[Told by John Sky of Those-born-at-Skedans]1

Over this island2 salt water extended, they say. Raven flew about. He looked for a place upon which

to sit. After a while he flew away to sit upon a flat rock which lay toward the south

end of the island. All the supernatural creatures lay on it like Genō′,3 with their necks laid across one another. The feebler supernatural beings were stretched

out from it in this, that, and every direction, asleep. It was light then, and yet

dark, they say.

[Told by Job Moody of the Witch People4]

The Loon’s place5 was in the house of Nᴀñkî′lsʟas. One day he went out and called. Then he came running

in and sat down in the place he always occupied. And an old man was lying down there,

but never looking toward him. By and by he went out a second time, cried, came in,

and sat down. He continued to act in this manner.

One day the person whose back was turned to the fire asked: “Why do you call so often?”

“Ah, chief, I am not calling on my own account. The supernatural ones tell me that

they have no place in which to settle. That is why I am calling.” And he said: “I

will attend to it (literally, ‘make’).”

[Continued by John Sky]

After having flown about for a while Raven was attracted by the neighboring clear

sky. Then he flew up thither. And running his beak into it from beneath he drew himself

up. A five-row town lay there, and in the front row the chief’s daughter had just

given birth to a child. In the evening they all slept. He then skinned the child from

the foot and entered [the skin]. He lay down in its place.

On the morrow its grandfather asked for it, and it was given to him. He washed it,

and he put his feet against the baby’s feet and pulled up. He then put it back. On

the next day he did the same thing and handed it back to its mother. He was now hungry.

They had not begun to chew up food to put into his mouth.

One evening, after they had all gone to bed and were asleep, Raven raised his head

and looked about upon everything inside the house. All slept in the same position.

Then by wriggling continually he [111]loosened himself from the cradle in which he was fastened and went out. In the corner

of the house lived a Half-rock being,6 who watched him. After she had watched for a while he came in, holding something

under his blanket, and, pushing aside the fire which was always kept burning before

his mother, he dug a hole in the cleared place and emptied what he held into it. As

soon as he had kneaded it with the ashes he ate it. It gave forth a popping sound.

He laughed while he ate. She saw all that from the corner.

Again, when it was evening and they were asleep, he went out. After he had been gone

for a while he again brought in something under his blanket, put it into the ashes

and stirred it up with them. He poked it out and laughed as he ate it. From the corner

of the house the Half-rock one looked on. He got through, went back, and lay down

in the cradle. On the next morning all the five villages talked about it. He heard

them.

The inhabitants of four of the five towns had each lost one eye. Then the old woman

reported what she had seen. “Behold what that chief’s daughter’s child does. Watch

him. As soon as they sleep he stands up out of himself.” His grandfather then gave

him a marten-skin blanket, and they put him into the cradle. At his grandfather’s

word some one went out. “Come to sing a song for the chief’s daughter’s baby outsi-i-ide,

outsi-i-ide.” As they sang for him one in the line, which extended along the entire

village front, held him. By and by he let him fall, and they watched him as he went.

Turning around to the right as he went, he struck the water.

And as he drifted about he cried without ceasing. By and by, wearied out with crying,

he fell asleep. After he had slept a while something said: “Your mighty grandfather

says he wants you to come into his house.” He turned around quickly and looked out

from under his blanket, but saw nothing. Again, as he floated about, something repeated

the same words. He looked quickly around toward it. He saw nothing. The next time

he looked through the eyehole in his marten-skin. A pied-billed grebe came out from under the water, saying “Your mighty grandfather

invites you in,” and dived immediately.

He then got up. He was floating against a kelp with two heads. He stepped upon it.

Lo! he stepped upon a house pole of rock having two heads. He climbed down it. The

sea was just as good as the world above.7

He then stood in front of a house. And some one called him in: “Enter, my son. Word

has arrived that you come to borrow something from me.” He then went in. An old man,

white as a sea gull, sat in the rear part of the house. He sent him for a box that

hung in the corner, and, as soon as he had handed it to him, he successively pulled

out five boxes. And out of the innermost box he handed him [112]two cylindrical objects, one covered with shining spots, the other black, saying “I

am you. That [also] is you.” He referred to something blue and slim that was walking

around on the screens whose ends point toward each other in the rear of the house.

And he said to him: “Lay this round [speckled] thing in the water, and after you have

laid this black one in the water, bite off a part of each and spit it upon the rest.”

But when he took them out he placed the black one in the water first and, biting off

part of the speckled stone, spit it upon the rest, whereupon it bounded off. Because

he did differently from the way he was told it came off. He now went back to the black

one, bit a part of it off and spit it upon the rest, where it stuck. Then he bit off

a part of the pebble with shiny points and spit it upon the rest. It stuck to it.

These were to be trees, they say.8

When he put the second one into the water it stretched itself out. And the supernatural

beings at once swam over to it from their places on the sea. In the same way Mainland9 was finished and lay quite round on the water.

He floated first in front of this island (i.e., the Queen Charlotte islands), they

say. And he shouted landward: “Gū′sga wag̣elai′dx̣ᴀn hā-ō-ō” (Tsimshian words meaning

“Come along quickly”) [but he saw nothing]. Then [he shouted]: “Ha′lᴀ gudᴀñā′ñ łg̣ā′gîñ

gwā′-ā-ā” (Haida equivalent of the preceding). Some one came toward the water. Then

he went toward Mainland. He called to them to hurry, [saying] “Hurry up in your minds,”

but he saw nothing. He spoke in the Tsimshian tongue. Then one with an old-fashioned

cape and a paddle over his shoulder came seaward. This is how he started it that the

Mainland people would be industrious.

Pushing off again toward this country, he disembarked near the south end of the island.

On a ledge a certain person was walking. Toward the woods, too, among fallen trees,

walked another. Then he knocked him who was walking along the shore into the water.

Yet he floated, face up. When he again knocked him in the same thing was repeated.

He was unable to drown him. This was because the Ninstints people were going to practise

witchcraft. And he who was walking among the trees had his face cut by the limbs.

He did not wipe it. This was Greatest-crazy-one (Qōnā′ñ-sg̣ā′na), they say.

He then turned seaward and started for the Heiltsuk coast (ʟdjîñ).10 As he walked along he came to a spring salmon that was jumping about and said to

it: “Spring-salmon, strike me over the heart.” Then it turned toward him. It struck

him. Just as he recovered from his insensibility it went into the sea. Then he built

a stone wall close to the sea and behind it made another. When he told it to do the

same thing again the spring salmon hit him, and, while he was on the ground, after

jumping along for a while, it knocked over the [113]nearer wall. But while it was yet moving along inside the farther wall he got up,

hit it with a club, killed it, and took it up.11

He then called in the crows to help him eat it. They made a fire and roasted it [on

hot stones]. He afterward lay down with his back to the fire. He told them to wake

him when it was cooked. He then overslept. And they took everything off from the fire

and ate. They ate everything. They then poked some of the salmon between his teeth.

And he awoke after he had slept a while and told them to take the covering off the

roast. And they said to him: “You ate it. After that you went to sleep.” “No, indeed,

you have not taken the coverings off yet.” “Well, poke a stick between your teeth.”

He then poked a stick between his teeth. He poked out some from his teeth. He thereupon

spit into the crows’ faces and said: “Future people shall not see you flying about

looking as you do now.” They were white, they say, but since that time they have been

black.

And walking away from that place he sat down near the end of a trail. After he had

wept there for a while some people with feathers on their heads and gambling-stick

bags on their backs came to him and asked him what the matter was. “Oh, my mother

and my father are dead. Because they told me I was born [in the same place] as you

I wander about seeking you.” They then started home with him. Lo, they came to a house.

Then they made him sit down. One of the men went around behind the screens by the

wall passage. After staying away for a while [he came in and] his legs were wet. He

brought a salmon with its back just broken. They rubbed white stones against each

other to make a fire. Near it they cut the salmon open. They put stones into the fire,

roasted the salmon, and, when it was cooked, made him sit down in the middle. There

they ate it. These were the Beavers, they say. They were going out to gamble, but

turned back on account of him.

One of them again went behind the screens. He brought out a dish of cranberries, and

that, too, they finished. Again he went in. He brought out the inside parts of a mountain

goat, and they divided them into three portions, and made Raven’s portion big. Then

they said to him: “You had better not go away. Live with us always.” They then put

their gambling-stick bags upon their backs and started off.

When it was near evening they came home. He was sitting in the place [where they had

left him]. Again one went in. He again brought out a salmon. They steamed it. And

they also brought out cranberries. They also brought out the inside parts of a mountain

goat. After they had eaten they went to bed. On the next day, early in the morning,

after they had eaten three sorts of food, they put the gambling-stick bags upon their

backs and started off again.

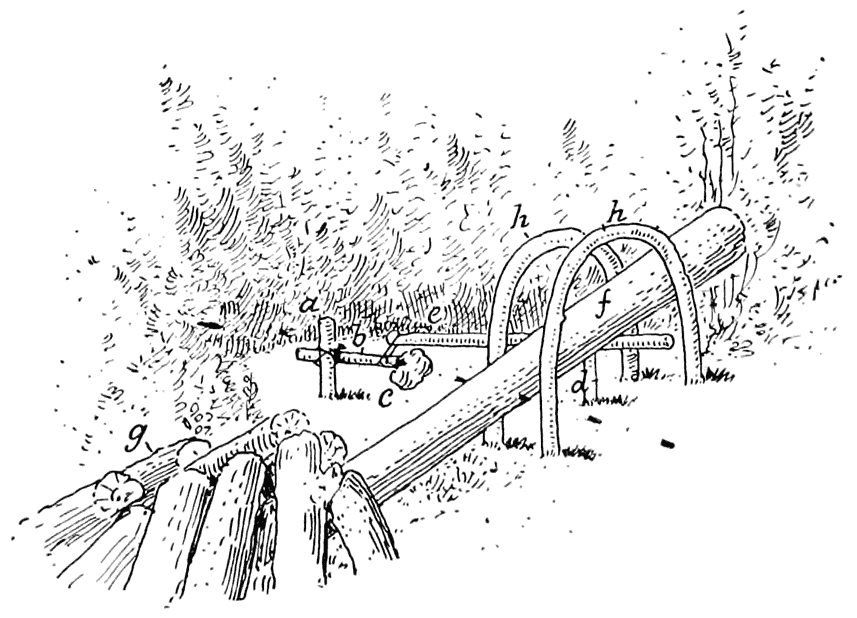

He then went behind the screen. Lo, a lake lay there. From it a creek flowed away

in which was a fish trap. The fish trap was so [114]full that it looked as if some one were shaking it. There were plenty of salmon in

it, and in the lake very many small canoes were passing one another. Several points

were red with cranberries. Lēn12 and women’s songs13 resounded.

Then he pulled out the fish trap, folded it together, and laid it down at the edge

of the lake. He rolled it up with the lake and house, put them under his arm, and

pulled himself up into a tree that stood close by. They were not heavy for his arm.

He then came down and straightened them out. And he lighted a fire, ran back quickly,

brought out a salmon, and cooked it hurriedly. He ate it quickly and put the fire

out again. Then, sitting beside it, he cried.

As he sat there, without having wiped away his tears, they came in. “Well, why are

you crying?” “I am crying because the fire went out some time ago.” They then talked

to each other, and one of them said to him: “That is always the way with it.”

They then lighted the fire. One of them brought out a salmon from behind [the screens]

and they cut it across, steamed, and ate it. After they had finished eating cranberries

and the inside parts of a mountain goat they went to bed. The next morning, very early,

after they had again eaten the three kinds of food, they took their gambling-stick

bags upon their backs and went off.

He at once ran inside. He brought out a salmon, cooked it, and ate it with cranberries

and the inside parts of a mountain goat. He then went in and pulled up the fish trap.

He flattened it together with the house.

After he had laid them down he rolled the lake up with them and put all into his armpit.

He pulled himself up into a tree standing beside the lake. Halfway up he sat down.

And after he had sat there for a while some one came. His house and lake were gone

from their accustomed place. After he had looked about the place for some time he

glanced up. Lo, he (Raven) sat there with their property. Then he went back, and both

came toward him. They went quickly to the tree. They began working upon it with their

teeth. When it began to fall, he (Raven) went to another one. When that, too, began

to fall he sat down with his [burden] on one that stood near it. After he had gone

ahead of them upon many trees in the same way they gave it up. They then traveled

about for a long time, they say. After having had no place for a long time they found

a lake and settled down in it.

Then, after he (Raven) had traveled around inland for a while, he came to a large

open place. He unrolled the lake there. There it lay. He did not let the fish trap

or the house go. He kept them to teach the Seaward (Mainland) people and the Shoreward

(Queen Charlotte islands) people, they say.

[115]

While he was walking along near the edge of the water [he saw] a part of some creature

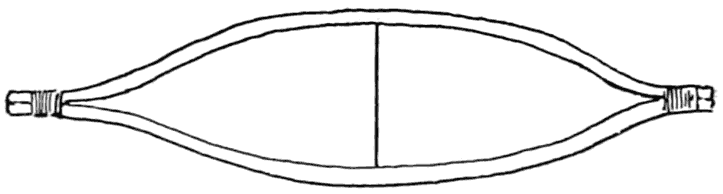

looking like a woman sticking out of the water at the mouth of Lalgī′mi.14 He was fascinated by her, made a canoe, and went to her. When he got near she went

under the water in front of him. After he had made a canoe of something different

he went to her again. When he got near to her she sank into the water. He made one

of something still different. Again she sank into the water before him.

Now, after he had searched about for a while, he opened a wild pea (xō′ya ʟū′g̣a,

“Raven’s canoe”) with a stick and went out to her in it. When he came near to get

her that time she did not go under the water. He came alongside of her and took her

in. She wore a dancing skirt and dancing leggings. He then got the canoe ashore, untied

her dancing leggings and dancing skirt, and wiped her all over. He ran to the woods,

got a tcā′łg̣a,15 and drew it over her for a blanket.

He then launched the canoe and put her in it, and they started landward.16 He set her ashore on the west arm of Cumshewa inlet (G̣a′oqons) and also took out

the house for her, but kept the fish trap in his armpit. He did so because he was

going to teach [some one] about it.

He then went back again. After he had passed along Seaward land (the mainland) in

his canoe for some time, behold, a person came along by canoe. The hair on the top

of his head was gathered in a pointed tuft. And he (Raven) held his canoe off at arm’s

length for a while. The canoe was full of hair seal. Then he questioned him: “Tell

me, where did you gather the things you have?” “Why, there are plenty of them” [he

replied], and he picked up his hunting spear. After he had looked between the canoes

he speared something. He pulled out a hair seal. “Look in” [he said], and he (Raven)

looked in. He could see nothing. “I say, I am this way (i.e., have bad eyesight) because

a clam spit upon me. Since then I have been unable to see anything.” He then stretched

his head over. He stretched it to him. And, having pulled a blood clot out of his

eye with his finger nails, he put it back again. He used bad words to him, therefore

he did not take it out for good. Now, he (Raven) treated him well. He made many advances

to him, but he could not get [what he wanted] and started off.

After he had gone along for some time, lo, Eagle17 was coming; and he said to him: “Comrade, I have been drinking sea water. You, too,

had better drink sea water.” And he drank some in his sight. At once he defecated

as he went along. Then Eagle, too, drank some. He also defecated as he went, and he

said: “Cousin, come, let us build a fire.” “Wait, I am looking for the place.” Then

Eagle pulled a water-tight basket out from under his armpit and drank from [116]it. At once what he had drunk spurted from his mouth as he went along. After they

had gone along for a while they landed upon certain flat rocks extending into the

sea.

Then Raven went up first and lighted a fire. He again watched Eagle as he kept taking

out his basket and drinking water. He intended to take it, but he did not have an

opportunity. Eagle also let the contents of his stomach run into the ground, and they

went out of sight. Then he (Raven) took a walk. “I am going to drink,” he said, and

passed into the woods. Having taken roots and put root sap into the hat he wore, he

went to him. While coming back he drank of it on the way. And he asked Eagle to taste

it. He handed it to him. He looked into it. He sniffed at it. “Tell me, cousin, why

does your water smell like pitch?” “Well, cousin, the water hole was in clay.”

He then broke off tips of branches from a hemlock that had clusters of twigs sticking

out all round them and gave them to him. “Cousin, put these upon the fire.” And he

put them upon the fire. Wā-ā-ā, it burned brightly. And after he had done this a while,

lo, Eagle pulled out his basket. As soon as he saw that, he (Raven) ran to the end

of a clump of limbs and stepped heavily upon it to break it. “Clump of branches, fall

down, fall down” [he said], and it broke and was coming down. Then he said to Eagle,

“Hukukukuk.”18 Eagle ran from his water in terror.

Then Raven put on his feather clothing and flew away with it. Eagle, too, put on his

feather clothing and flew after him. He tried to hook his claws into him, and water

was jerked out of [the basket]. As this happened the salmon streams were formed. Eagle

gave up the pursuit, and he (Raven) continued scattering water out of his mouth. After

a while he emptied the last where he had stretched out the first [lake]. He treated

this island in the same manner. After that he emptied [the last] at the head of Skeena.19

Eagle was also called Lā′g̣ałᴀm.20

Raven finished this. He then traveled northward. After he had traveled for a while

he came to where a village lay. He then put himself in the form of a conifer needle

into a water hole behind the chief’s house and floated about there awaiting the chief’s

daughter.

The chief’s child then went thither for water, and he floated in the water that she

dipped up. She threw this out and dipped a second time, but he was still there. And

when close to her he said: “Drink it.”

Not a long time after that she became pregnant. Then she gave birth [to a child],

and its grandfather washed the child all over and put his feet to its feet. It began

to creep about. After it had crept about for a while it cried so violently that no

one could stop it. “Boo hoo, moon,” it kept saying. After it had tired them out with

[117]its crying they stopped up the smoke hole, and, having pulled one box out of another

four times, they gave it a round thing. There came light throughout the house. After

it had played with this for a while it let it go and again started to cry. “Boo hoo,

smoke hole,” it cried. They then opened the smoke hole, and it cried again and said:

“Boo hoo, more.” And they made the space larger. Then he flew away with it. Marten21 pursued him below. Tā′ʟᴀtg̣ā′dᴀla,22 too, chased him above. They gave it up and returned.

He then put the moon into his armpit. And, after he had traveled about for a while,

he came to where Sea-gull and Cormorant sat. He made them quarrel with each other.

And he said to Cormorant: “People tell me to brace myself on the ground with my tongue

this way [when fighting].” He then did it, and [Raven] went quickly to him. He bit

off his tongue.

Then he made it into an eulachon. And he put on his cape and rubbed this all over

it, and he rubbed it on the inside of the canoe as well. Then he also put rocks in

and went in front of Qadadjâ′n.23 And he entered his house. “Hī, I, too, have become cold.” Qadadjâ′n was lying with

his back to the fire and, looking toward him, saw his canoe, covered with slime, lying

on the water as if full. He then became angry and pulled the screen down toward the

fire. Eulachon immediately poured forth. He then threw the stones out of the canoe and put them into it. When it was full, he went off with them.

After he had distributed the eulachon along the mainland in the places where they

now are and had put some in Nass inlet, he left a few in the canoe.

He then placed ten paddles under these, of which the bottom one had a knot hole running

through it. And he shouted landward to where a certain person lived. She then brought

out a basket24 on her back, and he said to her: “Help yourself, chieftainess.” After she had put

them into [the basket] a while, and her basket was nearly full, he stepped upon a

stalk of łqeā′ma25 which he had provided and said: “Ā-ā-ā, I feel my canoe cracking.” He then pushed

it from the land, and when she stretched out her arm for more [eulachon] he pulled

out the hairs under her armpit.

Fern-woman (Snᴀndjā′ñ-djat) at once called for her sons. Both her sons knew how to

throw objects by means of a stick, they say.26 He immediately fled. And one of them shot at him and broke his paddle. And after

they had broken ten he paddled with the one that had a knot hole. When they shot after

him again he said “Through the knot hole,” and through the knot hole went the stone.

Thus he was saved. He had dexterously got her armpit hair.

He then left the canoe. He came to a shore opposite some people who were fishing with

fish rakes in Nass. And he said: “Hallo, [118]throw one over to me. I will give you light.” But they said: “Hᴀ hā′-ā-ā, he who is

speaking is the one who is always playing tricks.” He then let a small part shine

and put it away again. They forthwith emptied their canoe in front of him several

times.

He then called a dog and said to it: “Shall I make (or ordain) four moons?” The dog

said that would not do. The dog wanted six. He (Raven) then said to him: “What will

you do when it is spring?” “When I am hungry I will move my feet in front of my face.”

And he made it as he (the dog) told him to do, they say.

He then bit off a part of the moon. After he had chewed it for a while he threw it

up [into the sky]. “Future people are going to see you there in fragments forever.”

He then broke the moon into halves by throwing it down hard and threw [half of] it

up hard into the air, the sun as well.

Thence he traveled northward. The smoke of House-point was near him. He then pulled

off his hair ribbon and threw one end of it over here. He at once ran across on it.

And he walked about the town, peering in [through the cracks]. The wife of the town

chief of House-point had given birth to a child. And he waited until evening. Then,

at the time when they went to bed, he entered [the child’s] skin and himself became

newly born.

Every morning they washed him, and his father held him on his knee. After a while

his aunt came down to the fire. They handed him to his aunt. After she had held him

for a while he pinched her teats. “Ha′oia,” she said. “Why do you say that, ʟ̣a?”27 “Why, he nearly fell from me.” The town chief was named “Hole-in-his-fin,” and his

nephew was named “Fin-turned-back.”

After a while he thought: “I wish the village children would go picnicking.” And on

the next day the children of the town went picnicking. They brought along all sorts

of good food. And his aunt brought him to the same place. When they had played for

a while they went away. After they had all gone his aunt sat there alone. He looked

about, entered his own skin quickly, and seized his aunt. And his aunt said: “Do not

take hold of me. I am single because your father is going to eat my gifts.”28

Then, as soon as she started off, he became a baby again. His aunt was crying and

as she went had it on her mind to tell what had happened. He wished his aunt would

forget it when she went in. And she went in. After her brother had looked at her a

while he asked: “What is the cause of those tear marks?” “Why, I discovered him eating

sand. That is why I am crying.”

He then started along by the sea and, having punched holes in the shells brought up

by the tide, he made two dancing rattles. And he ran toward the woods. He took grave

mats, frayed out the ends, and fastened shells upon these. He made them into a dancing

skirt. And [119]he said to the ghost: “Are you awake?” It got up for him, and he tied the dancing

skirt upon it. He also put the rattle into its hand. And he said to it: “Walk in front

of the town. When you reach the middle wave the rattle in front of you toward the

houses. A deep sleep will fall then upon them.”

Now it began to dance, they say. When it waved the rattle toward the town, just as

he had told it to do, they began to mumble in their sleep. They had nightmares. He

then went into the first house and, roughly pulling out a good-looking woman, lay

there with her. And he entered the next one. There, too, he lay with somebody. As

he went along doing this he entered his father’s house, went to where his aunt slept,

and lay with her.

And a certain old woman living in the house corner did not have a nightmare. She had

been observing the chief’s son in the cradle come out of himself. Then he went out

again. After he had been away for a while he came in and lay down to sleep in the

cradle. He made the ghost lie down again.

The town people told one another in whispers that he had lain with his aunt, and his

mother, Flood-tide-woman, as well. This went on for a while; then, all at once, there

was an outbreak. Then they drove Flood-tide-woman away with abusive language. Her

boy, too, they drove off with her with abusive words. She was the sister of Great-breakers,29 belonging to the Strait people, they say.

And they came along in this direction (i.e., toward Skidegate). After they had come

along for a while they found a young sea otter opposite the trail that runs across

Rose Spit (G̣o′łgustᴀ). His mother then skinned it and sewed it together. Now she

stretched it and, having scraped it, laid it out to dry. When it was dried she made

it into a blanket for her son. He was Nᴀñkî′lsʟ̣as-łiña′-i,30 they say.

And after they had traveled for a while she stood with her child in front of her brother’s

house. By and by somebody put his head out. “Ah, Flood-tide-woman stands without.”

“N-n-n, she has done as she always does (i.e., been unfaithful to her husband), and

for that reason comes back again,” said her brother. And again he spoke: “With her

is a boy. Come, come, come, let her in.”

Then she came in with her son. And her brother’s wife gave them something to eat.

By and by he asked of her: “Flood-tide-woman, what are you going to name the child?”

And she moved her hand over the back of her head. She scratched it [in embarrassment].

“Why, I am going to name your nephew Nᴀñkî′lsʟas-łiña′-i.” As she spoke she held back her words hesitatingly. “I tell you, name him differently,

lest the supernatural beings who are afraid to think of him (the bearer of that name)

hear that a common child is so called.”

While she was staying with her brother her child walked about. He banged the swinging

door roughly. “Flood-tide-woman, stop that [120]child from continually opening the door in that way.” “Why, chief, I never can stop

him.” “Just hear what she says. What a common child is continually doing the supernatural

beings ever fear to do.” On another day, while Great-breakers was lying down, he banged

the door again. He said to the mother: “Flood-tide-woman, a common child is doing

the same thing again. Try to stop him.” “Why, chief, I can never stop your slave nephew.”

And where he was sitting with his mother by the fire, on the side toward the door,

right there he defecated. And his uncle’s wife made a pooping sound at him. “I shall

indeed go with that husband’s nephew,” he heard his uncle’s wife say.31

On the next day, very, very early in the morning, he started off. After he had gone

along for some time he came to some persons who burst into singing sweet songs and

danced. They then asked him: “Tell us, what are you doing hereabout?” “I am gathering

woman’s medicine.” “Well, what do you call woman’s medicine? Is woman’s medicine each

other’s medicine?” “Yes; it is each other’s medicine.” Those women chewed gum as they

sang. Then one of these gave him a piece. “This is woman’s medicine.” And one of them

gave him directions: “Now, when you enter the house, pass round to the right. Chew

the gum as you go in. And when your uncle’s wife asks it of you, by no means give

it to her. Ask of her the thing her husband owns. When it is in your hands give the

gum to her.” And he went away from the singers. When he entered the gum stuck out

red from his mouth. Then his uncle’s wife said to him: “I say, Nᴀñkî′lsʟas-łîña′-i,

come, give me the gum.” He paid no attention to her. He then sat down beside his mother,

and to his mother he said: “Tell her to give me the thing my uncle owns. I will then

give her the gum.” Then his mother went to her. She told it her. And to her she gave

something white and round. He then handed her the gum. While his uncle’s wife chewed

it and swallowed the juice he saw that her mind was changed.

Some time after that his fathers32 went by on the sea. And he said to a dog sitting near the door: “Nᴀñki′lsʟas-łîña′-i

says he desires the place where his fathers now are to dry up and leave them.” And

immediately it went out and said so. The tide left them high and dry, and they were

in great numbers. They made a scraping sound in their efforts to move. He then said

to his mother: “I say, go and pour water upon my fathers.” She then went down to them,

and she did not look upon her husband. She poured it only upon Fin-turned-back. And

he went to his mother and told her to pour water upon his father. She acted as if

she did not hear his voice. They were going to the supernatural beings of Da′osgên33 to buy a whale, they say.

Then he came in and said to the dog again: “Go and say, ‘Nᴀñkî′lsʟas-łîña′-i says

he desires the tide to come in to his parents.’ ” He then went out quickly and said

it. X̣ū-ū-ū-ū-ū (noise of the waves coming in), and they at once were moving along

far off on the water.

[121]

And, after they had been gone a while, they returned to that place. And again he said

to the dog: “Go and say, ‘Nᴀñkî′lsʟas-łîña′-i says he wishes his parents to leave

something for him.’ ” He then went out quickly and said so. Something black was sent

to one end of the town. He went thither. A whale floated there.

After he had made a house of hemlock boughs he shot all kinds of birds there. By and

by a bufflehead came and ate of the whale. He then wanted it. And he aimed just above

the top of its head. When it flew it struck its head. He then skinned it and entered

[the skin]. And he wished for a heavy swell, and it became rough, and he walked toward

the water. And when a wave came toward him he quickly dived under it. After he had

done the same thing repeatedly he flopped up from the water, took the skin off, and

dried it in his branch house. He thus came to own it, they say. He kept it in the

fork of a tree.

After he had shot there all kinds of birds something blue and slender came and ate

of it. It flew down from above. It ate sitting upon it. He then shot it. He shot [only]

through its wings. He (Raven) was sad. And on the next day, early in the morning,

he entered his branch house. After he had sat there for a while it again came down

from above, making a noise as it came. And after it stood upon it and had begun to

eat he shot it. The arrow again passed quickly through its wings. His mind was sad.

And on the next day, very early in the morning, he again went into the branch house.

It came by and by and ate. And he now shot over it. As it started to fly it was struck

in the head. He then went down to get it. He brought it into the branch house.

When he had skinned it, he entered it. He then flew up. After he had flown for a while

he turned quickly and came down. He then ran his beak into a rocky point at the end

of the town. At the same time he cried out: “G̣ao” (Raven’s croak). Though the rock

was strong, he split it by his voice. After he had dried it in the branch house he

put it where he kept the bufflehead.

He then started off, they say. He went in and sat down by the side of his mother.

By and by his aunt said to her husband: “Why do you remain seated so long? Go and

hunt,” she said to him. And they brought out a war spear and a box of arrows, and

they put pitch on [the cord wound round the arrow point] for him. And at midnight

he went off in a canoe, and his place was vacant in the morning.

He (Raven) then went out and stood up out of himself (i.e., changed himself). He put

on two sky blankets and painted his face. And, as soon as he entered, his uncle’s

wife turned her head. He went around behind the screens. And, after some time had

passed, it thundered on the underground side of the island.

And her husband came back and asked his wife: “My child’s mother, what noise was that,

sounding like the one that is heard when I go to [122]bed with you?” And she laughed and said: “Why, I guess I am the same with Nᴀñkî′lsʟas-łîña′-i,

your nephew.”

On the next day, early in the morning, Great-breakers sat in the place where the fire

was. On the top of the chief’s hat (dadjî′ñ skîl) that he wore a round fleck of foam

swirled rapidly. Nᴀñkî′lsʟas-łîña′-i began to look around. And he went out, got his

two skins, put on his two sky blankets, and came in. His uncle had his hair tied in

two braids. Something on his head began turning around very rapidly.

Then a strong current of sea water poured from the corner of the house. And he put

his mother in his armpit, quickly entered his bufflehead skin, and swam about in the

current. He dived many times and again swam about. And when the sea water came up

to the roof of the house he floated out with it through the smoke hole.

He then quickly entered the raven’s skin. He at once flew up. He then ran his beak

into the sky. And his tail was afloat on the water. Then he kicked against the water.

“Enough. You, too, belong to me.” There it stopped (lit., “came to a point”). It began

to melt downward.

And he looked down. The smoke of his uncle’s house looked pleasing. He then became

angry with him, at the sight, and started to fly down. After he had flown for a while

he ran his beak into it from above, crying as he did so, “G̣ao.” “Oh, you shall own

the title of Chief-of-chiefs (Kî′lsʟekun)” [said his uncle].

He then became what he had been before. He entered with his mother. From that time

he often set out to hunt birds. When he came in one day he said to his mother: “Mother,

Qî′ñgi34 says he is coming to adopt me.” And his uncle said to her: “Qꜝā′la īdjā′xᴀn,35 Flood-tide-woman, stop that child from talking. We are, indeed, fit to be adopted.”

After this had happened many times they saw something wonderful, they say. People came dancing on ten canoes. He then went out, put on two sky blankets, and walked

around on the retaining planks. Said his uncle: “What he brought on by his talking

has happened. I wonder how we are going to supply people and food.”

And, after he had walked about for a while, he kicked upon the ground in the front

part of the house on the right side. There the ground cracked open. Out of it one

threw up a drum from his shoulder. They came pouring out. He went to the other side

as well. There he also kicked. “Earth, even, become people” [he said]. Thence, too,

one threw up a drum from his shoulder. And he did the same thing to the ground in

one of the rear corners. Out of that, too, some one threw up a drum from his shoulder.

He did as before on the other side. And they danced in four lines toward the beach.

Out of his uncle’s house Tsimshian, Haida, Kwakiutl, Tlingit [came] [123]singing different songs.36 Yet his uncle said [sarcastically]: “We shall indeed have lots to eat.” They sat

down in lines, and around the door was a crowd to serve the food.

Then Nᴀñkî′lsʟas-łîña′-i said: “Now go to my sister Sî′ndjugwañ to get food for me.”37 And a crowd of young men went to get it. They came back with silver salmon and cranberries.

And [he said]: “Go to Yał-kīñā′ñg̣o,38 too, to beg some for me.” Her house was also full of silver salmon, cranberries,

and sockeye salmon. They also brought some from the woman at the head of Skidegate

creek,39 and they brought some from the woman at the head of Qꜝā′dᴀsg̣o creek. It mounted

up level with the roof. The distribution of food was still going on when daylight

came. On the next day, too, and on the next day [it went on]. At the end of ten days

they went off in a crowd. These [days] were ten winters, they say.

And he went off with his father Qî′ñgi. Soon after they arrived at his village he

invited the people to come. He called them for a feast. He (Nᴀñkî′lsʟas) did not eat

the smallest bit. And on the next day he called them in to a feast for his son. Again

he did not eat. Two big-bellied fellows had come in. People took up cranberries by

the box, and when one of these opened his mouth they emptied a boxful into it. They

also emptied boxes into the mouth of the other.

On the next day his father invited them again, and they (the big-bellies) came in

and stood there. And again cranberries were emptied into their mouths. Then Nᴀñkî′lsʟas

went quickly toward the end of the town. As he was going along he came to open ground

where cranberries were being blown out. He stopped up this hole with moss, and he

did the same to another. After he had entered he questioned the big-bellied ones,

who stood near the door: “I say, tell me the reason why you eat [so much].” “Don’t

ask it, chief. We are always afflicted in this way.” “Yes; tell me. When my father

calls in the people, and you are going to eat, if you do not tell me I will make you

always full.” “Well, chief, sit close to me while I tell you. Early in the morning

take a bath, and when you lie down [after it] scratch yourself over your heart, and

when scabs have formed on the next day swallow them.”

He did at once as he was told. After he had sat still for a while [he said]: “Father,

I have become hungry.” Upon this his father sent to call the people. [The big-bellied

persons] again came in and stood there. Again was [food] emptied into their mouths.

It did them no good. And he again became hungry. He again called them in. Day after

day, for many days, he called them in. One day he went out [to defecate]. They saw

him eating the cranberries that had floated ashore upon the beach [from peoples’ dung].

Thereupon they shut the door upon him.

[124]

He now started off. By and by he came [back] and sat behind his father’s house. “Father,

please let me in.” They did not want him. “Father, please let me in. I will put grizzly

bears upon you. I will put mountain goats upon you.”40 He offered him all the mainland animals. “No, chief, my son, they might wake me up

by walking over me.”

He then began to sing a certain song. He beat time by striking his head against the

house. The house began to fall over. And at that time he nearly let him in, they say.

And when he went away they snatched off from him the black bear and marten [skins]

he wore.

That time he went away for a long period. By and by they saw him floating on the sea

in front of the town in a hair-seal canoe.41 He wore his uncle’s hat. On top of it the foam was swirling around as he floated.

As soon as they saw he had become changed in some unknown manner the town people all

entered Qîñgi’s house. And after they had talked over what they should do for a while

he dressed himself up. The town people put themselves between the joints of his tall

hat. After Nᴀñkî′lsʟas had remained there a while the sea water continued to increase. And Qîñgi, too, grew

up. Then he became angry and broke the hat by pulling it downward. Half the people

of his town were lost.

After he had been gone for a while he came and stopped in front of the town. “Nᴀñkî′lsʟas

is in front on a canoe.” And his father said: “Go and get him that I may see his face.”

They then spread out mats, and his comrades came in and sat there. His father continually

gave him food. His father was glad to see him.

After food had been given out for a long time and evening was come, his father sat

down near the door. By and by he said: “My son, chief’s child, let one of your companions

tell me a story.” He then asked the one who sat next to him: “Don’t you know a story?”42 “No,” they all said, and he turned in the other direction also. “Don’t you know one

story?” “No; we do not.” He then said to his father: “They do not know any stories.”

And his father, Qîñgi, said, “Ītꜝē′i, let one of your companions relate to me ‘Raven

traveling,’ ” by which he made Nᴀñkî′lsʟas so ashamed that he hung his head.

By and by, lo, a small, dark person, who sat on the right side, threw himself backward

where he sat. “Ya-yā′-ō-ō-ō-ō-ō, the village of the master of stories, Qîñgi.” When

he said this the people in the house were [startled], as if something were thrown

down violently. “Ya-yā′-ō-ō-ō-ō-ō, the supernatural beings came to look at a ten-jointed

łqeā′ma43 growing in front of the village of the master of stories, Qîñgi. There they were

destroyed.” “Ya-yā′-ō-ō-ō-ō-ō, the supernatural beings came and looked at a rainbow44 (a story name) moving up and down in front of the village of the master of stories,

Qîñgi. There they were destroyed [said the next].” “Ya-yā′-ō-ō-ō-ō-ō, the supernatural

[125]beings once came to look at Greatest-sea-gull and Greatest-white-crested-cormorant

throw a whale’s tail back and forth on a reef that first came up in front of Qîñgi’s

town. There they were destroyed.” “Ya-yā′-ō-ō-ō-ō-ō, the supernatural beings came

to see Harlequin-duck and Blue-jay run a race with each other on the property of the

master of stories, Qîñgi. There they were destroyed.” “Ya-yā′-ō-ō-ō-ō-ō, the supernatural

beings once came to look at the lower section of a wooden rattle lying around which

used to sing of itself.45 There they were lost.” “Ya-yā′-ō-ō-ō-ō-ō, the supernatural beings once came to look

at an inlet, which broke suddenly through white rocks at the end of Qîñgi’s town,

out of which Djila′qons came knitting. There they were destroyed.” “Ya-yā′-ō-ō-ō-ō-ō,

the supernatural beings once came to see Tā′dᴀlᴀt-g̣ā′dᴀla and Marten run a race with

each other in front of the village of the master of stories, Qîñgi. There they were

destroyed.” [What the other three said has been forgotten.46]

Then Nᴀñkî′lsʟas started off afoot. After he had traveled for a while he came to the

town of Ku′ndji. In front of it many canoes floated. They were fishing for flounders.47 They used for bait salmon roe that had been put up in boxes. He then desired some,

and changed himself into a flounder. And he went out. After he had been stealing the

salmon roe for a while they pulled out his beak.

Those people, who then sat gambling in rows in the town, looked at the beak one after

another. They handed it back and forth for the purpose. Nᴀñkî′lsʟas looked at it,

and said: “It is made of salmon roe.” He then went toward the woods and called Screech-owl.

And he pulled its beak out, put it upon himself, and put some common thing into [the

owl] in its stead.

By and by they went out again to fish and again he went out. And after he had jerked

off many pieces of salmon roe a hook entered one of his lips. They then pulled him

to the surface and came ashore, and [the owner] gave it to his child, and they ran

a stick through it [to put it over the fire]. And when his back became too warm he

thought: “I wish something would make them run over toward the end of the town.” After

some time had passed the whole town (i.e., the people of the town) suddenly moved.

And right before the child, who sat alone near by, he put on his feather clothing

and flew out through the smoke hole. The child then called to its mother: “My food

flew away, mother.”

He did not go away from the town, they say. On another day they prepared some food

in the morning. Crow invited the people to a feast of cakes made of the inner bark

of the hemlock and cranberries mixed together. Among them they called him (Raven).

And he refused. “No; you only call each other for mussels.” Afterward he sent Eagle

out to see what they did call each other for. And after [126]he had gone thither he said to him: “They call each other for cakes of hemlock bark

and cranberries.” “Now, cousin, be my messenger.” Eagle then said: “The chief is coming.” “No; we

call each other for mussels.”

Before they had begun eating he ran into the woods. After he had made rotten trees

into ten canoes he put in spruce cones, standing them up along the middle. Grass tops

he put into their hands for spears. They then came around the point, and he walked

near them with his blanket wrapped tightly around him. Terrible to behold, they came

around the point, men standing in lines along the middle of the canoes. Leaving their

food, the people fled at once. He then went into the house and ate the cakes. He ate.

He ate. Where the canoes landed they were washed about by the waves.

He then started off. He traveled about. On the way he got his sister neatly, they

say. He then left his sister with his wife. And he started off by canoe. He begged

Snowbird48 to go along with him, and took him for company. He also took along a spear. And short

objects49 lay one upon another on a certain reef. Then, when they came near to it, the bird

became different.50 He took him back. And he begged Blue-jay also to go, and he started with him. But

when they got near he, too, flapped his wings helplessly in the canoe. And, after

he had tried all creatures in vain, he made a drawing on a toadstool with a stick,

placed it in the stern, and said to it: “Bestir yourself and reverse the stroke” [to

stop the canoe]. He then started off with him. But when he got near it shook its head

[so strong was the influence].

He then speared a big one and a small one and took them back. And when he came home

he called his wife and placed the thing he had gone for upon her. And he put one upon

his sister as well. Then Sīwa′s (his sister) cried, and he said to her: “But yours

will be safe.”51

After he left that place he married Cloud-woman. And, as Cloud-woman had predicted,

a multitude of salmon came up for him. But, when they were on the point of moving

and he went through the middle passage of the smokehouse, salmon bones stuck in his

hair, and he used bad language that made his wife angry.52 She then said to the dog salmon: “Swim away.” From all the places where they lay

they began to swim off. And a box of salmon roe on which his sister sat was the only

food left in the house.

They then moved the camp empty-handed. And he made himself sick. He went along in

the bow beside the salmon roe. After he had gone along for a while his sister smelt

something, and he said it was a scab he had pulled off with his finger nails. After

she had spoken about it many times as they went along he threw Sīwa′s’s box empty

ashore.

[127]

And after they had gone along for a while they built a camp fire. He then put yellow

cedar upon the fire. After it had given forth sparks for a while one flew between

Sīwa′s’s legs. He then told her a remedy: “Now, go around in the woods exclaiming,

‘I call for medicine.’ When something says ‘Yes,’ go over to it and sit down where

a short red thing sticks up.” And after he had spoken to her, and she had called about

for a while, something said “Yes.” And after she had looked for it [she saw] something

red sticking up. Then she sat down there. Lo, she discovered her brother lying on

the ground under her.

He then became ashamed, and drew something with the tip of his finger. Right there

a child cried. And he took it out [of the ground]. And he put boards round it as people

were going to do in the future. Then the child became old enough to play. And he went

around after [the child]. One time when it went out to play it vanished forever.

Then he started to search for it. He put on his feather clothing and flew over the

whole of this country. He did the same upon Mainland. When he could by no means find

it, he heard that the supernatural beings had taken it because he (Raven) used to

fool them. He then stopped searching. When the boy stood up, lightning used to flash

around his knee-joints. He was named Sᴀqaiyū′ł.

One day some one with disheveled hair came in. “Father, I come in to you.” Then he

(Raven) spat upon his face. “Sᴀqaiyū′ł was not like that.” And when he went out, lightning

played around his knee-joints. He vanished at once. Then he cried; he cried.

Then he put his sister into his armpit and started off with her. And after Siwa′s

had finished her planting at Ramsey island he came, stood on the inner side of Ramsey

island, and begged all kinds of birds to accompany him. They went after cedar-bark

roofing in preparation for a potlatch. They soon got this out upon the open ground.

He then caused the cedar bark to be left there.53

And, when they became hungry, he called all kinds of animals. And, after they came

floating in front of him on their canoes, he came out wearing black, shabby clothing.

He then spoke. They did not understand. And they sent for Porpoise-woman. And when

she came he (Raven) said: “I am the sides and I am the ends, between which I qᴀlaastī′s.”54 Then she said: “How would they get along if I were absent? He wants them to fight

him with abalones and sea eggs.” They then threw these at him. And he ate. And, since

the house was too small, he started to potlatch outside. All the supernatural beings

whom he had invited came by canoe.

Then he made holes in the beaks of all kinds of birds. And Eagle, too, asked to have

his pierced. He became wearied by his importunities and made them anyhow. That is

why his nasal openings now run upward.

[128]

[Told by Abraham of the Qꜝā′dᴀsg̣o qē′g̣awa-i]

When he first started he decked out the birds. They were made of different varieties,

as they now appear to us, in one house. Then, as soon as he had dressed up the birds,

they went out together. At that time he refused to adorn two of them. When the house

was too full they said to those who sat next to the walls: “Let your heads be as thin

as the place where you sit.” Those have thin heads.

The two he had refused to adorn went crying to the [various] supernatural beings and

came to Rose Spit, where they heard a drum sound toward the woods. They went thither.

When they came and stood before Master Carpenter55 with tear marks on their faces, he asked: “What causes your tear marks?” They then

answered: “Raven56 decked out the other birds. He said we were not worth adorning.” “And yet you are

going to be handsomer than all others” [he said], and, having let them in, he painted

them up. He put designs on their skins (feathers). Those were the Qꜝē′da-kꜝō′xawa.57

[Continued by John Sky]

He went thence by canoe, and came to where herring had been spawning. He then filled

the canoe with herring, dipped them out of the place where the bilge water settles

and threw them toward the shore. “Future people will not see the place where you are.”58

[Continued by the chief of Kloo of Those-born-at-Skedans]

And when he went away he came to where a spider crab sat. And he said to it: “Comrade,

do you sit here? Don’t you know that we used to play together as children?” He then

put his wings into its mouth and took them out again. “A little farther off, spider

crab,” he said to it, and it closed its jaws together. It began at once to move seaward.

And he (Raven) said to it: “Comrade, let me go. When about to let me go you used to

look at me with eyes partly closed [as you are doing] now. Let me go. It will be better

for us to play with each other differently. Let me go.” By and by the sea water flowed

over him. Then it let him go.

And after he had traveled for a while he pulled off leaves from the salal-berry bushes,

stuck spruce needles into them, and came to where an old man lay with his back to

the fire. And he entered and sat down on the side opposite him. “Hē,” he said, as

if he, too, were cold from going after something. Then the old man looked over to

him and said: “Have I stretched out my legs, that one keeps saying he is getting cold?”

He then stretched out his legs, and it became low tide. And, with Eagle, he brought

up sea eggs to the woods. [Raven also brought up a red cod, but Eagle brought up a

black cod.]

They then made a camp fire. And Eagle roasted his.59 It began to drop fat into the fire. Then Raven roasted his, but it became dry. [129]And he asked to taste of Eagle’s. “Cousin, why does yours taste like cedar? Cousin,

I will bring you a small bundle of bark from the woods. When a stump comes to you,

rub this [black cod] upon its face.” As soon as he went off Eagle put some stones

into the fire. When they became red-hot, the stump came toward him. He then picked

up a stone with the tongs and rubbed it upon the stump, and the stump went back into

the woods out of sight. By and by, lo, he came to him with bark on his shoulder. His

face was blackened all over. “Why, cousin, what has happened to your face?” “Well,

cousin, I pulled some bark down upon my face.” “Why, cousin, it is as if something

had burned it.” “No, indeed, cousin, bark dropped upon me.”

[Continued by John Sky]

On the way from this place he begged for canoe companions.60 He begged all kinds of birds to come. Then Blue-jay offered himself to him, and he

said: “No: you are too old to come.” But he insisted. He then seized him by the top

of his head and pulled him into the canoe. For that reason the top of his head is

flattish. And he completed his begging for comrades.

They all got then into the canoe. And it set off. It went. It went. It went. It went.

They stopped in front of the Halibut people. Hu-hu-hu-hu-hu,61 they came down to the beach in crowds. “Raven is going to war,” they said one to

another as they came down to meet him. And he asked them to go, too, as companions,

and they went. They fixed themselves along the bottom of the canoe like skids62 and started. They went. They went. And before daylight they landed at the end of

his (the enemy’s) town. Then his Halibut people lay [in two rows], with their heads

outward, along the path which extended down from the house. Outside of them the birds

also stood in lines. They hid themselves behind the halibut. After they had been there

a while he came out wearing his dancing hat. When he came out one of the halibut flopped

his tail at him. He fell down. The next one, too, wriggled his tail. So they continued

to do until they brought him in.63 Then he asked them why they did this to him. And they said they did it because he

blew too long. They then let him go. And they started back. This was Southeast-wind,

they say. After they had gone along for a while they set down the halibut at their

homes, and the birds also went away.

And after he had traveled about for a while he came to some children playing and offered

to join them. “I say-y-y, playing children, let me play with you-ou-ou.” “No-o-o;

you would eat all of our hair se-e-e-al.” And he said: “My grandfather has gone after some for me. My father has gone after

some for me.” They then let him play with them. Then he devoured all of the children’s

hair seals, and they were all crying for them.

[130]

He also started away from that place. After he had gone along for a while he found

a flicker’s feather floating near the shore and said to it: “Become a flicker.” It

at once flapped its wings.

And after he had traveled thence for a while he came to the place where Master Fisherman64 and his wife lived. He wanted Raven’s flicker; so he gave it to him. “Things like

this are found on an island that I own.” And he said he would show it to him. And

after he said he would show it to him Master Fisherman baited a halibut hook taken

from among those hanging in bunches on the wall. When he had let it down into the

hole into which they used to vomit sea water he pulled out a halibut, and his wife

split it open and steamed it. When it was cooked the three ate it.

They went to bed, and next day he took him (Master Fisherman) to see the flicker island.

Then he arrived there and said to Master Fisherman: “Do not get off.” Then he (Raven)

landed. He broke off the ends of cedar limbs. And he wounded his nose. As he went

along he let the blood run down into his hands. And he threw around the cedar twigs

with blood upon them. “Change to flickers,” he repeated. Then they flew in a flock.

And he brought some in. “Now, get off. There are plenty of them,” he said to him.

Then he landed.

[Continued by the Chief of Kloo.]

And he (Raven) lay down in the canoe and began to drift away with the wind, and he

(Master Fisherman) shouted to him: “Say, you are drifting away. You are drifting away.”

He paid no attention to him.65 He got far off. Then he started away [by paddling]. Then he made himself appear like

Master Fisherman, and landed in front of his wife’s [house]. And he said: “Behold,

it was the one always doing such things. There is not a sign of the things he went

to show me.” And after he had had her as his wife a while he said: “My child’s mother,

differently from my former state, I am hungry.” Then she steamed a fat halibut for

him, and he ate it. After he had remained sitting for a while, he said: “My child’s

mother, differently from my former state, I would like it.”66 Then he again drank salt water. And after he had drunk salt water he baited the halibut

hook and let it down into the hole where sea water was vomited out. The same thing

as before happened. He pulled a halibut out.

And when his wife went after some water, lo, her husband sat near the creek and said

to her: “That was the same one who is always doing such things. Stop all the holes

in the house. As soon as he drifted away from it (the island) I wished my hair-seal

club would swim over to me.” And to him it swam out. Then it brought him to the land,

they say.

Then he ran in with the hair-seal club. And he (Raven) ran squawking about the house.

By and by he knocked him down with [131]his club. Then he threw him down into the latrine. And after he had lain there a while

he spoke up out of it.67 Then he took him out and pounded him up again. He even pounded up his bones. And

he went down to the beach at low tide and rolled a big rock over upon him.

[End of so-called “old man’s story” and beginning of “young man’s” part68]

Then he was nearly covered by the tide. And he changed himself in different ways.

By and by, when only his beak showed above water, his ten supernatural helpers came

to him. Then they rolled the rock off from him, and he drifted away. The first to

smell him among his supernatural helpers was a Tlingit, who wore a bone in his nose

[like the shamans.]

After he had drifted away for a while, some people came along in a canoe. “Why does

the chief float about upon the water?” And when they got within a short distance he

said: “He has a hard time for going after a woman.”

And after he had drifted about a while longer, a black whale came along blowing. And

he thought, “I wish it would swallow me.” And, as he wished, it swallowed him. Then

he ate up its insides. After he had eaten all he thought: “I wish it would drift ashore

with me in front of a town.” And in front of a town it drifted ashore with him.

After they had spent some time in cutting it up, they cut a hole through right where

he was, and he flew out. Then he flew straight up. And he turned down at the end of

the town, pulled off the skin of an old man living there, threw away his bones, went

into his skin, and lived in his place instead of him. By and by they asked him about

the something that came out of the whale’s belly. Then he said: “When something similar

happened a long time ago they fled from each other in fear.” At once they fled from

each other in fear. And afterward he ate the whale they were bringing up. This was

why he had changed himself.

[Told by Tom Stevens, chief of Those-born-at-House-Point.]

And one time he had Hair-seal as his wife. Then they had a child. And one day he went

after firewood with him. His son was fat, and, pleased at the sight of him, he wanted

to eat him. Then he said to him: “I am within a little of eating you.” And after they

had come home, and had got through eating, he said to his mother: “Ha ha⁺, mama, my

father said to me: ‘I am within a little of eating you.’ ” And Raven said: “Stop the

child.” He made him ashamed. After that he devoured him.69

[Continued by the Chief of Kloo.]

And after he had traveled about a while from that place he came to another town. And

he was eating the leavings cut off of the salmon they brought in. By and by some of

the milt70 hung out of his [132]nose. Then he said to his cousin [Eagle]: “When I pass in front of the town, cousin,

say: ‘Wā-ā-ā71, one goes along in front of the town with a weasel hanging from his nose.’ ” And

when he passed in front of the village [he said], “Wā-ā-ā, one passes in front of

the town with the milt of a salmon hanging from his nose.” Then he went back to him

and said: “Cousin, say, ‘Weasel, weasel.’ ” But when he went again he said the same

thing. Then he made him ashamed, and he went right along [without stopping].

And after he had gone along for a while he met some people coming back from the hunt

with many hair seals. Then he changed himself into a woman. And he found a long, slender

rock and said to it: “Change into a child,” and it became a human being. “Say, you

who are coming, come and marry me.” Then the canoe was pointed toward her. And she

picked up stones, too, they say. After they had gone along for a while she said: “The

child wants hair seal. He is crying for it.” Then one cut off a piece for it. Then

she wished a mist to fall, and it happened. Then they put mats over her, under which

she ate it. And she put grease on the stones and threw them overboard. And she kept

saying that it was the hair seal. Then they gave some to her again.

Then they gave her as wife to one of them. Some time after he had married her they

gave her salmon roe to eat. And she saw where they kept it. Then she went to the place

at night. And she ate in it. But when she lay down afterward she found that her labret

was lost. And when they went [to the box] to get some again in the morning they found

her labret in it. Upon this she touched it quickly with her lips and said: “Lg̣ᴀ′nsal

stā′-is72 was flapping her wings all night in my lip as she always does when she wants something

that smells bad.” Then they handed it to her, and she put it back into her lip.

And one day, when she went out with others to defecate, and stood up, the tail coming

from her buttocks was visible a moment. “Ai-ī, what is that sticking from my son’s

wife’s buttocks?” “Why, this is not the first time a Tlingit woman’s tail stuck out

from her buttocks.”

By and by she told her husband they were about to come after her, and she made them

bring together firewood in preparation for it. Then she changed excrement into people

and made them come by canoe. Then they landed; but when they came in and sat down

they began to perspire. Right there they were melted. And she became ashamed. Then

they were completely melted. And she flew away.

And after he (Raven) had traveled on from that place he came to where Water-ousel73 lived. And he (the bird) gave him food. By and by he drove a stick into his leg,

out of which salmon roe [such as has lain some days after hatching] ran in a stream.

He gave it to him to eat. Then he started from that place. After he had traveled [133]for a while he came to where Sea-lion lived. And after he had given him some food

he roasted his hand, out of which grease dropped. That he gave him to eat. He started

off, and when he had traveled a while came to where Hair-seal lived. Then he, too,

roasted his hand in the fire, and grease came out. He gave it to him to eat.

Then he went away and lived in one place for a while. After he had lived there for

a time Water-ousel came in to him. Then he drove something into his leg, but only

made himself faint away. And he (the bird) was ashamed. While he was in the faint

he went off. Then he came to himself. And after he had continued living there for

a while Sea-lion and Hair-seal came in.74 Then he roasted his hand, but it was burned. And they left him. Afterward he came

to life again.

[Parts of the young man’s story told by Walter McGregor of the Qā′-i-ał-lā′nas]

He began to offer his sister in marriage, and when any creature came in to him he

looked at its buttocks. When they were lean he refused it. After he had done [lit.,

said] this for a while Sea-lion wanted to many his sister. Then he looked at his buttocks.

They were fat, and he let him marry his sister. They had two children. G̣ē′noa75 was the elder. Iwā′ldjida was the younger. Once Raven went out fishing with his brother-in-law

and thought: “I wish halibut would come to me only.” Then he only caught halibut.

And his brother-in-law, Sea-lion, asked him: “Say, why do they come to you?” “That

is something people are not brave enough to ask for.” Then he again asked him, and

he said to him: “Well, they like me, because I use a piece of skin cut from my testes

for bait.” And he told him to do the same to his. When he just touched them with a

knife, “Wā-wa-wa-wā′, it hurts,” he said to him. “Don’t you see you are not brave

enough for it?” Then he told him to do as before. Then he cut off the whole of his

testes and ate the fat part of his brother-in-law. After he had consumed it he put

stones in him in its place, and came to his sister singing a crying song: “Siwa′s’s

husband, my sister’s husband. Siwa′s’s husband, my sister’s husband.” Then his sister

asked him: “What has happened, brother?” He paid no attention to her. He sang the

crying song. “What is it?” she kept saying. By and by she asked her brother: “What

has happened, my brother Raven?” And he said to her: “Where they always do so, [the

enemy] stood at House-point. With my great brother-in-law I met them. My great brother-in-law

fell without speaking a word. I, however, went around and around them calling.” Then

his sister, too, sang a crying song. She had G̣ē′noa on her back and held Iwā′ldjida

in her hands. Then she sang the crying song: “G̣ē′noa’s father, Iwā′ldjida’s father.

G̣ē′noa’s father, Iwā′ldjida’s father.” At once they carried him up in a mat. And

Siwa′s said: “Say, chief, [134]why is your brother-in-law so heavy?” Then Raven said: “You always talk nonsense.

This is not the first time a chief who has been killed is heavy.” The rocks put into

him made him heavy.

After they got him into the house they had Mallard-duck76 doctor him, and when he came in, and had gone around the fire for a while, he said:

“Hăn hăn hăn hăn (quacking of duck), his brother-in-law, his brother-in-law.” And Raven said: “[Speak]

differently, great doctor. [Speak] differently.” Then again he said, “Hăn hăn hăn hăn, his brother-in-law took out his insides.” Then he kicked him into the fire. And

just before he flew out he said the same thing. So they came to know that he had killed

his brother-in-law.

One time he let Cormorant marry Siwa′s, because he was the best fisherman. And he

went out fishing with him, and Cormorant alone caught halibut. He (Raven) caught only

a small one. Then he went toward the bow to Cormorant and said to him: “Let me see

what is upon your tongue.” And when he ran his tongue out he pulled it out, and his

voice was gone. That is why the cormorant has no voice.

Then he pulled the halibut round toward himself [so that their heads lay in his direction]

and turned the small one toward him (Cormorant).77 Then they went home, and he pulled off the halibut. Cormorant motioned his wife to

the halibut, and his sister asked: “Say, chief, why does he motion me to the halibut?”

Then Raven said: “He is trying to say he wants the head of a big one.” And she asked

her brother again: “Say, chief, what has happened to your brother-in-law?” “Why, while

I was fishing with him his voice left him.” He wanted to eat all the halibut. That

is why he took it out.

After he had gone on for some distance a sea anemone (?) looked out from under a rock.

He became fascinated at the sight of the corners of its eyes, which were bluish, and

said to it: “Say, cousin, come and let me kiss you.” And the sea anemone said: “I

know your words, Raven,” and made him angry. Then he threw aside the stones from it

and steamed it [in the ground]. When it was cooked he ate it while it was still hot.

Then his heart was burst with the burning. That is why ravens do not eat sea anemones.

After he had gone along from there for a while he came to a town. Having looked into

the house [he saw] no people there. Then he entered. Halibut and slices of smoked

hair seal lay on the drying frame. Only old wedges lay near the fire. But when he

started to carry off the halibut and slices of seal a wedge threw itself at his ankle

bone; on the other side the same thing happened, and he fainted with the pain. Then

he threw them from his shoulders and went out. And he looked into a house near by.

And he entered that, too. There were plenty of hair seals and halibut there. On the

wall was some design drawn with finger nails. Then he started to carry some out. When

he came to the door something pulled his hair. He saw [135]nothing. After they had pulled his hair until they made him weak, he went out. These

were the Shadow people, they say.

After he had traveled thence for a while he came to a house in which the Herring people

were dancing. The air (weather or sky)78 even shook above them. And when he looked in the Herring people spawned upon his

mustache. Then he ate the fish eggs. They tasted bad, and he threw away his mustache.79 Then, having pushed in a young hemlock he had broken off, he drew it out. The fish

eggs were thick upon it, and he ate them. They tasted good. He started the use [of

these limbs].

After he had gone on for a while he came to one who had a fire in his house. And he

did not know how to get his live coals. And [the man] had bought a deerskin. “Say,

cousin, I want to borrow your skin a while.” And he lent it to him. It had a long

tail, they say, and he tied a bundle of pitch wood to the end of the tail. Then he

came in and danced before him. As he danced his face was turned toward the fire only.

After he had danced for a time he struck his tail into the fire and the pitch wood

burned. Then his tail was burned off. That is why the deer’s tail is short. Then he

went into his own skin and flew away with the live coals. His beak, too, was burned

off. And they pursued him. They could not catch him and came back. He got the coals

neatly.

On traveling thence he found a devilfish’s nose (i.e., mouth) drifted ashore. And

he took it and came to Screech-owl. And he said to him: “Say, cousin, let me borrow

your beak a while,” and he lent it to him. Then he stuck the devilfish nose he had

found in its place and said to him: “Say, cousin, yours looks nice. You are fit to

travel about with the supernatural beings.”

After he had traveled on for a while his cousin (Eagle) came to him. And, after they

had traveled together for a while they came to an abundance of berries, which Eagle

consumed before he got there. On that account he was angry with him. And he went quickly

to the beach, found a sharp fish bone, and stuck it into the moss ahead of him (Eagle).

“Run into Eagle’s foot,” he said to the bone. And he said to Eagle: “Now, cousin,

go right on here before me.” And as he went along there the bone stuck into his foot.

“Cousin, let me see it,” and he pretended to take it out with his teeth, but instead

commenced to push it in farther. “Wā-wā-wā, cousin, you are pushing it in.” “No, cousin,

it is because I am trying to pull it out with my teeth.” By and by he pulled it out

and said to him: “Cousin, wait right here.” Then he examined the ground before him

[to select an easy path]. And he ordered a chasm to form. It did so. And, breaking

off a stalk of łqeā′ma,80 he laid it across the gulf and put moss upon it. He made it like a dead, fallen tree.

Then he went back toward Eagle, carried him on his back, and started over with [136]him upon the dead tree. When he got halfway over he let him go. “Yauwaiyā′, what I

carry on my back is heavy.” He burst open below. Then he went down to him and ate

his berries. He ate all and started off.

After he had traveled for a while he came to a woman with a good-sized labret weaving

a water-tight basket, and he asked her: “Say, skᴀñ,81 have you seen my cousin?” She paid no attention to him, and he again said to her:

“Say, skᴀñ, have you seen my cousin?” Again she paid no attention to him. “Skᴀñ, I

can knock out your labret.” “Don’t. Over yonder is a qꜝa′ła82 point, beyond which is a spruce point, beyond which is a hemlock point, beyond which

is an alder point. At that point in front of the shell of a sqā′djix̣ū83 on which he is drawing is your cousin.” Then he started over, and it was as she said.

“Say, cousin, is that you?” [he said], and he pulled him up straight, and they started

off together.

After they had gone on they came to a town. They (the people) were glad to see them.

Then they began giving them food. When they gave them berries to eat they asked Eagle:

“Does the chief eat these?” And Raven said: “Say that I like them very much.” But

Eagle said: “The chief says he never eats them.” And they only gave them to him (Eagle).

And again they gave him good berries to eat, and he said: “Those, too, the chief does

not like.”83

When he was going on from there he came to a town in which the chief’s son, who was

the strongest man, had had his arm pulled out. A shaman came to try to cure him. The

chief’s son was the strongest man. In trying strength with people of all ages by locking

hands with them he could beat them. By and by, through the smoke hole came a small

pale hand, and [they heard its owner] say: “Gū′sg̣a gᴀ′msiwa” (Tsimshian words meaning

“Let us have a try”). And he put his fingers to it. It pulled off his arm. They did

not know what it was. And he (Raven) alone knew that one of Gū′g̣ał’s84 sons had pulled his arm off. Then he flew to Gū′g̣ał’s town, went to an old man who

lived at the end of the town and asked him: “Say, old man, do you ever gamble?” And