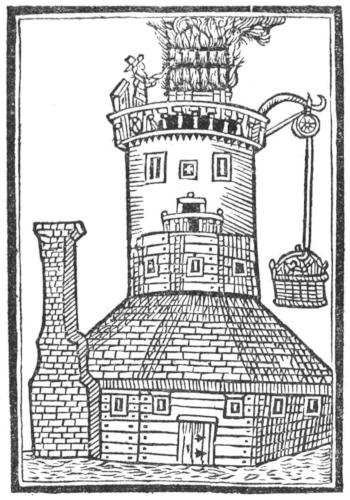

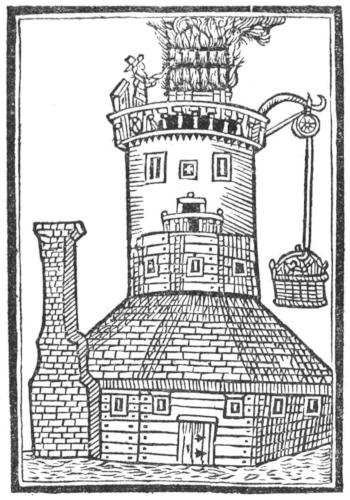

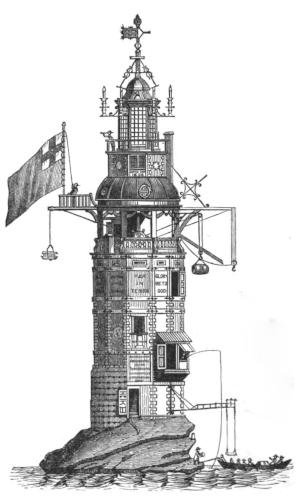

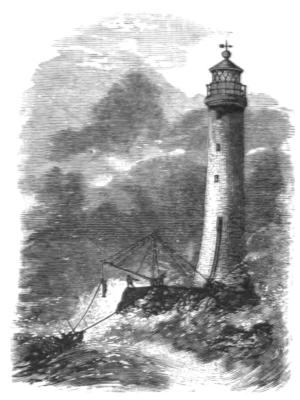

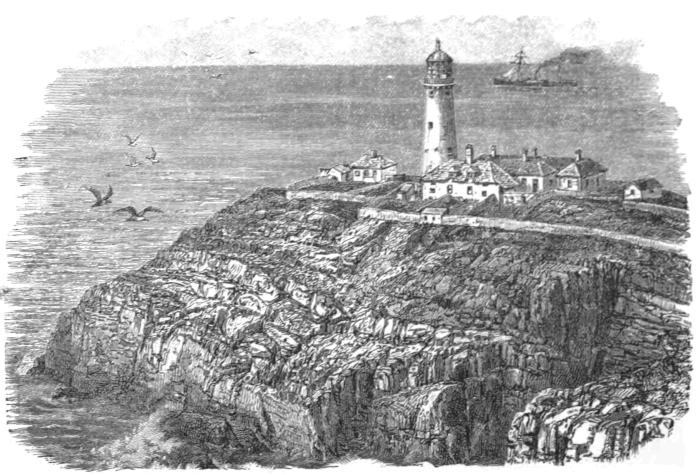

THE FIRST LIGHTHOUSE AT DUNGENESS.

(From a receipt for Lighthouse dues, dated December 19, 1690, in the possession of Lord Kenyon.)

Title: Lighthouses

Their history and romance

Author: William John Hardy

Release date: May 7, 2025 [eBook #76041]

Language: English

Original publication: Not Listed: The Religious Tract Society, 1895

Credits: Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Books project.)

Oxford

HORACE HART, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY

THE FIRST LIGHTHOUSE AT DUNGENESS.

(From a receipt for Lighthouse dues, dated December 19, 1690, in the possession of Lord Kenyon.)

LIGHTHOUSES

THEIR HISTORY AND ROMANCE

BY

W. J. HARDY, F.S.A.

AUTHOR OF ‘THE HANDWRITING OF THE KINGS AND QUEENS OF ENGLAND;’

‘BOOK PLATES,’ ETC.

WITH MANY ILLUSTRATIONS

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

56 Paternoster Row, and 65 St. Paul’s Churchyard

1895

I have for some years past devoted a good deal of time to the study of facts connected with the history of English coast-lighting, and I have now woven together into this volume such of the scattered references to the subject which I have found, and have entitled it, Lighthouses: their History and Romance. That there is much romantic incident in connection with our lighthouses, and that many of them possess[8] interesting histories, the reader of the following pages will, I think, admit; and it is really surprising that no history of them has before this been compiled.

I could not have obtained the facts I have here been able to bring together had I not received constant and generous assistance from all those in whose power it was to render it; and were I to attempt to convey to the officials of the British Museum and Public Record Office, who have assisted me, individual thanks, I should unduly prolong this preface. Yet I cannot leave unrecorded my gratitude to Mr. W. Y. Fletcher, F.S.A., late of the Printed Books Department, in the first-named office, and to Mr. G. H. Overend, F.S.A., in the latter.

Not one half of the facts here recorded could have been obtained had I not received free and full access to the muniments of the Corporation of the Trinity House. This was accorded to me through the instrumentality of Sir Edward Birkbeck, Bart., and my good friend, his brother, Mr. Robert Birkbeck, F.S.A. I presented their introduction to Sir Sydney Webb, K.C.M.G., the Deputy-Master of the Trinity House, and that gentleman, Mr. Kent, the Secretary, and[9] Mr. Weller, one of the officials of the department, gave me every assistance in their power and the freest access to their records. To Mr. Dibdin and his assistants at the National Lifeboat Institution I also desire to express my gratitude for various information supplied, and in particular for some of the wreck incidents I have mentioned.

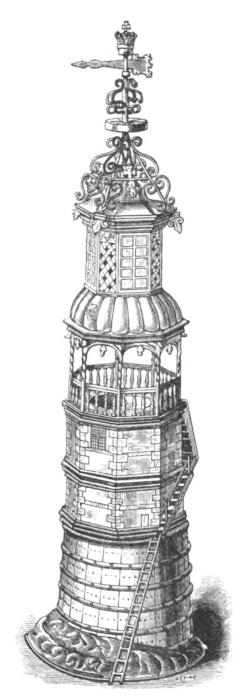

I am particularly grateful to Lord Kenyon for allowing the reproduction of two very interesting contemporary pictures of seventeenth-century lighthouses—those at Dungeness and the Scillies; and to Mr. Mill Stephenson, F.S.A., the Secretary of the Royal Archaeological Institute, for the use of one of the illustrations—the Silver Model of Winstanley’s Eddystone Lighthouse—that appeared, some years ago, in the Journal of the Society.

My thanks are due, and I return them with pleasure, to my fellow-worker, Mr. William Page, F.S.A., who has always brought to my knowledge any fact connected with Lighthouse history that he came upon in his researches.

In presenting to the public the last volume which I published through the Religious Tract Society, The[10] Handwriting of the Kings and Queens of England, I was permitted to thank the Rev. Richard Lovett, M.A., the Society’s Book Editor, for his constant help and advice in bringing out that work. I trust that I may be again accorded the privilege of thanking him for his unfailing courtesy and good nature in discussing and settling points of detail in connection with this present work.

W. J. HARDY.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Ancient and Mediaeval Lighthouses | 17 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Trinity House | 29 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Ancient Methods of Lighting | 39 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Grace Darling | 45 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Spurn Head | 53 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The Humber to the Thames | 62 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Nore Lightship | 71 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The Goodwin Sands and the Forelands | 79 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Dungeness Lighthouse | 95[12] |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| St. Catherine’s Point to the Eddystone | 101 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Suggestions for a Lighthouse on the Eddystone—Henry Winstanley | 108 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| The First Eddystone | 120 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Second Eddystone | 140 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Third and Fourth Lighthouses at the Eddystone | 148 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| The Lizard | 163 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The Wolf, the Land’s End, and the Longships | 176 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| The Scillies | 190 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Lighthouses on the Western Coast | 204 |

| PAGE | |

| The First Lighthouse at Dungeness | Frontispiece |

| The Eddystone Medal, 1757 | 7 |

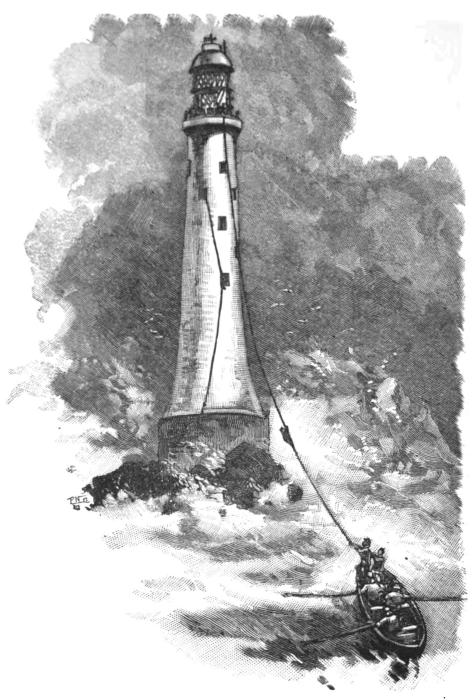

| The Bell Rock Lighthouse | 16 |

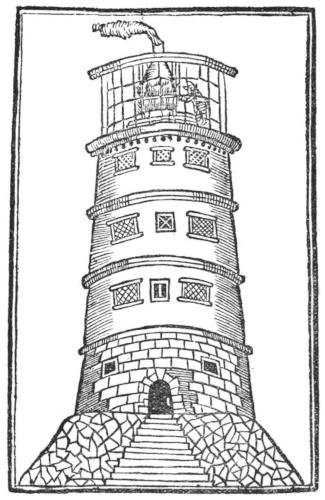

| The Pharos, Alexandria | 19 |

| Ancient Coast-light | 38 |

| Outer Farne Lighthouse | 45 |

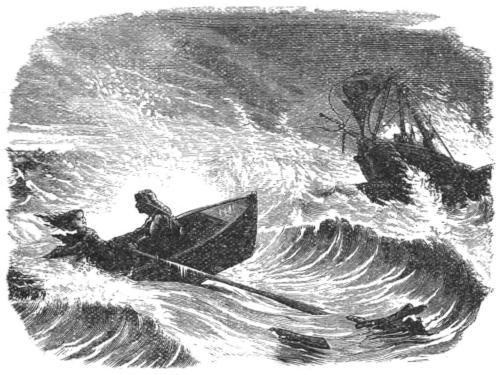

| Grace Darling and her Father on the way to the Wreck | 49 |

| Grace Darling | 51 |

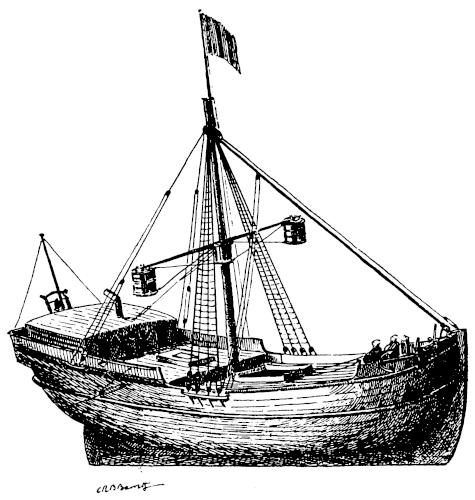

| Model of the first Lightship | 70 |

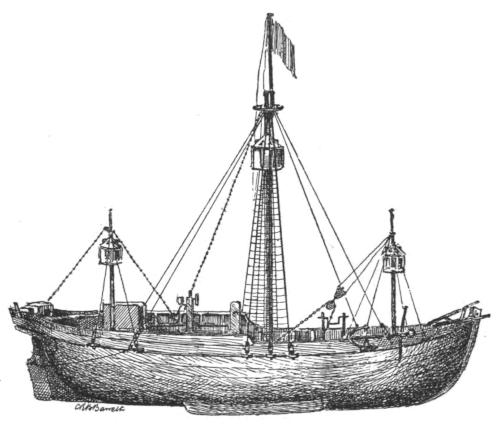

| Model of a Lightship built in 1790 | 73 |

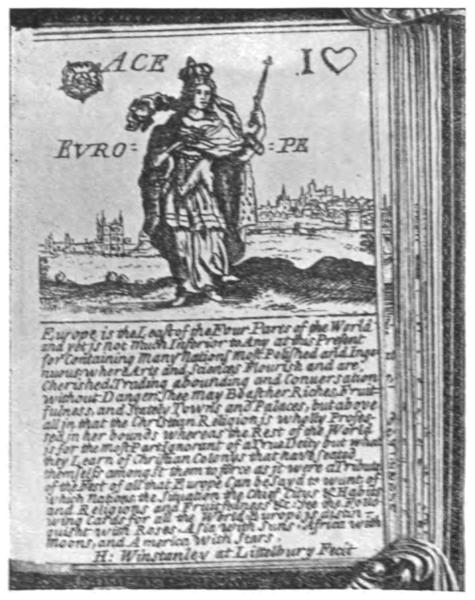

| Pack of Playing Cards designed by Winstanley | 116 |

| Winstanley’s Eddystone Lighthouse | 129 |

| Silver Model of Eddystone Lighthouse after alteration | 134 |

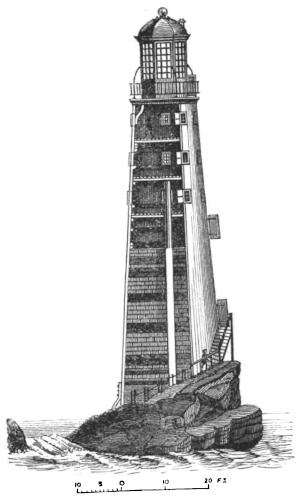

| Rudyerd’s Eddystone Lighthouse | 141 |

| The Eddystone built by Smeaton | 149 |

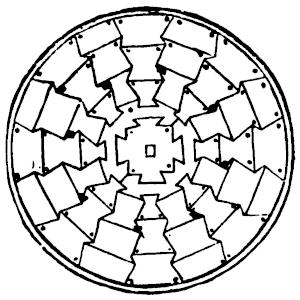

| Smeaton’s Mode of Dovetailing the Stones | 151 |

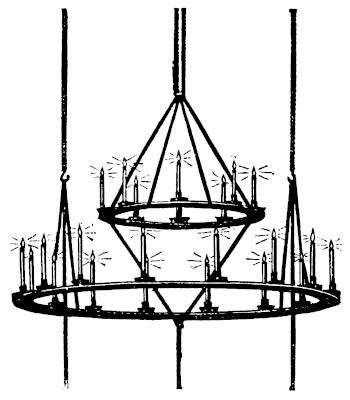

| Smeaton’s Chandelier | 154 |

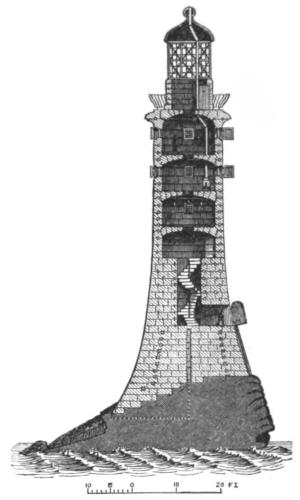

| Section of the Eddystone Lighthouse built by Smeaton | 156[14] |

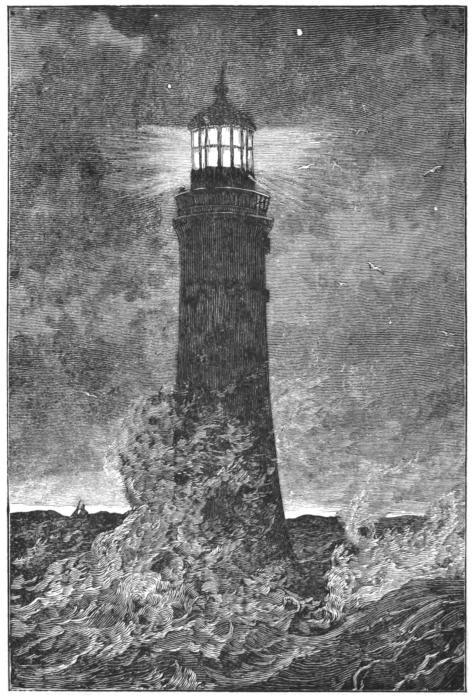

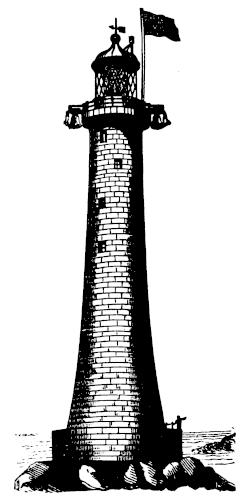

| The Present Eddystone Lighthouse | 159 |

| Wolf Rock Lighthouse | 178 |

| Longships Lighthouse | 182 |

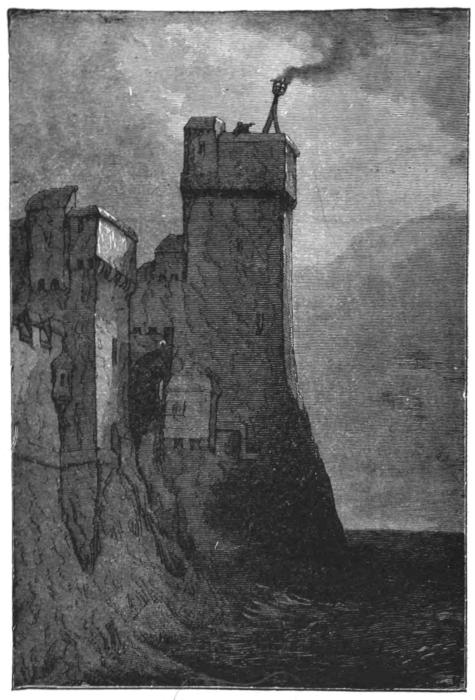

| The Wrecker | 186 |

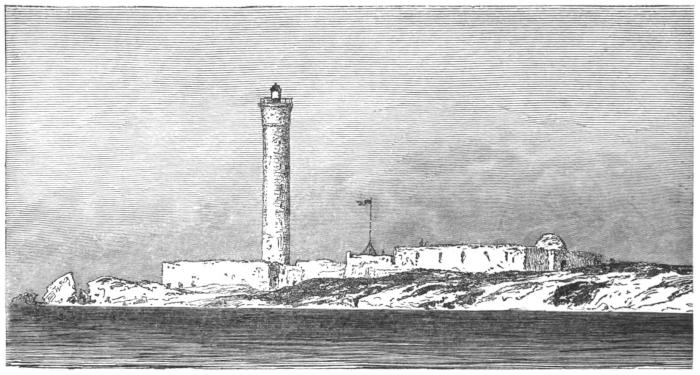

| St. Agnes Lighthouse, Scilly Isles | 193 |

| The Bishop’s Rock Lighthouse | 202 |

| The Smalls Lighthouse | 207 |

| Lighthouse at Holyhead | 218 |

THE BELL ROCK LIGHTHOUSE.

It was very good of the old abbot so to do; but in doing what he did, he was no better than a great many of his fellows. Marking dangerous reefs, and leading the mariner safely into port, were, formerly, the work of Christian charity; they were two of the many useful offices which the Church performed when there was no one else to carry them out, and for which we, who see the same things so much better done, often forget to bestow upon her even[18] a word of praise or gratitude. Bells on rocks, marks on shoals and sands, and beacon lights used to be maintained by the great monasteries, or by their various offshoots, in this country; and those beacon lights, dim, flickering, and uncertain though they may have been, were the direct ancestors of the modern lighthouse.

We do not, of course, claim for Christian charity the credit of originating the idea of these warning signals for ships. Long before the dawn of Christianity, Lybians, Cushites, Romans, Greeks, and Phoenicians had protected navigation by the means of lighthouses—high columns, on the summits of which were placed fires of wood in open grates, or lamps lit by oil, all similar in style, though on a smaller scale, to the wonderful tower of white marble, erected at Alexandria, nearly three centuries before the birth of Christ, by Ptolemy Philadelphus at a cost of about £170,000 of our money.

THE PHAROS, ALEXANDRIA.

Opinions differ as to whom should be ascribed the honour of paying for this mighty work; Alexander the Great and Cleopatra have been credited with it; but, on the whole, such reliable evidence as there is points more to Ptolemy as its projector. This being so, we may perhaps believe the story about the inscription that was placed upon the tower. The architect’s name was Sostratos, and he, desiring to be perpetually remembered in connection with the lighthouse, cut deeply into one[21] of the stones these words: ‘Sostratos of Guidos, son of Dixiphanus, to the Gods protecting those upon the sea.’ Then—being assured that Ptolemy would permit no name save his own to be remembered in connection with the work—he coated over the inscription with a layer of cement, and placed thereon one wholly laudatory of Ptolemy and associating his name alone with the erection of the pillar. Time went by; monarch and architect had been gathered to their fathers, and at last the cement began to crack, and then drop away; bit by bit it vanished together with the writing upon it, and the letters on the true face of the stone beneath stood out clear and readable—then the world knew to whose skill was due this blessing to sailors and travellers!

But it is not needful to speak further of these more ancient lighthouses, or their builders; reference is made to them only to remind the reader of the antiquity of coast lighting as a system. These pages concern the lighthouses of our own country alone, and there is no evidence to prove or suggest that the shores of England were lighted prior to the Roman occupation. Indeed, of direct evidence of lighthouses being used by the Romans in Britain, there is exceedingly little. The system was extensively employed by them in Gaul, and the Tour d’Ordre at Boulogne—or ‘the Old Man of Bullen,’ as Elizabethan sailors called it—is mentioned[22] as a lighthouse in the year 191 A.D.; so that it is hardly likely that the Romans would, for long, have left navigation around England unassisted by lights.

We may, therefore, accept the ruined tower at Dover, and some similar remains on the English and Welsh coasts, as remains of Roman lighthouses.

Whether or not, with the decay of the Roman power in England, lighthouses fell to ruin, we do not know; probably this was so, and probably, too, they were not resuscitated till Christianity had become firmly established here and was teaching men charity towards their fellow men. So early as the opening of the fourteenth century we find monks and hermits in England, and other maritime parts of Europe, doing their best to warn mariners of the dangers that lurked around their monasteries or hermitages, by means of lights maintained during the season of darkness.

To the north of the island of Jersey lie a cluster of sharp-pointed rocks, known as the Ecrehou. Sailors give them a wide berth when they can; as well they may, for their cruel spike-like reefs stretch far, and on calm days, when the water is not breaking upon them, they lie silently and treacherously in wait for the passing ship.

On the largest of these rocks there was, in the year 1309, a hermitage, or priory, served from the Norman[23] abbey of Val Richer. Land in Jersey had, years before, been given to support two monks here who, by day, used to sing masses for the souls of those who had perished by shipwreck, and then, as night closed in, kindle, and keep burning till daybreak, as good and bright a light as they could upon their tiny building.

Here is a picture romantic enough, and research would, no doubt, enable us to paint many such. The ruined chapels that one so often sees to-day, perched upon a rocky crag or headland of our coast, were often, in all probability, lighthouses to the mariner of old.

But it is not necessary to leave too much to imagination. A great deal more can be said to prove that the maintenance of sea-lights was, in mediaeval England, really a religious office. Most of us have heard of (many have seen) the famous lighthouse on St. Catherine’s Point in the Isle of Wight. It was built only at the close of the last century, but hard by it, from the hermitage chapel on Chale Down, a light had been nightly kept, by the monks there serving God, for more than five hundred years. I shall tell the history of this lighthouse later on.

So, too, in 1427, a hermit who had settled at Ravenspurn—close by the Spurn Point on the Humber—moved by the constant disasters to shipping that he witnessed, set to work to build a lighthouse to warn vessels entering[24] the river of the dangers of the point; and of this lighthouse also I shall have more to say presently.

Then on the chapel of St. Nicholas, which stood above the harbour of Ilfracombe, there was maintained by the priests who served in the chapel a fire of wood, which was lighted, throughout the winter, at dusk, and by being constantly tended gave throughout the night a light that to ships at a distance seemed like a bright star, and guided them safely into port. The site of this chapel is yet called Lantern Hill, and a light is still shown there from a lighthouse at night during the winter months.

In one instance, at least, the work of coast lighting was performed by a religious guild: the Brethren of the Blessed Trinity of Newcastle-upon-Tyne—the Trinity House of Newcastle, as it is now called. In 1537 Henry VIII committed to this guild the general care of all matters connected with the navigation of the Tyne, and amongst other things which the guild had expressed its willingness to do, was to build two towers on the north side of ‘Le Shelys,’ one a certain distance above the other, to embattle these towers for due defence of the port, and to maintain on each ‘a good and steady light by night,’ for the guidance of passing ships. In 1746 these two lighthouses, one of which was movable, were still standing; they were illuminated only by a few[25] candles, but were the sole lighthouses of which the River Tyne, at its entrance, could boast.

Then, to emphasize further the fact that, prior to the religious changes in the reign of Henry VIII, coast lighting was carried on as a work of Christian charity, we may call to mind the traditions, so often associated with the towers or steeples of parish churches on the coast, that those towers or steeples had once been lighthouses. Blakeney, in Norfolk, is one of these, Boston is another; from the summit of ‘Boston Stump’—as the marvellously high tower of the latter church is called—we are told that a light was formerly displayed by which sailors in the German Ocean could shape their course to enter ‘Boston Deeps’ in safety.

The dissolution of the monasteries swept away, almost at a blow, the men who tended these coast lights as a sacred duty, and it confiscated the property from the profits of which such lights had been maintained. Leland, when he travelled through England and Wales, after the dissolution had been some little time in progress, found few coast lights remaining: here and there he mentions them, but it is difficult, from his language, to decide whether those he refers to were still nightly lit, or whether he gained from the sailors and fisher-folk with whom he talked that they had been regularly lit shortly before.

That our coast, only a little previous to the dissolution, was well lit, and that lighthouses of some kind or other were not uncommon, we may gather from the writer of the Pilgrimage of Perfection, who, in the year 1526—when speaking of the benefit to the soul by frequent contemplation of death—says: ‘It depresseth all vanities, dissolution, and lightness of manners, and, like as the beacon lighted in the night, directeth the mariner to the port intended, so the meditation of death maketh man to eschew the rocks and perils of damnation’: and that, after the dissolution, all, or the great majority, of these lights were extinguished, we may certainly infer by a study of The Mariner’s Mirrour, compiled by Wagener, a Dutch navigator, in 1586, and translated into English two years later by Anthony Ashley. Wagener describes minutely every object on the sea-coast of England, but does not refer to any nocturnal lights, with the exception of those at Shields, which we have seen were established under peculiar circumstances and only just prior to the dissolution.

But the want of lighthouses must have been keenly felt by sailors; and those engaged in navigation, no longer able to get what was needed as charity, seem, after a while, to have suggested paying for it. One of the earliest post-reformation lighthouses suggested was that at Winterton, for which we hear proposals in 1585,[27] just about the time that Wagener wrote his description of the English coast. Now what was the site which naturally suggested itself for establishing this light? Why, the top of the church steeple; where, likely enough, a similar light had formerly been maintained as an act of charity.

The proposal emanated from ‘the masters of her Majesties Navye,’ and was made on behalf of the seamen of the counties of Norfolk and Suffolk; ‘there be,’ it says, ‘many perillous sandes in the sea, thwarte of Hasborrowe Winterton, and the towne of Great Yermouthe, wheruppon manye shippes and men are often perished in the night tyme.’

The danger of these sands might well be avoided ‘iffe a contynuall lighte were maynteyned uppon the steeple of Winterton,’ which might be easily done, without any ‘greate imposition or taxation,’ if every English ship trading by the coast, or to the East countries, paid some small contribution.

Nothing seems to have come of this proposal, and the next suggestion we hear of for a lighthouse at Winterton is one some twenty years later in 1607, made by the Trinity House to maintain a light, not on a church steeple, but in a building specially erected for the purpose.

Nor was this a solitary lighthouse scheme. We hear,[28] just then, of another—a very mad one, it is true, but none the less interesting on that account—for a lighthouse on the Goodwins, of which I shall speak later. Probably there were many more such proposals before Queen Elizabeth and her council just then, for it is impossible to conceive that men, many of whom must have had personal experience of the benefits of coast lighting, would be content to sit down and do without them just because the religious changes had swept away the machinery that had before supported them.

Now, some time before the monastic dissolution, there had been founded in Deptford Church a guild or fraternity of sailors who undertook to watch over the interests of all concerned in shipping. This guild, dedicated to the honour of the Trinity, had, by the time of which we are speaking, or a little later—say the opening years of the reign of James I—come to be known by the name we know it to-day, the Trinity House, and had developed into a rich and powerful corporation possessed of important royal charters, regulating the general management of navigation, and supporting and administering a number of exceedingly useful charities.

But this great corporation was ambitious, jealous of the powers it possessed, and greedy to usurp more; the superintendence of the buoys and beacons which marked[30] out channels by day had become vested in it, and its governing body alleged that it was also possessed of the sole right of establishing lighthouses.

The question had arisen in respect to one of the lighthouse schemes we have just mentioned. It had been proposed, as pointed out, not from charity, but as a commercial speculation. Persons had come forward and said they were willing to establish a lighthouse at such and such a place, and to maintain a light there throughout the night, in return for certain tolls which they should levy on passing ships; and they had applied to the sovereign for the necessary licence to gather the toll, and had received the desired warrant. But, said the Trinity House, if anybody is to have this privilege, we will; the right to erect lighthouses and gather money for their support is surely vested in us by our various charters and Acts of Parliament!

So began a very pretty squabble, that did not die out till hard on the end of the last century, between the Crown, the Trinity House, and the private lighthouse speculator or builder. The wealthy shipowners, many of whom were probably also colliery owners, became alarmed at the number of lighthouse projects that were quickly launched. It was all very well to give a voluntary contribution to support one or two lighthouses at specially dangerous points, but on the whole it paid[31] better to lose a ship or two now and then, and a few men’s lives, than be put to a regular fixed charge for the safety of navigation. That was their view, and as the Trinity House Board was largely composed of men whose interests were identical, that was their view also. Lighthouses were considered a luxury, and if bestowed at all the Board must be the bestowers, and the bestowals be made as seldom as possible.

Debates in Parliament and discussions in the Privy Council followed, and the opinion of the law officers of the crown was taken. The general impression seemed to be that the Trinity House was really charged with the erection and maintenance of coast lights, but that it could not impose rates for so doing. If it wanted to do that, it must get a special patent or licence from the crown, and this the crown might give either to the Trinity House or to any private individual.

And so the squabble went on till towards the end of the eighteenth century, and every lighthouse scheme emanating from a private person was opposed with ruthless vigour by the Trinity House. The watchful care of the present corporation for the interests of navigation, the perfect system of its machinery, and the public spirit of all concerned in its management, stand out in pleasant contrast to the policy and action of the Trinity House of the past, when schemes for lighting the Lizard,[32] St. Catherine’s, the Forelands, the Goodwins, Dungeness, the Spurn, the Farne Islands, and a host of others, were condemned as ‘needless,’ ‘useless,’ or ‘dangerous,’ and ‘a burthen and hindrance’ to navigation.

But despite opposition and hostility, lighthouses, for which rates were gathered, were built in considerable numbers, so that by the first half of the seventeenth century these welcome signals to the mariner broke forth into the gloom of night from many a dangerous headland of the English coast. Of course they were not erected in positions that called for the display of great engineering skill; reefs and shoals that lay far out at sea had to go unmarked till much more recent times. The ever-shifting Goodwins drew forth suggestions for indicating their dangers as early as the days of Queen Bess, but the suggestions emanated from those whose enterprise was greater than their capacity, and came to nought. The Eddystone lighthouse, fourteen miles from shore, was really the first great engineering triumph connected with coast lighting, and Winstanley, with all his pedantry, deserves a niche in the Temple of Fame for having erected a lighthouse there at all!

Floating lights, or lightships, were, I think, projected as early as 1623, though the project was not then actually carried into effect[1]; and they were proposed[33] again, as ‘a novelty,’ half a century later at the Nore. But the Trinity House laughed at the suggestion, and the Nore remained without a light till 1730, or thereabouts, when the first lightship actually established was anchored there.

But it is not fair to say thus much and no more about the Trinity House. Its history was written not long since by Mr. Barrett, and the reader who turns to this will see that if its ‘lighthouse policy’ was bad and illiberal, the utility of the corporation was manifested in many other ways; all through the reign of Charles I it was busy rendering efficient service to the Navy. The corporation dissuaded the king from building, merely for show, what was then a ‘big ship’—124 feet long, and 46 feet in breadth, and drawing 24 feet of water; no existing port could take such a ship, and no anchor or cable would hold her. The brethren might have preached from the lesson taught by the Armada; ours were the small craft that won in combat with the floating castles of Spain. ‘The wit and ingenuity of man,’ say the brethren, could not produce a seaworthy craft with three tiers of ordnance. If your majesty desires to serve the Navy, build two ships—the same money will do it!’ It is very curious to mark how Government got for nothing a great deal of valuable advice, and it is not very clear when the practical control of the[34] dockyard at Deptford ceased to be in the Trinity House.

All this time the corporation charities were not forgotten. Besides enlarging the almshouses at Deptford, they were building others at Stepney, and organizing means for the relief of aged seamen, which was practically a scheme for insurance against old age and sickness.

Let us also, before we leave the subject of the Trinity House, say something further as to its history up to the time of the control of all lighthouses around the English coast being vested in it by Act of Parliament. In the angry days of the struggle between the King and Parliament, the board was loyal to the former, and paid its debt to the latter by being superseded in its authority by a committee. But with the restoration of Charles II came also a restoration of the ancient privileges of the Trinity House, which were watched over by General Monk as master. Other famous men presided over the corporation somewhat later; amongst them Samuel Pepys, in whose Diary are many allusions to his work there.

In the Restoration year the corporation moved from its former home to the more central one in which we now know it, near the Tower of London. Trinity Monday was that year kept in good style by a dinner[35] for forty. But the corporation did not long enjoy the comforts of its new home; the flames of the fire of London licked round it, burnt the woodwork, and gutted it, destroying valuable pictures and also papers and parchments which would have drawn aside the veil that now shrouds the early history of the fraternity. It was not till August, 1670, that the house was built again; the rebuilding was no light matter, and in 1672 the corporation was £1,100 in debt, and some years elapsed ere that was wiped out. Meanwhile, every brother, elder or younger, seems to have behaved with a public spirit, foregoing any participation in the funds of the institution, leaving that for the poor and needy.

A little after this, whilst Pepys was master of the Trinity House, the suggestion was put forward of a compulsory purchase by the board of all existing lighthouses. We will not speculate as to the object the brethren had in desiring this acquisition; it is sufficient to state that its policy towards lighthouse schemes in general was not one which could have given the public much confidence; the time had not yet come for the scheme proposed.

But a little more than a century later the lighthouse policy of the Trinity House had entirely changed. The board no longer thwarted proposals for lighthouses and lightships in places needful; it was itself proposing[36] them and helping, with its powerful hand, the sailor to fight for his rights in demanding that, for the dues he paid, the private owner should show a good and a steady light, and was furthering every project put forth by men of science for improving the power and intensity of lighthouse luminants.

The result was inevitable. Sailors, merchants, the people at large, began to look upon the corporation as every one looks upon it to-day—as a public-spirited institution, labouring its hardest in the interests of navigation. So it came about that in the year 1836 privately maintained lights were altogether extinguished, and the entire control of our lighthouse system handed over to the corporation that now directs it.

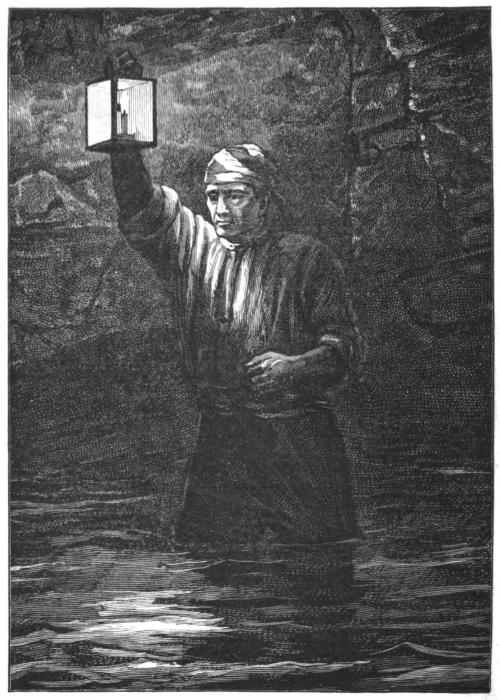

ANCIENT COAST-LIGHT.

So much for the general history of coast lighting. The reader will now wish to hear something about the luminants used of old, and of the improvements that have been made in the system of lighting. It has been said that the lighthouses of the ancients were tall columns, on the tops of which grates were placed, and in these fires of wood or coal were kept burning. The mediaeval lighthouses of England were, some of them, of similar construction, but there were varieties; if the light was placed on the steeple or tower of a church or chapel it would probably be of the kind mentioned; but if the light was shown from within the tower, candles or oil lamps would be used. The hermits of the Ecrehou refer to the fire which they kept burning all night to warn passing vessels; the monks or hermits[40] of Chale, in the Isle of Wight, displayed a light of candles or oil in the top story of their tower, which was an octagon with windows on every side.

After the Reformation the use of oil seems at first to have been entirely laid aside; a few of the lighthouses erected were lit by candles, but coal or wood fires certainly illuminated the majority. Given a properly filled grate and a fair breeze, this was certainly the best kind of light.

But towards the close of the seventeenth century it entered into the mind of economical man to enclose his coal or wood fire in a lantern with a funnel or chimney at the top. This saved the fuel, but, for that reason, it did not improve the light, and the fire, no longer fanned by the sturdy sea-breezes, needed the constant use of bellows to maintain a flame. Sailors complained a good deal of these shut-in lights, which were tried at Lowestoft, the North Foreland, and the Scilly Islands, and after a while the lanterns were removed; but coal or wood fires were used as lighthouse luminants as late as 1822.

The situation of the Eddystone—miles from the mainland, with no space for fuel-stacking—rendered it necessary to think of some other luminant than a fire of coal or wood, and candles, a considerable number of them, of course, were used there from the date of its[41] first construction till comparatively recent times, when oil lamps were substituted.

The use of oil as a luminant for lighthouses did not—after the Reformation—come in till almost the middle of the last century. This is strange, as oil was certainly used for that purpose by the mediaeval lighthouse-keepers. In November, 1729, a certain Thomas Corbett begged the permission of the Trinity House to try the experiment of lighting the South Foreland lighthouse with oil. I do not know if this trial was ever made, or what was thought of it if it were; but certainly oil was not generally re-adopted as a lighthouse luminant till much later.

In 1763 we first hear of an endeavour to increase the intensity of the light shown by means of a reflector. It was then successfully tried by William Hutchinson, a master mariner of the port of Liverpool, in connection with a rudely constructed flat-wick oil lamp; M. Argand, a citizen of Geneva, about the year 1780, improved on this system by his cylindrical-wick lamps in conjunction with a silvered reflector. This is probably the form of light which The Gentleman’s Magazine tells us was, in 1783, displayed from a hill near Norwood, and nightly viewed by an astonished crowd on Blackfriars Bridge. On Argand’s system Augustine Fresnel afterwards improved, by his large concentric-wick lamp and[42] lenses. Gas was suggested by Aldini of Milan in 1823; but for many years was used only for lighthouses on piers and harbours, or in places adjacent to gas works; and it was not till 1865 that we find gas construction taking place at out-of-the-way lighthouse stations for the purpose of supplying the light.

The year 1853 saw the first attempt at the use of electricity as a lighthouse luminant; a series of experiments with it were then carried out under Faraday’s supervision at the South Foreland. Nine years later Drummond tried the lime-light at the same lighthouse.

But there is yet one feature in the system of coast lighting which deserves attention. The difficulty felt by mariners in identifying a particular light when seen, was evidently experienced as early as the opening years of the last century, when lighthouses had begun to materially increase in number. It was not, however, till 1730 that we find any plan of distinction put forward. In that year Robert Hamblin, a barber at Lynn, patented his invention ‘for distinguishing of lights for the guidance of shipping,’ which was, that at each lighthouse station the lights should be placed ‘in such various forms, elevations, numbers, and positions that one of them should not resemble another,’ and he undertook—as soon as the distinguishing features were agreed upon—to prepare and publish a chart of the coasts of[43] England and Wales, in which such lights should be distinctly expressed. It is probable that in a measure Hamblin’s plan was acted upon, as lights erected after this date were mostly arranged in groups.

But the really effectual method of distinguishing one lighthouse from another is that at present in use, of hiding the light shown for a certain number of minutes or seconds, varying at different lighthouses. It is unnecessary to dwell upon the constructive skill displayed in the machinery by which this temporary eclipsing is produced; but of the antiquity of the system it is our province to speak. It seems to have been first tried at Marstrand, a once thriving port of Sweden, some twenty miles to the north of Gottenburg, and its effects and utility were discussed in maritime circles throughout the world. But France alone, of the various countries that considered the new system, adopted it; long before we in England had taken any steps in the matter, France had given public notice that the French coast would be illuminated by lights which might be known one from another by the differences in the periods of their being visible or eclipsed, and the French government issued an explanatory chart.

So much for the general history of coast lighting. Now that we have seen with what vigour the lighthouse battle was fought in the past, and the fierce opposition that[44] has been offered to almost every lighthouse scheme put forward, we shall not wonder that such ‘luxuries’ as lighthouses did not rapidly multiply on the English coast; a century ago there were not forty on our shores from Berwick round to the Solway Firth. Of some of these we shall speak in subsequent chapters, again reminding the reader that the general acquirement of all lighthouses by the Trinity House took place in the year 1836, and that, for many years before that date, the policy of the Trinity House towards lighthouse schemes had entirely changed. As I said at the close of the last chapter, all selfish hostility to privately maintained lights had ceased, and the Trinity House was working in the true interests of navigation, and its only desire for the entire control of our English lighthouses was that in regard to their management the very best should be done that could be done.

With the exception of the lights at the head of Berwick pier, those on the Farne Islands, on the Northumbrian coast, off Bamborough, are the most northerly in England. Legend tells us that from a now ruined tower on one of the islands a light was formerly shown as a warning to passing ships; and[46] if that was so, then in all probability it was one of those lights of which we have already spoken as being supported by charity, and was tended by a monk or hermit from the famous monastery of Holy Island. Such light would, of course, have been extinguished at the dissolution of the religious houses, and no other, however dim or flickering, marked the dangers of the Farne rocks till the year 1776. Proposals were made for a lighthouse on these islands some hundred years before, by a certain Sir John Clayton, who put forward many schemes for lighthouses, as objects of profit, at many points on the coast, but nothing came of it; it was crushed by the influence of the Newcastle traders, who did not relish having to pay for it. The sailors engaged in the northern coasting trade set these proposals afloat again in 1727, but they were stifled before they came to anything, though the then secretary to the Trinity House admits that he has heard ‘judicious commanders’ speak well of the suggestion.

OUTER FARNE LIGHTHOUSE.

However, opposition—honest or the reverse—kept the Farne rocks without a lighthouse till the year 1776, when the first of the two that at present light them was set up. The second, on the Longstones, was built in 1810, and it is this latter that has become familiar to us as the scene of Grace Darling’s heroism.

It was customary, sixty or seventy years ago, to place[47] a family in charge of a lighthouse—a man, his wife, and one or two children, all of whom, male and female, if above a certain age, received a trifling salary, and were looked upon—women and girls quite as much as men and boys—as assistant light-keepers; indeed, there were women light-keepers appointed by the Trinity House so late as 1860.

An arrangement such as this was adopted at the Longstones lighthouse; William Darling, his wife, and their daughter Grace, a girl of twenty-one, trimmed and tended the lights as recognized officials of the Trinity House.

Grace was born at Bamborough, but she had gone with her parents to live at the Longstones when but a few months old. In this desolate home she had grown accustomed to every form of weather; the laughter of a summer’s breeze equally with the wail of a winter’s gale had been her cradle song. As she grew up, she spent the time she was not helping her parents, in rowing and fishing, and when ten or eleven years old her father could trust her to manage the lighthouse boat even in the roughest weather. Grace was no scholar—her opportunities of acquiring information were obviously limited—but she could read and write well, and she made good use of the former accomplishment, eagerly drinking in every scrap of information that her father’s[48] twenty or thirty books contained regarding acts of courage and daring performed by the toilers of the sea either in peace or war. Her great ambition was that, one day, she might have the opportunity of emulating the example of those whose deeds she loved to study.

That opportunity came to her at last. At dusk, on September 6, 1838, the wind that throughout the day had been freshening was blowing considerably more than half-a-gale, and in the teeth of this the steamer Forfarshire, hailing from Hull and bound for Dundee, passed between the Farne rocks and the Northumberland coast. The ship was ‘labouring’ heavily, and Grace, as well as her father and mother, eagerly watched her progress till night closing in hid her from their view.

With the darkness the wind blew yet more fiercely; all through the night it raged with unpitying fury, and the watchers on the Longstones talked long and anxiously over the vessel that had passed them. Darling did not like the look of her, or the way the storm seemed to be handling her. Neither father, mother, nor daughter took any sleep that night: when not busy tending to the light or wiping the spray from the glass of the lantern they peered into the darkness, thinking perhaps they might catch a glimpse of some signal of distress[49] either from the steamer or some other vessel, yet no light or signal was observable.

GRACE DARLING AND HER FATHER ON THE WAY TO THE WRECK.

But the first rays of morning revealed to Darling that his apprehensions for the Forfarshire were well-founded. On Hawkers Rocks, a mile away from the lighthouse, could be seen the remains of the wrecked vessel, the remnant of her living freight clinging to it. What could be done? It seemed madness to launch the lighthouse boat in such a gale, but Grace begged her father to make the attempt; she would go with him, she said, and[50] God, she felt sure, would give them strength to perform the daring enterprise.

We know what happened. Darling yielded to his daughter’s prayer, and the survivors of the Forfarshire, few in number it is true, but all that outlived the fury of that awful night, were brought by Grace and her father safely back to the lighthouse and carefully nursed by the humane keepers till the weather changed and they were taken to Bamborough. Thus the ambition of Grace’s life had been realized; she had tested her courage, and it had not failed her.

All along the Northumbrian coast the news of the daring deed spread with wonderful rapidity: presents and letters were heaped upon Grace Darling in a manner she had never expected. The Trinity House granted the ‘family’ leave of absence from the lighthouse, and the Duke and Duchess of Northumberland entertained them at Alnwick, where, on leaving, Grace was presented with a purse containing £700. Her exploit was the talk of London and of all England, and the print-sellers’ windows gave a liberal display of her portraits.

She received all these tokens of approbation with an unaffected pleasure that added to her charms and her popularity, but her naturally retiring disposition would not allow her to accept the offer of an enterprising theatre manager to appear nightly on the London boards.

GRACE DARLING.

Neither were offers of a more permanent nature—offers of a heart and home—accepted by her; the very exploit that had made her famous seemed to bind her affections more closely to her insular home and her duties there. She spent the rest of her days on the lighthouse, helping her father and mother as before, and only paying an occasional visit to the mainland. Though innumerable accounts of her early days and of her daring exploit exist—the latter is the subject of poem, song, and story—we hear little of her subsequent life, or of the time when the illness which a few years later[52] terminated fatally first manifested itself. She died on October 20, 1842, and was buried in the churchyard at Bamborough. Her death was the signal for a fresh outburst of literary commemoration of her daring act; but no more appropriate tribute to her memory exists than the lifeboat now stationed at Bamborough, which bears her name, and which, winter after winter, renders good service to vessels wrecked or in distress, often on the very reef on which the Forfarshire stranded. Grace Darling is not forgotten by the stalwart Northumbrian sailors who man that lifeboat; her story and the song in praise of her courage has been taught to them by their fathers and mothers, and they may yet be heard to sing it, as in their well-fitted boat, possessed of the latest appliances to ensure safety, they make their way to some sinking ship, and think of the frail girl and her father, who in nothing more than an open rowing boat risked their lives to save a perishing crew.

Passing southwards from the Farne, the next lighthouse of which there is anything like ancient mention is Tynemouth; probably the monks at this important northern offshoot from St. Alban’s Abbey had shown a light from their priory, and when we first hear of the lighthouse there in the seventeenth century it was in great ruin. At Flamborough Head we have Camden’s authority for saying that the name was derived from a Roman pharos there; but there is no evidence of a mediaeval lighthouse at this spot, and before coming to one of these we must pass on to the Spurn Point, at the mouth of the Humber.

Here a lighthouse was erected in 1427, under circumstances which are in themselves interesting and romantic; so, in accordance with a promise in the first chapter, I will tell the story somewhat in detail.

The coast between Flamborough Head and the Wash has undergone very remarkable changes within historic times: the old chroniclers record very frequent inundations of the low-lying lands, and finally the entire washing away of a thriving port-town which sent a couple of members to Parliament. Its destruction—so the chroniclers say—was due to the extreme ungodliness of the inhabitants, who, such as escaped a watery grave, fled higher up the Humber to the then insignificant village of Hull, and soon raised it into a centre of commercial activity. These folk did very well, and, we will hope, lived to repent of their former wickedness; but how about the poor wretches who had been carried into eternity unrepentant? This was the thought that weighed on the pious mind of a monk at Meaux Abbey, and so strongly did it impress him that he determined to leave his brethren and lead a hermit’s life near the submerged town, spending his days in prayer for the perished souls.

Persons fired with religious enthusiasm sometimes forget to have a due regard for the minor requirements of the law. This is exactly what the pious monk from Meaux Abbey did: he endowed his hermitage with certain property from the profits of which he and his successors could support themselves, but he quite forgot to get the king’s licence for such a gift, which was, of[55] course, a gift in mortmain. Now all this happened in the closing years of Richard II’s luckless reign, and so much were the crown officers busied in other and weightier matters, that no one ever found out what a terrible thing Brother Matthew had done till Henry of Lancaster had been proclaimed king. A heavy pecuniary fine might have been the result of the monk’s hastiness, but for this fortunate circumstance. By an odd coincidence, Henry’s landing in England had taken place in the Humber close to the new hermitage which, small and mean though it was, gave him a comfortable shelter for the night. When the affair came to be looked into, this was remembered, and Brother Matthew was not only speedily forgiven, but he and his successors had bestowed upon them the important privilege of the right to take any wreck cast upon the shore within two leagues of the hermitage.

The monk’s successor was a certain Brother Richard Redbarrow, and a very good and charitable man he seems to have been: the constant wrecks around him, though they yielded him considerable profit, made his heart bleed for those who lost their lives by shipwreck. The possession of a full bag of treasure, or a cask of dainty wine, was no compensation for the sorrow which would fill his heart when the gray morning revealed a dozen or more lifeless bodies stretched upon the beach,[56] and he determined to do what he could to prevent or lessen shipwreck, and beside his hermitage he set to work to build a lighthouse.

Had Brother Richard possessed money enough to finish what he began, we might never have known of his Christian work; but he had not, and in the year 1427 he petitioned Parliament to obtain from the king the grant of a small toll on the shipping entering or leaving the port of Hull towards finishing his ‘beken’ tower; the cost of the light upon it he was ready to bear.

Parliament thought it an excellent plan, and so did the king. Brother Richard got his grant, and no doubt the lighthouse was built and did good service for many a year to come. But in time the sea encroached, acre by acre, till hermitage and lighthouse both disappeared, and in the general survey of monastic property taken at the dissolution, we find no mention of either one or the other.

But these inroads of the sea, these changes in the form of the coast-line, made the entrance to the Humber no safer. In Elizabeth’s days the Spurn was an exceedingly sharp headland, stretching far into the river, and collecting around it a quantity of shifting sand and shingle, so that the sailors of Hull determined to petition the queen in favour of a lighthouse there which one or their own countrymen—the famous navigator, Sir Martin Frobisher—was seeking leave to erect at the[57] Spurn Point, or hard by it. No doubt Sir Martin’s suit was opposed in the usual quarter, and before he could ride down the opposition he had been carried off by wounds from the Frenchmen’s guns, and nothing came of his proposal.

After this, in 1618, his kinsman, Peter Frobisher, put forward the same suggestion, but it was again laughed at as a madman’s scheme, and opposed and finally ‘shelved,’ so that ships got in and out of the Humber as best they could, the traders preferring risk to a settled tax.

The next proposals we hear of for a lighthouse at the Spurn came in the days of the Commonwealth; Sir Harry Vane—from whom the Lord Protector had not yet been delivered—submitted them to the committee for managing the affairs of the Trinity House[2], which committee actually approved the scheme. But the Trinity House of Hull, constituted as before, liked it not at all: a lighthouse at the Spurn, if erected, would not stand ‘three springs,’ and the only persons it could benefit would be an enemy seeking to enter the Humber by night; no native ship would do so mad a thing as that for fifty lighthouses.

These arguments are obviously weak, but somehow they managed to have the desired effect, and a lighthouse[58] at the Spurn was once more postponed till some years after the Restoration. Then a private individual, a certain Justinian Angel, built one, lit it, and applied to the king for leave to gather toll for its support. The opponents of the scheme now raved in vain: there was the light, and with it ships did come in and out of the Humber by night, and shipwreck grew to be the exception.

Charles II gave Angel his patent, remarking to Sam Pepys, then Master of the Trinity House, that as the patentee only asked for a voluntary contribution, it could be no hardship to anybody. Sam thought it wise to explain that, in so long opposing the scheme, the Trinity House had only done what it deemed its duty, to which the merry monarch replied that ‘caution’ was ‘always reasonable,’ and with that safe remark passed on.

There was nothing for it now but to influence as much as possible such shipowners as were willing to pay, against the light. The Trinity House seems to have thought the best way to do this was to circulate wild rumours of Angel’s huge profits; we are glad now that these rumours were set afloat, for they drew from Angel a statement as to his expenses and management, which gives us a very vivid picture of his lighthouse; this is what he says:—

At most other lighthouses—he is speaking of the ‘high’ or ‘upper’ lighthouse, they were generally in[59] pairs, a high light and a low light—the grate was fastened to a back like a chimney, and exposed only one way to the wind, namely, ‘that to the seaward,’ whilst in the low light there would be exhibited ‘two or three candles closed in with glass.’ But at the Spurn things were of necessity quite different. Here the fire on the high lighthouse must needs show ‘all round,’ and so it was entirely unscreened, standing upon ‘a swaype’ fourteen feet above the top of the lighthouse tower, and burning a vast amount more coal than a fire partly screened would burn; besides, the fire needed to be specially ‘bright,’ and so only ‘picked’ coal was used, which cost threepence a chaldron more than ordinary coal.

Then the cost of repairs was exceptional; in such an exposed situation the flames, fanned by a winter’s gale, blazed so fiercely that often three or four of the iron bars of the grate would be melted in a single night. Then the consumption of fuel would be enormous, and ‘four pair of hands’ was too little to feed the greedy furnace and keep it up to the requisite height.

If the ‘high’ light was costly to maintain, the ‘low’ light was—as a ‘low’ light—even more so: for at the Spurn this, too, was given by a coal fire instead of by the usual candles, and so cost as much ‘as two such lights elsewhere.’

In addition to all this, the carriage of coal to the Spurn Head was unusually costly, for the way from the nearest spot at which the Newcastle boats could discharge their coals lay, half of it, over soft sand, into which cart wheels sank deeply, and half over ‘a sharp shingle’ that lamed the oxen that drew it.

Light-keepers’ salaries were, too, a heavy item; two men and a competent overseer were always needed at the Spurn, and on rough and boisterous nights much additional help was required.

Altogether, from the first lighting of the lights in November, 1675, to Christmas, 1677, the expenditure had amounted to £905, and the receipts to £948, a profit of £43 in two years and a month.

Charles II thought this was not out-of-the-way; he gave Angel further powers and facilities for gathering his tolls, and at last the grumbling and the moaning died away, not to be renewed till nearly a century later. Then there were worthier grounds for them: the owner was lord of the manor within which the Spurn lighthouses stood, and he would not move them to a position rendered necessary by the continued alteration of the sand banks.

Parliament was applied to, and with an airy disregard of the claims of private property, vested the lighthouse rights in the Trinity House of Deptford Strand—the[61] very body that had for so long fought against the erection of lighthouses at the Spurn at all. Armed with these rights the Trinity House promptly rendered the old lighthouses useless by erecting, in a position where they really assisted navigation, those at present standing, and they called to their aid, as architect and engineer, John Smeaton, who had just then won his laurels by the wonderful stone tower he had built on the Eddystone rocks.

Of the disused lighthouses, as they appeared some twenty years before they were rendered useless by Smeaton’s buildings, we have a curious description, written by the then secretary to the Trinity House: the coals, he says, are placed in ‘a bricket or cradle of iron,’ which is suspended on a beam and hoisted or let down at pleasure. The upper light was then shown on the top of the tower, whilst the lower was placed against the tower on a platform a few feet from the ground. Perhaps it was this somewhat unusual arrangement with the beam that Dr. Johnson had in his mind when he described, in his Dictionary, a lighthouse as ‘a high building at the top of which lights are hung to guide ships at sea’—certainly not a very accurate description of a lighthouse as the thing was then generally constructed and arranged.

Leaving the Humber, and coming southwards to the mouth of the Thames, we pass some of the earliest post-Reformation lighthouses erected—Winterton, where we have seen a light was proposed to be shown from the church steeple in 1585; Caister, Yarmouth, Corton, Lowestoft, Orfordness, and Harwich; at all which places, and many others, lighthouses were erected in the early part of the seventeenth century.

There was a lighthouse at Caister some few miles south of Winterton, set up about the year 1600; soon afterwards we have a quaint account of the way in which this was maintained. It did not aspire to the dignity of being a coal fire; the building was merely a meanly constructed wooden tower with a lantern at the top, lit with candles—or should have been lit with[63] candles: but mark the italics—should. How was it actually illuminated? A contemporary report shall tell us. ‘Often but one candle of six to the pound ... or at the most two’ burnt in the lantern. This was insufficient: wrecks happened in consequence, and the shipowners grumbled louder than ever at having to pay dues. As stated before, the lighthouse at Caister was in the hands of the Trinity House, and it must be said to the credit of that body that on learning of the defects, it did its best to remedy them.

An inquiry was held, and revealed a sad laxity of duty in the appointed keeper. He ought to have lived at the tower, but he did not. Such a residence, when we consider the position of the Caister lighthouse, must have been solitary and dreary enough, and we can scarcely wonder that the keeper left his employment and went to labour more congenial. But he was dishonest over his retirement: he did not put his intention into writing, but went off without notice, and deputed ‘the preparing, lighting, and watching’ of the candles to an old and decrepid woman who dwelt some miles inland, and who, as might have been expected, was unable to perform her task with regularity. To reach the lighthouse, she had a lengthy walk; and in the teeth of an easterly gale she found this more than her strength could bear; thus on many a winter’s night she[64] had to retrace her steps without accomplishing the object of her journey: so that often when most needed no light at all showed from the Caister lighthouse. A new keeper was appointed; he was to live at the lighthouse, to light his candles—three in number—at sunset, snuff them, and replenish them as needful till ‘fair day.’

Surely a lighthouse, well and regularly tended, was needed at Caister! There was not, there is not, a more dangerous bit of coast on the eastern shore of England. Caister sandbanks rival the dreaded Goodwins in their terrors for the luckless ship that is driven upon them. Now, with a good system of signalling from the adjacent lightships, and with two or three well-appointed lifeboats, the loss of life is often considerable, and many are the risks run by the lifeboat crews in their gallant efforts to rescue the shipwrecked. Here is the story of one such risk, and it is typical of dozens more that have happened since lifeboats have been placed near Caister.

It was just midnight on March 11, 1875, when the schooner Punch, on her voyage from Newcastle to Dublin, ran upon the shoals off Caister. It was a ‘dirty’ night, pitch dark, and blowing hard from the east. The sands, partially uncovered at low water, are quicksands as the tide flows, and a ship once fairly driven on them has little hope of getting off again; as for[65] her crew—well, there is now this hope for them, that the lifeboat-men will see the signals of distress and hazard their lives to save them. The crew of the Punch knew what the grasp of Caister sands meant, and up flared their signal fires so soon as she struck. The waves, as though eager to secure for the greedy sands their prey, broke over the vessel in quick succession and dimmed the fire; but there was a plentiful supply of tar and oil on board, and their signals blazed up again. Then the lifeboat-men saw it and hastened to them. As their boat neared the sands her crew could see, by the fire flaring on deck, that the hulk was gradually sinking down, and that there was a stretch of uncovered sand still around the ship. Before their eyes, almost within speaking distance, the Punch would be sucked into the sand, and with her the half-dozen men on board! There was but one thing for it—anchor the lifeboat to the sand and jump on to the shifting mass. Leaving a couple of men in the lifeboat, her coxswain, heaving-line in hand, leaped overboard, followed by a number of his crew, and went staggering and stumbling towards the wreck—at one moment only ankle-deep in water and the next high up to their shoulders. And so they waded on for a hundred yards in the fury of the winter storm. They called to the crew, and the crew answered them. Think what the feelings of those sinking men[66] must have been, their gratitude to their deliverers. One threw a line from the deck, and it was clutched by the foremost of the rescuers, and, a communication once established, the schooner’s crew were one by one hauled through the broken water over the quicksand to the lifeboat, and with them the lifeboat-men rowed to shore. Yes, to shore, but not to rest! They had barely got to their homes when the cry was raised again. ‘Another ship on the sands!’ It was morning then, and back to the lifeboat they hastened, and a second time rowed out. Alas! their journey was in vain. Help had come too late, and only masses of tangled rigging, planks, and broken spars floated over the sands—the ship and her crew lay buried within them.

Oddly enough, we do not hear of any early lighthouse at Yarmouth. In the official catalogue of lights on the Norfolk coast the date of the first lighthouse of the Yarmouth group is that at Gorleston, said to have been established in the ‘fifties.’ But there was a lighthouse here nearly two centuries before; and Molloy, in his treatise on sea-law, in 1676, refers to the ‘great and pious care’ by King Charles II in erecting a lighthouse at Gorleston, or ‘Goldston,’ as he spells it, ‘at his own princely charge,’ from which expression we are, I suppose to imagine that his Majesty kept up a lighthouse at his own expense: the thing seems improbable[67] and requires confirmation before we can accept it as truth. Lighthouses in the neighbourhood at St. Nicholas Gatt were proposed and for a time established by Sir John Clayton between 1675 and 1678, and we find the seamen of Yarmouth still clamouring for them in 1692. In the seamen’s petition the loss to shipping, for want of them, is very clearly set forth; one petition says that as many as two hundred ships perished on the sandbanks there during the gale on one winter’s night.

A lightship now marks the dangers of Corton sands, some few miles further south of Yarmouth than St. Nicholas Gatt. But Corton was one of the places at which Sir John Clayton proposed to erect a lighthouse long before. When the Trinity House had crushed all his other lighthouse projects he offered the corporation something handsome to approve of a light at Corton only, but it would not: multiplicity of lights, it said, confused the navigator, and its own lighthouse at Lowestoft did all that was needed.

At Lowestoft, in 1778, were made the earliest experiments with reflectors; a thousand tiny mirrors were placed in the lantern, and with such success that the flame of the oil lamp appeared at sea, some four leagues off, like a huge globe of fire.

The lighthouse at Harwich is memorable for quite a different reason. It played—or rather was intended[68] to play—an important part in English politics. When at the eleventh hour James II and his advisers were trying might and main to ward off the Dutchman’s coming, and when the Trinity House officials, acting under Pepys’ orders, were busily engaged in removing buoys and altering the position of familiar coast marks, the small, or lower, lighthouse at Harwich was an object of consideration. It was—so went forth the order—to be ‘removed’ and set up in another place.’ But how? The operation could not be rapidly performed, for the building was a solid bit of masonry, and all depended on haste. A happy idea at last struck some one: the Dutch ships would be as easily misled by an erection of canvas, and that, ‘with the utmost secrecy,’ could be stretched on a timber frame, carried to the place appointed, and set up in less than an hour, whilst a charge or so of gunpowder would at the same time level the real lighthouse.

Whether this was ever done we do not know: the Trinity House records which tell the first part of the story are silent as to that point; but if it was, it certainly did not serve the object in view, for the Dutch ships, when they came, steered a very different course, and, as we all know, landed in quite another part of England.

MODEL OF THE FIRST LIGHTSHIP.

From the Trinity House Museum.

Coming southwards from Harwich, we are soon at the mouth of the great water-way to London and in view of the Nore light. This is the first lightship of which we have had occasion to speak in particular, though there are now many stationed along our eastern and northern coasts—one of them, that on the Dudgeon Sands, being almost as old as the Nore.

We have seen the spirit in which the Trinity House of 1674 regarded the proposals, made by a lighthouse speculator, to establish floating lights at the Nore and at some other parts; it regarded the proposition as that of a madman. Well, it sounds an odd opinion to us to-day, but really it is no more odd than the opinion expressed, sixty or seventy years ago, by men who knew[72] of what they talked, as to locomotive steam-engines and railway capabilities in general.

We do not hear of another proposal for floating lights at the Nore till 1730. Robert Hamblin had then devised a scheme for getting the whole of the lighting of the English coast into his own hands, and the dues therefrom into his own pocket. His plan was to fix floating lights at short distances from the shore, in such positions as would render the existing lighthouses absolutely useless. It was a bold stroke, and so far successful that he actually got his patent from the crown and established some of his lights, amongst them that at the Nore.

But his reign was short: the Trinity House addressed a powerful remonstrance to the law officers of the crown, the owners of private lighthouses joined in the complaint, and Hamblin’s patent was speedily cancelled.

But before the cancelling he had parted with any rights he possessed under his general patent with regard to the lightships at the Nore and at one or two other points, and in 1732, the purchaser, David Avery, placed a lightship at the east end of the Nore Sands. After circulating in shipping circles very glowing accounts of the benefits which this light would yield to navigation, he began to ask for his tolls, and by a little judicious dealing with the Trinity House he managed to get that body on his[73] side in doing so. This is what he did. He arranged that the Trinity House should itself apply for a new patent from the crown—not in general words, but simply for a lightship at the Nore—and that he should take a lease of this patent, when granted, for a term of sixty-one years at a yearly rent of £100. When we remember what the traffic in and out of the Thames was, even in 1730, we shall see that Avery must have made a good profit on the £100 a year he paid the Trinity House.

MODEL OF A LIGHTSHIP BUILT IN 1790.

(From the Trinity House Museum.)

The lightship at the Nore turned out fairly successful. Of course the arrangements for securing her in her position were of a very primitive type. Even now, with the strongest of cables and anchors, a lightship will sometimes break away from her moorings and scud before the gale. That is why the United States Government is replacing lightships by pile-lighthouses wherever the thing can be done. But in 1732 these breakings-away were far more frequent, and the first lightship at the Nore broke her moorings twice in three months of that year.

As a consequence, the number of lightships around the English coast did not rapidly multiply. However, every few years saw some improvement in the anchoring arrangements of these vessels, and the benefit, the utility, of lightships—when once they could be trusted[76] to keep their positions—became more and more apparent. To-day we have between forty and fifty of them round the coast of England.

The lighting arrangements on lightships were also, at first, very rude and unsatisfactory. Small lanterns—each containing a cluster of tiny candles that needed to be constantly replenished—were suspended from the yardarm of the vessel’s mast, and these, on a gusty night, were often blown out, and occasionally blown bodily away. Yet such arrangements were not altered till early in the present century, when Robert Stephenson invented the form of lantern at present used, which surrounds the mast of the lightship. Inside this lantern is a circular frame, on which are fixed Argand lamps with reflectors, and each light and each reflector swings, by means of gimbals, so that, let the lightship roll or plunge as she may, the light is always steady and kept perpendicular by its own weight.

We do not know with certainty what was the staff, or crew, maintained on one of these first lightships, but there were few lights to trim and manage, and there is reason to believe that, when everything with regard to coast lighting was done as cheaply as could be, there was but one man to perform the tasks. Surely the loneliness of his life is too awful to contemplate. Even at the Eddystone and other isolated lighthouses the[77] keeper was changed but seldom, and it is not likely that the lightship guard was oftener relieved.

The effect of such economical management must have been disastrous to the interests of navigation. Sudden death, illness, or accident might, at any moment, have rendered the single keeper incapable of lighting his lamps, and dire disaster to vessels, trusting to see the light, must, almost of necessity, have followed; but before long things were better ordered, and two men were kept in every lightship.

The immobility, so far as progress is concerned, of a lightship renders life upon one particularly tedious. Roll or pitch she may, but forward she never goes—that is, if all keeps well with her anchor and chains. It is of this that present-day dwellers on lightships most complain—the dull monotony of a life at anchor. Even the Flying Dutchman’s penance had advantages over it; he, at any rate, witnessed continual change of scene, he was permitted to enjoy the rest of progress.

But monotony is about all that a modern lightship keeper has to complain of, and even that is reduced to a minimum by the latest regulations. A keeper nowadays has never less than three companions; the Trinity House boats pay him frequent visits, bringing fresh water, fresh victuals, and a supply of books and papers; and he can now, in many cases, by means of the telegraph[78] or telephone, speak with the shore whenever needful. Besides, by her build, finish, and fittings, a modern lightship is, to a sailor, a really comfortable home. Each of these vessels costs between three and four thousand pounds to turn out complete and equipped for service.

Of course some lightship stations are much more lonely than others. The ever-passing stream of traffic in and out of the Thames renders the Nore one of the ‘gayest’ lightships on which to be stationed, and consequently one of the most popular. Life there is free from that singular and almost overpowering melancholy so wearying to the men at, say, the Seven Stones lightship, anchored midway between the Scillies and the Land’s End; indeed, the two stations cannot be for a moment contrasted. You might as well compare life ‘lived’ in Piccadilly with life ‘passed’ in a by-road at Finsbury Park.

Four miles seawards from Deal lie the Goodwin Sands, and the deep water between the two is known as the Downs—the great historic resting-place for ships, naval and mercantile, the scene of the gathering together of many a noble fleet of British war-ships, whose broadsides have helped to make England the mistress of the seas. The Goodwins shelter the Downs: that is their one good service, and surely the mariner pays dearly for it! No more treacherous shoal exists than that ever-shifting mass, that greedy monster that lies beneath the surface of the water, and grasps in the clasp of death every luckless vessel driven within its reach.

Deep in the Goodwin Sands lie the wrecks of centuries, the treasure of many lands. And the stories of those wrecks, what stirring reading they would be were they recorded! In the great storm of 1703—of which I shall speak later on in telling the story of the[80] Eddystone—thirteen men-of-war were driven on the Goodwins, dashed to pieces, and their crews engulfed in the rising tide. Now, in our own day, each succeeding winter brings some fresh piteous tale of disaster from the Sands, some grievous loss of human life which happens, despite the undauntable courage of the men who man the lifeboats stationed along the coast from Broadstairs to Dover. Our hearts bleed as we read of the lifeboat which, notwithstanding all that human skill and pluck can do, reaches the Goodwin Sands too late: there has been no unnecessary delay since the signal of distress was first noticed, no hanging back by the crew, no thought for their own safety. Simply the actual impossibility of reaching the wreck in time.

This is the story we read of yearly; and though it may fill us with sorrow for the sufferings of the luckless men and women on the wrecked ship, we can at least say, as we lay aside our newspaper, All was done that could be done to save them. Few, thank God, are now the occasions on which we cannot say this; but the loss of the Gutenberg, on the evening of New Year’s Day, 1860, is one of them. It was a wild night, bitterly cold, and the snow fell so thick that her pilot could not see the light from the lightship, and she struck the Goodwins about six o’clock. Her signals of distress were seen from Deal, but there was then no lifeboat stationed[81] there, and the Deal boatmen telegraphed to Ramsgate, ‘Ship on the Goodwins.’ The lifeboat-men there were ready as usual, and they hastened, as was customary, to the harbour-master to get permission for the steam-tug to tow them out.

The harbour-master was an important person, and he felt the dignity of his office. Perhaps he did not like the unceremonious way the would-be crew had come into his presence; one sometimes forgets to be duly respectful when the lives of an unknown number of one’s fellow-men are at stake, and may be saved by haste; any way, he heard this news from the breathless spokesmen without much visible sympathy. ‘Have the distress-signals been noticed at Ramsgate?’ he inquired.

‘No,’ cried the sailors, ‘at Deal; Deal has telegraphed here, and we want your orders for the harbour-tug to tow us out to the Sands.’ The harbour-master smiled. ‘That, I fear, is not official intimation,’ he said, and continued the discharge of important duties at his desk!

Ramsgate was astir? The official answer had somehow not been received by the knots of sailors who thirsted to save life with the admiration the harbour-master perhaps expected.

Further telegrams came from Deal at 8 and 9, that signals of distress were still going up from the Sands, and an angry crowd demanded the use of the tug, that, with[82] steam up, lay in the harbour. ‘Go in your own luggers, if you will go!’ shouted the harbour-master, whose official dignity was now relaxing into official indignation; but he knew that was practically an impossibility.

Then, at 9.15, came the welcome cry, ‘A signal from the South Sand lightship.’ The benevolent harbour-master forthwith untied the red tape that held the steam-tug to her moorings; and towing the lifeboat behind her, she plunged into the storm. On she went, steaming her hardest towards the Goodwins, and as those on board her and on the lifeboat neared the Sands they saw the lights of the breaking ship; nearer still, and the cries of the perishing crew could be heard. The lifeboat is set free, her sail hoisted, and she makes for the Sands!

The lights disappear, the shouting ceases, and presently a faint light shines from the sea nearer to them. Then, through the blackness of the night, the lifeboat crew can see a ship’s boat coming towards them; a rope is thrown, and she is hauled alongside the lifeboat. The men, five in number, drenched and exhausted, are taken on board: these are the remnant of the Gutenberg’s crew of thirty-one, that for nearly four hours clung to their ship as the waves dashed her to pieces on the Goodwins, and were sacrificed to an official’s ‘sense of duty!’

But what about the history of attempts to mark with lights the dangers of what legend calls the once cultivated[83] estate of Earl Godwin? These dangers were well known to the mariner of old, and have for long been sung in sea-song. But the ever-shifting nature of the sands left the lighthouse builder of bygone days without hope of the possibility of placing upon them a warning to navigators of their exact position.

However, ‘fools rush in where angels fear to tread’: the enthusiast and the mad speculator were often in evidence in the days of good Queen Bess. Those days of leaping and bounding prosperity that England then saw, as she followed new paths to fortune, encouraged such beings, and amongst them was one who came to court with a project to build a lighthouse on the Goodwins.

The projector was Gawen Smith; his proposals did not begin with this of which we have spoken. He had been an applicant for office before; a vacancy had happened in ‘Her Majestie’s bande,’ one of the drummers having been gathered to his fathers, and Gawen considered he was just the man for the post, for he could ‘sounde on the drumme’ all manner of ‘marches, daunces and songys.’ Had it been the post of chief-engineer for draining the Lincolnshire fens, our friend would, no doubt, have been able to make out a good case for his own fitness for the appointment. Poor man! his application for the band vacancy was never answered, so far as we know; perhaps Secretary Cecil thought him a[84] better sounder of his own trumpet than beater of her majesty’s drums!

But he was not daunted by failure to get an answer: in due course came the application which has made him of interest to the reader of these pages—the suggestion for a lighthouse on the Goodwins.

He tells Cecil that he has been ‘down upon the Goodwin Sands,’ in sundry parts of them, and though he found the place ‘very dangerous,’ yet by the May following he would be ready, if permitted, and if the queen would grant him the leave to gather toll—to build a beacon, ‘fyrme and staide uppon the foresaid Godwyne Sande,’ twenty or thirty feet above the high-water level; which beacon should, by night, ‘shewe his fyre’ for twenty or thirty miles, and be seen by day for hard on twenty miles.

It was no ordinary lighthouse that Gawen was going to build there. Should there—despite this wonderful erection—happen a wreck upon the sands, the beacon-tower would be an abiding-place for the shipwrecked, as it would furnish room for forty persons above the highest point to which the waves had been ever known to reach.

He had one other request, and when compared with the vastness of the undertaking, it was a modest one; it was that the queen would give him £1,000 when he should deliver to her hand ‘grasse, herbe, or flower,’[85] grown upon this desolate, shifting mass of sand, and £2,000 when the soil should be so firm that his tower would bear the weight of cannon for the defence of the channel!

Cecil carefully folded up the application and endorsed it: ‘The demands of Gawen Smith touchinge the placing of a beacon on the Goodwyn Sandes’; and there the matter ended.

Years went by, Gawen Smith died—probably a disheartened speculator; winter gales blew luckless vessels on the Goodwins; and the greedy shoal drank in life and treasure as before; but no project came prominently forward for indicating its danger till the year 1623. Then a more rational proposal was made, and made by men of a very different stamp from Gawen Smith. John, afterwards Sir John, Coke, a nautical expert, proposed means by which a light might be exhibited upon the Goodwins.