had been true and faithful subjects.’ They were alleged to be encouraged in their rebellious life by the marquis, who was properly answerable for them; so he was charged to present them on a certain day of February next, under pain of horning.

There was next a recital regarding a number of persons, including, besides several of the above, ‘Mr Alexander Irving, burgess of Aberdeen; Thomas Menzies of Balgownie; Walter Leslie, in Aberdeen; Robert Irwing, burgess there; John Gordon, appearand of Craig; James Forbes of Blackton; Robert Gordon, in Cushnie; James Philip, in Easton; James Con, in Knockie; John Gordon, in Bountie; Alexander Harvie, in Inverury; John Gordon, in Troups-mill; John Spence, notar in Pewsmill; Francis Leslie, brother to Capuchin Leslie; Alexander Leslie, brother to the Laird of Pitcaple; Thomas Cheyne, in Ranniston; William Seton of Blair; Thomas Laing, goldsmith, burgess of Aberdeen; Alexander Gordon, in Tilliegreg; Alexander Gordon, in Convach; Agnes Gordon his spouse; Margaret Gordon, spouse to Robert Innes, in Elgin;’ who had all been excommunicated and denounced rebels for the same reason: also seven men and two women, including, besides several of those formerly cited, Alexander Gordon, in Badenoch; Angus M‘Ewen M‘William there; and Alexander Gordon, ‘appearand’ of Cairnbarrow; and Helen Coutts his spouse; who had been put to the horn for not coming to answer for their ‘not conforming themselves to the religion presently professed within this kingdom, and for their scandalous behaviour otherwise, to the offence of God, disgrace of the Gospel, and misregard of his majesty’s authority.’ Having most ‘proudly and contemptuandly remained under excommunication this long time bygane,’ they went22 about everywhere as if they had been good subjects, ‘hunting and seeking all occasion where they may have the exercise of their false religion; for which purpose they are avowed resetters of Jesuits, seminary and mass priests, accompanying them through the country, armed with unlawful weapons.’ The Marquis of Huntly, as sheriff-principal of Aberdeen, and Lord Lovat, as ‘sheriff of Elgin and Forres,’ were charged to search for and capture these persons, in order that they might be punished.

There was, finally, an order regarding the priests, who, it was said, were not only corrupting the religion of the people, but perverting their loyalty—‘namely, Mr Andrew Steven, callit Father Steven; Mr John Ogilvie; Father Stitchill; Father Hegitts; Capuchin Leslie, commonly callit The Archangel; Father Ogilvie; Mr William Leslie, commonly callit The Captain; Mr Andrew Leslie; Mr John Leslie; —— Christie, commonly callit The Principal of Dowie; with other twa Christies; Father Brown, son to umwhile James Brown at the Nether Bow of Edinburgh; Father Tyrie; three Robertsons, callit Fathers; Father Robb; Father Paterson; Father Pittendreich; Father Dumbreck; and Doctor William Leslie.’ The Marquis of Huntly, as the proper legal authority for the purpose, ‘and the special man of power, friendship, authority, and commandment in the north parts of the kingdom, and who for many other respects is obleist to contribute his best means for the furtherance and advancement of his majesty’s authority and service,’ was charged to hunt out and apprehend these pestilent men, that the laws might be executed upon them.

To these measures was added a proclamation, chiefly to the people of the northern districts, pointing out the priests by name, as the ‘most pernicious pests in this commonweal,’ and commanding ‘that nane presume nor take upon hand to reset, supply, nor furnish meat, drink, house, nor harboury’ to them, ‘nor keep company with them, nor convoy them through the country, nor to have no kind of dealing nor trafficking with them,’ under the penalties laid down in the acts of parliament. There was a like proclamation regarding the excommunicated laymen and women above mentioned. At the same time, the bishop and magistrates of Aberdeen were commissioned to go with armed bands, and endeavour to apprehend both the priests and their resetters.

While charging the Marquis of Huntly with some duty against the papists on his own estates and those throughout his jurisdiction, the Council were quite aware of their false position in23 regard to him, and they deemed it proper (December 4) to send a letter to the king on that special point. They expressed their belief that the chief cause of the late increase of popery and insolency of the papists lay in the fact, that the execution of the laws on these matters was in the hands of notoriously avowed professors of the same faith—men of such power, that inferior officers, however well affected to their duty, were overawed. They in all grief and humility presented this case for his majesty’s serious consideration, entreating that he would debar from the Council and from public employments all who were suspected of popery; manifestly pointing to the marquis. Meanwhile, they said, we have directed warrants to the sheriffs and other authorities, ‘to apprehend the delinquents if they can or darr.’

The Marquis of Huntly, who had been last converted from popery a dozen years ago, and had since, as usual, relapsed, took little trouble with a commission which he felt to be so disagreeable. When the 3d of February arrived, his depute came before the Council, and made some excuse for him, on the ground that execution of the warrants had been delayed by the wintry weather until the delinquents had all escaped; adding a petition that they would not press him to remove his chamberlains till these men should have accounted to him for large sums which they owed to him. Feeling that the marquis had wilfully failed in his duty, they denounced him as a rebel.

On the 18th of June 1629, the Council issued a charge against Sir John Campbell of Caddell;13 Mr Alexander Irving, burgess of Aberdeen; Thomas Menzies of Balgownie; Mr Robert Bisset of Lessendrum; John Gordon of Craig; James Forbes of Blackton; Thomas Cheyne of Ranniston; William Seton of Blair; Alexander Gordon of Tilliegreg; Patrick Gordon of Tilliesoul; and Margaret Gordon, goodwife of Cornmellat; representing that, notwithstanding all that had been lately done, they continue obdurate against kirk and law, going about as if nothing were amiss, and enjoying possession of ‘their houses, goods, and geir, whilk properly belongs to his majesty as escheat.’ Seeing that by the latter circumstance they are ‘strengthened and fostered in their popish courses,’ the Council ordained that officers-at-arms ‘pass, pursue, and take the said rebels their houses, remove them and their families24 furth thereof, and keep and detein the same in his majesty’s name;’ also to search out, poind, and uplift all ‘geir’ of theirs wherever to be found, and bring it to the exchequer. All neighbours were commanded to assist in enforcing these orders.

It was ascertained that the acts against resetting of priests had been ‘eluded by the wives of persons repute and esteemed to be sound in religion, who, pretending misknowledge of the actions of their wives in thir cases, thinks to liberate themselves of the danger of the said resett, as if they were not to answer for their wives’ doings.’ Wherefore, the Council ordained that the husband shall be always, in such cases, answerable for the wife.

At the same time, to gratify the desire of his Scottish Council, the king sent an order that, for the detection of papists in high places, the communion should be administered to all his councillors and judges, all advocates, writers, and officers of the government, in his chapel at Holyroodhouse, and this to be repeated at least once a year. At his majesty’s command, a kind of convention of dignitaries of church and state met at the same place to give the Council their assistance. The result was a commission issued (July 25, 1629) to a great number of nobles and gentlemen, in the several districts popishly affected, to search for and bring to justice those ‘pernicious and wicked pests,’ ‘avowed enemies to God’s truth and all Christian government,’ the Jesuits, seminary and mass priests concealed throughout the country; also to seize all persons of whatever rank, ‘whom they sall deprehend going in pilgrimage to chapels and wells, or whom they sall know themselves to be guilty of that crime,’ that they may be punished according to act of parliament. Supposing the priests and other delinquents should fly to fortified places, then the commissioners were empowered and ordered to ‘follow, hunt, and pursue them with fire and sword, assiege the said strengths and houses, raise fire, and use all other force and warlike engine that can be had for winning and recovery thereof, and apprehending of the said Jesuits and excommunicat papists being therein.’ The commissioners at the same time received assurance that no act of bloodshed on either side, or any destruction of property occasioned in the execution of this order, should be imputed to them as a fault.

The dignitaries and ministers of the Established Church, without any appearance of unwillingness, took part in this persecution. Many of the bishops sat as members of the Privy Council, and we hear of the ‘dioceses and presbyteries’ helping the government to lists of avowed and suspected papists, against whom proceedings25 might be taken. None were more active than Spottiswoode, archbishop of St Andrews, and Forbes, bishop of Aberdeen. It was no blank fusillade for mere terror. A great number of the gentlemen and ladies aimed at in the fulminations of the Council were really struck in their persons and estates. We hear of many being thrown into prison, and kept there till they either professed conformity or gave caution that they would depart from the country. Their property was at the same time held as escheat to the crown.

Agreeably to the royal order, the communion was administered in the king’s chapel at Holyroodhouse in July, ‘by sound of trumpet,’ to all such of his majesty’s councillors, members of the College of Justice, and others, as were disposed thus to testify their worthiness of the royal favour. On the 6th of November, the king wrote a letter to his Scottish Council on this subject. ‘Understanding,’ he says, ‘that some popishly affected have neglected this course, we, out of our care and affection for the maintenance of the professed religion, are pleased to will and require that you remove from our council-table all such who are disobedient in that kind.’ This the Council (December 3) obediently resolved to do.

The Council was much importuned by the captive papists for relief; but it was pithily ordained that none now or hereafter ‘sall be relieved out of ward, but upon obedience and conformity to the true religion, or else upon their voluntary offer of banishment furth of his majesty’s whole dominions.’

One remarkable captive was the Marchioness of Abercorn, whom we have already seen manifesting some ultra-ardour on her own side. This lady had lain for a long time in the Tolbooth of Edinburgh—a lodging which was loathsome in the reign of George III., and may be presumed to have been still worse in that of Charles I. The confinement had procured her ladyship ‘many heavy diseases, so as this whole last winter she was almost tied to her bed,’ and she now ‘found a daily decay and weakness in her person.’ The severity of the fate of this, as of some other persons, may be measured by the mercy extended to her. It being represented to the king that her ladyship, being oppressed with sickness and disease of body, required the benefit of a watering-place, he, being inclined, on the one hand, to do nothing that would derogate from the authority of the church, but, on the other, being unwilling that the lady should be ‘brought to the extremity of losing her life for want of ordinary remedies,’ ordered (July 9, 1629) that she should have a licence to go to the baths of Bristol,26 but only on condition that she should not attempt to appear at court, and after her recovery, return and put herself again at the disposal of the Council.

Her ladyship, after all, did not go to the Bristol baths, but, after a further restraint of six months in the Canongate [jail?], was permitted to go to reside in the house of Duntarvie, on condition that ‘she sall contain herself [therein] so warily and respectively as she sall not fall under the break of any of his majesty’s laws;’ also that she should, while living there, have conference with the ministry, but allow none to Jesuits or mass priests. Her ladyship is found to have ‘contained herself’ in Duntarvie for a considerable time, but to have at length been under a necessity of resorting to Paisley for the ‘outred’ of some weighty affairs. In March 1631, when she had been under restraint about three years, she was formally licensed to go to Paisley, but only under condition that she should not, while there, ‘reset Thomas Algeo nor no Jesuits,’ and return by a certain day under penalty of five thousand merks.

Some, while preparing to pass into exile, were naturally concerned about the means of living abroad. These persons, therefore, petitioned that some portion of their confiscated fortunes might be granted to them for their subsistence. The king took these petitions into consideration, and ‘out of his gracious bounty and clemency, in hope of their timely reclaiming,’ ordained that the proceeds of their estates should be divided into three parts, ‘whereof twa sall wholly belong to his majesty, and the third part his majesty does freely bestow upon the said persons;’ this, however, to be wholly forfeited, if the inventory of their possessions rendered by them should prove to be untrue.

Even the princely Huntly was obliged to bow to the storm. Breaking through an order of the Scottish Privy Council, he proceeded direct to court, in the hope of gaining something from the royal favour. Having resigned into the king’s hands his sheriffship of Aberdeen, and made some excuses for his non-execution of the Council’s orders, he obtained certain ‘instructions for the clergy of Scotland,’ ordering them to use Huntly, Angus, Nithsdale, and Abercorn ‘with discretion,’ and not proceed further against them till he should be consulted; also commanding that papist peeresses be not excommunicated, provided their husbands be responsible for them, and that they reset no Jesuits.14 Huntly27 then came (November 3) in humble form before the Council, made excuses for his non-execution of their orders, and besought them for a gift of his own confiscated property in behalf of some person whom he might nominate. Notwithstanding the king’s favourable letter, they demurred to this petition, and put him off for some weeks, at the same time taking caution that he should not pass north of the Tay. Coming again before them on the 8th of December, he was told that he could not be excused from ‘exhibiting’ the papists residing on his estates. He was also commanded to return on a certain day, when he might witness his daughters being ‘sequestrat for their better breeding and instruction in the grounds of the true religion.’

Amongst the movements in this important cause was one regarding the children of noted papists. It was feared that the ordinances for having them brought up under Protestant tutors had been much disregarded. The Earl of Angus had been ordered to place his eldest son, James Douglas, under Principal Adamson of the Edinburgh University, to have remained with him some certain space, in order to have his doubts in religion resolved. The young man had given his tutor the slip. The earl was therefore called before the Council. He explained that he had no knowledge of what the youth had done till it was past, and he had since sent him to the Duke of Lennox, that he might be introduced to some English university. He was obliged to crave pardon of the Council for what he had done. The representative of the great Douglases of the fifteenth century compelled, in the seventeenth, to give up the right to educate his own son, and confess himself a delinquent for even attempting such a thing! ‘The Earl of Errol’s twa daughters, the Laird of Dalgetty’s bairns, and the bairns of Alexander Gordon of Dunkinty,’ were said to be under ‘vehement suspicion of being corrupted in their religion by remaining in their fathers’ company.’ So likewise were the daughters of the Marquis of Huntly, the children of Lord Gray, and many others. The Earl of Nithsdale was ordered to ‘exhibit’ his son, that the Council might see if he was right in the faith. Even Lord Gordon, who soon after undertook a commission for the government against the northern papists, was commanded to send his sons to a tutor approven of by the Archbishop of St Andrews.

We get a glimpse of some of the proceedings in regard to the estates of the Catholic gentlemen from a supplication presented to the Privy Council on the 15th of December 1629 by the commissioners28 of the diocese of Aberdeen. It proceeds to narrate that, it having pleased the Lords, ‘to the glory of God and comfort of all weel-affected subjects, for purging the land of popery, to grant sundry letters against excommunicat rebels, their persons, houses, and rents’—decreets, moreover, having been obtained in the Court of Session for poinding and arrestment—the officers had consequently dealt with certain friends of the victims, who had undertaken to labour the lands for the crop 1629, and to account for the result according to a valuation made ‘before the corns came to the hook;’ but there had been some slackness in the working out of these arrangements, ‘to the great hinder of his majesty’s service, and encouraging of these excommunicat rebels to continue in their obstinacy and disobedience.’ It was therefore necessary to take sharper methods; and a strict commission to the Bishop of Aberdeen was suggested. The Council accordingly ordered the bishop to call the officers before him, and have them ‘tried of their diligence’ and honest and dutiful carriage in this matter, and to see that they were prompted where necessary.

For further proceedings regarding the ‘excommunicat papists and rebels,’ see forward, under January 1630.

On this day—an unusual season for thunder in our climate—a thunder-clap fell upon Castle-Kennedy, the seat of the Earl of Cassillis in Ayrshire—‘which, falling into a room where there were several children, crushed some dogs and furniture; but happily the children escaped. From thence descending to a low apartment, it destroyed a granary of meal. At the same time, a gentleman in the neighbourhood had about thirty cows, that were feeding in the fields, struck dead by the thunder.’15

The case of John Weir ‘in Clenochdyke,’ who had married Isobel Weddell, the relict of his grand-uncle, and thus been guilty of ‘incest,’ was under the consideration of the Privy Council. Weir had been three years under excommunication for this crime, which the Council deemed ‘fit to procure the wrath and displeasure of God to the whole nation.’ The king’s advocate was now ordered to proceed with his trial, and, in the event of his conviction, to cause sentence to be passed; but they superseded execution till July. Weir was actually tried on the 25th of April, found guilty, and sentenced to be beheaded at the Cross of29 Edinburgh.16 After suffering a twelvemonth’s imprisonment under this sentence, he became a subject for the special mercy of the king, and was only banished the island for life.

Weir’s is not a solitary case. On the 19th of August in the same year, Henry Dick, ‘in Bandrum,’ was adjudged to lose his head for a transgression in connection with the sister of his wife, this offence being regarded as incest, and misinterpreted as a breach of a well-known text which is still the basis of an English law. In July 1649, Donald Brymer for the same offence was sentenced to the same punishment. It is worthy of notice that, in June 1643, Janet Imrie, who had been the paramour of two brothers, was for that reason condemned to be beheaded.

One of the most remarkable of a large class of cases of this kind was that of Alexander Blair, a tailor in Currie, who had married his first wife’s half-brother’s daughter.17 For this offence, under reverence for the same misinterpreted text, he was condemned to lose his head! (September 9, 1630.)

It is deplorable to see these severe punishments inflicted for acts which neither interfere with any principle of nature, nor tend in any way to injure the rights of individuals or to trouble society. At the same time, the marriage of first-cousins, which tends to the deterioration of the race, was not forbidden.18 And offences of real consequence, as affecting the condition of individuals, were visited with comparatively light penalties. Thus, on the same day when Alexander Blair, tailor in Currie, was sentenced to lose his head for marrying his first wife’s half-brother’s daughter, William Lachlane was adjudged to banishment for life for bigamy. The jurisprudence of the country on these points was mainly guided by a few semi-religious or rather superstitious views, while the voice of God through nature no one thought of listening to or applying.

30

Died Jean Gordon, remarkable in our history as the lady whom James Hepburn Earl of Bothwell divorced in 1567, in order to be enabled to ally himself to Queen Mary. She survived that frightful time, in peace and honour, for sixty-two years, exemplifying how durable are calmness and prudence in comparison with passion and guilt. Since her separation from Bothwell, she had been the wife of two other husbands—first, Alexander Earl of Sutherland; and second, the Laird of Boyne. ‘A virtuous and comely lady, judicious, of excellent memory, and of great understanding above the capacity of her sex; in this much to be commended, that, during the continual changes and particular factions of the court in the reign of Queen Mary, and in the minority of King James VI., (which were many,) she always managed her affairs with so great prudence and foresight, that the enemies of her family could never prevail against her, nor move those that were the chief rulers of the state at the time, to do anything to her prejudice; a time indeed both dangerous and deceitful. Amidst all these troublesome storms, and variable courses of fortune, she still enjoyed the possession of her jointure, which was assigned unto her out of the earldom of Bothwell, and kept the same until her death, yea, though that earldom had fallen twice into the king’s hands by forfeiture in her time.... By reason of her husband Earl Alexander his sickly disposition, together with her son’s minority at the time of his father’s death, she was in a manner forced to take upon her the managing of all the affairs of that house a good while, which she did perform with great care, to her own credit, and the weal of that family.... She was the first that caused work the coal heugh beside the river of Brora, and was the first instrument of making salt there. This coal [now interesting chiefly in a geological point of view, as connected with the oolitic formation] was found before by Earl John, father of Earl Alexander; but he, being taken away by an untimely death, had no time to enterprise this work. This lady built the house of Cracock, where she dwelt a long time.’—G. H. S.

This character, though drawn by the partial hand of a son, may be accepted as on the whole a true, as it is certainly a pleasing description, of the divorcée of Bothwell. The lady was buried in Dornoch Cathedral

A service to property depending at this time before the Court of Session between the Earl of Cassillis and the Earl of Wigton,31 these nobles appeared in Edinburgh, each with a multitude of followers, who paraded the streets in a tumultuous manner, and with such demonstrations of animosity as must have recalled the days of James VI. to many an anxious citizen. The Privy Council met in alarm, and appointed a committee to go and admonish the two litigant nobles about these unseemly appearances. It was enjoined that, while in town waiting on the service, they should not appear on the streets with more than twelve followers each, and that in peaceable manner, nor come to the bar with more than six, dismissing all others who had not known occasion to be present. At the same time, the noblemen who were the friends of the several parties were ‘to forbear the backing of them at this time,’ on pain of censure as ‘troublers of his majesty’s peace.’—P. C. R.

Throughout the whole time of the papist persecution, the Scottish authorities found it necessary to give a good deal of attention to matters of diablerie. Either witches and warlocks were particularly rife at that time, or the same enlightened spirit which assailed the papists was particularly keen-sighted and zealous in finding out offenders connected with the other world.

On the 30th of October 1628, the Earl of Monteath, Lord Justice-general of the kingdom, reported to the Privy Council the case of Janet Boyd, spouse to Robert Neill, burgess of Dumbarton, who had freely confessed that she had entered in covenant with the devil, had received his mark, had renounced her baptism, and been much too intimate with the above grisly personage, through whose power she had laid diseases upon sundry persons. The Council approved of a commission for trying Janet and for ‘the punishing of so foul and detestable a crime.’—P. C. R.

In the course of 1629, Isobel Young, spouse to George Smith, portioner in East Barns in Haddingtonshire, was burnt for witchcraft. She had been accused of both inflicting and curing diseases; and it appears that she and her husband had sent to the Laird of Lee to borrow his curing-stone for their cattle, which had the ‘routing ill.’ This is interesting as an early reference to the well-known Lee Penny, which is yet preserved in the family of Lockhart of Lee, being an ancient precious stone or amulet, set in a silver penny. It is related that Lady Lee declined to lend the stone, but gave flagons of water in which the penny had been steeped. This water, being drunk by the cattle, was believed to have effected their cure.

32

One Alexander Hamilton was apprehended as a notorious warlock, and put into the Tolbooth of Edinburgh—where he would have for a companion in captivity the Lady Abercorn, whose offence was not less metaphysical than his own. He ‘delated’ four women of the burgh of Haddington, and five other women of its neighbourhood, as guilty of witchcraft. The Privy Council sent orders (November 1629) to have the whole Circean nine apprehended; and as their poverty made it inconvenient to bring them to Edinburgh, the presbytery of Haddington was enjoined to examine them in their own district. What was done with them ultimately, we are not informed. Another woman, named Katherine Oswald, residing at Niddry near Edinburgh, was likewise accused by Hamilton, and taken into custody. This seems to have been considered an unusually important case, as four lawyers were appointed to act as assessors to the justices on her trial.—P. C. R. It was alleged of Katherine that she had that partial insensibility which was understood to be an undoubted proof of the witch quality. Two witnesses stated that they ‘saw ane preen put in to the heid, by Mr John Aird, minister, in the panel’s shoulder, being the devil’s mark, and nae bluid following, nor she naeways shrinking thereat.’19

Hamilton alleged that he had been with Katherine at a meeting of witches between Niddry and Edmondstone, where they met with the devil. It was also stated that she had been one of a witch-party who had met at Prestonpans, and used charms, on the night of the great storm at the end of March 1625. But the chief articles of her dittay bore reference to cures which she had wrought by sorcery. Katherine was convicted and burned.—B. A.

In November, the Privy Council issued a commission to the Bishop of Dumblane for the examination of John Hog and Margaret Nicolson his spouse, ‘upon their guiltiness of the crime of witchcraft, with power to confront them with others who best can give evidence.’ This pair were soon after brought to the Edinburgh prison, whence, however, they were speedily released on caution for reappearance. The Lords, on the same day, issued a charge against ‘Margaret Maxwell spouse to Nicol Thomson, and Jean Thomson her daughter, spouse to umwhile Edward Hamilton, in Dumfries,’ who, it was said, had procured the death of the said Edward ‘by the devilish and detestable practice of witchcraft.’ Claud Hamilton of Mauchline-hole, brother of the deceased33 Edward, soon after (December 22, 1629) presented a petition to the Privy Council, claiming that they should order an examination of Geillie Duncan of Dumfries, now in hands there on suspicion of a concern in the fact. The Council accordingly commissioned the magistrates and ministers of Dumfries to effect this examination.