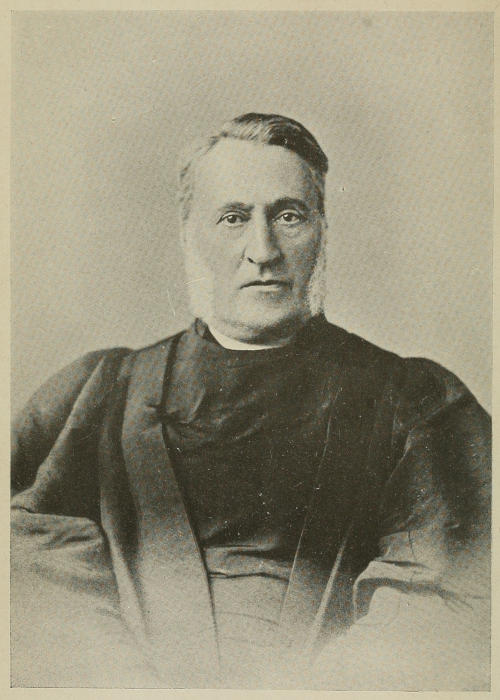

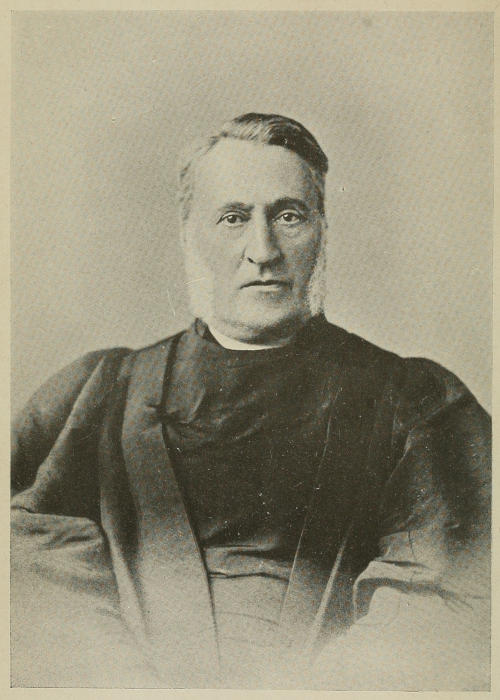

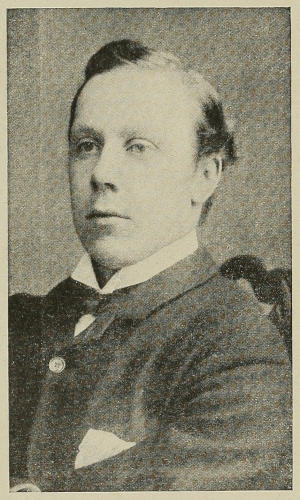

The Rev. D. Hornby, Provost of Eton.

[Frontispiece.

Title: Memories of an Old Etonian, 1860-1912

Author: G. Greville Moore

Release date: April 13, 2025 [eBook #75853]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Hutchinson & Co, 1919

Credits: MWS and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

The Rev. D. Hornby, Provost of Eton.

[Frontispiece.

Memories of an Old

Etonian :: 1860-1912

By George Greville :: Author of “Society Recollections

in Paris and Vienna” and “More Society Recollections.”

WITH 22 ILLUSTRATIONS

ON ART PAPER

LONDON: HUTCHINSON & CO.

:: :: PATERNOSTER ROW :: ::

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | 1 |

| Early Recollections—Thackeray—The Princess Liegnitz—The Austrian Bandmaster—Society at Homburg—Frankfurt—Goethe and Beethoven—A Racing Coincidence | |

| CHAPTER II. | 18 |

| An Adventure in the Oden Wald—The Coiners of the Black Forest—Kirchhofer’s School | |

| CHAPTER III. | 27 |

| Brussels—Ostend—General Sir John Douglas—Spa—“Captain Arthy”—Boulogne | |

| CHAPTER IV. | 40 |

| A Painting by Romney—Hunter’s School at Kineton—Corporal Punishment—A Sporting Parson—My Schoolfellows at Kineton—The Warre-Malets—Lord Charleville | |

| CHAPTER V. | 54 |

| My Mother’s Recollections—The Cercle des Patineurs—Patti—Our Appartement in the Rue d’Albe | |

| CHAPTER VI. | 63 |

| I go to Eton—New Boy Baiting—My House Master—Mr. James’s “Jokes”—My Room at Eton—Some Eton Masters—A Disorderly Form—Lacaita’s Silk Hat—“Billy” Portman[viii] | |

| CHAPTER VII. | 80 |

| An Amusing Incident—Lady Caroline Murray—An Anecdote of Queen Victoria—Lord Rossmore’s Wager—The Match at the Wall—Practical Jokes—Some Boys at James’s | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | 94 |

| Athletic Sports at Eton—A “Scrap”—Lord Newlands—An Old Boy on Eton of To-day | |

| CHAPTER IX. | 103 |

| Lady Grace Stopford—Tipperary in 1870—Robbed at Punchestown Races—I get my own back | |

| CHAPTER X. | 110 |

| Dieppe under Prussian Rule—A Toilette by Worth—A Confirmed Gambler | |

| CHAPTER XI. | 116 |

| The Princess von Metternich—The Lady of the Luxembourg Gardens | |

| CHAPTER XII. | 123 |

| Bonn—An Anecdote of Beethoven—The King’s Hussars—The Howard Vyses—A German Professor on England—Domesticated Habits of German Girls—Professor Delbrück | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | 136 |

| The Countess Czerwinska—The Countess Broel Plater—Mlle. de Laval—The Duchesse de Grammont—An Absent-Minded Gentleman—Dusauty, the Fencing Master—The Marquis of Anglesey—Charming Venezuelans—Miss Fanny Parnell | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | 155 |

| Captain Howard Vyse—An Anecdote of Paganini—New Hats for Old Ones—Albert Bingham—Baron Alphonse de Rothschild—Madame Alice Kernave—Gambetta | |

| CHAPTER XV. | 168 |

| My First Night at Mess—Life at Shorncliffe—The Charltons[ix] | |

| CHAPTER XVI. | 175 |

| An N.C.O. of the Old School—Major Blewett—Captain Byron—Sandhurst | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | 183 |

| I sail for India—Kandy—Dangerous Playmates—I arrive at Murree | |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | 190 |

| My Brother-Officers—“The Oyster”—In High Society—Our Menagerie | |

| CHAPTER XIX. | 198 |

| A Subalterns’ Court-Martial—A Terrible Experience—High Mess-bills | |

| CHAPTER XX. | 205 |

| Sialkote—Amateur Theatricals—An Ingenious Thief—Death of Albert Phipps—Agra—Voyage to England | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | 217 |

| Baroness James Édouard de Rothschild—At Carlsbad—Transferred to the 3rd Battalion | |

| CHAPTER XXII. | 222 |

| My Brother-Officers—A Mésalliance—Christy Minstrels and Tobogganing | |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | 229 |

| Sarah Bernhardt in Phèdre—Vienna and Buda-Pesth | |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | 233 |

| Percy Hope-Johnstone—A “Special” to Aldershot—A Costume-Ball at Folkestone | |

| CHAPTER XXV. | 238 |

| The Oppenheims—St. James’s and Winchester—The Colonel and Beauclerk | |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | 244 |

| Paris Again—Eccentricities of Captain “Rabelais”—A Fire in Barracks—A Trying Inspection[x] | |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | 252 |

| Madrid and Cordova—Seville—General von Goeben and the Bull-fight—A View from the Alhambra—I rejoin my Regiment | |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | 262 |

| I meet Byron Again—I endeavour to Exchange—Basil Montgomery—My Illness—Why I was not Placed on Half-pay |

| PAGE | ||

| The Rev. D. Hornby, Provost of Eton | Frontispiece | |

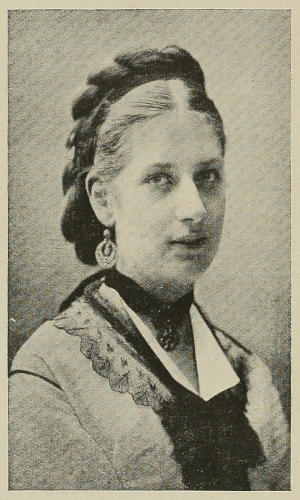

| Mrs. Ronalds | Facing p. | 2 |

| Mrs. R. C. Kemys-Tynte, of Halswell (now Mrs. Rawlins, mother of Lord Wharton) | ” | 3 |

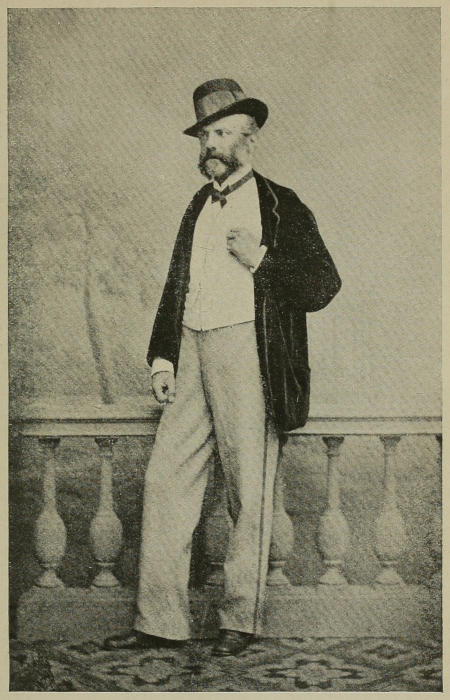

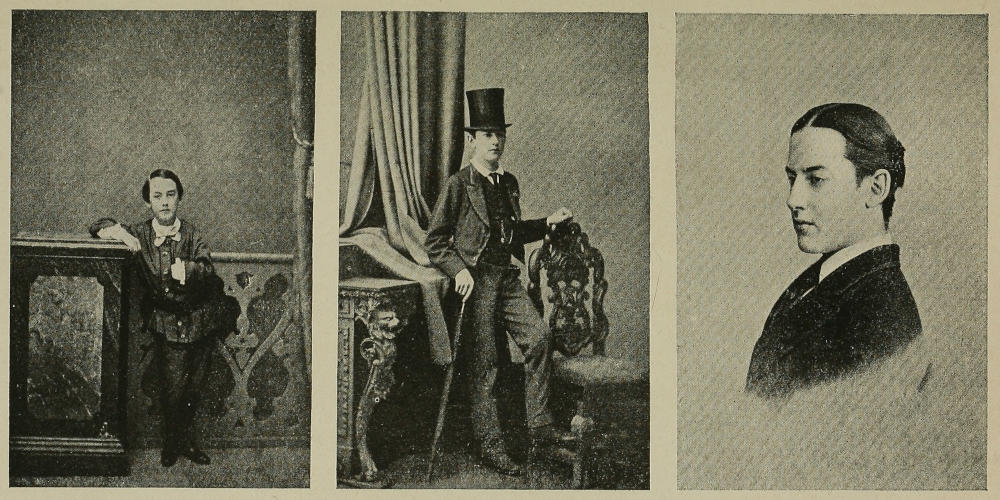

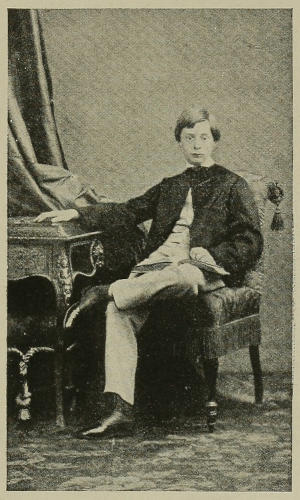

| The Author’s Father | ” | 6 |

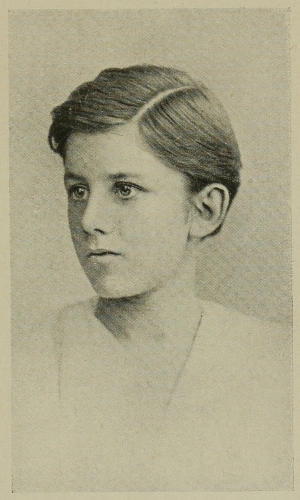

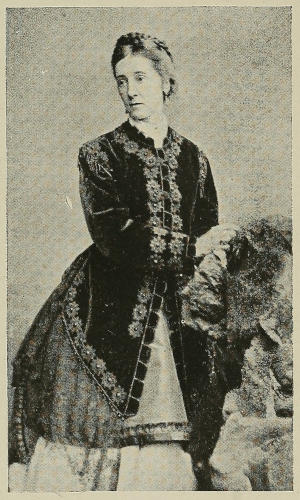

| The Author’s Mother | ” | 12 |

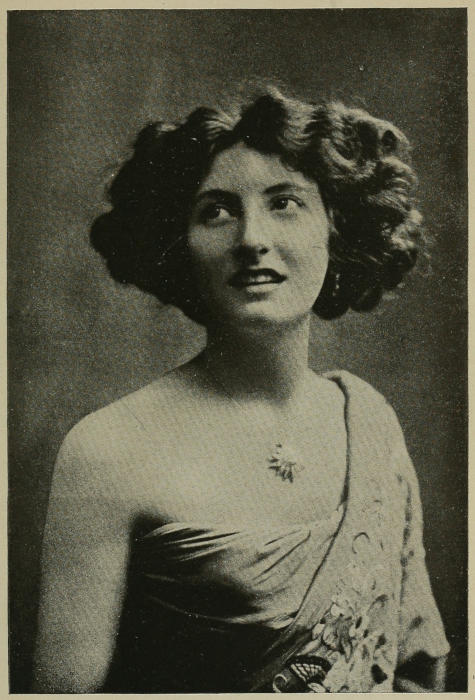

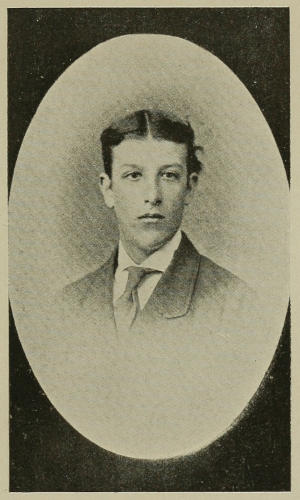

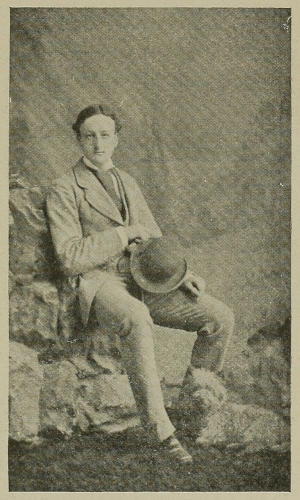

| The Author’s Daughter | ” | 20 |

| The Author’s Mother | ” | 40 |

| C. D. Williamson, at Eton with the Author | ” | 50 |

| Miss Mabel Warre-Malet | ” | 51 |

| The Author | ” | 62 |

| Charles Balfour, at Eton with the Author | ” | 80 |

| Miss Minnie Balfour, sister of Hilda, Lady de Clifford | ” | 81 |

| W. H. Onslow, aged 13, afterwards Lord Onslow | ” | 82 |

| The Hon. Emily Cathcart, Maid of Honour to Queen Victoria | ” | 83 |

| Henry Hooker Walker, at Eton with the Author | ” | 90 |

| The Hon. J. W. Lowther, present Speaker of the House of Commons | ” | 91 |

| The Duke of Rutland | ” | 98 |

| The Author’s Father | ” | 144 |

| Madame Alice Kernave | ” | 164 |

| The late Earl of Berkeley | ” | 165 |

| Miss Augusta Charlton | ” | 172 |

| Miss Ida Charlton | ” | 173 |

Early Recollections—Thackeray—The Princess Liegnitz—The Austrian Bandmaster—Society at Homburg—Frankfurt—Goethe and Beethoven—A Racing Coincidence

It happened so long ago, and I was so very young at the time—not more than five or six years old—that I should be almost tempted to believe that it was all a dream, were it not for certain incidents which made an unforgettable impression upon my childish imagination. The scene was the Hôtel de Russie at Frankfurt-on-the-Main; the occasion the birthday of King William I. of Prussia, afterwards Emperor of Germany. The spacious grand staircase of the hôtel was brilliantly lighted, and a red velvet carpet was laid down on the steps leading to the first floor. Up these steps came a succession of Ministers and generals, some in scarlet and gold lace, with the attila, heavily embroidered with gold lace and edged with brown fur, falling loosely over the left shoulder. Whenever an Austrian general, in his white uniform with scarlet facings and red trousers with deep gold lace stripe down the side, appeared, my heart, for some unknown reason, seemed to beat with delight. How I came to be there I don’t quite know, but I can remember my surprise when I saw the big chandelier which hung over the staircase being lighted in broad daylight, and the red blinds near the entrance being drawn down, which gave me a curious[2] impression, making me feel almost as though I were present at a funeral. It was, however, merely done to create a more imposing effect.

A great silence pervaded the whole of the Hôtel de Russie; no one but royal servants stood by the front door; and the only sound which I can recollect was the clinking of the sword worn by a general in full uniform as he mounted the red-carpeted stairs. On approaching a door on the first floor, the general or Minister gave his name in a mysterious whisper, when, after a few seconds, the door was opened, and I heard a kind of buzzing noise, as of several persons talking at once in low tones. Then I can remember that, after a long interval, which seemed hours to me, the mysterious folding-doors were thrown wide open, and a veritable kaleidoscope of colour presented itself to my wondering eyes. It was the effect of the various uniforms worn by the Ministers and generals, as they emerged en masse from the room and began to descend the staircase, talking loudly as they passed.

Soon afterwards, when they had all taken their departure, the brilliant lights were lowered, and silence again descended on the hôtel. That is all I can remember, and of what became of me afterwards I have no recollection. That afternoon remains in my memory like a fairy-tale, and so comical did it appear to me, that I have often thought of it since. There was something so mysterious about the way each Minister and general entered that door after whispering his name; and then the buzz of conversation, which was distinctly audible during the few seconds the door stood open, to be succeeded by an almost death-like silence.

Mrs. Ronalds.

[To face p. 2.

Mrs. R. C. Kemys-Tynte, of Halswell (now Mrs. Rawlins, mother of Lord Wharton).

[To face p. 3.

I can remember, just about this time, being alone in an immense salon with six windows, all of which overlooked the Zeil, one of the principal streets in Frankfurt. At either extremity of this room stood a big stove of white porcelain, and its walls were decorated with large pictures. One of these pictures represented the capture of Troy. The town was in flames, and a huge, grey wooden horse stood in the[3] foreground, with a hole in its side from which soldiers were emerging and descending a ladder supported against the horse’s flank. This was one of my favourite pictures in the room. Another represented the Cyclopes, with their one eye in the centre of their forehead, engaged in heating an iron bar in a furnace. I remember that I used frequently to contemplate this picture and wonder what it all meant, and if the Cyclopes really existed and where they lived. At night, it used rather to frighten me, particularly when I was left alone in the room, which frequently happened at this time. Another picture represented Venus, with Cupid aiming one of his arrows at her. This rather pleased me. I did not know then the mischief wrought by Cupid’s arrows, and, in my innocence, was simple enough to believe that Venus was an angel of love; and I pitied her for being struck by one of Cupid’s arrows, which, in another picture in the room, had penetrated her bosom, causing a stream of blood to trickle down the alabaster whiteness of her body. The room had two large chandeliers, but when I was alone in it, only one of them was lighted.

I can remember once, during the daytime, while looking out of the window, I saw some Prussian Hussars, in their dark-blue uniforms trimmed with silver lace, riding past. One of the horses shied at something, and its rider fell heavily, which caused a great crowd to assemble. I don’t know what happened afterwards; it was just one of those things that I saw as though in a dream.

I recollect on one occasion occupying the bedroom and sleeping in the bed used by the King of Prussia when he visited Frankfurt. This room was very gorgeously furnished, the walls being draped with dark-blue satin, while the bed had a canopy surrounded by heavy curtains of blue silk.

So far as I can remember, it must have been some months after this that I spent an evening in the room where the King of Prussia’s birthday-fête had been held. It was then occupied by the late Mrs. Ronalds, a lovely woman, quite young, with the most glorious smile one could possibly[4] imagine and most beautiful teeth. Her face was perfectly divine in its loveliness; her features small and exquisitely regular. Her hair was of a dark shade of brown—châtain foncé—and very abundant. I was in Mrs. Ronalds’s care on this occasion, and I can still see her before me as she was then, and remember that she spoke with a slight American accent. The late Captain Frederick Dorrien, of the 1st Life Guards, an old Etonian and a very handsome man, whom Queen Victoria called “her handsome lieutenant,” after inquiring his name when he rode beside her carriage one day in full uniform, came to pay Mrs. Ronalds a visit that evening; and I can still remember her singing in a very beautiful voice, which everyone praised enthusiastically, and also a tiny watch set in brilliants, and always very much admired, which she wore on her finger.

I used to be taken occasionally to the Zoological Gardens at Frankfurt, where a Prussian military band played on Sunday afternoons, and I took a fancy to what I thought was a large dog. I used to stroke it, and it often licked my hand after I had fed it with biscuits and seemed to know me. One day, however, to my surprise, I saw it put into the same cage as the wolves, and learned that it was a wolf, which had been placed for a time in a cage by itself. I still felt a great wish to stroke it, but was not allowed to do so.

Whether it was some months later or some months earlier than this I cannot say, for, with a child, such things as time and space are of no account, which brings a child nearer to the Divinity than grown-up people. I can only recall giving my hand, when at Homburg vor der Höhe, to what seemed to me an elderly gentleman, who often took me across the garden of the Kurhaus and up the steps of the Kursaal into the restaurant, where, seated at a buffet, was a stout, pleasant-looking old lady, who always greeted me affectionately and gave me, at the gentleman’s request, my favourite fruit, nectarines and amandes vertes. I can remember how kind this gentleman always was to me, taking me constantly for walks in the garden of the Kurhaus,[5] and always holding me by the hand. The name of the pleasant old lady was Madame Chevet, a Parisienne, to whom the restaurant at the Kurhaus belonged, and the gentleman, who was a great friend of my parents, was Thackeray, the author of “Vanity Fair.” I can remember nothing else about him, except that he appeared to be very devoted to me.[1]

I used to wear white frocks with lace and embroidery, some of which had been given to my mother for me by H.R.H. the Duchess of Gloucester, when my mother’s aunt, Lady Caroline Murray, was lady-in-waiting to Her Royal Highness.[2] I used at that time to be dressed like[6] a girl, with my hair in long, dark-brown ringlets, and on one occasion my mother took me up to a very plain English lady in the grounds of the Kursaal, when the latter exclaimed: “What a pretty boy? He is more like a girl!” Then, turning to me, she said: “My dear, will you allow me to kiss you?” “Yes,” I answered, and, holding up my bare arm, I added: “Kiss my elbow.” My mother tried to persuade me to allow the lady to kiss me, but I only cried and said: “Oh! not my face, only my elbow!”

One day, I remember, I was playing in the grounds of the Kursaal with a large india-rubber ball with two little girls, when a lady called them away, saying to the little girls, who were her daughters: “You must not play with a boy when you don’t know who he is.” That same evening, the Countess of Desart, who was lady-in-waiting to Queen Victoria, was dining at Madame Chevet’s restaurant at the Kurhaus with my parents, and, happening to hear of what had occurred to me in the morning, said to my mother: “I will pay that woman out for her insolence. She is a nobody, and only the wife of a Law lord.” When Lady C——, the mother of the two little girls, arrived for dinner at the Kurhaus, the countess purposely did not rise to enter the dining-room for a very long time, which annoyed Lady C—— immensely, as she dared not enter the dining-room until the countess had risen from her seat to do so. At dinner the countess said to Lady C: “I can understand how careful you have to be about whom your girls play with, as you don’t quite know how to discriminate between common children and others.” Lady C—— blushed crimson, but did not venture to make any reply.[3][7] The Countess of Desart maintained quite a princely establishment at Homburg, having a French chef at her villa and a number of English servants, with carriages and horses besides.

The Author’s Father.

[To face p. 6.

Among my father’s friends then at Homburg was Sir Edward Hutchinson, whom the Prince Consort said was the handsomest man in England. His brother, General Coote Hutchinson, was also at Homburg. He had been a colonel at six-and-twenty, and was for many years the youngest general in the English Army.

At Homburg we lived in a villa on the Unter Promenade, in which the Princess Liegnitz, the morganatic wife of Frederick III. of Prussia, also resided. I can remember so well a box of toys representing various animals which the Princess gave me, and also the Princess and her daughter driving up to the villa one day when I was walking with my father, when he made me go and speak to them. My father afterwards gave me a beautiful bouquet of red roses, which I took to Princess Liegnitz’s salon, at which she seemed pleased, and, when she thanked me for them, gave me a kiss. King William of Prussia often visited his father’s widow at the villa, where the Princess held a regular Court, and was treated as though she were Queen of Prussia, even by the King. When he met me in the grounds, His Majesty often gave me bonbons, and usually kissed me. I had at that time a very pretty English nurse, and King William was well known to be a great admirer of pretty faces. My pride was somewhat wounded when I was told that His Majesty’s attentions to me may have been due in a very great measure to the attractions of my nurse.

When the Princess Liegnitz left Homburg, great preparations were made at the villa for the Duc de Morny,[8] who intended to come and stay there. But before he left Paris for Homburg he was suddenly taken ill and died. His death caused a great sensation everywhere, and his servants, who had already arrived at the villa, went away at once and returned to Paris.

Once a fortnight, on Sunday, an Austrian military band used to come from Rastatt to play in the grounds of the Kursaal. It played both in the afternoon and evening, and people sat on the lawns, enjoying the very fine music. Sometimes the Prussian military band came from Frankfurt, on which occasions I invariably used to cry. I sometimes sat with my parents on a Sunday on the lawns. Count Perponcher, Oberst-Hofmeister to the King of Prussia,[4] the Countess of Desart, Sir Frederick Slade and his family, or other friends, generally sat with them. Count Perponcher was a most agreeable and distinguished-looking man, and a great admirer of the Countess of Desart. The latter was not only a great beauty, but had a certain “grand air” about her, which is, as a rule, only to be found amongst the old nobility.

One day, when the Austrian military band was playing, my nurse and I had our early dinner at the Hôtel de l’Europe. Opposite to us, sitting at the table d’hôte, was the bandmaster Jeschko, with a very pretty woman seated on either side of him. I noticed that he was making love to both of them, and said to my nurse:

“Look at the Austrian bandmaster: he has two such pretty wives!”

“You silly boy, why do you talk such nonsense?” answered my nurse.

“But he is making love to both, and so they are to him,” I persisted.

“You should not look at people you don’t know; they may be his sisters.”

“I am sure they are not, for look at papa and his sisters.”

“Well, whatever they may be, it is not for a child like you to ask about them. I’ve no doubt that one is the gentleman’s wife and the other his sister.”

“Couldn’t they both be his wives?”

“No; such a thing would not be allowed.”

I continued to gaze at this handsome man, with his very long, fair moustache, highly curled. He seemed so good-looking in his white uniform with its pink facings, and the two ladies kept stroking his hands on the table and looking with admiration into his blue eyes. They both addressed him as “Du,” and appeared so very fond of him, that I said to myself that I could quite understand these girls being in love with him, as he was so handsome. The white uniform and the fine military appearance of this Austrian bandmaster at table no doubt greatly impressed my childish imagination, as I had never seen any one like him before, while his fair companions were both excessively pretty and dressed in the most charming confections imaginable. It was a sight which, when I grew older, never faded from my memory, while many other events, perhaps of far greater importance, were entirely obliterated. Stilgebauer, a very celebrated modern German author, who wrote “Love’s Inferno,” says: “Only that which we do not wish to, or may not, remember is over; everything else is ours and never over or lost to us.”

At Homburg, when the Austrian military band played, the grounds at night were illuminated with red, white and blue lights, and the fireworks were the admiration of the whole world, as M. Blanc spared no expense whatever.[10] This, indeed, he could well afford to do, in view of the immense profits he derived from the gaming-tables.

There was at Homburg in those days a young French girl of noble family, who was about thirteen years of age and very lovely, with a beautiful complexion. She was always exquisitely dressed, usually in white tulle with a great deal of lace, and was admired by everyone. This youthful beauty used to play a game of forfeits in a ring with some boys, who always arranged as a forfeit for the girl that she should kiss them. One day, when I was about seven years old, the children invited me to play with them. I did so, and was kissed by the little girl, at which I was much ashamed, as, though I rather liked being kissed by her, I was decidedly bashful when the operation was performed in the presence of so many people. And so, when I was asked to play again, I refused. This young lady often got her lovely white dress torn to shreds by the rough boys who played with her, but she went on playing every day all the same.

I remember once travelling by train with my father from Homburg to Frankfurt, when Goldschmid, a wealthy Jewish banker with red hair, who was in the same compartment, went fast to sleep. My father told me he was going to have some fun with him, and was pretending to take away his watch and chain, when Goldschmid suddenly woke up and exclaimed:—

“Gott, wirklich ich dachte Sie hätten meine Uhr weggenommen!”

He was evidently under the impression that my father had evil intentions, and it was not for some time afterwards that he could understand that it was only a joke. Goldschmid, many years afterwards, was ruined by his own brother, and committed suicide by drowning himself in the Main. They were cent. per cent. Jew moneylenders and bankers, who helped to ruin many English people in those days at Homburg.

I can well recollect seeing my father on one occasion in conversation with Garcia, a dark, good-looking Italian, who had several times broken the bank at Homburg by his high play.[11] He had begun his gambling operations when quite a poor man. I can also recollect Madame Kisilieff, who was a great gambler in those days, and was a good deal with my parents at Homburg. She was an immensely wealthy Russian lady of noble birth, who lived there en grand luxe.

The English colony at Homburg during the gambling days was very different from what it is now. There was more youth and beauty to be seen there and more of the aristocracy; whereas to-day more old people and wealthy parvenus go to Homburg during the season. Chevet’s Restaurant, though dreadfully expensive, was excellent; while the modern German one, though also dear, is not especially good.

I cannot recollect what year it was, but I can remember the Railway King, Hudson, taking another boy named Jeffreys and myself, whom I afterwards met at Eton, to dine with him at Chevet’s Restaurant, where he regaled us with every kind of luxury that the place could provide. My mother once told me a story about Mrs. Hudson, which she had heard from her father:—

Mrs. Hudson one day received a visit from the Duke of Wellington, whom she saw arrive, accompanied by a well-dressed and very distinguished-looking man, who remained outside when the Duke entered the house. Presently it came on to rain heavily.

“I will ask your friend up out of the rain,” said Mrs. Hudson to the Duke.

The Duke replied that the man was his servant; but Mrs. Hudson, who could not bring herself to believe that such an aristocratic-looking person could be the servant even of the Duke of Wellington, and thought that the latter was joking, insisted on the man being shown upstairs.

My grandfather’s brother-in-law, General the Hon. Sir George Cathcart, was A.D.C. to the Duke of Wellington at Waterloo, and was second-in-command to Lord Raglan in the Crimea, where he was killed at Inkermann. He was my godfather, and I often heard my father say that he always had a cigar in his mouth, even in action. Once he was asked by the authorities at the War Office how long he required[12] to get ready for active service. His answer was that he was ready to go anywhere at twenty-four hours’ notice.

My parents, one year, lived at the Hôtel de Russie at Frankfurt, going to Homburg in the evenings. There was a Baron von Neii, an Austrian major of dragoons, staying at the “Russie.” He was married to an Englishwoman, but they had no children, and, taking a great fancy to me, he wanted to adopt me and give me the right to bear his name and title, which is frequently done in Austria. He and his wife lived afterwards at Beaulieu, near Nice, where they had a charming villa with a beautiful rose-garden, where I have been to see them in more recent years.

Baron von Neii told me that there was once an Englishman, a Major Isaacson, in his regiment, who could not speak two words of the Hungarian language. Nevertheless, he contrived to retain his place in the regiment for many years, being always prompted when he had to give orders by a sergeant. One day, however, during an inspection by a general, the sergeant happened to be away, with the consequence that the poor officer was perfectly helpless, and, after calling out several wrong words of command, was detected and placed on half-pay.

There were at this time at Homburg two Misses Lee Willing, nieces of the famous General Lee, of the Southerners. One was a great beauty, who, it was reported, had received innumerable offers of marriage, from a prince downwards, but had refused them all. She was called the “Destroying Angel,” because she had been the cause of so many duels being fought on her account. She was constantly in the company of my parents, and, many years later, we met her again in Paris. So far as I can remember, she could never decide to take a husband, and died in Paris while still a great beauty.

The Author’s Mother.

[To face p. 12.

Her cousin, Willing Lee Magruder, had been with the Emperor Maximilian of Mexico at the time he was shot by his revolted subjects, and only escaped a similar fate by the skin of his teeth. His sister was lady-in-waiting to the Empress Charlotte of Mexico, and, after the Emperor’s[13] death, the brother and sister occasionally dined with us in Paris, and we often met them in later years in Paris society. When leaving Mexico, Magruder and his sister were shipwrecked, and he told me that they passed several hours in the sea clinging to a plank. At night they were rescued by a passing ship, almost exhausted by hunger, thirst and fatigue. His sister never quite recovered from the shock to her system, and suffered much from a nervous complaint ever afterwards.

I can remember that, while at the Hôtel de Russie, my mother used constantly to be reading French novels, which, during her absences at Homburg, my French nurse used to get hold of. I was particularly interested in la Reine Margot and le Chevalier de Maison Rouge, by Alexandre Dumas père, which delighted me more than any other books. I read “Joseph Andrews,” which my father bought for me, but he told me that he thought I was not quite old enough to appreciate or even to understand most of it.

I used always to be much interested in the Eschenheimer Thor at Frankfurt, as at the top of it there was a tiny iron flag, in which nine holes were pierced, representing the figure nine. The story about this flag is that a certain poacher, who had been arrested and condemned to death for shooting deer, was offered a pardon, if he could put nine bullets into the flag in such a way as to form the figure nine. This he succeeded in doing, and was set at liberty.

When you looked at the flag this seemed hardly credible; it was so tiny, and the nine was so wonderfully pierced. The Eschenheimer Thor has since disappeared to make room for the so-called improvements of Frankfurt.

I can remember being taken to the celebrated Römer at Frankfurt, where the Emperors of Germany were formerly crowned. The Kaisersaal, where the coronation used to take place, was an immense room, containing portraits of the different Emperors. I was much interested in Karl I., and still more in Rudolph von Hapsburg, the ancestor of the present Emperor of Austria, and I also took particular note of those of Günther von Schwarzburg and Maximilian I.,[14] as I was very fond of German history. The coronation room was beautifully decorated, the walls and doors being sumptuously gilded. On the latter were represented several children, wearing royal crowns and garments of gold, which pleased me very much.

Another time, I was taken by my French nurse, so far as I can remember, to see Dannecker’s celebrated statue of Ariadne, and was somewhat startled at finding myself in a perfectly dark room, in which you could only see a red velvet curtain facing you. Soon, however, the curtain was drawn back, when a perfectly white statue of a nude woman riding upon a lion appeared before us. The woman was exquisitely formed, and was reclining indolently upon the animal’s back. A rose-coloured light was thrown upon the statue, which made its hue all the more dazzling, and it revolved slowly on its axis, so as to display the lovely form of the woman to better advantage. I was glad that it was dark, for I fancied that I should have felt more awkward if anyone had seen me. As it was, I blushed crimson, and was pleased to get into the street. All the same, I have never forgotten this lovely statue and the rose-coloured light employed to show off its beauty.

I went to the Jewish quarter, where the old tumbledown house in which the Rothschilds had once lived[5] was pointed out to me, but it was such a dirty quarter of the town that I never returned there. I once visited the Synagogue, and was surprised to see all the men wearing their hats. It made me think of the time of Christ, and that with certain Jews very little had altered since those days. I wondered[15] why such men as Goldschmid at Homburg were allowed to carry on their villainous trade with Christians.

The new theatre at Frankfurt is a very fine building, in which there is a statue of Goethe, which is greatly admired. An amusing anecdote is related of Goethe, who was born at Frankfurt. One day he and Beethoven were walking together, and many people who met them raised their hats. “How tiresome it often is to be recognized by so many persons!” complained Goethe. To which Beethoven replied somewhat maliciously: “Perhaps it is me they are greeting.”

Speaking of Goethe, the celebrated Austrian poet Grillparzer says:—

“Schiller geht nach oben, Goethe kommt von oben. His characters usually say everything beautiful that can be said about a subject, and for nothing in the world would I care to miss any of the beautiful speeches in Tasso and Iphigenia, but they are not dramatic. That is why Goethe’s plays are so charming to read and so bad to act. However much we may think of Goethe, the fact remains that his Wanderjahre is no work, the second part of Faust no poem, the maxims of the last period no lyrics. Goethe may be a greater poet, and no doubt is; but Schiller is a greater possession for the nation, which requires vivid impressions in our sickly times. Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister and Philine Sarto and the Countess have all distinct and artistically well-formed characters, though they are all in danger of being condemned as without any character. This fate they share with Hamlet and Phèdre, with King Lear and Richard II.; perhaps also with Macbeth and Othello. The Wahlverwandtschaften is a great masterpiece. In knowledge of humanity, wisdom, sentiment and poetic strain it has not its equal in any literature. With the exception of those produced by Goethe in his youth, his works were not popular with the nation, and the great respect shown him was the result of the admiration which his masterpieces of the past had aroused.”

Frederick the Great said of Goethe: “His early works[16] are too natural, and his late ones too artificial. Besides, he is an immoral poet. Fallen girls are his favourite characters.” A very true saying of Frederick the Great is: “A court of justice which pronounces an unjust sentence is worse than a band of murderers.” Frederick was always a great admirer of Voltaire, and one of his famous sayings is: “Unsere Unsterblichkeit ist, den Menschen Wohlthaten zu erweisen.” (“Our immortality consists in performing good deeds to mankind.”)

In recent years I went to the celebrated Palmen Garden in Frankfurt, where the palm-trees are all from the late Duke of Nassau’s beautiful palace at Biebrich. I went there with an English lady to an afternoon concert. My companion remarked how ordinary all the people looked compared with those one saw at a concert at Vienna, and drew my attention to a table at which sat four men dressed in very shabby, old-fashioned clothes. I was anxious to remain and hear the concert out, but was afraid the lady might decide to leave early, owing to the little interest she appeared to find in the audience. So I said at random:—

“You are quite right, but with regard to the men sitting at that table, I should not be surprised if they were millionaires.”

She laughed and seemed to be much amused at the idea, and a waiter coming up just at that moment with some coffee and cakes we had ordered, I asked him if he knew who the four men were. He replied at once:—

“They are four millionaires.”

I may mention that I had never seen these men before in my life, and was only staying at Frankfurt two days.

At Franzenbad, from which I had just come, I had a singular experience. On entering the Kursaal one Saturday afternoon a programme of the music was handed me. The piece which was being played was a polka, by Edward Strauss, called Con Amore, and I noticed that each of the eight pieces on the programme contained a letter of this name. I took this as a kind of presentiment, and the same day telegraphed to a bookmaker named Hörner, in the Krugerstrasse[17] at Vienna, to back the horse of this name running in the principal event in the Baden races the following Sunday. He duly executed my commission, and the horse won, though it did not start favourite. I won very little, however, as the odds were not as long as I had expected. The programme of the concert at Franzensbad was as follows:—

| Saturday, 25th June, 1904. Kurhaus, 4 p.m. | ||

| 1. | Wiedermann Marsch | Oelschlegel. |

| 2. | Ouverture, Oberon | Weber. |

| 3. | Ballerinen Walzer | Weinberger. |

| 4. | Potpourri aus Obersteiger | Zeller. |

| 5. | Con Amore Polka | Ed. Strauss. |

| 6. | Ouverture, Belagerung von Corinth | Rossini. |

| 7. | Am Spinnrad | Eilenberg. |

| 8. | Frisch heran Galop | Johann Strauss. |

The Hôtel de Russie, in those days, occupied the site of the present Post Office. It was originally a palace, and the rooms were magnificent, particularly those reserved for the King of Prussia, which my parents occupied for a time, as did Mrs. Ronalds. Otherwise, this suite of rooms was always kept for the King of Prussia when he cared to visit Frankfurt, which His Majesty often did, staying there usually some time. The proprietor of the Hôtel de Russie was a certain Herr Ried, and, on his death, it was purchased by the Drexel brothers, who are now wine-merchants of some celebrity in Frankfurt.

When I was seven years old, my parents left me at a school in Frankfurt, kept by Herr Kirchhofer, a good-looking, fair-haired man of thirty-five. He was married and had an only son named August, who in later years entered the Austrian Army, and got terribly into debt when a lieutenant. His father paid his debts, but after he married he got into further trouble, and ended by shooting himself, while still quite young. During my stay at this school I spoke nothing but German all day, with the exception of a little French occasionally, and, in consequence, completely forgot the English language for the time being.

One day, Herr Kirchhofer told one of the assistant masters, Herr Wolf, a young man of five-and-twenty, that he might take six of the boys, of whom I was one, for a three days’ excursion in the Oden Wald. We started at five o’clock in the morning and walked for some hours, when I became so tired that I could go no farther. So Close, an English boy of eighteen, who was going into the Austrian Army, and another boy, a German, carried me on a kind of camp-stool a long way.

When we got to the Oden Wald, we wandered about collecting plants, which Herr Wolf required for his lessons in botany. Then, after dining at an inn, we started again, with the intention of reaching a village which the master knew by name. On the way we passed a small village, where a man offered to take charge of me, and I was very[19] much afraid our master would leave me with him. I begged him not to do so, and was greatly relieved when he said:

“You don’t think I should be so foolish? Why, the man might run off with you.”

Some time afterwards, it began to grow quite dark, and Herr Wolf became much alarmed, as we had completely lost our way in the forest. However, we saw some lights in the distance, and walked on until we came to a small village, where there was a house which purported to be an inn, though all its windows were broken and mended with pieces of newspaper.

Herr Wolf entered this uninviting hostelry and inquired if we could have one large room to sleep in, as he told Close and another big boy, a German, that he was afraid that we might possibly be murdered in the night, if we were separated. I may here mention that, in those days, some parts of the Oden Wald were infested by gangs of robbers, and instances were known of people being given beds which revolved in the night and precipitated their unfortunate occupants into pits beneath the floor.

The inn-keeper, a sinister-looking personage, with his face almost entirely covered with hair, said that he had not a room large enough to accommodate our whole party, but that we could have two rooms. Herr Wolf asked if they were near each other, to which the man replied that one was upstairs, but the other on the ground floor. The master, looking much annoyed, asked to see the rooms, and, after inspecting them, inquired if Close had a revolver with him. The latter said he had not, though he had brought a sword-stick. But another boy, an American, called Sydney Chapin, exclaimed:—

“I have a loaded revolver with me.”

“That’s famous!” replied Herr Wolf. “Then you must give it me, for I will occupy the room on the ground floor with George, and you others must sleep upstairs.”

The master then took the revolver, and told Close that he must take charge of the other boys in the room upstairs.

When this had been arranged, we all entered the so-called dining-room, a large room, with whitewashed walls. Its windows, like all the rest in the house, were broken and patched with newspapers; the ceiling was so low that you could almost touch it with your hands, and crossed by large beams. In one part of this room, four rough-looking men were playing cards and drinking beer out of mugs. They were in their shirt sleeves, with sleeves tucked up to the elbow, displaying very muscular arms, while their shirts, open at the neck, showed their naked chests covered with hair. Although it was summer and excessively hot, all of them wore fur caps.

They were playing by the glimmer of a solitary tallow candle, which was the only light in the room, and when we took our seats with our master at another table, we found ourselves almost in the dark. Presently, our supper was brought us, consisting of cold meat and mugs of beer, and Herr Wolf asked for a candle. The inn-keeper muttered sullenly that he had none.

“What! Have you no light of any description?” asked the master.

“No, I have just told you so,” was the reply.

Herr Wolf was visibly alarmed, but Close whispered to him:—

“I have a box of matches.”

“Gott sei dank!” exclaimed the other.

After some whispered instructions to Close, the master rose from the table, when I observed the card-players casting surreptitious glances in our direction, although they pretended to be absorbed in their game. Herr Wolf then took me through the darkness into the bedroom on the ground floor, the gloom of which was partially relieved by a slight glimmer from the moon, which penetrated through the broken window. He struck a match, and, having shown me my bed, which stood near the window, told me to undress and go to bed. I did as he told me, and he then said that he was going upstairs to see after the other boys.

The Author’s Daughter.

[To face p. 20.

While I lay in bed, I heard some noisy women passing the[21] window. One of them put her head through one of the broken panes, and, on seeing me in bed, burst out laughing. Afterwards there was a dead silence, only interrupted occasionally by the loud oaths of the men playing cards in the dining-room, who appeared to be disputing about some money which had changed hands. The noise they made was becoming louder and louder, when I heard the door open, and Herr Wolf entered and inquired if I were asleep. He then went out again, saying that he would return later. The noise made by the gamblers then appeared to cease, and my weariness overcoming my fears, I suddenly dropped off to sleep.

Early in the morning I awoke, and saw Herr Wolf dressing himself. I hardly knew where I was, when, on seeing that I was awake, he said:—

“Du bist famos geschlafen, George.”

After I had dressed, he told me to come with him into the dining-room, where all the others were gathered, and, after taking some coffee and black bread, we left the inn. Soon afterwards, Herr Wolf told the boys that he had never been so alarmed in his life, and that he was quite positive that if the men at the inn had not known that some of the boys were armed, we should most probably have been murdered for the sake of our clothes and the money we had about us. He added that he had not slept a wink all night, as he knew what sort of men he had to deal with, and that they were of the very lowest type imaginable and capable of committing any crime to obtain a few groschen.

At the time of which I am speaking, there were so many murders perpetrated near Homburg, owing to the gambling which went on there, that the police never knew whether they had really to deal with a suicide or a murder. The Oden Wald had then quite as bad a reputation as the Black Forest, which was infested by whole gangs of robbers and murderers. Herr Wolf told us a story of a man who, having lost his way in the Oden Wald, put up for the night at a small inn near a village, where they gave him some coffee before he went to bed. He could not sleep, and in the[22] middle of the night he got up, lighted a candle and began examining a picture opposite his bed, which represented a man wearing a Rembrandt hat with a long feather. Gradually, it seemed to him that the feather was becoming shorter; soon he could see only a part of the hat, and then merely the face. The man, thinking that there must be something wrong with him, jumped out of bed and approached the picture, which he found was exactly as when he had first seen it. But, on looking at his bed, he perceived that the baldachin over the four-poster was suspended by a chain from above the ceiling, and was gradually working its way downwards. An examination of the moving baldachin revealed the fact that it was made of massive iron, beneath which he would infallibly have been crushed to death. Dressing in all haste, and holding a pistol which he had about him ready to fire in case of need, the destined victim left the room and stealthily descended the stairs. By good fortune he met no one, and letting himself out of the house, made his way to Homburg, where he informed the police of the murderous trap which had been laid for him. It was evident that the coffee which he had drank overnight had been drugged; but, most providentially for him, the drug had had the contrary effect to that intended, and had kept him awake, instead of sending him to sleep.

Herr Wolf told us other stories of the Black Forest, in which there were inns with revolving beds, which upset the persons who occupied them into pits beneath the floor, where the heavy fall generally killed them at once; and Baron Vogelsang, a good-looking Bavarian boy, with blue eyes and curly brown hair, related the following anecdote:

During the time of the great Napoleon,[6] the Emperor[23] sent on one of his aides-de-camp to Germany with important despatches. This A.D.C. had to traverse the Black Forest, and on arriving as evening was falling at a certain country house, asked if he could be accommodated for the night. A room was given him, but, at the same time, he was warned that the house was haunted, and, sure enough, in the middle of the night a ghost duly put in an appearance. The Frenchman, who had no belief in the supernatural, promptly snatched up a pistol and levelled it at the spectre, who thereupon vanished. The A.D.C. then hurried to the spot where the ghost had first appeared, when the floor suddenly gave way beneath him, and he fell what seemed a great distance. For the moment he was stunned by the fall, and, on recovering his senses, found himself surrounded by a number of men, who were debating whether they should kill him. He, however, explained who he was, and showed them the despatches from Napoleon of which he was the bearer; and the men, fearing the vengeance of the Emperor, should the crime they were meditating ever be discovered, agreed to set him at liberty, on condition that he would take an oath to say nothing of what had happened to him in that house. They then told him that they were coiners, and that they killed everyone who slept at the house, but that they usually frightened so many away by tales that very few people cared to stop there. The Frenchman took the oath demanded of him, and was set at liberty so soon as day came. Years afterwards, he received a magnificent pistol, set with brilliants and rubies, with the following inscription engraved upon it: “From those whose secret you have so generously kept.” The gift was accompanied by a letter, informing him that the coiners, having now succeeded in amassing an immense fortune, had retired from business.

The day after our adventure at the inn was passed by our party in walking leisurely through the forest homewards, through a most glorious country and in most lovely weather. When we reached Frankfurt, Herr Kirchhofer congratulated Herr Wolf on our escape, and told him that it was very lucky that we had returned at all.

Herr Wolf saw me in after days at Frankfurt, when he kissed me in German fashion, saying: “Kannst Du Dich erinnern von damals im Oden Walde, George?” I thought it was our last day upon earth, and that we were going to be murdered there, like many others have been there before and even since those days. But I pretended not to be alarmed at the time, and made the best of it.

The time—rather more than a year and a half—I spent at this school at Frankfurt was one of the happiest periods of my life; indeed, when my parents wanted me to stay at the Hôtel de Russie, I cried and begged not to be taken away from the school. Herr Kirchhofer was a very pleasant, kind and good-hearted man, and a fine orator, one of the best I have ever heard; and the lectures which he used to give on ancient Greek history were always extremely interesting. His lectures were always extempore, as his excellent memory made it unnecessary for him to refer to a book, and the way he declaimed was a pleasure to listen to, so well did he raise or lower his voice to suit the occasion. At times he became very dramatic, putting you in mind of some celebrated actor on the stage, as he walked up and down the room, reciting from the classics and quite carrying away his audience. The only punishment inflicted on boys at this school was to shake them and smack their faces, which Herr Kirchhofer did himself, as well as the other masters, of whom there were eight or nine, although the school consisted only of ten boarders and fifty day-boarders.

German and Austrian boys find more pleasure in taking long walks in the woods, making excursions, and running about than they do in games like football and cricket, for which few, if any, have any taste. In fact, I never knew any boys in Germany who cared much for any outdoor games at all. However, I have not the slightest doubt they enjoy their school-days quite as much as English boys, if not more; and there is much more friendship between master and boys in Germany than there ever can be in England. In the former country, the master devotes more time to ascertaining[25] the tastes of individual boys, and addresses them more like a friend than a master. When, afterwards, I was sent to an English school, I noticed the difference almost at once. At the school at Frankfurt I was most interested in the history of ancient Greece; I was also fond of German history. Latin was not taught there, for which I was by no means sorry. I had no great fancy for botany, though I tried to like it; but natural science rather piqued my curiosity. As for arithmetic, I hated it, and never knew the value of money; in fact, I don’t remember ever having any at that time, nor ever asking for any, as I had everything I required bought for me. I had a fancy for collecting stamps, and, in those days, there was a regular stamp market at Frankfurt, where they were sold in the street. I went there on one occasion, but was not very favourably impressed by the Jew dealers who hawked them about.

I was passionately fond of tin soldiers, and used to play with them with a boy named Louis Krebs, who had a fine collection of both Austrian and Prussian ones. He had a pretty little sister called Klara, who always wore pink coral earrings and would often play with us.

One day, Herr Kirchhofer told me that my parents were going to England and that they had arranged to take me with them. At first, I was quite unable to realize it, but when I learned that the news was true I was greatly distressed, and nearly cried my eyes out at having to leave Frankfurt and the school. I tried to prevail upon my parents to leave me behind, but my father would not hear of it, saying that I should have to go to a preparatory school for Eton, and that he had one in view, which my aunt, Lady Caroline Murray, had recommended. So I was forced, malgré moi, to submit to my parents’ wishes.

In recent years I met Krebs, the boy of whom I have just spoken, at Frankfurt, when he gave me a great deal of information about those who had been at school with us. He himself had become a millionaire; but he was the only one who had made money. Most of the others had been far from successful in life, and one of the wealthiest, Baron[26] Vogelsang, had lost almost the whole of his immense fortune. Many had died quite young. Herr Kirchhofer had only lived a few months after the suicide of his son August, and Herr Wolf had also died while still quite a young man.

On leaving Frankfurt, we went to Brussels, where we lived in a large house on the Boulevard de Waterloo, which looked out on to a very fine avenue of trees. Captain Dorrien came with us on a visit to my parents and stayed for some months. Captain Dorrien, in after years, lost his whole fortune, when the late Earl of Sheffield, who had been at Eton with him, insisted on his going to live at his fine house in Portland Place, where he was given full authority over all the servants, lived free of all cost to himself, and received a cheque for £500, while the Earl went for a six months’ cruise in his yacht. This was told me by Captain Dorrien himself, at a time when he was in far better circumstances.

Lord Howard de Walden was then the English Minister at Brussels, and my parents were on very friendly terms with him and his family. Two of the sons came often to our house; one was in the Royal Navy, and the other in the 60th Rifles. The eldest son, who afterwards succeeded to the title, was then in the 4th Hussars, but I never met him. Many years afterwards, I met Lady Howard de Walden, then a widow, in India, at Murree, in the Himalayas, where she dined at our mess with her daughter, Miss Ellis. The two ladies were about to start on a journey to Kashmir, on ponies, as Lady Howard de Walden said that it was her intention to see as much of the world as she could before she died. She was then seventy. She added that it was a singular coincidence that the two regiments in which her sons had served—the 4th Hussars and the 60th Rifles—both of which she visited,[28] should be quartered quite near Kashmir, the Hussars at Rawal Pindi, and the 2nd Battalion, 60th Rifles, at Murree. Lady Howard de Walden accomplished the difficult journey to Kashmir and returned in safety.

We were on friendly terms with the Baron de Taintegnies, who was in attendance on Leopold II., King of the Belgians, and also with his three lovely daughters, who, with their cousins, the daughters of Baron Danetan, were considered the most beautiful girls in Brussels society at that time. One of the former married, in later years, Captain Stewart Muirhead, of the Blues, a friend of my father and of Captain Dorrien.

Frederick Milbanke, of the Blues, an old Etonian, who was a great friend of my father, was at that time a good deal in Brussels, and married a Belgian actress there. Milbanke was heir to some of the Duke of Cleveland’s estates, but he died before coming into this property. The last time I saw him was at the Alexandra Hôtel, in London, where he and his wife had a very fine suite of rooms, when my father took me there to pay them a visit. Milbanke was a very handsome, fair man, and his wife a great beauty. I met the latter in after years at the Grosvenor Hôtel, where she was staying with her son, a nice-looking boy, who had come back from Eton for the holidays.

The winter at Brussels was rather a severe one, and there was plenty of good skating to be had. I remember learning to skate in the Bois de la Cambre, to which I went with my father. One day I was knocked down by some lady skaters, and had great difficulty in extricating myself from their petticoats. I fell very softly, but I was well-nigh smothered. I was glad when my parents left Brussels, as I had no companions there at all.

There was then at Ostend a Mrs. Clifton, who had an exceedingly pretty daughter. Mrs. Clifton was a widow, and afterwards contracted a second marriage with a brother of Sir Walter Carew. When I was at school at Kineton, in Warwickshire, the mother and daughter paid me a visit, as they had an estate not far from the school.

One day, on the Digue at Ostend, I suddenly caught sight of my little friend, Baron Vogelsang, who, leaving his father and mother, who were with him, ran up to me at once and kissed me on both cheeks. I saw a good deal of Vogelsang while I was at Ostend, going often on to the sands with him, and meeting him in the evening at the children’s dance at the Casino.

The Baron de Taintegnies’s daughter used to attend those dances, to which the Duc de Sequeira, a young boy I knew, generally went. Marie, the Baron’s eldest daughter, who was a lovely girl, afterwards became the Baronne Le Clément de Taintegnies. She lives at Minehead, where she has a fine estate and hunts with the Devon and Somerset Staghounds. I heard from her quite recently. Her sister Isa, who married Captain Stewart Muirhead, is now a widow, her husband having died in Paris in 1906. She also hunts with the staghounds in Devonshire, and both sisters are well-known horsewomen. Aline, the youngest sister, who was called “Bébé,” and whom I admired very much when a child at Brussels and Ostend, married, in 1871, Baron de Hérissem, and, after his death, went to Italy, where she married again and lived for several years. She died at Ancona in March, 1906.

There was a racing man at Ostend, named Captain Riddell, who won all the principal steeplechases that were run there. Mrs. Ind, the wife of the well-known brewer, was his sister. Riddell met with a very serious accident in a steeplechase at Ostend, injuring his spine. The horse which he was riding on that occasion was once ridden by my father on the sands, and he told me that he was a perfect devil to hold. When a young man, my father once rode a hundred miles in twelve hours on the same horse for a bet at Taunton, in Somerset, and won his wager easily, with plenty of time to spare. He and Charles Kinglake, a brother of the author of “Eöthen,” were the only persons who were willing to go up in a balloon at Taunton, when the first one came there, which was considered rather venturesome at the time. This reminds me that one of the oldest inhabitants of Bristol[30] told me lately that he remembered when the first iron ship was launched at that port, and how all the residents declared: “The idea of iron floating is too absurd to entertain for one instant; the ship is bound to sink, for iron can never be made to keep above water.”

The King and Queen of Würtemberg were both then at Ostend. Queen Olga, who was a Russian Grand Duchess by birth, was said to be the handsomest woman in Europe. She had very regular features, but was at that time excessively pale and thin. Her niece, the Grand Duchess Olga, was the first proposed fiancée of Ludwig II., King of Bavaria. His Majesty, however, refused to marry her. This is not generally known. The Grand Duchess Olga afterwards married the late King George of Greece.

King Leopold II. and Queen Henriette were at Ostend at that time with their children, who used to drive on the sands in a small carriage drawn by four cream-coloured ponies. Baron de Taintegnies was usually on the Digue of an afternoon with the King, sitting down or walking about.

Among my father’s friends at Ostend were Lord Orford and Lord Brownlow Cecil. The latter was very fond of music, and married a lady there who was a magnificent pianist. One day I can remember my father sitting in the Casino with Henry Labouchere, an old Etonian, who had formerly been in the Diplomatic Service. Labouchere was smoking a big cigar, and he and my father had a long conversation. What it was about, I cannot say, though they were continually laughing; and my father told me afterwards that Labouchere was very amusing, and, though sarcastic, witty, and that he rather liked him.[7]

General Sir John Douglas, K.C.B., Commander of the Forces in Scotland, and his wife, Lady Elizabeth Douglas, daughter of Earl Cathcart, were a good deal with my parents at Ostend. The General used to take long walks with my father, and he put my name down for his old regiment, the 79th Highlanders, and for the Scots Guards. Sir John Douglas was extremely kind to me in after years, and invited me to stay with him at Edinburgh; but I could not get leave from my colonel at the time, and consequently was obliged, to my great regret, to decline his kind invitation.

My parents used very often to spend the summer months at Ostend, and one year they occupied the apartments at the Hôtel de Prusse which the Russian Ambassador, Prince Orloff, had just vacated. One day, after washing my hands in my bedroom, I emptied the water out of the window, for some unaccountable reason. Later in the day, the Princess de Caraman-Chimay sent up her lady’s maid to say that a dress which the Princess had intended wearing the following evening at a Court ball at Brussels had been[32] completely spoiled by the water. I was well scolded by my mother for being the cause of this misfortune.

The English clergyman at Ostend was a Mr. Jukes. He had a very good-looking son, a boy about my own age. He told me that he was in the habit of walking in his sleep, and showed me his bedroom window, which had a padlock on it. When I asked him where the key of it was, he said that they would not tell him, in case he might get up in the night, unlock it, and walk on the roof of the house, which, he said, he had done before. His father once met me with mine in the street, and when told that I was going into the British Army, said that he entirely disapproved of soldiers, and thought that the time was near at hand when there would be no more wars and every dispute would be settled by arbitration. I fancied at that time that Mr. Jukes’s prophecy might come true, but, as subsequent events proved, we were very far indeed from its realisation.

Both the King and Queen of the Belgians were very popular with the inhabitants of Ostend. They used to walk on the Digue quite unattended, and seemed in no way inconvenienced by the crowd, who always treated them with the greatest respect. The King wore plain clothes, usually a dark suit with a tall white hat, and never appeared there in uniform. A very good story is told of Leopold II., who, some years ago, during the summer months, was at Luchon, in the Pyrenees. The day after he arrived there, the King sent for a hairdresser, and directed him to trim his silvery beard. When the operation was over, His Majesty inquired what he had to pay.

“It will be twenty francs, Your Majesty,” replied the hairdresser without hesitation.

The King pulled out a two-franc piece, which he handed to this too facetious Figaro.

“I am accustomed,” said he, “to pay very well. Here is a two-franc piece. It is a new Belgian coin, and you will see my head on it, as you wished to pay yourself for it.” (“Vous y verrez ma tête, puisque vous avez voulu vous la payer.”)

It is said that the hairdresser left without asking for the rest of the money, and that, since this adventure, he placed over his shop a fine board, inscribed: “Furnisher of H.M. the King of the Belgians.”

My mother spent a summer at Spa, where she took a house with a garden attached to it. I liked the place very much, and often went for rides on a pony in the woods with the late Captain Lennox Berkeley, who afterwards became Earl of Berkeley. The country round Spa is mountainous and very charming. Spa itself is an exceedingly pretty place, situated in a valley entirely surrounded by hills and woods, and the Ardennes are not far off. But in the summer months the heat is intense, and, when the sun once gets into the valley, there is often not a breath of air. The promenade, where the band plays morning and evening, is charming, and it is very pleasant to sit beneath the shady trees and listen to the excellent orchestra. I often used to go there with my mother, particularly of a morning, when all the monde élégant used to forgather to listen to the music. The gambling-rooms were then open for roulette and trente-et-quarante, and Captain Berkeley used often to try his luck at them, but, unfortunately, he was not successful. I can remember his giving me “Japhet in Search of a Father,” by Captain Marryat, and recommending me to read it. I did so, and it amused me very much.

Another of my father’s friends, the late Captain Bromley, an old Etonian, and a son of Sir Thomas Bromley, was at Spa at the same time. One day, when I happened to tell him that I was going into the Army, he smiled, and said that he never could hit off with his colonel. The latter complained that he was always late for parade, and asked him if he did not hear the bugles sound. He answered:—

“Yes, sir—I hear the bugles, but there must be something wrong with them, for they don’t sound the right note.” The Colonel soon found him incorrigible, and he himself that he was never made for a soldier.

Bromley told me that, when a boy, he was accustomed to dine off gold plates and that everything he used at table was of gold. Suddenly, his father died, and his elder brother inherited the title and estates, while he was obliged to live on a few hundreds a year. This, he said, was the fault of our law of primogeniture, which ought only to take effect in the case of ducal houses, where the bearer of the title should be made to pay an “appanage” to the other members of the family, as is the rule on the Continent.

It has often been asserted by authors of great authority that women are much meaner than men; but I have known some instances to the contrary. Once, during our stay at Spa, a gentleman called on my mother, and told her that he had lost all he possessed, and asked her to lend him £50, as he was anxious to rejoin his wife. My mother, who had known him for years, said that she would give him all she had in the house—nearly £40—for which he was very grateful, both at the time and when we met him and his wife in later years.

Once I was staying with my father at Desseins Hôtel, at Calais,[8] when he told me that he had made the acquaintance of an Englishman, a certain Captain Arthy, who was rather a singular character, indeed, highly eccentric. It appeared that he had just lost his wife, and that he was so distressed at her death that he wore all the trinkets which had belonged to her on his watch-chain, to show his affection for her. He had not, however, gone into mourning, and always affected a red tie, saying that he wore the mourning in his heart, upon which he used to lay his hand as he spoke. I was introduced to Captain Arthy, who was a bald-headed man, with black side-whiskers and rather a red face, dressed in a light suit of clothes. The quantity of charms on his watch-chain would have almost filled the window of a jeweller’s shop, while numerous rings adorned[35] his fingers. He was perpetually smiling, displaying a set of very fine teeth when he did so.

He invited my father and me to see his rooms, which were full of gold and silver cups, which he told us, had belonged to his late wife. The late Mrs. Winsloe, whose husband was a friend of my father, was staying at this hôtel. Mr. Winsloe was a well-known man in Somersetshire, but he had recently gone out of his mind. His wife had been a great beauty, but she was then terribly made up, with fair dyed hair.

Mrs. Winsloe, who lived in very luxurious fashion, and occupied a very fine set of rooms at Desseins Hôtel, said that Arthy was a cousin of her husband, and showed us a cutting from the Times about the death of Mrs. Arthy, which had occurred in rather a tragic manner. One evening, when my father and I were in her salon, she said to Arthy:—

“I wish you would give one of your lockets to that little boy, as a keepsake from me.” Arthy thereupon took off his watch-chain, and, after hunting amongst his innumerable lockets, at length chose one, which he unfastened, saying:—

“Here is a nice gold locket that will do. Will you give him your photo to put inside it?”

“I haven’t got one,” replied Mrs. Winsloe. “Give him one of yours instead.” So he cut round one of his photos and, inserting it in the locket, handed it to me. “Now kiss Mrs. Winsloe,” said he, “for it is her present to you.” I kissed the paint off her face, and she kissed me, and I felt sure that she left a coloured impression on my face. But I was so pleased with the locket, which I attached to my chain, that I did not care in the least.

Arthy drank champagne with Mrs. Winsloe, and the latter seemed rather infatuated with him, which was not surprising, as he was a fine-looking man, though his baldness detracted from his good looks. However, the lady could not afford to be very difficile, being only an artificial beauty, whose youth was but a memory. Formerly, she had had beautiful hair, and it still reached to her waist. My father complimented her upon it, observing:—

“I never saw such lovely hair in my life, or such a perfect colour.”

She looked pleased, and replied, smiling:—

“Yes, I don’t think there are many women who have such fine hair.”

“No, I am sure there are not,” remarked Arthy, who appeared to be thinking of the gold locket which he had given away, for he looked at his chain as he spoke.

“He doesn’t half admire you,” said my father, laughing.

“I am sure I do; I think my cousin the loveliest woman possible,” replied the other, who appeared annoyed at my father’s remark.

Mrs. Winsloe looked at Arthy and smiled, being evidently under the impression that he was jealous, as he appeared angry with my father.

The fact was that Arthy was anxious to ingratiate himself with Mrs. Winsloe, as she was very wealthy. Accordingly, he pretended to admire her, though it needed only half a glance to see that in reality he considered her very far from beautiful. Mrs. Winsloe not only paid for her own rooms at the hôtel, but all the expensive dinners which she and Arthy had together were entered to her account. The latter had a great partiality for naval officers, and as an American warship, the Alabama, of the Confederate Navy, happened to be lying at Calais at this time, he invited some of the officers to dine with him and Mrs. Winsloe. They accepted, and were most sumptuously entertained, champagne flowing like water.

After staying six weeks with his cousin, Arthy left for England. Soon afterwards, the officers of a British warship at Portsmouth received an invitation from the Duke of St. Albans to dine with him at an hôtel. The captain of the ship happened to be away, and, on his return, the other officers told him what a good dinner he had missed and loudly praised the ducal hospitality.

“The Duke of St. Albans!” exclaimed the captain, in astonishment. “How can you possibly have dined with him that evening? Why, the very same day I was shooting[37] quite near the duke’s property, and I happened to see him! I will go to the hôtel and find out who it can be.”

The captain lost no time in instituting inquiries, with the result that the supposed duke was laid by the heels just as he was preparing to leave Portsmouth, and turned out to be none other than the man who had passed as Captain Arthy at Calais. It was subsequently ascertained that he was a certain Comte d’Aubigny, a member of a very old and noble French family, and that he had deceived several people in the same way. My father, on hearing of this, remarked:—

“It is the first time that I have been taken in by a man, but I am glad I am not the only one he deceived.”

The enterprising gentleman was afterwards brought to trial and sentenced to seven years’ penal servitude.

My parents sometimes spent the summer months at Boulogne, one year taking a large house at some little distance from the sea, overlooking a public garden. The late Captain Elwes, a nephew of the Duchess of Wellington, who was Vice-Consul at Boulogne, was a friend of my parents. He was devoted to painting, and, many years later, painted a miniature of an American lady for his cousin, the Marquis of Anglesey. It was beautifully painted, but, unfortunately, when it was finished, the Marquis had fallen in love with another Transatlantic belle, so he did not appreciate the miniature quite as much as he might have done, if his affections had not been diverted from the original. Elwes hoped to be appointed Consul at Boulogne, but whether he ever obtained that post, I cannot say. The last time I met him was in Paris, many years later, at a dinner given by the Marquis of Anglesey, at the Hôtel d’Albe, in the Champs Elysées.

Lord Henry Paget, afterwards Marquis of Anglesey, was very fond of Boulogne, and lived there with his first wife. The latter died at Boulogne, quite suddenly, but the Marquis continued to visit the place, and my father saw a good deal of him.

George Lawrence, the author of “Guy Livingstone,” son[38] of Lady Emily Lawrence, was frequently at Boulogne, and often with my parents. I can remember my father relating how one day he went with him to see one of the lovely daughters of the Baron de Taintegnies off to Paris, and how Lawrence was so infatuated with the young lady, that he jumped into the train, without any luggage, merely to have the pleasure of travelling with her all the way to Paris, a journey of about five hours. On reaching Paris, he saw Mlle. de Taintegnies safely to her destination, and then took the train back to Boulogne.

My parents were particularly fond of Lawrence, who was good-humoured, clever, and very amusing. I heard that he had a quarrel with Tom Hohler, who married the Duchess of Newcastle, on account of having introduced him into one of his novels, called “Breaking a Butterfly.” Hohler was very friendly with my father in later years in Paris. We had a white Pomeranian dog, and Tom Hohler asked my father to show it to the Duke of Newcastle, who was then a child, living with his mother in the Avenue d’Antin. The dog took such a fancy to the young Duke that it forsook us for him entirely. I heard recently from the Duke of Newcastle, who was kind enough to be interested in this book, that he remembered this Pomeranian dog quite well, and told me its name—“Loulou”—which I had entirely forgotten. The name recalled many things to my recollection. It is strange how at times we forget a name, and then, when it is mentioned, associations and incidents connected with it are suddenly recalled to our memory and flash before us as in a dream.

Tom Hohler sang for a time at Her Majesty’s Theatre. I never heard him sing in operas, but I have been told that he had a very pleasing voice, though it was not a very powerful one. It was said that when he sang in private houses, he was paid £40 for every song.

Harry Slade, a son of Sir Frederick Slade, stayed for a time at Boulogne with his mother, of whom we saw a good deal; and, after Lady Slade’s death, her son stayed for a long time at the Hôtel du Nord, where my father and I[39] often went to see him. He was a good talker and always very entertaining.

Mrs. Joe Riggs, an American lady, who afterwards became Princess Ruspoli, was extremely fond of Boulogne, and generally spent the summer at the Hôtel Impérial; but this was in later years.

A Painting by Romney—Hunter’s School at Kineton—Corporal Punishment—A Sporting Parson—My Schoolfellows at Kineton—The Warre-Malets—Lord Charleville.

Before going to school in England, I was taken to Richmond to see my mother’s aunt, Lady Caroline Murray, who was now an old lady and lived in a house near the Thames, for, as the Duchess of Gloucester, to whom she had been lady-in-waiting, had been dead some years, she was no longer at Court. In her younger days, Lady Caroline had been a good horsewoman and had ridden very well to hounds. But, at this time, she was leading a very quiet life, receiving only her relatives and friends.

I can remember that in Lady Caroline’s drawing-room at Richmond there was a most beautiful picture of her mother, Viscountess Stormont, British Ambassadress to France and Austria, painted by Romney. It represented the Countess in her own right, as she afterwards became, sitting beneath a large tree and wearing a kind of loose peignoir of a pale yellow colour, like the colour of the sea just before a storm. The peignoir was fastened at the shoulder by a brooch, in which was a large yellow stone. Her hair was dressed high above the head, in the style of Marie Antoinette, in whose days her husband was Ambassador in France, and over it she had a Scottish plaid of the clan to which she belonged. One leg was crossed over the other, and her arms were folded. She was painted in profile; her peignoir, open at the front, displaying a perfect bosom and a beautiful, swan-like neck. Her hair possessed that glorious auburn tint with shades of gold in it, which made it appear as though the sun were shedding its full rays upon the gold tresses, one of which had[41] escaped from the rest and hung loose. Her face was of a tender oval, with expressive eyes of a peculiar shade of green, like that of the sea when the sun falls upon it, or as it is in Böcklin’s pictures. Her nose was straight and delicate, with nostrils like those of a Greek statue. Her mouth was unusually small, with a tiny upper lip, slightly curved; her chin short and classical. The expression on the face was of pride, of audacity, of childish innocence, of sentimentality, and it possessed a marvellous charm and attraction.

The Author’s Mother.

[To face p. 40.

This beautiful portrait, which Lady Caroline bequeathed to Earl Cathcart, as he was the head of her mother’s family, was once seen by a wealthy American, who said to the Earl, into whose possession it had then come:—

“Have you ever seen such a lovely woman as this in all your life?”

“No, I have not,” the Earl answered.

“Well, I guess you haven’t,” rejoined the other, “and I don’t think there ever was such a lovely woman on earth.”

And he offered Lord Cathcart £20,000 down for the picture, which the latter, though not a rich man, refused. The American then promised the Earl’s son, Viscount Greenock, £500, if he could persuade his father to accept the offer; but it was all of no avail.

I showed Mr. Noseda, the well-known print-seller in the Strand, the engraving of this picture by J. R. Smith, which had belonged to my grandfather, when Mr. Noseda told me that he very much preferred the engraving to the painting, as the latter had been so much touched up, whereas the former was so beautifully executed in every detail that he considered it finer than Romney’s portrait. This was after I had told him about the offer of £20,000 which the American had made for the original painting.

Viscountess Stormont had been Ranger of Richmond Park, and was allotted, as her official residence, the house which is now the Queen’s Hôtel. An old gentleman whom I met at Richmond in later years told me that he thought the hôtel ought to have been named after the Countess of Mansfield, as Lady Stormont became later, instead of being called the[42] “Queen’s.” He remembered Lady Caroline Murray, and remarked that she was one of those ladies of the old nobility who were scarce nowadays.