Title: When Oriole traveled westward

Author: Amy Bell Marlowe

Release date: June 4, 2025 [eBook #76223]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1921

Credits: Aaron Adrignola, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

By AMY BELL MARLOWE

AUTHOR OF

"WHEN ORIOLE CAME TO HARBOR LIGHT,"

"THE

OLDEST OF FOUR," "WYN'S CAMPING DAYS,"

"THE GIRLS OF RIVERCLIFF SCHOOL," ETC.

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1921, by

Grosset & Dunlap

When Oriole Traveled Westward

| I. | An Adventure on the Ice |

| II. | Teddy Ford |

| III. | Strange Actions |

| IV. | Oriole Is Worried |

| V. | What Happened in the Night |

| VI. | Teddy Ford's Story |

| VII. | Other People's Troubles |

| VIII. | Oriole's Own Troubles |

| IX. | A Great Change Coming |

| X. | Partings |

| XI. | A Great Deal That Is New |

| XII. | Exciting Times |

| XIII. | At the Range Camp |

| XIV. | Ching Foo |

| XV. | Molly |

| XVI. | The Spring Round-Up |

| XVII. | The Bird of Freedom |

| XVIII. | A New Deal |

| XIX. | An Exciting Fishing Party |

| XX. | Bruin on the Line |

| XXI. | News of Moment |

| XXII. | Something Going On |

| XXIII. | Suspicion Is Rife |

| XXIV. | The Twins in Trouble |

| XXV. | Nature's Wonders |

| XXVI. | At Close Quarters |

| XXVII. | The Wrist Watch |

| XXVIII. | Shall Oriole Be Told? |

| XXIX. | Of Course! |

| XXX. | The Promise of the Future |

Christmas had been so fair, if not balmy, that Oriole Putnam, for the first time spending the principal New England holidays at Littleport, scarcely expected the black frost that followed close on the heels of New Year's Day.

Indeed, the tale of that local celebrity, "the oldest inhabitant," was that for forty years previous the bays and inlets about Littleport had not been so chained by the Frost King as they were now.

Littleport Harbor was frozen over so solidly that a Government ice-breaker was sent to open a channel for the Paulmouth packet to get in and out of the port. This channel, however, did not offer a safe way for Oriole to reach Harbor Island Light in Nat Jardin's power dory.

"And I am so worried about Uncle Nat's rheumatism, and whether Ma Stafford has recovered from that felon she had on her finger," Oriole told Lyddy Ann, the maid-of-all-work at Mrs. Rebecca Joy's house and Oriole's confidante and friend. "I just must find some way of getting over to the island."

During the open season, and ever since she had come to stay with Mrs. Joy, in the big old Dexter mansion on State Street, Oriole had driven the dory back and forth between the port and Harbor Light at least once a week. To be debarred from this habit and association was really a trial for the girl.

Oriole was an active and ingenious girl, and this, her first winter away from her semi-tropical home near Bahia, Brazil, was a most marvelous experience for her. The fun and frolic to be had in her present environment was neglected in no particular by the girl.

Although she was quite familiar with roller-skating, for the first time that she could remember she now saw ice skating. It was not a difficult matter for the girl to become proficient upon ice skates.

Before the bay was frozen over, as it now was, she had learned to skate on a shallow pond near Mrs. Joy's, in company with Minnie and Flossy Payne and other members of the Busy Bees, as their school society was called. Minnie and Flossy were Oriole's closest chums of her own age. But since Mr. Harvey Langdon had come from the West to claim his twin children, Myron and Marian, Oriole Putnam had spent much time with them every day. And now, while the skating was so good, she took the little ones out on the ice quite frequently.

The ranchman could not do too much for the twins, and he fully trusted them in Oriole's care. That is how it came about that, on this rather bleak if sunshiny afternoon, Oriole was drawing the twins on their sled swiftly over the pebbly ice toward Harbor Light Island.

They were going to have supper with Nat Jardin and his housekeeper, Ma Stafford, and the pleasure in prospect was almost as great, in the opinion of the twins, as that which they were having on the ice.

"Say, Oriole!" shouted the boy twin from his seat on the sled. "Do you s'pose Ma Stafford will have hot cakes for supper?"

"M-m-m!" chanted Marian. "I des love hot cakes. With syrup, too."

"Everybody does," declared Oriole, replying first to the little girl. "And of course Ma Stafford will have hot cakes. She always does this time of year."

"I hope she will have plenty of 'em," Myron added. "If she doesn't——"

"Well, what if she doesn't?" asked Oriole.

"I'll have to give part of mine to Mawyann, and she's such a little pig."

"I'm not a pig!" wailed his sister. "But I like hot cakes."

"You should not say that about Marian," admonished Oriole. "Suppose your papa heard you?"

"He can't hear me clear out here on the ice," Myron said confidently. "And anyway, he's gone to see Nurse Brown. He couldn't hear me."

"That does not matter," Oriole told him, still with seriousness. "What are you? Just an eye-server?"

"What's that?" asked the little boy, startled. "My—my eyes are all right."

"I got sumfin in my eye once," cried Marian. "It was a singer. Nursie got it out with the corner of her han'kercher. She did!"

"I guess it was a cinder, not a singer," commented Oriole. She had halted with her back to the wind, the better to talk to and hear the twins. "But an 'eye-server,' Myron, is what Mrs. Rebecca Joy calls those people that you can't trust to do as well out of your sight as they do when you watch 'em. You ought to speak just as nicely of your sister when you are away from your papa as you do when he can hear."

"You're talking about hearing, not seeing, Oriole Putnam," said the young culprit promptly.

"It amounts to the same thing. But I can't stand here all day and argue because you are naughty, Myron Langdon. We must get on," and she caught up her stroke again and jerked the sled into motion.

Oriole was skating rapidly toward the island, the sled following her swift pace at the end of a long rope. Head down, breathing deeply, eyes and cheeks aglow, the girl pursued her flight at top speed while the twins on the sled screamed their delight.

Although Myron and Marian were not many months past their fourth birthday, they were plucky little youngsters. Myron was especially a brave child. He clung to the hand-lines of the sled while his sister sat close behind him, her plump, gaitered legs astraddle and clinging with both hands to the belt of her brother's coat.

There were a good many other skaters on the ice besides Oriole Putnam; but they were not so far down the harbor. But the several iceboats raced from the wharves to the edge of the Tide Flow where the current was always so strong that ice never formed.

Oriole was well away from the Flow and far from the channel the ice-breaking steamer had made, so that there was no danger of either her or the twins going into the water. At least, any one with judgment would have said the trio were quite safe.

There were, however, thin patches in the harbor ice. Usually they were to be observed rods away. The lift of the tide had opened holes here and there, and these holes had been skimmed over again with thin ice. These blue patches Oriole very carefully avoided. She was not the girl to take risks with her own life or that of her charges.

The objects before her on Harbor Light Island stood out distinctly in the afternoon sunshine. The tall white staff of the light, in the little barnacle-like cottage at the foot of which she had lived when she first came to the island, was an object that could be seen far, far at sea.

But now Uncle Nat and Ma lived in the old house at the northern end of the island, overlooking the main entrance to Littleport Harbor. Oriole was steering for the tiny cove just below the bluff on which this cottage stood.

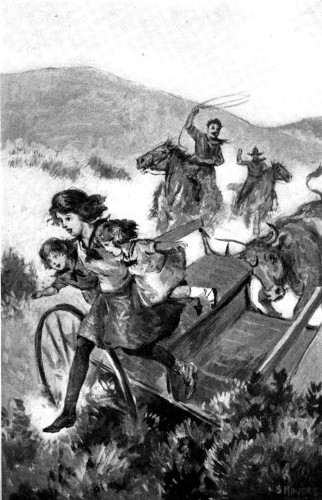

The girl and the sled were not a quarter of a mile from her destination when Anson Cope's Bluebird, the biggest ice-craft on the bay, came whirling down upon them. It did not seem that the steersman of the huge craft could escape seeing Oriole and the sled. And of course he did not. But he ran dangerously close to the small figures on the ice.

Marian looked over her shoulder and began to scream with terror. But it was several seconds before Oriole was aware of the close approach of the ice-craft. Then the peak of the big sail seemed to be hanging right over her head.

Oriole screamed, too, but she was not stricken helpless. She swerved in her course and tried to get the sled off to one side. The Bluebird tacked, and as the mainsail swung over, the steersman caught another glimpse of the girl and the sled and its burden.

The peril was too imminent then for the master of the iceboat to change his course. He had the Tide Flow directly ahead. In a moment he must tack again to escape disaster.

His starboard runners crashed through the thin ice upon the pool which Oriole was skirting. It was a terrific smash and the water flew high in the air—a regular geyser.

In falling, the deluge overwhelmed the girl. She fell upon her knees, and, sliding and scrambling, plunged suddenly into the cold sea. She could not cast off the drag-rope; and even that would not have saved the twins from a ducking. The sled was aimed right at the open water and it followed Oriole through the broken ice.

The force of the wind had driven the iceboat a mile on its way back toward the port by the time Oriole and the twins were actually in the water. The boatmen were too far away to render the least assistance. By the time they could return, the three in the water would have been under the ice.

But Oriole Putnam was not helpless. Fearful as she was for her own safety, she thought at once of Myron and Marian. She went down in her first plunge far below the surface of the sea; but during the previous summer while living at Harbor Light she had learned to swim and was not afraid of the water itself.

She made her way to the surface and rose as high as she could among the broken cakes of ice. The entire surface ice of the pool had been crushed by the weight of the iceboat. Its swift passage was all that had saved it from wreck.

There was nothing stable for Oriole to cling to. Nor was she at once looking for escape. She looked for the little heads of the twins.

She saw the sled. Two little blue-coated arms were about it, the mittened hands clinging fast.

She dashed the splintered ice out of her way and plunged toward the sled. One of the twins clung fast. Where was the other?

Oriole was sobbing in her throat, despairing and afraid. What should she say to Mr. Langdon, who had trusted the twins to her care? Oriole felt at this moment that she must be judged guilty for the accident.

She plunged forward and caught one of the blue arms. Myron's head popped up. The boy was actually self-possessed!

"I can't see Mawyann!" he sputtered. "I can't see her!"

"Wait! Wait!" begged Oriole. "She must be here—she must!"

"She ain't," said Myron. "She's so silly! She went right down under the ice."

His own teeth were chattering, but he managed to speak quite plainly. Oriole had all she could do to hold him up and keep above the surface herself. Had she caught sight of little Marian she would have had to desert Myron to get his sister.

Oriole could see nobody on the ice near enough to aid them in their terrible predicament. Little Marian did not appear upon the surface of the troubled water. As the moments slipped by the girl felt that here was tragedy. The little Langdon girl, who had been as much her care as Myron, must be drowned!

Holding Myron Langdon up in the crook of one arm, Oriole clung to the floating sled with her other hand and tried to kick herself and Myron toward the edge of the thicker ice. This was no light task. She was not at all sure that both Myron and herself would not sink as Marian had.

The girl from Bahia had been through so much tragedy during these last months that she did not give up hope easily. But the chill of the sea and the helplessness of her charge hampered Oriole dreadfully. Her progress in pushing the sled before her was slow indeed.

She had not tried to cry out for help. What would be the use? The iceboat was a long distance away and it would take many minutes for anybody aboard that craft to return to aid Oriole and the twins. And the girl had seen nobody else in the vicinity.

Suddenly, however, she saw a figure scrambling over the thick ice toward the hole where she struggled with her burden. The newcomer was a boy—a boy not much older than Oriole herself, she felt sure; and at this instant Oriole thought him the very handsomest boy she had ever seen!

He did not wear skates and he had some trouble in reaching the edge of the hole; but he came on with determination, and soon she heard him shouting:

"Hold on! Hold on! I'll get you out!"

"Get Marian! Oh, do, please, save Marian!" shrieked Oriole Putnam. "I can hang on to Myron a long time yet. And we've got the sled. Save Marian."

The boy, who had curly brown hair and a pink and white complexion, reached the edge of the broken ice and peered over the surface of the hole. Something dark rose almost to the surface and not very far out.

"I see it!" cried the stranger, who was already drawing off his coat.

Just as though it were summer and he was in his bathing suit, the boy dived into the ice-strewn water. Oriole was smitten with the thought that perhaps she had urged him to disaster. The chill of the sea was fast paralyzing her own limbs and the pressure about her heart was like that of a tightly drawn band.

She feared that she had encouraged this very good-looking boy to risk his life—and in an impossible attempt to drag forth the little girl. Oriole had not seen Marian's body rise so near the surface.

But when the big boy came up with a great splutter not far from Oriole and the sled, he bore the unconscious little girl in his arms. He trod water, standing almost erect, dashed the spray from his eyes and actually grinned at Oriole.

"I got her! The poor kid!" he cried.

It was when he smiled that Oriole saw he had such nice white teeth and that the expression of his face was very winning. She thought, even in this dangerous moment:

"He's ever so much better looking than Billy Bragg—and Billy was a nice boy, too."

Billy Bragg had been connected with the first great adventure of Oriole's life.

Brought up as she had been in the suburbs of the city of Bahia, a Brazilian metropolis, her quiet life with her mother and father, who had gone there years before from the United States, had scarcely prepared Oriole for what happened to her when the Putnam family decided to return to their own country.

Sailing on the British steamship Helvetia, the family expected to be in New York in a very few days. But the Helvetia met another and unknown ship in collision in mid-ocean and had the purser's boat not been picked up by the Adrian Marple, with Oriole as one of its rescued passengers, Oriole certainly would never have seen Harbor Light, and of course she would not have known Billy Bragg.

Billy was the cabin boy aboard the Adrian Marple. Billy was, Oriole had often told Nat Jardin and her other friends, the very nicest boy she had ever known. In spite of the fact that the cabin boy's character seemed to fit his name very closely—Bragg—the girl from Brazil always remembered Billy with interest.

Misfortune seemed to have followed hard upon Oriole Putnam. She believed her mother and father had been rescued by the ship that had collided with the Helvetia; but of this neither she nor anybody else could be positive.

The Adrian Marple, Boston bound from Mediterranean ports, suffered disaster, as well as the ship on which Oriole had sailed from Bahia, although in a different way. She "stubbed her toe," as old Nat Jardin, the lightkeeper, said, upon the Camper Reef off Harbor Island, and although Billy Bragg and Oriole were together when the steamship struck and Oriole was saved by the lightkeeper himself, she had never seen Billy since the hour of the wreck.

She often thought of Billy Bragg, as well as of her own dear mother and father. The uncertainty of her parents' safety had at first made Oriole very sad, although the lightkeeper and Ma Stafford, his housekeeper, loved and protected the girl as though she were their very own.

The fresh environment of Harbor Island gradually cheered Oriole and she came to the conclusion that her mother and father had been carried away around the world by the ship that had collided with the Helvetia. That ship might be a sailing vessel, and she knew that if it was so, and Mr. and Mrs. Putnam were aboard of it, it might be months and months before they reached an American port.

As related in a previous volume entitled "When Oriole Came to Harbor Light," many adventures had come to Oriole since she had landed upon the rock-riven island near which she was now struggling in the icy water. But nothing had really been as serious as this present predicament.

She feared that she could not much longer bear Myron, the boy twin, up above the sea. She tried to place him on the sled, but failed. If she had not been able to cling to the sled she would have gone down herself.

And what could she ever say to Mr. Harvey Langdon if she allowed either of the twins to drown? The big Western ranchman had only recently come East to recover his children after the wreck of the Portland steamboat. Myron and Marian had been saved from that disaster by Nat Jardin and Oriole; but the children's nurse, who had been with them, had received a heavy blow on the head and had not as yet recovered her memory.

Much against Oriole's and Nat Jardin's desires, the twins had been placed in the town orphan asylum and might never have been discovered by their father had not Oriole written and paid for an advertisement in the newspapers that drew the ranchman East in his search for his lost children.

That Mr. Langdon trusted her so fully with the twins was the thought that now so keenly rasped Oriole's mind. If the twins were lost—drowned! The thought was indeed shocking.

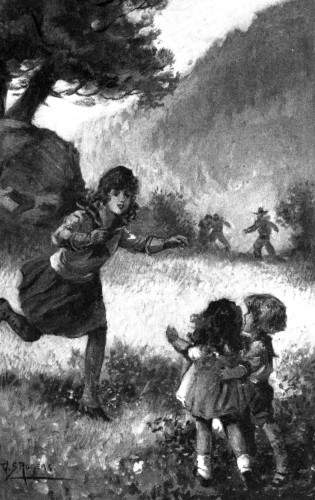

And then she saw this handsome boy who had come to her help lift the little saturated body of Marian out upon the thick ice. He turned swiftly and reached the sled in two strokes. He seized Myron just as Oriole's hold was slipping.

"Hang on to that sled, girl!" commanded the boy earnestly. "I'll come back for you."

"My—my name's Oriole Putnam," gasped Oriole faintly. But the boy evidently did not hear.

He raised Myron, who struggled a little and sputtered too, high in his arms and cast the boy out upon the ice beside his sister. Oriole began to kick again and force the sled nearer the thick ice.

"All right, girl!" shouted the very vigorous and able boy. "I'm going to lift you up, and you grab hold of the ice and try to pull yourself out."

He did as he said he would and Oriole tried to do as he commanded. It was a hard struggle, but it did not last many seconds. She found herself face downward on the ice, her feet still in the water, and kicking vigorously.

Oriole never had seen such a quick and muscular boy as this one. Even Billy Bragg had not been able to perform such feats of strength and agility. The stranger raised himself quickly upon the sled, which sank slowly under him; and then the boy scrambled out to the ice and drew the sled up after him.

"There!" he chattered, yet grinning, too. "I've saved the whole crew and the sled into the bargain. Where—where shall we take these kids?"

"Oh! To the island. Up there to Ma Stafford and Uncle Nat," cried Oriole, and she struggled to her feet and pointed to the bluff on which stood the old house where Nat Jardin and Ma Stafford now lived.

"Come on, girl," said the stranger, offering her a hand to steady her on her feet. "If you can carry yourself I'll take the kids."

"Can you carry both Myron and Marian?"

"I reckon," said the boy carelessly. "Gee! ain't it cold?"

"My name is—is Oriole Putnam," chattered the girl.

"Don't be so particular," said the boy, hurriedly grabbing at Myron and Marian. "My name's Teddy Ford. And I guess nobody knows me much around here, so there isn't anybody to introduce us. Come on! You'll freeze stiff."

Little Marian's coat had already frozen to the ice. She looked so blue in the face, with her eyes shut so tight, that Oriole was terribly frightened about her. Myron sputtered and squalled his objections when Teddy Ford dropped him on the ice again to tear his sister loose from the frost-hold.

"Run!" commanded the boy. "You'll get your death of cold. What's your name?"

"I—I tell yu-yu-you it—it's Oriole," chattered the girl.

"All right. You're a bird, Oriole. Fly!"

Thus adjured Oriole started at a rather stiff-legged trot across the ice. She had lost her skates in the water (and it was lucky for her she had) and found plowing over the ice a very uncertain procedure. But Teddy Ford seemed to be as sure footed as a cat!

He hugged a twin under each arm and ran after Oriole, soon overtaking her.

"Where's that place you are going to? Is there a fire?" he demanded.

"The cottage. Up there. On the island."

"Not to the lighthouse?" panted the boy.

"No, no! Uncle Nat and Ma are at this cottage. It is nearer, anyway."

"That is what we want—the nearest place. Gee! don't fall."

"I wish you would—wouldn't say that," admonished the chattering Oriole.

"Say what?"

"'Gee.' It sounds like driving ox—oxen. And I'm no—not an ox."

"Gee!" ejaculated Teddy Ford. Then: "Oh! I didn't meanter. I mean 'mean to.' You're—you're awful particular, ain't you?"

But Oriole was too cold to answer. This was no time and place, after all, to be "particular."

She fell down once—flat on her face and bumped her chin. But she scrambled up again before the boy could drop the twins to help her.

"Go on! Go on!" she begged. "Don't stop for me!"

"You see that you come, then," he shouted back at her, and hurried ahead, landing and climbing up the path to the top of the bluff several rods ahead of Oriole.

He had not actually known how very badly off Oriole Putnam was. She was as brave as girl could be, but she was chilled to the very marrow (or so Ma Stafford would have said) and when the boy had left her she made but slow headway.

Indeed, the girl was well nigh exhausted—she scarcely had breath to cry out—when the door of the old house opened and Nat Jardin put his head out to see who was approaching.

Oriole Putnam did not have breath to introduce Teddy Ford to the old lightkeeper. She just panted as she staggered to the open door of the cottage. But Nat Jardin did not need to be introduced to Myron and Marian.

"Sho! I wanta know what's happened to them babies?" he demanded. "You been trying to drown 'em? The poor leetle things! Bring 'em right in here——"

"For the good land's sake!" broke in Ma Stafford from behind the lightkeeper's rather bulky figure. "What's the meaning of such things, I want to know? Give me that child! She's as blue as indigo and nigh about gone!"

Ma Stafford grabbed Marian out of the boy's arms. Uncle Nat seized the other twin. For the minute the two old people scarcely noticed the boy and Oriole, both quite as wet as the twins—their clothing indeed already stiffening in the cold air.

But Jardin did shout for them to come in and shut the door. There was a hot fire in the kitchen stove and it was just like coming into a conservatory to enter that room from the open air. Oriole and the strange boy hurried to the stove.

"You all been in the water," clucked Ma Stafford. "I knew well enough that ice warn't safe, 'Thaniel. Now, didn't I tell you so?"

"'Twarn't safe where they got, sure 'nough," agreed Jardin. "This boy's all right, Ma. His eyes is open—and he's a plucky little feller, like I always said he was. Ain't you, Myron?"

"Is—is Mawyann all right?" gasped the twin.

"Sure she is," declared Jardin warmly. "Ma'll fix her up."

"Oriole!" cried the old woman, "you get me rough towels out of the dresser drawer. You know where they be. For the land's sake! You ain't fitten to do anything yourself, you are so sopping."

"Both she and this boy better git their wet clothes off," advised the old man, beginning to strip little Myron before the kitchen stove.

"I'm going to take this child into the sittin' room. There's a good fire in the base-burner. You come, too, Oriole, child," urged Ma. "There must be something dry of yours here that you can put on. How ever did it happen?"

That was what Uncle Nat wanted to know of Teddy Ford when they were left alone with Myron in the kitchen.

"I came over from Paulmouth on that boat of Captain Diggers. He said there might be a job over this way for a boy. And I started down toward that life saving station you can see from out yonder——"

"Cap'n Petty's station at the Flow," interjected Nat Jardin.

"I heard there was a man down there could use a boy. I think I would like to work on a boat, or alongshore. You see, I never saw the ocean before."

"Sho, now! That so?" queried the old man, interested.

"And I was walking on the ice because it was the shortest cut, they said, and it seemed so. I saw that big iceboat make that dive for this girl and the sled——"

"Whose boat was it?" asked Jardin quickly.

"I don't know. But it was a big one. It just slued right around, almost hitting that girl and the sled she was dragging, and the ice smashed right in—a big splotch of it. Gee! but they didn't have a chance. They all went into the water together."

"That's purt' serious, I cal'late," said Jardin, now, having stripped the little trembling body of Myron Langdon. "Gimme that towel. I got to rub this boy till he shines! You use that other one. What did ye say your name was?"

"Teddy Ford. I don't belong around here."

"No, I see ye don't. Not if you never saw the sea before," chuckled Nat Jardin. "You come from away back in the tall timber, I cal'late?"

"I ain't no greenhorn," declared Teddy Ford quickly, but he smiled, and Nat Jardin found that smile, as Oriole had found it, most winning. "But I come a long way to get here."

"And why did you come?" asked the old man, rubbing Myron until he was all in a pink glow.

The bigger boy flashed the lightkeeper a curious look. "Oh—I got restless, I guess. Seems to me I wanted to get as far away from my old stamping grounds as possible. And I guess I have. Gee!"

"H'm," considered the lightkeeper. "You look like a purt' nice boy. But that's kind of a swear-word you use so frequent, and I'd rather you didn't say it before this here little feller. Myron imitates just like a parrot."

"Oh!" exclaimed Teddy Ford. "I'm always saying 'gee,' but it don't mean anything."

"Then don't use it," advised the lightkeeper, quite unaware that he used exclamatory expressions himself at times that were quite as meaningless. "You getting warm?"

"Yes, sir."

"There's coffee in that pot. You shove it for'ard. You'll have a cup and it'll warm you up. Ma will make some cocoa or hot milk for these young ones and Oriole."

He wrapped Myron in a big shawl of Ma's, told him to sit still on the kitchen settee and not wriggle, and went off to his own room to find some dry garments for the strange boy.

"You—you are an awful good boy," stammered Myron, gazing at the other rubbing himself down. Myron was what Ma called "a noticing child," which meant that he was thoughtful for his age. "You saved Mawyann."

"'Marian'?" repeated Teddy Ford. "And your name is Myron? Say, that's funny, too!" and Ted stared at the little fellow reflectively.

"What is funny?" asked Myron.

But just then Nat Jardin came back with under-garments, socks, a pair of canvas shoes, and a suit of overalls that would at least cover the strange boy if they did not well fit him. Ted put them on, staring most of the time at little Myron.

By and by Oriole appeared in some of the old clothes she had left on the island when, several months before, she had gone to live with Mrs. Rebecca Joy on the mainland. She began to smile the moment she saw Teddy Ford.

"Oh, dear me!" she said, "how funny you look in those dungarees of Uncle Nat's. But I guess you were just as wet as I was, Teddy Ford."

"I went into the same water," he told her, grinning again.

Oriole thought that smile of the curly-haired boy quite entrancing. She really could not help looking at him.

"How's little Marian getting on?" asked Nat Jardin.

"She is going to be all right," was Oriole's reassuring reply. "Ma says she only swallowed a little water, and she is as warm as toast now."

"The poor child——"

"Sa-ay!" burst out Teddy Ford suddenly, "are these kids twins?"

"Of course they are," said Oriole.

"And their names are Myron and Marian?" insisted the big boy.

"Of course. You saved Marian, and her father will be so thankful to you—you wait and see."

"I want to know what their last name is," said the boy, growing suddenly very red in the face. "It can't be—Gee!"

"There you go again, son," said Nat Jardin. "I cal'late it is going to be some hard for you to break yourself of saying that."

But now Teddy Ford paid no attention to the old lightkeeper. He was staring at Oriole.

"Say!" he demanded, "does the father of these kids live around here?"

"He is living at the Littleport Inn. Yes, sir," replied the surprised girl.

"And—and their mother?"

Oriole put a finger upon her own lips and shook her head. "No, no!" she whispered. "They don't know anything about their mother. She—she is dead."

Oriole said this almost in Teddy Ford's ear so that Myron should not overhear what she said.

"Oh!" said the boy. "But they do live around here, then? What's their name?"

"Why! Myron and Marian."

"Gee! Don't I know that?" muttered Teddy Ford. "But the rest of it? Their family name?"

"Their father is Mr. Harvey Langdon——"

This time Teddy interrupted her with a very emphatic "Gee!" indeed. His face turned from fiery red to white, and his eyes glowed with what Oriole correctly guessed was anger.

"S-s-s-say!" he stuttered hoarsely, "you don't mean to say the father of these two kids is Harvey Langdon, the ranchman?"

"Why, yes. That is exactly who he is," said Oriole, her own eyes wide with wonder.

"I—I didn't know—I hadn't the first idea he was in the East," stammered Teddy Ford.

"He came on here to Littleport to find Myron and Marian. They were lost——"

"Yes, I heard talk about that," muttered the boy.

"You never came from away out West where Mr. Langdon and the twins live?" gasped Oriole.

"Never mind where I came from," growled Teddy Ford, seizing his still wet cap that he had hung behind the stove to dry. "I know these Langdons—you bet I do!"

"Why, Teddy Ford! you sound just as though you did not like them. And you saved Marian—and Myron and me too—from drowning."

"I would never have saved that kid if I'd known she was Harvey Langdon's!" exclaimed the boy angrily. "You can just bet I wouldn't!"

"Oh! How wicked!"

"I don't care!" muttered the boy. "Let it be wicked. Gee! if you'd gone through what I have——"

"But surely these little children never harmed you," began Oriole.

"Never mind. I know what their father is. I don't want to have a thing more to do with Harvey Langdon—nor those kids, either!"

Oriole was too amazed to speak. Uncle Nat had gone into the other room to see for himself how Marian was, while Myron was snuggled down on the settee almost asleep.

Teddy Ford started for the outer door, pulling his damp cap down over his curls. He carried his coat over his arm. That garment had not been in the sea.

"Oh! Oh!" cried Oriole.

"Never you mind. I'm not going to hang around here where Harvey Langdon may show up any minute. Not me!"

The next moment he had dashed out of the cottage. Oriole ran after him and looked out. But she could not see him, so fast had the strange boy moved. Besides, it was past sunset and fast growing dark.

"Well! did you ever?" murmured the amazed Oriole. "Such strange actions! That Teddy Ford is just the funniest boy I ever saw!"

Nat Jardin was quite as amazed as Oriole when he came out of the sitting room and found that Teddy Ford had departed. But when he considered the boy's garments drying around the stove, and the fact that those Teddy had on were quite too ridiculous for him to wear very far, the old lightkeeper was relieved.

"I cal'late he ain't gone far," he said to Oriole soothingly. "He'll come back. How did you get him mad?"

"I never, Uncle Nat!" cried the girl. "I never said a thing to him. But——" and she volubly told her old friend the strange things Teddy Ford had said about the father of the twins. "Did you ever?" was her conclusion.

"Never heard the beat of that," agreed Nat Jardin. "Looks like he came from clear out West—like Mr. Langdon did. Knowed him at home, I cal'late."

"Why—why, Teddy Ford must be a Western cowboy, too!" Oriole cried.

"He's a boy all right; and I cal'late he's from the West," chuckled Nat Jardin. "What he knows about cows is another matter. And I cal'late I better go milk our'n right now. 'Tis time."

He got his storm hat and coat and started out with the milk pail to do the chores. But actually he was more anxious to find out what had become of Teddy Ford than anything else. The night was bound to be a cold one, and the strange boy was but thinly dressed.

But he found him nowhere among the outbuildings which were nearer to the lighthouse tower than they were to the cottage on the northern bluff which Nat Jardin now occupied. During this winter, because of an accident that had occurred and a long siege of rheumatism he had suffered, Nat Jardin had been replaced in the care of the light by a substitute lightkeeper. But he expected to go back to his old job in the spring.

For more than twenty years Nat Jardin had lived on Harbor Island and had kept the Harbor Light. He would have been "fair on his beam ends" if he had been obliged to go elsewhere to live, as he often declared. But old as he was, he was of a vigorous constitution and save when the rheumatism took him down, he was quite able to attend to the lamp and to the heavier chores about the island. Finally Nat Jardin brought in the milk, announcing that everything was "shipshape" for the night.

"But I cal'late that boy laid a course for the main," he added. "And him only half dressed. I don't understand it, Oriole."

"He seemed like such a nice boy," sighed the girl.

"I guess if he plunged right into that water and saved you all, as he did, he must be nice," said Ma Stafford briskly.

"But we know Mr. Harvey Langdon is a nice man," said Oriole warmly.

Myron and Marian had been given bread and milk and were now in bed, with a hot flatiron at their feet. Ma Stafford was taking no chances in the matter of the twins taking cold after their exposure.

Marian had cried for "cakes." The ducking had not caused her to forget those delicacies, and she was an insistent little thing when she was roused.

"Never see the beat!" Ma exclaimed. "Let that young one see a new moon and she'd think 'twas a silver spoon and would cry for it. But bread and milk is all they are going to have this hour of the night. No knowing how much their stomachs are upsot."

Then she gave further attention to the discussion about the strange boy and his stranger actions.

"Mr. Langdon is a nice feller," said Nat Jardin reflectively. "But mebbe this boy don't know him as well as we do."

"He can't know him," cried Oriole. "And yet he spoke as though he came right from where Mr. Langdon lives."

"That he did," admitted the lightkeeper. "Well, 'tis a mystery. But I cal'late it'll be cleared up like most mysteries."

Oriole sighed again. "Like most mysteries 'cepting the whereabouts of my dear mother and father," she whispered. But neither Nat Jardin nor Ma Stafford heard this.

Oriole considered that she had many worries—and this was possibly true, when one considered her age; and this mystery about the curly-haired boy, Teddy Ford, was an added burden of anxiety. She could not understand anybody not liking Mr. Harvey Langdon. And that strange boy spoke as though he actually hated the father of the twins.

Ma Stafford said that Myron and Marian could not be taken back to the mainland that night. This began to worry Oriole.

"It will worry Mrs. Joy and Lyddy Ann if I don't get back," she said thoughtfully. "But it will be worse for Mr. Langdon when he returns to the hotel to-night and doesn't find the children in his rooms."

"Where did Langdon go?" asked Uncle Nat, smoking in the corner of the settee by the stove, while Ma fried fishcakes and watched a bannock turning golden brown in the oven.

"He went to the county seat, to the hospital there to see how Sadie Brown, the nurse, is getting along," explained Oriole. "He can't get back until after supper time. But he will expect me to be back with the twins by the time the train arrives."

"That poor creeter," said Ma Stafford, referring to the twins' nurse, who had been badly injured when Myron and Marian were rescued from the wreck of the Portland steamboat. "How is she gettin' on, anyway?"

"The doctors say she will recover. She is anxious to go back to the ranch with Mr. Langdon too. That is why he has waited so long before returning home."

Nat and Ma looked at each other. Oriole thought that was the whole reason for Harvey Langdon's delay in starting West with his recovered children. But the lightkeeper and his housekeeper knew better than that.

Ma suggested, however, that Mr. Langdon might not be much alarmed if he came back to the inn and found the twins and Oriole not there. "He will think, maybe, that you have taken them to Mrs. Joy's until morning."

"But what will Mrs. Joy and Lyddy Ann think?" demanded Oriole. "They will expect me back by bedtime."

"I never! I suppose that's so," murmured the housekeeper.

"And Mr. Langdon will go to Mrs. Joy's to make sure."

"I don't see for the life of me, then," said Ma, "what we're to do. We can't get word to the main."

"If only that boy hadn't run away——"

"I cal'late," put in Nat Jardin firmly, "that I can get over to the main somehow."

"I cal'late you won't," declared Ma. "I won't hear to your going, 'Thaniel."

"News travels fast around Littleport—'specially what ye might call bad news. The iceboat-men will tell about the accident all right. They see Oriole and the twins in the water."

"And they must have seen Teddy Ford pull us all out, too," said Oriole hopefully.

"They must be pretty funny folks," murmured Ma Stafford, "to sail right away and never try to stop and save you children. Reg'lar Floyd Iresons—that's what they are."

"Oh, my!" cried Oriole, who had a retentive memory, "you mean 'Old Floyd Ireson, for his har-rd hear-rt'—I know about him."

"And you know wrong about him—like Ma and other folks. That's an exploded doctrine," said Nat Jardin, puffing more quickly on his pipe. "If Cap'n Ireson ever left the crew of another craft without standin' by, 'twas 'cause his own crew or the weather wouldn't admit of it. And the women o' Marblehead ne'er tarred and feathered him, nor drug him in no cart. They was ladies, same as the women of Littleport air, and they wouldn't do such an unseemly thing.

"But that ain't neither here nor there. Them iceboats can't be stopped, as Ma supposes, within their own length. You can't tack, or back your wagon, just in a second or two. By the time they could have gone about in that racer and run down to the hole again, Oriole and the twins would have been fathoms deep."

"Don't talk of it, 'Thaniel," said Ma, shuddering.

"Anyhow," said Uncle Nat, "they'll take news of the accident back to town and it'll spread there like wildfire. Mr. Langdon will hear of it first thing he lands off that train. And I wager Becky Joy has heard the news before now."

"She will be dreadfully scared," said Oriole.

"I cal'late," said Uncle Nat, but smiling broadly, "that that Lyddy Ann woman will be wuss scare't than she was when she took Marm Joy for a ghost."

Ma clucked her tongue again at this, but Oriole smiled—then giggled.

"That was so funny," she said. "You ought to have seen poor Lyddy Ann with her apron over her head. But, dear me! wasn't it lucky we saw Mrs. Joy that time? Otherwise the silver casket might never have been found and lots of people would still think I stole it."

This mention was of a very serious incident in Oriole's career at Mrs. Joy's house, and one that she was not likely soon to forget.

While they were at supper a step sounded upon the porch. Oriole jumped up, hoping it might be the strange boy returning. But Uncle Nat boomed out:

"Ahoy, Payton Orr! Come aboard, shipmate. What's the good word?"

The substitute lightkeeper—a young, tanned, smiling and smooth-faced man—pushed open the door and entered. He was bundled up in a knitted "comforter" and mittens, as well as a thick pea-coat.

"Mighty cold, Nat," he declared. "How-de-do, Ma? And here's Oriole! I declare, Oriole, what you been doing now?"

"Er—why—eating," admitted Oriole.

"'Tain't to be wondered at. Anybody would eat Ma's fishcakes and Injun bannock. No, no! Don't you ask me! I stowed away a cargo o' biscuit and corned-beef hash 'fore I went up to light the lamp. Now I'm over here to get the news—not anything to eat."

"What kind of news are ye after?" chuckled Nat Jardin.

"I want to know what Oriole is falling into the breathin' holes out there for? And who it was that got her out, and then she chased off the island so fast? I want to know."

"Oh, Mr. Orr! did you see Teddy Ford? Did you see where he went to?"

"I don't know him by name," said the other. "But I seen where that boy run to, if you want to know that."

"Oh, I do!" gasped the girl. "If—if anything has happened to him——"

"And him not half dressed," put in Ma Stafford.

"Does seem as though the lad might not have been just right in his mind," ruminated Jardin, "to have gone off like that."

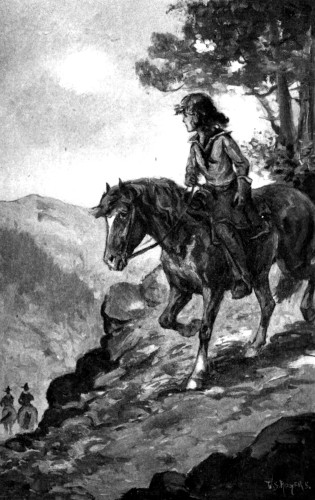

"There warn't nothin' the matter with his legs, if there is with his mind," said Payton Orr. "He run down and across the ice like a scare't rabbit."

"And where 'did he go, Mr. Orr?" begged Oriole.

"He made the Flow station—and he got there all right, too," said Orr. "I watched him close from the lamp gallery. He's some runner, that boy. Who did you say he was?"

"Said his name was Ford," Uncle Nat observed. "Stranger about here. But a real civil-spoken boy."

"And he certainly did snatch Oriole out o' the water. I seen that," said the caller.

"And the twins. He saved the twins, too," said Oriole emphatically, and proceeded to tell the story of the adventure in full.

"He's something of a boy, I do say!" declared Orr. "But what made him run away? 'Fraid to be thanked for what he done?"

Oriole was silent, but Uncle Nat nodded slowly. "I shouldn't wonder," he said composedly enough. "'Fraid to meet Mr. Langdon—and be thanked—like enough."

The old lightkeeper had mixed truth with guile. Ma stared at him, but Oriole was secretly delighted. Payton Orr had one very big fault. He was a dreadful gossip.

"What Payt Orr don't know won't ever hurt him—nor nobody else," said Nat Jardin, when the younger man had gone. "Tell him the particulars of what that boy said to us about Langdon, and the whole world and his wife will know it all. I cal'late a little caution is allowable with Payt."

"Humph! I'm thinkin' you're runnin' pretty close to the wind, 'Thaniel," admonished Ma. "You want to have a care what you're doin' on. Right before Oriole, too."

"I hope Oriole will take after my virtues not after my faults," chuckled Uncle Nat, smiling broadly at the girl he loved so well.

Oriole was getting sleepy and she nodded more than once before supper was over. Ma made her go to bed in her own little room upstairs without helping with the dish wiping.

"If you ain't got your death of cold plungin' into that icy water, it's more by good luck than good management," said the old woman. "You take a hot flat to bed with you, too. If you got sick, Oriole, what would happen to them little twins? I cal'late Mr. Langdon just about depends on you to look after them till that nurse of theirs gets on to her feet again."

"But he didn't expect me to drag them overboard in that sled," said Oriole, in an anxious tone. "I don't know what he will say. And about that Teddy Ford——"

She went off to bed rather stumblingly without finishing her speech. She was very sleepy indeed.

"Funny about that boy," Ma Stafford said to the old lightkeeper when Oriole was gone.

"You're right."

"He does seem to dislike Mr. Langdon, doesn't he? Do you suppose Mr. Langdon is a bad man, 'Thaniel?"

"Ain't none of us perfect," answered Nat Jardin.

"No. I s'pose not. But those Western men—they are pretty tough characters, ain't they?"

"They be in the movies," chuckled the old man. "But I wouldn't worry about Langdon none, if I was you, Ma. He seems a pretty nice feller."

"But he wants to take Oriole along with the twins—you know he does, 'Thaniel. Do you think it's safe? P'r'aps we ought to know more about him first. If Oriole's parents do turn up——"

Uncle Nat made a clucking noise with his tongue and shook his head, intimating that he could not hope much for this wished-for occurrence.

"Well, 'Thaniel, they might. And we are responsible for her. Besides loving her," Ma said earnestly. "We must not let her get into bad hands. Maybe that boy knows more about Harvey Langdon than we do."

"Maybe."

"Then we ought to find out," she said vigorously.

"Sho, Ma!" murmured the old lightkeeper, "you are as hungry for gossip as Payt Orr himself."

Ma sniffed angrily at this, but said no more.

Oriole slept so heavily when she first went to bed that an earthquake might have shaken Harbor Island without awaking her. The exposure to the cold and the heat of the kitchen afterward, together with the hearty supper she ate, served to deaden her senses.

If she dreamed—of the twins or of the strange boy, Teddy Ford, in whom she had become so greatly interested—the dream did not become a nightmare. She slept calmly even when some disturbance rose outside the cottage on the bluff.

Uncle Nat and Ma Stafford heard this noise however; for it came before they had thought of bed. First it was the creaking of sail-blocks and runners on the frozen harbor. Uncle Nat got his coat and hat and went to the door.

"Another o' them pesky iceboats, 'Thaniel?" asked Ma, busily threading a needle under the Argand lamp.

"I cal'late," agreed the lightkeeper, as he opened and shut the door quickly, himself on the outside.

He saw the falling sail of the ice-craft down in the cove. One of the men tumbled off and started across the ice and up the path.

"Sho!" muttered Nat Jardin, "it's Mr. Langdon, and he's some disturbed, now, ain't he?"

The burly ranchman seized upon Nat Jardin the moment he reached his side, crying in a muffled voice:

"My babies? What's happened to them, Mr. Jardin? Are they——"

"No, they ain't," said the lightkeeper coolly. "You can slat your sails and lash the tiller. Ain't a thing to worry about."

"Thank God!" ejaculated Harvey Langdon. "And Oriole?"

"Right as can be. Don't fret yourself."

"They told me that all the children had been in the water."

"And they didn't tell you no lie—for once," said the old man, leading the ranchman toward the cottage door. "But Ma's fixed them all up and they are abed."

"Oriole! She got them out of the water, did she?" said Langdon. "She is a wonder, that girl."

"Well, I cal'late she helped save the twins," said Nat Jardin, loyally. "Yes, Oriole is some girl."

"I can never repay her. But, Nat Jardin, I want to do much for that girl."

"Way it looks," muttered the lightkeeper, "somebody ought to do a lot for her. I don't cal'late her mother or father will ever show up this side of the River Jordan, Mr. Langdon."

"I am afraid you are right," admitted the ranchman. "I have been trying to find out about them on my own account, and it seems there is nothing to discover. The Helvetia sank, I am afraid, with all that were left aboard her."

"Sho!" muttered Nat Jardin, "I begun to believe that long ago."

"I must take the children back to the port at once," said Mr. Langdon, when he welcomed Ma Stafford. "They have no dry clothes here and I can take care of them better at the hotel. Besides, I shall not feel secure until the doctor has seen them. And Oriole——?"

"Now," said Ma, with conviction, "you wouldn't disturb the girl out of her first sleep. Just you send word to Becky Joy. Oriole can get back all right to-morrow. The twins is dif'rent. Though for my part I wouldn't risk them, nor myself, on one o' them iceboats."

"I have sailed those sort of things before," Mr. Langdon said carelessly. "You don't think the children have taken cold, Mrs. Stafford?"

"Not at all. You take 'em wrapped in blankets I'll give ye, and they will come to no harm—though 'tis a master cold night outside."

Nobody chanced to say anything about Teddy Ford, the boy who had really saved the twins and helped Oriole out of the sea. Langdon was anxious to get back to town. He had great faith in doctors, and he wanted Doctor Simms to look at the twins.

Marian did not even awaken when they lifted her out of Uncle Nat's bed; and as for Myron, he was too brave a boy to fuss. Their father carried them down to the ice without assistance, and Oriole did not even dream that the twins were disturbed. Uncle Nat and Ma Stafford went to bed and all was quiet about the cottage on the bluff when Oriole did awake.

She had no idea what time it was, only that it was pitch dark—or seemed to be—outside. Her first thought was of the twins. But, then, she supposed they were all right downstairs. Then she thought of that strange boy—Teddy Ford. She hoped he was all right over at the Flow station.

But what a strangely acting and talking boy he was! Oriole was worried about what he had said in regard to Mr. Langdon. Not for a moment did she believe that Mr. Langdon was not a good and kind man. Of course, there was some mistake. Yet, how earnest that boy had been when he spoke of the ranchman so bitterly.

"I have just got to know about that," Oriole said decidedly. "And there must be some way of straightening out the trouble. Of course Mr. Langdon will be anxious to do something fine for that boy. And—he's—so—handsome——"

Oriole yawned and snuggled down and would have been off to sleep again in a moment had her sharp ear not heard a noise below. It was outside the house. She sat up in the cold room, shivering. It was a step on the porch.

"Now, who can that be coming to the house this time of night?" Oriole asked herself. She was not at all alarmed. There was nothing or nobody to frighten her on Harbor Island, as she very well knew.

"Maybe Mrs. Orr is sick—or the baby," murmured Oriole, slipping out of bed and beginning to pull on a pair of warm stockings and afterward Ma's slippers that the old woman had given her. "Perhaps Payton Orr has come for Ma."

Oriole was interested in the Orr baby, too. She wanted to know if anything was wrong with the family of the substitute lightkeeper.

She hurried into a petticoat and gown, wrapped a fleecy shawl about her, and hastened downstairs. She had heard the person—whoever it was—enter the kitchen. But there was no sound of voices.

"Why! isn't that funny?" murmured Oriole Putnam, and, creeping down the well-carpeted stairs and tiptoeing across the narrow entry, she peered into the warm but dimly lighted kitchen. There was a certain glow from the stove in which there was banked a good fire; but not even a candle was lit.

She could see the figure at the stove, however, quite plainly. Nor was she uncertain in her recognition of it. There stood Teddy Ford, the strange boy who had saved the twins and her from the bay, just putting on his vest. His garments had all been left by Ma Stafford hanging about the stove, and by this time they must have been completely dry.

"Why, Teddy Ford!" gasped Oriole. "What are you doing now?"

"Oh, gee!" ejaculated the strange boy. "Are you up?"

"Well, I'm down," said Oriole. "And I guess Uncle Nat and Ma haven't heard you——"

"I didn't mean to wake any of you up," said the boy.

"I just happened to wake up. Then I heard you come in. But what do you mean to do? I thought you were at the Flow station?"

"Yes, I went there. And I helped the cook clean up after supper and he gave me a bunk. But I snuck out when the morning watch was called——"

"'Snuck out!'" gasped Oriole. "That—that's worse than saying 'gee'! I do believe."

"Gee! is it?"

"You mustn't say that so much," Oriole cried. "And what are you trying to do? You can't go away from here like that. I won't let you, Teddy Ford."

She closed the door into the entry so that they should not be heard by Uncle Nat in his room, or by Ma Stafford upstairs. Teddy looked at her curiously, and then grinned again.

"Ain't you a bossy girl?" he inquired. "You can't stop me from going."

"I guess I can stop you if I really try," said Oriole. "I'm pretty strong."

The boy laughed. "Pooh!" he said.

Now, under certain circumstances, there is no verbal sound in the language as aggravating as "Pooh!"

"Don't 'Pooh!' me. I am strong. So now!" Oriole cried quite furiously.

"Needn't get so huffed about it," said Teddy Ford, more mildly. "But girls ain't ever as strong as boys. They can't be."

"I—I don't think you're so awfully polite," announced Oriole. "And girls are strong like boys—sometimes. You just try to get me away from this door!" she challenged.

"Say! I don't fight girls. I was brought up better than that, I hope! Now, you let me go."

"But there is no reason why you should go. We mean well by you," said Oriole, using an old-fashioned expression that she had learned of late. "I am sure Uncle Nat and Ma——"

"Oh, say! I know you folks are all right. But that Harvey Langdon——"

"When Mr. Langdon hears what you did for the twins, he will do anything for you," she emphatically declared.

"That's all you know about it," said Teddy Ford sullenly.

"I guess I know as much about Mr. Langdon as you do!" cried Oriole, with considerable heat.

"I don't believe you do. You know only one side of him—the good side."

"Well!" she challenged, "do you know any more? You say you only know his bad side. Though it doesn't seem to me that the twins' papa can have much of a bad side."

"Gee!"

"I wish you'd stop using that word," complained Oriole again. "And I am sure if you would let him, Mr. Langdon would—would——"

"Gee! Send me to jail, maybe," and this time the boy smiled ruefully.

"Why, Teddy Ford! what have you ever done?" demanded Oriole.

"There you go!" exclaimed the boy. "You're just as quick to believe me in the wrong as the next one," and he started for the door.

But Oriole placed herself before him. She was both earnest and sympathetic. When she seized him by the wrinkled lapels of his jacket, he could not very well throw her off.

"Tell me! Please!" she begged. "Tell me all about it, Teddy Ford. Maybe we can help you. And I am sure Mr. Langdon must feel kindly toward you after what you have done for Myron and Marian."

"You ain't got no call to bother about me," said Teddy Ford rather sheepishly and backing away from the pressure of Oriole's hands on his chest. "I won't ever see you folks again."

"Oh, Teddy Ford! don't say that," murmured Oriole, almost weeping.

"Gee! it wouldn't bother you, would it?"

"Of course it would. We're your friends," declared the girl. "Uncle Nat admires you—and so does Ma Stafford. And when Mr. Langdon hears about Myron and Marian and what you did for them——"

"Oh, stop it!" exclaimed the boy. "You don't know Harvey Langdon."

"I do so too!" cried Oriole indignantly.

"How long have you known him?"

"Why—why, ever since he came East. You know he came to find his children. And now, when their nurse is well again, he is going to take them back to Montana."

"Huh! I know all about that. We didn't hear nothing else but those lost kids out on the ranch all last summer."

"Teddy Ford, did you come from away out there?"

"Yes. I came on with a carload of cattle. Several carloads. Export steers. And I'd have gone across to England with them, only they wouldn't take me on the cattle boat. Said I was too young."

"What a traveler you are," sighed Oriole. "So am I. I came from South America—from Brazil."

"That so? Well, I reckon you ain't been up against it like me," said the boy ruefully.

"I don't know about that," observed Oriole. "I have been wrecked twice." She said it with a little pride in her voice. "I don't know what you can call hard luck if that isn't."

"I say!" he said earnestly, "that sounds as though you had been through something. But I ain't afraid of being wrecked, or anything like that. When folks say you are a thief——"

"Oh, Teddy Ford!" gasped Oriole.

"Yes. I thought you'd change your tune when you heard they called me a thief," muttered the boy.

"Why, Teddy!" murmured the girl, tears in her eyes now, "I guess I ought to know what that means. Folks said I was a thief, too!"

"Gee! They never?" cried the boy. "Not a nice little thing like you?"

His face turned very red again and his eyes sparkled. Oriole thought that when he was indignant he was even better looking than before.

"Yes, they did. They said I stole that casket from Mrs. Joy. But she hid it herself when she was asleep."

"Look here!" demanded Ted. "Who said you did it? I bet I know! That Harvey Langdon."

"Oh, he never! He never, neither!" gasped the emphatic Oriole.

"Well, it would be just like him," grumbled Teddy.

"Teddy Ford! I don't believe you know Mr. Langdon at all."

"I ought to. I worked on his ranch. I worked there three months. And he said I stole the family silver—a whole chest full of it. Why! I couldn't have lifted it," choked the boy. "He is an awful mean man."

"How terrible! I am sure there must be some mistake," murmured Oriole.

"You bet there was a mistake," growled the boy again. "I never stole that plate. I told 'em so. But because I was seen around the ranch house when there was nobody else supposed to be there, Harvey Langdon hopped on me and said I knew all about it."

"And you didn't know a thing?" asked Oriole.

"No, I didn't. But I don't expect anybody to believe me," and the boy hung his head again.

"I do. I believe you," whispered Oriole, coming close to him again and putting her hand upon his sleeve. "Oh, Teddy! there must have been somebody out there on Mr. Langdon's ranch who believed in you."

"If they did they didn't mention it," said Teddy with scorn. "The only fellow out there that didn't think I was a thief was the fellow that stole that silver plate himself. Believe me!"

"Oh, Teddy! I can't imagine Mr. Langdon not being kind," sighed Oriole.

"That so? Well, you haven't much of an imagination then," scoffed the Western boy.

"How did you come to be working for Mr. Langdon?"

"'Cause he wanted hands and would take anybody that came along. I'd been working all through that region. You see, my mother died when I was a kid. Dad was a pocket hunter——"

"What is that?" demanded Oriole. "Why did he hunt pockets? Did—didn't he have any pockets of his own?"

"Gee! ain't you green?" ejaculated the boy. "I mean my father was a prospector. A gold miner."

"Oh! Then you must be very rich. Of course you wouldn't need to steal that silver from Mr. Langdon."

"How do you figure that?" the boy demanded. "Pocket hunters don't often get rich. They are just lone prospectors who wander about the hills trying to find gold. Dad never struck it rich—nor ever will!" declared Teddy Ford, with much emphasis.

"Anyway, he wandered off the last time in search of an old Indian mine somebody told him of, and he never came in again. So I had to leave school in Helena and hustle for myself. I ain't got any folks now at all."

"No more than I have—till my mother and father come back," murmured Oriole. "I understand."

"Well, that's how I wandered out to the Langdon ranges. I got a job around the corrals. He's got a big ranch and is worth oodles of money. He spent a fortune with detectives, so they say, trying to find the twins."

"He loves them dearly," said the girl. "And he loves them so much that no matter what he thinks you have done, if you will let him he will treat you right because you saved the twins from drowning."

"Gee!" scoffed Ted, "you're sure of him, aren't you? Maybe he treats girls different from what he does men. But believe me, he is a hard boss and a hard man.

"I don't want him to give me anything for saving his kids—if I saved them. And he never will give me a fair deal."

"I cannot believe that, Teddy Ford," whispered Oriole, shaking her head. "He is so good to me——"

"I don't care. I'm going back there to the Langdon ranch when I've got me a lot of money, and I'll make him own up that he was wrong. I never stole that silver," declared Teddy stolidly.

"But won't it be a long time, then, before you go back?"

"Huh?"

"You know, you can't make your fortune in a little while."

"Gee! that's so," admitted the boy. "Well, when I am rich——"

"But money won't help you prove your innocence, will it?" asked the girl quite sensibly.

"Money will do 'most anything," said Teddy with cheerful optimism.

"I don't know. There are some things—Anyway," said Oriole briskly, "you can't very well do anything toward proving that you never stole those things when you are away here in the East."

"Huh!"

"I should think you would want to be right there where it happened, and hunt for the real thief. I stayed with Mrs. Joy when they all said I stole her old casket. And finally the truth came out," said Oriole with satisfaction.

"How's the truth coming out about Harvey Langdon's silver?" demanded the boy.

"I—I don't know. But of course everything always does come out all right. Of course it does!"

"Gee! you believe a lot of old-fashioned stuff, don't you?" gruffly commented Teddy Ford.

"Why, Teddy Ford!" gasped Oriole. "I hope you are not a bad boy. Don't you believe in Providence?"

"I guess you are real religious, ain't you?" returned the boy. "I don't know much about it. But I know that a fellow gets a lot of hard knocks when he is alone in the world. My dad was pretty good to me; but he went off and left me all alone. Maybe he just had to. Those old prospectors have just got to keep traveling and looking for 'color,' like they say, until they drop. But it was pretty hard to be left alone."

Teddy kicked the toe of one shoe against the heel of the other and looked down.

"Then that Harvey Langdon treating me so mean——"

"Oh, Teddy!" cried Oriole, softly, "do let me talk to Mr. Langdon. I know he will listen after all you did, saving the twins."

"And just because I did save them," returned the boy, "he wouldn't believe I was innocent of that robbery. He'd just give in 'cause you asked him. No! I came over here to get my clothes and get away so that none of you folks could tell Harvey Langdon where I was."

"But—but, you won't run away!" cried Oriole, her lips quivering.

"Ain't got to run away. Nobody's got any hold on me. I'm just moving on."

"Oh, Teddy Ford!"

"Why, you ain't got any call to take on about it," declared the boy, looking at her wonderingly.

"Of course I have!" cried Oriole, half angrily. "Aren't you my friend? I feel just as bad for you, about that stolen silver, as though it was me that was being accused again."

"Gee!" murmured Teddy Ford.

"And you stop saying that word!" commanded the girl. "I won't have it. And I won't have you keep running away—first from one place and then another."

"G—Well!" murmured the boy.

"They will of course think you stole Mr. Langdon's silver if you hide away like a regular burglar," declared Oriole.

"Who's hid away like a burglar?" repeated Teddy Ford indignantly.

"Aren't you? You left Mr. Langdon's ranch——"

"He bounced me," interrupted Teddy, glumly enough.

"But you didn't have to leave that neighborhood, did you?"

"'Neighborhood'! What do you think? The nearest ranch to Langdon's is forty miles away. And Hempdell, the shipping town, is seventy-five miles. He takes two weeks to herd a shipment of steers to the railroad, or they'll lose so much weight they aren't worth shipping. Gee! there ain't any neighbors."

"Oh, dear me! won't you ever learn to stop saying that word?"

"G—Huh! I forgot," admitted Teddy Ford with real remorse. "You are an awful nice girl—the nicest girl I ever saw. But you can't change me. I'm too tough."

"What nonsense you talk!" ejaculated Oriole in her most grown-up way. "I know you can't be so bad a boy as Shedder Crabbe. And he's changed a lot—since he almost got drowned and I saved him."

"Mebbe I'd better jump into that hole in the ice down there again, and you pull me out," said Teddy, grinning.

"Now, don't try to be funny," Oriole told him seriously. "I want you to give Mr. Langdon a chance to get acquainted with you——"

"Not much! He kicked me off his ranch. That's enough—too much."

"I can't understand it," sighed Oriole. "He is so nice to me and so loving to the twins."

"You ain't ever got him mad," grumbled Teddy. "He's what they call out where I come from a regular rip-snorter when he gets mad."

"Oh, dear!"

"Why, Ching Foo, the ranch cook, told me Harvey Langdon ran one puncher clear off the ranch once—followed him thirty miles. Only the fellow had the best horse, Harvey would have got him."

Fortunately Oriole did not understand all the terms Ted used. But she was troubled. She loved Mr. Langdon, and she liked this very good looking boy from the West. She could not understand the ranchman being harsh without cause; yet she did not believe that Teddy was dishonest.

Indeed, her very shrewd young mind instantly evolved this question: "If Teddy Ford was guilty of stealing silver plate why was he dressed so poorly and why did he want to work on a cattle-boat?" It seemed to Oriole that he would be living on the proceeds of the robbery if he were a thief.

But he seemed so hopeless—so desperate! What could she say to him to make him do what she believed to be the right thing?

On the other hand, how could she influence the ranchman to give the boy a fair and square deal? Convinced as Mr. Langdon must be that Teddy Ford was a thief, Oriole Putnam wondered what she could do or say to change the man's belief.

The girl had lived so long among "grown-ups" that she usually considered matters deserving thought at all with more seriousness than most children. This trouble Teddy Ford was in was no light matter. Nor was Mr. Harvey Langdon's side of the question something that could easily be put aside or ignored.

The boy had been hurt to the quick by the ranchman's angry harshness. The ranchman (as he believed) had very good reason for being harsh with Teddy. There the matter stood. Oriole was very, very uncertain.

"Won't you wait and see Mr. Langdon when he comes for the twins, Teddy?" Oriole finally pleaded. She did not know that the ranchman had already been to the island and had taken Myron and Marian back to Littleport on the iceboat.

"Me see Harvey Langdon?" gasped Ted. "Gee! No!"

"But I know he will do something for you."

"I don't want him to do anything for me," said the boy independently. "Only just one thing. And he won't do that."

"Yes?"

"I want him to say he don't believe I stole that silver," growled Teddy.

"But how can you ever make him see that he—he made a mistake, if you have run away from the ranch country. You don't give Mr. Langdon a chance," said Oriole.

"A chance to chase me off his ranch again?"

"Don't you see, if you remained out there, something might turn up to give you—you a clew. You know what I mean? Of course, somebody stole that chest of silver."

"You bet they did. And got away with it slick, too. Nobody but me and Ching Foo about the ranch house—and I know I didn't see a soul."

"Is—is Mr. Ching Foo a Chinaman?"

"Yes. Cook, I tell you. Oh! he is not to be suspected. Ching Foo has been at the ranch for twenty years—and sent home long ago for his coffin and has it stored away in his bedroom."

"Goodness, Teddy Ford! what are you saying?" cried Oriole.

"That's right," said the boy. "Ching Foo is an old-fashioned Chinaman, and no American-made coffin would do for him. He showed it to me. All lacquer-work and dragons and fancy doo-dads on it. He will be put in that when he dies and be shipped back to Canton to sleep with his fathers. Mr. Langdon has promised him that it shall be done just as he says. Otherwise he would go back to China himself and die there, for he has plenty of money saved up."

"Dear me!" said Oriole in a worried tone, "I think that is too, too dreadful. Are all Chinamen like Mr. Ching Foo?"

"You got me there, Oriole," said the boy. "He's not a half bad old chap. And he said something funny to me when I was coming away from the Langdon Ranch. I ain't forgot it."

"What do you mean—funny?" asked the interested girl.

"Why, it sounded as though he might know—or suspect—more about who was the real thief than he let on. The Chinese are awfully closemouthed. He only said to Harvey Langdon: 'Me no catchee pidgin; him no my pidgin.'"

"Goodness me!" ejaculated Oriole. "I thought you said it was silver that was stolen, not pigeons."

"It was silver plate," chuckled Ted Ford. "But Ching Foo talks what they call pidgin English sometimes. He is a Canton Chinaman, and he can't say business. Pidgin is the nearest he can come to saying business. You see, he meant to tell Langdon it wasn't any of his business, and he shouldn't ask him about the lost silver."

"Oh!"

"It looked to me as though the old man was scared to tell everything he knew. I went after him alone in the kitchen, and asked him if he didn't suspect who stole the plate? He said:

"'Plenty bad mans here. Melican boy get away; mebbe get hurt.' And then he added the thing that afterward set me thinking. It was: 'Three topside bad men—alli same talkee-talkee. Melican boy look out!'"

Oriole still looked at the boy curiously.

"You see," said Teddy, his voice lowered, "afterward I remembered that Ridley, Shaffer and Tom Mudd were always roosting around on the fences when they weren't working, and talking together out of the corners of their mouths. Three tough fellows, they were, and don't you forget it. They had only just come to the ranch and, although they were good punchers, some of the boys said they were bad eggs."

"Why didn't you tell Mr. Langdon about them?"

"You can't talk to Harvey Langdon when he's mad and his mind is made up. And, besides, I never thought much about what Ching Foo said till I was half way across the continent on the cattle train."

"I think that is too bad," said Oriole soberly. "But I wish you would stay and talk with Mr. Langdon, Teddy Ford."

"Not me!" cried the boy emphatically.

"Then I wish you would go back home and see if you can't find those three bad men. It must be that they have made some use of the silver."

"Melted it up. Sell it for silver bullion at one of the mining towns. That would be their game."

"That is terrible! But if you could prove that they did just that?"

"It wouldn't prove they were the robbers," grumbled the boy, shaking his head.

"But it would look so. Mr. Langdon would believe you were innocent, then, I am sure."

"Not much he wouldn't. You have to show Harvey Langdon. You can't tell him. And anyway he would not listen to me."

"But he will listen to me," said Oriole firmly. "And I mean to tell him all about you—what you say and what you did in saving us from the water. You go back to Montana and fight this, Teddy Ford—that's what you do," said the girl earnestly.

"G-g-g—I mean, do you want me to?" he gasped.

"That is the way to do. Stay right there until you have proved your innocence."

"Well, I can work back that way. I know how," said Teddy, doubtfully. "Do you think that is the right thing to do?"

"So I believe," Oriole confidently responded.

"I imagine you know more about what's right than I do," said Teddy Ford soberly. "If you say so——"

"I do say so. And I will tell Mr. Langdon. He will meet you differently out there I am sure. He might just want to give you money here in the East and thank you for saving Marian and helping Myron and me. But if you go right to him at home and tell him you want to clear up that awful mystery I am sure he will think you really are honest."

And in her shrewd mind Oriole meant to talk to Mr. Langdon in such a way that he would be sure to meet Teddy Ford in just this way! The boy was impressed by her words. He nodded his head thoughtfully.

"That sounds right, Oriole. I guess you are giving me the 'real steer,' as the punchers say. I'm going to do it. I got a chance to go on a boat around to Boston, and I must start now. Good-by. You'll hear from me some time—though I ain't much on writing letters."

"Oh, Teddy, be sure to write to me!" Oriole cried, almost in tears as the boy pushed past her to open the door.

"You bet I will. Good-by!"

He turned back and squeezed her hand, blushing furiously as he did so. Then he ran out of the house. Oriole watched from the window but could see nothing of him after he crossed the porch and started down the path to the cove, it was so dark. Then she sighed.

"I do think other people have so very many troubles," she said, and she took this thought back to bed with her.

In the morning she certainly was surprised to learn that the twins as well as Teddy Ford had gone away in the night. Mr. Langdon had been right here at the island without seeing the boy from the West. Oriole was much disappointed.

But she made up her mind, nevertheless, to talk to Mr. Langdon about that lost chest of silver. It was impossible for her to believe that Teddy Ford was in any measure guilty of the robbery.

She hurried home, dragging the sled with her, and arrived at Mrs. Joy's before noon, finding that the widow and Lyddy Ann had been informed of Oriole's safety by Mr. Langdon after his return from the island the night before.

"I do think that bay is no place for you, Oriole," Mrs. Joy said. "It is too dangerous for anybody to risk themselves upon it. Now you must wait for open weather before you go to the island again."

"Tell you what," Lyddy Ann told the girl, "you might's well wait for one of these flying-machines to take you. 'Tis safer, I do allow. That Anson Cope ought to be lashed to the mast for ever running you down that way with his iceboat. You wait till I give him a piece of my mind!"

As Lyddy Ann was forever threatening to give people "a piece of her mind," Oriole wondered that she had any mind left at all. But of course she did not say just that.

Her own mind, in fact, was quite occupied with the trouble of Teddy Ford and how she should broach the subject to Mr. Langdon. She had told Uncle Nat all about her interview with the youth and what he had said and what she had advised him to do.

"You got the right idea, Oriole," the old lightkeeper declared. "Let the boy go back there to that ranch and prove his innocence. He can do it if he goes about it right. And I believe Mr. Harvey Langdon is a kind man at heart. You put a flea in his ear."

So Oriole started over to the hotel after the noon dinner to do just this. She knew the twins were all right, for Mr. Langdon had sent her word. Neither Myron nor Marian seemed a whit the worse for the plunge into the icy harbor.

"You are a mighty brave girl, my dear," said Harvey Langdon, warmly. "I know that few girls of your age could have kept their heads and saved the children."

"Oh, Mr. Langdon! I didn't save Myron and Marian. At least, little Marian would have been drowned had it not been for somebody else."

"I did hear from Anson Cope that somebody aided you."

"Why! he saved us. That's what Teddy Ford did. He jumped right in——"

"Who did you say?" broke in Harvey Langdon, with a queer look on his bronzed face. "What is his name?"

"Ted—Teddy Ford," stammered Oriole.

"Indeed! A boy?"

"Yes, sir. He is a boy. And he jumped right into the water and brought poor little Marian up from under the loose ice. Then he helped me with Myron, and finally he got me out and the sled too. Oh, he is a wonderful boy, Mr. Langdon!"

"He is, is he? And his name is Ford?"

"Yes, sir," hesitated Oriole. "You owe the twins' lives to him, and that's a fact."

"I do, do I?"

The ranchman continued to look so "funny," as Oriole expressed it in her thoughts, that she could scarcely tell the details of the rescue as she had intended to. But she managed to make a considerable impression on the man's mind—and, she hoped, in Teddy's favor.

"So that's how it was, eh?" commented Langdon. "And you think that this boy is more to be commended than you are?"

"Oh, yes, sir! For he really saved us."

"Where is he now?"

"He's—he's run away."

"You don't mean it?"

"Yes, Mr. Langdon," said Oriole sorrowfully. "He is afraid of you."