Title: History of the World War, Volume 1 (of 7)

An authentic narrative of the world's greatest war

Author: Jr. Francis A. March

Richard J. Beamish

Author of introduction, etc.: Peyton Conway March

Photographer: James H. Hare

Donald C. Thompson

Release date: November 12, 2024 [eBook #74726]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Leslie-Judge Company

Credits: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, Ed Leckert, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

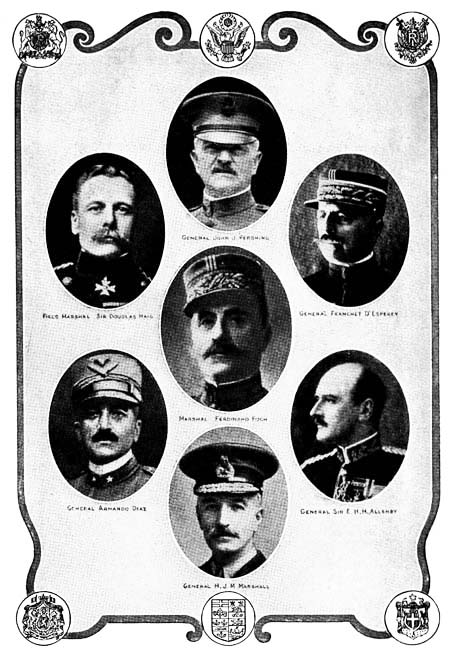

THE VICTORIOUS GENERALS

General Foch, Commander-in-Chief of all Allied forces. General Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American armies. Field Marshal Haig, head of the British armies. General d’Esperey (French) to whom Bulgaria surrendered. General Diaz, Commander-in-Chief of the Italian armies. General Marshall (British), head of the Mesopotamian expedition. General Allenby (British), who redeemed Palestine from the Turks.

COMPLETE EDITION

An Authentic Narrative of

The World’s Greatest War

By FRANCIS A. MARCH, Ph.D.

In Collaboration with

RICHARD J. BEAMISH

Special War Correspondent

and Military Analyst

With an Introduction

By GENERAL PEYTON C. MARCH

Chief of Staff of the United States Army

With Exclusive Photographs by

JAMES H. HARE and DONALD THOMPSON

World-Famed War Photographers

and with Reproductions from the Official Photographs

of the United States, Canadian, British,

French and Italian Governments

MCMXIX

LESLIE-JUDGE COMPANY

New York

Copyright, 1918

Francis A. March

This history is an original work and is fully

protected by the copyright laws, including the

right of translation. All persons are warned

against reproducing the text in whole or in

part without the permission of the publishers.

WAR DEPARTMENT,

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF STAFF,

WASHINGTON.

November 14, 1918.

With the signing of the Armistice on November 11, 1918, the World War has been practically brought to an end. The events of the past four years have been of such magnitude that the various steps, the numberless battles, and the growth of Allied power which led up to the final victory are not clearly defined even in the minds of many military men. A history of this great period which will state in an orderly fashion this series of events will be of the greatest value to the future students of the war, and to everyone of the present day who desires to refer in exact terms to matters which led up to the final conclusion.

The war will be discussed and re-discussed from every angle and the sooner such a compilation of facts is available, the more valuable it will be. I understand that this History of the World War intends to put at the disposal of all who are interested, such a compendium of facts of the past period of over four years; and that the system employed in safeguarding the accuracy of statements contained in it will produce a document of great historical value without entering upon any speculative conclusions as to cause and effect of the various phases of the war or attempting to project into an historical document individual opinions. With these ends in view, this History will be of the greatest value.

P. C. March.

General,

Chief of Staff,

United States Army.

THIS is a popular narrative history of the world’s greatest war. Written frankly from the viewpoint of the United States and the Allies, it visualizes the bloodiest and most destructive conflict of all the ages from its remote causes to its glorious conclusion and beneficent results. The world-shaking rise of new democracies is set forth, and the enormous national and individual sacrifices producing that resurrection of human equality are detailed.

Two ideals have been before us in the preparation of this necessary work. These are simplicity and thoroughness. It is of no avail to describe the greatest of human events if the description is so confused that the reader loses interest. Thoroughness is an historical essential beyond price. So it is that official documents prepared in many instances upon the field of battle, and others taken from the files of the governments at war, are[vi] the basis of this work. Maps and photographs of unusual clearness and high authenticity illuminate the text. All that has gone into war making, into the regeneration of the world, are herein set forth with historical particularity. The stark horrors of Belgium, the blighting terrors of chemical warfare, the governmental restrictions placed upon hundreds of millions of civilians, the war sacrifices falling upon all the civilized peoples of earth, are in these pages.

It is a work that mankind can well read and treasure.

| Introduction by General March | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| Chapter I. A War for International Freedom | |

| A Conflict that was Inevitable—The Flower of Manhood on the Fields of France—Germany’s Defiance to the World—Heroic Belgium—Four Autocratic Nations against Twenty-four Committed to the Principles of Liberty—America’s Titanic Effort—Four Million Men Under Arms, Two Million Overseas—France the Martyr Nation—The British Empire’s Tremendous Share in the Victory—A River of Blood Watering the Desert of Autocracy | 1 |

| Chapter II. The World Suddenly Turned Upside Down | |

| The War Storm Breaks—Trade and Commerce Paralyzed—Homeward Rush of Travelers—Stock Markets Closed—The Tide of Desolation Following in the Wake of War | 21 |

| Chapter III. Why the World Went to War | |

| The Balkan Ferment—Russia, the Dying Giant Among Autocracies—Turkey the “Sick Man” of Europe—Scars Left by the Balkan War—Germany’s Determination to Seize a Place in the Sun | 41 |

| Chapter IV. The Plotter Behind the Scene | |

| The Assassination at Sarajevo—The Slavic Ferment—Austria’s Domineering Note—The Plotters of Potsdam—The Mailed Fist of Militarism Beneath the Velvet Glove of Diplomacy—Mobilization and Declarations of War | 58 |

| Chapter V. The Great War Begins[viii] | |

| Germany Invades Belgium and Luxemburg—French Invade Alsace—England’s “Contemptible Little Army” Lands in France and Belgium—The Murderous Gray-Green Tide—Heroic Retreat of the British from Mons—Belgium Overrun—Northern France Invaded—Marshal Joffre Makes Ready to Strike | 88 |

| Chapter VI. The Trail of the Beast in Belgium | |

| Barbarities that Shocked Humanity—Planned as Part of the Teutonic Policy of Schrecklichkeit—How the German and the Hun Became Synonymous Terms—The Unmatchable Crimes of a War-Mad Army—A Record of Infamy Written in Blood and Tears—Official Reports | 117 |

| Chapter VII. The First Battle of the Marne | |

| Joffre’s Masterly Plan—The Enemy Trapped Between Verdun and Paris—Gallieni’s “Army in Taxicabs”—Foch, the “Savior of Civilization,” Appears—His Mighty Thrust Routs the Army of Hausen—Joffre Salutes Foch as “The First Strategist in Europe”—The Battle that Won the Baton of a Marshal | 153 |

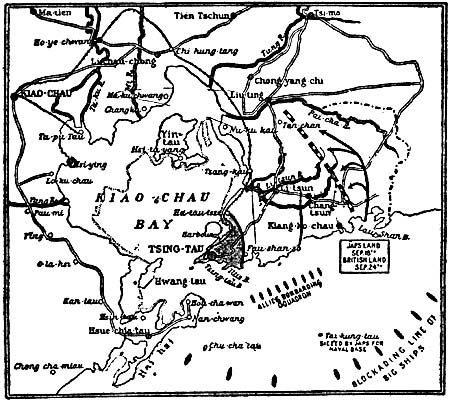

| Chapter VIII. Japan in the War | |

| Tsing-Tau Seized by the Mikado—German “Gibraltar” of Far East Surrendered After Short Siege—Japan’s Aid to the Allies in Money, Ships, Men and Nurses—German Propaganda in the Far East Fails | 170 |

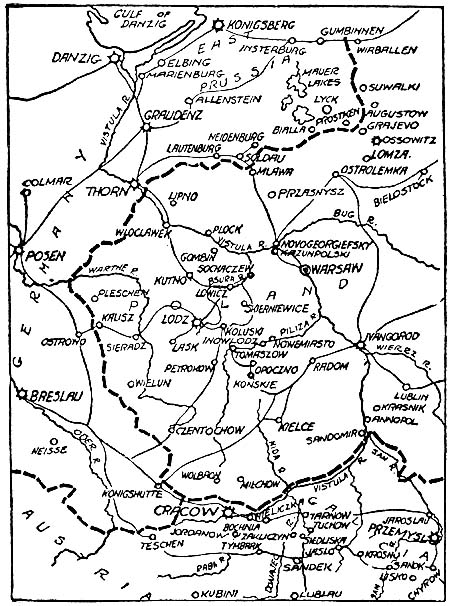

| Chapter IX. Campaign in the East | |

| Invasion of East Prussia—Von Hindenburg and Masurian Lakes—Battle of Tannenberg—Augustovo—Russians Capture Lemberg—The Offer to Poland | 184 |

| Chapter X. New Methods and Horrors of Warfare | |

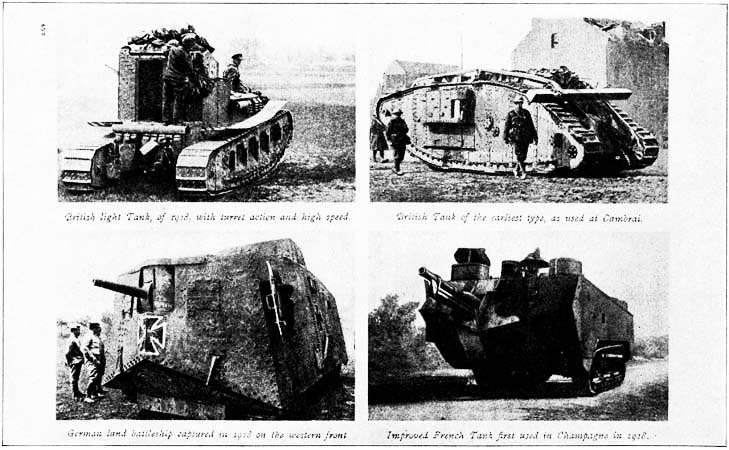

| Tanks—Poison Gas—Flame Projectors—Airplane Bombs—Trench Mortars—Machine Guns—Modern Uses of Airplanes for Liaison and Attacks on Infantry—Radio—Rifle and Hand Grenades—A War of Intensive Artillery Preparation—A Debacle of Insanities, Terrible Wounds and Horrible Deaths | 212 |

| The Victorious Generals | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

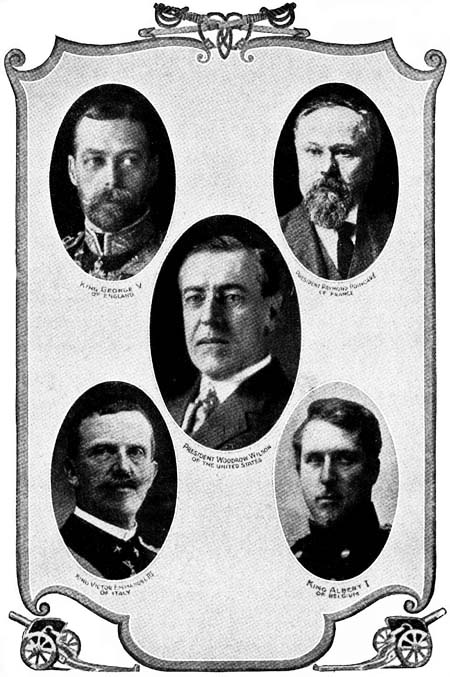

| Kings and Chief Executives of the Principal Powers Associated Against the German Alliance | 2 |

| The “Tiger of France” | 14 |

| The Right Honorable David Lloyd George | 36 |

| Francis Joseph I of Austria, The “Old Emperor” on a State Occasion | 44 |

| The Kaiser and his Six Sons | 82 |

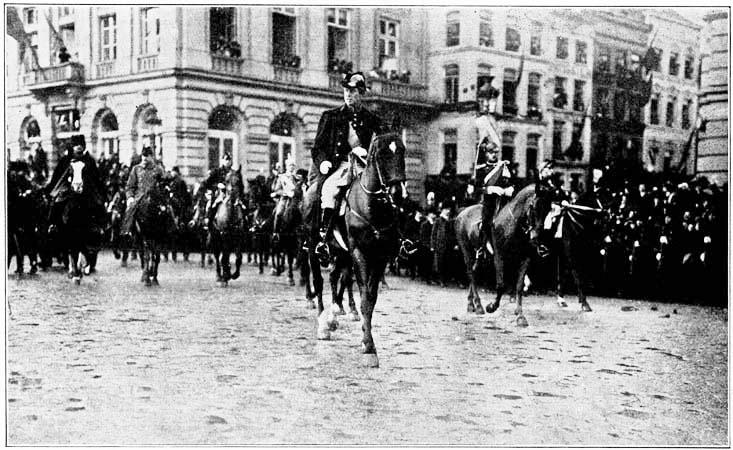

| King Albert at the Head of the Heroic Soldiers of Belgium | 94 |

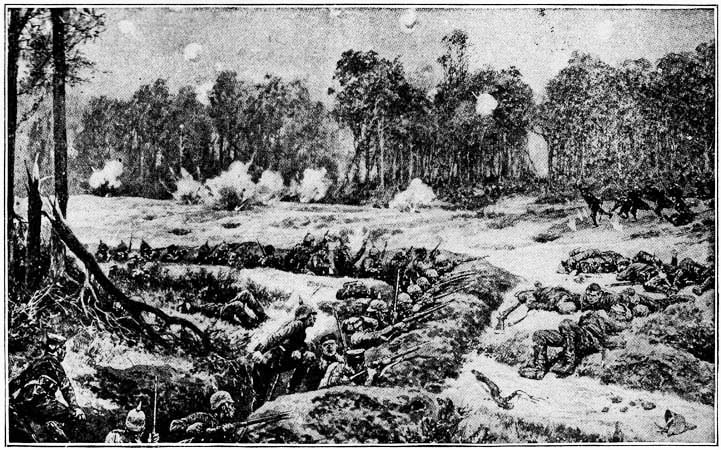

| A Scene from Early Trench Warfare | 114 |

| German Atrocities | 126 |

| The Supreme Exponents of German Frightfulness | 148 |

| General Pershing and Marshal Joffre | 156 |

| Marshal Ferdinand Foch, Commander-in-chief of the Allied Armies | 162 |

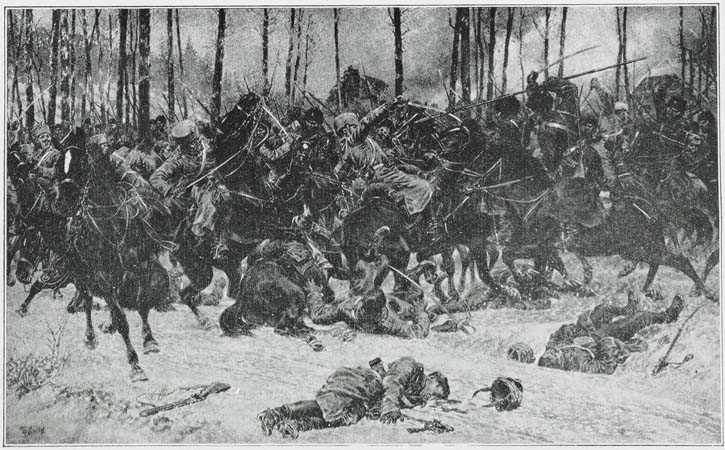

| Cossacks of the Don Attacking Prussian Cavalry | 188 |

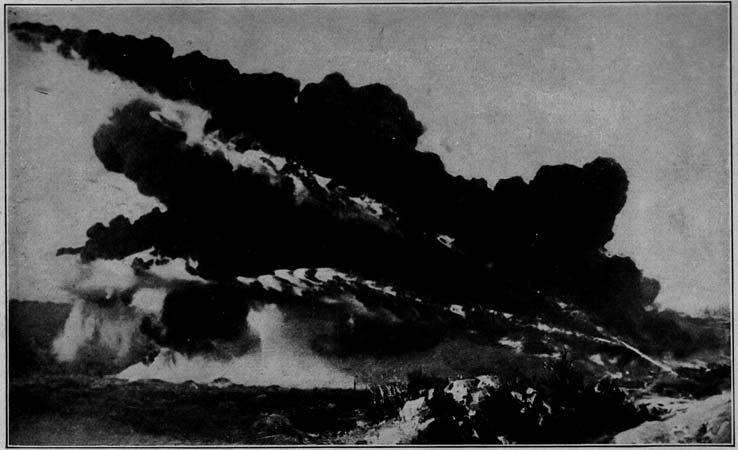

| The Made-to-order Inferno of the Flame-thrower | 230 |

| Types of Land Battleships Developed by Allies and Germans | 234 |

THE WORLD WAR

“MY FELLOW COUNTRYMEN: The armistice was signed this morning. Everything for which America fought has been accomplished. The war thus comes to an end.”

Speaking to the Congress and the people of the United States, President Wilson made this declaration on November 11, 1918. A few hours before he made this statement, Germany, the empire of blood and iron, had agreed to an armistice, terms of which were the hardest and most humiliating ever imposed upon a nation of the first class. It was the end of a war for which Germany had prepared for generations, a war bred of a philosophy that[2] Might can take its toll of earth’s possessions, of human lives and liberties, when and where it will. That philosophy involved the cession to imperial Germany of the best years of young German manhood, the training of German youths to be killers of men. It involved the creation of a military caste, arrogant beyond all precedent, a caste that set its strength and pride against the righteousness of democracy, against the possession of wealth and bodily comforts, a caste that visualized itself as part of a power-mad Kaiser’s assumption that he and God were to shape the destinies of earth.

When Marshal Foch, the foremost strategist in the world, representing the governments of the Allies and the United States, delivered to the emissaries of Germany terms upon which they might surrender, he brought to an end the bloodiest, the most destructive and the most beneficent war the world has known. It is worthy of note in this connection that the three great wars in which the United States of America engaged have been wars for freedom. The Revolutionary War was for the liberty of the colonies; the Civil War was waged for the freedom of manhood and for the principle of the indissolubility of the Union; the World War, beginning 1914, was fought for the right of small nations to self-government and for the right of every country to the free use of the high seas.

KINGS AND CHIEF EXECUTIVES OF THE PRINCIPAL POWERS ASSOCIATED AGAINST THE GERMAN ALLIANCE

[3]More than four million American men were under arms when the conflict ended. Of these, more than two million were upon the fields of France and Italy. These were thoroughly trained in the military art. They had proved their right to be considered among the most formidable soldiers the world has known. Against the brown rock of that host in khaki, the flower of German savagery and courage had broken at Château-Thierry. There the high tide of Prussian militarism, after what had seemed to be an irresistible dash for the destruction of France, spent itself in the bloody froth and spume of bitter defeat. There the Prussian Guard encountered the Marines, the Iron Division and the other heroic organizations of America’s new army. There German[4] soldiers who had been hardened and trained under German conscription before the war, and who had learned new arts in their bloody trade, through their service in the World War, met their masters in young Americans taken from the shop, the field, and the forge, youths who had been sent into battle with a scant six months’ intensive training in the art of war. Not only did these American soldiers hold the German onslaught where it was but, in a sudden, fierce, resistless counter-thrust they drove back in defeat and confusion the Prussian Guard, the Pommeranian Reserves, and smashed the morale of that German division beyond hope of resurrection.

The news of that exploit sped from the Alps to the North Sea Coast, through all the camps of the Allies, with incredible rapidity. “The Americans have held the Germans. They can fight,” ran the message. New life came into the war-weary ranks of heroic poilus and into the steel-hard armies of Great Britain. “The Americans are as good as the best. There are millions of them, and millions more are coming,”[5] was heard on every side. The transfusion of American blood came as magic tonic, and from that glorious day there was never a doubt as to the speedy defeat of Germany. From that day the German retreat dated. The armistice signed on November 11, 1918, was merely the period finishing the death sentence of German militarism, the first word of which was uttered at Château-Thierry.

Germany’s defiance to the world, her determination to force her will and her “kultur” upon the democracies of earth, produced the conflict. She called to her aid three sister autocracies: Turkey, a land ruled by the whims of a long line of moody misanthropic monarchs; Bulgaria, the traitor nation cast by its Teutonic king into a war in which its people had no choice and little sympathy; Austria-Hungary, a congeries of races in which a Teutonic minority ruled with an iron scepter.

Against this phalanx of autocracy, twenty-four nations arrayed themselves. Populations of these twenty-eight warring nations far exceeded the total population of all the remainder[6] of humanity. The conflagration of war literally belted the earth. It consumed the most civilized of capitals. It raged in the swamps and forests of Africa. To its call came alien peoples speaking words that none but themselves could translate, wearing garments of exotic cut and hue amid the smart garbs and sober hues of modern civilization. A twentieth century Babel came to the fields of France for freedom’s sake, and there was born an internationalism making for the future understanding and peace of the world. The list of the twenty-eight nations entering the World War and their populations follow:

| Countries | Population |

| United States | 110,000,000 |

| Austria-Hungary | 50,000,000 |

| Belgium | 8,000,000 |

| Bulgaria | 5,000,000 |

| Brazil | 23,000,000 |

| China | 420,000,000 |

| Costa Rica | 425,000 |

| Cuba | 2,500,000 |

| France[A] | 90,000,000 |

| Guatemala | 2,000,000 |

| Germany | 67,000,000 |

| Great Britain[A] | 440,000,000 |

| Greece | 5,000,000 |

| Haiti | 2,000,000 |

| Honduras | 600,000 |

| Italy | 37,000,000 |

| Japan | 54,000,000 |

| Liberia | 2,000,000 |

| Montenegro | 500,000 |

| Nicaragua | 700,000 |

| Panama | 400,000 |

| Portugal[A] | 15,000,000 |

| Roumania | 7,500,000 |

| Russia | 180,000,000 |

| San Marino | 10,000 |

| Serbia | 4,500,000 |

| Siam | 6,000,000 |

| Turkey | 42,000,000 |

| —————— | |

| Total | 1,575,135,000 |

| [A] Including colonies. | |

[7]

The following nations, with their populations, took no part in the World War:

| Countries | Population |

| Abyssinia | 8,000,000 |

| Afghanistan | 6,000,000 |

| Andorra | 6,000 |

| Argentina | 8,000,000 |

| Bhutan | 250,000 |

| Chile | 5,000,000 |

| Colombia | 5,000,000 |

| Denmark | 3,000,000 |

| Ecuador | 1,500,000 |

| Mexico | 15,000,000 |

| Monaco | 20,000 |

| Nepal | 4,000,000 |

| Holland[B] | 40,000,000 |

| Norway | 2,500,000 |

| Paraguay | 800,000 |

| Persia | 9,000,000 |

| Peru | 3,400,000 |

| Salvador | 1,250,000 |

| Spain | 20,000,000 |

| Sweden | 5,500,000 |

| Switzerland | 3,750,000 |

| Uruguay | 1,100,000 |

| Venezuela | 2,800,000 |

| —————— | |

| Total | 145,876,000 |

| [B] Including colonies. | |

Never before in the history of the world were so many races and peoples mingled in a military effort as those that came together under the command of Marshal Foch. If we divide the human races into white, yellow, red and black, all four were largely represented. Among the white races there were Frenchmen, Italians, Portuguese, English, Scottish, Welsh, Irish, Canadians, Australians, South Africans (of both British and Dutch descent), New Zealanders; in the American army, probably every other European nation was represented, with additional contingents from those already[8] named, so that every branch of the white race figured in the ethnological total.

There were representatives of many Asiatic races, including not only the volunteers from the native states of India, but elements from the French colony in Cochin China, with Annam, Cambodia, Tonkin, Laos, and Kwang Chau Wan. England and France both contributed many African tribes, including Arabs from Algeria and Tunis, Senegalese, Saharans, and many of the South African races. The red races of North America were represented in the armies of both Canada and the United States, while the Maoris, Samoans, and other Polynesian races were likewise represented. And as, in the American Army, there were men of German, Austrian, and Hungarian descent, and, in all probability, contingents also of Bulgarian and Turkish blood, it may be said that Foch commanded an army representing the whole human race, united in defense of the ideals of the Allies.

[9]

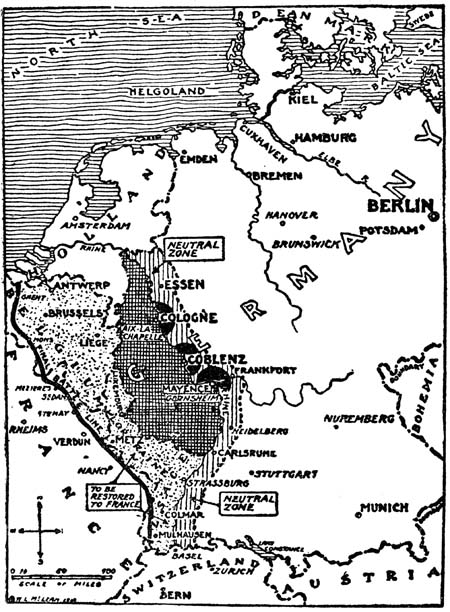

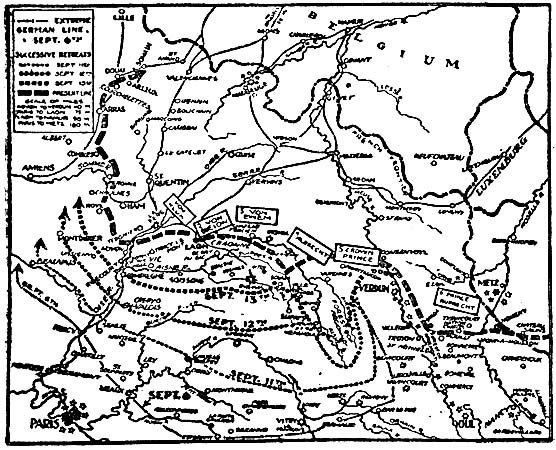

TERRITORIES OCCUPIED BY THE ALLIES UNDER THE ARMISTICE OF NOVEMBER 11, 1918

Dotted area, invaded territory of Belgium, France, Luxembourg and Alsace-Lorraine to be evacuated in fourteen days; area in small squares, part of Germany west of the Rhine to be evacuated in twenty-five days and occupied by Allied and U. S. troops; lightly shaded area to east of Rhine, neutral zone; black semi-circles, bridge-heads of thirty kilometers radius in the neutral zone to be occupied by Allied armies.

It will be seen that more than ten times the number of neutral persons were engulfed in[10] the maelstrom of war. Millions of these suffered from it during the entire period of the conflict, four years three months and fifteen days, a total of 1,567 days. For almost four years Germany rolled up a record of victories on land and of piracies on and under the seas.

Little by little, day after day, piracies dwindled as the murderous submarine was mastered and its menace strangled. On the land, the Allies, under the matchless leadership of Marshal Ferdinand Foch and the generous co-operation of Americans, British, French and Italians, under the great Generals Pershing, Haig, Pétain and Diaz, wrested the initiative from von Hindenburg and Ludendorf, late in July, 1918. Then, in one hundred and fifteen days of wonderful strategy and the fiercest fighting the world has ever witnessed, Foch and the Allies closed upon the Germanic armies the jaws of a steel trap. A series of brilliant maneuvers dating from the battle of Château-Thierry in which the Americans checked the Teutonic rush, resulted in the defeat and rout on all the fronts of the Teutonic commands.

[11]In that titanic effort, America’s share was that of the final deciding factor. A nation unjustly titled the “Dollar Nation,” believed by Germany and by other countries to be soft, selfish and wasteful, became over night hard as tempered steel, self-sacrificing with an altruism that inspired the world and thrifty beyond all precedent in order that not only its own armies but the armies of the Allies might be fed and munitioned.

Leading American thought and American action, President Wilson stood out as the prophet of the democracies of the world. Not only did he inspire America and the Allies to a military and naval effort beyond precedent, but he inspired the civilian populations of the world to extraordinary effort, efforts that eventually won the war. For the decision was gained quite as certainly on the wheat fields of Western America, in the shops and the mines and the homes of America as it was upon the battlefield.

This effort came in response to the following appeal by the President:

[12]These, then, are the things we must do, and do well, besides fighting—the things without which mere fighting would be fruitless:

We must supply abundant food for ourselves and for our armies, and our seamen not only, but also for a large part of the nations with whom we have now made common cause, in whose support and by whose sides we shall be fighting;

We must supply ships by the hundreds out of our shipyards to carry to the other side of the sea, submarines or no submarines, what will every day be needed there; and—

Abundant materials out of our fields and our mines and our factories with which not only to clothe and equip our own forces on land and sea but also to clothe and support our people for whom the gallant fellows under arms can no longer work, to help clothe and equip the armies with which we are co-operating in Europe, and to keep the looms and manufactories there in raw material;

Coal to keep the fires going in ships at sea and in the furnaces of hundreds of factories across the sea;

Steel out of which to make arms and ammunition both here and there;

Rails for worn-out railways back of the fighting fronts;

Locomotives and rolling stock to take the place of those every day going to pieces;

Everything with which the people of England and France and Italy and Russia have usually supplied themselves, but cannot now afford the men, the materials, or the machinery to make.

[13]I particularly appeal to the farmers of the South to plant abundant foodstuffs as well as cotton. They can show their patriotism in no better or more convincing way than by resisting the great temptation of the present price of cotton and helping, helping upon a large scale, to feed the nation and the peoples, everywhere who are fighting for their liberties and for our own. The variety of their crops will be the visible measure of their comprehension of their national duty.

The response was amazing in its enthusiastic and general compliance. No autocracy issuing a ukase could have been obeyed so explicitly. Not only did the various classes of workers and individuals observe the President’s suggestions to the letter, but they yielded up individual right after right in order that the war work of the government might be expedited. Extraordinary powers and functions were granted by the people through Congress, and it was not until peace was declared that these rights and powers returned to the people.

These governmental activities ceased functioning after the war:

Food administration;

Fuel administration;

Espionage act;

[14]War trade board;

Alien property custodian (with extension of time for certain duties);

Agricultural stimulation;

Housing construction (except for ship-builders);

Control of telegraphs and telephones;

Export control.

These functions were extended:

Control over railroads: to cease within twenty-one months after the proclamation of peace.

The War Finance Corporation: to cease to function six months after the war, with further time for liquidation.

The Capital Issues Committee: to terminate in six months after the peace proclamation.

The Aircraft Board: to end in six months after peace was proclaimed; and the government operation of ships, within five years after the war was officially ended.

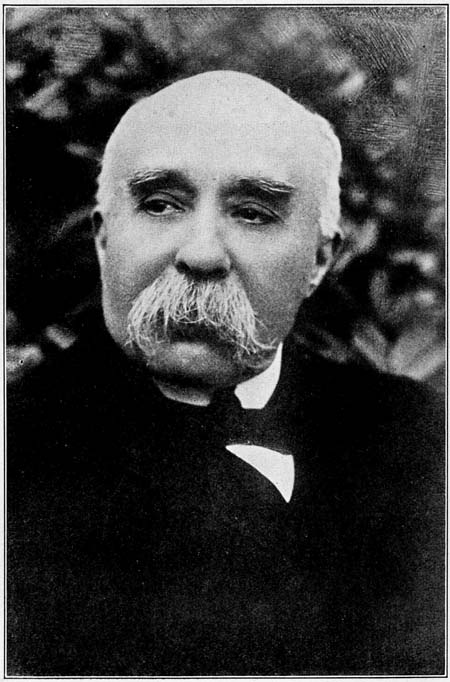

THE “TIGER OF FRANCE”

Georges Benjamin Eugene Clemenceau, world-famous Premier of France, who by his inspiring leadership maintained the magnificent morale of his countrymen in the face of the terrific assaults of the enemy.

[15]President Wilson, generally acclaimed as the leader of the world’s democracies, phrased for civilization the arguments against autocracy in the great peace conference after the war. The President headed the American delegation to that conclave of world re-construction. With him as delegates to the conference were Robert Lansing, Secretary of State; Henry White, former Ambassador to France and Italy; Edward M. House and General Tasker H. Bliss.

Representing American Labor at the International Labor conference held in Paris simultaneously with the Peace Conference were Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor; William Green, secretary-treasurer of the United Mine Workers of America; John R. Alpine, president of the Plumbers’ Union; James Duncan, president of the International Association of Granite Cutters; Frank Duffy, president of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners, and Frank Morrison, secretary of the American Federation of Labor.

[16]Estimating the share of each Allied nation in the great victory, mankind will conclude that the heaviest cost in proportion to pre-war population and treasure was paid by the nations that first felt the shock of war, Belgium, Serbia, Poland and France. All four were the battle-grounds of huge armies, oscillating in a bloody frenzy over once fertile fields and once prosperous towns.

Belgium, with a population of 8,000,000, had a casualty list of more than 350,000; France, with its casualties of 4,000,000 out of a population (including its colonies) of 90,000,000, is really the martyr nation of the world. Her gallant poilus showed the world how cheerfully men may die in defense of home and liberty. Huge Russia, including hapless Poland, had a casualty list of 7,000,000 out of its entire population of 180,000,000. The United States out of a population of 110,000,000 had a casualty list of 236,117 for nineteen months of war; of these 53,169 were killed or died of disease; 179,625 were wounded; and 3,323 prisoners or missing.

[17]To the glory of Great Britain must be recorded the enormous effort made by its people, showing through operations of its army and navy. The British Empire, including the Colonies, had a casualty list of 3,049,992 men out of a total population of 440,000,000. Of these 658,665 were killed; 2,032,122 were wounded, and 359,204 were reported missing. It raised an army of 7,000,000, and fought seven separate foreign campaigns, in France, Italy, Dardanelles, Mesopotamia, Macedonia, East Africa and Egypt. It raised its navy personnel from 115,000 to 450,000 men. Co-operating with its allies on the sea, it destroyed approximately one hundred and fifty German and Austrian submarines. It aided materially the American navy and transport service in sending overseas the great American army whose coming decided the war. The British navy and transport service during the war made the following record of transportation and convoy:

Twenty million men, 2,000,000 horses, 130,000,000 tons of food, 25,000,000 tons of explosives[18] and supplies, 51,000,000 tons of oil and fuels, 500,000 vehicles. In 1917 alone 7,000,000 men, 500,000 animals, 200,000 vehicles and 9,500,000 tons of stores were conveyed to the several war fronts.

The German losses were estimated at 1,588,000 killed or died of disease; 4,000,000 wounded; and over 750,000 prisoners and missing.

A tabulation of the estimates of casualties and the money cost of the war reveals the enormous price paid by humanity to convince a military-mad Germanic caste that Right and not Might must hereafter rule the world. These figures do not include Serbian losses, which are unavailable. Following is the tabulation:

| The Entente Allies | |

|---|---|

| Russia | 7,000,000 |

| France | 4,000,000 |

| British Empire (official) | 3,049,992 |

| Italy | 1,000,000 |

| Belgium | 350,000 |

| Roumania | 200,000 |

| United States (official) | 236,117 |

| ————— | |

| Total | 15,836,109 |

| The Central Powers | |

| Germany | 6,338,000 |

| Austria-Hungary | 4,500,000 |

| Turkey | 750,000 |

| Bulgaria | 200,000 |

| ————— | |

| Total | 11,788,000 |

[19]Grand total of estimated casualties, 27,624,109, of which the dead alone number perhaps 7,000,000.

| The Entente Allies | |

|---|---|

| Russia | $30,000,000,000 |

| Britain | 52,000,000,000 |

| France | 32,000,000,000 |

| United States | 40,000,000,000 |

| Italy | 12,000,000,000 |

| Roumania | 3,000,000,000 |

| Serbia | 3,000,000,000 |

| ———————— | |

| Total | $172,000,000,000 |

| The Central Powers | |

| Germany | $45,000,000,000 |

| Austria-Hungary | 25,000,000,000 |

| Turkey | 5,000,000,000 |

| Bulgaria | 2,000,000,000 |

| ———————— | |

| Total | $77,000,000,000 |

Grand total of estimated cost in money, $249,000,000,000.

Was the cost too heavy? Was the price of international liberty paid in human lives and in sacrifices untold too great for the peace that followed?

Even the most practical of money changers, the most sentimental pacifist, viewing the cost in connection with the liberation of whole nations, with the spread of enlightened liberty through oppressed and benighted lands, with the destruction of autocracy, of the military caste, and of Teutonic kultur in its materialistic aspect, must agree that the blood was well shed, the treasure well spent.

[20]Millions of gallant, eager youths learned how to die fearlessly and gloriously. They died to teach vandal nations that nevermore will humanity permit the exploitation of peoples for militaristic purposes.

As Milton, the great philosopher poet, phrased the lesson taught to Germany on the fields of France:

DEMORALIZATION, like the black plague of the middle ages, spread in every direction immediately following the first overt acts of war. Men who were millionaires at nightfall awoke the next morning to find themselves bankrupt through depreciation of their stock-holdings. Prosperous firms of importers were put out of business. International commerce was dislocated to an extent unprecedented in history.

The greatest of hardships immediately following the war, however, were visited upon those who unhappily were caught on their vacations or on their business trips within the area affected by the war. Not only men, but women and children, were subjected to privations of the severest character. Notes which[22] had been negotiable, paper money of every description, and even silver currency suddenly became of little value. Americans living in hotels and pensions facing this sudden shrinkage in their money, were compelled to leave the roofs that had sheltered them. That which was true of Americans was true of all other nationalities, so that every embassy and the office of every consul became a miniature Babel of excited, distressed humanity.

The sudden seizure of railroads for war purposes in Germany, France, Austria and Russia, cut off thousands of travelers in villages that were almost inaccessible. Europeans being comparatively close to their homes, were not in straits as severe as the Americans whose only hope for aid lay in the speedy arrival of American gold. Prices of food soared beyond all precedent and many of these hapless strangers went under. Paris, the brightest and gayest city in Europe, suddenly became the most sombre of dwelling places. No traffic was permitted on the highways at night. No lights were permitted and all the cafés were[23] closed at eight o’clock. The gay capital was placed under iron military rule.

Seaports, and especially the pleasure resorts in France, Belgium and England, were placed under a military supervision. Visitors were ordered to return to their homes and every resort was shrouded with darkness at night. The records of those early days are filled with stories of dramatic happenings.

On the night of July 31st Jean Leon Jaurès, the famous leader of French Socialists, was assassinated while dining in a small restaurant near the Paris Bourse. His assassin was Raoul Villein. Jaurès had been endeavoring to accomplish a union of French and German Socialists with the aim of preventing the war. The object of the assassination appeared to have been wholly political.

On the same day stock exchanges throughout the United States were closed, following the example of European stock exchanges. Ship insurance soared to prohibitive figures. Reservists of the French and German armies living outside of their native land were called[24] to the colors and their homeward rush still further complicated transportation for civilians. All the countries of Europe clamored for gold. North and South America complied with the demand by sending cargoes of the precious metal overseas. The German ship Kron Prinzessin with a cargo of gold, attempted to make the voyage to Hamburg, but a wireless warning that Allied cruisers were waiting for it off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, compelled the big ship to turn back to safety in America.

Channel boats bearing American refugees from the Continent to London were described as floating hells. London was excited over the war and holiday spirit, and overrun with five thousand citizens of the United States tearfully pleading with the American Ambassador for money for transportation home or assurances of personal safety.

[25]

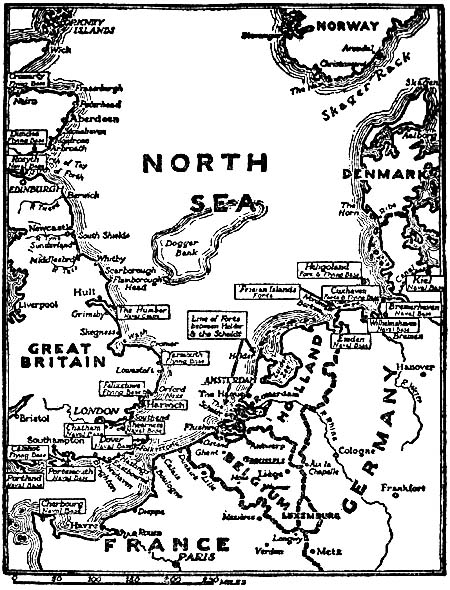

WHERE THE WORLD WAR BEGAN

The condition of the terror-stricken tourists fleeing to the friendly shores of England from Continental countries crowded with soldiers dragging in their wake heavy guns, resulted[26] in an extraordinary gathering of two thousand Americans at a hotel one afternoon and the formation of a preliminary organization to afford relief. Some people who attended the meeting were already beginning to feel the pinch of want with little prospects of immediate succor. One man and wife, with four children, had six cents when he appealed to Ambassador Page after an exciting escape from German territory.

Oscar Straus, worth ten millions, struck London with nine dollars. Although he had letters of credit for five thousand, he was unable to cash them in Vienna. Women hugging newspaper bundles containing expensive Paris frocks and millinery were herded in third-class carriages and compelled to stand many hours. They reached London utterly fatigued and unkempt, but mainly cheerful, only to find the hotels choked with fellow countrymen fortunate to reach there sooner.

The Ambassador was harassed by anxious women and children who asked many absurd questions which he could not answer. He said:

[27]“The appeals of these people are most distressing. They are very much excited, and no small wonder. I regret I have no definite news of the prospects or plans of the government for relief. I have communicated their condition to the Department of State and expect a response and assurances of coming aid as soon as possible. That the government will act I have not the slightest doubt. I am confident that Washington will do everything in her power for relief. How soon, I cannot tell. I have heard many distressing tales during the last forty-eight hours.”

A crowd filled the Ambassador’s office on the first floor of the flat building, in Victoria Street, which was mainly composed of women, school teachers, art students, and other persons doing Europe on a shoestring. Many were entirely out of money and with limited securities, which were not negotiable.

The action of the British Government extending the bank holiday till Thursday of that week was discouraging news for the new arrivals from the Continent, as it was uncertain[28] whether the express and steamship companies would open in the morning for the cashing of checks and the delivery of mail, as was announced the previous Saturday.

Doctors J. Riddle Goffe, of New York; Frank F. Simpson, of Pittsburgh; Arthur D. Ballon of Vistaburg, Mich., and B. F. Martin, of Chicago, formed themselves into a committee, and asked the co-operation of the press in America to bring about adequate assistance for the marooned Americans, and to urge the bankers of the United States to insist on their letters of credit and travelers’ checks being honored so far as possible by the agents in Europe upon whom they were drawn.

Dr. Martin and Dr. Simpson, who left London on Saturday for Switzerland to fetch back a young American girl, were unable to get beyond Paris, and they returned to London. Everywhere they found trains packed with refugees whose only object in life apparently was to reach the channel boats, accepting cheerfully the discomforts of those vessels if only able to get out of the war.

[29]Rev. J. P. Garfield, of Claremore, N. H., gave the following account of his experiences in Holland:

“On sailing from the Hook of Holland near midnight we pulled out just as the boat train from The Hague arrived. The steamer paused, but as she was filled to her capacity she later continued on her voyage, leaving fully two hundred persons marooned on the wharf.

“Our discomforts while crossing the North Sea were great. Every seat was filled with sleepers, the cabins were given to women and children. The crowd, as a rule, was helpful and kindly, the single men carrying the babies and people lending money to those without funds. Despite the refugee conditions prevailing it was noticeable that many women on the Hook wharf clung tenaciously to band boxes containing Parisian hats.”

Travelers from Cologne said that searchlights were operated from the tops of the hotels all night searching for airplanes, and machine guns were mounted on the famous Cologne Cathedral. They also reported that[30] tourists were refused hotel accommodations at Frankfort because they were without cash.

Men, women and children sat in the streets all night. The trains were stopped several miles from the German frontier and the passengers, especially the women and children, suffered great hardships being forced to continue their journey on foot.

Passengers arriving at London from Montreal on the Cunard Line steamer Andania, bound for Southampton, reported the vessel was met at sea by a British torpedo boat and ordered by wireless to stop. The liner then was led into Plymouth as a matter of precaution against mines. Plymouth was filled with soldiers, and searchlights were seen constantly flashing about the harbor.

Otis B. Kent, an attorney for the Interstate Commerce Commission, of Washington, arrived in London after an exciting journey from Petrograd. Unable to find accommodations at a hotel he slept on the railway station floor. He said:

“I had been on a trip to Sweden to see the[31] midnight sun. I did not realize the gravity of the situation until I saw the Russian fleet cleared for action. This was only July 26th, at Kronstadt, where the shipyards were working overtime.

“I arrived at the Russian capital on the following day. Enormous demonstrations were taking place. I was warned to get out and left on the night of the 28th for Berlin. I saw Russian soldiers drilling at the stations and artillery constantly on the move.

“At Berlin I was warned to keep off the streets for fear of being mistaken for an Englishman. At Hamburg the number of warnings was increased. Two Russians who refused to rise in a café when the German anthem was played were attacked and badly beaten. I also saw two Englishmen attacked in the street, but they finally were rescued by the police.

“There was a harrowing scene when the Hamburg-American Line steamer Imperator canceled its sailing. She left stranded three thousand passengers, most of them short of money, and the women wailing. About one[32] hundred and fifty of us were given passage in the second class of the American Line steamship Philadelphia, for which I was offered $400 by a speculator.

“The journey to Flushing was made in a packed train, its occupants lacking sleep and food. No trouble was encountered on the frontier.”

Theodore Hetzler, of the Fifth Avenue Bank, was appointed chairman of the meeting for preliminary relief of the stranded tourists, and committees were named to interview officials of the steamship companies and of the hotels, to search for lost baggage, to make arrangements for the honoring of all proper checks and notes, and to confer with the members of the American embassy.

Oscar Straus, who arrived from Paris, said that the United States embassy there was working hard to get Americans out of France. Great enthusiasm prevailed at the French capital, he said, owing to the announcement that the United States Government was considering[33] a plan to send transports to take Americans home.

The following committees were appointed at the meeting:

Finance—Theodore Hetzler, Fred I. Kent and James G. Cannon; Transportation—Joseph F. Day, Francis M. Weld and George D. Smith, all of New York; Diplomatic—Oscar S. Straus, Walter L. Fisher and James Byrne; Hotels—L. H. Armour, of Chicago, and Thomas J. Shanley, New York.

The committee established headquarters where Americans might register and obtain assistance. Chandler Anderson, a member of the International Claims Commission, arrived in London from Paris. He said he had been engaged with the work of the commission at Versailles, when he was warned by the American embassy that he had better leave France. He acted promptly on this advice and the commission was adjourned until after the war. Mr. Anderson had to leave his baggage behind him because the railway company would not[34] register it. He said the city of Paris presented a strange contrast to the ordinary animation prevailing there. Most of the shops were closed. There were no taxis in the streets, and only a few vehicles drawn by horses.

The armored cruiser Tennessee, converted for the time being into a treasure ship, left New York on the night of August 6th, 1914, to carry $7,500,000 in gold to the many thousand Americans who were in want in European countries. Included in the $7,500,000 was $2,500,000 appropriated by the government. Private consignments in gold in sums from $1,000 to $5,000 were accepted by Colonel Smith, of the army quartermaster’s department, who undertook their delivery to Americans in Paris and other European ports.

The cruiser carried as passengers Ambassador Willard, who returned to his post at Madrid, and army and naval officers assigned as military observers in Europe. On the return trip accommodations for 200 Americans were available.

The dreadnaught Florida, after being hastily[35] coaled and provisioned, left the Brooklyn Navy Yard under sealed orders at 9.30 o’clock the morning of August 6th and proceeded to Tompkinsville, where she dropped anchor near the Tennessee.

The Florida was sent to protect the neutrality of American ports and prohibit supplies to belligerent ships. Secretary Daniels ordered her to watch the port of New York and sent the Mayflower to Hampton Roads. Destroyers guarded ports along the New England coast and those at Lewes, Del., to prevent violations of neutrality at Philadelphia and in that territory. Any vessel that attempted to sail for a belligerent port without clearance papers was boarded by American officials.

The Texas and Louisiana, at Vera Cruz, and the Minnesota, at Tampico, were ordered to New York, and Secretary Daniels announced that other American vessels would be ordered north as fast as room could be found for them in navy yard docks.

At wireless stations, under the censorship ordered by the President, no code messages[36] were allowed in any circumstances. Messages which might help any of the belligerents in any way were barred.

The torpedo-boat destroyer Warrington and the revenue cutter Androscoggin arrived at Bar Harbor on August 6th, to enforce neutrality regulations and allowed no foreign ships to leave Frenchman’s Bay without clearance papers. The United States cruiser Milwaukee sailed the same day from the Puget Sound Navy Yard to form part of the coast patrol to enforce neutrality regulations.

Arrangements were made in Paris by Myron T. Herrick, the American Ambassador, acting under instructions from Washington, to take over the affairs of the German embassy, while Alexander H. Thackara, the American Consul General, looked after the affairs of the German consulate.

President Poincaré and the members of the French cabinet later issued a joint proclamation to the French nation in which was the phrase “mobilization is not war.”

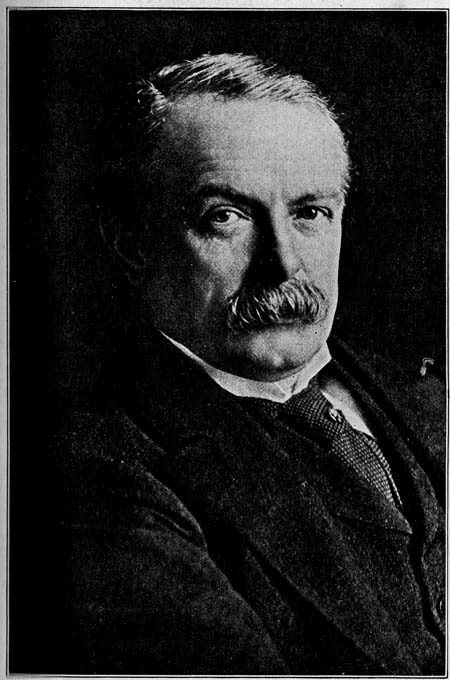

THE RIGHT HONORABLE DAVID LLOYD GEORGE

British Premier, who headed the coalition cabinet which carried England through the war to victory.

The marching of the soldiers in the streets[37] with the English, Russian and French flags flying, the singing of patriotic songs and the shouting of “On to Berlin!” were much less remarkable than the general demeanor and cold resolution of most of the people.

The response to the order of mobilization was instant, and the stations of all the railways, particularly those leading to the eastward, were crowded with reservists. Many women accompanied the men until close to the stations, where, softly crying, farewells were said. The troop trains left at frequent intervals. All the automobile busses disappeared, having been requisitioned by the army to carry meat, the coachwork of the vehicles being removed and replaced with specially designed bodies. A large number of taxicabs, private automobiles and horses and carts also were taken over by the military for transport purposes.

The wildest enthusiasm was manifested on the boulevards when the news of the ordering of the mobilization became known. Bodies of men formed into regular companies in ranks ten deep, paraded the streets waving the tri-color[38] and other national emblems and cheering and singing the “Marseillaise” and the “Internationale,” at the same time throwing their hats in the air. On the sidewalks were many weeping women and children. All the stores and cafés were deserted.

All foreigners were compelled to leave Paris or France before the end of the first day of mobilization by train but not by automobile. Time tables were posted on the walls of Paris giving the times of certain trains on which these people might leave the city.

American citizens or British subjects were allowed to remain in France, except in the regions on the eastern frontier and near certain fortresses, provided they made declaration to the police and obtained a special permit.

As to Italy’s situation, Rome was quite calm and the normal aspect made tourists decide that Italy was the safest place. Austria’s note to Serbia was issued without consulting Italy. One point of the Triple Alliance provided that no member should take action in the Balkans[39] before an agreement with the other allies. Such an agreement did not take place. The alliance was of defensive, not aggressive, character and could not force an ally to follow any enterprise taken on the sole account and without a notice, as such action taken by Austria against Serbia. It was felt even then that Italy would eventually cast its lot with the Entente Allies.

Secretary of the Treasury William G. McAdoo; John Skelton Williams, Comptroller of the Currency; Charles S. Hamblin and William P. G. Harding, members of the Federal Reserve Board, went to New York early in August, 1914, where they discussed relief measures with a group of leading bankers at what was regarded as the most momentous conference of the kind held in the country in recent years.

The New York Clearing House Committee, on August 2d, called a meeting of the Clearing House Association, to arrange for the immediate issuance of clearing house certificates.[40] Among those at the conference were J. P. Morgan and his partner, Henry P. Davison; Frank A. Vanderlip, president of the National City Bank, and A. Barton Hepburn, chairman of the Chase National Bank.

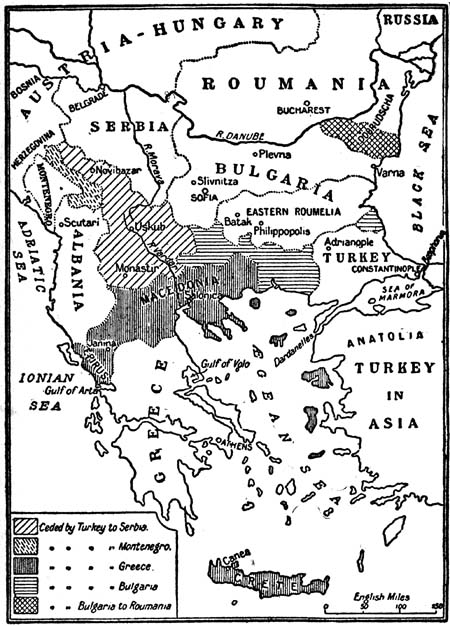

WHILE it is true that the war was conceived in Berlin, it is none the less true that it was born in the Balkans. It is necessary in order that we may view with correct perspective the background of the World War, that we gain some notion of the Balkan States and the complications entering into their relations. These countries have been the adopted children of the great European powers during generations of rulers. Russia assumed guardianship of the nations having a preponderance of Slavic blood; Roumania with its Latin consanguinities was close to France and Italy; Bulgaria, Greece, and Balkan Turkey were debatable regions wherein the diplomats of the rival nations secured temporary victories by devious methods.

[42]The Balkans have fierce hatreds and have been the site of sudden historic wars. At the time of the declaration of the World War, the Balkan nations were living under the provisions of the Treaty of Bucharest, dated August 10, 1913. Greece, Roumania, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro were signers, and Turkey acquiesced in its provisions.

The assassination at Sarajevo had sent a convulsive shudder throughout the Balkans. The reason lay in the century-old antagonism between the Slav and the Teuton. Serbia, Montenegro and Russia had never forgiven Austria for seizing Bosnia and Herzegovina and making these Slavic people subjects of the Austrian crown. Bulgaria, Roumania and Turkey remained cold at the news of the assassination. German diplomacy was in the ascendant at these courts and the prospect of war with Germany as their great ally presented no terrors for them. The sympathies of the people of Greece were with Serbia, but the Grecian Court, because the Queen of Greece was the only sister of the German Kaiser, was[43] whole heartedly with Austria. Perhaps at the first the Roumanians were most nearly neutral. They believed strongly that each of the small nations of the Balkan region as well as all of the small nations that had been absorbed but had not been digested by Austria, should cut itself from the leading strings held by the large European powers. There was a distinct undercurrent for a federation resembling that of the United States of America between these peoples. This was expressed most clearly by M. Jonesco, leader of the Liberal party of Roumania and generally recognized as the ablest statesman of middle Europe. He declared:

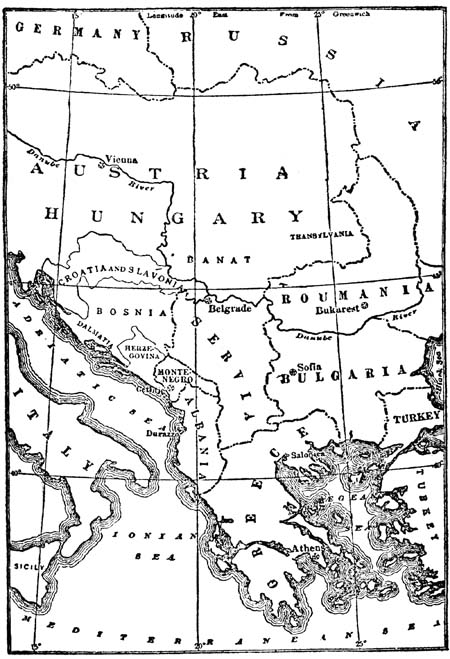

PROVISIONS OF THE TREATY OF BUCHAREST, 1913

[44]“I always believed, and still believe, that the Balkan States cannot secure their future otherwise than by a close understanding among themselves, whether this understanding shall or shall not take the form of a federation. No one of the Balkan States is strong enough to resist the pressure from one or another of the European powers.

© Underwood and Underwood, N. Y.

FRANCIS JOSEPH I OF AUSTRIA, THE “OLD EMPEROR,” ON A STATE OCCASION

Francis Joseph died before the war had settled the fate of the Hapsburgs. The end came on November 21, 1916, in the sixty-eighth year of his reign. His life was tragic. He lived to see his brother executed, his Queen assassinated, and his only son a suicide, with always before him the specter of the disintegration of his many-raced empire.

[45]“For this reason I am deeply grieved to see in the Balkan coalition of 1912 Roumania not invited. If Roumania had taken part in the first one, we should not have had the second. I did all that was in my power and succeeded in preventing the war between Roumania and the Balkan League in the winter of 1912-13.

“I risked my popularity, and I do not feel sorry for it. I employed all my efforts to prevent the second Balkan war, which, as is well known, was profitable to us. I repeatedly told the Bulgarians that they ought not to enter it because in that case we would enter it too. But I was not successful in my efforts.

“During the second Balkan war I did all in my power to end it as quickly as possible. At the conference at Bucharest I made efforts, as Mr. Pashich and Mr. Venizelos know very well, to secure for beaten Bulgaria the best terms. My object was to obtain a new coalition of all the Balkan States, including Roumania. Had I succeeded in this the situation would be much better. No reasonable man will deny that the Balkan States are neutralizing each other at the present time, which in[46] itself makes the whole situation all the more miserable.

“In October, 1913, when I succeeded in facilitating the conclusion of peace between Greece and Turkey, I was pursuing the same object of the Balkan coalition. On my return from Athens I endeavored, though without success, to put the Greco-Turkish relations on a basis of friendship, being convinced that the well-understood interest of both countries lies not only in friendly relations, but even in an alliance between them.

“The dissensions that exist between the Balkan States can be settled in a friendly way without war. The best moment for this would be after the general war, when the map of Europe will be remade. The Balkan country which would start war against another Balkan country would commit, not only a crime against her own future, but an act of folly as well.

“The destiny and future of the Balkan States, and of all the small European peoples as well, will not be regulated by fratricidal wars, but, with this great European struggle,[47] the real object of which is to settle the question whether Europe shall enter an era of justice, and therefore happiness for the small peoples, or whether we will face a period of oppression more or less gilt-edged. And as I always believed that wisdom and truth will triumph in the end, I want to believe, too, that, in spite of the pessimistic news reaching me from the different sides of the Balkan countries, there will be no war among them in order to justify those who do not believe in the vitality of the small peoples.”

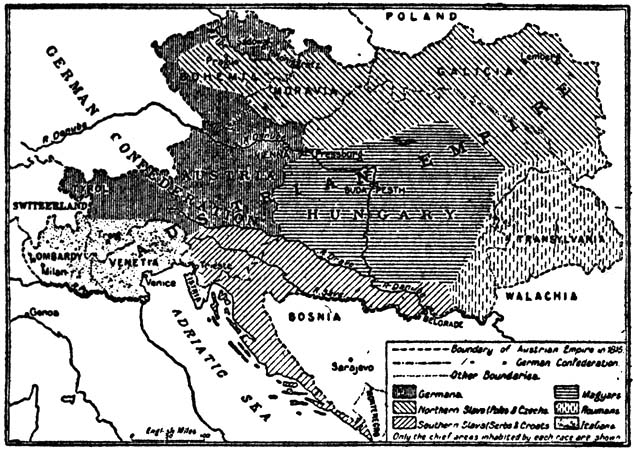

The conference at Rome, April 10, 1918, to settle outstanding questions between the Italians and the Slavs of the Adriatic, drew attention to those Slavonic peoples in Europe who were under non-Slavonic rule. At the beginning of the war there were three great Slavonic groups in Europe: First, the Russians with the Little Russians, speaking languages not more different than the dialect of Yorkshire is from the dialect of Devonshire; second, a central group, including the Poles, the Czechs or Bohemians, the Moravians, and[48] Slovaks, this group thus being separated under the four crowns of Russia, Germany, Austria and Hungary; the third, the southern group, included the Sclavonians, the Croatians, the Dalmatians, Bosnians, Herzegovinians, the Slavs, generally called Slovenes, in the western part of Austria, down to Gorizia, and also the two independent kingdoms of Montenegro and Serbia.

Like the central group, this southern group of Slavs was divided under four crowns, Hungary, Austria, Montenegro, and Serbia; but, in spite of the fact that half belong to the Western and half to the Eastern Church, they are all essentially the same people, though with considerable infusion of non-Slavonic blood, there being a good deal of Turkish blood in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The languages, however, are practically identical, formed largely of pure Slavonic materials, and, curiously, much more closely connected with the eastern Slav group—Russia and Little Russia—than with the central group, Polish and Bohemian. A Russian of Moscow will find it[49] much easier to understand a Slovene from Gorizia than a Pole from Warsaw. The Ruthenians, in southern Galicia and Bukowina, are identical in race and speech with the Little Russians of Ukrainia.

Of the central group, the Poles have generally inclined to Austria, which has always supported the Polish landlords of Galicia against the Ruthenian peasantry; while the Czechs have been not so much anti-Austrian as anti-German. Indeed, the Hapsburg rulers have again and again played these Slavs off against their German subjects. It was the Southern Slav question as affecting Serbia and Austria, that gave the pretext for the present war. The central Slav question affecting the destiny of the Poles—was a bone of contention between Austria and Germany. It is the custom to call the Southern Slavs “Jugoslavs” from the Slav word Yugo, “south,” but as this is a concession to German transliteration many prefer to write the word “Yugoslav,” which represents its pronunciation. The South Slav question was created by the incursions of three Asiatic[50] peoples—Huns, Magyars, Turks—who broke up the originally continuous Slav territory that ran from the White Sea to the confines of Greece and the Adriatic.

The Mixture of Races in South Central Europe

This was the complex of nationalities, the ferment of races existing in 1914. Out of the hatreds engendered by the domination over the liberty-loving Slavic peoples by an arrogant Teutonic minority grew the assassinations at Sarajevo. These crimes were the expression of hatred not for the heir apparent of[51] Austria but for the Hapsburgs and their Germanic associates.

By a twist of the wheel of fate, the same Slavic peoples whose determination to rid themselves of the Teutonic yoke, started the war, also bore rather more than their share in the swift-moving events that decided and closed the war.

Russia, the dying giant among the great nations, championed the Slavic peoples at the beginning of the war. It entered the conflict in aid of little Serbia, but at the end Russia bowed to Germany in the infamous peace treaty at Brest-Litovsk. Thereafter during the last months of the war Russia was virtually an ally of its ancient enemy, Turkey, the “Sick Man of Europe,” and the central German empires. With these allies the Bolshevik government of Russia attempted to head off the Czecho-Slovak regiments that had been captured by Russia during its drive into Austria and had been imprisoned in Siberia. After the peace consummated at Brest-Litovsk, these regiments determined to fight on the side of the[52] Allies and endeavored to make their way to the western front.

No war problems were more difficult than those of the Czecho-Slovaks. Few have been handled so masterfully. Surrounded by powerful enemies which for centuries have been bent on destroying every trace of Slavic culture, they had learned how to defend themselves against every trick or scheme of the brutal Germans.

The Czecho-Slovak plan in Russia was of great value to the Allies all over the world, and was put at their service by Professor Thomas G. Masaryk. He went to Russia when everything was adrift and got hold of Bohemian prisoners here and there and organized them into a compact little army of 50,000 to 60,000 men. Equipped and fed, he moved them to whatever point had most power to thoroughly disrupt the German plans. They did much to check the German army for months. They resolutely refused to take any part in Russian political affairs, and when it seemed no longer possible to work effectively in Russia, this remarkable[53] little band started on a journey all round the world to get to the western front. They loyally gave up most of their arms under agreement with Lenine and Trotzky that they might peacefully proceed out of Russia via Vladivostok.

While they were carrying out their part of the agreement, and well on the way, they were surprised by telegrams from Lenine and Trotzky to the Soviets in Siberia ordering them to take away their arms and intern them.

The story of what occurred then was told by two American engineers, Emerson and Hawkins, who, on the way to Ambassador Francis, and not being able to reach Bologda, joined a band of four or five thousand. The engineers were with them three months, while they were making it safe along the lines of the railroad for the rest of the Czecho-Slovaks to get out, and incidentally for Siberians to resume peaceful occupations. They were also supported by old railway organizations which had stuck bravely to them without wages and which every little while were “shot up” by the Bolsheviki.

[54]Distress in Russia would have been much more intense had it not been for the loyalty of the railway men in sticking to their tasks. Some American engineers at Irkutsk, on a peaceful journey, out of Russia, on descending from the cars were met with a demand to surrender, and shots from machine guns. Some, fortunately, had kept hand grenades, and with these and a few rifles went straight at the machine guns. Although outnumbered, the attackers took the guns and soon afterward took the town. The Czecho-Slovaks, in the beginning almost unarmed, went against great odds and won for themselves the right to be considered a nation.

Seeing the treachery of Lenine and Trotzky, they went back toward the west and made things secure for their men left behind. They took town after town with the arms they first took away from the Bolsheviki and Germans; but in every town they immediately set up a government, with all the elements of normal life. They established police and sanitary systems, opened hospitals, and had roads repaired,[55] leaving a handful of men in the midst of enemies to carry on the plans of their leaders. American engineers speaking of the cleanliness of the Czecho-Slovak army, said that they lived like Spartans.

The whole story is a remarkable evidence of the struggle of these little people for self-government.

The emergence of the Czecho-Slovak nation has been one of the most remarkable and noteworthy features of the war. Out of the confusion of the situation, with the possibility of the resurrection of oppressed peoples, something of the dignity of old Bohemia was comprehended, and it was recognized that the Czechs were to be rescued from Austria and the Slovaks from Hungary, and united in one country with entire independence. This was undoubtedly due, in large measure, to the activities of Professor Masaryk, the president of the National Executive Council of the Czecho-Slovaks. His four-year exile in the United States had the establishment of the new nation as its fruit.

[56]Professor Masaryk called attention to the fact that there is a peculiar discrepancy between the number of states in Europe and the number of nationalities—twenty-seven states to seventy nationalities. He explained, also, that almost all the states are mixed, from the point of nationality. From the west of Europe to the east, this is found to be true, and the farther east one goes the more mixed do the states become. Austria is the most mixed of all the states. There is no Austrian language, but there are nine languages, and six smaller nations or remnants of nations. In all of Germany there are eight nationalities besides the Germans, who have been independent, and who have their own literature. Turkey is an anomaly, a combination of various nations overthrown and kept down.

Since the eighteenth century there has been a continuing strong movement from each nation to have its own state. Because of the mixed peoples, there is much confusion. There are Roumanians in Austria, but there is a kingdom of Roumania. There are Southern Slavs,[57] but there are also Serbia and Montenegro. It is natural that the Southern Slavs should want to be united as one state. So it is with Italy.

There was no justice in Poland being separated in three parts to serve the dynasties of Prussia, Russia and Austria. The Czecho-Slovaks of Austria and Hungary claimed a union. The national union consists in an endeavor to make the suppressed nations free, to unite them in their own states, and to readjust the states that exist; to force Austria and Prussia to give up the states that should be free.

In the future, said Doctor Masaryk, there are to be sharp ethnological boundaries. The Czecho-Slovaks will guarantee the minorities absolute equality, but they will keep the German part of their country, because there are many Bohemians in it, and they do not trust the Germans.

ONE factor alone caused the great war. It was not the assassination at Sarajevo, not the Slavic ferment of anti-Teutonism in Austria and the Balkans. The only cause of the world’s greatest war was the determination of the German High Command and the powerful circle surrounding it that “Der Tag” had arrived. The assassination at Sarajevo was only the peg for the pendant of war. Another peg would have been found inevitably had not the projection of that assassination presented itself as the excuse.

Germany’s military machine was ready. A gray-green uniform that at a distance would fade into misty obscurity had been devised after exhaustive experiments by optical, dye and cloth experts co-operating with the military high command. These uniforms had been[59] standardized and fitted for the millions of men enrolled in Germany’s regular and reserve armies. Rifles, great pyramids of munitions, field kitchens, traveling post-offices, motor lorries, a network of military railways leading to the French and Belgian border, all these and more had been made ready. German soldiers had received instructions which enabled each man at a signal to go to an appointed place where he found everything in readiness for his long forced marches into the territory of Germany’s neighbors.

More than all this, Germany’s spy system, the most elaborate and unscrupulous in the history of mankind, had enabled the German High Command to construct in advance of the declaration of war concrete gun emplacements in Belgium and other invaded territory. The cellars of dwellings and shops rented or owned by German spies were camouflaged concrete foundations for the great guns of Austria and Germany. These emplacements were in exactly the right position for use against the fortresses of Germany’s foes. Advertisements[60] and shop-signs were used by spies as guides for the marching German armies of invasion.

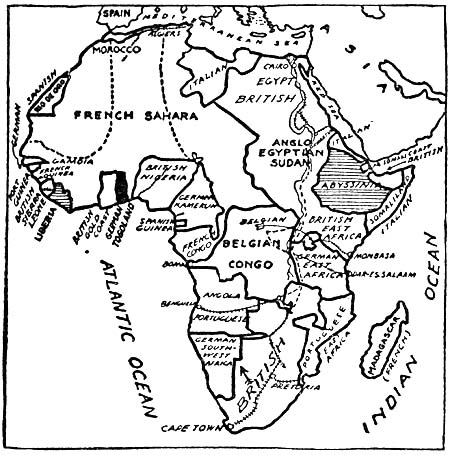

Germany’s Possessions in Africa Prior to 1914

In brief, Germany had planned for war. She was approximately ready for it. Under the shelter of such high-sounding phrases as “We demand our place in the sun,” and “The seas must be free,” the German people were[61] educated into the belief that the hour of Germany’s destiny was at hand.

German psychologists, like other German scientists, had co-operated with the imperial militaristic government for many years to bring the Germanic mind into a condition of docility. So well did they understand the mentality and the trends of character of the German people that it was comparatively easy to impose upon them a militaristic system and philosophy by which the individual yielded countless personal liberties for the alleged good of the state. Rigorous and compulsory military service, unquestioning adherence to the doctrine that might makes right and a cession to “the All-Highest,” as the Emperor was styled, of supreme powers in the state, are some of the sufferances to which the German people submitted.

German propaganda abroad was quite as vigorous as at home, but infinitely less successful. The German High Command did not expect England to enter the war. It counted upon America’s neutrality with a leaning toward[62] Germany. It believed that German colonization in South Africa and South America would incline these vast domains toward friendship for the Central Empire. How mistaken the propagandists and psychologists were events have demonstrated.

It was this dream of world-domination by Teutonic kultur that supplied the motive leading to the world’s greatest war. Bosnia, an unwilling province of Austria-Hungary, at one time a province of Serbia and overwhelmingly Slavic in its population, had been seething for years with an anti-Teutonic ferment. The Teutonic court at Vienna, leading the minority Germanic party in Austria-Hungary, had been endeavoring to allay the agitation among the Bosnian Slavs. In pursuance of that policy, Archduke Francis Ferdinand, heir-presumptive to the thrones of Austria and Hungary, and his morganatic wife, Sophia Chotek, Duchess of Hohenberg, on June 28, 1914, visited Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia. On the morning of that day, while they were being driven through the narrow streets of the ancient[63] town, a bomb was thrown at them, but they were uninjured. They were driven through the streets again in the afternoon, for purpose of public display. A student, just out of his ’teens, one Gavrilo Prinzep, attacked the royal party with a magazine pistol and killed both the Archduke and his wife.

Here was the excuse for which Germany had waited. Here was the dawn of “The Day.” The Germanic court of Austria asserted that the crime was the result of a conspiracy, leading directly to the Slavic court of Serbia. The Serbians in their turn declared that they knew nothing of the assassination. They pointed out the fact that Sophia Chotek was a Slav, and that Francis Ferdinand was more liberal than any other member of the Austrian royal household, and finally, that he, more than any other member of the Austrian court, understood and respected the Slavic character and aspirations.

At six o’clock on the evening of July 23d, Austria sent an ultimatum to Serbia, presenting eleven demands and stipulating that categorical replies must be delivered before six[64] o’clock on the evening of July 25th. Although the language in which the ultimatum was couched was humiliating to Serbia, the answer was duly delivered within the stipulated time.

The demands of the Austrian note in brief were as follows:

1. The Serbian Government to give formal assurance of its condemnation of Serb propaganda against Austria.

2. The next issue of the Serbian “Official Journal” was to contain a declaration to that effect.

3. This declaration to express regret that Serbian officers had taken part in the propaganda.

4. The Serbian Government to promise that it would proceed rigorously against all guilty of such activity.

5. This declaration to be at once communicated by the King of Serbia to his army, and to be published in the official bulletin as an order of the day.

6. All anti-Austrian publications in Serbia to be suppressed.

7. The Serbian political party known as the “National Union” to be suppressed, and its means of propaganda to be confiscated.

8. All anti-Austrian teaching in the schools of Serbia to be suppressed.

9. All officers, civil and military, who might be designated by Austria as guilty of anti-Austrian propaganda to be dismissed by the Serbian Government.

10. Austrian agents to co-operate with the Serbian[65] Government in suppressing all anti-Austrian propaganda, and to take part in the judicial proceedings conducted in Serbia against those charged with complicity in the crime at Sarajevo.

11. Serbia to explain to Austria the meaning of anti-Austrian utterances of Serbian officials at home and abroad, since the assassination.

To the first and second demands Serbia unhesitatingly assented.

To the third demand, Serbia assented, although no evidence was given to show that Serbian officers had taken part in the propaganda.

The Serbian Government assented to the fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh and eighth demands also.

Extraordinary as was the ninth demand, which would allow the Austrian Government to proscribe Serbian officials, so eager for peace and friendship was the Serbian Government that it assented to it, with the stipulation that the Austrian Government should offer some proof of the guilt of the proscribed officers.

The tenth demand, which in effect allowed Austrian agents to control the police and courts of Serbia, it was not possible for Serbia[66] to accept without abrogating her sovereignty. However, it was not unconditionally rejected, but the Serbian Government asked that it be made the subject of further discussion, or be referred to arbitration.

The Serbian Government assented to the eleventh demand, on the condition that if the explanations which would be given concerning the alleged anti-Austrian utterances of Serbian officials would not prove satisfactory to the Austrian Government, the matter should be submitted to mediation or arbitration.

Behind the threat conveyed in the Austrian ultimatum was the menacing figure of militant Germany. The veil that had hitherto concealed the hands that worked the string, was removed when Germany, under the pretense of localizing the quarrel to Serbian and Austrian soil, interrogated France and England, asking them to prevent Russia from defending Serbia in the event of an attack by Austria upon the Serbs. England and France promptly refused to participate in a tragedy which would deliver Serbia to Austria as Bosnia[67] had been delivered. Russia, bound by race and creed to Serbia, read into the ultimatum of Teutonic kultur a determination for warfare. Mobilization of the Russian forces along the Austrian frontier was arranged, when it was seen that Serbia’s pacific reply to Austria’s demands would be contemptuously disregarded by Germany and Austria.

During the days that intervened between the issuance of the ultimatum and the actual declaration of war by Germany against Russia on Saturday, August 1st, various sincere efforts were made to stave off the world-shaking catastrophe. Arranged chronologically, these events may thus be summarized: Russia, on July 24th, formally asked Austria if she intended to annex Serbian territory by way of reprisal for the assassination at Sarajevo. On the same day Austria replied that it had no present intention to make such annexation. Russia then requested an extension of the forty-eight-hour time limit named in the ultimatum.

Austria, on the morning of Saturday, July[68] 25th, refused Russia’s request for an extension of the period named in the ultimatum. On the same day, the newspapers published in Petrograd printed an official note issued by the Russian Government warning Europe generally that Russia would not remain indifferent to the fate of Serbia. These newspapers also printed the appeal of the Serbian Crown Prince to the Czar dated on the preceding day, urging that Russia come to the rescue of the menaced Serbs. Serbia’s peaceful reply surrendering on all points except one, and agreeing to submit that to arbitration, was sent late in the afternoon of the same day, and that night Austria declared the reply to be unsatisfactory and withdrew its minister from Belgrade.

England commenced its attempts at pacification on the following day, Sunday, July 26th. Sir Edward Grey spent the entire Sabbath in the Foreign Office and personally conducted the correspondence that was calculated to bring the dispute to a peaceful conclusion. He did not reckon, however, with a Germany determined upon war, a Germany whose manufacturers,[69] ship-owners and Junkers had combined with its militarists to achieve “Germany’s place in the sun” even though the world would be stained in the blood of the most frightful war this earth has ever known. Realization of this fact did not come to Sir Edward Grey until his negotiations with Germany and with Austria-Hungary had proceeded for some time. His first suggestion was that the dispute between Russia and Austria be committed to the arbitration of Great Britain, France, Italy and Germany. Russia accepted this but Germany and Austria rejected it. Russia had previously suggested that the dispute be settled by a conference between the diplomatic heads at Vienna and Petrograd. This also was refused by Austria.

Sir Edward Grey renewed his efforts on Monday, July 27th, with an invitation to Germany to present suggestions of its own, looking toward a settlement. This note was never answered. Germany took the position that its proposition to compel Russia to stand aside while Austria punished Serbia had been rejected[70] by England and France and it had nothing further to propose.

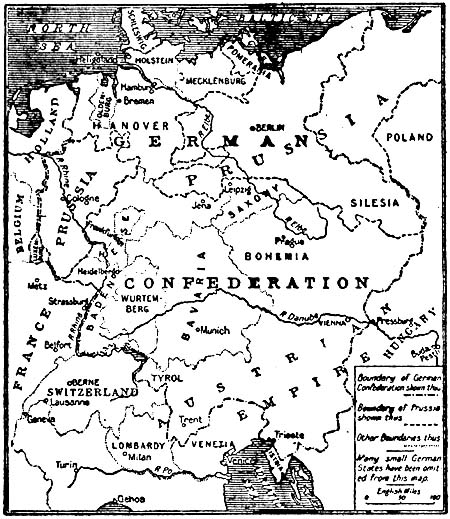

The German Confederation in 1815

During all this period of negotiation the German Foreign Office, to all outward appearances at least, had been acting independently[71] of the Kaiser, who was in Norway on a vacation trip. He returned to Potsdam on the night of Sunday, July 26th. On Monday morning the Czar of Russia received a personal message from the Kaiser, urging Russia to stand aside that Serbia might be punished. The Czar immediately replied with the suggestion that the whole matter be submitted to The Hague. No reply of any kind was ever made to this proposal by Germany.

All suggestions and negotiations looking forward to peace were brought to a tragic end on the following day, Tuesday, July 28th, when Austria declared war on Serbia, having speedily mobilized troops at strategic points on the Serbian border. Russian mobilization, which had been proceeding only in a tentative way, on the Austrian border, now became general, and on July 30th, mobilization of the entire Russian army was proclaimed.

Germany’s effort to exclude England from the war began on Thursday, July 30th. A note, sounding Sir Edward Grey on the question of British neutrality in the event of war[72] was received, and a curt refusal to commit the British Empire to such a proposal was the reply. Sir Edward Grey, in a last determined effort to avoid a world war, suggested to Germany, Austria, Serbia and Russia that the military operations commenced by Austria should be recognized as merely a punitive expedition. He further suggested that when a point in Serbian territory previously fixed upon should have been reached, Austria would halt and would submit her further action to arbitration in the conference of the Powers. Russia agreed unreservedly to this proposition. Austria gave a half-hearted assent to the principle involved. Germany made no reply.

The die was cast for war on the following day, July 31st, when Germany made a dictatorial and arrogant demand upon Russia that mobilization of that nation’s military forces be stopped within twelve hours. Russia made no reply, and on Saturday, August 1st, Germany set the world aflame with the dread of war’s horror by her declaration of war upon Russia.

Germany’s responsibility for this monumental[73] crime against the peace of the world is eternally fixed upon her, not only by these outward and visible acts and negotiations, not only by her years of patient preparation for the war into which she plunged the world. The responsibility is fastened upon her forever by the revelations of her own ambassador to England during this fateful period. Prince Lichnowsky, in a remarkable communication which was given to the world, laid bare the machinations of the German High Command and its advisers. He was a guest of the Kaiser at Kiel on board the Imperial yacht Meteor when the message was received informing the Kaiser of the assassination at Sarajevo. His story continues.

Being unacquainted with the Vienna viewpoint and what was going on there, I attached no very far-reaching significance to the event; but, looking back, I could feel sure that in the Austrian aristocracy a feeling of relief outweighed all others. His Majesty regretted that his efforts to win over the Archduke to his ideas had thus been frustrated by the Archduke’s assassination....