Title: Yorkshire

Author: Gordon Home

Release date: August 13, 2004 [eBook #9973]

Most recently updated: December 27, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Ted Garvin, Michael Lockey and PG Distributed

Proofreaders. Illustrated HTML file produced by David Widger

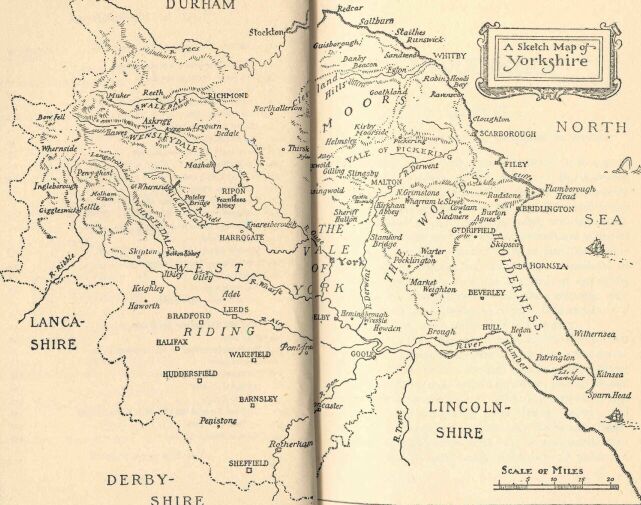

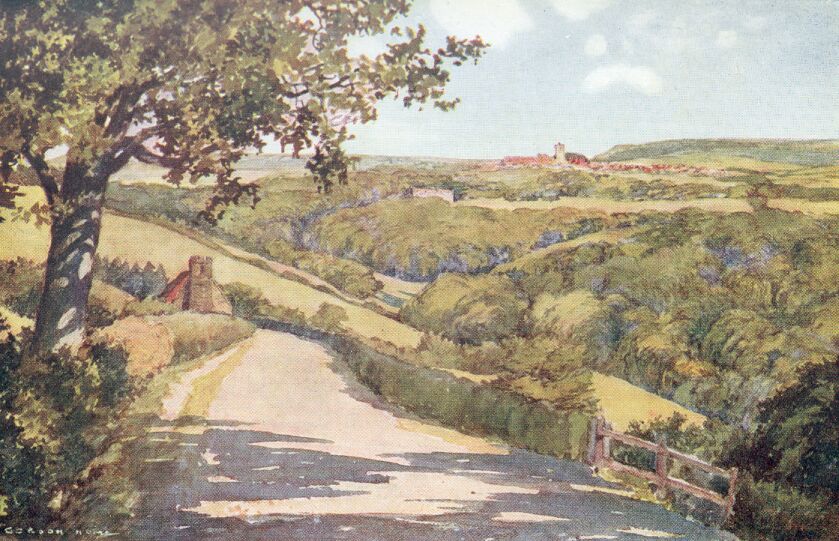

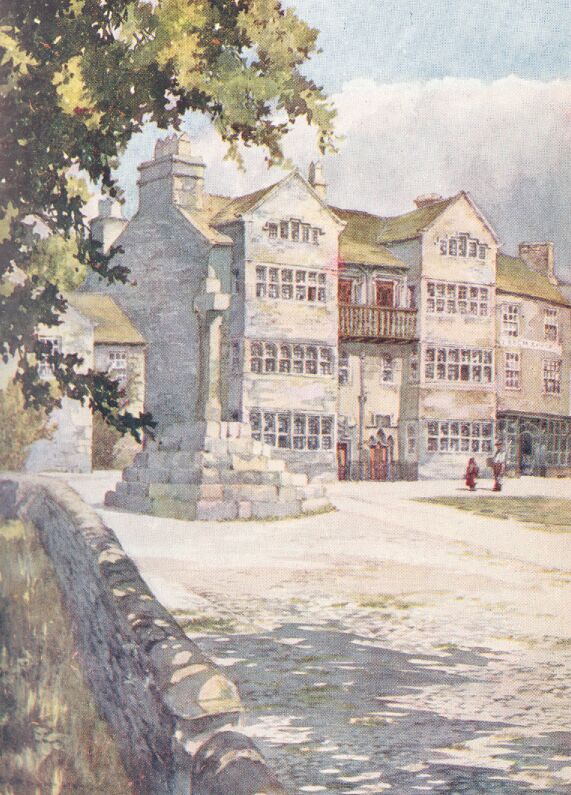

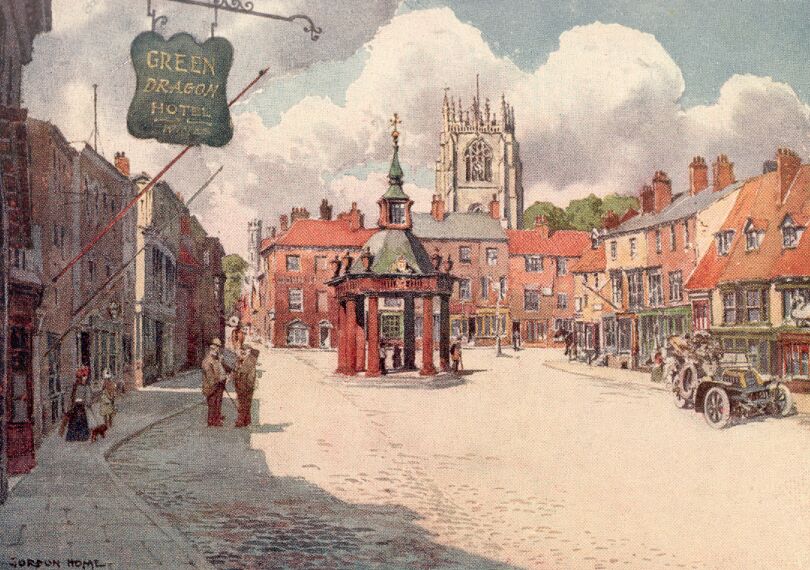

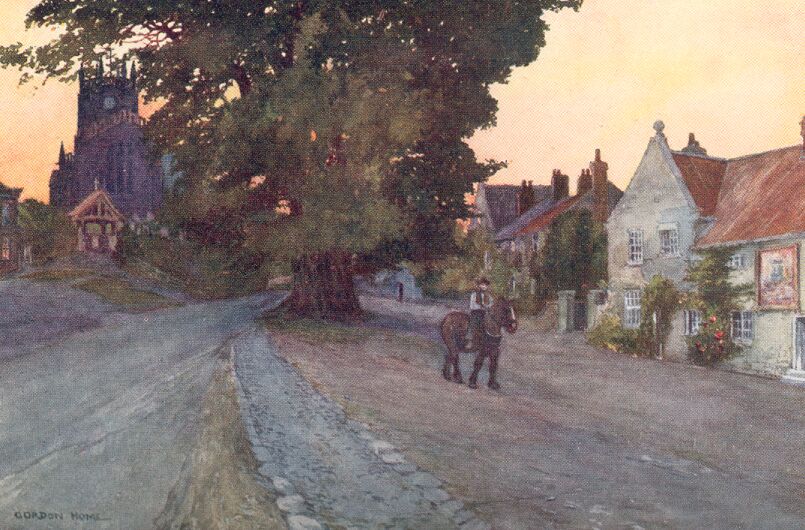

ACROSS THE MOORS FROM PICKERING TO WHITBY

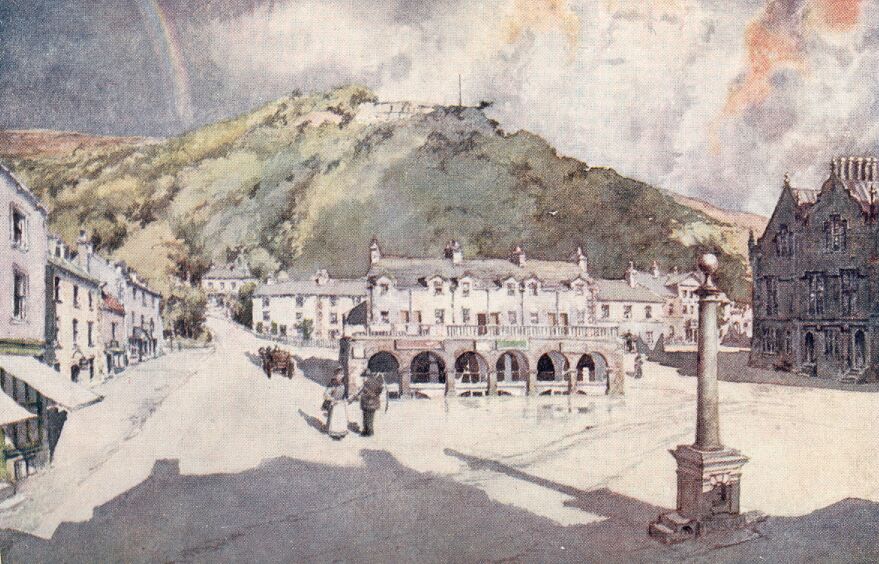

The ancient stone-built town of Pickering is to a great extent the gateway to the moors of North-eastern Yorkshire, for it stands at the foot of that formerly inaccessible gorge known as Newton Dale, and is the meeting-place of the four great roads running north, south, east, and west, as well as of railways going in the same directions. And this view of the little town is by no means original, for the strategic importance of the position was recognised at least as long ago as the days of the early Edwards, when the castle was built to command the approach to Newton Dale and to be a menace to the whole of the Vale of Pickering.

The old-time traveller from York to Whitby saw practically nothing of Newton Dale, for the great coach-road bore him towards the east, and then, on climbing the steep hill up to Lockton Low Moor, he went almost due north as far as Sleights. But to-day everyone passes right through the gloomy cañon, for the railway now follows the windings of Pickering Beck, and nursemaids and children on their way to the seaside may gaze at the frowning cliffs which seventy years ago were only known to travellers and a few shepherds. But although this great change has been brought about by railway enterprise, the gorge is still uninhabited, and has lost little of its grandeur; for when the puny train, with its accompanying white cloud, has disappeared round one of the great bluffs, there is nothing left but the two pairs of shining rails, laid for long distances almost on the floor of the ravine. But though there are steep gradients to be climbed, and the engine labours heavily, there is scarcely sufficient time to get any idea of the astonishing scenery from the windows of the train, and you can see nothing of the huge expanses of moorland stretching away from the precipices on either side. So that we, who would learn something of this region, must make the journey on foot; for a bicycle would be an encumbrance when crossing the heather, and there are many places where a horse would be a source of danger. The sides of the valley are closely wooded for the first seven or eight miles north of Pickering, but the surrounding country gradually loses its cultivation, at first gorse and bracken, and then heather, taking the place of the green pastures.

At the village of Newton, perched on high ground far above the dale, we come to the limit of civilization. The sun is nearly setting. The cottages are scattered along the wide roadway and the strip of grass, broken by two large ponds, which just now reflect the pale evening sky. Straight in front, across the green, some ancient barns are thrown up against the golden sunset, and the long perspective of white road, the geese, and some whitewashed gables, stand out from the deepening tones of the grass and trees. A footpath by the inn leads through some dewy meadows to the woods, above Levisham Station in the valley below. At first there are glimpses of the lofty moors on the opposite side of the dale where the sides of the bluffs are still glowing in the sunset light; but soon the pathway plunges steeply into a close wood, where the foxes are barking, and where the intense darkness is only emphasized by the momentary illumination given by lightning, which now and then flickers in the direction of Lockton Moor. At last the friendly little oil-lamps on the platform at Levisham Station appear just below, and soon the railway is crossed and we are mounting the steep road on the opposite side of the valley. What is left of the waning light shows the rough track over the heather to High Horcum. The huge shoulders of the moors are now majestically indistinct, and towards the west the browns, purples, and greens are all merged in one unfathomable blackness. The tremendous silence and the desolation become almost oppressive, but overhead the familiar arrangement of the constellations gives a sense of companionship not to be slighted. In something less than an hour a light glows in the distance, and, although the darkness is now complete, there is no further need to trouble ourselves with the thought of spending the night on the heather. The point of light develops into a lighted window, and we are soon stamping our feet on the hard, smooth road in front of the Saltersgate Inn. The door opens straight into a large stone-flagged room. Everything is redolent of coaching days, for the cheery glow of the fire shows a spotlessly clean floor, old high-backed settles, a gun hooked to one of the beams overhead, quaint chairs, and oak stools, and a fox's mask and brush. A gamekeeper is warming himself at the fire, for the evening is chilly, and the firelight falls on his box-cloth gaiters and heavy boots as we begin to talk of the loneliness and the dangers of the moors, and of the snow-storms in winter, that almost bury the low cottages and blot out all but the boldest landmarks. Soon we are discussing the superstitions which still survive among the simple country-folk, and the dark and lonely wilds we have just left make this a subject of great fascination.

Although we have heard it before, we hear over again with intense interest the story of the witch who brought constant ill-luck to a family in these parts. Their pigs were never free from some form of illness, their cows died, their horses lamed themselves, and even the milk was so far under the spell that on churning-days the butter refused to come unless helped by a crooked sixpence. One day, when as usual they had been churning in vain, instead of resorting to the sixpence, the farmer secreted himself in an outbuilding, and, gun in hand, watched the garden from a small opening. As it was growing dusk he saw a hare coming cautiously through the hedge. He fired instantly, the hare rolled over, dead, and almost as quickly the butter came. That same night they heard that the old woman, whom they had long suspected of bewitching them, had suddenly died at the same time as the hare, and henceforward the farmer and his family prospered.

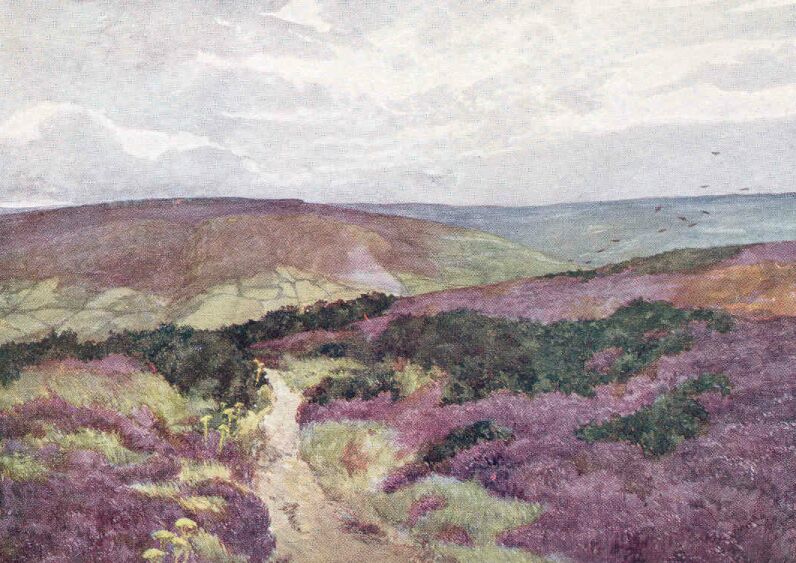

In the light of morning the isolation of the inn is more apparent than at night. A compact group of stable buildings and barns stands on the opposite side of the road, and there are two or three lonely-looking cottages, but everywhere else the world is purple and brown with ling and heather. The morning sun has just climbed high enough to send a flood of light down the steep hill at the back of the barns, and we can hear the hum of the bees in the heather. In the direction of Levisham is Gallows Dyke, the great purple bluff we passed in the darkness, and a few yards off the road makes a sharp double bend to get up Saltersgate Brow, the hill that overlooks the enormous circular bowl of Horcum Hole, where Levisham Beck rises. The farmer whose buildings can be seen down below contrives to paint the bottom of the bowl a bright green, but the ling comes hungrily down on all sides, with evident longings to absorb the scanty cultivation. The Dwarf Cornel a little mountain-plant which flowers in July, is found in this 'hole.' A few patches have been discovered in the locality, but elsewhere it is not known south of the Cheviots.

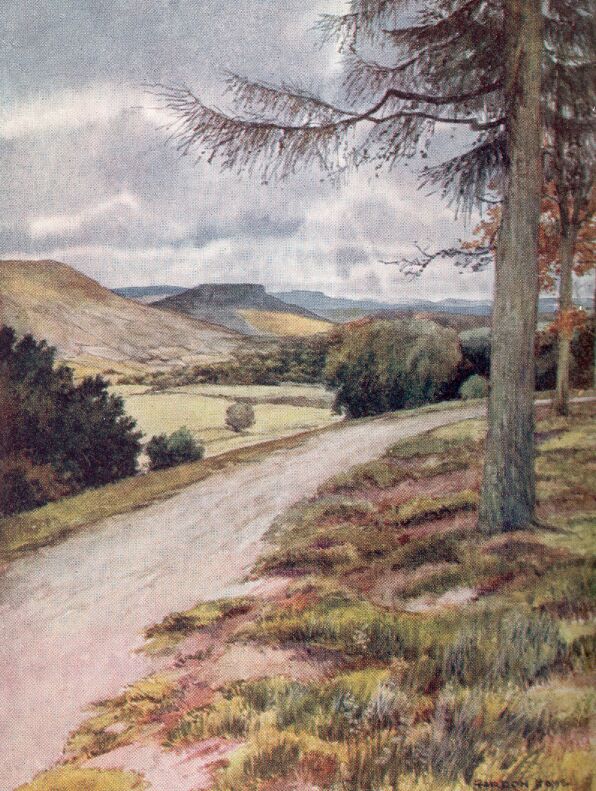

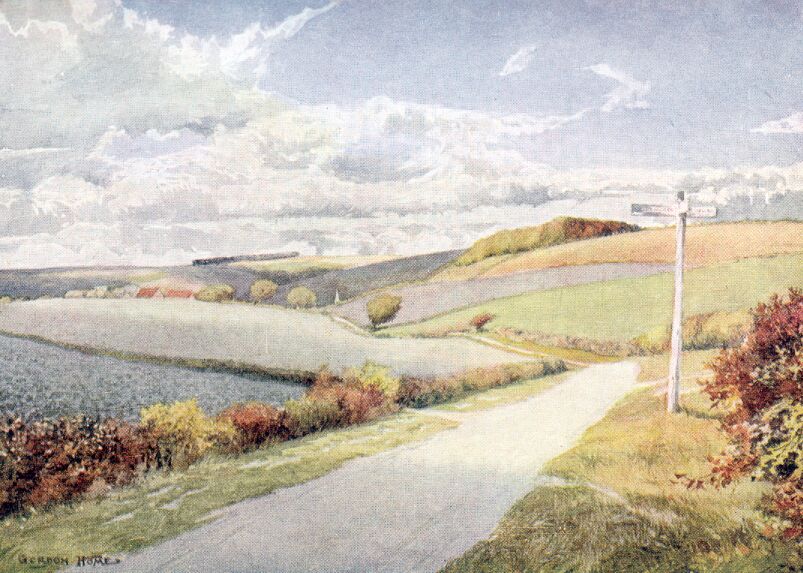

Away to the north the road crosses the desolate country like a pale-green ribbon. It passes over Lockton High Moor, climbs to 700 feet at Tom Cross Rigg and then disappears into the valley of Eller Beck, on Goathland Moor, coming into view again as it climbs steadily up to Sleights Moor, nearly 1,000 feet above the sea. An enormous stretch of moorland spreads itself out towards the west. Near at hand is the precipitous gorge of Upper Newton Dale, backed by Pickering Moor, and beyond are the heights of Northdale Rigg and Rosedale Common, with the blue outlines of Ralph Cross and Danby Head right on the horizon.

The smooth, well-built road, with short grass filling the crevices between the stones, urges us to follow its straight course northwards; but the sternest and most remarkable portion of Upper Newton Dale lies to the left, across the deep heather, and we are tempted aside to reach the lip of the sinuous gorge nearly a mile away to the west, where the railway runs along the marshy and boulder-strewn bottom of a natural cutting 500 feet deep. The cliffs drop down quite perpendicularly for 200 feet, and the remaining distance to the bed of the stream is a rough slope, quite bare in places, and in others densely grown over with trees; but on every side the fortress-like scarps are as stern and bare as any that face the ocean. Looking north or south the gorge seems completely shut in. There is much the same effect when steaming through the Kyles of Bute, for there the ship seems to be going full speed for the shore of an entirely enclosed sea, and here, saving for the tell-tale railway, there seems no way out of the abyss without scaling the perpendicular walls. The rocks are at their finest at Killingnoble Scar, where they take the form of a semicircle on the west side of the railway. The scar was for a very long period famous for the breed of hawks, which were specially watched by the Goathland men for the use of James I., and the hawks were not displaced from their eyrie even by the incursion of the railway into the glen, and only recently became extinct.

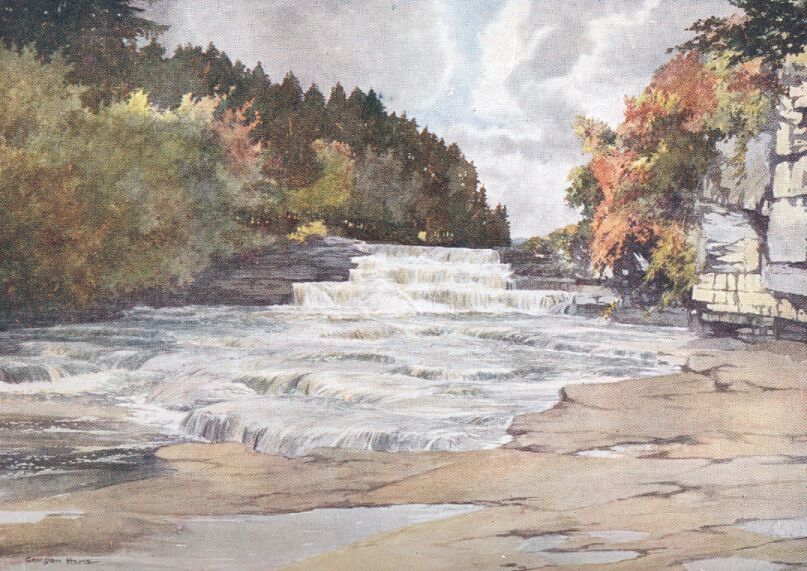

We can cross the line near Eller Beck, and, going over Goathland Moor, explore the wooded sides of Wheeldale Beck and its water-falls. Mallyan's Spout is the most imposing, having a drop of about 76 feet. The village of Goathland has thrown out skirmishers towards the heather in the form of an ancient-looking but quite modern church, with a low central tower, and a little hotel, stone-built and fitting well into its surroundings. The rest of the village is scattered round a large triangular green, and extends down to the railway, where there is a station named after the village.

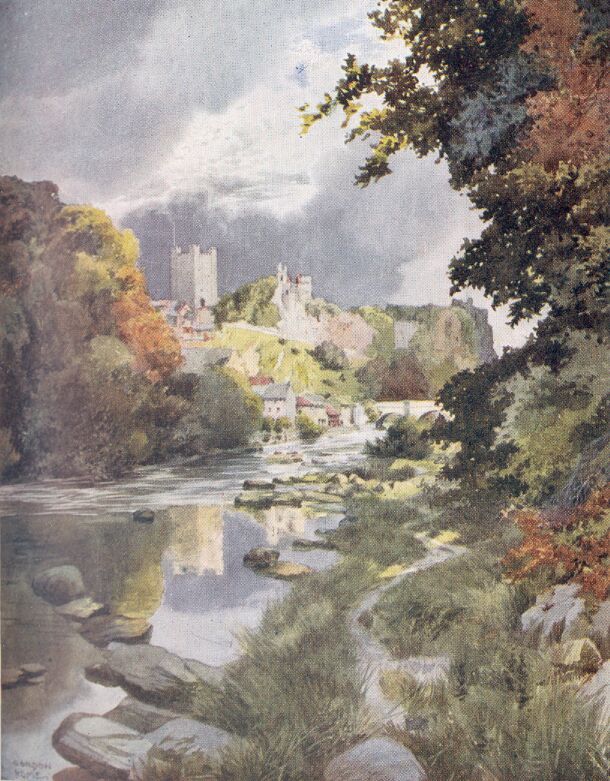

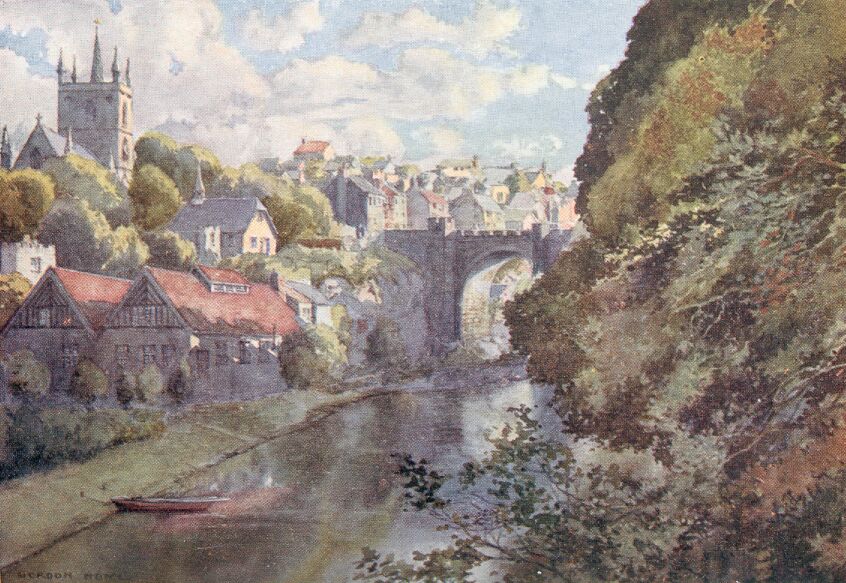

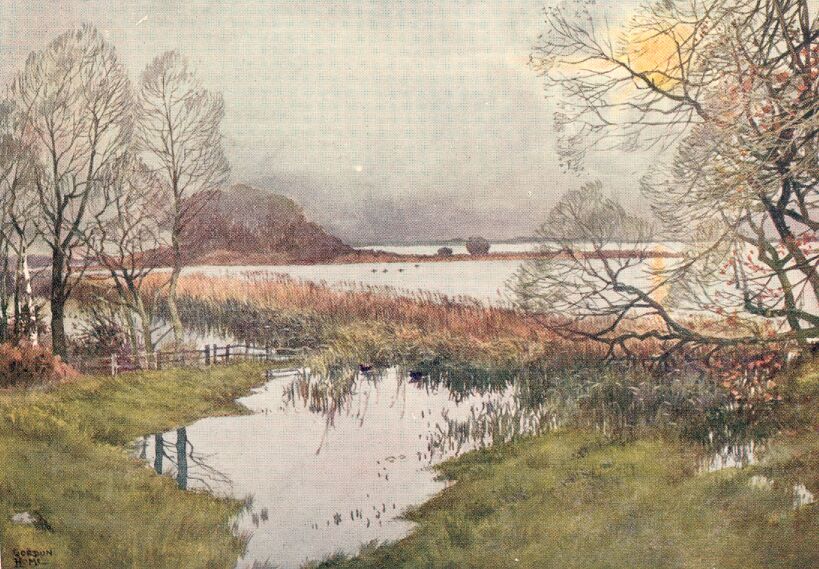

ALONG THE ESK VALLEY

To see the valley of the Esk in its richest garb, one must wait for a spell of fine autumn weather, when a prolonged ramble can be made along the riverside and up on the moorland heights above. For the dense woodlands, which are often merely pretty in midsummer, become astonishingly lovely as the foliage draping the steep hill-sides takes on its gorgeous colours, and the gills and becks on the moors send down a plentiful supply of water to fill the dales with the music of rushing streams.

Climbing up the road towards Larpool, we take a last look at quaint old Whitby, spread out before us almost like those wonderful old prints of English towns they loved to publish in the eighteenth century. But although every feature is plainly visible—the church, the abbey, the two piers, the harbour, the old town and the new—the detail is all lost in that soft mellowness of a sunny autumn day. We find an enthusiastic photographer expending plates on this familiar view, which is sold all over the town; but we do not dare to suggest that the prints, however successful, will be painfully hackneyed, and we go on rejoicing that the questions of stops and exposures need not trouble us, for the world is ablaze with colour.

Beyond the great red viaduct, whose central piers are washed by the river far below, the road plunges into the golden shade of the woods near Cock Mill, and then comes out by the river's bank down below, with the little village of Ruswarp on the opposite shore. The railway goes over the Esk just below the dam, and does is very best to spoil every view of the great mill built in 1752 by Mr. Nathaniel Cholmley.

The road follows close beside the winding river and all the way to Sleights there are lovely glimpses of the shimmering waters, reflecting the overhanging masses of foliage. The golden yellow of a bush growing at the water's edge will be backed by masses of brown woods that here and there have retained suggestions of green, contrasted with the deep purple tones of their shadowy recesses. These lovely phases of Eskdale scenery are denied to the summer visitor, but there are few who would wish to have the riverside solitudes rudely broken into by the passing of boatloads of holiday-makers. Just before reaching Sleights Bridge we leave the tree-embowered road, and, going through a gate, find a stone-flagged pathway that climbs up the side of the valley with great deliberation, so that we are soon at a great height, with a magnificent sweep of landscape towards the south-west, and the keen air blowing freshly from the great table-land of Egton High Moor.

A little higher, and we are on the road in Aislaby village. The steep climb from the river and railway has kept off those modern influences which have made Sleights and Grosmont architecturally depressing, and thus we find a simple village on the edge of the heather, with picturesque stone cottages and pretty gardens, free from companionship with the painfully ugly modern stone house, with its thin slate roof. The big house of the village stands on the very edge of the descent, surrounded by high trees now swept bare of leaves.

The first time I visited Aislaby I reached the little hamlet when it was nearly dark. Sufficient light, however, remained in the west to show up the large house standing in the midst of the swaying branches. One dim light appeared in the blue-grey mass, and the dead leaves were blown fiercely by the strong gusts of wind. On the other side of the road stood an old grey house, whose appearance that gloomy evening well supported the statement that it was haunted.

I left the village in the gathering gloom and was soon out on the heather. Away on the left, but scarcely discernible, was Swart Houe Cross, on Egton Low Moor, and straight in front lay the Skelder Inn. A light gleamed from one of the lower windows, and by it I guided my steps, being determined to partake of tea before turning my steps homeward. I stepped into the little parlour, with its sanded floor, and demanded 'fat rascals' and tea. The girl was not surprised at my request, for the hot turf cakes supplied at the inn are known to all the neighbourhood by this unusual name.

The course of the river itself is hidden by the shoulders of Egton Low Moor beneath us, but faint sounds of the shunting of trucks are carried up to the heights. Even when the deep valleys are warmest, and when their atmosphere is most suggestive of a hot-house, these moorland heights rejoice in a keen, dry air, which seems to drive away the slightest sense of fatigue, so easily felt on the lower levels, and to give in its place a vigour that laughs at distance. Up here, too, the whole world seems left to Nature, the levels of cultivation being almost out of sight, and anything under 800 feet seems low. Towards the end of August the heights are capped with purple, although the distant moors, however brilliant they may appear when close at hand, generally assume more delicate shades, fading into greys and blues on the horizon.

Grosmont was the birthplace of the Cleveland Ironworks, and was at one time more famous than Middlesbrough. The first cargo of ironstone was sent from here in 1836, when the Pickering and Whitby Railway was opened.

We will go up the steep road to the top of Sleights Moor. It is a long stiff climb of nearly 900 feet, but the view is one of the very finest in this country, where wide expanses soon become commonplace. We are sufficiently high to look right across Fylingdales Moor to the sea beyond, a soft haze of pearly blue over the hard, rugged outline of the ling. Away towards the north, too, the landscape for many miles is limited only by the same horizon of sea, so that we seem to be looking at a section of a very large-scale contour map of England. Below us on the western side runs the Mirk Esk, draining the heights upon which we stand as well as Egton High Moor and Wheeldale Moor. The confluence with the Esk at Grosmont is lost in a haze of smoke and a confusion of roofs and railway lines; and the course of the larger river in the direction of Glaisdale is also hidden behind the steep slopes of Egton High Moor. Towards the south we gaze over a vast desolation, crossed by the coach-road to York as it rises and falls over the swells of the heather. The queer isolated cone of Blakey Topping and the summit of Gallows Dyke, close to Saltersgate, appear above the distant ridges.

The route of the great Roman road from the south to Whitby can also be seen from these heights. It passes straight through Cawthorn Camp, on the ridge to the west of the village of Newton, and then runs along within a few yards of the by-road from Pickering to Egton. It crosses Wheeldale Beck, and skirts the ancient dyke round July or Julian Park, at one time a hunting-seat of the great De Mauley family. The road is about 12 feet wide, and is now deep in heather; but it is slightly raised above the general level of the ground, and can therefore be followed fairly easily where it has not been taken up to build walls for enclosures.

If we go down into the valley beneath us by a road bearing south-west, we shall find ourselves at Beck Hole, where there is a pretty group of stone cottages, backed by some tall firs. The Eller Beck is crossed by a stone bridge close to its confluence with the Mirk Esk. Above the bridge, a footpath among the huge boulders winds its way by the side of the rushing beck to Thomasin Foss, where the little river falls in two or three broad silver bands into a considerable pool. Great masses of overhanging rock, shaded by a leafy roof, shut in the brimming waters.

It is not difficult to find the way from Beck Hole to the Roman camp on the hill-side towards Egton Bridge. The Roman road from Cawthorn goes right through it, but beyond this it is not easy to trace, although fragments have been discovered as far as Aislaby, all pointing to Whitby or Sandsend Bay. Round the shoulder of the hill we come down again to the deeply-wooded valley of the Esk. And in time we reach Glaisdale End, where a graceful stone bridge of a single arch stands over the rushing stream. The initials of the builder and the date appear on the eastern side of what is now known as the Beggar's Bridge. It was formerly called Firris Bridge, after the builder, but the popular interest in the story of its origin seems to have killed the old name. If you ask anyone in Whitby to mention some of the sights of the neighbourhood, he will probably head his list with the Beggar's Bridge, but why this is so I cannot imagine. The woods are very beautiful, but this is a country full of the loveliest dales, and the presence of this single-arched bridge does not seem sufficient to have attracted so much popularity. I can only attribute it to the love interest associated with the beggar. He was, we may imagine, the Alderman Thomas Firris who, as a penniless youth, came to bid farewell to his betrothed, who lived somewhere on the opposite side of the river. Finding the stream impassable, he is said to have determined that if he came back from his travels as a rich man he would put up a bridge on the spot he had been prevented from crossing.

THE COAST FROM WHITBY TO REDCAR

Along the three miles of sand running northwards from Whitby at the foot of low alluvial cliffs, I have seen some of the finest sea-pictures on this part of the coast. But although I have seen beautiful effects at all times of the day, those that I remember more than any others are the early mornings, when the sun was still low in the heavens, when, standing on that fine stretch of yellow sand, one seemed to breathe an atmosphere so pure, and to gaze at a sky so transparent, that some of those undefined longings for surroundings that have never been realized were instinctively uppermost in the mind. It is, I imagine, that vague recognition of perfection which has its effect on even superficial minds when impressed with beautiful scenery, for to what other cause can be attributed the remark one hears, that such scenes 'make one feel good'?

Heavy waves, overlapping one another in their fruitless bombardment of the smooth shelving sand, are filling the air with a ceaseless thunder. The sun, shining from a sky of burnished gold, throws into silhouette the twin lighthouses at the entrance to Whitby Harbour, and turns the foaming wave-tops into a dazzling white, accentuated by the long shadows of early day. Away to the north-west is Sandsend Ness, a bold headland full of purple and blue shadows, and straight out to sea, across the white-capped waves, are two tramp steamers, making, no doubt, for South Shields or some port where a cargo of coal can be picked up. They are plunging heavily, and every moment their bows seem to go down too far to recover.

The two little becks finding their outlet at East Row and Sandsend are lovely to-day; but their beauty must have been much more apparent before the North-Eastern Railway put their black lattice girder bridges across the mouth of each valley. But now that familiarity with these bridges, which are of the same pattern across every wooded ravine up the coast-line to Redcar, has blunted my impressions, I can think of the picturesqueness of East Row without remembering the railway. It was in this glen, where Lord Normanby's lovely woods make a background for the pretty tiled cottages, the mill, and the old stone bridge, which make up East Row,1 that the Saxons chose a home for their god Thor. Here they built some rude form of temple, afterwards, it seems, converted into a hermitage. This was how the spot obtained the name Thordisa, a name it retained down to 1620, when the requirements of workmen from the newly-started alum-works at Sandsend led to building operations by the side of the stream. The cottages which arose became known afterwards as East Row.

1 [ Since this was written one or two new houses have been allowed to mar the simplicity of the valley.—G.H.]

Go where you will in Yorkshire, you will find no more fascinating woodland scenery than that of the gorges of Mulgrave. From the broken walls and towers of the old Norman castle the views over the ravines on either hand—for the castle stands on a lofty promontory in a sea of foliage—are entrancing; and after seeing the astoundingly brilliant colours with which autumn paints these trees, there is a tendency to find the ordinary woodland commonplace. The narrowest and deepest gorge is hundreds of feet deep in the shale. East Row Beck drops into this canon in the form of a water-fall at the upper end, and then almost disappears among the enormous rocks strewn along its circumscribed course. The humid, hot-house atmosphere down here encourages the growth of many of the rarer mosses, which entirely cover all but the newly-fallen rocks.

We can leave the woods by a path leading near Lord Normanby's modern castle, and come out on to the road close to Lythe Church, where a great view of sea and land is spread out towards the south. The long curving line of white marks the limits of the tide as far as the entrance to Whitby Harbour. The abbey stands out in its loneliness as of yore, and beyond it are the black-looking, precipitous cliffs ending at Saltwick Nab. Lythe Church, standing in its wind-swept graveyard full of blackened tombstones, need not keep us, for, although its much-modernized exterior is simple and ancient-looking, the interior is devoid of any interest.

The walk along the rocky shore to Kettleness is dangerous unless the tide is carefully watched, and the road inland through Lythe village is not particularly interesting, so that one is tempted to use the railway, which cuts right through the intervening high ground by means of two tunnels. The first one is a mile long, and somewhere near the centre has a passage out to the cliffs, so that even if both ends of the tunnel collapsed there would be a way of escape. But this is small comfort when travelling from Kettleness, for the down gradient towards Sandsend is very steep, and in the darkness of the tunnel the train gets up a tremendous speed, bursting into the open just where a precipitous drop into the sea could be most easily accomplished.

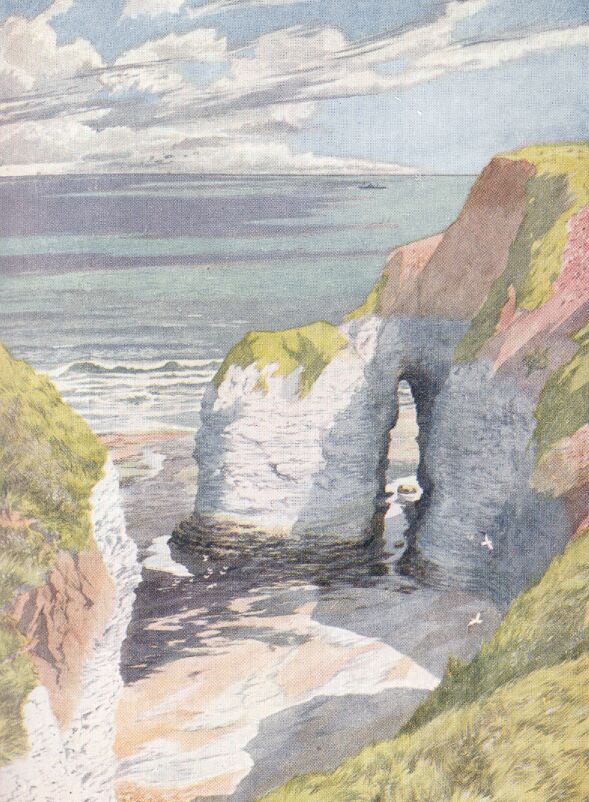

The station at Kettleness is on the top of the huge cliffs, and to reach the shore one must climb down a zigzag path. It is a broad and solid pathway until half-way down, where it assumes the character of a goat-track, being a mere treading down of the loose shale of which the enormous cliff is formed. The sliding down of the crumbling rock constantly carries away the path, but a little spade-work soon makes the track firm again. This portion of the cliff has something of a history, for one night in 1829 the inhabitants of many of the cottages originally forming the village of Kettleness were warned of impending danger by subterranean noises. Fearing a subsidence of the cliff, they betook themselves to a small schooner lying in the bay. This wise move had not long been accomplished, when a huge section of the ground occupied by the cottages slid down the great cliff and the next morning there was little to be seen but a sloping mound of lias shale at the foot of the precipice. The villagers recovered some of their property by digging, and some pieces of broken crockery from one of the cottages are still to be seen on the shore near the ferryman's hut, where the path joins the shore.

This sandy beach, lapped by the blue waves of Runswick Bay, is one of the finest and most spectacular spots to be found on the rocky coast-line of Yorkshire. You look northwards across the sunlit sea to the rocky heights hiding Port Mulgrave and Staithes, and on the further side of the bay you see tiny Runswick's red roofs, one above the other, on the face of the cliff. Here it is always cool and pleasant in the hottest weather, and from the broad shadows cast by the precipices above one can revel in the sunny land- and sea-scapes without that fishy odour so unavoidable in the villages. When the sun is beginning to climb down the sky in the direction of Hinderwell, and everything is bathed in a glorious golden light, the ferryman will row you across the bay to Runswick, but a scramble over the rocks on the beach will be repaid by a closer view of the now half-filled-up Hob Hole. The fisherfolk believed this cave to be the home of a kindly-disposed fairy or hob, who seems to have been one of the slow-dying inhabitants of the world of mythology implicitly believed in by the Saxons. And these beliefs died so hard in these lonely Yorkshire villages that until recent times a mother would carry her child suffering from whooping-cough along the beach to the mouth of the cave. There she would call in a loud voice, 'Hob-hole Hob! my bairn's getten t'kink cough. Tak't off, tak't off.'

The same form of disaster which destroyed Kettleness village caused the complete ruin of Runswick in 1666, for one night, when some of the fisherfolk were holding a wake over a corpse, they had unmistakable warnings of an approaching landslip. The alarm was given, and the villagers, hurriedly leaving their cottages, saw the whole place slide downwards, and become a mass of ruins. No lives were lost, but, as only one house remained standing, the poor fishermen were only saved from destitution by the sums of money collected for their relief.

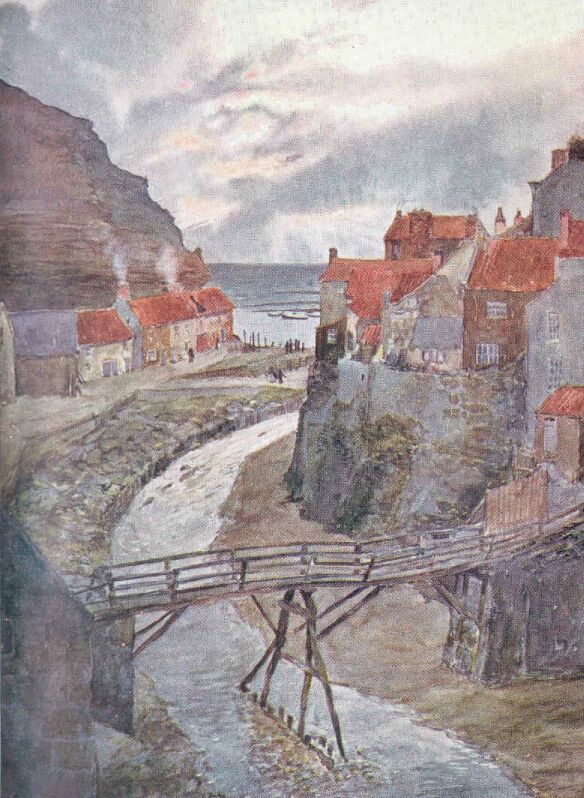

Scarcely two miles from Hinderwell is the fishing-hamlet of Staithes, wedged into the side of a deep and exceedingly picturesque beck.

The steep road leading past the station drops down into the village, giving a glimpse of the beck crossed by its ramshackle wooden foot-bridge—the view one has been prepared for by guide-books and picture postcards. Lower down you enter the village street. Here the smell of fish comes out to greet you, and one would forgive the place this overflowing welcome if one were not so shocked at the dismal aspect of the houses on either side of the way. Many are of comparatively recent origin, others are quite new, and a few—a very few—are old; but none have any architectural pretensions or any claims to picturesqueness, and only a few have the neat and respectable look one is accustomed to expect after seeing Robin Hood's Bay.

I hurried down on to the little fish-wharf—a wooden structure facing the sea—hoping to find something more cheering in the view of the little bay, with its bold cliffs, and the busy scene where the cobbles were drawn up on the shingle. Here my spirits revived, and I began to find excuses for the painters. The little wharf, in a bad state of repair, like most things in the place, was occupied by groups of stalwart fisherfolk, men and women.

The men were for the most part watching their womenfolk at work. They were also to an astonishing extent mere spectators in the arduous work of hauling the cobbles one by one on to the steep bank of shingle. A tackle hooked to one of the baulks of timber forming the staith was being hauled at by five women and two men! Two others were in a listless fashion leaning their shoulders against the boat itself. With the last 'Heave-ho!' at the shortened tackle the women laid hold of the nets, and with casual male assistance laid them out on the shingle, removed any fragments of fish, and generally prepared them for stowing in the boat again.

A change has come over the inhabitants of Staithes since 1846, when Mr. Ord describes the fishermen as 'exceedingly civil and courteous to strangers, and altogether free from that low, grasping knavery peculiar to the larger class of fishing-towns.' Without wishing to be unreasonably hard on Staithes, I am inclined to believe that this character is infinitely better than these folk deserve, and even when Mr. Ord wrote of the place I have reason to doubt the civility shown by them to strangers. It is, according to some who have known Staithes for a long long while, less than fifty years ago that the fisherfolk were hostile to a stranger on very small provocation, and only the entirely inoffensive could expect to sojourn in the village without being a target for stones.

No doubt many of the superstitions of Staithes people have languished or died out in recent years, and among these may be included a particularly primitive custom when the catches of fish had been unusually small. Bad luck of this sort could only be the work of some evil influence, and to break the spell a sheep's heart had to be procured, into which many pins were stuck. The heart was then burnt in a bonfire on the beach, in the presence of the fishermen, who danced round the flames.

In happy contrast to these heathenish practices was the resolution entered into and signed by the fishermen of Staithes, in August, 1835, binding themselves 'on no account whatever' to follow their calling on Sundays, 'nor to go out without boats or cobbles to sea, either on the Saturday or Sunday evenings.' They also agreed to forfeit ten shillings for every offence against the resolution, and the fund accumulated in this way, and by other means, was administered for the benefit of aged couples and widows and orphans.

The men of Staithes are known up and down the east coast of Great Britain as some of the very finest types of fishermen. Their cobbles, which vary in size and colour, are uniform in design and the brilliance of their paint. Brick red, emerald green, pungent blue and white, are the most favoured colours, but orange, pink, yellow, and many others, are to be seen.

Looking northwards there is a grand piece of coast scenery. The masses of Boulby Cliffs, rising 660 feet from the sea, are the highest on the Yorkshire coast. The waves break all round the rocky scaur, and fill the air with their thunder, while the strong wind blows the spray into beards which stream backwards from the incoming crests.

The upper course of Staithes Beck consists of two streams, flowing through deep, richly-wooded ravines. They follow parallel courses very close to one another for three or four miles, but their sources extend from Lealholm Moor to Wapley Moor. Kilton Beck runs through another lovely valley densely clothed in trees, and full of the richest woodland scenery. It becomes more open in the neighbourhood of Loftus, and from thence to the sea at Skinningrove the valley is green and open to the heavens. Loftus is on the borders of the Cleveland mining district, and it is for this reason that the town has grown to a considerable size. But although the miners' new cottages are unpicturesque, and the church only dates from 1811, the situation is pretty, owing to the profusion of trees among the houses, has railway-sidings and branch-lines running down to it, and on the hill above the cottages stands a cluster of blast-furnaces. In daylight they are merely ugly, but at night, with tongues of flame, they speak of the potency of labour. I can still see that strange silhouette of steel cylinders and connecting girders against a blue-black sky, with silent masses of flame leaping into the heavens.

It was long before iron-ore was smelted here, before even the old alum-works had been started, that Skinningrove attained to some sort of fame through a wonderful visit, as strange as any of those recounted by Mr. Wells. It was in the year 1535—for the event is most carefully recorded in a manuscript of the period—that some fishermen of Skinningrove caught a Sea Man. This was such an astounding fact to record that the writer of the old manuscript explains that 'old men that would be loath to have their credyt crackt by a tale of a stale date, report confidently that ... a sea-man was taken by the fishers.' They took him up to an old disused house, and kept him there for many weeks, feeding him on raw fish, because he persistently refused the other sorts of food offered him. To the people who flocked from far and near to visit him he was very courteous, and he seems to have been particularly pleased with any 'fayre maydes' who visited him, for he would gaze at them with a very earnest countenance, 'as if his phlegmaticke breaste had been touched with a sparke of love.'

The lofty coast-line we have followed all the way from Sandsend terminates abruptly at Huntcliff Nab, the great promontory which is familiar to visitors to Saltburn. Low alluvial cliffs take the place of the rocky precipices, and the coast becomes flatter and flatter as you approach Redcar and the marshy country at the mouth of the Tees. The original Saltburn, consisting of a row of quaint fishermen's cottages, still stands entirely alone, facing the sea on the Huntcliff side of the beck, and from the wide, smooth sands there is little of modern Saltburn to be seen besides the pier. For the rectangular streets and blocks of houses have been wisely placed some distance from the edge of the grassy cliffs, leaving the sea-front quite unspoiled.

The elaborately-laid-out gardens on the steep banks of Skelton Beck are the pride and joy of Saltburn, for they offer a pleasant contrast to the bare slopes on the Huntcliff side and the flat country towards Kirkleatham. But in this seemingly harmless retreat there used to be heard horrible groanings, and I have no evidence to satisfy me that they have altogether ceased. For in this matter-of-fact age such a story would not be listened to, and thus those who hear the sounds may be afraid to speak of them. The groanings were heard, they say, 'when all wyndes are whiste and the rea restes unmoved as a standing poole.' At times they were so loud as to be heard at least six miles inland, and the fishermen feared to put out to sea, believing that the ocean was 'as a greedy Beaste raginge for Hunger, desyers to be satisfyed with men's carcases.'

In 1842 Redcar was a mere village, though more apparent on the map than Saltburn; but, like its neighbour, it has grown into a great watering-place, having developed two piers, a long esplanade, and other features, which I am glad to leave to those for whom they were made, and betake myself to the more romantic spots so plentiful in this broad county.

THE COAST FROM WHITBY TO SCARBOROUGH

Although it is only six miles as the crow flies from Whitby to Robin Hood's Bay, the exertion required to walk there along the top of the cliffs is equal to quite double that distance, for there are so many gullies to be climbed into and crawled out of that the measured distance is considerably increased. It is well to remember this, for otherwise the scenery of the last mile or two may not seem as fine as the first stages.

As soon as the abbey and the jet-sellers are left behind, you pass a farm, and come out on a great expanse of close-growing smooth turf, where the whole world seems to be made up of grass and sky. The footpath goes close to the edge of the cliff; in some places it has gone too close, and has disappeared altogether. But these diversions can be avoided without spoiling the magnificent glimpses of the rock-strewn beach nearly 200 feet below. From above Saltwick Bay there is a grand view across the level grass to Whitby Abbey, standing out alone on the green horizon. Down below, Nab runs out a bare black arm into the sea, which even in the calmest weather angrily foams along the windward side. Beyond the sturdy lighthouse that shows itself a dazzling white against the hot blue of the heavens commence the innumerable gullies. Each one has its trickling stream, and bushes and low trees grow to the limits of the shelter afforded by the ravines; but in the open there is nothing higher than the waving corn or the stone walls dividing the pastures—a silent testimony to the power of the north-east wind.

After rounding the North Cheek, the whole of Robin Hood's Bay is suddenly laid before you. I well remember my first view of the wide sweep of sea, which lay like a blue carpet edged with white, and the high escarpments of rock that were in deep purple shade, except where the afternoon sun turned them into the brightest greens and umbers. Three miles away, but seemingly very much closer, was the bold headland of the Peak, and more inland was Stoupe Brow, with Robin Hood's Butts on the hill-top. The fable connected with the outlaw is scarcely worth repeating, but on the site of these butts urns have been dug up, and are now to be found in Scarborough Museum. The Bay Town is hidden away in a most astonishing fashion, for, until you have almost reached the two bastions which guard the way up from the beach, there is nothing to be seen of the charming old place. If you approach by the road past the railway station it is the same, for only garishly new hotels and villas are to be seen on the high ground, and not a vestige of the fishing-town can be discovered. But the road to the bay at last begins to drop down very steeply, and the first old roofs appear. The oath at the side of the road develops into a very lone series of steps, and in a few minutes the narrow street flanked by very tall houses, has swallowed you up.

Everything is very clean and orderly, and, although most of the houses are very old, they are generally in a good state of repair, exhibiting in every case the seaman's love of fresh paint. Thus, the dark and worn stone walls have bright eyes in their newly-painted doors and windows. Over their door-steps the fishermen's wives are quite fastidious, and you seldom see a mark on the ochre-coloured hearth-stone with which the women love to brighten the worn stones. Even the scrapers are sleek with blacklead, and it is not easy to find a window without spotless curtains. At high tide the sea comes half-way up the steep opening between the coastguards' quarters and the inn which is built on another bastion, and in rough weather the waves break hungrily on to the strong stone walls, for the bay is entirely open to the full force of gales from the east or north-east. All the way from Scarborough to Whitby the coast offers no shelter of any sort in heavy weather, and many vessels have been lost on the rocks. On one occasion a small sailing-ship was driven right into this bay at high tide, and the bowsprit smashed into a window of the little hotel that occupied the place of the present one.

The railway southwards takes a curve inland, and, after winding in and out to make the best of the contour of the hills, the train finally steams very heavily and slowly into Ravenscar Station, right over the Peak and 630 feet above the sea. On the way you get glimpses of the moors inland, and grand views over the curving bay. There is a station named Fyling Hall, after Sir Hugh Cholmley's old house, half-way to Ravenscar.

Raven Hall, the large house conspicuously perched on the heights above the Peak, is now converted into an hotel. There is a wonderful view from the castellated terraces, which in the distance suggest the remains of some ruined fortress. At the present time there is nothing to be seen older than the house whose foundations were dug in 1774. While the building operations were in progress, however, a Roman inscribed stone, now in Whitby Museum, was unearthed. It states that the 'Castrum' was built by two prefects whose names are given. This was one of the fortified signal stations built in the 4th century A.D. to give warning of the approach of hostile ships.

Following this lofty coast southwards, you reach Hayburn Wyke, where a stream drops perpendicularly over some square masses of rock.

There is a small stone circle not far from Hayburn Wyke Station, to be found without much trouble, and those who are interested in Early Man will scarcely find a neighbourhood in this country more thickly honey-combed with tumuli and ancient earth-works. There is no particularly plain pathway through the fields to the valley where this stone circle can be seen, but it can easily be found after a careful study of the large-scale Ordnance Map which they will show you at the hotel.

SCARBOROUGH

Dazzling sunshine, a furious wind, flapping and screaming gulls, crowds of fishing-boats, and innumerable people jostling one another on the sea-front, made up the chief features of my first view of Scarborough. By degrees I discovered that behind the gulls and the brown sails were old houses, their roofs dimly red through the transparent haze, and above them appeared a great green cliff, with its uneven outline defined by the curtain walls and towers of the castle which had made Scarborough a place of importance in the Civil War and in earlier times.

The wide-curving bay was filled with huge breaking waves which looked capable of destroying everything within their reach, but they seemed harmless enough when I looked a little further out, where eight or ten grey war-ships were riding at their anchors, apparently motionless.

From the outer arm of the harbour, where the seas were angrily attempting to dislodge the top row of stones, I could make out the great mass of grey buildings stretching right to the extremity of the bay.

I tried to pick out individual buildings from this city-like watering-place, but, beyond discovering the position of the Spa and one or two of the mightier hotels, I could see very little, and instead fell to wondering how many landladies and how many foreign waiters the long lines of grey roofs represented. This raised so many unpleasant recollections of the various types I had encountered that I determined to go no nearer to modern Scarborough than the pier-head upon which I stood. A specially big wave, however, soon drove me from this position to a drier if more crowded spot, and, reconsidering my objections, I determined to see something of the innumerable grey streets which make up the fashionable watering-place. The terraced gardens on the steep cliffs along the sea-front were most elaborately well kept, but a more striking feature of Scarborough is the magnificence of so many of the shops. They suggest a city rather than a seaside town, and give you an idea of the magnitude of the permanent population of the place as well as the flood of summer and winter visitors. The origin of Scarborough's popularity was undoubtedly due to the chalybeate waters of the Spa, discovered in 1620, almost at the same time as those of Tunbridge Wells and Epsom.

The unmistakable signs of antiquity in the narrow streets adjoining the harbour irresistibly remind one of the days when sea-bathing had still to be popularized, when the efficacy of Scarborough's medicinal spring had not been discovered, of the days when the place bore as little resemblance to its present size or appearance as the fishing-town at Robin Hood's Bay.

We do not know that Piers Gaveston, Sir Hugh Cholmley, and other notabilities who have left their mark on the pages of Scarborough's history, might not, were they with us to-day, welcome the pierrot, the switchback, the restaurant, and other means by which pleasure-loving visitors wile away their hardly-earned holidays; but for my part the story of Scarborough's Mayor who was tossed in a blanket is far more entertaining than the songs of nigger minstrels or any of the commercial attempts to amuse.

This strangely improper procedure with one who held the highest office in the municipality took place in the reign of James II., and the King's leanings towards Popery were the cause of all the trouble.

On April 27, 1688, a declaration for liberty of conscience was published, and by royal command the said declaration was to be read in every Protestant church in the land. Mr. Thomas Aislabie, the Mayor of Scarborough, duly received a copy of the document, and, having handed it to the clergyman, Mr. Noel Boteler, ordered him to read it in church on the following Sunday morning. There seems little doubt that the worthy Mr. Boteler at once recognized a wily move on the part of the King, who under the cover of general tolerance would foster the growth of the Roman religion until such time as the Catholics had attained sufficient power to suppress Protestantism. Mr. Mayor was therefore informed that the declaration would not be read. On Sunday morning (August 11) when the omission had been made, the Mayor left his pew, and, stick in hand, walked up the aisle, seized the minister, and caned him as he stood at his reading-desk. Scenes of such a nature did not occur every day even in 1688, and the storm of indignation and excitement among the members of the congregation did not subside so quickly as it had risen.

The cause of the poor minister was championed in particular by a certain Captain Ouseley, and the discussion of the matter on the bowling-green on the following day led to the suggestion that the Mayor should be sent for to explain his conduct. As he took no notice of a courteous message requesting his attendance, the Captain repeated the summons accompanied by a file of musketeers. In the meantime many suggestions for dealing with Mr. Aislabie in a fitting manner were doubtless made by the Captain's brother officers, and, further, some settled course of action seems to have been agreed upon, for we do not hear of any hesitation on the part of the Captain on the arrival of the Mayor, whose rage must by this time have been bordering upon apoplexy. A strong blanket was ready, and Captains Carvil, Fitzherbert, Hanmer, and Rodney, led by Captain Ouseley and assisted by as many others as could find room, seizing the sides, in a very few moments Mr. Mayor was revolving and bumping, rising and falling, as though he were no weight at all.

If the castle does not show many interesting buildings beyond the keep and the long line of walls and drumtowers, there is so much concerning it that is of great human interest that I should scarcely feel able to grumble if there were still fewer remains. Behind the ancient houses in Quay Street rises the steep, grassy cliff, up which one must climb by various rough pathways to the fortified summit. On the side facing the mainland, a hollow, known as the Dyke, is bridged by a tall and narrow archway, in place of the drawbridge of the seventeenth century and earlier times. On the same side is a massive barbican, looking across an open space to St. Mary's Church, which suffered so severely during the sieges of the castle. The maimed church—for the chancel has never been rebuilt—is close to the Dyke and the shattered keep, and so apparent are the results of the cannonading between them that no one requires to be told that the Parliamentary forces mounted their ordnance in the chancel and tower of the church, and it is equally obvious that the Royalists returned the fire hotly.

The great siege lasted for nearly a year, and although his garrison was small, and there was practically no hope of relief, Sir Hugh Cholmley seems to have kept a stout heart up to the end. With him throughout this long period of privation and suffering was his beautiful and courageous wife, whose comparatively early death, at the age of fifty-four, must to some extent be attributed to the strain and fatigue borne during these months of warfare. Sir Hugh seems to have almost worshipped his wife, for in his memoirs he is never weary of describing her perfections.

'She was of the middle stature of women,' he writes, 'and well shaped, yet in that not so singular as in the beauty of her face, which was but of a little model, and yet proportionable to her body; her eyes black and full of loveliness and sweetness, her eyebrows small and even, as if drawn with a pencil, a very little, pretty, well-shaped mouth, which sometimes (especially when in a muse or study) she would draw up into an incredible little compass; her hair a sad chestnut; her complexion brown, but clear, with a fresh colour in her cheeks, a loveliness in her looks inexpressible; and by her whole composure was so beautiful a sweet creature at her marriage as not many did parallel, few exceed her, in the nation; yet the inward endowments and perfections of her mind did exceed those outward of her body, being a most pious virtuous person, of great integrity and discerning judgment in most things.'

On one occasion during the siege Sir John Meldrum, the Parliamentary commander, sent proposals to Sir Hugh Cholmley, which he accompanied with savage threats, that if his terms were not immediately accepted he would make a general assault on the castle that night, and in the event of one drop of his men's blood being shed he would give orders for a general massacre of the garrison, sparing neither man nor woman.

To a man whose devotion to his beautiful wife was so great, a threat of this nature must have been a severe shock to his determination to hold out. But from his own writings we are able to picture for ourselves Sir Hugh's anxious and troubled face lighting up on the approach of the cause of his chief concern. Lady Cholmley, without any sign of the inward misgivings or dejection which, with her gentle and shrinking nature, must have been a great struggle, came to her husband, and implored him to on no account let her peril influence his decision to the detriment of his own honour or the King's affairs.

Sir John Meldrum's proposals having been rejected, the garrison prepared itself for the furious attack commenced on May 11.

The assault was well planned, for while the Governor's attention was turned towards the gateway leading to the castle entrance, another attack was made at the southern end of the wall towards the sea, where until the year 1730 Charles's Tower stood. The bloodshed at this point was greater than at the gateway. At the head of a chosen division of troops, Sir John Meldrum climbed the almost precipitous ascent with wonderful courage, only to meet with such spirited resistance on the part of the besieged that, when the attack was abandoned, it was discovered that Meldrum had received a dangerous wound penetrating to his thigh, and that several of his officers and men had been killed. Meanwhile, at the gateway, the first success of the assailants had been checked at the foot of the Grand Tower or Keep, for at that point the rush of drab-coated and helmeted men was received by such a shower of stones and missiles that many stumbled and were crushed on the steep pathway. Not even Cromwell's men could continue to face such a reception, and before very long the Governor could embrace his wife in the knowledge that the great attack had failed.

At last, on July 22, 1645—his forty-fifth birthday—Sir Hugh was forced to come to an agreement with the enemy, by which he honourably surrendered the castle three days later. It was a sad procession that wound its way down the steep pathway, littered with the debris of broken masonry: for many of Sir Hugh's officers and soldiers were in such a weak condition that they had to be carried out in sheets or helped along between two men, and the Parliamentary officer adds rather tersely, that 'the rest were not very fit to march.' The scurvy had depleted the ranks of the defenders to such an extent that the women in the castle, despite the presence of Lady Cholmley, threatened to stone the Governor unless he capitulated.

Three years later the castle was again besieged by the Parliamentary forces, for Colonel Matthew Boynton, the Governor, had declared for the King. The garrison held out from August to December, when terms were made with Colonel Hugh Bethell, by which the Governor, officers, gentlemen, and soldiers, marched out with 'their colours flying, drums beating, musquets loaden, bandeleers filled, matches lighted, and bullet in mouth, to a close called Scarborough Common,' where they laid down their arms.

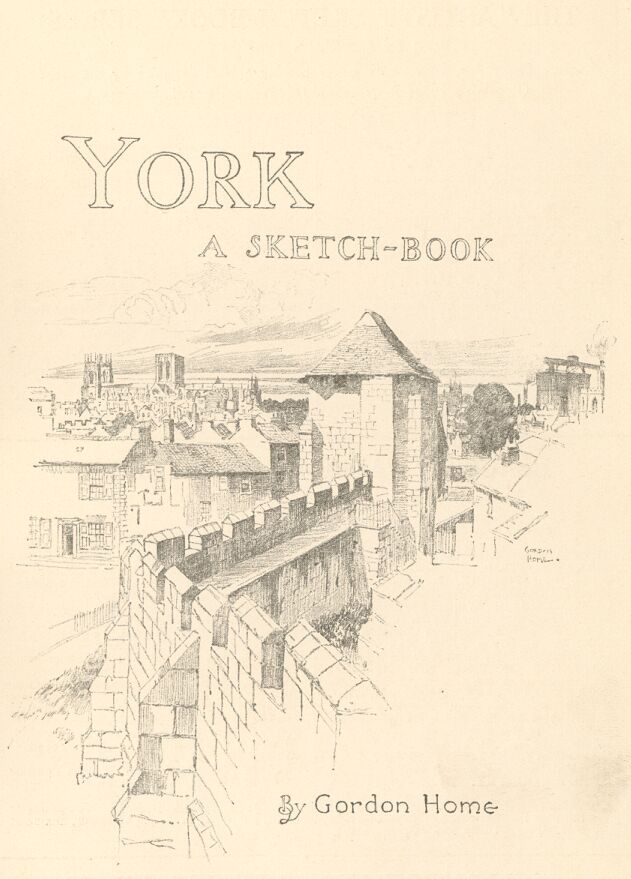

Before I leave Scarborough I must go back to early times, in order that the antiquity of the place may not be slighted owing to the omission of any reference to the town in the Domesday Book. Tosti, Count of Northumberland, who, as everyone knows, was brother of the Harold who fought at Senlac Hill, had brought about an insurrection of the Northumbrians, and having been dispossessed by his brother, he revenged himself by inviting the help of Haralld Hadrada, King of Norway. The Norseman promptly accepted the offer, and, taking with him his family and an army of warriors, sailed for the Shetlands, where Tosti joined him. The united forces then came down the east coast of Britain until they reached Scardaburgum, where they landed and prepared to fight the inhabitants. The town was then built entirely of timber, and there was, apparently, no castle of any description on the great hill, for the Norsemen, finding their opponents inclined to offer a stout resistance, tried other tactics. They gained possession of the hill, constructed a huge fire, and when the wood was burning fiercely, flung the blazing brands down on to the wooden houses below. The fire spread from one hut to another with sufficient speed to drive out the defenders, who in the confusion which followed were slaughtered by the enemy.

This occurred in the momentous year 1066, when Harold, having defeated the Norsemen and slain Haralld Hadrada at Stamford Bridge, had to hurry southwards to meet William the Norman at Hastings. It is not surprising, therefore, that the compilers of the Conqueror's survey should have failed to record the existence of the blackened embers of what had once been a town. But such a site as the castle hill could not long remain idle in the stormy days of the Norman Kings, and William le Gros, Earl of Albemarle and Lord of Holderness, recognising the natural defensibility of the rock, built the massive walls which have withstood so many assaults, and even now form the most prominent feature of Scarborough.

Until 1923 there was no knowledge of there having been any Roman occupation of the promontory upon which the castle stands. Excavations made in that year have shown that a massively-built watch tower was maintained there during the last phase of Roman control in Britain. This was one of a chain of signal or lookout stations placed along the Yorkshire coast when the threat of raiders from the mouths of the German rivers had become serious.

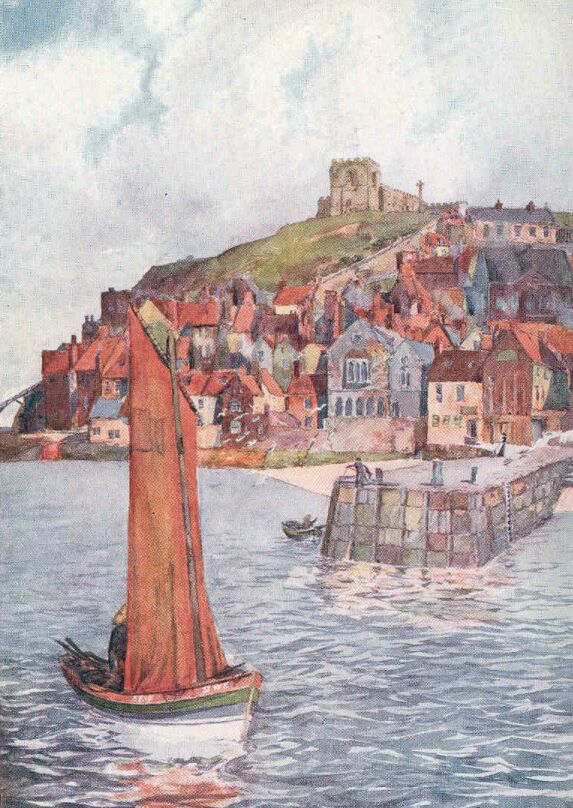

WHITBY

|

Behold the glorious summer sea As night's dark wings unfold, And o'er the waters, 'neath the stars, The harbour lights behold. E. Teschemacher. |

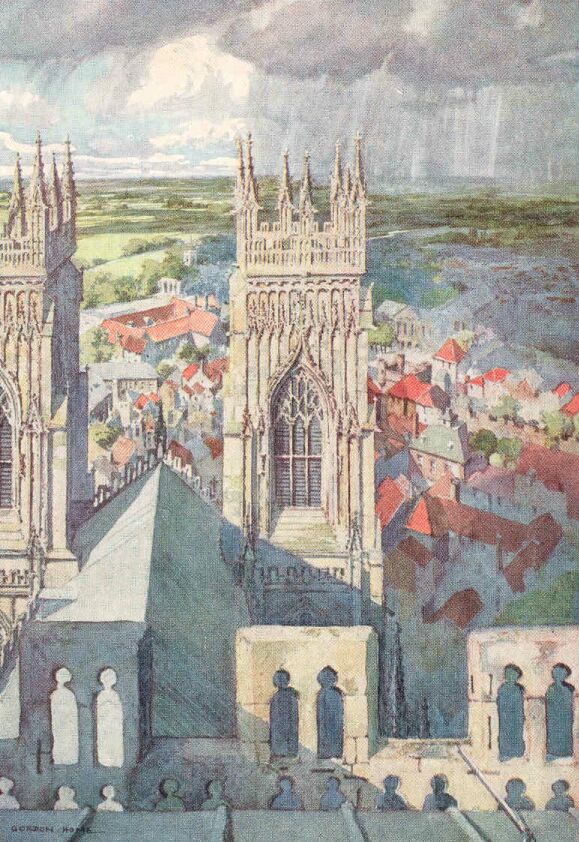

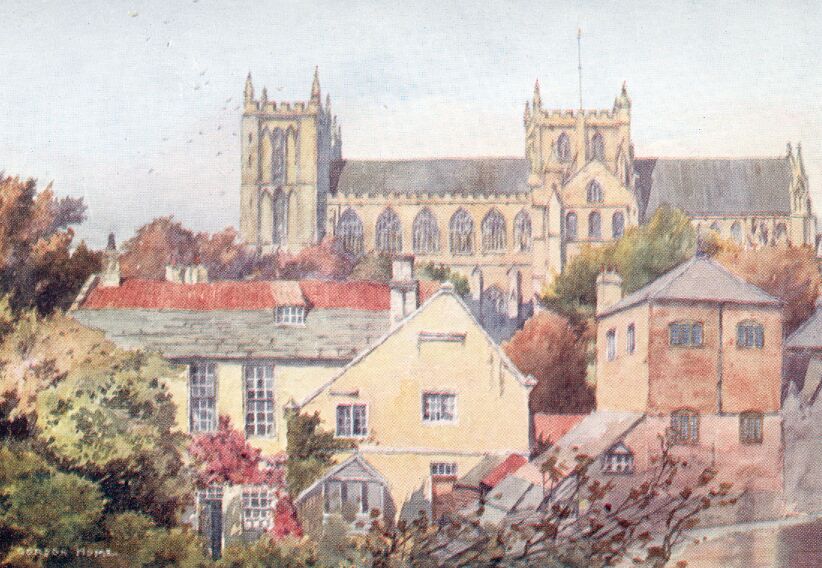

Despite a huge influx of summer visitors, and despite the modern town which has grown up to receive them, Whitby is still one of the most strikingly picturesque towns in England. But at the same time, if one excepts the abbey, the church, and the market-house, there are scarcely any architectural attractions in the town. The charm of the place does not lie so much in detail as in broad effects. The narrow streets have no surprises in the way of carved-oak brackets or curious panelled doorways, although narrow passages and steep flights of stone steps abound. On the other hand, the old parts of the town, when seen from a distance, are always presenting themselves in new apparel.

In the early morning the East Cliff generally appears as a pale grey silhouette with a square projection representing the church, and a fretted one the abbey.

But as the sun climbs upwards, colour and definition grow out of the haze of smoke and shadows, and the roofs assume their ruddy tones. At midday, when the sunlight pours down upon the medley of houses clustered along the face of the cliff, the scene is brilliantly coloured. The predominant note is the red of the chimneys and roofs and stray patches of brickwork, but the walls that go down to the water's edge are green below and full of rich browns above, and in many places the sides of the cottages are coloured with an ochre wash, while above them all the top of the cliff appears covered with grass. There is scarcely a chimney in this old part of Whitby that does not contribute to the mist of blue-grey smoke that slowly drifts up the face of the cliff, and thus, when there is no bright sunshine, colour and details are subdued in the haze.

In many towns whose antiquity and picturesqueness are more popular than the attractions of Whitby, the railway deposits one in some distressingly ugly modern excrescence, from which it may even be necessary for a stranger to ask his way to the old-world features he has come to see. But at Whitby the railway, without doing any harm to the appearance of the town, at once gives a visitor as typical a scene of fishing-life as he will ever find. When the tide is up and the wharves are crowded with boats, this upper portion of Whitby Harbour is at its best, and to step from the railway compartment entered at King's Cross into this picturesque scene is an experience to be remembered.

In the deepening twilight of a clear evening the harbour gathers to itself the additional charm of mysterious indefiniteness, and among the long-drawn-out reflections appear sinuous lines of yellow light beneath the lamps by the bridge. Looking towards the ocean from the outer harbour, one sees the massive arms which Whitby has thrust into the waves, holding aloft the steady lights that

|

'Safely guide the mighty ships Into the harbour bay.' |

If we keep to the waterside, modern Whitby has no terrors for us. It is out of sight, and might therefore have never existed. But when we have crossed the bridge, and passed along the narrow thoroughfare known as Church Street to the steps leading up the face of the cliff, we must prepare ourselves for a new aspect of the town. There, upon the top of the West Cliff, stand rows of sad-looking and dun-coloured lodging-houses, relieved by the aggressive bulk of a huge hotel, with corner turrets, that frowns savagely at the unfinished crescent, where there are many apartments with 'rooms facing the sea.'

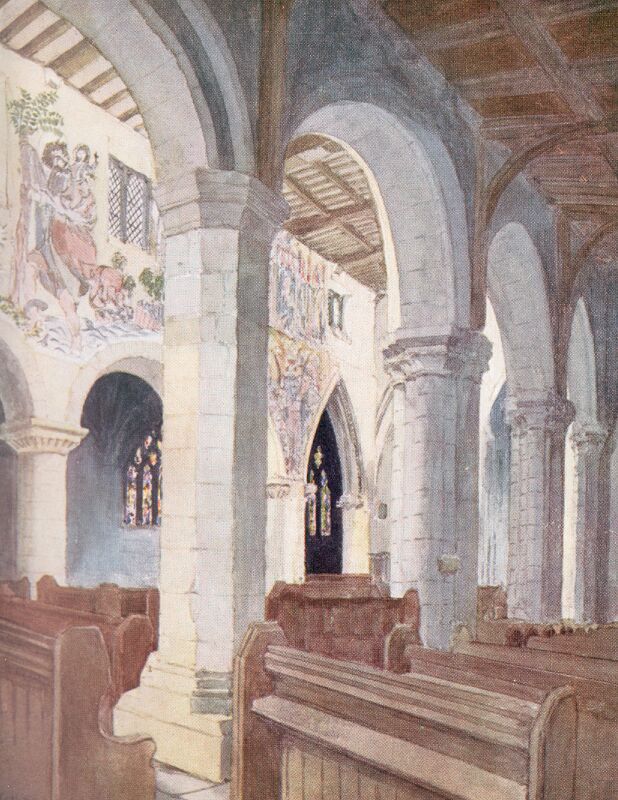

Turning landwards we look over the chimney stacks of the topmost houses, and see the silver Esk winding placidly in the deep channel it has carved for itself; and further away we see the far off moorland heights, brown and blue, where the sources of the broad river down below are fed by the united efforts of innumerable tiny streams deep in the heather. Behind us stands the massive-looking parish church, with its Norman tower, so sturdily built that its height seems scarcely greater than its breadth. There is surely no other church with such a ponderous exterior that is so completely deceptive as to its internal aspect, for St. Mary's contains the most remarkable series of beehive-like galleries that were ever crammed into a parish church. They are not merely very wide and ill-arranged, but they are superposed one abode the other. The free use of white paint all over the sloping tiers of pews has prevented the interior from being as dark as it would have otherwise been, but the result of all this painted deal has been to give the building the most eccentric and indecorous appearance.

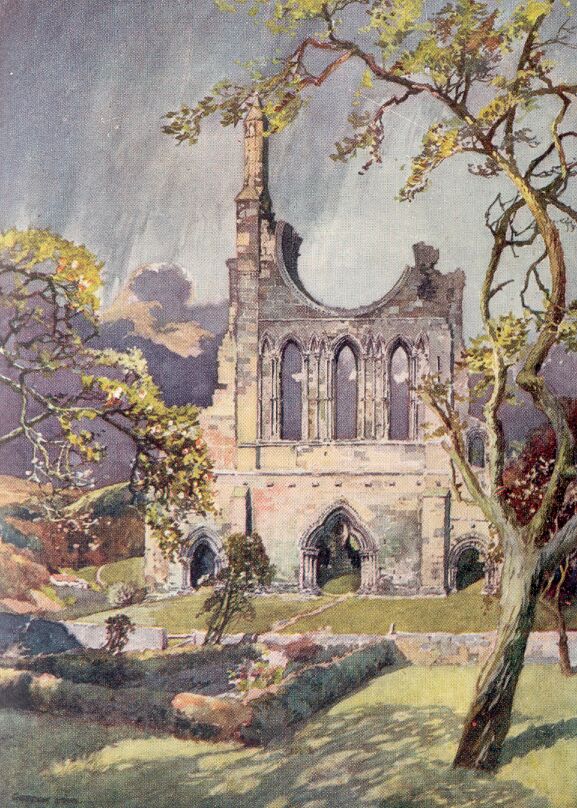

The early history of Whitby from the time of the landing of Roman soldiers in the inlet seems to be very closely associated with the abbey founded by Hilda about two years after the battle of Winwidfield, fought on November 15, A.D. 654; but I will not venture to state an opinion here as to whether there was any town at Streoneshalh before the building of the abbey, or whether the place that has since become known as Whitby grew on account of the presence of the abbey. Such matters as these have been fought out by an expert in the archaeology of Cleveland—the late Canon Atkinson, who seemed to take infinite pleasure in demolishing the elaborately constructed theories of those painstaking historians of the eighteenth century, Dr. Young and Mr. Lionel Charlton.

Many facts, however, which throw light on the early days of the abbey are now unassailable. We see that Hilda must have been a most remarkable woman for her times, instilling into those around her a passion for learning as well as right-living, for despite the fact that they worked and prayed in rude wooden buildings, with walls formed, most probably, of split tree-trunks, after the fashion of the church at Greenstead in Essex, we find the institution producing, among others, such men as Bosa and John, both Archbishops of York, and such a poet as Caedmon. The legend of his inspiration, however, may be placed beside the story of how the saintly Abbess turned the snakes into the fossil ammonites with which the liassic shores of Whitby are strewn. Hilda, who probably died in the year 680, was succeeded by Aelfleda, the daughter of King Oswiu of Northumbria, whom she had trained in the abbey, and there seems little doubt that her pupil carried on successfully the beneficent work of the foundress.

Aelfleda had the support of her mother's presence as well as the wise counsels of Bishop Trumwine, who had taken refuge at Streoneshalh, after having been driven from his own sphere of work by the depredations of the Picts and Scots. We then learn that Aelfleda died at the age of fifty-nine, but from that year—probably 713—a complete silence falls upon the work of the abbey; for if any records were made during the next century and a half, they have been totally lost. About the year 867 the Danes reached this part of Yorkshire, and we know that they laid waste the abbey, and most probably the town also; but the invaders gradually started new settlements, or 'bys,' and Whitby must certainly have grown into a place of some size by the time of Edward the Confessor, for just previous to the Norman invasion it was assessed for Danegeld to the extent of a sum equivalent to £3,500 at the present time.

After the Conquest a monk named Reinfrid succeeded in reviving a monastery on the site of the old one, having probably gained the permission of William de Percy, the lord of the district. The new establishment, however, was for monks only, and was for some time merely a priory.

The form of the successive buildings from the time of Hilda until the building of the stately abbey church, whose ruins are now to be seen, is a subject of great interest, but, unfortunately, there are few facts to go upon. The very first church was, as I have already suggested, a building of rude construction, scarcely better than the humble dwellings of the monks and nuns. The timber walls were most probably thatched, and the windows would be of small lattice or boards pierced with small holes. Gradually the improvements brought about would have led to the use of stone for the walls, and the buildings destroyed by the Danes may have resembled such examples of Anglo-Saxon work as may still be seen in the churches of Bradford-on-Avon and Monkwearmouth.

The buildings erected by Reinfrid under the Norman influence then prevailing in England must have been a slight advance upon the destroyed fabric, and we know that during the time of his successor, Serlo de Percy, there was a certain Godfrey in charge of the building operations, and there is every reason to believe that he completed the church during the fifty years of prosperity the monastery passed through at that time. But this was not the structure which survived, for towards the end of Stephen's reign, or during that of Henry II., the unfortunate convent was devastated by the King of Norway, who entered the harbour, and, in the words of the chronicle, 'laid waste everything, both within doors and without.' The abbey slowly recovered from this disaster, and the reconstruction commenced in 1220, still makes a conspicuous landmark from the sea. It was after the Dissolution that the abbey buildings came into the hands of Sir Richard Cholmley, who paid over to Henry VIII. the sum of £333 8s. 4d. The manors of Eskdaleside and Ugglebarnby, with all 'their rights, members and appurtenances as they formerly had belonged to the abbey of Whiby,' henceforward belonged to Sir Richard and his successors.

Sir Hugh Cholmley, whose defence of Scarborough Castle has made him a name in history, was born on July 22, 1600, at Roxby, near Pickering. He has been justly called 'the father of Whitby,' and it is to him we owe a fascinating account of his life at Whitby in Stuart and Jacobean times. He describes how he lived for some time in the gate-house of the abbey buildings, 'till my house was repaired and habitable, which then was very ruinous and all unhandsome, the wall being only of timber and plaster, and ill-contrived within: and besides the repairs, or rather re-edifying the house, I built the stable and barn, I heightened the outwalls of the court double to what they were, and made all the wall round about the paddock; so that the place hath been improved very much, both for beauty and profit, by me more than all my ancestors, for there was not a tree about the house but was set in my time, and almost by my own hand.'

In the spring of 1636 the reconstruction of the abbey house was finished, and Sir Hugh moved in with his family. 'My dear wife,' he says '(who was excellent at dressing and making all handsome within doors), had put it into a fine posture, and furnished with many good things, so that, I believe, there were few gentlemen in the country, of my rank, exceeded it.... I was at this time made Deputy-lieutenant and Colonel over the Train-bands within the hundred of Whitby Strand, Ruedale, Pickering, Lythe and Scarborough town; for that, my father being dead, the country looked upon me as the chief of my family.'

'I had between thirty and forty in my ordinary family, a chaplain who said prayers every morning at six, and again before dinner and supper, a porter who merely attended the gates, which were ever shut up before dinner, when the bell rung to prayers, and not opened till one o'clock, except for some strangers who came to dinner, which was ever fit to receive three or four besides my family, without any trouble; and whatever their fare was, they were sure to have a hearty welcome. As a definite result of his efforts, 'all that part of the pier to the west end of the harbour' was erected, and yet he complains that, though it was the means of preserving a large section of the town from the sea, the townsfolk would not interest themselves in the repairs necessitated by force of the waves. 'I wish, with all my heart,' he exclaims, 'the next generation may have more public spirit.'

THE CLEVELAND HILLS

On their northern and western flanks the Cleveland Hills have a most imposing and mountainous aspect, although their greatest altitudes do not aspire to more than about 1,500 feet. But they rise so suddenly to their full height out of the flat sea of green country that they often appear as a coast defended by a bold range of mountains. Roseberry Topping stands out in grim isolation, on its masses of alum rock, like a huge sea-worn crag, considerably over 1,000 feet high. But this strangely menacing peak raises his defiant head over nothing but broad meadows, arable land, and woodlands, and his only warfare is with the lower strata of storm-clouds, which is a convenient thing for the people who live in these parts; for long ago they used the peak as a sign of approaching storms, having reduced the warning to the easily-remembered couplet:

|

'When Roseberry Topping wears a cap, Let Cleveland then beware of a clap.' |

From the fact that you can see this remarkable peak from almost every point of the compass except south-westwards, it must follow that from the top of the hill there are views in all those directions. But to see so much of the country at once comes as a surprise to everyone. Stretching inland towards the backbone of England, there is spread out a huge tract of smiling country, covered with a most complex network of hedges, which gradually melt away into the indefinite blue edge of the world where the hills of Wensleydale rise from the plain. Looking across the little town of Guisborough, lying near the shelter of the hills, to the broad sweep of the North Sea, this piece of Yorkshire seems so small that one almost expects to see the Cheviots away in the north. But, beyond the winding Tees and the drifting smoke of the great manufacturing towns on its banks, one must be content with the county of Durham, a huge section of which is plainly visible. Turning towards the brown moorlands, the cultivation is exchanged for ridge beyond ridge of total desolation—a huge tract of land in this crowded England where the population for many square miles at a time consists of the inmates of a lonely farm or two in the circumscribed cultivated areas of the dales.

Eight or nine hundred years ago these valleys were choked up with forests. The Early British inhabitants were more inclined to the hill-tops than the hollows, if the innumerable indications of their settlements be any guide, and there is every reason for believing that many of the hollows in the folds of the heathery moorlands were rarely visited by man. Thus, the suggestion has been made that a few of the last representatives of now extinct monsters may have survived in these wild retreats, for how otherwise do we find persistent stories in these parts of Yorkshire, handed down we cannot tell how many centuries, of strange creatures described as 'worms'? At Loftus they show you the spot where a 'grisly worm' had its lair, and in many places there are traditions of strange long-bodied dragons who were slain by various valiant men.

On Easby Moor, a few miles to the south of Roseberry Topping, the tall column to the memory of Captain Cook stands like a lighthouse on this inland coastline. The lofty position it occupies among these brown and purply-green heights makes the monument visible over a great tract of the sailor's native Cleveland. The people who live in Marton, the village of his birthplace, can see the memorial of their hero's fame, and the country lads of to-day are constantly reminded of the success which attended the industry and perseverance of a humble Marton boy.

The cottage where James Cook was born in 1728 has gone, but the field in which it stood is called Cook's Garth. The shop at Staithes, generally spoken of as a 'huckster's,' where Cook was apprenticed as a boy, has also disappeared; but, unfortunately, that unpleasant story of his having taken a shilling from his master's till, when the attractions of the sea proved too much for him to resist, persistently clings to all accounts of his early life. There seems no evidence to convict him of this theft, but there are equally no facts by which to clear him. But if we put into the balance his subsequent term of employment at Whitby, the excellent character he gained when he went to sea, and Professor J.K. Laughton's statement that he left Staithes 'after some disagreement with his master,' there seems every reason to believe that the story is untrue.

I have seldom seen a more uninhabited and inhospitable-looking country than the broad extent of purple hills that stretch away to the south-west from Great Ayton and Kildale Moors. Walking from Guisborough to Kildale on a wild and stormy afternoon in October, I was totally alone for the whole distance when I had left behind me the baker's boy who was on his way to Hutton with a heavy basket of bread and cakes. Hutton, which is somewhat of a model village for the retainers attached to Hutton Hall, stands in a lovely hollow at the edge of the moors. The steep hills are richly clothed with sombre woods, and the peace and seclusion reigning there is in marked contrast to the bleak wastes above. When I climbed the steep road on that autumn afternoon, and, passing the zone of tall, withered bracken, reached the open moorland, I seemed to have come out merely to be the plaything of the elements; for the south-westerly gale, when it chose to do so, blew so fiercely that it was difficult to make any progress at all. Overhead was a dark roof composed of heavy masses of cloud, forming long parallel lines of grey right to the horizon. On each side of the rough, water-worn road the heather made a low wall, two or three feet high, and stretched right away to the horizon in every direction. In the lulls, between the fierce blasts, I could hear the trickle of the water in the rivulets deep down in the springy cushion of heather. A few nimble sheep would stare at me from a distance, and then disappear, or some grouse might hover over a piece of rising ground; but otherwise there were no signs of living creatures. Nearing Kildale, the road suddenly plunged downwards to a stream flowing through a green, cultivated valley, with a lonely farm on the further slope. There was a fir-wood above this, and as I passed over the hill, among the tall, bare stems, the clouds parted a little in the west, and let a flood of golden light into the wood. Instantly the gloom seemed to disappear, and beyond the dark shoulder of moorland, where the Cook monument appeared against the glory of the sunset, there seemed to reign an all-pervading peace, the wood being quite silent, for the wind had dropped.

The rough track through the trees descended hurriedly, and soon gave a wide view over Kildale. The valley was full of colour from the glowing west, and the steep hillsides opposite appeared lighter than the indigo clouds above, now slightly tinged with purple. The little village of Kildale nestled down below, its church half buried in yellow foliage.

The ruined Danby Castle can still be seen on the slope above the Esk, but the ancient Bow Bridge at Castleton, which was built at the end of the twelfth century, was barbarously and needlessly destroyed in 1873. A picture of the bridge has, fortunately, been preserved in Canon Atkinson's 'Forty Years in a Moorland Parish.' That book has been so widely read that it seems scarcely necessary to refer to it here, but without the help of the Vicar, who knew every inch of his wild parish, the Danby district must seem much less interesting.

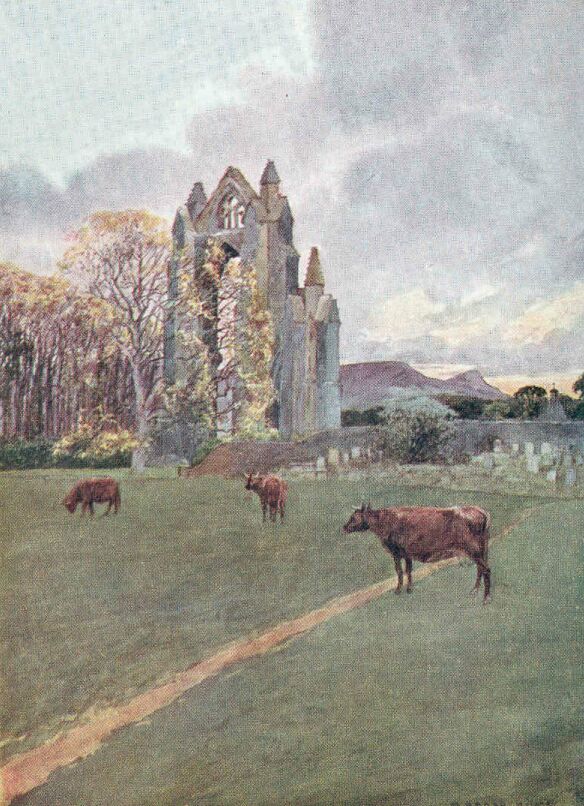

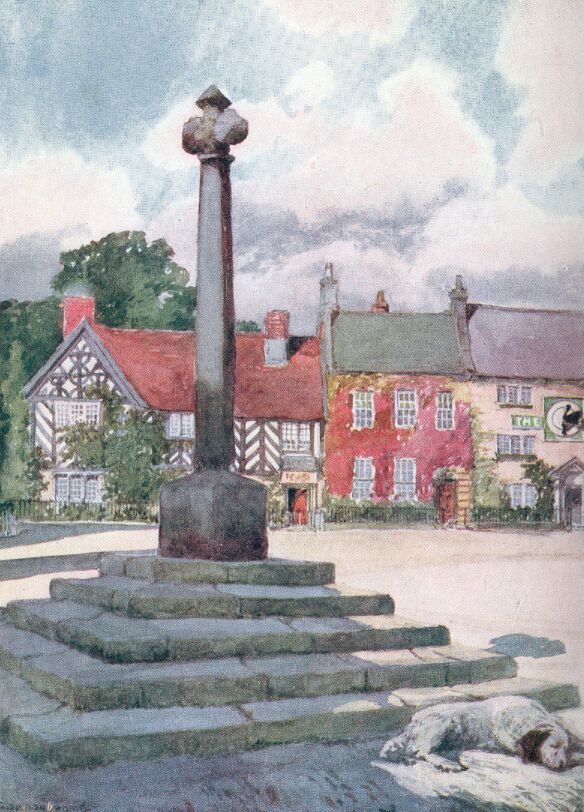

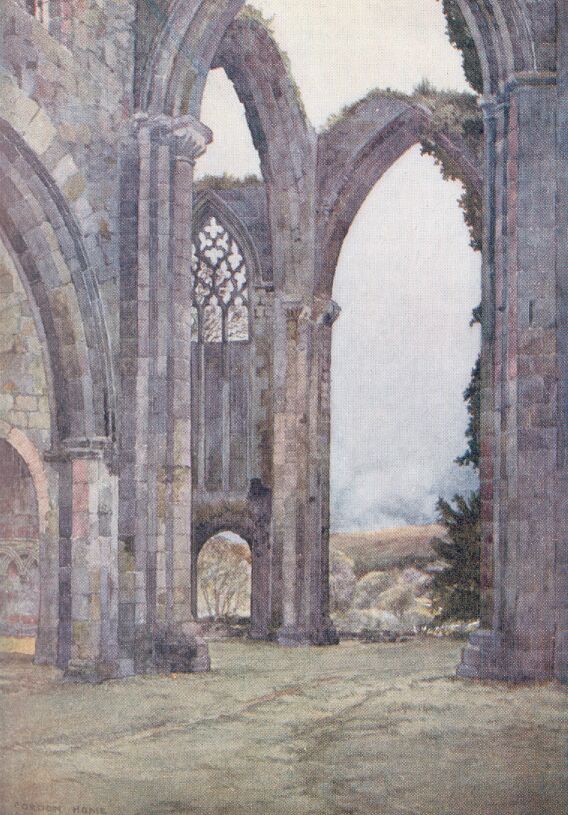

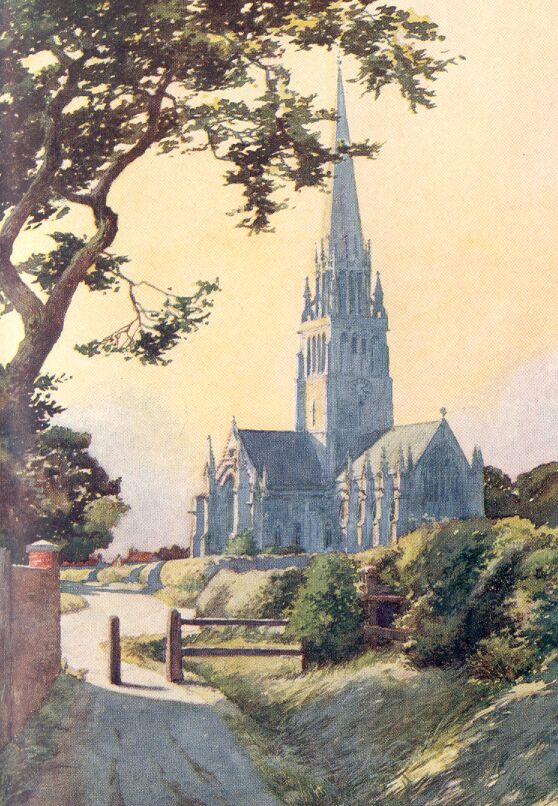

GUISBOROUGH AND THE SKELTON VALLEY

Although a mere fragment of the Augustinian Priory of Guisborough is standing to-day, it is sufficiently imposing to convey a powerful impression of the former size and magnificence of the monastic church. This fragment is the gracefully buttressed east-end of the choir, which rises from the level meadow-land to the east of the town. The stonework is now of a greenish-grey tone, but in the shadows there is generally a look of blue. Beyond the ruin and through the opening of the great east window, now bare of tracery, you see the purple moors, with the ever-formidable Roseberry Topping holding its head above the green woods and pastures.

The destruction of the priory took place most probably during the reign of Henry VIII., but there are no recorded facts to give the date of the spoiling of the stately buildings. The materials were probably sold to the highest bidder, for in the town of Guisborough there are scattered many fragments of richly-carved stone, and Ord, one of the historians of Cleveland, says: 'I have beheld with sorrow, and shame, and indignation, the richly ornamented columns and carved architraves of God's temple supporting the thatch of a pig-house.'