MAP OF EGYPT.

Title: A guide to the Egyptian collections in the British Museum

Creator: British Museum. Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities

Author of introduction, etc.: Sir E. A. Wallis Budge

Release date: May 2, 2025 [eBook #76000]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Harrison & Sons, 1909

Credits: Richard Hulse, Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net, with special thanks to Stephen Rowland for transcribing the hieroglyphics. (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Transcriber’s Note: This book contains text in Greek (στήλη), Coptic (ⲛⲁⲛ) and Egyptian hieroglyphs (𓏟𓈖𓊹𓌃𓏪). You may need to install additional fonts to properly render those languages. Noto Sans Egyptian Hieroglyphs is recommended.

Egyptian names may be rendered into English in many different ways, and in this book frequently are (e.g. Teḥutimes, Teḥuti-mes, Thothmes). Some minor changes were made (especially in the Index) to achieve consistency of capitalization and accents, but otherwise these differences have been preserved as printed.

BRITISH MUSEUM.

A GUIDE

TO THE

EGYPTIAN COLLECTIONS

IN THE

BRITISH MUSEUM.

WITH 53 PLATES AND 180 ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT.

PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES.

1909.

PRICE HALF-A-CROWN.

[All Rights Reserved.]

HARRISON AND SONS, LTD.,

PRINTERS IN ORDINARY TO HIS MAJESTY,

ST. MARTIN’S LANE, LONDON, W.C. 2.

PRINTED IN ENGLAND.

The Collection of Egyptian Antiquities in the British Museum comprises nearly fifty thousand objects, and many of its sections are unrivalled in completeness. It illustrates, in a more or less comprehensive manner, the history and civilization of the Egyptians from the time when their country was passing out of the Predynastic Period under a settled form of government, about B.C. 4500, to the time of the downfall of the power of the Queens Candace at Meroë, in the Egyptian Sûdân, in the second or third century after Christ. The monuments of Christian Egypt also form a very important series, and illustrate Coptic funerary sculpture and art between the sixth and eleventh centuries A.D.

The present Guide has been prepared with the view of providing the visitor to the British Museum with information of a more general character than can be conveniently given in the Guides to the several Galleries and Rooms of the Department. An attempt has here been made to present a sketch of the origin, the manners and customs, the language, the writing, the literature, the religion, and the burial rites of the peoples of Egypt, and of their history under the successive dynasties; embodying references to the several objects of the Collection which illustrate the different branches of the subject. The text is supplemented by an abundant selection of cuts and plates of the most important of the antiquities.

E. A. WALLIS BUDGE.

Department of Egyptian and Assyrian

Antiquities, British Museum,

September 29, 1908.

| PAGE | |||

| PREFACE | v | ||

| LIST OF PLATES | ix | ||

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT | xi | ||

| CHAPTER | I.— | THE COUNTRY OF EGYPT | 1 |

| ” | II.— | ETHNOGRAPHY. LANGUAGE. FORMS OF WRITING. DECIPHERMENT OF EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPHICS, ALPHABET, AND WRITING. NATIONAL CHARACTER | 20 |

| ” | III.— | EGYPTIAN LITERATURE, SACRED AND PROFANE | 58 |

| ” | IV.— | MANNERS AND CUSTOMS. MARRIAGE. EDUCATION. DRESS. FOOD. AMUSEMENTS. CATTLE BREEDING. TRADE. HANDICRAFTS | 76 |

| ” | V.— | ARCHITECTURE. PAINTING. SCULPTURE | 103 |

| ” | VI.— | THE KING AND HIS SUBJECTS. MILITARY SERVICE | 116 |

| ” | VII.— | EGYPTIAN RELIGION | 122 |

| ” | VIII.— | EMBALMING. THE EGYPTIAN TOMB | 158 |

| ” | IX.— | NUMBERS. DIVISIONS OF TIME. CHRONOLOGY | 180 |

| ” | X.— | HISTORY OF EGYPT. ANCIENT EMPIRE | 188 |

| ” | XI.— | HISTORY OF EGYPT. MIDDLE EMPIRE | 213 |

| ” | XII.— | HISTORY OF EGYPT. NEW EMPIRE | 228 |

| ” | XIII.— | HISTORY OF EGYPT. PTOLEMAÏC PERIOD | 268 |

| HISTORY OF EGYPT. ROMAN PERIOD | 275 | ||

| HISTORY OF EGYPT. ARAB PERIOD | 282 | ||

| A LIST OF THE PRINCIPAL KINGS OF EGYPT | 286 | ||

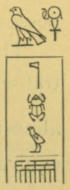

| CARTOUCHES OF THE PRINCIPAL KINGS OF EGYPT | 290 | ||

| INDEX | 303 | ||

| SEE PAGE | |||

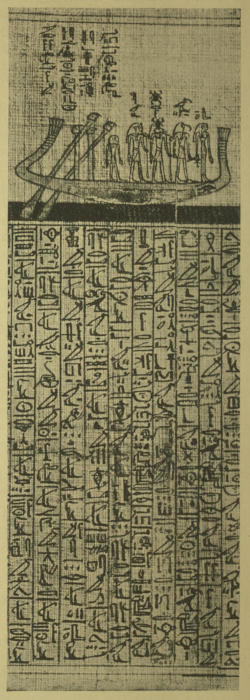

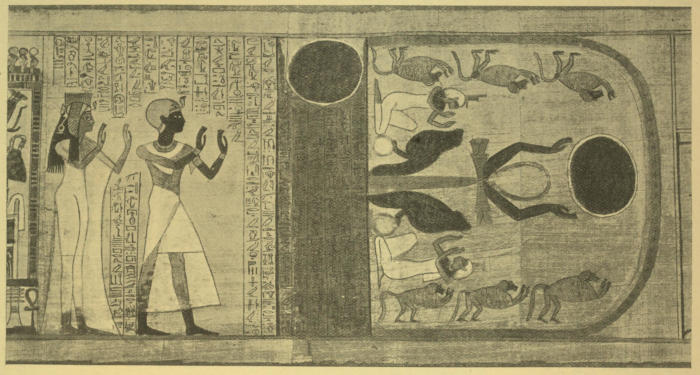

| Plate | I. | Vignette from the papyrus of Queen Netchemet | 61 |

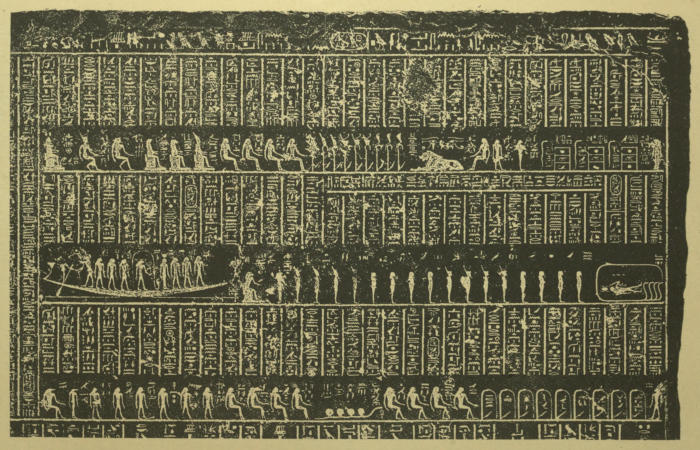

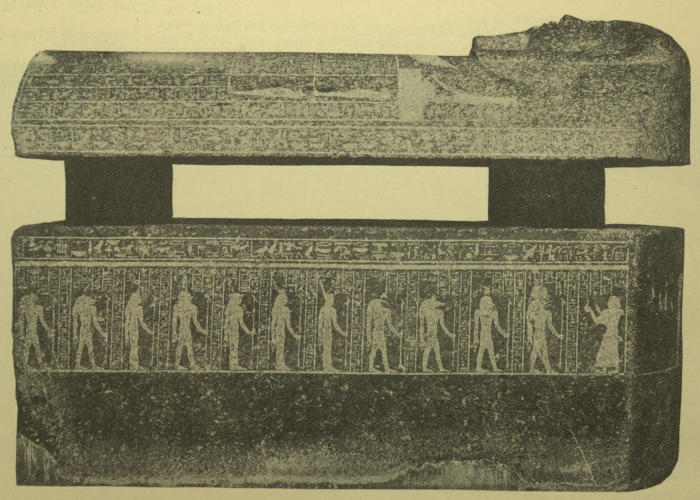

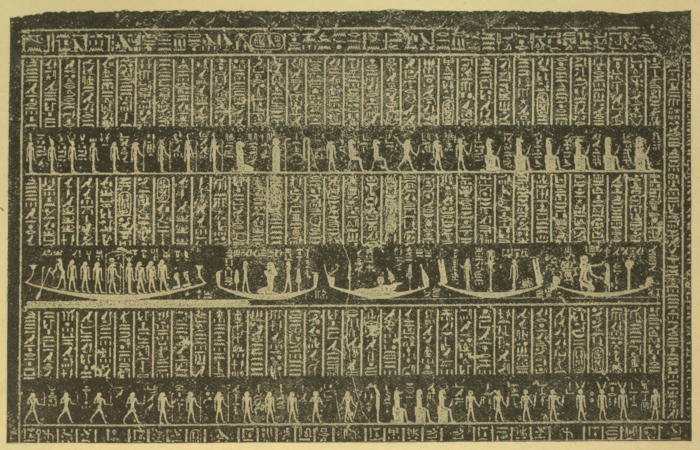

| ” | II. | Text and vignettes from the sarcophagus of King Nekht-Ḥeru-ḥebt | 66 |

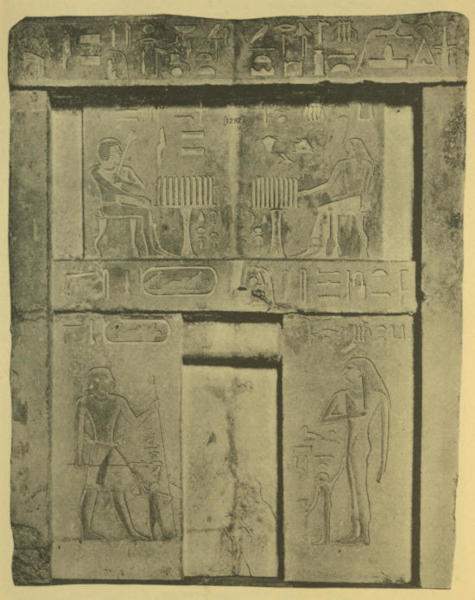

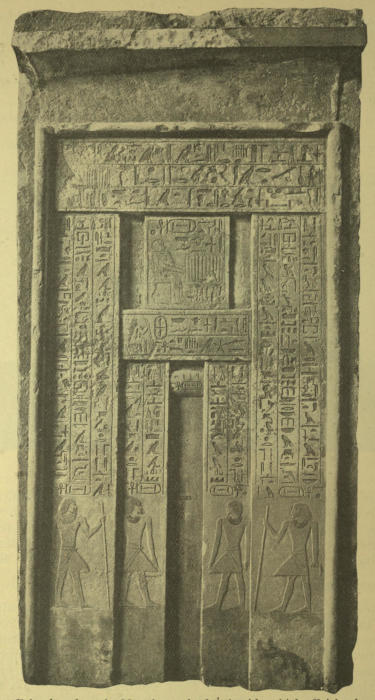

| ” | III. | False door from the tomb of Sheshȧ | 68 |

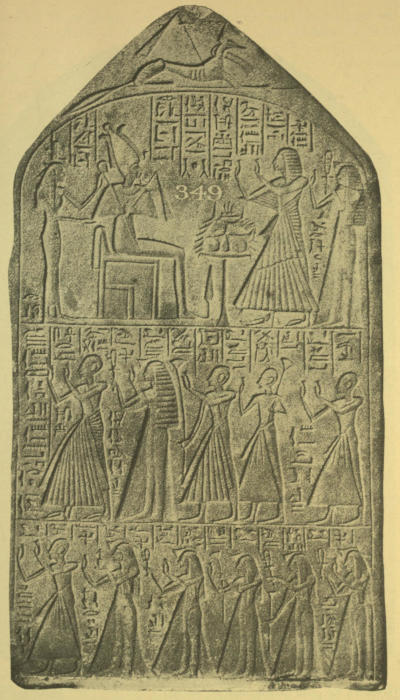

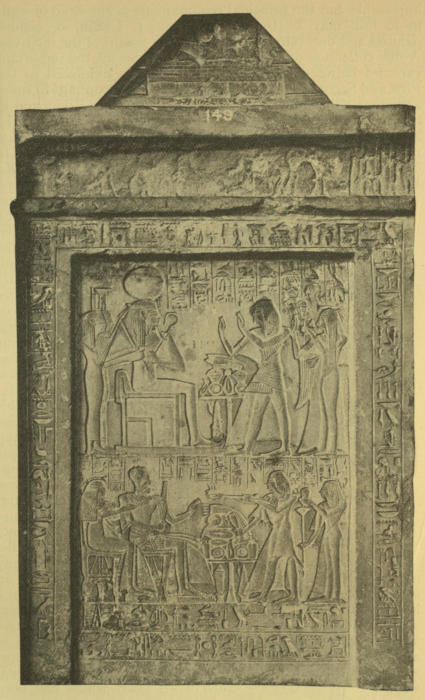

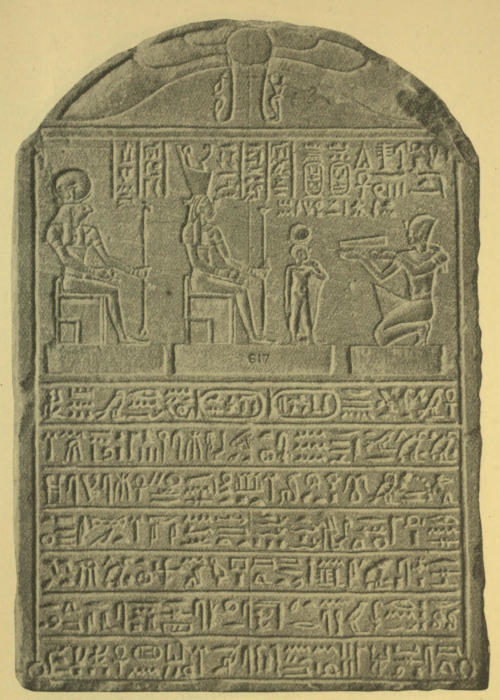

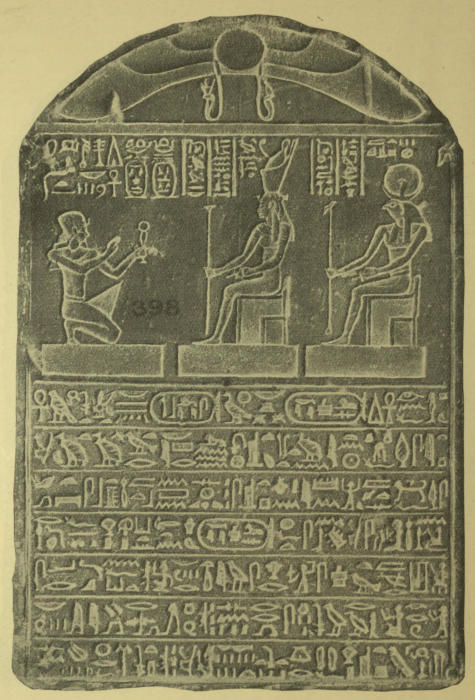

| ” | IV. | Sepulchral tablet of Thethȧ | 68 |

| ” | V. | Sepulchral tablet of Sebek-ḥetep | 68 |

| ” | VI. | Sepulchral tablet of Pai-neḥsi | 68 |

| ” | VII. | Sepulchral tablet of Bak-en-Ȧmen | 68 |

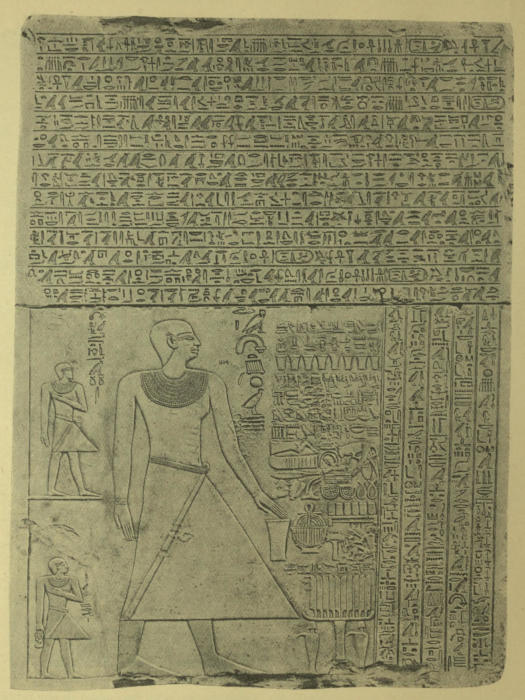

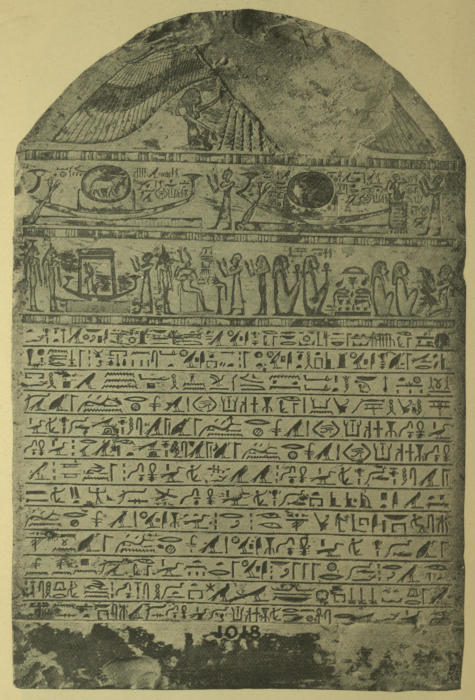

| ” | VIII. | Sepulchral tablet of Nes-Ḥeru | 68 |

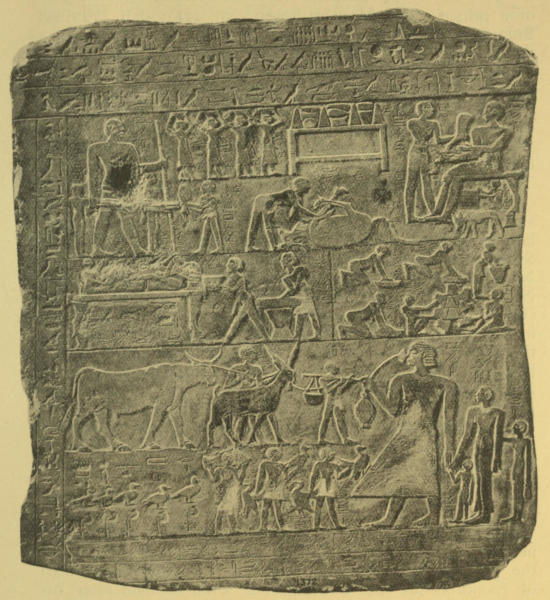

| ” | IX. | Painted relief from the tomb of Ur-ȧri-en-Ptaḥ | 81 |

| ” | X. | Painted sepulchral tablet of Kaḥu | 81 |

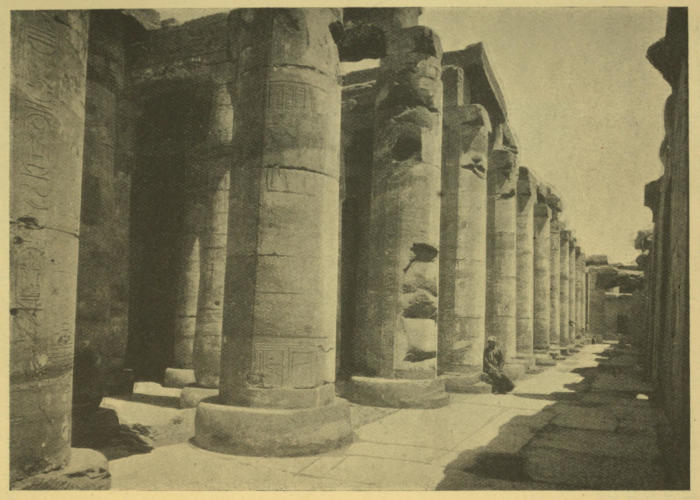

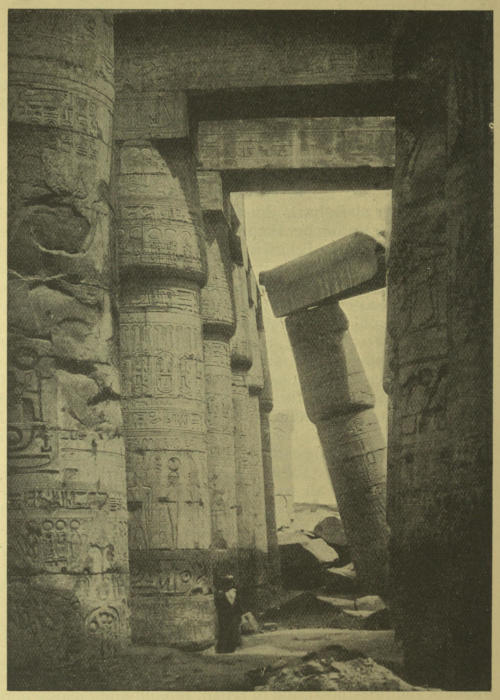

| ” | XI. | Columns in the temple of Seti I | 107 |

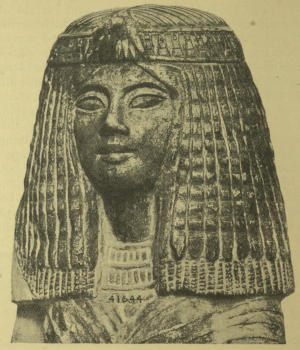

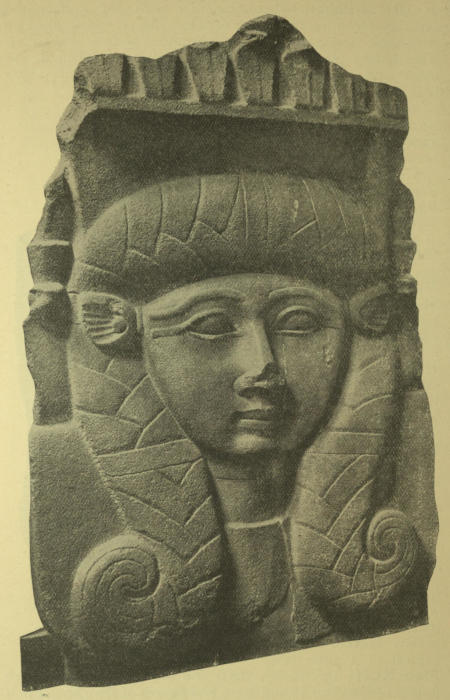

| ” | XII. | Head of a priestess | 115 |

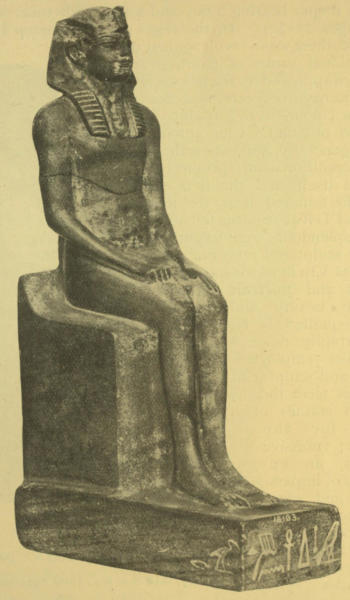

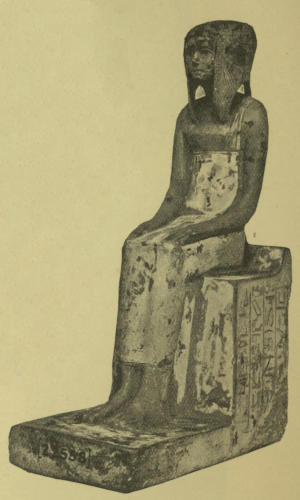

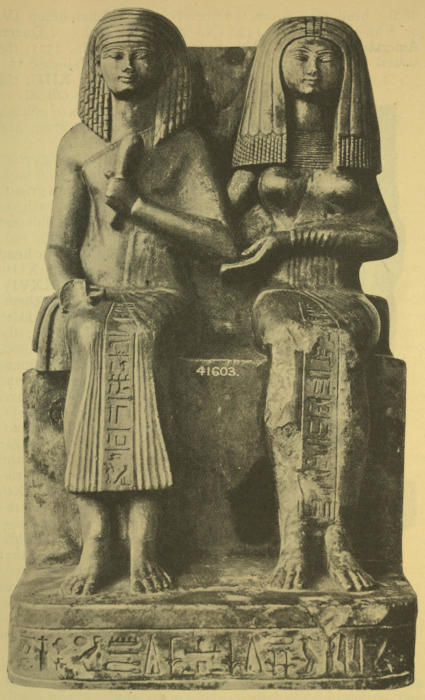

| ” | XIII. | Seated figures of Khā-em-Uast and his wife | 115 |

| ” | XIV. | False door from the tomb of Ȧsȧ-ānkh | 167 |

| ” | XV. | View of a painted chamber in the tomb of Nekht | 175 |

| ” | XVI. | Wall painting from a tomb | 175 |

| ” | XVII. | General view of the sarcophagus of Nekht-Ḥeru-ḥebt | 177 |

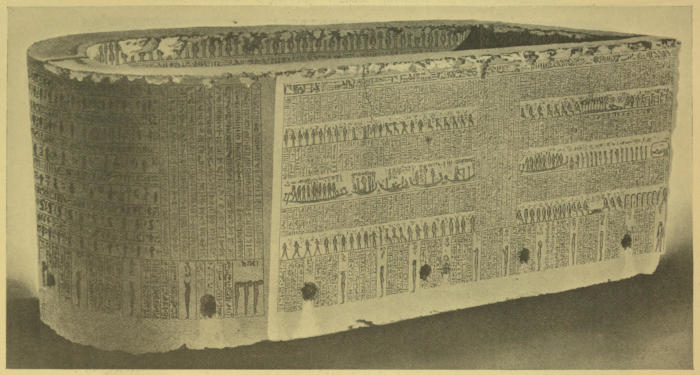

| ” | XVIII. | General view of the sarcophagus of Nes-Qeṭiu | 177 |

| ” | XIX. | Sepulchral tablet of Ban-āa | 177 |

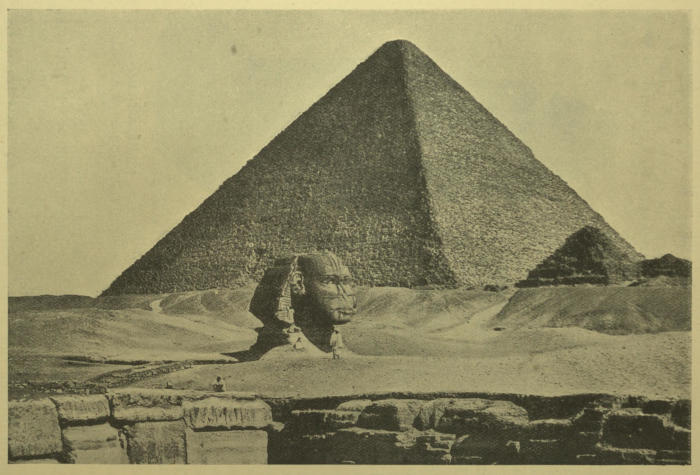

| ” | XX. | The Great Pyramid and Sphinx | 196 |

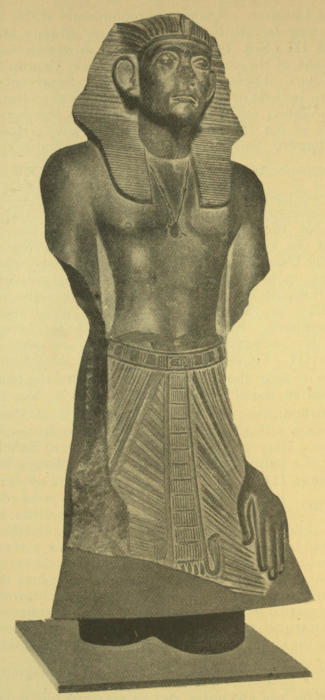

| ” | XXI. | The “Shêkh al-Balad” | 203 |

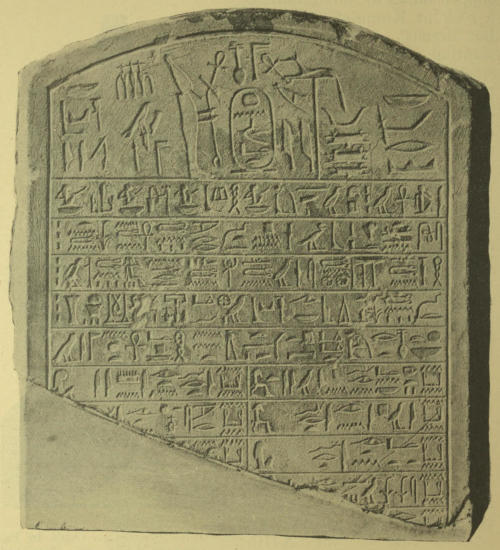

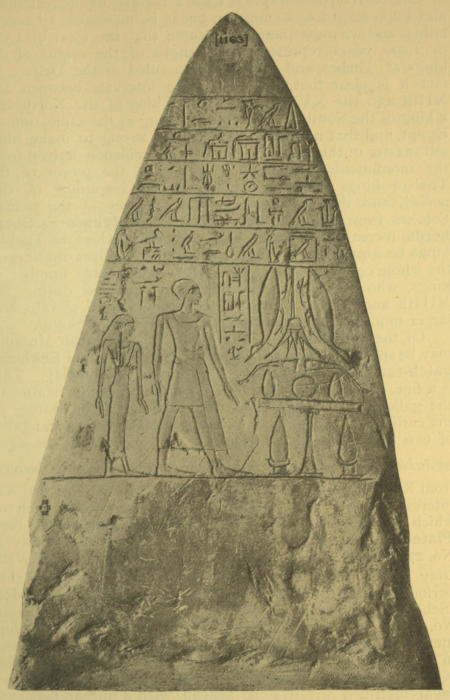

| ” | XXII. | Tablet of Ȧntef | 210 |

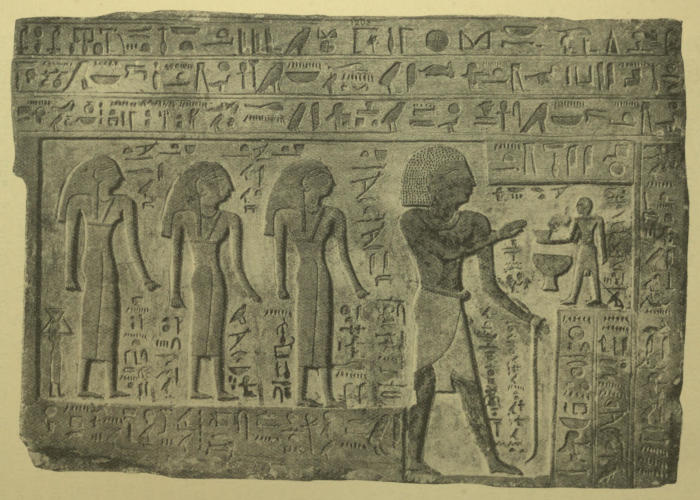

| ” | XXIII. | Tablet of Sebek-āa | 211 |

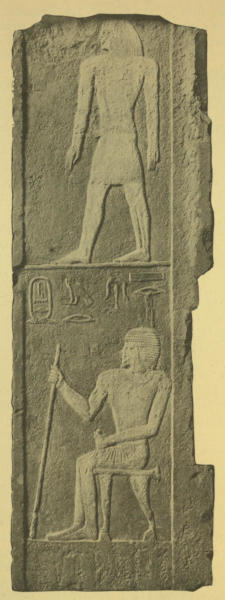

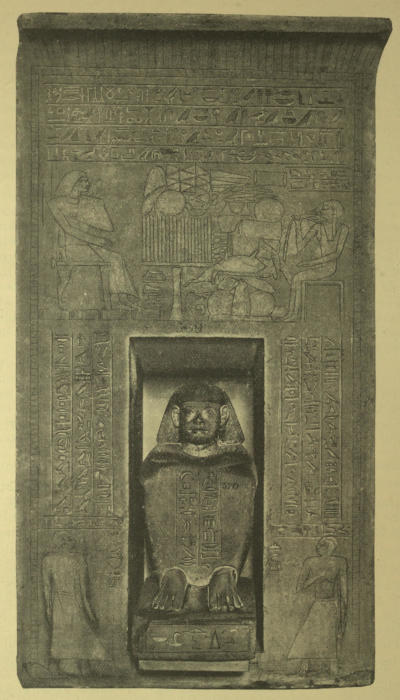

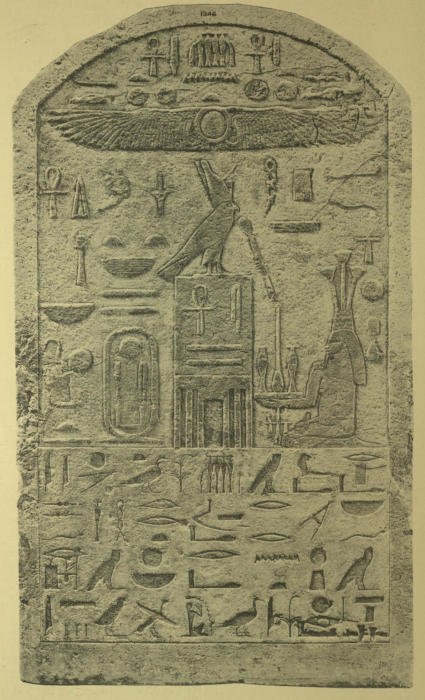

| ” | XXIV. | Tablet and figure of Sa-Hathor | 215[x] |

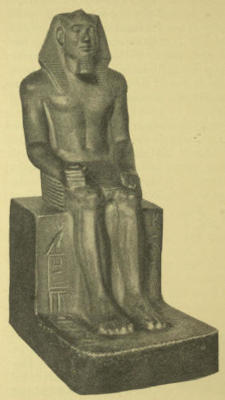

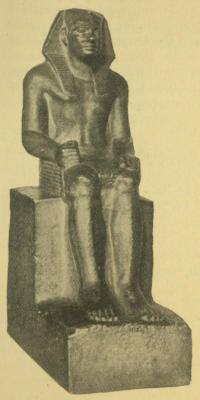

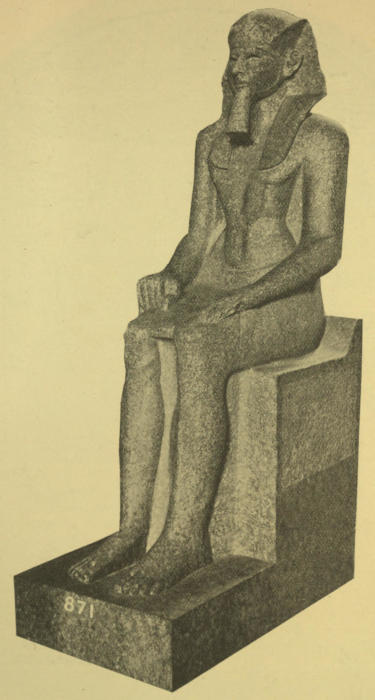

| ” | XXV. | Statue of Usertsen III | 217 |

| ” | XXVI. | Head of Ȧmen-em-ḥāt III | 218 |

| ” | XXVII. | Statue of Sekhem-uatch-taui-Rā | 223 |

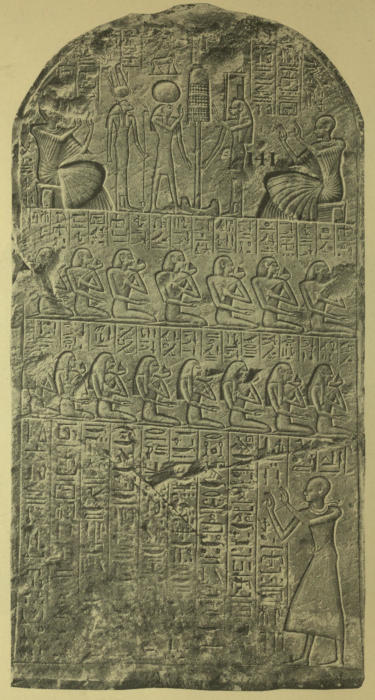

| ” | XXVIII. | Stele of the reign of Sekhem-ka-Rā | 223 |

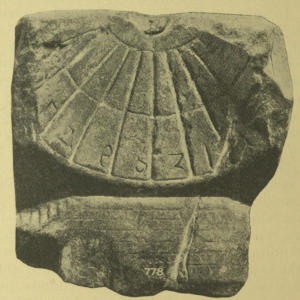

| ” | XXIX. | Memorial cone of Sebek-ḥetep | 223 |

| ” | XXX. | The Hall of Columns at Karnak | 231 |

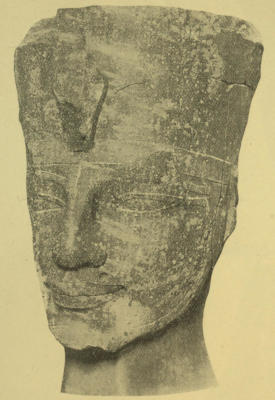

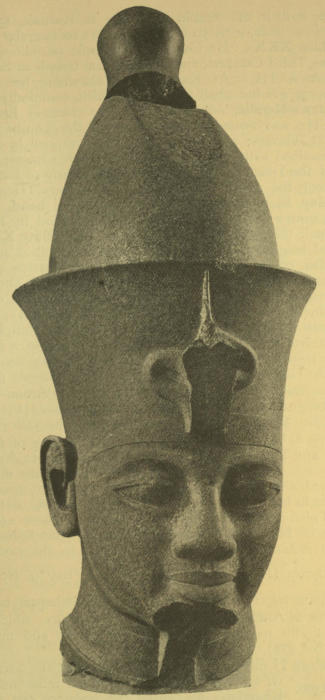

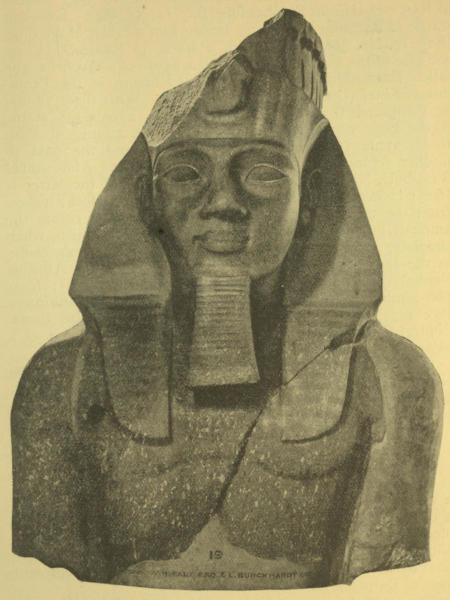

| ” | XXXI. | Head of a colossal statue of Thothmes III | 231 |

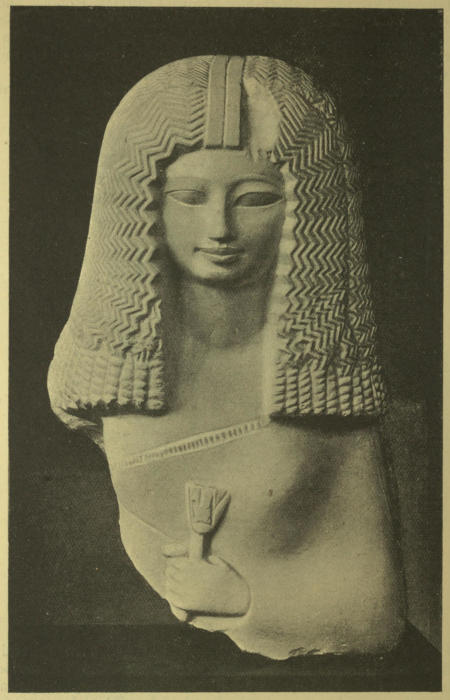

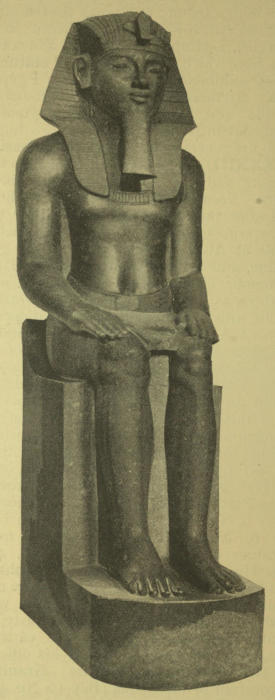

| ” | XXXII. | Statue of Ȧmen-ḥetep III | 234 |

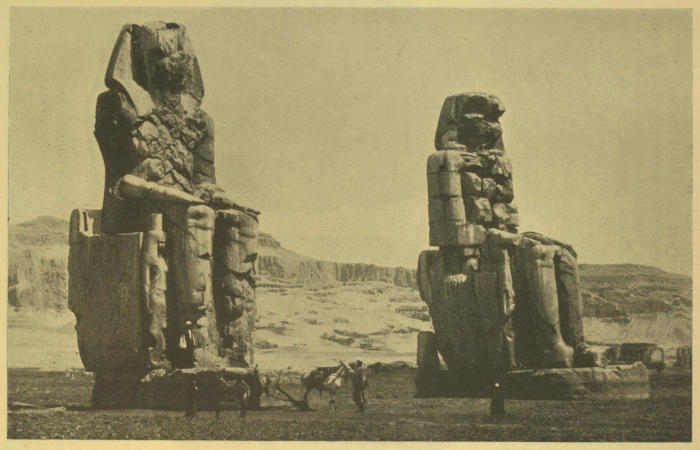

| ” | XXXIII. | The Colossi of Ȧmen-ḥetep III | 234 |

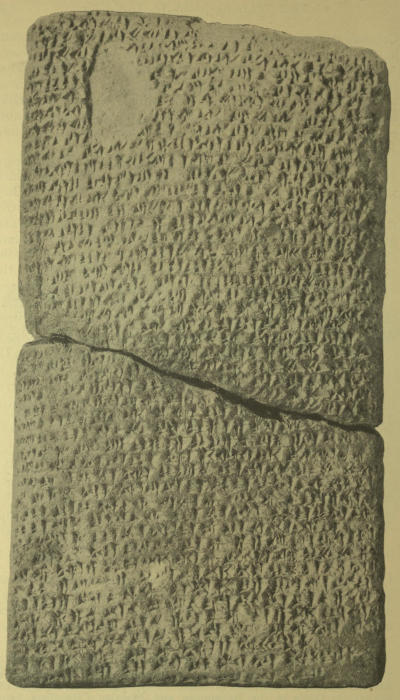

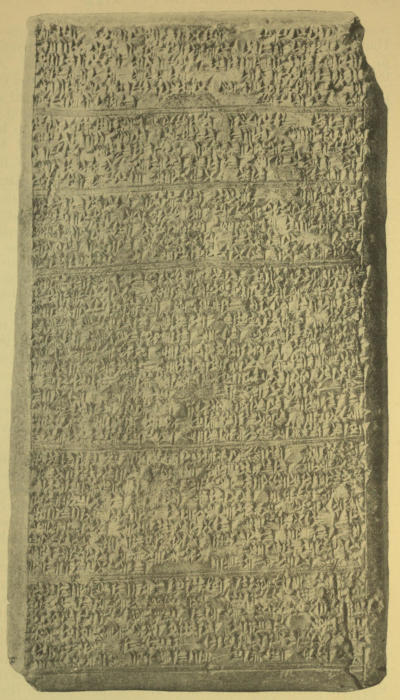

| ” | XXXIV. | Letter of Ȧmen-ḥetep III | 236 |

| ” | XXXV. | Letter of Tushratta, king of Mitani, to Ȧmen-ḥetep III | 236 |

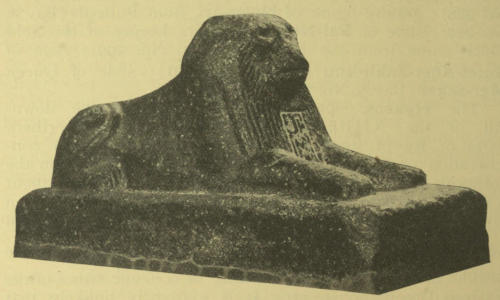

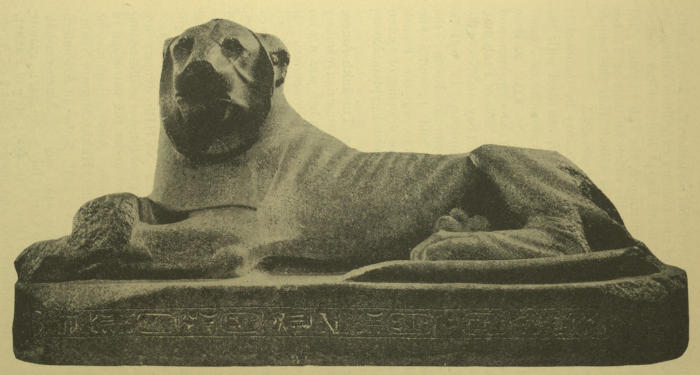

| ” | XXXVI. | Lion of Tut-ānkh-Ȧmen | 238 |

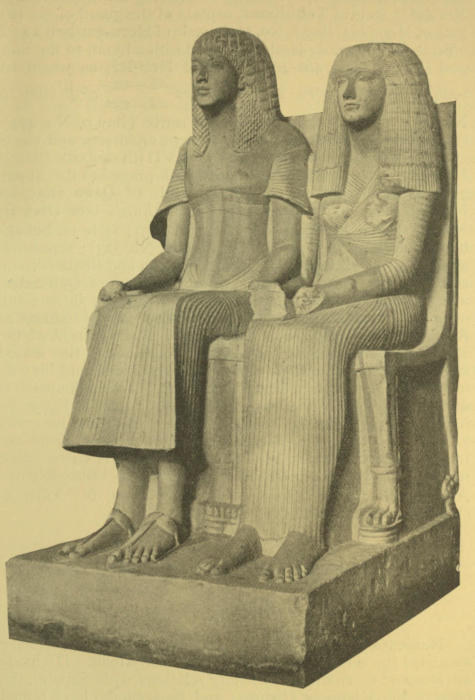

| ” | XXXVII. | Statues of a priest and his wife | 239 |

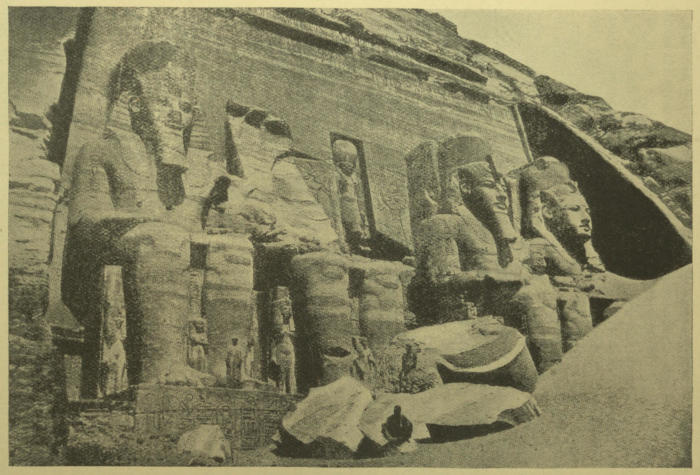

| ” | XXXVIII. | The temple of Abû Simbel | 242 |

| ” | XXXIX. | Head of a colossal statue of Rameses II | 245 |

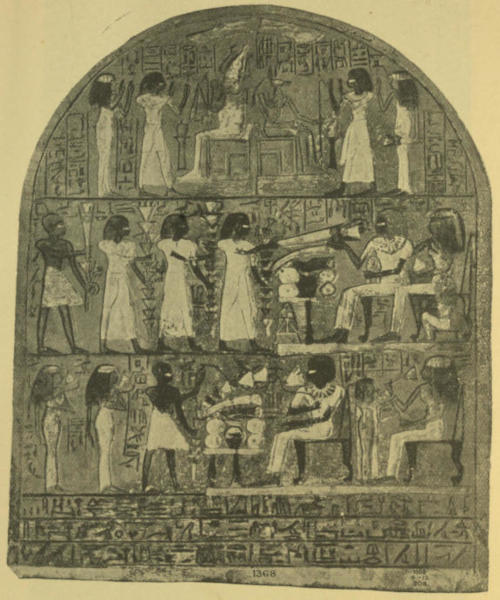

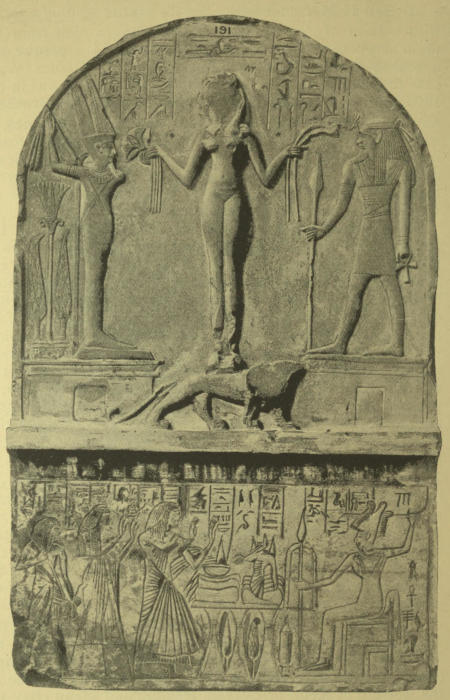

| ” | XL. | Sepulchral stele of Qaḥa | 248 |

| ” | XLI. | Vignettes from the papyrus of Queen Netchemet | 252 |

| ” | XLII. | Hathor-headed capital | 254 |

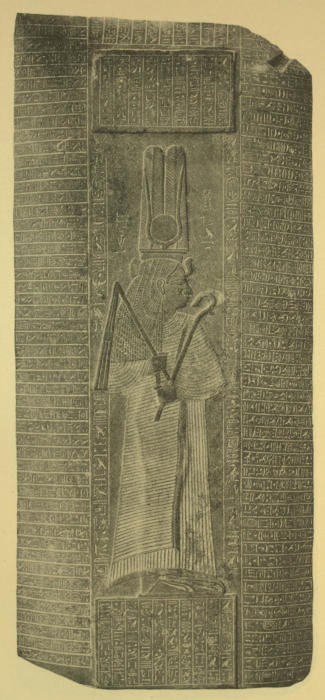

| ” | XLIII. | Relief of Queen Ānkhnes-neferȧb-Rā | 261 |

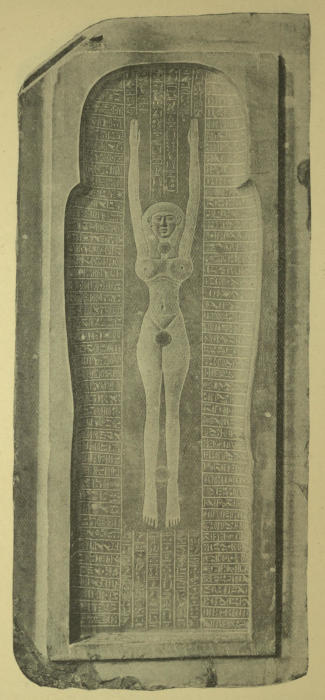

| ” | XLIV. | The goddess Nut | 261 |

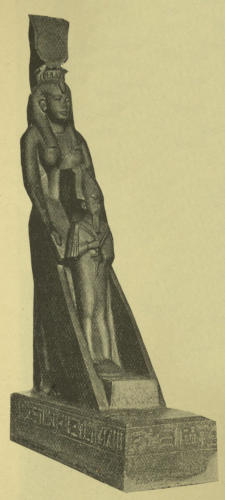

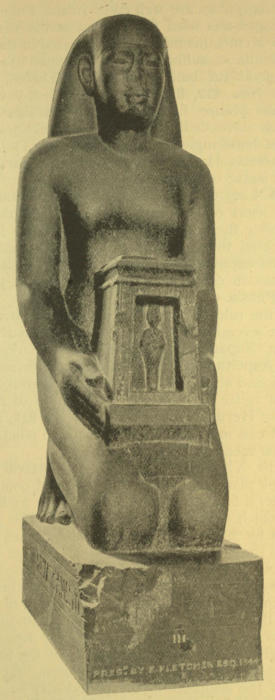

| ” | XLV. | Statue of Uaḥ-ȧb-Rā | 261 |

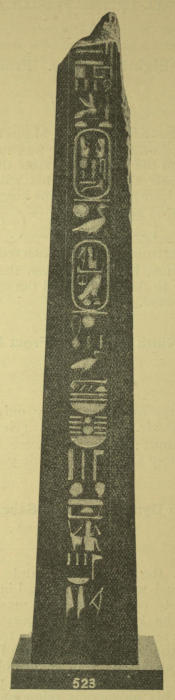

| ” | XLVI. | Obelisk dedicated to Thoth, Twice-great | 265 |

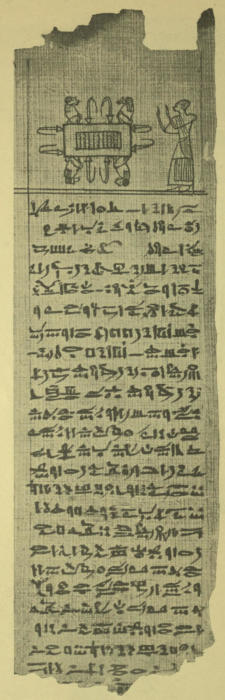

| ” | XLVII. | Vignettes and text from the sarcophagus of Nekht-Ḥeru-ḥebt | 265 |

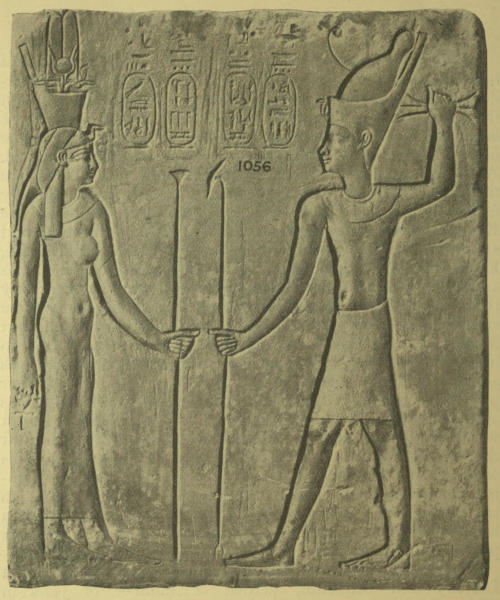

| ” | XLVIII. | Relief of Ptolemy II | 269 |

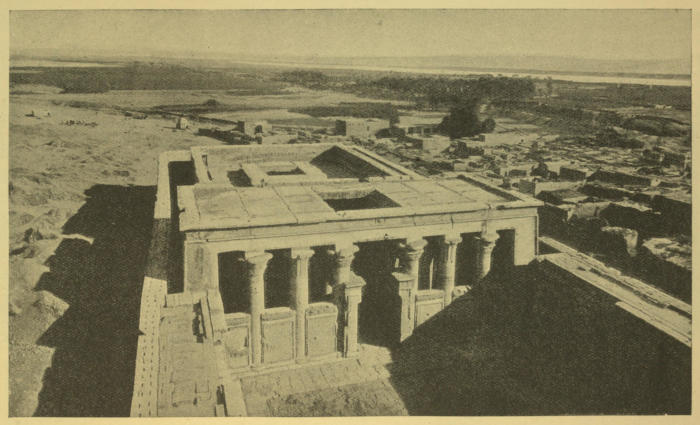

| ” | XLIX. | The temple of Edfû | 270 |

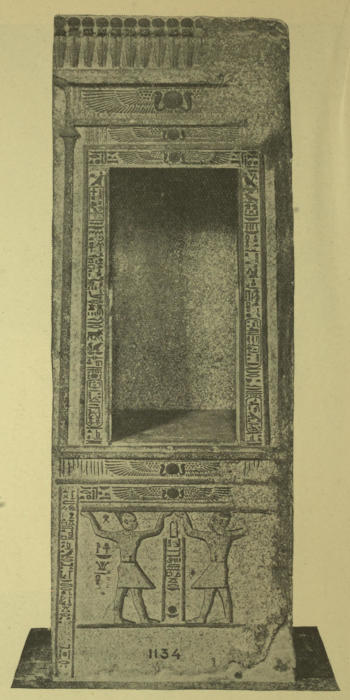

| ” | L. | Granite shrine from Philae | 271 |

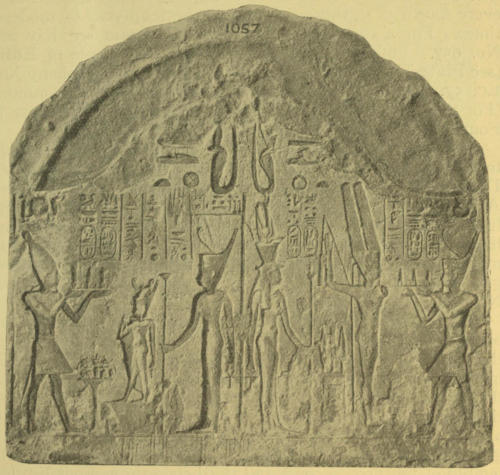

| ” | LI. | Tablet of Tiberius | 277 |

| ” | LII. | Tablet of Tiberius | 277 |

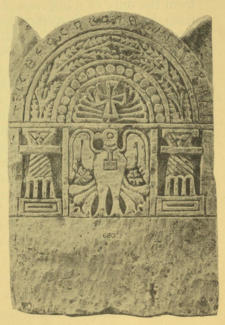

| ” | LIII. | Tablet of Apa Paḥomo | 283 |

| PAGE | |

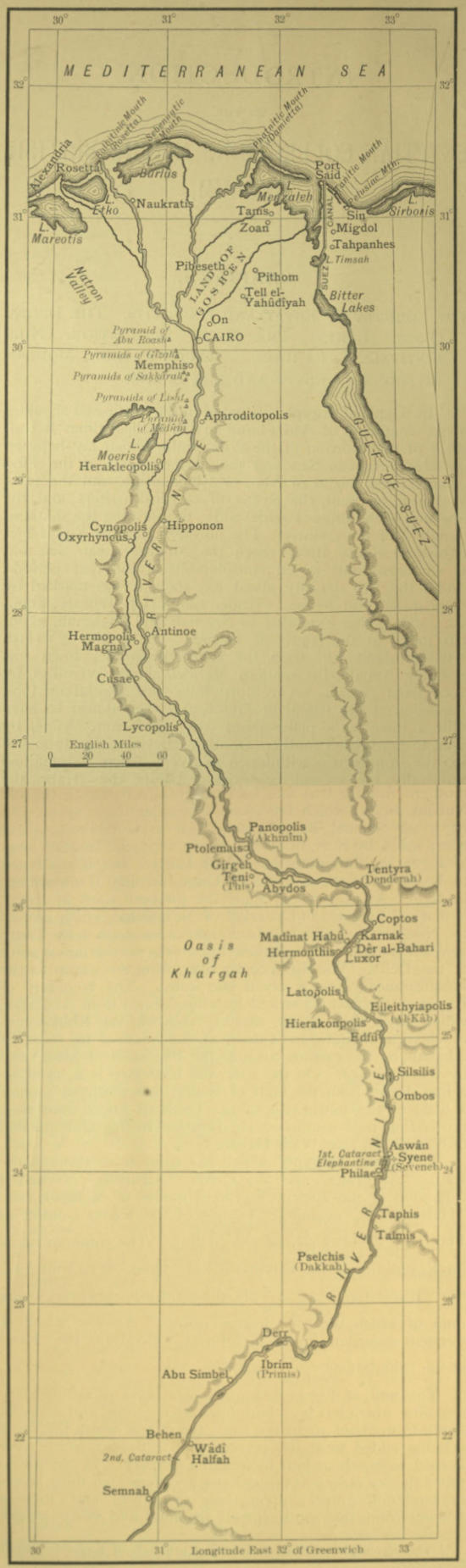

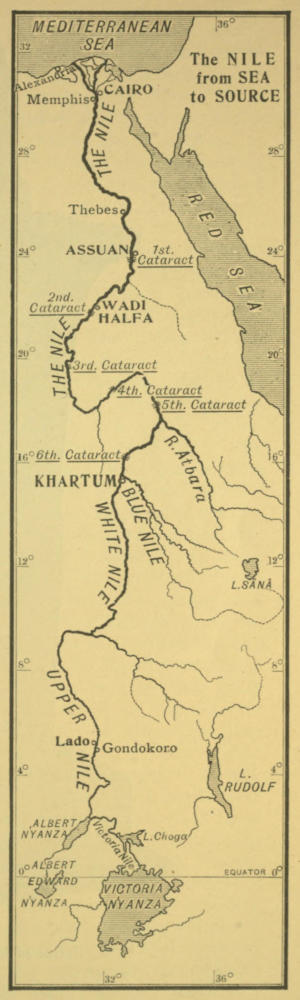

| Map of Egypt | 2, 3 |

| The Delta of Egypt | 5 |

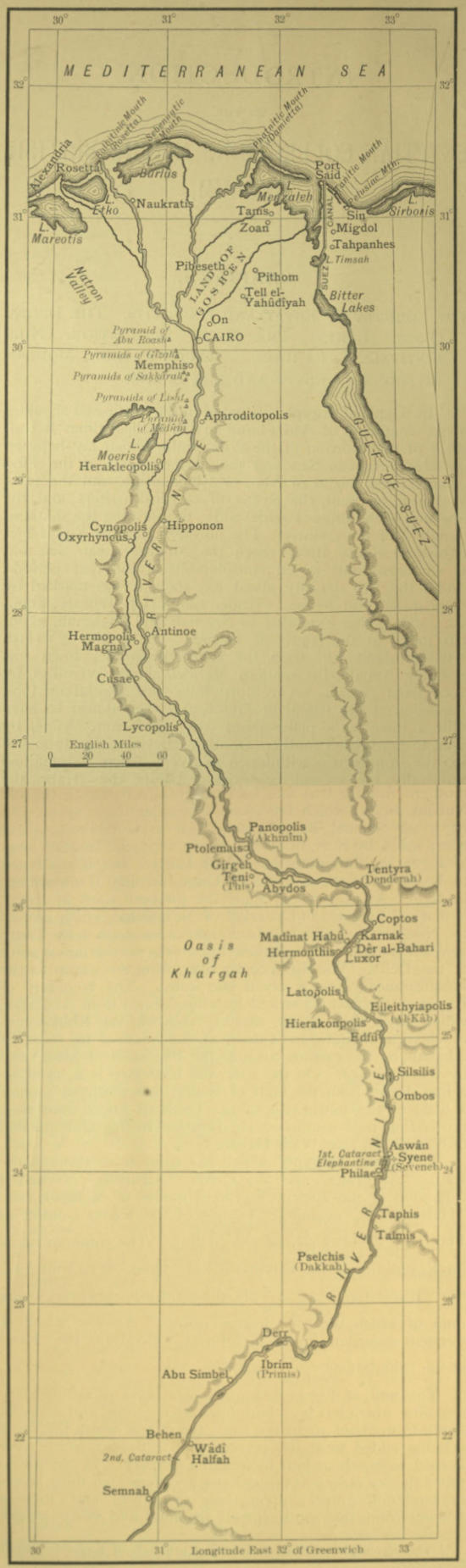

| The Entrance to the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings at Thebes | 6 |

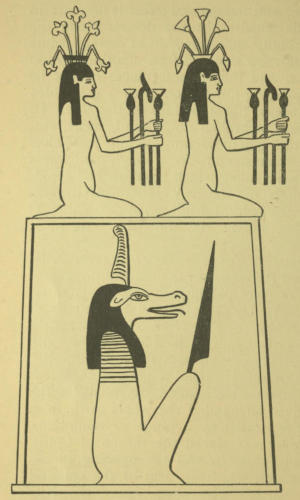

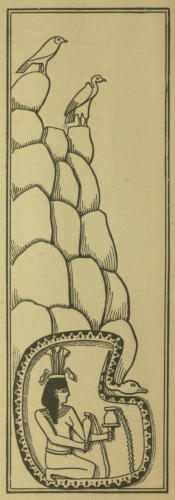

| The Nile-gods and their cavern | 8 |

| The Nile-god in his cavern | 8 |

| The Nile-god bearing offerings | 9 |

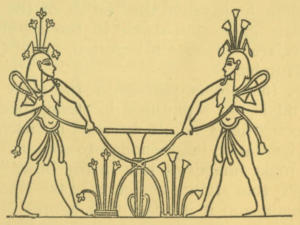

| The Nile-gods of the South and North | 9 |

| The Nile from sea to source | 11 |

| Statue of Ḥāpi the Nile-god | 12 |

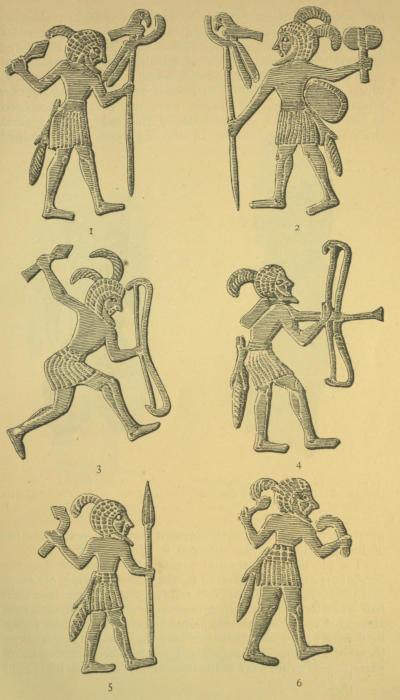

| Egyptian hunters of the Archaïc Period, Nos. 1-6 | 23 |

| Ivory figure of a king | 24 |

| Bone figure of a dwarf | 24 |

| Bone figure of a woman carrying a child | 25 |

| Bone figure of a woman with inlaid eyes | 25 |

| Figure of Betchmes | 26 |

| Figure of Nefer-hi | 26 |

| Fox playing the double pipes | 27 |

| Mouse seated on a chair | 28 |

| Cat herding geese | 29 |

| Lion and unicorn playing draughts | 30 |

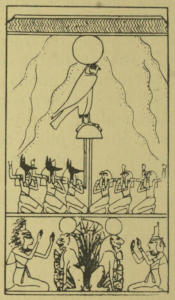

| The spearing of Āpep | 31 |

| A page of writing from the Great Harris Papyrus | 36 |

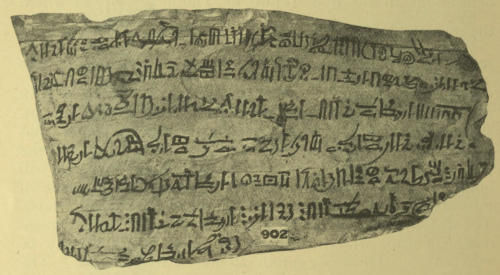

| Demotic writing | 38 |

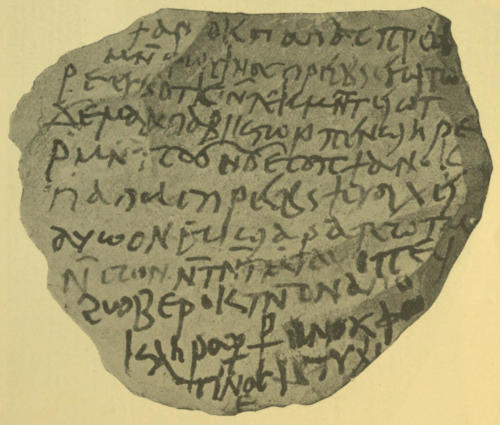

| Coptic inscription | 41 |

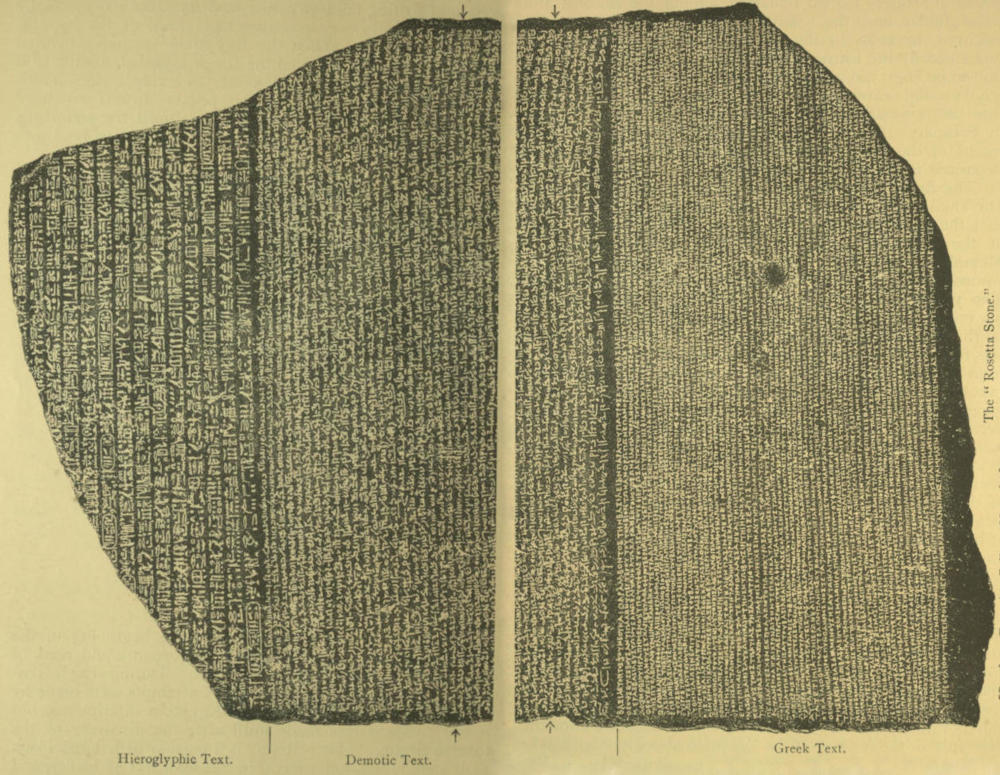

| The Rosetta Stone | 42, 43 |

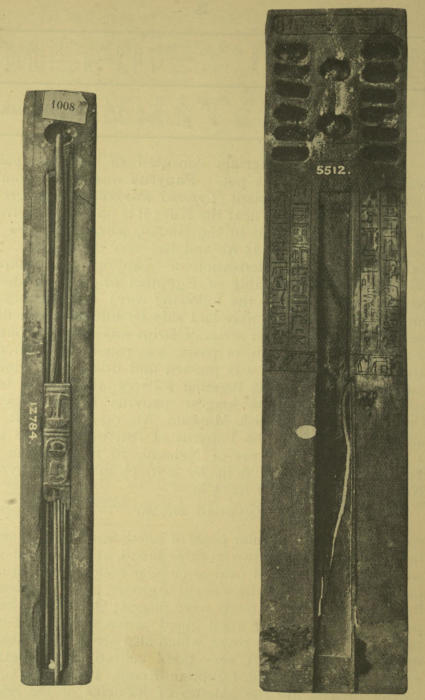

| Two wooden writing palettes | 54 |

| Slab of limestone inscribed in hieratic | 56[xii] |

| Vignette and text from the papyrus of Ani | 60 |

| Vignette and text from the papyrus of Nu | 60 |

| Vignette and text from the papyrus of Ḥeru-em-ḥeb | 61 |

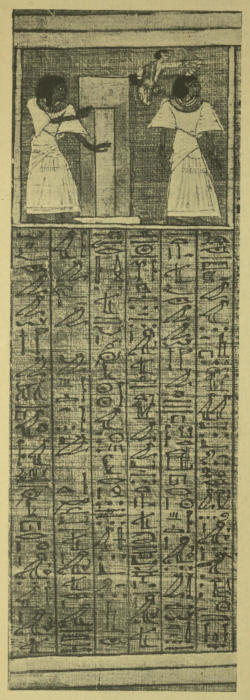

| Text from the Book “May my name flourish” | 63 |

| The ceremony of “Opening the mouth” | 64 |

| Marble sun-dial | 72 |

| Head of a priestess | 80 |

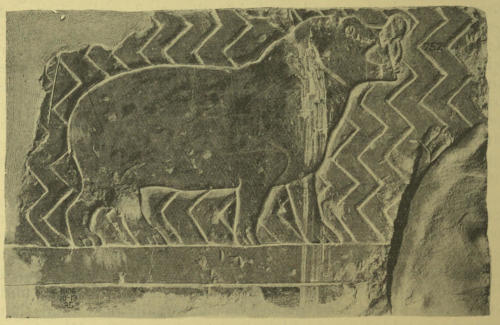

| Relief, with a hippopotamus | 84 |

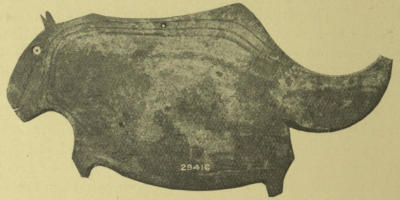

| Green schist bear | 86 |

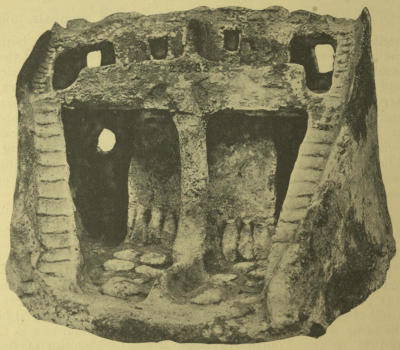

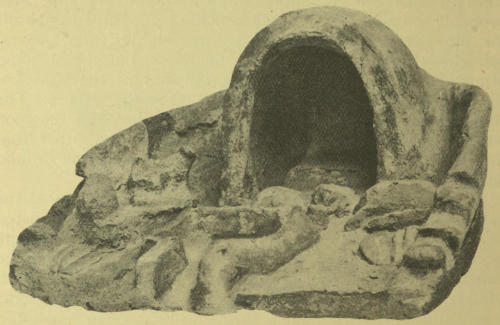

| Egyptian house | 88 |

| Egyptian hut | 90 |

| Ivory head-rest | 91 |

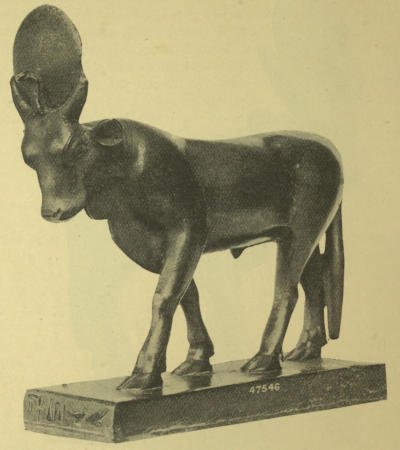

| The Bull Apis | 93 |

| The Bull Mnevis | 94 |

| Flint cow’s head | 95 |

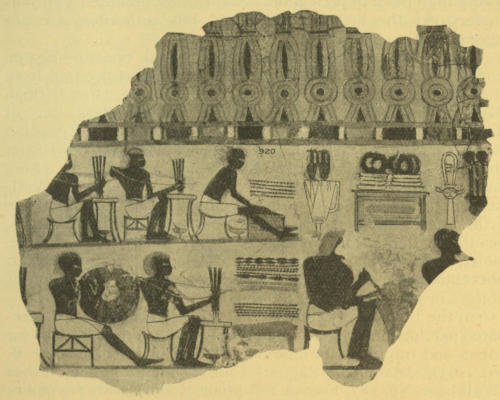

| Jewellers drilling and polishing beads | 99 |

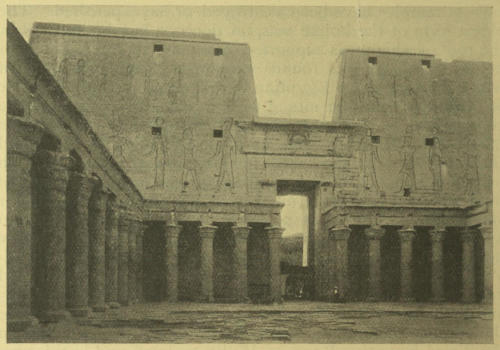

| Pylon and court of the temple of Edfû | 104 |

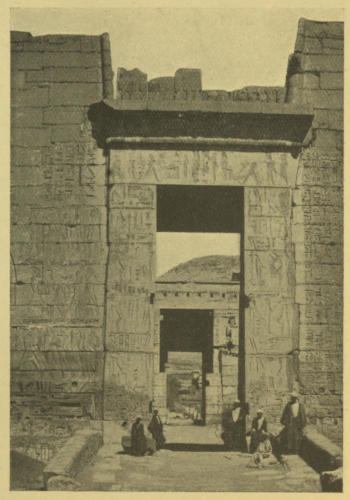

| Gateway to the temple of Rameses III | 105 |

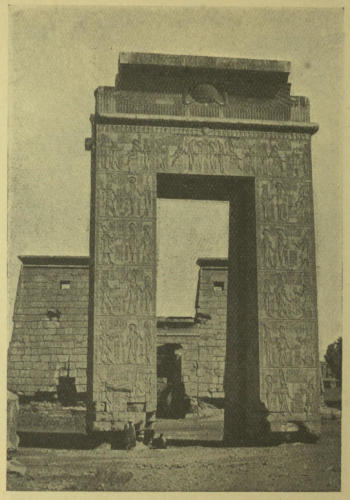

| Gateway of Ptolemy IX at Karnak | 106 |

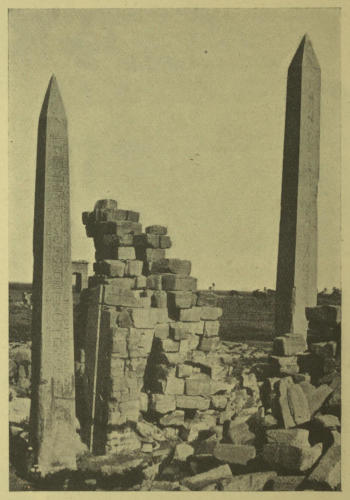

| Granite obelisks at Karnak | 107 |

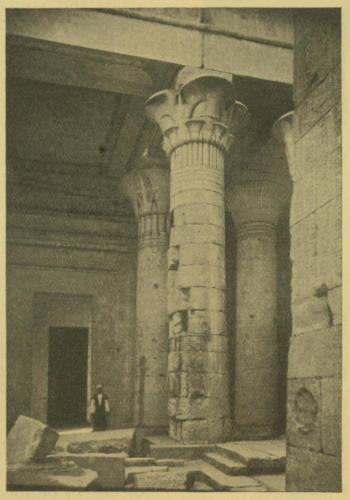

| Pillars at Philae | 108 |

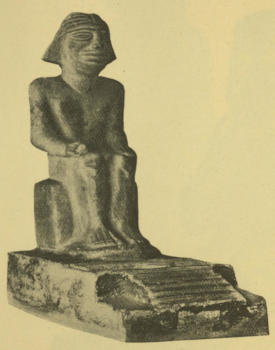

| Statue of Ȧn-kheft-ka | 109 |

| Figure of a priest | 110 |

| Head of a statue of Neb-ḥap-Rā | 110 |

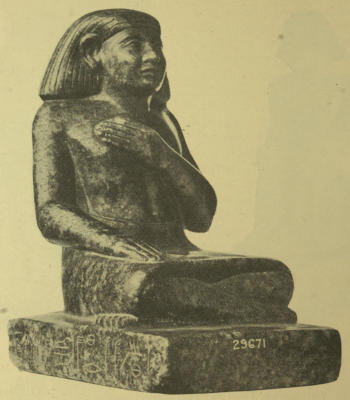

| Statue of Sebek-nekht | 111 |

| Figure of a king | 112 |

| Queen Tetȧ-Kharṭ | 113 |

| Head of Ȧmen-ḥetep III | 114 |

| Statue of Isis | 115 |

| Figure of Qen-nefer | 118 |

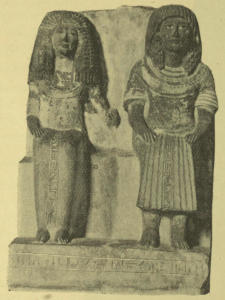

| Statues of Māḥu and Sebta | 119 |

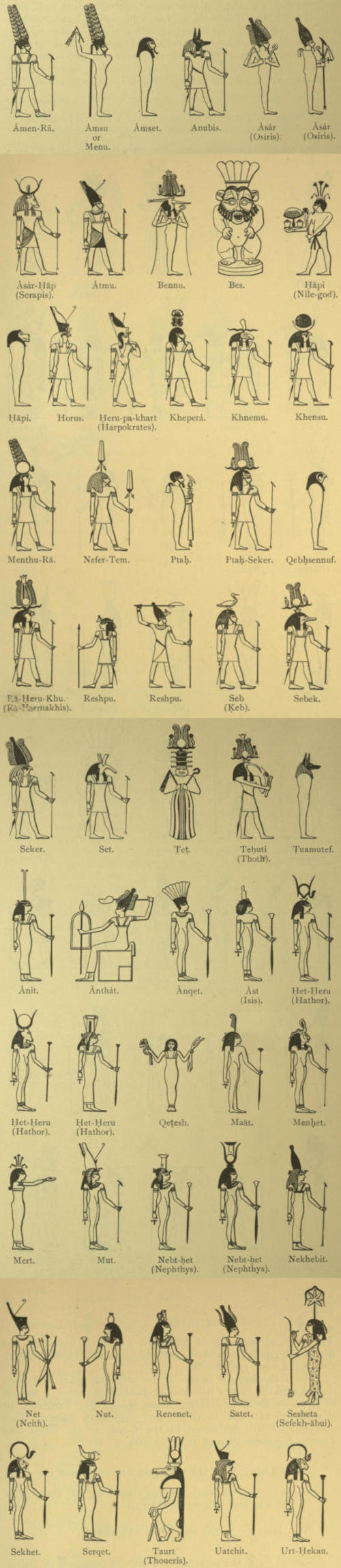

| The principal gods and goddesses of Egypt (57 figures) | 123-126 |

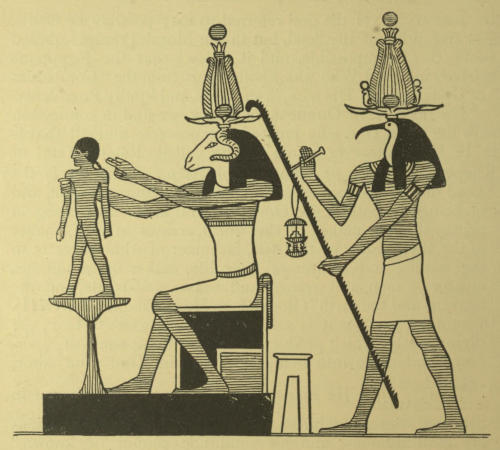

| Khnemu fashioning a man on a potter’s wheel | 135 |

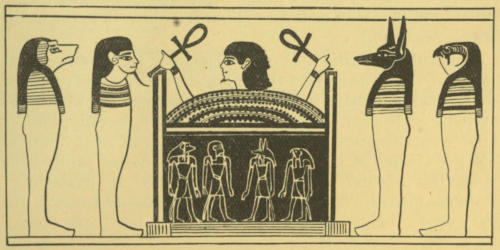

| Osiris rising from the sarcophagus | 138 |

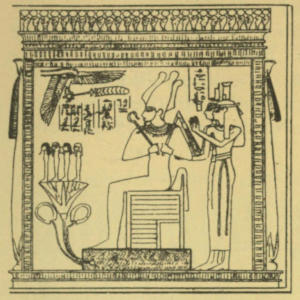

| Osiris in his shrine | 140 |

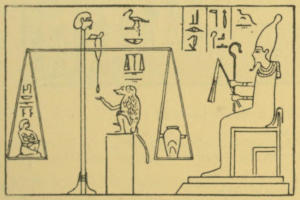

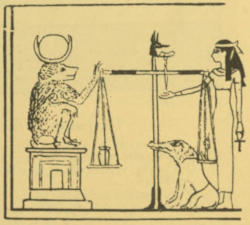

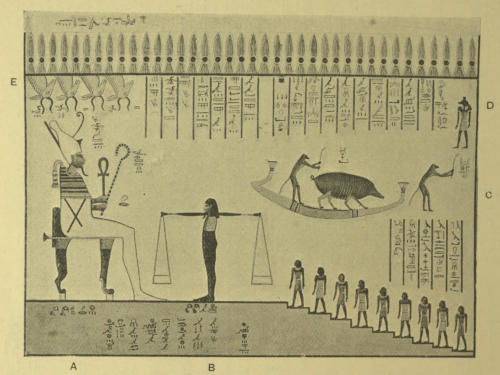

| Thoth weighing the heart | 140[xiii] |

| Maāt weighing the heart | 140 |

| Osiris on his Judgment Throne | 141 |

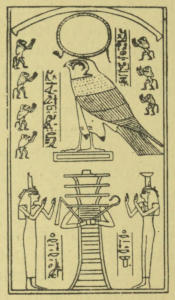

| Rā at sunrise | 143 |

| Rā at sunset | 143 |

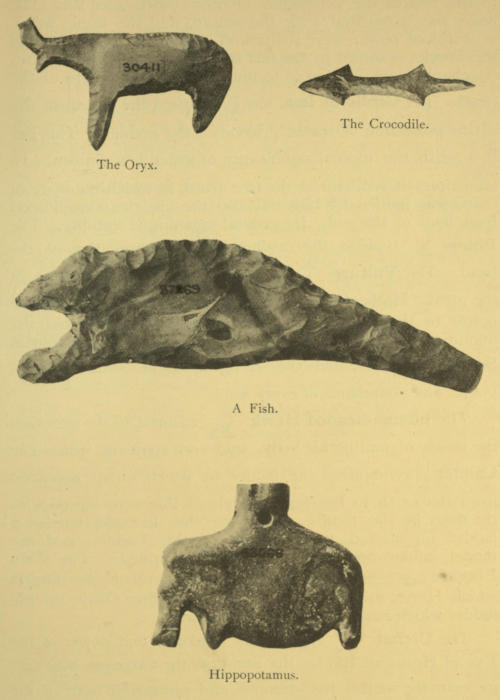

| Flint amulets (4 figures) | 148 |

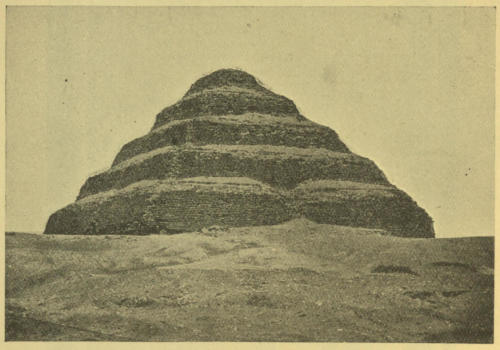

| The step pyramid at Ṣaḳḳârah | 166 |

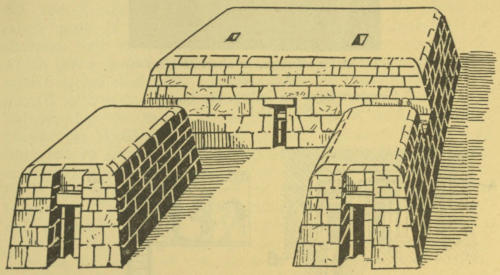

| A group of maṣṭaba tombs | 167 |

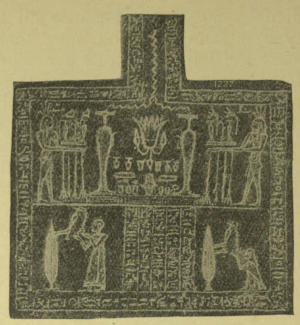

| Tablet for offerings | 168 |

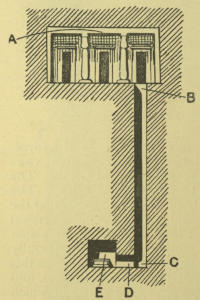

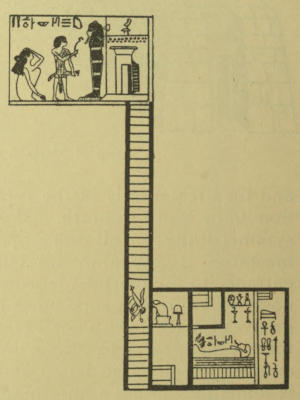

| An Egyptian tomb | 168 |

| The soul visiting the body | 168 |

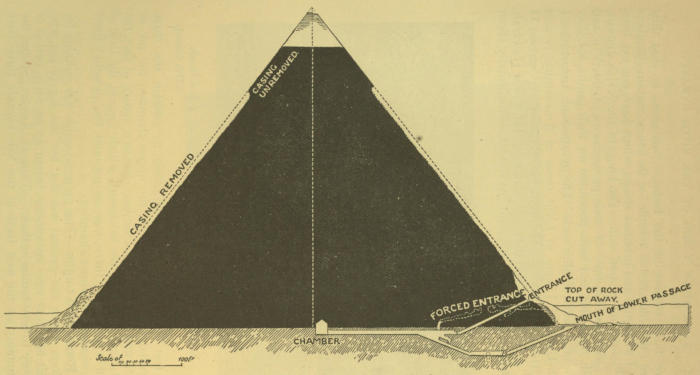

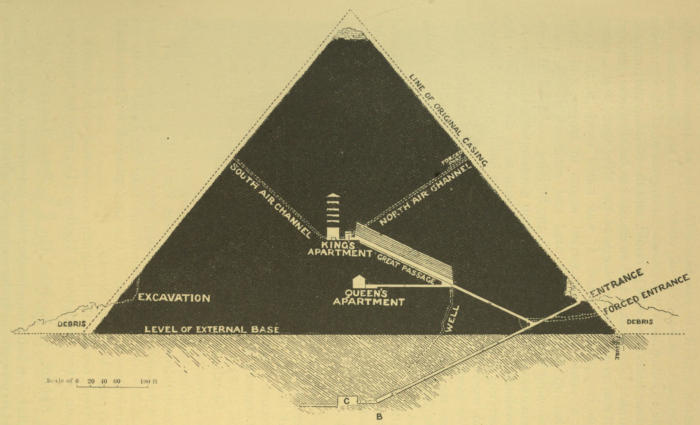

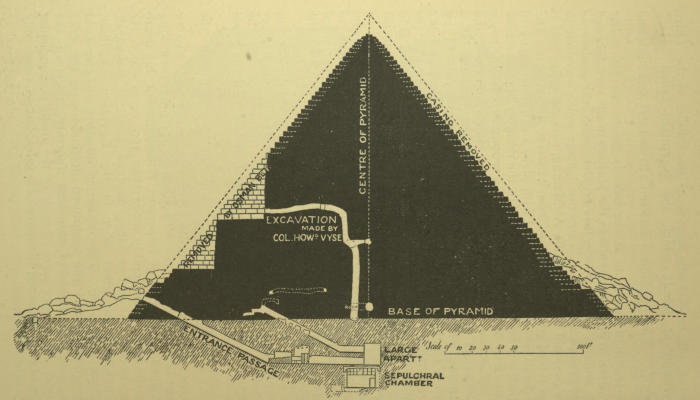

| Section of the Second Pyramid | 171 |

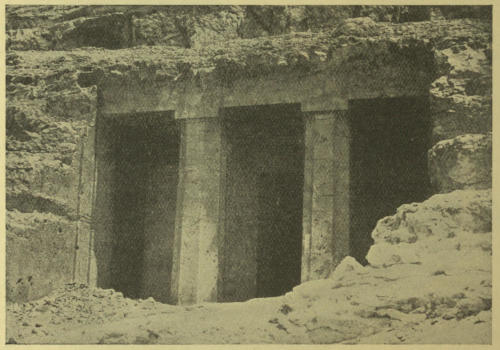

| Entrance to the tomb of Khnemu-ḥetep | 172 |

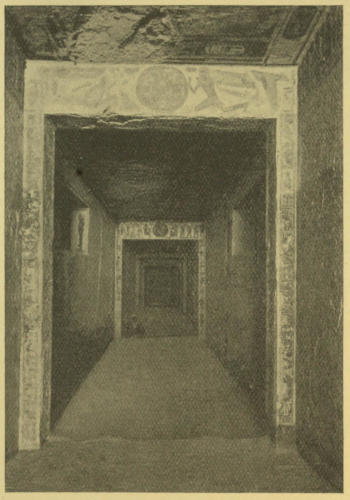

| Entrance to a royal tomb | 173 |

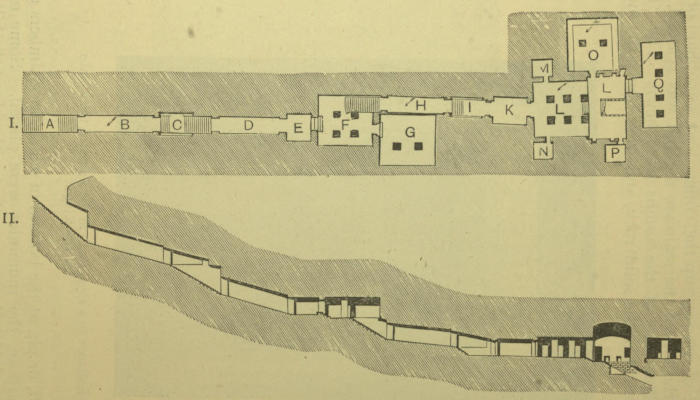

| Plan and section of the tomb of Seti I (2 cuts) | 174 |

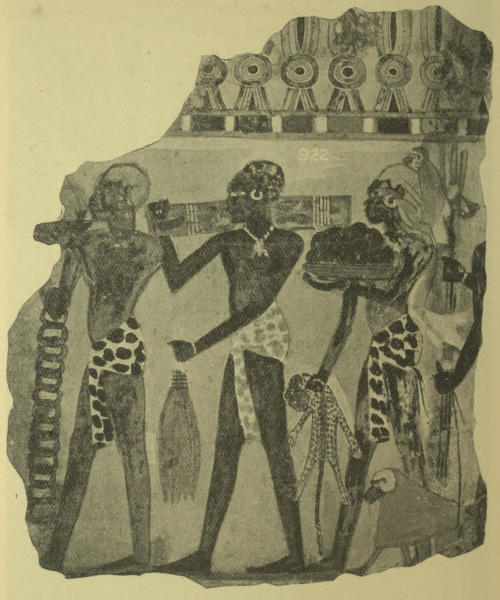

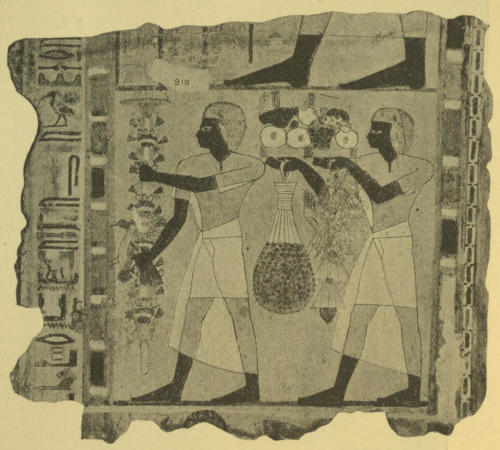

| Wall painting from a tomb | 175 |

| Coffin of Ḥes-Peṭān-Ȧst | 176 |

| Figures of Ka-ṭep and Ḥetep-ḥeres | 177 |

| King Semti dancing before a god | 190 |

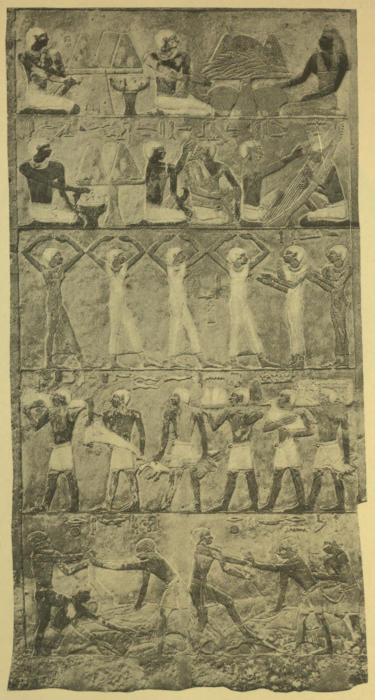

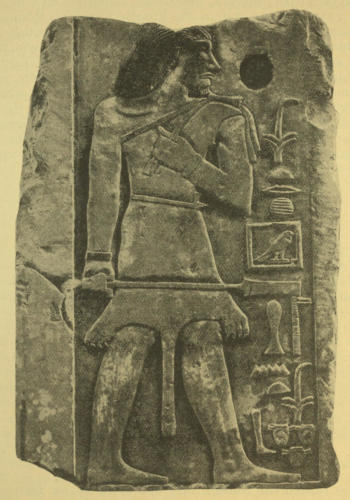

| Relief from the tomb of Sherȧ | 192 |

| Relief from the tomb of Suten-ȧbu | 194 |

| King Khufu | 196 |

| Section of the Great Pyramid | 197 |

| King Khāf-Rā | 199 |

| King Menkau-Rā | 200 |

| Section of the Third Pyramid | 202 |

| King Usr-en-Rā Ȧn | 204 |

| Shrine of Pa-suten-sa | 219 |

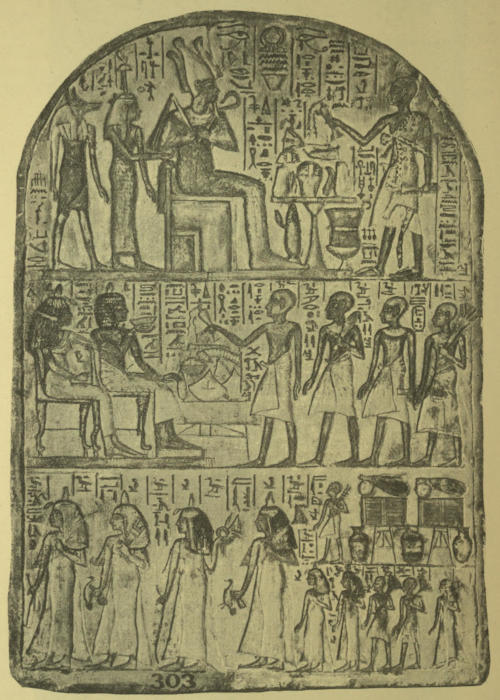

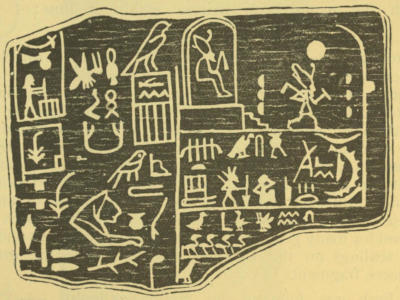

| Stele of Tatiankef | 220 |

| Lion of Khian | 225 |

| Statue of Ȧmen-ḥetep I | 229 |

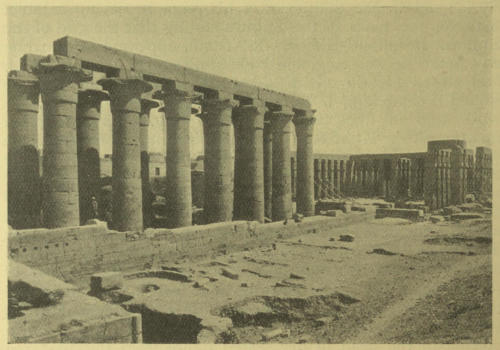

| The Temple of Luxor | 233 |

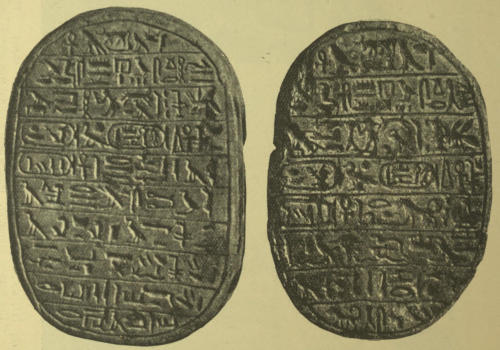

| Scarabs of Ȧmen-ḥetep III (2 cuts) | 235 |

| Kneeling statue of Rameses II | 241 |

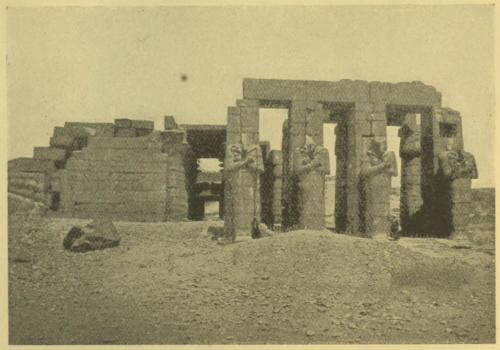

| Façade of the Ramesseum | 243 |

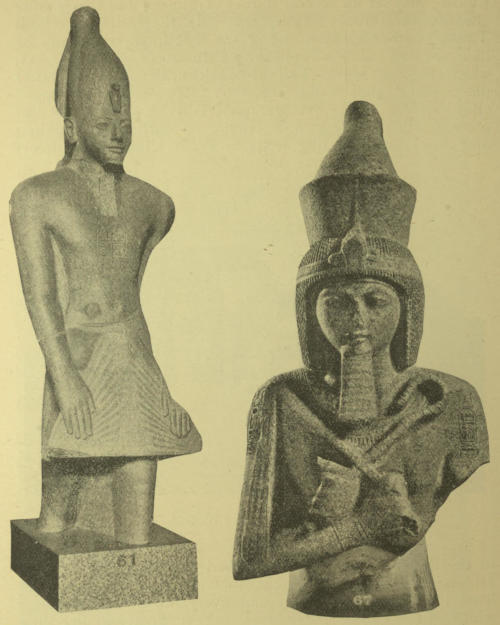

| Statues of Rameses II (2 cuts) | 244 |

| Statue of Khā-em-Uast | 246[xiv] |

| Statue of Seti II | 247 |

| Statue of Ānkh-renp-nefer | 254 |

| Head of Psammetichus II | 259 |

| Stele of Ptolemy II | 269 |

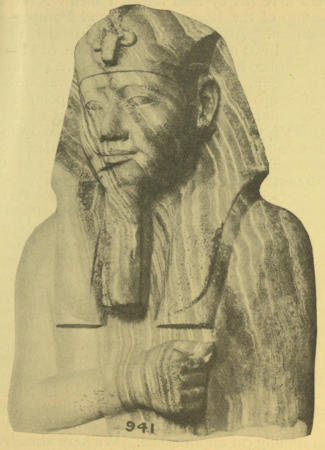

| Head of a statue of a Ptolemy | 271 |

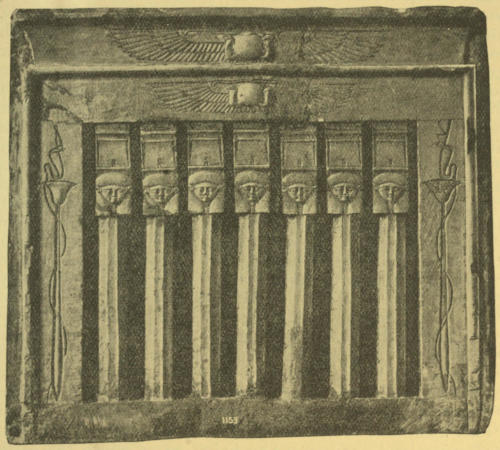

| Limestone window | 273 |

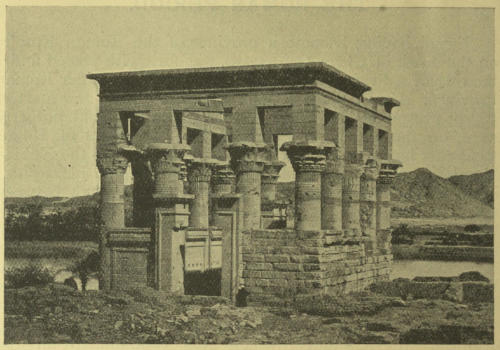

| “Pharaoh’s Bed” | 276 |

| Coptic sepulchral tablet | 279 |

| Tablet of Plêïnôs | 281 |

| Tablet of David | 281 |

| Tablet of Abraam | 284 |

| Tablet of Rachel | 284 |

The Country of Egypt and its Limits. The Delta. Oases. Lakes. The Nile. Inundation. Nile Festivals. Famines. Ancient and Modern Divisions of Egypt and the Sûdân.

The Land of Egypt is situated in the north-east shoulder of the continent of Africa, and in the earliest times it consisted of that portion of the Nile Valley which lay between the Mediterranean Sea and the northern end of the First Cataract; the Island of Ābu, or Elephantine, and the town of Sunnu, or Sunt, the Syene of classical writers and the Sewênêh of the Bible (Ezekiel xxix, 10), forming the southern boundary of the country. The northern limit of Egypt has, in historic times, always been the Mediterranean Sea, but its southern limit varied considerably at different periods. Under the Vth dynasty, about B.C. 3600, it was marked by Elephantine and Syene. Under the XIIth dynasty, about B.C. 2500, it was extended to Semnah and Kummah, about 250 miles to the south of Syene. Under the XVIIIth dynasty, about B.C. 1600, the southern frontier town was probably Napata, the modern Merawi, about 600 miles, by river, from Syene. A century later the Egyptians took possession of the Island of Meroë, and they appear to have built a town at a place about 930 miles from Syene, by river, to mark their southern frontier. Between B.C. 1200 and 600 the frontier was withdrawn to Syene, where it remained practically for several centuries. Under the Arabs, the southern frontier was fixed at Dongola (A.D. 1275), the old Nubian capital, which lay about 570 miles from Syene. In 1873, Sir Samuel Baker extended it to Gondókoro, about 2,823 miles, by river, from Cairo. In 1895, the frontier town of Egypt in the south was Wâdî Ḥalfah, and it continued to be so until the capture of Umm Darmân (Omdurmân) in 1898. At the present time, the southern limit of Egypt is marked by the 22nd parallel of N. latitude, which crosses the Nile at Gebel Sahaba, about eight miles north of the Camp at Wâdî Ḥalfah, and its northern limit is the northernmost point of the Delta. The distance, by river, from the Camp to the Mediterranean Sea, is about 960 miles. The boundary of Egypt on the east is marked by a line drawn from Ar-Rafah, which lies a little to the east of Al-Arîsh, the Rhinocolura of classical writers, to Tabah, at the head of the Gulf of Akabah, by the eastern coast of the Peninsula of Sinai,[1] and by the Red Sea. On the west, the boundary is marked by a line drawn from the Gulf of Solum due south to a point a little to the south-west of the Oasis of Sîwah, and then proceeding in a south-easterly direction to the 22nd parallel of N. latitude, near Wâdî Ḥalfah.

MAP OF EGYPT.

The name “Egypt,” which has come to us through the Latin “Aegyptus” and the Greek “Aiguptos,” is derived from one of the ancient Egyptian names of Memphis, viz., “Ḥet-ka-Ptaḥ,” meaning “Temple of the Ka, or Double, of Ptaḥ” 𓉗𓏏𓉐𓂓𓏤𓊪𓏏𓎛𓀭 or 𓉘𓂓𓏤𓊪𓏏𓎛𓀭𓉜. The common name for Egypt among the Egyptians was “Qem,” or “Qemt,” i.e., the “Black Land,” 𓆎𓏏𓊖, in allusion to the brownish-black mud of which the soil chiefly consists. Another name of frequent occurrence in the literature is “Ta-Merȧ,” the “Land of the Inundation,” 𓇾𓏤𓈇𓌻𓇋𓆳𓊖.

The soil of Egypt is formed of a layer of sedimentary deposits, which has been laid down by the Nile, and varies in depth from about 40 to 110 feet; the rate at which this layer is being added to at the present time in the bed of the river is said to be about four inches in a century. In prehistoric times the sea ran up as far as Esna, and deposited thick layers of sand and gravel; upon these the rivers and streams flowing from the south spread the mud and stony matter[5] which they brought down with them, and thus the soil of Egypt was gradually built up. Near Esna begins the layer of sandstone, which extends southward, and covers nearly the whole of Nubia, and rests ultimately on crystalline rock.

The Delta of Egypt.

The part of Egypt which lies to the north of the point where the Nile divides itself into two branches resembles in shape a lotus flower, or a triangle standing on its apex, and because of its similarity to the fourth letter of their alphabet, the Greeks called it Delta, Δ.

The Delta is formed of a deep layer of mud and sand, which rests upon the yellow quartz sands, and gravels and stiff clay, which were laid down by the sea in prehistoric times. The area of the Delta is about 14,500 square miles.

The Oases of Egypt are seven in number, and all are situated in the Western Desert. Their names are: 1. Oasis of Sîwah or Jupiter Ammon; 2. Oasis of Baḥarîyah, i.e., the Northern Oasis; 3. The Oasis of Farâfrah, the Ta-ȧḥet of the Egyptians; 4. The Oasis of Dâkhlah, i.e., the “Inner” Oasis, the Tchesti of the Egyptians; 5. The Oasis of Khârgah, i.e., the “Outer Oasis,” the Uaḥt-rest or “Southern Oasis” of the Egyptians; 6. The Oasis of Dailah, to the west of Farâfrah; 7. The Oasis of Kûrkûr, to the west of Aswân.

The principal Lakes of Egypt are: 1. Birkat al-Ḳurûn, a long, narrow lake lying to the north-west of the Province of the Fayyûm, and formerly believed to be a part of the Lake Moeris described by Herodotus; 2. The Natron Lakes, which lie in the Natron Valley, to the north-west of Cairo; from these the Egyptians obtained salt and various forms of soda, which were used for making incense, and in embalming the dead; 3. Lake Menzâlah, Lake Bûrlûs, Lake Edkû, Lake Abukîr, now almost reclaimed, and Lake Mareotis; all these are in the Delta. Lake Timsaḥ (i.e., Crocodile Lake) and the Bitter Lakes, which were originally mere swamps, came into existence with the making of the Suez Canal.

The Fayyûm which was in ancient times regarded as one of the Oases, is nothing more than a deep depression scooped out of the limestone, on which are layers of loams and marls covered over by Nile mud. The district was called by the Egyptians “Ta-she,” or “Land of the Lake”; at the present time it has an area of about 850 square miles, and is watered by a branch of the Nile called the “Baḥr Yûsuf,” which flows into it through an opening in the mountains on the west bank of the Nile. The Baḥr Yûsuf, or “River of Joseph,” is not called after the name of the patriarch Joseph, but that of some Muḥammadan ruler. It is not a canal as was once supposed, but an arm of the Nile, which, however, needs clearing out periodically. In the Fayyûm lay the large body of water to which Herodotus gave the name of Lake Moeris. He believed that this Lake had been constructed artificially, but modern irrigation authorities in Egypt have come to the conclusion that the mass of water which he saw and thought was a lake was merely the result of the Nile flood, or inundation, and that there never was a Lake Moeris.

The Entrance to the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings at Thebes.

Deserts. On each side of the Valley of the Nile lies a vast desert. That on the east is called the Arabian Desert,[7] or Red Sea Desert, and that on the west the Libyan Desert. The influence of the latter on the climate of Egypt is very great, as for six months of the year the prevailing wind blows from the west. At many places in the Eastern and Western Deserts there are long stretches of sand scores of miles in length, and immense tracts covered with layers of loose pebbles and stone, and the general effect is desolate in the extreme. The hills which skirt the deserts along the Valley of the Nile are usually quite low, but at certain points they rise to the height of a few hundred feet. Nothing grows on them, and more bare and inhospitable places cannot be imagined. The accompanying illustration gives a good idea of the general appearance of the stone hills on the Nile. In the fore-ground are masses of broken stone, sand, rocks, etc., and these stretch back to a gap in the range of hills just below the letter A, whence, between steep rocks, a rough road winds in and out along the dreary valley which contains the sepulchres of the great kings of the XVIIIth, XIXth and later dynasties. Under the light of a full moon the Valley is full of weird beauty, but in the day-time the heat in it resembles that of a furnace.

The chief characteristic of Egypt is the great river Nile, which has in all ages been the source of the life and prosperity of its inhabitants, and the principal highway of the country. The Egyptians of the early Dynastic Period had no exact knowledge about the true source of the river. In their hymns to the Nile-god they described him as the “hidden one,” and “unseen,” and his “secret places” are said to be “unknown.” The river over which he presided formed a part of the great celestial river, or ocean, upon which sailed the boats of the Sun-god daily. This river surrounded the whole earth, from which, however, it was separated by a range of mountains. On one portion of this river was placed the throne of Osiris, according to a legend, and close by was the opening in the range of mountains through which an arm of the celestial river flowed into the earth. The place where the Nile appeared on earth was believed to be situated in the First Cataract, and in late times the Nile was said to rise there, between two mountains which were near the Island of Elephantine and the Island of Philae. Herodotus gives the names of these mountains as “Krôphi” and “Môphi,” and their originals have probably been found in the old Egyptian “Qer-Ḥāpi” and “Mu-Ḥāpi”; these names mean “Cavern of Ḥāpi” and “Water of Ḥāpi” respectively.

The two Nile-gods and their Cavern, and the hippopotamus goddess, who is armed with a huge knife, their protectress.

The Nile-god in his cavern, under the rocks at Philae, pouring out the waters which formed the two Niles.

The underground caverns, or “storehouses of the Nile,”[8] from which the river welled up, are depicted in the illustrations here given. In the first the cavern is guarded by a hippopotamus-headed goddess, who is armed with a large knife and wears a feather on her head. Above are seated two gods, one wearing a cluster of papyrus plants on his head, and the other a cluster of lotus flowers; the former represents the Nile of the South, and the other the Nile of the North. Each god holds water-plants in one hand. In the second illustration the god is depicted kneeling in his cavern, which[9] is enclosed by the body of a serpent; he wears a cluster of water-plants on his head, and is pouring out from two vases the streams of water which became the South and North Niles.

The Egyptians called both their river and the river-god “Ḥāp” or “Ḥāpi” 𓎛𓂝𓊪, 𓎛𓂝𓊪𓏭𓈘𓈗𓀭, a name of which the meaning is unknown; in very early dynastic times the god was called “Ḥep-ur” 𓎛𓊪𓈘𓅨, i.e., the “great Ḥep.” The name “Nile,” by which the “River of Egypt” is generally known, is not of Egyptian origin, but is probably derived from the Semitic word nakhal “river”; this the Greeks turned into “Neilos,” and the Latins into “Nilus,” whence comes the common form “Nile.” The river appears in the form of a man wearing a cluster of water-plants on his head, and his fertility is indicated by a large pendent breast. In the accompanying illustration the gods of the South and North Niles are seen tying stems of the lotus and papyrus plants round the symbol of “union”; the scene represents the union of Upper and Lower Egypt.

The Nile-god bearing offerings of bread, wine, fruit, flowers, etc.

The Nile-gods of the South and North tying the stems of a lily and a papyrus plant round the symbol of “union,” symbolizing the union of Upper and Lower Egypt.

The ideas held by the Egyptians concerning the power of the Nile-god are well illustrated by a lengthy Hymn to the Nile preserved on papyrus in the British Museum (Sallier II, No. 10,182). “Homage to thee, O Ḥāpi, thou appearest in this land, and thou comest in peace to make Egypt to live. Thou waterest the fields which Rā hath created, thou givest life[10] unto all animals, and as thou descendest on thy way from heaven thou makest the land to drink without ceasing. Thou art the friend of bread and drink, thou givest strength to the grain and makest it to increase, and thou fillest every place of work with work.... Thou art the lord of fish ... thou art the creator of barley, and thou makest the temples to endure for millions of years.... Thou art the lord of the poor and needy. If thou wert overthrown in the heavens, the gods would fall upon their faces, and men would perish. When thou appearest upon the earth, shouts of joy rise up and all people are glad; every man of might receiveth food, and every tooth is provided with meat.... Thou fillest the storehouses, thou makest the granaries to overflow and thou hast regard to the condition of the poor and needy. Thou makest herbs and grain to grow that the desires of all may be satisfied, and thou art not impoverished thereby. Thou makest thy strength to be a shield for man.” Elsewhere he is called the “father of the gods of the company of the gods who dwell in the celestial ocean,” and he was declared to be self-begotten, and “One,” and in nature inscrutable.

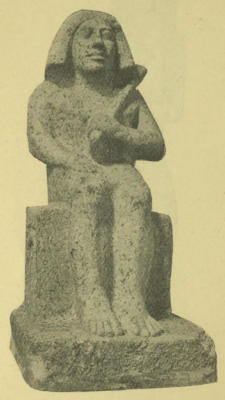

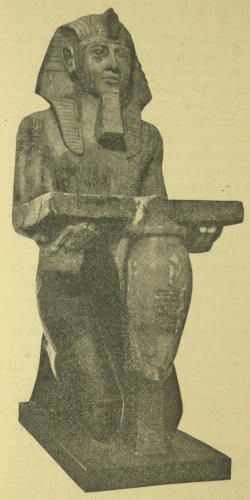

In another passage of the same hymn it is said that the god is not sculptured in stone, that images of him are not seen, “he is not to be seen in inscribed shrines, there is no habitation large enough to contain him, and thou canst not make images of him in thy heart.” These statements suggest that statues or figures of the Nile-god were not commonly made, and it is a fact that figures of the god, large or small, are rare. In the fine collection of figures of Egyptian gods exhibited in the Third Egyptian Room, which is certainly one of the largest in the world, there is only one figure of Ḥāpi (No. 108, Wall-case 125). In this the god wears on his head a cluster of papyrus plants 𓇇, before which is the Utchat, or Eye of Horus, 𓂀, and he holds an altar from which he pours out water. The only other figure of the god in the British Museum collection is the fine quartzite sandstone statue (Southern Egyptian Gallery, No. 766) which was dedicated to Ȧmen-Rā by Shashanq, the son of Uasarken and his queen Maāt-ka-Rā. Here the god bears on his out-stretched hands an altar, from which hang down bunches of grain, green herbs, flowers, waterfowl, etc. The statue was dedicated to Ȧmen-Rā, who included the attributes of Ḥāp among his own.

The NILE from SEA to SOURCE

The true source of the Nile is Victoria Nyanza, or Lake Victoria, which lies between the parallels of latitude 0° 20′ N. and 3° S., and the meridians of 31° 40′ and 35° E. of Greenwich; the lake is 250 miles in length and 200 in breadth, and was discovered in modern times by Speke, on August 3rd, 1858. Other contributory sources are Albert Nyanza, or Lake Albert, discovered by Sir Samuel Baker on March 16th, 1864, and Lake Albert Edward, discovered by Sir H. M. Stanley in 1875; the connecting channel between these lakes is the Semliki River. The portion of the Nile between Lake Victoria and Lake Albert is called the “Victoria Nile” (or the “Somerset River”); that between Lake Albert and Lake Nô is called the “Baḥr al-Gebel” or “Upper Nile”; and that between Lake Nô and Kharṭûm is called “Baḥr al-Abyaḍ,” or “White Nile.” The total length of these three portions of the Nile is about 1,560 miles. At Kharṭûm the White Nile is joined by the “Blue Nile” (or Abâî, the Astapos of Strabo, which rises in Lake Ṣânâ and is about 1,000 miles long), and their united streams form that portion of the river which is commonly known as the “Nile.” The distance from Kharṭûm to the Mediterranean Sea is about 1,913 miles, and thus the total length of the Niles is about 3,473 miles. Between Kharṭûm and the sea the Nile receives but one tributary, viz., the[12] Atbara, the Astaboras of Strabo, a torrential stream which brings into the Nile an immense quantity of dirty red water containing valuable deposits of mud. The Cataracts, or series of rapids, on the Nile are six in number: the first is between Aswân and Philae, the second is a little to the south of Wâdî Ḥalfah, the third is at Ḥannek, the fourth is at Adramîya, the fifth is at Wâdî al-Ḥamâr, and the sixth is at Shablûkah. On the White Nile is a series of cataracts known as the “Fôla Falls,” and on the Blue Nile there are cataracts from Rusêres southwards for a distance of 40 miles.

Statue of Ḥāpi the Nile-god.

[No. 766.]

The most important characteristic of the Nile is its annual flooding or Inundation. By the end of May, in Egypt, the river is at its lowest level. During the month of June the Nile, between Cairo and Aswân, begins to rise, and a quantity of “green water” appears at this time. The cause of the colour is said to be myriads of minute algae, which subsequently putrefy and disappear. During August the river rises rapidly, and its waters assume a red, muddy colour, which is due to the presence of the rich red earth which is brought into the Nile by the Blue Nile and the Atbara. The rising of the waters continues until the middle of September, when they remain stationary for about a fortnight or three weeks. In October a further slight rise occurs, and then they begin to fall; the fall continues gradually until, in the May following, they are at their lowest level once more. The cause of the Inundation is, as Aristotle (who lived in the fourth century B.C.) first showed, the spring and early summer rains in the mountains of Ethiopia and the Southern Sûdân; these are brought down in torrents by the great tributaries of the Nile, viz., the Gazelle River, the Sobat (the Astasobas of Strabo), the Giraffe River, the Blue Nile, and the Atbara. The Sobat rises about April 15, the Gazelle River and the Giraffe River about the 15th of May, the Blue Nile at the end of May, and the Atbara a little later. The united waters of these tributaries, with the water of the Upper Nile, reach Egypt about the end of August, and cause the Inundation to reach its highest level. The Nile rises from 21 feet to 28 feet, and deposits a thin layer of fertilizing mud over every part of the country reached by its waters. Formerly, when the rise was about 26 feet, there was sufficient water to cover the whole country; when it was less, scarcity prevailed; and when it was more, ruin and misery appeared through over-flooding. In recent years, the British irrigation engineers in Egypt have regulated, by means of the Aswân Dam, the Barrage at Asyûṭ, and the Barrage near Al-Manâshî,[14] a little to the north of Cairo,[2] the supply of water during the winter, or dry season, with such success, that, in spite of “low” Niles, the principal crops have been saved, and the people protected from want.

In connection with the adoration of the Nile, two important festivals were observed. The first of these took place in June and was called the “Night of the Tear,” 𓈖𓇉𓄿𓏏𓏲𓏭𓇌𓁻, Qerḥ en Ḥatui, because it was believed that at this time of the year the goddess Isis shed tears in commemoration of her first great lamentation over the dead body of her husband Osiris. Her tears fell into the river, and as they fell they multiplied and filled the river, and in this way caused the Inundation. This belief exists in Egypt, in a modified form, at the present time, and, up to the middle of last century the Muḥammadans celebrated, with great solemnity, a festival on the 11th day of Paoni (June 17th), which was called the “Night of the Drop,” Lêlat al-Nuḳtah. On the night of this day a miraculous drop of water was supposed to fall into the Nile and cause it to rise. The second ancient Nile-festival was observed about the middle of August, and has its equivalent in the modern Muḥammadan festival of the “Cutting of the Dam.” A dam of earth about 23 feet high was built in the Khalîg Canal, and when the level of the Nile nearly reached this height, a party of workmen thinned the upper portion of the dam at sunrise on the day following the “completion of the Nile,” and immediately afterwards a boat was rowed against it, and, breaking the dam, passed through it with the current.

The history of Egypt shows that in all periods the country has suffered from severe famines, which have been caused by successions of “low” Niles. Thus a terrible seven years’ famine began in A.D. 1066, and lasted till 1072. Dogs, cats, horses, mules, vermin fetched extravagant prices, and the people of Cairo killed and ate each other, and human flesh was sold in the public markets. In Genesis xli, we have another example of a seven years’ famine, and still an older one is mentioned in an inscription cut upon a rock on the Island of Sâḥal in the First Cataract. According to the text, this famine took place in the reign of Tcheser, a king of the IIIrd dynasty, about B.C. 4000, because there had been no satisfactory inundation of the Nile for seven years. The king says that by reason of this, grain was very scarce, vegetables[15] and garden produce of every description could not be obtained, the people had nothing to eat, and men were everywhere robbing their neighbours. Children wailed for food, young men had no strength to move, strong men collapsed for want of sustenance, and the aged lay in despair on the ground waiting for death. The king wrote to Matar, the Governor of the First Cataract, where the Nile was believed to rise, and asked him to enquire of Khnemu, the god of the Cataract, why such calamities were allowed to fall on the country. Subsequently the king visited Elephantine, and was received by Khnemu, the god of the Cataract, who told him that the Nile had failed to rise because the worship of the gods of the Cataract had been neglected. The king promised to dedicate offerings regularly to their temples in future, and, having kept his promise, the Nile rose and covered the land, and filled the country with prosperity.

Egyptian Geography.—From time immemorial Egypt has been divided into two parts, viz., the Land of the South, Ta-Resu, 𓇾𓏤𓈇𓇖𓊖, and the Land of the North, Ta-Meḥt, 𓇾𓏤𓈇𓇉𓏏𓊖. The Land of the South is Upper Egypt, and its northern limit in modern times is Cairo; the Land of the North is Lower Egypt, i.e., the Delta, and its southern limit is Cairo. The ancient Egyptians divided the Land of the South into twenty-two parts, and the Land of the North into twenty parts; each such part was called Ḥesp 𓎛𓊃𓊪𓈈, a word which the Greeks rendered by nome. Each nome was to all intents and purposes a little complete kingdom. It was governed by a ḥeq, 𓋾𓈎, or chief man, and it contained a capital town in which was the seat of the god of the nome and the priesthood, and every ḥeq administered his ḥesp as he pleased. The number of the nomes given by Greek and Roman writers varies between thirty-six and forty-four. In late times Egypt was divided into three parts, Upper, Central, and Lower Egypt; Central Egypt consisted of seven nomes, and was therefore called Heptanomis. The nomes were:

| UPPER EGYPT. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nome. | Capital. | God or Goddess. | |

| 1. | Ta-Kens. | Ābu.[3] Elephantine. Aswân. | Khnemu. |

| 2. | Tes-Ḥeru. | Ṭeb. Apollinopolis Magna. Edfû. | Ḥeru-Beḥuṭet. |

| 3. | Ten. | Nekheb. Eileithyiaspolis. Al-Kâb. | Nekhebit. |

| 4. | Uast. | Uast. Thebes (or Hermonthis). Luxor, Karnak | Ȧmen-Rā. |

| 5. | Ḥerui. | Ḳebti. Coptos. Ḳuft. | Ȧmsu, or Menu. |

| 6. | Ȧati. | Taenterert. Tentyris. Denderah. | Hathor. |

| 7. | Seshesh. | Ḥa. Diospolis Parva. Ḥau. | Hathor. |

| 8. | Ȧbt. | Teni. This. | Ȧn-Ḥer. |

| 9. | ... | Ȧpu. Panopolis. Ahkmîm. | Ȧmsu or Menu. |

| 10. | Uatchet. | Ṭebu. Aphroditopolis. | Hathor. |

| 11. | Set. | Shas-ḥetep. Hypselis. Shutb. | Khnemu. |

| 12. | Ṭu-... | Nut-ent-bȧk. Hierakonpolis. | Horus. |

| 13. | Ȧm-f-khent. | Saut. Lykopolis. Asyûṭ. | Ȧp-uat. |

| 14. | Ȧm-f-peḥ. | Kesi. Kusae. Al-Kusîyah. | Hathor. |

| 15. | Unt. | Khemennu. Hermopolis. Ashmnûnên. | Thoth. |

| 16. | Maḥetch. | Ḥebennu. | Horus. |

| 17. | Ȧnpu(?). | Kasa. Kynonpolis. Al-Kês. | Anubis. |

| 18. | Sepṭ. | Ḥet-suten. Al-Hîbah. | Anubis. |

| 19. | Bu-tchamui. | Pa-Mātchet. Oxyrrhynchus. Bahnassâ. | Set. |

| 20. | Ȧm-Khent. | Suten-ḥenen. Herakleopolis Magna. Ahnâs. (The Hânês of the Bible.) | Ḥeru-shefit. |

| 21. | Ȧm-peḥ. | Smen-Ḥeru. | Khnemu. |

| 22. | Maten. | Ṭep-Ȧḥet. Aphroditopolis. Atfîḥ. | Hathor.[17] |

| LOWER EGYPT. | |||

| Nome. | Capital. | God or Goddess. | |

| 1. | Ȧneb-ḥetch. | Men-nefert. Memphis. Mît-Rahînah. | Ptaḥ. |

| 2. | Ȧa. | Sekhem. Letopolis. | Ḥeru-ur. |

| 3. | Ȧment. | Pa-neb-Ȧmt. Apis. | Hathor. |

| 4. | Sȧpi-Rest. | Tchekā. | Ȧmen-Rā. |

| 5. | Sȧpi-Meḥt. | Saut. Saïs. Ṣâ. | Neith. |

| 6. | Ka-semt. | Khasut. Xoïs. | Ȧmen-Rā. |

| 7. | Nefer-Ȧment. | Pa-Aḥu-neb-Ȧment. Metelis (?). | Ḥu. |

| 8. | Nefer-Ȧbt. | Thekaut (Succoth), Pa-Tem (Pithom). Patumos. Tall al-Maskhûṭah. | Atem, or Temu. |

| 9. | Ȧthi(?). | Pa-Ȧsȧr. Busiris. Abû-Ṣîr. | Osiris. |

| 10. | Ka-Qam. | Ḥet-ta-ḥer-ȧbt. Athribis. | Ḥeru-Khenti-Khati. |

| 11. | Ka-ḥeseb. | Ḥesbet(?), Ka-Ḥebset(?). Kabasos. | Isis, or Sebek. |

| 12. | Theb-... | Theb-neter(?). Sebennytos. Sammanûd. | Ȧn-Ḥer. |

| 13. | Ḥeq-āṭ. | Ȧnnu (The On of the Bible). Heliopolis. Maṭarîyah. | Temu. |

| 14. | Khent-ȧbt. | Tchal. Tanis. Ṣân. | Horus. |

| 15. | Teḥuti. | Pa-Teḥuti. Hermopolis Minor. | Thoth. |

| 16. | Ḥātmeḥit. | Pa-Ba-neb Ṭeṭ. Mendes. Tmai al-Amdîd. | Osiris. |

| 17. | Sam-Beḥuṭet. | Pa-Khen-en-Ȧmen. Diospolis. | Ȧmen-Rā. |

| 18. | Ȧm-Khent. | Pa-Bast. Pibeseth Bubastis. Tall Basṭah. | Bast. |

| 19. | Ȧm-peḥ. | Pa-Uatchet. Buto. | Uatchet. |

| 20. | Sepṭ. | Kesem. Phakussa. Fakûs. | Sepṭ. |

The Sûdân was divided into 13 nomes:

Under the Ptolemies, the district between Elephantine and Philae was called Dodekaschoinos, because it contained twelve schoinoi, or measures of land, but later this term was applied to the whole region between Elephantine and Hiera Sykaminos.

Under the late Roman emperors many of the nomes were subdivided, probably for convenience in levying taxes, and in still later times the governor of a nome, or province, bore the title of Duke (Δουξ).

Modern Egypt is divided into 14 provinces:

| LOWER EGYPT. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Province. | Capital. | |

| 1. | Baḥêrah. | Damanhûr. |

| 2. | Ḳalyûbîyah. | Benha. |

| 3. | Sharkîyah. | Zaḳâzîḳ. |

| 4. | Dakhâlîyah. | Manṣûrah. |

| 5. | Manûfîyah. | Menûf. |

| 6. | Gharbîyah. | Ṭanṭa. |

| UPPER EGYPT. | ||

| Province. | Capital. | |

| 1. | Gîzah. | Gîzah. |

| 2. | Beni-Suwêf. | Beni-Suwêf. |

| 3. | Minyah. | Minyah. |

| 4. | Asyûṭ. | Asyûṭ. |

| 5. | Girgah. | Ṣûhâḳ. |

| 6. | Ḳena. | Ḳena. |

| 7. | Nûba. | Aswân. |

| 8. | Fayyûm. | Madînat al-Fayyûm. |

The towns of Cairo, Alexandria, Port Sa’îd, Suez, Damietta, etc., are generally governed each by a native ruler.

The provinces of the Sûdân are as follows:

1. Baḥr al-Ghazâl. 2. Berber. 3. Blue Nile Province. 4. Dongola. 5. Ḥalfah. 6. Kassala. 7. Kharṭûm Province. 8. Kordofân. 9. Mongalla. 10. Red Sea Province. 11. Sennaar. 12. Upper Nile Province. 13. White Nile Province.

Ethnography. The Land of Punt. National Character. Population. Language. Forms Of Writing. Decipherment of Egyptian Hieroglyphics. Young and Champollion. Hieroglyphic Alphabet and Writing. Writing Materials.

The Egyptians.—The evidence of the monuments and the literature of Egypt proves that the Egyptians were of African origin, and that they were akin to the light-skinned peoples who inhabited the north-east portion of the African Continent. Further evidence of this fact is supplied by the “table of nations” preserved in the tenth chapter of Genesis, where it is stated that Cush and Mizraim were the sons of Ham. Now this Cush, or Ethiopia, is not the country which we call Abyssinia, but the Northern Sûdân, or Nubia; therefore the Nubians (Cush) and the Egyptians (Mizraim) were brethren, and they were Hamites, or Africans. The relationship between the Nubians and the Egyptians is also asserted by Diodorus, who declared that the Egyptians were descended from a colony of Ethiopians, i.e., Nubians, who had settled in Egypt. And there is no doubt that from the earliest to the latest times a very close bond existed between the Northern Nubians and the Egyptians, which manifested itself in the religion and religious ceremonies of both peoples. The Cushites were dark in colour, sometimes actually black, but there is no evidence which proves they were negroes; and the Egyptians were red, or brown-red, or reddish yellow in colour. On the west of the Nile Valley lived the fair-skinned Libyans; on the east the remote ancestors of the Blemmyes and the modern Bîshârî tribes, who were of a light brownish colour, and on the south, near the Equator, were negro tribes, which formed part of the great belt of black peoples that extended right across Africa, from sea to sea.

The dynastic Egyptians appear to have regarded a country, or district, called Pun 𓊪𓃹𓈖𓏏𓈉 as their original home, and they certainly preserved down to the latest times[21] some of the peculiarities in dress of the primitive inhabitants of that region. That Punt was situated a considerable distance to the south of Egypt is certain, and that it could be reached by land, and also by water by way of the Red Sea, is clear from the inscriptions, but there is no evidence available which enables the exact limits of the country to be defined. The despatch of several expeditions to Punt by the Egyptians is recorded, for the purpose of bringing back ānti spice, 𓂝𓈖𓅂𓏊𓏧, or myrrh, which was used freely for embalming purposes. They started from some point on the Red Sea near the modern town of Ḳuṣêr, and sailed southwards until they reached the river of the port of Punt which was situated on the east coast of Africa, probably in Somaliland. The expedition despatched by Queen Ḥātshepset about B.C. 1550 brought back boomerangs, a huge pile of myrrh, logs of ebony, elephants’ tusks, sweet-smelling woods, eye-paint, various kinds of spices, dog-headed apes, monkeys, leopard (or panther) skins, “green” (i.e., pale) gold, and gold rings which are to this day used as currency in East Africa and are known as “ring money.” Now, all these things are products of the region which lies between the southern end of the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Valley of the Nile, and it is impossible not to conclude that Punt was situated somewhere in it. The Egyptian expeditions probably sailed up a river for a considerable distance, to a point where the products of Punt were brought by trading caravans for export, and there the Egyptians bartered for the myrrh, etc., which they required. The market place must have been inland, for the huts of the natives are represented in the bas-reliefs as standing close to the river.

The men of Punt wore a pointed beard and a loin cloth, which was kept in position by a kind of belt, from which hung down behind the tail of an animal. The beard of the Egyptian was also pointed, and gods, kings, and priestly officials on solemn, ceremonial occasions, wore tails. Thus in the Papyrus of Ani (Judgment Scene) the gods Thoth and Anubis wear tails, and the priestly official in the same scene wears the leopard’s skin, the tail of which is supposed to be hanging behind him. In two statues of Ȧmen-ḥetep III (Northern Egyptian Gallery, Nos. 412, 413), the tail is supposed to be brought forward under the body of the king, and its end is carefully sculptured on the space between his legs. The custom of wearing tails is common in Central Africa[22] at the present day, even the women, in some places, wearing long tails of bast (Schweinfurth, Heart of Africa, I, p. 295); and a recent traveller reports that the Gazum people wear tails, about six inches long, for which they dig holes in the ground when they sit down (Boyd Alexander, From the Niger, I, p. 78). Many other points of comparison between the Egyptians and the peoples of Central Africa could be mentioned in proof of the views that the indigenous dynastic Egyptians were connected with the people of Punt, and that Punt was situated in the South-Eastern Sûdân.

As to the succession of peoples in the Nile Valley, or rather of that portion of it which is called Egypt, many theories have been formulated in recent years. Some of the most competent authorities think that the earliest dwellers in Egypt were black folk, who were driven out or killed off by a race of people who possessed many of the characteristics of the Libyans, and who came from the west, or south-west, and took possession of Egypt. It is thought that the next invasions of the country were made by peoples who came from the east, or south-east, and, having settled down on the Nile, mingled with the inhabitants. After these it seems very probable that Egypt was invaded by tribes whose home was some part of Western Asia, probably the country now called Southern Babylonia. Some think that they entered Egypt by the Isthmus of Suez, and others that they crossed from Arabia to Africa by the straits of Bâb al-Mandib at the southern end of the Red Sea. Another view is that the invaders entered Egypt by the Wâdî Ḥammâmât, and that they arrived on the Nile at some place near the modern town of Ḳena. Little by little the invaders conquered the country, and introduced into it the arts of agriculture, brick-making, writing, working in metals, etc. Wheat, barley, and the domestic sheep seem to have been brought into Egypt about this time. The manners and customs of the new comers were very different from those of the men they conquered, and their civilization was of a much higher character than that of the primitive Egyptians; but, among the great bulk of the population, the beliefs, religion, and habits continued to preserve unchanged their characteristic African nature.

1 2 3 4 5 6

What the physical form of the primitive, pre-dynastic Egyptian was cannot be said, but it is probable that he resembled the dynastic Egyptians whose pictures are seen by hundreds in the tombs. If this be so, he was tall, slender of body, with long thin legs, small hands, and long feet. His hair was black and curly, but must not be confounded with the “wool” of the negro, his eyes black and slightly almond-shaped, his cheek-bones high and often prominent, his nose straight—sometimes aquiline—and inclined to be fleshy; his mouth wide, with somewhat full lips, his teeth small and regular and his chin prominent, because his under jaw was thrust slightly forward. The women were yellowish in colour, probably because their bodies were not so much exposed to the rays of the sun as those of the men. The general character of the physique of the Egyptian has remained practically unchanged to the present day, and no admixture of foreign elements has affected it permanently.

7

Ivory figure of a king.

1st dynasty (?)

[No. 197, Table-case L, Third Egyptian Room.]

8

Bone figure of a dwarf.

Archaïc Period.

[No. 42, Table-case L, Third Egyptian Room.]

9

Bone figure of a woman carrying a child on her shoulder.

Archaïc Period.

[No. 41, Table-case L, Third Egyptian Room.]

10

Bone figure of a woman, with inlaid lapis-lazuli eyes.

Archaïc Period.

[No. 40, Table-case L, Third Egyptian Room.]

The physical features and dress of the primitive dynastic Egyptians are well illustrated by the accompanying drawings and photographs. From Nos. 1-6 (page 23) we see that their hair was short and curly, their noses long and pointed, their eyes almond-shaped, their beards pointed, their arms and legs long, their hands large, and their feet long and flat. They wear in their hair feathers, probably red feathers from the tails of parrots, such as are worn at the present day, and their loin cloths[25] are fastened round their bodies by belts, from which hang short, bushy tails of jackals(?). No. 1 bears a hawk-standard, the symbol of the god of the tribe, and is armed with a mace having a diamond-shaped head. No. 2 bears a hawk-standard and wields a double-headed stone axe. No. 3 is armed with a mace and a bow. No. 4 is shooting a flint-tipped arrow from a bow. No. 5 is armed with a boomerang and a spear, and No. 6 with a mace and a boomerang. The above illustrations are drawn from the green slate shield exhibited in Table-case L in the Third Egyptian Room.

To about the same period belongs the ivory figure of a king here reproduced (No. 7). He wears the Crown of the South, and a garment worked with an elaborate diamond pattern. The[26] nose is flatter and more fleshy than in the drawings from the slate shield, and the lips are fuller and firmer. In figures 8-10 we have representations of the women of the Archaïc Period, about B.C. 4200. No. 8 is a female dwarf, or perhaps a woman who belonged to one of the pygmy tribes that lived near the Equator. No. 9 is a most interesting figure, for it illustrates the hair-dressing and dress of the period. The features of the child, who is carried partly on the back and partly on the left shoulder, as at the present day, are well preserved. No. 10 represents a woman of slim build, with blue eyes, and wearing an elaborate head-dress, which falls over her shoulders.

Portrait Figures of Officials of the IIIrd or IVth Dynasty. About B.C. 3700.

Figure of Betchmes, a royal kinsman.

[Vestibule, South Wall, No. 3.]

Painted limestone figure of Nefer-hi.

[No. 150, Wall-case 99, Third Egyptian Room.]

National Character.—Herodotus, who was an acute observer of the manners and customs of the Egyptians, states (ii, 64) that the Egyptians were “beyond measure scrupulous in all matters appertaining to religion,” and the monuments prove him to be absolutely correct. The Egyptian worshipped his God, whose chief symbol to him was the sun, daily and[27] regularly, and prayed to him morning and evening. His attitude towards his Maker was one of absolute resignation. The power of God, as displayed by the Sun, and the River Nile, and other forces of nature filled him with awe, and made him to realize his helplessness. His views as to the dependence of men on the sun are well illustrated by the following extract from a hymn to Ȧten, the god of the Solar Disk: “When thou settest in the western horizon of heaven, the earth becometh dark with the darkness of the dead. Men sleep in their houses, their heads are covered up, their nostrils are closed, and no man can see his neighbour; everything which they possess could be stolen from under their heads without their knowing it. All the lions come forth from their dens, every creeping thing biteth, the smithy is in blackness, and all the earth is silent because he who made them (i.e., all creatures) resteth in his horizon. When the dawn cometh, and thou risest and shinest from the Disk, darkness flieth away, thou givest forth thy rays, and the Two Lands (i.e., Egypt) are in festival. Men rise up, they stand upon their feet—it is thou who hast raised them—they wash their bodies, and dress themselves in their clothes, and they [stretch out] their hands to thee in thanksgiving for thy rising.” To the god of the city, or local deity, he also paid due reverence. He worshipped Osiris, the type and symbol of the resurrection, most truly, for on his help and succour depended his hope of eternal life. The Egyptians, who were men of means, spent largely during their lifetime in making preparations for their death, and they spared neither money[28] nor pains in their endeavours to secure for themselves life in the Other World. They observed the Religious and Civil Laws most carefully, and any breach they might make in either they thought could be amply atoned for by making offerings or payment.

The fox playing the double pipes for a flock of goats to march to.

[From a papyrus in the British Museum, No. 10,016.]

A mouse seated on a chair, with a table of food before it. A cat is presenting to it a palm branch, and behind it is a mouse bearing a fan, etc.

[From a papyrus in the British Museum, No. 10,016.]

The Egyptian was easy and simple in disposition, and fond of pleasure and of the good things of this world. He loved eating and drinking, and he lost no opportunity of enjoying himself. The literature of all periods is filled with passages in which the living are exhorted to be happy; and we may note that in the famous Dialogue between a man who is weary of life and his soul, the latter tells the man that to remember the grave only brings sorrow to the heart and fills the eyes with tears. And after several observations of the same import, the soul says: “Hearken unto me, for, behold, it is good for men to hearken; follow after pleasure and forget care.”[4] In the Song of the Harper we read: “Bodies (i.e., men) have come into being in order to pass away since the time of Rā, and young men come in their[29] places. Rā placeth himself in the sky in the morning, and Temu setteth in the Mountain of Sunset. Men beget children and women bring forth, and every nostril snuffeth the wind of dawn from the time of their birth to the day when they go to the place which is assigned to them. Make [thy] day happy! Let there be perfumes and sweet odours for thy nostrils, and let there be wreaths of flowers and lilies for the neck and shoulders of thy beloved sister who shall be seated by thy side. Let there be songs and the music of the harp before thee, and setting behind thy back unpleasant things of every kind, remember only pleasure, until the day cometh wherein thou must travel to the land which loveth silence.”

A cat herding geese.

[From a papyrus in the British Museum, No. 10,016.]

The advice to eat, drink, and be happy, is also given to a high-priest of Memphis by his dead wife That-I-em-ḥetep on her sepulchral tablet (Southern Egyptian Gallery, Bay 29, No. 1027). She says: “Hail, my brother, husband, friend, ... let[5] not thy heart cease to drink water, to eat bread, to[30] drink wine, to love women, to make a happy day, and to seek thy heart’s desire by day and by night. And set no care whatsoever in thy heart: are the years which [we pass] upon the earth so many [that we need do this]?”

The lion and the unicorn playing a game of draughts.

[From a papyrus in the British Museum, No. 10,016.]

The morality of the Egyptians was of a high character, and certainly higher than that of Oriental nations in general. Many of the Precepts of Ptaḥ-ḥetep, Kaqemna, and Khensu-ḥetep bear comparison with the moral maxims of the Books of Proverbs and Ecclesiasticus. The view of the Egyptian as to his duty towards his neighbour is well summed up by Pepi-Nekht, an old feudal lord of Elephantine, who flourished under the VIth dynasty, and said: “I am one who spoke good and repeated what was liked. Never did I say an evil word of any kind to a chief against anyone, for I wished it to be well with me before the great god. I gave bread to the hungry man, and clothes to the naked man. I never gave judgment in a case between two brothers whereby a son was deprived of his father’s goods. I was loved by my father, favoured by my mother, and beloved by my brothers and sisters.” Love of parents and home was a strong trait in the character of the Egyptian; and it was one cause of his hatred of military service and of any occupation which would take him away from his town or village. He prayed, too, that in the Other World he might have his parents, wife, children, and relatives, with him on his farm in[31] the Fields of Peace, and that when his spirit was on the way thither, the spirits of his kinsfolk would come to meet him, armed with their staves and weapons, so that they might protect him from the attack of hostile spirits. Like all African people he loved music, singing, and dancing, and was attracted by ceremonials, processions, and display of every kind; the satirical papyri (see the illustrations on pages 27-30), and even the wall-paintings in the tombs, show that he possessed a keen sense of humour. The peasant was then, as now, a laborious toiler, and as he was literally the slave of Pharaoh for thousands of years, the ideas of freedom and national independence, as we understand them, were wholly unknown to him.

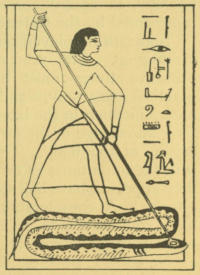

All classes were intensely superstitious, and they believed firmly in the existence of spirits, good and bad, witches, and fiends and devils, which they tried to cajole, or wheedle, or placate with gifts, or to vanquish by means of spells, magical names, words of power, amulets of all kinds, etc. The magician was the real priest, to the lower classes at least, as he is to this day in Central Africa, for by the use of magical figures he assured his clients that he could procure for them the death, or sickness, of an enemy, riches, the love of women, dreams wherein the future would be revealed to them, and above all, the assistance of the gods. We find that about B.C. 312 a service was regularly performed in the temple of Ȧmen-Rā at Thebes to make the sun rise. In the course of it a figure of the monster Āpep, who was supposed to be lying in wait to swallow the Sun-god, was made of wax, then wrapped in new papyrus on which the “accursed name” of the fiend was written in green ink, and solemnly burned in a fire fed by a special kind of herb, whilst the priest spurned it with his left foot and poured out curses on each of the thirty “accursed names” of the evil one. As the wax melted and was consumed, together with the papyrus and the green ink with which his name was written, so the body of Āpep was believed to be consumed in the flames of the rising sun in the eastern sky.

The spearing of Āpep.

From the evidence given at Thebes about B.C. 1200 against certain officials who were implicated in a case of conspiracy against Rameses III, it appeared that a certain man had stolen a book of magic from the temple library. From this he obtained instructions how to make the wax figures which caused the sickness, quakings of the limbs, and death of those in whose forms they were made. An example of the wax figures which were used in the Ptolemaïc period is exhibited in Table-case C in the Third Egyptian Room, No. 198. The core is made of inscribed papyrus, and in front, in the centre, is a piece of hair, presumably that of the person on whom the magician who made the figure sought to exert his influence. Every act of daily life had some magical or religious observance associated with it, and every day, either in whole or in part, was declared to be lucky or unlucky, in accordance with a series of events which were represented by the Calendar of lucky and unlucky days.

Superstition played as prominent a part in medicine as in religion. The practice of dismembering the dead in primitive times must have taught the Egyptians some practical anatomy, and the operations connected with mummification in the later period must have added largely to their knowledge of the arrangement of the principal internal organs of the body. The Egyptians were well acquainted with the importance of the heart in the human economy, and they appear to have had some knowledge of the functions of the arteries. A considerable number of medical prescriptions have come down to us, e.g., those which are inscribed on a papyrus in the British Museum (No. 10,059) and are said to be as old as the time of Khufu (Cheops), a king of the IVth dynasty, and those of the Ebers Papyrus, of the XVIIIth dynasty; from these it is easy to see that they closely resemble in many particulars the prescriptions given in English medical books printed two or three hundred years ago. Powders and decoctions made from plants and seeds were largely used, and the piths of certain trees, dates, sycamore-figs, and other fruits, salt, magnesia, oil, honey, sweet beer, formed the principal ingredients of many prescriptions. With these were often mixed substances of an unpleasant nature, e.g., bone dust, rancid fat, the droppings of animals, etc. In order that certain drugs might have the desired effect it was necessary for the physician to recite a magical formula four times (Ebers Papyrus CVIII). Other medicines again owed their efficacy to the belief that they had been actually taken by one or other of the gods whilst[33] they reigned upon earth, and the authorship of certain prescriptions was ascribed to Rā. Thus according to the Ebers Papyrus (XLVI) Rā suffered from attacks of boils of a most malignant kind, and he made up a salve, containing sixteen ingredients, which gave him instant relief, and which was therefore certain to cure ordinary mortals. The following is a characteristic example of a prescription which, as is evident, contains a number of substances which are well known to be good for inflamed eyes, and also some others the special value of which is not clear:—

| 𓎡𓏏𓈖𓏏𓂧𓂋𓂡𓇉𓄿𓍘𓏭𓅓𓁹𓏏𓏤 | “Another [prescription] for driving inflammation from the eye. | |

| 𓂝𓈖𓅂𓈒𓏦 | Myrrh | 1 |

| 𓎃𓏤𓏜𓏪𓅨𓂋𓈒𓏦 | ‘Great Protectors’ seed | 1 |

| 𓍱𓊃𓇌𓏏𓈒 | Oxide of copper | 1 |

| 𓍑𓄿𓂋𓏏𓈒𓏦 | Citron pips | 1 |

| 𓎼𓄿𓇌𓏏𓆰𓎖𓏲𓏰 | Northern cypress flowers | 1 |

| 𓇅𓏲𓈒𓏪 | Antimony | 1 |

| 𓈎𓄿𓇌𓏏𓐎𓏪𓈖𓏏𓎼𓎛𓋴𓄛 | Gazelle droppings | 1 |

| 𓏶𓅓𓏭𓈖𓈎𓄿𓂧𓇌𓏏𓄛 | Oryx offal | 1 |

| 𓌻𓂋𓎛𓏏𓏊𓏪𓌉𓆓𓏏𓇳 | White oil | 1[34] |

| [Directions for use.] | ||

| 𓂞𓁷𓏤𓈗𓁀 𓂜𓐎𓂝 𓁷𓂋𓋴𓂋𓇳𓏽𓎡𓇌𓆓𓂧 𓎘𓎛𓏲𓂡𓐍𓂋𓎡𓋴𓏏𓅓 𓆄𓆃𓈖𓏏𓈖𓂋𓏏𓅬 |

“Place in water, let stand for one night, strain through a cloth, and smear over [the eye] for four days; or, according to another prescription, paint it on [the eye] with a goose-feather.”[6] | |

The Egyptian physician was called upon not only to heal his patients, but to beautify them, and we find prescriptions for removing scurf from the skin, for changing the colour of the skin, for making the skin smooth, and the following for removing wrinkles from the face:—

| 𓎡𓏏𓈖𓏏𓂧𓂋𓂡𓈎𓂋𓆑𓏲𓏼𓏌𓏤𓁷𓏤 | “Another [prescription] for driving away wrinkles of the face.” | |

| 𓅮𓇌𓏏𓈒𓏼𓈖𓏏𓊹𓌣𓏏𓂋𓈒𓏼 | Ball of incense | 1 |

| 𓏠𓈖𓎛𓈒𓏼 | Wax | 1 |

| 𓆮𓏊𓏼𓇅𓆓𓏛 | Fresh oil | 1 |

| 𓎼𓇋𓏲𓆰𓏥 | Cypress berries | 1 |

| [Directions for use.] | ||

| 𓏌𓂡𓏟𓏜𓂋𓂞𓁷𓏤 𓎛𓋴𓐠𓄿𓈗𓏊𓏼𓂋𓂞 𓂋𓁷𓏤𓇳𓏤𓏿𓁹𓌴𓁹𓄿𓄿𓎡 |

“Crush, and rub down and put in new milk and apply it to the face for six days. Take good heed [to this].”[7] | |

The population of Egypt was, in 1897, 9,734,405 persons, of whom 8,978,775 were Muḥammadans, 25,200 Jews, and 730,162 Christians. The last census was taken on the 29th April, 1907, and the entire population of the country consisted of 11,272,000 persons, or nearly 16 per cent. more than in 1897.

The Egyptian Language is not Semitic, although it possesses many characteristics which resemble those of the Semitic languages, but in a less developed form. Of all the views on the subject which have been held in recent years, the most plausible one is that which makes Egyptian belong to the group of Proto-Semitic languages. The Egyptian and the Semitic languages appear to have sprung from a common stock, from which they separated before their grammars and vocabularies were consolidated. The Egyptian language developed rapidly under circumstances of which nothing is known, and then, apparently, became crystallized; the Semitic language developed less rapidly, but continued to develope for centuries after the growth of the Egyptian language was arrested. To the period when Egyptian separated itself from the parent stock no date can be assigned, but it must have taken place some thousands of years before Christ. Later, under the XVIIIth and XIXth dynasties, B.C. 1550 to 1300, a large number of Semitic words were introduced into the language, and in such compositions as the “Travels of an Egyptian” (see page 70) a great many are transcribed into Egyptian characters.

The Egyptian language as known to us appears in four divisions, viz.:—

1. The Egyptian of the Early Empire, which was studied and employed for literary purposes from about B.C. 4400 to about A.D. 200.

2. The Egyptian used in the ordinary business of life and for conversation, from about B.C. 2600 to 650.

3. The popular speech of the country, from about 600 or 500 B.C. to the end of the Roman Period.

4. The ordinary language of the country, after Christianity was introduced into it; this is called Coptic. It ceased to be used in Egypt as a spoken language, probably about the twelfth century, but the Holy Scriptures and the Services are in several places in Egypt read in Coptic on Sundays and Festivals, although very few people understand what is being read. Four dialects of Coptic are distinguished: (1) That of Upper Egypt, called “Sahidic.” (2) That of Lower Egypt, called “Boheiric.” (3) The dialect of Ṣûhâḳ and its neighbourhood. (4) The[36] dialect of the district of the Fayyûm. It is a noteworthy fact that, from the beginning of the second century of our era to the twelfth, the language of ancient Egypt was preserved, in a modified form, chiefly through the translations of the Holy Scriptures, which were made from Greek into Coptic.

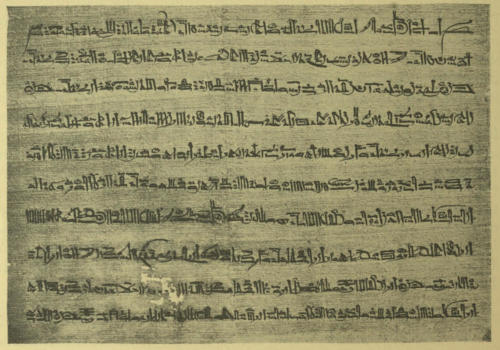

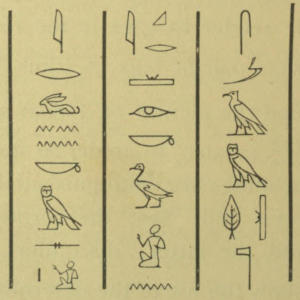

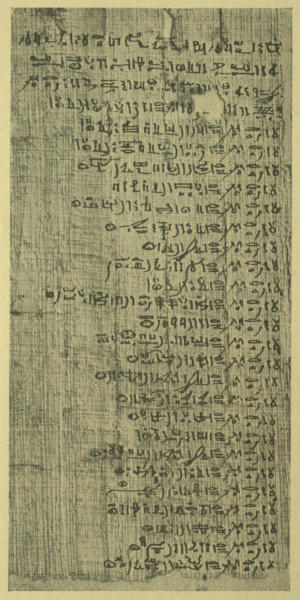

A page of hieratic writing from the Great Harris Papyrus.

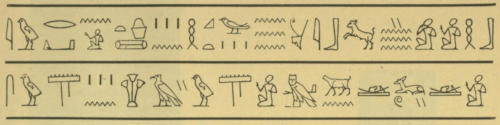

Egyptian Writing was of three kinds, which are called “Hieroglyphic,” “Hieratic,” and “Demotic.” The oldest form is the hieroglyphic (i.e., sacred engraved writing), or purely pictorial, which was employed in inscriptions upon temples, tombs, statues, sepulchral tablets, etc., and for monumental purposes generally. At a very early period it was found that the hieroglyphic form of writing was cumbrous, and that in cases where it was important to write quickly on papyrus, the pictorial characters were inconvenient. The scribes, therefore, began first to modify, and secondly to abbreviate the pictorial characters, and at length the form of writing called hieratic (i.e., the priests’ writing) was developed. Hieratic was a style of cursive writing much used by the priests in copying literary compositions on papyrus from the IVth or Vth dynasty to the XXVIth dynasty. This form of writing is well illustrated by the above reproduction of[37] a page from the Great Harris Papyrus in the British Museum (No. 9999), which was written about B.C. 1200. The text is read from right to left, and the following is a transcript into hieroglyphic characters of the first two lines:—

1. 𓆓𓂧𓇋𓈖𓇓𓏏𓈖𓀭𓍹𓇳𓄊𓌷𓏏𓆄𓌻𓇋𓏠𓈖𓀭𓍺𓀭𓋹𓍑𓋴𓅮𓄿𓊹𓀭𓉻𓏛𓐍𓂋𓀙𓏲𓀀𓏪𓄂𓏏𓏲𓏭𓏴𓂻𓀀𓏪𓏌𓏤𓇾𓏤𓈇𓀎𓀀𓏪𓈖𓏏𓎛𓏏𓂋𓇋𓆳𓄛𓏦𓆷𓄿𓏭𓂋𓂧𓏤𓄿𓈖𓄿𓌙𓀀𓏪𓌔𓏏𓏤𓀀𓏪𓆈𓏏𓏦

2. 𓋹𓈖𓐍𓏲𓀀𓏥𓎟𓏌𓏤𓇾𓏤𓈇𓈖𓇾𓏤𓈇𓌻𓇋𓆳𓊖𓊖𓄔𓅓𓏜𓏲𓈖𓏦𓂞𓏲𓀭𓂝𓌴𓄿𓅓𓏲𓁻𓏏𓈖𓏦𓅓𓈖𓄿𓇌𓏪𓀭𓅜𓐍𓏲𓏜𓏪𓇋𓀁𓁹𓂋𓏲𓀭𓇋𓏲𓀭𓅓𓇓𓏏𓈖𓀭𓈖𓂋𓐍𓇌𓅛𓀀𓁐𓏪𓃹𓈖𓅮𓄿𓇾𓏤𓈇𓈖

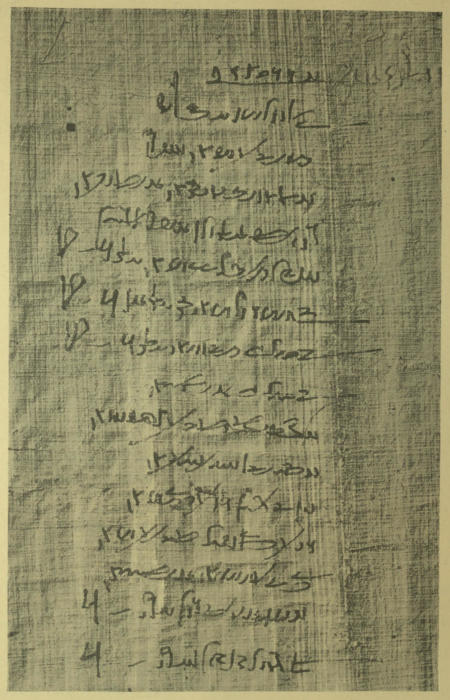

Between the end of the XXIInd and the beginning of the XXVIth dynasty the scribes, wishing to simplify hieratic still further, constructed from it a purely conventional system of signs from which most of the prominent characteristics of the hieroglyphic, or pictures, that had been preserved in the hieratic characters, disappeared. This new form of writing was called demotic (i.e., the people’s writing), but it was known among some of the early Egyptologists as enchorial (i.e., native writing, or writing of the country). On the Rosetta Stone (Egyptian Gallery, No. 960) the visitor will see an example of the hieroglyphic and demotic forms of writing placed one above the other, and in the text we find that the hieroglyphic portion is called “the writing of the divine words,” or letters, 𓏟𓈖𓊹𓌃𓏪, and the demotic “the writing of books,” i.e., rolls of papyrus, 𓏟𓋔𓈚𓂝𓇌𓍽. The invention of the art of writing was assigned to the god Thoth, who was the great scribe of the gods, and who is frequently represented holding a writing palette and a reed pen, and the hieroglyphics, or picture signs, were, therefore, called “divine, sacred, or holy.” Hieroglyphics were used for monumental purposes until about the end of the third century A.D., but it is tolerably certain that very few people could read them or understand them.

Demotic Writing.

During the Ptolemaïc Period, though Greek was the language of the kings and the upper classes of the country, the temples were covered with inscriptions in hieroglyphics, and the Ptolemies and the Romans adopted old Egyptian titles, and had their names transcribed into hieroglyphics and cut in cartouches like the Pharaohs. In the reigns of Euergetes I (B.C. 267 to 222) and Epiphanes (B.C. 205 to 181) the priests promulgated decrees in honour of their kings which were cut on slabs of basalt in the hieroglyphic, demotic, and Greek characters, but on the sepulchral tablets of the period the inscriptions are usually in hieroglyphics alone, because the natives throughout the country clung to these characters, which had, from time immemorial, been associated with their religious beliefs and ceremonies. In the Southern Egyptian Gallery, however, are exhibited several tablets which are inscribed in demotic as well as in hieroglyphics, and of these may be noted the tablet of Tut-i-em-ḥetep (No. 1028, Bay 25), who died B.C. 118; the tablet of Khā-em-ḥrȧ (No. 997, Bay 25); and the tablet of Peṭā Bast (No. 1030, Bay 27). In the Roman Period we find that the use of demotic sometimes superseded that of hieroglyphics in public documents, and as an example of this may be mentioned the fine sandstone tablet inscribed, wholly in demotic, with a decree recording the dedication of certain properties to the gods who were worshipped at Karnak (Thebes) in the first century of our era (No. 993, Bay 27). This tablet was found at Karnak, in the Hall of Columns, where, no doubt, it was set up originally, and its inscription was cut in demotic, because, at that period, that form of writing was better understood than hieroglyphics. In the Roman Period hieroglyphic inscriptions were sometimes accompanied by renderings into Greek and Latin, e.g., No. 257, Third Egyptian Room, Wall-case No. 109. This is a portion of a statue of a priest bearing a shrine of Osiris. On the back of the plinth is an inscription in hieroglyphics containing an address to Osiris by a priest of the “fourth order,” and on one side of the plinth are cut in Latin and Greek “priest bearing Osiris.”

Coptic is written with the letters of the Greek alphabet, and seven signs (ϣ, ϥ, ϧ, ϩ, ϫ, ϭ, ϯ), derived from demotic characters, the phonetic values of which could not be expressed by Greek letters. A fine collection of sepulchral tablets inscribed in Coptic is exhibited in the Southern Egyptian Gallery (Bay 32), and a long and most instructive[40] series of drafts of documents on potsherds and slices of limestone will be found in Table-case M in the Fourth Egyptian Room. In the copy of the Lord’s Prayer (St. Matthew vi, 9) here appended the reader will find all the signs which are peculiar to Coptic save one (ϭ). The dialect is that of Lower Egypt. The two words marked by asterisks are Greek, not Egyptian.

Coptic inscription on a slice of limestone.

[No. 10, Table-case M, Third Egyptian Room.]

Decipherment of Egyptian Hieroglyphics.—Before the close of the period of Roman rule in Egypt, the hieroglyphic system of writing fell into disuse, and its place was gradually taken by demotic, i.e., a conventional form of the hieratic, or cursive writing. When the Egyptians became converted to Christianity, they adopted the Greek alphabet, adding to it seven signs derived from demotic, to express the sounds peculiar to their language. The priests appear to have prosecuted some study of hieroglyphics until the end of the fifth century A.D., but soon after this the power to read and understand them was lost, and until the beginning of the nineteenth century, no Oriental or European could read or understand a hieroglyphic inscription. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries many attempts were made by scholars to read and translate the Egyptian inscriptions, but no real progress was made until after the discovery of the Rosetta Stone. This “Stone” is a portion of a large black basalt stele measuring 3 feet 9 inches by 2 feet 4½ inches, and is inscribed with fourteen lines of hieroglyphics, thirty-two lines of demotic, and fifty-four lines of Greek. (See Southern Egyptian Gallery, No. 960.) It was found in 1798 by a French officer of artillery named Boussard, among the ruins of Fort Saint Julien, near the Rosetta mouth of the Nile, and was removed, in 1799, to the Institut National at Cairo, to be examined by the learned; and Napoleon ordered the inscription to be engraved and copies of it to be submitted to the scholars and learned societies of Europe. In 1801 it passed into the possession of the British, and it was sent to England in February, 1802. It was exhibited for a few months in the rooms of the Society of Antiquaries, and then was finally deposited in the British Museum.

The “Rosetta Stone.”

[Southern Egyptian Gallery, No. 960.]

The first translation of the Greek text was made by Du Theil and Weston, in 1801-02, and they rightly declared that the stone was set up as the result of a Decree passed at the General Council of Egyptian priests assembled at Memphis to celebrate the first commemoration of the coronation of Ptolemy V, Epiphanes, king of all Egypt. The young king had been crowned in the eighth year of his reign, therefore the first commemoration took place in the ninth year, in the spring of the year, B.C. 196. The Decree sets forth that, because the king had given corn and money from his private resources to the temples, and had remitted taxes and released prisoners, and had abolished the press-gang and restored the worship of the gods, etc., the priests decreed that: Additional honours be paid to the king and his ancestors; an image of the king be set up in every temple; a statue and shrine be set up in every temple; a monthly festival be established on the birthday and coronation day of the king; this Decree be engraved upon a hard stone stele in the writing of the priests (hieroglyphic), in the writing of books (demotic), and in the writing of the Greeks (Greek), and set up in every temple of the first, second, and third class, by the side of the image of the king.

In 1802 Åkerblad succeeded in making out the general meaning of several lines of the demotic text, and in identifying the equivalents of the names Alexander, Alexandria, Ptolemy, etc. In 1819 Thomas Young published in the Encyclopaedia Britannica, vol. IV, the results of his studies of the texts, and among them was a list of several alphabetic Egyptian characters to which, in most cases, he had assigned correct values. He was the first to grasp the idea of a phonetic principle in the reading of the Egyptian hieroglyphics, and he was the first to apply it to their decipherment. Warburton, De Guignes, Barthélemy and Zoëga all suspected the existence[45] of alphabetic hieroglyphics, and the three last-named scholars believed that the oval, or cartouche 𓍷, contained a royal name; but it was Young who first proved both points and successfully deciphered the name of Ptolemy on the Rosetta Stone, and that of Berenice on another monument, and it was Bankes who first identified the name of Cleopatra. The list of alphabetic characters was much enlarged in 1822 by the eminent scholar Champollion, who not only correctly deciphered the names and titles of most of the Roman Emperors, but drew up classified lists of the hieroglyphics, and formulated a system of grammar and general decipherment which is the foundation upon which all subsequent Egyptologists have worked. The discovery of the correct alphabetic values of Egyptian signs was most useful for reading names, but, for translating the language, a competent knowledge of Coptic was required. Now Coptic is only another name for Egyptian. The Egyptian Christians are called “Copts,” and the Holy Scriptures, Liturgies, etc., which they translated from Greek soon after their conversion to Christianity, are said to be written in “Coptic.” The knowledge of Coptic has never been lost, and a comparatively large sacred literature has always been available for study by scholars. Champollion, quite early in the nineteenth century, realized the great importance of Coptic for the purpose of Egyptian decipherment, and he made himself the greatest Coptic scholar of his time. His knowledge of Coptic was deep and wide, and to this important qualification much of his success is due. Having once obtained a correct value of many alphabetic and syllabic characters, his knowledge of Coptic helped him to deduce the values of others, and to assign meanings to Egyptian words with marvellous accuracy.

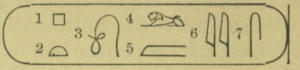

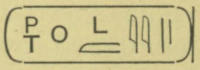

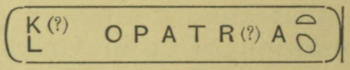

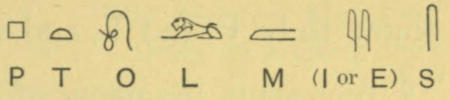

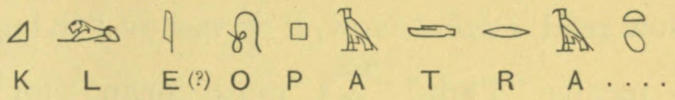

The method by which the greater part of the Egyptian alphabet was recovered is this: It was assumed correctly that the cartouche always contained a royal name. The only cartouche on the Rosetta Stone was assumed to contain the name Ptolemy. An obelisk brought from Philae about that time contained a hieroglyphic inscription, and a translation of it in Greek, which mentioned two names, Ptolemy and Cleopatra, and one of the cartouches was filled with hieroglyphic characters which were identical with those in the cartouche on the Rosetta Stone. Thus there was good reason to believe that the cartouche on the Rosetta Stone contained the name of Ptolemy written in hieroglyphic characters. Here is the cartouche which was assumed to[46] represent the name Ptolemaios, or Ptolemy, the hieroglyphics being numbered (A)—

A 𓍹𓊪𓏏𓍯𓃭𓐝𓇌𓋴𓍺

and here is the cartouche which was assumed to represent the name Cleopatra (B)—

B 𓍹𓈎𓃭𓇋𓍯𓊪𓄿𓂧𓂋𓄿𓏏𓆇𓍺

Now in B, the first sign, 𓈎, must represent K; it is not found in A. No. 2 sign, 𓃭, is identical with No. 4 sign in A. This was assumed to be L. No. 3 sign, 𓇋, represents a vowel, and doubled, 𓇌, is found in A, No. 6. No. 4 sign, 𓍯, is identical with No. 3 in A, and it must have the value of O in both A and B. No. 5 sign, 𓊪, is identical with No. 1 in A, and as A contains the name Ptolemy, the first sign, 𓊪, must be P. No. 6 sign, 𓄿, is wanting in A, but its value must be A, because it is the same sign as No. 9, which ends the name Kleopatra. No. 7, 𓂧, does not occur in A, but we see it in other cartouches taking the place of 𓏏 the second letter in the name of Ptolemaios, and it must therefore be some kind of T. No. 8, 𓂋, we assume is R, because it is the last letter but one in the name of Kleopatra. Nos. 10 and 11 signs, 𓏏𓆇, we find after the names of goddesses; the first of them is T; and the second is a “determinative.” We now insert the alphabetic values in the two cartouches and obtain the following results:

A 𓍹PTOL𓐝𓇌𓋴𓍺

B 𓍹KL(?) OPATR(?)A𓏏𓆇𓍺