Title: Jack and his ostrich

An African story

Author: Eleanor Stredder

Release date: April 17, 2025 [eBook #75898]

Language: English

Original publication: London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1900

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

JACK AND THE OSTRICH.

An African Story

BY

Eleanor Stredder.

——————————

"I've a friend at my side,

To lift me and aid me, whatever betide;

To trust to the world is to build on the sand:—

I'll trust but in Heaven and my good Right Hand."

MACKAY.

——————————

T. NELSON AND SONS

London, Edinburgh, and New York

——————————

1900

Contents.

Chapter.

IX. HOW TANTE MILLIGEN MANAGED

XIII. HOW THE LETTER WAS POSTED

XVI. THE SCHOOLMASTER'S GRATITUDE

JACK AND HIS OSTRICH.

A HOME ON THE VELDT.

JACK TREBY loved to say that he was an English boy, although he had never seen the dear old mother country of which his father so often talked; for he was born among the wide South African plains, where through the parching summer the sun-rays burn like fire, where the dry leaves shrivel with the heat, and the flowers can only bloom in sheltered places. Yet he was the proudest and happiest of boys when his father stroked his curly head and called him a "true-born Briton."

For Jack was his father's all—his joy and treasure. In that wide, lonely plain they had but each other. Their nearest neighbour was a good twenty miles distant across country, and he was a Dutch Boer.

There was a Hottentot woman, with arms and face as yellow as a duck's bill, who lived in a hut at the other side of the farm-yard. She cooked the dinner and washed the shirts for Jack and his father. She was always ready to do anything she could to make them comfortable, if she only knew how. Jack called her "Old Tottie," or "Granny Golden-face," when he was in a roguish mood; for she had been very good and kind to him when he was left a little motherless boy.

Then there were the Kafir men, as black as ebony, with naked legs and arms, and just a dirty scarlet blanket twisted round their waists—handsome fellows, who came and worked for Jack's father every now and then; working diligently and well until they had earned money enough to buy a rifle or a new blanket, when they would throw down the spade and flail and go back to their own people.

Jack's father was not a rich man. He had not much money when he came out to Africa, so he bought his farm where farms were the cheapest—right out in the wilds. It was life in the rough. No wonder he kept his little boy always at his side. It made a man of Jack, for he learned many things in his long talks with his father which a boy of ten in England would know nothing about. Jack learned more in this way than he did from books; for his school-hour was the last hour at night, when his father's work was done, and when both of them were very often sleepy.

On one delightful summer evening, when the brilliant African moon poured down its floods of silvery light, Jack sat nodding on the door-step with a coloured map of England spread upon his knees. He was trying to rub the sleep out of his winking eyes with one hand, whilst with the forefinger of the other he tried to trace the boundaries of the English counties.

"York; chief town, York," he cried triumphantly. "But, father, what word is this?"

Jack ran off with his map to where his father sat smoking on a rough bench, in what should have been their garden, only there was so much work to be done on the farm and so few to do it that the garden was left to Jack and nature. A hedge of prickly pear kept the oxen from trampling over it. Jack's watering-pot encouraged one tall cactus to show its scarlet flowers, under the shadow of the broad eaves of the low thatched roof of the farm-house.

Jack's father nodded, and then roused himself with a smile to answer his son's inquiry. "That, Jack? Why, that's Nottingham—the very town where your grandfather still lives."

"I'll make a mark against it," said Jack. Dashing back into their one sitting-room for the pen and ink, he made a good round blotch right over the name.

"Well done," laughed his father. "So you think erasing it in your map will stamp it in your mind, my boy. Come, we are dead-beat to-night, and must give it up. Tomorrow we will have a good spell at the figures. So now to bed; the faster the better."

Jack gathered up his books and went indoors.

His little bedstead was an officer's camp-chair, which his father had picked up second-hand at the Cape. It stood just opposite the bedroom window, in the same room with his father's. Between them were the well-battered black travelling-chests his father had brought with him from England; and on the pegs over the head of his father's bed lay his rifle. Every night it was loaded and ready for use. Jack was often in the room alone with it; but then Jack could be trusted anywhere.

He said his prayers and tumbled into bed; but not to sleep, for his thoughts were busy with Nottingham and grandfather.

The house was only one story high, and the room had no ceiling. Jack could look between the rough wooden rafters right up into the thatch, and watch the bright eyes of the tarantula spiders as they crawled along the beams. He heard his father speaking to Tottie's husband, a white-haired Hottentot, who knew the ways of the country, and was by turns ploughman, shepherd, and house-servant.

"Sheep all right," he heard them say, and lifted up his curly head to look at the white walls of the sheepfold; for an African sheepfold has a stone wall all round it, and a good strong gate, which is safely locked at night-fall. Jack knew very well that this flock was his father's chief wealth. There was not much ploughing and sowing with so few hands to depend upon. The sheep were everything.

By-and-by his father came in, gave his little son his customary good-night kiss, and stretched himself on the truckle-bed in the other corner, to enjoy the sweet sleep of the labouring man. Jack was careful not to wake him.

The glorious splendour of the South African moon made the room as light as day, while all without was flooded with a silvery radiance, so beautiful that our little Jack felt more wide awake than ever. He was watching for the stars as they shone out one by one, so much larger and brighter than we in England have ever seen them.

Presently he saw something black on the wall of the sheepfold. He sat upright. It moved. He saw it fling out its long dark arms; and then another and another patch of black seemed crawling up behind it.

Suddenly it flashed into Jack's head,—

"'Whosoever climbeth up by the wall into the sheepfold, the same is a

thief and a robber.'"

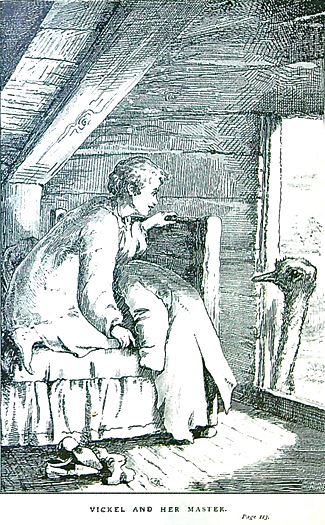

Out of bed he jumped, shouting, "Father! Father!" At the same moment, Jack's grand pet, the tame ostrich Vickel, set up a loud noisy scream.

Vickel, as Jack's father had often said, was as good a guard as a mastiff. She had been given to Jack when she was a three days' chicken, looking like a round ball of dirty yellow fluff, and he had fed her with his own hands every day; and now as she stretched out her long neck she seemed as tall as the porch. She was crying "Thief! thief!" in her bird fashion, as plainly as any English watch-dog would growl "Thief!" to his master.

Jack's father was out of bed in an instant, with his rifle in his hand, just as the last black figure dropped over the wall into the sheepfold. He fired his rifle into the air, hoping the sound of the report might scare away the thieves, and began to dress in all haste.

"Keep where you are, my boy," he said, "and on no account leave the house. Put the bar in the bedroom door as soon as I am gone. I'll shut Vickel in the outer room, and she'll keep everybody else from coming in. Be a brave boy, and just lie still until I return."

"I'll be as still as a mouse, father; but hadn't I better get into my jacket?" answered Jack.

"Yes, dress," returned his father; "only be still."

Mr. Treby reloaded his rifle and crept out.

Presently, Jack heard the brush of Vickel's wings as she made the tour of their sitting-room.

"Don't do mischief, Vickel," gasped Jack with a catch in his breath very suggestive of tears; but he choked them back with all his might.

He stood with his little hands clasped tightly together, watching through the window, yet not near enough to it to be seen from without.

He saw his father creep cautiously along, in the shadow of the farm-yard wall, towards the great open shed where the oxen were tethered, and saw him climb into the heavy broad-wheeled waggon, which was drawn under one end, to shelter it from the sun. Now that Mr. Treby was mounted in the waggon, where he could see and not be seen, Jack felt easier. He thought of his dying mother's words, "In every trouble, pray;" and kneeling down at the bedside, he whispered,—

"Save, Lord, or we perish—"

When the flash and report of his father's rifle seemed to shake the house. The oxen bellowed and tore the ground in their infuriated terror. Jack started to his feet and ran to the window.

"Maw wah!" groaned the old Hottentot, who was crouching under the eaves, and caught sight of Jack's pale face. "He'll take 'em as they come out," he whispered, making emphatic signs to the boy to go back.

Jack knew that he must not let himself be seen. He remembered his father's charge, and moved away! What happened next he could not tell. There was a shout of savage glee, a wild, unintelligible yell. Vickel screamed like mad. A sudden light without—a strange, oppressive heat—and then a dense smoke began to fill the room.

Jack dipped the towel in the water-jug and put it over his head, for bright red sparks began to fall between the rafters.

"Father! Father!" he shrieked, forgetting his promise to be still in this unthought-of danger.

The ostrich heard his piteous cry, and split the door between them with her powerful beak. Then Jack drew out the bar and let her in. She flew past him, and in her frantic efforts to escape dashed against the window, smashing glass and frame to atoms. Jack drove her with all speed through the flying splinters. She was almost out of the window, when the glare from the blaring roof so frightened her that she drew back with a scream. After wheeling round and round the room, Vickel tucked her head under her wing like a true ostrich, as if shutting her eyes to the danger she could no longer escape would save her.

Jack was so well used to Vickel's ways that he knew he could catch her now easily enough. He had seen his father throw a fishing-net over her and haul her off when she was doing mischief in the garden. He managed to pull the blanket off his bed and throw it over her; but his limbs were heavy, and he felt like one moving in a dream.

At last he heard his father calling, in an agony of desperation, "My boy! My boy! Heaven help me! Where's my boy?"

"Here, father, here," Jack tried to answer, but his voice sounded feeble and strange even in his own ears. Things were falling all around him. Lights were flashing, and confused noises rang in his head. He was going, going somewhere. Then the dreadful feeling of oppression lightened, and he knew that the strong arms which clasped him so tightly were his father's.

Something he murmured about getting a hood for Vickel, as his father lifted him through the broken window and gave him to the Hottentot.

Once in the open air, Jack began to revive. The Hottentot laid him under the garden hedge, and charging him not to cry, ran back to help his master.

Poor little Jack gazed at the blazing roof with a bewildered face, as his senses slowly returned to him. Suddenly it flashed upon his mind that his father was still in the burning house, and staggering to his feet, he tottered round the garden. He was just in time to see Vickel, who was still enveloped in the blanket, hauled out of the bedroom window, as if she had been a sack of wheat. Like himself, she was stupefied by the smoke, or it would not have been so easy to save her.

"Drag her away!" shouted his father, as one of the great black chests was hoisted into the opening.

The Hottentot tugged at the ends of the blanket. Down came the heavy chest with a thud, and Jack's father sprang on to the window-sill, with his face as black as a Kafir's and his shirt sleeves in a blaze. He threw himself on the ground and rolled over and over.

The Hottentot snatched the blanket from Vickel's head and wrapped it round his master. Between them the flames were soon extinguished; for Mr. Treby seized some heavy sods, that were lying in a heap where he had been digging the day before, and crushed the burning shirt beneath them, plunging his arms into the midst of the heap.

What could poor Jack be thinking of when he saw his father burrowing in the ground, and the Hottentot twisting the blanket round and round his shoulders, as if he were about to choke him? For he ran away!

UP IN THE MORNING.

YES, Jack left his father writhing on the ground and ran away. But it was to find Tottie. Ah, where was Tottie? Jack reached the hut, and it was empty.

Suddenly the two men looked up and missed him, and the shouts for the "The child! the child!" roused poor Tottie from her hiding-place.

At the first alarm she had crept into the "sloot," that is, the deep ditch which ran round the back of the farm. But the thought that Jack was missing conquered her terror, and she crawled out, plastered with mud from head to foot.

No one could have taken her for a woman; for she crept on her hands and knees, listening with her ear to the ground, as she heard the patter of the sheep, and felt sure that the thieves were driving them away. She was the first to catch sight of Jack coming out of her hut, and made signs to him to hide himself. He darted back into the corner of the hut, crouching in the dark, and waited while the sheep went by.

He heard his father's voice shouting "Jack!" round the burning house, but he dared not answer.

After a while, Tottie, still crawling on her hands and knees, peeped in at the door to see if he were safe. How she hugged him in her joy at their great deliverance, for she assured him that the thieves were gone; yet they dared not venture forth too soon. Tottie lay with her ear to the ground, almost afraid to breathe, listening to the roar of the flames and the falling of the rafters. A stealthy step was drawing near the hut; a gasping sigh was heard in the very doorway. Jack clung to Tottie now and shivered. A head was put in at the door. It was his father.

"Safe! All safe!" was echoed from lip to lip, as the four seated themselves on the ground, for the white-haired Hottentot was behind his master.

Then Tottie got up and found some food and water that were in the hut, and pressed them all to eat.

"The utmost we can do now," said Jack's father, "is to protect ourselves. The thieves must take what they will."

"They are gone," cried Tottie.

But the cautious old Hottentot dared not believe her; so they sat still and listened until the day began to break. Jack's head was resting on his father's shoulder but no one slept.

The flames were over but a dull, red glow still lit up the gray of the western sky when Mr. Treby ventured forth to reconnoitre.

The sheepfold and the shed were still standing, but not one lamb was left. His house lay in ruins. Every leaf in his garden which the sun had spared was burned and blackened with the fire.

But the agony of the night, when for one brief hour his scarcely-rescued Jack was missing, made him think far less of the actual loss than he would otherwise have done.

He fed the oxen, which were still lowing in the stalls, and dressed his blistered arms with a handful of their meal, thankful to find the little hut he used as a store still standing.

He had gone the round of the farm, and was slowly returning, when something moving on the other side of the sloot attracted his attention. Keeping a keen lookout, he crossed the ditch with his rifle on his shoulder, when he saw Vickel stretching out her long legs and gaping. His own shirt was dropping into tinder, and her beautiful gray wings were singed and shrivelled.

At the sound of her master's voice, the frightened bird ran after him, and tucking her head under his arm, expressed her consternation by sundry hoarse screams as he took her back with him to the Hottentot's hut.

Up sprang Jack, almost as overjoyed to find Vickel safe as his father had been to find him uninjured on Tottie's lap.

"Never so bad but it might be worse," said Jack's father, stroking the curly head more fondly than ever. "Jump on Vickel's back and ride after me, for I cannot bear you out of my sight. You could not know what you were doing to run away from me as you did in the night. You might have been killed."

"I was looking for Tottie," said Jack repentantly. He was afraid that he had made his father angry; for Mr. Treby turned his head away, but it was to brush the tears from his eyes, as he murmured,—

"God bless you, my brave, true-hearted boy!" Then he added with a laugh, "We must all to work. The first thing is to ask our neighbours to help us to get back the sheep. I shall send the Hottentot to Scarsdorp. Tottie must watch the ruins. She is better able to take care of herself than you think, for you can't beat her at hide-and-seek. Then you and I, Jack, must take the ox-waggon, and try the temper of our neighbour the Boer. We English do not reckon them the best of friends, for they do not want us here. But I found a stray cow of his last year, so he owes me a good turn."

Jack felt like a man as he followed his father from place to place, sometimes riding on Vickel's back, sometimes jumping down when he thought he could help in his father's preparations. He filled a sack with mealies, as they call the Indian corn, ready to feed the oxen by the way.

Soon after the sun had risen, whilst the morning air blew cool and fresh, Jack was seated by his father's side in the front of the big, lumbering ox-waggon. Everything which Mr. Treby had been able to save from the fire was packed inside, for he was afraid to leave them in an open shed, with no better guard than Tottie.

The fowls had all been scared away by the sight of the flames, and were wandering at will amongst the low bushes which dotted the plain they were crossing.

The sky above their heads was one unclouded blue, and in the red sand which covered the plain the dusty ants were fighting.

It was no easy matter to find the right path in such a wilderness of sand and bush, where there were no hills or trees to serve as land-marks. Jack's father had to look carefully on the ground for the ruts which had been made by the wheels of the post-cart.

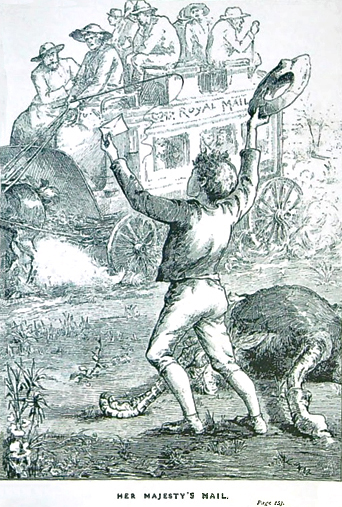

Jack knew that post-cart well with its six gray horses. It was their one link with the outward world. How often he had stood beside his father listening for the loud blast of the bugle which heralded its coming! For the arrival of the English mail is a day of joy to the colonist.

Presently Jack's father looked up and pointed with his whip to a heavy cloud of dust.

"It is the mail!" he exclaimed. "For once I am fortunate."

"No, father," persisted Jack, who was looking the other way; "I am positive it is Vickel."

Nearer and nearer came the storm of dust thrown up by the galloping horses, but Jack's eye was fastened on a light-gray figure skimming above that billowy sea of reddening sand.

Mr. Treby drew his waggon out of the path and halted. As the Pretoria mail-cart came in sight, with its usual freight of passengers filling the seats and even clinging to the sides, Mr. Treby waved his handkerchief, and the six powerful grays drew up, stamping and snorting.

"Any letters for me?" he asked anxiously.

"Any mischief doing in this neighbourhood?" was the answering inquiry, as Mr. Wilton, the postman, opened his bag and sorted over its contents for an English newspaper.

"We noticed an uncommon glow in the sky at our last halting-place," put in one of the passengers.

"A little past midnight," added another.

"We have kept a sharp lookout as we came along," continued the postman. "We were all of one opinion—there was a fire somewhere out on the veldt," for so the great African plains are usually called.

"A fire!" repeated Mr. Treby bitterly. "Look yonder, where the smoke-wreath rises above a smouldering ash-heap, where last night, gentlemen, you would have seen a happy home—my home," he repeated in tones that wakened the sympathy of his auditors.

For in those far-off wilds, Englishmen meet as brothers. Each is ready to help the other; for who can tell that, in the next turn of fortune's wheel, their own need may not be as pressing.

Grave and anxious faces were turned to Mr. Treby, and many a deep-voiced exclamation of anger and pity interrupted his account of the night-attack upon his farm.

"It is the beginning of a general rising among the Kafirs," said one.

"A very ominous occurrence," observed another, shaking his head.

"I'll do as you desire," promised Wilton. "I'll gallop on to Pretoria as hard as my horses can go and lodge the information with the captain of the mounted police. Had not you better come too?"

"No," returned Jack's father; "the journey would be too long for me. I was a poor man yesterday; to-day I'm but ten steps from beggarhood. I am on my way to warn my neighbour, Van Immerseel. He counts his sheep by the thousand, and the next attack may be upon them. It was the sheep the villains wanted; and I had no help on the farm but one old Hottentot and his wife, so that I was single-handed against five. They thought to stop my rifle by flinging the firebrand on the thatch; and indeed they gave me enough to do to rescue my little boy from the flames."

"Cheer up, old fellow," said one, "and tell us what we can do for you."

"A round of shot and a coat, if it is not asking too much," ventured Jack's father. "I shall be able to dig out something from the ruins as the ashes cool; but my bullets will be melted into one lump by this time and my money into another."

There was despair in the laugh with which this was said, but it was the despair of a brave man who, when he feels the wreck of hope, still works on.

More than one shot-case was opened and the contents divided, before Mr. Treby had finished speaking.

"What will you take for the fore ox with the crumpled horn?" asked a dark-haired man, who was holding on by the side of the post-cart.

"Market price," answered Jack's father eagerly.

Of course there was a show of disputing over the worth of the stalwart beast, after the usual fashion of buyers and sellers; but it did not last long. Mr. Treby unyoked the leader from his team and tied him by a long rope to the back of the post-cart.

While the stranger was counting out the ten pounds in English money, which he finally agreed to give for the ox, Vickel overtook the waggon. She flew wheeling round and round for a while, drawing nearer with every circle, until Jack, who had been listening most eagerly to the conversation, perceived her manœuvres. So, whilst his father was busy with the ox, he crept to the back of the waggon, and parting the heavy tilt, took her in.

Vickel sprang up eagerly enough at the sight of her Jack's face; but when she felt the waggon move she was frightened.

Jack's arm was round her neck in a moment, as if he thought he could hold her against her will.

"I'll keep you somehow, Vic," he whispered. "You have grown such a big chick I can't hold you. Come, you must go; bye-bye."

Pushing his fingers through a little hole in the sack of mealies, he got a few in his hand, and whilst she was picking them up, he slipped off one of his stockings. He poured another handful of the mealies into it and held it before Vic. Down went the long beak, snapping at the corn, which slipped lower and lower in the stocking. This was just what Jack wanted.

"You good old darling!" he exclaimed, pulling it right over her head and half-way down her long neck, until it fitted. The big bird became as passive as a dove. She folded her long legs under her and sat down on the sack of mealies. Much elated with his success, Jack climbed on to her back and held the stocking fast with both hands.

"Well done, my little man," said a diamond-digger who had been watching him from the back of the post-cart. "You've learned the trick of the ostrich-catchers, I can see."

"She is mine," answered Jack proudly. "She has followed me right across the veldt like a dog."

"And what shall I give you for her?" asked stranger, shaking some gold in his hand.

"I sell Vickel!" exclaimed Jack in anger and disgust. "No, never."

Mr. Treby hesitated for a moment. "In such a strait as ours, Jack—" he began.

Jack looked up into his father's face, and burst into a flood of tears.

"No, I can't do it, gentlemen; it would break his heart. I can't part them. She has been his only playfellow, you see. Thanks, many, all the same," added Mr. Treby, turning to the kindly passengers.

There was a broad grin on the diamond-digger's face; but the postman laughed good-naturedly. "How about the coat?" he asked.

"I can pay for it now," put in Jack's father, "if any one of you could accommodate me."

But not for love or money could a coat be obtained, simply because not one of those travel-stained, way-worn travellers had a second with him.

"Passengers by the Government mail from Natal to Pretoria have for the most part to leave their luggage behind them for the transport-rider's waggon," explained the postman. "Is there anything I can bring you from Pretoria as I return?"

Jack's father considered a moment or two, counted the money in his hand, and dictated a short list of necessaries, which the postman wrote down in his pocket-book.

As he gathered up his reins, he tossed a broken biscuit to the sobbing child, and with a chorus of farewell wishes from the passengers, set off his horses at a rattling pace. The lumbering waggon was soon distanced.

Mr. Treby saw the passengers lean forward in anxious discussion; and many a backward glance was cast upon the burnt rags, which were dropping from him at every step. But he knew that his wants would not be forgotten; and more than that, his warning would be faithfully given to every farm-house on their route.

He was lost in his own thoughts, whilst Jack munched his biscuit in silence, watching his father's troubled countenance.

A groan burst from Mr. Treby's lips as the post-cart was lost to sight, and not a sight or sound of human being disturbed the stillness of that vast treeless plain.

Then two small fearless arms were clasped about his neck, and little loving kisses covered his bearded face as Jack whispered, "Did you really mind me keeping Vickel?"

AFRICAN NEIGHBOURS.

FOR an hour or two during the burning heat in the middle of the day Mr. Treby was obliged to rest. Here and there the veldt was crossed by little streams. By the edge of one of these the waggon halted. In places it was nearly dry, yet the milk-bushes, with their long waxen leaves, grew taller by its margin.

Jack and his ostrich were glad to alight and stretch themselves, for Vickel could not stand upright beneath the tilt without knocking her head. A good play amidst the waving tufts of tambouki grass refreshed them both.

When Mr. Treby had fed his oxen, he sat down under the shadow of the nearest bush, and called Jack to share the dinner which Tottie had provided for them. The ostrich found her own amongst the loose stones and sprouting leaves by the brook.

When they were ready to start again on their journey, Jack's father gathered a nice bundle of the long, dry grass to make a bed for his little boy in a corner of the waggon. Jack coiled himself up in it like a bird in its nest, and found it very comfortable, whilst his father calculated how far the ten pounds could go. He had neither pencil nor paper, so he made his figures with the point of his penknife on the side of the waggon.

It was fortunate, he thought, that the knife was in the pocket of his trousers. As he felt for it, he pulled out the newspaper the postman had given to him. It was the last number of the "Illustrated London News." What a burlesque, it seemed to him, to receive it in such circumstances!

"Here, Jack," he said, "here is something for you to look at. Take care of it, my boy, for I was just thinking you might forget how to read before we had another book to call our own. We shall want so much to build the house again."

"I shall never forget how to read, father," answered Jack decidedly; "and I can write with a burned stick on the wall of Tottie's hut, or make figures, as you are doing now, for I have got my knife as well as you." He dived into the pocket of his jacket as he spoke, and produced a stout clasp-knife, which had seen a deal of service in the garden.

"All right," returned his father. "We must gather up the fragments. Every trifle may be of use."

Then Mr. Treby went on with his calculations, and Jack lay back in his nook, with the big rush-hat Tottie had found for him tilting over his eyes. How he enjoyed his lovely pictures; whilst Vickel, who had become more reconciled to the jolting waggon, diverted herself by enlarging the hole in the sack of mealies.

When Mr. Treby looked round again Jack was fast asleep, with the precious paper still in his hand. The poor child was worn out with the alarm and excitement of the previous night, so his father was careful not to disturb him; for he said to himself with a sigh, "No one can tell what may lie before us."

Jack did not rouse until the glorious African sunset had tinged the lonely veldt with molten gold. Hard-winged, spotted insects buzzed in and out of the waggon. One blood-thirsty mosquito refused all notice to quit until Vickel snapped at it most ferociously.

But they were near their journey's end. The zinc roofs of the Boer's farm-buildings glowed like fires in the distance. Behind them was the wide flat plain, one dull, monotonous red; before them rose the rocky hills, the boundary of Jack's horizon. He had seen them looming cloud-like in the distance as long as he could remember anything; but now, as the waggon rumbled on, and they came nearer and nearer, as the daylight faded, they seemed to alter into some big blur of brown, blotting out the ruddy sunset gold. The clumps of bush grew larger, and now and then a shy antelope darted across their path. Jack sat up, resting one hand on his father's knee. The weary oxen dragged heavily along.

"Jack," said his father, "just one more mile. We are close on Jaarsveldt. Cheer up, my boy."

Then Jack began to sing, but his father stopped him. "Hush, there is somebody coming."

A wild cat scampered over a ridge of stones and made the oxen bellow. She had been startled from her lair by the approaching horseman.

"There they come," continued Mr. Treby, as a powerful black horse with an equally ponderous rider emerged from the shadows; two Kafir attendants followed, dragging between them a buck antelope. Some smaller game was hanging to their master's saddle. "I ought to know that young giant," soliloquized Mr. Treby. "He must be a son of Van Immerseel." It was evident that the hunting party was returning to the farm.

As they drew near to each other, the young Boor stared hard at the ox-waggon and its ragged driver. But despite his forlorn appearance, Mr. Treby raised his hat with the air of an English gentleman, and pointing to the homestead before them, asked him if it were the residence of Van Immerseel.

The gigantic youngster stared and scratched his head, answering with a sullen "Jah" (Yes).

Mr. Treby's knowledge of Dutch was small, and young Immerseel knew nothing of English, but he comprehended that it was his father Mr. Treby wanted, and invited him by gestures to join company. He walked his horse by the side of the waggon, and laughed most heartily when Vickel poked her long neck through the tilt, which she had been strenuously endeavouring to slit for the last hour. But his exclamations were in Dutch, and Mr. Treby failed to catch their import.

When they passed the outlying ostrich camp belonging to his father's farm, he pointed it out, and Mr. Treby expressed his admiration for the large flock of majestic birds it contained, by nods and smiles. But the proximity of so many of her feathered kin disturbed poor Vickel sorely, and taxed Jack's ingenuity to the utmost to keep her in bounds. Young Immerseel soon sent his black followers to the right about, the antelope was left under the wall of the camp, and one of the Kafirs ran forward to apprise the family at Jaarsveldt of the approach of the waggon.

The house was large, low, and square, of substantial red brick. On one side was the orchard, on the other extensive sheep-kraals; for where Mr. Treby had counted his sheep by the score, Van Immerseel counted his by the thousand. The water in the dam shone like silver beside the dark row of Kafir huts where his servants lived. The house was surrounded by a low wall, which enclosed the garden and farm-yard. At the open gate stood the strong-built, broad-shouldered owner. His habitual hospitality was tempered by his surly dislike of the English.

"Walt," he shouted to his eldest son, in a voice so gruff and deep that Jack thought it might have belonged to the strongest of their oxen.

"We must not be dismayed at that, Jack. These 'Ooms and 'Tantes' are a worthy race, if you can but get on their right side," observed Mr. Treby.

"Ooms and tantes?" repeated Jack inquiringly.

"Yes; uncles and aunts, as we should say," laughed his father. "The Boers and their wives are uncles and aunts to all the rest of the world. Pray, don't forget that. Now take the reins."

Mr. Treby sprang lightly to the ground, and walked up to his burly neighbour with outstretched hand, offering the customary salutation of the Dutch, "Dagh, oom" (Good-day, uncle).

Slowly and sullenly the hand was taken, but the unwilling pressure tightened to a hearty grip as the Englishman hastened to explain his object. This was not an easy matter, but he pointed to his burned clothes, about which the smell of smoke still lingered, and then across the silent veldt to where a dull black column of smoke rose up ominously in the far distance.

"Burned out!" The Boer comprehended thus far in a moment.

The shepherds at Jaarsveldt had also seen the ruddy glow in the midnight sky.

The sullen frown began to change its character. The wrinkled brow was puckered still, but with most genuine concern. He slapped Mr. Treby on the back, and forced him to enter; whilst his son gave his horse to one of the Kafirs, and lifted Jack out of the waggon as if he had been a baby, mounted him on his shoulder, and marched off, laughing, to the house.

From such an unwonted elevation, Jack had an excellent view of the house they were approaching over his father's head. But this hardly consoled him for the loss of dignity.

A wooden staircase outside the house led to the upper story, which was little better than a loft, and was used as the general store for every variety of household goods and discarded lumber. The door of the house was cut in two, like an English stable door, and over the lower half, which was closed, Tante Milligen was hanging, anxious to see what sort of people her husband was bringing. Around her stood her black and yellow maids, excited and eager, for the arrival of the strangers was a pleasant break in the dull monotony of their daily life. At a word from the "oom," a woolly-haired black (with nothing but a dirty scarlet blanket twisted round her waist) was sent running with a message, but to whom or where Mr. Treby had no idea.

Tante Milligen threw open the door, and dispersing the little knot of servants and children, invited the travellers to enter.

Jack looked round the large white-washed room with some surprise. The heavy chairs and lumbering settee were covered with home-tanned skins; but the curiously-spotted floor attracted the most of his attention. It was made of clay, thickly dotted over with plum-stones, well polished by the friction of many feet.

An ample supper was awaiting the return of the young hunter—huge joints of beef, from which the rations for the numerous dependants had been already cut; piles of roaster-cake; and above all, a well-filled basket of grapes, oranges, and peaches.

At first poor Jack was almost dazed by the sudden change from the shadowy night to the bright lamp-light within the Boer's "sit-kamé" (sit-chamber, or sitting-room, as we should say in English). More bewildering still was the buzz of strange voices around him, every one speaking in a language he could not understand. Walt placed him on the wondrous floor, in the middle of the room, and called to his younger brother, a boy about Jack's age, but twice his size, "Zyl, Zyl."

Jack caught the name, and smiled, as a lumpy, sheepish-looking boy answered the brotherly appeal, by seizing him by both hands and dragging him to the table, around which the family were gathering. Their sister, a fat, freckled girl of thirteen, sat staring at him, with her thumb in her mouth, until poor Jack grew very hot and uncomfortable, for he was as black as a sweep and as shy as a wild rabbit. He wanted to keep close to his father, who was doing his best to cover up the awkwardness of his introduction, and make the most of the few Dutch phrases he could command.

In vain Jack tried to edge a little nearer to him. Between Walt and Zyl there was no escape. Tante Milligen loaded his plate with the tough beef, which at that hour of night he knew not how to eat. His eyes were fixed upon the corners of the room, in one of which lay a little bundle of blue and white check, and in the other the head and horns of the bullock whose ribs they were eating. Presently the bundle rolled over, and Jack discovered by its snoring that it really was a sleeping child.

Just then the black maid returned, followed by a young man in a pepper-and-salt suit, with an English hat. Jack's father brightened, for he saw by the cast of the stranger's countenance he was a German, and guessed that the Boer, who was probably his master, had summoned him to act as interpreter.

This new-comer was quickly seated at the family supper-table, between Van Immerseel and Mr. Treby. Yes, it was fortunate this young Otto, the German shepherd, knew about as much of English as Mr. Treby did of Dutch. With his assistance a sort of patch-work conversation was carried on.

"Vat ou zay?" the Boer inquired continually, for he was slow of understanding.

The one fact "burned out" had been made plain to him. To this he now added, "set on fire." When at last he was made to comprehend, "sheep gone," he laid down his knife and fork in sympathetic consternation. After a while they began to understand each other better. Walt, who seemed far more intelligent than his father, became an interested listener, and quickly grasped the position in which the unfortunate English farmer now stood. He scratched his head, as if recalling some occurrence to his memory; and then rubbing his hands gleefully, thundered in Mr. Treby's ear, as if he thought the loudness of his voice would make his meaning plainer.

He had been hunting "velderbeeste" all day. Jah, he was sure he had crossed fresh sheep-tracks, leading to the rocks among which the free Kafirs had their homes.

"Follow them," counselled his father, and Walt's eyes brightened at the prospect of a fight.

Then it was Mr. Treby's turn to explain. He managed to make them understand that he was alone, having sent his only man to Scarsdorp to warn his neighbour there.

Whilst this conversational medley was taking place, Tante Milligen perceived poor Jack's vain endeavour to get through his supper, and kindly exchanged the gigantic slice of beef for roaster-cakes and honey. Zyl and his sister Genderen watched these disappear, and before the last mouthful was finished, piled his plate with grapes and peaches. After his long and dusty drive, the fruit seemed delicious; but in spite of his utmost endeavours, Jack was nodding over his supper.

With a good-humoured smile, Tante Milligen made a sign. Walt took him up once more, and laid him on the sheep-skin by the snoring bundle.

It was intolerable to be treated like a baby, just because they were all so big and he so little. Jack started up belligerently, but his father's eye checked him. So he contented himself with shrugging his shoulders against the white-washed wall, and staring at his "vis-à-vis,"—the bull's head—for he was far too indignant to bestow a single glance upon his sleeping companion.

"I should just like to show them the sort of stuff an English boy is made of," he thought.

JAARSVELDT BY DAYLIGHT.

"OUT-SPAN by our gate," said Van Immersed to Mr. Treby. "In the morning we may find out which way the sheep were driven. What could you do single-handed in the open, suppose those fellows should return? I am off with Otto and the lads to my own sheep-kraals. When once such work begins, who knows where it may stop? Those black neighbours of ours won't catch me napping; but you are beaten out of time already. Turn in till daylight."

Otto duly translated, adding to his master's advice the comforting remark that the black beggars could not drive away the veldt.

So Jack's father decided to live in his waggon a day or two until he knew what course to take. The Boar's view of last night's proceedings was similar to the postman's, that he felt it would be unwise to risk returning to his burning farm at present. Until the ashes cooled, nothing could be done. He only wished Tottie was with them; but Tottie, who had seen the marauders pass while she lay hidden in the sloot, did not believe they were Kafirs at all, but a pack of half-caste thieves, who would make away with their booty as fast as they could, and never think of returning. When they were gone, she saw no reason why she should leave her hut.

Meanwhile some of the Boer's men had unyoked Mr. Treby's oxen and secured them for the night. His pleasant way of speaking was so different from the rough manners of the Boers, they helped him gladly. Whilst they were thus engaged "out-spanning," as they say in Africa, Walt Immerseel cut off the horns from the bull's head, and putting one in his own pocket, offered the other to Mr. Treby.

"With these we can make each other hear if anything occurs in the night," he said, and Otto repeated.

When the danger-signal was agreed upon, Walt marched off to play patrol on the other side of the sheep-kraals.

Jack was already in his grassy nest, and now his father lay down beside him.

"There is no word of comfort for us to-night, Jack," he said despondently. "Our Bible was on the shelf, wasn't it?"

"Yes," answered his boy; "so it is burnt. Everything must be burnt by this time—everything that was in the house, I mean, father."

"Yes, I am afraid so," was the gloomy answer. "We must fall back on memory. Tell me some verse or other, my dear, before we go to sleep."

Jack thought for a little while, and then he began repeat softly,—

"Let not your heart be troubled, neither let it be afraid."

"That's right," murmured his father. "Troubled and afraid! It is just what I am to-night; but it won't do. I can't see our way out of this; but the Lord will provide. Draw a little closer, Jack; let me have tight hold of you whilst we go to sleep."

The sleep they so sorely needed came at last; but it was broken before daybreak by the heavy tramp of the Boer and his son returning to the house, for with approaching daylight the fear of an attack from the thieves diminished.

"All right," shouted Walt Immerseel, very proud of the new English phrase he had beguiled the tedious night-watch by learning from Otto.

Mr. Treby waved his hat in reply; then the Boer stopped, and beckoning to Otto, who was following, came up to the waggon. He seated himself on the shaft, and entered into a long conversation; but as Jack was only half-awake, he could not understand what they were saying.

Walt had gone into the house, but he soon came back with a huge cup of steaming coffee and a plate of cold beef left from the last night's supper. Evidently the hospitable Boers did not mean to let the poor Englishman starve.

"Now, Jack," said his father as soon as they were alone, "I am going away with young Walt and his men to follow the sheep-tracks they saw yesterday, so I must leave you here. You will be quite safe, as all the farm people are astir, and they seem very kindly disposed. You must be a man, and take care of the few things we have saved. Tante Milligen has offered to look after you. Don't take offence at their queer ways. You were so tired last night you were almost cross. I have told them you would rather stay in the waggon, and we may not be gone long."

Jack felt a strange rising in his throat at the thought of being left behind, but he set his teeth hard. One thing he was quite sure about—he was not going to add to his father's trouble in any way; so he gulped back the rising tears, and answered bravely, "Never mind me, father; I shall get on somehow."

He drank a little coffee from his father's cup, and then lay down again in the dry grass. Mr. Treby covered him with the tattered remains of the blanket which had hooded Vickel, and then went to fetch a pail of water from the farm-pond. When he returned, Jack was fast asleep again.

His father took good care not to waken him. "The longer he sleeps the better," he said to himself. "It will do him good, and he will not miss me so much."

But Jack was sorely vexed when he roused at last to find his father fairly gone. With a stretch and a shake Jack got up, and gave Vickel her breakfast from the mealie sack; then he made himself a seat on the corner of the chest, much wondering what he should do for his own.

It was a glorious morning. He could hear the bleating of the calves in the farm-yard and the far-off tinkle from the sheepfold; but the big brown hills, with their rocky steeps, attracted the most of his attention, until he heard the shrill voices of the Kafir servants as they went about their daily work. Then Jack shrank back shyly, and contented himself with stroking Vickel's wings. It was grievous to see how her beautiful feathers were burnt and singed.

Jack tried to make her look a little better by brushing off the browned tips, when the tilt was suddenly parted at the back of the waggon and a smiling baby face peeped in; for when the Boer's children met at their early breakfast, they could talk of nothing but the little English boy. Zyl had already ascertained that he was still asleep in the waggon, and Genderen was looking forward to carrying him some breakfast. The presence of the little stranger seemed to them a very pleasant adventure. Jack's companion on the sheep-skin, baby Sannie, felt really aggrieved to think she was the only one in the household who had not seen him. But their mother charged them on no account to waken the poor child.

Still Zyl thought there could be no harm in letting his little sister have just one peep at their sleepy visitor. So when they ran out to play, he mounted her on his shoulder. Away they went through the gate, and climbing up the back of the waggon, startled Jack, who had never seen so young a child before. He paused in his grooming, lost in admiring surprise. It was a dear little face, in spite of its broad Dutch features, so sunburned and freckled; and the big blue eyes that stared at Jack looked so innocent under the mass of flaxen curls, which completely covered the low forehead, that he involuntarily exclaimed, "You little dear."

But Vickel was far from sharing her master's feelings. Her head was still full of thieves; and making a dart forward, she struck angrily at the infantine intruder. Zyl dragged his sister backwards, but Vickel had caught the blue-checked pinafore in her beak.

Jack was frightened. He sprang upon Vickel's back, and seizing her head with both his hands, tried to make her let it go. Zyl tugged with all his might; but Vickel was stronger than either of them. Zyl growled out something Jack could not understand. Little Sannie screamed vociferously. Before the boys could extricate the pinafore, it was torn to ribbons. Jack dared not release his bird, for fear she should fly on to Zyl, who had struck at her more than once with his clenched fists.

Sannie was more frightened than hurt. Zyl had tumbled her down on the ground whilst he tried to fasten the back of the tilt, for fear Vickel should swoop down upon them, in spite of Jack's endeavours to restrain her.

"Is your sister hurt?" asked Jack repeatedly, but Zyl only answered with angry snorts. He grasped Sannie's hand and ran off with her, banging the gate after them, whilst Jack alternately scolded and soothed his refractory pet.

"O Vickel," he groaned, "what have you done? That boy will tell his mother what a dreadful bird you've been; and then I don't know what will happen to us, and father is not here."

Jack laid his head on the ostrich's neck, and fairly sobbed in his dread of the consequences. The sound of a scolding voice in the farm-yard made him look up. As he was still perched on Vickel's back, he had a good view of the farm-house and its surroundings, through the slit which Vickel had made in the tilt on the previous day.

Sannie's screams had brought one of the Kafir maids to see what was the matter. She snatched the torn pinafore off the unfortunate little toddler, and held it up before Tante Milligen, whose head appeared above the half-door of the house at the same moment. The Dutch mother left her kneading trough, and tucking up the corner of her wide white apron, rushed out upon her youngest born, scolding and threatening at the top of her voice. Behind her crept Genderen, in her long blue and white checked pinafore reaching to the toes of her home-made sheep-skin shoes. The brown sun-kappje she was tying on very much resembled the head-gear of a Sister of Mercy.

Jack would have laughed at the grotesque figures before him if he had not been so full of consternation, a feeling which Genderen's pale face seemed to reciprocate.

"Footsack, Zyl," she cried.

And now Jack laughed in spite of his anxieties as the meaning of the queer Dutch word was made plain to him; for in accordance with his sister's advice, Zyl made a dart at the side gate into the farm-yard, but the Kafir maid frustrated his intention by setting her back against it.

The vocabulary of the scold in Dutch is by no means a limited one, and Tante Milligen seemed as if she would exhaust it all in her indignation at the state of Sannie's pinafore.

Poor Sannie's words were rendered unintelligible by her sobs; and Zyl was caught beyond all hope of escape. He stood before his angry mother, stolid and sullen as a young buffalo, and never opened his lips, whilst she knocked their heads together until Genderen began to cry in sympathy. But not one word of excuse or complaint would the Dutch boy utter.

How Jack's heart warmed to him, for he could so easily have told of Vickel and screened himself; but to see the baby struck was more than Jack could endure. He sprang off Vickel's back, and scooping great handfuls of mealies out of the hole in the sack, he left her eating them, and rushed to the gate. But Zyl, in his fear that the ostrich might follow him, had fastened it inside.

Jack knocked and shouted, "Mrs. Immerseel, Mrs. Immerseel, don't beat that poor little baby. Oh, pray don't. She could not help it. Let me in, and I'll tell you how it happened."

The Kafir maid opened the gate in answer to his summons; but, oh, it was dreadful to find no one could understand a single word he said. He marched up to Tante Milligen, and lifted his pent-house of a hat, as he had seen his father lift his, and held out his hand. But, alas, it looked so dirty, he drew it back again in disgust.

Although Jack's attempted explanations were all in vain, his sudden appearance created a diversion. Tante Milligen, supposing he had come to beg for a breakfast, smiled at him good-naturedly, and pointed to the kitchen-door. Jack shook his head, and tried to get between her and little Sannie.

"What can the child want?" thought the Dutch woman. "Something wrong with his father's beasts perhaps." So she sent her Kafir maid to see.

Off bounded Jack as soon as he perceived her destination, for he knew if he did not get to the waggon before her, Vickel would be sure to fly at her. He was white as ashes with fear as he scrambled on to the low, broad wheel, and stood with one eye on the ostrich and the other on the Kafir.

Jack half hoped, as they were both African born, they might take to each other. He was right so far; the Kafir was too wise to interfere with his bird, and Vickel, who was still quietly feeding, took no notice of her. The maid looked all round, saw that the oxen were quietly grazing, and feeling convinced there was nothing amiss, turned to Jack. He did not like the queer black creature, with her bare arms and legs, to stare at him so. She was not like his yellow-faced Tottie, who always wore a woman's gown, and on Sundays a clean white cap as well; and from this semi-savage, in her scarlet blanket, he shrank. Why wouldn't she go away?

It was very horrid to be stared at, so Jack got into the waggon to escape from those glittering, bead-like eyes, and away went the Kafir singing.

Her song called forth a burst of laughter from a Hottentot herdsman, who was coming to lead the oxen to water. Happily for Jack, he could speak a little English.

"No like de Black Antelope," he said with a grin; "much she likee you. Listen how she go, making songs of 'Dis pretty Ingleese lamb, left alone on de wide, wide veldt.'"

Then Jack laughed in his turn, and was rather glad to hear that she had gone to fetch him some breakfast.

But he could not forget little Sannie. Standing up tip-toe on the top of the chest, he once more reconnoitred the entrance to Jaarsveldt through the slit in the tilt.

Zyl had disappeared, but Genderen was trying to comfort to comfort her little sister. She took her in her arms and carried her round the farm-yard, holding her up to watch the little pigs tumbling one over another in their play. But it was of no use; the pitiful sobs continued. Then Genderen brought her outside the gate to try the diversion of a little walk, pointing out the Englishman's waggon, and trying to teach her to call "Jock! Jock Trairbee!"

Of course, poor Sannie only screamed the louder, and struggling from her sister's arms, ran away. Genderen's freckled face was pink with fatigue.

Jack ran to her help with his "Illustrated News." But Sannie would not look at him; so he took out the loose picture that was folded in it and spread it before them on the grass, with a nod to Genderen, and ran off.

It was happiness to Jack to watch the delight of the sisters from his peep-hole, as they cuddled together with the picture on their knees. There they sat, sucking the thumb of one hand, and tracing with the other the different figures in the picture.

When the Black Antelope returned with a bowl of milk and a hot roaster-cake, Jack felt unable to enjoy his breakfast and do full justice to Tante Milligen's hospitality. His head was aching and his hands were hot, so he sank down in his grassy nest to read his "Illustrated News," and was nearly falling asleep when a great stone was aimed at Vickel's head.

Jack was up in a moment, ready to defend his pet, for he caught sight of Zyl picking up a second stone under the garden wall.

With a great shout of defiance the two boys rushed at each other, and in spite of all Jack's father had said, a fight between English and Dutch was imminent. But Genderen's brown sun-kappje suddenly appeared on the scene, with the Hottentot cow-keeper behind it. The sister was evidently warning and her follower threatening the unmanageable youngster with "ein lecker slaat" when the "oom" came back, if he persisted in annoying the English boy. Zyl bent his head as if he were a young goat about to butt, but never uttered a word even to his sister.

He might throw stones at Vickel by way of revenge for her attack; but, for all that, he was not going to tell tales. Jack grew hot and cold by turns, for he thought there would be no mercy for his bird if it were known that she was the true culprit who had torn the pinafore, and his gratitude to Zyl for so doggedly holding his tongue got the better of his anger. The arm he had raised to strike the stone front the Dutch boy's hand went lovingly round his neck instead. Jack drew himself up beside him with a look at Genderen which said, "We two understand other; just let us alone, please."

Zyl gave him the queerest of glances from the corner of his eye. It was becoming evident to his slow intellect that Jack, having shared in the scrape, was ready to take his share in the punishment also. He rather liked that, and the grip which he gave Jack's other hand was as hearty as it was crushing.

MAKING FRIENDS.

GENDEREN alone, of all the Boer's household, had found out the truth from little Sannie's sobbing complaints. Dull and heavy as she appeared, there was more in her than Jack imagined. She suspected her brother of teasing the ostrich, but was so frightened at the thought of Sannie's danger that she could not rest. Her first care was to get the boys into the garden. The Black Antelope followed with Jack's untested breakfast—the bowl of milk and the once hot roaster-cake. There was twice as much as he could eat, but Zyl was quite ready to assist him with the overplus. They sat down together on one of the garden seats in the midst of a grove of orange-trees.

Genderen shook down some of their golden fruit to fill the English boy's pockets. Jack took out his precious "Illustrated News" to make room for them, and whilst the important business of the breakfast proceeded, Zyl stretched himself on the grass, absorbed in the delight its many pictures afforded.

When Genderen saw the two boys she had caught fighting had struck up such a sudden friendship, she felt somewhat amazed. Fearing it was too warm to last, she slipped away to execute the second part of her plan as quickly as she could. To feed the young ostrich chicks was Genderen's daily task, therefore she was not at all afraid of Vickel herself. Filling her lap with food, she went into the farm-yard, and calling her own majestic hen with her fluffy brood, began to feed them.

The cries of the young birds soon brought Vickel out of the waggon. Genderen saw her bright eyes peeping over the wall at her feathered kin. Then the Dutch girl showered the corn from her lap, inviting Vickel to come over the wall and share the feast; but the ostrich was shy, and retreated.

"No, she cannot get over the wall," thought the Dutch girl; "and if I can but coax her into the yard, she will be safe out of the children's way, or there will be more mischief between them, for somehow or other this bird is at the bottom of it."

Acting upon this conviction, she did her utmost to tempt the clever bird to follow her, but in vain. At last she set the gate wide open, and leading out the biggest of her chickens, she let them walk before the waggon, trusting that Vickel would join them of her accord. Ostriches have a decided partiality for women and girls, and when Genderen began to call her chicks together, Vic put her head on one side and listened.

The impression was deepened when a few grains of corn were flung at Vickel's feet. She eyed them askance for a while, but as the chicks moved on, she condescended to taste. Having once tasted, and found the breakfast Genderen provided for her chicks was much better than her own, she continued to follow them slowly and at a considerable distance, picking up the grains of corn Genderen was careful to scatter in their rear.

As the girl drew near the gate, the Hottentot came to her assistance. A heap of corn was placed in Vickel's sight to invite her to enter; and when she hovered hesitatingly round the gate of plenty, the cowherd cracked his whip behind her. In she flew with a bound. The gate was gently closed, and Jack's pet was a prisoner. Genderen, very happy in the success of her manœuvre, returned to the house.

Beautiful as the Boer's garden seemed to Jack on that lovely summer morning, he did not care to stay there long. His father had told him he must take care of all the things in the waggon, and he wanted to go back to it. But Zyl, who valued the pictures in the "Illustrated News" almost more than Jack himself, was loath to let them go. His sullen face lit up at the sight of men on horseback with their dogs at their side, and soldiers drawn up in battle array. Tents, too, and Japanese pagodas, all of which he must scrutinize until each picture was made out to his own satisfaction.

Jack's impatience nearly upset the good understanding so recently established between them; but nothing could turn the young Boer from his purpose. He had made up his mind to see all there was to be seen in the beautiful English paper, and he would. To add to Jack's uneasiness, he was sure he heard his ostrich calling; but after his father's charge to take care of the paper, he was afraid to go away without it. He tried to take it out of Zyl's hand, promising to bring it again.

But Zyl, who could not understand Jack's English, only retorted, "Jah! Jah!" and held it fast.

Then Jack ran to the gate, but Zyl was before him. The upper bolt, which was high above Jack's head, was drawn, and the Dutch boy stood laughing. Then he gave Jack a brotherly hug, and led him round the garden.

"Don't go," said Zyl by every action. He put back the little linen tents which were dotted about the beds, and showed him the lovely flowers blooming beneath their grateful shadows.

Oh, what a contrast to Jack's garden at home! The roses here seemed to spring up as easily as thistles, and the tulips from the Dutchman's "father-land" seemed to Jack, with his exceeding love of flowers, like fairy bells. And then the grapes and peaches, shining in their glossy leaves, filled him wonder and admiration. How was it all done? Why could not their garden at home be made like it?

FEEDING THE OSTRICH CHICKS.

He began to think these rough Boers knew more than he did after all. Perhaps he could find out how they managed it.

There was one particular corner at which Zyl paused with evident pride. It was a perfect square, marked off from the rest of the garden by a row of flowering cactus. In the angle of the wall stood a clumsy, three-cornered stool, which Zyl endeavoured to make Jack understand was his own handiwork. The frame of an old umbrella had been nailed to the wall, and as its silk covering had altogether disappeared, it had been skilfully thatched with grass. Two young creeping-plants were making haste to climb the wall to reach it.

A small orange-tree, which could have seen little more than a single summer, was planted in the very centre of the little square, with a ring of rice-plants round it, brought from an unfrequented dell among the neighbouring rocks. A circular path divided this from the side borders, where Jack observed an abundant crop of seed springing up in the shape of a Dutch "Z."

This was enough for Jack. He guessed once it was Zyl's own garden. How he envied him the possession. But this was a bad feeling, and Jack crushed it in its birth, smothering it with a burning desire to emulate the Dutch boy's skill, and, if possible, surpass it.

"I must have the seat big enough for two," thought Jack, "and father and I could have our supper there."

So the time slid by until Genderen returned, leading Sannie in a clean pinafore, with both her chubby hands filled with sweets, the Dutch child's delight. She held out one to Jack, who had given her the "beauty picture."

As he stooped to take it, he softly parted the curly mop of flaxen hair, and looked ruefully at the darkening bruise it shaded. This reminded him of Vickel.

"I must, I ought to go and look after her," he thought.

Now, Jack could climb like a cat; and as he despaired of making his new friends understand how much he wanted to go back to his father's waggon, he suddenly leaped upon Zyl's seat, and was over the wall in a moment. His astonished companions stared after him with their fingers in their mouths, utterly amazed. They would have said only a Kafir could have done it.

Once outside the wall of Jaarsveldt, Jack ran eagerly to the waggon. The oxen were leisurely ruminating. Everything was right but Vickel. Where was Vickel? A cry of bitter self-reproach burst from his lips. He tried to call her name, but his voice failed him. All the terrible excitement he had undergone seemed to culminate in that moment. A cold shiver ran through him, for this new trouble was of his own making. If he had not left Vickel so long, he would not have lost her.

He was blaming himself too keenly to know what he was doing. He tried to call her, but his voice sounded hoarse, and unlike his own. The echo from the neighbouring rocks repeated his heart-breaking call. He did not know what an echo was, and believed that some one else was calling his bird in the distance. Off he set, as fast as he could go, hoping to overtake the unknown somebody who was tempting his pet away. Once he thought he heard his ostrich screaming behind him. He paused, completely bewildered.

No; it was only Zyl shouting to him to stop. But Jack had had enough of Zyl's company for the present, and would not comply. So the two chased each other over the red sand, nearer and nearer to those sombre mosses of frowning brown which had exercised such a power over Jack's imagination.

The heat was now intense, but there was neither sight nor sound of Vickel. He ran till he could run no further, and had hardly breath enough left to call her name. Then he remembered Genderen's oranges, and sitting down under one of the low karroo bushes, which reminded him of home, he began to eat them. This helped him to recover his voice, and putting both hands to his mouth, he once more shouted, "Vickel," and again the rocks gave back his cry.

At this moment an ox-cart drove slowly out of one of the rocky defiles, in the direction of Jaarsveldt. Zyl, who was gaining on his flying friend, saw it also, and apparently recognizing the two men who were in it, waved his hat and shouted in his turn.

The Hottentot driver turned the head of his ox towards the boys, whilst his companion answered Zyl with the "view halloo" of an English sportsman.

Jack sprang to his feet at the sound of an English voice, realizing for the first time in his life all that word "countryman" means in a foreign land.

The ox-cart rumbled on. Zyl was running to meet it with eager joy. Jack had no eyes for the Hottentot driver; all his attention was centred on the big sun-umbrella which almost covered his companion.

As the boys came up to the cart, it was swung backwards. The owner of the umbrella, an aristocratic-looking young Englishman of twenty-two or twenty-three, held out his hand to Zyl with a smile. It was a pleasant smile as far as it went, for it only played around his lips; it never reached his eyes. About them there was a reckless, "don't care" expression which rather repelled Jack; but Zyl was obviously delighted to meet him.

"Please, sir, have you seen an ostrich?" asked Jack.

"Yes, dozens, my little man. But what is that to you?" was the somewhat curt reply.

"Please, sir, I have lost my Vickel, my own tame ostrich, and I have heard somebody calling her over there, the way you came," added Jack, pointing to the rocks.

"Somebody!" repeated the stranger, shaking with laughter. "I rather think it was Mr. Nobody. You little fool, to go chasing an echo! Come, jump in, both of you; for we are all risking a sunstroke crossing the veldt at noon. I did not bargain to be so late, I assure you."

Then he turned to Zyl and asked some questions in Dutch, to which the young Boer responded with more alacrity than usual. He scrambled up into the cart at once, trying to pull Jack after him.

"No, thanks," persisted Jack; "I don't want to ride; I must find my bird."

"Nonsense!" retorted the stranger. "Jump in this minute, or you will lose yourself. And where on earth will you be so likely to find your bird as in the ostrich camp at the next farm?"

"Perhaps you are right, sir," said Jack brightening.

"Boys do not say 'perhaps' to me," he continued, seating the two between himself and the Hottentot driver, who was by no means pleasant as a near neighbour on so hot a day.

Zyl got close to the Englishman, as if he had a special right to appropriate him, so Jack turned to the Hottentot, who did not laugh at his trouble, and promised readily, if he saw an ostrich with scorched wings, to catch her. Jack ventured to ask him in a whisper who the Englishman was that he was driving.

"He no father of mine," answered the driver; for to him father and master meant the same. "He be a Ingleese, who come and go from farm to farm, and he do cram little boys' heads with big words for three long days, till they sleepy, sleepy."

At this description of himself and his present occupation as itinerant schoolmaster, the Englishman laughed until he shook again. Then he laid one arm on Zyl's broad shoulders, and leaned across to question Jack.

"What makes you so curious about me?" he asked.

"Because you are an Englishman, and so is my father," replied the little fellow.

"Then I have a great mind to come and see him and cram your empty head; but mind you, if I find you going sleepy, sleepy, this will pretty quickly wake you up again," retorted the boyish schoolmaster, shaking the cane he carried.

Jack grew very red, being painfully conscious of his own short-comings; but he answered manfully, "I shouldn't be sleepy in the morning."

"All right," laughed the schoolmaster. "Zyl has been telling me all about you, John Treby, junior. Just give that to your father," he continued, tearing a leaf out of his pocket-book on which was written, "Sandford Algarkirke."

"Father will come back to Jaarsveldt to fetch me and the waggon, and then I will give it to him," answered Jack promptly.

"Will he come to-night?"

"Oh yes," answered Jack.

"Better and better!" cried young Algarkirke. "Then I shall see him to-night. I have not spoken to an Englishman for seven months. What part of the old country did your father come from?"

"Nottingham," returned Jack. "He told me only last night—no, I mean the last night at home, just before the thieves came—never to forget I have a grandfather living at Nottingham."

"Nottingham!" exclaimed Algarkirke in a tone that bordered on alarm, while for a moment the reckless "don't care" expression was banished from his brow.

THREE DAYS WITH THE BOOKS.

THE arrival of the schoolmaster quickened the slow paces of the Boer's family. The thrifty "tante" was anxious to make the most of his three days' sojourn.

The Black Antelope had dragged off Zyl and Sannie to the wash-tub. Being in disgrace already, they submitted, but not without a pout and a grimace at the inordinate scrubbing the zealous creature thought it her duty to inflict. Genderen, she insisted, ought to show her respect for "the man of books" by taking off the long checked pinafore and exhibiting the brightly-flowered cotton dress beneath it.

The Black Antelope's veneration for a man who make a white sheet talk, by just sprinkling it with something black, knew no bounds. She would have remained all day watching her charges whilst the lessons were going forward if her mistress would have allowed it, on the "qui vive" for other magical performances perhaps as wonderful. This was certainly a sign that pen and ink were not often required in the Boer's household when the schoolmaster was not present.

Tante Milligen was seated on the lumbering settee, smoothing down the sides of her voluminous apron, whilst the schoolmaster did justice to the ample lunch she had provided for him. Whilst he ate, she enlarged upon her own and her husband's satisfaction with their present arrangements. She hoped they were doing their duty by their children. They had always taken them to church twice a year, although it was such a long way to Pretoria; but now they had a schoolmaster in the neighbourhood again, they must all make up for lost time.

Young Algarkirke was not slow at taking a hint, so he professed himself quite ready to begin lessons at once.

The Black Antelope bustled in her charges, with their freckled faces polished to a deep rose-pink, and arranged the chairs. Books were brought out and selected from the heterogeneous contents of the capacious cupboard, and slates were dusted.

Sandford Algarkirke looked at Sannie with some dismay, for she was an addition to the party quite outside his hopes or expectations.

"She is young," remarked Tante Milligen; "but she will have to make a beginning some day, and there is no time like the present. We don't keep any schoolmaster amongst us over-long, and then there is often a year or two before we get another to settle, so I hope you will let her take her turn with her brother and sister."

Forthwith the assiduous Kafir produced an additional cushion, which raised the would-be learner to the level of the big table, and darting upon a Latin grammar Mr. Algarkirke had just taken out of his own pocket, she laid it open before her with great solemnity.

"That will do," said Tante Milligen, pointing her domestic to the door. "Now bring me that pinafore, and I'll see how I can patch it."

"Inkosi! (Kafir for mistress) Inkosi!" exclaimed the excited black. "One word, and I will trouble your ears no more this day. The little Ingleese lamb without a mother lies weeping in the dust by his father's oxen. Why? Because he is shut out while the books speak. Open to him, inkosi, that he too may learn wisdom."

"Listen to our black spider," muttered Zyl. "Has not she got eyes all round her head, and feet that can run every way at once? Oh, we are just dummies and blocks beside her."

"Be still," whispered Genderen; "she'll get him in."

"Let him come, then," said Tante Milligen.

"By all means," added the schoolmaster warmly.

A swifter messenger than the Black Antelope never lived. She ran at her fastest now. The fleetness of foot had won for her her name. But her volubility was lost on Jack, who could not understand any one of the endearing epithets she showered upon him. It was true he was crying bitterly, but her conjecture as to the cause of his grief was quite a mistake, for he was mourning over his folly in losing sight of Vickel.

She caught him by both his hands and whirled him away to the door of the sit-kamé, where Zyl was stumbling through a page of Dutch history, about which his teacher knew nothing, whilst Genderen, with her fingers in her mouth and her low forehead drawn into most painful puckers, was trying hard to cast up an addition sum.

Mr. Algarkirke's knowledge of Dutch had been picked up during a short stay in Amsterdam before he emigrated, and when he found himself at a loss for a word, he recalled attention by a rap with his cane.

Genderen sighed heavily, and Zyl tugged at his fore-lock. Lessons with the Dutch children were a very laborious matter. If they had not been so fully alive to their importance, the new schoolmaster would have been a failure. With stolid gravity Zyl pulled through blunders his master was quite unable to rectify, and closed his book at last with an air of satisfaction that would have convulsed an English school with merriment.

Mr. Algarkirke seated Jack beside him, for an English child was a welcome addition to his pupils. But alas! the school-books were all in Dutch, except the Latin grammar, at which Sannie was profoundly staring.

"May I do a sum?" asked Jack, who knew "the good spell at the figures" did not come off so frequently as his father desired.

Jack found it much easier to grapple with the difficulties of long division in the day-time, when he was wide awake, than in his brief but pleasant lessons between winks, when his father was often more weary than himself. He said he should like a good spell at arithmetic, using his father's words a little proudly. But when Mr. Algarkirke rewarded his painstaking by setting him another and a longer example in money division, he felt himself becoming something worse than sleepy, for he was downright stupid at the conclusion.

"Please, Mr. Algarkirke, may I have a book?" he asked.

"Touch a book with such dirty paws!" retorted the schoolmaster, who had considerably widened the distance between them. "No, sir; no, I say."

Jack crimsoned to the roots of his hair, and hid his hands under the table. The schoolmaster grumbled something in Dutch. All eyes turned on Jack.

"A travelling schoolmaster expects his pupils to be ready for him. It is not treating me with proper respect to come here covered with soot and dust," he continued sharply.

Jack got up slowly and went to the door.

The Black Antelope was told off to recall him; but her ready wit had already divined the cause of Mr. Algarkirke's offence. Poor, disconcerted Jack was whirled away into one of the side rooms, where tub and towel awaited him.

The touch of his hot head and burning hands distressed her, and ere the bathing was finished, she felt quite sure the poor child would be prostrate with African fever before many hours were over. Should she tell her mistress? The Boers were so hard and unfeeling to their slaves, the Kafir could not depend upon their sympathy. But her woman's heart went forth to the poor white lamb without a mother, and she made up her mind to steal out at night and watch over him, if he were sent back into the waggon to sleep alone.