The Pacific at Last!

Title: By motor to the Golden Gate

Author: Emily Post

Release date: June 6, 2024 [eBook #73784]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: D. Appleton

Credits: Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The Pacific at Last!

BY MOTOR

to the

GOLDEN GATE

BY

EMILY POST

ILLUSTRATED WITH

PHOTOGRAPHS and ROAD MAPS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

1916

Copyright, 1916, by

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

Copyright, 1915, by P. F. Collier & Son, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

“Qui s’excuse s’accuse.” Which, I suppose, proves this a defence to start with! But having been a few times accused, there are a few explanations I want very much to make.

When this cross-continent story was first suggested, it seemed the simplest sort of thing to undertake. All that was necessary was to put down experiences as they actually occurred. No imagination, or plot or characterization—could anything be easier? But when the serial was published and letters began coming in, it became unhappily evident that writing fact must be one of the most unattainably difficult accomplishments in the world.

In the first place, only those who, having lived long in a particular locality and knowing it in all its varying seasons, are qualified truly to present its picture. The observations of a transient tourist are necessarily superficial, as of one whose experiences are merely a series of instantaneous impressions; at one time colored perhaps too vividly, at another fogged; according to the sun or rain at one brief moment of time.

It would be very pleasant to write nothing but eulogies of people and places, but after all if a personal narrative were written like an advertisement, praising everything, there would be no point in praising anything, would there?

Compared with crossing the plains in the fifties, the[x] worst stretch of our most uninhabited country is today the easiest road imaginable. There are no longer any dangers, any insurmountable difficulties. To the rugged sons of the original pioneers, comments upon “poor roads”—that are perfectly defined and traveled-over highways—or “poor hotels”—where you can get not only a room to yourself, but steam heat, electric light, and generally a private bath—must seem an irritatingly squeamish attitude. “Poor soft weaklings” is probably not far from what they think of people with such a point of view.

On the other hand if I, who after all am a New Yorker, were to pronounce the Jackson House perfect, the City of Minesburg beautiful, the Trailing Highway splendid, everyone would naturally suppose the Jackson House a Ritz, Minesburg an upper Fifth Avenue, and the Trailing Highway a duplicate of our own state roads, to say the least!

I am more than sorry if I offend anyone—it is the last thing I mean to do—at the same time I think it best to let the story stand as it was written; taking nothing back that seems to me true, but acknowledging very humbly at the outset, that after all mine is only one out of a possible fifty million other American opinions.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | It Can’t Be Done—But Then, It Is Perfectly Simple | 1 |

| II. | Albany, First Stop | 15 |

| III. | A Breakdown | 18 |

| IV. | Pennsylvania, Ohio and Indiana | 23 |

| V. | Luggage and Other Luxuries | 37 |

| VI. | Did Anybody Say “Chicken”? | 41 |

| VII. | The City of Ambition | 46 |

| VIII. | A Few Chicagoans | 52 |

| IX. | Tins | 60 |

| X. | Mud!! | 67 |

| XI. | In Rochelle | 72 |

| XII. | The Weight of Public Opinion | 75 |

| XIII. | Muddier! | 79 |

| XIV. | One of the Fogged Impressions | 86 |

| XV. | A Few Ways of the West | 90 |

| XVI. | Halfway House | 99 |

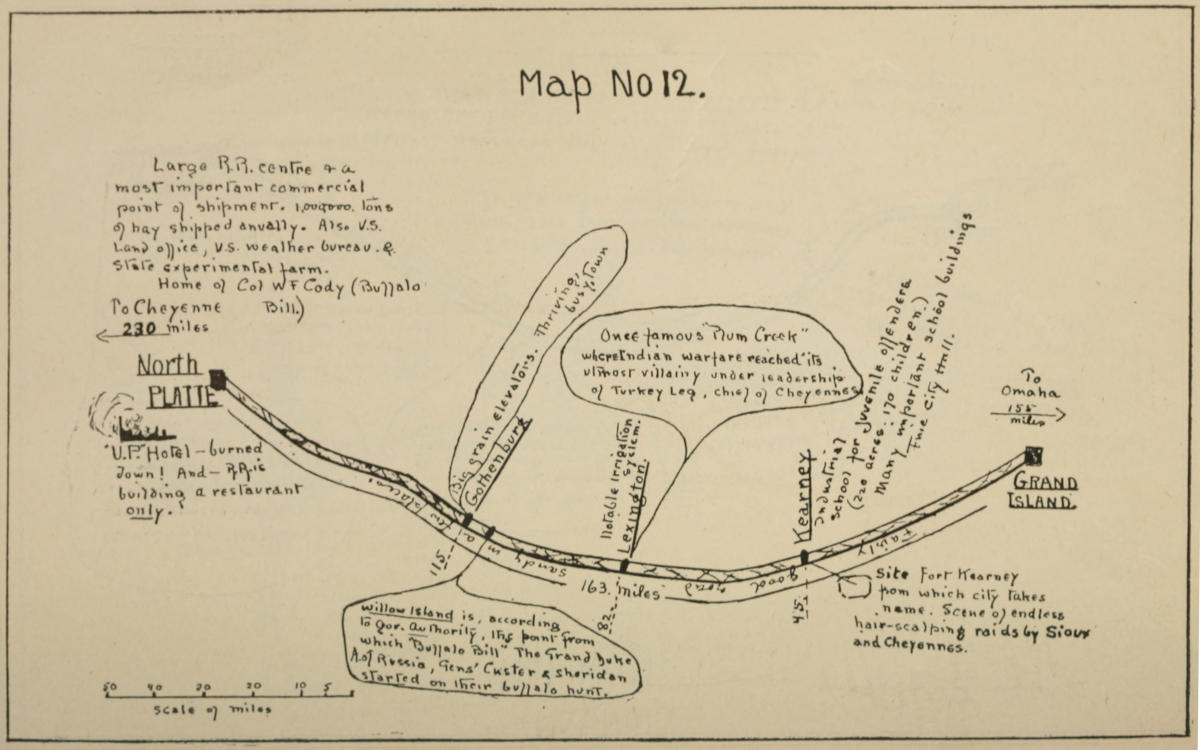

| XVII. | Next Stop, North Platte! | 107 |

| XVIII. | The City of Recklessness | 119 |

| XIX. | A Glimpse of the West That Was | 135 |

| XX. | Our Little Sister of Yesterday | 150 |

| XXI. | Ignorance With a Capital I | 155 |

| XXII. | Some Indians and Mr. X | 159 |

| XXIII. | With Nowhere to Go But Out | 172 |

| XXIV. | Into the Desert | 175 [xii] |

| XXV. | Through the City Unpronounceable to an Exposition Beautiful | 187 |

| XXVI. | The Land of Gladness | 198 |

| XXVII. | The Mettle of a Hero | 205 |

| XXVIII. | San Francisco | 211 |

| XXIX. | The Fair | 229 |

| XXX. | “Unending Sameness” Was What They Said | 237 |

| XXXI. | To Those Who Think of Following in Our Tire Tracks—To the Man Who Drives | 241 |

| XXXII. | On the Subject of Clothes—Food Equipment—Expenses—Daily Expense Account | 251 |

| XXXIII. | How Far Can You Go in Comfort?—Some Day | 278 |

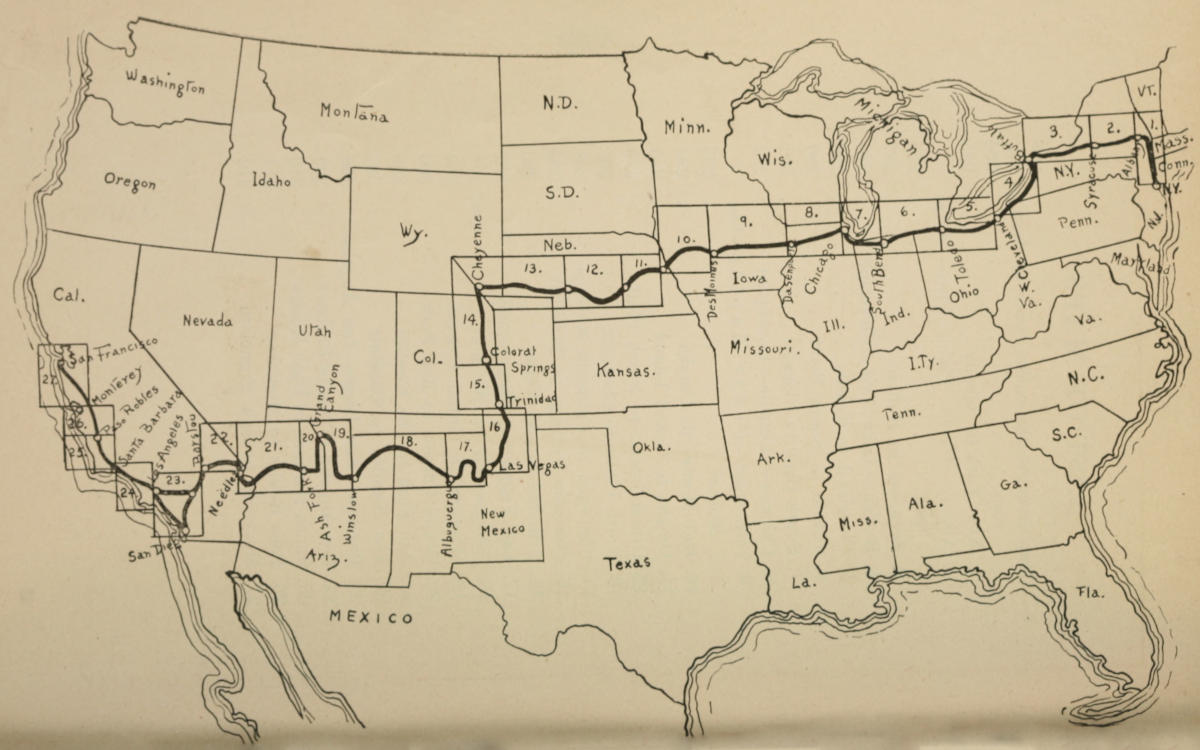

| The Pacific at last! | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

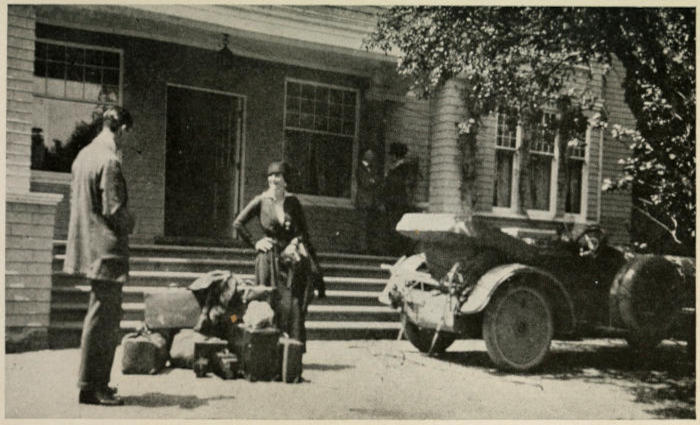

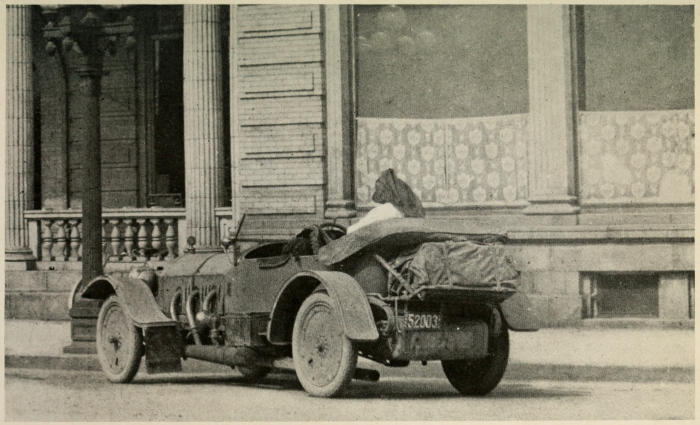

| What we finally carried | 8 |

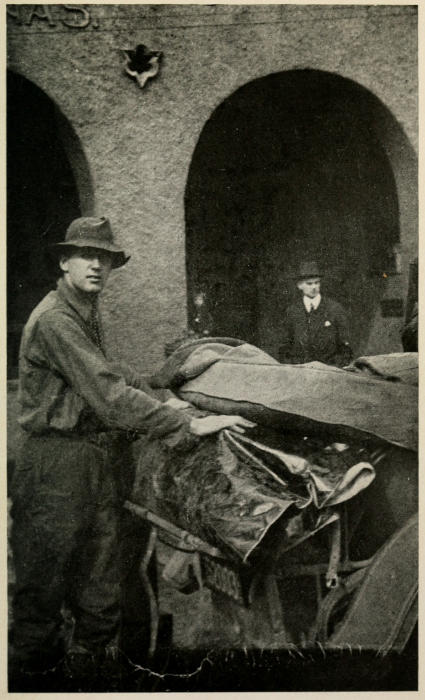

| Stowing the luggage | 12 |

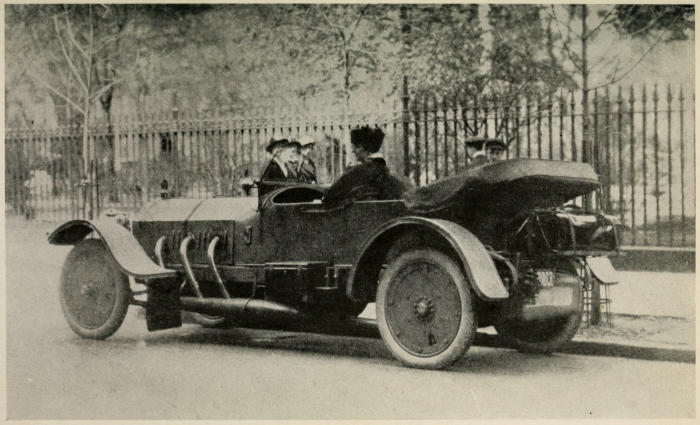

| Leaving Gramercy Park, New York | 16 |

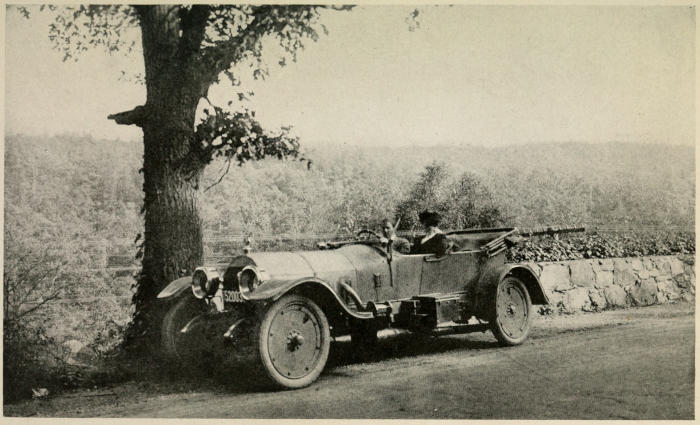

| Still in New York State | 20 |

| The crowd in less than a minute. “Out of the window” in Cleveland | 34 |

| One of the exciting things in motoring is wondering what sort of a hotel you will arrive at for the night | 44 |

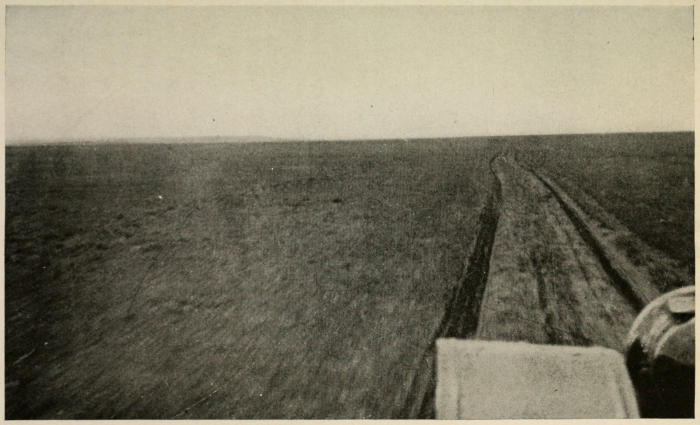

| Hours and hours, across land as flat and endless as the ocean | 84 |

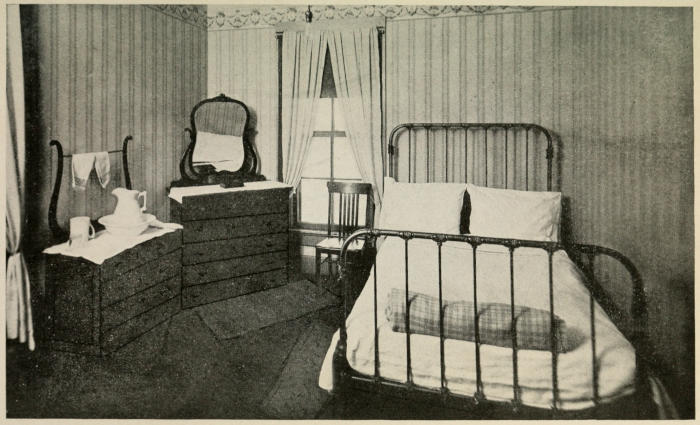

| A bedroom in the Union Pacific Hotel, North Platte—not much of a hardship, is it? | 108 |

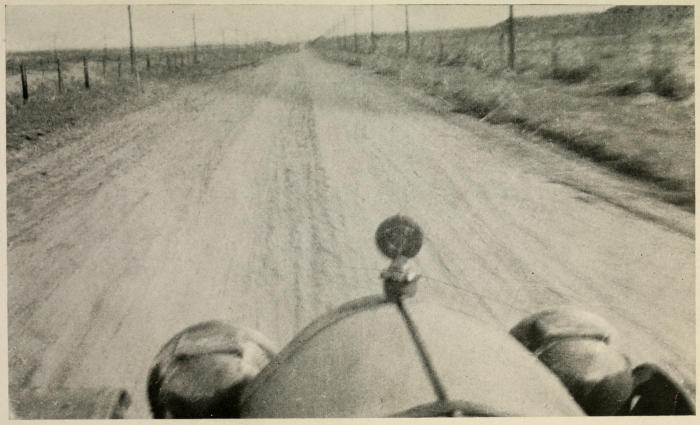

| A straight, wide road; not even a shack in sight—and a speed limit of twenty miles an hour | 112 |

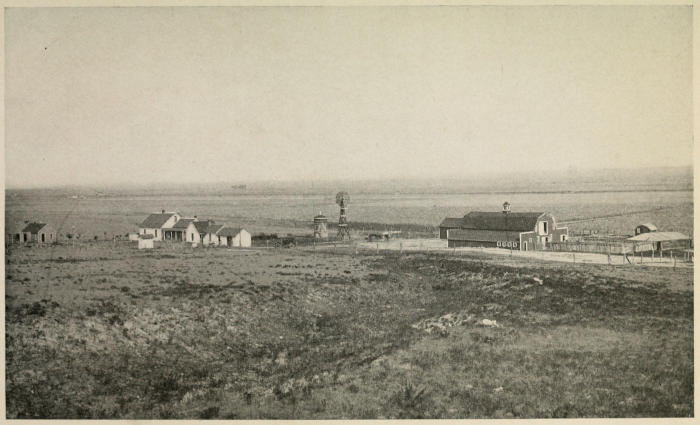

| Wyoming in the ranch country | 116 |

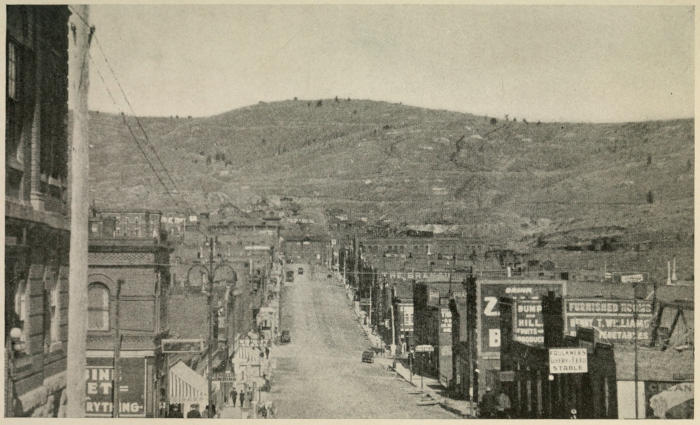

| Cripple Creek | 120 |

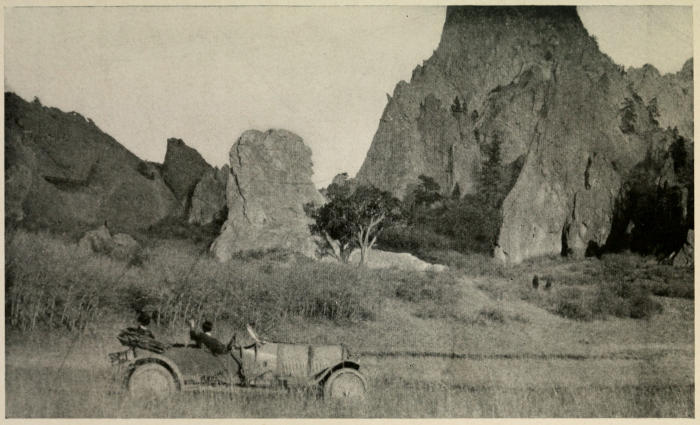

| In the Garden of the Gods | 124 |

| Colorado. Pike’s Peak in the distance | 128 |

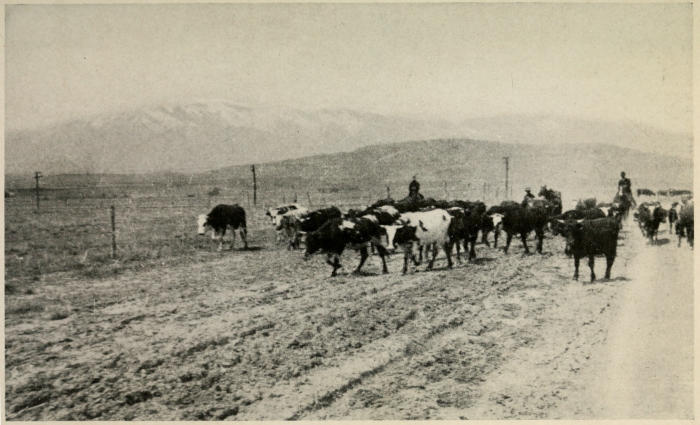

| First cowboys and cattle | 132 |

| Halfway across a thrilling ford, wide and deep, on the Huerfano River | 136 |

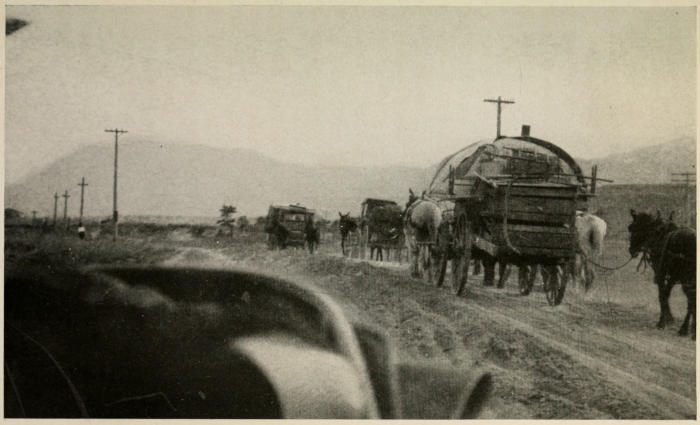

| A glimpse of the West of yesterday | 140 |

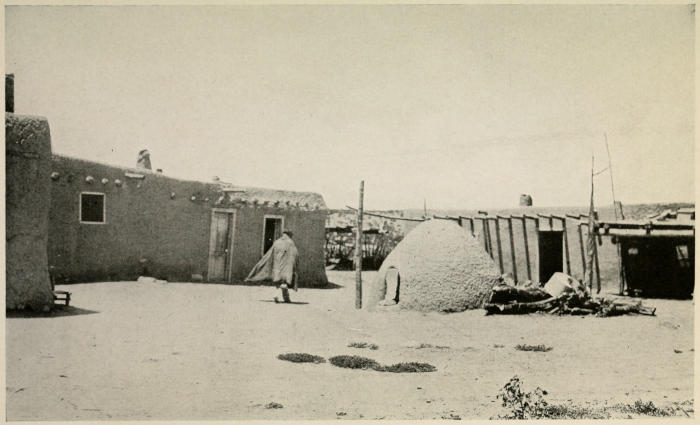

| Your route leads through many Mexican and Indian villages | 148 |

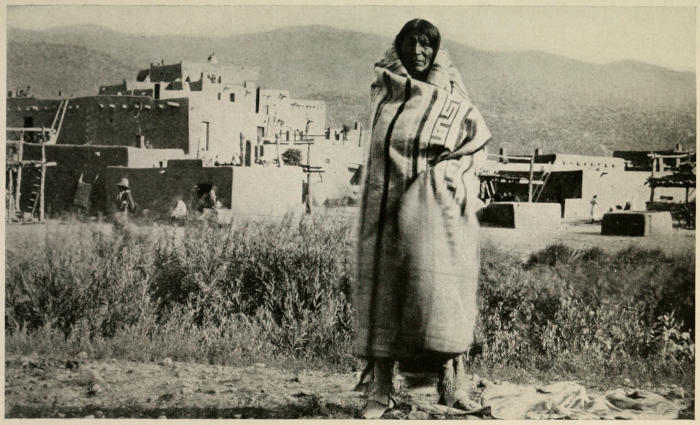

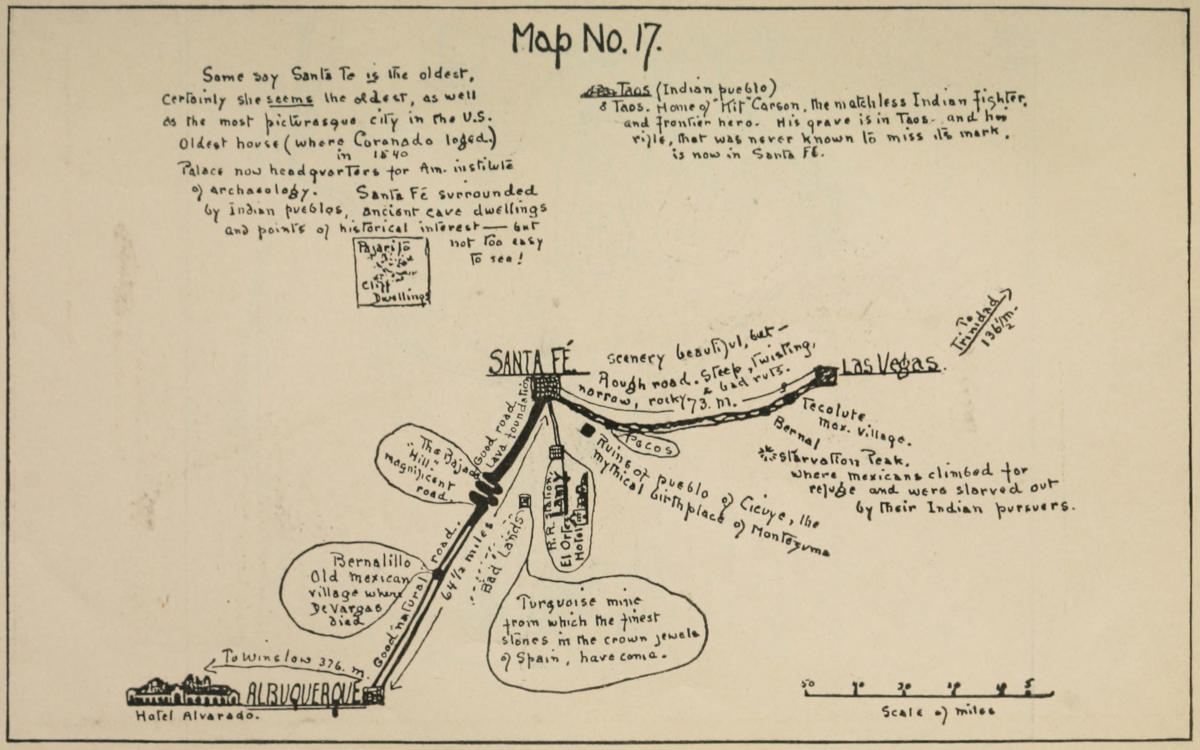

| The Indian pueblo of Taos | 160 [xiv] |

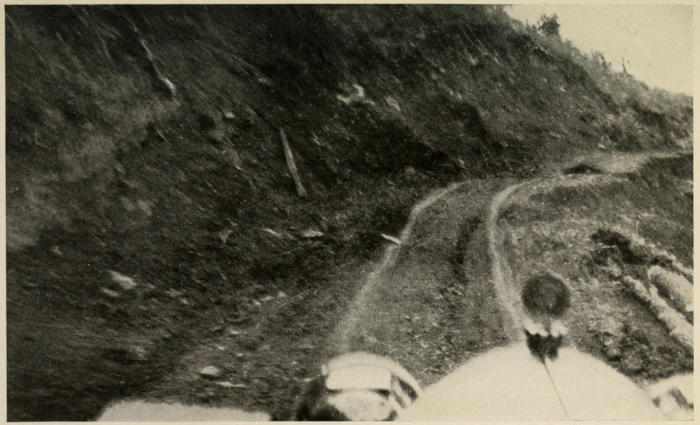

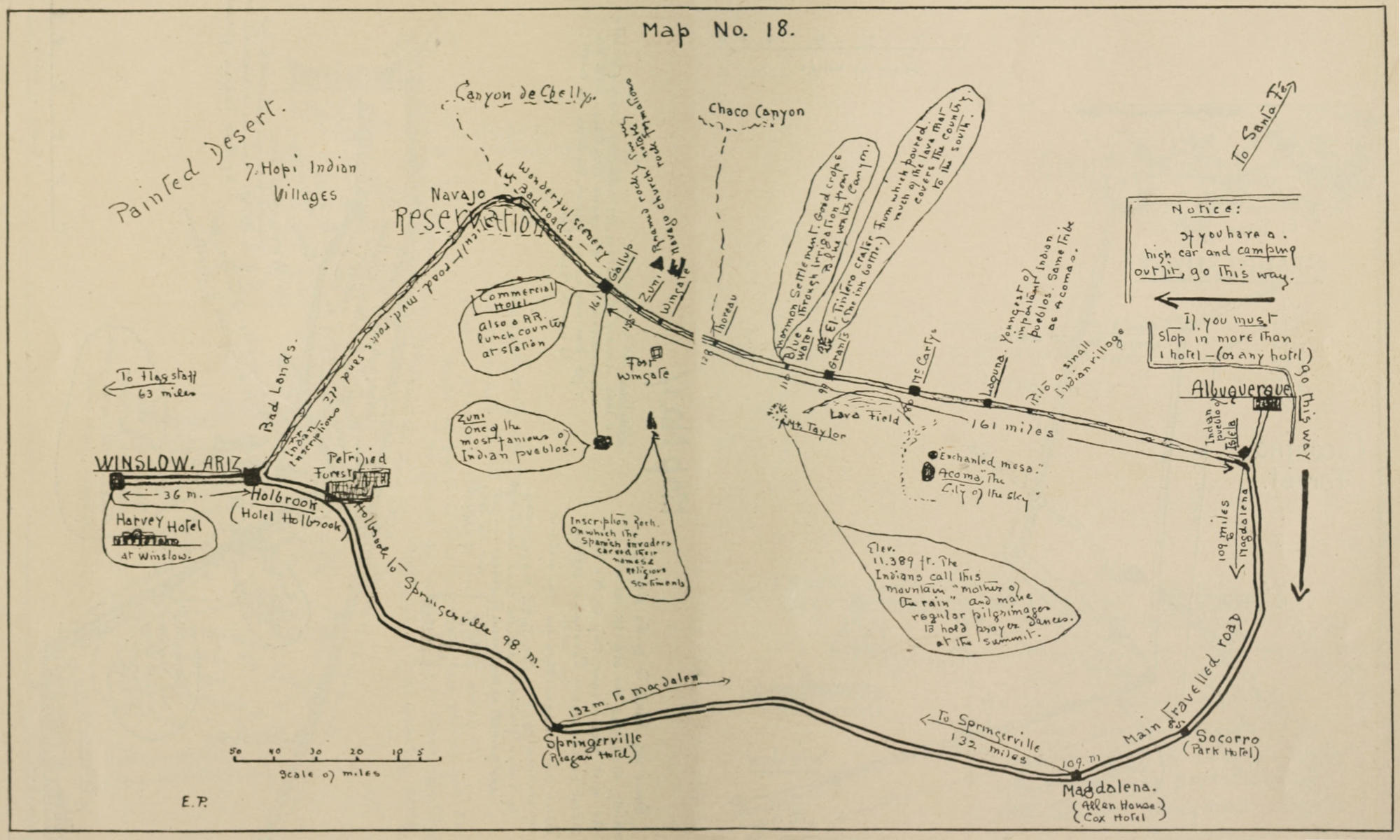

| To see the sleeping beauty of the Southwest, the path is by no means a smooth one to the motorist | 170 |

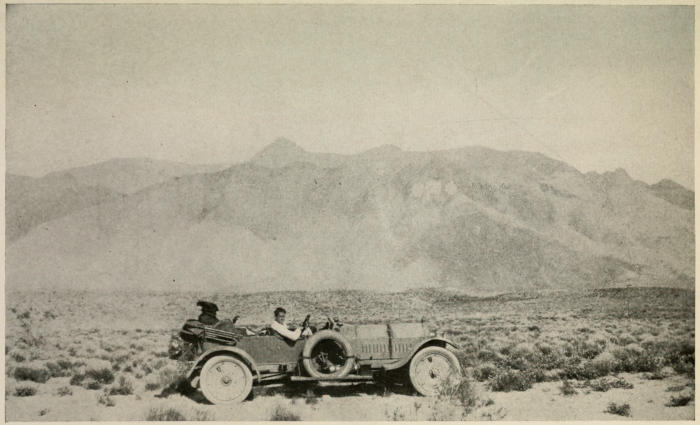

| Across the real desert | 180 |

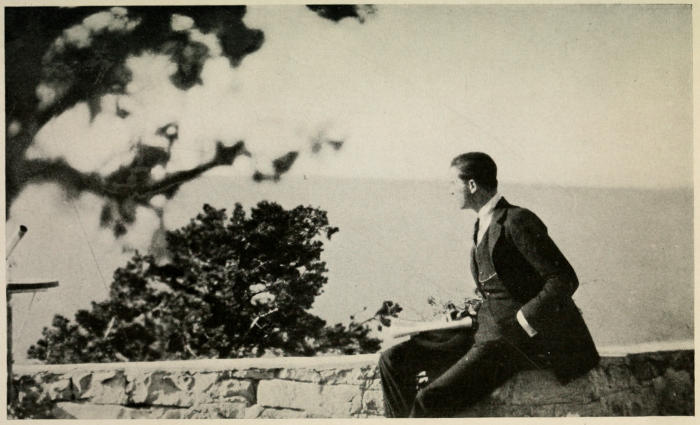

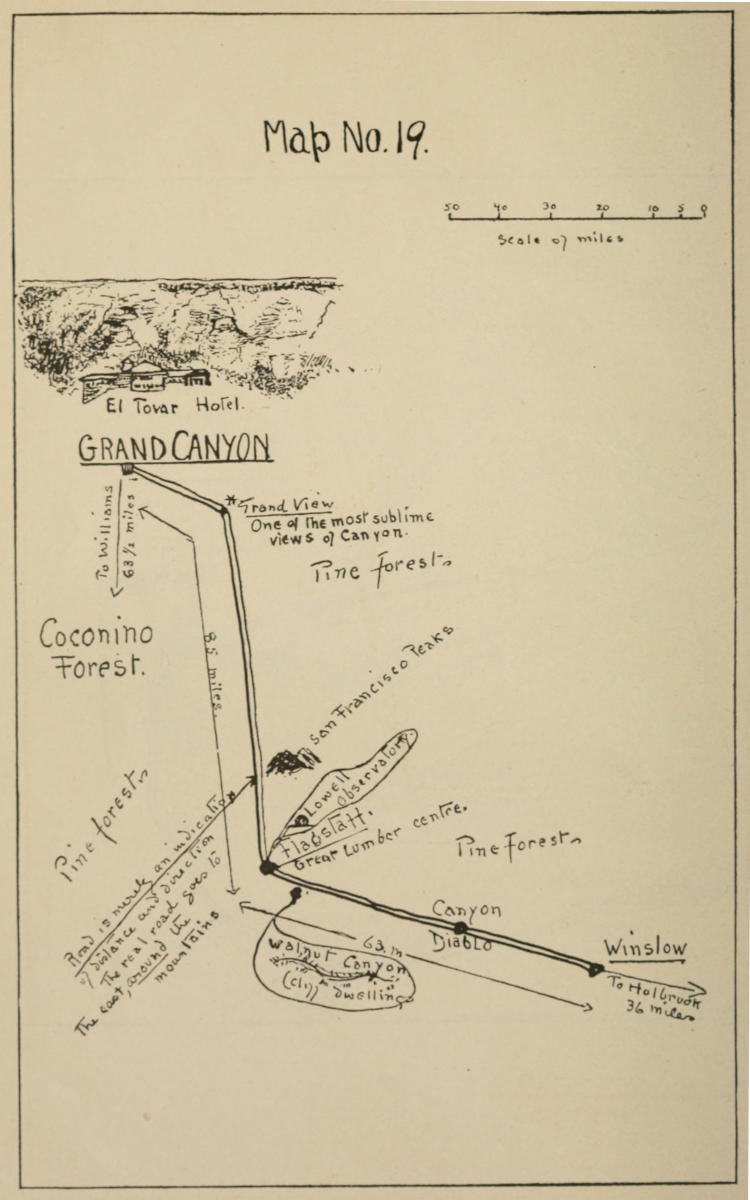

| Our chauffeur takes a day off at the Grand Canyon of the Colorado | 184 |

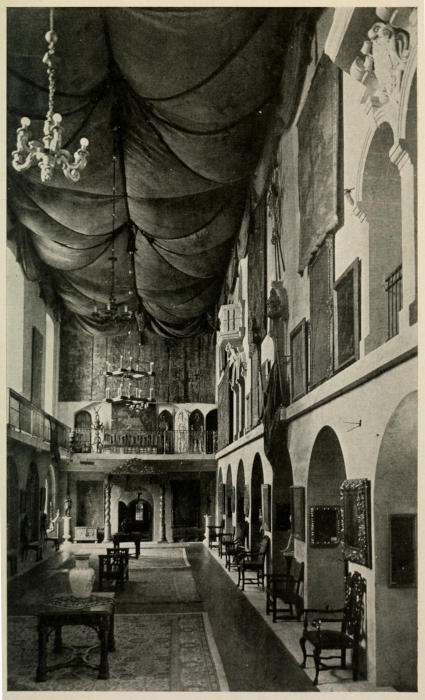

| This is not a gallery in a Spanish palace, but a gallery in the Mission Inn at Riverside, California | 188 |

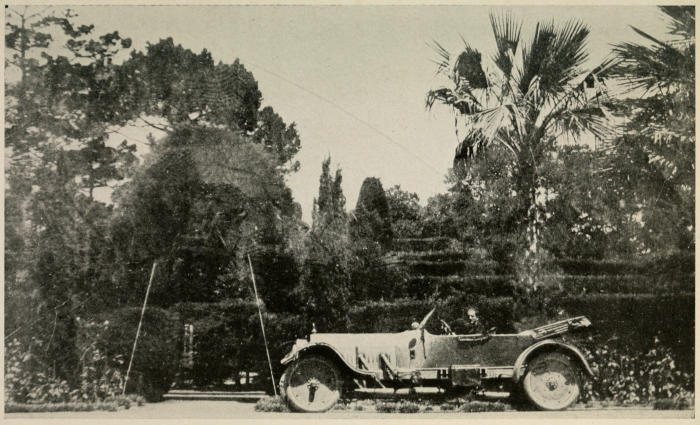

| In a California garden | 192 |

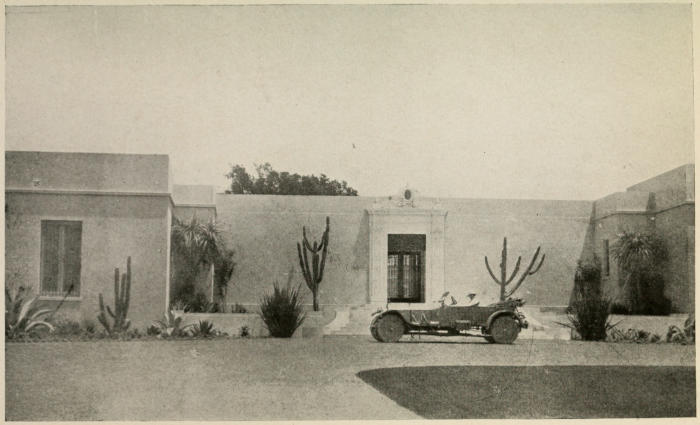

| Under Santa Barbara skies | 196 |

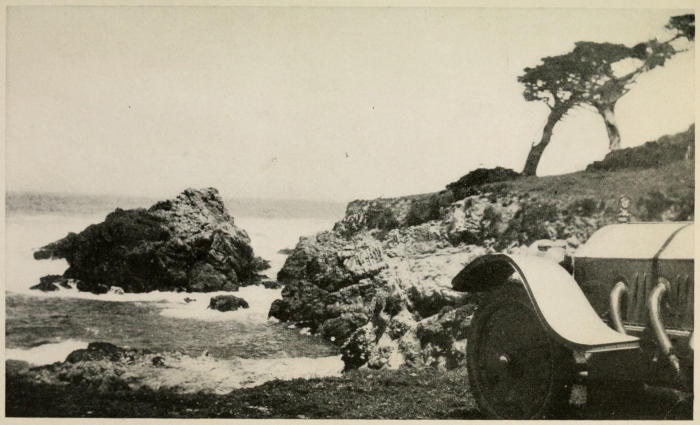

| Ostrich Rock, Monterey, California | 200 |

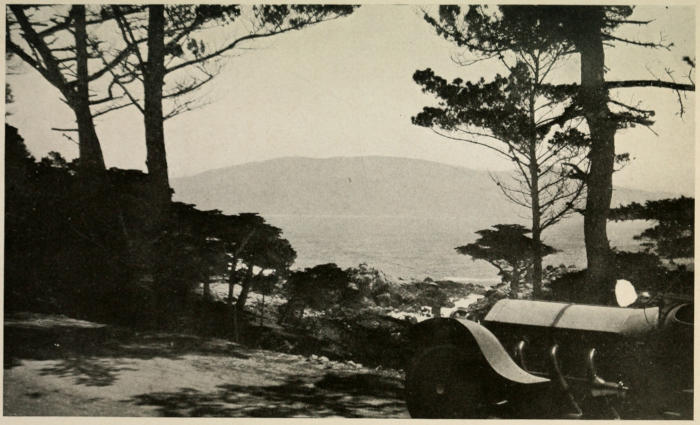

| On the seventeen-mile drive at Monterey | 208 |

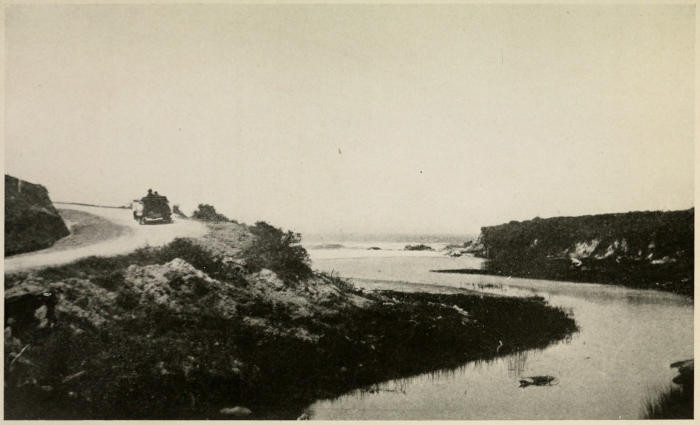

| On a beautiful ocean road of California | 216 |

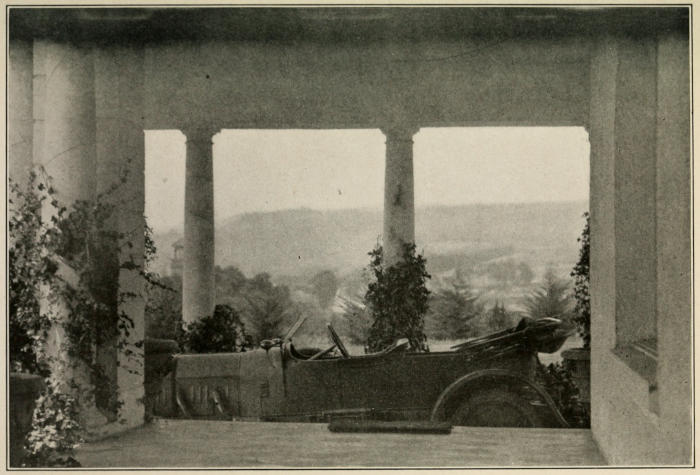

| The portico of a California house | 226 |

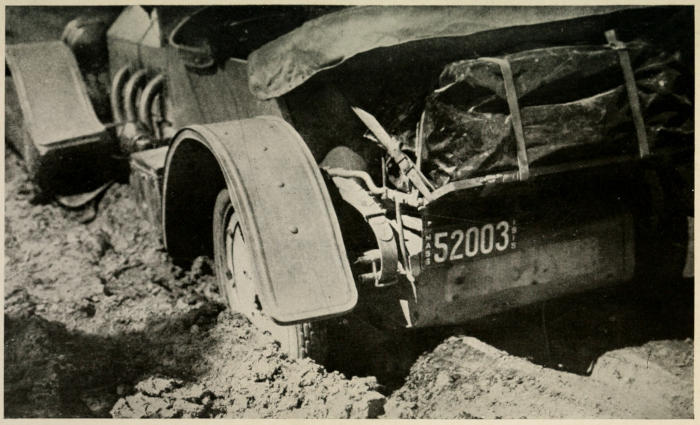

| Sometimes we struck a bad road | 244 |

| In order to cross here, E. M. built a bridge with the logs at the right | 248 |

| On the famous “staked plains” of the Southwest | 254 |

“Of course you are sending your servants ahead by train with your luggage and all that sort of thing,” said an Englishman.

A New York banker answered for me: “Not at all! The best thing is to put them in another machine directly behind, with a good mechanic. Then if you break down the man in the rear and your own chauffeur can get you to rights in no time. How about your chauffeur? You are sure he is a good one?”

“We are not taking one, nor servants, nor mechanic, either.”

“Surely you and your son are not thinking of going alone! Probably he could drive, but who is going to take care of the car?”

“Why, he is!”

At that everyone interrupted at once. One thought we were insane to attempt such a trip; another that it was a “corking” thing to do. The majority looked upon our undertaking with typical New York apathy. “Why do anything so dreary?” If we wanted to see the expositions, then let us take the fastest train, with plenty of[2] books so as to read through as much of the way as possible. Only one, Mr. B., was enthusiastic enough to wish he was going with us. Evidently, though, he thought it a daring adventure, for he suggested an equipment for us that sounded like a relief expedition: a block and tackle, a revolver, a pickaxe and shovel, tinned food—he forgot nothing but the pemmican! However, someone else thought of hardtack, after which a chorus of voices proposed that we stay quietly at home!

“They’ll never get there!” said the banker, with a successful man’s finality of tone. “Unless I am mistaken, they’ll be on a Pullman inside of ten days!”

“Oh, you wouldn’t do that, would you?” exclaimed our one enthusiastic friend, B.

I hoped not, but I was not sure; for, although I had promised an editor to write the story of our experience, if we had any, we were going solely for pleasure, which to us meant a certain degree of comfort, and not to advertise the endurance of a special make of car or tires. Nor had we any intention of trying to prove that motoring in America was delightful if we should find it was not. As for breaking speed records—that was the last thing we wanted to attempt!

“Whatever put it into your head to undertake such a trip?” someone asked in the first pause.

“The advertisements!” I answered promptly.[3] They were all so optimistic, that they went to my head. “New York to San Francisco in an X— car for thirty-eight dollars!” We were not going in an X— car, but the thought of any machine’s running such a distance at such a price immediately lowered the expenditure allowance for our own. “Cheapest way to go to the coast!” agreed another folder. “Travel luxuriously in your own car from your own front door over the world’s greatest highway to the Pacific Shore.” Could any motor enthusiasts resist such suggestions? We couldn’t.

We had driven across Europe again and again. In fact I had in 1898 gone from the Baltic to the Adriatic in one of the few first motor-cars ever sold to a private individual. We knew European scenery, roads, stopping-places, by heart. We had been to all the resorts that were famous, and a few that were infamous, but our own land, except for the few chapter headings that might be read from the windows of a Pullman train, was an unopened book—one that we also found difficulty in opening. The idea of going occurred to us on Tuesday and on Saturday we were to start, yet we had no information on the most important question of all—which route was the best to take. And we had no idea how to find out!

The 1914 Blue Book was out of print, and the new one for this year not issued. I went to various information bureaus—some of those whose[4] advertisements had sounded so encouraging—but their personal answers were more optimistic than definite. Then a friend telegraphed for me to the Lincoln Highway Commission asking if road conditions and hotel accommodations were such that a lady who did not want in any sense to “rough it” could motor from New York to California comfortably.

We wasted a whole precious thirty-six hours waiting for this answer. When it came, a slim typewritten enclosure helpfully informed us that a Mrs. Somebody of Brooklyn had gone over the route fourteen months previously and had written them many glowing letters about it. As even the most optimistic prospectus admitted that in 1914 the road was as yet not a road, and hotels along the sparsely settled districts had not been built, it was evident that Mrs. Somebody’s idea of a perfect motor trip was independent of roads or stopping-places.

Meanwhile I had been told that the best information was to be had at the touring department of the Automobile Club. So I went there.

A very polite young man was answering questions with a facility altogether fascinating. He told one man about shipping his car—even the hours at which the freight trains departed. To a second he gave advice about a suit for damages; for a third he reduced New York’s traffic complications to simplicities in less than a minute; then it was my turn:

“I would like to know the best route to San Francisco.”

“Certainly,” he said. “Will you take a seat over here for a moment?”

“This is the simplest thing in the world,” I thought, and opened my notebook to write down a list of towns and hotels and road directions. He returned with a stack of folders. But as I eagerly scanned them, I found they were all familiarly Eastern.

“Unfortunately,” he said suavely, “we have not all our information yet, and we seem to be out of our Western maps! But I can recommend some very delightful tours through New England and the Berkshires.”

“That is very interesting, but I am going to San Francisco.”

His attention was fixed upon a map of the “Ideal Tour.” “The New England roads are very much better,” he said.

“But, you see, San Francisco is where I am going. Do you know which route is, if you prefer it, the least bad?”

“Oh, I see.” He looked sorry. “Of course if you must cross the continent, there is the Lincoln Highway!”

“Can you tell me how much work has been done on it—how much of it is finished? Might it not be better on account of the early season to take a Southern route? Isn’t there a road called the Santa Fé trail?”

“Why, yes, certainly,” said the nice young man. “The road goes through Kansas, New Mexico and Arizona. It would be warmer assuredly.”

“How about the Arizona desert? Can we get across that?”

“That is the question!”

“Perhaps we had better just start out and ask the people living along the road which is the best way farther on?”

The young man brightened at once. “That would have been my suggestion from the beginning.”

Once outside, however, the feasibility of asking our road as we came to it did not seem very practical, so I went to Brentano’s to buy some maps. They showed me a large one of the United States with four routes crossing it, equally black and straight and inviting. I promptly decided upon the one through the Allegheny Mountains to Pittsburgh and St. Louis when two women I knew came in, one of them Mrs. O., a conspicuous hostess in the New York social world, and a Californian by birth. “The very person I need,” I thought. “She knows the country thoroughly and her idea of comfort and mine would be the same.”

“Can you tell me,” I asked her, “which is the best road to California?”

Without hesitating she answered: “The Union Pacific.”

“No, I mean motor road.”

Compared with her expression the worst skeptics I had encountered were enthusiasts. “Motor road to California!” She looked at me pityingly. “There isn’t any.”

“Nonsense! There are four beautiful ones and if you read the accounts of those who have crossed them you will find it impossible to make a choice of the beauties and comforts of each.”

She looked steadily into my face as though to force calmness to my poor deluded mind. “You!” she said. “A woman like you to undertake such a trip! Why, you couldn’t live through it! I have crossed the continent one hundred and sixty odd times. I know every stick and stone of the way. You don’t know what you are undertaking.”

“It can’t be difficult; the Lincoln Highway goes straight across.”

“In an imaginary line like the equator!” She pointed at the map that was opened on the counter. “Once you get beyond the Mississippi the roads are trails of mud and sand. This district along here by the Platte River is wild and dangerous; full of the most terrible people, outlaws and ‘bad men’ who would think nothing of killing you if they were drunk and felt like it. There isn’t any hotel. Tell me, where do you think you are going to stop? These are not towns; they are only names on a map, or at best two shacks and a saloon! This place North Platte why, you couldn’t stay in a place like that!”

I began to feel uncertain and let down, but I said, “Hundreds of people have motored across.”

“Hundreds and thousands of people have done things that it would kill you to do. I have seen immigrants eating hunks of fat pork and raw onions. Could you? Of course people have gone across, men with all sorts of tackle to push their machines over the high places and pull them out of the deep places; men who themselves can sleep on the roadside or on a barroom floor. You may think ‘roughing it’ has an attractive sound, because you have never in your life had the slightest experience of what it can be. I was born and brought up out there and I know.” She quietly but firmly folded the map and handed it to the clerk. “I am sorry,” she said, “if you really wanted to go! By and by maybe if they ever build macadam roads and put up good hotels—but even then it would be deadly dull.”

For about five minutes I thought I had better give it up, and I called up my editor. “It looks as though we could not get much farther than the Mississippi.”

“All right,” he said, cheerfully, “go as far as the Mississippi. After all, your object is merely to find out how far you can go pleasurably! When you find it too uncomfortable, come home!”

What We Finally Carried

No sooner had he said that than my path seemed to stretch straight and unencumbered to the Pacific Coast. If we could get no further information, we would start for Philadelphia, Pittsburgh[9] and St. Louis, as we had many friends in these cities, and get new directions from there, but as a last resort I went to the office of a celebrated touring authority and found him at his desk.

“I would like to know whether it will be possible for me to go from here to San Francisco by motor?”

“Sure, it’s possible! Why isn’t it?”

“I have been told the roads are dreadful and the accommodations worse.”

He surveyed me from head to foot with about the same expression that he might have been expected to use if I had asked whether one could safely travel to Brooklyn.

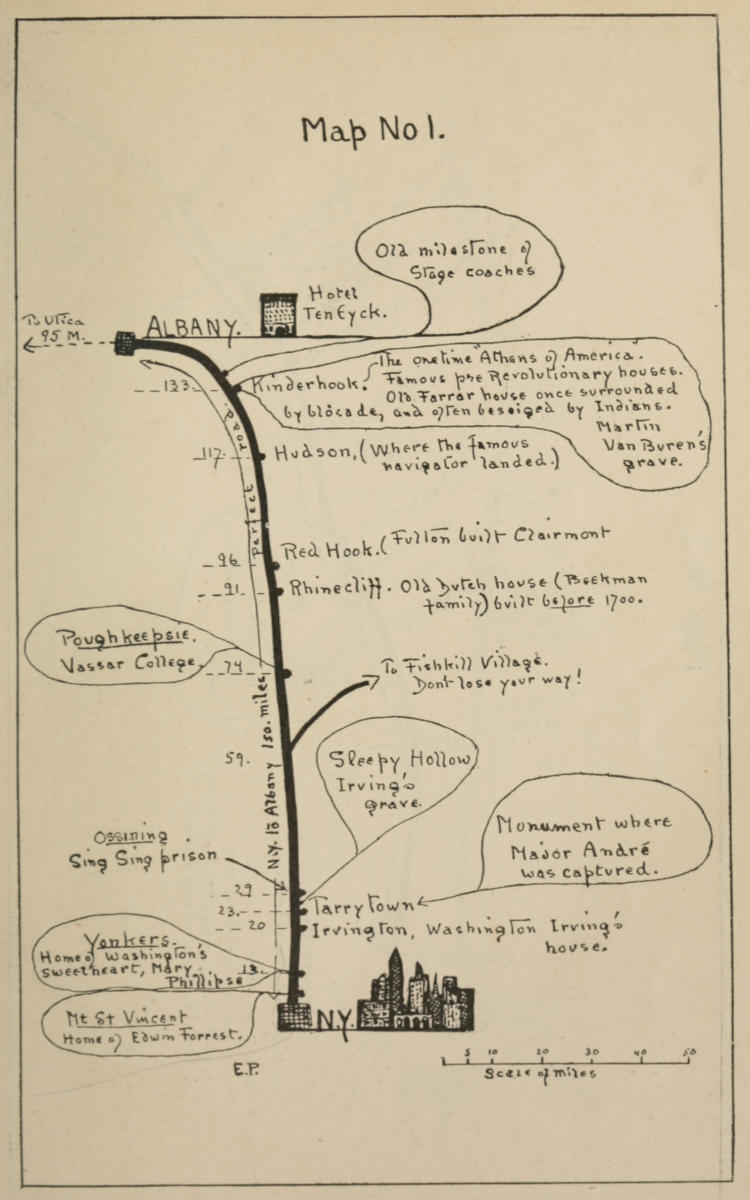

“You won’t find Ritz hotels every few miles, and you won’t find Central Park roads all of the way. If you can put up with less than that, you can go—easy!” Whereupon he reached up over his head without even looking, took down a map, spread it on the table before him, and unhesitatingly raced his blue pencil up the edge of the Hudson River, exactly as the pencil of Tad draws cartoons at the movies.

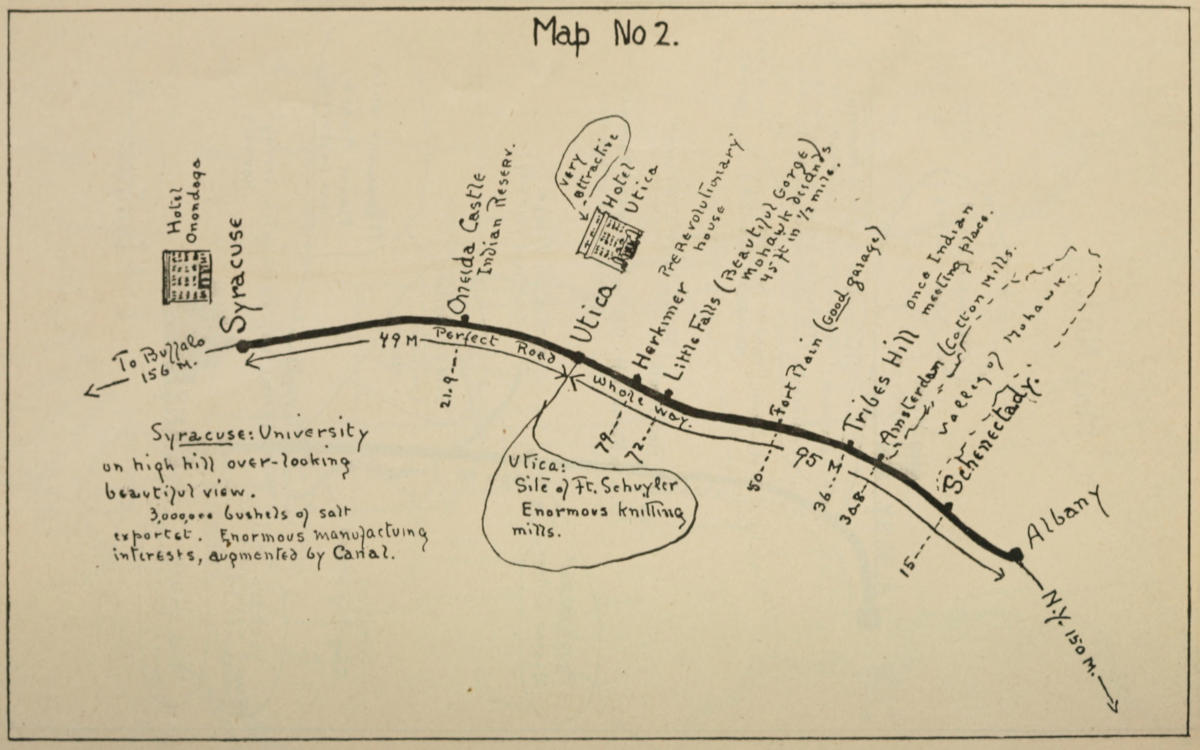

“You go here—Albany, Utica, Syracuse.”

“No, please!” I said. “I want to go by way of Pittsburgh and St. Louis.”

“You asked for the best route to San Francisco!” He looked rather annoyed.

“Yes, but I want to go by way of St. Louis.”

“Why do you want to go to St. Louis?”

“Because we have friends there.”

“Well, then, you had better take the train and go and see them!” Indifferently he took down another map and made a few casual blue marks on the mountains of Pennsylvania. “They’re rebuilding roads that will be fine later in the season, but at the moment [April, 1915] all of these places are detours. You’ll get bad grades and mud over your hubs! Of course, if you’re set on going that way, if you want to burn any amount of gasoline, cut your tires to pieces, and strain your engine—go along to St. Louis. It’s all the same to me; I don’t own the roads! But you said you wanted to take a motor trip.”

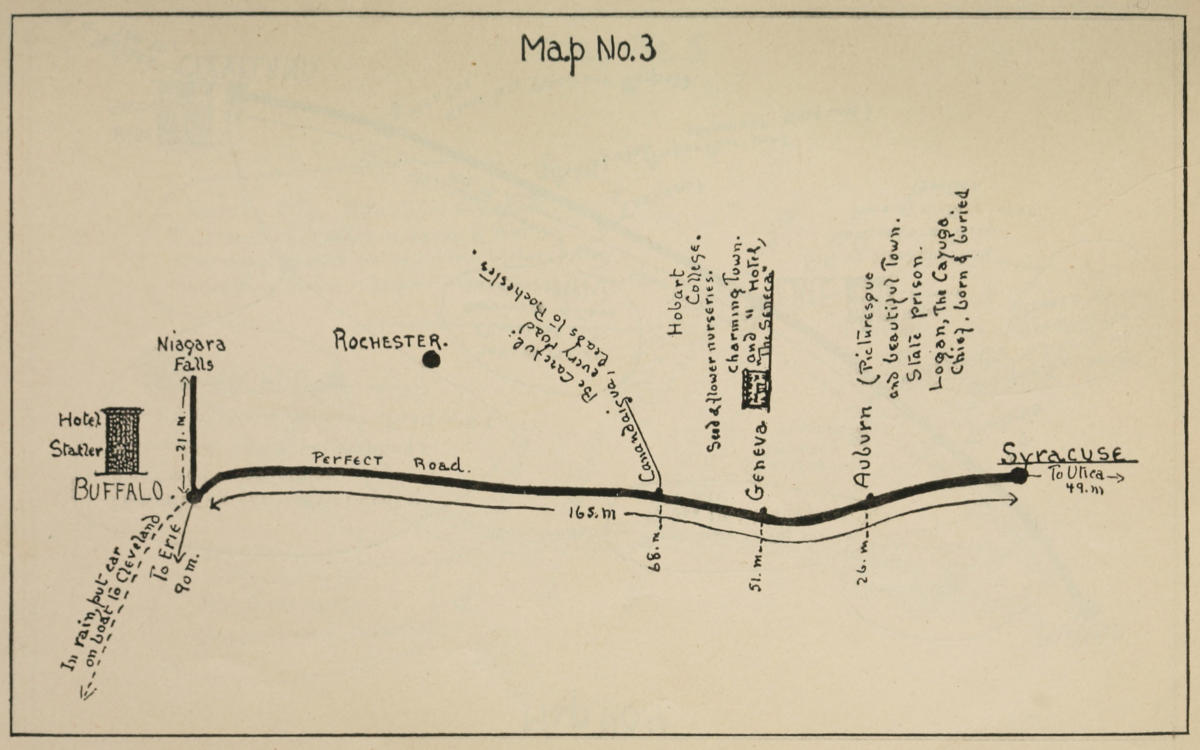

“Then Chicago is much the best way?”

“It is the only way!”

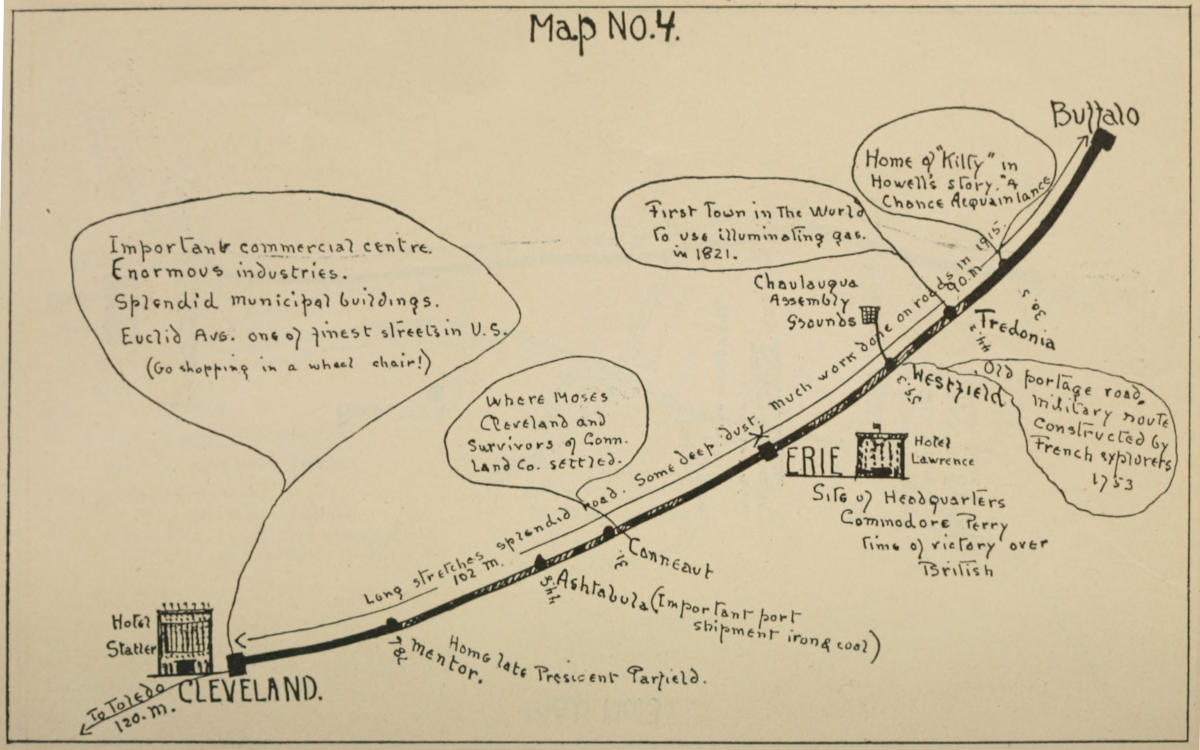

He did not wait for my agreement, but throwing aside the second map and turning again to the first, his pencil swooped down upon Buffalo and raced to Cleveland as though it fitted in a groove. He seemed to be in a mental aeroplane looking actually down upon the roads below.

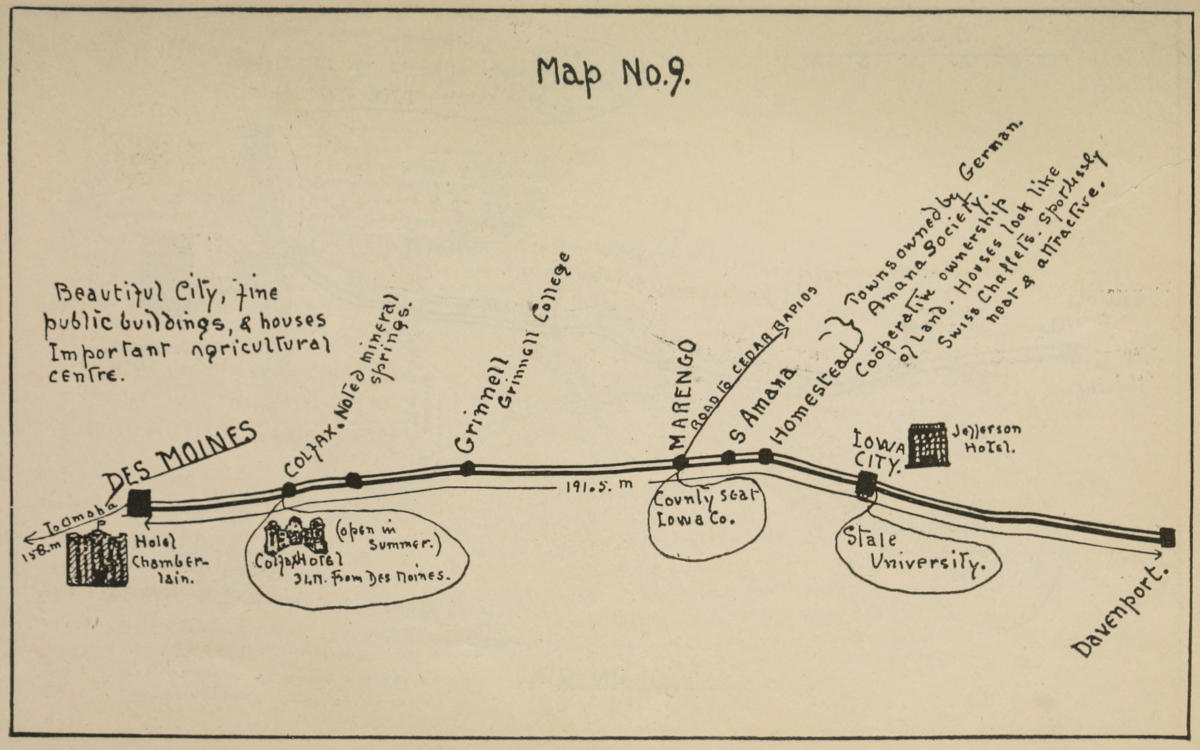

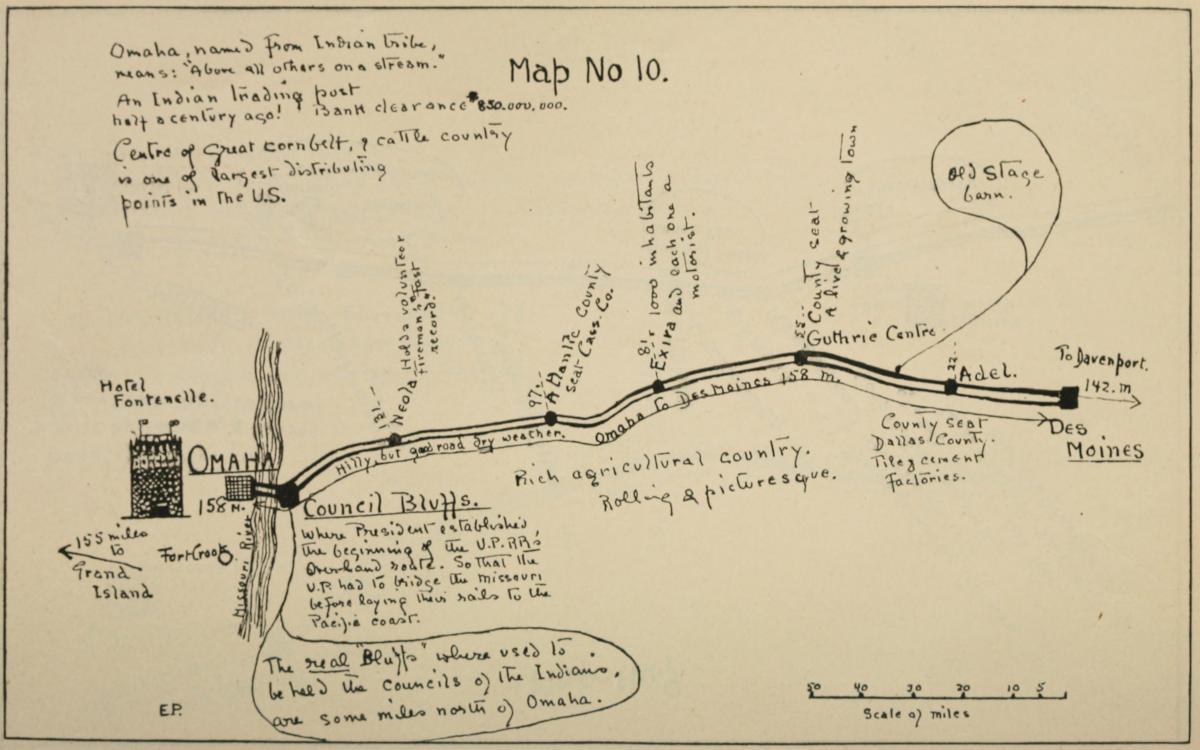

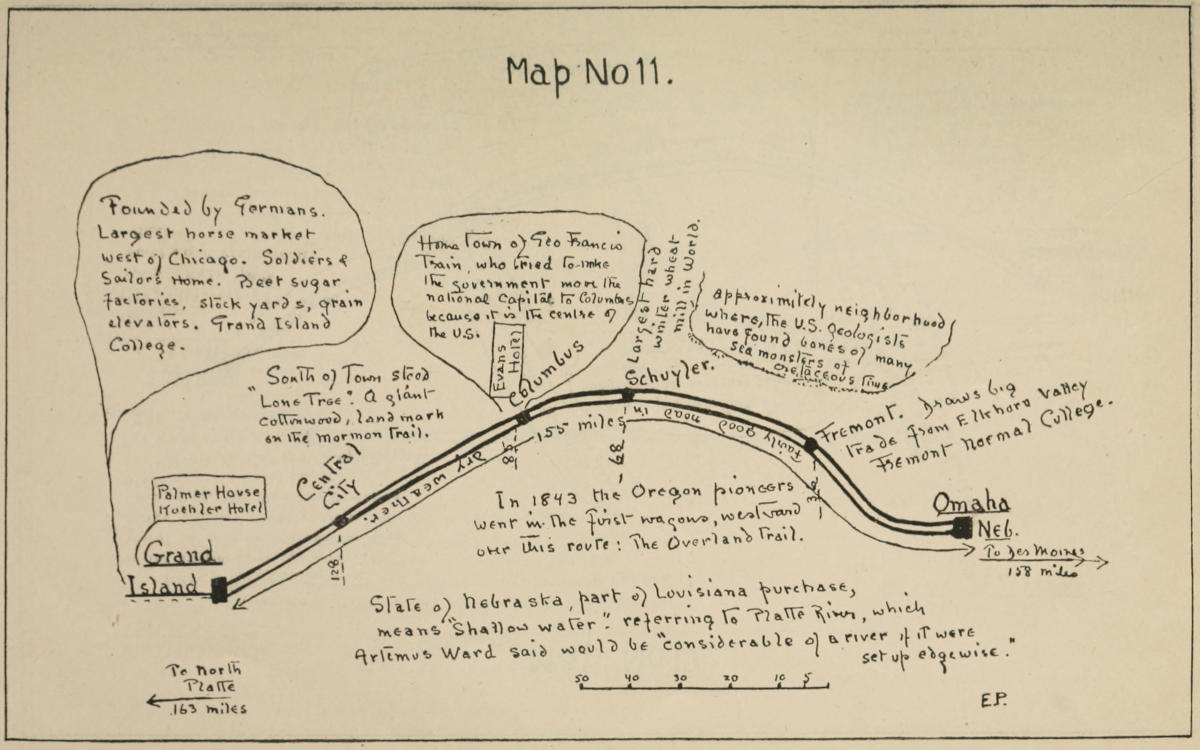

“There is a detour you will have to take here. You turn left at a white church. This stretch is dusty in dry weather, but along here,” his pencil had now reached Iowa and Nebraska, “you will have no trouble at all—if it doesn’t rain.”

“And if it rains?”

“Well, you can get out your solitaire pack!”

“For how long?” The vision of the sort of road it must be if that man thought it impassable was hard to imagine.

“Oh, I don’t know; a week or two, even three maybe. But when they are dry there are no faster roads in the country. What kind of a car are you going in?”

I told him proudly. Instead of being impressed by its make and power he remarked: “Humph! You’d better go in a Ford! But suit yourself! At any rate, you can open her wide along here, as wide as you like if the weather is right.” At the foot of the Rocky Mountains his pencil swerved far south.

“Way down there?” I asked. “That is all desert. Can we cross the desert?”

“Why can’t you?” He looked me over from head to foot. I had felt he held small opinion of me from the start. “I only wondered if the roads were passable,” I answered meekly.

“The roads are all right.” He accented the word “roads.”

“I was wondering if there were hotels.”

“And what if there aren’t? Splendid open dry country; won’t hurt anyone to sleep out a night or two. It’d do you good! A doctor’d charge you money for that advice. I’m giving it to you free!”

On the doorstep at home I met my amateur chauffeur.

“Have you found out about routes?” he asked.

“We go by way of Cleveland and Chicago.”

He looked far from pleased. “Is that so much the best way?”

“It is the only way,” and I imitated unconsciously[12] the voice of the oracle of the touring bureau.

One would have thought that we were starting for the Congo or the North Pole! Friends and farewell gifts poured in. It was quite thrilling, although myself in the rôle of a venturesome explorer was a miscast somewhere. Every little while Edwards, our butler, brought in a new package.

One present was a dark blue silk bag about twenty inches square like a pillow-case. At first sight we wondered what to do with it. It turned out afterward to be the most useful thing we had except a tin box, the story of which comes later. The silk bag held two hats without mussing, no matter how they were thrown in, clean gloves, veils, and any odd necessities, even a pair of slippers. The next friend of mine going on a motor trip is going to be sent one exactly like it!

By far the most resplendent of our presents was a marvel of a luncheon basket. Edwards staggered under its massiveness, and we all gathered around its silver-laden contents; bottles and jars, boxes and dishes, flat silver and cutlery, enamelware and glass, food paraphernalia enough to set before all the kings of Europe.

“I could not bear,” wrote the giver, “to think of your starving in the desert.”

Stowing the Luggage

Mr. B. brought us a block and tackle and two queer-looking canvas squares that he explained[13] were African water buckets. All we needed further, he told us, were fur sleeping-bags and we would be quite fixed!

Another thing sent us was an air cushion. Air cushions make me feel seasick, but the lady who traveled with us loved them. By the way, we added a passenger at the last moment. On Friday afternoon, a member of our family announced she was going with us to protect us.

“The only thing is,” we said, “there is no place for you to sit except in the back underneath the luggage.”

“I adore sitting under luggage; it is my favorite way of traveling,” she replied. And as we adore her, our party became three.

We had expected to leave New York about nine o’clock in the morning, but at eleven we were still making selections of what we most needed to take with us, and finally choosing the wrong things with an accuracy that amounted to a talent. Besides our regular luggage, the sidewalk was littered with all the entrancing-looking traveling equipment that had been sent us, and nowhere to stow it. By giving it all the floor space of the tonneau, we managed to get the big lunch basket in. Then we helped in the lady who traveled with us and added a collection of six wraps, two steamer rugs, and three dressing-cases, a typewriter, a best big camera and a little better one—with both of which we managed to take the highest possible percentage of worst pictures that anyone ever[14] brought home—a medicine chest, and various other paraphernalia neatly packed over and around her. Of this collection our passenger was allowed one of the dressing-cases, two wraps and a big bag. As there was not room for three bags on the back, my son and I divided a small motor trunk between us; I took the trays and he the bottom. It seemed at the time a simple enough arrangement.

On our way up Fifth Avenue, two or three times in the traffic stops, we found the motors of friends next to us. Seeing our quantity of luggage, each asked: “Where are you going?”

Very importantly we answered: “To San Francisco!”

“No, really, where are you going?”

“SAN-FRAN-CIS-CO!!!” we called back. But not one of them believed us.

We had intended making Syracuse our first night’s stopping-place. It can easily be done, but as we were so late starting—it was nearly half-past one—we decided upon Albany instead. We felt very self-important; it even seemed that people ought to cheer us a little as we passed. A number of persons, especially boys, did look with curiosity at our unusually foreign type of car—solid wheels and exhaust tubes through the side of the hood always attract attention in America—but no one seemed to divine or care about the thrilling adventure we were setting out upon!

For about thirty miles outside of New York the road grew worse and worse. Through Dobbs Ferry and Ardsley the surface looked fairly good, but was full of brittle places. Our chauffeur says that the word brittle has no sense, but it is the only one I can think of to convey the sudden sharp flaked-off places that would snap the springs of a car going at fair speed.

I was rather perturbed; because if the road was as bad as this near home, what would it be[16] further along? But the further we went the better it became, and for the latter seventy or eighty miles it was perfect.

The Hudson River scenery, the lower end of it, always oppressed me; I can never think of anything but the favorite fiction descriptions of the “mansions where the wealthy reside.” Such overwhelmingly serious piles of solid masonry, each set squarely in the middle of a seed catalog painter’s dream of pictorial lawn! Steep hills, steep houses, steep expenditure, typify the lower Hudson, but the scenery a hundred miles above the river’s mouth is enchanting! Wide, beautiful views of rolling country; great comfortable-looking houses with hundreds of acres about them; here, though many are worth fortunes, one feels that they were built solely to answer the individual need of their owners, and as homes.

Out on a knoll, with the river spread like a great silver mirror in the distance, we christened our tea-basket. It took us five minutes to burrow down and unpile all the things we had on top of it, and five more to find in which compartment were huddled a few sandwiches and in which other box was the cake. For twenty minutes we boiled water in our beautiful little silver kettle, but as at the end of that time the boiling water was tepid, we gave it up and ate our sandwiches as recommended by the Red Queen in “Alice” who offered her dry biscuits for thirst. Then we spent fifteen minutes in putting everything away again.

Leaving Gramercy Park, New York

“When we get out on the prairies, where can we get supplies enough to fill it?” I wondered. Our “chauffeur” mumbled something about “strain on tires” and “not driving a motor truck.”

“It is a most wonderfully magnificent basket,” said the lady who was traveling with us, rather wistfully, as she braced all the heaviest pieces of luggage between her and it.

Not counting the time out for tea, which we didn’t have, it took us five hours and a half from Fifty-ninth Street, New York, to the Ten Eyck at Albany.

The run should have been one hundred and fifty miles, but we made it one hundred and sixty because we lost our way at Fishkill. We had no Blue Book, but had been told we need only follow the river all the way. At Fishkill the road runs into the woods and the river disappears until it seems permanently lost! We wandered around and around a mountain in a wood for about ten miles before we discovered a signpost pointing the way to Albany!

Fortunately we had telegraphed ahead for rooms at the Ten Eyck, or they would not have been able to take us in. The hotel was filled to overflowing with senators and assemblymen, but we had very comfortable rooms and delicious coffee in the morning before we left for Syracuse.

Only two hundred miles from home and a breakdown! We had left Albany early in the morning and were running happily along over a road as smooth as a billiard table. Everything went beautifully until we were about twenty miles from Utica when our “chauffeur” said he heard a squeak. Gloom began to shadow his features. Half a mile further, the squeak became a knock and gloom deepened. He stopped the engine, got out and looked under the hood, lifted the cranking handle once or twice and threw his hands up in a gesture of abject despair. His lips framed all sorts of words but all he said aloud was: “It’s a bearing!” He looked so utterly dejected that in my sympathy for him (starting out on such a trip with a mother and a cousin and neither of us of the slightest use to him) I forgot that we were all equally concerned in whatever this misfortune about a “bearing” might be.

“Couldn’t we try to get to a garage?” timorously asked the one in the back.

Our “chauffeur” shook his head. “Not without wrecking the engine. There is nothing for it but to be towed to a machine shop.”

“And then?” I asked.

“That depends——” was his ambiguous answer, and we said nothing more.

Is there anything more exhilarating than an automobile running smoothly along? Is there anything more dispiriting than the same automobile unable to go? The bigger and heavier it is, the worse the situation seems to be. You might get out and push a little one, but a big car standing stonily silent portends something of the inexorability of Fate.

And there we sat. Presently an old man came jogging along in a buggy. “Any trouble?” He grinned as the owner of a horse always does grin under such circumstances. But after a few further exasperating remarks, he offered kindly, “Say, son, I’ll drive you to a good garage down the road; there are others a mile nearer, but Hoffman and Adams’ place at Fort Plain is first class.”

There had been nothing in our informer’s conversation to give us great confidence in his recommendation but the garage turned out even better than he said. There was a first-rate machine shop with an expert mechanic in charge of it, who peered into our engine dubiously:

“If it was only a Ford or a Cadillac,” said he, “I could fix you up right away! But a bearing for that car of yours’ll like as not have to be made. Can you get one in New York, do you think?”

An unusual and “special” car may be very smart-looking and be particularly easy to trace[20] if stolen, but in a breakdown a make of popular type would be best—a Ford ideal. You could buy a whole new one at the first garage you came to, or maybe get a missing part at the first ten-cent store. We discovered the difficulty, or inconvenience rather, of repairing ours, within twenty-four hours of leaving home.

The telephone service at Fort Plain was hopeless. For over four hours we tried to get the agency in New York; even then it was doubtful whether they would have the part. Meantime the engine had been taken down and the cause of the burnt-out bearing discovered to be a broken oil pipe. They mended that and our “chauffeur” was a little more cheerful when he discovered that they had all necessary tools and things to make a new bearing by hand, which they started to do. The lady who was traveling with us and I walked round and round the town. We sent picture postals by the dozen quite as though we had arrived where we had intended to be. We discovered a restaurant where we could, if it should be necessary, return for lunch, and a news stand where we fortified ourselves with chocolate and magazines. After which reconnoitering we returned to the garage prepared to stay where we were indefinitely. Mr. Hoffman made us comfortable in the office, where I found excitement in the workings of a very gorgeous and complicated cash register. It had all sorts of knobs and buttons in every variety of color, and was altogether fascinating! I wonder[21] if anyone ever has opened a store for the mere joy of playing on the cash register. I wanted to set up a shop at once!

Still in New York State

Finally New York telephoned they had a bearing, so we decided to go on to Utica by train. Someone told us—I can’t remember who it was—that beyond Albany the nearest good hotel was the Onondaga at Syracuse; but as we would surely have to stop at some poor hotels we thought we might as well get used to a lack of luxury first as last, so we took the train for Utica, to wait there until our car should be repaired.

Notwithstanding our altruistic intention to accept cheerfully whatever accommodations offered, our delighted surprise may be imagined when we entered the beautiful, wide, white marble lobby of the brand-new Hotel Utica! Our rooms were big and charmingly furnished. One had light blue damask hangings, and cane furniture; another mahogany and English chintz; each of them had its own bathroom with best sort of plumbing.

The food is very good and reasonable as to price. One dinner for instance was a dollar and thirty cents for each of us, including crêpes Suzette, which were delicious! There was music during dinner, and afterward dancing. As in most places outside of Broadway, they still call every sort of dance that is not a waltz the “tango.”

Sitting in the lobby for a little while in the evening, we noticed that the clerk at the desk, instead[22] of showing the blank indifference typical of hotels on Fifth Avenue and Madison Avenue, greeted all arriving guests with a hearty “How do you do?” They also gave us souvenirs. A little gilt powder pencil, a leather change purse, and a gilt stamped leather cardcase. We felt as though we had been to a children’s party.

Our “chauffeur,” who went back to Fort Plain at daybreak, returned with the car in the late afternoon, so that we were able to go on again after a delay of only a day and a half.

Erie is a nice, homelike little city, full of business; and our hotel, the Lawrence, very good. There was an irate man at the desk this morning. “Say, what kind of a hotel do you run? That dancing went on until three o’clock this morning! It’s an outrage!” The clerk was sorry, and willingly arranged to have the guest put in a quiet room, but he bit off the end of a cigar viciously and went out still storming about the disgrace of allowing such a performance in a reputable hotel.

“He ought to take a trip to little old New York if he thinks dancing till three is late,” said a bystander.

“He’d better go back to the farm and go to roost with the chickens!” answered another.

From Albany the roads have been wonderful, wide and smooth as a billiard table all the way. There were stretches of long straight road as in France—much better than any in France since the first year theirs were built. One thing that we have already found out; we are seeing our own country for the first time! It is not alone that a train window gives one only a piece of whirling[24] view; but the tracks go through the ragged outskirts of the town, past the back doors and through the poorest land generally, while the roads become the best avenues of the cities, and go past the front entrances of farms. And such farms! We had expected the scenery to be uninteresting! No one with a spark of sentiment for his own country could remain long indifferent. Well-fenced fields under perfect cultivation; splendid-looking grazing pastures, splendid-looking cows, horses, houses, barns. And in every barn, a Ford. And fruits, fruits, fruits! Miles and miles and miles of grapevines as neatly trimmed and evenly set in rows as soldiers on parade.

“It looks like Welch’s grape juice!” we said and laughed. It was!

So much for the country. The towns—only the humanizing genius of Julian Street could ever tell them apart. Small Utica dressed herself in taupe color, big Syracuse wore red with brown trimmings. The favorite hues were brown and red, though one or two were fond of gray, but all looked almost exactly alike. Each had a bustling and brown business center, with trolley cars swinging around the corners, pedestrians elbowing their way past big new dry-goods stores’ windows, and automobiles driving up to the curbs; each had a wide tree-bordered residence avenue, with block-shaped detached houses, garnished with cupolas and shelf-paper trimmings. The houses of Utica had deeper gardens than most, and there was a[25] stable at the rear of nearly every one on the proverbial Genesee Street. Syracuse, like the cities in Holland, was picturesquely crossed by canals and, like the thriving commercial center it is, by—this is just our personal opinion—all the freight trains of the world! It took us almost an hour to dodge between the continuous parade of box, refrigerator, and flat cars! Of the salt, for which Syracuse is so celebrated—the marshes were to the north of our road—we saw not an ounce. Perhaps those millions of freight cars were all full of it.

For a surprise we came upon Geneva, a perfect little Quaker, sitting on her own garden lawn at the edge of the road leading west. Facing an old Puritan church across a square of green, stood a row of little houses that suggested the setting of a play like “Pomander Walk.” To the moneyed magnates of the mansions of the lower Hudson, to the retired tradesmen residing in some of the red and brown residences of the various Genesee avenues, the demure little square of huddled houses of Geneva might seem contemptibly mean. Yet the mansions left us cold, while the little houses indescribably warmed our hearts. It was like the unexpected finding of a bit of fragile and beautiful old porcelain in a brickyard. We expected to see the counterpart of one of the heroines of Miss Austen’s novels come out of one of the quaint little doorways.

We would have liked to find a tea shop on the[26] square, for it was lunch time and we hated having to turn into Main Street and make our choice between several unprepossessing hotels. Geneva was certainly a town of unexpected contrasts. Although the little houses around the corner were so adorable, the Hotel Seneca from its façade of factory brick, sitting flat on the street, never for a moment warned us of an interior looking exactly like the illustrations in Vogue! White woodwork, French blue cut velvet, delicate spindly Adam furniture, a dining-room all white with little square-paned mirror doors, too attractive! Luncheon was delicious and well served by waitresses in white dresses, crisp and clean.

Our great surprise has been the excellence of the roads and the hotels, and our really beautiful and prosperous country. Going through these miles after miles of perfect vineyards and orchards, these wonderfully kept farms, it seems impossible to believe that in New York City are long bread lines, and that in other parts of our great country there is strife, hunger, poverty and waste.

In Buffalo we stopped at the Statler, a commercial hotel with a much advertised and really quite faultless service that carries the idea of personal attention to guests to its highest degree. When you register, the clerk reads your name and invariably thereafter everyone calls you by it. In fact they did even more than that. I had wired ahead for rooms and as soon as I went up to[27] register, the clerk, whose own name was printed and hung over the desk, said: “Your room is No. 355, Mrs. Post!” I had no idea where Room 355 was, but I felt as though I must have occupied it often before—as though in fact it in some personal way belonged to me. A decidedly pleasant contrast to a certain New York hotel where, after stopping four months under its roof, the clerks asked a guest her name!

The Buffalo hotel publishes a little pamphlet called the “Statler Service Codes.” It contains advice to employees, an explanation of what is meant by good service, a talk about tipping and a talk to patrons. A few of its sayings, copied at random, are:

“At rare intervals some perverse member of our force disagrees with a guest. He maintains that this sauce was ordered when the guest says the other. Or that the boy did go up to the room. Or that it was a room reserved and not dinner for six. Either may be right. But no employee of this hotel is allowed the privilege of arguing any point with a guest.”

“A door man can swing the door in a manner to assure the guest that he is in His Hotel, or he can sling it in a way that sticks in the guest’s crop and makes him expect to find at the desk a sputtery pen sticking in a potato.”

After giving every thought to the guest’s comfort, the end of the little book also asks fairness on the part of the guests. Such as, not to say you[28] waited fifteen minutes when you waited barely five; or not to object if the clerks can’t read your signature if you write in hieroglyphics.

In the morning at the Statler, a newspaper is pushed under your door and on it is a printed slip saying: “Good morning! This is your paper while you are in Buffalo.” And when you are ready to leave instead of calling, “Front! Get 355’s baggage!” the Statler clerk says, “Go up to Mrs. Post’s room and bring down her things!”

I certainly liked it very much. And I am sure other people must feel the same.

If the hotel tried to make us pleased with ourselves, we were not allowed to keep our self-complacence long. When we went to Niagara, we passed a sort of taxidermist’s museum; its windows at least were full of stuffed beasts. The proprietor, standing in front of it, tried his best to make us “step inside and see the mummied mermaid” and his museum of the greatest educational wonders of the world. When we showed no interest in his collection he burst out with:

“If you’re going to remain as ignorant about everything you come to, as you are about this wonderful museum, traveling won’t educate you any!”

Put a little differently, it might have hit a mark. We had ourselves been saying, only a little while before, that we were undoubtedly missing lots of interesting things because we did not quite know how or where to see them. Yet, though we are still[29] ignorant about the “wonders” of that particular museum, we are not always so indifferent. We have tried to look out for points of historical value and we have found many things of great diversion to ourselves. In Utica, for instance, we hung for hours over the railings of an exhibit of china making by the Syracuse pottery manufacturers. There is an irresistible fascination in watching the potter shaping pitchers, and the decorators putting decalcomania on plates and drawing fine gilt lines. The facility with which experts in any branch of industry use their hands is a marvel and a delight to me. I could stand indefinitely and watch a glass-blower, or a potter, or a blacksmith, or a paper hanger—anyone doing anything superlatively well.

I am not thinking of describing the world’s wonder of wonders, Niagara Falls, because everyone knows they are less than an hour’s run from Buffalo, with a splendid wide motor road leading out to them, and because their stupendous beauty has been described too often.

There were four bridal couples with us in the elevator that took us down to go under the Falls. One of the brides was apparently concerned about the unbecomingness of the black rubber mackintosh and hood that everyone puts on, for her evidently Southern husband said aloud:

“Don’t you fret about it, Nelly, you look real sweet in it, ’deed you do!” Whereupon each of the other three patted around the edge of the hood[30] where her hair ought to be, and glanced a little self-consciously at the arbiter of her own loveliness.

Later, the young Southerner linked his arm in that of his bride lest she go too close to that terrific torrent of drenching water. The other three pairs walked gingerly through the soaking rock galleries in three closely huddled units. And the rest of us looked at them with that smiling interest that one irresistibly feels for happy young couples on their honeymoon.

On Sunday evening in Buffalo a man who looked as though he had been lifted out of a yellow flour barrel had come into the lobby of the hotel. We could not tell whether he was black or white or even human. A clerk, seeing us staring, remarked casually: “Oh, he’s just a motorist who has come from Cleveland. Gives you some idea of the roads, doesn’t it?”

We started the next day therefore in a rather disturbed frame of mind, and soon saw how on a Sunday, when every motorist is out, he had looked as he did. Even on Monday the dust was so thick that the wind blew it in great yellow clouds, sometimes making it impossible to see ahead. But most of the way it blew to the left of us, leaving us fairly clean and not enveloping us unless we had to pass another car going our own way. As we had gone out to the Falls in the morning, we did not leave Buffalo until about two o’clock, but in spite of bumpy roads and dust so thick that it[31] made us swerve a little, we reached Erie easily at a little after six.

We left Erie the next day at two o’clock and arrived in Cleveland at seven—which was as fast as the Ohio speed limit of twenty miles an hour would allow. The road was much the same as it had been the day before. Forty miles of the whole distance was rather rough and very dusty; the rest was good, a little of it splendid.

At Mentor, about twenty-three miles before Cleveland, we came to a number of beautiful places that must have been the out-of-town homes of Cleveland people. The houses, many of them enormous, were long, low and white; not farmhouses and not Colonial manor houses, but a most happy adaptation of the qualities of both; dignified, homelike, imposing and enchanting.[2]

The remark of the man at the museum in Buffalo irresistibly recurs to me. We certainly won’t be “educated” if our chauffeur can help it! He is exactly like the time lock on a safe. Only instead of being set for an hour, he is set for distance. At Erie, for instance, he throws in his clutch, “Cleveland”? he asks, and snap! nothing can make him look to the left or the right of the road in front of him.

“Oh, look! That’s the house where President Garfield——”

Zip! we have passed it!

“Wait a minute, let me see that inscription——”

We are half a mile beyond! We arrive in Cleveland, when click goes the lock and he stops dead, and nothing will make him go further.

The food at the hotel in Cleveland, also a Statler, was so extraordinary good that I asked where the maître d’hôtel and his chefs had come from. I thought that possibly on account of the war they had secured the staff of Henri’s or Voisin’s or Paillard’s in Paris, and was really surprised to hear the head chef was from Chicago and the maître d’hôtel from New York.

The dining-room service was quite as good as the food. We did not wait more than a moment before they brought our first course, and as soon as we had finished that our plates were whisked away and the second put before us. Never, even in France, have we had better or more perfectly cooked chicken casserole, and the hollandaise sauce on the asparagus was of the exact smooth, golden consistency and flavor that it ought to be, instead of the various yellow acids, pastes, and eggy mixtures that too often masquerade under the name. Our waiter brought in crisp, fresh salad and expertly and quickly made his own dressing. He was in fact a paragon of his kind, serving all of our meals without that everlasting patting and fussing and fixing that most waiters go through with until what you have ordered is so shopworn and handled and cold that it is not fit to eat. Can[33] anything be more unappetizing than to have a waiter, or two of them, breathing over your food for half an hour?

Personally I hate hotel service. I hate to be helped. In our own houses even children of six resent it. I often wonder, why do we submit to having the piece we don’t want, in the amount we don’t want, put on the part of the plate we don’t want it on, covering it with sauce if we hate sauce, or giving us the dryest wisps if we like it otherwise, by a waiter who bends unpleasantly close? Why do we have everything we eat pinched between the fork and spoon in that one-handed lobster-claw fashion, and endure it in silence? All of this is no fault of the waiter who, after all, is trying to do the best he can in the way that has been taught him. But why is the service in a hotel so radically different from all good service in a private house?

Cleveland, “the Sixth City”—and she likes to have you know her rating—is certainly prosperous-looking and in many ways beautiful. She has wide, roomy streets with splendid lawns and trees and houses. A few of the older mansions are hideous but enormous, comfortable, and well built. They look like the homes of people with no end of money who are content to live in houses of American architecture’s darkest period because they are used to them and often because their fathers lived in them. There is no suggestion of the upstart in their ugliness. The whole city impresses one as[34] having a nice fat bank account and being in no hurry to spend it. The municipal buildings, however, are superb, and the newer dwelling houses all that money and taste can make them, but almost best of all, I liked the shops.

In a big new one on Euclid Avenue, two elderly ladies with much-befeathered bonnets were ensconced in a double rolling chair like those of the Atlantic City boardwalk. An attentive young man was pushing them about among bronzes and porcelains. Stopping before a shelf of samples he asked: “Are any of these at all like the coffee cups you are looking for, Mrs. Davis?”

Mrs. Davis was so absorbed in the conversation of her friend that the clerk had to repeat his question three times before her purple feathers bobbed toward the coffee cups casually.

“Coffee cups?” she added absently. “I don’t think I care about any today, thank you. But you might drive us through the linen department and the lamp shades. The lamp shades are always so pretty!” she added to her friend, exactly as though, after telling her coachman to drive around the east side of the park, she had remarked upon the beauty of the wistaria.

“Does that lady drive about town in a rolling chair?” I asked of the man waiting upon us.

“Oh, those chairs are ours,” he answered. “We have them so that customers can visit with each other and shop without getting tired. One of the clerks will be glad to push you about[35] in one. It is a very pleasant innovation,” he added, and out of courtesy he did not say for whom.

The Crowd in Less Than a Minute. “Out of the Window” in Cleveland

Cleveland is also the city of three-cent carfares—in fact three cents in Cleveland is almost as good as five cents in other cities. Lemonade three cents, moving pictures three cents, a ball of pop-corn three cents—a whole counter full of small articles in one of the big stores. Let’s all move to Cleveland!

One thing, though, struck us most particularly in the hotels of Utica and Cleveland; the people didn’t match the background. Dining in a white marble room quite faultlessly appointed, there was not a man in evening clothes and not a single woman smartly dressed or who even looked as though she had ever been! Men in unpressed business suits, women in black skirts and white shirtwaists are appropriate to the imitation wood or plaster walls of some of the eating places that we have been in, but in a beautiful hotel like the Statler in Cleveland, and especially in the evening, they spoil the picture.

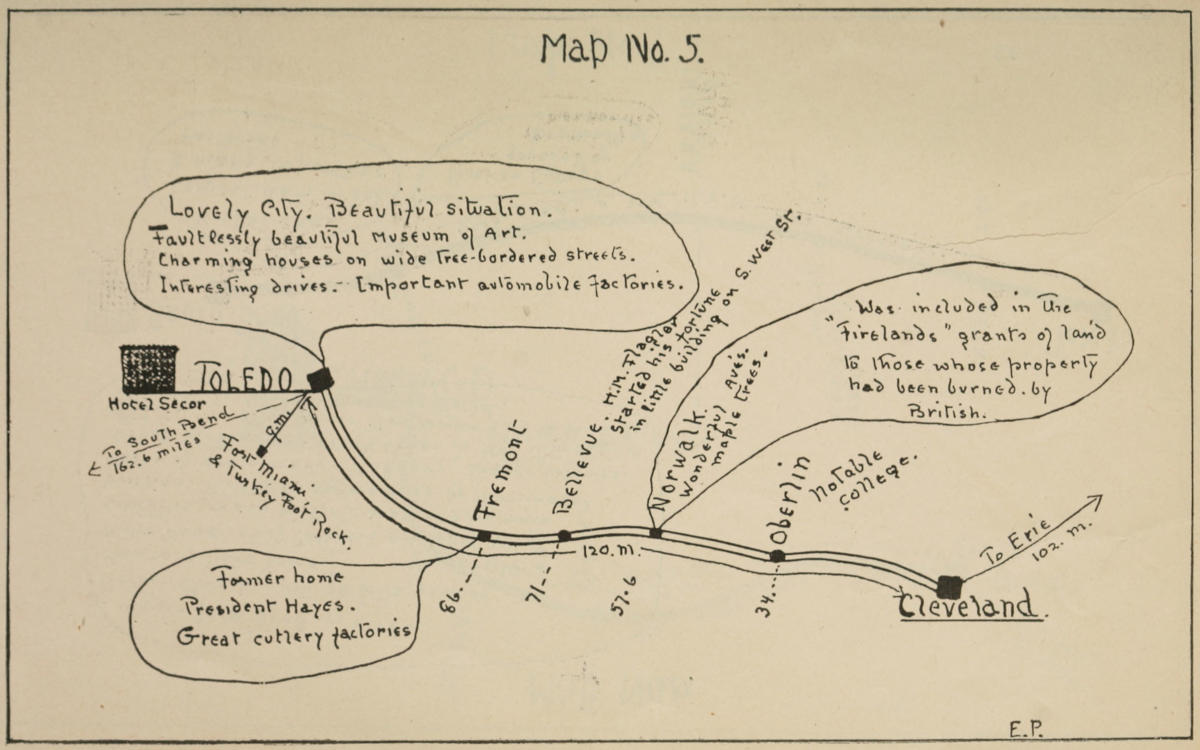

From Cleveland to Toledo the roads are very like those of France, they have wonderful foundations but badly worn surfaces. Much the best hotel in Toledo is the Secor, and the restaurant, which made no attempt at imitating French cooking, was good.

There was a most beautiful art museum in Toledo, a small building pure Greek in style and set[36] like a jewel against pyramidal evergreens. It is quite the loveliest thing we have seen.

Because of Ohio’s speed restrictions, twenty miles fastest going and eight for villages, etc., one must either spend days in crawling across the state or break the law. As is usually the case with unreasonable laws, few keep them, or else the motoring Ohioans interpret their speed laws rather liberally. Of the hundreds of motors we met in Ohio, especially near Cleveland, which is one of the biggest automobile centers in the country, scarcely one, even within the city limits, was going less than twenty-five miles an hour.

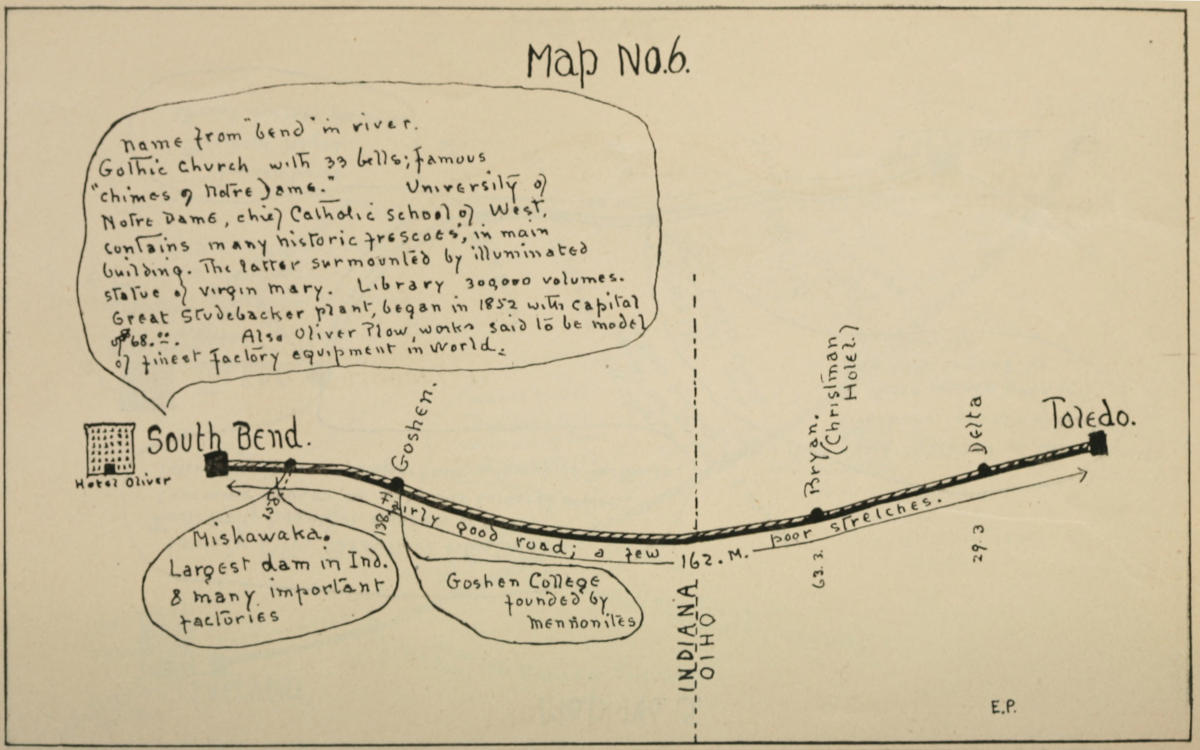

However, as it is not courteous for the stranger to dash lawlessly through at faster than the twelve-mile average prescribed by law, the run from Toledo to South Bend, a distance of one hundred and sixty-two miles, will take from twelve to fourteen hours. The road is good, most of it, but sandwiched between occasional poor stretches.

We lunched at Bryan at the Christman Hotel. It was here that I heard a new retort courteous. I had dropped a veil; a youth picked it up. I said, “Thank you.” He replied politely, “Yours truly!”

The Oliver, “Indiana’s finest hotel,” at South Bend is good, clean, well run, with a Louis Quatorze dining-room in black and white. The black and white craze is raging here quite as much as in New York.

Never in the world did people have so much luggage with nowhere to put it and nothing in it when it is put! Each black piece is bursting! Yet everything we have with us is the wrong thing and just so much to take care of without any compensating comfort. We have gradually eliminated everything we could until now we have just enough for three hallboys on our arrival and three porters on our departure to stagger under. Then too, although possibly all right for a man and wife, sharing the motor trunk with a son is an inconvenience unimagined! If the trunk is put in my room, he finds himself somewhere on another floor or at the end of an interminable corridor unable to get his pajamas without entirely redressing. If the trunk is in his room I have to hunt for him, get his key, and bring the trays to my room. Packing one trunk in two rooms at once is even more difficult. Consequently, he has in desperation bought a “suitcase.” It is orange-colored, made of paper, I think, and it also makes one more lump of baggage to be carried up and down and packed on top of our traveling companion.

The thermometer was at about thirty when we left home, so I could think of nothing but serge coats of heavy weight, plaited skirts also nice and warm, sweaters of various thicknesses, and fur coats. There came almost a break in a heretofore happy family when I insisted that over the Rocky Mountains our “chauffeur” would need his heaviest coat. He refused to take a coonskin—Heaven praise his intuition on that!—but obligingly brought a huge ulster. We had not gone fifty miles from New York when the sun came out hot and has ever since then been trying to show how heat is produced in the tropics. Our car is loaded down with wraps for the Rockies, and in this sweltering heat not one thin dress have I brought.

In every way my clothes are a trial and disappointment. A taffeta afternoon dress that was intended to give me a smart appearance whenever I might want to look otherwise than as a bedraggled tripper comes out of the trunk looking like crinkled crepon. I thought of pretending that it was crinkled crepon, but its crinkle was somehow not quite right in evenness or design. There is also a coat and skirt of a basket weave material that I had made especially to be serviceable motoring. I don’t know what sort of dresses would have packed better, but I am sure none could be worse. In fact, I unhesitatingly challenge these two of mine against the most perishable clothes that anyone can produce, that mine[39] will wrinkle more and deeper and sooner than any others in existence.

I have, however, found one small article that I happen to have brought, a great success, and that is a lace veil with a good deal of pattern—one of those things that make you look as though something queer was the matter with your face—unless there is something the matter with your face, in which case it takes all the blame. In doing the same thing every day you find you shake down to a rather regular system. As we come into the outskirts of the city where we are to spend the night, I take off, in the car, my goggles and the swathing of veils that I wear touring, and put on the lace one. The transformation from blown-about hair and dusty face to a tidy disguise of all blemishes is quite miraculous. Dusters are ugly things, but as every woman who motors knows, there is nothing so practical. I don’t think personally that silk ones can be compared for sense and comfort with those of dust-colored linen or cotton. Silk sheds the dust perhaps a little better, but wrinkles more. At all events, I find that by putting my lace veil on and taking my duster off, I can walk up to the desk and register without being taken for a vagrant. The lady who was traveling with us is one of those aggravating women who stay tidy. She keeps her gloves on and her hands dustless. But even she saw the transforming possibilities of a lace veil and soon bought one too.

Hotels, however, are very lenient in the matter of the appearance of guests, because of all the begrimed-looking tramps, our “chauffeur” after driving ten hours or so in the sifting dust is the grimiest. The only reason why he is not taken for a professional driver is because no one would hire anyone so disreputable-looking.

In one hotel, though, a grimy working mechanic having gone up in the elevator and a strange, perfectly well turned out person having come down, the confused clerk asked where the chauffeur went and did the new gentleman want a room?

Sometimes we take luncheon with us and sometimes we don’t. If we do, we see nice, clean-looking places on the road, such as the Parmly at Plainsville between Erie and Cleveland and the Avelon at Norwalk between Cleveland and Toledo; if we don’t we find nothing but hotels of the saloon-front and ladies’-entrance-in-the-back variety.

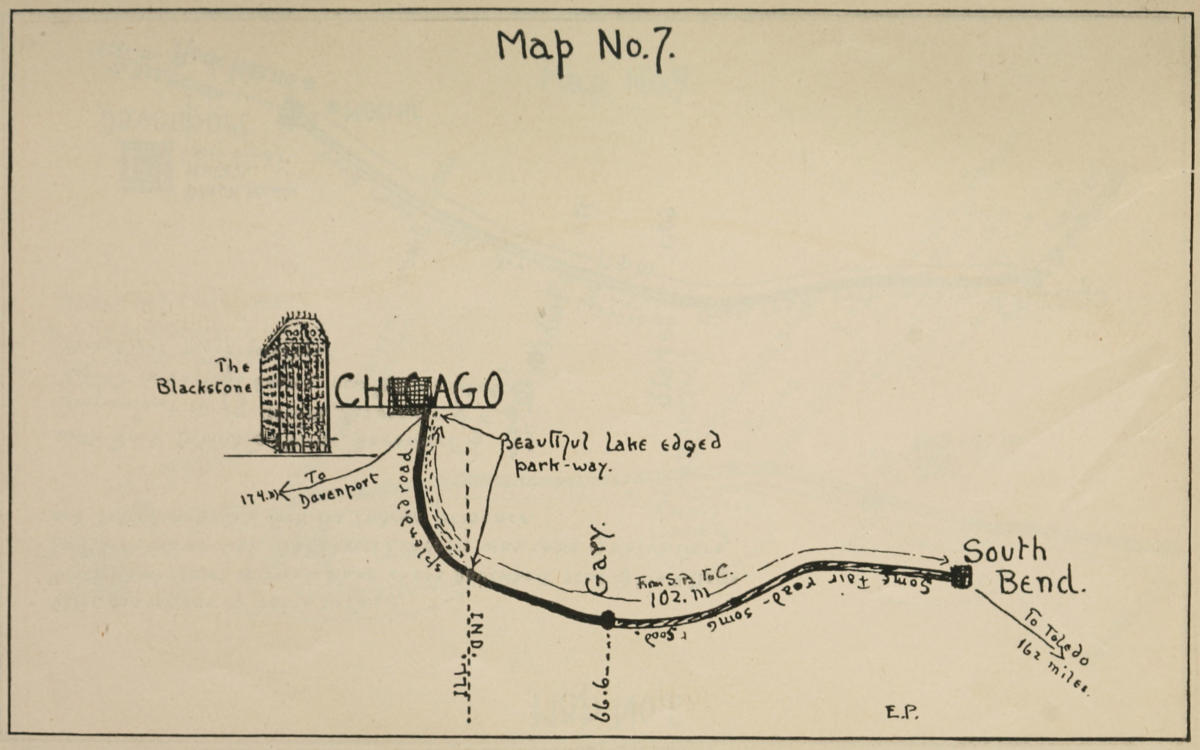

Between South Bend and Chicago we had not intended to stop, but found ourselves rather hungry and unwilling to wait until about three o’clock to lunch in Chicago. We looked in the Blue Book and saw the advertisement of a restaurant a few miles ahead. “Mrs. Seth Brown. Chicken dinners a specialty.” That is not her real name.

The very words “chicken dinner” made us suddenly conscious that we were ravenous.

“Do you remember the chicken dinners at the different places near Bar Harbor?” reminisced the lady-who-was-traveling-with-us. I am not going to call her that any more! It is too long to say. I will call her “Celia” instead. It is not her name, but it is an anagram of it, which will do as well. Also a repetition of our “chauffeur” sounds[42] tiresome, and his own initials of E. M. would be much simpler.

Anyway, all three of us conjured up visions of the chicken that was in a little while going to be set before us.

“Country chickens are so much better than town ones!” said Celia. “They are never the same after they have been packed in ice and shipped, and I do wonder whether it will be broiled, with crisp fried potatoes, or whether it will be fried with corn fritters and bacon!”

“—And pop-overs,” suggested E. M.

“Couldn’t we drive a little faster?” I asked. For by now my imagination had conjured up not only the actual aroma of deliciously broiled chicken, but I was already putting fresh country butter on crisp hot pop-overs. But in my greediness for the delectable dinner that was awaiting us, I lost my place in the Blue Book. Nothing that I could find any longer tallied with the road we were on, and it took us at least half an hour to find ourselves again. By the time we finally reached the little town of delectable dinners we were so hungry we would have thought any kind of old fowl good. But search as we might we could not discover any place that looked even remotely like a restaurant. There was a saloon, and a factory, and some small frame tenements. Nothing else in the place. Inquiring of some men standing on a corner, one of them answered, “The ladies’ entrance of the saloon is Mrs. Seth Brown’s place,[43] and the eating’s all right.” We were very hungry and the lure of chicken being strong, also feeling that perhaps the interior might prove better than the entrance promised, we went in. In the rear of a bar was a dingy room smelling of fried fat and stale beer. There were three groups of perfectly respectable-looking people sitting at three tables. A barkeeper with a collarless shirt, ragged apron, and a cigar in his mouth, sat us at a fourth table with a coffee-stained cloth on it, rusty black-handled cutlery, and plates that were a little dusty.

“What y’want!”

“Do you serve chicken dinners?” I asked.

“D’ye see it advertised?”

“Yes, in the Blue Book.”

“Y’ c’n have dinner,” he said as though he was obliged against his inclination to live up to his advertisement.

E. M. was drawing water out of the well to fill the radiator tank. Celia and I began wiping off the plates and forks on the corners of the tablecloth.

At the table nearest us were four men and a woman. One of the men kept hugging the woman, who paid no attention to him. Two of the others went continually back and forth to the bar, while the fourth was occupied solely with his food. At another table was a family motoring party, and at the third, a second family, with a baby that cried without stopping and a little child who screamed from time to time in chorus.

Our chicken dinner proved to be some greasy fried fish, cold bluish potatoes, sliced raw onions, pickled gherkins, bread and coffee.

We ate some bread and drank the coffee. If we had been blindfolded it wouldn’t have been so bad.

There is one consoling feature in such an incident, that although it is not especially enjoyable at the time, it is just such experiences and disappointments, of course, that make the high spots of a whole motor trip in looking back upon it. It is your troubles on the road, your bad meals in queer places, your unexpected stops at people’s houses; in short, your misadventures that afterwards become your most treasured memories. In fact, after years of touring, I have in a vague, ragged sort of way tried to hold to what might be called a motor philosophy. Anyway, I have found it a splendid idea when things go very uncomfortably to remember—if I can—what a very charming diplomat, who was also a great traveler, once told me: that in motoring, as in life, since trouble gives character, obstacles and misadventures are really necessary to give the trip character! The peaceful motorist who has no motor trouble or weather trouble or road trouble has a pleasant enough time, but after all he gets the least out of it in the way of recollections. Not that our one disappointment about our chicken dinner is meant to serve as a backbone of character for this trip, neither do I hope we shall run into any serious misadventure, but I really quite honestly hope[45] that everything will not be so easy as to be entirely colorless.

One of the Exciting Things in Motoring Is Wondering What Sort of a Hotel You Will Arrive at for the Night

I was turning these thoughts over in my mind as we sped on to Chicago and they suggested a most discouraging possibility, which I immediately confided to Celia:

“Suppose so little happens that there will be nothing to write about? No one wants descriptions of scenery or too many details of directions as to roads or hotels, and supposing that is all we know?”

“You could make some up, couldn’t you?” said she sympathetically.

“Do you think that I could tell you a lot of things that never happened and that you would believe me?” I asked.

She answered positively: “Of course you couldn’t.”

“Then I’m certain nobody else would believe me either.”

“No, I don’t suppose they would,” she agreed, but suddenly she suggested: “I tell you what we could do. We could stop over in little places and pass those where we mean to stop—and we can in many ways make ourselves uncomfortable, if you think it necessary for interesting material.”

But our conversation turned at that point into admiration of our surroundings; for we had come into a long drive through a park on the very edge of the Lake that is the beautiful, welcoming entrance to Chicago.

We arrived yesterday at “America’s most perfect hotel.” We are still a little overawed. So far we have only been in hotels that have prided themselves on being the “best hotel in the state” or the “best hotel in the Middle West,” but Chicago’s pride throws down the gauntlet to America, North and South, and coast to coast. I have never heard that Chicago did anything by halves! “The world will take you at your own valuation.” Maybe the maxim originated in Chicago.

America’s best hotel looks like a huge tower of chocolate cake covered with confectioner’s icing. If it were cake, it might easily be the biggest piece of chocolate in the world, but for “America’s best”—probably because the word “best” in America has come to mean also “biggest”—the Blackstone seems rather small. Still, I don’t think it boasts of being anything except the finest and foremost, most perfect and complete hotel in the Western Hemisphere.

The lobby as you enter it is very like the thick chocolate center of the cake and gives a slightly stuffy impression that is felt in no other part of[47] the really beautiful interior. The cerise and cream-colored dining-room, in which for afternoon tea they take up the center carpet and remove some tables, leaving a hollow square of gray marble tiling to dance on, is the most beautiful room that I have ever seen anywhere, not excepting Paris. The white marble simplicity of the second dining-room also appealed to me, and the upstairs halls are like those in a great private country house.

The restaurant we find for its standard of high prices not very good. The food at the Statler in Cleveland was the best we have had anywhere, and the prices were half. Perhaps we ordered, by luck, the Statler’s specialties and the dishes that the Blackstone prepares least well.

The room service, however, is well done, with a lamp under the coffee pot and a chafing dish for anything that ought to be kept hot. Yet my coffee this morning had a flavor not at all associated with memories of best hotels, but reminiscent of little inns that one stops at in motoring through France, Germany, or Italy. There should have been a sourish bread and fresh flower-flavored honey to go with it. It leaves a copperish taste in the mouth long afterward.

In defense of the management, I ought to add that we take our coffee at the abnormally early hour of seven, and the coffee for such as we is probably kept over in a copper boiler from the night before. Still, ought this to happen in the[48] best hotel, even if only of the Western Hemisphere?

Our rooms high up and overlooking the lake are lovely, perfectly appointed, and with an entrancing view of moonlight on the water. The furnishings of the bedrooms are very like those of the Ritz hotels, and the prices are reasonable considering the high quality of their accommodations. The three-dollar-and-a-half rooms are small, light, and completely comfortable; for seven dollars one can have a big room overlooking the lake, both of course including bathrooms with outside windows and all the latest Ritz-Carlton type of furnishings, and—I must not forget—linen sheets and pillow cases, the first real linen we have seen since we left home! Also the reading lamp by my bed has a shade, pink on the outside and lined with white and a generous flare, that I can read by.

At the Statler in Cleveland there was an exceedingly pretty bed table lamp with a silk shade on it of Alice blue and a little gold lace, but one might as well have tried to read by the light of a captured firefly tied up in blue tissue paper. I tried to get the shade off but it was locked on—to prevent guests from ironing or stealing the shade or the bulb? At any rate, since nothing could part the cover from the fixture, and reading in the blue, glimmering gloom was impossible, I was obliged to get to sleep by watching the members of a club in the building opposite smoking and lounging,[49] exactly like the drummers downstairs—downstairs in Cleveland, not here.

The ubiquitous drummer is not in evidence as he was in northern New York, Indiana, and Ohio. The people down these stairs are more like the people one sees in the hotels in New York, Boston, or Philadelphia. In the other cities we have come through there were traveling men to the right of us and traveling men to the left of us, with hats on the backs of their heads and cigars—segars, looks more like it—tilted in the corners of their mouths. Traveling men standing and leaning, traveling men leaning and sitting, but always men in cigar smoke, talking and lounging and taking their rest in the lobbies.

Like the drummers, I shall soon have all the hotels in the country at my finger ends; the advantages, disadvantages, and peculiarities of each. Already I could write a treatise on plumbing apparatus! The Statler in Cleveland had an “anti-scald” device. I read about it in the “service booklet” afterward. The curious-looking handles and levers occupying most of a white-tiled wall at the head of the bathtub so fascinated me that I had to try and see how they worked. I pulled knobs and pushed buttons that seemingly were for ornament merely, until suddenly a harmless-looking handle let loose a roaring spray of water that came from every part of the amateur Niagara at once. My bath was over before I had meant it to begin, and I got undressed afterward instead[50] of before. But I like the bathrooms with running ice-water faucets, and I love to examine the wares in the automatic machines, also placed in the bathrooms. They look like a miniature row of nickel telephone booths, each displaying a bottle or box through the closed glass door, each with a slot to drop a quarter in and a knob to pull your chosen box or bottle out with. The tantalizing thing about them is that they hold very little of use to me. I don’t like the kind of cold cream they carry; the toothbrushes are usually sold out, and razors and shaving soap don’t really tempt me.

There are paper bags in the closets to send your laundry away in and a notice that all washing sent to the desk before nine in the morning will be returned by five in the afternoon. If only they could run an owl laundry, taking your things at nine in the evening and returning them at five in the morning, it would be much more convenient for people who arrive at night and leave in the early dawn.

I should like to make a collection of hotel signs, such as plates on the bedroom doors saying, “Stop! Have you forgotten something?” And in the bathroom the same sentiments and an additional “How about that razor strop?”

While waiting for my change in one of the big department stores I overheard the following conversation between two women directly beside me:

“So you like living in the city, do you?” said one.

“Sure!” answered the other. “You can run into the stores as often as you feel like it, and if you get lonesome you can go to the movies or a vaudeville show, or you can walk up Michigan Avenue and see the styles—there’s always something going on in the city.”

“I dare say you get used to it and feel you couldn’t give it up, but what I never could get used to is one of them flats. Now out at home, we’ve got a fifteen-room house, all hardwood floors——”

“What d’you want all that room for? You’ve only got to spend money to furnish it and elbow grease to care for it. You need two girls or more. Now, we’ve got a flat all fixed up nice and cozy and one girl takes care of it easy.”

“Well, I guess it’s all right, but if I had to bring my babies out of the good country air and put them in a flat, I think they’d die!”

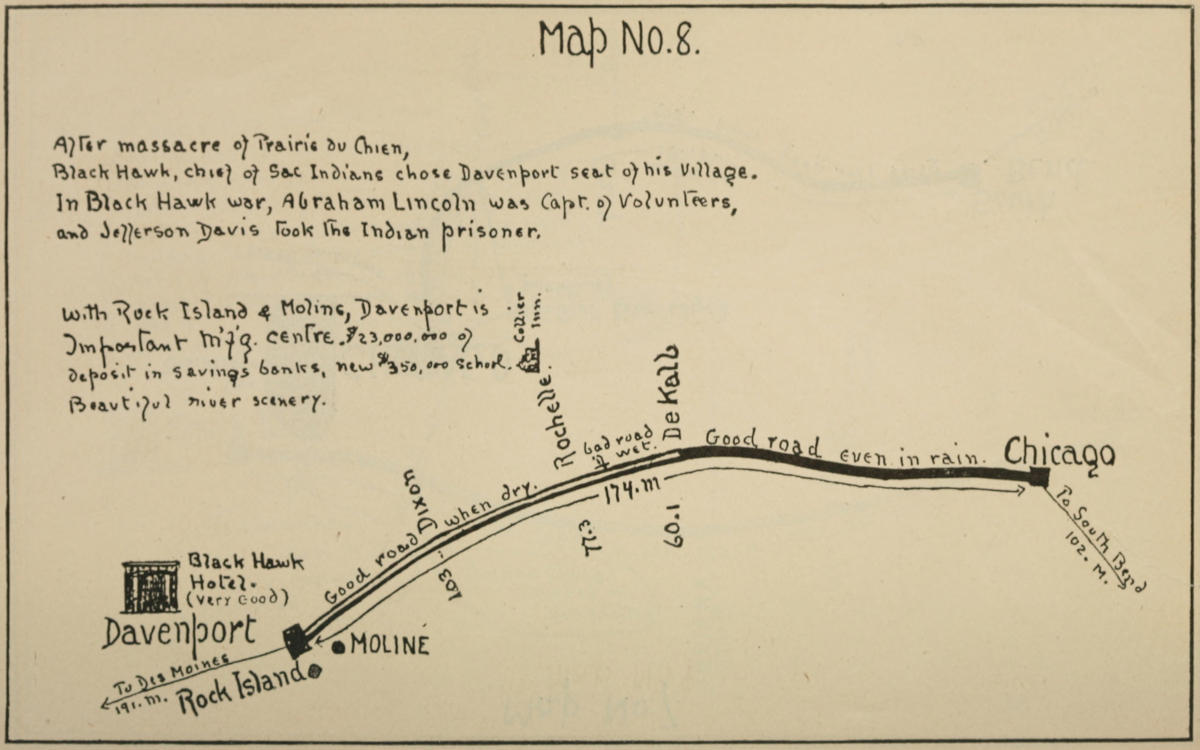

The disappointing and unsatisfactory thing about a motor trip is that unless you have unlimited time, which few people ever seem to have, you stop too short a while in each place to know anything at all about it. You arrive at night and leave early in the morning and all you see is one street driving in, and another going out, and the lobby, dining-room and a bedroom or two at the hotel.

Happily for us, we have been staying several days in Chicago, and, while we can scarcely be said to know the city well, we have had at least a few glimpses of her life and have met quite a few of her people.

Last evening at a dinner given for us, our hostess explained that she had asked the most typical Chicagoans she could think of, and that one of the most representative of them was to take me in to dinner. “He is so enthusiastic, he is what some people would call a booster,” she whispered just before she introduced him.

In books and articles I had read of persons called “boosters,” and had thought of them as persons slangy as their sobriquet; blustering,[53] noisy braggarts, disagreeable in every way. I think the one last night must have been a very superior quality. He was neither noisy nor disagreeable; on the contrary, he was most charming and seemed really trying not to be a booster at all if he could help it.

He began by asking me eagerly how we liked Chicago. Had we thought the Lake Shore Drive beautiful? Were we struck with Chicago’s smallness compared to New York? I told him we had, and we were not. He thereupon generously but reluctantly admitted—the list is his own—that probably New York had more tall buildings, more wholesale hat and ribbon houses, a bigger museum of art, a few more theaters, and yes, undoubtedly, more millionaires’ palaces, but—he suddenly straightened up—“Chicago has more real homes! And when it comes to beauty, has New York anything to compare with Chicago’s boulevard systems of parks edged by the lake and jeweled with lagoons? And yet she is the greatest railroad center in the whole world. And let me tell you this,” he paused. “New York can never equal Chicago commercially! How can she? Look on the map and see for yourself! From New York to San Francisco, north to the lakes and south to Mexico—that’s where Chicago’s trade reaches! What is there left for New York after that? She can, of course, trade north to Boston and south to Washington, but she can’t go west, because Chicago reaches all the way to New York herself, and[54] there is nothing on the east except the Atlantic Ocean!”

After dinner we were taken to the small dancing club, a one-storied pavilion containing only a ballroom with a service pantry in the back, that a few fashionables of Chicago built in a moment of dancing enthusiasm. Although we met comparatively few people and had little opportunity to talk to anyone, I noticed everywhere the same attitude as that of my companion at dinner. The women had it as much as the men. As soon as they heard we were from New York they began to laud Chicago.

Mrs. X., one of their most prominent hostesses and one of the most beautiful and faultlessly turned out people I have ever seen, instead of talking impersonalities as would a New York woman of like position, plunged immediately into the comparison of New York’s shoreline of unsightly docks with the view across her own lawn to the Lake. Imagine a typical hostess of Fifth Avenue greeting a stranger with: “How do you do, Mrs. Pittsburgh; our city is twice as clean as yours!” However, I felt I had to say something in defense of mine, so I remarked that the houses on Riverside Drive faced the Hudson, and across a green terrace, too.

“Oh, but the Palisades opposite are so hideously disfigured with signs,” she objected, “and besides none of your really fashionable world lives on your upper West Side.”

Having staked out our fashionable boundaries for us, she switched the topic to country clubs. Had we been to any of them?

We had been given a dinner at the Saddle and Cycle Club, and we had to admit it was quite true that New York had nothing in its immediate vicinity to compare with the terrace on which we had dined, directly on the Lake, and apparently in the heart of the wilderness, although the heart of Chicago was only a few minutes’ drive away.

“You must come out to Wheaton and lunch with us tomorrow!” Mrs. X. said. You could tell from her tone that she was now speaking of her particularly favorite club. “I think they will be playing polo, but anyway you must see what a beautiful spot we have made of it, and there wasn’t even a tree on the place when we started—we have done everything ourselves.”

Doing things themselves seemed to me chief characteristic of the Chicagoans. A “do-nothing” must be about the most opprobrious name that could be given a man. Nearly all of Chicago’s prominent citizens are self-made—and proud of it. Millionaire after millionaire will tell you of the day when he wore ragged clothes, ran barefooted, sold papers, cleaned sidewalks, drove grocers’ wagons, and did any job he could find to get along. And then came opportunity, not driving up in a golden chariot, either! But more often a trudging wayfarer to be accompanied long and wearily. You cannot but admire the straightforwardness—even[56] the pride with which these successful men recount their meager beginnings, as well as the ability that always underlies the success.

Another thing that impressed us was that cleverness is rather the rule than the exception, and the general topics of conversation are more worth listening to than average topics elsewhere. For instance, their city is a factor of vital interest to them, and therefore their keenness on the subject of politics and all municipal matters is equaled possibly in English society only. They are also interested in inventions, in science, in all real events and affairs, both at home and abroad. At least this is what we found there, and what I am told by many people who have spent much time in Chicago.