Title: Metipom's hostage

Being a Narrative of certain surprising adventures befalling one David Lindall in the first year of King Philip's War

Author: Ralph Henry Barbour

Illustrator: Remington Schuyler

Release date: July 28, 2024 [eBook #74148]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Houghton Mifflin Company

Credits: Produced by Donald Cummings and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

METIPOM’S HOSTAGE

BEING A NARRATIVE OF CERTAIN SURPRISING

ADVENTURES BEFALLING ONE DAVID LINDALL

IN THE FIRST YEAR OF KING PHILIP’S WAR

BY

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

The Riverside Press Cambridge

COPYRIGHT, 1921, BY THE BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA

COPYRIGHT, 1921, BY RALPH HENRY BARBOUR

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

| I. | The Red Omen | 1 |

| II. | The Meeting in the Woods | 14 |

| III. | Down the Winding River | 27 |

| IV. | The Spotted Arrow | 41 |

| V. | David visits the Praying Village | 53 |

| VI. | What happened at the Pool | 69 |

| VII. | Captured | 82 |

| VIII. | Metipom questions | 93 |

| IX. | The Village of the Wachoosetts | 105 |

| X. | Sequanawah pledges Friendship | 122 |

| XI. | The Cave in the Forest | 135 |

| XII. | David faces Death | 147 |

| XIII. | A Friend in Strange Guise | 159 |

| XIV. | Emissaries from King Philip | 172 |

| XV. | The Sachem decides | 180 |

| XVI. | Monapikot’s Message | 193 |

| XVII. | Metipom takes the War-Path | 204 |

| XVIII. | In King Philip’s Power | 219 |

| XIX. | The Island in the Swamp | 234 |

| XX. | David bears a Message | 249 |

| XXI. | To the Rescue | 260 |

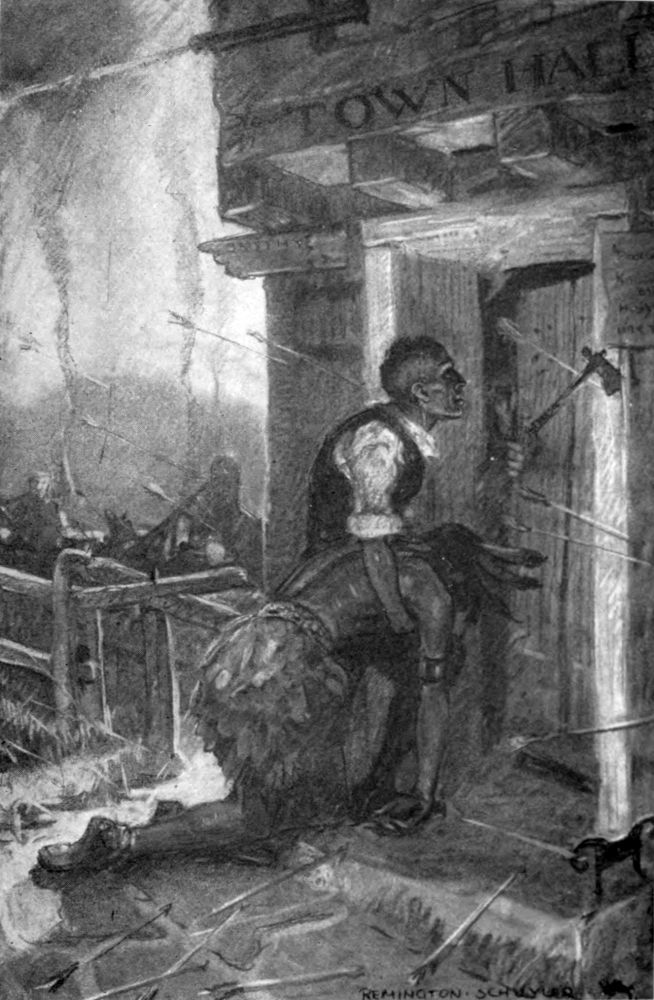

| XXII. | The Attack on the Garrison | 272 |

| XXIII. | Straight Arrow returns | 281 |

David Lindall stirred uneasily in his sleep, sighed, muttered, and presently became partly awake. Thereupon he was conscious that all was not as it had been when slumber had overtaken him, for, beyond his closed lids, the attic, which should have been as dark at this hour as the inside of any pocket, was illuminated. He opened his eyes. The rafters a few feet above his head were visible in a strange radiance. He raised himself on an elbow, blinking and curious. The light did not come from the room below, nor was it the yellow glow of a pine-knot. No sound came to him save the loud breathing of his father and Obid, the servant, the former near at hand, the latter at the other end of the attic: no sound, that is, save the soft sighing of the night breeze in the pines and hemlocks at the eastern edge of the clearing. That was[2] ever-present and so accustomed that David had to listen hard to hear it. But this strange red glow was new and disturbing, and now, wide awake, the boy sought the explanation of it and found it once his gaze had moved to the north window.

Above the tops of the distant trees beyond the plantation, the sky was like the mouth of a furnace, and against the unearthly glow the topmost branches of the taller trees stood sharply, like forms cut from black paper.

“Father!” called the boy.

Nathan Lindall was awake on the instant.

“You called, David?” he asked.

“Yes, father. The forest is afire!”

“Nay, ’tis not the forest,” answered Nathan Lindall when he had looked from the window. “The woods are too damp at this season, and I have never heard of the Indians firing them save in the fall. ’Tis some one’s house, lad, and I fear—” He did not finish, but turned instead to Obid Dawkin who had joined them. “What say you, Obid?” he questioned.

“I say as you, master,” replied Obid in his thin, rusty voice. “And ’tis the work of the heathens, I doubt not. But whose house[3] it may be I do not know, for it seems too much east to be any in Sudbury, and—”

“And how far, think you?”

“Maybe four miles, sir, or maybe but two. ’Tis hard to say.”

“Three, then, Obid: and that brings us to Master William Vernham’s, for none other lies in that direction and so near. Whether it be set afire by the Indians we shall know in time. But don your clothing, for there may be work for us, although I misdoubt that we arrive in time.”

“And may I go with you, father?” asked David eagerly.

“Nay, lad, for we must travel fast and ’twill be hard going. Do you bolt well the door when we are gone and then go back to bed. ’Tis nigh on three already and ’twill soon be dawn. Art ready, Obid?”

“Nay, for Sathan has hidden my breeches, Master Lindall,” grumbled the man, “and without breeches I will not venture forth.”

“Do you find them quickly or a clout upon your thick skull may aid you,” responded Nathan Lindall grimly.

“I have them, master,” piped Obid hurriedly.

“Look, sir, the fire is dying out,” said[4] David. “The sky is far less red, I think.”

“Maybe ’tis but a wild-goose chase we go on,” replied his father, “and yet ’tis best to go. David, do you slip down and set out the muskets and see that there be ammunition to hand. Doubtless in time this jabbering knave will be clothed.”

“I be ready now, master! And as for jabbering—”

“Cease, cease, and get you down!”

A minute or two later David watched their forms melt into the darkness beyond the barn. Then, closing the door, he shot home the heavy iron bolt and dropped the stout oak bar as well. In the wide chimney-place a few live embers glowed amidst the gray ashes and he coaxed them to life with the bellows and dropped splinters of resinous pine upon them until a cheery fire was crackling there. Then, rubbing out the lighted knot against the stones of the hearth, he drew a bench to the blaze and warmed himself, for the night, although May was a week old, was chill.

The room, which took up the whole lower floor of the house, was nearly square, perhaps six paces one way by seven the other. The ceiling was low, so low that Nathan[5] Lindall’s head but scantily escaped the rough-hewn beams. The furnishings would to-day be rude and scanty, but in the year 1675 they were considered proper and sufficient. In fact Nathan Lindall’s dwelling was rather better furnished than most of its kind. The table and the two benches flanking it had been fashioned in Boston by the best cabinet-maker in the Colony. The four chairs were comfortable and sightly, the chest of drawers was finely carved and had come over from England, and the few articles that were of home manufacture were well and strongly made. Six windows, guarded by heavy shutters, gave light to the room, and one end was almost entirely taken up by the wide chimney-place. At the other end a steep flight of steps led to the room above, no more than an attic under the high sloping roof.

David had lived in the house seven years, and he was now sixteen, a tall, well-made boy with pleasing countenance and ways which, for having dwelt so long on the edge of the wilderness, were older than his age warranted. His father had taken up his grant of one hundred acres in 1668, removing from the Plymouth Colony after the death of his[6] wife. David’s recollection of his mother was undimmed in spite of the more than eight years that had passed, but, as he had been but a small lad at the time of her death, his memory of her, unlike his father’s, held little pain. The grant, part woodland and part meadow, lay sixteen miles from Boston and north of Natick. It was a pleasant tract, with much fine timber and a stream which, rising in a spring-fed pond not far from the house, meandered southward and ultimately entered the Charles River. The river lay a long mile to the east and was the highway on which they traveled, whether to Boston or Dedham.

Nathan Lindall had brought some forty acres of his land under cultivation, and for the wheat, corn, and potatoes that he raised found a ready market in Boston.

The household consisted of Nathan Lindall, David, and Obid Dawkin. Obid had come to the Colony many years before as a “bond servant,” had served his term and then hired to Master Lindall. In England he had been a school-teacher, although of small attainments, and now to his duties of helping till and sow and harvest was added that of instructing David. Considering the lack of books, he had done none so badly, and David[7] possessed more of an education than was common in those days for a boy of his position. It may be said of Obid that he was a better farmer than teacher and a better cook than either!

It was a lonely life that David led, although he was never lonesome. There was work and study always, and play at times. His play was hunting and fishing and fashioning things with the few rude tools at hand. Of hunting there was plenty, for at that time and for many years later eastern Massachusetts abounded in animals and birds valuable for food as well as many others sought for pelt or plumage. Red deer were plentiful, and beyond the Sudbury Marshes only the winter before some of the Natick Indians had slain a moose of gigantic size. Wolves caused much trouble to those who kept cattle or sheep, and in Dedham a bounty of ten shillings had lately been offered for such as were killed within the town. Foxes, both red and gray, raccoons, porcupines, woodchucks, and rabbits were numerous, while the ponds and streams supplied beavers, muskrats, and otters. Bears there were, as well, and sometimes panthers; and many lynxes and martens. Turkeys, grouse, and pigeons were[8] common, the latter flying in flocks of many hundreds. Geese, swans, ducks, and cranes and many smaller birds frequented streams and marshes, and there were trout in the brooks and bass, pickerel, and perch in the ponds. At certain seasons the alewives ascended the streams in thousands and were literally scooped from the water to be used as fertilizer.

There was, therefore, no dearth of flesh for food nor skins for clothing so long as one could shoot a gun, set a trap, or drop a hook. Of traps David had many, and the south end of the house was never without several skins in process of curing. Larger game had fallen to his prowess, for he had twice shot a bear and once a panther: the skins of these lay on the floor in evidence. He was a good shot, but there was scant virtue in that at a time when the use of the musket, both for hunting and for defense against the Indians, was universal amongst the settlers. Rather, he prided himself on his skill in the making of traps and snowshoes and such things as were needed about the house. He had clever hands for such work. He could draw, too, not very skillfully, but so well that Obid could distinguish at the first glance which was the pig[9] and which the ox! And at such times his teacher would grumblingly regret that his talent did not run more to the art of writing. But, since Obid’s own signature looked more like a rat’s nest than an autograph, the complaint came none too well.

Sitting before the fire to-night, David followed in thought the journey of his father and Obid and wished himself with them. Nathan Lindall had spoken truly when he had predicted hard going, for the ice, which still lay in the swamps because of an unseasonable spell of frost the week gone, was too thin to bear one and the trail to Master Vernham’s must keep to the high ground and the longer distance. The three miles, David reflected, would become four ere the men reached their destination, and in the darkness the ill-defined trail through the woods would be hard to follow. It was far easier to sit here at home, toasting his knees, but no boy of sixteen will choose ease before adventure, and the possibility of the fire having been set by the Indians suggested real adventure.

A year and more ago such a possibility would have been little considered, for the tribes had been long at peace with the colonists,[10] but to-day matters were changed. It had been suspected for some time that Pometacom, or King Philip, as he was called, sachem of the Wampanoags, was secretly unfriendly toward the English. Indeed, nearly four years since he had been summoned to Taunton and persuaded to sign articles of submission, which he did with apparent good grace, but with secret dissatisfaction. Real uneasiness on the part of the English was not bred, however, until the year before our story. Then Sassamon, a Massachusett Indian who had become a convert of John Eliot’s at the village of Praying Indians at Natick, brought word to Plymouth of intended treachery by Philip. Sassamon had been with Philip at Mount Hope acting as his interpreter. Philip had learned of Sassamon’s treachery and had caused his death. Three Indians suspected of killing Sassamon were apprehended, tried, convicted, and, in June of the following year, executed. Of the three one was a counselor of Philip’s, and the latter, although avoiding any acts of hostility pending the court’s decision, was bitterly resentful and began to prepare for war. During the winter various annoyances had been visited upon the settlers by roaming[11] Indians. In some cases the savages were known to be Wampanoags; in other cases the friendly Indians of the villages and settlements were suspected, perhaps often unjustly. Even John Eliot’s disciples at Natick did not escape suspicion. Rumors of threatening signs were everywhere heard. Exaggerated stories of Indian depredations traveled about the sparsely settled districts. From the south came the tale of disaffection amongst the Narragansetts, and from the north like rumors regarding the Abenakis. There was a feeling of alarm everywhere amongst the English, and even in Boston there were timorous souls who feared an attack on that town. As yet, however, nothing untoward had occurred in the Massachusetts-Bay Colony, and the only Indians that David knew were harmless and frequently rather sorry-looking specimens who led a precarious existence by trading furs with the English or who dwelt in the village at Natick. Most of them were Nipmucks, although other neighboring tribes were represented as well. Save that they not infrequently stole from his traps—sometimes taking trap as well as catch—David knew nothing to the discredit of the Indians. Often they came to the house,[12] more often he ran across them on the river or in the forest. Always they were friendly. One or two he counted as friends; Monapikot, a Pegan youth of near his own age who dwelt at Natick, and Mattatanopet, or Joe Tanopet as he was known, who came and went as it pleased him, bartering skins for food and tobacco, and who claimed to be the son of a Wamesit chief; a claim very generally discredited. It is not to be wondered at, therefore, that David added a good seasoning of salt to the tales of Indian unfriendliness, nor that to-night he was little inclined to lay the burning of William Vernham’s house at the door of the savages.

And yet, since where there is much smoke there must be some fire, he realized that Obid’s surmise might hold more than prejudice. Obid was firmly of the belief that the Indian was little if any better than the beast of the forest and had no sympathy with the Reverend John Eliot’s earnest endeavors to convert them to Christianity, arguing that an Indian had no soul and that none, not even John Eliot, could save what didn’t exist! Nathan Lindall held opposite views both of the Indian and of John Eliot’s efforts, and many a long and warm argument took place[13] about the fire of a winter evening, while David, longing to champion his father’s contentions, maintained the silence becoming one of his years.

The fire dwindled and David presently became aware of the chill, and, yawning, climbed the stair and sought his bed with many shivers at the touch of the cold clothing. A fox barked in the distance, but save for that all was silent. Northward the red glow had faded from the sky and the blacker darkness that precedes the first sign of dawn wrapped the world.

It was broad daylight when David awoke, rudely summoned from slumber by the loud tattoo on the door below. He tumbled sleepily down the stair and admitted his father and Obid, their boots wet with the dew that hung sparkling in the pale sunlight from every spray of sedge and blade of grass. While Obid, setting aside his musket, began the preparation of breakfast, David questioned his father.

“By God’s favor ’twas not the house, David, but the barn and a goodly store of hay that was burned. Fortunately these were far enough away so that the flames but scorched the house. Master Vernham and the servants drew water from the well and so kept the roof wet. The worst of it was over ere we arrived. Some folks from the settlement at Sudbury came also: John Longstaff and a Master Warren, of Salem, who is on a visit there, and two Indians.”

“How did the fire catch, sir?” asked David.

“’Twas set,” replied Nathan Lindall grimly. “Indians were seen skulking about the woods late in the afternoon, and ’tis thought they were some that have set up their wigwams above the Beaver Pond since autumn.”

“But why, sir?”

“I know not, save that Master Vernham tells me that of late they have shown much insolence and have frequently come to his house begging for food and cloth. At first he gave, but soon their importunity wearied him and he refused. They are, he says, a povern and worthless lot; renegade Mohegans he thinks. But dress yourself, lad, and be about your duties.”

Shortly after the midday meal, Nathan Lindall and Obid again set forth, this time taking the Sudbury path, and David, left to his own devices, finished the ploughing of the south field which was later to be sown to corn, and then, unyoking the oxen and returning them to the barn, he took his gun and made his way along the little brook toward the swamp woods. The afternoon, half gone, was warm and still, and a bluish haze lay over the distant hills to the southeast. A rabbit sprang up from almost beneath[16] his feet as he entered the white birch and alder thicket, but he forbore to shoot, since its flesh was not esteemed as food and the pelt was too soft for use at that season of the year. For that matter, there was little game worth the taking in May, and David had brought his gun with him more from force of habit than aught else. It was enough to be abroad on such a day, for the spring was waking the world and it seemed that he could almost see the tender young leaves of the white birches unfold. Birds chattered and sang as he skirted the marsh and approached the deeper forest beyond. A chestnut stump had been clawed but recently by a bear in search of the fat white worms that dwelt in the decaying wood, and David found the prints of the beast’s paws and followed them until they became lost in the swamp. Turning back, his ears detected the rustling of feet on the dead leaves a few rods distant, and he paused and peered through the greening forest. After a moment an Indian came into view, a rather thick-set, middle-aged savage with a round countenance. He wore the English clothes save that his feet were fitted to moccasins instead of shoes and had no doublet above a frayed[17] and stained waistcoat that had once been bright green. Nor did he wear any hat, but, instead, three blue feathers woven into his hair. He carried a bow and arrows and a hunting-knife hung at his girdle. A string of wampum encircled his neck. That he had seen David as soon as David had seen him was evident, for his hand was already raised in greeting.

“’Tis you, Tanopet,” called David. “For the moment I took you for the bear that has been dining at yonder stump.”

“Aye,” grunted the Indian, approaching. “Greeting, brother. Where see bear?”

David explained, Joe Tanopet listening gravely the while. Then, “No good,” he said. “No catch um in swamp. What shoot, David?” He pointed to the boy’s musket.

“Nothing, Joe. I brought gun along for friend to talk to. Where you been so long? You haven’t been here since winter.”

Tanopet’s gaze wandered and he waved a hand vaguely. “Me go my people,” he answered. “All very glad see me. Make feast, make dance, make good time.”

“Is your father Big Chief still living, Joe?”

“Aye, but um very old. Soon um die.[18] Then Joe be chief. How your father, David?”

“Well, I thank you; and so is Obid.”

Joe Tanopet scowled and spat.

“Um little man talk foolish, no good. You see fire last night?”

“Aye. Father and Obid Dawkin went to give aid, but the flames were out when they reached Master Vernham’s. They say that the fire was set, Joe.”

“Aye.”

“They suspect some Indians who have been living near the Beaver Pond,” continued David questioningly.

Joe Tanopet shook his head. “Not Beaver Pond people.”

“Who then, Joe?”

“Maybe Manitou make fire,” replied the Indian evasively.

“Man or two, rather,” laughed David. “Anyhow, father and Obid have gone to Sudbury where they are to confer with others, and I fear it may go hard with the Beaver Pond Indians. How do you know that they did not set the fire, Joe?”

“Me know. You tell father me say.”

“Aye, but with no more proof than that I fear ’twill make little difference,” answered[19] the boy dubiously. “Joe, they say that there are many strange Indians in the forest this spring; that Mohegans have been seen as far north as Meadfield. Is it true?”

“Me no see um Mohegans. Me see um Wampanoags. Me see um Niantiks. Much trouble soon. Maybe when leaves on trees.”

“Trouble? You mean King Philip?”

“Aye. Him bite um nails long time. Him want um fight. Him great sachem. Him got many friends. Much trouble in summer.” Tanopet gazed past David as though seeing a vision in the shadowed forest beyond. “Big war soon, but no good. English win. Philip listen bad counsel. Um squaw Wootonekanuske tell um fight. Um Peebe tell um fight. All um powwows tell um make war. Tell um drive English into sea, no come back here. All um lands belong Indians once more. Philip um think so too. No good. Wampanoags big fools. Me know.”

“I hope you are mistaken, Joe, for such a war would be very foolish and very wrong. That Philip has cause for complaint against the Plymouth Colony I do not doubt, but it is true, too, my father says, that he has failed to abide by the promises he made. As for driving the English out of the country, that[20] is indeed an idle dream, for now that the Colonies are leagued together their strength of arms is too great. Not all the Indian Nations combined could bring that about. Philip should take warning of what happened to the Pequots forty years ago.”

“Um big war,” grunted Tanopet. “Many Indians die. Joe um little boy, but um see. Indians um fight arrow and spear, but now um fight guns. English much kind to Indian. Um sell um gun, um sell um bullet, um sell um powder.” Tanopet’s wrinkled face was slyly ironical. “Philip got plenty guns, plenty bullet.”

“But how can that be, Joe? ’Tis but four years gone that his guns were taken from him.”

“Um catch more maybe. Maybe um not give up all guns. Good-bye.”

Tanopet made a sign of farewell, turned and strode lightly away into the darkening forest, and David, his gun across his shoulder, sought his home, his thoughts busy with what the Indian had said. Joe Tanopet was held trustworthy by the colonists thereabouts, and, since he was forever on the move and having discourse with Indians of many tribes, it might well be that his words[21] were worthy of consideration. For the first time David found reason to fear that the dismal prophecies of Obid Dawkin might come true. He determined to tell his father of Tanopet’s talk when he returned.

But when David reached the house, he found only Obid there, preparing supper.

“Master Lindall will not be back until the morrow,” explained Obid. “He and Master Vernham have gone to Boston with four Indians that we made prisoners of, and who, I pray, will be hung to the gallows-tree.”

“Prisoners!” exclaimed David. “Mean you that there has been fighting, then?”

“Fighting? Nay, the infidels had no stomach for fighting. They surrendered themselves readily enough, I promise, when they saw in what force we had come. But some had already gone away, doubtless having warning of our intention, and only a handful were there when we reached their village. Squaws and children mostly, they were, and there was great howling and dismay when we burned the wigwams.”

“But is it known, Obid, that it was indeed they who did the mischief to Master Vernham’s place?”

“Well enough, Master David. They made[22] denial, but so they would in any case, and always do. One brave who appeared to be their leader—his name is Noosawah, an I have it right—told a wild tale of strange Indians from the north and how they had been seen near the High Hill two days since, and proclaimed his innocence most loudly.”

“And might he not have been telling the truth?”

“’Tis thought not, Master David. At least, it was deemed best to disperse them, for they were but a Gypsy-sort and would not say plainly from whence they came.”

“It sounds not just,” protested David. “Indeed, Obid, ’tis such acts that put us English in the wrong and give grounds for complaint to the savages. And now, when, by all accounts, there is ill-feeling enough, I say that it was badly done.”

Obid snorted indignantly. “Would you put your judgment against that of your father and Master Vernham and such men of wisdom as John Grafton, of Sudbury, and Richard Wight, Master David?”

“I know not,” answered David troubledly. “And yet it seems to me that a gentler policy were better. It may be that we shall need all the friends we can secure before many months, Obid.”

“Aye, but trustworthy friends, not these Sons of Sathan who offer peace with one hand and hide a knife in t’other! An I were this Governor Leverett I would not wait, I promise you, for the savages to strike the first blow, but would fall upon them with all the strength of the united Colonies and drive the ungodly creatures from the face of the earth.”

“Then it pleases me well that you are not he,” laughed David as he sat himself to the table. “But tell me, Obid, what of the Indians that father and Master Vernham are taking to Boston? Surely they will not execute them on such poor evidence!”

“Nay,” grumbled Obid, “they will doubtless be sold into the West Indies.”

“Sold as slaves? A hard sentence, methinks. And the women and children, what of them? You say the village was burned?”

“Aye, to the ground; and a seemly work, too. The squaws and the children and a few young men made off as fast as they might. I doubt they will be seen hereabouts again,” he concluded grimly. “For my part, I hold that Master Lindall and the rest were far too lenient, since they took but four prisoners, they being the older men, and let all others[24] go free. I thought to see Master Vernham use better wisdom, but ’tis well known that he has much respect for Preacher Eliot, and doubtless hearkened to his intercessions. If this Eliot chooses to waste his time teaching the gospel to the savages, ’tis his own affair, perchance, but ’twould be well for him to refrain from interfering with affairs outside his villages. Mark my words, Master David: if trouble comes with Philip’s Indians these wastrel hypocrites of Eliot’s will be murdering us in our beds so soon as they get the word.”

“That I do not believe,” answered David stoutly.

“An your scalp dangles some day from the belt of one of these same Praying Indians you will believe,” replied Obid dryly.

Nathan Lindall returned in the afternoon from Boston and heard David’s account of his talk with Joe Tanopet in silence. Nathan Lindall was a large man, well over six feet in height and broad of shoulder, and David promised to equal him for size ere he stopped his growth. A quiet man he was, with calm brown eyes deeply set and a grave countenance, who could be stern when occasion warranted, but who was at heart, as David[25] well knew, kind and even tender. He wore his hair shorter than was then the prevailing fashion, and his beard longer. His father, for whom David was named, had come to the Plymouth Colony from Lincolnshire, England, in 1625, by profession a ship’s-carpenter, and had married a woman of well-to-do family in the Colony, thereafter setting up in business there. Both he and his wife were now dead, and of their children, a son and daughter, only David’s father remained. The daughter had married William Elkins, of Boston, and there had been one child, Raph, who still lived with his father near the King’s Head Tavern. When David had ended his recital, his father shook his head as one in doubt.

“You did well to tell me, David,” he said. “It may be that Tanopet speaks the truth and that we are indeed destined to suffer strife with the Indians, though I pray not. In Boston I heard much talk of it, and there are many there who fear for their safety. I would that I had myself spoken with Tanopet. Whither did he go?”

“I do not know, father. Should I meet him again I will bid him see you.”

“Do so, for I doubt not he could tell much[26] were he minded to, and whether Philip means well or ill we shall be the better for knowing. So certain are some of the settlers to the south that war is brewing, according to your Uncle William—with whom I spent the night in Boston—that they even hesitate to plant their fields this spring. Much foolish and ungodly talk there is of strange portents, too, with which I have no patience. Well, we shall see what we shall see, my son, and meanwhile there is work to be done. Did you finish the south field?”

“Yes, father. The soil is yet too wet for good ploughing save on the higher places. What of the Indians you took to Boston, sir? Obid prays that they be hung, but I do not, since it seems to me that none has proven their guilt.”

“They will be justly tried, David. If deemed guilty they will doubtless be sold for slaves. A harsher punishment would be fitter, I think, for this is no time to quibble. Stern measures alone have weight with the Indians, so long as Justice dictates them. Now be off to your duties ere it be too dark.”

A fortnight later David set out early one morning for Boston to make purchases. Warm and dry weather had made fit the soil for ploughing and tilling, and Nathan Lindall and Obid were up to their necks in work, and of the household David could best be spared. He was to lodge overnight with his Uncle William Elkins and return on the morrow. The sun was just showing above the trees to the eastward when he left the house and made his way along the path that led to the river. He wore his best doublet, as was befitting the occasion, but for the rest had clothed himself for the journey rather than for the visit in the town. His musket lay in the hollow of his arm and a leather bag slung about his shoulder held both ammunition and food.

His spirits were high as he left the clearing behind and entered the winding path through the forest of pines and hemlocks, maples and beeches. The sunlight filtered through the upper branches and laid a pattern of pale[28] gold on the needle-carpeted ground. Birds sang about him, and presently a covey of partridges whirred into air beyond a beech thicket. It was good to be alive on such a morning, and better still to be adventuring, and David’s heart sang as he strode blithely along. The voyage down the river would be pleasant, the town held much to excite interest, and the visit to his uncle and cousin would be delightful. He only wished that his stay in the town was to be longer, for he and Raph, who was two years his elder, were firm friends, and the infrequent occasions spent with his cousin were always the most enjoyable of his life. This morning he refused to think of the trip back when, with a laden canoe, he would have to toil hard against the current. The immediate future was enough. Midges were abroad and attacked him bloodthirstily, but he plucked a hemlock spray and fought them off until, presently, the path ended at the bank of the river, here narrow and swift and to-day swollen with the spring freshets. Concealed under the trees near by lay a bark canoe and a pair of paddles, and David soon had the craft afloat and, his gun and bag at his feet, was guiding it down the stream.

The sun was well up by the time he had passed the first turns and entered the lake above Nonantum which was well over a half-mile in width, although it seemed less because of a large island that lay near its lower end. There were several deserted wigwams built of poles and bark on the shores of the island, left by Indians who a few years before had dwelt there to fish. David used his paddle now, for the current was lost when the river widened, and, keeping close to the nearer shore, glided from sunlight to shadow, humming a tune as he went. Once he surprised a young deer drinking where a meadow stretched down to the river, and was within a few rods of him before he took alarm and went bounding into a coppice. Again the river narrowed and he laid the paddle over the side as a rudder. A clearing running well back from the stream showed a dwelling of logs, and a yellow-and-white dog barked at him from beside the doorway. Then the tall trees closed in again and the swift water was shadowed and looked black beneath the banks.

At noon, then well below the settlement at Watertown, David turned toward the shore and ran the bow of the canoe up on a[30] little pebbly beach and ate the provender he had brought. It was but bread and meat, but hunger was an excellent sauce for it, and with draughts of water scooped from the river in his hand it was soon finished. Then, because there was no haste needed and because the sunshine was warm and pleasant, he leaned back and dreamily watched the white clouds float overhead, borne on a gentle southwesterly breeze. Behind him the narrow beach ended at a bank whereon alders and willows and low trees made a thin hedge that partly screened the wide expanse of fresh green meadow that here followed the river for more than five miles. Through it meandered little brooks between muddy banks, and here and there a rounded island of clustered oaks or maples stood above the level of the marsh. Swallows darted and from near at hand a kingfisher cried harshly. David’s dreaming was presently disturbed by the faint but unmistakable swish of paddles and he raised his head just as a canoe rounded a turn downstream.

The craft held three Indians, of whom two, paddling at bow and stern, were naked to the waist save for beads and amulets worn about the neck. The one who sat in the center was[31] clothed in a garb that combined picturesquely the Indian and the English fashions. Deerskin trousers, a shirt of blue cotton cloth, and a soft leather jacket made his attire. He wore no ornaments, nor was his bare head adorned in any way. A musket lay across his knees and a long-stemmed pipe of red clay was held to his lips. Before him were several bundles. At sight of David he raised a hand and then spoke to his companions, and the canoe left the middle of the stream and floated gently up to the marge. David jumped eagerly from his own craft and made toward the other.

“Pikot!” he called joyfully. “I had begun to think you were lost. ’Tis moons since I saw you last.”

“The heart sees when the eyes cannot,” replied the Indian, smiling, as he leaped to the beach and shook hands. “Often I have said, ‘To-morrow I will take the Long Marsh trail and visit my brother David’; but there has been much work at the village all through the winter, and the to-morrows I sought did not come. Where do you go, my brother?”

“To Boston to buy seeds and food and many things, Straight Arrow. And you?”

“To Natick with some goods for Master[32] Eliot that came from across the sea by ship. All has been well with you, David?”

“Aye, but I am glad indeed that the winter is over. I like it not. They say that in Virginia the winters are neither so long nor so severe, and I sometimes wish that we dwelt there instead.”

The Indian shook his head. “I know not of Virginia, but I know that my people who live in the North are greater and stronger and wiser than they who dwell in the South. ’Tis the cold of winter that makes strong and lean bodies. In summer we lose our strength and become fat, wherefore God divides the seasons wisely. I have something to say to you, David. Come a little way along the shore where it may not be overheard.”

David followed, viewing admiringly the straight, slim figure of his friend. Monapikot was a Pegan Indian. The Pegans were one of the smaller tribes of the Abenakis who lived southward in the region of Chaubunagunamog. He was perhaps three years David’s senior and had been born at Natick in the village of the Praying Indians. Although scarcely more than a lad in years, he was already one of Master Eliot’s most trusted[33] disciples and had recently become a teacher. He spoke English well and could read it fairly. He and David had been friends ever since shortly after the latter’s arrival in that vicinity, at which time David had been a boy of nine years and Pikot twelve. They had hunted together and lost themselves together in the Long Marsh, and had had the usual adventures and misadventures falling to the lot of boys whether they be white or red. For the last three years, though, Pikot’s duties had held him closer to the village and their meetings had been fewer. The Indian was a splendid-looking youth, tall and straight—for which David had once dubbed him Straight Arrow—with hard, lean muscles and a gracefulness that was like the swaying litheness of a panther. His features were exceptional for one of a tribe not usually endowed with good looks, for his forehead was broad, his eyes well apart, and his whole countenance indicated nobility. His gaze was direct and candid, and, which was unusual in his people, his mouth curved slightly upward at the corners, giving him a less grave expression than most Indians showed. Perhaps David had taught him to laugh, or, at least, to smile, for he did so frequently.[34] Had there been more like Monapikot amongst the five-score converts that dwelt in Natick, there might well have been a more universal sympathy toward John Eliot’s efforts.

“When we were little,” began Pikot after they had placed a hundred strides between them and the two Indians in the canoe, “you brought me safe from the water of the Great Pond when I would have drowned, albeit you were younger and smaller than I, my brother.”

“Yes, ’tis true, Pikot, but the squirrel is ever more clever than the woodchuck. Besides, then the woodchuck snared himself in a sunken tree root and, having not the sense to gnaw himself free, must needs call on the squirrel for aid.”

Pikot assented, but did not smile at the other’s nonsense. Instead, he laid one slim bronze-red hand against his heart. “You saved the life of Monapikot and he does not forget. Some day he will save the life of David just so.”

“What? Then I shall keep out of the water, Straight Arrow! I doubt not you would bring me ashore as I brought you, but[35] suppose you happened not to be by? Nay, I’ll take no risks, thank you!”

“I know not in what way you will be in danger,” answered the Pegan gravely. “But thrice I have dreamed the same dream, and in the dream ’tis as I have told.”

“Methinks your dreams smack of this witchcraft of which we hear so much of late,” said David slyly, “and belong not to that religion that you teach, Pikot.”

“Nay, for the Bible tells much of dreams. Did not Joseph, when sold by his wicked brothers in Egypt, tell truly what meant the dreams of the great King? My people in such way tell their dreams to the powwows, and the powwows explain them. It may be that dreams are the whisperings of the Great Spirit. But listen, my brother, to a matter that is of greater moment. Fifteen days ago your father and Master Vernham made captive three Indians and took them to Boston where they now wait judgment of the court. One is named Nausauwah, a young brave who is a son of Woosonametipom, whose lands are westward by the Lone Hill.”

“But my father thinks that they are Mohegans, Pikot.”

“Nay, they are Wachoosetts. Nausauwah[36] quarreled with Woosonametipom and came hither in the fall with four tens of his people. He is a lazy man and thought to find food amongst the English. Now, albeit the Sachem Woosonametipom did not try to hinder Nausauwah from leaving the lodge of his people, he is angry at what he has heard and says that he will come with all his warriors to Boston and recover his son. That is but boasting, for albeit he is a great sachem and has many warriors under him, and can count on the Quaboags to aid him, mayhap, he would not dare. But he has sworn a vengeance against these who have taken his son, David, and I fear he will seek to harm your father and Master Vernham. Do not ask me where I have learned this, but give warning to your father and be ever on your guard.”

“Thank you, Straight Arrow. My father and Master William Vernham, though, had no more to do with the taking of this Nausauwah than many others. It but so happened that they were chosen to convey the captives to the authorities in Boston. What means, think you, this Metipom will seek to get vengeance?”

“He is not friendly to the English, my brother, and it may be that he will be glad[37] of this reason to travel swiftly from his mountain home and make pillage. But ’tis more likely that he will send a few young men eager to win honor by returning with English scalps. Go not abroad alone, David, and see that the house be well secured at nightfall. The Wachoosetts are forest Indians and swift and sly, and I fear for your safety. It would be well to travel back in company with another, or else to take a party of Indians with you and see that they are armed with guns. Should Woosonametipom’s braves learn of your journey, I fear they would make the most of it. I would I could stay by you, but I must go on my way at once.”

“But surely they would not dare their deviltry so near the plantations!”

“Who knows?” Monapikot lapsed into the Indian tongue, which David understood a little and could speak haltingly to the extent of being understood. “The fox takes the goose where he finds him.”

“Then I will be no goose, Straight Arrow, but rather the dog who slays the fox,” laughed David.

Pikot smiled faintly. “You will ever be Noawama, He Who Laughs, my brother.[38] But see that while you laugh you close not your eyes. Now I must go, for Master Eliot awaits what I bring.”

“I will see you again soon, Pikot, for the fish are hungry and none can coax them to the hook as you can.”

“And none eat them as you can!” chuckled Pikot. “Within seven sleeps I will visit you and we will take food and go to the Long Pond. Farewell, my brother.”

“Farewell, Pikot. May your food do you much good.”

Monapikot stepped into his canoe, the Indians grunted and pushed off, and David, waving, watched the craft out of sight. Then he launched his own canoe and again took up his journey. Pikot’s warning held his thoughts, although it did not seem to him that this Wachoosett sagamore would dare dispatch his assassins so far into the plantations. As for any danger on the river, he smiled at that. Already the village of Newtowne, a good-sized settlement with many proper houses and a mile-long fenced enclosure about it, was in sight on the left of the river, and Boston itself was but a good four miles distant. But David told himself that Pikot’s fears might have ground and[39] that for a while at least it would be best to be cautious. As soon as he returned home he would repeat the Indian’s warning. He smiled as he reflected on the alarm that it would bring to Obid Dawkin.

In the early afternoon, skirting the mud flats and oyster banks below the town, he made landing at Blackstone’s Point, giving his canoe into custody of an Indian who dwelt in a hut close upon the water, and made his way up the hill, there being nothing in the way of a road save a cart track that wound deviously. His way led him presently along the slope of Valley Acre and thence into Hanover Street above where stood the house that had been the home of Governor Endicott before his death ten years ago. To David the sights and sounds of Boston were engaging indeed, and it took him the better part of an hour to complete his journey afoot. Many windows must be looked into that he might feast his eyes on the goods for sale within, and the signs hanging above the narrow streets were a never-failing source of interest. Even the sober-visaged citizens held his footsteps while he amused himself in wondering about them. There were strangers to be met as well, and these could be easily[40] distinguished, not only by their dress, but by the more cheerful countenances that they wore: ship’s captains and rolling-gaited sailors redolent of tar and, he feared, rum as well; Negroes and an occasional Indian; dark men who wore gold rings in their ears. But in the end he turned down toward the shore and so into Ship Street and saw the swinging sign of the King’s Head Tavern ahead and was presently beating a gay tattoo on the portal of Master William Elkins, Merchant.

The rest of that day passed quickly and enjoyably, for Raph Elkins took David under his wing and, until it was time for the evening meal, the two lads viewed the town and loitered along the shore and wharves where many ships were at anchor. Fascinating odors filled their nostrils and romantic sights held them enthralled. Perhaps Raph was less engaged than David, for he was more accustomed to the shipping, but he enjoyed his cousin’s pleasure and through it found a new enthusiasm. To David the sea and the ships that sailed it had ever held a strong appeal, and secretly he entertained the longing that most boys have for the feel of a swaying deck and for all the exciting adventures that were supposed to befall—and frequently did—the hardy mariners of those days. Piracy was still a popular trade in southern waters, and Teach and Bradish and Bellamy, and even the renowned William Kidd, were names to bring a romantic flutter[42] to the heart of a healthy lad. Whether, could he have had his way, David would have cast his lot with the privateers—who were but pirates under a more polite title—or with those who sought to suppress them, I do not know!

When they returned to the house, Master William Elkins had returned and they sat down to supper. David’s uncle was a somewhat pompous man of forty-odd, very proper as to dress and deportment, and who ruled his household with a stern hand. Yet withal he was kind of heart and secretly held David in much affection. Since his wife’s death the domestic affairs had been looked after by a certain Mistress Fairdaye, who occupied a position midway between that of servant and housewife, taking her meals with the family and ruling in her own realm quite as inflexibly as Master Elkins commanded over all. David often pitied Raph, for what between his father and Mistress Fairdaye he spent what seemed to the younger lad a very dreary and suppressed existence. But Raph appeared not to mind it. Indeed, unlike David, he had little of the adventurous in his make-up and restraint did not irk him. He was a rather thick-set youth, quiet in manner and[43] even sober, having doubtless found little to make him otherwise in his staid life. Yet when David was about he could be quite lively and would enter into their mild adventures with a fair grace.

Supper was a serious affair at Master Elkins’s. After the blessing had been asked, they set to in a silence that was seldom broken until the meal was at an end. David, who had experienced too much excitement to be heartily hungry, was finished before the rest and thereafter amused himself by kicking Raph’s shins beneath the table, maintaining an innocence of countenance that threw no light on the squirmings of his cousin who, in an effort to avoid punishment, called down a reprimand from his father for his unseemly antics.

The rest of the evening was spent in conversation, David delivering some messages to his uncle from his father and recounting the warning given by Monapikot and, in return, listening to a lengthy discourse on the political affairs of the Colony, much of which he did not comprehend. It was decided, though, by Master Elkins that David was not to make the return journey alone, but that three of the town Indians should accompany[44] him. David took no pleasure from the decision, for, as toilsome as the trip would have been, he had looked forward to it eagerly, anxious to put his strength and endurance to the test. But his uncle was not one to be disputed and David agreed to the arrangement with the best face he could. Bedtime came early, but, after he and Raph had put out the candle in the little sloping-roofed room at the top of the house, they talked for a long while. Even then it was Raph who first dropped off to slumber, and David lay for some time more quite wide awake in the darkness, watching through the little small-paned window the twinkling lights on the ships in the town cove.

His purchases were made by mid-morning and at a little after ten o’clock Raph accompanied him to Blackstone’s Point whither the porters from the stores had borne his goods and where three stolid and unattractive Indians were awaiting. Raph bade him farewell and repeated a promise to visit him in the summer, and the canoe, propelled by two of the savages, began its return voyage. Since but one of his copper-skinned companions carried a weapon, a battered flintlock, David could not see that he was much safer[45] from attack by hostiles than if he had made the journey alone. The armed savage was known as Isaac Trot, whatever his real name may have been, and was an ancient, watery-eyed Massachusett, one of the few remaining remnants of that once numerous tribe. He squatted forward of David, his gun across his knees, and, save for a grunted word of direction to the paddlers, gave all his attention to his pipe.

At noon they stopped for dinner, by which time they had reached the rapids near Watertown. Going down David had shot the rapids without difficulty, no hard task in an empty canoe, but now it was necessary to carry, and so when the food had been eaten, the bundles were lifted from the craft and they set out by the well-trodden path that skirted the river. David shared the burdens, taking for his load a sack of wheat for seeding and his gun. Isaac shouldered the canoe and the other two Indians managed the rest. David, well aware of the Indian weakness for thievery, watched attentively, and yet, when the canoe was again loaded above the rapids, one package was missing. He faced Isaac sternly.

“There were eight pieces, Isaac,” he said.[46] “Now there are but seven. Go back and catchum other piece.”

Isaac looked stupidly about the canoe and the ground, puffing leisurely on his pipe. At last: “No seeum,” he said stolidly.

“Go look,” commanded David. Then he pointed to the others. “You go look too. Catchum bundle or you catchum licking.”

Isaac shook his head. “Seven pieces,” he declared. “All there, master.”

“No, there were eight when we started,” replied the boy firmly. “You find the other one or you’ll go to jail, Isaac. All three go to jail. Quog quash! Hurry!”

Isaac looked cunningly from David to the others, considering. But something in the boy’s face told him he had best produce the missing bundle, and with a grunt he turned back, followed by his companions. Five minutes later they returned, one of the paddlers bearing the bundle. No explanation was offered, nor did David expect any. The package, containing tobacco and cloth, was placed in the canoe and the journey began again. The river was full and the current swift, especially where the banks were close together as was frequently the case between the carry and the lake, and the Indians made[47] slow progress. David had to acknowledge to himself that he would have found that return trip a hard task, and any lingering resentment felt toward his uncle disappeared. Had he been alone it would have taken him a good half-hour to have moved the goods over the carry, making no less than six trips, while the struggle against the current would doubtless have kept him from reaching home until well after darkness.

They met but three other voyagers on their journey and saw no Indians, friendly or hostile, and just at sunset pulled the canoe to shore and again shouldered the goods. David’s father was surprised at sight of the procession that came out of the woods toward the house, but, on hearing the boy’s story, agreed that Master Elkins had ordered wisely. The Indians were paid off and given food and tobacco and took themselves away again, while David, in spite of having done but little to earn his passage, fell to on his supper with noble hunger. As he ate—his father and Obid having already supped—he told of his meeting with Monapikot and of the latter’s news, and Master Lindall listened in all gravity and Obid Dawkin in unconcealed alarm.

“’Tis as I have told all along,” declared Obid, his thin voice more than ever like a rusted wheel in his excitement. “None is safe in his bed so long as these naked murderers be allowed to dwell in the same country! Think you I shall stay here to have my scalp lifted? I give you notice, Master Lindall, that so soon as the porridge be cooked in the morning I take my departure. The dear Lord knows that ’tis little enough hair I have left at best, and that little I would keep, an it please Him! To-morrow morning, Master Lindall! Say not that I failed to give you full notice.”

“Be quiet a moment,” replied the master calmly. “I must think what best to do. Master Vernham should be acquainted with this so soon as may be, for if it prove true that this Wachoosett sachem means mischief ’tis Master Vernham that, being nigher, they will first assail. Methinks I had best go over there at once and give him warning. You will go with me, Obid?”

Nathan Lindall’s eyes twinkled. Obid turned a dour face toward him. “Not I, in sooth, master! The forest has no liking for me since I have heard David’s tale.”

“Then David shall come and you shall remain[49] to guard the house. Perhaps that were better, for should the savages attack while we be gone you will be more able to cope with them than the lad.”

Obid’s dismay brought a chuckle from David. “Whether I go or stay,” he shrilled, “it seems I must be murdered, then! Nay, I will accompany you, for at least in the forest I may have a chance to save myself in flight, whereas an I bide here I must likely burn to death like a rabbit in a brush-heap! But in the morning, master—”

“Twice you have informed me of that, Obid. Get your hat and gun and let us be off, magpie. Mayhap if we haste we can be back before it be fully dark.”

Obid obeyed grumblingly, and soon they had set forth, leaving David to make fast the door and windows and await their return.

It would be untrue to say that David felt no uneasiness, but his uneasiness was not fear. Besides his own musket and the two that his father and Obid had taken with them there was a fourth at hand as well as a pistol that, although of uncertain accuracy, could be used if required, and against a few Indians armed only with bows and arrows[50] he felt more than a match. Small openings at the level of a man’s head, and none so greatly above the level of David’s, pierced the four walls and from these at intervals the boy peered out. The house was set in a clearing of sufficient area to protect from sudden attack, and from the nearer forest an arrow would fall spent before it reached the dwelling. Even when darkness had settled, the stars gave enough light to have revealed to sharp eyes the presence of a skulking figure. Between watching, David replenished the fire and dipped into one of two books that he had brought back with him, but he was in no mind for settled reading and, when the better part of two hours had passed, heard not without relief the sound of his father’s voice at the edge of the wood.

“Master Vernham had already heard rumors of mischief against him,” said Nathan Lindall when he had entered, “and we might have spared ourselves the journey. He seems not concerned, but has agreed to observe caution. He thinks the threats came first from the Indians we drove away and are but repeated and adorned as tales ever are. Yet for my part, David, I am not so easy. ’Tis a time of unrest, and for a while it will be[51] the part of wisdom to stray not far into the forest, and never unarmed. What say you, Obid?”

“I say naught, master. If you choose to bide here and be done to death, ’tis your own matter. But as for me, to-morrow morn I leave!”

“Then ’twere best you fortified yourself with sleep,” replied Nathan Lindall dryly, “for the journey is long.”

“Sleep, say you! Not a wink of sleep shall I have this night. If die I must ’twill be whilst I’m awake and command all my faculties.”

“Think you, Obid,” asked David slyly, “that being scalped be the more pleasant for missing no part of it?”

“Peace, David,” said his father. “’Tis not seemly to jest on so serious a matter. Be off to bed, lad.”

Once in the night David awoke and, listening to the hearty sounds that came from the farther end of the attic, smiled. “Faith,” he thought sleepily as he turned over, “if Obid be still awake he has not the sound of it!”

Perhaps sleep brought counsel to Obid, for in the morning there was no more talk[52] of leaving; though, for that matter, neither Nathan Lindall nor David had taken the servant’s threat seriously. Whatever could be said of Obid, he was no coward, while, even if he had been, his devotion to his master would have proved stronger than his timidity. That day all three worked hard in the fields. Although their muskets were ever within reach, no incident caused any alarm. And when a second day had likewise passed uneventfully, even Obid Dawkin grudgingly allowed that maybe the danger was not so present as he had feared. But on the third morning there was another tale to tell when Obid, opening the door to fetch water from the well, dropped his pail and fell back with a groan that brought the others to his side. Obid, white-faced, pointed to the stone step outside. There in the first ray of sunlight lay an arrow wrapped about with the dried skin of a rattlesnake.

“It seems he gives fair warning,” said Nathan Lindall quietly as he stooped and lifted the horrid token from the step. The snakeskin rustled as his hand touched it, and Obid, peering over his shoulder, shuddered in disgust. David was already outside, his keen eyes searching the moist ground. A dozen steps he took and then pointed toward the woods to the west.

“Thence he came, sir, and went,” he announced.

“One only?” asked his father.

“Aye, though there may have been more beyond the clearing.”

“What mean the blue spots on the arrow, master?” asked Obid troubledly.

Nathan Lindall looked at the three stains on the slender shaft and shook his head. “I know not, Obid, unless they be this sachem’s signature. Or mayhap they have a more trenchant meaning. What matter? He has put us on our guard, though for what reason I cannot discern.”

“Then can I, master,” said Obid bitterly. “Murder be enough for the bloody-minded savage, but he must even forewarn us that we may suffer first in anticipation of our fate.”

“Nay,” said David. “’Tis the Indian way to give challenge, and by so doing fight fairly, Obid. When all is said, father, he has done us a kindness, for now we know of a certainty that he means us harm and we can be more than ever on our guard.”

“’Tis a childish play,” said Nathan Lindall, “and none but a child would be disturbed thereby.” He made as if to break the arrow in his hands, but David spoke quickly.

“Let me have it, father. ’Tis like none other I have seen and I would keep it.”

“A pretty keepsake, indeed,” muttered Obid, as he went back to his tasks. “Have no fear but that they be waiting to give us plenty more of its like!”

The incident could not fail to cast a shade of gloom over the morning meal, and all three were more silent than usual. Soon after they had finished, there came a hail from the front and Master William Vernham and a servant approached. Their neighbor was a tall, grim-faced man of upwards[55] of fifty, long of leg and arm, clean-shaven save for the veriest wisp of grizzled hair upon his lip. He bore with him another such arrow as Obid had stumbled upon and was in a fine temper over it.

“On my very doorsill ’twas lain, Master Lindall! Did ever one know of such insolence? What, pray, is the Colony come to when these red devils be allowed to come and go at will, indulging themselves in all manner of mischief and seeking to frighten honest folk with such clownish tricks? Governor Leverett shall know of this ere night, and if he fail to dispatch militia to clear the country hereabouts of the varmints, then I shall call on you, Nathan Lindall, and all others within reach to aid me in the task, for patience is no longer a virtue.”

“The task will be no easy one,” answered Master Lindall, “for these Indians are but a handful and seeking for them will be like seeking a needle in a haymow. But you may count on me to aid, Master Vernham. As for asking help of the Governor, I fear ’twill be but a waste of time, for we be too far from the towns to cause him concern. ’Twill be best to take the law into our own hands, as you have said.”

“Aye, that be true. What disposition, think you, will be made of that Nausauwah that we took prisoner to Boston?”

“I know not. Perchance ’twere best for our heads were he set free with a fine, since, from what I make of it, this Metipom’s quarrel with us is on his account.”

William Vernham shook his head stoutly. “Nay, that were truckling with the villains. Rather shall I beg the Governor to hang the wastrel on Gallows Hill as soon as may be. ’Tis not fair dealing that the savages require, but harshness. They construe justice to be weakness in their heathen ignorance.” He continued in like vein, so finally working off his anger. Then: “What think you of this, Neighbor Lindall?” he asked at length. “Will these skulking devils try to burn our houses about our heads or pick us off the while we toil in the fields?”

“Perchance no more will come of it,” was the answer. “As I understand the sachem’s meaning, he bids us release his son or else our lives will be forfeit. Having sent his message he must wait a time for our answer. An he wait long enough his petty quarrel will be as but a flea-bite in the greater trouble that will be upon us.”

“You still look for a rising? Tush, tush, Master Lindall; I tell you this King Philip, as they call him, has not the courage. He but brags in his cups. Nay, nay, such annoyances as this we shall have to put up with until the country be cleaned of the vermin, but as for another such war as was fought with the Pequots, why, that cannot be. Well, I must be off. To-morrow you shall hear from me so soon as I return from Boston.”

“I would I were as certain as he,” murmured Nathan Lindall as the visitors departed.

Three days later, the Governor having dispatched one Sergeant Major Whipple to take command of the settlers, some sixteen of the latter met at Master Vernham’s, well armed, and made diligent search for many miles about, finding numerous wandering Indians to whom no blame could be laid, but failing to apprehend or even discover trace of any hostile savages. So for the time ended the incident of the spotted arrows, and the memory of it dimmed, and while Nathan Lindall and William Vernham and their households were careful to go well armed about their duties, and a watch was kept throughout the nights, yet after a fortnight vigilance waned,[58] and even Obid was found by David fast asleep one night when he should have been awake and watchful. By this time June had come in hot and the corn was planted in the south field, and the kitchen garden was already showing the green sprouts of carrots and parsnips and turnips and other vegetables which grew, it seemed, fully as well as in England. Then, on a day when there was a lapse of work for him to do, David set forth for Natick to see Monapikot again, since, in spite of the Pegan’s promise to come within the week, David had seen naught of him. By river the distance to the village of the Praying Indians was nearly twenty miles, so devious was the stream’s winding course, whereas on foot it was but a matter of four or five. And yet David might well hesitate in the choice of routes, for by land the way led through the Long Marsh, which would have been more appropriately called bog, and save for what runways the deer had made therein there was no sort of trail. It was the thought of having to remain at the village overnight that finally decided David to take the land route, and he set out early one morning with musket across his shoulder and bread and meat in his pouch, and in his[59] ears his father’s injunction to be watchful.

His way led him along the brook that flowed into the clearing, for it was by following that stream that he would unfailingly reach the first of the two large ponds lying between him and the Indian village. Now and then, after he had passed into the forest, he was able to walk briskly, but for the most part he had to make his own path, since for the last year or two the woods had not been fired thereabouts by the Indians and the underbrush had grown up rankly. Presently a small pond barred his way and he was some time finding the brook again. The most of two hours had gone before the first of the two large ponds lay before him. It was a full half-mile long and lay in a veritable quagmire over which David had to make his way with caution lest he step between the knolls or the uncertain hummocks of grass and sink to his middle, which had happened to him before. Many water birds swam upon the pond, and had he been minded to add game to his bag he might easily have done so. Mosquitoes attacked him ravenously, for the country was low-lying and no breeze dispelled the sultry stillness of the morning, and, when laden with a gun and balancing[60] one’s self on a swaying tuft of grass, fighting the vicious insects was no graceful task! Alders and swamp willows barred his path and creeping vines sought to trip him, and it was not long before he was in a fine condition of perspiration—and exasperation as well.

At length a well-defined trail came to his rescue and led him around the end of the first pond and above the head of the second, although he had to ford a shallow, muddy stream on the way. More marsh followed and then the ground grew higher and pines and hemlocks and big-girthed oaks took the place of the switches. This second pond was a handsome expanse, lying blue and unruffled under the June sky with the reflection of white, fluffy clouds mirrored therein. As he neared the southern extremity of it, where it ended in a small cove, his eyes fell on a canoe formed of a hollowed pine trunk from which two squaws were fishing. The Indian women viewed him incuriously as he passed amongst the trees. They were, as he knew, dwellers in Master Eliot’s village, now but a scant mile distant. Even as he watched, there was a splashing of the still surface beside the dugout and a fine bass leaped into[61] the sunlight. David paused and watched with a tingle of his pulse while the squaw who had hooked the fish cautiously drew him nearer the side of the canoe. The bass fought gamely, again and again flopping well out of the pond in the effort to shake free of the hook that held him, but his struggles were vain, and presently a short spear of sharpened wood was thrust from the canoe and a naked brown arm swept upward and the bass sparkled for an instant in the sunlight ere he disappeared in the bottom of the craft. No sign of pride or satisfaction disturbed the countenance of the Indian woman. She bent for a moment and then straightened and her newly baited hook again dropped quietly into the water.

“Had I brought such a monster to land,” reflected David, “I should be now singing for joy!”

In the spring of 1675 the Natick Indian village was a well-ordered community. It lay upon both banks of the Charles River, with an arched footbridge laid upon strong stone piers between. Several wide streets were laid out upon which the dwellings faced and each family had its own allotted ground for garden and pasture. Save for the meeting-house,[62] a story-and-a-half erection of rough-hewn timbers enclosed in a palisaded fort, wooden buildings were scarce, since the Indians clung to their own style of dwelling. Some half-hundred wigwams composed the village, although not all were then occupied. There were many neat gardens, and fruit-trees abounded. Altogether the village looked prosperous and contented as David came toward it that June morning. The streets were given over chiefly to the children, it seemed, and these used them as playgrounds. At the door of a wigwam a squaw sat here and there at some labor, but industry was not a notable feature of the village. Save that a dog barked at him, David’s arrival went unchallenged, and he crossed the long footbridge and sought the palisade where he thought to find Pikot at his duties of teaching the younger men and women. A lodge rather more pretentious than the rest was the residence of the sachem Waban, a Nipmuck who had lived previously at Nonantum and who had become the most prominent of Master Eliot’s disciples and, it is thought, the most earnest. Waban had married a daughter of the famous Tahattawan, sachem of the country about the Concord River, himself[63] a convert to Christianity and a teacher of it amongst his people. Besides being sachem, Waban likewise held the office of justice of the peace, and it was he who had a few years before written the laconic warrant for the arrest of an offender named Jeremiah Offscow: “To you big constable, quick you catch um, strong you hold um, safe you bring um afore me, Waban, justice peace.” David knew the sachem well and meant to visit him before he left, but now he kept on to the meeting-house wherein the school was held on week-days and where the Reverend John Eliot discoursed to the Indians, and, usually, to a few English besides, on the Sabbath. The preacher lived when at the village in a small chamber divided off from the attic above.

David found Pikot busy with another teacher inside the building, and seated himself within the door to wait. Some fourteen or fifteen pupils, the younger members of the community, were at their lessons, and David had perforce to own that they indeed behaved with more decorum than a like number of English would have. Now and then a sly glance of curiosity came David’s way from a pair of dark eyes, but for the most part his presence went unheeded. The Indians’[64] voices sounded flat and expressionless as they answered the questions put to them or recited in unison a portion of the lesson. Indeed, David much questioned that they fully understood what they said save as a parrot might! After a while the class was dismissed and went sedately forth, boys and girls alike, and Pikot joined David and led him out of the building and through the palisade gate and so to the river where, on a flat stone above the stream, they sat themselves and began their talk.

“You came not for the fishing, Straight Arrow,” charged David. “To an Indian who does not keep his word I have naught to say.”

Pikot smiled. “True, Noawama, yet ’twas not of choice that I failed you. I went a long journey that took many days and I could not send you word.”

“A long journey?” asked David eagerly. “Whither did you go?”

The Indian’s expression became strangely blank as he waved his hand vaguely westward. “Toward the Great River, David.”

“That they call the Connecticote? Tell me of your journey, Pikot. What did you go for?”

“The business was not mine, brother, and I may not talk.”

“Oh, well, have your secrets then. And I’ll have mine.”

Monapikot smiled faintly. “And if I guess them?”

“I give you leave, O Brother of the Owl,” jeered David.

The Indian half closed his eyes and peered at the tops of the tall pines that crowned the hill. “Came one by night through the forest,” he said slowly in his native tongue. “The skin of a panther hung about him and he was armed only with a knife. As the weasel creeps through the grass, so this one crept to the lodge of the white man where all were asleep. On the stone without the door he laid a message from his sachem. As the fox slinks homeward when the sun arises, so this one slunk away. The forest took him and he vanished.”

“How know you that?” asked David, affecting great surprise. “It but happened half a moon ago and none has heard of it save all the world! Can it be that you know also what the message was like?”

“An arrow wrapped with the cast skin of a rattlesnake, brother.”

“Wonderful! And it may be that you can tell how the arrow was made, O Great Powwow.”

“’Twas headed with an eagle’s claw and tipped with gray feathers. Three blue marks were on it, O Noawama.”

David frowned. “Now as to that I wonder,” he said. “None saw the arrow save we three. How then could you know that the head was not of stone or the horn of the deer?”

“Did I not tell you I could guess your secret?”

“Aye, but methinks you are not guessing, Pikot. And how know you that the messenger came unarmed and wearing a panther-skin?”

“How know you that I speak true?” asked Pikot, smiling.

“I do not know,” replied David ruefully, “but I would almost take oath to it. Saw you this Wachoosett, Pikot?”

Pikot shook his head. “Nay.”

“Then how—”

“The Wachoosetts be fond of panther-skins, David, and the braves wear them much, as I know. As for the knife, an Indian[67] has no use for bow and arrow at night, nor, on a long journey, does he weight himself with a tomahawk. The eagle nests in the great hill in the Wachoosett country and Wachoosett people arm their arrows with the eagle’s claws, and tip them with feathers from the eagle’s wing. As for the blue spots, that I heard, brother.”

“Oh!” But David viewed Pikot doubtfully. “I still think you knew more than you guessed. But ’tis no matter. This Metipom troubles us no more. Doubtless he waits to find whether his son be judged guilty or no. How far is this country of the Wachoosetts, Straight Arrow?”

“Maybe twelve leagues.”

“No farther than that? ’Tis but a half-day journey for an Indian, then.”

“Nay, for there be many streams and hills. One travels not as an eagle flies, brother.”

“True, and still this Metipom lives too near for my liking. Think you he still means mischief, Pikot?”

“Aye,” answered the Pegan gravely. “But it may be, as you say, that he will wait and see how his son fares in the court in Boston. You do ill to travel alone through the[68] forest, David, and when you return I will go with you.”

“I shall be glad of your company, but I have no fear.”

“Nor had the lion, and yet the wolves ate him.” Pikot glanced at the sun and arose. “Come and eat meat with me, David, and then we will start the journey back, for I would have you safe before the shadows are long.”

The sun was still above the hills when Pikot bade farewell to David beyond the little pond that lay somewhat more than a mile from his home. The Indian would have gone farther, but David protested against it.

When David reached the house, he learned the news that had come that day from Boston by travelers who had stopped on their way to Dedham. Two days before Poggapanossoo, otherwise known as Tobias, and Mattashinnamy had been hanged at Plymouth. These were two of the three Indians who had been convicted of killing Sassamon the year before, and Tobias was one of King Philip’s counselors. The third Indian under sentence had, it seemed, been reprieved, though the Dedham men did not know for what cause. David’s father took a gloomy view of the affair.

“’Twere better had they let them lie in jail for a while longer,” he said, “for their execution is likely to prove the last straw to Philip, who has long been seeking a nail[70] upon which to hang a quarrel. I fear the skies will soon be red again, David. I like it not.”

“But these Indians were fairly tried, father, and surely they merited their punishment.”

“Aye, lad, but there could have been no harm in delay.”

“But if, as you have said, a strong hand should be shown? Will not King Philip, mayhap, take warning by the fate of these murderers?”

“Wisely said,” piped Obid, busy at the hearth with the preparation of the evening meal. “An those of the Plymouth Colony, as well as we, were but to choose every other savage and hang him, ’twould put a quick end to these troubles. And I would that this Preacher Eliot were here to hearken.”

“Time alone will tell,” said Nathan Lindall soberly. “Yet the men from Dedham were not so minded. They foresee war with King Philip and dread that he will persuade the Narragansett Indians to join with him. ‘When the leaves are on the trees,’ said Tanopet.”

“We here are far distant from Philip, though,” said David.

“Little profit there will be in that,” said Obid dourly, “with fivescore savages but five miles distant and the country full of wandering marauders! For my part, I tell you, ’twill be a relief to me when my scalp be well dangling from an Indian belt and I have no longer to worry about the matter.”

“Waban, at Natick, is a firm friend of the English,” replied David stoutly. “There is naught to fear from there. Nor do I believe that any Nipmuck will take arms against us. Indeed, an I am to see fighting, I must, methinks, move up the river to Dedham or join the Plymouth men.”

“Do not jest, David,” counseled his father. “It may be that you will find more fighting than will suit your stomach.”

“Meanwhile,” answered the boy gayly, “here is what suits my stomach very well. ’Twould be a monstrous pity to scalp you, Obid, so long as you can make such stew as this!”

A week went by, during which the corn sprouted finely, coaxed upward by gentle rains that came at night and vanished with the sun. There was plenty of work in field and garden and David had scant time for play. Yet he found opportunity to fish in[72] the river in the long evenings, paddling up to the falls and dropping his line in the deep, black pools there. He had brought some English hooks back with him from Boston and liked them well. No more news came from the outer world save that at Boston there was much uneasiness of an uprising of the Indians and drilling of the militia each day. If Philip meant mischief he bided his time.