Title: The Baz-nama-yi Nasiri

A Persian treatise on falconry

Author: Shah of Iran grandson of Fath Ali Shah Prince Taymur Mirza

Translator: D. C. Phillott

Release date: August 23, 2024 [eBook #74303]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Bernard Quaritch

Credits: MFR, A Marshall, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

This book includes many accented charactors. These will display using Unicode combining diacriticals. Some examples of how these will appear on this device:

ḥ and Ḥ (h and H with dot below)Due to a size difference with the default font for Arabic on some browsers, words in Farsi may appear to be larger than usual.

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the chapter. Reference numbers to notes have been updated to continuous numbering.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

THE

BĀZ-NĀMA-YI NĀṢIRĪ

A PERSIAN TREATISE ON FALCONRY

TRANSLATED BY

LIEUT.-COLONEL D. C. PHILLOTT

SECRETARY, BOARD OF EXAMINERS, CALCUTTA,

GENERAL SECRETARY AND PHILOLOGICAL SECRETARY, ASIATIC SOCIETY OF BENGAL,

FELLOW OF THE CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY, EDITOR OF THE PERSIAN

TEXT OF THE QAWĀNĪNu ’Ṣ-ṢAYYĀD

ETC. ETC.

LONDON

BERNARD QUARITCH

1908

[500 copies of this book have been printed]

TO

HIS EXCELLENCY

THE ʿALAU ’L-MULK

formerly

Governor-General of Kirmān

and

Persian Baluchistan

THIS TRANSLATION IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED

In Memory

of

Certain Days not Unpleasant when we Met in the

BĀG͟H

AND MINGLED OUR TEARS OVER OUR

EXILE

[Pg xi]

The author of this work was Ḥusāmu ’d-Dawlah Taymūr Mīrzā, [1] one of the nineteen sons of Ḥusayn ʿAlī Mīrzā,[1] Farmān-Farmā, the Governor of the Province of Fārs, and one of the sons of Fatḥ ʿAlī Shāh, Qājār.

On the death of Fatḥ ʿAlī Shāh, in A.H. 1250 (A.D. 1834), general confusion prevailed: the claimants to the Crown were many. The details of these claims and the actions of the various aspirants to establish them are exceedingly complicated and difficult to follow. The old Z̤illu ’s-Sult̤ān first mounted the throne at Teheran. His nephew the young Muḥammad Mīrzā was then Governor of Tabrīz, and his troops had not been paid for some time. However, receiving pecuniary support from the English ambassador, and moral support from the Russian, he marched on Teheran (putting out the eyes of a brother or two en route), and was met by the army (hastily paid up to date, and even in advance), of the Z̤illu ’s-Sult̤ān. The moving spirit in Muḥammad Mīrzā’s army appears to have been an Englishman named Lynch, who, nominally in command of the artillery, virtually managed what cannot be better described than as “the whole show.” The camp of the Z̤illu ’s-Sult̤ān awoke in the morning to discover that, during the night, their General had gone over to the enemy; and that Mr. Lynch, having pointed four big guns at their camp, was haranguing them from his position, and exhorting them to go home. His arguments appeared reasonable. Part of the Z̤illu ’s-Sult̤ān’s army crossed over to Mr. Lynch, and part returned home. “In a moment, this fine army was disbanded, scattered like the stars of the Great Bear, every man going to his own place.”

Muḥammad Mīrzā now entered Teheran without the slightest opposition, and his uncle the Z̤illu ’s-Sult̤ān, “in the greatest despondency,” placed the crown on his head and handed him the state jewels. Muḥammad Shāh (no longer Mīrzā) then proceeded to [xii]despatch the Z̤illu ’s-Sult̤ān and most of his uncles and brothers to the dreaded fortress of Ardabīl.

Shayk͟h ʿAlī Mīrzā, Shayk͟hu ’l-Mulūk, “though he had none of the requisites of sovereignty except a band of music,” was another prince that made an even more feeble bid for the throne. He was then Governor of Tūy Sarkān. Royal governors, in Persia, have bands that play in the evening; but a morning band is a prerogative of the Shāh. Shayk͟h ʿAlī Mīrzā ordered his band to play in the morning as well as in the evening, and thought that by so doing he had become Shāh. However, on receiving the unexpected news that Muḥammad Shāh was in Teheran, he tendered his submission, and was soon packed off to join the “caravan” at Ardabīl.

Ḥaydar Qulī Mīrzā, Ṣāḥib Ik͟htiyār, another royal prince, also made a burlesque attempt to obtain sovereignty. His own adherents split into two parties, quarrelled amongst themselves, and then at a moment’s notice turned him out of the city of which he was Governor. On his way to Isfahan he fell off his horse, and was carried into that city in a prostrate condition. Once or twice, after this, he flits across the page of history as a fugitive from the wrath of Muḥammad Shāh.

It must not be supposed that all this time the Farmān-Farmā, the father of our author and the eldest living son of the late Fatḥ ʿAlī Shāh, was idle. He seems to have been popular in Fārs, for Shīrāz was kind enough to offer him the crown of Persia. He induced his brother the Shujāʿu ’s-Salt̤anah, the Governor of Kirmān, to have coins struck in his name there, and also the K͟hut̤bah read in his name at the Friday prayers. He further sat on a throne in Shīrāz. A few days later, news of the arrival of Muḥammad Shāh in Teheran and of the abdication of the Z̤illu ’s-Sult̤ān, reached him. The Shujāʿu ’s-Salt̤anah, who had arrived at Shīrāz from Kirmān, was then placed in command of an army, and under him were two of the Farmān-Farmā’s sons, Najaf Qulī Mīrzā in command of the Cavalry, and Riẓā Qulī Mīrzā in command of the Infantry. The destination of the army appears to have been Isfahan, the inhabitants of which, it was hoped, would declare for the Farmān-Farmā. The season was winter. The second march was commenced in a storm of snow and rain. The plains became a lake: the hill passes were blocked by snow: men and horses died: guns sank in the mud: property was lost. Rations, too, ran short, and[xiii] the country had lately been visited by locusts. Even proper guides were wanting. But worst of all, one march from Isfahan, Mr. Lynch was discovered blocking the way. In the night, three of Mr. Lynch’s artillerymen “deserted” to the Shīrāz camp, and tampered with its artillery. In the skirmish next morning, all the artillery horses of the Shīrāz camp went bodily over to Mr. Lynch. The remainder of the Shīrāz army scattered and disappeared, got entangled in the mountains, and retraced its steps to find Mr. Lynch with some artillery blocking one path, and a Mr. “Shir”—apparently another Englishman—blocking another.

The Shīrāz Commander-in-Chief, with his two nephews, and presumably a remnant of the army, eventually slunk back into Shīrāz, in a miserable plight from hunger and exhaustion. A grand Council was then held, and everybody talked, and the Farmān-Farmā listened to all in turn. One thing seems quite certain, no one did anything. Strange rumours now began to reach Shīrāz of weird Turkish troops that spoke no Persian, and were commanded by an ubiquitous Englishman. The merchants, panic-stricken, fled with their property. The city people revolted, and seized some towers; while the troops, of course, deserted to the other side. A faithful eunuch then informed the Farmān-Farmā that he had met some of the city people on their way to seize the gates, and that a plan had been concocted for capturing the Farmān-Farmā with all his relations, adding that the delay of one minute meant the loss of everything. Still the Farmān-Farmā shilly-shallied: still he maintained his attitude of keeping “one foot in the stirrup and one on the ground,” giving ear, first to the advice of his son to flee, and then to the advice of his brother the Shujāʿu ’s-Salt̤anah to stay. The result was, that the two elder princes were taken. The Farmān-Farmā was deported to Teheran, where he was honourably treated but speedily died. The Shujāʿu ’s-Salt̤anah was carried to Teheran, deprived of his sight en route, and then sent to enliven the family party at Ardabīl. The princes, Najaf Qulī Mīrzā, Riẓā Qulī Mīrzā, Taymūr Mīrzā the author of this Bāz-Nāma, with Nawāb Ḥājiya the mother of Najaf Qulī Mīrzā, and three more princes, brothers or half-brothers, narrowly effected their escape, and a month later reached Bag͟hdād in safety.

At that time relations between the English and Persian Courts were extremely friendly. The eldest prince, Riẓā Qulī Mīrzā, with[xiv] his brothers Najaf Qulī Mīrzā, and Taymūr Mīrzā our author, started for England to obtain the mediation of William IV., reaching London viâ Damascus and Beyrout in the summer of 1836. Their journey from Damascus to Beyrout was as feckless and mismanaged as their expedition to Isfahan.

For four months the princes were a popular feature of London Society, and during that time succeeded in losing their hearts several times. Then, as they had obtained the object of their journey, Lord Palmerston having arranged matters to their satisfaction, they returned to Bag͟hdād and exile.

Najaf Qulī Mīrzā wrote an account in Persian of the events that occurred on the death of their grandfather Fatḥ ʿAlī Shāh, and of their own adventures in consequence, and he also kept a diary of their tour to England and back.

Asʿad Yaʿqūb K͟hayyāt̤,[2] a Syrian Christian who had accompanied the princes to Europe as Dragoman, secured this MS. in Bag͟hdād; but on his journey back to Syria he was held up by Bedouins and deprived of that portion of the MS. that treated of the actual flight of the princes from Shīrāz and of the arrest of their father—the illiterate Arabs mistaking these pages for the Holy Qurʾān. The remainder of the journal was translated by him into English, and under the title of a “Journal of a Residence in England and of a Journey from and to Syria, of their Royal Highnesses Reeza Koolee Meerza, Najaf Koolee Meerza, and Taymoor Meerza of Persia,” was printed in London for private circulation only. The present tragi-comic page of Persian history has been compiled, partly from this narrative, and partly from Persian sources.

Some twenty-eight years after the bid for sovereignty, and fourteen years after the death of their cousin Muḥammad Shāh, the two princes Riẓā Qulī Mīrzā and Taymūr Mīrzā started from Bag͟hdād to revisit their native land. Who knows what secret hopes they cherished, what dreams they dreamt of royal favour? In a few pathetic words, our author, in his Preface, informs us that, at the second stage of their journey, the truth of the sacred text, ‘And ye know not in what land death shall overtake you,’ was forcibly revealed to him: his brother suddenly sickened and died.

[xv]

Taymūr Mīrzā was well received by Nāṣiru ’d-Dīn Shāh, whose constant companion he became in all sporting expeditions. He died in A.H. 1291 (A.D. 1874); I am told, in Teheran.

In Persia, and round Bag͟hdād, Taymūr Mīrzā’s name is still a household word. “Ah,” exclaim the Persians when hawking is mentioned, “if Taymūr Mīrzā were only here.”

His treatise on Falconry, of which the present book is a translation, was composed in A.H. 1285 (A.D. 1868) and was originally lithographed in Teheran. A second, and perhaps a third, edition was lithographed in Bombay, a few pages on pigeons and game-fowl, apparently written in India, being added as an Appendix.

The present translation has been made from a copy of the original Teheran edition to which marginal notes have been added by a former owner. For the versification I am indebted to the assistance of poetical friends.

D. C. P.

[xvii]

[1] Mīrzā after (not before) a name signifies Prince.

[2] In his translation of the Journal he transliterates his name Asaad Y. Kayat. K͟hayyāt̤ is a common family name amongst Syrian Christians.

Let us embroider this Treatise on Falconry with the design of the Praise of the All-Sufficient; and let us exalt our Pen by a votive offering of praise to the Great Fashioner, in the path of whose worship the wings of those falcon-like Pure Spirits of the Saints are spread wide open,[3] like as the portals of His Mercy are opened wide in the faces of those that truly love Him. Let us also praise the matchless beauty and grandeur and perfection of that high-soaring Bird,[4] the robe of whose being God adorned with this sacred verse: “And was at the distance of two bow-strings, or even less.”[5]

We further extol the Family, the Humā[6] of whose noble spirit soars aloft on the pinions of sure belief and true knowledge, winging its way to the eyrie of union with the Eternal Phœnix:—

[xviii]

Thus says this writer, His Royal Highness Prince Taymūr Mīrzā,[8] son of the Blessed[9] Ḥusayn ʿAlī Mīrzā, Farmān-Farmā,[10] and grandson of the Blessed[9] King Fatḥ ʿAlī Shāh, Qājār (whom Allah has clothed in the Robes of Light):—At the beginning of the reign of King Muḥammad Shāh (the Receiver of God’s Pardon[11] and a Dweller in Paradise), in the year of the Flight 1250 (a thousand blessings and praises on Him that performed it[12]) I with my brothers Riẓā Qulī Mīrzā[8], Nāqibu ’l-Iyāla, and Najaf Qulī Mīrzā, Wālī, both my elders, and Shāh-ruk͟h Mīrzā, and Iskandar Mīrzā, younger than the writer, departed from the Province of Fārs on a pilgrimage to the Sacred Karbalā[13]—best of blessings and perfect benedictions on its silent[14] inmates! After a residence of some months in that Celestial City, I, as God and Fate decreed, with my brother Riẓā Qulī Mīrzā and Najaf Qulī Mīrzā took a journey to Europe, returning to the Holy Places[15] after the space of a year and a half. By the grace of God we spent the long space of thirty years, in peace and freedom, in those Abodes of Peace, visiting the Holy Shrines and hawking and hunting in their environs.

When the throne of the Kingdom of Īrān—which God protect from the changes and vicissitudes of Time—was adorned and illuminated by the splendour of the auspicious accession of His[xix] Majesty Shāh Nāṣiru ’d-Dīn, a Jamshīd in rank, the shade of God’s Grace and His Blessing to men, the Divinely-aided, a King and the son of Kings; and when the fame of the Justice and the echo of the Clemency of this peerless Monarch spread and resounded throughout the world, nay reached even to the high oratories of Heaven’s Dome, I, your humble slave, with Riẓā Qulī Mīrzā, left Bag͟hdād, the Abode of Peace,[16] in the year of the Flight 1279, on a pilgrimage to Holy Meshed, in order to kiss the sacred shrine of the Eighth Imām,—the blessings of God Almighty on him, his honoured forefathers, and his descendants the Leaders of men!

In Kirmānshāh his pre-destined death overtook Riẓā Qulī Mīrzā, in the Fort known as Ḥājī Karīm, one of the stages on our journey; and in accordance with the passage, “All that breathes shall taste of death,” he passed away, and the hidden mystery of, “No living thing knoweth in what land it shall die” was manifested to us.

When the bird of his spirit spread its wings and soared to the eyrie of Rest we despatched his bier to the Holy City of Najaf[17] (thousands of blessings on him that has sanctified it) where was his dwelling-place and ancestral home, so that he might there be buried with his fathers, while I, alone, with my burden of grief continued on my way to the most Sacred City.[18]

When I was blessed by the pilgrimage to Haẓrat-i ʿAbdu ’l-ʿAz̤īm[19]—Peace and Honour be to him—the intense heat had already set in, and His Majesty and his Court were moving to the summer residence at Shimrānāt. Certain well-wishers of His [xx]Majesty and of the State informed him of my circumstances. Since the Creator of Existence, He who has made the heights and the depths, has decreed for every low estate a high estate, and for every grief a joy, and for every disgrace an honour, and for every pain a cure, the Royal mind was inspired to appoint Dūst ʿAlī K͟hān, the Minister of Public Works, to summon this attached slave to the Presence. So, according to Royal Mandate, I drove with the Minister in his carriage to Nayāvarān,[20] where the Royal Camp then was. After a short wait in the shade of the tent we were honoured by admittance to the sun-like Presence of the King—May our souls be his sacrifice! Such kindness he showed and so wide did he open the doors of his favour and kingly condescension, that what I had heard was but a thousandth part of the reality—as it were but a handful as a sample of an ass-load. I exclaimed:—

He spoke on various topics and strung the pearls of kingly words—and kings’ words are the kings of words—on the string of discourse. I too, his slave, according to my mean ability, presented my poor contribution to the conversation, which at last turned on sport. The Shadow of God (may our souls be his sacrifice) is an expert of experts in all sports, but especially in shooting. I have never seen or heard of his equal in shooting, either on foot, or off a galloping horse. For example, one day in the Kūh-i Shahristānak, I and Mahdī Qulī K͟hān the G͟hulām bachcha-bāshī, and Āqā Kushī K͟hān the gun-keeper, were sitting with him behind a stone—Muṣt̤afā Qulī K͟hān the Mīrshikār[21] with several other[xxi] rifles having made a circuit to drive the herd of wild sheep within range of the king’s rifle—when the herd suddenly turned aside and made off. Five three-year old rams that had not scented the danger came fearlessly on towards the stone behind which His Majesty and the rest of us were crouching. His Majesty had with him a double-barrelled gun for slugs, and three rifles. When the rams arrived within forty paces, His Majesty fired the gun and brought down one with one barrel, and a second with the second barrel. The three remaining rushed down the hill. His Majesty seized the rifles with his auspicious hand, and by the will of the One God brought down all three head one after the other:—

Now only an expert shot knows at what ranges to fire five successive and successful shots at a fleeing herd.

True it is that kings are the shadow of God and able to accomplish all by the help of their Master.

Many other feats, too, like this I’ve seen, up till now, the year 1285[24] (of the Flight).

Sixty-four years of my life have now passed, all spent in hunting and shooting. I have had no hobby but sport, no recreation but it.

This slave of the King’s Court, Taymūr, desired that like the ant he should present his offering to the Court of the Solomon of the [xxii]Age,[25] that is, compose a treatise on Falconry and its branches, and on the various species of hawks and their treatment in health and disease.

Although the old Falconers have written treatises on this subject, still in my humble opinion those old writers were by no means experts in their science and should not be classed as masters in their art. I, therefore, thought of myself writing on the subject and leaving a memento for all lovers of the sport, whether tyros or experts. When these are seated by a stream, refreshed and rested after the morning’s sport, I hope they will recall the writer in their prayers and pass over the shortcomings of his work.

I have honoured my book with the auspicious name of His Majesty the King, and have named it the Bāz-Nāma-yi Nāṣirī and have divided it into several bābs.[26]

[xxiii]

[3] Tajnīs: a play upon the words bāz, “a goshawk,” and bāz, “open.”

[4] i.e., Muḥammad.

[5] Qurān, liii, 9.

[6] Humā, the Lammergeyer; vide Journal and Proceedings Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. II, No. 10, 1906.

[7] i.e., the 14 Maʿṣūms, which are Muḥammad, Fāt̤imah, and his descendants the 12 Imāms.

[8] Mīrzā after a name signifies Prince: Mīrzā before a name signifies one whose mother is a Sayyida. But Mĭrzā (with short i) before a name signifies a “clerk, writer, etc.”

[9] Marḥūm, “blessed” (usually only of Muslims by Muslims), signifies “dead and pardoned by God,” i.e., “late.”

[10] Farmān-Farmā—a title, and also a Governor or Viceroy. Ḥusayn ʿAlī Mīrzā, much lauded by the Poet Qā,ānī, was Governor of Fārs.

[12] i.e., on the Prophet.

[13] ʿAtabāt-i ʿAlīyāt, the “Exalted Thresholds,” is a Shīʿah term for the city of Kerbalā, the burial place of the martyrs Imām Ḥusayn, his family and his followers; sometimes Najaf and Kāz̤imayn are included.

[14] i.e., those buried in those sacred spots.

[15] Amākin-i Musharrafa.

[16] Dāru ’s-Salām is an epithet or a name of Baghdad.

[17] Najaf-i Ashraf; near Kerbalā and the burial place of ʿAlī.

[18] Arẓ-i Aqdas is Mash,had-i Muqaddas.

[19] Probably the place of this name near Teheran, the burial place of the saint from which the place takes its name.

[20] Near Shimrānāt.

[21] Mīr-shikār; in Persia a head game-keeper, but in India a title of any bird-catcher, assistant falconer, etc.

[22] From the Shāh-Nāma.

[23] The Shāh, and in fact all kings, are styled “The Shadow of God.”

[24] A.D. 1868.

[25] The allusion is to some story of the ant presenting Solomon with the leg of a locust.

[26] The book, however, contains only two numbered bābs; the first, pages 1 to 26 (1st Edition) on “The species of Hunting-birds;” and the second, the remaining 157 pages of the book on other subjects. The 2nd bāb, however, commences with: “On the black-eyed birds of prey that have at various times of my life come into my possession and which....”

| PAGE | |||

| TRANSLATOR’S INTRODUCTION | xi | ||

PERSIAN AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION |

xvii | ||

| PART I | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| THE YELLOW-EYED BIRDS OF PREY | |||

| CHAP. | |||

| I. | On the Short-winged Hawks used in Falconry |

1 | |

| II. | The Goshawks |

3 | |

| III. | The Sparrow-hawk |

11 | |

| IV. | The Pīqū Sparrow-hawk |

15 | |

| V. | The Shikra |

17 | |

| VI. | The Serpent Eagle |

17 | |

| VII. | The Eagle Owl |

18 | |

| VIII. | Other Species of Owls |

22 | |

| IX. | The Harriers |

25 | |

| X. | The Lammergeyer or Bearded Vulture |

27 | |

| XI. | The Osprey |

29 | |

| PART II | |||

| THE DARK-EYED BIRDS OF PREY | |||

| XII. | The Eagles and Buzzards |

30 | |

| XIII. | Kites and Harriers |

33 | |

| XIV. | The Vultures |

34 | |

| XV. | The Raven |

35 | |

| XVI. | The Shunqār or Jerfalcon |

36 | |

| XVII. | The Shāhīn |

42 | |

| XVIII. | The Peregrine (Baḥrī) |

47 | |

| XIX. | The Saker Falcon (F. Cherrug) |

49 | |

| XX. | The Eyess Saker Falcon |

55 | |

| XXI. | Strange Arab Devices for Catching the Passage Saker |

57 | |

| XXII. | The Merlin |

61 | |

| XXIII. | The Hobby |

65 | |

| XXIV. | The Sangak |

68 | |

| XXV. | The Kestril |

68 | |

| XXVI. | The Shrike |

72 | |

| XXVII. | Miscellaneous Notes |

73 | |

| XXVIII. | Method of Snaring a Wild Goshawk with the Aid of a Lamp |

75 | |

| XXIX. | Training the T̤arlān or Passage Goshawk |

78 | |

| XXX. | “Reclaiming” the Passage Saker |

94 | |

| XXXI. | Anecdotes of a Baghdad Falconer |

98 | |

| XXXII. | Training the Passage Saker to Gazelle |

99 | |

| XXXIII. | Training the Eyess Saker to Eagles |

110 | |

| XXXIV. | Eyess Saker and Gazelle |

115 | |

| XXXV. | Another Method of Training the Eyess and Passage Sakers to Gazelle |

124 | |

| XXXVI. | Training the “Shāhīn” |

125 | |

| XXXVII. | Training the Passage Saker to Common Heron |

136 | |

| XXXVIII. | Training the Passage Saker to Common Crane |

140 | |

| XXXIX. | On Management During the Moult |

148 | |

| XL. | Remedies for Slow Moulting |

151 | |

| XLI. | On Feeding on Jerboas During the Moult |

152 | |

| XLII. | On Feeling the Pulse, and on the Signs of Health |

153 | |

| XLIII. | On Diseases of the Head and Eyes |

154 | |

| XLIV. | On Diseases of the Mouth |

155 | |

| XLV. | Diseases of the Nose |

157 | |

| XLVI. | On Diseases of the Ear |

157 | |

| XLVII. | On Epilepsy |

158 | |

| XLVIII. | On Palpitation |

160 | |

| XLIX. | The Sickness called Karaj, which is Costiveness |

162 | |

| L. | Hectic Fever or Phthisis |

163 | |

| LI. | On Canker of the Feathers |

166 | |

| LII. | Lice |

168 | |

| LIII. | Worms |

169 | |

| LIV. | Heat Stroke |

170 | |

| LV. | Palsy, etc. |

170 | |

| LVI. | Diseases of the Feet: the “Pinne” in the Feet |

172 | |

| LVII. | On Paralysis of a Toe |

176 | |

| LVIII. | Feathers Plucked Out by the Root |

176 | |

| LIX. | Operation of Opening the Stomach |

179 | |

| LX. | On the Number of Feathers in the Wing and Tail |

181 | |

| LXI. | Counsels and Admonitions |

182 | |

| LXII. | Accidental Immersion during Winter |

183 | |

| LXIII. | Expedient if Meat Fail |

184 | |

| LXIV. | Restoration after Drowning |

184 | |

| LXV. | Sage Advice |

185 | |

| LXVI. | Cure for the Vice of “Soaring” |

186 | |

| LXVII. | On Branding the Nostrils before Setting Down to Moult |

189 | |

| LXVIII. | A Hawk not to be Fed when “Blown” |

190 | |

| LXIX. | Miscellaneous Notes |

192 | |

| ILLUSTRATIONS | |||

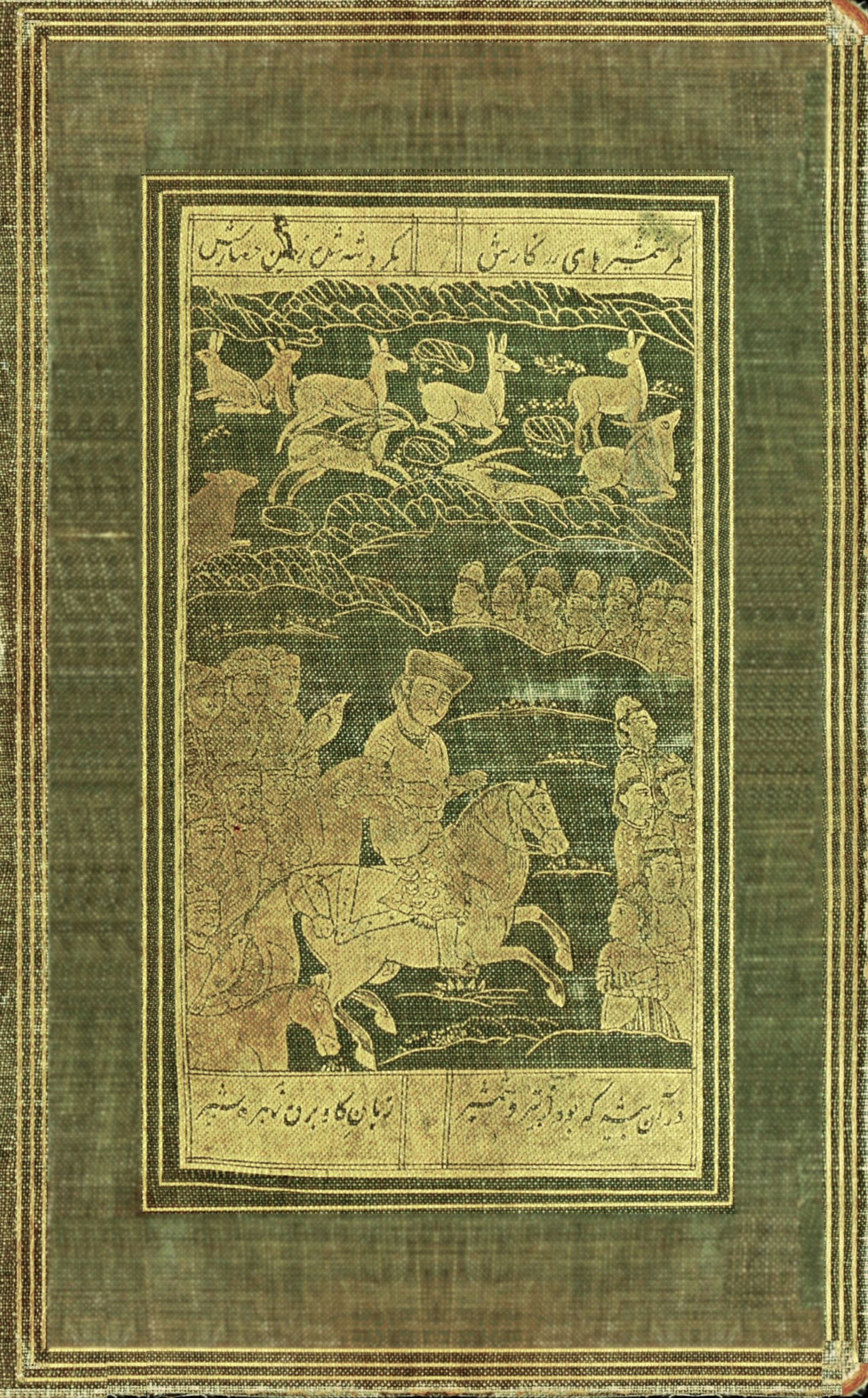

| I. | Hunting and Hawking Scene (from a painting in an ancient Persian MS.) |

Frontispiece | |

| II. | Facsimile of a page of the Teheran Lithographed Edition |

xvi | |

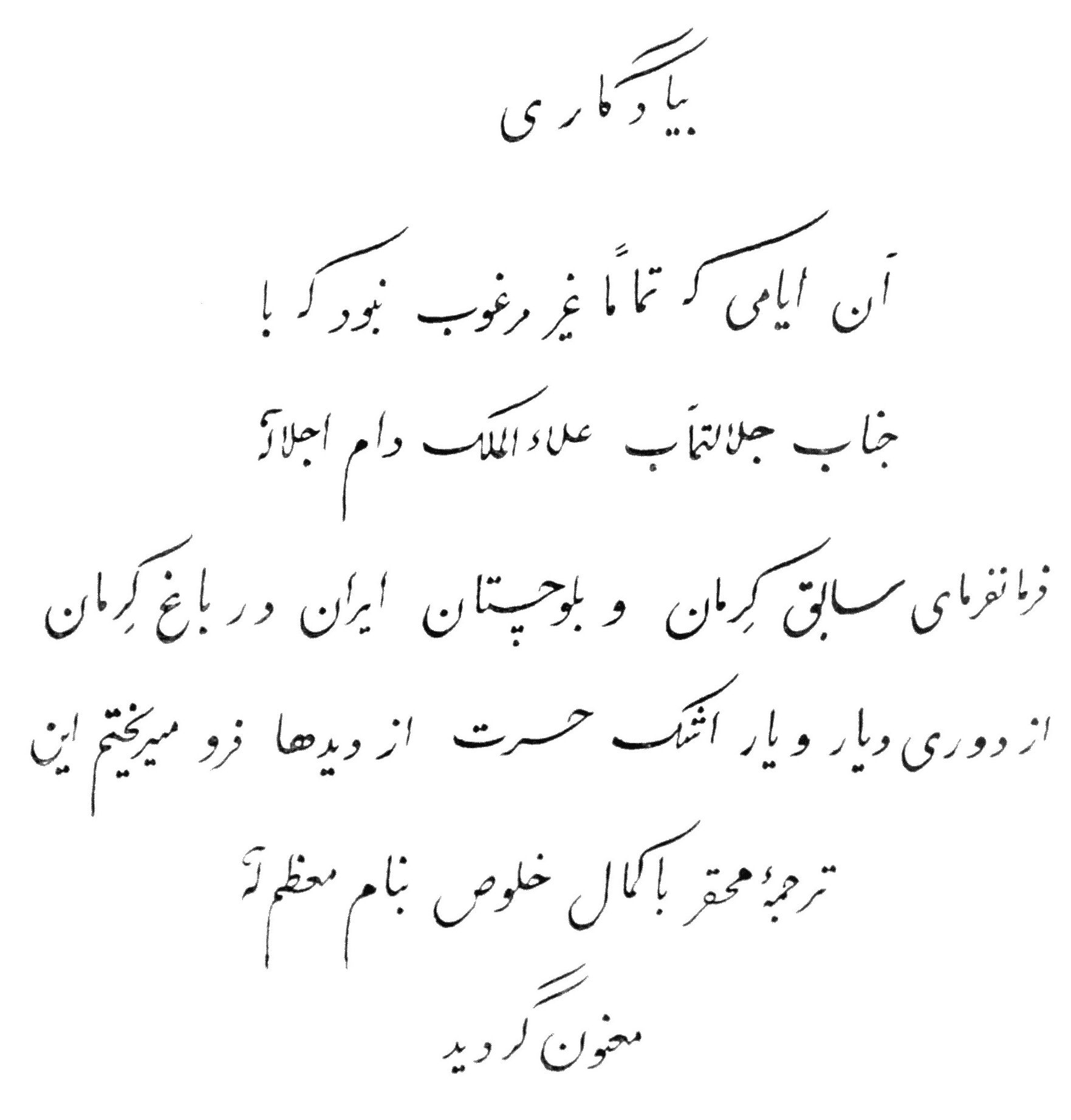

| III. | Persian Carpet depicting Hawking Scene |

2 | |

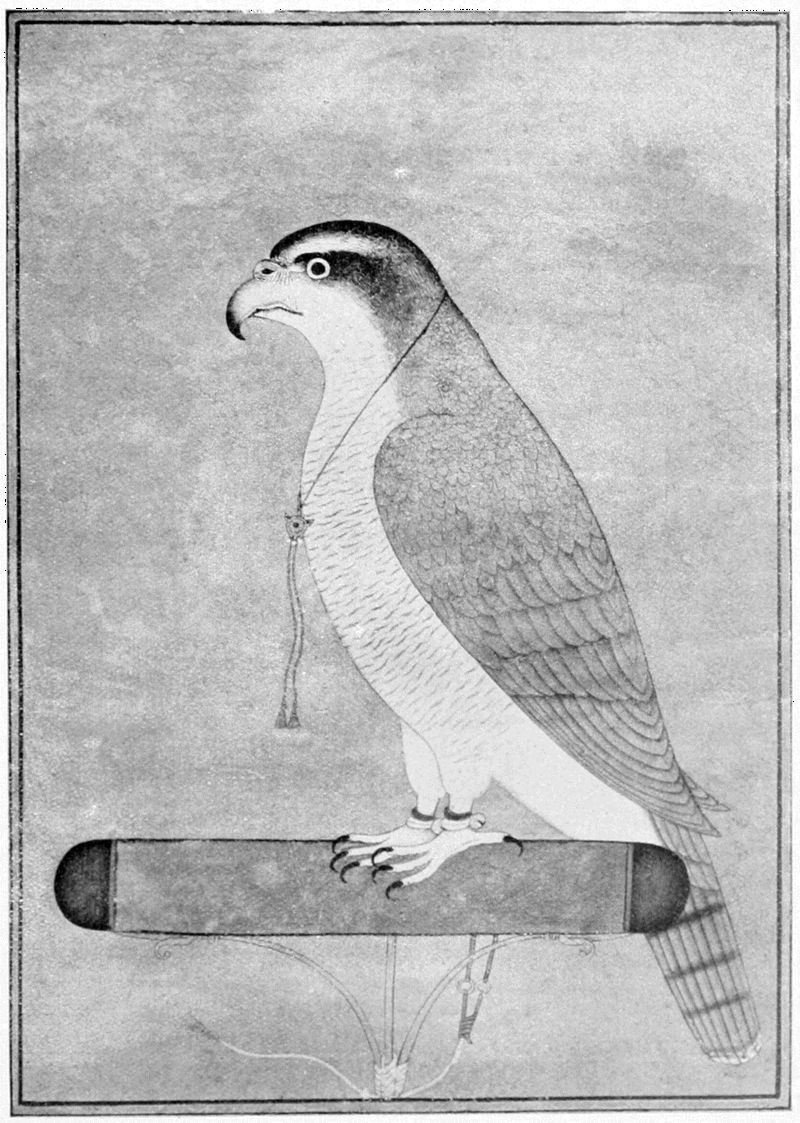

| IV. | From an old Persian painting, Indian, probably of the Mug͟hal Period |

5 | |

| V. | From a painting in an ancient Persian MS. written in India |

7 | |

| VI. | Persian Carpet depicting the Court of a Sikh Mahārājā |

9 | |

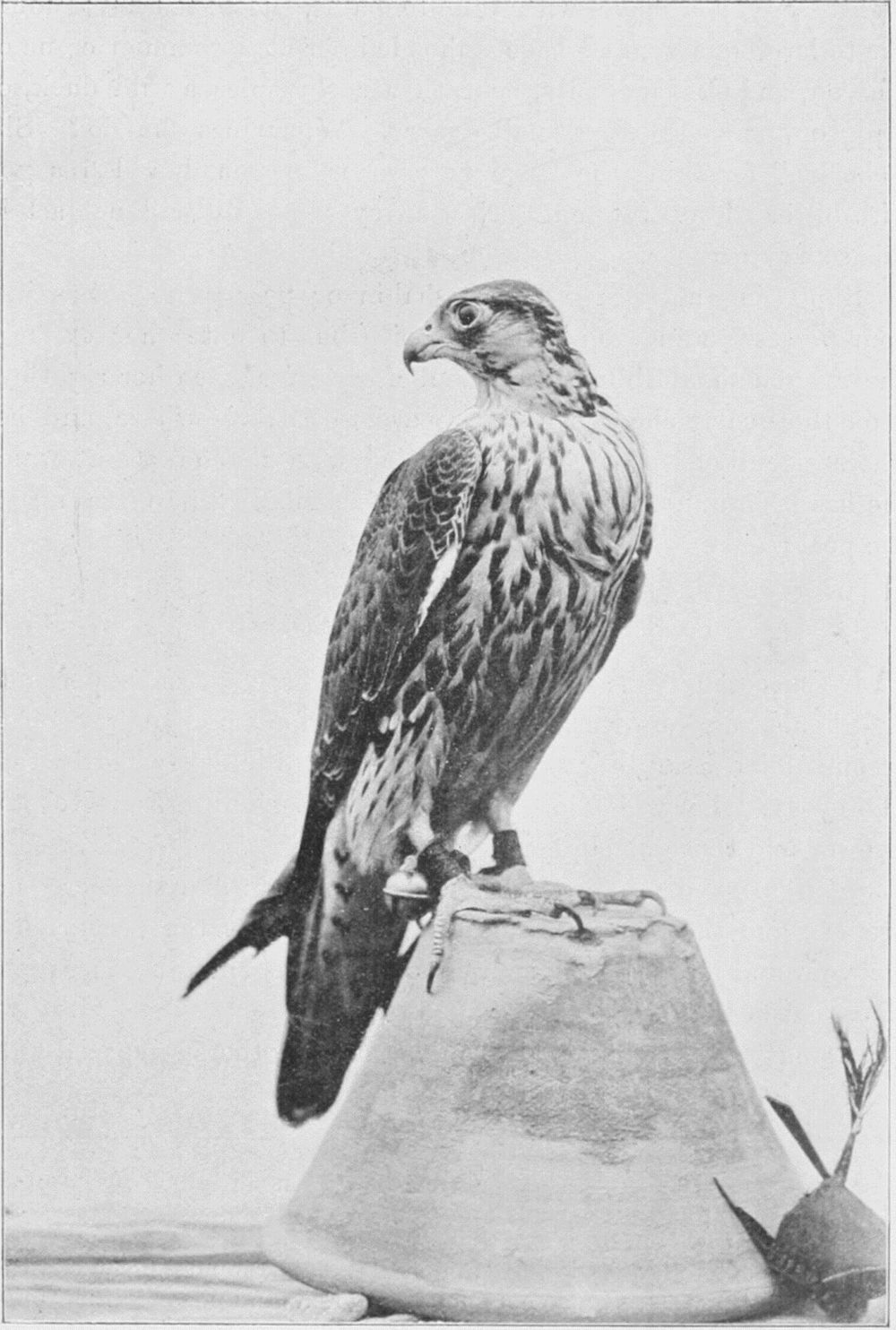

| VII. | Intermewed Peregrine |

43 | |

| VIII. | Young Peregrine (Indian Hood) |

45 | |

| IX. | Young Passage Saker (dark variety) |

51 | |

| X. | Young Passage Saker (dark variety) |

53 | |

| XI. | Hobby with Seeled Eyes |

64 | |

| XII. | Hobby with Seeled Eyes |

66 | |

| XIII. | Hobby with Seeled Eyes |

67 | |

| XIV. | Persian Falconer with Intermewed Goshawk (from a photograph by a Persian) |

77 | |

| XV. | Intermewed Goshawk on Eastern Padded Perch (from a Persian painting) |

79 | |

| XVI. | Arab Falconer with Young Saker on Padded and Spiked Perch |

95 | |

| XVII. | Young Gazelle |

101 | |

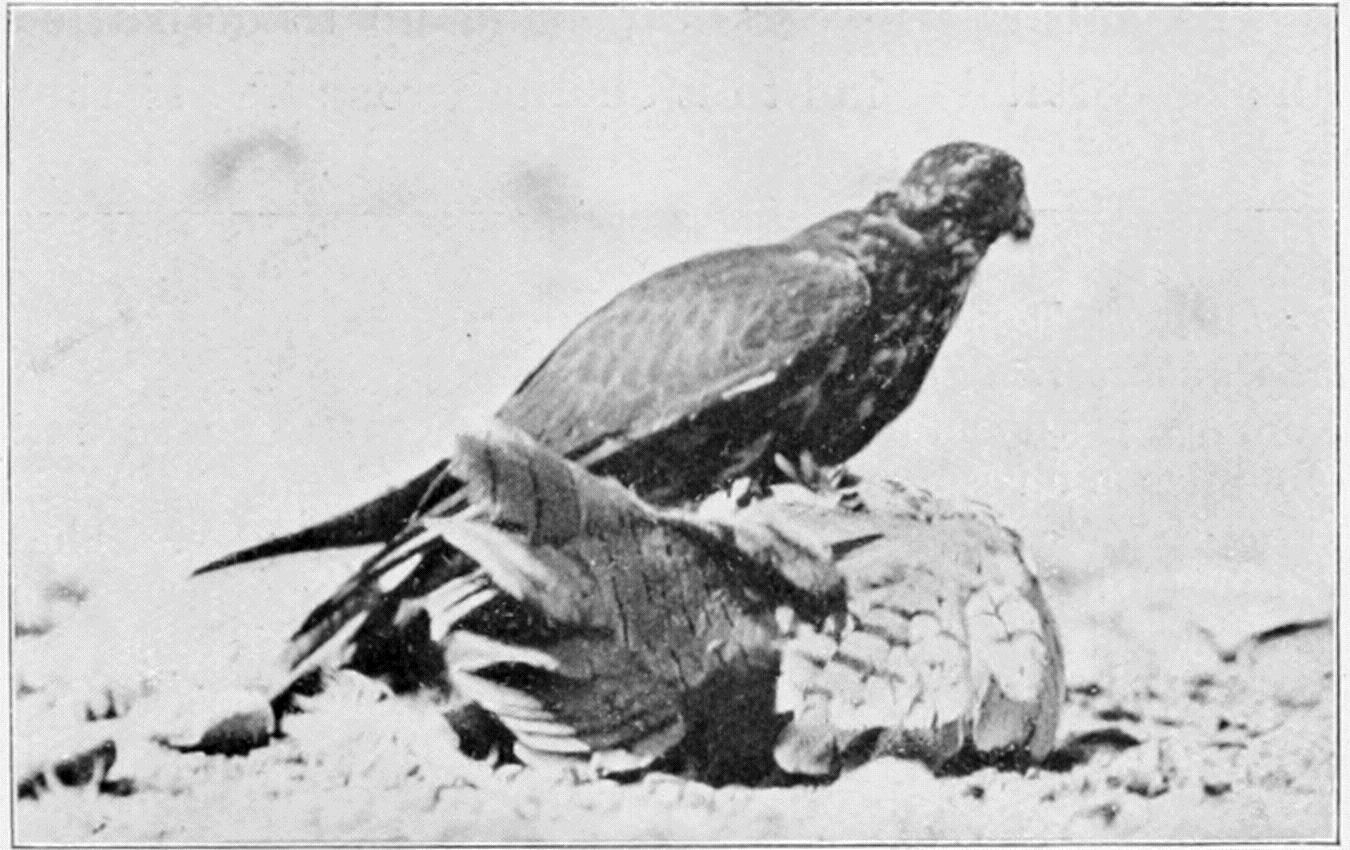

| XVIII. | Young Passage Saker (light variety) on Hubara |

117 | |

| XIX. | Young Passage Saker (dark variety) on Hubara |

119 | |

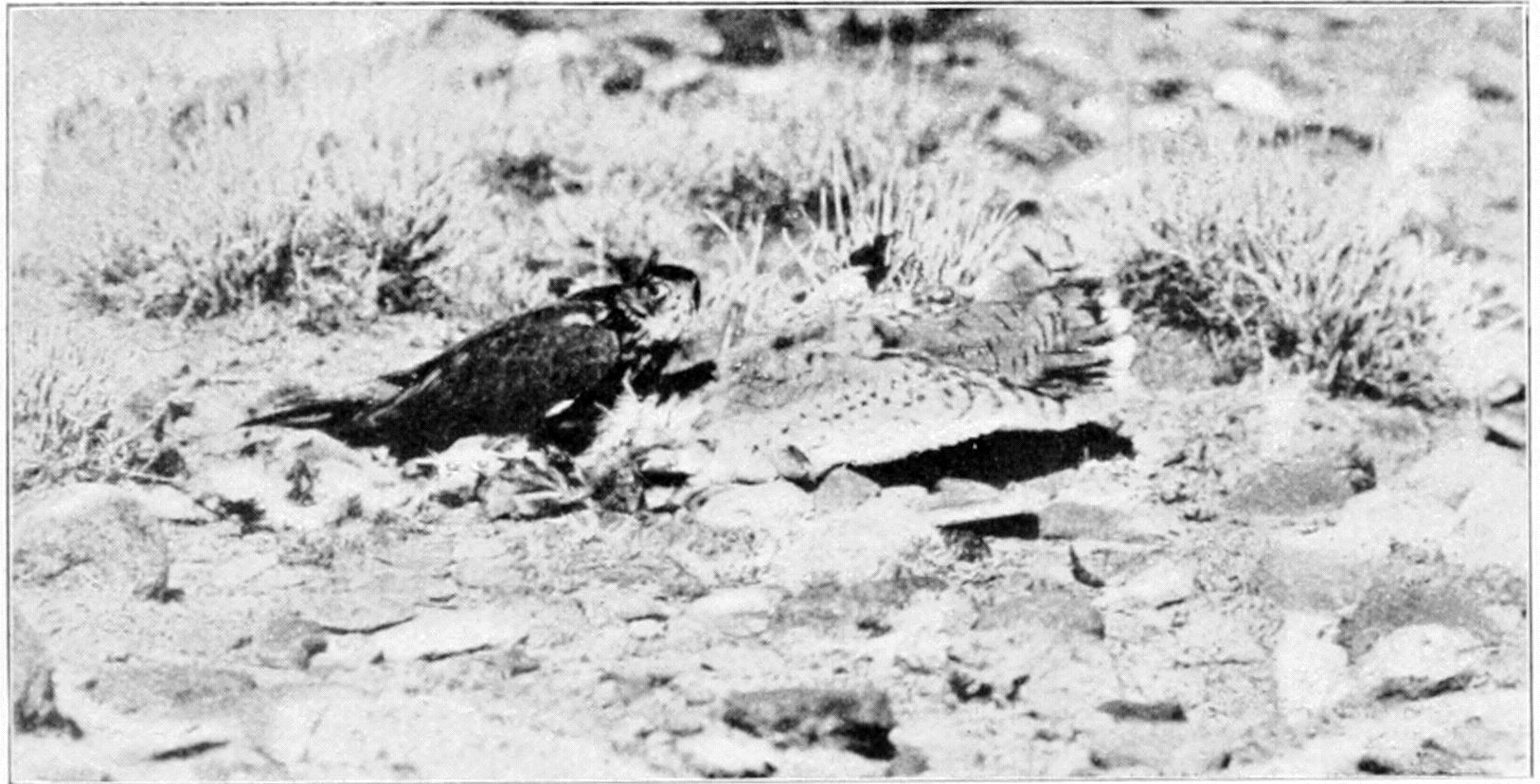

| XX. | Hubara sunning itself |

121 | |

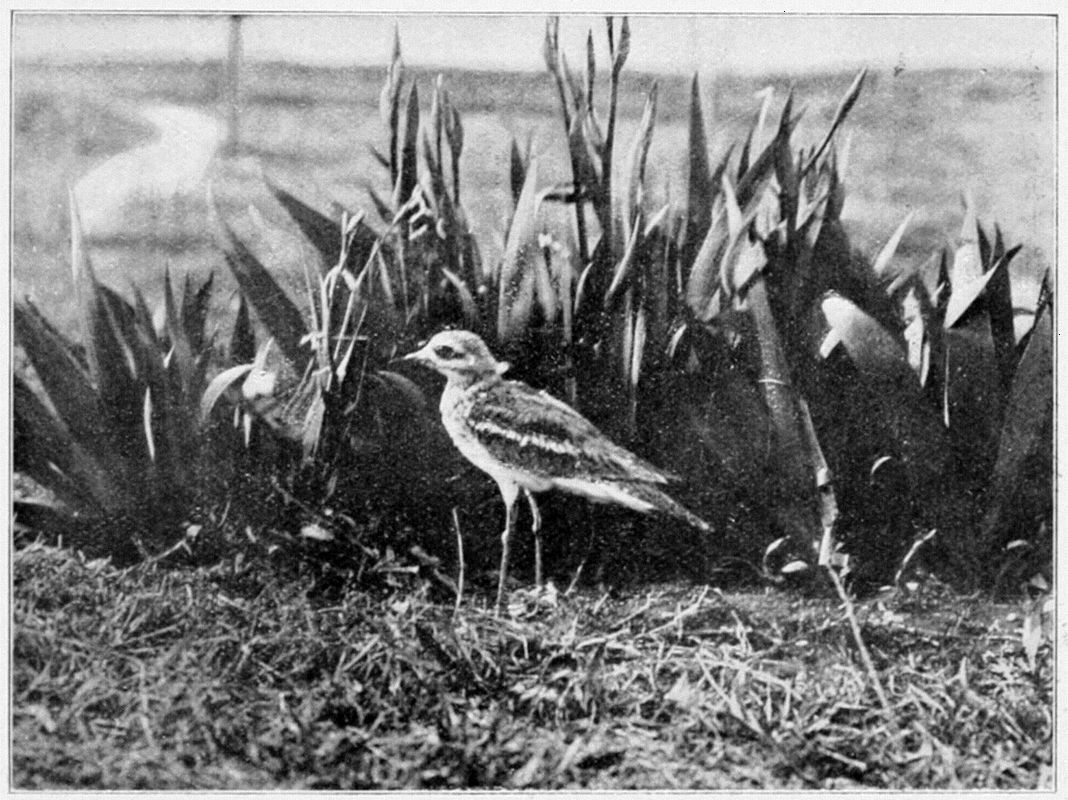

| XXI. | Stone-Plover |

127 | |

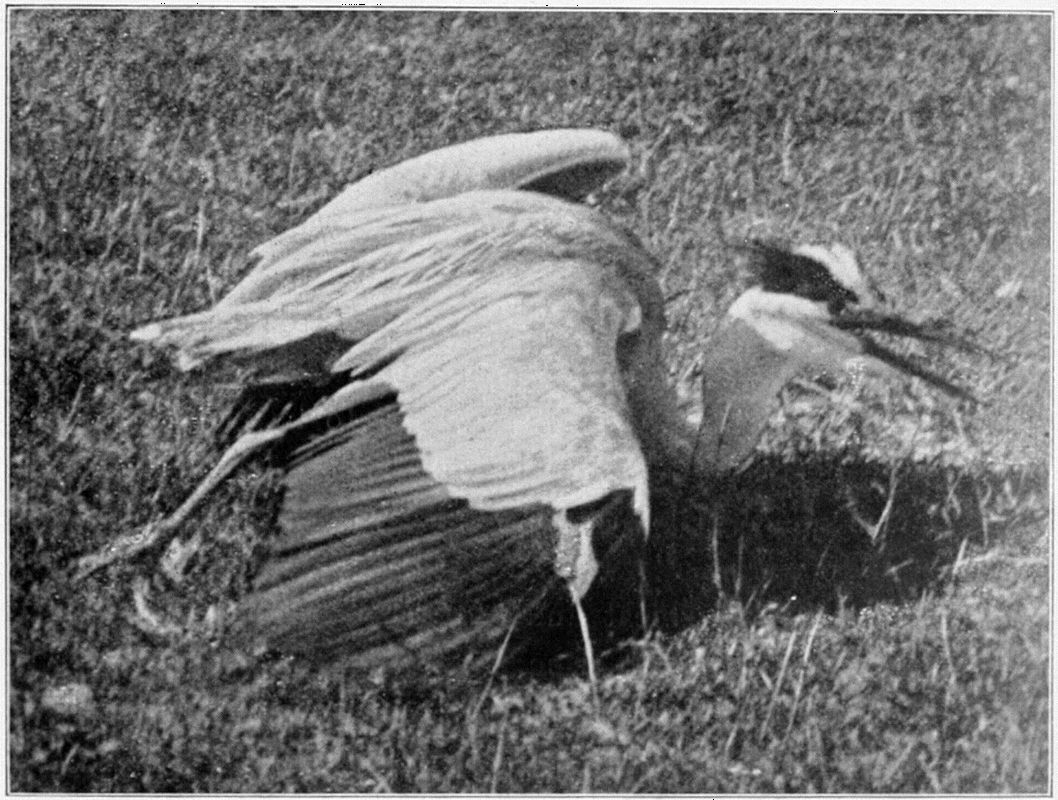

| XXII. | Heron Struck Down by Peregrine (photo taken just before the Heron touched the ground) |

129 | |

| XXIII. | Young Peregrine (English Block and Indian Hood) |

131 | |

| XXIV. | Intermewed Peregrines (from a photograph by Lieut.-Col. S. Biddulph) |

133 | |

| XXV. | Hunting and Hawking Scene |

195 | |

[1]

The Birds of Prey are divided into two great divisions, the “Yellow-eyed” and the “Black-eyed,” these being again sub-divided into numerous species.

We will first treat of the Yellow-eyed Division.

T̤ug͟hral [Crested Goshawk?]—The first species worthy of note is the T̤ug͟hral.[27] During my many wanderings I have searched diligently for this species, but in vain, and am, therefore, unable to describe it from personal knowledge. There is a current tradition, that a single specimen was once brought to Persia from China,[28] and presented as a curiosity to King Bahrām-i Gūr,[29] who treasured it greatly and guarded it jealously. One sad day, when the king was out hawking, the t̤ug͟hral suddenly took to “soaring” and was quickly lost to the sight of the disconsolate monarch. His retinue were soon scattered in every direction in search of the [3]missing hawk, and the king was left almost alone, being attended by a few only of the royal favourites. Bahrām-i Gūr and his party also took up the search; and wandering far and wide, at length happened on a large and shady garden, where they alighted. The bewildered owner of the garden advanced exclaiming:—

On being questioned about the lost hawk he replied, “What a T̤ug͟hral may be, I know not, but not two hours since a hawk with bells and a jewelled ‘halsband,’[31] took stand in a tree of this very garden; but taking fright at my attempt to secure it, it flew off and settled in that grove yonder.” Bahrām was overjoyed at this clue, which enabled him to recover his lost favourite.[32]

From this reference to a “halsband” and bells, and to the t̤ug͟hral’s habit of sitting on trees, the author concludes that this unknown species belongs to the yellow-eyed division of the birds of prey.

[27] T̤ug͟hral; a species frequently mentioned in old Persian MSS. on falconry. It is probably the “Crested Goshawk” (Astur trivirgatus) which is said to have been formerly trained in India. Jerdon, quoting Layard, says it is trained in Ceylon. The T̤ug͟hral is confused by Indian falconers with the Shāh-bāz, or “Royal Goshawk” which, according to Jerdon, is the name given by native falconers of Southern India to the Crested Hawk-Eagle (Limnætus cristatellus). The same author also quotes Major Pearse as his informant that the Rufous-bellied Hawk-Eagle (L. kienierii) is, “Very rarely procured from the N.W. Himalayas and trained for hunting and is known as the Shāh-bāz.”

[28] Chīn; under this name are included Yarkand, Khutan, Mongolia, Manchuria, etc.

[29] Bahrām was surnamed Gūr, from his passion for hunting the gūr or wild ass. He belonged to the Sassanian dynasty of Persian kings and his name frequently occurs in Persian poetry. The Greek Varanes is said to be a corruption of Bahrām.

Three species.—[The author now describes three races of goshawk, which he distinguishes by the names of Tīqūn; T̤arlān; and Qizil:[33] each of these three he sub-divides into varieties, only distinguishable from each other by slight differences in colouring, in marking, or in size. The first-named species is the white[4] goshawk; the second is that variety or race of the common goshawk that is caught after migration into Persia; while the third is the local race that breeds in the country.

After hazarding a conjecture that the white goshawks[34] are not a true species like the T̤arlān and Qizil, but are either albinos, or else accidental varieties produced by the pairing, for one or more generations, of two exceptionally light specimens of the common goshawk, the author proceeds to describe a pure white variety of the Tīqūn, which, he says, is known to the people of Turkistan by the name of Kāfūrī.[35] He remarks that he has caught albino specimens of the Saker Falcon, and has further observed albinos of the Shāhīn, “piebald crow,”[36] peacock, sparrow, sparrow-hawk, pin-tailed sand-grouse, chukor, hoopoe, English merlin, kākulī lark, and common crane. As regards the Kāfūrī, he states his opinion that it is the offspring of albino T̤arlāns that happen to have paired for two generations. He continues:—]

White Goshawk or Tīqūn-i kāfūrī.—The female of this variety of Tīqūn is noted for its large size, the male on the contrary for being extremely small. The head, neck, back, and breast are totally devoid of markings, the plumage being white as driven snow.[37] In the immature bird the eyes have only a slightly reddish tinge, but after the first moult their hue generally deepens and turns to a ruby-red.[38] The claws and beak, though frequently white, are more often a light grey, while the cere is greenish.

[5]

[6]

I remember having once seen a “cast”[39] of this variety—male and female—in the possession of Fatḥ ʿAlī Shāh[40] (now a resident of Paradise), both of which were exceptionally fine performers in the field.

The people of Turkistan, who are highly skilled in the art of training goshawks, call this variety lāziqī.[41]

It is commonly believed by falconers and bird-catchers, that in the early spring, when the female goshawk is desirous of the attentions of a male, she utters loud and plaintive cries, which attract to her many species of birds. From these she selects a male of a species different from herself,[42] and the result of this union is a diversiform progeny. However, the kāfūrī or lāziqī variety is the offspring of two white parents.

The following circumstance lends some colouring of truth to this quaint belief:—

Some years ago a hawk of this species was brought from Russia and presented as a curiosity to the late Shāh, who, in turn, bestowed it on Ḥusayn ʿAlī Mīrzā,[43] Governor of the Province of Fārs. The Governor (now in the abode of the Blessed) forwarded it to me—the contemptible. It must have been a bird of four or five moults, when it came into the possession of this slave. After infinite pains I succeeded in taking with it one solitary chukor,[44] and that, too, a bird harried and worn out by another hawk. It had a very villainous and scurvy disposition. The plumage of this hawk, an unusually large female, was peculiar, in that its feathers were alternately snow-white and raven-black; the claws and beak were of the colour of mother-of-pearl, and the eyes were[7] a reddish yellow. I feel confident her albino mother had mated with a raven, and that this spurious half-caste was the result of the union. There is some truth in the statements of the bird-catchers.

The above description is given, as it seems in some measure to support the stories of the bird-catchers. Sure and certain knowledge, however, rests with God.

Goshawk (T̤arlān).—There are three varieties of T̤arlān, the dark, the light, and the tawny. The last two are common, but though tractable and easily reclaimed,[45] they are not good at large quarry. The dark variety that has a reddish tinge, is universally acknowledged to be the best, and I have myself taken with it[8] common crane and great bustard.[46] The colouring should be very dark, with a tinge of red in it; though this variety may be sullen and self-willed, it is also hardy and keen, and, once thoroughly reclaimed, will be as docile and obedient as any falconer could desire.

Local Race of Goshawk (Qizil).—The third species, the Qizil,[47] breeds in Māzenderān,[48] and in many other parts of Persia, and a fair number are captured in nets, each Autumn, together with the T̤arlāns. Like the last-described species, this also contains three varieties, the dark, the light, and the tawny. The dark variety with the cheek-stripe[49] is the best, and the darker this marking—with a tinge of red in it—the better the bird. With a “passage-bird”[50] of this last variety, the author has himself taken common cranes, great bustards, and “ravine-deer”[51] fawns. The difference between the wild caught Qizil and the T̤arlān is in reality very small. The latter has a somewhat finer presence, a more noble disposition, and is rather faster in flight; also from its habit of mounting higher and thus commanding a more extensive view, it is better able to mark down or “put in”[52] its quarry. It is for these reasons only that the T̤arlān has a higher value than the Qizil.[53]

[9]

[10]

Eyess of Qizil.—The eyess[54] of the Qizil is more courageous than the “passage hawk,”[55] for it has the courage of inexperience. Reared with fostering care from its nestling days, what recks it of the frowns of Fortune? Untaught by Time, what knows it of the spoiling Eagle’s might? Though the eyess may at first excel the passage-hawk in courage, it is inferior to it in powers of flight. With increased knowledge, comes decreased courage. In a word, the nestling bears the same relation to the passage-hawk that the town-bred man does to the desert tentman.

Passage and Eyess Qizil COMPARED WITH T̤arlān.—Compared with the eyess, the passage Qizil is the better, especially that variety which has the reddish-black cheek-stripe.[56] Although inferior in powers of flight to the T̤arlān, it is better at taking large quarry, and in this quality, as well as in affection for its master, it improves moult by moult. The T̤arlān, on the contrary, with increasing age becomes a regular old soldier: it wastes the day excusing itself and shirking its duty and saying: “Oh! an eagle put me off that time;” or “Why! I didn’t see the partridge;” or else, “How clumsily you cast me! You hurt my back.” When the sun is near sinking, the cunning truant will suddenly rouse itself, and by a grand effort kill in the finest style. Well it knows that at that late hour, a full crop and no more work must needs be the reward of its single exertion. With hopes excited, its gulled master will rise early next day,[11] and start off to make a big bag. Alas for the fair promise of last night!

The T̤arlān, however, brings luck to its owner. Besides it has a nature sweet, and docile, and loyal, and true. Hence of the T̤arlān it has been said:—

[30] Kulāh is the felt hat worn by Muslims.

[31] Jalqū; “Halsband, lit. neck-band; a contrivance of soft twisted silk, placed like a collar round the hawk’s neck and the end held in the hand; ...”—Harting. The object of the halsband is to steady the hawk and enable it to start collectedly when the falconer casts it at the quarry. In the East it is considered an indispensable portion of the equipment of every Sparrow-Hawk. It is also very frequently attached to the Goshawk, but is not, however, used with the Shikra. Zang “bell.”

[32] This anecdote is from the Shāh-Nāma.

[33] The T̤arlān and the Qizil are the same species; the latter is the local race that breeds in Persia.

[34] In Blandford’s Zoology of Eastern Persia the author states his opinion that the white goshawk is merely a variety of the common goshawk.

[35] Kāfūrī; adj. from kāfūr, “camphor,” an emblem of whiteness.

[36] Kulāg͟h-i pīsa “the pied crow”; qil-i quiruq T. “the pin-tailed sand-grouse”; hudhud “hoopoe”; kākulī, vide page 24, note 104, “a species of crested lark”; durnā “common crane.”

[37] Jerdon mentions a pure white goshawk as being found in New Holland, and states that Pallas notices a white goshawk from the extreme north-east part of Asia. Some Afghan falconers call albinos of any species taig͟hūn (tīqūn).

[38] In the adult shikra (wild caught), the iris is sometimes a deep red and sometimes a bright yellow. In “eyess” shikras, even after the moult, the iris is frequently almost colourless, the result perhaps of confinement in dark native houses.

[39] “Cast of hawks, i.e., two; not necessarily a pair.”—Harting.

[40] A contemporary of Napoleon.

[41] Lāziqī T., is said to be the name of a white flower: this is said to be the same as the gul-i rāziqī P., a kind of jasmine (the bel phul of the Hindus).

[42] A similar belief is current in parts of England with regard to the cuckoo, which, by some country people, is supposed to mate with the wryneck or “cuckoo’s mate.”

[43] This Ḥusayn ʿAlī Mīrzā was apparently the father of the author.

[44] The chukor (Caccabis chukor) of India and kabk of Persia, with its “joyous laughter,” enters largely into Oriental fable. On account of its cheery cry, it is a favourite cage-bird with both Hindus and Muslims. The male is also trained to fight. It is not an uncommon sight to see a man strolling along the road with a chukor, or a grey partridge, trotting behind him like a little fox terrier.

[45] “‘Reclaim,’ v. Fr. réclamer, to make a hawk tame, gentle, and familiar.”—Harting.

[46] Mīsh-murg͟h, lit. “sheep-bird” (Otis tarda). In Albin’s Natural History of Birds, it is stated that the goshawk used to be flown at geese and cranes as well as at partridges and pheasants. In Hume’s Rough Notes, there is an account by Mr. R. Thompson of hawking with the goshawk in the forests of Gurhwal and the Terai, the quarry killed being jungle fowl, kālij pheasants, hares, peacocks, ducks and teal. The peacock knows well how to use its formidable feet and legs as weapons of defence, and is a more dangerous quarry than even the common crane.

[47] Qizil T., means “red.”

[48] Māzenderān, a hilly province on the south coast of the Caspian.

[49] Madāmiʿ Pl. Ar. The author explains this to mean “having black under the eyes and under the chin.” Vide also note 200, page 50.

[50] “‘Passage-Hawk,’ a wild hawk caught upon the passage or migration.”—Harting.

[51] Āhū; the Persian gazelle (Gazella subgutterosa). Unlike its congener, the Indian gazelle (the well-known chikāra or “ravine-deer” of the Panjab), the female of this species is hornless. A full-grown Indian gazelle weighs about thirty-six pounds, and stands a little over two feet high at the shoulder. “It [the goshawk] takes not only partridges and pheasants but also greater fowls as geese and cranes.”—Albin’s Nat. Hist. of Birds.

[52] “‘Put in,’ to drive the quarry into covert.”—Harting.

[53] A Persian falconer informed me that the Qizil is smaller, slower,

and inferior in courage to the other races, and that it can readily be

distinguished while in the immature plumage, but not after the first

moult. I was shown a moulted qizil and a moulted bāz side by side;

except that the former was slightly smaller, there was no outward

difference between the two.

[54] “‘Eyess;’ a nestling or young hawk taken from the ‘eyrie’ or nest; from the Fr. Niais....”—Harting.

[55] Vide page 8, note 50. Chapter V of Bert’s treatise is headed: “Of the Eyas Hawke, [Goshawk] upon whom I can fasten no affection, for the multitude of her follies and faults.” The following quaint derivation is from the Boke of St. Albans:—“An hawke is called an Eyes of hir Eyghen, for an hauke that is broght up under a Bussard or a Puttocke: as mony be: hath Wateri Eghen. For Whan thay be disclosed and kepit in ferme tyll thay be full summyd. ye shall knawe theym by theyr Wateri Eyghen. And also hir looke Will not be so quycke as a Brawncheris is. and so be cause the best knawlege is by the Eygh, they be calde Eyeses.” “Now to speke of hawkys. first thay ben Egges. and afterwarde they bene disclosed hawkys....”

[56] Siyāh-yashmāg͟hlī T.; yashmāg͟hlī T., is a black handkerchief worn by women round the head. Perhaps in the text it means “black-headed.”

Much that has been written of the T̤arlān Goshawk is also applicable to the Common Sparrow-hawk.[57] There are four varieties, the light, the dark, the khaki, and the tawny. Of these four, the khaki has the best heart. The eyes in this variety are small; and the smaller the markings on the breast, the more the hawk will be esteemed, for the more courageous it will prove: it is the opposite of the Qizil.

With the Sparrow-hawk, I have myself taken teal, chukor,[12] stone-plover,[58] black-bellied sand-grouse[59] and short-eared owl.[60] Considering its size, the Sparrow-hawk is the boldest as well as the most powerful of all the short-winged hawks used in falconry.[61] I have frequently seen sparrow-hawks (especially eyesses) “bate”[62] at hares, but I could never muster up courage to let one go, to see the result.

Young Passage Sparrow-hawk.—Should a very good young sparrow-hawk be brought to you about the time of year that the Sun first enters into Virgo,[63] which is about the time the Sparrow-hawks first arrive in the country, nurse her carefully, for she is well worth keeping. At this time she will be a mere nestling, scarcely in fact more than seven weeks old. Her bones will not be properly set and her whole appearance will be spare and weakly. Now, don’t be in a hurry to fly her, unless indeed you wish to spoil her. If you destine her for large quarry, such as chukor, seesee,[64] black-bellied sand-grouse, and the like, “man” her very carefully, and let her take no fright at dogs or water, etc. Next train her to come to the lure, or fist. When she will fly readily to the fist, kill a small chicken under her daily,[65] and gorge her on it,—day by day increasing the size of the chicken, till she will fly readily to it,[13] and seize it in your hand, the moment that you present it held firmly by both its legs. Proud of the progress made by your pupil, you may feel inclined to release your grasp of the chicken’s legs, in order to allow her to kill it unaided; but on no account must this fatal inclination be yielded to.

Now, after the hawk has been called to, and gorged on, two or three chickens given in the hand, she must be entered to two or three flying pigeons; the pigeons, with shortened wings, being released before her, in such a manner that she may take them. Each time she takes the pigeon, kill it cautiously, and let her take her pleasure on it.

When she has taken a few pigeons in this manner, call her as before to a live fowl held by the legs, but this time call her to it from some distance. As soon as she comes and seizes it, which she ought to without hesitation, kill it, and gorge her on it.

As soon as her training reaches this point, she should be confined in a cupboard, some seven feet long by three and a half broad. The cupboard, which should first be thoroughly swept and cleaned, must be kept to such a pitch of darkness, that it will be impossible for its occupant to distinguish the day from the night. If much more light be admitted, the hawk, by bating against the door or wall, will probably do herself some irremediable injury. She should be fed every evening, three or four hours after dark, by the light of a lamp, being taken on the fist for the purpose, and allowed to eat her fill. Her principal food should be sparrows and young pigeons, but in any case she must have constant change of diet. When so gorged that she can eat no more, offer her water in a cup, flicking the water with the finger to attract her attention to it. If she drink, so much the better, let her drink her fill: but if she evince no inclination to drink, remove the water and replace her in her prison. This treatment must be continued for at least forty days.

After the expiration of forty days, reduce the quantity of her food for four or five nights, and carry her by lamp light; in fact treat her in every respect like a wild-caught hawk. Evening by evening, the amount of carriage must be increased, until she is thoroughly “manned,”[66] when she will be ready to obey her master’s every behest.

[14]

The above method has certain special advantages. During the rest in confinement, the hawk’s bones will become thoroughly hard and set;[67] and from the high feeding during that forty days, she will attain the growth and strength of a twelvemonth; and her toes will be long and thick; and even large quarry, such as chukor, pigeons, and black-bellied sand-grouse, will stand a poor chance of breaking away from her clutches.

It is of course understood that, if destined for large quarry, she must never have been flown at sparrows nor even given any small bagged bird whole, from the day you first get her till the present. She must be made to forget that there is such a thing as small quarry in existence, or that any bird is fit for food except partridge, and sand-grouse, or such large game.

Eyess Sparrow-hawk.—I will now instruct you in another method of training the Sparrow-hawk, by which, in the field, it will be no whit inferior to the goshawks of most falconers. In the early Spring, get some trusty fowler to mark down a tree, in which a pair of Sparrow-hawks are “timbering.”[68] A strict watch must be kept on the nest, and the first time the parent birds are observed carrying food to their young, the tree must be scaled, and all the nestlings, except the largest female, removed. The nest will contain from three to five nestlings. The whole attention of the parent birds will now be bestowed on the solitary occupant, which, by thriving apace, will fully repay the care lavished on it. The nestling must be inspected by the fowler almost daily, until the whole of the quill feathers of the tail and wings are out.[69] Then four or five days before it is ready to fly, he must “seel”[70] its eyes while it is still in the nest and remove it, substituting for it, one of the nestlings originally[15] abducted. The nest will not then be forsaken: the parent birds will rear the restored substitute, and will year after year build in the same tree.

The nestling, its eyes “seeled,” must be conveyed carefully home, and its education conducted in precisely the same manner as already described. When taken up at the end of the forty days of confinement, your friends will probably delight you by mistaking her for a male goshawk,[71] so great will be her size. What a goshawk will do, she will do.

The author has also adopted the above plan with nestlings of the Shāhīn, the Saker and the Qizil Goshawk, with eminently satisfactory results. He humbly begs leave to add that the idea is an original one.

[57] Bāsha P.; qirg͟hī, qirqī, etc. T. (Accipiter nisus).

[58] Chāk͟hrūq, also called bachcha hubara, the common stone-plover (Œdicnemus crepitans).

[59] Pterocles arenarius. The common Persian name is siyāh sīna or “black breast.” The author, however, invariably gives it its Turki name bāqir-qara or bāg͟hir qara, a word having the same signification. The Pin-tailed Sand-grouse is called qil-i quiruq T.: it is the qat̤ā of the Arabs.

[60] Yāplāq, T.; vide under short-eared owl.

[61] The late Sir Henry Lumsden (who used to hawk “ravine deer” with charg͟hs in Hoti Mardan), told the translator in Scotland that he had frequently seen wild sparrow-hawks kill wood-pigeons, and that he had that very morning seen a sparrow-hawk knock over an old cock pheasant on the lawn, which is was of course unable to hold. Hume, in My Scrap Book (page 132), under the description of his “Dove Hawk” expresses a doubt whether the “true nisus” would kill a bird as large as a dove: vide note 72, page 15.

[62] T̤apīdan, “to bate.” “‘Bate, bating;’ fluttering or flying off the fist.... Literally to beat the air with the wings, from the French battre.”—Harting.

[63] i.e., about the middle of September.

[64] Tīhū or tayhū; the desert or sand-partridge, called in the Panjab sī-sī or sū-sū from its cry. It is not such a favourite cage-bird as the black partridge or the chukor. It is not used for fighting: both sexes are spurless. In Oudh the sparrow-hawk is flown at grey partridges without the assistance of dogs.

[65] The value of a fowl is about four pence.

[66] “‘Manning, manned’; making a hawk tame by accustoming her to man’s presence.”—Harting.

[67] Mag͟hz-i ustuk͟hwān-ash siyāh mī-shavad, lit. “the marrow of her bones becomes black.”

[68] “And we shall say that hawkys doon draw When they bere tymbering to their nestes.”—Boke of St. Albans. [“To timber,” in old English, is “to build a nest.”]

[69] Parhā-yi ḥalāl, lit. “lawful feathers.” There is a belief that until the quills of the tail and wings are produced a bird is not ‘lawful’ for food.

[70] “To seel,” is to sew up the eyes: a thread is passed through the centre of each lower eye-lid, near its edge; the two threads are then knotted together on the top of the head, being drawn so tight that the lower eye-lids cover and close the eyes. Wild birds so treated sit quite still and do not injure themselves.

The Pīqū (Shikra).—The next hawk to be described is the Pīqū. There are two varieties. The first, or tawny variety, has the markings on the breast large and distinct. The second, or dark variety, has a reddish tinge running through the darker colour of its plumage.

These hawks arrive in the country about the beginning of September, some twenty days before the advent of the Sparrow-hawks.

Inferiority of Eyess Pīqū.—Unlike the Sparrow-hawk, the eyess of the Pīqū is much inferior to the passage-hawk; the eyess, from its craven spirit, being with difficulty entered to quarry.[16] For this reason it is little esteemed. The eyess of the Sparrow-hawk, on the contrary, surpasses the passage-hawk.

Of the two varieties, the tawny is the better, surpassing, as it does, the Sparrow-hawk in appearance, more especially so after the first or second moult.

The dark variety, however, is sulky and runaway.

Though slower on the wing than the Sparrow-hawk, the tawny variety can take with success any quarry that the former can. In fact, from a working point of view, there is little to choose between them. The Pīqū is, however, by far the hardier of the two, enduring with indifference the extremes of heat and cold. Flown in the hot weather from morning till night, it shows no signs of distress, but rather seems to get brisker and brisker after each successive flight: it is impervious to fatigue. It is certainly quite ten times hardier than the Sparrow-hawk.

In affection for its master, it also surpasses the Sparrow-hawk, but as before stated, it is slow on the wing, and to be flown with success, requires to be thrown skilfully.[73] If unskilfully thrown, the quarry will get a start, and the hawk will meet with nothing but disappointment. The Pīqū must take its quarry right off or not at all.

In appearance the Pīqū very nearly resembles the Sparrow-hawk, but its feet are stouter, its “arms”[74] more powerful, and its wings shorter: it has also a conspicuous dark line under the chin. The larger this chin-line, the better the bird.[75]

[72] The Pīqū is merely the common Shikra of India (Astur badius—Blan.). In a wild state this hawk preys on lizards, small birds, rats, mice, locusts, and occasionally doves. I have once or twice seen it chase the common Indian ground squirrel round and round a tree, hovering in the air close to the tree and making sudden darts to the opposite side, the squirrel all the time keeping the trunk between it and its pursuer and chattering shrilly. I once caught a “haggard” shikra in a do-gaza, with a very large homing pigeon—a cock Antwerp—as a bait. The net had been set up for an eagle. Vide note 61, page 12.

[73] The Shikra, held in the right hand protected by a pad or glove, the breast lying in the palm of the hand held upwards, and the tail, legs, and points of the wings coming out between the fore-finger and thumb, is thrown at the quarry while the quarry is still on the ground, or else the moment it rises. The Sparrow-hawk being a bird of swift flight is carried on the fist in the usual manner, a “halsband” being used to steady it. It must be a very poor and badly trained Sparrow-hawk that requires to be thrown from the hand. The Sparrow-hawk, being a bird of nervous disposition, is hooded only when carried by rail, or on other necessary occasions: not so the Shikra.

[74] “‘Arms;’ the legs of a hawk from the thigh to the foot.”—Harting.

[75] The chin-stripe is not always present. The author describes its eyes as “Chashm-ash qarīb bi-zāq ast.” The meaning of bi-zāq I am unable to discover.

[17]

The Shikra[76] is said to be of stouter and finer appearance than either the Pīqū or the Sparrow-hawk and to be trained in India to take the pied crow.[77] It is rarely found in Persia. I have never come across it. God alone knows the facts of the case.[78]

[76] The author, writing from hearsay, has imagined the Shikra (Astur badius) to be a separate species from the Pīqū. In India, shikras are flown, or rather cast, at partridges, quails, mainās, and common crows. Vide also note to scavenger vulture.

[77] Kulāg͟h-i ablaq; the Royston crow, the common crow of Persia, is a different species from the common crow of India. The Royston or Hooked Crow is, for a falcon, a far easier quarry than the rook.

[78] Muhammadans frequently qualify their statements by some such expression, the inference being that men are prone to err and that exact knowledge lies with God alone. It is related of the Prophet that once, on being asked how many legs his horse had, he dismounted, counted with care, and then said, “Four.” Had he made a positive statement from memory, the Almighty might have altered the number to two, or to three, and so convicted him of error.

We now come to the Serpent Eagle,[79] so well known to every fowler. Should one be desired as a pet, it can either be captured by any of the ordinary fowler’s devices, or else taken with a chark͟h trained to eagles.[80] It must be fed principally on snakes, as it will not thrive on any other food.

[79] Sanj. Perhaps the Common Serpent Eagle (Circaëtus gallicus). The author in two lines of imperfect description—omitted in the translation—also states that in size and appearance it so nearly resembles the buzzard (sār), vide p. 32, note 133, that even an experienced falconer might easily mistake the two. The author does not include this amongst the ʿUqāb or Eagles, vide Chapter XII.

[80] For this poaching flight, vide pages 113-114.

[18]

We now come to the owls, of which there are eight or nine species, the most magnificent of them all being the Great Eagle Owl.[81]

Great Eagle Owl.—Nestlings of this species are frequently taken by fowlers, reared by hand, and then trained[82] for the sport of “owling.” When first taken from the nest, they must be well and frequently fed, and be kept in as high condition as possible; for if at all neglected at this age, the immature feathers become “strangled” and fall out.

As soon as Autumn commences and the weather begins to cool, i.e., as soon as the birds of prey and other birds have commenced their in-migration from the hills and other summer-quarters, the nestling owl is taken up, fitted with jesses,[83] carried on the fist, sparely dieted, and “manned,” just like a young hawk in training. When thoroughly “manned,” a stick is procured about twenty inches long: to one end of this a circular piece of black horse-blanket, or felt, is securely fastened. To this again a twist of black goat-hair rope[84] is attached, so that by its means the owl’s meat may be tied on to the black felt.

The fowler, in the morning, places the stick, garnished with meat, about two paces from him on the ground. He then takes the owl on his fist and shows it the meat on the stick. The owl will leave the fowler’s fist and fly to the meat. It is allowed to eat a little only of the meat, being taken up and flown at this lure a second, and a third time. It is then permitted to make a light meal and is removed.

[19]

In the late afternoon the lesson of the morning is repeated, the distance from which the owl is flown being slightly increased.

The above training is continued daily, the distance being increased step by step, till the owl will fly a good long way to the garnished stick laid on the ground. When this stage of the owl’s education is reached, the stick is no longer laid down, but, felt-side upwards, is planted lightly in the ground, in such a manner that the moment the owl settles on the felt to feed, the stick collapses. If the stick is planted too firmly, it will not fall flat to the ground, the result being that the owl remains suspended half way. As soon as the owl will fly readily to the upright stick, from a distance of five- or six-hundred paces,[85] its education may be considered complete.

Now, if accidents are to be avoided, the owl, during the whole of its training, must have been fed on nothing but red meat, meat without the vestige of a feather. If fed on pigeons or fowls, or any kind of “feather,” it may learn the fatal vice of bird-killing, a vice that will be fully appreciated by the fowler the first time a fine falcon becomes entangled in his net; for seeing the falcon struggling in the net, that dog-begotten owl will abandon the lure, and fastening on to the captive, will by a single squeeze of its deadly feet deprive her of life. Before the fowler can arrive, the murder is done, and his regrets—of what avail are they?

In addition to the owl, the fowler must procure a fine silk net. The silk thread from which it is made should be woven of six or seven fibres and should be dyed to match the ground where the net will eventually be set up. When in position, the net should be invisible. In size it should be about ten feet long by sixteen to eighteen feet broad.[86] A very long fine silk cord of the same colour as the net is threaded through its top meshes, and the net (erected much in the same manner as an ordinary du-gaza[87] for[20] catching sparrow-hawks), is supported in an upright position by two very light poles[88] as long as the breadth of the net, and these are placed under the cord, at fourteen to fifteen paces distance from the ends of the net. The ends of the cord are made fast to pegs driven into the ground at a good distance from the ends of the net. The poles must be so erected that, at any slight shock to the net, they will collapse suddenly.

The “luring-stick,” garnished with a shank of sheep or goat securely tied to the black felt, is now erected exactly in the centre of the net, and about five feet[89] from it. The net so arranged is in position for use.

The fowler now takes the owl on his fist, shows it the garnished “luring-stick,” and then turns about and walks off in the opposite direction for a distance of five- or six-hundred paces: he then halts, turns about again, and casting off the owl into the air, quickly conceals himself.

The owl, in accordance with its previous training, flies straight for the lure, and is soon closely mobbed by all the birds of the neighbourhood. Do not leave your ambush; watch. If you are near the hills, perhaps a goshawk, qizil or t̤arlān, or else a saker falcon will come down and join the crowd. The owl, however, having no other object but to reach its goal, ignores the clamouring presence of its pursuers and continues on its straight course. The first bird to buffet the owl, on its alighting on the lure, is a fast prisoner in the net.

Let us suppose a noble saker falcon has thus fallen a victim to your fowler toils. Leave your ambush, and, cautiously and gently, I adjure thee by God, go and secure thy prisoner, treating her with all honour and respect.

The eyes of a newly caught hawk should be “seeled” on the spot, and if a fine needle and fine thread (not silk) be used for the purpose,[21] the falconer into whose hands the hawk eventually falls, will call down blessings, not curses, on the operator’s head.

Nestling of Eagle-Owl Preferred.—For the above sport, the nestling is preferred to the wild caught bird. Being ignorant and inexperienced, and consequently more courageous, it treats eagles and other unknown dangers, with contempt. The nestling has also greater staying power.[90] The hours it should be flown are from early morning till about eleven o’clock, and from three in the afternoon till within half an hour of sunset. A hundred flights in the day are not too much for a really good bird.[91]

Disadvantages of wild-caught Owl.—The wild-caught owl soon gets done up, and after a few flights gets sulky and flies off aimlessly and settles on the ground.

Arab Name for Eagle-Owl.—The Arabs call the Eagle-Owl Fahdu ’l-Layl, or “Panther[92] of the Night.” What the Golden Eagle is to the day, the Eagle-Owl is to the night. Hares and foxes fall an easy prey to it.[93]

Riding Down Eagle-Owl.—Should you, by chance, when riding out in the open country, put up an Eagle-Owl, set your horse into a gallop and start in hot chase. If closely pressed, the owl will not rise more than thrice; after that it may be easily captured.[94]

Treatment of newly caught Eagle-Owl.—It is not at all necessary to “seel” the eyes of an owl captured in the above manner. It should at once be placed on the fist and “carried” like a short-winged hawk; if it declines to sit up, duck its head under water three or four times in rapid succession. This will[22] soon bring it to its senses and send away its perversity: plunging its head in cold water extinguishes the fire of pride in its heart and makes it steady as a rock.[95]

[81] Shāh-būf.

[82] Rasānīdan, “to train.”

[83] Pācha-band. “Jesses, the short narrow straps of leather fastened round a hawk’s legs to hold her by.”—Harting. The jesses are never removed from the hawk’s legs. In the East the jesses are frequently made of woven silk or cotton, with small rings or “varvels” attached to their ends: with the short-winged hawks, the use of leather jesses is the exception. The “leash” is a long narrow thong (or in the East a silk or cotton cord) that is attached to the end of the “jesses” by means of a swivel, or otherwise, and is used for tying up a hawk to a perch or block. Vide also page 78, note 315.

[84] Qātima, a word used by the E. Turks and Kurds for a rope of goat hair. In India gut, or the sinews of cranes, are used for binding lures, etc.

[85] Qadam; a short pace of about twenty inches.

[86] Ẕiraʿ. “Three ẕiraʿ long, by five or six ẕiraʿ broad.” The Persian ẕiraʿ is variously stated to be a measure of forty, and forty-two inches in length.

[87] Du-gaza; a light, large-meshed net, six feet or more long, by four and a half feet or more broad, and suspended between two light bamboos or sticks, which are shod with iron spikes. This net is planted upright, twenty yards or more away from a resting hawk, while a live bird is pegged down in the centre of the net, a few feet from it, and on the side opposite to the hawk. A certain amount of spare net is gathered towards its centre and allowed to rest loose on the ground. The hawk makes straight for the fluttering bait, through the invisible net; the loose portion on the ground permits the net to “belly” like a sail, while the shock given causes the light uprights to collapse inwards, thus effectually enveloping the hawk.

[88] Presumably the length of these poles should be somewhat less than the breadth of the net.

[89] “One and a half ẕiraʿ.” The old English name for hawk-catching nets was “urines” or “uraynes.”

[90] Perhaps it can be kept in higher condition.

[91] It must not be supposed from this description that hawk-catching is by any means an easy business. In India, in the course of two or three weeks, the fowler may not catch more than three hawks worth keeping, and that, too, at the season the birds are migrating into the country.

[92] Apparently a slip on the author’s part. Fahd is properly the cheeta or hunting-leopard and not the panther. In Persian the former is called yūz and sometimes yūz-palang, while the latter is called palang only.

[93] In Seebohm’s British Birds, it is stated that the eagle owl preys on capercailzie and fawns, besides hares and other game.

[94] Partridges are caught in this manner by the Baluchis round Dera Ghazi Khan. Vide also Shaw’s High Tartary, Yarkand and Kashgar.

[Short-eared Owl; Long-eared Owl.—The author now imperfectly describes five or six species of owl, which the translator is unable with any certainty to identify. The first species mentioned by him is the Yāplāg͟h or Yāplāq, and this species he again divides into two sub-species or races, viz., the “Desert or Plain Yāplāq,” and the “Garden or Grove Yāplāq.” The colour of the latter is said to be somewhat darker than that of the former. The first species is probably the Short-eared Owl (Otus brachyotus); while the second is probably either the Common Long-eared Owl (Otus vulgaris), or the Tawny Wood-Owl. The author also states that[23] the former species, once it has successfully shifted from the first stoop of the falcon and has begun to “tower,”[96] is an exceedingly difficult quarry, and that only a passage Shāhīn or Peregrine is equal to the flight, the Saker not being swift enough.[97] The latter species of owl, he adds, is a poor performer and unable to “ring up”[96] to any great distance without being overtaken and killed.

Indian Grass-Owl.—The Short-eared Owl is, however, an easier quarry than the Indian Grass-Owl (Strix candida), which in India is taken both with Sakers and Peregrines. If, however, the Saker is not in high condition (in much higher condition than it is usually kept by natives of India), both hawk and quarry will soon be lost to view, ringing up, on a calm day completely out of sight and almost perpendicularly into the sky. In this species the iris is dark; it is therefore presumed that neither it nor any nearly allied species can be included under the name yāplāq.

Indian falconers, however, in the Panjab, have only one name for both the Short-eared and the Grass-Owl.

Afghan falconers state that, in their country, the Short-eared Owl is a common quarry for the Saker, as well as for the Peregrine.

The author continues:]—

Bride of the Well.—The next species of owl is smaller than the Yāplāq, and is hornless. Its prevailing colour is a yellowish white, something like that of the Tīqūn Goshawk. This species is especially common in Baghdad and other sacred places.[98] It is known to the Arabs by the name of the “Bride of the Well.”[99] It preys principally on the pigeons of the “Sacred Precincts;”[100] for that cuckoldy pimp, lacking regard and consideration, has settled that the pigeons of the precincts[100] are its proper prey, so it hunts [24]them in the night-watches. In the Spring the attendants pull out the young owls from their holes in the walls, or from the interiors of the domes, and slay them. This species is smaller than the Yāplāq.

Little Owl (Spotted owlet?).—[The author next mentions a small owl that he styles Bāya-qūsh or Chug͟hd. In the Panjab, the spotted owlet (Athene Brama) is known by the latter name.[101] The author says of this species:]—It frequents old ruins. A young shāhīn, intended for the flight of the stone-plover, should first be given two or three pigeons from the hand, and then flown at a wild chug͟hd or two. After that it may be entered to stone-plover. The chug͟hd is useful for no other purpose but this.

“Bird of Night-melody”[102] or “Bird of Testimony.”[103]—The next species we come to is the “Bird of Night-melody,”[102] better known under its popular name of “The Bird of Testimony.”[103] The male of this beautifully marked little owlet is scarcely larger than a lark.[104]

All the above species of owl are strictly nocturnal in their habits.

[95] The following description of owling is taken from Blaine’s Encyclopedia of Rural Sports. It is stated there that any owl may be used, but that the great horned owl is the usual bait:—“The owl, confined between two wooden stands or rests, is taught to fly from one rest to the other without touching the ground. Between the rests, a cord is stretched, on which a ring plays, and to which another slacker cord is attached by one end, the other being fastened to the jesses on the legs of the owl, whose movements are thus confined to flying from one block or rest to the other. To this change of posture he is accustomed by presenting him with food on the opposite side to that on which he may happen to be resting, until he becomes completely habituated to this method of exercising himself. A saloon is now formed in the midst of a copse, of boughs, in the centre of which a log or stand rests, and without the saloon a similar one is placed about a hundred paces distant, the intermediate space on which the owl is placed being cleared away. It is necessary that the top and sides of this saloon should be covered with boughs in such a manner that although the outside is distinctly seen there is no opening that will admit any bird to enter with unfolded wings. Nets are placed against the top and sides, leaving open that part only opposite to the resting place of the owl. The fowler, now concealing himself, keeps watch, and when he observes the owl lower his head and turn it on one side, he becomes certain that some bird of prey is in the air. The hawk, now marking the owl for his own, follows him into his retreat; when, becoming hampered in the meshes of the net, he is easily secured.” Vide also History of Fowling, by the Rev. H. A. Macpherson: Edinburgh: David Douglas, 1896.

[96] “‘Tower;’ ‘ring up;’ to rise spirally to a height.”—Harting.

[97] The Indian grass-owl, Strix candida, though a much more difficult quarry than the short-eared owl, can be successfully flown by a trained saker, provided the latter is in high condition: a saker is not fit for this flight unless she weighs at least 2 lbs. 4 oz., better 2 lbs. 6 oz.

[98] Such as Kāz̤imayn, Najaf, Karbalā, etc.

[99] ʿArūs-i chāh; ʿarūs is the Arabic for “bride,” but chāh, “well,” is Persian.

[100] Ḥarām: the sacred precincts round both Mecca and Medina are known as ḥarām, and certain acts such as slaying game are forbidden within the boundaries. Ḥarām is also a name for the women’s apartments. The author by ḥarām probably means the sacred precincts of Mecca, but from the context his meaning is not clear.

[101] In the Derajat this owlet, called there chhapākī, is a quarry for the shikra, and also for the common and the red-headed merlin. Its blood is supposed to be a cure for prickly heat, hence its local name. (Chhapākī is a corruption of shapākī, “prickly heat”.) In some parts of India it is used as a decoy for small birds.

[102] Murg͟h-i shab-āhang.

[103] Murg͟h-i Ḥaqq. Ḥaqq means the “Truth” or “God.” This little owl, which is probably the Persian owlet (Athene Persica), is reverenced by Muhammadans: it clings to walls and cries “Ḥaqq, Ḥaqq,” after the manner of the dervishes.

[104] Kākulī. Elsewhere the author states that the Arabs call this lark quṃburah, which is an Arab name for the Crested Lark (Alauda cristata).

[25]

Harriers.—[The author next proceeds to describe what appear to be two species of harriers. He says:]—

We now come to the Bayl-bāqilī, called by the Kurds, Dasht-māla,[105] and by the Arabs, Abū-ḥikb. There are two species, one yellow-eyed, and one dark-eyed.[106]

Yellow-eyed Species.—In the yellow-eyed species, the plumage of the young bird is henna-coloured [chestnut brown], but after its first moult, some white feathers make their appearance. After the second or third moult, the plumage is very like that of the Tīqūn Goshawk, the back turning a bluish grey and the breast becoming white. The female is about the size of a small Qizil “tiercel.”[107] Only a falconer could distinguish the adult female from a Tīqūn tiercel. The “stalke” of this species is long and slender.

Dark-eyed Species.—In the dark-eyed species, there is no material difference between the plumage of the young and the adult bird. In the latter, however, the markings on the breast are larger. The general colouring of the dark-eyed species is darker than that of the yellow-eyed.

In habits, both species are similar; they haunt open plains, preying on mice and sparrows, and occasionally on quails. They are mean-spirited, ignoble birds, with poor and weakly frames.

Wager with the Shāh.—When in attendance on the Shāh (may our souls be sacrificed for him!) I once made a bet with some[26] fellow sportsmen that I would catch a harrier[108] and train it to take chukor. I made no idle boast. Praise be to God, I won my bet and proved myself a man of my word, for I trained it and took a chukor with it. The puissant King of Kings, who has surpassed in renown even Jamshed and Cyrus, regarded me with extreme condescension, and in just appreciation of my skill bestowed on me lavish commendation and a rich robe of honour.

On a second occasion, in Baghdad, I laid a wager of a Nejd mare with some sportsmen of that city, that within a space of fifty days I would “reclaim”[109] one of these hawks and successfully fly it at wild quarry. I flew it in the presence of my friends, and took with it one black partridge,[110] one quail, and one rail.[111]

As previously stated, it is quite possible to train these hawks, as indeed it is possible to train many other useless birds of prey: even—

The harrier is an ill-tempered bird with no great powers of flight. To train it is a matter of extreme difficulty, and the result by no means repays the labour. However, give the devil his due: it is very long-winded.

[105] Dasht-māla may be translated “desert-quarterer.” In the Panjab this is the name of the Pale Harrier (Circus Swainsonii) and probably also of Montague’s Harrier (Circus cineraceus).

[106] In the young of the Marsh Harrier, the iris is hazel. The iris of the female of Montague’s Harrier is also said to be hazel.

[107] “‘Tiercel, Tercel, Tassel’ (Shakespeare) and ‘Tarsell’ (Bert), the male of any species of hawk, the female being termed a falcon. The tiercel is said by some to be so called from being about one-third smaller in size than the falcon; by others it is derived from the old belief that each nest contained three young birds, of which two were females and the third and smallest a male. Note the familiar line in Romeo and Juliet: ‘Oh! for a falconer’s voice to lure this tassel gentle back again.’”—Harting.

[108] It is not clear which of the two species the author trained, but apparently the “black-eyed.”

[109] “Reclaim;” Fr. réclamer, to make a hawk tame, gentle and familiar.—Harting.

[110] Durrāj; the Common Francolin (F. vulgaris). It is a favourite cage-bird in India, especially with the Muhammadans, who liken its call to the words Subhān Teri Qudrat “Oh Lord! Thy Power” (i.e., who can fathom it?). The practical Hindus say its call is, Chha ser kī kacharī, “Twelve pounds of kacharī.”

[111] Yalva is a name incorrectly applied to several species of bird with long beaks, as the woodcock and snipe, etc. I am told that in Teheran it is applied to a rail.

[27]

[The description of the Bearded Vulture[112] as given by the author is sufficiently accurate for identification. He, however, adorns it with “two horns or ears like those of the horned owls.” He then continues:]—

The Lammergeyer is noted for its wondrous powers of flight. It soars aloft, bearing with ease a bone as large as the bleached thigh-bone of a donkey. This it drops on a rock, and then descends to eat the shattered fragments.[113] The Poet has said of it:—