Title: Her own way

Author: Eglanton Thorne

Release date: July 10, 2024 [eBook #74007]

Language: English

Original publication: London: The Religious Tract Society, 1899

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

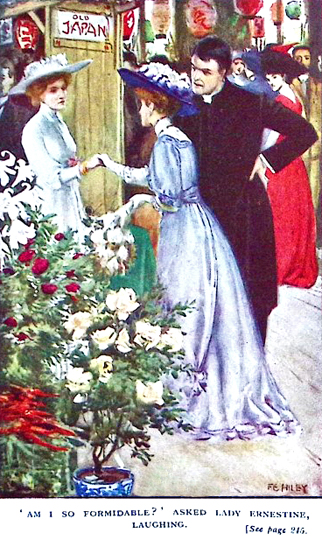

"AM I SO FORMIDABLE?" ASKED LADY ERNESTINE, LAUGHING.

By

EGLANTON THORNE

Author of "Aunt Patty's Paying Guests," "Beryl's Triumph,"

"My Brother's Friend," etc.

FIFTH IMPRESSION

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

4 Bouverie Street & 65 St. Paul's Churchyard

CONTENTS

Chapter

I. A House Divided Against Itself

VIII. Fortune Smiles On Juliet

XII. The Responsibility of Wealth

XVII. A Dream and an Awakening

HER OWN WAY

A HOUSE DIVIDED AGAINST ITSELF

"THE girls are late to-day."

"You mean that Hannah is late, mother; for there is no saying when Juliet will choose to appear, and they never come together. It is a strange thing for Hannah to be behind her time."

Mrs. Tracy sighed as she looked anxiously between the flower-pots which adorned the window-ledge, and rather obscured the view from where she sat in her low easy-chair.

The window looked into a grassy enclosure, too small to be dignified by the name of garden, though there was a fine show of primroses and wallflowers in the narrow bed beside the gravel path, and ferns were growing tall and strong in the rockery below the windows. On the farther side of the strip of grass, just within the iron railing that enclosed it from the road, stood three tall, leafy poplars, screening the house from the busy suburban thoroughfare in which it stood, and giving it its name.

As Mrs. Tracy looked forth, she caught glimpses through the trees of passing omnibuses and tramcars. The din of the traffic made itself heard, though the window was closed. Some of her acquaintance had tried to persuade Mrs. Tracy that the trees shut out air from the house, and it would be wiser to cut them down; but she always felt that it would be unendurable to live so near the high road without the slight shelter which their thick trunks and soaring boughs afforded. And the comparatively low rent asked for that old-fashioned residence, known as The Poplars, suited her narrow purse, and constrained her to endure its inconveniences as best she could.

Mrs. Tracy was a frail-looking little woman, with a face which had once been pretty and was still pleasant to look upon. It wore a somewhat careworn, anxious expression, but without a trace of fretfulness. As she rested in her low easy-chair, with her knitting lying in her lap, she had the air of one to whom exertion of any kind is distasteful. She was dressed in a manner perfectly becoming her fifty years, but the lace falling so prettily about her neck, and her dainty little lace head-dress with its cunning knot of pink ribbon, showed that she was by no means indifferent to the appearance she presented. Her small, soft, white hands glittered with handsome rings; the little feet outstretched on hassock were clothed with neat velvet slippers with bright jet buckles. At fifty Mrs. Tracy had not outlived her love for pretty things.

The daughter who stood near, and who was engaged in putting sundry finishing touches to the table which was prepared for their midday dinner, did not in the least resemble her mother. Salome Grant was a tall, well-grown young woman of seven-and-twenty. She had sandy hair, pale blue eyes with very light lashes, and a rather high complexion. Her abundant hair was brushed very smooth, and arranged in the neatest fashion. Her whole appearance, indeed, was severely neat. Her serge gown fitted her well, but it entirely lacked what dressmakers term "style," and no touch of colour relieved its sombre hue. One might have credited Salome with excellent qualities, but assuredly no one at first sight could have found her interesting, or felt eager to pursue her acquaintance.

"Here comes Hannah," she said, glancing through the window, as she heard the gate swing back.

And the next minute, Hannah entered the room. She was barely two years older than Salome, and resembled her sister far more than she did her mother. She was better-looking than Salome; her hair was darker, her complexion less high-coloured, her features stronger, and her eyes a deeper blue. Her ample square forehead, from which the hair was rigorously brushed back, seemed to denote considerable intellectual power, whilst the firm lines of mouth and chin showed a strength of will which might degenerate into obstinacy. She looked a strong, capable, energetic woman as she came quickly into the room, her countenance wearing a slightly harassed expression.

She was one of the staff of mistresses belonging to a large high school established in the North London suburb in which Mrs. Tracy lived. She had worked hard, and improved her position considerably since she entered the school, having won the character of a most efficient teacher and thorough disciplinarian. She and Salome were the daughters of Mrs. Tracy's first marriage with a sober, hard-working Glasgow man of business. They resembled their shrewd, staid, matter-of-fact Scotch father far more than they did the pretty, loving little Englishwoman, whom, with a strange lack of his usual prudence, he had taken to wife.

"I am sorry to be late, mother," Hannah said in clear, incisive tones, "but it is not my fault. I saw Juliet in the playground with that horrid Chalcombe girl, so I went to ask her if she were ready to come home. Juliet was in one of her tiresome moods, and was not too polite to me. At first, she would not say what she would do; but finally I understood her to say that she would come. However, after I had waited for ten minutes, I saw her walking away in the opposite direction with her new friend."

"Oh dear!" said Mrs. Tracy, a flush suffusing her delicate face.

"Did you really tell Juliet, mother, that she was not to make a friend of that girl?"

"Oh yes, dear, I spoke to her about it; but she seemed to think it hard that they could not be friendly when they were in the same form, and I thought that Juliet would soon be leaving school, and after that they are not likely to see much of each other, you know."

"But, meanwhile, there is time for Juliet to get a great deal of harm," replied Hannah. "However, if you like her to associate with the daughter of an actor, I have nothing more to say."

"My dear! I do not like it. You should not say that. Is the girl's father really an actor?"

"Well, I do not know that he acts," said Hannah deliberately; "I think someone said that he was the lessee of a theatre at Bow. He has a son who sings at music halls."

"What people for Juliet to take up with!" exclaimed Salome, in a tone of disgust. "She will be wanting to become an actress next. There is no accounting for what Juliet will do. She seems to have no sense at all."

"Don't make her out worse than she is," pleaded her mother. "She knows nothing of the father and son, and I daresay the girl is not so bad; Juliet seems very fond of her."

"I only wish you could see her!" said Hannah. "She dresses in the most extreme style, wears flashy jewellery, and is generally vulgar. Her complexion is frightfully got up. As for her work, their form-mistress tells me it could hardly be worse. We all wish she had not come to the school, for she will do us no credit."

"Juliet should be forbidden to have anything to say to her," remarked Salome.

"It is easy to say that," replied her mother, "but you know it does not do to take extreme measures with Juliet. Once drive her into defiance, and you can do nothing with her. I believe she is persisting in this intimacy just because she knows you are set against it."

"That is likely enough," said Hannah, in a bitter tone. "Well, I only hope that you may never regret that you have not taken more extreme measures with Juliet. You will not wait dinner for her, mother?"

Mrs. Tracy made a sign of dissent, and in a few minutes they were seated at the dinner-table. The mother was depressed, and ate with little appetite.

She stood in some awe of her elder daughters, with their exemplary conduct and correct views. She always felt that they had had some right to resent her marriage with Captain Tracy, a gay, dashing Irish officer, some years younger than herself. Hannah and Salome had been mere children at the time, but they had not failed to show their resentment. When, shortly after his marriage, the captain's regiment was ordered to India, a relative of their father offered to take charge of the two girls during their mother's absence abroad. Mrs. Tracy was well pleased with this arrangement.

She had been absent for seven years when she came back to England with her pretty though faded face, framed by a widow's sombre veil, and bringing with her a wilful, fascinating little girl, with sunny hair and violet eyes. The gay captain had met with an accident at a polo-match, from the effects of which he had died shortly afterwards. His widow mourned him sincerely, though he had been but a sorry husband, sublimely indifferent to her comfort and welfare, as long as he could squander her money on his own pleasures. But the indifference had been delicately veiled, and only on rare occasions had Mrs. Tracy, with a bitter heart-pang, suspected its existence. Captain Tracy pursued his extravagances in a gentlemanly manner, and never failed to treat his wife with lover-like, caressing tenderness, so that she loved him passionately to the last, and paid his debts of honour, time after time, with but faint remonstrance.

But the large sums she had realised for this purpose, in spite of every objection raised by the Scotch solicitor who managed her affairs, were a serious drain on her resources. She came home to find the property her first husband had left her considerably diminished, and to learn that it behoved her for the rest of her life, by rigid economy and self-denial, to make amends for Captain Tracy's extravagance. The lesson was a painful one, embittered by her sense that her elder girls had a right to reproach her with careless neglect of their interests.

By this time, Hannah and Salome were almost women. The high-bred, irreproachable, somewhat narrow-minded Scotch cousin in whose home they had been living had left her stamp on them. They hardly seemed like her own daughters to Mrs. Tracy now. They were far more orderly and methodic in their habits than she was herself, and held stricter views with regard to the expenditure of time and money. The mother felt half afraid of these very wise girls. She was thankful that they were so good, but she could not help wishing that they had been a little less strong-minded, and could have made some allowance for the faults of their pretty, perverse half-sister.

Then, with a sigh, she would remind herself that it was only natural that they should be hard upon poor little Juliet, and resent her presence in their home. And the mother's heart clung the more passionately to the child who seemed so much more her own than these others. The girls were quick to see that their mother loved Juliet best, and their minds were not too high-toned to admit of jealousy. Juliet became a constant thorn in their sides. They looked upon her as the disturber of the peace of their home. But Juliet was her mother's darling, though, in truth, a very naughty darling.

For a year or two after her return from India, Mrs. Tracy had a hard struggle to maintain a little home. But Hannah studied with an assiduity which astonished her mother, whose own education had been of the old-fashioned, superficial order; she passed one examination after another with honours, and finally attained the immediate goal of her ambition by being appointed assistant-mistress in a high school. Then it was that Mrs. Tracy felt justified in taking The Poplars as her residence, which had now been their home for over eight years.

The meal was half over, when a loud and very characteristic knock at the front door announced Juliet's return. The next minute she entered the room, a slight, graceful girl, whom no one would have taken to be more than seventeen, though, in truth, she had passed her nineteenth birthday.

A greater contrast than her appearance presented to that of her sisters it would be difficult to imagine. She was delicately fair, with eyes of that deep, soft hue which is better described as violet than blue. Masses of soft bright hair, which might justly be termed golden, though not of the deep reddish tinge which often wins that name, showed beneath the sailor hat which, either by intention or accident, was placed on her head at rather an unusual angle. Juliet's wavy, flossy locks were always more or less dishevelled. Perhaps she meant them to express a protest against her sisters' smooth, shining polls. Her serge gown had quite a different effect from Salome's, yet was made of the same material. It suited her charmingly, though it was shabby, and an ink-stain soiled the frilled cambric vest.

Mrs. Tracy turned with a smile of welcome on her face as the girl entered. It was a delight to her to see the sweet, bright face that smiled at her in response. She thought that no one could fail to feel the charm of that young face; but her sisters saw in Juliet's demeanour only the signs of those qualities of mind and character which they held in special abhorrence, and her prettiness was to them merely an aggravating circumstance, heightening the enormity of her heedlessness.

She came into the room swinging a strapful of books in one hand, and she surveyed the party at the table in the coolest manner for a moment, ere, advancing to her mother's side, she bent to kiss her.

"How is it you are so late, Juliet?" asked her mother, with only the faintest reproof in her tones. "See, we have almost finished dinner."

"I walked a few steps with Flossie Chalcombe," replied Juliet, her eyes flashing defiance at her sister Hannah; "she had something to tell me. I did not think it was so late."

"I told you it was getting late," said Hannah; "I warned you there was no time to spare."

"That was very good of you," returned the girl, with insolent coolness; "I fear I lost sight of the fact afterwards. But here I am at last, and desperately hungry too, mother dear; so don't let us waste time in words."

"My dear Juliet!" protested Mrs. Tracy; but she began quickly to serve her.

"You are surely not going to sit down as you are?" said Salome.

"Why not?" retorted Juliet. "It's quite proper to wear your hat at luncheon."

"But this is our dinner," said Hannah.

"What does it matter?" asked Juliet. "What's in a name? A potato, please, Salome. Oh, you need not look at my hands; they are quite clean, I assure you. I washed them in the dressing-room before I left school. Just fancy I am Mrs. Hayes, and it will be all right."

"Never mind, dears," said Mrs. Tracy hurriedly, as she met the disapproving glances of her elder daughters; "it is better she should take her dinner quickly. Ann is so put out when the meals are kept about."

"You had better speak to Juliet about that," said Salome. "It is not Hannah and I who keep the meals about."

"Oh, of course it is me," said Juliet, with more emphasis than grammar; "everything that happens is always my fault."

"Oh, hush, my dear!" said her mother, looking uneasy.

But Juliet was not easily subdued. Hannah and Salome fell into dignified silence, but Juliet continued to talk in her gayest, most careless manner, as though determined to show her sisters that she cared naught for their disapproval. She looked very charming, with a glow of soft, rich colour in her cheek and a mischievous sparkle in her eyes.

Her mother might be forgiven for the loving admiration her eyes so plainly expressed. Despite the daring freedom with which she often deported herself, there was no grain of coarseness perceptible in Juliet's bearing. Even in her most careless actions, her least conscious attitudes, there was always a subtle grace. She was as frank and bold of speech as a boy, yet had all the charm of fresh young maidenhood.

She was a grand favourite with both scholars and teachers at the high school, where she still studied. Even those who shook their heads over her thoughtlessness, and were most aware of her faults, felt the witchery of her prettiness and grace and sunny light-heartedness. Perhaps her sisters were the only exceptions to this rule. But then Juliet had never tried to ingratiate herself with them. She had always taken a perverse delight in shocking and vexing them.

When they had finished their dinner Hannah and Salome begged to be excused from sitting longer at the table, as they wanted to go out. Juliet heaved a sigh of relief as the door closed on them.

"Thank goodness, they are gone!" she said. "What wet blankets they are!"

"My dear! I don't think that is a nice way to speak of your sisters."

"No?" said Juliet, turning to her mother with a smile which seemed to take all the impertinence from the query. "But you and I are always happier when we are left alone together, mother dear. You can't deny that. There are two parties in this house; you and I on one side, and Hannah and Salome on the other. We are the Whigs, and they are the Tories. It is a house divided against itself."

"Oh, not so bad as that, I hope!" exclaimed Mrs. Tracy. "You know what the Bible says about a house divided against itself?"

"That it cannot stand," replied Juliet gravely. "Sometimes I wonder how long our house will stand. Hannah will have to learn somehow by the time I am twenty-one that I mean to take my own way and do as I like."

Mrs. Tracy looked troubled. "I wish you would not set yourself so against Hannah," she said; "she only desires your good."

"Oh, of course!" Juliet laughed scornfully. "I suppose it was my good she was seeking when she came after me in the playground, using so little tact in her efforts to draw me away from Flossie Chalcombe, that Flossie saw her intention, and was hurt."

"Ah, that was a pity!" said Mrs. Tracy, with feeling. "But, dear, I am afraid, from what I hear, that Miss Chalcombe is not a nice friend for you."

"But, mother dear, you can have heard nothing of her except what Hannah says, who is a most prejudiced person. Flossie is really a very nice girl. May I bring her here some day to see you?"

"I am afraid that would not do, Juliet. Your sisters would not like it."

"Oh, if you must consider them!" exclaimed Juliet impatiently. "They fancy Mr. Chalcombe cannot be respectable because he has something to do with the theatre, though if he were at the top of the profession, like Irving, they would be eager to make Flossie's acquaintance."

"I don't think that would make any difference to your sisters' feelings, Juliet."

"Well, perhaps not to theirs," the girl admitted; "but it would be the case with most of the teachers and girls at school. It is a shame the way they shun Flossie. I feel for her very much. She says I am the only friend she has, and I mean to be true to her. I will not give her up, whatever Hannah may say or do."

Mrs. Tracy received this defiant speech in silence. She could sympathise with Juliet's generous resolve to stand by the girl to whom others were disposed to turn the cold shoulder. She herself, as an officer's wife, had been wont to seek out and befriend those whom, for some trivial cause or other, the elite of the regiment were disposed to hold at arms' length. She hesitated to tell the girl that she must restrain her kindly impulses.

"You would do the same in my place, mother," said Juliet, as she fixed her large violet eyes on her mother's face, and read her mind.

Mrs. Tracy smiled. "Perhaps I should, Juliet; but still I do not like you to make undesirable acquaintances. You are so young, and know so little of the world."

"I may know little of the world," exclaimed Juliet hotly, "but at all events I know enough to see that people are not so bad as they are made out. If Flossie is an undesirable companion, I can only say that I like her infinitely better than any proper, correct, narrow-minded person like Hannah. I begin to doubt the advantages of the respectability on which Hannah and Salome pride themselves, when I see how much nicer people can be without it."

"Oh, child, don't talk like that! You frighten me. Hannah and Salome are right. They may be a little over-strict,—I do not say they are not,—but they are right in the main. It never does to defy social opinion. Bohemianism may look attractive to a young girl like you, who knows nothing about it, but it is a perilous borderland at the best. Oh, I do wish I could persuade you—"

"Not to give up being friendly with Flossie Chalcombe, who has no dear mother as I have, and really wants me," said Juliet, who had approached her mother, and now slipped one arm about Mrs. Tracy's neck, and deftly closed the lips, whose utterance she did not wish to hear, with her rosy finger-tips. "You would not wish me to do that, I am sure, mother mine." Then with a loving hug and kiss Juliet bounded away, laughing lightly as she quitted the room.

Thus the talk between Juliet and her mother ended as Hannah could have foretold that it would end.

THE ILL-CHOSEN FRIEND

HANNAH GRANT was an excellent person in every way. Her health was as sound as her principles, and she was a fine-looking, without being a winsome, woman.

Others beside her pupils shrank from the severe scrutiny of her cold blue eyes. Yet she was fairly liked by the girls she taught, for, whilst a strict disciplinarian, she was invariably just. Clear-headed and eminently practical, she had a knack of imparting knowledge in such a manner that even the least nimble-minded could not fail to grasp it. This, however, was not the outcome of mere chance, but the result of conscientious effort on her part.

Whatever Hannah undertook to do, she took infinite pains to do it well. She gloried in her thoroughness, her good sense, her subjection of inclination to duty. It followed that she had little patience with those whose conduct fell below her own standard. She lacked the imaginative insight and the gentle sympathy that might have led her to make allowance for her weaker sisters. The idle, thoughtless, and inconsequent amongst her pupils found no mercy with her.

Juliet was not in the form taught by her sister, and they came little into contact during school hours. Though by no means stupid, Juliet rarely took a good position in her classes. She had been frail and delicate as a child, as children born in India often are, and Mrs. Tracy refused to allow her education to be pressed. She should run wild until she had attained some robustness.

The running wild may have been of advantage to Juliet physically, but it developed in her qualities of mind and character which could not afterwards easily be eradicated. When she entered the high school she was far more backward in her studies than most girls of her age, and, having never learned to apply herself, her progress for some years was most tedious.

It vexed Hannah that Juliet should take so low a place in the school. She was irritated by seeing in her sister those faults of idleness, carelessness, and indifference which she knew must prove fatal to her advancement. She was persuaded that Juliet could have done better if she would.

But Juliet would not see the importance of her own education; there was no inducing her to take a serious view of the future that lay before her. She had wished to leave school long before this, and Mrs. Tracy would weakly have yielded to her desire, but for Hannah's strong representation of the necessity for Juliet being properly educated, since she would have to take a situation when she left school.

Mrs. Tracy shook her head in secret over the thought of her pretty Juliet becoming a governess, but she did not dare to openly oppose Hannah's suggestion. Though she remained at school longer than many girls do, Juliet never attained the dignity of the sixth form, and Hannah herself had decided that her young sister must leave at the end of the present term.

Hannah might be forgiven for feeling annoyance when Juliet, who could have had almost any girl in the school for her friend, chose to attach herself to Flossie Chalcombe. For undoubtedly the girl was of a lower social stamp than most of the scholars, though she was sufficiently bright and pretty to attract Juliet's somewhat fickle fancy. Her features were good and of a pronounced type; she had a quantity of dark hair, which she wore very much becurled on her forehead; long, rather peculiar greyish eyes; and a complexion which was suspiciously pink and white. She was wont to darken her eyelids and otherwise "get up" her eyes, and her lips were brilliantly red. She dressed smartly; but her clothes seldom looked fresh, and were never such as became a schoolgirl. She wore ornaments in her ears, and her hands were always adorned by rings and bangles. There was a disagreeable, underbred air about the girl.

Juliet, who with all her perversity was an innate little lady, could hardly be entirely unconscious of what was lacking in her friend. Flossie looked the elder, though in reality, some months younger than Juliet. Her life had been very different from that of Juliet. Ignorant of many things, with mind untrained and neglected, she yet had much of such knowledge of the world as she would have been better without. Hannah was right in deeming her an undesirable acquaintance for her young sister; but it was a pity she so openly opposed the friendship, since it had the effect of rendering Juliet, ever prone to resent Hannah's judgments, perversely bent on maintaining it. Left to herself, Juliet would probably soon have ceased to care for Flossie Chalcombe. She was rather given to becoming passionately attached to people for a short time. The fascination, enthralling whilst it lasted, was seldom of long duration.

On the day following that on which our story began, Juliet and Flossie came out of the schoolhouse together about four o'clock. They were not often at the school in the afternoon, but to-day they had been attending the class for calisthenics, for which no time could be found during the morning.

"Do come home with me, Juliet," said Flossie, as the gate swung to behind them; "you might as well. You have plenty of time this afternoon."

"I can't come home with you," said Juliet, somewhat startled by the proposition, "but I don't mind walking part of the way."

"Why cannot you come all the way?" asked Flossie. "You have never even seen where I live. But I know why it is. You are afraid of what Miss Grant will say. She does not consider me a proper acquaintance for you."

"Nonsense!" exclaimed Juliet, colouring.

"You know it is true, Juliet. You cannot deny it."

"Well, if it is, I don't care that for what Hannah says." And Juliet emphasised her words by kicking a piece of orange peel from the pavement into the gutter.

Flossie laughed.

"Bravo, Juliet! I admire your spirit. As I was saying to Algernon yesterday, you are not the girl to be domineered over by those old maids at home."

Juliet was silent. She did not quite like the way in which Flossie spoke of her sisters. In spite of her antagonism to them, she was not insensible to the family bond, but was ready to resent any detraction of them from an outsider. Flossie saw she had made a mistake, and tried to divert Juliet's thoughts by the remark—

"Algernon says he is sure you will not be an old maid."

Juliet blushed warmly.

"I wonder what he can know about it?" she exclaimed, in some embarrassment.

"Oh, he can judge; he has seen you."

"Has he?" exclaimed Juliet, in surprise. "When?"

"Oh, the other night at the school concert."

"Was he there? Oh, I wish I had seen him!" exclaimed Juliet naïvely, though the next moment she blushed for her words. Flossie constantly talked to her of this brother, of whom she seemed very proud, and Juliet had become interested in him.

"Yes, he came because he wanted to see you, and he hardly took his eyes off you all the time. He said there was no one else worth looking at. He paid no attention to the music; he only looked at you."

Juliet's blushes deepened.

"Of course he could not care about the music," she said hurriedly, "it must be so inferior, so different at least, from what he is accustomed to."

"Oh, of course."

"I wonder I never saw you," said Juliet. "I looked about a good deal, too."

"We were farther back, at your right. We did not stay till the end. Algie got tired of it—or rather, he had another engagement. We saw you well, Juliet. You looked so pretty in that white frock. I never saw you in white before. I suppose that nice-looking lady in black silk was your mother?"

"Yes, that was mother," said Juliet, with pleasure in her tones.

"But what an odd-looking individual it was who sat on the other side of you! I took her to be your other sister, by her likeness to Miss Grant. Does she always dress in that very severe style?"

"Always," said Juliet, with some sharpness in her tone, for she thought her companion a little too free with her comments. "Salome thinks it is wrong to dress like other people. You know she is very religious, works amongst the poor, and all that sort of thing, so she dresses plainly on principle."

"Oh dear, I am glad I do not feel it my duty to make a guy of myself!" laughed Flossie. "However, as Algernon remarked, she makes an excellent foil to you. Do you know he walked to school with me this morning because he wanted to see you? It was tiresome of you to come late."

"Oh, indeed! I do not at all regret it," said Juliet, tossing her head.

"Now don't be high and mighty. What harm would Algernon do by looking at you? He says you are an inspiration to him."

"An inspiration! Really! I like that!" And Juliet laughed merrily.

"Ah, you may laugh, but it is true. He has begun to write a dramatic play, and you are the heroine."

"Flossie!"

"It's quite true. You are a lovely maiden shut up in a castle, guarded by an ogre, and he is the hero who comes and delivers you. He told me so, indeed. Of course he may have been making fun; but I know he is writing a play."

"Has he written any before?" asked Juliet.

"Yes, but they have never been put on the stage. He thinks this will be a great success. He writes sometimes, and things of his have been published in the comic papers. Algernon is really very clever, though I say it."

"He must be," said Juliet, in a tone of conviction.

As they talked thus, Juliet had been walking on without noting how far she was going. Nov, as a turn of the road brought into view a wide grassy space enclosed by palings and intersected by paths running in various directions, she suddenly paused.

"Why, here we are at the Green!" she exclaimed. "I never meant to come so far. Now I must say good-bye, Flossie."

"No, indeed. You must come home with me, now you are so near. That is our house just over there on the other side of the Green. Do come, Juliet; Algernon will be so pleased if he is at home."

Juliet drew back, instinctively drawing up her slight figure.

"But he is hardly likely to be at home at this hour," said Flossie, with a quick perception that she had said the wrong thing. "I shall probably find the house empty. You might come and have a cup of tea with me, Juliet."

Juliet shook her head, but she felt tempted. She was curious as to her friend's home, and interested in the brother whom she had inspired to write a dramatic play. She shrank from the thought of meeting her admirer; but she would have liked well to get a clearer notion of him and his surroundings. But she knew that her mother would strongly object to her entering the Chalcombes' house, and to do so would be to flaunt the flag of defiance in Hannah's face.

"You need not tell them at home, if you are afraid of a row," suggested Flossie, as Juliet hesitated.

"I am afraid of nothing," exclaimed Juliet impetuously, "and I am not one to conceal what I do! But I cannot stay, Flossie. Mother would—"

"Consider that you had demeaned yourself by crossing our threshold," Flossie interrupted her, in a resentful tone. "I wonder what there is about us that people should shun us as if we were lepers."

"Mother does not feel so, Flossie; she does not know you. It is only Hannah who is—as horrid as possible."

"But you say you do not care for Hannah's opinion; you are not going to be controlled by her. Ha, ha! Juliet; I shall begin to think you are afraid of Miss Grant, after all, if you refuse to come in."

The colour rose in Juliet's face. She was one who could be dared into doing things, as Flossie knew well. Juliet forgot the pain her action would cause her mother, forgot every consideration which should have withheld her from entering the house of which she knew so little, in the passionate desire of her will to assert itself, and show she was in subjection to no one.

"I am afraid of nobody!" she exclaimed hotly; "I take my own way whenever I choose; and, just to show you that, I will come with you, Flossie; but you must not ask me to stay long."

Flossie smiled triumphantly as they started to walk across the Green. Juliet might boast of taking her own way; but in their intercourse it not seldom happened, as now, that it was Flossie and not Juliet who gained her end.

The house in which the Chalcombes lived stood back from the road, and was screened by a small shrubbery. The approach to the house was ill-kept, and the steps very dirty; but Juliet was not one to heed such details. On the top of the steps, a huge bull-dog was stretched. He roused himself at the sound of a strange voice, and broke into a fierce bark; but Juliet being absolutely fearless of animals, spoke soothingly to him and patted his broad head, whereupon his bark subsided into a whine, and he wagged his stump of a tail.

"Why, Sykes has quickly made friends with you," exclaimed Flossie, in surprise; "he is most suspicious of strangers, as a rule."

With that Flossie used the knocker vigorously, and, after some delay, the door was opened by a very untidy maid-of-all-work.

"Come in," said Flossie cheerfully.

And Juliet followed her across the threshold, not without an uneasy thought of how her mother would feel if she could see her.

A PEEP INTO BOHEMIA

FLOSSIE CHALCOMBE led Juliet into a square, lofty room, which was the dining-room of the house.

It was not an ill-furnished room, but it looked dingy, and had, even to Juliet's unobservant eyes, a most untidy appearance, whilst her sensitive nostrils were at once aware of the disagreeable odour of stale tobacco.

The ceiling was darkened by smoke; the curtains, once white, had, under the strain of smoke and dust from within, and damp and smuts from without, developed a greyish hue; the carpet, once handsome, was discoloured and threadbare, rather, perhaps, from the effects of careless usage than as the result of long service; a pipe-rack and a tobacco jar appeared amongst other odd ornaments on the mantelpiece, and the pier-glass above it presented a curious effect, being bordered on each side as high as hands could reach with papers, play-bills, photographs, etc., stuck for security within its rim. The chairs were of oak, curiously carved, with crimson leather seats. A handsome sideboard with a plate-glass back stood on one side, presenting an array of flagons and decanters flanked by a black bottle or two. A plated spirit-stand was in the centre. The cut-glass decanter labelled "whisky" had been drawn out and stood on the table beside two empty glasses. Near the door a cottage piano stood open, the top littered with sheets of music, and on the music-stand a piece bearing on its cover a marvellous representation of a gentleman in extravagantly fashionable attire making his bow to an imaginary audience.

As Juliet glanced round her, the misgivings with which she had entered the house increased.

"Is father at home?" Flossie asked of the servant, as her eyes fell on the empty glasses.

The maid answered in the affirmative.

Flossie slightly shrugged her shoulders, and Juliet fancied she was not best pleased.

"Make us some tea, Maria, as quickly as you can," said Flossie, "and let it be strong, mind. And stay, you had better run to the nearest shop for a cake; I don't suppose there is any in the house."

"Oh, Flossie, please don't," began Juliet.

"Nonsense, Juliet!" Flossie checked her laughingly. "I may surely order cake if I like. I want some, it you do not."

"But I really ought not to stay," faltered Juliet.

"You are not going till you have had some tea, so there," said Flossie imperiously. "Excuse me one moment." And she disappeared.

Juliet heartily wished that she had not entered the house. She foresaw that the maid's getting tea would be a long business; but it seemed impossible to hurry away now without hurting Flossie's feelings.

"What would Hannah say if she could see me!" she thought. "How shocked Salome, who always wears the blue ribbon, would be if she saw that sideboard!"

In fact, Juliet was slightly shocked herself. Decidedly the people who dwelt in this house were of a different set from her own. What a strange, disorderly room it was! She glanced at the pier-glass, and saw the likeness of a ballet-girl taken in such extreme attire, that, though she was alone, Juliet instinctively lowered her eyes with a sense of shame. But ere she had time to observe more there was a sound of voices in the hall, and Flossie entered followed by her brother.

"Juliet, this is Algernon, who has been wishing so much to make your acquaintance. I hardly thought he would be at home, but—"

"Fortune has been kind to me," added her brother, in a low, rich voice, as she hesitated.

The colour flew into Juliet's cheeks and deepened as she met the frankly admiring glance of Flossie's brother. She hardly knew how she acknowledged the introduction, so conscious was she of those tiresome blushes and the timid fluttering of her heart.

But there was nothing formidable in the appearance of Algernon Chalcombe, unless it were his extreme handsomeness. Juliet saw before her a well-formed, graceful man of middle height, whose dark beauty was well set off by the crimson and black "blazer" which he wore. His black hair was rather long and inclined to curl; he had fine dark lustrous eyes and regular features. The mouth was rather large in proportion to the rest of the face, with full lips, the chin large, full, and rounded. He had been told that he resembled the portraits of Lord Byron, and the suggestion flattered his vanity. He was amply endowed with that commodity, and his countenance revealed its presence, and betrayed tokens too of luxurious, self-indulgent habits.

But Juliet had not the experience that could discern these. She was struck with the graceful bearing and polished ease of the young man. Although his eyes plainly expressed admiration for her, there was no insolence in their gaze. On the contrary, he contrived to infuse into his manner a subtle suggestion of self-depreciation and humility inspired by her presence, and his tone in addressing her was charmingly deferential.

"He is a perfect gentleman," thought Juliet, with a sense of agreeable surprise.

And certainly Algernon Chalcombe lacked none of the externals of a gentleman. It had been his father's ambition to make him such, and his education had been expensive, and therefore presumably good. It had even comprised a sojourn at Oxford, but his career at the University had come to an abrupt termination, and he had reasons for preferring not to speak of that period of his life. At Oxford and elsewhere he had courted the society of men of a higher social standing than his own, and had been quick to catch their tone and learn their habits.

Thus it was that Juliet discerned in him what she took to be tokens of high breeding and superior personal refinement. Having no brother, and belonging to a wholly feminine household, her ideas as to what constitutes a gentleman were perhaps more crude than are those of most girls. Certain it is that Algernon Chalcombe's ready courtesy, his pleasant accent, the well-made garments which he wore with such careless grace, his white hands and polished nails, all combined to produce on her the impression of a personal distinction and innate chivalry befitting a hero of romance. Juliet had read few romances—Hannah had seen to that—but perhaps just because they were so few, those she had read had made the more impression on her vivid imagination.

Flossie was quick to see how Juliet was struck by Algernon's appearance and bearing. She was delighted, for she was very fond of this brother seven years older than herself. She was able to make a hero of him in her way, though she saw him under other aspects than that which he was so studiously presenting to Juliet.

"This is not the first time that I have had the pleasure of seeing you, Miss Tracy," remarked Algernon Chalcombe. "Flossie pointed you out to me at your school concert."

"Yes, so she told me," said Juliet hurriedly, blushing deeply the next moment, as she remembered all Flossie had said when she told her.

He did not appear conscious of her confusion, though in reality, he thought how pretty she looked when she blushed, and what a fresh, naïve, charming little girl she was.

"It was rather a slow affair that school concert, was it not?" he said, in his full, deep tones, with the fine drawl he affected.

"Oh yes—at least I do not know that I found it so," Juliet corrected herself; "but then I knew beforehand what it would be like. One cannot expect anything very startling at a school concert, when only the pupils perform. Of course it must have seemed a dull affair to you."

"Oh no; I liked it very much. I do not mean to say that I enjoyed the music particularly, but I liked being there. I was disappointed, though, to find that you were not amongst the performers. I had hoped to hear you play or sing."

"Flossie could have told you that was impossible. I do not learn music at school. I do not learn at all now, in fact."

"Do you really mean it? And yet I am sure you are musical."

Juliet shook her head. "I am afraid not. I am very fond of music, but I cannot play much. Salome used to teach me, but she gave me up in despair; and, indeed, I could never learn of her. We used to quarrel at every lesson."

"I don't wonder, if she taught you," said Flossie.

"Mother wanted me to have lessons of someone else, but Hannah said that would be an extravagance, when Salome is so well qualified to teach me. She gives lessons in music, you know, and is said to have an admirable method of training young strummers. I know her playing is quite correct, and all that, but can never feel that there is any music in it, somehow."

"I know the kind of playing you mean," said Algernon; "this is it, is it not?" He turned quickly to the piano, sat down and played a little air of Beethoven's; played it correctly, coldly, the time strictly accented, but without the least expression.

"That's it—that's it exactly!" exclaimed Juliet, delighted. "Salome always plays in that hard, woodeny manner."

"Do you know anyone who plays like this?" he asked. His hands now wandered over the keys in uncertain, fluttering movements, one hand always a little behind the other, as in staccato fashion, he struck out "Ye Banks and Braes."

"Oh yes, yes," said Juliet; "I have heard people play like that."

"What do you think of this?" he asked next. His hands descended with a crash upon the piano, tore at the notes, flew up and down the keyboard. Crash followed crash, run pursued run, there was a tumult in which hammer and tongs, tin-whistle and wooden drum might have been taking part, assisted by an enraged cat. The piano rocked beneath the violent onslaught, the room seemed to shake with it; then, suddenly, the din ceased, and the performer leaned back from the stool, laughing.

Flossie and Juliet were laughing too.

"Whatever is that remarkable composition?" asked his sister.

"'Battle, Murder, and Sudden Death,' an impromptu, by Algernon Chalcombe," he answered gravely.

"Won't you sing something to Juliet, now she is here?" suggested his sister. "She wants so much to hear you sing."

The colour rose in Juliet's face. She looked half-ashamed of hearing such a thing said. But the suggestion was very agreeable to Algernon Chalcombe.

"With pleasure, if she wishes it," he said, in his low, musical tones. "Her wish is a command to me."

He sang a song which was comic without being vulgar. His singing was very spirited, and his full, rich baritone was delightful to listen to. But when Juliet asked for another song, he chose one of a very different description. It was Blumenthal's "My Queen," and he sang it with great power and feeling.

The song is familiar enough to most persons now, but Juliet had not heard it before, and she was thrilled by the beauty of the words and the music. Still more was she thrilled when Algernon at its conclusion suddenly lifted his dark eyes to hers, and looked at her with a glance that seemed charged with unutterable meanings. Juliet trembled under the magnetism of that glance. She rose and looked about for her gloves, feeling a sudden desire to get away. But the tea had not yet appeared, and till now she had been unconscious how time was passing.

"You must not think of going yet," said Algernon, in his low, deep voice, as he came to her side. "Won't you sing something to me now? I am sure that you sing."

"Yes, indeed; she sings beautifully," exclaimed Flossie; "her voice is as clear as a bird's. Do sing, Juliet."

"Oh, I cannot! I never sing, except sometimes with mother some of the old songs that she used to sing when she was a girl."

"Won't you let me hear one of them?" said Algernon persuasively. "I love those good old songs."

"Oh no, indeed! I cannot sing, really," protested Juliet.

"Oh, but you must, you shall!" exclaimed Flossie. "I won't let you off, Juliet."

But her brother gravely interposed.

"Stay, Flossie. Miss Tracy shall not be urged to sing if the idea is really disagreeable to her. Of course it would have given me great pleasure; but it shall be just as she likes."

Juliet immediately felt convicted of ingratitude. He had been so kind in singing to her, it seemed horrid of her to refuse to gratify him in her turn.

"I will try, if you like," she faltered; "but you must please go to the other end of the room and promise not to listen."

"I cannot promise that," he said, with a gleam of amusement in his eyes, "but I assure you I will not listen critically."

He moved away as he spoke, and Juliet, sitting down at the piano, struck a few notes in uncertain fashion, and then trilled forth the sweet old song, "Where the bee sucks, there lurk I."

She loved singing, and in a few moments, she had forgotten her nervousness. Her voice was untrained, but it was singularly sweet and clear. Algernon, as he stood carelessly with his hands in his pockets looking out of the window, expected only to be amused by some school-girlish warbling. He was amazed at the strength and purity of the full, clear notes.

But Algernon Chalcombe was not the only listener who was surprised and delighted by the sweet, bird-like notes. As Juliet sang the last verse, a shuffling tread was heard crossing the hall towards the half-open door, and the next moment, Mr. Chalcombe senior entered the room.

He was a short, stoutish man, with a highly coloured complexion and a round bullet head, but scantily covered with greyish hair. Late though it was in the afternoon, he wore what he was wont to describe as his "dishabilles," a gay, much-beflowered dressing-gown, considerably the worse for wear, whilst on his feet were a pair of old carpet slippers, the easiness of which was an advantage counterbalanced by the difficulty of keeping on the loose, downtrodden things.

Flossie's face flushed as her father entered, and an impatient frown appeared on that of Algernon; but Mr. Chalcombe's face beamed with good-nature. He had no misgivings as to his welcome as he joined the little party.

"Bravo! Bravo!" he cried heartily as Juliet finished her song. "I congratulate you, young lady, whoever you are, on having such a voice as that."

"Father, this is Miss Tracy," said Flossie, in a tone suggestive of remonstrance.

"To be sure. Juliet Tracy, your chum at the 'igh school. I've often 'eard of you, my dear. You two are in the same class, ar'n't you? It's a mighty fine thing, that 'igh school. You young people nowadays 'ave great advantages. My hedjucation was all crowded into three years, which left little time for putting on the polish. Ha, ha! But there, I've done very well without it." And Mr. Chalcombe struck the table sharply with his hand, by way of giving emphasis to his words.

His son looked much annoyed. He moved quickly to Juliet's side, saying in a low voice, with an evident desire to cover his father's want of taste—

"Thank you so much, Miss Tracy. Your voice is indeed beautiful. One does not often have the chance of hearing such."

"Oh, but my singing is not good," said Juliet, looking much pleased, however. "You see, I have had no proper training."

"Yes, yes, I can tell that," said Mr. Chalcombe, taking the remark as addressed to him; "but it's not too late for it to be cultivated, and it's a lovely voice. You might make your fortune on the stage with such a voice as that."

Juliet looked at the speaker with a startled air. At the first moment she saw him and heard him speak, she had been conscious of a sensation of strong repulsion from one who was obviously such a vulgar member of society. But now his words were so agreeably suggestive and flattering to her self-love that she was disposed to view him more favourably.

"The stage!" she exclaimed. "Oh, I should never think of going on the stage!"

"And why not?" he demanded. "It's my belief you'd be a grand success as an opera singer. Patti, Neilson, Trebelli, and all the rest of them would 'ave to look to their laurels when you made your début. Oh, you need not laugh, my dear; I'm not joking."

"I think you must be, when you prophesy such things as that for me," said Juliet, with a merry laugh.

"Nonsense!" he exclaimed excitedly. "I tell you, there's many a one sings at 'er Majesty's opera whose voice is a less musical one than yours. You've 'eard Orféo?"

"I have heard nothing," said Juliet. "I have never been to the theatre or the opera in my life."

"You don't mean that?"

"Indeed I do. My mother and sisters do not approve of the theatre. They would never let me go."

Mr. Chalcombe muttered something that it was well Juliet did not catch, since it was not complimentary to the intelligence of her family. Flossie was listening rather nervously to the talk going on between her father and her friend. It was a relief to her that at this moment the maid appeared bearing the tea-tray, which she placed with some clatter on the table.

"Here's the tea at last!" Flossie exclaimed. "You must have thought, Juliet, that it was never coming."

Thus reminded of the flight of time, Juliet glanced at the clock, and was dismayed to see how late it was.

She rose from the piano. Algernon drew forward a chair for her, brought her some tea, and waited on her assiduously.

"Will you have some tea, father?" Flossie asked.

"No, thank you, my dear, no, thank you. Tea is all very well for women-folks, but I like something stronger. Oh dear, I am forgetting my letters! I must bid you good-day, Miss Tracy. Now think over what I've said, and when you've made up your mind, you come to me, and I'll put you in the way of things. It's my belief that with proper training you might soon be earning your thirty guineas a night, and that's not a sum to be sniffed at, let me tell you."

"No, indeed!" exclaimed Flossie. "Only think, Juliet, thirty guineas a night!"

"Juliet!" exclaimed Mr. Chalcombe. "There you are! The very name for an opera singer. She might play Juliet to your Romeo, eh, Algie? That would be the best use you could make of your good looks, as I often tell you. Ha, ha, ha!"

And laughing at his own joke, Mr. Chalcombe shuffled out of the room.

Juliet's cheeks were crimson as she sipped her tea, trying to look unconscious. Presently, glancing at Algernon Chalcombe, she perceived that he was gnawing his moustache savagely, and appeared much put out. Whereupon she reflected, not without sympathy, how trying a person of his refinement must find it to be saddled with such a parent.

"Have you really never been to a theatre, Juliet?" asked Flossie.

"Never," said Juliet, "and I do not suppose I ever shall."

"Oh, do not say that!" exclaimed Flossie. "How I wish you could go with us one, night! Father gets tickets for everything, you know."

And Algernon's expressive eyes said that he wished it too. But Juliet would not entertain such an idea for a moment. She rose to take her leave, and was not to be persuaded to stay longer.

As she hastened homewards at her quickest pace, her mind was in a strangely excited state. She knew that she might prepare to face a storm when she reached home, but she did not quail at the prospect. Her knowledge of the world seemed to have increased, and the horizon of her life to have widened with the experience of the afternoon. Her imagination played delightedly with words and looks which had been full of pleasant insinuation, as well as with the practical suggestions of Mr. Chalcombe senior. Her future seemed to be quite bewilderingly full of wonderful possibilities.

CONTRITION

SALOME GRANT seated herself at the tea-table behind the steaming urn. The clock on the mantelpiece had just struck six, and six was the hour at which they took their evening meal. The fact that Juliet had not yet come in was no reason for delaying it. Salome prided herself on her punctuality. Juliet could hardly be said to know what punctuality meant.

It was always Salome who made the tea, and her tea was excellent. She, indeed, attended generally to the housekeeping. Carefully trained by the Scotch cousin in whose home she had passed so many years, Salome had developed into as notable a housekeeper as her teacher. She was well versed in the niceties belonging to every department of domestic management. Her jams were always clear, her cakes light; her store cupboard never seemed to get out of order, and it was a pleasure to look into the linen-press, for Salome was a first-rate needlewoman also, and prided herself on the way she marked and kept the household linen.

Mrs. Tracy was well pleased, on the whole, to leave the care of the household in her daughter's capable hands. She was conscious that she was herself by no means a model housekeeper. As she moved with Captain Tracy from station to station, she had kept house in a careless, happy-go-lucky fashion, and the captain had never grumbled, though he seldom found it convenient to dine with his wife. But their expenses, though there was little to show for them, had mounted up wonderfully, and Mrs. Tracy had always an uneasy sense that she was being cheated, without being able to discover where the fraud originated.

Ere long they went to India, and there, as everyone knows, housekeeping differs considerably from the prosaic ordering of an English home. So Mrs. Tracy, on her return from abroad, had been thankful to find Salome such a clever manager, with quite an old head on her young shoulders. The mother, with her delicate health and languid dislike to exertion, had gradually fallen into the position of a merely nominal ruler, content to perform only such functions as her powerful prime minister would permit.

It had been necessary for Salome to leave school very early, though for some years afterwards she had pursued the study of music, with the result that she was now able, by giving lessons, to earn a sum which more than covered her modest personal expenses. There were times when Salome felt keenly the deficiencies in her education and the poverty of her mental attainments, compared with those of Hannah. But her sister never assumed airs of superiority. She was always ready to assure Salome that she had a special gift for domestic economy, and served the family interests as truly by her clever thrift and practical industry as she herself did by means of the good salary she earned.

A close bond united the sisters, though their affection was not demonstrative. Salome had the greatest admiration for Hannah's intellectual ability, and gladly set her free to devote her time to study, by undertaking Hannah's mending and making in addition to her own. She held Hannah's opinions in high esteem, and echoed them with a firm belief that they were her own. The two held together in most things, and on no matter were they more in accord than in their criticism of Juliet, and their mother's mistaken treatment of her.

Salome was pre-eminently a worker. Despite her many home duties, her music lessons, her sewing, she yet found time to take up outside work. She was a most exemplary Sunday-school teacher, and Mr. Hayes, the Vicar of St. Jude's, a church near The Poplars, counted on her help in various branches of his parish work.

Mrs. Hayes, herself a woman of considerable energy, which had to divide itself between the claims of her husband's parish and those of her rather numerous family, thought Miss Salome Grant a most excellent person, who would prove just the wife that Mr. Ainger, their single curate, needed; one who would make the very most of his slender stipend, and be capable of superintending any amount of cutting out and sewing for the poor of his parish, to say nothing of the management of soup-kitchens and blanket-clubs. Mr. Hayes was quite of the same opinion, though he made a mental note of the fact that Miss Grant was rather plain in appearance. But he himself had chosen his wife on the same principle that he chose his boots and broadcloth, for good wearing rather than showy qualities, with the additional advantage, which Salome lacked, that the lady had a few hundreds a year of her own.

Mr. Ainger, however, though ready to echo the praise which the vicar's wife bestowed on Miss Grant, evinced no desire to make her excellences his own. He remained obtuse to every hint, and Mrs. Hayes could only sigh over the perversity of men.

"Tea is ready, mother," said Salome, when she had filled all the cups, and Mrs. Tracy still remained at a distance bending over her needlework.

"In one moment, dear," said her mother; "I must finish this, now it is so nearly done."

Salome looked annoyed as she watched her mother's movements. Hannah had already taken her place at the table.

"There!" exclaimed Mrs. Tracy, holding up to view a tastefully made blue cotton blouse into which she had just set the last stitch. "How will that suit the child? She wants something cool to wear, now the weather has turned so warm."

"It is pretty," said Salome, in a tone which seemed to suggest that prettiness was a doubtful advantage.

"I do wonder, mother, when you will cease to think of Juliet as a child," said Hannah.

"Oh, not yet, I hope," said Mrs. Tracy cheerfully, pausing, to Salome's vexation, at the window to look up and down the road ere taking her place at the table. "After all, what is she but a child?" she added, as she turned towards the table.

"She was nineteen last February," said Hannah, in her most matter-of-fact tone. "I began to teach when I was nineteen."

"Ah, yes, my dear; but you were always so different from Juliet. And the youngest is usually more of a child than the others. Besides, you two are so much older. Why, you, Hannah, will be thirty on your next birthday."

"Yes, I shall be thirty," said Hannah calmly, with an air which said she was above being sensitive on the score of her age.

"Dear me, how old it makes me feel to think of having a daughter who is thirty!" observed Mrs. Tracy. "That is the worst of marrying young. You know, I was not twenty when I married your father. Why, how strange it seems! I was only a few months older than Juliet is now!"

"It is to be hoped that no one will be wanting to marry Juliet yet," said Salome, with a short laugh. "I should pity the man over whose household she presided."

"Oh, she would soon learn how to manage," said Mrs. Tracy, in her easy way; "that sort of thing comes to girls when they are married."

"I am not so sure of that," said Salome.

"Nor I," said Hannah. "It would certainly take Juliet a long time to learn to be such a housekeeper as you are, Salome. But Juliet must be taught to make herself useful when she leaves school."

"And she must find some employment," said Salome, "though I hardly know what she is fit for."

"Oh, there is time enough to consider that," said Mrs. Tracy, with an air of uneasiness. "There she is!" she added in a tone of relief, as Juliet's peculiar knock resounded through the house.

"So you're having tea?" said Juliet, thrusting her pretty, flushed face inside the door without entering. "I don't want any; I've had mine."

And she was off ere any questions could be asked, bounding upstairs three steps at a time.

"Where can she have had tea?" asked Salome wonderingly of her sister. "Do you think she went home with Frances Hayes?"

"Hardly. She and Frances have not seemed at all friendly of late."

"With Dora Felgate, perhaps," suggested Mrs. Tracy.

"I do not think so," said Hannah; "Juliet is by no means fond of Dora. I heard her call her a sneak only yesterday. No, if you ask me, I should say that most probably Juliet has been taking tea with her friend, Flossie Chalcombe."

"Oh no, Hannah," said Mrs. Tracy quickly; "Juliet would not go there."

Hannah made no reply, but smiled in a peculiar and exasperating manner. The subject was allowed to drop, but all three were feeling intensely curious as to how Juliet had passed the afternoon. That young lady did not appear to satisfy their curiosity.

As soon as tea was over, Salome went upstairs to get ready to go out. There was a committee meeting at the vestry that evening which she had promised to attend. On the first landing she paused, and, after a moment's hesitation, tapped on the closed door of the room Juliet shared with her mother.

"Come in!" rang out Juliet's voice, and Salome entered.

Juliet was seated on her little bed. She had not removed her hat, but it was thrust far back from the flossy curly mass of sunny hair above her forehead. Dusty shoes still covered the little feet, which she was swinging to and fro in undesirable proximity to the spotless counterpane.

Salome felt the natural irritation of an immaculate housewife who had recently sustained the burdens of a spring cleaning.

"Juliet, I wish you would not sit on your bed. It impossible to keep the counterpane clean if you do so."

"Oh, did you only come to say that?" Juliet's accents were provokingly cool.

Salome looked with angry disapproval at her flushed, excited face and saucy eyes.

"Of course not. How could I know that you were sitting on the bed till I opened the door? I came to ask if you really would have nothing to eat. There are some nice fresh scones downstairs."

"No, thank you, I am not hungry."

Juliet's tone expressed no gratitude. Already she divined that Salome had come mainly from a desire to find out how she had spent the afternoon.

"Where did you have tea?" asked Salome.

"With a friend," replied Juliet laconically, still retaining her position on the bed, and swinging her feet faster than before.

"Of course," replied Salome, with mild sarcasm; "I did not suppose it was with an enemy. That is no answer to my question."

"It is near enough," said Juliet. "I do not see that it matters to you with whom I took tea."

"Really, Juliet, it is hard if a sister cannot ask so simple a thing as that!"

"You may ask, of course,—as many questions as you like,—but I do not feel bound to answer them."

"I must say, Juliet, you are very polite."

"And I must say you are very inquisitive."

"Pray do not let us quarrel about such a thing," said Salome coldly. "You are welcome to make a mystery of it, if you please, only I must say it does not look well that you are ashamed to say with whom you have been taking tea."

And Salome quitted the room.

"I am not ashamed!" exclaimed Juliet, suddenly springing from the bed and darting after her. "And you know it is not my way to make mysteries of things. Since you are so consumed by curiosity, I will inform you that I went home with Flossie Chalcombe and had tea with her. There, now; are you satisfied?" And Juliet went back to her room flushed and triumphant.

A few minutes later, Salome, in her close-fitting, deaconess-like bonnet, with her waterproof cloak neatly folded on her arm, one or two dark clouds being apparent in the evening sky, came into the room where Hannah and her mother were sitting. Her face was rather more highly coloured than usual; but it was in a quiet, composed manner that she said—

"You were right about Juliet, Hannah. She has been taking tea with the Chalcombes."

"You do not mean that?" exclaimed Hannah. "But I am not surprised," she added the next moment.

Mrs. Tracy turned round with a startled air.

"Are you sure of what you are saying, Salome?" she asked, with unusual incisiveness.

"Quite sure, mother. Juliet told me so herself."

"She was perhaps joking," suggested Mrs. Tracy.

"Oh no; I am sure she was not joking," said Salome demurely. "But I must go now, or I shall be late." She passed quickly from the room, and the next moment they heard the hall door close behind her.

At the same instant, Mr. Ainger might have been seen crossing the road from his lodgings on the opposite side.

There was silence in the room for some minutes after she had gone. Mrs. Tracy was feeling intensely hurt and mortified.

"I should think, mother," Hannah said at last, "you must now see that it is desirable Juliet should take a situation as soon as she leaves school."

"Not at a distance," replied Mrs. Tracy, in quick, agitated tones. "I will not have my child sent away from me."

"It would be a very good thing for her to leave home for a time," said Hannah quietly. "It seems the only way of withdrawing her from undesirable connections."

"I will never give my consent to it!" said Mrs. Tracy, in an excited manner. And she rose and went hurriedly from the room, as if resolved not to listen further to Hannah's views on the subject.

Juliet was standing before the dressing-table when her mother entered their bedroom. She had removed her hat, and was engaged in arranging, somewhat fastidiously, her golden locks; but, careless as was her attitude, she was not so much at ease as she appeared. For the last ten minutes she had been hearing with the ears of her imagination the discussion of her conduct that was probably taking place below. Her reflections on the consequences of her confession to Salome were not agreeable.

"Juliet," said Mrs. Tracy, when she had closed the door, "I think you will break my heart."

Juliet had been hardening herself in anticipation of reproof, but she had not expected such words as these. As she heard her mother's faltering tones, and saw that there were tears in her eyes, her own face fell, and she said in tones that expressed unfeigned regret—

"Oh, mother! I am so sorry. I did not think you would mind so very much."

"My dear, after what I said to you only the other day, you must have known that I should very much dislike the idea of your entering the Chalcombes' house."

"Well, yes, I suppose I did know it," Juliet acknowledged ruefully; "but Flossie persuaded me so, and she taunted me with being afraid of Hannah. I could not stand that. But I am sorry if you are vexed with me. Oh dear! I am always doing the wrong thing."

"It is because you are so thoughtless, dear. You always act upon impulse. If only you would give yourself time to reflect."

"Oh, mother, don't preach to me!" exclaimed Juliet impatiently. "It is done now; and, after all, I am not entirely sorry, for, do you know, I was singing to Flossie, and Mr. Chalcombe heard me—"

"Oh, did you see him?" interrupted Mrs. Tracy, in a tone of vexation.

"Yes, he came into the room when I was singing. He is a vulgar little man, mother; but he knows about things, and he said my voice was beautiful, and that if it were properly trained I should be a great success as a public singer, and earn lots of money. Only think, mother, how much better that would be than teaching brats, as Hannah wants me to do!"

"I don't agree with you, dear. The idea is not at all to my mind."

"But, mother, would you not like to have a daughter who could sing like Antoinette Sterling? Fancy, he said I might earn thirty guineas a night! Only think! We should soon be as rich as Crœsus!"

"I daresay," said Mrs. Tracy, with a faint smile; "but you are a long way from that at present, my child. I expect he only said it to flatter you. You must not dream of being a public singer, Juliet. I hate the idea of a public career for a woman. The quieter and simpler her life, the happier she is, as a rule."

"I don't think so," said Juliet, vexed that her mother did not share her elation. "I know I am sick to death of the quietness and simplicity of my life. Oh! what is the matter, mother?"

Her mother had sunk on to a chair, and was pressing both hands to her temples. Her face was very pale.

"My head!" she moaned. "It has been aching all day, but now the pain has grown almost unendurable. I believe I shall have to go to bed."

"Oh dear it is all my fault!" exclaimed Juliet, greatly distressed. "You must go to bed, mother dear, and I will bathe your head with toilet vinegar, and give you the medicine which always sends you to sleep."

And, contrite and remorseful, Juliet waited on her mother in the deftest and tenderest manner. When, some time later, she lay down in her own little bed, her mind was still so uneasy that sleep did not come readily. She turned from side to side, though cautiously, that she might not disturb her mother, many times ere she fell asleep.

Mrs. Tracy, when once her dose began to take effect, slept soundly. She woke in the early morning to find that Juliet was already up and kneeling in her nightdress by the fender, engaged in some mysterious operation.

"What are you doing, dear?" her mother asked.

"I am getting you a cup of tea," Juliet replied, as she anxiously watched the little kettle she had placed to boil on a spirit-lamp; "it will soon be ready now."

"You are very good, darling," Mrs. Tracy said, as Juliet brought the cup of fragrant tea to her bedside. She liked the refreshment of an early cup of tea, though it was an indulgence she rarely allowed herself, since Salome regarded it as an extravagance, and Hannah condemned the habit as pernicious.

"How did you manage to get all the things?" Mrs. Tracy asked, with pleased curiosity.

"I brought them up last night," Juliet said exultantly.

"I do believe you love me a little, Juliet," her mother said.

"A little, mother! I love you a very great deal."

"Then, darling," said her mother, eager to embrace the favourable opportunity, "you will not mind giving me a promise that will be a great comfort to me."

"What is it?" Juliet asked reluctantly.

"Promise me you will not enter the Chalcombes' house again."

Juliet was silent for a few moments, and her colour deepened. She was not one to give a promise lightly, and she did not want to bind herself thus. But when she met her mother's tender, pleading glance, and noted how white and weary-looking was the face which pressed the pillow, it seemed impossible to refuse.

"I promise, mother," she said, in a low voice; and then her mother drew the girl's face down to hers, and kissed her with passionate warmth.

After all, the mother told herself with a throbbing heart, she was a good and loving child, this wayward, spoilt Juliet.

A DISAGREEABLE PROSPECT

"AT last I have heard of the very thing for Juliet," said Hannah, in tones of extreme satisfaction.

Mrs. Tracy looked up quickly from her needlework, her face expressing some anxiety. Hannah had just returned from an afternoon visit to the high school. It was a busy time with the teachers, for the school year was drawing to its close and the examinations were being held.

Already the beauty of the summer was past in London. The suburban trees looked dim and dusty; the grass was baked brown; the air was oppressively close and the sun's heat torrid. Everyone was talking or thinking of the seaside.

"Miss Tucker invited me into her room for a little talk," continued Hannah, in response to her mother's questioning glance. "She said she had heard of a situation which she thought Juliet might take. It is at Hampstead—just to teach two little girls. The elder, I believe, is only eight. Miss Tucker thinks Juliet might do well there if she chose."

"If she chose!" The proviso was an important one. Mrs. Tracy felt its significance.

"Miss Tucker says that she would have no hesitation in recommending Juliet for the situation. She thinks she might teach such little ones very nicely; but she is not fit to undertake older ones, for she is not taking at all a high place in the examinations."

Mrs. Tracy's countenance fell.

"Oh dear!" she said, with a sigh. "I am sorry to hear that."

"It is the result of idleness rather than lack of ability," said Hannah severely. "If Juliet were really stupid, one could forgive her. She trifles away her time with that horrid Chalcombe girl instead of working. I don't know whether you are aware, mother, that they are constantly together."

"Yes," said Salome, looking up from the accounts she was carefully auditing. "I asked Frances Hayes yesterday why she never came to see us now, and she said she fancied that Juliet had ceased to care for her visits since she had been so taken up with her new friend. Frances would have nothing to say to such a girl. Her mother is too careful of her."

Mrs. Tracy's colour rose. She looked annoyed—rather, it is to be feared, with her elder daughters than with the culprit they denounced.

"Perhaps Mrs. Hayes has cause to be distrustful of her daughter," she said proudly. "I am not afraid for Juliet. She is kind to that Chalcombe girl because she knows her to be lonely and friendless in the school. The intimacy will naturally cease when Juliet leaves school."

"I hope it will," said Hannah. "It is on that account that I am anxious to lose no time in getting an engagement for Juliet. This lady will want her from ten till five every day, which will leave her little time to herself."

"I wonder what Juliet will say to it!" said Mrs. Tracy, thinking aloud.

"It does not much natter what she says," returned Hannah decisively. "She must be shown what is her duty. The salary will be forty pounds. We cannot afford to throw away such a chance. It is time Juliet helped to maintain herself. Her clothes cost a good deal."

"Not very much," said Mrs. Tracy deprecatingly, "since I make most of her things myself. Of course I see that it is a good chance; but it will be hard for the dear child to get into harness at once. She has been counting on a little extra leisure, and meant to practise up her music. I had almost promised her that she should have singing lessons."

"Surely, mother, you are not going to encourage, Juliet in her absurd notion of becoming a public singer!" Salome exclaimed.

"By no means, dear; but the child has certainly a beautiful voice, and it is a pity that it should not be cultivated."

"Of course, if you have money to throw away on such lessons, there is no reason why you should not indulge her whim," said Hannah coldly.

Mrs. Tracy flushed. The words stung her, coming as they did from the one who contributed most largely to the support of the household. But ere she could defend herself against the insinuation they conveyed, the door opened, and Juliet walked into the room.

Mrs. Tracy made a quick movement, which expressed to her elder daughters her wish that no more should be said on the subject at present. But Juliet saw the signal, and she noted, too, her mother's flushed face and the excited air worn by all three. Little escaped the keen observation of that young lady. She felt sure that she had been under discussion when her entrance broke off the conversation.

"Dear me! How very warm you all look!" she remarked with the utmost sang-froid. "What agitating topic has excited you so? You should really, from sanitary considerations, avoid such discussions when the thermometer stands at eighty degrees in the shade. I am not surprised at you, mother darling; but I do wonder to find Hannah and Salome showing so little good sense."

"I suppose you think that is clever," said Salome, who could never endure Juliet's raillery.

"Oh, very; do not you?" said Juliet, with superb indifference in the glance of her violet eyes.

Salome turned away discomfited. She was not quick at repartee, and she knew that Juliet always got the better of her in a battle of words.

Juliet carried a large fan open in her hand. She now drew her mother's form back more comfortably into her chair and began to fan her. Hannah cast an expressive glance at Salome, and quitted the room Salome soon followed, wishing doubtless to talk over the situation with her sister.

"Well, mother," said Juliet, when they were alone, "what are the latest tactics of the enemy?"

"You should not speak of your sisters so, Juliet. They are not your enemies."

"No?" Juliet lifted her eyebrows comically. "Well, then, what is Hannah's latest plan—'for my good'?"

Her mother could not help smiling at the manner in which Juliet uttered the last words. Mrs. Tracy sometimes feared that she was guilty of encouraging the child in her naughtiness. But the little puss had such pretty, fascinating ways, and the eyes looking mischievously into hers were so full of charm.

Mrs. Tracy's face grew quickly grave again, and she sighed ere she replied to Juliet's question.